Project Gutenberg's True Stories of The Great War Volume III, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: True Stories of The Great War Volume III

Tales of Adventure-Heroic Deeds-Exploits told by the

Soldiers, Officers, Nurses, Diplomats, Eye Witnesses

Author: Various

Editor: Francis Trevelyan Miller

Release Date: May 31, 2015 [EBook #49099]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRUE STORIES OF THE GREAT WAR, VOL 3 ***

Produced by Brian Coe, Moti Ben-Ari and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRUE STORIES OF THE GREAT WAR

TALES OF ADVENTURE—HEROIC DEEDS—EXPLOITS

TOLD BY THE SOLDIERS, OFFICERS, NURSES,

DIPLOMATS, EYE-WITNESSES

Collected in Six Volumes

From Official and Authoritative Sources

(See Introductory to Volume I)

VOLUME III

Editor-in-Chief

FRANCIS TREVELYAN MILLER (Litt. D., LL.D.)

Editor of The Search-Light Library

1917

REVIEW OF REVIEWS COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1917, by

REVIEW OF REVIEWS COMPANY

The Board of Editors has selected for VOLUME III this group of stories told by Soldiers, Naval Officers, Nurses, Nuns, Refugees, Airmen, Spies, and other participants and eye-witnesses of the Great War. They have been collected from twenty-three of the most authentic sources in Europe and America, and include 143 personal adventures and episodes. The selections have been made according to the plan outlined in the Introductory to Volume I, for selecting from all sources the "Best Stories of the War." Full credit is given in every instance to the original source. All numerals are for the purpose of identifying the various episodes and do not relate to the chapters in the original volumes.—EDITORS.

VOLUME III—TWENTY-TWO STORY-TELLERS—143 EPISODES

| WHAT I FOUND OUT IN THE HOUSE OF A GERMAN PRINCE | 1 |

| STORIES OF INTIMATE TALKS WITH THE HOHENZOLLERNS | |

| Told by an English-American Governess | |

| (Permission of Frederick A. Stokes Company, of New York) | |

| "FROM CONVENT TO CONFLICT"—A VISION OF INFERNO | 18 |

| A NUN'S ACCOUNT OF THE INVASION OF BELGIUM | |

| Told by Sister Antonia, Convent des Filles de Marie | |

| (Permission of John Murphy Company, of Baltimore) | |

| "WAR LETTERS OF AN AMERICAN WOMAN"—IN BLEEDING FRANCE | 30 |

| Told by Marie Van Vorst, American Novelist | |

| (Permission of John Lane Company, London and New York) | |

| "A GERMAN DESERTER'S WAR EXPERIENCE"—HIS ESCAPE | 48 |

| "THE INSIDE STORY OF THE GERMAN ARMY" | |

| Told by—(Name Withheld) | |

| (Permission of B. W. Huebsch, of New York) | |

| "THE SOUL OF THE WAR"—TALES OF THE HEROIC FRENCH | 70 |

| REVELATIONS OF A WAR CORRESPONDENT | |

| Told by Philip Gibbs | |

| (Permission of Robert M. McBride and Company, New York) | |

| "TRENCHING AT GALLIPOLI"—IN THE LAND OF THE TURKS | 91 |

| ADVENTURES OF A NEWFOUNDLANDER | |

| Told by John Gallishaw | |

| (Permission of the Century Company, of New York) | |

| SCENES "IN A FRENCH HOSPITAL" | 106 |

| STORIES OF A NURSE | |

| Told by M. Eydoux-Demians | |

| (Permission of Duffield and Company, of New York) | |

| "FLYING FOR FRANCE"—HERO TALES OF BATTLES IN THE AIR | 126 |

| WITH THE AMERICAN ESCADRILLE AT VERDUN | |

| Told by James R. McConnell | |

| (Permission of Doubleday, Page and Company, of New York) | |

| THE LOG OF THE "MOEWE"—TALES OF THE HIGH SEAS | 166 |

| THE ADVENTURES OF A MODERN PIRATE | |

| Told by Count Dohna-Schlodien, her Commander | |

| (Permission of Wide-World Magazine) | |

| PRISONER'S VOYAGE ON GERMAN U-BOAT UNDER THE SEA | 196 |

| Told by—(Name Withheld by Request) | |

| (Permission of New York Times) | |

| THE DARKEST HOUR—FLEEING FROM THE BULGARIANS | 208 |

| OUR EXPERIENCES IN THE GREAT SERBIAN RETREAT | |

| Told by Alice and Claude Askew | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| A MAGYAR PALADIN—A RITTMEISTER OF THE HUSSARS | 222 |

| ALONG THE ROAD FROM POLAND TO BUDAPEST | |

| Told by Franz Molnar | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| OUR ESCAPE FROM GERMAN SOUTH-WEST AFRICA | 231 |

| Told by Corporal H. J. McElnea | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| WHAT AN AMERICAN WOMAN SAW ON THE SERBIAN FRONT | 261 |

| HOW I VIEWED A BATTLE FROM A PRECIPICE | |

| Told by Mrs. Charles H. Farnum of New York | |

| (Permission of New York Sun) | |

| "KAMERADS!"—CAPTURING HUNS IN THE ALPS WITHOUT | |

| A FIGHT | 270 |

| DIARY OF A LIEUTENANT OF ALPINE CHASSEURS | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| LIFE ON A FRENCH CRUISER IN WAR TIME | 282 |

| "LES VAGABONDS DE LA GUERRE" | |

| Told by René Milan | |

| (Permission of Current History) | |

| OVER THE TOP WITH THE AMERICANS IN THE FOREIGN LEGION | 293 |

| Told by Donald R. Thane | |

| (Permission of New York Herald) | |

| SECRET STORIES OF THE GERMAN SPY IN FRANCE | 306 |

| HOW SIXTY THOUSAND SPIES PREPARED FOR THE WAR | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| HOW STRONG MEN DIE—TALES OF THE WOUNDED | 329 |

| EXPERIENCES OF A SCOTTISH MINISTER | |

| Told by Rev. Lauchlan Maclean Watt | |

| (Permission of The Scotsman) | |

| THROUGH JAWS OF DEATH IN A SUNKEN SUBMARINE | 336 |

| Told by Emile Vedel in L'Illustration, Paris | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| ESCAPE OF THE RUSSIAN LEADER OF THE "TERRIBLE DIVISION" | 343 |

| TRUE STORY OF HOW GENERAL KORNILOFF ESCAPED | |

| ACROSS HUNGARY | |

| Told by Ivan Novikoff | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| THE AERIAL ATTACK ON RAVENNA | 358 |

| Told by Paoli Polettit in L'Illustrazione Italiana | |

| (Permission of Current History) |

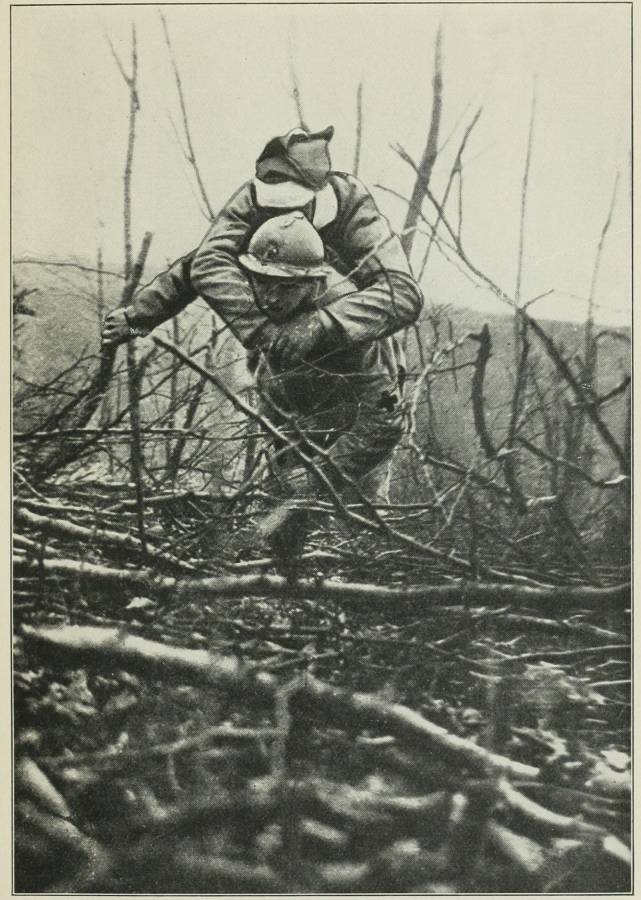

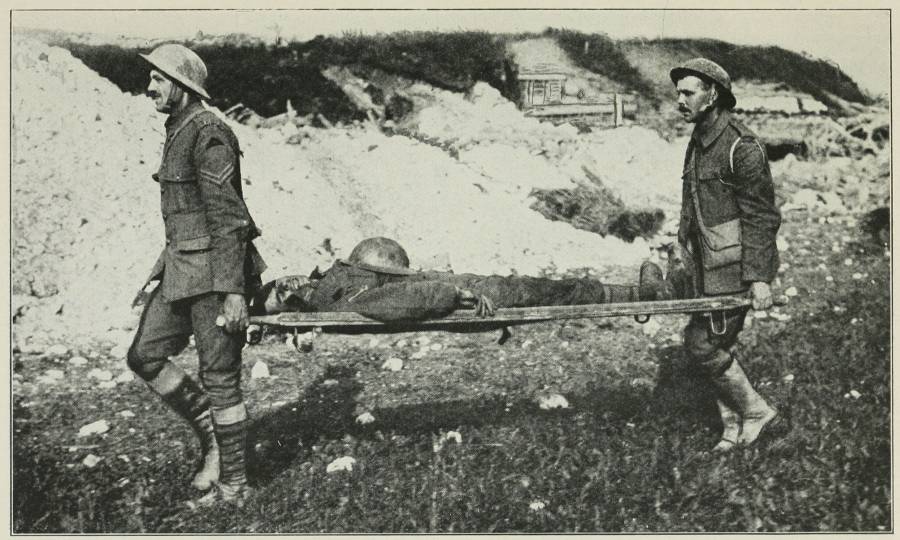

Underwood & Underwood.

BRINGING IN A WOUNDED COMRADE

Some of the Most Heroic Acts of the War Have Been Performed as Part of the "Day's Work" of the Ambulance Corps. This French Ambulance Attendant is Risking His Own Life During the French Offensive at Verdun to Carry a Fellow Poilu Back Through the Woods Razed by German Gun Fire.

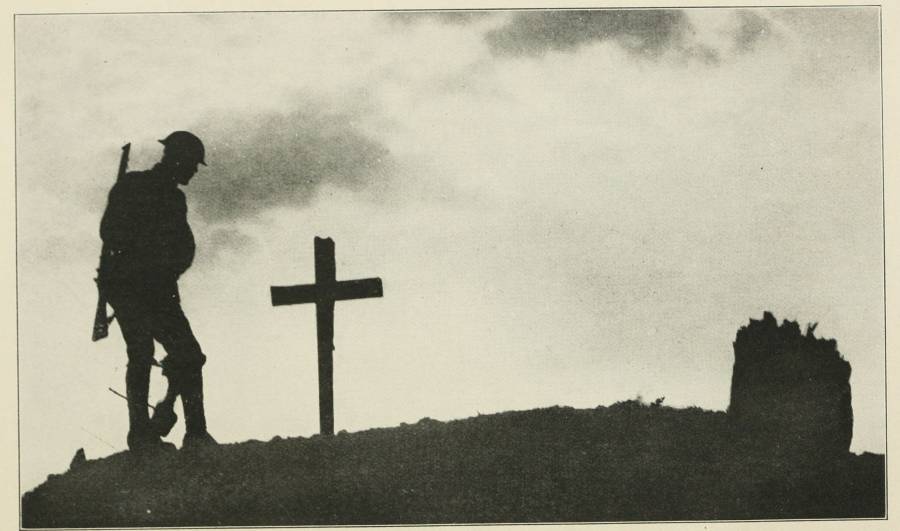

READING HOME NEWS BEFORE STARTING FOR THE TRENCHES

HE CHARGED WITH HIS BATTALION A FEW HOURS EARLIER

A FRIEND'S TURN YESTERDAY—HIS PERHAPS TODAY

Stories of Intimate Talks with the Hohenzollerns

Told by an English-American Governess

These true stories reveal for the first time the "inside workings" of the German Court. They are told by a woman who overheard conversations between the members of the House of Hohenzollern and the military and diplomatic castes. She was governess in a German princely house at the outbreak of the war, having secured her position through Prince Henry of Prussia, whom she met in Washington, during his visit to the United States. Her grandfather was an admiral in the United States Navy. She tells frankly of her conversations with the Kaiser, the Crown Prince, General von Bernhardi, the Krupps, Count Zeppelin, General von Kluck, Herr Dernburg, and important secret service people, who took her into their confidences. These revelations (which have been published by Frederick A. Stokes Co., of New York) are most absorbing reading. Here we are necessarily limited to a selection of but six anecdotes from the hundreds of entrancing stories in her book. The book is a valuable record of her experiences as governess of two young princes at their game, "destroying London before supper," to her final escape in disguise after the war began.

By a coincidence, it was five years ago, on the day of my internment in a German castle last August (1914), that I undertook to teach English and other things to the children of that castle's owner. During four of those years I did my duty to my three little charges as well as I knew how. For the rest of the time, up to two days before the declaration of war between France and Germany, my conduct may have been questionable: but that was because I put duty to my country ahead of duty to the family of a[2] German prince. They were my employers; they trusted me, and I am not sure whether I decided rightly or wrongly. All I know is that I would do the same if I had to live through the experience again....

As for the most important men who visited them, it is different. I owe those persons nothing, and see no reason for disguising their names. Most of them have now, of their own accord, thrown off their peace-masks, and revealed themselves as enemies of England, if not of humanity, outside German "kultur." What I have to tell will but show how long they have held their present sentiments....

[1] I—A CONVERSATION WITH THE KAISER

My two Princes and their cousin were having an English lesson with me in a summer-house close to their earthworks. It had been raining.

I was reading aloud a boys' book by George Henty which I had brought among others from England for that purpose, and stopping at exciting parts to get the children to criticize it in English. We were having an animated discussion, and all three were clamoring for me to "go on—go on!" when I heard footsteps crunching on the gravel path which led to the summer-house. I did not look up, because I thought it might be Lieutenant von X—— who was coming, and my charges were too much excited to pay attention. But presently I realized that the crunching had ceased, close to us. My back was half turned to the doorway, and before beginning to read again, I looked round rather impatiently.

Two gentlemen in uniform were standing in the path, one a step or two in advance of the other. Nobody who had seen any of the later photographs could have failed to recognize the foremost officer as the Kaiser, though the portraits were idealized. The face of the original was older, the nose heavier, and the figure shorter, stockier than I had expected. Nor had I been told about the scar high up on the left cheek. I was so taken by surprise that I lost my presence of mind. Jumping up, I dropped my book, and knocked over the light wicker chair which was supposed to be of British manufacture. I was so ashamed of my awkwardness—such a bad example to the children!—that I could have cried. To make matters worse the Emperor burst out laughing, a good-natured laugh, but embarrassing to me, as I was the object of his merriment.

"I have upset the United Kingdom and the United States of America!" his Imperial Majesty haw-hawed in good English, though in rather a harsh voice, making a gesture of the right hand toward the chair of alleged British make, and the fallen book with George Henty's name on its back, at the same time giving me one of the most direct looks I have ever had, full in the face. It seemed to challenge me, and I remembered having heard that a short cut to the Kaiser's favor was a smart repartee. The worst of it was that like a flash I thought of one which would be pat, if impertinent, but I dared not risk it.

Luckily my two Princes rushed past me to throw themselves upon their sovereign, and their cousin followed suit, more timidly. Perhaps she had discovered that his Imperial Majesty does not much care for little girls unless they are pretty.

The Kaiser was kind but short in his greeting of[4] the children, and did not seem to notice that they expected to be kissed. Probably he was not satisfied as to their state of health, as they had been sent out of an infected town, and he has never conquered his horror of contagious diseases. With his right hand (he seldom uses the left) on the dark head of the elder boy, he pivoted him round with rough playfulness. "Don't you see that Miss ——'s chair and book are on the floor?" inquired the "All Highest." "What is a gentleman's duty—I mean pleasure—when a lady drops anything?"

"To pick it up," replied the child, his face red as he hurried back into the summer-house and suited the action to the word.

"Very good, though late," said the Kaiser. Then, no doubt thinking that I had had time to recover myself, he turned to me, more quizzical than ever. "Perhaps according to present ideas in England I am old-fashioned? But I hope you are not English enough to be a suffragette, Miss ——?"

I recognized the great compliment of his knowing my name, as I am sure he expected. I had heard already that suffragettes were to the Emperor as red rags to a bull, and that he always brought up the subject with Englishwomen when he met them for the first time. I ventured to remark that to be English was not necessarily to be a suffragette.

He shook his finger at me like a schoolmaster, though he smiled.

"Ah, but you are not an Englishwoman, or you would not say that! All these modern Englishwomen are suffragettes. Well, we should show them what we think of them if they sent a deputation here. But while they confine themselves to their own soil we[5] can bless them. They are sowing good seed for us to reap."

I had no idea what his Majesty meant by the last sentences, though I could see that an innuendo was intended. His certainty that he was right about all modern Englishwomen was only what I had seen in visitors to Schloss ——, every one of whom, especially the Prussians, knew far more about English ideas and customs than the English knew about themselves. I had sometimes disputed their statements, though without effect, but I could not contradict the Emperor. All I could do was to wonder what he had meant by "sowing the good seed," and a glance he had thrown to his aide-de-camp (or "adjutant," as the officer might more Germanly be called), but it is only after these five years that I have perhaps guessed the riddle. The Kaiser must even then have begun to count on the weakening of England by its threatened "war of the sexes."

The Emperor proceeded to introduce his officer attendant, who was a Count von H——. He informed me that he and his suite had travelled all night in the royal train, to inspect the nearby garrison and breakfast with the officers. Having a short time to spare, he had arranged to motor up to Schloss —— and have a look at the children, in order that he might report on the Princes' health to their mother and father the next time they saw each other.

"No sign of the malady coming out in them?" he inquired. "And the youngest? He, too, is all right?"

On hearing that the baby was not as well as could be wished, he looked anxious, but cheered up when he heard that the feverishness was caused by cutting teeth.

"That is not contagious!" said he. "Though some of us might be glad to 'catch' a wisdom tooth."

When he made a "witticism," he laughed out aloud, opening his mouth, throwing back his head slightly with a little jerk, and looking one straight in the eyes to see if one had appreciated the fun of the saying. The more one laughed the better he seemed pleased, and the more lively he became, almost like a merry child. But when the subject was dismissed, and he began to think of something else, I noticed—not only on that day, but on others, later—that occasionally an odd, wandering, strained expression came into his eyes. For a moment he would appear older than his age; though when his mind was fixed upon himself, and he was "braced" by self-consciousness, he looked almost young and very vital, if fatter than his favorite photographs represented him.

That day at Schloss —— the Emperor did not stay with us longer than twenty minutes at most, but he managed to chat about many things in that time, the latter part of which was spent in talking with Lieutenant von X——, to find whom he sent the younger of my Princes.

I have heard that the Kaiser is always anxious as to the first impression he makes, even upon the most insignificant middle-class person; and having delivered himself of this harangue, he set to work to smooth me down before departing. He asked questions about myself, and the family (his friends) with whom I had lived in England. With his head thrust forward and wagging slightly, he mentioned several advantages which an English governess had over a German one; and then he blurted out, sharply and suddenly, that, if my little Princes' parents had listened[7] to his advice, they would have had an Englishwoman for their children two years sooner. "But the Princess —— is the most self-willed woman I know," he said. "You may think I am indiscreet! I am forever accused by newspapers of being indiscreet, because I speak what I think. But this is no secret. You will learn it for yourself if you are as intelligent as I suppose. She never was intended by nature to be a wife and mother, though she would be a charming person if she were neither. As it is she will do what she likes in spite of everything and everyone. There! I have said enough—or too much. Where is von X——?"

The Lieutenant was hovering in the background, ready for an auspicious moment: and the Emperor turned his attention to the governor of my elder Prince. It was not till he was ready to go that he had another word for me, and then it was only "Auf wiedersehen." He graciously put out his hand, palm down, for me to shake. I noticed how large it was in contrast with the left, which he kept out of the way. It was beautifully cared for, and there were more rings on it than an Englishman or American would wear, but it was not an attractive shape, and looked somehow unhealthy. As if in punishment to me for such a thought, the big hand gave mine a fearful grip. It was like the closing of a vise, and I could almost hear my bones crack. I wondered if the Emperor had cultivated this trick to show how strong he was; but I should have been glad to take his strength on faith.

I could not help wincing, though I tried not to let my face change. If it did, he appeared to take no notice. He had finished with me, after a military salute; and letting the children run by his side, he and his attendant,[8] with Lieutenant von X——, walked down the path....

II—STORY OF BERNHARDI AND THE KRUPPS

One of the most interesting things that happened to me in my first year was a visit (with the Princess, of course) to Villa Hügel, the house of Herr and Frau Krupp von Bohlen, in the Ruhr valley near Essen. Bertha Krupp, the "Cannon Queen" and richest German heiress in Germany, if not the world, had been married to the South German diplomat, Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, less than four years. She was only about twenty-four, but the coming of children had aged her as it does all German women apparently, and she had already ceased to look girlish. Her husband, who is sixteen or seventeen years senior to his wife, might have been no more than ten years older, to judge by their appearance when together. He put the name of Krupp in front of his own immediately after his marriage with the heiress, and few people add the "und Halbach" now, except officially....

While I was in the "Spatzenhaus" with the boys, Herr Krupp von Bohlen brought in these four gentlemen and another, to see the celebrated visitors' book kept there since Bertha and Barbara were children. General von Bernhardi had arrived the night previous, and this was my first sight of him, as well, of course, of Herr Eccius and Doctor Linden.

I was more interested in the last of the three, because I had listened while Frau Krupp von Bohlen repeated to the children a wonderful story about the intelligence of some fish in the Naples Aquarium; and all I knew then of General von Bernhardi was that he was considered a great soldier, and had been the first[9] officer to ride into Paris in 1871, or some tale of that sort. However, the minute I saw him I felt that here was a tremendous personality, and an intensely repellent one, a man to be reckoned with. I determined to ask a great many questions concerning him of the Countess, who knew everything about everybody, and did not object to telling what she knew with embellishments.

My name was politely mentioned by the host, and the visiting gentlemen all bowed to me. The only one who did so stiffly, as if he grudged bending his thick, short neck for my benefit, was General von Bernhardi. He gave me one sharp look from under his rather beetling eyebrows, and I wondered if he despised all women, or had merely taken a distaste to me.

"You are English?" he asked shortly, in German, his tone being that of a man accustomed to throw out commands as you might throw a battle-ax.

"She was born in Washington," said Herr Krupp von Bohlen, in his pleasant, cultivated voice. "Washington is the most interesting city of the United States, and holds pleasant memories for me. Miss ——'s grandfather was a distinguished American naval officer."

As he said this, he gave me a faint, rather humorous smile, which I interpreted as a warning or request not to try explaining my antecedents.

"Ach! That is better!" grunted the General. And I knew that, whatever might be his attitude toward women in general, Englishwomen were anyhow beyond the pale.

(Later I heard from the Countess that women were not much higher than the "four-footed animal kingdom" for Bernhardi; that he loudly contradicted his wife, even at hotel tables, when they traveled together;[10] that he always walked ahead of her in the street, and pushed past her or even other ladies, if strangers to him, in order to go first through a doorway.)

The General condescended to glance at me, and I thought again that he was the most ruthless, brutal-looking man I had ever met, the very type of militarism in flesh and blood—especially blood.

"You are a friend of the English?" he inquired.

I dared to stand up for England by answering that I thought her the greatest country in the world.

"That is nonsense," was his comment. I shall never forget it, or the cutting way in which it was spoken.

The Prince, though knowing me to be English (which Bernhardi, to do him justice, did not), backed the General up, explaining for my benefit as well as the children's that England might once have been nominally the most powerful nation, owing to her talent for grabbing possessions all over the world, and the cleverness of her diplomacy. But, he said, that was different now, under the Liberal Government. England was going down exactly as Rome had gone down, and the knell of her greatness was sounding already. Not one of her colonies would stand by her when her day of trouble should come, and most of them would go against her.

"You have only to read their own newspapers," said General Bernhardi, "to see that the English know they are degenerating fast. But the hand of Fate is on them. They are asleep, and they will wake up with a rude shock only when it is too late."

III—STORY OF THE CROWN PRINCE AND THE CROWN PRINCESS

Some quite innocent tales were told by the tattlers, of the Crown Princess. One was, that she had determined from the moment of her engagement to his Imperial Highness, to be the most beautiful and best dressed royal lady in Europe, as he strongly desired her to be, and that it almost broke her heart when she began to realize that being the mother of one baby after another was enlarging her slender waist. She was supposed to have had a wax model of herself made, soon after the birth of her first boy: face, hair, and figure all resembling her own as faithfully as possible. According to the story, she had every new fashion of hairdressing tried on this model, before deciding to use it herself, and would have milliners fit it with hats, rather than choose one to suit her own style merely from seeing it in the mirror. Gowns were shown to her in the same way when they arrived from Paris or Vienna, said the gossip who told me the tale, and the first time the measurements which fitted the figurine proved too small for the Princess's waist, there were tears.[2]

I did not fall in love with noisy Berlin, though Unter den Linden is so fine and imposing, with all its beautiful shops and trees. The city was so neat and square, so stolid and self-respecting that the capital of Prussia made me think of the Prussian character as I soon began to judge it. Potsdam I found more interesting because it is old and historic. We spent a good deal of time in both places, and I used often to see the Emperor motoring in a yellow car with a very small Prussian royal standard on it to show who was the owner. The Crown Prince was always dashing about, too, generally driving himself, very recklessly, with a cigarette in his mouth, and looking about here and there, everywhere except where he was going. He had a black imp for a "mascot" on his automobile, a thing that waved its arms in a way to frighten horses, though it never seemed to do so. And sometimes the car would be full of ladies and children and several quite large dogs that walked over their owners and tried to jump out. The crowds seemed to like him, and the Crown Princess, whom they called "the sunshine of Berlin," even more. She was always very gracious, bowing and smiling, while the Crown Prince looked extremely bored. Still, if he had not been hailed with enthusiasm, I am sure he would have been vexed. Sometimes he would appear at a window of the palace, perhaps with one of the royal children in his arms, pretending not to notice the people outside gazing at him. But I thought he looked self-conscious, as if he were doing it all for effect....

What I had heard from the Countess about the Crown Prince going to India and Egypt in the character of a "glorified spy" (even though I doubted the assertion) and the intimate talk of our Prince's "influence" in the Secret Service department, made me think more about spies and spying in a few months, than I had ever thought in my whole life. I began to look about for spies, and wonder if any of the much traveled, cultured people I met were engaged in spying with some of the highest in the land virtually at their head. The last person I should have connected[13] with the profession of spying, however, was Herr Steinhauer. Even now I cannot be sure that he and the famous "master spy" of whom I have heard so much since I came back to England, are one and the same; but everything goes to prove that they are....

IV—STORY OF A VISIT FROM COUNT ZEPPELIN

Once in Berlin, Count Zeppelin came, after having taken the Crown Prince, and my little Princes' father as well as one or two of their army friends, for a flight in his newest airship. Our Prince came back very enthusiastic after his trip, and wanted his elder son to go, but the Princess would not hear of this, and Count Zeppelin backed her up. He said that he did not know enough about children's nerves to risk an experiment, though he believed such boys as ours would stand it well. He told them, when they both begged to go, that they must content themselves with the "game" for a few years, and asked a good many questions of Lieutenant von X—— (who was present by request) as to how the little players got on with it. When he was talking of ordinary things, his face looked good-natured, even benevolent, with his rather scanty white hair and comfortable baldness. I thought, with a false beard, he would have exactly the right figure and face for Santa Claus; but as he listened to Lieutenant von X——'s account of how he taught the Princes to "play the game," and examined some of the toy buildings (so often powdered white with "bombs" that they could no longer be brushed completely clean), his face hardened, looking very stern and very old, his bright eyes almost hiding between wrinkled lids.

The Count took the elder boy between his knees, and catechised him as to some of the rules. The little boy was shy at first, but soon plucked up courage, and answered in a brisk and warlike way.

"This is a born soldier," said the airship inventor, laying his hand on the child's hair. "By the time he is ready for sky battles, we shall have something colossal to give him; but in the meantime, please Heaven, we shall make very good use of what we have got."...

V—STORY OF GENERAL VON KLUCK—"THE OLD DARE-DEVIL"

Among other distinguished men who came to see my Princes and their plays, was General von Kluck—another one of those "great dome heads!" To me, it seemed the best part of his personality, and certainly the development was far superior to what I had named the "German officer head," a crude, unfinished type of head, which gives the impression that the skull has hardened before the brain had time to finish growing. General von Kluck did not talk at all to me, or appear to take any interest in the toy soldiers' battle. He had the air of being absent-minded and thinking deeply of something far away, in space. I heard him say that "they" wanted him to go to France to look at it. Who "they" were, I do not know, or what "it" was that they wished General von Kluck to see. But I knew that nearly a year after that visit the children had a present of a fancy red velvet box of chocolate. The Princess herself brought it into the schoolroom (we seldom had a lesson that was not interrupted in some way or other), and as the covering had already been removed, I do not know if the box had been sent from a distance or had come by hand. The Princess[15] showed the boys General von Kluck's visiting card, and the writing on it, which said, "French chocolate from France, for two brave young German soldiers."

Later that day the Prince came and asked to see the box "from old von Kluck," which by that time was half empty. He looked at the card, and laughed. "The old dare-devil!" he chuckled. Then he said that, as we had eaten so much in such a short time it showed that French chocolate was good.

I seldom or never had any real conversation with the Prince, and it was not my place to ask questions; but I wondered why General von Kluck was an "old dare-devil" to go to France, and why the Prince seemed so pleased and amused about it. Also I remembered what I had heard the General say some months before, about France. I thought that there must be a mystery about it, either official, or something to do with a lady, perhaps a Frenchwoman. I know no more now than I knew then; but I have heard it said since I came back to England, by a Frenchman, that General von Kluck is supposed to have visited France incognito, to look at some quarries near Soissons, which Germans bought and secretly made ready to use as trenches, beginning their work a year before the war broke out.

VI—STORY OF THE CONFESSION OF LIEUTENANT VON X——

I often asked Lieutenant von X—— what the German army thought about the future of Germany, and I do not think he suspected in the least that I had any motive except "intelligent interest." He had come to look upon me as a family institution, and without telling lies in so many words, I allowed him to believe[16] that I felt Germany's vast superiority over the rest of the world. It is a simple thing for any woman to make any German man believe this. The only difficult thing for him to understand is that a creature can be benighted enough to have a contrary opinion.

Lieutenant von X—— admitted that the German army as well as navy prayed for "The Day." He thought that Germany could "walk through France," and she, being far superior to Russia in every way, could not help but win in a war against that power, even without the help of Austria. He seemed to feel contempt for Austria and everything Austrian compared with what was German, but he said "she can be useful to us." As for England, she might be a tougher job, but it would "have to come," and with the improved Zeppelins (which England had been a "stupid-head" not to copy as well as she could) and the Krupp secrets, there was no doubt who would come out on top: Germany, the one power on earth who deserved by her gloriousness to be over all others. America, too, eventually must become Germanized, as Lieutenant von X—— believed she was already well on the way to be, with her growing German population, immense German financial interests, and influential newspapers. The plans for American conquest were already mapped out by the German War Office, who never left anything to chance. He said that this was no secret, or he would not mention it. There was once a hope that Germany and England might make a combination against the United States, but that had been abandoned, he said. Once I should have taken this for a joke, and also the expectation that when France was conquered (with Belgium thrown in as a matter of course) Antwerp and Dunkirk and Calais would all be German, becoming the[17] strongest military ports in the world; but I had learned better now. I knew that Lieutenant von X——, who seldom originated any ideas of his own, was simply repeating to me the sort of talk he heard among his brother officers....

(The English-American Governess from this point relates a most remarkable story, every word of which is vouched for as the truth. She tells how Von Hindenburg, the Crown Prince, and other notables met in secret sessions at the palace where she was residing; about their relations with Prince Mohammed Ali and Enver Bey, the Envoy from Turkey; the intrigues in the days before the outbreak of the war; the scenes in the royal households when war was declared; and how she escaped at midnight, September 15, 1914. It is a revelation that gives one a clearer insight into the causes of the Great War and how the Hohenzollerns had planned for many years to enter upon a conquest of Europe and America.—Editor.)

[1] All numerals throughout this volume relate to the stories herein told—not to the chapters in the original books.

[2] The Governess here tells of an interesting little flirtation between the Crown Princess and an Englishman because the Crown Prince "had flirted furiously with several athletic but beautiful ladies at a Winter Sports place in the Engadine."

Or, A Nun's Account of the Invasion of Belgium

By Sister Antonia, Convent des Filles de Marie, Willebroeck, Province of Antwerp, Belgium

This is the appeal of a nun, who in the fullness of her heart tells the American people of the noble efforts of her Sisters to bring solace and comfort to agonized Belgium. Sisters Mary Antonia and Mary Cecilia were sent to the United States with the approval of Cardinal Mercier, Archbishop of Malines, with the following credentials: "The Superior of the Convent of the Daughters of Mary, Willebroeck, Provence of Antwerp, Belgium, state by this present (letter) that the Sisters Mary Antonia and Mary Cecilia are sent to the United States in order to examine if there are means of establishing a colony (mission) of the Daughters of Mary there; she gives to Sister M. Antonia the power to act in her name as to taking the measures necessary to this effect." Sister Antonia tells her noble story in a little volume (published by John Murphy Company, Baltimore. Copyright, 1916) with this introduction: "The hope is indulged that the harrowing scenes witnessed by the author in Belgium, after the German invasion in 1914, may induce her own countrymen and women to more fully appreciate the blessings of peace. The events narrated are set forth as actually occurring, and—'with malice to none, with charity for all.' Any profits derived from its favorable reception by the reading public or the charitably inclined are to be devoted to the reconstruction and repair of our school and convent, damaged during the engagement at the Fortress of Willebroeck, or for the establishment of a sewing school, with a lace making department, for young women in America or England, as our Reverend Superiors may decide." The editors take pleasure in commending this book and in extending their appreciation to the publishers for their courtesy in allowing these selections.

I—STORY OF THE FATEFUL DAY IN THE CONVENT

A merry group of Convent girls, in charge of Sister guardian, was seated in the shade of a huge old pear tree, discussing the joys and expectations of the approaching summer vacation. High are the walls enclosing this ancient cloister, and many are the gay young hearts protected and developed within its shady precincts.

Bright are the faces and happy the hearts of more than one hundred young girls on this midsummer day in the memorable year 1914....

July's sun sank gently away on the western horizon, and its last rays lit up the ripening fruit, the plants and flowers in the garden. It seemed to linger for a last farewell to the groups of merry children who, unconscious of their fast-approaching woe, were cheerfully singing Belgium's well-known national song, "The Proud Flemish Lion."

In a few moments the "Golden Gate" closed on a field of purple haze, shutting out that blessed glimpse of heaven, while the black shroud of the most dismal night in history darkened the sky of that hapless nation.

The Sisters were together in the evening recreation of that fateful day, when word was received that King Albert of Belgium, in order to fulfill his obligations of neutrality, had refused the Kaiser's army access to his territory to attack the French. Had a thunderbolt fallen from a clear sky, or an earthquake shaken the ground under foot, it would scarcely have surprised or terrorized the people more than did the Kaiser's declaration of war against this free and happy little kingdom....

One Sunday morning, about the middle of August, an unusual tumult was heard on the street. The door bell was loudly rung, and a messenger admitted with news that the officers of the Belgian War Department had commanded everything within firing range of the fortress to be cleared away at once. For some time previous the soldiers had been busy cutting down the groves and all the trees in the immediate vicinity of the fortress. The poor people were given just three hours to get away with bag and baggage.

This was a terrible misfortune for about six hundred families, whose dwellings, being located within the limits prescribed, had to be leveled to the ground. Even the tombstones in the cemetery, together with all the crops, trees, haystacks, barns and everything within range of the gaping mouths of the cannon, had to be laid flat or taken away.

No wonder that the people raced to and fro that hot Sunday morning, carrying bundles, dragging wagons with household furniture and fixtures; wheeling trunks, clothing, stoves, pictures, bedding and every article that could be taken up and carried away. Tears and perspiration rolled over the cheeks of men and women, whose faces glowed from the heat and intense excitement....

II—STORY OF THE SOLDIERS AT LIEGE

In the meantime a most terrible battle was taking place at the fortification of Liege. Was ever attack so strong or resistance more determined? Belgian officers said, "The enemy were twenty to one against us; but, being obliged to face the terrible fires of the fortress, their ranks were cut down in about the same manner as wheat is cut off by the reaper." "So great[21] was the number of the Germans that they seemed to spring up out of the ground." "They crawled ahead on hands and feet, and at a given signal sprang erect and fired, and then again prostrated themselves. Thus they advanced, avoiding as much as possible the heavy fires in front." Another Belgian officer at the fortress during the battle said: "It resembled a storm of fiery hailstones from a cloud of smoke, in an atmosphere suffocating with heat and the smell of powder."

Eye-witnesses relate that heaps of slain, yards high, were found on the battlefield, while columns of lifeless bodies were observed in a standing position, there being no place for the dead to fall.

A story was told by one of the Belgian officers of a German soldier who, when wounded by a Belgian in a hand-to-hand combat, took out a coin and presented it. The Belgian, surprised, exclaimed "Zijt gij zot?" (Are you crazy?) "Do you not know that I've broken your arm?" "Yes," said the German, "This is to show my gratitude for the favor you've rendered me, since it gives me the opportunity of leaving the battlefield."

Much was said about the valor of the soldiers on both sides during the siege of Liege. The Germans were obliged to advance in the face of destructive fires. If one should retreat, he would be pierced by the bayonet of the soldier behind him....

While facing death in this first great battle at the fortress of Liege, one of the soldiers began to sing the well-known national hymn, "The Proud Flemish Lion." Immediately the strains were taken up by the whole regiment, and thus singing, they advanced until hundreds of them fell in that awful conflict.

In the heaviest of the fray we were told that King Albert had placed himself in the lines with his soldiers. He did not desire to be called king, but comrade.[22] His military dress was distinguished from the others by only a small mark on one of the sleeves. He attended to the correspondence for his soldiers and was regarded by them as a friend and father, under whose guidance they were ready to fight and die.

When the siege was over he visited the wounded in many of the hospitals and addressed each soldier in person....

After the fall of Liege and Namur, the destruction of Louvain and a number of noted cities, towns and villages, our minds were concerned with that awe-inspiring event—the advance of the enemy to Brussels.

Well do we remember that beautiful summer evening, when our prayers and evening meditation in the chapel were disturbed for about an hour by the continuous whirl of automobiles passing the Convent. We were told that evening that it was the departure of the legislative body from Brussels to Antwerp, with the archives and treasures of the Government.

Our hearts seemed to grow cold and leaden within us as we sat there hoping, praying, fearing, yet instinctively feeling the doom so rapidly approaching.

One gloomy, rainy day, word came that over two thousand soldiers of the Civil Guard had lowered their weapons at the approach of the enemy and quietly surrendered the City of Brussels, Belgium's beautiful capital. To have fought without fortifications against such superior forces as the Germans possessed would have been a useless sacrifice of life.

III—STORY OF THE PRIESTS, DOCTORS AND RED CROSS NURSES

One afternoon in the middle of August a large, heavy wagon was drawn into the yard. It bore the[23] flag of the Red Cross on top, and on the side in great white letters the words "Military Hospital."

In a few minutes a fleshy little gentleman, who at once distinguished himself as the "Chef" (chief), and a number of other gentlemen, about thirty-five in all, wearing white bands with red crosses on their arms, and long white linen coats over their uniforms, such as bakers sometimes wear, were seen hurrying to and fro, unpacking and carrying their various instruments and utensils to the operating room.

A military chaplain and four or more doctors accompanied the group. All except the chaplain were dressed in uniform. Several young ladies of Willebroeck, former members of our Boarding-school, dressed in white and wearing the head-dress and arm-band of the Red Cross, came next day and graciously presented themselves to aid in taking care of the wounded.

Coffins were provided by our village for the soldiers who died in our hospital....

The condition of the poor maimed soldiers (as they were brought into the convent) was sad to behold. One man, we were told by the Red Cross nurses, had twenty bullets in his body; another was pierced through the lung by a bayonet; one, aged twenty, lost an arm to the shoulder; one had only one or two fingers left on the hand; one was crazed by a bullet which touched the brain; another was shot through the mouth, the bullet lodging in the back of the throat. His case was especially distressing, his the most intense suffering of all. He lived for a week without eating, drinking or speaking.

Three wounded Germans were brought in, being picked up on the battlefield by members of our division of the Red Cross. They seemed greatly distressed[24] and afraid, positively refusing to touch food or drink of which the Sisters or nurses did not first partake.

One day we were called upon to witness a most sorrowful sight. A small farmer's wagon drove up to the gate, bearing the lifeless bodies of two children, a girl aged eight and her brother, aged fourteen. The mother and a smaller child were also in the wagon. The mother related that they were taking flight as refugees. Seeing the enemy, they hastened to retreat, and were fired at by the soldiers. The children, who were in the back part of the wagon, were struck and wounded in a most frightful manner. The little girl's face was nearly all torn off, and the back of the boy's head had been shattered.

At the approach of Belgian soldiers, who fired at the enemy, the mother was enabled to pick up the lifeless bodies of her children, put them into the wagon and drive with them to our hospital, which was the nearest post.

A little after four o'clock one afternoon, shortly before the departure of the first division of the Red Cross, our attention was attracted by the heavy and continuous tread of cavalry and soldiers passing along the street. It was the Belgian army returning from a long and tiresome march.

Here was found a different kind of suffering from that which was ministered to in the hospital. Hunger and fatigue were stamped upon the countenance of each of these men, who, about a month before were industrious citizens at their daily occupations.

There were in the ranks priests, in their long black cassocks, wearing the arm-band of the Red Cross, who, as volunteer chaplains, had joined the army and were ever at the service of the soldiers on the march, and[25] even on the battlefield. We were informed that priests, and those preparing for the priesthood, were not obliged to serve in the army in time of peace; but, in case of war, they may be called upon to serve as military chaplains. When the present war broke out, hundreds of them joined as volunteers, marching in the ranks with the soldiers and undergoing their sufferings and hardships.

Many doctors rode along in motor cars. They were distinguished by a special dark-colored uniform, with a red collar and gilded trimmings. They also wore the arm-band of the Red Cross. Officers on horseback led each division of the army. The faces of all were disfigured with sweat and dust, while dust in abundance covered shoes and clothing. Some were staggering along, unable to walk straight, owing to the hard shoes and blistered feet. Hollow-cheeked, and with eyes which seemed to protrude from their sockets, they passed along, piteously imploring a morsel of bread.

Fortunately, the abundant supply of bread in the Convent had just been increased by the addition of forty of those immense loaves found only in Belgium. All of this was hastily cut, buttered and, with baskets full of pears, dealt out, piece by piece, to the passing soldiers, until, finally, only a small portion remained over for the supper of the wounded remaining in the hospital....

Before the command was given to enter the schools, we saw soldiers, among whom were also priests, lying on the ground on the opposite side of the street, even as horses which, having run a great distance, fall down from sheer exhaustion. Some of these, we learned afterwards, did not have their shoes off in nearly three weeks. The socks, hard and worn out,[26] were in some cases stamped into the blistered feet in such a manner as to cause excruciating pain. In some cases the feet were so painful and swollen that the patients had to be carried in on stretchers. In the meantime, several ambulance wagons had stopped at the school gate, and numerous wounded were carried in.

We retired at a late hour one night amid the incessant booming of cannon. Scarcely were our eyes closed when some one passed in the dormitory and knocked at each door. "Ave Maria," was the quiet greeting. "Deo Gratias," the response. "What is it?" was asked. "The Germans have entered and are crossing the bridge," was the reply.

With beating heart and trembling limbs, each sprang up and was dressed in a few minutes. In a state of great excitement, all stood in the hall ready to receive orders from the Superior, who had gone downstairs to make inquiries about the situation....

The crackling of shells, the heavy cannonade from the fortress and field cannon, and the occasional proximity of those hostile aeroplanes, together with the reports of atrocities and destruction taking place around us, were fearsome in the extreme.

In striking contrast to the noise and commotion on all sides, was the calm tranquility which reigned in the chapel. The Sacred Heart stretched forth that same Fatherly hand which assisted the apostle sinking on the Sea of Galilee. The altar was still and solitary, but the little red light flickered in the sanctuary lamp and told of Him whose word alone stilled the winds and calmed the angry waves....

IV—STORY OF THE HEROIC REFUGEES

Sorrowful scenes were witnessed along the streets. Our attention and sympathies were particularly attracted to the flight of the refugees.

For hours and days and weeks the doleful procession passed along the streets; a living stream made up of all ranks and classes of society. Here were seen the poor old farmer's household, whose sons had gone to the front; and young married women, with small children in their arms or by their sides, whose husbands had to don the soldier's uniform and go to the war. The sick, the old and the feeble were taken from their beds of suffering and, with shawls or blankets thrown over their shoulders, placed in carts or wagons and carried away, perhaps, to perish by the roadside. We have seen cripples and small children hurriedly driven along the street in wheelbarrows.

Packages carried on their arms, on their backs, or in little carts were about all that the poor people could take....

It was most pitiful to see these poor people, whose only object was to get away as far as possible from the scenes of conflict. Some carried small loaves of bread; others had a little hay or straw in their wagons; some led a cow or two; others two or three pigs. In some of the carts we recognized faces of our former pupils, who only one short month before were longing for the pleasant vacation days. Their fathers or brothers were in the army, and their homes forsaken. Some children had lost their parents and were crying piteously.

When the Sisters left the parish church, where they daily took part in the public devotions for peace, they[28] were besieged by hundreds of these poor, half-frantic refugees, beseeching shelter over night in the church or schools, which were already full to overflowing. The days were warm and pleasant, but the nights were very chilly and sometimes rainy. Where would those poor people go and what could they do without food or shelter for all those little children? The friendly stars looked down from the realms above upon thousands who lay along the roadside, while others crowded the barns and country schools, or made rude tent-like shelters in the bed of the new canal.

The Sisters, wholly absorbed in their work for the wounded, and relying on the word of the Belgian officers, that timely warning would be given as to the necessity of departure, had as yet no idea of joining the throngs of refugees who continuously filed through the main streets.

The shocks of the cannonade from the fortress caused the buildings to tremble on their foundations, while the ground under foot seemed agitated as by an earthquake. A large number of wounded soldiers had been brought in the night before, and three or four lay dead in the mortuary.

Our Sisters and servant maids, as also the generous women refugees of Willebroeck, continued their sickening task in the laundry. In wooden shoes they stood at those large cement tubs while suds and blood-dyed water streamed over the stone floor.

Night closed in again, but brought neither rest nor consolation. Fearing to retire, some of the Sisters remained in the chapel, while others spent the tedious hours of that dreary night in the refectory or adjoining rooms, and kept busy making surgical dressings for the wounded, of whom a larger number than usual had been brought into the hospital.

At intervals during the night the cannonade was heard, while the searchlights of the fortress penetrated the clouds on the lookout for the murderous Zeppelins. Morning came at last, with an increase of work and anguish. The enemy, with their usual determination, were trying to force their way through to Antwerp, while the Belgians were equally determined to prevent them, or to at least check their progress.

An officer called for the Reverend Superior and said in an excited manner, "Weg van hier, aanstonds! Geen tijd te verliezen." (Away from here at once! No time to be lost.) This message flew from one to another, even to the terror-stricken hearts of the numerous wounded.

Impossible to describe the scenes which followed. In a few minutes a long line of motor cars came whirling up to the gate to take away the wounded who, some of them in an almost dying condition, were being dragged out of their beds, dressed and hurriedly carried away to Antwerp, or to another place of refuge. One can never forget the look of anguish on some of their faces, while others seemed totally indifferent to all that was taking place around them....

(Sister Antonia here tells about the flight of the nuns with the refugees to Antwerp and the sea; the exodus to England and Holland; and finally her own voyage to America.—Editor.)

Experiences in the Siege of Paris

By Marie Van Vorst, Distinguished American Novelist Residing in Paris

These letters present a singularly vivid chronicle of an American woman's experiences during the Great War. She was living in Paris, but brought her mother to London for safety. Here she went through a course of Red Cross lectures and returned to become a nurse at the American Ambulance in the Pasteur Institute in Neuilly, then under the control of Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt. Her brilliant intellect and sympathizing heart are brought out in her letters to friends in America. Her whole soul is in the cause of the Allies and in her letters she tells many beautiful stories of her experiences in Paris, London, Nice and Rome. To read her impressions as she wrote them down for her friends is to recapture the thrill and the uplift, the sorrows and the hopes, the high resolves and unshakable purpose of those that will live forever in history. Several letters are reprinted here by permission of her publisher, John Lane Company, London and New York.

I—STORY OF ROBERT LE ROUX

To Miss Anna Lusk, New York.

Paris, Nov. 7th, 1914.

Dearest Anna:

In the contemplation of the great griefs of those who have lost their own, of those who have given their all; in the contemplation of the bravest country in the world—Belgium—ravaged from frontier to frontier, laid barren and waste, smoked, ruined, devastated and scarred by wholesale massacre of civilian women and children, our[31] hearts have been crushed. Our souls have been appalled by the burdens of others, and by the future problems of Belgium, not to speak of one quarter of France. Much of the north has been wiped out, and the stories of individual suffering and insults too terrible to dwell upon, you will say.

One of my old clerks in the Bon Marché has had his little nephew come back to him from Germany—a peaceful young middle-class man pursuing his studies in a German town—with both his hands cut off!

The other day in the Gare du Nord, waiting for a train, there was a stunning Belgian officer—not a private—he was a captain in one of the crack regiments. His excitement was terrible, he was almost beside himself with anguish and with anger. In a little village he had seen one woman violated by seven Germans in the presence of her husband; then the husband shot, the woman shot and her little baby cut in four pieces on a butcher's block. You can hardly call this the common course of war. He was a Belgian gentleman, and I should consider this a document of truth.

But there are so many that I cannot prolong, and will not—what is the use? Every now and then a people needs to be wiped off the face of the earth, or a contingent blotted out that a newer and finer civilization shall prevail. Certainly this is the case with Germany. They say here that the Emperor and Crown Prince will be tried by law and sentenced to death as common criminals, the Emperor as a murderer and the Crown Prince as a robber, for his goods trains were stacked with booty and loot. Think of it, a Prince! Everywhere the Germans pass they leave their filthy insults behind them, in the beautiful châteaux and in the delicate rooms of the French women—the indications of their passing, not deeds of noble heroism that can be told of foes as well[32] as of friends, but filthy souvenirs of the passing of creatures for whom the word "barbarism" is too mild!

Here is a more spiritual picture.

Robert Le Roux, jun., was buried yesterday. You will have read in the previous pages here the story of his exploits on the battlefield—the closing of his young life in bravely leading his troops up the hill to certain death. And yesterday I went to St. Germain to his funeral.

The last time I had seen young Robert he was a little boy, in short breeches and socks. His mother brought him to Versailles and he played with us in the garden there—a strong, splendid-looking young French boy. Now I was going to his funeral, and he was engaged to be married, with all his hopes before him, and on this same train was his little fiancée, in her long crêpe veil, broken-hearted; and his little sister, and the father, who had followed his son's campaign with such ardor and such tenderness; and his uncle, Dr. D., of whom I spoke previously—the splendid sergeant-major whose only son had just been killed by the enemy. A train of sorrow!—and only one of so many, so many.

The church at St. Germain is simple and very old. The doors were all hung with heavy snow-white cloth, and before the door stood the funeral car drawn by white horses, all in white, and instead of melancholy hearse plumes there were bunches of flags, and over all hung the November mist enveloping, softening, and there was a big company of Cuirassiers guarding the road.

We went in, and the church was crowded from the nave to the doors, and all the nave and the little chapels were blazing with the lily lights of the candles. It was all so white and so pure, so effulgent, so starry. There was an uplift about it, an élan; tragic as it all was, there was ever that feeling of beyond, beyond!

Before the altar lay the young man's coffin—that leaden coffin that had stood by his father in the fortress of Toul for three weeks, waiting for the dead. It was completely covered by the French flag, and the candles burnt around it.

Beside me was a woman with her husband. She wept so bitterly through the whole service that my heart was just wrung for her, and her husband's face, as his red-lidded eyes stared out in the misty church, was one of the most tragic things I ever saw. I wept, of course, and I have not cried very much since the war broke out, but her grief was too much for me. Finally she turned to me and said: "Madame, I only had one son, he was so charming, so good; he has fallen before the enemy, and I don't know where he is buried!" Just think of it! There she was, at the funeral of another man's son because he was a soldier! Link upon link of sorrow and suffering—such broken hearts....

The whole service was musical, nothing else but violins and harps. It was the most beautiful thing I ever heard, so quiet and so sweet; and that little group touched me profoundly—Le Roux with his daughter and the little fiancée—and that was all. In that coffin lying under the flag Bessie had placed at Toul her little silk pillow for the young soldier's head, and his love-letters in a little packet lay by his side. Around his arm he had worn a little ribbon taken from the hair of his sweetheart, and at the very last when he was dying and the hospital nurse was about to unknot it—I don't know why—the boy put up his feeble hand to prevent her; of course they buried it with him, and, as you think of it, you can hear that unknown voice on the battlefield, that, as the stretcher-bearers came to look for the wounded, called out: "Take him, he is engaged to be married; and leave me."

Oh, if out of it all arise a better civilization, purer motives, less greed for money, more humanitarian and unselfish aims, we can bear it.

I think of America with an ever-increasing love; I am proud to belong to that young and far-off country, but if our voice is raised now in encouragement for Belgium, encouragement for the Allies, and in reprobation of these acts of dishonorable warfare and cruel barbarism, I shall love my country more.

How superb the figure of the Belgian king is, standing there among the remnant of his army, and surrounded by his destroyed and ruined empire, and the cries of the people in his ears—a sublime figure....

II—STORY OF A SCHOOL TEACHER—AND A GARDENER

To Mr. F. B. Van Vorst, N. Y.

Nov. 20th, 1914.

My Dear Brother,

I wonder, as I sit here, in one of those rare, quiet moments that fall in a nurse's day, whilst I am preparing my charts, what they are thinking of in this silent room.

This group is singularly silent. They do not talk from bed to bed, as some of the more loquacious do. Directly opposite is one of those fragile bits of humanity that the violent wind of war has blown, like an unresisting leaf, into the vortex. Monsieur Gilet is a humble little school teacher from some humble little village school in a once peaceful commune, where in another little village school his humble little wife teaches school as he does. He is so light and so frail that I can lift him myself with ease. He has a shrapnel wound in his side and they have not found the ball. His thin cheeks are scarlet. He is gentleness[35] and sweetness itself. What has he ever done to be crucified like this? Monsieur Gilet is not thinking of his burning wound. He is thinking of the little woman in the province of Cher. How can she come to see him? She has no congé. When will she come to see him? For his life is all there in that war-shattered country. She has a baby twelve weeks old, born since he went to battle. That's what he is thinking of. When will she come?

On his right is a superb Arab, with an arm and hand so broken and so mutilated that it is hard to hold it without shuddering when the doctors drain it. On his head I have carefully adjusted a bright yellow flannel fez. His mild, docile eyes follow the nurse as she does for him the few little things she can to make him more at ease. For every service done, he thanks her in a sweet, soft voice. Just now, when I left him to come over here and sit down before my table, his eyes filled with tears. He can say a few words of French. He kisses my hand with Oriental grace. "Merci, ma mère."

On Monsieur Gilet's left lies a man whose language is as hard to understand, very nearly, as the Arab's—almost unintelligible—a patois of the Midi. He is a gardener, used only to the care of plants and flowers. He is a big, rugged giant, and so strong, and so silent a sufferer that since his entrance to the hospital he has not made one murmur or one complaint, or asked one service, and excepting when spoken to, he never says a word. Then he gives you a radiant smile and some token of gratitude. They operated on him to-day. There is shrapnel in his eye. He will never fully see his gardens again, and he is so strong and so patient and so able to bear pain, that they operated on him without anæsthetics, and he walked to and from the operating room—a brave, silent, docile giant, singularly appealing.... He is thinking of his gardens, trodden out of all semblance of[36] beauty, for he had been working in the north before the heel of the barbarian crushed out his flowers for ever and blotted out his sight.

III—STORY OF THE BOYS WHO SING "TIPPERARY"

To Mr. F. B. Van Vorst, Hackensack, N. J.

Paris, Dec. 4th, 1914.

My Dear Frederick,

To-morrow will be my last day at the hospital, as I start in the evening for Nice, on my way to Rome. I have lately found myself sole nurse in a ward with nine men....

It is full of English Tommies, and unless you nurse them and help those English boys, you don't know what they are. They are too lovely and too fine for words. One perfectly fine young fellow has had his leg amputated at the thigh—his life ruined for ever. Another is blind, staring into the visions of his past—he will never have anything else to look at again. The chief amusement of these fellows seems to be watching the funerals, and they call me to run to the window to see the hearses covered with the Union Jack or the French flag, and they find nothing mournful in the processions. One Sunday afternoon, as I sat there, leaning against a table in the middle of the room, a few country flowers in a vase near by—for Miss Hickman asks for country flowers for country lads—I asked them if they wouldn't sing me a song that I had heard a good deal about but had never heard sung. "What's that, nurse?" asked the boy without a leg. "Tipperary"—for I had never heard it. "Why, of course we will, won't we, lads?" and he said to his companion, only nineteen, from some English shire: "You[37] hit the tune." And the boy "hit it," and they sang me "Tipperary." Before they had finished I had turned away and walked out into the corridor to hide the way it made me feel, and I heard it softly through the door as they finished: "It's a long way to Tipperary." I shall never hear it again without seeing the picture of that ward, the country flowers and the country lads, and hearing the measure of that marching tune....

I have seen Mrs. Vanderbilt constantly. She seems to be ubiquitous. Wherever there's need, she is to be found—whether in the operating-room, the bandaging-room, or in one of the great wards where she has charge. I have found her everywhere, just at the right moment: calm, poised, dignified, capable and sweet. But none of this expresses the strength that she has been to the American Ambulance since its foundation—the heart and soul of its organization; and her personal gifts to it have been generous beyond words. I don't know what we shall do when she finally returns to America. She animates the whole place with her spirit and her soul....

IV—STORY OF THE "MIRACLES" OF THE BATTLES

Madame Le Roux, New York.

Paris, June 15th, 1915.

Dear Bessie,

Lady K. told such a beautiful thing, out at Bridget's, that I forgot to tell you before. She said that it was bruited in England that there had been a miracle wrought when von Kluck's army so unexpectedly turned back from Paris, which without doubt they could have taken. She said that it was rumored—and not only in the ranks, but[38] among higher men—that there appeared in the sky a singular phenomenon, and that the German prisoners bore witness that a cavalcade like heavenly archers suddenly filled the heavens and shot down upon the Germans a rain of deadly darts. As you know, this was long before the use of any asphyxiating gas or turpinite; but on the field were found hundreds of Germans, stone dead, immovable, who had fallen without any apparent cause. You remember the armies of the old Scriptures that "the breath of the Lord withered away."

Lady K. said that the rumor that the woods of Compiègne were full of troops when the Germans made that famous retreat was absolutely untrue. There were no troops in the forest, and what they saw were, again, celestial soldiers.

No doubt these tales come always in the history of war. But, my dear, how beautiful they are—how much more heavenly and inspired than the beatings on the slavish backs of the German Uhlans, of the half-drunken, brutish hordes! Everywhere is the same uplifting spirit. When I speak of Paris being sad, it is; but it is not depressing. There is a difference. If it were not for the absence of those I love, I would rather be here than anywhere. In church on Sunday, the Bishop said that at one of the services near the firing line, when he asked the question: "How many of the men here have felt, since they came out, a stirring in their hearts, an awakening of the spirit?" as far as he could see, every hand was raised. And men have gone home to England, without arms and without legs, maimed for life, and have been heard to say that in spite of their material anguish they regretted nothing, for they had found their souls....

I ought to tell you that all credulous and believing France thinks that the country is being saved by Jeanne[39] d'Arc. You hear them say it everywhere. Just think of it, in the twentieth century, my dear, when the war is being fought in the air and under the sea, by machines so modern that only the latest invention can triumph! Think of it, and then consider that there remains enough of spiritual faith to believe that the salvation of a country comes through prayer.

V—STORY OF COMPTE HENRY DADVISARD

To Mrs. Louis Stoddard, N. Y.

June 25th, 1915.

My Dear Molly, [3] Mme. de S. told me last night that once during the last year she had a little spray of blossoms that had been blessed by the Pope, and in writing to Henry on the field, she sent him a little bit of green—a tiny leaf pinned on a loving letter. When she looked through the uniform sent back to her, a few days ago, in his pocket was this little card, all stained with his blood. This card, with her few loving words, was all he carried on him into that sacred field. I must not forget the belt he wore around him, which she had made with her own hands, and it contained some money and in one of the folds of the chamois was a prayer that she had written out for him. The paper was so worn with reading and unfolding and folding that it was like something used by the years.

All the night before he went to that great battle, he spent in prayer. His aide told Mme. de S. that he had not closed his eyes. They say that if he could have been taken immediately from the field, he would have been saved, for he bled to death.

I only suppose that you will be interested in these details because they mark the going out of such a brilliant life, and it is the intimate story of one soldier who has laid down his life, after months and months of fighting and self-abnegation and loneliness, on that distant field.

From the time he left her in August until his death, he had never seen any of his family—not a soul. I want to tell you the way she said good-bye to him, for I never knew it until last night. She had expected him to lunch—imagine!—and received the news by telephone that he was leaving his "quartier" in an hour. She rushed there to see the Cuirassiers, mounted, in their service uniform, the helmets all covered with khaki, clattering out of the yard. She sat in the motor and he came out to her, all ready to go; and they said good-bye, there in the motor, he sitting by her side, holding her hands. She said he looked then like the dead—so grave. You know he was a soldier, passionately devoted to his career. He had made all the African campaign and had an illustrious record. She says he asked her for her blessing and she lightly touched the helmet covered with khaki and gave it him. And neither shed a tear. And he kissed her good-bye. She never saw him again....

She said that his General told her as follows: "The night before the engagement, Henry Dadvisard came into my miserable little shack on the field. He said to me: 'Mon général, just show me on the map where the Germans are.' A map was hanging on the wall and I indicated with my finger: 'Les Allemands sont là, mon enfant.' And Dadvisard said: 'Why, is that all there is to do—just to go out and attack them there? Why, we'll be coming back as gaily as if it were from the races!' He turned to go, saying: 'Au revoir, mon général.' But at the door he paused, and I looked up and saw him and he said: 'Adieu, mon général.' And then I saw in his[41] eyes a singular look, something like an appeal from one human soul to another, for a word, a touch, before going out to that sacrifice. I did not dare to say anything but what I did say: 'Bon courage, mon enfant; bonne chance!' And he went...."

After telling me this, Mme. de S. took out his watch, which she carries with her now—a gold watch, with his crest upon it—the one he had carried through all his campaigns, with the soldier's rough chain hanging from it. It had stopped at half-past ten; as he had wound it the night before, the watch had gone on after his heart had ceased to beat....

The day before Henry left his own company of Cuirassiers to go into the dangerous and terrible experiences of the trenches, to take up that duty which ended in his laying down his life, he gathered his men together and bade them good-bye. Last night dear Mme. de S. showed me his soldier's notebook, in which he had written the few words that he meant to say to his men. I begged her to let me have them: I give them to you. This address stands to me as one of the most beautiful things I have ever read.

General Foch paid him a fine tribute when he mentioned him in despatches, and this mention of him was accompanied by the bestowal of the Croix de Guerre.

"Henry Dadvisard, warm-hearted and vibrant; a remarkable leader of men. He asked to be transferred to the infantry, in order to offer more fully to his country his admirable military talents. He fell gloriously on the 27th of April, leading an attack at the head of his company."

VI—STORY OF THE MORGAN-MARBURY HOSPITAL

To Mrs. Morawetz, New York.

Paris, June 22nd, 1915.

Dearest Violet,

I went out the other day with Madame Marie to Versailles, en auto. I wanted to see the little hospital that Anne Morgan and Bessie Marbury have given out there. One of their pretty little houses is in the charge of some gentle-faced sisters of charity, and out in the garden, with the roses blooming and the sweet-scented hay being raked in great piles, were sitting a lieutenant, convalescing, and his commandant, who had come to see him, also wounded. Both men wore the Legion of Honor on their breasts. They were talking about the campaign. The lieutenant wore his képi well down over his face; he was totally blind for ever, at thirty! His interest in talking to his superior officer was so great that you can fancy I only stopped a second to speak to him. There were great scars on his hands and his face and neck were scarred too. I heard him say, as I turned to walk away: "J'aime aussi causer des jours quand nous étions collégiens à Saint-Cyr. Ces souvenirs sont plus doux." It was terribly touching.

VII—STORY OF THE GAY FRENCH OFFICER

To Miss B. S. Andrews, New York.

Paris, July 12th, 1915.

Dearest Belle,

Mme. de S. is going next week on the cruel and dreadful mission of disinterring her belovèd dead. She is[43] going down into the tomb in Belgium—if she can get through—to take her boy out of the charnel house, where he is buried under six other coffins. "God has his soul," she says; "I only ask his body" ... if she can find it. She has told no one of her griefs, but to me; and she bears herself like a woman of twenty-five, gallantly....

There is one gay officer of twenty-nine, and six feet two. I don't think you'd speak of "little insignificant Frenchmen" if you could see him! He's superb. One finger off on the left hand, and the right hand utterly useless. So we work at that for fifteen minutes, and all the little group of soldiers linger, because they love him so—he's so killing, so witty, so gay. He screams in mock agony, and laughs and makes the most outrageous jokes; and when he has gone, one of them says to me: "Il est adoré par ses hommes, madame; il est si courageux." The spirit between men and officers is so beautiful in the French army. They are all brothers. None of that lordly, arrogant oppression of the Germans. One of the soldiers said to me: "Il n'y a pas de grade, maintenant, madame. Nous sommes tous des hommes qui aiment le pays."

And Lieutenant ——, of whom I have just been speaking. I said to him: "Tell me something about the campaign, monsieur." And he answered: "Oh, madame, I would like to tell you about the men. They're superb. I have never seen anything like it. I had to lead a charge with 156 men into what we all believed was certain death. Why," he said, "they went like schoolboys—shouting, laughing, pushing each other up the parapet.... We came back nine strong," he said.

Dr. Blake has been magnificent. His operations are something beyond words. Men came in to me for treatment and told me that he worked actual miracles with faces that were blown off, building new jaws, and oh, Heavens! I don't know what not.

VIII—STORY OF A FRENCH MOTHER AT MASS

Paris, July 20th, 1915.

Dearest Violet,

I saw a very touching thing the other day in the Madeleine, where I went to Mass. A woman no longer young, in the heaviest of crape, came in and sat down and buried her face in her hands. She shook with suppressed sobs and terrible weeping. Presently there came in another worshipper, a stranger to her, and sat down by her side. He was a splendid-looking officer in full-dress uniform—a young man, with a wedding-ring upon his hand—one of those permissionnaires home, evidently, for the short eight days that all the officers are given now—a hiatus between the old war and the new. He bent too, praying; but the weeping of the woman at his side evidently tore his heart. Presently she lifted her face and wiped her eyes, and the officer put his hand on hers. And as I was sitting near, I heard what he said:

"Pauvre madame, pauvre madame!... Ma mère pleure comme vous."

She glanced at him, then bent again in prayer. But when she had finished, before she left her seat, I heard her say to him: