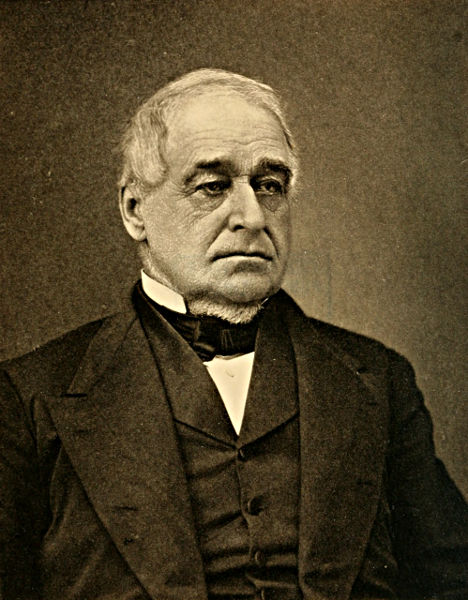

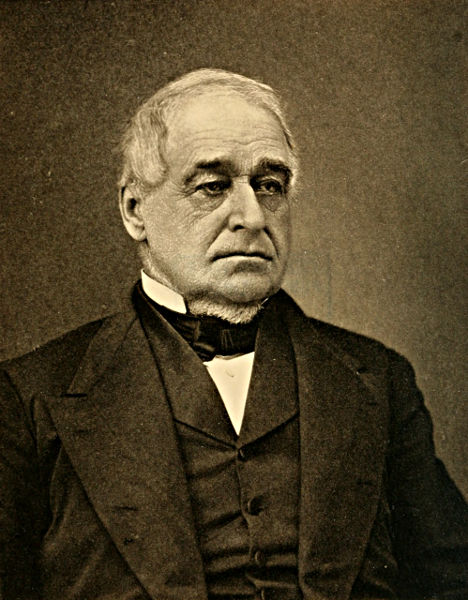

HANNIBAL HAMLIN

A. W. Elson & Co. Boston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Charles Sumner; his complete works, volume 9 (of 20), by Charles Sumner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Charles Sumner; his complete works, volume 9 (of 20) Author: Charles Sumner Editor: George Frisbie Hoar Release Date: February 15, 2015 [EBook #48266] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHARLES SUMNER, COMPLETE WORKS, VOL 9 *** Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

HANNIBAL HAMLIN

A. W. Elson & Co. Boston

COPYRIGHT, 1872,

BY

CHARLES SUMNER.

COPYRIGHT, 1900,

BY

LEE AND SHEPARD.

Statesman Edition.

Limited to One Thousand Copies.

Of which this is

Norwood Press:

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

Speech in the Senate, on his Bill for the Confiscation of Property and the Liberation of Slaves belonging to Rebels, May 19, 1862.

Wherefore he deserves to be punished, not only as an enemy, but also as a traitor, both to you and to us. And indeed treason is as much worse than war as it is harder to guard against what is secret than what is open,—and as much more hateful, as with enemies men make treaties again, and put faith in them, but with one who is discovered to be a traitor nobody ever enters into covenant, or trusts him for the future.—Xenophon, Hellenica, Book II. ch. 3, § 29.

[Pg 2]Tum, ex consulto Senatus adversariis hostibus judicatis, in præsentem Tribunum, aliosque diversæ factionis, jure sævitum est.—Florus, Epitome, Lib. III. cap. 21.

Ego semper illum appellavi hostem, cum alii adversarium; semper hoc bellum, cum alii tumultum. Nec hæc in Senatu solum; eadem ad populum semper egi.—Cicero, Oratio Philippica XII. cap. 7.

Except the Tax Bill, no subject occupied so much attention during this session as what were known generally as “Confiscation Bills,” all proposing, in different ways, the punishment of Rebels and the weakening of the Rebellion, by taking property and freeing slaves. In supporting these bills, Mr. Sumner did not disguise his special anxiety to assert the power of Congress over Slavery.

As early as January 15th, Mr. Trumbull reported from the Judiciary Committee a bill to confiscate the property and free the slaves of Rebels, which was considered from time to time and debated at length, many Senators speaking. Amendments were made, among which was one moved by Mr. Sumner, February 25th, requiring, that, whenever any person claimed another as slave, he should, before proceeding with his claim, prove loyalty.[1] Then came motions for reference of the pending bill and all associate propositions to a Select Committee. That of Mr. Clark prevailed. In a speech which will be found in the Congressional Globe[2] sustaining the reference, Mr. Sumner said:—

“Such are the embarrassments in which we are involved, such is the maze into which we have been led by these various motions, that a committee is needed to hold the clew. Never was there more occasion for such a committee than now, when we have all these multifarious propositions to be considered, revised, collated, and brought into a constitutional unit,—or, if I may so say, changing the figure, passed through an alembic, to be fused into one bill on which we can all harmonize.”

Mr. Clark reported from the Select Committee a bill “to suppress Insurrection and punish Treason and Rebellion,” which, on the 16th of May, was taken up for consideration. Mr. Sumner was among those who thought the bill inadequate, and on the day it was taken up he introduced a substitute in ten sections, which was printed by order of the Senate. The title was, “For the Confiscation of Property and the Liberation of Slaves belonging to Rebels.” The sections relating to Liberation were these.

“Sec. 6. And be it further enacted, That, if any person within any State or Territory of the United States shall, after the passage of this Act, wilfully [Pg 4]engage in armed rebellion against the Government of the United States, or shall wilfully aid or abet such rebellion, or adhere to those engaged in such rebellion, giving them aid or comfort, every such person shall thereby forfeit all claim to the service or labor of any persons commonly known as slaves; and all such slaves are hereby declared free, and forever discharged from such servitude, anything in the laws of the United States, or of any State, to the contrary notwithstanding. And whenever thereafter any person claiming the labor or service of any such slave shall seek to enforce his claim, it shall be a sufficient defence thereto that the claimant was engaged in the said rebellion, or aided or abetted the same, contrary to the provisions of this Act.

“Sec. 7. And be it further enacted, That, whenever any person claiming to be entitled to the service or labor of any other person shall seek to enforce such claim, he shall, in the first instance, and before any order shall be made for the surrender of the person whose service or labor is claimed, establish not only his claim to such service or labor, but also that such claimant has not in any way aided, assisted, or countenanced the existing Rebellion against the Government of the United States. And no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretence whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or deliver up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.”

May 19th, Mr. Sumner made the following speech, vindicating the powers of Congress.

A debate ensued, turning on the inadequacy of the pending bill, in which Mr. Sumner likened it to a glass of water with a bit of orange-peel, which, according to a character in one of Dickens’s novels, by making believe very hard, would be a strong drink, and said: “At a moment when the life of the Republic is struck at, Senators would proceed by indictment in a criminal court.” Mr. Wade said: “I do not know that we shall get anything; but if we only get this bill, we shall get next to nothing.”

In the course of the debate, Mr. Davis departed from the main question to say that he understood the Senators from Massachusetts sympathized with the mob in Boston, and its resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act. He never knew that Mr. Wilson had appeared “to back the Marshal of the United States in the execution of that law.” Then ensued a brief colloquy.

“Mr. Davis. I never heard that he did, or that either of them did, perform or attempt to perform that high, patriotic duty.

“Mr. Sumner. I was in my seat here.

“Mr. Davis. Did you not give your sympathy to those who resisted the law?

[Pg 5]“Mr. Sumner. My sympathy is always with every slave.

“Mr. Davis. That is a frank acknowledgment. His sympathy is with every slave against the Constitution and the execution of the laws of his country! If that is not a sentiment of treason, I ask what is.”[3]

Meanwhile the House of Representatives were considering the same subject, and on the 26th May passed a bill “to confiscate the property of Rebels for the payment of the expenses of the present Rebellion, and for other purposes,” which, on motion of Mr. Clark, was taken up in the Senate June 23d, when he moved to substitute the pending Senate bill. The debate on the general question was resumed. June 27th, Mr. Sumner made another speech, which will be found in its place, according to date,[4] especially in reply to Mr. Browning, who had claimed the War Powers for the President rather than for Congress.

June 28th, the substitute moved by Mr. Clark was agreed to, Yeas 19, Nays 17, and the bill as amended was then passed, Yeas 28, Nays 13.

July 3d, the House non-concurred in the Senate amendment. A Conference Committee reported in substance the Senate amendment, which was accepted in the Senate, Yeas 28, Nays 13, and in the House, Yeas 82, Nays 42. July 17th, the bill was signed by the President.

The sections of this bill, as it passed, relating to liberation, were these.

“Sec. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the Government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army, and all slaves captured from such persons, or deserted by them, and coming under the control of the Government of the United States, and all slaves of such persons found on [or] being within any place occupied by Rebel forces, and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

“Sec. 10. And be it further enacted, That no slave escaping into any State, Territory, or the District of Columbia, from any other State, shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty, except for crime, or some offence against the laws, unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath that the person to whom the labor or service of such fugitive is alleged to be due is his lawful owner, and has not borne arms against the United States in the present Rebellion, nor in any way [Pg 6]given aid and comfort thereto; and no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretence whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or surrender up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.”[5]

This speech in the Washington pamphlet was entitled “Indemnity for the Past and Security for the Future,” which points directly at its object. An edition was printed in New York by the Young Men’s Republican Union, with the title, “Rights of Sovereignty and Rights of War, Two Sources of Power against the Rebellion,” which describes the way in which this object might be accomplished.

It was noticed at the time as removing difficulties which perplexed many with regard to the powers of Congress.

In Paris, the Journal des Débats[6] referred to it as explaining the confiscation proposed in the United States, and quoted passages especially in reply to the Constitutionnel, which had attacked the measure.

A few opinions are given, merely to illustrate the tone of comment.

Hon. John Jay, afterwards our Minister at Vienna, who sympathized promptly with all that was done to crush the Rebellion, wrote from New York:—

“Your Confiscation speech is an admirable exposition of the subject, and will go far to remove any lingering doubts in the public mind in regard to the constitutionality and necessity of the measure.”

Then again he wrote:—

“I have re-read, with thorough satisfaction, your speech on Confiscation and Emancipation in the pamphlet you were good enough to send me. It is admirable in its tone, arrangement, and completeness, and the arguments and illustrations are overwhelming and unanswerable. The necessity of Emancipation is fast forcing itself upon our people by the stern logic of facts, but your speech will remove any lingering doubts.”

Hon. Amos P. Granger, former Representative in Congress, and a stern patriot, wrote from Syracuse, New York:—

“Your remarks of the 19th, as reported in the Tribune day before yesterday, are read in this vicinity with a great deal of pleasure and approbation. They are replete with prudence, skill, and wisdom. Such sentiments are rarely heard in Washington. It would seem that they would be decisive.”

Hon. William L. Marshall, an able Judge of Maryland, wrote from Baltimore:—

“You have exhausted the subject, it seems to me, so far as it involves legal questions. I have been greatly pleased and much interested by your argument.”

L. D. Stickney, of Florida, wrote from Washington:—

“I have read your speech on the confiscation of the property of Rebels with the liveliest interest and with entire approbation. Long a citizen of the South, I have nevertheless been a steadfast Republican of the school of Jefferson and of J. Quincy Adams,—a Republican to elevate men to the proper status of freemen, not to degrade them to slavery. While the unthinking and those of violent prejudices call you fanatical, no man properly qualified to judge of men and events can survey your parliamentary history without acknowledging your claim to the highest plane of statesmanship. I reverence Sir James Mackintosh as the brightest example of great men whom the world will not willingly let die. Tried by no other standard than your speeches in the Thirty-Seventh Congress alone, you will stand unchallenged by the enlightened judgment of mankind, his co-rival in that fame which makes his name cherished by scholars everywhere, and by all men of good report.”

While expressing sympathy with this speech, many at this time, like the last writer, referred to the series of efforts by Mr. Sumner during this session. Among these was Hon. Samuel E. Sewall, of Boston, the able lawyer and tried Abolitionist, who repeated the kindly appreciation which he had expressed on other occasions.

“Your course during the present session has not only delighted your friends, but I think has given great satisfaction to the mass of your constituents, as well as to all throughout the country whose opinions are of any value.

“Any man might think his life well spent, who, in its whole course, had said and done no more in the cause of freedom and justice than you have in the six months past.”

Hon. Charles W. Upham, the author, and former Representative in Congress, wrote from Salem:—

“You have nobly presented and thoroughly exhausted all the subjects you have treated. I rejoice in your success, and cordially indorse your sentiments. May you live to witness the progressive triumphs of the great cause to which you are devoted!”

Lewis Tappan, often quoted already, wrote from New York:—

“You have done a great work in the Senate during the last session. I [Pg 8]admire your consistency. Every utterance has been instinct with liberty and loyalty.… Thanking you again for the speech, and for your other speeches, and thanking God for the brilliancy of your entire Senatorial career.…”

Hon. Asaph Churchill, lawyer and fellow-student, expressed his sympathy, and gave a reminiscence, in a letter from Boston.

“Allow me to congratulate you upon the grand success of our country’s movement, and no less upon your own career, which has been crowned with such splendid success, during the past season, in the new, important, and delicate questions which you have been called upon to speak and act upon. Certainly your highest ambition ought to be satisfied with that which insures to you your place in the immortality of history; and you have had the most abundant opportunity for accomplishing upon the grandest scale that aspiration which I so well remember you gave utterance to at our Law School, when, boy-like, we were all telling what we most ardently sought to do or to be, that you ‘wished to do that which would do the most good to mankind.’”

Wendell Phillips, after his return from a lecture-tour, wrote:—

“Be of good courage. We all say amen to you. And your diocese, I can testify, extends to the Mississippi.”

Alfred E. Giles, lawyer, wrote from Boston:—

“During your Congressional career, I have so uniformly found my views and feelings on public affairs in accordance with those of your speeches, that I now feel myself obliged, for once at least (for I shall not often trouble you), to express my gratitude, and give a word of good cheer to you, who, amid so many discouragements, and under so much obloquy as has been attempted to be thrown upon you, have ever so faithfully and manfully stood up for the oppressed and for liberal principles.

“It appears to me, on reading your speeches, that I find my own views and principles announced, stated, and clothed with a richness and beauty of style and illustration that I admire, but cannot emulate.

“Again, I am much pleased that you always deal fairly with your opponents, not using misrepresentation and ad captandum argument, but drawing your weapons from the armory of truth and right.”

Professor Ordronaux, of Columbia College, New York, wrote:—

“Last year, while in England, I had the honor of meeting many gentlemen of your acquaintance, and, amid the many bitter things I was compelled to listen to, it was a source of constant satisfaction and pride to hear them acknowledge the great confidence they reposed in you, and the earnest wish they expressed for the success of that novus ordo sæclorum in the Senate, for which we are so much indebted to you. Reading over for the third time your famous Kansas speech, of May, 1856,[7] this morning, I was struck with the almost prophetic character of its language. The crime against Nature has indeed culminated. It struck you down, and then went dancing like a maniac, all the while approaching that bottomless abyss into which it is now descending. Can you doubt that Nemesis still wields her sword and flaming torch?”

These expressions of sympathy and good-will, overflowing from opposite quarters, are a proper prelude to other utterances, widely different in tone, aroused against Mr. Sumner by the very persistency of his course. Appearing in their proper place, these will be better comprehended from knowing already the other side.

MR. PRESIDENT,—If I can simplify this discussion, I shall feel that I have done something towards establishing the truth. The chief difficulty springs from confusion with regard to different sources of power. This I shall try to remove.

There is a saying, often repeated by statesmen and often recorded by publicists, which embodies the direct object of the war we are now unhappily compelled to wage,—an object sometimes avowed in European wars, and more than once made a watchword in our own country: “Indemnity for the past, and Security for the future.” Such should be our comprehensive aim,—nor more, nor less. Without indemnity for the past, this war will have been waged at our cost; without security for the future, this war will have been waged in vain, treasure and blood will have been lavished for nothing. But indemnity and security are both means to an end, and that end is the National Unity under the Constitution of the United States. It is not enough, if we preserve the Constitution at the expense of the National Unity. Nor is it enough, if we enforce the National Unity at the expense of the Constitution. Both must be maintained. Both will be maintained, if we do not fail to take counsel of that prudent courage[Pg 12] which is never so much needed as at a moment like the present.

Two things we seek as means to an end: Indemnity for the past, and Security for the future.

Two things we seek as the end itself: National Unity, under the Constitution of the United States.

In these objects all must concur. But how shall they be best accomplished?

The Constitution and International Law are each involved in this discussion. Even if the question itself were minute, it would be important from such relations. But it concerns vast masses of property, and, what is more than property, it concerns the liberty of men, while it opens for decision the means to be employed in bringing this great war to a close. In every aspect the question is transcendent; nor is it easy to pass upon it without the various lights of jurisprudence, of history, and of policy.

Sometimes it is called a constitutional question exclusively. This is a mistake. In every Government bound by written Constitution nothing is done except in conformity with the Constitution. But in the present debate there need be no difficulty or doubt under the Constitution. Its provisions are plain and explicit, so that they need only to be recited. The Senator from Pennsylvania [Mr. Cowan] and the Senator from Vermont [Mr. Collamer] have stated them strongly; but I complain less of their statement than of its application. Of course, any proposition really inconsistent with these provisions must be abandoned. But if, on the other hand, it be consistent, then is the way open to its consideration in the lights of history and policy.

If there be any difficulty now, it is not from the question,[Pg 13] but simply from the facts,—as often in judicial proceedings it is less embarrassing to determine the law than the facts. If things are seen as they really are and not as Senators fancy or desire, if the facts are admitted in their natural character, then must the constitutional power of the Government be admitted also, for this power comes into being on the occurrence of certain facts. Only by denying the facts can the power itself be drawn in question. But not even the Senator from Pennsylvania or the Senator from Vermont denies the facts.

The facts are simple and obvious. They are all expressed or embodied in the double idea of Rebellion and War. Both of these are facts patent to common observation and common sense. It would be an insult to the understanding to say that at the present moment there is no Rebellion or that there is no War. Whatever the doubts of Senators, or their fine-spun constitutional theories, nobody questions that we are in the midst of de facto Rebellion and in the midst of de facto War. We are in the midst of each and of both. It is not enough to say that there is Rebellion; nor is it enough to say that there is War. The whole truth is not told in either alternative. Our case is double, and you may call it Rebellion or War, as you please, or you may call it both. It is Rebellion swollen to all the proportions of war, and it is War deriving its life from rebellion. It is not less Rebellion because of its present full-blown grandeur, nor is it less War because of the traitorous source whence it draws its life.

The Rebellion is manifest,—is it not? An extensive territory, once occupied by Governments rejoicing[Pg 14] in allegiance to the Union, and sharing largely in its counsels, has undertaken to overthrow the National Constitution within its borders. Its Senators and Representatives have withdrawn from Congress. The old State Governments, solemnly bound by the oaths of their functionaries to support the National Constitution, have vanished; and in their place appear pretended Governments, which, adopting the further pretension of a Confederacy, have proceeded to issue letters of marque and to levy war against the United States. So far has displacement of the National Government prevailed, that at this moment, throughout this whole territory, there are no functionaries acting under the United States, but all are pretending to act under the newly established Usurpation. Instead of the oath to support the Constitution of the United States, required of all officials by the Constitution, another oath is substituted, to support the Constitution of the Confederacy; and thus the Rebellion assumes a completeness of organization under the most solemn sanctions. In point of fact, throughout this territory the National Government is ousted, while the old State Governments have ceased to exist, lifeless now from Rebel hands. Call it suicide, if you will, or suspended animation, or abeyance,—they have practically ceased to exist. Such is the plain and palpable fact. If all this is not rebellion, complete in triumphant treason, then is rebellion nothing but a name.

But the War is not less manifest. Assuming all the functions of an independent government, the Confederacy has undertaken to declare war against the United States. In support of this declaration it has raised armies, organized a navy, issued letters of marque, borrowed[Pg 15] money, imposed taxes, and otherwise done all that it could in waging war. Its armies are among the largest ever marshalled by a single people, and at different places throughout a wide-spread territory they have encountered the armies of the United States. Battles are fought with the varying vicissitudes of war. Sieges are laid. Fortresses and cities are captured. On the sea, ships bearing the commission of the Rebellion, sometimes as privateers and sometimes as ships of the navy, seize, sink, or burn merchant vessels of the United States; and only lately an iron-clad steamer, with the flag of the Rebellion, destroyed two frigates of the United States. On each side prisoners are made, who are treated as prisoners of war, and as such exchanged. Flags of truce pass from camp to camp, and almost daily during the winter this white flag has afforded its belligerent protection to communications between Norfolk and Fortress Monroe, while the whole Rebel coast is by proclamation of the President declared in a state of blockade, and ships of foreign countries, as well as of our own, are condemned by courts in Washington, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, as prize of war. Thus do all things attest the existence of war, which is manifest now in the blockade, upheld by judicial tribunals, and now in the bugle, which after night sounds truce, indubitably as in mighty armies face to face on the battle-field. It is war in all its criminal eminence, challenging all the pains and penalties of war, enlisting all its terrible prerogatives, and awaking all its dormant thunder.

Further effort is needless to show that we are in the midst of a Rebellion and in the midst of a War,—or, in yet other words, that unquestionable war is now waged[Pg 16] to put down unquestionable rebellion. But a single illustration out of many in history will exhibit this double character in unmistakable relief. The disturbances which convulsed England in the middle of the seventeenth century were occasioned by the resistance of Parliament to the arbitrary power of the Crown. This resistance, prolonged for years and maintained by force, triumphed at last in the execution of King Charles and the elevation of Oliver Cromwell. The historian whose classical work was for a long time the chief authority relative to this event styles it “The Rebellion,” and under this name it passed into the memory of men. But it was none the less war, with all the incidents of war. The fields of Naseby, Marston Moor, Dunbar, and Worcester, where Cavaliers and Puritans met in bloody shock, attest that it was war. Clarendon called it Rebellion, and the title of one of his works makes it “The Grand Rebellion,”—how small by the side of ours! But a greater than Clarendon—John Milton—called it War, when, in unsurpassed verses, after commemorating the victories of Cromwell, he uses words so often quoted without knowing their original application:—

The death of Cromwell was followed by the restoration of King Charles the Second; but the royal fugitive from the field of Worcester, where Cromwell triumphed in war, did not fail to put forth the full prerogatives of sovereignty in the suppression of rebellion; and all who sat in judgment on the king, his father, were saved from the fearful penalties of treason only by exile. Hugh[Pg 17] Peters, the Puritan preacher, and Harry Vane, the Puritan senator, were executed as traitors for the part they performed in what was at once rebellion and war, while the body of the great commander who defeated his king in battle, and then sat upon his throne, was hung in chains, as a warning against treason.

Other instances might be given to illustrate the double character of present events. But enough is done. My simple object is to exhibit this important point in such light that it will be at once recognized. And I present the Rebellion and the War as obvious facts. Let them be seen in their true character, and it is easy to apply the law. Because Senators see the facts only imperfectly, they hesitate with regard to the powers we are to employ,—or perhaps it is because they insist upon seeing the fact of Rebellion exclusively, and not the fact of War. Let them open their eyes, and they must see both. If I seem to dwell on this point, it is because of its practical importance in the present debate. For myself, I assume it as an undeniable postulate.

The persons arrayed for the overthrow of the Government of the United States are unquestionably criminals, subject to all the penalties of rebellion, which is of course treason under the Constitution of the United States.

The same persons arrayed in war against the Government of the United States are unquestionably enemies, exposed to all the incidents of war, with its penalties, seizures, contributions, confiscations, captures, and prizes.

They are criminals, because they set themselves traitorously against the Government of their country.

They are enemies, because their combination assumes the front and proportions of war.

It is idle to say that they are not criminals. It is idle to say that they are not enemies. They are both, and they are either; and it is for the Government of the United States to proceed against them in either character, according to controlling considerations of policy. This right is so obvious, on grounds of reason, that it seems superfluous to sustain it by authority. But since its recognition is essential to the complete comprehension of our present position, I shall not hesitate to illustrate it by judicial decisions, and also by an earlier voice.

A judgment of the Supreme Court of the United States cannot bind the Senate on this question; but it is an important guide, to which we all bow with respect. In the best days of this eminent tribunal, when Marshall was Chief Justice, in a case arising out of the efforts of France to suppress insurrection in the colony of San Domingo, it was affirmed by the Court that in such a case there were two distinct sources of power open to exercise by a government,—one found in the rights of a sovereign, the other in the rights of a belligerent, or, in other words, one under Municipal Law, and the other under International Law,—and the exercise of one did not prevent the exercise of the other. Belligerent rights, it was admitted, might be superadded to the rights of sovereignty. Here are the actual words of Chief-Justice Marshall:—

“It is not intended to say that belligerent rights may not be superadded to those of sovereignty. But admitting a sovereign, who is endeavoring to reduce his revolted subjects to obedience, to possess both sovereign and belligerent [Pg 19]rights, and to be capable of acting in either character, the manner in which he acts must determine the character of the act. If as a legislator he publishes a law ordaining punishments for certain offences, which law is to be applied by courts, the nature of the law and of the proceedings under it will decide whether it is an exercise of belligerent rights or exclusively of his sovereign power.”[9]

Here are the words of another eminent judge, Mr. Justice Johnson, in the same case:—

“But there existed a war between the parent state and her colony. It was not only a fact of the most universal notoriety, but officially notified in the gazettes of the United States.… Here, then, was notice of the existence of war, and an assertion of the rights consequent upon it. The object of the measure was … solely the reduction of an enemy. It was, therefore, not merely municipal, but belligerent, in its nature and object.”[10]

Although the conclusion of the Court in this case was afterwards reversed, yet nothing occurred to modify the judgment on the principles now in question; so that the case remains authority for double proceedings, municipal and belligerent.

On a similar state of facts, arising from the efforts of France to suppress the insurrection in San Domingo, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania asserted the same principle; and here we find the eminent Chief-Justice Tilghman—one of the best authorities of the American bench—giving to it the weight of his enlightened judgment. These are his words:—

“We are not at liberty to consider the island in any other [Pg 20]light than as part of the dominions of the French Republic. But supposing it to be so, the Republic is possessed of belligerent rights.…

“Although the French Government, from motives of policy, might not choose to make mention of war, yet it does not follow that it might not avail itself of all rights to which by the Law of Nations it was entitled in the existing circumstances.… This was the course pursued by Great Britain in the Revolutionary War with the United States.… Considering the words of the arrêté, and the circumstances under which it was made, it ought not to be understood simply as a municipal regulation, but a municipal regulation connected with a state of war with revolted subjects.”[11]

The principle embodied in these cases is accurately stated by a recent text-writer as follows.

“A sovereign nation, engaged in the duty of suppressing an insurrection of its citizens, may, with entire consistency, act in the twofold capacity of sovereign and belligerent, according to the several measures resorted to for the accomplishment of its purpose. By inflicting, through its agent, the judiciary, the penalty which the law affixes to the capital crimes of treason and piracy, … it acts in its capacity as a sovereign, and its courts are but enforcing its municipal regulations. By instituting a blockade of the ports of its rebellious subjects, … the nation is exercising the right of a belligerent, and its courts, in their adjudications upon the captures made in the enforcement of this measure, are organized as Courts of Prize, governed by and administering the Law of Nations.”[12]

The same principle has received most authentic declaration[Pg 21] in the recent judgment of an able magistrate in a case of Prize for a violation of the blockade. I refer to the case of the Amy Warwick, tried in Boston, where Judge Sprague, of the District Court, expressed himself as follows.

“The United States, as a nation, have full and complete belligerent rights, which are in no degree impaired by the fact that their enemies owe allegiance, and have superadded the guilt of treason to that of unjust war.”[13]

Among all the judges called to consider judicially the character of this Rebellion, I know of none whose opinion is entitled to more consideration. Long experience has increased his original aptitude for such questions, and made him an authority.

There is an earlier voice, which, even if all judicial tribunals had been silent, would be decisive. I refer to Hugo Grotius, who, by his work “De Jure Belli ac Pacis,” became the lawgiver of nations. Original in conception, vast in plan, various in learning, and humane in sentiment, this effort created the science of International Law, which, since that early day, has been softened and refined, without essential change in the principles then enunciated. His master mind anticipated the true distinction, when, in definition of War, he wrote as follows.

“The first and most necessary partition of war is this: that war is private, public, or mixed. Public war is that which is carried on under the authority of him who has jurisdiction; private, that which is otherwise; mixed, that which is public on one side and private on the other.”[14]

In these few words of this great authority is found the very discrimination which enters into the present discussion. The war in which we are now engaged is not precisely “public,” because on one side there is no Government; nor is it “private,” because on one side there is a Government; but it is “mixed,”—that is, public on one side and private on the other. On the side of the United States, it is under authority of the Government, and therefore “public”; on the other side, it is without the sanction of any recognized Government, and therefore “private.” In other words, the Government of the United States may claim for itself all belligerent rights, while it refuses them to the other side. And Grotius, in his reasoning, sustains his definition by showing that war becomes the essential agency, where public justice ends,—that it is the justifiable mode of dealing with those who are not kept in order by judicial proceedings,—and that, as a natural consequence, where war prevails, the Municipal Law is silent. And here, with that largess of quotation which is one of his peculiarities, he adduces the weighty words of Demosthenes: “Against enemies, who cannot be coerced by our laws, it is proper and necessary to maintain armies, to send out fleets, and to pay taxes; but against our own citizens, a decree, an indictment, the state vessel are sufficient.”[15] But when citizens array themselves in multitudes, they come within the declared condition of enemies. There is so much intrinsic reason in this distinction that I am ashamed to take time upon it. And yet it has been constantly neglected in this debate. Let it be accepted, and the constitutional[Pg 23] scruples which play such a part will be out of place.

Senators seem to feel the importance of being able to treat the Rebels as “alien enemies,” on account of penalties which would then attach. The Senator from Kentucky [Mr. Davis], in his bill, proposes to declare them so, and the Senator from Wisconsin [Mr. Doolittle] has made a similar proposition with regard to a particular class. But all this is superfluous. Rebels in arms are “enemies,” exposed to all the penalties of war, as much as if they were alien enemies. No legislation is required to make them so. They are so in fact. It only remains that they should be treated so, or, according to the Declaration of Independence, that we “hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends.”

Mark now the stages of the discussion. We have seen, first, that, in point of fact, we are in the midst of rebellion and in the midst of a war,—and, secondly, that, in point of law, we are at liberty to act under powers incident to either or both of these conditions, treat the people engaged against us as criminals, or as enemies, or, if we please, as both. Pardon me, if I repeat these propositions; but it is essential that they should not be forgotten.

Therefore, Sir, in determining our course, we may banish all question of power. The power is ample and indubitable, being regulated in the one case by the Constitution, and in the other case by the Rights of War. Treating them as criminals, then are we under the restraints of the Constitution; treating them as enemies, we have all the latitude sanctioned by the[Pg 24] Rights of War; treating them as both, then may we combine our penalties from the double source. What is done against them merely as criminals will naturally be in conformity with the Constitution; but what is done against them as enemies will have no limitation except the Rights of War.

The difference between these two systems, represented by two opposite propositions now pending, may be seen in the motive which is the starting-point of each. Treating those arrayed in arms against us as criminals, we assume sovereignty, and seek to punish for violation of existing law. Treating them as enemies, we assume no sovereignty, but simply employ the means known to war in overcoming an enemy, and in obtaining security against him. In the one case our cause is founded in Municipal Law under the Constitution, and in the other case in the Rights of War under International Law. In the one case our object is simply punishment; in the other case it is assured victory.

Having determined the existence of these two sources of power, we are next led to consider the character and extent of each under the National Government: first, Rights against Criminals, founded on sovereignty, with their limitations under the Constitution; and, secondly, Rights against Enemies, founded on war, which are absolutely without constitutional limitation. Having passed these in review, the way will then be open to consider which class of rights Congress shall exercise.

I begin, of course, with Rights against Criminals, founded on sovereignty, with their limitations under the Constitution.

Rebellion is in itself the crime of treason, which is usually called the greatest crime known to the law, containing all other crimes, as the greater contains the less. But neither the magnitude of the crime nor the detestation it inspires can properly move us from duty to the Constitution. Howsoever important it may be to punish rebels, this must not be done at the expense of the Constitution. On that point I agree with the Senator from Pennsylvania [Mr. Cowan], and the Senator from Vermont [Mr. Collamer]; nor will I yield to either in determination to uphold the Constitution, which is the shield of the citizen. Show me that any proposition is without support in the Constitution, or that it offends against any constitutional safeguard, and it cannot receive my vote. Sir, I shall not allow Senators to be more careful on this head than myself. They shall not have a monopoly of this proper caution.

In proceedings against criminals there are provisions or principles of the Constitution which cannot be disregarded. I will enumerate them, and endeavor to explain their true character.

1. Congress, it is said, has no power under the Constitution over Slavery in the States. This popular principle of Constitutional Law, which is without foundation in the positive text of the Constitution, is adduced against all propositions to free the slaves of Rebels. But this is an obvious misapplication of the alleged principle, which simply means that Congress[Pg 26] has no direct power over Slavery in the States, so as to abolish or limit it. For no careful person, whose opinion is of any value, ever attributed to the pretended property in slaves an immunity from forfeiture or confiscation not accorded to other property; and this is a complete answer to the argument on this head. Even in prohibiting Slavery, as in the Jeffersonian ordinance, there is a declared exception of the penalty of crime; and so in upholding Slavery in the States, there must be a tacit, but unquestionable, exception of this penalty.

2. There must be no ex post facto law; which means that there can be no law against crime retrospective in its effect. This is clear.

3. There must be no bill of attainder; which means that there can be no special legislation, where Congress, undertaking the double function of legislature and judge, shall inflict the punishment of death without conviction by due process of law. And there is authority for assuming that this prohibition includes a bill of pains and penalties, which is a milder form of legislative attainder, where the punishment inflicted is less than death.[16] And surely no constitutional principle is more worthy of recognition.

4. No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; which means, without presentment, or other judicial proceeding. This provision, borrowed from Magna Charta, constitutes a safeguard for all: nor can it be invoked by the criminal more than by the slave; for in our Constitution it is applicable to every “person,” without distinction of condition or color. But the criminal is entitled to its protection.

5. In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and District wherein the crime shall have been committed, which District shall have been previously ascertained by law. This is the sixth amendment to the Constitution, and is not to be lost sight of now. The accused, whoever he may be, though his guilt be open as noonday, can be reached criminally only in the way described. When we consider the deep and wide-spread prejudices which must exist throughout the whole Rebel territory, it is difficult to suppose that any jury could be found within the State and District where the treason was committed who would unite in the necessary verdict of Guilty. For myself, I do not expect it; and I renounce the idea of justice in this way. Jefferson Davis himself, whose crime has culminated in Virginia, could not be convicted by a jury of that State. But it is the duty of the statesman to consider how justice, impossible in one way, may be made possible in another way.

6. No attainder of treason shall work corruption of blood, or forfeiture except during the life of the person attainted. Perhaps no provision of the Constitution, supposed pertinent to the present debate, has been more considered; nor is there any with regard to which there is greater difference of opinion. Learned lawyers in this body insist broadly that it forbids forfeiture of real estate, although not of personal, as a penalty of treason; while others insist that all the real as well as personal estate belonging to the offender may be forfeited. The words of the Constitution are technical, so as to require interpretation; and as they are derived from the Common Law, we must look to this law for[Pg 28] their meaning. By “attainder of treason” is meant judgment of death for treason,—that is, the judgment of court on conviction of treason. “Upon judgment of death for treason or felony,” says Blackstone, “a man shall be said to be attainted.”[17] Such judgment, which is, of course, a criminal proceeding, cannot, under our Constitution, work corruption of blood; which means that it cannot create obstruction or incapacity in the blood to prevent an innocent heir from tracing title through the criminal, as was cruelly done by the Common Law.

Nor shall such attainder work “forfeiture except during the life of the person attainted.” If there be any question, it arises under these words, which, it will be observed, are peculiarly technical. As the term “attainder” is confined to “judgment of death,” this prohibition is limited precisely to where that judgment is awarded; so that, if the person is not adjudged to death, there is nothing in the Constitution to forbid absolute forfeiture. This conclusion is irresistible. If accepted, it disposes of the objection in all cases where there is no judgment of death.

Even where the traitor is adjudged to death, there is good reason to doubt if his estate in fee-simple, which is absolutely his own, and alienable at his mere pleasure, may not be forfeited. It is admitted by Senators that the words of the Constitution do not forbid the forfeiture of the personal estate, which in the present days of commerce is usually much larger than the real estate, although to an unprofessional mind these words are as applicable to one as to the other; so that a person attainted of treason would forfeit all his personal estate, of[Pg 29] every name and nature, no matter what its amount, even if he did not forfeit his real estate. But since an estate in fee-simple belongs absolutely to the owner, and is in all respects subject to his disposition, there seems no reason for its exemption which is not equally applicable to personal property. The claim of the family is as strong in one case as in the other. And if we take counsel of analogy, we find ourselves led in the same direction. It is difficult to say, that, in a case of treason, there can be any limitation to the amount of fine imposed; so that in sweeping extent it may take from the criminal all his estate, real and personal. And, secondly, it is very clear that the prohibition in the Constitution, whatever it be, is confined to “attainder of treason,” and not, therefore, applicable to a judgment for felony, which at the Common Law worked forfeiture of all estate, real and personal; so that under the Constitution such forfeiture for felony can be now maintained. But assuming the Constitution applicable to treason where there is no judgment of death, it is only reasonable to suppose that this prohibition is applicable exclusively to that posthumous forfeiture depending upon corruption of blood; and here the rule is sustained by intrinsic justice. But all present estate, real as well as personal, actually belonging to the traitor, is forfeited.

Not doubting the intrinsic justice of this rule, I am sustained by the authority of Mr. Hallam, who, in a note to his invaluable History of Literature, after declaring, that, according to the principle of Grotius, the English law of forfeiture in high treason is just, being part of the direct punishment of the guilty, but that of attainder or corruption of blood is unjust, being an infliction on the innocent alone, stops to say:—

“I incline to concur in this distinction, and think it at least plausible, though it was seldom or never taken in the discussions concerning those two laws. Confiscation is no more unjust towards the posterity of an offender than fine, from which, of course, it only differs in degree.”[18]

An opinion from such an authority is entitled to much weight in determining the proper signification of doubtful words.

This interpretation is helped by another suggestion, which supposes the comma in the text of the Constitution misplaced, and that, instead of being after “corruption of blood,” it should be after “forfeiture,” separating it from the words “except during the life of the person attainted,” and making them refer to the time when the attainder takes place, rather than to the length of time for which the estate is forfeited. Thus does this much debated clause simply operate to forbid forfeiture when not pronounced “during the life of the person attainted.” In other words, the forfeiture cannot be pronounced against a dead man, or the children of a dead man, and this is all.

Amidst the confusion in which this clause is involved, you cannot expect that it will be a strong restraint upon any exercise of power under the Constitution which otherwise seems rational and just. But, whatever its signification, it has no bearing on our rights against enemies. Bear this in mind. Criminals only, and not enemies, can take advantage of it.

Such, Mr. President, are the provisions or principles of Constitutional Law controlling us in the exercise of[Pg 31] rights against criminals. If any bill or proposition, penal in character, having for its object simply punishment, and ancillary to the administration of justice, violates any of these safeguards, it is not constitutional. Therefore do I admit that the bill of the Committee, and every other bill now before the Senate, so far as they assume to exercise the Rights of Sovereignty in contradistinction to the Rights of War, must be in conformity with these provisions or principles.

But the Senator from Vermont [Mr. Collamer], in his ingenious speech, to which we all listened with so much interest, was truly festive in allusion to certain proceedings much discussed in this debate. The Senator did not like proceedings in rem, although I do not know that he positively objected to them as unconstitutional. It is difficult to imagine any such objection. Assuming that criminals cannot be reached to be punished personally, or that they have fled, the Senator from Illinois [Mr. Trumbull], and also the Senator from New York [Mr. Harris], propose to reach them through their property,—or, adopting technical language, instead of proceedings in personam, which must fail from want of jurisdiction, propose proceedings in rem. Such proceedings may not be of familiar resort, since, happily, an occasion like the present has never before occurred among us; but they are strictly in conformity with established precedents, and also with the principles by which these precedents are sustained.

Nobody can forget that smuggled goods are liable to confiscation by proceedings in rem. This is a familiar instance. The calendar of our District Courts is crowded with these cases, where the United States are[Pg 32] plaintiff, and some inanimate thing, an article of property, is defendant. Such, also, are proceedings against a ship engaged in the slave-trade. Of course, by principles of the Common Law, a conviction is necessary to divest the offender’s title; but this rule is never applied to forfeitures created by statute. It is clear that the same sovereignty which creates the forfeiture may determine the proceedings by which it shall be ascertained. If, therefore, it be constitutional to direct the forfeiture of rebel property, it is constitutional to authorize proceedings in rem against it, according to established practice. Such proceedings constitute “due process of law,” well known in our courts, familiar to the English Exchequer, and having the sanction of the ancient Roman jurisprudence. If any authority were needed for this statement, it is found in the judgment of the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of the Palmyra, where it is said:—

“Many cases exist where there is both a forfeiture in rem and a personal penalty. But in neither class of cases has it ever been decided that the prosecutions were dependent upon each other; but the practice has been, and so this Court understand the law to be, that the proceeding in rem stands independent of, and wholly unaffected by, any criminal proceeding in personam.”[19]

The reason for proceedings in rem is, doubtless, that the thing is in a certain sense an offender, or at least has coöperated with the offender,—as a ship in the slave-trade. But the same reason prevails, although perhaps to less extent, in proceedings against rebel property, which, if not an offender, has at least coöperated with[Pg 33] the offender hardly less than the ship in the slave-trade. Through his property the traitor is enabled to devote himself to treason, and to follow its accursed trade, waging war against his country; so that his property may be considered guilty also. But the condemnation of the property cannot be a bar to proceedings against the traitor himself, should he fall within our power. The two are distinct, although identical in their primary object, which is punishment.

Pardon me, Sir, if, dwelling on these things, I feel humbled that the course of the debate imposes such necessity. Standing, as we do, face to face with enemies striking at the life of the Republic, it is painful to find ourselves subjected to all the embarrassments of a criminal proceeding, as if this war were an indictment, and the army and navy of the United States, now mustered on land and sea, were only a posse comitatus. It should not be so. The Rebels have gone outside of the Constitution to make war upon their country. It is for us to pursue them as enemies outside of the Constitution, where they wickedly place themselves, and where the Constitution concurs in placing them also. So doing, we simply obey the Constitution, and act in all respects constitutionally.

And this brings me to the second chief head of inquiry, not less important than the first: What are the Rights against Enemies which Congress may exercise in War?

Clearly the United States may exercise all the Rights[Pg 34] of War which according to International Law belong to independent states. In affirming this proposition, I waive for the present all question whether these rights are to be exercised by Congress or by the President. It is sufficient that every nation has in this respect perfect equality; nor can any Rights of War accorded to other nations be denied to the United States. Harsh and repulsive as these rights unquestionably are, they are derived from the overruling, instinctive laws of self-defence, common to nations as to individuals. Every community having the form and character of sovereignty has a right to national life, and in defence of such life may put forth all its energies. Any other principle would leave it the wretched prey of wicked men, abroad or at home. In vain you accord the rights of sovereignty, if you despoil it of other rights without which sovereignty is only a name. “I think, therefore I am,” was the sententious utterance by which the first of modern philosophers demonstrated personal existence. “I am, therefore I have rights,” is the declaration of every sovereignty, when its existence is assailed.

Pardon me, if I interpose again to remind you of the essential difference between these rights and those others just considered. Though incident to sovereignty, they are not to be confounded with those peaceful rights which are all exhausted in a penal statute within the limitations of the Constitution. The difference between a judge and a general, between the halter of the executioner and the sword of the soldier, between the open palm and the clenched fist, is not greater than that between these two classes of rights. They are different in origin, different in extent, and different in object.

I rejoice to believe that civilization has already done much to mitigate the Rights of War; and it is among long cherished visions, which present events cannot make me renounce, that the time is coming when all these rights will be further softened to the mood of permanent peace. Though in the lapse of generations changed in many things, especially as regards non-combatants and private property on land, these rights still exist under the sanction of the Law of Nations, to be claimed whenever war prevails. It is absurd to accord the right to do a thing without according the means necessary to the end. And since war, which is nothing less than organized force, is permitted, all the means to its effective prosecution are permitted also, tempered always by that humanity which strengthens while it charms.

I begin this inquiry by putting aside all Rights of War against persons. In battle, persons are slain or captured, and, if captured, detained as prisoners till the close of the war, unless previously released by exchange or clemency. But these rights do not enter into the present discussion, which concerns property only, and not persons. From the nature of the case, it is only against property, or what is claimed as such, that confiscation is directed. Therefore I say nothing of persons, nor shall I consider any question of personal rights. According to the Rights of War, property, although inanimate, shares the guilt of its owner. Like him, it is criminal, and may be prosecuted to condemnation in tribunals constituted for the purpose, without any of those immunities claimed by persons accused of crime. It is Rights of War against the property of an enemy which I now consider.

If we resort to the earlier authorities, not excepting Grotius himself, we find these rights stated most austerely. I shall not go back to any such statement, but content myself with one of later date. You may find it harsh; but here it is.

“Since this is the very condition of war, that enemies are despoiled of all right and proscribed, it stands to reason that whatever property of an enemy is found in his enemy’s country changes its owner and goes to the treasury. It is customary, moreover, in almost every declaration of war, to ordain that goods of the enemy, as well those found among us as those taken in war, be confiscated.… Pursuant to the mere Right of War, even immovables could be sold and their price turned into the treasury, as is the practice in regard to movables; but throughout almost all Europe only a register is made of immovables, in order that during the war the treasury may receive their rents and profits, but at the termination of the war the immovables themselves are by treaty restored to the former owners.”[20]

These are the words of the eminent Dutch publicist, Bynkershoek, in the first half of the last century. In adducing them now I present them as adopted by Mr. Jefferson, in his remarkable answer to the note of the British minister at Philadelphia on the confiscations of the American Revolution. There are no words of greater weight in any writer on the Law of Nations. But Mr. Jefferson did not content himself with quotation. In the same state paper he thus declares unquestionable rights:—

“It cannot be denied that the state of war strictly permits a nation to seize the property of its enemies found within its [Pg 37]own limits or taken in war, and in whatever form it exists, whether in action or possession.”[21]

This sententious statement is under date of 1792, and, when we consider the circumstances which called it forth, may be accepted as American doctrine. But even in our own day, since the beginning of the present war, the same principle has been stated yet more sententiously in another quarter. The Lord Advocate of Scotland, in the British House of Commons, as late as 17th March of the present year, declared:—

“The honorable gentleman spoke as if it was no principle of war that private rights should suffer at the hands of the adverse belligerent. But that was the true principle of war. If war was not to be defined—as it very nearly might be—as a denial of the rights of private property to the enemy, that denial was certainly one of the essential ingredients in it.”[22]

In quoting these authorities, which are general in their bearing, I do not stop to consider their modification according to the discretion of the belligerent power. I accept them as the starting-point in the present inquiry, and assume that by the Rights of War enemy property may be taken. But rights with regard to such property are modified by the locality of the property; and this consideration makes it proper to consider them under two heads: first, rights with regard to enemy property actually within the national jurisdiction; and, secondly, rights with regard to enemy property actually outside the national jurisdiction. It is easy to see, that,[Pg 38] in the present war, rights against enemy property actually outside the national jurisdiction must exist a fortiori against such property actually within the jurisdiction. But, for the sake of clearness, I shall speak of them separately.

First. I begin with the Rights of War over enemy property actually within the national jurisdiction. In stating the general rule, I adopt the language of a recent English authority.

“Although there have been so many conventions granting exemption from the liabilities resulting from a state of war, the right to seize the property of enemies found in our territory when war breaks out remains indisputable, according to the Law of Nations, wherever there is no such special convention. All jurists, including the most recent, such as De Martens and Klüber, agree in this decision.”[23]

This statement is general, but unquestionable even in its rigor. For the sake of clearness and accuracy it must be considered in its application to different kinds of property.

1. It is undeniable, that, in generality, the rule must embrace real property, or, as termed by the Roman Law and the Continental systems of jurisprudence, immovables; but so important an authority as Vattel excepts this species of property, for the reason, that, being acquired by consent of the sovereign, it is as if it belonged to his own subjects.[24] But personal property is also under the same safeguard, and yet it is not embraced within the exception. If such, indeed, be the reason for[Pg 39] the exception of real property, it loses all applicability where the property belongs to an enemy who began by breaking faith on his side. Surely, whatever the immunity of an ordinary enemy, it is difficult to see how a rebel enemy, whose hostility is bad faith in arms, can plead any safeguard. Cessante ratione, cessat et ipsa lex, is an approved maxim of the law; and since with us the reason of Vattel does not exist, the exception which he propounds need not be recognized, to the disparagement of the general rule.

2. The rule is necessarily applicable to all personal property, or, as it is otherwise called, movables. On this head there is hardly a dissenting voice, while the Supreme Court of the United States, in a case constantly cited in this debate, has solemnly affirmed it. I refer to Brown v. United States,[25] where the broad principle is assumed that war gives to the sovereign full right to confiscate the property of the enemy, wherever found, and that the mitigations of the rule, derived from modern civilization, may affect the exercise of the right, but cannot impair the right itself. Goods of the enemy actually in the country, and all vessels and cargoes afloat in our ports, at the commencement of hostilities, were declared liable to confiscation. In England, it is the constant usage, under the name of “Droits of Admiralty,” to seize and condemn property of an enemy in its ports at the breaking out of hostilities.[26] But this was not followed in the Crimean War, although the claim itself has never been abandoned.

3. The rule, in strictness, also embraces private debts due to an enemy. Although justly obnoxious to the[Pg 40] charge of harshness, and uncongenial with an age of universal commerce, this application is recognized by the judicial authorities of the United States. Between debts contracted under faith of laws and property acquired under faith of the same laws reason draws no distinction; and the right of the sovereign to confiscate debts is precisely the same with the right to confiscate other property within the country on the breaking out of war. Both, it is said, require some special act expressing the sovereign will, and both depend less on any flexible rule of International Law than on paramount political considerations, which International Law will not control. Of course, just so far as slaves are regarded as property, or as bound to service or labor, they cannot constitute an exception to this rule, while the political considerations entering so largely into its application have with regard to them commanding force. In their case, by natural metamorphosis, confiscation becomes emancipation.

Such are recognized Rights of War touching enemy property within the national jurisdiction.

Secondly. The same broad rule with which I began may be stated touching enemy property beyond the national jurisdiction, subject, of course, to mitigation from usage, policy, and humanity, but still existing, to be employed in the discretion of the belligerent power. It may be illustrated by different classes of cases.

1. Public property of all kinds belonging to an enemy,—that is, property of the government or prince,—including lands, forests, fortresses, munitions of war, movables,—is all subject to seizure and appropriation by the conqueror, who may transfer the same by valid[Pg 41] title, substituting himself, in this respect, for the displaced government or prince. It is obvious that in the case of immovables the title is finally assured only by the establishment of peace, while in the case of movables it is complete from the moment the property comes within the firm possession of the captor so as to be alienated indefeasibly. In harmony with the military prepossessions of ancient Rome, such title was considered the best to be had, and its symbol was a spear.

2. Private property of an enemy at sea, or afloat in port, is indiscriminately liable to capture and confiscation; but the title is assured only by condemnation in a competent court of prize.

3. While private property of an enemy on land, according to modern practice, is exempt from seizure simply as private property, yet it is exposed to seizure in certain specified cases. Indeed, it is more correct to say, with the excellent Manning, that it “is still considered as liable to seizure,” under circumstances constituting in themselves a necessity, of which the conqueror is judge.[27] It need not be added that this extraordinary power must be so used as not to assume the character of spoliation. It must have an object essential to the conduct of the war. But, with such object, it cannot be questioned. The obvious reason for exemption is, that a private individual is not personally responsible, as the government or prince. But every rebel is personally responsible.

4. Private property of an enemy on land may be taken as a penalty for the illegal acts of individuals, or of the community to which they belong. The exercise[Pg 42] of this right is vindicated only by peculiar circumstances; but it is clearly among the recognized agencies of war, and it is easy to imagine that at times it may be important, especially in dealing with a dishonest rebellion.

5. Private property of an enemy on land may be taken for contributions to support the war. This has been done in times past on a large scale. Napoleon adopted the rule that war should support itself. Upon the invasion of Mexico by the armies of the United States, in 1846, the commanding generals were at first instructed to abstain from taking private property without purchase at a fair price; but subsequent instructions were of a severer character. It was declared by Mr. Marcy, at the time Secretary of War, that an invading army had the unquestionable right to draw supplies from the enemy without paying for them, and to require contributions for its support, and to make the enemy feel the weight of the war.[28] Such contributions are sometimes called “requisitions,” and a German writer on the Law of Nations says that it was Washington who “invented the expression and the thing.”[29] Possibly the expression; but the thing is as old as war.

6. Private property of an enemy on land may be taken on the field of battle, in operations of siege, or the storming of a place refusing to capitulate. This passes under the offensive name of “booty” or “loot.” In the late capture of the imperial palace of Pekin by the allied forces of France and England, this right was illustrated by the surrender of its contents, including[Pg 43] silks, porcelain, and furniture, to the lawless cupidity of an excited soldiery.

7. Pretended property of an enemy in slaves may unquestionably be taken, and, when taken, will of course be at the disposal of the captor. If slaves are regarded as property, then will their confiscation come precisely within the rule already stated. But, since slaves are men, there is still another rule of public law applicable to them. It is clear, that, where there is an intestine division in an enemy country, we may take advantage of it, according to Halleck, in his recent work on International Law, “without scruple.”[30] But Slavery is more than an intestine division; it is a constant state of war. The ancient Scythians said to Alexander: “Between the master and slave no friendship exists; even in peace the Rights of War are still preserved.”[31] Giving freedom to slaves, a nation in war simply takes advantage of the actual condition of things. But there is another vindication of this right, which I prefer to present in the language of Vattel. After declaring that “in conscience and by the laws of equity” we may be obliged to restore “booty” recovered from an enemy who had taken it in unjust war, this humane publicist proceeds as follows.

“The obligation is more certain and more extensive with regard to a people whom our enemy has unjustly oppressed. For a people thus spoiled of their liberty never renounce the hope of recovering it. If they have not voluntarily incorporated themselves with the state by which they have been subdued, if they have not freely aided her in the war against us, we ought certainly so to use our victory as not merely to give [Pg 44]them a new master, but to break their chains. To deliver an oppressed people is a noble fruit of victory; it is a valuable advantage gained thus to acquire a faithful friend.”[32]

These are not the words of a visionary, or of a speculator, or of an agitator, but of a publicist, an acknowledged authority on the Law of Nations.

Therefore, according to the Rights of War, slaves, if regarded as property, may be declared free; or if regarded as men, they may be declared free, under two acknowledged rules: first, of self-interest, to procure an ally; and, secondly, of conscience and equity, to do an act of justice ennobling victory.

Such, Sir, are acknowledged Rights of War with regard to enemy property, whether within or beyond our territorial jurisdiction. I do little more than state these rights, without stopping to comment. If they seem harsh, it is because war in essential character is harsh. It is sufficient for our present purpose that they exist.

Of course, all these rights belong to the United States. There is not one of them which can be denied. They are ours under that great title of Independence by which our place was assured in the Family of Nations. Dormant in peace, they are aroused into activity only by the breath of war, when they all place themselves at our bidding, to be employed at our own time, in our own way, and according to our own discretion, subject only to that enlightened public opinion which now rules the civilized world.

Belonging to the United States by virtue of International Law, and being essential to self-defence, they are naturally deposited with the supreme power, which holds the issues of peace and war. Doubtless there are Rights of War, embracing confiscation, contribution, and liberation, to be exercised by any commanding general in the field, or to be ordered by the President, according to the exigency. Mr. Marcy was not ignorant of his duty, when, by instructions from Washington, in the name of the President, he directed the levy of contributions in Mexico. In European countries all these Rights of War which I have reviewed to-day are deposited with the executive alone,—as in England with the Queen in Council, and in France and Russia with the Emperor; but in the United States they are deposited with the legislative branch, being the President, Senate, and House of Representatives, whose joint action becomes the supreme law of the land. The Constitution is not silent on this question. It expressly provides that Congress shall have power, first, “to declare war,” and thus set in motion all the Rights of War; secondly, “to grant letters of marque and reprisal,” being two special agencies of war; thirdly, “to make rules concerning captures on land and water,” which power of itself embraces the whole field of confiscation, contribution, and liberation; fourthly, “to raise and support armies,” which power, of course, comprehends all means for this purpose known to the Rights of War; fifthly, “to provide and maintain a navy,” plainly according to the Rights of War; sixthly, “to make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces,” another power involving confiscation, contribution, and liberation; and, seventhly,[Pg 46] “to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions,” a power which again sets in motion all the Rights of War. But, as if to leave nothing undone, the Constitution further empowers Congress “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” In pursuance of these powers, Congress has already enacted upwards of one hundred articles of war for the government of the army, one of which provides for the security of public stores taken from the enemy. It has also sanctioned the blockade of the Rebel ports according to International Law. And only at the present session we have enacted an additional article to regulate the conduct of officers and men towards slaves seeking shelter in camp. Proceeding further on the present occasion, it will act in harmony with its own precedents, as well as with its declared powers, according to the very words of the Constitution. Language cannot be broader. Under its comprehensive scope there is nothing essential to the prosecution of the war, its conduct, its support, or its success,—yes, Sir, there can be nothing essential to its success, which is not positively within the province of Congress. There is not one of the Rights of War which Congress may not invoke. There is not a single weapon in its terrible arsenal which Congress may not grasp.

Such are indubitable powers of Congress. It is not questioned that these may all be employed against a public enemy; but there are Senators who strangely hesitate to employ them against that worst enemy of all, who to hostility adds treason, and teaches his country

The rebel in arms is an enemy, and something more; nor is there any Right of War which may not be employed against him in its extremest rigor. In appealing to war, he has voluntarily renounced all safeguards of the Constitution, and put himself beyond its pale. In ranging himself among enemies, he has broken faith so as to lose completely all immunity from the strictest penalties of war. As an enemy, he must be encountered; nor can our army be delayed in the exercise of the Rights of War by any misapplied questions of ex post facto, bills of attainder, attainder of treason, due process of law, or exemption from forfeiture. If we may shoot rebel enemies in battle, if we may shut them up in fortresses or prisons, if we may bombard their forts, if we may occupy their fields, if we may appropriate their crops, if we may blockade their ports, if we may seize their vessels, if we may capture their cities, it is vain to say that we may not exercise against them the other associate prerogatives of war. Nor can any technical question of constitutional rights be interposed in one case more than another. Every prerogative of confiscation, requisition, or liberation known in war may be exercised against rebels in arms precisely as against public enemies. Ours are belligerent rights to the fullest extent.

Sir, the case is strong. The Rebels are not only criminals, they are also enemies, whose property is actually within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States; so that, according to the Supreme Court, it only remains for Congress to declare the Rights of War to be exercised against them. The case of Brown,[33] so often cited in this debate, affirms that enemy property actually within our territorial jurisdiction can be seized only by[Pg 48] virtue of an Act of Congress, and recognizes the complete liability of all such property, when actually within such territorial jurisdiction. It is therefore, in all respects, a binding authority, precisely applicable; so that Senators who would impair its force must deny either that the Rebels are enemies or that their property is actually within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. Assuming that they are enemies, and that their property is actually within our territorial jurisdiction, the power of Congress is complete; and it is not to be confounded with that of a commanding general in the field, or of the President as commander-in-chief of the armies.