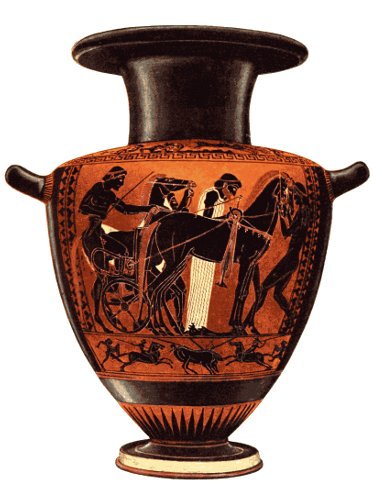

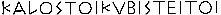

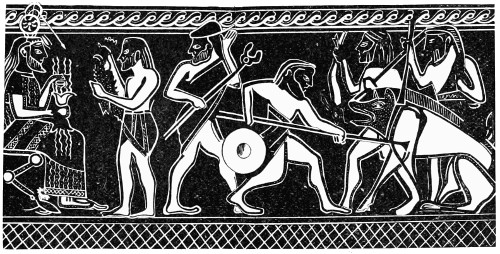

ATTIC BLACK-FIGURED HYDRIA:

HARNESSING OF HORSES TO CHARIOT

(British Museum).

Transcriber’s Note:

Minor errors in punctuation and formatting have been silently corrected. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered during its preparation. The end note also discusses the handling of the many Greek inscriptions.

Volume I of this text is available separately at Project Gutenberg at:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/48154

References to Volume I are linked as well for ease of navigation.

ATTIC BLACK-FIGURED HYDRIA:

HARNESSING OF HORSES TO CHARIOT

(British Museum).

| Page | |

| CONTENTS OF VOLUME II | v |

| LIST OF PLATES IN VOLUME II | ix |

| LIST OF TEXT-ILLUSTRATIONS IN VOLUME II | xi |

| PART III | |

| THE SUBJECTS ON GREEK VASES | |

| – | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| INTRODUCTORY—THE OLYMPIAN DEITIES | |

| Figured vases in ancient literature—Mythology and art—Relation of subjects on vases to literature—Homeric and dramatic themes and their treatment—Interpretation and classification of subjects—The Olympian deities—The Gigantomachia—The birth of Athena and other Olympian subjects—Zeus and kindred subjects—Hera—Poseidon and marine deities—The Eleusinian deities—Apollo and Artemis—Hephaistos, Athena, and Ares—Aphrodite and Eros—Hermes and Hestia | 1–53 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| DIONYSOS AND MISCELLANEOUS DEITIES | |

| Dionysos and his associates—Ariadne, Maenads, and Satyrs—Names of Satyrs and Maenads—The Nether World—General representations and isolated subjects—Charon, Erinnyes, Hekate, and Thanatos—Cosmogonic deities—Gaia and Pandora—Prometheus and Atlas—Iris and Hebe—Personifications—Sun, Moon, Stars, and Dawn—Winds—Cities and countries—The Muses—Victory—Abstract ideas—Descriptive names | 54–92 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| HEROIC LEGENDS | |

| Kastor and Polydeukes—Herakles and his twelve labours—Other contests—Relations with deities—Apotheosis—Theseus and his labours—Later scenes of his life—Perseus—Pelops and Bellerophon—Jason and the Argonauts—Theban legends—The Trojan cycle—Peleus and Thetis—The Judgment of Paris—Stories of Telephos and Troilos—Scenes from the Iliad—The death of Achilles and the Fall of Troy—The Odyssey—The Oresteia—Attic and other legends—Orpheus and the Amazons—Monsters—Historical and literary subjects | 93–153 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| SUBJECTS FROM ORDINARY LIFE | |

| Religious subjects—Sacrifices—Funeral scenes—The Drama and burlesques—Athletics—Sport and games—Musical scenes—Trades and occupations—Daily life of women—Wedding scenes—Military and naval subjects—Orientals and Barbarians—Banquets and revels—Miscellaneous subjects—Animals | 154–186 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| DETAILS OF TYPES, ARRANGEMENT, AND ORNAMENTATION | |

| Distinctions of types—Costume and attributes of individual deities— Personifications—Heroes—Monsters—Personages in everyday life—Armour and shield-devices—Dress and ornaments—Physiognomical expression on vases—Landscape and architecture—Arrangement of subjects—Ornamental patterns—Maeander, circles, and other geometrical patterns—Floral patterns—Lotos and palmettes—Treatment of ornamentation in different fabrics | 187–235 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| INSCRIPTIONS ON GREEK VASES | |

| Importance of inscriptions on vases—Incised inscriptions—Names and prices incised underneath vases—Owners’ names and dedications—Painted inscriptions—Early Greek alphabets—Painted inscriptions on early vases—Corinthian, Ionic, Boeotian, and Chalcidian inscriptions—Inscriptions on Athenian vases—Dialect—Artists’ signatures—Inscriptions relating to the subjects—Exclamations—Καλός-names—The Attic alphabet and orthography—Chronology of Attic inscriptions—South Italian vases with inscriptions | 236–278 |

| PART IV | |

| ITALIAN POTTERY | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| ETRUSCAN AND SOUTH ITALIAN POTTERY | |

| Early Italian civilisation—Origin of Etruscans—Terramare civilisation—Villanuova period—Pit-tombs—Hut-urns—Trench-tombs—Relief-wares and painted vases from Cervetri—Chamber-tombs—Polledrara ware—Bucchero ware—Canopic jars—Imitations of Greek vases—Etruscan inscriptions—Sculpture in terracotta—Architectural decoration—Sarcophagi—Local pottery of Southern Italy—Messapian and Peucetian fabrics | 279–329 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| TERRACOTTA IN ROMAN ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE | |

| Clay in Roman architecture—Use of bricks—Methods of construction—Tiles—Ornamental antefixae—Flue-tiles—Other uses—Inscriptions on bricks and tiles—Military tiles—Mural reliefs—List of subjects—Roman sculpture in terracotta—Statuettes—Uses at Rome—Types and subjects—Gaulish terracottas—Potters and centres of fabric—Subjects—Miscellaneous uses of terracotta—Money-boxes—Coin-moulds | 330–392 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| ROMAN LAMPS | |

| Introduction of lamps at Rome—Sites where found—Principal parts of lamps—Purposes for which used—Superstitious and other uses—Chronological account of forms—Technical processes—Subjects—Deities—Mythological and literary subjects—Genre subjects and animals—Inscriptions on lamps—Names of potters and their distribution—Centres of manufacture | 393–429 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| ROMAN POTTERY: TECHNICAL PROCESSES, SHAPES, AND USES | |

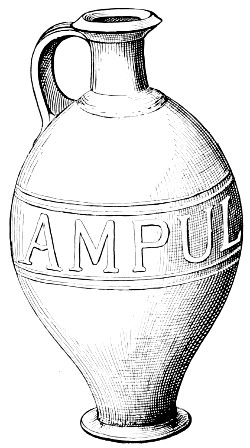

| Introductory—Geographical and historical limits—Clay and glaze—Technical processes—Stamps and moulds—Barbotine and other methods—Kilns found in Britain, Gaul, and Germany—Use of earthenware among the Romans—Echea—Dolia and Amphorae—Inscriptions on amphorae—Cadus, Ampulla, and Lagena—Drinking-cups—Dishes—Sacrificial vases—Identification of names | 430–473 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| ROMAN POTTERY, HISTORICALLY TREATED; ARRETINE WARE | |

| Roman Pottery mentioned by ancient writers—“Samian” ware—Centres of fabric—The pottery of Arretium—Characteristics—Potters’ stamps—Shapes of Arretine vases—Sources of inspiration for decoration—“Italian Megarian bowls”—Subjects—Distribution of Arretine wares | 474–496 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| ROMAN POTTERY (continued); PROVINCIAL FABRICS | |

| Distribution of Roman pottery in Europe—Transition from Arretine to provincial wares—Terra sigillata—Shapes and centres of fabric—Subjects—Potters’ stamps—Vases with barbotine decoration—The fabrics of Gaul—St. Rémy—Graufesenque—“Marbled” vases—Vases with inscriptions (Banassac)—Lezoux—Vases with medallions (Southern Gaul)—Fabrics of Germany—Terra sigillata in Britain—Castor ware—Upchurch and New Forest wares—Plain pottery—Mortaria—Conclusion | 497–555 |

| INDEX | 557 |

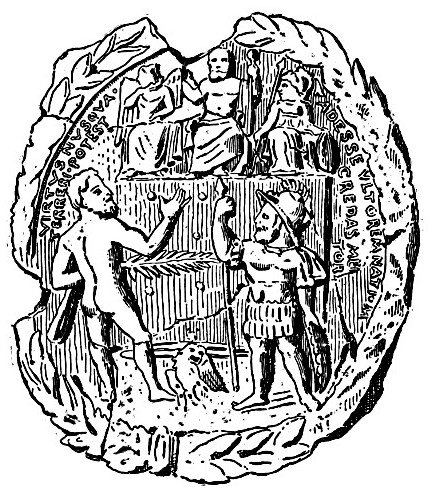

| PLATE | ||

| XLIX. | Attic black-figured hydria: Harnessing of horses to chariot (colours) | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | ||

| L. | Contest of Athena and Poseidon: vase at Petersburg (from Baumeister) | 24 |

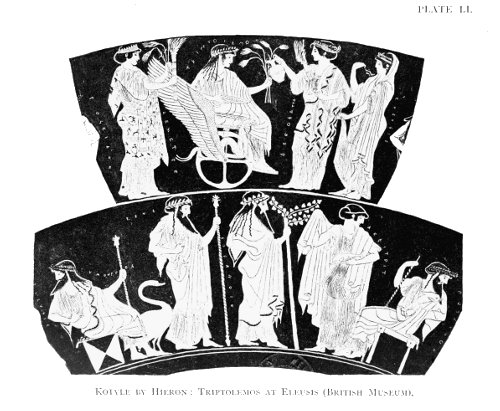

| LI. | Kotyle by Hieron: Triptolemos at Eleusis | 26 |

| LII. | The Under-world, from an Apulian vase at Munich (from Furtwaengler and Reichhold) | 66 |

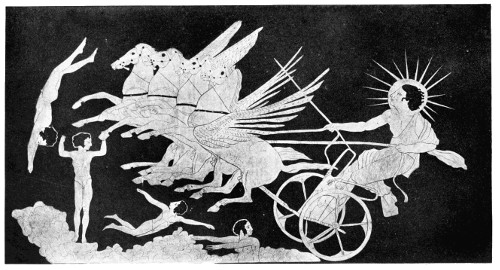

| LIII. | Helios and Stars (the Blacas krater) | 78 |

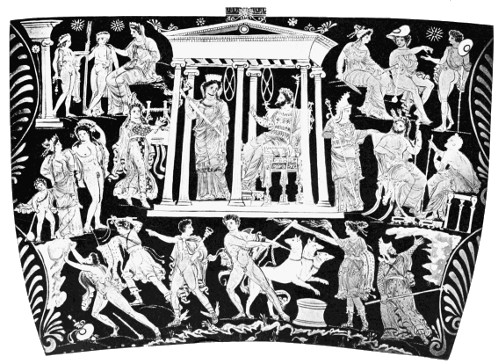

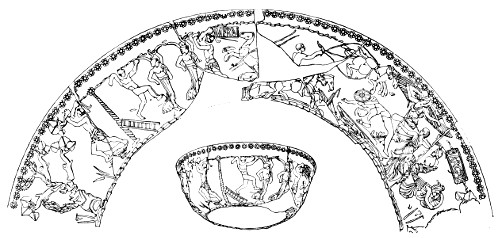

| LIV. | The Sack of Troy: kylix by Brygos in Louvre (from Furtwaengler and Reichhold) | 134 |

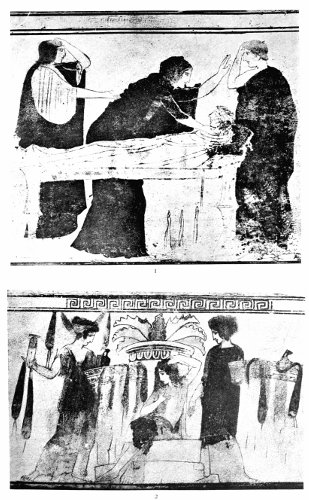

| LV. | Scenes from funeral lekythi (Prothesis and cult of tomb) | 158 |

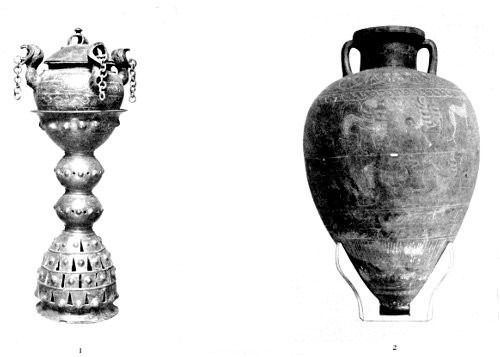

| LVI. | Early Etruscan red ware | 300 |

| LVII. | Etruscan hut-urn and Bucchero ware | 302 |

| LVIII. | Etruscan imitations of Greek vases | 308 |

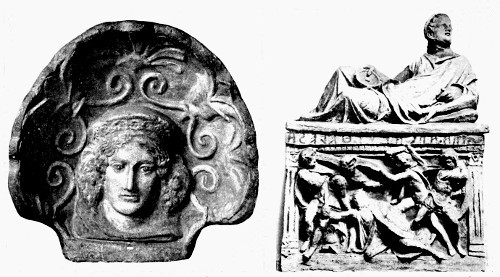

| LIX. | Etruscan antefix and sarcophagus | 316 |

| LX. | Sarcophagus of Seianti Thanunia | 322 |

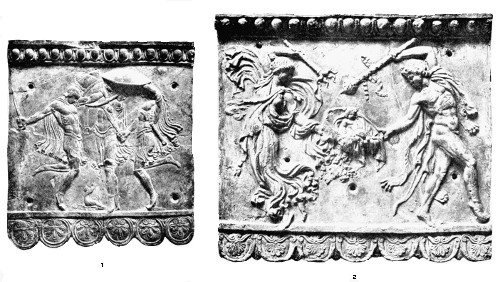

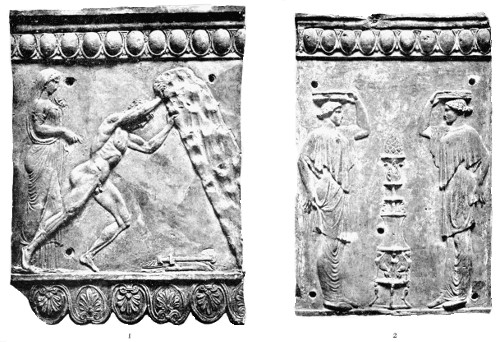

| LXI. | Roman mural reliefs: Zeus and Dionysos | 366 |

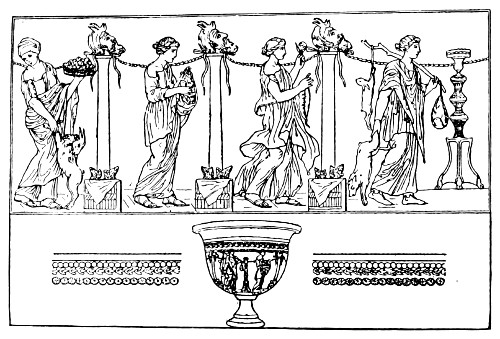

| LXII. | Roman mural reliefs: Theseus; priestesses | 370 |

| LXIII. | Roman lamps (1st century B.C.) | 402 |

| LXIV. | Roman lamps: mythological and literary subjects | 412 |

| LXV. | Roman lamps: miscellaneous subjects | 416 |

| LXVI. | Moulds and stamp of Arretine ware | 492 |

| LXVII. | Gaulish pottery (Graufesenque fabric) | 520 |

| LXVIII. | Gaulish pottery from Britain (Lezoux fabric) | 526 |

| LXIX. | Romano-British and Gaulish pottery | 544 |

| FIG. | PAGE | ||

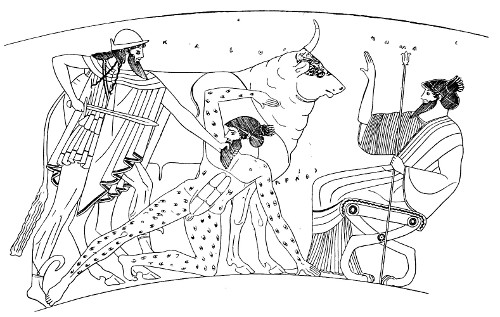

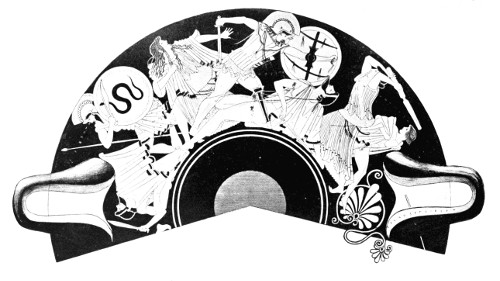

| 111. | Gigantomachia, from Ionic vase in Louvre | Mon. dell’ Inst. | 13 |

| 112. | Poseidon and Polybotes, from kylix in Berlin | Gerhard | 14 |

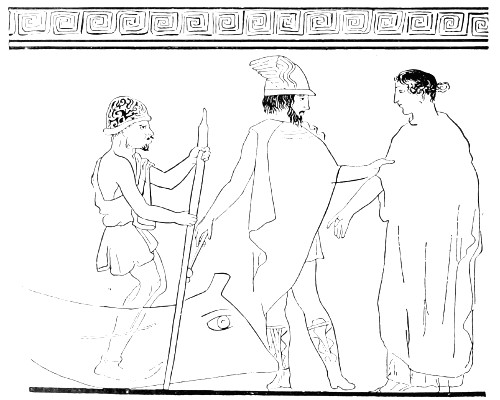

| 113. | The birth of Athena | Brit. Mus. | 16 |

| 114. | Hermes slaying Argos (vase at Vienna) | Wiener Vorl. | 20 |

| 115. | Poseidon and Amphitrite (Corinthian pinax) | Ant. Denkm. | 23 |

| 116. | Apollo, Artemis, and Leto | Mon. dell’ Inst. | 30 |

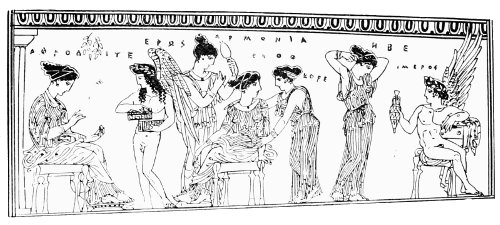

| 117. | Aphrodite and her following (vase at Athens) | Ἐφ. Ἀρχ. | 43 |

| 118. | Eros with kottabos-stand | Brit. Mus. | 48 |

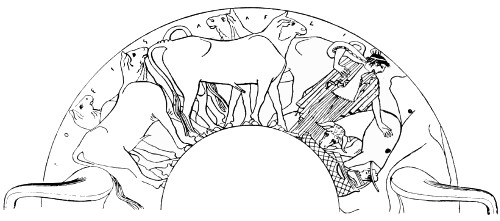

| 119. | Hermes with Apollo’s oxen (in the Vatican) | Baumeister | 51 |

| 120. | Dionysos with Satyrs and Maenads (Pamphaios hydria) | Brit. Mus. | 59 |

| 121. | Maenad in frenzy (cup at Munich) | Baumeister | 63 |

| 122. | Charon’s bark (lekythos at Munich) | Baumeister | 70 |

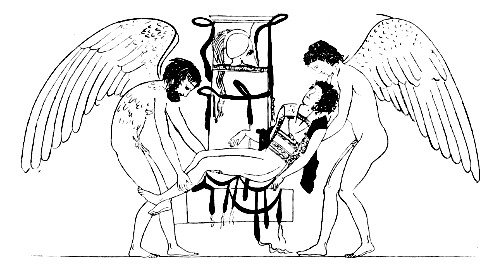

| 123. | Thanatos and Hypnos with body of warrior | Brit. Mus. | 71 |

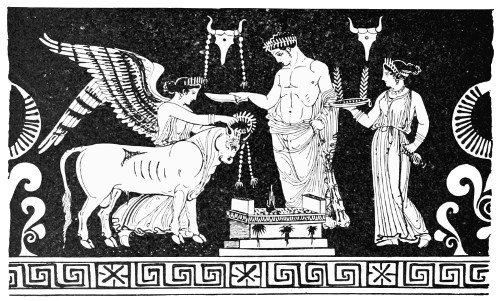

| 124. | Nike sacrificing bull | Brit. Mus. | 88 |

| 125. | Herakles and the Nemean lion | Brit. Mus. | 96 |

| 126. | Herakles bringing the boar to Eurystheus | Brit. Mus. | 97 |

| 127. | Apotheosis of Herakles (vase at Palermo) | Arch. Zeit. | 107 |

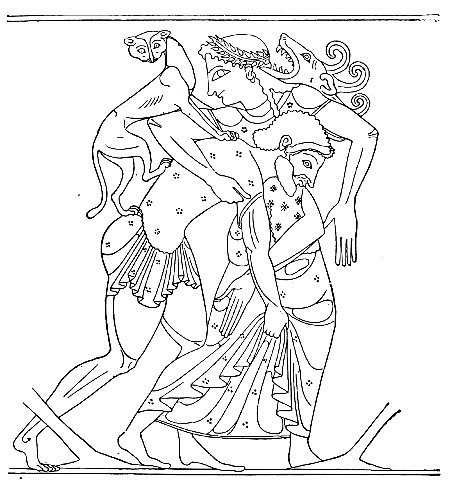

| 128. | Peleus seizing Thetis | Brit. Mus. | 121 |

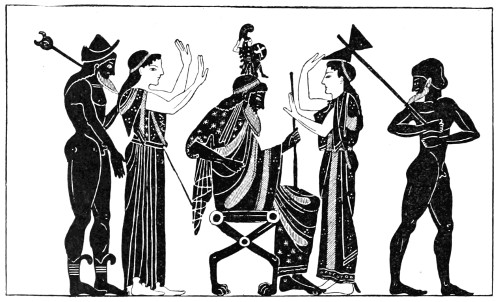

| 129. | Judgment of Paris (Hieron cup in Berlin) | Wiener Vorl. | 122 |

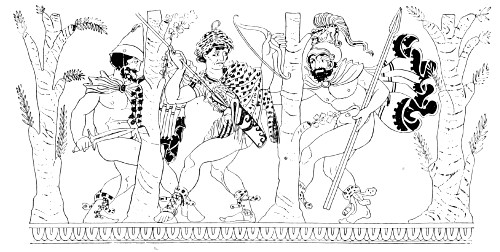

| 130. | Capture of Dolon | Brit. Mus. | 129 |

| 131. | Pentheus slain by Maenads | Brit. Mus. | 142 |

| 132. | Kroisos on the funeral pyre (Louvre) | Baumeister | 150 |

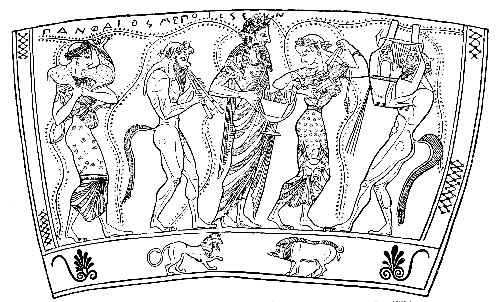

| 133. | Alkaios and Sappho (Munich) | Baumeister | 152 |

| 134. | Scene from a farce | Brit. Mus. | 161 |

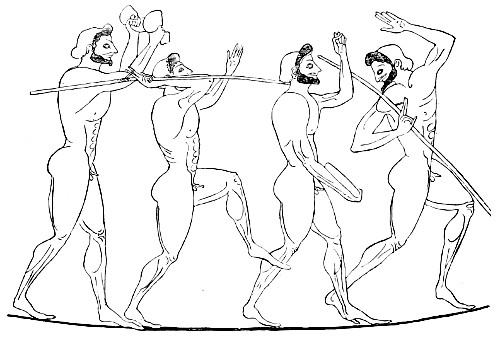

| 135. | Athletes engaged in the Pentathlon | Brit. Mus. | 163 |

| 136. | Agricultural scenes (Nikosthenes cup in Berlin) | Baumeister | 170 |

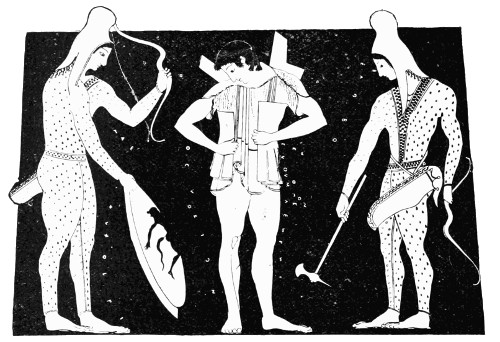

| 137. | Warrior arming; archers (Euthymides amphora in Munich) | Hoppin | 176 |

| 138. | Banqueters playing kottabos | Brit. Mus. | 181 |

| 139. | Maeander or embattled pattern | 212 | |

| 140. | Maeander (Attic) | 212 | |

| 141. | Maeander (Ionic) | 212 | |

| 142. | Maeander and star pattern | 212 | |

| 143. | Maeander (Attic, 5th century) | 213 | |

| 144. | Maeander (Attic, about 480 B.C.) | 213 | |

| 145. | Net-pattern | 215 | |

| 146. | Chequer-pattern | 216 | |

| 147. | Tangent-circles | 216 | |

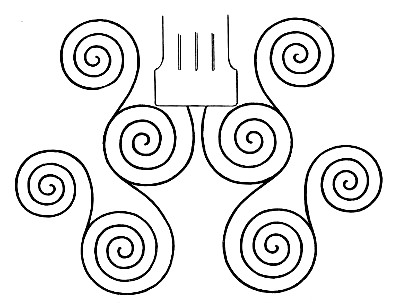

| 148. | Spirals under handles (Exekias) | 217 | |

| 149. | Wave-pattern (South Italy) | 218 | |

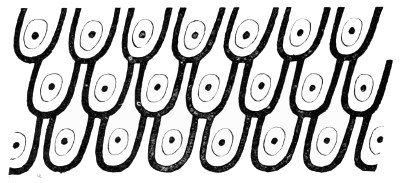

| 150. | Scale-pattern (Daphnae) | 218 | |

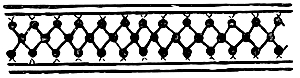

| 151. | Guilloche or plait-band (Euphorbos pinax) | 219 | |

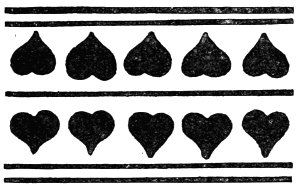

| 152. | Tongue-pattern | 219 | |

| 153. | Egg-pattern | 220 | |

| 154. | Leaf- or chain-pattern | 221 | |

| 155. | Ivy-wreath (black-figure period) | 222 | |

| 156. | Ivy-wreath (South Italian) | 222 | |

| 157. | Laurel-wreath (South Italian) | 223 | |

| 158. | Vallisneria spiralis (Mycenaean) | 224 | |

| 159. | Lotos-flower (Cypriote) | 224 | |

| 160. | Lotos-flowers and buds (Rhodian) | Riegl | 225 |

| 161. | Palmette-and lotos-pattern (early B.F.) | 225 | |

| 162. | Lotos-buds (Attic B.F.) | 226 | |

| 163. | Chain of palmettes and lotos (early B.F.) | 226 | |

| 164. | Palmettes and lotos under handles (Attic B.F.) | 227 | |

| 165. | Palmette on neck of red-bodied amphorae | 228 | |

| 166. | Enclosed palmettes (R.F. period) | 228 | |

| 167. | Oblique palmettes (late R.F.) | 229 | |

| 168. | Palmette under handles (South Italian) | 230 | |

| 169. | Rosette (Rhodian) | 231 | |

| 170. | Rosette (Apulian) | 231 | |

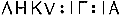

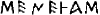

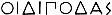

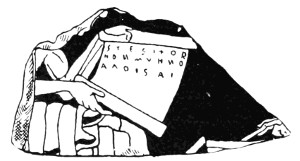

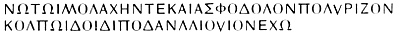

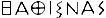

| 171. | Facsimile of inscription on Tataie lekythos | Brit. Mus. | 242 |

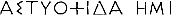

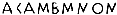

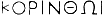

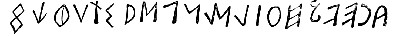

| 172. | Facsimile of Dipylon inscription | Ath. Mitth. | 243 |

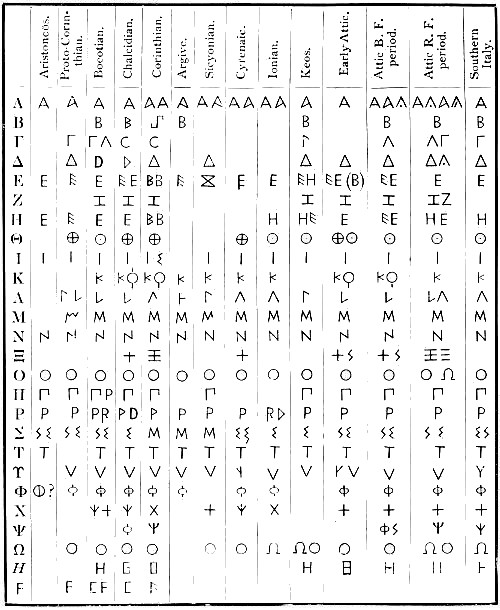

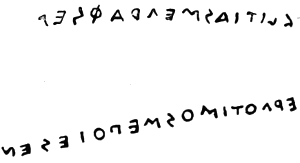

| 173. | Scheme of alphabets on Greek vases | 248 | |

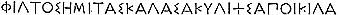

| 174. | Facsimile of inscription on Corinthian pinax | Roehl | 251 |

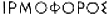

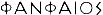

| 175. | Facsimile of signatures on François vase | Furtwaengler and Reichhold | 257 |

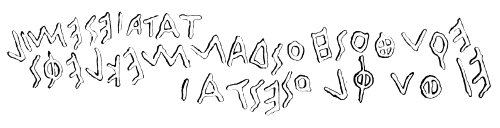

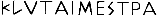

| 176. | Facsimile of signature of Nikias | Brit. Mus. | 259 |

| 177. | Figure with inscribed scroll (fragment at Oxford) | 264 | |

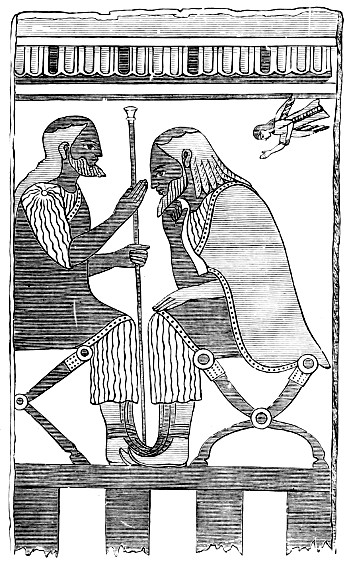

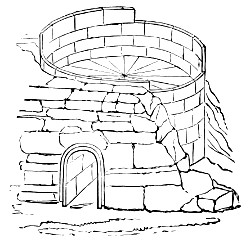

| 178. | Etruscan tomb with cinerary urn | Ann. dell’ Inst. | 285 |

| 179. | Villanuova cinerary urns from Corneto | Notizie | 286 |

| 180. | Painted pithos from Cervetri in Louvre | Gaz. Arch. | 293 |

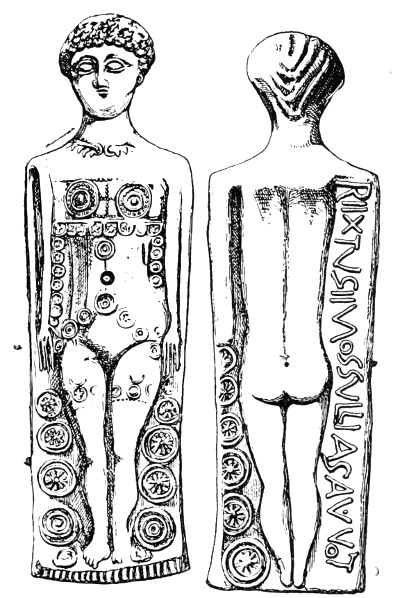

| 181. | Canopic jar in bronze-plated chair | Mus. Ital. | 305 |

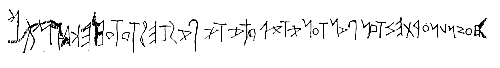

| 182. | Etruscan alphabet, from a vase | Dennis | 312 |

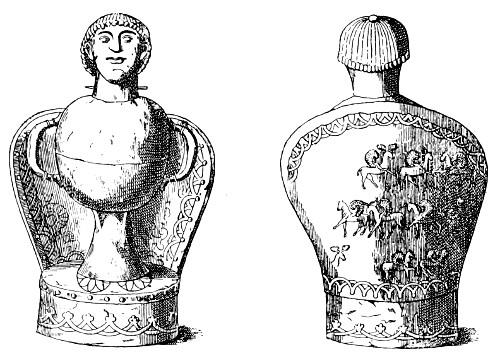

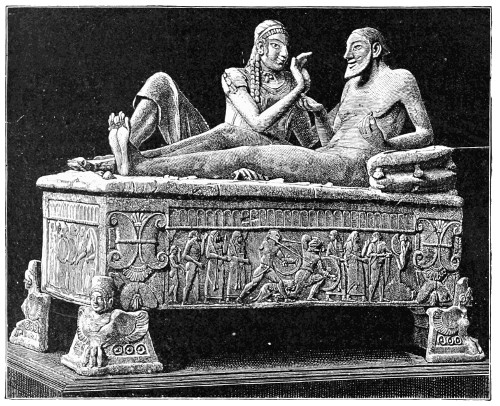

| 183. | Terracotta sarcophagus in Brit. Mus. | Dennis | 318 |

| 184. | Painted terracotta slab in Louvre | Dennis | 319 |

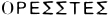

| 185. | Askos of local Apulian fabric | Brit. Mus. | 326 |

| 186. | Krater of “Peucetian” fabric | Notizie | 328 |

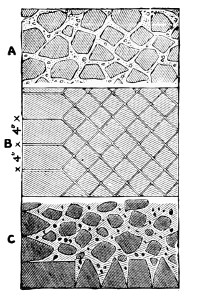

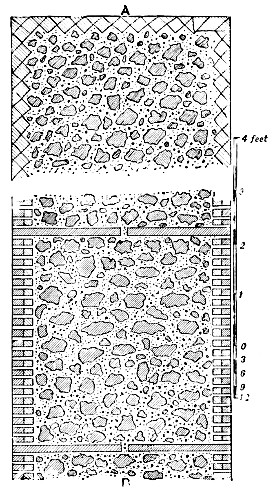

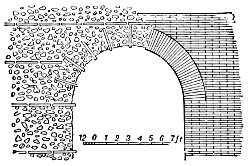

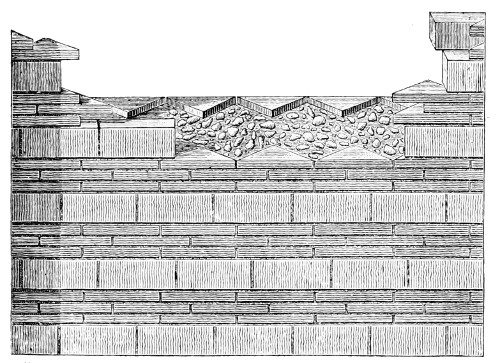

| 187. | Concrete wall at Rome | Middleton | 338 |

| 188. | Concrete wall faced with brick | Middleton | 339 |

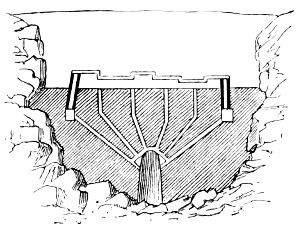

| 189. | Concrete arch faced with brick | Middleton | 339 |

| 190. | Diagram of Roman wall-construction | Blümner | 340 |

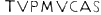

| 191. | Roman terracotta antefix | Brit. Mus. | 343 |

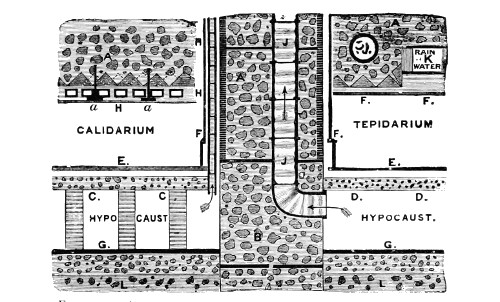

| 192. | Method of heating in Baths of Caracalla | Middleton | 347 |

| 193. | Flue-tile with ornamental patterns | 348 | |

| 194. | Stamped Roman tile | Brit. Mus. | 354 |

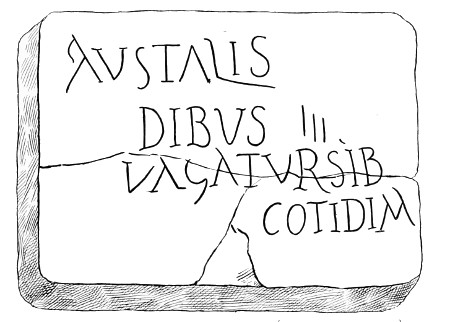

| 195. | Inscribed tile in Guildhall Museum | 359 | |

| 196. | Inscribed tile from London | 363 | |

| 197. | Mask with name of potter | Brit. Mus. | 377 |

| 198. | Gaulish figure of Aphrodite | Blanchet | 383 |

| 199. | Gaulish figure of Epona | Blanchet | 386 |

| 200. | Terracotta money-box | Jahrbuch | 390 |

| 201. | Terracotta coin-mould | Daremberg and Saglio | 392 |

| 202. | Lamp from the Esquiline | Ann. dell Inst. | 399 |

| 203. | “Delphiniform” lamp | 399 | |

| 204. | Lamp with volute-nozzle | 400 | |

| 205. | Lamp with pointed nozzle | 400 | |

| 206. | Lamp with grooved nozzle | 401 | |

| 207. | Lamp with plain nozzle | 401 | |

| 208. | Lamp with heart-shaped nozzle | 402 | |

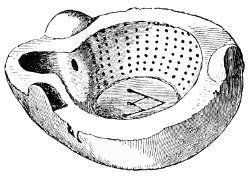

| 209. | Mould for lamp | Brit. Mus. | 405 |

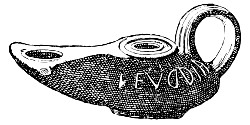

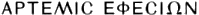

| 210. | Lamp with signature of Fortis | Brit. Mus. | 424 |

| 211. | Stamps used by Roman potters | 440 | |

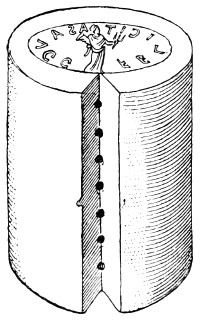

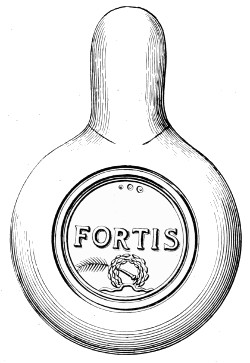

| 212. | Roman kiln at Heddernheim | Ann. dell’ Inst. | 444 |

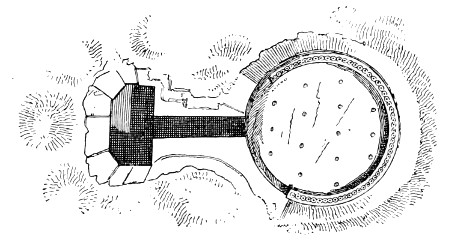

| 213. | Kiln found at Castor | 447 | |

| 214. | Plan of kiln at Heiligenberg | Daremberg and Saglio | 450 |

| 215. | Section of ditto | Daremberg and Saglio | 450 |

| 216. | Ampulla | Brit. Mus. | 466 |

| 217. | Lagena from France | 467 | |

| 218. | Arretine bowl in Boston: death of Phaëthon | Philologus | 484 |

| 219. | Arretine krater with Seasons | Brit. Mus. | 488 |

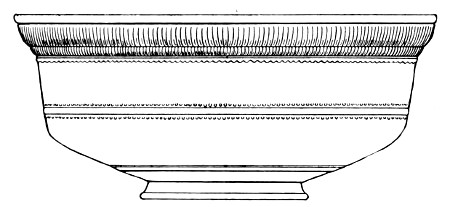

| 220. | “Italian Megarian” bowl | Brit. Mus. | 491 |

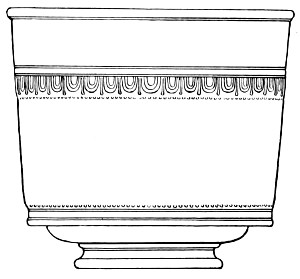

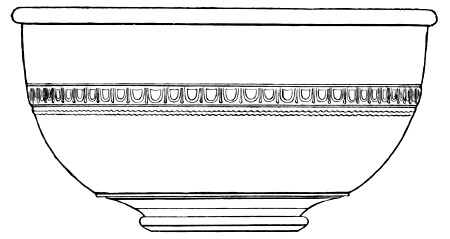

| 221. | Gaulish bowl of Form 29 | 500 | |

| 222. | Gaulish bowl of Form 30 | 501 | |

| 223. | Gaulish bowl of Form 37 | 502 | |

| 224. | Vase of St.-Rémy fabric | Déchelette | 517 |

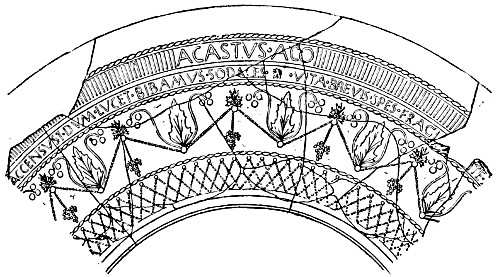

| 225. | Vase of Aco, inscribed | Déchelette | 518 |

| 226. | Vase of Banassac fabric from Pompeii | Mus. Borb. | 525 |

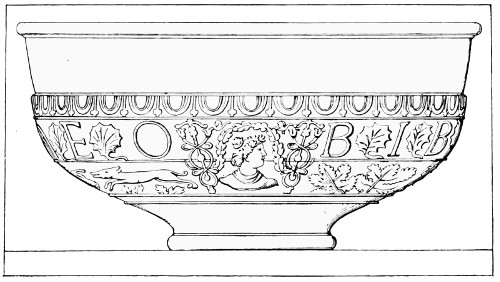

| 227. | Medallion from vase of Southern Gaul: scene from the Cycnus | Brit. Mus. | 531 |

| 228. | Medallion from vase: Atalanta and Hippomedon | Gaz. Arch. | 532 |

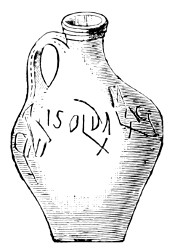

| 229. | Jar from Germany, inscribed | Brit. Mus. | 537 |

| 230. | Roman mortarium from Ribchester | Brit. Mus. | 551 |

Figured vases in ancient literature—Mythology and art—Relation of subjects on vases to literature—Homeric and dramatic themes and their treatment—Interpretation and classification of subjects—The Olympian deities—The Gigantomachia—The birth of Athena and other Olympian subjects—Zeus and kindred subjects—Hera—Poseidon and marine deities—The Eleusinian deities—Apollo and Artemis—Hephaistos, Athena, and Ares—Aphrodite and Eros—Hermes and Hestia.

The representation of subjects from Greek mythology or daily life on vases was not, of course, confined to fictile products. We know that the artistic instincts of the Greeks led them to decorate almost every household implement or utensil with ornamental designs of some kind, as well as those specially made for votive or other non-utilitarian purposes. But the fictile vases, from the enormous numbers which have been preserved, the extraordinary variety of their subjects, and the fact that they cover such a wide period, have always formed our chief artistic source of information on the subject of Greek mythology and antiquities.

Although (as has been pointed out in Chapter IV.) ancient literature contains scarcely any allusions to the painted vases, we have many descriptions of similar subjects depicted on other works of art, such as vases of wood and metal, from Homer downwards. The cup of Nestor (Vol. I. pp. 148, 172) was ornamented with figures of doves[1], and there is the famous description in the first Idyll of Theocritus[2] of the wooden cup (κισσύβιον) which represented a fisherman casting his net, and a boy guarding vines and weaving a trap for grasshoppers, while two foxes steal the grapes and the contents of his dinner-basket; the whole being surrounded, like the designs on some painted vases, with borders of ivy and acanthus. The so-called cup of Nestor (νεστορίς) at Capua[3] was inscribed with Homeric verses, and the σκύφος or cup of Herakles with the taking of Troy[4]. Anakreon describes cups ornamented with figures of Dionysos, Aphrodite and Eros, and the Graces[5]; and Pliny mentions others with figures of Centaurs, hunts and battles, and Dionysiac subjects[6]. Or, again, mythological subjects are described, such as the rape of the Palladion[7], Phrixos on the ram[8], a Gorgon and Ganymede[9], or Orpheus[10]; and other “storied” cups are described as being used by the later Roman emperors. But the nearest parallels to the vases described in classical literature are probably to be sought in the chased metal vases of the Hellenistic and Roman periods.[11] We read of scyphi Homerici, or beakers with Homeric scenes, used by the Emperor Nero, which were probably of chased silver[12]; and we have described in Chapter XI. what are apparently clay imitations of these vases, usually known as “Megarian bowls,” many bearing scenes from Homer in relief on the exterior.

In attempting a review of the subjects on the painted vases, we are met with certain difficulties, especially in regard to arrangement. This is chiefly due to the fact that each period has its group of favourite subjects; some are only found in early times, others only in the later period. Yet any chronological method of treatment will be found impossible, and it is hoped that it will, as far as possible, be obviated by the general allusions in the historical chapters of this work to the subjects characteristic of each fabric and period.

Embracing as they do almost the whole field of Greek myth and legend, the subjects on Greek vases are yet not invariably those most familiar to the classical student or, if the stories are familiar, they are not always treated in accordance with literary tradition. On the other hand, it must be borne in mind that the popular conception of Greek mythology is not always a correct one, for which fact the formerly invariable system of approaching Greek ideas through the Latin is mainly responsible. The mythology of our classical dictionaries and school-books is largely based on Ovid and the later Roman compilers, such as Hyginus, and gives the stories in a complete connected form, regarding all classical authorities as of equal value, and ignoring the fact that many myths are of gradual growth and only crystallised at a late period, while others belong to a relatively recent date in ancient history.[13]

The vases, on the other hand, are contemporary documents, free from later euhemerism and pedantry, and presenting the myths as the Athenian craftsmen knew them in the popular folk-lore and religious observances of their day. It cannot be too strongly insisted upon that a vase-painter was never an illustrator of Homer or any other writer, at least before the fourth century B.C. (see Vol. I. p. 499). The epic poems, of course, contributed largely to the popular acquaintance with ancient legends, and offered suggestions of which the painter was glad to avail himself; but he did not, therefore, feel bound to adhere to his text. This will be seen in the list of Homeric subjects given below (p. 126 ff.); and we may also refer here to the practice of giving fanciful names to figures, which obtains at all periods, and has before now presented obstacles to the interpreter.

The relation of the subjects on vases to Greek literature is an interesting theme for enquiry, though, in view of what has already been said, it is evident that it must be undertaken with great caution. The antiquity and wide popularity of the Homeric poems, for instance, would naturally lead us to expect an extensive and general use of their themes by the vase-painter. Yet this is far from being the case. The Iliad, indeed, is drawn upon more largely than the Odyssey; but even this yields in importance as a source to the epics grouped under the name of the Cyclic poets. It may have been that the poems were instinctively felt to be unsuited to the somewhat conventional and monotonous style of the earlier vase-paintings, which required simple and easily depicted incidents. We are therefore the more at a loss to explain the comparative rarity of subjects from the Odyssey, with its many adventures and stirring episodes; scenes which may be from the Iliad being less strongly characterised and less unique—one battle-scene, for instance, differing little from another in method of treatment. But any subject from the Odyssey can be at once identified by its individual and marked character. It may be that the Odyssey had a less firm hold on the minds of the Greeks than the Iliad, which was more of a national epic, whereas the Odyssey was a stirring romance.[14] It may also be worth noting that scenes from the Odyssey usually adhere more closely to the Homeric text than those from the Iliad.

Another reason for the scarcity of Iliad-scenes may be that the Tale of Troy as a whole is a much more comprehensive story, of which the Iliad only forms a comparatively small portion. Hence the large number of scenes drawn both from the Ante-Homerica and the Post-Homerica, such as the stories of Troilos and Memnon, or the sack of Troy. The writings of the Cyclic poets begin, as Horace reminds us, ab ovo,[15] from the egg of Leda, and the Kypria included the whole story of the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, the subsequent Judgment of Paris, and his journey to Greece after Helen, scenes from all these events being extremely popular on the vases.[16] The Patrokleia deals with the events of the earlier years of the war, the Aithiopis of Arktinos with the stories of Penthesileia and Memnon, and the death of Achilles, and the Little Iliad of Lesches with the events of the tenth year down to the fall of Troy. All provided frequent themes for the vase-painter, as may be seen by a reference to a later page (119 ff.). The Iliupersis of Arktinos and Lesches might almost be reconstructed from two or three large vases, whereon all the episodes of the catastrophe are collected together (see p. 134); but when we come to the Nostoi of Agias and the Telegonia, the vase-painters suddenly fail us, the stories of Odysseus’ wanderings and Orestes’ vengeance seeming to supply the deficiency.

Luckenbach[17] has pointed out that the only right method of investigating the relation is to begin with vase-paintings for which the sources are absolutely certain, as with scenes from the Iliad and Odyssey. In this way the subjects from other epics can be rightly estimated and the contents of the poems restored. Further, in investigating the sources of the vase-painters, and the extent to which they adhered to them or gave free play to the imagination, the three main periods of vase-painting must be separately considered, though the results in each case prove to be similar. By way of exemplifying these methods he enters in great detail into certain vase-subjects, their method of treatment on vases of the different periods, and their approximation to the text. Thus, the funeral games for Patroklos (Il. xxiii.) are depicted on the François vase (see p. 11) with marked deviations from Homer’s narrative; and not only this, but without characterisation, so that if the performers were not named the subject could hardly have been identified. To note one small point, all Homeric races took place in two-horse chariots (bigae), but on B.F. vases four-horse quadrigae are almost invariably found.[18]

Subjects of a more conventional character, such as battle scenes, farewell scenes, or the arming of a warrior, present even more difficulty. Even when names occur it is only increased. We must assume that the vase-painter fixed on typical names for his personages, without caring whether he had literary authority. In some cases the genre scenes seem to be developed from heroic originals, in others the contrary appears to be the case.[19] It is not, however, unfair to say that the Epos was the vase-painter’s “source.” The only doubtful question is the extent of his inspiration; and, at all events, it was a source in the sense that no other Greek literature was until we come to the fourth century.

Turning now to the consideration of later literature,[20] we find in Hesiod a certain parallelism of theme to the vases, but little trace of actual influence. Indirectly he may have affected the vase-painter by his crystallisation of Greek mythology in the Theogony, where he establishes the number of the Muses (l. 77), and also the names of the Nereids.[21] It is, however, interesting to note the Hesiodic themes which were also popular with the vase-painters: the creation of Pandora; the fights of Herakles and Kyknos, and of Lapiths and Centaurs, and the pursuit of Perseus by the Gorgons; the contest of Zeus with Typhoeus (or Typhon); and the birth of Athena.[22]

The influence of lyric poetry was even slighter. Somewhat idealised figures of some of the Greek lyrists appear on R.F. vases, such as Sappho and Anakreon (see p. 152); but this is all. In regard to Pindar and Bacchylides, the idealising and heroising tendencies of the age may be compared with the contemporary tendency of vase-paintings, and the latter may often be found useful to compare with—if not exactly to illustrate—the legends which the two poets commemorate. For instance, in the ode of Bacchylides in which he describes the fate of Kroisos, there is a curious deviation from the familiar Herodotean version, the king being represented as voluntarily sacrificing himself.[23] The only vase-painting dealing with this subject (Fig. 132, p. 150) apparently reproduces this tradition.

With the influence of the stage we have already dealt elsewhere.[24] With the exception of the Satyric drama, it can hardly be said to have made itself felt, except in the vases of Southern Italy, in the fourth century B.C., but indications of the Satyric influence may be traced in many R.F. Attic vases, no doubt owing to their connection with the popular Dionysiac subjects. On a vase in Naples[25] are represented preparations for a Satyric drama. When we reach the time of tragic and comic influence, we not only find the subjects reproduced, but even their stage setting; in other words, the vases are not so much intended to illustrate the written as the acted play, just as it was performed.

The whole question is admirably summed up by Luckenbach[26] in the following manner: (1) The Epos is the chief source of all vase-paintings from the earliest time to the decadence inclusive, and next comes Tragedy, as regards the later vases only; of the influence of other poetry on the formation of myths in vase-paintings there is no established example. (2) Vase-paintings are not illustrations, either of the Epos or of the Drama, and there is no intention of reproducing a story accurately; hence great discrepancies and rarity of close adherence to literary forms; but the salient features of the story are preserved. (3) Discrepancies in the naming of personages are partly arbitrary, partly due to ignorance; the extension of scenes by means of rows of bystanders, meaningless, but thought to be appropriate, is of course a development of the artist’s, conditioned by exigencies of space. Anachronisms on vases are of frequent occurrence. (4) Such scenes as those of warriors arming or departing are always the painter’s own invention, ordinary scenes being often “heroised” by the addition of names. But individuals are not necessarily all or always to be named; and, again, the artist often gives names without individualising the figures. (5) In the archaic period successive movements of time are often very naïvely blended (see p. 10); the difference between art and literature is most marked in scenes where a definite moment is not indicated. (6) Vase-paintings often give a general survey of a poem, the scene not being drawn from one particular passage or episode. The features of one poem are in art sometimes transferred to another.

The attention that has been paid now for many years to collecting, assorting, and critically discussing the material afforded by the vases has much diminished the difficulties of this most puzzling branch of archaeology. It has been chiefly lightened by the discovery from time to time of inscribed vases, though, as has just been noted, even these must be treated with caution; and even now, of course, there are numerous subjects the interpretation of which is either disputed or purely hypothetical. But we can at least pride ourselves on having advanced many degrees beyond the labours of early writers on the subject, down to the year 1850.

When painted vases first began to be discovered in Southern Italy, the subjects were supposed to relate universally to the Eleusinian or Dionysiac mysteries, and this school of interpretation for a long time found favour in some quarters, even in the days of Gerhard and De Witte. But it was obvious from the first that such interpretations did not carry the investigator very far, and even in the eighteenth century other systems arose, such as that of Italynski, who regarded the subjects as of historical import.[27] Subsequently Panofka endeavoured to trace a connection between the subjects and the names of artists or other persons recorded on the vases, or, again, between the subjects and shapes. The latter idea, of course, contained a measure of truth, as is seen in many instances[28]; but it was, of course, impossible to follow out either this or the other hypothesis in any detail.

The foundations of the more scientific and rational school of interpretation were laid as early as the days of Winckelmann, and he was followed by Lanzi, Visconti, and Millingen, and finally Otto Jahn, who, as we have seen, practically revolutionised the study of ceramography. Of late, however, the question of the interpretation of subjects has been somewhat relegated to the background, owing to the overwhelming interest evoked by the finds of early fabrics or by the efforts of German and other scholars to distinguish the various schools of painting in the finest period.

Millingen, in the Introduction to his Vases Grecs, drew up a classification of the subjects on vases which need not be detailed here, but which, with some modifications, may be regarded as holding good to the present day. He distinguishes ten classes, the first three mythological, the next four dealing with daily life, and the three last with purely decorative ornamentation. A somewhat similar order is adopted by Müller in his Handbuch, by Gerhard in his Auserlesene Vasenbilder, and by Jahn in his Introduction to the Munich Catalogue (p. cc ff.). In the present and following chapters the arrangement and classification of the subjects adhere in the main to the system laid down by these writers; and as the order is not, of course, chronological in regard to style, reference has been made where necessary to differences of epoch and fabric.[29] It may be convenient to recapitulate briefly the main headings under which the subjects are grouped.

I. The Olympian deities and divine beings in immediate connection with them, such as Eros and marine deities.

(a) In general; (b) individually. (Chapter XII.)

II. Dionysos and his cycle, Pan, Satyrs, and Maenads. (Page 54 ff.)

III. Chthonian and cosmogonic deities, personifications, and minor deities in general. (Page 66 ff.)

IV. Heroic legends and mythology in general.

(a) Herakles; (b) Theseus, Perseus, and other heroes; (c) local or obscure myths; (d) the Theban and Trojan stories; (e) monsters. (Chapter XIV.)

V. Historical subjects. (Page 149 ff.)

VI. Scenes from daily life and miscellaneous subjects (for detailed classification see p. 154). (Chapter XV.)

The number of subjects to be found on any one vase is of course usually limited to one, two, or at most three, according to the shape. Usually when there is more than one the subjects are quite distinct from one another; though attempts have been made in some cases, as in the B.F. amphorae, to trace a connection.[30] On the other hand, the R.F. kylikes of the strong period often show a unity of subject running through the interior and exterior scenes, whether the theme is mythological or ordinary.[31] It was only in exceptional cases that an artist could devote his efforts to producing an entire subject, as on some of the large kylikes with the labours of Theseus,[32] or the vases representing the sack of Troy.[33] The great François vase in Florence is a striking example of a mythology in miniature, containing as it does more than one subject treated in the fullest detail. And here reference may be made to the main principles which governed the method of telling a story in ancient art, and prevailed at different periods.[34] The earliest and most simple is the continuous method, which represents several scenes together as if taking place simultaneously, although successive in point of time. This method was often employed in Oriental art, but is not found in Hellenic times; it was, however, revived by the Romans under the Empire, and prevailed all through the early stages of Christian art. Secondly, there is the complementary method, which aims at the complete expression of everything relating to the central event. The same figures are not in this case necessarily repeated, but others are introduced to express the action of the different subjects, all being collected in one space without regard to time, as in the continuous style. This is of Oriental origin, and is first seen in the description of Achilles’ shield; it is also well illustrated in the François vase, in the story of Troilos. Here the death of Troilos is not indeed actually depicted, but the events leading up to it (the water-drawing at the fountain and the pursuit by Achilles) and those consequent on it (the announcement of the murder to Priam and the setting forth of Hector to avenge it) are all represented without the repetition of any figures. Lastly, there is the isolating method, which is purely Hellenic, being developed from the complementary. This is best illustrated by the Theseus kylikes, with their groups of the labours, which, it should be remembered, are not continuous episodes in one story, but single events separated in time and space, and collected together with a sort of superficial resemblance to the other methods.

Some description of the François vase has been given elsewhere (Vol. I. p. 370)[35]; but as it is unique in its comprehensiveness, and as a typical presentation of the subjects most popular at the time when vase-painters had just begun to pay special attention to mythology, it may be worth while to recapitulate its contents here. The subjects are no less than eleven in number, arranged in six horizontal friezes, with figures also on the handles, and there are in all 115 inscriptions explaining the names of the personages and even of objects (e.g. ὑδρία, for the broken pitcher of Polyxena). Eight of these subjects belong to the region of mythology:—(1) On the neck: the hunt of the Calydonian boar, and (2) the landing of Theseus and Ariadne at Naxos, accompanied by dancing youths and maidens. (3) On the shoulder: chariot race at the funeral games of Patroklos, and (4) combat of Centaurs and Lapiths (with Theseus). (5) On the body: the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, attended by the gods in procession. (6) On the body: the death of Troilos (see above), and (7) the return of Hephaistos to Olympos. (8) On each of the handles, Ajax with the body of Achilles. On the flat top of the lip is represented (9) a combat of pigmies and cranes; on either side of the foot (10) a lion and a panther devouring a bull and stag, Gryphons, Sphinxes, and other animals; and on the upper part of the handles (11) Gorgons and figures of the Asiatic Artemis (see p. 35) holding wild animals by the neck.

It is, of course, impossible to indicate all the subjects on the thousands of painted vases in existence; and it must also be remembered that many are of disputed meaning. The succeeding review must therefore only be considered as a general summary which aims at omitting nothing of any interest and avoiding as far as possible useless repetition. In the references appended under each subject the principle has been adopted of making them as far as possible representative of all periods, and also of selecting the most typical and artistic examples, as well as the most accessible, publications.[36]

In dealing with the subjects depicted on Greek vases, we naturally regard the Olympian deities as having the preeminence. We will therefore begin by considering such scenes as have reference to actions in which those deities were engaged, and, secondly, representations of general groups of deities, either as spectators of terrestrial events or without any particular signification. It will then be convenient to deal with the several deities one by one, noting the subjects with which each is individually connected. We shall in the following chapter proceed to consider the subordinate deities, such as those of the under-world and the Dionysiac cycle, and personifications of nature and abstract ideas. Chapter XIV. will be devoted to the consideration of heroic legends, mythological beings, and historical subjects; and in Chapter XV. will be discussed all such subjects as relate to the daily life of the Greeks.

One of the oldest and most continuously popular subjects is the Gigantomachia, or Battle of the Gods and Giants, which forms part of the Titanic and pre-heroic cosmogony, and may therefore take precedence of the rest. The Aloadae (Otos and Ephialtes), strictly speaking, are connected with a different event—the attack on Olympos and chaining of Ares; but the scenes in which they occur are so closely linked with the Gigantomachy proper that it is unnecessary to differentiate them. We also find as a single subject the combat of Zeus with the snake-footed Typhon.[37]

The locus classicus of Greek art for the Gigantomachia is of course the frieze of the great altar at Pergamon (197 B.C.), but several vases bear representations almost as complete, though it is not as a rule possible to identify the giants except where their names are inscribed.[38] Most vases give only one to three pairs of combatants.

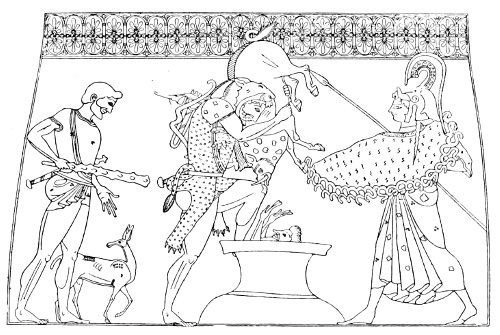

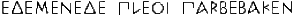

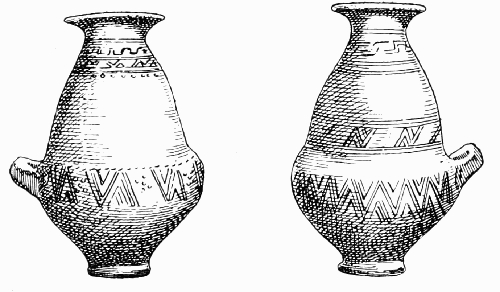

FIG. 111. GIGANTOMACHIA, FROM IONIC VASE IN LOUVRE.

Some pairs are found almost exclusively together, e.g. Athena and Enkelados, or Ares and Mimas; Artemis and Apollo are generally opposed to the Aloadae Otos and Ephialtes, Zeus to Porphyrion, and Poseidon to Polybotes (Fig. 112) or Ephialtes. Hestia alone, the “stay-at-home” goddess of the hearth, is never found in these scenes, but Dionysos, Herakles, and the Dioskuri all take their part in aiding the Olympian deities. Zeus hurls his thunderbolts[39]; Poseidon is usually depicted with his trident, or hurling the island of Nisyros (indicated as a rock with animals painted on it) upon his adversary[40]; Hephaistos uses a pair of tongs with a burning coal in them as his weapon[41]; and Dionysos is in some cases aided by his panther.[42] Aeolus occurs once with his bag of winds.[43]

FIG. 112. POSEIDON AND THE GIANT POLYBOTES, FROM THE KYLIX IN BERLIN.

The following groups can be identified on vases by inscriptions or details of treatment:—

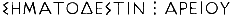

Among scenes supposed to take place in Olympos, the most important is the Birth of Athena from the head of Zeus.[44] Usually she is represented as a diminutive figure actually emerging from his head, but in one or two instances she stands before him fully developed,[45] as was probably the case in the centre of the east pediment of the Parthenon. This subject is commoner on B.F. vases, and does not appear at all after the middle of the fifth century.[46] In most cases several of the Olympian deities are spectators of the scene; sometimes Hephaistos wields his axe or runs away in terror at the result of his operations[47]; in others the Eileithyiae or goddesses of child-birth lend their assistance.[48] On a R.F. vase in the Bibliothèque Nationale Athena flies out backwards from Zeus’ head.[49]

In accordance with a principle already discussed (Vol. I. p. 378), the composition or “type” of this subject is sometimes adopted on B.F. vases for other groups of figures, where the absence of Athena shows clearly that the birth scene is not intended, and no particular meaning can be assigned to the composition.[50]

Representations of the Marriage of Zeus and Hera cannot be pointed to with certainty in vase-paintings. On B.F. vases we sometimes see a bridal pair in a chariot accompanied by various deities, or figures with the attributes of divinities[51]; but the chief figures are not in any way characterised as such, and it is better to regard these scenes as idealisations of ordinary marriage processions. On the other hand, there are undoubted representations of Zeus and Hera enthroned among the Olympian deities or partaking of a banquet.[52]

FIG. 113. THE BIRTH OF ATHENA (BRIT. MUS. B 244).

The story of the enchaining of Hera in a magic chair by Hephaistos, and her subsequent liberation by him, is alluded to on many vases, though one episode is more prominent than the others. Of the expulsion of Hephaistos from heaven we find no instance, and of the release of Hera there is only one doubtful example[53]; but we find a parody of the former’s combat with Ares, who forces him to liberate Hera.[54] The episode most frequent is that of the return of Hephaistos in a drunken condition to Olympos, conducted by Dionysos and a crowd of Satyrs; of this there are fine examples on vases of all periods.[55] On earlier vases Hephaistos rides a mule; on the later he generally stumbles along, leaning on Dionysos or a Satyr for support.

On the François vase we see Zeus and Hera, with an attendant train of deities, Nymphs, and Muses, going in a chariot to the nuptials of Peleus and Thetis; on many vases we have the reception of the deified Herakles among the gods of Olympos[56]; and on others groups of deities banqueting or without particular signification.[57] But on the late Apulian vases it is a frequent occurrence to find an upper row of deities as spectators of some event taking place just below: thus they watch battles of Greeks and Persians,[58] or such scenes as the contract between Pelops and Oinomaos,[59] the madness of Lykourgos,[60] the death of Hippolytos,[61] and others from heroic legend, which it is unnecessary to specify here; only a few typical ones can be mentioned.[62] They also appear as spectators of scenes in or relating to the nether-world.[63]

Zeus appears less frequently than some deities, and seldom alone; but still there are many myths connected with him, besides those already discussed. As a single figure he appears enthroned and attended by his eagle on a Cyrenaic cup in the Louvre[64]; or again in his chariot, hurling a thunderbolt[65]; in company with his brother-gods of the ocean and under-world, Poseidon and Hades, he is seen on a kylix by Xenokles.[66] He is also found with Athena,[67] with Hera, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, and Hermes[68]; and frequently with Herakles at the latter’s reception into heaven.[69] In one instance he settles a dispute between Aphrodite and Persephone.[70] He receives libations from Nike,[71] or performs the ceremony himself, attended by Hera, Iris, and Nike,[72] and is also attended by Hebe and Ganymede as cupbearers.[73] His statue, especially that of Ζεὺς Ἑρκεῖος at Troy, sometimes gives local colour to a scene.[74]

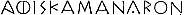

Most of the scenes in which he appears relate to his various love adventures, among which the legends of Europa, Io, and Semele are the most conspicuous; but first of his numerous amours should perhaps be mentioned his wooing of his consort Hera. He carries her off while asleep from her nurse in Euboea,[75] and also appears to her in the form of a cuckoo.[76] The rape of Ganymede by his eagle appears once or twice on vases,[77] but more generally Zeus himself seizes the youth while he is engaged in bowling a hoop or otherwise at play.[78] On a fine late vase with Latin inscriptions Ganymede appears in Olympos,[79] and he is also depicted as a shepherd.[80]

Semele Zeus pursues and slays with the thunderbolt[81]; the birth of her son Dionysos from his thigh is represented but rarely on vases, and is liable to confusion with other subjects. This story falls into three episodes: (1) the reception of the infant by Hermes from Dirke, in order to be sewn into Zeus’ thigh[82]; (2) the actual birth scene[83]; (3) the handing over of the child to the Nymphs.[84] Of his visit to Alkmena there are no certain representations, but two comic scenes on South Italian vases[85] may possibly refer to it, and one of them at least seems to be influenced by the burlesque by Rhinton, from which Plautus borrowed the idea of his Amphitruo. The apotheosis of Alkmena, when her husband places her on a funeral pyre after discovering her misdeed, is represented on two fine South Italian vases in the British Museum; in one case Zeus looks on.[86] His appearing to Leda in the form of a swan only seems to find one illustration on a vase, but in one case he is present at the scene of Leda with the egg.[87]

He is also depicted descending in a shower of gold on Danaë[88]; or as carrying off the Nymphs Aegina and Thaleia[89]; or, again, with an unknown Nymph, perhaps Taygeta.[90] In the form of a bull, on which Europa rides, he provides a very favourite subject, of which some fine specimens exist.[91] One variation of the type is found on an Apulian vase, where Europa advances to caress the bull sent by Zeus to fetch her.[92] The story of Io[93] resolves itself into several scenes, all of which find illustration on the vases: (1) the meeting of Io and Zeus when she rests at the shrine of Artemis after her wanderings[94]; (2) Io in the form of a cow, guarded by Argos[95]; (3) the appearance of her deliverer Hermes[96]; (4) Hermes attacks and slays Argos (Fig. 114).[97]

From Wiener Vorlegeblätter.

FIG. 114. HERMES SLAYING ARGOS IN PRESENCE OF ZEUS (VASE AT VIENNA).]

In addition, the presence of Zeus may be noted in various scenes from heroic or other legends, which are more appropriately discussed under other headings[98], such as the freeing of Prometheus[99], the combat of Herakles and Kyknos[100], or the weighing of the souls of Achilles and Hector[101]; at the sending of Triptolemos, the flaying of Marsyas, the death of Aktaeon, and that of Archemoros[102]; at the creation of Pandora and the Judgment of Paris[103]; the rape of the Delphic tripod and that of the Leukippidae, at Peleus’ seizing of Thetis,[104] and with Idas and Marpessa.[105] The story of the golden dog of Zeus, which was stolen by Pandareos, is referred to under a later heading.[106]

Hera apart from Zeus appears but seldom, but there are a few scenes in which she is found alone; of those in which she is an actor or spectator some have been already described, the most important being the story of Hephaistos’ return to heaven.[107] As her figure is not always strongly characterised by means of attributes, it is not always to be identified with certainty. As a single figure she forms the interior decoration of one fine R.F. kylix,[108] and her ξόανον, or primitive cult-idol, is sometimes found as an indication of the scene of an action.[109] On one vase she is represented at her toilet.[110]

There is a vase-painting which represents Hera on her throne offering a libation to Prometheus, an aged figure who stands before her.[111] She is also present at the liberation of Prometheus[112]; in a scene probably intended for the punishment of Ixion[113]; at the creation of Pandora[114]; and in scenes from the story of Io.[115] She suckles the child Herakles in one instance,[116] and in another appears with him in the garden of the Hesperides[117]; she is also present at his reconciliation with Apollo at Delphi,[118] and at his apotheosis,[119] receiving him and Iolaos.[120] On an early Ionic vase she appears contending with him in the presence of Athena and Poseidon, and wears a goat-skin head-dress, as in the Roman type of Juno Sospita or Lanuvina.[121]

The scene in which she appears most frequently is the Judgment of Paris (see below, p. 122); she is also present at the birth of Dionysos[122]; at the stealing of Zeus’ golden dog by Pandareos[123]; at the contest between Apollo and Marsyas[124]; at the slaughter of the Niobids[125]; and with Perseus and Athena.[126]

She appears sometimes with Hebe, Iris, and Nike, from whom she receives libations[127]; and in one scene, apparently from a Satyric drama, she and Iris are attacked by a band of Seileni and rescued by Herakles.[128]

From Ant. Denkm.

FIG. 115. POSEIDON AND AMPHITRITE ON A CORINTHIAN PINAX.

Poseidon is a figure somewhat rare in archaic art as a whole, especially in statuary, but is more frequently seen on vases, mostly in groups of deities, or as a spectator of events taking place in or under the sea, his domain. Among subjects already discussed, he is present at the birth of Athena,[129] at the nuptials of Zeus and Hera,[130] and in assemblies of the Olympian gods, generally with his consort Amphitrite[131]; he also takes part in the Gigantomachia and the reception of Herakles into Olympos.[132] He is represented in a group with his brother deities of the higher and nether world, Zeus and Hades[133]; with Apollo, Athena, Ares, and Hermes[134]; among the Eleusinian deities at the sending forth of Triptolemos[135]; and occasionally in Dionysiac scenes as a companion of the wine-god.[136] As a single figure he is frequently found on the series of archaic tablets or pinakes found near Corinth, and also in company with Amphitrite (Fig. 115)[137]; on later vases not so frequently.[138] In one instance he rides on a bull,[139] in others on a horse, sometimes winged[140]; elsewhere he drives in a chariot with Amphitrite and other deities[141]; he watches the Sun-god in his car rising out of the waves[142]; and one vase has the curious subject of Poseidon, Herakles, and Hermes engaged in fishing.[143]

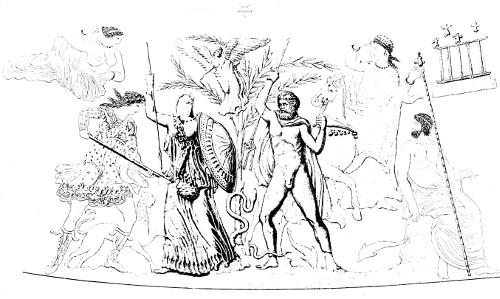

From Baumeister.

Athena and Poseidon Contending for Attica; Vase from Kertch (at Petersburg).

Among scenes in which he plays an active part the most interesting is the dispute with Athena for the ownership of Attica, also represented on the west pediment of the Parthenon[144]; his love adventures, especially his pursuit of Amymone[145] and Aithra,[146] are common subjects, but in many cases the object of his pursuit cannot be identified.[147] He receives Theseus under the ocean,[148] and possibly in one case Glaukos, on his acceptance as a sea-god[149]; he is also present at the former’s recognition by Aigeus.[150] He is seen at the death of Talos,[151] and with Europa crossing the sea.[152] In conjunction with other deities, chiefly on late Italian vases, he is present as a spectator of various episodes, such as the adventures of Bellerophon, Kadmos, or Pelops, the rape of Persephone, the creation of Pandora, the death of Hippolytos, and in one historical scene, a battle of Greeks and Persians.[153] He superintends several of the adventures of Herakles, notably those in which he is specially interested, as the contests with Antaios and Triton[154]; and he supports Hera in her combat with that hero.[155] He is also seen with Perseus on his way to slay Medusa,[156] and among the Gorgons after that event.[157]

In connection with Poseidon it may be convenient to mention here other divinities and beings with marine associations—such as Okeanos, Nereus, and Triton, and the Nereids or sea-nymphs, daughters of Nereus, with the more rarely occurring Naiads. Of these the name of Okeanos occurs but once, on the François vase. The figure itself has disappeared, but the marine monster on which he rides to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and the inscription, remain. Nereus appears as a single figure, with fish-tail and trident,[158] but is most frequently met with in connection with the capture of his daughter Thetis by Peleus, either as a spectator or receiving the news from a Nereid.[159] He also watches the contest of Herakles with Triton,[160] himself encountering the hero in some cases.[161] On one vase Herakles has seized his trident and threatens him by making havoc of his belongings.[162] He appears at Herakles’ combat with Kyknos,[163] and at his apotheosis,[164] and also offers a crown to Achilles.[165] In one case he is found in Dionysos’ company.[166] With his daughter Doris he watches the pursuit of another Nereid by Poseidon.[167]

Triton is found as a single figure,[168] and (chiefly on B.F. vases) engaged in a struggle with Herakles.[169] He also carries Theseus through the sea to Poseidon,[170] and watches the flight of Phrixos and Helle over the sea.[171] The group of deities represented by Ino and Leukothea, Palaimon, Melikertes, and Glaukos appear in isolated instances,[172] as do Proteus[173] and Skylla[174]—the latter as single figures, without reference to their connection with the Odyssey. A monstrous unidentified figure, with wings and a serpentine fish-tail, which may be a sea-deity (in one case feminine), is found on some early Corinthian vases[175]; possibly Palaimon is intended.

The Nereids, who are often distinctively named, are sometimes found in groups,[176] especially watching the seizure of Thetis or bearing the news to Nereus[177]; or, again, carrying the armour of Achilles over the sea and presenting it to him.[178] On one vase they mourn over the dead Achilles.[179] They are also present at the reception of Theseus,[180] the contest of Herakles and Triton,[181] and with Europa on the bull.[182] Kymothea offers a parting cup to Achilles[183]; the Naiads, who are similar beings, present to Perseus the cap, sword, shoes, and wallet.[184] They are also found grouped with various deities,[185] and even one in the under-world.[186] Thetis appears once as a single figure, accompanied by dolphins[187]; for her capture by Peleus and relations with Achilles, see p. 120 ff.

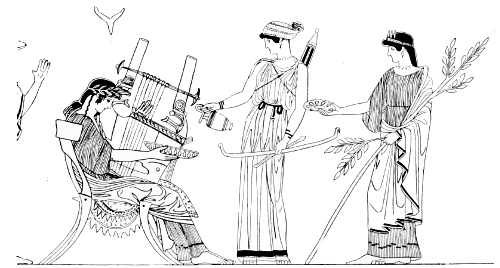

The Eleusinian deities Demeter and Persephone (or Kore) are usually found together, not only in scenes which have a special reference to their cult, but in general assemblies of the gods. They once appear in the Gigantomachia.[188] Scenes which refer to the Eleusinian cycle are found exclusively on later examples,[189] and as a rule merely represent the two chief deities grouped with others, such as Dionysos and Hekate, and with their attendants, Iacchos, Eumolpos, and Eubouleus.[190] One vase represents the initiation of Herakles, Kastor, and Polydeukes in the Lesser Mysteries of Agra[191]; another, the birth of Ploutos, who is handed to Demeter in a cornucopia by Gaia, rising from the earth, in the presence of Persephone, Triptolemos, and Iacchos[192]; and others, the birth of Dionysos or Iacchos—a very similar composition.[193] Demeter and Persephone are represented driving in their chariot, with attendant deities and other figures,[194] or standing alone, carrying sceptre and torches respectively,[195] or pouring libations at a tomb (on a sepulchral vase).[196] They are present at the carrying off of Basile by Echelos (a rare Attic legend),[197] and Demeter alone is seen, once at the birth of Athena,[198] once at the slaughter of the dragon by Kadmos,[199] once enthroned,[200] and once with Dionysos as Thesmophoros, holding an open roll with the laws (θεσμοί) of her cult.[201]

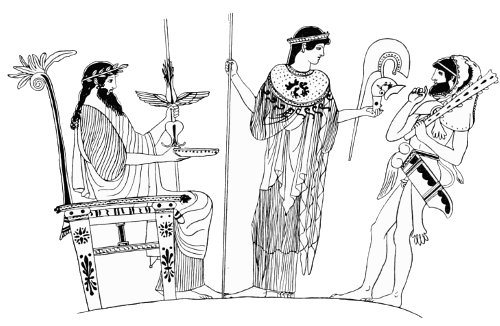

Kotyle by Hieron: Triptolemos at Eleusis (British Museum).

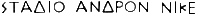

Closely connected with Eleusis is the subject of the sending forth of Triptolemos as a teacher of agriculture in his winged car. This is found on vases of all periods,[202] but is best exemplified on the beautiful kotyle of Hieron in the British Museum (Plate LI.), where, besides Olympian and Chthonian deities, the personification of Eleusis is present. Besides the other Eleusinian personages, Keleos and Hippothoon are also seen.[203] Triptolemos is generally seated in his car, but in one or two cases he stands beside it[204]; in another he is just mounting it.[205] On the latter vase Persephone holds his plough. On a vase in Berlin Triptolemos appears without his car, holding a ploughshare; Demeter presents him with ears of corn, and Persephone holds torches.[206]

Persephone is also seen with Iacchos,[207] who, according to various accounts, was her son or brother. She appears with Aphrodite and Adonis,[208] and one vase is supposed to represent the dispute between her and Aphrodite over the latter, which was appeased by Zeus.[209]

The story of the rape of Persephone by Hades, her sojourn in the under-world, and her return to earth is also chiefly confined to the later vases, especially the incident of the rape.[210] In the elaborate representations of the under-world on late Apulian vases she generally stands or sits with Hades in a building in the centre.[211] She is often depicted in scenes representing the carrying off of Kerberos by Herakles,[212] or banqueting with Hades.[213] On both early and late vases Hermes, in his character of Psychopompos, is seen preparing to conduct her back from the nether world (see Plate XLV.),[214] or actually on his way.[215] In another semi-mystical version of the return of Persephone, signifying the return of spring and vegetation, her head or part of her body emerges from the earth,[216] in one case accompanied by the head of Dionysos, whereat Satyrs and Maenads flee affrighted.[217] The interpretation of some of these scenes, however, has been much questioned.[218]

The number of vases with subjects representing the three Delphic deities—Apollo, Artemis, and Leto—is considerable. The appearances of Apollo, at any rate, are probably only exceeded in number by those of Athena, Dionysos, and Herakles. It is, in fact, impossible to make a complete enumeration of the groups in which Apollo occurs, and a general outline alone can be given.[219]

Apollo as a single figure is often found both on B.F. and R.F. vases, usually as Kitharoidos, playing his lyre; sometimes also he is distinguished by his bow.[220] As Kitharoidos he is usually represented standing,[221] but in some cases is seated.[222] He is sometimes accompanied by a hind[223] or a bull (Apollo Nomios?).[224] He is represented at Delphi seated on the Pythoness’ tripod,[225] or is seated at an altar,[226] or pours a libation.[227] He rides on a swan[228] or on a Gryphon,[229] and also crosses the sea on a tripod.[230] In some scenes he is characterised as Daphnephoros,[231] holding a branch of laurel, or is represented in the attitude associated with Apollo Lykeios, resting with one hand above his head.[232] In one scene the type of Apollo Kitharoidos closely resembles that associated with the sculptor Skopas.[233]

From Mon. dell’ Inst. ix.

FIG. 116. APOLLO, ARTEMIS, AND LETO.

When he is grouped with Artemis, the latter deity usually carries a bow and quiver,[234] or they pour libations to one another;[235] but more commonly they stand together, without engaging in any action. They are also depicted in a chariot.[236] More numerous are the scenes in which Leto is also included (as Fig. 116), though she is not always to be identified with certainty.[237] In this connection may be noted certain scenes relating to Apollo’s childhood: his birth is once represented,[238] and on certain B.F. vases a woman is seen nursing two children (one painted black, the other white), which may denote Leto with her infants, though it is more probably a symbolic representation of Earth the Nursing-mother (Gaia Kourotrophos; see p. 73).[239] Tischbein published a vase of doubtful authenticity, which represents Leto with the twins fleeing from the serpent Python at Delos[240]; but in two instances Apollo certainly appears in Leto’s arms, in one case shooting the Python with his bow.[241]

With these three is sometimes joined Hermes—in one instance at Delphi, as indicated by the presence of the omphalos[242]; or, again, Hermes appears with Apollo alone, or with Apollo and Artemis.[243] Poseidon is seen with Apollo, generally accompanied by Artemis and Hermes, also by Leto and other indeterminate female figures.[244] In conjunction with Athena, Apollo is found grouped with Hermes, Dionysos, Nike, and other female figures; also with Herakles.[245] With Aphrodite he is seen in toilet scenes, sometimes anointed by Eros.[246] In one case they are accompanied by Artemis and Hermes,[247] and on one vase Apollo is grouped with Zeus and with Aphrodite on her swan.[248] He accompanies the chariots of various deities, such as Poseidon, Demeter, and Athena,[249] especially when the latter conducts Herakles to heaven.[250]

Apollo, in one case, is associated with the local Nymph Kyrene on a fragment of a vase probably made in that colony.[251] He frequently receives libations from Nike,[252] and in one case is crowned by her.[253] With Nymphs and female figures of indeterminate character he occurs on many (chiefly B.F.) vases, sometimes as receiving a libation.[254] On several red-figured vases he is accompanied by some or all of the nine Muses, one representing their contest with Thamyris and Sappho.[255] He and Artemis are specially associated with marriage processions, whether of Zeus and Hera or of ordinary bridal couples.[256] Apollo also appears in a chariot drawn by a boar and a lion at the marriage of Kadmos and Harmonia.[257]

In Dionysiac scenes he is a frequent spectator[258]; he greets Dionysos among his thiasos,[259] joins him in a banquet,[260] or accompanies Ariadne’s chariot[261] or the returning Hephaistos[262]; listens to the Satyr Molkos playing the flutes,[263] or is grouped with Satyrs and Maenads at Nysa.[264] More important and of greater interest are the scenes which depict the legend of Marsyas, and they may fitly find a place here. The story is told in eight different episodes on the vases, which may be thus systematised:

1. Marsyas picks up the flutes dropped by Athena: Berlin 2418 = Baumeister, ii. p. 1001, fig. 1209: cf. Reinach, i. 342 (in Boston).

2. First meeting of Apollo and Marsyas: Millin-Reinach, i. 6.

3. The challenge: Berlin 2638.

4. Marsyas performing: B.M. E 490; Reinach, i. 452 (Berlin 2950), i. 511 (Athens 1921), ii. 312; Jatta 1093 = Reinach, i. 175 = Baumeister, ii. p. 891, fig. 965.

5. Apollo performing: Jatta 1364 = Él. Cér. ii. 63; Wiener Vorl. vi. 11.

6. Apollo victorious: Reinach, ii. 310; Petersburg 355 = Reinach, i. 14 = Wiener Vorl. iii. 5.

7. Condemnation of Marsyas: Naples 3231 = Reinach, i. 405; Reinach, ii. 324.

8. Flaying of Marsyas: Naples 2991 = Reinach, i. 406 (a vase with reliefs); Roscher, ii. 2455 = Él. Cér. ii. 64.

Among other scenes in which Apollo (generally accompanied by Artemis) plays a personal part, the following may be mentioned: the slaying of the Niobids by the two deities[265]; the slaying of Tityos by Apollo[266] (in one case Tityos is represented carrying off Leto, who is rescued by Apollo)[267]; and various love adventures in which Apollo is concerned.[268] The name of the Nymph pursued by him in the latter scenes cannot, as a rule, be identified; one vase appears to represent him contending with Idas for the possession of Marpessa.[269] He also heals the Centaur Cheiron (this appears in burlesque form),[270] and protects Creusa from the wrath of Ion.[271] He is seen seeking for the cattle stolen from him by Hermes, and contending with that god over the lyre.[272] He frequently appears in Birth of Athena scenes as Kitharoidos,[273] and also at the sending forth of Triptolemos[274] or in the under-world.[275] In one case he appears (with Athena, Artemis, and Herakles) as protecting deity of Attica, watching a combat of Greeks and Amazons.[276] On one vase there is a possible reference to Apollo Smintheus, with whom the mouse was especially associated.[277]

Like other deities, Apollo and Artemis are frequently found on Apulian vases as spectators of the deeds of heroes, or other events in which they are more or less interested; some of these subjects have already been specified (see above, p. 17). Apollo especially is often seen in connection with the story of Herakles, or the Theban and Trojan legends. One burlesque scene represents his carrying off the bow of Herakles to the roof of the Delphic temple,[278] and the subject of the capture of the tripod, with the subsequent reconciliation, is of very frequent occurrence.[279] As Apollo Ismenios, the patron of Thebes, he is a spectator of the scene of the infant Herakles strangling the snakes[280]; in one case he is represented disputing with Herakles over a stag,[281] which may be another version of the story of the Keryneian stag, a scene in which he also occurs.[282] He is seen with Herakles and Kyknos,[283] Herakles and Kerberos,[284] and is very frequently present at the apotheosis of the hero.[285]

Apollo and Artemis watch Kadmos slaying the dragon,[286] and one or other of them is present at the liberating of Prometheus[287]; Apollo alone is seen with Oedipus and Teiresias,[288] and watches the slaying of the Sphinx by the former.[289] Among Trojan scenes he is sometimes present at the Judgment of Paris,[290] also at the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, the pursuit of Troilos, the combats of Achilles and Ajax with Hector, and the recognition of Aithra by her sons.[291] He is, of course, frequently seen in subjects from the Oresteia, both in Tauris and at Delphi,[292] and at the death of Neoptolemos before the latter temple.[293] The pair are also seen at the carrying off of Basile by Echelos (see p. 140).[294]

The ξόανον, or primitive cult-statue, of Apollo is sometimes represented; in one case Kassandra takes refuge from Ajax before it, instead of the usual statue of Athena.[295]

The appearances of Artemis, as distinct from Apollo, need not detain us long; she is sometimes found in mythological scenes, but frequently as a single figure, of which there are some fine examples.[296] A winged goddess grasping the neck or paws of an animal or bird with either hand frequently occurs on early vases, and is usually interpreted as Artemis in her character of πότνια θηρῶν or mistress of the brute creation, sometimes called the Asiatic or Persian Artemis.[297] On an early Boeotian vase (with reliefs) at Athens is a curious representation of Artemis Diktynna, a quasi-marine form of the goddess, originally Cretan (?); on the front of her body is represented a fish, and on the either side of her is a lion.[298] As a single figure she appears either with bow or quiver, or with lyre, sometimes accompanied by a stag or hind, or dogs[299]; she also rides on a deer[300] or shoots at a stag.[301] Or, again, she is attended by a cortège of Nymphs[302] or rides in a chariot.[303] Like that of Apollo, her ξόανον is sometimes introduced into a scene as local colouring.[304]

The myth with which she is chiefly associated is that of Aktaeon, which may find a place here, though in most cases Aktaeon alone is represented, being devoured by his hounds.[305] A curious subject on a vase at Athens appears to be the burial of Aktaeon, Artemis being present.[306] She is also represented at the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, for whom a stag was substituted by her agency,[307] and in connection with the same story at her shrine in Tauris.[308] She is especially associated with Apollo in such scenes as the contest with and flaying of Marsyas,[309] the rape of the Delphic tripod by Herakles[310] and the subsequent reconciliation,[311] or the appearance of Orestes at Delphi.[312] The two deities sometimes accompany nuptial processions in chariots, Artemis as pronuba holding a torch, but it is not easy to say whether these scenes refer to the nuptials of Zeus and Hera or are of ordinary significance.[313] A scene in which she pursues a woman and a child with bow and arrow may have reference to the slaughter of the Niobids.[314]

Other scenes in which she is found are the Gigantomachia[315] and the Birth of Athena[316]; or she is seen accompanying the chariots of Demeter[317] and Athena,[318] and with Aphrodite and Adonis.[319] She disputes with Herakles over the Keryneian stag[320]; and is also present when he strangles the snakes,[321] and at his apotheosis in Athena’s chariot.[322] She attends the combat of Paris and Menelaos,[323] and as protecting deity of Attica she watches a combat of Greeks and Amazons.[324] A vase in Berlin, on which are depicted six figures carrying chairs (Diphrophori, as on the Parthenon frieze) and a boy with game, may perhaps represent a procession in honour of Artemis.[325]

Hephaistos is a figure who appears but seldom, and never as protagonist, except in the case of his return to Olympos,[326] a subject already discussed (p. 17), as has been his appearance in the Gigantomachia[327] and at the birth of Athena.[328] In conjunction with the last-named goddess he completes the creation and adornment of Pandora on two fine vases in the British Museum[329]; he is also present at the birth of Erichthonios.[330] His sojourn below the ocean with Thetis and the making of Achilles’ armour also occur.[331] Representations of a forge on some B.F. vases may have reference to the Lemnian forge of Hephaistos and his Cyclopean workmen.[332] He is also seen with Athena,[333] at the punishment of Ixion,[334] and taking part in a banquet with Dionysos.[335]

More important than any of the other Olympian deities, for the part she plays in vase-paintings, is Athena, the great goddess of the Ionic race, and especially of Athens. Of her birth from the head of Zeus we have already spoken, as also of the part she plays in the Gigantomachia (p. 15). The separate episode of her combat with Enkelados (her invariable opponent) is frequently depicted on B.F. vases[336]; but in one instance she tears off the arm of another giant, Akratos.[337] We have also seen her assisting at the creation of Pandora,[338] and contending with Poseidon for Attica.[339] She receives the infant Dionysos at the time of his birth,[340] and is also generally present at that of Erichthonios,[341] and once with Leto at that of Apollo and Artemis.[342] She is, of course, an invariable actor in Judgment of Paris scenes, in one of which she is represented washing her hands at a fountain in preparation for the competition.[343]

From assemblies of the gods she is rarely absent, and she is also associated with smaller groups of divinities, such as Apollo and Artemis (p. 31), with Ares or Hephaistos,[344] or with Hermes,[345] or in Eleusinian[346] or Dionysiac scenes.[347] Thus she assists at the slaying of the Niobids,[348] and on one vase is confronted with Marsyas, before whom she has just dropped the flutes.[349] Scenes in which she appears receiving a libation from Nike are extremely common[350]; and she is also found with Iris and Hebe.[351] In one instance she herself pours a libation to Zeus.[352]

Generally the companion of princes and patroness of heroes, she protects especially Herakles, whom she aids in his exploits and conveys finally in her chariot to Olympos, where he is introduced by her to Zeus.[353] Some scenes represent the two simply standing together[354]; in others she welcomes and refreshes him after his labours,[355] and in one case he is supposed to be represented pursuing her.[356] It is unnecessary to particularise here the various scenes in which she attends Herakles (see p. 95 ff.); but one may be mentioned as peculiar, where she carries him off in her chariot with the Delphic tripod which he has just stolen.[357] Another rare scene connected with the Herakles myths is one in which, after the fight with Kyknos (see p. 101), Zeus protects her from the wrath of Ares.[358] Another of her favourite heroes is Theseus,[359] and she is even more frequently associated with Perseus, whom she assists to overcome and escape from the Gorgons.[360] She gives Kadmos the stone with which to slay the dragon,[361] and is also seen with Bellerophon,[362] Jason and the Argonauts,[363] and Oedipus.[364] She is present at the rape of Oreithyia by Boreas,[365] at the punishment of Ixion,[366] and at the setting out of Amphiaraos[367]; at the stealing of Zeus’ golden dog by Pandareos[368]; also at the rape of the Leukippidae by the Dioskuri,[369] and of Basile by Echelos (see p. 140),[370] and in a scene from the tragedy of Merope.[371]

The scenes where she is assisting the Greek heroes in the Trojan War are almost too numerous to specify, her favourite being of course Achilles; her meeting with Iris (Il. viii. 409) is once depicted,[372] and she also appears in connection with the dispute over Achilles’ arms.[373] She is not so frequently seen with her other favourite, Odysseus, but in one instance she is present when he meets with Nausikaa,[374] and also when he blinds Polyphemos.[375] On the numerous vases representing Ajax and Achilles (or other heroes) playing at draughts, the figure or image of the goddess is generally present in the background.[376] The same type on B.F. vases is adopted for the subject of two heroes casting lots before her statue[377]; lastly, she appears as the friend and patron of Orestes when expiating the slaying of his mother.[378]

As a single figure Athena is represented under many types and with various attributes, seated with her owl[379] or in meditation,[380] writing on tablets[381] or holding the ἀκροστόλιον of a ship[382]; playing on a lyre[383] or flutes,[384] or listening to a player on the flute or lyre[385]; with a man making a helmet,[386] or herself making the figure of a horse,[387] and in a potter’s workshop.[388] On an early vase she appears between two lions[389]; or she is accompanied by a hind (here grouped with other goddesses).[390] She is depicted running,[391] and occasionally is winged[392]; or she appears mounting a chariot, accompanied by various divinities.[393] As the protecting goddess of Attica she watches a combat of Greeks and Amazons[394]; she also attends the departure or watches combats of ordinary warriors,[395] or receives a victorious one.[396] In one instance she carries a dead warrior home.[397]

There are many representations of her image, either as a ξόανον or cultus-statue, or recalling some well-known type of later art. Among the former may be mentioned her statue at Troy, whereat Kassandra takes refuge from Ajax,[398] and the Palladion carried off by Odysseus and Diomede.[399] Among the latter, three can be traced to or connected with creations of Pheidias: viz. the chryselephantine Parthenos statue[400]; the Lemnian type, holding her helmet in her hand (Plate XXXVI.)[401]; and the Promachos, in defensive attitude, with shield and spear.[402] The last-named type (earlier, of course, than the famous statue on the Acropolis) is that universally adopted for the figure of Athena on the obverse of the Panathenaic amphorae, on which she is depicted in this attitude between two Doric columns surmounted by cocks (on the later examples by figures of Nike or Triptolemos).[403] Her statue is also represented as standing in a shrine or heroön[404]; or as the recipient of a sacrifice or offering.[405] Her head or bust alone appears on several vases.[406]

Ares, in the few instances in which he appears on vases, is generally in a subordinate position; he is a spectator at the birth of Athena[407]; and appears twice on the François vase, at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and again in an attitude of shame and humility, to indicate the part he played in the story of Hephaistos and Hera; of his combat with the former god mention has already been made (p. 16). In the Gigantomachia his opponent is Mimas, with whom he also appears in single combat[408]; and he aids his son Kyknos against Herakles and Athena.[409] He is seen in several of the large groups of Olympian deities,[410] or in smaller groups, e.g. with Poseidon and Hermes,[411] with Apollo, Artemis, and Leto,[412] or with Athena[413] or his spouse Aphrodite[414]; also with Dionysos, Ariadne, and Nereus.[415] He also receives a libation from Hebe.[416] He is seen at the birth of Pandora,[417] the punishment of Ixion,[418] the slaying of the Niobids,[419] the apotheosis of Herakles,[420] and the contest of that hero with the Nemean lion.[421] In some cases his type is not to be distinguished from that of an ordinary warrior or hero, as in one case where he or a warrior is seen between two women.[422]

Aphrodite seldom appears as a protagonist on vases, and in fact plays a small personal part in mythology. Apart from scenes of a fanciful nature she is usually a mere spectator of events; but as she is not often characterised by any distinctive attribute, there is in many cases considerable difficulty in identifying her personality. This is especially the case on B.F. vases, on which her appearances are comparatively rare. One vase represents her at the moment of her birth from the sea in the presence of Eros and Peitho[423]; she also appears (on late vases only) with Adonis,[424] embracing him, and in two instances mourning for him after his death[425]; but caution must be exercised in most cases in identifying this subject, which is but little differentiated from ordinary love scenes. One scene apparently represents Zeus deciding a dispute between her and Persephone over Adonis.[426]