Towards the New World

THE OLD WORLD

IN THE NEW

BY

EDWARD ALSWORTH ROSS, Ph.D., LL.D.

Professor of Sociology in the University of Wisconsin

Author of "Social Control," "Social Psychology,"

"The Changing Chinese," "Changing

America," Etc.

ILLUSTRATED WITH

MANY PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1914

Copyright, 1913, 1914, by

The Century Co.

Published, October, 1914

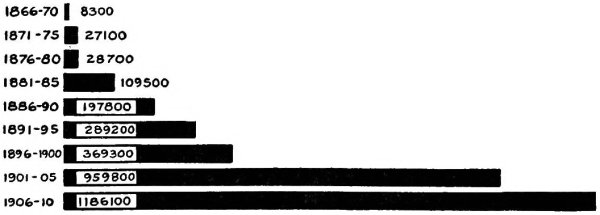

"Immigration," said to me a distinguished social worker and idealist, "is a wind that blows democratic ideas throughout the world. In a Siberian hut from which four sons had gone forth to America to seek their fortune, I saw tacked up a portrait of Lincoln cut from a New York newspaper. Even there they knew what Lincoln stood for and loved him. The return flow of letters and people from this country is sending an electric thrill through dwarfed, despairing sections of humanity. The money and leaders that come back to these down-trodden peoples inspire in them a great impulse toward liberty and democracy and progress. Time-hallowed Old-World oppressions and exploitations that might have lasted for generations will perish in our time, thanks to the diffusion by immigrants of American ideas of freedom and opportunity."

Rapt in these visions of benefit to belated humanity, my friend refused to consider any possible harm of immigration to this country. He did not doubt it so much as ignore it. How should the well-being of a nation be balanced against a blessing to humanity?

"Think what American chances mean to these poor people!" urged a large-hearted woman in settlement work. "Thousands make shipwreck, other thousands are disappointed, but tens of thousands do realize something of the better, larger life they had dreamed of. Who would exclude any of them if he but knew what a land of promise America is to the poor of other lands?" Her sympathy with the visible alien at the gate was so keen that she had no feeling for the invisible children of our poor, who will find the chances gone, nor for those at the gate of the To-be, who might have been born, but will not be.

I am not of those who consider humanity and forget the nation, who pity the living but not the unborn. To me, those who are to come after us stretch forth beseeching hands as well as the masses on the other side of the globe. Nor do I regard America as something to be spent quickly and cheerfully for the benefit of pent-up millions in the backward lands. What if we become crowded without their ceasing to be so? I regard it as a nation whose future may be of unspeakable value to the rest of mankind, provided that the easier conditions of life here be made permanent by high standards of living, institutions and ideals, which finally may be appropriated by all men. We could have helped the Chinese a little by letting their surplus millions swarm in upon us a generation ago; but we have helped them infinitely more by protecting our standards and having something worth their copying when the time came.

Edward Alsworth Ross.

The University of Wisconsin,

Madison, Wisconsin,

September, 1914.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| THE ORIGINAL MAKE-UP OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE | 3 |

| Traits of the Puritan stock—Elements in the peopling of Virginia—The indentured servants and convicts—Purification by free land—The Huguenots—The Germans—The Scotch-Irish—Ruling motives in the peopling of the New World—Selective agencies—The toll of the sea—The sifting by the wilderness—The impress of the frontier—How an American Breed arose—Its traits. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE CELTIC IRISH | 24 |

| The great lull—The Hibernian tide—Why it has run low—Effects on Ireland—Irish-Americans in the struggle for existence—Their improvidence and unthrift—Why they lacked the economic virtues—Drink their worst foe—Their small criminality—Loyalty to wife and child—Their occupational preferences—Their rapid rise—Their rank in intellectual contribution—Celtic traits—Place of the Irish in American society. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE GERMANS | 46 |

| Volume and causes of the German freshet—Why it has ceased—Distribution of the Germans in America—Deutschtum vs. assimilation—The "Forty-eighters"—Influence of the Germans on our farming, on our drinking, on our attitude toward recreation—Political tendencies of German voters—The Germans as pathbreakers for intellectual liberty—Their success in the struggle for existence—Moderation in alcoholism and in crime—Preferred occupations—Teutonic traits—Effect of the German infusion on the temper of the American people. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE SCANDINAVIANS | 67 |

| The size of the Scandinavian wave—Distribution of this element in the United States—Social characteristics—Crime and alcoholism—Occupational choices—Readiness of assimilation—Reaction to America—National contrasts among Scandinavians—Intellectual rating—Race traits—Moral and political significance of the Scandinavians. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE ITALIANS | 95 |

| Causes of the Italian outflow—Distribution of Italians—Social characteristics—Broad contrast between North Italians and South Italians—Occupations—Agricultural settlements—Freedom from alcoholism—Gaming—Addiction to violence—Camorra and Mafia in America—Difficulties in dealing with Italian immigrants—Their mental rating—Traits of character—The Italians as a social | |

| element. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE SLAVS | 120 |

| Place of the Slavs in history—Lateness of their awakening—Size of the Slav groups in America—Occupational tendencies of the Slavic immigrants—Distribution—Alcoholism—Criminality—Subjection of women—Extraordinary fecundity—Displacement of other elements—Resistance to Americanization—Clannishness—Social characteristics of Slav settlements—Industrial segregation—Mental rating—Prospects of Slavic immigration. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE EAST EUROPEAN HEBREWS | 143 |

| One-fifth of the Hebrew race in America—"The Promised Land"—Hebrew interest in free immigration—Waves of Russo-Hebrew immigration—Occupational preferences—Morals—Crime—Race traits—Intellectuality—Persistence of will—Growth of Anti-Semitism in America—Causes—Prospects—Why America is a powerful solvent of Judaism—Signs of Assimilation. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE LESSER IMMIGRANT GROUPS | 168 |

| African, Saracen and Mongolian blood in our immigrants—The Finns—Motives and characteristics—Political aptitude—Patriotism—The Magyars—Social condition and traits—The Portuguese—Origin and volume of the Portuguese influx—Distribution—Industrial and social characteristics—Resistance to assimilation—The Greeks—Immigration from Greece purely economic—Distribution and occupational preferences—Serfdom of Greek bootblacks—The Levantines—Racial and social characteristics. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF IMMIGRATION | 195 |

| Stimulators of migration—The commercial interests behind the movement—The new immigrant as an industrial tool—How tariff protection coupled with the open door augment the manufacturer's profits—Effect of the new immigration upon the cost of living, upon agricultural methods—Shall the penniless immigrant be helped to get upon the land—The utilization of foreign labor to break strikes—The foreign laborer as a hindrance to unionism—Effect upon wages and conditions—Is the foreigner indispensable—Immigrant women doing men's work—Fate of the displaced American—Immigration and crises—The inevitable rise of social pressure—Who bears the brunt? | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| SOCIAL EFFECTS OF IMMIGRATION | 228 |

| Immigration and social atavism—Community reversions to the Middle Ages—Immigrant illiteracy and ignorance—New readers of the yellow press—The spread of white peonage—Caste cleavage—Attitude of the foreign-born toward the claims of women—Split-family immigration and the social evil—How immigration makes acute the housing problem—Why overgrown cities—Immigrants who discount our charities—The wayward child of the immigrant—Insanity among the foreign-born—Obstructions to the operation of the public school—Signs of social decline—Peasantism vs. social progress. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| IMMIGRANTS IN POLITICS | 259 |

| The Hibernian domination of Northern cities—Political psychology of the Celts—Practical consequences—Immigration as foe to party traditionalism—Citizenship of the new immigrants compared with the old—Accumulation of voteless men—How this lessens the political strength of labor—Psychology of the ignorant naturalized immigrants—How the cunning boss acquires "influence"—Feudal relation between the boss and his humble constituents—Naturalization frauds—The Tammany way—The political machine—The liquor interest and the foreign-born voter—The foreign press in politics—The cost of losing political like-mindedness—Political mysticism vs. common sense. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| AMERICAN BLOOD AND IMMIGRANT BLOOD | 282 |

| Submergence of the pioneering breed—Growing heterogeneity—Primitive types among the foreign-born—How immigration will affect good looks in this country—Effect of crossing on personal beauty—Stature and physique of the newer immigrants—Do they revitalize the American people—Race morals of the South European stocks—Are the immigrants good samples of their own people—Appraisal of the different ethnic strains in the American people—Rating of present immigrant streams—How immigration has affected the fecundity of Americans—Evading a degrading competition by race suicide—The triumph of the low-standard elements over the high-standard elements. | |

| APPENDIX | 307 |

| INDEX | 321 |

| PAGE | |

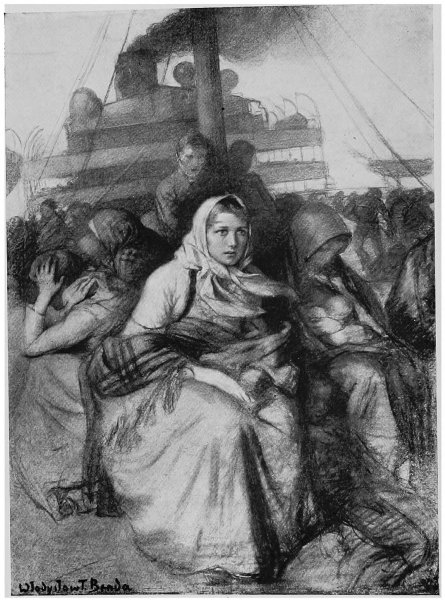

| Towards the New World | Frontispiece |

| Immigrant Women in Line for Inspection at Ellis Island | 6 |

| Slovaks, Ellis Island | 15 |

| Distribution of Irish and Natives of Irish Parentage—1910 | 38 |

| Distribution of Germans and Natives of German Parentage—1910 | 55 |

| Distribution of Scandinavians and Natives of Scandinavian Parentage—1910 | 78 |

| Typical Norwegian Boy | 87 |

| Typical Swedish Girl | 87 |

| Distribution of Italians and natives of Italian Parentage—1910 | 94 |

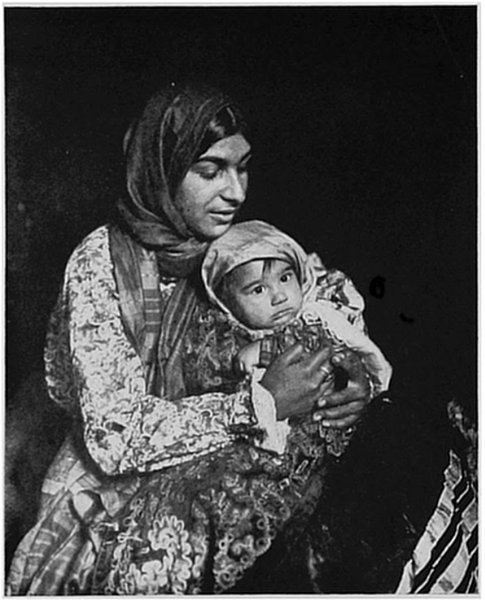

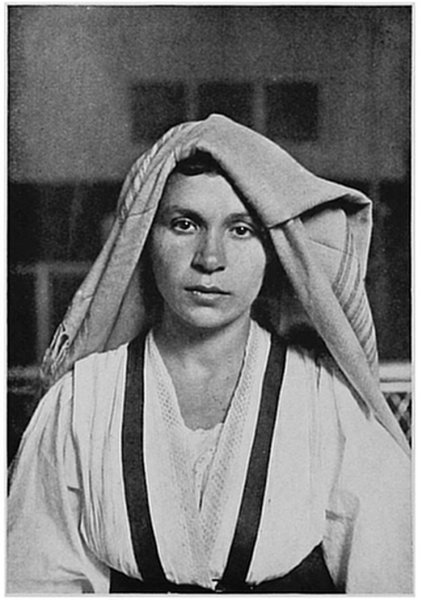

| Italian Gypsy Mother and Child | 100 |

| Italian Woman of Greek or Albanian Ancestry | 100 |

| Group of Italian Immigrants Lunching in Old Railroad Waiting Room, Ellis Island | 109 |

| Board of Special Inquiry, Ellis Island | 115 |

| Utter Weariness—Bohemian Woman on East Side, New York, after the Day's Work | 115 |

| Slav Sisters | 122 |

| Slovak Girl | 122 |

| Slav Woman and Italian Husband | 131 |

| Slovak Girls | 131 |

| Russian Jews, Ellis Island | 142 |

| Hindoo Immigrants | 142 |

| Slovak Woman and Jewish Man, Ellis Island | 151 |

| Jewish Girl in Chicago Sweat-Shop | 151 |

| Jewish Runner Soliciting Immigrants for the Steamship Company | 162 |

| Magyar | 171 |

| Croatian | 171 |

| Roumanian | 171 |

| Croatians Celebrating Their Going Home to the "Old Country" | 178 |

| Roumanian Couple in Gala Attire, Youngstown, Ohio | 178 |

| Magyar Peasant Woman | 186 |

| Molokan from Russia | 186 |

| A Finnish Woman by Her Cabin of Hewn Logs in Northern Wisconsin near Lake Superior | 191 |

| Some of Syracuse's Newer Citizens—A Greek and Two Turks | 191 |

| Sunday Group of Roumanian Steel Workers, Youngstown, Ohio | 199 |

| Sunday Roumanians, Youngstown, Ohio | 199 |

| The Unemployed—Middle of the Morning, Chicago | 206 |

| "Shack" of a Polish Iron Miner, Hibbing, Minn. | 211 |

| Cabin of an Austrian Iron Miner, Virginia, Minn. | 211 |

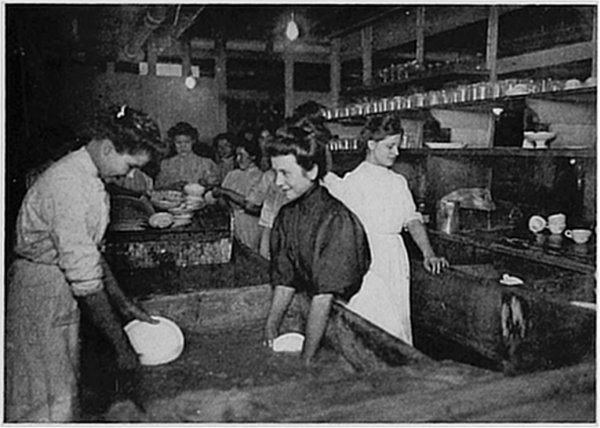

| Immigrant Girls Coming to Work in the Early Morning at the Union Stockyards | 217 |

| Polish Girls Washing Dishes Under the Sidewalk in a Chicago Restaurant | 217 |

| Roumanian Shepherds in Native Costume, Ellis Island | 224 |

| Distribution of Foreign-born Whites in the United States—1910 | 241 |

| Dependent Italian Family, Cleveland | 248 |

| Dependent Slovak Family, Cleveland | 248 |

| Italian Men's Civic Club, Rochester, N. Y. | 257 |

| A Civic Banquet to "New Citizens," July 4th | 268 |

| Y. M. C. A. Class of Slovenes in English Visiting a Session of the City Council of Cleveland | 277 |

| Class of Foreign-born Women (Carinthians) at the Cleveland Hardware Co., Cleveland, O., Meeting for Instruction in English in the Factory, Twice a Week from 5 to 6.30 | 277 |

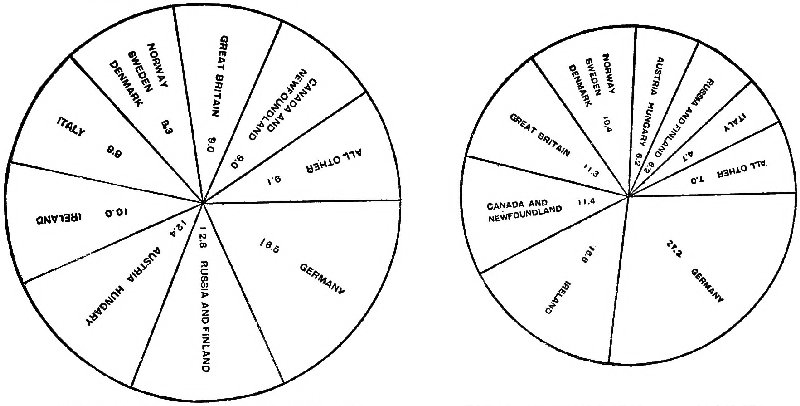

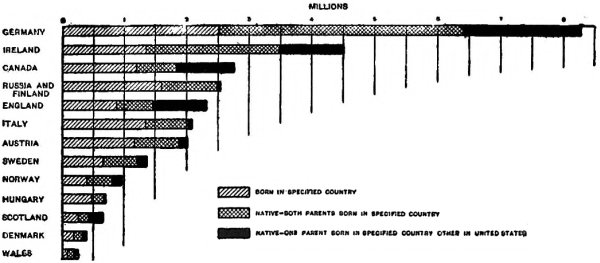

| Distribution of Foreign Stock in the United States—1910 | 284 |

| Distribution of Native White Stock in the United States—1910 | 301 |

"God sifted a whole nation that He might send choice grain into the wilderness." So thought the seventeenth century of the migration to Massachusetts Bay in the evil years of Charles I; but what are we to think of it? There is to-day so little sympathy with that remote, narrow New England theocracy that it is well to state again in living terms what part the coming of the best of the English Puritans bore in building up the American people.

As history makers, those who will suffer loss and exile rather than give up an ideal that has somehow taken hold of them are well nigh as unlike ordinary folk as if they had dropped from Mars. In every generation those who are capable of heroic devotion to any ideal whatsoever are only a remnant. Nine persons out of ten incline to the line of least resistance or of greatest profit, and will no more sacrifice themselves for an ideal than lead will turn to a magnet.

That the ideal should be final is of small consequence. It matters little whether it is a religious tenet, a mode of worship, a method of life, or a state of society. The essential thing is that it stands apart from the appetites, passions, and petty aims that govern most of us. Those who will face panther and tomahawk for the sake of their ideal are not to be swayed by the sordid motives and fitful passions that lord it over commonplace lives. Holding themselves to be instruments for the fulfilment of some larger purpose, men of this type make their mark upon the world. The fathers dedicate themselves to establishing godliness in the community. Their posterity fly to arms in behalf of the principle of "No taxation without representation." Their posterity, in turn, war upon the liquor traffic, slavery, or imperialism. As surely as one quarter of us are still of the blood of the twenty thousand Puritans who sought the wilderness between 1618 and 1640, so surely are there ideals not yet risen above the horizon that will inspire Americans in the generations to come.

The Dutch settled New Amsterdam from practical

motives, although some of them were Walloons

fleeing oppression in the Spanish Netherlands.

Gain prompted the peopling of Virginia,

and that colony received its share of human chaff.

The Council of Virginia early complained that

"it hurteth to suffer Parents to disburden themselves

of lascivious sonnes, masters of bad servants

and wives of ill husbands, and so clogge the[5]

[6]

[7]

business with such an idle crue, as did thrust

themselves in the last voiage, that will rather

starve for hunger, than lay their hands to labor."

In 1637 the collector of the port of London averred that "most of those that go thither ordinarily have no habitation ... and are better out than within the kingdom." After the execution of Charles I, a number of Royalist families removed to Virginia rather than brook the rule of Cromwell. This influx of the well-to-do registers itself in an abrupt increase in the size of the land-grants and in a sudden rise in the number of slaves. From this period one meets with the names of Randolph, Madison, Monroe, Mason, Marshall, Washington and many others that have become household words. On the whole, however, the exodus of noble "Cavaliers" to Virginia is a myth; for it is now generally admitted that the aristocracy of eighteenth-century Virginia sprang chiefly from "members of the country gentry, merchants and tradesmen and their sons and relatives, and occasionally a minister, a physician, a lawyer, or a captain in the merchant service," fleeing political troubles at home or tempted by the fortunes to be made in tobacco.

Less promising was the broad substratum that sustained the prosperity of the colony. For fifty years indentured servants were coming in at a rate from a thousand to sixteen hundred a year. No doubt many an enterprising wight of the English[8] or Irish laboring-class sold himself for a term into the tobacco-fields in order to come within reach of beckoning Opportunity; but we know, too, that the slums and alleys were raked for material to stock the plantations. Hard-hearted men sold dependent kinsfolk to serve in the colonies. Kidnappers smuggled over boys and girls gathered from the streets of London and Bristol. About 1670, no fewer than ten thousand persons were "spirited" from England in one year. The Government was slow to strike at the infamous traffic, for, as was urged in Parliament, "the plantations cannot be maintained without a considerable number of white servants."

Dr. Johnson deemed the Americans "a race of convicts," who "ought to be content with anything we allow them short of hanging." In the first century of the colonies, gallows'-birds were often given the option of servitude in the "plantations." Some prayed to be hanged instead. In 1717 the British Government entered on the policy of penal transportation, and thenceforth discharged certain classes of felons upon the colonies until the Revolution made it necessary to shunt the muddy stream to Botany Bay. New England happily escaped these "seven-year passengers," because she would pay little for them and because she had no tobacco to serve as a profitable return cargo. It is estimated that between 1750 and 1770 twenty thousand British convicts were exported to Maryland alone, so that even the school-masters there were mostly of this stripe. The[9] colonies bitterly resented such cargoes, but their self-protective measures were regularly disallowed by the selfish home government. American scholars are coming to accept the British estimate that about 50,000 convicts were marketed on this side the water.

It is astonishing how quickly this "yellow streak" in the population faded. No doubt the worst felons were promptly hanged, so that those transported were such as excited the compassion of the court in an age that recognized nearly three hundred capital offenses. Then, too, the bulk were probably the unfortunate, or the victims of bad surroundings, rather than born malefactors. Under the regenerative stimulus of opportunity, many persons reformed and became good citizens. A like purification of sewage by free land was later witnessed in Australia. The incorrigible, when they did not slip back to their old haunts, forsook the tide-water belt to lead half-savage lives in the wilderness. Here they slew one another or were strung up by "regulators," so that they bred their kind less freely than the honest. Thus bad strains tended to run out, and in the making of our people the criminals had no share at all corresponding to their original numbers. Blended with the dregs from the rest of the population, the convicts who were lazy and shiftless rather than criminal became progenitors of the "poor whites," "crackers," and "sandhillers" that still cumber the poorer lands of the southern Appalachians.

Probably no stock ever came here so gifted and prepotent as the French Huguenots. Though only a few thousand all told, their descendants furnished 589 of the fourteen thousand and more Americans deemed worthy of a place in "Appletons' Cyclopedia of American Biography." In 1790 only one-half of one per cent. of our people bore a French name; yet this element contributed 4.2 per cent. of the eminent names in our history, or eight times their due quota. Like the Puritans and the Quakers, the Huguenots were of an element that meets the test of fire and makes supreme sacrifices for conscience' sake. They had the same affinity for ideals and the same tenacity of character as the founders of New England, but in their French blood they brought a sensibility, a fervor, and an artistic endowment all their own.

It was likewise a sturdy stock, and in the early days of the settlement it was no unusual thing for parties to walk from New Rochelle to church in lower New York, a distance of twenty-three miles. As a rule they walked this distance with bare feet, carrying their shoes in their hands.

When seeking settlers for his new colony, William Penn gained much publicity for it in Germany, where he had a wide acquaintance. The[11] German Pietists responded at once, and a stream of picked families mingled with the English Quakers who founded the City of Brotherly Love. The first Germans to come were well-to-do people. Nearly all had enough money left on arrival to pay for the land they took up. In 1710, however, there arose in parts of Germany a veritable furor to reach the New World. The people of the ravaged Palatinate became agitated over the lure of America, and ship after ship breasted the Delaware, black with Palatines, Hanoverians, Saxons, Austrians, and Swiss. The cost of passage from the upper Rhine was equal to $500 to-day; but a vast number of penniless Germans got over the barrier by contracting with the ship-owner to sell themselves into servitude for a term of years. These were known as "redemptioners," and their service was commonly for from four to six years. Before the Revolution not fewer than 60,000 Germans had debarked at Philadelphia, to say nothing of the thousands that settled in the South.

Although not without a sectarian background, this great immigration bears clearly an economic impress. The virtues of the Germans were the economic virtues; invariably they are characterized as "quiet, industrious, and thrifty." Although Franklin wrote, "Those who come to us are the most stupid of their own nation," he spoke of them later, before a committee of the House of Commons, as "a people who brought with them the greatest of all wealth—industry and integrity,[12] and characters that have been superpoised and developed by years of persecution." It is likely that the intellectual stagnation of the Pennsylvania Germans and the smallness of their contribution to American leadership has been due to pietistic contempt for education rather than to the natural qualities of the stock.

The flailing of the clans after the futile rising of 1745 made the Scots restless, and in the last twelve years of the colonial era 20,000 Highlanders sought homes in America. But most of our Scottish blood came by way of Ireland. Early in the eighteenth century the discriminations of Parliament against the woolen industry of Ireland, and against Presbyterianism, provoked the largest immigration that occurred before the Revolution. The Ulster Presbyterians were descended from Scotsmen and English who had been induced between 1610 and 1618 to settle in the north of Ireland, and who were, in Macaulay's judgment, "as a class, superior to the average of the people left behind them." They cared for ideas, and at the beginning of the outflow there was probably less illiteracy in Ulster than anywhere else in the world. Entire congregations came, each headed by its pastor. "The whole North is in a ferment," lamented an Irish archbishop in 1728. "It looks as if Ireland were to send all her inhabitants hither," complained the governor of Pennsylvania. About 200,000 came[13] over, and on the eve of the Revolution the stock was supposed to constitute a sixth of the population of the colonies. They settled along the frontier, and bore the brunt of the warfare with the savage. It was owing chiefly to them that the Quakers and Germans of Pennsylvania were left undisturbed to live up to their ideals of peace and non-resistance. In eminence, the lead of the Scotch-Irish has been in government, exploration, and war, although they have not been lacking in contributors to education and invention. In art and music they have had little to offer.

The outstanding trait of the Scotch-Irish was will. No other element was so masterful and contentious. In a petition directed against their immigration, the Quakers characterized them as a "pernicious and pugnacious people" who "absolutely want to control the province themselves." The stubbornness of their character is probably responsible for the unexampled losses in the battles of our Civil War. They fought the Indian, fought the British with great unanimity in two wars, and were in the front rank in the conquest of the West. More than any other stock has this tough, gritty breed, so lacking in poetry and sensibility, molded our national character. If to-day a losing college crew rows so hard that they have to be lifted from their shell at the end of the boat-race, it is because the never-say-die Scotch-Irish fighters and pioneers have been the picturesque and glowing figures in the imagination of American youth.

Looked at broadly, the first peopling of this country owes at least as much to the love of liberty as to the economic motive. In the seventeenth century the peoples of the Old World seemed to be at odds with one another. Race trampled on race, and the tender new shoots of religious yearning were bruised by an iron state and an iron church. The rumor of a virgin land where the oppressed might dwell in peace drew together a population varied, but rich in the spirited and in idealists. What a contrast between the English colonies and those of the orthodox powers! For the intellectual stagnation of the French in Canada, thank Louis XIV, who would not allow Huguenots to settle in New France. Spain barred out the foreigner from her colonies, and even the Spaniard might not go thither without a permit from the Crown. Heretics were so carefully excluded that in nearly three centuries the Inquisition in Mexico put to death "only 41 unreconciled heretics, a number surpassed in some single days [in Spain] in Philip II's time." No wonder Spanish-American history shows men swayed by greed, ambition, pride, or fanaticism, but very rarely by a moral ideal.

Let no one suppose, however, that, as were the

original settlers, so must their descendants be.

When you empty a barrel of fish fry into a new

stream there is a sudden sharpening of their

struggle for existence. So, when people submit

themselves to totally strange conditions of life,[15]

[16]

[17]

Death whets his scythe, and those who survive are

a new kind of "fittest."

Were the Atlantic dried up to-day, one could trace the path between Europe and America by cinders from our steamers; in the old days it would have revealed itself by human bones. The conditions of over-sea passage then brought about a shocking elimination of the weaker. The ships were small and crowded, the cabins close, and the voyage required from six to ten weeks. "Betwixt decks," writes a colonist, "there can hardlie a man fetch his breath by reason there ariseth such a funke in the night that it causeth putrifacation of the blood and breedeth disease much like the plague."

In a circular, William Penn urged those who came to keep as much upon deck as may be, "and to carry store of Rue and Wormwood, or often sprinkle Vinegar about the Cabbin." The ship on which he came over lost a third of its passengers by smallpox. In 1639 the wife of the governor of Virginia writes that the ship on which she had come out had been "so pestered with people and goods ... so full of infection that after a while they saw little but throwing people overboard." One vessel lost 130 out of 150 souls. One sixth of the three thousand Germans sent over in 1710 perished in a voyage that lasted from January to June. No better fared a shipload of Huguenot refugees in 1686. A ship that left[18] Rotterdam with 150 Palatines landed fewer than fifty after a voyage of twenty-four weeks. In 1738 "malignant fever and flux" left only 105 out of 400 Palatines. In 1775 a brig reached New York, having lost a hundred Highlanders in passage. It was estimated that in the years 1750 and 1755 two thousand corpses were thrown overboard from the ships plying out of Rotterdam. In 1756, Mittelberger thus describes the horrors of the passage:

During the voyage there is aboard these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, vomiting, many kinds of sickness, fever, dysentery, scurvy, mouth-rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably.... Many hundred people necessarily perish in such misery and must be cast into the sea. The sighing and crying and lamenting on board the ship continues night and day.

Thus many poor-conditioned or ill-endowed immigrants succumbed en route. Those of greater resolution stood the better chance; for there was a striking difference in fate between those who lay despairing in the cabins and those who dragged themselves every day to the life-giving air of the deck.

Even after landing, the effects of the voyage pursued the unfortunates. In 1604, De Monts lost half his colony at St. Croix the first winter. More than half the Pilgrims were dead before[19] the Mayflower left for home, four months after reaching Plymouth. Of the Puritans who came to Massachusetts Bay in 1629, a fifth were under ground within a year. Of the 1500 who came over in the summer of 1630, 200 died before December. In 1754, a Philadelphia sexton testified that up to November 14 he had buried that year 260 Palatines.

In the South lay in wait the Indian and the malaria-bearing mosquito, and the latter slew more. The whites might patch a truce with the redskin, but never with the mosquito. They died as die raw Europeans to-day along the lower Niger or in the delta of the Amazon. In June, 1610, only 150 persons were living on the banks of the James River out of 900 who had been landed there within three years. By 1616, 1650 persons altogether had been sent out; of these 300 had returned, and about 350 were living in Virginia. During a twelvemonth in 1619-20, 1200 left England, but only 200 were alive in April, 1620. Fifty years later, Governor Berkeley stated: "There is not oft seasoned hands (as we term them) that die now, whereas heretofore not one out of five escaped the first year." A "seasoned" servant, having only one more year to serve, brought a better price than a new-comer, with seven and a half years to serve. Surely the survivors of such a shock had a tough fiber to pass on to their descendants. It is such selection that explains in part the extraordinary blooming of the colonies after the cruel initial period was over.

No doubt the iron hardihood of the South African Boers was built up by the succumbing of physical and moral weaklings amid a wilderness environment. In the same way our frontier made it hard for the soft basswood type to survive. Of the 380 persons whom Robertson collected in North Carolina in 1779 to found what is now Nashville, only 134 were alive at the end of a year, although not one natural death had occurred. Six months later only seventy were left alive. If there had been any weaklings in the party, by this time surely the tomahawk would have found them. No wonder, then, that when the vote was cast on the question of staying or going back, no one voted for going back. The less hardy, too, succumbed to the fever and ague, which decimated the settlers of the wooded country until they had cleared the forests and drained the marshes.

In the early days there streamed over the Wilderness Road that led to the settlements in Kentucky two tides, an outgoing tide of stout-hearted pioneers, seeking farms in the lovely blue-grass land, and a return flow of timid or shiftless people, affrighted by the horrors of Indian warfare or tired of the grim struggle for subsistence amid the stumps. The select character of those who built up these exposed settlements explains the wonderful forcefulness of the people of Kentucky and Ohio, especially before they had given so[21] many of their blood to found the commonwealths farther west. Thanks to the protecting frontier garrisons, the settlers of the trans-Mississippi States were perhaps not so rigorously selected as the trans-Alleghany pioneers; but, on the other hand, they were themselves largely of pioneer stock.

No doubt the "run of the continent" has improved the fiber of the American people. Of course the well established and the intellectuals had no motive to seek the West; but in energy and venturesomeness those who sought the frontier were superior to the average of those in their class who stayed behind. It was the pike rather than the carp that found their way out of the pool. Now, in the main, those who pushed through the open door of opportunity left more children than their fellows who did not. Often themselves members of large families, they had fecundity, as it were, in the blood. With land abundant and the outlook encouraging, they married earlier. In the narrow life of the young West, love and family were stronger interests than in the older society; hence all married. Thanks to cheap living and to the need of helpers, the big family was welcomed. Living by agriculture, the West knew little of cities, manufactures, social rivalry, luxury, and a serving class, all foes of rapid multiplication.

In 1802, Michaux found the families of the Ohio settlers "always very numerous," and of Kentucky he wrote: "There are few houses[22] which contain less than four or five children." Traveling in the Ohio Valley in 1807, Cumings observed: "Throughout this whole country, whenever you see a cabin you see a swarm of children"; and Woods wrote in 1819: "The first thing that strikes a traveler on the Ohio is the immense number of children." But there is solider proof of frontier prolificacy. The census of 1830 showed the proportion of children under five years in the States west of the Alleghanies to be a third to a half greater than in the seaboard region. The proportion of children to women between fifteen and fifty was from fifty to a hundred per cent. greater. In 1840, children were forty per cent. more numerous among the Yankees of the Western Reserve than among their kinsmen in Connecticut. The next half-century took the edge off the fecundity of the people of the Ohio Valley; but their sons and daughters who had pushed on into Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota, showed families a fifth larger. In 1900, the people of the agricultural frontier—Texas, Oklahoma, and the Dakotas—had a proportion of children larger by twenty-eight per cent. than that of the population between Pittsburgh and Omaha.

If the frontier drew from the seaboard population a certain element, and let it multiply more freely than it would have multiplied at home, the frontier must have made that element more plentiful in the American people, taken as a whole; and this, indeed, appears to be what actually occurred. No one ventures to assert that the Americans[23] are differentiated from the original immigrating stocks by superiority in any form of talent or in any kind of sensibility; but they impress all foreign observers with their high endowment of energy, tenacity of purpose, and willingness to take risks, and these are just the qualities that are fostered and made more abundant by the wilderness. I do not maintain that life in America has added any new trait to the descendants of transplanted Europeans, nor has it filled them all with the pioneer virtues. What I do mean is that, owing to the progressive peopling of the fertile wilderness, certain valuable strains that once were represented in, say, a sixth of the population, might come to be represented in a quarter of it; and the timid, inert sort might shrivel from a fifth of the population to a tenth. Such a shifting in the numerical strength of types would account both for the large contingent of the forceful in the normal American community, and for the prevalence of the ruthless, high-pressure, get-there-at-any-cost spirit which leaves in its wake achievement, prosperity, neurasthenia, Bright's disease, heart failure, and shattered moral standards.

From the outbreak of the Revolution until the fourth decade of the nineteenth century there was a lull in immigration. In a lifetime fewer aliens came than now debark in a couple of months. During these sixty years powerful forces of assimilation were rapidly molding a unified people out of the motley colonial population. In the fermenting West, the meeting-place of men from everywhere, elements of the greatest diversity were blending into a common American type which soon began to tinge the streams of life that ran distinct from one another in the seaboard States. Then came another epoch of vast immigration, which has largely neutralized the effect of the nationalizing forces, and has brought us into a state of heterogeneity like to that of the later colonial era.

After the great lull, the Celtic Irish were the first to come in great numbers. From 1820 to 1850 they were more than two-fifths of all immigrants, and during the fifties more than one-third. More than a seventh of our 30,000,000 immigrants have brought in their aching hearts memories of[25] the fresh green of the moist island in the Northern sea. The registered number is about 4,250,000, but the actual number is larger, for many of the earlier Irish, embarking in English ports, were counted as coming from England. No doubt the Irish who have suffered the wrench of expatriation to America outnumber the present population of the Green Isle, which is only a little more than one-half of what it was before the crisis of famine, rebellion, and misery that came about the middle of the nineteenth century. It is, indeed, a question whether there is not more Irish blood now on this side of the Atlantic than on the other. It is possible that during Victoria's reign more of her subjects left Ireland in order to live under the Stars and Stripes than left England in order to build a Greater Britain under the Union Jack.

In his "Coronation Ode," William Watson sees Ireland as

The truth of this shows in the way the wandering Irish still shun the lands under the British crown. Most of the inviting frontier left on our continent lies in western Canada. Already the opportunities there have induced land-hungry Americans to renounce their flag at the rate of a hundred thousand in a single year. Yet the resentful Irish turn to the narrower opportunities of what they regard as their land of emancipation.[26] During a recent nine-year period, while the English and the Scotch emigrants preferred Canada to "the States," eleven times as many Irish sought admission in our ports as were admitted to Canada, although Canada's systematic campaign for immigrants is carried on alike in England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Very likely the Irish exodus is a closed chapter of history. Ireland's population has been shrinking for sixty years, and she has now fewer inhabitants than the State of Ohio. People are leaving the land of heather twice as fast as they are abandoning the land of the shamrock. The early marriage and blind prolificacy that had overpopulated the land until half the people lived on potatoes, and two-fifths dwelt in one-room mud cabins, are gone forever, and Ireland has now one of the lowest birth-rates in Europe. Gradually the people are again coming to own the ground under their feet; native industries and native arts are reviving, and a wonderful rural coöperative movement is in full swing. The long night of misgovernment, ignorance, and superfecundity seems over, the star of home rule is high, and the day may soon come when these home-loving people will not need to seek their bread under strange skies.

During its earlier period, Irish immigration brought in a desirable class, which assimilated readily. Later, the enormous assisted immigration that followed the famine of 1846-48 brought in many of an inferior type, who huddled helplessly[27] in the poorer quarters of our cities and became men of the spade and the hod. After the crisis was past, there again came a type that was superior to those who remained behind. Of course the acquiescent property-owning class never emigrated, and those rising in trade or in the professions rarely came unless they had fallen into trouble through their patriotism. But of the common people there is evidence that the more capable part leaked away to America. The Earl of Dunraven testifies:

Those who have remained have, for the most part, been the least physically fit, the most mentally deficient, and those who correspond to the lowest industrial standard.... For half a century and more the best equipped, mentally and physically, of the population have been leaving Ireland. The survival of the unfittest has been the law, and the inevitable result, deterioration of the race, statistics abundantly prove.

Owing to this exodus of the young and energetic, Ireland has become the country of old men and old women. An eighth of her people are more than sixty-five years old as against an eleventh in England. In half a century the proportion of lunatics and idiots in the population of Ireland rose from one in 657 to one in 178. In 1906 the inspector of lunatics reported:

The emigration of the strong and healthy members of the community not alone increases the ratio of the insane who are left behind to the general population, but also lowers the general standard of mental and[28] bodily health by eliminating many of the members of the community who are best fitted to survive and propagate the race.

He may not have known that, compared with the rest of our immigrants, the Irish have twice their share of insanity. The commissioners of national education, after pointing with pride to half a century's great reduction of illiteracy, add:

The change for the better is remarkable when it is remembered that it was the younger and better educated who emigrated ... during this period, while the majority of the illiterate were persons who were too old to leave their homes.

A close study of two hundred workingmen's families in New York City showed the average German family thirty dollars ahead at the end of the year while the average Irish family of about the same income had spent ten dollars more than it had earned. Charity visitors know that the Irish are often as open-handed and improvident as the Bedouins. A Catholic educator accounts for the scarcity of Irish millionaires by declaring that his people are too generous to accumulate great fortunes. They are free givers, and no people are more ready to take into the family the orphans of their relatives. In a county of mixed nationalities there will be more mortgages and stale debts against Irish farmers than against any others. In a well-paid class of[29] workers there will be more renters and fewer home-owners among the Irish than among any other nationality of equal pay. Less habitually than others do the Irish make systematic provision for old age. They depend on the earnings of their children, who, indeed, are many and loyal enough. But if the children die early or scatter, the day-laborer must often eat the bread of charity. A decade ago the Irish were found to be relatively thrice as numerous in our almshouses as other non-native elements. In the Northeast, where they formed a quarter of the foreign-born population, they furnished three-fifths of the paupers. In Massachusetts, and in Boston as well, they were four times as common in the almshouses as out of them, although, to be sure, a part of this bad showing is due to more of them being aged. Nor do their children provide much better for the future. In Boston, those of Irish parentage produce two and one-half times their quota of paupers. In both first and second generations the frugal and fore-looking Germans there have less than a tenth of the pauperism of the Irish, while in 1910 in the country at large the tendency of the Irish toward the almshouse was nearly three times that of the Germans. Dr. Bushee, who has investigated the conditions in Boston, says:

It cannot be said that the ordinary Irishman is of a provident disposition; he lives in the present and worries comparatively little about the future. He is not extravagant in any particular way, but is wasteful[30] in every way; it is his nature to drift when he ought to plan and economize. This disposition, combined with an ever-present tendency to drink too much, is liable to result in insecure employment and a small income. And, to make matters worse, in families of this kind children are born with reckless regularity.

In extenuation, let it not be forgotten that at home the earlier Irish immigrants had lived under perhaps a more demoralizing social condition than that from which any other of our immigrants have come. Fleeing from plague and starvation, great numbers were dumped at our ports with no means of getting out upon the land. What was there for them to do but to rush their labor into the nearest market and huddle sociably together in wretched slums, where, despite their sturdy physique, they fell an easy prey to sickness and died off twice as fast as they should? They lived as poorly as do the Russian Jews when first they come; but, being a green country-folk, they understood less than do the town-bred Jews how to withstand the noxious influences of cities and slums.

Certainly, along with their courage and loyalty, the Irish did not bring the economic virtues. Straight from the hoe they came, without even the thrift of the farmer who owns the land he tills. Many of them were no better fitted to succeed in the modern competitive order than their ancestors of the septs in the days of Strongbow. In value-sense and foresight, how far they stand behind Scot, Fleming, or Yankee! In the acquisitive mêlée most of them are as children compared with[31] the Greek or the Semite. An observant settlement worker has said:

The Irish are apt to make their occupation a secondary matter. They remain idle if no man hires them; but not so the Jew. If he can get no regular employment, it is possible to gather rags and junk and sell them.... If employed under a hard master, he still works on under conditions that would drive the Irishman to drink and the American to suicide until finally he sees an opportunity to improve his condition.

We must not forget that Irish development had been forcibly arrested by the selfish policy of their conquerors. In the latter part of the seventeenth century the English Parliament, at the behest of English graziers and farmers, put an end to Ireland's cattle-trade to England, then to her exportation of provisions to the colonies. Afterward came export duties on Irish woolens, and, later, complete prohibition of the exportation of woolens to foreign countries. "Cotton, glass, hats, iron manufactures, sugar refining—whatever business Ireland turned her hand to, and always with success—was in turn restricted." The result was that the natural capacity of the people was repressed, the growth of industrial habits was checked, and the country was held down to simple agriculture under a blighting system of absentee landlordism. Still, we cannot overlook the success of the Scottish Lowlanders in Ulster under the same strangling discriminations, nor forget that the 3500 German Protestant refugees[32] who were settled in Munster in 1709 prospered as did their brother refugees in Pennsylvania, and became in time much wealthier than their Celtic neighbors.

A thousand years ago an Irish scholar, teaching at Liège, acknowledged his love for the cup in his invocation to the Muses, and addressed a poem to a friend who, being the possessor of a great vineyard, understood "how to awaken genius through the inspiration of the heavenly dew."

It is this same "heavenly dew"—whose Erse name usquebaugh, we have pronounced "whisky"—that, more than anything else, has held back the Irish in America. The Irishman is no more a craver of alcohol than other men, but his sociability betrays him to that beverage which is the seal of good fellowship. He does not sit down alone with a bottle, as the Scandinavian will do, nor get his friends round a table and quaff lager, as the German does. No "Dutch treat" for him. He drinks spirits in public, and, after a dram or two, his convivial nature requires that every stranger in the room shall seal friendship in a glass with him. His temperament, too, makes liquor a snare to him. Where another drinker becomes mellow or silent or sodden, the Celt becomes quarrelsome and foolish.

Twenty years ago an analysis of more than seven thousand cases of destitution in our cities showed that drink was twice as frequent a cause[33] of poverty among the Irish cases as among the Germans, and occurred half again as often among them as among the native American cases. Among many thousands of recent applications for charity, "intemperance of the bread-winner" crops out as a cause of destitution in one case out of twelve among old-strain Americans; but it taints one case out of seven among the Irish and one case out of six among the Irish of the second generation. In the charity hospitals of New York alcoholism is responsible for more than a fifth of all the cases. Drink is the root of the trouble in a quarter of the native Americans treated, in a third of the Irish patients, and in two-fifths of the cases among the native-born of Irish fathers. Contrast this painful showing with the fact that one Italian patient out of sixty, one Magyar patient out of seventy, one Polish patient out of eighty, and one Hebrew patient out of one hundred is in the hospital on account of drink!

In the quality of their crimes our immigrants differ more from one another than they do in complexion or in the color of their eyes. The Irishman's love of fighting has made Donnybrook Fair a byword; yet it is a fact that personal violence is six or seven times as often the cause of confinement for Italian, Magyar, or Finnish prisoners in our penitentiaries as for the Irish. Patrick may be quarrelsome, but he fights with his hands, and in his cups he is not homicidal,[34] like the South Italian, or ferocious, like the Finn. Three-fifths of the Hebrew convicts are confined for gainful offenses, but only one-fifth of the Irish. Among a score or more of nationalities, the Irish stand nearly at the foot of the list in the commission of larceny, burglary, forgery, fraud, or homicide. Rape, pandering, and the white-slave traffic are almost unknown among them. What could be more striking than the fact that more than half of the Irish convicts have been sent up for "offenses against public order," such as intoxication and vagrancy! One cannot help feeling that the Celtic offender is a feckless fellow, enemy of himself more than of any one else. It is usually not cupidity nor brutality nor lust that lodges him in prison, but conviviality and weak control of impulses.

It is certain that no immigrant is more loyal to wife and child than the Irishman. Out of nearly ten thousand charity cases in which a wife was the head of the family, the greatest frequency of widowhood and the least frequency of desertion or separation is among the Irish. In only eighteen per cent. of the Irish cases is the husband missing; whereas among the Hebrews, Slovaks, Lithuanians, and Magyars he is missing in from forty to fifty per cent. of the cases. But the sons of Irish, with that ready adaptation to surroundings characteristic of the Celt, desert their wives with just about the same frequency as men of pure American stock; namely, thirty-six per cent., or twice that of their fathers.

Thirty years ago, when the Irish and the Germans in America were nearly equal in number, there were striking contrasts in the place they took in industry. As domestic servants, laborers, mill-hands, miners, quarrymen, stone-cutters, laundry workers, restaurant keepers, railway and street-car employees, officials and employees of government, the Irish were two or three times as numerous as the Germans. On the other hand, as farmers, saloon-keepers, bookkeepers, designers, musicians, inventors, merchants, manufacturers, and physicians, the Germans far outnumbered the Irish. Where artistic skill is required, as in confectionery, cabinet-making, wood-carving, engraving, photography, and jewelry-making; where scientific knowledge is called for, as in brewing, distilling, sugar-refining, and iron manufacture, the Irish were hopelessly beaten by the trained and plodding Germans.

For a while, the bulk of Irish formed a pick-and-shovel caste, claiming exclusive possession of the poorest and least honorable occupations, and mobbing the Chinaman or the negro who intruded into their field. But the record of their children proves that there is nothing in the stock that dooms it forever to serve at the tail-end of a wheelbarrow. Take, for instance, those workers known to the statistician as "Female bread-winners." Of the first generation of Irish, fifty-four[36] per cent. are servants and waitresses; of the second generation, only sixteen per cent. Whither have these daughters gone? Out of the kitchen into the factory, the store, the office, and the school. In the needle trades they are twice as frequent as Bridget or Nora who came over in the steerage. Five times as often they serve behind the counter, seven times as often they work at the desk as stenographer or bookkeeper, five times as frequently they teach. One native girl out of twelve whose fathers were Irish is a teacher, as against one girl out of nine with American fathers. The Irish girls of the second generation are twice as well represented as the native-born German girls. Evidently it will not be long before they have their full share of school positions. In thirty leading cities eighteen per cent. of the teachers are second-generation Irish; and there are cities where these swift climbers constitute from two-fifths to a half of the teaching force.

'Tonio or Ivan now wields the shovel while

Michael's boy escapes competition with him by

running nimbly up the ladder of occupations.

As compared with their immigrant fathers, the

proportion of laborers among the sons of Irishmen

is halved, while that of professional men and

salesmen is doubled, and that of clerks, copyists,

and bookkeepers is trebled. The quota of saloon-keepers

remains the same. There is no drift into

agriculture or into mercantile pursuits. In the

cities the Irish suffer little from the competition

of the later immigrants because, thanks to their[37]

[38]

[39]

political control, they divide among themselves

much of the work carried on by the municipality

as well as the jobs under the great franchise-holding

corporations. So far, the strength of the

Irish has been in personal relations. They shine

in the forum, in executive work, in public guardianship,

and in public transportation, but not in

the more monotonous branches of manufacture.

In the colleges it has been noted that the students

of Irish blood are strong for theology and law,

but show little taste for medicine, engineering, or

technology.

Among the first thousand men of science in America the Irish are only a fourth as well represented as the Germans, a fifteenth as well as the English and Canadians, and a twentieth as well as the Scotch. This backwardness is in part due to the overhang of bad conditions; and the compilers of the table very properly suggest that "the native-born sons of Irish-born parents may not be inferior in scientific productivity to other classes of the community." The same comment may be made on the fact that of the persons listed in "Who's Who in America," two per cent. were German-born, another two per cent. were English-born, but only one per cent. came from the land of Erin.

No doubt the peaks of Celtic superiority are poetry and eloquence. Their gifts of emotion and imagination give the Irish the key to human[40] hearts. They are eloquent for the same reason that they are poor technicians and investigators, for the typical Celt sees things not as they really are, but as they are to him.

The Irishman still leans on authority and shows little tendency to think for himself. In philosophy and science he is far behind the head of the procession. Even when well-educated, he thinks within the framework formed by certain conventional ideas. Unlike the educated German or Jew, he rarely ventures to dissect the ideas of parental authority, the position of woman, property, success, competition, individual liberty, etc., that lie at the base of commonplace thought. Here, again, this limitation by sentiment and authority derives doubtless from the social history of the Irish rather than from their blood. They have been engrossed with an old-fashioned problem—that of freeing their country. Meanwhile, the luckier peoples have swept on to ripen their thinking about class relations, industrial organization, and social institutions.

With his Celtic imagination as a magic glass, the Irishman sees into the human heart and learns how to touch its strings. No one can wheedle like an Irish beggar or "blarney" like an Irish ward boss. Not only do the Irish furnish stirring orators, persuasive stump-speakers, moving pleaders, and delightful after-dinner speech-makers, but they give us good salesmen and successful[41] traveling-men. Then, too, they know how to manage people. The Irish contractor is a great figure in construction work. The Irish mine "boss" or section foreman has the knack of handling men. The Irish politician is an adept in "lining up" voters of other nationalities. More Germans than Irish enlisted in the Union armies, but more of the Irish rose to be officers. In the great corporations Americans control policy and finance, Germans are used in technical work, and Irishmen are found in executive positions. The Irish are well to the fore in organizing labor and in leading athletics. "Of two applicants," says a city school superintendent, "I take the teacher with an Irish name, because she will have less trouble in discipline, and hits it off better with the parents and the neighborhood."

Whatever is in the Irish mind is available on the instant, so that the Irish rarely fail to do themselves justice. They keep their best foot forward, and if they fall, they light on their feet. They succeed as lawyers not only because they can play upon the jury, but because they are quick in thrust and parry. They abound in newspaper offices because their imagination enables them to keep "in touch" with the public mind. The Irishman rarely attains the thorough knowledge of the German physician; but he makes his mark as surgeon, because he is quick to perceive and to decide when the knife discloses a grave, unsuspected condition.

The Irishman accepts the Erse proverb, "Contention is better than loneliness." "His nature goes out to the other fellow all the time," declares a wise priest. The lodge meeting of a Hibernian benevolent association is a revelation of kindness and delicacy of feeling in rough, toil-worn men. A great criminal lawyer tells me that if he has a desperate case to defend, he keeps the cold-blooded Swede off the jury and gets an Irishman on, especially one who has been "in trouble." Bridget becomes attached to the family she serves, and, after she is married, calls again and again "to see how the childher are coming on." Freda, after years of service, will leave you off-hand and never evince the remotest interest in your family. The Irish detest the merit system, for they make politics a matter of friendship and favor. In their willingness to serve a friend they are apt to lose sight of the importance of preparation, fitness and efficiency in the public servant. Hence they warm to a reform movement only when it becomes a fight on law-breakers. Then the Hibernian district attorney goes after the "higher-ups" like a St. George. When the Irish do renounce machine politics, they become broad democrats rather than "good government" men.

Imaginative and sensitive to what others think of him, the Celt is greatly affected by praise and criticism. Unlike the Teuton, he cannot plod patiently toward a distant goal without an appreciative word or glance. He does his best when he[43] is paced, for emulation is his sharpest stimulus. The grand stand has something to do with the Irish bent for athletic contests. Irish school-children love the lime-light, and distinguish themselves better on the platform than in the classroom. Irish teachers with good records in the training-school are less likely than other teachers to improve themselves by private study.

"The Irish are wilder than the rest in their expression of grief," observes the visiting nurse, "but they don't take on for long." The Irishman is less persistent than others in keeping up the premiums on his insurance policy, the payments on his building-and-loan association stock. He is quick to throw up his job or change his place in order to avoid sameness. "My will is strong," I heard a bright-eyed Kathleen say, "but it keeps changing its object; Gunda [her Norwegian friend] is so determined and fixed in purpose!" There is a proverb, "The Irishman is no good till he is kicked," meaning that he is unstable till his blood is up. Once his fighting spirit is roused, he proves to be a "last ditcher." As a soldier, he is better in a charge than in defense, and if held back, he frets himself to exhaustion.

A professor compares his Celtic students to the game trout, which makes one splendid dash for the fly, but sulks if he misses it. A bishop told me how his prize-man, an Irish youth, sent to Paris to study Hebrew, was amazed at the prodigious industry of his German and Polish chums. "I never knew before," he wrote, "what study[44] is." A settlement worker comments on the avidity with which night-school pupils in Irish neighborhoods select classes with interesting subjects of instruction, and the rapidity with which they drop off when the "dead grind" begins. Their temperament rebels at close, continuous application. The craftsman of Irish blood is likely to be a little slapdash in method, and he rarely stands near the top of his trade in skill. The Irishman succeeds best in staple farming—all wheat, all cotton, or all beets. With the advent of diversified farming, he is supplanted by the painstaking German, Scandinavian, or Pole. Work requiring close attention to details—like that of the nurseryman, the florist, or the breeder—falls into the hands of a more patient type. In banking and finance, men of a colder blood control.

The word "brilliant" is oftener used for the Irish than for any other aliens among us save the Hebrews. Yet those of Irish blood are far from manning their share of the responsible non-political posts in American society. Their contribution by no means matches that of an equal number of the old American breed. But, in sooth, it is too soon yet to expect the Irish strain to show what it can do. Despite their schooling, the children of the immigrant from Ireland often become infected with the parental slackness, unthrift, and irresponsibility. They in turn communicate some of the heritage to their children; so that we shall[45] have to wait until the fourth generation before we shall learn how the Hibernian stock compares in value with stocks that have had a happier social history.

More than 5,250,000 people have been contributed to our population by Germany in the last ninety years. Deducting the Poles from eastern Prussia, and counting Germans from Russia, Austria, Bohemia, and eastern Switzerland, we have, no doubt, received more than 7,000,000 whose mother-tongue was the speech of Luther and Goethe. It is probable that German blood has come to be at least a fourth part of the current in the veins of the white people of this country, so that this infusion alone equals the total volume of Spanish and Portuguese blood in South America.

From its rise in the thirties until after our Civil War, the stream of immigrants from Germany fluctuated with religious and political conditions on the other side of the Atlantic rather than with economic conditions on this side. Between 1839 and 1845 numerous Old Lutherans, resenting the attempt of their king to unite the Lutheran and the Reformed faiths, migrated hither from Pomerania and Brandenburg. The political reaction in the German states after the revolution of 1830, and again after the revolution of 1848, brought tens of thousands of liberty-lovers.[47] In 1851, in a book of advice to intending immigrants, Pastor Bogen of Boston set forth as the chief inducement to migrate the freedom the Germans would enjoy in America—freedom from oppression and despotism, from privileged orders and monopolies, from intolerable imposts and taxes, from constraint in matters of conscience, from restrictions on settling anywhere in this country of "exhaustless resources."

The political exiles famous as the "Forty-eighters" included many men of unusual attainments and character, who almost at once became leaders of the German-Americans, exercising an influence quite out of proportion to their numbers. These university professors, physicians, journalists, and even aristocrats, aroused many of their fellow-countrymen to feel a pride in German culture, and they left a stamp of political idealism, social radicalism, and religious skepticism which is slow to be effaced.

Thanks to the Hausfrau ideal for women and to the militarist demand for recruits, the German people has until recently persevered in a truly medieval fecundity. Despite an outflow of 6,500,000 between 1820 and 1893, population has doubled in seventy years and trebled in a hundred. Prince Bülow complains that "the Poles of eastern Prussia multiply like rabbits, while we Germans multiply like hares." The fact is, a generation ago the Germans, too, were multiplying like rabbits. This is the reason why during the seventies and eighties, although political conditions[48] had much improved, great numbers of farm-laborers, female servants, handicraftsmen, small tradesmen, and other members of the humbler classes, streamed out of crowded Germany in the hope of improving their material condition. The peasant living on black bread and potatoes heard of and longed for the white bread and fleshpots of the American West. Although the overwhelming majority of the 1,500,000 Germans who immigrated during the eighties represented the lower economic strata, they came in with fair schooling, considerable industrial skill, and, on an average, three times as much money as the Slav, Hebrew, or South European shows to-day at Ellis Island.

The German influx dropped sharply as soon as the panic of 1893 broke out, and when, after four and a half years of economic submergence, this country struggled to the surface, the tide of Teutons was not ready to flow again. America's free land was gone, and ruder peoples, with lower standards of living, were crowding into her labor markets. In the meantime, Germany's extraordinary rise as a manufacturing country, her successes in foreign trade, and her wonderful system of protection and insurance for her labor population, had made her sons and daughters loath to migrate oversea. The immigration from Germany into the United States is virtually a closed chapter, and has been so for twenty years. Such Germans as now arrive hail chiefly from Austria and Russia.

No other foreign element is so generally distributed over the United States as the Germans. A third of them are between Boston and Pittsburgh, fifty-five per cent. live between Pittsburgh and Denver, seven per cent. are in the South, and five per cent. are in the far West.

In the South they are more numerous than any other non-native element. They predominate, except in New England, where the Irish abound; in States along the northern border, into which filter many Canadians; in the Dakotas, where the Scandinavians lead; in the Mormon States, with their many converts from England; and in Louisiana and Florida, with their Italians and Cubans. In Milwaukee nearly half the people are of German parentage, in Cincinnati a quarter, in St. Louis a fifth. A third of the Germans are in the rural districts, whereas all but a sixth of the Irish are in cities. Whether one considers their distribution among the States, their partition between city and country, or their dispersion among the callings, the Germans will be found to be the most pervasive element so far added to our people.

Unlike the Irish immigrants, the Germans brought a language, literature, and social customs of their own; so that, although when scattered they Americanized with great rapidity, wherever they were strong enough to maintain churches and[50] schools in their own tongue they were slow to take the American stamp. For the sake of their beloved Deutschtum, about the middle of the last century the promoters of this migration dreamed of creating in the West a German state where Germans should hold sway and hand down their culture in all its purity. Missouri, Illinois, Texas, and later Wisconsin, seemed to hold out such a hope. But the immigrants would not remain massed, the Yankees pushed in, and "Little Germany" never found a place on the map.

After 1870 the Teutonic overflow was prompted by economic motives, and such a migration shows little persistence in flying the flag of its national culture. Numbers came, little instructed, or else bringing a knowledge of Old Testament worthies rather than of German poets, musicians, and artists. In the words of a German-American, Knortz: "Nine-tenths of all German immigrants come from humble circumstances and have had only an indifferent schooling. Whoever, therefore, expects pride in their German descent from these people, who owe everything to their new country and nothing to their fatherland, simply expects too much."

The "Forty-eighters" had given a great stimulus to all German forms of life,—schools, press, stage, festivals, choral societies, and gymnastic societies,—but since the passing of these leaders and the subsidence of the Teutonic freshet, Deutschtum has been on the wane. German newspapers are disappearing, German-American[51] books and journals become fewer, German book stores are failing, German theaters are closing, and the surviving German private schools may be counted on the fingers. Probably not more than ten per cent. of the children of German parentage hear anything but English spoken at home. Champions of Deutschtum admit sadly that nothing but a strong current of immigration can preserve it here. The spreading German-American National Alliance is bringing about a marked revival, but hardly will it succeed in persuading the majority of its people to lay upon their children the burden of a bi-lingual education. It is the apparent destiny of the descendants of the myriads of Germans who have settled here to lose themselves in the American people, and to take the stamp of a culture which is, in origin at least, eighty per cent. British.

It is no small tribute to the solvent power of American civilization that the stable and conservative Germans, who, as settlers in Transylvania, in Chili, or in Palestine, among the Russians on the lower Volga, or among the Portuguese in southern Brazil, are careful to keep themselves unspotted from the people about them, have proved, on the whole, easy to Americanize. Years ago, Prof. James Bryce, just back from Ararat, after noting the purity of the German culture preserved by the Swabian colony in Tiflis, added:

It was very curious to contrast this complete persistence of Teutonism here with the extremely rapid absorption of the Germans among other citizens which[52] one sees going on in those towns of the Western States of America, where—as in Milwaukee, for instance—the inhabitants are mostly Germans, and still speak English with a markedly foreign accent.... Here they are exiles from a higher civilization planted in the midst of a lower one; there they lose themselves among a kindred people, with whose ideas and political institutions they quickly come to sympathize.

The leanness of his home acres taught the German to make the most of his farm in the New World. The immigrant looked for good land rather than for land easy to subdue. Knowing that a heavy forest growth proclaims rich soil, he shunned the open areas, and chopped his homestead out of the densest woods. While the American farmer, in his haste to live well, mined the fertility out of the soil, the German conserved it by rotating crops and feeding live stock. In caring for his domestic animals, he set an example. Just as the county agricultural fair, and the state fair as well, is the development of the Pennsylvania-German Jahrmarkt, and the "prairie schooner" is the lineal descendant of the "Conestoga wagon," so the capacious red barns of the Middle West trace their ancestry back to the big barn which the Pennsylvania "Dutchman" provided at a time when most farmers let their stock run unsheltered.

Thanks partly to good farming and frugal living, and partly to the un-American practice of working their women in the fields, the German[53] farmers made money, bought choice acres from under their neighbors' feet, and so kept other nationalities on the move. This is the reason why a German settlement spreads on fat soil and why in time the best land in the region is likely to come into German hands. Unlike the restless American, with his ears ever pricked to the hail of distant opportunity, the phlegmatic German identifies himself with his farm, and feels a pride in keeping it in the family generation after generation. Taking fewer chances in the lottery of life than his enterprising Scotch-Irish or limber-minded Yankee neighbor, he has drawn from it fewer big prizes, but also fewer blanks.

In quest of vinous exhilaration, our grandfathers stood at a bar pouring down ardent spirits. It is owing to our German element that the mild lager beer has largely displaced whisky as the popular beverage, while sedentary drinking steadily gains on perpendicular drinking. Because the toping of beer has from time immemorial been interwoven with their social enjoyments, and because beer, unlike whisky, makes wassailers fraternal rather than wild and quarrelsome, the Germans, supported by the Bohemians, have offered, in the name of "personal liberty," the most determined opposition to liquor legislation. They may renounce the bowl, but taken away it shall not be! In their loyalty to beer, these Teutons out-German their cousins in the Fatherland, who are of late turning from the national beverage at an astonishing rate. At[54] the World's Fair in St. Louis a number of American scholars who had studied of yore in German universities gave a luncheon to the visiting German economists. Out of respect for their guests, the hosts all filled the mugs of their student days; but, to their astonishment, the Germans called unanimously for iced tea!

The influence of the Germans in spreading among us the love of good music and good drama is acknowledged by all. But there is a more subtle transformation that they have wrought on American taste. The social diversions of the Teutons, and their affirmance of the "joy of living," have helped to clear from our eyes the Puritan jaundice that made all physical and social enjoyment look sinful. If "innocent recreation" and "harmless amusement" are now phrases to conjure with, it is largely owing to the Germans and Bohemians, with their love of song and mirth and "having a good time." Few of the present generation realize that fifty years ago the principal place of amusement in the American town, although as innocent of opera as a Kaffir kraal, called itself the "opera-house," in order to avoid the damning stigma the reigning Puritanism had attached to the word "theater."

As voters, the Germans have shown little clannishness.

Their partizanship has not been

bigoted, and by their insistence on independent

voting they have perplexed and disgusted the

politicians. Before 1850, they saw in the Democratic

party the champion of the liberties for the[55]

[56]

[57]

sake of which they had expatriated themselves.

But when the slavery issue came to be overshadowing,

the "Forty-eighters" were able to

swing them to the newly formed Republican

party, to which, on the whole, they have remained

faithful, although in some States their loyalty

has been much shaken by prohibition. On money

questions the Germans have been conservative.

Bringing with them the notion of an efficient civil

service, they have despised office-mongering and

have befriended the merit system. No immigrants

have been more apt to look at public

questions from a common-welfare point of view

and to vote for their principles rather than

for their friends. If by "political aptitude" is

meant the skill to use politics for private advantage,

then in this capacity the German must be

ranked low among our foreign-born.

In the way of civil and political liberty, the Germans added nothing to the old-English heritage they found here; but in freedom of thought their contribution has been invaluable. Where there is no church, state, or upper class to hold it in check, the community is likely to show itself imperious toward the nonconformist. The New England Puritan, who was oak to any civil authority that he had not helped to constitute, was a reed before the pressure of community opinion. The sturdy Germans flouted this tyranny sans tyrant. At a time when the would-be-respectable American stifled under a pall of conventionality in regard to religion and manners, they asserted the[58] right to think and speak for themselves without incurring loss or ostracism. Then, too, the scholarly German immigrant imparted to us his sense of the dignity of science and its right to be free, although, to be sure, this spirit has been fostered among us chiefly by Americans who have studied in German universities. On the whole, in the way of intellectual liberty, the university-bred Liberals of 1848 had as much to offer as they gained in the way of political liberty.