The cover image was created by the transcriber, using the book's original title page, and is placed in the public domain.

Transcriber's Note:

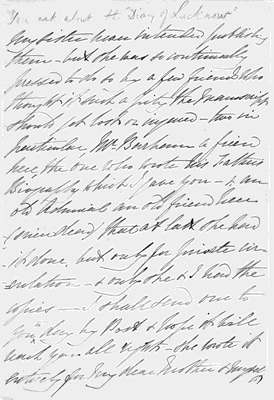

The following handwritten dedication and letter were included on the front leaves of the original book. They were written by Miss M. A. Garratt, sister of Mrs. R. C. Germon. A transcription of the letter is included below its scanned images, and the original line breaks have been preserved for easy comparison. Click on any image for a higher quality version.

Given to

Herbert Litchfield

by Miss M A Garratt sister of

Mrs Germon the Authoress

You ask about the "Diary of Lucknow"

My sister never intended publishing

them—but she was so continually

pressed to do so by a few friends who

thought it such a pity the manuscript

should get lost or injured—two in

particular, Mr Burham a friend

here, the one who wrote his Father's

Biography which I gave you—& an

old Admiral an old friend here

(since dead) that at last she had

it done, but only for private circulation—&

only she and I had the

copies—I shall send one to

you today by Post & hope it will

reach you all right—she wrote it

entirely for my dear mother & myself

& the report of each day is perfectly

correct—I suppose if nothing unforeseen

occurs we shall be going to London

as usual the end of May—but it

depends upon the time of the "Lucknow

dinner"—so as to bring that in during

my sister's & Colonel Germon's stay in

London—it is the old Garrison—the

Officers who were shut in all the

time—& year by year the party becomes

smaller, partly from some being

removed by death & others not able

perhaps to be in London at the time

When in London I shall hope to see

something of you—& with kind love

believe me your affecte Cousin

M A Garratt

my sister & the Col. send

kind remembrances

AT LUCKNOW,

BETWEEN THE MONTHS OF MAY AND DECEMBER,

1857.

LONDON:

WATERLOW AND SONS, CARPENTERS' HALL,

LONDON WALL.

1870.

ENTERED AT STATIONERS' HALL.

The Writer of the following Diary has frequently been requested to have a few copies printed for circulation amongst her friends; she has now acceded to their request, but wishes it to be understood that the Diary is in its original wording, as it was written by her day by day at Lucknow, with no attempts at embellishment. The names of those who were actors in the fearful scenes have been omitted, from a feeling of delicacy towards some who are still alive.

The writer is also indebted to her husband, who commanded one of the outposts throughout the siege, for the accuracy of the statements of some of the events that did not come immediately under her own observation.

1857. May 15th, Friday. I spent the day with the B——'s of the 71st N.I., he acting Brigade-Major of Lucknow: while sitting at dinner he told us of the horrible news from Meerut and Delhi; it was rather alarming for one living alone as I was, my husband being on city duty. Mr. B—— walked home with me about half-past 8, at 9 I went to bed, taking good care to have a shawl and dressing-gown close to the bed. Charlie's orderly slept in the verandah with the servants, as he had done all the week; the B——'s had kindly offered me a bed, but I had declined it. I had one door, as usual, open close to the bedroom at which the punkah-wallah pulled the punkah; the other two were sleeping by him; the watchman, bearer, orderly, and two doggies, forming quite a guard round the door: the Ayah and her child slept in a room adjoining; and, notwithstanding the alarm, I think I never slept sounder in my life.

Saturday, May 16th. I rose soon after gun-fire, and sent off Charlie's provisions for the day, bread [6]and butter, quail, mango-fool, and a few vegetables, and then sat in the garden and had my coffee; at 7 went into the house and prepared for a visit to the city, breakfasted at 10, and started at 11. I found Charlie had been with Sir Henry Lawrence, who was making admirable preparations in case of a rise here; Charlie said the old man was resting by a watercourse in the garden with quite a little party around him, he telling them all he knew, but advising them to spread the bad news as little as possible; and then consulting with them about precautionary measures, not objecting to a suggestion from even a captain, but catching at anything he thought good. I could see that Charlie felt perfect confidence in him; but I also saw that he thought very seriously of the state the country was in, for his remark was that we were in the position of a man sitting on a barrel of gunpowder. I sat talking with him till 1 o'clock, and then went over to the G——'s, as I had promised to spend the day with them. I found them in an awful state of alarm—talking of these murders at Delhi, and wondering if So-and-So had escaped. Miss N—— had a violent sick headache from the fright. At 2 Charlie came, and at 3 we tiffed; but Mr. G—— was so busy he could scarcely stay two minutes, and all the time was talking of the preparations. The Residency was being turned out to form a place of safety for the ladies and the sick. Charlie had to [7]leave early to superintend arrangements also. About half-past 5 I returned to his quarters, for I longed for a little talk with him before I went home. The heat had been intense all day, and the constant talking about these murders had made me feel quite uncomfortable. Charlie was still with his guards and did not return home for some time, so I lay down quietly on his bed. I felt so nervous that, when he did return, I begged him to let me stay in a chair by him all night. However, he talked and reasoned with me and I got better. He told me two companies of the 32nd Queen's were just coming into the banquetting house, and the sick from the hospital; also a lot of women and children into some rooms under his quarters. He made me a cup of tea and then would not let me stay any longer, as it was getting dusk, and Sir Henry just driving up at the moment, I started, as Charlie had to superintend the arrival of the troops. Just outside the city my carriage had to wait to let a regiment of Irregular Cavalry pass—Captain Gr——'s. They were to be stationed at the Dawk Bungalow between the city and Cantonments, to keep up communication between the two. Instead of going home I drove to the B——'s, for I was afraid of getting nervous again, sitting by myself. They were very glad to see me and again offered me a bed, but after taking ices with them I returned, telling them in case of alarm I should rush over to them, as our [8]bungalows adjoined each other. At home I had another cup of tea, for the heat and excitement gave one intense thirst. About 9 I went to bed, taking care to have an Affghan knife (a kind of dagger) close to me. I started at a few noises, but soon slept soundly, and fortunately heard nothing of an alarm that was given by an artilleryman of Captain Simons'—a Native—that the 13th were up in arms and were going to murder their officers. The Brigadier rode off to the lines and sent for the Adjutant and Captain Wilson, when it was discovered that the report had been caused by the preparations making for a company going off with Captain Francis to the Muchee Bawun. They walked through the lines and saw that all was right, and the Brigadier returned home; but it caused such a panic amongst some of the ladies that several rushed off to the Cantonments Residency and slept there.

Sunday, May 17th. I rose at gun-fire, and after sending off provisions to Charlie, went to church at 6, and while there seven companies of the 32nd Queen's entered Cantonments. I breakfasted at 10, and then finished my overland letters. While writing them there came a note from Mrs. A——, asking me to spend the day and night with them if I felt nervous; but I declined. Sir Henry had forty of our men (the 13th) up as a guard at the Residency, after the false report of them during the night, and told them he was perfectly satisfied [9] with them; that he had been so much pleased with them since he had been at Lucknow that he intended writing to Calcutta and stopping all the Raviel Pindee affair. At 3 I dined, and then lay down intending to go to church, but just before the time there was an immense deal of riding and driving about, and I saw a horse battery gallop off, which I took for the European battery, that I expected something must be up in the city. I wrote off to the B——'s for news, and also sent a note off to Charlie, but I got such a headache with the start that I did not feel fit for church. It proved to be an Oude Irregular battery going off to be stationed at the Dawk Bungalow. The B——'s again pressed me to sleep at their house, although the Padre and his wife (Mr. and Mrs. Harris) were already there. While taking tea about 8, the bearer came in to tell me the subadar of Charlie's company had sent his salaam, and would send up two Sepoys to guard my house at night. I hesitated a little, but agreed at last to have them, thinking I had better not show any want of confidence in the men, although it might be a great risk in these treacherous times. However, I wrote off to Captain W——, asking if he thought they might be trusted? Captain W—— was from home, but the Adjutant wrote and said I need not hesitate—he felt perfect confidence in the men; so they came and I retired to rest, making my usual defensive preparations, and slept soundly.

Monday, May 18th. Rose at gun-fire, and while I was arranging my flowers and taking coffee in the garden, the Adjutant called to see if I were all safe—and then came a note from Mrs. P——, saying she had heard we were to be turned out of our house to make room for the troops—and offering us two rooms. I declined, having received no orders to turn out. The Adjutant had told me the 13th mess-house had been given up to the European soldiers, and that several of the bachelors had offered their houses. About half-past 7 Charlie came home, to my great delight; the Europeans took possession of the mess-house and houses all round us, and we were well guarded: the day passed off without alarm.

Tuesday, May 19th. Charlie rose early, and went off to the lines to see after the Sepoys; on his return we went and took chota hazree (early breakfast) with the A——'s, and heard there that Mrs. Chambers, wife of the Adjutant of the 11th N.I. had been murdered at Delhi by a butcher out of the bazaar; but that the wretch had afterwards been caught by a sweeper, and roasted alive. We are beginning to receive a few reports of the sad massacre, but at present it is not known who have perished or who have escaped; it is true that Mr. Willoughby blew up the magazine at Delhi himself. This morning a bill was found stuck on some posts in the cavalry lines, calling on all good Mussulmen to join in this rise; the cavalry [11] brought it to their officers.[1] After breakfast came a Sepoy to Charlie to tell him that there was a panic in one of the bazaars, and that the people were all shutting up their shops and running away. Charlie went to the Brigade-Major, and soon after we saw Sir Henry drive by, and could see from our drawing-room window that the 32nd soldiers in the mess-house were all armed and accoutred, and a sergeant was stationed at the corner of the house to give the word; but after a time it subsided, and we heard the people were returning to their shops: the officer who had charge of the bazaars had been down with them, trying to make them comprehend that there was no cause for alarm. It originated in a Chuprasee (a Government servant) buying melons; he tried to get more than he ought for his money, which caused a little hubbub, and there being an order now-a-days to take up any one who makes a disturbance in the bazaar, two mounted Sepoys rode up to take him; he rushed off crying out "Shut your shops! shut your shops!" and the poor frightened wretches did it without question; the man was made prisoner, and so it ended. I have only named it to show the state of excitement we were in. While this was occurring, Capt. W—— came in and brought us a budget of Delhi news, written down by the Allyghur magistrate; it is said a party of officers were seen going into Kurnaul, [12]eighty miles north of Delhi; so it is possible they may be fugitives from Delhi—I trust so. Captain W—— also told us that Brigadier H—— was under arrest at Meerut. There must have been great delay and mismanagement there, for the insurgents were in Meerut all Sunday night, burning and murdering, and did not reach Delhi till 4 o'clock the Monday morning. Captain W—— complimented me on my remaining alone in the house during the panic; Charlie also seems well pleased that I have done so. In the evening we took our usual drive; our band was playing at the band-stand, but very few were driving about. We went to bed in peace—Charlie having his double-barrelled gun, loaded with a charge of shot, by the bedside; he says it is more useful than a bullet, for it would disable several, whereas a bullet might miss altogether: my weapon is the Affghan dagger, just suited to me, being neither too large nor heavy. I only trust we may have no occasion to use them, but one cannot be too guarded in these treacherous times.

Wednesday, May 20th. Charlie went off before gun-fire with Captain W—— to the city to see the Muchee Bawun, where Captain F—— is stationed. He is there with two companies of Natives, and there are also two Queen's officers and seventy men, also two guns in position besides field pieces, one to sweep the whole entrance street of Lucknow, the other the iron bridge; and then there are some Oude [13] Irregular troops: an Engineer officer was making the place habitable for them. While there, Sir Henry drove up, and scolded first this one, and then that, and then away again to superintend some other arrangements. The day passed off without alarm. At the band in the evening Charlie went over to the G——'s carriage, and heard that the Sappers (Natives) sent from Koorkee to Meerut, had proved treacherous, but that they had suffered severely for it, for in the same regiment was also a great number of Europeans, who had killed and wounded great numbers of them. He also heard that the Commander-in-Chief was marching down to Delhi, that he was at Kurnaal on the 18th; that he would have eight European regiments, and that he was bringing with him all the officers who had gone on leave to Simlah. Delhi is on the Grand Trunk road from Simlah.

Thursday, May 21st. While Charlie was dressing, just after gun-fire, to go and inspect his company, there came a notice round that all officers were to assemble at Sir Henry's at half-past 6. It was to inform them that he (Sir Henry) had been made Brigadier-General in Oude; that he had all power entirely in his own hands to reward or punish as he should think fit, without appealing to any higher power whatever—the finest thing that could have been done, and we cannot be too thankful for having such a man over us. Last [14]night a light was put into one of our Native officer's huts, but fortunately, it was put to leeward. No doubt the intention was for the fire to be carried to some bungalow; but one of our Sepoys saw it, and ran and pulled it off and smothered it, burning his hands in doing so—but it looked well of the man. The day passed without alarm, but at the band, our Doctor came up to the buggy, requesting us to take his wife and child in for the night, as he said there was going to be a rise. We went home and turned out Charlie's room for her, and placed a bed in it. Just as we were sitting at tea, the servants came running in giving an alarm of fire, and when we went out we saw the flames rising up from, apparently, the next bungalow to ours but one. The wind was high, and lay in the quarter to blow the sparks to us; Charlie sent several of the servants up on our thatched roof, each with a gurra of water. We quite looked for a disturbance now. Charlie took his double-barrelled gun, and told me, if there were any, to take my Affghan knife and escape at the back of the house over the garden wall to the Residency—it is only about four feet. There is only the road between us and the Residency, the garden wall of which is about five feet, but I could manage both with a chain. However, all seemed quiet, and, fortunately, it was the stables of a house which, being tiled, the sparks were not thrown up so high as they would have been from thatch, and in about [15]an hour and a half we saw it subside. Then came the Doctor and his family, in a fearful state of mind. We tried to quiet them, for really we did not fear much now, the fire having passed off without any rising; it was a good sign, and several of our Sepoys had come to see if our house was all right. After arranging Mrs. P——'s room, Charlie and I went to bed; it was past 10, and he was asleep in a few minutes. I listened for a time thinking I heard noises in the Bazaar, but soon fell asleep, and the night passed without further alarm.

Friday, May 22nd. Charlie went into the garden early, just as Sir Henry was passing. Sir Henry called to him, and told him to go and learn all he could about the fire, and whether the Sepoys worked to put it out, and to come over to him at 7, when he would be back from the city. I found my visitors had had a good night, so they dressed and went home, and are to come again to-night. There are fourteen ladies sleeping at the Residency here in Cantonments every night.

Saturday, May 23rd. The day passed without alarm, excepting that in the afternoon I was by myself and heard such a tremendous noise that I was quite frightened. It turned out to be at our mess-house. The Colonel of the 32nd would have the thatched roof well saturated with water in case of fire, and in the midst of it all a fire-engine rattled up from the city (the first I ever saw in India), and in my alarm I took it for a gun.

Sunday, May 24th. We went to church early, and the day passed off quietly.

Monday, May 25th. We were aroused at 3 A.M. by a message coming for Charlie to go over to Sir Henry. He dressed and went over immediately. I waited till gun-fire, and then went into the garden to arrange my flowers, little thinking what was coming. Charlie came back about half-past 5, when, to my astonishment, he told me it was Sir Henry's express orders that all ladies should leave Cantonments and go down to the Residency in the city; so I suspected he had heard bad news.[2] I commenced immediately collecting what I thought I should require, and what I considered valuable, not knowing how long I should be from home. The heat was intense, and I had to hurry my packing, for Charlie had had an offer of a seat in the H——'s carriage for me, as he could not take me down himself, being Captain of the week; and they were to call for me at half-past 7. He made me take some coffee, and packed up what he could of eatables and drinkables, not knowing how we should fare at the Residency. At the appointed time the H——'s and Mrs. B—— called for me, and we drove to the city, passing innumerable coolies with beds and baggage of all descriptions, carriages and buggies filled with ladies and children, all off[17] to the city—such a scene—and when we drove up to the Residency everything was looking so warlike, guns pointed in all directions, and barricades and European troops; everywhere nothing but bustle and confusion. We then heard there was hardly a room to be had—ladies had been arriving ever since gun-fire—so Mr. H—— went over to see if Dr. F—— could take us in. He came back saying he could, and away we went, thankful to get into such good quarters. Two ladies were there already, and five came after, with three children, so that every room was full. This house, as well as Mr. G——'s and Mr. O——'s (both also full) are within the Residency grounds, and are barricaded all round; still, in case of disturbance, we have orders to assemble at the Residency. Of course, there are all kinds of reports and alarms going about consequent on our flight. The heat was intense; I never experienced anything like it: at night it is fearful, I cannot sleep for it. Our beds are three under one punkah. I and Mrs. A—— are with Mrs. F—— in her room. In the other rooms they are as crowded, but it is nothing to the Residency. Our party here is a very agreeable one. We meet at chota hazree, and, after dressing, breakfast at 10. We then have working, reading and music—there are some very good performers amongst our party—lunch at 2, dine at half-past 7, and then the Padre reads a chapter and prayers, and we retire.

Tuesday, May 26th. The day passed quietly. Several husbands and fathers visited their beloveds, but mine could not leave his station duty. In the evening I went to the Residency to see Mrs. B——, whose baby was dying. I never witnessed such a scene—a perfect barrack—every room was filled with six or eight ladies; beds all round, and perhaps a dining-table laid for dinner in the centre—servants thick in all the verandahs—numbers of the 32nd soldiers and their officers; and underneath all, the women and children of the 32nd barracks—such a hubbub and commotion! It is an upper storeyed house, but the upper storey is not nearly so large as the under one, and yet in that, including servants and children, there are ninety-six people living! Poor Mrs. B—— was in great distress; she and another lady had a small room to themselves, with her five children. I was quite thankful I was not there: it was a complete rabbit warren. On my return I found Dr. F—— and Mr. H—— had been to Cantonments, and heard that the 13th Sepoys had taken up four city men, one of whom attempted to stab Mr. C——, the Adjutant.

Wednesday, May 27th. The day passed quietly. I went over to the Residency to see Mrs. P—— and Mrs. A—— in the evening, and found them in a small room with another lady. Mrs. P——'s child had bad fever—it was such a scene—they were having a punkah put up, and their beds were so thick you could hardly move, and scarcely a [19]breath of air to be had. Such a hubbub all round—some parties were grouped in a circle in the verandah, some in the compound—but it is impossible to describe the scene; I can compare it to nothing but a rabbit warren.

Thursday, May 28th. The day passed as usual. In the evening two of us drove with Dr. and Mrs. F—— to the Martinière College, he taking with him a very small pistol, and concealed from view, on the coach-box, a double-barrelled gun. The part of the city we drove through seemed perfectly quiet.

Friday, May 29th. About 5 A.M. I drove with Miss H—— to Cantonments, and had the inexpressible delight of seeing Charlie again, and the poor doggies I thought would have eaten me up. I had chota hazree with Charlie, and we sat chatting till 7, when the H——'s carriage came for me again. The day passed quietly. Some of the party drove out with Dr. and Mrs. F——, in the evening, but I did not. Dr. F——'s elephant is brought every evening to the verandah, where we are generally all assembled, to have his dinner. He has large cakes made of 32lbs. of ottah (coarse flour). This evening he performed various feats: taking the Mahout upon his back by his trunk, then putting out his forepaw for the Mahout to climb up that way; roaring, when he was told to speak, and then salaaming and taking his departure.

Saturday, May 30th. I went down to Cantonments again with Miss H——, and Col. H—— told us if we liked to remain till 11, he would take us back to the city himself. I was glad to accede to it, but it was against orders, for we are only allowed to go down to Cantonments morning and evening, and stay two hours. I enjoyed my time with Charlie; had a delightful bath, and appreciated the luxury of my own bathing and dressing rooms; then breakfasted with Charlie, who did not like my remaining in Cantonments so long against orders. The poor doggies were wild—"Prince," a little Scotch terrier, seemed to think himself privileged to be saucy as his mistress had come to see him, and got away under a sofa, and growled, and bid defiance to the servant who came to take him away to be washed, so that Charlie had to come to the rescue. However, the whole time Charlie was in a fidget about my remaining against orders. At 11 the carriage came. I little thought it was my last sight of the pretty garden and the home I had spent so many happy hours in, and of my poor little doggies. After taking up Col. H—— and his daughter, who should we meet but Sir H. Lawrence, returning from the city; and he stared me full in the face. I was in terror, for I feared Charlie would get a wigging for letting me remain so long in Cantonments, and he is always so particular not to disobey orders. The day passed quietly. The [21]elephant came to the verandah to be fed, and we sat down to dinner, laughing and talking—quite a merry party—when, about 9, the servants came running in, saying there was a great deal of firing going on in the direction of Cantonments. We all started up. Dr. F—— and Mr. H—— rushed off to discover the truth of it, and sure enough there was artillery and musketry plainly to be heard, and from the top of the house tremendous fires could be seen blazing up. Dr. F—— at first ordered us to get our bonnets and go to the Residency; then he said we had better go down to the underground part of the house: and he had all the doors locked, and they armed themselves. It was an awful time for us who had our husbands in Cantonments, for there was not a doubt but that the Native troops had risen, and were burning and murdering. Dr. F—— then told us to get together a little bundle of linen, and what we might require in case we were ordered off to the Muchee Bawun—we might be kept there some time—but it must be only a small bundle, that we could carry in our hands. We did so, and then all collected in the dining-room, awaiting our orders, Mrs. F——'s baby asleep in the midst of us; the suspense was fearful. About 2, came down Mr. J——, the commissariat officer, with a message from Sir Henry, that the Native troops had risen, but that we had held our own, and the [22]rebels had fled. Dr. F—— then said we had better all go and lie down in our clothes, with our bundles ready, and he would call us if there were any further alarm. We went; but I could only walk up and down the room, thinking of Charlie, and whether he had been wounded. Mrs. F—— gave me a cup of tea, and while I was drinking it they came running in to tell me Charlie was all right. He had ridden up with a despatch from Sir Henry for Mr. G——, escorted by twenty Irregular Cavalry men, and a few minutes after he made his appearance. I never shall forget the moment. I could only thank God he was safe. His trowsers, up to the knees, were covered with blood, but it was from his horse having been shot in the nose. He himself had had a most narrow escape; the Brigadier was shot about two yards from him. Of course all the ladies in the house crowded round him, and his first words were, "All belonging to the ladies in this house are safe." He then mentioned the Brigadier's death, and Mr. G——'s, of the 71st N.I.; also, that Mr. C—— had been wounded in the leg. They had just brought him down to the Residency, in Sir Henry's carriage. I could only shudder to think what an escape my own dear husband had had. He said they were sitting at mess when the alarm was given, and that he rushed off to the Brigadier, being his orderly officer that week. The Brigade-Major joined them, and they went into the Lines, when the Sepoy of the 13th, who had been rewarded [23]a few days previously, and who was carrying the Brigadier's gun, called out, "Save yourself, Sahib; they are going to fire!" A volley was fired, but the Brigadier was not hit then. Charlie was on foot; he had tried to mount a horse of Capt. W——'s, but it had thrown him—most fortunately for him as it turned out afterwards—then went on again and received another volley, and then a third, and Charlie says it was most marvellous they were not hit. They had then reached the European camp, when the Brigadier would go a little further, although the soldiers warned him not to. A shot immediately struck him in the breast, and he fell from his horse like a stone—quite dead. Charlie ordered some European soldiers to carry him into camp, which they did; and he said it was only from not being mounted himself that he was not hit—they fired too high. He and Mr. B—— rushed off, and Charlie's groom met him in the bazaar with his horse. He lost Mr. B—— in the bazaar, but dared not wait; they were all in arms around him. It was the 71st N.I. that commenced the mutiny—they rushed off and got their arms, and the bad ones of the other regiments joined them. However, the great guns settled them, and they made off into the district. Sir Henry then asked who would carry down a despatch to the city, and Charlie offered, for he thought of me, so he galloped off with his twenty Sowars,[3] [24]leaving the bungalows burning on all sides of him. He fancied not one would escape. Ours for that night did, owing to Charlie's orderly telling the party of the 48th, who had come to burn it, that there was a Havildar's party inside, who would fire instantly; so they passed on to the next. This man got 100 rupees afterwards from Sir Henry for this. Charlie did not go back to Cantonments that night, as his horse was quite done up, and he had had leave to do as he liked. He went back to Mr. G——, and we all went to bed. Never shall I forget this awful night, nor how much I have to thank God for having preserved my dear one.

Sunday, May 31st. Charlie came over to breakfast with us; we all then went into Dr. F——'s room, and Mr. H—— read prayers; Charlie then went to see if Sir Henry had arrived, and I wrote my overland letters and was just closing them, when an order came for all ladies to go over to the Residency, as they expected a rise in the city; we collected our bundles, and, under a burning sun, walked over to the Residency, where we were told not to congregate too many in one part, as the building was not safe; every room in the upper storey was crammed, we could hardly get space to put down our bundles: at last Miss N—— offered me a corner in one room, but the perfect Babel there was with the number of children and the fearful heat, with no punkahs going, was enough to drive one wild. We sat down [25] in this miserable state all day; there was luncheon going on when we arrived, and we were invited to partake, but Mrs. F—— kindly sent over for one from her own house for us. I saw my husband every now and then, but he was acting under Major A——. In the evening the two Padres tried to have prayers, but we could scarcely hear them from the Babel of tongues all round and the screams of so many children; it was perfect misery. I was dying with thirst, and had nothing of my own to quench it; at last a lady took pity on me, and ordered her servant to make me a cup of tea—a perfect luxury. We heard firing going on all the evening; it turned out to be an attack on the Dowlut Khana, but the rebels were repulsed, several shot, and others taken prisoners, who were afterwards hanged. Martial law is proclaimed now in Oude, so they are hanging several night and morning at the Muchee Bawun. About 7, Sir Henry came down from Cantonments with a large escort, and was received with great cheering; four more guns came down with him; every preparation was made, expecting an attack that night; every man was at his gun, and the slow matches lighted in readiness. There was no chance of sleeping down in this hot Babel, so I and several other ladies took our bedding up on the roof and slept there; it was a lovely moonlight night, and never shall I forget the scene. The panorama of Lucknow, from the top of the Residency, is [26] splendid; and down immediately below us, in the compound, we could see the great guns and all the military preparations; all, every instant, expecting an attack, and firing going on in the distance. However, I was so worn out with the previous night that I lay down and was asleep in a second; of course I did not undress, nor had I done so the night before. I started frequently, fancying I heard the tramp of the mob coming; we had the two Padres up with us and they determined to watch by turns. Mr. P—— began; he had a double-barreled gun, pistol and sword, and walked round and round for two hours, and then awoke Mr. H——, but we could not help laughing, for Mr. H—— was so sleepy he told him he did not think there was any necessity for watching up there. I shall never forget the night; the moon and stars were so brilliant overhead, looking so peaceful in contrast to the scene below. I fixed up an umbrella over my head to keep off the ill effects of the moon; every hour the sentinels were calling to one another and answering, "All's well!" It was certainly more a scene from romance than real life. Sir Henry slept out, like the others, between two guns.

Monday, June 1st. As soon as it was light, I rolled up my bundle of bedding and went down to find Charlie; he was just going off to Cantonments with Sir Henry, being made Acting Adjutant [27]in the room of Mr. C——, and they have all orders to remain in camp in Cantonments; so I must not expect to see him now. The heat is fearful in tents by day—there are two or three companies of Europeans and some guns, and all the Native troops who remained staunch to us, encamped together; our treasure and regimental colours are saved; the former entirely by Mr. L——'s bravery. One is hearing now of the wonderful escapes some of the officers had that night; the only wonder is that so many escaped; numbers have lost their all. To continue. Mrs. F—— gave me a cup of tea: one's thirst is fearful in this intense heat and excitement; I contrived to send a cup down to Charlie. Poor fellow! he has not undressed at night for more than a week; he went back in Sir Henry's carriage, for his own horse is quite done up. Just as I was wondering where I should find a corner to dress in, Dr. F—— gave us notice that we might go back to his house, for he thought it safer than the Residency, with that crowd; it was perfect paradise to get back again, and I had a lovely bath. I could not do much throughout the day, for I was overpowered with drowsiness; we had no alarms: at night we hardly liked undressing, but I thought it would rest one more, so I put on a thick dressing-gown and placed my bundle ready and fell asleep. We were aroused by a slight alarm, but it ended in nothing. I partly dressed, and lay down again. It was occasioned [28]by a sick man, in his delirium, calling out "Murder!" However, it caused a great commotion, and every one was ordered to arm himself; it only shows what an excited state we are all in.

Tuesday, June 2nd. The day passed quietly. In the evening Mr. C—— paid me a visit, and gave many particulars of that awful night; he is come down on city duty.

Wednesday, June 3rd. The first news we heard from without was the death of the Commander-in-Chief, from cholera, at Umballah; then about 1 o'clock came Major B—— and Mr. P—— to tell the F——'s Dr. F——'s brother had been killed by the insurgents; it was a day of bad news: also poor Captain H——, who has left a widow and seven children, and Mr. B——, a newly-married man. I believe they removed poor Mrs. H—— to Mrs. G——'s before telling her the sad news. As I and Mrs. A—— occupied Mrs. F——'s room, we offered to give it up to her and her husband, but they would not hear of it; we had no further alarm in the city.

Thursday, June 4th. I rose as soon as it was light, to get a little air; the heat is so intense in this house that this is the only breath of air one gets in the day. While sitting in the garden, fifty Europeans of the 84th arrived in dawk carriages, Dr. P—— and Major G—— with them. Major G——'s regiment had mutinied, and they had with [29]difficulty escaped with their lives. Dr. P—— said they expected an attack between this and Cawnpore, so as there were four soldiers to each carriage, two always kept watch outside with their muskets loaded, and the carriages were kept all together. Poor Mrs. F—— was looking out her mourning; it seemed so sad that neither she nor Dr. F—— had a room to themselves. After dinner news was brought that the 41st N.I. at Setapore had mutinied, and that the ladies and gentlemen were flying, so Dr. F—— and Mr. G—— sent off their carriages immediately to meet them; a party of gentlemen had ridden off already, and Dr. F—— and Dr. P—— followed them. At sunset I went over with Mr. C—— to see Mrs. A—— and Mrs. P——; the latter is in great distress for clothing, having lost everything the night of the mutiny, like many others. While I was sitting with them, the fugitives drove in, bringing in news that Colonel B——, the commandant of the 41st, had been shot by his men; his poor daughter was with the fugitives: there were many missing, and it was afterwards known that all living in or near the Civil Lines perished, excepting Sir M—— J—— and his sister, who formerly resided here with their uncle, Mr. C. C. J——, the chief commissioner.

Friday, June 5th. Rose at gun-fire, for the heat is so unbearable I am glad to get up. Several of the 32nd officers joined us while we were sitting in the garden, and the discussion was, why the hanging should be stopped? There has been none [30]the last two days, and before that they were hanging six or eight morning and evening in front of the Muchee Bawun. The day passed without alarm. In the evening, to our surprise, we heard the remainder of the 48th N.I. were ordered to Deriowbad for treasure; of course we concluded it was a great risk for the officers, although they are the Sepoys that remained staunch at the mutiny. It is quite risk enough being with them in Cantonments with only a handful of Europeans. I went over to see Mrs. B——, who is in great distress, having just lost her baby. She told me of her narrow escape the night of the mutiny in the Cantonments; she was down there with all her children, although Sir H. L—— had forbidden ladies to be there at night. She told me, she and the Major were in bed when a Havildar came rushing in, begging her to fly, for the Sepoys were up in the Lines, and immediately after the mutineers came to the house and asked for the Sahib and Mem-Sahib; she fled with her five children, escorted by three friendly Sepoys, first into the servants' houses, but the bullets came whistling so thick that the Sepoys cut a hole in the mud-wall for her to escape at the back. They fled to a village, but the villagers came out and threatened to take their lives if they remained, so they went and took refuge in a dry nullah (a bed of a stream); it was about fifteen or twenty feet deep, so that they had to sit and slide down the bank; the Sepoys lay [31]down on the bank and watched; her poor baby had dysentery, and had nothing on but its night-clothes: no wonder it died a day or two after; but, then, she ought not to have been in Cantonments. She drove up to the city next day, but Sir Henry was so angry with her for having disobeyed his orders that he would not allow her an escort. Mrs. M——, the Pension Paymaster's wife, has lost everything—she says 50,000 rupees' worth of property—for the bungalow was their own, and being stationary at Lucknow, they had everything in the greatest luxury; she had an immense amount of jewellery. Miss N—— spent the day with us.

Saturday, June 6th. Another quiet day. I had a great fright in the afternoon, for a fire was seen in Cantonments. However, I got a note from Charlie, saying all was quiet; the 71st Lines had been burnt down.

Sunday, June 7th. Rose at gun-fire, and went to church with nearly all our party, for Sir Henry said it was quite safe. The church is in the entrenchment. We stayed to the Sacrament, and it was quite comforting. The day passed quietly. Most attended service again in the evening, for there were sentries round the church; but the heat was so extreme I felt unequal to going.

Monday, June 8th. A quiet day. Firing has been heard for two days at Cawnpore. In the [32]evening a Mrs. A——, of the 41st, a fugitive from Setapore, called and gave a description of the mutiny there; and a Mr. V—— came in and reported he had seen the bodies of Mrs. C—— and the two Miss J——'s lying in the road.[4]

Tuesday, June 9th. Another quiet day; no news. I went to see Mrs. A——, who had been very ill, but was better. Mrs. F—— went to several of the ladies from Secroara, who are living in the Begum Kotee (another house in the Residency compound for the accommodation of the ladies) and told me she had seen Mrs. B—— and Mrs. K——; they were without even a change of clothes. I think they came in from Secroara with the Setapore party; Mrs. B—— had not even a change for her baby! They are still going on making our entrenchment stronger and stronger; two 18-pounders have been put in position, for the insurgents have guns at Cawnpore from the Rajah of Bhitoor,[5] who has joined them. We dine now at 4 o'clock, and have tea and ices in the garden in the evening; and, we are in luxury, compared with most.

Wednesday, June 10th. Went into the garden early, and heard that some women and children had been brought in from Setapore in dhoolies (palanquins for the sick) led by a sergeant who had his arm in splinters. They brought a frightful account of the atrocities committed there—too [33]barbarous and inhuman to be mentioned. I sent plates, cups and saucers, &c., &c., to the Secroara ladies, and linen to poor Mrs. B——. We were told, at breakfast, that we must not be alarmed if we heard a great explosion, for they were going to blow up a gateway near us. They are clearing as much as they can, a space around us, to give as little cover as possible for the enemy to fire from, in case it comes to a siege. In the evening, I and several others went over to the Begum's house, and saw Mrs. K—— and Mrs. B——; the place was very dirty, but the room lofty and good. Mrs. F—— brought away Mrs. B—— and four children to our house.

Thursday, June 11th. The atrocities committed at Setapore are beyond belief; a whole heap of babies was found,—the poor little creatures bayonetted and thrown on a heap. The ladies from Deriowbad came in, and Mr. B——, an artillery officer, from Secroara; his artillerymen (Natives) made him come in, and actually gave him fifty rupees for expenses on the road: so the rebels have his guns. A sergeant-major, from Setapore, brought news that the treasury there had been plundered, and that the rebels had then started for Gondah, intending to loot that also. The poor ladies from Setapore and Gondah were in a dreadful state about their husbands. I settled my Kitmagar's account, and paid a few rupees to [34]each of the servants. Mrs. F—— was taking in stores all day, in case of a siege. The explosion was expected this day, as it was a failure yesterday. In the evening I paid another visit to the ladies in the Begum's house.

Friday, June 12th. Captain W—— came over, and said the Sepoys were to be sent to their homes and the officers from Cantonments to come down here; this was good news indeed. Mr. G—— sent over to say that a messenger was going off to Benares in disguise and would take a small letter for each of us and try and post them there, as our last overlands were still lying at the post-office, the road having been closed for some days. We all commenced writing immediately, one sheet each, and when they were sent over, Mr. G——, to our great disgust, said they were all too large, and that we could only send a piece one quarter of the size; so we commenced again, and the puzzle then was how to fold so small a piece for overland passage. Soon after, while arranging with my servants and taking my Kitmagar's account for May, I heard two muskets fired and some of the great guns gallop off. I could hardly sit still, but I did not like the men to see me frightened. I finished the Kitmagar's account and paid it, but I must own he might have cheated me. When I went back into the drawing-room I found it was the police had mutinied. Soon after, the gentlemen came home and said the police had bolted, but two guns and a company of Europeans [35]had gone after them; also a body of gentlemen on horseback. In the evening I went over to see Mrs. A——, who was up for the first time. On my return, we had tea and ices in the garden, and while sitting there the guns and infantry returned bringing news that forty of the enemy had been killed and many taken prisoners. Three of the Europeans had fallen out by the way from the intense heat, and one had died from apoplexy. Two of our Sikhs were killed; and Mr. T——, a civilian, had been wounded by a bayonet in his shoulder; he walked in while we were there, and Dr. F—— took him into his room and dressed the wound. We all retired for the night. Mr. E——, 32nd Queen's, came in for a moment in passing, but appeared quite done up; he threw himself into a chair, and had a glass of soda-water, and told us that they and the guns had not been able to get up with the enemy; he told us, afterwards, he had been obliged to have leeches on his temples that same night.

Saturday, June 13th. Rose early, and wrote to Charlie I expected my piano up from Cantonments, as Mrs. F—— had offered to take it in. About 7, I went in to dress and bathe, and while there Captain W—— called and sent to say he must see me—no one else could give me his message—he must see me himself. I quickly dressed and threw on a shawl and received him [36]in Mrs. F——'s little room; it was to tell me that Charlie would be down at half-past 4, as the regiment was coming, but I was to say nothing about it till they arrived. After that, they brought me news that my piano was not allowed to pass the gate. I wrote Captain G——, who refused to let it pass, and then to Major A——, who said it was a peremptory order that no furniture could be taken into the entrenchments, but he very kindly offered to take it into his own house for me in the Teree Kotie, just outside; I, however, sent it to the Martinière. The day passed quietly, and about 6 came dear Charlie; he could not stay long, for he had engaged to dine with Sir Henry: however, he first sent off the buggy and two great boxes of property, which he had had brought up from Cantonments to the Martinière.

Sunday, June 14th. I rose early to see Charlie, and then went to church at 7. The day was quiet, but word was brought that Captain B—— and Mr. F—— of the 48th N.I., and Captain S——, and Mr. B—— of the 7th Cavalry, all out on detachment duty, had been murdered by their men. Charlie came again in the evening, and I had a nice chat with him.

Monday, June 15th. Charlie came again, and promised another visit in the evening. My Ayah also came, and seemed overjoyed to see me; it was agreed that she and her family should have a house in the bazaar: the only drawback was, that now something must be done with [37]the poor doggies, and they were under their charge. Poor Prince had such a sore back from the heat, living in the tents with Charlie, that Charlie had bought strychnine to give them before he came away, but had not the heart to do it. At 11, in came Charlie, unexpectedly, to say he had been ordered off to the Muchee Bawun with his Sikhs. I was greatly disappointed, hoping to have had him here. It was agreed that the poor pets were to be sent to him to the Muchee Bawun to be killed. I felt so wretched all day, and the heat was intense—all was quiet.

Tuesday, June 16th. The first news we heard was, that Major G——, who had gone off in disguise with despatches, had been betrayed by his men—ten of his own selecting—and killed at Roy Bareilly; and while we were at breakfast, Captain W—— brought news that a letter had come by a messenger from General W—— at Cawnpore, dated the 14th, 11 o'clock. They had held out till then, but had lost a great number of men—Captain W—— would not say how many—so I fear it was very bad news. The Ayah came, and the poor doggies were taken to Charlie. I had not the heart to take a last look at them. Charlie and the cook drowned them in the river. Poor Charlie! it was hard for him to have to do it. The day passed quietly, but bad news was arriving from the district constantly. Mrs. B—— and some others killed at Sultanpore. She in a Rajah's fort!—but one hears [38]now of nothing but wholesale massacres! Charlie came in the evening, and it did my heart good to see him.

Wednesday, June 17th. We heard to-day of Mr. C——, the civilian, being killed; he was engaged to Miss D——; her wedding things had arrived just before these troublous times, and the marriage had been postponed. We heard that Mr. B——, of the 48th, had been shot in the trenches at Cawnpore; his servant brought in the news. News was also brought that the Futteyghur people, 160 in number, had been murdered on the parade ground at Cawnpore, in sight of our people. They were going down the river in boats, but were stopped and taken to Cawnpore and there blown from guns. The day was quiet here. They are building a wall up against our windows to keep off musket shots; it is loop-holed, also, for our troops in case of necessity. The Fyzabad Rajah has joined the rebels, and is said to be very near us with his guns. Charlie came early in the evening.

Thursday, June 18th. I paid my bearer his account, and he went off to be with Charlie. Major B—— came in several times. All garrison officers were ordered to their posts this morning, to receive orders what they are to do when the enemy arrives. The Martinière boys were brought in. Just before breakfast, the groom brought me seven rupees, saying he had sold the [39]poor buggy horse. I felt much inclined for a good cry; I have driven him myself so often. We were obliged to sell him. Charlie came about half-past 6; one of his Sikhs had taken an immense quantity of churrus, and become quite frenzied, and then stabbed another Sikh; they called on him to put down his arms, or he would be shot, and he threw down his musket with such force that he broke it in pieces; the other poor man died.

Friday, June 19th. A quiet day. Charlie could not come to see me, as he was on duty at one of the gates of the Muchee Bawun; there are five gates, and four officers to each gate. Charlie takes it morning and evening, while the others are at gun drill. All, nearly, are obliged to learn the gun drill from some Artillery Sergeant, to be ready if wanted. Our entrenchments, they say, are now very strong; we have several mortars, and two 18-pounders are placed at the entrance to the Cawnpore road. A reconnoitering party went out, and returned in the evening, saying there was not an enemy to be seen for miles round. This evening there was a fire seen in Cantonments, but it was accidental; however, they got an alarm in the night, as several Sowars were seen riding about; they also had an alarm at the Muchee Bawun. Captain C—— woke them up and said a party of the enemy were coming, but it ended in nothing.

Saturday, June 20th. Charlie came about half-past 7, and stayed nearly an hour. After breakfast Dr. P—— read "Guy Mannering" to us while we worked. I cut out and made a flannel shirt for Charlie, as I could get no durzie. We are forbidden now to go over to the Residency or the Begum Kotee, as there is small-pox in both. In the former Mrs. B—— has it, and one of Mrs. B——'s children. Mrs. B—— is removed into a tent, in all this heat! To-day a letter came from General W—— at Cawnpore, saying they still held out, but had provisions and ammunition for only one fortnight longer; that no reinforcements had reached them, but that their greatest enemy was the sun: more had died from sunstroke than had been killed by the enemy, and that their greatest consolation was that they were keeping the enemy from us. It is most distressing that we cannot send them any troops; but if even we could spare them, they could never get across the river at Cawnpore, for the enemy have both sides of it; firing, both musketry and artillery, was heard all day in the district. The landowners are fighting amongst themselves, to get back what was taken from them at the annexation. A fire was seen burning in the district all night.

Sunday, June 21st. Rose at daybreak as usual, and went into the garden for a breath of air; the heat at night is fearful. Charlie came in at half-past 7; he is looking better, he is not so exposed [41]at the Muchee Bawun as he would be here; still, he has never taken off his clothes at night since he went on guard the week I left Cantonments; he is always sleeping at some gate or other: but he looks better than could be expected, and says his appetite has returned. We had service in the drawing-room—Mr. H—— performed it—for the church is filled with stores. In the evening, service was performed in Mr. G——'s garden, the two Padres reading and preaching under a tree; but the heat was so great I could not go. In the night we had the first fall of rain, and welcomed it accordingly.

Monday, June 22nd. Rose at daybreak and took the air in the verandah, as it was raining. However, it cleared in time for Charlie to pay me his visit. The day passed without a word of news, or any alarm. Dr. P—— went on with "Guy Mannering," and I worked at Charlie's flannel shirt. Miss N—— came over in the evening and said Sir M—— J—— and his two sisters were hourly expected. I had a note from Mrs. R——, at the Begum Kotee; her baby is very ill with dysentery, and she said the room was so filled with ladies and children with fever that when the poor little thing wanted to sleep it could not. She ended the note by saying she felt her child's illness and her anxiety for her husband's safety were almost too much for her.

Tuesday, June 23rd. Charlie came as usual; he [42]has been present at two hangings: the day passed without news, either good or bad.

Wednesday, June 24th. Charlie came late; I was quite proud to show him his flannel shirt, and sent it for him to try on. I went down with Mrs. F—— to her go-down (store-room) and saw all her stores in case of a siege—rice and flour—all in large earthen jars, that reminded one of the jars the forty thieves were put into, in "Ali Baba." Certain news reached us to-day that the enemy are closing round us; there are eight regiments with six guns at Nawab-Gunge, twenty miles from here; it is said they intend coming here, and encamping in the Dil Koosha.

Thursday, June 25th. Another day without a word of news, good or bad; even gentlemen begin to croak.

Friday, June 26th. The first news in the morning was good. Mrs. B—— heard of the safety of her husband. I went in, as usual, at 7, to take my bath, that I might be ready for Charlie; and Miss S—— came running in with the good news, sent by Sir H. Lawrence, that Delhi had fallen on the 13th—that Futteyghur, Mynpoorie, and Etawah were quiet—the telegraph open to Delhi—and the dawk to within twenty miles of Cawnpore.[6] Glorious news! a salute was fired. Charlie came, but would not stay; he [43]wanted to take back the news to the Muchee Bawun, and have the salute fired before ours. We cannot be too thankful! the insurgents at the best, are cowards; and this news will quite quell all spirit in them. Charlie had been to gun-drill—all in the garrison have to learn it. The rest of the day passed as usual, Dr. P—— reading to us till 4 o'clock dinner; after that I generally lie down till 6 and then take the air in the Compound—at 8 they generally bring tea and ices, and then Mr. H—— reads prayers and we all go to our rooms.

Saturday, June 27th. It was little Bobby F——'s birthday; he was one year old. Charlie came at a quarter to 8, and told us Capt. H——'s murderer had been captured at Allyghur; also that it was reported the 12th N.I. had mutinied at Jhansi, and killed every one of their officers; a letter came from Col. W——, at Cawnpore, with a list of the killed—about half their number; he said that their sufferings had surpassed anything ever written in history, and that their greatest enemy had been the sun; many ladies and children had died from it: but now they had dug underground places and put the women and children in. Brigadier Jack and his brother had both died from sunstrokes. In the course of the day came a pencilled letter from a Mr. M—— at Cawnpore, to his father, Col. M——, here, saying that they were treating with the enemy; this threw us all into consternation, for we [44]thought General W—— would have stood out to the last; however, it is said to be the Rajah of Bhitoor (the Nana), who has commenced the treating with them. A lac of rupees has been set on his head, if brought in within a week. I suppose he had heard of this and became frightened, for he offered General W—— to conduct them all down to Allahabad safely, if they would lay down their arms and give him a lac of rupees. This Rajah is a Mahratta, a notedly treacherous race, so that we were very glad to hear firing had commenced again at Cawnpore;[7] proof that, of course, Gen. Wheeler would not agree to such a treaty.

Sunday, June 28th. The rain had been pouring down all night, the first regular rain we had had; there had been nothing but a storm before, and now I was rather disappointed at its coming, for Charlie had agreed to come at half-past 5 and take me to Mr. I——s' house to get some things out of a wardrobe we have placed there, and he was to be back in time for service at 7 at the Muchee Bawun; however, he could not come, and we could not go to service here in the mess-house on account of the rain. About 2 we got a slight alarm, hearing that two guns, some Europeans, 13th Sepoys, and 71st Sikhs, had been ordered off somewhere; however, it turned out that they had [45]been sent to the King's palace for all the jewels. Two Nawabs were sent with them (I forgot to say we have five Nawabs prisoners in the Muchee Bawun), and they were made to understand that if there were the least disturbance they would be shot. Some fighting was expected, as there were armed men in the palace. Charlie came about 3, and stayed an hour. About 6, as we were going to church, we saw all the party returning, the carts filled with great boxes, and the golden throne, said to be worth a crore of rupees! Captain W—— told me some of the crowns were most elegant, the designs really beautiful, and also some of the necklaces, in one of which the diamonds are set in rays; one crown is silver set with amethysts. The King kept his own European jeweller, a man from H——'s in Calcutta. We set off walking to church, which was held in the Thug hospital belonging to the Thug goal; it is now the mess-house for all the infantry and cavalry officers. We had to enter by innumerable little arches of curious architecture, and up and down lots of steps and through two quadrangles, and then came in front of what appeared to be a Musjid,—the whole side open with beautiful arches,—they had begun service; rows of chairs had been placed for the congregation on either side of the mess-tables; the reading desk had been brought from the church. All round appeared to be little dark rooms, in which the officer's beds had been placed; also the [46]large platform outside was filled with chairs, and beds were standing about in all directions. It was a most extraordinary scene; there was an immense congregation, and the whole place was filled with ladies and gentlemen. Mr. P—— read prayers, and Mr. H—— preached; the poor people at Cawnpore were prayed for; also Dr. S—— of the 32nd, who is very ill; and all in hospital, sick and wounded: and then those who had lost relations in these frightful massacres. It was a most imposing service, and one could not but feel thankful for having been so mercifully preserved. Some officers came in late, all booted and spurred,—I fancy from the party that had just brought in the jewels. We had a thunderstorm during service, and at the end were rather alarmed at hearing three guns fired, but it must have been in the district; they are fighting and quarrelling amongst themselves. It rained when we came out of church, and was very dark, so I and Miss S—— stumbled on the best way we could over the steps and uneven ground, hardly knowing which way to take; it was such a novelty walking to church in India, and especially under an umbrella. Soon after our return it poured down famously; we had tea and ices, and then Mr. H—— read prayers, and we retired for the night.

Monday, June 29th. Sir H. Lawrence and his Staff came while we were sitting in the garden, [47]to take a survey of Dr. F——'s defences. Charlie came at 7, and I went with him to Mr. I——s' house, to my wardrobe. I could not recognise it for our old guard-house, where I had been so frequently with Charlie on city duty. All the buildings are thrown down round it; it is in the outer entrenchment. The Compound was filled with tents with Crannies and their wives; the day passed without alarm.

Tuesday, June 30th. I rose early, and found Dr.—— all booted and spurred for service. I then heard a detachment had been ordered off to meet the enemy, who were five miles off. Three hundred Europeans, nine guns, and an 8-inch howitzer, and 150 of the 13th N.I., &c., went out. I sat, as usual, in the garden, till 7, and then went in to bathe and dress, and be ready for Charlie. However, to my surprise, he never came, and I sent off a note to the Muchee Bawun asking the reason. While the servant was gone with it, some came flying back saying our troops had been surrounded by the mutineers, who were in great numbers, and that several of our officers had been killed. Just then, to my horror, came back the note I had sent with a message from Captain F—— that my husband had gone out with the detachment. I never shall forget that dreadful suspense as the news was brought in that Col. C——, Capt. S——, Mr. T——, and Mr. B——, of the 32nd were killed. The latter had always paid us a visit, mornings [48]and evenings. At last came Dr. P——, saying they were sorely pressed by the enemy, but that he had seen my husband all right. Soon after came a Sepoy, sent by Charlie himself, to say he was all safe; and immediately after a 13th Sepoy, of his own accord, came to tell me he had seen Charlie coming in on a gun as he was very faint, and that Major B—— was wounded. I was frightened, thinking Charlie had got a sunstroke. He told me, afterwards, he had had a most narrow escape, as he was far back in the retreat. It had proved far different to the expectations of the morning, for the Native Artillerymen had proved faithless; and, the enemy being in far greater numbers than our spies had led us to expect, our little party was almost surrounded, and it was only a wonder any escaped to tell the tale. The sun also was so overpowering that many fell down from sheer faintness, without a wound, and were cut to pieces by the enemy, for few had any horses to return with. The officers had dismounted to fall in with their men, and the horses disappeared; either the enemy or the servants made away with them,—poor Charlie's dear old charger amongst the rest; the poor horse that was shot in the nose the night of the mutiny. It was a fearful morning, never to be forgotten, this affair of Chinhut! Another providential escape for dear Charlie, for which we cannot be sufficiently thankful! The siege now commenced, the enemy began firing on us as they followed the retreating [49]party. Our gates were closed, we got a cup of tea and something for breakfast as best we could, sitting behind the walls to escape the balls; not that I fancy any of us had very much appetite. At last the balls came so thick that we were all ordered down into the Tye Khana (underground room), and kept there. Towards evening the firing slackened a little, and we sat in the portico to get a little air. There were twenty-four of us in the house—eleven ladies, six gentlemen and seven children. Captain W—— was the commandant of our garrison, which consisted of an officer and some twenty of the 32nd Queen's, with some Native Pensioners, and a mixed party of men to work the 18 and 9-pounder guns in the garden. At night we purposed sleeping in our own rooms, but Dr. F—— considered it not safe to do so; we therefore all stretched our bedding on the floor of the Tye Khana, putting the children in the centre for the benefit of the punkah. We took it by turns to watch for an hour.

Wednesday, July 1st.[8] We just managed to get to our rooms and dress, when the firing got very sharp—round shot and shell; already we began to distinguish the different sounds as they whizzed past: in the afternoon the enemy got into a building very near and fired away at us till evening, when they slackened again. I got a note [50] from dear Charlie, saying he was all right again I felt so thankful. Shortly after came Capt. W——, to whom I read it; he begged me to copy it for Sir Henry as there was more news in it than in any that had been received from the Muchee Bawun; he also said they had paid 100 rupees for getting one carried there. I copied it, and he told me that I should soon see Charlie; and we heard the garrison of the Muchee Bawun had been ordered to come in that night at half-past 12, evacuating the fort as silently as possible, and blowing it up. We all expected they would have to fight every inch of the way in, and were in great anxiety in consequence; however, we went to bed, and I even slept, when about half-past 12 we were awoke by the most horrible explosion. It shattered every bit of glass in the house! There were four doors to our Tye Khana, half glass, and the concussion covered us with the glass, and shook one of the doors off its hinges. I believe all of us thought our last hour was come; each started up with a kind of groan, for we had been expecting the enemy were mining, as we had fancied we had each night heard strokes of a pickaxe, about half a dozen at a time, and then a stoppage as if they feared to make too much noise: the gentlemen had been down to listen and heard it distinctly, so that when the explosion came, I certainly expected to go up into the air; and the inexpressible [51]relief it was to hear Dr. F——, at the head of the stairs, calling out "It is all right! The whole party are in safe, and the Muchee Bawun blown up!" No wonder the explosion was so terrific, there were upwards of 20,000 lbs. of powder, besides a vast quantity of musket ammunition!

Thursday, July 2nd. The attack on the Bailey Guard Gate and our Compound was tremendous, and while we were at breakfast we were all inexpressibly shocked and grieved to hear poor Sir Henry had been mortally wounded; a shell from the very 8-inch howitzer the enemy had taken from us at Chinhut, had burst in his room in the Residency, and given him a fearful wound in his hip! He was brought over into our verandah, and Mr. H—— administered the Sacrament to him. Sir Henry then sent for several whom he fancied he had spoken harshly to in their duty, and begged their forgiveness, and many shed tears to think the good old man would so soon be taken from us. Our only earthly hope in this crisis! Sir Henry then appointed Major B—— his successor. The firing was fearful; the enemy must have discovered from some spies that Sir Henry was at our house, for the attack on the gate was fearful. We all gave ourselves up for lost, for we did not then know the cowards they were, and we expected every moment they would be over our garden wall; there was no escape for us, if they were once in the garden! We [52]asked Mr. H—— to read prayers, and I believe every one of us prepared for the worst; the shots were now coming so thick into the verandah where Sir Henry was lying, that several officers were wounded, and he was obliged to be removed into the drawing-room. We gave out an immense quantity of rag to the poor soldiers, as they passed up and down from the roof of the house wounded. Towards evening the fire slackened, but we were not allowed to leave the Tye Khana. At night Mr. H—— came and read prayers again, and then we (ladies and children) lay down on the floor without undressing.

Friday, July 3rd. When we awoke we found all the servants had deserted excepting my Kitmagar and Mrs. B——'s, and one or two Ayahs. The F——'s had not one servant left, so we were obliged to get up and act as servants ourselves, and do everything, excepting the cooking, even to washing plates and dishes; and perhaps it was a good thing, for it kept us from dwelling on our misery. Dear Charlie came to see me in the afternoon, and brought a jug of milk for the poor children. I was glad to hear he had had a good luncheon, for the day before when he came he said he had had nothing for some days but dal (peas) and rice; we happened to be at dinner, and I gave him a piece of meat, but he seemed too much done up to eat it, and actually carried it away in a piece of paper to some other gentleman who could get none. No arrangements have been made for [53]messing at present, and no one can tell where to get anything.

Saturday, July 4th. Firing had been going on all night, and it continued all day, but we were so engaged in kitchen duties we scarcely noticed it. Poor Sir Henry died in the morning; he had been in great agony from his wound! He was buried with the rest at night, but even he did not have a separate grave; each corpse is sewn up in its own bedding, and those who have died during the day are put into the same grave at night.

Sunday, July 5th. The firing was incessant, and after breakfast Mr. H—— arranged all our duties, for up to this time they had been rather unequally performed; after that we had service in the Tye Khana, and the Holy Sacrament was administered. I so wished dear Charlie could have been present, it seemed so solemn and yet so comforting while the firing was going on around us!—nothing else occurred worth noting.

Monday, July 6th. The insurgents filled J——s' house, and kept firing into our Compound; we fired a number of shrapnell into the house, without dislodging them. We fancied they must be getting short of ammunition, for they fired all sorts of strange missiles—such as nails, pieces of ramrod, &c.

Tuesday, July 7th. Charlie came, after breakfast, and told me that a sortie was to be made [54]into J——s' house; this was done between 1 and 2 P.M.—two officers and some men of the 32nd and Mr. G—— and some of our Sikhs—a hole was made through the wall of the Brigade Mess, opposite J——s' house, an 18-pounder firing down our lane all the time to distract the enemy's attention. A rush was then made, and every Native in the house killed—numbering some thirty or forty. In the afternoon we had the first really heavy fall of rain, and the enemy's fire slackened in consequence. Poor Captain F—— this night had one leg taken off, and the other shattered, by a round shot, while sitting on the roof of the Brigade Mess! Mr. H—— saw him after the amputation had taken place, and said he was very composed. Mr. O—— died from his wound received at the Redan battery.

Wednesday, July 8th. Poor Mr. P—— was hit in the body by a musket shot; fortunately, the ball made a circuit round the body, instead of touching any vital part: he received the wound in the hospital. The firing was very sharp. I felt quite knocked up, after my morning duties. Charlie came, after dinner, and sat about an hour; he then went over to the hospital to see poor Captain F——. He found him insensible and very restless, and the doctors said he was not going on well; about 9 o'clock he died. He and Mr. O——, and two others, were buried in the same grave; the funerals are always at [55] night, as the fire then slackens a little. Sometimes, Mr. P—— and Mr. H—— have had to dig the graves themselves! Soon after we lay down for the night, we were aroused by an alarm; it was false, and had been caused by a soldier dreaming: but, towards the morning, we were alarmed again by the enemy making an attack on our gate. We all got up and prepared, in case we had to run to the Begum Kotee, for there had been a hole dug in the wall opposite one of our doors for us to escape by in case the enemy should pass the gate.

Thursday, July 9th. I rose and made the early tea for the whole party as Mrs. A—— was ill, and while engaged in it an order came down for bottles of hot water, Mr. D—— being taken with cholera; after breakfast he appeared better, but it did not last. About noon Mr. H—— administered the Sacrament to him, and at 1 o'clock he died. Mrs. D—— seemed wonderfully calm. After making tea in the evening I went and lay down on my bedding in the Tye Khana, feeling tired out, and fell so fast asleep, that they all came down and had prayers without my knowing anything about it.

Friday, July 10th. We were ordered to sit upstairs as much as possible, as the Tye Khana and Go-downs were considered unhealthy; fortunately, the firing was so slack, that we could sit at the front door. It was quite delightful to have a little [56] cessation from the constant noise. Mrs. D—— joined us, and seemed quite calm and cheerful. Charlie brought over six bottles of mustard, as we had very little and it was in great demand in cases of cholera; in the afternoon he came and chatted with me. Mr. H—— had only one funeral this evening.

Saturday, July 11th. There had been an alarm in the night, but I had heard nothing of it. I rose and made the early tea; and while carrying a cup to Mrs. F——, slipped down some steps and sprained my ancle: it became so painful that Dr. P—— recommended my fomenting it with hot water, and laying it up—so I was unfortunately hors de combat. Charlie sold poor Capt. F——s' property, and made 500 rupees of a box of second-hand clothes, such a great demand was there for them; he afterwards brought me a box of his papers and rings, which I locked up for his poor sister, in case I should ever be able to give it to her. Very slack firing all day; the enemy occasionally fired pieces of wood shaped liked nine-pins, and bound with iron. There was a report that the Nana was this day coming to join the rebels. There were five funerals this evening.

Sunday, July 12th. We had slept in the dining-room for the first time—but the mosquitoes were fearful—as the punkah was too heavy to be of any good. About half-past 10, Charlie came [57]and stayed to prayers; at 12 Dr. F—— made us all again dine in the Tye Khana, as the dinner upstairs brought such swarms of flies. In the evening the ladies sat under the portico and sang very prettily; Capt. W—— joining them just as they had sung one verse of the evening hymn: the enemy commenced firing so sharply that there was a call to arms, and the gentlemen all rushed off to their posts. The attack was first on Mr. G——s' house, and then came round to ours; we went to bed, but the firing was so loud and the mosquitoes so lively that we slept but little; in fact, we all wished ourselves down in the Tye Khana again.

Monday, July 13th. Rose, feeling wretched. My face is becoming covered with boils, but hardly any one is without them now. The firing still very sharp; a European soldier was wounded in the corner of our verandah. The enemy were said to be again in J——s' house; a Native was shot dead, coming from the Begum Kotee to our kitchen: altogether, eight were hit in our Compound during the day. Charlie could not come till the evening, and then stayed only a few minutes. Mrs. T—— very ill, with the small-pox, at the Begum Kotee.

Tuesday, July 14th. Dear J——'s birthday. I had slept soundly, though the firing had been very sharp all night. The 17th N.I. were seen with their colours amongst the rebels; there were all kinds of reports of relief—none true! Charlie [58]came over about dinner time, and sat some time, but I could not offer him any: I drank J——'s health in sherry. An attack was expected at night, and all preparations were made; we ladies were sent down to the Tye Khana to sleep. The rebels had placed an 18-pounder in position for our house; however, the ammunition for the gun was blown up, and we passed a quiet night, with the exception of a skirmish with the punkah coolies.

Wednesday, July 15th. Charlie came soon after breakfast, and told me the narrow escape he had had, from the careless firing of a 9-pounder by a sergeant who had been instructed by an artillery officer to fire shrapnell into J——s' house; he fired one into Capt. C——'s quarters, which Charlie had only a minute before vacated; he had been dressing on the very spot where the shrapnell burst. There was very little firing during the day, but Lieut. L—— was shot on the roof of Mr. G——s' house; Capt. F—— came for Dr. F——; they could not find the ball, but fancied it had touched the spine, as all the lower part of the body was paralysed. Our party sat in the verandah, singing songs and glees. It made me feel quite melancholy, for the round shots were whizzing overhead, and no one could tell but that the next might bring death with it!

Thursday, July 16th. We heard that our troops had had a fight with the insurgents at Futtehpore, who had come from Cawnpore to meet them, and [59] that we had taken four guns. No one knows if this be true, but it is possible, and that our troops are waiting there for reinforcements. Mrs. T—— died of small-pox. The heat and flies were dreadful; in the evening Mr. H—— had five funerals, one, poor Mrs. T——. He said he had had a most narrow escape; going to the churchyard, a shot struck the ground directly between the two dhoolies carried in front of him, and covered them with earth! That night I rebelled against watching; we had had quite a fight about it during the day.

Friday, July 17th. The enemy had an 18-pounder in position to fire on an angle of our house. Mrs. S——'s eldest child died of cholera. Dear Charlie paid me his daily visit. The firing was rather slack; the heat during the day was so intense, that the soldiers were allowed to lie down in the drawing-room. Mr. H—— had three funerals this night;—Lieut. A——, of the Artillery and Captain B——, were both wounded by a mortar that the former was superintending the loading of. Lieut. B——, Artillery, was wounded yesterday. About 11 P.M. we were aroused by a very sharp firing,—an attempt made again at the Bailey Guard Gate, but was unsuccessful; still I got up and prepared for a rush to the top of the house, as they say that is our safest place if the enemy get in; the gentlemen can defend us up there.