THE FIRST ACT at Mr. and Mrs. Telfer's Lodgings in No. 2 Brydon Crescent, Clerkenwell. May

THE SECOND ACT at Sir William Gower's, in Cavendish Square. June.

THE THIRD ACT again in Brydon Crescent. December.

THE FOURTH ACT on the stage of the Pantheon Theatre. A few days later.

PERIOD somewhere in the early Sixties. (1860s)

NOTE:—Bagnlgge (locally pronounced Bagnidge) Wells, formerly a popular mineral spring in Islington, London, situated not far from the better remembered Sadler's-Wells. The gardens of Bagnlgge-Wells were at one time much resorted to; but, as a matter of fact, Bagnigge-Wells, unlike Sadler's-Wells, has never possessed a playhouse. Sadler's-Wells Theatre, however, always familiarly known as the "Wells," still exists. It was rebuilt in 1876-77.

The costumes and scenic decoration of this little play-should follow, to the closest detail, the mode of the early Sixties, the period, in dress, of crinoline and the peg-top trouser; in furniture, of horsehair and mahogany, and the abominable "walnut -and -rep." No attempt should be made to modify such fashions in illustration, to render them less strange, even less grotesque, to the modern eye. On the contrary, there should be an endeavor to reproduce, perhaps to accentuate, any feature which may now seem particularly quaint and bizarre. Thus, lovely youth should be shown decked uncompromisingly as it was at the time indicated, at the risk (which the author believes to be a slight one) of pointing the chastening moral that, while beauty fades assuredly in its own time, it may appear to succeeding generations not to have been beauty at all.

The scene represents a sitting room on the first floor of a respectable lodging house. On the right are two sash-windows, having Venetian blinds and giving a view of houses on the other side of the street. The grate of the fireplace is hidden by an ornament composed of shavings and paper roses. Over the fireplace is a mirror: on each side there is a sideboard cupboard. On the left is a door, and a landing is seen outside. Between the windows stand a cottage piano and a piano stool. Above the sofa, on the left, stands a large black trunk, the lid bulging with its contents and displaying some soiled theatrical finery. On the front of the trunk, in faded lettering, appear the words "Miss Violet Sylvester, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane." Under the sofa there are two or three pairs of ladies' satin shoes, much the worse for wear, and on the sofa a white-satin bodice, yellow with age, a heap of dog-eared playbooks, and some other litter of a like character. On the top of the piano there is a wig-block, with a man's wig upon it, and in the corners of the room there stand some walking sticks and a few theatrical swords. In the center of the stage is a large circular table. There is a clean cover upon it, and on the top of the sideboard cupboards are knives and forks, plate, glass, cruet-stands, and some gaudy flowers in vases—all suggesting preparations for festivity. The woodwork of the room is grained, the ceiling plainly whitewashed, and the wall paper is of a neutral tint and much faded. The pictures are engravings in maple frames, and a portrait or two, in oil, framed in gilt. The furniture, curtains, and carpet are worn, but everything is clean and well-kept.

The light is that of afternoon in early summer.

Mrs. Mossop—a portly, middle-aged Jewish lady, elaborately attired—is laying the tablecloth. Ablett enters hastily, divesting himself of his coat as he does so. He is dressed in rusty black for "waiting."

[In a fluster.] Oh, here you are, Mr. Ablett——!

Good-day, Mrs. Mossop.

[Bringing the cruet-stands.] I declare I thought you'd forgotten me.

[Hanging his coat upon a curtain-knob, and turning up his shirt sleeves.] I'd begun to fear I should never escape from the shop, ma'am. Jest as I was preparin' to clean myself, the 'ole universe seemed to cry aloud for pertaters. [Relieving Mrs. Mossop of the cruet-stands, and satisfying himself as to the contents of the various bottles.] Now you take a seat, Mrs. Mossop. You 'ave but to say "Mr. Ablett, lay for so many," and the exact number shall be laid for.

[Sinking into the armchair.] I hope the affliction of short breath may be spared you, Ablett. Ten is the number.

[Whipping up the mustard energetically.] Short-breathed you may be, ma'am, but not short-sighted. That gal of yours is no ordinary gal, but to 'ave set 'er to wait on ten persons would 'ave been to 'ave caught disaster. [Bringing knives and forks, glass, etc., and glancing round the room as he does so.] I am in Mr. and Mrs. Telfer's setting-room, I believe, ma'am?

[Surveying the apartment complacently.] And what a handsomely proportioned room it is, to be sure!

May I h'ask if I am to 'ave the honor of includin' my triflin' fee for this job in their weekly book?

No, Ablett—a separate bill, please. The Telfers kindly give the use of their apartment, to save the cost of holding the ceremony at the "Clown" Tavern; but share and share alike over the expenses is to be the order of the day.

I thank you, ma'am. [Rubbing up the knives with a napkin.] You let fall the word "ceremony," ma'am——-

Ah, Ablett, and a sad one—a farewell cold collation to Miss Trelawny.

Lor' bless me! I 'eard a rumor——

A true rumor. She's taking her leave of us, the dear.

Ablett.

This will be a blow to the "Wells," ma'am.

The best juvenile lady the "Wells" has known since Mr. Phillips's management.

Report 'as it, a love affair, ma'am.

A love affair, indeed. And a poem into the bargain, Ablett, if poet was at hand to write it.

Reelly, Mrs. Mossop! [Polishing a tumbler.] Is the beer to be bottled or draught, ma'am, on this occasion?

Draught for Miss Trelawny, invariably.

Then draught it must be all round, out of compliment. Jest fancy! nevermore to 'ear customers speak of Trelawny of the "Wells," except as a pleasin' memory! A non-professional gentleman they give out, ma'am.

Yes.

Name of Glover.

Gower. Grandson of Vice Chancellor Sir William Gower, Mr. Ablett.

You don't say, ma'am!

No father nor mother, and lives in Cavendish Square with the old judge and a great aunt.

Then Miss Trelawny quits the Profession, ma'am, for good and all, I presoom?

Yes, Ablett, she's at the theaytre at this moment, distributing some of her little ornaments and fallals among the ballet. She played last night for the last time—the last time on any stage. [Rising and going to the sideboard-cupboard.] And without so much as a line in the bill to announce it. What a benefit she might have taken!

I know one who was good for two box tickets, Mrs. Mossop.

[Bringing the flowers to the table and arranging them, while Ablett sets out the knives and forks.] But no. "No fuss," said the Gower family, "no publicity. Withdraw quietly—" that was the Gower family's injunctions—"withdraw quietly, and have done with it."

And when is the weddin' to be, ma'am?

It's not yet decided, Mr. Ablett. In point of fact, before the Gower family positively say Yes to the union, Miss Trelawny is to make her home in Cavendish Square for a short term—"short term" is the Gower family's own expression—in order to habituate herself to the West End. They're sending their carriage for her at two o'clock this afternoon, Mr. Ablett—their carriage and pair of bay horses.

Well, I dessay a West End life has sooperior advantages over the Profession in some respecks, Mrs. Mossop.

When accompanied by wealth, Mr. Ablett. Here's Miss Trelawny but nineteen, and in a month-or-two's time she'll be ordering about her own powdered footman, and playing on her grand piano. How many actresses do that, I should like to know!

[Tom Wrench's voice is heard.]

[Outside the door.] Rebecca! Rebecca, my loved one!

Oh, go along with you, Mr. Wrench!

[Tom enters, with a pair of scissors in his hand. He is a shabbily-dressed ungraceful man of about thirty, with a clean-shaven face, curly hair, and eyes full of good-humor.]

My own, especial Rebecca!

Don't be a fool, Mr. Wrench! Now, I've no time to waste. I know you want something—

Everything, adorable. But most desperately do I stand in need of a little skillful trimming at your fair hands.

[Taking the scissors from him and clipping the frayed edges of his shirt-cuffs and collar.] First it's patching a coat, and then it's binding an Inverness! Sometimes I wish that top room of mine was empty.

And sometimes I wish my heart was empty, cruel Rebecca.

[Giving him a thump.] Now, I really will tell Mossop of you, when he comes home! I've often threatened it—-

[To Ablett.] Whom do I see! No—it can't be—but yes—I believe I have the privilege of addressing Mr. Ablett, the eminent greengrocer, of Rosoman Street?

[Sulkily.] Well, Mr. Wrench, and wot of it?

You possess a cart, good Ablett, which may be hired by persons of character and responsibility. "By the hour or job"—so runs the legend. I will charter it, one of these Sundays, for a drive to Epping.

I dunno so much about that, Mr. Wrench.

Look to the springs, good Ablett, for this comely lady will be my companion.

Dooce take your impudence! Give me your other hand. Haven't you been to rehearsal this morning with the rest of 'em?

I have, and have left my companions still toiling. My share in the interpretation of Sheridan Knowles's immortal work did not necessitate my remaining after the first act.

Another poor part, I suppose, Mr. Wrench?

Another, and to-morrow yet another, and on Saturday two others—all equally, damnably rotten.

Ah, well, well! somebody must play the bad parts in this world, on and off the stage. There [returning the scissors], there's no more edge left to fray; we've come to the soft. [He points the scissors at his breast.] Ah! don't do that!

You are right, sweet Mossop, I won't perish on an empty stomach. [Taking her aside.] But tell me, shall I disgrace the feast, eh? Is my appearance too scandalously seedy?

Not it, my dear.

Miss Trelawny—do you think she'll regard me as a blot on the banquet? [wistfully] do you, Beccy?

She! la! don't distress yourself. She'll be too excited to notice you.

H'm, yes! now I recollect, she has always been that. Thanks, Beccy.

[A knock, at the front-door, is heard. Mrs. Mossop hurries to the window down the stage.]

Who's that? [Opening the window and looking out.] It's Miss Parrott! Miss Parrott's arrived!

Jenny Parrott? Has Jenny condescended———?

Jenny! Where are your manners, Mr. Wrench? Tom.

[Grandiloquently.] Miss Imogen Parrott, of the Olympic Theatre.

[At the door, to Ablett.] Put your coat on, Ablett. We are not selling cabbages. [She disappears and is heard speaking in the distance.] Step up, Miss Parrott! Tell Miss Parrott to mind that mat, Sarah—!

Be quick, Ablett, be quick! The élite is below! More dispatch, good Ablett!

[To Tom, spitefully, while struggling into his coat.] Miss Trelawny's leavin' will make all the difference to the old "Wells." The season'll terminate abrupt, and then the comp'ny 'll be h'out, Mr. Wrench—h'out, sir!

[Adjusting his necktie, at the mirror over the piano.] Which will lighten the demand for the spongy turnip and the watery marrow, my poor Ablett.

[Under his breath. ] Presumpshus! [He produces a pair of white cotton gloves, and having put one on makes a horrifying discovery.] Two lefts! That's Mrs. Ablett all over!

[During the rest of the act, he is continually in difficulties, through his efforts to wear one of the gloves upon his right hand. Mrs. Mossop now re-enters, with Imogen Parrott. Imogen is a pretty, lighthearted young woman, of about seven-and-twenty, daintily dressed.]

[To Imogen.] There, it might be only yesterday you lodged in my house, to see you gliding up those stairs! And this the very room you shared with poor Miss Brooker!

[Advancing to Tom. ] Well, Wrench, and how are you?

[Bringing her a chair, demonstratively dusting the seat of it with his pocket-handkerchief]. Thank you, much the same as when you used to call me Tom.

Oh, but I have turned over a new leaf, you know, since I have been at the Olympic.

I am sure my chairs don't require dusting, Mr. Wrench.

[Placing the chair below the table, and blowing his nose with his handkerchief, with a flourish.] My way of showing homage, Mossop.

Miss Parrott has sat on them often enough, when she was an honored member of the "Wells"—haven't you, Miss Parrott.

[Sitting, with playful dignity. ] I suppose I must have done so. Don't remind me of it. I sit on nothing nowadays but down pillows covered with cloth of gold.

[Mrs. Mossop and Ablett prepare to withdraw.]

[At the door, to Imogen.] Ha, ha! ha! I could fancy I'm looking at Undine again—Undine, the Spirit of the Waters. She's not the least changed since she appeared as Undine—is she, Mr. Ablett?

[Joining Mrs. Mossop.] No—or as Prince Cammyralzyman in the pantomine. I never 'ope to see a pair o' prettier limbs——

[Sharply.] Now then!

[She pushes him out; they disappear.]

[After a shiver at Ablett's remark.] In my present exalted station I don't hear much of what goes on at the "Wells," Wrench. Are your abilities still—still——

Still unrecognized, still confined within the almost boundless and yet repressive limits of Utility—General Utility? [Nodding.] H'm, still.

Dear me! a thousand pities! I positively mean it. Tom.

Thanks.

What do you think! You were mixed up in a funny dream I dreamt one night lately.

[Bowing.] Highly complimented.

It was after a supper which rather—well, I'd had some strawberries sent me from Hertfordshire.

Indigestion levels all ranks.

It was a nightmare. I found myself on the stage of the Olympic in that wig you—oh, gracious! You used to play your very serious little parts in it——

The wig with the ringlets?

Ugh I yes.

I wear it to-night, for the second time this week, in a part which is very serious—and very little.

Heavens! it is in existence then!

And long will be, I hope. I've only three wigs, and this one accommodates itself to so many periods.

Oh, how it used to amuse the gallery-boys!

They still enjoy it. If you looked in this evening at half-past-seven—I'm done at a quarter-to-eight—if you looked in at half-past seven, you would hear the same glad, rapturous murmur in the gallery when the presence of that wig is discovered. Not that they fail to laugh at my other wigs, at every article of adornment I possess, in fact! Good God, Jennny—!

[Wincing.] Ssssh!

Miss Parrott—if they gave up laughing at me now, I believe I—I believe I should—miss it. I believe I couldn't spout my few lines now in silence; my unaccompanied voice would sound so strange to me. Besides, I often think those gallery-boys are really fond of me, at heart. You can't laugh as they do—rock with laughter sometimes!—at what you dislike.

Of course not. Of course they like you, Wrench. You cheer them, make their lives happier——

And to-night, by the bye, I also assume that beast of a felt hat—the gray hat with the broad brim, and the imitation wool feathers. You remember it?

Y-y-yes.

I see you do. Well, that hat still persists in falling off, when I most wish it to stick on. It will tilt and tumble to-night—during one of Telfer's pet speeches; I feel it will.

Ha, ha, ha!

And those yellow boots; I wear them to-night——

No!

Yes!

Ho, ho, ho, ho!

[With forced hilarity.] Ho, ho! ha, ha! And the spurs—the spurs that once tore your satin petticoat! You recollect———?

[Her mirth suddenly checked.] Recollect!

You would see those spurs to-night, too, if you patronized us—and the red worsted tights. The worsted tights are a little thinner, a little more faded and discolored, a little more darned—Oh, yes, thank you, I am still, as you put it, still—still—still——

[He walks away, going to the mantelpiece and turning his back upon her.]

[After a brief pause.] I'm sure I didn't intend to hurt your feelings, Wrench.

[Turning, with some violence.] You! you hurt my feelings! Nobody can hurt my feelings! I have no feelings—-!

[Ablett re-enters, carrying three chairs of odd patterns. Tom seizes the chairs and places them about the table, noisily.]

Look here, Mr. Wrench! If I'm to be 'ampered in performin' my dooties—-

More chairs, Ablett! In my apartment, the chamber nearest heaven, you will find one with a loose leg. We will seat Mrs. Telfer upon that. She dislikes me, and she is, in every sense, a heavy woman.

[Moving toward the door—dropping his glove.] My opinion, you are meanin' to 'arrass me, Mr. Wrench——-

[Picking up the glove and throwing it to Ablett—singing.] "Take back thy glove, thou faithless fair!" Your glove, Ablett.

Thank you, sir; it is my glove, and you are no gentleman. [He withdraws.]

True, Ablett—not even a Walking Gentleman.

Don't go on so, Wrench. What about your plays? Aren't you trying to write any plays just now?

Trying! I am doing more than trying to write plays. I am writing plays. I have written plays.

Well?

My cupboard upstairs is choked with 'em.

Won't anyone take a fancy——?

Not a sufficiently violent fancy.

You know, the speeches were so short and had such ordinary words in them, in the plays you used to read to me—no big opportunity for the leading lady, Wrench.

M' yes. I strive to make my people talk and behave like live people, don't I-?

I suppose you do.

To fashion heroes out of actual, dull, every-day men—the sort of men you see smoking cheroots in the club windows in St. James's Street; and heroines from simple maidens in muslin frocks. Naturally, the managers won't stand that.

Why, of course not.

If they did, the public wouldn't.

Is it likely? Is it likely?

I wonder!

Wonder—what?

Whether they would.

The public!

The public. Jenny, I wonder about it sometimes so hard that that little bedroom of mine becomes a banqueting hall, and this lodging house a castle.

[There is a loud and prolonged knocking at the front door.]

Here they are, I suppose.

[Pulling himself together.] Good Lord! Have I become disheveled?

Why, are you anxious to make an impression, even down to the last, Wrench?

[Angrily.] Stop that!

It's no good your being sweet on her any longer, surely?

[Glaring at her.] What cats you all are, you girls!

[Holding up her hands.] Oh! oh, dear! How vulgar—after the Olympic!

[Ablett returns, carrying three more chairs.]

[Arranging these chairs on the left of the table.] They're all 'ome! they're all 'ome! [Tom places the four chairs belonging to the room at the table. To Imogen.] She looks 'eavenly, Miss Trelawny does. I was jest takin' in the ale when she floated down the Crescent on her lover's arm. [ Wagging his head at Imogen admiringly.] There, I don't know which of you two is the——

[Haughtily.] Man, keep your place!

[Hurt.] H'as you please, miss—but you apperently forget I used to serve you with vegetables.

[He takes up a position at the door as Telfer and Gadd enter. Telfer is a thick-set, elderly man, with a worn, clean-shaven face and iron-gray hair "clubbed" in the theatrical fashion of the time. Sonorous, if somewhat husky, in speech, and elaborately dignified in bearing, he is at the same time a little uncertain about his H's. Gadd is a flashily-dressed young man of seven-and-twenty, with brown hair arranged à la Byron and mustache of a deeper tone.]

[Advancing to Imogen, and kissing her paternally.] Ha, my dear child! I heard you were 'ere. Kind of you to visit us. Welcome! I'll just put my 'at down——

[He places his hat on the top of the piano, and proceeds to inspect the table.]

[Coming to Imogen, in an elegant, languishing way.] Imogen, my darling. [Kissing her.] Kiss Ferdy!

Well, Gadd, how goes it—I mean how are you?

[Earnestly.] I'm hitting them hard this season, my darling. To-night, Sir Thomas Clifford. They're simply waiting for my Clifford.

But who on earth is your Julia?

Ha! Mrs. Telfer goes on for it—a venerable stopgap. Absurd, of course; but we daren't keep my Clifford from them any longer.

You'll miss Rose Trelawny in business pretty badly, I expect, Gadd?

[With a shrug of the shoulders.] She was to have done Rosalind for my benefit. Miss Fitzhugh joins on Monday; I must pull her through it somehow.

I would reconsider my bill, but they're waiting for my Orlando, waiting for it—

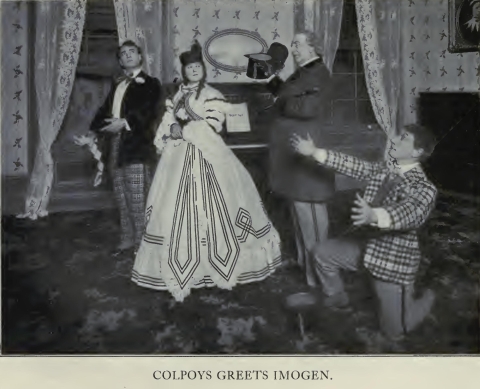

[Colpoys enters—an insignificant, wizen little fellow who is unable to forget that he is a low-comedian. He stands L., squinting hideously at Imogen and indulging in extravagant gestures of endearment, while she continues her conversation with Gadd.]

[Failing to attract her attention.] My love! my life!

[Nodding to him indifferently.] Good-afternoon, Augustus.

[Ridiculously.] She speaks! she hears me!

[Holding his glove before his mouth, convulsed with laughter.] Ho, ho! oh, Mr. Colpoys! oh, reelly, sir! ho, dear!

[To Imogen, darkly.] Colpoys is not nearly as funny as he was last year. Everybody's saying so. We want a low-comedian badly.

[He retires, deposits his hat on the wig-block, and joins Telfer and Tom.]

[Staggering to Imogen and throwing his arms about her neck.] Ah—h—h! after all these years!

[Pushing him away.] Do be careful of my things, Colpoys!

[Going out, blind with mirth.] Ha, ha, ha! ho, ho!

[He collides with Mrs. Telfer, who is entering at this moment. Mrs. Telfer is a tall, massive lady of middle age—a faded queen of tragedy.]

[As he disappears.] I'm sure I beg your pardon, Mrs. Telfer, ma'am.

Violent fellow! [Advancing to Imogen and kissing her solemnly.] How is it with you, Jenny Parrott?

Thank you, Mrs. Telfer, as well as can be. And you?

[Waving away the inquiry.] I am obliged to you for this response to my invitation, It struck me as fitting that at such a time you should return for a brief hour or two to the company of your old associates—— [Becoming conscious of Colpoys, behind her, making grimaces at Imogen.] Eh—h—h?

[Turning to Colpoys and surprising him.] Oh—h—h! Yes, Augustus Colpoys, you are extremely humorous off.

[Stung.] Miss Sylvester—Mrs. Telfer!

On the stage, sir, you are enough to make a cat weep.

Madam! from one artist to another! well, I—! 'pon my soul! [Retreating and talking under his breath. ] Popular favorite! draw more money than all the—old guys——

[Following him.] What do you say, sir! Do you mutter!

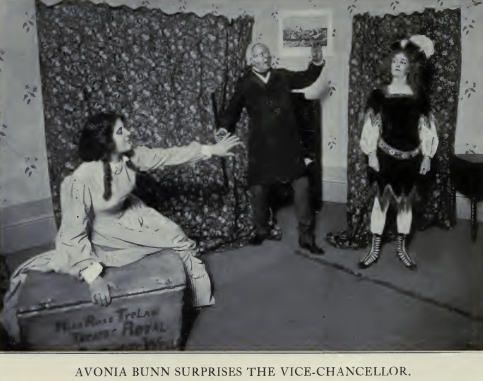

[They explain mutually. Avonia Bunn enters—an untidy, tawdrily-dressed young woman of about three-and-twenty, with the airs of a suburban soubrette.]

[Embracing Imogen.] Dear old girl!

Well, Avonia?

This is jolly, seeing you again. My eye, what a rig-out! She'll be up directly. [With a gulp.]She's taking a last look-round at our room.

You've been crying, 'Vonia.

No, I haven't. [Breaking down.] If I have I can't help it. Rose and I have chummed together—all this season—and part of last—and—it's a hateful profession! The moment you make a friend—————!

[Looking toward the door.] There! isn't she a dream? I dressed her——

[She moves away, as Rose Trelawny and Arthur Gower enter. Rose is nineteen, wears washed muslin, and looks divine. She has much of the extravagance of gesture, over-emphasis in speech, and freedom of manner engendered by the theatre, but is graceful and charming nevertheless. Arthur is a handsome, boyish young man—"all eyes" for Rose.]

[Meeting Imogen.] Dear Imogen!

[Kissing her.] Rose, dear!

To think of your journeying from the West to see me make my exit from Brydon Crescent! But you're a good sort; you always were. Do sit down and tell me—oh—! let me introduce Mr. Gower. Mr. Arthur Gower—Miss Imogen Parrott. The Miss Parrott of the Olympic.

[Reverentially.] I know. I've seen Miss Parrott as Jupiter, and as—I forget the name—in the new comedy——-[Imogen and Rose sit below the table.]

He forgets everything but the parts I play, and the pieces I play in—poor child! don't you, Arthur?

[Standing by Rose, looking down upon her.] Yes—no. Well, of course I do! How can I help it, Miss Parrott? Miss Parrott won't think the worse of me for that—will you, Miss Parrott?

I am going to remove my bonnet. Imogen Parrott—!

Thank you, I'll keep my hat on, Mrs. Telfer—take care!

[Mrs. Telfer, in turning to go, encounters Ablett, who is entering with two jugs of beer. Some of the beer is spilt.]

I beg your pardon, ma'am.

[Examining her skirts.] Ruffian! [She departs.]

[To Arthur.] Go and talk to the boys. I haven't seen Miss Parrott for ages.

[In backing away from them, Arthur comes against Ablett.]

I beg your pardon, sir.

I beg yours.

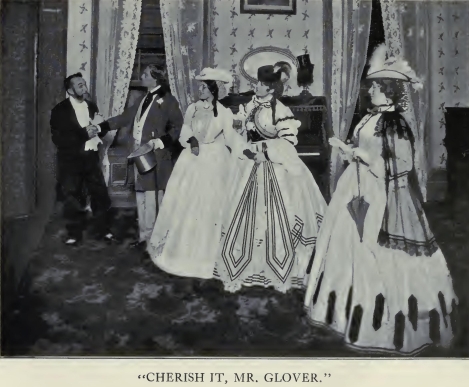

[Grasping Arthur's hand.] Excuse the freedom, sir, if freedom you regard it as——

Eh——-?

You 'ave plucked the flower, sir; you 'ave stole our ch'icest blossom.

[Trying to get away.] Yes, yes, I know——

Cherish it, Mr. Glover——!

I will, I will. Thank you——

[Mrs. Mossop's voice is heard calling "Ablett!" Ablett releases Arthur and goes out. Arthur joins Colpoys and Tom.]

[To Imogen.] The carriage will be here in half an hour. I've so much to say to you. Imogen, the brilliant hits you've made! how lucky you have been!

My luck! what about yours?

Yes, isn't this a wonderful stroke of fortune for me! Fate, Jenny! that's what it is—Fate! Fate ordains that I shall be a well-to-do fashionable lady, instead of a popular but toiling actress. Mother often used to stare into my face, when I was little, and whisper, "Rosie, I wonder what is to be your—fate." Poor mother! I hope she sees.

Your Arthur seems nice.

Oh, he's a dear. Very young, of course—not much more than a year older than me—than I. But he'll grow manly in time, and have mustaches, and whiskers out to here, he says.

How did you——?

He saw me act Blanche in the The Peddler of Marseilles, and fell in love.

Do you prefer Blanche——?

To Celestine? Oh, yes. You see, I got leave to introduce a song—where Blanche is waiting for Raphael on the bridge. [Singing, dramatically but in low tones.] "Ever of thee I'm fondly dreaming——"

I know—

[They sing together.]

"Thy gentle voice my spirit can cheer."

It was singing that song that sealed my destiny, Arthur declares. At any rate, the next thing was he began sending bouquets and coming to the stage-door. Of course, I never spoke to him, never glanced at him. Poor mother brought me up in that way, not to speak to anybody, nor look.

Quite right.

I do hope she sees.

And then?

Then Arthur managed to get acquainted with the Telfers, and Mrs. Telfer presented him to me. Mrs. Telfer has kept an eye on me all through. Not that it was necessary, brought up as I was—but she's a kind old soul.

And now you're going to live with his people for a time, aren't you?

Yes—on approval.

Ha, ha, ha I you don't mean that!

Well, in a way—just to reassure them, as they put it. The Gowers have such odd ideas about theatres, and actors and actresses.

Do you think you'll like the arrangement?

It 'll only be for a little while. I fancy they're prepared to take to me, especially Miss Trafalgar Gower——

Trafalgar!

Sir William's sister; she was born Trafalgar year, and christened after it—

[Mrs. Mossop and Ablett enter, carrying trays on which are a pile of plates and various dishes of Cold food—a joint, a chicken and a tongue, a ham, a pigeon pie, etc. They proceed to set out the dishes upon the table.]

[Cheerfully.] Well, God bless you, my dear. I'm afraid I couldn't give up the stage though, not for all the Arthurs——

Ah, your mother wasn't an actress.

No.

Mine was, and I remember her saying to me once, "Rose, if ever you have the chance, get out of it."

The Profession?

Yes. "Get out of it," mother said; "if ever a good man comes along, and offers to marry you and to take you off the stage, seize the chance—get out of it."

Your mother was never popular, was she?

Yes, indeed she was, most popular—till she grew oldish and lost her looks.

Oh, that's what she meant, then?

Yes, that's what she meant.

[Shivering.] Oh, lor', doesn't it make one feel depressed.

Poor mother!

Well, I hope she sees.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, everything is prepared, and I do trust to your pleasure and satisfaction.

Ladies and gentlemen, I beg you to be seated, [There is a general movement.] Miss Trelawny will sit 'ere, on my right. On my left, my friend Mr. Glower will sit. Next to Miss Trelawny—who will sit beside Miss Trelawny?

I will.

No, do let me!

[Gadd, Colpoys, and Avonia gather round Rose and wrangle for the vacant place.]

[Standing by her chair.] It must be a gentleman, 'Vonia. Now, if you two boys quarrel—-!

Please don't push me, Colpoys!

'Pon my soul, Gadd——!

I know how to settle it. Tom Wrench———!

[Coming to her.] Yes?

[Colpoys and Gadd move away, arguing.]

[Seating herself.] Mr. Gadd and Mr. Colpoys shall sit by me, one on each side.

[Colpoys sits on Imogen's right, Gadd on her left, Avonia sits between Tom and Gadd; Mrs. Mossop on the right of Colpoys. Amid much chatter, the viands are carved by Mrs. Mossop, Telfer, and Tom. Some plates of chicken, etc., are handed round by Ablett, while others are passed about by those at the table.]

[Quietly to Imogen, during a pause in the hubbub.] Telfer takes the chair, you observe. Why he—more than myself, for instance?

[To Gadd.] The Telfers have lent their room——

Their stuffy room I that's no excuse. I repeat, Telfer has thrust himself into this position.

He's the oldest man present.

True. And he begins to age in his acting too. His H's! scarce as pearls!

Yes, that's shocking. Now, at the Olympic, slip an H and you're damned for ever.

And he's losing all his teeth. To act with him, it makes the house seem half empty.

[Ablett is now going about pouring out the ale. Occasionally he drops his glove, misses it, and recovers it.]

[To Imogen.] Miss Parrott, my dear, follow the counsel of one who has sat at many a "good man's feast"—have a little 'am.

Thanks, Mr. Telfer. [Mrs. Telfer returns.]

Sitting down to table in my absence! [To Telfer.] How is this, James?

We are pressed for time, Violet, my love.

Very sorry, Mrs. Telfer.

[Taking her place, between Arthur and Mrs. Mossop—gloomily.] A strange proceeding.

Rehearsal was over so late. [To Telfer.] You didn't get to the last act till a quarter to one, did you?

[Taking off her hat and flinging it across the table to Colpoys.] Gus! catch! Put it on the sofa, there's a dear boy. [Colpoys perches the hat upon his head, and behaves in a ridiculous, mincing way. Ablett is again convulsed with laughter. Some of the others are amused also, but more moderately.] Take that off, Gus! Mr. Colpoys, you just take my hat off! [Colpoys rises, imitating the manners of a woman, and deposits the hat on the sofa.]

Ho, ho, ho! oh, don't Mr. Colpoys! oh, don't, sir!

[Colpoys returns to the table.]

[Quietly to Imogen.] It makes me sick to watch Colpoys in private life. He'd stand on his head in the street, if he could get a ragged infant to laugh at him. [Picking the leg of a fowl furiously.] What I say is this. Why can't an actor, in private life, be simply a gentleman? [Loudly and haughtily.] More tongue here!

[Hurrying to him.] Yessir, certainly, sir. [Again discomposed by some antic on the part of Colpoys.] Oh, don't, Mr. Colpoys! [Going to Telfer with Gadd's plate—speaking while Telfer carves a slice of tongue.] I shan't easily forget this afternoon, Mr. Telfer. [Exhausted.] This 'll be something to tell Mrs. Ablett. Ho, ho! oh, dear, oh, dear!

[Ablett, averting his face from Colpoys, brings back Gadd's plate. By an unfortunate chance, Ablett's glove has found its way to the plate and is handed to Gadd by Ablett.]

[Picking up the glove in disgust.] Merciful powers! what's this!

[Taking the glove.] I beg your pardon, sir—my error, entirely.

[A firm rat-tat-tat at the front door is heard. There is a general exclamation. At the same moment Sarah, a diminutive servant in a crinoline, appears in the doorway.]

[Breathlessly.] The kerridge has just drove up! [Imogen, Gadd, Colpoys, and Avonia go to the windows, open them, and look out. Mrs. Mossop hurries away, pushing Sarah before her.]

Dear me, dear me! before a single speech has been made.

[At the window.] Rose, do look!

[At the other window.] Come here, Rose!

[Shaking her head.] Ha, ha! I'm in no hurry; I shall see it often enough. [Turning to Tom.] Well, the time has arrived. [Laying down her knife and fork.] Oh, I'm so sorry, now.

[Brusquely.] Are you? I'm glad.

Glad! that is hateful of you, Tom Wrench!

[Looking at his watch.] The carriage is certainly two or three minutes before its time, Mr. Telfer.

Two or three——-! The speeches, my dear sir, the speeches! [Mrs. Mossop returns, panting.]

The footman, a nice-looking young man with hazel eyes, says the carriage and pair can wait for a little bit. They must be back by three, to take their lady into the Park——

[Rising.] Ahem! Resume your seats, I beg. Ladies and gentlemen——-

Wait, waitl we're not ready!

[Imogen, Gadd, Colpoys, and Avonia return to their places. Mrs. Mossop also sits again. Ablett stands by the door.]

[Producing a paper from his breast-pocket.] Ladies and gentlemen, I devoted some time this morning to the preparation of a list of toasts. I now 'old that list in my hand. The first toast——

[He pauses, to assume a pair of spectacles.]

[To Imogen.] He arranges the toast-list! he!

[To Gadd.] Hush!

The first toast that figures 'ere is, naturally, that of The Queen. [Laying his hand on Arthur's shoulder.] With my young friend's chariot at the door, his horses pawing restlessly and fretfully upon the stones, I am prevented from enlarging, from expatiating, upon the merits of this toast. Suffice it, both Mrs. Telfer and I have had the honor of acting before Her Majesty upon no less than two occasions.

[To Imogen.] Tsch, tsch, tsch! an old story!

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you—[to Colpoys]—the malt is with you, Mr. Colpoys.

[Handing the ale to Telfer.] Here you are, Telfer.

[Filling his glass. ] I give you The Queen, coupling with that toast the name of Miss Violet Sylvester—Mrs. Telfer—formerly, as you are aware, of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Miss Sylvester has so frequently and, if I may say so, so nobly impersonated the various queens of tragedy that I cannot but feel she is a fitting person to acknowledge our expression of loyalty. [Raising his glass.] The Queen I And Miss Violet Sylvester!

[All rise, except Mrs. Telfer, and drink the toast. After drinking Mrs. Mossop passes her tumbler to Ablett.]

The Queen! Miss Vi'lent Sylvester!

[He drinks and returns the glass to Mrs. Mossop. The company being reseated, Mrs. Telfer rises. Her reception is a polite one.]

[Heavily.] Ladies and gentlemen, I have played fourteen or fifteen queens in my time—-

Thirteen, my love, to be exact; I was calculating this morning.

Very well, I have played thirteen of 'em. And, as parts, they are not worth a tinker's oath. I thank you for the favor with which you have received me.

[She sits; the applause is heartier. During the demonstration Sarah appears in the doorway, with a kitchen chair.]

[To Sarah.] Wot's all this?

[To Ablett.] Is the speeches on?

H'on! yes, and you be h'off!

[She places the chair against the open door and sits, full of determination. At intervals Ablett vainly represents to her the impropriety of her proceeding.]

[Again rising.] Ladies and gentlemen. Bumpers, I charge ye! The toast I 'ad next intended to propose was Our Immortal Bard, Shakspere, and I had meant, myself, to 'ave offered a few remarks in response——

[To Imogen, bitterly.] Ha!

But with our friend's horses champing their bits, I am compelled—nay, forced—to postpone this toast to a later period of the day, and to give you now what we may justly designate the toast of the afternoon. Ladies and gentlemen, we are about to lose, to part with, one of our companions, a young comrade who came amongst us many months ago, who in fact joined the company of the "Wells" last February twelvemonth, after a considerable experience in the provinces of this great country.

Hear, hear!

[Tearfully.] Hear, hear! [With a sob.] I detested her at first.

Order!

Be quiet, 'Vonia!

Her late mother an actress, herself made familiar with the stage from childhood if not from infancy, Miss Rose Trelawny—for I will no longer conceal from you that it is to Miss Trelawny I refer——

[Loud applause.] Miss Trelawny is the stuff of which great actresses are made.

Hear, hear!

[Softly.] 'Ear, 'ear!

So much for the actress. Now for the young lady—nay, the woman, the gyirl. Rose is a good girl——

[Loud applause, to which Ablett and Sarah contribute largely. Avonia rises and impulsively embraces Rose. She is recalled to her seat by a general remonstrance.] A good girl——

[Clutching a knife.] Yes, and I should like to hear anybody, man or woman——!

She is a good girl, and will be long remembered by us as much for her private virtues as for the commanding authority of her genius. [More applause, during which there is a sharp altercation between Ablett and Sarah.] And now, what has happened to "the expectancy and Rose of the fair state"?

Good, Telfer! good!'

[To Imogen.] Tsch, tsch! forced! forced!

I will tell you—[impressively]—a man has crossed her path.

[In a low voice.] Shame!

[Turning to him.] Mr. Ablett!

A man—ah, but also a gentle-man. [Applause.] A gentleman of probity, a gentleman of honor, and a gentleman of wealth and station. That gentleman, with the modesty of youth,—for I may tell you at once that 'e is not an old man,—comes to us and asks us to give him this gyirl to wife. And, friends, we have done so. A few preliminaries 'ave, I believe, still to be concluded between Mr. Gower and his family, and then the bond will be signed, the compact entered upon, the mutual trust accepted. Riches this youthful pair will possess—but what is gold? May they be rich in each other's society, in each other's love! May they—I can wish them no greater joy—be as happy in their married life as my—my—as Miss Sylvester and I 'ave been in ours! [Raising his glass.] Miss Rose Trelawny—Mr. Arthur Gower! [The toast is drunk by the company, upstanding. Three cheers are called for by Colpoys, and given. Those who have risen then sit.] Miss Trelawny.

[Weeping.] No, no, Mr. Telfer.

[To Telfer, softly.] Let her be for a minute, James.

[Arthur rises and is well received.]

Ladies and gentlemen, I—I would I were endowed with Mr. Telfer's flow of—of—of splendid eloquence. But I am no orator, no speaker, and therefore cannot tell you how highly—how deeply I appreciate the—the compliment——

You deserve it, Mr. Glover!

Hush!

All I can say is that I regard Miss Trelawny in the light of a—a solemn charge, and I—I trust that, if ever I have the pleasure of—of meeting—any of you again, I shall be able to render a good—a—a—satisfactory—satisfactory—-

[In an audible whisper.] Account.

Account of the way—of the way—in which I—in which——- [Loud applause.] Before I bring these observations to a conclusion, let me assure you that it has been a great privilege to me to meet—to have been thrown with—a band of artists—whose talents—whose striking talents—whose talents——

[Kindly, behind his hand.] Sit down.

[Helplessly.] Whose talents not only interest and instruct the—the more refined residents of this district, but whose talents-

[Quietly to Colpoys.] Get him to sit down.

The fame of whose talents, I should say——

[Quietly to Mrs. Mossop.] He's to sit down. Tell Mother Telfer.

The fame of whose talents has spread to—to regions—-

[Quietly to Mrs. Telfer.] They say he's to sit down.

To—to quarters of the town—to quarters——

[To Arthur.] Sit down!

Eh?

You finished long ago. Sit down.

Thank you. I'm exceedingly sorry. Great Heavens, how wretchedly I've done it!

[He sits, burying his head in his hands. More applause.]

Rose. my child.

[Rose starts to her feet. The rest rise with her, and cheer again, and wave handkerchiefs. She goes from one to the other, round the table, embracing and kissing and crying over them all excitedly. Sarah is kissed, but upon Ablett is bestowed only a handshake, to his evident dissatisfaction. Imogen runs to the piano and strikes up the air of "Ever of Thee." When Rose gets back to the place she mounts her chair, with the aid of Tom and Telfer, and faces them with flashing eyes. They pull the flowers out of the vases and throw them at her.]

Mr. Telfer, Mrs. Telfer! My friends! Boys! Ladies and gentlemen! No, don't stop, Jenny! go on! [Singing, her arms stretched out to them.] "Ever of thee I'm fondly dreaming, Thy gentle voice." You remember! the song I sang in The Peddler of Marseilles—which made Arthur fall in love with me! Well, I know I shall dream of you, of all of you, very often, as the song says. Don't believe [wiping away her tears], oh, don't believe that, because I shall have married a swell, you and the old "Wells"—the dear old "Wells"!——

[Cheers.]

You and the old "Wells" will have become nothing to me! No, many and many a night you will see me in the house, looking down at you from the Circle—me and my husband——

Yes, yes, certainly!

And if you send for me I'll come behind the curtain to you, and sit with you and talk of bygone times, these times that end to-day. And shall I tell you the moments which will be the happiest to me in my life, however happy I may be with Arthur? Why, whenever I find that I am recognized by people, and pointed out—people in the pit of a theatre, in the street, no matter where; and when I can fancy they're saying to each other, "Look! that was Miss Trelawny! you remember—Trelawny! Trelawny of the 'Wells!'"——

[They cry "Trelawny!" and "Trelawny of the 'Wells!'" and again "Trelawny!" wildly. Then there is the sound of a sharp rat-tat at the front door. Imogen leaves the piano and looks out of the window.]

[To somebody below.] What is it?

Miss Trelawny, ma'am. We can't wait.

[Weakly.] Oh, help me down——

[They assist her, and gather round her.]

The scene represents a spacious drawing-room in a house in Cavendish Square. The walls are somber in tone, the ceiling dingy, the hangings, though rich, are faded, and altogether the appearance of the room is solemn, formal, and depressing. On the right are folding-doors admitting to a further drawing-room. Beyond these is a single door. The wall on the left is mainly occupied by three sash-windows. The wall facing the spectators is divided by two pilasters into three panels. On the center panel is a large mirror, reflecting the fireplace; on the right hangs a large oil painting—a portrait of Sir William Gower in his judicial wig and robes. On the left hangs a companion picture—a portrait of Miss Gower. In the corners of the room there are marble columns supporting classical busts, and between the doors stands another marble column, upon which is an oil lamp. Against the lower window there are two chairs and a card-table. Behind a further table supporting a lamp stands a threefold screen. The lamps are lighted, but the curtains are not drawn, and outside the windows it is twilight.

[Sir William Gower is seated, near a table, asleep, with a newspaper over his head, concealing his face. Miss Trafalgar Gower is sitting at the further end of a couch, also asleep, and with a newspaper over her head. At the lower end of this couch sits Mrs. de Foenix—Clara—a young lady of nineteen, with a "married" air. She is engaged upon some crochet work. On the other side of the room, near a table, Rose is seated, wearing the look of a boredom which has reached the stony stage. On another couch Arthur sits, gazing at his boots, his hands in his pockets. On the right of this couch stands Captain de Foenix, leaning against the wall, his mouth open, his head thrown back, and his eyes closed. De Foenix is a young man of seven-and-twenty—an example of the heavily-whiskered "swell" of the period. Everybody is in dinner-dress. After a moment or two Arthur rises and tiptoes down to Rose. Clara raises a warning finger and says "Hush!" He nods to her, in assent.]

[On Rose's left—in a whisper.] Quiet, isn't it?

[To him, in a whisper.] Quiet! Arthur—-! [Clutching his arm.] Oh, this dreadful half-hour after dinner, every, every evening!

[Creeping across to the right of the table and sitting there.] Grandfather and Aunt Trafalgar must wake up soon. They're longer than usual to-night.

[To him, across the table.] Your sister Clara, over there, and Captain de Foenix—when they were courting, did they have to go through this?

Yes.

And now that they are married, they still endure it!

Yes.

And we, when we are married, Arthur, shall we—-?

Yes. I suppose so.

[Passing her hand across her brow.] Phe—ew! [De Foenix, fast asleep, is now swaying, and in danger of toppling over. Clara grasps the situation and rises.]

[In a guttural whisper.] Ah, Frederick! no, no, no!

[Turning in their chairs.] Eh—what——-? ah—h—h—h!

[As Clara, reaches her husband, he lurches forward into her arms.]

[His eyes bolting.] Oh! who———<

Frederick dear, wake!

[Dazed.] How did this occur?

You were tottering, and I caught you.

[Collecting his senses.] I wemember. I placed myself in an upwight position, dearwest, to prewent myself dozing.

[Sinking on to the couch.] How you alarmed me! [Seeing that Rose is laughing, De Foenix comes down to her.]

[In a low voice.] Might have been a very serwious accident, Miss Trelawny.

[Seating herself on the footstool.] Never mind! [Pointing to the chair she has vacated.] Sit down and talk. [He glances at the old people and shakes his head.] Oh, do, do, do! do sit down, and let us all have a jolly whisper. [He sits.] Thank your Captain Fred. Go on! tell me something—anything; something about the military——

[Again looking at the old people, then wagging his finger at Rose.] I know; you want to get me into a wow. [Settling himself into his chair.] Howwid girl!

[Despairingly.] Oh—h—h!

[There is a brief pause, and then the sound of a street-organ, playing in the distance, is heard. The air is "Ever of Thee."]

Hark! [Excitedly.] Hark!

Arthur, and De Foenix.

Hush!

[Heedlessly.] The song I sang in The Peddler—The Peddler of Marseilles! the song that used to make you cry, Arthur! [They attempt vainly to hush her down, but she continues dramatically, in hoarse whispers.] And then Raphael enters—comes on to the bridge. The music continues, softly. "Raphael, why have you kept me waiting? Man, do you wish to break my heart—[thumping her breast] a woman's hear—r—rt, Raphael?"

[Sir William and Miss Gower suddenly whip off their newspapers and sit erect. Sir William is a grim, bullet-headed old gentleman of about seventy; Miss Gower a spare, prim lady, of gentle manners, verging upon sixty. They stare at each other for a moment, silently.]

What a hideous riot, Trafalgar!

dear, I hope I have been mistaken—but through my sleep I fancied I could hear you shrieking at the top of your voice.

[Sir William gets on to his feet; all rise, except Rose, who remains seated sullenly.]

Trafalgar, it is becoming impossible for you and me to obtain repose. [Turning his head sharply.] Ha! is not that a street-organ? [To Miss Gower.] An organ?

Undoubtedly. An organ in the Square, at this hour of the evening—singularly out of place!

[Looking round.] Well, well, well, does no one stir?

[Under her breath.] Oh, don't stop it!

[Clara goes out quickly. With a great show of activity Arthur and De Foenix hurry across the room and, when there, do nothing.]

[Coming upon Rose and peering down at her.] What are ye upon the floor for, my dear? Have we no cheers? [To Miss Gower—producing his snuff-box.] Do we lack cheers here, Trafalgar?

[Going to Rose.] My dear Rose! [Raising her.] Come, come, come, this is quite out of place! Young ladies do not crouch and huddle upon the ground—do they, William?

[Taking snuff.] A moment ago I should have hazarded the opinion that they do not. [Chuckling unpleasantly.] He, he, he!

[Clara returns. The organ music ceases abruptly.]

[Coming to Sir William.] Charles was just running out to stop the organ when I reached the hall, grandpa.

Ye'd surely no intention, Clara, of venturing, yourself, into the public street—the open Square——?

[Faintly.] I meant only to wave at the man from the door——

Oh, Clara, that would hardly have been in place!

[Raising his hands.] In mercy's name, Trafalgar, what is befalling my household?

[Bursting into tears.] Oh, William——!

[Rose and Clara creep away and join the others. Miss Gower totters to Sir William and drops her head upon his breast.]

Tut, tut, tut, tut!

[Between her sobs.] I—I—I—I know what is in your mind.

[Drawing a long breath.] Ah—h—h—h!

Oh, my dear brother, be patient!

Patient!

Forgive me; I should have said hopeful. Be hopeful that I shall yet succeed in ameliorating the disturbing conditions which are affecting us so cruelly.

Sm William.

Ye never will, Trafalgar; I've tried.

Oh, do not despond already! I feel sure there are good ingredients in Rose's character. [Clinging to him.] In time, William, we shall shape her to be a fitting wife for our rash and unfortunate Arthur——

[He shakes his head.] In time, William, in time!

[Soothing her.] Well, well, well! there, there, there! At least, my dear sister, I am perfectly aweer that I possess in you the woman above all others whose example should compel such a transformation.

[Throwing her arms about his neck.] Oh, brother, what a compliment——!

Tut, tut, tut! And now, before Charles sets the card-table, don't you think we had better—eh, Trafalgar?

Yes, yes—our disagreeable duty; let us discharge it. [Sir William takes snuff.] Rose, dear, be seated. [To everybody.] The Vice Chancellor has something to say to us. Let us all be seated.

[There is consternation among the young people. All sit.]

[Peering about him.] Are ye seated?

Yes.

What I desire to say is this. When Miss Trelawny took up her residence here, it was thought proper, in the peculiar circumstances of the case, that you, Arthur—[pointing a finger at Arthur] you——

Yes, sir.

That you should remove yourself to the establishment of your sister Clara and her husband in Holies Street, round the corner—

Yes, sir.

Yes, grandpa.

Certainly, Sir William.

Taking your food in this house, and spending other certain hours here, under the surveillance of your great-aunt Trafalgar.

Miss Gower.

Yes, William.

This was considered to be a decorous, and, toward Miss Trelawny, a highly respectful, course to pursue.

Yes, sir.

Any other course would have been out of place.

And yet—[again extending a finger at Arthur] what is this that is reported to me?

I don't know, sir.

I hear that ye have on several occasions, at night, after having quitted this house with Captain and Mrs. De Foenix, been seen on the other side of the way, your back against the railings, gazing up at Miss Trelawny's window; and that you have remained in that position for a considerable space of time. Is this true, sir?

[Boldly.] Yes, Sir William.

I venture to put a question to my grandson, Miss Trelawny.

Yes, sir, it is quite true.

Then, sir, let me acqueent you that these are not the manners, nor the practices, of a gentleman.

No, sir?

No, sir, they are the manners, and the practices, of a Troubadour.

A troubadour in Cavendish Square! quite out of place!

I—I'm very sorry, sir; I—I never looked at it in that light.

[Snuffing.] Ah—h—h—h! ho! pi—i—i—sh!

But at the same time, sir, I dare say—of course I don't speak from precise knowledge—but I dare say there were a good many—a good many——-

Good many—what sir?

A good many very respectable troubadours, sir——

[Starting to her feet, heroically and defiantly. ] And what I wish to say, Sir William, is this. I wish to avow, to declare before the world, that Arthur and I have had many lengthy interviews while he has been stationed against those railings over there; I murmuring to him softly from my bedroom window, he responding in tremulous whispers——

[Struggling to his feet]. You—you tell me such things—-! [All rise.]

The Square, in which we have resided for years——! Our neighbors——!

[Shaking a trembling hand at Arthur. ] The—the character of my house—-!

Again I am extremely sorry, sir—but these are the only confidential conversations Rose and I now enjoy.

[Turning upon Clara and De Foenix.] And you, Captain de Foenix—an officer and a gentleman! and you, Clara! this could scarcely have been without your cognizance, without, perhaps, your approval——!

[Charles, in plush and powder and wearing luxuriant whiskers, enters, carrying two branch candlesticks with lighted candles.]

The cawd-table, Sir William?

[Agitatedly.] Yes, yes, by all means, Charles; the card-table, as usual. [To Sir William.] A rubber will comfort you, soothe you——

[Charles carries the candlesticks to the card-table, Sir William and Miss Gower seat themselves upon a couch, she with her arm through his affectionately. Clara and De Foenix get behind the screen; their scared faces are seen occasionally over the top of it. Charles brings the card-table, opens it and arranges it, placing four chairs, which he collects from different parts of the room, round the table. Rose and Arthur talk in rapid undertones.]

Infamous! infamous!

Be calm, Rose, dear, be calm!

Tyrannical! diabolical! I cannot endure it.

[She throws herself into a chair. He stands behind her, apprehensively, endeavoring to calm her.]

[Over her shoulder.] They mean well, dearest——

[Hysterically.] Well! ha, ha, ha!

But they are rather old-fashioned people—-

Old-fashioned! they belong to the time when men and women were put to the torture. I am being tortured—mentally tortured——

They have not many more years in this world——-

Nor I, at this rate, many more months. They are killing me—like Agnes in The Specter of St. Ives. She expires, in the fourth act, as I shall die in Cavendish Square, painfully, of no recognized disorder—

And anything we can do to make them happy——

To make the Vice Chancellor happy! I won't try! I will not! he's a fiend, a vampire-!

Oh, hush!

[Snatching up Sir William's snuff-box, which he has left upon the table.] His snuff-box! I wish I could poison his snuff, as Lucrezia Borgia would have done. She would have removed him within two hours of my arrival—I mean, her arrival. [Opening the snuff-box and mimicing Sir William.] And here he sits and lectures me, and dictates to me! to Miss Trelawny! "I venture to put a question to my grandson, Miss Trelawny!" Ha, ha! [Talcing a pinch of snuffy thoughtlessly but vigorously.] "Yah—h—h—h! pish! Have we no cheers? do we lack cheers here, Trafalgar?" [Suddenly.] Oh!

What have you done?

[In suspense, replacing the snuff-box.] The snuff—-!

dear!

[Putting her handkerchief to her nose, and rising.] Ah——-!

[Charles, having prepared the card-table, and arranged the candlesticks upon it, has withdrawn. Miss Gower and Sir William now rise.]

The table is prepared, William. Arthur, I assume you would prefer to sit and contemplate Rose——?

Thank you, aunt.

[Rose sneezes violently, and is led away, helplessly, by Arthur.]

[To Rose.] Oh, my dear child! [Looking round.] Where are Frederick and Clara?

[Appearing from behind the screen, shamefacedly.] Here.

[The intending players cut the pack and seat themselves. Sir William sits facing Captain de Foenix, Miss Gower on the right of the table, and Clara on the left.]

[While this is going on, to Rose.] Are you in pain, dearest? Rose!

Agony!

Pinch your upper lip—-

[She sneezes twice, loudly, and sinks back upon the couch.]

[Testily.] Sssh! sssh! sssh! this is to be whist, I hope.

Rose! Rose! young ladies do not sneeze quite so continuously. [De Foenix is dealing.]

[With gusto.] I will thank you, Captain de Foenix, to exercise your intelligence this evening to its furthest limit.

I'll twy, sir.

[Laughing unpleasantly.] He, he, he! last night, sir——

Poor Frederick had toothache last night, grandpa.

[Tartly.] Whist is whist, Clara, and toothache is toothache. We will endeavor to keep the two things distinct, if you please. He, he!

Your interruption was hardly in place, Clara, dear,—ah!

Hey! what?

A misdeal.

[Faintly.] Oh, Frederick!

[Partly rising.] Captain de Foenix!

I—I'm fwightfully gwieved, sir——

[The cards are re-dealt by Miss Gower. Rose now gives way to a violent paroxysm of sneezing. Sir William rises.]

William——-! [The players rise.]

[To the players.] Is this whist, may I ask?

[They sit.]

[Standing.] Miss Trelawny—

[Weakly.] I—I think I had better—what d'ye call it?—withdraw for a few moments.

[Sitting again.] Do so.

[Rose disappears. Arthur is leaving the room with her.]

[Sharply.] Arthur! where are you going?

[Returning promptly.] I beg your pardon, aunt.

Really, Arthur—-!

[Rapping upon the table.] Tsch, tsch, tsch!

Forgive me, William. [They play.]

[Intent upon his cards.] My snuff-box, Arthur; be so obleeging as to search for it.

[Brightly.] I'll bring it to you, sir. It is on the——

Keep your voice down, sir. We are playing—[emphatically throwing down a card, as fourth player] whist. Mine.

[Picking up the trick.] No, William.

[Glaring.] No!

played a trump.

De Foenix.

Yes, sir, Clara played a trump—the seven——

I will not trouble you, Captain de Foenix, to echo Miss Gower's information.

Vevy sowwy, sir.

[Gently.] It was a little out of place, Frederick.

Sssh! whist. [Arthur is now on Sir William's right, with the snuff-box.] Eh? what? [Taking the snuff-box from Arthur.] Oh, thank ye. Much obleeged, much obleeged.

[Arthur walks away and picks up a book. Sir William turns in his chair, watching Arthur.]

You to play, William. [A pause.] William, dear——?

[She also turns, following the direction of his gaze. Laying down his cards, Sir William leaves the card-table and goes over to Arthur slowly. Those at the card-table look on apprehensively.]

[In a queer voice.] Arthur.

[Shutting his book.] Excuse me, grandfather.

Ye—ye're a troublesome young man, Arthur.

I—I don't mean to be one, sir.

As your poor father was, before ye. And if you are fool enough to marry, and to beget children, doubtless your son will follow the same course. [Taking snuff.] Y—y—yes, but I shall be dead 'n' gone by that time, it's likely. Ah—h—h—h! pi—i—i—sh! I shall be sitting in the Court Above by that time—- [From the adjoining room comes the sound of Rose's voice singing "Ever of Thee" to the piano. There is great consternation at the card-table. Arthur is moving towards the folding-doors, Sir William detains him.] No, no, let her go on, I beg. Let her continue. [Returning to the card-table, with deadly calmness.] We will suspend our game while this young lady performs her operas.

[Rising and taking his arm.] William——!

[In the same tone.] I fear this is no' longer a comfortable home for ye, Trafalgar; no longer the home for a gentlewoman. I apprehend that in these days my house approaches somewhat closely to a Pandemonium. [Suddenly taking up the cards, in a fury, and flinging them across the room.] And this is whist—whist——!

[Clara and De Foenix rise and stand together. Arthur pushes open the upper part of the folding-doors.]

stop! Rose!

[The song ceases and Rose appears.]

[At the folding-doors.] Did anyone call?

You have upset my grandfather!

Miss Trelawny, how—how dare you do anything so—so out of place?

There's a piano in there, Miss Gower.

You are acquainted with the rule of this household—no music when the Vice Chancellor is within doors.

But there are so many rules. One of them is that you may not sneeze.

Ha! you must never answer—-

No, that's another rule.

Oh, for shame!

You see, aunt, Rose is young, and—and—you make no allowance for her, give her no chance——

Great Heaven! what is this you are charging me with?

I don't think the "rules" of this house are fair to Rose I oh, I must say it—they are horribly unfair!

[Clinging to Sir William.] Brother!

Trafalgar! [Putting her aside and advancing to Arthur.] Oh, indeed, sir! and so you deliberately accuse your great-aunt of acting toward ye and Miss Trelawny mala fide——

Grandfather, what I intended to——

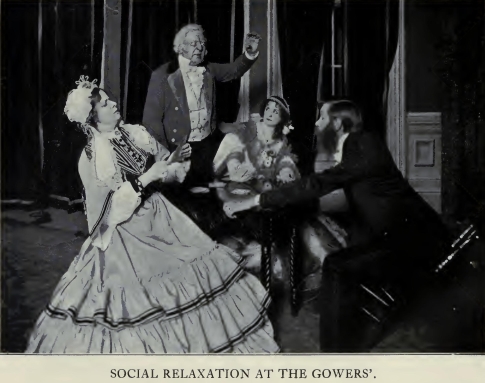

I will afford ye the opportunity of explaining what ye intended to convey, downstairs, at once, in the library. [A general shudder.] Obleege me by following me, sir. [To Clara and De Foenix.] Captain de Foenix, I see no prospect of any further social relaxation this evening. You and Clara will do me the favor of attending in the hall, in readiness to take this young man back to Holies Street. [Giving his arm to Miss Gower.] My dear sister—— [To Arthur.] Now, sir.

[Sir William and Miss Gower go out Arthur comes to Rose and kisses her.]

Good-night, dearest: Oh, good-night! Oh, Rose!

[Outside the door.] Mr. Arthur Gower!

I am coming, sir—- [He goes out quickly.]

[Approaching Rose and taking her hand sympathetically.] Haw——-! I—weally—haw!——

Yes, I know what you would say. Thank you, Captain Fred.

[Embracing Rose.] Never mind! we will continue to let Arthur out at night as usual. I am a married woman! [joining De Foenix], and a married woman will turn, if you tread upon her often enough——-!

[De Foenix and Clara depart.]

[Pacing the room, shaking her hands in the air desperately.] Oh—h—h! ah—h—h!

[The upper part of the folding-doors opens, and Charles appears.]

[Mysteriously.] Miss Rose—-

What—

[Advancing.] I see Sir William h'and the rest descend the stairs. I 'ave been awaitin' the chawnce of 'andin' you this, Miss Rose.

[He produces a dirty scrap of paper, wet and limp, with writing upon it, and gives it to her.]

[Handling it daintly.] Oh, it's damp!—

Yes, miss; a little gentle shower 'ave been takin' place h'outside—'eat spots, cook says.

[Reading.] Ah! from some of my friends. Charles.

[Behind his hand.] Perfesshunnal, Miss Rose?

[Intent upon the note.] Yes—yes—-

I was reprimandin' the organ, miss, when I observed them lollin' against the square railin's examinin' h'our premises, and they wentured for to beckon me. An egstremely h'affable party, miss. [Hiding his face.] Ho! one of them caused me to laff!

[Excitedly.] They want to speak to me—[referring to the note] to impart something to me of an important nature. Oh, Charles, I know not what to do!

[Languishingly.] Whatever friends may loll against them railin's h'opposite, Miss Rose, you 'ave one true friend in this 'ouse—Chawles Gibbons——

Thank you, Charles. Mr. Briggs, the butler, is sleeping out to-night, isn't he?

Yes, miss, he 'ave leave to sleep at his sister's. I 'appen to know he 'ave gone to Cremorne.

Then, when Sir William and Miss Gower have retired, do you think you could let me go forth; and wait at the front door while I run across and grant my friends a hurried interview?

Suttingly, miss.

If it reached the ears of Sir William, or Miss Gower, you would lose your place, Charles!

[Haughtily.] I'm aweer, miss; but Sir William was egstremely rood to me dooring dinner, over that mis'ap to the ontray——- [A bell rings violently.] S'william!

[He goes out. The rain is heard pattering against the window panes. Rose goes from one window to another, looking out. It is now almost black outside the windows.]

[Discovering her friends.] Ah! yes, yes! ah—h—h—h! [She snatches an antimacassar from a chair and jumping onto the couch, waves it frantically to those outside.] The dears! the darlings! the faithful creatures——! [Listening.] Oh———!

[She descends, in a hurry, and flings the antimacassar under the couch, as Miss Gower enters. At the same moment there is a vivid flash of lightning.]

[Startled.] Oh, how dreadful! [To Rose, frigidly.] The Vice Chancellor has felt the few words he has addressed to Arthur, and has retired for the night. [There is a roll of thunder. Rose alarmed, Miss Gower clings to a chair.] Mercy on us! Go to bed, child, directly. We will all go to our beds, hoping to awake to-morrow in a meeker and more submissive spirit. [Kissing Rose upon the brow.] Good-night. [Another flash of lightning.] Oh——! Don't omit to say your prayers, Rose—and in a simple manner. I always fear that, from your peculiar training, you may declaim them. That is so out of place—oh!

[Another roll of thunder. Rose goes across the room, meeting Charles, who enters carrying a lantern. They exchange significant glances, and she disappears.]

[Coming to Miss Gower.] I am now at liberty to accompany you round the 'ouse, ma'am——[A flash of lightning.]

Ah——-! [Her hand to her heart.] Thank you,

Charles—but to-night I must ask you to see that everything is secure, alone. This storm—so very seasonable; but, from girlhood, I could never—-

[A roll of thunder.] Oh, good-night!

[She flutters away. The rain beats still more violently upon the window panes.]

[Glancing at the window.] Ph—e—e—w! Great 'evans!

[He is dropping the curtains at the window when Rose appears at the folding-doors.]

[In a whisper.] Charles!

Miss?

[Coming into the room, distractedly.] Miss Gower has gone to bed.

Yes, miss—oh——! [A flash of lightning.]

Oh! my friends! my poor friends!

H'and Mr. Briggs at Cremorne! Reelly, I should 'ardly advise you to wenture h'out, miss——

Out! no! Oh, but get them in!

In, Miss Rose! indoors!

Under cover—— [A roll of thunder.] Oh!

[Wringing her hands.] They are my friends! is it a rule that I am never to see a friend, that I mayn't even give a friend shelter in a violent storm? [To Charles.] Are you the only one up?

I b'lieve so, miss. Any'ow the wimming-servants is quite h'under my control.

Then tell my friends to be deathly quiet, and to creep—to tip-toe— [The rain strikes the window again. She picks up the lantern which Charles has deposited upon the floor, and gives it to him.]

Make haste! I'll draw the curtains—[He hurries out. She goes from window to window, dropping the curtains, talking to herself excitedly as she does so.] My friends! my own friends! ah! I'm not to sneeze in this house! nor to sing! or breathe, next! wretches! oh, my! wretches! [Blowing out the candles and removing the candlesticks to the table, singing, under her breath, wildly.] "Ever of thee I'm fondly dreaming——" [Mimicking Sir William again.] "What are ye upon the floor for, my dear? Have we no cheers? do we lack cheers here, Trafalgar——?" [Charles returns.]

[To those who follow him.] Hush! [To Rose.] I

discovered 'em clustered in the doorway——

[There is a final peal of thunder as Avonia, Gadd, Colpoys, and Tom Wrench enter, somewhat diffidently. They are apparently soaked to their skins, and are altogether in a deplorable condition. Avonia alone has an umbrella, which she allows to drip upon the carpet, but her dress and petticoats are bedraggled, her finery limp, her hair lank and loose.]

'Vonia!

[Coming to her, and embracing her fervently.] Oh, ducky, ducky, ducky! oh, but what a storm!

Hush! how wet you are! [Shaking hands with Gadd] Ferdinand—[crossing to Colpoys and shaking hands with him] Augustus—[shaking hands with Tom] Tom-Wrench—

[To Charles.] Be so kind as to put my umbrella on the landing, will you? Oh, thank you very much, I'm sure.

[Charles withdraws with the umbrella. Gadd and Colpoys shake the rain from their hats on to the carpet and furniture.]

[Quietly, to Rose.] It's a shame to come down on you in this way. But they would do it, and I thought I'd better stick to 'em.

Gadd.

[Who is a little flushed and unsteady.] Ha! I shall remember this accursed evening.

Oh, Ferdy——!

Hush! you must be quiet. Everybody has gone to bed, and I—I'm not sure I'm allowed to receive visitors——

Oh!

Then we are intruders?

I mean, such late visitors.

[Colpoys has taken off his coat, and is shaking it vigorously.]

Stop it, Augustus! ain't I wet enough? [To Rose.] Yes, it is latish, but I so wanted to inform you—here—[bringing Gadd forward] allow me to introduce —my husband.

Oh! no!

[Laughing merrily.] Yes, ha, ha, ha!

Sssh, sssh, sssh!

I forgot. [To Gadd.] Oh, darling Ferdy, you're positively soaked! [To Rose.] Do let him take his coat off, like Gussy——

[Jealously.] 'Vonia, not so much of the Gussy!

There you are, flying out again I as if Mr. Colpoys wasn't an old friend!

Old friend or no old friend——

[Diplomatically.] Certainly, take your coat off, Ferdinand.

[Gadd joins Colpoys; they spread out their coats upon the couch.]

[Feeling Tom's coat sleeve.] And you?

[After glancing at the others—quietly.] No, thank you.

.

[Sitting.] Yes, dearie, Ferdy and I were married yesterday.

[Sitting. ] Yesterday!

.

Yesterday morning. We're on our honeymoon now. You know, the "Wells" shut a fortnight after you left us, and neither Ferdy nor me could fix anything, just for the present, elsewhere; and as we hadn't put by during the season—you know it never struck us to put by during the season—we thought we'd get married.

Oh, yes.

.

You see, a man and his wife can live almost on what keeps one, rent and ceterer; and so, being deeply attached, as I tell you, we went off to church and did the deed. Oh, it will be such a save. [Looking up at Gadd coyly.] Oh, Ferdy———!

[Laying his hand upon her head, dreamily.] Yes, child, I confess I love you—.

Colpoys

[Behind Rose, imitating Gadd.] Child, I confess I adore you.

[Taking Colpoys by the arm and swinging him away from Rose.] Enough of that, Colpoys!

What!

[Rising.] Hush!

[Under his breath.] If you've never learnt how to behave——

Don't you teach behavior, sir, to a gentleman who plays a superior line of business to yourself! [Muttering. ] 'Pon my soul! rum start!

[Going to Rose.] Of course I ought to have written to you, dear, properly, but you remember the weeks it takes me to write a letter—- [Gadd sits in the chair Avonia has just quitted; she returns and seats herself upon his knee.]And so I said to Ferdy, over tea, "Ferdy, let's spend a bit of our honeymoon' in doing the West End thoroughly, and going and seeing where Rose Trelawny lives." And we thought it only nice and polite to invite Tom Wrench and Gussy——

'Vonia, much less of the Gussy!

[Kissing Gadd.] Jealous boy! [Beaming.] Oh, and we have done the West End thoroughly. There, I've never done the West End so thoroughly in my life! And when we got outside your house I couldn't resist. [Her hand on Gadd's shirt sleeve.] Oh, gracious! I'm sure you'll catch your death, my darling—-!

I think I can get him some wine. [To Gadd.] Will you take some wine, Ferdinand?

[Gadd rises, nearly upsetting Avonia.]

Ferdy!

I thank you. [ With a wave of the hand.] Anything, anything——

[To Rose.] Anything that goes with stout, dear.

[At the door, turning to them.] 'Vonia—boys—be very still.

Trust us!

[Rose tiptoes out. Colpoys is now at the card-table, cutting a pack of cards which remains there.]

[To Gadd.] Gadd, I'll see you for pennies.

[Loftily.] Done, sir, with you!

[They seat themselves at the table, and cut for coppers. Tom is walking about, surveying the room.]

[Taking off her hat and wiping it with her handkerchief.] Well, Thomas, what do you think of it?

This is the kind of chamber I want for the first act of my comedy——-

Oh, lor', your head's continually running on your comedy. Half this blessed evening——

I tell you, I won't have doors stuck here, there, and everywhere; no, nor windows in all sorts of impossible places!

Oh, really! Well, when you do get your play accepted, mind you see that Mr. Manager gives you exactly what you ask for—won't you?

You needn't be satirical, if you are wet. Yes, I will I [Pointing to the left.] Windows on the one side [pointing to the right], doors on the other—just where they should be, architecturally. And locks on the doors, real locks, to work; and handles—to turn! [Rubbing his hands together gleefully.] Ha, ha! you wait! wait—!

[Rose re-enters, with a plate of biscuits in her hand, followed by Charles, who carries a decanter of sherry and some wine-glasses.]

Here, Charles——-

[Charles places the decanter and the glasses on the table.]

[Whose luck has been against him, throwing himself, sulkily, onto the couch.] Bah! I'll risk no further stake.

Just because you lose sevenpence in coppers you go on like this!

[Charles, turning from the table, faces Colpoys.]

======== below this needs correction ==

[Tearing his hair, and glaring at Charles wildly.] Ah—h—h, I am ruined! I have lost my all! my children are beggars——!

Ho, ho, ho! he, he, he!

Hush, hush! [Charles goes out laughing. To everybody;]Sherry?

[Rising.] Sherry!

[Avonia, Colpoys; and Gadd gather round the table, and help themselves to sherry and biscuits.]

[To Tom.] Tom, won't you——-?

[Watching Gadd anxiously.] No, thank you. The fact is, we—we have already partaken of refreshments, once or twice during the evening——

[Colpoys and Avonia, each carrying a glass of wine and munching a biscuit, go to the couch, where they sit.]

[Pouring out sherry—singing.] "And let me the canakin clink, clink—-"

[Coming to him.] Be quiet, Gadd!

[Raising his glass.] The Bride!

[Turning, kissing her hand to Avonia.] Yes, yes [Gadd hands Rose his glass; she puts her lips to it.] The Bride!

[She returns the glass to Gadd.]

[Sitting.] My bride!

[Tom, from behind the table, unperceived, takes the decanter and hides it under the table, then sits. Gadd, missing the decanter, contents himself with the biscuits.]

Well, Rose, my darling, we've been talking about nothing but ourselves. How are you getting along here?

Getting along? oh, I—I don't fancy I'm getting along very well, thank you!

Not——!

[His mouth full of biscuit.] Not——!

[Sitting by the card-table.] No, boys; no 'Vonia. The truth is, it isn't as nice as you'd think it. I suppose the Profession had its drawbacks—mother used to say so—but [raising her arms] one could fly. Yes, in Brydon Crescent one was a dirty little London sparrow, perhaps; but here, in this grand square——! Oh, it's the story of the caged bird, over again.

A love-bird, though.

Poor Arthur? yes, he's a dear. [Rising.] But the Gowers—the old Gowers! the Gowers! the Gowers I [She paces the room, beating her hands together. In her excitement, she ceases to whisper, and gradually becomes loud and voluble. The others, following her leady chatter noisily—excepting Tom, who sits thoughtfully, looking before him.]

The ancient Gowers! the venerable Gowers!

You mean, the grandfather——-?

And the aunt—the great-aunt—the great bore of a great-aunt! The very mention of 'em makes something go "tap, tap, tap, tap" at the top of my head.

Oh, I am sorry to hear this. Well, upon my word——!

Would you believe it? 'Vonia—boys—you'll never believe it! I mayn't walk out with Arthur alone, nor see him here alone. I mayn't sing; no, nor sneeze even——

[Shrilly.]Not sing or sneeze!

[Indignantly. ] Not sneeze!

No, nor sit on the floor—the floor!

Why, when we shared rooms together, you were always on the floor!

[Producing a pipe, and knocking out the ashes on the heel of his boot.] In Heaven's name, what kind of house can this be!

I wouldn't stand it, would you, Ferdinand?

[Loading his pipe.] Gad, no!

[To Colpoys.] Would you, Gus, dear?

[Under his breath.] Here! not so much of the Gus dear——

[To Colpoys.] Would you?

No, I'm blessed if I would, my darling.

[His pipe in his mouth.] Mr. Colpoys! less of the darling!

[Rising.] Rose, don't you put up with it! [Striking the top of the card-table vigorously.] I say, don't you stand it! [Embracing Rose.] You're an independent girl, dear; they came to you, these people; not you to them, remember.

[Sitting on the couch.] Oh, what can I do? I can't do anything.

Can't you! [Coming to Gadd.] Ferdinand, advise her. You tell her how to——

[Who has risen.] Miss Bunn—Mrs. Gadd, you have been all over Mr. Colpoys this evening, ever since we——

[Angrily, pushing him back into his chair.] Oh, don't be a silly!

Madam!

[Returning to Colpoys.] Gus, Ferdinand's foolish. Come and talk to Rose, and advise her, there's a dear boy——

[Colpoys rises; she takes his arm, to lead him to Rose. At that moment Gadd advances to Colpoys and slaps his face violently.]

Hey——!

Miserable viper!

[The two men close. Tom runs to separate them. Rose rises with a cry of terror. There is a struggle and general uproar. The card-table is overturned, with a crash, and Avonia utters a long and piercing shriek. Then the house-bells are heard ringing violently.]

Oh——! [The combatants part; all look scared. At the door, listening.] They are moving—coming! Turn out the——!