UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR/ GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

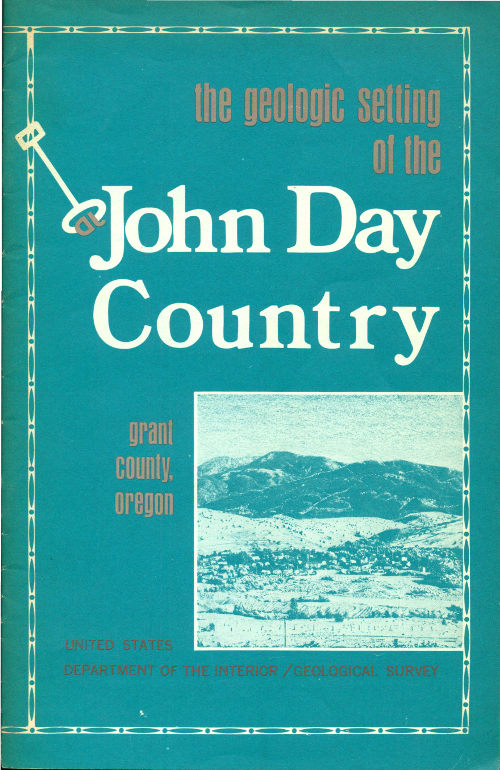

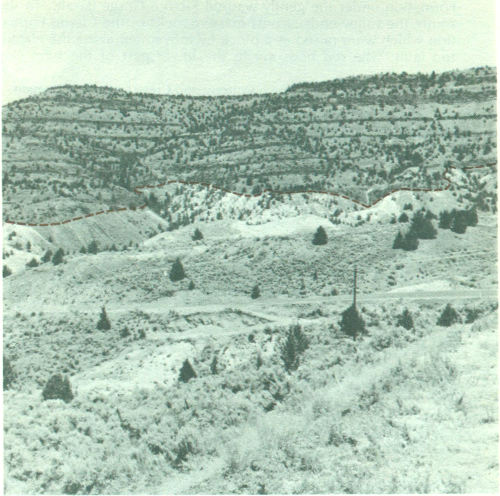

The town of John Day, the John Day River valley, and the Strawberry Range, looking south and southeast. The tailings piles left by gold dredges have been levelled for building sites since the photograph was taken in 1946.

One of the Pacific Northwest’s most notable outdoor recreation areas, the “John Day Country” in northeastern Oregon, is named after a native Virginian who was a member of the Astor expedition to the mouth of the Columbia River in 1812.

There is little factual information about John Day except that he was born in Culpeper County, Va. about 1770. It is known also that in 1810 this tall pioneer “with an elastic step as if he trod on springs” joined John Jacob Astor’s overland expedition under Wilson Price Hunt to establish a vast fur-gathering network in the western states based on a major trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River.

The expedition arrived in the vicinity of the Grand Tetons, in what is now Wyoming, in September 1811, and with the onset of winter met disaster along the Snake River. When they ran out of food near the present site of Twin Falls, Idaho, Hunt divided the expedition into four parties to seek food and a feasible route through the canyons. As described in Washington Irving’s Astoria, the party that included John Day became widely separated from the others; experienced terrible hardships while wintering with Indians near Huntington; and was eventually reduced to just John Day and Ramsey Crooks. By mid-April of the following year, Day and Crooks reached the junction of the Columbia and Mah-hah Rivers, where a band of Indians took everything they had, including their clothes. Because of this incident, the Mah-hah River was renamed the John Day. Returning up the Columbia to seek help from friendly Indians, they were rescued by a party of trappers in canoes, and finally reached Astoria on the 11th of May 1812.

Although the first discovery of gold in Oregon reportedly was made in 1845 on one of the upper branches of the John Day River by a member of an immigrant train, the settlement of the John Day Country really began in 1862, when gold was discovered in Canyon Creek just above Canyon City. Since then, possibly $30,000,000 worth of gold has been mined, mostly from gravels in and along Canyon Creek and along a 10-mile stretch of the John Day River. Lumbering and ranching are now the principal industries of the region.

The growth of tourism in Oregon and Grant County and the accompanying increase of interest in geology have stimulated the preparation of this leaflet. The Grant County Planning Commission and State Department of Geology and Mineral Industries have cooperated most cordially in the program to better inform interested visitors about the geology of the country they are seeing.

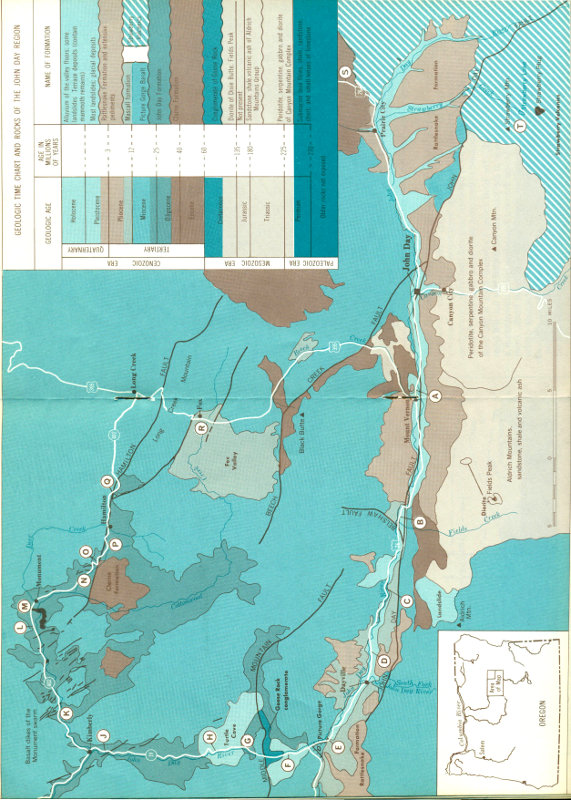

The John Day Country of today covers an area of 4,000-5,000 square miles in the southwestern part of the Blue Mountain region of Oregon, and is in the borderland between two major geologic provinces. One, to the north, is the Columbia Plateau which consists of flat or gently tilted flows of basalt covering about 100,000 square miles. The other, to the south, is the Basin and Range Province which extends into Mexico, and is characterized by a wide variety of complexly folded and faulted rocks. The Strawberry-Aldrich Mountain Range, rising from 7,000 to 9,000 feet in altitude along the south side of the John Day River valley (see Figure 13 on page 21), is part of a 150-mile long, east-trending mountain chain that locally separates the two provinces.

Many features that record events in the geologic history of northeastern Oregon may be seen in the rocks along the paved highways within the John Day Country. A road log describing some of these [5] features is included as a part of this booklet. The locations of principal points of interest, keyed in the road log to state highway mile posts, are shown on the map accompanying the road log.

The known part of the geologic history of the John Day Country began with lava flows and deposition of volcanic ash, sandstone, shale, and small lenses of limestone in a late Paleozoic sea more than 250 million years ago. Sometime between 200 and 250 million years ago, peridotite and gabbro (dark, magnesium-rich varieties of igneous rock) rose from great depths and, as molten material (magma), invaded the preexisting marine deposits. These igneous rocks now form the core of Canyon Mountain and can be seen along the precipitous walls of Canyon Creek. Masses of chromium ore (chromite) were carried upward with the molten material. After erosion had exposed the peridotite and gabbro, the area was submerged again and, during Late Triassic and Early Jurassic time (about 180 million years ago), the Aldrich Mountain area was part of a seaway into which lavas flowed. Thousands of feet of volcanic ash from active volcanoes accumulated in the sea, and between eruptions great thicknesses of mudstone and shale were deposited. The cuts along U. S. Highway 395 between Canyon Creek and Bear Valley are in these rocks. During part of this volcanic activity, Canyon Mountain stood as a high landmass, but finally it too was deeply buried. Again the region emerged and probably was dry land during the last half of Jurassic time (135 to 150 million years ago).

In Early Cretaceous time, molten material was intruded to form the granitic rocks in the Aldrich Mountains and near Dixie Butte, northeast of Prairie City. The gold veins in Canyon Mountain and in most of the Blue Mountain region probably were formed at that time by solutions from the granitic magma. Scattered patches of fossiliferous sandstone and conglomerate like that in Goose Rock (see Figure 5 on page 10) show that the sea encroached on the Blue Mountain region briefly during Cretaceous time after erosion had exposed the granites. The shoreline was not far east of the John Day area.

For the past 60 million years, eastern Oregon has been a land of volcanoes, mountain building, and erosion. After the retreat of the Cretaceous sea and an undefined period of erosion, volcanic eruptions from widely scattered centers during the Eocene Epoch buried the region under several thousand feet of volcanic rocks which now form the Clarno Formation; locally these rocks consist mostly of andesitic lava flows and coarse mud-flow breccias. The Clarno Formation was extensively folded and faulted and deeply eroded before another series of volcanoes in and somewhat east of the Cascade Mountains erupted rhyolitic ash that was blown eastward and deposited as the John Day Formation during the Oligocene Epoch. The John Day Formation appears to have been restricted to a lowland area which geologists today call the John Day basin, [6] located between the present site of the Cascade Mountains and the ancestral Blue Mountains. The Clarno and John Day beds in this basin are world famous, having yielded thousands of bones, leaves, and pieces of petrified wood that were buried and preserved by the volcanic ash in a manner similar to the burial of Pompeii by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A. D. Archaic large mammals such as the titanotheres, and small ancestors of modern mammals such as the 4-toed forest horse Eohippus, which was the size of a fox terrier, roamed subtropical forests during the Eocene Epoch. Many important links in the evolutionary chain of mammals have been found in the John Day fossil beds; for example, the 3-toed horse Mesohippus, which was a forest dweller the size of a sheep, had teeth for browsing instead of grazing.

The modern day landscape began to take form in Middle Miocene time, when the basalt flows which cover most of the area and are exposed in the walls of Picture Gorge (hence their name, Picture Gorge Basalt) buried the landscape formed on the John Day Formation and older rocks. The basalt erupted from long cracks or fissures in the Earth’s crust and formed floods of very fluid lava which flowed for distances up to one hundred miles. These basalts are recognized by geologists to be of a distinct type, commonly called plateau or flood basalt. Basalt, frozen in the fissures, forms dikes that commonly weather out above the adjoining softer rocks, as shown in the picture of Kimberly Dike on page 16.

While the Picture Gorge Basalt was flooding most of the John Day basin, several volcanoes in the vicinity of Strawberry Mountain erupted andesitic to rhyolitic lava and ash, and built up cones similar to Mt. Hood and the other high peaks of the Oregon Cascades. Geologists have named the remnants of these cones the Strawberry Volcanics. Because these volcanoes rose several thousand feet above the top of the Picture Gorge Basalt, ash and erosional debris from them washed out over the basalt; these materials constitute the Mascall Formation. Although the mountains were timbered, the lowlands probably were open and grassy. Bones and teeth of a pony-size three-toed horse, Merychippus, have been dug from the Mascall Formation. When the eruptions ceased in Early Pliocene time (about 10 million years ago), the entire Blue Mountain region probably resembled the eastern part of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon today, particularly the area between Mt. Hood and Crater Lake.

The present Strawberry-Aldrich Mountain range and the ridges and valleys north of it were formed when the Earth’s crust buckled and broke under strong compressive forces from the north and south. Partly by bending or folding, and partly by breaking along the John Day and other faults, the Strawberry-Aldrich Mountains were gradually raised a mile and a half to two miles above the valley to the north. The floor of the main John Day River valley [7] was filled with gravels eroded from the rising mountains and, as the folding and faulting and erosion slowed, an extensive, broad, gently sloping surface was formed on top of the valley fill. While these gravels (called the Rattlesnake Formation) were accumulating, however, a great volcanic eruption spread an ash flow more than 100 feet thick over the entire length of the John Day valley floor; remnants of this flow form prominent rim-rocks between the town of John Day and Picture Gorge. Bones of Hipparion, a horse the size of a pony which had feet and teeth like modern horses, have been found in the gravels under the ash flow.

Differences in the rates of erosion of various rocks were as important as folding and faulting in forming the topographic features in the John Day Country. The chief agents of erosion are chemical weathering processes that eventually break down or decompose all rocks, and running water which carries away the weathered or partly weathered and broken material. Picture Gorge is narrow because the basalts in the walls are very resistant to weathering and break along vertical joints into large blocks that do not move easily. In contrast, the John Day River has cut a broad, flat-floored valley in the Mascall Formation at the south end of Picture Gorge because the ashy beds weather to fine clay which is easily washed away.

Landslides have marked the face of the John Day Country. Large rock masses commonly slide where steep cliffs form in soft rocks that are capped by hard resistant rocks. When the cliff face becomes too high and steep, the soft beds give way and large blocks or masses slide downward, usually tilting backward as they move, as shown in the diagram of Cathedral Rock on page 15. Cathedral Rock and two small landslides north of the river, about two miles east of John Day, show this classic form. Many landslides, however, are just jumbled, hummocky masses of slumped material. Large-scale landsliding in the John Day Formation under the Picture Gorge Basalt is colorfully displayed along the river for 8 miles north of Picture Gorge. Some landslides occur suddenly, but many move forward only as fast as the toe or lower end is eroded away, as at Sunken Mountain.

Glaciers have sculptured the principal valleys that lie above an altitude of about 5,000 feet. Moving ice, hundreds of feet thick, plucked out semi-circular amphitheaters called cirques at the heads of the valleys. The 2,000-foot cliffs above Little Strawberry Lake were formed this way. Rocks held in the ice, like the teeth of a giant rasp, ground off irregularities and widened the valley bottoms to a broad U shape as the glaciers moved down the valleys. The effectiveness of ice scour can be seen by comparing glaciated Strawberry Creek above Strawberry Lake (as shown in figure 15 on page 22) with unglaciated Picture Gorge or with Canyon Creek just above Canyon City.

NOTE: Mileages at lettered stops on the map (Fig. 1) refer to nearby mile posts. These are not in numerical order because the route covers parts of four different numbered highways. By taking the tour clockwise, the traveler will be at higher altitudes later in the day.

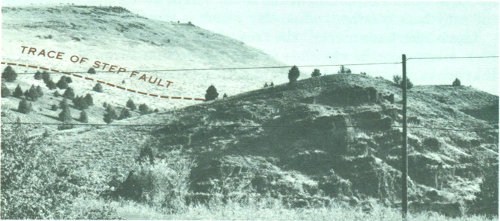

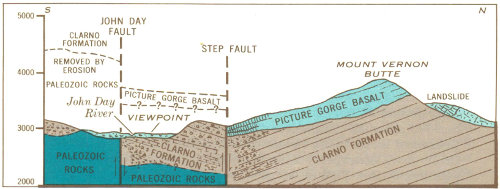

Holliday Rest Area. The main John Day fault, which here is buried under river gravel, is believed to be just south of the rest area. A parallel step fault (Fig. 2) cuts from left to right across the southern slope of Mt. Vernon Butte about where the juniper trees thin out. Flows of Picture Gorge Basalt in the upper part of the butte slope down to valley level on your left. Rocks in the foreground and to the right are rudely bedded volcanic breccias of the Clarno Formation. The Clarno Formation has been raised as much as 250 feet by movement along the fault to position it against the basalt as indicated in the diagram. The fault can be seen best in afternoon light in the ravine to the right, just south of some brick-red layers in the basalt.

Movement on the main John Day fault to the south appears to have raised the rocks at least 1,000 feet, so the two faults have stairstepped the rock layers. The main John Day fault has been traced about 80 miles.

Fig. 2.—View of Mount Vernon Butte and diagram of faulting along its south slope.

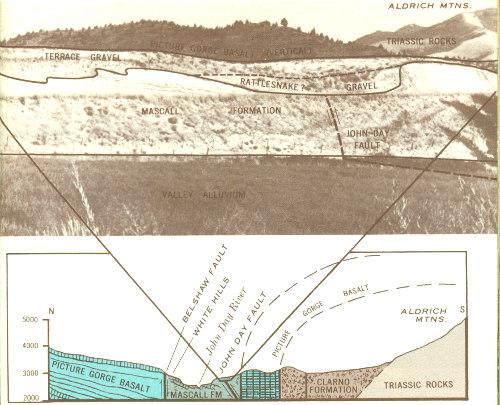

Fig. 3.—View of the John Day fault in Mascall Formation at the mouth of Fields Creek, and its relation to the structure of the John Day River valley.

Fields Creek Road. In the road cuts just south of the highway, the John Day fault (Fig. 3) passes through the Mascall Formation where the slope or dip of the beds changes abruptly from gently southward to steeply northward. The fault continues westward under the floor of the valley. Fossil leaves and snails can be found in the beds south of the fault, and 1,000 feet farther south vertical Picture Gorge Basalt flows are exposed.

To the north across the valley at the White Hills, beds of the Mascall Formation have been dropped down against the Picture Gorge Basalt along the Belshaw fault. The White Hills are a well-known locality for collecting fossil leaves.

Vertical Ribs. The prominent vertical ribs, visible south of the river in steep slopes below the high bench (pediment), are flows of Picture Gorge Basalt tilted vertically in the north limb of the Aldrich Mountain anticline. The John Day fault follows the base of the steep front in which the ribs are exposed.

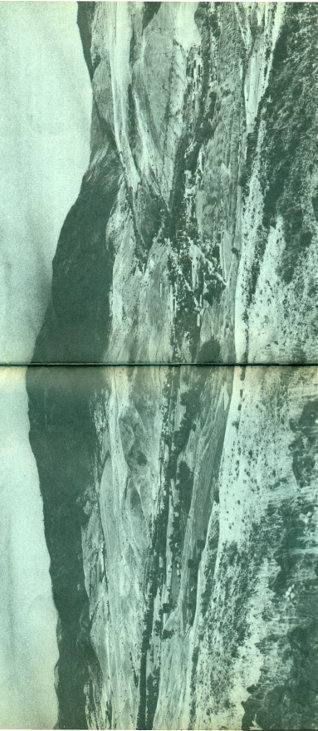

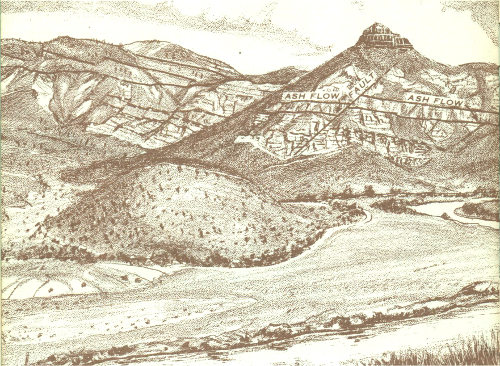

Volcanic Ash Flow. The rimrock north of the John Day River between here and Dayville is a volcanic ash flow that erupted about five million years ago as red hot pumice highly charged with gas. A rapidly moving incandescent cloud probably filled the ancient John Day River valley and deposited ash to a depth of more than 100 feet over a distance of 60 to 70 miles. As shown in Figure 4, the ash flow blankets about 200 feet of gravels that had been deposited in the valley. The rimrock and the gravels above and below it constitute the Rattlesnake Formation.

Fig. 4.—View northwest across the John Day River valley toward Picture Gorge.

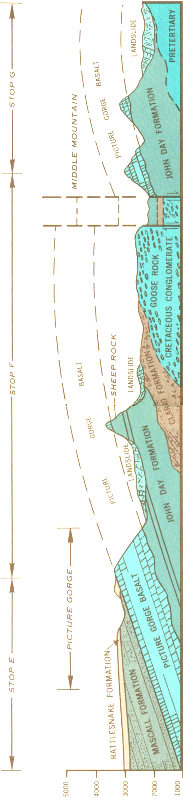

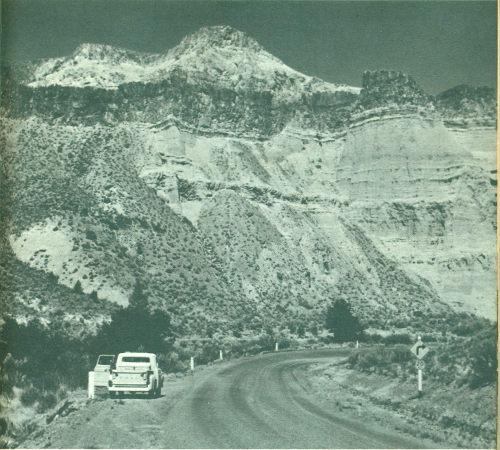

Picture Gorge. Visible to the left of Picture Gorge, from north around to west, in order of their deposition and geologic age from oldest to youngest, are the Picture Gorge Basalt, Mascall Formation, and Rattlesnake Formation (Fig. 5). The Picture Gorge Basalt flows and ashy beds of the Mascall Formation were tilted southward together and eroded before the Rattlesnake Formation was laid down horizontally across them. Picture Gorge and the present valley were then cut by the John Day River after the Rattlesnake Formation had been tilted in its turn. The five benches or terraces on the basalt just east of Picture Gorge mark temporary halts in downcutting of the John Day River.

Thomas Condon Viewpoint, John Day Fossil Beds State Park. From Picture Gorge to the cliffs opposite, the Picture Gorge Basalts and varicolored ash beds of the John Day Formation rise together nearly 2000 feet. The basalt that caps Sheep Rock is an erosional remnant. The lower beds in the John Day Formation are colored red by clay eroded from thick soil on the Clarno Formation, which is exposed in the farthest red hill. The soil was formed by tropical weathering some 30-35 million years ago, before the John Day Formation was laid down. Faulting on a small scale is illustrated in Sheep Rock, where the thick olive-drab ash flow in the middle of the John Day Formation is offset 75-100 feet (Fig. 6). The fault slopes about 45° eastward. About two miles downstream, large-scale movement on two faults has dropped the basalt flows in Middle Mountain 2000-2500 feet. One of the faults follows along the upstream base of Middle Mountain (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5—North-south section along the John Day River through Picture Gorge and Middle Mountain.

Fig. 1.—Geologic map of the John Day Country showing log route.

Munro Area, John Day Fossil Beds State Park. The valley of the John Day River has been widened to nearly five miles by erosion in the John Day Formation. Large tilted slide blocks of the John Day Formation and basalts jumbled together show how important landsliding of soft beds under hard rocks can be in widening valleys.

Fig. 6.—Sheep Rock from Thomas Condon viewpoint.

Here one can appreciate the regularity and extent of basalt flows of the flood or plateau type, which form the Columbia Plateau. Individual flows have been traced 100 miles. Travelers will see few other rocks between here and The Dalles, Wenatchee, Pendleton, or Spokane as they cross parts of the Columbia Plateau.

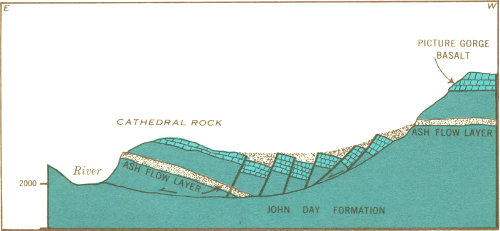

Cathedral Rock. The bluff called Cathedral Rock is the front face of a large block of the John Day Formation that has slid from the west (Fig. 7). Inside the next horseshoe bend downstream a large mass of basalt is tilted down against Cathedral Rock. From the highway 1.1 miles farther north one can see the side of the tilted block along the river, and the same two prominent red and olive-drab ash layers in the high bluff from which the block slid. The horseshoe bend was formed as the river was pushed eastward by the nose of the landslide.

Fig. 7.—View of Cathedral Rock and diagram of landsliding.

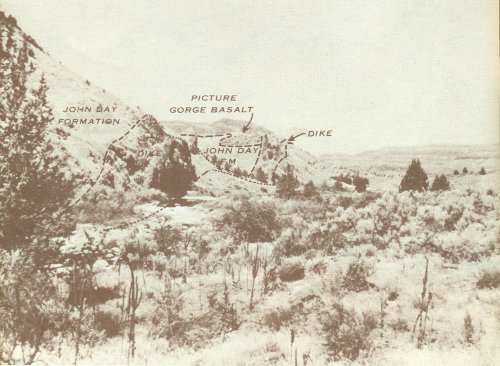

Kimberly Dike. The low bluff across the river is formed by a vertical dike of basalt which is about 60 feet wide. This dike cuts through the John Day Formation and, farther north, the Picture Gorge Basalt (Fig. 8). It crosses the river valley diagonally and can be traced nearly four miles. The dike is formed of once-molten rock that “froze” in a fissure which was a channelway for lava that fed a flow on the earth’s surface. Many similar dikes are visible along the road east of Kimberly. The basaltic magma is believed to have originated at depths of 40 miles or more within the part of the earth called the mantle.

(At 105.3 turn east on State Highway 402 along the North Fork of the John Day River)

Fig. 8.—Basalt dike two miles south of Kimberly.

Basalt Dike. A basalt dike 15 feet wide cuts basalt flows in bluffs north of the road and forms a wall 20 feet high in places; it is visible also across the river.

Parallel Dikes. Two prominent parallel dikes, among others, form crests of hogbacks south of the river. A small tapering dike cuts pink and white beds of the John Day Formation in the river bluff. This dike is the southwest end of an irregular intrusive mass of basalt in which the river has cut a steep-walled gorge.

Basalt Intrusion. The road is cut through 300 feet of basalt intruded into the John Day Formation. Both contacts are well exposed. The basalt—when molten—baked and reddened 3 to 6 inches of the adjacent beds.

(At 13.9 the highway crosses the North Fork of the John Day River and follows the Cottonwood Creek Valley.)

Irregular Dikes. Above the highway several small irregular basalt dikes cut the white beds of the John Day Formation. Parts of the largest dike are 10 to 15 feet high.

Cottonwood Creek Valley. The view northwestward down Cottonwood Creek toward Monument (Fig. 9) exemplifies the development of broad valleys by erosion in soft beds of the John Day Formation under the gently warped Picture Gorge Basalt. To the south, the valley ends against massive rocks of the Clarno Formation which were raised as a block by movement along the Hamilton fault. The red beds are in the lower part of the John Day Formation. Note the contrast between the irregular massive intrusion in the valley bottom west of Monument and the thin regular basalt flows.

Fig. 9.—Northwest view down Cottonwood Creek toward Monument.

On your right, the irregular contact between the John Day Formation and Picture Gorge Basalt reveals an ancient landscape buried under lava flows (Fig. 10). Some of the flows wedge out against former hillsides and one, marked by the dry falls, fills an old valley.

For the next two miles, to the Sunken Mountain viewpoint, the road winds through landslides in the John Day Formation and Picture Gorge Basalt.

Fig. 10.—Ancient landscape on John Day Formation buried under Picture Gorge Basalt.

Sunken Mountain. A small landslide in the lower part of the John Day Formation is called Sunken Mountain. When the valley wall was over-steepened by normal stream erosion, the jumbled material in the lower part broke away and slid down from the steep bare slopes above. Absence of tilted trees indicates that the slide is not very active now. The bare “badland” slopes are being eroded by rain wash. [19] The cliffs of the John Day Formation, which the road climbs half a mile farther east, are the result of rapid but normal headward erosion by the creek. Eventually, because of its lower elevation and steeper gradient, this branch of Cottonwood Creek will intercept and behead Deer Creek just east of Hamilton. A photogenic perspective view of the future stream piracy can be seen from the road on the ridge just south of Sunken Mountain, about a mile and a half from the highway.

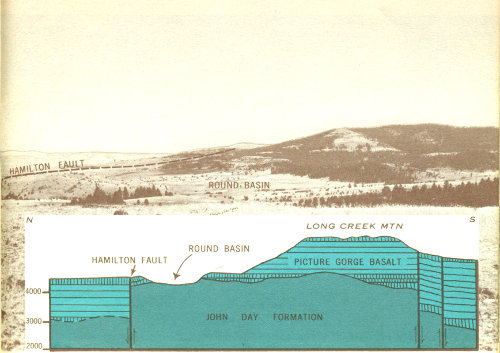

Long Creek Mountain. An uplifted block of Picture Gorge Basalt 1400-1500 feet thick forms Long Creek Mountain; Round Basin is eroded in the John Day Formation on which the basalt rests (Fig. 11). The base of the basalt can be seen in road cuts on either side of Basin Creek. The Hamilton fault follows the gulch to the left just below the parking area, goes up the tree-filled gulch across Basin Creek, along the low ridge at the northeast edge of Round Basin, and then along the northern foot of the mountain. The small slab of basalt south of the fault in Basin Creek has been tilted about 10° north by downward drag along the fault. The Hamilton fault system extends about 15 miles farther east.

(In Long Creek turn right—south—on U. S. Highway 395).

Fig. 11.—View of Long Creek Mountain and Round Basin, and diagram of the geologic structure.

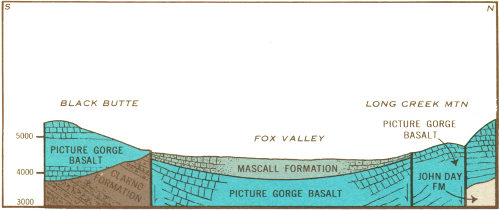

Fig. 12.—North-south section across Fox Valley, showing the faulted basin structure.

Fox Valley. Down-warped flows of Picture Gorge Basalt dip toward Fox Valley from all sides to form a basin (Fig. 12). The valley is eroded out of ashy beds and gravels of the Mascall Formation which fill the center of the basin to an estimated depth of 1000-1200 feet. Faults form parts of the northern and southern borders of the basin. The straight, timbered, northward-facing steep slope less than a mile southeast of the viewpoint marks a fault.

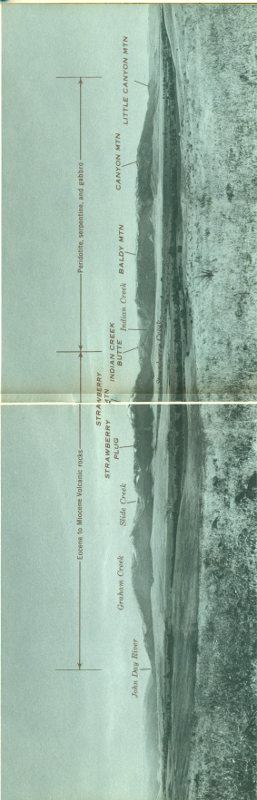

Strawberry Range. This range and the Aldrich Mountains form a mountain range 50 miles long; Strawberry Mountain, altitude 9038 feet above sea level, is its highest peak. The eastern two-thirds of the Strawberry Range (Fig. 13) was raised as a great block by uplift on the John Day fault, which follows the northern base of the mountains. The rocks in Strawberry Mountain and to the east are mostly lavas which poured out over the land, whereas the Canyon Mountain part of the range consists of gabbro and peridotite which were intruded at great depth, like granite.

The valleys in the higher parts of the range, above about 5000 feet, were widened from narrow V’s to their broad U profiles by glaciers during the Pleistocene Epoch, or Great Ice Age. The alluvial fans (Rattlesnake Formation) in front of the mountains were built up of bouldery gravels and finer sediments. These materials were eroded from the mountains, carried by streams down the steep narrow canyons, and spread out on the valley floor. Because much more material came into the John Day River from the Strawberry Mountains than from the lower mountains to the north, the river was pushed to the north side of its wide valley. Faulting and erosion have completely destroyed the cones of the volcanoes from which the volcanic rocks were erupted in Miocene and Pliocene time.

Fig. 13.—Panorama of the Strawberry Range and the John Day River valley from the north.

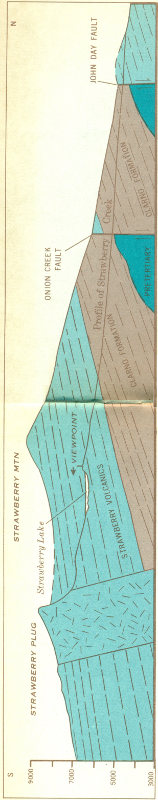

Fig. 14.—Section through the Strawberry Mountain, along Strawberry Creek.

[This image in higher resolution]

Strawberry Lake and Vicinity. At Strawberry Camp, about 12 miles south of Prairie City, the broad floor and steep walls of Strawberry Creek valley indicate that the valley has been glaciated. The precipitous cliffs and rounded valley bottom above Strawberry Lake are characteristic of glaciated mountains (Fig. 15). Strawberry Lake is dammed by landslides which probably came from the west wall of the valley after the glacier melted and left the valley wall over-steepened. The hummocky surface and blocky material in the slide are well shown along the last half mile of the trail to Strawberry Lake. Strawberry Falls mark the front of a glacial step over a massive flow of platy andesite. Little Strawberry Lake is dammed by a low glacial moraine.

Fig. 15.—Strawberry Lake, the glaciated valley of Strawberry Creek, and cirque walls formed by the Strawberry volcanic plug.

Most of the lavas in the Strawberry Mountains were erupted from a central vent about 4000 feet in diameter which is exposed in the cliffs above Little Strawberry Lake. The pinnacles known as “Rabbit Ears,” above the prominent talus in figure 15, are of vent breccias that consist mostly of welded blocks of scoriaceous basalt, but also contain volcanic bombs which were blown out as blobs of fluid lava. Huge blocks of the breccia have fallen onto a gentle bare slope west of Little Strawberry Lake. The massive, vertically-jointed cliffs are formed of basalt which cooled slowly and formed a plug in the throat of the volcano after the eruptions ceased. The thin irregular scoriaceous andesite flows, which are exposed in the cliffs east of Little Strawberry Lake adjoining the plug, contrast strikingly with the massive even flows of the Picture Gorge Basalt.

Tilting of the Strawberry Mountain block is shown by the southward dip of all the flows in the area. The flows in the cliffs west of Strawberry Lake, for example, originally must have sloped northward away from the vent where they erupted. Their present southward dip of about 15° therefore indicates that they have been rotated more than 15° by faulting, partly along the northern edge of the mountain range. (Fig. 14).

(From material provided by Thomas P. Thayer)

As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has basic responsibilities for water, fish, wildlife, mineral, land, park, and recreational resources. Indian and Territorial affairs are other major concerns of America’s “Department of Natural Resources.”

The Department works to assure the wisest choice in managing all our resources so each will make its full contribution to a better United States—now and in the future.