The cover of this book was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain. A more extensive transcriber’s note can be found at the end of this book.

METAPSYCHICAL PHENOMENA

All rights reserved

BY J. MAXWELL

Doctor of Medicine

Deputy-Attorney-General at the Court of Appeal, Bordeaux, France

WITH A PREFACE BY CHARLES RICHET

Member of the Academy of Medicine

Professor of Physiology in the Faculty of Medicine, Paris

AND AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR OLIVER LODGE

Also with a New Chapter containing

‘A COMPLEX CASE,’ BY PROFESSOR RICHET

AND AN ACCOUNT OF

‘SOME RECENTLY OBSERVED PHENOMENA’

BY THE TRANSLATOR L. I. FINCH

LONDON

DUCKWORTH and CO.

3 HENRIETTA STREET, W.C.

1905

The Translator has to thank sincerely a literary friend, a well-known English clergyman, who has been kind enough to revise the translation, and suggest many improvements.

Asked by my friends in France to introduce the author, Dr. Maxwell, to English readers, I willingly consented, for I have reason to know that he is an earnest and indefatigable student of the phenomena for the investigation of which the Society for Psychical Research was constituted; and not only an earnest student, but a sane and competent observer, with rather special qualifications for the task. A gentleman of independent means, trained and practising as a lawyer at Bordeaux, Deputy Attorney-General, in fact, at the Court of Appeal, he supplemented his legal training by going through a full six years’ medical curriculum, and graduated M.D. in order to pursue psycho-physiological studies with more freedom, and to be able to form a sounder and more instructed judgment on the strange phenomena which came under his notice. Moreover, he was fortunate in enlisting the services of one who appears to be singularly gifted in the supernormal direction, an educated and interested friend, who is anxious to preserve his anonymity, but is otherwise willing to give every assistance in his power towards the production and elucidation of the unusual things which occur in his presence and apparently through his agency.

In all this they have been powerfully assisted by Professor Charles Richet, the distinguished physiologist of Paris, whose name and fame are almost as well known in this country as in his own, and who gave the special evening lecture to the British Association on the occasion of its semi-international meeting at Dover in 1899.

In France it so happens that these problems have been attacked chiefly by biologists and medical men, whereas in this country they have attracted the attention chiefly, though not exclusively, of physicists and chemists among men of science. This gives a desirable diversity to the point of view, and adds to the value of the work of the French investigators. Another advantage they possess is that they have no arrière-pensée towards religion or the spiritual world. Frankly, I expect they would confess themselves materialists, and would disclaim all sympathy with the view of a number of enthusiasts in this country, who have sought to make these ill-understood facts the basis for a kind of religious cult in which faith is regarded as more important than knowledge, and who contemn the attitude of scientific men, even of those few who really seek to observe and understand the phenomena.

From Dr. Maxwell’s observations, so far, there arises no theory which he feels to be in the least satisfactory: the facts are recorded as observed, and though theoretical comments are sometimes attempted in the text, they are admittedly tentative and inadequate: we know nothing at present which will suffice to weld the whole together[vii] into a comprehensive and comprehensible scheme. But for the theoretical discussion of such phenomena the work of Mr. Myers on Human Personality is of course far more thorough and ambitious than the semi-popular treatment in the present book. And in the matter of history also, the English reader, familiar with the writings of Mr. Andrew Lang and Mr. Podmore, will not attribute much importance to the few historical remarks of the present writer. He claims consideration as an observer of exceptional ability and scrupulous fairness, and his work is regarded with the greatest interest by workers in this field throughout the world.

There is one thing which Dr. Maxwell does not do. He does not record his facts according to the standard set up by the Society for Psychical Research in this country: that is to say, he does not give a minute account of all the details, nor does he relate the precautions taken, nor seek to convince hostile critics that he has overlooked no possibility, and made no mistakes. Discouraged by previous attempts and failures in this direction, he has regarded the task as impossible, and has not attempted it. He has satisfied himself with three things:—

For the rest, he professes himself indifferent whether his assertions meet with credence or not. He has done his best to test the phenomena for himself, regarding them critically, and not at all in a spirit of credulity; and he has endangered his reputation by undertaking what he regards as a plain duty, that of setting down under his own name, for the world to accept or reject as it pleases, a statement of the experiences to which he has devoted so much time and attention, and of the actuality of which, though he in no way professes to understand them, he is profoundly convinced.

Equally convinced of their occurrence is Professor Richet, who has had an opportunity of observing many of them, and he too regards them from the same untheoretical and empirical point of view; but he has explained his own attitude in a Preface to the French edition, as Dr. Maxwell has explained his in ‘Preliminary Remarks,’—both of which are here translated—so there is no need to say more; beyond this:—

The particular series of occurrences detailed in these pages I myself have not witnessed. I may take an opportunity of seeing them before long; but though that will increase my experience, it will not increase my conviction that things like some of these can and do occur, and that any other patient explorer who had the[ix] same advantages and similar opportunity for observation, would undergo the same sort of experience, that is to say, would receive the same sensory impressions, however he might choose to interpret them.

That is what the scientific world has gradually to grow accustomed to. These things happen under certain conditions, in the same sense that more familiar things happen under ordinary conditions. What the conditions are that determine the happening is for future theory to say.

Dr. Maxwell is convinced that such things can happen without anything that can with any propriety whatever be called fraud; sometimes under conditions so favourable for observation as to preclude the possibility of deception of any kind. Some of them, as we know well, do also frequently happen under fraudulent and semi-fraudulent conditions; but those who take the easy line of assuming that hyper-ingenious fraud and extravagant self-deception are sufficient to account for the whole of the facts, will ultimately, I think, find themselves to have been deceived by their own a priori convictions. Nevertheless we may agree that at present the Territory under exploration is not yet a scientific State. We are in the pre-Newtonian, possibly the pre-Copernican, age of this nascent science; and it is our duty to accumulate facts and carefully record them, for a future Kepler to brood over.

What may be likened to the ‘Ptolemaic’ view of the phenomena seems on the whole to be favoured by the[x] French observers, viz. that they all centre round living man, and represent an unexpected extension of human faculty, an extension, as it were, of the motor and sensory power of the body beyond its apparent boundary. That is undoubtedly the first adit to be explored, and it may turn out to lead us in the right direction; but it is premature even to guess what will be the ultimate outcome of this extra branch of psychological and physiological study. That sensory perception can extend to things out of contact with the body is familiar enough, though it has not been recognised for the senses of touch or taste. That motor activity should also extend into a region beyond the customary range of muscular action is, as yet, unrecognised by science. Nevertheless that is the appearance.

The phenomena which have most attracted the attention and maintained the interest of the French observers, have been just those which convey the above impression: that is to say, mechanical movements without contact, production of intelligent noises, and either visible, tangible, or luminous appearances which do not seem to be hallucinatory. These constantly-asserted, and in a sense well-known, and to some few people almost familiar, experiences, have with us been usually spoken of as ‘physical or psycho-physical phenomena.’ In France they have been called ‘psychical phenomena,’ but that name is evidently not satisfactory, since that should apply to purely mental experiences. To call them ‘occult phenomena’ is not distinctive, for everything[xi] is occult until it is explained; and the business of science is to contemplate the mixed mass of heterogeneous appearances, such as at one time formed all that was known of Chemistry, for instance, or Electricity, and evolve from them an ordered scheme of science.

To emphasise the fact that these occurrences are at present beyond the scheme of orthodox psychology or psycho-physiology, in somewhat the same way as the germ of what we now call Metaphysics was once placed after, or considered as extra to, the course of orthodox Natural Philosophy or Physics, Professor Richet has suggested that they be styled ‘meta-psychical phenomena,’ and that the nascent branch of science, which he and other pioneers are endeavouring to found, be called for the present ‘Metapsychics.’ Dr. Maxwell concurs in this comparatively novel term, and as there seems no serious objection to it, the English version of Dr. Maxwell’s record will appear under this title.

The book will be found for the most part eminently readable—rather an unusual circumstance for a record of this kind—and the scrupulous fairness with which the author has related everything he can think of which tells against the genuineness of the phenomena, is highly to be commended. Whatever may be thought of the evidence it is manifestly his earnest wish never to make it appear to others better than it appears to himself.

If critics attack the book, as they undoubtedly will, with the objection that though it may contain a mass of well-attested assertions by a competent and careful[xii] observer, yet his observations are set down without the necessary details on which an outside critic can judge how far the things really happened, and how far the observer was deceived—let it be remembered that this is admitted. Dr. Maxwell’s defence is, that to give such details as will satisfy a hostile critic who was not actually present is impossible—in that I am disposed to agree with him—he has therefore not attempted the task; and I admit, though I cannot commend, his discretion.

It may be said that the attempt to give every detail necessarily produces a dreary and overburdened narrative. So it does. Nevertheless I must urge—as both in accordance with my own judgment of what is fitting, and in loyalty to the high standard of evidence, and the more stringent rules of testimony, inaugurated by the wise founders of the Society for Psychical Research—that observers should always make an effort to record precisely every detail of the circumstances of some at least of these elusive and rare phenomena; so as to assist in enabling a fair judgment to be formed by people who are not too inexperienced in the conditions attending this class of observation, and at any rate to add to the clearness of their apprehension of the events recorded. The opportunities for research are not yet ended, however, and I may be allowed to express a hope that in the future something of this kind will yet be done, when the occasion is favourable, after a study of such a record as that of the Sidgwick-Hodgson-Davy experiments in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, vol. iv.[xiii] Our gratitude to Dr. Maxwell would thus be still further increased.

And now, finally, I must not be understood as making myself responsible for the contents of the book, nor for the interjected remarks, nor for the translation. The author and translator must bear their own responsibility. My share in the work is limited to expressing my confidence in the good faith of Dr. Maxwell—in his impartiality and competence,—and while congratulating him on the favourable opportunities for investigation which have fallen to his lot, to thank him, on behalf of English investigators, for the single-minded pertinacity and strenuous devotion with which he has pursued this difficult and still nebulous quest.

Oliver Lodge.

There are books in which the author says so clearly and in such precise terms what he has to say that any commentary weakens their import; and a preface becomes superfluous, sometimes even prejudicial.

Dr. Maxwell’s work belongs to this category. The author, who has long given himself up to psychology, has had the opportunity of seeing many interesting things. He has observed everything with minute care; and having well thought out the method of observation, the consequences, and the nature itself of the phenomena, he lays bare his facts and deducts therefrom a few simple ideas, fearlessly, honestly, sine ira nec studio, before a public which he hopes to find impartial.

To this same public I address the short introduction, with which my friend Dr. Maxwell kindly asked me to head this excellent work.

My advice to the reader may be summed up in a few words. He must take up this book without prejudice. He must fear neither that which is new, nor that which is unexpected. In other words, while preserving the most scrupulous respect for the science of to-day, he must be thoroughly convinced that this science, whatever[xvi] measure of truth it may contain, is nevertheless terribly incomplete.

Those imprudent people who busy themselves with ‘occult’ sciences are accused of overthrowing Science, of destroying that bulwark which thousands of toilers, at the cost of an immense universal effort, have been occupied in constructing during the last three or four centuries.

This reproach seems to me rather unjust. No one is able to destroy a scientific fact.

An electric current decomposes water into one volume of oxygen and two of hydrogen. This is a fact which will be true in the eternal future, just as it has been true in the eternal past. Ideas may perhaps change on what it is expedient to call electric current, oxygen, hydrogen, etc. It may be discovered that hydrogen is composed of fifty different bodies, that oxygen is transformed into hydrogen, that the electric current is a ponderable force or a luminous emission. No matter what is going to be discovered, we shall never, in any case, prevent what we call to-day an electric current from transforming, under certain conditions of combined pressure and temperature, what we call water into two gases, each having different properties, gases which are emitted in volumetrical proportions of 2 to 1.

Therefore, there need be no fear, that the invasion of a new science into the old will upset acquired data, and contradict what has been established by savants.

Consequently psychical phenomena, however complicated, unforeseen, or appalling we may now and then imagine them to be, will not subvert any of those facts which form part of to-day’s classical sciences.

Astronomy and physiology, physics and mathematics, chemistry and zoology, need not be afraid. They are intangible, and nothing will injure the imposing assemblage of incontestable facts which constitute them.

But notions, hitherto unknown, may be introduced, which, without casting doubts upon pristine truths, may cause new ones to enter their domain, and change, or even upset, our established notions of things.

The facts may be unforeseen, but they will never be contradictory.

The history of sciences teaches us, that their bulwarks have never been overthrown by the inroad of a new science.

At one time no notion of tubercular infection existed. We now know that it is transmitted by microbes. This is a new notion, teeming with important conclusions, but it does not invalidate the clinical table of pulmonary phthisis drawn up by physicians of other days. The discovery of Hertzian waves has in nowise shaken Ampère’s laws. Newton’s and Fresnel’s optics have not been changed into a tissue of errors because Rœntgen rays and luminous vibrations are able to penetrate opaque bodies. It appears that radium can throw out unremittingly, without any appreciable chemical molecular phenomena, great quantities of[xviii] calorific energy; nevertheless, we may be quite sure, that the law of conservation of energy and thermo-dynamic principles will remain as true now as ever.

Likewise, if the facts called ‘occult’ become established, as seems more and more probable, we need not feel anxious as to the fate of classical science. New and unknown facts, however strange they may be, will not do away with old established facts.

To take an example from Dr. Maxwell’s work, let us admit that the phenomenon of raps—that is to say, sonorous vibrations in wood or other substances—is a real phenomenon, and that, in certain cases, there are sounds which no mechanical force known to us can explain, would the science of physics be overthrown? It would be a new force thrown out on to wood, etc., exercising its power on matter, but the old forces would none the less preserve their activity, and it is even likely that the transmission of vibrations by means of this new force would be found to be in obedience to the same laws as those governing the transmission of other vibrations;—the temperature, the pressure, the density of air or wood would continue to exercise their usual influence. There would be nothing new, save the existence of a force until then unknown.

Now, is there any savant worthy of the name who can affirm, that there are no forces, hitherto unknown, at work in the world?

However impregnable Science may be when establishing[xix] facts, it is miserably subject to error when claiming to establish negations.

Here is a dilemma, which appears to me to be very conclusive in that respect:—Either we know all Nature’s forces, or we do not. Now the first alternative is so ridiculous, that it is really not worth while refuting it. Our senses are so limited, so imperfect, that the world slips away from them almost entirely. We may say it is owing to an accident, that the magnet’s colossal force was discovered, and if hazard had not placed iron beside the loadstone, we might have always remained ignorant of the attraction which loadstone exercises upon iron. Ten years ago no one suspected the existence of the Rœntgen rays. Before photography, no one knew that light reduces salts of silver. It is not twenty years since the Hertzian waves were discovered. The property displayed by amber when rubbed was, until two hundred years ago, all that was known of that immense force called electricity.

Question a savage—nay a fellah or a moujik—upon the forces of Nature! He will not know even the tenth part of such forces as elementary treatises on physics in 1905 will enumerate. It appears to me that the savants of to-day, in respect to the savants of the future, stand in the same inferiority as the moujiks to the professors of the college of France.

Who then dare be so rash as to say that the treatises on physics in 2005 will but repeat what is to be found in the treatises of 1905? The probability—the certainty,[xx] one might say—is that new scientific data will shortly spring up out of the darkness, and that most powerful and altogether unknown forces will be revealed. Our great-grandchildren will be amazed at the blindness of our savants, who tacitly profess the immobility of science.

If science has made such progress of late, it is precisely because our predecessors were not afraid to make bold hypotheses, to suppose new forces, demonstrating their reality by dint of patience and perseverance. Our strict duty is to do likewise. The savant should be a revolutionist, and fortunately the time is over when truth had to be sought in a master’s book—magister dixit—be he Aristotle or Plato. In politics we may be conservative or progressive; it is a question of temperament. But when the research of truth is concerned we must be resolutely and unreservedly revolutionary, and must consider classical theories—even those which appear to be the most solid—as temporary hypotheses, which we must incessantly check and incessantly strive to overthrow. The Chinese believed that science had been fixed by their ancestors’ sapience; this example contains food for meditation.

Moreover—and why not proclaim it loudly—all that science of which we are so proud, is only knowledge of appearances. The real nature of things baffles us. The innermost nature of laws governing matter, whether living or inert, is inaccessible to our intelligence. A stone tossed up into the air falls back again to the earth.[xxi] Why? Newton says through attraction proportional to bulk and distance. But this law is only the statement of a fact; who understands that attractive vibration, which makes the stone fall? The fall of a stone is such a commonplace phenomenon, that it does not astonish us: but in reality no human intelligence has ever understood it. It is usual, common, accepted; but like all Nature’s phenomena without exception it is not understood. After fecundation an egg becomes an embryon; we describe as well as we can the phases of this phenomenon; but, in spite of the most minute descriptions, have we understood the evolution of that cellular protoplasm, which is transformed into a huge, living being? What prodigy is at work in these segmentations? Why do these granulations crowd together there? Why do they decay here to form again elsewhere?

We live in the midst of phenomena and have no adequate knowledge of any one of them. Even the simplest phenomenon is most mysterious. What does the combination of hydrogen with oxygen mean? Who has even once been thoroughly able to understand that word combination, annihilation of the properties of two bodies by the creation of a third body differing from the two first. How are we to understand that an atom is indivisible; it is constituted of a particle of matter, yet—even in thought—it cannot be divided!

Therefore it behoves the true savant to be very modest, yet very bold at the same time: very modest, for our science is a mere trifle—Ἡ ἀνθρωπίνη σοφία[xxii] ὀλίγου τινος ἄξιά ἐστι, καί οὐδενός—very bold, for the vast regions of worlds unknown lie open before him.

Audacity and prudence: such are the two qualities, in no wise contradictory, of Dr. Maxwell’s book.

Whatever be the fate in store for his ideas—ideas based upon facts—we may rest assured that the facts, which he has well observed, will remain. I think I see here the lineaments of a new science—though only a crude sketch so far.

Who knows but that physiology and physics may find herein some precious elements of knowledge? Woe to the savants who think that the book of Nature is closed, and that we puny men have nothing more to learn.

Charles Richet.

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| INTRODUCTION BY SIR OLIVER LODGE, | v | ||

| PREFACE BY PROFESSOR CHARLES RICHET, | xv | ||

| PRELIMINARY REMARKS, | 1 | ||

| CHAP. | |||

| I. | METHOD: | 23 | |

| I. | Material Conditions, | 33 | |

| II. | Composition of the Circle, | 42 | |

| III. | Methods of Operation, | 48 | |

| IV. | The Personification, | 64 | |

| II. | RAPS, | 72 | |

| III. | PARAKINESIS AND TELEKINESIS: | 93 | |

| I. | Parakinesis, | 93 | |

| II. | Telekinesis, | 98 | |

| IV. | LUMINOUS PHENOMENA, | 129 | |

| V. | PSYCHO-SENSORY AND INTELLECTUAL PHENOMENA: | 180 | |

| I. | Sensory Automatism, | 181 | |

| II. | Crystal Gazing, | 184 | |

| III. | Dreams, Telepathy, | 205[xxiv] | |

| IV. | Telæsthesia, | 211 | |

| V. | A Complex Case by Professor Richet, | 215 | |

| VI. | Motor Automatism, | 235 | |

| VII. | Automatic Writing, | 238 | |

| VIII. | Phonetic and Mixed Automatisms, | 251 | |

| IX. | The Psychology of Automatism, | 255 | |

| VI. | SOME RECENTLY OBSERVED PSYCHICAL PHENOMENA. By L. I. Finch, | 268 | |

| VII. | FRAUD AND ERROR: | 364 | |

| I. | Fraud, | 364 | |

| II. | Error, | 386 | |

| CONCLUSION, | 392 | ||

| APPENDICES, | 398 | ||

I hesitated for a long time before deciding to publish the impressions which ten years of psychical research have left me. These impressions are so uncertain upon several points, that I wondered if it were worth while expressing in book form the few and sparse conclusions I am able to formulate. If, finally, I decide to publish my opinions, it is because it seems incumbent upon me to do so. I am not blind to the fact that my testimony is of very little importance; but however modest it may be, it seems to me that it is my duty to offer this testimony, such as it is, to those who have undertaken to submit to scientific discipline the study of those phenomena which are, in appearance at least, so rebellious to such discipline. It might have been more convenient and advantageous for myself had I continued my researches in peace and quiet. I do not try to proselytise, and it is really a matter of indifference to me, whether my contemporaries share or do not share my views. But the sight of a few brave men fighting the battle alone is by no means a matter of indifference to me. There is a certain cowardliness in believing their teachings, whilst allowing them to bear all the brunt of the fray for upholding opinions, which require so much courage to champion. To these brave spirits I dedicate my book.

I care naught for public opinion: not that I disdain[2] it—on the contrary, I have the greatest respect for its judgment—but I am not addressing the public. The question I am studying is not ripe for the public; or the case may be the other way about.

I address those brave men of whom I have just spoken, to let them know I am of their mind, and that my observations confirm theirs on many points. I also address those who are seeking to establish the reality of the curious phenomena, treated of in this book. I have tried to fill a gap by showing them the best methods to adopt, in order to arrive at appreciable results,—such results being far less difficult to obtain than is commonly supposed.

A word about the method I have followed. I have purposely refrained from giving a purely scientific aspect to my book, though I might have done so had I chosen, for the usual scientific dressing is unsuitable to the subject in hand. It seemed preferable to relate what I have seen, leaving it to those for whom I write to believe me or not, as they think fit.

I might have accumulated not a little testimony and considerable external evidence, but to have done so would not have been the means of convincing a single extra reader. Those, whom my simple affirmation leaves sceptical, would not be convinced by reports signed by witnesses, whose sincerity and competence are frequently called into question. Neither did I wish to adopt the method followed by the Agnélas, Milan, and Carqueiranne experimenters, in giving a detailed report of all my sittings; this method too has its advantages and disadvantages. However exhaustive a report may be, it is difficult to indicate therein all the[3] conditions of the experiment; oversights are inevitable. Moreover, it would be useless to say that every precaution had been taken against fraud, for in enumerating such precautions, the omission of a single one would suffice to expose oneself to most justifiable criticism. Probably that very precaution was elementary and had been taken, or was considered useless and put aside deliberately; nevertheless such circumstances would not escape criticism. We wish to convince by pointing out the exact conditions of the experiment; but those, whom we would most wish to convince, are the very persons least prepared to judge of the conditions in which psychical experiences are obtained. These are physicists and chemists; but living matter does not react like inorganic matter or chemical substances.

I do not seek to convince these savants; my book is unassuming and makes no pretence of having been written for them. If they in their turn should be tempted to try for those effects which I have obtained, the methods indicated will be easily accessible to them. It is in this way they can be indirectly convinced, though to convince them is not my present aim. Others are better qualified than I am to try their hand at this most desirable but, for the moment, most difficult task.

Difficult! Ay, and for a thousand reasons. First of all because it is the fashion of to-day to look upon these facts as unworthy of science. I acknowledge taking a delicate pleasure in comparing the different opinions which many young Savants (I beg the printer not to forget a very big capital S) bring to bear upon their contemporaries. Here is a man surrounded by deferential spectators: solemnly he hands a paper-knife[4] to a sleeping hysterical subject, and gravely invites him to murder such or such an individual who is supposed to be where there is really only an empty chair. When the patient springs forward to carry out the suggestion, and strikes the chair with the paper-knife, the lookers-on behold a scientific fact, according to classical science. On the other hand, here is another man who, not a whit less solemnly, makes longitudinal passes upon his subject, puts him to sleep, and then tries to exteriorise the said subject’s sensibility; but the onlookers in this case are not recognised as witnessing a scientific fact! I have never been able to see wherein lies the difference between these two experimenters, the one experimenting with an hysterical subject more or less untrustworthy, the other examining a phenomenon which, if it be true, may be observed without the necessity of trusting oneself solely to the honesty of the individual asleep.

In fact there is a most intolerant clique among savants. Facts it seems are of no importance when pointed out by those who stand beyond the pale of official science. Unfortunately, psychical phenomena cannot be as easily and readily demonstrated as the X-rays or wireless telegraphy, incontestable facts which any one can prove to his entire satisfaction. Therefore young savants rejoice in making an onslaught on those who apply themselves to the study of these phenomena. It was the same thing in olden times when budding theologians made their débuts in the arena of theology against notorious arch-heretics, Arians, Manicheans, or gnostics. Nil novi sub sole.

......

I readily admit that many, who turn their attention to the curious phenomena of which I am going to speak, frequently lay themselves open to criticism. Sometimes they are not very strict concerning the conditions under which their experiments are conducted: they trust naïvely, and their conviction is quickly formed. I cannot too forcibly beg them to be on their guard against premature assertions: may they avoid justifying Montaigne’s saying, ‘L’imagination crée le cas.’ My remark is more particularly addressed to occult, theosophical, and spiritistic groups. The first-named follow an undesirable method. Their manner of reasoning is not likely to bring them many adepts, from among those who are given to thinking deeply. In ordinary logic, analogy and correspondence have not the same importance as deduction and induction. On the other hand it does not seem to me prudent to consider the esoteric interpretation of the Hebrew writings as being necessarily truth’s last word. I do not see why I should transfer a belief in their exoteric assertions to a belief in their talmudistic or kabbalistic commentaries. I can hardly believe that the Rabbis of the middle ages, or their predecessors, Esdras’ contemporaries, had a more correct notion of human nature than we have. Their errors in physics are not valid security for their accuracy in metaphysics. Truth cannot be usefully sought in the analysis of a very fine but very old book: all occult speculations upon secret hebraic exegeses seem to me but intellectual sport, to the results of which the words of Ecclesiastes might well be applied: Habel habalim vekol habel.

I may pass the same criticism upon theosophists.[6] The curious mystical movement to which the teachings of Madame Blavatsky, Colonel Olcott, and Mrs. Besant have given birth in Europe and in America has not yet been arrested. Many cultured minds and refined intelligences have allowed themselves to be led away by the neo-buddhistic evangile; doubtless they find what they look for in the ‘Secret Doctrine’ or in ‘Isis Unveiled.’ Trahit sua quemque voluptas. I cannot help thinking that the Upanishads have no more a monopoly of truth than the Bible has, and that every philosophy ought to hold fast to the study of Nature if it wishes to live and progress. This is, moreover, the advice of a man whom theosophists and occultists alike respect—I mean Paracelsus—‘Man is here below to instruct himself in the light of Nature.’

That is what spiritists claim to do. Their philosophy, to use the term which they themselves employ to designate their doctrine, is founded, they say, upon fact and experience. It is not a revelation, contemporary with the splendour of Thebes or the pomp of Açoka’s court, which gives the foundation to their dogmas. It is an everyday revelation, a real, continuous, and permanent revelation. Their ideas concerning our origin and destiny, their certitude of immortality and the persistence of human individuality, are due to well-informed witnesses. These are no less than the spirits of the dead, who come to enlighten them and to tell them what is done in the hereafter.

I envy them their simple faith, but I do not altogether share it. I am persuaded that our individuality has an infinitely longer period given it for its evolution than one human existence. But it is not from spiritistic[7] seances that I have derived my belief; no, my belief is of a philosophical kind, and is the result of pondering over what I know of life, of nature, and of the extremely slow development of the human species. It is true the knowledge I possess is limited, and my belief wavers; yet the probabilities seem to me favourable to the persistence of that mysterious centre of energy which we call individuality.

This opinion, however, has not been derived from spiritistic communications: I think these have an origin other than that given them by Allan Kardec’s disciples.

Naturally I am only speaking of my own personal experience; I do not permit myself to pronounce as erroneous those convictions based upon facts not seen by myself. Therefore I do not wish to say that spiritists are always the victims of delusion; I can only say that the messages, received by me and purporting to come from the other side of the grave, have seemed to me to emanate from a different source.

At the same time, to be exact and sincere I ought to add that, if my conviction has not been won, I have observed in one or two circumstances certain facts which have left me most perplexed.

Unfortunately for spiritism, an objection, which seems to me irrefutable, can be made to the spirits’ teaching. In all parts of Europe, the ‘spirits’ vouch for reincarnation. Often they indicate the moment they are going to reappear in a human body; and they relate still more readily the past avatars of their followers. On the contrary, in England the spirits assure us that there is no reincarnation. The contradiction is formal, positive, and irreconcilable. Those who are inclined[8] to doubt the correctness of what I affirm have only to glance through and compare the writings of English and French spiritists; for example, those of Allan Kardec, Denys, Delanne, and those of Stainton-Moses. How are we to form an opinion worthy of acceptance? Who speak the truth? European spirits or Anglo-Saxon spirits? Probably spiritistic messages do not emanate from very well-informed witnesses. Such is the conclusion arrived at by Aksakoff, one of the cleverest and most enlightened of spiritists. He himself acknowledges that one is never certain of the identity of the communicating intelligence at a spiritistic sitting.

Although I do not share the views of occultists, theosophists, and spiritists, I can indeed say that their groups—at least those which I have frequented—are composed of people worthy, sincere, and convinced. Occultists and theosophists devote themselves perhaps more particularly to the development of those mysterious faculties which, according to them, exist in man, while spiritists are more inclined to call forth communications from their spirit friends, but the anxious care of one and all is the moral development of their groups.

Solicitude for the ethical culture of humanity is characteristic of these mystic groups. Occultism and theosophy draw their recruits more especially from intellectual centres; the circle of spiritism is much wider. The simplicity of its teachings and methods attracts those who shrink before the personal edification of a creed: for it is a painful undertaking and a heavy task for each individual to form his own philosophy. It is more convenient to accept indications which are already made, and to believe affirmations which are—in[9] appearance—sincere and well informed. Long centuries of religious discipline have accustomed the human mind to certain acts of faith, and to shun all free discussion, as soon as there is any question of future destinies. It is difficult to shake off this atavism.

This is what makes the success of spiritism; it comes at its appointed time, and supplies a wide-felt need.

......

The psychological condition of society to-day is of an extremely perturbed nature, as slight reflection will suffice to show. Much has been said of the conflict between science and religion, but the truth has not yet been sounded. It is no ordinary conflict which is now taking place between science and revelation: it is a life-and-death struggle. And it is easy to foresee which side will succumb.

It even seems as though the final death-struggles of Christian dogma had already set in. What man, sincere and unbiased in his opinions, could repeat to-day the famous credo quia absurdum? Are we not insulting the Divinity—if He exists—when we refuse to make use of His most precious gifts? when we abstain from applying the full force of our intelligence and reason to the examination of our destiny and our duties to ourselves and to others?

This abdication is nevertheless demanded of us—by Roman Catholicism for example, which exacts unqualified adhesion to its dogmas, blind belief in its Church’s teachings, blind belief in the affirmations of its infallible pope. It seems to me inadmissible that the God of Roman Catholics should approve of such indifference.

It is obvious that I do not wish to write a history of ecclesiastical controversy. I have too much respect for others to allow myself to attack what are still widely accepted creeds. My duty is but to study the general aspect of revelation, and to draw therefrom such conclusions as are necessary to my acquirements.

It is an easy study. The most enlightened intellects stand aloof from revealed religions. I mean the majority, for there is still a small minority which remains faithful to dying creeds.

Even the less cultivated intelligences are beginning to feel the insufficiency of revelation. The Divinity’s incarnation and death, in order to redeem a race so unworthy of such a sacrifice, begins to astound them; they wonder at such solicitude for the inhabitants of one of the least important spheres in the universe. They are also surprised at the inexorable severity of a God who, before granting pardon to mankind, demands his only son’s death; a God who, for the petty trespasses of beings far removed from himself, demands an eternity of suffering as chastisement for such ephemeral insults. All this fails to satisfy those souls who are enamoured of truth and justice. These dogmas give man a cosmical importance which he does not possess, and imputes to God a susceptibility and cruelty altogether unworthy of the Supreme Being.

We could easily find other examples; but I do not think it necessary to bring them to bear upon my conclusion; a conclusion, moreover, which is admitted by the clergy themselves, who complain unceasingly of society’s growing indifference.

But is society really so indifferent? I do not think[11] so. We find indifference among the richer and more cultured classes, where some give themselves up to pleasure, others to science, in reality each one seeking only that which will amuse or interest him or herself; but those who are without resources, those whom life molests and wearies, those who are afraid at the idea of death and annihilation, those who have need of some consolation, of some hope, those people are not indifferent. If these forsake the churches and temples, it is because they do not find therein what they are seeking. The spiritual nourishment offered them has lost its savour; they ask for something more substantial and less contestable.

Besides, even in the most highly cultured classes, this need begins to make itself felt. Such men as Myers, Sidgwick, Gurney, to speak only of the dead, took up the study of psychical phenomena with the desire of finding therein the proof of a future life. Myers died after having found—or thought he had found—the sought-for demonstration.

Professor Haeckel of Jéna drew up a philosophy for himself! His materialistic monism is the outward expression of his belief: but this is also ill-adapted to satisfy that longing, the extent and force of which I have just touched upon.

......

Now spiritism lays claim to satisfying these longings; and it does satisfy them, when only simple souls are concerned, simple souls who do not dream of life’s complexities. The phenomena of spiritistic seances—and these are real phenomena—are the miracles which come[12] to confirm the spirits’ teachings. Why should they doubt?

Therefore the clients of spiritism are increasing in number with extraordinary rapidity. The extent to which this doctrine is spreading is one of the most curious things of the day. I believe we are beholding the dawn of a veritable religion; a religion without a ritual and without an organised clergy, and yet with assemblies and practices which make it a veritable cult. As for me, I take a great interest in these meetings; they give me the impression that I am assisting at the birth of a religious movement called to a great destiny.

Will my anticipations be realised? The future alone can tell. My opinion has been formed on impartial and disinterested observation. Notwithstanding the sympathy that I feel for those groups which have been kind enough to admit me into their midst, notwithstanding the friendship which binds me to many of their members, I have never wished to be of their propaganda, nor even to allow them to think that I shared their views. I have always plainly told them that I was by no means convinced of the constant intervention of spirits; I have not concealed from them that other and, as I thought, more probable explanations could be given to the phenomena they witnessed; perhaps they have appreciated my frankness. In any case, I am very grateful for the courtesy and kindliness with which they allowed me to observe the phenomena at their sittings, to listen to their mediums’ teachings, and to express my opinions, which are so unlike their own.

......

I am neither spiritist, nor theosophist, nor occultist.[13] I do not believe in occult sciences, nor in the supernatural, nor in miracles. I believe we know as yet very little of the world we are living in, and that we still have everything to learn. The cleverest men in all epochs show an unconscious tendency to suppose that facts, which are incompatible with their ideas, are supernatural or false. More modest but also more cruel, our forefathers, the theologians and lawyers, burnt sorcerers and magicians without accusing them of fraud: to-day most of our savants, being more affirmative and less rigorous, accuse mediums and thaumaturgists of fraud, but without condemning them to the stake. In reality their state of mind is the same as that of the ancient exorcists; they have the same intolerance, and the different treatment meted out to their subjects is only due to the progressive improvement in manners and customs.

Even those savants who are the most interested in psychical research are afraid of confessing their curiosity. It requires the broad-mindedness of a Crookes or a Lodge, of a Duclaux or a Richet, of a Rochas or a Lombroso to dare to take a stand and openly show an interest in this field of research. Some day, however, these same suspicious researches will be their experimenters’ best claim to fame. The present attitude of official science towards medianic phenomena is to be regretted; its scientific ‘cant’ has grievous results. The history of the International Psychological Institute is instructive in this respect. What a pity that such learned, remarkable, and competent men, as Janet for example, should have shrunk from the epithet ‘psychic’! The need for a psychical institute existed, not a psychological one, of which there are already enough.

It is precisely the attitude of respectable scientific circles which appears to me a mistake, demanding rectification. I understand perfectly and excuse this attitude. For so many incorrect things have been affirmed, so many ridiculous practices have been recommended by the leaders of the occult movement, that official representatives of science must have felt indignant. Unfortunately no one except Richet has ventured to do for the phenomena vouched for by occultists and spiritists, what Charcot has done for the magnetisers’ allegations. No doubt, this other Charcot will come when the time is ripe.

The preparatory work will have been done, and he need only resume the experiments of Richet, Crookes, Lodge, Rochas, Ochorowicz, and many others.

I class myself with these experimenters. Many of them are my friends, and, if our manner of thinking be not quite the same, my ideas upon the method to be used are much the same as theirs. And thus I find myself quite naturally led to say what my ideas are.

I believe in the reality of certain phenomena which I have been able to verify over and over again. I see no need to attribute these phenomena to any supernatural intervention. I am inclined to think that they are produced by some force existing within ourselves.

I believe also that these facts can be subjected to scientific observation. I say observation and not experimentation, because I do not think that it is yet possible to proceed on veritable experimental lines. In order to experiment one must understand the conditions necessary to produce a given result; now, in our case, we have a[15] most imperfect knowledge of the required conditions, which are, nevertheless, necessary antecedents to the sought-for phenomena. We are in the position of the astronomer who can put his eye to the telescope and observe the firmament, but who cannot provoke the production of a single celestial phenomenon.

My position is therefore very simple. It is that of an impartial observer. The occult sciences and spiritism never aroused my curiosity, and I was more than thirty years of age, when my attention was drawn towards psychical phenomena. I did not even try to turn a table before I was thirty-five, considering such facts as unworthy of serious examination. It is only since 1892 that I have become interested in these researches.

I cannot remember to-day how I was led to take up the study; it was not abruptly. I am certain that no striking incident was ever responsible for a sudden changing of my mind. As far as my recollection goes, I think it was the chance perusal of some theosophical works, which made me curious to know the extent of a mystical movement, whose existence I had not even suspected. My discoveries astonished me, for I never thought that mysticism could find adherents at the end of the nineteenth century. The opening address pronounced by me at the Court of Appeal at Limoges in 1893 was upon this subject.

This address brought me many correspondents, and I was led to experiment myself. My first results were negative, and except a few interesting experiments made at Limoges with a lady of that town—a remarkable medium—and her husband, the phenomena which I observed were not of a nature to convince me. In 1895[16] I went to l’Agnélas, and took part in the experiments of MM. de Rochas, Dariex, Sabatier, de Gramont and de Watteville. The report of these experiments has been published in the Annales des Sciences Psychiques.

Surprised at these manifestations, I became filled with the desire to investigate further; and soon afterwards curiosity prompted me to take advantage of a leisure moment to resume the l’Agnélas experiments. In 1896 Eusapia Paladino was kind enough to spend a fortnight at my house at Choisy, near Bordeaux. MM. de Rochas, Watteville, Gramont, Brincard, and General Thomassin were present at all or some of these experiments. The Attorney-General, M. Lefranc, my friend and chief, was also present at one of our sittings. M. Béchade and a Bordeaux medium, Madame Agullana, were also my guests. The results of these sittings have been noted down by M. de Rochas in a small volume which has not been made public. More and more interested, and desirous of investigating still further what I had seen with Eusapia, I begged her to pay me another visit. She consented, and returned in 1897, giving me another fortnight, this time in my home at Bordeaux. The phenomena which my friends and I obtained on that occasion were as demonstrative as before.

Eusapia is not the only medium with whom I have experimented. Madame Agullana of Bordeaux, with her customary disinterestedness, has given me many sittings: the results I obtained with her are of a different order. I also brought twice to Bordeaux the young mediums of Agen, where a previous opportunity had been given me of observing them; at Agen their phenomena had won[17] for their home the reputation of being haunted. Lastly, I have found some remarkable mediums at Bordeaux, among those who did me the honour of admitting me to their sittings. I also came across a large number of mediums manifesting automatic phenomena only; these, too, were interesting in their way, for they enabled me to note and understand the difference between so-called supernatural phenomena and phenomena which are but the expression of an activity, which, in appearance at least, is extraneous to the ordinary personality.

Finally, I have frequently come across fraud. This was instructive, and I observed the fraudulent with patience and interest. The tricks of voluntary fraud deserve to be known and studied, as one is then better able to frustrate and checkmate them. Involuntary fraud—far more common than voluntary fraud—is no less instructive, for it throws a vivid light upon the curious phenomena of automatic activity.

It is not always becoming to entertain one’s readers with personalities, but I think I ought to infringe a little upon decorum, in order to specify the state of mind in which I have pursued my observations. From the very beginning I was struck by a fact which seems beyond doubt. I saw that certain manifestations—to all appearances supernormal—could only be studied with the assistance of nervous and mental pathology. Therefore I went to school again, and for six years I studied assiduously clinical medicine at the University of Bordeaux. It is not within my present scope to write the panegyric of the masters to whose teachings I listened, their names would seem out of place in a book like this. But I may say that the interest which I took in my medical studies[18] became more lively, as I understood their importance better and better. Doubtless the notions which I have acquired are most rudimentary, but however unpretentious they may be, they have enabled me to understand the mechanism of certain manifestations, and to bring a more precise judgment to bear upon their psychological value.

I am, therefore, an interested but impartial onlooker. It matters little to me if a table or a chair moves of its own accord; I have no particular desire to see them accomplish these movements. The only interest, which I find in this fact, is its truth. Its reality alone is of value to me, and I have applied myself to establish this without any possible error. My unique preoccupation has been to make sure of the reality of the phenomena which I observed. The pursuit of truth has been my sole concern.

True, I sought it in my own way; for I preferred to build my conviction upon a basis which would satisfy my intelligence and my reason, rather than impose a priori conditions which the experiment ought to satisfy in order to convince me. I am ignorant of most of these conditions, and I think that every one else is also. Consequently, I consider it imprudent to establish beforehand the conditions under which the experiments are to be made, in order to merit being recorded. It might just happen, that one of the conditions thus laid down rendered the experiment impracticable. Therefore I have observed rather than experimented.

My manner of proceeding has been productive of many happy results; for the curious phenomena which I have been able to observe are capricious; they shun those who would force them, and offer themselves to[19] those who wait for them patiently. This behaviour, this spontaneity, is not the least astonishing feature in this line of observation.

I have always thought that there was nothing of a supernatural order in these phenomena. My conclusions have not changed; but let us understand the meaning of this expression. I do not mean to say that these phenomena are always in accordance with nature’s laws such as we understand them to-day. I am certain that we are in the presence of an unknown force; its manifestations do not seem to obey the same laws, as those governing other forces more familiar to us; but I have no doubt they obey some law, and perhaps the study of these phenomena will lead us to the conception of laws more comprehensive than those already known. Some future Newton will discover a more complete formula than ours.

My position, therefore, seems to me to be well defined. I have held myself aloof from those who denied upon bias, and also from those who asserted too rashly. I have remained within the margin of science. I have endeavoured to bring to bear upon my experiments methods of scientific observation. I wish to go in neither for occultism, nor for spiritism, nor for anything mysterious or supernatural. Many who know me imperfectly may think that I have given reins to my imagination, that I am an adept in theosophy, neo-martinism, or spiritism. Such is not the case. I seek, and I have found-very little; others have been more fortunate than I. Some day perhaps I shall have the same good luck. But I shall not touch upon what others have done, save as an accessory; I shall only[20] speak of what I myself have seen and what I myself think. My book is the statement of a witness—it has no other signification.

One word in conclusion. A great number of my experiments have been made with people who wish to preserve their incognito. I have never been wanting in discretion when this was asked of me, and have never disclosed the names of those who placed their confidence in me, permitting me to experiment with them whilst desirous of remaining unknown. I have sometimes found very remarkable mediums among these anonymous experimenters. Some of my sittings with them have been truly admirable on account of the clear, distinct nature of the phenomena obtained. I beg these trusting friends to accept my heartfelt thanks.

May my book have the good fortune to contribute, however feebly, towards removing the prejudices which keep away so many likely experimenters from these studies and researches. These prejudices are manifold: there is the fear of ridicule, the religious scruple, the delusive dread of nervous or mental disease, the terror of an unknown world peopled with strange, mysterious beings. But time will dispel all this, and I believe that a day will come, when these facts—well studied, well observed—will change our conceptions of things in a way little dreamt of to-day. The sphere of ‘Psychical Science’ is unmeasurable. A few pioneers only are exploring therein to-day; when the land has been tilled and cultivated it will yield, I am sure, a wonderful crop—the harvest will surpass the dreams of imagination.

But let those who, thanks to a scientific education, are particularly well qualified to undertake these studies,[21] cease to consider them unworthy of their attention. In holding themselves aloof they commit a mistake which they will bitterly regret some day. Allowing even that the first experimenter may be guilty of mistakes, there will always remain something out of the facts which they have observed. Mistakes are unavoidable in the début of a new science: the methods are uncertain, and the novelty of the phenomena makes their analysis difficult; time, labour in common, and experience will remedy these inevitable inconveniences.

It would be very easy to give examples of the delay which scientific prejudice has brought to bear upon scientific progress. This criticism has already been very frequently and wittily made. Even those men, whose discoveries have placed them at the head of the intellectual movement of their generation, are not altogether free from blame, yielding too often to the deplorable tendency of converting natural laws into dogmas. They commit the same fault they object to in theologians. Man has a wonderful aptitude for laying hold of his neighbours’ faults and remaining blind to his own, and probably it will be so for a long time to come. I would like to see science rid itself for good and all of this theological habit of mind.

Science has only to think about facts. There should be no distinction made between the various phenomena observed: it is not beseeming to adopt certain facts, and refuse analysis to others, excluding them on the ground, for example, that their examination belongs to religion. Every natural fact ought to be studied, and, if it be real, incorporated with the patrimony of knowledge. What matters its apparent contradiction with the laws of nature,[22] such as we understand them to-day? These laws are not principles superior to our experience; they are but the expression of our experience: our knowledge is very limited and our experience is still young—it will grow, and its development will bring the inevitable consequence of a corresponding modification in our conception of nature. Therefore, let us not be too positive of the accuracy of present ideas, and arbitrarily reject everything which we think runs counter to them. Do not dogmatise; let our only care be the impartial search for truth. Nothing will better enable us to understand the surroundings in the midst of which we are evolving than facts, which are apparently irreconcilable with current ideas: these facts betoken that the ideas are erroneous or incomplete; their attentive observation will reveal a more general formula which will explain at one and the same time the new and the old. And thus from antithesis to synthesis, more and more universal, our scientific ideas will tend towards absolute truth.

Alas! how far away from this ideal do we seem to be to-day! Laboremus!

A French proverb says, ‘we must have eggs to make an omelette’: in order to be able to study psychical phenomena we must have psychical phenomena. This seems an elementary proposition, and yet it is the very one we most readily overlook. I have already said why and wherefore.

Therefore, I deem it necessary to indicate at once the methods which have appeared to me to give the most favourable results. Those of my readers who may wish to verify the accuracy of my conclusions will, I am sure, have the opportunity of doing so, if they operate as I have done. First of all, I must warn them against caring for the world’s opinion. They must not be afraid of exposing themselves to ridicule. No doubt there is temptation to make a jest of the methods which I advise; but I strongly recommend them to think about the result, and not about the means used to obtain that result.

Psychical phenomena are of two orders: material and intellectual. The methods best suited to the study of the first are not, in my opinion, adapted to the study of the second. There is a distinction, therefore, to be made in the beginning between these two categories of facts.

Physical phenomena are the least frequently met with; they include:—

1. Knockings or ‘raps’ on furniture, walls, floors, or on the experimenters themselves.

2. Sundry noises other than raps.

3. Movements of objects without sufficient contact to explain the movement produced. There is here a distinction to be made between (a) movements produced without any contact whatever—telekinesis: e.g. the rising or sliding of a table or chair, the swaying of scales, etc., without their being touched; and (b) movements with contact, which is insufficient to explain them—parakinesis: e.g. the levitation of a table on which the experimenters lay their hands.

4. Apports: that is to say, the sudden appearance of objects—flowers, sweets, stones, etc.—which have not been brought by any of the assistants. This phenomenon—if it exists—supposes, in addition, the following:—

5. Penetrability, or the passage of matter through matter.

6. Visual phenomena, which are themselves subdivided into:—

7. Phenomena which leave permanent traces, such as imprints.

8. Alteration in the weight of material objects or of certain people: levitation.

9. Perceptible changes in the temperature: sensation of cold or heat; spontaneous combustion.

10. Cool breezes.

Such are the chief psychical phenomena of the material order, which have been pointed out by different experimenters. I have not verified all of them: raps, telekinetic, and a few luminous phenomena are all I have obtained in a thoroughly satisfactory manner.

Intellectual phenomena are those which imply the expression of a thought. I will class them in the following manner:—

1. Typtology: the table, upon which the experimenters lay their hands, leans to one side and recovers equilibrium by striking the ground.

2. Grammatology or spelt-out sentences. Various methods may be used. The principal are:—

3. Automatic writing: immediate, when the subject writes without the intermedium of an instrument; mediate, when he uses an instrument, such as a planchette, a wooden ball with handles fastened to it, a basket,[26] a hat, a stand, etc. In this case, several people can combine their action by laying their hands all together upon the object to which the pencil is attached.

4. Direct writing: i.e. writing which appears on slates, paper, etc., whether in or out of sight of the experimenters. If the letters seem to be formed without the aid of a pencil we have precipitated writing.

5. Incarnation or ‘control’: the subject, when asleep, speaks in the name of some entity or order, which possesses him.

6. Direct voices: when words are heard, appearing to emanate from vocal organs other than those of the persons present; some experimenters are supposed to have conversed in this way with materialised forms.

7. Certain automatisms other than writing are observable: e.g. crystal- and mirror-gazing; audition in conch-formed shells; sundry hallucinations, telepathy and telesthesia: ‘the communication of impressions of any kind from one mind to another, independently of the recognised channels of sense’; perception at a distance of positive impressions. These phenomena bring in their train clairvoyance or voyance, and lucidity, expressions which are by no means identical. Lucidity designates more particularly the faculty which certain people have, in magnetic sleep or in somnambulism, of getting exact impressions in a supernormal manner; clairvoyants or voyants are those who see forms invisible to other people. Clairaudience denotes phenomena of the same kind in the auditory sphere.

I have paid scarcely any attention to these intellectual phenomena, with the exception of automatic writing, crystal-gazing, typtology, and ‘control.’ If I have taken[27] greater interest in material than in intellectual phenomena, it is because they struck me as being more simple and easier to observe. This sentiment is not that of all experimenters, and my colleagues of the London Society for Psychical Research appear to be more affirmative in their conclusions, concerning survival after death and communication with the dead, than in their opinions on material phenomena. My personal experience has not led me to the same ideas.

Undoubtedly, experiments demonstrating the persistence of human personality after death would have an interest, in comparison with which all others would be blotted out. But the analysis of phenomena of this kind raises difficulties, which are much more complicated than is the simple observation of a physical fact. Intellectual phenomena always suppose some kind of motor automatism or other; of course, I am not speaking of manifestations where the will of the sensitive intervenes: this automatism is manifested by language, writing, or the less elevated motor phenomena, typtology for example; it may also be sensory and manifest itself in hallucinations of various kinds. To understand the infinite complication of intellectual phenomena it suffices to indicate the conditions under which they are observed. Before admitting that the cause of the apparent automatism is foreign to the sensitive, we must be able to eliminate with certitude the action of his personal or impersonal conscience. To what extent does the subliminal memory intervene?—a first difficulty which is scarcely solvable!

But supposing it to be solved, the problem still remains almost intact. If the knowledge of a positive[28] fact, certainly unknown to the medium, appears in his automatic communications, we must not thereupon conclude that this knowledge is due to the intervention of a disincarnated spirit. Telepathy may be able to explain it. Telepathy is, as we know, the transmission of an idea, an impression, a psychical condition of some kind or other from one person to another. We are altogether ignorant of its laws, and nothing warrants the assertion, that if telepathy is a fact—as appears most probable—it is therefore necessary that any particular motive condition should exist in the agent. We may suppose with just as much reason, that the existence of a souvenir in one mind can be discovered and recognised by another, under conditions solely depending on the mental state of the percipient. This is, properly speaking, telesthesia. Now it is very difficult to prove that the fact, of which automatism marks the knowledge, is unknown to everybody. It is even impossible to prove it. But supposing this were done, there would always remain the possibility of attributing the communication to some being other than human: by admitting even the existence of spiritual or immaterial beings distinct from ourselves, nothing warrants us to affirm that such beings are our deceased relatives or friends and not some facetious Kobolds.

Prediction and precognition, of which I have had proof, raise just as complicated questions as the preceding ones. I confine myself to recording without trying to explain these facts.

Therefore, I have given my preferences to the study of physical phenomena, because in such I have not to consider the mental condition of the subject, nor have[29] I any of those delicate analyses to make, the complexity of which I have just mentioned. I have to defend myself against only two enemies, the fraud of others and my own illusions. Now, I feel certain of never having been the victim of either. When, for example, in the refreshment-room of a railway-station, in a restaurant, in a tea-shop, I have observed, in broad daylight, a piece of furniture change place of its own accord, I have a right to think I am not in the presence of furniture especially arranged to produce such effects. When the unforeseen nature of the experiment excludes the hypothesis of preparation, when, by sight and touch, I make sure of the absence of contact between the experimenters and the article which is displaced, I have sufficient reasons for excluding the hypothesis of fraud. When I measure the distance between the objects before and after the displacement, I have also sufficient reason for excluding the hypothesis of the illusion of my senses. If this right be refused me, I should really like to know how any fact whatever can be observed. No one is more convinced than myself of the frailty of our impressions and the relativity of our perceptions; nevertheless, there must be some way of perceiving a phenomenon in order to submit it to impartial observation. Besides, the supposed reproach of illusion cannot be applied in a general sense; to admit its justice would be to do away with the very foundations of our sciences. It can only be applied to me as an individual, and I willingly admit that it is impossible for me to exculpate myself. In vain might I plead that I am persuaded of the regularity of my perceptions, in vain assert that I observe no tendency to illusion in myself, my testimony would remain none the less suspected.

Consequently, I have but one reply for those who mistrust my qualifications as an observer, and that is to invite them to take the trouble of experimenting on their own account, using the methods which I have adopted. If, a priori, they wish to lay down their own conditions, they run the risk of receiving no appreciable results. When they have obtained a few plain facts they will be able to vary the conditions of experimentation, and satisfy the legitimate exigencies of their own reason. That is what I did, and if I cannot solemnly affirm the reality of the phenomena which I have observed, I can at all events affirm my personal conviction of their existence. Maybe I am showing an exaggerated mistrust of myself by thus only affirming my subjective conviction, and in not venturing to affirm with a like energy the objective reality of the things I have seen. Yet I trust no one will blame me for my prudent reserve. What man can say he has never made a mistake?

Only those, who put themselves in the same conditions which enabled me to make my observations, have a right to criticise those observations.

To criticise without experience is unreasonable, and I recognise no competence in those judges whose decisions are made without preliminary information. For the rest, I have no wish to convert any one to my ideas, and am indifferent—respectfully indifferent, if you like—to the judgment which may be formed about me.

The methods recommended by diverse occult schools vary a great deal. Theosophists do not reveal to the profane the means they use to obtain supernormal facts. This discretion astonishes me, for the theosophical society is filled with a lively spirit of propagandism. It has its[31] chief centre at Adyar, and lodges or branches everywhere. The theosophical reviews venture to discuss the most elevated problems of philosophy, and are not at all sparing of the most extraordinary revelations of esoteric teaching; but they are remarkably sparing of practical indications.

Theosophical phenomenonalism appears to derive inspiration from Hindu-Yogism. I do not know the rules of training to which Yogis submit themselves. The most severe abstinence seems to be recommended them. Adepts are generally initiated by their Gurus or masters, and I have not been fortunate enough to be the chela of an initiated.

The French occultists who are connected with Eliphas Levy by Papus (Dr. Encausse), Guaita, Haven, Barlet, Sédir, recommend the practice of magic. Descriptions of the necessary magical material will be found in treatises by Papus and Eliphas Levy. The results which the Magi relate having been obtained are so vague, that I have had no curiosity to put into practice the strange proceedings of magic ceremonial recommended by them. These have a serious inconvenience; namely, to strike the imagination of credulous folk, and to facilitate auto-suggestion, sensorial illusions, and hallucinations. To accomplish the rites, moreover, it is necessary to dispose of rooms arranged in a particular way, and to submit oneself to a severe diet for a certain time. This makes it a complicated matter. Well, I must admit I was ashamed to try these methods. I lacked the courage to don the cloak and the linen robe, to trace the circle, and with lighted lamp and sword in hand await visions about to appear in the smoke arising from the burning incense. I own I was perhaps wrong[32] not to try what are apparently the less rational methods. Only caring for the result obtained, I certainly would not have hesitated to resort to white or even black magic, had I had any reason whatsoever to anticipate a positive result. In order to obtain an observable fact, I would not have hesitated laying myself open to ridicule. But the statements of experimenters of the occult school seemed to imply a poverty of practical results. If the magi of the present day had realised some operation easily accessible to observation, they would not have omitted acquainting us of the fact in one or other of their numerous reviews. Their silence struck me as significant.

Moreover, the very essence even of Hermetic doctrines, openly professed by occultists, is opposed to all such divulgence. The ancient doctrine exacted initiation. The Rosicrucians, if I am not mistaken, could only initiate an adept. Then again, they were allowed to use this privilege only upon attaining a certain age, and when convinced of having found a discreet and trustworthy pupil. All that publicity made to-day about Hermetic sciences is the actual negation of their first precepts. These indiscretions bring to my mind the words of one of my predecessors at the Bordeaux Court [successor of the ancient Parliament of Guyenne], the President Jean d’Espagnet, one of the three or four adepts who pass for having unriddled the great arcanum. ‘Facilia intellectu suspecta habeat,’ he says, speaking to the seeker, ‘maxime in mysticis nominibus et arcanis operationibus; in obscuris enim veritas delitescit; nec unquam dolosius quam quum aperte, nec verius quam quum obscure, scribunt philosophi.’

Then, again, I had a decisive reason for choosing spiritistic methods: they are not mysterious and they require no special subjective preparation. They are simple—in appearance, at least—and can be easily applied. Spiritists, and certain experimenters who have adopted their methods without sharing their theories, affirm having obtained surprising results. Therefore, I had nothing better to do than choose these same methods. Because of their simplicity, and the multiplicity of certified results, I considered it preferable to adopt the methods of spiritists. I will, therefore, indicate how I experiment when I am free to direct the sittings—which, unfortunately, is not always the case.

I shall divide my indications into three wide categories: 1. Material Conditions; 2. Composition of the Circle; 3. Methods of Operation.

I will add that these indications are not absolute.

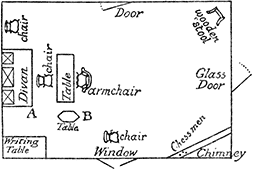

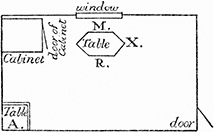

Results are generally better, when operations are carried on in a room whose dimensions do not exceed 15 to 20 square yards in area, and 12 to 15 feet in height. Smaller rooms may be used, but then the heat is sometimes trying.

The temperature of the room is an important factor. Heat, although it may inconvenience the experimenters and the medium, appears to exercise a favourable influence on the emission of the force. On the contrary, cold is an element of non-success. Of course, I am speaking of the temperature of the room. I would advise operating in a temperature of from 20 to 25 degrees centigrade. It[34] is decidedly necessary to avoid having cold hands and feet.

In winter the seance-room should be thoroughly warmed and the fire allowed to go out before the sitting, in case luminous phenomena should be forthcoming.

I fancied I saw an advantage, especially for movements without contact, in operating in an uncarpeted room. The carpet not only seems to be a bad element generally, it also hinders the gliding movements of the table, which are often only very slight.

As for exterior meteorological conditions, I have noticed that a dry cold favours the production of psychical phenomena: it is, I believe, the temperature optima. In any case, the dryness of the air is a very good condition. I have noticed that the phenomena were more easily obtained, when outside conditions favoured the production of numerous sparks under the wheels of electric trams. I have often noticed this coincidence between good sittings and the abundance of electric sparks above-mentioned. I believe that the hygrometrical state of the atmosphere is an important factor in the production of these sparks. Rain and wind are, on the contrary, causes of failure.

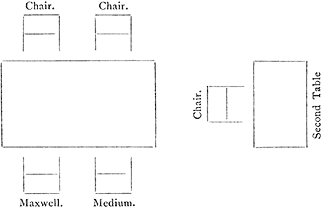

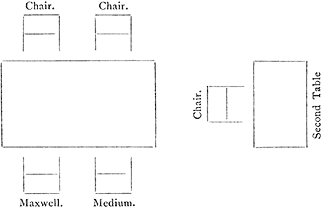

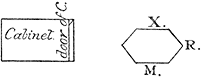

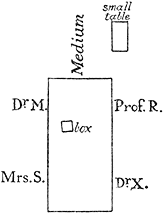

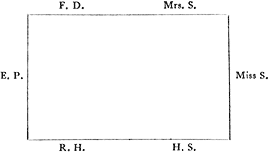

The lighting of the seance-room is one of the most important considerations in experimentation. Lamps and candles have the inconvenience of taking some time to light, and they do not allow of easy and rapid modification in the illumination of the room. Electric lighting is the best system, because, disposing of several lamps, it suffices to press a hand-lever in order to vary the quantity and quality of the light.