[241]

A THRILLING MOMENT; OR, GO IN AND WYNN.

The Rev. Stephen Wynn startled by a Woman with a good many Tails about her!

I'm in a yacht both first and last, and what becomes of me

I'm in a yacht both first and last, and what becomes of me

UNDER A CLOUD; OR, AN OXFORD (COMPACT) MIXTURE.

(By One who prefers the Old.)

[242]

[243]

A TASTE TO BE ACQUIRED.

Sporting Farmer (to young Pupil from provincial town, who has just made his first effort to ride over a Fence). "Now then, jump on again! Better luck next time! You'll like it after a bit!"

Pupil (still seeing stars). "Shall I, Sir? Seems to me as much like a Railway Collision as anything!"

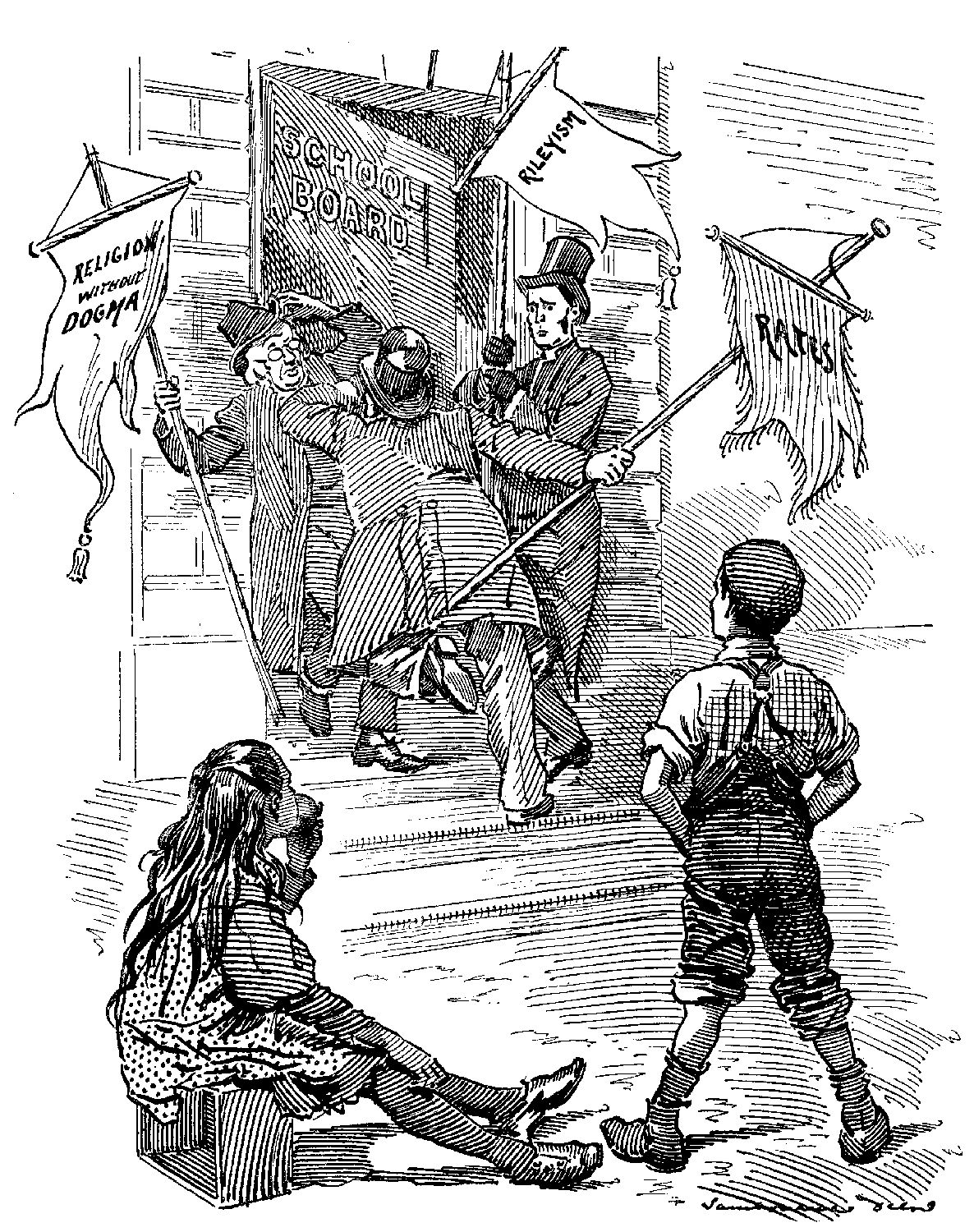

'Twas "The Three R's" they promised us, but now They're merged in a bad fourth—Religious (?) Row!

["The so-called 'compromise' of 1871 was based on the assumption that, when all the differences of our English Christendom were struck out, there would be found the beating heart of 'a common Christianity' sending a quickening life through all its members.... Believing it not impossible for 'all who profess and call themselves Christians' to reconcile themselves to these two forms, elementary and supplementary, I earnestly commend them for peaceful co-existence to the conflicting parties of School Board electors and members."—Dr. James Martineau's Letter to the "Times" of November 14.]

"THE FOURTH R;" OR, THE "RELIGIOUS"(?) ROW AT THE SCHOOLBOARD.

Quite Un-sectarian Girl. "Oh, my! What a jolly Row!"

Equally Un-sectarian Boy. "Ain't it! I 'ope they'll keep it up, and we shan't 'have to Learn nothink!"

[244]

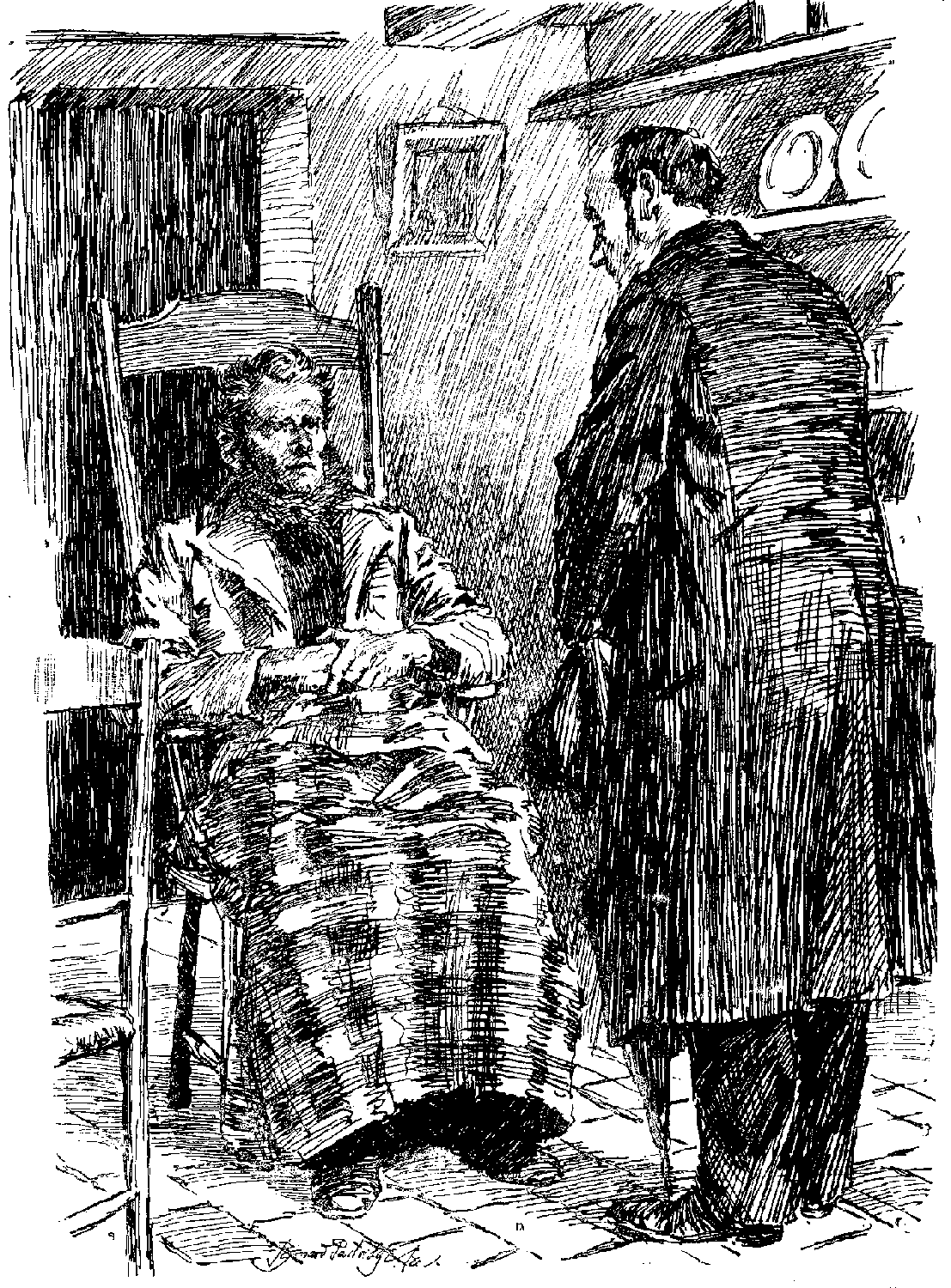

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART XXI.—THE FEELINGS OF A MOTHER.

Scene XXXI.—The Morning Room. Time—Sunday morning; just after breakfast.

Captain Thicknesse (outside, to Tredwell). Dogcart round, eh? everything in? All right—shan't be a minute. (Entering.) Hallo, Pilliner, you all alone here? (He looks round disconcertedly.) Don't happen to have seen Lady Maisie about?

Pilliner. Let me see—she was here a little while ago, I fancy.... Why? Do you want her?

Capt. Thick. No—only to say good-bye and that. I'm just off.

Pill. Off? To-day! You don't mean to tell me your chief is such an inconsiderate old ruffian as to expect you to travel back to your Tommies on the Sabbath! You could wait till to-morrow if you wanted to. Come now!

Capt. Thick. Perhaps—only, you see, I don't want to.

Pill. Well, tastes differ. A cross-country journey in a slow train, with unlimited opportunities of studying the Company's bye-laws and traffic arrangements at several admirably ventilated junctions, is not my own idea of the best way to spend a cheery Sunday, that's all.

Capt. Thick. (gloomily). Daresay it will be about as cheery as stoppin' on here, if it comes to that.

Pill. I admit we were most of us a wee bit chippy at breakfast. The Bard conversed—but he seemed to diffuse a gloom somehow. Shut you up once or twice in a manner that might almost be described as d—d offensive.

Capt. Thick. Don't know what you all saw in what he said that was so amusin'. Confounded rude I thought it!

Pill. Don't think anyone was amused—unless it was Lady Maisie. By the way, he might perhaps have selected a happier topic to hold forth to Sir Rupert on than the scandalous indifference of large landowners to the condition of the rural labourer. Poor dear old boy, he stood it wonderfully, considering. Pity the Countess breakfasted upstairs; she'd have enjoyed herself. However, he had a very good audience in little Lady Maisie.

Capt. Thick. I do hate a chap that jaws at breakfast.... Where did you say she was?

Lady Maisie's voice (outside, in Conservatory). Yes, you really ought to see the Orangery and the Elizabethan Garden, Mr. Blair. If you will be on the terrace in about five minutes, I could take you round myself. I must go and see if I can get the keys first.

Pill. If you want to say good-bye, old fellow, now's your chance!

Capt. Thick. It—it don't matter. She's engaged. And, look here, you needn't mention that I was askin' for her.

Pill. Of course, old fellow, if you'd rather not. (He glances at him.) But I say, my dear old chap, if that's how it is with you, I don't quite see the sense of chucking it up already, don't you know. No earthly affair of mine, I know; still, if I could manage to stay on, I would, if I were you.

Capt. Thick. Hang it all, Pilliner, do you suppose I don't know when the game's up! If it was any good stayin' on—— And besides, I've said good-bye to Lady C., and all that. No, it's too late now.

Tredwell (at the door). Excuse me, Sir, but if you're going by the 10.40, you haven't any too much time.

Pill. (to himself, after Captain Thicknesse has hurried out). Poor old chap, he does seem hard hit! Pity he's not Lady Maisie's sort. Though what she can see in that long-haired beggar——! Wonder when Vivian Spelwane intends to come down; never knew her miss breakfast before.... What's that rustling?... Women! I'll be off, or they'll nail me for church before I know it.

[He disappears hastily in the direction of the Smoking Room as Lady Cantire and Mrs. Chatteris enter.

Lady Cantire. Nonsense, my dear, no walk at all; the church is only just across the park. My brother Rupert always goes, and it pleases him to see the Wyvern pew as full as possible. I seldom feel equal to going myself, because I find the necessity of allowing pulpit inaccuracy to pass without a protest gets too much on my nerves; but my daughter will accompany you. You'll have just time to run up and get your things on.

Mrs. Chatteris (with arch significance). I don't fancy I shall have the pleasure of your daughter's society this morning. I just met her going to get the garden keys; I think she has promised to show the grounds to——Well, I needn't mention whom. Oh dear me, I hope I'm not being indiscreet again!

Lady Cant. I make a point of never interfering with my daughter's proceedings, and you can easily understand how natural it is that such old friends as they have always been——

Mrs. Chatt. Really? I thought they seemed to take a great pleasure in one another's society. It's quite romantic. But I must rush up and get my bonnet on if I'm to go to church. (To herself, as she goes out.) So she was "Lady Grisoline," after all! If I was her mother—— But dear Lady Cantire is so advanced about things.

Lady Cant. (to herself). Darling Maisie! He'll be Lord Dunderhead before very long. How sensible and sweet of her! And I was quite uneasy about them last night at dinner; they scarcely seemed to be talking to each other at all. But there's a great deal more in dear Maisie than one would imagine.

Sir Rupert (outside). We're rather proud of our church, Mr. Undershell—fine old monuments and brasses, if you care about that sort of thing. Some of us will be walking over to service presently, if you would like to——

Undershell (outside—to himself). And lose my tête-à-tête with Lady Maisie! Not exactly! (Aloud.) I am afraid, Sir Rupert, that I cannot conscientiously——

Sir Rup. (hastily). Oh, very well, very well; do exactly as you like about it, of course. I only thought——(To himself.) Now that other young chap would have gone!

Lady Cant. Rupert, who is that you are talking to out there? I don't recognise his voice, somehow.

Sir Rup. (entering with Undershell). Ha, Rohesia, you've come down, then? slept well, I hope. I was talking to a gentleman whose acquaintance I know you will be very happy to make—at last. This is the genuine celebrity this time. (To Undershell.) Let me make you known to my sister, Lady Cantire, Mr. Undershell. (As Lady Cantire glares interrogatively.) Mr. Clarion Blair, Rohesia, author of hum—ha—Andromache.

Lady Cant. I thought we were given to understand last night that Mr. Spurrell—Mr. Blair—you must pardon me, but it's really so very confusing—that the writer of the—ah—volume in question had already left Wyvern.

Sir Rup. Well, my dear, you see he is still here—er—fortunately for us. If you'll excuse me, I'll leave Mr. Blair to entertain you; got to speak to Tredwell about something.

[He hurries out.

Und. (to himself). This must be Lady Maisie's mamma. Better be civil to her, I suppose, but I can't stay here and entertain her long! (Aloud.) Lady Cantire, I—er—have an appointment for which I am already a little late; but before I go, I should like to tell you how much pleasure it has given me to know that my poor verse has won your approval; appreciation from——

Lady Cant. I'm afraid you must have been misinformed, Mr.—a—Blair. There are so many serious publications claiming attention in these days of literary over-production that I have long made it a rule to read no literature of a lighter order that has not been before the world for at least ten years. I may be mistaken, but I infer from your appearance that your own work must be of a considerably more recent date.

Und. (to himself). If she imagines she's going to snub Me——! (Aloud.) Then I was evidently mistaken in gathering from some expressions in your daughter's letter that——

Lady Cant. Entirely. You are probably thinking of some totally different person, as my daughter has never mentioned having written to you, and is not in the habit of conducting any correspondence without my full knowledge and approval. I think you said you had some appointment; if so, pray don't consider yourself under any necessity to remain.

Und. You are very good; I will not. (To himself, as he retires.) Awful old lady, that! I quite thought she would know all about that letter, or I should never have——However, I said nothing to compromise anyone, luckily!

Lady Culverin (entering). Good morning, Rohesia. So glad you felt equal to coming down. I was almost afraid—after last night, you know. [245]

Lady Cant. (offering a cold cheekbone for salutation). I am in my usual health, thank you, Albinia. As to last night, if you must ask a literary Socialist down here, you might at least see that he is received with common courtesy. You may, for anything you can tell, have advanced the Social Revolution ten years in a single evening!

Lady Culv. My dear Rohesia! If you remember, it was you yourself who——!

Lady Cant. (closing her eyes). I am in no condition to argue about it, Albinia. The slightest exercise of your own common sense would have shown you——But there, no great harm has been done, fortunately, so let us say no more about it. I have something more agreeable to talk about. I've every reason to hope that Maisie and dear Gerald Thicknesse——

Lady Culv. (astonished). Maisie? But I thought Gerald Thicknesse spoke as if——!

Lady Cant. Very possibly, my dear. I have always refrained from giving him any encouragement, and I wouldn't put any pressure upon dear Maisie for the world—still, I have my feelings as a mother, and I can't deny that, with such prospects as he has now, it is gratifying for me to think that they may be coming to an understanding together at this very moment; she is showing him the grounds; which I always think are the great charm of Wyvern, so secluded!

Lady Culv. (puzzled). Together! At this very moment! But—but surely Gerald has gone?

Lady Cant. Gone! What nonsense, Albinia! Where in the world should he have gone to?

Lady Culv. He was leaving by the 10.40, I know. For Aldershot. I ordered the cart for him, and he said good-bye after breakfast. He seemed so dreadfully down, poor fellow, that I quite fancied from what he said that Maisie must have——

Lady Cant. Impossible, my dear, quite impossible! I tell you he is here. Why, only a few minutes ago, Mrs. Chatteris was telling me—— Ah, here she is to speak for herself. (To Mrs. Chatteris, who appears, arrayed for public service.) Mrs. Chatteris, did I, or did I not, understand you to say just now that my daughter Maisie——?

Mrs. Chatt. (alarmed). But, dear Lady Cantire, I had no idea you would disapprove. Indeed you seemed——And really, though she certainly takes an interest in him, I'm sure—almost sure—there can be nothing serious—at present.

Lady Cant. Thank you, my dear, I merely wished for an answer to my question. And you see, Albinia, that Gerald Thicknesse can hardly have gone yet, since he is walking about the grounds with Maisie.

Mrs. Chatt. Captain Thicknesse? But he has gone, Lady Cantire! I saw him start. I didn't mean him.

Lady Cant. Indeed? then I shall be obliged if you will say who it is you did mean.

Mrs. Chatt. Why, only her old friend and admirer—that little poet man, Mr. Blair.

Lady Cant. (to herself). And I actually sent him to her! (Rising in majestic wrath.) Albinia, whatever comes of this, remember I shall hold you entirely responsible!

[She sweeps out of the room; the other two ladies look after her, and then at one another, in silent consternation.

Isn't our good friend of the P. M. G. a little extravagant with his culinary raptures? However, we will not be outdone. If he rhapsodises the "Magnificent Mushroom," we have discovered a still more exalting theme, which, taking "whelk" as pronounced, we will call

Would you learn the divinest glory of a goddess among molluscs? Would you note the gastronomic charms of a succulent sea-nymph? Ostracise, then, from your table the blue-point impostor that foists his bearded banality on the faithful elect. Let the cult of that lusty Titan, the Limpet, sink awhile into the limbo of outworn idolatries. Forbear, if you are wise, to hymn the stern masculinity of the Mussel, gregarious demi-god but taciturn, hermetically sealed within the wilful valves of a sulky self-effacement. And let that other fakir of the sea-marge, the fantastic and Pharisaic Scallop, ply his Eleusinian rites, unrevered by the devout and metaphor-mixing epicure. Rather let it be ours to celebrate, though baldest prose were all-insufficient, the allurements of a pandemic Aphrodite, the seductive Whitechapel Whelk, and the coy grace of her sister, the wanton Winkle of Rosherville.

Let us take the first—assume that the siren is yours, then consider how fitliest she shall be dressed. And here it shall be seen whether you have true chivalry and romance in your soul, or whether you grovel in mere sensual gourmandise. What says Master Bill Nupkins, master-cook to the Blue Pig chop-house in Skittle-alley? Is there not an idyllic flavour of Cocaigne, a very fervour of simplicity about his spelling which goes straight to the gizzard of the whelk-worshipper? Listen to his wise counsel on whelks à la Shoreditch:—

"Tyke three 'aputh of whilks, 'Erne By sort fer choice, and chuck 'em wiv a saveloy and a kipper into a sorcepan, if you can nick one from a juggins. Bile 'em till they're green, and add 'arf a glorss of unsweetened, tho it's a pity to wyste it. If toimes is 'ard, the kids and the missus can 'ave the rinsings, or go wivout. Taike my tip, and don't you be a bloomin' mug. You can blyme well stick to the juggins' sorcepan. You may, I dessay, raise arf a dollar on it." There speaks the true gourmet, with single-hearted straight-forward egotism, worthy of a City alderman, in all the glory of a civic banquet. To none but an artist in guttlery would that touch of genius about the kids and the missus occur.

Again, disdain not the sweetly subtle recipes and romantic fancies that you may gather during your sojourn at Colney Hatch. For there, far from the dull Philistinism of house-dinners and fried-fish shops, with all wild Mænad orgies may your divinity be adored. Learn but one magic formula, and you shall see the wizard-working of your incantation, as, like an enchantress herself bewitched, she assumes you an ensorceled, faery shape. Here, mark you, is this potent spell, culled from the inspired lips of a frenzied chef.

To Make Whelk Fritters.—Take one ripe whelk, draw and truss it until you are black in the face, tie up the forequarter with chickweed, sit down, and smoke a pipe; parboil anything you like for a few hours, or don't, if you don't care to; rub the purée through a tammy (I don't know what this is); flavour with elbow-grease, egg-faisandé, mud-salad, and bêtes noire; dredge the gallimaufrey, and hold your nose; write some letters; the vol-au-vent will then explode; wrap the pieces in an old sock, and bury for six weeks; take the 2.13 train to town, and have your hair cut, or pay some calls; then start again with another whelk, and proceed as before; but it is better to buy the fritters ready-made."

Is not this a lesson in devotion and perseverance? Rejoice greatly, and work out your sybaritic salvation.

And now that you have food for pious reflection, after a space you shall, to your exceeding great advantage, be further instructed in the liturgy of the Winkle.

"ALL IS NOT GOLD," &c.

Gentleman (in waiting for his Wife, at "Great Annual Sale," to Head of Department). "You must do an enormous Business on Days like this."

Head of Department. "Not so much as you might fancy. The great majority of the People here to-day are Shopping—not Buying!"

[246]

THE WORST OF HAVING "A DAY."

Edith. "Here come those dreadful Bores, the Brondesbury-Browns! How Tactless of them, to come and see us on the only Day in the Week we're at Home!"

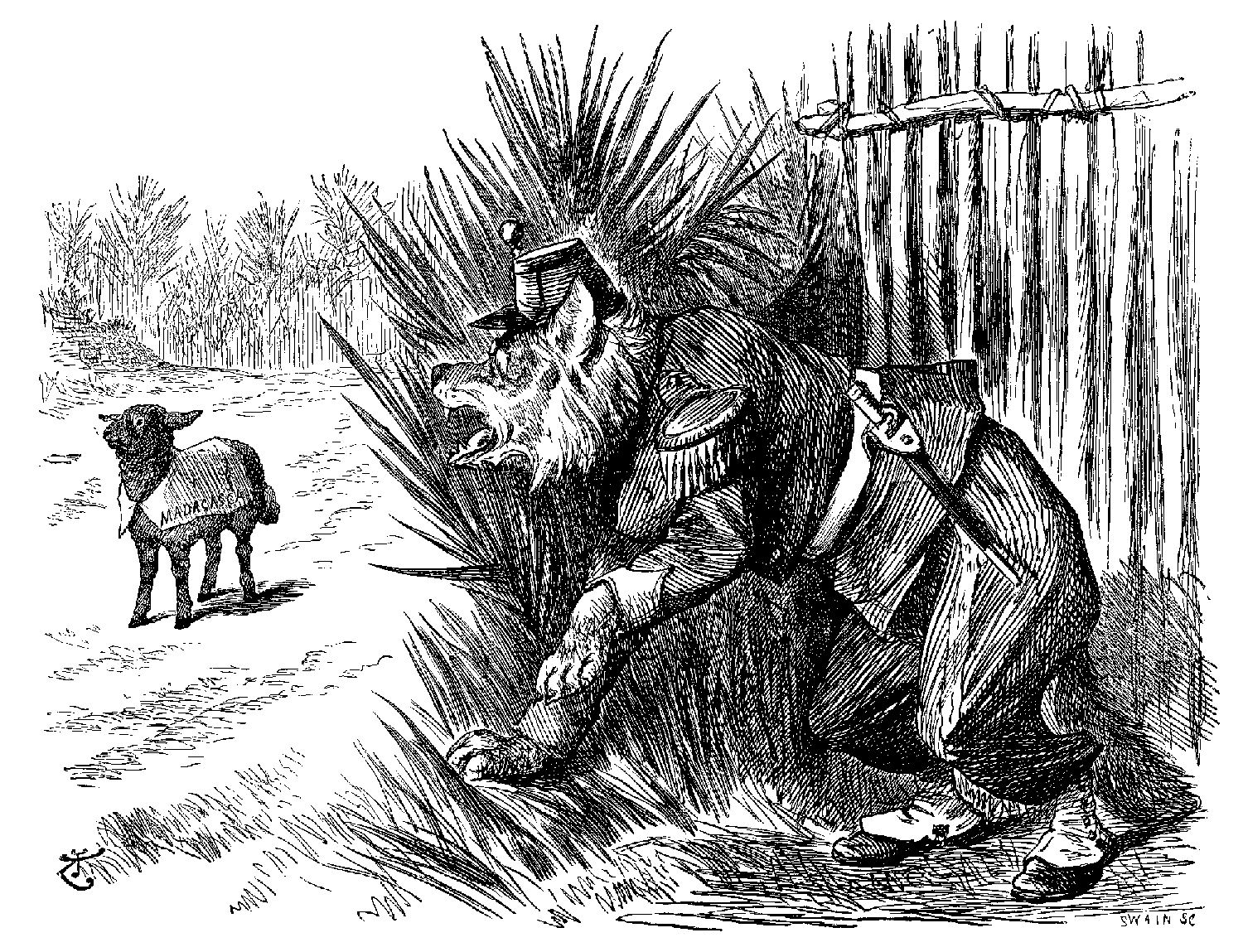

["We will not evacuate Madagascar ... we will pursue the advantages we have gained ... Madagascar will become a flourishing French Colony. (Cheers.) ... Our freedom of action is complete. There can be no foreign interference."—M. Hanotaux on the French Expedition to Madagascar.]

Lupus, on the prowl, loquitur:—

French Wolf (to himself). "AHA! THE SHEEP-DOGS ARE ASLEEP! I SHALL EAT YOU, MY LITTLE DEAR!"

"Our freedom of action is complete. There can be no foreign interference."—Speech of M. Hanotaux.

The L. C. C. Again.—Is it possible that the Government is about to back up the London County Council in another attack on one of our time-hallowed institutions? I see that Mr. Asquith told a deputation that "one of the first acts of a Local Authority, if it had the power, would be to abolish the Ring." What on earth has a Local Authority to do with the mode in which marriages are celebrated? Englishmen should rise in their thousands to defend the wedding-ring, symbolising as it does the sanctity of the nuptial tie, and should hurl from power a Government which is about to hand us over, fingers and souls, to a tyrannical set of County Council busybodies. Mr. Asquith went on to talk rather disconnectedly, it seems to me, about gambling; perhaps he holds the cheap modern view that "Marriage is a Lottery." But I want to know why a Home Secretary meddles with subjects of this sort? And how long is this conspiracy between a Radical Ministry and the L. C. C. to be allowed to continue?

[247]

[248]

[249]

(By Iōpna, Author of "A Yellow Plaster.")

"Virginibus puerisque," said Miss Constantia Demning; "and it's by a man!"

"By a man!" echoed the awe-struck Athanasia.

"And to think that in spite of all our pioneering and efforts to confine her studies to the New Woman Series our niece may even now have tasted of the tree and be bursting out into throbbing nerve-centres and palpable possibilities. Compare we two with her! Have you noted her restless craving after Philistine delights such as man-worship and a literary style? Thank Heaven, she never got that from us or our books."

The speakers were a pair of old Purgatorial Twins, not without alleviations, designed by Nature to multiply. But aloofness, coupled in harness with anæmia, had nipped the wilding shoots in the bud and won hands down at the distance. True, in the scraggy past, there had been a male creature, less curate than Cupid, that each of them had saved her soul alive in the memory of. But the cares of celibacy, cruel-heavy as a portmanteau-metaphor, now weighed on their shoulders; they could not crush them with a burial-spade like complete natures; they stamped their faces (the cares did the twins' faces) with their ponderous crow's feet.

Still, at times, like spring-cleanings, came spring-hankerings. A whiff of yellow tulip on the breeze, and they would drink in the sunlight and the flowers and the beasts and the fishes and the dew and the early worm.

Even now as they peered into this book of forbidden sentiment at the words—"The presence of the two lovers is so enchanting to each other that it seems it must be the best thing possible for everybody else"—from some faded, twilit cellar of the past came the bleating lyre-bird of carnal reverie; but the astuter of the two scented tangibly the cloven hoof, and coming to her better self with a strangled "Oh!" she cast the book into the stove of the Queen Anne parlour, so suggestive of their own aloofness, void as it was of dog or waste-paper basket, or English grammar, or any such humanizing influence.

At that moment a pair of swift, Pagan feet sounded in the passage.

When Margerine entered there was the usual family aloofness in her face, but also a new element of alleviation. Always plastic as the compound from which she derived her name she had now reached five feet seven and a half inches, and from the crest of her unutterably pullulating womanhood could afford to look down impersonally on her maiden aunts as they struggled in the trough like square pegs in a round hole.

The spectacle of burning leather was in her nostrils, and the vile smell of it gave her an insight into the situation. Plunging her Aunt's best silver-plated sugar-tongs into the flames, she rescued her shrivelled treasure, waved it above the coming tempest like a brand, and faced them, rigid with wrath, half-seas-over with the glamour of things.

An odd, earnest, ineffable look jumped into her eyes, changing their grey to pitch-black, with patches of ethereal blue, where the soul shone through. To their dying day the twins never forgot the smell, or ceased from the pain of their incapacity to grasp the fresh, unmellowed point of view. Points of view are the very dickens.

At last she got less rigid, and became nasty in soft, sweet, labial gutturals, like the whoop of a bull-frog on the sleepy pool just above the dam.

"Is this well-born and well-bred in you, I ask?" There was a defiant abasement in her tone. "Of course you can't help it. You never loved! Pooh!"

The two elder Miss Demnings crushed the fledgling secret of the late curate into its nest, and vituperated till they fell short of matter, being but poorly winded. "Unregenerate—abandoned—viper—alleviator! Pass from our twin presence!"

Margerine moved toward the door; then, by a quaint habit that was a third nature to her (she had two others), she stood there absently, ajar and aloof. Her air of distinction came right out through her wretched frock. Then she went to the drawing-room, singeing her Pagan cheek with the smouldering volume, her young, expansive brain hot with the thought that there were no other copies in the village. "Unless he sends for another from town I shall never be able to keep up my unreasoning, palpitating ecstasy. I must have some ventilation for my inevitableness, or burst."

She rang for fresh tea. The crumpets were crystal-cold. She tasted one, and had a qualm, as if her sympathies were getting enlarged. For a moment she wondered what a headache such as she had read about in books could be like. The next, she was down by the trout-stream, familiar in all she-notes, and lay there gurgling with gutturals.

The peculiarity of Chamois Hyde was that he could not bear making other people—college dons, for instance—ridiculous. About himself it did not so much matter. Oxford had succeeded Eton, and hard on the heels of a good degree had come a cropper in the hunting-field, a nurse, a complicated kiss, a proposal, marriage, disillusionment, in the order named. A poorer, singler man, with the same prancing tip-toe spirit, would have lost all sense of decency, and written a book. But being rich, and, by profession, married, he also was on his way to the usual trout-stream. Which was a thousand pities, and comes into the next chapter.

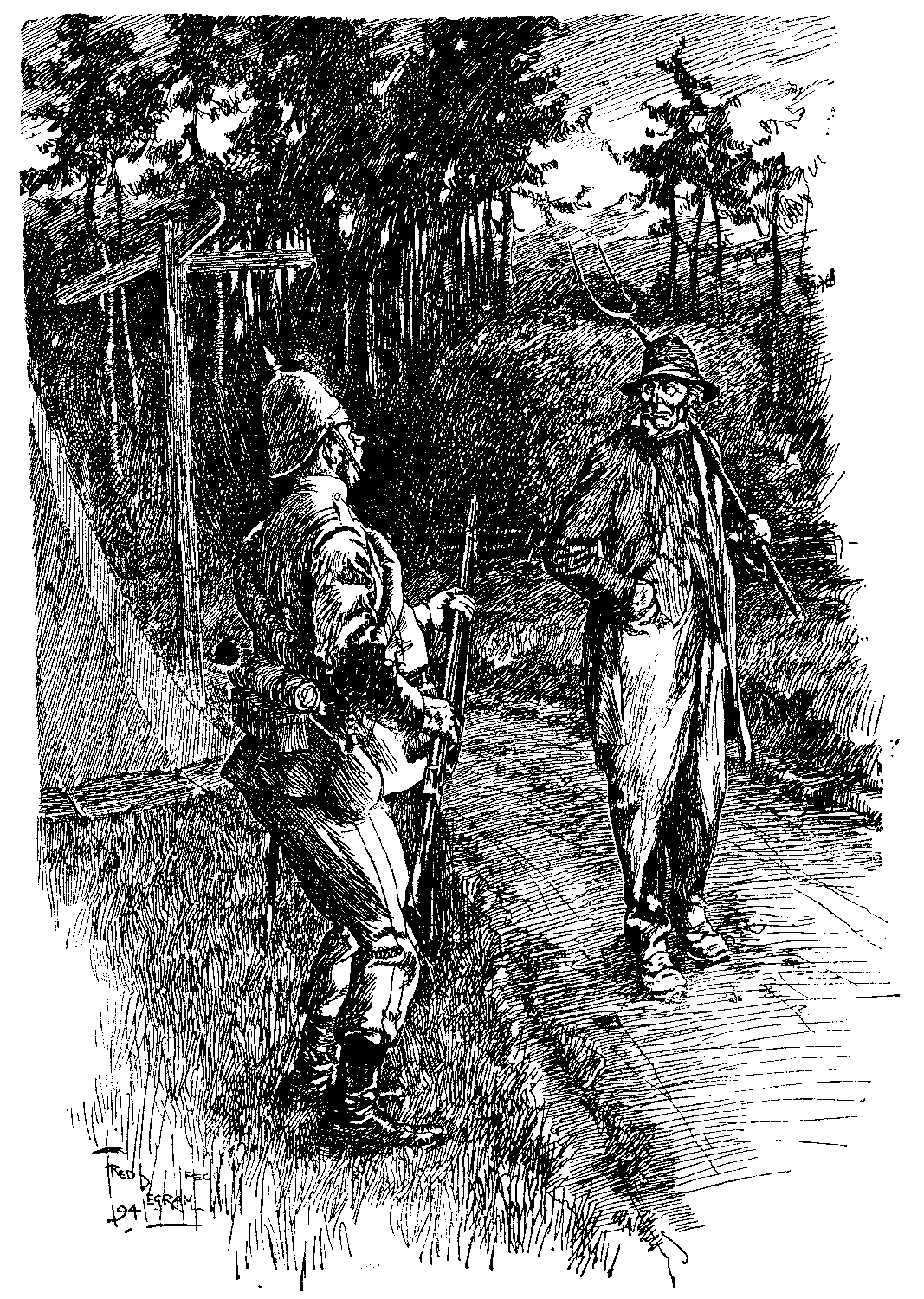

"ALL'S WELL!"

Cockney Volunteer (on Sentry go). "Halt! Who goes there?"

Rustic. "It's all roight, Man. Oi cooms along 'ere ev'ry Maarnin'!"

Flirts of a feather spoon together;

Amorous pairs flock on the stairs.

Jap and Chin.—"What a curious metamorphosis!" writes to us our esteemed contributor-at-a-distance, Herr von Sagefried. "Herr John Chinaman is suing for peace! so that the Chinese party becomes the real Chap-on-knees!"

Comment by a Laboucherian.—Resolutions cannot be made with Rosebery.

The New Man.—Woman.

[250]

Minister. "Oh dear, no, James. There'll be no necessity for Whisky in Heaven."

Parishioner (dubiously). "Necessity or no necessity, I maun say I aye like to see it on the Table!"

I promised last week that the third chapter should be devoted to my meeting, and a Winkins's word is as good as his bond, in point of fact, if anything a trifle better. But I think I ought first to mention that since the account of my interview with Mrs. Letham Havitt and Mrs. Arble March appeared in print, I have been subjected to the annoyance of receiving an anonymous letter. I should be the last to suggest that either of these ladies, for whom my admiration is equalled only by my respectful awe, had anything to do with this missive, but here is what it contained. "It is easy to jeer at Woman, but be warned in time. Her day will come. Already, married or single, she may vote, already County Councils tremble at her word. Treat Woman with respect, or it will be the worse for you." These last words were written in red ink. I confess I'm not easily frightened, but I don't like this kind of thing. And all my wife says is that it serves me right for getting mixed up in these public affairs at my time of life, and that I ought to know better.

"You're not fitted for it, Timothy," she says, "and you'll only be made a fool for your pains." I am very fond of my wife, but I wished she wasn't a prophetess.

It is time to come to the meeting. It was held in the Voluntary Schoolroom, granted to me by the Vicar, on the express condition that I should be strictly non-political. The room was crammed with persons, men and women, married and single. The Vicar brought his daughters, two charming girls. Black Bob and his mates were there, in solid rows, whilst Mrs. Havitt and Mrs. March both turned up, attended by body-guards—the one of Women Liberals, the other of Primrose Leaguers. When the Chairman rose at half-past seven it is no exaggeration to say that the scene was striking and impressive. Then, two minutes later, I rose, and commenced my magnum opus of oratory. I had fifty-two pages of notes, I drank six glasses of water, and twenty-three people left before I had done, which was not until an hour and five minutes had elapsed. I don't for a moment complain that twenty-three left; my complaint is that the number was so few. My peroration, to which I had devoted days of care, somehow hardly had the effect I had hoped for.

"This is indeed a memorable year," I said; "a year of truly rural significance. It remains with you to show that you are prepared to rise to the height of the occasion. If you do this, if you grasp firmly the benefits which this Act offers you, then when next New Year's Day the gladsome bells ring out once again to tell a listening world that one year is dead and that another lives, they will sound all the clearer, all the more joyous, because they ring in a year in which Mudford will have a Parish Council."

Then I sat down, amidst subdued applause, which, I admit, disappointed me. The Vicar's daughters never even took the trouble to applaud at all, and both seemed to have something to confide to their handkerchiefs. Black Bob whispered to his neighbour, "Laying it on thick to-night, isn't he?" I wonder what he meant.

After this commenced a torrent of questions, forty-six in all before they were done. May I never live to have such another experience! All the points I had evaded, because I had not understood them, came up with hardly a single exception. One man asked, "Can the Parish Council remove the parson?"—a most embarrassing question, which evoked roars of laughter from the audience, and a look of indignation from the Vicar. And the awful conundrums!—most of which I had to content myself with giving up. Here is one. "Supposing only eight people come to the Parish Meeting, and a Parish Council of seven has to be elected, and suppose seven of the eight are nominated for election, and the seven are elected chairmen of the Meeting in succession, and have all to retire because they are candidates for the Council, and suppose the eighth man cannot read or write, and when he's proposed as chairman, goes home, how will the Parish Council be elected?" I simply said I would consult my lawyer, and, if necessary, take counsel's opinion.

Of course there was a vote of thanks, and of course it was carried. When I got home, my wife, who had declined to go, asked me how it had all gone off. "My dear Maria," was all I said; "you are quite right. A man at my time of life ought never to start taking part in public affairs." [251]

THINGS THAT ARE SAID.

"Now, Major do your very best to come to us on Tuesday. I shall expect you. But if you can't come, of course I shall not be disappointed!"

(To a Girl at a Distance.)

(An Imaginary Sketch of How Things can not Possibly be Done.)

Scene—The Composing Room of an Illustrious Musician. The Illustrious Musician discovered deep in thought in front of a Piano.

Illustrious Musician (picking out the notes with one finger). "Dumty dumty, dumty dum dum." No, that isn't it! I am sure I had it just now. (Tries again.) "Dumty dumty, dumty dum dum." No, that's not it either! I must try it again—oh, of course, with Herr Von Bangemnöt. Now to summon him. (Blows trumpet). That ought to bring my aide-de-camp.

[Flourish of trumpets, drums; doors thrown open, and enter a Regiment of Infantry, with its full complement of officers.

Colonel (saluting). Your Majesty required assistance?

I. M. (considering). Yes, I knew I wanted something. Oh, to be sure. Will you please send Herr Von Bangemnöt to me at once.

Colonel (saluting). Yes, your Majesty. (To troops.) Right about turn.

[Flourish of trumpets, drums. The Regiment retires. Enter Herr Von Bangemnöt.

Herr Von Bangemnöt (making obeisance). Your Majesty required my assistance?

I. M. Well, scarcely that, old Double Bass. The fact is, I've just composed a very pleasing trifle, but I can't write it down for the life of me. Would you like to hear it?

H. V. B. Certainly, your Majesty. I shall be overjoyed.

I. M. Well, it goes like this—"Dumty dumty, dumty dum dum." See. "Dumty dumty, dumty dum dum." Now, you repeat it.

H. V. B. (who has been listening intently). "Dumty dumty—dum dum."

I. M. (interrupting). No, no; you've got it all wrong. See here, "Dumty dumty, dumty dum dum."

H. V. B. (in an ecstacy). "Dumpty dumpty, dumpty dum dum." Perfectly charming! It is really excellent!

I. M. (pleased, but suspicious). You really think it good?

H. V. B. Good! that isn't the word for it. Excellent! first rate! capital!

I. M. I am so glad you like it. I daresay you could write it out for me?

H. V. B. Oh, certainly. Beautiful! Only wants a little amplification to take the musical world by storm.

I. M. (much pleased). You really are exceedingly complimentary. You are indeed. I suppose it could be scored for an orchestra?

H. V. B. I should think so. I will turn it into a march for the Cavalry.

I. M. And for the Infantry, too? You see, there might be jealousy if you didn't.

H. V. B. Quite so. And there should be marches for the Artillery and Engineers. Then of course we should have a version to be played by the Navy, first in fine weather and then in a storm.

I. M. I think we ought to do as much. And of course the children should have a version suitable for their shrill voices. And it could be used as an opera, and played on the organ. All this, of course, you could manage?

H. V. B. Certainly, you may be sure it shall become universally popular. I will score it for every conceivable instrument, and every possible audience. It shall be played or sung in hospitals, railway stations, schools, and in fact everywhere!

I. M. It shall! But there must be one version teaching a man how to play the tune with a solitary finger.

H. V. B. May I venture to ask by whom that last version will be used?

I. M. Why, old Double Bass, can't you guess? Why, man alive, I shall play from it myself!

Talk about the Chinese eating dogs and cats, and the partiality of the South Sea Islanders for Missionary, what price this, from the Daily Telegraph?—

ROAST COOK (single) WANTED, for large hotel. State age, and last reference.

The cannibal advertiser evidently is a gourmet, for he is particular as to age, and never eats them married. Or is it that he likes them single in preference to double, as, per contra, one might prefer double stout to single stout. After this, we shall expect such delicacies as Boiled Butler, Sauce Maître d'Hotel, Fried Footman, garnished with Calves-foot jelly, or Pickled Pageboy with Button mushrooms. Every fashion must have some inaugurator; and who knows but that we are on the eve of cannibalism, and that the Advertiser and the Daily Telegraph are its joint pioneers! [252]

Writes a Baronitess, "How quaint and simple appear the affectations of Miss Jane Austen's heroines in Pride and Prejudice, especially now that one's mind is confused with the vagaries of the newspaper-created but impossible 'New Woman.'" Rather different days then, when girls addressed their mothers as "Ma'am," and were afraid of getting their feet wet, which was unromantic, and bread-and-butter romance was the fashion of those times. No matter, these romantic young women knew how to dress, according to the exquisite illustrations of Hugh Thomson. What could be expected but sentiment, when the young men also appeared so picturesquely attired. This new edition of an old work is charmingly got up and published by George Allan. Turning from these very early nineteenth century attractions, I find A Battle and a Boy staring at me from a brilliant red binding. The colour suggests a gory fight, but there is nothing martial about it, only a Tyrolean peasant-boy in a pugilistic attitude with another boy. He is having it out before starting on his battle of life, which, taking place in the gay Tyrol, where things happen out-of-the-way, Blanche Willis Howard has made it more interesting than an every-day fight.

Most young women nowadays like to be here, there, and everywhere, and so you will find them in the Fifty-two Stories of Girl-life, by some of our best women writers, and edited by Alfred H. Miles. Messrs. Hutchinson who, publish this work, might head their advertisement with "Go for Miles—and you won't find anything better than this." Other jokes on "miles" they may discover or invent for themselves. These are mostly for our big girls, but the little ones will find a gorgeously gay Rosebud Annual for 1895, quite a prize-flower, exhibited by James Clark & Co.; whilst Rosy Mite; or, the Witch's Spell, by Vera Petrowna Jelibrovsky,—this is a nice easy name to ask for!—is a most thrilling nursery tale of how a little girl, who ought to be an arithmetician after being reduced to the size of her little finger, is able to subtract much adventurous interest from among the insects and the insect-world, and is full of undivided wonders. The illustrations, by T. Pym, show how charmingly unconventional life can be in such circumstances.

So charming, after long years of parting, to come again on Mr. Micawber! Of all things, he has been writing an account of The Life and Adventures of Thomas Edison (Chatto and Windus). The book purports to be the joint work of W. K. L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson. But that is only his modesty. The literary style is unmistakable. "Released from the swaddling clothes of error and superstition," no one but Mr. M. could have written, "the inherent virility of man has reasserted itself, and to the untrammelled vision and ripened energies of the scientist the arcana of nature have been gradually disclosed." "Edison's literary proclivities," he adds, in a sentence that recalls struggles in the house in Windsor Terrace, City Road, where David Copperfield was a lodger, "were seriously hampered by the collapse of the family fortunes, and the early necessity of gaining his own living. Despite his paucity of years, and the practical claims which life had already imposed, Edison devoted every spare moment to the improvement of his mind, and profited to the utmost by the wise and gentle tuition of his mother." My Baronite can almost hear Mr. Micawber's voice choked by a sob as he declaimed this last sentence. Fortunately (or unfortunately) Mr. Micawber does not last long. After the first chapter his hand is rarely seen, he probably, the God of Day gone down upon him, having been carried to the King's Bench prison. For the rest, the book is an admirable account of one of the most marvellous lives the world has known. Much of it is told in Edison's own words, conveying simple records of magic achievements. The book, luxuriously printed on thick glazed paper, is adorned by innumerable sketches and portraits, illustrating the life and work of the Wizard of the Nineteenth Century.

Florence is undoubtedly one of the best places in the world for studying pictures. Resolve to visit the Pitti Palace. Now I shall see something like a palace—the home of the Medici, adorned with all the beauty of architecture and sculpture which they loved so well! No monotonous, painted barrack like Buckingham Palace, no shabby brick house like St. James's. And now I shall see a collection of pictures worthily housed in a magnificent building! No contemptible piece of architecture like our National Gallery, where you fall over the staircase directly you go in at the door, and where, when you have recovered yourself, you find three staircases, facing you like the heads of Cerberus at another entrance, and always go up the wrong one, and have to come down again and clamber up another before you find what you want. Even then, if you seek the watercolours of the greatest English landscape painter, you must go down yet another staircase into the cellar.

Ascertain the position of the Pitti Palace, and stroll gently towards it. There is plenty of time, for the daylight will last another three hours. Cross the Ponte Vecchio, and reach a large open space opposite a magnificent jail. Yes! Even the jails here are magnificent! Continue strolling on until I arrive at the open country. Ask the way to the Palace, and am told that it is about two kilomètres back along the way I have come. Curious that I should not have noticed it. Return, looking carefully right and left, but do not see it anywhere, and again arrive opposite the jail. Ask a man I meet how that prison calls itself. He informs me courteously that it is the Palazzo Pitti. That! That dismal, monotonous, gloomy, brown structure? Why, Buckingham Palace is a joy for ever compared to it, and even Wormwood Scrubbs Prison reveals unsuspected charms! Would like to sit down to recover from the shock, but as one is more likely to find a public seat in a London square than in an Italian piazza, this is impossible. Therefore, totter to the great central entrance. Perhaps the grand staircase leading to the galleries may be as attractive as the exterior is forbidding.

Discover that the entrance to the galleries is by a small side door, where I leave my walking-stick, and climb a narrow, steep staircase. Then climb a narrower and steeper staircase, and finally reach a staircase so steep and narrow that it might more accurately be called a ladder. Begin to think I have mistaken the way. Perhaps I shall find myself in the attics of the Palace, and be arrested as an anarchist. Have left my stick below, and have not even a passport with which to protect myself. Step cautiously up the first rounds of the ladder, when suddenly a large body completely fills the space above, and comes slowly down. It is impossible to go on; it is impossible to remain where I am. Must therefore go down to the least narrow staircase, and wait till the obstruction has passed. Do so. Awful pause....

[What the obstruction was, "A First Impressionist" will tell us in our next.—Ed.]

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation are as in the original.