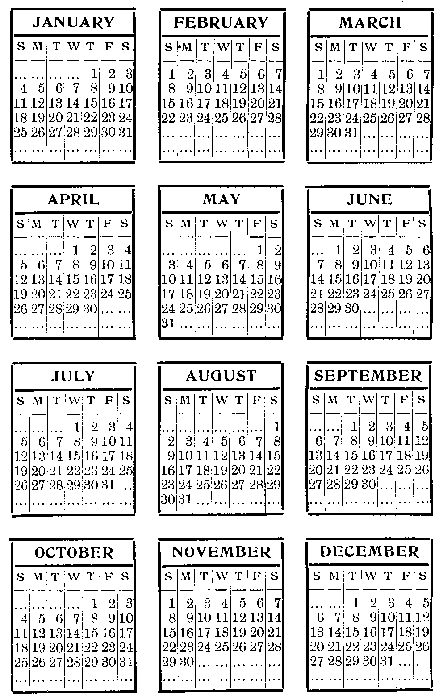

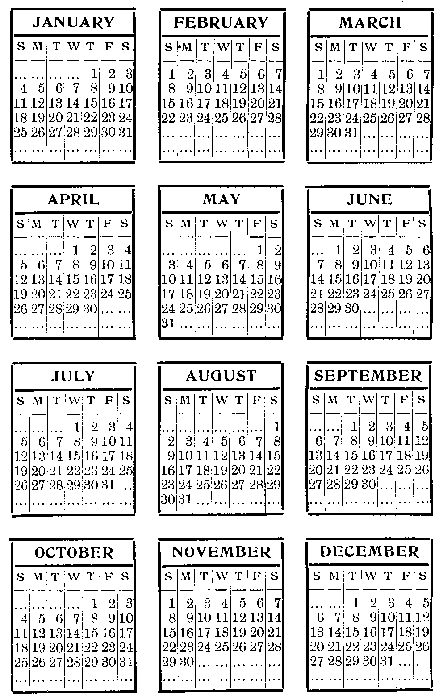

Calendar 1914

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Annual Register 1914, by Anonymous

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Annual Register 1914

A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1914

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: August 1, 2014 [EBook #46471]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ANNUAL REGISTER 1914 ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Juliet Sutherland and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE

ANNUAL REGISTER

1914

ALL THE VOLUMES OF THE NEW SERIES OF THE

ANNUAL REGISTER

1863 to 1913

MAY BE HAD

NEW SERIES

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT, & CO., Ltd.; S. G. MADGWICK

SMITH, ELDER, & CO.; J. & E. BUMPUS, Ltd.

BICKERS & SON; J. WHELDON & CO.; R. & T. WASHBOURNE, Ltd.

1915

| PART I. | |

|---|---|

| ENGLISH HISTORY. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| BEFORE THE SESSION. | |

| The Political Outlook: the Chancellor of the Exchequer on Armament Expenditure, [1], and the Liberal Programme, [2]. The Kikuyu Controversy, [2]. Labour Unrest, [3]. Mr. Chamberlain's Retirement, [4]. Views on Ulster, [4]. Mr. Bonar Law at Bristol, [5]. Sir Edward Carson at Belfast, [6]. Mr. Birrell on the Situation, [7]. The Armament Controversy, [7]. Position of Parties, [8]. Mr. Long on Urban Land Reform, [8]. International Conference on Safety of Life at Sea, [9]. Coal Porters' Strike, [9]. Other Labour Disputes, [10]. Militant Suffragists and the Bishop of London, [10]. Home Rule: Mr. Redmond at Waterford; Sir E. Carson at Lincoln, [11]. Other Speeches, [12]. Labour Leaders' Deportation from South Africa, [12]. North Durham Election, [13]. Chancellor of the Exchequer at Glasgow, [13]. The Bootle Estate, [15]. Sir Edward Grey at Manchester, [15]. Meetings on Naval Expenditure, [16], Mr. Austen Chamberlain at Birmingham, [16]. The Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Insurance Act, [17]. Mr. Redmond at the National Liberal Club, [17]. Other Utterances: Sir Horace Plunkett's Plan, [18]. Political Prospects, [19]. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE SESSION UNTIL EASTER. | |

| Opening of Parliament: the King's Speech, [19]. Opposition Amendment to the Address in the Commons, [20]; in the Lords, [24]. Labour Amendment on the South African Question, [24]; on Railway and Mining Accidents, [26]. Temperance Amendment, [27]. Ministerial Changes, [27]. Address: Amendment on Welsh Church Bill, [27]; on Tariff Reform, [28]; on Housing and the Land Agitation, [29]; on the Dublin Strike, [30]; on the Road Board, [31]; on Local Taxation, [31]; on Purity in Public Life, [32]. Statement by Lord Murray of Elibank: Committee Appointed, [32]. Home Rule Discussions and Suggestions, [33]. Bye-Elections, [33]. Opposition Resolutions on Home Rule and the Insurance Act, [34]. Titles and Party Funds, [34]. Labour and Militancy, [34]. Arrival of the South African Deportees, [35]. Leith Burghs Election, [36]. British Covenant, [36]. Supplementary Navy Estimates, [36]. Attack on the Insurance Act, [38]. Motion on Redistribution of Seats, [38], Home Rule: the Amending Bill and its Reception (March 9), [39]. Army Estimates, [41]. Debate, [42]. The Navy and Invasion, [44]. Territorial Forces Bill, [45]. Attack on the Chancellor of the Exchequer's Inaccuracies, [45]. Navy Estimates, [46]. Debate, [48], Home Rule Crisis: Mr. Churchill at Bradford, [52]. Further[Pg vi] Statement by Prime Minister, [52]. Vote of Censure, [53]. Expected Military Action in Ulster, [55]. Sir A. Paget in Dublin: Officers Object to Serve, [56]. Ministerial Explanations and Debate, [57]. Labour Views, [59]. Army Council's Minute, [60]. Naval Movements, and Further Explanations: Debates, [60]. Resignation of Sir John French and Sir J. S. Ewart, [63]. New Army Order, [64]. War Minister Resigns, Mr. Asquith Succeeding Him, [64]. Further Debates on the "Plot," [65]. The Arms Proclamation Invalidated, [66]. Royal Visit to Lancashire and Cheshire, [66]. Home Rule Bill: Resumed Debate, [67]. Hyde Park Demonstration, [68]. Mr. Asquith at Ladybank, [68]. Home Rule Bill Debate Concluded, [69]. Suffragist Outrages, [71]. Labour Troubles, [72]. Report on Urban Land Reform, [72]. Commons' Resolution on the South African Deportations, [73]. Minor Legislation, [74]. Colonel Seely at Ilkeston, [75]. The Ulster Appeal to Germany, [75]. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| FROM EASTER TO WHITSUNTIDE. | |

| Easter Conferences, [76]. Report on the Civil Service, [76]. The Session Resumed, [77]. The Dogs Bill, [77]. Proposal to Shorten Speeches, [78]. Housing in Ireland, [78]. Welsh Church Bill: Second Reading, [78]. Ulster Unionist Council on the "Plot," [80]. Demand for a Judicial Inquiry, [82]. Further White Paper, [82]. Army (Annual) Bill, [82]. Royal Visit to Paris, [82]. Plural Voting Bill, [83]. Gun-running into Ulster, [84]. Motion for Inquiry, [85]. Division, [89]. Army (Annual) Bill Passed, [89]. Lord Lansdowne at the Primrose League, [89]. Report on the Charges against Lord Murray, [90]. Post Office Estimates, [91]. Civil Service Estimates, [91]. Budget Introduced, [93]. Budget Tables, [96]. Reception of the Budget: Debate, [97]. Women's Enfranchisement Bill, [99]. Debates on Capture of Private Property at Sea and State Provision of Grain in War, [101]. Visit of King and Queen of Denmark, [101]. Guillotine on Parliament Bills: Debate, [102]. Grimsby Election, [103]. Welsh Church Bill: Financial Resolution, [104]. Government of Scotland Bill, [104]. Welsh Church Bill: Third Reading, [105]. Home Rule Bill: Financial Resolution, [107]. Storm in the House, [109]. North-East Derbyshire and Ipswich Elections, [109]. Home Rule Bill: Third Reading, [110]. Division, [111]. Traffic in Titles and Hereditary Titles (Termination) Bills, [111]. Suffragist Outrages, [112]. Labour Unrest, [113]. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE POLITICAL STRUGGLE AND ITS CLOSE. | |

| Whitsuntide: Political Situation, [114]. Chancellor of the Exchequer at Criccieth, [114]. Recess Speeches, [115]. Parliament: National Insurance Amendment and Milk and Dairies Bills, [115]. Post Office Vote again, [116]. Foreign Companies Control Bill, [116]. Home Office Vote: Militancy, and the Remedies, [116]. Outrage in Westminster Abbey, [119]. Further Home Rule Agitation, [119]. Plural Voting Bill, [120]. The Irish Volunteers and Mr. Redmond, [121]: Debates, [121]. Oil Fuel for the Navy, [123]. Board of Agriculture Vote, [126]. Local Government Board Vote, [126]. Great Trade Union Alliance, [127]. Suffragist Deputation to the Premier, [127]. Chancellor of the Exchequer at Denmark Hill, [128]. Liberal Opposition to the Budget, [128]. Finance Bill: Second Reading Debate, [129]. Division, [134]. The Lord Chancellor on the Budget, [134]. The Amending Bill Introduced, [135]. Welsh Church Bill Referred to a Committee, [136]. Their Majesties in the Midlands, [137]. Foreign Office Vote, [137]. Address on the Murder of the Archduke Francis-Ferdinand, [138]. Denial of an Anglo-Russian Naval Agreement, [139]. Attempt to Revive the Marconi Scandal, [139]. Finance Bill: Committee, [139]. Amending Bill: Second Reading, [140]. Division, [144]. Death of Mr. J. Chamberlain: Tributes to his Memory, [144]. Finance Bill Guillotined, [146]. Board of Trade Vote, [147]. Foreign Office Vote: Further Debate, [147]. Council of India Bill, [148]. Amending Bill Transformed in Committee, [149]. Strike at Woolwich Arsenal, [150]. Further Suffragist Outrages: Successes of the "Women's Movement,"[Pg vii] [151], Their Majesties in Scotland, [152], The Agitation in Ulster, [152]. Amending Bill: Third Reading, [153]. Plural Voting Bill Rejected, [154]. Government Plans, [154]. Finance Bill: Committee, [155]. Chancellor of the Exchequer at the Mansion House, [157]. The Government and the Amending Bill, [157]. The Fleet at Spithead, [157]. Conference on the Ulster Problem, [158]. King's Speech on Opening It, [159]. Finance Bill: Report Stage, [160]. Third Reading, [160]. Failure of the Conference, [161]. Gun-running at Dublin: Troops Fire on the Crowd, [162]. Debate in the Commons, [163]. Report on the Affray, [165]. Demonstration in Favour of the Government, [165]. Colonial Office Vote, [165]. Education Vote, [166]. Report of Welsh Land Committee, [166]. The European Crisis and Great Britain, [167]. War Preparations, [168]. Liberal Attitude, [169]. Postponement of Payments Bill, [170]. Sir Edward Grey's Speech, [170]. Promises of Support by Party Leaders: Debate, [172]. Further War Measures, [172]. Ministerial Resignations, [173]. Definitive Anglo-German Rupture, [174]. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| GREAT BRITAIN AT WAR. | |

| More War Preparations, [175]. War Legislation, [175]. White Paper on the European Crisis: England's Action, [175]. Prime Minister on the Vote of Credit, [178]. Debate, [180]. Measures for the Relief of Distress, [180]. Was Funds, [181]. The Königin Luise and Amphion, [181]. Press Bureau Established, [181]. War Legislation: First Instalment, [181]. Current Controversies Suspended, [182]. Lord Kitchener's Army, [183]. Naval Combats, [183]. Successes in Africa, [183], Charitable Aid, [183]. The Supply of Food, [184]. Spy Scares, [185]. Treatment of Alien Enemies: Relief Measures for Tourists, [186]. Day of Intercession: British Feeling on the War, [187]. The War Extends, [188]. Arrival of the British Expeditionary Force in France: Message from the King; Lord Kitchener's Instructions, [188]. The Retreat from Mons: Sir John French's Despatch, [189]. Earl Kitchener's Statement, [190]. Address to Belgium: Speech of the Prime Minister, [191]. Indian Troops to Come, [192]. Precautions on the East Coast, [193]. The "Scrap of Paper" Despatch: Naval Warfare; Engagement off Heligoland, [193]. Destruction of Louvain: British Recruiting Campaign, [194]. The Retreat from Mons: the Press and the Press Bureau, [195]. Further War Legislation, [195]. The War and the Parliament Act, [196]. Recruiting Campaign, [196]. Myth of Russian Troops, [196]. The Prime Minister and other Leaders at the Guildhall, [196]. Encouragement to British Hopes: Agreement of the Allies not to Conclude Peace separately; Further Operations in France, [198]. Naval Sweep of the North Sea, [199]. Chancellor of the Exchequer on Local Loans, [200]. Parliament Reassembles: Offers of Help from India, [200]. King's Message to the Dominions, [201]; to India, [202]. Further Vote of 500,000 Men: Prime Minister's Statement, [202]. Recruiting Movement: Speeches by the First Lord of the Admiralty and Others, [203]. Treatment of the Home Rule and Welsh Church Bills: Party Controversy; Debates, [203]. Earl Kitchener on the Military Situation, [207]. Prorogation of Parliament, [208]. Legislation of the Session, [209]. Bills Dropped, [210]. Mr. Asquith at Edinburgh, [210]. Mr. Lloyd George at Queen's Hall, [211]. Other Speeches, [212]. Sinking of British Cruisers: Air Raid on Düsseldorf, [212]. From the Marne to the Aisne: Sir John French's Despatch, [213]. Protection of London against Air Raids, [214]. German Responsibility for the War: Fresh Evidence, [214]. The Prime Minister at Dublin, [215]. The Chancellor of the Exchequer at Criccieth and Cardiff, [216]. Ulster Day Celebrated, [216]. German and British Theologians on the War, [217]. Recruiting Campaign, [218]. The Prime Minister at Cardiff, [218]. Recruiting in Ireland, [219]. Incidents of the War, [219]. Fall of Antwerp, [220]. Effects, [221]. Labour Manifesto, [221]. British Operations in Flanders, [222]; on the Belgian Coast, [224]. Incidents of the Naval War, [225]. Turkey Enters the War, [226]. Prince Louis of Battenberg Resigns, [226]. British Naval Defeat off Chile, [226]. Ministers at the Guildhall, [227]. Mr. Lloyd George at the City Temple, [229]. Opening of Parliament, [230]. Debates, [231]. The Press Bureau Criticised, [232]. Allowances to Soldiers' Dependents, [233]. Vote of Credit, [233]. Funeral of Earl Roberts, [234]. War Budget,[Pg viii] [235]. Table, [237]. Concessions, [237]. Further Debates, [238]. The Bulwark Blown Up, [239]. The Spy Peril, [239]. Earl Kitchener on the War, [240]. Financial Position: Statement by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, [241]. The First Lord of the Admiralty on the Naval Position, [243]. Further War Legislation, [244]. New Departure in Recruiting, [245], Progress of the War: Flanders, Friedrichshafen, the Persian Gulf, [245]. The King at the Front, [245]. The Prince of Wales at the Front, [246]. Continuance of Football, [246]. Naval Warfare: Battle off the Falkland Islands, [247]. A Turkish Battleship Sunk, [248]. German Raid on Hartlepool, Scarborough, and Whitby, [248]. Mr. Balfour on the War, [249], The Opposition Leaders and National Unity, [249]. Liberal Friction at Swansea, [250]. Gifts of the Colonies, [250]. Egypt a British Protectorate, [250]. Mission to the Vatican, [250]. Committee on German Atrocities, [251]. Mr. Bonar Law at Bootle, [251]. Treatment of Soldiers' Wives, [251]. German Air Raids on Dover and Sheerness: British Raid on Cuxhaven, [252], British Grounds of Hope of Victory, [252]. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Scotland and Ireland | page [254 |

| SUPPLEMENTARY CHAPTER. | |

| Finance and Trade in 1914 | [261 |

| FOREIGN AND COLONIAL HISTORY. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| France and Italy | [268 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Germany and Austria-Hungary | [305 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Russia, Turkey, and the Minor States of South-Eastern Europe | [385 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Lesser States of Western and Northern Europe: Belgium—The Netherlands—Switzerland—Spain—Portugal—Denmark—Sweden—Norway | [362 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| (By Sir Charles Roe, late Chief Judge of the Chief Court of the Punjab.) | |

| Asia (Southern): Persia—The Persian Gulf and Baluchistan—Afghanistan—The North-West Frontier—British India—Native States—Tibet | [402[Pg ix] |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| (By W. R. Cables, O.M.G., late H.M. Consul-General at Tien-Tsin and Pekin.) | |

| The Far East: Japan—China | page [411 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| (By H. Whates, Author of "The Third Salisbury Administration, 1895-1900," etc.) | |

| Africa (with Malta): South Africa—Egypt and the Sudan—North-East Africa and the Protectorates—North and West Africa | [418 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| America: The United States of America and its Dependencies—Canada —Newfoundland—Mexico and Central America (by H. Whates)—The West Indies and the Guianas (by H. Whates)—South America (by H. Whates) | [452 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Australasia: Australia—New Zealand—Polynesia | [494 |

| PART II. | |

| CHRONICLE OF EVENTS IN 1914 | page 1 |

| RETROSPECT OF THE YEAR'S LITERATURE (by Miss Alice Law), SCIENCE (by J. Reginald Ashworth, D.Sc., and others), ART (by W. T. Whitley), DRAMA (by the Hon. Eveline O. Godley), and MUSIC (by Robin H. Legge) | 38 |

| OBITUARY OF EMINENT PERSONS DECEASED IN 1914 | 75 |

| INDEX | 116 |

Calendar 1914

The Editor of the Annual Register thinks it necessary to state that in no case does he claim to offer original reports of speeches in Parliament or elsewhere. For the former he cordially acknowledges his great indebtedness to the summary and full reports, used by special permission of The Times, which have appeared in that journal, and he has also pleasure in expressing his sense of obligation to the Editors of "Ross's Parliamentary Record," The Spectator, and The Guardian, for the valuable assistance which, by their consent, he has derived from their summaries and reports, towards presenting a compact view of the course of Parliamentary proceedings. To the Editors of the two last-named papers he further desires to tender his best thanks for their permission to make use of the summaries of speeches delivered outside Parliament appearing in their columns.

In deference to suggestions which have been made on the subject, a Calendar has been added to facilitate reference to dates.

[THE ABOVE FORM THE CABINET.]

Scotland.

Ireland.

ANNUAL REGISTER

FOR THE YEAR

1914.

The year opened amid continuing apprehension for the peace of Ulster, and sharp controversies on subjects so widely different as the discipline of the Church of England and the needs of naval defence. Though conversations were understood to have been resumed between the Liberal and Unionist leaders regarding the possible terms of settlement of the Home Rule question, it was clear that much difficulty would be found in effecting a solution; and the Bishop of Durham advised the clergy of his diocese to make the first Sunday of the year a day of intercession for peace in Ireland—advice which was followed in other parts of the country also. And the dissatisfaction of the Ministerialist rank and file at the shipbuilding expenditure of the Board of Admiralty was expressed by Sir John Brunner, the President of the National Liberal Federation, and powerfully stimulated by an interview with the Chancellor of the Exchequer published on the first day of the year by the Daily Chronicle.

Mr. Lloyd George declared that, had British armament expenditure remained at the figure regarded by Lord Randolph Churchill in 1887 as "bloated and extravagant," a saving would have been effected equivalent to 4s. in the pound on local rates, or, on Imperial taxes, to the abolition of the duties on tea, sugar, coffee, and cocoa, and all but 2d. in the pound of the income tax. The question might now be reconsidered for three reasons: (1) Anglo-German relations were far more friendly than for years past; (2) Continental nations were devoting their attention more[Pg 2] and more to strengthening their land forces, so that Germany in particular must be thus precluded from any idea of challenging British naval supremacy; (3) a revolt against military supremacy was spreading throughout Christendom, or at any rate Western Europe. Unless Liberalism seized the opportunity, it would be false to its noblest traditions, and those who had its conscience in their charge would be written down for ever as having betrayed their trust. Sir John Brunner, as chairman of the National Liberal Federation, urged that Liberal associations should pass resolutions in favour of reduction of armament expenditure before the Army and Navy Estimates were settled, and he and several Liberal papers urged, as one means of reduction, the exemption of private property from capture at sea.

The Chancellor's statement met with little response in the German Press, and caused some apprehension in France. It was said that the First Lord, who was just then visiting Paris, did his best to allay this feeling; but at home it was regarded as indicating a sharp division in the Cabinet, and a suggestion by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (Jan. 6) in a speech to his constituents at East Bristol, that a reduction might be agreed on jointly by Germany and England in the size and speed of new battleships, was spoken of as ranging him on the Chancellor's side. The Navy League appealed to the Mayors or chief magistrates of all towns in Great Britain to call public meetings in support of naval defence, and gave reasons for its contention that the actual and prospective naval forces of Great Britain were inadequate to the needs of the Empire. It also arranged other meetings, especially in the constituencies of Liberals favouring reduction. Mr. F. E. Smith told his constituents (Jan. 8 and 10) that the Chancellor was a "bungling amateur," and promised Unionist support to the Government in this matter against its own followers; but the Solicitor-General at Keighley (Jan. 8) declared that there was no Liberal division; the Government policy was to maintain British naval supremacy, but to build no more ships than were required for purely defensive needs.

The Chancellor, in the interview in question, had also pointed to the success of his land campaign, and had indicated, as other urgent items in the Liberal programme, legislative devolution, the reform of local taxation, and measures for the promotion of education, housing, and temperance. He had also reaffirmed his faith in women's suffrage, declaring that, but for militancy, he believed the Liberal party would then be pledged to carrying it out. But other subjects competed with it for public attention. The Kikuyu controversy (A.R., 1913, p. 439) had raised the question, not only of the practical necessity of co-operation and intercommunion among the Anglican and Protestant Christian missions in Africa, but of the precise attitude of the Church of England in regard both to the Episcopate and the advanced views[Pg 3] of Biblical criticism among her younger members. The controversy went on actively in the columns of The Times and elsewhere; and the cohesion of the Church was thought to be in grave danger. Even High Churchmen acquainted with missionary work argued that the native churches must not be hampered by restrictions which were the outcome of historical conditions in Europe, or Anglican missions weakened in the face of the progress of those carried on by British and American Nonconformists. Presbyterians and Anglican clergy drew attention to the practice of admitting Scotsmen and other non-Anglicans to the Lord's Supper in the Church of England, and to the neglect of the rite of confirmation in the past. Missionaries and colonial administrators pointed out that an African Nonconformist could not be repelled from communion in an Anglican church when, as often happened, his own form of worship was inaccessible to him, without the risk of estranging him from Christianity altogether; and Lord George Hamilton (in The Times, Jan. 6) urged that division among Christian missions in East Africa would mean the triumph of Mohammedanism. The Archbishop of Canterbury, in a letter published on January 1, had mentioned that he had not yet been informed of the precise question which the Bishop of Zanzibar desired to raise; and, after the matter had been actively canvassed, it was allowed to rest pending a further pronouncement by the heads of the Anglican Church.

A subject of more pressing interest was to be found in the various movements among organised labour. The ballots under the Trade Union Act of 1913 as to the establishment of a political fund, which were being taken in the first fortnight of the year, tended to reassure those who feared the growth of a strong Labour party, inasmuch as the vote was generally light (the miners, however, being a notable exception) and substantial minorities were unfavourable to the establishment of such a fund, and therefore presumably wished to keep their unions out of politics. But against this was to be set the marked prevalence of Labour unrest. A national movement was expected for a minimum wage and an eight hours' day for surface workers about mines, which might lead to local strikes, and ultimately to a general stoppage. A lock-out was threatened in the London building trade, where the presence of a single non-unionist was now the signal for an instant refusal to continue to work with him. A conflict was expected in the engineering and shipbuilding trade on the expiry in March of the existing working agreement. The abandonment of the Brooklands agreement threatened the peace of the cotton trade. There were signs of trouble among the gas-workers and transport workers in various places; and the railwaymen were preparing for a struggle towards the end of the year on the questions of recognition of the union, an amended conciliation scheme, and a shorter working day.

Meanwhile the Unionist party was prepared for the loss of one of its most imposing figures by Mr. Chamberlain's letters to the Presidents of the Liberal Unionist and Conservative Associations in his constituency of West Birmingham, announcing that he would retire from Parliament at the general election. He had not appeared in the House except to take the oath and his seat, since his disablement by gout and partial paralysis in the summer of 1906 (A.R., 1906, p. 180); and, though his health was not worse than it had been for some time, it had long been realised that he could never again take an active part in political life. Still, the announcement marked the close of an epoch, and of his Parliamentary connexion of more than thirty-seven years with Birmingham, twenty-nine of them as the first member for his actual constituency; and it was received with general regret and with acknowledgment, even by opponents, of his distinguished services to Great Britain and to the Empire. It was arranged that Mr. Austen Chamberlain should stand for his father's seat in West Birmingham. A few days later another Parliamentary veteran of Liberal Unionism, Mr. Jesse Collings, retired likewise after thirty-three years' service in Parliament, of which he had spent twenty-seven as member for Bordesley. He had worked, he said, for over half a century with Mr. Chamberlain, "and it seems fitting, even as a matter of sentiment only, that we should put off our harness together and at the same time."

However, the supreme questions were the attitude and the future of Ulster; and the period of interchange of views and of respite was rapidly drawing to a close. As The Times noticed (Jan. 5), responsible Unionists during the period of "conversations" had observed the "rule of reticence"; and such voices as had been heard were those of more independent politicians. Mr. William O'Brien, speaking at Douglas, near Cork (Jan. 4), regretted that the Nationalists had not accepted Lord Loreburn's proposals or the concessions suggested by the "All for Ireland" party, which in that event, had Sir Edward Carson refused them, might have been the subject of an appeal to the country. He again denounced the idea of the separation of Ulster from the rest of Ireland. A method of averting this and yet satisfying the fears of the Ulster Unionists was suggested by Mr. T. Lough, M.P., himself an Ulsterman and a Liberal, and had the support of Dr. Mahaffy and other eminent Protestant Irishmen. It was, briefly, to give the Protestant and Unionist minority a larger representation in the Irish House of Commons than their numerical strength would entitle them to claim. But the indemnity fund to compensate the Ulster Volunteers for their sacrifices for the cause had exceeded 1,000,000l. by January 9; and it was freely reported that the "conversations" had broken down, and the first important utterances by Unionists confirmed this opinion.

Addressing a Primrose League mass meeting at Manchester, on[Pg 5] January 14, Earl Curzon of Kedleston dealt mainly with the naval question and with Ulster. The Chancellor of the Exchequer's statement, he said, was inconsistent with his speech in August, 1913 (A.R., 1913, p. 194). There was something humiliating in these appeals from British Ministers for a reduction, and British reductions had merely led to a German increase. The "naval holiday" proposal had produced no response, and the policy of independent and isolated reduction would provoke the exultation of Great Britain's enemies and the anger of her friends. Collective man seemed to be as selfish, bloodthirsty and brutal as in the dark ages, and the only guarantee of safety was the knowledge that a nation could not be attacked with impunity. Giving reasons for increased expenditure, he said that by the Navy alone could Great Britain keep her treaties with foreign Powers, maintain the balance of power in Europe, and be of any value to her friends. A Little Navy campaign would rouse Unionist protest throughout the country, not for party purposes, but because it tended to national suicide. As to Home Rule, he intimated that the conversations between the leaders had hitherto had no result; and, after pressing for either a referendum or a general election, he indicated that the Unionists might accept the Bill were it considerably altered and Ulster excluded. In gaining Ulster by force, the Nationalists would lose it for ever. To secure a peaceful Ireland, the Unionists would make sacrifices; but they could not consent to Home Rule within Home Rule, which Ulster would not accept. They desired to save the country from a great disaster and must appeal to the national instincts of the people.

The Lord Chancellor, speaking at Hoxton on January 15, advised his hearers not to be pessimistic about the discussions between the leaders; but at Bristol on the same evening Mr. Bonar Law gave no hope of a successful outcome. The country, he said, was rapidly and inevitably drifting to civil war. The conversations so far had been without result, and he expected that there would be none. It was not for the Unionists to make proposals, and, anxious as they were to avoid a terrible upheaval, they would accept no proposal which did not meet the just claims of Ulster. He had thought from the speeches of Mr. Churchill, Sir E. Grey, and even the Prime Minister at Ladybank, that the Government were prepared to face the facts, but the Nationalist leaders had claimed the right to govern Ulster, which they could not govern by their own strength. The Government knew that if they appealed to the people and were defeated their whole work of the last two years would be lost; and they had also incurred obligations to the Nationalists, and were resolved to carry their policy through. If they were right, the Ulstermen and the Unionists, who meant to assist them, were traitors; if the Unionists were right, the Government were acting as tyrants, and had lost the right to obedience. He argued once more that[Pg 6] Home Rule was not before the electorate at the election of 1910, and pointed out that the American colonies in 1776, though their cause for revolt was trivial as compared with that of Ulster, had revolted on a question of principle while suffering was still distant. He contrasted the apathy in Dublin with the determination in Ulster, daily becoming more immovable, and interpreted Sir Edward Grey's statement at Bradford (A.R., 1913, p. 250) that the Government would put down an outbreak in Ulster as signifying that the Government hoped that Ulster would give occasion to put its existence down by force. That was gambling in human life. The position in Ulster was no longer in doubt. The people in Ulster, and the Unionist party, had no alternative. The Unionist leaders fully recognised their responsibility, past and future; but the path of duty was that of national safety, for, if the Government once realised that the Unionist party was in earnest, they would see that they must appeal to the people.

The impression of hopelessness produced by this speech was seen in the appeal of the Archbishop of York, at Edinburgh, in a sermon on the following Sunday (Jan. 18), from the text "Blessed are the Peacemakers," that efforts at compromise should continue so as to save the country from civil war. But the Nationalists held that compromise was impossible until the Bill had reached its final stage in the Commons; and the rank and file of the Ulstermen desired that the negotiations should fail. Hence, though Mr. William O'Brien sacrificed his seat (Jan. 17) and stood again in order to prove that, in spite of the defeat of his following at the Cork municipal elections, the constituency continued to support the policy of "conference, conciliation, and consent," the mass both of Ulstermen and of Nationalists showed no disposition to make peace. The anxiety was heightened by the proceedings in Belfast (Jan. 17-19). Sir Edward Carson arrived on the 17th, inspected the East Belfast Regiment, and emphasised the determination of the force to resist Home Rule. On the 19th the Ulster Unionist Council met in private; and, addressing them at a luncheon afterwards, he said that Mr. Chamberlain had told him a few weeks before that "he would fight it out," and they would take his advice. "Conversations" as to a settlement had been taking place, but negotiations were useless unless based on the continuance, under the Imperial Parliament, of the rights which their ancestors had won. Further conversations might be necessary, but their preparations should keep pace with their diplomacy. He paid a tribute to the sacrifices made by the Volunteer Force, and concluded by saying that their loyalty to the Throne would last to the end, even if they were shot down cheering the King. An enthusiastic demonstration in the Ulster Hall followed, and was addressed by the Marquess of Londonderry, Mr. Long (who assured Ulster of the support of the English Unionists), and Sir Edward Carson, who again advised "peace, but preparation."

Following this advice, the Ulster Unionist Standing Committee prepared for action; and at the annual meeting of the Ulster Women's Unionist Council Sir E. Carson again urged them to stand firm. He recognised the kindness of the English Unionists in preparing to receive the Ulster women and children in the event of civil war, but he believed "the women of Ulster would stand by their men." The women, it must be added, were actively engaged in preparing to take part in nursing, signalling, and telegraphic and postal work; and the meeting passed a resolution declaring its unabated loyalty to the Covenant and its resolve to continue in the pursuance of the cause and the maintenance of civil and religious freedom.

Speaking at Batley next day Mr. Birrell said that there was great prosperity in Ireland, except in Dublin, where, however, things were settling themselves; and he scoffed at the readiness of the Unionist party, while detesting Home Rule, to accept the decision of the odd men at a general election. He welcomed Sir Edward Carson's declaration that he would not close the door on negotiations; but they must leave the matter there for the present, resting satisfied that the Liberal party and its leader were conscious of the sacrifices Liberals had made to get the question into its actual position. From that they did not desire to see it recede in the least degree, except in pursuance of the object they had in view.

Meanwhile the Chancellor's utterance on naval expenditure had encouraged Liberal expressions of the demand for reduction at meetings at Manchester, Newcastle-on-Tyne, and elsewhere, even in the City of London (Jan. 16). This last meeting, at the Cannon Street Hotel, though not large, was influential, but there was a considerable dissentient element, and a protest was made in the name of "a great majority of members of the Stock Exchange." The chairman, Mr. F. W. Hirst, editor of the Economist, condemned the First Lord for not keeping to his own standard of sixteen to ten; and two resolutions were moved, one advocating a searching examination into all departments of expenditure, in order that the Sinking Fund might be maintained without additions to the taxes; the other urging savings in expenditure on armaments, "in view of the improved relations with all other Powers and the reduction in the naval programme of Germany," the next strongest Continental naval Power. Sir John Brunner and three M. P.'s—Mr. D. A. Thomas, Mr. Lough, and Mr. D. M. Mason—addressed the meeting, the first-named advocating the abolition of the right of capture of private property at sea.

One result of the protests was that the Daily Telegraph (Jan. 20), by an ingenious conjecture, declared that there was a grave crisis in the Cabinet, and that both the naval and civil members of the Board of Admiralty had expressed their intention to re[Pg 8]tire if the Cabinet refused the supplies asked for, which they regarded as the bare minimum necessary; the statement, however, was promptly contradicted officially.

A day earlier the Postmaster-General, speaking at Henley-on-Thames, had stated that, besides the measures to be passed under the Parliament Act, the Prime Minister within the year would lay before Parliament proposals for the complete elimination from it of the hereditary principle and the thorough democratising of the Second Chamber.

The Ministry thus sat tight and defied its assailants, and the Opposition felt that their best chance lay in Ulster. Mr. Austen Chamberlain made it the chief theme of his speech at Shirley, Hants, on January 23, when he declared that Ulster, in the last resort, would save herself by her own right arm, and that England would follow her example.

But within the Unionist party itself there was fresh trouble on fiscal reform. The Farmers' Tariff League appealed by advertisement to Unionist agriculturists, manufacturers, and those dependent on fixed incomes, to vote against supporters of the existing Unionist fiscal policy; Mr. Rowland Hunt, at the Horncastle branch of the Farmers' Union (Jan. 14), denounced the postponement of food duties (A. R., 1912, p. 267) as disastrous, and the existing tariff policy as "rotten." A 10 per cent. duty was too low for manufactured goods, and home food producers were left unprotected, although their contribution to rates and taxes was equivalent to a duty of 15 per cent. Mr. Hunt, of course, was an independent and irresponsible Unionist, but he did not stand alone.

More responsible Unionists, too, were constrained by the Government programme to concede that something must be done to redress the alleged social grievances, and to propound an alternative and more moderate policy. Thus Mr. Long, speaking at the Holloway Empire (Jan. 17), after referring briefly to the threatening cloud of civil war, and promising that a Unionist Ministry would ask for power to make the Navy adequate, criticised the Chancellor of the Exchequer's statement in that hall (A. R., 1913, p. 247), pointing out that the number of separate freehold estates in St. Pancras was not ten, but 1,550. He went on to suggest that instead of the Chancellor's reform proposals, which would take some years to carry out and entail a horde of officials and much un-English Government interference, there should be (1) facility for continuity of tenure by industrial tenants in London and large towns under reasonable conditions, or else compensation for loss of tenancy; (2) reasonable compensation for tenants' improvements which increased the letting value; (3) protection or relief from unreasonable covenants restricting the development of property. The Unionists would give redress through a tribunal modelled on the Wreck Commissioners' Court,[Pg 9] and a non-controversial Bill embodying these changes might be introduced in the coming session. This would redress the existing grievances in six or eight months, but, as with housing reform (A. R., 1912, p. 57) the Radicals were determined that the Unionist party should not have the credit of carrying a measure of social reform. [Other items of a Unionist "social programme" were understood to be in preparation.]

Meanwhile an important subject of non-contentious legislation for any Ministry that might be in office was afforded by the International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea, originally suggested by the German Emperor and called by King George, which had met in London on November 12, 1913, and signed a Convention as the result of its deliberations on January 20. Publication was postponed till it had been communicated to the eighteen Governments participating (among them those of Canada, Australia and New Zealand); but the results were summarised in a speech by Lord Mersey, the Chairman of the Conference. Five Committees had dealt respectively with Safety of Navigation, Safety of Construction, Wireless Telegraphy, Lifesaving Appliances, and Certificates. The provisions are too numerous to be given in detail here; it may be said that an international service under the control of the United States was established for dealing with ice and dangerous derelicts within certain limits in the North Atlantic; ice must be reported, speed reduced at night in its neighbourhood or the course altered, boat decks properly lighted, and Morse signal lamps carried. Steps were taken to revise the international regulations dealing with collisions. Strict regulations were laid down as to the subdivision of ships into watertight compartments, and other provisions against sinking, fire, or collision; and also as to the equipment of all merchant vessels of the contracting States, when on international voyages and carrying more than fifty persons, with wireless telegraphy; lifeboats or their equivalents must be provided for all on board, and there were minute regulations both as to these and as to other forms of life-saving apparatus; a specified number of men must be carried competent to handle boats and life-rafts; and provision was made for the detection of fire. Ships of the contracting States complying with the requirements of the Convention would receive certificates which each of the States would acknowledge. The Convention was to come into force on July 1, 1915.

A foretaste of the expected Labour troubles was afforded in London by a strike (Jan. 21), in very cold weather, of the coal porters, after the failure of negotiations with the employers for increased pay; two days later the coal carmen came out also, and the number on strike was about 10,000. Permits were at first given by the strikers, but afterwards stopped, for the carriage of coal to hospitals and infirmaries; but the clerks and travellers of[Pg 10] the employers, and the students at the hospitals, volunteered to take the places of the strikers, and vehicles of all sorts, including motor-cars, were lent to replace the carts. The strike ended (Jan. 28) with concessions by the employers, one firm having previously given way. But the dispute in the London building trade (p. 3) was more serious. The Master Builders' Association complained that, some twenty times in the past nine months, men employed on one or other building job had suddenly refused to work with a non-unionist; and they demanded that each employee individually should sign an undertaking not to strike against the employment of non-unionists, under penalty of a fine of 20s. The men declined to discuss these conditions; and on Saturday, January 24, a number were dismissed, and a general lock-out was threatened. There was some doubt if the proposed fine would be legally enforceable; and, as the men were dismissed, they claimed unemployment benefit under the Insurance Act, but in vain. And the dispute was complicated by the raising of other questions as a condition of the resumption of work. About a thousand of the men submitted; the great majority remained firm. Among other examples of unrest was a prolonged strike of chairmakers at High Wycombe, which led to some rioting; of the taxi-drivers of London; of the municipal employees at Blackburn; and of the elementary school-teachers in Herefordshire. And the Prime Minister (Feb. 3) felt constrained to decline the request made by a deputation of the Miners' Federation to extend the principle of the Minimum Wage Act to surface workers, thus widening the visible rift between Labour and the Government.

The militant suffragists, meanwhile, had not been inactive. A conservatory in the Glasgow Winter Garden had been damaged, and an unoccupied house near Lanark fired, on January 24; and two days later a deputation from the militant organisation submitted to the Bishop of London a statement (based wholly on inference) from Miss Ansell, a prisoner in Holloway Jail, to the effect that a fellow-prisoner, Rachel Peace, was being forcibly fed and brutally treated by the jail authorities. The Bishop, however, after personally investigating the matter and talking to Miss Peace, satisfied himself that the statement was unfounded. The Home Secretary was willing to advise Miss Peace's absolute release if she would undertake to abstain from crime; this she was conscientiously unable to promise, and, though the Bishop had pleaded that she might be released on licence, and she had agreed to abide by its terms, this course was impracticable under the Act. The Bishop's letter stating these facts was published January 31; the militants met it by interrupting the service while he was consecrating a church at Golder's Green next day, and on the day following another militant deputation asked him to visit two other women prisoners in Holloway, and state his ex[Pg 11]periences at a meeting of the Women's Social and Political Union. This last invitation he declined, but he visited the prison, talked to the two women, Miss Marian and Miss Brady, and found that while forcible feeding made one of them sick and gave the other indigestion, no harshness was shown them by the officials, and they complained of no personal unkindness. He told the militants, in conclusion, that their action was not only wrong, but impolitic. The militants were furious at this reply, and the Bishop's house was picketed by their emissaries, who were, however, unable to see him.

But none of these disturbing questions could interrupt the Home Rule controversy for long. Speaking at a Home Rule meeting of some 15,000 persons in Waterford on Sunday, January 25, Mr. John Redmond said that the British people remained absolutely unshaken in their support of Home Rule, and that, putting aside two unlikely contingencies, the Bill would in the current year automatically become law. The Prime Minister would not be intimidated into dropping it; he was the strongest and sanest Englishman of the day in British politics. Alarmist shrieks were filling the air, but business in Belfast and Ulster was booming, and the great body of the people of Great Britain remained unmoved. There could not be a war without two contending parties; and the Ulster "army" was for defence only, and would not be attacked. He saw no prospect of Ulster goodwill being purchased by any concession, but it was almost a blasphemy to say that "the Nationalists could do without them." Long ago he had said that there were no lengths, short of the abandonment of the principle of nationalism, to which he would not go, no safeguards to which he would object, which would satisfy the fears of Ulstermen for their religious interests. Subject to the limits recently laid down by the Premier (A. R. 1913, p. 220) he said the same that day, and was prepared to pay a big price for settlement by consent. The Nationalists of Ulster had shown admirable loyalty and self-restraint, and those of North Cork "magnificent discipline" in refusing a contest which, whatever its result, would greatly injure their cause (p. 6). Ireland's travail was almost ended, and they were about to witness the rebirth of Irish freedom, prosperity, and happiness. Before the meeting Mr. Redmond had been presented with a number of addresses from public bodies, and had said that under Home Rule there would be a need for practical business men; politics would disappear, and their task would be to apply themselves to practical problems, and to lift Ireland from the slough of despond in which it had been for the past thirty years.

Sir Edward Carson replied next day, at Lincoln, that Mr. Redmond seemed to speak as if he held the Government in the hollow of his hand. If his speech were the last word, the country was in a lamentable and critical position. On the other[Pg 12] hand, Mr. Birrell, at North Bristol, ridiculed the Unionist insistence on the danger of civil war as a mere party move; eulogised Mr. Redmond's speech, and said that before civil war began, Mr. Asquith would have stated to the world the opportunity offered to Ulster and refused. All Governments were experimental; Liberals saw that the only Government now possible for Ireland was one which should have the authority of the people and time for legislative work. Should the Tories come in, they would within six months be introducing a measure only colourably different from that on which they were threatening civil war.

Mr. Long, at Nottingham (Jan. 28), denounced the obscurity of this speech, and hinted at a suspicion that the Government were trying to force Ulster to prejudice its case by committing some act of violence; and Mr. Austen Chamberlain also replied to the Chief Secretary for Ireland at Skipton (Jan. 30), denouncing the Government for forcing on, during a time of turmoil abroad and at home, the Welsh Church, Home Rule, and Plural Voting Bills. They had found Ireland at peace, and brought it to the verge of civil war. Their methods had destroyed the moral basis of their authority. No concession worth speaking of would avert the dangers then threatening, unless it provided for the exclusion of Ulster from the sphere of a Union Parliament. The Chief Secretary's paper safeguards were of no value. The Lord-Lieutenant would be distracted between the advice of his Ministers and of the Imperial Government. He could not trust the Nationalists, nor, judging by the provisions in the Bill, could the Government. England was to conquer a province and hold it down at the expense of her friends and for the benefit of her enemies. Against this Ulster appealed to the nation, and the Unionist party would stand by them.

The Nationalist comment was expressed by Mr. Devlin at Moate, Westmeath (Feb. 1). After saying that, without compulsion, which was one of the vital provisions of the pending Land Bill, the land problem would not be solved either in this generation or the next, he declared that the only obstacle in the way of Home Rule was the threat of civil war in Ulster, which had failed to convince or intimidate anybody, not least in Ulster itself. The so-called Volunteer movement and the Provisional Government had been reduced to a miserable fiasco, and the whole thing was a gigantic game of bluff. Among business men in favour of Home Rule he cited Lord Pirrie, Sir Hugh Mack, Mr. Glendinning, and Mr. Thomas Shillington, "out of a host of others."

Another brief interruption in the Home Rule controversy, to the temporary disadvantage of the Government, was now occasioned by the news (Jan. 28) of the deportation, by the South African Government, of ten of the Labour leaders concerned in the strike disturbances (post, For. and Col. Hist., chap. VII., 1). The indignation was heightened by the evasion by that Government[Pg 13] of a legal decision on the validity of the deportation, which was carried out under martial law, and by its reliance on an Act of Indemnity. The Labour Party Congress in Glasgow at once passed a resolution protesting against the suppression of trade union action in South Africa by armed force, expressing sympathy with the deported leaders, and requesting the Labour members in the Imperial Parliament to call for a full inquiry, and demand, if necessary, Lord Gladstone's recall; and next day it passed a further resolution calling upon the Government to instruct Lord Gladstone to withhold assent to the Bill until it had been submitted to the King. Strong speeches were made by Mr. Ramsay Macdonald, Mr. Keir Hardie, and other members, the first-named declaring that if the Imperial authority could not stop this attack on the right of combination, he had rather the South African Union were a foreign Power. On the other hand, Mr. Illingworth, the chief Liberal Whip, pointed out (at Clayton, Jan. 30) that South Africa was governed by a Parliament elected on a very free and wide franchise and quite uncontrolled by the Imperial Government, and that interference with such independent assembly would wreck the Empire; Lord Gladstone had acted on the advice of his responsible Ministers, as the King would in Great Britain; and the Home Government was blameless. At Hull, on the same evening, Mr. F. E. Smith asked for a suspension of judgment, and pointed out the inconsistency of demanding that the King should veto a Bill of Indemnity and repudiating that course on Home Rule. The South African Government, he reminded his hearers, had been created with the help of the Labour party.

The Liberal Press had anticipated the Chief Whip's arguments; but at the North Durham bye-election (Chron., Jan. 30) though the Liberals held the seat, which had always been regarded as safe for them, it was said that the deportations had caused the transfer from the Liberal to the Labour candidate of some 500 votes. In view of this transfer, the Postmaster-General, speaking at Harrogate, on February 2, had explained that Lord Gladstone's assent to the deportation of the Labour leaders was not required by the Constitution of South Africa, and, in fact, had not been asked. He added that the North Durham result did not support Mr. Bonar Law's prophecy of an early general election.

Should such an event occur, however, there were plenty of other questions for the electors besides Home Rule, Some of them, indeed, might prove dangerous for the Government, notably the land question, on which its programme did not go far enough for the single-taxers, a strong body in some districts, especially in Scotland. For this reason special interest was felt in the speech, which had been repeatedly deferred, of the Chancellor of the Exchequer at Glasgow on February 4. Many opponents got in[Pg 14] with forged tickets; nevertheless he had a fair hearing. After ridiculing the explanations in the Press of the postponement as due to differences in the Cabinet, or difficulties with the Ulster Unionists or the "single-taxers," he said that the underlying principle of land legislation was that the land was created for the benefit of all dwellers on it, and that any rights of ownership inconsistent with this principle should be ruthlessly overridden. That was the principle of the Scottish Land Act, but there were still anomalies; the peasantry was emigrating largely, and could not be spared. While indicating that rural conditions were not so bad in Scotland as in England, he pointed out that the effect of the Scottish Land Act had been to reduce the rents on many well-managed estates, a proof that under the system of competitive rents, part of a farmer's labour was unconsciously confiscated by rent. After indicating afresh the main points in the Ministerial scheme, he passed to the urban problem. Housing was even worse in some Scottish towns than in England. The cost of clearing the slums was prohibitive. Municipalities should be able (1) to acquire land at a fair market price, and (2) in advance of existing needs; (3) there should be an expeditious method of arriving at the price, and (4) the land must contribute to public expenditure on the basis of its real value. He alleged certain instances of the contrary—the Duke of Montrose had received 2,000 years' purchase from the people of Glasgow on the basis of his contribution to the public funds; the Cathcart School Board had paid 3,270l. 17s., or 920 years' purchase, for an acre and a half of the rateable value of 3l. 10s.; and 27,255l., or 2,452 years' purchase of the rateable value, had been paid for ten acres for a torpedo range near Greenock. The Clyde Trustees had had to pay to a Peer 84,000l. for nineteen acres—1,400 years' purchase of the rateable value. A new rating system was wanted, which should rate property on its real value and not discourage improvement; and high authorities had approved the rating of site values, notably Lord Rosebery and Mr. Chamberlain. Of the two proposals—to rate site value only, and not to rate it at all—he regarded the first as impracticable, the second as pusillanimous; there were several alternative methods between these limits, but whichever one was adopted, there must be a national valuation, and it would be ready in 1915. Of his statements on the Highland clearances he withdrew none; of course mountains were unsuitable for agriculture, but the glens were capable of tillage and the hillsides of afforestation. As to the Sutherland clearances he cited Sir Walter Scott, Hugh Miller, and a recent book by Mr. Sage, an Established Church minister, to show the suffering caused, and denounced the Duke of Sutherland (A. R., 1913, p. 262) for trying to get money out of the proposed redress of the wrong done by his ancestors. As to the discrepancy between the offer and the valuation for death[Pg 15] duties, "there had never been such a case since the days of Ananias and Sapphira." In 1748 the Duke of Sutherland had claimed compensation for the abolition of the right to hang his subjects; he asked for 10,000l. and got 1,000l. This was an instance of the patience with which the people had endured great injustice. Outside the Highlands hundreds of thousands of men were working for a wage barely keeping their families above privation, seeing their children die for lack of light, air, and space; in the cities there were quagmires of fermenting human misery; but the chariots of retribution were drawing nigh, and there would be elbow-room for the poor.

This speech incidentally led to a sharp controversy between the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Duke of Montrose, who pointed out that the land sold by him to the Corporation was sold at a price awarded on arbitration, and covering many items besides the value of the land, and that he had no interest in the Cathcart School or its site.

Two days earlier, the Earl of Derby, speaking at Liverpool, had elaborately and effectively rebutted attacks made by the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the management of the Bootle estate, and, in view of a statement by Baron de Forest in a memorandum attached to the Land Report (A. R., 1913, p. 212) that the value of the site of Bootle had risen from 7,000l. in 1724 to three or four millions in 1913, he had offered the estate to Baron de Forest for 1,500,000l. The Baron accepted, on condition that the transfer should include all sums realised since 1724 by sales, fines, or mortgages—a condition which terminated the negotiations, though not the epistolary controversy.

The day before the Chancellor of the Exchequer had appeased the single-taxers, the Foreign Secretary had again disquieted the Liberal advocates of naval reduction at a dinner given him by the Manchester Chamber of Commerce (Feb. 3). Beginning with a reference to the Lancashire cotton industry and the promotion of trade by the Consular service, he said that one duty of the Foreign Office was to keep open the world's markets; but further difficulties might be raised by the effort to do so—in Persia, for example—and the Great Powers could not as yet interfere to prevent war without the danger of an outbreak of war among themselves. Happily in the Balkan War the Great Powers had left the settlement in the main to the States concerned, and had preserved peace among themselves. British policy, throughout, had made for peace. But trade was damaged, not only by war, but by the waste involved in armament expenditure. A slackening by one country, however, would rather stimulate the others than cause them to slacken; British naval expenditure was a great factor in that of Europe, but the forces making for increase were beyond control. To reduce the British naval programme would probably produce no response in Europe; at any rate, it[Pg 16] would be staking too much on a gambling chance. England, though she felt the financial strain the least, was calling out against this expenditure, because, as business men, Englishmen were shocked by the waste and apprehensive of its effect on the credit of Europe. She had several times proposed reduction by consent, but had met with no response. The only schoolmaster for other Powers was finance, and he thought at no distant date it might begin to be effectual. He closed with a reference to the great traditions of the Manchester School, and an expression of hope for the solution of the current problems of industrial discontent.

The outlook in Europe had been improved, and the position of Great Britain strengthened, by the reception of the British Note to the Powers on the solution of the Near Eastern problem (A. R., 1913, p. 357; For. Hist., Chap. III.); but the case for reduction of naval expenditure had been weakened by the Canadian Premier's announcement (Jan. 20), that he would not proceed with his naval policy till after a general election. Nevertheless, a strong feeling in favour of economy was exhibited in many quarters, notably by the Chambers of Commerce of Manchester, Bradford, and Burnley, and at public meetings at Manchester and elsewhere. A meeting to advocate reduction at Queen's Hall, London (Feb. 3), was addressed by Sir Herbert Leon (chairman), the Bishop of Hereford, Lord Courtney of Penwith, and Mr. Ponsonby, M. P. The chairman said it was folly to pay such a rate of insurance against an impossible catastrophe; the Bishop of Hereford feared that some Government departments were affected with the poison of Jingo Imperialism; Lord Courtney of Penwith denounced the "armaments gang," and suggested that Great Britain might renounce all notions of alliances, and get rid even of the elusive aspect of ententes; and Mr. Ponsonby ridiculed the futile diplomacy of the First Lord in proposing a naval holiday in a party platform speech. On the other hand, a meeting called at the request of a thousand business men in the City of London (Feb. 9) assured the Government of the support of the commercial community in any measures necessary to secure the supremacy of the British Navy and the adequate protection of the trade routes of the Empire. The Lord Mayor presided, and the non-party character of the meeting was exhibited by the circumstance that Lord Southwark, a former Liberal whip, moved the main resolution, and the Hon. Thomas Mackenzie, Agent-General for New Zealand, supported it.

Speaking at the annual dinner of the Birmingham Jewellers' and Silversmiths' Association (Feb. 7), Mr. Austen Chamberlain expressed his grave misgiving at the outlook for the session. The Parliament Act, he said, paralysed the discussion for the first two years of measures placed under it, and the desire for the reduction of naval expenditure was unshared by any responsible person who[Pg 17] had access to the real history of the past two years. Foreign policy had happily been kept outside party, the Government accepting the policy of its predecessors. The Foreign Secretary should take the House and the people more into his confidence, to ensure that they should be united in a great emergency, and should give a reasoned review of the position in relation to the affairs of the world such as that accorded by the Foreign Ministers of other Great States to Parliaments to which they were less responsible than the British Foreign Secretary was to that of Great Britain.

To return to domestic politics, the friction set up by the Insurance Act seemed to be gradually abating; and the results of the Act were set forth by the Chancellor of the Exchequer at a complimentary non-political dinner to Dr. Addison, Liberal M. P. for Hoxton, organised by members of the medical profession, at the Hotel Metropole on February 6. After eulogising Dr. Addison's services in effecting, with Sir George Newnes, the medical treatment of school-children and State provision for medical research, he laid stress on Dr. Addison's aid, coupled with absolute loyalty to his profession, during the struggle with the medical men (A. R., 1913, pp. 2, 49). There were now, including doctors on more than one panel under the same Insurance Committee, over 20,000 general practitioners on the panels out of 22,500 in Great Britain; nearly 4,500,000l. had been distributed among them, and the average for each was 230l., rising in London to 330l. and in Birmingham to 380l. Besides this there was 933,000l. for drugs, and a balance of 310,000l. unallotted as between doctors and chemists. That was for only one-third of the population. Millions of people must before the Act have been without medical attendance. A locum tenens had previously received two guineas a week, now he received eight, nine, or even twelve. Assistants had received 120l. with board and lodging, or 180l. without them, now they got 200l. and 250l. respectively, or even more. That was the settlement which was to ruin the profession. They were at last getting a survey of the health of the nation such as they had never had before.

But the supreme problem was still Home Rule; and the Nationalist position had again been emphasised by Mr. John Redmond at a dinner given him by the National Liberal Club on February 6, the first time the club had officially entertained a leader of the Nationalist party in Parliament. He declared that the Unionist opposition to the Home Rule Bill was essentially directed against the Parliament Act: the Unionists, he believed, would be Home Rulers to-morrow if it suited their party interests, and he referred to Lord Carnarvon's historic interview with Mr. Parnell in 1885, and to the Constitutional Conference of 1910. Even in 1911 a Tory paper had stated that there was much to be said for the principle of Home Rule under the name of federation, devolution, and self-government. The Unionists, however, had[Pg 18] to fall back on Ireland for a policy and a party cry, though the principle of self-government had been bitterly opposed by their predecessors for Canada and for South Africa, and they disliked it for Ireland, having an ingrained belief in the inferiority of the Irish race. But the Irish would no longer submit to be made the pawns and playthings of British parties. Were the Home Rule Bill killed, Ireland would be absolutely ungovernable under the old regime. The issue was whether the will of Parliament, of Ireland, and of the Empire, was to be overborne by a threat of civil war from a minority in one province. As Mr. Balfour had said in 1902, civilised government on such terms was impossible. But the Nationalists were passionately desirous to avoid conflict with any section of their own countrymen; they wanted Ireland to be one nation; and, consistently with an Irish Parliament with an Executive responsible to it, and consistently with the integrity of Ireland, he could conceive of no reasonable length to which he would not be prepared to go to meet even the unreasonable fears of a section of his countrymen for the sake of an agreement. But any concession must be as the price to be paid for consent to an agreement; if no agreement was come to, the Bill must go through as it stood.

Speaking two days later at Longford, Mr. Devlin again promised every possible concession to the fears of the Protestants, short of the abandonment of Home Rule, and expressed his belief in an early Nationalist victory which would bring Ireland peace and goodwill. A compromise was suggested in a pamphlet by Mr. F. S. Oliver ("Pacificus") and an unnamed collaborator—viz. suspension of the Home Rule Bill, which gave Ireland more powers than she would have as a State in a Federation, until a Federal system should be created for the United Kingdom in which she should be treated like England and Scotland. But a more appropriate and impressive contribution to the controversy was made by Sir Horace Plunkett—who had just visited Ulster in the interest of peace—in a lengthy communication to The Times (Feb. 10). Each side, he said, misunderstood the other. The Government and the Liberal party regarded the Parliament Act as designed to overcome the hostility of the House of Lords to Liberal measures; those passed under it were being passed in order to clear the ground for social reform; the Ulster Unionists believed that the Parliament Act was passed solely with a view to Home Rule and under Nationalist dictation; and they would fight rather than submit to what they regarded as an incapable and priest-ridden Nationalist majority. If the Bill passed in the coming session there would be either civil war or sectarian outrages, possibly leading to retaliation. Objecting both to "Home Rule within Home Rule" and to the exclusion of Ulster, as tending to impair the solidarity of Ireland, he suggested that the Ulster Unionists should accept the Bill under three conditions: (1) A de[Pg 19]finite area of Ulster should have a right to secede, after a term of years, the decision to be by plebiscite in it; (2) both Nationalists and Unionists, preferably in conference, should be invited to suggest amendments to be incorporated in the Bill by consent; (3) the Ulster Volunteers should be allowed to become a Territorial Force, partly as an ultimate safeguard for the Ulster Unionists. He laid stress on the other issues which made a settlement of the Home Rule controversy imperative—the growing unrest among the masses, the education on the Continent and in India, and the danger involved by "the reopening of Irish sores" to Anglo-American relations and the consolidation of the Empire.

And so the questions were set for the first period of the session. Home Rule stood in the foreground, with some sort of compromise as to the treatment of Ulster, though the nature of the compromise divided both parties in both islands; then followed increased naval expenditure; and, in the background, Welsh disestablishment, the Plural Voting Bill, reform of the House of Lords, and Social legislation. All these questions might easily widen the rifts which seemed to be beginning in the ranks of the Ministerialists; but there was no indication that the Unionists could produce a practicable programme, or unite in its support. Still, their organisation was understood to be preparing for a general election, to take place in May; but the Ministry were certain not to concede it, partly because they held that the electors did not demand it, partly because the concession of it would nullify the Parliament Act. Nor could they amend the Home Rule Bill except by fresh legislation, or by suggestions accepted by the House of Lords. If otherwise amended, it would lose the benefit of the Parliament Act, by becoming a different Bill from that of 1912 and 1913.

In spring-like weather and brilliant sunshine the King, accompanied by the Queen, drove in state to open Parliament on Tuesday, February 10. The crowds on the route were greater than usual, and the occasion was marked by no untoward incident, suffragist or otherwise. The ceremony in the House of Lords was even more numerously attended and more brilliant than in former years, and the King's Speech was listened to with profound attention, rewarded by the significant paragraph, read by His Majesty in measured tones, dealing with Home Rule.

The Speech opened with the usual statement that relations with foreign Powers continued friendly, and went on to express pleasure at the King's coming visit to the French President, and to the opportunity thereby afforded him of testifying to the cordial[Pg 20] relations existing between the two countries. Reference was next made to the recent consultation with the other Powers respecting the settlement of Albania and the Ægean Islands, with the view of giving effect to resolutions adopted by the Powers during the Ambassadors' Conference in London, and to the measures adopted for erecting the new administration in Albania. The Baghdad Railway and Persian Gulf problems were, it was intimated, likely to be solved satisfactorily. Gratification was expressed at the signature of the Convention on the safety of life at sea, and a Bill carrying out its provisions was promised; and regret at the drought, fortunately limited in area, in India. The Estimates were promised, without the usual reference to economy. The Bills to be passed under the Parliament Act were dealt with as follows:—

"My Lords and Gentlemen,—The measures in regard to which there were differences last session between the two Houses will be again submitted to your consideration. I regret that the efforts which have been made to arrive at a solution by agreement of the problems connected with the Government of Ireland have, so far, not succeeded. In a matter in which the hopes and the fears of so many of my subjects are keenly concerned, and which, unless handled now with foresight, judgment, and in the spirit of mutual concession, threatens grave future difficulties, it is my most earnest wish that the goodwill and co-operation of men of all parties and creeds may heal dissension and lay the foundations of a lasting settlement."

Bills were also promised reconstituting the Second Chamber; carrying into effect those recommendations of the Royal Commission on Delay in the King's Bench Division which required the concurrence of Parliament; providing for Imperial naturalisation (prepared in consultation with the Dominion Governments); authorising public works loans to the Governments of the East African Protectorates; dealing with housing, national education, juvenile offenders; and, should time and opportunity permit, providing for other purposes of social reform. The Speech concluded with the usual invocation of the Divine blessing.

In both Houses the Opposition had determined to emphasise the gravity of the situation in Ulster by at once moving an amendment to the Address, humbly representing "that it would be disastrous to proceed further with the Government of Ireland Bill until it has been submitted to the judgment of the people." There had been rumours of coming disorder in the Commons; but they were falsified. Mr. Long (U., Strand) moved this amendment, after the Address had been moved by Mr. W. F. Roch (L., Pembroke) and seconded by Mr. Hewart (L., Leicester). Before Mr. Long rose the Speaker, in reply to Mr. Ramsay Macdonald (Lab., Leicester), ruled that the usual general debate might follow the impending discussion.

The debate covered much well-worn ground, but it resulted in a marked sense of relief. Mr. Long asked how the Opposition could consider the legislative programme of the Ministry in the face of a threatened civil war; but his speech was distinctly temperate. Incidentally he mentioned that there was grave anxiety in the Army and Navy, but he believed that the Unionists, whenever they had been asked, had advised the members of the Services to do their duty.

The Prime Minister, after reminding the House that when the Bill was introduced he had offered to consider further safeguards, if suggested, for Ulster, pointed out that in the earliest stages of the Parliament Bill it was contemplated that that measure should be applied to the Home Rule Bill (A. R., 1910, p. 87 seq.). The Unionists said that during the general election of 1910 Ministers had indulged in a gigantic system of mystification; he did not think that in all the annals of anthropology there had ever been a case in which a myth had so quickly crystallised into a creed. He himself had made it clear that the first use of the Parliament Act would be to carry the Home Rule Bill. The recent bye-elections showed a somewhat increased majority for Home Rule. The average elector was not seriously excited. A dissolution would admit that, so far as concerned Home Rule—the Parliament Act was an absolute nullity, and, of its three conceivable results, a stalemate would not improve the prospects of a solution, a Unionist majority would be faced with the problem of governing three-fourths or four-fifths of the Irish people against their will, and a Liberal victory would not lead the Ulstermen to drop their resistance. Would the Unionists, in that case, acquiesce in the passing unmutilated of the Government of Ireland Bill? He did not believe any such guarantee could be given. His conclusion was that if the matter was to be settled by a general agreement, it would be much better settled than by "a dissolution here and now." The King's Speech had mentioned the "conversations" between leaders; they were, and must remain, under the goal of confidence, The one satisfactory feature about them was that the Press had been completely at sea as to what was going on; and, though they had not resulted in any definite agreement, he did not despair. The language of the King's Speech ought to find an echo in every quarter of the Chamber. After touching on the proposed exclusion of Ulster, and Sir Horace Plunkett's plan (p. 18), he said that the Government recognised that they could not divest themselves of responsibility of initiative in the way of suggestion, but suggestions must not be taken as an admission that the Home Rule Bill was effective; they would be put forward as the price of peace,—meaning thereby not merely the avoidance of civil strife, but a favourable atmosphere for the start of the new system. There was nothing the Government would not do, consistently with their fundamental principles, to avoid civil war.[Pg 22] He agreed that there ought to be no avoidable delay, and the Governments when the necessary financial business had been disposed of, would submit suggestions to the House.

The debate was continued for some hours by Liberal and Unionist members. Mr. Austen Chamberlain was not very responsive to the Prime Minister's concessions; but Sir Edward Carson next day (Feb. 11) was more conciliatory. In an impressive speech, which later speakers recognised as contributing to the change in the situation, he emphasised the extreme gravity of the statement in the King's Speech, and the inability of the House to meet the situation by amending the Bill. The Prime Minister gave no indication of the steps proposed, and he thought the Government was manœuvring for position. Its proposals could only be made by an amending Bill. The insults offered to the Ulstermen had made a settlement far more difficult. Ulster must go on opposing the Bill to the end whatever happened; but if its exclusion were proposed, it would be his duty to go to Ulster at once and take counsel with the people there. But if the Ulstermen were to be compelled to come into a Dublin Parliament, he would, regardless of personal consequences, go on with them in their resistance to the end. The Government must either coerce Ulster, or try in the long run, by showing that good government could come under the Home Rule Bill, to win her over to the care of the rest of Ireland. He did not believe that Mr. Redmond wanted to triumph any more than he did, and one false step taken in relation to Ulster would render for ever impossible a solution of the Irish question. Hoping that peace would continue to the end, he declared that, if resistance became necessary, he would not refuse to join in it.