The Project Gutenberg EBook of Merrie England In The Olden Time, Vol. 2

(of 2), by George Daniel

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Merrie England In The Olden Time, Vol. 2 (of 2)

Author: George Daniel

Illustrator: John Leech

Robert Cruikshank

Thomas Gilks

Release Date: July 19, 2014 [EBook #46332]

Last Updated: March 15, 2018

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MERRIE ENGLAND ***

Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

My friends,”—continued Mr. Bosky, after an approving smack of the lips, and “Thanks, my kind mistress! many happy returns of St. Bartlemy!” had testified the ballad-singer's hearty relish and gratitude for the refreshing draught over which he had just suspended his well-seasoned nose, *—“never may the mouths be stopped—

* “Thom: Brewer, my Mus: Servant, through his proneness to

good fellowshippe, having attained to a very rich and

rubicund nose, being reproved by a friend for his too

frequent use of strong drinkes and sacke, as very pernicious

to that distemper and inflammation in his nose. 'Nay,

faith,' says he, 'if it will not endure sacke, it is no

nose for me.'”—L' Estrange, No. 578. Mr. Jenkins.

—(except with a cup of good liquor) of these musical itinerants, from whose doggrel a curious history of men and manners might be gleaned, to humour the anti-social disciples of those pious publicans who substituted their nasal twang for the solemn harmony of cathedral music; who altered St. Peter's phrase, 'the Bishop of your souls,' into 'the Elder (!!) of your souls;' for 'thy kingdom come,' brayed 'thy Commonwealth come!' and smuggled the water into their rum-puncheons, which they called wrestling with the spirit, and making the enemy weaker! 'Show me the popular ballads of the time, and I will show you the temper and taste of the people.' *

* “Robin Consciencean ancient ballad, (suggested by

Lydgate's “London Lackpenny,”) first printed at Edinburgh in

1683, gives a curious picture of London tradesmen, &c. Robin

goes to Court, but receives cold welcome; thence to

Westminster Hall. “It were no great matter,” quoth the

lawyers, “if Conscience quite were knock'd on the head.” He

visits Smithfield, and discovers how the “horse-cowrsers'

artfully coerce their “lame jades” to “run and kick.” Then

Long Lane, where the brokers hold conscience to be “but

nonsense.” The butter-women of Newgate-market claw him, and

the bakers brawl at him. At Pye Corner, a cook, glancing at

him “as the Devil did look o'er Lincoln,” threatens to spit

him.

The salesmen of Snow Hill would have stoned him; the

“fishwives” of Turn-again Lane rail at him; the London

Prentices of Fleet Street, with their “What lack you,

countryman?” seamper away from him. The “haberdashers, that

sell hats I the mercers and silk-men, that live in

Paternoster Row,” all set upon him. He receives no better

treatment in Cheapside—A cheesemonger in Bread Street; “the

lads that wish Lent were all the year,” in Fish Street; a

merchant on the Exchange; the “gallant girls,” whose “brave

shops of ware” were “up stairs and the drapers and

poulterers of Graccchurch Street, to whom conscience was

“Dutch or Spanish,” flout and jeer him. A trip to Southwark,

the King's Bench, and to the Blackman Street demireps,

proves that “conscience is nothing.” In St. George's Fields,

“rooking rascals,” playing at “nine pins,” tell him to prate

on till he is hoarse.” Espying a windmill hard by, he hies

to the miller, whose excuse for not dealing with him was,

that he must steal out of every bushel “a peek, if not three

gallons.” Conscience then trudges on “to try what would

befall i' the country,” whither we will not follow him.

I delight in a Fiddler's Fling, and revel in the exhilarating perfume of those odoriferous garlands * gathered on sunshiny holidays and star-twinkling nights, bewailing how disappointed lovers go to sea, and how romantic young lasses follow them in blue jackets and trousers!

* “When I travelled,” said the Spectator, “I took a

particular delight in hearing the songs and fables that are

come from father to son, and are most in vogue among the

common people of the countries through which I passed; for

it is impossible that anything should be universally tasted

and approved by a multitude (though they are only the rabble

of a nation), which hath not in it some peculiar aptness to

please and gratify the mind of man.”

Old tales, old songs, and an old jest,

Our stomachs easiliest digest.

“Listen to me, my lovly shepherd's joye,

And thou shalt heare, with mirth and muckle glee,

Some pretie tales, which, when I was a boye,

My toothless grandame oft hath told to mee.

Nay, rather than the tuneful race should be extinct, expect to see me some night, with my paper lantern and cracked spectacles, singing you woeful tragedies to love-lorn maids and cobblers' apprentices.” *

* Love in a Tub, a comedy, by Sir George Etherege.

And, carried away by his enthusiasm to the days of jolly Queen Bess, the Lauréat of Little Britain, with a countenance bubbling with hilarity, warbled con spirito, as a probationary ballad for the Itinerant ship, (!)

Elizabeth Tudor her breakfast would make

On a pot of strong beer and a pound of beefsteak,

Ere six in the morning was toll'd by the chimes—

O the days of Queen Bess they were merry old times!

From hawking and hunting she rode back to town,

In time just to knock an ambassador down;

Toy'd, trifled, coquetted, then lopp'd off a head;

And at threescore and ten danced a hornpipe to bed.

With Nicholas Bacon,1 her councillor chief,

One day she was dining on English roast beef;

That very same day when her Majesty's Grace *

Had given Lord Essex a slap on the face.

* When Queen Elizabeth came to visit Sir Nicholas Bacon,

Lord Keeper, at his new house at Redgrave, she observed,

alluding to his corpulency, that he had built his house too

little for him. “Not so, madam,” answered he; “but your

Highness has made me too big for my house!”

The term “your Grace' was addressed to the English Sovereign

during the earlier Tudor reigns. In her latter years

Elizabeth assumed the appellation of “Majesty” The following

anecdote comprehends both titles. “As Queen Elizabeth passed

the streets in state, one in the crowde cried first, 'God

blesse your Royall Majestie!' and then, 'God blesse your

Noble Grace!' 'Why, how now,' sayes the Queene, 'am I tenne

groates worse than I was e'en now?'” The value of the old

“Ryal,” or “Royall,” was 10s., that of the “Noble” 6s. Sd.

The Emperor Charles the Fifth was the first crowned head

that assumed the title of “Majesty.”

My Lord Keeper stared, as the wine-cup she kiss'd,

At his sovereign lady's superlative twist,

And thought, thinking truly his larder would squeak,

He'd much rather keep her a day than a week.

“What call you this dainty, my very good lord?”—

“The Loin,”—bowing low till his nose touch'd the

board—

“And—breath of our nostrils, and light of our eyes! *

Saving your presence., the ox was a prize.”

* Queen Elizabeth issued an edict commanding every artist

who should paint the royal portrait to place her “in a

garden with a full light upon her, and the painter to put

any shadow in her face at his peril!” Oliver Cromwell's

injunctions to Sir Peter Lely were somewhat different. The

knight was desired to transfer to his canvass all the

blotches and carbuncles that blossomed in the Protector's

rocky physiognomy. Sir Joshua Reynolds, ( ———— with

fingers so lissom, Girls start from his canvass, and ask us

to kiss 'em!) having taken the liberty of mitigating the

utter stupidity of one of his “Pot-boilers,” i. e. stupid

faces, and receiving from the sitter's family the reverse of

approbation, exclaimed, “I have thrown a glimpse of meaning

into this fool's phiz, and now none of his friends know

him!” At another time, having painted too true a likeness,

it was threatened to be thrown upon his hands, when a polite

note from the artist, stating that, with the additional

appendage of a tail, it would do admirably for a monkey, for

which he had a commission, and requesting to know if the

portrait was to be sent home or not, produced the desired

effect. The picture was paid for, and put into the fire!

“Unsheath me, mine host, thy Toledo so bright.

Delicious Sir Loin! I do dub thee a knight.

Be thine at our banquets of honour the post;

While the Queen rules the realm, let Sir Loin rule the

roast!

And'tis, my Lord Keeper, our royal belief,

The Spaniard had beat, had it not been for beef!

Let him come if he dare! he shall sink! he shall quake!

With a duck-ing, Sir Francis shall give him a Drake.

Thus, Don Whiskerandos, I throw thee my glove!

And now, merry minstrel, strike up 'highly Love,'

Come, pursey Sir Nicholas, caper thy best—

Dick Tarlton shall finish our sports with a jest.”

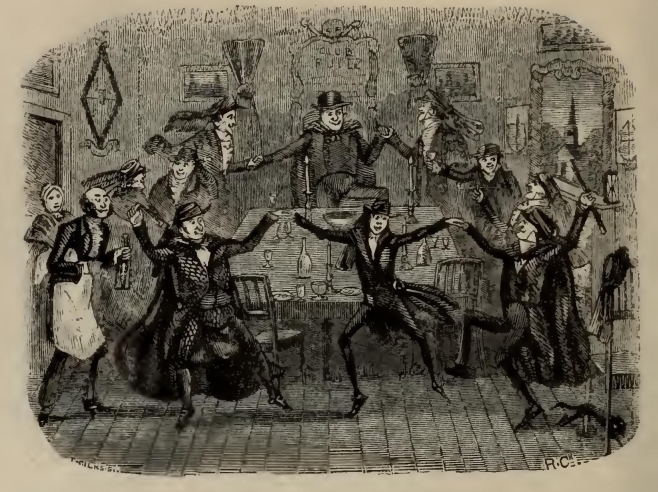

The virginals sounded, Sir Nicholas puff'd,

And led forth her Highness, high-heel'd and be-ruff'd—

Automaton dancers to musical chimes!

O the days of Queen Bess, they were merry old times!

“And now, leaving Nestor Nightingale to propitiate Uncle Timothy for this interpolation to his Merrie Mysteries, let us return and pay our respects, not to the dignified Count Haynes, the learned Doctor Haynes, but to plain Joe Haynes, the practical-joking Droll-Player of Bartholomew Fair: *

* Antony, vulgo Tony Aston, a famous player, and one of

Joe's contemporaries. The only portrait (a sorry one) of

Tony extant, is a small oval in the frontispiece to the

Fool's Opera, to which his comical harum-scarum

autobiography is prefixed.

In the first year of King James the Second, * our hero set up a booth in Smithfield Rounds, where he acted a new droll, called the Whore of Babylon, or the Devil and the Pope. Joe being sent for by Judge Pollixfen, and soundly rated for presuming to put the pontiff into such bad company, replied, that he did it out of respect to his Holiness; for whereas many ignorant people believed the Pope to be a blatant beast, with seven heads, ten horns, and a long tail, like the Dragon of Wantley's, according to the description of the Scotch Parsons! he proved him to be a comely old gentleman, in snow-white canonicals, and a cork-screw wig. The next morning two bailiffs arrested him for twenty pounds, just as the Bishop of Ely was riding by in his coach. Quoth Joe to the bailiffs, “Gentlemen, here is my cousin, the Bishop of Ely; let me but speak a word to him, and he will pay the debt and charges.”

* Catholicism, though it enjoined penance and mortification,

was no enemy, at appointed seasons, to mirth. Hers were

merry saints, for they always brought with them a holiday. A

right jovial prelate was the Pope who first invented the

Carnival! On that joyful festival racks and thumbscrews,

fire and faggots, were put by; whips and hair-shirts

exchanged for lutes and dominos; and music inspired equally

their diversions and devotions.

The Bishop ordered his carriage to stop, whilst Joe (close to his ear) whispered, “My Lord, here are a couple of poor waverers who have such terrible scruples of conscience, that I fear they'll hang themselves.”—“Very well,” said the Bishop. So calling to the bailiffs, he said, “You two men, come to me to-morrow, and I'll satisfy you.” The bailiffs bowed, and went their way; Joe (tickled in the midriff, and hugging himself with his device) went his way too. In the morning the bailiffs repaired to the Bishop's house. “Well, my good men,” said his reverence, “what are your scruples of conscience?”—“Scruples!” replied the bailiffs, “we have no scruples, We are bailiffs, my Lord, who yesterday arrested your cousin Joe Haynes for twenty pounds. Your Lordship promised to satisfy us to-day, and we hope you will be as good as your word.” The Bishop, to prevent any further scandal to his name, immediately paid the debt and charges.

The following theatrical adventure occurred during his pilgrimage to the well-known shrine,

“Which at Loretto dwelt in wax, stone, wood.

And in a fair white wig look'd wondrous fine.”

It was St. John's day, and the people of the parish had built a stage in the body of the church, for the representation of a tragedy called the Decollation of the Baptist. * Joe had the good luck to enter just as the actors were leaving off their “damnable faces,” and going to begin.

* The Chester Mysteries, written by Randle or Ralph Hig-den,

a Benedictine of St. Werburg's Abbey in that city, were

first performed during the mayoralty of John Arneway, who

filled that office from 1268 to 1276, at the cost and

charges of the different trading companies therein. They

were acted in English (“made into partes and pagiantes”)

instead of in Latin, and played on Monday, Tuesday, and

Wednesday in Whitsun week. The companies began at the abbey

gates, and when the first pageant was concluded, the

moveable stage (“a high scaffolde with two rowmes; a higher

and a lower, upon four wheeles”) was wheeled to the High

Cross before the Mayor, and then onward to every street, so

that each street had its pageant. “The Harrowing of Hell” is

one of the most ancient Miracle Plays in our language. It is

as old as the reign of Edward the Third, if not older. The

Prologue and Epilogue were delivered in his own person by

the actor who had the part of the Saviour. In 1378, the

Scholars of St. Paul's presented a petition to Richard the

Second, praying him to prohibit some “inexpert people” from

representing the History of the Old Testament, to the

serious prejudice of their clergy, who had been at great

expense in order to represent it at Christmas. On the 18th

July, 1390, the Parish Clerks of London played Religious

Interludes at the Skinners' Well, in Clerkenwell, which

lasted three days. In 1409, they performed The Creation of

the World, which continued eight days. On one side of the

lowest platform of these primitive stages was a dark pitchy

cavern, whence issued fire and flames, and the howlings of

souls tormented by demons. The latter occasionally showed

their grinning faces through the mouth of the cavern, to the

terrible delight of the spectators! The Passion of Our

Saviour was the first dramatic spectacle acted in Sweden, in

the reign of King John the Second. The actor's name was

Lengis who was to pierce the side of the person on the

cross. Heated by the enthusiasm of the scene, he plunged his

lance into that person's body, and killed him. The King,

shocked at the brutality of Lengis, slew him with his

scimetar; when the audience, enraged at the death of their

favourite actor, wound up this true tragedy by cutting off

his Majesty's head!

They had pitched upon an ill-looking surly butcher for King Herod, upon whose chuckle-head a gilt pasteboard crown glittered gloriously by the candlelight; and, as soon as he had seated himself in a rickety old wicker chair, radiant with faded finery, that served him for a throne, the orchestra (three fifes and a fiddle) struck up a merry tune, and a young damsel began so to shake, her heels, that with the help of a little imagination, our noble comedian might have fancied himself in his old quarters at St. Bartholomew, or Sturbridge Fair. *

* Stourbridge, or Sturbridge Fair, originated in a grant

from King John to the hospital of lepers at that place. By a

charter in the thirtieth year of Henry the Eighth, the fair

was granted to the magistrates and corporation of Cambridge.

In 1613 it became so popular, that hackney coaches attended

it from London; and in after times not less than sixty

coaches plied there. In 1766 and 1767, the “Lord of the Tap,”

dressed in a red livery, with a string over his shoulders,

from whence depended spigots and fossetts, entered all the

booths where ale was sold, to determine whether it was fit

beverage for the visitors. In 1788, Flockton exhibited at

Sturbridge Fair. The following lines were printed on his

bills:—

“To raise the soul by means of wood and wire,

To screw the fancy up a few pegs higher;

In miniature to show the world at large,

As folks conceive a ship who 've seen a barge.

This is the scope of all our actors' play,

Who hope their wooden aims will not be thrown away!”

The dance over, King Herod, with a vast profusion of barn-door majesty, marched towards the damsel, and in “very choice Italian” (which the parson of the parish composed for the occasion, and we have translated) thus complimented her:

“Bewitching maiden I dancing sprite!

I like thy graceful motion:

Ask any boon, and, honour bright!

It is at thy devotion.”

The danseuse, after whispering to a saffron-complexioned crone, who played Herodias, fell down upon both knees, and pointing to the Baptist, a grave old farmer! exclaimed,

“If, sir, intending what you say,

Your Majesty don't flatter,——

I would the Baptist's head to-day

Were brought me in a platter.”

The bluff butcher looked about him as sternly as one of Elkanah's * blustering heroes, and, after taking a fierce stride or two across the stage to vent his royal choler, vouchsafed this reply,

* Elkanah Settle, the City Lauréat, after the Revolution,

kept a booth at Bartholomew Fair, where, in a droll, called

St. George for England, he acted in a dragon of green

leather of his own invention. In reference to the sweet

singer of “annual trophies” and “monthly wars” hissing in

his own dragon, Pope utters this charitable wish regarding

Colley,

“Avert it, heaven, that thou, my Cibber, e'er Shouldst wag a

serpent-tail in Smithfield Fair!”

“Fair cruel maid, recall thy wish,

O pray think better of it!

I'd rather abdicate, than dish

The cranium of my prophet.”

Miss still continued pertinacious and positive.

“Your royal word's not worth a fig,

If thus in flams you glory;

I claim your promise for my jig,

The Baptist's upper story.”

This satirical sally put the imperial butcher upon his mettle; he bit his thumbs, scratched his carrotty poll, paused; and, thinking he had lighted on a loop-hole, grumbled out with stiff-necked profundity,

“ A wicked oath, like sixpence crack'd,

Or pie-crust, may be broken.”

The damsel, however, was “down upon him” before he could articulate “Jack Robinson,” with

“But not the promise of a King,

Which is a royal token.”

This polished off the rough edges of his Majesty's misgivings, and the decollation of John the Baptist followed; but the good people, resolving to make their martyr some small amends, permitted his representative to receive absolution from a portly priest who stood as a spectator at one corner of the stage; while the two soldiers who had decapitated him in effigy, with looks full of contrition, threw themselves into the confessional, and implored the ghostly father to assign them a stiff penance to expiate their guilt. Thus ended this tragedy of tragedies, which, with all due deference to Joe's veracity, we suspect to have had its origin in Bartholomew Fair.

Joe Haynes shuffled off his comical coil on Friday, the 4th of April 1701. The Smithfield muses mourned his death in an elegy, * a rare broadside, with a black border, “printed for J. B. near the Strand, 1701.”

* “An Elegy on the Death of Mr. Joseph Haines, the late

Famous Actor in the King's Play-House,” &c. &c.

“Lament, you beaus and players every one,

The only champion of your cause is gone:

The stars are surly, and the fates unkind,

Joe Haines is dead, and left his Ass behind!

Ah, cruel fate! our patience thus to try,

Must Haines depart, while asses multiply?

If nothing but a player down would go,

There's choice enough besides great Haines the beau!

In potent glasses, when the wine was clear,

Thy very looks declared thy mind was there.

Awful, majestic, on the stage at sight,

To play (not work) was all thy chief delight:

Instead of danger and of hateful bullets,

Roast beef and goose, with harmless legs of pullets!

Here lies the Famous Actor, Joseph Haines,

Who, while alive, in playing took great pains,

Performing all his acts with curious art,

Till Death appear'd, and smote him with his dart.”

Thomas Dogget, the last of our triumvirate, was “a little lively sprat man.” He dressed neat, and something fine, in a plain cloth coat and a brocaded waistcoat. He sang in company very agreeably, and in public very comically. He was the Will Kempe of his day. He danced the Cheshire Round full as well as the famous Captain George, but with more nature and nimbleness. *

* Dogget had a sable rival. “In Bartholomew Fair, at the

Coach-House on the Pav'd Stones at Hosier-Lane-End, you

shall see a Black that dances the Cheshire Rounds, to the

admiration of all spectators.” Temp. William Third.

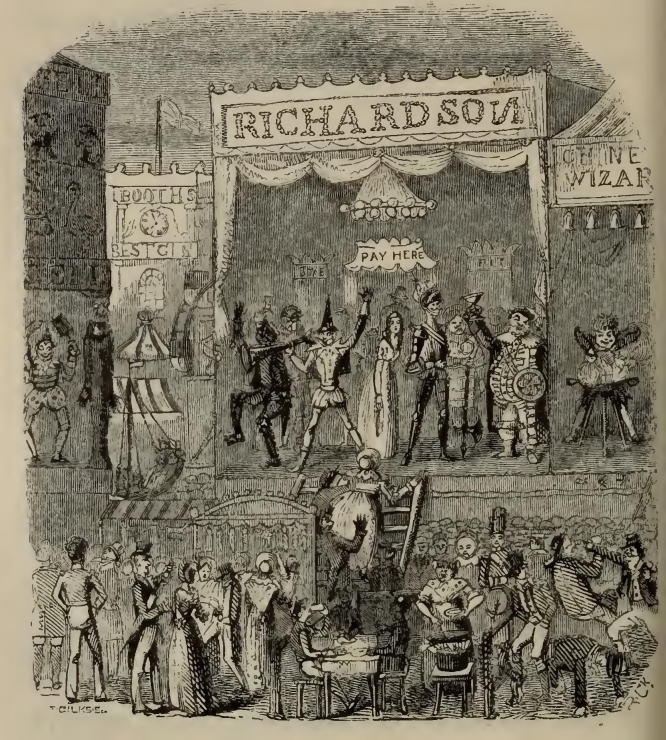

Here, too, is Dogget's own bill! “At Parker's and Dogget's

Booth, near Hosier-Lane-End, during the time of Bartholomew

Fair, will be presented a New Droll, called Fryar Bacon, or

the Country Justice; with the Humours of Tollfree the

Miller, and his son Ralph, Acted by Mr. Dogget. With variety

of Scenes, Machines, Songs, and Dances. Vivat Rex, 1691.”

A writer in the Secret Mercury of September 9, 1702, says, “At last, all the childish parade shrunk off the stage by matter and motion, and enter a hobbledehoy of a dance, and Dogget, in old woman's petticoats and red waistcoat, as like Progue Cock as ever man saw. It would have made a stoic split his lungs if he had seen the temporary harlot sing and weep both at once; a true emblem of a woman's tears!” He was a faithful, pleasant actor. He never deceived his audience; because, while they gazed at him, he was working up the joke, which broke out suddenly into involuntary acclamations and laughter. He was a capital face-player and gesticulator, and a thorough master of the several dialects, except the Scotch; but was, for all that, an excellent Sawney.

His great parts were Fondlewife, in the Old Bachelor; Ben, in Love for Love; Hob, in the Country Wake, &c. Colley Cibber's account of him is one glowing panegyric. Colley played Fondle wife so completely after the manner of Dogget, copying his voice, person, and dress with such scrupulous exactness, that the audience, mistaking him for the original, applauded vociferously. Of this Dogget himself was a witness, for he sat in the pit..

“Whoever would see him pictured, * may view him in the character of Sawney, at the Duke's Head in Lynn-Regis, Norfolk.” Will the jovial spirit of Tony Aston point out where this interesting memento hides its head? “Go on, I'll follow thee.” He died at Eltham in Kent, 22nd September 1721.

* The only portrait of Dogget known is a small print,

representing him dancing the Cheshire Round, with the motto

“Ne sut or ultra crepidam

** Baddeley, the comedian, bequeathed a yearly sum for ever,

to be laid out in the purchase of a Twelfth-cake and wine,

for the entertainment of the ladies and gentlemen of Drury

Lane Theatre.

How small an act of kindness will embalm a man's memory! Baddeley's Twelfth Cake ** shall be eaten, and Dogget's coat and badge * rowed for,

While Christmas frolics, and while Thames shall flow.

“And shall not,” said Mr. Bosky, “a bumper flow, in spite of the 'Sin of drinking healths?” ** to

Three merry men, three merry men,

Three merry men they be!

Two went dead, like sluggards, in bed;

One in his shoes died of a noose

That he got at Tyburn-Tree!

Three merry men, three merry men,

Three merry men are we!

Push round the rummer in winter and summer,

By a sea-coal fire, or when birds make a choir

Under the green-wood tree!

The sea-coal burns, and the spring returns,

And the flowers are fair to see;

But man fades fast when his summer is past,

Winter snows on his cheeks blanch the rose—

No second spring has he!

Let the world still wag as it will,

Three merry wags are we!

A bumper shall flow to Mat, Thomas, and Joe

A sad pity that they had not for poor Mat

Hang'd dear at Tyburn-Tree.

* “This day the Coat and Badge given by Mr. Dogget, will

be rowed for by six young watermen, out of their

apprenticeship this year, from the Old Swan at Chelsea.”—

Daily Advertiser, July 31, 1753.

** The companion books to the “Sin of Drinking healths,”

were the “Loathsomness of Long Haire,” and the “Unlove-

liness of Love Locks,” by Messrs. Praise-God-Barebones and

Fear-the-Lord Barbottle.

It would require a poetical imagination to paint the times when a gallant train of England's chivalry rode from the Tower Royal through Knight-rider Street and Giltspur Street (how significant are the names of these interesting localities, bearing record of their former glory!) to their splendid tournaments in Smithfield,—or proceeding down Long Lane, crossing the Barbican (the Specula or Watch-tower of Romanum Londinium), and skirting that far-famed street * where, in ancient times, dwelt the Fletchers and Bowyers, but which has since become synonymous with poetry—

* In Grub Street resided John Fox, the Martyrologist, and

Henry Welby, the English hermit, who, instigated by the

ingratitude of a younger brother, shut himself up in his

house for forty-four years, without being seen by any human

being. Though an unsociable recluse, he was a man of the

most exemplary charity.

—and poverty,—ambled gaily through daisy-dappled meads to Finsbury Fields, * to enjoy a more extended space for their martial exercises.

* In the days of Fitzstephen, Finsbury or Fensbury was one

vast lake, and the citizens practised every variety of

amusement on the ice. “Some will make a large cake of ice,

and, seating one of their companions upon it, they take hold

of one's hand, and draw him along. Others place the leg-

bones of animals under the soles of their feet, by tying

them round their ancles, and then, taking a pole shod with

iron into their hands, they push themselves forward with a

velocity equal to a bolt discharged from a crossbow.”

We learn from an old ballad called “The Life and Death of

the Two Ladies of Finsbury that gave Moorfields to the city,

for the maidens of London to dry their cloaths,” that Sir

John Fines, “a noble gallant knight,” went to Jerusalem to

“hunt the Saracen through fire and flood,” but before his

departure, he charged his two daughters “unmarried to

remain,” till he returned from “blessed Palestine.” The

eldest of the two built a “holy cross at 'Bedlam-gate,

adjoining to Moorfield and the younger “framed a pleasant

well,” where wives and maidens daily came to wash. Old Sir

John Fines was slain; but his heart was brought over to

England from the Holy Land, and, after “a lamentation of

three hundred days,” solemnly buried in the place to which

they gave the name of Finesbury. When the maidens died “they

gave those pleasant fields unto the London citizens,

“Where lovingly both man and wife May take the evening air;

And London dames to dry their cloaths May hither still

repair!”

Then was Osier Lane (the Smithfield end of which is immortalised in Bartholomew Fair annals) a long narrow slip of greensward, watered on both sides by a tributary streamlet from the river Fleet, on the margin of which grew a line of osiers, that hung gracefully over its banks. Smithfield, once “a place for honourable justs and triumphs,” became, in after times, a rendezvous for bravoes, and obtained the title of “Ruffians' Hall” Centuries have brought no improvement to it. The modern jockeys and chaunters are not a whit less rogues than the ancient “horse-coursers,” and the many odd traits of character that marked its former heroes, the swash-bucklers, * are deplorably wanting in the present race of irregulars, who are monotonous bullies, without one redeeming dash of eccentricity or humour. The stream of time, that is continually washing away the impurities of other murky neighbourhoods, passes, without irrigating, Smithfield's blind alleys and the squalid faces of their inhabitants.

* In ancient times a serving-man carried a buckler, or

shield, at his back, which hung by the hilt or pommel of his

sword hanging before him. A “swash-buckler” was so called

from the noise he made with his sword and buckler to

frighten an antagonist.

Yet was it Merryland in the olden time,—and, forgetting the days, when an unpaved and miry slough, the scene of autos da fê for both Catholics and Protestants, as the fury of the dominant party rode religiously rampant, as such let us consider it. Pleasant is the remembrance of the sports that are past, which

To all are delightful, except to the spiteful!

To none offensive, except to the pensive;

yet if the pensiveness be allied to, “a most humorous sadness,” the offence will be but small.

At the “Old Elephant Ground over against Osier Lane, in Smithfield, during the time of the fair,” in 1682, were to be seen “the Famous Indian Water-works, with masquerades, songs, and dances,”—and at the Plough-Musick Booth (a red flag being hung out as a sign) the fair folks were entertained with antic-dances, jigs, and sarabands; an Indian dance by four blacks; a quarter-staff dance; the merry shoemakers; a chair-dance; a dance by three milkmaids, with the comical capers of Kit the Cowherd; the Irish trot; the humours of Jack Tars and Scaramouches; together with good wine, cider, mead, music, and mum.

Cross we over from “Osier Lane-end” (the modern H is an interpolation,) to the King's Head and Mitre Music Booth, “over against Long Lane-end.” Beshrew me, Michael Root, thou hast an enticing bill of fare—a dish of all sorts—and how gravely looketh that apathetic Magnifico William, by any grace, but his own, “Sovereign Lord” at the head and front of thy Scaramouches and Tumblers! To thy merry memory, honest Michael! and may St. Bartlemy, root and branch, flourish for ever!

“Michael Root, from the King's-head at Ratcliff-cross, and Elnathan Root, from the Mitre in Wapping, now keep the King's-head and Mitre Musick-Booth in Smithfield Rounds, where will be exhibited A dance between four Tinkers in their proper working habits, with a song in character; Four Satyrs in their Savage Habits present you with a dance; Two Tumblers tumble to admiration; A new Song, called A hearty Welcome to Bartholomew Fair; Four Indians dance with Castinets; A Girl dances with naked rapiers at her throat, eyes, and mouth; a Spaniard dances a saraband incomparably well; a country-man and a country-woman dance Billy and Joan; & young lad dances the Cheshire rounds to admiration; a dance between two Scaramouches and two Irishmen; a woman dances with sixteen glasses on the backs and palms of her hands, turning round several thousand times; an entry, saraband, jig, and hornpipe; an Italian posture-dance; two Tartarians dance in their furious habits; three antick dances and a Roman dance; with another excellent new song, never before performed at any musical entertainment.”

John Sleep, or Sleepe, was a wide-awake man in “mirth and pastime famous for his mummeries and mum; of a locomotive turn, and emulated the zodiac in the number of his signs. He kept the Gun, in Salisbury Court, and the King William and Queen Mary in Bartholomew Fair; the Rose, in Turnmill Street (the scene, under the rose! of Falstaff's early gallantries ); and the Whelp and Bacon in Smithfield Rounds. That he was a formidable rival to the Messrs. Root; a “positive” fellow, and a polite one; teaching his Scaramouches civility, (one, it seems, had made a hole in his manners!) and selling “good wines, &C.” let his comically descriptive advertisement to “all gentlemen and ladies” pleasantly testify.

“John Sleepe keepeth the sign of the King William and Queen Mary, in Smithfield Rounds, where all gentlemen and ladies will be accommodated with good wines, &c. and a variety of musick, vocal and instrumental; besides all other mirth and pastime that wit and ingenuity can produce.

“A little boy dances the Cheshire rounds; a young gentlewoman dances the saraband and jigg extraordinary fine, with French dances, that are now in fashion; a Scotch dance, composed by four Italian dancing-masters, for three men and a woman; a young gentlewoman dances with six naked rapiers, so fast, that it would amaze all beholders; a young lad dances an antick dance extraordinary finely; another Scotch dance by two men and one woman, with a Scotch song by the woman, so very droll and diverting, that I am positive did people know the comick humour of it, they would forsake all other booths for the sight of them.”

In the following bill Mr. Sleep becomes still more “wonderful and extraordinary—

“John Sleep now keeps the Whelp and Bacon in Smithfield Rounds, where are to be seen, a young lad that dances a Cheshire round to the admiration of all people, The Silent Comedy, a dance representing the love and jealousy of rural swains, after the manner of the Great Turk's mimick dances performed by his mutes; a lad that tumbles to the admiration of all beholders; a young woman that dances with six naked rapiers, to the wonderful divertisement of all spectators; & young man that dances after the Morocco fashion, to the wonderful applause of all beholders; a nurse-dance, by a woman and two drunkards, wonderful diverting to all people; a young man that dances a hornpipe the Lancaster way, extraordinary finely; a lad that dances a Punch, extraordinary pleasant and diverting; a grotesque dance, called the Speak-ing Movement, shewing in words and gestures the humours of a musick booth, after the manner of the Venetian Carnival; and a new Scaramouch, more civil than the former, and after a far more ingenious and divertinger way!”

Excellent well, somniferous John! worthy disciple of St. Bartlemy.

Green, at the “Nag's Head and Pide Bull,” advertises eight “comical and diverting” exhibitions; hinting that he hath “that within which passeth shew but declines publishing his “other ingenious pastimes in so small a bill.” Yet he contrives to get into this “small bill” as much puff as his contemporaries. His pretensions are as superlative as his Scaramouches, and quite as diverting. “A young man dances with twelve naked swords,” and “a young woman with six naked rapiers, after a more pleasant and far inge-niuser fashion than had been danced before.”

These Bartholomew Fair showmen are sadly deficient in gallantry. With them the “gentlemen” always take precedence of the “ladies.” The Smithfield muses should have taught them better manners.

Manager Crosse * “at the Signe of the George,” advertises a genuine Jim Crow, “a black lately from the Indies, who dances antic dances after the Indian manner.” In those days the grinning and sprawling of an ebony buffoon were confined to the congenial timbers of Bartlemy fair!

* Managers Crosse, Powell, Luffingham, &c. Temp. Queen Anne

and George I.

Was the “young gentlewoman with six naked rapiers” ubiquitous, or had she rivals in the Rounds? But another lady, no less attractive, “invites our steps, and points to yonder” booth—where, “By His Majesty's permission, next door to the King's Head in Smithfield, is to be seen a woman-dwarf, * but three foot and one inch ** high, born in Somersetshire, and in the fortieth year of her age.”

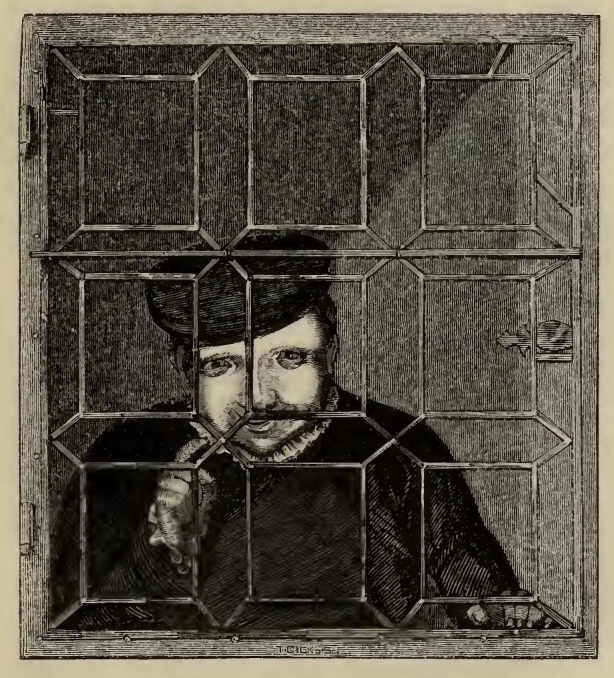

* “One seeing a Dwarfe at Bartholomew Fair, which was

sixteen inches high, with a great head, a body, and no

thighs, said he looked like a block upon a barber's stall:—

* 'No!' says another, 'when he speaks, he is like the Brazen

Head of Fryer Bacon's.'”—The Comedian's Tales, 1729.

** A few seasons after appeared “The wonderful and

surprising English dwarf, two feet eight inches high, born

at Salisbury in 1709; who has been shewn to the Royal

Family, and most of the Nobility and Gentry of Great

Britain.”

And, as if we had not seen enough of “strange creatures alive? mark the following “advertisement”:—

“Next door to the Golden Hart, in Smithfield, is to be seen a live Turkey ram. Part of him is covered with black hair, and part with white wool. He hath horns as big as a bull's; and his tail weighs sixty pounds! Here is also to be seen alive the famous civet cat, and one of the holy lambs curiously spotted all over like a leopard, that us'd to be offered by the Jews for a sacrifice. Vivat Rex.”

This Turkey ram's tail is a tough tale, * even for the ad libitum of Smithfield Rounds. Such a tail wagged before such a master must have exhibited the two greatest wags in the fair.

* “A certain officer of the Guards being at the New Theatre,

behind the scenes, was telling some of the comedians of the

rarities he had seen abroad. Amongst other things, he had

seen a pike caught six foot long. 'That 's a trifle,' says

the late Mr. Spiller, the celebrated actor, 'I have seen

half a pike in England longer by a foot, and yet not worth

twopence!'”

The Roots were under ground, or planted in a cool arbour, quaffing—not Bartlemy “good wines,” (doctors never take their own physic!)—but genuine nutbrown. Their dancing-days were over; for “Root's booth” (temp. Geo.I.) was now tenanted by Powell, the puppet-showman, and one Luf-fingham, who, fired with the laudable ambition of maintaining the laughing honours of their predecessors, issued a bill, at which we cry “What next?” as the sailor did when the conjuror blew his own head off.

“At Root's booth, Powell from Russell Court, and Luffingham from the Cyder Cellar, in Covent-Garden, now keep the King Charles's Head, and Man and Woman fighting for the Breeches, in Bartholomew Fair, near Long Lane: where two figures dance a Scaramouch after a new grotesque fashion; a little boy, five years old, vaults from a table twelve foot high on his head, and drinks the King's health standing on his head, with two swords at his throat; a Scotch dance by three men and a woman; an Irishwoman dances the Irish trot; Roger of Coventry is danced by one in a countryman's habit; a cradle dance, being a comical fancy between a woman and her drunken husband fighting for the breeches; a woman dances with fourteen glasses on the back of her hands full of wine. Also several entries, as Almands Pavans, Galliads, Gavots, English Jiggs, and the Sabbotiers dance, so mightily admired at the King's Playhouse. The company will be entertained with vocal and instrumental musick, as performed at the late happy Congress at Reswick, in the presence of several princes and ambassadors.”

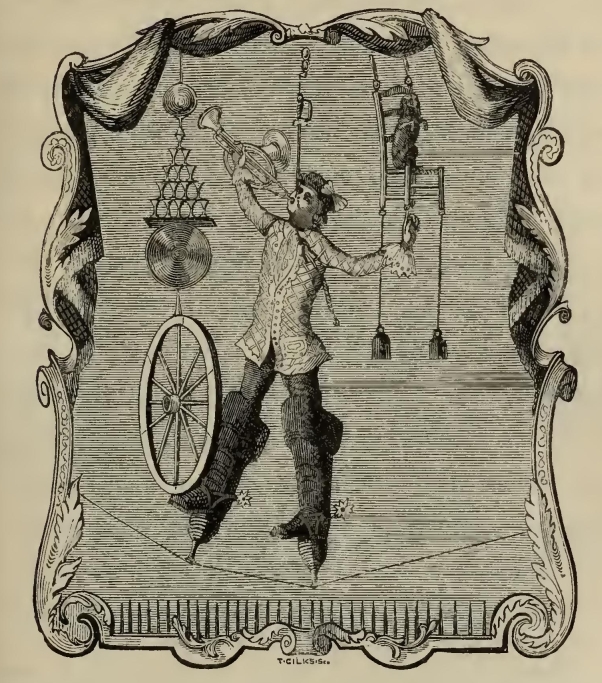

Here will I pause. For the present, we have supped full with Scaramouches. “Six naked rapiers” at my throat all night would be a sorry substitute for the knife and fork I hope to play anon, after a “more pleasant and far ingeniuser” fashion, with some plump roast partridges. A select coterie of Uncle Timothy's brother antiquaries have requested to be enlightened on Bartlemy fair lore. Will you, my friend Eugenio, during the Saint's saturnalia, join us in the ancient “Cloth quarter”? On, brave spirit! on. Rope-dancers invite thee; conjurors conjure thee; Punch squeaks thee a screeching welcome; mountebanks and posture-masters, * with every variety of physiognomical and physical contortion, lure thee to their dislocations.

* “From the Duke of Marlborough's Head in Fleet Street,

during the fair, is to be seen the famous posture-master,

who far exceeds Clarke and Higgins. He twists his body into

all deformed shapes, makes his hip and shoulder-bones meet

together, lays his head upon the ground, and turns his body

round twice or thrice without stirring his face from the

place.”—1711.

Fawkes's dexterity of hand; the moving pictures; Pinchbeck's musical clock; Solomon's Temple; the waxwork, all alive! the Corsican fairy; * the dwarf that jumps down his—

* “The Corsican Fairy, only thirty-four inches high, and

weighing but twenty-six pounds, well-proportioned and a

perfect beauty. She is to be seen at the corner of Cow-Lane,

during Bartholomew Fair.”—1743.

—own throat! * the High German Artist, born without hands or feet; ** the cow with Jive legs; the—

* “Lately arrived from Italy Signor Capitello Jumpedo, a

surprising dwarf, not taller than a common tobacco-pipe. He

will twist his body into ten thousand shapes, and then open

wide his mouth, and jump down his own throat! He is to be

spoke with at the Black Tavern, Golden Lane.” January 18,

1749. This is the renowned “Bottle Conjuror.” Some such

deception was practised either by himself, or an imitator,

at Bartholomew Fair.

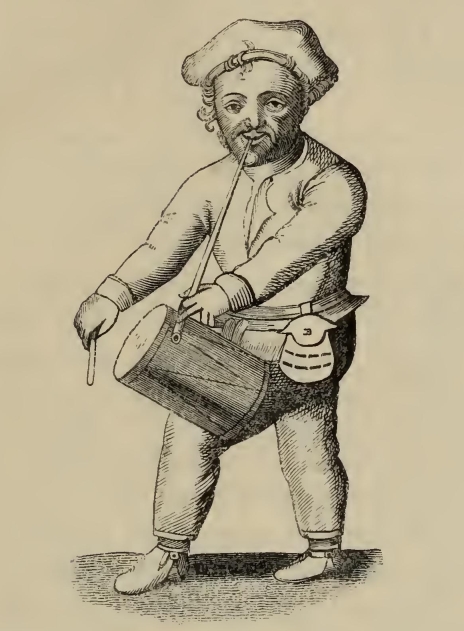

** “Mr. Mathew Buchinger, twenty-nine inches high, born

without hands or feet, June 2, 1674, in Germany, near Nu-

remburgh. He has been married four times, and has eleven

children. He plays on the hautboy and flute; and is no less

eminent for writing and drawing coats of arms and pictures,

to the life, with a pen. He plays at cards, dice, and nine-

pins, and performs tricks with cups, balls, and live birds.”

Every Jack has his Jill; and as a partner, not in a

connubial sense, my little Plenipo! we couple thee with

“The High German Woman, born without hands or feet, that

threads her needle, sews, cuts out gloves, writes, spins

fine thread, and charges and discharges a pistol. She is now

to be seen at the corner of Hosier Lane, during the time of

the fair.”—Temp. Geo. II.

Apropos of dwarfs—William Evans, porter to King Charles the

First, who was two yards and a half in height, “dancing in

an antimask at court, drew little Jeffrey the dwarf out of

his pocket, first to the wonder, then to the laughter of the

beholders.” Little Jeffrey's height was only three feet nine

inches. But even the gigantic William Evans, and George the

Fourth's tall porter whom we remember to have seen peep over

the gates of Carlton House, were nothing to the modern

American, who is so tall as to be obliged to go up a ladder

to shave himself!

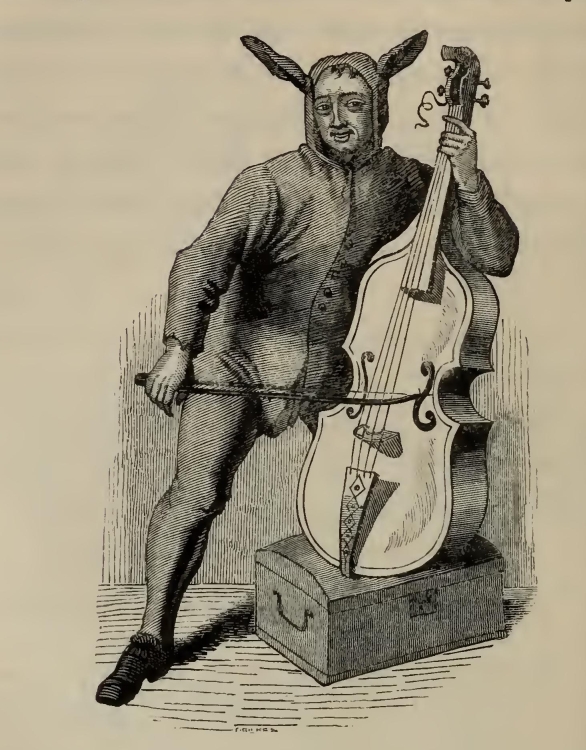

—hare that beats a drum; * the Savoyard's puppet-shew; the mummeries of Moorfields, ** urge thee forward on thy ramble of two centuries through Bartholomew Fair, which, like

'Th' adventure of the Bear and Fiddle

Is sung—but breaks off in the middle.'”

* Ben Jonson, in his play of Bartholomew Fair, mentions this

singular exhibition having taken place in his time; and

Strutt gives a pictorial description of it, copied from a

drawing in the Harleian collection (6563) said to be upwards

of four centuries old.

** Moorfields, spite of its “melancholy Moor Ditch” was

formerly famous for,

“Hills and holes, and shops for brokers,

Open sinners, canting soakers;

Preachers, doctors, raving, puffing,

Praying, swearing, solving, huffing,

Singing hymns, and sausage frying,

Apple roasting, orange shying;

Blind men begging, fiddlers drawling,

Raree-shows and children bawling—

Gingerbread! and see Gibraltar!

Humstrums grinding tunes that falter;

Maim'd and halt aloft are staging,

Bills and speeches mobs engaging;

'Good people, sure de ground you tread on,

Me did put dis voman's head on!'”

“The Flying Horse, a noted victualling house in Moor-fields,

next to that of the late Astrologer Trotter, has been

molested for several nights past, stones, and glass bottles

being thrown into the house, to the great annoyment and

terror of the family and guests.”—News Letter of Feb. 25,

1716.

As the Lauréat closed his manuscript, the door opened, and who should enter but Uncle Timothy.

“Ha! my good friends, what happy chance has brought you to the business abode and town Tusculum of the Boskys for half-a-dozen generations of Drysalters?”

“Something short of assault and battery, fine and imprisonment.”

And Mr. Bosky, after helping Uncle Timothy off with his great coat, warming his slippers, wheeling round his arm-chair to the chimney-corner, and seeing him comfortably seated, gave a detail of our late encounter at the Pig and Tinder-Box.

The old-fashioned housekeeper delivered a note to Mr. Bosky, sealed with a large black seal.

“An ominous looking affair!” remarked the middle-aged gentleman.

“A death's head and cross-bones!” replied the Lauréat of Little Britain. “'Ods, rifles and triggers! if it should be a challenge from the Holborn Hill Demosthenes.”

“A challenge! a fiddlestick!” retorted Uncle

Tim, “he's only a tame cheater!' Every bullet that he fires I 'll swallow for a forced-meat ball.” Mr. Bosky having broken the black seal, read out as follows:—

“Mr. Merripall presents his respectful services to Benjamin Bosky, Esq. and begs the favour of his company to dine with the High Cockolorum Club * of associated Undertakers at the Death's Door, Battersea Rise, to-morrow, at four. If Mr. Bosky can prevail upon his two friends, who received such scurvy treatment from a fraction of the Antiqueeruns, to accompany him, it will afford Mr. M. additional pleasure.”

* It may be curious to note down some of the odd clubs that

existed in 1745, viz. The Virtuoso's Club; the Knights of

the Golden Fleece; the Surly Club; the Ugly Club; the Split-

Farthing Club; the Mock Heroes Club; the Beau's Club; the

Quack's Club; the Weekly Dancing Club; the Bird-Fancier's

Club; the Chatter-wit Club; the Small-coal Man's Music Club;

the Kit-cat Club; the Beefsteak Club; all of which and many

more, are broadly enough described in “A Humorous Account of

all the Remarkable Clubs in London and Westminster.” In

1790, among the most remarkable clubs were, The Odd Fellows;

the Humbugs, (held at the Blue Posts, Russell Street, Covent

Garden,) the Samsonic Society; the Society of Bucks; the

Purl-Drinkers; the Society of Pilgrims (held at the

Woolpack, Kingsland Road); the Thespian Club; the Great

Bottle Club; the Je ne sçai quoi Club (held at the Star and

Garter, Pall Mall, and of which the Prince of Wales, and the

Dukes of York, Clarence, Orleans (Philip Egalité), Norfolk,

Bedford, &c. &c. were members); the Sons of the Thames

Society (meeting to celebrate the annual contest for

Dogget's Coat and Badge); the Blue Stocking Club; and the No

pay, no liquor Club, held at the Queen and Artichoke,

Hampstead Road, where the newly-admitted member, having paid

his fee of one shilling, was invested with the inaugural

honours, viz. a hat fashioned in the form of a quart pot,

and a gilt goblet of humming ale, out of which he drank the

healths of the brethren. In the present day, the Author of

Virginius has conferred classical celebrity on a club called

“The Social Villagers” held at the Bedford Arms, a merry

hostelrie at Camden Town.

It was at one of these festivous meetings that Uncle Timothy

produced the following Lyric of his own.

Fill, fill a bumper! no twilight, no, no!

Let hearts, now or never, and goblets o'erflow!

Apollo commands that we drink, and the Nine,

A generous spirit in generous wine.

The bard, in a bumper; behold, to the brim

They rise, the gay spirits of poesy—whim!

Around ev'ry glass they a garland entwine

Of sprigs from the laurel, and leaves from the vine.

A bumper! the bard who, in eloquence bold,

Of two noble fathers the story has told;

What pangs heave the bosom, what tears dim the eyes,

When the dagger is sped, and the arrow it flies.

The bard, in a bumper! Is fancy his theme?

'Tis sportive and light as a fairy-land dream;

Does love tune his harp? 'tis devoted and pure;

Or friendship? 'tis that which shall always endure.

Ye tramplers on liberty, tremble at him;

His song is your knell, and the slave's morning hymn!

His frolicksome humour is buxom and bland,

And bright as the goblet I hold in my hand.

The bard! brim your glasses; a bumper! a cheer!

Long may he live in good fellowship here.

Shame to thee, Britain, if ever he roam,

To seek with the stranger a friend and a home!

Fate in his cup ev'ry blessing infuse,

Cherish his fortune, and smile on his muse;

Warm be his hearth, and prosperity cheer

Those he is dear to, and those he holds dear.

Blythe be his autumn as summer hath been;—

Frosty, but kindly, and sweetly serene

Green be his winter, with snow on his brow;

Green as the wreath that encircles it now!

To dear Paddy Knowles, then, a bumper we fill,

And toast his good health as he trots down the hill;

In genius he 5s left all behind him by goles!

But he won't leave behind him another Pat Knowles!

“An unique invitation!” quoth Uncle Tim. “Gentlemen, you must indulge the High Coclcoorums, and go by all means.”

Mr. Bosky promised to rise with the lark, and be ready for one on the morrow; and, anticipating a good day's sport, we consented to accompany him.

Supper was announced, and we sat down to that social meal. In a day-dream of fancy, Uncle Timothy re-peopled the once convivial chambers of the Falcon and the Mermaid, with those glorious intelligences that made the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. the Augustan age of England. We listened to the wisdom, and the wit, and the loud laugh, as Shakspere and “rare Ben,” * in the full confidence of friendship, exchanged “thoughts that breathe, and words that burn,” so beautifully described by Beaumont in his letter to Jonson.

* “Shakespeare was god-father to one of Ben Jonson's

children, and after the christening, being in a deepe study,

Jonson came to cheere him up, and ask't him why he was so

melancholy? 'No, faith, Ben, (says he,) not I, but I have

been considering a great while what should be the fittest

gift for me to bestow upon my god-child, and I have resolv'd

at last.'—'I pr'y thee, what' says he,—'F faith, Ben, I'le

e'en give him a douzen good Lattin spoones, and thou shalt

translate them.'”—L'Estrange, No. 11. Mr. Dun.—Latten was

a name formerly used to signify a mixed metal resembling

brass. Hence Shakspere's appropriate pun, with reference to

the learning of Ben Jonson.

Many good jests are told of “rare Ben.” When he went to

Basingstoke, he used to put up his horse at the “Angel,”

which was kept by Mrs. Hope, and her daughter, Prudence.

Journeying there one day, and finding strange people in the

house, and the sign changed, he wrote as follows:—

“When Hope and Prudence kept this house, the Angel kept the

door;

Now Hope is dead, the Angel fled, and Prudence turn'd a w——!”

At another time he designed to pass through the Half Moon in

Aldersgate Street, but the door being shut, he was denied

entrance; so he went to the Sun Tavern at the Long Lane end,

and made these verses:—

“Since the Half Moon is so unkind,

To make me go about;

The Sun my money now shall have,

And the Moon shall go without.”

That he was often in pecuniary difficulties the following

extracts from Henslowe's papers painfully demonstrate. “Lent

un to Bengemen Johnson, player, the 28 of July, 1597, in

Redy money, the some of fower powndes, to be payed agayne

when so ever ether I, or any for me, shall demande yt,—

Witness E. Alleyn and John Synger.”—“Lent Bengemyne

Johnson, the 5 of Janewary, 1597-8, in redy money, the some

of Vs.”

“What things have we seen

Done at the Mermaid! heard words that have been

So nimble, and so full of subtle flame,

As if that every one from whom they came,

Had meant to put his whole wit in a jest!”

Travelling by the swift power of imagination, we looked in at Wills and Buttons; beheld the honoured chair that was set apart for the use of Dryden; and watched Pope, then a boy, lisping in numbers, regarding his great master with filial reverence, as he delivered his critical aphorisms to the assembled wits. Nor did we miss the Birch-Rod that “the bard whom pilfer'd pastoral renown” hung up at Buttons to chastise “tuneful Alexis of the Thames' fair side,” his own back smarting from some satirical twigs that little Alexis had liberally laid on! We saw St. Patrick's Dean “steal” to his pint of wine with the accomplished Addison; and heard Gay, Arbuthnot, and Boling-broke, in witty conclave, compare lyrical notes for the Beggar's Opera—not forgetting the joyous cheer that welcomed “King Colley” to his midnight troop of titled revellers, after the curtain had dropped on Fondle wife and Foppington. And, hey presto! snugly seated at the Mitre, we found Doctor Johnson, lemon in hand, demanding of Goldsmith, *—

* If ever an author, whether considered as a poet, a critic,

an historian, or a dramatist, deserved the name of a

classic, it was Oliver Goldsmith. His two great ethic poems,

“The Traveller,” and “The Deserted Village,” for sublimity

of thought, truth of reasoning, and poetical beauty, fairly

place him by the side of Pope. The simile of the bird

teaching its young to fly, and that beginning with “As some

tall cliffy” have rarely been equalled, and never surpassed.

For exquisite humour and enchanting simplicity of style, his

essays may compare with the happiest effusions of Addison;

and his “Vicar of Wakefield,” though a novel, has advanced

the cause of religion and virtue, and may be read with as

much profit as the most orthodox sermon that was ever

penned. As a dramatist, he excelled all his contemporaries

in originality, character, and humour. As long as a true

taste for literature shall prevail, Goldsmith will rank as

one of its brightest ornaments: for while he delighted the

imagination, and alternately moved the heart to joy or

sorrow, he “gave ardour to virtue and confidence to truth.”

A tale of woe was a certain passport to his compassion; and

he has given his last guinea to an indigent suppliant.

To Goldsmith has been imputed a vain ambition to shine in

company; it is also said that he regarded with envy all

literary fame but his own. Of the first charge he is

certainly guilty; the second is entirely false; unless a

transient feeling of bitterness at seeing preferred merit

inferior to his own, may be construed into envy. A great

genius seldom keeps up his character in conversation: his

best thoughts, clothed in the choicest terms, he commits to

paper; and with these his colloquial powers are unjustly

compared. Goldsmith well knew his station in the literary

world; and his desire to maintain it hi every society, often

involved him in ridiculous perplexities. He would fain have

been an admirable Crichton. His ambition to rival a

celebrated posture-master had once very nearly cost him his

shins. These eccentricities, attached to so great a man,

were magnified into importance; and he amply paid the tax to

which genius is subject, by being envied and abused by the

dunces of his day. Yet he wanted not spirit to resent an

insult; and a recreant bookseller who had published an

impudent libel upon him, he chastised in his own shop. How

delightful to contemplate such a character! If ever there

was a heart that beat with more than ordinary affection for

mankind, it was Goldsmith's.

—Garrick, * Boswell, and Reynolds, “Who's for poonch?”——

* Garrick was born to illustrate what Shakspere wrote;—to

him Nature had unlocked all her springs, and opened all her

stores. His success was instantaneous, brilliant, and

complete. Colley Cibber was constrained to yield him

unwilling praise; and Quin, the pupil of Betterton and

Booth, openly declared, “That if the young fellow was right,

he, and the rest of the players, had been all wrong.” The

unaffected and familiar style of Garrick presented a

singular contrast to the stately air, the solemn march, the

monotonous and measured declamation of his predecessors. To

the lofty grandeur of tragedy, he was unequal; but its

pathos, truth, and tenderness were all his own. In comedy,

he might be said to act too much; he played no less to the

eye than to the ear,—he indeed acted every word. Macklin

blames him for his greediness of praise; for his ambition to

engross all attention to himself, and disconcerting his

brother actors by “pawing and pulling them about.” This

censure is levelled at his later efforts, when he adopted

the vice of stage-trick; but nothing could exceed the ease

and gaiety of his early performances. He was the delight of

every eye, the theme of every tongue, the admiration and

wonder of foreign nations; and Baron, Le Kain, and Clairon,

the ornaments of the French Stage, bowed to the superior

genius of their illustrious friend and contemporary. In

private life he was hospitable and splendid: he entertained

princes, prelates, and peers—all that were eminent in art

and science. If his wit set the table in a roar, his

urbanity and good-breeding forbade any thing like offence.

Dr. Johnson, who would suffer no one to abuse Davy but

himself! bears ample testimony to the peculiar charm of his

manners; and, what is infinitely better, to his liberality,

pity, and melting charity. By him was the Drury Lane

Theatrical Fund for decayed actors founded, endowed, and

incorporated. He cherished its infancy by his munificence

and zeal; strengthened its maturer growth by appropriating

to it a yearly benefit, on which he acted himself; and his

last will proves that its prosperity lay near his heart,

when contemplating his final exit from the scene of life. In

the bright sun of his reputation there were, doubtless,

spots: transient feelings of jealousy at merit that

interfered with his own; arts that it might be almost

necessary to practise in his daily commerce with dull

importunate playwrights, and in the government of that most

discordant of all bodies, a company of actors. His grand

mistakes were his rejection of Douglass and The Good Na-

tured Man; and his patronage of the Stay-maker, and the

school of sentiment. As an author, he is entitled to

favourable mention: his dramas abound in wit and character;

his prologues and epilogues display endless variety and

whim; and his epigrams, for which he had a peculiar turn,

are pointed and bitter. Some things he wrote that do not add

to his fame; and among them are The Fribbleriad, and The

Sick Monkey. One of the most favourite amusements of his

leisure was in collecting every thing rare and curious that

related to the early drama; hence his matchless collection

of old plays, which, with Roubilliac's statue of Shakspere,

he bequeathed to the British Museum: a noble gift! worthy of

himself and of his country!

The 10th of June, 1776, was marked by Garrick's retirement

from the stage. With his powers unimpaired, he wisely

resolved (theatrically speaking) to die as he had lived,

with all his glory and with all his fame. He might have,

indeed, been influenced by a more solemn feeling—

“Higher duties crave

Some space between the theatre and grave;

That, like the Roman in the Capitol,

I may adjust my mantle, ere I fall,”

The part he selected upon this memorable occasion was Don

Felix, in the Wonder. We could have wished that, like

Kemble, he had retired with Shakspere upon his lips; that

the glories of the Immortal had hallowed his closing scene.

His address was simple and appropriate—he felt that he was

no longer an actor; and when he spoke of the kindness and

favours that he had received, his voice faltered, and he

burst into a flood of tears. The most profound silence, the

most intense anxiety prevailed, to catch every word, look,

and action, knowing they were to be his last; and the public

parted from their idol with tears for his love, joy for his

fortune, admiration for his vast and unconfined powers, and

regret that that night had closed upon them for ever.

Garrick had long been afflicted with a painful disorder. In

the Christmas of 1778, being on a visit with Mrs. Garrick at

the country seat of Earl Spencer, he had a recurrence of it,

which, after his return to London, increased with such

violence, that Dr. Cadogan, conceiving him to be in imminent

danger, advised him, if he had any worldly affairs to

settle, to lose no time in dispatching them. Mr. Garrick

replied, “that nothing of that sort lay on his mind, and

that he was not afraid to die.” And why should he fear? His

authority had ever been directed to the reformation, the

good order, and propriety of the Stage; his example had

incontestibly proved that the profession of a player is not

incompatible with the exercise of every Christian and moral

duty, and his well-earned riches had been rendered the mean

of extensive public and private benevolence. He therefore

beheld the approach of death, not with that reckless

indifference which some men call philosophy, but with

resignation and hope. He died on Wednesday, January 20th,

1779, in the sixty-second year of his age.

“Sure his last end was peace, how calm his exit!

Night dews fall not more gently to the ground,

Nor weary worn-out winds expire so soft.”

On Monday, February 1st, his body was interred with great

funeral pomp in Westminster Abbey, under the monument of the

divine Shakspere.

——“And Sir John Hawkins,” exclaimed Uncle Timothy, with unwonted asperity, “whose ideas of virtue never rose above a decent exterior and regular hours! calling the author of the Traveller an Idiot' It shakes the sides of splenetic disdain to hear this Grub Street chronicler * of fiddling and fly-fishing libelling the beautiful intellect of Oliver Goldsmith! Gentle spirit! thou wert beloved, admired, and mourned by that illustrious cornerstone of religion and morality, Samuel Johnson, who delighted to sound forth thy praises while living, and when the voice of fame could no longer soothe 'thy dull cold ear,' inscribed thy tomb with an imperishable record! Deserted is the village; the hermit and the traveller have laid them down to rest; the vicar has performed his last sad office; the good-natured man is no more—He stoops but to conquer!”

* The negative qualities of this sober Knight long puzzled

his acquaintances (friends we never heard that he had any! )

to devise an epitaph for him. At last they succeeded—

“Here lies Sir John Hawkins,

Without his shoes and stockings!”

The Lauréat, well comprehending an expressive look from his Mentor, rose to the pianoforte, and accompanied him slowly and mournfully in

Ah! yes, to the poet a hope there is given

In poverty, sorrow, unkindness, neglect,

That though his frail bark on the rocks may be driven,

And founder—not all shall entirely be wreck'd;

But the bright, noble thoughts, that made solitude sweet,

His world! while he linger'd unwillingly here,

Shall bid future bosoms with sympathy beat,

And call forth the smile and awaken the tear.

If, man, thy pursuit is but riches and fame;

If pleasure alluring entice to her bower;

The Muse waits to kindle a holier flame,

And woos thee aside for a classical hour.

And then, by the margin of Helicon's stream,

Th' enchantress shall lead thee, and thou from afar

Shalt see, what was once in life's feverish dream,

A poor broken spirit, * a bright shining star!——

Hail and farewell! to the Spirits of Light,

Whose minds shot a ray through this darkness of ours—

The world, but for them, had been chaos and night,

A desert of thorns, not a garden of flowers!

* Plautus turned a mill; Terenee was a slave; Boethius died

in a jail; Tasso was often distressed for a shilling; Benti-

voglio was refused admission into an hospital he had himself

founded; Cervantes died (almost) of hunger; Camoens ended

his days in an almshouse; Vaugelas sold his body to the

surgeons to support life; Burns died penniless,

disappointed, and heart-broken; and Massinger, Lee, and

Otway, were “steeped in poverty to the very lips.” Yet how

consoling are John Taylor the Water Poet's lines! Addressing

his friend, Wm. Fennor, he exclaims,

“Thou say'st that poetry descended is From poverty: thou

tak'st thy mark amiss—

In spite of weal or woe, or want of pelf,

It is a kingdom of content itself,!”

To the above unhappy list may be added Thomas Dekker the

Dramatist. “Lent unto the Company the 'of February, 1598, to

discharge Mr. Dicker out of the Counter in the Poultry, the

some of Fortie Shillinges.” In another place Mr. Henslowe

redeems Dekker out of the Clinke.

This was a subject that awakened all Uncle Timothy's enthusiasm!

“Age could not wither it, nor custom stale

Its infinite variety.”

But it produced fits of abstraction and melancholy; and Mr. Bosky knowing this, would interpose a merry tale or song. Upon the present occasion he made a bold dash from the sublime to the ridiculous, and striking up a comical voluntary, played us out of Little Britain.—

When I behold the setting sun,

And shop is shut, and work is done,

I strike my flag, and mount my tile,

And through the city strut in style;

While pensively I muse along,

Listening to some minstrel's song,

With tuneful wife, and children three—

O then, my love! I think on thee.

In Sunday suit, to see my fair

I take a round to Russell Square;

She slyly beckons while I peep.

And whispers, “down the area creep!”

What ecstacies my soul await;

It sinks with rapture—on my plate!

When cutlets smoke at half-past three—

And then, my love! I think on thee.

But, see the hour-glass, moments fly—

The sand runs out—and so must I!

Parting is so sweet a sorrow,

I could manger till to-morrow!

One embrace, ere I again

Homeward hie to Huggin Lane;

And sure as goose begins with G,

I then, my love! shall think on thee.

Mr. William Shakspere says

In one of his old-fashion'd plays,

That true love runs not smooth as oil—

Last Friday week we had a broil.

Genteel apartments I have got,

The first floor down the chimney-pot;

Mount Pleasant! for my love and me—

And soon one pair shall walk up three!

“Gentlemen,” said Uncle Timothy, as he bade us good night, “the rogue, I fear, will be the spoil of you, as he hath been of me!”

With the fullest intention to rise early the next morning, without deliberating for a mortal half-hour whether or not to turn round and take t' other nap, we retired to a tranquil pillow.

But what are all our good intentions?

Vexations, vanities, inventions!

Macadamizing what?—a certain spot,

To ears polite” politeness never mentions—

Tattoos, t' amuse, from empty drums.

Ah! who time's spectacles shall borrow?

And say, be gay to-day—to-morrow—

When query if to-morrow comes.

To-morrow came; so did to-morrow's bright sun; and so did Mr. Bosky's brisk knock. Good report always preceded Mr. Bosky, like the bounce with which champagne sends its cork out of the bottle! But (there are two sides of the question to be considered—the inside of the bed and the out!) they found us in much such a brown study as we have just described. Leaving the Lauréat to enjoy his triumph of punctuality, (an “alderman's virtue!”) we lost no time in equipping ourselves, and were soon seated with him at breakfast. He was in the happiest spirits. “'Tis your birthday, Eugenio! Wear this ring for my sake; let it be friendship's * talisman to unite our hearts in one. Here,” presenting some tablets beautifully wrought, “is Uncle Timothy's offering. Mark,” pointing to the following inscription engraved on the cover, “by what poetical alchemy he hath transmuted the silver into gold!”

* Bonaparte did not believe in friendship: “Friendship is

but a word. I love no one—no, not even my brothers; Joseph,

perhaps, a little. Still, if I do love him, it is from

habit, because he is the eldest of us. Duroc! Yes, Mm I

certainly love: but why? His character suits me: he is cold,

severe, unfeeling; and then, Duroc never weeps!” Bonaparte

counted his fortunate days by his victories, Titus by his

good actions.

“Friendship, peculiar boon of Heaven,

The noble mind's delight and pride,

To men and angels only given,

To all the lower world denied.”—Dr. Johnson.

Life is short, the wings of time

Bear away our early prime,

Swift with them our spirits fly,

The heart grows chill, and dim the eye.——

Seize the moment I snatch the treasure!

Sober haste is wisdom's leisure.

Summer blossoms soon decay;

“Gather the rose-buds while you may!”

Barter not for sordid store

Health and peace; nor covet more

Than may serve for frugal fare

With some chosen friend to share!

Not for others toil and heap,

But yourself the harvest reap;

Nature smiling, seems to say,

“Gather the rose-buds while you may!”

Learning, science, truth sublime,

Fairy fancies, lofty rhyme,

Flowers of exquisite perfume!

Blossoms of immortal bloom!

With the gentle virtues twin'd,

In a beauteous garland bind

For your youthful brow to-day,—

“Gather the rose-buds while you may!”

Life is short—but not to those

Who early, wisely pluck the rose.

Time he flies—to us 'tis given

On his wings to fly to Heaven.

Ah! to reach those realms of light,

Nothing must impede our flight;

Cast we all but Hope away!

“Gather the rose-buds while we may!”

Now a sail up or down the river has always been pleasant to us in proportion as it has proved barren of adventure. A collision with a coal-barge or steam-packet,—a squall off Chelsea Reach, may do vastly well to relieve its monotony: but we had rather be dull than be ducked. We were therefore glad to find the water smooth, the wind and tide in our favour, and no particular disposition on the part of the larger vessels to run us down. Mr. Bosky, thinking that at some former period of our lives we might have beheld the masts and sails of a ship, the steeple of a church, the smoke of a patent shot manufactory, the coal-whippers weighing out their black diamonds, a palace, and a penitentiary, forbore to expatiate on the picturesque objects that presented themselves to our passing view; and, presuming that our vision had extended beyond some score or two of garden-pots “all a-growing, all a-blow-ing,” and as much sky as would cover half-a-crown, he was not over profuse of vernal description. But, knowing that there are as many kinds of minds as moss, he opened his inquisitorial battery upon the waterman. At first Barney Binnacle, though a pundit among the wet wags of Wapping Old Stairs, fought shy; but there is a freemasonry in fun; and by degrees he ran through all the changes from the simple leer to the broad grin and horse-laugh, as Mr. Bosky “poked” his droll sayings into him. He had his predilections and prejudices. The former were for potations drawn from a case-bottle presented to him by Mr. Bosky, that made his large blue lips smack, and his eyes wink again; the latter were against steamers, the projectors of which he would have placed at the disposal of their boilers! His tirade against the Thames Tunnel was hardly less severe; but he reserved the magnums of his wrath for the Greenwich railroad. What in some degree reconciled us to Barney's anathemas, were his wife and children, to whom his wherry gave their daily bread: and though these gigantic monopolies might feather the nests of wealthy proprietors, they would not let poor Barney Binnacle feather either his nest or his oar.

“There's truth in what you say, Master Barney,” observed the Lauréat; “the stones went merrily into the pond, but the foolish frogs could not fish out the fun. I am no advocate for the philosophy of expediency.”

“Surely, Mr. Bosky, you would never think of putting a stop to improvement!”

“My good friends, I would not have man become the victim of his ingenuity—a mechanical suicide! Where brass and iron, hot water and cold, can be made to mitigate the wear and tear of his thews and sinews, let them be adopted as auxiliaries, not as principals. I am no political economist. I despise the muddle-headed dreamers, and their unfeeling crudities. But for them the heart of England would have remained uncorrupted and sound. * Trifle not with suffering. Impunity has its limit. A flint will show fire when you strike it.

* We quite agree with Mr. Bosky. Cant and utilitarianism

have produced an insipid uniformity of character, a money-

grubbing, care-worn monotony, that cry aloof to eccentricity

and whim. Men are thinking of “stratagems and wars,” the

inevitable consequence of lots of logic, lack of amusement,

and lean diet. No man is a traitor over turtle, or hatches

plots with good store of capon and claret in his stomach.

Had Cassius been a better feeder he had never conspired

against Cæsar. Three meals a day, and supper at night, are

four substantial reasons for not being disloyal, lank, or

lachrymose.

“In this world ninety-nine persons out of one hundred must toil for their bread before they eat it; ask leave to toil,—some philanthropists say, even before they hunger for it. I have therefore yet to learn how that which makes human labour a drug in the market can be called, an improvement. The stewardships of this world are vilely performed. What blessings would be conferred, what wrongs prevented, were it not for the neglect of opportunities and the prostitution of means. Is it our own merit that we have more? our neighbour's delinquency that he has less? The infant is born to luxury;—calculate his claims! Virtue draws its last sigh in a dungeon; Vice receives its tardy summons on a bed of down! The titled and the rich, the purse-proud nobodies, the noble nothings, occupy their vantage ground, not from any merit of their own; but from that lucky or unlucky chance which might have brought them into this breathing world with two heads on their shoulders instead of one! I believe in the theoretical benevolence, and practical malignity of man.”

We never knew Mr. Bosky so eloquent before; the boat became lop-sided under the fervent thump that he gave as a clencher to his oration. Barney Binnacle stared; but with no vacant expression.

His rugged features softened into a look of grateful approval, mingled with surprise.

“God bless your honour!”

“Thank you, Barney Some people's celestial blessings save their earthly breeches-pockets. But a poor mans blessing is a treasure of which Heaven keeps the register and the key.”

Barney Binnacle bent on Mr. Bosky another inquiring look, that seemed to say, “Mayhap I've got a bishop on board.”

“If every gentleman was like your honour,” replied Barney, “we should have better times; and a poor fellow wouldn't pull up and down this blessed river sometimes for days together, without yarning a copper to carry home to his hungry wife and children.” And he dropped his oar, and drew the sleeve of his threadbare blue jacket across his weather-beaten cheek.

This was a result that Mr. Bosky had not anticipated.