DECEMBER.

Vol. IV. No. 5

THE

INTERNATIONAL

MAGAZINE.

New-York:STRINGER & TOWNSEND.

1851.

J.W. ORR, N.Y.

| NAUVOO AND DESERET: THE MORMONS. Six Engravings, | 577 |

| WINDSOR CASTLE AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS. Two Engravings, | 585 |

| M. JULES GERARD AND THE BARON MUNCHAUSEN, IN AFRICA, | 587 |

| WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT, AND HIS WORKS: Portrait, | 588 |

| SLIDING SCALES OF DESPAIR, | 592 |

| DEATH IN YOUTH: By H. W. Parker, | 593 |

| A GERMAN HAND-BOOK OF AMERICA, | 593 |

| GONDOLETTAS: TWO SONGS: By Alice B. Neal, | 597 |

| THE DUTCH GOVERNORS OF NEW AMSTERDAM: By J. R. Brodhead, | 597 |

| AN AUTUMN BALLAD: By W. A. Sutliffe, | 598 |

| CARLYLE'S LIFE OF JOHN STERLING, | 599 |

| SONGS OF THE CASCADE: By A. Oakey Hall, | 602 |

| HERMAN MELVILLE'S NEW NOVEL OF "THE WHALE," | 602 |

| A STORY WITHOUT A NAME: By G. P. R. James. Concluded, | 604 |

| CALCUTTA: SOCIAL, INDUSTRIAL, POLITICAL.—Bentley's Miscellany, | 611 |

| REVOLUTIONS IN RUSSIA. By Alexander Dumas.—Sharpe's Magazine, | 616 |

| DRINKING EXPERIENCES: A Temperance Lecture by "Nimrod," | 621 |

| AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN SCENERY COMPARED: By the late J. F. Cooper, | 625 |

| A BULL FIGHT AT RONDA.—United Service Magazine, | 631 |

| VAGARIES OF THE IMAGINATION.—Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, | 638 |

| THE FRENCH FLOWER GIRL.—Dickens's Household Words, | 641 |

| THE THREE ERAS OF OTTOMAN HISTORY.—The Antheneum, | 643 |

| THE CAPTAIN AND THE NEGRO.—United Service Magazine, | 646 |

| THE VEILED PICTURE: A TRAVELLER'S STORY.—New Monthly Magazine, | 648 |

| THE SPENDTHRIFT'S DAUGHTER: In Six Chapters.—Household Words, | 664 |

| MY NOVEL: By Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton. Continued, | 683 |

| AUTHORS AND BOOKS: | |

| Pendant to Professor Creasy's Decisive Battles of the World, 693.—Correspondence respecting the Thirty Years' War, 693.—German collection of English Songs, 693.—German Philologists, 693.—Weil's History of the Califs, 693.—The Germans in Bohemia, 693.—Andree's Work on America, 694.—Works on Spinoza, 694.—New Gœthean Literature, 694.—The British Empire in Europe, by Meidinger, 694.—The Play of the Resurrection, 694.—German History of French Literature, 694.—New work on German Knighthood, &c., 694.—German Romance in the 18th Century, 695.—Madame Blaze de Bury's New Novel, 695.—Richter's History of the Evangelical German Churches, 695.—German Life of Sir Robert Peel, 695.—Zimmermann on the English Revolution, 695.—History of Norway, 695.—Reguly, the Hungarian Traveller, 695.—Political Notabilities of Hungary, 695.—Speeches, &c., by King William of Prussia, 695.—Pictures from the North, 695.—History of the Swiss Confederation, 695.—Bern's System of Chronology, by Miss Peabody, 695.—French Almanacs, 695.—M. Croce-Spinelli's Work on Popular Government, 696.—Works by the Paris Asiatic Society, 696.—Cæsar Daly on Parisian Architecture, 696.—Figuier's Modern Discoveries, 696.—The Annuaire des Deux Mondes, 696.—Calvin's Inedited Letters, 697.—Lacretelle, 697.—Critical Studies of Socialism, 697.—Memoirs of Mademoiselle Mars, 697.—The Institute of France, 697.—Grille, on the War in La Vendée, 697.—History of the Bourgeoisie of Paris, 697.—Archives des Missions Scientifiques, &c., 697.—Travels in Africa, 698.—Spirit of New Roman Catholic Literature, 698.—Gardin de Tassy on Mr. Salisbury's Unpublished Arabic Documents, 699.—New Travels in Palestine, 698.—The Abbadie Travellers, 699.—French, English, and American Missionaries, as Scholars, 699.—The Westminster Review, 690.—A Grandson of Robert Burns, 699.—Friends in Council, &c., by Mr. Helps, 699.—New English Announcements, 700.—New Dissenters' College, 700.—Sir Charles Lyell, and the "Free Thinkers," 700.—Professor Wilson, 700.—Miss Kirkland's Evening Book, 700.—Works by Mrs. Lee, 701.—Mr. Boyd's edition of Young's Night Thoughts, 702.—"Injustice to the South," 702.—Splendid American Gift Books for 1852, 703.—New American Works in Press, 703, &c. | |

| THE FINE ARTS: | |

| Leutze's Washington, 703.—Colossal Statue of Washington at Munich, 703.—Kaulbach's Frescoes, 703.—Cadame's Compositions of the Seasons, 703.—Portraits of Bishop White and Daniel Webster, 703. | |

| HISTORICAL REVIEW OF THE MONTH: | |

| The American Elections, 704.—Kossuth In England, 704.—Europe, and the East, 704. | |

| RECENT DEATHS: | |

| Archibald Alexander. D. D., 705.—J. Kearney Rogers, M. D., 705.—Rev. William Croswell, D. D., 706.—Granville Sharpe Pattison, M. D., 706.—Mr. Stephens, author of The Manuscripts of Erdely, 706.—Mr. Gutzlaff, the Missionary, 707.—Don Manuel Godoy, the Prince of the Peace, 708.—George Baker, 708.—M. De Savigny, 708.—Archbishop Wingard, 708.—Samuel Beaseley, author of The Roué, 708.—H. P. Borrell, 708.—James Tyler. R. D., 708.—Emma Martin, 709.—Yar Mohammed, 709.—Alexander Lee, 710.—Prince Frederick of Prussia, 710. | |

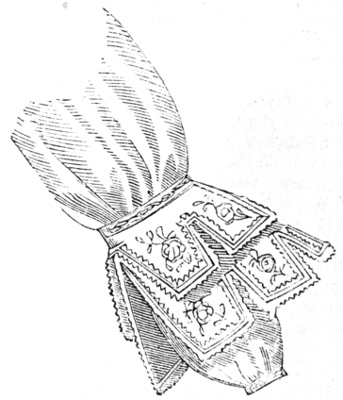

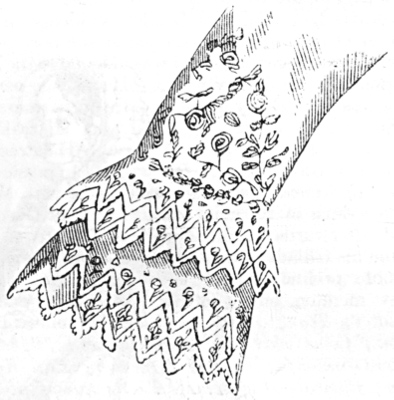

| GENTLEMEN'S AND LADIES FASHIONS FOR DECEMBER. Seven Engravings, | 718 |

THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE Of Literature, Art, and Science.

Vol. IV. NEW-YORK, DECEMBER 1, 1851. No. V.

IMPOSTURE AND HISTORY OF THE MORMONS.

Among the many extraordinary chapters in the history of the Nineteenth Century none will seem in the next age more incredible and curious than that in which is related the Rise and Progress of Mormonism. The creed of the Latter Day Saints, as they style themselves, is not, indeed, more absurd and ridiculous than that of the Millerites, but this last sect had but a very brief existence, and is now almost forgotten; while the imposture of Smith and his associates, commencing before Miller began his prophecies, is still successful, and represented by missionaries in almost every state throughout the world.

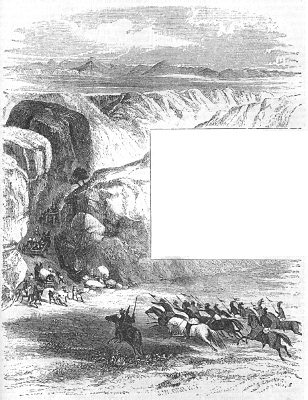

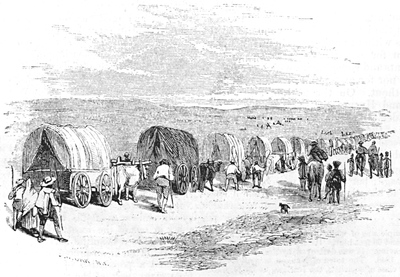

THE MORMON EXODUS: PASSING THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS.

It has been observed with some reason, that had a Rabelais or a Swift told the story of the Mormons under the veil of allegory, the sane portion of mankind would probably have entered a protest against the extravagance of the satirist. The name of the mock hero, his own and his family's ignorance and want of character, the low cunning of his accomplices, the open and shameless vices in which they indulged, and the extraordinary success of the sect they founded, would all have been thought too obviously conceived with a view to ludicrous effects. Yet the Mormon movement has assumed the condition of an important popular feature, and after much suffering and many reverses, its authors have achieved a condition of eminent industrial prosperity. In twenty years the company, consisting of the impostor and his father and brother, has increased to nearly half a million; they occupy one of the richest portions of this continent, have a regularly organized government, and are represented in the Congress of the United States by a delegate having all the powers usually conferred on the members for territories. With missions in every part of the country, in every capital of Europe, in Mecca, in Jerusalem, and among the islands of the Pacific and the Indian Oceans, all of whom are charged with the duty of making converts and gathering them to the Promised Land of Deseret, they must very soon have a population sufficiently large to claim admission as an equal member to the Union, and perhaps to hold the balance of power in its affairs.

To illustrate the energy and success with which their missions are prosecuted, we may cite the statement contained in a work just published in London, The Mormons, or Latter Day Saints, a Contemporary History, that more than fourteen thousand persons have left Great Britain since 1840 for the "Holy City." The emigrants passing through Liverpool in 1849, amounted to 2,500, generally of the better class of mechanics and farmers, and it was estimated that at least 30,000 converts remained behind. In June, 1850, there were in England and Scotland, 27,863, of whom London contributed 2,529; Liverpool, 1,018; Manchester, 2,787; Glasgow, 1,846; Sheffield, 1,920; Edinburgh, 1,331; Birmingham, 1,909; and Wales, 4,342. And the Mormon census was again taken last January, giving the entire number in the British Isles at 30,747. In fourteen years, more than 50,000 had been baptized in England, of whom nearly 17,000 had "emigrated to Zion." Although the Mormon emigration is commonly of the better class, there are also poor Mormons; and that these as well as their more prosperous brethren may be "gathered to the holy city," there is now amassed in Liverpool a very large fund, under the control of officers appointed by the "Apostles," destined exclusively for the equipment and transportation of converts to their place of Refuge.

The interest which recent events have attracted to the community in Deseret or Utah, will render interesting a more particular survey of its origin, progress, and condition.

In 1825 there lived near the village of Palmyra, in New-York, a family of small farmers of the name of Smith. They were of bad repute in the neighborhood, notorious for being continually in debt, and heedless of their business engagements. The eldest son, Joseph, says one of his friends, "could read without much difficulty, wrote a very imperfect hand, and had a very limited understanding of the elementary rules of arithmetic." Associated in some degree with Sidney Rigdon, who comes before us in the first place as a journeyman printer, he was the founder of the new faith. The early history of the conspiracy of these worthies is imperfectly known; but it is evident that Rigdon must have been in Smith's confidence from the first. Rigdon, indeed, probably had more to do with the matter than even Smith; but it was the latter who was first put conspicuously forward, and who managed to retain the pre-eminence. The account of the pretended revelation, as given by Smith, is as follows: He all at once found himself laboring in a state of great darkness and wretchedness of mind—was bewildered among the conflicting doctrines of the Christians, and could find no comfort or rest for his soul. In this state, he resorted to earnest prayer, kneeling in the woods and fields, and after long perseverance was answered by the appearance of a bright light in heaven, which gradually descended until it enveloped the worshipper, who found himself standing face to face with two supernatural beings. Of these he inquired which was the true religion? The reply was, that all existing religions were erroneous, but that the pure doctrine and crowning dispensation of Christianity should at a future period be miraculously revealed to himself. Several similar visitations ensued, and at length he was informed that the North American Indians were a remnant of Israel; that when they first entered America they were a powerful and enlightened people; that their priests and rulers kept the records of their history and doctrines, but that, having fallen off from the true worship, the great body of the nation were supernaturally destroyed—not, however, until a priest and prophet named Mormon, had, by heavenly direction, drawn up an abstract of their records and religious opinions. He was told that this still existed, buried in the earth, and that he was selected as the instrument for its recovery and manifestation to all nations. The record, it was said, contained many prophecies as to these latter days, and instructions for the gathering of the saints into a temporal and spiritual kingdom, preparatory to the second coming of the Messiah, which was at hand. After several very similar visions, the spot in which the book lay buried was disclosed. Smith[Pg 579] went to it, and after digging, discovered a sort of box, formed of upright and horizontal flags, within which lay a number of plates resembling gold, and of the thickness of common tin. These were bound together by a wire, and were engraved with Egyptian characters. By the side of them lay two transparent stones, called by the ancients, "Urim and Thummim," set in "the two rims of a bow." These stones were divining crystals, and the angels informed Smith, that by using them he would be enabled to decipher the characters on the plates. What ultimately became of the plates—if such things existed at all—does not appear. They were said to have been seen and handled by eleven witnesses. With the exception of three persons, these witnesses were either members of Smith's family, or of a neighboring family of the name of Whitmer. The Smiths, of course, give suspicious testimony. The Whitmers have disappeared, and no one knows any thing about them. Another witness, Oliver Cowdrey, was afterwards an amanuensis to Joseph; and another, Martin Harris, was long a conspicuous disciple. There is some confusion, however, about this person. Although he signs his name, as a witness who has seen and handled the plates, he assured Professor Anthon that he never had seen them, that "he was not sufficiently pure of heart," and that Joseph refused to show him the plates, but gave him instead a transcript on paper of the characters engraved on them. It is difficult to trace the early advances of the imposture. Every thing is vague and uncertain. We have no dates, and only the statements of the prophet and his friends.

Meantime, Smith must have worked successfully on the feeble and superstitious mind of Martin Harris. This man, as we have just said, received from him a written transcript of the mysterious characters, and conveyed it to Professor Anthon, a competent philological authority. Dr. Anthon's account of the interview is one of the most important parts of the entire history. Harris told him he had not seen the plates, but that he intended to sell his farm and give the proceeds to enable Smith to publish a translation of them. This statement, with what follows, shows that Smith's original intention, quoad the alleged plates, was to use them as a means for swindling Harris. The Mormons have published accounts of Professor Anthon's judgment on the paper submitted to him, which he himself states to be "perfectly false." The Mormon version of the interview represents Dr. Anthon "as having been unable to decipher the characters correctly, but as having presumed that, if the original records could be brought, he could assist in translating them." On this statement being made, Dr. Anthon described the document submitted to him as having been a sort of pot-pourri of ancient marks and alphabets. "It had evidently been prepared by some person who had before him a book containing various alphabets; Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters, inverted or placed sideways, were arranged in perpendicular columns, and the whole ended in a rude delineation of a circle, divided into various compartments, decked with numerous strange marks, and evidently copied after the Mexican Calendar given by Humboldt, but copied in such a way as not to betray the source whence it was derived." This account disposes of the statement that the characters were Egyptian, while the very jumble of the signs of different nations, languages, and ages, proves that the impostor was deficient both in tact and knowledge. The scheme seems to have been, at all events, in petto when Smith communicated with Harris; but a satisfactory clue to the fabrication is lost in our ignorance of the time and circumstances under which Smith and Rigdon came together. It must have been subsequent to that event that the "translation," by means of the magic Urim and Thummim, was begun. This work Smith is represented as having labored at steadily, assisted by Oliver Cowdrey, until a volume was produced containing as much matter as the Old Testament, written in the Biblical style, and containing, as Smith said the Angel had informed him, a history of the lost tribes in their pilgrimage to and settlement in America, with copious doctrinal and prophetic commentaries and revelations.

The devotion of Harris to the impostor secured a fund sufficient for defraying the cost of printing the pretended revelation, and the sect began slowly to increase. The doctrines of Smith were not at first very clearly defined; it is probable that neither he nor Rigdon had determined what should be their precise character; but like their early contemporary the prophet Matthias (the interesting history of whose career was published in New-York several years ago by the late Colonel Stone), they had no hesitation in deciding on one cardinal point, that the revelations made to Smith at any time should be received with unquestioning and implicit faith, and the earliest of these revelations contemplated a liberal provision for all the prophet's personal necessities. Thus, in February, 1831, it was revealed to the disciples that they should immediately build the prophet a house; on another occasion it was enjoined that, if they had any regard for their own souls, the sooner they provided him with food and raiment, and every thing he needed, the better it would be for them; and in a third revelation, Joseph was informed that "he was not to labor for his living." All these "revelations" were received, and though the impostor seemed to intelligent men little better than a buffoon, his followers soon learned to regard him as almost deserving of adoration, and he began to revel in whatever luxury and profligacy was most[Pg 580] agreeable to his vulgar taste and ambition. As in the case of the scarcely more respectable pretender, Andrew Jackson Davis, it was asserted that his original want of cultivation precluded the notion of his having by the exercise of any natural or acquired faculties produced his "revelations." Everywhere his followers said, "The prophet is not learned in a human sense: how could he have become acquainted with all the antiquarian learning here displayed, if it were not supernaturally communicated to him?" But to this question there was soon an answer equally explicit and satisfactory. The real author of the Book of Mormon was a Rev. Solomon Spaulding, who wrote it as a romance. Its entire history and the means by which it came into the possession of Smith are described, in the following statement, by Mr. Spaulding's widow:—

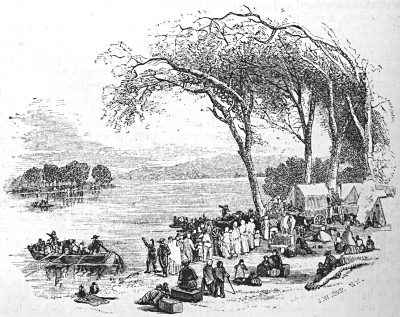

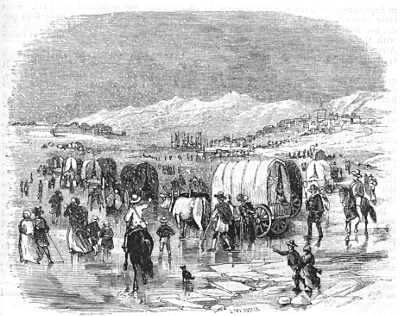

CROSSING THE MISSOURI.

"Since the Book of Mormon, or Golden Bible (as it was originally called), has excited much attention, and is deemed by a certain new sect of equal authority with the sacred Scriptures, I think it a duty to the public to state what I know of its origin.... Solomon Spaulding, to whom I was married in early life, was a graduate of Dartmouth college, and was distinguished for a lively imagination, and great fondness for history. At the time of our marriage, he resided in Cherry Valley, New York. From this place, we removed to New Salem, Ashtabula County, Ohio, sometimes called Conneaut, as it is situated on Conneaut Creek. Shortly after our removal to this place, his health failed, and he was laid aside from active labors. In the town of New Salem there are numerous mounds and forts, supposed by many to be the dilapidated dwellings and fortifications of a race now extinct. These relics arrest the attention of new settlers, and become objects of research for the curious. Numerous implements were found, and other articles evincing skill in the arts. Mr. Spaulding being an educated man, took a lively interest in these developments of antiquity; and in order to beguile the hours of retirement, and furnish employment for his mind, he conceived the idea of giving an historical sketch of the long-lost race. Their antiquity led him to adopt the most ancient style, and he imitated the Old Testament as nearly as possible. His sole object in writing this imaginary history was to amuse himself and his neighbors. This was about the year 1812. Hull's surrender at Detroit occurred near the same time, and I recollect the date well from that circumstance. As he progressed in his narrative, the neighbors would come in from time to time to hear portions read, and a great interest in the work was excited among them. It claimed to have been written by one of the lost nation, and to have been recovered from the earth; and he gave it the title of 'The Manuscript Found.' The neighbors would often inquire how Mr. Spaulding advanced in deciphering the manuscript; and when he had a sufficient portion prepared, he would inform them, and they would assemble to hear it read. He was enabled, from his acquaintance with the classics and ancient history, to introduce many singular names, which were particularly noticed by the people, and could be easily recognized by them. Mr. Solomon Spaulding had a brother, Mr. John Spaulding, residing in the place at the time, who was perfectly familiar with the work, and repeatedly heard the whole of it. From New Salem we removed to Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania. Here Mr. Spaulding found a friend and acquaintance, in the person of Mr. Patterson, an editor of a newspaper. He exhibited his manuscript to Mr. Patterson, who was much pleased with it, and borrowed it for perusal. He retained it a long time, and informed Mr. Spaulding that if he would make out a title-page and preface, he would publish it, and it might be a source of profit. This Mr. Spaulding refused to do. Sidney Rigdon, who has figured so largely in the history of the Mormons, was at that time connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson, as is well known in that region, and, as[Pg 581] Rigdon himself has frequently stated, became acquainted with Mr. Spaulding's manuscript, and copied it. It was a matter of notoriety and interest to all connected with the printing establishment. At length the manuscript was returned to its author, and soon after we removed to Amity, Washington county, where Mr. Spaulding died, in 1816. The manuscript then fell into my hands, and was carefully preserved. It has frequently been examined by my daughter, Mrs. M'Kenstry, of Monson, Massachusetts, with whom I now reside, and by other friends. After the Book of Mormon came out, a copy of it was taken to New Salem, the place of Mr. Spaulding's former residence, and the very place where the 'Manuscript Found' was written. A woman appointed a meeting there; and in the meeting read copious extracts from the Book of Mormon. The historical part was known by all the older inhabitants, as the identical work of Mr. Spaulding, in which they had all been so deeply interested years before. Mr. John Spaulding was present, and recognized perfectly the production of his brother. He was amazed and afflicted that it should have been perverted to so wicked a purpose. His grief found vent in tears, and he arose on the spot, and expressed to the meeting his sorrow that the writings of his deceased brother should be used for a purpose so vile and shocking. The excitement in New Salem became so great, that the inhabitants had a meeting, and deputed Dr. Philastus Hurlbut, one of their number, to repair to this place, and to obtain from me the original manuscript of Mr. Spaulding, for the purpose of comparing it with the Mormon Bible—to satisfy their own minds and to prevent their friends from embracing an error so delusive. This was in the year 1834. Dr. Hurlbut brought with him an introduction and request for the manuscript, which was signed by Messrs. Henry, Lake, Aaron Wright, and others, with all of whom I was acquainted, as they were my neighbors when I resided at New Salem. I am sure that nothing would grieve my husband more, were he living, than the use which has been made of his work. The air of antiquity which was thrown about the composition doubtless suggested the idea of converting it to the purposes of delusion. Thus, an historical romance, with the addition of a few pious expressions, and extracts from the sacred Scriptures, has been construed into a new Bible, and palmed off upon a company of poor deluded fanatics as Divine."

Similar evidence as to the Spaulding MS. was given by several private friends, and by the writer's brother, all of whom were familiar with its contents. The facts thus graphically detailed have of course been denied, but have never been disproved. Indeed, without them it is impossible to explain the hold which Rigdon always possessed on the Prophet; for he was a poor creature, without education and without talents. At one time—a critical moment in the history of the new church—a quarrel arose between the accomplices; but it ended in Smith's receiving a "revelation," in which Rigdon was raised by divine command to be equal with himself, having plenary power given to him to bind and loose both on earth and in heaven.

A MORMON CARAVAN ON THE PRAIRIES.

The remaining history of the Mormons is eminently interesting. Ignorant and superstitious as have been the chief part of the disciples, and atrocious as have been the tricks of the knaves who have led them on amid all the varieties of their good and evil fortune, there have occasionally been displayed among them an enthusiasm and bravery of endurance that demand admiration. Nearly from the beginning the leaders of the sect seem to have contemplated settling in the thinly populated regions of the western states, where lands were to be purchased for low prices, and after a short residence at Kirkland, in Ohio, they determined to found a New Jerusalem in Missouri. The interests of the town were confided to suitable officers, and Smith spent his time in travelling through the country and preaching, until the real or pretended immoralities of the sect led to such discontents that[Pg 582] in 1839 they were forcibly and lawlessly expelled from the state. We are inclined to believe that they were not only treated with remarkable severity, but that there was not any reason whatever to justify an interference in their affairs.

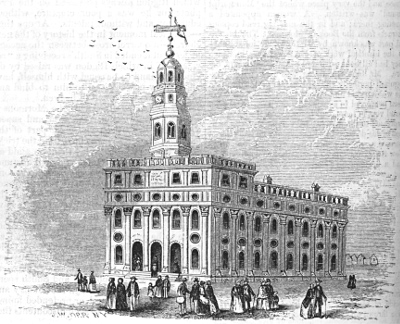

THE MORMON TEMPLE AT NAUVOO.

From Missouri the saints proceeded to Illinois, and on the sixth of April, 1841, with imposing ceremonies, laid at their new city of Nauvoo the corner-stone of the Temple,[1] an immense edifice, without any architectural order or attraction, which in a few months was celebrated every where as not inferior in size and magnificence to that built by Solomon in Jerusalem. Nauvoo is delightfully situated in the midst of a fertile district, and a careful inquirer will not be apt to deny that it became the home of a more industrious, frugal, and generally moral society, than occupied any other town in the state. Whatever charges were preferred against Smith and his disciples, to justify the outrages to which they were subjected, the history of their expulsion from Nauvoo is simply a series of illustrations of the fact that the ruffian population of the neighboring country set on foot a vast scheme of robbery in order to obtain the lands and improvements of the Mormons without paying for them. We have not room for a particular statement of the discontents and conspiracies which grew up in the city, nor for any detail of the aggressions from without. On the 27th of June, 1844, Joseph and Hyrum Smith were murdered, while under the especial protection of the authorities of the state. A writer in the Christian Reflector newspaper, soon after, observed of Joseph Smith:

"Various are the opinions concerning this singular personage; but whatever may be thought in reference to his principles, objects, or moral character, all agree that he was a most remarkable man.... Notwithstanding the low origin, poverty, and profligacy of these mountebanks, they have augmented their numbers till more than 100,000 persons are now numbered among the followers of the Mormon Prophet, and they never were increasing so rapidly as at the time of his death. Born in the very lowest walks of life, reared in poverty, educated in vice, having no claims to even common intelligence, coarse and vulgar in deportment, the Prophet Smith succeeded in establishing a religious creed, the tenets of which have been taught throughout America; the Prophet's virtues have been rehearsed in Europe; the ministers of Nauvoo have found a welcome in Asia; Africa has listened to the grave sayings of the seer of Palmyra; the standard of the Latter-Day Saints has been reared on the banks of the Nile; and even the Holy Land has been entered by the emissaries of this impostor. He founded a city in one of the most beautiful situations in the world, in a beautiful curve of the 'Father of Waters,' of no mean pretensions, and in it he had collected a population of twenty-five thousand, from every part of the world. The acts of his [Pg 583]life exhibit a character as incongruous as it is remarkable. If we can credit his own words and the testimony of eye-witnesses, he was at the same time the vicegerent of God and a tavern-keeper—a prophet and a base libertine—a minister of peace, and a lieutenant-general—a ruler of tens of thousands, and a slave to all his own base passions—a preacher of righteousness, and a profane swearer—a worshipper of Bacchus, mayor of a city, and a miserable bar-room fiddler—a judge on the judicial bench, and an invader of the civil, social, and moral relations of men; and, notwithstanding these inconsistencies of character, there are not wanting thousands willing to stake their souls' eternal salvation on his veracity. For aught we know, time and distance will embellish his life with some new and rare virtues, which his most intimate friends failed to discover while living with him. Reasoning from effect to cause, we must conclude that the Mormon Prophet was of no common genius: few are able to commence and carry out an imposition like his, so long, and so extensively. And we see, in the history of his success, most striking proofs of the credulity of a large portion of the human family."

[1] The temple was of white limestone, 128 feet long, 83 feet wide, and 60 feet high. Its style will be seen in the above engraving. It was destroyed by fire, on the 19th of November, 1848. The town of Nauvoo is now occupied by another class of socialists, the Icarians, under M. Cabet, of Paris.

THE EXPULSION FROM NAUVOO.

After some dissensions, in which the party of Brigham Young triumphed over that of Sidney Rigdon, the sect were reorganized and for some time were permitted quietly to prosecute their plans at Nauvoo. But early in 1846 they were driven out of their city and compelled in mid winter to seek a new home beyond the farthest borders of civilization. The first companies, embracing sixteen hundred persons, crossed the Mississippi on the 3d February, 1846, and similar detachments continued to leave until July and August, travelling by ox-teams towards California, then almost unknown, and quite unpeopled by the Anglo-Saxon race. Their enemies asserted that the intention of the Saints was to excite the Indians against the government, and that they would return to take vengeance on the whites for the indignities they had suffered. Nothing appears to have been further from their intentions. Their sole object was to plant their Church in some fertile and hitherto undiscovered spot, where they might be unmolested by any opposing sect. The war against Mexico was then raging, and, to test the loyalty of the Mormons, it was suggested that a demand should be made on them to raise five hundred men for the service of the country. They consented, and that number of their best men enrolled themselves under General Kearney, and marched 2,400 miles with the armies of the United States. At the conclusion of the war they were disbanded in Upper California. They allege that it was one of this band who, in working at a mill, first discovered the golden treasures of California; and they are said to have amassed large quantities of gold before the secret was made generally known to the "Gentiles." But faith was not kept with the Mormons who remained in Nauvoo. Although they had agreed to leave in detachments, as rapidly as practicable, they were not allowed necessary time to dispose of their property; and[Pg 584] in September, 1846, the city was besieged by their enemies upon the pretence that they did not intend to fulfil the stipulations made with the people and authorities of Illinois. After a three days' bombardment, the last remnant was finally driven out.

The terrible hejira of the Mormon emigrants over the Rocky Mountains has been described by Mr. Kane of Philadelphia, in an interesting pamphlet, which is honorable to his own character for good sense and for benevolent feeling. No religious emigration was ever attended by more suffering, no emigration of any kind was ever prosecuted with more bravery. It resulted in the permanent establishment of the "Commonwealth of the New Covenant," in Utah, or Deseret, one of the most attractive portions of the interior of this Continent, near its western border. Of this territory Mr. Kane says:

Deseret is emphatically a new country; new in its own characteristic features, newer still in its bringing together within its limits the most inconsistent peculiarities of other countries. I cannot aptly compare it to any. Descend from the mountains, where you have the scenery and climate of Switzerland, to seek the sky of your choice among the many climates of Italy, and you may find welling out of the same hills the freezing springs of Mexico and the hot springs of Iceland, both together coursing their way to the Salt Sea of Palestine, in the plain below. The pages of Malte Brun provide me with a less truthful parallel to it than those which describe the Happy Valley of Rasselas, or the Continent of Ballibarbi.

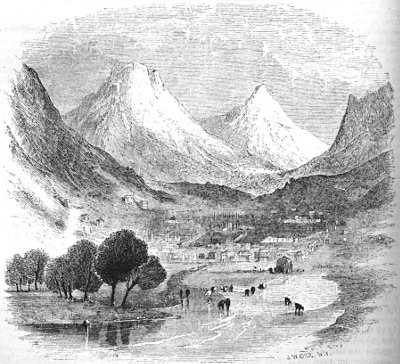

GREAT SALT LAKE CITY OR NEW JERUSAL'M.

The history of the Mormons has ever since been an unbroken record of prosperity. It has looked as though the elements of fortune, obedient to a law of natural re-action, were struggling to compensate their undue share of suffering. They may be pardoned for deeming it miraculous. But, in truth, the economist accounts for it all, who explains to us the speedy recuperation of cities, laid in ruin by flood, fire, and earthquake. During its years of trial, Mormon labor had subsisted on insufficient capital, and under many difficulties, but it has subsisted, and survives them now, as intelligent and powerful as ever it was at Nauvoo; with this difference, that it has in the mean time been educated to habits of unmatched thrift, energy, and endurance, and has been transplanted to a situation where it is in every respect more productive. Moreover, during all the period of their journey, while some have gained by practice in handicraft, and the experience of repeated essays at their various halting-places, the minds of all have been busy framing designs and planning the improvements they have since found[Pg 585] opportunity to execute. Their territory is unequalled as a stock-raising country; the finest pastures of Lombardy are not more estimable than those on the east side of the Utah Lake and its tributary rivers, and it is scarcely less rich in timber and minerals than the most fortunate portions of the continent.

From the first the Mormons have had little to do in Deseret, but attend to mechanical and strictly agricultural pursuits. They have made several successful settlements; the farthest north is distant more than forty miles, and the farthest south, in a valley called the Sanpeech, two hundred, from that first formed. A duplicate of the Lake Tiberias empties its waters into the innocent Dead Sea of Deseret, by a fine river, which they have named the Western Jordan. It was on the right bank of this stream, on a rich table land, traversed by exhaustless waters falling from the highlands, that the pioneers, coming out of the mountains in the night of the 24th of July, 1847, pitched their first camp in the Valley, and consecrated the ground. This spot proved the most favorable site for their chief settlement, and after exploring the whole country, they founded on it their city of the New Jerusalem. Its houses are diffused, to command as much as possible the farms, which are laid out in wards or cantons, with a common fence to each. The farms in wheat already cover a space nearly as large as Rhode Island. The houses of New Jerusalem, or Great Salt Lake City, as it is commonly called, are distributed over an area nearly as great as that of New York. The foundations have been laid for a temple more vast and magnificent than that which was erected at Nauvoo. The Deseret News, a paper established under the direction of the ecclesiastical authority came to us lately with several columns descriptive of the fourth anniversary celebration of the arrival of the disciples in their Promised Land.

Since the preceding paragraphs were written some important information has been received from Utah, justifying apprehensions that the ambition of the chief of the sect, and territorial governor, Brigham Young, will be continually productive of difficulties. It appears that in consequence of his unwarrantable assumptions of authority, the larger and most respectable portion of the territorial officers, including B. O. Harris, Secretary of the Territory, G. K. Brandenburg, Chief Justice, E. P. Bracchas, Associate Justice, H. R. Day, Indian Agent, and Messrs. Gillette and Young, were preparing to leave for the Atlantic States.

The particulars of the difficulty are not stated, but it is said that $20,000 appropriated by Congress for territorial purposes had been squandered by Young, and an attempt made by him to take $24,000 from the Treasurer, who refused, and applied to the Court to support him. This was done, and an injunction granted restraining the proceedings of the Governor.

Of the numerous objects of interest with which the banks of the Thames are so thickly studded, none are of such surpassing grandeur and regal magnificence as Windsor Castle, with its adjacent chapel of St. George, and Eton College. This massive and stately pile is richly storied with poetic associations, and venerable for its antiquity, in having proudly defied the ravages of Time for some eight centuries. Here kings were born; here they kept royal state amid the blaze of fashion and luxurious indulgence; and here in the adjoining mausoleum, they were buried. Here[Pg 586] deeds of chivalry and high renown that shine on us from ancient days were enacted; and it is here the most exemplary of England's monarchy still prefers to hold her suburban residence. This brave old fortress, unlike the Tower of London, with its dark records of crime, is rife with pleasant memories. Not only is the edifice itself, with its gigantic towers, its broad bastions, and its kingly halls, sacred with incident and story, but Shakespeare has also rendered classical the very ground on which it stands.

DISTANT VIEW OF WINDSOR CASTLE.

Windsor Forest, with its magnificent old oaks and its richly variegated scenery, of "upland, lawn and stream," has afforded a fruitful theme for the pens of Gray and the poet of "The Seasons;" and Pope, it will be remembered, has felicitously pictured forth its changeful beauties. As far back as the days of the Saxons we have records of palatial residence at Old Windsor, or as its name then was, Windleshora, so called from the windings of the Thames in its vicinity. William the Norman built some portions of the Castle, which, until the time of Richard I., seems ever to have been the peaceful abode of royalty. During the civil wars, of which Windsor was a principal scene, the Castle became the most important military establishment in the kingdom. The sanguinary struggles connected with the signing of Magna Charta, are familiar to the reader. The birth of Edward III., which took place at Windsor, forms another epoch in its history—that prince having reconstructed the greater part of the Castle, and very largely extended it. William of Wykeham was the architect, with the liberal salary of a shilling a day. It is said he and six hundred workmen employed on the building, at the rate of one penny a day. It was here Richard II. heard the appeal of high treason, brought by the Duke of Lancaster against Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, which resulted in the former becoming Henry IV. It was here the Earl of Surrey, imprisoned for the high crime of eating flesh in Lent, beguiled his solitude, with his muse; and here was the last prison of that unfortunate monarch, Charles I. In Windsor Castle also resided the haughty Elizabeth; and along its terrace might have been seen in the days of the Commonwealth the stern figure of the lion-hearted Cromwell. It was the residence of Henry VIII., and the prison of James I. of Scotland. It is indebted for most of its modern splendor, to the luxurious taste and prodigal expenditure of George IV., who obtained from the House of Commons the sum of £300,000 for the purpose. The suites of royal apartments at present in use by the Queen are superb in the extreme, especially the state drawing rooms, in which are nine pictures by Zuccarelli; and St. George's Hall—a vast apartment in which the state banquets are given.

The long walk, extending about three miles in a direct line to the Palace, presents the finest vista of its kind in the world. It extends from the grand entrance of the Castle, to the top of a commanding hill in the Great Park, which affords a panoramic view of enchanting beauty, including many places memorable in history. On the right is the Thames, seen beyond Charter Island, and the plain of[Pg 587] Runnymede, where the Barons extorted Magna Charta, whilst in the hazy distance are the rising eminences of Harrow and Hampstead. On the summit of this hill stands the equestrian statue of George III. Near the avenue called Queen Elizabeth's Walk, tradition still points out a withered tree as the identical oak of "Herne the Hunter," who, as the tale goes,

[We derive this article from an interesting and beautifully illustrated volume of "Memories of the Great Metropolis," by Frederic Saunders, to be issued in a few days by one of our leading publishers. We shall notice it again.]

AND M. LE BARON MUNCHAUSEN, WHO BEAT HIM.

Jules Gerard is an officer in the famous army of Africa, who has a passion for lion killing. He is the Gordon Cumming of France. He follows lions alone; hunts them like sheep, for miles; sleeps near them; and patiently awaits their coming. Last year we published (article "Wild Sports in Algeria," International, vol. ii. p. 121,) an account of one of his exploits, to which he now refers us. His last adventure is sufficiently exciting, and incredibly daring. It is told in a letter to a friend, and published in the Journal des Chasseurs:—

"My dear Léon,—In my narrative of the month of August, 1850, I spoke of a large old lion which I had not been able to fall in with, and of whose sex and age I had formed a notion from his roarings. On the return of the expeditionary column from Kabylia, I asked permission from General St. Armand to go and explore the fine lairs situated on the northern declivity of Mount Aures, in the environs of Klenchela, where I had left my animal. Instead of a furlough, I received a mission for that country, and accordingly had during two months to shut my ears against the daily reports that were brought to me by the Arabs of the misdeeds of the solitary. In the beginning of September, when my mission was terminated, I proceeded to pitch my tent in the midst of the district haunted by the lion, and set about my investigations round about the douars to which he paid the most frequent visits. In this manner I spent many a night beneath the open sky, without any satisfactory result, when, on the 15th, in the morning, after a heavy rain which had lasted till midnight, some natives, who had explored the cover, came and informed me that the lion was ensconced within half a league of my tent. I set out at three o'clock, taking with me an Arab to hold my horse, another carrying my arms, and a third in charge of a goat most decidedly unconscious of the important part it was about to perform. Having alighted at the skirt of the wood, I directed myself towards a glade situated in the midst of the haunt, where I found a shrub to which I could tie the goat, and a tuft or two to sit upon. The Arabs went and crouched down beneath the cover, at a distance of about 100 paces. I had been there about a quarter of an hour, the goat meanwhile bleating with all its might, when a covey of partridges got up behind me, uttering their usual cry when surprised. I looked about me in every direction, but could see nothing. Meanwhile the goat had ceased crying, and its eyes were intently fixed at me. She made an attempt to break away from the fastening, and then began trembling in all her limbs. At these symptoms of fright I again turned round, and perceived behind me, about fifteen paces off, the lion stretched out at the foot of a juniper-tree, through the branches of which he was surveying us and making wry faces. In the position I was in, it was impossible for me to fire without facing about. I tried to fire from the left shoulder but felt awkward. In turning gently round without rising, I was in a favorable position, and just as I was levelling my piece the lion stood up and began to show me all his teeth, at the same time shaking his head, as much as to say, 'What the devil are you doing there?' I did not hesitate a moment, and fired at his mouth. The animal fell on the spot as if struck by lightning. My men ran up at the shot; and as they were eager to lay hands on the lion, I fired a second time between the eyes, in order to secure his lying perfectly still. The first bullet had taken the course of the spine throughout its entire length, passing through the marrow, and had come out at the tail. I had never before fired a shot that penetrated so deeply, and yet I had only loaded with sixty grains. It is true the rifle was one of Devisme's and the bullets steel-pointed. The lion, a black one and among the oldest I have ever shot, supplied the kettles of four companies of infantry who were stationed at Klenchela. Receive, my dear Léon, the assurance of my devoted affection.

Jules Gerard."

The exploit of 1850 was the chasing of two lions, one of which he killed; the other, supposed to be the one now shot, running away from him and escaping, after a vigorous chase of many miles. Some one—a celebrated author, indeed, with whose astonishing adventures we have been familiar from boyhood—envious of the recent fame of Mr. Arthur Gordon Cumming and M. Jules Gerard, has sent the following letter to the editor of the London Times:

Sir,—The exploit of M. Jules Gerard, recorded in The Times of the 14th inst., is certainly very wonderful, but by no means equals one performed by myself in South Africa. Observing on one occasion a large black lion, about 18 feet in length, reposing under a caoutchouc tree, I fired, and the bullet, like that of M. Gerard, went right through the backbone and came out at the tail; but, wonderful to relate, it hit against the tree, and rebounding, came back the same way and went straight into the barrel of my rifle, just after I had reloaded with powder. I instantly presented my piece at the lioness, which was reposing by the side of her lord, and fired; and thus I killed two animals (so large that they supplied three regiments of the line and 200 irregular cavalry with food for nearly a week) with one and the same bullet. In case any of your readers should doubt the truth of this statement, I eschew the usual fashion of writing under a false name, and subscribe myself, your very obedient servant,

BARON MUNCHAUSEN.

London, Oct. 15.

We present to the readers of the International Magazine, this month, from a recent Daguerrotype by Brady, the best portrait ever published of the greatest living poet who writes the English language.

William Cullen Bryant was born on the third of November, 1794, in the village of Cummington, Massachusetts. His father, Dr. Peter Bryant of that place, one of the most eminent physicians of the day, was possessed of extensive literary and scientific acquirements, an unusually vigorous and well-disciplined mind, and an elegant and refined taste. He was fond of study, and sought to infuse into the minds of his young and growing family, those habits of intellectual exertion which had been to himself a source of so much exalted pleasure. It was fortunate for the subject of this notice, that such was his character; for when his own genius began to discover signs of its power, he found in his father an able and skilful instructor, who chastened, improved, and encouraged the first rude efforts of his boyhood. That parent did not, like the father of Petrarch, burn the poetic library of his son, amid the tears and groans of the boy; nor, like the relatives of Alfieri, suppress, for nearly one-third of his existence, the poetic fervor which consumed his heart; but, looking upon poetry as a high, perhaps the highest of arts, and poetic eminence as the noblest fame, he nourished with cheerful care the least indications of its presence, and supplied the youth with the means of its culture and growth. Nor were his services unrewarded, as it appears from Mr. Bryant's solemn Hymn to Death, by the subsequent gratitude and success of his pupil.

When only ten years of age, Mr. Bryant produced several small poems, which, though of course marked by the defects and puerilities of so immature an age, were yet thought to possess sufficient merit to be published in the newspaper of a neighboring village—the Hampshire Gazette. His friends, though pleased with these early evidences of talent, did not injure him with injudicious flattery, but, in the spirit of Dryden's simile, treated them

Mr. Bryant acquired the rudiments of his school education under the care, first of the Rev. Mr. Snell of Brookfield, and then under that of the Rev. Mr. Hallock of Plainfield, Massachusetts. They found in him a sprightly and intelligent pupil, better pleased to lay up knowledge from books, and the silent meditation of nature, than to join in the ordinary pastimes of children. He was quick of apprehension, and diligent in pursuit. He rapidly ran through the usual preliminary studies; and in 1810, then in the sixteenth year of his age, was entered a member of the sophomore class of Williams' College. In that[Pg 589] institution, he continued his studies with the same ardor and enthusiasm. He was particularly noted for his fondness for the classics, and in a little while made himself master of the more interesting portions of the literature of Greece and Rome. But he had not been in college more than a year or two, when he asked and procured an honorable dismission, for the purpose of devoting himself to the study of the law. This he did in the office of Judge Howe of Worthington, and afterwards in that of the Hon. William Baylies of Bridgewater, and, in 1815, was admitted to practice at the bar of Plymouth.

But, during the period of his studies, Mr. Bryant had not neglected the cultivation of his poetic abilities. In 1808, before he went to college, he had published, in Boston, a satirical poem, which attracted so much attention, that a second edition was demanded in the course of the next year. "When it is remembered," observes Mr. Leggett, "that this work was given to the public by an author who had not completed his fourteenth year, it cannot but be considered a remarkable instance of early maturity of mind. Pope's Ode to Solitude was written at twelve years of age; but it possesses neither fancy nor feeling, and except for the harmony of its versification, is entitled to no particular praise. His Translation of Sappho to Phaon is indeed an extraordinary production, and has uniformly received the warmest commendation from the critics. Yet, it is but a translation, while the poem of our author, written still earlier in life, is an original effort, and as such cannot but be received with greater surprise, on account of the wonderful precocity of judgment, wit, and fancy it exhibits. Like Cowley's Poetical Blossoms, it must have been composed when the writer was little more than thirteen; but in point of merit, it is decidedly superior to these effusions of unripened genius." Certain political strictures on Mr. Jefferson and his party, which this poem contained, have given rise, since Mr. Bryant has become conspicuous as an ardent friend of democracy, to charges of political inconsistency and faithlessness. They are charges, however, that require no refutation; and we refer to them now only to remark, that it is a singular evidence of Mr. Bryant's integrity and discernment, that the only point of attack which embittered enemies have found in his whole life, are his unconsidered mutterings when a stripling of only thirteen, living in times of high political excitement, and among a people who were all of one way of thinking. How few pass through life with characters so pure and unassailable!

But what chiefly contributed to give Mr. Bryant rank as a poet, was the publication, in the North American Review of 1816, of the poem of Thanatopsis, written four years before, in 1812. That a young man, not yet nineteen, should have produced a poem so lofty in conception, and so beautiful in execution, so full of chaste language, and delicate and striking imagery—and above all, so pervaded by a noble and cheerful religious philosophy—may well be regarded as one of the most wonderful events of literary history. And the wonder is increased when we learn, that this sublime lyric was followed, in the course of the few next years, by the "Inscription for an Entrance into a Wood," written in 1813, and published in the North American in 1817; by the "Waterfowl," written in in 1816, and published in 1818; and by the "Fragment of Simonides," written in 1811, and published in 1818. In 1821, he wrote his largest poem, "The Ages," which was delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard College, and soon after published at Boston, in a small volume, in connection with the poems we have already mentioned, and some others. The appearance of this volume at once established the fame of Mr. Bryant as a poet.

In the same year Mr. Bryant married a young and amiable lady, Miss Fairchild, of Great Barrington, Mass., whither he had removed to prosecute his profession. He was both skilful and successful as a lawyer, but the labor of the vocation clashing with his poetic and moral sensibilities, induced him, after a ten years' practice, to remove, in 1825, to the city of New-York, to commence a career of literary effort. His fame, which had preceded him, soon procured him the editorship of the New-York Review, which he managed, in connection with other gentlemen, with great industry and talent. About the same time he joined Mr. Gulian C. Verplanck, Mr. Robert Sands, and Fitz-Greene Halleck, and several young artists of the city, in the production of an Annual called "The Talisman," which for beauty and variety of contents, has not been surpassed, even in these more prolific days of Annuals. Some of Mr. Bryant's contributions to it place him as a prose writer beside the best of any nation. The narrative of the "Whirlwind," for accurate description, condensed energy and eloquence of expression, and touching incident, has always struck us as one of the master-pieces of writing.

In 1827, Mr. Bryant became an editor of the New-York Evening Post, and since then, with the exception of the years 1834 and '49, when he travelled with his family in Europe, has had the almost exclusive control of that journal. It is by his conduct in this capacity, that he has acquired his standing as a politician.

We have cause, then, to speak of Mr. Bryant's political character. When he first undertook the management of the Evening Post, that paper had taken no decided stand in the politics of the day. Its leanings, however, were towards the aristocratic party. Mr. Bryant soon infused into its columns some portion of his native originality and spirit. Its politics assumed a higher tone, its disquisitions[Pg 590] on public measures became daily more pointed and stirring, and, finally, it declared with great boldness on what was considered the more liberal side. From that day to this, it has taken a leading part in political controversies, and exerted a controlling influence over public opinion. In the fierce excitement kindled by General Jackson's attack upon the United States Bank, in the hot debates of the tariff and internal improvement questions, and in the deeply-agitating, almost convulsive contest which prostrated the banking system, the Evening Post maintained the strongest ground, was generally in advance of its day, and never faltered or flinched in the assertion of the severest tenets of the democratic creed. Unlike most journals, it did not satisfy itself with an undiscriminating defence of the temporary doctrines of party, but, regardless alike of friend and foe, yet cautiously and calmly, it expressed the whole truth in its length and breadth.

The manner in which Mr. Bryant has conducted these controversies is in the highest degree honorable to him. He has disdained the miserable arts by which small minds achieve the triumphs of their party or their own profit. Drawing his principles from the independent conclusions of his own mind, he has not shifted with every wind of doctrine. He has regarded politics, not as the strife of opposing interests, nor as a factious struggle for party supremacy, nor yet as a predatory warfare for the spoils of success, but as the solemn conflict of great principles. He has studied it as a comprehensive science, in which the rights and happiness of millions of men are interested, and which has issues and dependencies spreading over the events of many years. In this light, he has sought to teach its truths, with conscientious fidelity.

His intellectual adaptation to his calling is in many respects a striking one. With a mind of quick sagacity, strong reasoning powers, ready wit, and an inexhaustible fertility, he has been able to perform its incessant and laborious duties with signal success. Disciplined, as well as enriched by severe study, he has added to the learning of books the attainments of extensive observation and travel. His style is remarkable for its purity and elegance, no less than for the felicity of its illustrations. In controversy, he most frequently resorts to a caustic but graceful irony. He is playful without being vulgar, pointed without grossness, sharp as a Damascus blade, and just as polished. Nor are the compactness and strength of his expression less to be admired, than his uniform perspicuity and ease. That he is sometimes unnecessarily cutting, as some complain, is a fault, if it exist, that springs from the native integrity of his mind, and the secluded and refined nature of his pursuits. It has seemed to us, however, that this alleged severity is no more than the spirit of justice as it manifests itself in a pure and honest mind. For we doubt if a man more perfectly just, and less liable to be warped by the questionable compliances of society, ever lived.

We shall not enter into any criticism of Mr. Bryant's poetry here, because it has been so fully estimated before, that there is no need of doing so again; but there is one view which has been taken of it, on which we shall offer a few remarks. That view occurs in the following passage of Mr. J. R. Lowell's Fable for Critics:

Now, what is the main charge here: that Mr. Bryant, while he has great sympathy with external nature, with mountains and precipices, has no sympathy with his fellow-man. 'Tis a weighty charge—the weightiest that can be made against a man or a poet. It says virtually that he has no soul, no heart, no impulse, no feeling, except for brutes and vegetables; in short, that he is no better than a heathen savage, a regular worshipper of stocks and stones, without natural affection, or without God in the world. "For," as the apostle queries very wisely, "if he love not man, whom he hath seen, how can he love God, whom he hath not seen?" Your lines, then, Mr. Quiz, imply nothing less than black, bleak, barren, unredeemed practical Atheism!

But can there be the remotest semblance of truth in them? Is our Bryant such a heathen or atheist as not to know his fellow-men[Pg 591] except they present themselves in the disguise of mountains, or he see them, like the prophet, as trees walking? We appeal to you, young ladies, who have been melted into tears by his pathos. We appeal to you, young men, whose every purpose of good has been quickened into livelier action by his words; and to you, old heads, whose experience has learned a riper and mellower wisdom from his fine meditative views of the ends and aims of life.

Yet, before you render your concurrent answers, with somewhat of indignation that anybody could put you upon the task, let us, in good American sort, begin with a few statistics. This is a question of fact, and since it has been raised, we will determine it by facts.

There are, in Carey & Hart's splendid edition of Bryant—we mean splendid as to the typography and paper, and not inclusive of those ill-drawn sketches of Leutze, who has made the women all German and given Mr. William Tell of Switzerland a straddle as wide as the Dardanelles, to say nothing of the hideous face of Rizpah and that Monk so excessively huge as to stand some forty feet from the pillar against which he leans—this splendid edition, we say, contains just one hundred and thirty-two poems, all told, to which,—stand up and listen, to the sentence, Mr. Lowell!—more than seventy refer wholly to subjects of an exclusively human interest—man in his being and doing, while nine out of ten of the rest, though occupied primarily with some phase of external nature, are yet so managed as to weave a deep and beautiful human philosophy,—with the dull and dead proceedings of the mechanical world. Yes, Mr. Critic, we say that there is a very fine, a very rich, a very noble and very touching vein of human sentiment, which runs through all of Bryant's writings, whereby, even as much as Wordsworth, he makes these mountains and precipices a part of our human life, and whereby, too, he makes the whole of us, who read him lovingly, that is, who read him at all, much better men and women, in our several spheres. No human sympathies forsooth! Why there are hundreds, nay, thousands, of us, who have derived many of their tenderest and noblest humanities from this very cold-blooded He-Daphne; this fleshless marble Apollo,—this Ice-Palace and Alpine glacier,—far shining brilliant, but oh how frigid!

By poems of an exclusive human interest, we mean, such as bear directly on man's experience and duties and relations in this life: such as the Ages, for instance, which commemorates the progress of humanity, through all its trials and triumphs: such as Thanatopsis, which makes the grave glorious, and pours the light of a lofty and serene religion around our darkest hour: such as the Old Man's Funeral, more divine in its descriptive beauty than the best sermon we ever heard: such as the Battle Field, which animates us with the voice of trumpet to meet the stern struggles of daily warfare: and such as many others in the same vein, to say nothing of the Murdered Traveller, the Massacre at Scio, the Hunter of the Prairies, the Living Lost, the Crowded Street, the Greek Boy, the Arctic Lover, the African Chief, the Child's Funeral, &c., &c. These could only have been prompted by a strong feeling of sympathy with man, and though executed with the nicest finish of art, are yet full of touching pathos and sentiment. The best proof of this is, that they invariably excite the emotions they were intended to excite—and that, too, in no milk and waterish way. They sink straight into the heart; they open the fountains of the feelings; they send the salt water to the eyes (if that be needed); they make the blood tingle; in short, they produce that all-overishness which comes upon one when he sees a fine action on the stage, or reads a noble passage in an oration, or looks at Lentze's Washington. Try it on yourself, if you don't believe it, or, what is better, try it on your little girl and boy, whose feelings are not yet case-hardened or frozen over! It will be a queer kind of frigidity that they will be witness to. Why, bless your soul, Mr. Lowell, we are free to confess that we have ourselves long, long ago, cried over the Indian Girl's Lament, and the Death of the Flowers,—yes, cried, and we say it without shame,—indeed, with a strange sense of regret that we cannot cry now over things of that sort. Eheu, eheu fugaces, &c.

More than that, we have asseverated that even in poems which are not immediately emotional, which are directed to some phase of mere external nature, the humanitary tendencies of Bryant break out, or shine through as veins of silver from the rocks. It is, in fact, one of his most charming peculiarities, that he habitually connects great moral and social truths with the various aspects of nature. His muse is never satisfied with celebrating the pomp and glory of the external world; she must find a deeper meaning in all than what the eye sees or the ear hears; she must trace some beautiful analogy, some spiritual significance on which both mind and heart can repose. Bryant's descriptions of nature, it is granted, are accurate to a line; what he speaks he knows; he finds no nightingales nor cowslips just three thousand miles away from where it is possible for them to live; and he never writes from his memory of books; yet his descriptions are more than mere descriptions,—dull scientific catalogues of quantities,—herbariums of dried plants,—museums of withered lifeless twigs, and of stuffed animals standing thereupon! They have all a meaning under them—a hidden wisdom—a genial yet profound human soul. It is thus that he has wound our affections around the North Star, the Winds, Monument Mountain, and even the Ruffled Grouse.[Pg 592] How often, too, in the midst of his general meditations and philosophizings, does some touching individual allusion creep in, to show that the poet's heart is all alive with sensibility: as in the Hymn to Death, which closes with that solemn monody on the Departure of his Father:

Does an iceberg write in that strain, we should like to know? Or does it mourn the death of the flowers, in this wise:

Or do icebergs yearn thus for communion in the after world with the beloved spirits of this:

Truly, that iceberg theory must be surrendered, it must melt and give way before the gentle warmth of these words, and the thousand other such words which any reader of Bryant will instantly recall.

But, having convinced and confuted Mr. Critic, we will proceed to observe that there is after all a foundation of truth—a slender one—for his towering superstructure of ridicule. It is this: that in the outset of his career, Mr. Bryant's sympathies were, not too much with external Nature, but too little with Man. At the same time, we maintain that he has been constantly correcting this fault, and has written more and more, the older he has grown, to the human heart. He is not, and we hope never will be, a passionate writer, like Byron: he is not one who deals, like Burns, with the warm, gushing, homely affections of the poor every where: he has none of Schiller's energy of conviction: none of the naive, playful garrulous bonhomie of Beranger; simply, because he is of another order of man from all these. He is quiet, gentle, contemplative, modest,—wise. Yet if no lava-tides of passion burn through his veins, as were said to run through the veins of Alfieri; if he is not, as Carlyle said of Dante, "a red-hot cone of fire" shooting steadily up into the sky; if he cannot, with Shakespeare, or Goethe, make the blood quiver and thrill for weeks by a single word; he is still not a frigid, heartless writer, not altogether an ice mountain, which dazzles always but never warms. He is too earnest, too truthful, too good for that; too deeply penetrated by the spiritual realities of life, too democratic in his aspirations for our race, too hopeful of the future developments of society, in short, too finely touched with that feminine element which is the characteristic of genius. Besides, the great internal fires of the Earth, which shoot up in terrific and explosive violence, stupendous as they are, do not nurse the tender bud into life, nor cover the earth with verdure and fruit. This is left to the genial sunshine and the warm summer rains.

In private intercourse, Mr. Bryant is what all his writings, poetical as well as prose, indicate. His life is that of a student of elegant and lofty literature. He is reserved in his manner, almost to repulsiveness, yet in the social circle is witty, amiable, and affectionate. When his sympathies are interested, the spirit of tenderness and benevolence gleams like a flame from his eyes, and plays around his features in a beautiful radiance. In his opinions of men, he endeavors to be just; but when he is not just, the leaning is towards the side of mercy. A strong natural irritability has been disciplined by stern effort into the subjection of reason; and his tastes and habits, though refined by careful culture, are as simple as those of a child. Those who know him best are at a loss which most to admire, the superiority of his faculties, or the modesty of his deportment.

The London Morning Chronicle, after an observation that a hurriedly written epitaph always appears, in the course of time, to require revisal, expresses its admiration for the good sense of a Parisian sculptor, who, when he took his instructions for a monument, insisted upon the veuve inconsolable or the heartstricken husband penning the intended inscription, and even signing the holograph, as a further authority to him for immortalizing so much utter despair. "The day before the record was actually to be cut for eternity, his habit was to send the inscription book to the mourner's house, lest any correction should be desired. The havoc which, upon receiving back the volume, he usually found made among laudatory adjectives and adverbs of infinity, was, to a good man, a delightful evidence of the cooling and healing powers of time."

WRITTEN FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY MAGAZINE.

BY H. W. PARKER.

We have at present in our hands several recently published European works relative to America, all of which possess more than ordinary claims to attention. We have, however, chosen the most unpretending as the subject of our present remarks, since, for the thinking majority of our readers, it will undoubtedly prove the most interesting. The volume to which we allude is entitled, Des Auswanderers' Handbuch, or, The Emigrants' Hand-book: a True Sketch of the United States of North America, and Reliable Counsellor for Men of every Rank and Condition who propose Emigrating Thither: by George M. von Ross, of North America, Editor of the "Allgemeinen Auswanderungs-Zeitung" (Universal Emigration Journal). Published at Elberfeld and Iserlohn, by Julius Baedeker.

The author, according to his preface, is an American by birth, and was for many years a farmer in the eastern, western, and southwestern sections of the United States. That he is not without learning and ability is evinced by his remarkably excellent work entitled Taschen-Fremdwörterbuch, oder Verdeutschung von mehr als 16,000 Fremdwörter—(i. e. a Pocket Dictionary of Foreign Words, or the adoption into German of more than Sixteen Thousand Foreign Words). This book is familiar in Germany, and exhibits great philological acumen, as well as a thorough knowledge of German in its minutest difficulties. At one time Mr. Ross distinguished himself by attacking Schröter's well-known pamphlet relative to the Catholic emigration to St. Mary's, in Pennsylvania, and he has since published a smaller work for emigrants, entitled Rathschlage und Warnungen, or, Counsels and Warning.

The performance now before us is written in that straightforward practical style which may be best characterized by the statement that "He had something to say, and he said it." That it is impartial is not its least merit. A foreigner, it is true, may occasionally be found who passes unprejudiced judgments on another country, but that any one still retaining home-born sympathies and feelings with his native land should do so is a wonder. And we deem it a creditable thing in this work, that where he is called upon to describe any calling, trade, or profession, he is not afraid to say boldly—In this calling the German cannot succeed—in that, he is unapt—in a third, the American surpasses him; while, on the other hand, he amply encourages the emigrant as regards occupations for which he is qualified. Many writers of such books have cast a couleur de rose light over every thing (well knowing that by such means their books would be more saleable), and induced industrious men, following callings unheard of in this country, to emigrate, in the absurd hope of finding more constant and better paid employment here than at home. An intelligent American, who would not cross the Atlantic, or hardly ascend in a balloon, without previously calculating the time and chances of arrival or descent, and who certainly would do neither without first informing himself as to every imaginable particular of his ultimate destination, can hardly conceive the vast necessity of such books. He would, by every means, gather information from those who had visited in person the destined land. Not so the common German emigrant. Thousands embark in the belief that New-York is some mysterious golden-glowing Indian city, surrounded by orange groves and palm-trees. In the village of Weinsberg, in Suabia, several years since, a well-educated student was overheard to remark of some peasants, "Tell them that in your country the people have two heads, and they'll believe you."

Let us now, by extracts, give our readers an idea of the manner in which Mr. Von Ross describes the land of his birth to the land of his adoption. The first item of interest is his sketches of the respective characteristics of the Yankee and Southerner.

"Superficial observers have spoken of the inhabitant of the Northern States as if money were his only aim—as if he were inspired only by selfishness and avarice—and as if he estimated men by the weight of their purses. But those who regard him closely, and judge otherwise than by first appearances, will discover in him a calculating (berechnenden), enterprising, thoroughly practical man, caring little for pleasure, and seeking his recreation (erholung) in the domestic circle. They will find in him a man who, with iron[Pg 594] industry, fights his way through life, esteeming wealth, it is true—not the inherited, however, but the earned, which testifies to the ability of its possessor. A man, in fine, who with unbending courage bears the blow of destiny, and is thereby only stimulated to new exertions. The Southerner, on the contrary, is more chivalresque—he lives to live. The climate in which he is born has also a material influence upon his manners, customs, and character: effecting, in reality, the same difference which we observe between the cool, reflective, tough North German, and the jovial, genial, easily excited South German, or Frenchman. We would hardly have deemed it necessary to inform the reader that in thus sketching the inhabitants of the United States in light outlines, we do not include the mixed and Europeanized population of the Atlantic cities, had we not learned by experience that many travellers slightly acquainted only with the Atlantic States and their vicinity, have from these sketched all North America and its people. He who would know the American, must also know the cities of the interior.

"If, in addition to these characteristics, we should describe the personal and distinctive appearance of the Northerner and Southerner, we would say that the first are, generally speaking, large, tall, and spare—their ladies beautiful and of delicate complexion; while the Southerners are broad-shouldered and powerful—the female sex being voluptuously formed and beautiful, but when not subject to the influence of exercise and fresh air of a sallow complexion.

"Every North American is—and who has a better right so to be—an enthusiastic honorer (vereher) of his fatherland, but he does not measure out by inches the limits of his native land, or bound his patriotism by the clod on which his cradle rested—for to him the roar of the Rio del Norte, the thunder-peal of Niagara, and the murmur of the Pacific or Atlantic oceans have equally a familiar, home-like sound. Nor less than the land of his birth does he esteem its laws, constitution, and institutions, and regards them in nowise as oppressive, but as protective. Those laws he made for himself, and chose himself as their executor. Respect for the Law is to the American self-respect.

"The so often blamed national pride of the American, if not really praiseworthy, is at least pardonable; for a nation which could rise like a single man, and, at every sacrifice, throw off the yoke of England—a nation which has given birth to such men as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and many others whose names are mentioned with wonder all over this world—a nation which occupies the first rank in trade, commerce, and industry, may be proud, and must be proud, as long as its power is free from sloth and lethargy."

And here we may be permitted to interrupt for an instant our noble Man of Ross (the reader will observe that he wears the aristocratic von), for the sake of saying a good word over this honest, hard-fisted go-ahead eulogium of our country. There be those ultra-Europeanized, or soi-disant refinedly educated Americans, who will complacently smile at this recapitulation of United States excellencies, and if slangily inclined, brand it as "pea-nut," "stump eloquence," and "Fourth-of-Julyism." The sum-total being, that it is vulgar rhodomontade. With all due respect, we think differently. Let the reader remember that this is addressed to a German—a foreign—audience, who are greatly in need just at present of a few scraps of such oratory as this, were it only to counteract the malignant influences of the English tourists, whose works are far more extensively read in Germany than we imagine. Mrs. Trollope's work on America, which, at the present day, is regarded only with contempt or laughter by the educated in England, has been, and is even yet, read with a feeling akin to wonder by the honest simple-hearted Germans. A wonder indeed so intense, at the marvellous marvels therein narrated, that it generally results in inspiring in the mind of the reader credulous enough to believe, an intense desire to visit the land of liberty.