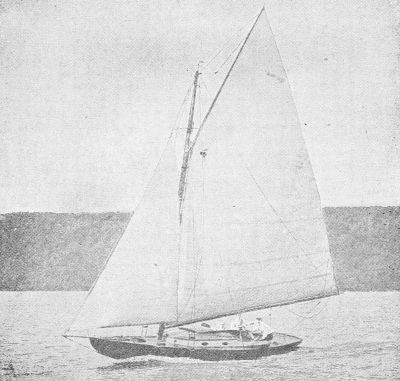

ON THE WIND.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of On Yacht Sailing, by Thomas Fleming Day

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: On Yacht Sailing

A simple Treatise for Beginners upon the Art of Handling

Small Yachts and Boats

Author: Thomas Fleming Day

Release Date: April 25, 2014 [EBook #45493]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ON YACHT SAILING ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Marc-Andre Seekamp and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

A SIMPLE TREATISE FOR BEGINNERS

UPON THE ART OF HANDLING

SMALL YACHTS AND BOATS

BY

THOMAS FLEMING DAY

Editor of “The Rudder,” Author of “On Yachts and Yacht Handling,” “Hints to Young Yacht Skippers,” “Songs of Sea and Sail,” etc.

NEW YORK AND LONDON:

The Rudder Publishing Company

1904

COPYRIGHT 1904

BY

Thomas Fleming Day

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRESS OF

THOMSON & CO.

9 MURRAY STREET, N. Y.

UNIFORM EDITION

RUDDER![]() ON

ON![]() SERIES

SERIES

Bound in blue buckram and gold, 32mo. illustrated

ON YACHTS AND YACHT HANDLING. By Thomas Fleming Day.Price $1.

ON YACHT SAILING. By Thomas Fleming Day.Price $1.

ON MARINE MOTORS AND MOTOR LAUNCHES. By E. W. Roberts, M. E.Price $1.

ON YACHT ETIQUETTE. Second Edition Revised. By Captain Patterson.Price $1.

SOUTHWARD BY THE INSIDE ROUTE. Reprint from The Rudder.

HINTS TO YOUNG YACHT SKIPPERS. By Thomas Fleming Day.Price $1.

There is no difficulty in the learned writing for the learned, but it is extremely difficult to compose a work for the instruction of the ignorant. The more comprehensive and exact knowledge the writer has of his subject the more arduous is the effort to express his thoughts in such simplicity as will make it understandable to those who have little or no knowledge of the subject he treats. This is doubly so when the subject is one like sailing—an art whose language is wholly technical and almost totally divorced from the common expressions of life. It is impossible to translate sea language into land language; nor is it possible to explain the conditions and operations of the art without employing sea terms.

In this work I have endeavored to avoid as far as is possible the employment of intricate or obscure technical language, and where it is used have endeavored to explain the meaning and define the application. This[8] book is intended for the use of persons who are supposed to be altogether ignorant of the art of sailing. It is a primer and, therefore, is almost absurdly simple and profuse in explanatory details. But my experience as a teacher has taught me that such books cannot be too simple, and that in order to be understandable they must be loaded with explanations of explanations until nothing is left to explain. To those who know, this will seem unnecessary, but it must be remembered that many who will learn from this book, have not only never handled a sailing boat, but have never seen one before, and have but extremely crude notions of how the canvas and helm are employed to drive and direct them.

In regard to the glossary: The definitions given are those that define the terms as used in sailing or navigating small craft, and may have a different meaning when applied to larger vessels. It is very difficult to exactly define many nautical terms, as they are words in action, and consequently present different phases, as they are differently employed. In many cases only one who is a trained seaman can comprehend their exact purport or understand their significant application.

The first question before you start to learn to sail is: Do you know how to swim? If you don’t, you have no business in a sailing boat—in fact you have no business on the water. No parent should allow his boy or girl to have a sailboat until they have learned to swim. It is not difficult to learn to swim; any child can be taught that art in ten days, and it should be a compulsory course in all our schools. If people knew how to swim, nine-tenths of the drowning accidents that do happen would not. Every summer a large number of young people are drowned in this country through the overturning of boats or by falling overboard. Had these persons been taught to swim the majority of them would not have been drowned. A person who can swim has confidence. If suddenly thrown in the water he or she retain their presence of mind, but if unable to[10] swim they become panic stricken, and are not only drowned but in their struggles frequently drown others.

Another custom prolific of accident on the water is the overloading of boats. The green hand should be warned against this practice. Never take a lot of people out in a boat, particularly a sailboat; especially do not take out women and children, or men who are not familiar with boats.

Another thing, never play the fool in a boat. A man who with others in a boat plays such tricks as rocking or trying to carry large sail in a breeze, climbing a mast, or any other silly stunt, is a fool, and is not fit to be trusted with any sort of a craft.

A properly designed and well-constructed boat is perfectly safe in the hands of a sensible person, and if properly used be made to give pleasure not only to the owner but to others. Sailing is one of the safest of our sports; very few yachtsmen lose their lives while boating. It is nothing like so dangerous a sport as bicycling, automobiling or carriage driving. I have met thousands of yachtsmen during my long service in the sport, but of all my acquaintances I can only recall one who was drowned.

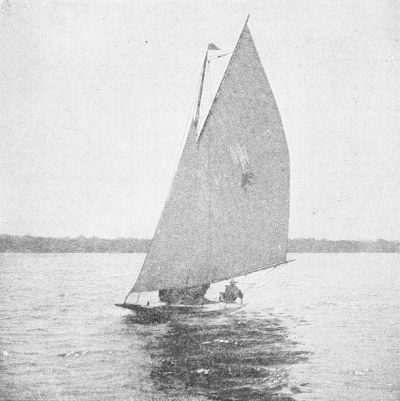

If you are going to learn to sail get a small boat. Men who learn in large boats seldom become good helmsmen. Another thing, do not learn in what is called a non-capsizable boat; get a boat that can be upset. The modern outside ballast, non-capsizable, finkeel or semi-finkeel, is a very easy vessel to handle, and it requires very little skill to sail them; as a fact, you don’t sail them; you simply steer them. The old-fashioned, inside ballast, capsizable, long-keel craft was a very different proposition, and it required considerable skill to handle such properly. It is for this reason that the best sailors we have ever had graduated from the helms of that type of boat.

The best boat for a boy to get to learn in is one of not more than twenty feet length; a fifteen-footer is better. She should be half-decked, and be of such construction[13] and weight that even if filled she will float. It is better to have a boat that requires little or no ballast. If in a place where the water is generally smooth, the Lark type is an excellent craft to learn in; if where it is rough, get one of those cheap sailing dories. The Rudder Skip is also a good boat, but is somewhat more expensive. Another good boat for a beginner is a 15-foot, half-decked, cat-rigged boat; a boat with considerable freeboard and a water-tight cockpit. Such a boat can be built in first-class style for about $250 or $300. I strongly advise the beginner to use the cat rig, no matter what type of hull he employs.

Many begin in a rowboat, fitted with a sail. These are generally poor craft, not being of the proper form for sailing. While they will do, if nothing better can be had, they are far inferior to a properly designed sailing dory or a Lark. If the beginner starts in a poor sailing craft he is apt to get disgusted with the results of his work and give up.

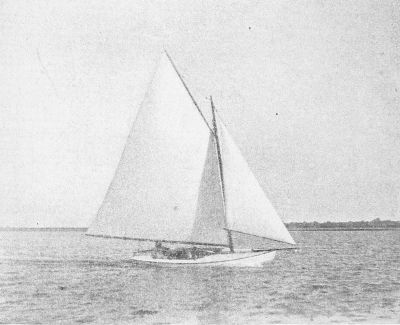

After you have learned to handle a boat under cat rig you can get one with a jib, and learn to sail the more complicated rig. It is not best at first to go in for too many sails, as it means much more gear and [15]this is apt to confuse the beginner, and make the task of learning harder.

By starting to learn to sail in a capsizable boat you will gather the first and most important part of sailorizing, and that is caution, and you will gain from sailing such a boat that nicety of touch which is the acme of helming skill, and which can never be acquired in an uncapsizable craft. Knowing that inattention to your work will perhaps result in a spill, you will be constantly on the alert, and you will learn that by quick and proper movements of the helm you can control and maneuvre your boat so as to keep her on her bottom at all times.

If you have your boat ready take a day when the wind is light and steady and get somebody to go with you who understands sailing. Let the old hand tend the sheet while you handle the tiller. Then sail up and down in a quiet place until you get confidence in the boat and in yourself. This will soon come when you find that you can perform the different sailing maneuvres. It is a good plan after you have the hang of handling the tiller to choose a mark to windward, and to start and beat up to it, then turn the mark and [17]run back again. Repeat this several times as it will give you practice in sailing both on and off the wind.

If the wind is strong and you feel afraid of the boat, don’t go out, but wait until the conditions are more favorable to have your first try. If you get afraid or rattled, as it is called, by the boat getting a knockdown in a puff, just let her come up in the wind and rest, and you will see that she is perfectly safe, and your courage will soon return.

I have taught many—both boys and girls—to sail, and I always put them right at the helm, and insist upon them staying there. If they get in a tight place the beginner will generally want to give up the helm. At such a time I make them retain it, and by a little judicious advice and a few words of encouragement get them through the difficulty. This at once instills confidence. One of my favorite tricks is when the green hand is approaching the shore on a tack to leave him and go below, pretending to pay no attention to his actions. If he is good for anything, he will when the right time arrives go about. Once he has done this by himself he is confident, and will not hesitate to do it again. This is the principal thing to make a beginner understand,[18] that he must depend upon his own judgment and not rely upon yours.

Some persons can never be taught to sail. They can learn to steer perhaps, but never can learn to handle a sailing boat. I have found that comparatively few females can learn to sail, but when they have the sailor’s instinct it is very strongly developed, and they make excellent skippers. They are far more fearless than men, and can invariably be relied upon to carry out orders, even to the death.

Having picked out the boat that best suits your ideas and pocket, start right in and learn all about her. Study out her rig, and learn the proper names of everything from keel to truck. Nothing sounds worse than to hear a man who is sailing a boat call the ropes, spars, etc., by wrong names, and use in speaking of the boat and her actions unnautical language. One of the quickest and easiest ways to learn the nomenclature of the boat is to build and rig a small model. You will in this way not only learn the proper terms but also get an understanding of how a boat is rigged. The first lesson I had was in trying to re-rig a topsail schooner, the model of an old U. S. man-of-war. I was about seven or eight years old, but having the boat mania stuck to the task, although it was long and difficult, and at last, with the kind assistance of a lady, [21]succeeded in completing the job. In this way I captured at an early age a thorough knowledge of how to rig. You need not make a block model, just step your mast in a flat board.

If you are going to buy a boat, not having the opportunity to borrow or steal one, look about for a good second-hand craft. This if in fair condition will do to start with, for you will, as soon as you have learned, want a bigger and better one. If you can use tools, and have the materials and space, I would advise building your own boat, as by so doing you will gather knowledge that will prove invaluable to you in your after days. But don’t build from your own design. Such boats are invariably failures. A man must have considerable knowledge of boats before he can design a proper one. A deal of money has been wasted, and many have been sadly disheartened and made sick of the sport at the outset because they have built a boat after their own plans, and it has turned out a failure. If you are going to build get one of The Rudder How-to Books, and you will from it be able to construct a good sailing craft for a reasonable price, with the least amount of labor.

If you buy a boat be sure the hull is in good condition,[22] and that the boat is not a heavy and consistent leaker. Also, find out if the boat will sail on the wind, for many small boats will not. If the hull is all right, buy the boat. The condition of the sail and rigging is not so important, as you can renew these for a few dollars, and it is better to start off with a new sail and first-class gear. A boat with old canvas and weather-wasted gear will not be satisfactory, and it is better to spend a few dollars and get these things right.

In rigging the boat use as few ropes as possible. A green hand, like a canoeman, generally wants to decorate his spars with all the strings he can get on, but the less rope and the simpler tackles you use the easier will it be to handle the craft.

Whatever you use be sure it is strong. Always use the best cordage you can buy; the difference in price per pound is only a few cents, but there is considerable difference in the way the two kinds will work. A rope used for running should render freely through the block. To do this it must be soft and pliable. Use blocks with a larger swallow than the rope size you intend to run through them, then the rope won’t stick when it gets swollen with dampness or rain.

The sides of a boat have two sets of names, the use of which is apt to confuse the green hand, but if you once clearly understand how these terms are applied you will experience no trouble in properly employing them.

The right-hand side of a vessel when standing looking toward the bow is called the starboard side.

The left-hand side of a vessel when standing looking toward the bow is called the port side.

These names are permanent, and no matter which way the boat is turned the starboard side is always the starboard side and the port side always the port side.

The other names for the sides of a vessel are not permanent, but are always changing, shifting from side to side, as the boat is turned about. Their particular position is determined by the direction of the wind.

These names are lee side and weather side.

The weather side is that side of a vessel upon which the wind blows.

The lee side is that side of the vessel which is farthest from the wind, and is, in a fore-and-aft rigged craft, the side on which the sail is stretched.

Now you will understand that, in consequence of the vessel turning round and presenting first one side to the wind and then the other, these names are continually shifting from side to side.

For instance, if the wind is blowing on the port—left-hand side—that is the weather side, and the starboard—right-hand side—is the lee side. Turning the vessel round, so that the wind blows on the starboard side, that becomes the weather side, and the port side becomes the lee side.

Having these sides and their names clearly fixed in your mind you will be able to understand what a tack is.

When a vessel is sailing on a wind we say she is on the port tack or starboard tack, meaning the way she is heading in regard to the direction of the wind. This tack is determined by the side upon which the wind blows.

A vessel is on the starboard tack when the wind strikes upon her starboard side and the boom of her[26] mainsail is over on the port side. The reverse of this puts her on the port tack.

Or, to be more concise, when the starboard side is the weather side the boat is on the starboard tack. When the port side is the weather side the boat is on the port tack.

A boat or any vessel is steered by a contrivance called a rudder, which is hung like a door on hinges, and swings freely from side to side. This rudder is moved by a handle called a tiller, which is attached to the post and projects forward into the boat. The whole apparatus for steering the boat is called the helm, but in this chapter, when we speak of the helm, it must be understood to mean the tiller.

When the helm is put, i. e., pushed in one direction, the rudder moves in the other. For instance, if the helm is turned to the right the rudder moves to the left, and vice versa. The result of such a movement of the helm is to turn the boat’s bow in the direction the rudder points, so that the boat’s bow, or head as we say, turns the opposite way to the way the tiller is pushed. Remember, that if you put the helm to the left the boat’s [29]head will turn to the right; if you put the helm to the right it will turn to the left.

The left side of the boat, as I have explained, is always called the port side; therefore, if I order you to put your helm to port you must push the tiller toward the left. This will move the rudder toward the starboard side, and as the boat’s bow moves the same way as the rudder it will also move to starboard.

But in a sailing vessel, when going under canvas, we do not usually order the helm to be put to starboard or port, but employ terms that derive their signification from the direction of the wind under whose influence the vessel is moving. These terms are up and down, and a-lee and a-weather.

To put the helm up you push the tiller toward the side of the boat on which the wind is blowing. This causes the vessel to move her head away from the wind—to fall off, as it is called.

To put the helm down you push the tiller toward the side on which the sail is. This causes the vessel to move her head toward the wind—to luff, as it is called.

The easiest way to fix these two actions in the wind is this: When a boat is heeled, i. e., tipped, as she usually[30] is when sailing on the wind, the helm is put up by moving it toward the high or up side, and it is put down by moving it toward the low or down side.

To put the helm a-weather is the same as putting it up, or toward the weather side of the boat. To put the helm a-lee is the same as putting it down or toward the lee side of the boat.

Up—a-weather.

Down—a-lee.

The green hand must get the above information firmly fixed in his mind, as it will save him lots of future trouble. I have met men who have sailed for years who confuse these orders through not thoroughly understanding what they mean.

You will frequently hear a man when conning the helm of a boat—that is, directing the steering—tell the helmsman to keep off, meaning by that to put the helm up and cause the boat to move further away from the wind or course which the boat has been holding; or else he will order the helmsman to luff, meaning for him to put the helm down, and bring the boat’s bow nearer to the wind.

The order to steady or right the helm means to bring the tiller amidships, or in such position that it does not influence the boat in either direction.

Large boats are steered by a wheel, which is simply an apparatus used to give additional power, so that the helm can be turned easily; but as we are dealing with small boats using a tiller, we will not bother at present to understand its working.

Downhaul—A rope for hauling down a sail.

Clewline—A line used to draw together a sail so that it can be easily furled.

Halyards—The tackles by which a sail is hoisted.

Guys—Are ropes used to support or control a spar, and are either permanent or shifting. On spars they generally act in opposition to the sheet.

Topping lift—A rope or tackle for lifting and holding up the end of a boom.

Sheet—The rope or tackle by which a sail is controlled or trimmed. It is made fast to the clew of the sail, or to the boom.

Shrouds—Ropes generally of wire employed to support a mast or bowsprit by holding it sideways. They are attached to the rail by chain plates, and are set up with either lanyards or rigging screws.

Stays—Ropes used to support or control a spar in a fore-and-aft direction.

Luff—The fore edge of a sail.

Leach—The after edge of a sail.

Head—The upper edge of a sail.

Foot—The lower edge of a sail.

Peak—The upper outer corner of a triangular sail, also the upper corner of a jib or gaff topsail. In this book the more common name head is used. See sail plans.

Throat—The upper fore corner of a triangular sail, also called the nock.

Tack—The lower fore corner of a sail.

Clew—The after lower corner of a sail.

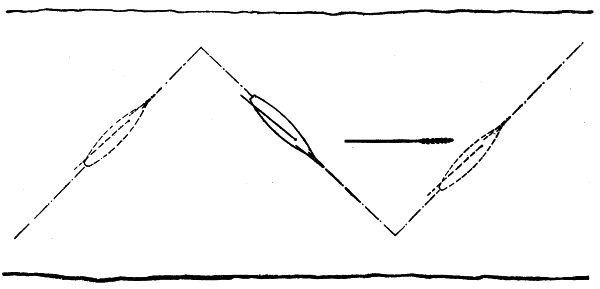

DIAGRAM B.—BEATING OR SAILING TO WINDWARD. BOAT, DOTTED LINES, IS ON STARBOARD TACK; BOAT, FILLED LINES, IS ON PORT TACK.

Sailing on the wind, or by the wind, or close-hauled, is a purely mechanical action, the motion being the result of opposing two forces, the wind pressure and the water pressure. The wind pressing on the canvas forces the boat sideways, her form causes the water to resist this movement, and as it is easier for her to progress in the direction of her length she moves that way. Her sails being arranged so as to transfer this movement in the direction of the bow, she moves ahead. It is to prevent her going sideways that a boat is given a keel or centerboard.

In sailing to windward a boat’s sails are trimmed flat—that is, the sheet is hauled in until the foot of the sail lies nearly parallel to the line of the keel. How close to being parallel depends largely upon the form of the hull, an easily driven model being able to sail with a flatter[36] sheet than one of coarser dimensions. No rule can be laid down for trimming the sheets of a boat when sailing on the wind, it depending upon the form of the vessel, the strength of the wind, and the condition of the water.

As the movement of the boat is dependent upon the pressure exerted upon her canvas by the wind, it is necessary that the wind strike the sail on one side and fill it, and that it exert this pressure in a constant manner. Therefore, the boat’s bow cannot be kept pointing in the direction of the wind, but must be made to approach it at an angle. This angle, in a good sailing vessel, is one of 45 degrees, or four points by compass.

Let us suppose that the wind is blowing from the North. Now, if the boat’s bow is pointed North the current of air will pass along both sides of her sail and exert no pressure upon the canvas, acting just as it does upon the fly of a flag. But if we turn her head slowly round to the West we will find that the breeze begins to press on the canvas, gradually filling it until when her bow is pointed Northwest, or four points away from the wind, the whole sail will be distended with pressure. She is now said to be on a tack or board, and will move ahead in the direction Northwest.

But let us suppose that the point we wish to reach is directly North. If we continue sailing on this Northwest tack we can never reach it. In order to do so we must have the boat move in another direction. Four points, or forty-five degrees, on the other side of North is the direction Northeast. If our boat will fill her sail with a North wind when pointed Northwest she will also necessarily fill it when pointed Northeast. But how are we to get her into a position so that she will point Northeast? By performing a maneuvre which is called tacking or going about.

To do this we put the helm down, or a-lee—that is, push the tiller toward the side on which the sail is, the rudder going in the opposite direction. In consequence of this the boat’s bow begins to move toward the North. As it does so the wind leaves the sail, the canvas shakes, and then as her head swings past North the sail begins to fill again, with the breeze on the opposite side, until when she at last points Northeast it is rap full once more. That is what is called tacking a vessel.

If we continue to tack, remaining for an equal distance on each board or leg, the boat will gradually approach the North point by a zig-zag movement, until she reaches it.

Sometimes, owing to the wind not being directly ahead, we are able to remain longer on one tack than on the other. This is what is called making a long and short leg.

To properly sail a boat on the wind requires constant and minute attention to the helm and the canvas. The best way for the new hand is to sit low down in the cockpit to leeward of the tiller; this places him nearly under the boom. Let him look up and watch his sail just at the throat; here is where it will shake first. To sail the boat close he must just keep that portion of the sail shaking—or lifting as it is termed. After a few days at this work he will get so that he can tell instinctively by the feel of the boat just where she is, and will be able to keep her close without constantly watching the luff. Some skippers sail a boat by the jib luff, sitting to windward to see it; others by the feel of the wind on the face. This is a good guide at night when you cannot see the sail. But those things will come to the novice in time.

You should constantly practice altering the sheets of your boat, until you find out under which trim she goes best. You can mark the positions of the sheets by[40] inserting between the strands of the rope a bit of colored worsted; also alter the position of the weights, either ballast or live, until you get the boat to her proper trim, as this has much to do with a boat sailing well to windward.

If when trimmed to sail on the wind a boat shows herself to be hard on the helm it may be the result of her form, of the position of her ballast, or centerboard, or through having too much after sail. If she gripes—that is, tries to go up in the wind—slack off a little mainsheet, and if she has a jib trim it flatter. If she tries to do the other thing run off to leeward; ease the jib sheets. The worst fault a boat can have is that of carrying a lee helm. Never buy a slack-headed boat; they are an abomination.

In rough-water sailing a boat going to windward wants her sheet eased. Do not trim the sails dead flat, nor try to sail the boat very close to the wind; give her what is called a good full, and keep her moving all the time. Remember, that every wave is a hill that the boat has to climb over, and she needs all the drive possible in order to do it. You must learn how to help her with the helm to take these seas easily, first by luffing and then by bearing away.

A man can only become a good windward helmsman by constant practice and by paying attention to every detail. He must have a quick eye, a firm hand and plenty of grit and strength.

Sailing off the wind, or going free, is a different action from that of sailing on the wind. Sailing free is purely a natural movement, complicated by the fact that a vessel, owing to her weight obliging her to rest in the water, cannot move as freely as a fabric wholly sustained by the air. The fact that friction of the water retards her so that she moves at a less speed than the wind that presses her onward permits of her being steered. Another complication that effects the speed of a vessel going free is the unevenness of the water, the effect of the wind raising surface waves; these greatly retard and hamper her movements. If, instead of rising in waves the sea remained smooth a sailing vessel could be driven nearly as fast as the wind moves, as is the case with ice boats, which on smooth ice move as fast as the wind.

In sailing to windward the faster a vessel moves the[44] more pressure the wind exerts upon her sail. In sailing to leeward this is just the reverse; the faster she goes the less pressure the wind exerts. In the first action she is constantly approaching the source of the wind, in the second receding from it. For instance, if the wind is blowing at the rate of 20 miles an hour and a vessel sailing before it makes 10 miles an hour the pressure in her sails will only be equal to a rate of 10 miles. In calculating how much sail to carry the young yachtsman must remember this: That a windward breeze is nearly double the wind’s velocity, that a leeward breeze is equal to the wind’s velocity minus the boat’s speed; so that more sail can be carried off the wind that can be carried on it.

The amount of sail that can be carried off the wind depends largely upon the form of the boat and the height and action of the sea. If the boat is of a good form for running and the water smooth you can carry all the sail her spars will stand and she can be steered under. But if she is a bad runner, a boat that roots—goes down by the head—or chokes up forward, she will do better with less sail. On all boats there is a time when they reach their maximum speed running and when[45] they will go along easier and better with less canvas. To do her best when running a boat should be kept on an even line—that is, level in the water, and not be allowed to shove her head up or drop her stern down.

In straight stem boats with very little fullness in the forward sections the weight of the crew should be kept aft, as they have a tendency to root—shove their bows down—but in boats with long, full overhangs the weights should be kept forward, as the shape of these craft causes them to shove out the bow and depress and drag the after end.

The most difficult helming of a boat is off the wind in a tall following sea, and great care is necessary then in steering a vessel. If the sea is very heavy and the wind strong do not try to run directly before it, but beat to leeward, first taking the wind on one quarter, and then on the other. If you run dead before, be careful not to let the boat sheer off the helm on either side, or she will be brought by the lee or broach to. If she is brought by the lee her mainsail will jibe over.

You must watch your boat carefully, and you will soon learn to anticipate her next movement, first by noticing the wave that passes, and second by the feeling[46] how she lifts on the one just overtaking her. As soon as the stern lifts she will begin to yaw, as it is called, and then you must at once check this movement by altering the position of the rudder to prevent her swinging too far. This is what is called meeting her with the helm.

One piece of advice when running before a sea: Never get frightened or rattled, and never look behind you, for the sight of a big sea curling up just ready to drop on the stern will scare any one but a hardened sea-dog. Always carry enough sail to keep the boat racing with the waves, or you are liable to get pooped. But do not carry too much sail, for if you do the boat when on top of a wave if struck, as she usually is in such position by a hard puff, is likely to become unmanageable and get away from you.

If you have a boat with a jib, set that and sheet it flat amidships; this when she tries to broach to will fill and drive her head off. If she steers hard trim your mainsheet aft and it will ease her. Lowering the peak and topping up the boom will also ease the steering. Always top up the boom if the sea is heavy, so as to prevent the end of the spar striking the water. Never in[47] heavy weather square the main boom right off; always keep it away from the rigging.

The light sails commonly employed off the wind are the spinnaker and balloon jib. The former is of very little use except with the wind dead aft—that is, directly behind. The moment you have to guy the boom forward to make it draw it loses its power and the balloon jib is a better sail to use. Do not have these sails cut too large, as they are then unhandy and cannot be kept properly sheeted. Never sheet running sails down hard; give them plenty of lift, especially light jibs. A small spinnaker is a great help in steering a boat when running before a strong breeze.

By reefing is meant the means by which a sail is reduced in size by rolling up and tying part of it down to a spar. The sail that you will have to reef is the mainsail, as the jib on a small boat is generally too little to be bothered with in that way. You will notice on a sail, stretching across it from luff to leach, a band, or sometimes two or three bands, in which are inserted short lengths of small line. This is the reef band, and the small lengths of rope are called points, or knittles. At either end of the band in the edge of the sail you will find a hole—or cringle, as it is called. The hole at the after end in the leach of the sail is for the pendant, a small rope that hauls the canvas aft or back towards the stern. The hole at the fore end in the luff of the sail is for the tack, a short length of rope that ties the luff of the sail down to the boom.

There are two ways of reefing. The first and easiest way, which can be performed when the boat is at anchor or lying to a dock, is to hoist the sail up until the reef band is as high as the boom; then take the tack and pass the ends round the boom, pass the ends back again through the cringle several times, if it will go, and then tie hard. Having the tack fast, haul out on the pendant, which should be rove through a beehole or cheek block on the boom; pull on this until the sail’s foot is out taut, but do not pull until the cloth is strained. When the foot is out taut make the pendant fast; then take a short piece of rope and pass it round the boom and pendant just at the cringle and through that hole. Tie this down hard. This is called the clew lashing. Always put on a clew lashing, as it will save the sail from being torn.

Having the tack and pendant fast, begin to tie in the points. Get all the slack canvas on one side and roll it up tight; then pass one end of the reef point through between the lacing and the sail, not round the boom. Tie the point ends together with a bow knot, which is a reef knot with the loop caught in the tie. Pull all your points taut, but be sure and put the same strain on all.[50] Begin to tie in the middle first, and then work toward both ends.

To shake out a reef reverse these operations. First untie the points, then the clew lashing, then slack in the pendant, and last cast loose the tack lashing. Be careful to untie all the points, because if you do not you are liable to tear the sail when hoisting it. Before shaking out a reef, if you have a topping lift fitted pull up on that so as to take the weight of the boom off the sail. If the air is damp, or rain or spray knocking about, don’t haul the sail out very taut or tie the points down hard, as the wet will cause the rope and canvas to shrink and strain the sail out of shape. Never leave reefs tied in sail when stowed, as the canvas will mildew and rot.

Jibing is the operation of passing a boom sail over from one side of the boat to the other when sailing off the wind. A great deal of nonsense has been written and talked about jibing, and it is commonly supposed to be a very dangerous maneuvre. So it is, if carried out by incompetent persons or reckless fools in a bad boat, but if common sense and caution are used there is no danger whatever in jibing a sail at any time.

The first and most important thing is to keep control[51] of the sheet, and to have as little of it out as possible when the sail goes over. In order to do this you must use the helm with great care to bring the boat slowly round. If it is blowing hard top up the boom and lower the peak; in this way you can always safely jibe.

To jibe: Haul in the sheet slowly but steadily, and when well aft carefully put the helm up until the wind strikes the fore side of the sail. As the boom swings across right the helm and then put it the other way, so as to catch the boat as she swings off.

If you have to jibe all standing—what is called a North River jibe—that is, with the sheet all off—just as soon as boom goes over put your helm hard the other way; this will throw the boat’s head so the wind will strike the fore side of the sail and break the force of the swing. It is a very dangerous method, unless you are a skillful skipper, and should never be employed except in an emergency. Never jibe in a seaway with the sheet off; at such time it is better to lower the peak.

You must not only learn to sail, but you must learn to take care of your boat, to keep her neat and clean, and have everything above and below decks in shipshape order. Nothing looks worse than a slovenly kept and dirty yacht; a boat with fag ends of rope hanging about, loose and tangled messes of gear, sails not properly stowed, and a general air of untidiness apparent everywhere. The first attribute of good seamanship is order. Therefore, if you want to be considered a skillful sailor, keep your boat both above and below decks in shipshape fashion.

To do this means considerable work. It is no easy job to take proper care of even a small yacht, but if you regularly attend to the work you will find it come easier as you grow more familiar and used to the task. In the first place, the boat should be kept pumped out if she[53] has a leak, as most boats have; next, her decks and cockpit should be thoroughly scrubbed and kept as clean as possible; the paint round the house and rails washed regularly, and her topsides looked to at least once a week.

Next, keep good watch over the gear; don’t let the ends of the ropes get fagged out; keep them whipped. Always, after coming in from a sail, coil down and clear up all the ends of the gear. Keep your rodes and warps neatly coiled or Flemished, and not heaped in a tangled mass, thrown in any way. Take up on your tackles so that ropes don’t swing loose, but be careful not to take up too hard, if you are not staying on the boat, because if dampness or rain sets in the rope will absorb the moisture and swell, causing it to contract and shrink lengthways. This not only is bad for the cordage, but in small vessels it frequently strains and distorts the spars.

If you have to leave your boat for several days with no one to care for her, do not stow your sails too tightly; roll them up loosely, and gasket so that they cannot shake out if it comes on to blow. If sails are furled in hard rolls the dampness in the canvas will cause them to sweat and rot; canvas to keep good wants the air. Sail covers are not good things to use, unless they are frequently[54] removed, so as to let the air and sun get at the sails.

If your boat is rigged with metal blocks, turnbuckles, etc., these should be frequently oiled and greased, as should also the gooseneck and the jaws of the gaff. By keeping rust and verdigris off the working parts of these things you will increase their length of service and always have them in good working order. The steering gear, if you use a wheel, should be frequently inspected and oiled. If you use a tiller see that it is in good condition and not split or weakened where it is attached to the head of the rudder post. Steering gear accidents are more frequent than any others, and sometimes lead to disagreeable consequences.

The chain plates, and the shrouds where they go over the mast should be looked at, and also the bobstay and other headgear. Make a practice of going over your rigging at least once a week during the season, and you will be less likely to meet with any mishaps or accidents through something unexpectedly giving way.

Nothing looks better or reflects more credit on a young yacht sailor than to have his boat from truck to keel in first-class order. It is a certain sign that he understands[55] his business, takes an interest in sport, and is a thorough and skilled sailorman. Of course, he cannot if he only spends, say, two days out of the week on board keep the boat up to the highest notch of completeness and order as a yacht is kept that carries a professional crew, but he can keep her neat and clean by giving a few hours of his time to the task. But to make the work easy let him refrain from covering his deck with brass or other fancy gewgaws. Stick to things that don’t need polishing; the less brass the less work.

Another thing I would point out to you, and that is, when painting the decks or cockpit of a boat do not use light-colored paints. One reason for this is that a light color shows every speck of dirt and never can be made to look clean, especially if the boat is harbored in places where the water is muddy or dirty; the other reason is that light paint reflects the sun and is very trying on the eyes. For cockpit, decks and the top of cabin houses, use a dark shade of green, grey or slate; green is the best for the eyes.

To tack:

When ready to tack first put the helm up slightly so as to give the boat a good full, then put it down slowly and steadily. As the vessel’s bow comes into the wind, right the helm, and then as she falls off catch her with the helm before she gets too far away from the wind. If the water is rough and the boat shows an inclination to miss-stay, give her a good full, slacking the sheet slightly to help her get headway, then as you put the helm down, haul in smartly on the sheet.

To tack a sloop:

A sloop or any rig carrying headsails can be tacked as follows: When ready to go about, ease the jib sheet, putting down the helm at the same time; as the boat’s head comes into the wind, haul in the same sheet that you just eased, so as to get that sail aback; as she swings off slack the weather sheet and haul aft the lee one.

To tack a yawl:

Proceed same as for tacking a sloop, but to aid her haul dead-flat the mizzen before putting the helm down. In a light air and a lob of sea when a yawl refuses to go round, you can sometimes cause her to stay by lighting up the jib and hauling the mizzen boom up on the weather side.

Tacking small boats:

Small open boats such as dingeys and skiffs which are slow at staying can be materially helped by moving the weight of the crew forward as they come to the wind, and again aft as they fall off.

Miss-staying:

Our modern yachts unlike the old fashioned kind seldom miss-stay, except when attempted to tack in a heavy seaway. The cause of miss-staying is generally either carelessness or haste. Always give the boat a good full and have way on her before you put the helm down. If a boat miss-stay and get in irons do not jam the helm hard over, but keep it amidship until she gathers stern-way then move it over slowly. Remember that the helm when a boat is going stern first acts the opposite to what it does when she is going ahead. If[58] a centerboard boat pull up the board. If she still refuses to fill, drop the peak.

To wear:

Wearing or veering is the opposite of tacking. In a heavy sea when there is danger of a boat miss-staying it is better to wear. To wear, get your sheet in flat, then put the helm up slowly and as she pays-off, ease the sheet gradually. To wear a yawl ease off the mizzen, keep the mainsail flat, and haul the jib a-weather. In a centerboard boat haul up the board. In a catboat if she refuse to wear drop the peak.

To anchor:

The one prime rule of anchoring is never to let go the anchor until the boat has stopped going ahead and is beginning to go sternwards. In this way you prevent the anchor being turned over, and brought foul of the hawser. Always give an anchor plenty of line or scope as it is called. Six times the depth of water is sufficient under ordinary conditions. In bad weather give all you can spare.

To get underway:

If at anchor before making sail heave in short on your hawser or chain, but be careful not to take in[59] enough to trip the hook, then cast loose and hoist the sail, when ready heave in and break the anchor out of the bottom.

To cast:

To cast a vessel is to turn her head from an anchorage or mooring so as to make her go off on a chosen tack. This is sometimes necessary when anchored between other vessels or close to shore. Supposing it is necessary in order to clear to take the port tack: Haul your mainsail over to starboard, putting your helm the same way. This wall cause her to make a sternboard and her bow will fall off to port. A surer way if at a mooring is to pass a light line to the buoy; carry this aft outside of the rigging to the starboard quarter, then let go the mooring warp and haul in on the spring line. This will cause her head to pay off to port; when on the course let go the spring. To cast her to starboard reverse these proceedings.

The rules of the road are the rules governing the movements of vessels when underway. They are laws enacted by an agreement between all maritime nations, and obedience to them is compulsory. If in case of a collision, it is proved that one of the parties has violated a rule of the road, the damages lie against the violator. Yachtsmen should thoroughly learn and understand these rules, and should always maintain and obey them.

A steam vessel is any vessel propelled by machinery—this includes naphtha, gasolene, kerosene and electric launches.

A sailing vessel is a vessel wholly propelled by sails.

An auxiliary yacht when using her engines, no matter whether she has sail set or not is a steam vessel. If not using her engine she is a sailing vessel.

Steam vessels must keep out of the way of sailing[61] vessels; sailing vessels must keep out of the way of row-boats.

Vessels of all kinds, when underway, must keep clear of anchored craft or craft lying idle or hove-to.

Overtaking vessels must keep clear of vessels overtaken. A sailing vessel overtaking a launch must keep clear of the launch.

When two sailing vessels are approaching one another, so as to involve risk of collision, one of them shall keep out of the way of the other as follows:

A vessel which is running free shall keep out of the way of a vessel which is close-hauled.

A vessel which is close-hauled on the port tack shall keep out of the way of a vessel which is close-hauled on the starboard tack.

When both are running free, with the wind on different sides, the vessel which has the wind on the port side shall keep out of the way of the other.

When both are running free, with the wind on the same side, the vessel which is to the windward shall keep out of the way of the vessel which is to the leeward.

A vessel which has the wind aft shall keep out of the way of the other vessel.

A sailing vessel, when running at night, carries a green light on her starboard side, and a red light on her port side. Such lights are generally carried in the rigging, about six feet above the rail.

A rowboat must carry a white light in a lantern to show when in danger of being run down.

A steam vessel carries the same lights as a sailing vessel, with the addition of a white light at the foremast head, or on launches on top of the pilot house.

A steam vessel, when towing another vessel, carries two white lights; if she is towing more than one vessel, tandem fashion, she shall carry three white lights.

A vessel when at anchor must keep burning a white light, throwing an unbroken flare in every direction; this light should be hoisted above the deck the height of the vessel’s breadth.

All lights must be carried from sunset to sunrise; no other lights should be shown.

A steam vessel must be provided with a whistle operated by steam or air.

A sailing vessel must be provided with a horn.

In fog, mist, falling snow, or heavy rainstorms, whether by day or night, the signals described shall be used:

A steam vessel underway shall sound, at intervals of not more than one minute, a prolonged blast.

A sailing vessel underway shall sound, at intervals of not more than one minute, when on the starboard tack, one blast; when on the port tack, two blasts in succession, and when with the wind abaft the beam, three blasts in succession.

A vessel when at anchor shall, at intervals of not more than one minute, ring the bell rapidly for about five seconds.

A steam vessel when towing shall, instead of the signal prescribed above, at intervals of not more than one minute, sound three blasts in succession, namely, one prolonged blast followed by two short blasts. A vessel[64] towed may give this signal and she shall not give any other.

All rafts or other water craft, not herein provided for, navigating by hand power, horse-power, or by the current of the river, shall sound a blast of the fog horn, or equivalent signal, at intervals of not more than one minute.

One blast—I am directing my course to starboard.

Two blasts—I am directing my course to port.

Three blasts—I am going astern.

The vessel that blows first has the right of way.

Passing through narrow channels a vessel must keep to that bank of the fairway which is on her starboard hand.

Aback—Said of a sail when the wind blows on the back or wrong side of it and forces the boat sternwards.

Abaft—Towards the stern, as abaft the mast.

Abeam—At right angles to the length of the vessel, as a dock is abeam when it bears directly off one side.

Aboard—On the vessel, as come aboard, get the anchor aboard, etc.

About—To go about is to tack.

Adrift—Broken loose, as the boat is adrift, the sheet is adrift, etc.

Aft—Back or behind, as come aft, haul the mainsheet aft, meaning to pull it towards the stern.

After—As after sails, meaning the sails set behind the mast. In a sloop the mainsail is an after sail and the jib a foreward one.

Ahead—In front of, as a buoy is ahead when steering towards it.

A-lee—An order to put the helm over towards the lee side. The helm is hard a-lee when it is as far over towards the lee side as it will go.

Aloft—Up above.

Alongside—Close to the side.

Amidships—In line with the keel.

Anchor—The instrument used to hold a vessel to the bottom, usually made of iron.

Astern—Behind the vessel.

Athwart—Across, as athwartships, meaning that a thing is lying across the vessel.

Avast—An order to stop.

A-weather—An order to put the helm towards the windward side.

Ballast—Weight placed in or hung to the bottom of a boat to keep her upright.

Beating—Tacking. Sailing towards the source of the wind by making a series of tacks.

Becalmed—Being without enough wind to propel the boat.

Beehole—A hole bored in a spar for a rope to pass through and move freely.

Belay—To make a rope fast to cleat or pin.

Bend—To bend is to fasten, as to bend a sail, i. e., lace it to the spars. Bend the cable, meaning to fasten it to the anchor.

Bight—The slack or loop of a rope.

Bilge—The inside of the lower part of the bottom of a boat, where the water she leaks in stands.

Binnacle—A box for the steering compass which can be lighted at night.

Blocks—The instrument through which ropes are rove so as to facilitate the hoisting and trimming of the sails, called by landsmen pulleys.

Board—A tack.

Bobstay—A rope generally of wire extending from the end of the bowsprit to the stem to hold the spar down.

Bolt-rope—The rope sewn round the edge of a sail to strengthen it.

Boom—The spar used to extend the foot of the mainsail or foresail.

Bow—The forward end of a boat.

Bowsprit—The spar thrust out from the bow upon which the jib is set.

Burgee—The ensign or house flag of a yacht club.

By the head—A boat is said to be by the head, when she is drawing more water forward than aft, or is out of trim owing to her bows being overloaded and depressed.

By the stern—The opposite to by the head.

By the wind—Same as on the wind, or close-hauled.

Cable—A rope or chain used to anchor a boat.

Capsize—To upset.

Cast off—To loosen, as cast off that line.

Casting—To pay a boat’s head off from a mooring by getting the sails aback or by using a spring line.

Cat rig—A vessel with one mast, placed right in the bow, and carrying a single sail.

Centerboard—A keel that can be lifted up and down. It is hung in a trunk or box which is built up inside the boat to keep the water out.

Cleat—A piece of wood, iron or brass used to fasten or belay ropes to.

Clews—The corners of a sail.

Close-hauled—A vessel is close-hauled when she is sailing as close to the wind as possible.

Coil—To gather a rope into a series of circles so that it will roll out again without getting tangled.

Con—To direct a helmsman how to steer.

Course—The direction or path which a boat sails.

Cringle—An eye worked in the bolt rope of a sail for a small line to pass through.

Crotch—Two pieces of wood put together like a pair of scissors and used to hold the boom up when the vessel is at anchor.

Downhaul—A rope used to haul a sail down.

Draught—The depth of water necessary to float a boat, the amount in feet and inches a vessel’s hull is immersed.

Drift—To move sideways or sternways, as when a boat is becalmed. The drift of a tide or current is its velocity.

Ensign—The national flag always flown furthest aft, either from the gaff end or on a flagpole over the stern.

Fathom—Six feet. A measure used by seamen principally to designate depths of water.

Flukes—The broad, arrow-shaped parts of an anchor.

Fore—The part of a vessel nearest to the bow.

Fore and aft—Parallel to the keel. A fore-and-after is a vessel without square sails like a sloop or schooner.

Foul—Entangled or caught, as a rope is foul, meaning it is caught in someway. To foul another boat is to run into it.

Furl—To roll up and make sails fast so that the wind cannot distend them.

Gaff—The spar that extends the head of a main or foresail.

Gasket—A short piece of rope used to tie up sails with, frequently called a stop.

Gripe—A boat is said to gripe when she tries to force her bow up in the wind, and has to be held off by putting the helm up.

Halyards—Ropes used to hoist a sail.

Hanks—Rings made fast to the luff of a jib to hold it to the stay up which it is hoisted. On small boats snap-hooks are generally used.

Haul—To pull.

Heel—A vessel is said to heel when she leans to one side. This term is often confused with careen.

Helm—The tiller.

Hitch—To hitch is to make fast. A hitch is a simple turn of rope used to make fast with.

Hove-to—Brought to the wind and kept stationary by having the sails trimmed so that part of the canvas pushes the vessel backward and part pushes her forward; often confused with lying-to.

Hull—The body of a vessel.

Irons—A vessel is in irons when having lost steerageway she refuses to obey the helm.

Jibing—Passing a sail from one side to the other when a vessel is sailing free.

Keel—The largest and lowest timber of a vessel, upon which the hull is erected.

Leach—The after edge of a sail.

Leeward—The direction toward which the wind is blowing.

Long leg—The tack upon which a vessel in beating to windward remains longest, owing to her point of destination not lying directly in the wind. See diagram.

Log—The record kept of a vessel’s work. A ship’s diary. Also an instrument for ascertaining a vessel’s speed through the water.

Luff—The fore edge of a sail, also an order to bring a vessel closer to the wind.

Lying-to—A vessel is lying-to when she is brought close to the wind under short sail and allowed to ride out a storm. See hove-to.

Moor—To anchor a vessel with two or more anchors. To tie up to a mooring.

Mooring—A permanent anchor.

Near—A vessel is said to be near when her sails are not properly full of wind, owing to her being steered too close.

Miss-stay—To fail to tack or go about.

Off and on—When beating to windward to approach the land on one tack and leave it on the other.

Overhaul—To haul a rope through a block so as to see it all clear. To overtake another vessel.

Painter—The rope attached to the bow of boat by which it is made fast.

Part—To part a rope is to break it.

Pay off—To pay off is to recede from the wind or from a dock.

Peak up—To peak up a sail is to haul on the peak halyards so as to elevate the outer end of the gaff.

Pooping—A vessel is said to be pooped when, owing to her not moving fast enough ahead, the sea breaks over her stern.

Port—The left-hand side of a vessel looking forward, formerly called larboard. Designating color, red.

Preventer—A rope used to prevent the straining or breaking of a spar or sail.

Pennant—A narrow flag, also a short piece of rope commonly spelled pendant.

Quarter—See diagram A.

Rake—The inclination of a spar out of the perpendicular.

Reef—To reduce a sail by rolling up and tying part of it to a spar.

Reeve—To pass a rope through a block.

Ride—As to ride at anchor.

Right—A vessel is said to right when after being on her side she regains an upright position.

Right the helm—To put it amidships.

Rode—A hawser used to anchor with.

Scope—The length of cable a vessel is riding to when at anchor.

Serve—To wind cord or canvas round a rope or spar to protect it from chafing.

Seize—To make fast by taking a number of turns with small line.

Sheer—To sheer is to move away from the proper course. The sheer of a vessel is the fore-and-aft curve of the deck line.

Ship—To ship is to take on board.

Shiver—To shake the canvas by bringing the luff in the wind.

Slack—The part of a rope that hangs loose.

Slip—To slip is to let go of a cable without taking it on board.

Snub—To check the cable when running out.

Sound—To try the depth of water by casting the lead.

Spill—To throw the wind out of a sail by putting the helm down or by easing the sheet.

Spring—To spring a spar is to crack it.

Spring—A rope used to cast or turn a vessel.

Stand on—To keep a course—to proceed in the same direction.

Stand-by—To be ready for action, as stand-by to let go the anchor.

Starboard—The right-hand side looking forward. Designating color, green.

Steer—To direct a vessel by employing the helm.

Stow—To furl. Properly speaking, a boom sail or any sail that lowers down is stowed. Square sails are furled.

Swig—To haul a rope by holding a turn round a cleat and pulling off laterally.

Tack—To beat to windward. See diagram.

Tackle—An assemblage of blocks and rope used to hoist and control sails, lift spars, etc.

Taut—Tight.

Tender—The small boat carried by a yacht generally called a dingey.

Tow—To drag behind.

Truck—The uttermost upper end of the mast through which the signal halyard is rove.

Unbend—To untie, as—unbend the cable.

Wake—The furrow left by the passage of the vessel through the water.

Wear or veer—The opposite of tacking—to turn from the wind.

Warp—A hawser used to make fast with. To warp is to haul or move a vessel by pulling on such a rope.

Watch—A division of the crew, also the space of time they are on duty.

Way—A vessel’s progress through the water. To get underway—to set sail, to move off.

Weather—To weather a vessel or object is to pass to windward of it.

Weather side—The side upon which the wind blows.

Weather shore—The weather shore is the shore from off of which the wind blows if viewed from the sea, but it is the shore upon which the wind blows if viewed from the land.

Weigh or way—To way the anchor is to lift it from the bottom.

Wind’s eye—The exact direction from which the wind blows.

Windward—Toward the place from where the wind comes. To go to windward of another vessel is to pass between her and the source of the wind.

Yaw—To swerve from side to side as a vessel does when running free.

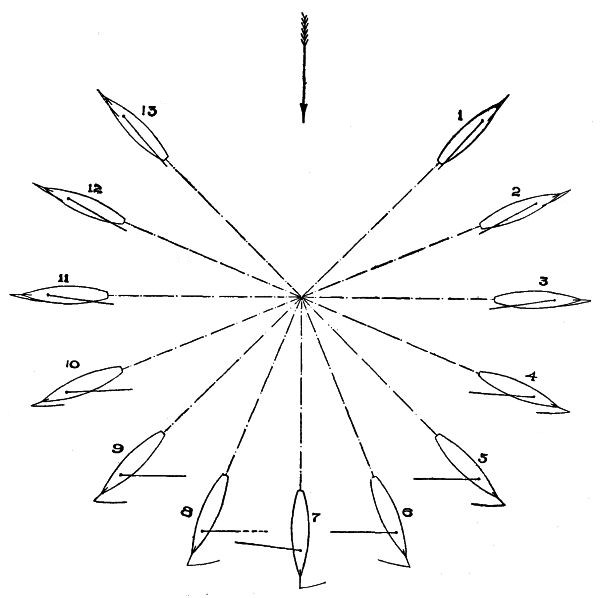

DIAGRAM D.—BOAT, FROM 1 TO 6, IS BEARING AWAY OR KEEPING OFF FROM THE WIND; BOAT, FROM 8 TO 13, IS LUFFING OR NEARING THE WIND.

| 1— | Close-hauled on port tack. | 8— | Jibed over to starboard tack. | ||

| 2— | Wind forward of the beam. | 9— | Wind | on the quarter. | |

| 3— | Wind | abeam. | 10— | “ | abaft the beam. |

| 4— | “ | abaft the beam. | 11— | “ | abeam. |

| 5— | “ | on the quarter. | 12— | “ | forward of the beam. |

| 6— | “ | astern. | 13— | Close-hauled on starboard tack. | |

| 7— | “ | dead astern. | |||

| 1— | Hull. | 10— | Peak | halyards. | ||

| 2— | Cabin house. | 12— | “ | “ | bridle. | |

| 3— | Main | mast. | 11— | Throat | “ | |

| 4— | “ | boom. | 13— | Jaws of gaff. | ||

| 5— | “ | gaff. | 15— | Head stay. | ||

| 6— | Companionway or hatch. | 16— | Shroudy. | |||

| 7— | Main sheet. | 17— | Strut. | |||

| 8— | Topping lift. | 18— | Bitts. | |||

| 9— | Lazy jacks. | 19— | Cockpit. | |||

| 1— | Mainsail. | 6— | Mainsail | throat. | |

| 2— | “ | luff. | 7— | “ | peak. |

| 3— | “ | leach. | 8— | “ | tack. |

| 4— | “ | head. | 8— | “ | clew. |

| 5— | “ | foot. |

| 1— | Freeboard. | 14— | Preventer or shifting backstay. | ||

| 2— | Rail. | 15— | Gaff jaws. | ||

| 3— | Mast. | 16— | Boom jaws or gooseneck. | ||

| 4— | Main boom. | 17— | Shroud | to hounds. | |

| 5— | Gaff. | 18— | “ | to mast head. | |

| 6— | Bowsprit. | 19— | Peak halyard bridle. | ||

| 7— | Bobstay. | 20— | Fore stay. | ||

| 8— | Strut. | 21— | Jib stay. | ||

| 9— | Main sheet. | 22— | Fore staysail halyards. | ||

| 10— | Peak | halyards. | 23— | Jib halyards. | |

| 11— | Throat | “ | 24— | Cockpit coaming. | |

| 12— | Topping lift. | ||||

| 13— | Lazy jacks. | ||||

| 1— | Mainsail. | 9— | Fore | staysail | tack. | ||

| 4— | “ | peak. | 10— | “ | “ | clew. | |

| 5— | “ | throat. | 3— | Jib. | |||

| 5— | “ | tack. | 11— | “ | head. | ||

| 5— | “ | clew. | 12— | “ | tack. | ||

| 2— | Fore | staysail. | 13— | “ | clew. | ||

| 8— | “ | “ | head. | ||||

| 1— | Mainsail. | 14— | Jib | tack. | |||

| 6— | “ | peak. | 15— | “ | clew. | ||

| 7— | “ | throat. | 4— | Jib | topsail. | ||

| 8— | “ | tack. | 16— | “ | “ | head. | |

| 9— | “ | clew. | 17— | “ | “ | tack. | |

| 2— | Fore | staysail. | 18— | “ | “ | clew. | |

| 10— | “ | “ | head. | 5— | Topsail. | ||

| 11— | “ | “ | tack. | 19— | “ | head. | |

| 12— | “ | “ | clew. | 20— | “ | clew. | |

| 3— | Jib. | 21— | “ | tack. | |||

| 13— | “ | head. |

| 1— | Hull. | 13— | Main throat | halyards. | |||

| 2— | Cabin house. | 14— | Mizzen | peak | “ | ||

| 3— | Cockpit rail or coaming. | 15— | “ | throat | “ | ||

| 4— | Main mast. | 16— | Main | topping | lift. | ||

| 5— | Mizzen mast. | 17— | Mizzen | “ | “ | ||

| 6— | Main | boom. | 18— | Main | shrouds. | ||

| 7— | “ | gaff. | 19— | Mizzen | “ | ||

| 8— | Mizzen | boom. | 20— | Jib | stay. | ||

| 9— | “ | gaff. | 21— | “ | halyards. | ||

| 10— | Main | sheet. | 22— | Bowsprit. | |||

| 11— | Mizzen | “ | 23— | Bobstay. | |||

| 12— | Main peak halyards | 24— | Boomkin. | ||||

| 25— | “ | stay. | |||||

| 1— | Mainsail. | 10— | Mizzen | throat. | |

| 4— | “ | peak. | 11— | “ | tack. |

| 5— | “ | tack. | 12— | “ | clew. |

| 6— | “ | throat. | 3— | Jib. | |

| 8— | “ | clew. | 13— | “ | head. |

| 2— | Mizzen. | 14— | “ | tack. | |

| 9— | “ | peak. | 15— | “ | clew. |

| 1— | Mainsail. | 17— | Fore staysail clew. | ||||

| 7— | “ | peak. | 4— | Jib. | |||

| 8— | “ | throat. | 18— | “ | head. | ||

| 9— | “ | tack. | 19— | “ | tack. | ||

| 10— | “ | clew. | 20— | “ | clew. | ||

| 2— | Mizzen. | 5— | Jib | topsail. | |||

| 11— | “ | peak. | 21— | “ | “ | head. | |

| 12— | “ | throat. | 22— | “ | “ | tack. | |

| 13— | “ | tack. | 23— | “ | “ | clew. | |

| 14— | “ | clew. | 6— | Topsail. | |||

| 3— | Fore | staysail. | 24— | “ | head. | ||

| 15— | “ | “ | head. | 25— | “ | clew. | |

| 16— | “ | “ | tack. | 26— | “ | tack. | |

| 1— | Freeboard. | 22— | Main | sheet. | ||||

| 2— | Rail. | 23— | “ | peak | halyards. | |||

| 3— | Cabin house. | 24— | “ | throat | “ | |||

| 4— | Wheel. | 25— | “ | peak | halyards | bridles. | ||

| 5— | Fore | hatch. | 26— | Fore | topping | lift. | ||

| 6— | “ | mast. | 27— | Main | “ | “ | ||

| 7— | “ | topmast. | 28— | Preventer backstay or runner. | ||||

| 8— | “ | truck. | 29— | Topmast preventer backstay. | ||||

| 9— | “ | doublings. | 30— | Bowsprit. | ||||

| 10— | Main | mast. | 31— | Bobstay. | ||||

| 11— | “ | topmast. | 32— | Fore stay. | ||||

| 12— | “ | truck. | 33— | Fore staysail halyards. | ||||

| 13— | Head of main mast and doublings. | 34— | Jib | stay. | ||||

| 14— | Fore | boom. | 35— | “ | halyards. | |||

| 15— | “ | gaff. | 36— | “ | topsail | stay. | ||

| 16— | Main | boom. | 37— | “ | “ | halyards. | ||

| 17— | “ | gaff. | 38— | Triatic stay. | ||||

| 18— | Fore | sheet. | 39— | Spring stay. | ||||

| 19— | “ | peak | halyards. | 40— | Main topmast stay. | |||

| 20— | “ | throat | “ | |||||

| 21— | “ | peak halyard bridles. | ||||||

| 1— | Mainsail. | 5— | Jib | topsail. | ||||

| 9— | “ | peak. | 22— | “ | “ | head. | ||

| 10— | “ | throat. | 23— | Jib | topsail | tack. | ||

| 11— | “ | tack. | 24— | “ | “ | clew. | ||

| 12— | “ | clew. | 6— | Main | topsail. | |||

| 2— | Fore | sail. | 25— | “ | “ | head. | ||

| 13— | “ | “ | peak. | 26— | “ | “ | clew. | |

| 14— | “ | “ | tack. | 27— | “ | “ | tack. | |

| 15— | “ | “ | clew. | 7— | Fore | topsail. | ||

| 3— | Fore | staysail. | 28— | “ | “ | head. | ||

| 16— | “ | “ | head. | 29— | “ | “ | clew. | |

| 17— | “ | “ | tack. | 8— | Main | topmast | stays. | |

| 18— | “ | “ | clew. | 30— | “ | “ | “ | head. |

| 4— | Jib. | 31— | Upper tack. | |||||

| 19— | “ | head. | 32— | Lower tack. | ||||

| 20— | “ | tack. | 33— | Clew. | ||||

| 21— | “ | clew. | ||||||

The following books are recommended to the young yachtsman. From them he can obtain information of value, and a study of their pages will materially aid him in gaining a thorough knowledge of the seaman’s art:

| On Yachts and Yacht Handling | Day |

| Hints to Young Yacht Skippers | Day |

| Small Boat Sailing | Knight |

| Boat Sailor’s Manual | Qualtrough |

| Knots and Splices | Jutsum |

| Canoe Handling | Vaux |

| Elements of Navigation | Henderson |

| How to Swim | Dalton |

THE RUDDER

The policy of The Rudder is to give to yachtsmen a thoroughly practical periodical, dealing with the sport of yachting in all its phases, and especially to furnish them with the designs and plans of vessels adapted to their wants in all localities.

In each issue is a design of a sailing or power craft, and at least four times a year a complete set of working drawings is given, so that the unskilled can try a hand at building with a certainty of making a success of the attempt.

In the last two years over 500 boats have been built from designs printed in the magazine, and in almost every case have given satisfaction.

Outside of the strictly practical, the magazine has always a cargo of readable things in the way of cruises and tales, while its illustrations are noted for their novelty and beauty.

The editor desires to increase the size of the magazine and to add to its features. In order to do this it is necessary that it be given the hearty support of all who are interested in the sport. The cost of a subscription, $2 a year rolled or $2.50 mailed flat, is as low as it is possible to make it and furnish a first-class publication, and he asks yachtsmen to subscribe, as in that way they can materially assist him in keeping the magazine up to its present standard of excellence.

$2 a year rolled$2.50 a year flat

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING COMPANY

9 Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

How to Remit: The cheapest way is to send post-office or express money order, payable to the RUDDER PUBLISHING COMPANY. If bank check is more convenient, include 10c. for bank exchange; if postage stamps or bills, letter must be REGISTERED, OTHERWISE AT SENDER’S RISK.

RUDDER ON SERIES

On Yachts and Yacht Handling

By Thomas Fleming Day

The first volume of a series of technical books that will be an invaluable addition to every yachtsman’s library.

CONTENTS

On Seamanship

On Boats in General

On One-Man Boats

On Seagoing Boats

On Sails as an Auxiliary

CONTENTS

On Reefing

On Anchors and Anchoring

On Rigging

On Stranding

In this book Mr. Day has dropped all technical terms that are apt to be confusing to the novice, and has made a simple explanation of the handling and care of a boat. The book is written in a most interesting way. The chapters on anchors alone is worth more than the price of the book.

Price, $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

Hints to Young

Yacht Skippers

By THOMAS FLEMING DAY

Hints on buying, rigging, keeping, handling, maneuvering, repairing, canvasing and navigating small yachts and boats.

Experience compounded with common sense and offered in a condensed form.

Illustrated with drawings and plans.

Blue cloth, uniform in size to Rudder-ON-Series books.

Price One Dollar Prepaid

Send for complete Catalog of Books for The Yachtsman’s Library

| The Rudder Pub. Co., | 9 Murray Street |

| New York City, U. S. A. |

Canoe Handling and Sailing

By C. Bowyer Vaux (“Dot”)

The Canoe—history, uses, limitations and varieties; practical management and care, and relative facts. New and revised edition with additional matter.

Illustrated, cloth, 168 pages

Price, postpaid, $1.00

Small Boat Sailing

By Knight

A very readable and instructive book containing useful information of all types of craft.

Price, postpaid, $1.50

Yacht Sails and how to handle them

By Captain Howard Patterson

A comprehensive treatise on working and racing sail; how they are made; the running rigging belonging to them; the manner in which they are confined to there respective spars, stays, etc.; the way they are bent and unbent, etc. A book as applicable for the small boat as for the large yacht. It should be in the library of every Corinthian sailor. Illustrated. Convenient size for the pocket.

Price, postpaid, $1.00

Elements of Yacht Design

By Norman L. Skene, S. B.

A simple and satisfactory explanation of the art of designing yachts. Contents—General Discussions, Methods of Calculations, Displacement, The Lateral Plane, Design, Stability, Ballast, The Sail Plan, Construction.

Fully Illustrated with Diagrams and Tables.

Price, postpaid, $2.00

THE RUDDER PUB. COMPANY, 9 Murray Street, N. Y.

How to Swim

By Capt. Davis Dalton

Champion Long-distance Swimmer of the World. Chief Inspector of the U. S. Volunteer Life-Saving Corps, etc.

A practical treatise upon the art of natation, together with instruction as to the best methods of saving persons imperilled in the water, and of resuscitating those apparently drowned. With 31 illustrations.

12mo., 120 pages

Price, postpaid, $1.00

Elements of Navigation

By W. J. Henderson

This little book, a very clever abridgement and complication of the heavier works of several authorities, is one that has had quite an extensive sale, and has met with universal approval. It is very clearly and very carefully written, and the explanations of the problems are so lucid that no man should be forgiven who fails to understand them. I have seen many books of this kind intended for beginners, but to my mind this is the best of the lot, and I recommend it to those who are anxious to study navigation.—Editor of The Rudder.

Price, postpaid, $1.00

Knots and Splices

By Captain Jutsum

How to make them; showing various strands in different colors in course of construction. Also tables of strength of ropes, wire rigging, chains, etc.

Price, postpaid, $1.00

The Boat Sailors’ Manual

By E. F. Qualtrough, U. S. N.

A complete treatise of the management of sailing boats of all kinds and under all conditions of weather.

Price, postpaid, $1.50

THE RUDDER PUB. COMPANY, 9 Murray Street, N. Y.

RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES

How to Build a Racer for $50

THE WORLD-FAMOUS LARK

Simplest, safest and fastest boat that can be built. 16 feet over all; 5 feet beam. The working plans are such that a boy can build from them. The plans were published in 1898, and since then some 1,000 boats have been built from them. The book has numerous illustrations of boats in and after construction, and also gives experience of builders in all parts of the world. Bound in cloth, size of page 9 × 12 inches. Large, clearly-drawn plans.

Price $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES

How to Build a Racing Sloop

THE WORLD-WIDE WINNING SWALLOW

Most successful small racing machine ever designed. A prize-winner in America, Europe, Asia and Australia. Has defeated boats designed by Herreshoff, Gardner, Payne and a host of other designers. No trouble to build if directions are followed. Materials costs about $100; sometimes less. Book contains story of Swallow’s work. Bound in cloth, size of page 9 × 12 in. Large clearly-drawn plans.

Price $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES

How to Build a Skipjack

Complete plans and directions for building a 19-foot sloop, the materials of which will cost less than $100; and pictures of numerous boats that have been built in all parts of the world from these plans. Bound in cloth, size of page 9 × 12 inches. Large clearly-drawn plans.

Price $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES

How to Build a Knockabout

The most wholesome type of boat for all-around cruising and racing. 32 feet over all; 20 feet w. l.; 10 feet beam; 20 inches draught. Stanch, fast and powerful. Easily handled by one man. Full working drawings and plans, with descriptive illustrations and instructions for building. Bound in cloth, size of page 9 x 12 inches. Large, clearly-drawn plans.

Price $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

The Latest How-To Book

How to build

a ROWBOAT

Full plans for a 10-foot,

12-foot and 14-foot Rowing Craft

| Price, postpaid, to any part of the world | $1.00 |

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York City

RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES

How to Build a Model Yacht

HOW TO SAIL A MODEL YACHT,

HOW TO CUT AND MAKE SAILS

Complete and understandable description of the process of model building, profusely illustrated with drawings. Everything is explained fully and clearly. Good book for a beginner; excellent for an old hand. Lines and plans of several fast boats by different designers. Plans of skiff used to follow models. Bound in cloth, size of page 9 × 12 inches. Large, clearly-drawn plans.

Price $1.00 postpaid

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO.

Nine Murray Street, New York, U. S. A.

RUDDER WHAT-TO SERIES

Designs and plans of many of the best boats whose lines have appeared in The Rudder during the last nine years. Invaluable to the man who is planning to build. It will save him time, money and worry. Should be in every yachtsman’s library as a book of reference. Handy and handsome.

The Cat Book

Containing the designs and plans of twelve Cabin Cats

Price, $1.00

The Yawl Book

Contains designs and plans of twelve Yawl-Rigged Boats

Price, $1.00

The Schooner Book

Contains the designs of twelve Schooner-Rigged Yachts

Price, $1.00

The Racer Book

Contains the designs and plans of twelve Racing Yachts

Price, $1.00

The Cabin Plan Book

Containing accommodation plans of twenty sail craft

Price, $1.00

SENT ANYWHERE. EXPRESS PREPAID

| Send postal for Catalogue of Yachting and Boatbuilding Books |

THE RUDDER PUBLISHING CO., 9 MURRAY STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y., U. S. A. |

TECHNICAL AND PRACTICAL

| Amateur Sailing. By Biddle | $1.50 |

| Art and Science of Sailmaking. By Sadler | 5.00 |

| A Text-Book on Marine Motors. By Captain Du Boulay | 2.50 |

| Astronomy for Everybody. By S. Newcombe | $2.00; by express paid, 2.15 |

| American Merchant’s Marine. By Marvin | $2.00;““2.22 |

| American Yachting. By W. P. Stephens | $2.00; by mail 2.15 |

| A, B, C of Swimming. By ex-Captain of a London Swimming Club | .50 |

| A B C of Motoring | .50 |

| Aids to Stability. By H. Owen | 1.50 |

| A Manual of Mechanical Drawing. By P. D. Johnson | 2.00 |

| Boat Sailor’s Manual. By E. F. Qualtrough | 1.50 |

| Building Model Boats. By P. N. Hasluck | .50 |

| Canoe Handling. By C. B. Vaux | 1.00 |

| Coast Pilot for Atlantic Coast, Illustrated | 1.25 |

| Coast Pilot for the Lakes. By Scott | 1.50 |

| Corinthian Yachtsman | 1.50 |

| Canvas Canoes—How to Build Them. By Field | .50 |

| Canoe Cruising and Camping. By P. D. Frazer | 1.00 |

| Canoe and Camera. By Steele | 1.00 |

| Canoe and Boatbuilding for Amateurs. By Stevens | 2.00 |

| Canoe and Camp Cookery. By Seneca | 1.00 |

| Dry Batteries. By a Dry Battery Expert | .25 |

| Eldredge’s Tide-Book | .50 |

| Elements of Navigation. By Henderson | 1.00 |

| Elements of Yacht Design. By Norman L. Skene | 2.00 |

| Fore-and-Aft Seamanship | .50 |

| Gas Engine Handbook. By Roberts. 2nd edition | 1.50 |

| Gas Engines and Their Troubles | 1.50 |

| Handbook of Naval Gunnery. By Radford | 2.00 |

| RUDDER HOW-TO SERIES— | |

| How to Build a Racer for $50 | 1.00 |

| How to Build a Skip Jack | 1.00 |

| How to Build a Racing Sloop | 1.00 |

| How to Build a Knockabout | 1.00 |