The Project Gutenberg EBook of A System of Practical Medicine By American

Authors, Vol. II, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A System of Practical Medicine By American Authors, Vol. II

General Diseases (Continued) and Diseases of the Digestive System

Author: Various

Editor: William Pepper

Louis Starr

Release Date: April 3, 2014 [EBook #45313]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SYSTEM OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE, VOL II ***

Produced by Ron Swanson

|

RHEUMATISM. By R. PALMER HOWARD, M.D.

GOUT. By W. H. DRAPER, M.D.

RACHITIS. By ABRAHAM JACOBI, M.D.

SCURVY. By PHILIP S. WALES, M.D.

PURPURA. By I. EDMONDSON ATKINSON, M.D.

DIABETES MELLITUS. By JAMES TYSON, A.M., M.D.

SCROFULA. By JOHN S. LYNCH, M.D.

HEREDITARY SYPHILIS. By J. WILLIAM WHITE, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE MOUTH AND TONGUE. By J. SOLIS COHEN, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE TONSILS. By J. SOLIS COHEN, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE PHARYNX. By J. SOLIS COHEN, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE OESOPHAGUS. By J. SOLIS COHEN, M.D.

FUNCTIONAL AND INFLAMMATORY DISEASES OF THE STOMACH. By SAMUEL G. ARMOR, M.D., LL.D.

SIMPLE ULCER OF THE STOMACH. By W. H. WELCH, M.D.

CANCER OF THE STOMACH. By W. H. WELCH, M.D.

HEMORRHAGE FROM THE STOMACH. By W. H. WELCH, M.D.

DILATATION OF THE STOMACH. By W. H. WELCH, M.D.

MINOR ORGANIC AFFECTIONS OF THE STOMACH (Cirrhosis; Hypertrophic Stenosis of Pylorus; Atrophy; Anomalies in the Form and the Position of the Stomach; Rupture; Gastromalacia). By W. H. WELCH, M.D.

INTESTINAL INDIGESTION. By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

CONSTIPATION. By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

ENTERALGIA (INTESTINAL COLIC). By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

ACUTE INTESTINAL CATARRH (DUODENITIS, JEJUNITIS, ILEITIS, COLITIS, PROCTITIS). By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

CHRONIC INTESTINAL CATARRH. By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

CHOLERA MORBUS. By W. W. JOHNSTON, M.D.

INTESTINAL AFFECTIONS OF CHILDREN IN HOT WEATHER. By J. LEWIS SMITH, M.D.

PSEUDO-MEMBRANOUS ENTERITIS. By PHILIP S. WALES, M.D.

DYSENTERY. By JAMES T. WHITTAKER, A.M., M.D.

TYPHLITIS, PERITYPHLITIS, AND PARATYPHLITIS. By JAMES T. WHITTAKER, A.M., M.D.

INTESTINAL ULCER. By JAMES T. WHITTAKER, A.M., M.D.

HEMORRHAGE OF THE BOWELS. By JAMES T. WHITTAKER, A.M., M.D.

INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION. By HUNTER MCGUIRE, M.D.

CANCER AND LARDACEOUS DEGENERATION OF THE INTESTINES. By I. EDMONSON ATKINSON, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE RECTUM AND ANUS. By THOMAS G. MORTON, M.D., and HENRY M. WETHERILL, JR., M.D., PH.G.

INTESTINAL WORMS. By JOSEPH LEIDY, M.D., LL.D.

DISEASES OF THE LIVER. By ROBERTS BARTHOLOW, A.M., M.D., LL.D.

DISEASES OF THE PANCREAS. By LOUIS STARR, M.D.

PERITONITIS. By ALONZO CLARK, M.D., LL.D.

DISEASES OF THE ABDOMINAL GLANDS (TABES MESENTERICA). By SAMUEL C. BUSEY, M.D.

ARMOR, SAMUEL G., M.D., LL.D.,

Brooklyn.

ATKINSON, I. EDMONDSON, M.D.,

Professor of Pathology and Clinical Medicine and Clinical Professor of Dermatology in the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

BARTHOLOW, ROBERTS, A.M., M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Materia Medica, General Therapeutics, and Hygiene in the Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia.

BUSEY, SAMUEL C., M.D.,

An Attending Physician and Chairman of the Board of Hospital Administration of the Children's Hospital, Washington, D.C.

CLARK, ALONZO, M.D., LL.D.,

Late Professor of Pathology and Practical Medicine in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York.

COHEN, J. SOLIS, M.D.,

Professor in Diseases of the Throat and Chest in the Philadelphia Polyclinic; Physician to the German Hospital, Philadelphia.

DRAPER, W. H., M.D.,

Attending Physician to the New York and Roosevelt Hospitals, New York.

HOWARD, R. PALMER, M.D.,

Professor of Theory and Practice of Medicine in McGill University, Montreal; Consulting Physician to Montreal General Hospital, Canada.

JACOBI, ABRAHAM, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of Children in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, etc.

JOHNSTON, W. W., M.D.,

Professor of Theory and Practice of Medicine in the Columbian University, Washington.

LEIDY, JOSEPH, M.D., LL.D.,

Professor of Anatomy in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

LYNCH, JOHN S., M.D.,

Professor of Principles and Practice of Medicine in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Baltimore.

MORTON, THOMAS G., M.D.,

Surgeon to the Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia.

MCGUIRE, HUNTER, M.D.,

Richmond, Va.

SMITH, J. LEWIS, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of Children in the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, New York.

STARR, LOUIS, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of Children in the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

TYSON, JAMES, A.M., M.D.,

Professor of General Pathology and Morbid Anatomy in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

WALES, PHILIP S., M.D.,

Washington.

WELCH, WILLIAM H., M.D.,

Professor of Pathology in Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

WETHERILL, HENRY M., JR., M.D.,

Assistant Physician to the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia.

WHITE, J. WILLIAM, M.D.,

Surgeon to the Philadelphia Hospital; Assistant Surgeon to the University Hospital; Demonstrator of Surgery and Lecturer on Venereal Diseases and Operative Surgery in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

WHITTAKER, JAMES T., M.D.,

Professor of Theory and Practice of Medicine in the Medical College of Ohio, Cincinnati.

| FIGURE | |

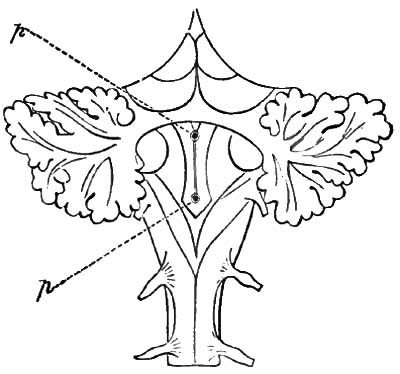

| 1. | POSITION OF PUNCTURES IN DIABETIC AREA OF MEDULLA OBLONGATA NECESSARY TO PRODUCE GLYCOSURIA |

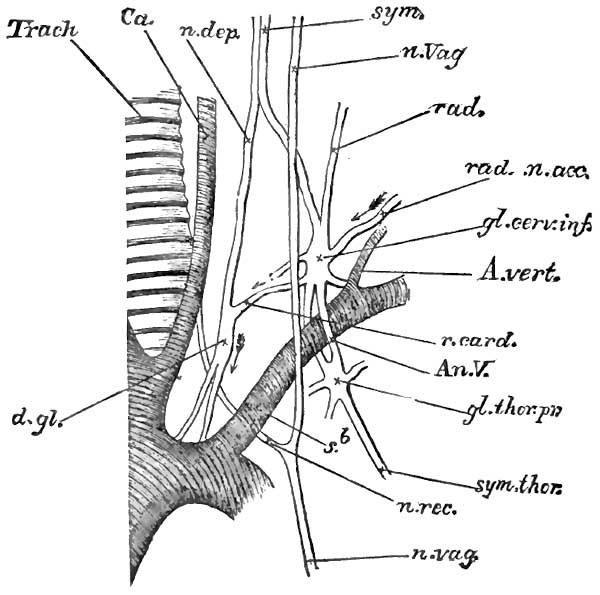

| 2. | THE LAST CERVICAL AND FIRST THORACIC GANGLIA, WITH CIRCLE OF VIEUSSENS, IN THE RABBIT, LEFT SIDE |

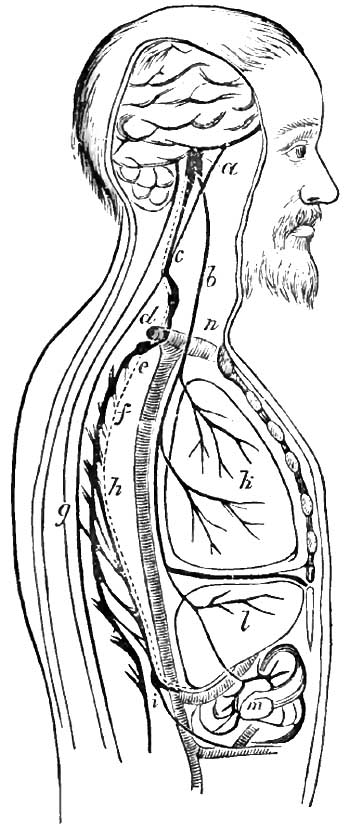

| 3. | DIAGRAM SHOWING COURSE OF THE VASO-MOTOR NERVES OF THE LIVER, ACCORDING TO CYON AND ALADOFF |

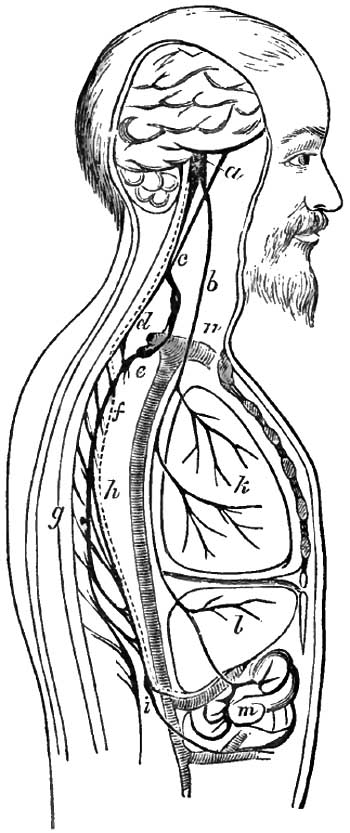

| 4. | DIAGRAM SHOWING ANOTHER COURSE WHICH THE VASO-MOTOR NERVES OF THE LIVER MAY TAKE |

| 5. | JOHNSON'S PICRO-SACCHARIMETER |

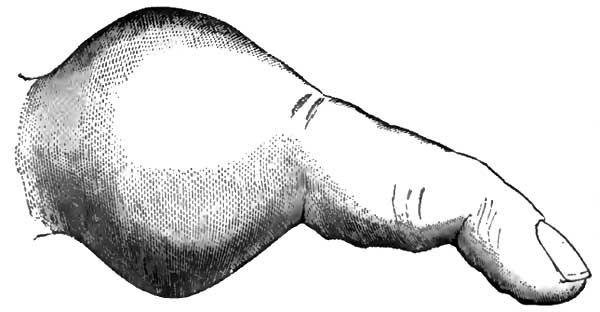

| 6. | PEMPHIGUS BULLA FROM A NEW-BORN SYPHILITIC CHILD |

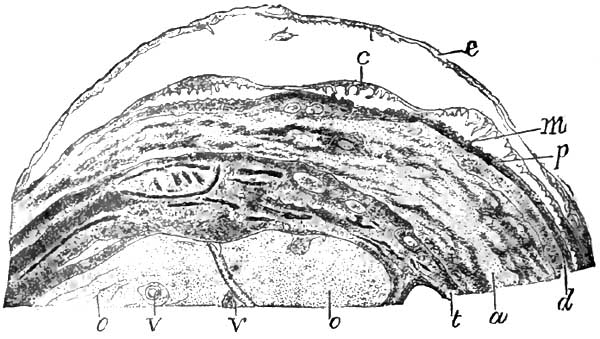

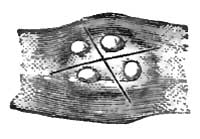

| 7. | SECTION OF RETE MUCOSUM AND PAPILLÆ FROM SAME CASE OF PEMPHIGUS AS FIG. 6 |

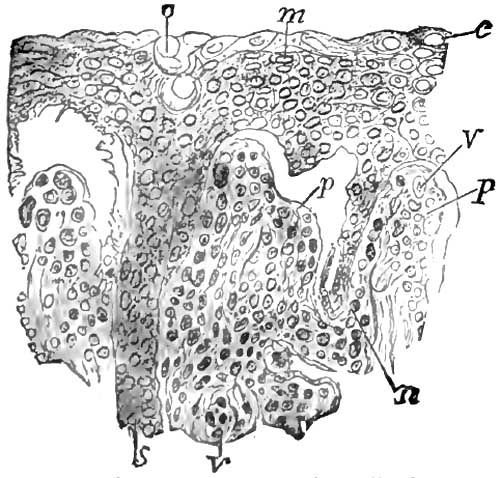

| 8. | SECTION OF AN OLD GUMMA OF THE LIVER |

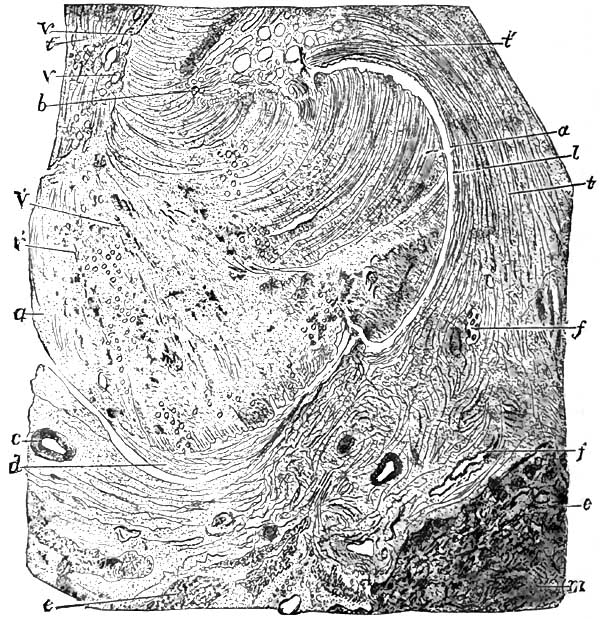

| 9. | SYPHILITIC DACTYLITIS, FROM BUMSTEAD |

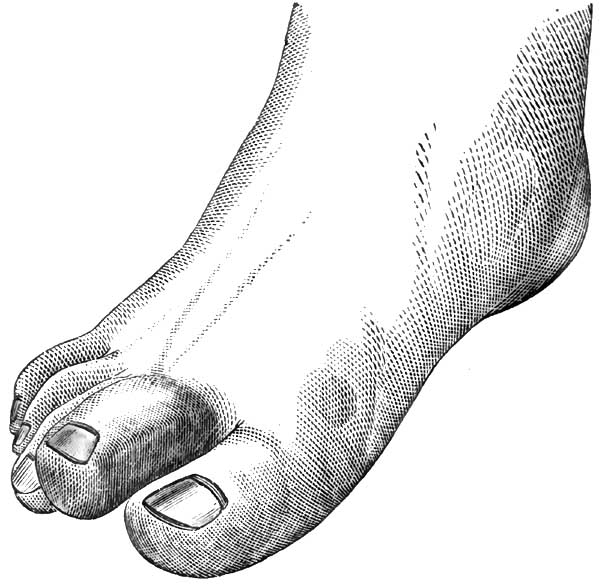

| 10. | THE SAME AS FIG. 9 |

| 11. | SERRATIONS OF NORMAL INCISOR TEETH |

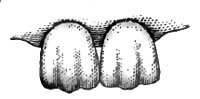

| 12. | NOTCHING OF SYPHILITIC INCISOR TEETH |

| 13. | OÏDIUM ALBICANS FROM THE MOUTH IN A CASE OF THRUSH |

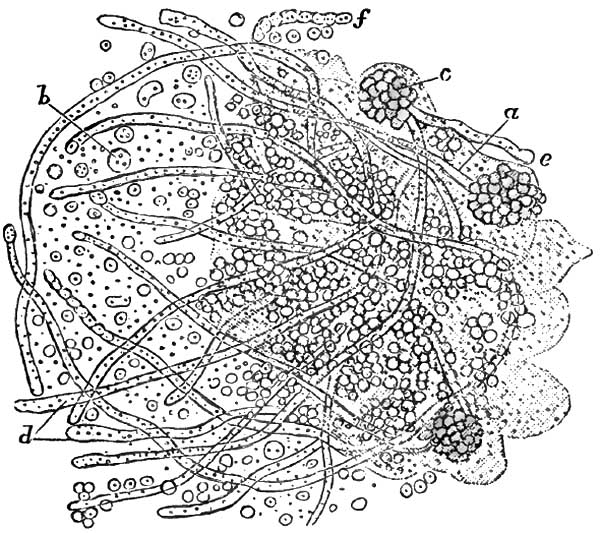

| 14. | CHRONIC INTUMESCENCE OF THE TONGUE (HARRIS) |

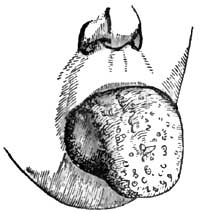

| 15. | HYPERTROPHY OF TONGUE (HARRIS), BEFORE OPERATION AND AFTER |

| 16. | GLOSSITIS (LISTON) |

| 17. | INCISION FOR A CUSPID TOOTH (WHITE) |

| 18. | INCISION FOR A MOLAR TOOTH (WHITE) |

| 19. | FUSIFORM DILATATION OF OESOPHAGUS (LUSCHKA) |

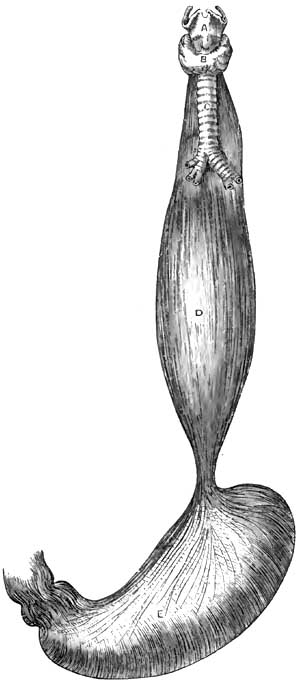

| 20. | FAUCHER'S TUBE FOR WASHING OUT THE STOMACH |

| 21. | FAUCHER'S TUBE FOR WASHING OUT THE STOMACH |

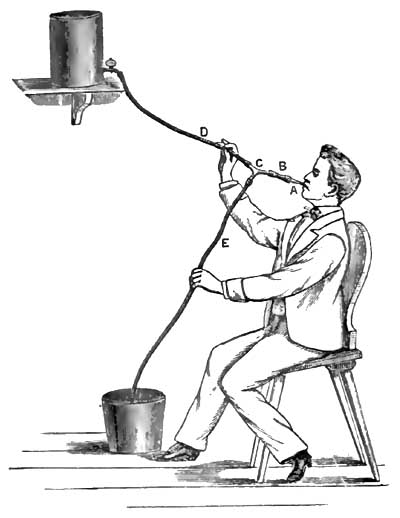

| 22. | ROSENTHAL'S METHOD OF WASHING OUT THE STOMACH |

| 23. | ANTERIOR VIEW OF A STRANGLUATED INTESTINE AND STRICTURE |

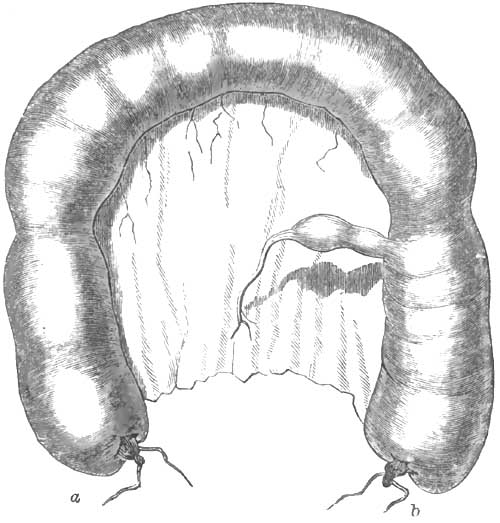

| 24. | POSTERIOR VIEW OF A STRANGULATED INTESTINE AND STRICTURE |

| 25. | APPEARANCE OF THE NATURAL RELATIONS OF THE DIVERTICULUM TO THE INTESTINE |

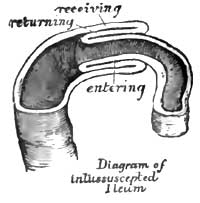

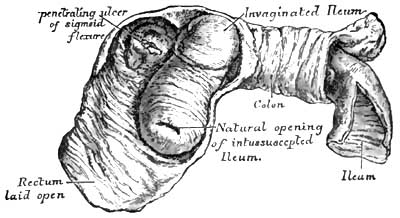

| 26. | SIMPLE INVAGINATION OF THE ILEUM |

| 27. | SIMPLE INVAGINATION, WITH OCCLUSION OF BOWEL, FROM INFLAMMATORY CHANGES |

| RHEUMATISM. | PURPURA. |

| GOUT. | DIABETES MELLITUS. |

| RACHITIS. | SCROFULA. |

| SCURVY. | HEREDITARY SYPHILIS. |

SYNONYMS AND DEFINITION.—Acute Rheumatism, Acute Rheumatic Polyarthritis, Rheumarthritis, Rheumatic Fever, Polyarthritis Synovialis Acuta (Heuter).

Acute articular rheumatism is a general non-contagious, febrile affection, attended with multiple inflammations, pre-eminently of the large joints and very frequently of the heart, but also of many other organs; these inflammations observing no order in their invasion, succession, or localization, but when affecting the articulations tending to be temporary, erratic, and non-suppurating; when involving the internal organs proving more abiding, and often producing suppuration in serous membranes. It is probably connected with a diathesis—the arthritic—which may be inherited or acquired. It may present such modifications of its ordinary characters as to justify being called (2d) subacute articular rheumatism, and it may sometimes pass into the (3d) chronic form.

ETIOLOGY.—There is a general consensus of opinion that acute articular rheumatism belongs especially to temperate climates, and that it is exceedingly rare in polar regions; but respecting its prevalence in the tropics contradictory statements are made. Saint-Vel declares that it is not a disease of hot climates; Rufz de Levison saw only four cases of acute articular rheumatism, and not one of chorea, in Martinique during twenty years' practice; while Pruner Bey says it is common in Egypt, and Webb remarks the same for the East Indies. Even in temperate climates, like those of the Isle of Wight, Guernsey, Cornwall, some parts of Belgium (Hirsch), the disease is very rare—a circumstance not to be satisfactorily explained at present.

Acute articular rheumatism is never absent; it occurs at all seasons of the year, although subject to moderate variations depending mainly upon atmospheric conditions. It is the general opinion that it prevails most during the cold and variable months of spring, but this is not true of every place, nor invariably of the same place. Indeed, Besnier,1 after a long and special observation of the disease in Paris, concludes that there it is most frequent in summer and in spring. In Montreal, during ten years, the largest number of cases of acute rheumatism admitted to the General Hospital obtained in the spring months (March to June [p. 20]inclusive), when they averaged 51 a month; 33 was the average for all the other months, except October and November, when 26½ was the average. The statistics of Copenhagen, Berlin, and Zurich show a minimum prevalence in summer or in summer and autumn.

1 Dictionnaire Encyclopédique des Sciences Méd., Troisième Serie, t. iv.

Occupations involving muscular fatigue or exposure to sudden and extreme changes of temperature, especially during active bodily exertion, predispose to acute articular rheumatism; hence its frequency amongst cooks, maid-servants, washerwomen, smiths, coachmen, bakers, soldiers, sailors, and laborers generally.

While no age is exempt from acute articular rheumatism, it is, par excellence, an affection of early adult life, the largest number of cases occurring between fifteen and twenty-five years of age, and the next probably between twenty-five and thirty-five. A marked decline in its frequency takes place after the age of thirty-five, and a still greater after forty-five. It is not uncommon in children between five and ten, and especially between ten and fifteen, but is very rare under five, although now and then one meets with an example of the disease in children three or four years of age. While the acute articular affections observed in sucklings are, as a general rule, either syphilitic or pyæmic, some authentic instances of rheumatic polyarthritis are recorded. Kauchfuss's two cases among 15,000 infants at the breast, Widerhofer's case, only twenty-three days old, Stager's, four weeks old, and others, are cited by Senator.2

2 Ziemssen's Cyclop. of Pract. Med., xvi. 17.

An analysis of 4908 cases of acute rheumatism admitted to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London,3 during fifteen years, and of 456 treated in the Montreal General Hospital during ten years,4 gives the following percentages at given periods of life:

| London. | Montreal. | ||

| Under 10 years | 1.79 per cent. | ||

| From 10 to 15 years | 8.1 per cent. | Under 15 years | 4.38 per cent. |

| From 15 to 25 years | 41.8 per cent. | From 15 to 25 years | 48.68 per cent. |

| From 25 to 35 years | 24.5 per cent. | From 25 to 35 years | 25.87 per cent. |

| From 35 to 45 years | 14.2 per cent. | From 35 to 45 years | 13.6 per cent. |

| Above 45 years | 9.5 per cent. | Above 45 years | 7.4 per cent. |

The close correspondence existing in the two tables for all the periods of life above fifteen is very striking: the disparity between them below the age of fifteen may, I believe, be explained by the circumstance that the pauper population of Montreal is, when compared with that of London, relatively very small, and by the further fact that the practice of sending children into hospitals hardly obtains here.

3 St. Bartholomew's Hospital Reports, xiv. 4.

4 Dr. James Bell, in Montreal General Hospital Reports, i. 350.

No doubt the above tables do not correctly represent the liability of children to acute articular rheumatism, but they are probably a fair statement of the relative frequency of the disease in the adult hospital populations of London and Montreal. If primary attacks of the disease only were tabulated, the influence of youth would be more evident, for it is scarcely possible to find on record an authentic instance of the disease showing itself for the first time after sixty. Dr. Pye-Smith5 has done [p. 21]this in 365 cases, and the results prove the great proclivity of very young persons to acute rheumatism: Between five and ten years, 6 per cent. occurred; between eleven and twenty, 49 per cent.; from twenty-one to thirty, 32.3 per cent.; from thirty-one to forty, 9.5 per cent.; from forty-one to fifty, 2.2 per cent.; and from fifty-one to sixty-one, 1.1 per cent. The same author has also shown that secondary attacks are most common in the young; so that advancing age not only renders a first attack of the disease improbable, but lessens the risk of a recurrence of it. The influence of age upon acute rheumatism is further shown in the fact that the disease is less severe, and less apt to invade the heart, in elderly than in young persons.

5 Guy's Hospital Reports, 3d Series, xix. 317.

The general opinion that sex exercises no direct influence beyond exposing males more than females to some of the predisposing and exciting causes of acute rheumatism is perhaps true if the statement be confined to adults, to whom, indeed, most of the available statistics apply; but it should be borne in mind that a larger proportion of men than of women resort to hospitals, and there is some reason to believe that in childhood the greater liability to the disease is on the part of the female sex. Thus, the number of cases of rheumatism treated at the Children's Hospital in London from 1852 to 1868 was 478, of whom 226 were males and 252 females.6 Of Goodhardt's 44 cases of acute rheumatism in children, 26 were girls and 18 were boys.7 Of 57 examples of rheumatism in connection with chorea observed by Roger in children under fourteen, 33 were girls and 24 were boys.8

6 Vide Dr. Tuckwell's "Contributions to the Pathology of Chorea," in St. Bartholomew's Hospital Reports, v. 102.

7 Guy's Hospital Reports, 3d Series, xxv. 106.

8 Arch. Gén., vol. ii. 641, 1866, and vol. i. 54, 1867, quoted by Tuckwell.

That heredity predisposes to acute articular rheumatism is admitted by nearly all modern authorities, even Senator, while speaking of it as "a traditional belief," not venturing to deny it. The frequency of the inherited predisposition Fuller placed at 34 per cent.; Beneke, quoted by Homolle,9 at 34.6 per cent; Pye-Smith at 23 per cent.10 Such predisposition favors the occurrence of the disease in early life, but does not necessarily determine an attack of acute rheumatism in the absence of the other predisposing or exciting causes. That the inherited bias or mode of vital action or condition of tissue-health may be so great as, per se, to induce an attack of the disease, is held by some authorities. It is probable that not only acute articular rheumatism in the parents, but simple chronic articular rheumatism and those forms grouped under the epithet rheumatoid arthritis, may impart a predisposition to the acute as well as to the chronic varieties of articular disease just mentioned. But owing to the obscurity which still surrounds the relations existing between acute articular rheumatism and rheumatoid arthritis this point needs further investigation. In what the inherited predisposition to acute articular rheumatism consists we are ignorant; to say that it imparts to the tissues or organs a disposition to react or act according to a fixed morbid type, or that some of the nutritive processes are perverted by it, is merely to state a theory, not to explain the nature of the predisposition.

9 Nouv. Dict. de Méd. et de Chir., t. 31, 557.

10 Guy's Hospital Reports, 3d Series, xix. 320.

No type of bodily conformation or temperament can be described that [p. 22]certainly indicates a proclivity to acute articular rheumatism; nor is there any change in the constitution of the tissues or fluids of the body by which the proclivity may be recognized. We infer the existence of the inherited predisposition—the innate bias—when rheumatism is found in the family history; when acute rheumatism or cardiac disease, or chorea not produced by mental causes, occurs in childhood; when the first attack of acute articular rheumatism is succeeded by subsequent attacks; and especially when the intervals between the attacks are short. Goodhardt has recently furnished valuable, but not conclusive, evidence to prove that in children obstinate headaches, night-terrors, severe anæmia, various neuro-muscular derangements, such as torticollis, tetany, muscular tremors, stammering, incontinence of urine, recurring attacks of abdominal pain, with looseness of the bowels quickly succeeding a meal, the cutaneous affection erythema nodosum, are indications of a rheumatic bias or predisposition.11

11 Guy's Hospital Reports, 3d Series, xxv.

There is some basis for the opinion that residence in damp, cold dwellings predisposes somewhat to acute articular rheumatism, although not at all to the same degree that it does to the chronic articular and muscular forms. Chomel and Jaccoud especially have insisted that it will gradually create a predisposition to the disease, even if it has not been inherited. All pathologists agree that cold is the most frequent exciting cause of acute articular rheumatism, and that it is especially effective when applied while the body is perspiring freely or is overheated or fatigued by exercise. There is no necessary ratio between the degree of cold or its duration and the severity of the resulting rheumatism. A slight chilling or a momentary exposure to a current of cold air will in some act as powerfully and as certainly as a prolonged immersion in cold water or a night spent sleeping on the damp grass. This circumstance, together with the fact that cold applied in the same way may also produce a pharyngitis or a bronchitis, a pneumonia or a nephritis, etc., is held to indicate that the cold acts according to individual predisposition; and Jaccoud, Flint, and others maintain that unless a rheumatic proclivity exists cold will not produce an attack of the disease under consideration. I doubt that we are yet in a position to assert that absolutely, although the weight of argument is in its favor. Let it suffice to say, that while a prolonged residence in a cold, damp dwelling may gradually develop a predisposition to rheumatism, a short exposure to cold will be likely to induce an attack of rheumatism if the predisposition exist.

There are other influences which may be regarded as auxiliaries to cold in exciting an attack, as they seem to increase the susceptibility of the patient to its operation: they establish what has been felicitously called a state of morbid opportunity. Such are all influences that reduce the resisting powers of the organs and organism, as bodily fatigue, mental exhaustion, the depressing passions, excessive venery, prolonged lactation, losses of blood, etc. It is probably in such a manner that local injuries (traumatism) sometimes appear to induce an attack of rheumatism. A blow on a finger (Cotain), the extraction of a tooth (Homolle), a hypodermic injection (ibid.), etc., may act powerfully in some persons upon and through the nervous system, and by lessening their resisting power [p. 23]may favor the overt manifestation of the rheumatic predisposition. But doubtless some such cases have been examples of mere coincidence.

There are certain pathological and even physiological conditions during or after which an inflammatory affection of one or several joints closely resembling acute articular rheumatism more or less frequently arises. Thus, during the early desquamating stage of scarlatina a mild inflammation of the joints of the hands and feet, and frequently of the large articulations as well, is very often seen, and it is attended with profuse perspiration, with a condition of urine like that of ordinary acute rheumatism, and occasionally with inflammation of the heart or pleura. During convalescence from dysentery an affection of a single or of several articulations resembling rheumatism has been noticed, and the two affections have even alternated in the same patient. That singular epidemic disease dengue is attended with a polyarticular affection closely resembling acute articular rheumatism, occasionally pursuing a protracted course, and not seldom leaving after it a cardiac lesion. In hæmophilia polyarticular and muscular disorders frequently arise which closely resemble, and appear to be sometimes identical with, ordinary acute articular and muscular rheumatism. Gonorrhoea too is often associated with a febrile polyarthritis, and rarely with an endocarditis at the same time. In the puerperal state an inflammation of one or several articulations is not unfrequently observed (puerperal rheumatism).

Respecting the real nature of these polyarticular inflammations very much has to be made out; and it must suffice at present to say that while many of them are of a pyæmic nature, as some examples of puerperal and scarlatinal arthritis, in which pus forms in or about the joints and in the serous cavities and viscera, some of them are no doubt examples of genuine rheumatism occurring in persons of rheumatic predisposition, which have either been induced by the lowering influence of the disease upon which they have supervened, or by the accidental coincidence of some of the other causes of acute rheumatism. There remains, however, the ordinary form of scarlatinal arthritis, which so closely resembles true acute articular rheumatism in its symptoms, course, visceral complications, and morbid anatomy that it cannot be said that the two affections are distinct and different. And much the same appears to be true of the articular affection of dengue. Yet so frequently does the articular affection accompany scarlatina and dengue respectively that it cannot logically be referred to a coexisting rheumatic predisposition, and must be a consequence of the disturbing influences of the specific poison of those zymotic affections per se.

PATHOLOGY.—The pathology of acute articular rheumatism is a very much debated question, and is not at all satisfactorily known. Hence a mere statement of the most prominent theories now held by different pathologists will be given.12

12 The reader may consult with advantage Dr. Morris Longstreth's fourth chapter in his recent excellent monograph upon Rheumatism, Gout, and some Allied Disorders, New York, 1882.

The latest modification of the lactic-acid theory of Prout is founded upon the modern physiological teaching that during muscular exercise sarcolactic acid and acid phosphate of potassium are formed, and carbon dioxide set free, in the muscular tissue, and that cold, acting on [p. 24]the surface under such circumstances, may check the elimination of these substances and cause their accumulation in the system. This view, it is held, explains why the muscles and their associated organs, the joints and tendons, suffer first and chiefly, because the morbific influence is exerted upon them when exhausted by functional activity; and it further accounts for the visceral manifestations and the apparent excess of acid eliminated during the course of the disease. The circumstance that in three cases of diabetes (Foster,13 Kuelz14) the administration of lactic acid appeared to induce polyarticular rheumatism favors the idea that acid is the materies morbi in rheumatism.

13 Brit. Med, Jour., ii. 1871.

14 Beiträge zur Path. und Therapie des Diabetes, u. s. w., ii. 1875.

Now it must be admitted that, as yet, no sufficient proof is forthcoming that a considerable excess of lactic acid exists in the fluids or solids of the body or in the excretions in rheumatism (it is true the point has not been sufficiently investigated). On the other hand, that acid has been found in the urine of rickets, and its excess in the system is regarded by Heitzmann and Senator15 as the cause of the peculiar osteoplastic disturbances of that disease—an affection altogether different from rheumatism. It is quite improbable that the amount of sarcolactic acid produced by over-prolonged muscular exertion, and whose elimination has been prevented by a chill or a mental emotion, is sufficient to maintain the excessive acidity of the urine and other fluids during a long rheumatic fever; and arguments can be adduced favorable to the view that excessive formation of acid is an effect rather than the cause of rheumatism: cases of that disease occur in which neither excessive muscular exertion nor exposure to chill have preceded the rheumatic outbreak. Lastly, lactic acid is not the only principle retained when the functions of the skin are arrested by cold, the usual exciting cause of rheumatism; why should not the retained acetic, formic, butyric, and other acids, for example, play their rôle in the production of the symptoms observed under such conditions?

15 Ziemssen's Cyclop., xvi. p. 177.

The same objections apply to Latham's16 hypothesis that hyperoxidation of the muscular tissue is the starting-point of acute rheumatism. He assumes, with other physiologists, the existence of a nervous centre which inhibits the chemical changes that would take place if the tissues were out of the body. If this centre be changed or weakened, the muscle, instead of absorbing and fixing the oxygen and giving out carbonic acid, disintegrates; lactic acid is formed, and, passing into the blood, may be there oxidized and produce the pyrexia of acute rheumatism. It need hardly be remarked that the existence of a chemical inhibitory centre has yet to be proved, although much may be advanced in its favor; and, secondly, the recent investigations of Zuntz render it highly probable that in all febrile affections it is the muscles chiefly, if not solely, which suffer increased oxidation, and that this is due to increased innervation—views not easily reconciled with Latham's theory.

16 Brit. Med. Jour., ii. 1880, p. 977.

The nervous theory of rheumatism and of articular diseases originated with Dr. J. K. Mitchell of Philadelphia17 in 1831, and was afterward elaborated by Froriep in 1843,18 Scott Alison19 in 1846, Constatt in 1847,20 [p. 25]Gull in 1858, Weir Mitchell in 1864,21 Charcot in 1872, and by very many others since. According to present physiological doctrine, the exciting cause of rheumatism, cold, either acts directly upon the vaso-motor or the trophic (?) nerves of the articulations, and excites inflammation of them, or else it irritates the peripheral ends of the centripetal nerves, and through these excites actively the vaso-motor and trophic nerve-centres. The local lesions, on this hypothesis, are of trophic origin; the fever is due to hyperactivity of the centres supposed to control the chemical changes going on in the tissues; the excessive perspiration to stimulation of the sweat-centres; and so on. It is not held that a definite centric lesion of the nervous system exists in rheumatism, analogous to the lesions which in myelitis or locomotor ataxia develop the arthropathies of those affections, but rather a functional disturbance. One of the latest and ablest advocates of the neurosal theory of rheumatism in all its forms (simple, rheumatoid, gonorrhoeal, urethral, etc.), Jonathan Hutchinson, calls it "a catarrhal neurosis, the exposure of some tract of skin or mucous membrane to cold or irritation acting as the incident excitor influence."22

17 Am. Jour. Med. Sci., 1831; ib., 1833.

18 Die Rheumatische Schwiele, Weimar, 1843.

19 Lancet, 1846, i. 227.

20 Spec. Pathologie und Therapie, 1847, ii. p. 609.

21 Vide Am. Jour. Med. Sciences, April, 1875, vol. lxix. 339-348.

22 Trans. International Med. Congress, 1881, ii. 93.

In order that peripheral irritation shall thus induce inflammation of the joints and the other affections of muscles, tendons, fasciæ, etc. which are called rheumatic, he holds with the French School that the arthritic diathesis must exist, or that state of tissue-health which involves a tendency to temporary inflammation of many joints or fibrous structures at once, or to repeatedly recurrent attacks of inflammation of one joint or fibrous structure. If I understand Mr. Hutchinson correctly, he also holds that a nerve-tissue peculiarity exists which renders persons liable to rheumatism. He does not indicate either the cause or the nature of the nerve-tissue peculiarity. But modern pathology teaches that the functional conditions of the nervous centres known as neuroses, whether inherited or acquired, reveal themselves as morbid manifestations of nerve-function on the part of special portions of or the entire nervous system, and, as Dr. Dyce Duckworth has well pointed out, these neuroses may be originated, when not inherited, in various ways, as by excessive activity of the nervous system, by prolonged or habitual excesses, etc. "Thus, undue mental labor, gluttony, alcoholic intemperance, debauchery, and other indulged evil propensities in the parent come to be developed into definite neurotic taint and tendency in the offspring."

But is there nothing more in acute articular rheumatism than an inflammation of certain structures, articular and visceral, lighted up in an individual of a neuro-arthritic diathesis? What do we learn from that closely-allied affection, gout, which involves especially the same organs as rheumatism, and is held by many of the ablest pathologists to belong to the same basic diathesis as it? Duckworth23 has very ably advocated a neurotic theory of gout, but it is admitted on all hands—and by Duckworth himself—that in gout a large part of the phenomena is due to perverted relations of uric acid and sodium and to the presence of urate of soda in the blood. May we not from analogy, as well as from other evidence, infer that in that so-called other neurosis, rheumatism, a considerable part of the phenomena is due to perversions of [p. 26]the processes of assimilation and excretion, and to the presence of some unknown intermediate product of destructive metamorphosis—lactic or other acid? This is admitted by Maclagan and strongly advocated by Senator; and in this way the pathology of the disease may be said to embrace the humoral as well as the solidist doctrines—the resulting theory being a neuro-humoral one. No doubt pathological chemistry and clinical investigation will ere long make important discoveries respecting the pathology of acute rheumatism which shall maintain the close alliance believed to exist between that affection and gout.

23 Brain, April, 1880.

The miasmatic theory, so ably advocated by Maclagan,24 assumes that rheumatism is due to the entrance into the system from without of a miasm closely allied to, but quite distinct from, malaria. His argument on this topic is ingenious and elaborate, yet has not been favorably received by pathologists. Opposed to it are the following amongst other considerations: Heredity exercises a marked influence upon the occurrence of rheumatism; unlike malarial disease, no climate or locality is immune from rheumatism; the many indications that a diathesis plays a chief rôle in rheumatism; the remarkable influence exerted by cold and dampness in the etiology of the disease.

24 Rheumatism: its Nature, Path., etc., London, 1881, pp. 60-95.

Heuter's25 infective-germ theory, like the miasmatic, refers rheumatism to a principle not generated in the system, but introduced from without. A micrococcus enters the dilated orifices of the sweat-glands, and, reaching the blood, first sets up an endocarditis, and then capillary emboli produce the articular inflammations. This is a reversal of what really happens, so far as the time of invasion of the endocardium and the synovial membranes is concerned; and Fleischauer's case, in which miliary abscesses were found in the heart, lungs, and kidneys, was probably one of ulcerative endocarditis, which, after all, is a rare complication of acute articular rheumatism. Moreover, it is a gratuitous assertion to say that endocarditis exists in all cases of the disease. If, however, Heuter were content to say that acute articular rheumatism was produced by a specific germ, as held by Recklinghausen and Klebs, which on entering the system acted specially upon the joints and the fibro-serous tissues, as the poison of small-pox does upon the skin, while at the same time it sets up general disturbances of the entire economy as other zymotic poisons do, there would be nothing opposed to general pathological laws. Even the existence of a diathesis capable of favoring the action of the specific germ would be analogous to the tuberculous diathesis, which favors the action of the bacillus of tubercle; and cold, its ordinary exciting cause, might be regarded simply as a condition which renders the system more susceptible to the action of the germ, and the modus operandi of cold in doing this might be variously explained.

25 Klinik der Gelenkkrankheiten, Leipzig, 1871.

SYMPTOMS.—The disease has no uniform mode of invasion. (a) Very frequently slight disorder of health, such as debility, pallor, failure of appetite, unusual sensibility to atmospheric changes, grumbling pains in the joints or limbs, or even in some muscle or fascia, precedes by one or more days the fever and general disturbance. (b) Not infrequently a mild rigor or repeated chilliness, accompanied or soon followed by moderate or high fever, ushers in the illness, and in from a few hours to one [p. 27]or at most two days the characteristic articular symptoms ensue. (c) In very rare cases febrile disturbance, ushered in by chills, may be followed by inflammation of the endo- or pericardium or pleura before the joints become affected.

Whatever the mode of invasion, the symptoms of the established disease are well defined, and marked febrile disturbance, transient inflammation of several of the larger articulations, excessive activity of the cutaneous functions, and a great proclivity to inflammation of the endo- and pericardium constitute the stereotyped features of the disease.

As a very general rule, the temperature early in the disease promptly attains its maximum of 102° F. to 104° F., yet the surface does not feel very hot; the pulse ranges from 90 to 100 or 110, and is regular, large, and often bounding; the tongue is moist, but thickly coated with a white fur; there are marked thirst, impaired appetite, and constipation; the stools are usually dark; the urine scanty, high colored, very acid, of great density, and holding in solution an excess of uric acid and urates, which are frequently deposited when the urine cools. The general surface is covered with a profuse sour-smelling perspiration, whose natural acid reaction, as a general rule, is markedly increased; indeed, the naturally alkaline saliva is also acid. Beyond a little wandering during sleep, occasionally observed in irritable, nervous patients, there is very rarely any delirium, and this notwithstanding that sleep is frequently much disturbed by the pain in the joints and the excessive sweating.

If the local articular symptoms have not set in almost simultaneously with the pyrexia, or even preceded it, they will follow it in from a few to twenty-four or forty-eight hours. At first one or more joints, usually the knees or ankles, become painful, sensitive to pressure, hot, more or less swollen, and exhibiting a slight blush of redness or none at all. The swelling may consist of a mere puffiness, due to slight infiltration of the soft parts external to the joint, or of a more or less considerable tumefaction, caused by effusion into the synovial capsule. In the knees, elbows, shoulders, and hips the swelling is usually confined to the articulations, and there is but little redness of the integument, but in the wrists and ankles the inflammatory process is often more severe, and may invade the whole dorsum of the hand or foot, rendering the integument tense, tumid red, and shining. Pitting of the swollen parts, although quite exceptional in acute articular rheumatism, will exist under the conditions just mentioned. The metacarpo-phalangeal articulations are likewise often a good deal swollen and of a bright-red color.

The pain in the affected articulations varies from a trifling uneasiness or dull ache to excruciating anguish; sometimes the pain is felt only on moving or pressing the joint; pressure always aggravates it; even the weight of the bed-clothes may be intolerable; and in severe cases the slightest movement of the joint or a jar of the bed produces great suffering. The pain, like the swelling, sometimes extends beyond the affected joints to the tendinous sheaths, the tendons, and muscles, and even to the nerves of the neighborhood.

It is a striking peculiarity of acute rheumatism that the inflammation tends to invade fresh joints from day to day, the inflammation usually, but not invariably, declining in those first affected; and sometimes this retrocession of the inflammation in a joint is so sudden, and so coincident [p. 28]with the invasion of a different one, that it is often regarded as a true metastasis. Exceptionally, however, one or several joints remain painful and swollen, although this occurs chiefly in subacute attacks. In this way most of the large joints may successively suffer once, twice, or oftener during an attack of acute rheumatism. And as the inflammation commonly lasts in each articulation from two to four or more days, it is usual to have six or eight of the joints affected by the end of the first week. While the ankles and knees, wrists, elbows, and shoulders, are especially liable to be affected, and with a frequency pretty closely corresponding to the above order, the joints of the hands occasionally, and the hips even more frequently, escape. The intervertebral and tempero-maxillary articulations have very rarely suffered in the writer's experience.

If the ear be applied to the cardiac region in acute rheumarthritis, another local inflammation than the articular will very frequently be detected, which otherwise would probably be unrecognized, and yet it is the most important feature of the disease. In the first or second, or even as late as the fourth, week of the fever the signs of endocarditis of the mitral valve, occasionally of the aortic, and sometimes of both, will exist in an uncertain but large proportion of cases, or those of pericarditis, but in a less proportion, will obtain. Indeed, the cardiac inflammation may even precede the articular, and some believe it may be the only local evidence of rheumatic fever. As a general rule, the implication of the endo- or pericardium in acute rheumarthritis gives rise to no marked symptoms or abrupt modification of the clinical features of the case, and a careful physical examination must be instituted to discover its existence. But the recurrence of pain or tightness either in the precordial or sternal region, of marked anxiety or pallor of the face, of sudden increase in the weakness or frequency of the pulse, or of irregularity in its rhythm, of restlessness or delirium, of oppression of breathing, or of short, dry cough,—may indicate the invasion of the endo- or peri- or myocardium, and a physical examination will be needed to detect the cardiac disease and to exclude the presence of pleuritis, pneumonia, or bronchitis. Sometimes, however, especially in severe cases, an extensive pericarditis, with or without myocarditis, will produce grave constitutional disturbance, in which sleeplessness, delirium, stupor, generally associated with a very high temperature and marked prostration, will, as it were, mask both the articular and the cardiac affection.26

26 See Stanley's case, Med.-Chir. Trans., 1816, vol. vii. 323, and Andral's Clinique Médicale, t. i. 34.

As regards the murmurs which arise in acute rheumatic endo- or pericarditis, while they are usually present and quite typical, this is not always so. The only alteration of the cardiac sounds may be at first and for some time a loss of clearness and sharpness, passing into a prolongation of the sound, which usually develops into a distinct murmur, or the sounds may be simply muffled. In pericarditis limited to that portion of the membrane which covers the great vessels no friction murmur may be audible, or it may be heard and be with difficulty distinguished from an endocardial murmur. On the other hand, a systolic basic murmur not due to endo- or pericarditis frequently exists, sometimes in the early, but usually in the later, stages of rheumatic fever.

[p. 29]Other local inflammations occasionally arise in the course of acute rheumatism: pneumonia is one of the most frequent; left pleuritis is not infrequent, and is doubtless often caused by the extension of a pericarditis; but both pneumonia and pleurisy are occasionally double in rheumatic fever. Severe bronchitis is observed now and then, and very rarely peritonitis, and even meningitis. These several affections, together with delirium, coma, convulsions, chorea, and hyperpyrexia, which are likewise occasional incidents of the disease, will be considered under the head of non-articular manifestations and complications of acute articular rheumatism.27

27 See observations of W. S. Cheesman, M.D., New York Medical Record, Feb. 25, 1882, 202.

Some of the symptoms of acute articular rheumatism need individual notice.

The temperature in acute articular rheumatism maintains no typical course, and usually exhibits a series of exacerbations and remissions, which correspond closely in time and degree with the period, duration, and severity of the local inflammatory attacks. As a very general rule in average cases, the temperature attains by the end of the first or second day to 102° F., and while the subsequent evening exacerbations may reach 104°, 104.4°, or very rarely 105°, yet in the great majority of cases the maximum temperature does not exceed 103° F., and in a very considerable number falls short of 102°. An analysis of one of Dr. Southey's tables28 shows that in 84 cases of acute rheumatism 1 attained the temperature of 105.8°; 8, that of 104° to 105°; 15, that of 103° to 104°; 32, that of 102° to 103°; 17, that of 101° to 102°; 10, that of 100° to 101°; and 1, that of 99.8°; that is, the temperature was below 103° in five-sevenths, and below 104° in about ten-twelfths, of the whole. In very mild cases, in which but a few joints are inflamed, and only to a slight degree, the temperature may not reach 100° at any time, and there may be intervals of complete apyrexia. On the other hand, in a few rare severe cases of rheumatic fever, especially when complicated with pericarditis, pneumonia, or delirium, or other disturbance of the cerebral functions, the temperature attains to 106°, 108°,29 109.4°,30 110.2°,31 or even 111°,32 or 112°. Such cases are now spoken of as examples of rheumatic hyperpyrexia.

28 St. Bartholomew's Hospital Reports, xiv. p. 12.

29 Weber, Clinical Society's Trans., vol. v. p. 136.

30 Th. Simon, quoted by Senator, Ziemssen's Cyclop. of Prac. Med., xvi. p. 46.

31 Murchison and Burdon-Sanderson, two cases, Clinical Society's Trans., vol. i. pp. 32-34.

32 Ringer, Med. Times and Gaz., vol. ii., 1867, p. 378.

There is no rule about the mode of invasion of this high temperature. It may ensue gradually or suddenly, the previous range having been low, moderate, or high, steady or oscillating.

Defervescence in rheumatic fever takes place, as a very general rule, gradually—i.e. by lysis—but exceptionally it is completed in forty-eight or even twenty-four hours. An interesting observation, which will be of much prognostic value if it be confirmed hereafter, has been made by Reginald Southey,33 to the effect "that a short period of defervescence, or a sudden remission and an early remission, betokens the relapsing form of the disease, and the likelihood of frequent relapses, as well as of slow ultimate recovery, in the direct ratio as this defervescence has been early and abrupt."

33 St. Bartholomew's Hospital Reports, xiv. p. 16.

[p. 30]The characters of the urine in acute rheumatism are tolerably uniform, but far from constantly so. Its quantity in the majority of cases is reduced, frequently not exceeding twenty-four ounces per diem, and occasionally not exceeding fourteen. This is owing in some degree to profuse sweating, but also, as in other febrile affections, to retention of water. Its density is usually high—1020 to 1030, or even 1035—which is due chiefly to its concentration, and not, as has been generally supposed, mainly to an increase in the total solids excreted.34 Its color is a very dark red or deep reddish-yellow, partly from concentration; but it is yet not known whether the deep hue is partly from increase of the normal pigments or of one of them (urobilin),35 or from the presence of some abnormal coloring matter. Its reaction is generally highly acid, and continues so for many hours after its discharge, unless in subacute cases, when it is occasionally neutral or sometimes alkaline at the time of its escape, or becomes so in a very short time afterward. It is commonly toward the decline of the attack that the urine becomes neutral or alkaline. As a very general rule, the amount of urea and of uric acid excreted during the febrile stage exceeds what is physiological, and begins to decline when convalescence commences; but this may be reversed (Parkes,36 Lede,37 Marrot38). The sulphuric acid is notably increased (Parkes), the chlorides often diminished and sometimes absent, and the phosphoric acid very variable (Beneke, Brattler39), but usually lessened (Marrot).

34 See Guy's Hospital Reports, 3d Series, vol. xii. 441.

35 Jaffe, Virchow's Archiv, xlvii. 405, quoted in Ziemssen's Cyclopæd. Prac. Med., xvi. 41.

36 On Urine, p. 286.

37 Recherches sur l'Urine dans le Rheumatisme Artic. Aigue, Paris, 1879.

38 Contribution à l'Étude du Rheumatisme Artic., etc., Paris, 1879, 41.

39 Quoted by Parkes, op. cit., 290.

During convalescence the urine increases in quantity, while, as a general rule, the urea and uric acid lessen relatively and absolutely, and the chlorides resume their normal proportions to the other ingredients. The reaction frequently becomes alkaline, and the specific gravity falls considerably, although not always as soon as the articular inflammation subsides. Temporary albuminuria occurs very frequently in the febrile and occasionally in the declining stage, but generally disappears when convalescence is completed. It obtained on admission in 8 out of 43 cases lately reported by Dr. Greenhow.40 A more abiding albuminuria, due very rarely to acute parenchymatous nephritis, may be met with (Johnson, Bartels, Hartmann, Corm). Blood, even in considerable amounts, has also rarely appeared in the urine,41 sometimes in connection with embolic nephritis and endocarditis, for such appear to have been the nature of Rayer's nephrite rheumatismale.42

40 Lancet, 1882, i. 913.

41 Clinical Lectures, R. B. Todd, edited by Beale, 1861, p. 346.

42 Traité des Maladies Reins. See also Dr. Weber, Path. Trans. of London, xvi. p. 166.

The saliva, which is normally alkaline, has usually a decidedly acid reaction in acute articular rheumatism, and Dr. Bedford Fenwick states that it always in this disease contains a great excess of the sulpho-cyanides, and that these slowly and steadily diminish, till at the end of the third week or so they become normal in amount.

A profuse, very acid, sour-smelling perspiration is one of the striking symptoms occurring in the course of acute articular rheumatism, and [p. 31]until very lately it has been generally held to indicate an excessive formation in, and elimination of acid from, the system, either lactic acid or some of the acids normal to the perspiration, as acetic, butyric, and formic. However, not only have chemists failed to detect lactic acid in the perspiration of acute rheumatism, but late research tends to show that the excessive acidity of the perspiration in this disease is but very partially due to the perspiration itself, and is chiefly owing to chemical changes taking place in the overheated and macerated surface of the skin and its epidermis, and to the retention of solid products accumulated on that surface. Besnier says that if in acute articular rheumatism or other disease attended with much perspiration the surface be kept well washed, the sweat will be found in the greater number of cases at the moment of its secretion to be nearly neutral as soon as actual diaphoresis occurs, more decidedly acid when the perspiration is less abundant or begins to flow, and exceptionally alkaline. Most physicians are aware that the profuse perspiration of acute rheumatism is non-alleviating; it is not a real critical discharge of noxious materials from the system, nor is it followed by prompt reduction of the temperature and other symptoms. It is but a symptom of the disease, and occurs especially in severe cases, and when it continues long after the reduction of the temperature it is a source of exhaustion, and may be checked with advantage.

The blood is deficient in red globules, Malassez finding in men from 2,850,000 to 3,700,000 per cubic millimeter instead of 4,500,000 to 5,000,000, and in women 2,300,000 to 2,570,000 instead of 3,500,000 to 4,000,000. The hæmoglobin and the oxidizing power of the blood are also considerably reduced; the fibrin is largely increased (6 to 10 parts in 1000 instead of 3); the albumen and albuminates are lessened, the extractives increased; the proportion of urea is normal, and no excess of uric acid is found in the blood. Instead of that fluid being less alkaline than normal, Lepine and Conard have recently stated that its alkalinity is increased in acute rheumatism, but constantly diminished in chronic rheumatism,43 and no excess of lactic acid has been proved to exist in the blood in either acute or chronic rheumatism. A condition of excessive coagulability of the fibrin, independently of its excessive amount (inopexia), is an habitual character of acute rheumatism; however, in very bad cases, especially those attended with hyperpyrexia and grave cerebral symptoms, the blood after death has been black and coagulated and the fluid in the serous cavities has given an acid reaction. The above alterations in the blood usually are proportionate to the intensity of the fever and the number of the joints and viscera involved.

43 Lepine, "Note sur la determination de l'Alcalinité du Sang," Gaz. Méd. de Paris, 1878, 149; Conard, Essai sur l'Alcalinité du Sang dans l'État de Sante, etc., Thèse, Paris, 1878.

The manifestations of acute articular rheumatism other than the articular are various, and some of them, more especially those observed in the heart, may be regarded as integral elements of the disease, for they occur in a large proportion of the cases, often coincidentally with the articular affection, and may even precede it, and probably may be the sole local manifestation of acute rheumatism, although under the last-mentioned circumstances it is difficult to prove the rheumatic nature of the ailment.

The cardiac affections may be divided into inflammatory and [p. 32] non-inflammatory. The former consist of pericarditis, endocarditis, and myocarditis; the latter embrace deposition of fibrin on the valves, temporary incompetence of the mitral or tricuspid valves, and the formation of thrombi in the cavities of the heart. For practical purposes hæmic murmurs may be included in the latter group.

No reliable conclusions can be drawn respecting the gross frequency of recent cardiac affections in rheumatic fever, for not only do authors differ widely on this point, but they do not all distinguish recent from old disease, nor inflammatory from non-inflammatory affections, nor hæmic from organic murmurs. Nor does it appear probable, from the published statistics, that these differences are owing to peculiarities of country or race. The gross proportion of heart disease of recent origin in acute and subacute articular rheumatism was in Fuller's44 cases 34.3 per cent.; in Peacock's,45 32.7 per cent.; in Sibson's46 (omitting his threatened or probable cases), 52.3 per cent.;47 in 3552 St. Bartholomew's Hospital cases analyzed by Southey,48 29.8 per cent.; in Bouilland's cases, quoted by Fuller,49 5.7 per cent.; in Lebert's,50 23.6 per cent.; in Vogel's,50 50 per cent.; in Wunderlich's,50 26.3 per cent. I am not aware of any analysis, published in this country, of a large number of cases of rheumatism with reference to cardiac complications, but Dr. Austin Flint,51 after quoting Sibson's percentage of cases of pericarditis, which was (63 in 326 or) 19 to the 100, remarks, "I am sure that this proportion is considerably higher than in my experience."

44 On Rheumatism, Rheumatic Gout, etc., 3d ed., p. 280.

45 St. Thomas's Hospital Reports, vol. x. p. 19.

46 Reynolds's Syst. of Med., Eng. ed., vol. iv. 186.

47 Those familiar with the accuracy and diagnostic skill of the lamented Sibson will not hesitate to add his 13 cases of very probable endocarditis to his 170 positive cases of cardiac inflammation in 325 examples of acute rheumatism, which will raise his percentage to 56.3.

48 Lib. cit., vol. xiv. 6.

49 Lib. cit., 264.

50 See Senator in Ziemssen's Cyclopæd. Pract. of Med., xvi. 49.

51 Pract. Med., 5th ed., 314.

The frequency of cardiac complications in rheumatism is influenced by several circumstances. Some unexplained influence, such as is implied in the terms epidemic and endemic constitution, appears to obtain. Peacock found the proportion of cardiac complications in rheumatism to range from 16 to 40 per cent. during the five years from 1872 to 1876, and a similar variability is shown in Southey's statistical table52 covering the eleven years from 1867 to 1877. Be it observed that these variations occurred in the same hospitals and under, it may be presumed, very similar conditions of hygiene and therapeusis. Youth predisposes to rheumatic inflammation of the heart, so that it may still be said that the younger the patient the greater the proclivity. Of Fuller's cases, 58 per cent. were under twenty-one, and the liability diminished very markedly after thirty. Of Sibson's cases, 62 per cent. were under twenty-one. In infancy and early childhood the liability is very great, and at those periods of life the heart, and more especially the endocardium, rarely escapes; and the cardiac inflammation often precedes by one or two days the articular. The careful observations of Sibson confirm the spirit, but not the letter, of Bouilland's original statement, and proves that the danger of heart disease is greater in severe than in mild cases of acute rheumatism, and that this is especially true of pericarditis. (It may be remarked here, en parenthese, that the number of joints affected is [p. 33]very generally in proportion to the severity of the attacks.) However, the mildest case of subacute rheumatism is not immune from cardiac inflammation, and it has occasionally been observed even in primary chronic rheumatism.53 Occupations involving hard bodily labor or fatigue, whether in indoor or outdoor service, render the heart very obnoxious to rheumatic inflammation. Existing valvular disease, the result of a previous attack of rheumatism, favors the occurrence of endocarditis in that disease. Some authorities maintain that treatment modifies the liability to rheumatic affection of the heart, and this will be spoken of hereafter. The period of the rheumatic fever at which cardiac inflammation sets in varies very much, but it may be confidently stated that it occurs most frequently in the first and second weeks, not infrequently in the third week, seldom in the fourth, and very exceptionally after that, although it has happened in the seventh. An analysis of Fuller's experience54 in 22 cases of rheumatic fever and 56 of endocarditis—a total of 78—shows that the disease declared itself under the sixth day in 8; from the sixth to the tenth in 29; from the tenth to the fifteenth in 17; from the fifteenth to the twenty-fifth in 18; and after the twenty-fifth in 6. The friction sound was audible in Sibson's 63 cases of rheumatic pericarditis—from the third to the sixth day in 10, and before the eleventh day in 30, or nearly one-half of the whole. That observer concludes "that in a certain small proportion of the cases, amounting to one-eighth of the whole," the cardiac inflammation took place at the very commencement of the disease, and simultaneously with the invasion of the joints.55

52 Lib. cit.

53 Raynaud, Nouveau Dict. de Méd. et de Chir., t. viii. 367.

54 Lib. cit., pp. 77-278.

55 Lib. cit., p. 209. See also Dickinson in Lancet, i., 1869, 254; Bauer in Ziemssen's Cyclopæd., vi. 557.

Of the several forms of rheumatic cardiac inflammation, endocarditis is the most frequent, and in a large proportion of cases it may exist alone; pericarditis is also very often observed, but it seldom is found per se, being in the vast majority of cases combined with endo- and occasionally with myocarditis. It is generally the ordinary verrucose endocarditis that obtains. The ulcerative form occurs sometimes, and should be suspected if in a mild or protracted case of acute rheumatism endocarditis sets in with, or is accompanied by, rigors, and the general symptoms are of pyæmic or typhoid character or both, even although an endocardial murmur is not present, for extensive vegetating ulcerative endocarditis frequently exists without audible murmur. It is remarkable, as Osler has shown,56 how few instances of ulcerative endocarditis developing during the course of acute rheumatism are reported; and I would add that by no means all of these were examples of first attacks, chronic valvular lesions, the consequence of former illness, existing in many of them at the time of the final acute attack. Southey's57 patient, and both of Bristowe's,58 had had previous rheumatic seizures. However, Peabody's case,59 one of Ross's three cases,60 and Pollock's61 case appear to have been examples of ulcerative [p. 34]endocarditis occurring during a first attack of acute articular rheumatism. The united and thickened condition of two segments of the aortic valve in one of Ross's cases indicates old-standing disease, although no history of former rheumatism is given. Goodhardt62 has lately insisted upon the tendency of ulcerative endocarditis to appear in groups or epidemics, but the evidence is not conclusive.

56 Archives Médecine, vol. v., 1881; Trans. International Med. Cong., vol. i. 341.

57 Clin. Soc. Trans., xiii. 227.

58 Brit. Med. Jour., i., 1880, 798.

59 Medical Record N.Y., 24th Sept., 1881, 361.

60 Canada Med. and Surg. Journ., vol. xi., 1882, 1, and ib., vol. ix., 1881, 673.

61 Lancet, ii., 1882, 976.

62 Trans. Path. Soc. London, xxxiii. 52.

Space will not permit any detailed description of the symptoms and signs of endo- or pericarditis: these will be found in their proper places in this work, but a few observations are needed upon myocarditis, which occasionally occurs in combination with rheumatic pericarditis, and is a source of much more danger than the latter is, per se. Dr. Maclagan63 is almost the only authority who recognizes the occurrence of rheumatic myocarditis independently of inflammation of the membranes of the heart. He maintains that the rheumatic poison probably and not infrequently acts directly on the cardiac muscle; in which case the resulting inflammation is apt to be diffused over the left ventricle and to produce grave symptoms, while in other instances the inflammatory process begins in the fibrous rings which surround the orifices of the heart (especially the mitral), extends to the substance at the base of the heart, and is there localized. As in this latter form the inflammation usually extends also to the valves, "any symptoms to which the myocarditis gives rise are lost in the more obvious indications of the valvulitis." However, this limited inflammation of the myocardium is not dangerous. Dr. Maclagan asserts that the more diffused and dangerous inflammation of the walls of the left ventricle, while always difficult, and sometimes impossible, of diagnosis, can be determined with tolerable certainty in some cases. In this view, however, he has been preceded by Dr. Hayden,64 who states that the diagnosis of myocarditis is quite practicable irrespective of the accompanying inflammation of the membranes of the heart.

63 Rheumatism: its Nature, Pathology, and Successful Treatment, 1881.

64 Diseases of the Heart and Aorta, 1875, 746.

From the observations of the author just named, as well as of many others, it may be inferred that acute diffused myocarditis of the left ventricle exists in rheumatic fever when either with or without coexisting pericarditis there are marked smallness, weakness, and frequency of pulse, anguish or pain or great oppression at the præcordia, severe dyspnoea, the respiration being gasping and suspirious, feeble, rapid, and irregular action of the heart, great weakness of the cardiac sounds, and almost extinction of the impulse, evidence of deficient aëration of the blood combined with coldness of surface, tendency to deliquium, and when these symptoms and signs cannot be fairly attributed to extensive pericardial effusion or to pulmonary disease, or to obstructed circulation in the heart consequent upon endocarditis with intra-cardiac thrombosis or upon rupture of a valve. It might, however, be impossible to exclude endocarditis complicated with thrombosis, conditions which do occur in rheumatic endocarditis, or a ruptured valve, which, although rarely, has been occasionally observed. Grave cerebral symptoms, delirium, convulsions, coma, though frequently present, are not peculiar to acute myocarditis.65 [p. 35]Hence, even with the above group of clinical facts, the diagnosis at best can be but probable. The disease, too, may be latent, or, like Stanley's66 celebrated case, produce disturbances of the cerebral system rather than of the circulatory.

65 In illustration see case by Southey in which the symptoms and signs agree very well with the above description, and yet, although the heart's substance was of dirty-brown color and the striation of its fibre lost, Southey did not believe these appearances due to carditis. (Clin. Trans., xiii. p. 29.)

66 Med.-Chir. Trans., vol. vii.

Dr. Maclagan has advanced the opinion that a subacute myocarditis is not of uncommon occurrence in acute articular rheumatism, and may be unattended by endo- or pericarditis. Such a condition, he says, may be diagnosed when early in the course of the case the heart's sounds quickly become muffled rather than feeble. As he quotes but one case67 in which an autopsy revealed alterations in the walls of the heart, and as endocarditis and a little effusion in the pericardium coexisted, it is premature to accept the evidence as final, and the great importance of the subject demands further investigation.

67 Lib. cit., p. 175.

Admitting with Fuller the occasional deposition of fibrin upon the valves and endocardium in rheumatic fever independently of endocarditis, the murmur resulting therefrom could not be reliably distinguished from that of inflammatory origin. It remains to speak briefly of temporary incompetence of the mitral and tricuspid valves and their dynamic murmurs, and of hæmic murmurs. Occasionally, in severe cases of rheumatic fever, more especially in the advanced stage, there may be heard a systolic murmur of maximum intensity either in the mitral area or over the body of the left ventricle, unaccompanied by accentuation of the second sound, or, as a general rule, by evidence of pulmonary obstruction. Such murmurs are apt to be intermittent, and as they disappear on the return of health, they have been satisfactorily referred to temporary weakness of the walls of the heart, so that the auriculo-ventricular orifices are not sufficiently contracted during the ventricular systole for their valves to close them, and regurgitation follows. Yet, inasmuch as Stokes distinctly mentions the absence of murmur in many cases of softening of the heart in typhus, it is probable that an excessive weakness of the ventricular wall is incompatible with the production of murmur, and that the presence of murmur in such circumstances is evidence of some remaining power in the heart.

Dr. D. West68 has published some cases of acute dilatation of the heart in rheumatic fever which strongly corroborate these views. The murmur in one of them became appreciable only as the heart's sounds increased in loudness and the dilatation lessened. One ended fatally, and acute fatty degeneration of the heart's fibres was found in patches.69 I believe that some of these temporary mitral murmurs in acute rheumatism depend upon a moderate degree of valvulitis quite capable of complete resolution. Sibson70 has lately stated that he has met with the murmur of tricuspid regurgitation without a mitral murmur in 13 out of 107 cases of rheumatic endocarditis, and with a recent mitral murmur in 27 out of 50 [p. 36]cases. "The tricuspid murmur generally comes into play about the tenth or twelfth day of the primary attack, along with symptoms of great general illness;" it appears earlier, as a rule, in those cases in which it is associated with mitral regurgitation than when it exists alone; it is of variable duration, but usually short—from one to nineteen days or more. He regards it as of non-inflammatory origin, and dependent upon regurgitation due to the so-called safety-valve function of the tricuspid valve; and when limited to the region of the right ventricle he infers that it is usually the effect and the evidence of endocarditis affecting the left side of the heart. These novel statements are confirmed by the observations of Parrot, Balfour, and William Russell,71 which go to prove that tricuspid regurgitation occurs frequently in the more advanced stages of debility. No other authority than Sibson, however, insists upon its frequent occurrence in acute rheumatism.

68 Barth. Hosp. Repts., xiv. 228.

69 On this subject see Stokes, Dis. Heart and Aorta, pp. 423, 435, 502; Stark, Archives générales de Méd., 1866; DaCosta, American Journal Med. Sci., July, 1869; Hayden, Dis. Heart and Aorta, 1875; Balfour, Clin. Lects. on Heart and Aorta, 1876; Cuming, Dublin Quart. Jour. Med. Sci., May, 1869; Nixon, ib., June, 1873. I. A. Fothergill has seen several cases in which such mitral murmurs have followed sustained effort in boys, and have disappeared after a time: The Heart and its Diseases, 2d ed., 1879, p. 177.

70 Reynolds's System. Med., Eng. ed., vol. iv. 463.

71 See Brit. Med. Jour., i. 1883, 1053.

The anæmia which is so striking a symptom of rheumatic fever, especially when several joints are severely inflamed, coexists very frequently with a systolic basic murmur, which is most often louder over the pulmonary artery (in second left intercostal space and more or less to left of sternum) than over the aorta. The murmur may appear early in the disease, but sets in most frequently when the disease is subsiding. When thus appearing late in a case accompanied by endocarditis and pulmonary congestion, it is of favorable omen and indicates improvement in the thoracic affection. The growing opinion, however, respecting so-called anæmic murmurs is, that they depend chiefly upon regurgitation through the tricuspid orifice, although Dr. W. Russell refers them to pressure of a distended left auricle upon the pulmonary artery.72

72 Ib., 1065.

Pulmonary affections in form of pleuritis, pneumonia, or bronchitis are common complications of rheumatic fever. Adding Latham's,73 Fuller's,74 Southey's,75 Gull and Sutton's,76 Pye-Smith's,77 and Peacock's78 cases together, we have a total of 920 in which some one or more of the above pulmonary affections obtained in 109 instances, or 11.8 per centum. A further analysis of Latham's and Fuller's cases shows that it is especially when rheumatic fever is complicated with cardiac disease that the lungs suffer; thus, pulmonary affections obtained in 26.5 per cent. of cases complicated with heart disease, and in only 7 per cent. of cases free from that disease. It is more especially when pericarditis complicates rheumatic polyarthritis that pulmonary affections occur. Thus, these were found in only 10.5 per cent. of cases of recent rheumatic endocarditis, in 58 per cent. of cases of pericarditis, and in 71 per cent. of cases of endo-pericarditis. The tendency which inflammation of the pericardium has to extend to the pleura probably partially accounts for the more frequent association of the pulmonary affections with rheumatic peri- than with rheumatic endocarditis. (Sibson found pleuritic pain in the side twice as frequent in pericarditis, usually accompanied with endocarditis (31 in 63), as in simple endocarditis, 26 in 108.79) But the greater severity of those cases of rheumatic fever complicated with peri- or endo-pericarditis must also have a decided influence in developing the pulmonary affections. [p. 37]Pneumonia and pleuritis are very frequently double in rheumatic fever, and are often latent, requiring a careful physical examination for their detection. So suddenly does the exudation take place in some cases of rheumatic pneumonia that the first stage is not to be detected either by symptoms or signs. On the other hand, in some cases the absence of the typical signs of hepatization, the want of persistence in the physical signs, and their rapid removal, and even in rare instances an obvious alternation between the pulmonary and the articular symptoms, suggest that the process often stops short of true hepatization, and partakes rather of congestion and splenization, with or without pulmonary apoplexy—a view which has been occasionally confirmed by the autopsy.80

73 Latham's Works, Syd. Soc., i. 98 et seq.

74 Lib. cit., 317.

75 Bartholomew Hospital Reports, xv. 14.

76 Guy's Hosp. Reports, 3d Series, xi. 434.

77 Ib. xix. 324.

78 St. Thomas's Hospital Reports, x. 12-17.

79 Reynolds's System Med., iv. 233.

80 Vide Sturges, Natural History and Relations of Pneumonia, 1876, pp. 70-78; T. Vasquez, Thèse, Des complications Pleuro-pulmonaires du Rheumatisme Artic. Aigue, Paris, 1878, pp. 25-31; M. Duveau, Dictionnaire de Méd. et de Chir., t. xxviii. p. 443.

Active general congestion of the lungs has occasionally been observed in this disease, and has proved fatal in five minutes81 and in an hour and a half82 from the invasion of the symptoms. The rheumatic poison frequently excites pleuritis, some of the characters of which are—the suddenness with which free effusion occurs; the promptness with which it is removed, only perhaps to invade the other pleura, and then to reappear in the cavity first affected; the diffusion of the pain over the side and its persistence during the effusion; and its frequent concurrence with pericarditis, and in children with endocarditis; its little tendency to become chronic, and its marked proclivity to become double. It is often latent and unattended with pain. Sibson asserts that if in rheumatic pericarditis "pain over the heart is increased or excited by pressure over the region of the organ, it may with an approach to certainty be attributed to inflammation of the pleura," etc. The product of the inflammation is commonly serous, but occasionally purulent.

81 Thèse d'Aigue pleur., 1866, par B. Ball.

82 M. Aran, quoted by Vasquez, lib. cit., p. 14.

The disturbances of the nervous system are amongst the most important complications of acute rheumatism, and are due either to functional disorder or very rarely to obvious organic lesions of the nerve-centres or their membranes. The dominant functional disturbance may be delirium, which is greatly the most frequent; or coma, which is rare; or chorea, very frequently observed in children; or tetaniform convulsions, which occur very seldom per se. As a rule, two or more of these forms coexist or alternate with or succeed one another, and the grouping, as well as the variety, of the symptoms may be greatly diversified. In 127 observations there were 37 of delirium only, 7 of convulsions, 17 of coma and convulsions, 54 of delirium, convulsions, and coma, 3 of other varieties (Ollivier et R., cited by Besnier).

Rheumatic Delirium.—Either with or without subsidence of the articular inflammation, about from the eighth to the fourteenth day of the illness, but occasionally at its beginning, or sometimes on the eve of apparent convalescence, the patient becomes restless, irritable, excited, and talkative; sleep is wanting or disturbed; some excessive discharge from the bowels or kidneys occasionally occurs; profuse perspiration is usually present, and may continue, but frequently lessens or altogether ceases; the skin becomes pungently hot, the temperature generally—not always, however—rising rapidly toward a hyperpyrexial point, and ranging from [p. 38]104° to 111°; and transient severe headache and disturbances of special sense sometimes obtain. At a later period, or from the outset in hyperacute cases, flightiness of manner or incoherence in ideas is quickly succeeded either by a low muttering delirium, twitchings of the muscles, violent tetaniform movements and general tremors, and a condition perhaps of coma-vigil, or by an active, noisy, even furious, delirium. The articular pains are no longer complained of, and sometimes the local signs of arthritis also quickly disappear; but neither statement is uniformly true. The pulse becomes rapid; prostration extreme; semi-consciousness or marked stupor gradually or rapidly supervenes; the temperature continues to rise; the face, previously pale or flushed, becomes cyanotic; and very frequently death ensues, either by gradual asthenia or rapid collapse, often preceded by profound coma or rarely by convulsions. Deep sleep often precedes prompt recovery.

The duration of the nervous symptoms varies from one or two, or more usually six or seven, hours in very severe cases, to three or four days in moderate ones, or occasionally seven, eight, or sixteen83 or twenty-nine days84 in unusually protracted cases. In the last-mentioned, however, the delirium is not usually constant, and frequently disappears as the temperature falls, and recurs when its rises. Moreover, a rapid and extreme elevation of temperature is frequently altogether wanting.

83 Southey's case, Clin. Soc. Trans., xiii. p. 25. Sleeplessness preceded it for four days, and there was no hyperpyrexia.

84 Graham's case, ib., vi. p. 7. Delirium set in on the seventh day of illness, and three days after invasion of joints. Temperature 104.8° early in disease; never exceeded 106°, probably owing to repeated use of cold baths. Temperature at death, 104.2°.

No real distinction can be established between these protracted cases of rheumatic delirium and so-called rheumatic insanity, in which occur prolonged melancholia, with stupor, mania, hallucinations, illusions, etc., often associated with choreiform attacks. This variety may be of short duration or continue until convalescence is established, or may rarely persist after complete recovery from the articular affection.

Coma may occur in acute rheumatism without having been preceded or followed by delirium or convulsions, although it is very rare; and, like delirium, it may obtain without as well as with peri- or endocarditis or hyperpyrexia. It usually proves very rapidly fatal. In Priestly's case, an anæmic woman of twenty-seven, during a mild attack of acute rheumatism, one night became restless; at 3 A.M. the pain suddenly left the joints; apparent sleep proved to be profound coma, and at 6 A.M. she was in articulo mortis.85 Southey relates the history of a girl of twenty who, without previous delirium or high temperature, suddenly became unconscious, and died in half an hour.86 One of Wilson Fox's cases had become completely comatose, and was apparently dying nine hours after the temperature had rapidly risen to 109.1°, when she was restored to consciousness by a cold bath and ice to her chest and spine.87

85 Lancet, ii., 1870, 467.

86 Clin. Soc. Trans., xiii. p. 29.

87 The Treatment of Hyperpyrexia, 1871, 4.

Convulsions of epileptiform, choreiform, or tetaniform character frequently succeed the delirium, but in exceptional cases they occur independently of it, and may even prove fatal.

Besides the choreiform disturbances which occur in connection with delirium, stupor, tremor, etc. in cerebral rheumatism, simple chorea is [p. 39]frequently observed as a complication or a sequence, or even as an antecedent, of acute articular rheumatism, and they occasionally alternate in the same patient and in the same family. Chorea is perhaps most frequently seen in mild cases and in the declining and convalescent stages of rheumatic fever, and, while very common in childhood and adolescence (five to twenty), it is very rare later in life.