WAR BOOKS

BRITISH REGIMENTS AT THE FRONT

| Cloth 1/- net each |

WAR BOOKS |

Post free 1/3 each |

PUBLISHED FOR THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

BY HODDER & STOUGHTON, WARWICK SQUARE,

LONDON, E.C.

BY

REGINALD HODDER

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXIV

The Author wishes to express his indebtedness to Mr. J. Norvill for his valuable assistance and suggestions.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER—NICKNAMES OF THE REGIMENTS AND HOW THEY WERE WON | 9 | |

| I. | 5TH DRAGOON GUARDS | 41 |

| II. | THE CARABINIERS | 43 |

| III. | THE SCOTS GREYS | 49 |

| IV. | 15TH HUSSARS | 57 |

| V. | 18TH HUSSARS | 61 |

| VI. | THE GRENADIER GUARDS | 63 |

| VII. | THE COLDSTREAM GUARDS | 71 |

| VIII. | THE ROYAL SCOTS | 76 |

| IX. | THE "FIGHTING FIFTH" | 84 |

| X. | THE LIVERPOOL REGIMENT | 89 |

| XI. | THE NORFOLKS | 92 |

| XII. | THE BLACK WATCH | 100 |

| XIII. | THE MANCHESTER REGIMENT | 113 |

| XIV. | THE GORDON HIGHLANDERS | 118 |

| XV. | THE CONNAUGHT RANGERS | 139 |

| XVI. | THE ARGYLL AND SUTHERLAND HIGHLANDERS | 142 |

| XVII. | THE DUBLIN FUSILIERS | 146 |

| XVIII. | FUENTES D'ONORO AND ALBUERA | 156 |

| XIX. | BALACLAVA AND INKERMAN | 178 |

"The Rusty Buckles."

The 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays) got their name of "The Bays" in 1767 when they were mounted on bay horses—a thing which distinguished them from other regiments, which, with the exception of the Scots Greys, had black horses. Their nickname, "The Rusty Buckles," though lending itself to a ready explanation, is doubtful as to its origin; but one thing is certain that the rust remained on the buckles only because the fighting was so strenuous and prolonged that there was no time to clean it off.

"The Royal Irish."

The 4th Dragoon Guards received this title in 1788, in recognition of its long service in Ireland since 1698. The regiment also has the name of the "Blue Horse" from the blue facings of the uniform.

"The Green Horse."

The 5th Dragoon Guards were given this name in 1717 when their facings were changed from buff to green. Some time later, after Salamanca, they were also called the "Green Dragoon Guards."

"Tichborne's Own."

The 6th Dragoon Guards, or Carabiniers, have been known as "Tichborne's Own" ever since the trial of Arthur Orton, as Sir Roger Tichborne had served for some time in the regiment. The name of "Carabiniers" has distinguished them ever since 1692, when they were armed with long pistols or "carabins." With these weapons they did signal work in Ireland in 1690-1.

"Scots Greys."

This regiment, the 2nd Dragoons, has been known by many names: "Second to None," "The Old Greys," "Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons," (in 1681, when they were commanded by the famous Claverhouse); "The Grey Dragoons" in 1700, the "Scots Regiment of White Horses," the "Royal Regiment of North British Dragoons" in 1707, the "2nd Dragoons" in 1713, and the "2nd Royal North British Dragoons" in 1866.

Associated with them and all their different names is the memorable cry of "Scotland for ever"—that wild shout they raised as they charged the French infantry at Waterloo. At Ramillies they captured the colours of the French Régiment du Roi and by this gained the right to wear grenadier caps instead of helmets. "Bubbly Jocks" is a nickname frequently used among themselves—a name derived from the fact that their dress in its general effect is not unlike that of the "Bubbly Jock" or turkey cock.

"Lord Adam Gordon's Life Guards."

The 3rd Hussars received this nickname from the fact that when Lord Adam Gordon commanded the regiment in Scotland he kept it there for such a long time—"for life" so to speak. When it was raised, in 1685, the regiment was called "The Queen Consort's Regiment of Dragoons." In 1691 it was known as "Leveson's Dragoons." In the time of the George's it was called variously "King's Own Dragoons" and "Bland's Horse." In 1818 it was made a "Light Dragoon" regiment, and it was not until 1861 that it became Hussars.

"Paget's Irregular Horse."

The 4th Hussars received this title on its return from foreign service, when it was remarked that its drill was less regular than that of the other regiments. In 1685 it was called the "Princess Ann of Denmark's Regiment of Dragoons." Like the 3rd it was formed into a regiment of Hussars in 1861.

"The Red Breasts."

The 5th Lancers, or Royal Irish, are called "Red Breasts" because of their scarlet facings. In 1689 they were known as the "Royal Irish Dragoons," having been raised to assist at the siege of Londonderry in 1688. They became the "5th Royal Irish Lancers" in 1858. This regiment has also been called the "Daily Advertisers," but the derivation of this name is somewhat obscure.

"The Delhi Spearmen."

The 9th Lancers received this name from the rebels of the Indian Mutiny, against whom they used their long lances with such deadly effect. In 1830 they were known as the "Queen's Royal Lancers," and "Wynne's Dragoons."

"The Cherry Pickers."

The 11th Hussars were dubbed "Cherry Pickers" because some of their men during the Peninsular War were taken prisoners in a fruit garden while supposed to be on outpost duty. They are known also as "Prince Albert's Own" from the fact that they formed part of the Prince's escort from Dover to Canterbury when he arrived in England in 1840 as the late Queen's chosen Consort. One hears them sometimes referred to as the "Cherubims," from their crimson overalls, busby bag, and crimson and white plume.

"The Supple 12th."

It was at Salamanca that the 12th Lancers received this honoured name, because of their dash and rapid movements.

"The Fighting 15th."

It was at Emsdorf that the 15th Hussars won this name, and their feat of arms on that field gained them the privilege to wear on their helmets the following inscription: "Five battalions of French defeated and taken by this Regiment with their colours and nine pieces of cannon at Emsdorf, 16th July, 1760." In 1794, at Villiers-en-Couché, they charged with the Austrian Leopold Hussars against vastly superior numbers to protect the person of the Austrian Emperor. In recognition of this the then Kaiser presented each of the eight surviving officers with a medal. In 1799 they received the Royal honour of decking their helmets with scarlet feathers. The "Fighting 15th" are also known in history as "Elliot's Light Horse."

"The Dumpies."

The 20th Hussars, together with the 19th and 21st, received the name of "Dumpies" from the fact that the regiment when formed of volunteers from the disbanded Bengal European Cavalry of the East India Company were short and dumpy. Though nowadays there is many a giant among the 20th, the name of "Dumpies" still survives.

"The Mudlarks."

The Royal Engineers received this name from the nature of their ordinary business in war. In 1722 they were called the "Soldier Artificers Corps"; and, in 1813, "The Royal Sappers and Miners."

"The Gunners."

The Royal Artillery have held this name from their regular formation in 1793. Formerly, after the rebellion in Scotland, they were known as the "Royal Regiment of Artillery," and, though not in any way formed into a regiment, they date still further back, one might say even to the early days when guns were made of wood and leather. That was before 1543, when the first gun was cast in England. In 1660 the master gunner was called the "Chief Fire Master". The Honourable Artillery Company was founded in 1537 and is the oldest Volunteer Corps in Great Britain.

"The Sandbags."

The Grenadier Guards gained this peculiar name from their special privilege of working in plain clothes for wages at coal or gravel heaving, and for this same reason they were often called "Coalheavers." They seem to have got this name in Flanders, where they excelled at trench work. Another of their nicknames is "Old Eyes." In 1657 they were known as the "Royal Regiment of Guards," and in 1660 as the "King's Regiment of Guards."

"The Coldstreamers."

The Coldstream Guards received their name in 1666 when Monk marched them from Coldstream to assist Charles II to regain his throne. They have been called the "Nulli Secundus Club," in memory of the fact that Charles, before he hit on the name "Coldstream Guards," wished to call them the "2nd Foot Guards," a thing to which they strongly objected, saying that they were "second to none."

"The Jocks."

The origin of this name for the Scots Guards is obvious. History is a little uncertain about their record, as their papers were burnt by accident in 1841; but this is certain, that they were raised as Scots Guards in 1639 and were called later the "Scots Fusilier Guards" and the "3rd Foot Guards," after which, in 1877, they resumed the name of "Scots Guards."

"Pontius Pilate's Bodyguard."

This strange nickname of the Royal Scots Regiment is based on an equally strange story. As long ago as 1637, when most other regiments were as yet unborn, a dispute arose between the Royal Scots and the Picardy Regiment on the point of priority in age. The Picardy Regiment claimed to have been on duty the night after the Crucifixion. But the Royal Scots met this with a withering volley. "Had we been on duty then," they said, "we should not have slept at our post." This incident caused some wag to dub the Royal Scots "Pontius Pilate's Bodyguard," and the name has stuck to them ever since. There is another tradition that this regiment represents the body of Scottish Archers, who for many centuries formed the guard of the French Kings. It fought in the seven years' war under Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, and was incorporated in the British Army in 1633. Since then, whenever war has been declared, every man of "Pontius Pilate's Bodyguard" has been among the last to stay at home.

"The Lions."

The Royal Lancaster Regiment bears upon its colour the Lions of England, disposed, as in Trafalgar Square, one at each quarter. This distinction was given them by the Prince of Orange, as they were the first regiment to join him in 1688 when he landed at Torbay. They have also been called "Barrell's Blues" from their Commander and their blue facings. They received the title of "King's Own" from George I., in 1715, and our late King Edward became their Colonel-in-Chief in 1903. Our present King is now the Colonel-in-Chief.

"Kirke's Lambs."

The Royal West Surrey Regiment (The Queen's) derived this name from Kirke and from the Paschal Lamb in each of the four corners of its colour. The name has also an ironical derivation from the fact that they were employed to enforce the cruelties of "Bloody Judge Jeffreys." Another nickname of theirs is the "First Tangerines," because they were raised in 1661 as the "Tangiers Regiment of Foot," for the purpose of garrisoning Tangiers, at that time a British possession. John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, began his career in this Regiment. Another nickname, "Sleepy Queen's" is derived from a slight omission of theirs at Almeida, when, through some oversight, they allowed General Brennier to escape. But they have so far lived this down that now, ut lucus a non lucendo, they are called "sleepy" because they are always very wide awake.

"The Shiners."

The Northumberland Fusiliers deserve that name because they are always so spic-and-span. They also deserve the name of "Fighting Fifth" because they have many a time proved their right to it. At the battle of Kirch Denkern (1761) they captured a whole regiment of French infantry, and, in the following year, at Wilhelmsthal, they took twice their own number prisoners. They have also the name of "Lord Wellington's Body Guard" because, in 1811, they were attached to Headquarters. Another name is "The Old and Bold." On St. George's day the "Fighting Fifth" wear roses in their caps, but the origin of this is not clear, unless it may be that one of their badges is "St. George and the Dragon," and another "The Rose and Crown." They also wear the white feathers of the French Grenadiers on the anniversary of the battle of La Vigie, when Comte de Grasse attempted to relieve the Island of St. Lucia in the West Indies. On that occasion the "Old and Bold" took the white plumes from the caps of their defeated opponents, the French Grenadiers. To-day, the white in the red and white hackle now worn by them refers back to that terrible death-struggle. The 5th is the only foot regiment which has the distinction of a red and white pompon. It is worth recording here that they formed part of a force which repulsed overwhelming numbers of the enemy on the heights of El Bodon (1811) during the investment of Ciudad Rodrigo. The Iron Duke spoke of this achievement as "a memorable example of what can be done by steadiness, discipline and confidence."

"The Elegant Extracts."

The word sounds like a fashionable chemical compound, but its real meaning is derived from the fact that the officers of the Royal Fusiliers—except 2nd Lieutenants and Ensigns, of which at the time they had none—were "extracted" from other corps. In the eighteenth century they were known as the "Hanoverian White Horse." Those who have lived to remember the Crimean War will remember also that brave song, "Fighting with the 7th Royal Fusiliers"—a song which became so popular that the regiment could have been recruited four times over had it been necessary.

"The Leather Hats."

The King's (Liverpool) Regiment gained their name from their head-gear. They were raised by James II. in 1685. In the American War an officer and 40 men of the "Leather Hats" captured a fort held by 400 of the enemy. It is interesting to know that this regiment has an allied regiment of the Australian Commonwealth—the 8th Australian Infantry Regiment.

"The Holy Boys."

The Norfolk Regiment has had this name ever since the Peninsular War. In that campaign the Spaniards, seeing the figure of Britannia on the cross-belts of the 9th, thought that it was a representation of the Virgin Mary. There is another story to the effect that they derive their name from their reputed practice of selling their Bibles to buy drink during the Peninsular War. But this I do not believe. Another name for them is the "Fighting Ninth"—a title which no one can refuse to believe. Their bravery at the siege of St. Sebastian might alone justify it.

"The Springers."

The Lincolnshire Regiment received this nickname during the American War because they were remarkable in their readiness to spring into action when called upon. It was the first infantry regiment to enter Boer territory during the late South African War. Their other name of "Lincolnshire Poachers" has no satisfactory derivation.

"The Bloody Eleventh."

There are two stories to account for this nickname of the Devonshire Regiment. One is that at Salamanca they were in a very sanguinary condition after the battle. The other is that when they were in Dublin in 1690 the regiment's contractor supplied bad meat, on which they swore that if he did so again they would hang the butcher. There was no improvement in the meat, so they hanged the delinquent in front of his own shop on one of his own meat-hooks. It is no doubt the first story that is the true one. Another name for the Devonshires is "One and All." It was a man in this regiment who wounded Napoleon at Toulon in 1793.

"The Old Dozen."

The Suffolk Regiment won glory for itself at the siege of Gibraltar. It also behaved with the greatest gallantry at Minden, and that is why on the 1st of August (Minden Day) the "Old Dozen" parade with a rose in the head-dress of each man. In connection with this they are also called the "Minden Boys."

"The Peacemakers."

The Bedfordshire Regiment were first known as the "Peacemakers" because at that time there were no battles on its colours. For the same reason no doubt they were also called "Bloodless Lambs." Another nickname of theirs is "The Old Bucks"—a title justified by their hard fighting in the Netherlands under William III. and also under Marlborough.

"The Bengal Tigers."

The Leicestershire Regiment gets its name from the Royal Green Tiger on its badge. This distinction was given it for a brilliant achievement in the Nepal War of 1814, when they captured a Standard bearing a tiger. They are also called "Lily Whites," from their white facings.

"The Green Howards."

The Yorkshire Regiment was commanded by Colonel Howard, and has green facings. They are also called "Howard's Garbage," and must not be confused with the 24th Foot, also once commanded by a Colonel Howard, and styled "Howard's Greens."

"The Earl of Mar's Grey Breeks."

The Royal Scots Fusiliers received this name from the colour of their breeches at the time the regiment was raised in 1678. "The Grey Breeks" wear a white plume in their head-dress—an honour bestowed in recognition of their services during the Boer War.

"The Lightning Conductors."

There is some doubt as to how the Cheshire Regiment acquired this name. But it may be connected in some way with the fact that at Dettingen, when George II. was attacked by the French Cavalry, they formed round him under an oak tree and drove the enemy off. In remembrance of this occasion the oak leaf is worn by them at all inspections and reviews in obedience to the wish of George II. when he plucked a leaf from the tree and handed it to the Commander. They are also known as the "Two Twos" from their number, the 22nd. Another of their names is "The Red Knights," because, when recruiting at Chelmsford in 1795, red jackets, breeches and waistcoats were served out to them instead of the proper uniform. This regiment, under the name of the "Soulsburg Grenadiers," was under Wolfe when he was mortally wounded at Quebec.

"The Nanny Goats."

The Royal Welsh Fusiliers are known as "Nanny Goats" or "Royal Goats" because they always have a goat, with shields and garlands on its horns, marching bravely at the head of the drum. This has been their custom for over a hundred years. A glance at the back of their tunics reveals a small piece of silk known as a "flash." It has been there ever since the days when its office was to keep the powdered pigtail from soiling the tunic. The King is Colonel-in-Chief of the "Nanny Goats."

"Howard's Greens."

The South Wales Borderers were at one time commanded by a Colonel Howard. It was a company of this regiment which achieved immortal glory at Rorke's Drift, which they defended against 3,000 Zulus. In Africa they gained no less than eight V.C.'s. On the Queen's colour of each battalion may be seen a silver wreath. This was bestowed by Queen Victoria in memory of Lieutenants Melville and Coghill, who died to save the colours at Isandlhwana.

"The Botherers."

The King's Own Scottish Borderers—the only regiment that was allowed to beat up for recruits in Edinburgh without asking the Lord Provost's permission—were called "Botherers," partly on this account and partly by corruption from "Borderers." They bear also the name of "Leven's Regiment," from the remarkable fact that in 1689 they were raised by the Earl of Leven in Edinburgh, in the space of four hours. They are also known as the "K.O.B.s."

"The Cameronians."

The 1st Battalion of the Scottish Rifles are the descendants of the Glasgow Cameronian Guard which was raised during the Revolution of 1688 from the Cameronians, a strict set of Presbyterians founded by Archibald Cameron, the martyr. The 2nd Battalion is known as "Sir Thomas Graham's Perthshire Grey Breeks." It received this name from the fact that when Lord Moira ordered the regiment to be equipped and trained as a Light Infantry Corps, their uniforms consisted of a red jacket faced with buff, over a red waistcoat, with buff tights and Hessians for the officers, and light grey pantaloons for the men. Both battalions now wear dark green doublets and tartan "trews."

"The Slashers."

The Gloucestershire Regiment derives its name of "Slashers" from its achievements in the battle of the White Plains in 1777. There is another story, however, that the name arose from a report that, on one occasion, a magistrate having refused shelter to the women of the regiment during a severe winter, some of the officers disguised themselves as Indians and slashed off both his ears. In Torres Straits there is a reef which is marked on the charts as the "Slashers' Reef" because, after the Khyber Pass disaster of 1842, the "Slashers" were on the way from Australia to India when the transport conveying them grounded on this reef. Their other name of the "Old Braggs" is derived from their Commander, General Braggs, of 1734. In regard to this there is the tradition of an order given by a wag of a Colonel when the "Old Braggs" were brigaded with other regiments with Royal Titles. The order runs:

"The Vein Openers."

The Worcestershire Regiment were dubbed "The Vein Openers" by the people of Boston, (U.S.A.) in 1770, because they were the first to draw blood in the preliminary disturbances before the war. After the Peninsular War they were called "Old and Bold." Another name for them is "Star of the Line," from the eight-pointed star on their pouches—a distinction peculiarly their own. The 2nd Battalion were known as the "Saucy Greens" from the colour of their facings and, presumably, their extreme sauciness.

"The Young Buffs."

The 1st Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment derived their nickname from a peculiar royal mistake. At the battle of Dettingen, King George II., mistaking them for the "3rd Buffs," called out "Bravo Old Buffs!" Being reminded that they were not the "Old Buffs" but the 31st, His Majesty at once corrected his cry to "Bravo, Young Buffs!" and the name has stuck to the battalion ever since. The 2nd Battalion was raised at Glasgow in 1756 and takes its name of "Glasgow Greys" from that and the facings of the uniform.

"The Red Feathers."

The 2nd Battalion of the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry gained their nickname by a signal act of defiant heroism. During the American War of Independence they learned that the enemy had marked them down as men to whom no quarter was to be given. On this the Light Company, wishing to restrict the full force of this threat to themselves, and to prevent others suffering by mistake, stained their plume feathers red as a distinguishing mark. For this fine act they were authorised to wear a red feather, and this honour is perpetuated in the red cloth of the helmet and cap badge and the red pughri worn on foreign service. Their other nickname "The Lacedæmonians" has a dash of grim humour in its origin. During the same war, at the time of all times when the men were under a withering fire, their Colonel made a long speech to them—all about the Lacedæmonians, a brave race enough, but terribly ignorant of rifle fire.

"The Havercake Lads."

The West Riding Regiment (The Duke of Wellington's) is said to have derived its nickname from the fact that the recruiting sergeants in the old days carried an oat cake on the points of their swords. There is a joke among "The Havercakes" as old as their first recruiting sergeant. This enterprising man was in the habit of addressing the Yorkshire crowd as follows: "Come, my lads; don't lose your time listening to what them foot sojers says about their ridgements. List in my ridgement and you'll be all right. Their ridgements are obliged to march on foot, but my ridgement is the gallant 33rd, the First Yorkshire West Riding Ridgement, and when ye join headquarters ye'll be all mounted on horses."

The 2nd Battalion is known as "The Immortals," from the fact that in the Indian wars under Lord Lake every man bore the marks of wounds. They were also called "The Seven and Sixpennies" from their number (76th) and from the fact that seven and sixpence represented a lieutenant's pay.

"The Orange Lilies."

The 1st Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment was named "The Orange Lilies" from their early facings, orange, a mark of favour from William III., in 1701, and the white plume taken from the Roussillon French Grenadiers at Quebec in 1759. They were originally called "The Belfast Regiment" then "The Prince of Orange's Own." The orange facings were replaced by blue in 1832, and the white plumes disappeared in 1810; but the white (Roussillon) plume is still a badge of the Royal Sussex.

"The Pump and Tortoise."

The 1st Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment earned half their nickname from their extreme sobriety and the other half from the slow way they set about their work when actually stationed at Malta. The 2nd Battalion is known as "The Staffordshire Knots."

"Sankey's Horse."

The 2nd Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment, under Colonel Sankey in 1707, arrived at Almanza during the battle mounted on mules, hence the term "Sankey's Horse," applied to a foot regiment. They were the first King's regiment to land in India, in memory of which they have for their motto "Primus in Indis." In 1742 the regiment was popularly known as "The Green Linnets" from the "sad green" facings of its uniform. The 2nd Battalion acquired the name of "The Flamers" from their large share in the destruction of the town and stores of New London, together with twelve privateers, by fire in 1781.

"The Excellers."

This name was fastened upon the 1st Battalion South Lancashire Regiment from its number (XL the 40th). It is also known as "The Fighting Fortieth." Until its amalgamation with the 82nd it had the honour of being next to the Royal Scots in the number of battle honours on its colour.

"The 1st Invalids."

The 1st Battalion Welsh Regiment is set down in old Army Lists under this name because it was first raised as a regiment of Invalids, in 1719. In George II's, time it was known as "Wardour's Regiment." The nickname of the 2nd Battalion is a curious play on words—or rather figures. They are called the "Ups and Downs" because their number (69th) reads the same when inverted. The 69th are also called "The Old Agamemnons," a fancy title bestowed on them by Lord Nelson at St. Vincent after the name of his ship, on which a detachment was serving as marines.

"The Black Watch."

The Royal Highlanders won this honoured name from the sombre colour of their tartan some ten years before their Highland Companies were formed into a regiment known as "The Highland Regiment." Its first Colonel, Lord Crawford, being a lowlander, had no family tartan, so, it is said, this special tartan was devised. The bright colours in the various tartans are said to have been extracted, leaving only the dark green ground. The French, under the impression that in their own mountainous country they ran wild and naked, called them "Sauvages d'Ecosse." The red hackle in their bonnets was won at Guildermalsen in 1794.

"The Cauliflowers."

The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment have this nickname from the former colour of the facings of the 1st Battalion. They are also called "The Lancashire Lads." After Quebec the 47th were nicknamed "Wolfe's Own" and to this day the officers of both battalions wear a black worm in their lace gold as a sign of sorrow for their general's death. This is the only regiment that is officially styled "Loyal," the 2nd Battalion having been known prior to 1881 as the 81st (Loyal Lincoln Volunteers).

"The Steelbacks."

This is the name applied to the Northamptonshire Regiment because of the unflinching way in which they took their floggings. While under Wellington in the Peninsular War one, Hovenden, a private, was flogged for breach of discipline. At the twentieth stroke he fainted and this so disgusted his comrades that on his recovery they cut him dead. Much annoyed at this Hovenden marched up to the Colonel and called him a fool, and for this he was ordered to be flogged again. That night the regiment was attacked by the French, and Hovenden, evading the guard, arrived on the battlefield in time to see his Colonel captured by the enemy. With his musket he shot down the captors and then liberated the Colonel and bound up his wounds. After this he returned to make sure of his flogging, but was struck by a bullet and killed.

The Northamptonshires have also the honoured name, "Heroes of Talavera," because they turned the tide of battle on that victorious day.

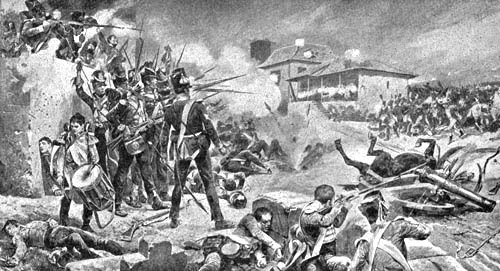

THE "DIE HARDS" AT ALBUERA.

From a Painting by R Caton Woodville

"The Blind Half Hundred."

The 1st Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment suffered greatly from ophthalmia in Egypt in 1801, hence this nickname. They were called also "The Dirty Half Hundred" because the men, when in action in hot weather, used to wipe their faces with their black cuffs, with obvious results. Another of their names is "The Devil's Royals," and yet another "The Gallant 50th"—this last because at Vimiera, in 1807, 900 of them routed 5,307 of the enemy.

"The Kolis."

The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry derive their name of "Kolis" from their initials. The name often takes the corrupted form of "Coalies."

"The Die-Hards."

The 1st Battalion Duke of Cambridge's Own (Middlesex Regiment) were styled "Die Hards" from the memorable words of Inglis at Albuera: "Die hard, my men; die hard!"—words which were endorsed by Stanley at Inkerman when he said: "Die hard! Remember Albuera!" The 2nd Battalion are called "The Pothooks," from their number (77).

"The Royal American Provincials."

This distinguished popular name was bestowed on the King's Royal Rifle Corps because they were raised in America.

"The Bloodsuckers."

The Manchester Regiment appear to have acquired this name from general and warlike reasons. The 1st Battalion displayed great courage and steadiness in the defence of Ladysmith. The 2nd Battalion was formerly the "Minorca Regiment" and became part of the Line in 1804 as the 97th (Queen's German) Regiment, becoming later the 96th Foot.

"The Strada Reale Highlanders."

The Gordon Highlanders (92nd and 75th) would propound a riddle to you: What is the difference between the 92nd and the 75th? The answer is that the 92nd are real Highlanders, and the 75th are Real(e) Highlanders.

"The Cia mar tha's."

The Cameron Highlanders owe this nickname to Sir Allen Cameron, who raised the regiment. It was his word to everybody: "Cia mar tha!" (How d'ye do!)

"The Garvies."

The Connaught Rangers are called "Garvies" because their recruits, when first the regiment was raised, were both lean and raw. Now a "garvie" is a small herring.

"The Blue Caps."

At the time of the relief of Cawnpore, a despatch of Nana Sahib was intercepted, containing a reference to those "blue-capped English soldiers who fought like devils." These "Blue-Caps" were the Madras Fusiliers, then a "John Company" regiment, but now the 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The name was later stamped in perpetuity by Havelock, at the bridge of Charbagh. The question was put to him by Outram as to who could possibly carry the bridge under so deadly a fire. "My Blue Caps!" replied Havelock, and his faith in them was justified, for they carried it against overwhelming odds. The Bombay Fusiliers (another "John Company" regiment) now the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers, have an equally distinguished record. They have been known as "The Old Toughs."

BRITISH REGIMENTS AT THE FRONT

The 5th Dragoon Guards were raised by the Earl of Shrewsbury to support James against "King Monmouth" at Sedgmoor. For the same reasons that "Britons never, never will be slaves," they refused, on consideration, to support James, and sided with William, for whom they threw in their weight at the Boyne. They were also at a former siege of Namur, and bore themselves bravely at Blenheim.

The story is told that, after that battle, a Sunday Church parade was called, in which the British army deployed to fire a volley of victory, and Marshal Tallard, who was a prisoner, was reluctantly present on that occasion. After the volley, the Duke of Marlborough turned to Tallard, and asked what he thought of the British army. "Well enough," replied Tallard, shrugging his shoulders, "but the troops they defeated, why, those are the best soldiers in the world!" "If that is so," said the Duke, "what will the world think of the fellows who thrashed them?" All obvious enough, but the Duke would never have slept quietly in his bed if he had left it unstated.

At Salamanca, with the 3rd and 4th Light Dragoons, the 5th Dragoon Guards carved their way through a treble thickness of French army columns, under a heavy fire. For this marvellous achievement "Salamanca" is writ large on their colours.

THEIR BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Motto.—"Vestigia nulla retrorsum."

Battle Honours.—Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Salamanca, Vittoria, Toulouse, Peninsula, Balaclava, Sevastopol, S. Africa 1899-1902, Defence of Ladysmith.

Uniform.—Scarlet, dark green facings, red and white plume.

There is not a woman in our vast Empire who has not good cause to regard with admiration and gratitude those noble protectors and terrible avengers of the honour of their sex—the Carabiniers. During the Indian Mutiny—but first a brief word as to their history.

It dates from the time of Monmouth's rebellion, when they were raised by Lord Lumley to support King James. Owing to the fact, however, that Lord Lumley was no supporter of the king's tyrannies, the regiment seceded, and later, when the Prince of Orange landed, threw in their lot with him whole-heartedly. Their title, "The Carabiniers," was bestowed upon them in recognition of the great part they played in the battle of the Boyne, for William had in mind the famous carabiniers of Louis XIV.

In the list of the glories of the Carabiniers is Aughrim. Macaulay says about this occasion: "St. Ruth laughed when he saw the Carabiniers and the Blues struggling through a morass under a fire which, at every moment, laid some gallant hat and feather on the earth." "What did they mean?" he asked, and then he swore it was a pity to see such fine fellows marching to certain destruction. Nevertheless, at the issue of that business, it was he, and his troops, that reaped the destruction.

It was some little time later that the Carabiniers saved the situation for King William at Landen, by an obstinate stand against his pursuers, while he crossed the bridge. As Corporal Trim in "Tristram Shandy" says; "If it had not been for the regiments of Wyndham, (i.e., the Carabiniers) Lumley and Galway, which covered the retreat over the bridge at Neerspecken, the king himself could scarcely have gained it."

In three continents the Carabiniers have fought their way to an exalted fame. At Ramillies they captured the standard of the Royal Regiment of Bombardiers of France. At Malplaquet they measured steel and courage with the formidable Household Brigade of France and came out victorious. And from that time onward their glorious career can be traced through Europe, Asia and Africa in such clear lines that the enemy who runs has read.

But it was during the time of the Indian Mutiny that they performed feats of valour for which we British men, as well as the women, owe them heartfelt gratitude. They were among the reinforcements sent out to stay the terrible tide of massacre and rapine. How they struggled for life and empire at Delhi; repulsed the rebels outside Lucknow with fearful carnage, with loss of their leader; and, finally, when Lucknow had fallen, pursued the rebels with relentless wrath, dealing vengeance with a heavy hand—all this has been written by many pens. It has been the theme to make the driest book most vivid reading. It was the story of stern, ruthless punishment and revenge for the horrible crimes committed by the then unregenerate Sepoy against helpless women and children—crimes of torture, murder, wholesale massacre, and unconceivable outrage.

One has only to remember the horrible atrocities of the Indian Mutiny to acquit the Carabiniers of any charge of undue ferocity; one has only to remember Cawnpore, and the women and the babies, in order to admire their offices of stern, relentless retribution. And all this happened at the very time when all London was celebrating the centenary of the sublime victory of Plassey, and the brilliant acquisition of the Indian Empire under the genius of Clive.

When, at Meerut, on that never-to-be-forgotten Sunday, they pursued the fiends responsible for that awful massacre, the Carabiniers, together with the 60th Rifles drew a very determined line between righteous revenge and feeble long-sufferance; between just wrath, that ever-potential factor in heroic blood: primitive wrath, and its cognate barbarity of act. "Remember the women! Remember the babies!" ran through the ranks on that occasion; and, with one heart and mind, the Carabiniers and the 60th, an avenging host, pursued the rebels, and cut them to pieces, right up to the very gates of Delhi, imprecating as they slew. And well they might be forgiven for that. Never were the lives of the innocent and defenceless so quickly, terribly, yet justly avenged; never has a more awful nemesis from human hands fallen upon the destroyers of women and women's honour. And, remembering all this, we defend it and uphold it, for we know full well that, in this present war, the barbarities and atrocities committed by an unprincipled enemy must again meet with this righteous kind of vengeance. And, if it is the traditional and special aspiration of the Carabiniers of to-day to cry "Remember Louvain! Remember the women and babies of Belgium!" shall we say "Hold and spare!" No! shall we say, "Vengeance is God's: God will repay!" Yes, with all our heart and soul; and what better agency for repayment than that of our noble Carabiniers! They are not of the kind to repay barbarity with barbarity; but they are of the kind to use their swords with singular effect, and like English gentlemen, whose special office it is to wreak proper vengeance to-day as in the past on the destroyers of women and children.

At Gungaree the Carabiniers lost three of their officers, but for this they took a heavy toll. Meeting the rebels three days later, they defeated them completely, taking their leaders prisoners. Again the terrible work began. Hotly they pursued the flying rebels, and put them to the sword without a show of quarter. Rebel blood flowed like water for the rebel deeds they had committed against right and honour.

THEIR BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Battle Honours.—Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Sevastopol, Delhi, Afghanistan 1879-80, S. Africa 1889-1902, Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg.

Uniform.—Blue, white facings, white plume.

CHARGE OF SCOTS GREYS AT WATERLOO.

From a Painting by R. Caton Woodville.

"Greys, gallant Greys! I am 61 years old, but, if I were young again, I should like to be one of you."—Sir Colin Campbell at Balaclava.

The 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys), whose motto is "Second to None," are pictured to British eyes and imaginations in that wonderful painting, "Scotland for Ever." The Charge of the Light Brigade, great and glorious as it was, is, and ever will be, is perpetually linked with the Charge of the Heavy Brigade, under Scarlett, when, faced with a vastly superior force of the enemy, it offered such heroic assistance, that, had it not been for this, the glory of the immortal six hundred might not have been sung in the same triumphant voice. It was a gallant feat on the part of the "Heavies"—a feat which, though somewhat overshadowed by the dazzling "Charge of the Six Hundred," was nevertheless greatly influential in turning the tide of battle.

(Inseparately connected with the Scots Greys at the front to-day, is the Prince of Wales' Royal Lancers—the 12th. At Salamanca the "supple 12th" joined in the final charge which routed the French cavalry. At Vittoria the Greys saw Joseph deprived of his crown, and were fortunately present at the conquest of San Sebastian. In Egypt they won honours under Abercromby, and to-day the emblazonment of the mystic sphinx on their standard bears witness to the most heroic deeds. What they have done, that they can do, and their gallant deeds in the present super-war show that while the Scots Greys are still second to none, the 12th Lancers are among the first in every glorious deed.)

The charge of the Greys and Inniskillings has been graphically described by many writers. Perhaps the words "Up the hill, up the hill, up the hill," describe most vividly the terrific struggle. But Kinglake tells the story tensely:

"As lightning flashes through a cloud, the Greys and Inniskillings pierced through the dark masses of the Russians. The shock was but for a moment. There was a clash of steel, and a light play of sword blades in the air, and then the Greys and the Red Coats disappeared in the midst of the shaken and quivering columns. In another moment we saw them marching in diminished numbers, and charging against the second line…. The first line of Russians, which had been utterly smashed by our charge, were coming back to swallow up our handful of men. By sheer steel and sheer courage, Inniskilliner and Scot were winning their desperate way right through the enemies' squadrons."

When we read to-day that the 5th British Cavalry Brigade, under General Chetwode, fought a brilliant action with German cavalry, in the course of which the 12th Lancers and Royal Scots Greys routed the enemy, spearing large numbers in flight, our thoughts fly back to the old days, when the 12th Lancers and the "Second to Nones" anticipated these feats of valour.

It was at Ramillies that the Scots Greys galloped straight through a difficult morass, with an infantry battle raging round them. On they went, till they gained the approach to the heights beyond. Then they dashed up the steep acclivity to the heights, and down the other side, where they thundered like an avalanche on the enemy's Household Brigade. The impact of that sudden crash seemed to shake the battlefield. Says one who was there: "The crash of our meeting rose above the noise of battle; it was like sudden thunder." The French fought with the utmost desperation, but they were matched this time, not with nondescript and poorly trained Continental troops, but with picked British, and were literally swept away before the Scots Greys. Many battalions of infantry under their protection were cut to pieces by the Scots Greys and the Royal Irish Dragoons, the predecessors of the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers. Still the Greys pursued their devastating career through Autreglise, and, at a point beyond, overtook the French Régiment du Roi, and secured its surrender. All that night, like flying demons, they pursued the retreating enemy, and what they did is traditionally summed up in the fact that they returned with no less than sixteen standards—truly a noble achievement!

Again, at Malplaquet, the Scots Greys and the Royal Irish Dragoons came up against their old enemies the French Household Brigade. In three victorious charges they sustained the honour of their old victories over them, routing them utterly. Fate seems specially to have designed the Scots Greys and the Royal Irish to combat the French Household Brigade in days gone by, for, on many occasions when they have met, the pride of the latter has fallen before the valour of the former. Not only at Malplaquet, but also at Dettingen, the Greys, having cut their way through the French Cuirassiers, launched themselves irresistibly upon the French Household Cavalry. On this occasion, they swept them from the banks of the river, and wrested from them their crowning glory—their white standard of damask, embroidered with gold and silver, bearing in its centre a thunderbolt above their motto "Sensere Gigantes." So to-day it may be said that the giants who fell three times before the Scots Greys are now in the company of the Brobdignags.

Some other battles in which the Greys multiplied their glories are as follow:—Drouet, Oudenarde, Bethune, St. Venant, Aire, Bouchain, Sheriffmuir, and Fontenoy.

Apart, and not yet apart, from their glorious traditions of battle, the Greys have a peculiar romance centring round one of their number, who fought for long years in their midst before it was ultimately discovered that their comrade of many fights was a woman. How, why, and where Christian Davies (née Cavanagh) first entered the army is a matter of some doubt, but we first hear of her in the Netherlands as a private soldier, whither, as the story goes, she had gone to find her husband. Here she lived the life of the ordinary soldier, and maintained her disguise through everything, even flirting with the Dutch girls to such an extent that she was forced to fight a duel with a jealous sergeant, whom she wounded severely. On account of this she was obliged to leave the regiment, but immediately joined the Scots Greys. While living and fighting with these, she discovered her husband, but, being enamoured of the free soldier's life more than of him, she bade him wait till the conclusion of the war. Mean while, at her desire, he and she passed as brothers.

It was during the charge of the Scots Greys at Ramillies that Christian Davies met with a serious wound at the hands of a French dragoon, and, being brought to hospital, she confessed, to the surprise and admiration of all, that she was a woman. On her recovery, she still accompanied the army, as a vivandière, in which capacity she was extremely popular. Ultimately, when the terrors of war had made her twice a widow, she returned to England, where Queen Anne graciously received her in audience, and presented her with a bounty of £50, together with a pension of 1s. a day. At her funeral in Chelsea, in 1739, she was accorded full military honours, and all the Scots Greys, at least, know well that three full volleys were fired above her grave.

It is worth noting that the Royal Scots Greys, who, in the past, have fought fiercely against the Russians, have now as their Colonel-in-Chief H.I.M. Nicolas II., Emperor of Russia, K.G.—no longer an enemy, but a friend and an ally.

THEIR BADGES AND BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Badges.—The Thistle within the Circle and Motto of the Order of the Thistle. An Eagle.

Motto.—"1546."

Battle Honours.—Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Dettingen, Waterloo, Balaclava, Sevastopol, S. Africa 1899-1902, Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg.

Uniform.—Scarlet, blue facings, white plume.

"Merebimur."—Their Motto.

One of the most thrilling and romantic episodes in cavalry fighting is the historic achievement of the 15th Hussars at Emsdorf. It was in July, 1760, that Major Erskine halted his troopers near the German village of Emsdorf, and bade them pluck the fresh twigs from the overhanging oaks, with a word of exhortation to the effect that they would acquit themselves with the firmness and stubbornness which have always been ascribed to that symbolic tree. Not long after this, the 15th formed part of the Prince of Brunswick's troops, which had surrounded six battalions of French infantry, together with some artillery, and a regiment of hussars. The enemy eventually broke through, and fled, pursued by the 15th, who were unassisted. So hot was the pursuit, and so terrible the punishment inflicted by our hussars, that the enemy was forced to surrender no less than 177 officers, 2,482 men, nine guns, six pairs of colours, and all the rams and baggage.

All England rang with this achievement of the 15th Light Dragoons, and never has a squadron received so whole-hearted a eulogy as that contained in the General Order issued by the Prince of Brunswick. For many a day "Elliott's Regiment" bore "Emsdorf" on its guidons and appointments, while upon their helmets was written, "Five battalions of French defeated and taken by this regiment, with their colours, and nine pieces of cannon. Emsdorf, 16th July, 1760." Now, as the regiment has become Hussars, the helmet has given place to the busby with no inscription; the guidons have disappeared, but the name "Emsdorf" may still be seen on the drum-cloth.

The 15th were prominent in all the achievements of our army during the next few years of that campaign. Many are the stories of dashing assault, grim fighting and heroic rescue, related of them during that time. When the Duke of Brunswick was surrounded by French Hussars at Friedburg, and it seemed impossible to prevent his capture, the 15th Hussars clapped spurs to their horses, and, with a terrific yell, swept down upon the French at full gallop. It was a body of determined men against overwhelming numbers; for, when they had driven back the hussars, they were still involved with the converging squadrons. But, with desperate valour they held their own until they had extricated their leader, and then they rode back, leaving double their number of the enemy dead on the field.

The 15th Hussars were in the thick of the fight at Waterloo, and they bravely upheld that honour. After suffering great loss in the enemy's fire they made a dashing charge through storms of lead from both flanks against a superior force of cuirassiers, whom they drove back with heavy losses. The Official Record states: "From this period the regiment made furious charges … at one moment it was cutting down the musketeers, at the next it was engaged with lancers, and, when these were driven back, it encountered cuirassiers." For this glorious exploit they paid honourably with three officers, two sergeants, and twenty-three privates killed; seven officers, three sergeants and forty privates wounded.

The 15th Hussars rendered heroic service in the Afghan War of 1878-80, when the treacherous Shere Ali was discovered favouring Russian intrigue. Many were the brilliant achievements of the 15th during this war, from Ali Musjid up to the investment of the Sherpur Cantonments, the final relief by Gough's Brigade, and the complete victory at Kandahar.

THEIR BADGE AND BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Badge.—The Crest of England within the Garter.

Motto.—"Merebimur."

Battle Honours.—Emsdorf, Villers-en-Couché, Egmont-op-Zee, Sahagun, Vittoria, Peninsula, Waterloo, Afghanistan 1878-80.

Uniform.—Blue, scarlet busby-bag and plume.

The generic name of the 18th Hussars (Drogheda Light Horse) was bestowed specifically upon the corps raised in Ireland in 1759 by the Marquis of Drogheda, and numbered as the 19th Light Dragoons. It was renumbered as the 18th Light Dragoons in 1763, became a Hussar corps in 1807, and was disbanded as the 18th Light Dragoons in 1821.

The present 18th Hussars were raised at Leeds in 1858, and inherited the honours of the Drogheda Light Horse proper. The silver trumpets used by the Drogheda Light Horse, and now in the possession of the 18th Hussars, were provided out of the proceeds of the sale of the captured horses at the Battle of Waterloo. The motto of the 18th Hussars is "Pro Rege, pro Lege, pro Patria Conamur" (We fight for King, Law, and Country).

There is a traditional romance in the annals of the 18th Hussars which has its confirmation in modern history. A beautiful Spanish lady, finding herself a refugee with Wellington's forces in the Peninsula, fell in love with a young English officer named Harry Smith, and married him. By statesmanship and prowess in war he rose to be Sir Harry Smith, who commanded the forces that defeated the Boers at Boomplatz. Subsequently, the town of Ladysmith was so named after his wife. In this way the Peninsula is linked with South Africa in the annals of the 18th Hussars, not only by equal deeds in each campaign, but by a never-to-be-forgotten romance of real life.

THEIR BATTLE HONOURS. ETC.

Motto.—"Pro Rege, pro Lege, pro Patria conamur."

Battle Honours.—Peninsula, Waterloo, S. Africa 1899-1902, Defence of Ladysmith.

Uniform.—Blue, blue bushy-bag, scarlet and white plume.

High in the estimation of every son and daughter of Britain stands that heroic band, the British Grenadiers. Their deeds have brought a fine thrill to every heart, and a stirring song to every voice; and, though there have been times when a pall of necessary silence, covering a "certain liveliness," has been imposed by the fog of a world-war, we have felt calmly assured that behind that fog our British Grenadiers were doing, or dying, in a way that must awaken the old thrill, and inspire a new song.

It has always been one of the greatest aids to success in battle to sum up the daring deeds of the past; the successes against fearful odds; the forlorn hopes bravely led; the breaches filled with our British dead; the stubborn resistance, and sometimes complete annihilation of one part for the success of the whole; the lofty sacrifice of the foremost, so that the hindmost may turn the tide of battle; and the heroic dash to certain death, which has always given birth to victory. And this aid of tradition has been accorded by their own deeds, and by the nation's appreciation, to none more strongly than to the British Grenadiers.

Yet it must be remembered that the Grenadier Guards, though they share the honour and glory of all Grenadiers, were never really Grenadiers proper. They won the name at Waterloo, where they vanquished the French Grenadiers. Sharing the name, they share and perpetuate the memory of the song, which in the first place referred to the Grenadiers who threw the grenades "from the glacis." But, as a good old British song may gain in volume as it rolls down the years, there is no reason why the well-known air in question should not attach to the Grenadier Guards.

Well does the historian say that "their annals indeed may almost be said to be identical with those of the British Army, as in every campaign of importance—every campaign which has had a material bearing on the fortunes of the Commonwealth—their services have been called into requisition. They have shared in our greatest battles. Their serried ranks stood firm at Fontenoy; turned the tide of battle at Quatre Bras; withstood unshaken the assaults of Napoleon's brilliant chivalry at Waterloo, and ascended with stately movement the bristling heights of the Alma."

Mr. J. J. Hart, who was with the Grenadiers in the Boer War, gives a graphic description of the battle near Senekal:

"With the advent of quick-firing guns," says he, "the ancient magnificence of armies in battle array has disappeared for ever…. There is no shining armour; there are no waving plumes; and the blare of the trumpet is unheard. Watch those grey-clad figures as they silently scatter over the plain. They are the colour of the withered grass of the veldt. No two will walk together lest they should be a more conspicuous mark for those deadly guns. See them as they walk with bent heads. You might compare them to poachers or partridge-shooters travelling over a moor, only their advance is more cautious….

"It was noon, and my battalion had halted on the plain. Far away for miles on our right the battle was raging, and, we with our grand fighting history, were left to act the inglorious part of lying on the grass waiting to cut off a possible retreat of the enemy. (Col.) Bunker stamped and swore and chewed his moustache…. Confusion to the General who crushed the flower of the British infantry so; but it was orders, and soldiers must obey. The Boers, however, were more generous to us than the General, and, in the working out of a little plan of their own, they were destined to cover us with wounds if not with glory. While we were lying musing on our fate, and thinking if the news of our being left out of the action should ever reach London, what we might expect at the hands of our enemies the cabdrivers, a force of Boers, of whose presence on a hill about half a mile in front we were blissfully ignorant, were preparing to open fire on us. They began proceedings by killing Bunker's horse with a percussion shell, which dropped right under him, and blew the animal to bits. Our artillery soon limbered up and replied to the shot, keeping up a continuous fire for about an hour, when, as they were unable to silence the gun, we advanced to take it by assault. We moved towards the hill in short rushes, lying down every fifty yards to fire a volley. The Boer shells which exploded between our extended line did little damage, and it looked as if we were going to make an easy capture of the gun. If there were any rifles on the hill they were certainly very careful about reserving their fire. We had got within 500 yards of the base of the hill, and had risen to make another rush when the rattling noise of a thousand rifle bolts together came to our ears. The whole of the front rank went down at the first volley; evidently the marksmen on the hill had taken very careful aim; then there followed a veritable hailstorm of lead, in the face of which no man could advance and live. We remained lying down and firing in the same position for about five hours.

"The shadows of night were falling, and still the firing was kept up without intermission; when a new danger was observed to threaten us. A shell had ignited the long grass in our rear and a light breeze which was blowing soon turned the spark into a conflagration. The Boers, observing this, extended their flanks on our right and left, thus completely cutting off our retreat. Then followed a scene of tumult which is hard to describe. Wounded men who were unable to move … gazed with wild staring eyes at the flames, which, slowly but surely, crept towards them. Our left wing made one desperate rush to charge the Boers, but had to fall before the leaden hail. When the flames drew near many of our men made heroic efforts to remove our wounded through the blinding smoke and flame…. Others pulled their helmets over their faces and rushed through the fire. In all this confusion I noticed one man who showed rare presence of mind. He was badly wounded, and, being unable to get out of reach of the flames, he took some matches from his pocket and burnt the grass near him. He then crawled on to the black ground, and thus secured for himself a comparatively safe position when the fire approached him. The flames were now upon us, and fighting had ceased. Two men picked me up where I lay wounded, and, rushing with me through the flames, threw me down on the other side, and ran…. The fire burned itself out at the foot of the hill, and then all was darkness till the moon, shining out, showed us the blackened bodies of the dead, and men writhing in pain on the burned earth.

"Now the Boers came amongst us, and, passing from one wounded man to another, gave us water from their bottles. Then we heard a crackling of whips and a rumbling of wheels. The Boers left us, and we knew the ambulance wagons were coming."

THEIR COLOURS, BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

The King's Colours.—1st Battn., Gules (crimson): in the centre the Imperial Crown; in base a grenade fired proper. 2nd Battn., Gules (crimson): in the centre the Royal Cypher reversed and interlaced or, ensigned with the Imperial Crown; in base a grenade fired proper, in the dexter canton the Union. 3rd Battn.: as for 2nd Battn., and for distinction, issuing from the Union in bend dexter, a pile wavy or.

Regimental Colours.—The Union: in the centre a company badge ensigned with the Imperial Crown; in base a grenade fired proper. The thirty company badges are borne in rotation, three at a time, one on the regimental colour of each of the Battns.

Battle Honours.—Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Dettingen, Lincelles, Corunna, Barrosa, Peninsula, Waterloo, Alma, Inkerman, Sevastopol, Egypt 1882, Tel-el-Kebir, Suakin 1885, Khartoum, S. Africa 1899-1902, Modder River.

Uniform.—Scarlet, blue facings.

"Sire! this regiment refuses to be known as second to any in the British Army."—Monk (to Charles II.)

History tells again how, in 1661, Charles, distrusting the soldiers in his service, called the 1st Foot Guards back to England. Following upon this, he speedily dismissed his Commonwealth soldiers, and, of all the Puritan regiments, he retained but one—the Coldstream Guards. This was the regiment which Monk had marched from Coldstream to the King's aid; hence their retention. An interesting story is related about them. It is said that when they were ordered to lay down their arms in repudiation of the Commonwealth, and commanded to resume them again, as the 2nd Foot Guards, they stood obstinately defiant, on the verge of mutiny. King Charles was dumbfounded, but Monk was equal to the situation. "Sire," he said, "this regiment refuses to be known as second to any in the British Army." On this, Charles, who was quick to the occasion with unworded gratitude for their timely help in a critical situation, cried: "Coldstream Guards, take up your arms!" and from that time forward they have been the Coldstream Guards.

Who can ever forget the glorious achievement of the Coldstream Guards at St. Amand in 1793? As soon as the Brigade of Guards gained contact with our then Allies-the Prussians and the Austrians—General Knobelsdorf, of the Prussian Army, welcomed them with, "I have reserved for the Coldstream Guards the honour, the especial glory, of dislodging the French from their entrenchments. As British troops you have only to show yourselves, and the enemy will retire."

The Coldstreamers rather wondered at his flowery flattery. They did not know, and he omitted to tell them, that the honour he had reserved for them was one which had been offered three times to 5,000 Austrians and three times missed by them, with a loss of 1,700 men. The Coldstreamers, therefore, prepared for the battle in complete ignorance of the fact that they were expected to do, with 600 rank and file, what 5,000 Austrians had failed to accomplish in three attempts. Not that it would have made much difference, for the British soldier can always count on doing the impossible about fifty times in a century.

The Coldstreamers, ready and eager, moved to the attack, and the Prussian General moved with them as far as safety would permit; then, desirous apparently that they should achieve this "especial glory" without any interference from him, he waved them on with his sword and magnanimously galloped away.

Hell opened then on the Coldstream Guards. The wood before them spurted flame. Batteries from right and left lumbered up, and, under cover of the undergrowth, tore lanes through them at close range. Never, up to that time, in the history of battles, had there been such quick and fearful slaughter of our troops. In a few minutes two of the companies were reduced by one-half. Ensign Howard went down with the colours, and on every hand rank and file were blown to pieces. Sergeant-Major Darling, one of the many heroes of that awful fight, had one arm shattered by a cannon ball, but he fought on with the other with such tenacity that his deeds were afterwards described as "prodigies of valour." A French officer, seeing so many men go down before him, pressed forward and engaged him in a fierce combat. But Darling laid him low and continued his terrible work until another ball carried away one of his legs. Thus, bereft of a leg and an arm, he was taken prisoner. General Knobelsdorf, the Prussian, lived through that day, but many, too many, of the Coldstreamers went to their last account, fighting gloriously. You may, under some conditions, beat a Coldstreamer, but you will never, never convince him that you have done so.

At Inkerman the Coldstream Guards, a few hundred strong, actually stood up to 4,000 Russians for a time, during which there was the bloodiest struggle ever witnessed. The fight was round the Sandbag Battery, where 700 British had held their own until reinforced by the Guards, and it was of such a nature that each guard must needs be a small battalion on his own account to do any good at all. Back to back the Coldstreamers fought till their ammunition was exhausted. Then they took their muskets and clubbed the pressing hosts in such fashion that they made space enough to form into line. Thus, with levelled steel, they charged. The enemy was thrown into utter confusion by their terrific onslaught, and, taking advantage of this, the Coldstreamers regained their own lines, having inflicted tremendous loss.

And the Russian in Germany to-day knows all about it. He has not forgotten the Coldstreamer of former days, any more than the Coldstreamer has forgotten the glorious deeds of the Russian; and, no doubt, if they could sit by the same camp-fire, many such a battle story would be told, through the interpreter, of those good old days "when we flew at each other's throats."

THEIR COLOURS.

The King's Colours.—1st Battn., Gules (crimson): in the centre the Star of the Order of the Garter proper, ensigned with the Imperial Crown; in base the Sphinx superscribed Egypt. 2nd Battn., Gules (crimson): in the centre a star of eight points argent within the garter, ensigned with the Imperial Crown; in base the Sphinx superscribed Egypt, in the "dexter" canton the Union. 3rd Battn., as for the 1st Battn., and for difference in the dexter canton, the Union and issuing therefrom in bend dexter a pile wavy or.

"A volley, my lads, and then the steel!"—Their Captain at Wepener.

The Royal Scots (1st Foot, or Lothian Regiment) are old in story. Several hundreds of years before the battle of Blenheim, which is among the first of their honours, the Royal Scots had traced their earlier glories on the roll of fame. Few European battlefields could disclaim acquaintance with them, and there are few on which they have not been responsible for terrific slaughter, and a large share in the crux of victory. Their ancestors far back fought under Gustavus Adolphus: their lineal descendents fight now under King George; and the bridge between that time and this has been held by them heroically.

It is interesting to trace their battles from the first. Long, long ago, fighting for Sweden, they captured and defended Rugenwald in Pomerania. Being wrecked on a hostile coast, with Adolphus eighty miles away, these Scots were led by Munro, with what might seem to us an absurd hope of victory. All day they waited in the caves by the sea shore, starving, wet, and cold—waited for the night, so that, under the cover of darkness, they might bring their desperate plan to fruition. Darkness fell; the moon rose, and these hungry Scots went forth to the attack. In one stroke they captured Rugenwald, and held it against repeated attempts on the part of the enemy to retake it. For nine weeks they gripped this place, and held on tooth and nail till Hepburn's men, fighting mile after mile to their relief, came up.

Hepburn's men! They were Scots, every one of them. Men who, led by Hepburn himself, captured Frankfort on the Oder. He took them to the attack waist deep through the mud and water of the moat. At the great battle of Leipzig, "the battle of the Nations," Gustavus held these men in reserve. Then, when the issue was in danger, he flung them forward. The musketry fire galled them severely, but through it all the pikemen went cheering on, and put the enemy to an inglorious rout.

Later, in 1632, Hepburn, who was somewhat a soldier of fortune, found himself on his way to aid the King of France. In 1634 he led his regiments against the Austrians and Spaniards. Here he was joined by Scots from France, and Scots from Sweden. Other Scots came up from the four quarters of the compass, as if by a gathering of the clans, and three years later there were 8,000 of them serving under the King of France. Those 8,000 are the martial sires of the present Royal Scots.

As to the heroic achievements of the Royal Scots, we may instance the battle of Wynendale. General Webb (Thackeray's favourite General of "Colonel Esmond") won that battle with an army of 8,000 men against 22,000 Frenchmen. It was his work to take supplies from Ostend to Marlborough's army in the field. Near the wood of Wynendale he detected the preponderating force of the enemy intent on intercepting his mission, but, in order to do this, they must traverse the wood. The odds were nearly three to one against Webb, but, relying on his men as much as on his own generalship, he decided to put up a fight of fights. The way of the enemy's approach was a great glade through the wood, and to right and left of this he placed detachments of his troops while he stationed the main body of his army at the point where they must debouch. Then he waited. That long wait for the oncoming host has been much described: how for a time they gazed up the long avenue through which the foe must come; how every man felt that tense expectancy, which lends to the simple sounds of nature a meaning of their own, and how 8,000 staunch hearts went back to the old folks at home with tenderness, and possible regret, before the descent of an avalanche which threatened to bereave their hearths.

But at length the enemy teemed in at the further end of the glade. On they came, warily scanning the wood, but it was not till the Royal Scots poured a volley into them that the enemy actually realized what was happening. When the smoke cleared away, confusion reigned in their ranks; they rallied, and came on with greater determination, but again they were hurled into disorder and death by the British fire. Yet a third time they attempted it, and with all the bravery of the French, but a third time they met with that penetrating fire that none but the British, with their ugly bulldog pertinacity, can stand. They failed to forge their way through the storm of lead, and at last retired in confusion, leaving one third their number of British as victors of the field.

The Royal Scots have more than once been helped out of a difficulty by other regiments. For instance, at Schellenberg in 1714, the ultimate victory, after three daring attempts on the part of the Royal Scots, who fought their way up against a heavy fire from the heights above, was made sure by the Scots Greys, who dismounted and rushed to their assistance. This engagement cost the French a valuable position, and 16 guns.

This help in the time of extreme peril was balanced by the Royal Scots at the battle of Lundy's Lane, where they arrived in the nick of time to make up 2,800 British against 5,000 Americans. After a hard fight the enemy was driven back, but they opened again with a devastating fire of musketry and artillery, following it up with a most determined charge. So desperate was their onslaught that the British guns were captured, and immediately following on this, the Royal Scots performed a deed which is underlined in history. They recaptured those guns, and left the enemy bewildered. This was the closest fight imaginable. In the thick of it, the opposing cannon almost spoke into each others' mouths. So close they were, that neither side could say, "This is my gun." In point of fact, in the heat of the moment a British limber carried off an American gun, and an American a British gun. On that field the contact between British and American was extremely close. In these days it is just as close, but not exactly in the same fierce spirit.

One of the foremost of the exploits of the Royal Scots was the defence of Tangier against the Moors in 1678. In Port Henrietta some 160 of the Royal Scots had been isolated. In order to facilitate their escape their comrades in the town created a diversion by leading a general attack. In the midst of this the Scots got as far as the first trench surrounding the fort, but, at the outer one, which was 12 feet deep, they came into close grips with the enemy. There it was sheer knife-fighting, and many Royal Scots went to the bottom of the pit. One hundred and twenty of them filled it full, and over that bridge of silence forty survivors hewed their way through.

The last charge at Wepener is described in the History of the Boer War as follows "The Royal Scots saw the Boers rushing and their warrior hearts beat quick with joy. Shortly, like a man in a dream, their Captain gave the word, 'Fix bayonets!' It was done in a trice. 'Ready!' The men loaded their rifles. 'A volley, my lads, and then the steel! Altogether—' The whistle blows, the flame flies along the parapet. Then, over the stone wall, sprang the Royal Scots. Once they shouted, once only. Then the slaying began…. Fifty thousand savage throats swelled the battle chorus. Ever since the siege began the black warriors had been gathered in their thousands on the heights, watching with fascinated interest the struggle of the white men. Like the spectators of a medieval tournament they had applauded the gallant deeds of the combatants, and, as they saw the British soldiers holding out day after day, night after night, against the assault of numerous odds, they came to have a profound trust and confidence in the 'big heart' of the Queen's soldiers. When, therefore, they saw the Royal Scots launch themselves like a living bolt at five times their number, they held their breath for a time, wondering what the end might be. But when they saw the bloody bayonets of the 1st Foot scatter and utterly destroy the hated Dutchman they opened their throats and yelled their applause across the river."

THEIR BADGES, BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Badges.—The Royal Cypher within the Collar of the Order of the Thistle with the Badge appendant. In each of the four corners the Thistle within the Circle and motto of the Order, ensigned with the Imperial Crown.

Battle Honours.—The Sphinx, superscribed Egypt. Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Louisburg, St. Lucia, Egmont-op-Zee, Corunna, Busaco, Salamanca, Vittoria, St. Sebastian, Nive, Peninsula, Niagara, Waterloo, Nagpore, Maheidpore, Ava, Alma, Inkerman, Sevastopol, Taku Forts, Pekin, S. Africa 1889-1902.

Uniform.—Regular and Reserve Battns., scarlet with blue facings.

[This distinguished corps is the oldest regiment in the Army, hence its nickname of Pontius Pilate's Body Guard. There is a tradition that it represents the body of Scottish Archers who for centuries formed the guard of the French kings. It fought under Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, in the Seven Years' War, and was incorporated in the British Army in 1633. Since that date it has seen service in every part of the globe.]

The "Fighting Fifth" (Northumberland Fusiliers) have a peculiar paradox in their history. They were first raised in 1674 by Prince William of Orange, the Dutchman, and, in the last Boer War, they were fighting against the Dutch themselves. But even stranger things than that have come to pass in these later days when we have good cause to call our old allies our enemies, and our old enemies our allies.

The "Fighting Fifth" derived their regimental name, the Northumberland Fusiliers, from Hugh, Earl Percy, afterwards Duke of Northumberland, who commanded the regiment during the American War of Independence. For their fighting in the seventeenth century Prince William assembled them before the whole army, and publicly rewarded them for their services. It must be remembered that there were still services to come, for, when the Prince returned to England, fourteen years later, to deprive his father-in-law of his throne, the "Fighting Fifth" had not forgotten his kind offices. On this occasion they were regarded by the English with pride and admiration. "Even the peasants," says Macaulay, "whispered to one another as they marched by: 'There be our own lads; there be the brave fellows who hurled back the French on the field of Seneffe!'"

The "Fighting Fifth" gained many laurels in Portugal and Spain, where, on more than one occasion, they drove the enemy before them in utter confusion. It is in this war that their fighting traditions are chiefly founded.

At Ciudad Rodrigo it was the "Fighting Fifth" who stormed the approach. Afterwards they fought their way with fusil and steel through Salamanca, Nivelle, Vittoria, Orthes, and Toulouse, right up to Paris.

One of their greatest achievements was the successful defence of Gibraltar, when the Spaniards made their first attempt to recover it. Since that time there is scarce a page of fighting history up to the time of the Napoleonic Wars that contains no deed of this bull-dog regiment.

Their nickname is almost as old as their regiment. It was at the siege of Maestricht in 1676, when the regiment was only two years old, that a section of these men, only 200 strong, assaulted the Dauphin bastion—an affair out of which, after the most sanguinary combat, no more than fifty emerged. Yet maddened, rather than daunted, these fifty, with some few reinforcements, made a further attack on the bastion; and this time they took it, but only to meet with disaster. The place was mined, and a terrible explosion killed a large number, and covered others in wreckage. Many, however, emerged, and these proceeded to hold the position.

The tale of how they entered Badajoz stirs the blood. The 2nd Battalion led the storming party. Their way led over a narrow bridge. Here, under a terrible fire, the foremost fell in heaps; but their comrades pressed forward over their prostrate bodies, and planted ladders against the beetling walls of the castle. For a time the "Fighting Fifth" suffered heavily. Again and again the desperate attackers reached the summit of the walls, only to be hurled back by the enemy. Here they swarmed up like bees, to be swept down again by a raking fire; there, another ladder broken, another overturned, with men everywhere falling and climbing, climbing and falling. The chance of scaling those walls seemed hopeless, and at length the Fifth paused, and looked at one another. Then, at that psychological moment, the cheering of the enemy above broke the spell. Their cheers were answered by a fierce shout from our men, who rushed to the attack with a never-give-in determination that finally gained the ramparts, and drove the garrison out of the castle, out of the town, and into the distance, not without great slaughter. It was at Badajoz that the Fifth lost their brave colonel, who struck in at that psychological moment, and led the final victorious onslaught. He fell, shot through the heart, at the very moment that victory was assured. "None that night," says Napier, "died with more glory; yet many died, and there was much glory." The taking of Badajoz was indeed a piece of work which required all the dogged tenacity of purpose to be found in such fearless heroes as the "Fighting Fifth."

THEIR BADGES AND BATTLE HONOURS, ETC.

Badges.—St. George and the Dragon. In each of the four corners the united Red and White Rose slipped, ensigned with the Royal Crest.

Motto.—"Quo fata vocant."