Project Gutenberg's To and Through Nebraska, by Frances I. Sims Fulton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: To and Through Nebraska Author: Frances I. Sims Fulton Release Date: January 17, 2014 [EBook #44688] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TO AND THROUGH NEBRASKA *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

THIS LITTLE WORK, WHICH CLAIMS NO MERIT BUT TRUTH

IS HUMBLY DEDICATED TO THE MANY DEAR FRIENDS,

WHO BY THEIR KINDNESS MADE THE LONG

JOURNEY AND WORK PLEASANT TO

The Author,

FRANCES I. SIMS FULTON.

LINCOLN, NEB.

JOURNAL COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS,

1884.

If you wish to read of the going and settling of the Nebraska Mutual Aid Colony, of Bradford, Pa., in Northwestern Neb., their trials and triumphs, and of the Elkhorn, Niobrara, and Keya Paha rivers and valleys, read Chapter I.

Of the country of the winding Elkhorn, Chapter II.

Of the great Platte valley, Chapter III.

Of the beautiful Big Blue and Republican, Chapter IV.

Of Nebraska's history and resources in general, her climate, school and liquor laws, and Capital, Chapter V.

If you wish a car-window view of the Big Kinzua Bridge (highest in the world), and Niagara Falls and Canada, Chapter VI.

And now, a word of explanation, that you may clearly understand just why this little book—if such it may be called, came to be written. We do not want it to be thought an emigration scheme, but only what a Pennsylvania girl heard, saw, and thought of Nebraska. And to make it more interesting we will give our experience with all the fun thrown in, for we really thought we had quite an enjoyable time and learned lessons that may be useful for others to know. And simply give everything just as they were, and the true color to all that we touch upon, simply stating facts as we gathered them here and there during a stay of almost three months of going up and down, around and across the state from Dakota to Kansas—306 miles on the S.C. & P.R.R., 291 on the U.P.R.R., and 289 on the B. & M.R.R., the three roads that traverse the state from east to west. It is truly an unbiased work, so do not chip and shave at what may seem incredible, but, as you read, remember you read ONLY TRUTH.

My brother, C. T. Fulton, was the originator of the colony movement; and he with father, an elder brother, and myself were members. My parents, now past the hale vigor of life, consented to go, providing the location was not chosen too far north, and all the good plans and rules were fully carried out. Father made a tour of the state in 1882, and was much pleased with it, especially central Nebraska. I was anxious to "claim" with the rest that I might have a farm to give to my youngest brother, now too young to enter a claim for himself—claimants must be twenty-one years of age. When he was but twelve years old, I promised that for his abstaining from the use of tobacco and intoxicating drinks in every shape and form, until he was twenty-one years old, I would present him with a watch and chain. The time of the pledge had not yet expired, but he had faithfully kept his promise thus far, and I knew he would unto the end. He had said: "For a gold watch, sister, I will make it good for life;" but now insisted that he did not deserve anything for doing that which was only right he should do; yet I felt it would well repay me for a life pledge did I give him many times the price of a gold watch. What could be better than to put him in possession of 160 acres of rich farming land that, with industry, would yield him an independent living? With all this in view, I entered with a zeal into the spirit of the movement, and with my brothers was ready to go with the rest. As father had served in the late war, his was to be a soldier's claim, which brother Charles, invested with the power of attorney, could select and enter for him. But our well arranged plans were badly spoiled when the location was chosen so far north, and so far from railroads. My parents thought they could not go there, and we children felt we could not go without them, yet they wrote C. and I to go, see for ourselves, and if we thought best they would be with us. When the time of going came C. was unavoidably detained at home, but thought he would be able to join me in a couple of weeks, and as I had friends among the colonists on whom I could depend for care it was decided that I should go.

When a little girl of eleven summers I aspired to the writing of a "yellow backed novel," after the pattern of Beadle's dime books, and as a matter of course planned my book from what I had read in other like fiction of the same color. But already tired of reading of perfection I never saw, or heard tell of except in story, my heroes and heroines were to be only common, every-day people, with common names and features. The plan, as near as I can remember, was as follows:

A squatter's cabin hid away in a lonely forest in the wild west. The squatter is a sort of out-law, with two daughters, Mary and Jane, good, sensible girls, and each has a lover; not handsome, but brave and true, who with the help of the good dog "Danger," often rescues them from death by preying wolves, bears, panthers, and prowling Indians.

The concluding chapter was to be, "The reclaiming of the father from his wicked ways. A double wedding, and together they all abandon the old home, and the old life, and float down a beautiful river to a better life in a new home."

Armed with slate and pencil, and hid away in the summer-house, or locked in the library, I would write away until I came to a crack mid-way down the slate, and there I would always pause to read what I had written, and think what to say next. But I would soon be called to my neglected school books, and then would hastily rub out what I had written, lest others would learn of my secret project; yet the story would be re-written as soon as I could again steal away. But the crack in my slate was a bridge I never crossed with my book.

Ah! what is the work that has not its bridges of difficulties to cross? and how often we stop there and turning back, rub out all we have done?

"Rome was not built in a day," yet I, a child, thought to write a book in a day, when no one was looking. I have since learned that it takes lesson and lessons, read and re-read, and many too that are not learned from books, and then the book will be—only a little pamphlet after all.

THROUGH NEBRASKA.

Going and Settling of the Nebraska Mutual Aid Colony of Bradford, Pa., in Northern Nebraska — A Description of the Country in which they located, which embraces the Elkhorn, Niobrara and Keya Paha Valleys — Their First Summer's Work and Harvest.

True loyalty, as well as true charity, begins at home. Then allow us to begin this with words of love of our own native land,—the state of all that proud Columbia holds within her fair arms the nearest and dearest to us; the land purchased from the dusky but rightful owners, then one vast forest, well filled with game, while the beautiful streams abounded with fish. But this rich hunting ground they gave up in a peaceful treaty with the noble Quaker, William Penn; in after years to become the "Keystone," and one of the richest states of all the Union.

Inexhaustible mineral wealth is stored away among her broad mountain ranges, while her valleys yield riches to the farmer in fields of golden grain. Indeed, the wealth in grain, lumber, coal, iron, and oil that are gathered from her bosom cannot be told—affording her children the best of living; but they have grown, multiplied, and gathered in until the old home can no longer hold them all; and some must needs go out from her sheltering arms of law, order, and love, and seek new homes in the "far west," to live much the same life our forefathers lived in the land where William Penn said: "I will found a free colony for all mankind."

Away in the northwestern part of the state, in McKean county, a pleasant country village was platted, a miniature Philadelphia, by Daniel Kingbury, in or about the year 1848. Lying between the east and west branches of the Tunagwant—or Big Cove—Creek, and hid away from the busy world by the rough, rugged hills that surround it, until in 1874, when oil was found in flowing wells among the hills, and in the valleys, and by 1878 the quiet little village of 500 inhabitants was transformed into a perfect beehive of 18,000 busy people, buying and selling oil and oil lands, drilling wells that flowed with wealth, until the owners scarce knew what to do with their money; and, forgetting it is a long lane that has no turning, and a deep sea that has no bottom, lived as though there was no bottom to their wells, in all the luxury the country could afford. And even to the laboring class money came so easily that drillers and pumpers could scarce be told from a member of the Standard Oil Company.

Bradford has been a home to many for only a few years. Yet years pass quickly by in that land of excitement: building snug, temporary homes, with every convenience crowded in, and enjoying the society of a free, social, intelligent people. Bradford is a place where all can be suited. The principal churches are well represented; the theaters and operas well sustained. The truly good go hand in hand; those who live for society and the world can find enough to engross their entire time and attention, while the wicked can find depth enough for the worst of living. We have often thought it no wonder that but few were allowed to carry away wealth from the oil country; for, to obtain the fortune sought, many live a life contrary to their hearts' teachings, and only for worldly gain and pleasure. Bradford is nicely situated in the valley "where the waters meet," and surrounded by a chain or net-work of hills, that are called spurs of the Alleghany mountains, which are yet well wooded by a variety of forest trees, that in autumn show innumerable shades and tinges. From among the trees many oil derricks rear their "crowned heads" seventy-five feet high, which, if not a feature of beauty, is quite an added interest and wealth to the rugged hills. From many of those oil wells a flow of gas is kept constantly burning, which livens the darkest night.

Thus Bradford has been the center of one of the richest oil fields, and like former oil metropolis has produced wealth almost beyond reckoning. Many have come poor, and gone rich. But the majority have lived and spent their money even more lavishingly than it came—so often counting on and spending money that never reached their grasp. But as the tubing and drills began to touch the bottom of this great hidden sea of oil, when flowing wells had to be pumped, and dry holes were reported from territory that had once shown the best production, did they begin to reckon their living, and wonder where all their money had gone. Then new fields were tested, some flashing up with a brilliancy that lured many away, only to soon go out, not leaving bright coals for the deluded ones to hover over; and they again were compelled to seek new fields of labor and living, until now Bradford boasts of but 12,000 inhabitants.

Thus people are gathered and scattered by life in the oil country. And to show how fortunes in oil are made and lost, we quote the great excitement of Nov., 1882, when oil went up, up, and oil exchanges, not only at Bradford, but from New York to Cincinnati, were crowded with the rich and poor, old and young, strong men and weak women, investing their every dollar in the rapidly advancing oil.

Many who had labored hard, and saved close, invested their all; dreaming with open eyes of a still advancing price, when they would sell and realize a fortune in a few hours.

Many rose the morning of the 9th, congratulating themselves upon the wealth the day would bring.

What a world of pleasure the anticipation brought. But as the day advanced, the "bears" began to bear down, and all the tossing of the "bulls of the ring" could not hoist the bears with the standard on top. So from $1.30 per barrel oil fell to $1.10. The bright pictures and happy dreams of the morning were all gone, and with them every penny, and often more than their own were swept.

Men accustomed to oil-exchange life, said it was the hardest day they had ever known there. One remarked, that there were not only pale faces there, but faces that were green with despair. This was only one day. Fortunes are made and lost daily, hourly. When the market is "dull," quietness reigns, and oil-men walk with a measured tread. But when it is "up" excitement is more than keeping pace with it.

Tired of this fluctuating life of ups and downs, many determined to at last take Horace Greeley's advice and "go west and grow up with the country," and banded themselves together under the title of "The Nebraska Mutual Aid Colony." First called together by C. T. Fulton, of Bradford Pa., in January, 1883, to which about ten men answered. A colony was talked over, and another meeting appointed, which received so much encouragement by way of interest shown and number in attendance, that Pompelion hall was secured for further meetings. Week after week they met, every day adding new names to the list, until they numbered about fifty. Then came the electing of the officers for the year, and the arranging and adopting of the constitution and by-laws. Allow me to give you a summary of the colony laws. Every name signed must be accompanied by the paying of two dollars as an initiation fee; but soon an assessment was laid of five dollars each, the paying of which entitled one to a charter membership. This money was to defray expenses, and purchase 640 acres of land to be platted into streets and lots, reserving necessary grounds for churches, schools, and public buildings. Each charter member was entitled to two lots—a business and residence lot, and a pro rata share of, and interest in the residue of remaining lots. Every member taking or buying lands was to do so within a radius of ten miles of the town site. "The manufacture and sale of spirituous or malt liquors shall forever be prohibited as a beverage. Also the keeping of gambling houses."

On the 13th of March, when the charter membership numbered seventy-three, a committee of three was sent to look up a location.

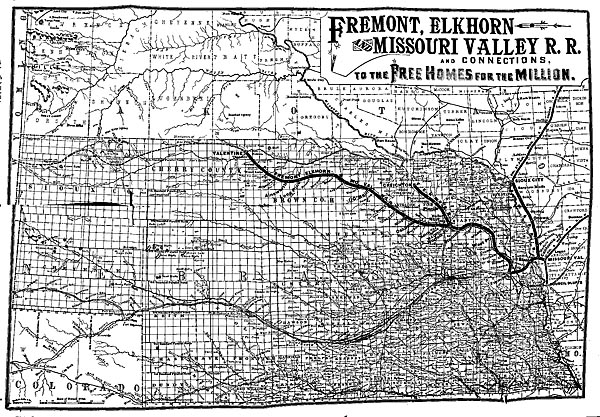

The committee returned April 10th; and 125 members gathered to hear their report, and where they had located. When it was known it was in northern Nebraska, instead of in the Platte valley, as was the general wish, and only six miles from the Dakota line, in the new county of Brown, an almost unheard of locality, many were greatly disappointed, and felt they could not go so far north, and so near the Sioux Indian reservation, which lay across the line in southern Dakota. Indeed, the choosing of the location in this unthought-of part of the state, where nothing but government land is to be had, was a general upsetting of many well laid plans of the majority of the people. But at last, after many meetings, much talking, planning, and voting, transportation was arranged for over the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern, Chicago and Northwestern, and Sioux City and Pacific R. Rs., and the 24th of April appointed for the starting of the first party of colonists.

We wonder, will those of the colony who are scattered over the plains of Nebraska, tell, in talking over the "meeting times" when anticipation showed them their homes in the west, and hopes ran high for a settlement and town all their own, tell how they felt like eager pilgrims getting ready to launch their "Mayflower" to be tossed and landed on a wild waste of prairie, they knew not where?

We need scarce attempt a description of the "getting ready," as only those who have left dear old homes, surrounded by every strong hold kindred, church, school, and our social nature can tie, can realize what it is to tear away from these endearments and follow stern duty, and live the life they knew the first years in their new home would bring them; and, too, people who had known the comforts and luxuries of the easy life, that only those who have lived in the oil country can know, living and enjoying the best their money could bring them, some of whom have followed the oil since its first advent in Venango county, chasing it in a sort of butterfly fashion, flitting from Venango to Crawford, Butler, Clarion, and McKean counties (all of Penna.); making and losing fortune after fortune, until, heart-sick and poorer than when they began, they resolve to spend their labor upon something more substantial, and where they will not be crowded out by Standard or monopoly.

The good-bye parties were given, presents exchanged, packing done, homes broken up, luncheon prepared for a three days' journey, and many sleepless heads were pillowed late Monday night to wake early Tuesday morning to "hurry and get ready." 'Twas a cold, cheerless morning; but it mattered not; no one stopped to remark the weather; it was only the going that was thought or talked of by the departing ones and those left behind.

And thus we gathered with many curious ones who came only to see the exodus, until the depot and all about was crowded. Some laughing and joking, trying to keep up brave hearts, while here and there were companies of dear friends almost lost in the sorrow of the "good-bye" hour. The departing ones, going perhaps to never more return, leaving those behind whom they could scarce hope to again see. The aged father and mother, sisters and brothers, while wives and children were left behind for a season. And oh! the multitude of dear friends formed by long and pleasant associations to say "good bye" to forever, and long letters to promise telling all about the new life in the new home.

One merry party of young folks were the center of attraction for the hilarity they displayed on this solemn occasion, many asking, "Are they as merry as they appear?" while they laughed and chattered away, saying all the funny things they could summon to their tongues' end, and all just to keep back the sobs and tears.

Again and again were the "good byes" said, the "God bless you" repeated many times, and, as the hour-hand pointed to ten, we knew we soon must go. True to time the train rolled up to the depot, to take on its load of human freight to be landed 1,300 miles from home. Another clasping of hands in the last hurried farewell, the good wishes repeated, and we were hustled into the train, that soon started with an ominous whistle westward; sending back a wave of tear-stained handkerchiefs, while we received the same, mingled with cheers from encouraging ones left behind. The very clouds seemed to weep a sad farewell in flakes of pure snow, emblematic of the pure love of true friends, which indeed is heaven-born. Then faster came the snow-flakes, as faster fell the tears until a perfect shower had fallen; beautifying the earth with purity, even as souls are purified by love. We were glad to see the snow as it seemed more befitting the departing hour than bright sunshine. Looking back we saw the leader of the merry party, and whose eyes then sparkled with assumed joyousness, now flooded with tears that coursed down the cheeks yet pale with pent up emotion. Ah! where is the reader of hearts, by the smiles we wear, and the songs we sing? Around and among the hills our train wound and Bradford was quickly lost sight of.

But, eager to make the best of the situation, we dried our tears and busied ourselves storing away luggage and lunch baskets, and arranging everything for comfort sake.

This accomplished, those of us who were strangers began making friends, which was an easy task, for were we not all bound together under one bond whose law was mutual aid? All going to perhaps share the same toil and disadvantages, as well as the same pleasures of the new home?

Then we settled down and had our dinners from our baskets. We heard a number complain of a lump in their throat that would scarcely allow them to swallow a bite, although the baskets were well filled with all the good things a lunch basket can be stored with.

When nearing Jamestown, N.Y., we had a good view of Lake Chautauqua, now placid and calm, but when summer comes will bear on her bosom people from almost everywhere; for it is fast becoming one of the most popular summer resorts. The lake is eighteen miles long and three miles wide. Then down into Pennsylvania, again. As we were nearing Meadville, we saw the best farming land of all seen during the day. No hills to speak of after leaving Jamestown; perhaps they were what some would call hills, but to us who are used to real up-and-down hills, they lose their significance. The snow-storm followed us to Meadville, where we rested twenty minutes, a number of us employing the time in the childish sport of snow-balling. We thought it rather novel to snow-ball so near the month of buds and blossoms, and supposed it would be the last "ball" of the season, unless one of Dakota's big snow-storms would slide over the line, just a little ways, and give us a taste of Dakota's clime. As we were now "all aboard" from the different points, we went calling among the colonists and found we numbered in all sixty-five men, women, and children, and Pearl Payne the only colony babe.

Each one did their part to wear away the day, and, despite the sad farewells of the morning, really seemed to enjoy the picnic. Smiles and jokes, oranges and bananas were in plenty, while cigars were passed to the gentlemen, oranges to the ladies, and chewing gum to the children. Even the canaries sang their songs from the cages hung to the racks. Thus our first day passed, and evening found us nearing Cleveland—leaving darkness to hide from our view the beautiful city and Lake Erie. We felt more than the usual solemnity of the twilight hour, when told we were going over the same road that was once strewn with flowers for him whom Columbia bowed her head in prayers and tears, such as she never but once uttered or shed before, and brought to mind lines I then had written:

Songs sang in the early even-tide were never a lullaby to me, but rather the midnight hoot of the owl, so, while others turn seats, take up cushions and place them crosswise from seat to seat, and cuddled down to wooing sleep, I will busy myself with my pen. And as this may be read by many who never climbed a mountain, as well as those who never trod prairie land, I will attempt a description of the land we leave behind us. But Mr. Clark disturbs me every now and then, getting hungry, and thinking "it's most time to eat," and goes to hush Mr. Fuller to sleep, and while doing so steals away his bright, new coffee pot, in which his wife has prepared a two days' drinking; but Mr. C's generosity is making way with it in treating all who will take a sup, until he is now rinsing the grounds.

Thus fun is kept going by a few, chasing sleep away from many who fain would dream of home. "Home!" the word we left behind us, and the word we go to seek; the word that charms the weary wandering ones more than all others, for there are found the sweetest if not the richest comforts of life. And of home I now would write; but my heart and hand almost fail me. I know I cannot do justice to the grand old mountains and hills, the beautiful valleys and streams that have known us since childhood's happy days, when we learned to love them with our first loving. Everyone goes, leaving some spot dearer than all others behind. 'Tis not that we do not love our homes in the East, but a hope for a better in a land we may learn to love, that takes us west, and also the same spirit of enterprise and adventure that has peopled all parts of the world.

When the sun rose Wednesday morning it found us in Indiana. We were surprised to see the low land, with here and there a hill of white sand, on which a few scrubby oaks grew. It almost gave me an ague chill to see so much ground covered with water that looked as though it meant to stay. Yet this land held its riches, for the farm houses were large and well built, and the fields were already quite green. But these were quickly lost sight of for a view of Lake Michigan, second in size of the five great lakes, and the only one lying wholly in the U.S. Area, 24,000 square miles; greatest length, 340 miles, and greatest width, 88 miles. The waters seemed to come to greet us, as wave after wave rolled in with foamy crest, only to die out on the sandy shore, along which we bounded. And, well, we could only look and look again, and speed on, with a sigh that we must pass the beautiful waters so quickly by, only to soon tread the busy, thronged streets of Chicago.

The height of the buildings of brick and stone gives the streets a decidedly narrow appearance. A party of sight-seers was piloted around by Mr. Gibson, who spared no pains nor lost an opportunity of showing his party every attention. But our time was so limited that it was but little of Chicago we saw. Can only speak of the great court house, which is built of stone, with granite pillars and trimmings. The Chicago river, of dirty water, crowded with fishing and towing boats, being dressed and rigged by busy sailors, was quite interesting. It made us heartsick to see the poor women and children, who were anxiously looking for coal and rags, themselves only a mere rag of humanity.

I shook my head and said, "wouldn't like to live here," and was not sorry when we were seated in a clean new coach of the S.C. & P.R.R., and rolled out on the C. & N.W. road. Over the switches, past the dirty flagmen, with their inseparable pipe (wonder if they are the husbands and fathers of the coal and rag pickers?) out on to the broad land of Illinois—rolling prairie, we would call it, with scarcely a slump or stone. Farmers turning up the dark soil, and herds of cattle grazing everywhere in the great fields that were fenced about with board, barb-wire, and neatly trimmed hedge fence, the hedge already showing green.

The farms are larger than our eastern farms, for the houses are so far apart; but here there are no hills to separate neighbors.

Crossed the Mississippi river about four P.M., and when mid-way over was told, "now, we are in Iowa." River rather clear, and about a mile in width. Iowa farmers, too, were busy: some burning off the old grass, which was a novel sight to us.

Daylight left us when near Cedar Rapids. How queer! it always gets dark just when we come to some interesting place we wanted so much to see.

Well, all were tired enough for a whole night's rest, and looking more like a delegation from "Blackville"—from the soot and cinder-dirt—than a "party from Bradford," and apparently as happy as darkies at a camp-meeting, we sought our rest early, that we might rise about three o'clock, to see the hills of the coal region of Boone county by moonlight. I pressed my face close to the window, and peered out into the night, so anxious to see a hill once more. Travelers from the East miss the rough, rugged hills of home!

The sun rose when near Denison, Iowa,—as one remarked, "not from behind a hill, but right out of the ground"—ushering in another beautiful day.

At Missouri Valley we were joined by Mr. J. R. Buchanan, who came to see us across the Missouri river, which was done in transfer boats—three coaches taken across at a time. As the first boat was leaving, we stood upon the shore, and looked with surprise at the dull lead-color of the water. We knew the word Missouri signified muddy, and have often read of the unchanging muddy color of the water, yet we never realize what we read as what we see. We searched the sandy shore in vain for a pebble to carry away as a memento of the "Big Muddy," but "nary a one" could we find, so had to be content with a little sand. Was told the water was healthy to drink, but as for looks, we would not use it for mopping our floors with. The river is about three-fourths of a mile in width here. A bridge will soon be completed at this point, the piers of which are now built, and then the boats will be abandoned. When it came our turn to cross, we were all taken on deck, where we had a grand view. Looking north and south on the broad, rolling river, east to the bluffy shores of Iowa we had just left, and west to the level lands of Nebraska, which were greeted with "three rousing huzzahs for the state that was to be the future home of so many of our party." Yet we knew the merry shouts were echoed with sighs from sad hearts within. Some, we knew, felt they entered the state never to return, and know no other home.

To those who had come with their every earthly possession, and who would be almost compelled to stay whether they were pleased or not, it certainly was a moment of much feeling. How different with those of us who carried our return tickets, and had a home to return to! It was not expected that all would be pleased; some would no doubt return more devoted to the old home than before.

We watched the leaden waves roll by, down, on down, just as though they had not helped to bear us on their bosom to—we did not know what. How little the waves knew or cared! and never a song they sang to us; no rocks or pebbles to play upon. Truly, "silently flow the deep waters." Only the plowing through the water of the boat, and the splash of the waves against its side as we floated down and across. How like the world are the waters! We cross over, and the ripple we cause dies out on the shore; the break of the wave is soon healed, and they flow on just as before. But, reader, do we not leave footprints upon the shores that show whence we came, and whither we have gone? And where is the voyager upon life's sea that does not cast wheat and chaff, roses and thorns upon the waves as they cross over? Grant, Father, that it may be more of the wheat than chaff, more of the roses than thorns we cast adrift upon the sea of our life; and though they may be tempest tossed, yet in Thy hands they will be gathered, not lost.

When we reached the shore, we were again seated in our coach, and switched on to Nebraska's terra firma.

Mr. J. R. Buchanan refers to Beaver county, Pa., as his birth-place, but had left his native state when yet a boy, and had wandered westward, and now resides in Missouri Valley, the general passenger agent of the S.C. & P.R.R. Co., which office we afterward learned he fills with true dignity and a generosity becoming the company he represents. He spoke with tenderness of the good old land of Pennsylvania, and displayed a hearty interest in the people who had just come from there. Indeed, there was much kindness expressed for "the colony going to the Niobrara country" all the way along, and many were the compliments paid. Do not blame us for self praise; we flattered ourselves that we did well sustain the old family honors of "The Keystone." While nearing Blair, the singers serenaded Mr. B. with "Ten thousand miles away" and other appropriate songs in which he joined, and then with an earnest "God bless you," left us. Reader, I will have to travel this road again, and then I will tell you all about it. I have no time or chance to write now. The day is calm and bright, and more like a real picnic or pleasure excursion than a day of travel to a land of "doubt." When the train stopped any time at a station, a number of us would get off, walk about, and gather half-unfolded cottonwood and box elder leaves until "all aboard" was sung out, and we were on with the rest—to go calling and visit with our neighbors until the next station was reached. This relieved the monotony of the constant going, and rested us from the jog and jolt of the cars.

One of the doings of the day was the gathering of a button string; mementos from the colony folks, that I might remember each one. I felt I was going only to soon leave them—they to scatter over the plains, and I to return perhaps never to again see Nebraska, and 'twas with a mingling of sadness with all the fun of the gathering, that I received a button from this one, a key or coin from that one, and scribbled down the name in my memorandum. I knew they would speak to me long after we had separated, and tell how the givers looked, or what they said as they gave them to me, thinking, no doubt, it was only child's play.

Mr. Gibson continued with the party, just as obliging as ever, until we reached Fremont, where he turned back to look after more travelers from the East, as he is eastern passenger agent of the S.C. & P.R.R. He received the thanks of all for the kindness and patience he displayed in piloting a party of impatient emigrants through a three days' journey.

Mr. Familton, who joined us at Denison, Iowa, and was going to help the claim hunters, took pity on our empty looking lunch baskets, and kindly had a number to take dinner at West Point and supper at Neligh with him. It was a real treat to eat a meal from a well spread table again.

I must say I was disappointed; I had fancied the prairies would already be in waving grass; instead, they were yet brown and sere with the dead grass of last year excepting where they had been run over with fire, and that I could scarcely tell from plowed ground—it has the same rough appearance, and the soil is so very dark. Yet, the farther west we went, the better all seemed to be pleased. Thus, with song and sight-seeing, the day passed. "Old Sol" hid his smiling face from us when near Clearwater, and what a grand "good night" he bade us! and what beauty he spread out before us, going down like a great ball of fire, setting ablaze every little sheet of water, and windows in houses far away! Indeed, the windows were all we could see of the houses.

We were all wide awake to the lovely scene so new to us. Lizzie saw this, Laura that, and Al, if told to look at the lovely sunset (but who had a better taste for wild game) would invariably exclaim: Oh! the prairie chickens! the ducks! the ducks! and wish for his gun to try his luck. Thus nothing was lost, but everything enjoyed, until we stopped at a small town where a couple of intoxicated men, claiming to be cow-boys, came swaggering through our car to see the party of "tenderfeet," as new arrivals from the East are termed by some, but were soon shown that their company was not congenial and led out of the car. My only defense is in flight and in getting out of the way; so I hid between the seats and held my ears. Oh! dear! why did I come west? I thought; but the train whistle blew and away we flew leaving our tormenters behind, and no one hurt. Thus ended our first battle with the much dreaded cow-boys; yet we were assured by others that they were not cow-boys, as they, with all their wildness, would not be guilty of such an act.

About 11 o'clock, Thursday night, we arrived at our last station, Stuart, Holt county. Our coach was switched on a side-track, doors locked, blinds pulled down, and there we slept until the dawning of our first morning in Nebraska. The station agent had been apprised of our coming, and had made comfortable the depot and a baggage car with a good fire; that the men who had been traveling in other coaches and could not find room in the two hotels of the town, could find a comfortable resting place for the night.

We felt refreshed after a night of quiet rest, and the salubrious air of the morning put us in fine spirits, and we flocked from the car like birds out of a cage, and could have flown like freed birds to their nests, some forty miles farther north-west, where the colonists expected to find their nests of homes.

But instead, we quietly walked around the depot, and listened to a lark that sang us a sweet serenade from amid the grass close by; but we had to chase it up with a "shoo," and a flying clod before we could see the songster. Then by way of initiation into the life of the "wild west," a mark was pinned to a telegraph pole; and would you believe it, reader, the spirit of the country had so taken hold of us already that we took right hold of a big revolver, took aim, pulled the trigger, and after the smoke had cleared away, looked—and—well—we missed paper and pole, but hit the prairie beyond; where most of the shots were sown that followed.

A number of citizens of Stuart had gathered about to see the "pack of Irish and German emigrants," expected, while others who knew what kind of people were coming, came with a hearty welcome for us. Foremost among these were Messrs. John and James Skirving, merchants and stockmen, who, with their welcome extended an invitation to a number to breakfast. But before going, several of us stepped upon the scales to note the effect the climate would have upon our avoirdupois. As I wrote down 94 lbs., I thought, "if my weight increases to 100 lbs., I will sure come again and stay." Then we scattered to look around until breakfast was ready. We espied a great red-wheeled something—I didn't know what, but full of curiosity went to see.

A gentleman standing near asked: "Are you ladies of the colony that arrived last night?"

"Yes, sir, and we are wondering what this is."

"Why, that's an ox plow, and turns four furrows at one time."

"Oh! we didn't know but that it was a western sulky."

It was amusing to hear the guesses made as to what the farming implements were we saw along the way, by these new farmers. But we went to breakfast at Mr. John Skirving's wiser than most of them as far as ox-plows were concerned.

What a breakfast! and how we did eat of the bread, ham, eggs, honey, and everything good. Just felt as though we had never been to breakfast before, and ate accordingly. That noted western appetite must have made an attack upon us already, for soon after weighing ourselves to see if the climate had affected a change yet, the weight slipped on to—reader, I promised you I would tell you the truth and the whole truth; but it is rather hard when it comes right down to the point of the pen to write ninety-six. And some of the others that liked honey better than I did, weighed more than two pounds heavier. Now what do you think of a climate like that?

But we must add that we afterwards tested the difference in the scales, and in reality we had only eaten—I mean we had only gained one and a half pound from the salubrious air of the morning. Dinner and supper were the same in place, price, and quality, but not in quantity.

When we went to the car for our luggage, we found Mr. Clark lying there trying to sleep.

"Home-sick?" we asked.

"No, but I'm nigh sick abed; didn't get any sleep last night."

No, he was not homesick, only he fain would sleep and dream of home.

First meeting of the N.M.A.C. was held on a board pile near the depot, to appoint a committee to secure transportation to the location.

The coming of the colony from Pennsylvania had been noised abroad through the papers, and people were coming from every direction to secure a home near them, and the best of the land was fast being claimed by strangers, and the colonists felt anxious to be off on the morrow.

The day was pleasant, and our people spent it in seeing what was to be seen in and about Stuart, rendering a unanimous "pleased" in the evening. Mr. John Skirving kindly gave three comfortable rooms above his store to the use of the colonists, and the ladies and children with the husbands went to house-keeping there Friday evening.

Saturday morning. Pleasant. All is bustle and stir to get the men started to the location, and at last with oxen, horses, mules, and ponies, eight teams in all, attached to wagons and hacks, and loaded with the big tent and provisions, they were off. While the ladies who were disappointed at being left behind; merrily waved each load away.

But it proved quite fortunate that we were left behind, as Saturday was the last of the pleasant days. Sunday was cool, rained some, and that western wind commenced to blow. We wanted to show that we were keepers of the Sabbath by attending services at the one church of the town. But, as the morning was unpleasant, we remained at the colony home and wrote letters to the dear ones of home, telling of our safe arrival. Many were the letters sent post haste from Stuart the following day to anxious ones in the East.

In the afternoon it was pleasant enough for a walk across the prairie, about a quarter of a mile, to the Elkhorn river. When we reached the river I looked round and exclaimed: Why! what town is that? completely turned already and didn't know the town I had just left.

The river has its source about fifteen miles south-west of Stuart, and is only a brook in width here, yet quite deep and very swift. The water is a smoky color, but so clear the fish will not be caught with hook and line, spears and seine are used instead.

Like all the streams we have noticed in Nebraska it is very crooked, yet we do not wonder that the water does not know where to run, there is no "up or down" to this country; it is all just over to us; so the streams cut across here, and wind around there, making angles, loops, and turns, around which the water rushes, boiling and bubbling,—cross I guess because it has so many twists and turns to make; don't know what else would make it flow so swiftly in this level country. But hear what Prof. Aughey says:

"The Elkhorn river is one of the most beautiful streams of the state. It rises west of Holt and Elkhorn counties. Near its source the valley widens to a very great breadth, and the bluffs bordering it are low and often inappreciable. The general direction of the main river approximates to 250 miles. Its direction is southeast. It empties into the Platte in the western part of Sarpy county. For a large part of its course the Elkhorn flows over rock bottom. It has considerable fall, and its steady, large volume of waters will render it a most valuable manufacturing region."

We had not realized that as we went west from the Missouri river we made a constant ascent of several feet to the mile, else we would not have wondered at the rapid flow of the river. The clearness of the water is owing to its being gathered from innumerable lakelets; while the smoky color is from the dead grass that cover its banks and some places its bed.

Then going a little farther on we prospected a sod house, and found it quite a decent affair. Walls three feet thick, and eight feet high; plastered inside with native lime, which makes them smooth and white; roof made of boards, tarred paper, and a covering of sod. The lady of the house tells me the house is warm in winter, and cool in summer. Had a drink of good water from the well which is fifteen feet deep, and walled up with barrels with the ends knocked out.

The common way of drawing water is by a rope, swung over a pulley on a frame several feet high, which brings to the top a zinc bucket the shape and length of a joint of stove pipe, with a wooden bottom. In the bottom is a hole over which a little trap door or valve is fastened with leather hinges. You swing the bucket over a trough, and let it down upon a peg fastened there, that raises the trap door and leaves the water out. Some use a windlass. It seemed awkward to us at first, but it is a cheap pump, and one must get used to a good many inconveniences in a new country. But we who are used to dipping water from springs, are not able to be a judge of pumps. Am told the water is easily obtained, and generally good; though what is called hard water.

The country is almost a dead level, without a tree or bush in sight. But when on a perfect level the prairie seems to raise around you, forming a sort of dish with you in the center. Can see the sand hills fifteen miles to the southwest quite distinctly. Farm houses, mostly sod, dot the surrounding country.

Monday, 30th. Cool, with some rain, high wind, and little sunshine. For the sake of a quiet place where I could write, I sought and found a very pleasant stopping place with the family of Mr. John Skirving, of whom I have before spoken, and who had but lately brought his family from Jefferson City, Iowa.

Tuesday. A very disagreeable day; driving rain, that goes through everything, came down all day. Do wonder how the claim hunters in camp near the Keya Paha river will enjoy this kind of weather, with nothing but their tent for shelter.

Wednesday. About the same as yesterday, cold and wet; would have snowed, but the wind blew the flakes to pieces and it came down a fine rain.

Mrs. S. thinks she will go back to Iowa, and I wonder if it rains at home.

Thursday. And still it rains and blows!

Friday. A better day. Last night the wind blew so hard that I got out of bed and packed my satchel preparatory to being blown farther west, and dressed ready for the trip. The mode of travel was so new to me I scarcely knew what to wear. Everything in readiness, I lay me down and quietly waited the going of the roof, but found myself snug in bed in the morning, and a roof over me. The wind was greatly calmed, and I hastened to view the ruins of the storm of the night, but found nothing had been disturbed, only my slumber. The wind seems to make more noise than our eastern winds of the same force; and eastern people seem to make more noise about the wind than western people do. Don't think that I was frightened; there is nothing like being ready for emergencies! I had heard so much of the storms and winds of the West, that I half expected a ride on the clouds before I returned. The clouds cleared away, and the sun shone out brightly, and soon the wind had the mud so dried that it was pleasant walking. The soil is so mixed with sand that the mud is never more than a couple of inches deep here, and is soon dried. When dry a sandy dust settles over everything, but not a dirty dust. A number of the colony men returned to-day.

Saturday. Pleasant. The most of the men have returned. The majority in good heart and looking well despite the weather and exposure they have been subject to, and have selected claims. But a few are discouraged and think they will look for lands elsewhere.

They found the land first thought of so taken that they had to go still farther northwest—some going as far west as Holt creek, and so scattered that but few of them can be neighbors. This is a disappointment not looked for, they expected to be so located that the same church and school would serve them all.

Emigrant wagons have been going through Stuart in numbers daily, through wind and rain, all going in that direction, to locate near the colony. The section they had selected for a town plot had also been claimed by strangers. Yet, I am told, the colonists might have located more in a body had they gone about their claim-hunting more deliberately. And the storm helped to scatter them. The tent which was purchased with colony funds, and a few individual dollars, proved to be a poor bargain. When first pitched there was a small rent near the top, which the wind soon whipped into a disagreeably large opening. But the wind brought the tent to the ground, and it was rightly mended, and hoisted in a more sheltered spot. But, alas! down came the tent again, and as many as could found shelter in the homes of the old settlers.

Some selected their claims, plowed a few furrows, and laid four poles in the shape of a pen, or made signs of improvement in some way, and then went east to Niobrara City, or west to Long Pine, to a land office and had the papers taken out for their claims. Others, thinking there was no need of such hurried precautions, returned to Stuart to spend the Sabbath, and lost their claims. One party selected a claim, hastened to a land office to secure it, and arrived just in time to see a stranger sign his name to the necessary documents making it his.

Will explain more about claim-taking when I have learned more about it.

Sunday, 6 May. Bright and warm. Would not have known there had been any rain during the past week by the ground, which is nicely dried, and walking pleasant.

A number of us attended Sunday school and preaching in the forenoon, and were well entertained and pleased with the manner in which the Sunday school was conducted, while the organ in the corner made it quite home-like. We were glad to know there were earnest workers even here, where we were told the Sabbath was not observed; and but for our attendance here would have been led to believe it were so. Teams going, and stores open to people who come many miles to do their trading on this day; yet it is done quietly and orderly.

The minister rose and said, with countenance beaming with earnestness: "I thank God there are true christians to be found along this Elkhorn valley, and these strangers who are with us to-day show by their presence they are not strangers to Christ; God's house will always be sought and found by his people." While our hearts were filled with thanksgiving, that the God we love is very God everywhere, and unto him we can look for care and protection at all times.

In the evening we again gathered, and listened to a sermon on temperance, which, we were glad to know, fell upon a temperance people, as far as we knew our brother and sister colonists. After joining in "What a friend we have in Jesus" we went away feeling refreshed from "The fountain that freely flows for all," and walked home under the same stars that made beautiful the night for friends far away. Ah! we had begun to measure the distance from home already, and did not dare to think how far we were from its shelter.

But, as the stars are, so is God high over all; and the story of his love is just the same the wide world over.

Monday. Pleasant. Colonists making preparation to start to the location to-morrow, with their families. Some who have none but themselves to care for, have started.

Tuesday. Rains. Folks disappointed.

Wednesday. Rains and blows. Discouraging.

Thursday. Blows and rains. Very discouraging.

The early settlers say they never knew such a long rain at this season. Guess it is raining everywhere; letters are coming telling of a snow in some places nine and ten inches deep, on the 25th of April; of hard frozen ground, and continuous rains. It is very discouraging for the colony folks to be so detained; but they are thankful they are snug in comfortable quarters, in Stuart, instead of out they scarcely know where. Some have prepared muslin tents to live in until they can build their log or sod houses. They are learning that those who left their families behind until a home was prepared for them, acted wisely. I cannot realize as they do the disappointment they have met with, yet I am greatly in sympathy with them.

With the first letter received from home came this word from father: "I feel that my advanced years will not warrant me in changing homes." Well, that settled the matter of my taking a claim, even though the land proved the best. Yet I am anxious to see and know all, now that I am here, for history's sake, and intend going to the colony grounds with the rest. Brother Charley has written me from Plum Creek, Dawson county, to meet him at Fremont as soon as I can, and he will show me some of the beauties of the Platte valley; but I cannot leave until I have done this part of Nebraska justice. Mr. and Mrs. S. show me every kindness, and in such a way that I am made to feel perfectly at home; in turn I try to assist Mrs. S. with her household duties, and give every care and attention to wee Nellie, who is quite ill. I started on my journey breathing the prayer that God would take me into His own care and keeping, and raise up kind friends to make the way pleasant. I trusted all to Him, and now in answer, am receiving their care and protection as one of their own. Thus the time passes pleasantly, while I eat and sleep with an appetite and soundness I never knew before—though I fancy Mrs. S's skill as a cook has a bearing on my appetite, as well as the climate—yet every one experiences an increase of appetite, and also of weight. One of our party whom we had called "the pale man" for want of his right name, had thrown aside his "soft beaver" and adopted a stockman's wide rimmed sombrero traded his complexion to the winds for a bronze, and gained eight pounds in the eleven days he has been out taking the weather just as it came, and wherever it found him.

Friday. Rain has ceased and it shows signs of clearing off.

It does not take long for ground and grass to dry off enough for a prairie fire, and they have been seen at distances all around Stuart at night, reminding us of the gas-lights on the Bradford hills. The prairies look like new mown hay-fields; but they are not the hay-fields of Pennsylvania; a coarse, woody grass that must be burnt off, to allow the young grass to show itself when it comes in the spring. Have seen some very poor and neglected looking cattle that have lived all winter upon the prairie without shelter. I am told that, not anticipating so long a winter, many disposed of their hay last fall, and now have to drive their cattle out to the "divides,"—hills between rivers—to pasture on the prairie; and this cold wet weather has been very hard on them, many of the weak ones dying. It has been a novel sight, to watch a little girl about ten years old herding sheep near town; handling her pony with a masterly hand, galloping around the herd if they begin to scatter out, and driving them, into the corral. I must add that I have also seen some fine looking cattle. I must tell you all the bad with the good.

During all this time, and despite the disagreeable weather, emigrants keep up the line of march through Stuart, all heading for the Niobrara country, traveling in their "prairie schooners," as the great hoop-covered wagon is called, into which, often are packed their every worldly possession, and have room to pile in a large family on top. Sometimes a sheet-iron stove is carried along at the rear of the wagon, which, when needed, they set up inside and put the pipe through a hole in the covering. Those who do not have this convenience carry wood with them and build a fire on the ground to cook by; cooking utensils are generally packed in a box at the side or front. The coverings of the wagons are of all shades and materials; muslin, ducking, ticking, overall stuff, and oil-cloth. When oil-cloth is not used they are often patched over the top with their oil-cloth table covers. The women and children generally do the driving, while the men and boys bring up the rear with horses and cattle of all grades, from poor weak calves that look ready to lay them down and die, to fine, fat animals, that show they have had a good living where they came from.

Many of these people are from Iowa, are intelligent and show a good education. One lady we talked with was from Michigan; had four bright little children with her, the youngest about a year old; had come from Missouri Valley in the wagon; but told us of once before leaving Michigan and trying life in Texas; but not being suited with the country, had returned, as they were now traveling, in only a wagon, spending ten weeks on the way. She was driver and nurse both, while her husband attended to several valuable Texas horses.

Another lady said: "Oh! we are from Mizzurie; been on the way three weeks."

"How can you travel through such weather?"

"Oh! we don't mind it, we have a good ducking cover that keeps out the rain, and when the wind blows very hard we tie the wagon down."

"Never get sick?"

"No."

"Not even a cold?"

"Oh! no, feel better now than when we started."

"How many miles can you go in a day?"

"We average about twenty."

The sun and wind soon tans their faces a reddish brown, but they look healthy, happy, and contented. Thus you see, there is a needed class of people in the West that think no hardship to pick up and thus go whither their fancy may lead them, and to this class in a great measure we owe the opening up of the western country.

Saturday morning. Cloudy and threatened more storm, but cleared off nicely after a few stray flakes of "beautiful snow" had fallen. All getting ready to make a start to the colony location. Hearing that Mr. Lewis, one of the colonists, would start with the rest with a team of oxen, I engaged a passage in his wagon. I wanted to go West as the majority go, and enter into the full meaning and spirit of it all; so, much to the surprise of many, I donned a broad brimmed sombrero, and left Stuart about one o'clock, perched on the spring seat of a double bed wagon, in company with Mrs. Gilman, who came from Bradford last week. Mr. Lewis finds it easier driving, to walk, and is accompanied by Mr. Boggs, who I judge has passed his three score years.

Thinking I might get hungry on the way or have to tent out, Mrs. S. gave me a loaf of bread, some butter, meat, and stewed currants to bring along; but the first thing done was the spilling of the juice off the currants.

Come, reader, go with me on my first ride over the plains of Nebraska behind oxen; of course they do not prance, pace, gallop, or trot; I think they simply walk, but time will tell how fast they can jog along. Sorry we cannot give you the shelter of a "prairie schooner," for the wind does not forget to blow, and it is a little cool.

Mr. L. has already named his matched brindles, "Brock and Broady," and as they were taken from the herd but yesterday, and have not been under the yoke long, they are rather untutored; but Mr. L. is tutoring them with a long lash whip, and I think he will have them pretty well trained by the time we reach the end of our journey.

"Whoa, there Broady! get up! it's after one and dear only knows how far we have got to go. Don't turn 'round so, you'll upset the wagon!" We are going directly north-west. This, that looks like great furrows running parallel with the road, I am told, is the old wagon train road running from Omaha to the Black Hills. It runs directly through Stuart, but I took it to be a narrow potato patch all dug up in deep rows. I see when they get tired of the old ruts, they just drive along side and make a new road which soon wears as deep as the old. No road taxes to pay or work done on the roads here, and never a stone to cause a jolt. The jolting done is caused in going from one rut to another.

Here we are four miles from Stuart, and wading through a two-mile stretch of wet ground, all standing in water. No signs of habitation, not even Stuart to be seen from this point.

Mr. Lewis wishes for a longer whip-stock or handle; I'll keep a look out and perhaps I will find one.

Now about ten miles on our way and Stuart in plain view. There must be a raise and fall in the ground that I cannot notice in going over it. Land is better here Mr. B. says, and all homesteaded. Away to our right are a few little houses, sod and frame. While to the left, 16 miles away, are to be seen the sand-hills, looking like great dark waves.

The walking is so good here that I think I will relieve the—oxen of about 97 pounds. You see I have been gaining in my avoirdupois. I enjoy walking over this old road, gathering dried grasses and pebbles, wishing they could speak and tell of the long emigrant trains that had tented at night by the wayside; of travelers going west to find new homes away out on the wild plains; of the heavy freight trains carrying supplies to the Indian agencies and the Black Hills; of the buffalo stampede and Indian "whoop" these prairies had echoed with, but which gave way to civilization only a few years ago, and now under its protection, we go over the same road in perfect safety, where robbery and massacres have no doubt been committed. Oh! the change of time!

Twelve miles from Stuart, why would you believe it, here's a real little hill with a small stream at the bottom. Ash creek it is called, but I skip it with ease, and as I stop to play a moment in the clear water and gather a pebble from its gravelly bed, I answer J. G. Holland in Kathrina with: Surely, "the crystal brooks are sweeter for singing to the thirsty brutes that dip their bearded muzzles in their foam," and thought what a source of delight this little stream is to the many that pass this way. Then viewed the remains of a sod house on the hillside, and wondered what king or queen of the prairie had reigned within this castle of the West, the roof now tumbled in and the walls falling.

Ah! there is plenty of food for thought, and plenty of time to think as the oxen jog along, and I bring up the rear, seeing and hearing for your sake, reader.

Only a little way from the creek, and we pass the first house that stands near the road, and that has not been here long, for it is quite new. The white-haired children playing about the door will not bother their neighbors much, or get out of the yard and run off for awhile at least, as there is no other house in sight, and the boundless prairie is their dooryard. Happy mother! Happy children!

Now we are all aboard the wagon, and I have read what I have written of the leave taking of home; Mr. B. wipes his eyes as it brings back memories of the good byes to him; Mr. L. says, "that's very truly written," and Mrs. G. whispers, "I must have one of your books, Sims." All this is encouraging, and helps me to keep up brave heart, and put forth every effort to the work I have begun, and which is so much of an undertaking for me.

"Oh! Mr. Lewis, there it is!"

"Is what?"

"Why, that stick for a whip-handle."

I had been watching all the way along, and it was the only stick I had seen, and some poor unfortunate had lost it.

The sun is getting low, and Mr. L. thinks we had better stop over night at this old log-house, eighteen miles from Stuart, and goes to talk to the landlord about lodging. I view the prospects without and think of way-side inns I have read of in story, but never seen before, and am not sorry when he returns and reports: "already crowded with travelers," and flourishing his new whip starts Brock and Broady, though tired and panting, into a trot toward the Niobrara, and soon we are nearing another little stream called Willow creek, named from the few little willow bushes growing along its banks, the first bushes seen all the way along. It is some wider than Ash creek, and as there is no bridge we must ride across. Mr. L. is afraid the oxen are thirsty and will go straight for the water and upset the wagon. Oh, dear! I'll just shut my eyes until we are on the other side.

There, Mr. B. thinks he sees a nest of prairie chicken eggs and goes to secure some for a novelty, but changes his mind and thinks he'll not disturb that nest of white puff-balls, and returns to the wagon quite crestfallen. Heavy looking clouds gathering in the west, obscure the setting sun, which is a real disappointment. The dawning and fading of the days in Nebraska are indeed grand, and I did so want a sunset feast this evening, for I could view it over the bluffy shores of the Niobrara river. Getting dark again, just when the country is growing most interesting.

Mr. B. and L. say, "bad day to-morrow, more rain sure;" I consult my barometer and it indicates fair weather. If it is correct I will name it Vennor, if not I shall dub it Wiggins. Thermometer stands at 48°, think I had better walk and get warmed up; a heavy cloth suit, mohair ulster and gossamer is scarcely sufficient to keep the chilly wind out.

One mile further on and darkness overtakes us while sticking on the banks of Rock creek, a stream some larger than Willow creek, and bridged with poles for pedestrians, on which we crossed; but the oxen, almost tired out, seemed unequal for the pull up the hill. Mr. L. uses the whip, while Mr. B. pushes, and Mrs. G. and I stand on a little rock that juts out of the hill—first stone or rock seen since we entered the state, and pity the oxen, but there they stick. Ah! here is a man coming with an empty wagon and two horses; now he will help us up the hill. "Can you give me a lift?" Mr. L. asks. "I'm sorry I can't help you gentlemen, but that off-horse is terribly weak. The other horse is all right, but you can see for yourself, gentlemen, how weak that off-horse is." And away he goes, rather brisk for a weak horse. While we come to the conclusion that he has not been west long enough to learn the ways of true western kindness. (We afterwards learned he was lately from Pennsylvania.) But here comes Mr. Ross and Mr. Connelly who have walked all the way from Stuart. Again the oxen pull, the men push, but not a foot gained; wagon only settling firmer into the mud. The men debate and wonder what to do. "Why not unload the trunks and carry them up the hill?" I ask. Spoopendike like, someone laughed at my suggestion, but no sooner said than Mr. L. was handing down a trunk with, "That's it—only thing we can do; here help with this trunk," and a goodly part of the load is carried to the top of the hill by the men, while I carry the guns. How brave we are growing, and how determined to go west; and the oxen follow without further trouble.

When within a mile and a half of the river, those of us who can, walk, as it is dangerous driving after dark, and we take across, down a hill, across a little canyon, at the head of which stands a little house with a light in the window that looks inviting, but on we go, across a narrow channel of the river, on to an island covered with diamond willow bushes, and a few trees. See a light from several "prairie schooners" that have cast anchor amid the bushes, and which make a very good harbor for these ships of the west.

"What kind of a shanty is this?"

"Why that is a wholesale and retail store, but the merchant doesn't think worth while to light up in the evening."

On we walk over a sort of corduroy road made of bushes, and so tired I can scarcely take another step.

"Well, is this the place?" I asked as we stopped to look in at the open door of a double log house, on a company of people who are gathered about an organ and singing, "What a friend we have in Jesus."

"No, just across the river where you see that light."

Another bridge is crossed, and we set us down in Aunty Slack's hotel about 9 o'clock. Tired? yes, and so glad to get to somewhere.

Mr. John Newell, who lives near the Keya Paha, left Stuart shortly after we did, with Mrs. and Miss Lizzie, Laura, and Verdie Ross, in his hack, but soon passed us with his broncho ponies and had reached here before dark.

Three other travelers were here for the night, a Keya Paha man, a Mr. Philips, of Iowa, and Mr. Truesdale, of Bradford, Pa.

"How did the rest get started?" Mrs. R. asks of her husband.

"Well, Mr. Morrison started with his oxen, with Willie Taylor, and Mrs. M. and Mrs. Taylor rode in the buggy tied to the rear end of the wagon. Mr. Barnwell and several others made a start with his team of oxen. But Mr. Taylor's horses would not pull a pound, so he will have to take them back to the owner and hunt up a team of oxen." We had expected to all start at the same time, and perhaps tent out at night. A good supper is refreshing to tired travelers, but it is late before we get laid down to sleep. At last the ladies are given two beds in a new apartment just erected last week, and built of cedar logs with a sod roof, while the men throw themselves down on blankets and comforts on the floor, while the family occupies the old part.

About twelve o'clock the rain began to patter on the sod shingles of the roof over head, which by dawn was thoroughly soaked, and gently pouring down upon the sleepers on the floor, causing a general uprising, and driving them from the room. It won't leak on our side of the house, so let's sleep awhile longer; but just as we were dropping into the arms of Morpheus, spat! came a drop on our pillow, which said, "get up!" in stronger terms than mother ever did. I never saw a finer shower inside a house before. What a crowd we made for the little log house, 14×16 feet, built four years ago, and which served as kitchen, dining room, chamber, and parlor, and well crowded with furniture, without the addition of fourteen rain-bound travelers, beside the family, which consisted of Mrs. Slack, proprietress, a daughter and son-in-law, and a hired girl, 18 heads in all to be sheltered by this old sod roof made by a heavy ridge pole, or log laid across at the comb, which supports slabs or boards laid from the wall, then brush and dried grass, and then the sod. The walls are well chinked and whitened. The door is the full height of the wall, and the tallest of the men have to strictly observe etiquette, and bow as they enter and leave the house. Mr. Boggs invariably strikes a horse shoe suspended to the ceiling with his head, and keeps "good luck" constantly on the swing over us. The roof being old and well settled, keeps it from leaking badly; but Mrs. S. says there is danger of it sliding off or caving in. Dear me! I feel like crawling under the table for protection.

Rain! rain! think I will give the barometer the full name of R. Stone Wiggins! Have a mind to throw him into the river by way of immersion, but fear he would stick in a sand-bar and never predict another storm, so will just hang him on the wall out side to be sprinkled.

The new house is entirely abandoned, fires drowned out, organ, sewing machine, lunch baskets, and bedding protected as well as can be with carpet and rubber coats.

How glad I am that I have no luggage along to get soaked. My butter and meat was lost out on the prairie or in the river—hope it is meat cast adrift for some hungry traveler—and some one has used my loaf for a cushion, and how sad its countenance! Don't care if it does get wet! So I just pin my straw hat to the wall and allow it to rain on, as free from care as any one can be under such circumstances. I wanted experience, and am being gratified, only in a rather dampening way. Some find seats on the bed, boxes, chairs, trunk, and wood-box, while the rest stand. We pass the day talking of homes left behind and prospects of the new. Seven other travelers came in for dinner, and went again to their wagons tucked around in the canyons.

The house across the river is also crowded, and leaking worse than the hotel where we are stopping. Indeed, we feel thankful for the shelter we have as we think of the travelers unprotected in only their wagons, and wonder where the rest of our party are.

The river is swollen into a fretful stream and the sound of the waters makes us even more homesick.

"More rain, more grass," "more rain, more rest," we repeated, and every thing else that had a jingle of comfort in it; but oftener heard, "I do wish it would stop!" "When will it clear off?" "Does it always rain here?" It did promise to clear off a couple of times, only to cloud up again, and so the day went as it came, leaving sixteen souls crowded in the cabin to spend the night as best we could. Just how was a real puzzle to all. But midnight solves the question. Reader, I wish you were here, seated on this spring wagon seat with me by the stove, I then would be spared the pain of a description. Did you ever read Mark Twain's "Roughing It?" or "Innocents Abroad?" well, there are a few innocents abroad, just now, roughing it to their hearts' content.

The landlady, daughter, and maid, with Laura, have laid them down crosswise on the bed. The daughter's husband finds sleep among some blankets, on the floor at the side of the bed. Mr. Ross, almost sick, sticks his head under the table and feet under the cupboard and snores. Mrs. Ross occupies the only rocker—there, I knew she would rock on Mr. Philips who is stretched out on a one blanket just behind her! Double up, Mr. P., and stick your knees between the rockers and you'll stand a better chance.

If you was a real birdie, Mrs. Gilman, or even a chicken, you might perch on the side of that box. To sleep in that position would be dangerous; dream of falling sure and might not be all a dream, and then, Mr. Boggs would be startled from his slumbers. Poor man! We do pity him! Six feet two inches tall; too much to get all of himself fixed in a comfortable position at one time. Now bolt upright on a chair, now stretched out on the floor, now doubled up; and now he is on two chairs looking like the last grasshopper of the raid. Hush! Lizzie, you'll disturb the thirteen sleepers.

Mr. Lewis has turned the soft side of a chair up for a pillow before the stove, and list—he snores a dreamy snore of home-sweet-ho-om-me.

Mr. Truesdale is rather fidgety, snugly tucked in behind the stove on a pile of kindling wood. I'm afraid he will black his ears on the pots and kettles that serve as a back ground for his head, but better that than nothing. Am afraid Mr. Newell, who is seated on an inverted wooden pail, will loose his head in the wood-box, for want of a head rest, if he doesn't stop nodding so far back.

Hold tight to your book, Mr. N., you may wake again and read a few more words of Kathrina.

Here, Laura, get up and let your little sister, Verdie, lie down on the bed. "That table is better to eat off than sleep on," Lizzie says, and crawls down to claim a part of my wagon seat in which I have been driving my thoughts along with pencil and paper, and by way of a jog, give the stove a punch with a stick of wood, every now and then; casting a sly glance to see if the old lady looks cross in her sleep, because we are burning all her dry wood up, and dry wood is a rather scarce article just now. But can't be helped. The feathery side of these boards are down, the covers all wet in the other room, and these sleepers must be kept warm.

Roll over, Mr. Lewis, and give Mrs. Ross room whereon to place her feet and take a little sleep! Now Mrs. R.'s feet are not large if she does weigh over two hundred pounds; small a plenty; but not quite as small as the unoccupied space, that's all.

Well, it's Monday now, 'tis one o'clock, dear me; wonder what ails my eyes; feels like there's sand in them. I wink, and wink, but the oftener, the longer. Do believe I'm getting sleepy too! What will I do? To sleep here would insure a nod over on the stove; no room on the floor without danger of kicks from booted sleepers. Lizzie, says, "Get up on the table, Sims," it will hold a little thing like you. So I leave the seat solely to her and mount the table, fully realizing that "necessity is the mother of invention," and that western people do just as they can, mostly. So

As there is no room for the muses to visit me here I'll not attempt further poetizing but go to sleep and dream I am snug in my own little bed at home. Glad father and mother do not know where their daughter is seeking rest for to-night.

"Get up, Sims, it's five o'clock and Mrs. S. wants to set the table for breakfast," and I start up, rubbing my eyes, wishing I could sleep longer, and wondering why I hadn't come west long ago, and hadn't always slept on a table?

I only woke once during the night, and as the lamp was left burning, could see that Mrs. R. had found a place for her feet, and all were sound asleep. Empty stomachs, weariness, and dampened spirits are surely three good opiates which, taken together, will make one sleep in almost any position. Do wonder if "Mark" ever slept on an extension table when he was out west? Don't think he did, believe he'd use the dirty floor before he'd think of the table; so I am ahead in this chapter.

Well, the fun was equal to the occasion, and I think no one will ever regret the time spent in the little log house at "Morrison's bridge," and cheerfully paid their $1.75 for their four meals and two nights' lodging, only as we jogged along through the cold next day, all thought they would have had a bite of supper, and not gone hungry to the floor, to sleep.

Monday morning. Cold, cloudy, and threatening more rain. Start about eight o'clock for the Keya Paha, Mr. N. with the Ross ladies ahead, while the walkers stay with our "span of brindles" to help push them up the hill, and I walk to relieve them of my weight.

But we have reached the table-land, and as I have made my impress in the sand and mud of this hill of science, I gladly resume my seat in the wagon with Mrs. Gilman, who is freezing with a blanket pinned on over her shawl. Boo! The wind blows cold, and it sprinkles and tries to snow, and soon I too am almost freezing with all my wraps on, my head well protected with fascinator, hat, and veil. How foolish I was to start on such a trip without good warm mittens. "Let's get back on the trunks, Mrs. G., and turn our backs to the wind." But that is not all sufficient and Mr. L. says he cannot wear his overcoat while walking and kindly offers it to me, and I right willingly crawl into it, and pull it up over my ears, and draw my hands up in the sleeves, and try hard to think I am warm. I can scarcely see out through all this bundling, but I must keep watch and see all I can of the country as I pass along. Yet, it is just the same all the way, with the only variation of, from level, to slightly undulating prairie land. Not a tree, bush, stump, or stone to be seen. Followed the old train road for several miles and then left it, and traveled north over an almost trackless prairie. During the day's travel we met but two parties, both of whom were colonists on their way to Long Pine to take claims in that neighborhood. Passed close to two log houses just being built, and two squads of tenters who peered out at us with their sunburnt faces looking as contented as though they were perfectly satisfied with their situation.

The oxen walked right along, although the load was heavy and the ground soft, and we kept up a steady line of march toward the Keya Paha, near where most of the colonists had selected their claims, and as we neared their lands, the country took on a better appearance.

The wind sweeps straight across, and the misting rain from clouds that look to be resting upon the earth, makes it a very gloomy outlook, and very disagreeable. Yet I would not acknowledge it. I was determined, if possible, to make the trip without taking cold. So Mrs. G. and I kept up the fun until we were too cold to laugh, and then began to ask: "How much farther do we have to go? When will we reach there?" Until we were ashamed to ask again, so sat quiet, wedged down between trunks and a plow, and asked no more questions.

"Oh, joy! Mrs. G., there's a house; and I do believe that is Mrs. Ross with Lizzie and Laura standing at the door. I'll just wave them a signal of distress, and they will be ready to receive us with open arms."