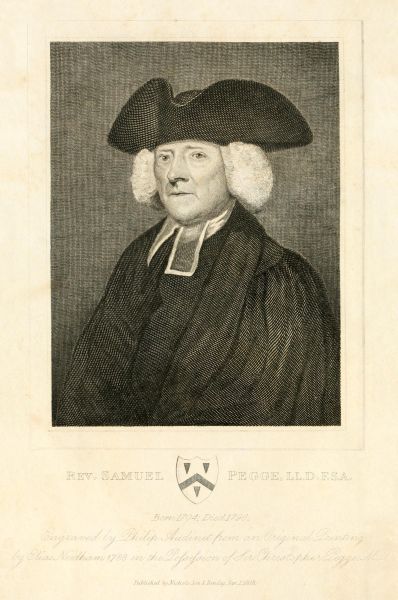

Rev. Samuel Pegge, LL.D F.S.A.

Born 1704; Died 1796.

Engraved by Philip Audinet from an Original Painting

by Elias Needham 1788 in the Possession of Sir Christopher Pegge, M.D.

Published by Nichols, Son & Bentley, Jan. 1, 1818.

———

Author of the "CURIALIA,"

AND OF

"ANECDOTES OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE."

———

PRINTED BY AND FOR J. NICHOLS, SON, AND BENTLEY,

AT THE PRINTING-OFFICE OF THE NOTES OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS,

25, PARLIAMENT STREET, AND 10, KING STREET, WESTMINSTER;

SOLD ALSO AT THEIR OLD OFFICE IN RED LION PASSAGE,

FLEET STREET, LONDON.

1818.

| Portrait of the Rev. Samuel Pegge, LL.D. | Frontispiece. |

| Whittington Church | lix. |

| Whittington Rectory | lxii. |

| Whittington Revolution House | lxiii. |

The publication of this Volume is strictly conformable to the testamentary intentions of the Author, who consigned the MSS. for that express purpose to the present Editor[1].

Mr. Pegge had, in his life-time, published Three Portions of "Curialia, or an Account of some Members of the Royal Houshold;" and had, with great industry and laborious research, collected materials for several other Portions, some of which were nearly completed for the press.

Mr. Pegge was "led into the investigation," he says, "by a natural and kind of instinctive curiosity, and a desire of knowing what was the antient state of the Court to which he had the honour, by the favour of his Grace William the late Duke of Devonshire, to compose a part."

Two more Portions were printed in 1806 by the present Editor. Long, however, and intimately acquainted as he was with the accuracy and diffidence of Mr. Pegge, he would have hesitated in offering those posthumous Essays to the Publick, if the plan had not been clearly defined, and the Essays sufficiently distinct to be creditable to the reputation which Mr. Pegge had already acquired, by the Parts of the "Curialia" published by himself, and by his very entertaining (posthumous) "Anecdotes of the English Language;"—a reputation which[v] descended to him by Hereditary Right, and which he transmitted untarnished to a worthy and learned Son.

It was the hope and intention of the Editor to have proceeded with some other Portions of the "Curialia;" but the fatal event which (in February 1808) overwhelmed him in accumulated distress put a stop to that intention. Nearly all the printed Copies of the "Curialia" perished in the flames; and part of the original MS. was lost.

A few detached Articles, which related to the College of Arms, and to the Order of Knights Bachelors (which, had they been more perfect, would have formed one or more succeeding Portions) have since been deposited in the rich Library of that excellent College.

The Volume now submitted to the candour of the Reader is formed from the wreck of the original materials. The arranging of the several detached articles, and the revisal of them through the press, have afforded the Editor some amusement; and he flatters himself that the Volume will meet with that indulgence which the particular circumstances attending it may presume to claim.—If the Work has any merit, it is the Author's. The defects should, in fairness, be attributed to the Editor.

J. N.

Highbury Place, Dec. 1, 1817.

⁂ Extract from Mr. Pegge's Will.

"Having the Copy-right of my little Work called Curialia in myself, I hereby give and bequeath all my interest therein, together with all my impressions thereof which may be unsold at the time of my decease, to my Friend Mr. John Nichols, Printer, with the addition of as much money as will pay the Tax on this Legacy. I also request of the said Mr. John Nichols, that he would carefully peruse and digest all my Papers and Collections on the above subject, and print them under the title of Curialia Miscellanea, or some such description.—There is also another Work of mine, not quite finished, intitled Anecdotes of the English Language, which I wish Mr. Nichols to bring forward from his Press. Samuel Pegge."

| PARENTALIA: or, Memoirs of the Rev. Dr. Samuel Pegge, compiled by his Son | Page ix-lviii |

| Appendix to the Parentalia: | |

| Description of Whittington Church | lix |

| Description of Whittington Rectory | lxii |

| Description of The Revolution House at Whittington | ibid. |

| Origin of the Revolution in 1688 | lxiv |

| Celebration of the Jubilee in 1788 | lxv |

| Stanzas by the Rev. P. Cunningham | lxxi |

| Ode for the Revolution Jubilee | lxxiii |

| Extracts from Letters of Dr. Pegge to Mr. Gough | lxxiv |

| Memoirs of Samuel Pegge, Esq. by the Editor | lxxvii |

| Appendix of Epistolary Correspondence | lxxxiii |

| Hospitium Domini Regis: | |

| or, The History of the Royal Household. | |

| Introduction | Page 1 |

| William I. | 6 |

| William Rufus | 18 |

| Henry I. | 24 |

| Stephen | 38 |

| Henry II. (Plantagenet) | 48 |

| Richard I. | 63 |

| Henry IV. | 68 |

| Edward IV. | 69 |

| Extracts from the Liber Niger | 71 |

| Knights and Esquires of the Body | 73 |

| Gentleman Usher | 74 |

| Great Chamberlain of England | 76 |

| Knights of Household | 77 |

| Esquires of the Body | 79 |

| Yeomen of the Crown | 84 |

| [viii]A Barber for the King's most high and dread Person | 86 |

| Henxmen | 88 |

| Master of Henxmen | 89 |

| Squires of Household | 91 |

| Kings of Arms, Heralds, and Pursuivants | 95 |

| Serjeants of Arms | 97 |

| Minstrels | 99 |

| A Wayte | 101 |

| Clerk of the Crown in Chancery | 103 |

| Supporters, Crests, and Cognizances, of the Kings of England | 104 |

| Regal Titles | 109 |

| On the Virtues of the Royal Touch | 111 |

| Ceremonies for Healing, for King's Evil | 154 |

| Ceremonies for blessing Cramp-Rings | 164 |

| Stemmata Magnatum: Origin of the Titles of some of the English Nobility | 173 |

| English Armorial Bearings | 201 |

| Origin and Derivation of remarkable Surnames | 208 |

| Symbola Scotica: Mottoes, &c. of Scottish Families | 213 |

| Dissertation on Coaches and Sedan Chairs | 269 |

| Dissertation on the Hammer Cloth | 304 |

| Articles of Dress.—Gloves | 305 |

| Ermine—Gentlewomen's Apparel | 312 |

| Apparel for the Heads of Gentlewomen | 313 |

| Mourning | 314 |

| Beard, &c. | 316 |

| Origin of the Name of the City of Westminster | 320 |

| Memoranda relative to the Society of the Temple in London, written in 1760 | 323 |

| Dissertation on the Use of Simnel Bread, and the Derivation of the Word Simnel | 329 |

| Historical Essay on the Origin of "Thirteen Pence Half-penny," as Hangman's Wages | 331 |

| Custom observed by the Lord Lieutenants of Ireland | 349 |

OR,

MEMOIRS OF THE REV. DR. PEGGE,

COMPILED BY HIS SON.

————

The Rev. Samuel Pegge, LL. D. and F.S.A. was the Representative of one of four Branches of the Family of that name in Derbyshire, derived from a common Ancestor, all which existed together till within a few years. The eldest became extinct by the death of Mr. William Pegge, of Yeldersley, near Ashborne, 1768; and another by that of the Rev. Nathaniel Pegge, M.A. Vicar of Packington, in Leicestershire, 1782.

The Doctor's immediate Predecessors, as may appear from the Heralds-office, were of Osmaston, near Ashborne, where they resided, in lineal succession, for four generations, antecedently to his[x] Father and himself, and where they left a patrimonial inheritance, of which the Doctor died possessed[2].

Of the other existing branch, Mr. Edward Pegge having [1662] married Gertrude, sole daughter and heir of William Strelley, Esq. of Beauchief, in the Northern part of Derbyshire, seated himself there, and was appointed High Sheriff of the County in 1667; as was his Grandson, Strelley Pegge, Esq. 1739; and his Great-grandson, the present Peter Pegge, Esq. 1788.

It was by Katharine Pegge, a daughter of Thomas Pegge, Esq. of Yeldersley, that King Charles II. (who saw her abroad during his exile) had a son born (1647), whom he called Charles Fitz-Charles, to whom he granted the Royal arms, with a baton sinister, Vairé, and whom (1675) his Majesty created Earl of Plymouth, Viscount Totness, and Baron Dartmouth[3]. He was bred to the Sea, and, having been educated abroad, most probably in Spain, was known by the name of Don Carlos[4]. The Earl married the Lady Bridget Osborne, third Daughter of Thomas Earl[xi] of Danby, Lord High Treasurer (at Wimbledon, in Surrey), 1678[5], and died of a flux at the siege of Tangier, 1680, without issue. The body was brought to England, and interred in Westminster Abbey[6]. The Countess re-married Dr. Philip Bisse, Bishop of Hereford, by whom she had no issue; and who, surviving her, erected a handsome tablet to her memory in his Cathedral.

Katharine Pegge, the Earl's mother, married Sir Edward Greene, Bart. of Samford in Essex, and died without issue by him[7].

But to return to the Rev. Dr. Pegge, the outline only of whose life we propose to give. His Father (Christopher) was, as we have observed, of Osmaston, though he never resided there, even after he became possessed of it; for, being a younger Brother, it was thought proper to put him to business; and he served his time with a considerable woollen-draper at Derby, which line he followed till the death of his elder Brother (Humphry, who died without issue 1711) at Chesterfield[xii] in Derbyshire, when he commenced lead-merchant, then a lucrative branch of traffick there; and, having been for several years a Member of the Corporation, died in his third Mayoralty, 1723.

He had married Gertrude Stephenson (a daughter of Francis Stephenson, of Unston, near Chesterfield, Gent.) whose Mother was Gertrude Pegge, a Daughter of the before-mentioned Edward Pegge, Esq. of Beauchief; by which marriage these two Branches of the Family, which had long been diverging from each ether, became reunited, both by blood and name, in the person of Dr. Pegge, their only surviving child.

He was born Nov. 5, 1704, N.S. at Chesterfield, where he had his school education; and was admitted a Pensioner of St. John's College, Cambridge, May 30, 1722, under the tuition of the Rev. Dr. William Edmundson; was matriculated July 7; and, in the following November, was elected a Scholar of the House, upon Lupton's Foundation.

In the same year with his Father (1723) died the Heir of his Maternal Grandfather (Stephenson), a minor; by whose death a moiety of the real estate at Unston (before-mentioned) became the property of our young Collegian, who was[xiii] then pursuing his academical studies with intention of taking orders.

Having, however, no immediate prospect of preferment, he looked up to a Fellowship of the College, after he had taken the degree of A.B. in January 1725, N.S.; and became a candidate upon a vacancy which happened favourably in that very year; for it was a Lay-fellowship upon the Beresford Foundation, and appropriated to the Founder's kin, or at least confined to a Native of Derbyshire.

The competitors were, Mr. Michael Burton (afterwards Dr. Burton), and another, whose name we do not find; but the contest lay between Mr. Burton and Mr. Pegge. Mr. Burton had the stronger claim, being indubitably related to the Founder; but, upon examination, was declared to be so very deficient in Literature, that his superior right, as Founder's kin, was set aside, on account of the insufficiency of his learning; and Mr. Pegge was admitted, and sworn Fellow March 21, 1726, O. S.

In consequence of this disappointment, Mr. Burton was obliged to take new ground, to enable him to procure an establishment in the world; and therefore artfully applied to the College for a testimonial, that he might receive orders, and undertake some cure in the vicinity of Cambridge.[xiv] Being ordained, he turned the circumstance into a manœuvre, and took an unexpected advantage of it, by appealing to the Visitor [the Bishop of Ely, Dr. Thomas Greene], representing, that, as the College had, by the testimonial, thought him qualified for Ordination, it could not, in justice, deem him unworthy of becoming a Fellow of the Society, upon such forcible claims as Founder's kin, and also as a Native of Derbyshire.

These were irresistible pleas on the part of Mr. Burton; and the Visitor found himself reluctantly obliged to eject Mr. Pegge; when Mr. Burton took possession of the Fellowship, which he held many years[8].

Thus this business closed; but the Visitor did Mr. Pegge the favour to recommend him, in so particular a manner, to the Master and Seniors of the College, that he was thenceforward considered as an honorary member of the body of Fellows (tanquam Socius), kept his seat at their table and in the chapel, being placed in the situation of a Fellow-commoner.

In consequence, then, of this testimony of the Bishop of Ely's approbation, Mr. Pegge was[xv] chosen a Platt-fellow on the first vacancy, A. D. 1729[9]. He was therefore, in fact, twice a Fellow of St. John's.

There is good reason to believe that, in the interval between his removal from his first Fellowship, and his acceding to the second, he meditated the publication of Xenophon's "Cyropædia" and "Anabasis," from a collation of them with a Duport MS. in the Library at Eton—to convince the world that the Master and Seniors of St. John's College did not judge unworthily in giving him so decided a preference to Mr. Burton in their election.

It appears that he had made very large collections for such a work; but we suspect that it was thrown aside on being anticipated by Mr. Hutchinson's Edition, which was formed from more valuable manuscripts.

He possessed a MS "Lexicon Xenophonticum" by himself, as well as a Greek Lexicon in MS.; and had also "An English Historical Dictionary," in 6 volumes folio; a French and Italian, a Latin, a British and Saxon one, in one volume each; all corrected by his notes; a "Glossarium Generale;" and two volumes of "Collections in English History."

During his residence in Kent, Mr. Pegge formed a "Monasticon Cantianum," in two folio MS volumes; a MS Dictionary for Kent; an Alphabetical List of Kentish Authors and Worthies; Kentish Collections; Places in Kent; and many large MS additions to the account of that county in the "Magna Britannia."

He also collected a good deal relative to the College at Wye, and its neighbourhood, which he thought of publishing, and engraved the seal, before engraved in Lewis's Seals. He had "Extracts from the Rental of the Royal Manor of Wye, made about 1430, in the hands of Daniel Earl of Winchelsea;" and "Copy of a Survey and Rental of the College, in the possession of Sir Windham Knatchbull, 1739."

While resident in College (and in the year 1730) Mr. Pegge was elected a Member of the Zodiac Club, a literary Society, which consisted of twelve members, denominated from the Twelve[xvii] Signs. This little institution was founded, and articles, in the nature of statutes, were agreed upon Dec. 10, 1725. Afterwards (1728) this Society thought proper to enlarge their body, when six select additional members were chosen, and denominated from six of the Planets, though it still went collectively under the name of the Zodiac Club[10]. In this latter class Mr. Pegge was the original Mars, and continued a member of the Club as long as he resided in the University. His secession was in April 1732, and his seat accordingly declared vacant.

In the same year, 1730, Mr. Pegge appears in a more public literary body;—among the Members of the Gentlemen's Society at Spalding, in Lincolnshire, to which he contributed some papers which will be noticed below[11].

Having taken the degree of A. M. in July 1729, Mr. Pegge was ordained Deacon in December in the same year; and, in the February following, received Priest's orders; both of which were conferred by Dr. William Baker, Bishop of Norwich.

It was natural that he should now look to employment in his profession; and, agreeably to his wishes, he was soon retained as Curate to the Rev. Dr. John Lynch (afterwards [1733] Dean of Canterbury), at Sundrich in Kent, on which charge he entered at Lady-day 1730; and in his Principal, as will appear, soon afterwards, very unexpectedly, found a Patron.

The Doctor gave Mr. Pegge the choice of three Cures under him—of Sundrich, of a London Living, or the Chaplainship of St. Cross, of which the Doctor was then Master. Mr. Pegge preferred Sundrich, which he held till Dr. Lynch exchanged, that Rectory for Bishopsbourne, and then removed thither at Midsummer 1731.

Within a few months after this period, Dr. Lynch, who had married a daughter of Archbishop Wake, obtained for Mr. Pegge, unsolicited, the Vicarage of Godmersham (cum Challock), into which he was inducted Dec. 6, 1731.

We have said unsolicited, because, at the moment when the Living was conferred, Mr. Pegge[xix] had more reason to expect a reproof from his Principal, than a reward for so short a service of these Cures. The case was, that Mr. Pegge had, in the course of the preceding summer (unknown to Dr. Lynch) taken a little tour, for a few months, to Leyden, with a Fellow Collegian (John Stubbing, M. B. then a medical pupil under Boerhaave), leaving his Curacy to the charge of some of the neighbouring Clergy. On his return, therefore, he was not a little surprized to obtain actual preferment through Dr. Lynch, without the most distant engagement on the score of the Doctor's interest with the Archbishop, or the smallest suggestion from Mr. Pegge.

Being now in possession of a Living, and independent property, Mr. Pegge married (April 13, 1732) Miss Anne Clarke, the only daughter of Benjamin, and sister of John Clarke, Esqrs. of Stanley, near Wakefield, in the county of York, by whom he had one Son [Samuel, of whom hereafter], who, after his Mother's death, became eventually heir to his Uncle; and one Daughter, Anna-Katharina, wife of the Rev. John Bourne, M.A. of Spital, near Chesterfield, Rector of Sutton cum Duckmanton, and Vicar of South Winfield, both in Derbyshire; by whom she had two daughters, Elizabeth, who married Robert Jennings,[xx] Esq. and Jane, who married Benjamin Thompson, Esq.

While Mr. Pegge was resident in Kent, where he continued twenty years, he made himself acceptable to every body, by his general knowledge, his agreeable conversation, and his vivacity; for he was received into the familiar acquaintance of the best Gentlemen's Families in East Kent, several of whom he preserved in his correspondence after he quitted the county, till the whole of those of his own standing gave way to fate before him.

Having an early propensity to the study of Antiquity among his general researches, and being allowedly an excellent Classical Scholar, he here laid the foundation of what in time became a considerable collection of books, and his little cabinet of Coins grew in proportion; by which two assemblages (so scarce among Country Gentlemen in general) he was qualified to pursue those collateral studies, without neglecting his parochial duties, to which he was always assiduously attentive.

The few pieces which Mr. Pegge printed while he lived in Kent will be mentioned hereafter, when we shall enumerate such of his Writings as are most material. These (exclusively of Mr. Urban's obligations to him in the Gentleman's[xxi] Magazine) have appeared principally, and most conspicuously, in the Archæologia, which may be termed the Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries. In that valuable collection will be found more than fifty memoirs, written and communicated by him, many of which are of considerable length, being by much the greatest number hitherto contributed by any individual member of that respectable Society.

In returning to the order of time, we find that, in July 1746, Mr. Pegge had the great misfortune to lose his Wife; whose monumental inscription, at Godmersham, bears ample testimony of her worth:

"MDCCXLVI.

Anna Clarke, uxor Samuelis Pegge

Vicarii hujus parochiæ;

Mulier, si qua alia, sine dolo,

Vitam æternam et beatam fidenter hic sperat;

nec erit frustra."

This event entirely changed Mr. Pegge's destinations; for he now zealously meditated on some mode of removing himself, without disadvantage, into his Native County. To effect this, one of two points was to be carried; either to obtain some piece of preferment, tenable in its nature with his Kentish Vicarage; or to exchange the[xxii] latter for an equivalent; in which last he eventually succeeded beyond his immediate expectations.

We are now come to a new epoch in the Doctor's life; but there is an interval of a few years to be accounted for, before he found an opportunity of effectually removing himself into Derbyshire.

His Wife being dead, his Children young and at school, and himself reduced to a life of solitude, so ungenial to his temper (though no man was better qualified to improve his leisure); he found relief by the kind offer of his valuable Friend, Sir Edward Dering, Bart.

At this moment Sir Edward chose to place his Son[12] under the care of a private Tutor at home, to qualify him more competently for the University. Sir Edward's personal knowledge of Mr. Pegge, added to the Family situation of the latter, mutually induced the former to offer, and the latter to accept, the proposal of removing from Godmersham to Surrenden (Sir Edward's mansion-house) to superintend Mr. Dering's education for a short time; in which capacity he continued about a year and a half, till Mr. Dering was admitted of St. John's College, Cambridge, in March 1751.

Sir Edward had no opportunity, by any patronage of his own, permanently to gratify Mr. Pegge, and to preserve him in the circle of their common Friends. On the other hand, finding Mr. Pegge's propensity to a removal so very strong, Sir Edward reluctantly pursued every possible measure to effect it.

The first vacant living in Derbyshire which offered itself was the Perpetual Curacy of Brampton, near Chesterfield; a situation peculiarly eligible in many respects. It became vacant in 1747; and, if it could have been obtained, would have placed Mr. Pegge in the centre of his early acquaintance in that County; and, being tenable with his Kentish living, would not have totally estranged him from his Friends in the South of England. The patronage of Brampton is in the Dean of Lincoln, which Dignity was then filled by the Rev. Dr. Thomas Cheyney; to whom, Mr. Pegge being a stranger, the application was necessarily to be made in a circuitous manner, and he was obliged to employ more than a double mediation before his name could be mentioned to the Dean.

The mode he proposed was through the influence of William the third Duke of Devonshire; to whom Mr. Pegge was personally known as a Derbyshire man (though he had so long resided in Kent), having always paid his respects to his[xxiv] Grace on the public days at Chatsworth, as often as opportunity served, when on a visit in Derbyshire. Mr. Pegge did not, however, think himself sufficiently in the Duke's favour to make a direct address for his Grace's recommendation to the Dean of Lincoln, though the object so fully met his wishes in moderation, and in every other point. He had, therefore, recourse to a friend, the Right Rev. Dr. Fletcher, Bishop of Dromore, then in England; who, in conjunction with Godfrey Watkinson, of Brampton Moor, Esq. (the principal resident Gentleman in the parish of Brampton) solicited, and obtained, his Grace's interest with the Dean of Lincoln: who, in consequence, nominated Mr. Pegge to the living.

One point now seemed to be gained towards his re-transplantation into his native soil, after he had resisted considerable offers had he continued in Kent; and thus did he think himself virtually in possession of a living in Derbyshire, which in its nature was tenable with Godmersham in Kent. Henceforward, then, he no doubt felt a satisfaction that he should soon be enabled to live in Derbyshire, and occasionally visit his friends in Kent, instead of residing in that county, and visiting his friends in Derbyshire.

But, after all this assiduity and anxiety (as if admission and ejection had pursued him a second[xxv] time), the result of Mr. Pegge's expectations was far from answering his then present wishes; for, when he thought himself secure by the Dean's nomination, and that nothing was wanting but the Bishop's licence, the Dean's right of Patronage was controverted by the Parishioners of Brampton, who brought forward a Nominee of their own.

The ground of this claim, on the part of the Parish, was owing to an ill-judged indulgence of some former Deans of Lincoln, who had occasionally permitted the Parishioners to send an Incumbent directly to the Bishop for his licence, without the intermediate nomination of the Dean in due form.

These measures were principally fomented by the son of the last Incumbent, the Rev. Seth Ellis, a man of a reprobate character, and a disgrace to his profession, who wanted the living, and was patronised by the Parish. He had a desperate game to play; for he had not the least chance of obtaining any preferment, as no individual Patron, who was even superficially acquainted with his moral character alone, could with decency advance him in the church. To complete the detail of the fate of this man, whose interest the deluded part of the mal-contents of the parish so warmly espoused, he was soon after[xxvi] suspended by the Bishop from officiating at Brampton[13].

Whatever inducements the Parish might have to support Mr. Ellis so strenuously we do not say, though they manifestly did not arise from any pique to one Dean more than to another; and we are decidedly clear that they were not founded in any aversion to Mr. Pegge as an individual; for his character was in all points too well established, and too well known (even to the leading opponents to the Dean), to admit of the least personal dislike in any respect. So great, nevertheless, was the acrimony with which the Parishioners pursued their visionary pretensions to the Patronage, that, not content with the decision of the Jury (which was highly respectable) in favour of the Dean, when the right of Patronage was tried in 1748; they had the audacity to carry the cause to an Assize at Derby, where, on the fullest and most incontestable evidence, a verdict was given in favour of the Dean, to the confusion and indelible disgrace of those Parishioners who espoused[xxvii] so bad a cause, supported by the most undaunted effrontery.

The evidence produced by the Parish went to prove, from an entry made nearly half a century before in the accompts kept by the Churchwardens, that the Parishioners, and not the Deans of Lincoln, had hitherto, on a vacancy, nominated a successor to the Bishop of the Diocese for his licence, without the intervention of any other person or party. The Parish accompts were accordingly brought into court at Derby, wherein there appeared not only a palpable erasement, but such an one as was detected by a living and credible witness; for, a Mr. Mower swore that, on a vacancy in the year 1704, an application was made by the Parish to the Dean of Lincoln in favour of the Rev. Mr. Littlewood[14].

In corroboration of Mr. Mower's testimony, an article in the Parish accompts and expenditures of that year was adverted to, and which, when Mr. Mower saw it, ran thus:

"Paid William Wilcoxon, for going to Lincoln to the Dean concerning Mr. Littlewood, five shillings."

The Parishioners had before alleged, in proof[xxviii] of their title, that they had elected Mr. Littlewood; and, to uphold this asseveration, had clumsily altered the parish accompt-book, and inserted the words "to Lichfield to the Bishop," in the place of the words "to Lincoln to the Dean."

Thus their own evidence was turned against the Parishioners; and not a moment's doubt remained but that the patronage rested with the Dean of Lincoln.

We have related this affair without a strict adherence to chronological order as to facts, or to collateral circumstances, for the sake of preserving the narrative entire, as far as it regards the contest between the Dean of Lincoln and the Parish of Brampton; for we believe that this transaction (uninteresting as it may be to the publick in general) is one of very few instances on record which has an exact parallel.

The intermediate points of the contest, in which Mr. Pegge was more peculiarly concerned, and which did not prominently appear to the world, were interruptions and unpleasant impediments which arose in the course of this tedious process.

He had been nominated to the Perpetual Curacy of Brampton by Dr. Cheyney, Dean of Lincoln; was at the sole expence of the suit respecting the right of Patronage, whereby the verdict was given in favour of the Dean; and he was actually[xxix] licensed by the Bishop of Lichfield. In consequence of this decision and the Bishop's licence, Mr. Pegge, not suspecting that the contest could go any farther, attended to qualify at Brampton, on Sunday, August 28, 1748, in the usual manner; but was repelled by violence from entering the Church.

In this state matters rested regarding the Patronage of Brampton, when Dr. Cheyney was unexpectedly transferred from the Deanry of Lincoln to the Deanry of Winchester, which (we may observe by the way) he solicited on motives similar to those which actuated Mr. Pegge at the very moment; for Dr. Cheyney, being a Native of Winchester, procured an exchange of his Deanry of Lincoln with the Rev. Dr. William George, Provost of Queen's college, Cambridge, for whom the Deanry of Winchester was intended by the Minister on the part of the Crown.

Thus Mr. Pegge's interests and applications were to begin de novo with the Patron of Brampton; for, his nomination by Dr. Cheyney, in the then state of things, was of no validity. He fell, however, into liberal hands; for his activity in the proceedings which had hitherto taken place respecting the living in question had rendered fresh advocates unnecessary, as it had secured the unasked favour of Dr. George, who not long afterwards[xxx] voluntarily gave him the Rectory of Whittington, near Chesterfield, in Derbyshire; into which he was inducted Nov. 11, 1751, and where he resided for upwards of 44 years without interruption[15].

Though Mr. Pegge had relinquished all farther pretensions to the living of Brampton before the cause came to a decision at Derby, yet he gave every possible assistance at the trial, by the communication of various documents, as well as by his personal evidence at the Assize, to support the claim of the new Nominee, the Rev. John Bowman, in whose favour the verdict was given, and who afterwards enjoyed the benefice.

Here then we take leave of this troublesome affair, so nefarious and unwarrantable on the part of the Parishioners of Brampton; and from which Patrons of every description may draw their own inferences.

Mr. Pegge's ecclesiastical prospect in Derbyshire began soon to brighten; and he ere long obtained the more eligible living of Whittington. Add to this that, in the course of the dispute[xxxi] concerning the Patronage of Brampton, he became known to the Hon. and Right Rev. Frederick (Cornwallis) Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry; who ever afterwards favoured him not only with his personal regard, but with his patronage, which extended even beyond the grave, as will be mentioned hereafter in the order of time.

We must now revert to Mr. Pegge's old Friend Sir Edward Dering, who, at the moment when Mr. Pegge decidedly took the living of Whittington, in Derbyshire, began to negotiate with his Grace of Canterbury (Dr. Herring), the Patron of Godmersham, for an exchange of that living for something tenable with Whittington.

The Archbishop's answer to this application was highly honourable to Mr. Pegge: "Why," said his Grace, "will Mr. Pegge leave my Diocese? If he will continue in Kent, I promise you, Sir Edward, that I will give him preferment to his satisfaction[16]."

No allurements, however, could prevail; and Mr. Pegge, at all events, accepted the Rectory of[xxxii] Whittington, leaving every other pursuit of the kind to contingent circumstances. An exchange was, nevertheless, very soon afterwards effected, by the interest of Sir Edward with the Duke of Devonshire, who consented that Mr. Pegge should take his Grace's Rectory of Brinhill[17] in Lancashire, then luckily void, the Archbishop at the same time engaging to present the Duke's Clerk to Godmersham. Mr. Pegge was accordingly inducted into the Rectory of Brindle, Nov. 23, 1751, in less than a fortnight after his induction at Whittington[18].

In addition to this favour from the Family of Cavendish, Sir Edward Dering obtained for Mr. Pegge, almost at the same moment, a scarf from the Marquis of Hartington (afterwards the fourth Duke of Devonshire), then called up to the House of Peers, in June 1751, by the title of Baron Cavendish of Hardwick. Mr. Pegge's appointment is dated Nov. 18, 1751; and thus, after all his solicitude, he found himself possessed of two livings and a dignity, honourably and indulgently conferred, as well as most desirably connected, in the same year and in the same month; though this latter circumstance may be[xxxiii] attributed to the voluntary lapse of Whittington[19]. After Mr. Pegge had held the Rectory of Brinhill for a few years, an opportunity offered, by another obliging acquiescence of the Duke of Devonshire, to exchange it for the living of Heath (alias Lown), in his Grace's Patronage, which lies within seven miles of Whittington: a very commodious measure, as it brought Mr. Pegge's parochial preferments within a smaller distance of each other. He was accordingly inducted into the Vicarage of Heath, Oct. 22, 1758, which he held till his death.

This was the last favour of the kind which Mr. Pegge individually received from the Dukes of Devonshire; but the Compiler of this little Memoir regarding his late Father, flatters himself that it can give no offence to that Noble Family if he takes the opportunity of testifying a sense of his own personal obligations to William the fourth Duke of Devonshire, when his Grace was Lord Chamberlain of his Majesty's Household.

As to Mr. Pegge's other preferments, they shall only be briefly mentioned in chronological order;[xxxiv] but with due regard to his obligations. In the year 1765 he was presented to the Perpetual Curacy of Wingerworth, about six miles from. Whittington, by the Honourable and Reverend James Yorke, then Dean of Lincoln, afterwards Bishop of Ely, to whom he was but little known but by name and character. This appendage was rendered the more acceptable to Mr. Pegge, because the seat of his very respectable Friend Sir Henry Hunloke, Bart. is in the parish, from whom, and all the Family, Mr. Pegge ever received great civilities.

We have already observed, that Mr. Pegge became known, insensibly as it were, to the Honourable and Right Reverend Frederick (Cornwallis), Bishop of Lichfield, during the contest respecting the living of Brampton; from whom he afterwards received more than one favour, and by whom another greater instance of regard was intended, as will be mentioned hereafter.

Mr. Pegge was first collated by his Lordship to the Prebend of Bobenhull, in the Church of Lichfield, in 1757; and was afterwards voluntarily advanced by him to that of Whittington in 1763, which he possessed at his death[20].

In addition to the Stall at Lichfield, Mr. Pegge enjoyed the Prebend of Louth, in the Cathedral of Lincoln, to which he had been collated (in 1772) by his old acquaintance, and Fellow-collegian, the late Right Reverend John Green, Bishop of that See[21].

This seems to be the proper place to subjoin, that, towards the close of his life, Mr. Pegge declined a situation for which, in more early days, he had the greatest predilection, and had taken every active and modest measure to obtain—a Residentiaryship in the Church of Lichfield.

Mr. Pegge's wishes tended to this point on laudable, and almost natural motives, as soon as his interest with the Bishop began to gain strength; for it would have been a very pleasant interchange, at that period of life, to have passed a portion of the year at Lichfield. This expectation, however, could not be brought forward till he was too far advanced in age to endure with tolerable convenience a removal from time to[xxxvi] time; and therefore, when the offer was realized, he declined the acceptance.

The case was literally this: While Mr. Pegge's elevation in the Church of Lichfield rested solely upon Bishop (Frederick) Cornwallis, it was secure, had a vacancy happened: but his Patron was translated to Canterbury in 1768, and Mr. Pegge had henceforward little more than personal knowledge of any of his Grace's Successors at Lichfield, till the Hon. and Right Reverend James Cornwallis (the Archbishop's Nephew) was consecrated Bishop of that See in 1781.

On this occasion, to restore the balance in favour of Mr. Pegge, the Archbishop had the kindness to make an Option of the Residentiaryship at Lichfield, then possessed by the Rev. Thomas Seward. It was, nevertheless, several years before even the tender of this preferment could take place; as his Grace of Canterbury died in 1783, while Mr. Seward was living.

Options being personal property, Mr. Pegge's interest, on the demise of the Archbishop, fell into the hands of the Hon. Mrs. Cornwallis, his Relict and Executrix, who fulfilled his Grace's original intention in the most friendly manner, on the death of Mr. Seward, in 1790[22].

The little occasional transactions which primarily brought Mr. Pegge within the notice of Bishop (Frederick) Cornwallis at Eccleshall-castle led his Lordship to indulge him with a greater share of personal esteem than has often fallen to the lot of a private Clergyman so remotely placed from his Diocesan. Mr. Pegge had attended his Lordship two or three times on affairs of business, as one of the Parochial Clergy, after which the Bishop did him the honour to invite him to make an annual visit at Eccleshall-castle as an Acquaintance. The compliance with this overture was not only very flattering, but highly gratifying, to Mr. Pegge, who consequently waited upon his Lordship for a fortnight in the Autumn, during several years, till the Bishop was translated to the Metropolitical See of Canterbury in 1768. After this, however, his Grace did not forget his humble friend, the Rector of[xxxviii] Whittington, as will be seen; and sometimes corresponded with him on indifferent matters.

About the same time that Mr. Pegge paid these visits at Eccleshall-castle, he adopted an expedient to change the scene, likewise, by a journey to London (between Easter and Whitsuntide); where, for a few years, he was entertained by his old Friend and Fellow-collegian the Rev. Dr. John Taylor, F. S. A. Chancellor of Lincoln, &c. (the learned Editor of Demosthenes and Lysias), then one of the Residentiaries of St. Paul's.

After Dr. Taylor's death (1766), the Bishop of Lincoln, Dr. John Green, another old College-acquaintance, became Mr. Pegge's London-host for a few years, till Archbishop Cornwallis began to reside at Lambeth. This event superseded the visits to Bishop Green, as Mr. Pegge soon afterwards received a very friendly invitation from his Grace; to whom, from that time, he annually paid his respects at Lambeth-palace, for a month in the Spring, till the Archbishop's decease, which took place about Easter 1783.

All these were delectable visits to a man of Mr. Pegge's turn of mind, whose conversation was adapted to every company, and who enjoyed the world with greater relish from not living in it every day. The society with which he intermixed, in such excursions, changed his ideas,[xxxix] and relieved him from the tædium of a life of much reading and retirement; as, in the course of these journeys, he often had opportunities of meeting old Friends, and of making new literary acquaintance.

On some of these occasions he passed for a week into Kent, among such of his old Associates as were then living, till the death of his much-honoured Friend, and former Parishioner, the elder Thomas Knight, Esq. of Godmersham, in 1781[23]. We ought on no account to omit the mention of some extra-visits which Mr. Pegge occasionally made to Bishop Green, at Buckden, to which we are indebted for the Life of that excellent Prelate Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln;—a work upon which we shall only observe here, that it is Dr. Pegge's chef-d'œuvre, and merits from the world much obligation. To these interviews with Bishop Green, we may also attribute those ample Collections, which Dr. Pegge left among his MSS. towards a History of the Bishops of Lincoln, and of that Cathedral in general, &c. &c.

With the decease of Archbishop Cornwallis (1783), Mr. Pegge's excursions to London terminated.[xl] His old familiar Friends, and principal acquaintance there, were gathered to their fathers; and he felt that the lot of a long life had fallen upon him, having survived not only the first, but the second class of his numerous distant connexions.

While on one of these visits at Lambeth, the late Gustavus Brander, Esq. F. S. A. who entertained an uncommon partiality for Mr. Pegge, persuaded him, very much against his inclination, to sit for a Drawing, from which an octavo Print of him might be engraved by Basire. The Work went on so slowly, that the Plate was not finished till 1785, when Mr. Pegge's current age was 81. Being a private Print, it was at first only intended for, and distributed among, the particular Friends of Mr. Brander and Mr. Pegge. This Print, however, now carries with it something of a publication; for a considerable number of the impressions were dispersed after Mr. Brander's death, when his Library, &c. were sold by auction; and the Print is often found prefixed to copies of "The Forme of Cury," a work which will hereafter be specified among Mr. Pegge's literary labours[24].

The remainder of Mr. Pegge's life after the year 1783 was, in a great measure, reduced to a state of quietude; but not without an extensive correspondence with the world in the line of Antiquarian researches: for he afterwards contributed largely to the Archæologia, and the Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, &c. &c. as may appear to those who will take the trouble to compare the dates of his Writings, which will hereafter be enumerated, with the time of which we are speaking.

The only periodical variation in life, which attended Mr. Pegge after the Archbishop's death, consisted of Summer visits at Eccleshall-castle to the present Bishop (James) Cornwallis, who (if[xlii] we may be allowed the word) adopted Mr. Pegge as his guest so long as he was able to undertake such journeys.

We have already seen an instance of his Lordship's kindness in the case of the intended Residentiaryship; and have, moreover, good reasons to believe that, had the late Archdeacon of Derby (Dr. Henry Egerton) died at an earlier stage of Mr. Pegge's life, he would have succeeded to that dignity.

This part of the Memoir ought not to be dismissed without observing, to the honour of Mr. Pegge, that, as it was not in his power to make any individual return (in his life-time) to his Patrons, the two Bishops of Lichfield of the name of Cornwallis, for their extended civilities, he directed, by testamentary instructions, that one hundred volumes out of his Collection of Books should be given to the Library of the Cathedral of Lichfield[25].

During Mr. Pegge's involuntary retreat from his former associations with the more remote parts of the Kingdom, he was actively awake to such objects in which he was implicated nearer home.

Early in the year 1788 material repairs and considerable alterations became necessary to the[xliii] Cathedral of Lichfield. A subscription was accordingly begun by the Members of the Church, supported by many Lay-gentlemen of the neighbourhood; when Mr. Pegge, as a Prebendary, not only contributed handsomely, but projected, and drew up, a circular letter, addressed to the Rev. Charles Hope, M. A. the Minister of All Saints (the principal) Church in Derby, recommending the promotion of this public design. The Letter, being inserted in several Provincial Newspapers, was so well seconded by Mr. Hope, that it had a due effect upon the Clergy and Laity of the Diocese in general; for which Mr. Pegge received a written acknowledgment of thanks from the present Bishop of Lichfield, dated May 29, 1788.

This year (1788), memorable as a Centenary in the annals of England, was honourable to the little Parish of Whittington, which accidentally bore a subordinate local part in the History of the Revolution; for it was to an inconsiderable public-house there (still called the Revolution-house) that the Earl of Devonshire, the Earl of Danby, the Lord Delamere, and the Hon. John D'Arcy, were driven for shelter, by a sudden shower of rain, from the adjoining common (Whittington-Moor), where they had met by appointment, disguised as farmers, to concert measures, unobservedly, for promoting the succession of[xliv] King William III. after the abdication of King James II.[26]

The celebration of this Jubilee, on Nov. 5, 1788, is related at large in the Gentleman's Magazine of that month[27]; on which day Mr. Pegge preached a Sermon[28], apposite to the occasion, which was printed at the request of the Gentlemen of the Committee who conducted the ceremonial[29], which proceeded from his Church to Chesterfield in grand procession.

In the year 1791 (July 8) Mr. Pegge was created D. C. L. by the University of Oxford, at the Commemoration. It may be thought a little extraordinary that he should accept an advanced Academical Degree so late in life, as he wanted no such aggrandizement in the Learned World, or among his usual Associates, and had voluntarily closed all his expectations of ecclesiastical[xlv] elevation. We are confident that he was not ambitious of the compliment; for, when it was first proposed to him, he put a negative upon it. It must be remembered that this honour was not conferred on an unknown man (novus homo); but on a Master of Arts of Cambridge, of name and character, and of acknowledged literary merit[30]. Had Mr. Pegge been desirous of the title of Doctor in earlier life, there can be no doubt but that he might have obtained the superior degree of D. D. from Abp. Cornwallis, upon the bare suggestion, during his familiar and domestic conversations with his Grace at Lambeth-palace.

Dr. Pegge's manners were those of a gentleman of a liberal education, who had seen much of the world, and had formed them upon the best models within his observation. Having in his early years lived in free intercourse with many of the principal and best-bred Gentry in various parts of Kent; he ever afterwards preserved the same attentions, by associating with respectable company, and (as we have seen) by forming honourable attachments.

In his avocations from reading and retirement, few men could relax with more ease and cheerfulness, or better understood the desipere in loco;—could[xlvi] enter occasionally into temperate convivial mirth with a superior grace, or more interest and enliven every company by general conversation.

As he did not mix in business of a public nature, his better qualities appeared most conspicuously in private circles; for he possessed an equanimity which obtained the esteem of his Friends, and an affability which procured the respect of his dependents.

His habits of life were such as became his profession and station. In his clerical functions he was exemplarily correct, not entrusting his parochial duties at Whittington (where he constantly resided) to another (except to the neighbouring Clergy during the excursions before-mentioned) till the failure of his eye-sight rendered it indispensably necessary; and even that did not happen till within a few years of his death.

As a Preacher, his Discourses from the pulpit were of the didactic and exhortatory kind, appealing to the understandings rather than to the passions of his Auditory, by expounding the Holy Scriptures in a plain, intelligible, and unaffected manner. His voice was naturally weak, and suited only to a small Church; so that when he occasionally appeared before a large Congregation (as on Visitations, &c.), he was heard to a disadvantage. He left in his closet considerably more[xlvii] than 230 Sermons composed by himself, and in his own hand-writing, besides a few (not exceeding 26) which he had transcribed (in substance only, as appears by collation) from the printed works of eminent Divines. These liberties, however, were not taken in his early days, from motives of idleness, or other attachments—but later in life, to favour the fatigue of composition; all which obligations he acknowledged at the end of each such Sermon.

Though Dr. Pegge's life was sedentary, from his turn to studious retirement, his love of Antiquities, and of literary acquirements in general; yet these applications, which he pursued with, great ardour and perseverance, did not injure his health. Vigour of mind, in proportion to his bodily strength, continued unimpaired through a very extended course of life, and nearly till he had reached "ultima linea rerum:" for he never had any chronical disease; but gradually and gently sunk into the grave under the weight of years, after a fortnight's illness, Feb. 14, 1796, in the 92d year of his age.

He was buried, according to his own desire, in the chancel at Whittington, where a mural tablet of black marble (a voluntary tribute of filial respect) has been placed, over the East window with the following short inscription:

"At the North End of the Altar Table, within the Rails,

lie the Remains of

Samuel Pegge, LL. D.

who was inducted to this Rectory Nov. 11, 1751,

and died Feb. 14, 1796;

in the 92d year of his Age."

Having closed the scene; it must be confessed, on the one hand, that the biographical history of an individual, however learned, or engaging to private friends, who had passed the major part of his days in secluded retreats from what is called the world, can afford but little entertainment to the generality of Readers. On the other hand, nevertheless, let it be allowed that every man of acknowledged literary merit, had he made no other impression, cannot but have left many to regret his death.

Though Dr. Pegge had exceeded even his "fourscore years and ten," and had outlived all his more early friends and acquaintance; he had the address to make new ones, who now survive, and who, it is humbly hoped, will not be sorry to see a modest remembrance of him preserved by this little Memoir.

Though Dr. Pegge had an early propensity to the pursuit of Antiquarian knowledge, he never indulged himself materially in it, so long as more essential and professional occupations had a claim upon him; for he had a due sense of the nature[xlix] and importance of his clerical function. It appears that he had read the Greek and Latin Fathers diligently at his outset in life. He had also re-perused the Classicks attentively before he applied much to the Monkish Historians, or engaged in Antiquarian researches; well knowing that a thorough knowledge of the Learning of the Antients, conveyed by classical Authors, was the best foundation for any literary structure which had not the Christian Religion for its cornerstone.

During the early part of his incumbency at Godmersham in Kent, his reading was principally such as became a Divine, or which tended to the acquisition of general knowledge, of which he possessed a greater share than most men we ever knew. When he obtained allowable leisure to follow unprofessional pursuits, he attached himself more closely to the study of Antiquities; and was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, Feb. 14, 1751, N. S. in which year the Charter of Incorporation was granted (in November), wherein his name stands enrolled among those of many very respectable and eminently learned men[31].

Though we will be candid enough to allow that Dr. Pegge's style in general was not sufficiently terse and compact to be called elegant; yet he made ample amends by the matter, and by the accuracy with which he treated every copious subject, wherein all points were matured by close examination and sound judgment[32].

and a fund of knowledge, more than would have displayed itself in any greater work, where the subject requires but one bias, and one peculiar attention[33].

It is but justice to say, that few men were so liberal in the diffusion of the knowledge which he had acquired, or more ready to communicate it, either vivâ voce, or by the loan of his MSS. as many of his living Friends can testify.

In his publications he was also equally disinterested as in his private communications; for he never, as far as can be recollected, received any pecuniary advantage from any pieces that he printed, committing them all to the press, with the sole reserve of a few copies to distribute among his particular Friends[34]. —No. III. 1766. "An Essay on the Coins of Cunobelin; in an Epistle to the Right Rev. Bishop of Carlisle [Charles Lyttelton], President of the Society of Antiquaries." [105 pages, 4to.] [This collection of coins is classed in two plates, and illustrated by a Commentary, together with observations on the word tascia. N. B. The impression consisted of no more than 200 copies.]—No. IV. 1772. "An Assemblage of Coins fabricated by Authority of the Archbishops of Canterbury. To which are subjoined, Two Dissertations." [125 pages, 4to.] 1. On a fine Coin of Alfred the Great, with his Head. 2. On an Unic, in the Possession of the late Mr. Thoresby, supposed to be a Coin of St. Edwin; but shewn to be a Penny of Edward the Confessor. [An Essay is annexed on the origin of metropolitical and other subordinate mints; with an Account of their Progress and final Determination: together with other incidental Matters, tending to throw light on a branch of the Science of Medals, not perfectly considered by English Medalists.]—No. V. 1772. "Fitz-Stephen's Description of the City of London, newly translated from the Latin Original, with a necessary Commentary, and a Dissertation on the Author, ascertaining the exact Year of the Production; to which are added, a correct Edition of the Original, with the various Readings, and many Annotations." [81 pages, 4to.] [This publication (well known now to have been one of the works of Dr. Pegge) was, as we believe, brought forward at the instance of the Hon. Daines Barrington, to whom it is inscribed. The number of copies printed was 250.]—No. VI. 1780. "The Forme of Cury. A Roll of antient English Cookery, compiled about the Year 1390, Temp. Ric. II. with a copious Index and Glossary." [8vo.] [The curious Roll, of which this is a copy, was the property of the late Gustavus Brander, esq. It is in the hand-writing of the time, a facsimile of which is given facing p. xxxi. of the Preface. The work before us was a private impression; but as, since Mr. Brander's decease, it has fallen, by sale, into a great many hands, we refer to the Preface for a farther account of it. Soon after Dr. Pegge's elucidation of the Roll was finished, Mr. Brander presented the autograph to the British Museum.]—No. VII. 1789. "Annales Eliæ de Trickenham, Monachi Ordinis Benedictini. Ex Bibliothecâ Lamethanâ." To which is added, "Compendium Compertorum. Ex Bibliothecâ Ducis Devoniæ." [4to.] [Both parts of this publication contain copious annotations by the Editor. The former was communicated by Mr. John Nichols, Printer, to whom it is inscribed. The latter was published by permission of his Grace the Duke of Devonshire, to whom it is dedicated. The respective Prefaces to these pieces will best explain the nature of them.]—No. VIII. 1793. "The Life of Robert Grosseteste, the celebrated Bishop of Lincoln." [4to.] [This Work we have justly called his chef-d'œuvre; for, in addition to the life of an individual, it comprises much important history of interesting times, together with abundant collateral matter.]—The two following works have appeared since the Writer's death: No. IX. 1801. "An Historical Account of Beauchief Abbey, in the County of Derby, from its first Foundation to its final Dissolution. Wherein the three following material Points, in opposition to vulgar Prejudices, are clearly established: 1st, That this Abbey did not take its name from the Head of Archbishop Becket, though it was dedicated to him. 2d, That the Founder of it had no hand in the Murder of that Prelate; and, consequently, that the House was not erected in Expiation of that Crime. 3d, The Dependance of this House on that of Welbeck, in the County of Nottingham; a Matter hitherto unknown." [4to.]—No. X. 1809. "Anonymiana; or, Ten Centuries of Observations on various Authors and Subjects. Compiled by a late very learned and reverend Divine; and faithfully published from the original MS. with the Addition of a copious Index." [8vo.]]

In the following Catalogue we must be allowed to deviate from chronological order, for the sake[liv] of preserving Dr. Pegge's contributions to various periodical and contingent Publications, distinct from his independent Works; to all which,[lv] however, we shall give (as far as possible) their respective dates.

The greatest honour, which a literary man can obtain, is the eulogies of those who possessed[lvii] equal or more learning than himself. "Laudatus à laudatis viris" may peculiarly and deservedly be said of Dr. Pegge, as might be exemplified from the frequent[lviii] mention made of him by the most respectable contemporary writers in the Archæological line; but modesty forbids our enumerating them.

The annexed View was taken in 1789, by the ingenious Mr. Jacob Schnebbelie; and the following concise account of it was communicated in 1793, by the then worthy and venerable Rector.

"Whittington, of whose Church the annexed Plate contains a Drawing by the late Mr. Schnebbelie, is a small parish of about 14 or 15 hundred acres, distant from the church and old market-place of Chesterfield about two miles and a half. It lies in the road from Chesterfield to Sheffield and Rotherham, whose roads divide there at the well-known inn The Cock and Magpye, commonly called The Revolution House.

The situation is exceedingly pleasant, in a pure and excellent air. It abounds with all kinds of conveniences for the use of the inhabitants, as coal, stone, timber, &c.; besides its proximity to a good market, to take its products.

The Church is now a little Rectory, in the gift of the Dean of Lincoln. At first it was a Chapel of Ease to Chesterfield, a very large manor and parish; of which I will give the following short but convincing proof. The Dean of Lincoln, as I said, is Patron of this Rectory, and yet William Rufus gave no other church in this part of Derbyshire to the church of St. Mary at Lincoln but the church of Chesterfield; and, moreover, Whittington is at this day a parcel of the great and extensive manor of Chesterfield; whence it follows, that Whittington must have been once a part both of the rectory and manor of Chesterfield. But whence comes it, you will say, that it became a rectory, for such it has been many years? I answer, I neither know how nor when; but it is certain that chapels of ease have been frequently converted into rectories, and I suppose by mutual agreement of the curate of the chapel, the rector of the mother church, and the diocesan. Instances of the like emancipation of chapels, and transforming them into independent rectories, there are several in the county of Derby, as Matlock, Bonteshall, Bradley, &c.; and others may be found in Mr. Nichols's "History of Hinckley," and in his "Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica," No. VI.

Fig. 1 is an inscription on the Ting-tang, or Saints Bell, of Whittington Church, drawn by Mr. Schnebbelie, 27 July, 1789, from an impression taken in clay. This bell, which is seen in the annexed view, hangs within a stone frame, or tabernacle, at the top of the church, on the outside between the Nave and the Chancel. It has a remarkable fine shrill tone, and is heard, it is said, three or four miles off, if the wind be right. It is very antient, as appears both from the form of the letters, and the name (of the donor, I suppose), which is that in use before surnames were common. Perhaps it may be as old as the fabrick of the church itself, though this is very antient.

Fig. 2 is a stone head, near the roof on the North side of the church.

In the East window of the church is a small Female Saint.

In this window, A. a fess Vaire G. and O. between three water-bougets Sable. Dethick.

Cheque A. and G. on a bend S. a martlet. Beckering.

At the bottom of this window an inscription,

Rogero Cric.

Roger Criche was rector, and died 1413, and probably made the window. He is buried within the rails of the communion-table, and his slab is engraved in the second volume of Mr. Gough's "Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain," Plate XIX. p. 37. Nothing remains of the inscription but Amen.

In the upper part of the South window of the Chancel, is a picture in glass of our Saviour with the five Wounds; an angel at his left hand sounding a trumpet[35].—On a pane of the upper tier of the West window is the portrait of St. John; his right hand holding a book with the Holy Lamb upon it: and the forefinger of his left hand pointing to the Cross held by the Lamb, as uttering his well-known confession: "Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world[35]."

In the South window of the Chancel is, Barry wavy of 6 A. and G. a chief A. Ermine and Gules. Barley.

Ermine, on a chief indented G. or lozengé.

In the Easternmost South window of the nave is A. on a chevron Sable, three quatrefoils Argent. Eyre.

This window has been renewed; before which there were other coats and some effigies in it.

Jan. 1, 1793.

Samuel Pegge, Rector."

This View was taken also, in 1789, by Mr. Schnebbelie; and the account of it drawn up in 1793 by Dr. Pegge, then resident in it, at the advanced age of 88.

"The Parsonage-house at Whittington is a convenient substantial stone building, and very sufficient for this small benefice. It was, as I take it, erected by the Rev. Thomas Callice, one of my predecessors; and, when I had been inducted, I enlarged it, by pulling down the West end, making a cellar, a kitchen, a brew-house, and a pantry, with chambers over them. There is a glebe of about 30 acres belonging to it with a garden large enough for a family, and a small orchard. The garden is remarkably pleasant in respect to its fine views to the North, East, and South, with the Church to the West. There is a fair prospect of Chesterfield Church, distant about two miles and a half; and of Bolsover Castle to the West; and, on the whole, this Rectorial house may be esteemed a very delightful habitation.

S. Pegge."

In this Parsonage the Editor of the present Volume, accompanied by his late excellent Friend Mr. Gough, spent many happy hours with the worthy Rector for several successive years, and derived equal information and pleasure from his instructive conversation.

To complete the little series of Views at Whittington more immediately connected with Dr. Pegge, a third plate is here given, from another Drawing by Mr. Schnebbelie, of the small public-house at Whittington, which has been handed down to posterity for above a century under the honourable appellation of "The Revolution House." It obtained that name from the accidental meeting of two noble personages, Thomas Osborne Earl of Danby, and William Cavendish Earl of Devonshire, with a third person, Mr. John[lxiii] D'Arcy[36], privately one morning, 1688, upon Whittington, Moor, as a middle place between Chatsworth, Kniveton, and Aston, their respective residences, to consult about the Revolution, then in agitation[37]; but a shower of rain happening to fall, they removed to the village for shelter, and finished their conversation at a public-house there, the sign of The Cock and Pynot[38].

The part assigned to the Earl of Danby was, to surprize York; in which he succeeded: after which, the Earl of Devonshire was to take measures at Nottingham, where the Declaration for a free Parliament, which he, at the head of a number of Gentlemen of Derbyshire, had signed Nov. 28, 1688[39], was adopted by the Nobility, Gentry, and Commonalty of the Northern Counties, assembled there for the defence of the Laws, Religion, and Properties[40].

The success of these measures is well known; and to the concurrence of these Patriots with the proceedings in favour of the Prince of Orange in the West, is this Nation indebted for the establishment of her rights and liberties at the glorious Revolution.

The cottage here represented stands at the point where the road from Chesterfield divides into two branches, to Sheffield and Rotherham. The room where the Noblemen sat is 15 feet by 12 feet 10, and is to this day called The Plotting Parlour. The old armed chair, still remaining in it, is shewn by the landlord with particular satisfaction, as that in which it is said the Earl of Devonshire sat; and he tells with equal pleasure, how it was visited by his descendants, and the descendants of his associates, in the year 1788. Some new rooms, for the better accommodation of customers, were added about 20 years ago.

The Duke of Leeds' own account of his meeting the Earl of Devonshire and Mr. John D'Arcy[41] at Whittington, in the County of Derby, A. D. 1688.

The Earl of Derby, afterwards Duke of Leeds, was impeached, A.D. 1678, of High Treason by the House of Commons, on a charge of being in the French interest, and, in particular, of being Popishly affected: many, both Peers and Commoners, were misled, and had conceived an erroneous opinion concerning him and his political conduct. This he has stated himself, in the Introduction to his Letters, printed A. 1710, where he says, "That the malice of my accusation did so manifestly appear in that article wherein I was charged to be Popishly affected, that I dare swear there was not one of my accusers that did then believe that article against me."

His Grace then proceeds, for the further clearing of himself, in these memorable words, relative to the meeting at Whittington, the subject of this memoir.

"The Duke of Devonshire also, when we were partners in the secret trust about the Revolution, and who did meet me and Mr. John D'Arcy, for that purpose, at a town called Whittington, in Derbyshire, did, in the presence of the said Mr. D'Arcy, make a voluntary acknowledgment of the great mistakes he had been led into about me; and said, that both he, and most others, were entirely convinced of their error. And he came to Sir Henry Goodrick's house in Yorkshire purposely to meet me there again, in order to concert the times and methods by which he should act at Nottingham (which was to be his post), and one at York (which was to be mine); and we agreed, that I should first attempt to surprize York, because there was a small garrison with a Governor there; whereas[lxv] Nottingham was but an open town, and might give an alarm to York, if he should appear in arms before I had made my attempt upon York; which was done accordingly[42]; but is mistaken in divers relations of it. And I am confident that Duke (had he been now alive) would have thanked nobody for putting his prosecution of me amongst the glorious actions of his life."

Celebration of the Revolution Jubilee, at Whittington and Chesterfield, on the 4th and 5th of November, 1788.

On Tuesday the 4th instant, the Committee appointed to conduct the Jubilee had a previous meeting, and dined together at the Revolution House in Whittington. His Grace the Duke of Devonshire, Lord Stamford, Lord George and Lord John Cavendish, with several neighbouring Gentlemen, were present. After dinner a subscription was opened for the erecting of a Monumental Column, in Commemoration of the Glorious Revolution, on that spot where the Earls of Devonshire and Danby, Lord Delamere, and Mr. John D'Arcy, met to concert measures which were eminently instrumental in rescuing the Liberties of their Country from perdition. As this Monument is intended to be not less a mark of public Gratitude, than the memorial of an important event; it was requested, that the present Representatives of the above-mentioned families would excuse their not being permitted to join in the expence.

On the 5th, at eleven in the morning, the commemoration commenced with divine service at Whittington Church. The Rev. Mr. Pegge, the Rector of the Parish, delivered an excellent Sermon from the words "This is the day, &c." Though of a great age, having that very morning entered his 85th year, he spoke with a spirit which seemed to be derived from the occasion, his sentiments were pertinent, well arranged, and his expression animated.

The descendants of the illustrious houses of Cavendish, Osborne, Boothe, and Darcy (for the venerable Duke of Leeds, whose age would not allow him to attend, had sent his two grandsons, in whom the blood of Osborne and D'Arcy is united); a numerous and powerful gentry; a wealthy and respectable yeomanry; a hardy, yet decent and attentive peasantry; whose intelligent countenances shewed that they understood, and would be firm to preserve that blessing, for which they were assembled to return thanks to Almighty God, presented a truly solemn spectacle, and to the eye of a philosopher the most interesting that can be imagined.

After service the company went in succession to view the old house, and the room called by the Anti-revolutionists "The Plotting-Parlour," with the old armed-chair in which the Earl of Devonshire is said to have sitten, and every one was then pleased to partake of a very elegant cold collation, which was prepared in the new rooms annexed to the cottage. Some time being spent in this, the procession began:

Constables with long staves, two and two.

The Eight Clubs, four and four; viz.

1. Mr. Deakin's: Flag, blue, with orange fringe, on it the figure of Liberty, the motto, "The Protestant Religion, and the Liberties of England, we will maintain."

2. Mr. Bluett's: Flag, blue, fringed with orange, motto, "Libertas; quæ sera, tamen respexit inertem."[lxvii] Underneath the figure of Liberty crowning Britannia with a wreath of laurels, who is represented sitting on a Lion, at her feet the Cornucopiæ of Plenty; at the top next the pole, a Castle, emblematical of the house where the club is kept; on the lower side of the flag Liberty holding a Cap and resting on the Cavendish arms.

3. Mr. Ostliff's: Flag, broad blue and orange stripe, with orange fringe; in the middle the Cavendish arms; motto as No. 1.

4. Mrs. Barber's: Flag, garter blue and orange quarter'd, with white fringe, mottoes, "Liberty secured." "The Glorious Revolution 1688."

5. Mr. Valentine Wilkinson's: Flag, blue with orange fringe, in the middle the figure of Liberty; motto as No. 1.

6. Mr. Stubbs: Flag, blue with orange fringe, motto, "Liberty, Property, Trade, Manufactures;" at the top a head of King William crowned with laurel, in the middle in a large oval, "Revolution 1688." On one side the Cap of Liberty, on the other the figure of Britannia; on the opposite side the flag of the Devonshire arms.

Mrs. Ollerenshaw's: Flag, blue with orange fringe; motto as No. 1. on both sides.

Mr. Marsingale's: Flag, blue with orange fringe; at the top the motto, "In Memory of the Glorious Assertors of British Freedom 1688," beneath, the figure of Liberty leaning on a shield, on which is inscribed, "Revolted from Tyranny at Whittington 1688;" and having in her hand a scroll with the words "Bill of Rights" underneath a head of King William the Third; on the other side the flag, the motto, "The Glorious Revolter from Tyranny 1688" underneath the Devonshire arms; at the bottom the following inscription, "Willielmus Dux Devon. Bonorum Principum Fidelis Subditus; Inimicus et Invisus Tyrannis."

The Members of the Clubs were estimated 2000

persons, each having a white wand in his hand

with blue and orange tops and favours, with

the Revolution stamped upon them.

The Derbyshire militia's band of music.

The Corporation of Chesterfield in their formalities,

who joined the procession on entering the town.

The Duke of Devonshire in his coach and six.

Attendants on horseback with four led horses.

The Earl of Stamford in his post chaise and four.

Attendants on horseback.

The Earl of Danby and Lord Francis Osborne in their

post-chaise and four.

Attendants on horseback.

Lord George Cavendish in his post-chaise and four.

Attendants on horseback.

Lord John Cavendish in his post-chaise and four.

Attendants on horseback.

Sir Francis Molyneux and Sir Henry Hunloke, Barts.

in Sir Henry's coach and six.

Attendants on horseback.

And upwards of forty other carriages of the neighbouring

gentry, with their attendants.

Gentlemen on horseback, three and three.

Servants on horseback, ditto.

The procession in the town of Chesterfield went along Holywell-Street, Saltergate, Glumangate, then to the left along the upper side of the Market-place to Mr. Wilkinson's house, down the street past the Mayor's house, along the lower side of the Market-place to the end of the West Barrs, from thence past Dr. Milnes's house to the Castle, where the Derbyshire band of music formed in the centre and played "Rule Britannia," "God save the King, &c." the Clubs and Corporation still proceeding in the same order to the Mayor's and then dispersed.

The whole was conducted with order and regularity, for notwithstanding there were fifty carriages, 400[lxix] gentlemen on horseback, and an astonishing throng of spectators, not an accident happened. All was joy and gladness, without a single burst of unruly tumult and uproar. The approving eye of Heaven shed its auspicious beams, and blessed this happy day with more than common splendour.

The company was so numerous as scarcely to be accommodated at the three principal inns. It would be a piece of injustice not to mention the dinner at the Castle, which was served in a style of unusual elegance.

The following toasts were afterwards given:

1. The King.

2. The glorious and immortal Memory of King William the IIId.

3. The Memory of the Glorious Revolution.

4. The Memory of those Friends to their Country, who, at the risk of their lives and fortunes, were instrumental in effecting the Glorious Revolution in 1688.

5. The Law of the Land.

6. The Prince of Wales.

7. The Queen, and the rest of the Royal Family.

8. Prosperity to the British Empire.

9. The Duke of Leeds, and prosperity to the House of Osborne.

10. The Duke of Devonshire, and prosperity to the House of Cavendish.

11. The Earl of Stamford, and prosperity to the united House of Boothe and Grey.

12. The Earl of Danby, and prosperity to the united House of Osborne and Darcy.

13. All the Friends of the Revolution met this year to commemorate that glorious Event.

14. The Dke of Portland.

15. Prosperity to the County of Derby.

16. The Members for the County.

[lxx]17. The Members for the Borough of Derby.

18. The Duchess of Devonshire, &c.

In the evening a brilliant exhibition of fireworks was played off, under the direction of Signor Pietro; during which the populace were regaled with a proper distribution of liquor. The day concluded with a ball, at which were present near 300 gentlemen and ladies; amongst whom were many persons of distinction. The Duchess of Devonshire, surrounded by the bloom of the Derbyshire hills, is a picture not to be pourtrayed. Near 250 ball-tickets were received at the door.

The warm expression of gratitude and affection sparkling in every eye, must have excited in the breasts of those noble personages, whose ancestors were the source of this felicity, a sensation which Monarchs in all their glory might envy. The utmost harmony and felicity prevailed throughout the whole meeting. An hogshead of ale was given to the populace at Whittington, and three hogsheads at Chesterfield; where the Duke of Devonshire gave also three guineas to each of the eight clubs.

It was not the least pleasing circumstance attending this meeting, that all party distinctions were forgotten. Persons of all ranks and denominations wore orange and blue, in memory of our glorious Deliverer; And the most respectable Roman Catholic families, satisfied with the mild toleration of government in the exercise of their Religion, vied in their endeavours to shew how just a sense they had of the value of Civil Liberty.

Letter from the Rev. P. Cunningham to Mr. Pegge.

Eyam, near Tideswal,

Nov. 2, 1788.Rev. and dear Sir,

You will please to accept of the inclosed Stanzas, and the Ode for the Jubilee, as a little testimony of the Author's respectful remembrance of regard; and of his congratulations, that it has pleased Divine Providence to prolong your days, to take a distinguished[lxxi] part in the happy commemoration of the approaching Fifth of November.

Having accidentally heard yesterday the Text you proposed for your Discourse on Wednesday, I thought the adoption of it, as an additional truth to the one I had chosen, would be regarded as an additional token of implied respect. In that light I flatter myself you will consider it.

I shall be happy if these poetic effusions should be considered by you as a proof of the sincere respect and esteem with which I subscribe myself,

Dear Sir, your faithful humble servant,

P. Cunningham.

Stanzas, by the Rev. P. Cunningham, occasioned by the Revolution Jubilee, at Whittington and Chesterfield, Nov. 5, 1788. Inscribed to the Rev. Samuel Pegge, Rector of Whittington.

"This is the day which the Lord hath made; we will rejoice and be glad in it." Psalms.

"Esto perpetua!" F. P. Sarpi da Venez.

Eyam, Derbyshire.

P. C.

Ode for the Revolution Jubilee, 1788.

Dear Sir,

Whittington, Oct. 11, 1788.

We are to have most grand doings at this place, 5th of November next, at the Revolution House, which I believe you saw when you was here. The Resolutions of the Committee were ordered to be inserted in the London prints[49]; so I presume you may have seen them, and that I am desired to preach the Sermon.

I remain your much obliged, &c.

S. Pegge.

Whittington, Nov. 29, 1788.

My dear Mr. Gough,