| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/earlywesterntrav14thwa |

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE——

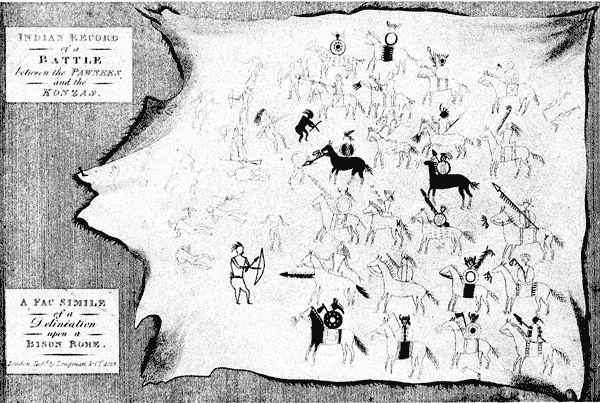

This ebook reproduces the 1905 Arthur H. Clark Company Edition, which is itself based on an 1823 London edition of Part I of James's Account of S. H. Long's Expedition. The 1905 edition incorporated portions from several differing published editions of the account, plus a map which does not appear to have been directly related to James's account. The original pagination of the 1823 London edition was included in the 1905 edition, and is shown in this ebook by numbers enclosed in brackets, e.g. {135}.

Further details of this transcription are located at the end of this e-book.

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel, descriptive

of the Aborigines and Social and

Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Editor of "The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents," "Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition," "Hennepin's New Discovery," etc.

Volume XIV

Part I of James's Account of S. H. Long's Expedition,

1819-1820

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1905

Copyright 1905, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

| Preface to Volumes XIV-XVII. The Editor | 9 |

| Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains, performed in the Years 1819, 1820. By order of the Hon. J. C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, under the command of Maj. S. H. Long, of the U. S. Top. Engineers. Compiled from the Notes of Major Long, Mr. T. Say, and other Gentlemen of the Party. [Part I, being chapters i-x of Volume I of the London edition, 1823.] Edwin James, Botanist and Geologist to the Expedition | |

| Dedication | 33 |

| Preliminary Notice [from Philadelphia edition, 1823] | 35 |

| Text: | |

| CHAPTER I—Departure from Pittsburgh. North-western slope of Alleghany Mountains. Rapids of the Ohio | 39 |

| CHAPTER II—The Ohio below the Rapids at Louisville. Ascent of the Mississippi from the mouth of the Ohio to St. Louis | 77 |

| CHAPTER III—Tumuli and Indian graves about St. Louis, and on the Merameg. Mouth of the Missouri. Charboniere. Journey by land from St. Charles to Loutre Island | 108 |

| CHAPTER IV—Settlement of Cote Sans Dessein. Mouths of the Osage. Manito Rocks. Village of Franklin | 136 |

| CHAPTER V—Death of Dr. Baldwin. Charaton River, and Settlement. Pedestrian Journey from Franklin to Fort Osage | 153 |

| CHAPTER VI—Mouth of the Konzas. Arrival at Wolf River. Journey by land from Fort Osage to the Village of the Konzas | 171 |

| CHAPTER VII—Further Account of the Konza Nation. Robbery of Mr. Say's Detachment by a War-party of Pawnees. Arrival at the Platte | 199 |

| CHAPTER VIII—Winter Cantonment near Council Bluff. Councils with the Otoes, Missouries, Ioways, Pawnees, &c. | 221 |

| CHAPTER IX—Animals. Sioux and Omawhaw Indians. Winter Residence at Engineer Cantonment | 250 |

| CHAPTER X—Account of the Omawhaws. Their Manners, and Customs, and Religious Rites. Historical Notices of Black Bird, Late Principal Chief | 288 |

The present volume and the three which succeed it are devoted to a reprint of Edwin James's Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains, performed in the Years 1819, 1820, . . . under the Command of Maj. S. H. Long. This exploration was the outcome, and almost the only valuable result, of the ill-starred project popularly known at the time as the Yellowstone expedition, which had been designed to establish military posts on the upper Missouri for the several purposes of protecting the growing fur-trade, controlling the Indian tribes, and lessening the influence which British trading companies were believed to exert upon them.[1] The movement gave rise to great expectations, for interest in our Western territories was already keen; it was confidently hoped that an era of rapid development was about to open in the trans-Mississippi region, under government initiative and protection. [2]

As originally planned, the scientific observations of the expedition were to be conducted by a company of specialists under the command of Major Long, to whom detailed instructions were issued by Secretary of War Calhoun.[3] The military branch, under Colonel Henry[pg010] Atkinson,[4] was set in motion in the autumn of 1818, and a considerable body of troops passed the following winter near the present site of Leavenworth, Kansas. In the spring of 1819, however, defects in the plans began to hamper the execution of the enterprise. Those were the early days of steam navigation, and the waters of the Missouri had not yet been stirred by paddle-wheels. Prudence counselled that the success of the movement should not be staked on the behavior of steamboats in untried waters. Nevertheless, the authorities decided against the old-fashioned keel-boats recommended by Atkinson;[5] in arranging for transportation, a further blunder was made in engaging a contractor without competition or adequate securities. The service proved entirely inefficient, and it was not until late in September of 1819 that the troops were concentrated at Council Bluffs, where, perforce, a halt was made for the winter.

The scientific members of the expedition had meanwhile assembled at Pittsburg, and on May 5, 1819, they began the descent of the Ohio in the steamer "Western Engineer."[6] Stephen Harriman Long, the chief of this party, was born at Hopkinton, New Hampshire, in 1764. After being graduated at Dartmouth (1809), and teaching [pg011] for a few years, he entered the army (1814) as lieutenant in the corps of engineers. Until 1816 he was assistant professor of mathematics at West Point, being then transferred to the topographical engineers, with the brevet rank of major. Previous to the exploration which forms the subject of our text, he travelled extensively in the South-west, between the Arkansas and Red rivers, and his journals, although never published, ranked among the most useful sources of information for that region. Major Long's associates in the present undertaking were Major John Biddle, journalist of the party; Dr. William Baldwin, physician and botanist; Dr. Thomas Say, zoologist; Augustus Edward Jessup, geologist; T. R. Peale, assistant naturalist; Samuel Seymour, painter; and Lieutenant James D. Graham and Cadet William H. Swift, assistant topographers. [7]

The "Western Engineer" arrived at St. Louis on the ninth of June, and proceeded again on the twenty-first, after the party had completed certain arrangements for their journey and examined the Indian mounds in the vicinity. The voyage up the Missouri was begun on the twenty-second, being marked by no more important incident than an occasional halt to repair the machinery or clean the boiler. Notwithstanding it drew but nineteen inches of water, the boat grounded twice on sand-bars within four miles of the Mississippi; but on the whole, it worked fairly well and gave comparatively little annoyance. At St. Charles, on June 27, the party was joined by Benjamin O'Fallon, agent for Indian affairs, and John Dougherty, his interpreter. Here Messrs. Say, Jessup, Peale, and Seymour left the boat and made a land excursion, rejoining[pg012] the party at Loutre Island. At Franklin, then the uppermost town of any importance on the Missouri, a halt of several days was made; here Dr. Baldwin, who had been ill since the departure from Pittsburg, was left behind, his death occurring on the thirty-first of August. From Franklin a party under Dr. Say proceeded by land to Fort Osage, where they arrived on July 24, a week in advance of the boat. On the sixth of August Dr. Say left Fort Osage in command of a party bound for the principal village of the Kansa Indians, then situated near the site of the present village of Manhattan, Kansas. Arriving there on the twentieth, they were hospitably entertained for four days; but after their departure were set upon and robbed by a war party of Pawnee braves, and consequently forced to abandon further progress by land and return to the boat.

Meantime the steamer had left Fort Osage on August 10, and eight days later arrived at Cow Island, near Leavenworth, where a portion of the troops of the Yellowstone expedition had wintered. Here another week was spent in a council with the Kansa Indians. On the twenty-ninth of August, Say and his companions arrived at Cow Island, four days after the departure of the boat; both Say and Jessup were ill, and the party had decided to return to the river at that point instead of attempting the longer journey to Council Bluffs, the appointed rendezvous. The others succeeded in overtaking the steamer, the invalids remaining for a time at Cow Island.

Near the quarters of the troops at Council Bluffs (Camp Missouri), Long's party also halted, on September 17, and prepared a winter camp, named "Engineer Cantonment." Here Long left his companions, and, accompanied by Jessup, returned to the East for the winter. His colleagues[pg013] at the cantonment pursued such studies as were possible in the winter season, collecting much valuable information relative to the neighboring tribes of Pawnee, Oto, Iowa, Missouri, and Omaha Indians, and making short excursions which gave them some knowledge of the geology and natural history of the vicinity.

Long returned to the West in the spring of 1820. Leaving St. Louis on April 24, he crossed the intervening wilderness to Council Bluffs by land, arriving at Engineer Cantonment on May 28. With him came Captain J. R. Bell, to replace Major Biddle, also the author of the account herewith reprinted; the latter assumed the duties which had originally been assigned to Baldwin and Jessup. Edwin James was born at Weybridge, Vermont, in 1797, and after graduation at Middlebury College (1816) pursued the study of medicine under a brother, Daniel James, who was a practising physician of Albany, New York. At the same time he prosecuted studies in botany and geology under Dr. John Torrey and Professor Amos Eaton, joining the expedition in 1820 fresh from the tutelage of these men.

Long was also the bearer of fresh instructions. Congress, annoyed at the first season's operations, the results of which had been out of all proportion to the heavy expenditures, had refused further appropriations, and the progress of the Yellowstone expedition was necessarily arrested. Long's party, however, with the exception of Lieutenant Graham, who with the steamboat was assigned to special duty on the Missouri and Mississippi, was to ascend the Platte to its source, and return to the Mississippi by way of the Arkansas and the Red.

The company as now organized, in addition to the scientific[pg014] gentlemen already named, included Dougherty and four other men to serve as interpreters, baggage handlers, and the like, and a detachment of seven soldiers from the troops at Camp Missouri—a total of twenty. Leaving the Missouri on June 6, the expedition visited the Pawnee villages on Loup River, where two Frenchmen were engaged as guides and interpreters. An effort was made to introduce the process of vaccination among the Pawnee, who, in common with other tribes, had suffered heavily from the ravages of smallpox; but the vaccine having been thoroughly drenched by the wreck of one of the keel-boats of the Yellowstone expedition, the attempt was unsuccessful. After two days at the villages, progress was resumed on the thirteenth, and from this time until the mountains were reached, little was encountered to excite interest, save herds of buffalo and the mirage. From near Grand Island the company followed the north bank of the Platte, until they reached the forks, where they crossed to the south bank of the South Fork.

On the thirtieth the Rockies were first sighted—their route along the Platte having borne directly towards the mountain which has since received Long's name, and which was, at first, mistaken for Pike's Peak. The fourth of July, which they had hoped to celebrate in the mountains, found them still at some distance from them; on the fifth they encamped upon the site of the present city of Denver, and the following day directly in front of the chasm through which issues the South Platte. Here two days were passed while James and Peale, with two companions, sought to cross the first range and gain the valley of the Platte beyond; but after surmounting several ridges, each of which appeared to be the summit, only to find[pg015] higher land beyond, the undertaking was abandoned. They did reach, however, an elevated point from which they could distinguish the two forks of the South Platte.

A few days later, members of the expedition performed a more memorable exploit. On the twelfth of July, the camp then being a few miles south of the site of Colorado Springs, James set out with two men, and two days later succeeded in reaching the summit of Pike's Peak, being, so far as history records, the first to accomplish this feat. In honor of the achievement, Major Long christened the mountain James's Peak; but by force of local usage, the present name supplanted this appropriate designation. Lieutenant Swift had meanwhile quite accurately calculated the height of the peak above the basal plains, although an erroneous estimate of the elevation of the latter produced an error of nearly three thousand feet in the determination for the elevation of the summit above sea level. Here, as elsewhere, the observations for longitude and latitude involved a considerable error.

On the sixteenth the party again broke camp, and moved southwest to the Arkansas, which they reached twelve or fifteen miles above the present city of Pueblo. The following day Captain Bell, Dr. James, and two of the men ascended the river to the site of Cañon City, at the entrance of Royal Gorge, where they turned back, again baffled by what seemed to them impassable barriers.

The expedition began the descent of the Arkansas on the nineteenth. After two days' march a camp was made a few miles above the future site of La Junta, Colorado; here a division into two parties was effected, for the purpose of carrying out the instructions of the War Department to explore the courses of both the Arkansas and the[pg016] Red. The division assigned to the exploration of Red River, consisting of James, Peale, and seven men, was commanded by Major Long himself, for this was one of the principal objects of the expedition; the other division, charged with the less important task of descending the Arkansas, the entire course of which had already been examined by Pike and his assistants, was led by Captain Bell.

Leaving the Arkansas on the twenty-fourth, Long's party crossed Purgatory Creek and the upper waters of Cimarron River, and after six days reached a small tributary of Canadian River, which, after five days' still further travel, brought them to the latter near the present Texas-New Mexico boundary line. As the region in which they had encountered the waters of the Canadian was that wherein the sources of the Red had, previous to that time, been universally supposed to lie, they naturally at first believed that they were upon the latter stream. Their suspicions were soon aroused by the deviation of the river's course from that which they expected the Red to pursue; but it was not until they arrived at the confluence of this waterway with the Arkansas that they became certain of their error. During their descent of the Canadian they encountered parties of Kaskaia and Comanche Indians, whose conduct was not uniformly friendly. Few incidents of interest, however, broke the painful monotony of a journey accompanied by almost constant suffering from exposure to violent storms and intense heat, lack of food and water, and the attacks of wood ticks. On the thirteenth of September the explorers arrived at Fort Smith, the appointed rendezvous, where they found Bell's party awaiting them. [pg017]

The experience of the Arkansas division had, in most particulars, been quite similar to that of Long's, but on the whole less vexatious. The chief event, however, involved an irreparable loss to the expedition. This was the desertion, on the night of the thirtieth of August, of three soldiers, who wantonly took with them all the manuscripts completed by Dr. Say and Lieutenant Swift since leaving the Missouri. The stolen books contained notes on the manners, habits, history, and languages of the Indians, and on the animals which had been examined, a journal of the expedition, and a mass of topographical data. During part of the journey, Bell's party was even more astray than Long's. Soon after passing the Great Bend of the Arkansas, they mistook the Nennescah River for the Negracka, or Salt Fork of the Arkansas; similar errors added to their bewilderment, and for some time they were unaware whether they were near Fort Smith or still far distant—until, on the first of September, they met friendly Osage Indians near Verdigris River. They reached Fort Smith on the ninth.

From Fort Smith the reunited party followed the Arkansas to the Cherokee towns on Illinois Creek, in Pope County, Arkansas, whence they proceeded overland directly to Cape Girardeau, Missouri. James and Swift, parting from their companions at the Cherokee towns, visited the Arkansas Hot Springs, now a famous health resort, and returning to the Arkansas at Little Rock, also crossed the country to Cape Girardeau, where all members of the expedition were assembled on October 12. Here nearly all of the party were attacked by intermittent fever.

Two or three weeks later, the expedition being now disbanded, [pg018] Major Long and Captain Bell set out for Washington, leaving their colleagues to act according to their own pleasure. About the first of November, Messrs. Say, Seymour, and Peale departed by steamboat, intending to return home by way of New Orleans. They were accompanied by Lieutenant Graham, who, on completion of the special duties assigned to him at Engineer Cantonment, had met the exploring party at Cape Girardeau with the "Western Engineer." Lieutenant Swift and Dr. James essayed to ascend the Ohio to Louisville with the vessel; but at Golconda, Illinois, James experienced a recurrence of fever, which for some time prevented his proceeding farther, while Swift, leaving the boat at Smithland, Kentucky, continued his journey on horseback.

James's Account is the only narrative of the expedition, and his connection with the party gives his work the authority of an official report. Moreover, he not only had access to the notes of his associates, but received much personal assistance, especially from Long and Say. The original edition was published at Philadelphia in 1823, by Carey and Lea; it consisted of two volumes of 503 and 442 pages respectively, containing James's narrative, with appendices giving a catalogue of animals observed at Engineer Cantonment, the Indian sign language, Indian speeches at the councils held by Major O'Fallon, astronomical and meteorological records, and vocabularies of Indian languages, especially those of the Oto, Kansa, Omaha, Sioux, Minitaree, and Pawnee tribes. Extracts from Major Long's report to the secretary of war, dated January 20, 1821, and from the report made by his assistants to Long on the mineralogy and geology of the region explored, were incorporated in the second volume. A[pg019] third volume contained the maps and plates, and the edition was provided with a brief index and "Preliminary Notice."

The same year another edition was published in London, by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown. This edition, the one selected by us for reprinting, was in three volumes, and contained the text essentially as printed in the Philadelphia edition.[8] In the arrangement of notes, however, a different plan was adopted; in the Philadelphia issue, all annotation was given at the foot of the appropriate pages, while in the London edition the notes for each volume were grouped in the back of the book. In the present reprint the former plan is followed. The Preliminary Notice found in the Philadelphia edition was omitted from the London version, but is supplied in the present reprint. The appendices giving astronomical and meteorological data and Indian vocabularies, which were omitted from the London edition, are also included in our reprint. Finally, instead of the atlas which accompanied the Philadelphia edition, selected illustrations, including a map of the region explored, were incorporated with the text in the various volumes of the London print.

In certain ways the results of the expedition were disappointing, even to those persons whose expectations were far less extravagant than the Missourian who had declared that "ten years shall not pass away before we shall have the rich productions of [China] transported from Canton to the Columbia, up that river to the mountains, over the[pg020] mountains and down the Missouri and Mississippi, all the way (mountains and all), by the potent power of steam." To this class, the report which the expedition made on the trans-Mississippi country was far from encouraging. Said Major Long in his final estimate: "In regard to this extensive section of country, I do not hesitate in giving the opinion, that it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. Although tracts of fertile land considerably extensive are occasionally to be met with, yet the scarcity of wood and water, almost uniformly prevalent, will prove an insuperable obstacle in the way of settling the country. This objection rests not only against the section immediately under consideration, but applies with equal propriety to a much larger portion of the country. . . . This region, however, viewed as a frontier, may prove of infinite importance to the United States, inasmuch as it is calculated to serve as a barrier to prevent too great an extension of our population westward, and secure us against the machinations or incursions of an enemy that might otherwise be disposed to annoy us in that part of our frontier." In similar vein is the comment of Dr. James: "We have little apprehension of giving too unfavourable an account of this portion of the country. Though the soil is in some places fertile, the want of timber, of navigable streams, and of water for the necessities of life, render it an unfit residence for any but a nomad population. The traveller who shall at any time have traversed its desolate sands, will, we think, join us in the wish that this region may for ever remain the unmolested haunt of the native hunter, the bison, and the jackall." Such a verdict was not welcomed by an expansive[pg021] people, eager to enter into and possess a land which imagination pictured as suitable for the seat of an empire.

The teeming animal life of the great plains might have suggested to Long and his associates its adaptability to the needs of man; but for the occupation of the land without political peril, at least two agencies were required, which were, in their day, hardly more than dreams. We cannot blame the explorers for failing to anticipate the marvels of the railroad and the irrigating ditch; indeed, the repulse of the agricultural vanguard which attempted the invasion of the plains west of the hundredth meridian only half a generation ago, vindicates the prediction that the country could not be possessed by methods then known. It may be doubted whether their conservatism was not wiser than the confidence of the more ardent expansionists; yet it is doubtless true that their report, by depreciating the estimate of the value of the region, put weapons into the hands of those Eastern men who cherished a traditional jealousy of Westward expansion, and caused the government rather to follow than to lead the movement.

Another apparent ground for criticism is the failure of the expedition to accomplish either of the great objects mentioned in the instructions—the discovery of the sources of the Platte and of the Red. The readiness with which the explorers relinquished their efforts to penetrate the mountains at the cañons of the Platte and Arkansas, although the season was midsummer, seems to indicate inefficiency as well as indifference to instructions. Likewise, when the Canadian was reached and mistaken for the Red, no effort was made to ascend the stream to its source; the explorers were content to descend the river,[pg022] leaving the exact location of its head undetermined. Some excuse for this conduct is afforded by the inadequacy of the equipment provided by Congress for this enterprise. The federal government supplied six horses; the remainder of the thirty-four were furnished by the members of the party. "Our saddles and other articles of equipage," wrote James, "were of the rudest kind, being, with a few exceptions, such as we had purchased from the Indians, or constructed ourselves;" and, he adds, that the "very inadequate outfit . . . was the utmost our united means enabled us to furnish." Consequently, the party was compelled to subsist largely upon the country explored, and its movements were in no small degree dictated by the fear of want. That many of the hardships experienced were due to the slender outfit, is proved by the comparative comfort with which later parties followed in their footsteps. Twenty-five years afterwards, Colonel Abert, starting from Bent's Fort, on the upper Arkansas, not many miles from the point where Long's forces had divided, crossed the upland to the Canadian and descended to its mouth, following essentially Long's route, and making the whole journey in wagons, for which, save in a few places, a smooth course was found. This party succeeded in finding sufficient water at almost every camp, while the entire trip resembled more an outing for pleasure than it did the harrowing journey of Major Long. The route up the Canadian afterward became a much-used pathway to New Mexico. [9]

When all allowances have been made, much carelessness is evident in the explorations of the Long expedition. The bewilderment of Bell's party was inexcusable in men of science possessing instruments for determining latitude and longitude; their geographical errors to some extent nullified their observations of natural features. Cimarron River, the most important tributary of the Arkansas next to the Canadian, they missed entirely, and the relative size and location of the tributaries of the Arkansas remained uncertain for years after. Upon beginning the descent of the Arkansas they travelled two hundred miles without, so far as James's Account shows, making a note on geography or topography; but possibly some allowance for this omission should be made because of the theft of manuscripts by the deserters. Of the itinerary of the expedition from the Platte to the Canadian, it has been said, "It would be scarcely possible to find in any narrative of Western history so careless an itinerary, and in a scientific report like that of Dr. James it is quite inexcusable."[10] To the account of the country traversed by the expedition, James added information relative to portions of Arkansas and Louisiana, much of which was already accessible to the public through the reports and writings of Hunter and Dunbar, Sibley, Darby, Stoddard, Schoolcraft, and others. However, this portion of James's narrative also draws data from Major Long's manuscript[pg024] journals, not elsewhere available, and gives the only account of the attempted exploration of Red River under Captain Richard Sparks, based on the memoranda of members of the expedition.

After all criticisms have been urged to the utmost, the work of the expedition was, and is, of considerable value. The exploration of the Canadian River was an important contribution to American geography. It was thenceforth evident that the sources of the Red must be looked for farther south than had previously been supposed, although a generation was to elapse before their discovery. Otherwise, the exploration added greatly to the knowledge of a portion of the country but imperfectly known through hunters and traders. Especially is this true as regards details relative to natural history and ethnology; for the work was done in the spirit of modern scientific investigation, and in this respect anticipated later expeditions, for which American public sentiment in 1820 was hardly ripe. The collections included more than sixty skins of new or rare animals, several thousand insects, of which many hundreds were new, nearly five hundred undescribed plants, mineral specimens, many new species of shells, numerous fossils, a hundred and twenty-two animal sketches, and a hundred and fifty landscape views. While not primarily designed as a scientific report on these collections, James's Account gives in the form of notes[11] much of the more important information derived from them. Perhaps no other portions of the work, however equal in value those devoted to the aborigines;[pg025] as an authoritative source of knowledge of the sociology of the Kansa and Omaha tribes, the Account has no rival.

Soon after his return from the Rockies, Major Long was sent upon another expedition, this time to the sources of the St. Peter's (now Minnesota) River. This enterprise was contemplated by the original instructions issued to Long at the time of the Yellowstone project; but the subsequent abandonment of the latter compelled alterations in the programme of the scientific division. As in the case of the first journey, the report of the St. Peter's exploration is the work of another person—William H. Keating, author of Long's Expedition to the Source of St. Peter's River, Lake of the Woods, etc. (Philadelphia, 2 vols., 1824).

For these several explorations, Long was breveted lieutenant-colonel. In 1827 he assumed charge of the survey of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and for many years thereafter was much engaged in railroad engineering. His Railroad Manual (1829) was the first original treatise on railroad building published in this country. Upon the organization of the Topographical Engineers as a separate corps (1838), he became a major; later (1861) he was made chief of the corps, with the rank of colonel. He was retired from active service in 1863, still being entrusted with important duties, which were interrupted by his death, occurring at Alton, Illinois, the following year.

After the publication of his account of Long's expedition, Dr. James received an appointment as army surgeon, and was on the frontier for six years, which he utilized in studying Indian dialects; during this period he translated the New Testament into the Chippewa tongue (1833), and published The Narrative of John Tanner (New York,[pg026] 1830), the story of a child who had been stolen by the Indians, and became a well-known interpreter. Resigning his army post (1830), James became associate editor of the Temperance Herald and Journal, at Albany; later (1834) he removed to Iowa, and settled (1836) as an agriculturist near Burlington, where he died in 1861.

In the preparation for the press of this reprint of James's Account, the Editor has had throughout the assistance of Homer C. Hockett, B.A., instructor in history in the University of Wisconsin.

R. G. T.

Madison. Wis., March, 1905.

Part I of James's Account of S. H. Long's Expedition, 1819-1820

Preliminary Notice reprinted from Volume I of Philadelphia edition, 1823. Text reprinted from Volume I of London edition, 1823.

[From the Philadelphia edition, 1823]

In selecting from a large mass of notes and journals the materials of the following volumes, our design has been to present a compendious account of the labors of the Exploring Party, and of such of their discoveries as were thought likely to gratify a liberal curiosity. It was not deemed necessary to preserve uniformity of style, at the expense of substituting the language of a compiler for that of an original observer. Important contributions of entire passages from Major Long and Mr. Say, will be recognized in various parts of the work, though we have not always been careful to indicate the place of their introduction. Those gentlemen have indeed been constantly attentive to the work, both to the preparation of the manuscript and its revision for the press.

In the following pages we hope to have contributed something towards a more thorough acquaintance with the Aborigines of our country. In other parts of our narrative where this interesting topic could not be introduced, we have turned our attention towards the phenomena of nature, to the varied and beautiful productions of animal and vegetable life, and to the more magnificent if less attractive features of the inorganic creation.

{2} If in this attempt we have failed to produce any thing to amuse or instruct, the deficiency is in ourselves. The few minute descriptions of animals and plants that were thought admissible, have been placed as marginal[pg036] notes, and we hope they will not be the less acceptable to the scientific reader, for being given in the order in which they occurred to our notice.

Descriptions of the greater number of the animals and plants collected on the Expedition, remain to be given. These may be expected to appear from time to time, either in periodical journals or in some other form.

Not aspiring to be considered historians of the regions we traversed, we only aimed at giving a sketch true at the moment of our visit, and which, as far as it embraces the permanent features of nature, will we trust, be corroborated by those who shall follow our steps. Much remains to be done not only on the ground we have occupied, but in those vast regions in the interior of our continent, to which the foot of civilized man has never penetrated. We cannot but hope, that the enlightened spirit which has already evinced itself in directing a part of the energies of the nation, towards the development of the physical resources of our country, will be allowed still farther to operate; that the time will arrive, when we shall no longer be indebted to the men of foreign countries, for a knowledge of any of the products of our own soil, or for our opinions in science.

We feel it a duty incumbent upon us, to acknowledge our obligations to many distinguished individuals, both {3} military and scientific, and particularly to several members of the Philosophical Society at Philadelphia, for their prompt offers of any aid in their power to contribute towards advancing the objects of the expedition at its commencement. We are indebted more especially to Professors James, Walsh, and Patterson, to Dr. Dewees and Mr. Duponceau; each of whom furnished a number[pg037] of queries, and a list of objects, by which to direct our observations. These we found eminently useful, and we regret to state that, with many of our manuscripts they were inadvertently mislaid, otherwise, they should have been published in this place, for the information of future travellers.

An interesting communication from Messrs. Gordon and Wells, of Smithland, Kentucky, was received after the first volume had gone to press, consequently too late for insertion.

As a farther introduction to our narrative, we subjoin an extract from the orders of the Honourable Secretary of War to Major Long, exhibiting an outline of the plan and objects of the Expedition.

"You will assume the command of the Expedition to explore the country between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains."

"You will first explore the Missouri and its principal branches, and then, in succession, Red river, Arkansa and Mississippi, above the mouth of the Missouri."

"The object of the Expedition, is to acquire as thorough and accurate knowledge as may be practicable, of a portion of our country, which is daily becoming {4} more interesting, but which is as yet imperfectly known. With this view, you will permit nothing worthy of notice, to escape your attention. You will ascertain the latitude and longitude of remarkable points with all possible precision. You will if practicable, ascertain some point in the 49th parallel of latitude, which separates our possessions from those of Great Britain. A knowledge of the extent of our limits will tend to prevent collision between our traders and theirs."[pg038]

"You will enter in your journal, every thing interesting in relation to soil, face of the country, water courses and productions, whether animal, vegetable, or mineral."

"You will conciliate the Indians by kindness and presents, and will ascertain, as far as practicable, the number and character of the various tribes, with the extent of country claimed by each."

"Great confidence is reposed in the acquirements and zeal of the citizens who will accompany the Expedition for scientific purposes, and a confident hope is entertained, that their duties will be performed in such a manner, as to add both to their own reputation and that of our country."

"The Instructions of Mr. Jefferson to Capt. Lewis, which are printed in his travels, will afford you many valuable suggestions, of which as far as applicable, you will avail yourself."

It will be perceived that the travels and researches of the Expedition, have been far less extensive than {5} those contemplated in the foregoing orders:—the state of the national finances, during the year 1821, having called for retrenchments in all expenditures of a public nature,—the means necessary for the farther prosecution of the objects of the Expedition, were accordingly withheld. [pg039]

EXPEDITION FROM PITTSBURGH

TO THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS

[PART I.]

Departure from Pittsburgh—North-western slope of the Alleghany Mountains—Rapids of the Ohio.

Early in April, 1819, the several persons constituting the exploring party had assembled at Pittsburgh. It had been our intention to commence the descent of the Ohio, before the middle of that month; but some unavoidable delays in the completion of the steam boat, and in the preparations necessary for a long voyage, prevented our departure until the first of May. On the 31st of March, the following instructions were issued by the commanding officer, giving an outline of the services to be performed by the party, and assigning to each individual[001] the appropriate duties:—

"Pursuant to orders from the Hon. Secretary of War, Major Long assumes the command of the expedition about to engage in exploring the Mississippi, Missouri, and their navigable tributaries, on board the United States' steam-boat, Western Engineer.

"The commanding officer will direct the movements and operations of the expedition, both in relation {2} to military and scientific pursuits. A strict observance of all orders, whether written or verbal, emanating from him, will be required of all connected with the expedition. The prime object of the expedition being a topographical description of the country to be explored, the commanding officer will avail himself of any assistance he may require of any persons on board to aid in taking the necessary observations. In this branch of duty,[pg041] Lieutenant Graham and Cadet Swift will officiate as his immediate assistants.

"The journal of the expedition will be kept by Major Biddle, whose duty it will be to record all transactions of the party that concern the objects of the expedition, to describe the manners and customs, &c. of the inhabitants of the country through which we may pass; to trace in a compendious manner the history of the towns, villages, and tribes of Indians we may visit; to review the writings of other travellers, and compare their statements with our own observations; and in general to record whatever may be of interest to the community in a civil point of view, not interfering with the records to be kept by the naturalists attached to the expedition.

"Dr. Baldwin will act as botanist for the expedition.[pg042] A description of all the products of vegetation, common or peculiar to the countries we may traverse, will be required of him, also the diseases prevailing among the inhabitants, whether civilized or savages, and their probable causes, will be subjects for his investigation; any variety in the anatomy of the human frame, or any other phenomena observable in our species, will be particularly noted by him. Dr. Baldwin will also officiate as physician and surgeon for the expedition.

"Mr. Say will examine and describe any objects in zoology, and its several branches, that may come under our observation. A classification of all land and water animals, insects, &c. and a particular description {3} of the animal remains found in a concrete state will be required of him.

"Geology, so far as it relates to earths, minerals, and fossils, distinguishing the primitive, transition, secondary, and alluvial formations and deposits, will afford subjects of investigation for Mr. Jessup. In this science, as also in botany and zoology, facts will be required without regard to the theories or hypotheses that have been advanced on numerous occasions by men of science.

"Mr. Peale will officiate as assistant naturalist. In the several departments above enumerated, his services will be required in collecting specimens suitable to be preserved, in drafting and delineating them, in preserving the skins, &c. of animals, and in sketching the stratifications of rocks, earths, &c. as presented on the declivities of precipices.

"Mr. Seymour, as painter for the expedition, will furnish sketches of landscapes, whenever we meet with any distinguished for their beauty and grandeur. He[pg043] will also paint miniature likenesses, or portraits, if required, of distinguished Indians, and exhibit groups of savages engaged in celebrating their festivals, or sitting in council, and in general illustrate any subject, that may be deemed appropriate in his art.

"Lieutenant Graham and Cadet Swift, in addition to the duties they may perform in the capacity of assistant topographers, will attend to drilling the boat's crew, in the exercise of the musket, the field-piece, and the sabre.

"Their duties will be assigned them, from time to time, by the commanding officer.

"All records kept on board the steam-boat, all subjects of natural history, geology, and botany, all drawings, as also journals of every kind relating to the expedition, will at all times be subject to the inspection of the commanding officer, and at the conclusion of each trip or voyage, will be placed at his disposal, as agent for the United States' government.

{4} "Orders will be given, from time to time, whenever the commanding officer may deem them expedient.

"S. H. Long, Major U. S. Engineers,

commanding Expedition."

On the 3d of May we left the arsenal,[002] where the boat had been built, and after exchanging a salute of twenty-two[pg044] guns, began to descend the Alleghany, towards Pittsburgh. Great numbers of spectators lined the banks of the river, and their acclamations were occasionally noticed by the discharge of ordnance on board the boat. The important duties assigned the expedition rendered its departure a subject of interest, and some peculiarities in the structure of the boat attracted attention.

We were furnished with an adequate supply of arms and ammunition, and a collection of books and instruments.

On Wednesday the 5th of May, having completed some alterations, which it appeared necessary to make in our engine, and received on board all our stores, we left Pittsburgh and proceeded on our voyage. All the gentlemen of the party, except Dr. Baldwin, were in good health, and entered upon this enterprise in good spirits and with high expectations. Fourteen miles below Pittsburgh, we passed a steam-boat lying aground; we received and returned their salute, as is customary with the merchants' boats on the Ohio and Mississippi.

At evening we heard the cry of the whip-poor-will;[003] and among other birds saw the pelecanus carbo, several turkey vultures, and the tell-tale sand-piper. The spring was now rapidly advancing, the dense forests of the Ohio bottoms were unfolding their luxuriant foliage, and the scattered plantations assuming the cheering aspect of summer.

{5} A few weeks' residence at and near Pittsburgh, and several journies across the Alleghany mountains, in different parts, have afforded us the opportunity of collecting[pg045] a few observations relative to that important section of country, which contains the sources of the Ohio.

In the Alleghany river we found several of those little animals, which have been described as a species of Proteus, but which to us appear more properly to belong to the genus Triton. [004]

The north-western slope of that range of mountains, known collectively as the Alleghanies, has a moderate inclination towards the bed of the Ohio, and the St. Lawrence, which run nearly in opposite directions along its base. This mountain chain extends uninterrupted along the Atlantic coast, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence south-west to the great alluvial formation of the Mississippi. It crosses the St. Lawrence at the rapids above Quebec, and has been supposed to be connected as a spur to a group of primitive mountains occupying a large portion of the interior of the continent, north of the great Lakes.[005] An inspection of any of the late maps of North America, will show that this range holds the second place among the mountain chains of this continent. All our rivers of the first magnitude have their sources, either in the Rocky Mountains, or in elevated spurs, projecting from the sides of that range. The largest of the rivers, flowing from the Alleghanies, is the Ohio; and even this, running almost parallel to the range, and receiving as many, and, with a few exceptions, as large rivers from the north as from the south, seems in a great measure independent of it. From the most elevated part of the continent, at the sources of the Platte, and Yellow Stone, branches of the Missouri, the descent towards the Atlantic is at least {6} twice obstructed by ranges of hills nearly parallel, in direction, to each other. Erroneous impressions have heretofore prevailed respecting the character of that part of the country called the Mississippi Valley. If we consider attentively that extensive portion of our continent, drained by the Mississippi, we shall find it naturally divided into two nearly equal sections. This division is made by a range of hilly country, to be hereafter particularly described, running from near the north-western angle of the Gulf of Mexico north-eastwardly to Lake Superior. Eastward, from this range, to the summit of the Alleghanies, extends a country of forests, having usually a[pg049] deep and fertile soil, reposing upon extensive strata of argillaceous sandstone, compact limestone, and other secondary rocks. Though these rocks extend almost to the highest summits of the Alleghanies, and retain even there the horizontal position which they have in the plains, the region they underlay is not to be considered as forming a district of table lands. On the contrary, its surface is varied by deep vallies and lofty hills; and there are extensive tracts elevated probably not less than eight hundred feet above the Atlantic ocean. The north-western slope of the Alleghany mountains, though more gradual than the south-eastern, is, like it, divided by deep vallies, parallel to the general direction of the range. In these vallies, many of the rivers, which derive their sources from the interior and most elevated hills of the group, pursue their courses for many miles, descending either towards the south-west, or the north-east, until they at length acquire sufficient force to break through the opposing ridges, whence they afterward pursue a more direct course. As instances, we may mention the Monongahela river, which runs nearly parallel, but in an opposite direction, to the Ohio; the great Kenhawa, whose course above the falls forms an acute angle with the part below; also the Cumberland, and Tennessee, which run a {7} long distance parallel to each other, and to the Ohio. This fact seems to justify the inference, that some other agent than the rivers has been active in the production of the vallies between the subordinate ridges of the Alleghany. There appears some reason to believe that the rocky hills, along the immediate course of the Ohio and the larger western rivers, have received, at least, their present form from[pg050] the operation of streams of water. They do not, like the accessory ridges of the Alleghany, form high and continuous chains, apparently influencing the direction of rivers, but present groups of conic eminences separated by water-worn vallies, and having a sort of symmetric arrangement. The structure of these hills does not so much differ from that of the Alleghany mountains, as their form and position. The long chains of hills, which form the ascent to the Alleghany, on the western side, are based either on metalliferous limestone, or some of the inclined rocks belonging to the transition formation of Werner, and have their summits capped with the more recent secondary aggregates in strata without inclination, and greatly resembling those found in the plains west of the Ohio. It is not easy to conceive how these horizontal strata, unless originally continuous, should appear so similar at equal elevations in different hills, and hills separated by vallies of several miles in width. If that convulsion which produced the inclination of the strata, of the metalliferous limestone, the clay-slate, and the gray wacke, happened before the deposition of the compact limestone, and the argillaceous sandstones, why are not these later aggregates found principally in the vallies, where their integrant particles would be supposed most readily to have accumulated? On the other hand, if the secondary rocks had been deposited previous to that supposed change, how have their stratifications retained the original horizontal {8} position, while that of the transition strata has been changed?

Most of the rivers which descend from the western side of the Alleghany mountains are of inconsiderable magnitude,[pg051] and by no means remarkable, on account of the straightness of their course, or the rapidity of their currents. The maps accompanying this work, will, in the most satisfactory manner, illustrate the great contrast in this respect, between the district now under consideration and the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. The Tennessee, the Cumberland, the Kentucky, the Kenhawa and Alleghany rivers, though traversed in their courses by rocky dikes, sometimes compressing their beds into a narrow compass, occasioning rapids, and in other instances causing perpendicular falls, yet compared to the Platte, and the western tributaries of the Missouri generally, can be considered neither shoal nor rapid. Their immediate banks are permanent, often rocky, and the sloping beach covered with trees or shrubs, and the water, except in time of high floods, nearly transparent. The waters of the Ohio, and its tributaries, and perhaps of most other rivers, when they do not suspend such quantities of earthy matter as to destroy their transparency, reflect, from beneath their surface, a greenish colour. This colour has been thought to be, in some instances, occasioned by minute confervas, or other floating plants, or to result from the decomposition of decaying vegetable matter. That it depends on neither of these causes, however, is sufficiently manifest, for when seen by transmitted light, the green waters are usually transparent and colourless. Some rivers of Switzerland, and some of South America, which descend from lofty primitive mountains, consisting of rocks of the most flinty and indestructible composition, covered with perpetual snows, and almost destitute of organic beings, or exuviæ, either animal or {9} vegetable, and whose waters have a temperature, even in[pg052] summer, raised but a few degrees above the freezing point, which circumstance, together with the rapidity of their currents, render them unfit for the abode of vegetable life, and is incompatible with the existence of putrefaction, notwithstanding the transparency of their waters, and the reddish, or yellowish colour of the rocks which pave their beds, have a tinge of green, like the Ohio and Cumberland, at times of low water. It is well known that the water of the ocean, though more transparent than any other, is usually green near the shores; and on soundings, while at main ocean, its colour is blue. Perhaps the power which transparent waters have of decomposing the solar light, and reflecting principally the green rays, may have some dependence upon the depth of the stratum. If this were the case, we might expect all rivers, equally transparent and of equal depth, to reflect similar colours, which is not always the case.

In the southern part of Pennsylvania, the range called particularly the Alleghany ridge, is near the centre, and is most elevated of the group. Its summit divides the waters of the Susquehannah on the east from those of the Ohio on the west.

This mountain consists principally of argillite and the several varieties of grey wacke, grey wacke slate, and the other aggregates, which in transition formations usually intervene between the metalliferous limestone and the inclined sandstone. The strata have less inclination than in the Cove, Sideling, and South mountains, and other ridges east of the Alleghany. The summit is broad, and covered with heavy forests. Something of the fertility of the Mississippi valley seems to extend, in this direction, to the utmost limits of the secondary formation. The western[pg053] descent of the Alleghany ridge is more gradual than the eastern, and the inclination of the strata in some measure reversed. It is proper to remark, that, {10} throughout this group of mountains, much irregularity prevails in the direction as well as of the dip and inclination of strata. If any remark is generally applicable, it is, perhaps, that the inclination of the rocks is towards the most elevated summits in the vicinity.

Laurel ridge, the next in succession, is separated from the Alleghany by a wide valley. Its geological features are, in general, similar to those of the eastern ranges; but about its summit, the sandstones of the coal formation begin to appear alternating with narrow beds of bituminous clay-slate. Near the summit of this ridge, coal beds have been explored, and, at the time of our visit, coals were sold at the pits for ten cents per bushel. In actual elevation, the coal strata at the summit of Laurel-hill, fall but little below the summits of the Alleghany. Thus, in traversing from east to west the state of Pennsylvania, there is a constant but gradual ascent from the gneiss at Philadelphia, the several rocky strata occurring one above another, in the inverse order of their respective ages, the points most elevated being occupied by rocks of recent origin, abounding in the remains of animal and vegetable life.

Near the summit of this ridge some change is observed in the aspect of the forest. The deep umbrageous hue of the hemlock spruce, the Weymouth pine, and other trees of the family of the coniferæ, is exchanged for the livelier verdure of the broad-leaved laurel, the rhododendron, and the magnolia acuminata.

Chesnut ridge, the last of those accessary to the Alleghany on the west, deserving the name of a mountain, is[pg054] somewhat more abrupt and precipitous, than those before mentioned. This ridge is divided transversely by the bed of the Loyalhanna, a rapid, but beautiful stream, along which the turnpike is built. Few spots in the wild and mountainous regions {11} of the Alleghanies, have a more grand and majestic scenery than this chasm. The sides and summits of the two overhanging mountains, were, at the time of our journey, brown, and to appearance almost naked; the few trees which inhabit them being deciduous, while the laurels and rosebays gave the deep and narrow vallies the luxuriant verdure of spring.

The Monongahela rises in Virginia, in the Laurel ridge, and running northward, receives in Pennsylvania the Yohogany, whose sources are in the Alleghany mountain, opposite those of the Potomac. This river, like most of those descending westward from the Alleghany, has falls and rapids at the points where it intersects Laurel-hill, and some of the smaller ranges. Along the fertile bottoms of the Alleghany river, we begin to discover traces of those ancient works so common in the lower parts of the Mississippi valley, the only remaining vestiges of a people once numerous and powerful, of whom time has destroyed every other record. These colossal monuments, whatever may have been the design of their erection, have long since outlived the memory of those who raised them, and will remain for ages affecting witnesses of the instability of national, as well as individual greatness; and of the futility of those efforts, by which man endeavours to attach his name and his memorial to the most permanent and indestructible forms of inorganic matter.

In the deep vallies west of the Alleghany, and even west of the Laurel ridge, the metalliferous limestone, which[pg055] appears to be the substratum of this whole group of mountains, is again laid bare. In this part of the range, we have not observed those frequent alternations of clay-slate with this limestone, which have been noticed by Mr. Eaton and others in New England.[006] In its inclination, and in most particulars {12} of external character, it is remarkably similar to the mountain limestone of Vermont, and the western counties of Massachusetts. Many portions of the interior of the state of Pennsylvania have a basis of this limestone. When not overlaid by clay-slate, and particularly when not in connexion with sandstone, the soils resting on the transition limestone are found peculiarly fertile and valuable, having usually a favourable disposition of surface for agricultural purposes, and abounding with excellent water.

The transition limestone is not, however, of frequent occurrence westward of the Alleghany ridge. It appears only in the vallies,[007] and is succeeded by clay-slate and the old sandstone lying almost horizontally. The coal, with the accompanying strata of argillaceous sandstone and shale, are, as far as we have seen, entirely horizontal.

The country westward from the base of the Chesnut ridge has an undulating surface. The hills are broad, and terminated by a rounded outline, and the landscape, presenting a grateful variety of fields and forests, is often beautiful, particularly when, from some elevation, the view overlooks a great extent of country, and the blue[pg056] summits of the distant mountains are added to the perspective.

Pittsburgh has been so often described, the advantages and disadvantages of its situation, and the gloomy repulsiveness of its appearance, have been so often and so justly portrayed, that we should not think ourselves well employed in recounting our own observations. The Alleghany and the Monongahela at Pittsburgh, where they unite to form the Ohio, are nearly equal in magnitude; the former, however, on account of the rapidity of its current, and the transparency of its waters, is a far more beautiful river than the latter. Its sources are distributed along the margin of Lake Erie, and a portage, of only fifteen miles, connects its navigation with that of the St. Lawrence.

{13} About the sources of the Alleghany are extensive forests of pine, whence are drawn great supplies of lumber for the country below as far as New Orleans. On French Creek, and other tributary streams, are large bodies of low and rather fertile lands, closely covered with forests, where the great Weymouth pine, and the hemlock spruce, are intermixed with beech, birch, and the sugar maple. The great white or Weymouth pine, is one of the most beautiful of the North American species. Its trunk often attains the diameter of five or six feet, rising smooth and straight from sixty to eighty feet, and terminated by a dense conical top. This tree, though not exclusively confined to the northern parts of our continent, attains there its greatest magnitude and perfection. It forms a striking feature in the forest scenery of Vermont, New Hampshire, and some parts of Canada, and New York; rising by nearly half its elevation above the summits of the other trees, and resembling, like[pg057] the palms of the tropics, so beautifully described by M. De Saint Pierre, and M. De Humboldt, "a forest planted upon another forest."[008] The sighing of the wind in the tops of these trees, resembles the scarce audible murmurings of a distant waterfall, and adds greatly to the impression of solemnity produced by the gloom and silence of the pine forest. In the southern parts of the Alleghany mountains, pines are less frequent, and in the central portions of the valley of the Mississippi, they are extremely rare.

The coal formation, containing the beds which have long been wrought near Pittsburgh, appears to be of great extent; but we are unable particularly to point out its limits towards the north and east.[009] One hundred miles above Pittsburgh, near the Alleghany river, is a spring, on the surface of {14} whose waters are found such quantities of a bituminous oil, that a person may gather several gallons in a day. This spring is most probably connected with coal strata, as are numerous similar ones in Ohio, Kentucky, &c.[010] Indeed, it appears reasonable to believe that the[pg058] coal strata are continued along the western slope of the Alleghanies with little interruption, at least as far northward as the brine springs of Onondago. Of all the saline springs belonging to this formation, and whose waters are used for the manufacture of salt, the most important are those of the Kenhawa, a river of Virginia. Others occur in that country of ancient monuments, about Paint Creek, between the Sciota and the Muskinghum, near the Silver Creek hills in Illinois; and indeed in almost all the country contiguous to the Ohio river. Wherever we have had the opportunity of observing these brine springs, we have usually found them in connexion with an argillaceous sandstone, bearing impressions of phytolytes, culmaria, and those tessellated zoophytes, so common about many coal beds.[011] It appeared to us worthy of remark, that in many places, where explorations have been made for salt water, and where perpendicular shafts have been carried to the depth of from two to four hundred feet, the water, when found, rises with sufficient force to elevate itself several feet above the surface of the earth. This effect appears to be produced by the pressure of an aërial fluid, existing in connexion with the water, in those cavities beneath the strata of sandstone, where the latter is confined, or escaping from combination with it, as soon as the requisite enlargement is given, by perforating the superincumbent[pg059] strata. We have had no opportunity of examining attentively the gaseous substances which escape from the brine pits, but from their sensible properties we are induced to suppose, that carbonic acid, and carburetted hydrogen, are among those of most frequent occurrence.[012]

{15} The little village of Olean,[013] on the Alleghany river, has been for many years a point of embarkation, where great numbers of families, migrating from the northern and eastern states, have exchanged their various methods, of slow and laborious progression by land, for the more convenient one of the navigation of the Ohio. From Olean downward, the Alleghany and Ohio bear along with their currents fleets of rude arks laden with cattle, horses, household furniture, agricultural implements, and numerous families having all their possessions embarked on the same bottom, and floating onward toward that imaginary region of happiness and contentment, which, like the "town of the brave and generous spirits," the expected heaven of the aboriginal American, lies always "beyond the place where the sun goes down."

This method of transportation, though sometimes speedy[pg060] and convenient, is attended with uncertainty and danger. A moderate wind blowing up the river, produces such swells in some parts of the Ohio, as to endanger the safety of the ark; and these heavy unmanageable vessels are with difficulty so guided in their descent, as to avoid the planters, sunken logs, and other concealed obstructions to the navigation of the Ohio. We have known many instances of boats of this kind so suddenly sunk, as only to afford time for the escape of the persons on board.

On the 6th we arrived at Wheeling,[014] a small town of Virginia, situate on a narrow margin along the bank of the Ohio, at the base of a high cliff of sandstone. Here the great national road from Cumberland comes in conjunction with that of Zanesville, Columbus, and Cincinnati. The town of Cumberland, from which this great national work has received the appellation of the Cumberland road, lies on the north side of the Potomac, one hundred and forty miles E. by S. from Wheeling. The road between these two points was constructed by the government {16} of the United States, at a cost of one million eight hundred thousand dollars.[015] The bridges and other works of masonry, on the western portion of this road, are built of a compact argillaceous sandstone, of a light gray or yellowish white colour, less durable than the stone used in the middle and eastern sections, which is the blue metalliferous limestone, one of the most beautiful and imperishable among the materials for building which our country affords. A few miles from Wheeling, a small but beautiful bridge, forming[pg061] a part of this road, is ornamented with a statue of that distinguished statesman, Mr. Clay; erected, as we were informed, by a gentleman who resides in that neighbourhood.

In an excursion on shore, near the little village of Charleston,[016] in Virginia, we met with many plants common to the eastern side of the Alleghanies; beside the delicate sison bulbosum, whose fruit was now nearly ripened. In shady situations we found the rocks, and even the trunks of trees to some little distance from the ground, closely covered with the sedum ternatum, with white flowers fully unfolded. The cercis canadensis, and the cornus florida, were now expanding their flowers, and in some places occurred so frequently, as to impart their lively colouring to the landscape. In their walks on shore, the gentlemen of the party collected great numbers of the early-flowering herbaceous plants, common to various parts of the United States.[017] An enumeration of a few of[pg062] the species most commonly known, with the dates of their flowering, is given in the note.

The scenery of the banks of the Ohio, for two or three hundred miles below Pittsburgh, is eminently beautiful, but is deficient in grandeur and variety. The hills usually approach on both sides nearly to the brink of the river; they have a rounded and graceful form, and are so grouped as to produce a pleasing effect. Broad and gentle swells of two or three hundred feet, covered with the verdure of the almost unbroken {17} forest, embosom a calm and majestic river; from whose unruffled surface, the broad outline of the hills is reflected with a distinctness equal to that with which it is imprinted upon the azure vault of the sky. In a few instances near the summits of the hills, the forest trees become so scattered, as to disclose here and there a rude mass, or a perpendicular precipice of gray sandstone, or compact limestone, the prevailing rocks in all this region. The hills are, however, usually covered with soil on all sides, except that looking towards the river, and in most instances are susceptible of cultivation to their summits. These hilly lands are found capable of[pg063] yielding, by ordinary methods of culture, about fifty bushels of maize per acre. They were originally covered with dense and uninterrupted forests, in which the beech trees were those of most frequent occurrence. These forests are now disappearing before the industry of man; and the rapid increase of population and wealth, which a few years have produced, speaks loudly in favour of the healthfulness of the climate, and of the internal resources of the country. The difficulty of establishing an indisputable title to lands, has been a cause operating hitherto to retard the progress of settlement, in some of the most fertile parts of the country of the Ohio; and the inconveniences resulting from this source still continue to be felt.

On the 7th, we passed the mouth of the Kenhawa, and the little village of Point Pleasant. The spot now occupied by this village is rendered memorable, on account of the recollections connected with one of the most affecting incidents in the history of the aboriginal population. It was here that a battle was fought, in the autumn of 1774, between the collected forces of the Shawanees, Mingoes, and Delawares on one side, and a detachment of the Virginia militia, on the other. In this battle, Logan, the friend of the whites, avenged himself in a signal manner of the injuries of one man, by whom all his women {18} and children had been murdered. Notwithstanding his intrepid conduct, the Indians were defeated, and sued for peace; but Logan disdained to be seen among the suppliants. He would not turn on his heel to save his life. "For my country," said he, "I rejoice in the beams of peace; but, do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. Who is there to mourn for Logan! Not one." This story is eloquently related by[pg064] Mr. Jefferson, in his "Notes on Virginia," and is familiar to the recollection of all who have read that valuable work.[018]

In the afternoon of the 8th, we encountered a tremendous thunder-storm, in which our boat, in spite of all the exertions we were able to make, was driven on shore; but we fortunately escaped with little injury, losing only our flag-staff with the lantern attached to it, and some other articles of little importance. On the following day we passed Maysville,[019] a small town of Kentucky. On our return to Philadelphia, in 1821, we were delayed some time at this place; and taking advantage of the opportunity thus afforded, we made an excursion into that beautiful agricultural district, south-east of Maysville, about the large village of Washington.[020] The uplands here are extremely fertile, and in an advanced state of cultivation. The disposition of the surface resembles that in the most moderately hilly parts of Pennsylvania; and to the same graceful undulation of the landscape, the same pleasing alternation of cultivated fields, with dense and umbrageous forests, is[pg065] added an aspect of luxuriant fertility, surpassing any thing we have seen eastward of the Alleghanies. Having prolonged our walk many miles, we entered after sunset a tall grove of elms and hickories; towards which we were attracted by some unusual sounds. Directed by these, we at length reached an open quadrangular area of several acres, where the forest had been in part cleared away, and much grass had sprung up. Here we found several hundreds of people, part sitting {19} in tents and booths, regularly arranged around the area, and lighted with lamps, candles, and fires; part assembled about an elevated station, listening to religious exhortations. The night had now become dark, and the heavy gloom of the forest, rendered more conspicuous by the feeble light of the encampment, together with the apparent solemnity of the great numbers of people, assembled for religious worship, made considerable impression on our feelings.

On the 9th May, we arrived at Cincinnati.[021] Since our departure from Pittsburgh, Dr. Baldwin's illness had increased, and he had now become so unwell, that some delay appeared necessary on his account; as we wished also for an opportunity of making some repairs and alterations in the machinery of the boat, it was resolved to remain at Cincinnati some days. Dr. Baldwin was accordingly moved on shore, to the house of Mr. Glen, and Dr. Drake was requested to attend him. Cincinnati is the largest town on the Ohio. It is on the north bank of the river, and the ground on which it stands is elevated, rising gradually from the water's edge.[022]

Compact limestone appears here, in the bed of the Ohio, and extends some distance in all directions. This limestone has been used in paving the streets, for which purpose its tabular fragments are placed on edge, as bricks are sometimes used in flagging. The formation of limestone, to which this rock belongs, is one of great extent, occupying a large part of the country from the shores of Lake Erie, to the southern boundary of the state of Tennessee.[023] It appears, however, to be occasionally interrupted, or overlaid by fields of sandstone. It abounds in casts, and {20} impressions of marine animals. An orthocerite, in the museum of the college[024] at Cincinnati, measures near three feet in length. Very large specimens of what has been considered lignite, have also been discovered and parts of them deposited in that collection. We saw here no remains of ammonites. Numerous other species appear to be similar to those found in the limestone of the Catskill and Hellebergh mountains.

The soil, which overlays the limestone of Cincinnati, is a deep argillaceous loam, intermixed with much animal[pg067] and vegetable matter. Vegetation is here luxuriant; and many plants unknown eastward of the Alleghany mountains, were constantly presenting themselves to our notice. Two species of æsculus are common. One of these has a nut as large as that of the Æ. hippocastanum, of the Mediterranean, the common horse-chesnut of the gardens.

These nuts are round, and after a little exposure become black, except in that part which originally formed the point of attachment to the receptacle, which is an oblong spot three-fourths of an inch in diameter; the whole bearing some resemblance to the eyeball of a deer, or other animal. Hence the name buck-eye, which is applied to the tree. The several species of æsculus are confined principally to the western states and territories. In allusion to this circumstance, the indigenous backwoodsman is sometimes called buck-eye, in distinction from the numerous emigrants who are introducing themselves from the eastern states. The opprobrious name of Yankee is applied to these last, who do not always stand high in the estimation of the natives of the south and west. Few of these sectional prejudices are, however, to be discovered in Ohio, the greater part of the population here having been derived from New England. Cincinnati, which in 1810, contained 2500 inhabitants, is now said to number about 12,000.[025] Its plan is regular, and most of the buildings are of {21} brick. The dwellings are neat and capacious, and sometimes elegant.

The site of the town was heretofore an aboriginal station, as appears from the numerous remains of ancient works still visible. We forbear to give any account of[pg068] these interesting monuments, as they have already been repeatedly described.[026]

On Tuesday, the 18th, the weather becoming clear and pleasant, Dr. Baldwin thought himself sufficiently recovered to proceed on the voyage; accordingly, having assisted him on board the boat, we left Cincinnati at ten o'clock.

During our stay at that place, we had been gratified by the hospitable attentions of the inhabitants of the town. Mr. Glen was unremitting in his exertions to promote the recovery of Dr. Baldwin's health; to him, as well as to Dr. Drake, and several other gentlemen of Cincinnati, all the members of our party were indebted for many friendly attentions.

Below Cincinnati the scenery of the Ohio becomes more monotonous than above. The hills recede from the river, and are less elevated. Heavy forests cover the banks on either side, and intercept the view from all distant objects. This is, however, somewhat compensated by the magnificence of the forests themselves. Here the majestic platanus attains its greatest dimensions, and the snowy whiteness of its branches is advantageously contrasted with the deep verdure of the cotton-wood, and other trees which occur in the low grounds.

The occidental plane tree is, perhaps, the grandest of the American forest trees, and little inferior, in any respect, to the boasted plane tree of the Levant. The platanus orientalis attains, in its native forests, a diameter of from ten to sixteen feet. An American plane tree, which we measured, on the bank of the Ohio, between Cincinnati and the rapids at Louisville, was fourteen feet in diameter.[pg069] One which stood, some years since, near the village of {22} Marietta, was found, by M. Michaux, to measure 157⁄10 ft. in diameter, at twenty feet from the ground.[027] They often rise to an elevation of one hundred and fifty feet. The branches are very large and numerous, forming a spreading top, densely covered with foliage. Many of those trees, which attain the greatest size, are decayed in the interior of the trunk, long after the annual increase continues to be added at the exterior circumference. The growth of the American plane tree does not appear to be very rapid. It was remarked by Humboldt, that in the hot and damp lands of North America, between the Mississippi and the Alleghany mountains, the growth of trees is about one-fifth more rapid than in Europe, taking for examples the platanus occidentalis, the liriodendron tulipifera, and the cupressus disticha, all of which reach from nine to fifteen feet in diameter. It is his opinion that the growth in these trees does not exceed a foot in diameter in ten years.[028] As far as our observation has enabled us to judge, this estimate rather exceeds than falls short of the truth. This growth is greatly exceeded in rapidity by the baobab, and other trees in the tropical parts of America; also by the gigantic adansonia of the eastern continent,[029] and equalled, perhaps, by several trees in our own climate, whose duration is less extended than that of those above mentioned. [030]