Dilucida et negligenter quoque audientibus aperta; ut in animum ratio tanquam sol in oculos, etiamsi in eam non intendatur, occurrat. Quare, non ut intelligere possit, sed ne omnino possit non intelligere, curandum.

QUINTIL.

If you would make a speech, or write one,

Or get some artist to indite one,

Don't think, because 'tis understood

By men of sense, 'tis therefore good;

But let your words so well be plann'd,

That blockheads can't misunderstand.

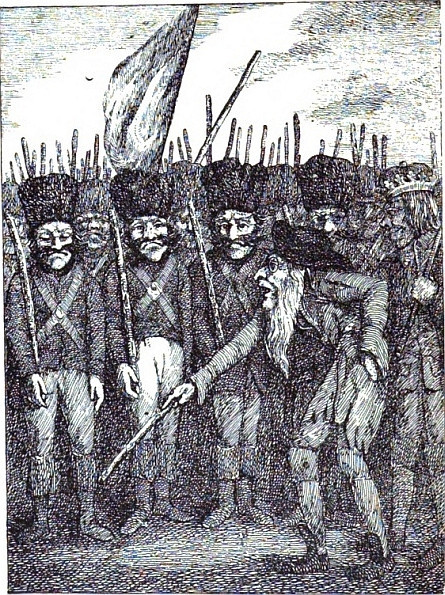

Homer casting pearls before Swine.

Atrides, as the story goes,

Took parson Chrysis by the nose.

Apollo, as the gods all do,

Of Christian, Pagan, Turk, or Jew,

On that occasion did not fail

To back his parson tooth and nail.

This caus'd a dev'lish quarrel 'tween

Pelides and the king of men;

Which ended to Achilles' cost,

Because a buxom wench he lost.

On which great Jove and's wife fell out,

And made a damn'd confounded rout:

And, had not honest Vulcan seen 'em

Ready for blows, and stepp'd between 'em;

'Tis two to one but their dispute

Had ended in a scratching-bout.

Juno at last was over-aw'd,

Or Jove had been well clapper-claw'd.

Good people, would you know the reason

I write at this unlucky season,

When all the nation is so poor

That few can keep above one whore,

Except the lawyers—(whose large fees

Maintain as many as they please)—

And Pope, with taste and judgement great,

Has deign'd this author to translate—

The reason's this:—He may not please

The jocund tribe so well as these;

For all capacities can't climb

To comprehend the true sublime.

Another reason I can tell,

Though silence might do full as well;

But being charg'd—discharge I must,

For bladder, if too full, will burst.

The writers of the merry class,

E'er since the time of Hudibras,

In this strange blunder all agree,

To murder short-legg'd poetry.

Words, though design'd to make ye smile,

Why mayn't they run as smooth as oil?

No poetaster can convince

A man of any kind of sense,

That verse can be the greater treasure,

Because it wants both weight and measure

Or can persuade, that false rough metre,

Than true and smooth, by far is sweeter.

This is the wherefore; and the why,

Have patience, you'll see by-and-by.

Come, Mrs. Muse, but, if a maid,

Then come Miss Muse, and lend me aid!

Ten thousand jingling verses bring,

That I Achilles' wrath may sing,

That I may chant in curious fashion

This doughty hero's boiling passion,

Which plagu'd the Greeks; and gave 'em double

A Christian's share of toil and trouble,

And, in a manner quite uncivil,

Sent many a Broughton to the devil;

Leaving their carcasses on rows,

Food for great dogs and carrion crows.

To this sad pass the bully's freaks

Had brought his countryfolks the Greeks!

But who the devil durst say no,

Since surly Jove would have it so?

Come tell us then, dear Miss, from whence

The quarrel rose: who gave th' offence?

Latona's son, with fiery locks,

Amongst them sent both plague and pox.

And prov'd most damnably obdurate,

Because the king had vex'd his curate;

For which offence the god annoy'd 'em,

And by whole waggon-loads destroy'd 'em.

"A red nosed priest came hobbling after

With presents to redeem his daughter.

Like a poor supplicant did stand,

With an old garland in his hand,

Filch'd from a maypole.—"

The case was this: These sons of thunder

Took a plump wench amongst their plunder.

A red-nos'd priest came hobbling after,

With presents to redeem his daughter;

Like a poor supplicant did stand,

With an old garland in his hand

Filch'd from a May-pole, and to boot

A constable's short staff lugg'd out.

These things, he told the chief that kept her,

Were his old master's crown and sceptre;

Then to the captains made a speech,

And to the brothers joint, and each:

Ye Grecian constables so stout,

May you all live to see Troy out;

And when you've pull'd it to the ground,

May you get home both safe and sound!

Was Jove but half the friend that I am,

You quickly should demolish Priam;

But, since the town his godship spares,

I'll help you all I can with pray'rs.

For my part, if you'll but restore

My daughter, I'll desire no more.

You'll hardly guess the many shifts

I made to raise you all these gifts.

If presents can't for favour plead,

Then let your pity take the lead.

Should you refuse, Apollo swears,

He'll come himself, and lug your ears.

The Grecians by their shouts declare

Th' old gentleman spoke very fair;

They swore respect to him was due,

And he should have his daughter too:

For he had brought, to piece the quarrel,

Of Yarmouth herrings half a barrel.

No wonder then their mouths should water

More for his herrings than his daughter.

But Agamemnon, who with care

Had well examin'd all her ware,

And guess'd that neither Troy nor Greece

Could furnish such another piece,

Roars out: You make a cursed jargon!

But take me with ye ere you bargain:

My turn's to speak; and as for you, Sir,

This journey you may chance to rue, Sir:

Nor shall your cap and gilded stick

Preserve your buttocks from a kick,

Unless you show your heels, and so

Escape the rage of my great toe.

What priest besides thyself e'er grumbled

To have his daughter tightly tumbled?

Then don't provoke me by your stay,

But get you gone, Sir, whilst you may.

I love the girl, and sha'nt part with her

Till age has made her hide whit-leather.

I'll keep her till I can no more,

And then I will not turn her o'er,

But with my goods at Argos land her,

And to my own old mansion hand her,

Where she shall card, and spin, and make

The bed which she has help'd to shake.

From all such blubb'ring rogues, depend on't,

I'll hold her safe, so mark the end on't.

Then cease thy canting sobs and groans,

And scamper ere I break thy bones.

Away then sneak'd the harmless wizard,

Grumbling confoundedly i' th' gizzard,

And, as in doleful dumps he pass'd,

Look'd sharp for fear of being thrash'd.

But out of harm's way when he got,

To Phœbus he set up his throat:

Smintheus, Latona's son and heir,

Cilla's chief justice, hear my pray'r!

Thou link-boy of the world, that dost

In Chrysa's village rule the roast,

And know'st the measure, inter nos,

Of ev'ry wench in Tenedos,

Rat-catcher general of heaven,

Remember how much flesh I've given

To stay your stomach; beef and mutton

I never fail'd your shrine to put on;

And, as I knew you lik'd them dearly,

I hung a dozen garlands yearly

About your church, nor charg'd the warden

Or overseers a single farthing;

But paid the charge and swept the gallery

Out of my own poor lousy salary.

This I have done, I'll make't appear,

For more than five-and-fifty year.

In recompense I now insist

The Grecians feel thy toe and fist;

For sure thou canst not grudge the least

To vindicate so good a priest.

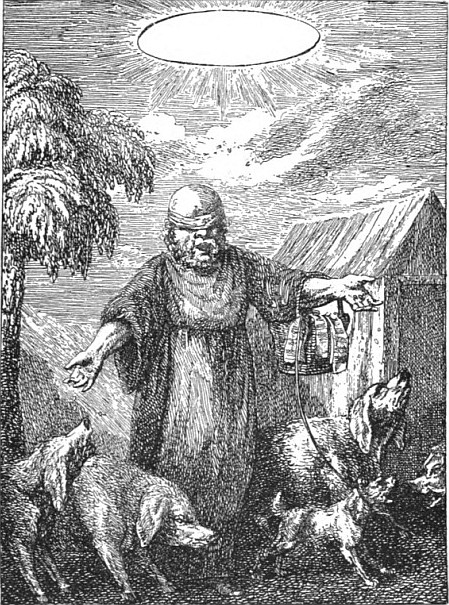

Thus Chrysis pray'd: in dreadful ire,

The carrot-pated god took fire;

But ere he stirr'd he bent his bow,

That he might have the less to do,

Resolv'd before he did begin

To souse 'em whilst his hand was in.

Fierce as he mov'd the Greeks to find,

He made a rumbling noise behind;

His guts with grumbling surely never

Could roar so loud—it was his quiver,

Which, as he trotted, with a thwack

Rattled against his raw-bone back.

In darkness he his body shrouds,

By making up a cloak of clouds.

But, when he came within their view,

Twang went his trusty bow of yew:

He first began with dogs and mules,

And next demolish'd knaves and fools.

Nine nights he never went to sleep,

And knock'd 'em down like rotten sheep;

And would have sous'd 'em all, but Juno,

A scolding b——h as any you know,

Came and explain'd the matter fully

To Thetis' son, the Grecian bully,

Who ran full speed to summon all

The common council to the hall.

When seated, with a solemn look

Achilles rose, and thus he spoke:

Neighbours, can any Grecian say

We ought not all to run away

From this curst place without delay?

Else soon our best and bravest cocks

Will be destroy'd by plague or pox.

We cannot long, though Jove doth back us,

Resist, whilst two such foes attack us.

I think 'tis time to spare the few

Our broils have left; but what think you?

A cunning man perhaps may tell us

The reason why this plague befel us

Or an old woman, that can dream,

May help us out in this extreme;

For dreams, if rightly you attend 'em,

Are true, when Jove thinks fit to send 'em.

Thus may we form some judgment what

This same Apollo would be at;

Whether he mauls each wicked sinner,

Because a mighty pimping dinner

He often had but then he knew

That we had damn'd short commons too.

If 'tis for that he makes such stir,

He's not the man I took him for:

But, as I've reason for my fears,

I vote to pay him all arrears.

Therefore let such a man be found,

Either above or under ground,

To tell us quickly how we may

In proper terms begin to pray,

That he may ease us of these curses,

And stay at home and mind his horses—

Much better bus'ness for the spark

Than shooting Grecians in the dark.

He said, and squatting on his breech,

Calchas rose up, and look'd on each:

With caution he began to speak

A speech compos'd of purest Greek.

He was a wizard, and could cast

A figure to find out things past;

And things to come he could foretel,

Almost as well as Sydrophel.

The diff'rent languages he knew

Of every kind of bird that flew,

Each word could construe that they spoke.

Or screech-owl's scream, or raven's croak,

And, by a science most profound,

Distinguish rotten eggs from sound.

When first the Grecians mann'd their boats

To sail and cut the Trojans' throats,

Safely to steer 'em through the tide,

They chose this wizard for their guide.

As slow as clock-work he arose,

Then with his fingers wip'd his nose:

Dubious to speak or hold his tongue,

His words betwixt his teeth were hung:

But, having shook 'em from his jaws,

As dogs shake weasels from their nose,

Away they came both loud and clear,

And told his mind, as you shall hear:

Thou that art Jove's respected friend,

To what I speak be sure attend,

And in a twinkling shalt thou know,

Why Phœbus smokes the Grecians so,

But promise, should the chief attack me,

That thou my bully-rock wilt back me;

Because I know things must come out,

Will gripe him to the very gut.

These monarchs are so proud and haughty,

Subjects can't tell them when they're faulty,

Because, though now their fury drops,

Somehow or other out it pops.

And this remember whilst you live,

When kings can't punish, they'll forgive.

Achilles thus: Old cock, speak out,

Speak freely without fear or doubt.

Smite my old pot-lid! but, so long

As I draw breath amidst this throng.

The bloodiest cur in all the crew

Sha'n't dare so much as bark at you:

Not e'en the chief, so grum and tall,

Who sits two steps above us all.

These words the doubtful conj'ror cheer,

Who then proceeded without fear:

To th' gods you never play'd the thief,

But paid them well with tripe or beef;

But 'tis our chief provok'd Apollo

With this curst plague our camp to follow

Because his priest was vilely us'd,

His daughter kiss'd, himself abus'd.

The curate's pray's caus'd these disorders:

Gods fight for men in holy orders.

Nor will he from his purpose flinch,

Nor will his godship budge one inch,

But without mercy, great and small,

Will never cease to sweat us all,

If Agamemnon doth not send her,

With cooks and statesmen to attend her.

Then let's in haste the girl restore

Without a ransom; and, what's more,

Let's rams, and goats, and oxen give,

That priests and gods may let us live.

Ready to burst with vengeful ire,

That made his bloodshot eyes strike fire,

Atrides, with an angry scowl,

Replies, The devil fetch your soul!

I've a great mind, you lousy wizard,

To lay my fist across your mazzard.

Son of an ugly squinting bitch,

Pray who the pox made you a witch?

I don't believe, you mongrel dog,

You ken a handsaw from a hog;

Nor know, although you thus dare flounce,

How many f——s will make an ounce;

And yet, an imp, can always see

Some mischief cooking up for me,

And think, because you are a priest,

You safely may with captains jest.

But I forewarn thee, shun the stroke,

Nor dare my mighty rage provoke.

A pretty fellow thou! to teach

Our men to murmur at thy speech,

Tell lies as thick as you can pack 'em,

And bring your wooden gods to back 'em

And all because a girl I keep

For exercise, to make me sleep.

Besides, the wench does all things neatly,

And handles my affairs completely.

She hems, marks linen, and she stitches,

And mends my doublet, hose, and breeches,

My Clytemnestra well I love,

But not so well as her, by Jove!

Yet, since you say we suffer slaughter

Because I kiss this parson's daughter,

Then go she must; I'll let her go,

Since the cross gods will have it so;

Rather than Phœbus thus shall drive,

And slay the people all alive,

From this dear loving wench I'll part,

The only comfort of my heart.

But, since I must resign for Greece,

I shall expect as good a piece:

'Tis a great loss, and by my soul

All Greece shall join to make me whole!

Don't think that I, of all that fought,

Will take a broken pate for nought.

Achilles, starting from his breech,

Replies, By Jove, a pretty speech!

Think'st thou the troops will in her stead

Send what they got with broken head;

Or that we shall esteem you right in

Purloining what we earn'd by fighting?

You may with bullying face demand,

But who the pox will understand?

If thou for plunder look'st, my boy,

Enough of that there is in Troy:

Her apple-stalls we down may pull,

And then we'll stuff thy belly full.

The chief replies: For you, Achilles,

I care not two-pence; but my will is

Not to submit to be so serv'd,

And thou lie warm whilst I am starv'd.

Though thou in battle mak'st brave work,

Can beat the devil, pope, and Turk,

With Spaniards, Hollanders, and French,

I won't for that give up my wench:

Nor shall I, Mr. Bluff, d'ye see,

Resign my girl to pleasure thee.

Let something be produc'd to view,

Which I may have of her in lieu,

Something that's noble, great and good,

Worthy a prince of royal blood;

Just such another I should wish her,

As sev'n years since was Kitty Fisher;

Or else I will, since you provoke,

At all your prizes have a stroke;

Ulysses' booty will I seize,

Or thine or Ajax', if I please.

The man that's hurt may bawl and roar,

And swear, but he can do no more.

But this some other time may do,

I must go launch a sand-barge now:

Victuals and cooks I must take care,

With oars and pilots, to prepare;

See the ropes tarr'd, the bottom mended,

And the old sails well piec'd and bended

Then put the wench on board the boat,

Attended by some man of note,

By Creta's chief, or, if he misses,

By Ajax, or by sly Ulysses;

Or, if I please, I'll make you skip

Aboard, as captain of the ship.

We make no doubt but you with ease

His angry godship may appease;

Or else your goggle eyes, that fright us,

May scare him so he'll cease to smite us.

You would have sworn this mortal twitch

Had given old Peleus' son the itch,

So hard he scratch'd; at last found vent,

And back to him this answer sent:

Thou wretch, to all true hearts a stain,

Thou damn'd infernal rogue in grain!

Thou greater hypocrite than G-ml-y,

Thou dirtier dog than Jeremy L——y!

Whose deeds, like thine, will ever be

A scandal to nobility;

From this good day I hope no chief

Will fight thy broils, or eat thy beef.

How canst thou hope thy men will stand,

When under such a rogue's command?

What bus'ness I to fight thy battle?

The Trojans never stole my cattle.

My farm, secur'd by rocks and sands,

Was safe from all their thieving bands.

My steeds fed safe, both grey and dapple;

Nor could they steal a single apple

From any orchard did belong

To me, my fences were so strong.

I kept off all such sons of bitches

With quick-set hedges fac'd with ditches.

Our farm can all good things supply,

Our men can box, and so can I.

Hither we came, 'tis shame I'm sure,

To fight, for what? an arrant whore!

A pretty story this to tell.

Instead of being treated well,

As a reward for all our blows,

We're kick'd about by your dog's nose.

And dar'st thou think to seize my plunder,

For which I made the battle thunder,

And men and horses truckle under?

No! since it was the Grecians' gift,

To keep it I shall make a shift.

What wouldst thou have? thou hadst the best

Of every thing; nay, 'tis no jest:

But you take care to leave, I see,

The fighting trade to fools like me.

In this you show the statesman's skill,

To let fools fight whilst you sit still.

First I'm humbugg'd with some poor toy,

Then clapp'd o' th' back, and call'd brave boy.

This shall no more hold water, friend:

My 'prenticeship this day shall end.

When I go, and my men to boots,

I leave thee then a king of clouts.

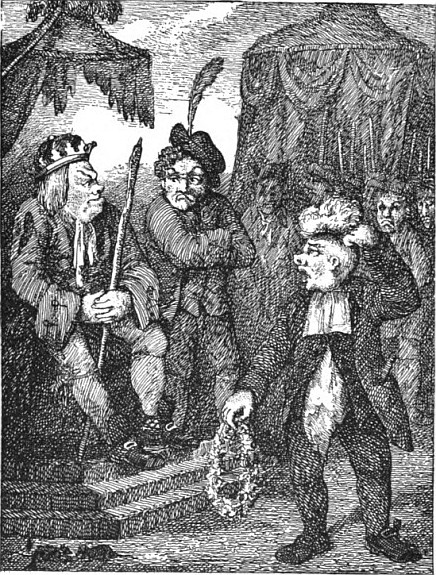

The general gave him tit for tat,

And answer'd, cocking first his hat:

Go, and be hang'd, you blust'ring whelp,

Pray who the murrain wants your help?

When you are gone, I know there are

Col'nels sufficient for the war,

Militia bucks that know no fears,

Brave fishmongers and auctioneers.

Besides, great Jove will fight for us,

What need we then this mighty fuss?

Thou lov'st to quarrel, fratch, and jangle,

To scold and swear, and fight and wrangle.

Great strength thou hast, and pray what then?

Art thou so stupid, canst not ken,

The gods, that ev'ry thing can see,

Give strength to bears as well as thee?

Of all Jove's sons, a bastard host,

For reasons good, I hate thee most.

Prithee be packing; thou'rt not fit,

Or here to stand, or there to sit:

In your own parish kick your scrubs,

They're taught to bear such kind of rubs;

But, for my part, I scorn the help

Of such a noisy, bullying whelp:

Go therefore, friend, and learn at school,

First to obey, and then to rule.

The gods they say for Chryseis send,

And to restore her I intend;

But look what follows, Mr. Bully!

See if I don't convince thee fully,

That thy bluff wench with sandy hair

The loss I suffer shall repair:

I'll let thee feel what 'tis to be

A rival to a chief like me;

That thou and all these folks may know,

Great men are only subject to

The gods, or right or wrong they do.

Had you but seen Achilles fret it,

I think you never could forget it;

A sight so dreadful ne'er was seen,

He sweat for very rage and spleen:

Long was he balanc'd at both ends;

When reason mounted, rage descends;

The last commanded sword lug out;

The first advis'd him not to do't.

With half-drawn weapon fierce he stood,

Eager to let the general blood;

When Pallas, swift descending down,

Lent him a knock upon the crown;

Then roar'd as loud as she could yelp,

Lugging his ears, 'Tis I, you whelp!

Now Mrs. Juno, 'cause they both

Were fav'rites, was exceeding loth

To have 'em quarrel; so she sent

This wench all mischief to prevent,

And, to obstruct her being seen,

Lent her a cloud to make a screen.

Pelides wonder'd who could be

So bold, and turn'd about to see:

He knew the twinkling of her eyes,

And loud as he could bawl, he cries,

Goddess of Wisdom! pray what weather

Has blown your goatskin doublet hither?

Howe'er, thou com'st quite opportune

To see how basely I'm run down;

Thou com'st most à-propos incog.

To see how I will trim this dog:

For, by this trusty blade, his life

Or mine shall end this furious strife!

To whom reply'd the blue-ey'd Pallas,

I come to save thee from the gallows:

Thou'rt surely either mad or drunk,

To threaten murder for a punk:

Prithee, now let this passion cool;

For once be guided by a fool.

From heav'n I sous'd me down like thunder,

To keep your boiling passion under;

For white-arm'd Juno bid me say,

Let reason now thy passion sway,

And give it vent some other day;

Sheathe thy cheese-toaster in its case,

But call him scoundrel to his face.

To Juno both alike are dear,

And both alike to me, I'll swear.

In a short time the silly whelp

Will give a guinea for thy help;

Only just now revenge forbear,

And be content to scold and swear.

Achilles thus: With ears and eyes

I mind thee, goddess bold and wise!

'Tis hard; but since 'tis your command,

Depend upon't I'll hold my hand—

Knowing, if your advice I take,

Some day a recompense you'll make:

Besides, of all the heavenly crew,

I pay the most regard to you.

This said, he rams into the sheath

His rusty instrument of death.

(Pallas then instantly took flight,

Astride her broom-stick, out of sight;

And ere you could repeat twice seven,

Had reach'd the outward gate of heaven.)

His gizzard still was mighty hot,

And boil'd like porridge in a pot;

Atrides he did so randan,

He call'd him all but gentleman;

By Jove, says he, thou'rt always drunk,

And always squabbling for a punk.

Thou dog in face! thou deer in heart!

Thou call'd a fighter! thou a f—t!

When didst thou e'er in ambush lie,

Unless to seize some mutton pie?

And there you're safe, because you can

Run faster than the baker's man.

When fighting comes you bid us fight,

And claim the greatest profit by't.

Great Agamemnon safer goes,

To rob his friends than plunder foes:

And he who dares to contradict

Is sure to have his pockets pick'd:

Hear then, you pilfering dirty cur,

Whose thieving makes so great a stir;

And let the crowd about us hear

What I by this same truncheon swear,

Which to the tree whereon it grew

Will never join, nor I with you,

The devil fetch me if I do!

Therefore, I say, by this same stick,

Expect no more I'll come i' th' nick

Your luggs to save: let Hector souse ye,

And with his trusty broomshaft douse ye.

God help us all, I know thou'lt say,

Then stare and gape, and run away:

All this will happen, I conjecture,

The very next time you see Hector;

And then thyself thou'lt hang, I trow,

For using great Achilles so.

This said, his truncheon, gilded all

Like ginger-bread upon a stall,

Around the top and bottom too,

Slap bang upon the floor he threw.

His wrath Atrides could not hold,

But cock'd his mouth again to scold,

And talk'd away at such a rate,

He distanc'd hard-mouth'd scolding Kate,

The orator of Billingsgate.

Whilst thus they rant and scold and swear

Old Square-toes rises from his chair;

With honey words your ears he'd sooth,

Pomatum was not half so smooth.

Nestor had fill'd the highest stations

For almost three whole generations;

At ev'ry meeting took the chair,

Had been a dozen times lord-mayor,

And, what you hardly credit will,

Remain'd a fine old Grecian still.

On him with gaping jaws they look,

Whilst the old coney-catcher spoke:

To Greece 'twill be a burning shame,

But to the Trojans special game,

That our best leaders, men so stout,

For whores and rogues should thus fall out:

Young men the old may treat as mules,

We know full well young men are fools;

Therefore, to lay the case before ye

Plain as I can, I'll tell a story:

I once a set of fellows knew,

All hearts of oak, and backs of yew:

To look for such would be in vain,

I ne'er shall see the like again.

Though bruis'd from head to foot they fought on,

Pirithous was himself a Broughton.

Bold Dryas was as hard as steel,

His knuckles would make Buckhurst feel;

And strong-back'd Theseus, though a sailor,

Would single-handed beat the Nailor.

Great Polyphemus too I brag on,

He fought and kick'd like Wantley's dragon;

And Cineus often would for fun

Make constables and watchmen run.

Such were my cronies, rogues in buff,

Who taught me how to kick and cuff.

With these the boar stood little chance;

They made the four-legg'd Centaurs prance.

Now these brave boys, these hearts of oak,

Were all attention when I spoke;

And listen'd to my fine oration

Like Whitfield's gaping congregation:

Though I was young, they thought me wise;

You sure may now with me advise.

Atrides, don't Briseis seek;

For, if you do, depend, each Greek,

The dastard rogue as well as brave,

Will say our king's both fool and knave.

The want of brains is no great shame,

'Cause nature there is most to blame;

But this plain fact by all is known,

If you're a rogue, the fault's your own.

Achilles, don't you play the fool,

And snub the king; for he must rule.

Thou art in fight the first, I grant;

As brave as Mars, or John-a-Gaunt:

But then you must allow one thing,

No man should scold and huff a king.

Matters you know are just this length,

He has got pow'r, and you have strength

Of each let's take a proper sup

To make a useful mixture up.

Do you, Atrides, strive to ease

Your heart; this bully I'll appease.

I'd rather give five hundred pound

Than have Pelides quit the ground.

Bravo! old boy! the king replies,

I swear my vet'ran's wondrous wise:

But that snap-dragon won't submit

To laws, unless he thinks 'em fit;

Because he can the Trojans swinge,

He fancies I to him should cringe:

But I, in spite of all his frumps,

Shall make him know I'm king of trumps.

Achilles quickly broke the thread

Of this fine speech; and thus he said:

Now, smite me, but I well deserv'd

To be so us'd, when first I serv'd

So great a rogue as you; but damn me

If you another day shall flam me:

Seize my Briseis, if you list,

I've pass'd my word I won't resist;

Safely then do it, for no more,

For any woman, wife or whore,

Achilles boxes; but take care

Your scoundrels steal no other ware:

No more Achilles dare t'affront,

Lest he should call thee to account,

And the next scurvy squabble close,

By wringing off thy snotty nose.

This Billingsgate affair being o'er,

Sullen they turn'd 'em to the door.

Achilles in a hurry went,

And sat down sulky in his tent:

Patroclus, as a friend should do,

Both grumbled and look'd sulky too.

Mean time Atrides fitted out

From Puddle Dock a smuggling-boat.

On deck Miss Chryseis took her stand;

Ulysses had the chief command.

The off'rings in the hold they stuff'd,

Then, all sails set, away they luff'd.

The chol'ric chief doth next essay

The soldiers' filth to wash away;

A cart and horse to every tent,

He with a noisy bellman sent:

The bell did signify, You must

Without delay bring out your dust:

Then made 'em stand upon the shore,

And wash their dirty limbs all o'er:

Next, by advice of Doctor Grimstone,

He rubb'd their mangey joints with brimstone,

Because, when first they sally'd forth,

Some mercenaries from the north

Had brought a queer distemper, which

The learned doctors call'd the itch.

He next begins to cut the throats

Of bulls, and sheep, and lambs, and goats;

The legs and loins in order laid,

To Phœbus all his share is paid:

Apollo, as the smoke arose,

Snuff'd ev'ry atom up his nose;

And, rather than they would provoke him,

They sent him smoke enough to choke him.

Still in the midst of all this coil,

Atrides felt his ewer boil:

Talthybius and Euribates,

Two ticket porters, did await his

Dread will, to carry goods and chattels,

Or run with messages in battles:

To these he speaks:—Ye scoundrels two,

What I command observe ye do;

Run to Achilles' tent, take heed,

And bring away his wench with speed;

Tell him you're order'd to attend her,

And I expect he'll quickly send her;

Else with a file of musqueteers

I'll beat his tent about his ears.

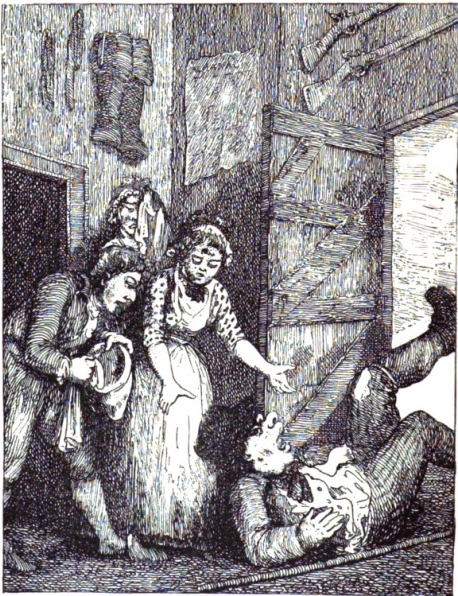

The hero in his tent they found,

His day-lights fixt upon the ground.

They hung an arse, what could they do?

They'd rather not, but yet must go:

Pensive they trod the barren sand,

On this side sea, on that side land,

And look'd extreme disconsolate,

Fearing at least a broken pate.

The hero in his tent they found,

His day-lights fix'd upon the ground:

They relish'd not his surly look,

So out of fear their distance took:

Quickly he guess'd they were in trouble,

And scorn'd to make their burden double

But with his finger, or his thumb,

Beckon'd the tardy knaves to come.

Ye trusty messengers, draw near,

And don't bedaub yourselves for fear,

Though you smell strong; but if 'tis so,

Pray clean yourselves before ye go;

Your master, if my thoughts prove true,

Will soon smell stronger far than you.

I partly guess for what you came;

Poor rogues, like you, should bear no blame.

Compell'd, you hither bent your way;

And servants always should obey.

Patroclus, fetch this square-stern'd jade,

Let her be to his tent convey'd:

But hark, ye messengers declare,

What I by Gog and Magog swear,

That though in blood all Greece shall wallow,

With fretting I'll consume no tallow,

But coolly let, and so I tell ye,

The Trojans beat your bones to jelly;

And if to me they are but civil,

May drive you scoundrels to the devil.

Your muddy-pated, hot-brain'd chief,

(Whose folly far exceeds belief)

When he has got a broken pate,

Will find himself an ass too late.

Mean time the bold Patroclus bears

The red-hair'd wench all drown'd in tears;

Who, with a woful heavy heart,

(As loth from his strong back to part)

Whilst with the porters twain she went,

Kept squinting backward to his tent.

Now, when the buxom wench was gone,

What think you doth this lubber-loon,

But, when he found no mortal near him,

Roar so, 'twould do you good to hear him;

And hanging his great jolter head

O'er the salt sea, he sobb'd, and said:

Oh, mother! since I'm to be shot,

Or some way else must go to pot,

I think great Jove, if he did right,

Should scour my fame exceeding bright.

'Tis quite reverse: yon brazen knave

Has stole the plumpest wench I have;

And in the face of all the throng

Of constables has done me wrong.

The goddess heard him under water,

And ran as fast as she could patter:

She saw he'd almost broke his heart,

And, like good mother, took his part:

My son, I'm vext to hear thee cry;

Come, tell mamma the reason why.

From th' bottom of his wame he sigh'd,

And to his mammy thus reply'd:

For what that rogue has made me cry,

You know, I'm sure, as well as I:

Yet since you bid me tell my story,

I'll whip it over in a hurry.

What think you that vile scoundrel's done,

That Agamemnon, to your son?

Because his pretty girl was gone,

He must have mine, forsooth, or none.

The Grecians gave to me this prize:

He huffs the Greeks, and damns their eyes.

We went to Thebes, and sack'd a village,

And brought away a world of pillage:

Amongst the plunder that was taken,

Besides fat geese, and eggs, and bacon,

We got some wenches plump and fair,

Of which one fell to that rogue's share:

But in the middle of our feast,

There came a hobbling red-nos'd priest;

In a great wallet that old dreamer

Had brought some presents to redeem her,

And made such humble supplication,

Attended with a fine oration,

That ev'ry Greek, except Atrides,

On the old hobbling parson's side is.

But he, of no one soul afraid,

Swore blood-and-oons he'd keep the maid

And, with an answer most uncivil,

Damn'd the old fellow to the devil.

The priest walk'd home in doleful dumps

(Like Witherington upon his stumps):

But, it is plain, he made a holla

That reach'd his loving friend Apollo;

For he in wrath, most furiously,

Began to smite us hip and thigh;

And had not I found out a prophet,

That told us all the reason of it,

Burn my old shoes, if e'er a sinner

Had now been left to eat a dinner;

But that, as sure as cits of London

Oft leave their spouses' business undone,

And trudge away to Russel-street

Some little dirty whore to meet,

Whilst the poor wife, to cure her dumps,

Works her apprentice to the stumps;

So sure this god, for rage or fun,

Had pepper'd ev'ry mother's son.

'Twas I, indeed, did first advise

To cook him up a sacrifice,

And then his pardon strive to gain

By sending home the wench again;

For which the damn'd confounded churl

Swore he would have my bouncing girl:

And I this minute, you must know,

Like a great fool, have let her go:

For which, no doubt, it will be said

Your son has got a chuckle head.

To Jove then go, and catch him by

The hand, or foot, or knee, or thigh;

Hold him but fast, and coax him well.

And mind you that old story tell,

How you of all the gods held out

When they once rais'd a rebel rout,

And brought a giant from Guildhall

With face so grim he scar'd 'em all:

When once you'd got him rais'd above,

And plac'd him by the side of Jove,

So fast with both his hands he thunder'd,

The rebels swore he'd got a hundred,

Threw down the ropes they'd brought to bind 'em,

And, scamp'ring, never look'd behind 'em:

Tell him, for this, to drive pell mell

The Grecian sons of whores to hell,

That Atreus' son, that stupid fool,

May have no scoundrels left to rule;

And then he'll hang himself for spite,

He durst the boldest Grecian slight.

His mother's heart was almost broke,

To hear how dolefully he spoke:

But having belch'd, she thus replies,

The salt brine running from her eyes:

O Killey, since the Fates do stint

Thy precious life, the devil's in't

That thou must likewise bear to boots

This scurvy, mangey rascal's flouts:

But take thy mammy's good advice,

And his thee homeward in a trice;

Or, if thou'd rather choose to stay,

Don't help the dogs in any fray.

Depend upon't, to Jove I'll go,

And let him all the matter know:

He junkets now with swarthy faces

(For he, like men, has all his paces),

And will continue at the feast

Ten or eleven days at least:

Taking, like our Jamaica planters,

Their fill of what our vilest ranters

Would puke at but these kind of beast

Esteem it as a noble feast;

I mean the breaking-up the trenches

Of sooty, sweaty negro wenches

(Though most o' th' planters that thus roam,

Like Jove, have wife enough at home.)

Soon as his guts have got their fill,

I'll tell him all, by Jove I will!

Till he has granted my petition,

Don't stir to keep 'em from perdition;

Not e'en to save their souls, plague rot 'em!

So souse she plung'd, and reach'd the bottom.

Mean time Ulysses, full of cares,

Had moor'd his boat at Chrysa's stairs:

When sails were furl'd, and all made snug,

They tipp'd the can, and pass'd the jug;

Then fell to work, and brought their store

Of cows and rotten sheep ashore:

This done, the last of all came out

The girl that caus'd this woful rout.

Ulysses, ever on the lurch,

Hurries the girl away to church,

Knowing full well that there he had

Best chance of finding her old dad;

And as he gave her to th' old man,

To lie[1] and cant he thus began:

I come upon my bended knees,

Thine and Apollo's wrath t' appease;

And that I'm in good earnest, see

Thy girl come back, and ransom-free;

And, what I own is boldly said,

I've brought her with her maidenhead;

For which, I hope, our friend you'll stand,

That Sol may hold his heavy hand,

The parson hugg'd and kiss'd his daughter,

And shak'd the hands of them that brought her

So pleas'd to see the girl again,

He fell to prayers might and main;

And, whilst the Greeks the cattle slay,

The parson thus was heard to pray:

Apollo, pr'ythee hear me now,

As eke thou didst nine days ago:

As thou at my request didst murder

The Grecians, pr'ythee go no further;

Hear, once again, thy priest's petition,

And mend their most bedaub'd condition.

Apollo, as the sound drew near,

To ev'ry syllab lent an ear:

And now they fell to cutting throats

Of bulls and oxen, sheep and goats.

After the day-light god was serv'd,

The priest for all the people carv'd.

But how the hungry whoresons scaff'd;

How eagerly the beer they quaff'd,

Till they had left no single chink,

Either to hold more meat or drink,

None can describe: they grew so mellow,

Nothing was heard but whoop and halloo;

Rare songs they sung, and catches too—

(The composition good and true)

Apollo made 'em, but took care

They should not last above a year,

Well knowing that the future race

Of men all knowledge would disgrace,

And that his lines must have great luck,

Not to give place to Stephen Duck.

At sun-set all hands went from shore

On board their oyster-boat to snore.

I' th' morning, when they hoist their sail,

Apollo lent a mack'rel gale,

With which they nimbly cross'd the main,

And haul'd their boat ashore again.

But now 'tis time we look about

And find the bold Achilles out:

Pensive he sat, and bit his thumbs;

No comfort yet, no mammy comes:

The days had number'd just eleven,

When Jupiter return'd to heaven;

He'd got his belly full of smacks

From thick-lip'd Ethiopian blacks.

The mother on her word must think;

So up she mounted in a twink,

Approach'd his godship, whom she took

Fast by the hand, and thus she spoke:

If ever I had luck to be

Useful in time of need to thee,

(Which, I am sure, you can't deny,

Unless you tell a cursed lie)

Quickly revenge th' affront that's done

By Agamemnon to my son.

Let Hector thrash 'em, if he list,

Till ev'ry Grecian rogue's bepiss'd,

And make them run like frighten'd rats

From mother Dobson's tabby cats.

Whilst Jove considers what to say,

Onward she goes; she'll have no nay:

You must with my request comply,

My dearest dad, so don't deny;

But let the heavenly rabble see

Some kindness is reserv'd for me.

Then answers he who rolls the thunder:

I'm much amaz'd, and greatly wonder,

That you should thus attempt, with tears,

To set my rib and me by th' ears;

This, by my soul! will make rare work:

Juno will rate me like a Turk:

You surely know, and have known long,

The devil cannot match her tongue:

To Troy, I'm sure, I wish full well,

She ne'er forgets that tale to tell:

But his away from hence, lest she

Should spy you holding chat with me.

If I but say I'll grant your suit,

You may depend upon't I'll do't:

With head (observe) I'll make a nod,

That cannot be revers'd by god.

The thund'rer then his noddle shakes,

And Greece, like city custard, quakes.

Thetis, well pleas'd the Greeks to souse,

Dives under water like a goose;

Whilst Jove to th' upper house repairs,

And calls about him all his peers;

Who ran t' attend his call much faster

Than schoolboys run to meet their master.

All silent stood the gaping bevy,

Like sneaking courtiers at a levee,

Juno excepted: fear she scorns,

She hates all manners, damns all forms;

And because Jove had just been talking

With Thetis (nothing more provoking),

Her passion rose, and she ding dong

Would quarrel with him, right or wrong.

'Tis mighty civil, on my life,

To keep all secrets from your wife:

Is this the method, Mr. Jove,

You take to show your wife your love?

Pray who's that brimstone-looking quean,

With whom you whispering was seen?

Perhaps you're set some secret task,

And I'm impertinent to ask.

Is there a wife 'tween here and Styx,

Like me, would bear your whoring tricks?

But, goodman Roister! I'd have you know,

Though you are Jove, I still am Juno!

Madam, says Jove, by all this prate,

I partly guess what you'd be at;

You want the secrets to disclose,

Which I conceal from friends and foes;

You only seek your own disquiet;

Secrets to women are bad diet.

A secret makes a desp'rate rumble,

Nor ceases in the gut to grumble

Till vent it finds; then out it flies,

Attended with ten thousand lies;

All characters to pieces tears,

And sets the neighbourhood by th' ears.

What's proper I'll to you relate,

The rest remains with me and Fate:

But from this day I'll order, no man

That's wise shall trust a tattling woman.

The goddess with the goggle eyes

Roll'd 'em about, and thus replies:

I find 'twill be in vain to plead,

When once you get it in your head

To contradict your loving wife;

You value neither noise nor strife,

But, spite of all that we can say,

You mules will always have your way.

But yet for Greece I'm sore afraid,

E'er since that cunning white-legg'd jade,

That Thetis, a long conf'rence had;

I'm sure she's hatching something bad,

And hath some mighty favour won

For her dear ranting roaring son?

Else, by my soul, you'd not have given

A nod that shook both earth and heaven;

Perhaps you'll take the whore's-bird's side,

And thrash my Grecians back and hide.

Flux me! quoth Jove, thy jealous pate,

Instead of love, will move my hate.

I tell thee, cunning thou must be

To worm this secret out of me;

'Tis better far, good wife, to cease

To plague me thus, and study peace;

Or if you want to make resistance,

Call all the gods to your assistance;

So all your jackets will I baste,

You'll not rebel again in haste.

Juno, with face as broad as platter,

Soon found she had mista'en the master;

She relish'd not this surly dish,

So sat her down as mute as fish:

At which the guests were so confounded,

That all their mirth was well nigh drowned

Their knives and forks they every one

Before their greasy plates laid down;

Each mouth was ready cock'd, to beg

Leave to depart, and make a leg;

When Juno's son, ycleped Vulcan,

A special fellow at a full can,

Who was of handicrafts the top,

And kept a noted blacksmith's shop,

Where he made nets, steel caps, and thunder,

And finish'd potlids to a wonder;

He, finding things were going wrong,

And that they'd fall by th' ears ere long,

Starts up, and in a merry strain

Hammer'd a speech from his own brain.

Quoth he, What pity 'tis that we,

Who should know nought but jollity,

Should scold and squabble, brawl and wrangle,

And about mortal scoundrels jangle!

In peace put we the can about,

Let Englishmen in drink fall out,

And, at the meetings of the trade,

Fight when the reck'ning should be paid.

Mother, you know not what you're doing;

To CALLOT thus will be your ruin;

He'll some time, in a dev'lish fury,

Do you some mischief, I'll assure you:

Yet, I'll lay sixpence to a farthing,

He'll kiss you, if you ask his pardon.

This said, a swingeing bowl he takes,

And drank it off for both their sakes;

Then with a caper fill'd another,

Which he presented to his mother:

Not courtier-like I hand this bowl:

But take it from an honest soul,

That means and thinks whate'er he says;

It won't be so in future days:

Here, drink Jove's health, and own his sway:

You know all women must obey.

When once my father's in a passion,

He's dev'lish cross, hear my relation:

In your good cause I felt his twist,

My leg he seiz'd in his strong wrist;

In vain it was with him to grapple,

He grasp'd me as you would an apple;

And from his mutton-fist when hurl'd,

For three long days and nights I twirl'd;

At last upon the earth fell squash,

My legs were broken all to smash:

'Tis true, they're set, as you may see,

But most folks think damn'd awkwardly.

He then the bowl, with clownish grace,

Fill'd round, and wip'd his sooty face,

Then limp'd away into his place.

This cur'd them all from being dull,

And made 'em laugh their bellies full:

Once more their teeth to work they set,

And laid about 'em till they sweat,

Drinking, like well-fed aldermen,

A bumper every now and then,

Which they took care their guts to put in

Whilst t' other slice of beef was cutting;

For they, like cits, allow'd no crime

So great as that of losing time,

At home, abroad, or any meeting

Where the debate must end in eating.

Now they were in for't, all day long

They booz'd about, and had a song:

The fiddlers scrap'd both flat and sharp;

Apollo thrum'd the old Welch harp:

Nine ballad-singers from the street

Were fetch'd, with voices all so sweet,

Compar'd with them, Mansoli's squeaking

Would seem like rusty hinges creaking.

At sun-set[2], with a heavy head,

Each drunkard reel'd him home to bed,

Vulcan, who was the royal coiner,

Besides both carpenter and joiner,

Had built for every god a house,

And scorn'd to take a single sous.

Now night came on, the thund'rer led

His helpmate to her wicker bed;

There they agreed, and where's the wonder?

His sceptre rais'd, she soon knock'd under.

[1] Every body knows Ulysses could lie with a very grave face.

[2] Homer makes the gods go home at sun-set; I wish he could make all country justices and parsons do the same.

Jove, or by fame he much bely'd is,

Sends off a Dream to hum Atrides:

His conscience telling him it meet is

To make his promise good to Thetis;

Gave it commission as it went,

To tell the cull by whom 'twas sent;

And bid it fill his head top full,

Of taking Troy, and cock and bull.

The Vision goes as it was bid,

And fairly turns the poor man's head,

Who eagerly began to stare

At castles building in the air,

And fancy'd, as the work went on,

He heard Troy's walls come tumbling down.

But ere he starts, he has an eye

The metal of his rogues to try:

He tells the chiefs, when he proposes

That homeward all shall point their noses,

They must take care, when he had sped,

To come and knock it all o' th' head.

The plot succeeds; they're glad to go;

But sly Ulysses answer'd, No;

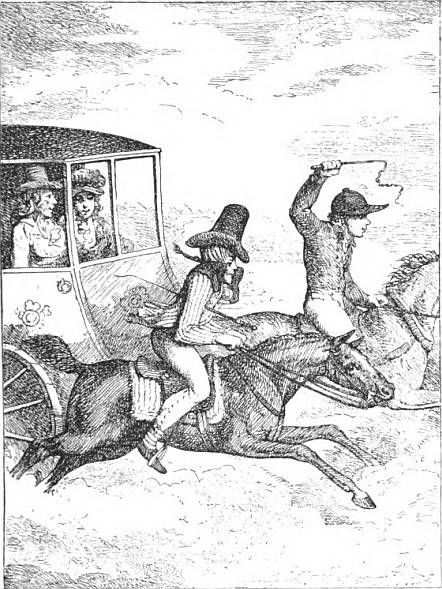

Then drove his broomstick with a thwack

Upon Thersites' huckle back;

Check'd other scoundrels with a frown,

And knock'd the sauciest rascals down;

Proving, that at improper times

To speak the truth's the worst of crimes.

Th' assembly met; old Nestor preaches,

And all the chiefs, like schoolboys, teaches

Orders each diff'rent shire to fix

A rendezvous, nor longer mix,

But with their own bluff captains stay,

Whether they fight or run away:

And whilst thus gather'd in a cluster,

They nick the time, and make a muster.

The watch past twelve o'clock were roaring,

And citizens in bed were snoring,

And all the gods of each degree

Were snoring hard for company,

Whilst Jove, whose mind could get no ease,

Perplex'd with cares as well as fleas

(For cares he in his bosom carried,

As every creature must that's married),

Was plotting, since he had begun,

How he might honour Thetis' son;

And scratch'd, and scratch'd, but yet he could

Not find a method for his blood

To keep his word. At last he caught,

By scratching hard, a lucky thought

(And 'faith, I think, 'twas no bad scheme);

To send the Grecian chief a Dream,

Made of a Cloud, on which he put

A coat and waistcoat, ready cut

Out of the self-same kind of stuff,

But yet it suited well enough

To give it shape: Now, Mr. Dream,

Take care you keep the shape you seem,

Says Jove; then do directly go

To Agamemnon's tent below:

Tell him to arm his ragged knaves

With cudgels, spits, and quarter-staves,

Then instantly their time employ

To rattle down the walls of Troy.

Tell him, in this, Miss Destiny

And all the heav'nly crew agree:

For Juno has made such a riot,

The gods do aught to keep her quiet.

Away goes Dream upon the wing,

And stands before the snoring king:

Grave Nestor's coat and figure took,

As old as he, as wise his look,

Rubs the cull's noddle with his wings,

And, full of guile, thus small he sings:

Monarch, how canst thou sleeping lie,

When thou hast other fish to fry?

O Atreus' son, thou mighty warrior,

Whose father was a skilful farrier,

Hast thou no thought about decorum,

Who art the very head o'th' quorum?

I shame myself to think I'm catching

Thee fast asleep, instead of watching.

Is not all Greece pinn'd on thy lap?

Rise, and for once postpone thy nap,

Lest by some rogue it should be said,

The chief of chiefs went drunk to bed:

For Jove, by whom you are respected,

Says your affairs sh'an't be neglected;

So sends you word he now is poring

On your concerns, whilst you are snoring:

He bids thee arm thy ragged knaves

With cudgels, spits, and quarter-staves,

Then instantly thy time employ

To rattle down the walls of Troy:

To this, he adds, Miss Destiny

And all the heav'nly crew agree:

For Juno has made such a riot,

The gods do aught to keep her quiet.

Then nothing more this Nothing says,

But turn'd about, and went his ways.

Up starts the king, and with his nail

Scratch'd both his head, and back, and tail;

And all the while his fancy's tickl'd,

To think how Troy would soon be pickl'd.

A silly goose! he little knew

What surly Jove resolv'd to do;

What shoals of sturdy knaves must tumble

Before they could the Trojans humble.

Down on an ancient chopping-block

This mighty warrior clapp'd his dock

(The block, worn out with chopping meat,

Now made the chief a rare strong seat):

Then don'd his shirt with Holland cuff,

For, Frenchman-like, he lay in buff;

Next o'er his greasy doublet threw

A thread-bare coat that once was blue,

But dirt and time had chang'd its hue;

Slipp'd on his shoes, but lately cobbled,

And to the board of council hobbled;

But took his sword with brazen hilt,

And wooden sceptre finely gilt.

Now, Madam Morn popp'd up her face,

And told 'em day came on apace;

When Agamemnon's beadles rouse

The Greeks to hear this joyful news.

He long'd, like breeding wife, it seems,

To tell his tickling, pleasing dreams.

I' th' int'rim, trotting to the fleet,

Old Nestor there he chanc'd to meet,

Whose tent he borrows for that morn,

To make a council-chamber on;

And reason good he had, I ween,

It kept his own apartment clean.

Now all-hands met, he takes his time,

And told his case in prose or rhyme:

Friends, neighbours, and confed'rates bold,

Attend, whilst I my tale unfold:

As in my bed I lay last night,

I saw an odd-look'd kind of sprite;

It seem'd, grave Nestor, to my view,

Just such a queer old put as you—

'Tis fact, for all your surly look—

And this short speech distinctly spoke:

How canst thou, monarch, sleeping lie,

When thou hast other fish to fry?

O Atreus' son, thou mighty warrior,

Whose father was a special farrier

(Which, by the by, although 'tis true,

Yet I'd be glad you'd tell me how

This bushy-bearded spirit knew),

Hast thou no thought about decorum,

Who art the very head o' th' quorum?

I shame myself to think I'm catching

Thee fast asleep, instead of watching.

Is not all Greece pinn'd on thy lap?

Rise, and for once postpone thy nap;

Or by some rogue it will be said,

The chief of chiefs went drunk to bed:

For Jove, by whom you are respected,

Says your affairs sha'n't be neglected:

But now on your affair he's poring,

Whilst you lie f—ting here and snoring:

He bids thee arm thy ragged knaves

With cudgels, spits, and quarter-staves;

For now the time is come, he swears,

To pull Troy's walls about their ears:

Nay more, he adds, the gods agree

With Fate itself it thus shall be.

Jove and his queen have had their quantum

Of jaw, and such-like rantum-scantum:

She now puts on her best behaviours,

And they're as kind as incle-weavers.

Then nothing more the Vision said,

But kick'd me half way out of bed.

This very token did, I vow,

Convince me that the dream was true;

For, waking soon, I found my head

And shoulders on the floor were laid,

Whilst my long legs kept snug in bed:

Therefore, since Jove, with good intent,

So rare a messenger has sent,

We should directly, I've a notion,

Put all our jolly boys in motion:

But first, what think you if we settle

A scheme to try the scarecrows' mettle,

As with nine years they're worn to th' stumps?

I'll feign my kingship in the dumps

With Jove himself, and then propose

That homeward they direct their nose.

But take you care, if I succeed,

To show yourselves in time of need:

Swear you don't mind the gen'ral's clack,

But in a hurry drive 'em back.

He spoke, and squatting on his breech,

Square-toes got up and made a speech:

I think our chief would not beguile us,

Says the old constable of Pylos.

Had any soul though, but our leader,

For dreams and visions been a pleader,

I should, my boys, to say no worse,

Have call'd him an old guzzling nurse.

I seldom old wives' tales believe,

Nurses invent 'em to deceive.

But now there can be no disguise,

For kings should scorn to tell folks lies;

So let us e'en, with one accord,

Resolve to take his royal word:

For though the speech is queerish stuff,

'Tis the king's speech, and that's enough.

I therefore say, My buffs so stout,

Of this same vision make no doubt;

The tokens are so very clear,

There can be little room for fear.

Did not our monarch, as he said,

Feel the Dream kick him out of bed,

And, by his waking posture, knew

His sense of feeling told him true?

Then, since affairs so far are gone,

Let's put our fighting faces on.

He said; nor did they longer stay,

But from the council haste away.

The leaders bring their men along;

They still were many thousands strong;

As thick as gardens swarm with bees,

Or tailors' working-boards with fleas:

And Jove, for fear they should not all

Attend, and mind their general's call,

Bid Fame, a chatt'ring, noisy strumpet,

To sound her longest brazen trumpet:

He haw'd and hemm'd before he spoke,

Then raised his truncheon made of oak,

'Twas Vulcan's making, which Jove gave

To Mercury, A thieving knave.

This brought such numbers on the lawn,

The very earth was heard to groan,

Nine criers went to still their noise;

That they might hear their leader's voice.

He haw'd and hemm'd before he spoke,

Then rais'd his truncheon made of oak:

'Twas Vulcan's making, which Jove gave

To Mercury, a thieving knave;

Who going down to Kent to steal hops,

Resign'd his staff to carter Pelops;

From Pelops it to Atreus came;

He to Thyestes left the same,

Who kept it dry, lest rain should rot it,

And when he dy'd Atrides got it:

With this he rules the Greeks with ease,

Or breaks their noddles if he please;

Now leaning on't, he silence broke,

And with so grum an accent spoke,

Those people that the circle stood in,

Fancy'd his mouth was full of pudding.

Thus he began: We've got, my neighbours,

Finely rewarded for our labours:

On Jove, you know, we have rely'd,

And several conjurers have try'd,

But both, I shame to say't, have ly'd.

One says, that we on board our scullers

Should all return with flying colours;

Another, we should cram our breeches

As full as they can hold with riches,

For presents to our wives and misses,

Which they'll repay us back with kisses.

Instead of this, we're hack'd and worn,

Our money spent, and breeches torn;

And, to crown all, our empty sculls

Fill'd with strange tales of cocks and bulls.

Now Jove is got on t'other tack,

And says we all must trundle back:

Dry blows we've got, and, what is more,

Our credit's lost upon this shore:

Nor can I find one soul that's willing

To trust us now a single shilling.

No longer since than yesterday,

Our butcher broke, and ran away:

The baker swears too, by Apollo,

If times don't mend he soon must follow:

As for the alehouse-man, 'tis clear

That half-penny a pot on beer

Will send him off before next year;

And then we all must be content

To guzzle down pure element.

A time there was, when who but we!

Now were humbugg'd, you plainly see;

And, what's the worst of all, you'll say,

A handful makes us run away:

For, if our numbers I can ken,

Where Troy has one man, we have ten.

Nine years, and more, the Grecian host

Have been upon this cursed coast;

And Troy's as far from being sack'd

As when it was at first attack'd;

The more we kill, the more appear;

They grow as fast as mushrooms here!

Like Toulon frigates rent and torn,

Our leaky boats to stumps are worn;

Then let's be packing and away;

For what the vengeance should we stay?

Our wives without it won't remain;

Pray how the pox should they contain?

For one that fasts, I'll lay there's ten

Are now employing journeymen:

If that's the case, I know you'll say

'Tis time indeed to hyke away;

Let us no more then make this fuss,

Troy was not doom'd to fall by us.

Most of the rabble, that were not

Consulted in this famous plot,

Were hugely pleas'd, and straight begin

To cry, God save our noble king!

He that spoke last, spoke like a man.

So whipp'd about, and off they ran.

As they jogg'd on, their long lank hair

Did like the dyers' rags appear;

Which you in every street will find

Waving like streamers in the wind:

To it they went with all their heart,

To get things ready to depart;

And made a sort of humming roar,

Like billows rumbling to the shore.

Halloo, cry'd some, here lend a hand

To heave the lighters off the strand;

Don't lounging stand to bite your nails,

But bustle, boys, and bend the sails.

Now all the vessels launch'd had been,

If scolding Juno had not seen:

That noisy brimstone seldom slept,

But a sharp eye for ever kept;

Not out of love to th' Grecian state,

But to poor harmless Paris hate,

Because on Ida's mountain he

Swore Venus better made than she:

And most are of opinion still,

He show'd himself a man of skill;

For Juno, ever mischief hatching,

Had wrinkled all her bum with scratching,

Whilst this enchanting Venus was

As smooth all o'er as polish'd glass.

Since then there was so wide a difference,

Pray who can wonder at the preference?

For wrinkles I'm myself no pleader:

Pray what are you, my gentle reader?

A simple answer to the question

Will put an end to this digression:

Why can't you speak now, when you're bid?

You like smooth skins? I thought you did:

And, since you've freely spoke your mind,

We'll back return, and Juno find.

Upon a cloud she sat astride,

(As now-a-days our angels ride)

Where calling Pallas, thus she spoke:

Would it not any soul provoke,

To see those Grecian hang-dogs run,

And leave their bus'ness all undone?

This will be pretty work, indeed;

For Greece to fly, and Troy succeed.

Rot me! but Priam's whoring race

(Sad dogs, without one grain of grace)

Shan't vamp it thus, whilst lovely Helen

Is kept for that damn'd rogue to dwell in;

That whoring whelp, who trims her so

She never thinks of Menelau:

But I shall stir my stumps, and make

The Greeks once more their broomsticks shake,

Then fly, my crony, in great haste,

Lest opportunity be past.

The cause, my girl, is partly thine;

He scorn'd thy ware as well as mine:

And, just as if he'd never seen us,

Bestow'd the prize on Madam Venus,

A blacksmith's wife, or kettle-mender,

And one whose reputation's slender;

Though her concerns I scorn to peep in,

Yet Mars has had her long in keeping.

Pallas obeys, and down the slope

Slides, like a sailor on a rope.

Upon the barren shore she found

Ulysses lost in thoughts profound:

His head with care so very full,

He look'd as solemn as an owl;

Was sorely grip'd, nor at this pinch

Would launch his boats a single inch.

And is it thus, she says, my king,

The Greeks their hogs to market bring?

See how they skip on board each hoy,

Ready to break their necks for joy!

Shall Priam's lecherous son, that thrives

By kissing honest tradesmen's wives,

Be left that heaven of bliss to dwell in,

The matchless arms of beauteous Helen?

O, no; the very thought, by Gad,

Makes Wisdom's goddess almost mad!

Though, by thy help, I think 'tis hard.

But yet I singe the rascal's beard.

Then fly, Ulysses, stop 'em all;

The captains must their troops recall.

Thou hast the gift o' th' gab, I know;

Be quick and use it, prithee do:

From Pallas thou shalt have assistance,

Should any scoundrel make resistance.

Ulysses ken'd her voice so shrill,

And mov'd to execute her will;

Then pull'd his breeches up in haste,

Which being far too wide i' th' waist,

Had left his buttocks almost bare—

He guess'd what made the goddess stare;

Next try'd his coat of buff to doff,

But could not quickly get it off,

So fast upon his arms it stuck,

Till Pallas kindly lent a pluck.

Off then it came, when, like a man,

He took him to his heels and ran.

The first that in his race he met

Was Agamemnon in a pet,

Striving, for breakfast, with his truncheon

To bruise a mouldy brown-bread luncheon.

Ulysses tells him, with a laugh,

I've better bus'ness for that staff,

And must request you'll lend it me

To keep up my authority.

Which having got, he look'd as big

As J-n-n's coronation wig;

Then flew, like wild-fire, through the ranks?

'Twas wond'rous how he ply'd his shanks.

Each captain by his name he calls;

I'm here, each noble captain bawls.

Then thus: O knights of courage stout,

Pray, what the devil makes this rout?

You that exalted are for samples,

Should set your soldiers good examples:

Instead of that, I pray, why strove ye

To run as if the devil drove ye?

You knew full well, or I belie ye,

Our general only spoke to try ye:

All that he meant by't was to know,

Whether we'd rather stay or go?

And is more vext to find us willing

To run, than if he'd lost a shilling;

Because at council-board, this day,

Quite different things you heard him say.

But if he met a common man,

That dar'd to contradict his plan;

Or, if the scoundrel durst but grumble;

Nay, if he did but seem to mumble;

He, with his truncheon of command,

First knock'd him down, then bid him stand

By this good management they stopp'd;

But not till eight or ten were dropp'd.

From launching boats, with one accord,

They trudg'd away to th' council-board.

The hubbub then began to cease:

The noise was hush'd, and all was peace.

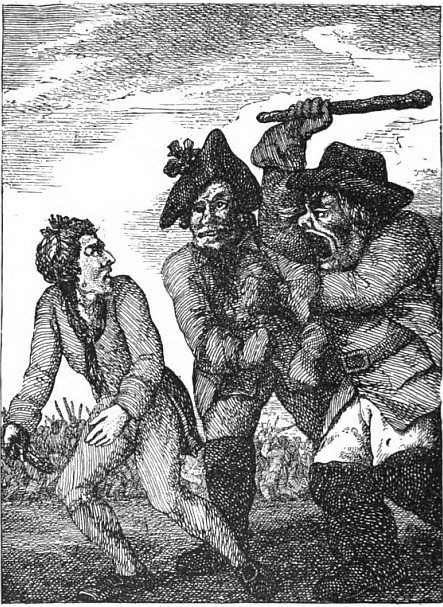

Only one noisy ill-tongu'd whelp,

Thersites call'd, was heard to yelp:

The rogue had neither shame nor manners;

His hide was only fit for tanners:

With downright malice to defame

Good honest cocks, was all his aim:

All sorts of folks hard names he'd call,

But aldermen the worst of all.

Grotesque his figure was and vile,

Much in the Hudibrastic style:

One shoulder 'gainst his head did rest,

The other dropp'd below his breast;

His lank lean limbs in growth were stinted,

And nine times worse than Wilkes he squinted:

His pate was neither round nor flat,

But shap'd like Mother Shipton's hat.

You'd think, when this baboon was speaking,

You heard some damn'd blind fiddler squeaking.

Now this sad dog by dirty joking

Was every day the chief provoking:

The Greeks despis'd the rogue, and yet

To hear his vile harangues they'd sit

Silent as though he'd been a Pitt.

His screech-owl's voice he rais'd with might

And vented thus his froth and spite:

Thersites from the matter wide is,

Or something vexes great Atrides;

But what the murrain it can be,

The Lord above can only see!

No man alive can be censorious,

His reign has been so very glorious:

Then what has lodg'd the heavy bullet

Of discontent within his gullet,

That makes him look as foul as thunder,

To me's a secret and a wonder:

He had the best, the Grecians know,

Of gold, and handsome wenches too.

Best did I say? Bar Helen's bum,

He had the best in Christendom,

And yet's not pleas'd: but tell us what

Thy mighty kingship would be at?

Say but, shall Greece and I go speed

To Troy, and bring thee in thy need

The race of royal sons of whores,

By ransom to increase thy stores?

When we return, prepare to seize

Whate'er the royal eye shall please:

This thou mayst do sans dread and fear;

'Tis mighty safe to plunder here.

When the fit moves thee for that same,

Take any captain's favourite dame;

Our master wills, and 'tis but fit

Such scrubs as we should all submit.

Ye women Greeks, a sneaking race,

Take my advice to quit this place;

And leave this mighty man of pleasure

To kiss his doxies at his leisure.

When Hector comes, we'll then be mist

When Hector comes, he'll be bepist.

The man that makes us slaves submit,

When Hector comes, will be be—t;

He'll rue the dire unlucky day

He forc'd Achilles' girl away:

That buxom wench we all agreed

To give the bully for his need.

Achilles, though in discontent,

Don't think it proper to resent:

But if the bully's patience ceases,

He'll kick thee into half-crown pieces.

Sudden Ulysses with a bound

Rais'd his backside from off the ground,

Ready to burst his very gall

To hear this scurvy rogue so maul

The constable of Greece—an elf,

Famous for hard-mouth'd words himself;

His eyes look'd fierce, like ferrets red;

Hunchback he scans; and thus he said:

Moon-calf, give o'er this noisy babbling,

And don't stand prating thus and squabbling.

If thy foul tongue again dispute

The royal sway, I'll cut it out;

Thou art, and hast been from thy birth,

As great a rogue as lives on earth.

What plea canst thou have names to call,

Who art the vilest dog of all?

Think'st thou a single Greek will stir

An inch for such a snarling cur?

How dar'st thou use Atrides' name,

And of a constable make game?

For safe return great Jove we trust:

'Tis ours to fight, and fight we must

If to our noble chief a few

Make presents, pray, what's that to you?

What mighty gifts have you bestow'd,

Except your venom? scurvy toad!

If the bold bucks their plunder gave,

Thou canst not think' among the brave

We reckon such a lousy knave.

May I be doom'd to keep a tin-shop,

Or smite my soul into a gin-shop,

There to be drawn by pint or gill,

For drunken whores to take their fill;

Or may I find my dear son Telley

With back and bones all beat to jelly;

Or in his stead behold another,

Got by some rascal on his mother;

If I don't punish the next fault,

By stripping off thy scarlet coat,

That shabby, ragged, thread-bare lac'd coat

Then with a horsewhip dust thy waistcoat;

I'll lay on so that all the navy

Shall hear thy curship roar peccavi.

This said, his broomshaft with a thwack

He drove against his huckle back.

It fell with such a dev'lish thump,

It almost rais'd another hump.

The poor faint-hearted culprit cries,

And tears ran down his blood-shot eyes:

With clout he wip'd his ugly face,

And sneak'd in silence to his place.

Then might you hear the mob declare

Their thoughts on courage, and on fear.

Up to the stars they cry'd Ulysses,

A braver fellow never pisses;

Of insolence he stops the tide,

Nor gives it time to spread too wide.

We want but half a score such samples,

To make all prating knaves examples:

'Twould teach the mob much better things,

Than dare to chatter about kings.

Whilst thus they sing Ulysses' praises,

The constable his body raises.

The gen'ral's truncheon of command

He flourish'd in his dexter hand.

Pallas in herald's coat stood by,

And with great noise did silence cry,

That all the rabble far and near

This crafty Grecian's speech might hear.

With staring looks and open jaws

They catch each syllab as it flows.

First, with his hand he scratch'd his head,

To try if wit's alive or dead:

But, when he found his wit was strong,

And ready to assist his tongue,

To clear his throat he hem'd aloud,

And thus humbugg'd the list'ning crowd:

Unlucky chief, to be so us'd,

Deserted first, and then abus'd!

At Argos, when we came to muster,

And were all gather'd in a cluster,

The general voice was heard to say,

The de'il fetch him that runs away!

Then took a bible oath that night,

They never would return from fight

Till the old Trojan town should tumble;

And yet you see for home they grumble.

I own myself, 'tis very hard

To be from home so long debarr'd:

If but a single fortnight we

Are kept confin'd upon the sea

From our good wives and bantlings dear,

How do we rave, and curse, and swear!

Then, after nine years' absence, sure

These folks may look a little sour.

They're not to blame for being sad;

But thus bamboozled, makes one mad:

Though wizard Calchas plainly said,

If we the space of nine years staid,

The tenth we surely should destroy

This paltry mud-wall'd borough Troy.

Have patience then, and let's endure

To box it out a few weeks more.

Remember how a mighty dragon

A plane-tree mounted from a waggon;

He found a bird's nest at the top,

And quickly ate eight young ones up;

To make the ninth there wants another;

On which the serpent snapp'd the mother:

Though, after he had made this rout,

He ne'er had time to shit 'em out;

For twenty minutes were not gone

Before he chang'd to solid stone,

Where, on the summit of a hill,

At Aulis, you may see him still.

When Calchas saw this wondrous thing,

Like Endor's witch, he drew a ring;

And, standing by himself i' th' middle,

Began this wonder to unriddle:

My friends, if you'll but lend an ear,

I'll quickly ease you of your fear:

Give you but credit to my speeches,

And then you'll all keep cleaner breeches.

This prodigy from Jove was sent ye,

To show that something good he meant ye:

As many birds, so many years

Should we be kept in hopes and fears;

But 'ware the tenth, for then shall Ilion

Tumble, though guarded by a million.

All this may happen, if you stay,

But cannot, if you run away:

For, be the captains e'er so cunning,

No towns were ever ta'en by running.

Can you remember Helen's rape,

And let those Trojan whelps escape?

Let that eternal rascal go

That made poor Helen cry O! O?

Up started then old chitter chatter,

And lent his hand to clench the matter:

You are fine fellows, smite my eyes,

If blust'ring words could get a prize:

At first you all could say great things,

And swear you'd pull down popes and kings;

In a great splutter take, like Teague,

The solemn covenant and league;

For Ilion's walls resolve to steer,

And store of bread and cheese prepare.

Now all, I find, was but a joke;

Your bouncing's vanish'd into smoke.

But precious time by talk is spent;

To pull down Troy is our intent;

And we will do't without delay,

If you, Atrides, lead the way.

Whoever here are not content,

Pray let 'em all be homeward sent.

Their help we value not three farthings:

Cowards make excellent churchwardens;

Then let them to their parish go,

And serve their town in noise and show.

No weapon should they touch but needles,

Or staves for constables and beadles:

Such posts as these will suit men right,

That eat much keener than they fight;

Therefore, whoever dare not stay,

I'd have directly sneak away.

When we the Trojan hides shall curry

Without their help, they'll be so sorry

That they will hang themselves, I hope—

And, by my soul, I'll find 'em rope.

Then how the rogues will wish they'd fought!

But wishes will avail 'em nought.

Did not great Jove, when we set out,

Make a most damn'd confounded rout?

Did he not roll the ball, and roll

Till he half crack'd his mustard bowl[1];

And kept the noise upon our right,

To hearten us to go and fight,