The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 108, January 19, 1895, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 108, January 19, 1895 Author: Various Editor: Sir Francis Burnand Release Date: April 7, 2013 [EBook #42480] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, JANUARY 19, 1895 *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(By Mr. Punch's own Short Story-teller.)

I.—THE PINK HIPPOPOTAMUS.

The island of Seringapatam is without exaggeration one of the fairest jewels in the imperial diadem of our world-wide possessions. Embosomed in the blue and sparkling wavelets of the Pacific Ocean, breathed upon by the spicy breezes that waft their intoxicating perfumes through endless groves of gigantic acacias, feathery fern trees, and gorgeously coloured Indian acanthoids; studded with the glittering domes of a profusion of jasper palaces beside which the trumpery splendours of Windsor or Versailles are but as dust, and guarded by the loyal devotion of an ancient warrior race noted not less for the supreme beauty of its women than for the matchless courage and endurance of its men, the Kingdom of Seringapatam offered during a period of more than one hundred years a stubborn resistance even to the arms of the all-conquering Britons. So great indeed, was the respect extorted from the victors by the vanquished that when, owing to the marvellous strategy of my old friend Major-General Sir Bonamy Battlehorn, K.C.B., K.C.M.G., the island was finally subdued, it was agreed that in all but their acknowledgment of a British Suzerainty and the payment of an annual tribute of fifteen hundred gold lakhs, the proud islanders were to maintain their independence and to continue those forms of government which long tradition had invested in their eyes with all the sanctity of a religion.

I had been present with my dear father at the great battle of the Dead Marshes by which the fortunes of the islanders were finally shattered. Never shall I forget the glow of exultant gratitude with which towards the end of the day gallant old Sir Bonamy came cantering towards me on his elephant. "Thank you, thank you a thousand times, my dear Orlando," said the glorious veteran as he approached me; "it was that last charge of yours at the head of your magnificent Thundershakers that has converted defeat into victory, and assured Westminster Abbey to the bones of Bonamy Battlehorn. All that is now necessary," he continued, rising in his stirrups and waving his sword, "is that you should complete the work that you have begun. Dost see that battery of fifty guns still served by the haughty remnants of the Seringapatamese bombardiers? Let them be captured, and nothing will stand between us and the Diamond City of the Ranee."

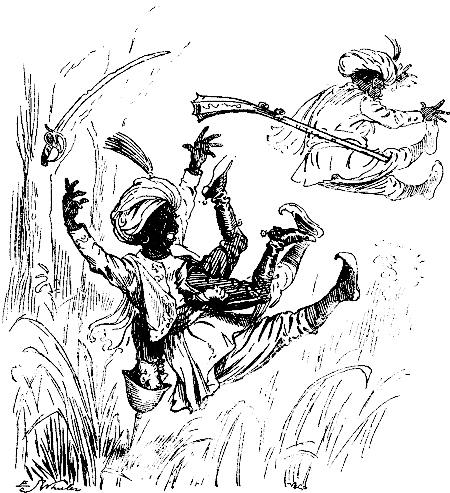

I needed no further incitement. Gathering round me the few Thundershakers who had escaped unscathed, I bade the standard-bearer unfurl the flag of the brigade. In another moment we were upon them. Cutting, slashing, piercing, parrying, trampling, crushing, we dashed into the midst of the foe. Far over the field of carnage sounded our war-cry, the famous "Higher up Bayswater!" which was to our horses as the prick of spur. In vain the doughty bombardiers belaboured us; in vain did they answer with the awful shout of "Benkcitibenk," which none hitherto had been able to withstand. The work was hot, but in less than three minutes the battery was ours, and the broken host of the Ranee was streaming in full flight down the slopes from which so lately they had dealt death amongst the English army. In another moment we had limbered up—two men to each gun, except the largest, which was assigned to me as the chief of the band—and helter skelter down the hill we went, and so, with shouting and with laughter, deposited our spoils at the feet of the British General.

I do not recount this incident in order to magnify my own exploits. My deeds themselves are my best record, those deeds which a factious majority in successive Parliaments has, to its everlasting shame, refused to recognise, but which not even the voice of malice, always busy in the task of depreciating genuine achievement, can rob of one particle of their brilliant and immortal lustre. But the fight is indissolubly connected with the stirring story which I have here set out to relate, and for this reason alone have I mentioned it. During the brief struggle round the guns I became momentarily separated from the main body of my men. Seizing the opportunity, and noticing, too, that in the previous melée I had been unhorsed, two gigantic artillerymen made at me. My sword was broken, my revolver was empty! What was I to do? But little time for reflection was left to me. With savage shouts the two dusky Titans sprang upon me. I gave myself up for lost, shut my eyes, thought of my poor mother, saw in a flash my happy country home, the thatched roofs of the cottages, the grey old church, the babbling stream, the village school, the little shop where my infant mouth had first become acquainted with the succulent bull's-eye—in short, I went through all the symptoms that are understood to accompany the imminence of a violent death. Suddenly, however, the desire to live awoke once more. The smaller of my two foes had outstripped his companion. He was just about to seize me, when, lowering my head, which was encased in a spiked helmet, I bounded at him. Fair and full I caught him, and so terrific was the force engendered by my spring and the foeman's rush, that not the spike alone, but the helmet and the head too, pierced him through and through.

Down on his back he fell crashing, bearing me with him as he went over and fixing the spike firmly in the earth, pinned like some huge beetle by a human pin. As my legs flew up they encountered the second giant, and, winding round his chest, crushed every vestige of life out of him and flung his mangled body full twenty yards to the rear. I had escaped, but my position was still uncomfortably awkward. By this time, however, the rout was complete, and four of my men, by dint of tremendous exertions, succeeded in extricating me from my curious entanglement. My pinned foeman turned out to be the Ranee's brother, Hadju Thar Meebhoy. We bore him back with us to camp, where, marvellous to relate, after a prolonged illness, he eventually recovered.

Of course he has never been quite the same man since. He has to be careful about his diet, but with the childlike simplicity of an Oriental he finds a constant pleasure in opening and shutting the little aluminium doors which our dear old surgeon, Toby O'Grady, constructed to replace the Khan's stomach and the small of his back. I came to be great friends with him and it was through him that I gained the knowledge which prompted the adventure I am now about to relate.

(To be continued.)

There is something in a name, especially when it happens to be the title of a play. At the St. James's, Mr. Alexander's latest venture has been Guy Domville, by the American novelist Henry James, who if he knew as much about play-writing as he does about novel-writing would probably be in the first flight of dramatists; and he would not have chosen so hopeless a name for his hero and for his play as Guy Domville. For the anti-James jokers would delight in finding that Guy could be "guy'd," and to say as to "Domville" that "a first night audience 'vill dom' the play." For all that, if Alexander be the sagacious commander in the dramatic field that he has hitherto shown himself, it is not likely that he should have been completely mistaken in accepting a play which a portion of the public has refused to accept. Of course, a manager cannot afford to keep a play going until the public come en masse to see it, and therefore, unless there is "a turn of the tide" (and such things have happened before now, and a condemned piece has had a long and prosperous career), Mr. Alexander will himself be obliged to do to the play what those who ridicule and chaff it have already done, i.e. "take it off."

Mrs. R. admits that she has always been very fond of sweets at dinner. What she is especially fond of is, she says, "a dish of pommes d'Ananias;" and she always adds, "But, my dear, why the French choose such awful names for such nice things is what I never can understand."

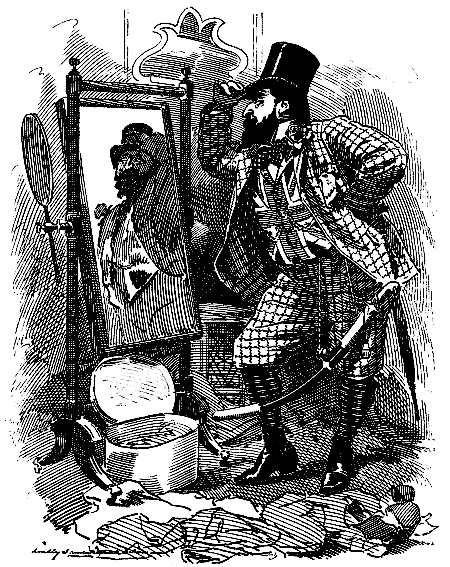

Abdurrahman Khan (to himself). "I think this'll fetch 'Em!"

["Should the Ameer happily accomplish the visit to this country on which he has set his heart, he may be assured of the warm welcome due to one who, since his accession to supreme power in Afghanistan, has been the steady friend of Great Britain."—Times.]

(Cabulee Version of a popular Comic Song.)

Air—"The Dandy Coloured Coon."

Ameer, dressing for a projected Visit, sings:—

Fools called me a mere "Nigger" when I felt Dame Fortune's frown;

Up and down—I have known;

But now the folks all say, "Why, you're fit to wear a crown.

Black or brown—you've won renown."

Now a lot of gossips they patter and spy.

Someone says, "He wants to have the Muscovite hard by."

"Muscovite!" said I,—"hard by!—you're mistooken!

This Ameer wants to see no Muscovite.

Not at all!—not a bit!—

'Tain't for him at all the Afghan crown is meant!"

"Go on!"—say they,—"Who is it?"

Chorus.

"Why, it's Ab-dur-rahman, son of Afzul, son of Dost

Mohammed, means to rule the fierce Afghan!

Don't you know me?—Go on!—Well, you will, my good man,

For I'm Ab-dur-rahman the dandy Afghan Khan!"

Now a man like me is a terror to the tribes,

The Shinwaris,—the Ghilzais!

And Ishak Khan and others found me galling to their kibes,

When revolts—they would raise.

They've been putting it about the Ameer is ill.

(Wouldn't they delight to administer a pill!)

"Ameer, you're ill—mortal ill!"—but I wasn't!

"You've palpitation," the quidnuncs state,

"From your soles—to your scalp.

Ishak at Samarcand makes your heart palpitate!"

"Go on!"—said I,—"nary palp!"

Chorus.—For I'm Ab-dur-rahman, &c.

Now I've long had an ambition to far England for to go,

Don't you know,—that is so!

See Empress-Queen Victoria and Mister Wales also.

I'm asked to go—to that show!

The Empress-Queen to visit me doesn't care.

(And doubtless Afghan fashions might make Victoria stare.)

But there—I swear—I'll go!—and I'm going!

Men may say "It's the Shah that this show's about!"—

And another "You're an ass, Sir!

'Taint the Shah-in-Shah at all—you're a long way out!"—

"Go on!"—he'll say,—"ain't it Nass'r?"

Chorus.—No, it's Ab-dur-rahman, &c.

So I'll dress the part as near as can be,

Please John B.—don't you see!

My close-fitting lambswool and silver filagree,

Empress V.—might find "free."

Should the tribesmen twig this peculiar rig

They'd think their Ameer had turned Infidel Pig.

What a toff!—Well, I'll say—I'm here—to see the Empress!—

What is that "coon" all the comics sing about?

Mister Brown—John James!

If as to me Mister Bull has a doubt,

Go on!—I'll say.—My names?

Chorus.

Why, they're Ab-dur-rahman, son of Afzul, son of Dost

Mahommed, wearer of the Afghan Crown.

Don't you know me?—Go on?—Well, you will very soon,

For I'm Ab-dur-rahman Khan, the dandy Afghan coon!

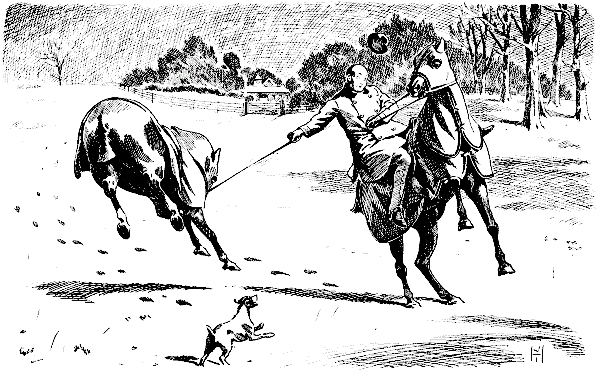

Smithson, having recently bought a Country Place and gone in for Sport, has been advised by a Friend to do his own exercising during hard weather, "as it insures your Horses against the neglect of Grooms, and also keeps you in form."

"Hale Fellow, well met."—"Pierre Blanc, the hale Savoyard of eighty-eight, took his usual place in the French Chamber," reports the Times correspondent last week, "and delivered one of his customary addresses."

What a charming party of three,

Bismarck, Blanc, and Mr. G.,

Decidedly very much alive,

United ages Two Four Five!

(An Episode in the Life of A. Briefless, Junior, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, in Three Parts.)

Part II.—The Passing of the Picture.

It may be remembered that the gift of my grateful if eccentric client had been put in the box-room at Justinian Gardens. There the presentment of the donkey languidly watching jaded villagers reposed, amidst the possibly congenial surroundings of broken perambulators, superannuated folding-doors, and half-forgotten wide-awake hats. I rather regretted the fate of the picture, as it seemed to me that it might have served as a not invaluable advertisement. As a large proportion of the forensic world knows, I not infrequently during the Yuletide season entertain some of my friends at the Bar, and I should have been pleased to have been able to point to the canvas as a sort of testimonial. However, the painting had disappeared, and there was nothing more to be said about it.

I am reminded by this reference to my vacation entertainments, that it was at one of "these feasts of reason and flows of soul" (as my learned and distinguished friend Appleblossom, Q.C., is kind enough to call them) that my fortunes underwent a change for the better. The inhabitants of Justinian Gardens are accustomed to do things very well. When there is a ball, the number of vehicles (always with one horse apiece, and sometimes with a pair) is quite considerable. On such occasions a stranger might imagine that the Gardens had the advantage of a chronic cab-stand. At 97 (which I think I may describe as our show-house) there is a butler, and there are few at Justinian Gardens who cannot boast of a "buttons." I do not secure the services of a man-retainer myself, and am consequently not quite in the fashion. However, when I entertain, I do my best to be worthy of the prestige of my neighbours, and put forth all my strength in making my house an object of interest. The walls of my modest dwelling-place are adorned with several mementoes of my not-altogether-common-place career. For instance, I have had my commission as a Lieutenant of Volunteers (I served for many years in the Bishop's Own, and was graciously permitted by Her Majesty to retire with my rank) glazed and framed, and have treated the pasteboard distinctions I won at school in a similar fashion. When I purpose entertaining my friends at the Bar, I have these gratifying landmarks in my life's history polished up by an individual known in my household as "the handy man." This person (towards whom I entertain a friendly regard), for a certain sum an hour undertakes to do anything I require. I believe that he can paint a house, build a conservatory, cut down a forest, and reconstruct an aquarium with equal facility. But it is only right to say that I make this statement on the faith of his guarantor—the gentleman who was good enough to procure for me the advantage of his services—and cannot speak from personal knowledge. So far I have only had the opportunity of testing his capabilities in window-cleaning and the dusting of works of art. In performing these domestic duties he shows great energy, and even daring. He seems to delight in standing on window-ledges and the outer edges of flights of stairs. I have been given to understand that he glories in these displays of hardihood, as they remind him of the days and nights when he acted as a rather prominent member of the Fire Brigade.

"Mr. Wilkins," I said, on my departure for the Temple, "I shall esteem it a favour if you will be so good as to employ your leisure to-day in repainting the waterbutts, sweeping the kitchen chimney, putting glass in the conservatory, regilding the mirror in the study, and, if you have time, dusting my testimonial."

"Certainly, Sir," replied my valued acquaintance, and before I had closed the hall door, the sounds of the rumbling sticks told me that he had already commenced to remove the superfluous soot from the culinary smoke-hole.

I had rather an arduous day at Pump-Handle Court. I had quite an accumulation of circulars, and a consent brief that required very careful attention. The latter was not endorsed with my name, but I saw to it on behalf of a colleague. After I had spent some hours in the little frequented (during the vacation) realms of the Temple, I returned to Justinian Gardens, which I need scarcely tell an experienced cabman is in the neighbourhood of that continually rising locality—Earl's Court. The door was opened by Mr. Wilkins in person, who anticipated the turning of the proprietorial latch-key.

"I am sorry to say, Sir," said my trusted employé, "that I have had an accident. While I was dusting the military enlistment card——"

"You mean my commission?"

"I do, Sir. It came down with a run. You see, Sir, you have had him rather heavily framed. Unfortunately, Sir, when I passed the polish brush over him the nail did not hold, and it gave suddenly. The picture made a nasty mark on the wall, and smashed up when he got to the flooring. I would have reframed him, but all the shops close early on a Thursday, and I can get no glass."

"Well, what have you done?" I asked, in a tone of some annoyance, for I pride myself on my commission, and am proud of showing it to my friends.

"Well, Sir, I went up to the box-room to see if I could find anything that would do, and have looked up an affair that I think will meet with your approval."

By this time I had reached the place where the wall was damaged. The spot was covered by a picture.

"I did my best, Sir. I washed the canvas with soap and water, and put the polishing brush over the frame. Of course the subject ain't worth much, but for a stop-gap it isn't bad. Now is it?"

I then found that Mr. Wilkins had hidden the faulty hall paper with the picture that had been presented to me by the gentleman who had raised a claim to the throne of the Celestial Empire. Secretly pleased that I could now have an opportunity of referring to the gratitude of my client to my learned and distinguished friend, Appleblossom, Q.C., who had promised to dine with me that evening, I readily accepted the apologies of the penitent Wilkins.

"I will put it allright to-morrow, Sir," said my distressed employé. "I will get some glass, fix up your enlistment card, and have it done before I rebuild the pantry and whitewash the ceiling of the bath-room."

Satisfied with the promise I thought no more of the contretemps until after dinner, when my attention was directed to it by Appleblossom, Q.C., who had made himself vastly agreeable after the ladies had retired and left us to discuss the chestnuts and the port.

"Hullo, Briefless," he exclaimed; "where did you get that Old Boots?"

I told my story of the grateful client, and young Bands, who I fancy is thinking of reading in my chambers, regarded me (I venture to believe) with increased respect.

"Bless me, you have a treasure!" continued Appleblossom, Q.C., who seemed wrapt in admiration. "That is a genuine Old Boots. You can always tell him from Young Boots by the manipulation of his animal's ears. Look at those, Sir! Splendid! Why, who could [pg 29] paint a donkey like that? By Jove, Briefless, you are in luck! You ought to make a fortune out of it at Christies!"

"Why, is it very valuable?" I asked. "I am not much of an art connoisseur, and I frankly confess I know very little of Old Shoes."

"Old Boots, Sir!" cried Appleblossom, Q.C. "Why I thought all the world knew Old Boots! One of the grandest painters of the eighteenth century! He got that particular delicacy of touch which you can trace in that donkey's ears by never commencing to paint his animals until he was recovering from delirium tremens. Why, Sir, that animal is simply superb. Look at his mane, Sir! Why, it is simply marvellous!"

I did look at the donkey's ears and mane, and, with the assistance of young Bands, went into an ecstasy. The ears of the animal were certainly magnificent.

I must admit I was excited during the rest of that eventful evening. I determined to keep the secret of my good fortune to myself. I thought I would surprise the lady who does me the honour to bear my name, by telling her that I had become a rich man after I had cashed the cheque I was sure to receive. All the following day I made plans for the spending of my fortune. I would have a box in the Highlands, a pied-à-terre in Paris, and a pyramid in Egypt. I would present my Inn with a massive gold snuff-box, and Portington should have a silver-mounted meerschaum. If my age did not bar my progress, I would seek service in the Militia—as a lieutenant-colonel. There was no limit to my ambition.

When I returned, Mr. Wilkins (who is thoroughly conscientious), having finished the rebuilding of the pantry and the whitewashing of the bath-room, had departed. He does not waste his time, and only charges me for the hours he actually expends in honest labour. I hurried to the spot where my Old Boots was temporarily resting before removal to the far-famed auction-rooms in King Street, St. James's. I turned pale.

"Why, what is this?" I asked, trembling with emotion.

"Your commission, dear," said my better seven-eighths. "It looks better than the picture, although I must say the donkey improves on acquaintance. It really was very well painted. I am quite sorry Mr. Wilkins has taken it away."

"Wilkins taken it away?" I gasped out.

"Yes. He said that you didn't seem to care for it, so he went off to try and sell it."

"Why!" I exclaimed, and my voice, through my deep emotion, dropped almost to a whisper, "it is an Old Boots!"

"An Old Boots!" cried my better seven-eighths, becoming as excited as myself. "Why, our fortunes are made! An Old Boots! Oh, why didn't you tell me! An Old Boots! Fancy having an Old Boots!"

"But we haven't," I returned, almost in tears. "The handy-man has gone off with it! What are we to do without our Old Boots!"

"We will get it back!" returned my better and more important fraction, with determination.

Whether we did recover our lost treasure, or fail in the attempt, must, owing to the exigencies of space (so I am given to understand), form the subject of another and concluding contribution. The chase after our Old Boots was not without adventures of a distinctly exciting character.

Air—"My Pretty Jane."

My Jayne, my Jayne, my Bishop Jayne,

O never, never more be sly,

You'll meet, you'll meet with no green even in

This correspondent's eye.

"Charge, Chester, charge." Do what you th-i-nk

Your di-o-cese will stand.

But do not, do not stain with i-n-k

Your Gothenburgian hand.

So Jayne, my Jayne, my petty Jayne,

O never, never more be sly.

You'll meet, you'll meet with no green even in

This correspondent's eye.

* See recent letters and article in Times within the last fortnight.

"To Rome for Sixteen Guineas."—The travellers, it is announced, will be "lectured by the Bishop of Peterborough and Mr. Oscar Browning." What a delightful prospect for a pleasant trip! Fancy being lectured all the way as to what to eat, drink, and avoid, on comportment and deportment, on smoking, on registration of baggage, on economy, etc., etc., by a Bishop and one of the Oscar's. O what a time they will have of it!

["'We were caught in a snowdrift' was Mr. Gladstone's explanation. 'In Scotland they would have cleared it away in no time, but here they are not accustomed to deal with snow;' and, with upright bearing, and carrying a travelling rug which he refused to give up to a servant, he marched out of the station with a springy gait."—Central News Telegram from Cannes.]

Air—"Bonnie Dundee."

To our own G. O. M. 'twas the doctor who spoke;

"You'd better get out of our frost, fog, and smoke.

You are now eighty-five, though a wonder you be;

So follow the sun, bonnie W. G.!

Come flit from cold Hawarden, and fly off to Cannes,

The sunny South calls you, our own Grand Old Man!

Take the first train de luxe, and be off, fair and free,

To Rendel and roses, dear W. G.!"

The G. O. M.'s off to the southward—to meet

Not sunshine, but train-stopping snow-drift and sleet.

Yet he "pops up" at Cannes as alert as can be,

After five hours long snow-block, our W. G.

Then fill up the cup to our Crichton at Cannes.

Nestor wasn't a patch on our own Grand Old Man;

May he come back as bonnie as bonnie can be,

For we've not seen the last of our W. G.!

It is noteworthy how in recent years, in the matter of fiction, the star of Empire shineth in the North. After Walter Scott established the sovereignty of Scotland in the world of British fiction, there was a long pause. In our generation William Black came to the front. Later, we have had Stevenson, Barrie, and Crockett. Now here is Ian Maclaren with his cluster of gem-like stories gathered Beside the Bonnie Briar Bush (Hodder And Stoughton). My Baronite tells me that of the collection Mr. Gladstone likes best "A Doctor of the Old School." Where all is good it is difficult to establish supremacy. But for simple pathos and for the skill of drawing with a few touches living figures of flesh and blood, this sketch is certainly hard to beat. Yet "A Lad of Pairts" runs it close. A very beautiful book, full of human nature in its simplest form and most pathetic circumstances.

Says the Baron, "What I who have read Mr. Bram Stoker's latest romance could tell you about The Watter's Mou' would make your mou' watter with longing desire to devour it. It is excellent: first because it is short; secondly, because the excitement is kept up from first page to last; and thirdly, because it is admirably written throughout; the scenic descriptive portion being as entrancing as the dramatic. It is brought out in the Acme Series in charge of A Constable, and its full price is only one shilling."

A good short story is to be found in A Clear Case of the Supernatural, by Reginald Lucas, only as it is by no means "a clear case," it might have been appropriately entitled, Fluke or Spook.

Most Appropriate.—"Gunner J. C. Rockett promoted to rank of Chief Gunner in the Queen's Navy." Of course, quite right to send up a Rockett. Only got to present him with a house at Gunnersbury and the thing is complete.

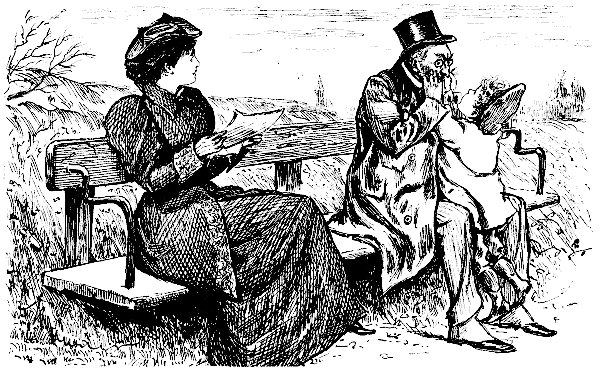

Proud Mother (to irritable Old Gentleman, whose beard her little Boy is pulling out by the roots). "Little Darling! It's not often he takes so kindly to Strangers!"

["What we fail to perceive, at least to any adequate extent, in the pleadings of the spokesman of the Lancashire Cotton Trade, is a recognition of the paramount importance, even from a commercial point of view, of the Imperial interests that depend on the just and liberal government of India." —The Times.]

Mr. John Bull sings:—

Ding-dong the lasses go! My patience it quite passes, O!

My brain it turns, though with Rob Burns, I dearly love the lasses, O!

There's right and wrong on either hand; that's clear to all but asses, O!

So hold your whist, drop each your fist, and to me list, fair lasses, O!

Lancashire lass, I like you well. You're buxom, brave, and bonny, O!

But do not slight your sense of right in hasty greed of money, O!

When North v. South "clemmed" many a mouth, what patient, patriot spirit, O!

Lancashire showed! All England glowed. That spirit you inherit, O!

But in your wrath you've missed the path of fair and patriot dealing, O!

Nay, do not pout. You'll wake, no doubt, to right Imperial feeling, O!

The Empire's wide and can't be tied by shackles greed-begotten, O!

My only duty now, my beauty, 's not—to sell your cotton, O!

Of bulk and bale your sale won't fail—if you keep up the quality, O!

And do not trust to "devil's-dust"—which mars our merchant-polity, O!

Some rascal-muffs, with loaded stuffs, have spoiled the Eastern market, O!

Miss India there will tell you where, and when she whispers, hark it, O!

But with good goods you'll hold your own, despite that import duty, O!

But you can't have all your own way, my bold—but angry—beauty, O!

Miss India, there needs constant care; she has not your resources, O!

You raise your voice against my choice 'twixt two unwelcome courses, O!

But I—though loth—considering both on my responsibility, O!

Have done my best, and for my pains from both meet incivility, O!

I've tried to bear the balance fair, 'twixt countries, trades, and classes, O!

And lo! my lot is anger hot from both you bickering lasses, O!

Miss India's eyes, at the Excise, excitedly are flashing, O!

My dusky dear, 'tis hard to steer 'twixt interests wildly clashing, O!

I love ye both, and I were loth to make—or see—ye quarrel, O!

But—a divided duty's mine, and that's my homily's moral, O!

And so, my dears, abate your fears, and likewise stint your shindy, O!

The Lass of Lancashire should shake hands with the Lass from "Indy," O!

I'll do my best for East and West. Brim high three bumper glasses, O!

And let's drink health, and love, and wealth to both my bonny lasses, O!

"Bored to blues by a Blue-Book"? I fear you are not

Up to date in your choice of a tint, my dear fellow.

The type of sheer boredom, and dulness, and rot,

Is not now the Blue of old days, but the Yellow.

As Blue-Stockings now half the sex might be mustered,

The New Woman doubtless wears hose hued like custard.

Next best thing to the Persian Locomotive Carpet of Eastern Fable.—The "Travelling Rug" of Western fact.

Mr. Æsopus Delasparre. "I will ask you to favour me, Madam, by refraining from laughing at me on the Stage during my Third Act."

Miss Jones (sweetly). "Oh, but I assure you you're mistaken, Mr. Delasparre; I never laugh at you on the Stage—I wait till I get Home!"

London.—Jones is going to be married. Of course, I must give him something. But what? A biscuit box? Commonplace. Good idea to look for something more interesting and unusual during my holiday. Just off to North Italy. Will keep my eyes open along the way.

Paris.—Walk in the Rue de la Paix and Boulevards. Everything labelled "Article Anglais." Must really get him something made abroad. Give up looking in Paris. Shall find something farther on.

Lucerne.—No good to take Swiss wood carving. Can't carry home a huge sideboard. All the smaller things can be bought in London.

Milan.—The very place. There is an exhibition here. Shall probably see something beautiful. Italy, cradle of the arts, and all that sort of thing. Besides, so nice to say to Jones, "My dear fellow, here's a little trifle; got it in Milan, you know. It's modern, but then the Italians are always so artistic." To exhibition. Why, there are pictures here! Of course, just suit me. Hurry to picture gallery. Several rooms. Enter eagerly. After a short time, totter feebly out and ask the official at the door where I can obtain a little brandy. He, evidently alarmed by my horror-stricken face and staggering movements, asks civilly if I am ill. Would I like a chair? Should he fetch a doctor? Thank him, and say it is nothing serious. I have only been looking at a few modern Italian pictures. Crawl to the refreshment bar, and am revived with cognac. Then inspect the rest of the exhibition. Am the only visitor, which is not surprising, for there is nothing to see but bottles! An exhibition of bottles! They are said to be full of wine, but I do not see how that makes them more beautiful. Absurd to buy Jones some bottles. And equally absurd to buy him some Italian wine when he can get good French wine in England. Besides, can't carry bottles in my Gladstone bag. Therefore, give up Milan.

Venice.—The chief manufactures here are lace and glass. Now Jones never wears any lace, except in his boots, and never wears any glass, not even in his eye. So what good would these be to him? See one or two palaces to be sold. But can't take them home. So give up Venice.

Bologna.—More useless local productions! Here they make sausages and soap. Jones is not a starving scarecrow for want of sausages, nor a Simeon Stylites for want of soap. Must therefore give up Bologna. This wedding present begins to weigh me down. At each new place it obtrudes itself between me an all the beautiful things I look at. Must really get something in Florence.

Florence.—Great Scott! It's worse here. A life-size marble statue, or a mosaic table weighing nearly a ton. Have serious thoughts of buying, at a great reduction, an extra large statue, hitherto unsaleable on account of its size, and then telling Jones that his wedding present is waiting for him here, if he will come and fetch it. The dealer asks 2,000 lire. I understand shopping in Italy. Early one morning offer him 50. He at once comes down to 1,000. I go up to 100. Discuss for one hour, haggle for another hour, dispute angrily for a third. Then go off to déjeuner. Closing prices—dealer 725, myself 250. Back again after interval for refreshment. Begin quietly. Opening prices—dealer 720, myself 251. Discussion, haggling, dispute as before. Indignant marchings out by me, frantic pursuits by the dealer. Final prices—dealer 403, myself 396. Each of us, hoarse and exhausted, refuses to yield another centesimo. So do not buy statue for Jones, and give up Florence. Genoa is the last chance.

Genoa.—Velvet? What's the good of velvet to Jones? Besides it is fabulously dear, something like attar of roses at so much a drop. Must give up even Genoa.

London.—Back again. Have bought a biscuit box and sent it to Jones. Since then have met Jones's cousin, and Smith, and Jones's brother-in-law, and Mrs. Robinson, and a few other mutual friends. We disagree in many things, but in one we seem to be unanimous. We have all given him biscuit boxes!

Mr. Meenister MacGlucky (of the Free Kirk, after having given way more than usual to an expression "a wee thing strong"—despairingly). "Oh! Aye! Ah, w-e-el! I'll hae ta gie 't up!"

Mr. Elder MacNab. "Wha-at, Man, gie up Gowf?"

Mr. Meenister MacGlucky. "Nae, nae! Gie up the Meenistry!"

Tell me not, in Christmas Numbers,

Yule is a dyspeptic dream,

A tradition that but cumbers

What smugs call "the social scheme."

Yule is jolly, Yule is earnest!

A sick-bed is not its goal;

Prig who rich plum-pudding spurnest,

Thou art destitute of soul.

Not mere "sapping," which means sorrow,

Is youth's destined end or way:

But—to think that each to-morrow

Brings us nearer Christmas Day!

Terms are long, and Vacs. are fleeting,

And our "tums," though big and brave,

Know that there's an end to eating

When at lessons we must slave.

Oh, the railway's welcome rattle!

Oh, the feeling of fresh life!

Oh, the Christmas Show of Cattle!

Oh, the fun of fork and knife!

Blow the Future! it's unpleasant;

Put the Past clean out of head.

What I like's the (Christmas) Present,

No mere ghost, as Dickens said.

All his jolly books remind us

Christmas is a glorious time.

Don't let bilious bogies blind us

To its larks, which are sublime.

Only wish there was another

Coming—in a month—again!

Stodge is bad for boys? Oh, bother!

I can stand it, right as rain!

Let us, then, be up and doing,

(With a knife and fork and plate,)

All our tips at tuck-shops blueing,

Learn to stodge, ere 'tis too late!

X.—The Chair.

As soon as we had agreed to allow the Parish Meeting Chairman to preside, Black Bob jumped up and proposed that Mrs. Letham Havitt should be elected to the chair. She was a lady whose excellences he need not dilate on. She had excellent business habits, and, with all respect to Mrs. March, she had as much right to a seat on the Council as that lady. Then a miracle happened. Mrs. March not only did not resent this reference, but actually seconded Mrs. Havitt. It was essential, she said, that women should be represented as fully as possible, and she should, without hesitation, embrace this opportunity of securing a woman colleague. This made the situation serious, not to say hopeless. After she had sat down, there was an ominous pause. At length I rose and proposed myself. In impressive tones I pointed put that the hand of the electors had pointed in no uncertain way to myself, and that since no one else had proposed my election, at the risk of being misunderstood once more, I had, on public grounds, to do it myself. After another painful pause the Parson seconded my nomination. Then the voting. Mrs. Havitt's name was put first. She got 4 votes—Mrs. March, Black Bob, and his two comrades. I got 3—the Squire, the Parson, and my self. And so I was foiled again—by the Eternal Feminine.

And so our Parish Council is at last complete, and ready for action, a corporate body in the eyes of the law. Possibly, in these pages I may from time to time be permitted to relate how Mudford progresses under our rule. Possibly, I may not. But in any case I ought to add that, being beaten by Mrs. Havitt has not—well, improved the domestic atmosphere. Wifely devotion seems to be out of fashion in these fin de siècle days.

The question of alien immigration as affecting the British Labour Market is one that occasionally occupies the attention of the Legislature. The subjoined advertisement cut from the Daily News suggests something even worse:—

H OLLAND.—THE FIRST NETHERLAND STEAM MUSTARD and SPICE MILLS, visiting the whole country, wishes to represent a first English house in articles of daily consumption.

It is bad enough to have foreign labourers competing with our people. But if they are going to send over, bodily, their mills and other labour shops, John Bull will be obliged to put his foot down and kick somebody.

Seasonable(?) Greeting for a Chinaman.—A Jappy New Year to you!

["Le duc d'Orléans a voulu donner une leçon aux mauvais patriotes; il habite Londres, il charge un tailleur parisien du soin de garnir sa garde-robe."—French Press.]

Along the boulevard's busy curb

That bristles bravely with étrennes,

A thing has threatened to disturb

The careless vie parisienne;

It isn't spies or journalist blackmailers,

It is the question of monarchic tailors.

For lo! from perfide Albion

Has lately come a ducal note

With patterns for a pantalon

And therewithal a redingote;

(Observe, in passing, that the royal billet

Says nothing of the corresponding gilet).

Now while in matters of the gown

The monde of Paris sets the mode,

Their gay flâneurs that paint the town

Long since affect a foreign code,

Developing in fact a steady passion

For dressing in the latest London fashion.

With any perfect patriot

How bitterly it stirs the bile,

This craze for being clothed in what

Is thought to be the English style;

It makes the language of his heated brain

Occasionally verge on the profane.

And now the Exile, armed with red

Hot coals of living anthracite,

Projects them on his country's head,

And more in pity than in spite

Bids France that hunted him and his like rabbits

Henceforth to execute his daily habits.

Some fancy, romping at results,

The constitution's overthrow,

A view unworthy of adults,

According to the Figaro;

It makes a democrat extremely nettled.

To hear the thing is practically settled.

Of course there may be something in

That strange omission of the vest,

Yet were it little short of sin

To lay this unction to the breast;

A person isn't worth a paltry filet

Who stakes the Third Republic on a gilet.

There lacks, you see, a final law

To guide in France the statesman's game

The casual ignited straw

Will set the camel's hump aflame;

A redingote may raise enough éclat

To bring about a pretty coup d'état.

"Lord H-lsb-ry will be the principal guest at a smoking 'At Home,'

Jan. 25th, at the W-stm-nst-r P-l-ce Hotel."—Daily Paper.

There is a Jappy land

Far, far away,

Where Art they understand;

None more than they.

Now in fair battle's ring

They've pummelled poor Ping-Wing,

All men their praises sing

Who've won the day.

Bright in that Jappy land

Beams every eye.

But, though their pluck be grand,

Bar-bar-i-ty

Their choicest gifts will mar,

Blood stains their rising star,

Foul slaughter is not war.

Fie, Jappy, fie!

(Fragment for the Historian of the Future.)

[After the Cabinet several of the Ministers present took luncheon with the Chancellor of the Exchequer.—Daily Paper.]

There had been an exciting meeting of the Members of the Ministry. The gathering had taken place at noon, and after several angry altercations it had been adjourned. But the objector-in-chief had admirably kept his temper. He came of a gallant and illustrious race, and blood is thicker than water.

"I must not forget the teachings of my Uncle Dick," he had murmured, as it was suggested that two of his favourite projects should be slaughtered, like the infant Princes in the Tower.

Then, when there was an inclination on the part of his colleagues to quarrel amongst themselves, he cleverly fanned the fire, and increased the incipient strife.

"It was the mode adopted by my maiden Aunt, Queen Elizabeth, and it succeeded in her time. Why should the passing of three or four centuries make any difference? After all, human nature is—in fact—human nature!"

And so the dull minutes passed away. The time came for luncheon. Then he smiled a smile full of mystic hospitality.

"It will put the bloodhounds of the Press off the scent if I ask them to luncheon with me. It is sure to be reported in the papers, and who will imagine that I would willingly entertain a possible opponent to the coming Budget? Moreover, revenge is sweet; not that I would take it! not that I would take it!"

And then he entreated several of his colleagues to "crush a cup with him," using a phraseology that had found favour in the mouths of the Crusaders.

"And Rosey, will not you come?" The question was asked with much cordiality. The Premier did not reply. He merely smiled, and the smile seemed to be a sufficient answer.

* * *

Shortly afterwards (as subsequently reported in the newspapers) the noble Earl took luncheon at his own home.

"I wonder what wine he has given them?" And he smiled again.

Santa Claus, the afternoon pantomime at the Lyceum, is even better than Mr. Oscar Barrett's Cinderella of last year. There is plenty of splendour in the fairy piece, considered merely as a "spectacle," enough, indeed, to make a "pair of spectacles," and to cause much speculation as to how they manage to stow away all the scenery, properties, and costumes at five o'clock every afternoon, in order to make room for King Arthur, who, on the temporary abdication of Santa Claus (a part admirably acted and declaimed by Mr. William Rignold), reigns at the Lyceum from eight till eleven. But besides the dazzling brilliancy of fairy pantomime, there is in it not only real fun which delights the youngsters, for whom the entertainment is primarily intended, but also a touch of dramatic pathos, as shown in the death of the devoted dog Tatters, a dog who has his day and dies, whose cruel fate excites the compassion of old and young alike. All are rejoiced when they find out that clever Mr. Charles Lauri, of whom it can be complimentarily said that "he is a perfect beast," is restored to life, and that the Heavenly Twins are happily revived.

As the two toy soldiers Messrs. Harry and Fred Kitchen—the front and back kitchen—are first-rate. But where all are so good it is impossible, within the limits of a paragraph, to particularise. Messrs Barrett and Lennard are to be congratulated, and, as Hamlet says, "The Pantomime's the thing," and, as Shakspearian readers will remember, Hamlet's father went to matinées,—wasn't it "his custom always of an afternoon"?—only there's no sleeping here, but everyone very wide awake, and all "going home to tea" thoroughly satisfied with Santa Claus. Who says Le Roi Pantomime est mort, when the Lyceum is crowded for matinées, and, outside the doors of Old Drury, daily and nightly appear the placards, "House Full"?

A "Tit Bit."—When they speak of some one of the Baby Baronets, i.e. the recently created Baronets, they don't say he is among the Old'uns; but "He is among the New'nes."

(An Entertainment Antagonistic to Amusement.)

Scene—Anywhere. Characters distributed about the Stage in more or less admired confusion.

Anybody. So we are living in a penny romance. And this is Society.

Charles his Friend. Society is everything but sociable.

Somebody. But why should the Prime Minister be threatened by a professional blackmailer?

Charles his Friend. In matters of this kind the Premier is the dernier.

Someone Else. But surely the same sort of thing has been done by Sardou in Dora?

Charles his Friend. Why not? A dramatist has only one virtue, he never invents a drama.

A Casual Visitor. Then we have only to regard the Adelphi as a model, and take the Wyldest license with the dialogue.

Charles his Friend. Quite so. After all, a paradox is merely a platitude.

A Caller. But do great men do these things?

Charles his Friend. The great do all things because they are little.

A Lady. Surely a wife should look up to her husband?

Charles his Friend. So she does—unless she wears high heels.

A Person. And a wife, if she found her husband in trouble, would surely cleave to him?

Charles his Friend. So she would, if she only knew where to find him.

Another Person. That reminds me that a play, to be successful, must have the plot of a shilling shocker—much diluted.

Charles his Friend. A shocker shocks no one save its—publisher.

A New Comer. Then the blackmailer was defeated in the end—as bad people invariably are when vice is at a discount and virtue at a premium.

Charles his Friend. Virtue never is at a premium, save when it is mistaken for vice.

A blasé Man of the World. And yet, in spite of all this, I have had a pleasant evening.

Charles his Friend. So has an author when he is laughing in his sleeve and confuses black with white.

Someone. But does the author never know the difference?

Charles his Friend. What does it matter? If he thinks himself right, everybody will know that he is wrong!

The Audience. All this is very clever because it is unintelligible.

The Author. So I believe. Only I stand upon my irresponsibility. But is anyone satisfied with anything in a playhouse?

Charles his Friend. Only with the fall of the curtain!

[Scene closes in upon nothing in particular.

"Is this the New Baby, Daddy?"—"Yes, dear."

"Why, he's got no Teeth!"—"No, dear."

"And he's got no Hair!"—"No, dear."

"Oh, Daddy, it must be an Old Baby!"

I own there are heights that she cannot attain.

She is not at home with a gun.

In pastimes where one living creature is slain

She cannot perceive any fun;

And never a poor feathered songster has died

Her hat or her bonnet to grace;

And after the hounds it were torture to ride,

Lest Reynard should lose in the race.

And much she ignores that New Women should learn,

And still she refuses to smoke:

One wine from another she cannot discern,

But she's splendid at seeing a joke.

Her love and her friendship no labour can fret,

No jealousy seems to alarm.

In truth, not a mortal could ever forget

Her humour, her kindness, her charm.

Though dozens of friends of her fealty boast,

Her desk with epistles is packed,

Her very own relatives love her the most—

A somewhat remarkable fact!

With bores and with fools she ungrudgingly bears,

And though it may end in her loss,

With cabmen she never can wrangle for fares,

Or haggle a counter across.

Her eyes, that are loyal and fearless and kind,

At wrong or injustice will flame,

But they never seem anxious a failure to find,

They never are hasty to blame;

And well she is loved by the best and the worst,

For sympathy, courage, and truth,

For friendship unfailing they love her, the first;

The last, for her infinite ruth.

Oh, what if she never should do or should dare

In regions by Woman untrod?

Yet, when her step passes, men turn from despair,

And trust in the world and in God.

Oh, what if no "record" she cares to eclipse,

Nor manners nor morals defies?

But pain she would face with a smile on her lips,

And death with a light in her eyes!

"The Ghizeh Museum."—A question has been asked in the Times as to why the name of Professor Petrie has been omitted from the Commission for the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. The answer, whether satisfactory or not, is that considering the overwhelming learning on this special subject of the distinguished Professor it is probable that the energies of the other members would be "Petrie-fied."

Motto for Horrid Cold Weather.—"Bed's the Best."

["The news of the death of Mrs. Bloomer, at Council Bluffs, Iowa, revives many memories of a distant past."—Daily Graphic.]

So Mrs. Bloomer's gone! but let her name

Once more appear in Mr. Punch's pages.

'Twas long ago, almost the Middle Ages,

That Leech's pencil advertised her fame!

Her costume was unlovely—let it fade

For ever from the ken of human vision!

Though nowadays 'twould scarce provoke derision,

If worn by pretty girls and tailor-made.

For by the lady-cyclist, as she plies

Her pedal, neatly clad in knickerbockers.

See Mrs. Bloomer, first of Grundy-shockers.

Now vindicated in Dame Fashion's eyes!

But, not in dress alone a pioneer,

She edited the temp'rance Water Bucket,

And many a blow 'gainst drink with pluck hit;

Then let us o'er her passing shed a tear!

At the Empire.—The celebrated chanteuse Mlle. Mealy is engaged. We've not yet heard her, but of course this lady's songs should be of a very delicate nature, as she herself must be "Mealy-mouthed."

Page 25: 'change' corrected to 'charge'.

"it was that last charge of yours at the head of your magnificent Thundershakers that has converted defeat into victory,..."

Page 27: 'The Dandy Afghan Khan': 'Dost Mohammed' in the first Chorus, becomes 'Dost Mahommed' in the last. Wikipedia gives 'Dost Mohammed.'

Page 28: 'Applebossom' corrected to 'Appleblossom'.

""Bless me, you have a treasure!" continued Appleblossom, Q.C.,..."

Page 29: 'seven-eights' corrected to 'seven-eighths.'

""An Old Boots!" cried my better seven-eighths,..."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

108, January 19, 1895, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, JANUARY 19, 1895 ***

***** This file should be named 42480-h.htm or 42480-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/2/4/8/42480/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.