TROPICAL AMERICAN HUMMING-BIRDS

TROPICAL AMERICAN HUMMING-BIRDS

YOUNG FOLKS' TREASURY

In 12 Volumes

Hamilton Wright Mabie

Editor

Edward Everett Hale

Associate Editor

New York

The University Society Inc.

Publishers

Copyright, 1909, by

The University Society Inc.

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

Editor

EDWARD EVERETT HALE

Associate Editor

Nicholas Murray Butler, President Columbia University.

William R. Harper, Late President Chicago University.

Hon. Theodore Roosevelt, Ex-President of the United States.

Hon. Grover Cleveland, Late President of the United States.

James Cardinal Gibbons, American Roman Catholic prelate.

Robert C. Ogden, Partner of John Wanamaker.

Hon. George F. Hoar, Late Senator from Massachusetts.

Edward W. Bok, Editor "Ladies' Home Journal."

Henry Van Dyke, Author, Poet, and Professor of English Literature, Princeton University.

Lyman Abbott, Author, Editor of "The Outlook."

Charles G. D. Roberts, Writer of Animal Stories.

Jacob A. Riis, Author and Journalist.

Edward Everett Hale, Jr., English Professor at Union College.

Joel Chandler Harris, Late Author and Creator of "Uncle Remus."

George Gary Eggleston, Novelist and Journalist.

Ray Stannard Baker, Author and Journalist.

William Blaikie, Author of "How to Get Strong and How to Stay So."

William Davenport Hulbert, Writer of Animal Stories.

Joseph Jacobs, Folklore Writer and Editor of the "Jewish Encyclopedia."

Mrs. Virginia Terhune ("Marion Harland"), Author of "Common Sense in the Household," etc.

Margaret E. Sangster, Author of "The Art of Home-Making," etc.

Sarah K. Bolton, Biographical Writer.

Ellen Velvin, Writer of Animal Stories.

Rev. Theodore Wood, F. E. S., Writer on Natural History.

W. J. Baltzell, Editor of "The Musician."

Herbert T. Wade, Editor and Writer on Physics.

John H. Clifford, Editor and Writer.

Ernest Ingersoll, Naturalist and Author.

Daniel E. Wheeler, Editor and Writer.

Ida Prentice Whitcomb, Author of "Young People's Story of Music," "Heroes of History," etc.

Mark Hambourg, Pianist and Composer.

Mme. Blanche Marchesi, Opera Singer and Teacher.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | xi | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | Apes and Gibbons | 1 |

| II | Baboons | 7 |

| III | The American Monkeys and the Lemurs | 16 |

| IV | The Bats | 26 |

| V | The Insect-Eaters | 33 |

| VI | The Larger Cats | 47 |

| VII | The Smaller Cats | 60 |

| VIII | The Civets, the Aard-Wolf, and the Hyenas | 68 |

| IX | The Dog Tribe | 78 |

| X | The Weasel Tribe | 91 |

| XI | The Bear Tribe | 102 |

| XII | The Seal Tribe | 113 |

| XIII | The Whale Tribe | 121 |

| XIV | The Rodent Animals | 136 |

| XV | The Wild Oxen | 157 |

| XVI | Giraffes, Deer, Camels, Zebras, Asses, and Horses | 179 |

| XVII | The Elephants, Rhinoceroses, Hippopotamuses, and Wild Swine | 201 |

| XVIII | Edentates, or Toothless Mammals | 212 |

| XIX | The Marsupials[viii] | 218 |

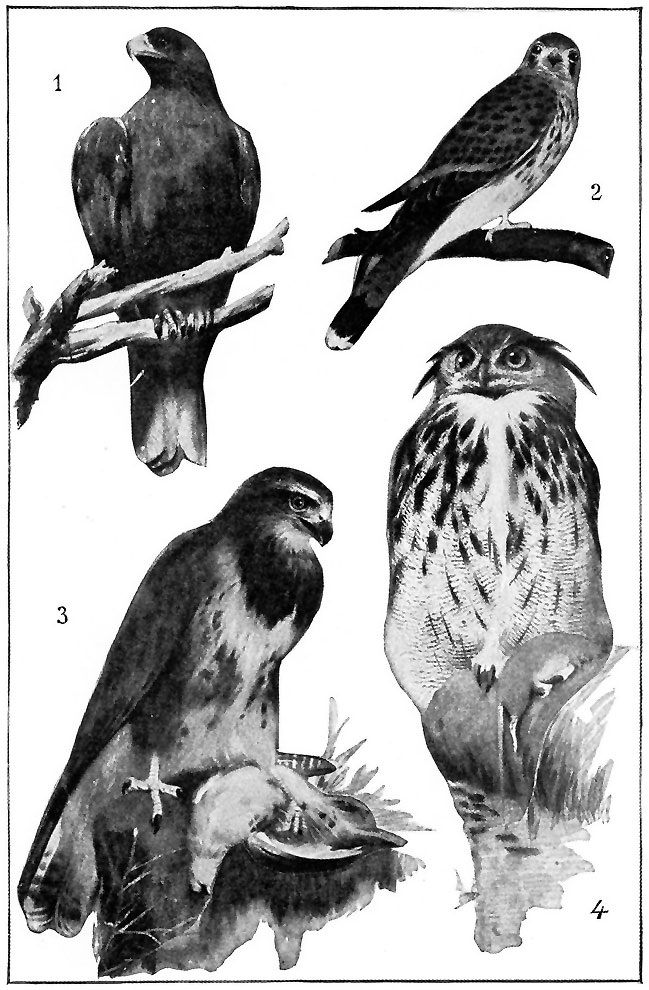

| XX | Birds of Prey | 232 |

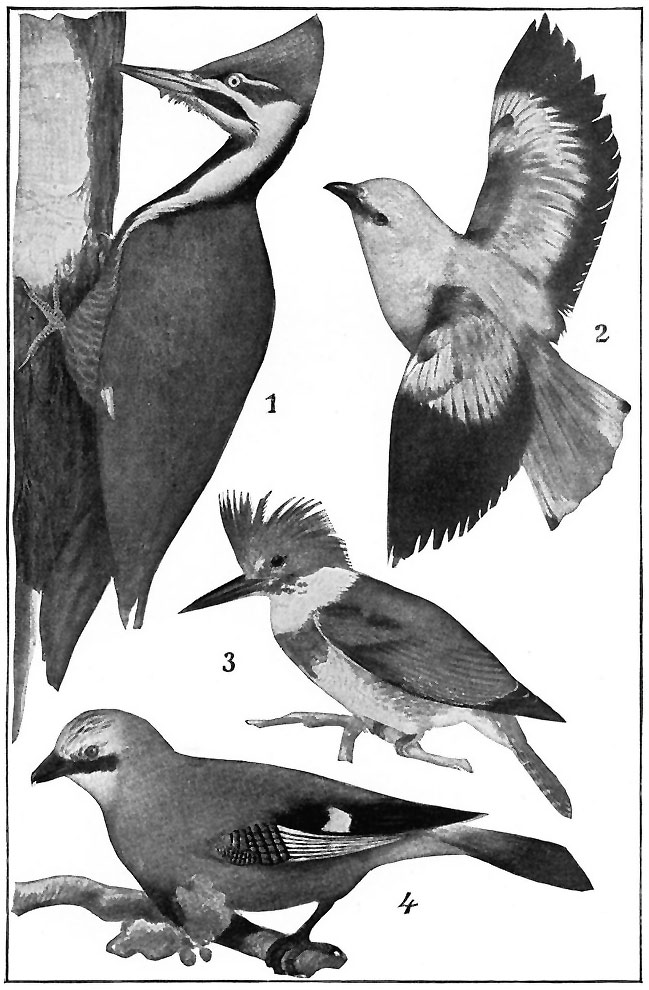

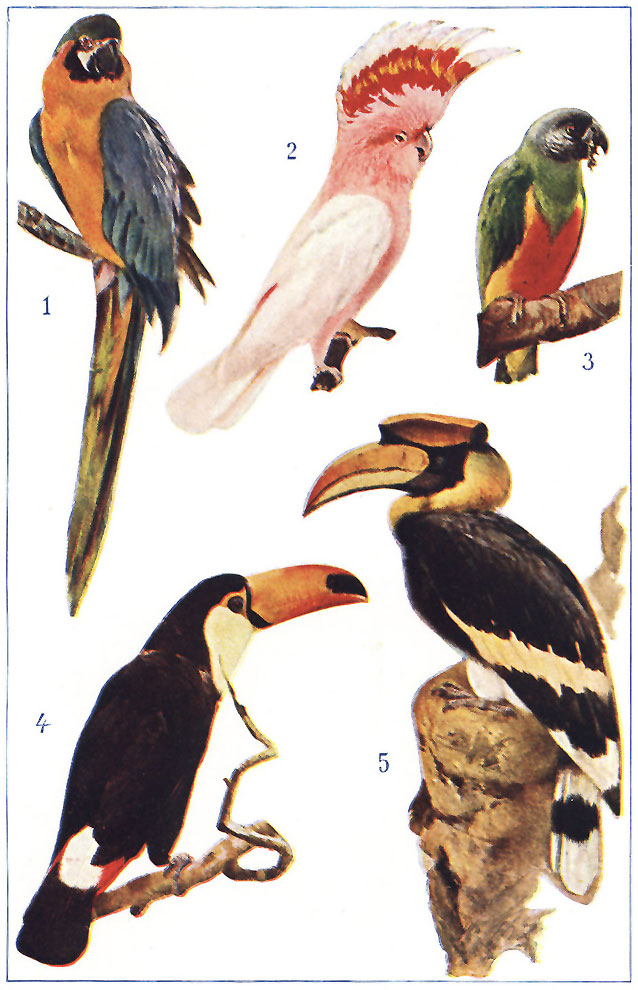

| XXI | Cuckoos, Nightjars, Humming-Birds, Woodpeckers, and Toucans | 243 |

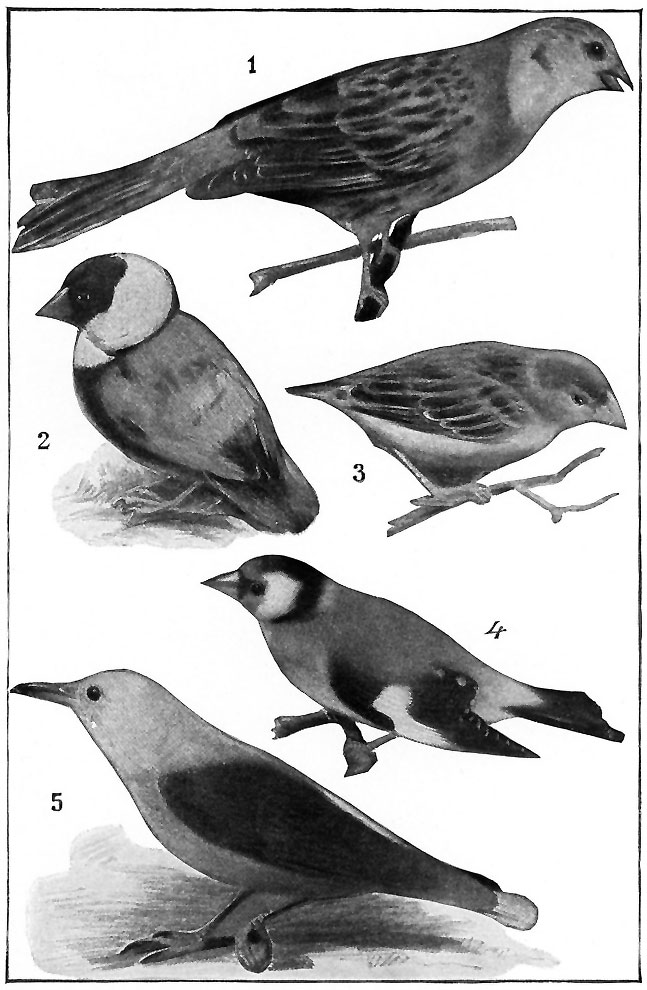

| XXII | Crows, Birds of Paradise, and Finches | 254 |

| XXIII | Wagtails, Shrikes, Thrushes, etc. | 263 |

| XXIV | Parrots, Pigeons, Pea-Fowl, Pheasants, etc. | 273 |

| XXV | Ostriches, Herons, Cranes, Ibises, etc. | 281 |

| XXVI | Swimming Birds | 291 |

| XXVII | Tortoises, Turtles, and Lizards | 299 |

| XXVIII | Snakes | 311 |

| XXIX | Amphibians | 321 |

| XXX | Fresh-water Fishes | 326 |

| XXXI | Salt-water Fishes | 337 |

| XXXII | Insects | 354 |

| XXXIII | Insects (continued) | 369 |

| XXXIV | Spiders and Scorpions | 387 |

| XXXV | Crustaceans | 397 |

| XXXVI | Sea-Urchins, Starfishes, and Sea-Cucumbers | 409 |

| XXXVII | Mollusks | 414 |

| XXXVIII | Annelids and Cœlenterates | 427 |

| Walks with a Naturalist | 437 | |

| Nature-study at the Seaside | 457 | |

| Our Wicked Waste of Life | 487 | |

| Index | 497 | |

(Much of the material in this volume is published by permission of E. P.

Dutton & Company, New York City, owners of American rights.)

| Tropical American Humming-Birds | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Types of Apes and Monkeys | 6 |

| Photographic Portraits of Monkeys | 16 |

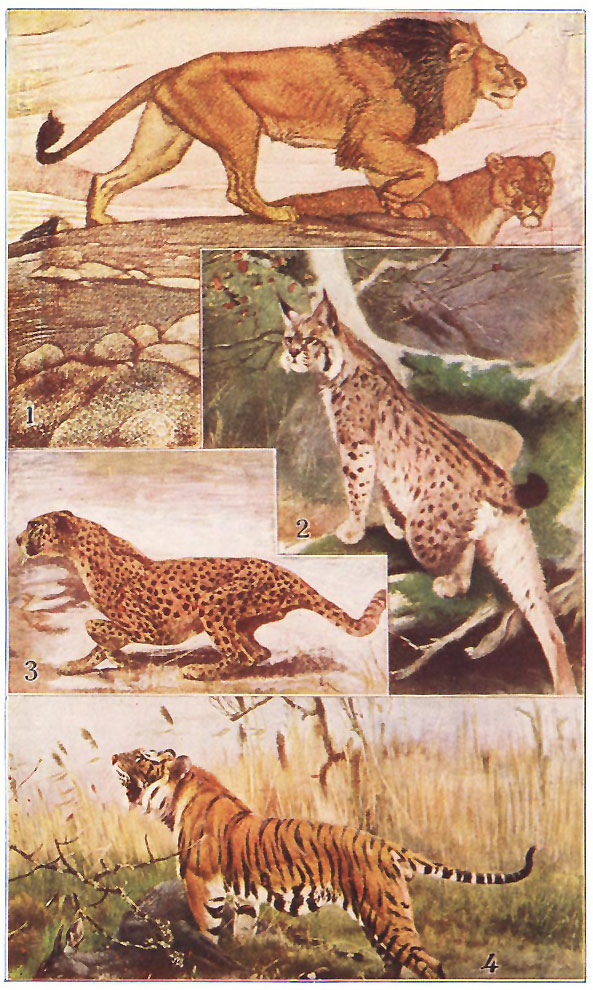

| Four Great Cats | 48 |

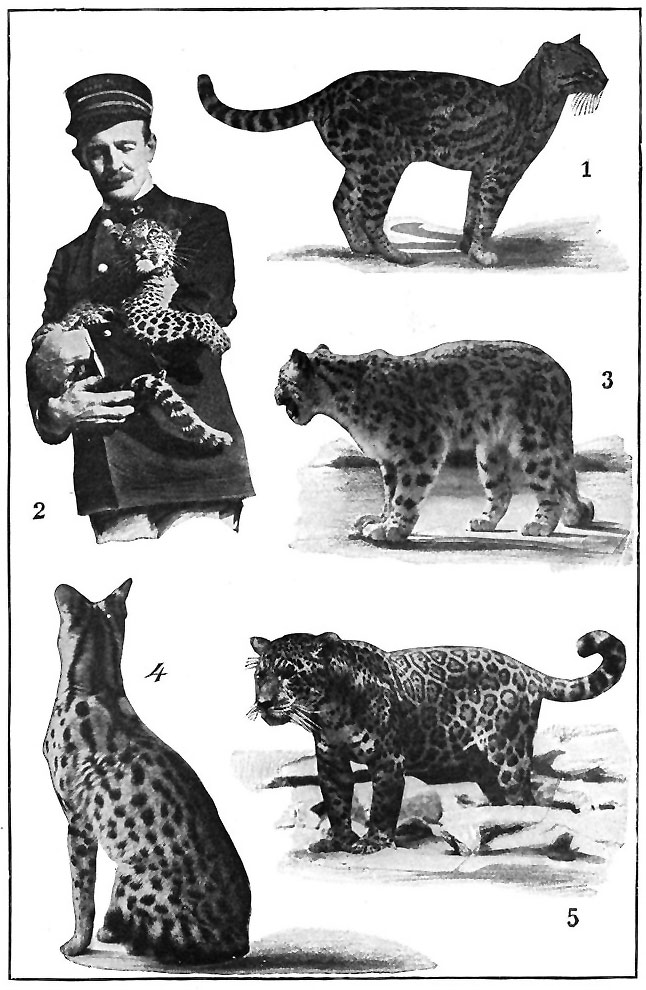

| Some Fierce Cats | 64 |

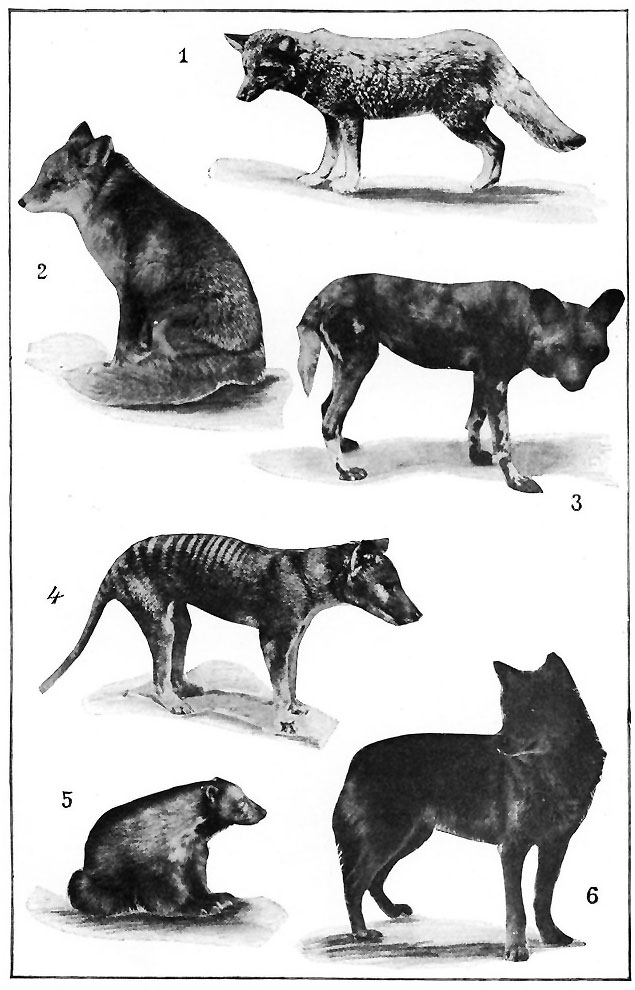

| A Wolfish Group | 80 |

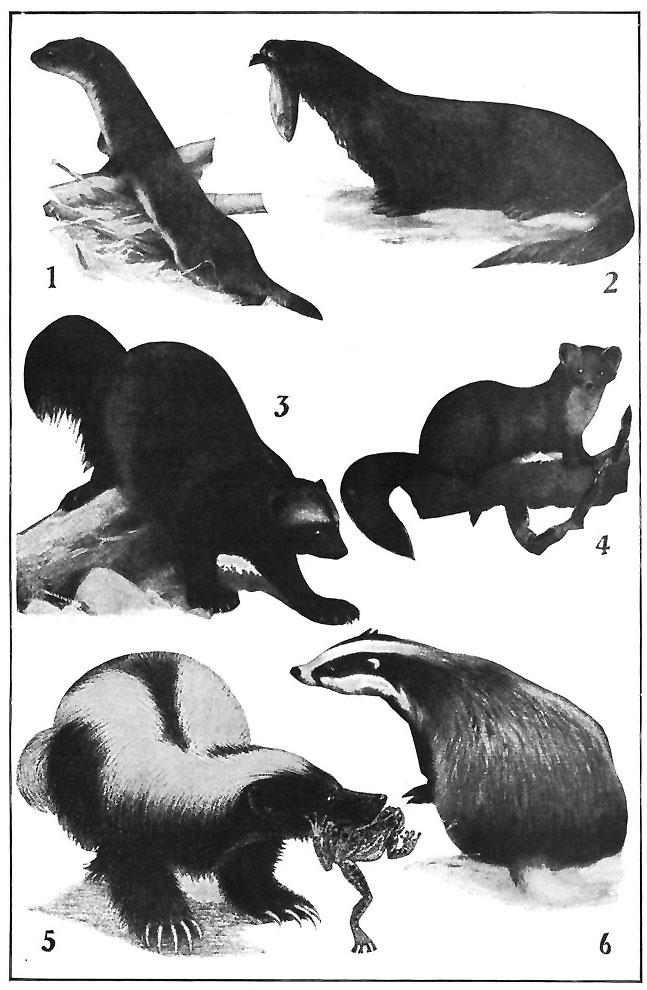

| Types of Fur-Bearers | 96 |

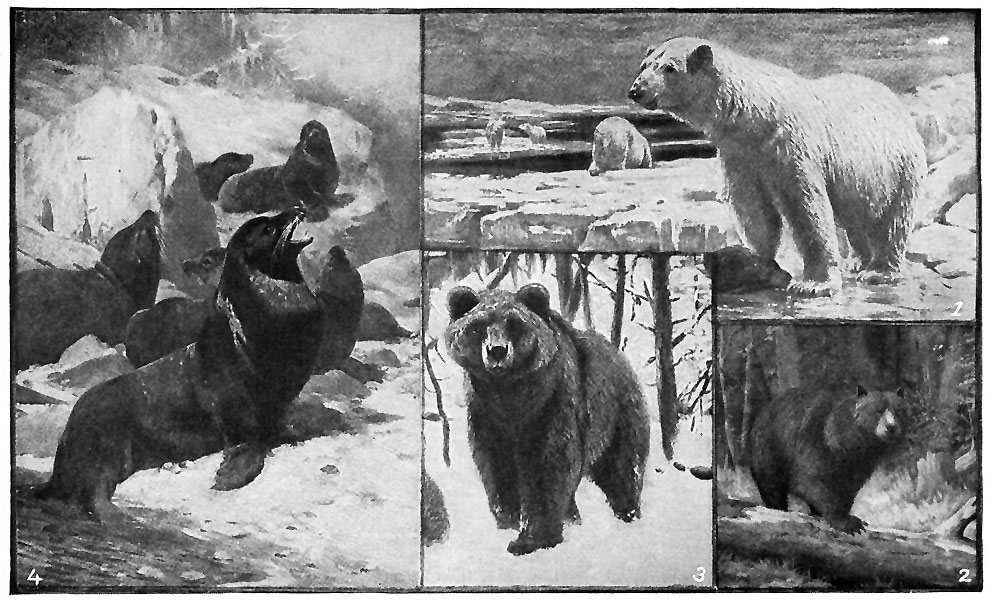

| Types of Bears | 128 |

| Types of Rodents | 144 |

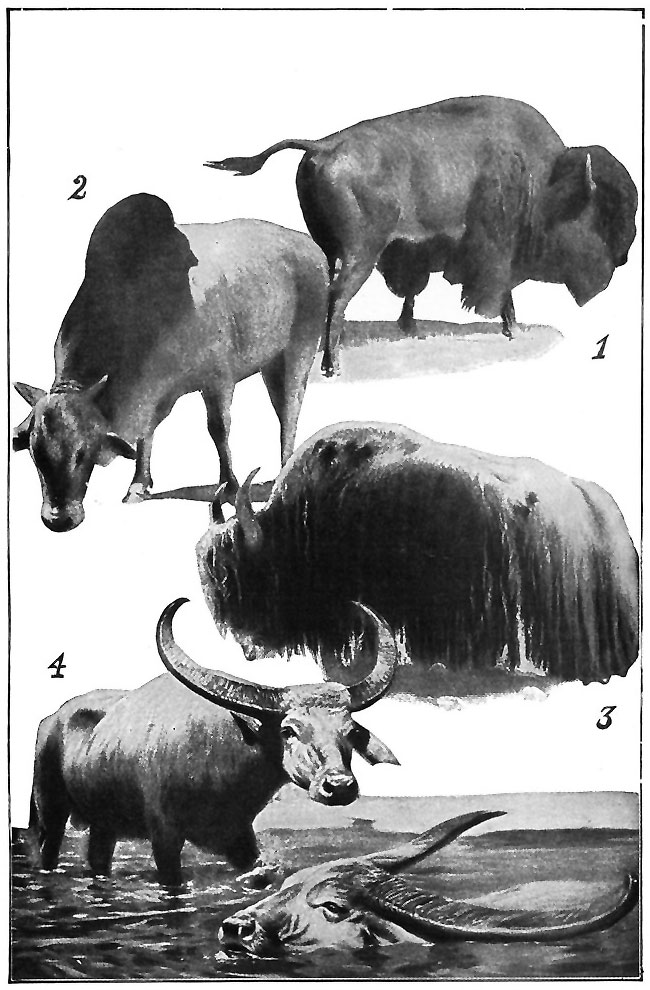

| Four Types of Cattle | 156 |

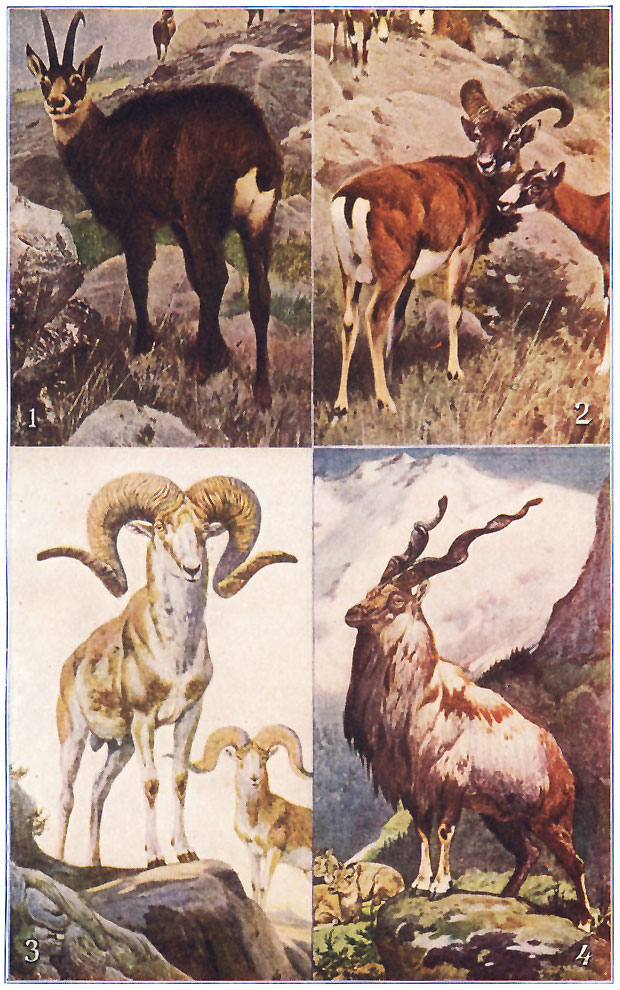

| Wild Sheep and Goats | 164 |

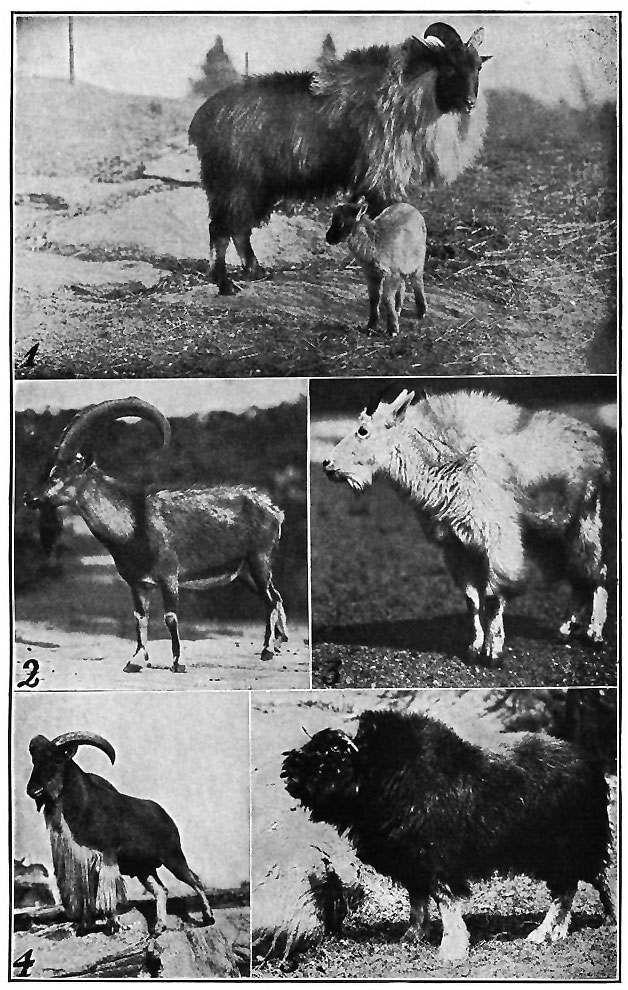

| Goats and Goat-Antelopes | 166 |

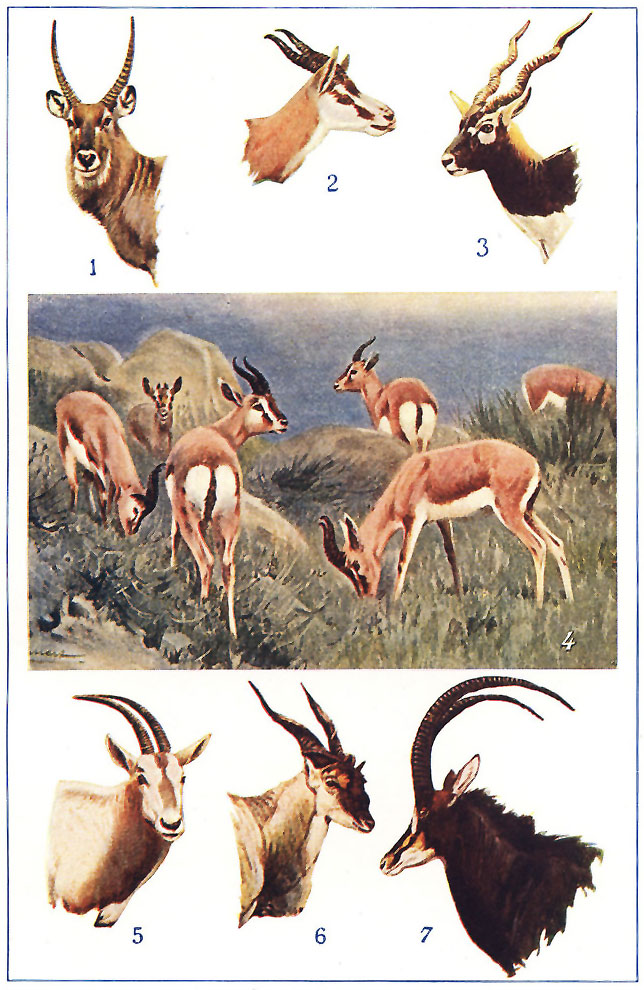

| Types of Antelopes | 176 |

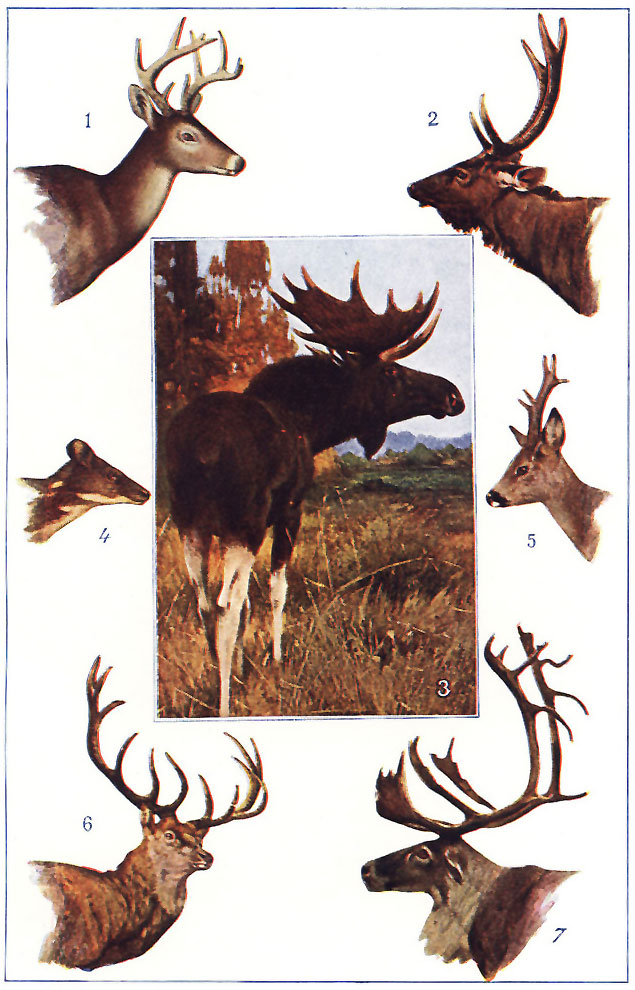

| The Antlered Deer | 184 |

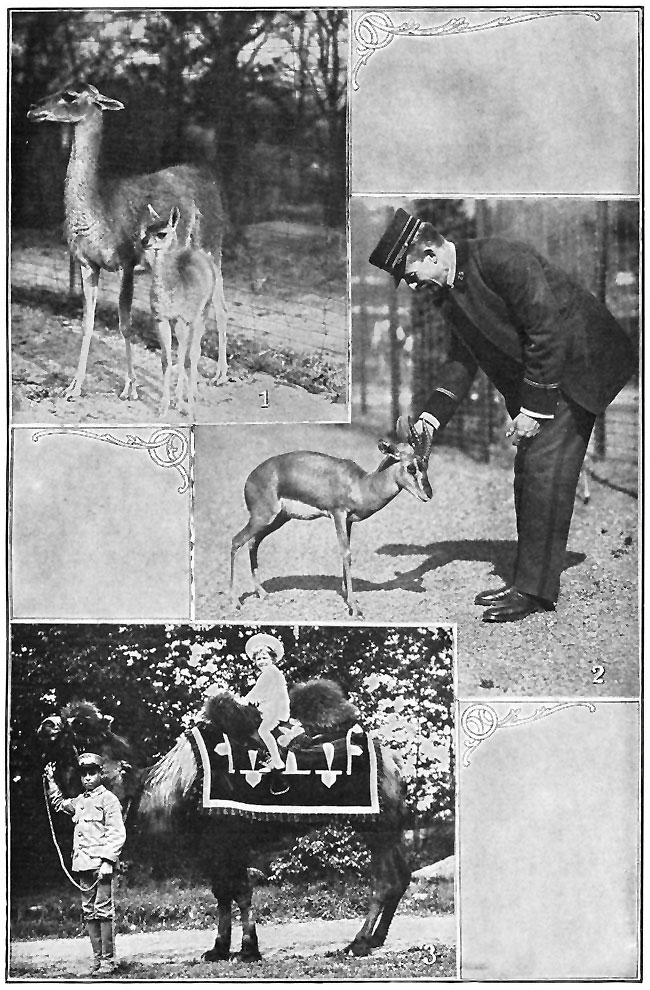

| Children's Pets at the Zoo | 189 |

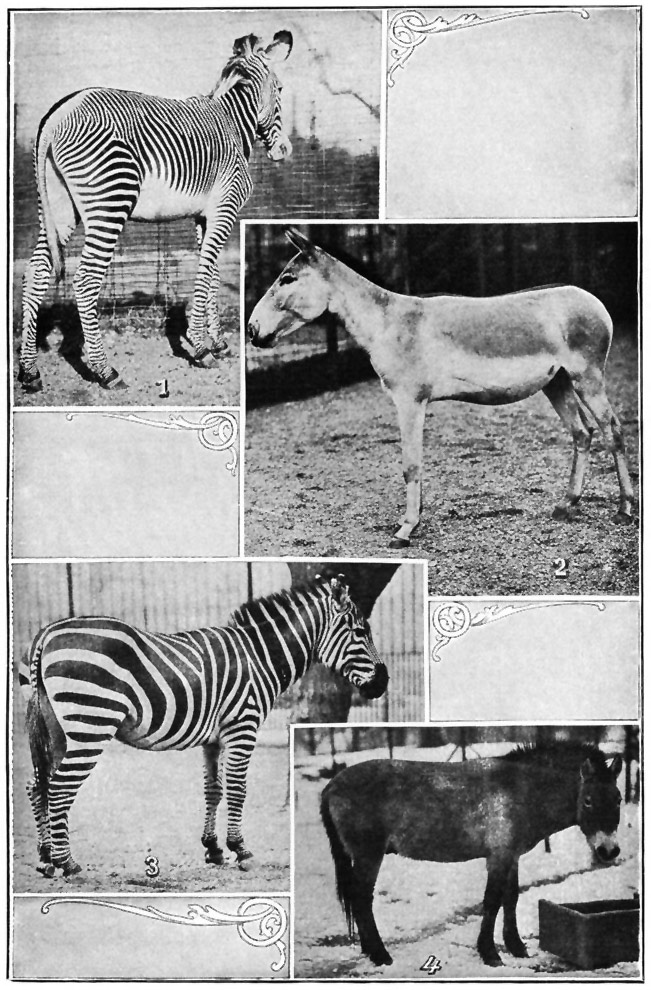

| Wild Relatives of the Horse | 196 |

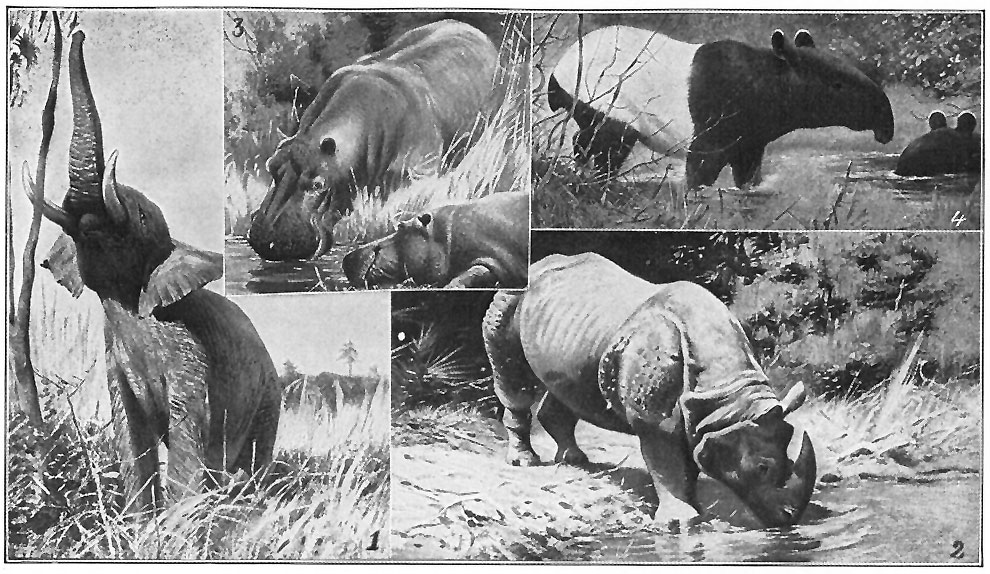

| Pachyderms and Tapir | 206 |

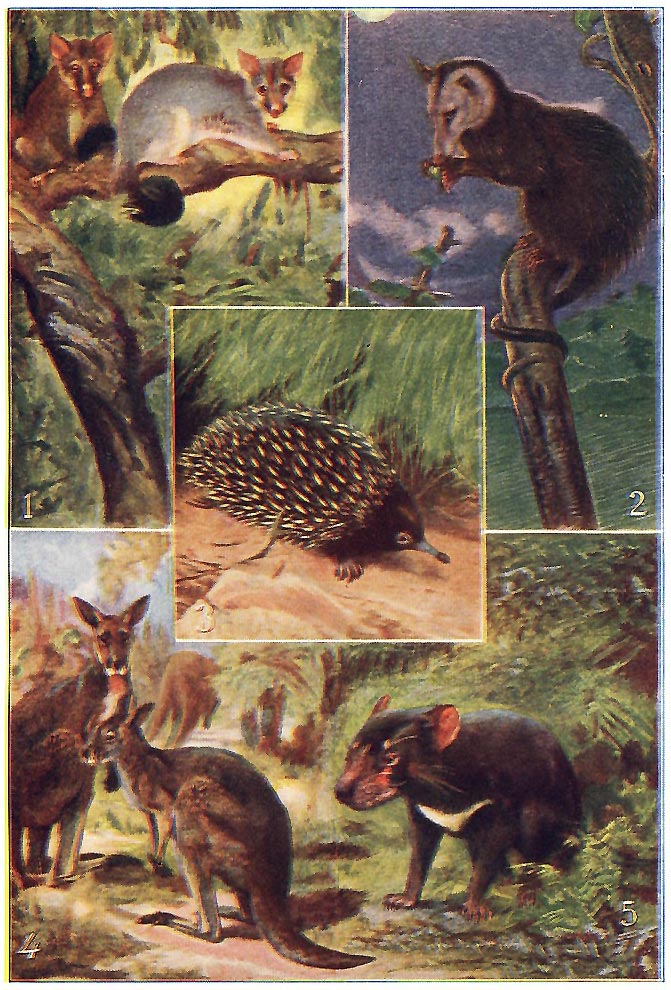

| Types of Marsupials | 220 |

| Typical Birds of Prey[x] | 232 |

| Four Handsome Birds | 246 |

| Finches and Weaver-Birds | 260 |

| American Insect-eating Song-Birds | 264 |

| Gaudy Tropical Birds | 272 |

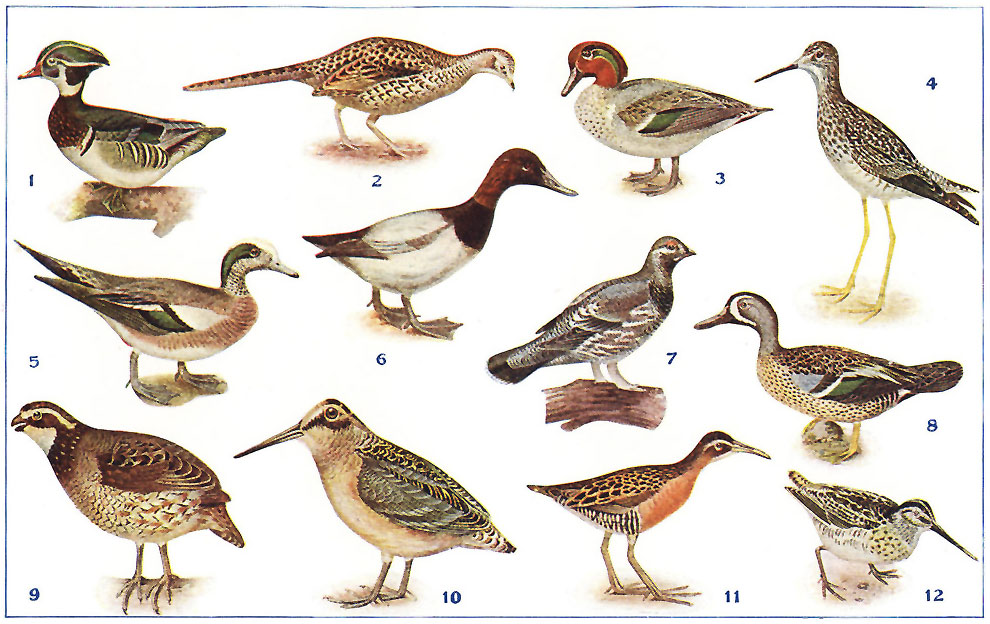

| American Game-Birds | 278 |

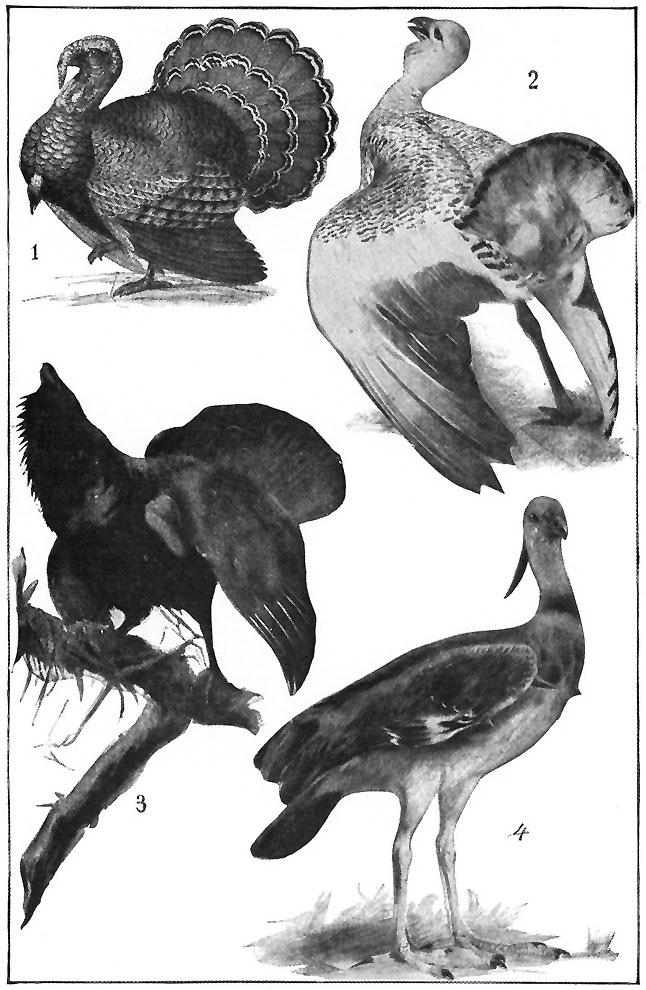

| Four Great Game-Birds | 280 |

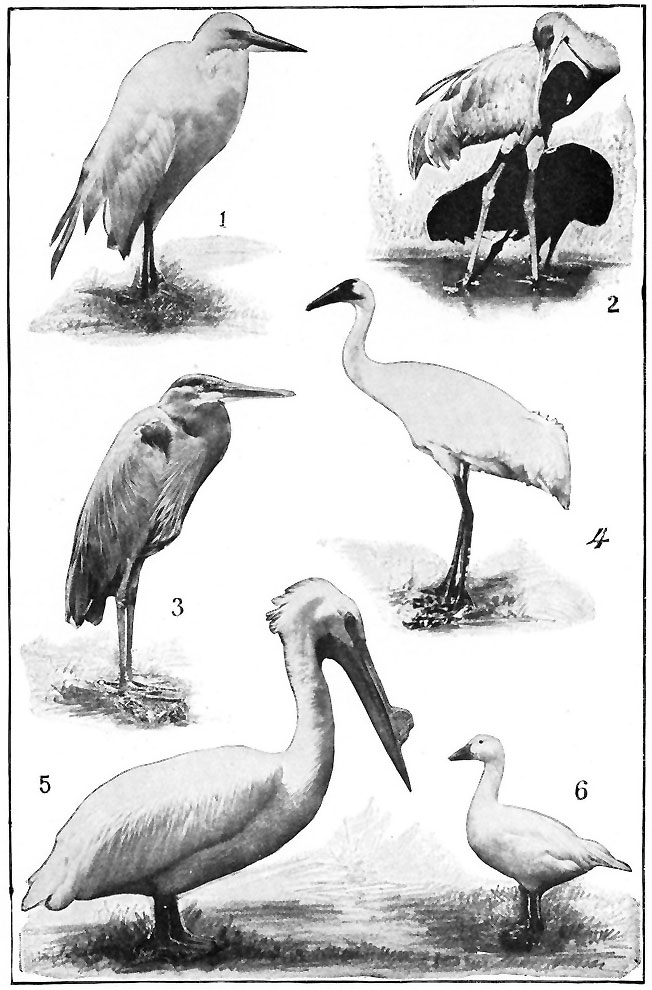

| American Wading Birds | 296 |

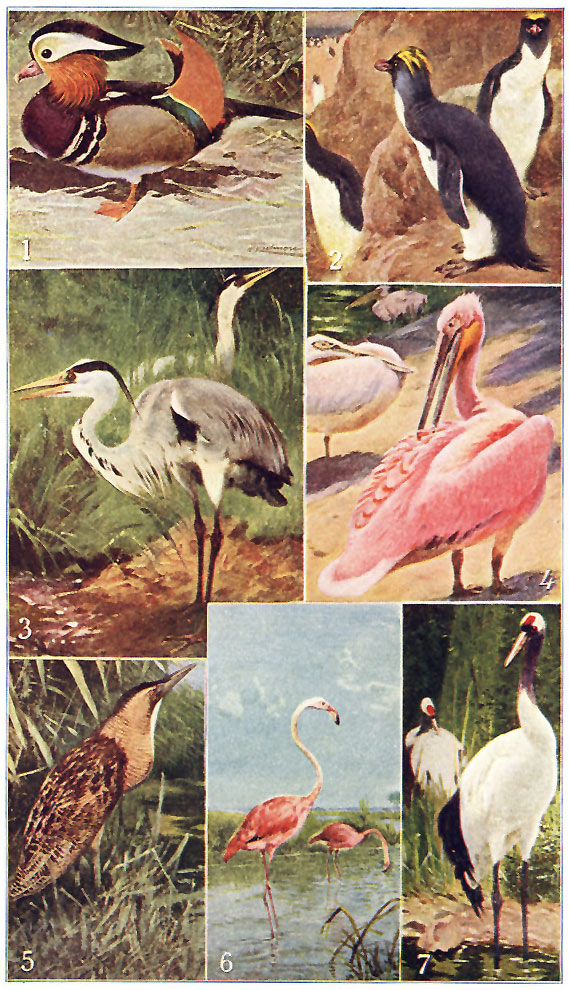

| Types of Water-Birds | 300 |

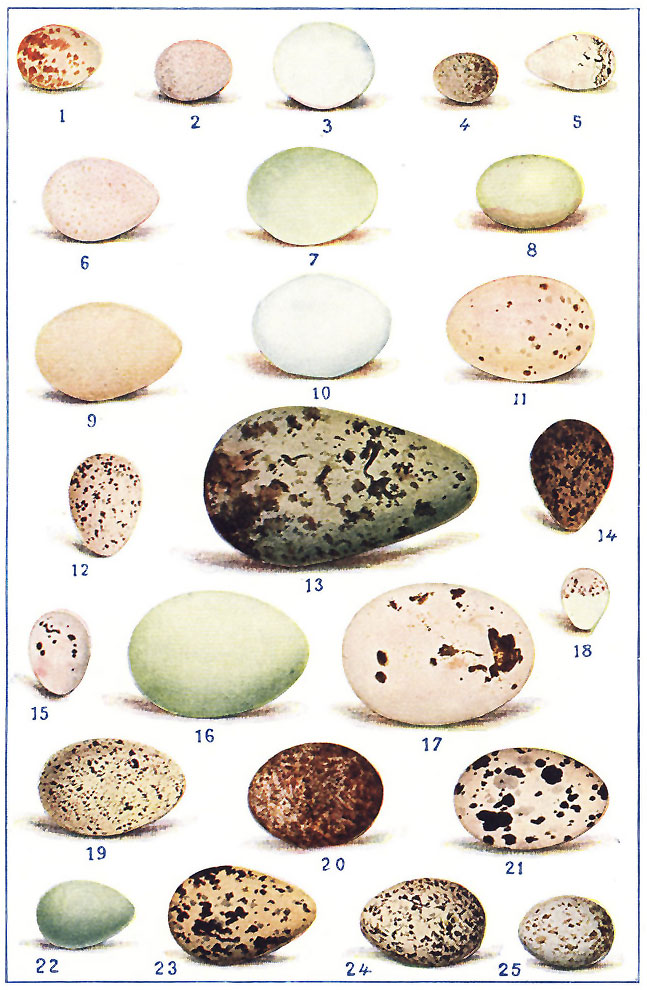

| Characteristic Forms and Markings of American Birds Eggs | 312 |

| North American Food and Game Fishes | 328 |

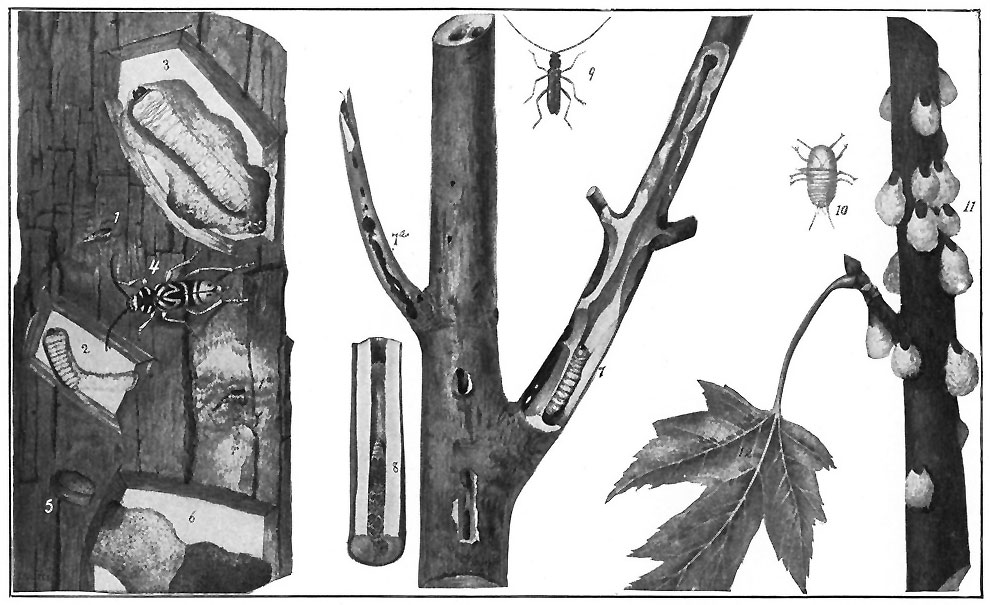

| Insects Injurious To American Maple-Trees | 360 |

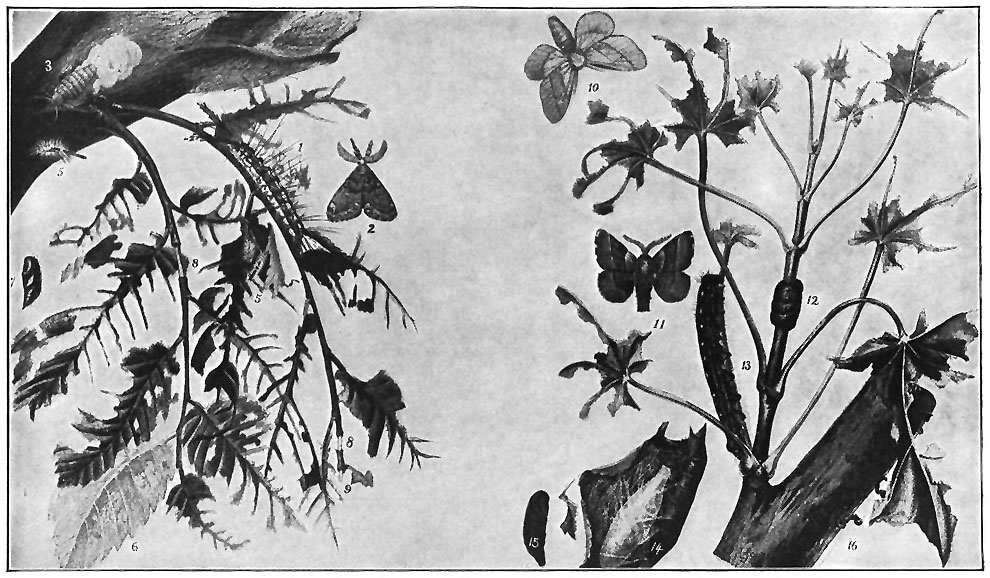

| Leaf-eating Insects of Shade-Trees | 376 |

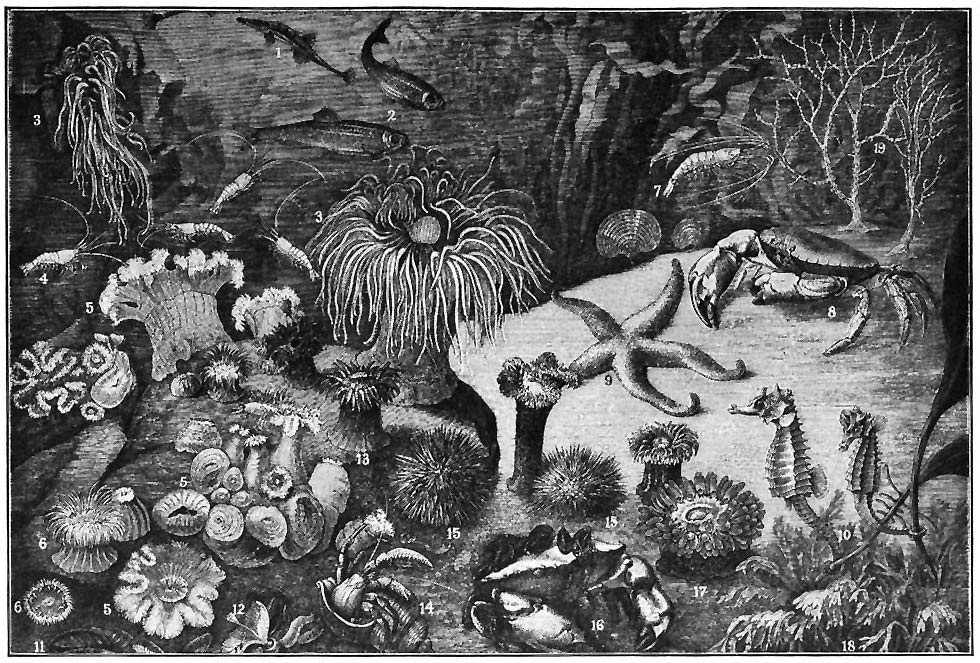

| Life on the Sea-Bottom | 408 |

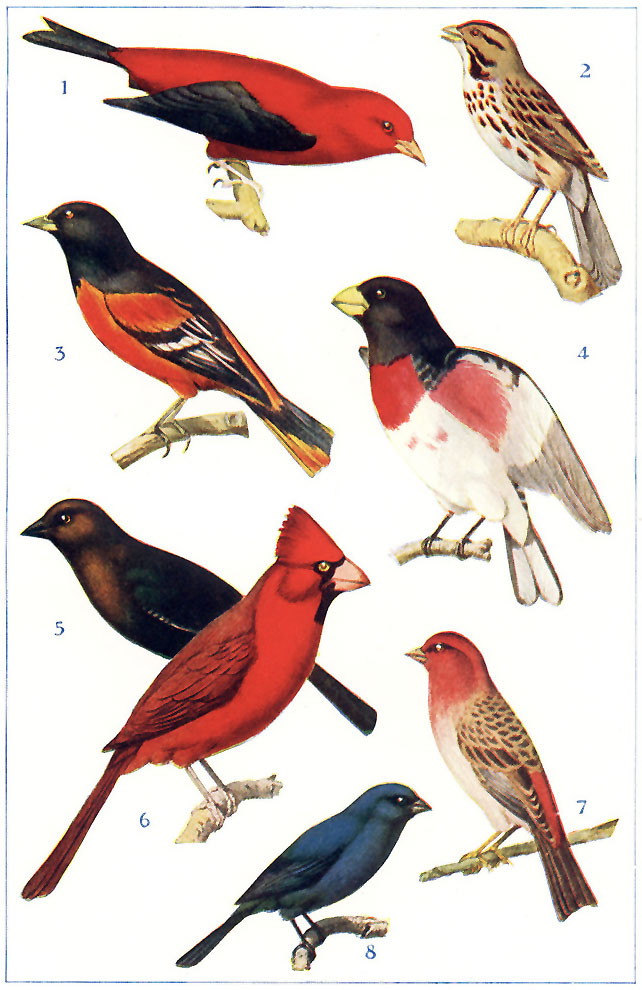

| North American Seed-eating Song-Birds | 436 |

| Chickadee and White-breasted Nuthatch | 448 |

This volume is a sketch of the animal life of the whole world. More than a sketch it could not be in the space at the author's command; but he has so skilfully selected his examples to illustrate both the natural groups and the faunas which they represent, that his work forms a most commendable ground-plan for the study of natural history.

Few writers have been so successful in handling this subject. His style is singularly attractive to the young readers whom he has in view; yet he does not depart from accuracy, nor exaggerate with false emphasis some unusual phase of an animal's character, which is the fault of many who try to "popularize" zoölogy.

One may feel confident, therefore, that the boy or girl who opens this volume will enjoy it and profit by it. The sketch dwells on the animals most often to be seen in nature, or in menageries, or read of in books of travel and adventure, and will thus serve as a valuable reference aid in such reading. But it will, and ought to, do more. It will arouse anew that interest in the creatures about us which is as natural as breath to every youngster, but is too rarely fostered by parents and teachers.

Nothing is more valuable in the foundation of an education than the faculty and habit of observation—the power of noting understandingly, or at least inquiringly, what happens within our sight and hearing. To go about with one's eyes half shut, content to see the curtain and never curious to look at the play on nature's stage behind it, is to miss a very large part of the possible pleasure in life. That his child should not suffer this loss ought to be the concern of every parent.[xii]

Little more than encouragement and some opportunity is needed to preserve and cultivate this disposition and faculty. Direct a youngster's attention to some common fact of woodland life new to him, and his interest and imagination will be excited to learn more. Give him a hint of the relationship of this fact to other facts, and you have started him on a scientific search, and he has begun to train his eye and his mind without knowing it. At this point such books as this are extremely helpful, and lead to a desire for the more special treatises which happily are now everywhere accessible.

This suggestion is not made with the idea that every youngster is to become a full-fledged naturalist; but with the sense that some knowledge of nature will be a source of delight throughout life; and with the certainty that in no direction can quickness of eye and accuracy of sight and reasoning be so well and easily acquired. These are qualities which make for success in all lines of human activity, and therefore are to be regarded as among the most important to be acquired early in life.

The physical benefit of an interest in animal life, which leads to outdoor exercise, needs no argument. The mental value has been touched upon. The moral importance is in the sense of truth which nature inculcates, and the kindliness sure to follow the affectionate interest with which the young naturalist must regard all living things.

No matter what is to be their walk in life, the observing study of nature should be regarded as the corner-stone of a boy's or girl's education.

Ernest Ingersoll

MAMMALS

First among the mammals come the monkeys. First among the monkeys come the apes. And first among the apes come the chimpanzees, almost the largest of all monkeys.

Chimpanzees

When it is fully grown a male chimpanzee stands nearly five feet high. And it would be even taller still if only it could stand upright.

But that is a thing which no monkey can ever do, because instead of having feet as we have, which can be planted flat upon the ground, these animals only have hind hands. There is no real sole to them, no instep, and no heel; while the great toe is ever so much more like a huge thumb. The consequence is that when a monkey tries to stand upright he can only rest upon the outside edges of these hand-like feet, while his knees have to be bent awkwardly outward. So he looks at least three inches shorter than he really is, and he can only hobble along in a very clumsy and ungraceful manner.

But then, on the other hand, he is far better able to climb about in the trees than we are, because while we are only able to place our feet flat upon a branch, so as to stand upon it, he can grasp the branches with all four hands, and obtain a very much firmer hold.[2]

Chimpanzees are found in the great forests of Central and Western Africa, where they feed upon the wild fruits which grow there so abundantly. They spend almost the whole of their lives among the trees, and have a curious way of making nests for their families to live in, by twisting the smaller branches of the trees together, so as to form a small platform. The mother and her little ones occupy this nest, while the father generally sleeps on a bough just underneath it. Sometime quite a number of these nests may be seen close together, the chimpanzees having built a kind of village for themselves in the midst of the forest.

A Clever Specimen

If you visit the zoölogical gardens in New York, London, or some other city, you may be quite sure of seeing one or more chimpanzees. They are nearly always brought to the zoos when they are quite young, and the keepers teach them to perform all kinds of clever tricks. One of them in the London Zoo, who was called "Sally," and who lived there for several years, actually learned to count! If she was asked for two, three, four, or five straws, she would pick up just the right number from the bottom of her cage and hand them to the keeper, without ever making a mistake. Generally, too, she would pick up six or seven straws if the keeper asked for them. But if eight, nine, or ten were asked for she often became confused, and could not be quite sure how many to give. She was a very cunning animal, however, and when she became tired of counting she would sometimes pick up two straws only and double them over, so as to make them look like four!

"Sally" could talk, too, after a fashion, and used to make three different sounds. One of these evidently meant "Yes," another signified "No," and the third seemed to be intended for "Thank you," as she always used it when the keeper gave her a nut or a banana.

Two kinds of chimpanzees are known, namely the common chimpanzee, which is by far the more plentiful of the two, and[3] the bald chimpanzee, which has scarcely any hair on the upper part of its head. One very intelligent bald chimpanzee was kept in Barnum's menagerie, and was even more clever, in some ways, than "Sally" herself.

The Gorilla

Larger even than the chimpanzee is the gorilla, the biggest and strongest of all the apes, which sometimes grows to a height of nearly six feet. It is only found in Western Africa, close to the equator, and has hardly ever been seen by white travelers, since it lives in the densest and darkest parts of the great forests. But several gorillas—nearly all quite small ones—have been caught alive and kept in captivity in zoos, where, however, they soon died.

One of these, named "Gena," lived for about three weeks in the Crystal Palace, near London. She was a most timid little creature, and if anybody went to look at her she would hide behind a chimpanzee, which inhabited the same cage, and watched over her in the most motherly way. Another, who was called "Pongo," lived for rather more than two months in the London Zoo, and seemed more nervous still, for he used to become terrified if even his keeper went into the cage. But when the animal has grown up it is said to be a most savage and formidable foe, and the natives of Central Africa are even more afraid of it than they are of the lion.

Like most of the great apes, the gorilla has a most curious way of sheltering itself during a heavy shower of rain. If you were to look at its arms, you would notice that the hair upon them is very thick and long, and that while it grows downward from the shoulder to the elbow, from the elbow to the wrist it grows upward. So when it is caught in heavy rain, the animal covers its head and shoulders with its arms. Then the long hair upon them acts just like thatch and carries off the water, so that the gorilla hardly gets wet at all.

When the gorilla is upon the ground it generally walks upon all fours, bending the fingers of the hands inward, so that it rests upon the knuckles. But it is much more active in the trees,[4] and is said to be able to leap to the ground from a branch twenty or thirty feet high, without being hurt in the least by the fall.

The Orang-Utan

Another very famous ape is the orang-utan, which is found in Borneo and Sumatra. It is reddish brown in color, and is clothed with much longer hair than either the gorilla or the chimpanzee, while its face is surprisingly large and broad, with a very high forehead. But the most curious feature of this animal is the great length of its arms. When a man stands upright, and allows his arms to hang down by his sides, the tips of his fingers reach about half-way between his hips and his knees. When a chimpanzee stands as upright as possible, the tips of its fingers almost touch its knees. But when an orang-utan does the same its fingers nearly touch the ground. Of course, when the animal is walking, it finds that these long arms are very much in its way. So it generally uses them as crutches, resting the knuckles upon the ground, and swinging its body between them.

But the orang seldom comes down to the ground, for it is far more at its ease among the branches of the trees. And although it never seems to be in a hurry, it will swing itself along from bough to bough, and from tree to tree, quite as fast as a man can run below. Like the gorilla and the chimpanzee, it makes rough nests of twisted boughs, in which the female animal and the little ones sleep. And if it is mortally wounded, it nearly always makes a platform of branches in the same way, and sits upon it waiting for death.

Orangs are often to be seen in zoölogical gardens, although they are so delicate that they do not thrive well in captivity. One of these animals, which lived in the London Zoo for some time, had learned a very clever trick. Leaning up against his cage was a placard, on which were the words "The animals in this cage must not be fed." The orang very soon found out that when this notice was up nobody gave him any nuts or biscuits. So he would wait until the keeper's back was[5] turned, knock the placard down with the printed words underneath, and then hold out his paw for food!

As a general rule, orangs seem far too lazy to be at all savage. Those in zoos nearly always lie about on the floor of their cage all day, wrapped in their blankets, with a kind of good-humored grin upon their great broad faces. But when they are roused into passion they seem to be very formidable creatures, and Alfred Russel Wallace tells us of an orang that turned upon a Dyak who was trying to spear it, tore his arm so terribly with his teeth that he never recovered the proper use of the limb, and would almost certainly have killed him if some of his companions had not come to his rescue.

Gibbons

Next we come to the gibbons, which are very wonderful animals, for they are such astonishing gymnasts. Most monkeys are very active in the trees, but the gibbons almost seem to be flying from bough to bough, dashing about with such marvelous speed that the eye can scarcely follow their movements. Travelers, on seeing them for the first time, have often mistaken them for big blackbirds. They hardly seem to swing themselves from one branch to another. They just dart and dash about, upward, downward, sideways, backward, often taking leaps of twenty or thirty feet through the air. And yet, so far as one can see, they only just touch the boughs as they pass with the tips of their fingers.

If you should happen to see a gibbon in the next zoo that you visit, be sure to ask the keeper to offer the animal a grape, or a piece of banana, and you will be more than surprised at its marvelous activity.

The arms of the gibbons are very long—although not quite so long as those of the orang-utan—so that when these animals stand as upright as they can the tips of their fingers nearly touch the ground. But they do not use these limbs as crutches, as the orang does. Instead of that, they either clasp their hands behind the neck while they are walking, or else stretch out the arms on either side with the elbows bent downward,[6] to help them in keeping their balance. So that when a gibbon leaves the trees and takes a short stroll upon the ground below, it looks rather like a big letter W suspended on a forked pole!

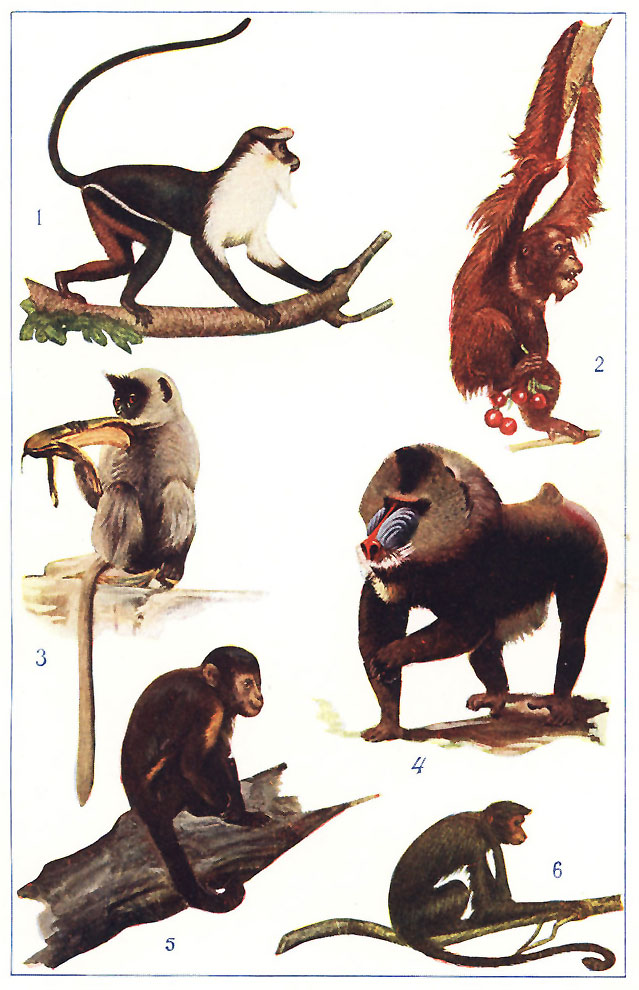

| 1. Diana Monkey. | 2. Orang-utan. | 3. Hanuman Monkey. |

| 4. Mandrill Baboon. | 5. Capuchin Monkey. | 6. Spider Monkey. |

Gibbons generally live together in large companies, which often consist of from fifty to a hundred animals, and they have a very odd habit of sitting in the topmost branches of tall trees at sunrise, and again at sunset, and joining in a kind of concert. The leader always seems to be the animal with the strongest voice, and after he has uttered a peculiar barking cry perhaps half a dozen times, the others all begin to bark in chorus. Often for two hours the outcry is kept up, so loud that it may be heard on a still day two or three miles. Then by degrees it dies away, and the animals are almost silent until the time for their next performance comes round.

Several different kinds of gibbons are known, the largest of which is the siamang. This animal is found only in Sumatra. It is a little over three feet high when fully grown. If you ever see it at a zoo you may know it at once by its glassy black color, and its odd whitish beard. Then there is the hoolock, which is common in many parts of India, and has a white band across its eyebrows, while the lar gibbon, of the Malay Peninsula, has a broad ring of white all round its face. Besides these there are one or two others, but they are all so much alike in their habits that there is no need to mention them separately.

How can we tell a baboon from an ape?

That is quite easy. Just glance at his face. You will notice at once that he has a long, broad muzzle, like that of a dog, with the nostrils at the very tip. For this reason the baboons are sometimes known as dog-faced monkeys. Then look at his limbs. You will see directly that his arms are no longer than his legs. That is because he does not live in the trees, as the apes do. He lives in rough, rocky places on the sides of mountains, where there are no trees at all, so that arms like those of the gibbons or the orang-utan would be of no use to him. He does not want to climb. He wants to be able to scamper over the rocks, and to run swiftly up steep cliffs where there is only just room enough to gain a footing. So his limbs are made in such a way that he can go on all fours like a dog, and gallop along so fast among the stones and boulders that it is hard to overtake him.

The Chacma

Perhaps the best known of the baboons is the chacma, which is found in South Africa. The animal is so big and strong, and so very savage, that if he is put into a large cage in company with other monkeys, he always has to be secured in a corner by a stout chain. A chacma that lived for some years in the Crystal Palace was fastened up in this way, and the smaller monkeys, who knew exactly how far his chain would allow him to go, would sit about two inches out of his reach and eat their nuts in front of him. This used to make the chacma furious, and after chattering and scolding away for some time, as if telling his tormentors what dreadful things he would do to them[8] if ever he got the chance, he would snatch up an armful of straw from the bottom of his cage and fling it at them with both hands.

"If I fed the smaller monkeys with nuts, instead of giving them to him," says a visitor, "he would fling the straw at me."

Chacmas live in large bands among the South African mountains, and are very difficult to watch, as they always post two or three of their number as sentinels. As soon as any sign of danger appears one of the watchers gives a short, sharp bark. All the rest of the band understand the signal, and scamper away as fast as they can.

Sometimes, however, the animals will hold their ground. A hunter was once riding over a mountain ridge when he came upon a band of chacmas sitting upon a rock. Thinking that they would at once run away, he rode at them, but they did not move, and when he came a little closer they looked so threatening that he thought it wiser to turn back again.

An angry chacma is a very formidable foe, for it is nearly as big as a mastiff, and ever so much stronger, while its great tusk-like teeth cut like razors. When one of these animals is hunted with dogs it will often gallop along until one of its pursuers has outstripped the rest, and will then suddenly turn and spring upon him, plunge its teeth into his neck, and, while its jaws are still clenched, thrust the body of its victim away. The result is that the throat of the poor dog is torn completely open, and a moment later its body is lying bleeding on the ground, while the chacma is galloping on as before.

These baboons are very mischievous creatures, for they come down from their mountain retreats by night in order to plunder the orchards. And so cautiously is the theft carried out, that even the dogs on guard know nothing of what is going on, and the animals nearly always succeed in getting away.

When it cannot obtain fruit, the chacma feeds chiefly upon the bulb of a kind of iris, which it digs out of the ground with its paw, and then carefully peels. But it is also fond of insects, and may often be seen turning over stones, and catching the beetles which were lying hidden beneath them. It will even eat scorpions, but is careful to pull off their stings before doing so. [9]

The Mandrill

Another interesting baboon is the mandrill, which one does not often see in captivity. It comes from Western Africa. While it is young there is little that is remarkable about it. But the full-grown male is a strange-looking animal, for on each of its cheeks there is a swelling as big as a large sausage, which runs upward from just above the nostrils to just below the eyes. These swellings are light blue, and have a number of grooves running down them, which are colored a rich purple, while the line between them, as well as the tip of the nose, is bright scarlet. The face is very large in proportion to the size of the body, and the forehead is topped by a pointed crest of upright black hair, while under the chin is a beard of orange yellow. On the hind quarters are two large bare patches of the same brilliant scarlet as the nose. So you see that altogether a grown-up male mandrill is a very odd-looking creature.

The female mandrill has much smaller swellings on her face. They are dull blue in color, without any lines of either purple or scarlet.

Almost all monkeys are subject at times to terrible fits of passion, but the mandrill seems to be the worst tempered of all. Fancy an animal dying simply from rage! It sounds impossible, yet the mandrill has been known to do so. And the natives of the countries in which it lives are quite as much afraid of it as they are of a lion.

Yet it has once or twice been tamed. In the Natural History Museum, at South Kensington, London, is the skin of a mandrill which lived for some years in that city in the earlier part of the nineteenth century. His name was "Jerry," and he was so quiet and contented that he was generally known as "Happy Jerry." He learned to smoke a pipe. He was very fond of a glass of beer. He even used to sit at table for his meals, and to eat from a plate by means of a knife and fork. And he became so famous that he was actually taken down to Windsor to appear before King George the Fourth!

There is another baboon called the drill, which is not unlike[10] the mandrill in many respects, but the swellings on its face are not nearly as large, and they remain black all through its life. It is a much smaller animal, too, and looks, on the whole, very much like a mandrill while it is quite young.

The Gelada

Almost as odd-looking as the mandrill, though in quite a different way, is the gelada, which is found in Abyssinia. Perhaps we may compare it to a black poodle with a very long and thick mane upon its neck and shoulders. When the animal sits upright this mane entirely covers the upper part of its shoulders, so that a gelada looks very much as if it were wearing a coachman's mantle of long fur.

In some parts of Abyssinia geladas are very numerous, living among the mountains in bands of two or three hundred. Like the chacmas in South Africa, they are very mischievous in the orchards and plantations, always making their raids by night. It is said that on one occasion they actually stopped no less a personage than a Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and prevented him from proceeding on his journey for several hours.

The story is, that as the Duke was traveling in Abyssinia his road lay through a narrow pass, overhung with rocky cliffs; that one of his attendants, catching sight of a number of geladas upon the rocks above, fired at them; that the angry baboons at once began to roll down great stones upon the path below, and that before they could be driven off they succeeded in completely blocking the road, so that the Duke's carriage could not be moved until the stones had been cleared away.

Whether this story is altogether true or not, we cannot say. But there can be no doubt that geladas are very warlike animals. Not only will they attack human beings who interfere with them, they also attack other baboons. When they are raiding an orchard, for instance, they sometimes meet with a band of Arabian baboons, which have come there for the same purpose as themselves. A fierce battle then takes place. First of all the geladas try to roll down stones upon their rivals. Then they rush down and attack them with the utmost fury, and very[11] soon the orchard is filled with maddened baboons, tumbling and rolling over one another, biting and tearing and scratching each other, and shrieking with furious rage.

The Arabian baboon itself is a very interesting creature, for it is one of the animals which were venerated by the ancient Egyptians. They considered it as sacred to their god Thoth, and treated it with the greatest possible honor; and when it died they made its body into a mummy, and buried it in the tombs of the kings. Sometimes, too, they made use of the animal while it lived, for they would train it to climb a fig-tree, pluck the ripe figs, and hand them down to the slaves waiting below.

These baboons sometimes travel in great companies. The old males always go first, and are closely followed by the females, those which have little ones carrying them upon their backs. As they march along, perhaps one of the younger animals finds a bush with fruit upon it, and stops to eat a little. As soon as they see what he is doing, a number of others rush to the spot, and begin fighting for a share. But generally one of the old males hears the noise, boxes all their ears and drives them away, and then sits down and eats the fruit himself.

The Proboscis-Monkey

Next we come to a group of animals called dog-shaped monkeys, and the most curious of them all is the proboscis-monkey. This is the only monkey which really possesses a nose. Some monkeys have nostrils only, and some have muzzles, but the proboscis-monkey has not merely a nose, but a very long nose, so long, in fact, that when one of these monkeys is leaping about in the trees it is said always to keep its nose carefully covered with one hand, so that it may not be injured by a knock against a bough.

Strange to say, it is only the male animal that has this very long nose, and even he does not get it until he is grown up. Indeed, you can tell pretty well how old a male proboscis-monkey is just by glancing at his nose. When he is young it is quite small. As he gets older it grows bigger. And by the[12] time that he reaches his full size it is three or four inches long. Naturally this long nose gives him a very strange appearance, and his great bushy whiskers, which meet under his chin, make him look more curious still.

We do not know much about the habits of the proboscis-monkey. In Borneo, its native country, it lives in the thick forests, and is said to be almost as active among the branches of the trees as the gibbons themselves. The Dyaks do not believe that it is a monkey at all, but say that it is really a very hairy man, who insists on living in the forests in order to escape paying taxes.

The Hanuman

The hanuman, another of the dog-shaped monkeys, lives in India, where it is treated with almost as much reverence as the Arabian baboon was in Egypt in days of old.

The natives do not exactly worship these monkeys, but they think that they are sacred to the god Hanuman, from whom they take their name. Besides that, they believe that these animals are not really monkeys at all, but that their bodies are inhabited by the souls of great and holy men, who lived and died long ago, but have now come back to earth again in a different form. So no Hindu will ever kill a hanuman monkey or injure it in any way, no matter how much mischief it may do. The consequence is that these animals are terrible thieves. They know perfectly well that no one will try to kill them, or even to trap them, so they come into the villages, visit the bazaars, and help themselves to anything to which they may take a fancy. Yet all that the fruit-sellers will do is to place thorn-bushes on the roofs of their shops to prevent the monkeys from sitting there.

European sportsmen, however, often find the hanuman very useful. For its greatest enemy is the tiger, and when one of these animals is being hunted a number of hanumans will follow it wherever it goes, and point it out to the beaters by their excited chattering.

Next to the tiger, the hanuman dislikes snakes more than any living creature, and when it finds one of these reptiles asleep[13] it will creep cautiously up to it, seize it by the neck, and then rub its head backward and forward upon a branch till its jaws have been completely ground away.

The hanuman belongs to a group of monkeys which are called langurs. They may be known by their long and almost lanky bodies, by the great length of their tails, and by the fact that they do not possess the cheek-pouches which many other monkeys find so useful. And it is very curious that while the arms of the apes are longer than their legs, the legs of the langurs—which are almost as active in the trees—are longer than their arms.

If you ever happen to see a hanuman you may know it at once by its black face and feet, and by its odd eyebrows, which are very bushy, and project quite away in front of its face.

The Guenons

We now come to the guenons, of which there are a great many kinds. Let us take two of these as examples of the rest. The first is the green monkey, which comes from the great forests of Western Africa. You may know it by sight, because it is the commonest monkey in every menagerie. It is one of the monkeys, too, which organ-grinders so often carry about on their organs. But they do not care to have it except when it is quite young, for although it is very gentle and playful until it reaches its full size, it afterward becomes fierce and sullen, and is apt at any moment to break out into furious passion.

Like most of the guenons, green monkeys go about in droves, each under the leadership of an old male, who wins and keeps his position by fighting all his rivals. Strange to say, each of these droves seems to have its own district allotted to it; and if by any chance it should cross its boundary, the band into whose territory it has trespassed will at once come and fight it, and do their utmost to drive it back.

Wouldn't it be interesting to know how the animals mark out their own domains, and how they let one another know just how far they will be permitted to go?

Our second example of the guenons is the diana monkey,[14] which you may at once recognize by its long, pointed, snow-white beard. It seems to be very proud of this beard, and while drinking holds it carefully back with one hand, in order to prevent it from getting wet.

Why is it called the "diana" monkey? Because of the curious white mark upon its forehead, which is shaped like the crescent which the ancients used to think was borne by the goddess Diana. It is a very handsome animal, for its back is rich chestnut brown in color, and the lower part of its body is orange yellow, while between the two is a band of pure white. Its face and tail and hands and feet are black. It is a very gentle animal, and is easily tamed.

The Mangabeys

These are very odd-looking monkeys, for they all have white eyelids, which are very conspicuous in their sooty-black faces. Indeed, they always give one a kind of idea that they must spend their whole lives in sweeping chimneys.

They are among the most interesting of all monkeys to watch, for they are not only so active and full of life that they scarcely seem able to keep still, but they are always twisting their bodies about into all sorts of strange attitudes. When in captivity they soon find out that visitors are amused by their antics, and are always ready to go through their performances in order to obtain a nut or a piece of cake.

Then they have an odd way, when they are walking about their cages, of lifting their upper lips and showing their teeth, so that they look just as if they were grinning at you. And instead of carrying their tails behind them, as monkeys generally do, or holding them straight up in the air, they throw them forward over the back, so that the tip comes just above the head.

Only four kinds of mangabey are known, and they are all found in Western Africa.

Macaques

There is one more family of monkeys found in the Old World which we must mention, and that consists of the animals[15] known as macaques. They are natives of Asia, with one exception, and that is the famous magot, the only monkey which lives wild in any part of Europe. It inhabits the Rock of Gibraltar, and though it is not nearly as common as it used to be, there is still a small band of these animals with which nobody is allowed to interfere. They move about the Rock a good deal. When the weather is warm and sunny, they prefer the side that faces the Mediterranean, but as soon as a cold easterly wind springs up they all travel round to the western side, which is much more sheltered. They always keep to the steepest parts of the cliff, and it is not easy to get near enough to watch them. Generally the only way to see them at all is by means of a telescope.

The magot is sometimes known as the Barbary ape, although of course it is not really an ape at all. But it is very common in Barbary, and two or three times, when the little band of monkeys on the Rock seemed in danger of dying out, a few specimens have been brought over from Africa just to make up the number.

The only other member of this family that we can mention is the crab-eating macaque, which is found in Siam and Burma. It owes its name to its fondness for crabs, spending most of its time on the banks of salt-water creeks in order to search for them. But perhaps the strangest thing about it is that it is a splendid swimmer, and an equally good diver, for it has been known to jump overboard and to swim more than fifty yards under water, in its attempts to avoid recapture.

A great many very curious monkeys live in America; and in several ways they are very different from those of Africa and Asia.

Most of the Old World monkeys, for example, possess large cheek-pouches, in which, after eating a meal, they can carry away nearly enough food for another. No doubt you have often seen a monkey with its cheeks perfectly stuffed out with nuts. But in the American monkeys these pouches are never found.

Then no American monkey has those bare patches on its hind quarters, which are present in all the monkeys of the Old World, with the exception of the great apes, and which are often so brightly colored. And, more curious still, no American monkey has a proper thumb. The fingers are generally very long and strong; but the thumb is either wanting altogether, or else it is so small that it cannot be of the slightest use.

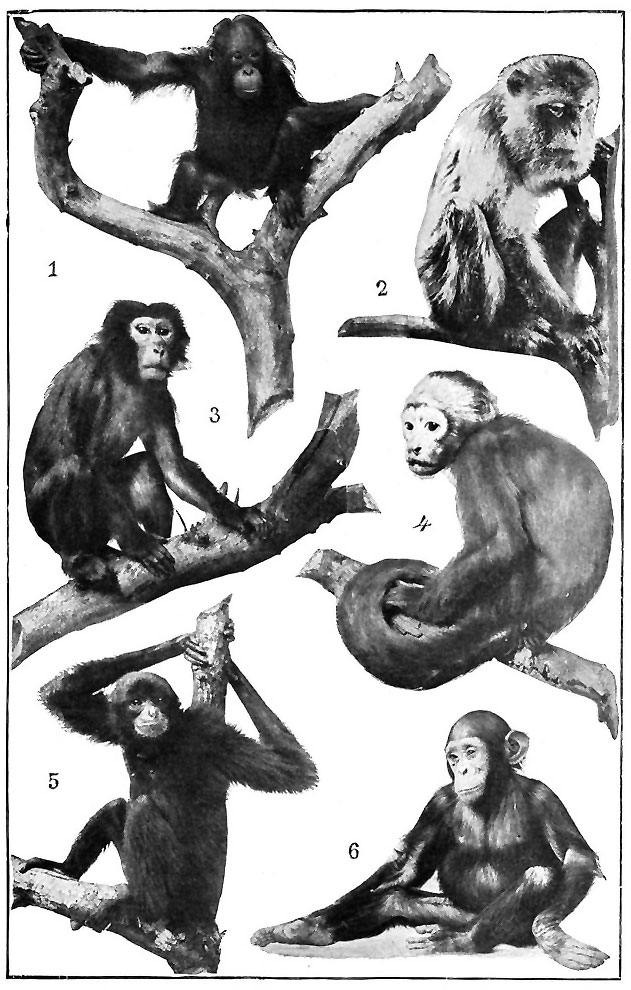

| 1. Young Orang-utan "Dohong." | 2. Barbary Ape. |

| 3. Japanese Red-faced Monkey. | 4. White-faced Sapajou. |

| 5. Siamang Gibbon. | 6. Chimpanzee "Polly." |

All lived in the New York Zoölogical Park.

Spider-Monkeys

Perhaps the most curious of all the American monkeys are the spider-monkeys, which look very much like big black spiders when one sees them gamboling among the branches of the trees. The reason is that their bodies are very slightly built, and their arms and legs are very long and slender, while the tail is often longer than the head and body together, and looks just like an extra limb. And indeed it is used as an extra limb, for it is prehensile; that is, it can be coiled round any small object so tightly as to obtain a very firm hold. A spider-monkey never likes to take a single step without first twisting the tip of its tail round a branch, so that this member really serves as a sort of fifth hand. Sometimes, too, the animal will feed itself with its tail instead of with its paws. And it can even[17] hang from a bough for some little time by means of its tail alone, in order to pluck fruit which would otherwise be out of its reach.

Owing partly, no doubt, to constant use, the last few inches of this wonderful tail are quite bare underneath—without any hair at all. It is worth while to remember, just here, that while in many American monkeys the tail has this prehensile grasp, no monkey of the Old World is provided with this convenience.

When a spider-monkey finds itself upon level ground, where its tail, of course, is of no use to it, it always seems very uncomfortable. But it manages to keep its balance as it walks along by holding the tail over its back, and just turning it first to one side and then to the other, as the need of the moment may require. It uses it, in fact, very much as an acrobat uses his pole when walking upon the tight rope.

It is rather curious to find that while other monkeys are very fond of nibbling the tips of their own tails, often making them quite raw, spider-monkeys never do so. They evidently know too well how useful those members are to injure them by giving way to such a silly habit—which is even worse than biting one's nails.

When a spider-monkey is shot as it sits in a tree, it always coils its tail round a branch at once. And even after it dies, the body will often hang for several days suspended by the tail alone.

These monkeys spend almost the whole of their lives in the trees, feeding upon fruit and leaves, and only coming down to the ground when they want to drink. As a general rule they are dreadfully lazy creatures, and will sit on a bough for hours together without moving a limb. But when they are playful, or excited, they swing themselves to and fro and dart from branch to branch, almost as actively as the gibbons.

Howlers

Very much like the spider-monkeys are the howlers, which are very common in the great forests of Central America.[18] They owe their name to the horrible cries which they utter as they move about in the trees by night. You remember how the gibbons hold a kind of concert in the tree-tops every morning and every evening, as though to salute the rising and the setting sun. Well, the howlers behave in just the same way, except that their concert begins soon after dark and goes on all through the night. They have very powerful voices, and travelers who are not used to their noise say that it is quite impossible to sleep in the forest if there is a troop of howlers anywhere within two miles. And it is hard to believe that the outcry comes from the throats of monkeys at all. "You would suppose," says a famous traveler, "that half the wild beasts of the forest were collecting for the work of carnage. Now it is the tremendous roar of the jaguar, as he springs upon his prey; now it changes to his terrible and deep-toned growlings, as he is pressed on all sides by superior force; and now you hear his last dying groan beneath a mortal wound. One of them alone is capable of producing all these sounds; and if you advance cautiously, and get under the high and tufted trees where he is sitting, you may have a capital opportunity of witnessing his wonderful powders of producing these dreadful and discordant sounds."

If one monkey alone is capable of roaring as loudly as a jaguar, think what the noise must be when fifty or sixty howlers are all howling at the same time. No wonder travelers find it difficult to sleep in the forest.

Perhaps the best known of these monkeys is the red howler. Its color is reddish brown, with a broad band of golden yellow running along the spine, while its face is surrounded by bushy whiskers and beard.

The Ouakari

Another very curious American monkey is the red-faced ouakari. If you were to see it from a little distance you would most likely think that it was suffering from a bad attack of scarlet fever; for the face and upper part of the neck are bright red in color, as though they had been smeared with vermilion[19] paint. And as its whiskers and beard are sandy yellow, it is a very odd-looking animal.

If a ouakari is unwell, strange to say, the bright color of its face begins to fade at once, and very soon after death it disappears altogether.

Ouakaris are generally caught in a very singular way. They are only found in a very small district on the southern bank of the Amazon River, and spend their whole lives in the topmost branches of the tallest trees, where it is quite impossible to follow them. And if they were shot with a gun, of course they would almost certainly be killed. So they are shot with a blowpipe instead. A slender arrow is dipped into a kind of poison called wourali, which has been diluted to about half its usual strength, and is then discharged at the animal from below. Only a very slight wound is caused, but the poison is still so strong that the ouakari soon faints, and falls from its perch in the branches. But the hunter, who is carefully watching, catches it in his arms as it falls, and puts a little salt into its mouth. This overcomes the effect of the poison, and very soon the little animal is as well as ever.

Ouakaris which are caught in this way, however, are generally very bad-tempered, and the gentle and playful little animals sometimes seen in zoos have been taken when very young. They are very delicate creatures and nearly always die after a few weeks of confinement.

The Couxia

If you were to see a couxia, or black saki, as it is often called, the first thing that you would say would most likely be, "What an extraordinary beard!" And your next remark would be, "Why, it looks as if it were wearing a wig!" For its projecting black beard is as big as that of the most heavily bearded man you ever saw, while on its head is a great mass of long black hair, neatly parted in the middle, and hanging down on either side, so that it looks just like a wig which has been rather clumsily made.

The couxia is extremely proud of its beard, and takes very[20] great pains to prevent it from getting either dirty or wet. Do you remember how the diana monkey holds its beard with one hand while drinking, so as to keep it from touching the water? Well, the couxia is more careful still, for it will not put its lips to the water at all, but carries it to its mouth, a very little at a time, in the palm of its hand. But the odd thing is that it seems rather ashamed of thinking so much about its "personal appearance," and, if it knows that anybody is looking at it, will drink just like any other monkey, and pretend not to care at all about wetting its beard.

Like most of the sakis, the couxia is not at all a good-tempered animal, and is apt to give way to sudden fits of fury. So savagely will it bite when enraged, that it has been known to drive its teeth deeply into a thick board.

The Douroucoulis

Sometimes these odd little animals are called night-monkeys, because all day long they are fast asleep in a hollow tree, and soon after sunset they wake up, and all night long are prowling about the branches of the trees, searching for roosting birds, and for the other small creatures upon which they feed. They are very active, and will often strike at a moth or a beetle as it flies by, and catch it in their deft little paws. And their eyes are very much like those of cats, so that they can see as well on a dark night as other monkeys can during the day.

The eyes, too, are very large. If you were to look at the skull of a douroucouli, you would notice that the eye-sockets almost meet in the middle, only a very narrow strip of bone dividing them. And the hair that surrounds them is set in a circle, just like the feathers that surround the eyes of an owl.

But perhaps the most curious fact about these animals is that sometimes they roar like jaguars, and sometimes they bark like dogs, and sometimes they mew like cats.

There are several different kinds of these little monkeys, the most numerous, perhaps, being the three-banded douroucouli, which has three upright black stripes on its forehead. They are all natives of Brazil and other parts of tropical America. [21]

Marmosets

One of the prettiest—perhaps the very prettiest—of all monkeys is the marmoset, which is found in the same part of the world. It is quite a small animal, being no bigger in body than a common squirrel, with a tail about a foot long. This tail, which is very thick and bushy, is white in color, encircled with a number of black rings, while the body is blackish with gray markings, and the face is black with a white nose. But what one notices more than anything else is the long tufts of snow-white hair upon the ears, which make the little animal look something like a white-haired negro.

Marmosets are very easily tamed, and they are so gentle in their ways, and so engaging in their habits, that if only they were a little more hardy we should most likely see them in this country as often as we see pet cats. But they are delicate little creatures, and cannot bear cold. What they like to eat most of all is the so-called black beetle of our kitchens. If only we could keep pet marmosets, they would very soon clear our houses of cockroaches, as these troublesome creatures are correctly called. They will spend hours in hunting for the insects, and whenever they catch one they pull off its legs and wings, and then proceed to devour its body.

When a marmoset is suddenly alarmed, it utters an odd little whistling cry. Owing to this habit it is sometimes known as the ouistiti, or tee-tee.

Lemurs

Relatives of the monkeys, and yet in many respects very different from them, are those very strange animals, the lemurs, which are sometimes called half-apes. The reason why that name has been given to them is this: Lemurs by the ancients were supposed to be ghosts which wandered about by night. Now most of the lemurs are never seen abroad by day. Their eyes cannot bear the bright sunlight; so all day long they sleep in hollow trees. But when it is quite dark[22] they come out, prowling about the branches so silently and so stealthily that they really seem more like specters than living animals.

When you see them close, they do not look very much like monkeys. Their faces are much more like those of foxes, and they have enormous staring eyes without any expression.

The true lemurs are only found in Madagascar, where they are so numerous that two or three at least may be found in every little copse throughout the island. More than thirty different kinds are known, of which, however, we cannot mention more than two.

The first of these is the ring-tailed lemur, which may be recognized at once by the fact that its tail is marked just like that of the marmoset. The head and body are shaped like those of a very small fox, and the color of the fur is ashy gray, rather darker on the back, and rather lighter underneath. It lives in troops in Central Madagascar, and every morning and every night each troop joins in a little concert, just like the gibbons and the howlers.

But, oddly enough, this lemur is seldom seen in the trees. It lives on the ground, in rough and rocky places, and its hands and feet are made in such a way, as to enable it to cling firmly to the wet and slippery boulders. In fact, they are not at all unlike the feet of a house-fly. The body is clothed with long fur, and when a mother lemur carries her little one about on her back it burrows down so deep into her thick coat that one can scarcely see it at all.

The ruffed lemur is the largest of these curious animals, being about as big as a good-sized cat. The oddest thing about it is that it varies so very much in color. Sometimes it is white all over, sometimes it is partly white and partly black, and sometimes it is reddish brown. Generally, however, the shoulders and front legs, the middle of the back, and the tail are black, or very dark brown, while the rest of the body is white. And there is a great thick ruff of white hairs all round the face.

The eyes of this lemur are very singular. You know, of course, how the pupil of a cat's eye becomes narrower and[23] narrower in a strong light, until at last it looks merely like an upright slit in the eyeball. Well, that of the lemur is made in very much the same way, except that the pupil closes up from above and below instead of from the sides, so that the slit runs across the eyeball, and not up and down.

The slender loris may be described as a lemur without a tail, It is found in the forests of Southern India and Ceylon. It is quite small, the head and body being only about eight inches long, and in general appearance it gives one rather the idea of a bat without any wings. In color it is dark gray, with a narrow white stripe between the eyes.

This animal has a very queer way of going to sleep. It sits on a bough and rolls itself up into a ball with its head tucked away between its thighs, while its hands are tightly folded round a branch springing up from the one on which it is seated. In this attitude it spends the whole of the day. At night it hunts for sleeping birds, moving so slowly and silently among the branches as never to give the alarm, and always plucking off their feathers before it proceeds to eat them. Strange to say, while many monkeys have no thumbs, the slender loris has no forefingers, while the great toes on its feet are very long, and are directed backward instead of forward.

Lemuroids

There are two lemur-like animals which are so extraordinary that each of them has been put into a family all by itself.

The first of these is the tarsier, which is found in several of the larger islands in the Malay Archipelago. Imagine an animal about as big as a small rat, with a long tail covered thickly with hair at the root and the tip, the middle part being smooth and bare. The eyes are perfectly round, and are so big that they seem to occupy almost the whole of the face—great staring eyes with very small pupils. The ears are very long and pointed, and stand almost straight up from the head. Then the hind legs are so long that they remind one of those of a kangaroo, while all the fingers and all the toes have large round pads under the tips, which seem to be used as suckers, and to[24] have a wonderful power of grasp. Altogether, the tarsier scarcely looks like an animal at all. It looks like a goblin.

This singular creature seldom seems to walk. It hops along the branches instead, just as a kangaroo hops on the ground. And when it wants to feed it sits upright on its hind quarters, and uses its fore paws just as a squirrel does.

Even more curious still is the aye-aye, of Madagascar, which has puzzled naturalists very much. For its incisor teeth—the sharp cutting teeth, that is, in the middle of each jaw—are formed just like those of the rat and the rabbit. They are made not for cutting but for gnawing; and as fast as they are worn away from above they grow from beneath. All of its fingers are long and slender; but the middle one is longer than all the rest, and is so thin that it looks like nothing but skin and bone. Most likely this finger, which has a sharp little claw at the tip, is used in hooking out insects from their burrows in the bark of trees. But the aye-aye does not feed only upon insects, for it often does some damage in the sugar plantations, ripping up the canes with its sharp front teeth in order to get at the sweet juices. It is said at times to catch small birds, either for the purpose of eating them or else to drink their blood. And it seems also to eat fruit, while in captivity it thrives on boiled rice.

The aye-aye is about as big as a rather small cat, and its great bushy tail is longer than its head and body put together. It is not a common animal, even in Madagascar, and its name of aye-aye is said to have been given to it on account of the exclamations of surprise uttered by the natives when it was shown to them for the first time by a European traveler. But it is more likely that the name comes from the cry of the animal, which is a sort of sharp little bark twice repeated.

Strange to say, the natives of Madagascar are much afraid of the aye-aye. Of course it cannot do much mischief with its teeth or claws; but they seem to think that it possesses some magic power by means of which it can injure those who try to catch it, or even cause them to die. So that they cannot be bribed to capture it even by the offer of a large reward. Sometimes, however, they catch it by mistake, finding an aye-aye in a[25] trap which has been set for lemurs. In that case they smear it all over with fat, which they think will please it very much, and then allow it to go free.

The aye-aye is seldom seen in captivity, and when in that state it sleeps all day long.

Next in order to the monkeys come the bats, the only mammals which are able to fly. It is quite true that there are animals known as flying squirrels, which are sometimes thought to have the power of flight. But all that these can do, as we shall see by and by, is to take very long leaps through the air, aided by the curious manner in which the loose skin of the body is fastened to the inner surface of the legs.

How Bats Fly

Bats, however, really can fly, and the way in which their wings are made is very curious. If you were to look at a bat's skeleton, you would notice, first of all, that the front limbs were very much larger than the hinder ones. The upper arm-bone is very long indeed, the lower arm-bone is longer still, and the bones of the fingers are longest of all. The middle finger of a bat, indeed, is often longer than the whole of its body! Now these bones form the framework of the wing. You know how the silk or satin of a lady's fan is stretched upon the ribs. Well, a very thin and delicate skin is stretched upon the bones of a bat's arm and hand in just the same way. And when the little animal wants to fly, it stretches its fingers apart, and so spreads the wing. When it wants to rest it closes them, and so folds it against its body.

Then you would notice that a high bony ridge runs down the bat's breast-bone. Now such a ridge as this always signifies great strength, because muscles must be fastened at each end to bones; and when the muscles are very large and powerful, the bones must be very strong in order to carry them. So, when an animal needs very strong breast-muscles, so that it may be able to fly well, we always find a high bony ridge running[27] down its breast-bone; and to this ridge the great muscles which work the wings are fastened.

Something more is necessary, however, if the animal is to fly properly. It must be able to steer itself in the air just as a boat has to be steered in the water. Otherwise it would never be able to fly in the right direction. So nature has given it a kind of air-rudder; for the skin which is stretched upon the wings is carried on round the end of the body, and is supported there, partly by the hind legs, and partly by the bones of the tail. And by turning this curious rudder to one side or the other, or tilting it just a little up or a little down, the bat is able to alter its course at will.

The Useful Claw

But you would notice something else on looking at a bat's skeleton. You would notice that the bones of the thumb are not long and slender, like those of the fingers, but that they are quite short and stout, with a sharp hooked claw at the tip. The bat uses this claw when it finds itself on the ground. It cannot walk, of course, as it has no front feet; so it hitches itself along by means of its thumbs, hooking first one claw into the ground and then the other, and so managing to drag itself slowly and awkwardly forward.

It is not at all fond of shuffling along in this way, however, and always takes to flight as soon as it possibly can. But as it cannot well rise from the ground it has to climb to a little height and let itself drop, so that as it falls it may spread its wings and fly away. And it always climbs in a very curious manner, with its tail upward and its head toward the ground, using first the claws of one little foot and then those of the other.

When a bat goes to sleep it always hangs itself up by the claws of its hind feet. In an old church tower, or a stable loft, you may often find bats suspended in this singular way. And there is a reason for it. The bat wants to be able, at the first sign of danger, to fly away. Now if it lay flat upon the ground to sleep, as most animals do, it would not be able to fly quickly; for it would have to clamber up a wall or a post to some little[28] height before it could spread its wings. And this would take time. But if it should be alarmed while it is hanging by its hind feet, all that it has to do is to drop into the air and fly off at once.

Bats in the Dark

There is something else, too, that we must tell you about bats. They have the most wonderful power of flying about on the darkest night, without ever knocking up against the branches of trees, or any other obstacles which they may meet on their way. It used to be thought that this was because they had very keen eyes. But it has been found out that even a blind bat has this power, which seems really to be due to very sensitive nerves in the wings. You can feel a branch by touching it. But a bat is able to feel a branch without touching it, while it is eight or ten inches away, and so has time to swerve to one side without striking against it.

The Winter Sleep

Bats, like hedgehogs and squirrels, pass through the winter in a kind of deep sleep, which we call hibernation. It is more than ordinary sleep, for they do not require any food for months together, while they scarcely breathe once in twenty-four hours, and their hearts almost cease to beat. If the winter is cold throughout, they do not wake at all until the spring. But two or three hours' warm sunshine arouses them from their slumber. They wake up, feel hungry, go out to look for a little food, and then return to their retreats and pass into the same strange sleep again.

An Interesting Specimen

"I once kept a long-eared bat as a pet," says a writer, "and a most interesting little creature he was. One of his wings had been injured by the person who caught him, so that he could not fly, and was obliged to live on the floor of his cage. Yet,[29] although he could take no exercise, he used to eat no less than seventy large bluebottle flies every evening. As long as the daylight lasted, he would take no notice of the flies at all. They might crawl about all over him, but still he would never move. But soon after sunset, when the flies began to get sleepy, the bat would wake up. Fixing his eyes on the nearest fly, he would begin to creep toward it so slowly that it was almost impossible to see that he was moving. By degrees he would get within a few inches. Then, quite suddenly, he would leap upon it, and cover it with his wings, pressing them down on either side of his body so as to form a kind of tent. Next he would tuck down his head, catch the fly in his mouth, and crunch it up. And finally he would creep on toward another victim, always leaving the legs and the wings behind him, which in some strange way he had managed to strip off, just as we strip the legs from shrimps.

"I often watched him, too, when he was drinking. As he was so crippled, I used to pour a few drops of water on the floor of his cage, and when he felt thirsty he would scoop up a little in his lower jaw, and then throw his head back in order to let it run down his throat. But in a state of freedom bats drink by just dipping the lower jaw into the water as they skim along close to the surface of a pond or a stream, and you may often see them doing so on a warm summer's evening."

The Pipistrelle

The pipistrelle, a common European bat, is said to feed chiefly upon gnats, of which it must devour a very large number, and as it much prefers to live near human habitations, there can be no doubt that it helps to keep houses free from these disagreeable insects. In captivity it will feed freely upon raw meat chopped very small. It appears earlier in the spring than the other bats, and remains later in the autumn.

Horseshoe Bats

These bats of the Old World have a most curious leaf-like membrane upon the face, which gives them a very odd appearance.[30] In the great horseshoe bat this membrane is double, like one leaf placed above another. The lower one springs from just below the nostrils, and spreads outward and upward on either side, so that it is shaped very much like a horseshoe, while the upper one is pointed and stands upright, so as partly to cover the forehead. The ears, too, are very large, and are ribbed crosswise from the base to the tips; so that altogether this bat is a strange-looking creature.

Perhaps none of the bats is more seldom seen than this, for it cannot bear the light at all, and never comes out from its retreat until darkness has quite set in. And one very seldom finds it asleep during the day, for it almost always hides in dark and gloomy caverns, which are hardly ever entered by any human being. In France, however, there are certain caves in which great numbers of these bats congregate together for their long winter sleep. As many as a hundred and eighty of them have been counted in a single colony. And it is a very strange fact that all the male bats seem to assemble in one colony, and all the female bats in another.

Vampires

In Central and South America, and also in the West Indian Islands, a number of bats are found which are known as vampires. Some of these eat insects, just like the bats of other countries, and one of them—known as the long-tongued vampire—has a most singular tongue, both very long and very slender, with a brush-like tip, so that it can be used for licking out insects from the flowers in which they are hiding. Then there are other vampires which eat fruit, like the flying foxes, about which we shall have something to tell you soon. But the best known of these bats, and certainly the strangest, are those which feed upon the blood of living animals.

If you were to tether a horse in those parts of the forest where these vampires live, and to pay it a visit just as the evening twilight was fading into darkness, you would be likely to see a shadowy form hovering over its shoulders, or perhaps even clinging to its body. This would be a vampire bat; and when[31] you came to examine the horse, you would find that, just where you had seen the bat, its skin would be stained with blood. For this bat has the singular power of making a wound in the skin of an animal, and sucking its blood, without either alarming it or appearing to cause it any pain. And if a traveler in the forest happens to lie asleep in his hammock with his feet uncovered, he is very likely to find in the morning that his great toe has been bitten by one of these bats, and that he has lost a considerable quantity of blood. Yet the bat never wakes him as it scrapes away the skin with its sharp-edged front teeth.

Strangely enough, however, there are many persons whom vampires will never bite. They may sleep night after night in the open, and leave their feet entirely uncovered, and yet the bats will always pass them by. Charles Waterton, a famous English traveler, was most anxious to be bitten by a vampire, so that he might learn by his own experience whether the infliction of the wound caused any pain. But though he slept for eleven months in an open loft, through which the bats were constantly passing, they never attempted to touch him, while an Indian lad who slept in the same loft was bitten again and again.

But as these bats cannot always obtain blood, it is most likely that they do not really live upon it, but only drink it when they have the chance, and that as a rule their food consists of insects.

Flying Foxes

Of course these are not really foxes. They are just big bats which feed on fruit, instead of on insects or on blood. They are called also fruit-bats. But their long, narrow faces are so curiously fox-like that we cannot feel surprised that the name of flying foxes should have been given to them.

Flying foxes are found in many parts of Asia, as well as in Madagascar and in Australia, and in some places they are very common. In India, long strings of these bats may be seen regularly every evening, as they fly off from their sleeping-places to the orchards in search of fruit. In some parts of India, early in the morning, and again in the evening, the sky is often black with them as far as the eye can reach, and they[32] continue to pass overhead in an unbroken stream for nearly three-quarters of an hour. And as they roost in great numbers on the branches of tall trees, every bat being suspended by its hinder feet, with its wings wrapped round his body, they look from a little distance just like bunches of fruit.

It is rather curious to find that when they are returning to the trees in which they roost, early in the morning, these bats quarrel and fight for the best places, just as birds do.

In districts where they are at all plentiful, flying foxes do a great deal of mischief, for it is almost impossible to protect the orchards from their attacks. Even if the trees are covered all over with netting they will creep underneath it, and pick out all the best and ripest of the fruit; while, as they only pay their visits of destruction under cover of darkness, it is impossible to lie in wait for them and shoot them as they come.

The flight of the fruit-bats is not at all like that of the bats with which we are familiar, for as they do not feed upon insects there is no need for them to be constantly changing their course, and darting first to one side and then to the other in search of victims. So they fly slowly and steadily on, following one another just as crows do, and never turning from their course until they reach their feeding-ground.

The largest of these fruit-bats is the kalong, which is found in the islands of the Malay Archipelago. It measures over five feet from tip to tip of the extended wings. The Malays often use it for food, and its flesh is said to be delicate and well flavored.

Next to the bats comes the important tribe of the insect-eaters, containing a number of animals which are so called because most of them feed chiefly upon insects.

The Colugo

One of the strangest of these is the colugo, which lives in Siam, Java, and the Islands of the Malay Archipelago. It is remarkable for its wonderful power of leaping, for it will climb a tall tree, spring through the air, and alight on the trunk of another tree seventy or eighty yards away. For this reason it has sometimes been called the "flying colugo"; but it does not really fly. It merely skims from tree to tree. And if you could examine its body you would be able to see at once how it does so.

First of all, you would notice that the skin of the lower surface is very loose. You know how loose the skin of a dog's neck is, and how you can pull it up ever so far from the flesh. Well, the skin of the colugo is quite as loose as that on the sides and lower parts of its body.

Then you would notice that this loose skin is fastened along the inner side of each leg, so that the limbs are connected by membrane just like the toes of a duck's foot. And you would also see that when the legs are stretched out at right angles to the body, this membrane must be stretched out with them.

Now when a colugo wishes to take a long leap, it springs from the tree on which it is resting, spreads out its limbs, and skims through the air just as an oyster-shell does if you throw it sideways from the hand. The air buoys it up, you see, and enables it to travel ten times as far as it could without this loose skin. But of course this is not flight. The animal does not[34] beat the air with the membrane between the legs, as bats and birds do with their wings. It cannot alter its course in the air; and it is always obliged to alight at a lower level than that from which it sprang.

The colugo is about as big as a good-sized cat, and its fur is olive or brown in color, mottled with whitish blotches and spots. When it clings closely to the trunk of a tree, and remains perfectly motionless, it may easily be overlooked, for it looks just like a patch of bark covered with lichens and mosses. It is said to sleep suspended from a branch with its head downward, like the bats; and whether this is the case or not, its tail is certainly prehensile, like that of a spider-monkey. And strangest of all, perhaps, is the fact that, although it belongs to the group of the insect-eaters, it feeds upon leaves.

The Hedgehog

In European countries, where it is common, one can scarcely walk through the meadows on a summer's evening without seeing this curious animal as it moves clumsily about in search of prey. There everybody is familiar with its spiky coat, which affords such an excellent protection against almost all its enemies.

But it is not everybody who knows how the animal raises and lowers its spines. It has them perfectly under control; we all know that. If you pick a hedgehog up it raises its spines at once, even if it does not roll itself up into a ball and so cause them to project straight out from its body in all directions. But if you keep the creature as a pet, and treat it kindly, it will very soon allow you to handle it freely without raising its spines at all.

The fact is this. The spines are shaped just like slightly bent pins, each having a sort of rounded head at the base. And they are pinned, as it were, through the skin, the heads lying underneath it. Besides this, the whole body is wrapped up in a kind of muscular cloak, and in this the heads of the spines are buried. So if the muscle is pulled in one direction, the spines must stand up, because the heads are carried along with it. If[35] it is pulled in the other direction they must lie down, for the same reason. And it is just by pulling this muscle in one direction or the other that the animal raises and lowers its spines.

Hedgehog Habits

The hedgehog is not often seen wandering about by day, because it is then fast asleep, snugly rolled up in a ball under the spreading roots of a tree, or among the dead leaves at the bottom of a hedge. But soon after sunset it comes out from its retreat, and begins to hunt about for food. Sometimes it will eat bird's eggs, being very fond of those of the partridge; for which reason it is not at all a favorite with the gamekeeper. It will devour small birds, too, if it can get them, also lizards, snails, slugs, and insects. It has often been known to kill snakes and to feed upon their bodies afterward. It is a cannibal, too, at times, and will kill and eat one of its own kind. But best of all it likes earthworms.

The number of these which it will crunch up one after another is astonishing. "I once kept a tame hedgehog," says a naturalist, "and fed him almost entirely upon worms; and he used to eat, on an average, something like an ordinary jampotful every night of his life. He never took the slightest notice of the worms as long as the daylight lasted; but when it began to grow dark he would wake up, go sniffing about his cage till he came to the jampot, and then stand up on his hind feet, put his fore paws on the edge, and tip it over. And after about an hour and a half of steady crunching, every worm had disappeared."

In many places farmers persecute the hedgehog, and kill it whenever they have a chance of doing so. And if you ask the reason the answer is generally to the effect that hedgehogs steal milk from sleeping cows at night. Now it does not seem very likely that a cow would allow such a spiky creature as a hedgehog to come and nestle up against her body. But, on the other hand, it cannot be denied that hedgehogs are often to be seen close by cows as they rest upon the ground. But they have not gone there in search of milk. Don't you know what happens if you lay a heavy weight, such as a big paving-stone, on the[36] ground? The worms buried under it feel the pressure, and come up to the surface in alarm. Now a cow is a very heavy weight; so that when she lies down a number of worms are sure to come up all round her. And the hedgehog visits the spot in search, not of milk, but of worms!

The young of the hedgehog, which are usually four in number, do not look in the least like their parents, and you might easily mistake them for young birds; for their spikes are very soft and white, so that they look much more like growing feathers. The little creatures are not only blind, but also deaf, for several days after birth, and they cannot roll themselves up till they have grown somewhat. The mother animal always makes a kind of warm nest to serve as a nursery, and thatches it so carefully that even a heavy shower of rain never seems to soak its way through.

Strange to say, the hedgehog appears to be quite unaffected by many kinds of poison. It will eat substances which would cause speedy death to almost any other animal. And over and over again it has been bitten by a viper without appearing to suffer any ill results.

In England, about the middle of October, the hedgehog retires to some snug and well-hidden retreat, and there makes a warm nest of moss and dry leaves. In this it hibernates, just as bats do in hollow trees, only waking up now and then for an hour or two on very mild days, and often passing three or four months without taking food.

Shrews

During the earlier part of the autumn, you may very often find a curious mouse-like little animal lying dead upon the ground. But if you look at it carefully, you will see at once that in several respects it is quite different from the true mice.

In the first place you will notice that its mouth is produced into a long snout, which projects far in front of the lower jaw. Now no mouse ever has a snout like that. Then you will find that all its teeth are sharply pointed, while the front teeth of a mouse have broad, flat edges specially meant for nibbling[37] at hard substances. And, thirdly, you will see that its tail, instead of gradually tapering to a pointed tip, is comparatively short, and is squared in a very curious manner. The fact is that the little animal is not a mouse at all, but a kind of shrew, of which there are many American species. One is large, and pushes through the top-soil like a mole. Another, smaller, is blackish, and has a short tail. The commonest one is mouse-gray and only two inches long plus a very long tail. It is fond of water, but has no such interesting habits as those of the European shrew next described.

These creatures are very common almost everywhere. But we very seldom see them alive, because they are so timid that the first sound of an approaching footstep sends them away into hiding. Yet they are not at all timid among themselves. On the contrary, they are most quarrelsome little creatures, and are constantly fighting. If two shrews meet, they are almost sure to have a battle, and if you were to try to keep two of them in the same cage, one would be quite certain to kill and eat the other before very long. They are not cannibals as a rule, however, for they feed upon worms and insects, and just now and then upon snails and slugs. And no doubt they do a great deal of good by devouring mischievous grubs.