Bolax,

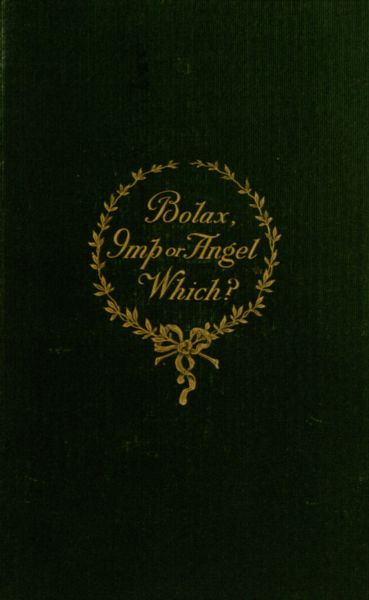

Bolax,Imp or Angel

Which?

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bolax, by Josephine Culpeper

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Bolax

Imp or Angel--Which?

Author: Josephine Culpeper

Release Date: January 14, 2013 [EBook #41846]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOLAX ***

Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

Je suis moi, le Génèrale Boome.

Je suis moi, le Génèrale Boome.

BY MRS. JOSEPHINE CULPEPER

JOHN MURPHY COMPANY.

|

Baltimore: 200 W. Lombard Street. |

New York: 70 Fifth Avenue. |

1907.

Copyright 1907, by

Mrs. Josephine Culpeper

PRINTED BY JOHN MURPHY COMPANY

"Bolax: Imp or Angel—Which?"

Being favorably criticised by priests of

literary ability, is hereby recommended

most heartily by me to all Catholics.

As a study in child-life and as a rational object lesson in the religious and moral training of children, Mrs. Culpeper's book should become popular and the jolly little Bolax be made welcome in many households.

Faithfully yours in Xt,

Dedicated to my best beloved pupils, especially the children of the Late Dr. William V. Keating, and those of Joseph R. Carpenter, by their old governess.

—Anonymous.

Amy's Company.

"Come children," said Mrs. Allen, "Mamma wants to take you for a nice walk."

"Oh, please, dear Mamma, wait awhile! Bolax and I have company!" This from little Amy, Bo's sister.

Mrs. Allen looked around the room, and saw several chairs placed before the fire; but seeing no visitors, was about to sit in the large arm chair.

"Oh, dear Mamma," said Amy, "please do not take that chair! That's for poor old St. Joseph; he will be here presently."

Turning toward the chair nearest the fire, the child bowed down to the floor, saying: "Little Jesus I love you! When will St. Joseph be here?"

Then bowing before the next chair: "Blessed Mother, are you comfortable? Here is a footstool."

Mrs. Allen went into the hall, and was about to close the door, when Bolax called out: "Oh, Ma dear, please don't shut the door. Here comes St. Joseph and five beautiful angels."

Mrs. Allen was rather startled at the positive manner in which this was said, and unconsciously stepped aside, as if really to make way for the celestial visitors. Then leaving the children to amuse themselves, she listened to them from an adjoining room. This is what she heard:

Amy—Dear St. Joseph please sit down; blessed angels, I am sorry that I haven't enough chairs, but you can rest on your beautiful wings.

Bolax—Little Jesus, I'm so glad you've come. Mamma says you are very powerful, even if you are so little. I want to ask you lots of things. Do you see these round pieces of tin? Well, won't you please change them all into dollars, so we can have money for the poor, and sister Amy won't be crying in the street when she has no money to give all the blind and the lame people we meet. And dear Jesus, let me whisper—I want a gun.

Amy—Dear Blessed Mother please make poor Miss Ogden well. I heard her tell my Mamma she was afraid to die; and she is very sick. She has such a sad face, and she looks mis'able.

Bolax—Sister, won't you ask lots of things for me? I'm afraid to ask 'cause I was naughty this morning. I dyed pussy's hair with Papa's red ink.

Amy—No, I won't ask any more favors; Mamma says we must be thankful for all we get, so let us sing a hymn of thanks.

Here Papa came upstairs calling for his babies. Mrs. Allen not wishing to disturb the children, beckoned him into her room, hoping he would listen to the innocent prattle of his little ones. All unconscious of being observed, the children continued to entertain their heavenly guests.

Mr. Allen not being a Catholic, was more shocked than edified at what he thought the hallucination of the children, and spoke rather sternly to his wife. "All this nonsense comes from your constant talk on subjects beyond the comprehension of children.[Pg 3] Amy is an emotional child; she will become a dreamer, a spiritualist; it will affect her nervous system and you will have yourself to blame.

"As for Bolax, I have no fear for him. He'll never be too pious. I'm willing to——" Here they were startled by a most unearthly yell, and Master Bo rushed into the room, saying that Amy would not let him play with her.

"Why won't she?" asked Papa.

"Oh, because I upset St. Joseph; I wanted to take the chairs for a train of cars."

Papa broke into a fit of laughter, and said: "Bo, Bo, you're the funniest youngster I ever heard of."

Poor Little Amy came into the room, looking as if ready to cry, telling her mother she would never again have that boy when her company came. "Just think, dear Ma, Bo said he liked monkeys better than angels."

The serious face of the little girl caused her mother to wonder if the child really saw the holy spirits.

Mrs. Allen consoled her little daughter, telling her Bo would be more thoughtful and better behaved when he should be a few years older.

"Come now," said she, "we will go to see poor little Tommie Hoden. I am sure from the appearance of the boy, the family must be in very great distress."

It was a beautiful day. The hyacinths were in bloom, and there were daffodils, tulips, and forget-me-nots, almost ready to open; the cherry trees were white with blossoms, and the apple trees covered with buds. The glad beautiful spring had fully[Pg 4] come with its lovely treasures and everything seemed delighting in the sweet air and sunshine.

Miss Beldon, a neighbor, was digging her flower-beds, and asked where they were going.

"I want to visit that poor little fellow, Tommy Hoden, who comes here so often," said Mrs. Allen.

"You're not going to Hoden's," cried Miss Beldon; "why the father is an awful man!"

"So much the more need of helping him, and that poor neglected boy of his," answered Mrs. Allen. "Can you tell me exactly where they live?"

"Yes, in a horrid old hut, near Duff Mills. You can't miss it, for it is the meanest of all those tumble-down shanties. I do wish you wouldn't go, it won't do any good."

"Our Lord will take care of that," said Mrs. Allen. "I am only going to do the part of the work He assigns me, and take food to the hungry."

"Well," said Miss Beldon, "I wouldn't go for fifty dollars. The man is never sober, and he won't like to be interfered with. I shouldn't wonder if he would shoot at you."

Mrs. Allen laughed, and said anything so tragic was not likely to happen, and then went to get a basket of food to take to Tommy Hoden.

They set forth on their walk, Bo holding fast to his mother's hand while Amy loitered on the way, gathering wild flowers. "Do you really, truly think Tom's father would shoot at us?" asked Bo.

"No, indeed, dear. I hope you are not afraid."

"Well—no—dear Ma, not very afraid;" and the little fellow drew a deep sigh; "only I—I—hope he won't shoot you, dear Ma."

"Well I am afraid!" said Amy, in a somewhat shamefaced manner.

"Please, Ma dear, let me go back and I will kneel before our Blessed Lady's picture and pray for the poor man all the time you are away."

"That is very sweet of you, dear. Now Bo, perhaps you had better return with Amy. I can go alone."

"No; no; I won't go back. I want to take care of my own dear Mamma. I'm not a bit afraid now."

"Well, dear," said Mrs. Allen, "I will tell you what I want to do for Tom and his father. I will try to get Tom to go to school every day and to catechism class on Sundays. I think that would make a better boy of him. Then I hope to persuade his father to sign the temperance pledge and go to work."

Bolax understood what his mother meant by this, for Mrs. Allen made a constant companion of the child; and although only five, she taught him to recite a piece on Temperance.

The walk to the mills was very pleasant, with the exception of about half a mile of the distance, just as the road turned off from the village; here were a number of wretched old buildings, occupied by very poor and, for the most part, very wicked people.

Somewhat removed from the others stood a hovel more dilapidated, if possible, than the rest. Towards this Mrs. Allen, still holding Bolax by the hand, bent her steps, and gently rapped at the door.

No one answered, but something that sounded like the growl of a beast proceeded from within.[Pg 6] After repeating the rap twice or three times, she pushed the door wider open and walked in. The room upon which it opened was small and low, and lighted by a single window, over which hung a thick network of spider webs; the dingy walls were festooned in like manner; the clay floor was so filthy, that, for a moment, Mrs. Allen shrunk from stepping upon it.

In a corner of the wretched room sat Tom's father, smoking an old pipe. He was a rough, bad-looking man with shaggy hair hanging over his face and bleared eyes that glared at his visitors with no gentle expression.

"What do you want?" he growled.

"Your little boy sometimes comes to our place," answered Mrs. Allen, "so I thought I would come to see him, and bring him some cakes; children are so fond of sweets."

"Very kind of you, I'm sure, ma'am, though I don't know why you should take the trouble," and the glare of his eyes softened a little; "you're the first woman that's crossed that ere threshold since Molly was carried out. I ha'n't got no chair."

"Oh, never mind. I did not come to make a long call," said Mrs. Allen.

The lady looked around the wretched room in vain, for a shelf or table on which to deposit the contents of her basket. At last she saw a closet, and while placing the articles of food in it, talked to old Hoden as if he had been the most respectable man in the county.

"Is Tom at home, Mr. Hoden?"

"What d'ye want of him? I never know where he is."

"I heard you ought to be a Catholic," continued Mrs. Allen, "and I thought you would not object to Tom's coming to my catechism class on Sunday."

"He ain't got no clothes fit to go; besides I reckon it wouldn't do no good to send him, for he ain't never seen the inside of a church."

"Well, Mr. Hoden, couldn't you come yourself?"

"It is me, ma'am? I haven't been near a church or priest for twenty-five years. Poor Molly tried to make me go, but she gave it up as a bad job. You may try your hand on Tom for all I care."

"I am much obliged to you for giving me leave to try," said Mrs. Allen, smiling; "I should not have asked Tom to come without your permission, Mr. Hoden. Good-bye, sir."

The poor wretch seemed dazed, and did not reply to the lady's polite leave-taking.

After she was gone, he said to himself "I wonder what that one is up to. I never heard such smooth talk in my life. Well it do make me feel good to be spoke to like I were a gentleman. I'd give a good bit to know who sent her here, and why she come."

Ah, poor soul, it was the charity of Jesus Christ that prompted the lady to go to you; and many a fervent prayer she and her children will say for your conversion.

"Mamma," said Bolax, on the way home, "that man is not so dreadful bad."

"Why do you think that, dear?"

"Because I saw a picture of the Sacred Heart[Pg 8] pasted on the wall inside the closet; it is all over grease and flyspecks, but you know you told me Jesus gave a blessing to any house that had a picture of His Sacred Heart in it."

The Wonderful Ride.

"Hurrah! Hurrah!" shouted Bolax, "Amy where are you? 'Want to tell you something fine." Amy was watering her flower-bed, and did not pay much attention to the little brother who was always having something "fine" to tell.

"What is it now, Bo dear?" "Oh something real splendid this time."

"Please tell me then," said Amy getting a little impatient.

"You'll be so glad, Amy. Mamma and auntie say they are going to have a party on the 21st because it is your birthday and St. Aloysius' birthday."

"Did they? really truly!" exclaimed Amy; and the staid little lady danced up and down the porch wild with delight at the prospect of a "really truly" party.

Just then Aunt Lucy came up the steps laden with roses, for it was June, the month of the beautiful queen of flowers.

Mrs. Allen took particular pains to cultivate with her own hands, all varieties of red roses, from deep crimson to the brilliant Jacqueminot, so that she could always have a bouquet to send to the Church every Sunday and Friday, during the month of the[Pg 10] Sacred Heart, besides keeping her own little altar well supplied.

"Oh, Auntie, dear!" said Amy, "I'm so happy! Bo says I'm to have a party." "Well, yes, darling; you know you will be seven on the 21st, so Mamma and I want to make you happy because you have always tried to be a good obedient little girl."

"Thank you, thank you, auntie," and Amy gave Aunt Lucy a big hug and kiss.

"May I carry the roses to the Oratory auntie, dear?"

"Yes, Child, but I must go too, for I forgot to light the lamp before the picture of the Sacred Heart, and it should never be extinguished during this month."

While arranging the altar Amy began with her usual string of questions, which were always listened to, and answered, for Mrs. Allen and her sister never allowed themselves to be "too busy to talk to children."

"Auntie, why do we burn lamps before statues and holy pictures? Mollie Lane asked me that question when she was in here yesterday, and I did not know how to explain, then she laughed and said it was so funny to have artificial light in the day time."

"My dear, we burn lamps and candles on the altar for several reasons, which it would take too long to tell you just now; when you are older, I will give you a little book called "Sacramentals," which explains all about the lights on our altars, the use of holy water, blessed palm, the crucifix, etc. For the present it suffices to tell any one who questions you that the lamp in our Oratory is kept burning as a[Pg 11] mark of respect towards the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and besides it is a pretty ornament."

What a bower of loveliness, peace and rest was the little hall-room which Mrs. Allen set apart as a "Holy of Holies" for her household. A subdued light glimmered through the latticed windows, which also admitted the soft summer air that wafted the fragrance of flowers over the family, as they knelt at their devotion.

There was time to pray in that house, and although its head was not a Catholic, he approved of his family living up to all they professed; in fact he was proud of the little tabernacle in his house, and frequently, when he had visitors, invited them upstairs to see the Oratory.

While Aunt Lucy and Amy were occupied, Bolax went out to the stable hoping Pat, the hired man, would talk to him; but Pat had gone to the village on an errand, then Bo came back to the house and called for his Mamma. As mother did not respond immediately he screamed as loud as he could: "Ma, dear! Ma, dear!"

Mrs. Allen opened her door and asked why he spoke in such a disagreeable tone of voice.

"Well, I have no one to play with," he whined. "I want sister, can't she come down?"

"Now dearie be a good little man, don't whine, go and amuse yourself; Amy is at her lessons with Aunt Lucy, and I am writing to Papa. I should like to be able to tell him you were a good boy."

"Where is Papa now?" asked Bo. "Away off in Kansas, dear."

"There, do not disturb me and I will be with you presently."

Thus left to himself Bo went to his never-failing source of amusement—swinging on the gate. While enjoying himself, he heard the rumble of wagon-wheels, and jumped down to see what was coming. It happened to be the milk boy, Pete Hopkins—"Hello, Pete!" said Bo. "Hello yourself," said Pete. "Give me a ride," begged Bo. "I don't mind," said the good-natured fellow and jumping out of his cart, lifted the child to the seat beside him.

Bolax had often been allowed to ride to the end of the road with Pete, because Mrs. Allen knew him to be a respectable boy.

When he came to the usual getting-off place, Pete forgot somehow to put the child down, and, of course, Bo couldn't think, he was too much interested in a story Pete was telling about his pet goose, that always followed one of the cows, and came to him to have her head scratched.

Pete did not realize how far he was taking the boy, until the horse stopped before his own door. "Great Scot!" exclaimed he, "I'll ketch it, youngster. I didn't mean to carry you all this way."

"But as you are here, I'll show you the calves and my pet goose." Saying this, Pete lifted Bo out of the cart. The child clapped his hands and shouted with delight as he caught sight of a flock of sheep feeding in the meadow next to the barn, then Pete called Nancy, the pet goose, and Bo laughed at her queer way of waddling from side to side after her master, and gabbling as if trying to talk to him.

"I want to see your colt now," said Bo, Pete asked[Pg 13] him to wait a minute while he went into the stable to make sure the colt was tied securely, for the animal was quite unbroken, and children were not to be trusted near him.

Bo waited a "hundred hours," which was always his manner of computing time, when in anticipation of pleasure; then spying a nice white pig in a field nearby, rubbing her back against the fence, he made a dash towards her, put one leg through the rails just across piggie's back. Up jumped the pig with the boy astride, whether by accident or design, no one could tell.

Bo was delighted at the unexpected pleasure of a real piggie-back ride, and laughed and shouted in his glee.

Pete having fastened the door of the colt's stall, and made sure he could be safely approached, went out of the stable to call Bolax, but by this time master harum scarum was off on his prancing steed. For a moment, Pete stood amazed not knowing what to make of the strange sight, then finding his voice, called out lustily "Hi! Hi! little fellow, stop! you'll be killed!" At the same time he could scarcely keep his feet for laughing.

Two farmhands tried to "head off" the animal, but Bo had caught hold of her ears to keep himself balanced, and the tighter he held on the wilder ran poor piggie.

Pete's mother came rushing out, and seeing the dangerous position of the child began scolding, her harsh voice striking terror into the heart of unlucky Pete.

"You big stupid. How come you to let that baby do such a fool trick?"

"Don't stand there gaping. Head off the wild critter or she'll get out on the road."

But the warning came too late, for at that moment down the lane flew the frightened animal, Bolax boldly clinging to its back.

Mrs. Hopkins, her hair all flying, rushed after him making the echoes ring with her screams. Pete bewildered, did not know which way to run; the two hired men and several neighbors joined in the chase.

Finally piggie plunged into a little creek by the roadside and Bo was dismounted. He got a thorough ducking and a few bruises, but received no serious injury.

Mrs. Hopkins carried the child into the house, and having changed his clothes made Pete hitch up the buggy, for, as she said: "I'll take the little imp to his mother, and tell her never to let him show his nose on my place again.

"As for you, Pete Hopkins, if ever I ketch you bringing any child on these premises, you'll be sore for a month."

When Mrs. Allen had written her letter she called Bolax, not finding him on the lawn, she went into the kitchen, supposing Hetty, the cook, was entertaining him, for she often had the children in roars of laughter, with her funny stories about "Brer Rabbit" and the "Pickaninys down Souf."

But Hetty "hadn't laid an eye on dat boy since breakfus."

Mrs. Allen waited a while longer, then became quite uneasy.

Going to the gate she looked up and down the road.

Miss Beldon saw her and asked if she was looking for Bolax. "Yes," said Mrs. Allen, "he has been missing for two hours and I am very much worried about him."

"Well, I saw him get into a wagon right at your gate," said Miss Beldon. Poor Mrs. Allen began to think of Charlie Ross, and every other kidnapping story she had ever heard of. Aunt Lucy and Amy shared her anxiety.

Pat went into the woods to look for him and Hetty took the road to the village, thinking he might be found in that direction.

Mrs. Allen went to her refuge in all trouble, the Oratory.

There she knelt and implored the Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph to help her find her darling boy; she felt sure the Divine Mother would sympathize with her, in remembrance of the anxiety she had suffered when the Holy Child was lost for three days.

It was nearly noon when Mrs. Hopkins' buggy stopped at the gate. Miss Beldon and Aunt Lucy were overjoyed on seeing the child, Amy ran down the path to meet him, calling back to Mamma that Bolax had been found.

Mrs. Allen, being a very nervous person became hysterical on hearing the good news. Aunt Lucy took the boy in her arms, and the usually happy little face assumed a grave expression when he saw his mother seated on the piazza with her handkerchief to her eyes.

Mrs. Hopkins told the whole story of the wild[Pg 16] ride and begged the ladies never to trust children with her "Pete," for she said: "I must tell you he ain't got the sense of a kitten and he is no more use than a last year's bird's nest with the bottom knocked out."

When Bo saw the state his mother was in, he realized how naughty he had been to leave home without permission. "Dear Ma," said he, "I'm so sorry, I didn't mean to stay away. Pete took me by mistake, and I didn't know I was staying so long."

Mrs. Allen said not a word of reproof to the child, but taking his hand, led him quietly upstairs to the Oratory, and left him. Bo felt his mother's silence more keenly than if she had given him a long lecture.

Calling her sister, Mrs. Allen said: "Lucy go to that child, he is in the Oratory. When he comes out, put him to bed. I must keep away from him while I am so excited and nervous; I will wait until I shall have become calm, to reprimand him."

Aunt Lucy went to the door to peep in at Bo; this is the prayer she heard him say: "Dear little Jesus and Holy Mother, I'm sorry I frightened my darling mamma. I didn't know I was away such a long time, but it was such fun, dear Jesus, you would laugh yourself if you had seen me on that pig."

Aunt Lucy ran away from the door, trying to smother her laughter, and going to her sister's room told what she had heard.

"Now, sister," she begged, "do forgive our boy this time, there is no guile in the little soul, and the way he speaks to Our Lord is so sweet, I cannot have the heart to scold him."

"That is all very well, Lucy, but I fear if I trusted[Pg 17] him to you always, he would be a very spoiled child."

Here a little voice was heard begging mamma to come and see how sorry her boy was.

Mrs. Allen let the little delinquent off with a mild reproof, and two hours in bed, which he needed as a rest after his wonderful exertions of the morning.

Little Amy begged Mamma to allow her to remain with Brother and offered to tell him a story, but he preferred having her recite a new piece she had just learned.

By Margaret Sidney.

"Wasn't she a naughty girl," said Bo, "I wouldn't do that. I never touch Aunt Lucy's banjo—only sometimes—but I don't break it."

The Party.

Great preparations were made for Amy's seventh birthday. Uncle Dick, who was an electrician, sent a number of portable electric lamps to help in the decorations.

Aunt Lucy proposed having tableaux and pieces for the evening entertainment, as a welcome home to Papa Allen, who was expected soon to return from his Western trip.

Amy wanted everything arranged in "sevens," as she expressed it. So she invited seven girls and seven boys and seven grown up people. There were to be seven kinds of candy and cakes, etc., and Mamma and Aunt Lucy worked with all their hearts to make Amy's seventh birthday a never-to-be-forgotten pleasure.

It was agreed that every eatable which was set on the table for the children, should be made at home, so Miss Sweetwood, who was an expert in candy making, came to spend a week, and devoted her time to the manufacture of all manner of dainty bonbons.

Aunt Lucy and Hetty took charge of the cooking, and the birthday cake came from their hands a most beautiful, as well as delicious, confection. There were seven sugar ornaments made like sconces to hold the candles, the one in the centre resembling a white lily, was for a blessed candle; Mrs. Allen always managed to smuggle a pious thought into every act connected with the children.

Two days before the party, Papa Allen arrived, bringing a present for Amy, which was received with wildest shouts of delight from both children, but was not so welcome to the grown-up members of the family, viz.—A goat.

Hetty came to bid a "welcome home" with the rest of the family, but held up her hands when she saw the new arrival and exclaimed. "Fo' de land's sake! Massa Allen, you done brought a match for Bolax now, for sure."

Early on the morning of the twenty-first, before anyone else in the house thought of stirring, Bo's eyes were wide open.

A robin perched on a bough of an apple tree just outside the window, was singing his merriest, the sun was shining straight into the room and upon Bo's crib. "Guess that sun woke me up," said he, watching with delight the bright beams as they glanced and shimmered about the walls and over the carpet. "When it gets to Mamma's bed it will wake her up too." "Oh! I'm so tired waiting." Then jumping out of his crib, he ran over to Amy's bed, and sang out. "One, two, three, four, five, six, seven. Hurrah! for your birthday, sister." Amy rubbed her eyes, and having made the sign of the cross, for she never forgot to give her first thought to God, was ready to join Bolax in hurrahing for the anticipated pleasures of the day.

First of all, the goat was remembered, and scarcely waiting to dress, both children ran to play with the new pet.

For a short time Bo allowed Amy to enjoy her[Pg 21] present, but soon he began to tease, and would not let her lead the goat where she pleased.

"It's my own pet!" cried she, "Papa brought it to me." "Well," said Bo, "you might let me have a lend of it." "Yes, but you take such a long lend, and you are so cruel," and Amy tried to pull the goat away, but Bo held on, screaming and getting into a temper.

Papa heard the noise and called out to know the cause of the disturbance. "Papa," said the gentle little girl, "I am willing to let Bo have Nanny for a long time, but he won't give me a chance to play with her at all, and he's tormenting the poor thing, making Don bark at her, just to see her try to butt."

Aunt Lucy ran out to settle the dispute. Just then the breakfast bell rang and Nanny was left in peace. After breakfast Mamma recommended the children not to tire themselves, as the party would begin at four o'clock in the afternoon, and they must be ready to receive their little friends and help to amuse them. But nothing would induce Bo to give up playing with the goat, at dinner time he was still taking "one more lend of her."

Gentle Amy, who generally gave up to her little brother, could not help feeling sorry for the unfortunate animal, and begged to have it sent to the stable.

"Bo, dear," said Aunt Lucy, "do let poor Nanny rest a while, you have not given her time to eat today." "Why Auntie she's had lots to eat. I gave her two of my handkerchiefs, and one of Amy's, and she ate them up, but she seems not to like colored handkerchiefs, for I gave her one of Hetty's, and she just took a bite, then spit it out."

Hetty happened to come to the pump just as Bo was showing the handkerchief, and she fairly screamed when she saw it.

"For de land's sake! you Bolax. Look what you been a doin'. Here's my best Bandanna half chewed up by dat goat." "Well, Hetty, you told me goats like to eat clothes, and I thought your bandanna would taste good to Nanny, because it is so pretty, but she didn't like it."

"Oh, you just shut up, you bad boy: you is made up of mischief; you' bones is full of it. Clar to goodness, I never was so put upon, no time, no whars."

Bo was very much surprised at Hetty's outburst of anger and looked quite frightened, he offered to give her all the pennies in his bank to buy a new bandanna, but she would not be pacified, and still continued to scold.

"Hetty, dear," said the little culprit, "please don't speak so hard, it hurts my heart." But angry Hetty continued with: "You certainly is one of dem. Massa Bo, you'se done so much mischief dis here day, and it's Miss Amy's birthday too; if I was you I'd go to de Oritey and pray de good Lord to hold you in, if He kin, just for de rest of dis day. I'se afraid you g'wine to spile all de fun dis arternoon by some of your fool tricks."

Bo seeing Hetty was determined to remain angry, ran off to escape further scolding. When he was gone Aunt Lucy told Hetty she must blame herself for the loss of her handkerchief, as she had told the child about the calves and goats feeding on such things. "You see, Hetty, as yet Bo does not know what an untruth means, and cannot distinguish between[Pg 23] joke and earnest, he firmly believes all that grown up people tell him, and I have no doubt, thought that he was giving a dainty morsel to the goat, when he offered her your best bandanna."

"Oh you! Miss Lucy, you always takes up for dat boy."

"Yes, and there's some one else, 'takes up' for him, sometimes, and her name is Hetty."

At three o'clock Mamma and Aunt Lucy dressed the children. Amy was as usual in blue and white, for she had been consecrated to the Blessed Virgin, from the time she was a baby. Her dress for the occasion was very beautiful, trimmed with soft laces, a present from her Godmother, and she looked like a little princess, with her long golden curls and dark eyes.

Bo wore his black velvet kilt, with a large lace collar, and the sweet little face, peeping out from beneath his crown of curls, might have been taken for something angelic, if one did not get a glimpse of his mischievous gray eye.

Promptly at four, the children trooped in; Amy did the honors in a most charming manner, and Bo amused the boys by showing them his numerous pets. Games of all kinds were played, and judging from the laughter and noise, Amy's guests were having what is called "a good time."

Never was there a more glorious twenty-first of June; the sky was so blue and bright, not the least bit of a cloud was to be seen, the air was balmy and entirely free from dampness, so the table for the children was set under the trees on the lawn. A snowy white cloth was spread and places arranged for fourteen.[Pg 24] Before each cover was a pretty box containing candied fruit, to each box was attached a card with these words in gilt letters: From Amy to her friends; this was to be carried home as a souvenir. In the centre of the table the birthday cake stood on a bank of red and white roses. These bouquets of flowers were placed between pyramids of ice cream and mounds of toothsome dainties. Delicious white and red and pink raspberries were served on plates resembling green leaves.

As the clock struck six, the children were called to take their places at the table, but just as they were seated, who should walk up the garden path, but Father Leonard, the dearest friend of the family. Mr. and Mrs. Allen hastened to greet him: "Well, well," said he, "what is all this?" Amy ran to welcome her favorite and told him it was her birthday party. "Now my little daughter," said the good father. "I feel very much slighted at not receiving an invitation." "Oh!" replied the little lady, "please do not be offended, but come sit at the head of the table and ask blessing on my feast." This the good father did most joyfully, and when the youngsters were seated, every one showed his appreciation of the good things by the dispatch with which the platters were cleared. Aunt Lucy's famous drop cakes disappeared in such numbers, that some of the Mammas began to fear they would have to nurse cases of indigestion.

At length the time came to cut the birthday cake. The seven candles upon it had remained lighted during the repast and Mr. Allen put them out before dividing it; he was just going to extinguish the last[Pg 25] one, when Master Bo jumped on the table, regardless of all propriety, and cried out, "Oh, Papa, let me blow out the middle candle, that is a blessed one and I want to breathe the holy smoke."

There was a hearty laugh at this and Father Leonard enjoyed the joke more than any one. When he could manage to speak after the hilarity had subsided he asked: "Bo, why did you want to breathe the holy smoke?" "Because," answered the boy, "Hetty says the mischief spirit is in me, and I wanted to smoke it out." Again there was an outburst of laughter, although only the older folks understood the wit of Bo's remark.

After supper the children prepared for the entertainment. Those who were to speak or sing went with Aunty Lucy and Miss May to have some last finishing touches put to their toilet, and make sure they remembered their pieces.

The end of the piazza had been arranged as a stage. Three large Japanese screens formed a back ground and an arch of white climbing roses and honey suckles served instead of a drop curtain. Groups of electric lamps had been placed so as to have the light fall directly on the little actors. Chairs and benches for the audience were arranged on the lawn just opposite the arch. At half past eight o'clock, it was sufficiently dark to bring out the illumination on the piazza, so the show began.

The first scene represented Amy seated on a chair, which was draped with gilt paper, festooned with flowers and resembled a veritable golden throne. From behind the scene came seven children carrying flowers and singing:

Then one of the little girls placed a crown of Lilies of the Valley on the little queen's head, and the other children laid their flowers at her feet.

This was a total surprise to Amy, for the children had been told not to let her know they were learning the song; her sweet face was a study while she received the homage of her little friends, but she was equal to the occasion, and rising from her seat made a profound bow and said, "Thank you! Oh! I thank you so much." After this came a violin solo by Adolph Lane, which was extremely well rendered. Edith Scot and her brother danced the "Sailors' Hornpipe" dressed in fancy costume.

Bolax and his chum, Robbie Thornton, spoke Whitcomb Riley's "When the World Busts Through." Suggested by an earthquake.

The little fellows recited this with scared faces and such comical gravity as to keep every one laughing. Amy came next with "Songs of Seven," by Jean Ingelow.

This was beautifully rendered and such a very appropriate selection for a seventh birthday. The entertainment ended, every one prepared to go home, one and all expressing their delight and declaring it was the most enjoyable birthday party they had ever witnessed.

Pleasant Controversy.

Mr. Allen sat on the porch smoking, when Mr. Steck, the Lutheran minister, opened the gate and walked in. Mr. Allen greeted him cordially and invited him to be seated.

The day was warm, but there was always a breeze on the corner of that porch, where the odor of the honeysuckle and climbing roses, which gave shade, made it a most inviting spot to rest.

"Have a segar, Mr. Steck." "Thank you, Mr. Allen, I am glad to see you at home on a week day, it is so seldom you take a holiday." "Holidays are not for men with a family to support; you may thank your stars, you are a bachelor." "That sounds as though you think I have a great share of leisure time. Well, I acknowledge my duties in this village are not very onerous, still I find enough to do. By the way, I have just been to see Miss Ogden. It is wonderful how the poor girl clings to life. As I left her house, I met Amy and Bolax, the dear children asked so kindly after the dying girl, but Bo—now don't be offended Mr. Allen, I have always taken a great interest in that boy having known him from a baby; he is wonderfully bright, makes such witty remarks," "and does such tormenting mischief at times," interrupted Mr. Allen. "Well," continued Mr. Steck, "When I told the children how ill Miss Ogden was, Bo gave me this medal of St. Benedict, telling me to put it on the poor girl's neck, and she[Pg 30] would be sure to get well. I asked who told him that? Then Amy looked at me so earnestly and said: 'Oh, Saint Benedict can cure anybody. You know he was a great doctor when he was on earth, and he was so good our Lord gave him power to cure people who wear his medal.' 'Yes, and he cured Nannie,' said Bo, 'see I have the medal on her yet;' and lifting a daisy chain he showed me the medal on the goat's neck." "Ha! ha! ha!" laughed Mr. Allen, "that's so like Bolax, he is a mixture of imp and angel."

"Now my friend," continued Mr. Steck, "allow me to ask you, who have been brought up an Episcopalian, if you approve of such superstitions? I did not suppose that educated Romanists entered into ridiculous practices of this sort; putting faith in—well, I might as well say it: Idols!" "—Hold on, Mr. Steck, I am not versed in the theology of the Catholic Church, and do not try to account for a great many little customs such as my little ones spoke about, but I'll venture to assert they do not injure the souls or bodies of those who believe in them. My wife never bothers me about her religion, never enters into controversy, although I have a notion, that on the sly, she is praying me into it."

"And from what you say," remarked Mr. Steck, "I think her prayers are being heard. I don't object to the Catholic religion; I think many of its doctrines are good and sound, but it would be more edifying to the general run of Christians, if there were not so many superstitious practices allowed." "Come, now Mr. Steck do not condemn what you do not understand. I travel a great deal as you know,[Pg 31] and often attend churches of different denominations; but whenever I try to get an explanation of their various beliefs, one and all answer me somewhat in this manner: 'Well, I don't believe thus and so;' 'I don't approve of this or that doctrine,' etc. I never can get any of them to say right out what they do believe. One point only do they all agree upon and that is, condemnation of the Roman Catholic Church." Opening a memorandum book, Mr. Allen took out a paper saying, "here is a hymn which I heard sung in a Campbellite Sunday School:

"Very poor verse, but I copied it from one of the Hymn Books. Now, what can be gained by teaching children such absurdities? If you were intimately acquainted with Catholic little ones, you would find they bring Jesus into their daily lives more than do those who are taught to ridicule them."

"Oh," said Mr. Steck, "I admit there are many ignorant preachers out West, who think they honor God by abusing the Catholic religion, but you never hear me or Mr. Patton make use of an uncharitable word in connection with any one religion."

"Mr. Steck let me tell you that even the children of illiterate parents, who are practical Catholics, you will find able to answer questions about their religion, and keep Jesus in their thoughts. Just to give you an example: yesterday my wife went over to Miss Scrips and found her tying up a rosebush in the garden, the cook's little boy, about seven years old, held the branch for her, while doing this, he uttered a cry of pain, tears came into his eyes, but checking himself, he said: "Oh, if one thorn hurts so much how dreadful He must have suffered with His head all covered with thorns. Poor Jesus!"

"Indeed," said Mr. Steck, "that was extraordinary. He must be an exceptional boy. Such a child will die young, or be a great preacher some day." "Well, I just tell this one instance," replied Mr. Allen, "to let you see the impression made on the heart of Catholic children by constantly keeping before them incidents in the life of Christ.

"Papa! Papa!" was heard in the distance. Mr. Allen got up saying: "That sounds like Bolax." Going to the gate he saw a crowd of youngsters following Bo, who was vainly trying to catch the goat. Nan was tearing down the road with Roy, Buz and Don his pet dogs, in full chase after her. It was too funny to see Nan turn on the dogs, stand on hind legs and with a loud Ma-a-a! start off again.

"I wish I were a few years younger," said Mr. Steck, "I'd join in the chase." Mr. Allen tried to head Nan off, Bo kept yelling—"Papa make the dogs stop barking, it frightens poor Nan." In going to the rescue, Mr. Allen left the garden gate open, Nannie rushed in tearing over the flower beds, to the[Pg 33] great dismay of the onlookers, especially Hetty who had come out to see what the row was about, grumbling to herself: "If yo' flower beds is spiled, youse got yu' own self to blame, Mr. Allen, it ain't no sense in havin' so many live creters round de place no how."

Pat came on the scene laughing in his good-natured way and catching the goat led her off to the stable.

"Don't whip poor Nannie," cried Bolax, "it wasn't her fault, it was the dogs that made her run through the flowers, but, oh—Pat don't whip them neither; it was the boys who sicked them on Nan." "I'll not bate any of them shure," said Pat, "Master Bo, it's yourself is the tender-hearted spalpeen after all." Mr. Steck patted the boy, who looked ready to cry and consoled him by promising him a ride on horse-back. "Good-bye, my little man. Good-bye Mr. Steck," said Mr. Allen, "come again whenever you want to see a circus."

Papa did not say much about the wreck of his flower beds, seeing the distress of his little boy. Hetty took him into the kitchen to comfort him and put on a clean blouse. Mamma, Aunt Lucy and Amy had been out all the afternoon, so Bolax tried to amuse himself. Looking out of the window, he saw Buz, Roy and Don hunting something in the strawberry patch. Off he started to see what they were after. To his surprise, all three dogs were eating the nice big strawberries; he chased them out, and going through the fence went into the woods followed by the three rascals. Bo gathered all sorts of "plunder," as Hetty called his treasures.

When Aunt Lucy came home, he called to her saying he had such a beautiful horrible bug to show her. "I know you'll like him, he's a tremendous big fellow, I put him in your soap dish to save him for you." On opening the soap dish, however, the "beautiful horrible bug" was nowhere to be seen, although Aunt Lucy looked carefully in every corner and crevice for she did not fancy sleeping in a room with such company.

To pacify Bolax for the loss of his treasure Aunt Lucy told him about a stag-beetle her uncle had as a pet. "Uncle would put a drop of brandy and water in a spoon, and Mr. Beetle would sip a little, and then dance about, sometimes he would get quite frolicsome, and behave in such a funny way, staggering round, going one-sided, try to fly and at last give it up and go into a sound sleep. When he awoke he would make a buzzing noise, stretch out a leg or two, then fly as well as ever. Uncle kept him six months; I don't know how he happened to die, but one morning he was stiff—we were all so sorry."

Bolax listened, seeming quite interested, but when his aunt stopped speaking he began to whine: "But I want my beautiful horrible bug, I just do want him. Papa go upstairs and look for him, I had such trouble catching him in the woods. He has a red saddle under his black wings, and big horns, and stiff legs and red eyes. Please find him, Papa; I want to make a pet of him."

Here Mamma came up on the porch, and hearing about her boy going into the woods alone, was inclined to scold, as she had strictly forbidden the children to venture into lonely places without some one[Pg 35] to watch over them. Bolax, then said, Adolph Layne had been with him. "Well," said Mamma, "I'm glad to know that—no doubt, we will find your 'beautiful horrible bug' in the morning. It cannot get away as the windows are all screened. He may have the room to himself and Aunt Lucy can sleep in the spare room."

Amy spied a Lady bug on the climbing rosebush, she caught it and gave it to her little brother to comfort him for his loss. Papa told the children never to harm a Lady bug because they are very useful insects. "In fact," said he, "I would like to have them on all my vines and bushes, for they always feed on the plant lice, which infest our choicest flowers. Indeed, I never could think of a Lady bug as a mere insect." "Oh!" said Amy, "why can't we call her Lady bird. She has strong little wings, and really seems like a tiny bird." "Well," continued Papa, "when I was very small, I often caught the dear little things, and firmly believed they understood when I said: 'Lady bug fly away home.' When one flew from my hand, I followed, watched her going home and found where she laid her eggs. She always selects a rosebush or honeysuckle or a hop vine, because they are more likely than others to have plant lice upon them. Lady bug's eggs are a bright yellow, small, flat and oval; when they are hatched out, the babies find their food all ready for them.

"At first, when just out of the egg, is the time the young ones eat millions of plant lice; after a few weeks good feeding, they get fat, and round, and casting off their first skin appear in their shining[Pg 36] beauty coats." "Thank you, Papa, dear," said Amy, I always did love 'Lady birds,' but now I shall love them more than ever." "Papa, may I ask you, do you know anything about snakes?"

"Snakes!" cried Mamma and Aunt Lucy. "Yes, Mamma dear, the poor things everybody hates them, and no one says a good word about them."

"Ow! ow! help! for de Lord's sake!" It was Hetty's voice coming from the cellar. All rushed to the rescue, thinking the poor soul might have fallen. On opening the cellar door, Hetty was seen tumbling up the stairs, her eyes starting out of her head, scarcely able to articulate. "Oh, Miss Allen, de debble is arter me. He down dere, I done seed him plain. Oh! Oh! I'm done frustrated to death!" All tried to pacify the frightened creature, but it was no use. "I'se done gone dis time. My heart's pumpin' out of me!" Mr. Allen went to see what could have given Hetty such a shock, when he too, gave a very undignified yell, as he caught sight of a big black snake. Bolax ran to him, calling out, "Why Papa, what is the matter, what made you screech?" "Don't come down here," called Mr. Allen, "Lucy bring the poker." "Oh, what on earth is it, brother? A snake! I don't wonder Hetty is scared to death."

"Oh, Papa, dear," called Bolax. "Don't kill him. Tommy Hoden gave him to me to put in the cellar to catch mice. I thought Hetty would be glad, but she is such a scare cat."

Mrs. Allen told her sister to give Hetty some valerniate of ammonia to quiet her nerves, and let her rest for the evening; we will attend to dinner; stay with her until she is soothed.

"Bolax, come upstairs. What are we to do with you? Positively you must stop handling reptiles and insects; you will be poisoned some day."

The little fellow listened to all his mother had to say, but seemed surprised that every one found fault when he expected to be praised. "Ma, dear," said he, "I didn't mean to frighten anyone. I'm not afraid of snakes, and Tommy Hoden is a good boy now, since you have him in Catechism class, and he wanted that snake for himself, but he spared it just to please Hetty."

"Well, dear, I believe you would not willingly give pain to Hetty, but you are nearly six years old and it is time you should have some thought about you, say your prayers and go to bed." Bo's prayer:

Dear Jesus, Bless Hetty and don't let her be such a scare cat. Holy Mother of Jesus, bless me and don't let me be doing wrong things when I mean to do right things; help all the poor and the sick, and all the people in the world and don't let anyone be cruel to animals. Bless every one in the whole world, Amen. Oh, I forgot, bless Mamma and Papa and Sister and Auntie, but you know I always have them in my heart. Amen.

The Picnic.

The feast of the Assumption. What a glorious day! Clear and bright, more like June than August.

Mrs. Allen and Amy went to early Mass. After breakfast Aunt Lucy proposed taking Bolax to high Mass, as the music was to be unusually fine. St. James' choir from the city volunteered their services. Mr. Van Horn sent out a fine organ to replace the squeaky, little melodeon, for it was the first anniversary of the dedication of the little country church, and all wanted to have an especially fine service.

Bo promised to be "better than good" while in Church. There was a very large congregation, the country people coming for miles around to hear the music and assist at the grand high Mass.

When Aunt Lucy and her charge entered the Church every seat seemed to be taken. Mrs. Allen's pew was filled with strangers, so dear old Madame Harte beckoned her to come into her pew.

From the beginning of the service, Bo was in an ecstasy of delight, except for an occasional tapping of his feet when the music was very inspiriting, he sat motionless.

Not to impose on the child's patience too long, Madame Harte offered to take him out during the sermon. "Oh, dear Hartie, is it all over?" said Bo. "No pet, but the priest is going to give a sermon, and you would be so tired." "No, I wouldn't, what is a sermon?" said Bo. "Oh, a very long talk, dear;[Pg 39] come out with me," whispered Madame, "and I will bring you back when the music begins again."

"Will the priest tell stories?" asked Bo, when he got outside. "I like long talks when the talk is stories."

"Come dear, let us sit under that tree over there and I will tell you a true story." "Oh, thank you, Hartie dear."

"Once long ago, our dear Lord died and—" "Rose again and went up into Heaven," said Bo all in one breath. "Mamma tells me that every day at my prayers."

"Well," continued Mrs. Harte, "after Jesus went up to Heaven His holy Mother was very lonely, so she prayed and prayed to Jesus to take her up to Heaven, that she might be with Him forever. Well, one beautiful day, just like this, Jesus called a company of angels and sent them down to the earth to bring His blessed Mother up to Him."

"Did the Angels march out of Heaven like soldiers?" asked Bo.

"Yes, dear; they put on their brightest robes, and beautiful clouds of crimson and gold surrounded them, and then they carried the holy Mother up, up, until they came to the golden throne where Jesus sat, ready to welcome her; He placed her beside Him and there she remains happy forever."

When the organ began the grand music of the Credo, Bo made a dash for the door, and could scarcely be persuaded to enter the Church quietly. After he was seated, he listened intently and was apparently very much interested in the Altar boys.

At length came the "Agnus Dei," which ends, as all have heard, with "Dona nobis pacem." The music score called for a repetition of the word "Pacem," somewhat in this manner, "Dona Pacem, Pacem," the basso calling out "Pacem! Pacem!"

With startling suddenness, Bo exclaimed: "Why are they singing about a Possum?"

Aunt Lucy caught him by the hand and hurried him to the side door, which was fortunately near; those who were within hearing, with difficulty controlled their laughter. "Are you crying, Aunty?" said the funny youngster, as he saw the flushed face of his aunt. "No, Bo, dear; I came out because you spoke so loud." "Oh, I forgot; please forgive me; let me go in again; I'll be so good, but Aunty dear, I didn't know they ever let possums into Church." Mass was not over, and as it was a holy day of obligation, Aunt Lucy felt unwilling to leave until the last Gospel. On reflection, however, she thought it best not to give further distraction by returning to her seat.

On her way home, she stopped to see a child, who belonged to the Catechism class, hoping to find him able to join the rest of the children, who were going to have their annual picnic. The little fellow had hurt his foot, but his mother said he was now able to walk nicely.

After Mass, Miss Devine and Madame Harte drove over to Allen's to see about the proposed outing. There they met the ladies Keating, all discussed Bo's latest exploit and laughed heartily about the Possum.

"Our class has increased so largely this year, I[Pg 41] fear we cannot have room for all the children on my grounds," observed Mrs. Allen. "Suppose we make it a straw ride," said Miss Keating. "We can give a substantial lunch, with ice cream and cake for dessert, and a bag of candy to take home." "Oh, grand! grand!" said Amy, clapping her hands, "and Ma, dear, I have two children I want to invite; they don't come to the class because they live so far away; I mean little Johnny Burke, who is lame, and Dotty, the blind child. I love them because they are afflicted."

"My darling, you shall invite the poor little ones, and I am glad to see you have such a compassionate heart." "Suppose we hire Johnson's big hay wagon," said Miss Keating, "it will hold all the children and two grown folks to look after them."

"That will be just the thing," said Miss Devine, "my contribution shall be the ice cream and cake." "and mine," said Madame Harte, "the candy." "I will help with the substantials and let the little things have more than enough for once in their lives," this from Miss Keating, whose whole time seemed to be taken up with helping the poor. "We can drive to Silver Lake woods," she proposed, "that is just six miles away and will not be too long a ride." After making all arrangements, the ladies took leave of Mrs. Allen, promising to be on hand on Thursday, August 20th.

The next day was Sunday. At Catechism class Mrs. Allen told the children of the proposed ride and picnic, which should take place on the next Thursday; all expressed their delight and you may be[Pg 42] sure, thought of nothing else during the intervening days.

The next morning Bolax was playing with his dogs on the lawn when Tom Hoden made his appearance; he stood outside the gate, looking wistfully at Bo. Mrs. Allen called him in and gave him some breakfast. "Did your father tell you of my visit?" said the lady. Tom answered in his surly manner: "Yes, the old man said you was to the house, but I don't want to go to Sunday School, the fellows would call me 'rags,' and I ain't got no shoes." "That can be easily remedied," said Mrs. Allen, "come here tomorrow and see what I will have for you."

The poor boy's face brightened up, and making an awkward attempt to thank the lady, he ran out of the gate.

When Tom presented himself next day, Pat was called upon to give him a bath and dress him in a good suit of clothes. "Here he is, ma'am," said Pat, "and ye'd hardly believe it's the same boy."

Tom held up his head and seemed quite happy; so true it is, that be one ever so poor, a clean, respectable appearance makes one feel at ease with himself and on better terms with his fellows. "Now Tom, I expect you to be here on next Thursday morning at nine o'clock." Tom promised to come and thanked Mrs. Allen.

The appointed day arrived. Long before the wagon came, the children flocked into the garden. Pat was on the alert lest his flower beds should suffer.

Miss Keating and Mrs. Allen made all be seated, and to while away the time sang:

The children clapped for this; then Aunt Lucy played on the piano which could be heard distinctly out on the lawn.

Amy and Aunt Lucy sang:

Mary Dowry called Amy's attention to a charming little girl about six years old, who smiled through the railing and looked wistfully at the children.[Pg 44] She was dressed in a pink frock, which set off her soft dark eyes.

Amy went towards her and she said, "Good morning," so sweetly. "I believe she wants to come with us," said Amy. "Oh, don't let her," cried Nellie Day, "she's only a Dago."

"Well, I'll give her some candy," said Bolax, "I like nice Dagos," and going to his mother, he told about the strange child. Mrs. Allen gave him a large bag of candy which he handed to the little girl.

On receiving it she said, "gracias, gracias." What is she saying "grassy ice for?" said Nellie Day, "perhaps she wants ice cream." "No" said Aunt Lucy "she is saying 'Thank you' in Italian. What pretty manners she has. I think some of our American children might profit by her sweet ways."

"I'm sure she has a nice mother," said Amy. "Let us take her with us." "I would, willingly dear," said Aunt Lucy, "but her people would think her lost, and we do not know where to send them word."

Great was the jubilation of the children, and not a little surprise among the ladies when the wagon appeared festooned with bunting, the driver carrying a flag, and the horses' heads decked in like manner. It was so kind of Mr. Johnson to give the decorations. Miss Keating and Aunt Lucy seated themselves and the children in the straw; then as the old song says:

Old and young joined in the fun and made the welkin ring with their mirth. Hetty and Pat put[Pg 45] the lunch baskets and ice cream into the dayton, and with Miss Devine, Madame Harte and Mrs. Allen in the large carry-all followed the procession to Silver Lake woods.

The road strolled leisurely out of the village and then, abruptly left it behind, and curved about a hillside. Silver Lake woods sat on a hill slope studded with pine trees; at the foot of the hill could be seen a most beautiful piece of water glistening in the sunshine. This was the lake. Life of the forest seemed to enter into the veins of the children and they ran and capered like wild deer. The horses were unharnessed so that they might rest.

Pat and Mr. Johnson's man put up swings and hammocks. The Misses Keating and Aunt Lucy set the children to play games; Hare and Hounds suited the boys and they raced to hearts' content. The Lake was guarded by Miss Devine's coachman, John, so that no venturesome lad would put himself in danger. The girls were easily made happy with quiet games, swings and hammocks.

To the children, of course, the lunch was the principal feature, so the ladies spread an immense white cloth on the grass, around which all sat, and were served to as many chicken and ham sandwiches as they could eat. Tin cups of delicious milk and lots of sweet buns followed. Then came the ice cream and cake; by the time this was disposed of, it became evident the children could hold no more, so Madame Harte's candy was reserved for the homeward trip.

The men were not forgotten, and were well supplied with a substantial dinner of cold roast beef,[Pg 46] pickles, bread and butter, a dozen of lemons and a pound of sugar to make lemonade. For, as Hetty, said, "dem dere fellows ain't goin' to care for soft vittles; dey wants sumpin' dat will keep dem from gettin' hollow inside." After the feast Pat and the other men gathered everything up, and packed all into the dayton, then Pat started for home.

The ladies were rather fatigued after their exertions in amusing and waiting on the children, so they rested in the hammocks awhile. As for the little ones, nothing seemed to tire them, they tore around as fresh and lively as if the day were just beginning. At four o'clock Mrs. Allen rang a bell to summon all to prepare for home. When the wagon came all piled in, laughing and shouting in their glee. Amy was most attentive to her little proteges, waiting on them and attending to all their wants. Little Dotty kept saying: "Dear Miss Amy, I love you; I thank you, and I'll always pray for you for giving me such a happy, happy day."

Bolax took little lame Johnny under his care, when the children were being placed in the wagon, he called out to the driver, "be sure to seat Johnny on a soft bunch of hay, because his leg is not strong." "Why did you say that?" said Nellie Day. "You ought to have said, because his is lame." "No, I just wouldn't say that," said Bo, "it might hurt Johnny's heart; my Mamma says we must never let lame people know we see their lameness, and never look at crooked-backed children, because it makes then feel worse."

When the wagon was ready to start, the driver offered to see all the children safely to their homes;[Pg 47] he said most of them lived near the quarry, and he would take the pike road, which passed within a few minutes' walk of it. Johnny and little Dotty he promised to deliver into the hands of their mothers.

The ladies Keating had ordered their carriage to call for them, and Miss Devine's "carry-all" held the rest of the party, including Bo and Amy.

This ended one happy day filled with love and kindness, and sweet charity towards God's poor little ones.

On the Sunday after the picnic, the Catechism class met. All the pupils were eager to show their appreciation of the happy day their kind teachers had given them.

The subject of instruction was the Ten Commandments. Mrs. Allen made a few remarks in simple, plain words, showing the advantages of truth over falsehood; dwelling particularly on the Seventh and Eighth Commandments, saying how happy one felt when his conscience told him, he was entirely free from the mean habit of lying and taking little things which were the property of others.

After class was dismissed, Tom lingered on the piazza. Mrs. Allen went to him, and asked him if he wanted to speak to her. "Yes, ma'am;" said the boy, "I once took a wheelbarrow out of your yard; I am very sorry; if you will trust me, I'll work out the price of it on your place. I could help Pat if he'd let me. I'm strong; I'm twelve now." Mrs. Allen was touched with the evident sincerity of the[Pg 48] boy, and thanked God that the good seed was already bearing fruit. Taking the boy's hand, she told him our Lord would certainly forgive and bless him since he bravely acknowledged his fault. "You may come tomorrow and I will give you work and keep you here until I can get you a permanent situation." Tom thanked his kind benefactress, promising to return the next day.

As he was passing out the gate Bo hailed him. "You're a good boy now Tom, so I can walk with you a little way; I am going to give you a pair of my darling white rats. They're such cute little things; they eat corn out of my mouth and run all over me." "Thank you, Bo, but I'd better don't take 'em, our place is full of black rats and they'd be sure to eat up the white ones." As Tom was speaking, he threw a stone at a bird that was hopping along the path. "Stop that!" said Bo, "you're getting bad again; that's a robin. Robins are blessed birds, because when our Lord was nailed on the Cross, a robin flew near and tried to pull the thorns out of His dear head, but robin was not strong, so he only could pull one thorn out, and the blood of poor Jesus got on the bird's feathers so that is why robin's breast is red." "Is that really so, who told you?" "My dear Mamma told me, and she knows everything in the world, so it is true Tom, and if you want my Mamma to love you, you must be kind to animals and kind to birds especially to robins."

"Well, little fellow, I will try for your sake. You see I never knowed about nothing, so I done bad acts. Now since I go to Catechism class I'll try to do good acts."

After leaving Tom, Bolax loitered on the way home, amusing himself with his dogs; when he went into the house, Hetty called him. "Where you done been such a long time, boy?" "Oh, I was only down the hill," replied Bo. "Well, here's me and sister a working while you'se playin'; just you come, let me wash you' hands and den you kin help us make dese here cookies." Amy was already busy rolling out dough and cutting cakes, so Bo was delighted to help. "Hetty, dear," said he, "if I roll this dough into cannon balls will they bake nice?" "Cannon balls in my oven," said Hetty, "suppose they go on to bust, what den?" "Oh, they won't bust, Hetty dear." So Hetty put the cannon balls to bake with the pan full of cookies and when they were done, she spread a nice white cloth on a little table near the window in the kitchen, bringing out the crabapple jelly, which the children always considered a treat. Then she put a bouquet in the center of the table and a pitcher of creamy milk. This with the cookies and some peaches made a delightful lunch. Amy understood why Hetty was particular to set the table so nicely and kept dancing 'round and talking nonsense.

Mamma and Aunt Lucy had gone out for the day and she wanted to keep Bo from noticing their absence. After enjoying the feast and feeding their pets, their friend, Adele, came and took them out in her pretty pony cart. It was five in the afternoon when the children returned. As soon as Bolax entered the house, he began his usual refrain: "Ma, dear." As he received no answer, he suddenly remembered he had not seen his mother all day.[Pg 50] "Why Hetty," said he, "is Mamma not at home?" "No, honey," said Hetty, "she's been in town; she'll be home soon now, and she g'wan to give you a nice present when I tell her what a good boy you done been. Come now eat yon' supper, so you' Ma will find you in bed when she comes home."

Bo and Amy sat at the little table where they had had lunch. Hetty gave them a nice supper and allowed them each to have a doggie beside them, with a plate to eat from.

After supper they went upstairs to prepare for bed. Buz and Roy followed. Amy took Bo into the Oratory to say night prayer. Bo began very piously "Our Father," but just here Buz bit his foot. "Stop that, Buz, don't you see I'm saying my prayers. Our Father, who art in Heaven. Buz won't behave." Bo called out laughing, at the same time. "Hetty," said Amy, "you had better come up here, Bo's just giggling instead of saying his prayers." "I comin' up; you dogs git out of dis here Oritey; it ain't no place for laughin'. Now you better don't be a mockin' of de Lord, Bo. I tell you somethin' might come arter you some night." But Bo couldn't stop, he was so full of merriment. "Well, I was saying my prayers with a humble and contrite heart when Roy came and thumped me in the back." "Yes," replied Amy, "and you just let him; you had better stop your nonsense." Hetty tried all her arts to get Bo to bed, at last she said: "Well, you always wasn't a religion child, anyway. I remember one time when you was three years old, you' mother was a dressin' you up in a lovely coat and hat with white plume, she was buttoning of the coat and you kept wigglin',[Pg 51] then she told you to try to be a good boy, else you' angel wouldn't love you. You said: 'Where is my angel.' 'Right behind you,' says you' Ma; then you pushed up against the wall and rubbed you back so hard. I was settin' dere and tried to make you stop. Your Ma, she say: 'What you doin' you bad boy,' and you answer 'Squashing the angel!' You' Ma couldn't help smilin' and I jest fall down on de floor with laughin,' We was so taken by surprise."

"Well, Hetty," said Amy, "that's the reason Bolax is bad, because people laugh at him." "Oh, I wouldn't say that now," said Bo, "I'm near six, and I do love my angel; the laughing is all gone now; I can say my prayers." So Bo said his prayers respectfully and went to bed.

A little after midnight, he ran into his mother's room. "Oh, Mamma, dear, did you hear it? Oh, it is awful, and I did say my prayers."

Out in the entry Hetty was heard saying: "For de Lord sake! Oh, Miss Allen, dere it is again."

Mrs. Allen and the whole household heard a most unearthly shriek, but immediately remembered it was the new fire alarm. After quieting the little boy and making Hetty understand what it was, Mrs. Allen looked out of the window, and saw that a large house on the top of a high hill was ablaze; as it was only a frame building it was soon destroyed, for the firemen could not reach it.

After the disturbance was over and all were going back to bed, Bo put his arm around his mother's neck, and said: "I guess I had better stay with you Mamma, dear; you might get afraid again."

A Talk About Our Boys.

Mrs. Carpenter, who was President of the Christian Mothers' Society, delivered a most entertaining lecture on "Our Boys." A subject in which every mother is always deeply interested.

It is an acknowledged fact that many a boy who has had the advantage of good training at home and at school, fails to avail himself of his opportunities and grows up careless in dress and language, and, while not absolutely vicious yet, looking leniently upon much that his parents and friends regard as reprehensible.

Among the various causes that lead to such physical, mental and moral laxity, none is more potent than companionship with dirty, idle or immoral boys. Many a lad spends hours with comrades whom he despises, at first, then excuses, and finally associates with on terms of close intimacy.

We all desire that our sons should keep good company, and we cannot and should not deprive them of outdoor companionship with boys of their own age. What we most desire is that they themselves should choose their comrades among honest, studious, manly boys, and avoid the society of the mean, idle and vicious; yet at the same time they should treat all[Pg 53] with the courtesy due from one human being to another.

We can scarcely understand the character of our boy's companions by his own description of them; since like the rest of humanity our boys regard their favorites with eyes that see only their good qualities, forgetting the coarse language, the vulgar jest, the cruel trick, the truant playing: "He is such a jolly fellow, plays such a good game."

Although we may notice occasionally that our boy is coarse in speech or manifests an unusual spirit of rebellion at school regulations still we do not often associate these effects with "such a good fellow always ready for fun." But if we occasionally saw this "good fellow" then indeed the cause would not be far to seek. Our boy himself would feel ashamed of his acquaintance, if he saw him in the home circle; he would suddenly discover that his friend was not ashamed that his hands were dirty, that he "talked to mother" with his hat on.

These boys of ours are apt to be very chivalrous about "mother," and then they learn not to care about companions of whom they are ashamed.

I once heard a mother say to her son, "Harry, I wonder at you to be seen on the street with that Murray boy. Why he is dressed like a beggar."

Now, I too, had seen Harry and the "Murray boy," and while the boy's clothes were old, they were whole and clean too, and I knew him to be an upright manly lad, more so indeed than Harry was ever likely to be with such training.

Provided a boy is truthful, clean and careful in his language we should not let the pecuniary circumstances[Pg 54] of his family enter into consideration; for our desire is to build up a noble manhood in our boys, and how despicable is that man who esteems his friends according to the length of their purses. There is only one way of judging our boy's companions, and that is by knowing them ourselves. This we can do by encouraging him to invite his friends to visit him not always formally, but now and then, as it may happen. We can pleasantly welcome them, but let us be careful not to entertain them too much, for there is nothing a boy hates more than to have a "fuss" made over him.

An occasional taffy pulling is not an expensive luxury and a little hot water removes all traces from the kitchen, to which it should be limited. Some time when it is convenient, let us tell our boy to invite some of his friends to spend the evening, and use the best china and the preserves and cake he likes the best.

Do not say, "It is only those boys." Let him feel that his guests are well treated, and he will be the more anxious to have friends worthy of the treatment they receive.

I think that the clownish behavior of boys arises from the only-a-boy treatment they experience; feeling slighted they instinctively resent it, by being as disagreeable as possible.

Nor is it necessary that one's house should be turned into a barn for boys to carouse in. On the contrary, our boy should always tell mother when he wishes to invite a friend, or, if he knows that his friends are coming; not as a rigid rule, but as a courtesy due a lady in her own house; no matter[Pg 55] whether the home consists of one room or twenty, the mother is always the hostess, and she can train her son into a well-bred man, or allow him, even though well educated to grow up a boor.

Many men owe their success in life to their observance of the minor courtesies in which they were trained by a good mother. These habits and that of correct speech should be insisted upon by every refined mother. There is another, and to me the most important point in the education of our boys, I refer to their religious training. Merely sending them to a short service on Sunday, will never impress boys with the respect they should have for God, and if they are not taught love and reverence for their Heavenly Father, they will disregard the authority of their parents and in after life, defy the laws of the land.

Above all things see to your boy's religious training, see that he does not associate with people who make flippant remarks about sacred things. Give a little time in the evening to conversations with your children. As I speak, one little mother comes to my mind, she always made it a duty to sit with her boys and talk over the incidents of the day, she inquired what new ideas they had received, etc.; they laughed and chatted together, "Ma dear" had their entire confidence. This mother warned her sons against vice, showing them the horrid pitfalls of sin.

Judicious advice coming from a loving mother will keep boys from sins, the memory of which even when repented of, would haunt them forever.

After Mrs. Carpenter's address she introduced[Pg 56] Mrs. Blondell, who gave her thoughts on the duties of mothers towards their children.

We often hear severe criticisms on the manners of young people of the present day and contrast them unfavorably with the manners of a generation ago. No doubt much of this criticism is warranted. The great mass of young people of today are lacking in deference, courtesy and respect. But the fathers and mothers who complain of these faults rarely question themselves if they are not wholly or in part to blame for the bad manners of their offspring.

I have known parents who sit at table or in the home circle, and in the presence of their children freely criticise or comment on the conduct of their neighbors or friends, permitting their children to tell all they have seen or heard in a neighbor's house.

Such parents must not be disappointed if those children grow up with the habit of gossiping and commenting just as freely on themselves. Now there is no one thing more destructive of good manners than the gossiping and tale-bearing habit.

If urbanity were persistently taught and practiced in the home there would not be so much to learn, and especially to unlearn with regard to intercourse with the world at large.

People would not then have two manners, one to use in public and one in private. There would be less self-consciousness and less affectation, for these arise from trying to do a thing of which we are uncertain, to assume a manner which we have imperfectly acquired.

Sometimes one meets with children who seem to lack the idea of truth, then it must be developed, and[Pg 57] great exactness is demanded of the mother in every statement.

In describing a garden with five trees, say five, not five or six or several. Go to extremes in accuracy of detail, for the sake of giving the child the habit of telling only the exact truth.

If a promise has been made to such a child there is more than ordinary necessity for keeping it to the letter.

Some time ago I heard of a gentleman who promised his little son that he should be present at the building of a stone wall, while the boy was absent the wall was built. Coming home he was greatly disappointed. "Papa you promised I should see it." "So I did my child." And the father ordered the wall to be torn down and rebuilt. Being expostulated with regarding the expense and time which he could ill afford, he replied: "I had rather spend many times the amount than have my son feel that I would be knowingly false to my word, or that it mattered little if a promise was broken."

Though truth and faithfulness might have been taught and the wall remained, because all accidents of life are not under our control, no one can doubt the impression made upon that boy's mind.

A mother speaking to me about two of her children said that they tell her most wonderful stories of school life and play time. She hears them quietly and says: "That is very interesting; now, how much did you see and hear, and how much do you think you saw and heard." They stop, think, and sift out the actual from the imaginative, sometimes correcting each other. One day the little boy said: "I really[Pg 58] thought, Mamma, it was all so, but I guess only this part was."

Much license is commonly allowed in order to tell a "good story," and many a child thus unconsciously gains a light conception of the value of truth, or they think their elders are privileged to use prevarications. I will give an illustration of this.

One day a group of ladies seated on the porch of a hotel were entertaining each other, among them was one notorious for her habit of exaggeration. We were all listening to one of this lady's "good stories" when her eldest little girl, a child of seven, came towards us, leading her small sister of four. Going up to her mother the child said in a most serious tone of voice: "Mamma, Elsie told a lie. You said it was naughty for little girls to tell lies; they must wait until they are big ladies; musn't they?"