No excuse need be offered to archers for presenting to them a new edition of the late Mr. Horace A. Ford's work on the Theory and Practice of Archery. It first appeared as a series of articles in the columns of the 'Field,' which were republished in book form in 1856; a second edition was published in 1859, which has been long out of print, and no book on the subject has since appeared. Except, therefore, for a few copies of this book, which from time to time may be obtained from the secondhand booksellers, no guide is obtainable by which the young archer can learn the principles of his art. On hearing that it was in contemplation to reprint the second edition of Mr. Ford's book, it seemed to me a pity that this should be done without revision, and without bringing it up to the level of the knowledge of the present day. I therefore purchased the copyright of the work from Mr. Ford's representatives, and succeeded in inducing Mr. Butt, who was for many years the secretary of the Royal Toxophilite Society, to undertake the revision.

A difficulty occurred at the outset as to the form in which this revision should be carried out. If it had been possible, there would have been advantages in printing Mr. Ford's text[vi] untouched, and in giving Mr. Butt's comments in the form of notes. This course would, however, have involved printing much matter that has become entirely obsolete, and, moreover, not only would the bulk of the book have been increased to a greater extent even than has actually been found necessary, but also Mr. Butt's portion of the work, which contains the information of the latest date, and is therefore of highest practical value to young archers, would have been relegated to a secondary and somewhat inconvenient position. Mr. Butt has therefore rewritten the book, and it would hardly perhaps be giving him too much credit to describe the present work as a Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Archery by him, based on the work of the late Horace A. Ford.

In writing his book, Mr. Ford committed to paper the principles by means of which he secured his unrivalled position as an archer. After displaying a clever trick, it is the practice of some conjurers to pretend to take the spectators into their confidence, and to show them 'how it is done.' In such cases the audience, as a rule, is not much the wiser; but a more satisfactory result has followed from Mr. Ford's instructions.

Mr. Ford was the founder of modern scientific archery. First by example, and then by precept, he changed what before was 'playing at bows and arrows' into a scientific pastime. He held the Champion's medal for eleven years in succession—from 1849 to 1859. He also won it again in 1867. After this time, although he was seen occasionally in the archery field, his powers began to wane. He died in the year 1880. His best scores, whether at public matches or in private practice, have never been surpassed. But, although no one has risen who can claim that on him has fallen the mantle of[vii] Mr. Ford, his work was not in vain. Thanks to the more scientific and rational principles laid down by this great archer, any active lad nowadays can, with a few months' practice, make scores which would have been thought fabulous when George III. was king.

The Annual Grand National Archery Meetings were started in the year 1844 at York, and at the second meeting, in 1845, held also at York, when the Double York Round was shot for the first time, Mr. Muir obtained the championship, with 135 hits, and a score of 537. Several years elapsed before the championship was won with a score of over 700. Nowadays, a man who cannot make 700 is seldom in the first ten, and, moreover, the general level both among ladies and gentlemen continues to rise. We have not yet, however, found any individual archer capable of beating in public the marvellous record of 245 hits and 1,251 score, made by Mr. Ford at Cheltenham in 1857.

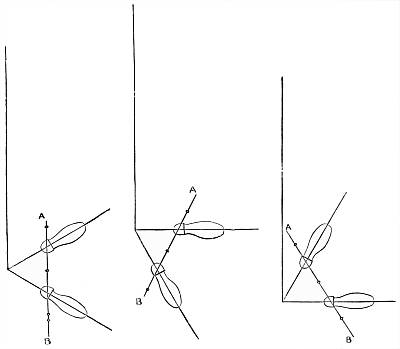

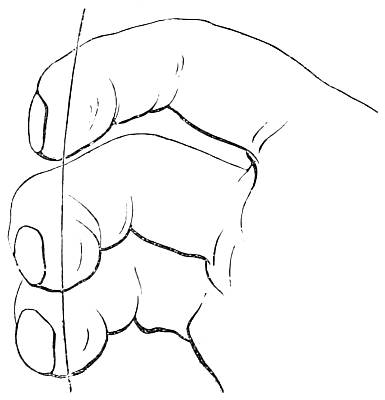

One chief cause of the improvement Mr. Ford effected was due to his recognising the fallacy in the time-honoured saying that the archer should draw to the ear. When drawn to the ear, part of the arrow must necessarily lie outside the direct line of sight from the eye to the gold. Consequently, if the arrow points apparently to the gold, it must fly to the left of the target when loosed, and in order to hit the target, the archer who draws to the ear must aim at some point to the right. Mr. Ford laid down the principle that the arrow must be drawn directly beneath the aiming eye, and lie in its whole length in the same vertical plane as the line between the eye and the object aimed at.

It is true that in many representations of ancient archers the arrow is depicted as being drawn beyond the eye, and[viii] consequently outside the line of sight. No doubt for war purposes it was a matter of importance to shoot a long heavy arrow, and if an arrow of a standard yard long or anything like it was used, it would be necessary for a man to draw it beyond his eye, unless he had very long arms indeed. But in war, the force of the blow was of more importance than accuracy of aim, and Mr. Ford saw that in a pastime where accuracy of aim was the main object, this old rule no longer held good. This was only one of many improvements effected by Mr. Ford; but it is a fact that this discovery, which seems obvious enough now that it is stated, was the main cause of the marvellous improvement which has taken place in shooting.

The second chapter in Mr. Ford's book, entitled 'A Glance at the Career of the English Long-Bow,' has been omitted. It contained no original matter, being compiled chiefly from the well-known works of Roberts, Moseley, and Hansard. The scope of the present work is practical, not historical; and to deal with the history of the English long-bow in a satisfactory manner would require a bulky volume. An adequate history of the bow in all ages and in all countries has yet to be written.

In the chapters on the bow, the arrow, and the rest of the paraphernalia of archery, much that Mr. Ford wrote, partly as the result of the practice and experiments of himself and others, and partly as drawn from the works of previous writers on the subject, still holds good; but improvements have been effected since his time, and Mr. Butt has been able to add a great deal of useful information gathered from the long experience of himself and his contemporaries.

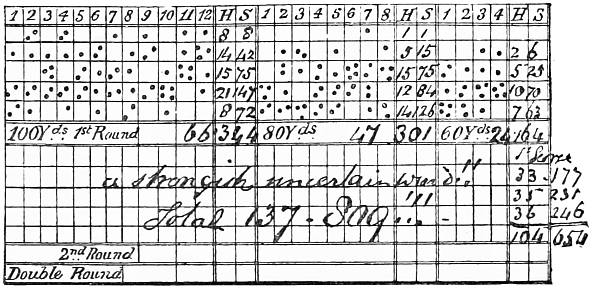

The chapters which deal with Ascham's well-known five points of archery—standing, nocking, drawing, holding, and[ix] loosing—contain the most valuable part of Mr. Ford's teaching, and Mr. Butt has endeavoured to develope further the principles laid down by Mr. Ford. The chapters on ancient and modern archery practice have been brought up to date, and Mr. Butt has given in full the best scores made by ladies or gentlemen at every public meeting which has been held since the establishment of the Grand National Archery Society down to 1886.

The chapter on Robin Hood has been omitted for the same reasons which determined the omission of the chapter on the career of the English long-bow, and the rules for the formation of archery societies, which are cumbrous and old-fashioned, have also been left out.

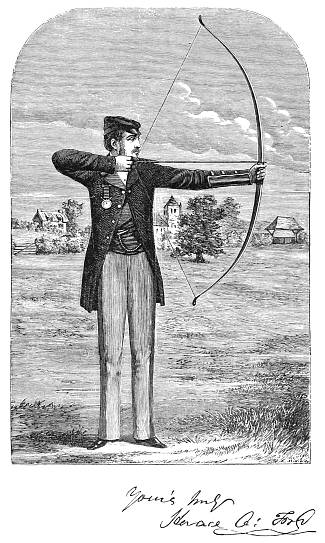

The portrait of Major C. H. Fisher, champion archer for the years 1871-2-3-4, is reproduced from a photograph taken by Mr. C. E. Nesham, the present holder of the champion's medal.

In conclusion, it is hoped that the publication of this book may help to increase the popularity of archery in this country. It is a pastime which can never die out. The love of the bow and arrow seems almost universally planted in the human heart. But its popularity fluctuates, and though it is now more popular than at some periods, it is by no means so universally practised as archers would desire. One of its greatest charms is that it is an exercise which is not confined to men. Ladies have attained a great and increasing amount of skill with the bow, and there is no doubt that it is more suited to the fairer sex than some of the more violent forms of athletics now popular. Archery has perhaps suffered to some extent from comparison with the rifle. The rifleman may claim for his weapon that its range is greater and that it shoots more accurately than the bow. The first position may be granted[x] freely, the second only with reserve. Given, a well-made weapon of Spanish or Italian yew, and arrows of the best modern make, and the accuracy of the bow is measured only by the skill of the shooter. If he can loose his arrow truly, it will hit the mark; more than that can be said of no weapon. That a rifleman will shoot more accurately at ranges well within the power of the bow than an archer of similar skill is certain; but the reason is that the bow is the more difficult, and perhaps to some minds on that account the more fascinating, weapon. The reason why it is more difficult is obvious, and in stating it we see one of the many charms of archery. The rifleman has but to aim straight and to hold steady, and he will hit the bull's-eye. But the archer has also to supply the motive force which propels his arrow. As he watches the graceful flight of a well-shot shaft, he can feel a pride in its swiftness and strength which a rifleman cannot share. And few pastimes can furnish a more beautiful sight than an arrow speeding swiftly and steadily from the bow, till with a rapturous thud it strikes the gold at a hundred yards.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | OF THE ENGLISH LONG-BOW | 1 |

| II. | HOW TO CHOOSE A BOW, AND HOW TO USE AND PRESERVE IT WHEN CHOSEN | 17 |

| III. | OF THE ARROW | 27 |

| IV. | OF THE STRING, BRACER, AND SHOOTING-GLOVE | 44 |

| V. | OF THE GREASE-BOX, TASSEL, BELT, ETC. | 67 |

| VI. | OF BRACING, OR STRINGING, AND NOCKING | 78 |

| VII. | OF ASCHAM'S FIVE POINTS, POSITION STANDING, ETC. | 83 |

| VIII. | DRAWING | 94 |

| IX. | AIMING | 107 |

| X. | OF HOLDING AND LOOSING | 122 |

| XI. | OF DISTANCE SHOOTING, AND DIFFERENT ROUNDS | 132 |

| XII. | ARCHERY SOCIETIES, 'RECORDS,' ETC. | 140 |

| XIII. | THE PUBLIC ARCHERY MEETINGS AND THE DOUBLE YORK AND OTHER ROUNDS | 148 |

| XIV. | CLUB SHOOTING AND PRIVATE PRACTICE | 279 |

| PORTRAIT OF MR. FORD | Frontispiece |

| PORTRAIT OF MAJOR C. H. FISHER | To face p. 122 |

Of the various implements of archery, the bow demands the first consideration. It has at one period or another formed one of the chief weapons of war and the chase in almost every nation, and is, indeed, at the present day in use for both these purposes in various parts of the world. It has differed as much in form as in material, having been made curved, angular, and straight; of wood, metal, horn, cane, whalebone, of wood and horn, or of wood and the entrails and sinews of animals and fish combined: sometimes of the rudest workmanship, sometimes finished with the highest perfection of art.

No work exists which aims at giving an exhaustive description of the various forms of bows which have been used by different nations in ancient and modern times, and such an undertaking would be far beyond the scope of the present work. The only form of the bow with which we are now concerned is the English long-bow, and especially with the English long-bow as now used for target-shooting as opposed to the more powerful weapon used by our forefathers for the purposes of war. The cross-bow never took a very strong hold on the English nation as compared with the long-bow,[2] and, as it has never been much employed for recreation, it need not be here described.

It is a matter of surprise and regret that so few genuine specimens of the old English long-bow should remain in existence at the present day. One in the possession of the late Mr. Peter Muir of Edinburgh is said to have been used in the battle of Flodden in 1513: it is of self-yew, a single stave, apparently of English growth, and very roughly made. Its strength has been supposed to be between 80 and 90 lbs.; but as it could not be tested without great risk of breaking it, its actual strength remains a matter of conjecture only. This bow was presented to Mr. P. Muir by Colonel J. Ferguson, who obtained it from a border house contiguous to Flodden Field, where it had remained for many generations, with the reputation of having been used at that battle.

There are likewise in the Tower two bows that were taken out of the 'Mary Rose,' a vessel sunk in the reign of Henry VIII. They are unfinished weapons, made out of single staves of magnificent yew, probably of foreign growth, quite round from end to end, tapered from the middle to each end, and without horns. It is difficult to estimate their strength, but it probably does not exceed from 65 to 70 lbs. Another weapon now in the Museum of the United Service Institution came from the same vessel. Probably the oldest specimen extant of the English long-bow is in the possession of Mr. C. J. Longman. It was dug out of the peat near Cambridge, and is unfortunately in very bad condition. It can never have been a very powerful weapon. Geologists say that it cannot be more recent than the twelfth or thirteenth century, and may be much more ancient. Indeed, from its appearance it is more probable that it is a relic of the weaker archery of the Saxons than that it is a weapon made after the Normans had introduced their more robust shooting into this country.

Before the discussion of the practical points connected with the bow is commenced, it must be borne in mind that these[3] pages profess to give the result of actual experience, and nothing that is advanced is mere theory or opinion unsupported by proof, but the result only of long, patient, and practical investigation and of constant and untiring experiment. Whenever, therefore, one kind of wood, or one shape of bow, or one mode or principle of shooting, &c., is spoken of as being better than another, or the best of all, it is asserted to be so simply because, after a full and fair trial of every other, the result of such investigation bore out that assertion. No doubt some of the points contended for were in Mr. Ford's time in opposition to the then prevailing opinions and practice, and were considered innovations. The value of theory, however, is just in proportion as it can be borne out by practical results; and in appealing to the success of his own practice as a proof of the correctness of the opinions and principles upon which it was based, he professed to be moved by no feeling of conceit or vanity, but wholly and solely by a desire to give as much force as possible to the recommendations put forth, and to obtain a fair and impartial trial of them.

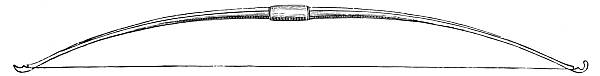

The English bows now in use may be divided primarily into two classes—the self-bow and the backed bow; and, to save space and confusion, the attention must first be confined to the self-bow, reserving what has to be said respecting the backed bow. Much, however, that is said of the one applies equally to the other.

The self-bow of a single stave is the real old English weapon—the one with which the mighty deeds that rendered this country renowned in bygone times were performed; for until the decline and disappearance of archery in war, as a consequence of the superiority of firearms, and the consequent cessation of the importation of bow-staves, backed bows were unknown. Ascham, who wrote in the sixteenth century, when archery had already degenerated into little else than an amusement, mentions none other than self-bows; and it may therefore be concluded that such only existed in his day. Of the[4] woods for self-bows, yew beyond all question carries off the palm. Other woods have been, and still are, in use, such as lance, cocus, Washaba, rose, snake, laburnum, and others; but they may be summarily dismissed (with the exception of lance, of which more hereafter) with the remark that self-bows made of these woods are all so radically bad, heavy in hand, apt to jar, dull in cast, liable to chrysal, and otherwise prone to break, that no archer should use them so long as a self-yew or a good backed bow is within reach.

The only wood, then, for self-bows is yew, and the best yew is of foreign growth (Spanish or Italian), though occasionally staves of English wood are met with which almost rival those of foreign growth. This, however, is the exception; as a rule, the foreign wood is the best: it is straighter, and finer in grain, freer from pins, stiffer and denser in quality, and requires less bulk in proportion to the strength of the bow.

The great bane of yew is its liability to knots and pins, and rare indeed it is to find a six-feet stave without one or more of these undesirable companions. Where, however, a pin occurs, it may easily be rendered comparatively harmless by the simple plan of raising it—i.e. by leaving a little more wood than elsewhere round the pin in the belly and back of the bow. This strengthens the particular point, and diminishes the danger of a chrysal or splinter. A pin resembles a small piece of wire, is very hard and troublesome to the bowmaker's tools, runs right through the bow-stave from belly to back, and is very frequently the point at which a chrysal starts. This chrysal (also called by old writers a 'pinch') is a sort of disease which attacks the belly of a bow. At first it nearly resembles a scratch or crack in the varnish. Its direction is always diagonal to the line of the bow, and it gradually eats deeply into the bow and makes it appear as if it had been attacked with a chopper. If many small chrysals appear, much danger need not be feared, though their progress should be watched; but if one chrysal becomes deeply[5] rooted, the bow should be sent to the bowmaker for a new belly. A chrysal usually occurs in new bows, and mostly arises from the wood being imperfectly seasoned; but it occasionally will occur in a well-seasoned bow that has been lent to a friend who uses a longer draw and dwells longer on the point of aim, thus using the weapon beyond its wont. Another danger to the life of a bow arises from splinters in the back. These mostly occur in wet weather, when the damp, through failure of the varnish, has been able to get into the wood. Directly the rising of a splinter is observed, that part of the bow should be effectually glued and wrapped before it is again used. After this treatment the bow will be none the worse, except in appearance. Yew and hickory only should be used for the backs of bows. Canadian elm, which is occasionally used for backs, is particularly liable to splinter. It is obvious whenever a bow is broken the commencement of the fracture has been in a splinter or a chrysal, according as the first failure was in the back or the belly; therefore in the diagnosis of these disorders archers have to be thankful for small mercies. The grain of the wood should be as even and fine as possible, with the feathers running quite straight, and as nearly as possible consecutively from the handle to the horn in each limb, and without curls; also, care should be taken, in the manufacture of a bow, that the sap or back be of even depth, and not in some places reduced to the level of the belly. The feathering of a yew bow means the gradual disappearance of some of the grain as the substance of the bow is reduced between the handle and horn. A curl is caused by a sudden turn in the grain of the wood, so that this feathering is abruptly interrupted and reversed before it reappears. This is a great source of weakness in a bow, both in belly and back. There should be nothing of the nature of feathering in the back of a bow, and it is believed that the best back is that in which nothing but the bark has been removed from the stave. Any interruption of the grain of the back is a source[6] of weakness and a hotbed of splinters. A bow that follows the string should never be straightened, for the same reason that anything of the nature of a carriage-spring should on no account be reversed in application. The wood should be thoroughly well seasoned and of a good sound hard quality. The finest[7] and closest dark grain is undoubtedly the most beautiful and uncommon; but the open or less close-grained wood, and wood of paler complexion, are nearly, if not quite, as good for use.

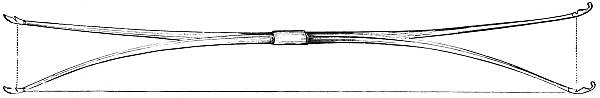

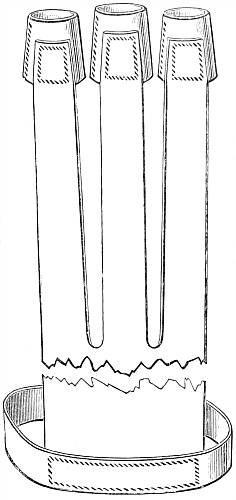

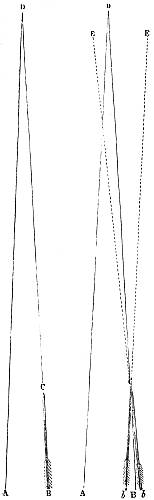

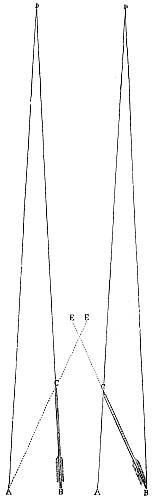

(Figs. 5 and 6 show the different distances which the limbs of well-shaped and of reflex bows have to go to their rest when unstrung.)

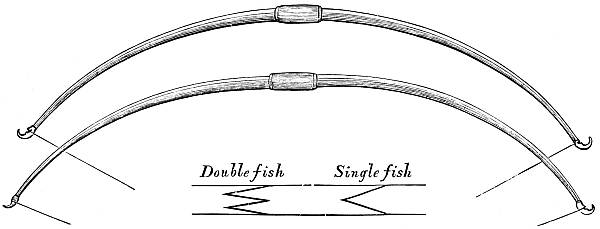

Doublefish Singlefish

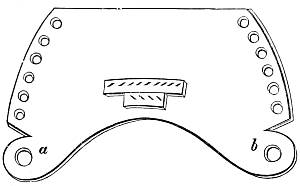

The self-yew bow may be a single-stave—that is to say,[8] made of a single piece of wood, or may be made of two pieces dovetailed or united in the handle by what is called a fish. In a single-stave bow the quality of the wood will not be quite the same in the two limbs, the wood of the lower growth being denser than that of the upper; whilst in the grafted bow, made of the same piece of wood, cut or split apart, and re-united in the handle, the two limbs will be exactly of the same nature. The joint, or fishing (fig. 7), should be double, not single. The difference, however, between these two sorts of self-yew bows is so slight as to be immaterial. In any unusually damp or variable climate single staves should be prepared; and in the grafted bows care should be taken in ascertaining that they be firmly put together in the middle. A single-stave bow has usually a somewhat shorter handle, as it becomes unnecessary to cover so much of the centre of the bow when the covering is not used as a cover to the joint, but for the purpose of holding the bow only.

In shape all bows should be full and inflexible in the centre, tapering gradually to each horn. They should never bend in the handle, as bows of this shape (i.e. a continuous curve from horn to horn) always jar most disagreeably in the hand. A perfectly graduated bend, from a stiff unbending centre of at least nine inches, towards each horn is the best. Some self-yew bows are naturally reflexed, others are straight, and some follow the string more or less. The slightly reflexed bows are perhaps more pleasing to the eye, as one cannot quite shake off the belief that the shape of Cupid's bow is agreeable. Bows which follow the string somewhat are perhaps the most pleasant to use.

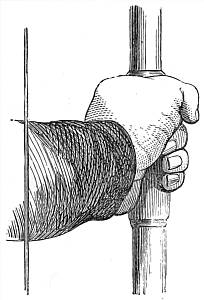

The handle of the bow, which in size should be regulated to the grasp of each archer, should be in such a position that the upper part of it may be from an inch to an inch and a quarter above the true centre of the bow, or the point in the handle whereon the bow will balance. If this centre be lower down in the handle, as is usual in bows of Scotch manufacture,[9] the cast of the bow may be somewhat improved, but at the cost of a tendency to that unpleasant feeling of kicking and jarring in the hand. Again, if the true centre be higher, or, as is the case in the old unaltered Flemish bows, at the point where the arrow lies on the hand, the cast will be found to suffer disadvantageously. If the handle be properly grasped (inattention to which will endanger the bow's being pulled out of shape), the fulcrum, in drawing, will be about the true balancing centre, and the root of the thumb will be placed thereon. Considering a bow to consist of three members—a handle and two limbs—the upper limb, being somewhat longer, must of necessity bend a trifle more, and this it should do. The most usual covering for the handle is plush; but woollen binding-cloth, leather, and india-rubber are also in constant use.

The piece of mother-of-pearl, ivory, or other hard substance usually inserted in the handle of the bow, at the point where the arrow lies, is intended to prevent the wearing away of the bow by the friction of the arrow; but this precaution overreaches itself, as in the course of an unusually long life the most hard-working bow will scarcely lose as much by this friction as must, to start with, be cut away for this insertion.

The length of the bow, which is calculated from nock to nock—and this length will vary a little from the actual length, according as it may be said to hold itself upright or stoop, i.e. follow the string—should be regulated by its strength and the length of the arrow to be used with it. It may be taken as a safe rule that the stronger the bow the greater its length should be; and so also the longer the arrow the longer should be the bow. For those who use arrows of the usual length of from 27 to 28 inches, with bows of the strength of from 45 lbs. to 55 lbs., a useful and safe length will be not less than 5 ft. 10 in. If this length of arrow or weight of bow be increased or diminished, the length of bow may be proportionally[10] increased or diminished, taking as the two extremes 5 ft. 8 in. and 6 feet. No bow need be much outside either of these measurements. It may be admitted that a short bow will cast somewhat farther than a longer one of the same weight, but this extra cast can only be gained by a greater risk of breakage. As bows are usually weighed and marked by the bowmakers for a 28-inch arrow fully drawn up, a greater or less pull will take more or less out of them, and the archer's calculations must be made accordingly.

To increase or diminish the power of a bow, it is usual to shorten it in the former case, and to reduce the bulk in the latter; but to shorten a bow will probably shorten its life too, and mayhap spoil it, unless it be certain that it is superfluously long or sufficiently strong in the handle. On the other hand, to reduce a bow judiciously, if it need to be weaker, can do it no harm; but the reduction should not be carried quite up to the handle. It is a good plan to choose a bow by quality, regardless of strength, and have the best bow that can be procured reduced to the strength suitable. In all cases the horns should be well and truly set on, and the nocks should be of sufficient bulk to enclose safely the extremities of the limbs of the bow running up into them, and the edges of the nocks should be made most carefully smooth. If the edge of the nock be sharp and rough, the string must be frayed, and in consequence break sooner or later, and endanger the safety of the bow. The lower nock is not unfrequently put on or manufactured a trifle sideways as to its groove on the belly side. This is done with a view to compensate the irregularity of the loop: but this is a mistake, as it is quite unnecessary in the case of a loop, and must be liable to put the string out of position when there is a second eye to the string—and this second eye every archer who pays due regard to the preservation of his bows and strings should be most anxious to adopt as soon as possible.

From all that can be learned respecting the backed bow, it would appear that its use was not adopted in this country[11] until archery was in its last stage of decline as a weapon of war, when, the bow degenerating into an instrument of amusement, the laws relating to the importation of yew staves from foreign countries were evaded, and the supply consequently ceased. It was then that the bowyers hit upon the plan of uniting a tough to an elastic wood, and so managed to make a very efficient weapon out of very inferior materials. This cannot fairly be claimed as an invention of the English bowyers, but is an adaptation of the plan which had long been in use amongst the Turks, Persians, Tartars, Chinese, and many other nations, including Laplanders, whose bows were made of two pieces of wood united with isinglass. As far as regards the English backed bow (this child of necessity), the end of the sixteenth century is given as the period of its introduction, and the Kensals of Manchester are named as the first makers—bows of whose make may be still in existence and use—and these were generally made of yew backed with hickory or wych-elm. At the time of the revival of archery—at the close of the last century, and again fifty years ago—all backed bows were held in great contempt by any that could afford self-yews, and were always slightingly spoken of as 'tea-caddy' bows; meaning that they were made of materials fit for nothing but ornamental joinery, Tunbridge ware, &c.

The backed bows of the present day are made of two or more strips of the same or different woods securely glued, and compressed together as firmly as possible, in frames fitted with powerful screws, which frames are capable of being set to any shape. Various woods are used, most of which, though of different quality, make serviceable bows. For the backs we have the sap of yew, hickory, American, Canadian, or wych-elm, hornbeam, &c.; and for the bellies, yew, lance, fustic, snake, Washaba, and letter-wood, which is the straight grained part of snake, and some others. Of all these combinations Mr. Ford gave the strongest preference to bows of yew backed with yew. These he considered the only possible rivals of the self-yew.[12] Next in rank he classed bows of yew backed with hickory. Bows made of lance backed with hickory, when the woods used are well seasoned and of choice quality, are very steady and trustworthy, but not silky and pleasant in drawing like bows made of yew. One advantage of this combination of bow is that both these woods can be had of sufficient length to avoid the trouble in making and insecurity in use of the joint in the handle. Of bows into which more than two woods are introduced, the combination of yew for the belly, fustic or other good hard wood for the centre, and hickory for the back cannot well be improved upon, and such bows have been credited with excellent scores. There is also a three-wooded modification of the lance and hickory bow. In this a tapering strip of hard wood is introduced between the back and belly; this strip passes through the handle and disappears at about a foot from the horn in each limb. The lancewood bows are the cheapest, and next to these follow the lance-and-hickory bows, and then those of the description last mentioned. On this account beginners who do not wish to go to much expense whilst they are, as it were, testing their capacity for the successful prosecution of this sport, would do well to make a start with a bow of one or other of these descriptions. It will often be useful to lend to another beginner, or to a friend, to whom it might not be wise to lend a more valuable bow; or it may even be of use to the owner at a pinch. Bows have often been made of many more than three pieces; but nothing is gained by further complications, unless it be necessary in the way of repair.

Next in importance to the consideration of the material of which backed bows should be made comes the treatment of their shape. Judging from such specimens of backed bows, made by Waring and others, before the publication of Mr. H. A. Ford's articles on archery in the 'Field,' as have survived to the present day, and whose survival may be chiefly attributed to the fact that they were so utterly harsh and disagreeable in use[13] that it was but little use they ever got, the author was probably right in saying that they all bent in the handle more or less when drawn, and were too much reflexed. There is but little doubt that—as the joint in the handle, necessitating extra bulk and strength, could be dispensed with in these bows—the makers considered it an excellent opportunity to give their goods what (however erroneously) was then considered the best shape (when drawn), namely, the perfect arc; and this harmonious shape they obtained most successfully by making the bows comparatively weak in the handle and unnecessarily strong towards the horns; with the result that these 'tea-caddy bows' met the contemptuous fate they well deserved. Modern archers have to be thankful to Mr. Ford for the vast improvement in backed bows (even more than in the case of self-bows), which are now perfectly steady in hand, and taper gradually, and as much as is compatible with the safety of the limbs, and this in spite of their being still made somewhat more reflex when new than appears necessary in the manufacture of self-yew bows. Yet Mr. Ford was perfectly right to condemn all reflexity that does not result in a bow becoming either straight or somewhat to follow the string after it has been in use sufficiently long for its necessary training to its owner's style. The first quality of a bow is steadiness. Now this quality is put in peril either by a want of exact balance between the two limbs—when the recoil of one limb is quicker than that of the other—or by undue reflexity. These causes of unsteadiness occur in self-bows as well as in backed bows, and are felt in the shape of a jar or kick in the hand when loosed. This unsteadiness from want of balance in the limbs may be cured by a visit of the bow to the maker for such fresh tillering (as it is called) as will correct the fault of one or other limb. If the unsteadiness arise from excessive reflexity, which cannot be reduced by use, a further tapering of the limbs must be adopted. No bow of any sort that cannot be completely cured of kicking should be kept, as no[14] steady shooting can be expected from such a bow. A bow that is much reflexed will be more liable to chrysals and splinters, as the belly has to be more compressed and the back more strained than in a bow of proper shape; also, such a bow is much more destructive to strings, as a greater strain is put upon the strings by the recoil of the limbs than is the case with a bow that follows the string or bends inwards naturally. It is the uneven or excessive strain upon the string after the discharge of the arrow that causes the kicking of the bow.

When the question arises, 'Which is the best sort of bow?' it is found that the solution has only been rendered more complicated since 1859 by the great improvement in the manufacture of various sorts of backed bows: as the following remarks, then applied to the comparison between the self-yew and the yew-backed yew only, must now be extended to all the best specimens of backed bows of different sorts. The advocates of the self-yew affirm that good specimens of their pet weapon are the sweetest in use, the steadiest in hand, the most certain in cast, and the most beautiful to the eye; and in all these points, with the exception of certainty of cast, they are borne out by the fact. This being the state of the case, how is it, then, that a doubt can still remain as to which it is most profitable for an archer to use? Here are three out of four points (two of which are most important) in which it is admitted that the self-yew is superior; and yet, after much practical and experimental testing of all sorts, it must be left to the taste and judgment of each man to decide for himself. The fact undoubtedly is, that the self-yew is the most perfect weapon. But it is equally an undoubted fact that it requires more delicate handling; since, its cast lying very much in the last three or four inches of its pull, any variation in this respect, or difference in quickness or otherwise of loose, varies the elevation of the arrow to a much greater extent than the same variation of pull or loose in the others, whose cast is more uniform throughout. Now, were a man[15] perfect in his physical powers, or always in first-rate shooting condition, there would be no doubt as to which bow he should use, as he would in this case be able to attain to the difficult nicety required in the management of the self-yew; but as this constant perfection never can be maintained, the superior merits of this bow are partially counteracted by the extreme difficulty of doing justice to them; and the degree of harshness of pull and unsteadiness in hand of the others being but trifling, the greater certainty with which they accomplish the elevation counterbalances, upon average results, their inferiority in other respects. Another advantage the self-yew possesses is, that it is not so liable to injury from damp as are the backed bows; but then the latter are much less costly, and, with common care, need cause no fear of harm from damp, as an inch of lapping at either end covering the junction with the horns will preserve them from this danger. As regards chrysals, and breakage from other causes than damp, bows of all sorts of wood are about equally liable to failure. The main results of the comparison, then, resolve themselves into these two prominent features: namely, that the self-yew bow, from its steadiness, sweetness, and absence of vibration, ensures the straightness of the shot better than backed bows; whilst the latter, owing to the regularity of their cast not being confined quite to a hair's breadth of pull, carry off the palm for greater certainty in the elevation of the shot.

It is almost unnecessary to say that there are bad bows of all sorts, many being made of materials that are fit for nothing but firewood; and yet the bowmakers seem to be almost justified in making up such materials by the fact that occasionally the most ungainly bow will prove itself almost invaluable in use, while a perfect beauty in appearance may turn out a useless slug.

Though it may be no easy matter to decide which particular sort of bow an individual archer should adopt, yet, when that individual has once ascertained the description of[16] bow that appears to suit him best, he will be wise to confine his attention to that same sort in his future acquisition of bows. An archer who shoots much will find his bowmaker's account a serious annual matter if he keep none but the best self-yew bows; and therefore any who find it necessary to count the cost of this sport should do their best to adapt themselves to the cheaper though not much inferior backed bows. This also may be further said of the difference between self-yews and backed bows—namely, that there appears to be a sort of individuality attached to each self-yew bow, apart from the peculiarities of its class, which makes it difficult (not regarding the cost) to remedy the loss of a favourite self-yew bow. It is very much easier to replace any specimen of the other sorts of bows, as there is much less variation of character in each class.

The 'carriage bow' is made to divide into two pieces by means of a metal socket in the handle, after the fashion of the joint of a fishing-rod. The object of this make of bow is to render it more convenient as a travelling-companion; but, as the result is a bow heavy in hand and unpleasant in use, the remedy appears to be worse than the disease.

It is often asserted that the best bows should be made of steel, as superior in elasticity to wood; but this is not borne out by the results of experiment. The late Hon. R. Hely-Hutchinson, a member of the R. Tox. Soc., took a great deal of pains to have long-bows manufactured of steel both in England and in Belgium. The best of these, weighing about 50 lbs. for the 28-inch draw, with the aim and elevation which with a good wooden bow would carry an arrow 100 yards, scarcely carried its shaft as far as 60 yards, so deadly slow appeared the recoil; and besides this, the actual weight in the hand of the implement was so considerable that it would be a most serious addition to the toil of the day, on account of its being so frequently held out at arm's length, to say nothing of its having to be carried about all day.

The next point to be considered is the strength of the bow to be chosen; and respecting this, in the first place, the bow must be completely under the shooter's command—within it, but not much below it. One of the greatest mistakes young archers (and many old ones too) commit is that they will use bows that are too strong for them. In fact, there are but few to whom, at one or other period of their archery career, this remark has not applied. The desire to be considered strong appears to be the moving agent to this curious hallucination; as if a man did not rather expose his weakness by straining at a bow evidently beyond his strength, thereby calling attention to that weakness, than by using a lighter one with grace and ease, which always give the idea of force, vigour, and power. Another incentive to the use of strong bows is the passion for sending down the arrows sharp and low, and the consequent employment of powerful bows to accomplish this; the which is perhaps a greater mistake than the other, for it is not so much the strength of the bow as the perfect command of it that enables the archer to obtain this desideratum. The question is not so much what a man can pull as what he can loose; and he will without doubt obtain a lower flight of arrow by a lighter power of bow under his command, than he will by a stronger one beyond his proper management. This mania for strong bows has destroyed many a promising archer, in an archery sense of the term. Not only did one of[18] the best shots of his day, a winner of the second and first prizes at successive Grand National Meetings, dwindle beneath mediocrity in accuracy through this infatuation, but another brought himself to death's door by a dangerous illness of about a year's duration, by injury to his physical powers, brought on by the same failing, only carried to a much greater excess. And, after all, the thing so desired is not always thus attained.

Let the reader attend any Grand National Archery Meeting, and let him observe some fifty or so picked shots of the country arranged at the targets, and contending with all their might for the prizes of honour and skill. Whose arrows fly down the sharpest, steadiest, and keenest? Are they those of the archers who use the strongest bows? Not at all. Behold that archer from an Eastern county just stepping so unpretendingly forward to deliver his shafts. See! with what grace and ease the whole thing is done!—no straining, no contortions there! Mark the flight of his arrows—how keen, and low, and to the mark they fly! None fly sharper, few so sharp. And what is the strength of that beautiful self-yew bow which he holds in his hand? Scarce 50 lbs.! And yet the pace of his shaft is unsurpassed by any; and it is close upon five shillings in weight too. There is another. Mark his strength and muscular power! Possibly a bow of 80 lbs. would be within his pull; yet he knows better than to use any such, when the prizes are awarded to skill, not brute force. The bow he employs is but 48 lbs.; yet how steady and true is the flight of his arrow! And so on all through the meeting: it will be found that it is not the strongest bows, but those that are under the perfect command of their owners, that do their work the best.

Inasmuch, then, as the proper flight of an arrow from any bow depends almost entirely upon the way in which it is loosed, the strength of the bow must not be regulated by the mere muscular powers of the individual archer; for he may be able[19] to draw even a 29-inch arrow to the head in a very powerful bow without being able during a match to loose steadily a bow of more than 50 lbs. Not the power of drawing, but of loosing steadily, must therefore be the guide here. The bow must be within this loosing power, but also well up to it; for it is almost as bad to be under- as over-bowed. The evils attendant upon being over-bowed are various: the left (bow) arm, wrist, and elbow, the fingers of the right (loosing) hand and its wrist, are strained and rendered unsteady; the pull becomes uncertain and wavering, and is never twice alike; the whole system is overworked and wearied; and, besides this, the mind is depressed by ill-success; the entire result is disappointment and failure. On the other hand, care must be taken not to fall into the opposite extreme of being under-bowed, as in this case the loose becomes difficult, and generally unsteady and unequal. The weight of the bows now in general use varies from 45 lbs. to 54 lbs., stronger ones forming the exception; and the lowest of these weights is ample for the distances now usually shot. Each archer must therefore find out how much he can draw with ease and loose with steadiness throughout a day's shooting, and choose accordingly. If a beginner, 50 lbs. is probably the outside weight with which he should commence; a few pounds less, in most cases, would even be better for the starting-point. As lately as twenty years ago bows were very carelessly marked in the indication of their strength, many bows being marked as much as 10 lbs. above their actual measure; but in the present day all the bowmakers incline towards the custom of marking a new bow to weigh rather less, perhaps by 3 lbs., than its actual weight. The reason of this is that in the opinion of the marker the bow will arrive at the strength marked in the course of use. It is indeed a very rare case when a new bow does not with use get somewhat weaker.

Besides keeping the bows for his own use mostly of the same description, every archer should also keep them of just[20] about the same weight; and if he shoot much he should possess at the fewest three, as much alike as possible, and use them alternately. This will prove an economy in the end, as each will have time to recover its elasticity, and will thus last a much longer time. It is an agreeable feature in bows that they have considerable facility in recovery from the effects of hard work. This fact may be easily tested by weighing a bow on a steelyard before and after shooting a single York round with it, when a difference of one pound or more will be found in the strength of it, more particularly if the day be hot; but with a few days' rest this lost power will be regained by the bow.

In the choice of a bow a beginner should secure the assistance of an experienced friend, or content himself with an unambitious investment in a cheap specimen of backed-bow or a self-lance, on which he may safely expend his inexperience. When an archer is sufficiently advanced to know the sort and weight of bow that best suits him, let him go to the maker he prefers, and name the price he can afford to give—the prices of trustworthy self-yews vary from twenty to five guineas, of yew-backed yews from five to three guineas, and of other backed bows from three guineas to thirty shillings; whilst self-lance bows may be procured for as little as twelve shillings—and he will soon find what choice there is for him. If there appears one likely to suit, let him first examine the bow to see that there be no knots, curls, pins, splinters, chrysals, or other objectionable flaws; then let him string it, and, placing the lower end on the ground in such a position that the whole of the string shall be under his eye and uppermost, let him notice whether the bow be perfectly straight. If it be so, the bow, so balanced between the ground at the lower and a finger at the upper end, will appear symmetrically divided by the string into two parts. Should there appear to be more on one side of the string than on the other in either limb, the bow is not straight, and should be rejected. A bow is said to have a cast[21] when it is tilted in its back out of the perpendicular to the plane passing through the string and the longitudinal centre of the bow. Any bow that has this fault should also be rejected. This fault, if it should happen to exist, will be easily detected by reversing the position of the bow just previously described, i.e. by holding the bow as before, but with the back upwards. The next step is to watch the bow as it is drawn up, so as to be able to judge whether it bend evenly in both its limbs and show no sign of weakness in any particular point. The upper limb, as before stated, being the longest, should appear to bend a trifle the most, so that the whole may be symmetrical, when considered as bending from the real centre. It may next be tested, to ascertain whether it be a kicker; thus the string must be drawn up six inches or so and then loosed (of course without an arrow). If the bow have the fault of kicking ever so little, experience will easily detect it by the jolt in the hand. But on no account in this experiment should the string (without an arrow) be fully drawn and loosed. Care should be taken that the bow be sufficiently long for its strength. What has hitherto been said applies to all bows; but in self-bows attention must be paid to the straightness of the feathering of the wood. As a general rule, the lightest wood in a yew-bow will have the quickest cast, and the heaviest will make the most lasting implement. Between two bows of the same strength and length, the one being slight and the other bulky, there will be about the same difference as between a thoroughbred and a cart-horse. Therefore the preference should be given to bows that are light and slight for their strength. Light-coloured and dark yew make equally good bows, though most prefer the dark colour for choice. Fine and more open grain in yew are also equally good, but the finer is more scarce. If there be no bow suitable—i.e. none of the right weight—let the choice fall upon the best bow of greater power, and let it be reduced. Failing this, the purchaser may select an unfinished stave[22] and have it made to his own pattern; but it is not easy to foretell how a stave will make up.

There remains one point about a bow, hitherto unnoticed, and this is its section, as to shape. This may vary, being broad and flat across its back, or the contrary—deep and pointed in the belly. Here again extremes should be avoided—the bow should in shape be neither too flat nor too deep. If it be an inch or so across the back just above the handle, it should also have about the same measurement through from back to belly. This much being granted, it is further declared that the back should be almost as flat and angular as possible, showing that it has been reduced as little as may be after the removal of the bark; but the belly should be rounded; and as the back should not be reduced in its depth towards the horns, and should not get too narrow across, it will follow that the chief reduction, to arrive at the proper curvature when the bow is drawn, must be in the belly, and therefore towards the horn. A well-shaped bow will in measurement become somewhat shallower from back to belly than it is across the back as it advances towards the horns.

Bows are broken from several causes: by means of neglected chrysals in the belly, or splinters in the back; by a jerking, uneven, or crooked style of drawing; by dwelling over-long on the point of aim after the arrow is fully drawn; by the breaking of the string; by damp, and oftentimes by carelessness; and even by thoughtlessness. Bows, moreover, may be broken on the steelyard in the weighing of them. A few years ago, when the Americans first took up archery very keenly, one of their novices wrote to a prominent English archer saying that he had broken nearly seventy bows in a couple of years, and asking the reason. He was told that he must either keep his bows in a damp place or the bows must be very bad ones, or else (to which view the writer inclined) he must be in the habit of stringing them the reverse way with the belly outwards. This would certainly have a fatal effect, but it is true[23] that the Americans bought a number of very bad bows about that time from inferior makers in England. Whenever chrysals appear they must be carefully watched, and, as has already been said, if they become serious, a new belly must be added. This will not be a serious disfigurement, even to a self-yew bow. A splinter should be glued and lapped at once, but no one nowadays seems to care to have the covering patch painted as formerly, to represent as nearly as possible the colours of the different parts of the bow. Care should be taken not to stab the belly of the bow with the point of the arrow when nocking it; and the dents in the back of the bow made with the arrow as it is carelessly pulled out of the target should be avoided. A glove-button will often injure the back of the bow whilst it is being strung. As other ornaments—buttons, buckles, &c.—may also inflict disfigurements, it is better to avoid their presence as far as possible. Breakages from a bad style of drawing, or from dwelling too long on the aim, can only be avoided by adopting a better and more rational method. In order to avoid fracture through the breaking of strings, any string that shows signs of failure from too much wear or otherwise should be discarded; and strings that are too stiff, too hard, and too thin should be avoided. If a string break when the arrow is fully or almost drawn, there is but little hope for the bow; but if it break in the recoil after the arrow is shot, which fortunately is more frequently the case, the bow will seldom suffer. Yet if after the bow is strung the archer should observe that the string is no longer trustworthy, and decide to discard it, he should on no account cut it whilst the bow is braced, as the result of so doing will be an almost certain fracture. If the string be looped at both ends and the loop at either end be made too large, so that it slip off the nock in stringing, the bow may break, so that an archer who makes his own loops at the lower end of the string must be careful not to make them too loose. Breakage from damp is little to be feared in self-bows, except in localities where it[24] is exceptionally moist, or, after long neglect, when damp has taken possession of the joint in the handle. In these cases single staves only are safe. Amongst backed bows there is much mortality from this cause. Commonly, it will be the lower limb that will fail, as that is most exposed to damp, arising either from the ground whilst shooting, or from the floor when put away. If the bow has been used in damp weather it should be carefully dried and rubbed with waxed flannel or cloth. A waterproof case, an 'Ascham' raised an inch or so above the floor in a dry room, and the bow hung up, not resting on its lower horn, are the best-known precautions. Half an inch of lapping, glued and varnished, above and below the joint of the horn is also a safe precaution against damp; also an occasional narrow lap in the course of the limb will assist to 'fast bind, fast find.' As regards the danger of carelessness, bows have been broken through attempts to string them the wrong way, or by using them upside down; and thoughtlessness will lead the inexperienced to attempt to bring a bow that follows the string upright, to its infinite peril. In such cases the verdict of 'Serve him right' should be brought against the offender if he be the owner. In weighing a bow on the steelyard care must be taken to see that the peg indicating the length to be drawn be at the right point; otherwise a lady's bow, for instance, may be destroyed in the mistaken attempt to pull it up twenty-eight inches, or three inches too much.

It has already been stated that a belly much injured by chrysals may be replaced by a new belly; any incurable failure of the back may also be cured by its renewal. A weak bow or limb may also be strengthened by these means. Also, if either limb be broken or irretrievably damaged, and the remaining one be sound, and worth the expense, another limb may be successfully grafted on to the old one. If possible, let this be an old limb also, as the combination of new and old wood is not always satisfactory; the former (though well seasoned,[25] being unseasoned by use), being more yielding, is apt after a little use to lose its relative strength, and so spoil the proper balance of the bow. This grafting of one broken limb upon another may be carried to the length of grafting together two limbs of different sorts. Mr. P. Muir, who was as good a bowyer as he was an accurate shot, had a favourite bow, that did him good service in 1865 at Clifton, when he took the third place at the Grand National Archery Meeting. This bow in one limb was yew-backed yew, and in the other lance backed with hickory. A bow that is weak in the centre, and not sufficiently strong to allow of the ends being further reduced, may be brought to the required shape, and strengthened by the addition of a short belly.

With regard to unstringing the bow during the shooting, say, of a York Round of 144 arrows, at the three distances, a good bow will not need it, if the shooting be moderately quick, excepting at the end of each of the distances. If there happen to be many shooters, or very slow ones, it may be unstrung after every three or four double ends; and of course it should be unstrung whenever an interruption of the shooting may occur from rain, or any other cause; but it certainly appears unnecessary to unstring the bow after each three shots, as this is an equally uncalled-for strain upon the muscles of the archer and relief to the grain of the wood. In a discussion on this subject, however, between Mr. James Spedding and Mr. P. Muir, the latter maintained that to be unstrung at each end was as agreeable to the bow as to rest on a camp-stool was to the archer. Some archers contend that it is better to have the bow strung some few minutes before the commencement of the shooting.

All that has been said respecting men's bows, with the exception of strength and length, applies equally to those used by ladies. The usual strength of these latter varies from 24 lbs. to 30 lbs. In length they should not be less than five feet. The usual length of a lady's arrow being twenty-five inches,[26] whilst that of a gentleman is twenty-eight inches, it appears that, when fully drawn, a lady's bow must be bent more in proportion to its length than that of a gentleman. The proportion between the bows being as 5 to 6, whilst that of the arrows is as 6-1/4 to 7; yet ladies' bows appear to be quite capable of bearing this extra strain safely.

As bows of three pieces are seldom to be met with manufactured for the use of ladies, their choice of weapons is limited to self-yews, yew-backed yews, yew backed with hickory, and lance backed with hickory; also self-lance bows for beginners, &c. Ladies' bows of snake and other hard woods are still to be met with; but they are so vastly inferior to those above-mentioned that it is scarcely necessary to refer to them.

It is too common a practice amongst archers to throw the consequences of their own faults upon the bowmakers, accusing the weapon of being the cause of their failures, instead of blaming their own carelessness or want of skill. But, before this can be justly done, let each be quite certain that he has chosen his bow with care, and kept it with care; if otherwise, any accidents occurring are, ten to one, more likely to be the result of his own fault than that of the bowmaker.

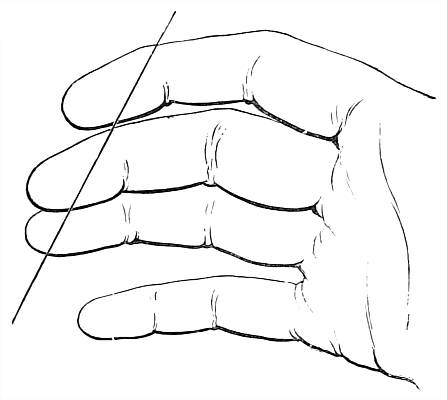

The arrow is perhaps the most important of all the implements of the archer, and requires the greatest nicety of make and excellence of materials; for, though he may get on without absolute failure with an inferior bow or other tackle, unless the arrow be of the best Robin Hood himself would have aimed in vain. Two things are essential to a good arrow, namely, perfect straightness, and a stiffness or rigidity sufficient to stand in the bow, i.e. to receive the force of the bow as delivered by the string without flirting or gadding; for a weak or supple is even worse than a crooked arrow—and it need hardly be said how little conducive to shooting straight is the latter. The straightness of the arrow is easily tested by the following simple process. Place the extremities of the nails of the thumb and middle finger of the left hand so as just to touch each other, and with the thumb and same finger of the right hand spin the arrow upon the nails at about the arrow's balancing-point; if it revolve truly and steadily, keeping in close and smooth contact with the nails, it is straight; but if it jump in the very least the contrary is the case. In order to test its strength or stiffness the arrow must be held by the nock, with its pile placed on some solid substance. The hand at liberty should now be pressed downwards on the middle of the arrow. A very little experience as to whether the arrow offer efficient resistance to this pressure will suffice to satisfy the archer about its stiffness. An arrow that is weaker on one side than on the other should also be rejected.

[28] Arrows are either selfs or footed; the former being made of a single piece of wood (these are now seldom in use, except for children), and the latter have a piece of different and harder wood joined on to them at the pile end. 'A shaft,' says old Roger Ascham,' hath three principal parts—the stele, the feather, and the head.' The stele, or wooden body of the arrow, used to be, and still is occasionally, made of different sorts of wood; but for target use, and indeed for any other description of modern shooting, all may be now discarded save one—red deal, which when clean, straight of grain, and well seasoned, whether for selfs or footed shafts, is incomparably superior to all others. For the footing any hard wood will do; and if this be solid for one inch below the pile it will be amply sufficient. Lance and Washaba are perhaps the best woods for this purpose; the latter is the toughest, but the former Mr. Ford preferred, as he thought the darkness of the Washaba had a tendency to attract the eye. The darker woods, however, are now mostly in use. This footing has three recommendations: the first, that it enables the arrow to fly more steadily and get through the wind better; the second, that, being of a substance harder than deal, it is not so easily worn by the friction it unavoidably meets with on entering the target or the ground; and the third, that this same hardness saves the point from being broken off should it happen to strike against any hard substance—such, for instance, as a stone in the ground or the iron leg of a target-stand. Before the shooting is commenced, and after it is finished, the arrows should be rubbed with a piece of oiled flannel. This will prevent the paint of the target from adhering to them. If in spite of this precaution any paint should adhere to them, sandpaper should on no account be used to clean them: this is most objectionable, as it will wear away the wood of the footing. Turpentine should be applied, or the blunt back of a knife.

Before entering upon the subject of the best shape for the[29] 'stele' of the arrow for practical use, it is necessary to say a few words upon a point where the theory and practice of archery apparently clash.

If the arrow be placed on the bowstring as if for shooting, the bow drawn, and an aim taken at an object, and if the bow be then slowly relaxed, the arrow being held until it returns to the position of rest—i.e. if the passage of the arrow over the bow be slow and gradual—it will be found, if the bow be held quite firmly during this action, that the arrow does not finally point to the object aimed at, but in a direction deviating considerably to the left of it—in fact, that its direction has been constantly deviating more and more from the point of aim at each point during its return to the position of rest. This is, of course, due to the half-breadth of the bow, the nock of the arrow being carried on the string, in a plane passing through the string and the axis of the bow's length; and this deviation will be greater if the arrow be chested (i.e. slighter at the pile than at the nock), and less if it be bobtailed (i.e. slighter at the nock than at the pile) than if the arrow be cylindrical throughout. If the same arrow, when drawn to the head, be loosed at the object aimed at—i.e. if the passage of the arrow over the bow be impulsive and instantaneous—it will go straight to the object aimed at, the shooting being in all respects perfect.

How, then, is the difference of the final direction of the arrow in the two cases to be explained?

It must be observed that the nock of the arrow being constrained to move, as it does move in the last case, causes a pressure of the arrow upon the bow (owing to its slanting position on the bow, and its simultaneous rapidity of passage), and therefore a reacting pressure of the bow upon the arrow. This makes the bow have quite a different effect upon the deviation from what it had in the first case, when the arrow moved slowly and gradually upon the bow (being held by the nock), the obstacle presented by the half-breadth of the bow[30] then causing a deviation wholly to the left. The pressure now considered, however, has a tendency to cause deviation to the left only during the first part of the arrow's passage upon the bow, whilst during the second part it causes a deviation to the right; or, more correctly speaking, the pressure of the bow upon the arrow has a tendency to cause a deviation to the left so long as the centre of gravity of the arrow is within the bow, and vice versâ. So that, if this were the only force acting upon the arrow, its centre of gravity (this is, of course, the point upon which the arrow, balanced horizontally, will poise) should lie midway in that part of the arrow which is in contact with the bow during the bow's recoil. There is another force which contributes towards this acting and reacting pressure between the arrow and the bow at the loose if the nocking-place of the string be properly fitted to the arrow, but not otherwise. As the fingers are disengaged from the string they communicate a tendency to spin to the string, and this spin immediately applies the arrow to the bow if it should happen to be off the bow through side-wind or that troublesome failing of beginners and others of a crooked pinch between the fingers upon the nock of the arrow. It will be observed that if the nocking-place be too small to fill the nock of the arrow this tendency to spin in the string will not affect the replacement of the arrow; but if the nocking-place be a good fit to the nock, the former must be a trifle flattened, and so communicate the spin of the string to the arrow in the shape of a blow upon the bow. It is not pretended that no arrow will fly straight unless the nocking-place fit the arrow. If the string be home in the nock the shot will still be correctly delivered, because the very close and violent pressure of the string on the nock will arrest the spin and so apply the arrow; but if the string be not home in the nock at the delivery of the loose, there is great danger that the nock will be broken, either from the nocking-place being too small, or from the other fault of its being too big. It is this spin given to the string as the[31] arrow is loosed that necessitates the delivery of the arrow from the other side of the bow when the thumb-loose of the Oriental archer is employed, because this loose communicates the same spin, but reversed, to the string.

The struggle of these forces is clearly indicated by the appearance of the arrow where it comes in contact with the bow when it leaves the string. It is here that the arrow always shows most wear. It is also shown by the deep groove that gets worn by the arrow in a bow that has seen much service.

The nature of the dynamical action may be thus briefly explained. The first impulse given to the arrow, being instantaneous and very great (sufficient, as has been seen, to break the arrow if the string be not home in the nock) in proportion to any other forces which act upon it, impresses a very high initial velocity in the direction of the aim, and this direction the arrow recovers notwithstanding the slight deviations caused by the mutual action between the arrow and bow before explained—these in fact, as has been shown, counteracting each other.

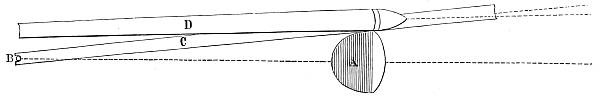

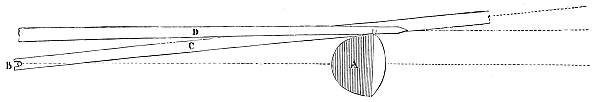

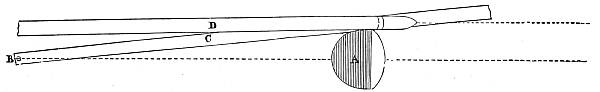

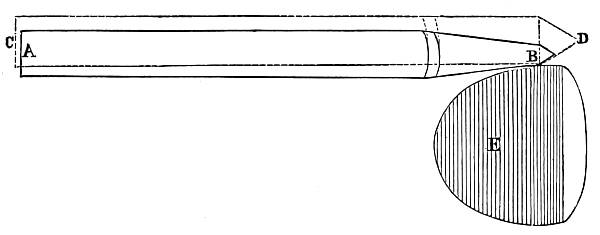

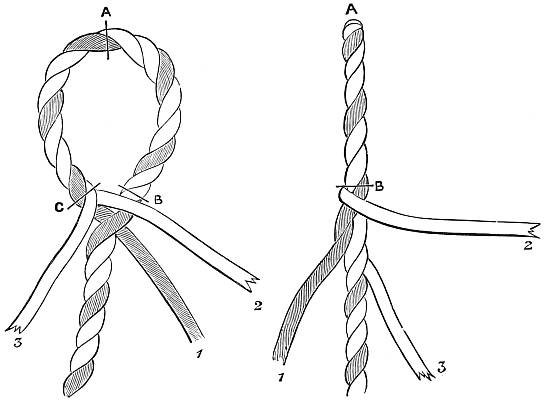

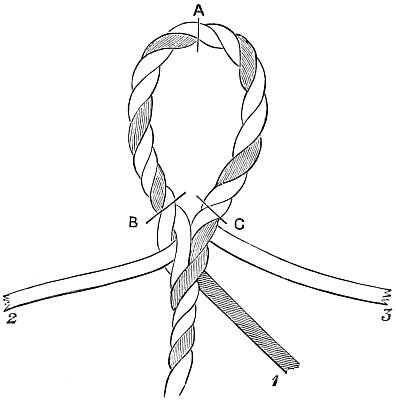

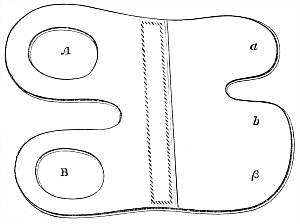

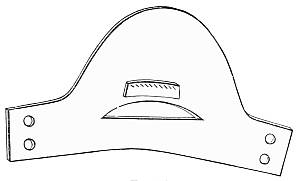

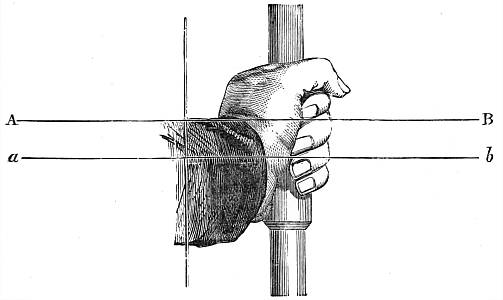

A, section of bow. B, string in nock. C, arrow nocked but not drawn. D, arrow drawn 27 inches.

The recoil of the bow, besides the motion in the direction of aim, impresses a rotary motion upon the arrow about its centre of gravity. This tendency to rotate, however, about an axis through its centre of gravity is counteracted by the feathers. For, suppose the arrow to be shot off with a slight rotary motion about a vertical axis, in a short time its point will deviate to the left of the plane of projection, and the centre of gravity will be the only point which continues in that plane. The feathers of the arrow will now be turned to the right of the same plane, and, through the velocity of the arrow, will cause a considerable resistance of the air against them. This resistance will twist the arrow until its point comes to the right of the plane of projection, when it will begin to turn the arrow the contrary way. Thus, through the agency of the feathers, the deviation of the point of the arrow from[32] the plane of projection is confined within very narrow limits. Any rotation of the arrow about a horizontal axis will be counteracted in the same way by the action of the feathers. Both these tendencies may be distinctly observed in the actual[33] initial motion of the arrow. In the discussion of these rotations of the arrow about vertical and horizontal axes the bow is supposed to be held in a vertical position.

If the foregoing reasoning be carefully considered, it will be seen how prejudicial to the correct flight of the arrow in the direction of the aim any variation in the shape of that part of it which is in contact with the bow must necessarily be; for by this means an additional force is introduced into the elements of its flight. Take for example the chested arrow, which is smallest at the point and largest at the feathers: here there is during its whole passage over the bow a constant and increasing deviation to the left of the direction of aim, caused by the arrow's shape, independent of, and in addition to, a deviation in the like direction caused by the retention of the nock upon the string. Thus this description of arrow has greater difficulty in recovering its initial direction, the forces opposed to its doing so being so much increased. Accordingly, in practice, the chested arrow has always a tendency to fly to the left. These chested arrows are mostly flight-arrows, made very light, for long-distance shooting, and they are made of this shape to prevent their being too weak-waisted to bear steadily the recoil of very strong bows.

As regards the bobtailed arrow, which is largest at the point and smallest at the feathers, the converse is true to the extent that this description of arrow will deviate towards the left less than either the straight or chested arrow; moreover, any considerable bobtailedness would render an arrow so weak-waisted that it would be useless.

There is another arrow, known as the barrelled arrow, which is largest in the middle, and tapers thence towards each end. The quickest flight may be obtained with this sort of arrow, as to it may be applied a lighter pile without bringing on either the fault of a chested arrow or the weak-waistedness of a bobtailed arrow.

[34] If the tapering be of equal amount at each end of the arrow, the pressure will act and react in precisely the same manner as in the case of the cylindrical arrow, with the result that this arrow will fly straight in the direction in which it is aimed. The cylindrical and the barrelled shapes are therefore recommended as the best for target-shooting. And as the barrelled is necessarily stronger in the waist and less likely to flirt, even if a light arrow be used with a strong bow, this shape is perhaps better than the cylindrical.

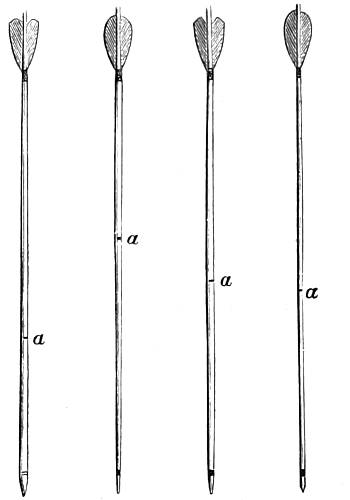

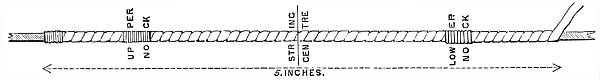

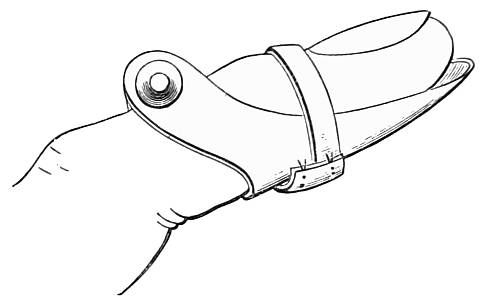

bobtail chested barrelled straight

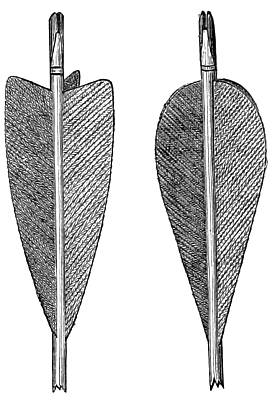

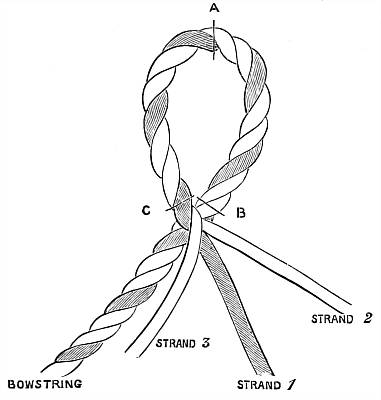

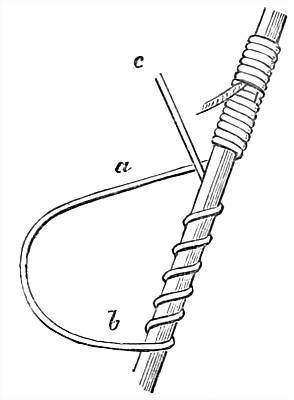

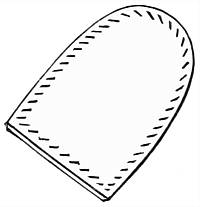

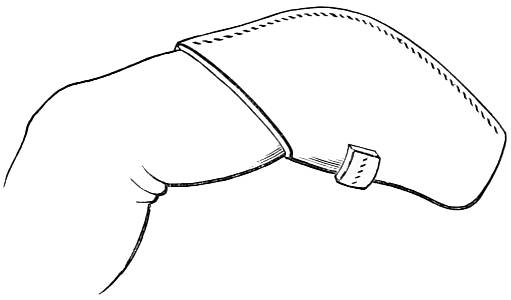

Fig. 11. a, different balancing points of thin arrows.The feathering of the arrow is about the most delicate part of the fletcher's craft, and it requires the utmost care and experience to effect it thoroughly well. It seems difficult now to realise why the feathering of the arrow came to have grown to the size in use during Mr. Ford's time, when the feather occupied the whole distance between the archer's fingers and[35] the place on the bow where the arrow lies when it is nocked previous to shooting—i.e. the length of the feather was upwards of five inches. Mr. H. Elliott was the first archer who, about fifteen years ago, reduced the dimensions of the feathers of his arrows by cutting off the three inches of each feather furthest from the nock. He found this reduction enabled the arrow to fly further. Others soon followed his example, and in the course of about twelve months all the arrow-makers had supplied their customers with arrows of the new pattern, which, however, cannot be called a new pattern, as Oriental arrows, and many flight-arrows, were much less heavily feathered. The long feathering is now scarcely ever seen, except occasionally when it is erroneously used to diminish the difficulty of shooting at sixty yards. Mr. Ford recommended rather full-sized feathers 'as giving a steadiness to the flight.' With the reduced feathers arrows fly as steadily, and certainly more keenly towards the mark. A fair amount of rib should be left on the feather, for if the rib be pared too fine the lasting quality of the feather will be diminished. The three feathers of an arrow should be from the same wing, right or left; and as none but a raw beginner will find any difficulty in nocking his arrow the right way—i.e. with what is known as the cock feather upwards, or at right angles to the line of the nock—without having this cock feather of a different colour, it is advisable to have the three feathers all alike. Perhaps the brown feathers of the peacock's wing are the best of all, but the black turkey-feathers are also highly satisfactory. The white turkey-feathers are also equally good, but had better be avoided, as they too readily get soiled, and are not to be easily distinguished from white goose-feathers. These last, as well as those of the grey goose, though highly thought of by our forefathers, are now in no repute, and it is probable that our ancestors, if they had had the same plentiful supply of peafowls and turkeys as ourselves, would have had less respect for the wings of geese. The reason why the three feathers[36] must be from the same wing is that every feather is outwardly convex and inwardly concave. When the feathers are correctly applied, all three alike, this their peculiarity of form rifles the arrow or causes it to rotate on its own axis. This may be tested by shooting an arrow through a pane of glass, when it will be found that the scraping against the arrow of the sharp edges of the fracture passes along the arrow spirally. Some years ago a very unnecessary patent was taken out for rifling an arrow by putting on the feathers spirally, over-doing what was already sufficient. As regards the position of the feather, it should be brought as near as possible to the nock. Some consider an inch in length of feather quite sufficient. It is certain that any length between two inches and one inch will do; so each individual may please himself and suit the length of the feathering to the length and weight of his arrows. The two shapes in use are the triangular and the parabolic or balloon-shaped. Of these both are good—the former having the advantage of carrying the steerage further back, whilst the latter is a trifle stiffer.

[37] The feathers are preserved from damp by a coat of oil paint laid on between them and for one-eighth of an inch above and below them. This should afterwards be varnished, and the rib of the feather should be carefully covered, but care must be taken to avoid injuring the suppleness of the feather with the varnish. Feathers laid down or ruffled by wet may be restored by spinning the arrow before a warm fire carefully.

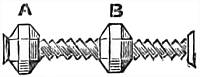

The pile, or point, is an important part of the arrow. Of the different shapes that have been used, the best for target-shooting—now almost the only survivor—is the square-shouldered parallel pile. Its greatest advantage is, that if the arrow be overdrawn so that the pile be brought on to the bow, the aim will not be injured, as must be the case with all conical piles so drawn. (Very light flight-arrows, for which the piles provided for ladies are considered too heavy, must still be furnished with the conical piles used for children's arrows.) This parallel pile is mostly made in two pieces—a pointed cone for its point, which is soldered on to the cylindrical part, which itself is made of a flat piece of metal soldered into this form. This same-shaped pile has occasionally been made turned out of solid metal; but this pile is liable to be so heavy as to be unsuitable for any but the heaviest arrows, and the fletchers aver that it is difficult to fix it on firmly owing to the grease used in its manufacture. Great care should be taken, in the manufacture of arrows, that the footing exactly fits the pile,[38] so as to fill entirely the inside of it; unless the footing of the arrow reach the bottom of the pile, the pile will either crumple up or be driven down the stele when the pile comes in contact with a hard substance. It is, of course, fixed on with glue; and to prevent its coming off from damp, a blow, or the adhesiveness of stiff clay, it is well to indent it on each side with a sharp hard-pointed punch fitted for the purpose with a groove, in which the arrow is placed whilst the necessary pressure is applied. This instrument may be procured of Hill & Son, cutlers, 4 Haymarket.

The nock should be strong, and very carefully finished, so that no injury may be done by the string or to the string. Of course the nock must be of the same size in section as the stele of the arrow; and this furnishes an additional argument against the bobtailed arrow, which is smallest at this end. The notch or groove in which the string acts should be about one-eighth of an inch wide and about three-sixteenths of an inch deep. The bottom of this notch will be much improved by the application of a round file of the right gauge, i.e. quite a trifle more than the eighth of an inch in diameter; but great care must be taken to apply this uniformly, and the nock must not be unduly weakened. This application will enable the archer to put thicker, and therefore safer, lapping to the nocking-place of the string, and the danger of the string being loose in the nock will be lessened. It is possible that this additional grooving of the nock may to a very trifling extent impede the escape of the arrow from the string. Mr. Ford recommended the application of a copper rivet through the nock near to the bottom of the notch to provide against the danger of splitting the nock. But it is so doubtful whether any rivet fine enough for safe application would be strong enough to guard against this danger, that the better plan will be to avoid the different sorts of carelessness that lead towards this accident.