"WHAT ON EARTH POSSESSED YOU TO ASK A LITERARY FELLOW DOWN HERE?"

"WHAT ON EARTH POSSESSED YOU TO ASK A LITERARY FELLOW DOWN HERE?"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lyre and Lancet, by F. Anstey

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Lyre and Lancet

A Story in Scenes

Author: F. Anstey

Release Date: December 9, 2012 [EBook #41589]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LYRE AND LANCET ***

Produced by David Clarke, JoAnn Greenwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BY

F. ANSTEY

AUTHOR OF

"VICE VERSÂ," "THE GIANT'S ROBE," "VOCES POPULI," ETC.

LONDON:

SMITH, ELDER & CO., 15, WATERLOO PLACE.

1895.

(All rights reserved.)

Reprinted from "Punch" by permission of the Proprietors.

| PART | PAGE | |

| I. | Shadows cast Before | 1 |

| II. | Select Passages from a Coming Poet | 11 |

| III. | The Two Andromedas | 21 |

| IV. | Rushing to Conclusions | 31 |

| V. | Cross Purposes | 42 |

| VI. | Round Pegs in Square Holes | 53 |

| VII. | Ignotum pro Mirifico | 64 |

| VIII. | Surprises—Agreeable and Otherwise | 76 |

| IX. | The Mauvais Quart d'Heure | 87 |

| X. | Borrowed Plumes | 98 |

| XI. | Time and the Hour | 109 |

| XII. | Dignity Under Difficulties | 119 |

| XIII. | What's in a Name? | 130 |

| XIV. | Le Vétérinaire Malgré Lui | 141 |

| XV. | Trapped! | 152 |

| XVI. | An Intellectual Privilege | 163 |

| XVII. | A Bomb Shell | 174 |

| XVIII. | The Last Straw | 184 |

| XIX. | Unearned Increment | 194 |

| XX. | Different Persons have Different Opinions | 204 |

| XXI. | The Feelings of a Mother | 213 |

| XXII. | A Descent from the Clouds | 224 |

| XXIII. | Shrinkage | 234 |

| XXIV. | The Happy Dispatch | 244 |

CHARACTERS

LYRE AND LANCET

A STORY IN SCENES

In Sir Rupert Culverin's Study at Wyvern Court. It is a rainy Saturday morning in February. Sir Rupert is at his writing-table, as Lady Culverin enters with a deprecatory air.

Lady Culverin. So here you are, Rupert! Not very busy, are you? I won't keep you a moment. (She goes to a window.) Such a nuisance it's turning out wet, with all these people in the house, isn't it?

Sir Rupert. Well, I was thinking that, as there's nothing doing out of doors, I might get a chance to knock off some of these confounded accounts, but—(resignedly)—if you think I ought to go and look after——

Lady Culverin. No, no; the men are playing billiards, and the women are in the morning-room—they're all right. I only wanted to ask you about to-night. You know the Lullingtons, and the dear Bishop and Mrs. Rodney, and one or two other people are coming to dinner? Well, who ought to take in Rohesia?

Sir Rupert (in dismay). Rohesia! No idea she was coming down this week!

Lady Culverin. Yes, by the 4.45. With dear Maisie. Surely you knew that?

Sir Rupert. In a sort of way; didn't realize it was so near, that's all.

Lady Culverin. It's some time since we had her last. And she wanted to come. I didn't think you would like me to write and put her off.

Sir Rupert. Put her off? Of course I shouldn't, Albinia. If my only sister isn't welcome at Wyvern at any time—I say at any time—where the deuce is she welcome?

Lady Culverin. I don't know, dear Rupert. But—but about the table?

Sir Rupert. So long as you don't put her near me—that's all I care about.

Lady Culverin. I mean—ought I to send her in with Lord Lullington, or the Bishop?

Sir Rupert. Why not let 'em toss up? Loser gets her, of course.

Lady Culverin. Rupert! As if I could suggest such a thing to the Bishop! I suppose she'd better go in with Lord Lullington—he's Lord Lieutenant—and then it won't matter if she does advocate Disestablishment. Oh, but I forgot; she thinks the House of Lords ought to be abolished too!

Sir Rupert. Whoever takes Rohesia in is likely to have a time of it. Talked poor Cantire into his tomb a good ten years before he was due there. Always lecturing, and domineering, and laying down the law, as long as I can remember her. Can't stand Rohesia—never could!

Lady Culverin. I don't think you ought to say so, really, Rupert. And I'm sure I get on very well with her—generally.

Sir Rupert. Because you knock under to her.

Lady Culverin. I'm sure I don't, Rupert—at least, no more than everybody else. Dear Rohesia is so strong-minded and advanced and all that, she takes such an interest in all the new movements and things, that she can't understand contradiction; she is so democratic in her ideas, don't you know.

Sir Rupert. Didn't prevent her marrying Cantire. And a democratic Countess—it's downright unnatural!

Lady Culverin. She believes it's her duty to set an example and meet the People half-way. That reminds me—did I tell you Mr. Clarion Blair is coming down this evening, too?—only till Monday, Rupert.

Sir Rupert. Clarion Blair! never heard of him.

Lady Culverin. I suppose I forgot. Clarion Blair isn't his real name, though; it's only a—an alias.

Sir Rupert. Don't see what any fellow wants with an alias. What is his real name?

Lady Culverin. Well, I know it was something ending in "ell," but I mislaid his letter. Still, Clarion Blair is the name he writes under; he's a poet, Rupert, and quite celebrated, so I'm told.

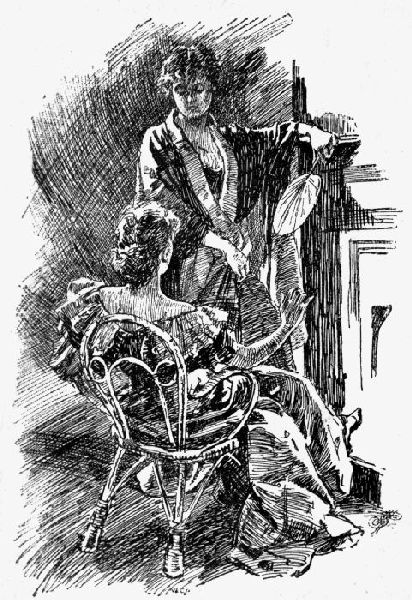

Sir Rupert (uneasily). A poet! What on earth possessed you to ask a literary fellow down here? Poetry isn't much in our way; and a poet will be, confoundedly!

"WHAT ON EARTH POSSESSED YOU TO ASK A LITERARY FELLOW DOWN HERE?"

"WHAT ON EARTH POSSESSED YOU TO ASK A LITERARY FELLOW DOWN HERE?"

Lady Culverin. I really couldn't help it, Rupert. Rohesia insisted on my having him to meet her. She likes meeting clever and interesting people. And this Mr. Blair, it seems, has just written a volume of verses which are finer than anything that's been done since—well, for ages!

Sir Rupert. What sort of verses?

Lady Culverin. Well, they're charmingly bound. I've got the book in the house, somewhere. Rohesia told me to send for it; but I haven't had time to read it yet.

Sir Rupert. Shouldn't be surprised if Rohesia hadn't, either.

Lady Culverin. At all events, she's heard it talked about. The young man's verses have made quite a sensation; they're so dreadfully clever and revolutionary, and morbid and pessimistic, and all that, so she made me promise to ask him down here to meet her!

Sir Rupert. Devilish thoughtful of her.

Lady Culverin. Wasn't it? She thought it might be a valuable experience for him; he's sprung, I believe, from quite the middle-class.

Sir Rupert. Don't see myself why he should be sprung on us. Why can't Rohesia ask him to one of her own places?

Lady Culverin. I dare say she will, if he turns out to be quite presentable. And, of course, he may, Rupert, for anything we can tell.

Sir Rupert. Then you've never seen him yourself! How did you manage to ask him here, then?

Lady Culverin. Oh, I wrote to him through his publishers. Rohesia says that's the usual way with literary persons one doesn't happen to have met. And he wrote to say he would come.

Sir Rupert. So we're to have a morbid revolutionary poet staying in the house, are we? He'll come down to dinner in a flannel shirt and no tie—or else a red one—if he don't bring down a beastly bomb and try to blow us all up! You'll find you've made a mistake, Albinia, depend upon it.

Lady Culverin. Dear Rupert, aren't you just a little bit narrow? You forget that nowadays the very best houses are proud to entertain Genius—no matter what their opinions and appearance may be. And besides, we don't know what changes may be coming. Surely it is wise and prudent to conciliate the clever young men who might inflame the masses against us. Rohesia thinks so; she says it may be our only chance of stemming the rising tide of Revolution, Rupert!

Sir Rupert. Oh, if Rohesia thinks a revolution can be stemmed by asking a few poets down from Saturday to Monday, she might do her share of the stemming at all events.

Lady Culverin. But you will be nice to him, Rupert, won't you?

Sir Rupert. I don't know that I'm in the habit of being uncivil to any guest of yours in this house, my dear, but I'll be hanged if I grovel to him, you know; the tide ain't as high as all that. But it's an infernal nuisance, 'pon my word it is; you must look after him yourself. I can't. I don't know what to talk to geniuses about; I've forgotten all the poetry I ever learnt. And if he comes out with any of his Red Republican theories in my hearing, why——

Lady Culverin. Oh, but he won't, dear. I'm certain he'll be quite mild and inoffensive. Look at Shakespeare—the bust, I mean—and he began as a poacher!

Sir Rupert. Ah, and this chap would put down the Game Laws if he could, I dare say; do away with everything that makes the country worth living in. Why, if he had his way, Albinia, there wouldn't be——

Lady Culverin. I know, dear, I know. And you must make him see all that from your point. Look, the weather really seems to be clearing a little. We might all of us get out for a drive or something after lunch. I would ride, if Deerfoot's all right again; he's the only horse I ever feel really safe upon, now.

Sir Rupert. Sorry, my dear, but you'll have to drive then. Adams tells me the horse is as lame as ever this morning, and he don't know what to make of it. He suggested having Horsfall over, but I've no faith in the local vets myself, so I wired to town for old Spavin. He's seen Deerfoot before, and we could put him up for a night or two. (To Tredwell, the butler, who enters with a telegram.) Eh, for me? just wait, will you, in case there's an answer. (As he opens it.) Ah, this is from Spavin—h'm, nuisance! "Regret unable to leave at present, bronchitis, junior partner could attend immediately if required.—Spavin." Never knew he had a partner.

Tredwell. I did hear, Sir Rupert, as Mr. Spavin was looking out for one quite recent, being hasthmatical, m'lady, and so I suppose this is him as the telegram alludes to.

Sir Rupert. Very likely. Well, he's sure to be a competent man. We'd better have him, eh, Albinia?

Lady Culverin. Oh yes, and he must stay till Deerfoot's better. I'll speak to Pomfret about having a room ready in the East Wing for him. Tell him to come by the 4.45, Rupert. We shall be sending the omnibus in to meet that.

Sir Rupert. All right, I've told him. (Giving the form to Tredwell.) See that that's sent off at once, please. (After Tredwell has left.) By the way, Albinia, Rohesia may kick up a row if she has to come up in the omnibus with a vet, eh?

Lady Culverin. Goodness, so she might! but he needn't go inside. Still, if it goes on raining like this—I'll tell Thomas to order a fly for him at the station, and then there can't be any bother about it.

In the Morning Room at Wyvern. Lady Rhoda Cokayne, Mrs. Brooke-Chatteris, and Miss Vivien Spelwane are comfortably established near the fireplace. The Hon. Bertie Pilliner, Captain Thicknesse, and Archie Bearpark, have just drifted in.

Miss Spelwane. Why, you don't mean to say you've torn yourselves away from your beloved billiards already? Quite wonderful!

Bertie Pilliner. It's too horrid of you to leave us to play all by ourselves! We've all got so cross and fractious we've come in here to be petted!

[He arranges himself at her feet, so as to exhibit a very neat pair of silk socks and pumps.

Captain Thicknesse (to himself). Do hate to see a fellow come down in the mornin' with evenin' shoes on!

Archie Bearpark (to Bertie Pilliner). You speak for yourself, Pilliner. I didn't come to be petted. Came to see if Lady Rhoda wouldn't come and toboggan down the big staircase on a tea-tray. Do! It's clinkin' sport!

Captain Thicknesse (to himself). If there's one thing I can't stand, it's a rowdy bullyraggin' ass like Archie!

Lady Rhoda Cokayne. Ta muchly, dear boy, but you don't catch me travellin' downstairs on a tea-tray twice—it's just a bit too clinkin', don't you know!

Archie Bearpark (disappointed). Why, there's a mat at the bottom of the stairs! Well, if you won't, let's get up a cushion fight, then. Bertie and I will choose sides. Pilliner, I'll toss you for first pick up—come out of that, do.

Bertie Pilliner (lazily). Thanks, I'm much too comfy where I am. And I don't see any point in romping and rumpling one's hair just before lunch.

Archie Bearpark. Well, you are slack. And there's a good hour still before lunch. Thicknesse, you suggest something, there's a dear old chap.

Captain Thicknesse (after a mental effort). Suppose we all go and have another look round at the gees—eh, what?

Bertie Pilliner. I beg to oppose. Do let's show some respect for the privacy of the British hunter. Why should I go and smack them on their fat backs, and feel every one of their horrid legs twice in one morning? I shouldn't like a horse coming into my bedroom at all hours to smack me on the back. I should hate it!

Mrs. Brooke-Chatteris. I love them—dear things! But still, it's so wet, and it would mean going up and changing our shoes too—perhaps Lady Rhoda——

[Lady Rhoda flatly declines to stir before lunch.

Captain Thicknesse (resentfully). Only thought it was better than loafin' about, that's all. (To himself.) I do bar a woman who's afraid of a little mud. (He saunters up to Miss Spelwane and absently pulls the ear of a Japanese spaniel on her knee.) Poo' little fellow, then!

Miss Spelwane. Poor little fellow? On my lap!

Captain Thicknesse. Oh, it—ah—didn't occur to me that he was on your lap. He don't seem to mind that.

Miss Spelwane. No? How forbearing of him! Would you mind not standing quite so much in my light? I can't see my work.

Captain Thicknesse (to himself, retreating). That girl's always fishin' for compliments. I didn't rise that time, though. It's precious slow here. I've a good mind to say I must get back to Aldershot this afternoon.

[He wanders aimlessly about the room; Archie Bearpark looks out of window with undisguised boredom.

Lady Rhoda. I say, if none of you are goin' to be more amusin' than this, you may as well go back to your billiards again.

Bertie Pilliner. Dear Lady Rhoda, how cruel of you! You'll have to let me stay. I'll be so good. Look here, I'll read aloud to you. I can—quite prettily. What shall it be? You don't care? No more do I. I'll take the first that comes. (He reaches for the nearest volume on a table close by.) How too delightful! Poetry—which I know you all adore.

[He turns over the leaves.

Lady Rhoda. If you ask me, I simply loathe it.

Bertie Pilliner. Ah, but then you never heard me read it, you know. Now, here is a choice little bit, stuck right up in a corner, as if it had been misbehaving itself. "Disenchantment" it's called.

[He reads.

Archie Bearpark. Jove! The Johnny who wrote that must have been feelin' chippy!

Bertie Pilliner. He gets cheaper than that in the next poem. This is his idea of "Abasement."

[He reads.

Now, do you know, I rather like that—it's so deliciously decadent!

Lady Rhoda. I should call it utter rot, myself.

Bertie Pilliner (blandly). Forgive me, Lady Rhoda. "Utterly rotten," if you like, but not "utter rot." There's a difference, really. Now, I'll read you a quaint little production which has dropped down to the bottom of the page, in low spirits, I suppose. "Stanza written in Depression near Dulwich."

[He reads.

Archie Bearpark. I should be inclined to back the toad, myself.

Miss Spelwane. If you must read, do choose something a little less dismal. Aren't there any love songs?

Bertie Pilliner. I'll look. Yes, any amount—here's one. (He reads.) "To My Lady."

Miss Spelwane (interested). So that's his type. Does he mention whether she did kiss him?

Bertie Pilliner. Probably. Poets are always privileged to kiss and tell. I'll see ... h'm, ha, yes; he does mention it ... I think I'll read something else. Here's a classical specimen.

[He reads.

And so on, don't you know.... Now I'll read you a regular rouser called "A Trumpet Blast." Sit tight, everybody!

[He reads.

[General hilarity, amidst which Lady Culverin enters.

"NOW I'LL READ YOU A REGULAR ROUSER CALLED 'A TRUMPET BLAST.'"

"NOW I'LL READ YOU A REGULAR ROUSER CALLED 'A TRUMPET BLAST.'"

Lady Culverin. So glad you all contrive to keep your spirits up, in spite of this dismal weather. What is it that's amusing you all so much, eh, dear Vivien?

Miss Spelwane. Bertie Pilliner has been reading aloud to us, dear Lady Culverin—the most ridiculous poetry—made us all simply shriek. What's the name of it? (Taking the volume out of Bertie's hand.) Oh, Andromeda, and other Poems. By Clarion Blair.

Lady Culverin (coldly). Bertie Pilliner can turn everything into ridicule, we all know; but probably you are not aware that these particular poems are considered quite wonderful by all competent judges. Indeed, my sister-in-law——

All (in consternation). Lady Cantire! Is she the author? Oh, of course, if we'd had any idea——

Lady Culverin. I've no reason to believe that Lady Cantire ever composed any poetry. I was only going to say that she was most interested in the author, and as she and my niece Maisie are coming to us this evening——

Miss Spelwane. Dear Lady Culverin, the verses are quite, quite beautiful; it was only the way they were read.

Lady Culverin. I am glad to hear you say so, my dear, because I'm also expecting the pleasure of seeing the author here, and you will probably be his neighbour to-night. I hope, Bertie, that you will remember that this young man is a very distinguished genius; there is no wit that I can discover in making fun of what one doesn't happen to understand.

[She passes on.

Bertie (plaintively, after Lady Culverin has left the room). May I trouble somebody to scrape me up? I'm pulverised! But really, you know, a real live poet at Wyvern! I say, Miss Spelwane, how will you like to have him dabbling his matted head next to you at dinner, eh?

Miss Spelwane. Perhaps I shall find a matted head more entertaining than a smooth one. And, if you've quite done with that volume, I should like to have a look at it.

[She retires with it to her room.

Archie (to himself). I'm not half sorry this Poet-johnny's comin'; I never caught a Bard in a booby-trap yet.

Captain Thicknesse (to himself). She's coming—this very evenin'! And I was nearly sayin' I must get back to Aldershot!

Lady Rhoda. So Lady Cantire's comin'; we shall all have to be on our hind legs now! But Maisie's a dear thing. Do you know her, Captain Thicknesse?

Captain Thicknesse. I—I used to meet Lady Maisie Mull pretty often at one time; don't know if she'll remember it, though.

Lady Rhoda. She'll love meetin' this writin' man—she's so fearfully romantic. I heard her say once that she'd give anythin' to be idealized by a great poet—sort of—what's their names—Petrarch and Beatrice business, don't you know. It will be rather amusin' to see whether it comes off—won't it?

Captain Thicknesse (choking). I—ah—no affair of mine, really. (To himself.) I'm not intellectual enough for her, I know that. Suppose I shall have to stand by and look on at the Petrarchin'. Well, there's always Aldershot!

[The luncheon gong sounds, to the general relief and satisfaction.

Opposite a Railway Bookstall at a London Terminus. Time—Saturday, 4.25 P.M.

Drysdale (to his friend, Galfrid Undershell, whom he is "seeing off"). Twenty minutes to spare; time enough to lay in any quantity of light literature.

Undershell (in a head voice). I fear the merely ephemeral does not appeal to me. But I should like to make a little experiment. (To the Bookstall Clerk.) A—do you happen to have a copy left of Clarion Blair's Andromeda?

Clerk. Not in stock, sir. Never 'eard of the book, but dare say I could get it for you. Here's a Detective Story we're sellin' like 'ot cakes—The Man with the Missing Toe—very cleverly written story, sir.

"HERE'S A DETECTIVE STORY WE'RE SELLING LIKE 'OT CAKES."

"HERE'S A DETECTIVE STORY WE'RE SELLING LIKE 'OT CAKES."

Undershell. I merely wished to know—that was all. (Turning with resigned disgust to Drysdale.) Just think of it, my dear fellow. At a bookstall like this one feels the pulse, as it were, of Contemporary Culture; and here my Andromeda, which no less an authority than the Daily Chronicle hailed as the uprising of a new and splendid era in English Song-making, a Poetic Renascence, my poor Andromeda, is trampled underfoot by—(choking)—Men with Missing Toes! What a satire on our so-called Progress!

Drysdale. That a purblind public should prefer a Shilling Shocker for railway reading when for a modest half-guinea they might obtain a numbered volume of Coming Poetry on hand-made paper! It does seem incredible,—but they do. Well, if they can't read Andromeda on the journey, they can at least peruse a stinger on it in this week's Saturday. Seen it?

Undershell. No. I don't vex my soul by reading criticisms on my work. I am no Keats. They may howl—but they will not kill me. By the way, the Speaker had a most enthusiastic notice last week.

Drysdale. So you saw that then? But you're right not to mind the others. When a fellow's contrived to hang on to the Chariot of Fame, he can't wonder if a few rude and envious beggars call out "Whip behind!" eh? You don't want to get in yet? Suppose we take a turn up to the end of the platform.

[They do.

James Spurrell, M.R.C.V.S., enters with his friend, Thomas Tanrake, of Hurdell and Tanrake, Job and Riding Masters, Mayfair.

Spurrell. Yes, it's lucky for me old Spavin being laid up like this—gives me a regular little outing, do you see? going down to a swell place like this Wyvern Court, and being put up there for a day or two! I shouldn't wonder if they do you very well in the housekeeper's room. (To Clerk.) Give me a Pink Un and last week's Dog Fancier's Guide.

Clerk. We've returned the unsold copies, sir. Could give you this week's; or there's The Rabbit and Poultry Breeder's Journal.

Spurrell. Oh, rabbits be blowed! (To Tanrake.) I wanted you to see that notice they put in of Andromeda and me, with my photo and all; it said she was the best bull-bitch they'd seen for many a day, and fully deserved her first prize.

Tanrake. She's a rare good bitch, and no mistake. But what made you call her such an outlandish name?

Spurrell. Well, I was going to call her Sal; but a chap at the College thought the other would look more stylish if I ever meant to exhibit her. Andromeda was one of them Roman goddesses, you know.

Tanrake. Oh, I knew that right enough. Come and have a drink before you start—just for luck—not that you want that.

Spurrell. I'm lucky enough in most things, Tom; in everything except love. I told you about that girl, you know—Emma—and my being as good as engaged to her, and then, all of a sudden, she went off abroad, and I've never seen or had a line from her since. Can't call that luck, you know. Well, I won't say no to a glass of something.

[They disappear into the refreshment room.

The Countess of Cantire enters with her daughter, Lady Maisie Mull.

Lady Cantire (to Footman). Get a compartment for us, and two foot-warmers, and a second-class as near ours as you can for Phillipson; then come back here. Stay, I'd better give you Phillipson's ticket. (The Footman disappears in the crowd.) Now we must get something to read on the journey. (To Clerk.) I want a book of some sort—no rubbish, mind; something serious and improving, and not a work of fiction.

Clerk. Exactly so, ma'am. Let me see. Ah, here's Alone with the 'Airy Ainoo. How would you like that?

Lady Cantire (with decision). I should not like it at all.

Clerk. I quite understand. Well, I can give you Three 'Undred Ways of Dressing the Cold Mutton—useful little book for a family, redooced to one and ninepence.

Lady Cantire. Thank you. I think I will wait till I am reduced to one and ninepence.

Clerk. Precisely. What do you say to Seven 'Undred Side-splitters for Sixpence? 'Ighly yumerous, I assure you.

Lady Cantire. Are these times to split our sides, with so many serious social problems pressing for solution? You are presumably not without intelligence; do you never reflect upon the responsibility you incur in assisting to circulate trivial and frivolous trash of this sort?

Clerk (dubiously). Well, I can't say as I do, particular, ma'am. I'm paid to sell the books—I don't select 'em.

Lady Cantire. That is no excuse for you—you ought to exercise some discrimination on your own account, instead of pressing people to buy what can do them no possible good. You can give me a Society Snippets.

Lady Maisie. Mamma! A penny paper that says such rude things about the Royal Family!

Lady Cantire. It's always instructive to know what these creatures are saying about one, my dear, and it's astonishing how they manage to find out the things they do. Ah, here's Gravener coming back. He's got us a carriage, and we'd better get in.

[She and her daughter enter a first-class compartment; Undershell and Drysdale return.

Drysdale (to Undershell). Well, I don't see now where the insolence comes in. These people have invited you to stay with them——

Undershell. But why? Not because they appreciate my work—which they probably only half understand—but out of mere idle curiosity to see what manner of strange beast a Poet may be! And I don't know this Lady Culverin—never met her in my life! What the deuce does she mean by sending me an invitation? Why should these smart women suppose that they are entitled to send for a Man of Genius, as if he was their lackey? Answer me that!

Drysdale. Perhaps the delusion is encouraged by the fact that Genius occasionally condescends to answer the bell.

Undershell (reddening). Do you imagine I am going down to this place simply to please them?

Drysdale. I should think it a doubtful kindness, in your present frame of mind; and, as you are hardly going to please yourself, wouldn't it be more dignified, on the whole, not to go at all?

Undershell. You never did understand me! Sometimes I think I was born to be misunderstood! But you might do me the justice to believe that I am not going from merely snobbish motives. May I not feel that such a recognition as this is a tribute less to my poor self than to Literature, and that, as such, I have scarcely the right to decline it?

Drysdale. Ah, if you put it in that way, I am silenced, of course.

Undershell. Or what if I am going to show these Patricians that—Poet of the People as I am—they can neither patronise nor cajole me?

Drysdale. Exactly, old chap—what if you are?

Undershell. I don't say that I may not have another reason—a—a rather romantic one—but you would only sneer if I told you! I know you think me a poor creature whose head has been turned by an undeserved success.

Drysdale. You're not going to try to pick a quarrel with an old chum, are you? Come, you know well enough I don't think anything of the sort. I've always said you had the right stuff in you, and would show it some day; there are even signs of it in Andromeda here and there; but you'll do better things than that, if you'll only let some of the wind out of your head. I take an interest in you, old fellow, and that's just why it riles me to see you taking yourself so devilish seriously on the strength of a little volume of verse which—between you and me—has been "boomed" for all it's worth, and considerably more. You've only got your immortality on a short repairing lease at present, old boy!

Undershell (with bitterness). I am fortunate in possessing such a candid friend. But I mustn't keep you here any longer.

Drysdale. Very well. I suppose you're going first? Consider the feelings of the Culverin footman at the other end!

Undershell (as he fingers a first-class ticket in his pocket). You have a very low view of human nature! (Here he becomes aware of a remarkably pretty face at a second-class window close by). As it happens, I am travelling second.

[He gets in.

Drysdale (at the window). Well, good-bye, old chap. Good luck to you at Wyvern, and remember—wear your livery with as good a grace as possible.

Undershell. I do not intend to wear any livery whatever.

[The owner of the pretty face regards Undershell with interest.

Spurrell (coming out of the refreshment room). What, second—with all my exes. paid? Not likely! I'm going to travel in style this journey. No—not a smoker; don't want to create a bad impression, you know. This will do for me.

[He gets into a compartment occupied by Lady Cantire and her daughter.

Tanrake (at the window). There—you're off now. Pleasant journey to you, old man. Hope you'll enjoy yourself at this Wyvern Court you're going to—and, I say, don't forget to send me that notice of Andromeda when you get back!

[The Countess and Lady Maisie start slightly; the train moves out of the station.

In a First-class Compartment.

Spurrell (to himself). Formidable old party opposite me in the furs! Nice-looking girl over in the corner; not a patch on my Emma, though! Wonder why I catch 'em sampling me over their papers whenever I look up! Can't be anything wrong with my turn out. Why, of course, they heard Tom talk about my going down to Wyvern Court; think I'm a visitor there and no end of a duke! Well, what snobs some people are, to be sure!

Lady Cantire (to herself). So this is the young poet I made Albinia ask to meet me. I can't be mistaken, I distinctly heard his friend mention Andromeda. H'm, well, it's a comfort to find he's clean! Have I read his poetry or not? I know I had the book, because I distinctly remember telling Maisie she wasn't to read it—but—well, that's of no consequence. He looks clever and quite respectable—not in the least picturesque—which is fortunate. I was beginning to doubt whether it was quite prudent to bring Maisie; but I needn't have worried myself.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Here, actually in the same carriage! Does he guess who I am? Somehow—— Well, he certainly is different from what I expected. I thought he would show more signs of having thought and suffered; for he must have suffered to write as he does. If mamma knew I had read his poems; that I had actually written to beg him not to refuse Aunt Albinia's invitation! He never wrote back. Of course I didn't put any address; but still, he could have found out from the Red Book if he'd cared. I'm rather glad now he didn't care.

Spurrell (to himself). Old girl seems as if she meant to be sociable; better give her an opening. (Aloud.) Hem! would you like the window down an inch or two?

Lady Cantire. Not on my account, thank you.

Spurrell (to himself). Broke the ice, anyway. (Aloud.) Oh, I don't want it down, but some people have such a mania for fresh air.

Lady Cantire (with a dignified little shiver). Have they? With a temperature as glacial as it is in here! They must be maniacs indeed!

Spurrell. Well, it is chilly; been raw all day. (To himself.) She don't answer. I haven't broken the ice.

[He produces a memorandum book.

Lady Maisie (to herself). He hasn't said anything very original yet. So nice of him not to pose! Oh, he's got a note-book; he's going to compose a poem. How interesting!

"HE'S GOING TO COMPOSE A POEM. HOW INTERESTING!"

"HE'S GOING TO COMPOSE A POEM. HOW INTERESTING!"

Spurrell (to himself). Yes, I'm all right if Heliograph wins the Lincolnshire Handicap; lucky to get on at the price I did. Wonder what's the latest about the City and Suburban? Let's see whether the Pink Un has anything about it.

[He refers to the Sporting Times.

Lady Maisie (to herself). The inspiration's stopped—what a pity! How odd of him to read the Globe! I thought he was a Democrat!

Lady Cantire. Maisie, there's quite a clever little notice in Society Snippets about the dance at Skympings last week. I'm sure I wonder how they pick up these things; it quite bears out what I was told; says the supper arrangements were "simply disgraceful; not nearly enough champagne; and what there was, undrinkable!" So like poor dear Lady Chesepare; never does do things like anybody else. I'm sure I've given her hints enough!

Spurrell (to himself, with a suppressed grin). Wants to let me see she knows some swells. Now ain't that paltry?

Lady Cantire (tendering the paper). Would you like to see it, Maisie? Just this bit here; where my finger is.

Lady Maisie (to herself, flushing). I saw him smile. What must he think of us, with his splendid scorn for rank? (Aloud.) No, thank you, mamma: such a wretched light to read by!

Spurrell (to himself). Chance for me to cut in! (Aloud.) Beastly light, isn't it? 'Pon my word, the company ought to provide us with a dog and string apiece when we get out!

Lady Cantire (bringing a pair of long-handled glasses to bear upon him). I happen to hold shares in this line. May I ask why you consider a provision of dogs and string at all the stations a necessary or desirable expenditure?

Spurrell. Oh—er—well, you know, I only meant, bring on blindness and that. Harmless attempt at a joke, that's all.

Lady Cantire. I see. I scarcely expected that you would condescend to such weakness. I—ah—think you are going down to stay at Wyvern for a few days, are you not?

Spurrell (to himself). I was right. What Tom said did fetch the old girl; no harm in humouring her a bit. (Aloud.) Yes—oh yes, they—aw—wanted me to run down when I could.

Lady Cantire. I heard they were expecting you. You will find Wyvern a pleasant house—for a short visit.

Spurrell (to himself). She heard! Oh, she wants to kid me she knows the Culverins. Rats! (Aloud.) Shall I, though? I dare say.

Lady Cantire. Lady Culverin is a very sweet woman; a little limited, perhaps, not intellectual, or quite what one would call the grande dame; but perhaps that could scarcely be expected.

Spurrell (vaguely). Oh, of course not—no. (To himself.) If she bluffs, so can I! (Aloud.) It's funny your turning out to be an acquaintance of Lady C.'s, though.

Lady Cantire. You think so? But I should hardly call myself an acquaintance.

Spurrell (to himself). Old cat's trying to back out of it now; she shan't, though! (Aloud.) Oh, then I suppose you know Sir Rupert best?

Lady Cantire. Yes, I certainly know Sir Rupert better.

Spurrell (to himself). Oh, you do, do you? We'll see. (Aloud.) Nice cheery old chap, Sir Rupert, isn't he? I must tell him I travelled down in the same carriage with a particular friend of his. (To himself.) That'll make her sit up!

Lady Cantire. Oh, then you and my brother Rupert have met already?

Spurrell (aghast). Your brother! Sir Rupert Culverin your——! Excuse me—if I'd only known, I—I do assure you I never should have dreamt of saying——!

Lady Cantire (graciously). You've said nothing whatever to distress yourself about. You couldn't possibly be expected to know who I was. Perhaps I had better tell you at once that I am Lady Cantire, and this is my daughter, Lady Maisie Mull. (Spurrell returns Lady Maisie's little bow in the deepest confusion.) We are going down to Wyvern too, so I hope we shall very soon become better acquainted.

Spurrell (to himself, overwhelmed). The deuce we shall! I have got myself into a hole this time; I wish I could see my way well out of it! Why on earth couldn't I hold my confounded tongue? I shall look an ass when I tell 'em.

[He sits staring at them in silent embarrassment.

In a Second-class Compartment.

Undershell (to himself). Singularly attractive face this girl has; so piquant and so refined! I can't help fancying she is studying me under her eyelashes. She has remarkably bright eyes. Can she be interested in me? Does she expect me to talk to her? There are only she and I—but no, just now I would rather be alone with my thoughts. This Maisie Mull whom I shall meet so soon; what is she like, I wonder? I presume she is unmarried. If I may judge from her artless little letter, she is young and enthusiastic, and she is a passionate admirer of my verse; she is longing to meet me. I suppose some men's vanity would be flattered by a tribute like that. I think I must have none; for it leaves me strangely cold. I did not even reply; it struck me that it would be difficult to do so with any dignity, and she didn't tell me where to write to.... After all, how do I know that this will not end—like everything else—in disillusion? Will not such crude girlish adoration pall upon me in time? If she were exceptionally lovely; or say, even as charming as this fair fellow-passenger of mine—why then, to be sure—but no, something warns me that that is not to be. I shall find her plain, sandy, freckled; she will render me ridiculous by her undiscriminating gush.... Yes, I feel my heart sink more and more at the prospect of this visit. Ah me!

[He sighs heavily.

His Fellow Passenger (to herself). It's too silly to be sitting here like a pair of images, considering that—— (Aloud.) I hope you aren't feeling unwell?

Undershell. Thank you, no, not unwell. I was merely thinking.

His Fellow Passenger. You don't seem very cheerful over it, I must say. I've no wish to be inquisitive, but perhaps you're feeling a little low-spirited about the place you're going to?

Undershell. I—I must confess I am rather dreading the prospect. How wonderful that you should have guessed it!

His Fellow Passenger. Oh, I've been through it myself. I'm just the same when I go down to a new place; feel a sort of sinking, you know, as if the people were sure to be disagreeable, and I should never get on with them.

Undershell. Exactly my own sensations! If I could only be sure of finding one kindred spirit, one soul who would help and understand me. But I daren't let myself hope even for that!

His Fellow Passenger. Well, I wouldn't judge beforehand. The chances are there'll be somebody you can take to.

Undershell (to himself). What sympathy! What bright, cheerful common sense! (Aloud.) Do you know, you encourage me more than you can possibly imagine!

His Fellow Passenger (retreating). Oh, if you are going to take my remarks like that, I shall be afraid to go on talking to you!

Undershell (with pathos). Don't—don't be afraid to talk to me! If you only knew the comfort you give! I have found life very sad, very solitary. And true sympathy is so rare, so refreshing. I—I fear such an appeal from a stranger may seem a little startling; it is true that hitherto we have only exchanged a very few sentences; and yet already I feel that we have something—much—in common. You can't be so cruel as to let all intimacy cease here—it is quite tantalising enough that it must end so soon. A very few more minutes, and this brief episode will be only a memory; I shall have left the little green oasis far behind me, and be facing the dreary desert once more—alone!

His Fellow Passenger (laughing). Well, of all the uncomplimentary things! As it happens, though, "the little green oasis"—as you're kind enough to call me—won't be left behind; not if it's aware of it! I think I heard your friend mention Wyvern Court! Well, that's where I'm going.

Undershell (excitedly). You—you are going to Wyvern Court! Why, then, you must be——

[He checks himself.

His Fellow Passenger. What were you going to say; what must I be?

Undershell (to himself). There is no doubt about it; bright, independent girl; gloves a trifle worn; travels second-class for economy; it must be Miss Mull herself; her letter mentioned Lady Culverin as her aunt. A poor relation, probably. She doesn't suspect that I am—— I won't reveal myself just yet; better let it dawn upon her gradually. (Aloud.) Why, I was only about to say, why then you must be going to the same house as I am. How extremely fortunate a coincidence!

His Fellow Passenger. That remains to be seen. (To herself.) What a funny little man; such a flowery way of talking for a footman. Oh, but I forgot; he said he wasn't going to wear livery. Well, he would look a sight in it!

In a First-class Compartment.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Poets don't seem to have much self-possession. He seems perfectly overcome by hearing my name like that. If only he doesn't lose his head completely and say something about my wretched letter!

Spurrell (to himself). I'd better tell 'em before they find out for themselves. (Aloud; desperately.) My lady, I—I feel I ought to explain at once how I come to be going down to Wyvern like this.

[Lady Maisie only just suppresses a terrified protest.

Lady Cantire (benignly amused). My good sir, there's not the slightest necessity; I am perfectly aware of who you are, and everything about you!

Spurrell (incredulously). But really I don't see how your ladyship—— Why, I haven't said a word that——

Lady Cantire (with a solemn waggishness.) Celebrities who mean to preserve their incognito shouldn't allow their friends to see them off. I happened to hear a certain Andromeda mentioned, and that was quite enough for Me!

Spurrell (to himself, relieved). She knows; seen the sketch of me in the Dog Fancier, I expect; goes in for breeding bulls herself, very likely. Well, that's a load off my mind! (Aloud.) You don't say so, my lady. I'd no idea your ladyship would have any taste that way; most agreeable surprise to me, I can assure you!

Lady Cantire. I see no reason for surprise in the matter. I have always endeavoured to cultivate my taste in all directions; to keep in touch with every modern development. I make it a rule to read and see everything. Of course, I have no time to give more than a rapid glance at most things; but I hope some day to be able to have another look at your Andromeda. I hear the most glowing accounts from all the judges.

Spurrell (to himself). She knows all the judges! She must be in the fancy! (Aloud.) Any time your ladyship likes to name I shall be proud and happy to bring her round for your inspection.

Lady Cantire (with condescension). If you are kind enough to offer me a copy of Andromeda, I shall be most pleased to possess one.

Spurrell (to himself). Sharp old customer, this; trying to rush me for a pup. I never offered her one! (Aloud.) Well, as to that, my lady, I've promised so many already, that really I don't—but there—I'll see what I can do for you. I'll make a note of it; you mustn't mind having to wait a bit.

Lady Cantire (raising her eyebrows). I will make an effort to support existence in the meantime.

Lady Maisie (to herself). I couldn't have believed that the man who could write such lovely verses should be so—well, not exactly a gentleman! How petty of me to have such thoughts. Perhaps geniuses never are. And as if it mattered! And I'm sure he's very natural and simple, and I shall like him when I know him better.

[The train slackens.

Lady Cantire. What station is this? Oh, it is Shuntingbridge. (To Spurrell, as they get out.) Now, if you'll kindly take charge of these bags, and go and see whether there's anything from Wyvern to meet us—you will find us here when you come back.

On the Platform at Shuntingbridge.

Lady Cantire. Ah, there you are, Phillipson! Yes, you can take the jewel-case; and now you had better go and see after the trunks. (Phillipson hurries back to the luggage-van; Spurrell returns.) Well, Mr.—I always forget names, so I shall call you "Andromeda"—have you found out—— The omnibus, is it? Very well, take us to it, and we'll get in.

[They go outside.

Undershell (at another part of the platform—to himself). Where has Miss Mull disappeared to? Oh, there she is, pointing out her luggage. What a quantity she travels with! Can't be such a very poor relation. How graceful and collected she is, and how she orders the porters about! I really believe I shall enjoy this visit. (To a porter.) That's mine—the brown one with a white star. I want it to go to Wyvern Court—Sir Rupert Culverin's.

Porter (shouldering it). Right, sir. Follow me, if you please.

[He disappears with it.

Undershell (to himself). I mustn't leave Miss Mull alone. (Advancing to her.) Can I be of any assistance?

Phillipson. It's all done now. But you might try and find out how we're to get to the Court.

[Undershell departs; is requested to produce his ticket, and spends several minutes in searching every pocket but the right one.

SEARCHING EVERY POCKET BUT THE RIGHT ONE.

SEARCHING EVERY POCKET BUT THE RIGHT ONE.

In the Station Yard at Shuntingbridge.

Lady Cantire (from the interior of the Wyvern omnibus, testily, to Footman). What are we waiting for now? Is my maid coming with us—or how?

Footman. There's a fly ordered to take her, my lady.

Lady Cantire (to Spurrell, who is standing below). Then it's you who are keeping us!

Spurrell. If your ladyship will excuse me. I'll just go and see if they've put out my bag.

Lady Cantire (impatiently). Never mind about your bag. (To Footman.) What have you done with this gentleman's luggage?

Footman. Everything for the Court is on top now, my lady.

[He opens the door for Spurrell.

Lady Cantire (to Spurrell, who is still irresolute). For goodness' sake don't hop about on that step! Come in, and let us start.

Lady Maisie. Please get in—there's plenty of room!

Spurrell (to himself). They are chummy, and no mistake! (Aloud, as he gets in.) I do hope it won't be considered any intrusion—my coming up along with your ladyships, I mean!

Lady Cantire (snappishly). Intrusion! I never heard such nonsense! Did you expect to be asked to run behind? You really mustn't be so ridiculously modest. As if your Andromeda hadn't procured you the entrée everywhere!

[The omnibus starts.

Spurrell (to himself). Good old Drummy! No idea I was such a swell. I'll keep my tail up. Shyness ain't one of my failings. (Aloud, to an indistinct mass at the further end of the omnibus, which is unlighted.) Er—hum—pitch dark night, my lady, don't get much idea of the country! (The mass makes no response.) I was saying, my lady, it's too dark to—— (The mass snores peacefully.) Her ladyship seems to be taking a snooze on the quiet, my lady. (To Lady Maisie.) (To himself.) Not that that's the term for it!

Lady Maisie (distantly). My mother gets tired rather easily. (To herself.) It's really too dreadful; he makes me hot all over! If he's going to do this kind of thing at Wyvern! And I'm more or less responsible for him, too! I must see if I can't—— It will be only kind. (Aloud, nervously.) Mr.—Mr. Blair!

Spurrell. Excuse me, my lady, not Blair—Spurrell.

Lady Maisie. Of course, how stupid of me. I knew it wasn't really your name. Mr. Spurrell, then, you—you won't mind if I give you just one little hint, will you?

Spurrell. I shall take it kindly of your ladyship, whatever it is.

Lady Maisie (more nervously still). It's really such a trifle, but—but, in speaking to mamma or me, it isn't at all necessary to say "my lady" or "your ladyship." I—I mean, it sounds rather, well—formal, don't you know!

Spurrell (to himself). She's going to be chummy now! (Aloud.) I thought, on a first acquaintance, it was only manners.

Lady Maisie. Oh—manners? yes, I—I dare say—but still—but still—not at Wyvern, don't you know. If you like, you can call mamma "Lady Cantire," and me "Lady Maisie," now and then, and, of course, my aunt will be "Lady Culverin," but—but if there are other people staying in the house, you needn't call them anything, do you see?

Spurrell (to himself). I'm not likely to have the chance! (Aloud.) Well, if you're sure they won't mind it, because I'm not used to this sort of thing, so I put myself entirely in your hands,—for, of course, you know what brought me down here?

Lady Maisie (to herself). He means my foolish letter! Oh, I must put a stop to that at once! (In a hurried undertone.) Yes—yes; I—I think I do I mean, I do know—but—but please forget it—indeed, you must!

Spurrell (to himself). Forget I've come down as a vet? The Culverins will take care I don't forget that! (Aloud.) But, I say, it's all very well; but how can I? Why, look here; I was told I was to come down here on purpose to——

Lady Maisie (on thorns). I know—you needn't tell me! And don't speak so loud! Mamma might hear!

Spurrell (puzzled). What if she did? Why, I thought her la—your mother knew!

Lady Maisie (to herself). He actually thinks I should tell mamma! Oh, how dense he is! (Aloud.) Yes—yes—of course she knows—but—but you might wake her! And—and please don't allude to it again—to me or—or any one. (To herself.) That I should have to beg him to be silent like this! But what can I do? Goodness only knows what he mightn't say, if I don't warn him!

Spurrell (nettled). I don't mind who knows. I'm not ashamed of it, Lady Maisie—whatever you may be!

Lady Maisie (to herself, exasperated). He dares to imply that I've done something to be ashamed of! (Aloud, haughtily.) I'm not ashamed—why should I be? Only—oh, can't you really understand that—that one may do things which one wouldn't care to be reminded of publicly? I don't wish it—isn't that enough?

Spurrell (to himself). I see what she's at now—doesn't want it to come out that she's travelled down here with a vet! (Aloud, stiffly.) A lady's wish is enough for me at any time. If you're sorry for having gone out of your way to be friendly, why, I'm not the person to take advantage of it. I hope I know how to behave.

[He takes refuge in offended silence.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Why did I say anything at all! I've only made things worse—I've let him see that he has an advantage. And he's certain to use it sooner or later—unless I am civil to him. I've offended him now—and I shall have to make it up with him!

Spurrell (to himself). I thought all along she didn't seem as chummy as her mother—but to turn round on me like this!

Lady Cantire (waking up). Well, Mr. Andromeda, I should have thought you and my daughter might have found some subject in common; but I haven't heard a word from either of you since we left the station.

Lady Maisie (to herself). That's some comfort! (Aloud.) You must have had a nap, mamma. We—we have been talking.

Spurrell. Oh yes, we have been talking, I can assure you, Lady Cantire!

Lady Cantire. Dear me. Well, Maisie, I hope the conversation was entertaining?

Lady Maisie. M—most entertaining, mamma!

Lady Cantire. I'm quite sorry I missed it. (The omnibus stops.) Wyvern at last! But what a journey it's been, to be sure!

Spurrell (to himself). I should just think it had. I've never been so taken up and put down in all my life! But it's over now; and, thank goodness, I'm not likely to see any more of 'em!

[He gets out with alacrity.

In the Entrance Hall at Wyvern.

Tredwell (to Lady Cantire). This way, if you please, my lady. Her ladyship is in the Hamber Boudwore.

Lady Cantire. Wait. (She looks round.) What has become of that young Mr. Androm——? (Perceiving Spurrell, who has been modestly endeavouring to efface himself.) Ah, there he is! Now, come along, and be presented to my sister-in-law. She'll be enchanted to know you!

Spurrell. But indeed, my lady, I—I think I'd better wait till she sends for me.

Lady Cantire. Wait? Fiddlesticks! What! A famous young man like you! Remember Andromeda, and don't make yourself so ridiculous!

Spurrell (miserably). Well, Lady Cantire, if her ladyship says anything, I hope you'll bear me out that it wasn't——

Lady Cantire. Bear you out? My good young man, you seem to need somebody to bear you in! Come, you are under my wing. I answer for your welcome—so do as you're told.

Spurrell (to himself, as he follows resignedly). It's my belief there'll be a jolly row when I do go in; but it's not my fault!

Tredwell (opening the door of the Amber Boudoir). Lady Cantire and Lady Maisie Mull (To Spurrell.) What name, if you please, sir?

"WHAT NAME, IF YOU PLEASE, SIR?"

"WHAT NAME, IF YOU PLEASE, SIR?"

Spurrell (dolefully). You can say "James Spurrell"—you needn't bellow it, you know!

Tredwell (ignoring this suggestion). Mr. James Spurrell.

Spurrell (to himself, on the threshold). If I don't get the chuck for this, I shall be surprised, that's all!

[He enters.

In a Fly.

Undershell (to himself). Alone with a lovely girl, who has no suspicion, as yet, that I am the poet whose songs have thrilled her with admiration! Could any situation be more romantic? I think I must keep up this little mystification as long as possible.

Phillipson (to herself). I wonder who he is? Somebody's Man, I suppose. I do believe he's struck with me. Well, I've no objection. I don't see why I shouldn't forget Jim now and then—he's quite forgotten me! (Aloud.) They might have sent a decent carriage for us instead of this ramshackle old summerhouse. We shall be hours getting to the house at this rate!

Undershell (gallantly). For my part, I care not how long we may be. I feel so unspeakably content to be where I am.

Phillipson (disdainfully). In this mouldy, lumbering old concern? You must be rather easily contented, then!

Undershell (dreamily). It travels only too swiftly. To me it is a veritable enchanted car, drawn by a magic steed.

Phillipson. I don't know whether he's magic—but I'm sure he's lame. And stuffiness is not my notion of enchantment.

Undershell. I'm not prepared to deny the stuffiness. But cannot you guess what has transformed this vehicle for me—in spite of its undeniable shortcomings—or must I speak more plainly still?

Phillipson. Well, considering the shortness of our acquaintance, I must say you've spoken quite plainly enough as it is!

Undershell. I know I must seem unduly expansive, and wanting in reserve; and yet that is not my true disposition. In general, I feel an almost fastidious shrinking from strangers——

Phillipson (with a little laugh). Really? I shouldn't have thought it!

Undershell. Because, in the present case, I do not—I cannot—feel as if we were strangers. Some mysterious instinct led me, almost from the first, to associate you with a certain Miss Maisie Mull.

Phillipson. Well, I wonder how you discovered that. Though you shouldn't have said "Miss"—Lady Maisie Mull is the proper form.

Undershell (to himself). Lady Maisie Mull! I attach no meaning to titles—and yet nothing but rank could confer such perfect ease and distinction. (Aloud.) I should have said Lady Maisie Mull, undoubtedly—forgive my ignorance. But at least I have divined you. Does nothing tell you who and what I may be?

Phillipson. Oh, I think I can give a tolerable guess at what you are.

Undershell. You recognize the stamp of the Muse upon me, then?

Phillipson. Well, I shouldn't have taken you for a groom exactly.

Undershell (with some chagrin). You are really too flattering!

Phillipson. Am I? Then it's your turn now. You might say you'd never have taken me for a lady's maid!

Undershell. I might—if I had any desire to make an unnecessary and insulting remark.

Phillipson. Insulting? Why, it's what I am! I'm maid to Lady Maisie. I thought your mysterious instinct told you all about it?

Undershell (to himself—after the first shock). A lady's maid! Gracious Heaven! What have I been saying—or rather, what haven't I? (Aloud.) To—to be sure it did. Of course, I quite understand that. (To himself.) Oh, confound it all, I wish we were at Wyvern!

Phillipson. And, after all, you've never told me who you are. Who are you?

Undershell (to himself). I must not humiliate this poor girl! (Aloud.) I? Oh—a very insignificant person, I assure you! (To himself.) This is an occasion in which deception is pardonable—even justifiable!

Phillipson. Oh, I knew that much. But you let out just now you had to do with a Mews. You aren't a rough-rider, are you?

Undershell. N—not exactly—not a rough-rider. (To himself.) Never on a horse in my life!—unless I count my Pegasus. (Aloud.) But you are right in supposing I am connected with a muse—in one sense.

Phillipson. I said so, didn't I? Don't you think it was rather clever of me to spot you, when you're not a bit horsey-looking?

Undershell (with elaborate irony). Accept my compliments on a power of penetration which is simply phenomenal!

Phillipson (giving him a little push). Oh, go along—it's all talk with you—I don't believe you mean a word you say!

Undershell (to himself). She's becoming absolutely vulgar. (Aloud.) I don't—I don't; it's a manner I have; you mustn't attach any importance to it—none whatever!

Phillipson. What! Not to all those high-flown compliments? Do you mean to tell me you are only a gay deceiver, then?

Undershell (in horror). Not a deceiver, no; and decidedly not gay. I mean I did mean the compliments, of course. (To himself.) I mustn't let her suspect anything, or she'll get talking about it; it would be too horrible if this were to get round to Lady Maisie or the Culverins—so undignified; and it would ruin all my prestige! I've only to go on playing a part for a few minutes, and—maid or not—she's a most engaging girl!

[He goes on playing the part, with the unexpected result of sending Miss Phillipson into fits of uncontrollable laughter.

At a Back Entrance at Wyvern. The Fly has just set down Phillipson and Undershell.

Tredwell (receiving Phillipson). Lady Maisie's maid, I presume? I'm the butler here—Mr. Tredwell. Your ladies arrived some time back. I'll take you to the housekeeper, who'll show you their rooms, and where yours is, and I hope you'll find everything comfortable. (In an undertone, indicating Undershell, who is awaiting recognition in the doorway.) Do you happen to know who it is with you?

Phillipson (in a whisper). I can't quite make him out—he's so flighty in his talk. But he says he belongs to some Mews or other.

Tredwell. Oh, then I know who he is. We expect him right enough. He's a partner in a crack firm of Vets. We've sent for him special. I'd better see to him, if you don't mind finding your own way to the housekeeper's room, second door to the left, down that corridor. (Phillipson departs.) Good evening to you, Mr.—ah—Mr.——?

Undershell (coming forward). Mr. Undershell. Lady Culverin expects me, I believe.

Tredwell. Quite correct, Mr. Undershell, sir. She do. Leastwise, I shouldn't say myself she'd require to see you—well, not before to-morrow morning—but you won't mind that, I dare say.

Undershell (choking). Not mind that! Take me to her at once!

Tredwell. Couldn't take it on myself, sir, really. There's no particular 'urry. I'll let her ladyship know you're 'ere; and if she wants you, she'll send for you; but, with a party staying in the 'ouse, and others dining with us to-night, it ain't likely as she'll have time for you till to-morrow.

Undershell. Oh, then whenever her ladyship should find leisure to recollect my existence, will you have the goodness to inform her that I have taken the liberty of returning to town by the next train?

Tredwell. Lor! Mr. Undershell, you aren't so pressed as all that, are you? I know my lady wouldn't like you to go without seeing you personally; no more wouldn't Sir Rupert. And I understood you was coming down for the Sunday!

Undershell (furious). So did I—but not to be treated like this!

Tredwell (soothingly). Why, you know what ladies are. And you couldn't see Deerfoot—not properly, to-night, either.

Undershell. I have seen enough of this place already. I intend to go back by the next train, I tell you.

Tredwell. But there ain't any next train up to-night—being a loop line—not to mention that I've sent the fly away, and they can't spare no one at the stables to drive you in. Come, sir, make the best of it. I've had my horders to see that you're made comfortable, and Mrs. Pomfret and me will expect the pleasure of your company at supper in the 'ousekeeper's room, 9.30 sharp. I'll send the steward's room boy to show you to your room.

[He goes, leaving Undershell speechless.

Undershell (almost foaming). The insolence of these cursed aristocrats! Lady Culverin will see me when she has time, forsooth! I am to be entertained in the servants' hall! This is how our upper classes honour Poetry! I won't stay a single hour under their infernal roof. I'll walk. But where to? And how about my luggage?

[Phillipson returns.

Phillipson. Mr. Tredwell says you want to go already! It can't be true! Without even waiting for supper?

Undershell (gloomily). Why should I wait for supper in this house?

Phillipson. Well, I shall be there; I don't know if that's any inducement.

[She looks down.

Undershell (to himself). She is a singularly bewitching creature; and I'm starving. Why shouldn't I stay—if only to shame these Culverins? It will be an experience—a study in life. I can always go afterwards. I will stay. (Aloud.) You little know the sacrifice you ask of me, but enough; I give way. We shall meet—(with a gulp)—in the housekeeper's room!

Phillipson (highly amused). You are a comical little man. You'll be the death of me if you go on like that!

[She flits away.

Undershell (alone). I feel disposed to be the death of somebody! Oh, Lady Maisie Mull, to what a bathos have you lured your poet by your artless flattery—a banquet presided over by your aunt's butler!

The Amber Boudoir at Wyvern immediately after Lady Cantire and her daughter have entered.

Lady Cantire (in reply to Lady Culverin). Tea? oh yes, my dear; anything warm! I'm positively perished—that tedious cold journey and the long drive afterwards! I always tell Rupert he would see me far oftener at Wyvern if he would only get the company to bring the line round close to the park gates, but it has no effect upon him! (As Tredwell announces Spurrell, who enters in trepidation.) Mr. James Spurrell! Who's Mr.——? Oh, to be sure; that's the name of my interesting young poet—Andromeda, you know, my dear! Go and be pleasant to him, Albinia, he wants reassuring.

Lady Culverin (a trifle nervous). How do you do, Mr.—ah—Spurrell? (To herself.) I said he ended in "ell"! (Aloud.) So pleased to see you! We think so much of your Andromeda here, you know. Quite delightful of you to find time to run down!

Spurrell (to himself). Why, she's chummy, too! Old Drummy pulls me through everything! (Aloud.) Don't name it, my la—hum—Lady Culverin. No trouble at all; only too proud to get your summons!

Lady Culverin (to herself). He doesn't seem very revolutionary! (Aloud.) That's so sweet of you; when so many must be absolutely fighting to get you!

Spurrell. Oh, as for that, there is rather a run on me just now, but I put everything else aside for you, of course!

Lady Culverin (to herself). He's soon reassured. (Aloud, with a touch of frost.) I am sure we must consider ourselves most fortunate. (Turning to the Countess.) You did say cream, Rohesia? Sugar, Maisie dearest?

Spurrell (to himself). I'm all right up to now! I suppose I'd better say nothing about the horse till they do. I feel rather out of it among these nobs, though. I'll try and chum on to little Lady Maisie again; she may have got over her temper by this time, and she's the only one I know. (He approaches her.) Well, Lady Maisie, here I am, you see. I'd really no idea your aunt would be so friendly! I say, you know, you don't mind speaking to a fellow, do you? I've no one else I can go to—and—and it's a bit strange at first, you know!

Lady Maisie (colouring with mingled apprehension, vexation, and pity). If I can be of any help to you, Mr. Spurrell——!

Spurrell. Well, if you'd only tell me what I ought to do!

Lady Maisie. Surely that's very simple; do nothing; just take everything quietly as it comes, and you can't make any mistakes.

Spurrell (anxiously). And you don't think anybody'll see anything out of the way in my being here like this?

Lady Maisie (to herself). I'm only too afraid they will! (Aloud.) You really must have a little self-confidence. Just remember that no one here could produce anything a millionth part as splendid as your Andromeda! It's too distressing to see you so appallingly humble! (To herself.) There's Captain Thicknesse over there—he might come and rescue me; but he doesn't seem to care to!

Spurrell. Well, you do put some heart into me, Lady Maisie. I feel equal to the lot of 'em now!

Pilliner (to Miss Spelwane). Is that the poet? Why, but I say—he's a fraud! Where's his matted head? He's not a bit ragged, or rusty either. And why don't he dabble? Don't seem to know what to do with his hands quite, though, does he?

Miss Spelwane (coldly). He knows how to do some very exquisite poetry with one of them, at all events. I've been reading it, and I think it perfectly marvellous!

Pilliner. I see what it is, you're preparing to turn his matted head for him? I warn you you'll only waste your sweetness. That pretty little Lady Maisie's annexed him. Can't you content yourself with one victim at a time?

Miss Spelwane. Don't be so utterly idiotic! (To herself.) If Maisie imagines she's to be allowed to monopolise the only man in the room worth talking to!——

Captain Thicknesse (to himself, as he watches Lady Maisie). She is lookin' prettier than ever! Forgotten me. Used to be friendly enough once, though, till her mother warned me off. Seems to have a good deal to say to that poet fellow; saw her colour up from here the moment he came near; he's begun Petrarchin', hang him! I'd cross over and speak to her if I could catch her eye. Don't know, though; what's the use? She wouldn't thank me for interruptin'. She likes these clever chaps; don't signify to her if they are bounders, I suppose. I'm not intellectual. Gad, I wish I'd gone back to Aldershot!

Lady Cantire (by the tea-table). Why don't you make that woman of yours send you up decent cakes, my dear? These are cinders. I'm afraid you let her have too much of her own way. Now, tell me—who are your party? Vivien Spelwane! Never have that girl to meet me again, I can't endure her; and that affected little ape of a Mr. Pilliner—h'm! Do I see Captain Thicknesse? Now, I don't object to him. Maisie and he used to be great friends.... Ah, how do you do, Captain Thicknesse? Quite pleasant finding you here; such ages since we saw anything of you! Why haven't you been near us all this time? ... Oh, I may have been out once or twice when you called; but you might have tried again, mightn't you? There, I forgive you; you had better go and see if you can make your peace with Maisie!

Captain Thicknesse (to himself, as he obeys). Doosid odd, Lady Cantire comin' round like this. Wish she'd thought of it before.

Lady Cantire (in a whisper). He's always been such a favourite of mine. They tell me his uncle, poor dear Lord Dunderhead, is so ill—felt the loss of his only son so terribly. Of course it will make a great difference—in many ways.

Captain Thicknesse (constrainedly to Lady Maisie). How do you do? Afraid you've forgotten me.

Lady Maisie. Oh no, indeed! (Hurriedly.) You—you don't know Mr. Spurrell, I think? (Introducing them.) Captain Thicknesse.

Captain Thicknesse. How are you? Been hearin' a lot about you lately. Andromeda, don't you know; and that kind of thing.

Spurrell. It's wonderful what a hit she seems to have made—not that I'm surprised at it, either; I always knew——

Lady Maisie (hastily). Oh, Mr. Spurrell, you haven't had any tea! Do go and get some before it's taken away.

[Spurrell goes.

Captain Thicknesse. Been tryin' to get you to notice me ever since you came; but you were so awfully absorbed, you know!

Lady Maisie. Was I? So absorbed as all that! What with?

Captain Thicknesse. Well, it looked like it—with talkin' to your poetical friend.

Lady Maisie (flushing). He is not my friend in particular; I—I admire his poetry, of course.

Captain Thicknesse (to himself). Can't even speak of him without a change of colour. Bad sign that! (Aloud.) You always were keen about poetry and literature and that in the old days, weren't you? Used to rag me for not readin' enough. But I do now. I was readin' a book only last week. I'll tell you the name if you give me a minute to think—book everybody's readin' just now—no end of a clever book.

[Miss Spelwane rushes across to Lady Maisie.

Miss Spelwane. Maisie, dear, how are you? You look so tired! That's the journey, I suppose. (Whispering.) Do tell me—is that really the author of Andromeda drinking tea close by? You're a great friend of his, I know. Do be a dear, and introduce him to me! I declare the dogs have made friends with him already. Poets have such a wonderful attraction for animals, haven't they?

[Lady Maisie has to bring Spurrell up and introduce him; Captain Thicknesse chooses to consider himself dismissed.

Miss Spelwane (with shy adoration). Oh, Mr. Spurrell, I feel as if I must talk to you about Andromeda. I did so admire it!

Spurrell (to himself). Another of 'em! They seem uncommonly sweet on "bulls" in this house! (Aloud.) Very glad to hear you say so, I'm sure. But I'm bound to say she's about as near perfection as anything I ever—I dare say you went over her points——

Miss Spelwane. Indeed, I believe none of them were lost upon me; but my poor little praise must seem so worthless and ignorant!

Spurrell (indulgently). Oh, I wouldn't say that. I find some ladies very knowing about these things. I'm having a picture done of her.

Miss Spelwane. Are you really? How delightful! As a frontispiece?

Spurrell. Eh? Oh no—full length, and sideways—so as to show her legs, you know.

Miss Spelwane. Her legs? Oh, of course—with "her roseal toes cramped." I thought that such a wonderful touch!

Spurrell. They're not more cramped than they ought to be; she never turned them in, you know!

Miss Spelwane (mystified). I didn't suppose she did. And now tell me—if it's not an indiscreet question—when do you expect there'll be another edition?

Spurrell (to himself). Another addition! She's cadging for a pup now! (Aloud.) Oh—er—really—couldn't say.

Miss Spelwane. I'm sure the first must be disposed of by this time. I shall look out for the next so eagerly!

Spurrell (to himself). Time I "off"ed it. (Aloud.) Afraid I can't say anything definite—and, excuse me leaving you, but I think Lady Culverin is looking my way.

Miss Spelwane. Oh, by all means? (To herself.) I might as well praise a pillar-post! And after spending quite half an hour reading him up, too! I wonder if Bertie Pilliner was right; but I shall have him all to myself at dinner.

Lady Cantire. And where is Rupert? too busy of course to come and say a word! Well, some day he may understand what a sister is—when it's too late. Ah, here's our nice unassuming young poet coming up to talk to you. Don't repel him, my dear!

Spurrell (to himself). Better give her the chance of telling me what's wrong with the horse, I suppose. (Aloud.) Er—nice old-fashioned sort of house this, Lady Culverin. (To himself.) I'll work round to the stabling by degrees.

Lady Culverin (coldly). I believe it dates from the Tudors—if that is what you mean.

Lady Cantire. My dear Albinia, I quite understand him; "old-fashioned" is exactly the epithet. And I was born and brought up here, so perhaps I should know.

[A footman enters, and comes up to Spurrell mysteriously.

Footman. Will you let me have your keys, if you please, sir?

Spurrell (in some alarm). My keys! (Suspiciously.) Why, what do you want them for?

"MY KEYS! WHY, WHAT DO YOU WANT THEM FOR?"

"MY KEYS! WHY, WHAT DO YOU WANT THEM FOR?"

Lady Cantire (in a whisper). Isn't he deliciously unsophisticated? Quite a child of nature! (Aloud.) My dear Mr. Spurrell, he wants your keys to unlock your portmanteau and put out your things; you'll be able to dress for dinner all the quicker.

Spurrell. Do you mean—am I to have the honour of sitting down to table with all of you?

Lady Culverin (to herself). Oh, my goodness, what will Rupert say? (Aloud.) Why, of course, Mr. Spurrell; how can you ask?

Spurrell (feebly). I—I didn't know, that was all. (To Footman.) Here you are, then. (To himself.) Put out my things?—he'll find nothing to put out except a nightgown, sponge bag, and a couple of brushes! If I'd only known I should be let in for this, I'd have brought dress-clothes. But how could I? I—I wonder if it would be any good telling 'em quietly how it is. I shouldn't like 'em to think I hadn't got any. (He looks at Lady Cantire and her sister-in-law, who are talking in an undertone.) No, perhaps I'd better let it alone. I—I can allude to it in a joky sort of way when I come down!

In the Amber Boudoir. Sir Rupert has just entered.

Sir Rupert. Ha, Maisie, my dear, glad to see you! Well, Rohesia, how are you, eh? You're looking uncommonly well! No idea you were here!

Spurrell (to himself). Sir Rupert! He'll hoof me out of this pretty soon, I expect!

Lady Cantire (aggrieved). We have been in the house for the best part of an hour, Rupert—as you might have discovered by inquiring—but no doubt you preferred your comfort to welcoming so unimportant a guest as your sister!

Sir Rupert (to himself). Beginning already! (Aloud.) Very sorry—got rather wet riding—had to change everything. And I knew Albinia was here.

Lady Cantire (magnanimously). Well, we won't begin to quarrel the moment we meet; and you are forgetting your other guest. (In an undertone.) Mr. Spurrell—the poet—wrote Andromeda. (Aloud.) Mr. Spurrell, come and let me present you to my brother.

Sir Rupert. Ah, how d'ye do? (To himself, as he shakes hands.) What the deuce am I to say to this fellow? (Aloud.) Glad to see you here, Mr. Spurrell—heard all about you—Andromeda, eh? Hope you'll manage to amuse yourself while you're with us; afraid there's not much you can do now though.

Spurrell (to himself). Horse in a bad way; time they let me see it. (Aloud.) Well, we must see, sir; I'll do all I can.

Sir Rupert. You see, the shooting's done now.

Spurrell (to himself, professionally piqued). They might have waited till I'd seen the horse before they shot him! After calling me in like this! (Aloud.) Oh, I'm sorry to hear that, Sir Rupert. I wish I could have got here earlier, I'm sure.

Sir Rupert. Wish we'd asked you a month ago, if you're fond of shooting. Thought you might look down on sport, perhaps.

Spurrell (to himself). Sport? Why, he's talking of birds—not the horse! (Aloud.) Me, Sir Rupert? Not much! I'm as keen on a day's gunning as any man, though I don't often get the chance now.

Sir Rupert (to himself, pleased). Come, he don't seem strong against the Game Laws! (Aloud.) Thought you didn't look as if you sat over your desk all day! There's hunting still, of course. Don't know whether you ride?

Spurrell. Rather so, sir! Why, I was born and bred in a sporting county, and as long as my old uncle was alive, I could go down to his farm and get a run with the hounds now and again.

Sir Rupert (delighted). Capital! Well, our next meet is on Tuesday—best part of the country; nearly all grass, and nice clean post and rails. You must stay over for it. Got a mare that will carry your weight perfectly, and I think I can promise you a run—eh, what do you say?

Spurrell (to himself, in surprise). He is a chummy old cock! I'll wire old Spavin that I'm detained on biz; and I'll tell 'em to send my riding-breeches and dress-clothes down! (Aloud.) It's uncommonly kind of you, sir, and I think I can manage to stop on a bit.

Lady Culverin (to herself). Rupert must be out of his senses! It's bad enough to have him here till Monday! (Aloud.) We mustn't forget, Rupert, how valuable Mr. Spurrell's time is; it would be too selfish of us to detain him here a day longer than——

Lady Cantire. My dear, Mr. Spurrell has already said he can manage it; so we may all enjoy his society with a clear conscience. (Lady Culverin conceals her sentiments with difficulty.) And now, Albinia, if you'll excuse me, I think I'll go to my room and rest a little, as I'm rather overdone, and you have all these tiresome people coming to dinner to-night.

[She rises and leaves the room; the other ladies follow her example.

Lady Culverin. Rupert, I'm going up now with Rohesia. You know where we've put Mr. Spurrell, don't you? The Verney Chamber.

[She goes out.

Sir Rupert. Take you up now, if you like, Mr. Spurrell—it's only just seven, though. Suppose you don't take an hour to dress, eh?

Spurrell. Oh dear no, sir, nothing like it! (To himself.) Won't take me two minutes as I am now! I'd better tell him—I can say my bag hasn't come. I don't believe it has, and, anyway, it's a good excuse. (Aloud.) The—the fact is, Sir Rupert, I'm afraid that my luggage has been unfortunately left behind.

Sir Rupert. No luggage, eh? Well, well, it's of no consequence. But I'll ask about it—I dare say it's all right.

[He goes out.

Captain Thicknesse (to Spurrell). Sure to have turned up, you know—man will have seen that. Shouldn't altogether object to a glass of sherry and bitters before dinner. Don't know how you feel—suppose you've a soul above sherry and bitters, though?

Spurrell. Not at this moment. But I'd soon put my soul above a sherry and bitters if I got a chance!

Captain Thicknesse (after reflection). I say, you know, that's rather smart, eh? (To himself.) Aw'fly clever sort of chap, this, but not stuck up—not half a bad sort, if he is a bit of a bounder. (Aloud.) Anythin' in the evenin' paper? Don't get 'em down here.

"I SAY, YOU KNOW, THAT'S RATHER SMART, EH?"

"I SAY, YOU KNOW, THAT'S RATHER SMART, EH?"

Spurrell. Nothing much. I see there's an objection to Monkey-tricks.