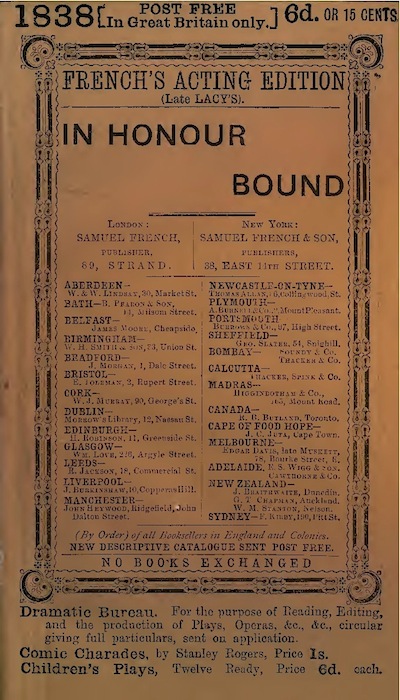

IN HONOUR BOUND.

AN ORIGINAL PLAY,

IN ONE ACT.

(Suggested by Scribe’s Five Act Comedy, “Une Chaine.”)

By

SYDNEY GRUNDY,

Author of

Mammon, The Snowball, The Vicar of Bray, Rachel, The Queen’s Favourite, The Glass of Fashion, A Little Change, Man Proposes, &c.

| London: SAMUEL FRENCH, PUBLISHER, 89, STRAND. |

New York: SAMUEL FRENCH & SON, PUBLISHERS, 38, EAST 14TH STREET. |

Produced at the Prince of Wale’s Theatre, under the management of Mr. Edgar Bruce, 25th September, 1880.

CHARACTERS.

| Sir George Carlyon, Q.C., M.P. | Mr. Edgar Bruce. | |

| Philip Graham | Mr. Eric Bayley. | |

| Lady Carlyon | Mrs. Bernard Beere. | |

| Rose Dalrymple | Miss Kate Pattison. |

Scene:—SIR GEORGE CARLYON’S.

IN HONOUR BOUND.

Scene.—Room at Sir George Carlyon’s. Fire lit, R.; in front of it, a wide, luxurious lounge with high back; against it, C., a writing table, piled high with briefs, so as to help to obscure the view of the lounge from anybody sitting at the desk; in front of desk a writing chair; a piano, music seat and davenport, L.; doors, R. U. E. and L. 1 E.; window at back with curtains drawn. The room is lighted by a lamp which stands upon the desk, a box of cigars by the side of it.

Sir George discovered, seated at the desk, reading and under-scoring rapidly an open brief. He is in evening dress.

Sir G. (folding up brief) Ah, the old story! I need read no more. (lays down the brief and rises) What’s this? (picks up a letter lying on the edge of the desk) Oh—ah!—the letter that came by this morning’s post for Philip. A woman’s writing. How alike they write! The very double of my niece’s hand! (throws down the letter and looks at watch) Eleven o’clock. What has become of Philip?

Enter Philip Graham, L., evening dress.

Ah, there you are!

Philip. Are you at liberty?

Sir G. Yes, I have done work for to-night. Come in. I am afraid I have neglected you.

Philip. Not in the least. I stayed upstairs on purpose, knowing you were busy. I have been unpacking.

(Sir George draws forward chair, C.)

Sir G. Sit down. You must be tired after your journey.

(sits on the end of the lounge, facing audience)

Philip. (sits, C.) I was tired and hungry, but your cook has kindly seen to that.

Sir G. Lady Carlyon had quite given you up, or she would have stayed in to welcome you.

Philip. My train was very late.

Sir G. Oh, by-the-bye (rises) there is a letter waiting for you. (gives it him)

Philip. Thanks. (Sir George resumes his seat—aside) Rose’s hand. (pockets it)

Sir G. My wife is at the theatre.

Philip. Oh!

Sir G. We have had another visitor to-day—a niece of mine, who has come from abroad. I promised I would take her to the play, but just as I was leaving chambers some[Pg 4] briefs tumbled in, and I thought it might be as well to glance them over; so my wife has taken her.

Philip. Lady Carlyon is quite well, I hope.

Sir G. Perfectly, thank you.

Philip. It is two years since I saw her.

Sir G. So it is. We have seen nothing of you lately—you, whom we used to see so much of. Where have you been?

Philip. Well, all over the world. The day I met you, when you were so kind as to invite me here, was the day of my arrival home.

Sir G. So kind as to invite you! My dear boy, you raised objections enough to my invitation.

Philip. I was afraid of trespassing on your hospitality.

Sir G. And so you have been round the world?

Philip. From Dan to Beersheba.

Sir G. And you found all barren?

Philip. On the contrary, I’ve had a very jolly time—especially upon the voyage home.

Sir G. You look the better for it.

Philip. I am a new man.

Sir G. You weren’t well when you went away.

Philip. I was depressed and out of sorts.

Sir G. So I observed.

Philip. You noticed it?

Sir G. And I remember thinking at the time there was a woman in the case.

Philip. That is all over now. I am as happy as the sandboy in the saying.

Sir G. Then, there’s another woman in the case.

Philip. My dear Sir George, according to your views, there is a woman in every case.

Sir G. (pointing to table) There are some twenty briefs. Open which one of them you please, and somewhere in the folds you’ll find a petticoat.

Philip. What, twenty women hidden in these briefs?

Sir G. At least. There never was a case without a woman in it, and I never leave one till I’ve found her; for I know well enough until I do I have not mastered it. There is a woman in your case, my friend.

Philip. To tell the truth, there is. A charming girl I met upon the voyage home.

Sir G. The jolly voyage home!

Philip. I am in love this time, Sir George.

Sir G. Oh, yes! we always are in love this time.

Philip. I thought I was before, but I was wrong.

Sir G. Of course! we never were before!

Philip. And, better still, I am engaged.

Sir G. What, to the charming girl?

Philip. The only girl in the wide world for me.

Sir G. Well, you’ve been round it, so you ought to know. I hope you will be happy. It’s a toss-up, Philip.

Philip. I’m afraid your profession makes you cynical.

Sir G. Gad, it would make an angel cynical.

Philip. No doubt, you meet with some extraordinary cases.

(turning over briefs)

Sir G. Never. All ordinary. To a man who has had twenty years’ experience, no possible case can appear extraordinary. There aren’t three there of which I didn’t know the end before I turned a page. No wonder we don’t always read our briefs, for we know most of them by heart.

(lies back)

Philip. Hallo! (smiling)

Sir G. What have you found?

Philip. A breach of promise case. This looks amusing.

Sir G. Very amusing for the judge and jury. Very amusing for the public too. Very amusing for the new-made wife to read in all the newspapers her husband’s past.

Philip. Is the defendant married, then?

Sir G. Of course he is. They always are. And of course he was on with the new love before he was off with the old. They always will be. The old love was no better than she need be, and no more was he. Very amusing for the new love, isn’t it?

Philip. Of course the letters will be read in court?

Sir G. And published in the papers. “November, 1877—your own loving and devoted Harry. (laughter) November, 1878—Yours most affectionately, Henry. (loud laughter) November, 1879—Yours truly, Henry Horrocks. (roars of laughter).” Oh, it’s a most amusing case—for Mrs. Henry Horrocks.

Philip. Why don’t you settle it? You are for the defendant.

Sir G. We’ve tried, but it’s too late. Take warning by my client.

Philip. I?

Sir G. You be in time, if you are not too late already.

Philip. Excuse me, mine was quite a different case. Thank heaven, I have no reason to reproach myself. There was no love, at any rate on my side, in the matter you allude to.

Sir G. And yet you fled the country to avoid the lady. (sitting up)

Philip. I never said so.

Sir G. No, my boy; you never said that two and two makes four, but it does, doesn’t it? (looking at Philip through his glasses)

Philip. No doubt. I felt that my position was——(hesitates)

Sir G. Equivocal.

Philip. That is the word I wanted.

Sir G. Useful word.

Philip. And feeling that, I thought the best course was to——

Sir G. Run away.

Philip. But as for promises of marriage, there was nothing of that sort. In fact, there couldn’t be.

Sir G. Because the lady was already——

Philip. Hang it, Sir George, you’re telling me my case!

Sir G. (drops glasses) You’ll find it in the third brief on your right.

Philip. (looking at brief) “Winter v. Winter and Hockheimer”?

Sir G. That’s your case, as far as it has gone.

Philip. (takes up brief and reads endorsement) “In the High Court of Justice—Probate and”—— But this is a divorce case!

Sir G. Just so.

Philip. Oh, that’s not my case. (puts brief back in its place)

Sir G. I said as far as it had gone. Hockheimer ran away. You ran away. But Hockheimer came back again. And I observe that you’ve come back again.

Philip. But I’m not Hockheimer!

Sir G. As far as you have gone. Hockheimer was a friend of Winter’s——

Philip. But I’m not! I never saw the man in my life!

Sir G. No, but the other man?

Philip. What other man?

Sir G. The husband.

Philip. I didn’t say he was my friend!

Sir G. Oh, yes, you did.

Philip. When did I say so?

Sir G. When you ran away. (puts glasses up)

Philip. Spare me, Sir George. You make me feel like a witness under cross-examination. I didn’t mean to breathe a word of this, and somehow I have told you everything.

Sir G. Well, you have told me a good deal. (drops glasses) Now, will you let me give you my advice?

Philip. By all means.

Sir G. Keep those women apart.

Philip. Which women?

Sir G. (smiling) The charming girl and the neglected wife.

Philip. I never said she was neglected.

Sir G. But she is, isn’t she? (putting up his eye-glasses)

Philip. Those glasses worry me.

Sir G. (dropping the eye-glasses) I beg your pardon; it’s the force of habit. Off with the old love—friend—or what you will—and never let the new one see her. Off with her entirely! That’s my advice; and many a hundred guineas have been paid for worse.

Philip. Oh, they will never meet. I mean to live abroad. The girl I am engaged to is a South Australian. (Sir George lifts his head quickly) And she has only come to England on a visit. Her parents are both dead, and she came over with a maiden aunt with whom she is now stopping.

Sir G. Where?

Philip. At Bayswater. In a few weeks she will go back to Melbourne; and then all danger, if there be any, is over.

Sir G. So you have come from Melbourne in the “Kangaroo”? (rises)

Philip. Who told you what boat I came over in?

Sir G. I gathered it from what you said yourself.

Philip. I won’t say a word more, or in two minutes you will guess the lady’s name.

Sir G. I have already guessed it.

Philip. What!

Sir G. Rose Dalrymple.

Philip. (springs up) This is inexplicable!

Sir G. Not at all.

Philip. I have told nobody!

Sir G. You have told me.

Philip. You know Miss Dalrymple?

Sir G. She is my niece. (Philip steps back) She is a South Australian. She came to England in the “Kangaroo,” and has been stopping with a maiden aunt at Bayswater.

Philip. Your niece!

Sir G. I am her guardian, since my sister died.

Philip. Then, she is your wife’s——

Sir G. Niece by marriage. (crosses, L.) They have just come back from the theatre.

Philip. Oh! (drops into chair, C.)

Sir G. I hear them.

Enter Rose Dalrymple, in evening dress, as if returning from the theatre.

Rose. Ah, Uncle George! (about to embrace)

Philip. (springs up again) Rose!

Rose. Philip! (rushes to his arms)

Sir G. Humph. Exit Uncle George.

(arranges papers on desk)

Rose. How late you are! We’ve been expecting you all the afternoon.

Philip. (taking her aside, R.) You didn’t say that you were coming here!

Rose. No! didn’t I tell you I would give you a surprise?

Philip. When?

Rose. In my letter. Haven’t you received it?

Philip. Yes, but I haven’t had time to open it. (produces it—breaks the seal—and replaces it in his pocket, unnoticed by Sir George) And when I told you of my invitation here, you didn’t tell me that you knew Sir George.

Rose. Because I wanted to surprise you, dear.

Philip. Well, you have done so most effectually. Tell me, does Lady Carlyon know of our engagement?

Rose. No, not yet. I never saw her till to-day, and I didn’t like to be so confidential.

Philip. (relieved) Ah!

Rose. You’re not angry with me for not having told her?

Philip. Not at all. We will surprise her.

Rose. Shall we?

Philip. To-night we will pretend we are strangers.

Rose. But I shall pretend very badly, I am sure.

Philip. Oh, you can keep a secret. You have shown me that.

Rose. I’ll try, at any rate.

Sir G. (putting chair, C., into its place at desk) Now, Miss Dalrymple, if you are at liberty, perhaps you will be kind enough to tell me what has become of my wife.

Rose. (going to him, C.) She’ll be here directly. She is only speaking to the servants. (kisses him)

Enter Lady Carlyon, L., also in evening dress, with a bouquet; she at once sees Philip and he her; Philip, R., turns full front to audience.

Lady C. (aside) Philip! (stops short)

Sir G. (seeing her) Ah, here she is! (goes to her, L.) My dear, you don’t look well!

Lady C. The theatre was so close.

Sir G. It always makes you ill. But you have not seen Philip. (indicates Philip)

Lady C. Ah, Mr. Graham! (advances C.—Philip advances to meet her) Excuse me for not recognising you. (they shake hands rather ceremoniously)

Sir G. What has turned Philip into Mr. Graham, pray?

Lady C. He has not been to see us for so long.

Philip. Allow me. (helps to remove her cloak)

Sir G. No wonder, if you make a stranger of him when he comes. (sits C.)

Lady C. If Philip is a stranger, he has made one of himself.

Philip. The fault is mine entirely. (takes cloak)

Lady C. Thanks.

Goes L. again with bouquet and sits down—Rose has meanwhile deposited her cloak at the farther end of the lounge—she takes the other cloak from Philip and flings it upon her own, then leans over the desk—Philip sits upon the end of the lounge.

Sir G. Well, how did you enjoy the play?

Rose. Oh, so much, Uncle George! Although it was in French, I followed every word.

Philip. It is the French plays you have been to?

Sir G. What was the piece?

Lady C. “Une Chaine,” by Eugène Scribe.

Sir G. I don’t remember it.

Rose. And it is so exciting. There is a young man in it—such a nice young man, with a moustache—oh, such a sweet moustache!

Sir G. Well?

Rose. He’s in love.

Sir G. Of course.

Rose. With a young girl—oh, such a stupid girl! I can’t think what he could have seen in her—and she’s in love with him.

Sir G. And they get married, I suppose.

Rose. In the last act; but in the meantime there is such a to-do.

Sir G. Why?

Rose. It appears, before the play began, the hero—the young man——

Philip. With the moustache——

Rose. Had been in love with someone else.

Sir G. Ah!

Rose. But now he doesn’t care for her a bit.

Sir G. What is the difficulty, then?

Rose. She cares for him; and though he’s trying through the whole four acts, do what he will, he can’t get rid of her.

Sir G. I see. That is the chain.

Rose. He nearly breaks it half a dozen times, but something always happens to prevent him. You’ve no idea how interesting it is—although, of course, it’s very, very wrong.

Sir G. Why wrong?

Rose. Well, you see, someone else is married; and of course she oughtn’t to care anything about the nice young man.

Sir G. Although he has so lovely a moustache.

Rose. But she does—which is wicked—but it’s very interesting.

Sir G. (to Lady Carlyon) What did you think of it, my dear?

Lady C. It is a painful subject.

Rose. Aunt Bell didn’t like it; but she took it all so seriously. If it were real, it would be very sad; but after all what is it but a play? Besides, it all takes place in Paris: nobody pretends that such things happen here.

Lady C. Of course. (quickly)

Philip. Of course. (quickly)

Sir G. (ironically) Of course. (takes up the third brief on his right—and plays with it)

Rose. I read a notice of the piece this morning, and I quite agreed with it.

Sir G. What did the notice say?

Rose. It said it was “an admirable play, but that an English version of it was impossible.”

Sir G. Why so?

Rose. “Because”—how did it put it?—oh, “because these vivid but unwholesome pictures of French life have happily no”—something—I forget exactly what—“to the chaste beauty of our English homes.” I can’t remember the precise words, but I know the criticism made me long to see the play.

Sir G. (putting the brief back in its place, after he sees it has caught Philip’s eyes) Of course it filled the theatre?

Lady C. The house was crowded, and the atmosphere was insupportable. (smells bouquet)

Sir G. No doubt; if you were bending all night long over those sickly flowers. (crosses to her—she rises) Give them to me. (takes bouquet) Why, they are almost withered.

(comes, C., with bouquet)

Lady C. They were fresh yesterday.

Sir G. (C.) To-days and yesterdays are different things.

(holds the bouquet, head downwards)

Rose. It wasn’t the flowers, though. Aunt Bell didn’t like the play

Philip. It isn’t everybody who admires French plays.

Sir G. (to Lady Carlyon) What, were you scandalised? You must know, Philip—you do know, of course—Lady Carlyon is a dragon in her way—the very pink and pattern of propriety. Now, I’ll be bound, she didn’t like the moral of that comedy.

Lady C. Had it a moral?

Sir G. Certainly! and one men would do well to lay to heart. If that young man——

Rose. The one with the moustache?

Sir G. Had buried his first love when it was dead, he wouldn’t have been haunted by its ghost. When passion is burnt out, sweep the hearth clean, and clear away the ash, before you set alight another fire. It is a law of life. Old things give place to new. The loves of yesterday are like these faded flowers, fit only to be cast into the flames. (flings bouquet into fire) That is the moral: and I call it excellent. (sits, C., and looks at Philip)

Lady C. (aside) He doesn’t speak to me. Am I a faded flower? (sits, L.)

Rose. Very good, Uncle George. That ought to get the verdict. (leaning upon his shoulder)

Sir G. Let us hope it will. (looking at Philip)

Rose. If all your speeches are as nice as that, I must come down to court and hear you plead.

Sir G. I shall be proud to have so fair an auditor. But we’ve not told your aunt the news.

Lady C. What news?

Sir G. Philip informs me, much to my surprise——

Philip. (rising) Sir George! I have considered your advice, and have resolved to act on it. Till I have done so it would perhaps be better——

Sir G. Not to say anything? I will respect your confidence.

Lady C. You have some private matter to discuss. Shall we go? (rises)

Sir G. We will go, if you will excuse us. (rises)

Lady C. Certainly.

Sir G. (to Philip) Come with me. (Exit, L.)

Philip. In case I don’t see you again, Miss Dalrymple, good night. (bows)

Rose. Good evening, Mr. Graham. (she curtseys ceremoniously)

Lady C. (aside) What can they have to talk about—those two? (reflectively)

Philip comes, L., and stands before Lady Carlyon.

Philip. Good night. (puts out his hand)

Lady C. (giving him her hand slowly, which he takes and drops) Good night. (exit Philip, quickly, L.) How glad he is to go! (drops down on seat again, L., leaning her head back, pressed between her hands—slight pause—Rose comes down)

Rose. Is anything the matter?

Lady C. I beg your pardon, dear. (rises and puts her arm round Rose and leads her to the lounge) I don’t feel very well to-night.

Rose. Sit down and let me talk to you. A chat will cheer you perhaps.

Lady Carlyon sits upon the lounge before the fire—Rose kneels beside her, on the further side from audience, so that both their faces are visible.

Lady C. I am so glad to have you with me, Rose. I wish I had you always. I am very lonely.

Rose. You have Uncle George!

Lady C. Sir George is always busy, and I do not care to interrupt him.

Rose. But he has some leisure.

Lady C. I never knew him to have any, since I was his wife. It’s not his fault. A man in his position has so much to do. When he is not in court, he is in Parliament.

Rose. He is at home to-night.

Lady C. And when he is at home, he is at work.

Rose. Poor lonely aunt! (clasps her arms round her) I told[Pg 12] you at the theatre how like you were to Madame de Saint Géran in the play.

Lady C. Don’t let us talk about that cruel play.

Rose. Why was it cruel?

Lady C. What did it make you think of Madame de Saint Géran?

Rose. Well—I thought she was a very wicked woman. Wasn’t she?

Lady C. Perhaps. But if we had been told her history—if we had ever been in her position—we might have sympathised with her. Were you ever in love?

Rose. Yes! I mean no! I can’t exactly say.

Lady C. If you had been, you wouldn’t hesitate. There is no doubt about it. It is a weird thing. Sometimes it leads to heights, sometimes to depths. I do not say it is an excuse. All I say is, those who have never loved are not entitled to judge those who have. Wait till you are in love yourself, before you judge poor Madame de Saint Géran. And if you ever should be——

Rose. Oh, I shall be!

Lady C. Marry for love, my dear, or not at all.

Rose. What did you marry for?

Lady C. (stroking Rose’s hair) I didn’t marry; I was married. Don’t ask me any more.

Rose. Poor Aunt Bell! lie down, and let me play to you. (rises)

Lady C. Do, dear. I am too tired to talk. (she lies back on the lounge, Rose goes to the piano)

Rose. (sitting at piano) What shall I play you?

Lady C. Anything you please.

Rose plays on the piano—Lady Carlyon, with the firelight flickering about her, gradually falls asleep.

Music.

Rose. Aunt! (turning) Aunt! (rises and goes on tip-toe to the back of the lounge) She’s fast asleep. (covers Lady Carlyon with the cloaks, until the upper part of her figure is quite hidden, and then stands surveying her) How pretty she looks! but how pale! I like you, aunt! I never saw you till to-day, but I like you. (comes down) If I stop I shall wake her. (crosses to C.) I’ll lower the lamp and go. (lowers the lamp and crosses behind desk to R. at back) Good night, Aunt Bell! (bending over the further end of the lounge) Good night—(kisses her softly)—and pleasant dreams! (Exit, R.)

The room is now in darkness, except for the firelight, which throws a strong glow over Lady Carlyon, so that her slightest movement is quite visible to the audience, but not from the L. side of the desk. At present she is fast asleep and motionless.

Re-enter Sir George, L., followed by Philip.

Sir G. Yes, they have gone to bed. The lamp has been turned down. Now we can smoke. (about to turn lamp up)

Philip. Don’t turn it up, please. This half light is charming.

Sir G. Just as you like, but I can scarcely see you. (takes up cigar box)

Philip. (aside) So much the better.

Sir G. A cigar? (offers box)

Philip. Thanks. (takes one)

Sir G. Now we can talk more comfortably. (takes a cigar himself while Philip lights his with a match which he then hands to Sir George) Thanks. (Philip sits, L., Sir George, C.) As I was saying, Rose being my ward, I am concerned in this affair, and what I just now recommended as a friend, in my position as her guardian I can insist upon.

Philip. I have already said, Sir George, that I intend to act on your advice.

Sir G. How does the matter stand?

Philip. Exactly as it stood when I left England. It was a friendship, nothing but a friendship.

Sir G. Friendship?

Philip. Dangerous, no doubt; that’s why I went abroad.

Sir G. Have you communicated with the lady since?

Philip. Never.

Sir G. Nor she with you? (pause) Eh?

Philip. Once.

Sir G. Ah! Now I understand the case. May I inquire what you propose to do?

Philip. To see her and to tell her I am going to be married.

Sir G. What does that put an end to?

Philip. Everything.

Sir G. What, friendship?

Philip. Well——

Sir G. You said friendship.

Philip. Yes.

Sir G. Does marriage put an end to friendship? I hope not.

Philip. Of course it doesn’t, but——

Sir G. That friendship must be put an end to. Philip, you are the son of an old comrade, and I believe that, if you start fair, you will make an admirable husband. But you must start fair, or you won’t. I don’t ask you to bring to me a spotless character—a history without a speck or flaw; all I ask—and on that I insist—is that you shall begin your future life unhampered by the past.

Philip. What would you have me do?

Sir G. Make your fair friend distinctly understand that all—however little that all may have been—is over.

Philip. Will that satisfy you?

Sir G. Yes; but I must have proof she understands it.

Philip. What sort of proof?

Sir G. We lawyers have great faith in black and white. You laymen think it a cumbrous form; but I have seen too many fortunes turn on a forgotten sheet of notepaper, not to appreciate its value.

Philip. What do you mean?

Sir G. That you must bring to me a letter from your friend——

Philip. A letter from her!

Sir G. A mere acknowledgment that all is over.

Philip. A letter!

Sir G. Signed, mind you, signed.

Philip. Signed! (his cry wakes Lady Carlyon)

Sir G. Nothing like a signature.

Philip. (rising) Wouldn’t you like it stamped as well, Sir George? (Lady Carlyon moves slightly)

Sir G. A penny postage stamp will be enough.

Philip. That is impossible.

Sir G. It must be got. (lays down cigar. Philip sinks back into seat again—Lady Carlyon, who has gone through the first processes of waking, lifts her head; at the sound of Sir George’s voice she starts half up and holds herself in that position during the rest of the conversation, but always so as not to be visible to the others. Sir George rises and stands by Philip) I feel so strongly that is the right course, because in my own life I have pursued the opposite; and I have paid—nay, I have not yet paid the penalty. I claim to be no better than my kind. When I was married, I too was entangled. I was a rising man—and it was necessary that I should obtain a seat in Parliament. Lady Carlyon’s father had much influence in the county which I represent. My marriage was political. I had a charming wife, who did her best to love me, heaven knows; and I might have loved her, if this entanglement from which I could not extricate myself had not been there. But there it was, and with a woman’s quickness she discovered it. I know she did, although she never spoke; and with a generosity which I can never repay, she did not add to my embarrassment. What was the sequel? Death cut the knot which I could not unravel. I am free. Now, many a time amongst these dead dry bones (pointing to briefs) I hunger for the love it is too late to win. Still that accursed past stands like a wall betwixt my wife and me. (returns, C.) Profit by my experience. (sits, C. )

Philip. No doubt, the course you recommend would be the proper course to take, if it were possible; but in the circumstances it is quite impossible.

Sir G. Difficult, perhaps, but not impossible. Have no[Pg 15] false delicacy in a case like this. This lady—I presume, whoever she may be, she is a lady—who is fond of you, for that is evident, but of whose friendship you are weary, must be sacrificed. I pity her, but there is no help for it.

Philip. None! but a letter is out of the question.

Sir G. Why?

Philip. How could I ask her—oh, it is impossible!

Sir G. Then, you do feel for her?

Philip. I can’t help pitying her.

Sir G. Perhaps still care for her—a little?

Philip. Sir George (rises), I give you my assurance as a gentleman, nothing has passed between us but kind words. I never loved her; and when I think of all the trouble she has brought on me—how she has banished me for months abroad—how nearly she has made me a false friend—I hate the very mention of her name!

Lady C. (who has followed his words in an agony, unable to restrain herself) Philip! (remembering herself, drops back upon the lounge, and feigns to be asleep)

Philip. (turning, L., quickly) What’s that?

Sir G. (rising and turning up the lamp, sees her upon the lounge) My wife! (going round at back of desk to lounge) She is asleep. (moving her) Bell! Isabel! (she pretends to wake, then starts up suddenly)

Lady C. Oh, how you startled me!

Sir G. Nay, how you startled us!

Lady C. How so?

Sir G. By calling out.

Lady C. Forgive me for disturbing you, but I was dreaming.

Sir G. And not a pleasant dream, apparently. Why, you are trembling all over.

Lady C. (smiling) So I am.

Sir G. And you cried out as though you were in pain.

Lady C. It was in terror. I dreamt that I was walking on the edge of a high cliff.

Sir G. Pshaw!

Lady C. Philip was with me.

Sir G. You had a safe escort.

Lady C. But the path grew so difficult, we had to separate. I followed him; when suddenly he turned and——

Sir G. And what?

Lady C. Flung me over! I shrieked out, “Philip!”—and awoke.

Sir G. That was what startled us.

Lady C. Forgive me. Mr. Graham, for having even dreamt that you could be so little chivalrous.

Sir G. You are not well, my dear. It’s time you went upstairs. I’ll ring for your maid.

Lady C. She has gone to bed. It doesn’t matter. I can go alone.

Sir G. Where is Miss Dalrymple?

Lady C. I’ll look for her.

Sir G. Stay where you are. I’ll look for her. (Exit, L. The two stand opposite each other—pause)

Lady C. Well, Philip?

Philip. Was this really a dream?

Lady C. No.

Philip. You have overheard my conversation with Sir George?

Lady C. The end of it.

Philip. And you cried out because——

Lady C. I realised the truth.

Philip. I didn’t weigh my words. Perhaps I over-stated——

Lady C. That will do. (pause) You chose a curious confidant!

Philip. I had no choice. Sir George is so acute; he guessed so much, I had to pass it off by asking him to give me his advice.

Lady C. It was a dangerous expedient. Does he suspect—who——

Philip. No.

Lady C. Though he is so acute?

Philip. Those who are gifted with long sight are often blind to what is at their feet.

Lady C. How did you come to talk on such a subject?

Philip. I had been telling him——

Lady C. Go on.

Philip. That I am going to be married.

Lady C. Oh. (quite calmly) That was your secret? (sits)

Philip. Yes. He guessed the reason why I went abroad, and putting this and that together, he divined there was a difficulty.

Lady C. What is the difficulty?

Philip. The lady to whom I am engaged is not yet of age, and those who have the care of her insist upon some proof that our acquaintanceship is at an end.

Lady C. They also know——

Philip. Not who you are!

Lady C. You make too many confidants. What proof do they require?

Philip. A monstrous proof!

Lady C. What?

Philip. Why, a letter with your signature! It is outrageous!

Lady C. Does Sir George think so?

Philip. He agrees with them.

Lady C. What does he say you ought to do?

Philip. To ask for such a letter.

Lady C. Then why don’t you?

Philip. Oh, have some pity on me!

Lady C. That is but fair: for you have pitied me. (rises) You shall not ask me for the document you want; but you shall have it.

Philip. Ah, you don’t understand——

Lady C. A letter with my signature. I understand.

Philip. But——

Lady C. I only ask one favour in return.

Philip. Whatever I can do——

Lady C. Once whilst you were away, I was so foolish as to write to you. Whether or not my note was forwarded, I don’t know; but if you received it——

Philip. I did.

Lady C. Please to return it to me; that is all I ask. (slight pause) Well?

Philip. I regret——

Lady C. Surely you will do that?

Philip. I can’t.

Lady C. Can’t! Why? (slight pause)

Philip. (drops his head) I have destroyed it.

Lady C. Ah! (turns up and sits at desk) Sit down a moment whilst I write the letter. (writes rapidly)

Philip. It would be to no purpose.

Lady C. Oh, I will make it to the purpose. (writing)

Philip. Ah, if you only understood my situation!

Lady C. Pray sit down. (continues writing)

Philip. (sits on the end of lounge facing the audience—aside) How shall I tell her who it is requires it? (rises—aloud) Lady Carlyon——

Lady C. (writing) In one moment.

Philip. (sits—aside) How am I to say it? (pause—during which Lady Carlyon finishes and folds up the letter)

Lady C. (rising and advancing) There is the letter. (puts it in his hand)

Philip. It is of no use. (rises)

Lady C. It is signed.

Philip. That is the very reason. How can I show your signature——

Lady C. You have my leave. The guardian is a gentleman, I hope.

Philip. Undoubtedly.

Lady C. Then he will not betray me.

Philip. But you don’t know—— (door opens, L.)

Lady C. My husband! hush!

Re-enter Sir George, L. Philip hides behind his back the hand which holds the letter.

Sir G. Rose has gone up stairs, but I’ve sent word you want her. Are you no better? You’re upset to-night.

Philip. It is my fault, Sir George. I’ve just been telling your wife of my difficulties.

Sir G. You couldn’t have done better. I’m sure she will agree with me, that you should get the signature required. That is the only difficulty in the matter.

Philip. But it is insurmountable. If I had the signature, how could I use it?

Sir G. Not without permission.

Philip. No!

Lady C. But you have permission!

(quickly and inadvertently)

Sir G. What?

Lady C. (aside) I’ve said too much.

Sir G. How did you get it? There’s no post at this hour.

Philip. (with his disengaged hand produces Rose’s envelope from his pocket) In the letter which you gave to me——

Sir G. Oh—ah!

Philip. And which I have just opened.

Sir G. The letter in the lady’s handwriting.

Philip. Of her own accord, she releases me——

Sir G. This is a marvellous coincidence.

Philip. (shows letter) But here the letter is.

Sir G. How alike you women write! I could almost have sworn that envelope was in my niece’s hand.

Lady C. How could that be?

Sir G. Why not?

Lady C. Rose write to Philip, whom she doesn’t know!

Sir G. Not know?

Lady C. They never saw each other till to-night.

Sir G. You said Philip had told you——

Philip. All but that.

Sir G. You have not told my wife it’s Rose you are engaged to?

Lady C. Rose!

Sir G. You may well look surprised. It seems they met on board the “Kangaroo.”

Lady C. He is engaged to Rose?

Philip. Yes.

Lady C. Then the guardian is——

Sir G. I. (touches his breast, advances one step forward, and puts out his hand) Give me the letter. (Lady Carlyon and Philip both recoil one step—pause—they stand breathless, gazing at Sir George) You hesitate.

Philip. Sir George, you must make some allowances. This letter is addressed to me, and I should not be justified in letting it go out of my possession.

Sir G. How, then, do you propose to satisfy me?

Lady C. Might he not read it?

Sir G. Thank you, my dear, for the suggestion. That will meet the difficulty.

Philip. Then, I will read it. (reads nervously, the letter trembling in his hands) “I hear you are going to be married. Good-bye, Philip. You need not fear that I shall trouble you again; I have your happiness too much at heart; but if I should, this letter puts me at your mercy. Should the necessity arise, you have my leave to give it to whoever has the right to ask for it.—Yours, for the last time——”

Sir G. Stop. Is the letter signed?

Philip. In full.

Sir G. Now, give it me.

Philip. Sir George——

Sir G. The ground is cut from under you. You are expressly authorised to give that letter to whoever has the right to ask for it. I have the right——

Philip. But you never will exercise it!

Sir G. Now. I have a reason.

Philip. Lady Carlyon!

Sir G. I accept the arbiter. Lady Carlyon, am I right or wrong?

Lady C. (in a low voice and with an effort) Right.

Sir G. The award’s against you.

Lady C. Give him the letter.

Philip. But——

Sir G. Sir, I demand it! (Philip gives it him) I want it for a very special purpose. (folding the letter up into a spill, but never letting his eyes fall upon it) The woman who wrote this will never trouble you. If she has done wrong, she has borne her punishment. Therefore, in pity, let us hide her shame. (lights spill at lamp, and holds it in his hand—all three stand watching it, until the ashes drop upon the floor, then turn aside, Lady Carlyon, R., Philip, L., Sir George to back of scene)

Re-enter Rose, R., in a dressing-gown.

Rose. You want me, aunt?

Sir G. I want you, Rose. (leads her to Philip) Philip has asked for my consent to your engagement. I give it cordially. He is the son of a good father, and I think he will make you a good husband.

Rose. Uncle George! (embraces him—turns to Philip) You haven’t kept our secret!

Philip. No, I couldn’t wait.

Sir G. (crosses to Lady Carlyon) Won’t you congratulate them? (stands, R., thoughtfully)

Lady C. Yes. (crosses to Rose and Philip)

Rose. (embracing her) Aren’t you surprised, Aunt Bell?

Lady C. I was, when first I heard. I hope you will be very happy. You, too, Philip.

(gives him her hand, then crosses to Sir George)

Rose. Why don’t you kiss her, Philip?

Philip. I’ll kiss you instead.

(they sit aside, L., without noticing the others)

Lady C. (laying her hand upon Sir George’s arm) What are you thinking of?

Sir G. I was just wondering if that poor woman’s love, which had so gone astray, will ever go back to her husband.

Lady C. Yes, if he is as generous as you.

Sir G. How was I generous?

Lady C. In sparing her.

Sir G. I was not generous. (each looking in the other’s eyes with meaning) I simply paid a debt of honour I have owed too long. If I was generous, was it not you who taught me generosity?

Lady C. George, you have guessed her name!

Sir G. But I shall never mention it. (embrace)

Curtain.

Transcriber’s Note

This transcription is based on scanned images posted by the Internet Archive:

archive.org/details/inhonourboundano00grunuoft

These images, which were scanned from a copy made available by the University of Toronto Libraries, are of an undated edition printed in London by Samuel French. The estimated date of publication is 1885. A secondary source, also posted by the Internet Archive, was consulted:

archive.org/details/inhonorboundorig00grun

These images, which were made available by the University of California, are of an edition printed in Philadelphia by the Penn Publishing Company in 1912.

French’s Acting Editions from the nineteenth century tend to have minor editorial inconsistencies and errors as well as errors introduced in the printing process, depending on the condition and inking of the plates. Thus, for example, it is at times difficult to determine whether a certain letter is an “c,” “e,” or “o” or whether a certain punctuation mark is a period or a comma. Where context made the choice obvious, the obvious reading was given the benefit of the doubt without comment.

The following changes were noted:

- Throughout the text, the use of dashes has been made consistent.

- p. 3: Based on the Penn edition and editorial practice in other contemporaneous French’s Acting Editions, three colons in the opening scene description were changed to semicolons.

- p. 4: The only girl in the wide world for me—Added a period at the end of the sentence.

- p. 8: Sir George (putting chair…—Changed “Sir George” to “Sir G.” for consistency.

- p. 9: Of course. (quickl y)—Deleted space in “quickl y” in two consecutive lines.

- p. 10: Sir. G. Why so?—Deleted period after “Sir”.

- p. 10: Sib G. (putting the brief…—Changed “Sib G.” to “Sir G.”.

- p. 10: Sir. G. Let us hope it will.—Deleted period after “Sir”.

- p. 10: …and hear you plead,—Changed comma to period.

- p. 11: What can they have to talk about—those two? (reflectiv ly)—Inserted “e” in reflectiv ly.

- p. 12: It is a weird thing Sometimes—Inserted period after “thing”.

- p. 14: I know she did, although she never spoke: and…—Changed colon to semicolon, as in Penn edition.

- p. 17: Are youno better?—Inserted space after “you”.

- p. 18: Sir G. What—Added a question mark after “What”.

- p. 19: (reads nervously, the l trembling in his hands)—Changed “l” to “letter”.

The html version of this etext attempts to reproduce the layout of the printed text. However, some concessions have been made. For example, in the printed text stage directions following a line of dialogue were placed a couple spaces after the dialogue, flush right on the same printed line, or flush right on the next line. In the etext, all stage directions printed on the same line were placed right after the dialogue. Stage directions printed on the next line were indented from the left margin, and coded as hanging paragraphs.