*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 41199 ***

William Le Queux

"The Great God Gold"

Preface.

An Explanation.

The remarkable secret revealed in the following pages is not purely fiction.

The discovery, much in the form that I have here presented it, has actually been made, and its discoverer, a well-known professor at one of the Universities in the North of Europe, recently placed the extraordinary statement in my hands.

In consequence, I consulted a number of the first living authorities on the subject, who most courteously gave me their opinions and to whom I owe much assistance, while several other Hebrew scholars, less noted, evinced the greatest curiosity.

Therefore I trust that the reader himself may find this hitherto unheard-of statement of facts of equal importance and interest.

William Le Queux.

Devonshire Club, London, 1910.

Chapter One.

Introduces the Stranger.

“My name? Why—what does that matter, Doctor? In an hour—perhaps before—I won’t trouble anybody further.”

“But surely it is your duty, my friend, to let me know your name?” argued the other. “Even if it be in confidence.”

The dying man slowly shook his head in the negative, moved uneasily, and stretching forth his thin trembling hand, answered in indifferent French.

“I regret that I cannot satisfy your curiosity. I have a reason—a—a strong private reason. Here is my key,” he went on, speaking very slowly and with great difficulty in a weak voice scarce above a whisper. “Open my bag, doctor, and;—and you’ll find there a—a big envelope. Will you give it to me?”

The Doctor, a queer, deformed little man shabbily dressed, with grey hair and short grey beard, rose from the bedside and with the key crossed to where a well-worn leather bag lay upon the floor.

As he turned his back upon his nameless patient and knelt beside the bag, a curious look of craft and cunning overspread his hard, furrowed countenance. But it was only for a second. Next instant it had vanished, and given place to that serious expression of sympathy which his face had previously worn.

He found a large blue, linen-lined envelope which he gave into the white trembling hands of the stranger.

The prostrate man looked about fifty, his unkempt hair and moustache just tinged with grey, unshaved, and with white drawn face betraying long and intense suffering.

Why was he so determined to conceal his name? What secret of his life had he to hide?

Upon his blanched features was written the history of a curious and adventurous past. Perhaps he held some strange and amazing secret. He was eccentric in only one particular—that though he knew himself to be dying, he would leave no message for any relative; refusing absolutely and stubbornly to give his name, even to the man who, now at his side, had befriended him.

The room was a small and not over cleanly one, high up in a fourth-rate hotel close to the Gare du Nord, in Paris, a room with a single bed, a threadbare carpet, and a cheap wooden washstand with the grey December light filtering through lace curtains that hung limp and yellow. The wallpaper was greasy and faded, and the bed itself the reverse of inviting.

To Doctor Raymond Diamond the dying man had been an entire stranger until three days before—a chance acquaintance which adversity had brought him. Both men were, as a matter of fact, stranded in Paris. They had, in ascending the narrow stairs of their little hotel, wished each other “Good-day.” Men who are hard up always form easy acquaintanceships. The stranger had told him that he was a Dane, from Copenhagen, but the name, Jules Blanc, which he had given to the proprietor was certainly not Danish. Indeed, he had admitted to Diamond that he had not given his real name. He had reasons for withholding it.

He was a mystery, and the Doctor strongly suspected him of having absconded from his native land, and coming to the end of his resources, was now in fear of the police.

That he was well educated had been quickly apparent. Though he spoke French badly it was evident that he had nevertheless travelled extensively, and had, in his better days, been possessed of considerable means. He had been in the Near East, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine and Egypt, and appeared to possess an intimate knowledge of those countries.

Yet his luggage had been reduced to that one small bag containing a big blue envelope and a change of linen.

For two days they had idled about Paris together, both practically without a sou.

The Doctor, when he had discovered the true state of his friend’s finances, had explained that he too was “temporarily embarrassed owing to his many recent investments;” whereat they had both laughed in chorus and with light hearts spent half the day lazily lolling upon the seats in the Tuileries Gardens watching the children at play.

It was during those idle hungry hours that the stranger’s remarks aroused within the Doctor the greatest curiosity. Diamond himself, an Englishman, had in his student days taken his M.D. at Edinburgh, and was also a scholar of no mean attainments, yet this Dane’s knowledge of many occult matters appeared amazingly profound.

Why did he so resolutely refuse to give his name?

On the day the Doctor had met the Dane, his financial resources consisted of one solitary franc and a twenty-five centime nickel piece. His newly found friend had less. Hence the food they had had was not very abundant. The two men, however, brothers in adversity, faced the hunger problem gaily. It was not the first time that either of them had been face to face with the streets and starvation, therefore it was no new experience.

Yet the stranger ever and anon seemed deeply depressed. He knit his brows, set his teeth hard, and drew deep sighs—sighs over the might-have-beens of his past. His business in Paris was an important, an entirely secret one, he had declared. In a few days—in a week at most—it must be completed.

“And then,” he added with a laugh of confidence, “I shall probably move on to the Grand.”

That same evening, however, as they were walking up the Rue Lafayette towards the obscure hotel, the stranger had been suddenly seized with sharp pains in the region of his heart. Neither man had tasted food for twenty-four hours, and both were cold and faint.

Diamond, however, took the man’s arm and managed to get him back to his room. There he examined him carefully, and having diagnosed the case, recognised the extreme danger, but told the patient nothing decisive.

He saw the proprietor, and from him borrowed three francs. Then he wrote a prescription which he took round to the big Pharmacie du Nord, at the corner.

The mixture revived the invalid, but in the night he collapsed again. At mid-day Diamond obtained a cup of bouillon from a cheap restaurant near, and brought it to the man who had refused his name. And he had now sat by the bedside with his fingers upon the patient’s pulse all through that short gloomy afternoon.

“I’m sorry things are so bad as they are,” the Doctor was saying, as he handed the invalid the big blue envelope, for he had, an hour before, told him the truth. “You ought to have had advice long ago.”

The dying man smiled faintly and shook his head.

“I was warned in Stockholm,” he answered in a low tone. “But I didn’t heed. I—I was a fool.”

The Doctor sighed. What could he say? He had recognised that the poor fellow was already beyond human aid. He had probably been suffering from the affection of the heart for the past six or seven years—perhaps more.

“And you are certain?” asked the ugly little man at last, again taking the thin, bony hand in his. “Are you quite certain that you wish to send no message to anybody?”

For a few seconds the prostrate man struggled hard to speak.

“No,” he succeeded in gasping at last. “No message—to—anybody.”

The Doctor pursed his lips at the rebuff. The eccentricity of the stranger had become more marked in those moments of finality.

His thin, nerveless fingers were fumbling with the bulky envelope, which seemed to contain a quantity of folded papers.

“Doctor,” he whispered at last, “I—I want to burn—all these—all—every one of them. Burn them entirely.”

“As you wish, my dear friend,” responded the hunchback, eyeing the envelope eagerly, and wondering what it might contain. “I’ll put a match to them in the stove yonder.”

The invalid, by dint of great effort, managed to move himself so that his eyes could fall upon the little door in the round iron stove, in which, however, no fire was burning, even though the day was bitterly cold.

Yet he hesitated, hesitated as though he dared not trust the hungry little man who had befriended him.

“Do you wish them destroyed?” the Doctor again inquired.

The dying man nodded, at the same moment raising his finger and motioning that he could not speak.

Diamond waited. He saw that the patient was vainly endeavouring to articulate some words.

For several moments there was a dead silence.

At last the nameless man spoke again, very softly and indistinctly. Indeed, the Doctor was compelled to bend low to catch the words:

“Take them,” he said. “Take them—and burn them in the stove. Mind—destroy every one.”

“Certainly I will,” answered the other. “Give them to me, and you shall see me burn them. I’ll do so there—before your eyes.”

The man held the envelope in his dying grip. He still hesitated. His eyes were fixed upon the papers wistfully, as though filled with poignant regret at a mission unaccomplished.

“Ah!” he gasped with difficulty. “To think that this is the end—the end of a lifetime’s study and struggle! Death defeats me, vanquishes me—as it has vanquished every other man who has striven to learn the secret.”

Diamond stood listening in wonder and curiosity. He noticed the dying man’s reluctance to destroy the papers.

Perhaps he would succumb, and leave them undestroyed! What secret could they contain?

There was a long silence. The grey light over the thousands of chimney-pots was fast fading into gloom. The room was darkening.

The patient lay motionless as one dead, yet his dull eyes were still open. In his hand he still held his treasured envelope.

Again Diamond spoke, but the man with a secret made no reply. He only raised his wan hand, and shook his head sadly, indicating inability to speak.

The queer little Doctor bent once more closer to the stranger and saw that the end was near. He was hoping against hope that the man would expire before he had strength to order the destruction of those documents, whatever they were. The mysterious statements of the dying man had indicated that the papers in question contained some remarkable secret, and naturally his curiosity had been aroused.

During those three brief days of their acquaintance he had, in vain, tried to form some conclusion as to who the stranger might be. At first he had believed him to be a broken-down medical man like himself. But that surmise had been quickly negatived. He was a professional man without a doubt, but he had carefully concealed even his profession as well as his name.

The doctor had re-seated himself in the rickety rush-bottomed chair at the bedside, and sat in patience for the end, as he had sat beside hundreds of other dying men and women in the course of his career.

The patient breathed heavily, and again stirring uneasily, cast a longing look at the glass of lemonade upon the little table near by. Diamond recognised his wish, and held the tumbler to the man’s parched lips.

The dying stranger motioned, and the Doctor bent his head until his ear was near the other’s mouth.

“Doctor,” he managed to whisper after great difficulty, “it’s no use. There’s no hope! Therefore will you take them to the stove—and—and burn them—burn them all!”

“Certainly I will,” was the Doctor’s reply, rising and slowly taking the envelope from the prostrate man’s reluctant fingers.

He felt crisp papers within as he turned his back upon the dying man and bent down to the stove, placing himself between the invalid’s line of vision and the stove itself.

A moment later, however, he opened the stove-door, placed the envelope within, and applied a match to it.

Next moment a blood-red light fell across the darkening room upon the pallid face lying on the pillow.

A pair of dull, anxious, deep-set eyes watched the flames leap up and quickly die down again, watched the crinkling tinder as the sparks died out one by one—watched until Diamond stirred up the charred folios in order that every one should be consumed.

Then he turned slightly in his bed and, stretching forth his hand as though wishing to speak, drew a long, hard breath.

“And—and so—vanishes all my hope—my life,” the stranger managed to sob bitterly in a voice almost inaudible.

Again he sighed—a long-drawn sigh. And then—in the room, now almost dark, reigned a complete silence.

Death had entered there. The man with the secret had passed to that land which lies beyond human ken.

Chapter Two.

Describes the Doctor’s Doings.

Raymond Diamond’s unfortunate deformity had always been against his advancement in his profession.

The only son of old Doctor Diamond, a country practitioner of the old school, in Norfolk, he had had a brilliant career at Edinburgh, and after some years of changeful life as a locum tenens had bought a partnership in a practice on the outskirts of Birmingham.

His partner turned out to be a rogue who had misrepresented facts, and six months afterwards absconded to America. Diamond, however, betrayed a sharp resourcefulness. He advertised the practice in the Lancet, and when a prospective purchaser came to view it, he hired fourteen or fifteen men to come into the surgery, one after the other, and pay fees. Such an impression did this ruse cause upon the newly married medico, who came from London to investigate, that he bought it at once, and Diamond netted nearly twice the sum he originally gave for his partnership.

Finding that his deformity precluded him from forming anything like a lucrative practice, he accepted a berth as ship’s doctor in the P&O service, and for some years sailed the Indian and China seas.

Back in London again, he drifted from one suburban practice to another, doing locum work, and at last built up a semblance of a practice in a cheap new suburban district down at Catford.

Even there, however, his ugliness proved much against him, and at last he was forced to retire into a Northamptonshire village, where he and his wife eked out a modest living by adopting children upon yearly payments.

It was not a very creditable means of livelihood, yet the several children beneath their cottage roof were all well treated and well cared for. And after all, Raymond Diamond, a brilliant man in many ways, was only a failure because of his physical shortcomings.

He knew his Paris well. In his younger days he had often been there. Indeed, he once resided at St. Cloud with an invalid gentleman for close upon two years. Long years of travel had rendered him a thorough-going cosmopolitan, even though his lot was now cast in a sleepy country village.

The reason of his present visit to Paris was in order to interview the father of one of his adopted daughters, but the man had not kept the appointment, and by waiting from day to day in hope of finding him, he had exhausted his slender finances, and he knew that his patient wife was in a similar condition of penury at home.

He was certainly a strikingly ugly man. His forehead was broad and bulgy, and his face narrowed to the point of the beard. His head seemed too large, his arms too long and ungainly, while his face was deeply furrowed by long years at sea. His mouth, too, was wide and ugly and when he laughed he displayed an uneven row of teeth much discoloured by tobacco.

With folded arms, he was standing by the dead stranger, silently contemplating the white upturned face which showed distinctly in the fading twilight.

“I wonder who he was?” he exclaimed aloud. “Why did he refuse his name, and why was he so particular to burn those papers? He was a queer stick—poor fellow! I suppose they have inquests in France, and I’ll get something as a witness.”

And he pulled the sheet tenderly across to hide the lifeless visage.

“But,” he added, “perhaps I’ve rendered myself liable because I didn’t call in a French doctor!”

Then, suddenly arousing himself, he walked softly across to the stove and, spreading his handkerchief on the floor, raked out all the tinder into it. To his satisfaction he saw, as he had anticipated, that some of the papers, closely folded as they were, had only been burned at the edges.

One of them he opened, and found it covered with typewriting.

“These will, no doubt, prove interesting,” he remarked to himself as he gathered every particle up into the handkerchief, and very carefully folded it over to protect it.

The lid of an old cardboard box which he found under the bed he broke up, and placing one piece above the handkerchief and the other below, he put the whole into the breast-pocket of his shabby frock-coat.

The stranger’s bag he next examined. It was old, and covered with labels of first-class hotels—many of them in cities in the Near East and the Levant. The contents were disappointing, only a couple of shirts marked with the initials “P.H.”, several dirty collars, a cravat or two, and a safety razor, together with a few unimportant odds and ends.

“The proprietor must have these, in lieu of his bill, I suppose,” Diamond said. “I wonder what ‘P.H.’ stands for? He was a well-read man without a doubt. By Jove! he took his blow as bravely as any fellow I’ve seen go under. With a heart like that, it’s a marvel that he lived so long. If I knew who his relatives were, I’d ‘wire’ to them—providing I had the money,” he added with a bitter smile.

Then he shrugged his shoulders, and after striking a match to reassure himself that nothing had been left inside the stove to betray the fact that papers had been burned there, he turned upon his heel and left the room.

Below, in his dingy little back room on the first floor, he saw the proprietor, and told him what had occurred.

The old man grunted in his armchair and ordered the greasy-looking valet-de-chambre to inform the police, but to first go and search the dead man’s effects and ascertain if he had left any money.

“Monsieur Blanc was penniless, like myself,” Diamond said. “Neither of us had eaten all day yesterday.”

“No money to pay his bill!” croaked the old Frenchman, who looked more like a concierge than a hotel proprietor. “And you are also without money?” he asked glaring.

“I regret that such is the truth,” was Diamond’s answer with much politeness. “Has not m’sieur noticed in life that honest men are mostly poor? Thieves and rogues are usually in funds.”

“Then I must ask you to leave my hotel at once,” said the old man testily.

The Doctor grinned, and bowed.

“If that is m’sieur’s decision, I can do nothing else but obey,” was his polite answer.

“You will leave your luggage, of course.”

“M’sieur is quite welcome to all he finds,” was the Doctor’s response, and with another bow he turned and strode out.

His plan had worked admirably. He had no desire to remain there in the present circumstances. To be ordered out was certainly better than to flee.

So he walked gaily down the stairs, and a few minutes later was strolling airily down the Rue Lafayette, in the direction of the Opera.

The hotel proprietor and the valet-de-chambre quickly searched the dead man’s room, but beyond the bag and its contents found nothing. Afterwards they informed the police.

Meanwhile Raymond Diamond walked on, undecided how to act. He had already reached the Place de l’Opera, now bright beneath its many electric lamps, before he had made up his mind. He would go once again in search of little Aggie’s father, the man who owed him money.

Therefore he turned into the narrow Rue des Petit-Champs, and half-way down entered a house, passed the concierge, and ascended to a flat on the second floor.

Fully twenty times he had called there before, but the place was shut, as its owner, an Englishman, was absent somewhere in the Midi. When, however, he rang, he heard movement within.

His heart leapt for joy, for when the door opened there stood Mr Mullet, a tall, thin, red-haired man with a long pale face and a reddish, bristly moustache, who, the moment he recognised his visitor, stretched forth his hand in welcome.

“Come in, Doctor,” he cried cheerily. “I got back only this morning, and the concierge gave me your card. I expected, however, you’d grown tired of waiting, and returned to England. How’s my little Aggie?”

“She grows a bonnie girl, Mr Mullet—quite a bonnie girl,” answered the ugly little man. “Gets on wonderfully well at school. And Lady Gavin, at the Manor, takes quite an interest in her.”

“That’s right. I’m glad to hear it—very glad. Though I’m a bit of a rover, Doctor, I’m always thinking of the child you know. Why—she must be nearly thirteen now.”

“Nearly. It’s fully six years since I took her off your hands.”

“Fully.”

And the two men sat down in the rather comfortable room of the tall, cadaverous-looking man, a mining engineer, whose adventures would have filled a volume.

David Mullet, or “Red Mullet” as his friends called him on account of the colour of his hair, offered the Doctor a good cigar from his case, poured out two glasses of brandy and soda, and after a chat took out two notes of a thousand francs from the pocket-book he carried and handed them to his visitor, receiving a receipt in return.

“I’ve been a long time paying, I’m afraid, Doctor,” laughed the man airily. “But you know what kind of fellow I am! Sometimes I’m flush of money, and at others devilish hard up.”

“I’m hard up, or I wouldn’t press for this.”

“My dear Doctor, it’s been owing for two years. And I’m very glad to get out of your debt.”

“Well, Mr Mullet,” Diamond said, “eighty pounds is a lot to me just now. I haven’t had a square meal for days, and to tell the truth I’ve just been ordered out of my hotel.”

“My dear fellow, that’s happened to me dozens of times,” laughed the other. “I never feel sorry for the proprietor. I only regret that I can’t give tips to the servants. I suppose you’ll go back home—eh?”

“To-night, or by the first service in the morning.”

“By Jove, I’d like to see my little Aggie. I wonder,” exclaimed the man, “I wonder if I could manage to get across?”

“It isn’t far,” urged the Doctor.

But “Red Mullet” hesitated. He had a cause to hesitate. There was a hidden reason why for the past three years he had not put foot on English soil.

He shook his head sadly as he recognised that discretion was the better part of valour. He was too wary a man to run his neck into a noose.

“No,” he said, “I think that in a few weeks I’ll ask you to bring little Aggie over here to see me. You won’t mind the trip—eh?”

“Not at all,” was the reply. “Aggie will hardly know her father, I expect. She looks upon me as her parent.”

“That was what we arranged, Doctor. She was to take your name, and you were to bring her up as your own daughter. I have a reason for that.”

“So you told me six years ago.”

“Red Mullet” nodded, and stretched out his long legs lazily as he contemplated the smoke of his cigar ascending to the ceiling. Recollections of his child had struck a sympathetic chord in his memory. There were incidents in his life that he would fain have forgotten. One of them was now recalled.

Quickly, however, the shadow passed, and his brow cleared. He became the same easy-going, humorous man he always had been, possessing a merry bonhomie and a fund of stories regarding his own amusing experiences in various out-of-the-way corners of the world.

At last the Doctor, with eighty pounds in his pocket, rose and wished his friend adieu.

Then he walked to a brasserie in the Avenue de l’Opera, where he dined well, concluding his meal with coffee and a liqueur, and at nine o’clock he left the Gare du Nord for Calais and London.

The reason of his sudden flight from Paris was the fear of having contravened the law by not calling in a French medical man when he knew that the case of the mysterious Blanc was hopeless. Detention would mean trouble and much expense. Therefore he deemed it best to get across to England at the earliest possible moment.

At six o’clock next morning he found himself in a small hotel called the Norfolk in Surrey Street, Strand, where he had on one or two occasions stayed. The waiter having brought up his breakfast, he locked the door and, going to the table, he took from his pocket the packet of charred paper and broken tinder which he had abstracted from the stove in Paris.

With infinite care he opened the handkerchief and spread it out. The tinder had broken into tiny fragments and some had been reduced to black powder, while the half-charred paper split as he attempted to open it.

He had switched on the light, for the London dawn had not yet spread. Then, seating himself at the table, he proceeded to examine and decipher the remains of the papers which the dying man believed he had entirely destroyed.

For some time he could make nothing of the lines of written words, which had neither beginning nor end.

Suddenly, however, he held his breath. He sat erect, statuesque, his dark eyes staring at the paper.

Then he re-read the written lines eagerly.

“Great Heavens! How strange!” he cried. “How utterly astounding! That man who refused his name had learned the greatest and most important secret this modern world of ours contains! And it is in my hands—mine! My God! Is it true—is it really true what this man alleges?”

He paused and again re-read the smoke-blackened, half-burned pages. For some moments he sat with his mouth open in utter astonishment. He could scarcely believe his own eyes.

“His secret—his amazing secret, one unheard of—is mine!” he gasped, glancing around the room, as though half-fearful lest he had been overheard. “I shall be a rich man—one of the richest in all Europe! Before six months is out the whole world will be at the feet of Raymond Diamond!”

Chapter Three.

Shows One of the Fragments.

“Well,” declared the Doctor, speaking to himself, “even my success in intra-laryngeal operations was not half so interesting as this!”

And again he bent to examine the half-charred fragments before him. Some were in typewriting, one was in a small fine script. One hardly legible was in German, others were in English, interspersed here and there with words which he recognised were in Hebrew character.

In that small bedroom, beneath the rather dim electric light, the deformed little man sat pouring over the folios so dry that they cracked and crumbled when touched.

Much was undecipherable; the greater part had indeed been utterly consumed, but here and there he was enabled to read consecutive sentences, and those he made out utterly staggered him.

Indeed, so full of interest, so curious, and so amazing they would have staggered anybody.

He held in his hands the dead man’s secret—a secret that on the face of it, seemed to be the strangest and at the same time the most unsuspected in all the world.

Suddenly he sat back, and, staring straight across the narrow room, exclaimed aloud:

“Why, there are men in the city this very day who’d give me ten thousand pounds for the remains of these papers! But would I sell them? No—not for ten times that amount! Who knows what this discovery may not be worth?”

He chuckled to himself. Already he felt himself a wealthy man, a man who could dictate his own terms in financial circles—a man who would be welcomed in audience by crowned heads themselves!

He sighed, and the heavy exhalation blew a quantity of fragments of tinder away upon the carpet.

“I wish I hadn’t burned them quite so much,” he said regretfully. “Had I had a newspaper handy I could have lit that instead. Or—or I might easily have delayed their destruction until—until after the end. Yet he seemed quite conscious, up to the very last moment. No wonder he regretted death before the fulfilment of the great work he had commenced—no wonder he contemplated moving to the Grand Hotel at an early date! And yet,” he added, after a pause, “it’s all very intricate, very indistinct, and requires a greater scholar than myself to properly understand and unravel it.”

The chief document, consisting of about ten typewritten pages in English, had been badly burned. It was this which he was now engaged in trying to decipher. At the top left-hand corner the sheets had originally been held together by a paper-fastener, but that corner had been consumed as well as all round the edges. The centre alone of three folios remained readable, even though it had been yellowed by smoke.

“There seem very many references to Israel, to Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, and to the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel. Yet they seem to convey nothing. Ah!” he sighed, “if only I could reconstruct the context. There are Biblical references, too. I must obtain a Bible.”

So he rose, rang for a waiter, and asked him whether there was such a thing in the hotel as a copy of Holy Writ.

The man, a young German, naturally regarded the visitor as an eccentric person or a religious crank, but he went at once and borrowed a small Bible from the chambermaid—a volume which afterwards proved to contain, between its leaves, small texts of her Sunday-school days, several pressed flowers, and a lock of hair.

A reference given upon one of the crinkled folios was “Ezekiel xxviii, 24.”

Reseating himself after the young German had left, Raymond Diamond hastily turned over the pages of the little well-thumbed Bible and found what proved to be the prophecy of the restoration of Israel.

Another reference in the next line of the half-burnt screed was Ezekiel xl, xli and xlii, no verses being designated.

On turning to these chapters, the doctor found that they contained a description of Ezekiel’s vision of the measuring of the temple.

Continuing, he read the further dimensions of the temple, the size of the chambers for the priests, and the measures of the outer court “to make a separation between the sanctuary and the profane place.”

All this conveyed to the deformed man but little.

That it had some connection with the strange secret was apparent, but in what manner he failed to distinguish.

He had gathered broadly that the dead man’s discovery was an amazing one, and that a strange secret was revealed by those documents when they were intact, but it was all so mystifying, so astounding, that he could scarce give it shape within his own bewildered brain.

The enormous possibilities of the discovery had utterly dumbfounded him—it was a discovery that was unheard of.

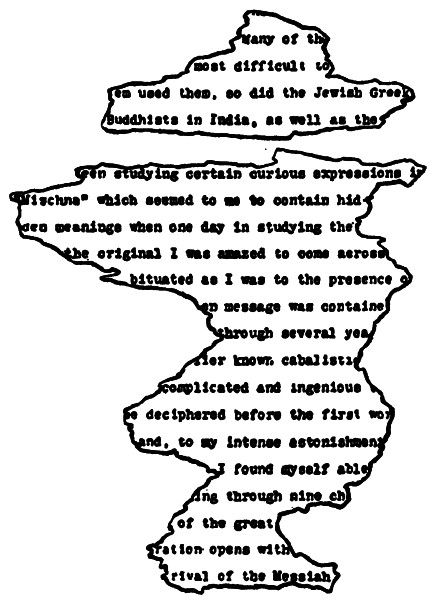

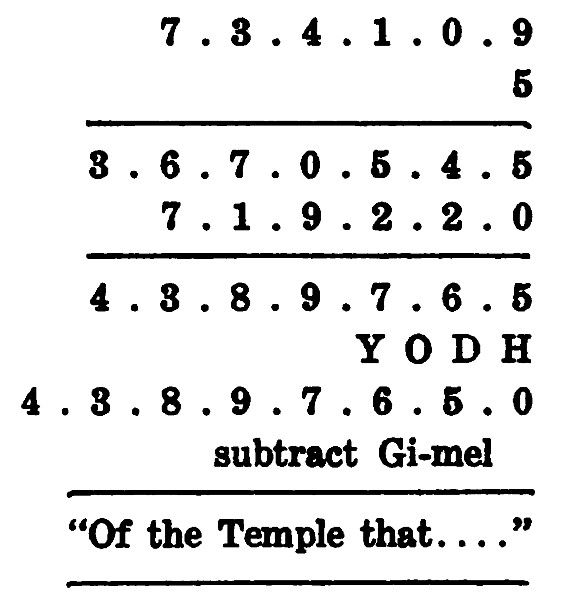

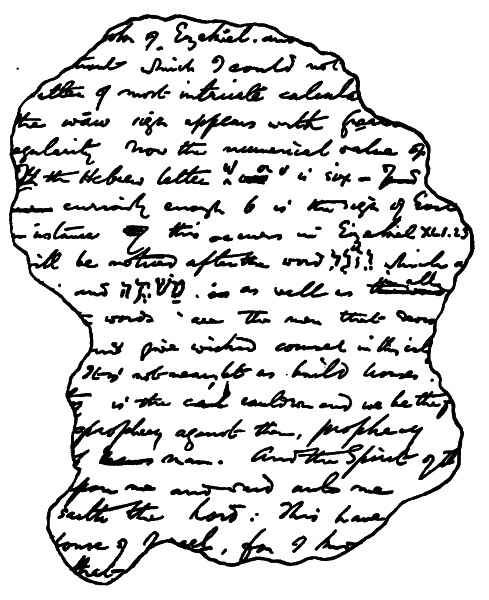

In order to present to the reader some idea of the fragments of the dead man’s papers lying upon the table before him, it may be of interest if the present writer gives a photographic representation of one of the badly burned folios.

As will easily be seen, the undestroyed fragment of the document showed but little that was tangible. Of interest, it was true, but the interest was, alas! a well-concealed one. The dead man was a scholar. Of that there was no doubt whatsoever. The doctor had recognised from the first that he was no ordinary person.

The document seemed to be a portion of some statement made by a person as to the curious and unexpected result of certain studies.

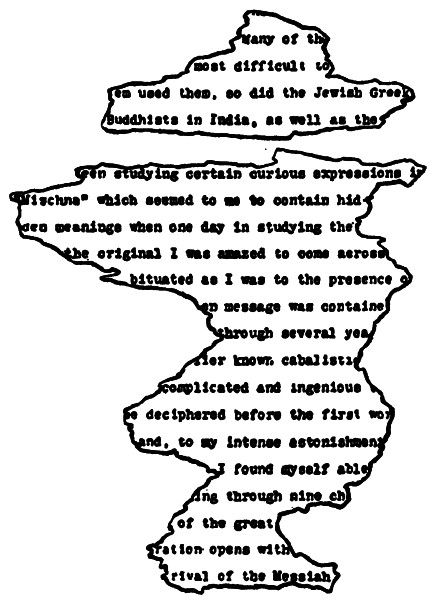

He who made the declaration had apparently been a student of the Talmud, and especially the school of the Amoraim, or debaters, who about A.D. 250 expounded the “Mishna.”

Raymond Diamond had long ago read Wunsche, Bacher and Strack, and from them had learned how the Amoraim had expounded the “Mishna,” and how their labours had formed the Gemara, while the united Mishna and Gemara formed the books of the Talmud. By that time, and even earlier, the teachers of Judaism were also working in the schools of Babylonis. Hence the Talmud now exists in two forms—the Palestinian Talmud, or Talmud of Jerusalem, and the Babylonian Talmud. Rabbi Jehuda compiled the “Mishna” which, in general, sums up the outcome of the activity of the Sopherim, Zugoth and Tannaim, and thus became the canonical book of the oral law.

He was recalling these facts as he sat staring at the half-charred fragments on the table before him.

“The person making the declaration,” he said aloud to himself, “appears to have discovered certain hidden meanings in the ‘Mishna.’ Well—one can read hidden meanings in most writings, I believe, if one wishes. Yet he seems to have come across something which amazed him—some cabalistic message very complicated and ingenious. It caused him great astonishment when he found himself able to—able to what? Ah! that’s the point,” he sighed.

Then, after another long pause, he decided that “nine ch—” meant “nine chapters,” and that the final lines of the page dealt with some declaration opening with the arrival of the Messiah.

“Yes,” he said in a hard decisive tone, straightening his crooked back as well as he was able. “There is a mystery explained here—a great and most astounding mystery.”

Chapter Four.

Concerns a Consultation.

Late that same afternoon Raymond Diamond walked up the long muddy by-road which led from Horsford station to the village, about a mile distant.

Horsford was an obscure little place, still quite out-of-the-world, even in these days of trains and motor-cars.

About four miles west of Peterborough on the edge of the fox-hunting country, it was a pleasant little spot consisting of a beautiful old Norman church, with one of the finest towers in England and one long, straggling street mostly of thatched houses.

There were only two large houses—Horsford House, at the top of the hill on the Peterborough side, and the Manor, an old seventeenth-century mansion, half-way down the village.

It was not yet dark when the Doctor, the only arrival by train, turned the corner by the Wheel Inn and entered the village. As he did so, Warr, who combined the business of publican and village butcher, wished him a cheery “Good evenin’, Doctor.”

And as the little man trudged up the long street he was greeted with many such salutes, to all of which he answered mechanically, for he was thinking—thinking deeply.

The fragrant smell of burning wood from the cottages greeted his nostrils—the smell of that quiet little village which for some years had been his home.

He breathed again in that rural peace, as a dozen cows slowly plodded past him.

At last he turned from the main street, up a short, steep hill where, at the end of a small cul-de-sac, stood a long, old-fashioned, two-storied cottage with its dormer-windows peeping forth from the brown thatch. In summer, over the whole front of it spread a wealth of climbing roses, but now, in winter, only the brown leafless branches remained.

In the small, well-kept front garden were a number of well-trimmed evergreens, while an old box-hedge ran around the tiny domain.

As he lifted the latch of the gate, Mrs Diamond, a neat, well-preserved woman in black, threw open the door with a cheery welcome, and a moment later he was in his own old-fashioned little dining-room, warming himself at the fire, which, sending forth a ruddy glow, illuminated the room.

For such a humble home, it was quite a cosy apartment. Upon the old-fashioned oak-dresser at the end were one or two pieces of blue china, and on the oak overmantel were a few odd pieces of Worcester and Delft. On the walls were one or two engravings, while the furniture was of antique pattern and well in keeping with the place.

The doctor possessed artistic tastes, and was also a connoisseur to no small degree. In the days when he had possessed means, he had been fond of hunting for curios or making purchases of old furniture and china, but, alas! in these latter days of his adversity he had experienced even a difficulty in making both ends meet.

“I received your telegram, Raymond dear,” exclaimed Mrs Diamond. “I’m so glad you were successful in finding Aggie’s father. It’s taken a great weight from my mind.”

“And from mine also,” he said with a sigh seated before the fire with his hands outstretched to the flames. “Mullet wants me to take the child over to Paris to see him in a week or so.”

“Why does he not come over here?”

The Doctor pulled a wry face, and shrugged his shoulders ominously.

His wife, by her speech, showed herself to be a woman of refinement. She had been the widow of a medical man in Manchester before Diamond had married her. Though it was much against her grain to submit to registration as a foster-mother of children, yet it had been their only course. Raymond Diamond was too ugly to succeed in his profession. The public dislike a deformed doctor.

He told his wife how he had been at the end of his resources in Paris, and how, just at the moment when things had looked blackest, “Red Mullet” had returned. But he made no mention of meeting the stranger, or of the record of the curious secret which, between two pieces of cardboard, now reposed carefully in his breast-pocket.

Its possession held him in a kind of stupor. From what he had been able to gather—or rather from what he imagined the truth to be—he already felt himself an immensely wealthy man. He was, in fact, already planning out his own future.

The dead stranger had said he intended to remove to the Grand Hotel. Diamond’s intention was to go further—to purchase a fine estate somewhere in the grass-country, and in future live the life of a gentleman.

Mrs Diamond noticed her husband’s preoccupied manner, and naturally attributed it to financial embarrassment.

A few moments later the door opened, and a pretty, fair-haired girl, about thirteen, entered, and finding the doctor had returned, rushed towards him and, throwing her arms about his neck, kissed him, saying:

“I had no idea you were back again, dad. I went down the station-path half-way, expecting to meet you.”

“I came by the road, my child,” was the Doctor’s reply as he stroked her long fair hair. “I’ve been to Paris—to see your dad, Aggie,” he added.

“My other dad,” repeated the child reflectively. “I—I hardly remember him. You are my own dear old dad!” And she stroked his cheek with her soft hand.

Aggie was the doctor’s favourite. He was devoted to the daughter of that tall, thin man who was such a cosmopolitan adventurer, the child who was now the eldest of his family, and who had, ever since she had arrived, a wee weakly little thing, always charmed him by her bright intelligence and merry chatter.

She was a distinctly pretty child, neat in her dark-blue frock and white pinafore. In the village school she was head of her class, and Mr Holmes, the popular, good-humoured schoolmaster, had already suggested to the Doctor, and also to Lady Gavin at the Manor, that she should be sent to the Secondary School at Peterborough now that he could teach her no more.

The Doctor drew Aggie upon his knee, and told her of her father’s inquiries and of his suggestion that she should go to Paris to see him.

Paris seemed to the child such a long way off. She had seen it marked upon the wall-maps in school, but to her youthful mind it was only a legendary city.

“I don’t want to leave Horsford, dad,” replied the girl with a slight pout. “I want to remain with you.”

“Not in order to see and know your father?”

“You are my dad—my only dad,” she declared quickly. “I don’t want to see my other dad at all,” she added decisively. “If he wants to see me, why doesn’t he come here?”

“He can’t my dear,” replied the doctor. “But tell me. Have you seen Lady Gavin since I’ve been away?”

“No, dad. Mr Farquhar and his sister have come to stay at the Manor, so she’s always engaged.”

“Frank Farquhar is down here again, eh?” asked Diamond quickly. Then he reflected deeply for a few moments.

He was wondering if Farquhar could help him—if he dare take the young man into his confidence.

Nowadays he was “out of it.” He knew nobody, buried there as he was in that rural solitude.

“Is Sir George at home?” he asked the child, who, like all other children, knew the whole gossip of the village.

“No, dad. He started for Egypt yesterday. Will Chapman told me so.”

The Doctor ate his tea, with his wife and five “daughters” of varying ages, all bright, bonnie children, who looked the picture of good health.

Then, after a wash and putting on another suit, he went out, strolling down the village to where the big old Manor House, with its quaint gables and wide porch, stood far back behind its sloping lawn.

Generations of squires of Horsford had lived and died there, as their tombs in the splendid Norman church almost adjoining testified. It was a house where many of the rooms were panelled, where the entrance-hall was of stone, with a well staircase and a real “priests’ hole” on the first floor.

He ascended the steps, and his ring was answered by a smart Italian man-servant. Yes. Mr Farquhar was at home. Would the doctor kindly step into the library?

Diamond entered that well-known room on the right of the hall—a room lined from floor to ceiling with books in real Chippendale bookcases, and in the centre a big old-fashioned writing-table. Over the fireplace were several ancient manuscripts in neat frames, while beside the blazing fire stood a couple of big saddle-bag chairs.

Sir George Gavin, Baronet, posed to the world as a literary man, though he had risen from the humble trade of a compositor to become owner of a number of popular newspapers. He knew nothing about literature and cared less. He left all such matters to the editors and writers whom he paid—clever men who earned for him the magnificent income which he now enjoyed. Upon the cover of one of his periodicals it was stated that he was editor. But as a matter of fact he hardly ever saw the magazine in question, except perhaps upon the railway bookstalls. His sole thought was the handsome return its publication produced. And, like so many other men in our England to-day, he had simply “paid up” and received his baronetcy among the Birthday honours, just as he had received his membership of the Carlton.

Diamond had not long to wait, for in a few moments the door opened, and there entered a smart-looking, dark-haired young man in a blue serge suit.

“Hulloa, Doc! How are you?” he exclaimed. “I’m back again, you see—just down for a day or two to see my sister. And how has Horsford been progressing during my absence—eh?” he laughed.

Frank Farquhar, Lady Gavin’s younger brother, occupied an important position in the journalistic concern of which Sir George was the head. He was recognised by journalistic London as one of its smartest young men. His career at Oxford had been exceptionally brilliant, and he had already distinguished himself as special correspondent in the Boer and Russo-Japanese campaigns before Sir George Gavin had invited him to join his staff.

Tall, lithe, well set-up, with a dark, rather acquiline face, a small dark moustache, and a pair of sharp, intelligent eyes, he was alert, quick of movement, and altogether a “live” journalist.

The two men seated themselves on either side of the fireplace, and Farquhar, having offered his visitor a cigar, settled himself to listen to Diamond’s story.

“I’ve come to you,” the Doctor explained, “because I believe that you, and perhaps Sir George also, can help me. Don’t think that I want any financial assistance,” he laughed. “Not at all. I want to put before you a matter which is unheard of, and which I am certain will astound even you—a journalist.”

“Well, Doc,” remarked the young man with a smile, “it takes a lot to surprise us in Fleet Street, you know.”

“This will. Listen.” And then, having extracted a promise of silence, Diamond related to the young man the whole story of the dead stranger, and the curious document that had been only half-consumed.

When the Doctor explained that the papers had not been wholly burned, Frank Farquhar rose quickly in pretence of obtaining an ash-tray, but in reality in order to conceal the strange expression which at that, moment overspread his countenance.

Then, a few seconds later, he returned to his chair apparently quite unmoved and unconcerned. Truth to tell, however, the statement made by the dwarfed and deformed man before him had caused him to tighten his lips and hold his breath.

Was it possible that he held certain secret knowledge of which the Doctor was ignorant, and which he could turn to advantage?

He remained silent, with a smile of incredulity playing about his mouth.

The truth was this. Within his heart he had already formed a fixed intention that the dead man’s secret—the most remarkable secret of the age—should be his, and his alone!

Chapter Five.

Spreads the Net.

The deformed man existed in a whirl of excitement. He already felt himself rich beyond his wildest dreams. He built castles in the air like a child, and smiled contentedly when rich people—some of the hunting crowd—passed him by unrecognised.

During the three days that followed, Frank Farquhar held several consultations with him—long earnest talks sometimes at the Manor or else while walking across that heath-land around the district known to the followers to hounds as the Horsford Hanglands.

The villagers who saw them together made no comment. As was well known, the little Doctor and Lady Gavin’s clever young brother were friends.

Diamond had enjoined the strictest secrecy, but Farquhar, as a keen man of business and determined to put his knowledge to the best advantage, had already exchanged several telegrams with some person in London, and was now delaying matters with Diamond until he obtained a decided reply.

On the fourth day, just after breakfast, Burton, the grave old butler, handed the young man a telegram which caused him to smile with satisfaction. He crushed it into his pocket and, seizing his hat, walked along to the Doctor’s cottage. Then the pair took a slow stroll up the short, steep hill on to the Peterborough road, through the damp mists of the winter’s morning. Away across the meadows on the left, hounds were in full cry, a pretty sight, but neither noticed the incident.

“Do you know, Doctor,” exclaimed the young man as soon as they got beyond the village, “I’ve been thinking very seriously over the affair, and I’ve come to the conclusion that unless we put it before some great Hebrew scholar we shall never get down to the truth. The whole basis of the secret is the Hebrew language, without a doubt. What can we do alone—you and I?”

The little Doctor shook his head dubiously.

“I admit that neither of us is sufficiently well versed in Jewish history properly to understand the references which are given in the fragments which remain to us,” he said. “Yet if we go to a scholar, explain our views, and show him the documents, should we not be giving away what is evidently a most valuable secret?”

“No. I hardly think that,” answered the shrewd young man. “Before putting it to any scholar we should first make terms with him, so that he may not go behind our backs and profit upon the information.”

“You can’t do that!” declared Diamond.

“Among scholars there are a good many honourable men,” replied Frank Farquhar, with a glance of cunning. “If we proposed to deal with City sharks, it would be quite a different matter.”

“Then to whom do you propose we should submit the documents for expert opinion?” inquired the deformed man, as he trudged along at his side.

“I know a man up in London whom I implicitly trust, and who will treat the whole matter in strictest confidence,” was the other’s reply. “We can do nothing further down here. I’m going up to town this afternoon, and if you like I’ll call and see him.”

The Doctor hesitated. He recognised in the young man’s suggestion a desire to obtain his precious fragments and submit them to an expert. Most deformed men are gifted with unusually shrewd intelligence, and Raymond Diamond was certainly no exception. He smiled within himself at Frank Farquhar’s artless proposal.

“Who is the man?” he asked, as though half-inclined to adopt the suggestion.

“I know two men. One is named Segal—a professor who writes for our papers; an exceedingly clever chap, who’d be certain to make out something more from the puzzle than we ever can hope to do. I also know Professor Griffin.”

“I shall not allow the papers out of my possession.”

“Or all that remains of them, you mean,” laughed the young man uneasily. “Why, of course not. That would be foolish.”

“Foolish in our mutual interests,” Diamond went on. “You are interested with myself, Mr Farquhar, in whatever profits may accrue from the affair.”

“Then if our interests are to be mutual, Doctor, why not entrust the further investigation to me?” suggested the wily young man. “I hope you know me sufficiently well to have confidence in my honesty.”

The Doctor cast a sharp look at the little young fellow at his side.

“Why, of course, Mr Farquhar,” he laughed. “As I’ve already said, you possess facilities for investigating the affair which I do not. If what I suspect be true, we have, in our hands, the solution of a problem which will startle the world. I have sought your assistance, and I’m prepared to give you—well, shall we say fifteen per cent, interest on whatever the secret may realise?”

“It may, after all, be only historical knowledge,” laughed young Farquhar. “How can you reduce that into ‘the best and brightest?’ Still, I accept. Fifteen per cent is to be my share of whatever profit may accrue. Good! I only wish Sir George were home from Egypt. He would, no doubt, give us assistance.”

The Doctor purposely disregarded this last remark. He held more than a suspicion that young Farquhar intended to “freeze him out.”

“When are you going up to town?” he asked.

“This afternoon. I shall see my man in the morning, and I feel sure that if I put the problem before him he’ll be able, before long, to give us some tangible solution,” was Frank’s reply. “When I act, I act promptly, you know.”

The Doctor was undecided. He knew quite well that young Farquhar was acquainted with all sorts of writers and scholars, and that possibly among them were men who were experts in Hebrew, and in the history of the House of Israel.

He reflected. If the young man were content with fifteen per cent, what had he further to fear?

Therefore, after some further persuasion on Frank’s part, he promised to write out an agreement upon a fifteen per cent, basis, and submit the fragments to the young man’s friend.

They returned to the village, and the Doctor promised to call upon him at noon with an agreement written out.

This he did, and in the library at the Manor Frank appended his signature, receiving in return the precious fragments carefully preserved between the two pieces of cardboard.

When the deformed man had left, Frank Farquhar lit a cigarette, and stretching his legs as he sat in the armchair, laughed aloud in triumph.

“Now if I tie down old Griffin the secret will be mine,” he remarked aloud. “I’ve already ‘wired’ to Gwen, so she’ll expect me at eight, and no doubt tell her father.”

At five o’clock Sir George’s red “Mercedes” came round to the front of the house to take Frank into Peterborough, and half an hour later he was in the “up-Scotsman” speeding towards King’s Cross, bearing with him the secret which he felt confident was to set the whole world by the ears.

He dropped his bag at his rooms in Half Moon Street, had a wash and a snack to eat at his club, the New Universities, round in St. James’s Street, and then drove in a taxi-cab to a large, rather comfortable house in Pembridge Gardens, that turning exactly opposite Notting Hill Gate Station.

Standing behind the neat maid-servant who opened the door was a tall, dark-haired, handsome girl not yet twenty, slim, narrow-waisted, and essentially dainty and refined.

“Why, Frank!” she cried, rushing towards him. “What’s all this excitement. I’m so interested. Dad has been most impatient to see you. After your letter the day before yesterday, he’s been expecting you almost every hour.”

“Well, the fact is, Gwen, I couldn’t get the business through,” he said with a laugh. “We had terms to arrange—and all that.”

“Terms of what?” asked the girl, as he linked his arm in hers and they walked together into the long, well-furnished dining-room.

“I’ll tell you all about it presently, dear,” he replied.

“About the secret?” she asked anxiously. “Dad showed me your letter. It is really intensely interesting—if what you suspect be actually the truth.”

“Interesting!” he echoed. “I should rather think it is. It’s a thing that will startle the whole civilised world in a few days. And the curious and most romantic point is that we can’t find out who was the original holder of the information. He died in Paris, refusing to give his real name, or any account of himself. But there,” he added, “I’ll tell you all about it later on. How is my darling?”

And he bent until their lips met in a long, fervent caress.

Her arms were entwined about his neck, for she loved him with the whole strength of her being, and her choice was looked upon with entire favour by her father. Frank Farquhar was a rising man, the adopted candidate for a Yorkshire borough, while from his interest in Sir George Gavin’s successful publications he derived a very handsome income for a man of his years.

“I’ve been longing for your return, dearest,” she murmured in his ear as he kissed her. “It seems ages ago since you left town.”

“Only a month. I went first to Perthshire, where I had to speak at some Primrose League meetings. Then I had business in both Newcastle and Manchester, and afterwards I went to Horsford to see my sister. I was due to stay there another fortnight, but this strange discovery brings me up to consult your father.”

“He’s upstairs in the study. We’d better go up at once. He’s dying to see you,” declared the bright-eyed girl, who wore a big black silk bow in her hair. She possessed a sweet innocent face, a pale soft countenance indicative of purity of soul. The pair were, indeed, well matched, each devoted to the other; he full of admiration of her beauty and her talents, and she proud of his brilliant success in journalism and literature.

At the throat of her white silk blouse she wore a curious antique brooch, an old engraved sapphire which Sir Charles Gaylor, a friend of Dr Griffin, had some years ago brought from the excavation he had made in the mound of Nebi-Yunus, near Layard’s researches in the vicinity of Nineveh. The rich blue gleamed in the gaslight, catching Frank’s eye as he ascended the stair, and he remarked that she was wearing what she termed her “lucky brooch,” a gem which had no doubt adorned some maiden’s breast in the days of Sennacherib or Esarhaddon.

The first-floor front room, which in all other houses in Pembridge Gardens was the drawing-room, had in the house of Professor Griffin been converted into the study—a big apartment lined with books which, for the most part, were of “a dry-as-dust” character.

As they entered, the Professor, a short, stout, grey-haired man in round steel-framed spectacles, raised himself from his armchair, where he had been engrossed in an article in a German review.

“Ah! my dear Farquhar!” he cried excitedly. “Gwen told me that you were on your way—but there, you are such a very erratic fellow that I never know when to expect you.”

“I generally turn up when least expected,” laughed the young man, with a side-glance at the girl.

“Well, well,” exclaimed the man in spectacles; “now what is all this you’ve written to me about? What ‘cock-and-bull’ story have you got hold of now—eh?”

“I briefly explained in my letter,” he answered. “Isn’t it very remarkable? What’s your opinion?”

“Ah! you journalists!” exclaimed the old professor reprovingly. “You’ve a lot to answer for to the unsuspecting public.”

“I admit that,” laughed Frank. “But do you really dismiss the matter as a ‘cock-and-bull’ story?”

“That is how I regard it at the moment—without having been shown anything.”

“Then I can show you everything,” was Farquhar’s prompt reply. “I have it all with me—at least all that remains of it.”

The old man smiled satirically. As Regius Professor of Hebrew at Cambridge, Dr Arminger Griffin was not a man to accept lightly any theory placed before him by an irresponsible writer such as he knew Frank Farquhar to be.

He suspected a journalistic “boom” to be at the bottom of the affair, and of all things he hated most in the world was the halfpenny press.

Frank had first met Gwen while he had been at college, and had often been a visitor at the professor’s house out on Grange Road, prior to his retirement and return to London. He knew well in what contempt the old man held the popular portion of the daily press, and especially the London evening journals. Therefore he never sought to obtrude his profession when in his presence.

“Well?” said the old gentleman at last, peering above his glasses. “I certainly am interested in the story, and I would like to examine what you’ve brought. Burnt papers—aren’t they?”

“Yes.”

“H’m. Savours of romance,” sniffed the professor. “That’s why I don’t like it. The alleged secret itself is attractive enough, without an additional and probably wholly fictitious interest.”

Frank explained how the fragments had fallen into his hands, and the suggestion which Doctor Diamond had made as to the possibility of a financial value of the secret.

“My dear Frank,” replied the professor, “if it were a secret invention, a new pill, or some scented soap attractive to women, it might be worth something in the City. But a secret such as you allege,”—and he shrugged his shoulders ominously without concluding his sentence.

“Ah!” laughed the young man. “I see you’re sceptical. Well, I don’t wonder at that. Some men of undoubted ability and great knowledge declare that the Bible was not inspired.”

“I am not one of those,” the professor hastened to declare.

“No, Frank,” exclaimed the girl. “Dad is not an agnostic. He only doubts the genuineness of this secret of yours.”

“He condemns the whole thing as a ‘cock-and-bull’ story, without first investigating it!” said Farquhar with a grin. “Good! I wonder whether your father will be of the same opinion after he has examined the fragments of the dead man’s manuscript which remain to us?”

“Don’t talk of the dead man’s manuscript!” exclaimed the old professor impatiently, “even though the man is dead, it’s in typewriting, you say—therefore there must exist somebody who typed it. He, or she, must still be alive!”

“By Jove!” gasped the young man quickly, “I never thought of that! The typing is probably only a copy of a written manuscript. The original may still exist. And in any case the typist would be able to supply to a great degree the missing portions of the document.”

“Yes,” said the other. “It would be far more advantageous to you to find the typist than to consult me. I fear I can only give you a negative opinion.”

Chapter Six.

Gives Expert Opinion.

Frank Farquhar was cleverly working his own game. The Professor had scoffed at the theory put forward by Diamond, therefore he was easily induced to give a written undertaking to regard the knowledge derived from the half-burnt manuscript as strictly confidential, and to make no use of it to his own personal advantage.

“I have to obtain this,” the young man explained, “in the interests of Diamond, who, after all, is possessor of the papers. He allowed me to have them only on that understanding.”

“My dear Frank,” laughed the great Hebrew scholar, “really all this is very absurd. But of course I’ll sign any document you wish.”

So amid some laughter a brief undertaking was signed, “in order that I may show to Diamond,” as Frank put it.

“It’s really a most businesslike affair,” declared Gwen, who witnessed her father’s signature. “The secret must be a most wonderful one.”

“It is, dear,” declared her lover. “Wait and hear your father’s opinion. He is one of the very few men in the whole kingdom competent to judge whether the declaration is one worthy of investigation.”

The Professor was seated at his writing-table placed near the left-hand window, and had just signed the document airily, with a feeling that the whole matter was a myth. Upon the table was his green-shaded electric reading-lamp, and with his head within the zone of its mellow light he sat, his bearded chin resting upon his palm, looking at the man to whom he had promised his daughter’s hand.

A scholar of his stamp is always very slow to commit himself to any opinion. The Hebrew professor, whoever he may be, follows recognised lines, and has neither desire nor inclination to depart from them. It was so with Griffin. Truth to tell, he was much interested in the problem which young Farquhar had placed before him, but at the same time the suggestion made by Doctor Diamond was so startling and unheard of that, within himself, he laughed at the idea, regarding it as a mere newspaper sensation, invented in the brain of some clever Continental swindler.

From his pocket the young man drew forth the precious envelope, and out of it took the cards between which reposed three pieces of crinkled and smoke-blackened typewriting, the edges of which had all been badly burned.

The first which he placed with infinite care, touching it as lightly as possible, upon the Professor’s blotting-pad was the page already reproduced—the folio which referred to the studying of the “Mishna” and the cabalistic signs which the writer had apparently discovered therein.

The old man, blinking through his heavy round glasses, examined the disjointed words and unfinished lines, grunted once or twice in undisguised dissatisfaction, and placed the fragment aside.

“Well?” inquired Farquhar, eagerly, “does that convey anything to you?”

The Professor pursed his lips in quiet disbelief.

“The prologue of a very elegant piece of fiction,” he sneered. “The man who makes this statement ought certainly to have been a novelist.”

“Why?”

“Because of the clever manner in which he introduces his subject. But let us continue.”

With delicate fingers Frank Farquhar handled the next scrap of typewriting and placed it before the great expert.

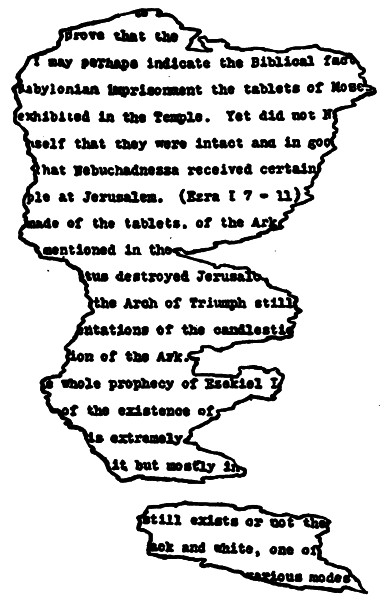

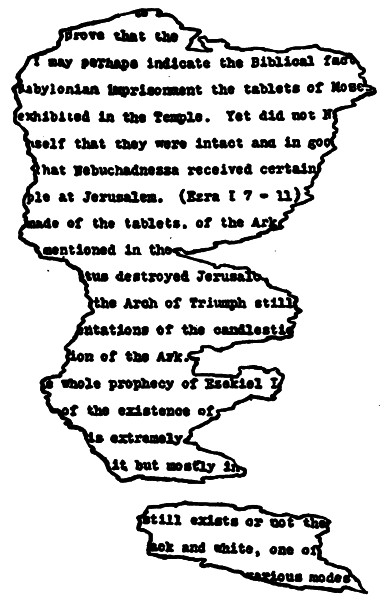

The folio in question apparently attracted Professor Griffin much more than the first one presented to him. He read and re-read it, his grey face the whole time heavy and thoughtful. He was reconstructing the context in his own mind, and its reconstruction evidently caused him deep and very serious reflection.

A dozen times he re-read it, while Frank and Gwen stood by exchanging glances in silence.

“The first portion of the statement on this folio is quite plain,” remarked the Professor at last, looking up and blinking at the young man. “The writer indicates the Biblical fact that, after the Babylonian imprisonment the tablets of Moses were never again exhibited in the Temple. Surely this is not any amazing discovery! Every reader of the Old Testament is aware of that fact. The prophet Ezekiel himself was one of the temple priests deported to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar in 597 B.C. You’ll find mention of it in Ezekiel, i, 2-8. His message consisted at first of denunciations of his countrymen, both in Babylon and in Palestine, but after the fall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. he became a prophet of consolation, promising the eventual deliverance and restoration of the chosen people. Give me down the Bible, Gwen, dear, and also Skinner—the ‘Expositor’s Bible.’ You’ll see it in the second case—third shelf to the left.”

The girl crossed the room, and after a moment’s search returned with the two volumes, which she placed before her father.

“Nebuchadnezzar received certain vessels from the temple at Jerusalem. Well, we know that,” remarked the old man, as he opened the copy of Holy Writ and slowly turned its pages.

“The reference in the book of Ezra,” he said, referring to the open book before him, “concerns the proclamation of Cyrus, King of Persia, for the building of the temple in Jerusalem, how the people provided for the return, and how Cyrus restored the vessels of the temple to Sheshbazzar, the Prince of Judah.” Then, turning to Gwen, he said: “Read the verses referred to, dear—seventh to the eleventh in the first chapter.”

The girl bent over the Bible, and read the verses aloud as follows:

“Also Cyrus the King brought forth the vessels of the house of the Lord, which Nebuchadnezzar had brought forth out of Jerusalem, and had put them in the house of his gods;

“Even those did Cyrus King of Persia bring forth by the hand of Mithredath the treasurer, and numbered them unto Sheshbazzar, the Prince of Judah.

“And this is the number of them: thirty chargers of gold, a thousand chargers of silver, nine and twenty knives,

“Thirty basons of gold, silver basons of a second sort four hundred and ten, and other vessels a thousand.

“All the vessels of gold and silver were five thousand and four hundred. All these did Sheshbazzar bring up with them of the captivity that were brought up from Babylon unto Jerusalem.”

“Surely that is sufficient historical fact!” the old Professor said in his hard, “dry-as-dust” voice. “Again, farther on, there is, you see, a statement that Titus destroyed Jerusalem and that he built the Arch of Triumph in Rome and placed a representation of the candlesticks upon it. Does not every schoolboy know that! Bosh! my dear Frank!”

“True,” exclaimed Frank, “but see! in the next line but one is a reference to the existence of something in ‘the whole prophecy of Ezekiel’—something in ‘black and white.’”

Professor Griffin shrugged his shoulders.

“Ezekiel develops the doctrine of individual responsibility and of the Messianic kingdom as no prophet before him,” was the Professor’s reply. “It may refer to that. The prophet’s style is not of the highest order, but is extraordinarily rich and striking in its imagery. The authenticity of the book is now admitted, all but universally, but the corrupt state of the Hebrew text has, for ages, been the despair of students. Cornhill, in 1886, made a brilliant attempt to reconstruct the Hebrew text with the aid of the Septuagint.”

Griffin noticed that his young friend did not quite follow that last remark, so he added:

“The Septuagint is, as you may perhaps know, the earliest Greek translation of the Old Testament scriptures made directly from the Hebrew original during the third century before Christ for the use of the Hellenistic Jews. In the literary forgery produced about the Christian era, known as the ‘Letter of Aristeas,’ and accepted as genuine by Josephus and others, it is alleged that the translation was made by seventy-two men at the command of Ptolemy II. You will find portions of it in the British Museum, and from it we find that the translation is not of uniform value or of the same style throughout. The Pentateuch and later historical books, as well as the Psalms, exhibit a very fair rendering of the original. The prophetical books, and more especially Ezekiel, show greater divergence from the Hebrew, while Proverbs frequently display loose paraphrase.”

“But is there anything in those typed lines which strikes you as unusually curious?” demanded young Farquhar, pointing to the smoked and charred fragment upon the blotting-pad.

The Professor was silent for a moment, his eyes fixed upon the disjointed and unfinished sentences.

“Well—yes. There is something,” was his answer. “That statement that something exists in ‘the whole prophecy of Ezekiel.’ What is that something?”

“Is it what Doctor Diamond suspects it to be, do you think?”

“I can form no definite conclusion until I have investigated the whole,” was the great scholar’s response. “But I would, at this point, withdraw my own light remarks of half an hour ago. There may be something of interest in it, but what the picturesque story is all leading up to I cannot quite imagine.”

“To a secret—to the solution of a great and undreamed-of mystery!” declared Frank excitedly.

“The last few lines of this scrap before me certainly leads towards that supposition,” was the answer of Gwen Griffin’s father.

“Then you do not altogether negative Diamond’s theory that there is here, if we can only supply the context, the key to the greatest secret this world has ever known!”

“Ah! that is saying a good deal,” was the reply. “Let me continue the investigation of this wonderful document which the dying man was so anxious to destroy.”

And by the sphinx-like expression upon the old man’s face it was apparent that he had already gathered more information than he was willing to admit.

The truth was that the theory he had already formed within his own mind held him bewildered. His thin fingers trembled as he touched the dried, crinkled folio.

There was a secret there—without a doubt, colossal and astounding—one of which even the greatest scholars in Europe through all the ages had never dreamed!

The old man sat staring through his spectacles in abject wonder.

Was Doctor Diamond’s theory really the correct one? If so, what right had these most precious papers to be in the hands of an irresponsible journalist?

If there was really a secret, together with its solution—then the latter must be his, and his alone, he decided. How it would enhance his great reputation if he were the person to launch it forth upon the world!

Therefore the old man’s attitude suddenly changed and he pretended to regard the affair humorously, in the hope of putting Frank off his guard.

If the world was ever to be startled by the discovery it should, he intended, be by Professor Arminger Griffin, and not through any one of those irresponsible halfpenny sheets controlled by Sir George Gavin and his smart and ingenious young brother-in-law.

Both Frank Farquhar and Gwen noticed the old man’s sudden change of manner, and stood puzzled and wondering, little dreaming what was passing with his mind.

Few men are—alas!—honest where their own reputations are at stake.

Chapter Seven.

In which the Professor Exhibits Cunning.

Frank was fully aware that Professor Griffin was an eccentric man, full of strange moods and strong prejudices. Most scholars and writers are.

“But, dad,” exclaimed his daughter, placing her soft hand upon his shoulder, “what do you really think of it? Is there anything in this Doctor Diamond’s theory?”

“My dear child, I never jump to conclusions, as you know. It is against my habit. It’s probably one of the many hoaxes which have been practised for the last thousand years.”

The girl exchanged a quick glance with her lover. She could see that Frank was annoyed by the light manner with which her father treated the alleged secret.

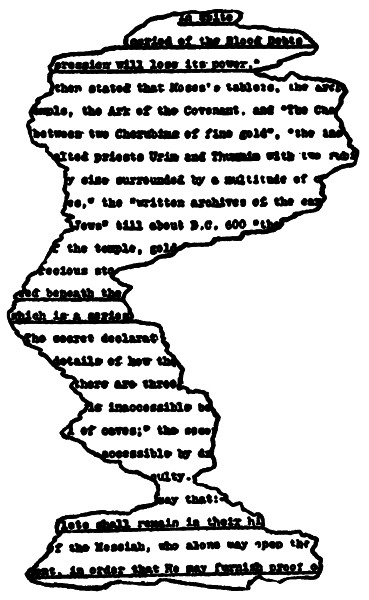

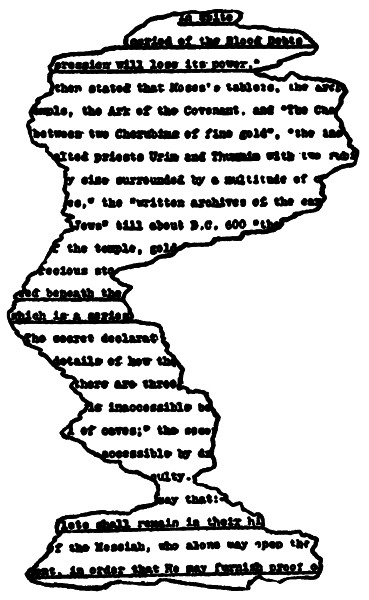

“Well, Professor,” said the young man at last, “this, apparently, is the next folio, though the numbering of each has been destroyed,” and he placed before the man in spectacles another scrap which presented the appearance as shown.

In an instant the old man became intensely interested though he endeavoured very cleverly to conceal the fact. He bent, and taking up a large magnifying-glass mounted in silver—a gift from Frank on the previous Christmas—he carefully examined each word in its order.

“Ah!” he exclaimed, “the first three lines, underlined as you see, are apparently a portion of some prophecy regarding the captivity of the Jews in Babylon, ‘the period of the Blood-debts,’ after which comes the period when the oppression will lose its power, which means their release by Cyras. Come now, this is of some interest!”

“Read on, dad,” urged the dainty girl, excitedly. “Tell us what you gather from it.”

The pair were standing hand-in-hand, at the back of the old man’s writing-chair.

“Not so quickly, dear—not so quickly. That’s the worst of women. They are always so erratic, always in such an uncommon hurry,” he added with a laugh.

Then, after a pause during which he carefully examined the lines which followed, he pointed out: “You see that somebody—not the writer of the document, remember—has stated that Moses’ tablets ‘The Cha—’, which must mean the Chair of Grace, between two cherubims of fine gold, a number of other things, including the Ark of the Covenant itself and the archives of the Temple down to B.C. 600 are—what?”

And he raised his head staring at the pair through his round and greatly magnifying-glasses.

“Doctor Diamond’s theory is that the treasures of Solomon’s Temple are still concealed at the spot where they were hidden by the priests before the taking of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar.”

The Professor laughed aloud.

“My dear Farquhar,” he exclaimed, “on the face of this folio it would, of course, appear so. One may read it as a statement of fact that all the relics of the Temple and all the great treasures of the ages bygone—the Treasure of Israel—are concealed ‘beneath’, somewhere—‘which is a series’ of something. To this, there are three entrances, one only being accessible. Then in the final lines, we have another prophecy that the tablets shall ‘remain in their hiding-place—that is with the Ark of the Covenant—till the coming of the Messiah who alone may open the treasure-house, or place of concealment, in order that he may show proof of—’, and the rest is lost.” he added with a sigh of disappointment.

“I admit,” said Frank, “that is one reading of it. But what is your reading—that of an expert?”

The old man merely shrugged his shoulders and said:

“I don’t think that the Doctor’s theory is the correct one. The belief that the Treasure of Solomon’s Temple still exists is far too wild and unsubstantiated. Of course, it is not quite clear in history what became of the contents of the Temple, but I think we may safely at once dismiss any possibility of the relics of Moses as being intact after a couple of thousand years or so. Stories of hidden treasure have appealed to the avarice of man throughout all the ages, from the days of the Roman Emperors, down to the day before yesterday, when a ship went forth to search for the lost gold of President Kruger. There have been hundreds, nay thousands of expeditions to search for treasure, but in nearly every case the searchers have returned sadder and poorer men. No, Frank,” he exclaimed, decisively, “I don’t think any one would be such an utter fool as to attempt to suggest that the Treasure of Israel still exists. At least no scholar would. Whoever would do such a thing would be a clumsy bungler, ignorant of both the Hebrew language and the history of the Hebrew nation. Doctor Diamond, from what you tell me, is, I gather, one of such.”

“But they are not the Doctor’s documents,” Frank hastened to point out. “As I’ve told you, a man dying in Paris ordered him to burn them. He did so, but they were not all consumed.”

“The Doctor worked a trick upon a dying man,” sniffed the Professor. “Hardly played the game—eh?”

“I quite agree with you there,” answered young Farquhar. “Yet, according to the Doctor’s version, he was in no way responsible for the fact that only half the folios were consumed.”

“Well, whatever it is,” declared the Professor, very decisively, “it seems to be some rather clumsy ‘cock-and-bull’ story. In what I’ve read. I, as a scholar, could pick many holes. Indeed, such a screed as this could never have been concocted by any one with any pretence of knowledge of old Testament history. There are certain statements which are utterly absurd on the face of them.”

“Which are they?” inquired Frank eagerly.

“Oh—several,” was the rather light reply. “As you are not a scholar, my dear boy, it would be useless me going into long and technical explanations. The disjointed bits of prophecy are, I admit, really most artistic,” he added with a laugh.

If the truth be told, Arminger Griffin was concealing the intense excitement that had been aroused within him. He was making a discovery—a wonderful, an amazing discovery. But to this young journalist, who would merely regard it as a good “boom” for one of his irresponsible halfpenny journals, he intended to pooh-pooh it as a mere clumsy fairy tale.

“Well,” he asked, a moment later, in an incredulous tone. “What else have you to show me?”

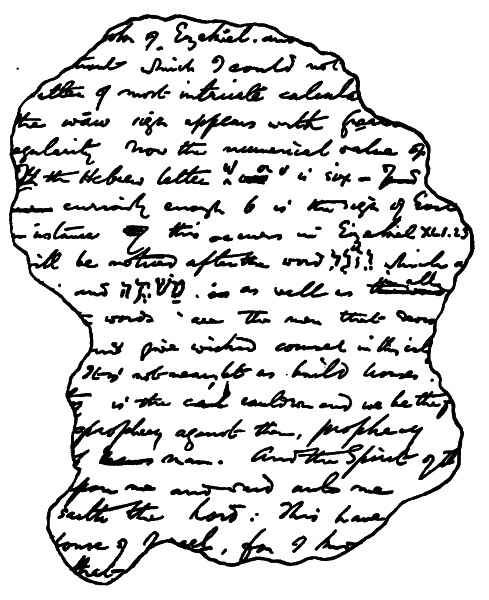

“No more typewriting,” was Frank’s reply. “The only other folio is one of manuscript, and it will probably interest you, for it contains two Hebrew words,” and he placed before the great expert a half-consumed fragment of lined manuscript paper which bore some close writing in English of which the present writer gives a facsimile here.

“H’m,” grunted the old man, after a swift glance at it. “A copy, evidently. The Hebrew words are too clumsily written. No scholar wrote them. Probably it’s a translation from German or Danish—I think you said that the man who called himself Blanc, was really a Dane—eh?”

“Yes. He told Diamond that he came from Copenhagen,” Farquhar replied.

But the old man was too deeply engrossed in the study of the neat manuscript. How he wished that the context had been preserved, for here, he recognised, was the key, or rather the commencement of the key to the whole secret. He was now anxious to get rid of Frank Farquhar, and be allowed to pursue his investigations alone. There was certainly much more in it than he had at first suspected.

With such a sensation as that contained in the half-burnt documents to launch upon the world, he would be acclaimed the most prominent scholar of the day. The whole of academic Europe would shower honours upon him.

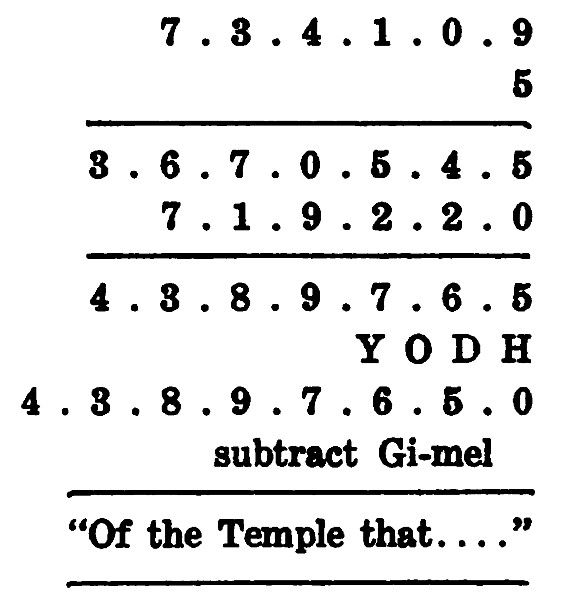

“What does it mean about the ‘wāw’ sign?” inquired the young man. “Does that convey anything?”