| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

JOINTS, in anatomy. The study of joints, or articulations, is known as Arthrology (Gr. ἄρθρον), and naturally begins with the definition of a joint. Anatomically the term is used for any connexion between two or more adjacent parts of the skeleton, whether they be bone or cartilage. Joints may be immovable, like those of the skull, or movable, like the knee.

|

|

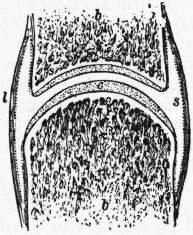

| Fig. 1.—Vertical section through a synchondrosis. b, b, the two bones; Sc, the interposed cartilage; l, the fibrous membrane which plays the part of a ligament. | Fig. 2.—Vertical section through a cranial suture, b, b, the two bones; s, opposite the suture; l, the fibrous membrane, or periosteum, passing between the two bones, which plays the part of a ligament, and which is continuous with the interposed fibrous membrane. |

Immovable joints, or synarthroses, are usually adaptations to growth rather than mobility, and are always between bones. When growth ceases the bones often unite, and the joint is then obliterated by a process known as synostosis, though whether the union of the bones is the cause or the effect of the stoppage of growth is obscure. Immovable joints never have a cavity between the two bones; there is simply a layer of the substance in which the bone has been laid down, and this remains unaltered. If the bone is being deposited in cartilage a layer of cartilage intervenes, and the joint is called synchondrosis (fig. 1), but if in membrane a thin layer of fibrous tissue persists, and the joint is then known as a suture (fig. 2). Good examples of synchondroses are the epiphysial lines which separate the epiphyses from the shafts of developing long bones, or the occipito-sphenoid synchondrosis in the base of the skull. Examples of sutures are plentiful in the vault of the skull, and are given special names, such as sutura dentata, s. serrata, s. squamosa, according to the plan of their outline. There are two kinds of fibrous synarthroses, which differ from sutures in that they do not synostose. One of these is a schindylesis, in which a thin plate of one bone is received into a slot in another, as in the joint between the sphenoid and vomer. The other is a peg and socket joint, or gomphosis, found where the fangs of the teeth fit into the alveoli or tooth sockets in the jaws.

|

| Fig. 3.—Vertical section through an amphiarthrodial joint. b, b, the two bones; c, c, the plate of cartilage on the articular surface of each bone; Fc, the intermediate fibro-cartilage; l, l, the external ligaments. |

Movable joints, or diarthroses, are divided into those in which there is much and little movement. When there is little movement the term half-joint or amphiarthrosis is used. The simplest kind of amphiarthrosis is that in which two bones are connected by bundles of fibrous tissue which pass at right angles from the one to the other; such a joint only differs from a suture in the fact that the intervening fibrous tissue is more plentiful and is organized into definite bundles, to which the name of interosseous ligaments is given, and also that it does not synostose when growth stops. A joint of this kind is called a syndesmosis, though probably the distinction is a very arbitrary one, and depends upon the amount of movement which is brought about by the muscles on the two bones. As an instance of this the inferior tibio-fibular joint of mammals may be cited. In man this is an excellent example of a syndesmosis, and there is only a slight play between the two bones. In the mouse there is no movement, and the two bones form a synchondrosis between them which speedily becomes a synostosis, while in many Marsupials there is free mobility between the tibia and fibula, and a definite synovial cavity is established. The other variety of amphiarthrosis or half-joint is the symphysis, which differs from the syndesmosis in having both bony surfaces lined with cartilage and between the two cartilages a layer of fibro-cartilage, the centre of which often softens and forms a small synovial cavity. Examples of this are the symphysis pubis, the mesosternal joint, and the joints between the bodies of the vertebrae (fig. 3).

The true diarthroses are joints in which there is either fairly free or very free movement. The opposing surfaces of the bones are lined with articular cartilage, which is the unossified remnant of the cartilaginous model in which they are formed and is called the cartilage of encrustment (fig. 4, c). Between the two cartilages is the joint cavity, while surrounding the joint is the capsule (fig. 4, l), which is formed chiefly by the superficial layers of the original periosteum or perichondrium, but it may be strengthened externally by surrounding fibrous structures, such as the tendons of muscles, which become modified and acquire fresh attachments for the purpose. It may be said generally that the greater the intermittent strain on any part of the capsule the more it responds by increasing in thickness. Lining the interior of the capsule, and all other parts of the joint cavity except where the articular cartilage is present, is the synovial membrane (fig. 4, dotted line); this is a layer of endothelial cells which secrete the synovial fluid to lubricate the interior of the joint by means of a small percentage of mucin, albumin and fatty matter which it contains.

|

|

| Fig. 4.—Vertical section through a diarthrodial joint. b, b, the two bones; c, c, the plate of cartilage on the articular surface of each bone; l, l, the investing ligament, the dotted line within which represents the synovial membrane. The letter s is placed in the cavity of the joint. | Fig. 5.—Vertical section through a diarthrodial joint, in which the cavity is subdivided into two by an interposed fibro-cartilage or meniscus, Fc. The other letters as in fig. 4. |

A compound diarthrodial joint is one in which the joint cavity is divided partly or wholly into two by a meniscus or interarticular fibro-cartilage (fig. 5, Fc).

The shape of the joint cavity varies greatly, and the different divisions of movable joints depend upon it. It is often assumed that the structure of a joint determines its movement, but there is something to be said for the view that the movements to which a joint is 484 subject determine its shape. As an example of this it has been found that the mobility of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb in a large number of working men is less than it is in a large number of women who use needles and thread, or in a large number of medical students who use pens and scalpels, and that the slightly movable thumb has quite a differently shaped articular surface from the freely movable one (see J. Anat. and Phys. xxix. 446). R. Fick, too, has demonstrated that the concavity or convexity of the joint surface depends on the position of the chief muscles which move the joint, and has enunciated the law that when the chief muscle or muscles are attached close to the articular end of the skeletal element that end becomes concave, while, when they are attached far off or are not attached at all, as in the case of the phalanges, the articular end is convex. His mechanical explanation is ingenious and to the present writer convincing (see Handbuch der Gelenke, by R. Fick, Jena, 1904). Bernays, however, pointed out that the articular ends were moulded before the muscular tissue was differentiated (Morph. Jahrb. iv. 403), but to this Fick replies by pointing out that muscular movements begin before the muscle fibres are formed, and may be seen in the chick as early as the second day of incubation.

The freely movable joints (true diarthrosis) are classified as follows:—

(1) Gliding joints (Arthrodia), in which the articular surfaces are flat, as in the carpal and tarsal bones.

(2) Hinge joints (Ginglymus), such as the elbow and interphalangeal joints.

(3) Condyloid joints (Condylarthrosis), allowing flexion and extension as well as lateral movement, but no rotation. The metacarpo-phalangeal and wrist joints are examples of this.

(4) Saddle-shaped joints (Articulus sellaris), allowing the same movements as the last with greater strength. The carpo-metacarpal joint of the thumb is an example.

(5) Ball and socket joints (Enarthrosis), allowing free movement in any direction, as in the shoulder and hip.

(6) Pivot-joint (Trochoides), allowing only rotation round a longitudinal axis, as in the radio-ulnar joints.

Embryology.

Joints are developed in the mesenchyme, or that part of the mesoderm which is not concerned in the formation of the serous cavities. The synarthroses may be looked upon merely as a delay in development, because, as the embryonic tissue of the mesenchyme passes from a fibrous to a bony state, the fibrous tissue may remain along a certain line and so form a suture, or, when chondrification has preceded ossification, the cartilage may remain at a certain place and so form a synchondrosis. The diarthroses represent an arrest of development at an earlier stage, for a part of the original embryonic tissue remains as a plate of round cells, while the neighbouring two rods chondrify and ossify. This plate may become converted into fibro-cartilage, in which case an amphiarthrodial joint results, or it may become absorbed in the centre to form a joint cavity, or, if this absorption occurs in two places, two joint cavities with an intervening meniscus may result. Although, ontogenetically, there is little doubt that menisci arise in the way just mentioned, the teaching of comparative anatomy suggests that, phylogenetically, they originate as an ingrowth from the capsule pushing the synovial membrane in front of them. The subject will be returned to when the comparative anatomy of the individual joints is reviewed. In the human foetus the joint cavities are all formed by the tenth week of intra-uterine life.

Anatomy

Joints of the Axial Skeleton.

The bodies of the vertebrae except those of the sacrum and coccyx are separated, and at the same time connected, by the intervertebral disks. These are formed of alternating concentric rings of fibrous tissue and fibro-cartilage, with an elastic mass in the centre known as the nucleus pulposus. The bodies are also bound together by anterior and posterior common ligaments. The odontoid process of the axis fits into a pivot joint formed by the anterior arch of the atlas in front and the transverse ligament behind; it is attached to the basioccipital bone by two strong lateral check ligaments, and, in the mid line, by a feebler middle check ligament which is regarded morphologically as containing the remains of the notochord. This atlanto-axial joint is the one which allows the head to be shaken from side to side. Nodding the head occurs at the occipito-atlantal joint, which consists of the two occipital condyles received into the cup-shaped articular facets on the atlas and surrounded by capsular ligaments. The neural arches of the vertebrae articulate one with another by the articular facets, each of which has a capsular ligament. In addition to these the laminae are connected by the very elastic ligamenta subflava. The spinous processes are joined by interspinous ligaments, and their tips by a supraspinous ligament, which in the neck is continued from the spine of the seventh cervical vertebra to the external occipital crest and protuberance as the ligamentum nuchae, a thin, fibrous, median septum between the muscles of the back of the neck.

The combined effect of all these joints and ligaments is to allow the spinal column to be bent in any direction or to be rotated, though only a small amount of movement occurs between any two vertebrae.

The heads of the ribs articulate with the bodies of two contiguous thoracic vertebrae and the disk between. The ligaments which connect them are called costo-central, and are two in number. The anterior of these is the stellate ligament, which has three bands radiating from the head of the rib to the two vertebrae and the intervening disk. The other one is the interarticular ligament, which connects the ridge, dividing the two articular cavities on the head of the rib, to the disk; it is absent in the first and three lowest ribs.

The costo-transverse ligaments bind the ribs to the transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae. The superior costo-transverse ligament binds the neck of the rib to the transverse process of the vertebra above; the middle or interosseous connects the back of the neck to the front of its own transverse process; while the posterior runs from the tip of the transverse process to the outer part of the tubercle of the rib. The inner and lower part of each tubercle forms a diarthrodial joint with the upper and fore part of its own transverse process, except in the eleventh and twelfth ribs. At the junction of the ribs with their cartilages no diarthrodial joint is formed; the periosteum simply becomes perichondrium and binds the two structures together. Where the cartilages, however, join the sternum, or where they join one another, diarthrodial joints with synovial cavities are established. In the case of the second rib this is double, and in that of the first usually wanting. The mesosternal joint, between the pre- and mesosternum, has already been given as an example of a symphysis.

Comparative Anatomy.—For the convexity or concavity of the vertebral centra in different classes of vertebrates, see Skeleton: axial. The intervertebral disks first appear in the Crocodilia, the highest existing order of reptilia. In many Mammals the middle fasciculus of the stellate ligament is continued right across the ventral surface of the disk into the ligament of the opposite side, and is probably serially homologous with the ventral arch of the atlas. A similar ligament joins the heads of the ribs dorsal to the disk. To these bands the names of anterior (ventral) and posterior (dorsal) conjugal ligaments have been given, and they may be demonstrated in a seven months’ human foetus (see B. Sutton, Ligaments, London, 1902). The ligamentum nuchae is a strong elastic band in the Ungulata which supports the weight of the head. In the Carnivora it only reaches as far forward as the spine of the axis.

The Jaw Joint, or temporo-mandibular articulation, occurs between the sigmoid cavity of the temporal bone and the condyle of the jaw. Between the two there is an interarticular fibro-cartilage or meniscus, and the joint is surrounded by a capsule of which the outer part is the thickest. On first opening the mouth, the joint acts as a hinge, but very soon the condyle begins to glide forward on to the eminentia articularis (see Skull) and takes the meniscus with it. This gliding movement between the meniscus and temporal bone may be separately brought about by protruding the lower teeth in front of the upper, or, on one side only, by moving the jaw across to the opposite side.

Comparative Anatomy.—The joint between the temporal and mandibular bones is only found in Mammals; in the lower vertebrates the jaw opens between the quadrate and articular bones. In the Carnivora it is a perfect hinge; in many Rodents only the antero-posterior gliding movement is present; while in the Ruminants the lateralizing movement is the chief one. Sometimes, as in the Ornithorhynchus, the meniscus is absent.

Joints of the Upper Extremity.

The sterno-clavicular articulation, between the presternum and clavicle, is a gliding joint, and allows slight upward and downward and forward and backward movements. The two bony surfaces are separated by a meniscus, the vertical movements taking place outside and the antero-posterior inside this. There is a well-marked capsule, of which the anterior part is strongest. The two clavicles are joined across the top of the presternum by an interclavicular ligament.

The acromio-clavicular articulation is also a gliding joint, but allows a swinging or pendulum movement of the scapula on the clavicle. The upper part of the capsule is strongest, and from it hangs down a partial meniscus into the cavity.

Comparative Anatomy.—Bland Sutton regards the interclavicular ligament as a vestige of the interclavicle of Reptiles and Monotremes. The menisci are only found in the Primates, but it must be borne in mind that many Mammals have no clavicle, or a very rudimentary one. By some the meniscus of the sterno-clavicular joint is regarded as the homologue of the lateral part of the interclavicle, but the fact that it only occurs in the Primates where movements in different planes are fairly free is suggestive of a physiological rather than a morphological origin for it.

The Shoulder Joint is a good example of the ball and socket or enarthrodial variety. Its most striking characteristic is mobility at the expense of strength. The small size of the glenoid cavity in comparison with the head of the humerus, and the great laxity of the capsule, favour this, although the glenoid cavity is slightly deepened by a fibrous lip, called the glenoid ligament, round its margin. The presence of the coracoid and acromial processes of the scapula, with the coraco-acromial ligament between them, serves as an overhanging protection to the joint, while the biceps tendon runs over the head of the humerus, inside the capsule, though surrounded by a sheath of synovial membrane. Were it not for these two extra safeguards the shoulder would be even more liable to dislocation than it is. The upper part of the capsule, which is attached to the base of the coracoid process, is thickened, and known as the coracohumeral ligament, while inside the front of the capsule are three folds of synovial membrane, called gleno-humeral folds.

Comparative Anatomy.—In the lower Vertebrates the shoulder is adapted to support rather than prehension and is not so freely movable as in the Primates. The tendon of the biceps has evidently sunk through the capsule into the joint, and even when it is intra-capsular there is usually a double fold connecting its sheath of synovial membrane with that lining the capsule. In Man this has been broken through, but remains of it persist in the superior gleno-humeral fold. The middle gleno-humeral fold is the vestige of a strong ligament which steadies and limits the range of movement of the joint in many lower Mammals.

The Elbow Joint is an excellent example of the ginglymus or hinge, though its transverse axis of movement is not quite at right angles to the central axis of the limb, but is lower internally than externally. This tends to bring the forearm towards the body when the elbow is bent. The elbow is a great contrast to the shoulder, as the trochlea and capitellum of the humerus are closely adapted to the sigmoid cavity of the ulna and head of the radius (see Skeleton: appendicular); consequently movement in one plane only is allowed, and the joint is a strong one. The capsule is divided into anterior, posterior, and two lateral ligaments, though these are all really continuous. The joint cavity communicates freely with that of the superior radio-ulnar articulation.

The radio-ulnar joints are three: the upper one is an example of a pivot joint, and in it the disk-shaped head of the radius rotates in a circle formed by the lesser sigmoid cavity of the ulna internally and the orbicular ligament in the other three quarters.

The middle radio-ulnar articulation is simply an interosseous membrane, the fibres of which run downward and inward from the radius to the ulna.

The inferior radio-ulnar joint is formed by the disk-shaped lower end of the ulna fitting into the slightly concave sigmoid cavity of the radius. Below, the cavity of this joint is shut off from that of the wrist by a triangular fibro-cartilage. The movements allowed at these three articulations are called pronation and supination of the radius. The head of that bone twists, in the orbicular ligament, round its central vertical axis for about half a circle. Below, however, the whole lower end of the radius circles round the lower end of the ulna, the centre of rotation being close to the styloid process of the ulna. The radius, therefore, in its pronation, describes half a cone, the base of which is below, and the hand follows the radius.

Comparative Anatomy.—In pronograde Mammals the forearm is usually permanently pronated, and the head of the radius, instead of being circular and at the side of the upper end of the ulna, is transversely oval and in front of that bone, occupying the same place that the coronoid process of the ulna does in Man. This type of elbow, which is adapted simply to support and progression, is best seen in the Ungulata; in them both lateral ligaments are attached to the head of the radius, and there is no orbicular ligament, since the shape of the head of the radius does not allow of any supination. The olecranon process of the ulna forms merely a posterior guide or guard to the joint, but transmits no weight. No better example of the maximum changes which the uses of support and prehension bring about can be found than in contrasting the elbow of the Sheep or other Ungulate with that of Man. Towards one or other of these types the elbows of all Mammals tend. It may be roughly stated that, when pronation and supination to the extent of a quarter of a circle are possible, an orbicular ligament appears.

The Wrist Joint, or radio-carpal articulation, lies between the radius and triangular fibro-cartilage above, and the scaphoid, semilunar, and cuneiform bones below. It is a condyloid joint allowing flexion and extension round one axis, and slight lateral movement (abduction and adduction) round the other. There is a well-marked capsule, divided into anterior, posterior, and lateral ligaments. The joint cavity is shut off from the inferior radio-ulnar joint above, and the intercarpal joints below.

The intercarpal joints are gliding articulations, the various bones being connected by palmar, dorsal, and a few interosseous ligaments, but only those connecting the first row of bones are complete, and so isolate one joint cavity from another. That part of the intercarpal joints which lies between the first and second rows of carpal bones is called the transverse carpal joint, and at this a good deal of the movement which seems to take place at the wrist really occurs.

The carpo-metacarpal articulations are, with the exception of that of the thumb, gliding joints, and continuous with the great intercarpal joint cavity. The carpo-metacarpal joint of the thumb is the best example of a saddle-shaped joint in Man. It allows forward and backward and lateral movement, and is very strong.

The metacarpo-phalangeal joints are condyloid joints like the wrist, and are remarkable for the great thickness of the palmar ligaments of their capsules. In the four inner fingers these glenoid ligaments, as they are called, are joined together by the transverse metacarpal ligament.

The interphalangeal articulations are simple hinges surrounded by a capsule, of which the dorsal part is very thin.

Comparative Anatomy.—The wrist joint of the lower Mammals allows less lateral movement than does that of Man, while the lower end of the ulna is better developed and is received into a cup-shaped socket formed by the cuneiform and pisiform bones. At the same time, unless there is pretty free pronation and supination, the triangular fibro-cartilage is only represented by an interosseous ligament, which may be continuous above with the interosseous membrane between the radius and ulna, and suggests the possibility that the fibro-cartilage is largely a derivative of this membrane. In most Mammals the wrist is divided into two lateral parts, as it is in the human foetus, but free pronation and supination seem to cause the disappearance of the septum.

Joints of the Lower Extremity.

The sacro-innominate articulation consists of the sacro-iliac joint and the sacro-sciatic ligaments. The former is one of the amphiarthroses or half-joints by which the sacrum is bound to the ilium. The mechanism of the human sacrum is that of a suspension bridge slung between the two pillars or ilia by the very strong posterior sacro-iliac ligaments which represent the chains. The axis of the joint passes through the second sacral vertebra, but the sacrum is so nearly horizontal that the weight of the body, which is transmitted to the first sacral vertebra, tends to tilt that part down. This tendency is corrected by the 486 great and small sacro-sciatic ligaments, which fasten the lower part of the sacrum to the tuberosity and spine of the ischium respectively, so that, although the sacrum is a suspension bridge when looked at from behind, it is a lever of the first kind when seen from the side or in sagittal section.

The pubic symphysis is the union between the two pubic bones. It has all the characteristics of a symphysis, already described, and may have a small median cavity.

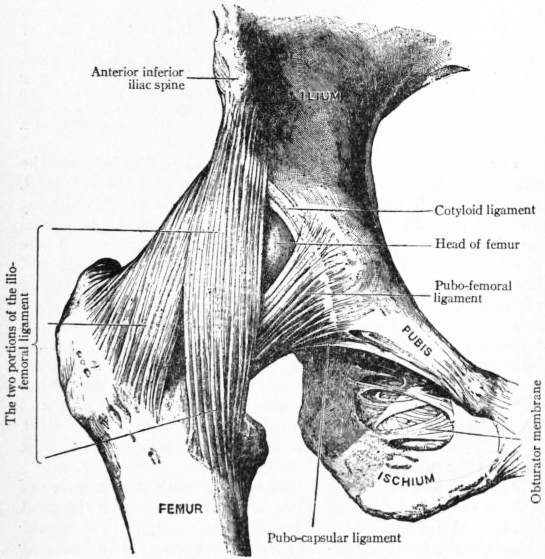

|

| (From David Hepburn, Cunningham’s Text-book of Anatomy.) |

| Fig. 6.—Dissection of the Hip Joint from the front. |

The Hip Joint, like the shoulder, is a ball and socket, but does not allow such free movement; this is due to the fact that the socket or acetabulum is deeper than the glenoid cavity and that the capsule is not so lax. At the same time the loss of mobility is made up for by increased strength. The capsule has three thickened bands, of which the most important is the ilio-femoral or Y-shaped ligament of Bigelow. The stalk of the Y is attached to the anterior inferior spine of the ilium, while the two limbs are fastened to the upper and lower parts of the spiral line of the femur. The ligament is so strong that it hardly ever ruptures in a dislocation of the hip. As a plumb-line, dropped from the centre of gravity of the body, passes behind the centre of the hip joint, this ligament, lying as it does in front of the joint, takes the strain in Man’s erect position. The other two thickened parts of the capsule are known as pubo-femoral and ischio-femoral, from their attachments. Inside the capsule, and deepening the margin of the acetabulum, is a fibrous rim known as the cotyloid ligament, which grips the spherical head of the femur and is continued across the cotyloid notch as the transverse ligament. The floor of the acetabulum has a horseshoe-shaped surface of articular cartilage, concave downward, and, occupying the “frog” of the horse’s hoof, is a mass of fat called the Haversian pad. Attached to the inner margin of the horseshoe, and to the transverse ligament where that is deficient, is a reflexion of synovial membrane which forms a covering for the pad and is continued as a tube to the depression on the head of the femur called the fossa capitis. This reflexion carries blood-vessels and nerves to the femur, and also contains fibrous tissue from outside the joint. It is known as the ligamentum teres.

Comparative Anatomy.—Bland Sutton regards the ilio-femoral ligament as an altered muscle, the scansorius, though against this is the fact that, in those cases in which a scansorius is present in Man, the ligament is as strong as usual, and indeed, if it were not there in these cases, the erect position would be difficult to maintain. He also looks upon the ligamentum teres as the divorced tendon of the pectineus muscle. The subject requires much more investigation, but there is every reason to believe that it is a tendon which has sunk into the joint, though whether that of the pectineus is doubtful, since the intra-capsular tendon comes from the ischium in Reptiles. In many Mammals, and among them the Orang, there is no ligamentum teres. In others, such as the Armadillo, the structure has not sunk right into the joint, but is connected with the pubo-femoral part of the capsule.

The Knee Joint is a hinge formed by the condyles and trochlea of the femur, the patella, and the head of the tibia. The capsule is formed in front by the ligamentum patellae, and on each side special bands form the lateral ligaments. On the outer side there are two of these: the anterior or long external lateral ligament is a round cord running from the external condyle to the head of the fibula, while the posterior is slighter and passes from the same place to the styloid process of the fibula. The internal lateral ligament is a flat band which runs from the inner condyle of the femur to the internal surface of the tibia some two inches below the level of the knee joint. The posterior part of the capsule is strengthened by an oblique bundle of fibres running upward and outward from the semimembranosus tendon, and called the posterior ligament of Winslow.

The intra-articular structures are numerous and interesting. Passing from the head of the tibia, in front and behind the spine, are the anterior and posterior crucial ligaments; the former is attached to the outer side of the intercondylar notch above, and the latter to the inner side. These two ligaments cross like an X. The semilunar fibro-cartilages—external and internal—are partial menisci, each of which has an anterior and a posterior cornu by which they are attached to the head of the tibia in front and behind the spine. They are also attached round the margin of the tibial head by a coronary ligament, but the external one is more movable than the internal, and this perhaps accounts for its coronary ligament being less often ruptured and the cartilage displaced than the inner one is. In addition to these the external cartilage has a fibrous band, called the ligament of Wrisberg, which runs up to the femur just behind the posterior crucial ligament. The external cartilage is broader, and forms more of a circle than the internal. The synovial cavity of the knee runs up, deep to the extensor muscles of the thigh, for about two inches above the top of the patella, forming the bursa suprapatellaris. At the lower part of the patella it covers a pad of fat, which lies between the ligamentum patellae and the front of the head of the tibia, and is carried up as a narrow tube to the lower margin of the trochlear surface of the femur. This prolongation is known as the ligamentum mucosum, and from the sides of its base spring two lateral folds called the ligamenta alaria. The tendon of the popliteus muscle is an intra-capsular structure, and is therefore covered with a synovial sheath. There are a large number of bursae near the knee joint, one of which, common to the inner head of the gastrocnemius and the semimembranosus, often communicates with the joint. The hinge movement of the knee is accompanied by a small amount of external rotation at the end of extension, and a compensatory internal rotation during flexion. This slight twist is enough to tighten up almost all the ligaments so that they may take a share in resisting over-extension, because, in the erect position, a vertical line from the centre of gravity of the body passes in front of the knee.

Comparative Anatomy.—In some Mammals, e.g. Bradypus and Ornithorhynchus, the knee is divided into three parts, two condylo-tibial and one trochleo-patellar, by synovial folds which in Man are represented by the ligamentum mucosum. In a typical Mammal the external semilunar cartilage is attached by its posterior horn to the internal condyle of the femur only, and this explains the ligament of Wrisberg already mentioned. In the Monkeys and anthropoid Apes this cartilage is circular. The semilunar cartilages first appear in the Amphibia, and, according to B. Sutton, are derived from muscles which are drawn into the joint. When only one kind of movement (hinge) is allowed, as in the fruit bat, the cartilages are not found. In most Mammals the superior tibio-fibular joint communicates with the knee.

The tibio-fibular articulations resemble the radio-ulnar in position but are much less movable. The superior in Man is usually cut off i from the knee and is a gliding joint; the middle is the interosseous 487 membrane, while the lower has been already used as an example of a syndesmosis or fibrous half joint.

The Ankle Joint is a hinge, the astragalus being received into a lateral arch formed by the lower ends of the tibia and fibula. Backward dislocation is prevented by the articular surface of the astragalus being broader in front than behind. The anterior and posterior parts of the capsule are feeble, but the lateral ligaments are very strong, the external consisting of three separate fasciculi which bind the fibula to the astragalus and calcaneum. To avoid confusion it is best to speak of the movements of the ankle as dorsal and plantar flexion.

|

| (From D. Hepburn, Cunningham’s Text-book of Anatomy.) |

| Fig. 7.—Dissection of the Knee-joint from the front: Patella thrown down. |

The tarsal joints resemble the carpal in being gliding articulations. There are two between the astragalus and calcaneum, and at these inversion and eversion of the foot largely occur. The inner arch of the foot is maintained by a very important ligament called the calcaneo-navicular or spring ligament; it connects the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneum with the navicular, and upon it the head of the astragalus rests. When it becomes stretched, flat-foot results. The tarsal bones are connected by dorsal, plantar and interosseous ligaments. The long and short calcaneocuboid are plantar ligaments of special importance, and maintain the outer arch of the foot.

The tarso-metatarsal, metatarso-phalangeal and interphalangeal joints closely resemble those of the hand, except that the tarso-metatarsal joint of the great toe is not saddle-shaped.

Comparative Anatomy.—The anterior fasciculus of the external lateral ligament of the ankle is only found in Man, and is probably an adaptation to the erect position. In animals with a long foot, such as the Ungulates and the Kangaroo, the lateral ligaments of the ankle are in the form of an X, to give greater protection against lateral movement. In certain marsupials a fibro-cartilage is developed between the external malleolus and the astragalus, and its origin from the deeper fibres of the external lateral ligament of the ankle can be traced. These animals have a rotatory movement of the fibula on its long axis, in addition to the hinge movement of the ankle.

For further details of joints see R. Fick, Handbuch der Gelenke (Jena, 1904); H. Morris, Anatomy of the Joints (London, 1879); Quain’s, Gray’s and Cunningham’s Text-books of Anatomy; J. Bland Sutton, Ligaments, their Nature and Morphology (London, 1902); F. G. Parsons, “Hunterian Lectures on the Joints of Mammals,” Journ. Anat. & Phys., xxxiv. 41 and 301.

Diseases and Injuries of Joints

The affection of the joints of the human body by specific diseases is dealt with under various headings (Rheumatism, &c.); in the present article the more direct forms of ailment are discussed. In most joint-diseases the trouble starts either in the synovial lining or in the bone—rarely in the articular cartilage or ligaments. As a rule, the disease begins after an injury. There are three principal types of injury: (1) sprain or strain, in which the ligamentous and tendinous structures are stretched or lacerated; (2) contusion, in which the opposing bones are driven forcibly together; (3) dislocation, in which the articular surfaces are separated from one another.

A sprain or strain of a joint means that as the result of violence the ligaments holding the bones together have been suddenly stretched or even torn. On the inner aspect the ligaments are lined by a synovial membrane, so when the ligaments are stretched the synovial membrane is necessarily damaged. Small blood-vessels are also torn, and bleeding occurs into the joint, which may become full and distended. If, however, bleeding does not take place, the swelling is not immediate, but synovitis having been set up, serous effusion comes on sooner or later. There is often a good deal of heat of the surrounding skin and of pain accompanying the synovitis. In the case of a healthy individual the effects of a sprain may quickly pass off, but in a rheumatic or gouty person chronic synovitis may obstinately remain. In a person with a tuberculous history, or of tuberculous descent, a sprain is apt to be the beginning of serious disease of the joint, and it should, therefore, be treated with continuous rest and prolonged supervision. In a person of health and vigour, a sprained joint should be at once bandaged. This may be the only treatment needed. It gives support and comfort, and the even pressure around the joint checks effusion into it. Wide pieces of adhesive strapping, layer on layer, form a still more useful support, and with the joint so treated the person may be able at once to use the limb. If strapping is not employed, the bandage may be taken off from time to time in order that the limb and the joint may be massaged. If the sprain is followed by much synovitis a plaster of Paris or leather splint may be applied, complete rest being secured for the limb. Later on, blistering or even “firing” may be found advisable.

Synovitis.—When a joint has been injured, inflammation occurs in the damaged tissue; that is inevitable. But sometimes the attack of inflammation is so slight and transitory as to be scarcely noticeable. This is specially likely to occur if the joint-tissues were in a state of perfect nutrition at the time of the hurt. But if the individual or the joint were at that time in a state of imperfect nutrition, the effects are likely to be more serious. As a rule, it is the synovial membrane lining the fibrous capsule of the joint which first and chiefly suffers; the condition is termed synovitis. Synovitis may, however, be due to other causes than mechanical injury, as when the interior of the joint is attacked by the micro-organisms of pyæmia (blood-poisoning), typhoid fever, pneumonia, rheumatism, gonorrhœa or syphilis. Under judicious treatment the synovitis generally clears up, but it may linger on and cause the formation of adhesions which may temporarily stiffen the joint; or it may, especially in tuberculous, septic or pyæmic infections, involve the cartilages, ligaments and bones in such serious changes as to destroy the joint, and possibly call for resection or amputation.

The symptoms of synovitis include stiffness and tenderness in the joint. The patient notices that movements cause pain. Effusion of fluid takes place, and there is marked fullness in the neighbourhood. If the inflammation is advancing, the skin over the joint may be flushed, and if the hand is placed on the skin it feels hot. Especially is this the case if the joint is near the surface, as at the knee, wrist or ankle.

The treatment of an inflamed joint demands rest. This may be conveniently obtained by the use of a light wooden splint, padding and bandages. Slight compression of the joint by a bandage is useful in promoting absorption of the fluid. If the inflamed joint is in the lower extremity, the patient had best remain in bed, or on the sofa; if in the upper extremity, he should wear his arm in a sling. The muscles acting on the joint must be kept in complete control. If the inflammation is extremely acute 488 a few leeches, followed by a fomentation, will give relief; or an icebag or an evaporating lotion may, by causing constriction of the blood-vessels, lessen the congestion of the part and the associated pain. As the inflammation is passing off, massage of the limb and of the joint will prove useful. If the inflammation is long continued, the limb must still be kept at rest. By this time it may be found that some other material for the retentive apparatus is more convenient and comfortable, as, for instance, undressed leather which has been moulded on wet and allowed to dry and harden; poro-plastic felt, which has been softened by heat and applied limp, or house-flannel which has been dipped in a creamy mixture of plaster-of-Paris and water, and secured by a bandage.

Chronic Disease of a Joint may be the tailing off of an acute affection, and under the influence of alternate douchings of hot and cold water, of counter-irritation by blistering or “firing,” and of massage, it may eventually clear up, especially if the general health of the individual is looked after. But if chronic disease lingers in the joint of a child or young person, the probability of its being under the influence of tuberculous infection must be considered. In such a case prolonged and absolute rest is the one thing necessary. If the disease be in the hip, knee, ankle or foot, the patient may be fitted with an appropriate Thomas’s splint and allowed to walk about, for it is highly important to have these patients out in the fresh air. If the disease be in the shoulder, elbow, wrist or hand, a leather or poro-plastic splint should be moulded on, and the arm worn in a sling. There must be no hurry; convalescence will needs be slow. And if the child can be sent to a bracing sea-side place it will be much in his favour.

As the disease clears up, the surface heat, the pains and the tenderness having disappeared, and the joint having so diminished in size as to be scarcely larger than its fellow—though the wasting of the muscles of the limb may cause it still to appear considerably enlarged—the splint may be gradually left off. This remission may be for an hour or two every other day; then every other night; then every other day, and so on, the freedom being gained little by little, and the surgeon watching the case carefully. On the slightest indication of return of trouble, the former restrictive measures must be again resorted to. Massage and gentle exercises may be given day by day, but there must be no thought of “breaking down the stiffness.” Many a joint has in such circumstances been wrecked by the manipulations of a “bone-setter.”

Permanent Stiffness.—During the treatment of a case of chronic disease of a joint, the question naturally arises as to whether the joint will be left permanently stiff. People have the idea that if an inflamed joint is kept long on a splint, it may eventually be found permanently stiff. And this is quite correct. But it should be clearly understood that it is not the rest of the inflamed joint which causes the stiffness. The matter should be put thus: in tuberculous and other forms of chronic disease stiffness may ensue in spite of long-continued rest. It is the destructive disease, not the enforced rest which causes it; for inflammation of a joint rest is absolutely necessary.

The Causes of permanent Stiffness are the destructive changes wrought by the inflammation. In one case it may be that the synovial membrane is so far destroyed by the tuberculous or septic invasion that its future usefulness is lost, and the joint ever afterwards creaks at its work and easily becomes tired and painful. Thus the joint is crippled but not destroyed. In another case the ligaments and the cartilages are implicated as well as the synovial membrane, and when the disease clears up, the bones are more or less locked, only a small range of motion being left, which forcible flexion and other methods of vigorous treatment are unable materially to improve. In another set of cases the inflammatory germs quickly destroy the soft tissues of the joint, and then invade the bones, and, the disease having at last come to an end, the softened ends of the bones solidly join together like the broken fragments in simple fracture. As a result, osseous solidification of the joint (synostosis) ensues without, of course, the possibility of any movement. And, inasmuch as the surgeon cannot tell in any case whether the disease may not advance in this direction, he is careful to place the limb in that position in which it will be most useful if the bony union should occur. Thus, the leg is kept straight, and the elbow bent.

In the course of a tuberculous or other chronic disease of a joint, the germs of septic disease may find access to the inflamed area, through a wound or ulceration into the joint, or by the germs being carried thither by the blood-stream. A joint-abscess results, which has to be treated by incision and fomentations. If chronic suppuration continues, it may become necessary to scrape out or to excise the joint, or even to amputate the limb. And if tuberculous disease of the joint is steadily progressing in spite of treatment, vigorous measures may be needed to prevent the fluid from quietly ulcerating its way out and thus inviting the entrance of septic germs. The fluid may need to be drawn off by aspiration, and direct treatment of the diseased synovial membrane may be undertaken by injections of chloride of zinc or some other reagent. Or the joint may need scraping out with a sharp spoon with the view of getting rid of the tuberculous material. Later, excision may be deemed necessary, or in extreme cases, amputation. But before these measures are considered, A. C. G. Bier’s method of treatment by passive congestion, and the treatment by serum injection, will probably have been tried. If a joint is left permanently stiff in an awkward and useless position, the limb may be greatly improved by excision of the joint. Thus, if the knee is left bent and the joint is excised a useful, straight limb may be obtained, somewhat shortened, and, of course, permanently stiff. If after disease of the hip-joint the thigh remains fixed in a faulty position, it may be brought down straight by dividing the bone near the upper end. A stiff shoulder or elbow may be converted into a useful, movable joint by excision of the articular ends of the bones.

A stiff joint may remain as the result of long continued inflammation; the unused muscles are wasted and the joint in consequence looks large. Careful measurement, however, may show that it is not materially larger than its fellow. And though all tenderness may have passed away, and though the neighbouring skin is no longer hot, still the joint remains stiff and useless. No progress being made under the influence of massage, or of gentle exercises, the surgeon may advise that the lingering adhesion be broken down under an anaesthetic, after which the function of the joint may quickly return.

There are the cases over which the “bone-setter” secures his greatest triumphs. A qualified practitioner may have been for months judiciously treating an inflamed joint by rest, and then feels a hesitation with regard to suddenly flexing the stiffened limb. The “bone-setter,” however, has no such qualms, and when the case passes out of the hands of the perhaps over-careful surgeon, the unqualified practitioner (because he, from a scientific point of view, knows nothing) fears nothing, and, breaking down inflammatory adhesions, sets the joint free. And his manipulations prove triumphantly successful. But, knowing nothing and fearing nothing, he is apt to do grievous harm in carrying out his rough treatment in other cases. Malignant disease at the end of a bone (sarcoma), tuberculosis of a joint, and a joint stiffened by old inflammation are to him the same thing. “A small bone is out of place,” or, “The bone is out of its socket; it has never been put in,” and a breaking down of everything that resists his force is the result of the case being taken to him. For the “bone-setter” has only one line of treatment. Of the improvement which he often effects as if by magic the public are told much. Of the cases over which the doctor has been too long devoting skill and care, and which are set free by the “bone-setter,” everybody hears—and sometimes to the discomfiture of the medical man. But of the cases in which irreparable damage follows his vigorous manipulation nothing is said—of his rough usage of a tuberculous hip, or of a sarcomatous shoulder-joint, and of the inevitable disaster and disappointment, those most concerned are least inclined to talk! A practical surgeon with common-sense has nothing to learn from the “bone-setter.”

Rheumatoid Arthritis, or chronic Osteo-arthritis, is generally found in persons beyond middle age; but it is not rare in young people, though with them it need not be the progressive disease which it too often is in their elders. It is an obscure affection of the cartilage covering the joint surfaces of the bones, and it eventually involves the bones and the ligaments. A favourite joint for it is the knee or hip, and when one large joint is thus affected the other joints may escape. But when the hands or feet are implicated pretty nearly all the small joints are apt to suffer. Whether the joint is large or small, the cartilages wear away and new bone is developed about the ends of the bones, so that the joint is large and mis-shapen, the fingers being knotted and the hands deformed. When the spine is affected it becomes bowed and stiff. This is the disease which has crippled the old people in the workhouses and almshouses, and with them it is steadily progressive. Its early signs are stiffness and creaking or cracking in the joints, with discomfort and pain after exercise, and with a little effusion into the capsule of the joint. As regards treatment, medicines are of no great value. Wet, cold and damp being bad for the patient, he should be, if possible, got into a dry, bright, sunny place, and he should dress warmly. Perhaps there is no better place for him in the winter than Assuan. Cairo is not so suitable as it used to be before the dam was made, when its climate was drier. For the spring and summer certain British and Continental watering-places serve well. But if this luxury cannot be afforded, the patient must make himself as happy as he can with such hot douchings and massage as he can obtain, keeping himself warm, and his joints covered by flannel bandages and rubbed with stimulating liniments. In people advanced or advancing in years, the disease, as a rule, gets slowly worse, sometimes very slowly, but sometimes rapidly, especially when its makes its appearance in the hip, shoulder or knee as the result of an injury. In young people, however, its course may be cut short by attention being given to the principles stated above.

Charcot’s Disease resembles osteo-arthritis in that it causes destruction of a joint and greatly deforms it. The deformity, however, comes on rapidly and without pain or tenderness. It is usually associated with the symptoms of locomotor ataxy, and depends upon disease of the nerves which preside over the nutrition of the joints. It is incurable.

A Loose Cartilage, or a Displaced Cartilage in the Knee Joint is apt to become caught in the hinge between the thigh bone and the leg bone, and by causing a sudden stretching of the ligaments of the joint to give rise to intense pain. When this happens the individual is 489 apt to be thrown down as he walks, for it comes on with great suddenness. And thus he feels himself to be in a condition of perpetual insecurity. After the joint has thus gone wrong, bleeding and serous effusion take place into it, and it becomes greatly swollen. And if the cartilage still remains in the grip of the bones he is unable to straighten or bend his knee. But the surgeon by suddenly flexing and twisting the leg may manage to unhitch the cartilage and restore comfort and usefulness to the limb. As a rule, the slipping of a cartilage first occurs as the result of a serious fall or of a sudden and violent action—often it happens when the man is “dodging” at football, the foot being firmly fixed on the ground and the body being violently twisted at the knee. After the slipping has occurred many times, the amount of swelling, distress and lameness may diminish with each subsequent slipping, and the individual may become somewhat reconciled to his condition. As regards treatment, a tightly fitting steel cage-like splint, which, gripping the thigh and leg, limits the movements of the knee to flexion and extension, may prove useful. But for a muscular, athletic individual the wearing of this apparatus may prove vexatious and disappointing. The only alternative is to open the joint and remove the loose cartilage. The cartilage may be found on operation to be split, torn or crumpled, and lying right across between the joint-surfaces of the bones, from which nothing but an operation could possibly have removed it. The operation is almost sure to give complete and permanent relief to the condition, the individual being able to resume his old exercises and amusements without fear of the knee playing him false. It is, however, one that should not be undertaken without due consideration and circumspection, and the details of the operation should be carried out with the utmost care and cleanliness.

An accidental wound of a joint, as from the blade of a knife, or a spike, entering the knee is a very serious affair, because of the risk of septic germs entering the synovial cavity either at the time of the injury or later. If the joint becomes thus infected there is great swelling of the part, with redness of the skin, and with the escape of blood-stained or purulent synovia. Absorption takes place of the poisonous substances produced by the action of the germs, and, as a result, great constitutional disturbance arises. Blood-poisoning may thus threaten life, and in many cases life is saved only by amputation. The best treatment is freely to open the joint, to wash it out with a strong antiseptic fluid, and to make arrangement for thorough drainage, the limb being fixed on a splint. Help may also be obtained by increasing the patient’s power of resistance to the effect of the poisoning by injections of a serum prepared by cultivation of the septic germs in question. If the limb is saved, there is a great chance of the knee being permanently stiff.

Dislocation.—The ease with which the joint-end of a bone is dislocated varies with its form and structure, and with the position in which it happens to be placed when the violence is applied. The relative frequency of fracture of the bone and dislocation of the joint depends on the strength of the bones above and below the joint relatively to the strength of the joint itself. The strength of the various joints in the body is dependent upon either ligament or muscle, or upon the shape of the bones. In the hip, for instance, all three sources of strength are present; therefore, considering the great leverage of the long thigh bone, the hip is rarely dislocated. The shoulder, in order to allow of extensive movement, has no osseus or ligamentous strength; it is, therefore, frequently dislocated. The wrist and ankle are rarely dislocated; as the result of violence at the wrist the radius gives way, at the ankle the fibula, these bones being relatively weaker than the respective joints. The wrist owes its strength to ligaments, the elbow and the ankle to the shape of the bones. The symptoms of a dislocation are distortion and limited movement, with absence of the grating sensation felt in fracture when the broken ends of the bone are rubbed together. The treatment consists in reducing the dislocation, and the sooner this replacement is effected the better—the longer the delay the more difficult it becomes to put things right. After a variable period, depending on the nature of the joint and the age of the person, it may be impossible to replace the bones. The result will be a more or less useless joint. The administration of an anaesthetic, by relaxing the muscles, greatly assists the operation of reduction. The length of time that a joint has to be kept quiet after it has been restored to its normal shape depends on its form, but, as a rule, early movement is advisable. But when by the formation of the bones a joint is weak, as at the outer end of the collar-bone, and at the elbow-end of the radius, prolonged rest for the joint is necessary or dislocation may recur.

Congenital Dislocation at the Hip.—Possibly as a result of faulty position of the subject during intra-uterine life, the head of the thigh-bone leaves, or fails throughout to occupy, its normal situation on the haunch-bone. The defect, which is a very serious one, is probably not discovered until the child begins to walk, when its peculiar rolling gait attracts attention. The want of fixation at the joint permits of the surgeon thrusting up the thigh-bone, or drawing it down in a painless, characteristic manner.

The first thing to be done is to find out by means of the X-rays whether a socket exists into which, under an anaesthetic, the surgeon may fortunately be enabled to lodge the end of the thigh-bone. If this offers no prospect of success, there are three courses open: First, to try under an anaesthetic to manipulate the limb until the head of the thigh-bone rests as nearly as possible in its normal position, and then to endeavour to fix it there by splints, weights and bandaging until a new joint is formed; second, to cut down upon the site of the joint, to scoop out a new socket in the haunch-bone, and thrust the end of the thigh-bone into it, keeping it fixed there as just described; and third, to allow the child to run about as it pleases, merely raising the sole of the foot of the short leg by a thick boot, so as to keep the lower part of the trunk fairly level, lest secondary curvature of the spine ensue. The first and second methods demand many months of careful treatment in bed. The ultimate result of the second is so often disappointing that the surgeon now rarely advises its adoption. But, if under an anaesthetic, as the result of skilful manipulation the head of the thigh-bone can be made to enter a more or less rudimentary socket, the case is worth all the time, care and attention bestowed upon it. Sometimes the results of prolonged treatment are so good that the child eventually is able to walk with scarce a limp. But a vigorous attempt at placing the head of the bone in its proper position should be made in every case.

JOINTS, in engineering, may be classed either (a) according to their material, as in stone or brick, wood or metal; or (b) according to their object, to prevent leakage of air, steam or water, or to transmit force, which may be thrust, pull or shear; or (c) according as they are stationary or moving (“working” in technical language). Many joints, like those of ship-plates and boiler-plates, have simultaneously to fulfil both objects mentioned under (b).

All stone joints of any consequence are stationary. It being uneconomical to dress the surfaces of the stones resting on each other smoothly and so as to be accurately flat, a layer of mortar or other cementing material is laid between them. This hardens and serves to transmit the pressure from stone to stone without its being concentrated at the “high places.” If the ingredients of the cement are chosen so that when hard the cement has about the same coefficient of compressibility as the stone or brick, the pressure will be nearly uniformly distributed. The cement also adheres to the surfaces of the stone or brick, and allows a certain amount of tension to be borne by the joint. It likewise prevents the stones from slipping one on the other, i.e. it gives the joint very considerable shearing strength. The composition of the cement is chosen according as it has to “set” in air or water. The joints are made impervious to air or water by “pointing” their outer edges with a superior quality of cement.

Wood joints are also nearly all stationary. They are made partially fluid-tight by “grooving and tenoning,” and by “caulking” with oakum or similar material. If the wood is saturated with water, it swells, the edges of the joints press closer together, and the joints become tighter the greater the water-pressure is which tends to produce leakage. Relatively to its weaker general strength, wood is a better material than iron so far as regards the transmission of a thrust past a joint. So soon as a heavy pressure comes on the joint all the small irregularities of the surfaces in contact are crushed up, and there results an approximately uniform distribution of the pressure over the whole area (i.e. if there be no bending forces), so that no part of the material is unduly stressed. To attain this result the abutting surfaces should be well fitted together, and the bolts binding the pieces together should be arranged so as to ensure that they will not interfere with the timber surfaces coming into this close contact. Owing to its weak shearing strength on sections parallel to the fibre, timber is peculiarly unfitted for tension joints. If the pieces exerting the pull are simply bolted together with wooden or iron bolts, the joint cannot be trusted to transmit any considerable force with safety. The stresses become intensely localized in the immediate neighborhood of the bolts. A tolerably strong timber tension-joint can, however, be made by making the two pieces abut, and connecting them by means of iron plates covering the joint and bolted to the sides of the timbers by bolts passing through the wood. These plates should have their surfaces which lie against the wood ribbed in a direction transverse to the pull. The bolts should fit their holes slackly, and should be well tightened up so as to make the ribs sink into the surface of the timber. There will then be very little localized shearing stress brought upon the interior portions of the wood.

Iron and the other commonly used metals possess in variously 490 high degrees the qualities desirable in substances out of which joints are to be made. The joint ends of metal pieces can easily be fashioned to any advantageous form and size without waste of material. Also these metals offer peculiar facilities for the cutting of their surfaces at a comparatively small cost so smoothly and evenly as to ensure the close contact over their whole areas of surfaces placed against each other. This is of the highest importance, especially in joints designed to transmit force. Wrought iron and mild steel are above all other metals suitable for tension joints where there is not continuous rapid motion. Where such motion occurs, a layer, or, as it is technically termed, a “bush,” of brass is inserted underneath the iron. The joint then possesses the high strength of a wrought-iron one and at the same time the good frictional qualities of a brass surface. Leakage past moving metal joints can be prevented by cutting the surfaces very accurately to fit each other. Steam-engine slide-valves and their seats, and piston “packing-rings” and the cylinders they work to and fro in, may be cited as examples. A subsidiary compressible “packing” is in other situations employed, an instance of which may be seen in the “stuffing boxes” which prevent the escape of steam from steam-engine cylinders through the piston-rod hole in the cylinder cover. Fixed metal joints are made fluid tight—(a) by caulking a riveted joint, i.e. by hammering in the edge of the metal with a square-edged chisel (the tighter the joint requires to be against leakage the closer must be the spacing of the rivets—compare the rivet-spacing in bridge, ship and boiler-plate joints); (b) by the insertion between the surfaces of a layer of one or other of various kinds of cement, the layer being thick or thin according to circumstances; (c) by the insertion of a layer of soft solid substance called “packing” or “insertion.”

Apart from cemented and glued joints, most joints are formed by cutting one or more holes in the ends of the pieces to be joined, and inserting in these holes a corresponding number of pins. The word “pin” is technically restricted to mean a cylindrical pin in a movable joint. The word “bolt” is used when the cylindrical pin is screwed up tight with a nut so as to be immovable. When the pin is not screwed, but is fastened by being beaten down on either end, it is called a “rivet.” The pin is sometimes rectangular in section, and tapered or parallel lengthwise. “Gibs” and “cottars” are examples of the latter. It is very rarely the case that fixed joints have their pins subject to simple compression in the direction of their length, though they are frequently subject to simple tension in that direction. A good example is the joint between a steam cylinder and its cover, where the bolts have to resist the whole thrust of the steam, and at the same time to keep the joint steam-tight.

JOINTS, in geology. All rocks are traversed more or less completely by vertical or highly inclined divisional planes termed joints. Soft rocks, indeed, such as loose sand and uncompacted clay, do not show these planes; but even a soft loam after standing for some time, consolidated by its own weight, will usually be found to have acquired them. Joints vary in sharpness of definition, in the regularity of their perpendicular or horizontal course, in their lateral persistence, in number and in the directions of their intersections. As a rule, they are most sharply defined in proportion to the fineness of grain of the rock. They are often quite invisible, being merely planes of potential weakness, until revealed by the slow disintegrating effects of the weather, which induces fracture along their planes in preference to other directions in the rock; it is along the same planes that a rock breaks most readily under the blow of a hammer. In coarse-textured rocks, on the other hand, joints are apt to show themselves as irregular rents along which the rock has been shattered, so that they present an uneven sinuous course, branching off in different directions. In many rocks they descend vertically at not very unequal distances, so that the spaces between them are marked off into so many wall-like masses. But this symmetry often gives place to a more or less tortuous course with lateral joints in various apparently random directions, more especially where in stratified rocks the beds have diverse lithological characters. A single joint may be traced sometimes for many yards or even for several miles, more particularly when the rock is fine-grained and fairly rigid, as in limestone. Where the texture is coarse and unequal, the joints, though abundant, run into each other in such a way that no one in particular can be identified for so great a distance. The number of joints in a mass of rock varies within wide limits. Among rocks which have undergone little disturbance the joints may be separated from each other by intervals of several yards. In other cases where the terrestrial movement appears to have been considerable, the rocks are so jointed as to have acquired therefrom a fissile character that has almost obliterated their tendency to split along the lines of bedding.

The Cause of Jointing in Rocks.—The continual state of movement in the crust of the earth is the primary cause of the majority of joints. It is to the outermost layers of the lithosphere that joints are confined; in what van Hise has described as the “zone of fracture,” which he estimates may extend to a depth of 12,000 metres in the case of rigid rocks. Below the zone of fracture, joints cannot be formed, for there the rocks tend to flow rather than break. The rocky crust, as it slowly accommodates itself to the shrinking interior of the earth, is subjected unceasingly to stresses which induce jointing by tension, compression and torsion. Thus joints are produced during the slow cyclical movements of elevation and depression as well as by the more vigorous movements of earthquakes. Tension-joints are the most widely spread; they are naturally most numerous over areas of upheaval. Compression-joints are generally associated with the more intense movements which have involved shearing, minor-faulting and slaty cleavage. A minor cause of tension-jointing is shrinkage, due either to cooling or to desiccation. The most striking type of jointing is that produced by the cooling of igneous rocks, whereby a regularly columnar structure is developed, often called basaltic structure, such as is found at the Giant’s Causeway. This structure is described in connexion with modern volcanic rocks, but it is met with in igneous rocks of all ages. It is as well displayed among the felsites of the Lower Old Red Sandstone, and the basalts of Carboniferous Limestone age as among the Tertiary lavas of Auvergne and Vivarais. This type of jointing may cause the rock to split up into roughly hexagonal prisms no thicker than a lead pencil; on the other hand, in many dolerites and diorites the prisms are much coarser, having a diameter of 3 ft. or more, and they are more irregular in form; they may be so long as to extend up the face of a cliff for 300 or 400 ft. A columnar jointing has often been superinduced upon stratified rocks by contact with intrusive igneous masses. Sandstones, shales and coal may be observed in this condition. The columns diverge perpendicularly from the surface of the injected altering substance, so that when the latter is vertical, the columns are horizontal; or when it undulates the columns follow its curvatures. Beautiful examples of this character occur among the coal-seams of Ayrshire. Occasionally a prismatic form of jointing may be observed in unaltered strata; in this case it is usually among those which have been chemically formed, as in gypsum, where, as noticed by Jukes in the Paris Basin, some beds are divided from top to bottom by vertical hexagonal prisms. Desiccation, as shown by the cracks formed in mud when it dries, has probably been instrumental in causing jointing in a limited number of cases among stratified rocks.

Movement along Joint Planes.—In some conglomerates the joints may be seen traversing the enclosed pebbles as well as the surrounding matrix; large blocks of hard quartz are cut through by them as sharply as if they had been sliced by a lapidary’s machine. A similar phenomenon may be observed in flints as they lie embedded in the chalk, and the same joints may be traced continuously through many yards of rock. Such facts show that the agency to which the jointing of rocks was due must have operated with considerable force. Further indication of movement is supplied by the rubbed and striated surfaces of some joints. These surfaces, termed slickensides, have evidently been ground against each other.

Influence of Joints on Water-flow and Scenery.—Joints form natural paths for the passage downward and upward of subterranean water and have an important bearing upon water supply. Water obtained directly from highly jointed rock is more liable to become contaminated by surface impurities than that from a more compact rock through which it has had to soak its way; for this reason many limestones are objected to as sources of potable water. On exposed surfaces joints have great influence in determining the rate and type of weathering. They furnish an effective lodgment for surface water, which, frozen by lowering of temperature, expands into ice and wedges off blocks of the rock; and the more numerous the joints the more rapidly does the action proceed. As they serve, in conjunction with bedding, to divide stratified rocks into large quadrangular blocks, their effect on cliffs and other exposed places is seen in the splintered and dislocated aspect so familiar in mountain scenery. Not infrequently, by directing the initial activity of weathering agents, joints have been responsible for the course taken by large streams as well as for the type of scenery on their banks. In limestones, which succumb readily to the solvent action of water, the 491 joints are liable to be gradually enlarged along the course of the underground waterflow until caves are formed of great size and intricacy.

Infilled Joints.—Joints which have been so enlarged by solution are sometimes filled again completely or partially by minerals brought thither in solution by the water traversing the rock; calcite, barytes and ores of lead and copper may be so deposited. In this way many valuable mineral veins have been formed. Widened joints may also be filled in by detritus from the surface, or, in deep-seated portions of the crust, by heated igneous rock, forced from below along the planes of least resistance. Occasionally even sedimentary rocks may be forced up joints from below, as in the case of the so-called “sandstone dykes.”

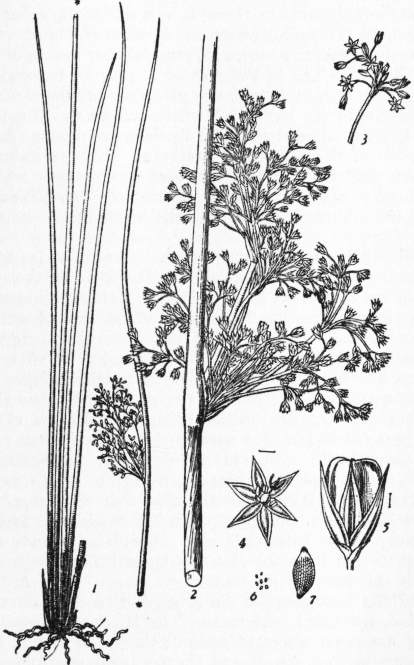

|

| Joints in Limestone Quarry near Mallow, co. Cork. (G. V. Du Noyer.) |

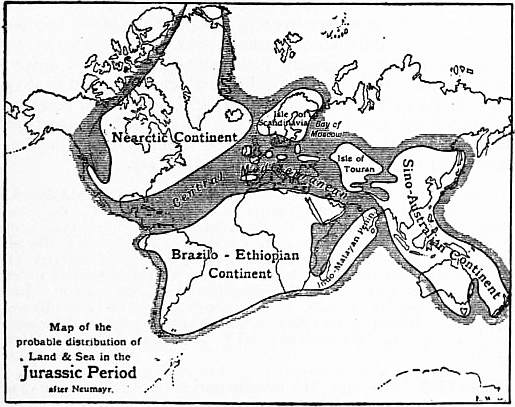

Practical Utility of Joints.—An important feature in the joints of stratified rocks is the direction in which they intersect each other. As the result of observations we learn that they possess two dominant trends, one coincident in a general way with the direction in which the strata are inclined to the horizon, the other running transversely approximately at right angles. The former set is known as dip-joints, because they run with the dip or inclination of the rocks, the latter is termed strike-joints, inasmuch as they conform to the general strike or mean outcrop. It is owing to the existence of this double series of joints that ordinary quarrying operations can be carried on. Large quadrangular blocks can be wedged off that would be shattered if exposed to the risk of blasting. A quarry is usually worked on the dip of the rock, hence strike-joints form clean-cut faces in front of the workmen as they advance. These are known as backs, and the dip-joints which traverse them as cutters. The way in which this double set of joints occurs in a quarry may be seen in the figure, where the parallel lines which traverse the shaded and unshaded faces mark the successive strata. The broad white spaces running along the length of the quarry behind the seated figure are strike-joints or backs, traversed by some highly inclined lines which mark the position of the dip-joints or cutters. The shaded ends looking towards the spectator are cutters from which the rock has been quarried away on one side. In crystalline (igneous) rocks, bedding is absent and very often there is no horizontal jointing to take its place; the joint planes break up the mass more irregularly than in stratified rocks. Granite, for example, is usually traversed by two sets of chief or master-joints cutting each other somewhat obliquely. Their effect is to divide the rock into long quadrangular, rhomboidal, or even polygonal columns. But a third set may often be noticed cutting across the columns, though less continuous and dominant than the others. When these transverse joints are few in number, columns many feet in length can be quarried out entire. Such monoliths have been from early times employed in the construction of obelisks and pillars.

JOINTURE, in law, a provision for a wife after the death of her husband. As defined by Sir E. Coke, it is “a competent livelihood of freehold for the wife, of lands or tenements, to take effect presently in possession or profit after the death of her husband, for the life of the wife at least, if she herself be not the cause of determination or forfeiture of it” (Co. Litt. 36b). A jointure is of two kinds, legal and equitable. A legal jointure was first authorized by the Statute of Uses. Before this statute a husband had no legal seisin in such lands as were vested in another to his “use,” but merely an equitable estate. Consequently it was usual to make settlements on marriage, the most general form being the settlement by deed of an estate to the use of the husband and wife for their lives in joint tenancy (or “jointure”), so that the whole would go to the survivor. Although, strictly speaking, a jointure is a joint estate limited to both husband and wife, in common acceptation the word extends also to a sole estate limited to the wife only. The requisites of a legal jointure are: (1) the jointure must take effect immediately after the husband’s death; (2) it must be for the wife’s life or for a greater estate, or be determinable by her own act; (3) it must be made before marriage—if after, it is voidable at the wife’s election, on the death of the husband; (4) it must be expressed to be in satisfaction of dower and not of part of it. In equity, any provision made for a wife before marriage and accepted by her (not being an infant) in lieu of dower was a bar to such. If the provision was made after marriage, the wife was not barred by such provision, though expressly stated to be in lieu of dower; she was put to her election between jointure and dower (see Dower).

JOINVILLE, the name of a French noble family of Champagne, which traced its descent from Étienne de Vaux, who lived at the beginning of the 11th century. Geoffroi III. (d. 1184), sire de Joinville, who accompanied Henry the Liberal, count of Champagne, to the Holy Land in 1147, received from him the office of seneschal, and this office became hereditary in the house of Joinville. In 1203 Geoffroi V., sire de Joinville, died while on a crusade, leaving no children. He was succeeded by his brother Simon, who married Beatrice of Burgundy, daughter of the count of Auxonne, and had as his son Jean (q.v.), the historian and friend of St Louis. Henri (d. 1374), sire de Joinville, the grandson of Jean, became count of Vaudémont, through his mother, Marguerite de Vaudémont. His daughter, Marguerite de Joinville, married in 1393 Ferry of Lorraine (d. 1415), to whom she brought the lands of Joinville. In 1552, Joinville was made into a principality for the house of Lorraine. Mlle de Montpensier, the heiress of Mlle de Guise, bequeathed the principality of Joinville to Philip, duke of Orleans (1693). The castle, which overhung the Marne, was sold in 1791 to be demolished. The title of prince de Joinville (q.v.) was given later to the third son of King Louis Philippe. Two branches of the house of Joinville have settled in other countries: one in England, descended from Geoffroi de Joinville, sire de Vaucouleurs, and brother of the historian, who served under Henry III. and Edward I.; the other, descended from Geoffroi de Joinville, sire de Briquenay, and son of Jean, settled in the kingdom of Naples.

See J. Simonnet, Essai sur l’histoire et la généalogie des seigneurs de Joinville (1875); H. F. Delaborde, Jean de Joinville et les seigneurs de Joinville (1894).