[larger view] (227kb)

[largest view] (845kb)

A HISTORY OF SPAIN

[larger view] (227kb)

[largest view] (845kb)

![]()

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS

ATLANTA SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

BY

CHARLES E. CHAPMAN, PH.D.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1918

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1918,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1918.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

TO MY SON

SEVILLE DUDLEY CHAPMAN

BORN IN THE CITY WHOSE NAME

HE BEARS

THE present work is an attempt to give in one volume the main features of Spanish history from the standpoint of America. It should serve almost equally well for residents of both the English-speaking and the Spanish American countries, since the underlying idea has been that Americans generally are concerned with the growth of that Spanish civilization which was transmitted to the new world. One of the chief factors in American life today is that of the relations between Anglo-Saxon and Hispanic America. They are becoming increasingly important. The southern republics themselves are forging ahead; on the other hand many of them are still dangerously weak, leaving possible openings for the not unwilling old world powers; and some of the richest prospective markets of the globe are in those as yet scantily developed lands. The value of a better understanding between the peoples of the two Americas, both for the reasons just named and for many others, scarcely calls for argument. It is almost equally clear that one of the essentials to such an understanding is a comprehension of Spanish civilization, on which that of the Spanish American peoples so largely depends. That information this volume aims to provide. It confines itself to the story of the growth of Spanish civilization in Spain, but its ultimate transfer to the Americas has been constantly in the writer’s mind in the choice of his material, as will appear from the frequent allusions in the text. An attempt is made to treat Spanish institutions not as static (which they never were) but in process of evolution, from period to period. The development of Spanish institutions in the colonies and the later independent states, it is hoped, will be the subject of another volume. Neither story has ever been presented according to the present plan to the American public.

Emphasis here has been placed on the growth of the civilization, or institutions, of Spain rather than on the narrative of political events. The latter appears primarily as a peg on which to hang the former. The volume is topically arranged, so that one may select those phases of development which interest him. Thus one may confine himself to the narrative, or to any one of the institutional topics, social, political, religious, economic, or intellectual. Indeed, the division may be carried even further, so that one may single out institutions within institutions. As regards proportions the principal weight is given to the periods from 1252 to 1808, with over half of the volume devoted to the years 1479 to 1808. The three centuries from the sixteenth to the nineteenth are singled out for emphasis, not only because they were the years of the transmission of Spanish civilization to the Americas, but also because the great body of the Spanish institutions which affected the colonies did so in the form they acquired at that time. To treat Spain’s gift to Spanish America as complete by the year 1492 is as incorrect as to say that the English background of United States history is necessary only to the year 1497, when John Cabot sailed along the North American coast, or certainly not later than 1607, when Jamestown was founded. In accord with the primary aim of this work the place of Spain in general European history is given relatively little space. The recital of minor events and the introduction of the names of inconsequential or slightly important persons have been avoided, except in some cases where an enumeration has been made for purposes of illustration or emphasis. For these reasons, together with the fact that the whole account is compressed into a single volume, it is hoped that the book may serve as a class-room text as well as a useful compendium for the general reader.

The writer has been fortunate in that there exists a monumental work in Spanish containing the type of materials which he has wished to present. This is the Historia de España y de la civilización española, which has won a world-wide reputation for its author, Rafael Altamira y Crevea.[1] Indeed, the present writer makes little claim to originality, since for the period down to 1808 he has relied almost wholly on Altamira. Nevertheless, he has made, not a summary, but rather a selection from the Historia (which is some five times the length of this volume) of such materials as were appropriate to his point of view. The chapter on the reign of Charles III has been based largely on the writer’s own account of the diplomacy of that monarch, which lays special emphasis on the relation of Spain to the American Revolution.[2] For the chapter dealing with Spain in the nineteenth century the volumes of the Cambridge modern history have been used, together with those on modern Spain by Hume and Butler Clarke. The last chapter, dealing with present-day Spain, is mainly the result of the writer’s observations during a two years’ residence in that country, 1912 to 1914. In the course of his stay he visited every part of the peninsula, but spent most of his time in Seville, wherefore it is quite possible that his views may have an Andalusian tinge.

In the spelling of proper names the English form has been adopted if it is of well-established usage. The founder of the Carlists and Carlism, however, is retained as “Don Carlos” for obvious reasons of euphony. In all other cases the Spanish has been preferred. The phrase “the Americas” is often used as a general term for Spain’s overseas colonies. It may therefore include the Philippines sometimes. The term “Moslems” has been employed for the Mohammedan invaders of Spain. The word “Moors” has been avoided, because it is historically inaccurate as a general term for all the invaders; the Almohades, or Moors, were a branch of the Berber family, and other Moslem peoples had preceded them in Spain by upwards of four hundred years. Their influence both as regards culture and racial traits was far less than that of the Arabs, who were the most important of the conquering races, and this fact, together with their late arrival, should militate against the application of their name to the whole era of Moslem Spain. All of these alien peoples were Mohammedans, which would seem to justify the use of the word “Moslems.” The word “lords” in some cases indicates ecclesiastics as well as nobles. “Town” has been employed generally for “villa,” “concejo,” “pueblo,” “aldea,” and “ciudad,” except when special attention has been drawn to the different types of municipalities. Spanish institutional terms have been translated or explained at their first use. They also appear in the index.

As on previous occasions, so now, the writer finds himself under obligations to his colleagues in the Department of History of the University of California. Professor Stephens has read much of this manuscript and has made helpful suggestions as to content and style. Professors Bolton and Priestley and Doctor Hackett, of the “Bancroft Library group,” have displayed a spirit of coöperation which the writer greatly appreciates. Professor Jaén of the Department of Romance Languages gave an invaluable criticism of the chapter on contemporary Spain. Señor Jesús Yanguas, the Sevillian architect, furnished the lists of men of letters and artists appearing in that chapter. Professor Shepherd of Columbia University kindly consented to allow certain of the maps appearing in his Historical atlas to be copied here. Doctors R. G. Cleland, C. L. Goodwin, F. S. Philbrick, and J. A. Robertson have aided me with much valued criticisms. The writer is also grateful to his pupils, the Misses Bepler and Juda, for assistance rendered.

CHARLES E. CHAPMAN.

Berkeley, January 5, 1918.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | vii | |

| Introduction by Rafael Altamira | xiii | |

| I. | The Influence of Geography on the History of Spain | 1 |

| II. | The Early Peoples, to 206 B.C. | 6 |

| III. | Roman Spain, 206 B.C.-409 A.D. | 15 |

| IV. | Visigothic Spain, 409-713 | 26 |

| V. | Moslem Spain, 711-1031 | 38 |

| VI. | Christian Spain in the Moslem Period, 711-1035 | 53 |

| VII. | Era of the Spanish Crusades, 1031-1276 | 67 |

| VIII. | Social and Political Organization in Spain, 1031-1276 | 84 |

| IX. | Material and Intellectual Progress in Spain, 1031-1276 | 102 |

| X. | Development Toward National Unity: Castile, 1252-1479 | 111 |

| XI. | Development Toward National Unity: Aragon, 1276-1479 | 125 |

| XII. | Social Organization in Spain, 1252-1479 | 137 |

| XIII. | The Castilian State, 1252-1479 | 151 |

| XIV. | The Aragonese State, 1276-1479 | 166 |

| XV. | Economic Organization in Spain, 1252-1479 | 174 |

| XVI. | Intellectual Progress in Spain, 1252-1479 | 180 |

| XVII. | Institutions of Outlying Hispanic States, 1252-1479 | 192 |

| XVIII. | Era of the Catholic Kings, 1479-1517 | 202 |

| XIX. | Social Reforms, 1479-1517 | 210 |

| XX. | Political Reforms, 1479-1517 | 219 |

| XXI. | Material and Intellectual Progress, 1479-1517 | 228 |

| XXII. | Charles I of Spain, 1516-1556 | 234 |

| XXIII. | The Reign of Philip II, 1556-1598 | 246 |

| XXIV. | A Century of Decline, 1598-1700 | 258 |

| XXV. | Social Developments, 1516-1700 | 272 |

| XXVI. | Political Institutions, 1516-1700 | 287 |

| XXVII. | Religion and the Church, 1516-1700 | 303 |

| XXVIII. | Economic Factors, 1516-1700 | 324 |

| XXIX. | The Golden Age: Education, Philosophy, History, and Science, 1516-1700. | 338 |

| XXX. | The Golden Age: Literature and Art, 1516-1700 | 351 |

| XXXI. | The Early Bourbons, 1700-1759 | 368 |

| XXXII. | Charles III and England, 1759-1788 | 383 |

| XXXIII. | Charles IV and France, 1788-1808 | 399 |

| XXXIV. | Spanish Society, 1700-1808 | 411 |

| XXXV. | Political Institutions, 1700-1808 | 425 |

| XXXVI. | State and Church, 1700-1808 | 443 |

| XXXVII. | Economic Reforms, 1700-1808 | 458 |

| XXXVIII. | Intellectual Activities, 1700-1808 | 471 |

| XXXIX. | The Growth of Liberalism, 1808-1898 | 488 |

| XL. | The Dawn of a New Day, 1898-1917 | 508 |

| Bibliographical Notes | 527 | |

| Index | 541 | |

| MAPS | ||

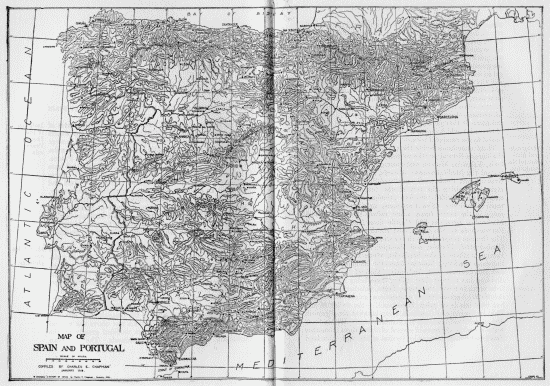

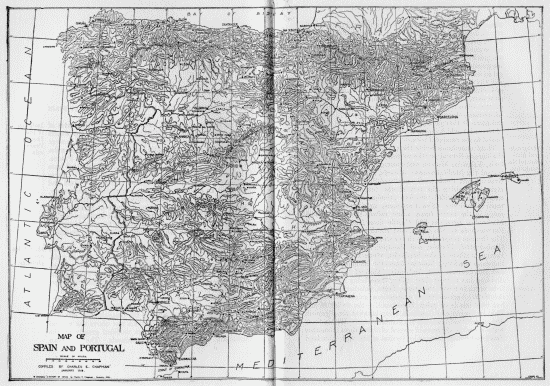

| General Reference Map | Frontispiece | |

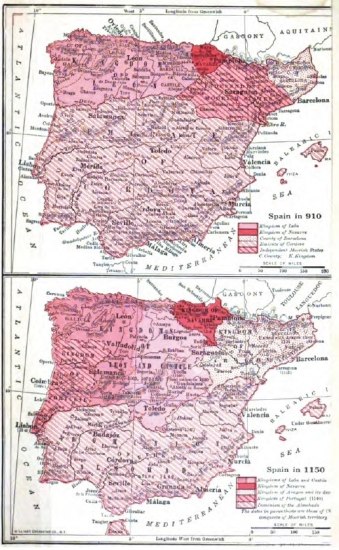

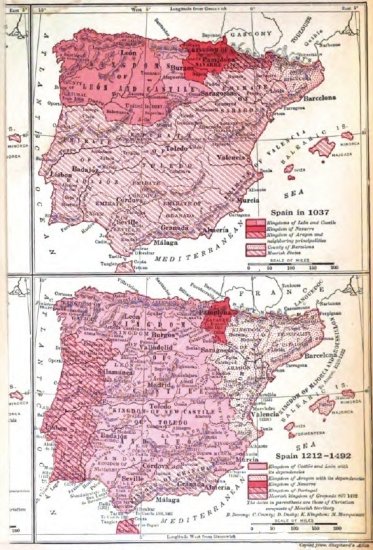

| Development Toward National Unity, 910-1492 | 67 | |

THE fact that this book is in great part a summary, or selection, from one of mine, as is stated in the Preface, makes it almost a duty for me to do what would in any event be a great pleasure in the case of a work by Professor Chapman. I refer to the duty of writing a few paragraphs by way of introduction. But, at the same time, this circumstance causes a certain conflict of feelings in me, since no one, unless it be a pedant, can act so freely in self-criticism as he would if he were dealing with the work of another. Fortunately, Professor Chapman has incorporated much of his own harvest in this volume, and to that I may refer with entire lack of embarrassment.

Obviously, the plan and the labor of condensing all of the material for a history of Spain constitute in themselves a commendable achievement. In fact, there does not exist in any language of the world today a compendium of the history of Spain reduced to one volume which is able to satisfy all of the exigencies of the public at large and the needs of teaching, without an excess of reading and of labor. None of the histories of my country written in English, German, French, or Italian in the nineteenth century can be unqualifiedly recommended. Some, such as that by Hume, entitled The Spanish people, display excellent attributes, but these are accompanied by omissions to which modern historiography can no longer consent. As a general rule these histories are altogether too political in character. At other times they offend from an excess of bookish erudition and from a lack of a personal impression of what our people are, as well as from a failure to narrate their story in an interesting way, or indeed, they perpetuate errors and legends, long since discredited, with respect to our past and present life. We have some one-volume histories of Spain in Castilian which are to be recommended for the needs of our own secondary schools, but not for those of a foreign country, whose students require another manner of presentation of our history, for they have to apply an interrogatory ideal which is different from ours in their investigation of the deeds of another people,—all the more so if that people, like the Spanish, has mingled in the life of nearly the whole world and been the victim of the calumnies and fanciful whims of historians, politicians, and travellers.

For all of these reasons the work of condensation by Professor Chapman constitutes an important service in itself for the English-speaking public, for it gives in one volume the most substantial features of our history from primitive times to the present moment. Furthermore, there are chapters in his work which belong entirely to him: XXXII, XXXIX, and XL. The reason for departing from my text in Chapter XXXII is given by Professor Chapman in the Preface. As for the other two he was under the unavoidable necessity of constructing them himself. His, for me, very flattering method of procedure, possible down to the year 1808, if indeed it might find a basis for continuation in a chapter of mine in the Cambridge modern history (v. X), in my lectures on the history of Spain in the nineteenth century (given at the Ateneo of Madrid, some years ago), in the little manual of the Historia de la civilización española (History of Spanish civilization) which goes to the year 1898, and even in the second part of a recent work, España y el programa americanista (Spain and the Americanist program), published at Madrid in 1917, nevertheless could not avail itself of a single text, a continuous, systematized account, comprehensive of all the aspects of our national life as in the case of the periods prior to 1808. Moreover, it is better that the chapters referring to the nineteenth century and the present time should be written by a foreign pen, whose master in this instance, as a result of his having lived in Spain, is able to contribute that personal impression of which I have spoken before, an element which if it is at times deceiving in part, through the influence of a too local or regional point of view, is always worth more than that understanding which proceeds only from erudite sources.

I would not be able to say, without failing in sincerity (and therefore in the first duty of historiography), that I share in and subscribe to all the conclusions and generalizations of Professor Chapman about the contemporary history and present condition of Spain. At times my dissent would not be more than one of the mere shade of meaning, perhaps from the form of expression, given to an act which, according as it is presented, is, or is not, exact. But in general I believe that Professor Chapman sees modern Spain correctly, and does us justice in many things in which it is not frequent that we are accorded that consideration. This alone would indeed be a great merit in our eyes and would deserve our applause. The English-speaking public will have a guarantee, through this work, of being able to contemplate a quite faithful portrait of Spain, instead of a caricature drawn in ignorance of the facts or in bad faith. With this noble example of historiographical calm, Professor Chapman amply sustains one of the most sympathetic notes which, with relation to the work of Spain in America, has for some years been characteristic, that which we should indeed call the school of North American historians.

RAFAEL ALTAMIRA.

February, 1918.

THE Iberian Peninsula, embracing the modern states of Spain and Portugal, is entirely surrounded by the waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, except for a strip in the north a little less than three hundred miles in length, which touches the southern border of France. Even at that point Spain is almost completely shut off from the rest of Europe, because of the high range of the Pyrenees Mountains. Portugal, although an independent state and set apart to a certain extent by a mountainous boundary, cannot be said to be geographically distinct from Spain. Indeed, many regions in Spain are quite as separate from each other as is Portugal from the Spanish lands she borders upon. Until the late medieval period, too, the history of Portugal was in the same current as that of the peninsula as a whole.

The greatest average elevation in Spain is found in the centre, in Castile and Extremadura, whence there is a descent, by great steps as it were, to the east and to the west. On the eastern side the descent is short and rapid to the Mediterranean Sea. On the west, the land falls by longer and more gradual slopes to the Atlantic Ocean, so that central Spain may be said to look geographically toward the west. There is an even more gentle decline from the base of the Pyrenees to the valley of the Guadalquivir, although it is interrupted by plateaus which rise above the general level. All of these gradients are modified greatly by the mountain ranges within the peninsula. The Pyrenean range not only separates France from Spain, but also continues westward under the name Cantabrian Mountains for an even greater distance along the northern coast of the latter country, leaving but little lowland space along the sea, until it reaches Galicia in the extreme northwest. Here it expands until it covers an area embracing northern Portugal as well. At about the point where the Pyrenees proper and the Cantabrian Mountains come together the Iberian, or Celtiberian, range, a series of isolated mountains for the most part, breaks off to the southeast until near the Mediterranean, when it curves to the west, merging with the Penibética range (better known as the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the name of that part of the range lying south of the city of Granada), which moves westward near the southern coast to end in the cape of Tarifa.

These mountains divide the peninsula into four regions: the narrow littoral on the northern coast; Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia, and most of La Mancha, looking toward the Mediterranean; Almería, Málaga, and part of Granada and Cádiz in the south of Spain; and the vast region comprising the rest of the peninsula. The last-named is subdivided into four principal regions of importance historically. The Carpetana, or Carpeto-Vetónica, range in the north (more often called the Guadarrama Mountains) separates Old Castile from New Castile and Extremadura to the south, and continues into Portugal. The Oretana range crosses the provinces of Cuenca, Toledo, Ciudad Real, Cáceres, and Badajoz, also terminating in Portugal. Finally, the Mariánica range (more popularly known as the Sierra Morena) forms the boundary of Castile and Extremadura with Andalusia. Each of the four sub-divisions has a great river valley, these being respectively, from north to south, the Douro, Tagus, Guadiana, and Guadalquivir. Various other sub-sections might be named, but only one is of prime importance,—the valley of the Ebro in Aragon and Catalonia, lying between the Pyrenees and an eastward branch of the Iberian range. Within these regions, embracing parts of several of them, there is another that is especially noteworthy,—that of the vast table-land of central Spain between the Ebro and the Guadalquivir. This is an elevated region, difficult of access from all of the surrounding lands. Geologists have considered it the “permanent nucleus” of the peninsula. It is in turn divided into two table-lands of unequal height by the great Carpeto-Vetónica range. The long coast line of the peninsula, about 2500 miles in length, has also been a factor of no small importance historically. Despite the length of her border along the sea, Spain has, next to Switzerland, the greatest average elevation of any country in Europe, so high are her mountains and table-lands.

These geographical conditions have had important consequences climatically and economically and especially historically. The altitude and irregularity of the land have produced widely separated extremes of temperature, although as a general rule a happy medium is maintained. To geographical causes, also, are due the alternating seasons of rain and drought in most of Spain, especially in Castile, Valencia, and Andalusia, which have to contend, too, with the disadvantages of a smaller annual rainfall than is the lot of most other parts of Europe and with the torrential rains which break the season of drought. When it rains, the water descends in such quantity and with such rapidity from the mountains to the sea that the river beds are often unable to contain it, and dangerous floods result. Furthermore, the sharpness of the slope makes it difficult to utilize these rivers for irrigation or navigation, so swift is the current, and so rapidly do the rivers spend themselves. Finally, the rain is not evenly distributed, and some regions, especially the high plateau country of Castile and La Mancha, are particularly dry and are difficult of cultivation.

On the other hand the geographical conditions of the peninsula have produced distinct benefits to counterbalance the disadvantages. The coastal plains are often very fertile. Especially is this true of the east and south, where the vine and the olive, oranges, rice, and other fruits and vegetables are among the best in the world. The northern coast is of slight value agriculturally, but, thanks to a rainfall which is constant and greater than necessary, is rich pastorally. Here, too, there is a very agreeable climate, due in large measure to a favoring ocean current, which has also been influential in producing the forests in a part of Galicia. These factors have made the northern coast a favorite summer resort for Spaniards and, indeed, for many other Europeans. The mountains in all parts of the peninsula have proved to contain a mineral wealth which many centuries of mining have been unable to exhaust. Some gold and more silver have been found, but metals of use industrially—such, for example, as copper—have been the most abundant. The very difficulties which Spaniards have had to overcome helped to develop virile traits which have made their civilization of more force in the world than might have been expected from a country of such scant wealth and population.[3]

The most marked result of these natural conditions has been the isolation, not only of Spain from the rest of the world, but also of the different regions of Spain from one another. Spaniards have therefore developed the conservative clinging to their own institutions and the individuality of an island people. While this has retarded their development into a nation, it has held secure the advances made and has vitalized Spanish civilization. For centuries the most isolated parts were also the most backward, this being especially true of Castile, whereas the more inviting and more easily invaded south and east coasts were the most susceptible to foreign influence and the most advanced intellectually as well as economically. When at length the centre accepted the civilization of the east and south, and by reason of its virility was able to dominate them, it imposed its law, its customs, and its conservatism upon them, and reached across the seas to the Americas, where a handful of men were able to leave an imperishable legacy of Spanish civilization to a great part of two continents.

Specific facts in Spanish history can also be traced very largely to the effects of geography. The mineral wealth of the peninsula has attracted foreign peoples throughout recorded history, and the fertility of the south and east has also been a potent inducement to an invasion, whether of armies or of capital. The physical features of the peninsula helped these peoples to preserve their racial characteristics, with the result that Spain presents an unusual variety in traits and customs. The fact that the valley of the Guadalquivir descends to the sea before reaching the eastern line of the Portuguese boundary had an influence in bringing about the independence of Portugal,—for while Castile still had to combat the Moslem states Portugal could turn her energies inward. Nevertheless, one must not think that geography has been the only or even the controlling factor in the life and events of the Iberian Peninsula. Others have been equally or more important,—such as those of race and, especially, the vast group of circumstances involving the relations of men and of states which may be given the collective name of history.

THE Iberian Peninsula has not always had the same form which it now has, or the same plants, animals, or climate which are found there today. For example, it is said that Spain was once united by land with Africa, and also by way of Sicily, which had not yet become an island, with southern Italy, making a great lake of the western Mediterranean. The changes as a result of which the peninsula assumed its present characteristics belong to the field of geology, and need to be mentioned here only as affording some clue to the earliest colonization of the land. In like manner the description of the primitive peoples of Spain belongs more properly to the realm of ethnology. It is worthy of note, however, that there is no proof that the earliest type of man in Europe, the Neanderthal, or Canstadt, man,[4] existed in Spain, and it is believed that the next succeeding type, the Furfooz man, entered at a time when a third type, the Cromagnon, was already there. Evidences of the Cromagnon man are numerous in Spain. Peoples of this type may have been the original settlers of the Iberian Peninsula.[5] Like the Neanderthal and Furfooz men they are described generally as paleolithic men, for their implements were of rough stone. After many thousands of years the neolithic man, or man of the polished stone age, developed in Spain as in other parts of the world. In some respects the neolithic man of Spain differed from the usual European type, but was similar to the neolithic man of Greece. This has caused some writers to argue for a Greek origin of the early Spanish peoples, but others claim that similar manifestations might have developed independently in each region. Neolithic man was succeeded by men of the ages of the metals,—copper, bronze, and iron. The age of iron, at least, coincided with the entry into Spain of peoples who come within the sphere of recorded history. As early as the bronze age a great mixture of races had taken place in Spain, although the brachycephalic successors of the Cromagnon race were perhaps the principal type. These were succeeded by a people who probably arrived in pre-historic times, but later than the other races of those ages—that dolichocephalic group to which has been applied the name Iberians. They were the dominating people at the time of the arrival of the Phœnicians and Greeks.

The early Spanish peoples left no literature which has survived, wherefore dependence has to be placed on foreign writers. No writings prior to the sixth century B.C. which refer to the Iberian Peninsula are extant, and those of that and the next two centuries are too meagre to throw much light on the history or the peoples of the land. These accounts were mainly those of Greeks, with also some from Carthaginians. In the first two centuries B.C. and in the first and succeeding centuries of the Christian era there were more complete accounts, based in part on earlier writings which are no longer available. One of the problems resulting from the paucity of early evidences is that of the determination of Iberian origins. Some hold that the name Iberian should not have an extensive application, asserting that it belongs only to the region of the Ebro (Iberus), the name of which river was utilized by the Greek, Scylax, of the sixth century B.C., in order to designate the tribes of that vicinity. Most writers use the term Iberians, however, as a general one for the peoples in Spain at the dawn of recorded history, maintaining that they were akin to the ancient Chaldeans and Assyrians, who came from Asia into northern Africa, stopping perhaps to have a share in the origin of the Egyptian people, and entering Spain from the south. According to some authors the modern Basques of northern Spain and the Berbers of northern Africa are descendants of the same people, although there are others who do not agree with this opinion. Some investigators have gone so far as to assert the existence of a great Iberian Empire, extending through northern Africa, Spain, southern France, northern Italy, Corsica, Sicily, and perhaps other lands. This empire, they say, was founded in the fifteenth century B.C., and fought with the Egyptians and Phœnicians for supremacy in the Mediterranean, in alliance, perhaps, with the Hittites of Asia Minor, but was defeated, and fell apart in the twelfth or eleventh century B.C., at which time the Phœnicians entered Spain.

The origin of the Celts is more certain. Unlike the Iberians they were of Indo-European race. In the third century B.C. they occupied a territory embracing the greater part of the lands from the modern Balkan states through northern Italy and France, with extremities in Britain and Spain. They entered the peninsula possibly as early as the sixth century B.C., but certainly not later than the fourth, coming by way of the Pyrenees. It is generally held that they dominated the northwest and west, the regions of modern Galicia and Portugal, leaving the Pyrenees, eastern Spain, and part of the south in full possession of the Iberians. In the centre and along the northern and southern coasts the two races mingled to form the Celtiberians, in which the Iberian element was the more important. These names were not maintained very strictly; rather, the ancient writers were wont to employ group names of smaller sub-divisions for these peoples, such as Cantabrians, Turdetanians, and Lusitanians.

It is not yet possible to distinguish clearly between Iberian and Celtic civilization; in any event it must be remembered that primitive civilizations resemble one another very greatly in their essentials. There was certainly no united Iberian or Celtic nation within historic times; rather, these peoples lived in small groups which were independent and which rarely communicated with one another except for the commerce and wars of neighboring tribes. For purposes of war tribal bodies federated to form a larger union and the names of these confederations are those which appear most frequently in contemporary literature. The Lusitanians, for example, were a federation of thirty tribes, and the Galicians of forty. The social and political organization of these peoples was so similar to others in their stage of culture, the world over, that it need only be indicated briefly. The unit was the gens, made up of a number of families, forming an independent whole and bound together through having the same gods and the same religious practices and by a real or feigned blood relationship. Various gentes united to form a larger unit, the tribe, which was bound by the same ties of religion and blood, although they were less clearly defined. Tribes in turn united, though only temporarily and for military purposes, and the great confederations were the result. In each unit from gens to confederation there was a chief, or monarch, and deliberative assemblies, sometimes aristocratic, and sometimes elective. The institutions of slavery, serfdom, and personal property existed. Nevertheless, in some tribes property was owned in common, and there is reason to believe that this practice was quite extensive. In some respects the tribes varied considerably as regards the stage of culture to which they had attained. Those of the fertile Andalusian country were not only far advanced in agriculture, industry, and commerce, but they also had a literature, which was said to be six thousand years old. This has all been lost, but inscriptions of these and other tribes have survived, although they have yet to be translated. On the other hand the peoples of the centre, west, and north were in a rude state; the Lusitanians of Portugal stood out from the rest in warlike character. Speaking generally, ancient writers ascribed to the Spanish peoples physical endurance, heroic valor, fidelity (even to the point of death), love of liberty, and lack of discipline as salient traits.

The first historic people to establish relations with the Iberian Peninsula were the Phœnicians. Centuries before, they had formed a confederation of cities in their land, whence they proceeded to establish commercial relations with the Mediterranean world. The traditional date for their entry into Spain is the eleventh century, when they are believed to have conquered Cádiz. Later they occupied posts around nearly all of Spain, going even as far as Galicia in the northwest. They exploited the mineral wealth of the peninsula, and engaged in commerce, using a system not unlike that of the British factories of the eighteenth century in India in their dealings with the natives. Their settlements were at the same time a market and a fort, located usually on an island or on an easily defensible promontory, though near a native town. Many of these Phœnician factories have been identified,—among others, those of Seville, Málaga, Algeciras, and the island of Ibiza, as well as Cádiz, which continued to be the most important centre. These establishments were in some cases bound politically to the mother land, but in others they were private ventures. In either case they were bound by ties of religion and religious tribute to the cities of Phœnicia. To the Phœnicians is due the modern name of the greater part of the peninsula. They called it “Span,” or “Spania,” meaning “hidden (or remote) land.” In course of time they were able to extend their domination inland, introducing important modifications in the life of the Iberian tribes, if only through the articles of commerce they brought.

The conquest of Phœnicia by the kings of Assyria and Chaldea had an effect on far-away Spain. The Phœnician settlements of the peninsula became independent, but they began to have ever more extensive relations with the great Phœnician colony of Carthage on the North African coast. This city is believed to have acquired the island of Ibiza in much earlier times, but it was not until the sixth century B.C. that the Carthaginians entered Spain in force. At that time the people of Cádiz are said to have been engaged in a dangerous war with certain native tribes, wherefore they invited the Carthaginians to help them. The latter came, and, as has so often occurred in history, took over for themselves the land which they had entered as allies.

Meanwhile, the Greeks had already been in Spain for some years. Tradition places the first Greek voyage to the Spanish coast in the year 630 B.C. Thereafter there were commercial voyages by the Greeks to the peninsula, followed in time by the founding of settlements. The principal colonizers were the Phocians, proceeding from their base at Marseilles, where they had established themselves in the seventh century B.C. Their chief post in Spain was at Emporium (on the site of Castellón de Ampurias, in the province of Gerona, Catalonia), and they also had important colonies as far south as the Valencian coast and yet others in Andalusia, Portugal, Galicia, and Asturias. Their advance was resisted by the Phœnicians and their Carthaginian successors, who were able to confine the Greeks to the upper part of the eastern coast as the principal field of their operations. The Greek colonies were usually private ventures, bound to the city-states from which they had proceeded by ties of religion and affection alone. They were also independent of one another. Their manner of entry resembled that already described in the case of the Phœnicians, for they went first to the islands near the coast, and thence to the mainland, where at length they joined with native towns, although having a separate, walled-off district of their own,—comparable to the situation at the present day in certain ports of European nations on the coast of China. Once masters of the coast the Greeks were able to penetrate inland and to introduce Greek goods and Greek influences over a broad area of the peninsula. To them is attributed the introduction of the vine and the olive, which ever since have been an important factor in the economic history of Spain.

The principal objects of the Carthaginians in Spain were to develop the rich silver mines of the land and to engage in commerce. In furtherance of these aims they established a rigorous military system, putting garrisons in the cities, and insisting on tribute in both soldiers and money. In other respects they left both the Phœnician colonies and the native tribes in full enjoyment of their laws and customs, but founded cities of their own on the model of Carthage. They did not attempt a thorough conquest of the peninsula until their difficulties with the rising power of Rome pointed out its desirability. In the middle of the third century B.C., Carthage, which had long been the leading power in the western Mediterranean, came into conflict with Rome in the First Punic War. As a result of this war, which ended in 242 B.C., Rome took the place of Carthage in Sicily. It was then that Hamilcar of the great Barca family of Carthage suggested the more thorough occupation of Spain as a counterpoise to the Roman acquisition of Sicily, in the hope that Carthage might eventually engage with success in a new war with Rome. He at length entered Spain with a Carthaginian army in 236 B.C., having also been granted political powers which were so ample that he became practically independent of direction from Carthage. The conquest was not easy, for while many tribes joined with him, others offered a bitter resistance. Hamilcar achieved vast conquests, built many forts, and is traditionally supposed to have founded the city of Barcelona, which bears his family name. He died in battle, and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal. Hasdrubal followed a policy of conciliation and peace, encouraging his soldiers to marry Iberian women, and himself wedding a Spanish princess. He made his capital at Cartagena, building virtually a new city on the site of an older one. This was the principal military and commercial centre in Spain during the remainder of Carthaginian rule. There the Barcas erected great public buildings and palaces, and ruled the country like kings. Hasdrubal was at length assassinated, leaving his command to Hannibal, the son of Hamilcar. Though less than thirty years of age Hannibal was already an experienced soldier and was also an ardent Carthaginian patriot, bitterly hostile to Rome. The time now seemed ripe for the realization of the ambitions of Hamilcar.

In order to check the Carthaginian advance the Romans had long since put themselves forward as protectors of the Greek colonies of Spain. Whether Saguntum was included in the treaties they had made or whether it was a Greek city at all is doubted today, but when Hannibal got into a dispute with that city and attacked it Rome claimed that this violated the treaty which had been made by Hasdrubal. It was in the year 219 B.C. that Hannibal laid siege to Saguntum. The Saguntines defended their city with a heroic valor which Spaniards have many times manifested under like circumstances. When resistance seemed hopeless they endeavored to destroy their wealth and take their own lives. Nevertheless, Hannibal contrived to capture many prisoners, who were given to his soldiers as slaves, and to get a vast booty, part of which he forwarded to Carthage. This arrived when the Carthaginians were discussing the question of Saguntum with a Roman embassy, and, coupled with patriotic pride, it caused them to sustain Hannibal and to declare war on Rome in the year 218 B.C.

Hannibal had already organized a great army of over 100,000 men, in great part Spanish troops, and had started by the land route for Italy. His brilliant achievements in Italy, reflecting, though they do, not a little glory on Spain, belong rather to the history of Rome. The Romans had hoped to detain him in Spain, and had sent Gnæus Scipio to accomplish this end. When he arrived in Spain he found that Hannibal had already gone. He remained, however, and with the aid of another army under his brother, Publius Cornelius Scipio, was able to overrun a great part of Catalonia and Valencia. In this campaign the natives followed their traditional practice of allying, some with one side, others with the other. Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal was at length able to turn the tide, defeating the two Scipios in 211 B.C. He then proceeded to the aid of Hannibal in Italy, but his defeat at the battle of the Metaurus was a deathblow to Carthage in the war against Rome. The Romans, meanwhile, renewed the war in Spain, where the youthful Publius Cornelius Scipio, son of the Scipio of the same name who had been killed in Spain, had been placed in command. By reckless daring and good fortune rather than by military skill Scipio won several battles and captured the great city of Cartagena. He ingratiated himself with native tribes by promises to restore their liberty and by several generous acts calculated to please them,—as, for example, his return of a native girl who had been given to him, on learning that she was on the point of being married to a native prince. These practices helped him to win victory after victory, despite several instances of desperate resistance, until at length in 206 B.C. the Carthaginians abandoned the peninsula. It was this same Scipio who later defeated Hannibal at Zama, near Carthage, in 202 B.C., whereby he brought the war to an end and gained for himself the surname Africanus.

The Carthaginians had been in Spain for over two hundred years, and, as was natural, had influenced the customs of the natives. Nevertheless, their rule was rather a continuation, on a grander scale, of the Phœnician civilization. From the standpoint of race, too, they and their Berber and Numidian allies, who entered with them, were perhaps of the same blood as the primitive Iberians. They had developed far beyond them, however, and their example assisted the native tribesmen to attain to a higher culture than had hitherto been acquired. If Rome was to mould Spanish civilization, it must not be forgotten that the Phœnicians, Greeks, and Carthaginians had already prepared the way.

UNDOUBTEDLY the greatest single fact in the history of Spain was the long Roman occupation, lasting more than six centuries. All that Spain is or has done in the world can be traced in greatest measure to the Latin civilization which the organizing genius of Rome was able to graft upon her. Nevertheless, the history of Spain in the Roman period does not differ in its essentials from that of the Roman world at large, wherefore it may be passed over, with only a brief indication of events and conditions in Spain and a bare hint at the workings and content of Latin civilization in general.

The Romans had not intended to effect a thorough conquest of Spain, but the inevitable law of expansion forced them to attempt it, unless they wished to surrender what they had gained, leaving themselves once more exposed to danger from that quarter. The more civilized east and south submitted easily to the Roman rule, but the tribes of the centre, north, and west opposed a most vigorous and persistent resistance. The war lasted three centuries, but may be divided into three periods, in each of which the Romans appeared to better advantage than in the preceding, until at length the powerful effects of Roman organization were already making themselves felt over all the land, even before the end of the wars.

The first of these periods began while the Carthaginians were still in the peninsula, and lasted for upwards of seventy years. This was an era of bitter and often temporarily successful resistance to Rome,—a matter which taxed the resources of the Roman Republic heavily. The very lack of union of the Spanish peoples tended to prolong the conflict, since any tribe might make war, then peace, and war again, with the result that no conquests, aside from those in the east and south, were ever secure. The type of warfare was also difficult for the Roman legionaries to cope with, for the Spaniards fought in small groups, taking advantage of their knowledge of the country to cut off detachments or to surprise larger forces when they were not in the best position to fight. These military methods, employed by Spaniards many times in their history, have been given, very appropriately, a Spanish name,—guerrilla (little war). Service in Spain came to be the most dreaded of all by the Roman troops, and several times Roman soldiers refused to go to the peninsula, or to fight when they got there, all of which encouraged the Spanish tribes to continue the revolt. The Romans employed harsh methods against those who resisted them, levelling their city walls and towers, selling prisoners of war into slavery, and imposing heavy taxes on conquered towns. They often displayed an almost inhuman brutality and treachery, which probably harmed their cause rather than helped it. Two incidents stand out as the most important in this period, and they illustrate the way in which the Romans conducted the war,—the wars of the Romans against the Lusitanians and against the city of Numantia in the middle years of the second century B.C.

The Roman leader Galba had been defeated by the Lusitanians, whereupon he resorted to an unworthy stratagem to reduce them. He granted them a favorable peace, and then when they were returning to their homes unprepared for an attack he fell upon them, and mercilessly put them to death. He could not kill them all, however, and a determined few gathered about a shepherd named Viriatus to renew the war. Viriatus was a man of exceptional military talent, and he was able to reconquer a great part of western and central Spain. For eight or nine years he hurled back army after army sent against him, until at length the Roman general Servilianus recognized the independence of the lands in the control of Viriatus. The Roman government disavowed the act of Servilianus, and sent out another general, Cæpio by name, who procured the assassination of Viriatus. Thereafter, the Lusitanians were unable to maintain an effective resistance, and they were obliged to take up their abode in lands where they could be more easily controlled should they again attempt a revolt.

Meanwhile, the wars of Numantia, which date from the year 152 B.C., were still going on. Numantia was a city on the Douro near the present town of Soria, and seems to have been at that time the centre, or capital, of a powerful confederation. Around this city occurred the principal incidents of the war in central Spain, although the fighting went on elsewhere as well. Four times the Roman armies were utterly defeated and obliged to grant peace, but on each occasion their treaties were disavowed by the government or else the Roman generals declined to abide by their own terms. Finally, Rome sent Scipio Æmilianus, her best officer, with a great army to bring the war to an end. This general contrived to reach the walls of Numantia, and was so skilful in his methods that the city was cut off from its water-supply and even from the hope of outside help. The Numantines therefore asked for terms, but the conditions offered were so harsh that they resolved to burn the city and fight to the death. This they did, killing themselves if they did not fall in battle. Thus ended the Numantine wars at a date placed variously from 134 to 132 B.C. The most serious part of the fighting was now over.

In the next period, lasting more than a hundred years, there were not a few native revolts against the Romans, but the principal characteristic of the era was the part which Spain played in the domestic strife of the Roman Republic. Spain had already become sufficiently Romanized to be the most important Roman province. When the party of Sulla triumphed over that of Marius in Rome, Sertorius, a partisan of the latter, had to flee from Italy, and made his way to Spain and thence to Africa. In 81 B.C. he returned to Spain, and put himself at the head of what purported to be a revolt against Rome. Part Spanish in blood he was able to attract the natives to his standard as well as the Romans in Spain who were opposed to Sulla, and in a short time he became master of most of the peninsula. He was far from desiring a restoration of native independence, however, but wished, through Spain, to overthrow the Sullan party in Rome. The real significance of his revolt was that it facilitated the Romanization of the country, for Sertorius introduced Roman civilization under the guise of a war against the Roman state. His governmental administration was based on that of Rome, and his principal officials were either Romans or part Roman in blood. He also founded schools in which the teachers were Greeks and Romans. It was natural that not a few of the natives should view with displeasure the secondary place allotted to them and their customs and to their hopes of independence. Several of the Roman officers with Sertorius also became discontented, whether through envy or ambition. Thus it was that the famous Roman general Pompey was at length able to gain a victory by treachery which he could not achieve by force of arms. A price was put on Sertorius’ head, and he was assassinated in 72 B.C. by some of his companions in arms, as Viriatus had been before him. In the course of the next year Pompey was able to subject the entire region formerly ruled by Sertorius. In the war between Cæsar and Pompey, commencing in 49 B.C., Spain twice served as a battle-ground where Cæsar gained great victories over the partisans of his enemy, at Ilerda (modern Lérida) in 49, and at Munda (near Ronda) in 45 B.C. It is noteworthy that by this time a Cæsar could seek his Roman enemy in Spain, without paying great heed to the native peoples. The north and northwest were not wholly subdued however. This task was left to the victor in the next period of civil strife at Rome, Octavius, who became the Emperor Augustus. His general, Agrippa, finally suppressed the peoples of the northern coasts, just prior to the beginning of the Christian era.

For another hundred years there were minor uprisings, after which there followed, so far as the internal affairs of the peninsula were concerned, the long Roman peace. On several occasions there were invasions from the outside, once by the Franks in the north, and various times by peoples from Africa. The latter are the more noteworthy. In all, or nearly all, of the wars chronicled thus far troops from northern Africa were engaged, while the same region was a stronghold for pirates who sailed the Spanish coasts. A large body of Berbers successfully invaded the peninsula between 170 and 180 A.D., but they were at length dislodged. This danger from Africa has been one of the permanent factors in the history of Spain, not only at the time of the great Moslem invasion of the eighth century, but also before that and since, down to the present day.

Administratively, Spain was divided into, first two provinces (197 B.C.), then three (probably in 15 or 14 B.C.), and four (216 A.D.), and at length five provinces (under Diocletian),[6] but the principal basis of the Roman conquest and control and the entering wedge for Roman civilization was the city, or town. In the towns there were elements which were of Roman blood, at least in part, as well as the purely indigenous peoples, who sooner or later came under the Roman influence. Rome sent not only armies to conquer the natives but also laborers to work in the mines. Lands, too, were allotted to her veteran soldiers, who often married native women, and brought up their children as Romans. Then there was the natural attraction of the superior Roman civilization, causing it to be imitated, and eventually acquired, by those who were not of Roman blood. The Roman cities were distinguished from one another according to the national elements of which they were formed, and the conquered or allied cities also had their different sets of rights and duties, but in all cases the result was the same,—the acceptance of Roman civilization. In Andalusia and southern Portugal the cities were completely Roman by the end of the first century, and beginning with the second century the rural districts as well gradually took on a Roman character. Romanization of the east was a little longer delayed, except in the great cities, which were early won over. The centre and north were the most conservatively persistent in their indigenous customs, but even there the cities along the Roman highways imitated more and more the methods of their conquerors. It was the army, especially in the early period, which made this possible. Its camps became cities, just as occurred elsewhere in the empire,[7] and it both maintained peace by force of arms, and ensured it when not engaged in campaigns by the construction of roads and other public works.

The gift of Rome to Spain and the world was twofold. In the first place she gave what she herself had originated or brought to a point which was farther advanced than that to which other peoples had attained, and secondly she transmitted the civilization of other peoples with whom her vast conquests had brought her into contact. Rome’s own contribution may be summed up in two words,—law and administration. Through these factors, which had numerous ramifications, Rome gave the conquered peoples peace, so that an advance in wealth and culture also became possible. The details need not be mentioned here, especially since Roman institutions will be discussed later in dealing with the evolution toward national unity between 1252 and 1479. The process of Romanization, however, was a slow one, not only as a result of the native opposition to innovation, but also because Roman ideas themselves were evolving through the centuries, not reaching their highest state, perhaps, until the second century A.D. Spain was especially favored in the legislation of the emperors, several of whom (Trajan, Hadrian, and possibly Theodosius, who were also among the very greatest) were born in the town of Itálica (near Seville), while a fourth, the philosopher Marcus Aurelius, was of Spanish descent.

In the third and fourth centuries Spain suffered, like the rest of the empire, from the factors which were bringing about the gradual dissolution of imperial rule. Population declined, in part due to plagues, and taxes increased; luxury and long peace had also softened the people, so that the barbarians from the north of Europe, who had never ceased to press against the Roman borders, found resistance to be less and less effective. Indeed, the invaders were often more welcome than not, so heavy had the weight of the laws become. The dying attempt of Rome to bolster up her outworn administrative system is not a fact, however, to which much space need be given in a history of Spain.

In Spain as elsewhere there were a great many varying grades of society during the period of Roman dominion. There were the aristocratic patricians, the common people, or plebeians, and those held in servitude. Each class had various sub-divisions, differing from one another. Then, too, there were “colleges,” or guilds, of men engaged in the same trade, or fraternities of a religious or funerary nature. The difference in classes was accentuated in the closing days of the empire, and hardened into something like a caste system, based on lack of equal opportunity. Artisans, for example, were made subject to their trade in perpetuity; the son of a carpenter had no choice in life but to become a carpenter. Great as was the lack of both liberty and equality it did not nearly approximate what it had been in more primitive times, and it was even less burdensome than it was to be for centuries after the passing of Rome. Indeed, Rome introduced many social principles which tended to make mankind more and more free, and it is these ideas which are at the base of modern social liberty. Most important among them, perhaps, was that of the individualistic tendency of the Roman law. This operated to destroy the bonds which subordinated the individual to the will of a communal group; in particular, it substituted the individual for the family, giving each man the liberty of following his own will, instead of subjecting him forever to the family. The same concept manifested itself in the Roman laws with reference to property. For example, freedom of testament was introduced, releasing property from the fetters by which it formerly had been bound.

Even though Rome for a long time resisted it, she gave Christianity to the world almost as surely as she did her Roman laws, for the very extent and organization of the empire and the Roman tolerance (despite the various persecutions of Christians) furnished the means by which the Christian faith was enabled to gain a foothold. In the fourth century the emperors gave the new religion their active support, and ensured its victory over the opposing faiths. There is a tradition that Saint Paul preached in Spain, but at any rate Christianity certainly existed there in the second century, and in the third there were numerous Christian communities.[8] The church was organized on the basis of the Roman administrative districts, employing also the Roman methods and the Roman law. Thus, through Rome, Spain gained another institution which was to assist in the eventual development of her national unity and to play a vital part in her subsequent history,—that of a common religion. In the fourth century the church began to acquire those privileges which at a later time were to furnish such a problem to the state. It was authorized to receive inheritances; its clergy began to be granted immunities,—exemptions from taxation, among others; and it was allowed to have law courts of its own, with jurisdiction over many cases where the church or the clergy were concerned. Church history in Spain during this period centres largely around the first three councils of the Spanish church. The first was held at Iliberis (Elvira) in 306, and declared for the celibacy of the clergy, for up to that time priests had been allowed to marry. The second, held at Saragossa in 380, dealt with heresy. The third took place at Toledo in 400, and was very important, for it unified the doctrine of the Christian communities of Spain on the basis of the Catholic, or Nicene, creed. It was at this time, too, that monasteries began to be founded in Spain. The church received no financial aid from the state, but supported itself out of the proceeds of its own wealth and the contributions of the faithful.

As in other parts of the Roman world, so too in Spain, heresies were many and varied at this time. One of the most prominent of them, Priscillianism, originated in Spain, taking its name from its propounder, Priscillian. Priscillian was a Galician, who under the influence of native beliefs set forth a new interpretation of Christianity. He denied the mystery of the Trinity; claimed that the world had been created by the Devil and was ruled by him, asserting that this life was a punishment for souls which had sinned; defended the transmigration of souls; held that wine was not necessary in the celebration of the mass; and maintained that any Christian, whether a priest or not, might celebrate religious sacraments. In addition he propounded much else of a theological character which was not in accord with Catholic Christianity. It was to condemn Priscillianism that the Council of Saragossa was called. Nevertheless, this doctrine found favor even among churchmen of high rank, and Priscillian himself became bishop of Ávila. In the end he and his principal followers were put to death, but it was three centuries before Priscillianism was completely stamped out. In addition to this and other heresies the church had to combat the religions which were already in existence when it entered the field, such as Roman paganism and the indigenous faiths. It was eventually successful, although many survivals of old beliefs were long existent in the rural districts.

The Romans continued the economic development of Spain on a greater scale than their predecessors. Regions which the other peoples had not reached were for the first time benefited by contact with a superior civilization, and the materials which Spain was already able to supply were diversified and improved. Although her wealth in agricultural and pastoral products was very great, it was the mines which yielded the richest profits. It is said that there were forty thousand miners at Cartagena alone in the second century B.C. Commerce grew in proportion to the development of wealth, and was facilitated in various ways, one of which deserves special mention, for its effects were far wider than those of mere commercial exchange. This was the building of public works, and especially of roads, which permitted the peoples of Spain to communicate freely with one another as never before. The roads were so extraordinarily well made that some of them are still in use. The majority date from the period of the empire, being built for military reasons as one of the means of preserving peace. They formed a network, crossing the peninsula in different directions, not two or three roads, but many. The Romans also built magnificent bridges, which, like the roads, still remain in whole or in part. Trade was fostered by the checking of fraud and abuses through the application of the Roman laws of property and of contract.

In general culture Spain also profited greatly from the Romans, for, if the latter were not innovators outside the fields of law and government, they had taken over much of the philosophy, science, literature, and the arts of Greece, borrowing, too, from other peoples. The Romans had also organized a system of public instruction as a means of disseminating their culture, and this too they gave to Spain. The Spaniards were apt pupils, and produced some of the leading men in Rome in various branches of learning, among whom may be noted the philosopher Seneca, the rhetorician Quintilian, the satirical poet Martial, and the epic poet Lucan. The Spaniards of Cordova were especially prominent in poetry and oratory, going so far as to impose their taste and style of speech on conservative Rome. This shows how thoroughly Romanized certain parts of the peninsula had become. In architecture the Romans had borrowed more from the Etruscans than from the Greeks, getting from them the principle of the vault and the round arch, by means of which they were able to erect great buildings of considerable height. From the Greeks they took over many decorative forms. Massiveness and strength were among the leading characteristics of Roman architecture, and, due to them, many Roman edifices have withstood the ravages of time. Especially notable in Spain are the aqueducts, bridges, theatres, and amphitheatres which have survived, but there are examples, also, of walls, temples, triumphal arches, and tombs, while it is known that there were baths, though none remain. In a wealthy civilization like the Roman it was natural, too, that there should have been a great development of sculpture, painting, and the industrial arts. The Roman type of city, with its forum and with houses presenting a bare exterior and wealth within, was adopted in Spain.

In some of the little practices of daily life the Spanish peoples continued to follow the customs of their ancestors, but in broad externals Spain had become as completely Roman as Rome herself.

THE Roman influence in Spain did not end, even politically, in the year 409, which marked the first successful invasion of the peninsula by a Germanic people and the beginning of the Visigothic era. The Visigoths themselves did not arrive in that year, and did not establish their rule over the land until long afterward. Even then, one of the principal characteristics of the entire era was the persistence of Roman civilization. Nevertheless, in spite of the fact that the Visigoths left few permanent traces of their civilization, they were influential for so long a time in the history of Spain that it is appropriate to give their name to the period elapsing from the first Germanic invasion to the beginning of the Moslem conquest. The northern peoples, of whom the Visigoths were by far the principal element, reinvigorated the peninsula, both by compelling a return to a more primitive mode of life, and also by some intermixture of blood. They introduced legal, political, and religious principles which served in the end only to strengthen the Roman civilization by reason of the very combat necessary to the ultimate Roman success. The victory of the Roman church came in this era, but that of the Roman law and government was delayed until the period from the thirteenth to the close of the fifteenth century.

In the opening years of the fifth century the Vandals, who had been in more or less hostile contact with the Romans during more than two centuries, left their homes within modern Hungary, and emigrated, men, women, and children, toward the Rhine. With them went the Alans, and a little later a group of the Suevians joined them. They invaded the region of what is now France, and after devastating it for several years passed into Spain in the year 409. There seems to have been no effective resistance, whereupon the conquerors divided the land, giving Galicia to the Suevians and part of the Vandals, and the southern country from Portugal to Cartagena to the Alans and another group of Vandals. A great part of Spain still remained subject to the Roman Empire, even in the regions largely dominated by the Germanic peoples. The bonds between Spain and the empire were slight, however, for the political strife in Italy had caused the withdrawal of troops and a general neglect of the province, wherefore the regions not acknowledging Germanic rule tended to become semi-independent nuclei.

The more important Visigothic invasion was not long in coming. The Visigoths (or the Goths of the west,—to distinguish them from their kinsmen, the Ostrogoths, or Goths of the east) had migrated in a body from Scandinavia in the second century to the region of the Black Sea, and in the year 270 established themselves north of the Danube. Pushed on by the Huns they crossed that river toward the close of the fourth century, and entered the empire, contracting with the emperors to defend it. Their long contact with the Romans had already modified their customs, and had resulted in their acceptance of Christianity. They had at first received the orthodox faith, but were later converted to the Arian form, which was not in accord with the Nicene creed. After taking up their dwelling within the empire the Visigoths got into a dispute with the emperors, and under their great leader Alaric waged war on them in the east. At length they invaded Italy, and in the year 410 captured and sacked the city of Rome, the first time such an event had occurred in eight hundred years. Alaric was succeeded by Ataulf, who led the Visigoths out of Italy into southern France. There he made peace with the empire, being allowed to remain as a dependent ally of Rome in the land he had conquered. In all of these wanderings the whole tribe, all ages and both sexes, went along. From this point as a base the Visigoths made a beginning of the organization which was to become a powerful independent state. There, too, in this very Roman part of the empire, they became more and more Romanized.

The Visigoths were somewhat troublesome allies, for they proceeded to conquer southern France for themselves. Thereupon, war broke out with the emperor, and it was in the course of this conflict that they made their first entry into Spain. This occurred in the year 414, when Ataulf crossed the Pyrenees and captured Barcelona. Not long afterward, Wallia, a successor of Ataulf, made peace with the emperor, gaining title thereby to the conquests which Ataulf had made in southern France, but renouncing those in Spain. The Visigoths also agreed to make war on the Suevians and the other Germanic peoples in Spain, on behalf of the empire. Thus the Visigoths remained in the peninsula, but down to the year 456 made no conquests on their own account. Wallia set up his capital at Toulouse, France, and it was not until the middle of the sixth century that a Spanish city became the Visigothic seat of government.

The Visigoths continued to be rather uncertain allies of the Romans. They did indeed conquer the Alans, and reduced the power of the Vandals until in 429 the latter people migrated anew, going to northern Africa. The Suevians were a more difficult enemy to cope with, however, consolidating their power in Galicia, and at one time they overran southern Spain, although they were soon obliged to abandon it. It was under the Visigothic king Theodoric that the definite break with the empire, in 456, took place. He not only conquered on his own account in Spain, but also extended his dominions in France. His successor, Euric (467-485), did even more. Except for the territory of the Suevians in the northwest and west centre and for various tiny states under Hispano-Roman or perhaps indigenous nobles in southern Spain and in the mountainous regions of the north, Euric conquered the entire peninsula. He extended his French holdings until they reached the river Loire. No monarch of western Europe was nearly so powerful. The Visigothic conquest, as also the conquests by the other Germanic peoples, had been marked by considerable violence, not only toward the conquered peoples of a different faith, but also in their dealings with one another. The greatest of the Visigothic kings often ascended the throne as a result of the assassination of their predecessors, who were in many cases their own brothers. Such was the case with Theodoric and with Euric, and the latter was one of the fortunate few who died a natural death. This condition of affairs was to continue throughout the Visigothic period, supplemented by other factors tending to increase the disorder and violence of the age.

The death of Euric was contemporaneous with the rise of a new power in the north of France. The Franks, under Clovis, were just beginning their career of conquest, and they coveted the Visigothic lands to the south of them. In 496 the Franks were converted to Christianity, but unlike the Visigoths they became Catholic Christians. This fact aided them against the Visigoths, for the subject population in the lands of the latter was also Catholic. Clovis was therefore enabled to take the greater part of Visigothic France, including the capital city, in 508, restricting the Visigoths to the region about Narbonne, which thenceforth became their capital. In the middle of the sixth century a Visigothic noble, Athanagild, in his ambition to become king invited the great Roman emperor Justinian (for the empire continued to exist in the east, long after its dissolution in the west in 476) to assist him. Justinian sent an army, through whose aid Athanagild attained his ambition, but at the cost of a loss of territory to the Byzantine Romans. Aided by the Hispano-Romans, who continued to form the bulk of the population, and who were attracted both by the imperial character and by the Catholic faith of the newcomers, the latter were able to occupy the greater part of southern Spain. Nevertheless, Athanagild showed himself to be an able king, and it was during his reign (554-567) that a Spanish city first became capital of the kingdom, for Athanagild fixed his residence in Toledo. The next king returned to France, leaving his brother, Leovgild, as ruler in Spain. On the death of the former in 573 Leovgild became sole ruler, and the capital returned to Toledo to remain thereafter in Spain.

Leovgild (573-586) was the greatest ruler of the Visigoths in Spain. He was surrounded by difficulties which taxed his powers to the utmost. In Spain he was confronted by the Byzantine provinces of the south, the Suevian kingdom of the west and northwest, and the Hispano-Roman and native princelets of the north. All of these elements were Catholic, for the Suevians had recently been converted to that faith, and therefore might count in some degree on the sympathy of Leovgild’s Catholic subjects. Furthermore, like kings before his time and afterward, Leovgild had to contend with his own Visigothic nobles, who, though Arian in religion, resented any increase in the royal authority, lest it in some manner diminish their own. In particular the nobility were opposed to Leovgild’s project of making the monarchy hereditary instead of elective; the latter had been the Visigothic practice, and was favored by the nobles because it gave them an opportunity for personal aggrandizement. The same difficulties had to be faced in France, where the Franks were the foreign enemy to be confronted. All of these problems were attacked by Leovgild with extraordinary military and diplomatic skill. While he held back the Franks in France he conquered his enemies in Spain, until nothing was left outside his power except two small strips of Byzantine territory, one in the southwest and the other in the southeast. Internal issues were complicated by the conversion of his son Hermenegild to Catholicism. Hermenegild accepted the leadership of the party in revolt against his father, and it was six years before Leovgild prevailed. The rebellious son was subsequently put to death, but there is no evidence that Leovgild was responsible.

Another son, Reccared (586-601), succeeded Leovgild, and to him is due the conversion of the Visigoths to Catholic Christianity. The mass of the people and the Hispano-Roman aristocracy were Catholic, and were a danger to the state, not only because of their numbers, but also because of their wealth and superior culture. Reccared therefore announced his conversion (in 587 or 589), and was followed in his change of faith by not a few of the Visigoths. This did not end internal difficulties of a religious nature, for the Arian sect, though less powerful than the Catholic, continued to be a factor to reckon with during the remainder of Visigothic rule. Reccared also did much of a juridical character to do away with the differences which separated the Visigoths and Hispano-Romans, in this respect following the initiative of his father. After the death of Reccared, followed by three brief reigns of which no notice need be taken, there came two kings who successfully completed the Visigothic conquest of the peninsula. Sisebut conquered the Byzantine province of the southeast, and Swinthila that of the southwest. Thus in 623 the Visigothic kings became sole rulers in the peninsula,—when already their career was nearing an end.

The last century of the Visigothic era was one of great internal turbulence, arising mainly from two problems: the difficulties in the way of bringing about a fusion of the races; and the conflict between the king and the nobility, centring about the question of the succession to the throne. The first of these was complicated by a third element, the Jews, who had come to Spain in great numbers, and had enjoyed high consideration down to the time of Reccared, but had been badly treated thereafter. Neither in the matter of race fusion nor in that of hereditary succession were the kings successful, despite the support of the clergy. Two kings, however, took important steps with regard to the former question. Chindaswinth established a uniform code for both Visigoths and Hispano-Romans, finding a mean between the laws of both. This was revised and improved by his son and successor, Recceswinth, and it was this code, the Lex Visigothorum (Law of the Visigoths), which was to exercise such an important influence in succeeding centuries under its more usual title of the Fuero Juzgo.[9] Nevertheless, it was this same Recceswinth who conceded to the nobility the right of electing the king. Internal disorder did not end, for the nobles continued to war with one another and with the king. The next king, Wamba (672-680), lent a dying splendor to the Visigothic rule by the brilliance of his military victories in the course of various civil wars. Still, the only real importance of his reign was that it foreshadowed the peril which was to overwhelm Spain a generation later. The Moslem Arabs had already extended their domain over northern Africa, and in Wamba’s time they made an attack in force on the eastern coast of Spain, but were badly defeated by him. A later invasion in another reign likewise failed.