The Project Gutenberg EBook of Farmer George, Volume 1, by Lewis Melville This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Farmer George, Volume 1 Author: Lewis Melville Release Date: July 1, 2012 [EBook #39980] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FARMER GEORGE, VOLUME 1 *** Produced by Cathy Maxam, Heather Clark and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

Enlargements are provided for 5 of the illustrations in this book, in order for the reader to more easily see printed text within the images. By hovering the cursor over the images which have enlargements, you will see the message: "Click here to enlarge the image."

FARMER GEORGE

BY

LEWIS MELVILLE

Author of "The First Gentleman of Europe,"

"The Life of William Makepeace Thackeray,"

&c., &c.

WITH FIFTY-THREE PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

In Two Volumes

Vol. I

LONDON: SIR ISAAC PITMAN AND SONS, LTD.

NO. 1 AMEN CORNER, E. C. 1907

Printed by

Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

Bath.

(2002)

To

Thomas Seccombe

To whom the Author is indebted for

many valuable suggestions

CONTENTS

Vol. I

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Introduction | ix | |

| I. | Frederick, Prince of Wales | 1 |

| II. | Boyhood of George III | 33 |

| III. | The Prince Comes of Age | 62 |

| IV. | The New King | 71 |

| V. | "The Fair Quaker" | 86 |

| VI. | Lady Sarah Lennox and George III | 105 |

| VII. | The Royal Marriage | 120 |

| VIII. | The Rise and Fall of "The Favourite" | 136 |

| IX. | The Court of George III | 167 |

| X. | The Private Life of the King and Queen | 202 |

| XI. | "No. XLV" | 235 |

| XII. | The King under Grenville | 269 |

VOL. I

| PAGE | ||

| George III | frontispiece | |

| Frederick, Prince of Wales | facing | 5 |

| The Prince and Princess of Wales, Miss Vane and her Son | " | 11 |

| Caroline, Consort of George II | " | 15 |

| George II | " | 15 |

| Prince George of Wales, Prince Edward of Wales, and Dr. Ayscough | " | 35 |

| Augusta, Princess Dowager of Wales | " | 41 |

| Leicester House | " | 45 |

| George, Prince of Wales | " | 55 |

| George III | " | 62 |

| George III in his Coronation Robes | " | 71 |

| "The Button Maker" | " | 75 |

| Miss Axford (Hannah Lightfoot) | " | 86 |

| Lady Sarah Lennox Sacrificing to the Muses | " | 105 |

| Queen Charlotte | " | 120 |

| John, Earl of Bute | " | 136 |

| Windsor Castle | " | 167 |

| "The Kitchen Metamorphoz'd" | " | 178 |

| "Learning to make Apple Dumplings" | " | 190 |

| The King Relieving Prisoners in Dorchester Gaol | " | 196 |

| "Summer Amusements at Farmer George's" | " | 198 |

| Buckingham House | " | 202 |

| "The Constant Couple" | " | 220 |

| Kew Palace | " | 223 |

| John Wilkes | " | 235 |

| "The Bruiser" (Charles Churchill) | " | 243 |

| The King's Life Attempted | " | 258 |

| "The Reconciliation" | " | 268 |

| The Right Hon. George Grenville | " | 270 |

FARMER GEORGE

Vol. I

This work is an attempt to portray the character of George III and to present him alike in his private life and in his Court. It is, therefore, not essential to the scheme of this book to treat of the political history of the reign, but it is impossible entirely to ignore it, since the King was so frequently instrumental in moulding it.[1] Only those events in which he took a leading part have been introduced, and consequently these volumes contain no account of Irish and Indian affairs, in which, apart from the Catholic Emancipation and East India Bills, the King did not actively interest himself.

This difficulty was not met with by the author when[Pg x] writing a book on the life and times of George IV,[2] because that Prince had little to do with politics. It is true that he threw his influence into the scale of the Opposition as soon as, or even before, he came of age, but this was for strictly personal reasons. Fox and Sheridan were the intimates of the later years of his minority, and his association with them gave him the pleasure of angering his father: it was his protest against George III for refusing him the income to which he considered himself, as Prince of Wales, entitled. He had, however, no interest in politics, as such, either before or after he ascended the throne; and, indeed, as King, the only measure that interested him was the Bill for the emancipation of the Catholics, which he opposed because resistance to it had made his father and his brother Frederick popular.

With George III the case was very different. He came to the throne in his twenty-third year, with his mother's advice, "Be King, George," ringing in his ears, and, fully determined to carry out this instruction to the best of his ability, he was not content to reign without making strenuous efforts to rule. "Farmer George," the nickname that has clung to him ever since it was bestowed satirically in the early days of his reign, has come, except[Pg xi] by those well versed in the history of the times, to be accepted as a tribute to his simple-mindedness and his homely mode of living. To these it will come as a shock to learn that "Farmer George" was a politician of duplicity so amazing that, were he other than a sovereign, it might well be written down as unscrupulousness. Loyalty, indeed, seems to have been foreign to his nature: he was a born schemer. When the Duke of Newcastle was in power, George plotted for the removal of Pitt, knowing that the resignation of the "Great Commoner" must eventually bring about the retirement of the Duke, and so leave Bute in possession of supreme authority. When within a year "The Favourite" was compelled to withdraw, George, unperturbed, appointed George Grenville Prime Minister, but finding him unsubservient, intrigued against him, was found out, compelled to promise to abstain from further interference against his own ministers, broke his word again and again, and finally brought about the downfall of Grenville, who was succeeded by the Marquis of Rockingham. Again George employed the most unworthy means to get rid of Rockingham, and during the debates on the repeal of the Stamp Act encouraged his Household to vote against the Government, assuring them they should not lose their places, indeed would rise higher[Pg xii] in his favour, because of their treachery to the head of the Administration of the Crown; and all the while he was writing encouraging notes to Rockingham assuring him of his support! This strange record of underhand intrigues has been traced in the following pages.

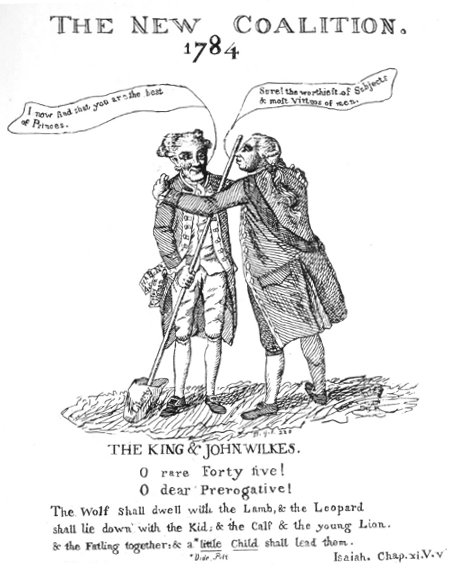

George had not even the excuse of success for his treachery. It is true that he contrived to compel the resignation of various ministers, but his incursions into the political arena were fraught with disaster. He forced Bute on the nation, and Bute could not venture to enter the City except with a band of prize-fighters around his carriage to protect him! He took an active part against Wilkes, and Wilkes became a popular hero! He encouraged the imposition of the Stamp Act in America, and in the end America was lost to England! Having no knowledge of men and being ignorant of the world, he was guided at first by secret advisers, and subsequently by his own likes and dislikes, coupled with a regard for his dignity, that did not, however, prevent him from personally canvassing Windsor in favour of the Court candidate when Keppel was standing for the parliamentary representation of the town.

George III was, according to his lights, a good man—

a kind master; a well-meaning, though unwise father; a faithful husband, possessing

which was the more creditable as his nature was vastly susceptible. He was pious, anxious to do his duty, and deeply attached to his country, but believing himself always in the right, was frequently led by his feelings into courses such as justified Byron's magnificent onslaught:—

Yet, notwithstanding all the mistakes George III made, and all the mischief he did, his reign ended in a blaze of glory. England had survived the French Revolution without disastrous effects; and had taken a leading part in the subjugation of Napoleon. Nelson and Wellington, Wordsworth and Keats, Fox and Pitt, reflected their[Pg xiv] glory and the splendour of their actions upon the country of their birth. Yet—such is the irony of fate at its bitterest—while the world acknowledged the supremacy of England on land, at sea, and in commerce, while a whole people, delighted with magnificent achievements, acclaimed their ruler, crying lustily "God save the King," George, in whose name these great deeds were done, was but "a crazy old blind man in Windsor Tower."

FREDERICK, PRINCE OF WALES

Historians have found something to praise in George I, and the bravery of George II on the field of battle has prejudiced many in favour of that monarch. George III has been extolled for his domestic virtues, and his successor held up to admiration for his courtly manners, while William IV found favour in the eyes of many for his homely air. Of all the Hanoverian princes in the direct line of succession to the English throne, alone Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, lacks a solitary admirer among modern writers.

Frederick was born at Hanover on January 6, 1707, was there educated; and there, after the accession of George II to the English throne, remained, a mere lad, away from parental control, compelled to hold a daily Drawing-room, at which he received the adulation of unscrupulous and self-seeking courtiers in a dull, vulgar, and immoral Court. George II, remembering his behaviour to his father, was in no hurry to summon his son to England; and Frederick might have remained the ornament of the Hanoverian capital until his[Pg 2] death, but that the English thought it advisable their future king should not be allowed to grow up in ignorance of the manners and customs of the land over which in the ordinary course of nature he would reign. Neither the King nor the Queen had any affection for the young man; and they were so reluctant to bring him into prominence, or even into frequent intercourse with themselves, that they disregarded the murmur of the people, and were inclined even to ignore the advice of the Privy Council—when news from Hanover caused them hurriedly to send for him.

Queen Sophia Dorothea of Prussia had years earlier said to Princess Caroline, afterwards Queen of England, "You, Caroline, Cousin dear, have a little Prince, Fritz, or let us call him Fred, since he is to be English; little Fred, who will one day, if all go right, be King of England. He is two years older than my little Wilhelmina, why should they not wed, and the two chief Protestant Houses, and Nations, thereby be united?" There was nothing to be said against this proposal, and much in its favour. "Princess Caroline was very willing; so was Electress Sophie, the Great-Grandmother of both the parties; so were the Georges, Father and Grandfather of Fred: little Fred himself was highly charmed, when[Pg 3] told, of it; even little Wilhelmina, with her dolls, looked pleasantly demure on the occasion. So it remained settled in fact, though not in form; and little Fred (a florid milk-faced foolish kind of Boy, I guess), made presents to his little Prussian Cousin, wrote bits of love-letters to her and all along afterwards fancied himself, and at length ardently enough became, her little lover and intended—always rather a little fellow:—to which sentiments Wilhelmina signifies that she responded with the due maidenly indifference, but not in an offensive manner."[5] Then Prussian Fritz or Fred was born, and it was further agreed that Amelia, George II's second daughter, should marry him. George I sanctioned the arrangement, but the treaty in which it was incorporated was never signed; and on his accession, George II, for many reasons, was no longer desirous to carry out the marriage. Only Queen Sophia held to her project, and Frederick, the intended husband. The latter, doubtless incited by his father's opposition to imagine himself in love with Wilhelmina, caused it to be intimated to Queen Sophia that, if she would consent, he would travel secretly to Prussia and marry his cousin. The Queen was[Pg 4] delighted, and summoned her husband to be present at the nuptials, but, anxious to share her joy, must needs select as a confidant the English ambassador Dubourgay, who, of course, could not treat such a communication as a confidence, and, to the Queen's horror, told her he must dispatch the news to his sovereign. In vain Sophia Dorothea pleaded for silence: it would spell ruin for it to be said that the envoy had known of the secret and had not informed his master. The only chance for the successful issue of the scheme was that Frederick should arrive before his father could interfere, but this was not to be. Colonel Launay came from England charged to return with the heir-apparent; and so the marriage was, at least, postponed. Frederick arrived in England on December 4, 1728, and early in the following year Sir Charles Hotham went as minister plenipotentiary to the King of Prussia to propose the carrying out of the double-marriage project, but while the latter was willing to consent to the marriage of his daughter with the Prince, he would not accept for his son the hand of Princess Amelia, declaring that he ought to espouse the Princess Royal. Neither party would give way, and the dislike of the potentates for each other resulted in 1730 in a definite rupture of the negotiations.

On[Pg 5] his arrival in England Frederick[6] was received with acclamation by the populace, but his relations with his parents were strained from the start. The original cause of quarrel is unknown to the present generation, and even at the time few were acquainted with it, though Sir Robert Walpole knew it, and Lord Hervey,[7] who wrote it down, only for his memorandum to be destroyed by his son, the Earl of Bristol.[8] It may be assumed, however, that his father's conduct in the negotiations for the marriage with the Princess of Prussia widened the breach. The Prince of Wales was certainly not an agreeable person. In Hanover he had indulged to excess in "Wein, Weib, und Gesang," and he was the unfortunate possessor of a mean, paltry, despicable nature that revolted those with whom he was brought into contact. His mother hated him—"He is such an ass that one cannot tell what he thinks"; his sister Amelia loathed him and wished he were dead—"He is the greatest liar that ever spoke, and will put one arm round anybody's neck to kiss them, and then stab them with the other if he[Pg 6] can"; and his father detested him. "My dear first born is the greatest ass, the greatest liar, the greatest canaille and the greatest beast in the whole world, and I heartily wish he was out of it," so said George II, and it must be conceded that in the main he was right.

Of course, the faults were not all on the side of the Prince of Wales: indeed, they were fairly evenly distributed between father and son. From the first he was publicly ignored by George II. "Whenever the Prince was in the room with the King it put one in mind of stories that one has heard of ghosts that appear to part of the company, and were invisible to the rest; and in this manner wherever the Prince stood, though the King passed him ever so often, or ever so near, it always seems as if the King thought the Prince filled a void of space."[9] The father took advantage of his position to keep the son short of money; and the son, after the manner of Hanoverian heirs-apparent, retorted by throwing himself into the arms of the Opposition. The Prince of Wales's great grievance was that he received an allowance only of £50,000 and that at the King's pleasure: and he contended that as George II, when Prince of Wales, had received £100,000 a year from George I's Civil List of £700,000, it was manifestly unfair[Pg 7] that as the Civil List had been increased to £800,000, the Prince of Wales's income should be reduced by half and that dependent on the sovereign's humour.

Frederick, who had left Hanover in debt, had been further embarrassed in London, and, to free himself from financial trouble discussed with Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, a marriage between himself and her granddaughter, Lady Diana Spencer,[10] conditional on the dowry being £100,000. The ambitious old lady was favourable to the scheme—it has been said, and perhaps with truth, that it was her proposal—and arrangements were made for the ceremony to take place privately at the Lodge in Windsor Great Park; but Sir Robert Walpole heard of it—that wily statesman learnt most secrets—and told the King, who forbade the marriage.

The Prince did not at first commit any serious offence against the King, but he contrived, with or without intention, to irritate or affront him almost daily. He wrote, or inspired, the "History of Prince Titi," in which the King and Queen were caricatured; and, with the guidance of Bubb Dodington,[11] formed a Court that became a[Pg 8] rendezvous of the Opposition and the disaffected generally. It became his object in life to outshine his father in popularity, and as George II was not a favourite, and as Frederick could be agreeable when he wanted to make a good impression, and, besides, had the invaluable asset of a reasonable grievance, he did to a large extent succeed in his quest. "The Prince's character at his first coming over, though little more respectable, seemed much more amiable than, upon his opening himself further and being better known, it turned out to be; for, though there appeared nothing in him to be admired, yet there seemed nothing in him to be hated—neither anything great nor anything vicious. His behaviour was something that gained one's good wishes while it gave one no esteem for him, for his best qualities, whilst they prepossessed one the most in his favour, always gave one a degree of contempt for him at the same time."[12]

If George II was jealous of the Prince of Wales, the latter in turn was jealous of his sister, the Princess Royal, and he regarded it as a personal affront when in 1734 she was united to the Prince of Orange; thus, in spite of his two endeavours, marrying before him, and securing a settled income. A quarrel ensued, and the rivalry between the two[Pg 9] convulsed the operatic world into which, being in itself opera bouffe, it was suitably carried. The Princess Royal was a friend and patron of Handel at the Haymarket Theatre: and therefore must her brother and his companions support the rival Buononcini at Lincoln's Inn Fields. The King and Queen sided with their daughter, and, says Hervey, "The affair grew as serious as that of the Greens and Blues under Justinian at Constantinople; and an anti-Handelist was looked upon as an anti-courtier, and voting against the Court in Parliament was hardly a less remissible or more venial sin than speaking against Handel or going to the Lincoln's Inn Fields Opera."[13] The victory in this Tweedledum-Tweedledee controversy fell to the Prince, though the sovereigns would not for a long time admit defeat, which gave Chesterfield[14] the opening for a môt: he told the Prince he had been that evening to the Haymarket Theatre, "but there being no one there but the King and Queen, and as I thought they might be talking business, I came away."

When the Princess Royal was married, the Prince of Wales presented himself before the King, and made three demands—permission to serve[Pg 10] in the Rhine campaign, a settled and increased income, and a suitable marriage. George II gave an immediate and decided refusal to the first, but consented to consider the other proposals. As a result of negotiations arising from this conversation, the Prince of Wales married on April 26, 1736, Augusta, daughter of Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Gotha. There were great national rejoicings, and "I believe," said Horace Walpole, "the Princess will have more beauties bestowed on her by all the occasional poets than ever a painter would afford her. They will cook up a new Pandora, and in the bottom of the box enclose Hope that all they have said is true." Indeed, a salvo of eulogistic addresses in rhyme greeted the nuptial pair, headed by William Whitehead, the Laureate, who, on such occasions, could always be relied upon to write ridiculously fulsome lines.

The new Princess of Wales was a mere girl, straight from her mother's country house, and ignorant[Pg 11] of courts, but not lacking self-possession nor good sense. "The Princess is neither handsome nor ugly, tall nor short, but has a lively, pretty countenance enough,"[15] and she found favour in the eyes of her husband, who, though attracted by her, was not content to be faithful. "The chief passion of the Prince was women," says Horace Walpole; "but, like the rest of his race, beauty was not a necessary ingredient." Soon after he came to England he had an intrigue with Anne Vane, the eldest daughter of Gilbert, Baron Barnard, and one of the Queen's maids of honour. "Beautiful Vanelia" was not immaculate, and she gave birth to a child in her apartments in St. James's Palace; the first Lord Hartington and Lord Hervey both believed themselves to be the father, but she, to make the most of her opportunity, wisely accredited the paternity to the Prince of Wales, who thus earned the undying hatred of Hervey.[16] The proud father then turned his attention to Lady Archibald Hamilton (wife of the Duke of Hamilton's brother), who had ten children, was neither young nor beautiful, but clever enough to let her husband believe she was faithful, although the intimacy between her and her[Pg 12] royal lover was patent to all the world besides.

Realising the advisability to be off with the old love before he was on with the new, Frederick sent Lord Baltimore to Miss Vane, commanding her to live abroad for a period, on pain of forfeiting the allowance of £1,600 that he had made her since her dismissal from court—"if she would not live abroad, she might starve for him in England." Miss Vane sent for Hervey, who recommended her to refuse obedience—a step that infuriated the Prince with the adviser; but eventually she reminded her erstwhile lover of all she had sacrificed for the love she bore him, and this so tickled his vanity that not only did he permit her to retain her son and the income, and to remain in England, but gave her a house in Grosvenor Street wherein to live.

Following the example of George II, who had appointed his mistress, Mrs. Howard, to be woman of the bedchamber to his wife, Frederick made Lady Archibald Hamilton a lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Wales. Lady Archibald, however, was soon replaced in his favour by Lady Middlesex, who, although not good-looking, was the possessor of many accomplishments; but she had to be content to share his affections with Miss Granville and various opera dancers and singers.

The[Pg 13] Prince, being unable to secure an increased income from his father, resorted to the usual princely device of borrowing money wherever he could get it. "They have found a way in the city to borrow £30,000 for the Prince at ten per cent. interest, to pay his crying debts to tradespeople; but I doubt that sum will not go very far," wrote the Duchess of Marlborough. "The salaries in the Prince's family are £25,000 a year, besides a good deal of expense at Cliefden in building and furniture; and the Prince and Princess's allowance for their clothes is £6,000 a year each. I am sorry there is such an increase in expense more than in former times, when there was more money a great deal: and I really think it would have been more for the Prince's interest if his counsellors had advised him to live only as a great man, and to give the reasons for it; and in doing so he would have made a better figure, and been safer, for nobody that does not get by it themselves can possibly think the contrary method a right one." The debts accumulated so rapidly, that there was really some show of reason for Lord Hervey (always on the look-out to revenge himself for the defection of his mistress) saying to the Queen that there actually "was danger of the King's days being shortened by the profligate usurers who lent the Prince of Wales[Pg 14] money on condition of being paid at his Majesty's death, and who, he thought, would want nothing but a fair opportunity to hasten the day of payment; and the King's manner of exposing himself would make it easy for the usurers to accomplish such a design."[17]

Hitherto in his quarrels with his parents Frederick had not always been in the wrong, but in 1737 he committed an unpardonable offence in connexion with the birth of his first legitimate child, Augusta, afterwards Duchess of Brunswick, and the mother of Caroline, the unhappy consort of George IV. Though he had known for many months that the Princess of Wales was with child he did not inform his parents of the approaching event until July 5. But that was the least part of his transgression. Twice in that month he took the Princess secretly from Hampton Court to St. James's Palace, and on the second occasion, with only Lady Archibald Campbell in attendance, arrived in London but a few hours before the accouchement.

|

|

| Photo by Emery Walker From a portrait by Enoch Seaman |

Photo by Emery Walker From a portrait by T. Worlidge |

| CAROLINE, CONSORT OF GEORGE II | GEORGE II |

The Queen had determined to be present at the birth.—"She [the Princess of Wales] cannot be brought to bed as quick as one can blow one's nose," she had told the King, "and I will be sure it is her child." Both were furious at being circumvented,[Pg 15] and the King expressed his anger in no measured terms. "See now, with all your wisdom, how they have outwitted you," the King addressed his wife. "This is all your fault. There is a false child will be put upon you, and how will you answer it to all your children? This has been fine care and fine management for your son William: he is much indebted to you." The Queen drove to St. James's without delay, saw the child, and abandoned her suspicions. "God bless you, poor little creature," she said as she kissed it, "you have come into a disagreeable world." Had it been a big, healthy boy, instead of a girl, she said, she might not so readily have accepted the paternity claimed for it.

"The King has commanded me," Lord Essex[18] wrote from Hampton Court to the Prince of Wales on August 3, "to acquaint your Royal Highness that his Majesty most heartily rejoices at the safe delivery of the Princess; but that your carrying away of her Royal Highness from Hampton Court, the then residence of the King, the Queen, and the Royal Family, under the pains and certain indication of immediate labour, to the imminent danger and hazard both of the Princess and her child, and after sufficient warnings for a week before, to have made the necessary preparations[Pg 16] for this happy event, without acquainting his Majesty, or the Queen, with the circumstances the Princess was in, or giving them the least notice of your departure, is looked upon by the King to be such a deliberate indignity offered to himself and to the Queen, that he resents it to the highest degree."[19]

A lengthy correspondence ensued, wherein, on the one hand, the Prince excused himself on the ground that the Princess was seized with the pains of labour earlier than was expected, and that at Hampton Court he was without a midwife or any assistance; and, on the other, the King declined to accept these reasons as true, refused to receive his son, and ordered him to leave St. James's as soon as possible, summing up the situation in a final letter, dated September 10.

"GEORGE R.

"The professions you have lately made in your letters, of your peculiar regards to me, are so contradictory to all your actions, that I cannot suffer myself to be imposed upon by them. You know very well you did not give the least intimation to me or to the Queen that the Princess was[Pg 17] with child or breeding, until within less than a month of the birth of the young Princess: you removed the Princess twice in the week immediately preceding the day of her delivery from the place of my residence, in expectation, as you have voluntarily declared, of her labour; and both times upon your return, you industriously concealed from the knowledge of me and the Queen every circumstance relating to this important affair: and you, at last, without giving any notice to me, or to the Queen, precipitately hurried the Princess from Hampton Court, in a condition not to be named. After having thus, in execution of your own determined measures, exposed both the Princess and her child to the greatest perils, you now plead surprise and tenderness for the Princess, as the only motives that occasioned these repeated indignities offered to me and to the Queen your mother.

"This extravagant and undutiful behaviour in so essential a point as the birth of an heir to my crown, is such evidence to your premeditated defiance of me, and such a contempt of my authority and of the natural right belonging to your parents, as cannot be excused by the pretended innocence of your intentions, nor palliated or disguised by specious words only.

"But the whole tenour of your conduct for a considerable[Pg 18] time has been so entirely void of all real duty to me, that I have long had reason to be highly offended with you. And until you withdraw your regard and confidence from those by whose instigation and advice you are directed and encouraged in your unwarrantable behaviour to me and your Queen, and until your return to your duty, you shall not reside in my palace: which I will not suffer to be made the resort of them who, under the appearance of an attachment to you, foment the division which you have made in my family, and thereby weaken the common interest of the whole.

"In the meantime, it is my pleasure that you leave St. James's with all your family, when it can be done without prejudice or inconvenience to the Princess. I shall for the present leave to the Princess the care of my granddaughter, until a proper time calls upon me to consider of her education.

"(signed) G. R." [20]

The Prince, through Lord Baltimore, expressed a desire to make a personal explanation to the Queen, who, through Lord Grantham, declined to receive it; and later the Princess, doubtless prompted[Pg 19] by her husband, wrote to the King and Queen to express a desire for reconciliation, but in vain, for, in the sovereign's eyes, their son's offence was rank. Indeed, the King went so far as to print the correspondence between himself and the Prince of Wales, to which the latter made the effectual reply of publishing the not dissimilar letters of his father, when Prince of Wales, to George I. This reduced the King to impotent fury: he declared he did not believe Frederick could be his son, and insisted that he must be "what in German we call a Wechselbalch—I do not know if you have a word for it in English—it is not what you call a foundling, but a child put in a cradle instead of another."

What induced Frederick to risk the life of his wife and his unborn child, and to put to hazard the succession was a mystery at the time, and must for ever remain without satisfactory explanation. That it was done solely to annoy his parents seems insufficient reason, though it is all that offers, and Hervey suggests the hasty nocturnal removal was effected to prevent the presence of the Queen at the birth. This certainly seems insufficient to account for the unwarrantable proceeding, but no other solution offers itself.

The Prince of Wales had in 1730 taken a lease from the Capel family of Kew House (the fee[Pg 20] of which was many years after purchased by George III from the Dowager Countess of Essex), and there he and his wife repaired for a while after being evicted from St. James's Palace; but soon they came back to London, and held their court, first at Norfolk House, St. James's Square, placed at their disposal by the Duke of Norfolk, and later at Leicester House, Leicester Square. The King expressed a wish that no one should visit his son, and actually caused it to be intimated to foreign ambassadors that to call on the Prince of Wales was objectionable to him; but this injunction was so generally disregarded that he took the extraordinary step of issuing, through his Chamberlain, a threat.

"His Majesty, having been informed that due regard has not been paid to his order of September 11, 1737, has thought fit to declare that no person whatsoever, who shall go to pay their court to their Royal Highnesses, the Prince and Princess of Wales, shall be admitted into his Majesty's presence, at any of his royal palaces.

"(signed) Grafton."

Even this measure failed of its effect, for while those who sought the King's favour had not been to Leicester House, the Opposition, knowing they had nothing to lose, were not affected by this command. Indeed, the Opposition, delighted to[Pg 21] have so influential a chief, flocked around Frederick; and Bolingbroke,[21] Chesterfield, Pulteney,[22] Dodington, Carteret,[23] Wyndham,[24] Townshend[25] and Cobham,[26] were soon numbered among his regular visitors; while Huish has compiled a long list of peers[27] who frequently attended his levées.

The Prince made a very determined bid for popularity among all classes. He put himself at the head of "The Patriots," and in 1739 recorded his first vote as a peer of Parliament against the Address and in favour of the war policy; subsequently, when war was declared, taking part with the Opposition in the public celebrations. He encouraged British manufactures, and neither he nor the Princess wore, or encouraged[Pg 22] the wearing of, foreign materials. He gave entertainments to the nobility at his seat at Cliefden in Buckinghamshire, and visiting Bath in 1738, cleared the prison of all debtors and made a present of £1,000 towards the general hospital. Nor did he neglect letters and art, for which he had some slight regard. He patronised Thomson and Vertue the engraver, employed Dr. Freeman to write a "History of the English Tongue" as a text-book for Prince George and the younger princes;[28] sent two of his court to Cave, the publisher, to inquire the name of the author of the first issue of "The Rambler"; and exchanged badinage with Pope, whom he visited at Twickenham. Pope received him with great courtesy and expressions of attachment. "'Tis well," said Frederick, "but how shall we reconcile your love to a prince with your professed indisposition to kings, since princes will be kings in time?" "Sir," said the poet, "I consider Royalty under that noble and authorized type of the lion: while he is young and before his nails[Pg 23] are grown, he may be approached and caressed with safety and pleasure."[29]

Frederick became very popular. "The truth is," Mr. McCarthy has said unkindly but with undoubted truth, "that the people in general, knowing little about the Prince, and knowing a great deal about the King, naturally leaned to the side of the man who might at least turn out to be better than his father."[30]

There was a general impression that he had been ill-treated, and there was a disposition among the lower classes to make amends for such a slight as having to live as a private gentleman at Norfolk House, without even the usual appanage of a sentry.

"My God, popularity makes me sick; but Fritz's popularity makes me vomit," exclaimed the Queen, perhaps after hearing that when Frederick assisted[Pg 24] to extinguish a fire, the mob cried, "Crown him! crown him!" "I hear that yesterday, on his side of the House, they talked of the King's being cast aside with the same sang froid as one would talk of a coach being overturned; and that my good son strutted about as if he had been already King. Did you mind the air with which he came into my Drawing-room in the morning, though he does not think fit to honour me with his presence or ennui me with that of his wife's of a night. I swear his behaviour shocked me so prodigiously that I could hardly bring myself to speak to him when he was with me afterwards; I felt something here in my throat that swelled and half choked me." The King was as bitter, and refused to admit Frederick to the Queen's deathbed. "His poor mother is not in a condition to see him act his false, whining, cringing tricks now," while the Queen declared that she was sure he wanted to see her only to have the delight of knowing she was dead a little sooner than if he had to await the tidings at home.

An attempt in 1742 to bring to an end the crying scandal of the open enmity between the King and the heir-apparent was made by Walpole, who thought, by detaching the Prince from the Opposition, to strengthen his steadily decreasing majority.[Pg 25] The Bishop of Oxford[31] was sent to Norfolk House to intimate that if the Prince would make his peace with his father through the medium of a submissive letter, ministers would prevail upon the King to increase his income by £50,000, pay his debts to the tune of £200,000 and find places for his friends. The terms were tempting, but the Prince, knowing that Walpole's position was precarious, declined them, stating that he knew the offer came, not from the King, but from the minister, and that, while he would gladly be reconciled to his father, he could do so without setting a price upon it. "Walpole," he declared, "was a bar between the King and his people, between the King and foreign powers; between the King and himself." The refusal was politic, for Walpole was most unpopular. "I have added to the debt of the nation," so ran the inscription on a scroll issuing from the mouth of an effigy of Walpole, sitting between the King and the Prince; "I have subtracted from its glory; I have multiplied its embarrassments;[Pg 26] and I have divided its Royal Family." The Prince's refusal to entertain the overture was a blow to the minister, who contended against a majority in the House of Commons, until February 2, 1742, when he declared he would regard the question of the Chippenham election as a vote of confidence, and, if defeated upon it, would never again enter that House. He was beaten by sixteen, and on the 18th inst. took his seat "in another place" as the Earl of Oxford.

Immediately after Walpole's downfall, messages were exchanged between Norfolk House and St. James's, and on February 17 father and son met and embraced at the palace. The Prince's friends came into office, and so happy was the Prince that he testified to his joy by liberating four-and-twenty prisoners from his father's Bench—the amount of their debts being added to his own. He was indeed so overcome with delight at his virtue in being reconciled to his father that he ventured upon a joke when Mr. Vane, who was notoriously in the court interest, congratulated him on his reappearance at St. James's. "A vane," quoth he to the courtier, "is a weathercock, which turns with every gust of the wind, and therefore I dislike a vane." Witty, generous Prince!

The[Pg 27] reconciliation was shortlived, and thereafter, for the rest of his life, Frederick was again in opposition to the court; but of these later years there is little or nothing to record, save that he solicited in vain the command of the royal army in the rebellion of '45. In March, 1751, he caught cold, and on the 20th inst., while, by his bedside, Desnoyers was playing the violin to amuse him, crying, "Je sens la mort," he expired suddenly—it is said from the bursting of an abscess which had been formed by a blow from a tennis ball. The King received the news at the whist table, and, showing neither surprise nor emotion, he crossed the room to where the Countess of Yarmouth sat at another table, and, after saying simply, "Il est mort," retired to his apartments. "I lost my eldest son," he remarked subsequently, "but I am glad of it."

The writers of the day were fulsome in their praise of the deceased Prince. Robert Southy says, Frederick died "to the unspeakable affliction of his royal consort, and the unfeigned sorrow of all who knew him;" and he sums him up as "a tender and obliging husband, a fond parent, a kind master, liberal, candid and humane, a munificent patron of the arts, an unwearied friend to merit, well-disposed to assert the rights of[Pg 28] mankind, in general, and warmly attached to the interests of Great Britain."[32] In fact, Sir Galahad and the Admirable Crichton in one! Southy was not alone in his outspoken admiration, for Mr. McCarthy reminds us of a volume issued by Oxford University, "Epicedia Oxoniensia in obitum celsissimi et desideratissimi Frederici Principis Walliæ. Here all the learned languages, and not the learned languages alone, contributed the syllables of simulated despair. Many scholastic gentlemen mourned in Greek; James Stillingfleet found vent in Hebrew; Mr. Betts concealed his tears under the cloak of the Syriac speech; George Costard sorrowed in Arabic that might have amazed Abu l'Atahiyeh; Mr. Swinton's learned sock stirred him to Phoenician and Etruscan; and Mr. Evans, full of national fire and the traditions of the bards, delivered himself, and at great length, too, in Welsh."[33] Amusing, too, was a sermon preached at Mayfair Chapel, in the course of which the preacher, lamenting the demise of the royal personage, declared that his Royal Highness "had no great parts, but he had great virtues; indeed, they degenerated into vices; he was very generous, but I hear his generosity has ruined a great many people; and then[Pg 29] his condescension was such that he kept very bad company."

Very differently spoke those who knew the Prince. "He was indeed as false as his capacity would allow him to be, and was more capable in that walk than in any other, never having the least hesitation, from principle or fear of future detection, in telling any lie that served his future purpose. He had a much weaker understanding, and, if possible, a more obstinate temper than his father; that is, more tenacious of opinions he had once formed, though less capable of ever forming right ones. Had he had one grain of merit at the bottom of his heart, one should have had compassion for him in the situation to which his miserable poor head soon reduced him, a mother that despised him, sisters that betrayed him, a brother set up against him, and a set of servants that neglected him, and were neither of use nor capable of being of use to him, or desirous of being so."[34] So said Lord Hervey, and, though his known enmity to Frederick makes one reluctant to accept his estimate, yet it must be admitted that his remarks are borne out by others well qualified to judge. "A poor, weak, irresolute, false, lying, dishonest, contemptible wretch, that nobody loves, that nobody believes, that[Pg 30] nobody will trust, and that will trust everybody by turns, and that everybody by turns will impose upon, betray, mislead, and plunder." Thus Sir Robert Walpole, who, during the Prince's lifetime, thought that, if the King should die, the Queen and her unmarried children would be in a bad way. "I do not know any people in the world so much to be pitied," he said to Hervey, "as that gay young company with which you and I stand every day in the drawing-room at that door from which we this moment came, bred up in state, in affluence, caressed and courted, and to go at once from that into dependence upon a brother who loves them not, and whose extravagance and covetousness will make him grudge every guinea they spend, as it must come out of a purse not sufficient to defray the expenses of his own vices."

A later generation has not been more kind. "If," said Leigh Hunt, "George the First was a commonplace man of the quiet order, and George the Second of the bustling, Frederick was of an effeminate sort, pretending to taste and gallantry, and possessed of neither. He affected to patronise literature in order to court popularity, and because his father and grandfather had neglected it; but he took no real interest in the literati, and would meanly stop their pensions when[Pg 31] he got out of humour. He passed his time in intriguing against his father, and hastening the ruin of a feeble constitution by sorry amours." "His best quality was generosity," Horace Walpole has recorded; "his worst insincerity and indifference to truth, which appeared so early that Earl Stanhope wrote to Lord Sunderland, 'He has his father's head, and his mother's heart.'"[35]

What is to be said in his favour? That through his intercession Flora Macdonald, imprisoned for harbouring the Chevalier, received her liberty: that when Richard Glover, the author of "Leonidas," fell upon evil days he sent him five hundred pounds; that he was a plausible speaker,[36] fond of music, the author of two songs, and had sufficient sense of humour to institute an occasional practical[Pg 32] joke. On the other hand, he was a gambler and a spendthrift without a notion of common honesty; he was unstable and untruthful, a feeble enemy and a lukewarm friend; and is, indeed, best disposed of in the well-known verse:

BOYHOOD OF GEORGE III

George William Frederick, afterwards George III, was born on June 4, 1738. His advent into the world was so little expected at that time that on the previous day his mother had walked in St. James's Park, had scarcely returned from that exercise when she was taken ill, and between seven and eight o'clock the following morning gave birth to a seven-months' child. Frederick, therefore, could not be held responsible because again no preparation for an accouchement had been made, nor could he be blamed because the King had only a few hours' notice of the event.

The baby was so weak that it was thought it would not live, and at eleven o'clock at night it was baptized by the Bishop of Oxford,[37] and though it survived, its health was so delicate that it was thought advisable, and indeed imperative, to abandon the[Pg 34] strict court etiquette dictating that a royal infant must be reared by a lady of good family, and instead "the fine, healthy, fresh-coloured wife of a gardener" was chosen. The woman was proud of her charge, but inclined to independence, and when told that, in accordance with tradition, the baby could not sleep with her, "Not sleep with me!" she exclaimed. "Then you may nurse the boy yourselves!" As she remained firm on this point, tradition was wisely cast to the winds, with the fortunate result that the young Prince throve lustily and soon acquired a sound and vigorous frame of body.[38]

It would be to throw away an opportunity for mirth to omit the lines with which Whitehead greeted the birth of a son of the Prince of Wales. These were enthusiastically acclaimed by a contemporary as "a beautiful, prophetic compliment to the future monarch," but the present generation may conceivably find another epithet.

Photo by Emery Walker From a painting by Richard Wilson

PRINCE GEORGE OF WALES, PRINCE EDWARD OF WALES, AND DR. AYSCOUGH

A prince's education begins early, and George was not more than six years of age when he was put into harness. The first tutor selected for him was Dr. Francis Ayscough,[40] whose principal claim to distinction was as brother-in-law to "good Lord Lyttelton," for at best he has been described as a well-meaning but uninspired pedagogue, and at worst, by Walpole, as "an insolent man, unwelcome to the clergy on suspicion of heterodoxy, and of no fair reputation for integrity."[41] Ayscough, as a courtier, was not unsuccessful,[Pg 36] for, introduced by Lyttelton[42] and Pitt to Frederick, Prince of Wales, he contrived to ingratiate himself with that invertebrate royal personage; but as an instructor of youth he was not the right man in the right place. He was ignorant of the course to pursue in laying the foundation of a lad's education, and when George was eleven years old, the Princess of Wales found to her dismay her son could not read English, although (so Ayscough assured her) he could make Latin verses. This latter accomplishment could not be accepted as of sufficient importance to excuse ignorance of more practical subjects, and a new preceptor, George Scott, was introduced on the recommendation of Lord Bolingbroke, who, Walpole states significantly, "had lately seen the Prince two or three times in private." This appointment marks the beginning of the intrigues that centred round the young Prince.

Tempted by the promise of an earldom, in October, 1750, Lord North [43] became Governor—"an amiable, worthy man," says Walpole, "of no great genius, unless compared with his successor;" but this arrangement did not long endure, for[Pg 37] the Pelhams, finding themselves in power, thought it behoved them to endeavour to retain it perpetually by surrounding the future king with their creatures. Lord North retired in April, 1751, and, when the post had been offered to and declined by Lord Hartington, he was replaced by Lord Harcourt,[44] a Lord of the Bedchamber to the King, a "civil and stupid" person who, though unfitted for the post by his ignorance of most things save hunting and drinking, was thought unlikely to interfere with the ministers' plans. The real agent of the Pelhams was the sub-governor, Andrew Stone,[45] the Duke of Newcastle's private secretary, "a dark, proud man, very able and very mercenary," in high favour with George II. Scott remained as Sub-Preceptor, and with him as Preceptor was now put Dr. Hayter, Bishop of Norwich,[46] a sensible man of the world. Lord Sussex, Lord Robert Bertie, and Lord Downe were appointed Lords, and Peachy, Digby and Schulze, Grooms of the Bedchamber to the young Prince; while his Treasurer was Colonel John Selwyn, who, dying in December, was[Pg 38] succeeded by Cresset, the holder of the same position in the Household of the Princess, now Dowager Princess of Wales.

For a while there was peace in the tutors' camp, but soon dissension broke out, and it became an open secret that Harcourt and Hayter were in opposition to Stone and Scott. The quarrel began when Hayter found in the Prince of Wales's hands a copy of Father d'Orleans's "Revolution d'Angleterre," a work written at the instigation of James II of England to justify his measures. Stone was taxed with having introduced it into the royal apartments, when he denied ever having seen it in thirty years, and expressed his willingness to stand or fall by the truth or falseness of the accusation; but when Hayter showed a desire to take him at his word, it was admitted that the Prince had the book, and the defence set up was that Prince Edward had borrowed it of his sister Augusta. Then other works not suitable for use in the training of a constitutional monarch were, it is said, discovered to be in the possession of the Prince; and though Stone and Scott aped humility and regret, they contrived notwithstanding to irritate their superior officers, until one day Hayter lost his temper, and removed Scott from the royal chamber "by an imposition of hands, that had at least as much of the flesh as the spirit[Pg 39] in the force of the action."[47] When matters came to this pass, Cresset took a hand in the quarrel, and finally Murray[48] added fuel to the flame by telling the Bishop that Stone should be shown more consideration. Hayter replied, "He believed that Mr. Stone found all proper regard, but that Lord Harcourt, the chief of the trust, was generally present;" to which Murray retorted, "Lord Harcourt, pho! he is a cypher, and must be a cypher, and was put in to be a cypher." That was the last straw. There are men who are cyphers without knowing it, and men who know they are cyphers and do not resent their unimportance, but there are few who can with impunity be told that they are cyphers, and of these Harcourt was not one, for, with all his faults, he was not the man to acquiesce in the use of himself as a cat's-paw.

When the King returned in November, 1752, from Hanover, Harcourt complained that dangerous and arbitrary principles were being instilled into the Prince, and stated it was useless for him to remain as Governor unless those who were misleading the lad were removed from their official positions about his person. A few days after[Pg 40] this protest was registered, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor sent word that by the King's command they would wait on Lord Harcourt for further particulars of his grievance, but the latter declined to receive them on the ground that, "His complaints were not proper to be told but to the King himself." At a private interview with George II on December 6, Harcourt tendered his resignation, which was accepted; but a similar concession was not granted to the Bishop of Norwich, whose resignation the King preferred to receive through the medium of the Archbishop of Canterbury.[49]

The position of the Governor and Preceptor had gradually become untenable, for they were exposed to the cross-influences of the Princess Dowager of Wales and the ministers, and, in their efforts to secure for themselves the favour of their charge,[Pg 41] they took no trouble to win the good graces of the Princess or to live at peace with their subordinates. "The Bishop, thinking himself already minister to the future King, expected dependence from, never once thought of depending upon, the inferior governors. In the education of the two Princes, he was sincerely honest and zealous; and soon grew to thwart the Princess whenever, as an indulgent, or perhaps a little as an ambitious mother (and this happened but too frequently), she was willing to relax the application of her sons. Lord Harcourt was minute and strict in trifles; and thinking that he discharged his trust conscientiously if on no account he neglected to make the Prince turn out his toes, he gave himself little trouble to respect the Princess, or to condescend to the Sub-governor."[50] To this testimony must be added that of Bubb Dodington, who declared that Lord Harcourt not only behaved ill to the Princess Dowager and spoke to the children of their dead father in a manner most disrespectful, but also did all in his power to alienate them from their mother. "George," he says, "had mentioned it once since Lord Harcourt's departure, that he was afraid he had not behaved as well to her sometimes as he ought, and wondered how he could be so misled."[51][Pg 42] The Princess was therefore overjoyed to be rid of Lord Harcourt, not only for these reasons, but for another that will presently be discussed.

Stone and Scott retained their posts, but it was not found easy to replace the men who had resigned. Ministers desired to appoint as Preceptor Dr. Johnson,[52] the new Bishop of Gloucester, but the Whigs were so bitterly opposed to the nomination, and had the support of the Archbishop's objections, that eventually Dr. Thomas[53] was given the office. "It was still more difficult to accommodate themselves with a Governor," Walpole has recorded. "The post was at once too exalted, and they had declared it too unsubstantial, to leave it easy to find a man who could fill the honour, and digest the dishonour of it."[54] Overtures were made in several quarters but without success, until at last, at the request of the King, Lord Waldegrave[55] consented to accept the[Pg 43] responsibility. This he did only after "repeated assurances of the submission and tractability of Stone," and then with great reluctance, for he was a man of pleasure rather than of affairs, and reluctant to be embroiled in intrigue. "If I dared," he said to a friend, "I would make this excuse to the King, 'Sir, I am too young to govern, and too old to be governed.'" Even this appointment was censured by the Whigs, for, though Waldegrave was a man of great common sense and undoubted honour, it was objected that "his grandmother was a daughter of King James; his family were all Papists, and his father had been but the first convert"!

The refusal of Lord Harcourt to discuss his complaints with any one but the King was doubtless due to the fact that he traced the objectionable doctrines taught to his pupil to Lord Bute.[56] In his earlier years Bute had taken no part nor, indeed, shown any interest in politics. In 1723, at the age of twenty, he had succeeded to the earldom on the death of his father; had married Mary, only daughter of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu,[Pg 44] and so came into possession of the Wortley estates; and, though in 1737 elected representative peer of Scotland, had spent most of his time on his estates, occupying himself with the theoretical and practical study of agriculture and architecture.

A great change in Bute's life was made in 1747 through a chance meeting with Frederick, Prince of Wales. The Earl was then staying at Richmond, and one day his neighbour, an apothecary, drove him over to Moulsey Hurst to see a cricket match that had been organized by the Prince. It came on to rain, the game had to be stopped, and Frederick retired to his tent, proposing a rubber of whist to while away the time until the weather should clear. Only two other players could be found, but some one espied Bute in the carriage and, learning that he could play, invited him to make up the table. The Prince, who had never before met him, was charmed with his manners, and invited him to Kew. "How often do great events arise from trifling causes," exclaims the worthy but sententious Seward. "An apothecary keeping his carriage may have occasioned the Peace of Paris, the American War, and the National Assembly in France." Without going so far as that chronicler, it may be said that the game of whist had far-reaching effects.

Bute[Pg 45] became a member of his patron's court,[57] where his influence became a factor that could not be ignored. Nor did his power at Leicester House wane after the death of the Prince, for he was high in the Princess's favour, which latter good fortune was attributed not so much to his intellectual attainments as to his personal qualities. Scandal was busy coupling his name with that of the lady he served: indeed, for years there was no caricature so popular with the public as that of the Boot and the Petticoat, the symbols of the Peer and the Princess. What truth there was in this charge, if, indeed, there was any truth at all, is not, and probably never will be, known; but at the time the intimacy was almost universally assumed. "It had already been whispered that the assiduities of Lord Bute at Leicester House, and his still more frequent attendance in the gardens at Kew and Carlton House, were less addressed to the Prince of Wales than to his mother," says Walpole. "The eagerness of the pages of the back-stairs to let her know whenever Lord Bute arrived (and some other symptoms) contributed to dispel the ideas that had been conceived of the rigour of her widowhood. On the other hand, the favoured personage, naturally ostentatious[Pg 46] of his person, and of haughty carriage, seemed by no means desirous of concealing his conquest. His bows grew more theatric; his graces contracted some meaning; and the beauty of his leg was constantly displayed in the eye of the poor captivated Princess.... When the late Prince of Wales affected to retire into gloomy allées with Lady Middleton, he used to bid the Princess walk with Lord Bute. As soon as the Prince was dead, they walked more and more, in honour of his memory."[58] The same authority was on another occasion even more explicit. "I am as much convinced of the amorous connexion between Bute and the Princess Dowager as if I had seen them together," he said;[59] and what he said was thought by the more reticent.

Whether there was "amorous connexion" or not, Bute was the most detested man of his day, and the more prominently he came before the public the more violent was the abuse heaped upon him. "Bute was hated with a rage of which there have been few examples in English history. He was the butt for everybody's abuse; for Wilkes's devilish mischief; for Churchill's slashing satire; for the hooting of the mob that roasted the boot, his emblem, in a thousand bonfires; that hated him because he was a favourite and a Scotchman, calling[Pg 47] him 'Mortimer,' 'Lothario,' I know not what names, and accusing his royal mistress of all sorts of crimes—the grave, lean, demure, elderly woman, who, I daresay, was quite as good as her neighbours."[60]

In those days to be a Scotchman was alone enough to secure the cordial ill-will of the English, for national rivalries had not then been even partially eliminated; and it was said that Bute used his power to promote his countrymen, which, though to-day it does not seem a very heinous crime, was then regarded as a sin unequalled in horror by any enumerated in the decalogue. An amusing defence of Bute against this charge is made by Huish who, however, was certainly unconscious of the humour of the passage. "The truth of this charge rests upon no solid foundation. That Bute brought forward his countrymen is true enough, but it was by extending to them the patronage of office, not, except in some few instances, by directly introducing them to the personal favour of the King."[61] One of these exceptions was Charles Jenkinson,[62] Bute's private secretary,[Pg 48] who, when his master had, ostensibly, at least, retired from the direction of affairs, was the go between the King and the ex-minister.

"Lord Bute was my schoolfellow," says Walpole. "He was a man of taste and science, and I do believe his intentions were good. He wished to blend and unite all parties. The Tories were willing to come in for a share of power, after having been so long excluded—but the Whigs were not willing to grant that share. Power is an intoxicating draught; the more a man has, the more he desires."[63] The effects of power upon Bute will soon appear. It was not, however, this man's power or his use or abuse of it, but his qualities, that earned for him the hatred of his equals. Lord Chesterfield wrote him down as "dry, unconciliatory, and sullen, with a great mixture of pride. He never looked at those he spoke to, or who spoke to him, a great fault in a minister, as in the general opinion of mankind it implies conscious guilt; besides that it hinders him from penetrating others.... He was too proud to be respectable or respected; too cold and silent to be amiable; too cunning to have great abilities; and his inexperience made him too precipitately what it disabled him from executing."[64] Further, he[Pg 49] showed little savoir faire, for he chose as his subordinates, men who were incapable, or those who, disgusted by him, were undesirous to help him, and, giving no man his confidence, found himself severely handicapped consequently by receiving none. Indeed, his arrogance on occasion angered even the Prince of Wales, who quarrelled with him before the death of George II, and on his accession employed him only after the severest pressure of the Princess Dowager.[65] However, Bute soon regained his ascendency over the young King.

One result of the intimacy between the Princess Dowager and Bute was that the actual superintendence, and, indeed, control of the education of the Prince of Wales was indirectly exercised by him. This was particularly unfortunate because Bute was a disciple of Bolingbroke's doctrine of absolute monarchy, and his "high prerogative prejudice and Tory predilections," similar to those that caused the Revolution of 1688, were specially dangerous at a time when the new dynasty had not long been firmly established; and it seemed that while at worst they might lead to a conflict between the Crown and the people, at best they would, when the Prince of Wales became King, make Bute a dictator. Even so early as 1752[Pg 50] Waldegrave "found his Royal Highness full of princely prejudices, contracted in the nursing, and improved by the society of bed-chamber women, and the pages of the back-stairs,"[66] and he records the endeavours to make him resign his Governorship so that the place might be open for Bute.

"A notion has prevailed," says Nicholls, "that the Earl of Bute had suggested political opinions to the Princess Dowager, but this was certainly a mistake. In understanding, the Princess Dowager was far superior to the Earl of Bute; in whatever degree of favour he stood with her, he did not suggest, but he received, her opinions and her directions."[67] As a matter of fact, the Princess Dowager was a woman of very sound understanding up to a certain point, but her training at the Court of Saxe-Gotha, where the Duke was practically a despot, unfitted her for the task of bringing up a future King of England. Constitutional monarchy was beyond the range of her experience, and she could never accept the doctrine in force in this country that, while a sovereign may choose his ministers, having chosen them he should either be guided by their advice or change them. "Be a King, George," she[Pg 51] preached to the heir-apparent; and in her eyes to be a king was to be omnipotent.

Though well-meaning and shrewd enough, the Princess Dowager's outlook on life was narrow; she had many prejudices, and in the light of these planned the education of her children so far as it lay in her power. She was so afraid lest George should be influenced by the vulgarity and immorality of the Court, that she tied him to her apron-strings. "The Prince of Wales lived shut up with his mother and Lord Bute; and must have thrown them into some difficulties: their connexion was not easily reconcilable to the devotion which they had infused into the Prince; the Princess could not wish him always present, and yet dreaded him being out of her sight. His brother Edward, who received a thousand mortifications, was seldom suffered to be with him; and Lady Augusta, now a woman, was, to facilitate some privacy for the Princess, dismissed from supping with her mother, and sent back to cheese-cakes, with her little sister Elizabeth, on pretence that meat at night would fatten her too much."[68] The result of this treatment was not only that the children were miserable, but that they were all too well aware of their state of mind. When the Princess Dowager, struck one day by the silence[Pg 52] of one of her sons, asked if he were sulking, "I was thinking," the lad replied, "what I should feel if I had a son as unhappy as you make me."

There were not wanting those who declared that in secluding the Prince of Wales, and in keeping from him all knowledge of the world—that knowledge, valuable to all, but essential to the making of a useful King—the Princess Dowager had formed the project herself to exercise the regal power that would one day be his; and that her policy was approved by Lord Bute, who, also with an eye to the future, saw that his influence over an ignorant monarch was likely to be much greater than over one well acquainted with men and matters. "The plan of tutelage and future dominion over the heir-apparent, laid many years ago at Carlton House, between the Princess Dowager and her favourite, the Earl of Bute, was as gross and palpable as that which was concerted between Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin, to govern Lewis the Fourteenth, and in effect to prolong his minority until the end of their lives. That Prince had strong natural parts, and used frequently to blush for his own ignorance and want of education, which had been wilfully neglected by his mother and her minion. A little experience, however, soon showed him how shamefully he had[Pg 53] been treated, and for what infamous purposes he had been kept in ignorance. Our great Edward, too, at an early period, had sense enough to understand the nature of the connexion between his abandoned mother and the detested Mortimer. But since that time human nature, we may observe, is greatly altered for the better. Dowagers may be chaste, and minions may be honest. When it was proposed to settle the present King's household as Prince of Wales, it is well known that the Earl of Bute was forced into it in direct contradiction to the late King's inclination. That was the salient point from which all the mischiefs and disgraces of the present reign took life and motion. From that moment Lord Bute never suffered the Prince of Wales to be an instant out of his sight. We need not look farther."[69]

But while the Princess Dowager and Lord Bute agreed apparently as to the advantage of keeping the heir-apparent in a backward state, each desiring the mastery, they differed on other points. "The Princess began to perceive an alteration in the ardour of Lord Bute, which grew less assiduous about her, and increased towards her son," Walpole noted in 1758. "The Earl had attained such an ascendency over the Prince, that he became more remiss to the mother; and no doubt[Pg 54] it was an easier function to lead the understanding of a youth than to keep up to the spirit required by an experienced woman. The Prince even dropped hints against women interfering in politics. These clouds, however, did not burst; and the creatures of the Princess vindicated her from any breach with Lord Bute with as much earnestness as if their union had been to her honour."[70]

The Princess did not deny that the seclusion of her son had its drawbacks. "She was highly sensible how necessary it was that the Prince should keep company with men: she well knew that women could not inform him, but if it was in her power absolutely, to whom could she entrust him? What company could she wish him to keep? What friendships desire he should contract? Such was the universal profligacy, such the character and conduct of the young people of distinction, that she was really afraid to have them near her children." However, the Princess Dowager made little or no effort to provide suitable companions for George, and the only youth with whom he was allowed to have even a restricted intercourse was his brother, Edward.

Frederick, Prince of Wales, had not set his wife a good example by showing much interest in his son,[Pg 55] though when he was on his deathbed he sent for the child. "Come, George," he said, "let us be good friends while we may." Occasionally, however, he had gone with him to a concert at the Foundling Hospital, or to see various processes of manufactures; and now and then had taken him for a walk in the city at night—which latter proceeding gave rise to a lampoon when in 1749 the little boy was installed a Knight of the Garter,—the Earl of Inchiquin appearing as his proxy.

On the death of his father, George succeeded to the title of Electoral Prince of Brunswick-Lünenburg, Duke of Edinburgh, Marquis of the Isle of Ely, Earl of Eltham, Viscount of Launceston and Baron of Snowdon; and the "Gazette" of April 11, 1751, announced that, "His Majesty had been pleased to order Letters Patent to pass under the Great Seal of Great Britain for creating his Royal Highness George William Frederick ... Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester." George II at this time began to show a personal interest in his successor, inviting him to St. James's, taking him to Kew, even for a while removing him from Leicester House and lodging him at Kensington. The[Pg 56] King did not approve of his daughter-in-law's method of bringing up her son, and, when visiting her unexpectedly one day, heard she had taken the Princes to visit a tapestry factory in which she was interested. "D——n dat tapestry," he cried, "I shall have de Princes made women of." Calling again at Leicester House the next day, he inquired: "Gone to de tapestry again?" and, on being told the Princes were at home, commanded that they should be sent to Hyde Park where he had "oder things to show dem dan needles and dreads." The "oder things" was a review, and, Princess Augusta being dressed to go out, her grandfather took her with him. "This circumstance gave rise to some unpleasant altercation between the King and the Princess Dowager of Wales; for, on the latter being informed of the expressions which his Majesty had used regarding her visit to the tapestry manufactory, she retorted upon his Majesty by declaring if he thought the view of a manufactory was beneath the attentions of her sons, she considered the sight of a review to be attended with no benefit to her daughter."[71]

The Princess Dowager's retort to the King in this case was typical of her character, for she was a strong-minded, fearless woman, and not lightly to[Pg 57] be brow-beaten or opposed.[72] On the whole, however, George II and his daughter-in-law were not on unfriendly terms since, after the death of her husband, she had thrown herself upon his protection. "The King and she both took their parts at once," Walpole noted; "she of flinging herself entirely into his hands and studying nothing but his pleasure, but with wondering what interest she got with him to the advantage of her son and the Prince's friends; the King of acting the tender grandfather, which he, who had never acted the tender father, grew so pleased with representing, that he soon became it in earnest." This was made clear when the question arose of appointing a regent in case of the sovereign's death before his successor was of age, for the King advocated her right to be selected for that exalted position in a Royal Message to the Houses of Parliament:

"That[Pg 58] nothing could conduce so much to the preservation of the Protestant succession in his royal family as proper provision for the tuition of the person of his successor, and for the regular administration of the government, in case the successor should be of tender years: his Majesty, therefore, earnestly recommended this weighty affair to the deliberation of Parliament and proposed that when the imperial crown of these realms should descend to any of the late Prince's sons, being under the age of eighteen years, his mother, the Princess Dowager of Wales, should be guardian of his person, and Regent of these kingdoms, until he should attain the age of majority; with such powers and limitations as should appear necessary and expedient for these purposes."

A Bill embodying these recommendations was accordingly introduced by the Duke of Newcastle into the House of Lords, when the King sent a second Message proposing that such a council to assist the Regent as the Bill advised should consist of the Duke of Cumberland, then Commander-in-Chief, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, the Lord High Treasurer, or First Lord Commissioner of the Treasury, the President of the Council, the Lord Privy Seal, the Lord High Admiral of Great Britain, or First Commissioner of the Admiralty, the two principal Secretaries of State,[Pg 59] and the Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench—all those great officers except, of course, the Duke of Cumberland, for the time being.

This aroused the bitterest opposition, and many members dwelt on the danger of leaving in command of a large standing army a prince of the blood, who was the only permanent member of the Council as well as the uncle of the minor, and the names of all the wicked uncles in history, John Lackland, Humphrey of Gloucester, and the rest were freely introduced into the discussion. William Augustus Duke of Cumberland, was indeed a deeply hated man, and the astonishing popularity of his elder brother, Frederick, was perhaps due more to the fact that he stood between William and the throne than to any other reason. Indeed, when Frederick died, in many cases the lament was phrased "Would that it had been his brother!" "Would that it had been 'the butcher!'" and Walpole is careful to mention that the nickname was not given in the sense it was formerly: "Le boucher étoit anciennement un surnom glorieux qu'on donnoit à un general àpres une victoire, en reconnoissance du carnage qu'il avoit fait de trente ou quarante mille hommes."[73] Yet, "there never was a prince so popular, so winning in his ways, as William of Cumberland during[Pg 60] his minority," says Dr. Doran, who adds that "the Duke," as he was called, was "gentlemanlike without affectations, accomplished without being vain of his accomplishments."[74] He had courage in plenty, and distinguished himself at Dettingen and Culloden, but his severities after the latter battle secured him the undesirable nickname that clung to him for life—in his defence it may be offered that this same harshness might well have earned for him the gratitude of those who hated civil war, for it scotched further rebellion and made his father's throne secure. He had hoped to be appointed regent, although Walpole tells us "the consternation that spread on the apprehensions that the Duke would be regent on the King's death, and have the sole power in the meantime, was near as strong as what was occasioned by the notice of the rebels being at Derby."[75] None the less, when the Lord Chancellor was sent to inform him that his hope would not be realized, the Duke bore the blow well, and said, "I return my duty and thanks to the King for the communication of the plan of regency; while, for the post allotted to me, I would submit to it, because he commands it, be that regency what it will." He felt[Pg 61] resentful, however, wished "the name of William could be blotted out of the English annals," and declared he now felt his insignificance, "when even Mr. Pelham would dare to use him thus." The opposition to the inclusion of his name even on the council to assist the regent gave him pain; but he was much more deeply wounded when, the young Prince of Wales calling upon him, to amuse his visitor he took down a sword and drew it, and noticed that the lad turned pale and trembled. "What must they have told him about me," he wondered, and in no measured terms complained to the Princess of Wales of the impression that had been instilled into his nephew.

THE PRINCE COMES OF AGE