The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 14, Slice 8, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, Slice 8

"Isabnormal Lines" to "Italic"

Author: Various

Release Date: May 15, 2012 [EBook #39700]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 14, SL 8 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

ISABNORMAL (or Isanomalous) LINES, in physical geography, lines upon a map or chart connecting places having an abnormal temperature. Each place has, theoretically, a proper temperature due to its latitude, and modified by its configuration. Its mean temperature for a particular period is decided by observation and called its normal temperature. Isabnormal lines may be used to denote the variations due to warm winds or currents, great altitudes or depressions, or great land masses as compared with sea. Or they may be used to indicate the abnormal result of weather observations made in an area such as the British Isles for a particular period.

ISAEUS (c. 420 B.C.-c. 350 B.C.), Attic orator, the chronological limits of whose extant work fall between the years 390 and 353 B.C., is described in the Plutarchic life as a Chalcidian; by Suidas, whom Dionysius follows, as an Athenian. The accounts have been reconciled by supposing that his family sprang from the settlement (κληρουχία) of Athenian citizens among whom the lands of the Chalcidian hippobotae (knights) had been divided about 509 B.C. In 411 B.C. Euboea (except Oreos) revolted from Athens; and it would not have been strange if residents of Athenian origin had then migrated from the hostile island to Attica. Such a connexion with Euboea would explain the non-Athenian name Diagoras which is borne by the father of Isaeus, while the latter is said to have been “an Athenian by descent” (Ἀθηναῖος τὸ γένος). So far as we know, Isaeus took no part in the public affairs of Athens. “I cannot tell,” says Dionysius, “what were the politics of Isaeus—or whether he had any politics at all.” Those words strikingly attest the profound change which was passing over the life of the Greek cities. It would have been scarcely possible, fifty years earlier, that an eminent Athenian with the powers of Isaeus should have failed to leave on record some proof of his interest in the political concerns of Athens or of Greece. But now, with the decline of personal devotion to the state, the life of an active citizen had ceased to have any necessary contact with political affairs. Already we are at the beginning of that transition which is to lead from the old life of Hellenic citizenship to that Hellenism whose children are citizens of the world.

Isaeus (who was born probably about 420 B.C.) is believed to have been an early pupil of Isocrates, and he certainly was a student of Lysias. A passage of Photius has been understood as meaning that personal relations had existed between Isaeus and Plato, but this view appears erroneous.1 The profession of Isaeus was that of which Antiphon had been the first representative at Athens—that of a λογογράφος, who composed speeches which his clients were to deliver in the law-courts. But, while Antiphon had written such speeches chiefly (as Lysias frequently) for public causes, it was with private causes that Isaeus was almost exclusively concerned. The fact marks the progressive subdivision of labour in his calling, and the extent to which the smaller interests of private life now absorbed the attention of the citizen.

The most interesting recorded event in the career of Isaeus is one which belongs to its middle period—his connexion with Demosthenes. Born in 384 B.C., Demosthenes attained his civic majority in 366. At this time he had already resolved to 861 prosecute the fraudulent guardians who had stripped him of his patrimony. In prospect of such a legal contest, he could have found no better ally than Isaeus. That the young Demosthenes actually resorted to his aid is beyond reasonable doubt. But the pseudo-Plutarch embellishes the story after his fashion. He says that Demosthenes, on coming of age, took Isaeus into his house, and studied with him for four years—paying him the sum of 10,000 drachmas (about £400), on condition that Isaeus should withdraw from a school of rhetoric which he had opened, and devote himself wholly to his new pupil. The real Plutarch gives us a more sober and a more probable version. He simply states that Demosthenes “employed Isaeus as his master in rhetoric, though Isocrates was then teaching, either (as some say) because he could not pay Isocrates the prescribed fee of ten minae, or because he preferred the style of Isaeus for his purpose, as being vigorous and astute” (δραστήριον καὶ πανοῦργον). It may be observed that, except by the pseudo-Plutarch, a school of Isaeus is not mentioned,—for a notice in Plutarch need mean no more than that he had written a textbook, or that his speeches were read in schools;2 nor is any other pupil named. As to Demosthenes, his own speeches against Aphobus and Onetor (363-362 B.C.) afford the best possible gauge of the sense and the measure in which he was the disciple of Isaeus; the intercourse between them can scarcely have been either very close or very long. The date at which Isaeus died can only be conjectured from his work; it may be placed about 350 B.C.

Isaeus has a double claim on the student of Greek literature. He is the first Greek writer who comes before us as a consummate master of strict forensic controversy. He also holds a most important place in the general development of practical oratory, and therefore in the history of Attic prose. Antiphon marks the beginning of that development, Demosthenes its consummation. Between them stand Lysias and Isaeus. The open, even ostentatious, art of Antiphon had been austere and rigid. The concealed art of Lysias had charmed and persuaded by a versatile semblance of natural grace and simplicity. Isaeus brings us to a final stage of transition, in which the gifts distinctive of Lysias were to be fused into a perfect harmony with that masterly art which receives its most powerful expression in Demosthenes. Here, then, are the two cardinal points by which the place of Isaeus must be determined. We must consider, first, his relation to Lysias; secondly, his relation to Demosthenes.

A comparison of Isaeus and Lysias must set out from the distinction between choice of words (λέξις) and mode of putting words together (σύνθεσις). In choice of words, diction, Lysias and Isaeus are closely alike. Both are clear, pure, simple, concise; both have the stamp of persuasive plainness (ἀφέλεια), and both combine it with graphic power (ἐνάργεια). In mode of putting words together, composition, there is, however a striking difference. Lysias threw off the stiff restraints of the earlier periodic style, with its wooden monotony; he is too fond indeed of antithesis always to avoid a rigid effect; but, on the whole, his style is easy, flexible and various; above all, its subtle art usually succeeds in appearing natural. Now this is just what the art of Isaeus does not achieve. With less love of antithesis than Lysias, and with a diction almost equally pure and plain, he yet habitually conveys the impression of conscious and confident art. Hence he is least effective in adapting his style to those characters in which Lysias peculiarly excelled—the ingenuous youth, the homely and peace-loving citizen. On the other hand, his more open and vigorous art does not interfere with his moral persuasiveness where there is scope for reasoned remonstrance, for keen argument or for powerful denunciation. Passing from the formal to the real side of his work, from diction and composition to the treatment of subject-matter, we find the divergence wider still. Lysias usually adheres to a simple four-fold division—proem, narrative, proof, epilogue. Isaeus frequently interweaves the narrative with the proof.3 He shows the most dexterous ingenuity in adapting his manifold tactics to the case in hand, and often “out-generals” (καταστρατηγεῖ) his adversary by some novel and daring disposition of his forces. Lysias, again, usually contents himself with a merely rhetorical or sketchy proof; Isaeus aims at strict logical demonstration, worked out through all its steps. As Sir William Jones well remarks, Isaeus lays close siege to the understandings of the jury.4

Such is the general relation of Isaeus to Lysias. What, we must next ask, is the relation of Isaeus to Demosthenes? The Greek critic who had so carefully studied both authors states his own view in broad terms when he declares that “the power of Demosthenes took its seeds and its beginnings from Isaeus” (Dion. Halic. Isaeus, 20). A closer examination will show that within certain limits the statement may be allowed. Attic prose expression had been continuously developed as an art; the true link between Isaeus and Demosthenes is technical, depending on their continuity. Isaeus had made some original contributions to the resources of the art; and Demosthenes had not failed to profit by these. The composition of Demosthenes resembles that of Isaeus in blending terse and vigorous periods with passages of more lax and fluent ease, as well as in that dramatic vivacity which is given by rhetorical question and similar devices. In the versatile disposition of subject-matter, the divisions of “narrative” and “proof” being shifted and interwoven according to circumstances, Demosthenes has clearly been instructed by the example of Isaeus. Still more plainly and strikingly is this so in regard to the elaboration of systematic, proof; here Demosthenes invites direct and close comparison with Isaeus by his method of drawing out a chain of arguments, or enforcing a proposition by strict legal argument. And, more generally, Demosthenes is the pupil of Isaeus, though here the pupil became even greater than the master, in that faculty of grappling with an adversary’s case point by point, in that aptitude for close and strenuous conflict which is expressed by the words ἀγών, ἐναγώνιος.5

The pseudo-Plutarch, in his life of Isaeus, mentions an Art of Rhetoric and sixty-four speeches, of which fifty were accounted genuine. From a passage of Photius it appears that at least6 the fifty speeches of recognized authenticity were extant as late as A.D. 850. Only eleven, with a large part of a twelfth, have come down to us; but the titles of forty-two7 others are known.8

The titles of the lost speeches confirm the statement of Dionysius that the speeches of Isaeus were exclusively forensic; and only three titles indicate speeches made in public causes. The remainder, concerned with private causes, may be classed under six heads:—(1) κληρικοί—cases of claim to an inheritance; (2) ἐπικληρικοί—cases of claim to the hand of an heiress; (3) διαδικασίαι—cases of claim of property; (4) ἀποστασίου—cases of claim to the ownership of a slave; (5) ἐγγύης—action brought against a surety whose principal had made default; (6) ἀντωμοσία (as = παραγραφή)—a special plea; (7) ἔφεσις—appeal from one jurisdiction to another.

Eleven of the twelve extant speeches belong to class (1), the κληρικοί, or claims to an inheritance. This was probably the branch of practice in which Isaeus had done his most important and most characteristic work. And, according to the ancient custom, this class of speeches would therefore stand first in the manuscript collections of his writings. The case of Antiphon is parallel: his speeches in cases of homicide (φονικοί) were those on which his reputation mainly depended, and stood first in the manuscripts. Their exclusive preservation, like that of the speeches made by Isaeus in will-cases, is thus primarily an accident of manuscript tradition, but partly also the result of the writer’s special prestige.

Six of the twelve extant speeches are directly concerned with claims to an estate; five others are connected with legal proceedings arising out of such a claim. They may be classified thus (the name given in each case being that of the person whose estate is in dispute):

I. Trials of Claim to an Inheritance (διαδικασίαι).

1. Or. i., Cleonymus. Date between 360 and 353 B.C.

2. Or. iv., Nicostratus. Date uncertain.

3. Or. vii., Apollodorus. 353 B.C.

4. Or. viii., Ciron. 375 B.C.

5. Or. ix., Astyphilus. 369 B.C. (c. 390, Schömann).

6. Or. x., Aristarchus. 377-371 B.C. (386-384, Schömann).

II. Actions for False Witness (δίκαι ψευδομαρτυριῶν).

1. Or. ii., Menecles. 354 B.C.

2. Or. iii., Pyrrhus. Date uncertain, but comparatively late.

3. Or. vi., Philoctemon. 364-363 B.C.

III. Action to Compel the Discharge of a Suretyship (ἐγγύης δίκη).

Or. v., Dicaeogenes. 390 B.C.

IV. Indictment of a Guardian for Maltreatment of a Ward (εἰσαγγελία κακώσεως ὀρφανοῦ).

Or. xi., Hagnias. 359 B.C.

V. Appeal from Arbitration to a Dicastery (ἔφεσις).

Or. xii., For Euphiletus. (Incomplete.) Date uncertain.

The speeches of Isaeus supply valuable illustrations to the early history of testamentary law. They show us the faculty of adoption, still, indeed, associated with the religious motive in which it originated, as a mode of securing that the sacred rites of the family shall continue to be discharged by one who can call himself the son of the deceased. But practically the civil aspect of adoption is, for the Athenian citizen, predominant over the religious; he adopts a son in order to bestow property on a person to whom he wishes to bequeath it. The Athenian system, as interpreted by Isaeus, is thus intermediate, at least in spirit, between the purely religious standpoint of the Hindu and the maturer form which Roman testamentary law had reached before the time of Cicero.9 As to the form of the speeches, it is remarkable for its variety. There are three which, taken together, may be considered as best representing the diversity and range of their author’s power. The fifth, with its simple but lively diction, its graceful and persuasive narrative, recalls the qualities of Lysias. The eleventh, with its sustained and impetuous power, has no slight resemblance to the manner of Demosthenes. The eighth is, of all, the most characteristic, alike in narrative and in argument. Isaeus is here seen at his best. No reader who is interested in the social life of ancient Greece need find Isaeus dull. If the glimpses of Greek society which he gives us are seldom so gay and picturesque as those which enliven the pages of Lysias, they are certainly not less suggestive. Here, where the innermost relations and central interests of the family are in question, we touch the springs of social life; we are not merely presented with scenic details of dress and furniture, but are enabled in no small degree to conceive the feelings of the actors.

The best manuscript of Isaeus is in the British Museum,—Crippsianus A (= Burneianus 95, 13th century), which contains also Antiphon, Andocides, Lycurgus and Dinarchus. The next best is Bekker’s Laurentianus B (Florence), of the 15th century. Besides these, he used Marcianus L (Venice), saec. 14, Vratislaviensis Z saec. 1410 and two very inferior MSS. Ambrosianus A. 99, P (which he dismissed after Or. i.), and Ambrosianus D. 42, Q (which contains only Or. i., ii.). Schömann, in his edition of 1831, generally followed Bekker’s text; he had no fresh apparatus beyond a collation of a Paris MS. R in part of Or. i.; but he had sifted the Aldine more carefully. Baiter and Sauppe (1850) had a new collation of A, and also used a collation of Burneianus 96, M, given by Dobson in vol. iv. of his edition (1828). C. Scheibe (Teubner, 1860) made it his especial aim to complete the work of his predecessors by restoring the correct Attic forms of words; thus (e.g.) he gives ἠγγύα for ἐνεγύα, δέδιμεν for δεδίαμεν, and the like,—following the consent of the MSS., however, in such forms as the accusative of proper names in -ην rather than -η, or (e.g.) the future φανήσομαι rather than φανοῦμαι, &c., and on such doubtful points as φράτερες instead of φράτορες, or Εἰληθυίας instead of Εἰλειθυίας.

Editions.—Editio princeps (Aldus, Venice, 1513); in Oratores Attici, by I. Bekker (1823-1828); W. S. Dobson (1828); J. G. Baiter and Hermann Sauppe (1850); separately, by G. F. Schömann, with commentary (1831); C. Scheibe (1860) (Teubner series, new ed. by T. Thalheim, 1903); H. Buermann (1883); W. Wyse (1904). English translation by Sir William Jones, 1779.

On Isaeus generally see Wyse’s edition; R. C. Jebb, Attic Orators; F. Blass, Die attische Beredsamkeit (2nd ed., 1887-1893); and L. Moy, Étude sur les plaidoyers d’Isée (1876).

1 See further Jebb’s Attic Orators from Antiphon to Isaeus, (ii. 264).

2 Plut. De glor. Athen. p. 350 c, where he mentions τοὺς Ἰσοκράτεις καὶ Ἀντιφῶντας καὶ Ἰσαίους among τοὺς ἐν ταῖς σχολαῖς τὰ μειράκια προδιδάσκοντας.

3 Here he was probably influenced by the teaching of Isocrates. The forensic speech of Isocrates known as the Aegineticus (Or. xix.), which belongs to the peculiar province of Isaeus, as dealing with a claim to property (ἐπιδικασία), affords perhaps the earliest example of narrative and proof thus interwoven. Earlier forensic writers had kept the διήγησις and πίστεις distinct, as Lysias does.

4 This is what Dionysius means when he says (Isaeus, 61) that Isaeus differs from Lysias—τῷ μὴ κατ᾿ ἐνθύμημα τι λέγειν ἀλλὰ κατ᾿ ἐπιχείρημα. Here the “enthymeme” means a rhetorical syllogism with one premiss suppressed (curtum, Juv. vi. 449); “epicheireme,” such a syllogism stated in full. Cf. R. Volkmann, Rhetorik der Griechen und Römer, 1872, pp. 153 f.

5 Cleon’s speech in Thuc. iii. 37, 38, works out this image with remarkable force; within a short space we have ξυνἐσεως ἀγών—τῶν τοιῶνδε ἀγώνων—ἀγωνιστής—ἀγωνίζεσθαι—ἀνταγωνίζεσθαι—ἀγωνοθετεῖν. See Attic Orators, vol. i. 39; ii. 304.

6 For the words of Photius (cod. 263), τούτων δὲ οἱ τὸ γνήσιον μαρτυρηθέντες ν΄ καταλείπονται μόνον, might be so rendered as to imply that, besides these fifty, others also were extant. See Att. Orat. ii. 311, note 2.

7 Forty-four are given in Thalheim’s ed.

8 The second of our speeches (the Meneclean) was discovered in the Laurentian Library in 1785, and was edited in that year by Tyrwhitt. In editions previous to that date, Oration i. is made to conclude with a few lines which really belong to the end of Orat. ii. (§ 47, ἀλλ᾿ ἐπειδὴ τὸ πρᾶγμα ... ψηφίσασθε), and this arrangement is followed in the translation of Isaeus by Sir William Jones, to whom our second oration, was, of course, then (1779) unknown. In Oration i. all that follows the words μὴ ποιήσαντες in § 22 was first published in 1815 by Mai, from a MS. in the Ambrosian Library at Milan.

9 Cf. Maine’s Ancient Law, ch. vi., and the Tagore Law Lectures (1870) by Herbert Cowell, lect. ix., “On the Rite of Adoption,” pp. 208 f.

10 The date of L and Z is given as the end of the 15th century in the introduction to Wyse’s edition.

ISAIAH. I. Life and Period.—Isaiah is the name of the greatest, and both in life and in death the most influential of the Old Testament prophets. We do not forget Jeremiah, but Jeremiah’s literary and religious influence is secondary compared with that of Isaiah. Unfortunately we are reduced to inference and conjecture with regard both to his life and to the extent of his literary activity. In the heading (i. 1) of what we may call the occasional prophecies of Isaiah (i.e. those which were called forth by passing events), the author is called “the son of Amoz” and Rabbinical legend identifies this Amoz with a brother of Amaziah, king of Judah; but this is evidently based on a mere etymological fancy. We know from his works that (unlike Jeremiah) he was married (viii. 3), and that he had at least two sons, whose names he regarded as, together with his own, symbolic by divine appointment of certain decisive events or religious truths—Isaiah (Yesha’-yāhū), meaning “Salvation—Yahweh”; Shear-Yāshūb, “a remnant shall return”; and Maher-shalal-hash-baz, “swift (swiftly cometh) spoil, speedy (speedily cometh) prey” (vii. 3, viii. 3, 4, 18). He lived at Jerusalem, perhaps in the “middle” or “lower city” (2 Kings xx. 4), exercised at one time great influence at court (chap. xxxvii.), and could venture to address a king unbidden (vii. 4), and utter the most unpleasant truths, unassailed, in the plainest fashion. Presumably therefore his social rank was far above that of Amos and Micah; certainly the high degree of rhetorical skill displayed in his discourses implies a long course of literary discipline, not improbably in the school of some older prophet (Amos vii. 14 suggests that “schools” or companies “of the prophets” existed in the southern kingdom). We know but little of Isaiah’s predecessors and models in the prophetic art (it were fanaticism to exclude the element of human preparation); but certainly even the acknowledged prophecies of Isaiah (and much more the disputed ones) could no more have come into existence suddenly and without warning than the masterpieces of Shakespeare. In the more recent commentaries (e.g. Cheyne’s Prophecies of Isaiah, ii. 218) lists are generally given of the points of contact both in phraseology and in ideas between Isaiah and the prophets nearly contemporary with him. For Isaiah cannot be studied by himself.

The same heading already referred to gives us our only traditional information as to the period during which Isaiah prophesied; it refers to Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah as the contemporary kings. It is, however, to say the least, doubtful whether any of the extant prophecies are as early as the reign of Uzziah. Exegesis, the only safe basis of criticism for the prophetic literature, is unfavourable to the view that even chap. i. belongs to the reign of this king, and we must therefore regard it as most probable that the heading in i. 1 is (like those of the Psalms) the work of one or more of the Sōpherīm (or students and editors of Scripture) in post-exilic times, apparently the same writer (or company of writers) who prefixed the headings of Hosea and Micah, and perhaps of some of the other books. Chronological study had already begun in his time. But he would be a bold man who would profess to give trustworthy dates either for the kings of Israel or for the prophetic writers. (See Bible, Old Testament, Chronology; the article “Chronology” in the Encyclopaedia Bíblica; and cf. H. P. Smith, Old Testament History, Edin., 1903, p. 202, note 2.)

II. Chronological Arrangement, how far possible.—Let us now briefly sketch the progress of Isaiah’s prophesying on the basis of philological exegesis, and a comparison of the sound results of the study of the inscriptions. If our results are imperfect and liable to correction, that is only to be expected in the present position of the historical study of the Bible. Chap. vi., which describes a vision of Isaiah “in the death-year of King Uzziah” (740 or 734 B.C.?) may possibly have arisen out of notes put down in the reign of Jotham; but for several reasons it is not an acceptable view that, in its present form, this striking chapter is earlier than the reign of Ahaz. It seems, in short, to have originally formed the preface to the small group of prophecies which now follows it, viz. vii. i.-ix. 7. The portions which may represent discourses of Jotham’s reign are chap. ii. and chap. ix. 8-x. 4—stern denunciations which remind us somewhat of Amos. But the allusions in the greater part of chaps. ii.-v. correspond to no period so closely as the reign of Ahaz, and the same remark applies still more self-evidently to vii. 1-ix. 7.1 Chap. xvii. 1-11 ought undoubtedly to be read in immediate connexion with chap. vii.; it presupposes the alliance of Syria and northern Israel, whose destruction it predicts, though opening a door of hope for a remnant of Israel. The fatal siege of Samaria (724-722 B.C.) seems to have given occasion to chap. xxviii.; but the following 863 prophecies (chaps. xxix.-xxxiii.) point in the main to Sennacherib’s invasion, 701 B.C., which evidently stirred Isaiah’s deepest feelings and was the occasion of some of his greatest prophecies. It is, however, the vengeance taken by Sargon upon Ashdod (711) which seems to be preserved in chap. xx., and the striking little prophecy in xxi. 1-10, sometimes referred of late to a supposed invasion of Judah by Sargon, rather belongs to some one of the many prophetic personages who wrote, but did not speak like the greater prophets, during and after the Exile. It is also an opinion largely held that the prophetic epilogue in xvi. 13, 14, was attached by Isaiah to an oracle on archaic style by another prophet (Isaiah’s hand has, however, been traced by some in xvi. 4b, 5). In fact no progress can be expected in the accurate study of the prophets until the editorial activity both of the great prophets themselves and of their more reflective and studious successors is fully recognized.

Thus there were two great political events (the Syro-Israelitish invasion under Ahaz, and the great Assyrian invasion of Sennacherib) which called forth the spiritual and oratorical faculties of our prophet, and quickened his faculty of insight into the future. The Sennacherib prophecies must be taken in connexion with the historical appendix, chaps, xxxvi.-xxxix. The beauty and incisiveness of the poetic prophecy in xxxvii. 21-32 have, by some critics, been regarded as evidence for its authenticity. This, however, is, on critical grounds, most questionable.

A special reference seems needed at this point to the oracle on Egypt, chap. xix. The comparative feebleness of the style has led to the conjecture that, even if the basis of the prophecy be Isaianic, yet in its present form it must have undergone the manipulation of a scribe. More probably, however, it belongs to the early Persian period. It should be added that the Isaianic origin of the appendix in xix. 18-24 is, if possible, even more doubtful, because of the precise, circumstantial details of the prophecy which are not like Isaiah’s work. It is plausible to regard v. 18 as a fictitious prophecy in the interests of Onias, the founder of the rival Egyptian temple to Yahweh at Leontopolis in the name of Heliopolis (Josephus, Ant. xii. 9, 7).

III. Disintegration Theories.—We must now enter more fully into the question whether the whole of the so-called Book of Isaiah was really written by that prophet. The question relates, at any rate, to xiii.-xiv. 23, xxi. 1-10, xxiv.-xxvii., xxxiv., xxxv. and xl.-lxvi. The father of the controversy may be said to be the Jewish rabbi, Aben Ezra, who died A.D. 1167. We need not, however, spend much time on the well-worn but inconclusive arguments of the older critics. The existence of a tradition in the last three centuries before Christ as to the authorship of any book is (to those acquainted with the habits of thought of that age) of but little critical moment; the Sōpherīm, i.e. students of Scripture, in those times were simply anxious for the authority of the Scriptures, not for the ascertainment of their precise historical origin. It was of the utmost importance to declare that (especially) Isaiah xl.-lxvi. was a prophetic work of the highest order; this was reason sufficient (apart from any presumed phraseological affinities in xl.-lxvi.) for ascribing them to the royal prophet Isaiah. When the view had once obtained currency, it would naturally become a tradition. The question of the Isaianic or non-Isaianic origin of the disputed prophecies (especially xl.-lxvi.) must be decided on grounds of exegesis alone. It matters little, therefore, when the older critics appeal to Ezra i. 2 (interpreted by Josephus, Ant. xi. 1, 1-2), to the Septuagint version of the book (produced between 260 and 130 B.C.), in which the disputed prophecies are already found, and to the Greek translation of the Wisdom of Jesus, the son of Sirach, which distinctly refers to Isaiah as the comforter of those that mourned in Zion (Eccles. xlviii. 24, 25).

The fault of the controversialists on both sides has been that each party has only seen “one side of the shield.” It will be admitted by philological students that the exegetical data supplied by (at any rate) Isa. xl.-lxvi. are conflicting, and therefore susceptible of no simple solution. This remark applies, it is true, chiefly to the portion which begins at lii. 13. The earlier part of Isa. xl.-lxvi. admits of a perfectly consistent interpretation from first to last. There is nothing in it to indicate that the author’s standing-point is earlier than the Babylonian captivity. His object is (as most scholars, probably, believe) to warn, stimulate or console the captive Jews, some full believers, some semi-believers, some unbelievers or idolaters. The development of the prophet’s message is full of contrasts and surprises: the vanity of the idol-gods and the omnipotence of Israel’s helper, the sinfulness and infirmity of Israel and her high spiritual destiny, and the selection (so offensive to patriotic Jews, xlv. 9, 10) of the heathen Cyrus as the instrument of Yahweh’s purposes, as in fact his Messiah or Anointed One (xlv. 1), are brought successively before us. Hence the semi-dramatic character of the style. Already in the opening passage mysterious voices are heard crying, “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people”; the plural indicates that there were other prophets among the exiles besides the author of Isa. xl.-xlviii. Then the Jews and the Asiatic nations in general are introduced trembling at the imminent downfall of the Babylonian empire. The former are reasoned with and exhorted to believe; the latter are contemptuously silenced by an exhibition of the futility of their religion. Then another mysterious form appears on the scene, bearing the honourable title of “Servant of Yahweh,” through whom God’s gracious purposes for Israel and the world are to be realized. The cycle of poetic passages on the character and work of this “Servant,” or commissioned agent of the Most High, may have formed originally a separate collation which was somewhat later inserted in the Prophecy of Restoration (i.e. chaps. xl.-xlviii., and its appendix chaps. xlix.-lv.).

The new section which begins at chap. xlix. is written in much the same delightfully flowing style. We are still among the exiles at the close of the captivity, or, as others think, amidst a poor community in Jerusalem, whose members have now been dispersed among the Gentiles. The latter view is not so strange as it may at first appear, for the new book has this peculiarity, that Babylon and Cyrus are not mentioned in it at all. [True, there was not so much said about Babylon as we should have expected even in the first book; the paucity of references to the local characteristics of Babylonia is in fact one of the negative arguments urged by older scholars in favour of the Isaianic origin of the prophecy.] Israel himself, with all his inconsistent qualities, becomes the absorbing subject of the prophet’s meditations. The section opens with a soliloquy of the “Servant of Yahweh,” which leads on to a glorious comforting discourse, “Can a woman forget her sucking child,” &c. (xlix. 1, comp. li. 12, 13). Then his tone rises, Jerusalem can and must be redeemed; he even seems to see the great divine act in process of accomplishment. Is it possible, one cannot help asking, that the abrupt description of the strange fortunes of the “Servant”—by this time entirely personalized—was written to follow chap. lii. 1-12?

The whole difficulty seems to arise from the long prevalent assumption that chaps. xl.-lxvi. form a whole in themselves. Natural as the feeling against disintegration may be, the difficulties in the way of admitting the unity of chaps. xl.-lxvi. are insurmountable. Even if, by a bold assumption, we grant the unity of authorship, it is plain upon the face of it that the chapters in question cannot have been composed at the same time or under the same circumstances; literary and artistic unity is wholly wanting. But once admit (as it is only reasonable to do) the extension of Jewish editorial activity to the prophetic books and all becomes clear. The record before us gives no information as to its origin. It is without a heading, and by its abrupt transitions, and honestly preserved variations of style, invites us to such a theory as we are now indicating. It is only the inveterate habit of reading Isa. xlix.-lxvi. as a part of a work relating to the close of the Exile that prevents us from seeing how inconsistent are the tone and details with this presupposition.

The present article in its original form introduced here a survey of the portions of Isa. xl.-lxvi. which were plainly of Palestinian origin. It is needless to reproduce this here, because the information is now readily accessible elsewhere; in 1881 there was an originality in this survey, which gave promise of a still more radical treatment 864 such as that of Bernhard Duhm, a fascinating commentary published in 1892. See also Cheyne, Jewish Quarterly Review, July and October 1891; Introd. to Book of Isaiah (1895), which also point forward, like Stade’s Geschichte in Germany, to a bolder criticism of Isaiah.

IV. Non-Isaianic Elements in Chaps. i.-xxxix.—We have said nothing hitherto, except by way of allusion, of the disputed prophecies scattered up and down the first half of the book of Isaiah. There is only one of these prophecies which may, with any degree of apparent plausibility, be referred to the age of Isaiah, and that is chaps. xxiv.-xxvii. The grounds are (1) that according to xxv. 6 the author dwells on Mount Zion; (2) that Moab is referred to as an enemy (xxv. 10); and (3) that at the close of the prophecy, Assyria and Egypt are apparently mentioned as the principal foes of Israel (xxvii. 12, 13). A careful and thorough exegesis will show the hollowness of this justification. The tone and spirit of the prophecy as a whole point to the same late apocalyptic period to which chap. xxxiv. and the book of Joel; and also the last chapter (especially) of the book of Zechariah, may unhesitatingly be referred.

A word or two may perhaps be expected on Isa. xiii., xiv. and xxxiv., xxxv. These two oracles agree in the elaborateness of their description of the fearful fate of the enemies of Yahweh (Babylon and Edom are merely representatives of a class), and also in their view of the deliverance and restoration of Israel as an epoch for the whole human race. There is also an unrelieved sternness, which pains us by its contrast with Isa. xl.-lxvi. (except those passages of this portion which are probably not homogeneous with the bulk of the prophecy). They have also affinities with Jer. l. li., a prophecy (as most now agree) of post-exilic origin.

There is only one passage which seems in some degree to make up for the aesthetic drawbacks of the greater part of these late compositions. It is the ode on the fall of the king of Babylon in chap. xiv. 4-21, which is as brilliant with the glow of lyric enthusiasm as the stern prophecy which precedes it is, from the same point of view, dull and uninspiring. It is in fact worthy to be put by the side of the finest passages of chaps. xl.-lxvi.—of those passages which irresistibly rise in the memory when we think of “Isaiah.”

V. Prophetic Contrasts in Isaiah.—From a religious point of view there is a wide difference, not only between the acknowledged and the disputed prophecies of the book of Isaiah, but also between those of the latter which occur in chaps. i.-xxxix., on the one hand, and the greater and more striking part of chaps. xl.-lxvi. on the other. We may say, upon the whole, with Duhm, that Isaiah represents a synthesis of Amos and Hosea, though not without important additions of his own. And if we cannot without much hesitation admit that Isaiah was really the first preacher of a personal Messiah whose record has come down to us, yet his editors certainly had good reason for thinking him capable of such a lofty height of prophecy. It is not because Isaiah could not have conceived of a personal Messiah, but because the Messiah-passages are not plainly Isaiah’s either in style or in thought. If Isaiah had had those bright visions, they would have affected him more.

Perhaps the most characteristic religious peculiarities of the various disputed prophecies are—(1) the emphasis laid on the uniqueness, eternity, creatorship and predictive power of Yahweh (xl. 18, 25, xli. 4, xliv. 6, xlviii. 12, xlv. 5, 6, 18, 22, xlvi. 9, xlii. 5, xlv. 18, xli. 26, xliii. 9, xliv. 7, xlv. 21, xlviii. 14); (2) the conception of the “Servant of Yahweh”; (3) the ironical descriptions of idolatry (Isaiah in the acknowledged prophecies only refers incidentally to idolatry) xl. 19, 20, xli. 7, xliv. 9-17, xlvi. 6; (4) the personality of the Spirit of Yahweh (mentioned no less than seven times, see especially xl. 3, xlviii. 16, lxiii. 10, 14); (5) the influence of the angelic powers (xxiv. 21); (6) the resurrection of the body (xxvi. 19); (7) the everlasting punishment of the wicked (lxvi. 24); (8) vicarious atonement (chap. liii.).

We cannot here do more than chronicle the attempts of a Jewish scholar, the late Dr Kohut, in the Z.D.M.G. for 1876 to prove a Zoroastrian influence on chaps. xl.-lxvi. The idea is not in itself inadmissible, at least for post-exilic portions, for Zoroastrian ideas were in the intellectual atmosphere of Jewish writers in the Persian age.

There is an equally striking difference among the disputed prophecies themselves, and one of no small moment as a subsidiary indication of their origin. We have already spoken of the difference of tone between parts of the latter half of the book; and, when we compare the disputed prophecies of the former half with the Prophecy of Israel’s Restoration, how inferior (with all reverence be it said) do they appear! Truly “in many parts and many manners did God speak” in this composite book of Isaiah! To the Prophecy of Restoration we may fitly apply the words, too gracious and too subtly chosen to be translated, of Renan, “ce second Isaïe, dont l’âme lumineuse semble comme imprégnée, six cent ans d’avance, de toutes les rosées, de tous les parfums de l’avenir” (L’Antéchrist, p. 464); though, indeed, the common verdict of sympathetic readers sums up the sentence in a single phrase—“the Evangelical Prophet.” The freedom and the inexhaustibleness of the undeserved grace of God is a subject to which this gifted son constantly returns with “a monotony which is never monotonous.” The defect of the disputed prophecies in the former part of the book (a defect, as long as we regard them in isolation, and not as supplemented by those which come after) is that they emphasize too much for the Christian sentiment the stern, destructive side of the series of divine interpositions in the latter days.

VI. The Cyrus Inscriptions.—Perhaps one of the most important contributions to the study of II. Isaiah has been the discovery of two cuneiform texts relative to the fall of Babylon and the religious policy of Cyrus. The results are not favourable to a mechanical view of prophecy as involving absolute accuracy of statement. Cyrus appears in the unassailably authentic cylinder inscription “as a complete religious indifferentist, willing to go through any amount of ceremonies to soothe the prejudices of a susceptible population.” He preserves a strange and significant silence with regard to Ahura-mazda, the supreme God of Zoroastrianism, and in fact can hardly have been a Zoroastrian believer at all. On the historical and religious bearings of these two inscriptions the reader may be referred to the article “Cyrus” in the Encyclopaedia Biblica and the essay on “II. Isaiah and the Inscriptions” in Cheyne’s Prophecies of Isaiah, vol. ii. It may, with all reverence, be added that our estimate of prophecy must be brought into harmony with facts, not facts with our preconceived theory of inspiration.

Authorities.—Lowth, Isaiah: a new translation, with a preliminary dissertation and notes (1778); Gesenius, Der Proph. Jes. (1821); Hitzig, Der Proph. Jes. (1833); Delitzsch, Der Pr. Jes. (4th ed., 1889); Dillmann-Kittel, Isaiah (1898); Duhm (1892; 2nd ed., 1902); Marti (1900); Cheyne, The Prophecies of Isaiah (2 vols., 1880-1881); Introd. to Book of Isaiah (1898); “The Book of the Prophet Isaiah,” in Paul Haupt’s Polychrome Bible (1898); S. R. Driver, Isaiah, his life and times (1888); J. Skinner, “The Book of Isaiah,” in Cambridge Bible (2 vols., 1896, 1898); G. A. Smith, in Expositor’s Bible (2 vols., 1888, 1890); Condamin (Rom. Cath.) (1905); G. H. Box (1908); Article on Isaiah in Ency. Bib. by Cheyne; in Hastings’ Dict. of the Bible by Prof. G. A. Smith. R. H. Kennett’s Schweich Lecture (1909), The Composition of the Book of Isaiah in the Light of Archaeology and History, an interesting attempt at a synthesis of results, is a brightly written but scholarly sketch of the growth of the book of Isaiah, which went on till the great success of the Jews under Judas Maccabaeus. The outbursts of triumph (e.g. Isa. ix. 2-7) are assigned to this period. The most original statement is perhaps the view that the words of Isaiah were preserved orally by his disciples, and did not see the light (in a revised form) till a considerable time after the crystallization of the reforms of Josiah into laws.

1 On the question of the Isaianic origin of the prophecy, ix. 1-6, and the companion passage, xi. 1-8, see Cheyne Introd. to the Book of Isaiah, 1895, pp. 44, 45 and 62-66. Cf., however, J. Skinner “Isaiah i.-xxxix.” in Cambridge Bible.

ISAIAH, ASCENSION OF, an apocryphal book of the Old Testament. The Ascension of Isaiah is a composite work of very great interest. In its present form it is probably not older than the latter half of the 2nd century of our era. Its various constituents, however, and of these there were three—the Martyrdom of Isaiah, the Testament of Hezekiah and the Vision of Isaiah—circulated independently as early as the 1st century. The first of these was of Jewish origin, and is of less interest than the other two, which were the work of Christian writers. The Vision of Isaiah is important for the knowledge it affords us of 865 1st-century beliefs in certain circles as to the doctrines of the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Resurrection, the Seven Heavens, &c. The long lost Testament of Hezekiah, which is, in the opinion of R. H. Charles, to be identified with iii. 13b-iv. 18, of our present work, is unquestionably of great value owing to the insight it gives us into the history of the Christian Church at the close of the 1st century. Its descriptions of the worldliness and lawlessness which prevailed among the elders and pastors, i.e. the bishops and priests, of the wide-spread covetousness and vainglory as well as the growing heresies among Christians generally, agree with similar accounts in 2 Peter, 2 Timothy and Clement of Rome.

Various Titles.—Origen in his commentary on Matt. xiii. 57 (Lommatzsch iii. 4, 9) calls it Apocryph of Isaiah—Ἀπόκρυφον Ἡσαίου, Epiphanius (Haer. xl. 2) terms it the Ascension of Isaiah—τὸ ἀναβατικὸν Ἡσαίου, and similarly Jerome—Ascensio Isaiae. It was also known as the Vision of Isaiah and finally as the Testament of Hezekiah (see Charles, The Ascension of Isaiah, pp. xii.-xv.).

The Greek Original and the Versions.—The book was written in Greek, though not improbably the middle portion, the Testament of Hezekiah, was originally composed in Semitic. The Greek in its original form, which we may denote by G, is lost. It has, however, been in part preserved to us in two of its recensions, G¹ and G². From G¹ the Ethiopic Version and the first Latin Version (consisting of ii. 14-iii. 13, vii. 1-19) were translated, and of this recension the actual Greek has survived in a multitude of phrases in the Greek Legend. G² denotes the Greek text from which the Slavonic and the second Latin Version (consisting of vi.-xi.) were translated. Of this recension ii. 4-iv. 2 have been discovered by Grenfell and Hunt.1 For complete details see Charles, op. cit. pp. xviii.-xxxiii.; also Flemming in Hennecke’s NTliche Apok.

Latin Version.—The first Latin Version (L¹) is fragmentary (=ii. 14-iii. 13, vii. 1-19). It was discovered and edited by Mai in 1828 (Script. vet. nova collectio III. ii. 238), and reprinted by Dillmann in his edition of 1877, and subsequently in a more correct form by Charles in his edition of 1900. The second version (L²), which consists of vi.-xi., was first printed at Venice in 1522, by Gieseler in 1832, Dillmann in 1877 and Charles in 1900.

Ethiopic Version.—There are three MSS. This version is on the whole a faithful reproduction of G¹. These were used by Dillmann and subsequently by Charles in their editions.

Different Elements in the Book.—The compositeness of this work is universally recognized. Dillmann’s analysis is as follows, (i.) Martyrdom of Isaiah, of Jewish origin; ii. 1-iii. 12, v. 2-14. (ii.) The Vision of Isaiah, of Christian origin, vi. 1-xi. 1, 23-40. (iii.) The above two constituents were put together by a Christian writer, who prefixed i. 1, 2, 4b-13 and appended xi. 42, 43. (iv.) Finally a later Christian editor incorporated the two sections iii. 13-v. 1 and xi. 2-22, and added i. 3, 4a, v. 15, 16, xi. 41.

This analysis has on the whole been accepted by Harnack, Schürer, Deane and Beer. These scholars have been influenced by Gebhardt’s statement that in the Greek Legend there is not a trace of iii. 13-v. 1, xi. 2-22, and that accordingly these sections were absent from the text when the Greek Legend was composed. But this statement is wrong, for at least five phrases or clauses in the Greek Legend are derived from the sections in question. Hence R. H. Charles has examined (op. cit. pp. xxxviii.-xlvii.) the problem de novo, and arrived at the following conclusions. The book is highly composite, and arbitrariness and disorder are found in every section. There are three original documents at its base, (i.) The Martyrdom of Isaiah = i. 1, 2a, 6b-13a, ii. 1-8, 10-iii. 12, v. 1b-14. This is but an imperfect survival of the original work. Part of the original work omitted by the final editor of our book is preserved in the Opus imperfectum, which goes back not to our text, but to the original Martyrdom, (ii.) The Testament of Hezekiah = iii. 13b-iv. 18. This work is mutilated and without beginning or end. (iii.) The Vision of Isaiah = vi.-xi. 1-40. The archetype of this section existed independently in Greek; for the second Latin and the Slavonic Versions presuppose an independent circulation of their Greek archetype in western and Slavonic countries. This archetype differs in many respects from the form in which it was republished by the editor of the entire work.

We may, in short, put this complex matter as follows: The conditions of the problem are sufficiently satisfied by supposing a single editor, who had three works at his disposal, the Martyrdom of Isaiah, of Jewish origin, and the Testament of Hezekiah and the Vision of Isaiah, of Christian origin. These he reduced or enlarged as it suited his purpose, and put them together as they stand in our text. Some of the editorial additions are obvious, as i. 2b-6a, 13a, ii. 9, iii. 13a, iv. 1a, 19-v. 1a, 15, 16, xi. 41-43.

Dates of the Various Constituents of the Ascension.—(a) The Martyrdom is quoted by the Opus Imperfectum, Ambrose, Jerome, Origen, Tertullian and by Justin Martyr. It was probably known to the writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews. Thus we are brought back to the 1st century A.D. if the last reference is trustworthy. And this is no doubt the right date, for works written by Jews in the 2nd century would not be likely to become current in the Christian Church. (b) The Testament of Hezekiah was written between A.D. 88-100. The grounds for this date will be found in Charles, op. cit. pp. lxxi.-lxxii. and 30-31. (c) The Vision of Isaiah. The later recension of this Vision was used by Jerome, and a more primitive form of the text by the Archontici according to Epiphanius. It is still earlier attested by the Actus Petri Vercellenses. Since the Protevangel of James was apparently acquainted with it, and likewise Ignatius (ad. Ephes. xix.), the composition of the primitive form of the Vision goes back to the close of the 1st century.

The work of combining and editing these three independent writings may go back to early in the 3rd or even to the 2nd century.

Literature.—Editions of the Ethiopic Text: Laurence, Ascensio Isaiae vatis (1819); Dillmann, Ascensio Isaiae Aethiopice et Latine, cum prolegomenis, adnotationibus criticis et exegeticis, additis versionum Latinarum reliquiis edita (1877); Charles, Ascension of Isaiah, translated from the Ethiopic Version, which, together with the new Greek Fragment, the Latin Versions and the Latin translation of the Slavonic, is here published in full, edited with Introduction, Notes and Indices (1900); Flemming, in Hennecke’s NTliche Apok. 292-305; NTliche Apok.-Handbuch, 323-331. This translation is made from Charles’s text, and his analysis of the text is in the main accepted by this scholar. Translations: In addition to the translations given in the preceding editions, Basset, Les Apocryphes éthiopiens, iii. “L’Ascension d’Isaïe” (1894); Beer, Apok. und Pseud. (1900) ii. 124-127. The latter is a German rendering of ii.-iii. 1-12, v. 2-14, of Dillmann’s text. Critical Inquiries: Stokes, art. “Isaiah, Ascension of,” in Smith’s Dict. of Christian Biography (1882), iii. 298-301; Robinson, “The Ascension of Isaiah” in Hastings’ Bible Dict. ii. 499-501. For complete bibliography see Schürer,3 Gesch. des jüd. Volks, iii. 280-285; Charles, op. cit.

1 Published by them in the Amherst Papyri, an account of the Greek papyri in the collection of Lord Amherst (1900), and by Charles in his edition.

ISANDHLWANA, an isolated hill in Zululand, 8 m. S.E. of Rorke’s Drift across the Tugela river, and 105 m. N. by W. of Durban. On the 22nd of January 1879 a British force encamped at the foot of the hill was attacked by about 10,000 Zulus, the flower of Cetewayo’s army, and destroyed. Of eight hundred Europeans engaged about forty escaped (see Zululand: History).

ISAR (identical with Isère, in Celtic “the rapid”), a river of Bavaria. It rises in the Tirolese Alps N.E. from Innsbruck, at an altitude of 5840 ft. It first winds in deep, narrow glens and gorges through the Alps, and at Tölz (2100 ft.), due north from its source, enters the Bavarian plain, which it traverses in a generally north and north-east direction, and pours its waters into the Danube immediately below Deggendorf after a course of 219 m. The area of its drainage basin is 38,200 sq. m. Below Munich the stream is 140 to 350 yards wide, and is studded with islands. It is not navigable, except for rafts. The total fall of the river is 4816 ft. The Isar is essentially the national stream of the Bavarians. It has belonged from the earliest times to the Bavarian people and traverses the finest corn land in the kingdom. On its banks lie the cities of Munich and Landshut, and the venerable episcopal see of Freising, and the inhabitants of the district it waters are reckoned the core of the Bavarian race.

See C. Gruber, Die Isar nach ihrer Entwickelung und ihren hydrologischen Verhältnissen (Munich, 1889); and Die Bedeutung der Isar als Verkehrsstrasse (Munich, 1890).

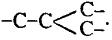

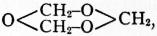

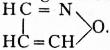

ISATIN, C8H5NO2, in chemistry, a derivative of indol, interesting on account of its relation to indigo; it may be regarded as the anhydride of ortho-aminobenzoylformic or isatinic acid. It crystallizes in orange red prisms which melt at 200-201° C. It may be prepared by oxidizing indigo with nitric or chromic acid (O. L. Erdmann, Jour. prak. Chem., 1841, 24, p. 11); by boiling ortho-nitrophenylpropiolic acid with alkalis (A. Baeyer, Ber., 1880, 13, p. 2259), or by oxidizing carbostyril with alkaline potassium permanganate (P. Friedlander and H. Ostermaier, Ber., 1881, 14, p. 1921). P. J. Meyer (German Patent 26736 (1883)) obtains substituted isatins by condensing para-toluidine with dichloracetic acid, oxidizing the product with air and then hydrolysing the oxidized product with hydrochloric acid. T. Sandmeyer (German Patents 113981 and 119831 (1899)) obtained isatin-α-anilide by condensing aniline with chloral hydrate and hydroxylamine, an intermediate product isonitrosodiphenylacetamidine being obtained, which is converted into isatin-α-anilide by sulphuric acid. This can be converted into indigo 866 by reduction with ammonium sulphide. Isatin dissolved in concentrated sulphuric acid gives a blue coloration with thiophene, due to the formation of indophenin (see Abst. J.C.S., 1907). Concentrated nitric acid oxidizes it to oxalic acid, and alkali fusion yields aniline. It dissolves in soda forming a violet solution, which soon becomes yellow, a change due to the transformation of sodium N-isatin into sodium isatate, the aci-isatin salt being probably formed intermediately (Heller, Abst. J.C.S., 1907, i. p. 442). Most metallic salts are N-derivatives yielding N-methyl ethers; the silver salt is, however, an O-derivative, yielding an O-methyl ether (A. v. Baeyer, 1883; W. Peters, Abst. J.C.S., 1907, i. p. 239).

ISAURIA, in ancient geography, a district in the interior of Asia Minor, of very different extent at different periods. The permanent nucleus of it was that section of the Taurus which lies directly to south of Iconium and Lystra. Lycaonia had all the Iconian plain; but Isauria began as soon as the foothills were reached. Its two original towns, Isaura Nea and Isaura Palaea, lay, one among these foothills (Dorla) and the other on the watershed (Zengibar Kalé). When the Romans first encountered the Isaurians (early in the 1st century B.C.), they regarded Cilicia Trachea as part of Isauria, which thus extended to the sea; and this extension of the name continued to be in common use for two centuries. The whole basin of the Calycadnus was reckoned Isaurian, and the cities in the valley of its southern branch formed what was known as the Isaurian Decapolis. Towards the end of the 3rd century A.D., however, all Cilicia was detached for administrative purposes from the northern slope of Taurus, and we find a province called at first Isauria-Lycaonia, and later Isauria alone, extending up to the limits of Galatia, but not passing Taurus on the south. Pisidia, part of which had hitherto been included in one province with Isauria, was also detached, and made to include Iconium. In compensation Isauria received the eastern part of Pamphylia. Restricted again in the 4th century, Isauria ended as it began by being just the wild district about Isaura Palaea and the heads of the Calycadnus. Isaura Palaea was besieged by Perdiccas, the Macedonian regent after Alexander’s death; and to avoid capture its citizens set the place alight and perished in the flames. During the war of the Cilician and other pirates against Rome, the Isaurians took so active a part that the proconsul P. Servilius deemed it necessary to follow them into their fastnesses, and compel the whole people to submission, an exploit for which he received the title of Isauricus (75 B.C.). The Isaurians were afterwards placed for a time under the rule of Amyntas, king of Galatia; but it is evident that they continued to retain their predatory habits and virtual independence. In the 3rd century they sheltered the rebel emperor, Trebellianus. In the 4th century they are still described by Ammianus Marcellinus as the scourge of the neighbouring provinces of Asia Minor; but they are said to have been effectually subdued in the reign of Justinian. In common with all the eastern Taurus, Isauria passed into the hands of Turcomans and Yuruks with the Seljuk conquest. Many of these have now coalesced with the aboriginal population and form a settled element: but the district is still lawless.

This comparatively obscure people had the honour of producing two Byzantine emperors, Zeno, whose native name was Traskalisseus Rousoumbladeotes, and Leo III., who ascended the throne of Constantinople in 718, reigned till 741, and became the founder of a dynasty of three generations. The ruins of Isaura Palaea are mainly remarkable for their fine situation and their fortifications and tombs. Those of Isaura Nea have disappeared, but numerous inscriptions and many sculptured stelae, built into the houses of Dorla, prove the site. It was the latter, and not the former town, that Servilius reduced by cutting off the water supply. The site was identified by W. M. Ramsay in 1901. The only modern exploration of highland Isauria was that made by J. S. Sterrett in 1885; but it was not exhaustive.

Bibliography.—W. M. Ramsay, Historical Geography of Asia Minor (1890), and article “Nova Isaura” in Journ. Hell. Studies (1905); A. M. Ramsay, ibid. (1904); J. R. S. Sterrett, “Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor,” Papers Amer. Inst. of Arch. iii. (1888); C. Ritter, Erdkunde, xix. (1859); E. J. Davis, Life in As. Turkey (1879).

ISCHIA (Gr. Πιθηκοῦσα, Lat. Aenaria, in poetry Inarime), an island off the coast of Campania, Italy, 16 m. S.W. of Naples, to the province of which it belongs, and 7 m. S.W. of the Capo Miseno, the nearest point of the mainland. Pop. about 20,000. It is situated at the W. extremity of the Gulf of Naples, and is the largest island near Naples, measuring about 19 m. in circumference and 26 sq. m. in area. It belongs to the same volcanic system as the mainland near it, and the Monte Epomeo (anc. Ἐπωπεύς, viewpoint), the highest point of the island (2588 ft.), lies on the N. edge of the principal crater, which is surrounded by twelve smaller cones. The island was perhaps occupied by Greek settlers even before Cumae; its Eretrian and Chalcidian inhabitants abandoned it about 500 B.C. owing to an eruption, and it is said to have been deserted almost at once by the greater part of the garrison which Hiero I. of Syracuse had placed there about 470 B.C., owing to the same cause. Later on it came into the possession of Naples, but passed into Roman hands in 326, when Naples herself lost her independence. The ancient town, traces of the fortifications of which still exist, was situated near Lacco, at the N.W. corner of the island. Augustus gave it back to Naples in exchange for Capri. After the fall of Rome it suffered attacks and devastations from the successive masters of Italy, until it was finally taken by the Neapolitans in 1299.

Several eruptions are recorded in Roman times. The last of which we have any knowledge occurred in 1301, but the island was visited by earthquakes in 1881 and 1883, 1700 lives being lost in the latter year, when the town of Casamicciola on the north side of the island was almost entirely destroyed. The hot springs here, which still survive from the period of volcanic activity, rise at a temperature of 147° Fahr. and are alkaline and saline; they are much visited by bathers, especially in summer. They were known in Roman times, and many votive altars dedicated to Apollo and the nymphs have been found. The whole island is mountainous, and is remarkable for its beautiful scenery and its fertility. Wine, corn, oil and fruit are produced, especially the former, while the mountain slopes are clothed with woods. Tiles and pottery are made in the island. Straw-plaiting is a considerable industry at Lacco; and a certain amount of fishing is also done. The potter’s clay of Ischia served for the potteries of Cumae and Puteoli in ancient times, and was indeed in considerable demand until the catastrophe at Casamicciola in 1883.

The chief towns are Ischia on the E. coast, the capital and the seat of a bishop (pop. in 1901, town, 2756; commune, 7012), with a 15th-century castle, to which Vittoria Colonna retired after the death of her husband in 1525; Casamicciola (pop. in 1901, town, 1085; commune, 3731) on the north, and Forīo on the west coast (pop. in 1901, town, 3640; commune, 7197). There is regular communication with Naples, both by steamer direct, and also by steamer to Torregaveta, 2 m. W.S.W. of Baiae and 12½ m. W.S.W. of Naples, and thence by rail.

See J. Beloch, Campanien (Breslau, 1890), 202 sqq.

ISCHL, a market-town and watering-place of Austria, in Upper Austria, 55 m. S.S.W. of Linz by rail. Pop. (1900) 9646. It is beautifully situated on the peninsula formed by the junction of the rivers Ischl and Traun and is surrounded by high mountains, presenting scenery of the finest description. To the S. is the Siriuskogl or Hundskogl (1960 ft.), and to the W. the Schafberg (5837 ft.), which is ascended from St Wolfgang by a rack-and-pinion railway, built in 1893. It possesses a fine parish church, built by Maria Theresa and renovated in 1877-1880, and the Imperial Villa is surrounded by a magnificent park. Ischl is one of the most fashionable spas of Europe, being the favourite 867 summer residence of the Austrian Imperial family and of the Austrian nobility since 1822. It has saline and sulphureous drinking springs and numerous brine and brine-vapour baths. The brine used at Ischl contains about 25% of salt and there are also mud, sulphur and pine-cone baths. Ischl is situated at an altitude of 1533 ft. above sea-level and has a very mild climate. Its mean annual temperature is 49.4° F. and its mean summer temperature is 63.5° F. Ischl is an important centre of the salt industry and 4 m. to its W. is a celebrated salt mine, which has been worked as early as the 12th century.

ISEO, LAKE OF (the Lacus Sebinus of the Romans), a lake in Lombardy, N. Italy, situated at the southern foot of the Alps, and between the provinces of Bergamo and Brescia. It is formed by the Oglio river, which enters the northern extremity of the lake of Lovere, and issues from the southern end at Sarnico, on its way to join the Po. The area of the lake is about 24 sq. m., it is 17½ m. in length, and 3 m. wide in the broadest portion, while the greatest depth is said to be about 984 ft. and the height of its surface above sea-level 607 ft. It contains one large island, that of Siviano, which culminates in the Monte Isola (1965 ft.) that is crowned by a chapel, while to the south is the islet of San Paolo, occupied by the buildings of a small Franciscan convent now abandoned, and to the north the equally tiny island of Loreto, with a ruined chapel containing frescoes. At the southern end of the lake are the small towns of Iseo (15 m. by rail N.W. of Brescia) and of Sarnico. From Paratico, opposite Sarnico, on the other or left bank of the Oglio, a railway runs in 6¼ m. to Palazzolo, on the main Brescia-Bergamo line. Towards the head of the lake, the deep wide valley of the Oglio is seen, dominated by the glittering snows of the Adamello (11,661 ft.), a glorious prospect. Along the east shore (the west shore is far more rugged) a fine carriage road rims from Iseo to the considerable town of Pisogne (13½ m.), situated at the northern end of the lake, and nearly opposite that of Lovere, on the right bank of the Oglio. The portion of this road some way S. of Pisogne is cleverly engineered, and is carried through several tunnels. The lake’s charms were celebrated by Lady Mary Wortley-Montagu, who spent ten summers (1747-1757) in a villa at Lovere, then much frequented by reason of an iron spring. The lake has several sardine and eel fisheries.

ISÈRE [anc. Isara], one of the chief rivers in France as well as of those flowing down on the French side of the Alpine chain. Its total length from its source to its junction with the Rhône is about 180 m., during which it descends a height of about 7550 ft. Its drainage area is about 4725 sq. m. It flows through the departments of Savoie, Isère and Drôme. This river rises in the Galise glaciers in the French Graian Alps and flows, as a mountain torrent, through a narrow valley past Tignes in a north-westerly direction to Bourg St Maurice, at the western foot of the Little St Bernard Pass. It now bends S.W., as far as Moutiers, the chief town of the Tarentaise, as the upper course of the Isère is named. Here it again turns N.W. as far as Albertville, where after receiving the Arly (right) it once more takes a south-westerly direction, and near St Pierre d’Albigny receives its first important tributary, the Arc (left), a wild mountain stream flowing through the Maurienne and past the foot of the Mont Cenis Pass. A little way below, at Montmélian, it becomes officially navigable (for about half of its course), though it is but little used for that purpose owing to the irregular depth of its bed and the rapidity of its current. Very probably, in ancient days, it flowed from Montmélian N.W. and, after passing through or forming the Lac du Bourget, joined the Rhône. But at present it continues from Montmélian in a south-westerly direction, flowing through the broad and fertile valley of the Graisivaudan, though receiving but a single affluent of any importance, the Bréda (left). At Grenoble, the most important town on its banks, it bends for a short distance again N.W. But just below that town it receives by far its most important affluent (left) the Drac, which itself drains the entire S. slope of the lofty snow-clad Dauphiné Alps, and which, 11 m. above Grenoble, had received the Romanche (right), a mountain stream which drains the entire central and N. portion of the same Alps. Hence the Drac is, at its junction with the Isère, a stream of nearly the same volume, while these two rivers, with the Durance, drain practically the entire French slope of the Alpine chain, the basins of the Arve and of the Var forming the sole exceptions. A short distance below Moirans the Isère changes its direction for the last time and now flows S.W. past Romans before joining the Rhône on the left, as its principal affluent after the Saône and the Durance, between Tournon and Valence. The Isère is remarkable for the way in which it changes its direction, forming three great loops of which the apex is respectively at Bourg St Maurice, Albertville and Moirans. For some way after its junction with the Rhône the grey troubled current of the Isère can be distinguished in the broad and peaceful stream of the Rhône.

ISÈRE, a department of S.E. France, formed in 1790 out of the northern part of the old province of Dauphiné. Pop. (1906) 562,315. It is bounded N. by the department of the Ain, E. by that of Savoie, S. by those of the Hautes Alpes and the Drôme and W. by those of the Loire and the Rhône. Its area is 3179 sq. m. (surpassed only by 7 other departments), while its greatest length is 93 m. and its greatest breadth 53 m. The river Isère runs for nearly half its course through this department, to which it gives its name. The southern portion of the department is very mountainous, the loftiest summit being the Pic Lory (13,396 ft.) in the extensive snow-clad Oisans group (drained by the Drac and Romanche, two mighty mountain torrents), while minor groups are those of Belledonne, of Allevard, of the Grandes Rousses, of the Dévoluy, of the Trièves, of the Royannais, of the Vercors and, slightly to the north of the rest, that of the Grande Chartreuse. The northern portion of the department is composed of plateaux, low hills and plains, while on every side but the south it is bounded by the course of the Rhône. It forms the bishopric of Grenoble (dating from the 4th century), till 1790 in the ecclesiastical province of Vienne, and now in that of Lyons. The department is divided into four arrondissements (Grenoble, St Marcellin, La Tour du Pin and Vienne), 45 cantons and 563 communes. Its capital is Grenoble, while other important towns in it are the towns of Vienne, St Marcellin and La Tour du Pin. It is well supplied with railways (total length 342 m.), which give access to Gap, to Chambéry, to Lyons, to St Rambert and to Valence, while it also possesses many tramways (total length over 200 m.). It contains silver, lead, coal and iron mines, as well as extensive slate, stone and marble quarries, besides several mineral springs (Allevard, Uriage and La Motte). The forests cover much ground, while among the most flourishing industries are those of glove making, cement, silk weaving and paper making. The area devoted to agriculture (largely in the fertile valley of the Graisivaudan, or Isère, N.E. of Grenoble) is about 1211 sq. m.

ISERLOHN, a town in the Prussian province of Westphalia, on the Baar, in a bleak and hilly region, 17 m. W. of Arnsberg, and 30 m. E.N.E. from Barmen by rail. Pop. (1900) 27,265. Iserlohn is one of the most important manufacturing towns in Westphalia. Both in the town and neighbourhood there are numerous foundries and works for iron, brass, steel and bronze goods, while other manufactures include wire, needles and pins, fish-hooks, machinery, umbrella-frames, thimbles, bits, furniture, chemicals, coffee-mills, and pinchbeck and britannia-metal goods. Iserlohn is a very old town, its gild of armourers being referred to as “ancient” in 1443.

ISFAHĀN (older form Ispahān), the name of a Persian province and town. The province is situated in the centre of the country, and bounded S. by Fars, E. by Yezd, N. by Kashān, Natanz and Irāk, and W. by the Bakhtiāri district and Arabistān. It pays a yearly revenue of about £100,000, and its population exceeds 500,000. It is divided into twenty-five districts, its capital, the town of Isfahān, forming one of them. These twenty-five districts, some very small and consisting of only a little township and a few hamlets, are Isfahān, Jai, Barkhār, Kahāb, Kararaj, Baraān, Rūdasht, Marbin, Lenjān, Kerven, Rār, Kiar, Mizdej, Ganduman, Somairam, Jarkūyeh, Ardistan, Kūhpāyeh, Najafabad, Komisheh, Chadugan, Varzek, Tokhmaklu, 868 Gurji, Chinarūd. Most of these districts are very fertile, and produce great quantities of wheat, barley, rice, cotton, tobacco and opium. Lenjān, west of the city of Isfahān, is the greatest rice-producing district; the finest cotton comes from Jarkūyeh; the best opium and tobacco from the villages in the vicinity of the city.

The town of Isfahān or Ispahān, formerly the capital of Persia, now the capital of the province, is situated on the Zāyendeh river in 32° 39′ N. and 51° 40′ E.1 at an elevation of 5370 ft. Its population, excluding that of the Armenian colony of Julfa on the right or south bank of the river (about 4000), is estimated at 100,000 (73,654, including 5883 Jews, in 1882). The town is divided into thirty-seven mahallehs (parishes) and has 210 mosques and colleges (many half ruined), 84 caravanserais, 150 public baths and 68 flour mills. The water supply is principally from open canals led off from the river and from several streams and canals which come down from the hills in the north-west. The name of the Isfahān river was originally Zendeh (Pahlavi zendek) rūd, “the great river”; it was then modernized into Zindeh-rūd, “the living river,” and is now called Zayendeh rūd, “the life-giving river.” Its principal source is the Janāneh rūd which rises on the eastern slope of the Zardeh Kuh about 90 to 100 m. W. of Isfahān. After receiving the Khursang river from Feridan on the north and the Zarīn rūd from Chaharmahal on the south it is called Zendeh rūd. It then waters the Lenjan and Marbin districts, passes Isfahān as Zayendeh-rūd and 70 m. farther E. ends in the Gavkhani depression. From its entrance into Lenjan to its end 105 canals are led off from it for purposes of irrigation and 14 bridges cross it (5 at Isfahān). Its volume of water at Isfahān during the spring season has been estimated at 60,000 cub. ft. per second; in autumn the quantity is reduced to one-third, but nearly all of it being then used for feeding the irrigation canals very little is left for the river bed. The town covers about 20 sq. m., but many parts of it are in ruins. The old city walls—a ruined mud curtain—are about 5 m. in circumference.

Of the many fine public buildings constructed by the Sefavis and during the reign of the present dynasty very little remains. There are still standing in fairly good repair the two palaces named respectively Chehel Sitūn, “the forty pillars,” and Hasht Behesht, “the eight paradises,” the former constructed by Shah Abbas I. (1587-1629), the latter by Shah Soliman in 1670, and restored and renovated by Fath Ali Shah (1797-1834). They are ornamented with gilding and mirrors in every possible variety of Arabesque decoration, and large and brilliant pictures, representing scenes of Persian history, cover the walls of their principal apartments and have been ascribed in many instances to Italian and Dutch artists who are known to have been in the service of the Sefavis. Attached to these palaces were many other buildings such as the Imaretino built by Amīn ed-Dowleh (or Addaula) for Fath Ali Shah, the Imaret i Ashref built by Ashref Khan, the Afghan usurper, the Talār Tavīleh, Guldasteh, Sarpushīdeh, &c., erected in the early part of the 19th century by wealthy courtiers for the convenience of the sovereign and often occupied as residences of European ministers travelling between Bushire and Teheran and by other distinguished travellers. Perhaps the most agreeable residence of all was the Haft Dast, “the seven courts,” in the beautiful garden of Saādetabad on the southern bank of the river, and 2 or 3 m. from the centre of the city. This palace was built by Shah Abbas II. (1642-1667), and Fath Ali Shad Kajār died there in 1834. Close to it was the Aineh Khaneh, “hall of mirrors” and other elegant buildings in the Hazar jerib (1000 acre) garden. All these palaces and buildings on both sides of the river were surrounded by extensive gardens, traversed by avenues of tall trees, principally planes, and intersected by paved canals of running water with tanks and fountains. Since Fath Ali Shah’s death, palaces and gardens have been neglected. In 1902 an official was sent from Teheran to inspect the crown buildings, to report on their condition, and repair and renovate some, &c. The result was that all the above-mentioned buildings, excepting the Chehel Sitūn and Hasht Behesht, were demolished and their timber, bricks, stone, &c., sold to local builders. The gardens are wildernesses. The garden of the Chehel Sitūn palace opens out through the Alā Kapū (“highest gate, sublime porte”) to the Maidān-i-Shah, which is one of the most imposing piazzas in the world, a parallelogram of 560 yds. (N.-S.) by 174 yds. (E.-W.) surrounded by brick buildings divided into two storeys of recessed arches, or arcades, one above the other. In front of these arcades grow a few stunted planes and poplars. On the south side of the maidan is the famous Masjed i Shah (the shah’s mosque) erected by Shah Abbas I. in 1612-1613. It is covered with glazed tiles of great brilliancy and richly decorated with gold and silver ornaments and cost over £175,000. It is in good repair, and plans of it were published by C. Texier (L’Arménie, la Perse, &c., vol. i. pls. 70-72) and P. Coste (Monuments de la Perse). On the eastern side of the maidan stands the Masjed i Lutf Ullah with beautiful enamelled tiles and in good repair. Opposite to it on the western side of the maidan is the Alā Kapū, a lofty building in the form of an archway overlooking the maidan and crowned in the fore part by an immense open throne-room supported by wooden columns, while the hinder part is elevated three storeys higher. On the north side of the maidan is the entrance gate to the main bazaar surmounted by the Nekkāreh-Khaneh, or drumhouse, where is blared forth the appalling music saluting the rising and setting sun, said to have been instituted by Jamshīd many thousand years ago. West of the Chehel Sitūn palace and conducting N.-S. from the centre of the city to the great bridge of Allah Verdi Khan is the great avenue nearly a mile in length called Chahār Bagh, “the four gardens,” recalling the fact that it was originally occupied by four vineyards which Shah Abbas I. rented at £360 a year and converted into a splendid approach to his capital.

It was thus described by Lord Curzon of Kedleston in 1880: “Of all the sights of Isfahān, this in its present state is the most pathetic in the utter and pitiless decay of its beauty. Let me indicate what it was and what it is. At the upper extremity a two-storeyed pavilion,2 connected by a corridor with the Seraglio of the palace, so as to enable the ladies of the harem to gaze unobserved upon the merry scene below, looked out upon the centre of the avenue. Water, conducted in stone channels, ran down the centre, falling in miniature cascades from terrace to terrace, and was occasionally collected in great square or octagonal basins where cross roads cut the avenue. On either side of the central channel was a row of oriental planes and a paved pathway for pedestrians. Then occurred a succession of open parterres, usually planted or sown. Next on either side was a second row of planes, between which and the flanking walls was a raised causeway for horsemen. The total breadth is now fifty-two yards. At intervals corresponding with the successive terraces and basins, arched doorways with recessed open chambers overhead conducted through these walls into the various royal or noble gardens that stretched on either side, and were known as the Gardens of the Throne, of the Nightingale, of Vines, of Mulberries, Dervishes, &c. Some of these pavilions were places of public resort and were used as coffee-houses, where when the business of the day was over, the good burghers of Isfahān assembled to sip that beverage and inhale their kalians the while; as Fryer puts it: ’Night drawing on, all the pride of Spahaun was met in the Chaurbaug and the Grandees were Airing themselves, prancing about with their numerous Trains, striving to outvie each other in Pomp and Generosity.’ At the bottom, quays lined the banks of the river, and were bordered with the mansions of the nobility.”