The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 13, Slice 3, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 13, Slice 3

"Helmont, Jean" to "Hernosand"

Author: Various

Release Date: April 12, 2012 [EBook #39435]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 13, SLICE 3 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

HELMONT, JEAN BAPTISTE VAN (1577-1644), Belgian chemist, physiologist and physician, a member of a noble family, was born at Brussels in 1577.1 He was educated at Louvain, and after ranging restlessly from one science to another and finding satisfaction in none, turned to medicine, in which he took his doctor’s degree in 1599. The next few years he spent in travelling through Switzerland, Italy, France and England. Returning to his own country he was at Antwerp at the time of 250 the great plague in 1605, and having contracted a rich marriage settled in 1609 at Vilvorde, near Brussels, where he occupied himself with chemical experiments and medical practice until his death on the 30th of December 1644. Van Helmont presents curious contradictions. On the one hand he was a disciple of Paracelsus (though he scornfully repudiates his errors was well as those of most other contemporary authorities), a mystic with strong leanings to the supernatural, an alchemist who believed that with a small piece of the philosopher’s stone he had transmuted 2000 times as much mercury into gold; on the other hand he was touched with the new learning that was producing men like Harvey, Galileo and Bacon, a careful observer of nature, and an exact experimenter who in some cases realized that matter can neither be created nor destroyed. As a chemist he deserves to be regarded as the founder of pneumatic chemistry, even though it made no substantial progress for a century after his time, and he was the first to understand that there are gases distinct in kind from atmospheric air. The very word “gas” he claims as his own invention, and he perceived that his “gas sylvestre” (our carbon dioxide) given off by burning charcoal is the same as that produced by fermenting must and that which sometimes renders the air of caves irrespirable. For him air and water are the two primitive elements of things. Fire he explicitly denies to be an element, and earth is not one because it can be reduced to water. That plants, for instance, are composed of water he sought to show by the ingenious quantitative experiment of planting a willow weighing 5 ℔ in 200 ℔ of dry soil and allowing it to grow for five years; at the end of that time it had become a tree weighing 169 ℔, and since it had received nothing but water and the soil weighed practically the same as at the beginning, he argued that the increased weight of wood, bark and roots had been formed from water alone. It was an old idea that the processes of the living body are fermentative in character, but he applied it more elaborately than any of his predecessors. For him digestion, nutrition and even movement are due to ferments, which convert dead food into living flesh in six stages. But having got so far with the application of chemical principles to physiological problems, he introduces a complicated system of supernatural agencies like the archei of Paracelsus, which preside over and direct the affairs of the body. A central archeus controls a number of subsidiary archei which move through the ferments, and just as diseases are primarily caused by some affection (exorbitatio) of the archeus, so remedies act by bringing it back to the normal. At the same time chemical principles guided him in the choice of medicines—undue acidity of the digestive juices, for example, was to be corrected by alkalies and vice versa; he was thus a forerunner of the iatrochemical school, and did good service to the art of medicine by applying chemical methods to the preparation of drugs. Over and above the archeus he taught that there is the sensitive soul which is the husk or shell of the immortal mind. Before the Fall the archeus obeyed the immortal mind and was directly controlled by it, but at the Fall men received also the sensitive soul and with it lost immortality, for when it perishes the immortal mind can no longer remain in the body. In addition to the archeus, which he described as “aura vitalis seminum, vitae directrix,” Van Helmont had other governing agencies resembling the archeus and not always clearly distinguished from it. From these he invented the term blas, defined as the “vis motus tam alterivi quam localis.” Of blas there were several kinds, e.g. blas humanum and blas meteoron; the heavens he said “constare gas materiâ et blas efficiente.” He was a faithful Catholic, but incurred the suspicion of the Church by his tract De magnetica vulnerum curatione (1621), which was thought to derogate from some of the miracles. His works were collected and published at Amsterdam as Ortus medicinae, vel opera et opuscula omnia in 1668 by his son Franz Mercurius (b. 1618 at Vilvorde, d. 1699 at Berlin), in whose own writings, e.g. Cabbalah Denudata (1677) and Opuscula philosophica (1690), mystical theosophy and alchemy appear in still wilder confusion.

See M. Foster, Lectures on the History of Physiology (1901); also Chevreul in Journ. des savants (Feb. and March 1850), and Cap in Journ. pharm. chim. (1852). Other authorities are Poultier d’Elmoth, Mémoire sur J. B. van Helmont (1817); Rixner and Sieber, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Physiologie (1819-1826), vol. ii.; Spiers, Helmont’s System der Medicin (1840); Melsens, Leçons sur van Helmont (1848); Rommelaere, Études sur J. B. van Helmont (1860).

1 An alternative date for his birth is 1579 and for his death 1635 (see Bull. Roy. Acad. Belg., 1907, 7, p. 732).

HELMSTEDT, or more rarely Helmstädt, a town of Germany, in the duchy of Brunswick, 30 m. N.W. of Magdeburg on the main line of railway to Brunswick. Pop. (1905) 15,415. The principal buildings are the Juleum, the former university, built in the Renaissance style towards the close of the 16th century, and containing a library of 40,000 volumes; the fine Stephanskirche dating from the 12th century; the Walpurgiskirche restored in 1893-1894; the Marienberger Kirche, a beautiful church in the Roman style, and the Roman Catholic church. The Augustinian nunnery of Marienberg founded in 1176 is now a Lutheran school. The town contains the ruins of the Benedictine abbey of St Ludger, which was secularized in 1803. The educational institutions include several schools. The principal manufactures are furniture, yarn, soap, tobacco, sugar, vitriol and earthenware. Near the town is Bad Helmstedt, which has an iron mineral spring, and the Lübbensteine, two blocks of granite on which sacrifices to Woden are said to have been offered. Near Bad Helmstedt a monument has been erected to those who fell in the Franco-German War; in the town there is one to those killed at Waterloo. Helmstedt originated, according to legend, in connexion with the monastery founded by Ludger or Liudger (d. 809), the first bishop of Münster. There appears, however, little doubt that this tradition is mythical and that Helmstedt was not founded until about 900. It obtained civic rights in 1099 and, although destroyed by the archbishop of Magdeburg in 1199, it was soon rebuilt. In 1457 it joined the Hanseatic League, and in 1490 it came into the possession of Brunswick. In 1576 Julius, duke of Brunswick, founded a university here, and throughout the 17th century this was one of the chief seats of Protestant learning. It was closed by Jerome, king of Westphalia, in 1809.

See Ludewig, Geschichte und Beschreibung der Stadt Helmstedt (Helmstedt, 1821).

HELMUND, a river of Afghanistan, in length about 600 m. The Helmund, which is identical with the ancient Etymander, is the most important river in Afghanistan, next to the Kabul river, which it exceeds both in volume and length. It rises in the recesses of the Koh-i-Baba to the west of Kabul, its infant stream parting the Unai pass from the Irak, the two chief passes on the well-known road from Kabul to Bamian. For 50 m. from its source its course is ascertained, but beyond that point for the next 50 no European has followed it. About the parallel of 33° N. it enters the Zamindawar province which lies to the N.W. of Kandahar, and thenceforward it is a well-mapped river to its termination in the lake of Seistan. Till about 40 m. above Girishk the character of the Helmund is that of a mountain river, flowing through valleys which in summer are the resort of pastoral tribes. On leaving the hills it enters on a flat country, and extends over a gravelly bed. Here also it begins to be used in irrigation. At Girishk it is crossed by the principal route from Herat to Kandahar. Forty-five miles below Girishk the Helmund receives its greatest tributary, the Arghandab, from the high Ghilzai country beyond Kandahar, and becomes a very considerable river, with a width of 300 or 400 yds. and an occasional depth of 9 to 12 ft. Even in the dry season it is never without a plentiful supply of water. The course of the river is more or less south-west from its source till in Seistan it crosses meridian 62°, when it turns nearly north, and so flows for 70 or 80 m. till it falls into the Seistan hamuns, or swamps, by various mouths. In this latter part of its course it forms the boundary between Afghan and Persian Seistan, and owing to constant changes in its bed and the swampy nature of its borders it has been a fertile source of frontier squabbles. Persian Seistan was once highly cultivated by means of a great system of canal irrigation; but for centuries, since the country was devastated by Timur, it has been a barren, treeless waste of flat alluvial plain. In years of exceptional flood the Seistan lakes spread southwards into an overflow channel called the 251 Shelag which, running parallel to the northern course of the Helmund in the opposite direction, finally loses its waters in the Gaod-i-Zirreh swamp, which thus becomes the final bourne of the river. Throughout its course from its confluence with the Arghandab to the ford of Chahar Burjak, where it bends northward, the Helmund valley is a narrow green belt of fertility sunk in the midst of a wide alluvial desert, with many thriving villages interspersed amongst the remains of ancient cities, relics of Kaiani rule. The recent political mission to Seistan under Sir Henry McMahon (1904-1905) added much information respecting the ancient and modern channels of the lower Helmund, proving that river to have been constantly shifting its bed over a vast area, changing the level of the country by silt deposits, and in conjunction with the terrific action of Seistan winds actually altering its configuration.

HELM WIND, a wind that under certain conditions blows over the escarpment of the Pennines, near Cross Fell from the eastward, when a helm (helmet) cloud covers the summit. The helm bar is a roll of cloud that forms in front of it, to leeward.

See “Report on the Helm Wind Inquiry,” by W. Marriott, Quart. Journ. Roy. Met. Soc. xv. 103.

HELOTS (Gr. εἴλωτες or εἱλῶται), the serfs of the ancient Spartans. The word was derived in antiquity from the town of Helos in Laconia, but is more probably connected with ἕλος, a fen, or with the root of ἑλεῖν, to capture. Some scholars suppose them to have been of Achaean race, but they were more probably the aborigines of Laconia who had been enslaved by the Achaeans before the Dorian conquest. After the second Messenian war (see Sparta) the conquered Messenians were reduced to the status of helots, from which Epaminondas liberated them three centuries later after the battle of Leuctra (371 B.C.). The helots were state slaves bound to the soil—adscripti glebae—and assigned to individual Spartiates to till their holdings (κλῆροι); their masters could neither emancipate them nor sell them off the land, and they were under an oath not to raise the rent payable yearly in kind by the helots. In time of war they served as light-armed troops or as rowers in the fleet; from the Peloponnesian War onwards they were occasionally employed as heavy infantry (ὁπλῖται), distinguished bravery being rewarded by emancipation. That the general attitude of the Spartans towards them was one of distrust and cruelty cannot be doubted. Aristotle says that the ephors of each year on entering office declared war on the helots so that they might be put to death at any time without violating religious scruple (Plutarch, Lycurgus 28), and we have a well-attested record of 2000 helots being freed for service in war and then secretly assassinated (Thuc. iv. 80). But when we remember the value of the helots from a military and agricultural point of view we shall not readily believe that the crypteia was really, as some authors represent it, an organized system of massacre; we shall see in it “a good police training, inculcating hardihood and vigour in the young,” while at the same time getting rid of any helots who were found to be plotting against the state (see further Crypteia).

Intermediate between Helots and Spartiates were the two classes of Neodamodes and Mothones. The former were emancipated helots, or possibly their descendants, and were much used in war from the end of the 5th century; they served especially on foreign campaigns, as those of Thibron (400-399 B.C.) and Agesilaus (396-394 B.C.) in Asia Minor. The mothones or mothakes were usually the sons of Spartiates and helot mothers; they were free men sharing the Spartan training, but were not full citizens, though they might become such in recognition of special merit.

See C. O. Müller, History and Antiquities of the Doric Race (Eng. trans.), bk. iii. ch. 3.; G. Gilbert, Greek Constitutional Antiquities (Eng. trans.), pp. 30-35; A. H. J. Greenidge, Handbook of Greek Constitutional History, pp. 83-85; G. Busolt, Die griech. Staats- u. Rechtsaltertümer, § 84; Griechische Geschichte, i.[2] 525-528; G. F. Schömann, Antiquities of Greece: The State (Eng. trans.) pp. 194 ff.

HELPS, SIR ARTHUR (1813-1875), English writer and clerk of the Privy Council, youngest son of Thomas Helps, a London merchant, was born near London on the 10th of July 1813. He was educated at Eton and at Trinity College, Cambridge, coming out 31st wrangler in the mathematical tripos in 1835. He was recognized by the ablest of his contemporaries there as a man of superior gifts, and likely to make his mark in after life. As a member of the Conversazione Society, better known as the “Apostles,” a society established in 1820 for the purposes of discussion on social and literary questions by a few young men attracted to each other by a common taste for literature and speculation, he was associated with Charles Buller, Frederick Maurice, Richard Chenevix Trench, Monckton Milnes, Arthur Hallam and Alfred Tennyson. His first literary effort, Thoughts in the Cloister and the Crowd (1835), was a series of aphorisms upon life, character, politics and manners. Soon after leaving the university Arthur Helps became private secretary to Spring Rice (afterwards Lord Monteagle), then chancellor of the exchequer. This appointment he filled till 1839, when he went to Ireland as private secretary to Lord Morpeth (afterwards earl of Carlisle), chief secretary for Ireland. In the meanwhile (28th October 1836) Helps had married Bessy, daughter of Captain Edward Fuller. He was one of the commissioners for the settlement of certain Danish claims which dated so far back as the siege of Copenhagen; but with the fall of the Melbourne administration (1841) his official experience closed for a period of nearly twenty years. He was not, however, forgotten by his political friends. He possessed admirable tact and sagacity; his fitness for official life was unmistakable, and in 1860 he was appointed clerk of the Privy Council, on the recommendation of Lord Granville.

His Essays written in the Intervals of Business had appeared in 1841, and his Claims of Labour, an Essay on the Duties of the Employers to the Employed, in 1844. Two plays, King Henry the Second, an Historical Drama, and Catherine Douglas, a Tragedy, published in 1843, have no particular merit. Neither in these, nor in his only other dramatic effort, Oulita the Serf (1858) did he show any real qualifications as a playwright.

Helps possessed, however, enough dramatic power to give life and individuality to the dialogues with which he enlivened many of his other books. In his Friends in Council, a Series of Readings and Discourse thereon (1847-1859), Helps varied his presentment of social and moral problems by dialogues between imaginary personages, who, under the names of Milverton, Ellesmere and Dunsford, grew to be almost as real to Helps’s readers as they certainly became to himself. The book was very popular, and the same expedient was resorted to in Conversations on War and General Culture, published in 1871. The familiar speakers, with others added, also appeared in his Realmah (1868) and in the best of its author’s later works, Talk about Animals and their Masters (1873).

A long essay on slavery in the first series of Friends in Council was subsequently elaborated into a work in two volumes published in 1848 and 1852, called The Conquerors of the New World and their Bondsmen. Helps went to Spain in 1847 to examine the numerous MSS. bearing upon his subject at Madrid. The fruits of these researches were embodied in an historical work based upon his Conquerors of the New World, and called The Spanish Conquest in America, and its Relation to the History of Slavery and the Government of Colonies (4 vols., 1855-1857-1861). But in spite of his scrupulous efforts after accuracy, the success of the book was marred by its obtrusively moral purpose and its discursive character.

The Life of Las Casas, the Apostle of the Indians (1868), The Life of Columbus (1869), The Life of Pizarro (1869), and The Life of Hernando Cortes (1871), when extracted from the work and published separately, proved successful. Besides the books which have been already mentioned he wrote: Organization in Daily Life, an Essay (1862), Casimir Maremma (1870), Brevia, Short Essays and Aphorisms (1871), Thoughts upon Government (1872), Life and Labours of Mr Thomas Brassey (1872), Ivan de Biron (1874), Social Pressure (1875).

His appointment as clerk of the Council brought him into personal communication with Queen Victoria and the Prince 252 Consort, both of whom came to regard him with confidence and respect. After the Prince’s death, the Queen early turned to Helps to prepare an appreciation of her husband’s life and character. In his introduction to the collection (1862) of the Prince Consort’s speeches and addresses Helps adequately fulfilled his task. Some years afterwards he edited and wrote a preface to the Queen’s Leaves from a Journal of our Life in the Highlands (1868). In 1864 he received the honorary degree of D.C.L. from the university of Oxford. He was made a C.B. in 1871 and K.C.B. in the following year. His later years were troubled by financial embarrassments, and he died on the 7th of March 1875.

HELSINGBORG, a seaport of Sweden in the district (län) of Malmöhus, 35 m. N. by E. of Copenhagen by rail and water. Pop. (1900), 24,670. It is beautifully situated at the narrowest part of Öresund, or the Sound, here only 3 m. wide, opposite Helsingör (Elsinore) in Denmark. Above the town the brick tower of a former castle crowns a hill, commanding a fine view over the Sound. On the outskirts are the Öresund Park, gardens containing iodide and bromide springs, and frequented sea-baths. On the coast to the north is the royal château of Sofiero; to the south, the small spa of Ramlösa. A system of electric trams is maintained. North and east of Helsingborg lies the only coalfield in Sweden, extending into the lofty Kullen peninsula, which forms the northern part of the east shore of the Sound. Potter’s clay is also found. Helsingborg ranks among the first manufacturing towns of Sweden, having copper works, using ore from Sulitelma in Norway, india-rubber works and breweries. The artificial harbour has a depth of 24 ft., and there are extensive docks. The chief exports are timber, butter and iron. The town is the headquarters of the first army division.

The original site of the town is marked by the tower of the old fortress, which is first mentioned in 1135. In the 14th century it was several times besieged. From 1370 along with other towns in the province of Skåne, it was united for fifteen years with the Hanseatic League. The fortress was destroyed by fire in 1418, and about 1425 Eric XIII. built another near the sea, and caused the town to be transported thither, bestowing upon it important privileges. Until 1658 it belonged to Denmark, and it was again occupied by the Danes in 1676 and 1677. In 1684 its fortifications were dismantled. It was taken by Frederick IV. of Denmark in November 1709, but on the 28th of February 1710 the Danes were defeated in the neighbourhood, and the town came finally into the possession of Sweden, though in 1711 it was again bombarded by the Danes. A tablet on the quay commemorates the landing of Bernadotte after his election as successor to the throne in 1810.

HELSINGFORS (Finnish Helsinki), a seaport and the capital of Finland and of the province of Nyland, centre of the administrative, scientific, educational and industrial life of Finland. The fine harbour is divided into two parts by a promontory, and is protected at its entrance by a group of small islands, on one of which stands the fortress of Sveaborg. A third harbour is situated on the west side of the promontory, and all three have granite quays. The city, which in 1810 had only 4065 inhabitants, Åbo the then capital having 10,224, has increased with great rapidity, having 22,228 inhabitants in 1860, 61,530 in 1890 and 111,654 in 1904. It is the centre of an active shipping trade with the Baltic ports and with England, and of a railway system connecting it with all parts of the grand duchy and with St Petersburg. Helsingfors is handsome and well laid out with wide streets, parks, gardens and monuments. The principal square contains the cathedral of St Nicholas, the Senate House and the university, all striking buildings of considerable architectural distinction. In the centre is the statue of the Tsar Alexander II., who is looked upon as the protector of the liberties of Finland, the monument being annually decorated with wreaths and garlands. The university has a teaching staff of 141 with (1906) 1921 students, of whom 328 were women. The university is well provided with museums and laboratories and has a library of over 250,000 volumes. Other public institutions are the Athenaeum, with picture gallery, a Swedish theatre and opera house, a Finnish theatre, the Archives, the Senate House, the Nobles’ House (Riddarhuset) and the House of the Estates, the German (Lutheran) church and the Russian church. Some of the scientific societies of Helsingfors have a wide repute, such as the academy of sciences, the geographical, historical, Finno-Ugrian, biblical, medical, law, arts and forestry societies, as also societies for the spread of popular education and of arts and crafts. There are a polytechnic, ten high schools, navigation and trade schools, institutes for the blind and the mentally deficient, and numerous elementary schools. The general standard of education is high, the publication of books, reviews and newspapers being very active. The language of culture is Swedish, but owing to recent manufacturing developments the majority of the population is Finnish-speaking. Helsingfors displays great manufacturing and commercial activity, the imports being coal, machinery, sugar, grain and clothing. The manufactures of the city consist largely of tobacco, beer and spirits, carpets, machinery and sugar.

HELST, BARTHOLOMAEUS VAN DER, Dutch painter, was born in Holland at the opening of the 17th century, and died at Amsterdam in 1670. The date and place of his birth are uncertain; and it is equally difficult to confirm or to deny the time-honoured statement that he was born in 1613 at Amsterdam. It has been urged indeed by competent authority that Van der Helst was not a native of Amsterdam, because a family of that name lived as early as 1607 at Haarlem, and pictures are shown as works of Van der Helst in the Haarlem Museum which might tend to prove that he was in practice there before he acquired repute at Amsterdam. Unhappily Bartholomew has not been traced amongst the children of Severijn van der Helst, who married at Haarlem in 1607, and there is no proof that the pictures at Haarlem are really his; though if they were so they would show that he learnt his art from Frans Hals and became a skilled master as early as 1631. Scheltema, a very competent judge in matters of Dutch art chronology, supposes that Van der Heist was a resident at Amsterdam in 1636. His first great picture, representing a gathering of civic guards at a brewery, is variously assigned to 1639 and 1643, and still adorns the town-hall of Amsterdam. His noble portraits of the burgomaster Bicker and Andreas Bicker the younger, in the gallery of Amsterdam, of the same date no doubt as Bicker’s wife lately in the Ruhl collection at Cologne, were completed in 1642. From that time till his death there is no difficulty in tracing Van der Helst’s career at Amsterdam. He acquired and kept the position of a distinguished portrait-painter, producing indeed little or nothing besides portraits at any time, but founding, in conjunction with Nicolaes de Helt Stokade, the painters’ guild at Amsterdam in 1654. At some unknown date he married Constance Reynst, of a good patrician family in the Netherlands, bought himself a house in the Doelenstrasse and ended by earning a competence. His likeness of Paul Potter at the Hague, executed in 1654, and his partnership with Backhuysen, who laid in the backgrounds of some of his pictures in 1668, indicate a constant companionship with the best artists of the time. Wagen has said that his portrait of Admiral Kortenaar, in the gallery of Amsterdam, betrays the teaching of Frans Hals, and the statement need not be gainsaid; yet on the whole Van der Helst’s career as a painter was mainly a protest against the systems of Hals and Rembrandt. It is needless to dwell on the pictures which preceded that of 1648, called the Peace of Münster, in the gallery of Amsterdam. The Peace challenges comparison at once with the so-called Night Watch by Rembrandt and the less important but not less characteristic portraits of Hals and his wife in a neighbouring room. Sir Joshua Reynolds was disappointed by Rembrandt, whilst Van der Helst surpassed his expectation. But Bürger asked whether Reynolds had not already been struck with blindness when he ventured on this criticism. The question is still an open one. But certainly Van der Helst attracts by qualities entirely differing from those of Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Nothing can be more striking than the contrast between the strong concentrated light and the deep gloom of Rembrandt and the contempt of chiaroscuro 253 peculiar to his rival, except the contrast between the rapid sketchy touch of Hals and the careful finish and rounding of van der Helst. “The Peace” is a meeting of guards to celebrate the signature of the treaty of Münster. The members of the Doele of St George meet to feast and congratulate each other not at a formal banquet but in a spot laid out for good cheer, where de Wit, the captain of his company, can shake hands with his lieutenant Waveren, yet hold in solemn state the great drinking-horn of St George. The rest of the company sit, stand or busy themselves around—some eating, others drinking, others carving or serving—an animated scene on a long canvas, with figures large as life. Well has Bürger said, the heads are full of life and the hands admirable. The dresses and subordinate parts are finished to a nicety without sacrifice of detail or loss of breadth in touch or impast. But the eye glides from shape to shape, arrested here by expressive features, there by a bright stretch of colours, nowhere at perfect rest because of the lack of a central thought in light and shade, harmonies or composition. Great as the qualities of van der Helst undoubtedly are, he remains below the line of demarcation which separates the second from the first-rate masters of art.

His pictures are very numerous, and almost uniformly good; but in his later creations he wants power, and though still amazingly careful, he becomes grey and woolly in touch. At Amsterdam the four regents in the Werkhuys (1650), four syndics in the gallery (1656), and four syndics in the town-hall (1657) are masterpieces, to which may be added a number of fine single portraits. Rotterdam, notwithstanding the fire of 1864, still boasts of three of van der Helst’s works. The Hague owns but one. St Petersburg, on the other hand, possesses ten or eleven, of various shades of excellence. The Louvre has three, Munich four. Other pieces are in the galleries of Berlin, Brunswick, Brussels, Carlsruhe, Cassel, Darmstadt, Dresden, Frankfort, Gotha, Stuttgart and Vienna.

HELSTON, a market town and municipal borough in the Truro parliamentary division of Cornwall, England, 11 m. by road W.S.W. of Falmouth, on a branch of the Great Western railway. Pop. (1901) 3088. It is pleasantly situated on rising ground above the small river Cober, which, a little below the town, expands into a picturesque estuary called Looe Pool, the water being banked up by the formation of Looe Bar at the mouth. Formerly, when floods resulted from this obstruction, the townsfolk of Helston acquired the right of clearing a passage through it by presenting leathern purses containing three halfpence to the lord of the manor. The mining industry on which the town formerly depended is extinct, but the district is agricultural and dairy farming is carried on, while the town has flour mills, tanneries and iron foundries. As Helston has the nearest railway station to the Lizard, with its magnificent coast-scenery, there is a considerable tourist traffic in summer. Some trade passes through the small port of Porthleven, 3 m. S.W., where the harbour admits vessels of 500 tons. On the 8th of May a holiday is still observed in Helston and known as Flora or Furry day. It has been regarded as a survival of the Roman Floralia, but its origin is believed by some to be Celtic. Flowers and branches were gathered, and dancing took place in the streets and through the houses, all being thrown open, while a pageant was also given and a special ancient folk-song chanted. This ceremony, after being almost forgotten, has been revived in modern times. The borough is under a mayor, 4 aldermen and 12 councillors. Area, 309 acres.

Helston (Henliston, Haliston, Helleston), the capital of the Meneage district of Cornwall, was held by Earl Harold in the time of the Confessor and by King William at the Domesday Survey. At the latter date besides seventy-three villeins, bordars and serfs there were forty cervisarii, a species of unfree tenants who rendered their custom in the form of beer. King John (1201) constituted Helleston a free borough, established a gild merchant, and granted the burgesses freedom from toll and other similar dues throughout the realm, and the cognizance of all pleas within the borough except crown pleas. Richard, king of the Romans (1260), extended the boundaries of the borough and granted permission for the erection of an additional mill. Edward I. (1304) granted the pesage of tin, and Edward III. a Saturday market and four fairs. Of these the Saturday market and a fair on the feast of SS. Simon and Jude are still held, also five other fairs of uncertain origin. In 1585 Elizabeth granted a charter of incorporation under the name of the mayor and commonalty of Helston. This was confirmed in 1641, when it was also provided that the mayor and recorder should be ipso facto justices of the peace. From 1294 to 1832 Helston returned two members to parliament. In 1774 the number of electors (which by usage had been restricted to the mayor, aldermen and freemen elected by them) had dwindled to six, and in 1790 to one person only, whose return of two members, however, was rejected and that of the general body of the freemen accepted. In 1832 Helston lost one of its members, and in 1885 it lost the other and became merged in the county.

HELVETIC CONFESSIONS, the name of two documents expressing the common belief of the reformed churches of Switzerland. The first, known also as the Second Confession of Basel, was drawn up at that city in 1536 by Bullinger and Leo Jud of Zürich, Megander of Bern, Oswald Myconius and Grynaeus of Basel, Bucer and Capito of Strassburg, with other representatives from Schaffhausen, St Gall, Mühlhausen and Biel. The first draft was in Latin and the Zürich delegates objected to its Lutheran phraseology.1 Leo Jud’s German translation was, however, accepted by all, and after Myconius and Grynaeus had modified the Latin form, both versions were agreed to and adopted on the 26th of February 1536.

The Second Helvetic Confession was written by Bullinger in 1562 and revised in 1564 as a private exercise. It came to the notice of the elector palatine Friedrich III., who had it translated into German and published. It gained a favourable hold on the Swiss churches, who had found the First Confession too short and too Lutheran. It was adopted by the Reformed Church not only throughout Switzerland but in Scotland (1566), Hungary (1567), France (1571), Poland (1578), and next to the Heidelberg Catechism is the most generally recognized Confession of the Reformed Church.

See L. Thomas, La Confession helvétique (Geneva, 1853); P. Schaff, Creeds of Christendom, i. 390-420, iii. 234-306; Müller, Die Bekenntnisschriften der reformierten Kirche (Leipzig, 1903).

1 Some of the delegates, especially Bucer, were anxious to effect a union of the Reformed and Lutheran Churches. There was also a desire to lay the Confession before the council summoned at Mantua by Pope Paul III.

HELVETII (Ἑλουήτιοι, Ἑλβήττιοι), a Celtic people, whose original home was the country between the Hercynian forest (probably the Rauhe Alp), the Rhine and the Main (Tacitus, Germania, 28). In Caesar’s time they appear to have been driven farther west, since, according to him (Bell. Gall. i. 2. 3) their boundaries were on the W. the Jura, on the S. the Rhone and the Lake of Geneva, on the N. and E. the Rhine as far as Lake Constance. They thus inhabited the western part of modern Switzerland. They were divided into four cantons (pagi), common affairs being managed by the cantonal assemblies. They possessed the elements of a higher civilization (gold coinage, the Greek alphabet), and, according to Caesar, were the bravest people of Gaul. The reports of gold and plunder spread by the Cimbri and Teutones on their way to southern Gaul induced the Helvetii to follow their example. In 107, under Divico, two of their tribes, the Tougeni and Tigurini, crossed the Jura and made their way as far as Aginnum (Agen on the Garonne), where they utterly defeated the Romans under L. Cassius Longinus, and forced them to pass under the yoke (Livy, Epit. 65; according to a different reading, the battle took place near the Lake of Geneva). In 102 the Helvetii joined the Cimbri in the invasion of Italy, but after the defeat of the latter by Marius they returned home. In 58, hard pressed by the Germans and incited by one of their princes, Orgetorix, they resolved to found a hew home west of the Jura. Orgetorix was thrown into prison, being suspected of a design to make himself king, but the Helvetii themselves persisted in their plan. Joined by the Rauraci, Tulingi, Latobrigi and some of the Boii—according to their own reckoning 368,000 in all—they agreed to meet on the 28th of 254 March at Geneva and to advance through the territory of the Allobroges. They were overtaken, however, by Caesar at Bibracte, defeated and forced to submit. Those who survived were sent back home to defend the frontier of the Rhine against German invaders. During the civil wars and for some time after the death of Caesar little is heard of the Helvetii.

Under Augustus Helvetia (not so called till later times, earlier ager Helvetiorum) proper was included under Gallia Belgica. Two Roman colonies had previously been founded at Noviodunum (Colonia Julia Equestris, mod. Nyon) and at Colonia Rauracorum (afterwards Augusta Rauracorum, Augst near Basel) to keep watch over the inhabitants, who were treated with generosity by their conquerors. Under the name of foederati they retained their original constitution and division into four cantons. They were under an obligation to furnish a contingent to the Roman army for foreign service, but were allowed to maintain garrisons of their own, and their magistrates had the right to call out a militia. Their religion was not interfered with; they managed their own local affairs and kept their own language, although Latin was used officially. Their chief towns were Aventicum (Avenches) and Vindonissa (Windisch). Under Tiberius the Helvetii were separated from Gallia Belgica and made part of Germania Superior. After the death of Galba (A.D. 69), having refused submission to Vitellius, their land was devastated by Alienus Caecina, and only the eloquent appeal of one of their leaders named Claudius Cossus saved them from annihilation. Under Vespasian they attained the height of their prosperity. He greatly increased the importance of Aventicum, where his father had carried on business. Its inhabitants, with those of other towns, probably obtained the ius Latinum, had a senate, a council of decuriones, a prefect of public works and flamens of Augustus. After the extension of the eastern frontier, the troops were withdrawn from the garrisons and fortresses, and Helvetia, free from warlike disturbances, gradually became completely romanized. Aventicum had an amphitheatre, a public gymnasium and an academy with Roman professors. Roads were made wherever possible, and commerce rapidly developed. The old Celtic religion was also supplanted by the Roman. The west of the country, however, was more susceptible to Roman influence, and hence preserved its independence against barbarian invaders longer than its eastern portion. During the reign of Gallienus (260-268) the Alamanni overran the country; and although Probus, Constantius Chlorus, Julian, Valentinian I. and Gratian to some extent checked the inroads of the barbarians, it never regained its former prosperity. In the subdivision of Gaul in the 4th century, Helvetia, with the territory of the Sequani and Rauraci, formed the Provincia Maxima Sequanorum, the chief town of which was Vesontio (Besançon). Under Honorius (395-423) it was probably definitely occupied by the Alamanni, except in the west, where the small portion remaining to the Romans was ceded in 436 by Aëtius to the Burgundians.

See L. von Haller, Helvetien unter den Römern (Bern, 1811); T. Mommsen, Die Schweiz in römischer Zeit (Zürich, 1854); J. Brosi, Die Kelten und Althelvetier (Solothurn, 1851); L. Hug and R. Stead, “Switzerland” in Story of the Nations, xxvi.; C. Dändliker, Geschichte der Schweiz (1892-1895), and English translation (of a shorter history by the same) by E. Salisbury (1899); Die Schweiz unter den Römern (anonymous) published by the Historischer Verein of St Gall (Scheitlin and Zollikofer, St Gall, 1862); and G. Wyss, “Über das römische Helvetien” in Archiv für schweizerische Geschichte, vii. (1851). For Caesar’s campaign against the Helvetii, see T. R. Holmes, Caesar’s Conquest of Gaul (1899) and Mommsen, Hist. of Rome (Eng. trans.), bk. v. ch. 7; ancient authorities in A. Holder, Altkeltischer Sprachschatz (1896), s.v. Elvetii.

HELVÉTIUS, CLAUDE ADRIEN (1715-1771), French philosopher and littérateur, was born in Paris in January 1715. He was descended from a family of physicians, whose original name was Schweitzer (latinized as Helvetius). His grandfather introduced the use of ipecacuanha; his father was first physician to Queen Marie Leczinska of France. Claude Adrien was trained for a financial career, but he occupied his spare time with writing verses. At the age of twenty-three, at the queen’s request, he was appointed farmer-general, a post of great responsibility and dignity worth a 100,000 crowns a year. Thus provided for, he proceeded to enjoy life to the utmost, with the help of his wealth and liberality, his literary and artistic tastes. As he grew older, however, his social successes ceased, and he began to dream of more lasting distinctions, stimulated by the success of Maupertuis as a mathematician, of Voltaire as a poet, of Montesquieu as a philosopher. The mathematical dream seems to have produced nothing; his poetical ambitions resulted in the poem called Le Bonheur (published posthumously, with an account of Helvétius’s life and works, by C. F. de Saint-Lambert, 1773), in which he develops the idea that true happiness is only to be found in making the interest of one that of all; his philosophical studies ended in the production of his famous book De l’esprit. It was characteristic of the man that, as soon as he thought his fortune sufficient, he gave up his post of farmer-general, and retired to an estate in the country, where he employed his large means in the relief of the poor, the encouragement of agriculture and the development of industries. De l’esprit (Eng. trans. by W. Mudford, 1807), intended to be the rival of Montesquieu’s L’Esprit des lois, appeared in 1758. It attracted immediate attention and aroused the most formidable opposition, especially from the dauphin, son of Louis XV. The Sorbonne condemned the book, the priests persuaded the court that if was full of the most dangerous doctrines, and the author, terrified at the storm he had raised, wrote three separate retractations; yet, in spite of his protestations of orthodoxy, he had to give up his office at the court, and the book was publicly burned by the hangman. The virulence of the attacks upon the work, as much as its intrinsic merit, caused it to be widely read; it was translated into almost all the languages of Europe. Voltaire said that it was full of commonplaces, and that what was original was false or problematical; Rousseau declared that the very benevolence of the author gave the lie to his principles; Grimm thought that all the ideas in the book were borrowed from Diderot; according to Madame du Deffand, Helvétius had raised such a storm by saying openly what every one thought in secret; Madame de Graffigny averred that all the good things in the book had been picked up in her own salon. In 1764 Helvétius visited England, and the next year, on the invitation of Frederick II., he went to Berlin, where the king paid him marked attention. He then returned to his country estate and passed the remainder of his life in perfect tranquillity. He died on the 26th of December 1771.

His philosophy belongs to the utilitarian school. The four discussions of which his book consists have been thus summed up: (1) All man’s faculties may be reduced to physical sensation, even memory, comparison, judgment; our only difference from the lower animals lies in our external organization. (2) Self-interest, founded on the love of pleasure and the fear of pain, is the sole spring of judgment, action, affection; self-sacrifice is prompted by the fact that the sensation of pleasure outweighs the accompanying pain; it is thus the result of deliberate calculation; we have no liberty of choice between good and evil; there is no such thing as absolute right—ideas of justice and injustice change according to customs. (3) All intellects are equal; their apparent inequalities do not depend on a more or less perfect organization, but have their cause in the unequal desire for instruction, and this desire springs from passions, of which all men commonly well organized are susceptible to the same degree; and we can, therefore, all love glory with the same enthusiasm and we owe all to education. (4) In this discourse the author treats of the ideas which are attached to such words as genius, imagination, talent, taste, good sense, &c. The only original ideas in his system are those of the natural equality of intelligences and the omnipotence of education, neither of which, however, is generally accepted, though both were prominent in the system of J. S. Mill. There is no doubt that his thinking was unsystematic; but many of his critics have entirely misrepresented him (e.g. Cairns in his Unbelief in the Eighteenth Century). As J. M. Robertson (Short History of Free Thought) points out, he had great influence upon Bentham, and C. Beccaria states that he himself was largely inspired by Helvétius in his attempt to modify penal laws. The keynote of his thought was 255 that public ethics has a utilitarian basis, and he insisted strongly on the importance of culture in national development.

A sort of supplement to the De l’esprit, called De l’homme, de ses facultés intellectuelles et de son éducation (Eng. trans. by W. Hooper, 1777), found among his manuscripts, was published after his death, but created little interest. There is a complete edition of the works of Helvétius, published at Paris, 1818. For an estimate of his work and his place among the philosophers of the 18th century see Victor Cousin’s Philosophie sensualiste (1863); P. L. Lezaud, Résumés philosophiques (1853); F. D. Maurice, in his Modern Philosophy (1862), pp. 537 seq.; J. Morley, Diderot and the Encyclopaedists (London, 1878); D. G. Mostratos, Die Pädagogik des Helvétius (Berlin, 1891); A. Guillois, Le Salon de Madame Helvétius (1894); A. Piazzi, Le Idee filosofiche specialmente pedagogiche de C. A. Helvétius (Milan, 1889); G. Plekhanov, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Materialismus (Stuttgart, 1896); L. Limentani, Le Teorie psicologiche di C. A. Helvétius (Verona, 1902); A. Keim, Helvétius, sa vie et son œuvre (1907).

HELVIDIUS PRISCUS, Stoic philosopher and statesman, lived during the reigns of Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian. Like his father-in-law, Thrasea Paetus, he was distinguished for his ardent and courageous republicanism. Although he repeatedly offended his rulers, he held several high offices. During Nero’s reign he was quaestor of Achaea and tribune of the plebs (A.D. 56); he restored peace and order in Armenia, and gained the respect and confidence of the provincials. His declared sympathy with Brutus and Cassius occasioned his banishment in 66. Having been recalled to Rome by Galba in 68, he at once impeached Eprius Marcellus, the accuser of Thrasea Paetus, but dropped the charge, as the condemnation of Marcellus would have involved a number of senators. As praetor elect he ventured to oppose Vitellius in the senate (Tacitus, Hist. ii. 91), and as praetor (70) he maintained, in opposition to Vespasian, that the management of the finances ought to be left to the discretion of the senate; he proposed that the capitol, which had been destroyed in the Neronian conflagration, should be restored at the public expense; he saluted Vespasian by his private name, and did not recognize him as emperor in his praetorian edicts. At length he was banished a second time, and shortly afterwards was executed by Vespasian’s order. His life, in the form of a warm panegyric, written at his widow’s request by Herennius Senecio, caused its author’s death in the reign of Domitian.

Tacitus, Hist. iv. 5, Dialogus, 5; Dio Cassius lxvi. 12, lxvii. 13; Suetonius, Vespasian, 15; Pliny, Epp. vii. 19.

HELY-HUTCHINSON, JOHN (1724-1794), Irish lawyer, statesman, and provost of Trinity College, Dublin, son of Francis Hely, a gentleman of County Cork, was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and was called to the Irish bar in 1748. He took the additional name of Hutchinson on his marriage in 1751 with Christiana Nixon, heiress of her uncle, Richard Hutchinson. He was elected member of the Irish House of Commons for the borough of Lanesborough in 1759, but after 1761 he represented the city of Cork. He at first attached himself to the “patriotic” party in opposition to the government, and although he afterwards joined the administration he never abandoned his advocacy of popular measures. He was a man of brilliant and versatile ability, whom Lord Townshend, the lord lieutenant, described as “by far the most powerful man in parliament.” William Gerard Hamilton said of him that “Ireland never bred a more able, nor any country a more honest man.” Hely-Hutchinson was, however, an inveterate place-hunter, and there was point in Lord North’s witticism that “if you were to give him the whole of Great Britain and Ireland for an estate, he would ask the Isle of Man for a potato garden.” After a session or two in parliament he was made a privy councillor and prime serjeant-at-law; and from this time he gave a general, though by no means invariable, support to the government. In 1767 the ministry contemplated an increase of the army establishment in Ireland from 12,000 to 15,000 men, but the Augmentation Bill met with strenuous opposition, not only from Flood, Ponsonby and the habitual opponents of the government, but from the Undertakers, or proprietors of boroughs, on whom the government had hitherto relied to secure them a majority in the House of Commons. It therefore became necessary for Lord Townshend to turn to other methods for procuring support. Early In 1768 an English act was passed for the increase of the army, and a message from the king setting forth the necessity for the measure was laid before the House of Commons in Dublin. An address favourable to the government policy was, however, rejected; and Hely-Hutchinson, together with the speaker and the attorney-general, did their utmost both in public and private to obstruct the bill. Parliament was dissolved in May 1768, and the lord lieutenant set about the task of purchasing or otherwise securing a majority in the new parliament. Peerages, pensions and places were bestowed lavishly on those whose support could be thus secured; Hely-Hutchinson was won over by the concession that the Irish army should be established by the authority of an Irish act of parliament instead of an English one. The Augmentation Bill was carried in the session of 1769 by a large majority. Hely-Hutchinson’s support had been so valuable that he received as reward an addition of £1000 a year to the salary of his sinecure of Alnagar, a major’s commission in a cavalry regiment, and a promise of the secretaryship of state. He was at this time one of the most brilliant debaters in the Irish parliament, and he was enjoying an exceedingly lucrative practice at the bar. This income, however, together with his well-salaried sinecure, and his place as prime serjeant, he surrendered in 1774, to become provost of Trinity College, although the statute requiring the provost to be in holy orders had to be dispensed with in his favour.

For this great academic position Hely-Hutchinson was in no way qualified, and his appointment to it for purely political service to the government was justly criticized with much asperity. His conduct in using his position as provost to secure the parliamentary representation of the university for his eldest son brought him into conflict with Duigenan, who attacked him in Lacrymae academicae, and involved him in a duel with a Mr Doyle; while a similar attempt on behalf of his second son in 1790 led to his being accused before a select committee of the House of Commons of impropriety as returning officer. But although without scholarship Hely-Hutchinson was an efficient provost, during whose rule material benefits were conferred on Trinity College. He continued to occupy a prominent place in parliament, where he advocated free trade, the relief of the Catholics from penal legislation, and the reform of parliament. He was one of the very earliest politicians to recognize the soundness of Adam Smith’s views on trade; and he quoted from the Wealth of Nations, adopting some of its principles, in his Commercial Restraints of Ireland, published in 1779, which Lecky pronounces “one of the best specimens of political literature produced in Ireland in the latter half of the 18th century.” In the same year, the economic condition of Ireland being the cause of great anxiety, the government solicited from several leading politicians their opinion on the state of the country with suggestions for a remedy. Hely-Hutchinson’s response was a remarkably able state paper (MS. in the Record Office), which also showed clear traces of the influence of Adam Smith. The Commercial Restraints, condemned by the authorities as seditious, went far to restore Hely-Hutchinson’s popularity which had been damaged by his greed of office. Not less enlightened were his views on the Catholic question. In a speech in parliament on Catholic education in 1782 the provost declared that Catholic students were in fact to be found at Trinity College, but that he desired their presence there to be legalized on the largest scale. “My opinion,” he said, “is strongly against sending Roman Catholics abroad for education, nor would I establish Popish colleges at home. The advantage of being admitted into the university of Dublin will be very great to Catholics; they need not be obliged to attend the divinity professor, they may have one of their own; and I would have a part of the public money applied to their use, to the support of a number of poor lads as sizars, and to provide premiums for persons of merit, for I would have them go into examinations and make no distinction between them and the Protestants but such as merit might claim.” And after sketching a scheme for increasing the number of diocesan schools where Roman Catholics might receive free education, he went on to 256 urge that “it is certainly a matter of importance that the education of their priests should be as perfect as possible, and that if they have any prejudices they should be prejudices in favour of their own country. The Roman Catholics should receive the best education in the established university at the public expense; but by no means should Popish colleges be allowed, for by them we should again have the press groaning with themes of controversy, and subjects of religious disputation that have long slept in oblivion would again awake, and awaken with them all the worst passions of the human mind.”1

In 1777 Hely-Hutchinson became secretary of state. When Grattan in 1782 moved an address to the king containing a declaration of Irish legislative independence, Hely-Hutchinson supported the attorney-general’s motion postponing the question; but on the 16th of April, after the Easter recess, he read a message from the lord lieutenant, the duke of Portland, giving the king’s permission for the House to take the matter into consideration, and he expressed his personal sympathy with the popular cause which Grattan on the same day brought to a triumphant issue (see Grattan, Henry). Hely-Hutchinson supported the opposition on the regency question in 1788, and one of his last votes in the House was in favour of parliamentary reform. In 1790 he exchanged the constituency of Cork for that of Taghmon in County Wexford, for which borough he remained member till his death at Buxton on the 4th of September 1794.

In 1785 his wife had been created Baroness Donoughmore and on her death in 1788, his eldest son Richard (1756-1825) succeeded to the title. Lord Donoughmore was an ardent advocate of Catholic emancipation. In 1797 he was created Viscount Donoughmore,2 and in 1800 (having voted for the Union, hoping to secure Catholic emancipation from the united parliament) he was further created earl of Donoughmore of Knocklofty, being succeeded first by his brother John Hely-Hutchinson (1757-1832) and then by his nephew John, 3rd earl (1787-1851), from whom the title descended.

See W. E. H. Lecky, Hist. of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (5 vols., London, 1892); J. A. Froude, The English in Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (3 vols., London, 1872-1874); H. Grattan, Memoirs of the Life and Times of Henry Grattan (8 vols., London, 1839-1846); Baratariana, by various writers (Dublin, 1773).

1 Irish Parl. Debates, i. 309, 310.

2 It is generally supposed that the title conferred by this patent was that of Viscount Suirdale, and such is the courtesy title by which the heir apparent of the earls of Donoughmore is usually styled. This, however, appears to be an error. In all the three creations (barony 1783, viscountcy 1797, earldom 1800) the title is “Donoughmore of Knocklofty.” In 1821 the 1st earl was further created Viscount Hutchinson of Knocklofty in the peerage of the United Kingdom. The courtesy title of the earl’s eldest son should, therefore, apparently be either “Viscount Hutchinson” or “Viscount Knocklofty.” See G. E. C. Complete Peerage (London, 1890).

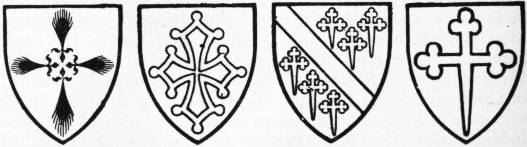

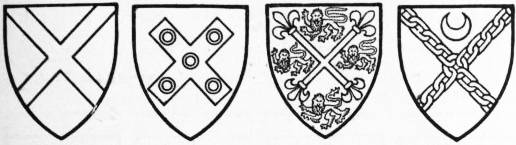

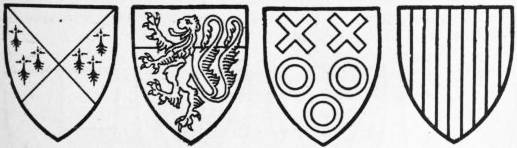

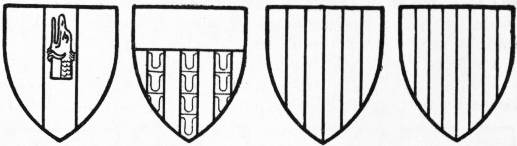

HELYOT, PIERRE (1660-1716), Franciscan friar and historian, was born at Paris in January 1660, of supposed English ancestry. After spending his youth in study, he entered in his twenty-fourth year the convent of the third order of St Francis, founded at Picpus, near Paris, by his uncle Jérôme Helyot, canon of St Sepulchre. There he took the name of Père Hippolyte. Two journeys to Rome on monastic business afforded him the opportunity of travelling over most of Italy; and after his final return he saw much of France, while acting as secretary to various provincials of his order there. Both in Italy and France he was engaged in collecting materials for his great work, which occupied him about twenty-five years, L’Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux, et militaires, et des congrégations séculières, de l’un et de l’autre sexe, qui ont été établies jusqu’à présent, published in 8 volumes in 1714-1721. Helyot died on the 5th of January 1716, before the fifth volume appeared, but his friend Maximilien Bullot completed the edition. Helyot’s only other noteworthy work is Le Chrétien mourant (1695).

The Histoire is a work of first importance, being the great repertory of information for the general history of the religious orders up to the end of the 17th century. It is profusely illustrated by large plates exhibiting the dress of the various orders, and in the edition of 1792 the plates are coloured. It was translated into Italian (1737) and into German (1753). The material has been arranged in dictionary form in Migne’s Encyclopédie théologique, under the title “Dictionnaire des orders religieux” (4 vols., 1858).

HEMANS, FELICIA DOROTHEA (1793-1835), English poet, was born in Duke Street, Liverpool, on the 25th of September 1793. Her father, George Browne, of Irish extraction, was a merchant in Liverpool, and her mother, whose maiden name was Wagner, was the daughter of the Austrian and Tuscan consul at Liverpool. Felicia, the fifth of seven children, was scarcely seven years old when her father failed in business, and retired with his family to Gwrych, near Abergele, Denbighshire; and there the young poet and her brothers and sisters grew up in a romantic old house by the sea-shore, and in the very midst of the mountains and myths of Wales. Felicia’s education was desultory. Books of chronicle and romance, and every kind of poetry, she read with avidity; and she also studied Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and German. She played both harp and piano, and cared especially for the simple national melodies of Wales and Spain. In 1808, when she was only fourteen, a quarto volume of her Juvenile Poems, was published by subscription, and was harshly criticized in the Monthly Review. Two of her brothers were fighting in Spain under Sir John Moore; and Felicia, fired with military enthusiasm, wrote England and Spain, or Valour and Patriotism, a poem afterwards translated into Spanish. Her second volume, The Domestic Affections and other Poems, appeared in 1812, on the eve of her marriage to Captain Alfred Hemans. She lived for some time at Daventry, where her husband was adjutant of the Northamptonshire militia. About this time her father went to Quebec on business and died there; and, after the birth of her first son, she and her husband went to live with her mother at Bronwylfa, a house near St Asaph. Here during the next six years four more children—all boys—were born; but in spite of domestic cares arid failing health she still read and wrote indefatigably. Her poem entitled The Restoration of Works of Art to Italy was published in 1816, her Modern Greece in 1817, and in 1818 Translations from Camoens and other Poets.

In 1818 Captain Hemans went to Rome, leaving his wife, shortly before the birth of their fifth child, with her mother at Bronwylfa. There seems to have been a tacit agreement, perhaps on account of their limited means, that they should separate. Letters were interchanged, and Captain Hemans was often consulted about his children; but the husband and wife never met again. Many friends—among them the bishop of St Asaph and Bishop Heber—gathered round Mrs Hemans and her children. In 1819 she published Tales and Historic Scenes in Verse, and gained a prize of £50 offered for the best poem on The Meeting of Wallace and Bruce on the Banks of the Carron. In 1820 appeared The Sceptic and Stanzas to the Memory of the late King. In June 1821 she won the prize awarded by the Royal Society of Literature for the best poem on the subject of Dartmoor, and began her play, The Vespers of Palermo. She now applied herself to a course of German reading. Körner was her favourite German poet, and her lines on the grave of Körner were one of the first English tributes to the genius of the young soldier-poet. In the summer of 1823 a volume of her poems was published by Murray, containing “The Siege of Valencia,” “The Last Constantine” and “Belshazzar’s Feast.” The Vespers of Palermo was acted at Covent Garden, December 12, 1823, and Mrs Hemans received £200 for the copyright; but, though the leading parts were taken by Young and Charles Kemble, the play was a failure, and was withdrawn after the first performance. It was acted again in Edinburgh in the following April with greater success, when an epilogue, written for it by Sir Walter Scott at Joanna Baillie’s request, was spoken by Harriet Siddons. This was the beginning of a cordial friendship between Mrs Hemans and Scott. In the same year she wrote De Chatillon, or the Crusaders; but the manuscript was lost, and the poem was published after her death, from a rough copy. In 1824 she began “The Forest Sanctuary,” 257 which appeared a year later with the “Lays of Many Lands” and miscellaneous pieces collected from the New Monthly Magazine and other periodicals.

In the spring of 1825 Mrs Hemans removed from Bronwylfa, which had been purchased by her brother, to Rhyllon, a house on an opposite height across the river Clwyd. The contrast between the two houses suggested her Dramatic Scene between Bronwylfa and Rhyllon. The house itself was bare and unpicturesque, but the beauty of its surroundings has been celebrated in “The Hour of Romance,” “To the River Clwyd in North Wales,” “Our Lady’s Well” and “To a Distant Scene.” This time seems to have been the most tranquil in Mrs Hemans’s life. But the death of her mother in January 1827 was a second great breaking-point in her life. Her heart was affected, and she was from this time an acknowledged invalid. In the summer of 1828 the Records of Woman was published by Blackwood, and in the same year the home in Wales was finally broken up by the marriage of Mrs Hemans’s sister and the departure of her two elder boys to their father in Rome. Mrs Hemans removed to Wavertree, near Liverpool. But, although she had a few intimate friends there—among them her two subsequent biographers, Henry F. Chorley and Mrs Lawrence of Wavertree Hall—she was disappointed in her new home. She thought the people of Liverpool stupid and provincial; and they, on the other hand, found her uncommunicative and eccentric. In the following summer she travelled by sea to Scotland with two of her boys, to visit the Hamiltons of Chiefswood.

Here she enjoyed “constant, almost daily, intercourse” with Sir Walter Scott, with whom she and her boys afterwards stayed some time at Abbotsford. “There are some whom we meet, and should like ever after to claim as kith and kin; and you are one of those,” was Scott’s compliment to her at parting. One of the results of her Edinburgh visit was an article, full of praise, judiciously tempered with criticism, by Jeffrey himself for the Edinburgh Review. Mrs Hemans returned to Wavertree to write her Songs of the Affections, which were published early in 1830. In the following June, however, she again left home, this time to visit Wordsworth and the Lake country; and in August she paid a second visit to Scotland. In 1831 she removed to Dublin. Her poetry of this date is chiefly religious. Early in 1834 her Hymns for Childhood, which had appeared some years before in America, were published in Dublin. At the same time appeared her collection of National Lyrics, and shortly afterwards Scenes and Hymns of Life. She was planning also a series of German studies, one of which, on Goethe’s Tasso, was completed and published in the New Monthly Magazine for January 1834. In intervals of acute suffering she wrote the lyric Despondency and Aspiration, and dictated a series of sonnets called Thoughts during Sickness, the last of which, “Recovery,” was written when she fancied she was getting well. After three months spent at Redesdale, Archbishop Whately’s country seat, she was again brought into Dublin, where she lingered till spring. Her last poem, the Sabbath Sonnet, was dedicated to her brother on Sunday April 26th, and she died in Dublin on the 16th of May 1835 at the age of forty-one.

Mrs Hemans’s poetry is the production of a fine imaginative and enthusiastic temperament, but not of a commanding intellect or very complex or subtle nature. It is the outcome of a beautiful but singularly circumscribed life, a life spent in romantic seclusion, without much worldly experience, and warped and saddened by domestic unhappiness and physical suffering. An undue preponderance of the emotional is its prevailing characteristic. Scott complained that it was “too poetical,” that it contained “too many flowers” and “too little fruit.” Many of her short poems, such as “The Treasures of the Deep,” “The Better Land,” “The Homes of England,” “Casabianca,” “The Palm Tree,” “The Graves of a Household,” “The Wreck,” “The Dying Improvisatore,” and “The Lost Pleiad,” have become standard English lyrics. It is on the strength of these that her reputation must rest.

Mrs Hemans’s Poetical Works were collected in 1832; her Memorials &c., by H. F. Chorley (1836).

HEMEL HEMPSTEAD, a market-town and municipal borough in the Watford parliamentary division of Hertfordshire, England, 25 m. N.W. from London, with a station on a branch of the Midland railway from Harpenden, and near Boxmoor station on the London and North Western main line. Pop. (1891) 9678; (1901) 11,264. It is pleasantly situated in the steep-sided valley of the river Gade, immediately above its junction with the Bulbourne, near the Grand Junction canal. The church of St Mary is a very fine Norman building with Decorated additions. Industries include the manufacture of paper, iron founding, brewing and tanning. Boxmoor, within the parish, is a considerable township of modern growth. Hemel Hempstead is governed by a mayor, 6 aldermen and 18 councillors. Area, 7184 acres.

Settlements in the neighbourhood of Hemel Hempstead (Hamalamstede, Hemel Hampsted) date from pre-Roman times, and a Roman villa has been discovered at Boxmoor. The manor, royal demesne in 1086, was granted by Edmund Plantagenet in 1285 to the house of Ashridge, and the town developed under monastic protection. In 1539 a charter incorporated the bailiff and inhabitants. A mayor, aldermen and councillors received governing power by a charter of 1898. The town has never had parliamentary representation. A market on Thursday and a fair on the feast of Corpus Christi were conferred in 1539. A statute fair, for long a hiring fair, originated in 1803.

HEMEROBAPTISTS, an ancient Jewish sect, so named from their observing a practice of daily ablution as an essential part of religion. Epiphanius (Panarion, i. 17), who mentions their doctrine as the fourth heresy among the Jews, classes the Hemerobaptists doctrinally with the Pharisees (q.v.) from whom they differed only in, like the Sadducees, denying the resurrection of the dead. The name has been sometimes given to the Mandaeans on account of their frequent ablutions; and in the Clementine Homilies (ii. 23) St John the Baptist is spoken of as a Hemerobaptist. Mention of the sect is made by Hegesippus (see Euseb. Hist. Eccl. iv. 22) and by Justin Martyr in the Dialogue with Trypho, § 80. They were probably a division of the Essenes.

HEMICHORDA, or Hemichordata, a zoological term introduced by W. Bateson in 1884, without special definition, as equivalent to Enteropneusta, which then included the single genus Balanoglossus, and now generally employed to cover a group of marine worm-like animals believed by many zoologists to be related to the lower vertebrates and so to represent the invertebrate stock from which Vertebrates have been derived. Vertebrates, or as they are sometimes termed Chordates, are distinguished from other animals by several important features. The chief of these is the presence of an elastic rod, the notochord, which forms the longitudinal axis of the body, and which persists throughout life in some of the lowest forms, but which appears only in the embryo of the higher forms, being replaced by the jointed backbone or vertebral column. A second feature is the development of outgrowths of the pharynx which unite with the skin of the neck and form a series of perforations leading to the exterior. These structures are the gill-slits, which in fishes are lined with vascular tufts, but which in terrestrial breathing animals appear only in the embryo. The third feature of importance is the position of structure of the central nervous system, which in all the Chordates lies dorsally to the alimentary canal and is formed by the sinking in of a longitudinal media dorsal groove. Of these structures the Vertebrata or Craniata possess all three in a typical form; the Cephalochordata (see Amphioxus) also possess them, but the notochord extends throughout the whole length of the body to the extreme tip of the snout; the Urochordata (see Tunicata) possess them in a larval condition, but the notochord is present only in the tail, whilst in the adult the notochord disappears and the nervous system becomes profoundly modified; in the Hemichorda, the respiratory organs very closely resemble gill-slits, and structures comparable with the notochord and the tubular dorsal nervous system are present.

The Hemichorda include three orders, the Phoronidea (q.v.), the Pterobranchia (q.v.) and the Enteropneusta (see Balanoglossus), 258 but the relationship to the Chordata expressed in the designation Hemichordata cannot be regarded as more than an attractive theory with certain arguments in its favour.

HEMICYCLE (Gr. ἡμι-, half, and κύκλος, circle), a semicircular recess of considerable size which formed one of the most conspicuous features in the Roman Thermae, where it was always covered with a hemispherical vault. A small example exists in Pompeii, in the street of tombs, with a seat round inside, where those who came to pay their respects to the departed could rest. An immense hemicycle was designed by Bramante for the Vatican, where it constitutes a fine architectural effect at the end of the great court.

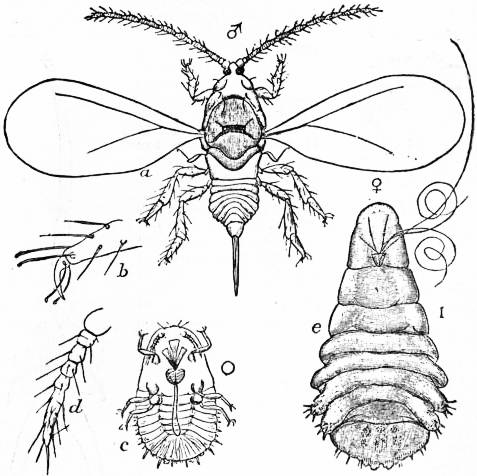

HEMIMERUS, an Orthopterous or Dermapterous insect, the sole representative of the family Hemimeridae, which has affinities with both the Forficulidae (earwigs) and the Blattidae (cockroaches). Only two species have been discovered, both from West Africa. The better known of these (H. hanseni) lives upon a large rat-like rodent (Cricetomys gambianus) feeding perhaps upon its external parasites, perhaps upon scurf and other dermal products. Like many epizoic or parasitic insects, Hemimerus is wingless, eyeless and has relatively short and strong legs. Correlated also with its mode of life is the curious fact that it is viviparous, the young being born in an advanced stage of growth.

|

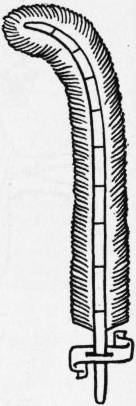

HEMIMORPHITE, a mineral consisting of hydrous zinc silicate, H2Zn2SiO5, of importance as an ore of the metal, of which it contains 54.4%. It is interesting crystallographically by reason of the hemimorphic development of its orthorhombic crystals; these are prismatic in habit and are differently terminated at the two ends. In the figure, the faces at the upper end of the crystal are the basal plane k and the domes o, p, l, m, whilst at the lower end there are only the four faces of the pyramid P. Connected with this polarity of the crystals is their pyroelectric character—when a crystal is subjected to changes of temperature it becomes positively electrified at one end and negatively at the opposite end. There are perfect cleavages parallel to the prism faces (d in the figure). Crystals are usually colourless, sometimes yellowish or greenish, and transparent; they have vitreous lustre. The hardness is 5, and the specific gravity 3.45. The mineral also occurs as stalactitic or botryoidal masses with a fibrous structure, or in a massive, cellular or granular condition intermixed with calamine and clay. It is decomposed by hydrochloric acid with gelatinization; this property affords a ready means of distinguishing hemimorphite from calamine (zinc carbonate), these two minerals being, when not crystallized, very like each other in appearance. The water contained in hemimorphite is expelled only at a red heat, and the mineral must therefore be considered as a basic metasilicate, (ZnOH)2SiO3.

The name hemimorphite was given by G. A. Kenngott in 1853 because of the typical hemimorphic development of the crystals. The mineral had long been confused with calamine (q.v.) and even now this name is often applied to it. On account of its pyroelectric properties, it was called electric calamine by J. Smithson in 1803.

Hemimorphite occurs with other ores of zinc (calamine and blende), forming veins and beds in sedimentary limestones. British localities are Matlock, Alston, Mendip Hills and Leadhills; at Roughten Gill, Caldbeck Fells, Cumberland, it occurs as mammillated incrustations of a sky-blue colour. Well-crystallized specimens have been found in the zinc mines at Altenberg near Aachen in Rhenish Prussia, Nerchinsk mining district in Siberia, and Elkhorn in Montana.

HEMINGBURGH, WALTER OF, also commonly, but erroneously, called Walter Hemingford, a Latin chronicler of the 14th century, was a canon regular of the Austin priory of Gisburn in Yorkshire. Hence he is sometimes known as Walter of Gisburn (Walterus Gisburnensis). Bale seems to have been the first to give him the name by which he became more commonly known. His chronicle embraces the period of English history from the Conquest (1066) to the nineteenth year of Edward III., with the exception of the years 1316-1326. It ends with the title of a chapter in which it was proposed to describe the battle of Creçy (1346); but the chronicler seems to have died before the required information reached him. There is, however, some controversy as to whether the later portions which are lacking in some of the MSS. are by him. In compiling the first part, Hemingburgh apparently used the histories of Eadmer, Hoveden, Henry of Huntingdon, and William of Newburgh; but the reigns of the three Edwards are original, composed from personal observation and information. There are several manuscripts of the history extant—the best perhaps being that presented to the College of Arms by the earl of Arundel. The work is correct and judicious, and written in a pleasing style. One of its special features is the preservation in its pages of copies of the great charters, and Hemingburgh’s versions have more than once supplied deficiencies and cleared up obscurities in copies from other sources.

The first three books were published by Thomas Gale in 1687, in his Historiae Anglicanae scriptores quinque, and the remainder by Thomas Hearne in 1731. The first portion was again published in 1848 by the English Historical Society, under the title Chronicon Walteri de Hemingburgh, vulgo Hemingford nuncupati, de gestis regum Angliae, edited by H. C. Hamilton.

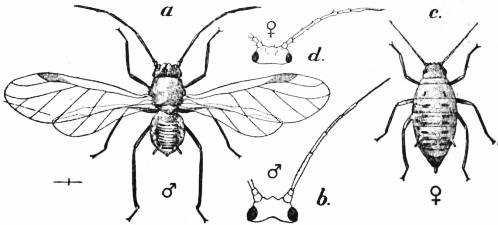

HEMIPTERA (Gr. ἡμι-, half and πτερόν, a wing), the name applied in zoological classification to that order of the class Hexapoda (q.v.) which includes bugs, cicads, aphids and scale-insects. The name was first used by Linnaeus (1735), who derived it from the half-coriaceous and half-membranous condition of the forewing in many members of the order. But the wings vary considerably in different families, and the most distinctive feature is the structure of the jaws, which form a beak-like organ with stylets adapted for piercing and sucking. Hence the name Rhyngota (or Rhynchota), proposed by J. C. Fabricius (1775), is used by many writers in preference to Hemiptera.

|

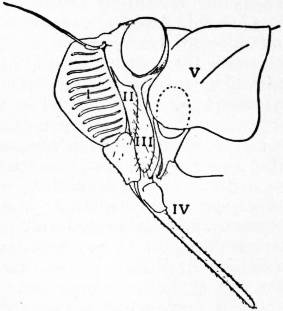

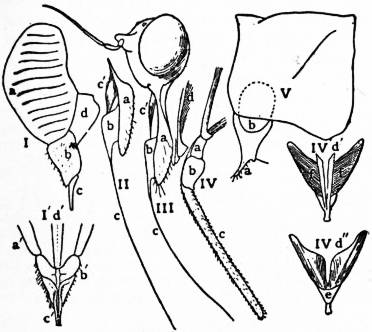

| After Marlatt, Bull. 14 (N.S.) Div. Ent. U.S. Dept. Agr. |

| Fig. 1.—Head and Prothorax of Cicad from side. |

I., Frons. II., Base of mandible. III., Base of first maxillae. IV., Second maxillae forming rostrum. V., Pronotum. |