Project Gutenberg's Loss of the Steamship 'Titanic', by British Government

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Loss of the Steamship 'Titanic'

Author: British Government

Release Date: April 15, 2012 [EBook #39415]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LOSS OF THE STEAMSHIP 'TITANIC' ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

PRICE $6.00

62D Congress

2d Session |

|

SENATE |

|

{ |

DOCUMENT

No. 933 |

LOSS OF THE

STEAMSHIP "TITANIC"

———

| REPORT |

OF A FORMAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE

CIRCUMSTANCES ATTENDING THE FOUND-

ERING

ON APRIL 15, 1912, OF THE BRITISH

STEAMSHIP "TITANIC," OF LIVERPOOL,

AFTER STRIKING ICE IN OR NEAR LATI-

TUDE

41° 46“ N., LONGITUDE 50° 14“ W.,

NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN, AS CONDUCTED |

| BY THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT |

PRESENTED BY MR. SMITH OF MICHIGAN

AUGUST 20, 1912.—Ordered to be printed with illustrations

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Page. |

| Introduction | 7 |

| I. | Description of the ship | 10 |

| | | The White Star Co. | 10 |

| | | The steamship Titanic | 11 |

| | | Detailed description | 13 |

| | | Water-tight compartments | 14 |

| | | Decks and accommodation | 16 |

| | | Structure | 23 |

| | | Life-saving appliances | 25 |

| | | Pumping arrangements | 26 |

| | | Electrical installation | 27 |

| | | Machinery | 29 |

| | | General | 31 |

| | | Crew and passengers | 32 |

| II. | Account of the ship's journey across the Atlantic, the messages she received, and the disaster | 32 |

| | | The sailing orders | 32 |

| | | The route followed | 33 |

| | | Ice messages received | 35 |

| | | Speed of the ship | 39 |

| | | The weather conditions | 40 |

| | | Action that should have been taken | 40 |

| | | The collision | 41 |

| III. | Description of the damage to the ship and of its gradual and final effect, with observations thereon | 42 |

| | | Extent of the damage | 42 |

| | | Time in which the damage was done | 42 |

| | | The flooding in the first 10 minutes | 42 |

| | | Gradual effect of the damage | 43 |

| | | Final effect of the damage | 44 |

| | | Observations | 45 |

| | | Effect of additional subdivision upon floatation | 46 |

| IV. | Account of the saving and rescue of those who survived | 48 |

| | | The boats | 48 |

| | | Conduct of Sir C. Duff Gordon and Mr. Ismay | 53 |

| | | The third-class passengers | 53 |

| | | Means taken to procure assistance | 54 |

| | | The rescue by the steamship "Carpathia" | 54 |

| | | Numbers saved | 55 |

| V. | The circumstances in connection with the steamship "Californian" | 56 |

| VI. | The Board of Trade's administration | 60 |

| VII. | Finding of the court | 77 |

| VIII. | Recommendations | 85 |

| | | Water-tight subdivision | 85 |

| | | Lifeboats and rafts | 86 |

| | | Manning the boats and boat drills | 87 |

| | | General | 87 |

REPORT ON THE LOSS OF THE STEAMSHIP "TITANIC."

The Merchants Shipping Acts, 1894 to 1906.

In the matter of the formal investigation held at the Scottish

Hall, Buckingham Gate, Westminster, on May 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14,

15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24, June 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12,

13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 21, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, and 29; at the Caxton

Hall, Caxton Street, Westminster, on July 1 and 3; and at the

Scottish Hall, Buckingham Gate, Westminster, on July 30, 1912,

before the Right Hon. Lord Mersey, Wreck Commissioner, assisted by

Rear Admiral the Hon. S. A. Gough-Calthorpe, C. V. O., R. N.; Capt.

A. W. Clarke; Commander F. C. A. Lyon, R. N. R.; Prof. J. H. Biles,

D. Sc., LL. D. and Mr. E. C. Chaston, R. N. R., as assessors, into

the circumstances attending the loss of the steamship Titanic, of

Liverpool, and the loss of 1,490 lives in the North Atlantic Ocean,

in lat. 41° 46“ N., long. 50° 14“ W. on April 15 last.

REPORT OF THE COURT.

The court, having carefully inquired into the circumstances of the

above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds, for the reasons appearing in

the annex hereto, that the loss of the said ship was due to collision

with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship

was being navigated.

Dated this 30th day of July, 1912.

MERSEY,

Wreck Commissioner.

We concur in the above report.

ARTHUR GOUGH-CALTHORPE,

A. W. CLARKE,

F. C. A. LYON,

J. H. BILES,

EDWARD C. CHASTON,

Assessors.

LOSS OF THE STEAMSHIP "TITANIC."

REPORT OF A FORMAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE CIRCUMSTANCES ATTENDING

THE FOUNDERING ON APRIL 15, 1912, OF THE BRITISH STEAMSHIP TITANIC,

OF LIVERPOOL, AFTER STRIKING ICE IN OR NEAR LATITUDE 41° 46“ N.,

LONGITUDE 50° 14“ W., NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN, WHEREBY LOSS OF LIFE

ENSUED.

Annex to the Report.

INTRODUCTION.

On April 23, 1912, the Lord Chancellor appointed a wreck commissioner

under the merchant shipping acts, and on April 26 the home secretary

nominated five assessors. On April 30 the board of trade requested that

a formal investigation of the circumstances attending the loss of the

steamship Titanic should be held, and the court accordingly commenced

to sit on May 2. Since that date there have been 37 public sittings, at

which 97 witnesses have been examined, while a large number of

documents, charts, and plans have been produced. The 26 questions

formulated by the board of trade, which are set out in detail below,

appear to cover all the circumstances to be inquired into. Briefly

summarized, they deal with the history of the ship, her design,

construction, size, speed, general equipment, life-saving apparatus,

wireless installation, her orders and course, her passengers, her crew,

their training, organization and discipline; they request an account of

the casualty, its cause and effect, and of the means taken for saving

those on board the ship; and they call for a report on the efficiency of

the rules and regulations made by the board of trade under the merchant

shipping acts and on their administration, and, finally, for any

recommendations to obviate similar disasters which may appear to the

court to be desirable. The 26 questions, as subsequently amended, are

here attached:

1. When the Titanic left Queenstown on or about April 11 last—

(a) What was the total number of persons employed in any capacity on

board her, and what were their respective ratings?

(b) What was the total number of her passengers, distinguishing sexes

and classes, and discriminating between adults and children?

2. Before leaving Queenstown on or about April 11 last did the Titanic

comply with the requirements of the merchant shipping acts, 1894-1906,

and the rules and regulations made thereunder with regard to the safety

and otherwise of "passenger steamers" and "emigrant ships"?

3. In the actual design and construction of the Titanic what special

provisions were made for the safety of the vessel and the lives of those

on board in the event of collisions and other casualties?

4. Was the Titanic sufficiently and efficiently officered and manned?

Were the watches of the officers and crew usual and proper? Was the

Titanic supplied with proper charts?

5. What was the number of the boats of any kind on board the Titanic?

Were the arrangements for manning and launching the boats on board the

Titanic in case of emergency proper and sufficient? Had a boat drill

been held on board; and, if so, when? What was the carrying capacity of

the respective boats?

6. What installations for receiving and transmitting messages by

wireless telegraphy were on board the Titanic? How many operators were

employed on working such installations? Were the installations in good

and effective working order, and were the number of operators sufficient

to enable messages to be received and transmitted continuously by day

and night?

7. At or prior to the sailing of the Titanic what, if any,

instructions as to navigation were given to the master or known by him

to apply to her voyage? Were such instructions, if any, safe, proper,

and adequate, having regard to the time of year and dangers likely to be

encountered during the voyage?

8. What was in fact the track taken by the Titanic in crossing the

Atlantic Ocean? Did she keep to the track usually followed by liners on

voyages from the United Kingdom to New York in the month of April? Are

such tracks safe tracks at that time of the year? Had the master any,

and, if so, what, discretion as regards the track to be taken?

9. After leaving Queenstown on or about April 11 last did information

reach the Titanic by wireless messages or otherwise by signals of the

existence of ice in certain latitudes? If so, what were such messages or

signals and when were they received, and in what position or positions

was the ice reported to be, and was the ice reported in or near the

track actually being followed by the Titanic? Was her course altered

in consequence of receiving such information; and, if so, in what way?

What replies to such messages or signals did the Titanic send, and at

what times?

10. If at the times referred to in the last preceding question or later

the Titanic was warned of or had reason to suppose she would encounter

ice, at what time might she have reasonably expected to encounter it?

Was a good and proper lookout for ice kept on board? Were any, and, if

so, what, directions given to vary the speed; if so, were they carried

out?

11. Were binoculars provided for and used by the lookout men? Is the use

of them necessary or usual in such circumstances? Had the Titanic the

means of throwing searchlights around her? If so, did she make use of

them to discover ice? Should searchlights have been provided and used?

12. What other precautions were taken by the Titanic in anticipation

of meeting ice? Were they such as are usually adopted by vessels being

navigated in waters where ice may be expected to be encountered?

13. Was ice seen and reported by anybody on board the Titanic before

the casualty occurred? If so, what measures were taken by the officer on

watch to avoid it? Were they proper measures and were they promptly

taken?

14. What was the speed of the Titanic shortly before and at the moment

of the casualty? Was such speed excessive under the circumstances?

15. What was the nature of the casualty which happened to the Titanic

at or about 11.45 p. m. on April 14 last? In what latitude and longitude

did the casualty occur?

16. What steps were taken immediately on the happening of the casualty?

How long after the casualty was its seriousness realized by those in

charge of the vessel? What steps were then taken? What endeavors were

made to save the lives of those on board and to prevent the vessel from

sinking?

17. Was proper discipline maintained on board after the casualty

occurred?

18. What messages for assistance were sent by the Titanic after the

casualty, and at what times, respectively? What messages were received

by her in response, and at what times, respectively? By what vessels

were the messages that were sent by the Titanic received, and from

what vessels did she receive answers? What vessels other than the

Titanic sent or received messages at or shortly after the casualty in

connection with such casualty? What were the vessels that sent or

received such messages? Were any vessels prevented from going to the

assistance of the Titanic or her boats owing to messages received from

the Titanic or owing to any erroneous messages being sent or received?

In regard to such erroneous messages, from what vessels were they sent

and by what vessels were they received, and at what times, respectively?

19. Was the apparatus for lowering the boats on the Titanic at the

time of the casualty in good working order? Were the boats swung out,

filled, lowered, or otherwise put into the water and got away under

proper superintendence? Were the boats sent away in seaworthy condition

and properly manned, equipped, and provisioned? Did the boats, whether

those under davits or otherwise, prove to be efficient and serviceable

for the purpose of saving life?

20. What was the number of (a) passengers, (b) crew taken away in

each boat on leaving the vessel? How was this number made up, having

regard to (1) sex, (2) class, (3) rating? How many were children and how

many adults? Did each boat carry its full load; and if not, why not?

21. How many persons on board the Titanic at the time of the casualty

were ultimately rescued and by what means? How many lost their lives

prior to the arrival of the steamship Carpathia in New York? What was

the number of passengers distinguishing between men and women and adults

and children of the first, second, and third classes, respectively, who

were saved? What was the number of the crew, discriminating their

ratings and sex, that were saved? What is the proportion which each of

these numbers bears to the corresponding total number on board

immediately before the casualty? What reason is there for the

disproportion, if any?

22. What happened to the vessel from the happening of the casualty until

she foundered?

23. Where and at what time did the Titanic founder?

24. What was the cause of the loss of the Titanic, and of the loss of

life which thereby ensued or occurred? What vessels had the opportunity

of rendering assistance to the Titanic; and if any, how was it that

assistance did not reach the Titanic before the steamship Carpathia

arrived? Was the construction of the vessel and its arrangements such as

to make it difficult for any class of passengers or any portion of the

crew to take full advantage of any of the existing provisions for

safety?

25. When the Titanic left Queenstown, on or about April 11 last, was

she properly constructed and adequately equipped as a passenger steamer

and emigrant ship for the Atlantic service?

26. The court is invited to report upon the rules and regulations made

under the merchant shipping acts, 1894-1906, and the administration of

those acts and of such rules and regulations, so far as the

consideration thereof is material to this casualty, and to make any

recommendations or suggestions that it may think fit, having regard to

the circumstances of the casualty with a view to promoting the safety of

vessels and persons at sea.

In framing this report it has seemed best to divide it into sections in

the following manner:

First. A description of the ship as she left Southampton on April 10 and

of her equipment, crew, and passengers.

Second. An account of her journey across the Atlantic, of the messages

she received and of the disaster.

Third. A description of the damage to the ship and of its gradual and

final effect with observations thereon.

Fourth. An account of the saving and rescue of those who survived.

Fifth. The circumstances in connection with the steamship Californian.

Sixth. An account of the board of trade's administration.

Seventh. The finding of the court on the questions submitted; and

Eighth. The recommendations held to be desirable.

I.—Description of the Ship.

THE WHITE STAR LINE.

The Titanic was one of a fleet of 13 ships employed in the transport

of passengers, mails, and cargo between Great Britain and the United

States, the usual ports of call for the service in which she was engaged

being Southampton, Cherbourg, Plymouth, Queenstown, and New York.

The owners are the Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. (Ltd.), usually known as

the White Star Line, a British registered company, with a capital of

£750,000, all paid up, the directors being Mr. J. Bruce Ismay

(chairman), the Right Hon. Lord Pirrie, and Mr. H. A. Sanderson.

The company are owners of 29 steamers and tenders; they have a large

interest in 13 other steamers, and also own a training sailing ship for

officers.

All the shares of the company, with the exception of eight held by

Messrs. E. C. Grenfell, Vivian H. Smith, W. S. M. Burns, James Gray, J.

Bruce Ismay, H. A. Sanderson, A. Kerr, and the Right Hon. Lord Pirrie,

have, since the year 1902, been held by the International Navigation Co.

(Ltd.), of Liverpool, a British registered company, with a capital of

£700,000, of which all is paid up, the directors being Mr. J. Bruce

Ismay (chairman), and Messrs. H. A. Sanderson, Charles F. Torrey, and H.

Concannon.

The debentures of the company, £1,250,000, are held mainly, if not

entirely, in the United Kingdom by the general public.

The International Navigation Co. (Ltd.), of Liverpool, in addition to

holding the above-mentioned shares of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Co.

(Ltd.), is also the owner of—

1. Practically the whole of the issued share capital of the British &

North Atlantic Steam Navigation Co. (Ltd.), and the Mississippi &

Dominion Steamship Co. (Ltd.), (the Dominion Line).

2. Practically the whole of the issued share capital of the Atlantic

Transport Co. (Ltd), (the Atlantic Transport Line).

3. Practically the whole of the issued ordinary share capital and about

one-half of the preference share capital of Frederick Leyland & Co.

(Ltd.), (the Leyland Line).

As against the above-mentioned shares and other property, the

International Navigation Co. (Ltd.) have issued share lien certificates

for £25,000,000.

Both the shares and share lien certificates of the International

Navigation Co. (Ltd.) are now held by the International Mercantile

Marine Co. of New Jersey, or by trustees for the holders of its

debenture bonds.

THE STEAMSHIP "TITANIC."

The Titanic was a three-screw vessel of 46,328 tons gross and 21,831

net register tons, built by Messrs. Harland & Wolff for the White Star

Line service between Southampton and New York. She was registered as a

British steamship at the port of Liverpool, her official number being

131,428. Her registered dimensions were—

| Feet |

| Length | 852.50 |

| Breadth | 92.50 |

Depth from top of keel to top of beam at lowest point of sheer of C deck,

the highest deck which extends continuously from bow to stern | 64.75 |

| Depth of hold | 59.58 |

| Height from B to C deck | 9.00 |

| Height from A to B deck | 9.00 |

| Height from boat to A deck | 9.50 |

| Height from boat deck to water line amidships at time of accident, about | 60.50 |

| Displacement at 34 feet 7 inches is | tons | 52,310 |

The propelling machinery consisted of two sets of four-cylinder

reciprocating engines, each driving a wing propeller, and a turbine

driving the center propeller. The registered horsepower of the

propelling machinery was 50,000. The power which would probably have

been developed was at least 55,000.

Structural arrangements.—The structural arrangements of the Titanic

consisted primarily of—

(1) An outer shell of steel plating, giving form to the ship up to the

top decks.

(2) Steel decks.—These were enumerated as follows:

| |

Height

to next

deck

above. |

Distance from

34 feet 7 inches water

line amidships. |

| |

|

Above. |

Below. |

| |

Ft. in. |

Ft. in. |

Ft. in. |

| Boat deck, length about 500 feet | | 58 0 | |

| A deck, length about 500 feet | 9 6 | 48 6 | |

| B deck, length about 550 feet, with 125 feet forecastle and 105 feet poop | 9 0 | 39 6 | |

| C deck, whole length of ship | 9 0 | 30 6 | |

| D deck, whole length of ship | 10 6 | 20 0 | |

| |

|

(Tapered

down at

ends.) |

|

| E deck, whole length of ship | 9 0 | 11 0 | |

| F deck, whole length of ship | 8 6 | 2 6 | |

| G deck, 190 feet forward of boilers, 210 feet aft of machinery | 8 0 | | 5 6 |

| Orlop deck, 190 feet forward of boilers, 210 feet aft of machinery | 8 0 | | 13 6 |

C, D, E, and F were continuous from end to end of the ship. The decks

above these were continuous for the greater part of the ship, extending

from amidships both forward and aft. The boat deck and A deck each had

two expansion joints, which broke the strength continuity. The decks

below were continuous outside the boiler and engine rooms and extended

to the ends of the ship. Except in small patches none of these decks was

water-tight in the steel parts, except the weather deck and the orlop

deck aft.

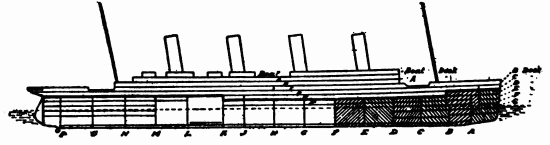

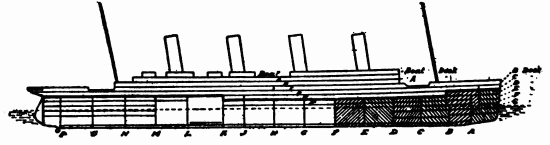

(3) Transverse vertical bulkheads.—There were 15 transverse

water-tight bulkheads, by which the ship was divided in the direction of

her length into 16 separate compartments. These bulkheads are referred

to as "A" to "P," commencing forward.

The water-tightness of the bulkheads extended up to one or other of the

decks D or E; the bulkhead A extended to C, but was only water-tight to

D deck. The position of the D, E, and F decks, which were the only ones

to which the water-tight bulkheads extended, was in relation to the

water line (34 feet 7 inches draft) approximately as follows:

| |

Height above water line

(34 feet 7 inches). |

| |

Lowest

part

amid-

ships. |

At bow. |

At stern. |

| |

Ft. in. |

Ft. in. |

Ft. in. |

| D |

20 0 |

33 0 |

25 0 |

| E |

11 0 |

24 0 |

16 0 |

| F |

2 6 |

15 6 |

7 6 |

These were the three of the four decks which, as already stated, were

continuous all fore and aft. The other decks, G and orlop, which

extended only along a part of the ship, were spaced about 8 feet apart.

The G deck forward was about 7 feet 6 inches above the water line at the

bow and about level with the water line at bulkhead D, which was at the

fore end of boilers. The G deck aft and the orlop deck at both ends of

the vessel were below the water line. The orlop deck abaft of the

turbine engine room and forward of the collision bulkhead was

water-tight. Elsewhere, except in very small patches, the decks were not

water-tight. All the decks had large openings or hatchways in them in

each compartment, so that water could rise freely through them.

There was also a water-tight inner bottom, or tank top, about 5 feet

above the top of the keel, which extended for the full breadth of the

vessel from bulkhead A to 20 feet before bulkhead P, i.e., for the whole

length of the vessel except a small distance at each end. The transverse

water-tight divisions of this double bottom practically coincided with

the water-tight transverse bulkheads; there was an additional

water-tight division under the middle of the reciprocating engine-room

compartment (between bulkheads K and L). There were three longitudinal

water-tight divisions in the double bottom, one at the center of the

ship, extending for about 670 feet, and one on each side, extending for

447 feet.

All the transverse bulkheads were carried up water-tight to at least the

height of the E deck. Bulkheads A and B, and all bulkheads from K (90

feet abaft amidships) to P, both inclusive, further extended water-tight

up to the underside of D deck. A bulkhead further extended to C deck,

but it was water-tight only to D deck.

Bulkheads A and B forward, and P aft, had no openings in them. All the

other bulkheads had openings in them, which were fitted with water-tight

doors. Bulkheads D to O, both inclusive, had each a vertical sliding

water-tight door at the level of the floor of the engine and boiler

rooms for the use of the engineers and firemen. On the Orlop deck there

was one door, on bulkhead N, for access to the refrigerator rooms. On G

deck there were no water-tight doors in the bulkheads. On both the F and

E decks nearly all the bulkheads had water-tight doors, mainly for

giving communication between the different blocks of passenger

accommodation. All the doors, except those in the engine-rooms and

boiler rooms, were horizontal sliding doors workable by hand, both at

the door and at the deck above.

There were 12 vertical sliding water-tight doors which completed the

water-tightness of bulkheads D to O, inclusive, in the boiler and engine

rooms. Those were capable of being simultaneously closed from the

bridge. The operation of closing was intended to be preceded by the

ringing from the bridge of a warning bell.

These doors were closed by the bringing into operation of an electric

current and could not be opened until this current was cut off from the

bridge. When this was done the doors could only be opened by a

mechanical operation manually worked separately at each door. They

could, however, be individually lowered again by operating a lever at

the door. In addition, they would be automatically closed, if open,

should water enter the compartment. This operation was done in each case

by means of a float, actuated by the water, which was in either of the

compartments which happened to be in the process of being flooded.

There were no sluice valves or means of letting water from one

compartment to another.

DETAILED DESCRIPTION.

The following is a more detailed description of the vessel, her

passenger and crew accommodation, and her machinery.

WATER-TIGHT COMPARTMENTS.

The following table shows the decks to which the bulkheads extended, and

the number of doors in them:

Bulkhead

letter. |

Extends

up to

under-

side of

deck. |

Engine

and boiler

spaces (all

controlled

from

bridge). |

Orlop to

G deck. |

F to E

deck. |

E to D

deck. |

| A | C | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| B | D | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| C | E | ... | ... | 1 | ... |

| D | E | [1]1 | ... | 1 | ... |

| E | E | [2]1 | ... | ... | ... |

| F | E | [2]1 | ... | 2 | ... |

| G | E | [2]1 | ... | ... | ... |

| H | E | [2]1 | ... | 2 | ... |

| J | E | [2]1 | ... | 2 | ... |

| K | D | 1 | ... | ... | 2 |

| L | D | 1 | ... | ... | 2 |

| M | D | 1 | ... | 1 | 2 |

| N | D | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| O | D | 1 | ... | ... | 1 |

| P | D | ... | ... | ... | ... |

The following table shows the actual contents of each separate

water-tight compartment. The compartments are shown in the left column,

the contents of each compartment being read off horizontally. The

contents of each water-tight compartment is separately given in the deck

space in which it is:

Water-tight

compartment |

Length

of each

water-tight

compartment

in fore

and aft

direction. |

Hold. |

Orlop

to G

deck. |

G to F

deck. |

F to E

deck. |

E to D

deck. |

| |

Feet. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bow to A | 46 |

Forepeak

tank (not

used

excepting

for

trimming

ship).

| Forepeak

storeroom.

| Forepeak

storeroom.

| Forepeak

storeroom.

| Forepeak

storeroom. |

| A-B | 45 |

Cargo. |

Cargo. |

Living

spaces for

firemen,

etc. |

Living

spaces for

firemen.

|

Living

spaces for

firemen.

|

| B-C | 51 |

do |

do |

Third-class

passenger

accommo-

dation. |

Third-class

passenger

accommo-

dation.

|

Third-class

passenger

and seamen's

spaces. |

| C-D | 51 |

Alternati-

vely coal

and cargo.

|

Luggage

and

mails.

|

Baggage,

squash

rackets, &

third-class

passengers.

|

do |

Third-class

passenger

accommo-

dation. |

| D-E | 54 |

No. 6

boiler

room.

|

No. 6

boiler

room.

|

Coal and

boiler

casing.

|

do |

First-class

passenger

accommo-

dation. |

| E-F | 57 |

No. 5

boiler

room.

|

No. 5

boiler

room.

|

Coal bunker

and boiler

casing and

swimming

bath.

|

Linen rooms

and

swimming

bath.

|

Do. |

| F-G | 57 |

No. 4

boiler room. |

No. 4

boiler room. |

Coal bunker

and boiler

casing.

|

Steward's,

Turkish

baths, etc.

|

First-class

and

stewards. |

| G-H | 57 |

No. 3

boiler room. |

No. 3

boiler room. |

do. |

Third-class

saloon. |

First and

second

class and

stewards. |

| H-J | 60 |

No. 2

boiler room. |

No. 2

boiler room. |

do. |

do. |

First class. |

| J-K | 35 |

No. 1

boiler room. |

No. 1

boiler room. |

do. |

Third-class

galley,

stewards,

etc.

|

First class

and

stewards. |

| K-L | 69 |

Reciprocat-

ing-engine

room.

|

Reciprocat-

ing-engine

room.

|

Reciprocat-

ing-engine

room casing,

workshop and

engineers'

stores.

|

Engineers'

and recipro-

cating-

engine

casing.

|

First class

and

engineers'

mess, etc.

|

| L-M | 57 |

Turbine-

engine room. |

Turbine-

engine room. |

Turbine-

engine room

casing and

small

stewards'

stores.

|

Second-class

and turbine-

engine room

casing.

|

Second class

and stewards

etc. |

| M-N | 63 |

Electric-

engine room. |

Provisions

and electric

engine

casing.

|

Provisions. |

Second class |

Second and

third class. |

| N-O | 54 |

Tunnel |

Refrigerated

cargo. |

Third class |

do |

Do. |

| O-P | 57 |

do |

Cargo |

do |

Third class |

Third class. |

P to

stern | |

Afterpeak

tank for

trimming

ship.

|

Afterpeak

tank for

trimming

ship.

|

Stores |

Stores |

Stores. |

The vessel was constructed under survey of the British Board of Trade

for a passenger certificate, and also to comply with the American

immigration laws.

Steam was supplied from six entirely independent groups of boilers in

six separate water-tight compartments. The after boiler room No. 1

contained five single-ended boilers. Four other boiler rooms, Nos. 2, 3,

4, and 5, each contained five double-ended boilers. The forward boiler

room, No. 6, contained four double-ended boilers. The reciprocating

engines and most of the auxiliary machinery were in a seventh separate

water-tight compartment aft of the boilers; the low-pressure turbine,

the main condensers, and the thrust blocks of the reciprocating engine

were in an eighth separate water-tight compartment. The main electrical

machinery was in a ninth separate water-tight compartment immediately

abaft the turbine engine room. Two emergency steam-driven dynamos were

placed on the D deck, 21 feet above the level of the load water line.

These dynamos were arranged to take their supply of steam from any of

the three of the boiler rooms Nos. 2, 3, and 5, and were intended to be

available in the event of the main dynamo room being flooded.

The ship was equipped with the following:

(1) Wireless telegraphy.

(2) Submarine signaling.

(3) Electric lights and power systems.

(4) Telephones for communication between the different working positions

in the vessel. In addition to the telephones, the means of communication

included engine and docking telegraphs, and duplicate or emergency

engine-room telegraph, to be used in the event of any accident to the

ordinary telegraph.

(5) Three electric elevators for taking passengers in the first class up

to A deck, immediately below the boat deck, and one in the second class

for taking passengers up to the boat deck.

(6) Four electrically driven boat winches on the boat deck for hauling

up the boats.

(7) Life-saving appliances to the requirements of the board of trade,

including boats and life belts.

(8) Steam whistles on the two foremost funnels, worked on the

Willett-Bruce system of automatic control.

(9) Navigation appliances, including Kelvin's patent sounding machines

for finding the depth of water under the ship without stopping; Walker's

taffrail log for determining the speed of the ship; and flash signal

lamps fitted above the shelters at each of the navigating bridge for

Morse signaling with other ships.

DECKS AND ACCOMMODATION.

The boat deck was an uncovered deck, on which the boats were placed. At

its lowest point it was about 92 feet 6 inches above the keel. The

overall length of this deck was about 500 feet. The forward end of it

was fitted to serve as the navigating bridge of the vessel and was 190

feet from the bow. On the after end of the bridge was a wheel house,

containing the steering wheel and a steering compass. The chart room was

immediately abaft this. On the starboard side of the wheel house and

funnel casing were the navigating room, the captain's quarters, and some

officers' quarters. On the port side were the remainder of the officers'

quarters. At the middle line abaft the forward funnel casing were the

wireless-telegraphy rooms and the operators' quarters. The top of the

officers' house formed a short deck. The connections from the Marconi

aerials were made on this deck, and two of the collapsible boats were

placed on it. Aft of the officers' house were the first-class

passengers' entrance and stairways and other adjuncts to the passengers'

accommodation below. These stairways had a minimum effective width of 8

feet. They had assembling landings at the level of each deck, and three

elevators communicating from E to A decks, but not to the boat deck,

immediately on the fore side of the stairway.

All the boats except two Engelhardt life rafts were carried on this

deck. There were seven lifeboats on each side, 30 feet long, 9 feet

wide. There was an emergency cutter, 25 feet long, on each side at the

fore end of the deck. Abreast of each cutter was an Engelhardt life

raft. One similar raft was carried on the top of the officers' house on

each side. In all there were 14 lifeboats, 2 cutters, and 4 Engelhardt

life rafts.

The forward group of four boats and one Engelhardt raft were placed on

each side of the deck alongside the officers' quarters and the

first-class entrance. Further aft at the middle line on this deck was

the special platform for the standard compass. At the after end of this

deck was an entrance house for second-class passengers with a stairway

and elevator leading directly down to F deck. There were two vertical

iron ladders at the after end of this deck leading to A deck for the use

of the crew. Alongside and immediately forward of the second-class

entrance was the after group of lifeboats, four on each side of the

ship.

In addition to the main stairways mentioned there was a ladder on each

side amidships giving access from the A deck below. At the forward end

of the boat deck there was on each side a ladder leading up from A deck

with a landing there, from which by a ladder access to B deck could be

obtained direct. Between the reciprocating engine casing and the third

funnel casing there was a stewards' stairway, which communicated with

all the decks below as far as E deck. Outside the deck houses was

promenading space for first-class passengers.

A deck.—The next deck below the boat deck was A deck. It extended

over a length of about 500 feet. On this deck was a long house extending

nearly the whole length of the deck. It was of irregular shape, varying

in width from 24 feet to 72 feet. At the forward end it contained 34

staterooms and abaft these a number of public rooms, etc., for

first-class passengers, including two first-class entrances and

stairway, reading room, lounge, and the smoke room. Outside the deck

house was a promenade for first-class passengers. The forward end of it

on both sides of the ship, below the forward group of boats and for a

short distance farther aft, was protected against the weather by a steel

screen, 192 feet long, with large windows in it. In addition to the

stairway described on the boat deck, there was near the after end of the

A deck and immediately forward of the first-class smoke room another

first-class entrance, giving access as far down as C deck. The

second-class stairway at the after end of this deck (already described

under the boat deck) had no exit on to the A deck. The stewards'

staircase opened onto this deck.

B deck.—The next lowest deck was B deck, which constituted the top

deck of the strong structure of the vessel, the decks above and the side

plating between them being light plating. This deck extended

continuously for 550 feet. There were breaks or wells both forward and

aft of it, each about 50 feet long. It was terminated by a poop and

forecastle. On this deck were placed the principal staterooms of the

vessel, 97 in number, having berths for 198 passengers, and aft of these

was the first-class stairway and reception room, as well as the

restaurant for first-class passengers and its pantry and galley.

Immediately aft of this restaurant were the second-class stairway and

smoke room. At the forward end of the deck outside the house was an

assembling area, giving access by the ladders, previously mentioned,

leading directly to the boat deck. From this same space a ladderway led

to the forward third-class promenade on C deck. At the after end of it

were two ladders giving access to the after third-class promenade on C

deck. At the after end of this deck, at the middle line, was placed

another second-class stairway, which gave access to C, D, E, F, and G

decks.

At the forward end of the vessel, on the level of the B deck, was

situated the forecastle deck, which was 125 feet long. On it were

placed the gear for working the anchors and cables and for warping (or

moving) the ship in dock. At the after end, on the same level, was the

poop deck, about 105 feet long, which carried the after-warping

appliances and was a third-class promenading space. Arranged above the

poop was a light docking bridge, with telephone, telegraphs, etc.,

communicating to the main navigating bridge forward.

C deck.—The next lowest deck was C deck. This was the highest deck

which extended continuously from bow to stern. At the forward end of it,

under the forecastle, was placed the machinery required for working the

anchors and cables and for the warping of the ship referred to on B deck

above. There were also the crew's galley and the seamen's and firemen's

mess-room accommodation, where their meals were taken. At the after end

of the forecastle, at each side of the ship, were the entrances to the

third-class spaces below. On the port side, at the extreme after end and

opening onto the deck, was the lamp room. The break in B deck between

the forecastle and the first-class passenger quarters formed a well

about 50 feet in length, which enabled the space under it on C deck to

be used as a third-class promenade. This space contained two hatchways,

the No. 2 hatch, and the bunker hatch. The latter of these hatchways

gave access to the space allotted to the first and second class baggage

hold, the mails, specie and parcel room, and to the lower hold, which

was used for cargo or coals. Abaft of this well there was a house 450

feet long and extending for the full breadth of the ship. It contained

148 staterooms for first class, besides service rooms of various kinds.

On this deck, at the forward first-class entrance, were the purser's

office and the inquiry office, where passengers' telegrams were received

for sending by the Marconi apparatus. Exit doors through the ship's side

were fitted abreast of this entrance. Abaft the after end of this long

house was a promenade at the ship's side for second-class passengers,

sheltered by bulwarks and bulkheads. In the middle of the promenade

stood the second-class library. The two second-class stairways were at

the ends of the library, so that from the promenade access was obtained

at each end to a second-class main stairway. There was also access by a

door from this space into each of the alleyways in the first-class

accommodation on each side of the ship and by two doors at the after end

into the after well. This after well was about 50 feet in length and

contained two hatchways called No. 5 and No. 6 hatches. Abaft this well,

under the poop, was the main third-class entrance for the after end of

the vessel leading directly down to G deck, with landings and access at

each deck. The effective width of this stairway was 16 feet to E deck.

From E to F it was 8 feet wide. Aft of this entrance on B deck were the

third-class smoke room and the general room. Between these rooms and the

stern was the steam steering gear and the machinery for working the

after-capstan gear, which was used for warping the after end of the

vessel. The steam steering gear had three cylinders. The engines were in

duplicate to provide for the possibility of breakdown of one set.

D deck.—The general height from D deck to C deck was 10 feet 6

inches, this being reduced to 9 feet at the forward end, and 9 feet 6

inches at the after end, the taper being obtained gradually by

increasing the sheer of the D deck. The forward end of this deck

provided accommodation for 108 firemen, who were in two separate

watches. There was the necessary lavatory accommodation, abaft the

firemen's quarters at the sides of the ship. On each side of the middle

line immediately abaft the firemen's quarters there was a vertical

spiral staircase leading to the forward end of a tunnel, immediately

above the tank top, which extended from the foot of the staircase to the

forward stokehole, so that the firemen could pass direct to their work

without going through any passenger accommodation or over any passenger

decks. On D deck abaft of this staircase was the third class promenade

space which was covered in by C deck. From this promenade space there

were 4 separate ladderways with 2 ladders, 4 feet wide to each. One

ladderway on each side forward led to C deck, and one, the starboard,

led to E deck and continued to F deck as a double ladder and to G deck

as a single ladder. The two ladderways at the after end led to E deck on

both sides and to F deck on the port side. Abaft this promenade space

came a block of 50 first-class staterooms. This surrounded the forward

funnel. The main first-class reception room and dining saloon were aft

of these rooms and surrounded the No. 2 funnel. The reception room and

staircase occupied 83 feet of the length of the ship. The dining saloon

occupied 112 feet, and was between the second and third funnels. Abaft

this came the first-class pantry, which occupied 56 feet of the length

of the ship. The reciprocating engine hatch came up through this pantry.

Aft of the first-class pantry, the galley, which provides for both first

and second class passengers, occupied 45 feet of the length of the ship.

Aft of this were the turbine engine hatch and the emergency dynamos.

Abaft of and on the port side of this hatch were the second-class pantry

and other spaces used for the saloon service of the passengers. On the

starboard side abreast of these there was a series of rooms used for

hospitals and their attendants. These spaces occupied about 54 feet of

the length. Aft of these was the second-class saloon occupying 70 feet

of the length. In the next 88 feet of length there were 38 second-class

rooms and the necessary baths and lavatories. From here to the stern was

accommodation for third-class passengers and the main third-class

lavatories for the passengers in the after end of the ship. The

water-tight bulkheads come up to this deck throughout the length from

the stern as far forward as the bulkhead dividing the after boiler room

from the reciprocating engine room. The water-tight bulkhead of the two

compartments abaft the stem was carried up to this deck.

E deck.—The water-tight bulkheads, other than those mentioned as

extending to D deck, all stopped at this deck. At the forward end was

provided accommodation for three watches of trimmers, in three separate

compartments, each holding 24 trimmers. Abaft this, on the port side,

was accommodation for 44 seamen. Aft of this, and also on the starboard

side of it, were the lavatories for crew and third-class passengers;

further aft again came the forward third-class lavatories. Immediately

aft of this was a passageway right across the ship communicating

directly with the ladderways leading to the decks above and below and

gangway doors in the ship's side. This passage was 9 feet wide at the

sides and 15 feet at the center of the ship.

From the after end of this cross passage main alleyways on each side of

the ship ran right through to the after end of the vessel. That on the

port side was about 8-1/2 feet wide. It was the general communication

passage for the crew and third-class passengers and was known as the

working passage. In this passage at the center line in the middle of the

length of the ship direct access was obtained to the third-class dining

rooms on the deck below by means of a ladderway 20 feet wide. Between

the working passage and the ship's side was the accommodation for the

petty officers, most of the stewards, and the engineers' mess room. This

accommodation extended for 475 feet. From this passage access was

obtained to both engine rooms and the engineers' accommodation, some

third-class lavatories and also some third-class accommodation at the

after end. There was another cross passage at the end of this

accommodation about 9 feet wide, terminating in gangway doors on each

side of the ship. The port side of it was for third-class passengers and

the starboard for second class. A door divided the parts, but it could

be opened for any useful purpose, or for an emergency. The second-class

stairway leading to the boat deck was in the cross passageway.

The passage on the starboard side ran through the first and then the

second-class accommodation, and the forward main first-class stairway

and elevators extended to this deck, whilst both the second-class main

stairways were also in communication with this starboard passage. There

were 4 first-class, 8 first or second alternatively, and 19 second-class

rooms leading off this starboard passage.

The remainder of the deck was appropriated to third-class accommodation.

This contained the bulk of the third-class accommodation. At the forward

end of it was the accommodation for 53 firemen constituting the third

watch. Aft of this in three water-tight compartments there was

third-class accommodation extending to 147 feet. In the next water-tight

compartment were the swimming bath and linen rooms. In the next

water-tight compartments were stewards' accommodation on the port side,

and the Turkish baths on the starboard side. The next two water-tight

compartments each contained a third-class dining room.

The third-class stewards' accommodation, together with the third-class

galley and pantries, filled the water-tight compartment. The engineers'

accommodation was in the next compartment directly alongside the casing

of the reciprocating engine room. The next 3 compartments were allotted

to 64 second-class staterooms. These communicated direct with the

second-class main stairways. The after compartments contained

third-class accommodation. All spaces on this deck had direct ladderway

communication with the deck above, so that if it became necessary to

close the water-tight doors in the bulkheads an escape was available in

all cases. On this deck in the way of the boiler rooms were placed the

electrically driven fans which provided ventilation to the stokeholes.

G deck.—The forward end of this deck had accommodation for 15 leading

firemen and 30 greasers. The next water-tight compartment contained

third-class accommodation in 26 rooms for 106 people. The next

water-tight compartment contained the first-class baggage room, the

post-office accommodation, a racquet court, and 7 third-class rooms for

34 passengers. From this point to the after end of the boiler room the

space was used for the 'tween deck bunkers. Alongside the reciprocating

engine room were the engineers' stores and workshop. Abreast of the

turbine engine room were some of the ship's stores. In the next

water-tight compartment abaft the turbine room were the main body of the

stores. The next two compartments were appropriated to 186 third-class

passengers in 60 rooms; this deck was the lowest on which any passengers

or crew were carried.

Below G deck were two partial decks, the orlop and lower orlop decks,

the latter extending only through the fore peak and No. 1 hold; on the

former deck, abaft the turbine engine room, were some storerooms

containing stores for ship's use.

Below these decks again came the inner bottom, extending fore-and-aft

through about nine-tenths of the vessel's length, and on this were

placed the boilers, main and auxiliary machinery, and the electric-light

machines. In the remaining spaces below G deck were cargo holds or

'tween decks, seven in all, six forward and one aft. The firemen's

passage, giving direct access from their accommodation to the forward

boiler room by stairs at the forward end, contained the various pipes

and valves connected with the pumping arrangements at the forward end of

the ship, and also the steam pipes conveying steam to the windlass gear

forward and exhaust steam pipes leading from winches and other deck

machinery. It was made thoroughly water-tight throughout its length, and

at its after end was closed by a water-tight vertical sliding door of

the same character as other doors on the inner bottom. Special

arrangements were made for pumping this space out, if necessary. The

pipes were placed in this tunnel to protect them from possible damage by

coal or cargo, and also to facilitate access to them.

On the decks was provided generally, in the manner above described,

accommodation for a maximum number of 1,034 first-class passengers, and

at the same time 510 second-class passengers and 1,022 third-class

passengers. Some of the accommodation was of an alternative character

and could be used for either of two classes of passengers. In the

statement of figures the higher alternative class has been reckoned.

This makes a total accommodation for 2,566 passengers.

Accommodation was provided for the crew as follows: About 75 of the deck

department, including officers and doctors, 326 of the engine-room

department, including engineers, and 544 of the victualing department,

including pursers and leading stewards.

Access of passengers to the boat deck.—The following routes led

directly from the various parts of the first-class passenger

accommodation to the boat deck: From the forward ends of A, B, C, D, and

E decks by the staircase in the forward first-class entrance direct to

the boat deck. The elevators led from the same decks as far as A deck,

where further access was obtained by going up the top flight of the main

staircase.

The same route was available for first-class passengers forward of

midships on B, C, and E decks.

First-class passengers abaft midships on B and C decks could use the

staircase in the after main entrance to A deck, and then could pass out

onto the deck and by the midships stairs beside the house ascend to the

boat deck. They could also use the stewards' staircase between the

reciprocating-engine casing and Nos. 1 and 2 boiler casing, which led

direct to the boat deck. This last route was also available for

passengers on E deck in the same divisions who could use the forward

first-class main stairway and elevators.

Second-class passengers on D deck could use their own after stairway to

B deck and could then pass up their forward stairway to the boat deck,

or else could cross their saloon and use the same stairway throughout.

Of the second-class passengers on E deck, those abreast of the

reciprocating-engine casing, unless the water-tight door immediately

abaft of them was closed, went aft and joined the other second-class

passengers. If, however, the water-tight door at the end of their

compartment was closed, they passed through an emergency door into the

engine room and directly up to the boat deck by the ladders and gratings

in the engine-room casing.

The second-class passengers on E deck in the compartment abreast the

turbine casing on the starboard side, and also those on F deck on both

sides below could pass through M water-tight bulkhead to the forward

second-class main stairway. If this door were closed, they could pass by

the stairway up to the serving space at the forward end of the

second-class saloon and go into the saloon and thence up the forward

second-class stairway.

Passengers between M and N bulkheads on both E and F decks could pass

directly up to the forward second-class stairway to the boat deck.

Passengers between N and O bulkheads on D, E, F, and G decks could pass

by the after second-class stairway to B deck and then cross to the

forward second-class stairway and go up to the boat deck.

Third-class passengers at the fore end of the vessel could pass by the

staircases to C deck in the forward well and by ladders on the port and

starboard sides at the forward end of the deck houses, thence direct to

the boat deck outside the officers' accommodation. They might also pass

along the working passage on E deck and through the emergency door to

the forward first-class main stairway, or through the door on the same

deck at the forward end of the first-class alleyway and up the

first-class stairway direct to the boat deck.

The third-class passengers at the after end of the ship passed up their

stairway to E deck and into the working passage and through the

emergency doors to the two second-class stairways and so to the boat

deck, like second-class passengers. Or, alternatively, they could

continue up their own stairs and entrance to C deck, thence by the two

ladders at the after end of the bridge onto the B deck and thence by the

forward second-class stairway direct to the boat deck.

Crew.—From each boiler room an escape or emergency ladder was

provided direct to the boat deck by the fidleys, in the boiler casings,

and also into the working passage on E deck, and thence by the stair

immediately forward of the reciprocating-engine casing, direct to the

boat deck.

From both the engine rooms ladders and gratings gave direct access to

the boat deck.

From the electric engine room, the after tunnels, and the forward pipe

tunnels escapes were provided direct to the working passage on E deck

and thence by one of the several routes already detailed from that

space.

From the crew's quarters they could go forward by their own staircases

into the forward well and thence, like the third-class passengers, to

the boat deck.

The stewards' accommodation being all connected to the working passage

or the forward main first-class stairway, they could use one of the

routes from thence.

The engineers' accommodation also communicated with the working passage,

but as it was possible for them to be shut between two water-tight

bulkheads, they had also a direct route by the gratings in the

engine-room casing to the boat deck.

On all the principal accommodation decks the alleyways and stairways

provided a ready means of access to the boat deck, and there were clear

deck spaces in way of all first, second, and third class main entrances

and stairways on boat deck and all decks below.

STRUCTURE.

The vessel was built throughout of steel and had a cellular double

bottom of the usual type, with a floor at every frame, its depth at the

center line being 63 inches, except in way of the reciprocating

machinery, where it was 78 inches. For about half of the length of the

vessel this double bottom extended up the ship's side to a height of 7

feet above the keel. Forward and aft of the machinery space the

protection of the inner bottom extended to a less height above the keel.

It was so divided that there were four separate water-tight compartments

in the breadth of the vessel. Before and abaft the machinery space there

was a water-tight division at the center line only, except in the

foremost and aftermost tanks. Above the double bottom the vessel was

constructed of the usual transverse frame system, reenforced by web

frames, which extended to the highest decks.

At the forward end the framing and plating was strengthened with a view

to preventing panting and damage when meeting thin harbor ice.

Beams were fitted on every frame at all decks from the boat deck

downward. An external bilge keel about 300 feet long and 25 inches deep

was fitted along the bilge amidships.

The heavy ship's plating was carried right up to the boat deck, and

between the C and B decks was doubled. The stringer or edge plate of the

B deck was also doubled. This double plating was hydraulic riveted.

All decks were steel plated throughout.

The transverse strength of the ship was in part dependent on the 15

transverse water-tight bulkheads, which were specially stiffened and

strengthened to enable them to stand the necessary pressure in the event

of accident, and they were connected by double angles to decks, inner

bottom, and shell plating.

The two decks above the B deck were of comparatively light scantling,

but strong enough to insure their proving satisfactory in these

positions in rough weather.

Water-tight subdivision.—In the preparation of the design of this

vessel it was arranged that the bulkheads and divisions should be so

placed that the ship would remain afloat in the event of any two

adjoining compartments being flooded and that they should be so built

and strengthened that the ship would remain afloat under this condition.

The minimum freeboard that the vessel would have in the event of any two

compartments being flooded was between 2 feet 6 inches and 3 feet from

the deck adjoining the top of the water-tight bulkheads. With this

object in view, 15 water-tight bulkheads were arranged in the vessel.

The lower part of C bulkhead was doubled and was in the form of a

cofferdam. So far as possible the bulkheads were carried up in one plane

to their upper sides, but in cases where they had for any reason to be

stepped forward or aft, the deck, in way of the step, was made into a

water-tight flat, thus completing the water-tightness of the

compartment. In addition to this, G deck in the after peak was made a

water-tight flat. The orlop deck between bulkheads which formed the top

of the tunnel was also water-tight. The orlop deck in the forepeak tank

was also a water-tight flat. The electric-machinery compartment was

further protected by a structure some distance in from the ship's side,

forming six separate water-tight compartments, which were used for the

storage of fresh water.

Where openings were required for the working of the ship in these

water-tight bulkheads they were closed by water-tight sliding doors

which could be worked from a position above the top of the water-tight

bulkhead, and those doors immediately above the inner bottom were of a

special automatic closing pattern, as described below. By this

subdivision there were in all 73 compartments, 29 of these being above

the inner bottom.

Water-tight doors.—The doors (12 in number) immediately above the

inner bottom were in the engine and boiler room spaces. They were of

Messrs. Harland & Wolff's latest type, working vertically. The doorplate

was of cast iron of heavy section, strongly ribbed. It closed by

gravity, and was held in the open position by a clutch which could be

released by means of a powerful electromagnet controlled from the

captain's bridge. In the event of accident, or at any time when it might

be considered desirable, the captain or officer on duty could, by simply

moving an electric switch, immediately close all these doors. The time

required for the doors to close was between 25 and 30 seconds. Each door

could also be closed from below by operating a hand lever fitted

alongside the door. As a further precaution floats were provided beneath

the floor level, which, in the event of water accidentally entering any

of the compartments, automatically lifted and thus released the

clutches, thereby permitting the doors in that particular compartment to

close if they had not already been dropped by any other means. These

doors were fitted with cataracts, which controlled the speed of closing.

Due notice of closing from the bridge was given by a warning bell.

A ladder or escape was provided in each boiler room, engine room, and

similar water-tight compartment, in order that the closing of the doors

at any time should not imprison the men working therein.

The water-tight doors on E deck were of horizontal pattern, with

wrought-steel doorplates. Those on F deck and the one aft on the Orlop

deck were of similar type, but had cast-iron doorplates of heavy

section, strongly ribbed. Each of the between-deck doors, and each of

the vertical doors on the tank top level could be operated by the

ordinary hand gear from the deck above the top of the water-tight

bulkhead, and from a position on the next deck above, almost directly

above the door. To facilitate the quick closing of the doors, plates

were affixed in suitable positions on the sides of the alleyways,

indicating the positions of the deck plates, and a box spanner was

provided for each door, hanging in suitable clips alongside the deck

plate.

Ship's side doors.—Large side doors were provided through the side

plating, giving access to passengers' or crew's accommodation as

follows:

On the saloon (D) deck on the starboard side in the forward third-class

open space, one baggage door.

In way of the forward first-class entrance, two doors close together on

each side.

On the upper (E) deck, one door each side at the forward end of the

working passage.

On the port side abreast the engine room, one door leading into the

working passage. One door each side on the port and starboard sides aft

into the forward second-class entrance.

All the doors on the upper deck were secured by lever handles, and were

made water-tight by means of rubber strips. Those on the saloon deck

were closed by lever handles, but had no rubber.

Accommodation ladder.—One teak accommodation ladder was provided, and

could be worked on either side of the ship in the gangway door opposite

the second-class entrance on the upper deck (E). It had a folding

platform and portable stanchions, hand rope, etc. The ladder extended to

within 3 feet 6 inches of the vessel's light draft, and was stowed

overhead in the entrance abreast the forward second-class main

staircase. Its lower end was arranged so as to be raised and lowered

from a davit immediately above.

Masts and rigging.—The vessel was rigged with two masts and fore and

aft sails. The two pole masts were constructed of steel, and stiffened

with angle irons. The poles at the top of the mast were made of teak.

A lookout cage, constructed of steel, was fitted on the foremast at a

height of about 95 feet above the water line. Access to the cage was

obtained by an iron vertical ladder inside of the foremast, with an

opening at C deck and one at the lookout cage. An iron ladder was fitted

on the foremast from the hounds to the masthead light.

LIFE-SAVING APPLIANCES.

Life buoys.—Forty-eight, with beckets, were supplied, of pattern

approved by the board of trade. They were placed about the ship.

Life belts.—Three thousand five hundred and sixty life belts, of the

latest improved overhead pattern, approved by the board of trade, were

supplied and placed on board the vessel and there inspected by the board

of trade. These were distributed throughout all the sleeping

accommodation.

Lifeboats.—Twenty boats in all were fitted on the vessel, and were of

the following dimensions and capacities:

Fourteen wood lifeboats, each 30 feet long by 9 feet 1 inch broad

by 4 feet deep, with a cubic capacity of 655.2 cubic feet,

constructed to carry 65 persons each.

Emergency boats:

One wood cutter, 25 feet 2 inches long by 7 feet 2 inches broad by

3 feet deep, with a cubic capacity of 326.6 cubic feet, constructed

to carry 40 persons.

One wood cutter, 25 feet 2 inches long by 7 feet 1 inch broad by 3

feet deep, with a cubic capacity of 322.1 cubic feet, constructed

to carry 40 persons.

Four Engelhardt collapsible boats, 27 feet 5 inches long by 8 feet

broad by 3 feet deep, with a cubic capacity of 376.6 cubic feet,

constructed to carry 47 persons each.

Or a total of 11,327.9 cubic feet for 1,178 persons.

The lifeboats and cutters were constructed as follows:

The keels were of elm. The stems and stern posts were of oak. They were

all clinker built of yellow pine, double fastened with copper nails,

clinched over rooves. The timbers were of elm, spaced about 9 inches

apart, and the seats pitch pine, secured with galvanized-iron double

knees. The buoyancy tanks in the lifeboats were of 18 ounce copper, and

of capacity to meet the board of trade requirements.

The lifeboats were fitted with Murray's disengaging gear, with

arrangements for simultaneously freeing both ends if required. The gear

was fastened at a suitable distance from the forward and after ends of

the boats, to suit the davits. Life lines were fitted round the gunwales

of the lifeboats. The davit blocks were treble for the lifeboats and

double for the cutters. They were of elm, with lignum vitę roller

sheaves, and were bound inside with iron, and had swivel eyes. There

were manila rope falls of sufficient length for lowering the boats to

the vessel's light draft, and when the boats were lowered, to be able to

reach the boat winches on the boat deck.

The lifeboats were stowed on hinged wood chocks on the boat deck, by

groups of three at the forward and four at the after ends. On each side

of the boat deck the cutters were arranged forward of the group of three

and fitted to lash outboard as emergency boats. They were immediately

abaft the navigating bridge.

The Engelhardt collapsible lifeboats were stowed abreast of the cutters,

one on each side of the ship, and the remaining two on top of the

officers' house, immediately abaft the navigating bridge.

The boat equipment was in accordance with the board of trade

requirements. Sails for each lifeboat and cutter were supplied and

stowed in painted bags. Covers were supplied for the lifeboats and

cutters, and a sea anchor for each boat. Every lifeboat was furnished

with a special spirit boat compass and fitting for holding it; these

compasses were carried in a locker on the boat deck. A provision tank

and water beaker were supplied to each boat.

Compasses.—Compasses were supplied as follows:

One Kelvin standard compass, with azimuth mirror on compass platform.

One Kelvin steering compass inside of wheelhouse.

One Kelvin steering compass on captain's bridge.

One light card compass for docking bridge.

Fourteen spirit compasses for lifeboats.

All the ships' compasses were lighted with oil and electric lamps. They

were adjusted by Messrs. C. J. Smith, of Southampton, on the passage

from Belfast to Southampton and Southampton to Queenstown.

Charts.—All the necessary charts were supplied.

Distress signals.—These were supplied of number and pattern approved

by Board of Trade—i. e., 36 socket signals in lieu of guns, 12 ordinary

rockets, 2 Manwell Holmes deck flares, 12 blue lights, and 6 lifebuoy

lights.

PUMPING ARRANGEMENTS.

The general arrangement of piping was designed so that it was possible

to pump from any flooded compartment by two independent systems of

10-inch mains having cross connections between them. These were

controlled from above by rods and wheels led to the level of the

bulkhead deck. By these it was possible to isolate any flooded space,

together with any suctions in it. If any of these should happen

accidentally to be left open, and consequently out of reach, it could be

shut off from the main by the wheel on the bulkhead deck. This

arrangement was specially submitted to the Board of Trade and approved

by them.

The double bottom of the vessel was divided by 17 transverse water-tight

divisions, including those bounding the fore and aft peaks, and again

subdivided by a center fore-and-aft bulkhead, and two longitudinal

bulkheads, into 46 compartments. Fourteen of these compartments had

8-inch suctions, 23 had 6-inch suctions, and 3 had 5-inch suctions

connected to the 10-inch ballast main suction; 6 compartments were used

exclusively for fresh water.

The following bilge suctions were provided for dealing with water above

the double bottom, viz, in No. 1 hold two 3-1/2-inch suctions, No. 2

hold two 3-1/2-inch and 2 3-inch suctions, bunker hold, two 3-1/2-inch

and two 3-inch suctions.

The valves in connection with the forward bilge and ballast suctions

were placed in the firemen's passage, the water-tight pipe tunnel

extending from No. 6 boiler room to the after end of No. 1 hold. In this

tunnel, in addition to two 3-inch bilge suctions, one at each end, there

was a special 3-1/2-inch suction with valve rod led up to the lower deck

above the load line, so as always to have been accessible should the

tunnel be flooded accidentally.

In No. 6 boiler room there were three 3-1/2-inch, one 4-1/2-inch, and

two 3-inch suctions.

In No. 5 boiler room there were three 3-1/2-inch, one 5-inch, and two

3-inch suctions.

In No. 4 boiler room there were three 3-1/2-inch, one 4-1/2-inch, and

two 3-inch suctions.

In No. 3 boiler room there were three 3-1/2-inch, one 5-inch, and two

3-inch suctions.

In No. 2 boiler room there were three 3-1/2-inch, one 5-inch, and two

3-inch suctions.

In No. 1 boiler room there were two 3-1/2-inch, one 5-inch, and two

3-inch suctions.

In the reciprocating engine room there were two 3-1/2-inch, six 3-inch,

two 18-inch, and two 5-inch suctions.

In the turbine engine room there were two 3-1/2-inch, three 3-inch, two

18-inch, two 5-inch, and one 4-inch suctions.

In the electric engine room there were four 3-1/2-inch suctions.

In the storerooms above the electric engine room there was one 3-inch

suction.

In the forward tunnel compartment there were two 3-1/2-inch suctions.

In the water-tight flat over the tunnel compartment there were two

3-inch suctions.

In the tunnel after compartment there were two 3-1/2-inch suctions.

In the water-tight flat over the tunnel after compartment there were two

3-inch suctions.

ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION.

Main generating sets.—There were four engines and dynamos, each

having a capacity of 400 kilowatts at 100 volts and consisting of a

vertical three-crank compound-forced lubrication inclosed engine of

sufficient power to drive the electrical plant.

The engines were direct-coupled to their respective dynamos.

These four main sets were situated in a separate water-tight compartment

about 63 feet long by 24 feet high, adjoining the after end of the

turbine room at the level of the inner bottom.

Steam to the electric engines was supplied from two separate lengths of

steam pipes, connecting on the port side to the five single-ended

boilers in compartment No. 1 and two in compartment No. 2, and on the

starboard side to the auxiliary steam pipe which derived steam from the

five single-ended boilers in No. 1 compartment, two in No. 2, and two in

No. 4. By connections at the engine room forward bulkhead steam could be

taken from any boiler in the ship.

Auxiliary generating sets.—In addition to the four main generating

sets, there were two 30-kilowatt engines and dynamos situated on a

platform in the turbine engine room casing on saloon deck level, 20 feet

above the water line. They were the same general type as the main sets.

These auxiliary emergency sets were connected to the boilers by means of

a separate steam pipe running along the working passage above E deck,

with branches from three boiler rooms, Nos. 2, 3, and 5, so that should

the main sets be temporarily out of action the auxiliary sets could

provide current for such lights and power appliances as would be

required in the event of emergency.

Electric lighting.—The total number of incandescent lights was

10,000, ranging from 16 to 100 candlepower, the majority being of

Tantallum type, except in the cargo spaces and for the portable

fittings, where carbon lamps were provided. Special dimming lamps of

small amount of light were provided in the first-class rooms.

Electric heating and power and mechanical ventilation.—Altogether 562

electric heaters and 153 electric motors were installed throughout the

vessel, including six 50-hundredweight and two 30-hundredweight cranes,

four 3-ton cargo winches, and four 15-hundredweight boat winches.