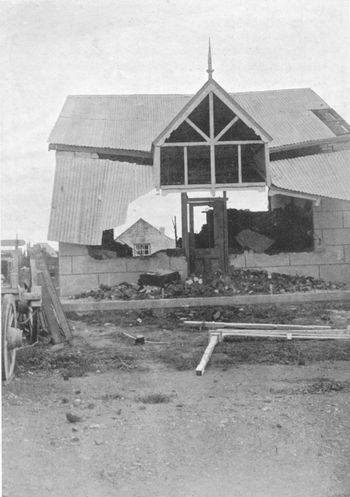

THE COLONEL AT WORK.

Project Gutenberg's The Siege of Mafeking (1900), by J. Angus Hamilton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Siege of Mafeking (1900) Author: J. Angus Hamilton Release Date: April 2, 2012 [EBook #39348] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SIEGE OF MAFEKING (1900) *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Christine P. Travers and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE COLONEL AT WORK.

BY

J. ANGUS HAMILTON

WITH FIFTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS AND TWO PLANS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

1900

I have to acknowledge gratefully permission to publish in this book certain articles contributed before and during the siege of Mafeking to The Times and Black and White. To the editor of the latter paper I am indebted also for leave to reproduce photographs taken by myself and published, from time to time, in that journal.

I would acknowledge, too, in anticipation, any kindly toleration my readers may extend to me for the many shortcomings, of which I am dismally conscious, arising from the hasty preparation of this volume. When I explain that between the date of my return to England and this date—when I start for China—barely a fortnight has elapsed, I shall make good, perhaps, some small claim upon the indulgence of the critics and the public.

J. A. H.

July 21, 1900

R.M.S. Dunvegan Castle, September 16th, 1899.

A breeze was freshening, tufting the heaving billows with white crests and driving showers of spray and clots of foam upon the decks of the Dunvegan. Passengers stood in strained attitudes about the ship, fidgeting with the desire to be ill and the wish to appear comfortable—even dignified. In the end, however, circumstances were too strong for the passengers, transforming them, from a state of calm despair, into a condition of sickness and temporary dejection. Every one was perturbed, and those delicate attentions which the sea-sick demand were being offered by a much-worried deck steward. Here and there groups of more hardy voyagers were spending their feeble wit in unseasonable jokes; here and there bedraggled people, wet with spray and racked by the anguish of an aching void, were clutching at the possibility of gaining the privacy of their cabins before their feelings quite overpowered them. In this mad rush, not unlike the scramble of a shuttlecock to escape the buffetings of the battledore, I also joined, fetching my berth with much (p. 2) unfortunate sensation. Alas! I am a wretched sailor, and travelling far and near these many years, crossing strange seas to distant lands at oft-recurring periods, has not even tutored me to stand the stress of the ocean wave. I cannot endure the sea.

The Dunvegan Castle was steaming to the Cape, carrying the mails, together with a number of tedious and most tiresome people, whose hours aboard were passed in periods of distracting energy—in deck quoits, in impossible cricket matches, in angry squabbles upon the value of the monies which, day by day, were collected by the crafty from the foolish and pooled in prizes upon the daily run of the steamer. It was said that these were pleasant gambles, but the Gentiles paid and the Hebrews, returning to their diamonds, their stocks and shares, scooped the stakes. It is a way that the people of Israel and Threadneedle Street have made peculiarly their own; and, indeed, the multitude and variety of Jews upon this evil-smelling steamer suggested that she might have held within her walls the nucleus of an over-sea Israelitish colony, such another as the Rothschilds founded.

Time was idle, dreary, and so empty! There was nothing to do, since nothing could be done. The monotony was appalling, and if this were the condition in the saloon, how distressful must have been the lot of the third class, who constituted in themselves, as good a class of people as that contained in the saloon. Surely in these days of systematic philanthropy something more might be done to brighten the lot and welfare of third-class passengers. Is it, for example, quite impossible to supply them with that not uninteresting development of the musical-box—the megaphone? Of (p. 3) course it should be quite possible; but antiquated, even antediluvian, in its arrangements, the Castle Company cannot initiate anything which has not yet been adopted by the other lines of ocean shipping. And yet I have been told by numerous merchant captains that it is the steerage which provides the profits, making lucrative the business of carrying cargoes of goods and human freight from our shores to more distant lands. But that also is the way of the world; yet when a rude prosperity enables the emigrant Jew and Gentile to throng the saloons, making them altogether impossible for the gentler classes, we shall find the economy of the third class appealing to an ever-increasing and ever-superior body of people until these "superior" people will not endure the dirt, unwholesome surroundings, and fetid atmosphere of the steerage accommodation of ocean-going steamers, but will cry to Heaven upon the niggard's policy which controls the vessels.

As the days wore away, and Madeira came and went, even the flying fishes ceased to attract, and the noises of the ship grew more distant, the people less obtrusive. Moreover, I became at rest within myself, and the gaping, aching void which has filled my vitals these many days, became assuaged. It was then we began to inspect the passengers; to consider almost kindly the African Jew millionaire who ate peas with his fingers and mixed honey with his salad, thought not disdainfully of the poor lady his wife, who, suffering the tortures of the damned when at sea, shone at each meal valiantly and heroically until the menu was pierced by her in its entirety, and she made still further happy by the administration of an original preventative against (p. 4) mal de mer of sweet wine biscuits bathed in plentiful and sticky treacle. It was her way of pouring oil on troubled waters. Oh, those were dreadful people, never ill, always eating, ever complaining of a curious dizziness which, nevertheless, occasioned them no loss of appetite. Surely they, of all others, were indeed of the specially select! Then there was Mr. Clarke, a friend of the two Presidents, who, undaunted by the most violent motions of the steamer, kept to the deck in a constant promenade, discoursing amicably the while, and punctuating his utterances, of a somewhat patriarchal order, with brief pauses, in which he stroked, with much dignity, a long white beard. He was a dear old man, and, unlike other Boers, he did not quote from the Scriptures, a concession which, to be properly appreciated, demands the lassitude and extreme prostration of violent nausea. There is something inordinately irritating about the man who proposes to soothe the irruptions attendant upon sea voyages by the assurance that such discomfiture is to be endured, since in Chapter i., verse 1, of a pious writer, the Lord hath there written that the ungodly shall be everlastingly punished. Personally I objected only to the form of punishment.

The friend of the President, a fine specimen of sturdy masculinity, touching eighty-two years of age, was quite the most impressive figure aboard this particular Castle packet. He had been a sojourner in the Orange Free State for forty years, coming to it from Australia shortly after the riots at Ballarat goldfields. The old fellow had fought against the Boers, championed their arms against the Basutos, raided the blacks in Queensland, and tumbled through a variety of enterprises ranging from mining (p. 5) in Australia to successful sheep farming near the Fickersburg. I liked him, taking an intense anxiety in his future movements, and wondering whether this fine old specimen of life would also become our enemy. Who could tell! So much depended upon the situation, so much upon the action of the President and the will of Providence. He stood, as he himself was apt to remark, upon the border of the next world—looking back upon a span of four score years, possessing a knowledge of the affairs of these African Republics which had obtained for him the friendship of President Steyn and President Kruger; indeed, they had been comrades-in-arms, Oom Paul and himself, while he had seen Steyn spring into manhood from a stripling, and when his thoughts dwelt upon those days the voice of the old man became flooded with emotion. These tears of memory were a sidelight to his real character, and I was convinced that if he shouldered arms at all these earlier friendships were held by such ties as were too sacred to be violated. In his heart he hated fighting, yearning merely for the attentions of his children, the cool delights of his mountain home. In his domestic environment he was a happy man, since prosperity had brought him certain cares of office, much as the dignity of his age had brought him the respect of his fellow-burghers. And yet he figured as an illustration of countless hundreds, each one of whom was in close relationship with the crisis in the politics of the country.

Morning, noon and night he strolled, the one figure of interest in the ill-assorted company of passengers which the good ship—to my nostrils an evil-smelling tub—was carrying to the Cape. There were few others of importance upon this (p. 6) journey. There was a colonel of the Royal Engineers, who had a snug billet in the War Office, and who was leaving Pall Mall to inspect the barracks at Cape Town, St. Helena, Ascension, and all those other places to which certain preposterous War Office officials devoted that attention which should so much more properly have been paid to the defenceless condition of the frontiers in South Africa. But then, after all, what is the destiny of the War Office unless to meddle and make muddle? If Colonel Watson might be said to have represented the Imperial Government among the passengers, Mynheer Van der Merure, Commissioner of Mines in Johannesburg, might be considered as representing the Pretorian Government. It seemed to me that these two worthies were quite harmless, representing, each in his own way, the acme of good nature, the gallant—all colonels imagine that they be gallant—colonel by reason of his advanced age; the worthy—all commissioners imagine that they be worthy—commissioner because he lived off the spoil of the mines. But even the spectacle of these three—the grand old man, the War Office attaché, the wealthy Randsman—did not suffice to break the hideous monotony of a most depressing voyage.

With the peace of nature enveloping us in a feeling of security, it was difficult to realise that each day we drew a little nearer to a possible seat of war. There was much rumour aboard; the stewards hinted that the hold was filled with a cargo of munitions of war. The captain flatly denied it, even the War Office pensioner thought it improbable. "You must understand, sir," said he one morning, across the breakfast table, "that it is contrary to the custom of her Majesty's Government, and, if I may (p. 7) say so, sir, especially contrary to the custom of her Majesty's War Office, to squander the finances of our great Empire upon unnecessary munitions of war because the Times and other papers choose to send half a dozen irresponsible individuals to South Africa. Now, sir—pooh!" When Colonel Watson broke out like this the friend of the President would intervene, suggesting in his kindly, paternal fashion that "the War Office—given half a dozen colonels, gallant or otherwise—might well afford to follow the lead of the Times newspaper." "It has been my experience," the Colonel retaliated on one occasion, "that when people begin to interfere they cease to understand." It was always quite delightful to watch these two cross swords; the elder invariably took refuge in his age when the sallies of the War Office could not be directly countered. "Experience! You are only old enough to be my son." The Colonel spluttered—colonels do. By these means the elder man usually carried off the honours, replying, as it were, by a flank movement to the frontal attack of his superior adversary.

The farmer from the Orange Free State talked much to me, giving me, towards the end of the voyage, an invitation to his home. It was a visit in which I should have found much pleasure, since the splendour of his years, his gentleness and nobility of character were attractive. It seemed to me that among all sorts and conditions of men this one was indeed, a man, and I do most sincerely hope that the end of the war may find him still living and enjoying his farm in his usual prosperity. He was so set against the war, and dreaded the consequences of hostile invasion into the Orange Free State, insomuch that he realised, if some immunity (p. 8) were not guaranteed, the ruin and desolation which would spread over the land. In August as we left England there was nothing known about the future action of the Orange Free State. The question was one of debate, altogether confused, almost intangible, and this man, knowing Steyn as he knew Kruger, was convinced that the Orange Free State would alienate itself from the Transvaal difficulty. But who can tell? We look to the sea for our answer, and it throws back to us only the echoes of the sighing waves, the pulsing throbs of the screws pounding the green masses of water in an effort to reach the Cape. Nevertheless, I am inclined to believe that there will be war. I hope that there may be, since it is to be my field of labour.

The journey nears its end, and the weather breaks, for a few hours into grey cold; while the sea, where it laps the bay at Cape Town, darkening into thin ridges of foam, tumbling and tossing amid the eddies of the bleak water, looks menacing. A fog lies off the land, dense and weighty, impeding the navigation and impressing no little conception of the perils of the deep upon the minds of timorous passengers, and folding the surface of the ocean in its expanse. The weather threatens to be wild. All day the sea fog broke and mingled, merging, as the day wore on, into one conglomerate mass of cloud, impenetrable to the mariner and screening the signs of the sea from those who were upon land. Here and there, low down upon the horizon, the storm fiend from the shore had broken into the garland of mist which hung so drearily upon sea as upon moor, detaching parcels of cloud from the main and toying with them with the coy and heartless grace of Zephyr! But as yet the wind only came in minor lapses, and was followed (p. 9) by intervals in which there was no movement in the fog. From the waste of sea came a ceaseless, muffled roar which seemed loudest and most full of mystery when carried upon the wings of the wind. Then these echoes of mighty waters, tumbling upon the rocks off the land, seemed ominous and charged with deadly peril, and, as the fog belts lifted or dispersed before the gusts of the wind, the sea would look as though swept with growing anger, heaving in tremulous passion, until the great reach of quivering waves was flecked with white. Closer and closer lapped the tiny waves, until, under the pressure of the freshening wind they mingled their crests, rising and falling in foam-capped billows of growing volume and increasing majesty. Thus developed the storm; the wind beating on the face of the waters and breaking against the clouds until rain fell, in the end assuaging, by its raging downpour, the tempest of the ocean. Down came the storm in one panting burst of tempestuous deluge. The heaving waves threw sheets of foam from their rain-pierced summits, and the wind whistled and screamed as it swept through the rigging. Flashes of lightning and thunder claps parried one another in quick succession. The rain fell in torrents, the decks, shining in the lightning flashes, roared with rushing water. So that night we rode at anchor, rocking idly at our cables within the shadow of the mountain, and upon the morrow, beneath the light of coming dawn, we drew nearer through the cool greyness of the bounding ocean. At first the figures, the walls of the fort, the cranes, the shipping, and the scarred and crinkled facing of the mountain were silhouetted in black against the grey of early morning, but as the day broke more firmly across its slopes, the finer and more subtle (p. 10) light gave to everything its actual proportion. All kept growing clearer and yet clearer, and more and more thoroughly outlined, until the sun, shooting over the horizon, bestowed upon the coming day its first wink of glory.

And so we landed, passing from a sluggish state of peace into a world where everything was lighted with martial glamour.

Cape Town, September 20th, 1899.

To be in Cape Town in September would seem to be visiting the capital of Cape Colony in its least enjoyable month; since, more especially than at any other time in the year, the place be thronged with bustling people, who plough their way through streets which, by the stress of recent bad weather, are choked with mud and broken by pools of slush and rain-scourings. The rain is falling with a determination and force of penetration which soaks the pedestrian in a few minutes and makes life altogether miserable. Moreover, there are signs of further foul weather. There is a white mist upon the mountain and a sea fog enshrouds the shipping in the harbour: everywhere it is cold, colourless and damp. Everywhere the people are depressed. It is as though the wet has drenched the population of the town to the bone and drowned their spirits in the cheerless prospect which the rainy season in Cape Town provides. If the sun were to shine the aspect might be brighter, a little warmth might be infused in the character and disposition of the constantly shifting streams of mud-splashed, bedraggled (p. 12) pedestrians who, despite the rain and mud and an air of general despondency, impart some little animation to the dirty thoroughfares.

Other than this air of depression there is but little external evidence of the momentous crisis which impends. It may be that the Cape Town colonist has forgotten the responsibilities of his colony in the cares of his own office, and is become that mechanical development of commerce, a money-making man. Who can tell? Is it even fair to hazard an estimation of the man in his present environment? But it would assuredly seem that the troubles of the Government, the menace which is imposed upon the colony by the Bond Ministry, do not touch him, do not even stir his loyalty to the ebullition of a little doubtful enthusiasm. Just now, although there may be war upon his borders, although the spirit of disturbed patriotism be in the air, and although his neighbours may be thinking of joining some one of the Irregular Corps who are advertising for recruits, the ordinary inhabitant of Cape Town is unmoved. He is too lethargic, or is it that his loyalty is not of that degree which regards with concern the arming of the border republics, the near outbreak of bloody war? It would seem that each, after his own caste, be happy if he be left alone; the money grubber to gain more shekels, the idler and the casual to bore each other with their stupendous, even studied indifference to the propinquity of the latest national crisis. Within a few days, it may even be within a few hours, our questions with the Pretorian Government will have reached their final adjustment or their perpetual confusion, and it may be that we shall be at war. It may be also, although it be difficult to believe, that a (p. 13) peaceful solution will be derived. At this moment the services of such pacific measures as can be adopted should be utilised, since if war should come within a brief measure the position of the people of this country will indeed be grave—the utter absence of adequate defensive measures, the entire lack of efficient military preparations being factors which are calculated to incite to rebellion those who incline to the Dutch cause, and indeed, most positively, their name is Legion. There is, I think, the essence of revolt beneath this heavy and depressed condition of the people: it were not possible otherwise, to exist within such intimate proximity to a state of war and be unmoved; it is not possible either to find other explanation. It may be that in their hearts, as in their heads, they are weighing the consequences of revolt, succouring one another in their distress of mind and body with seditious sympathies, maintaining a spirit of antagonism to the Imperial fusion under pretence of the mere expression of a lip loyalty. And in their immediate prospect there is everything which may be calculated to disturb their equanimity, and to force upon them the consciousness of their impotency. It is perhaps this knowledge of their actual weakness which subdues them since they cannot afford to openly avow feelings which are inimical to us and which would betoken their own hostility. Nevertheless, Great Britain can do nothing which could encourage these people in their loyalty; nor can they themselves, in reality, assist to remove their unfortunate predicament, since they must needs sacrifice their possessions to substantiate their views, and to do this implies complete disintegration of their fortunes. This they will not do; since they cannot suffer it. They will remain discontented (p. 14) partisans, however; slaves of commerce, restrained by the possibilities of further aggrandisement from declaring their mutual connection, and manacled by the bonds of free trade and crooked dealings. They will be neutral, as indeed the greater proportion of the inhabitants of the towns along the coast and within the littoral zone will be, since with every feeling of unctuous rectitude in relation to the values of their trade, they will leave to the provincial areas, which lie between the borders of the Orange Free State and the metropolitan circuits, the onus of the situation, the work of supplying active and more potential supporters of the Republican arms.

This is the middle of September, and I am assured that the crisis should not be expected before the middle of October, inclining to the first two weeks of the coming month. If this be possible, and the information is difficult to discount, our sin of indifference is the greater, our apathy the more criminal. Indeed, everywhere there is nothing doing—God forbid that the steady warlike preparations of the Transvaal Government should intimidate us, but let us at least be heedful and not over sleepy. If we can gauge the situation by the public press of the Empire it is most critical, and the time is rather overripe in which we also should indulge in a few military exercises. There is a situation to be faced which will tax all the resources of the Castle, and strain even the vaunted excellence of the home administration—that army for which Lord Wolseley has claimed such splendid mobilisation, such insensate volition. If these fifty thousand men were here now the turns of the political wheel would not be regarded with such intense apprehension, while in their absence there lies perhaps the answer to the rain-drenched (p. 15) dulness of the population. The land is naked; from Basutoland to Buluwayo and back to Beira, mile upon mile of smiling frontier rests without protection of any sort. We are inviting invasion, and it is impossible that such a movement will not be attempted. To invade our territory—it will sound so well round the camp fires of the Boer laagers—a mere scamper across the frontier, a pell-mell, hell-for-leather retreat to their own lines, and the manœuvres would be executed felicitously and with every sign of success. But such a contingency is submerged under an accumulation of theories and official explanations each of which deny the possibility of the Boer taking upon himself the responsibility of rushing the situation. Moreover, it does not seem that the Boers require much instigation to attempt such an act. We have laid open our borders to such an enterprise, even taking the trouble to leave unguarded many towns whose adjacency to the border is singularly perilous. In many cases a Boer force need only make a short march to arrive in the very heart of some one of these border towns, when, should they appear, the turn of affairs could be said to be complex; and some emotions might be felt by those worthy and effete military noodles who so persistently shout down the "pessimists" who, knowing the country, the ambition and resourcefulness of the Boers, persist in declaiming upon the hideous neglect which characterises our frontier defences, and strenuously assert the probability of Boer invasion into those districts which superimpose themselves upon the borders of the Transvaal and Orange Free State Republics, and which, possessing values of their own, can be held as hostages against the slings and arrows of an outrageous fortune elsewhere.

(p. 16) It is the duty of the Crown at the present juncture to bear this contingency in mind, to confront it with the determined resolution to repair the negligence of the past at once and at all costs, and to allow neither the opinion of the Bond Ministry, nor the ignorance of the existing military advisers to the Governor, to persuade the Executive from adopting the only course which remains to us, which is to push men and materials of war to the border with the least possible delay. If we do not take these steps now it will be too late in a little time, and the course of the war must necessarily be the more protracted. There are many who would have us delay lest our premature acts should expedite the despatch of the ultimatum, and we should lose the opportunity, which the next few days will give to us, of receiving delivery of the troops who are already upon the water. But the presence of these men means little and forebodes, in reality, a slight accentuation of the gravity of the actual situation. It is with the forces that we can control at this moment that we must count, and it is with them that we must deal. It does not suffice to have parade-ground drills in Cape Town as a preliminary flourish; we should at least show ourselves as ready as the Boers be willing. This of course we cannot do, since, with a handful of exceptions, we have not a modern piece of artillery in the country. Moreover we do not quite know what armaments the Transvaal Government possess; it is with a pretty display of pretence that we conceal the nakedness of our borders and bolster up the situation. There is Kimberley, Ramathlabama, and Buluwayo—what is to happen upon the western frontier?—and although it be doubtful if the Boers would pierce the Rhodesian border and seize Buluwayo, (p. 17) it is not too much to expect that if they should inaugurate any movement into the Colony from the Orange Free State, even if their activity only should assume the shape of a demonstration against Kimberley, that this southern advance would receive sympathetic co-operation from a parallel movement in a northerly direction by which they might temporarily secure possession of our line of communication and menace Buluwayo by encroaching upon Rhodesia.

Then there is the position of Natal, which must be more or less hampered by the war in the Transvaal if it does not become actually and potentially concerned. That Natal will play an important rôle is elaborately evident from the Boer patrols who, even now, are reported to be in possession of all strategical points in the mountains, and who are also said to be busily engaged in fortifying the rocky fastnesses of the Drakensburg Mountains, and to dominate Laing's Nek tunnel as well as the line of railway which curvets through the chain, by having emplaced some heavy ordnance upon prominent and immediate commanding slopes. It would seem as though Natal may play a part, so distinctive and so vitally important in its own history as a colonial dependency, that the prospect of the war there may become a campaign in itself, and one which will be almost detached and isolated from the movements in the Orange Free State and Transvaal, where I have reason to believe there is some intention of formulating, what may be regarded as a dual campaign, which will avoid all invasion of the Transvaal territory until the Orange Free State has been completely pacified and the lines of communication effectively and securely held. In support of this scheme it is generally conceded that it will (p. 18) be impossible to carry war into the Transvaal until every provision has been made against the risk of local rising in the areas of the Orange Free State, and thus endangering our lines of communication, as well as our flanks.

These, then, are the signs of the day, and in such signs do we read something of the terrible struggle upon which we are so soon to be engaged, and in appreciation of which, local opinion is in such marked contrast—I almost wrote conflict—with the opinion and views of the special service officers from India and England. To whom, then, belongs the honours of accurate estimation; to the man from home as it were, or to the man who has passed his life in South Africa and understands the Dutchman as the mere military interloper can never hope to understand him? There is, I think, no doubt as to what point of view be erroneous, and it is because we so persistently ignore the worth and reliability of the men who are upon the spot, that we shall have the falsity of our intelligence some day brought home to us by the tidings of a terrible disaster. South Africa is already the grave of too many fine reputations; but let us, at least, hope that we shall not add to the disgrace of the private individual any loss of national prestige. The wind soughs ominously just now, however, while there is a note in it which I do not like, and which I cannot understand. At the Castle they talk airily of being home by Christmas! If they be sailing within twelve months they will be lucky, and at Government House Sir Alfred Milner is beset with the difficulties of his very onerous position. For the moment he takes—I am glad to be able to say it, since I would have him upon the side of sound common sense—a somewhat depressed view of (p. 19) the general outlook. Kimberley and Ramathlabama were his especial concerns when I called there to-day, insomuch that they extend an especial invitation to the mobility of a Boer commando, while it is quite beyond his powers to save them from their fate. It seemed to me that he despairs of these towns in particular, but I will withhold his remarks upon them until I myself have been there. Yet it may be taken as granted that, should Sir Alfred Milner be concerned for their immediate and eventual safety, the gravity of their situation is extreme, pointing even to the closeness of the danger which would arise from a Boer invasion into those areas.

But in this hurried letter I am dealing with the colony, and singularly enough we have to consider how our colonists will behave, what may be their attitude, and how near are we to rebellion? It is of course an all-important question, and one which, in relation to a British colony, is untoward. If I were asked to localise the possible area of revolt I should decline, since the question be so serious and infringes so much upon the life and existence—the central forces—of the colony that it would be difficult, definitely and evenly, to demarcate any zone of loyalty, as opposed to any area of disaffection, without unduly trespassing upon the sentiments of less favoured districts. But I do think that the possibilities of this question are enormous, emanating as it does from the life teachings and doctrines of the people of the country, and however much we try to draw a line between what constitutes due loyalty and what infringes the spirit as well as the letter of the individual's allegiance, we must unconsciously perpetrate much injustice either upon the one or upon the other side of the question, which, (p. 20) owing to the dualistic temperament and inclinations of no small majority of the people, it is impossible to avoid, and which will have to be endured by individuals, loyal or disloyal, as their penalty. The spirit of the Dutch pioneers still impregnates much of Cape Colony; its presence south of the Orange Free State and in the actual territory of the colony receiving direct support and sympathy by the increasing numbers of the Dutch population in these African Republics; an increase which, being unrestricted in its development, has spread far and wide until it has created a partial exodus from the recognised centres of Dutch influence and Dutch population into those areas from which the traces of the earliest Dutch occupation were rapidly vanishing—if they have not altogether disappeared—and which has been the medium of resuscitating a feeling of sympathy and clanship which, augmented by still closer ties of commerce, has promoted the functions of matrimony and friendship and gradually released a current of feeling throughout the district which was avowedly Dutch, and, equally avowedly, in silent and semi-subdued opposition to the instincts and ideals of the Anglo-Saxon colonist. And it is against the rapid spread of this feeling which we have to contend, much as we must guard against the conversion of these prejudices into tacit support and effective co-operation with the armed burghers of the sister Republics should their arms secure any initial successes. With this danger in our midst, in itself an almost insurmountable obstacle, no precaution which could render the safety of these districts the less precarious should be omitted; and to effect this—and it is quite essential to our temporal salvation—men and materials of war should be in readiness to forestall, or, at least, to (p. 21) circumvent, the consummation of the Boer operations. If we can accomplish even so little, it maybe possible to prevent the no small proportion of the colonists discharging their obligations to the Crown by combining with the Boer forces. To this end our efforts will have to be seriously directed, and the sooner this simple fact is realised by the authorities in South Africa as in London, the more convincing will the scope and measures of our policy become. At present it is chimerical, and we hesitate.

The Camp, De Aar,

September 23rd, 1899.

Africa was streaming past the dusty windows of the railway carriage, presenting an endless spectacle of flat, depressed-looking country, with here and there a hut, here and there a native. I am in the earliest stages of a journey which should lead to Ramathlabama, and the command of Colonel Baden-Powell. Slowly and with much effort the train drags itself along; the road is steep, the carriages hot and uncomfortable, and there is nothing to attract attention, nothing to fill the emptiness of the mind. I slept at intervals, to awaken at some roadside station where fussy people were struggling to eat too much in too short a space of time. There, for a moment, was the scamper of bustling, hurrying passengers, who pushed and menaced one another in a thirsty rush to the refreshment room; with a cloud of officers, orderlies, and troopers I stood apart, listless, bored, and travel-stained, feebly interested, more feebly talking in disconnected phrases, until, with shrill blasts of his whistle, the guard signalled the departure of the train. Then (p. 23) off again, the jerking, swaying flight of eighteen miles an hour—the rumbling monotony of express speed which was conducive to drowsiness and nothing more. The landscape faded in the distance, a raucous voice sang of 'Ome, while, in a monotonous buzz of nothingness, I slept again.

The train was slowly thrusting itself forward as, with much panting and purring and some screaming, it cut the borders of the Great Karoo. Slowly the wheels clenched the metals as the waggons rocked in a lullaby of motion, and the passengers were fanned with draughts of scented air. The Great Karoo, lying in the shades of evening, hearkening to the secret calling of mysterious voices, heeding not the ravages of time, wearing majestically the massive dignity of its grandeur, threw back its barriers of resistance to our intrusion and delighting our senses with ever-changing and oft-recurring glimpses of its beauty. But the picture faded with the passing of the train, the golden and crimson delights of the overgrowing flowers gave place to a soulless expanse destitute of beauty.

I stopped at De Aar, which is the junction where the Orange Free State and Transvaal lines connect with the Cape Colony system. At De Aar I was anxious to observe the press of traffic. From Cape Town for Kimberley, Borderside, Fourteen Streams, and Mafeking, truck loads of horses and mules, waggon loads of general military stores were passing northwards to the front. In the interval, there were Imperial troops and men of the Cape Mounted Police. Indeed, the scene upon the platform was animated by martial spirit. If the train from the south was loaded with war material, the trains from the two Republics were (p. 24) packed with fugitives, among whom were many men who, in the hour of necessity, will, it is to be hoped, consider flight as the least satisfactory means of procedure. However, no goods are going through to the two Republics from Cape Colony, unless Mr. Schreiner has passed more ammunition over the Cape lines to the Transvaal. But things are working more satisfactorily down in Cape Town since it became known that the Cabinet would be discharged by the Governor, unless——and to a discerning politician of the Bond, whose income depends upon his salary from the House, a blank conveys many wholesome home truths.

Travelling, even with the variety of emotion which the Karoo excites, is no great comfort in South Africa. One lives in an atmosphere of dust and Keating's. If the trains go no faster to Cairo when the rails be through, than they do to Buluwayo, the steamers will still retain the monopoly of passenger traffic. It takes a "week of Sundays" to reach railhead at Buluwayo, but there is some small consideration in the fact that such a journey has been made. It will become a feature in our Sabbatarian domesticity some day, and among railway journeys at the present time it is unique. Where else do express trains arrive several hours in advance of their scheduled time? Where else do goods trains arrive several days late? These are but the manifold and maddening perplexities of railway travelling in Africa. Yet if one kicks against the uncertainties of the desert service, there is sure to be an Eliphaz somewhere upon the train, whose philosophy being greater than his hurry, recognises that the element of expedition, when his train does arrive, is greater (p. 25) than the prospect of moving at all where no train comes. Time passes somehow on these journeys, and the chance prospect of obtaining a good meal, when one is dead certain to get a bad one, is enlivening. If it were not for such trifles, the journey would have no interest. To look forward to luncheon and an afternoon nap, to anticipate dinner and then digest it, makes the day run with pleasant monotony into the night. And night is worth the inspection. The beds in the train are comfortable enough, but the night is vested with misty beauty, and its fascination woos the traveller from his rest. There is the roar of the engine, the rumble of the carriages, the buzz of insects, and the faint rustle of the night wind over the plains. Then, looking into the night, one falls asleep, tired and stunned by the spectacle of the never-ending desert. But, in the morning there comes a change. The stretches of the Karoo are past, and breakfast at De Aar is in sight.

At De Aar—a sea of tents with here and there a man—there begins the outward and visible signs of preparation against the necessities of the coming struggle. There are men and arms at De Aar and munitions of war, comprising the Yorkshire regiment, a wing of the King's Own Light Infantry under Major Hunt, and a section of the Seventh Field Company of Engineers under Lieutenant Wilson; but their numbers are impossible, much as their supplies be limited and seriously insufficient; and, as a consequence, I must not talk much about the interior linings of the British camp which has sprung up at De Aar, and which, within a few days of what must be the turning point of the present crisis, is so little able to cope with the exigencies of the situation. (p. 26) It is a protective measure, this little camp at the junction of the divergence in the railway system of the colony, placed in its present situation to guarantee the safety of the permanent way, and to ensure a modicum of safety to the traffic which is crowding north over the points at the meeting of the rails. It is a gorgeous piece of impudence; this minute establishment of British soldiers, and if it be impressed with the might and majesty of our Imperial Empire, it is also beset with the innumerable difficulties and trials which attend an isolated State.

We are guarding the lines of communication between De Aar Junction and Norvals Pont, the bridge across the Orange River which unites the territory of the Orange Free State with the land of the Colony, between De Aar and the Camp at Orange River, between De Aar and many miles to the south in the direction of Cape Town. I believe that the practical influence of this particular unit extends so far south as Beaufort West, where the custody and patrol of the line is handed over to the care of the railway authorities, whose men are detailed to the all-important duty of guarding the culverts and bridges of the system. The greatest menace to our weakness in the present situation springs from the vast lines of communication over which we must watch and which, although lying well within our own borders, are endangered through the contributary sympathy of the Dutch who, resident and settled within our own Colony, and boasting some sort of idle observance of the obligations entailed upon them by such residence, have seldom by word, and not at all in spirit, forsworn their entire and cheerful assistance to the cause of the Transvaal. In any other campaign these fatigues (p. 27) would be unnecessary, and the services of the innumerable small detachments delegated to the duty would be released for more active work, but with this war the safe maintenance of our lines of communication will become a problem of most vital concern, and will be necessarily imbued with absorbing interest. Moreover, whatever the nature of the scheme for efficiently guarding these lines may be, due attention must be paid and every consideration given to the superior mobility of the Boer forces to that of our own troops, an advantage which will increase their facilities and chances of success should they exert themselves to harass any particular section of our inordinately long lines of communication.

With the formation of a camp at De Aar, the trend which our campaign may assume becomes more definite. De Aar is but a little removed from Norvals Pont, an important bridge into the Orange Free State, which it is proposed to protect from the immediate base of the troops at De Aar, or to hold altogether from an ultimate base in the same direction at Colesberg. I propose to visit there before the next mail departs, since it be rumoured here that the town of Colesberg has been left entirely undefended by the military authorities, and that the end of the bridge, remote from this border and within the limits of the Orange Free State, is in the hands of an armed patrol from that Republic. When these things happen, and De Aar becomes the centre of a big base camp, the position will constitute another link in the chain of towns which are to be occupied by the Imperial forces along the western and southern borders of the Orange Free State, and whose occupation, should the troops arrive in time thus to execute the initiative, indicates our probable line of advance to be from a (p. 28) number of points, so that General Joubert will be unable to concentrate his troops before any one force. Upon our side, also, those frontier detachments that may be in occupation of the towns, will harass Transvaal and Free State borderside, suppress any rising within our own border areas, and be entirely subsidiary to the main columns, which will be simultaneously thrown forward from these three or four special points on the same extreme line of progression.

Moreover, this plan of operations accentuates the detached and especial character of the Natal Field Force, restraining them to service in that colony, and restricting their activities to that sphere. These troops will occupy Laing's Nek, the ten thousand men already assembled in that Colony being reinforced before hostilities are declared, until the Field Service footing of the Natal Field Force will equal that of an army corps. The critical points in the present situation are the western and eastern borders of the Transvaal, where the young bloods from the backwoods are mostly gathered, and in their present state eminently calculated to force the hand of Oom Paul into an impromptu declaration of belligerency. The movements of the Natal forces will be confined for the moment to holding Laing's Nek, maintaining communication with the permanent base at Ladysmith and Pietermaritzburg, and in occupying Dundee, Colenso, and all such towns as fall within the limits of its exterior lines.

From De Aar a division will support the left flank of the advance of the First Army Corps, divided, for purposes of more speedy concentration upon its ultimate base, into two divisions, which will reunite at Burghersdorp, viâ the railways, to Middelburg and Stormberg Junction from their immediate bases of (p. 29) disembarkation at Port Elizabeth and East London. The total force will then advance in exterior lines upon the Orange Free State, maintaining the railway system upon their individual western flanks, so far as possible, as their individual lines of communication.

While the Second Army Corps supports the situation in Natal, it is hoped that our forces in the Orange Free State border will either crush or drive the Boers back upon their ulterior lines towards Bloemfontein, which, with the assistance of the De Aar flanking column traversing the watershed of the Modder River in the direction of Kimberley, and in possible co-operation with a force from that base, they should be in a position to occupy. The capital will be held by the De Aar and Kimberley divisions, upon whom will then fall the work of protecting the lines of communication of the Southern Army Corps as it advances.

After supporting De Aar, Kimberley, and the lines of communication with defensive units, and maintaining a western column by employing the service of the Mafeking force, the First Army Corps will begin the move upon Pretoria, in collaboration with the Second (Natal) Army Corps, the former once again advancing in twin columns from a mutual base. The western border will probably be held from Kimberley to Fort Tuli by the forces composing the western column, while a flying column is to be in readiness lest a wider area be given to the theatre of war, and it become necessary to cross the Limpopo River. It would appear, too, that there is also some possibility of a column moving from Delagoa Bay. By this advance Pretoria becomes the objective of the campaign after the occupation of the Orange Free State, but this depends to a great extent upon (p. 30) the policy pursued by General Joubert and the nature of the Natal operations. If the Boers give way and, acting upon interior lines, fall back upon Pretoria, as General Jackson fell back upon Richmond in 1864-1865, the Transvaal capital will at once become the objective of the British forces advancing upon exterior lines, the object of the campaign, once the Transvaal has been invaded, being to force a battle upon the combined forces of the Boers or to beset Pretoria. It will thus be seen that the theory of the British advance favours the concentration of troops upon the Transvaal and Orange Free State frontiers so that the Boer forces may be dislocated, retaining the railways and their lines of communication and, leaving the actual protection and pacification of the frontier to the local mounted police and to the special service corps assisted by a few detachments of Imperial troops, while no progressive movement will be made from any one point until the exterior line, upon which the entire advance will be conducted, has been thoroughly established. For the nonce extraordinary precautions are being taken to conceal the movements of troops, and I have withheld from publication at this moment much which could be given in support of the lines by which I have suggested our advance will be governed. This plan of campaign reads very prettily, but it seems to me, that we are making no allowances for possible disasters, for possible defeats, for unavoidable delays, which, should they occur, will hamper the mobility of our advance and restrict the celerity of our movements to a great and most serious extent. Despite the fact that the massing of troops at the selected points between De Aar and Mafeking, between Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, and the ultimate and interested bases (p. 31) will proceed almost immediately, the successful evolution of our plans, the wisdom or foolishness of which are so soon to be put to the test, demands much greater forces than are calculated to be available during the next few weeks. At present, and until the latter days of October, the combined strengths of the Regular and Irregular forces in South Africa will not equal twenty thousand men, and yet we are dabbling with and making preparations against a plan of campaign which requisitions two Army Corps at least, and will probably require the services of not less than one hundred thousand men. I dread to think of what may happen if war should come within a few days, but we can do nothing but face what is a most intolerable position, and one which most easily might have been avoided. The outlook in the absence of efficient men and stores is indeed disheartening.

Since I arrived upon the Orange Free State border I have omitted no opportunity to discuss with the Boers the question of the war. A friendly Boer, hailing from Utrecht, suggested the probable direction which the Boer plans, so far as they concerned Natal, might assume, and while they appear to be feasible, they reveal how curiously predominant among them is the idea that their arms will again defeat the British troops. The Transvaal Boers from Vryheid and Utrecht propose to attempt raids upon Natal and Zululand as the preliminaries to a rush upon Maritzburg and the southern district of Natal, by Weenen and Umvoti; Orange Free State Boers from the border areas will harass our soldiers as they move towards Laing's Nek, and, thus drawing the attention of the British troops, the road will be clear for those marching south on their attack upon (p. 32) the capital of Natal. All approaches to Laing's Nek upon the Dutch side of the border, already alien, have been fortified, fourteen guns being actually in position at the more important points. The British troops soon after leaving Ladysmith will have the Transvaal Boers on one side, the Free State Boers upon the other, and long before the Imperial troops can occupy the extreme border a commando of Boers from Wakkerstroom will have concentrated upon it. In the opinion of the Boers the effective occupation of Laing's Nek by either force will decide the war. The Boers all seem convinced that they can sweep the British forces from South Africa. The procedure of a campaign which finds much favour in their eyes includes the rising of the Swazis, the Zulus and the Basutos, who will be permitted to devastate Natal and as much of the south as they can penetrate, and whom they claim will be easily stirred against the Rooineks. The Boers will then feint with a small force upon the centre of our military occupation, while their entire army marches down upon Port Elizabeth, East London, or Cape Town, or proceeds by railway if they can secure the lines. They will hold open no lines of communication, because by that time Imperial arms will have been defeated, and it will only remain for President Kruger to dictate peace from Cape Town.

This is actually the opinion of a Boer who administers for the Transvaal Government an important district, and who is under orders to proceed to the Natal border without loss of time. Surely he must be consumed with delusion and impotent fanaticism; nevertheless, educated Boers from the border side and living in the Cape Colony, who have come to the camp to invite the officers to a cricket match or some buck (p. 33) shooting, have all expressed this view. At present I have not met the Boer who can conceive the defeat of his own countrymen, while both Imperial and Republican Governments count upon the assistance of the natives. Upon the other hand, however, I am informed that there are many Boers who do not wish to fight, since they recognise the futility of any effort which they can direct against British troops; but, at the same time, should they be called out upon commando, there is no fear of their declining to obey, while, so far as my inquiries go, they have failed to elicit anything which would show the Boers to be moved by any view so eminently sound as this would be.

The Camp, Orange River,

September 26th, 1899.

Soldiers and sand—clouds of sand whirring and eddying through the air, drifting through closed windows, piling in swift-mounting heaps against barred doors. That is the camp here, stretching upon both sides of the railway line in orderly rows, flanked upon either extremity by a ragged outspan of waggons, empty to-day but soon creating work for numerous fatigue parties when the orders come to push forward the supplies. At present it is only a small cluster of tents, many more tents than men—this to confuse the friendly Boers who, visiting the railway station refreshment bar for the purposes of espionage, stop to drink in an effort to gauge the strength of the camp by counting the ranks of dirty white tents which flap and quiver in the breezes. Such an impossible little camp, but so impressed with the true spirit.

Colonel Kincaid, R.E., commands at Orange River, and his force comprises a few companies of the Loyal Lancashire Regiment, a troop or two of the Cape Police District II., sections of the Field Company of Engineers, a composite field battery and a few stores—but (p. 35) a general numerical insufficiency of men and munitions. Major Jackson, with Major Coleridge, commands the companies of the Loyal Lancashires that were detailed with him from Kimberley, where his regiment lies, for duty at this camp. Surgeon-Major O'Shanahan takes care of the field hospital which has been attached to the camp, and Captain Mills, R.A., controls the artillery. It is a happy family, this British camp in which the necessity for hard work is understood and the members of whose circle willingly endure the difficulties and privations of their situation. From the ends of the earth they have come together to be dumped down upon the Orange River flats, where for many days they will remain an important unit in the scheme of preparation, but one which stands alone and aside from the general hurry and scurry of our belated movements. There is a bridge across the Orange River at this point, and it is the duty of protecting it and guaranteeing it from the attentions of the Boers, guarding its approaches by cunningly contrived gun emplacements and enveloping its definite security in a network of defensive measures, which is, for the time, the sole objective of the various officers and detachments that compose Colonel Kincaid's command.

The conformation of the country abutting upon Orange River presents those composite peculiarities of construction which contribute more generally to the setting of the high veldt. Orange River is broken by hills and river-beds, dry courses with rock-strewn banks, patches of sand, sparsely grassed and destitute of bushes. The land to the west rolls smoothly to the watershed of the river, breaking into bush and short rises about the banks of the stream. The (p. 36) water clatters among stones and rocks to the north-west, leaving to the south-west and due west the same barren open sand flats. Upon the east there is a slight contrast to the evenness of the pastureless country which meets the sunset; but the fall of the land due south, south-east, south-west, is unchanging, the compass shifting due east and north-east before the abrupt and rugged lines of the country are exposed. Then, and then only, does the face of the country reveal its uncouth and uncomfortable character. East, whence the waters stream beneath the railway bridge, the watershed is herring-backed, concealing, beneath rough folds of rising ground, stretches of bush veldt and stony patches. High ridges debouch at right angles to the stream, with uncertain contours and abrupt declivities; detached kopjes rise from upon the face of the country, claiming classification with the ages around them, but standing aloof with forbidding mien—a formidable menace to the chance of successful storming. Parallel hills and ridges distinguish the hinterland of this watershed so far inland as the areas of the Orange Free State, while the broken and dangerous character of the country east-north-east, continuing until the watershed of the Modder River, still further prolongates these disturbing features. The valley of the river, within a mile from the stretch of flats which rolls away from the bases of the hills, converges until the sides lie within a few hundred yards of each other. There the stream rushes and roars with some force, until the wider reaches of the plain give to the pent-up waters a greater space of revolt. From the mouth of the valley the river wanders with easy indifference across a broader course to the west; gathering its volume from the seasons, and leaving (p. 37) in the hot weather a margin of shining stones upon both sides of the river bed. The hills are in pleasant contrast to the even tenour of the veldt, and the cool waters of the river invite repose. Small game lurk within the cover of the scrub, mountain duck haunt the mountain cataract; cattle roam across the land, snatching mouthfuls of dry herbage, while just now the sides of the hills throw back the echo of the military occupation, the noises of the camp, the calls of the horses upon the picket lines, the heavy thudding of the picks, the shrill rasping of the shovels in the places where the men are throwing up the necessary field works.

Everywhere is the spectacle of orderly bustle. The summits of the hills are crowned with earthworks, brown lines of trenches traverse the valley, block houses command the entrances of the bridge. These are the signs of the times, encompassed in an unremitting rapidity of execution. Colonel Kincaid rides from point to point, throwing advice here, praise there, and expressing general satisfaction over the labours of his men, as the scheme of defences runs to its conclusion. Out across the plain, upon Reservoir Hill, the sappers are constructing an entrenched position under the direction of Captain Mills, R.A., and especially designed to protect the water supply. Roads have been cut across the rear face of the hill, a breastwork of stones and earth encircles the Reservoir, and gun emplacements flank either extremity. It is a pretty work, carefully conceived, skilfully constructed, commanding the portion of the camp, and sweeping the approaches to the bridge. From the top of Reservoir Hill, no great eminence, the surrounding country is easily inspected, and the more one scans and studies the peculiarities of its (p. 38) formation, the more one becomes impressed with the fact that it presents the gravest obstacles to the British principles of military operations. A well-equipped and mobile force will hold the hills for eternity—but God help the troops who are launched against these awful kopjes which create the strength of such positions. The officers commanding these detached units along this border have received instructions to prepare extensive lines of fortifications round their bases, and at De Aar, as at Orange River and elsewhere, these commands have been complied with, until now the positions need only the service of some good artillery to be made impregnable. When cables be at the disposal of a possible enemy, it is as well to be reticent upon the cardinal weaknesses within our lines, but already there are signs of the extreme haste with which the troops have been despatched to the front. No unit would appear to be complete, despite the months of warning in which there has been ample opportunity to prepare. Everything is rushed through at the last, and although urgent orders be issued to make ready against attack, no artillery is available for the purpose. Everything is obscured in idle talk or deferred by empty promise, and the authorities appear to be continuing a policy which gives to the Boers some justification of their hopes of success. The Imperial authorities, in relying so much upon the moral effect of their artillery, appear to forget that the better it is, the more important the results it achieves; the more important the position to be defended, the better it should be. The Boers lose nothing by possessing modern weapons of defence. But with a wing only of the King's Own Light Infantry to occupy De Aar, and four companies of the Loyal Lancashires (p. 39) to hold Orange River, the need of strong artillery support is manifest. It has been laid down that the proportion of guns to men is as near as possible three guns to one thousand men, but this proportion must depend upon the nature of the service upon which the force is to be employed, the topography of the theatre of war and the quality of the troops. A force intended more for the occupation of strong positions, must have a larger proportion of guns than an army intended for offensive operations in the field. De Aar, as one base of operations toward the lines of least resistance to the western, southern, and south-eastern approaches to the Orange Free State, is even more important than our position at Orange River, which is intended, in the event of any campaign, to protect the railway bridge and the lines of communication with the north. But at De Aar the lines of railway, which converge upon it, link Pretoria and Bloemfontein to Cape Town, connect the north with the south, join Cape Town with the south and south-east by a stretch of line almost parallel with the southern border of the Orange Free State. Yet, so dilatory have been the efforts of headquarters to obtain the necessary artillery, that, having reduced South Africa to a condition of war, they split up between De Aar, Orange River, and other defenceless, but important, strategic positions along the western border, improvised field batteries drawn from any garrison lumber room which came handy.

The artillery at present upon this border is, as a consequence, the seven-pound muzzle-loader which was obsolete when the passing generation of officers were at the "shop." The inadequacy of the artillery is a matter of the gravest concern, since, even if the troops at these places be sufficient to police the (p. 40) disaffected areas, and to hold in check the local disposition to rebel, in face of the weapons of precision with which the Boer forces be armed, it would be impossible, should they move forward, for the British artillery to maintain any position which was incumbent upon the possession of good artillery. So well is this realised by our Intelligence Department, that elaborate precautions are taken by that Bureau, as well as all commanding officers, to prevent the enemy from discovering that, in its main part, the strength of the batteries in opposition has been drawn from derelicts in the garrison stores. These improvised field batteries might be of service in maintaining the line of communication if any advance of British troops be made, but as an actual factor in any defensive or offensive movements which the forces may undertake, their restricted utility escapes all serious consideration, and puts our present artillery almost at once out of action. The physical configuration of the country urgently calls for the immediate despatch of modern weapons, similar to those which the Sirdar used in his Soudan campaign. In addition to this an exchange, piece by piece, between these seven-pounder muzzle-loading monstrosities and the converted twelve-pounders, breech-loaders and high-velocity quick firers, might be seasonably effected. Five-inch howitzers, too, should also be sent forward. But the lack of reliable artillery is scandalous, and the sooner that guns, of a calibre which is in a true proportion to the importance of the positions which they will command, arrive upon the scene, the less uncertain will be the results of any actual contact between our forces in their present deplorable condition and those of the African Republics with whom we are so soon to be at war.

The Camp, Kimberley,

September 28th, 1899.

This usually dull and dirty mining station has now been occupied by a small detachment of British troops. The force arrived here from the camp at Orange River within the week, and include the 1st Loyal North Lancashire, with its usual complement of machine guns, No. 1 Section of the 7th Field Company of Royal Engineers, 23rd Company of Garrison Artillery with 2·5 seven-pound muzzle-loaders on mountain carriages (which are almost useless and certainly obsolete weapons), an organised Army Medical Staff, and a transport most indifferently equipped if it be intended for immediate and prolonged field service. Yet it is claimed that nothing has been omitted which could make this force an imposing factor in the chance of attack to which, from its exposed situation, the hapless Kimberley is threatened. The Loyal Lancashire Regiment is in full strength, but the battalions have been divided between the positions here and the camp just south of the Orange River. It is, of course, doubtful whether much be gained by splitting up our forces (p. 42) along the border into small units, but at the present juncture, when so few troops be in the colony, this policy is receiving its own justification. We are all urgently hoping for the arrival of troops, since if there were a general advance of the Dutch troops, a contingency not by any means altogether remote, upon any one of these well-defined but indifferently manned places, the task of maintaining the advanced lines would be a severe strain upon the efforts of the very limited number of men that are available at each point. It is surely only within the limits of the British Empire that a frontier line over 1,500 miles in extent would be kept absolutely without any defensive measures; while it is Boer activity during the past few weeks that has induced the Colonial authorities to adopt their present precautions. Our troops are now more or less efficiently prepared at certain points along this Western boundary, and, if no order has yet come for their mobilisation, the steps necessary to effect it have all been completed. At Kimberley, in the few days which have elapsed, wonders in the preparation of the town's defences have been worked, and the alarm which caused so much panic there before the arrival of the soldiers has now, in part, subsided.

For many hours before the arrival of the troops at Kimberley crowds of interested spectators besieged the railway station and thronged the dusty thoroughfares of the town. The Imperial men detrained very smartly to the sound of the bugle, off-loading the guns and ammunition to the plaudits and delights of an admiring crowd. The actual detraining took place at the Beaconsfield siding, two miles from Kimberley, the men not making their camp in the town until the next morning. For the time the (p. 43) transport was stored in the goods sheds, and the troops arranged to bivouac beside the railway. The traffic manager had prepared fires and boiling water before the men came, so that soon after their arrival they were all served with dinner. The detailing of guards, posting of sentries, and other evolutions incidental to open camp, permitted Kimberley to indulge its taste for military pomp and vanities. Imperial troops have not been here since two squadrons of the 11th Hussars passed through from Mashonaland in November, 1890, and the presence of the troops has inspired the townfolk with a magnificent appreciation of the gallant men who have come up for their protection. It is hoped that special means will be taken to interest the troops in the few hours which they have free from work. At present all attention is being devoted to the construction of the defences of the town, to the formation of adequate volunteer assistance, to the arrangement of a complete system of alarm and rallying spots. Lieut.-Colonel Kekewich, in command of the Imperial camp here, is anxious to assist the people in rifle practice and field-firing; while the Diamond Fields Artillery and the De Beers Artillery are to be called out for temporary service in conjunction with the Imperial Artillery.

The rumour that a Boer force is within the vicinity of Kimberley has done much to assist in the speedy formation of local forces, and now that the train mules and private bullock teams have been requisitioned for the Imperial service, there is much solemn speculation upon the date of hostilities. The fact is that no one here can, with any certainty, predict an hour. A shot anywhere will set the borderside aflame. Moreover, the Boers are daily growing more (p. 44) impudent. At Borderside, where the frontiers are barely eighty yards apart, a field cornet and his men, who are patrolling their side of the line, greet the pickets of the Cape Police who are stationed there with exulting menaces and much display of rifles. But if the Dutch be thirsting in this fashion for our blood, people at home can rest confident in the fact that there will be no holding back upon the part of our men once the fun begins. Seldom has such a determined and ferocious spirit animated any British force as that one which is now stimulating the troops in South Africa. Every man is sick of the Cabinet's delay, but they find consolation in the fact that the slow movement of the Ministerial machine is undertaken to avoid any precipitation of the crisis before the forces to be engaged have arrived upon the scene. Then it is every man's ambition to take his own share in "whopping" Kruger.

I did not hurry to leave Kimberley; but the place where the diamonds come from, the least admirable of any town on earth, is no longer essential to my existence. It has neither charm nor elegance, and it is sufficiently irregular in its construction to be the most barbarous example of architecture in South Africa. It greets the traveller enveloped in the haze of heat, and it bids him farewell through a cloud of sand. But if one has once imagined what the appearance of the mining town may be, let him give it a wide berth. It is a conglomerate jumble of tin houses with dusty streets dedicated to modern industry, and palpitating with the mere mechanical energy of native labour.

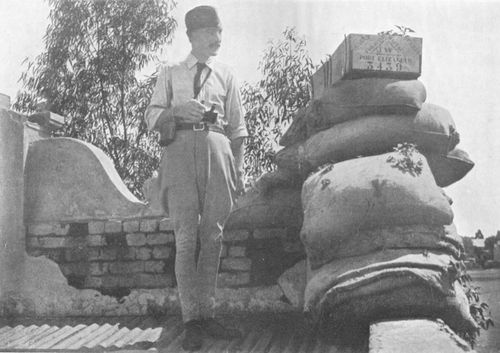

MAJOR LORD EDWARD CECIL, C.S.O.

Kimberley, however, was a convenient immediate base between Orange River and Mafeking. Around these two places rumour was spreading a well-woven (p. 45) net of probabilities, intimate yet inherently impossible. War, bloody and fierce, was alternately looming large in the horizon just above their situations, so for the moment I tarried, watching the approach of impending battle from afar off. It was a fine feeling, the constant thrill caused by the mere vividness of martial rumours. They came from Buluwayo in the North, they came from Cape Town in the South, they were brought daily from Bloemfontein; and if they gave infinite zest to the passing hours, it was but the happenings of the hour that they were doomed to be misbelieved. To listen to the gossip and rumours of Headquarters at once became the most serious interest which our life contained just now. Spies are seen everywhere. Within the shade of every shadow there is said to lurk a Boer secret service agent, and, as a consequence, the attitude of the public is one in which each figuratively lays a grimy finger to his nose and breathes blasphemies in whispers to his confiding friend. The spy mania which swept through France but a few weeks ago has appeared here, endowed with magnificent vitality. At Mafeking it has dominated both the military and the public, and, as an illustration, I append the official notice, on page 46, in which many of these gentry are warned from the town by Lord Edward Cecil, Chief Staff Officer to Colonel Baden-Powell.

NOTICE.

SPIES

There are in town to-day nine

known spies. They are hereby

warned to leave before 12 noon to-morrow

or they will be apprehended.

By order,

E. H. CECIL, Major,

C.S.O.

Mafeking,

7th Oct., 1899.

THE NOTICE TO SPIES ISSUED BY COL. BADEN-POWELL.

Kimberley has not yet gone so far as this notice, but a similar step is in serious consideration, and the notice will soon be promulgated. What with spies, war scares, reports of Boer invasion, and of active hostilities having commenced, the Western border is living in a seethe of excitement, and appreciating the crisis with but doubtful enjoyment, and many signs of such indisputable terror. Kimberley has (p. 47) called forth its volunteers, who in name are glorious, but in utility uncertain. The Town Guard, after fortifying itself with much Dutch courage, has taken unto itself a weapon of precision of which it knows nothing. Infantry and musketry drill have not existed for the town of diamonds; they are for the Cape Police, for the Mounted Rifles, for Imperial troops; but for those who are regular in their mining, but irregular in their drill, there is none of it. These heroes shake with terror in private, but they gnash their teeth with impotent valour in public; at heart they are rank cowards, for the most part leaving to the few decently spirited the duties of volunteer defence, and to the soldiery and constabulary the rigours of the coming battle.

Nothing perhaps has been so discreditable as the hurried flight of men from these towns which are within the area of possible hostilities. It is perhaps different where they belong to the Transvaal, but one would expect Englishmen, who have seen their womenfolk to places of security, to proffer such service as could be turned to account in these hours of emergency. It is an unpleasant fact to reflect upon that the leaders of the general panic and consequent exodus from these towns are mostly Britishers. From sheer force of numbers the white-feathered brigade merits solicitous contempt.

Such is Kimberley in the passing hour, and as I waited there to see whether the rumours would crystallise into actualities, the word was passed round that three commandos of the Boers were concentrating upon Mafeking. Heavens! how the specials skittled! By horse and on foot, by cab and cart, they dashed to the station. Lord! and the train had gone some hours! But, with the instinct of true (p. 48) war-dogs, they fled in special expresses to the scene where attack was threatened. They might have crawled from Kimberley to Mafeking on hands and knees, for Boers may camp and Boers may trek, but war is still afar off. Had we not travelled in such haste, the journey might have proved of interest, but impatience made the time speed quickly, and the frontier posts upon the road went by unnoticed. Just now these frontier stations are of public interest. At Fourteen Streams, at Borderside, at Vryburg, Boer commandos have laagered within a few yards of the frontier fence, and since human nature is ever prone to politeness, it has become the daily fashion for Boer and Britisher to swear at one another across the intervening wires. John Bosman, a Borderside notoriety, implicated in a late rising of the natives against Imperial authority, is in command of one hundred and fifty "cherubs," as the Boer captain dubs his gallant band. Matutinal and nocturnal greetings have enabled the two forces to become acquainted with one another, and it is held to be a sporting thing for men, from either force, to invade each other's territory, inviting blasphemies and creating some excitement, since at Borderside the friendly relations between the two countries be altogether gainsaid.

The Camp, Mafeking,

October 9th, 1899.

Mafeking lies a day's journey by the train from Vryburg, and was once the terminus of the Cape railway system pending its extension northwards. Just now it is the embodiment of a fine Imperialism. There is the dignity of empire in the shape of her Majesty's Imperial Commissioner, Major Gould Adams, C.B., C.M.G.; the majesty of might, as suggested by Colonel Baden-Powell, of the Frontier Force; by Colonel Hore, of the Protectorate Regiment; by Colonel Walford, of the British South Africa Police; by Colonel Vyvyan, base commandant; and there are, too, the various strengths attached to the respective commands. For weeks this little place has been terrorised by Boer threats, until the presence of the military has reassured them. Now, however, the veldt beyond the town has been effectively occupied by the different commands, while within the town, or beyond its outer walls, noise and bustle everywhere embody the grim reality of war. It has not been possible to visit the different camps, in time for this mail, since the exigencies of war have interfered with (p. 50) the dispatch of the English letters from the more remote districts, and until the country is more settled the night train service is altogether discontinued. This week's mail is two days in advance of its usual fixture; but perhaps we are fortunate, since the mail coach to Johannesburg has discontinued running, its last journey from Mafeking being confined to taking back to the Transvaal the few things which belonged to it in Mafeking. The supplementary coach was behind, its harness was stored in sacks upon the top, and thus it made its departure. It had better have remained at Mafeking, for no sooner had the coach passed the border-line than its mules were commandeered for transport by order of the Transvaal Government.