The Project Gutenberg EBook of Baron Bruno, by Louisa Morgan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Baron Bruno

Or, the Unbelieving Philosopher, and Other Fairy Stories

Author: Louisa Morgan

Illustrator: Randolph Caldecott

Release Date: March 26, 2012 [EBook #39274]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BARON BRUNO ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

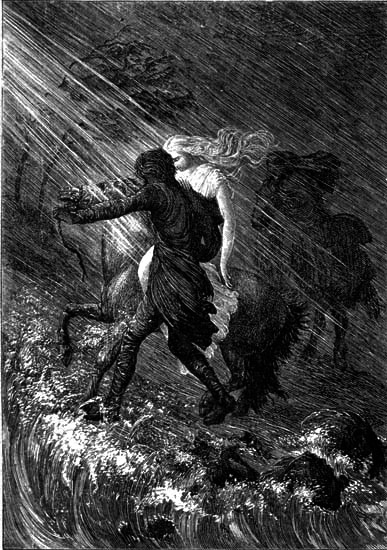

ESGAIR.

Frontispiece.

BARON BRUNO;

OR,

THE UNBELIEVING PHILOSOPHER,

BY

LOUISA MORGAN.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY R. CALDECOTT.

London:

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1875.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| BARON BRUNO AND THE STARS; OR, THE UNBELIEVING PHILOSOPHER | 3 |

| ESGAIR: THE BRIDE OF LLYN IDWYL | 49 |

| EOTHWALD: THE YOUNG SCULPTOR | 91 |

| FIDO AND FIDUNIA | 115 |

| EUDÆMON; OR, THE ENCHANTER OF THE NORTH | 199 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

| ESGAIR | Frontispiece. |

| VIGNETTE | Title. |

| "THE DREAMER STARTED FROM HIS CHAIR" | 8 |

| BARON BRUNO AND ALCYONE | 22 |

| EOTHWALD AND DUVA IN THE CAVE | 102 |

| FIDO AND FIDUNIA | 123 |

| FIDO AND FIDUNIA | 170 |

| EUDÆMON | 199 |

BARON BRUNO AND THE STARS;

OR,

Baron Bruno was the Prime Minister of the Hereditary Grand Duke of Rumpel Stiltzein. Besides being Prime Minister, he was the cleverest man in the kingdom. This is saying a good deal, for were there not (besides all the men of science, the physicians, the literati, and the great philosophers of the day) the General-in-Chief of the Grand-Ducal army, Prince Edlerkopf; the great High Almoner, Herr von Pfenig; and also the accomplished Graf von Wild Kranz, the most able lawyer and the politest man about court? So humble and gentle, indeed, were his manners, that strangers sometimes took it upon themselves to dispute the opinion of their modest neighbour. But such hardy persons seldom repeated the experiment after Wild Kranz had completely overturned their arguments in his quiet, hesitating tone, with a shrewd glance of enjoyment twinkling in his small wary eye; and woe to the man who a second time opposed his will or challenged his decision.

Very different was Baron Bruno. Impetuous, fiery, and caustic, gifted with inexhaustible memory, and brimming over with barbed sarcasm, he was often misunderstood and disliked in the outer world, but invariably beloved by those who knew him intimately.

Pfenig and Edlerkopf were devoted friends, as well as ministers at court. They had been educated together, and while Edlerkopf lent to the counsels of state the aid of wise and deliberate judgment and the weight of his nobly impartial character, Pfenig was the most wonderful manager of the public purse, and could not only calculate the incoming revenue within a hairsbreadth, but could also regulate government expenditure so exactly as to keep all departments amply supplied, and yet preserve a due regard to economy.

You may well imagine that with four ministers such as these the Grand Duke had little difficulty in maintaining peace and contentment in his beautiful kingdom of Rumpel Stiltzein; and that from every side artisans, labourers, and mechanics flocked to the small domain, within whose narrow boundaries prosperity sat enthroned. To add to his happiness, the Grand Duchess became the proud mother of twin children, the spirited handsome Prince Bertrand and the lovely gentle Princess Berta. They were now in their tenth year, and seemed only born to give pleasure and hope to their parents and to the whole principality.

Edlerkopf, Wild Kranz and Pfenig were all married, but Bruno had a solitary home; and no one without ocular demonstration would have believed in what a shabby den this great statesman passed much of his time. In his town-house he had magnificent saloons, where all that was fair and choice delighted his guests; but near the roof of this dwelling, and far above the haunts of men, there, like the eagle, Bruno had his eyrie, where, with ill-concealed impatience, he would hardly even permit the cleaning incursions of his maids, and few and far between were the footsteps that trod those time-worn boards. Here the Baron sat surrounded by dusty piles of books, now poring intently over the records of the past, now eagerly scanning the papers of the day, now striding up and down the narrow chamber, composing his speech for the Reichstag, or dashing off answers to his numerous correspondents. There also at the threshold would pause the faithful messengers who bore from minister to minister the secret boxes of state papers, and waited to obtain from each his signature before proceeding on their rounds.

A few steps and a small door led from the sanctuary which I have described to the roof. Here Bruno had a little observatory on one side fitted up with a revolving cupola; so that when he sat in the centre of this round miniature house he could turn his telescope, without himself moving, upon any part of the heavens, and seek with keen unfaltering eye the verification of calculations he had made, or diligently mark the alteration and movement among the visible planets. But the rest of the roof was a free uncovered space, upon which a comfortable chair and rug, generally kept within the observatory, to be safe from the wear and tear of the elements, were often placed. From this lonely elevated seat the Baron would then study the myriads of stars with his own unaided and unerring vision, until they became to him dear and well-known companions.

During such silent hours of the night, when all around teemed with nature's glorious presence, Bruno indulged in long soliloquies. Sometimes he pondered curiously over the strange difference between himself and his colleagues. He well knew that, when weary with the lengthened debates and vitiated air of the Reichstag (which often extended its sittings till long after midnight), Pfenig and Edlerkopf hastened home to their faithful wives, and derived from their society a pleasure little short of bliss; and found endless interest in watching and fostering the mental and physical growth of their children; while Wild Kranz, though often delayed in his law chambers till near daybreak, (the keenest and hardest lawyer of his day,) considered no happiness like the sacred domestic felicity he also experienced when surrounded by his family. When these and other similar reflections weighed on Bruno's mind, he would lift his piercing eyes heavenward, and, shrugging his shoulders, murmur, half aloud: "O, ye stars! ye are wife and children to me. As I gaze alone on you by night, I feel a secret satisfaction surpassing the keenest emotions experienced by these weak dreamers in their so-called felicity. O, immortal heavens! enfold me in your vast space, and teach a finite mortal to comprehend in faint measure your infinite beauty and eternal unswerving laws." Bruno's fervid nature suffered no chill from such midnight exposure; his iron frame was proof against fatigue; his restless intellect but seldom needed or courted repose.

It was a hot night in July, worried and jaded, after a wearisome debate in the Reichstag, the Baron walked through the empty streets. The latest revellers were already housed, a strange hush hung over the noisy, populous city, and refreshing breezes blew on his burning brow, as he at length reached his home, and ascended to his upper chamber. With a sigh of contentment he stepped on the roof, and prepared to enjoy his well-earned repose. Throwing himself into his easy-chair, and drawing his soft rug across his feet, he became absorbed in the contemplation of the firmament above.

As the night wore on, thoughts, till now strangers to him, took possession of his mind. A new yearning for companionship awoke in his world-wearied bosom. In vague, uneasy discontent with his solitary condition, he turned restlessly from side to side, and at length exclaimed aloud: "To you, distant stars! I nightly offer the homage of a constant worshipper; would that you in return could give me to know the spell of love, and teach me what it is that inspires the painter, the poet, and the lover."

Hardly had the thought crossed his mind, or the half-uttered words risen to his lips, when a meteor fell swiftly rushing from the stars on which he gazed. He strove to follow it with his eye, but was dazzled by the blinding flash of light. For a moment fire seemed to surround him. When the bright glow became less intense, lo! upon the roof near at hand, where that vivid ray had fallen, shone a shimmering shape. The dreamer started from his chair. Bewildered and entranced, he deemed her the creature of his imagination; and surely mortal eye had never beheld a form so fair. In trailing garments of palest azure there stood the perfect ideal of a poet's dream. From her hair gleamed a faint effulgence, and her deep tender eyes sent a strange thrill to the philosopher's heart.

THE DREAMER STARTED FROM HIS CHAIR.

P. 8.

The burden of many years fell from Bruno; the ardour of youth rushed through his veins; ambition, politics, calculations, all disappeared like fallen leaves before the autumn wind; and in agitated tones he besought his beautiful visitant to tell him whence she came.

"Son of earth!" replied the fair unknown, "thou hast watched and loved our stars for long years. We in our turn have known thee, and have guarded thee and thy fortunes in many a time of danger. Thou wouldest know the spell of love. It is even now awakening within thy rugged breast; but beware! Thou hast disbelieved in immortality, and doubted the eternal power of our great Creator. We love thee! we yearn to save thy soul! We long to soften thee through human affection; that when thy poor earth is no more, thou mayst find an everlasting home, where

'Infinite day excludes the night,

And pleasures banish pain.'

I—Alcyone, sent by my sisters—I am here to speed thine upward way."

Bruno, spell-bound, eagerly listened. Deeply enamoured of the lovely messenger, he succeeded in winning from the fair denizen of the stars her consent to remain with him on one condition. She stipulated that she should be permitted every month to spend the evening hours of this self-same night entirely alone beneath the canopy of heaven, without interruption or intrusion, for her life depended on the due observance of this time of "retreat."

She also added, falteringly, that if her faith were once doubted she must quit for ever the pleasant paths of human fellowship, and be claimed again by her immortal sisters. The Baron gladly vowed to keep what seemed to him such wondrously simple promises by which to gain so peerless a bride. The time passed swiftly as these arrangements were made, and ere long the first streaks of daylight appeared in the east. Alcyone, faint and weary, was conducted to a chamber for rest and repose; and the Baron aroused his servants and informed them that he was about to be married.

In the country of Rumpel Stiltzein it was customary to celebrate marriages in the evening; there were therefore still available a good many hours for the requisite preparations.

The court of the Grand Duke was considerably agitated by the unexpected news. Strange rumours were set afloat regarding the newly-elected bride. The Prime Minister's answer to all inquiries was the same. He let it be understood that the Lady Alcyone was an orphan relative lately committed to his charge; that she had suddenly arrived from the country the evening before, when he came to the conclusion that the best way of taking care of her would be to marry her, and having gained the lady's consent, all was well.

It is true that Bruno had a private interview with his Prince; but as it was held with closed doors, the substance of their conversation is unknown. The only thing certain is, that the Grand Duke himself consented to give away the bride.

Edlerkopf, Pfenig and Wild Kranz, with their wives and families, and all the chief members of the court promised to attend at the ceremony, and great were the rejoicings that the solitary philosopher was about to enjoy the sweet pleasures of home life. All rejoiced, because they believed the change would be for the Baron's happiness; but there was one dissentient mind. The Countess Olga von Dunkelherz, one of the ladies-in-waiting on the Grand Duchess, was a spinster of a certain age, and of undisputed ability; celebrated for her witty tongue and smart sayings. She was not displeased when rumour coupled her name with that of the Prime Minister, and when the courtiers rallied her about the Baron's attentions. The truth was that Bruno had never for a moment regarded her in the light of his future Baroness; her manners wanted the repose and softness which to him constituted a woman's chief charm. In spite of her masterly intellect, her conversation often bored him. For in his moments of relaxation he turned to the fair and softer sex for sympathy and recreation, not to involve his wearied brain in arguments about the last geological discovery, or the newest theory of electricity.

But as he remained single, and they were constantly together, the Countess Olga had insensibly grown to regard him as her own property. Imagine therefore her astonishment and her displeasure when the Grand Duchess, summoning her ladies to her apartment, gave them instructions to lay out her state robes, and prepare for a grand court ceremonial, as Baron Bruno's wedding was to take place that very evening within the palace.

All was bustle and confusion; but the labours of the court cook were something superhuman. It required, indeed, the utmost efforts of genius and industry combined to produce so splendid a feast at such short notice. It is only due, however, to Francabelli's reputation as first chef of the Grand Duchy, if not of the world at large, to record that the execution of his designs was on this occasion carried out with peculiar success.

At last the nuptial hour approached, and excited curiosity was gratified by the sight of the bride, as she was led slowly through the palace by the Grand Duke. Her wondrous beauty amazed every one, as also the radiant simplicity of her attire. She wore her robes of flowing azure, and over her forehead there sparkled a gem of extraordinary brilliancy, which seemed absolutely to blaze with light.

As Alcyone advanced towards the altar, Baron Bruno, clad in his splendid court uniform, embroidered with gold, and covered with decorations, stepped forth to meet her, and the wedding ceremony was soon completed. The priest dipped his hand in the holy water and sprinkled some over bride and groom during his final benediction; as he did so, the Countess Olga, who stood near with her royal mistress, rushed forward, exclaiming, "She is a witch! she is a witch! the holy water has scared her!" All eyes turned instantly on Alcyone, who shuddered visibly, and would have fallen to the ground where she knelt had not her husband's strong arm encircled and held her up. A mortal pallor overspread her fair countenance, and, strange to relate, the glittering gem on her forehead became opaque, and was clouded over with a dim moisture. By the aid of strong perfumes she gradually revived, but was thoroughly shaken and overcome. Baron Bruno, therefore, craving the indulgence of the Grand Duke, begged permission to retire at once with his bride, and entreated that their absence should not be allowed to cast a shadow over the rejoicings at court.

Now Bombastes, the Grand Duke, though of a choleric temperament, was still at heart a man of just and keen perception. He perceived that the newly-made baroness was indisputably overfatigued, and that it was only natural her bridegroom should wish to take every care of her. He instantly, therefore, granted his Prime Minister's request, and calling the other great officers of state around him, invoked their aid to carry on the court revels with due spirit and merriment; at the same time adding, in an undertone, that he trusted his faithful servant had not undone himself by marrying an unknown beauty without parents, relations, or antecedents!

The three ministers, Edlerkopf, Pfenig, and Wild Kranz, with their wives and children, joined heart and soul in the gaieties of the evening. The children, with their friends Prince Bertrand and Princess Berta, were, as a great treat, allowed to sit up to supper, and had a small side-table to themselves. Here old Donnerfuss, the head butler, kept them well supplied with all they demanded, and they behaved with decorum for a considerable time. At length, wearied with the protracted courses, and finding it impossible to eat any more, the thoughtless boys amused themselves by sticking burrs on the footmen's silken calves as they passed to and fro. These naughty children had purposely provided themselves with a quantity of these instruments of torture, in hopes of finding some use for them during the dull state supper. For some time they pursued their fun unnoticed during the general bustle, and quite undisturbed by the muttered maledictions of their victims. At last Bombastes, having an observant eye, became aware of some interruption in the serving of the dinner. Looking round the hall, he noticed on every side agitated footmen carefully examining their lower extremities. In a voice of thunder he demanded of the Lord Chamberlain an explanation of such unprecedented behaviour. The Lord Chamberlain called up the High Steward of the Household, who, in his turn, required Donnerfuss to explain this breach of discipline. Thereupon the fifty red-faced footmen, seeing all eyes turned upon them, at once resumed their duties, regardless of pricking sensations about the leg and unseemly excrescences upon the otherwise fair white proportions of their well-filled stockings. Donnerfuss, in a frightened whisper, revealed the truth to the High Steward, and he, in his turn, narrated the mischievous exploit of the boys to the Lord High Chamberlain. Bombastes now impatiently beckoned the latter to his Grand-ducal chair, and insisted upon hearing the whole root of the matter. Sanftschriften, who was himself a parent, and naturally kind-hearted, tried to soften down the affair; but as Bombastes listened, his large, round, prominent eyes seemed as if they would absolutely start from his head at the recital of this outrage on decorum. He sternly commanded the culprits to retire to bed; and, glancing wrathfully at Edlerkopf, Pfenig, and Wild Kranz (who sat quaking in their shoes), he added further: "As to the well-brought-up sons of these great noblemen, their domestic life is beyond the control of their poor sovereign; but for the next month I give orders that no dessert of any kind shall pass the lips of Prince Bertrand, who has thus misbehaved himself in so shameful and public a manner." Princess Berta and the other little girls, distressed at the disgrace of their playmates, rose also at once from the table, and accompanied them from the hall. Thus it came to pass that the court children had no very pleasant associations with the day of Baron Bruno's wedding. Indeed, you may be very certain that the three ministers gave their sons the same punishment as Prince Bertrand; and therefore for a whole month the boys had good reason to remember the marriage feast, as their tutors, governesses, and nurses, were strictly enjoined to carry out the Grand Duke's peremptory edict. Princess Berta and the other small girls, tender and soft-hearted as little maidens ever should be, did their best to alleviate the punishment of their playmates by voluntarily depriving themselves of all sweet things for the same period, which, I am sure you will agree with me, required much self-denial, on the part of those dessert-loving damsels, and was no small proof of affection.

In the meantime Bruno had taken his bride to a small cottage he owned on the borders of a wide and gloomy forest. Here they passed the few days which, by the indulgence of his royal master, Bruno was enabled to spare from the affairs of state. When they were alone together, his wife expressed to him her conviction that some ill-disposed person had tampered with the holy water, so as to affect that which was sprinkled over them. She had also felt during the ceremony the near presence of an anti-pathetic and malign influence. Alcyone furthermore explained to her husband that the gem on her forehead was a talisman, which paled and grew dim on the approach of danger, or when exposed to poison. The Baron at once remembered the dull appearance presented by the jewel when the holy water fell near it, but he also became unreasonably vexed when his bride refused to loosen it, even for one moment, from her hair, to permit him to examine it in his hand.

He gradually grew to regard its brilliance with a certain amount of suspicion, and more than once, when the gentle Alcyone laid her head upon his shoulder, he felt as if a fiery eye shone guardian over her and watched unsleepingly his every movement. When in his vexation Bruno allowed himself to speak harshly for the first time to his young wife, Alcyone tearfully deprecated his displeasure. She assured him her life was bound up in her talisman, and that if she parted with it, for ever so brief a space, she must at once return to the regions whence she came. After this explanation Bruno rarely referred to the disputed point, but it is not too much to say that the lurid ray of the strange gem often in their happiest moments sent a sudden thrill to his heart's core, and gave a feeling of insecurity to his most private hours of retirement.

"It is the little rift within the lute

That by and by will make the music mute,

And, ever widening, slowly silence all.

"The little rift within the lover's lute,

Or little pitted speck in garnered fruit,

That rotting inwards slowly moulders all."

I have already hinted that Bruno was of a sceptical turn of mind. Possessed of rare intellectual powers, he had studied metaphysics to such an extent, and become so thoroughly master of the strange theories propounded by the deep-thinking German philosophers of the day, that he could not bend himself to the simplicity of that religion which only demands the faith of a little child; he disbelieved the immortality of the soul, and professed to doubt the existence of a future state.

But though he and his bride widely differed in faith, yet day by day she became more and more endeared to him, by the lovely nature of her mind no less than by the graces of her person. Her exceeding humility and true-hearted simplicity showed to him in a new light those religious duties at which in less peaceful days he was wont to cavil. Well would it have been for both could their lives have been thus spent far from the busy world, in the calm retreat, where for the first time the gray-haired man recalled soft prayers which a mother's lips (long since silent and cold) had murmured over his infant head.

But the calls of duty had to be obeyed, and ere long the prime minister and his bride returned to Aronsberg, to take their place at court and in society, and to have endless fêtes and receptions given in their honour. Here Alcyone's gentle unassuming manners, added to her great beauty, made her a universal favourite. The malicious Gräfin von Dunkelherz, however, disseminated strange stories concerning the new Baroness, and aroused the suspicions of those who were already perhaps somewhat jealous of the many charms united in the fair person of the young stranger.

Amid the series of festivities given in honour of the newly-married couple, it was observed that whenever a storm of thunder and lightning broke over the neighbourhood Alcyone was painfully agitated. Wherever she and her husband might be, she implored him to convey her home as soon as possible; the electric influence so entirely overcame her that more than once she seemed completely gone—so utterly did she lose colour and consciousness—so deadly pale did she become. To Bruno's impetuous nature this unfortunate tendency proved a serious annoyance. He considered that by a little firm exercise of moral courage his wife could have retained her senses. Often after conveying her home and reappearing alone (by her earnest request) at some state banquet, he would be universally rallied about her captiousness, and even made to see (owing to Olga's kind offices) that his friends considered the whole affair in a somewhat mysterious light. It will be remembered that Alcyone stipulated for one night of retirement every month, when, undisturbed and alone, she spent long solitary hours upon the roof. She entreated Bruno, by all his affection for her, neither to approach the place himself nor to suffer any one else to intrude upon her privacy. Somehow or other this circumstance, with numerous additions, became bruited abroad, and it was whispered that the Baron's wife was in regular communication with demons. Bribed and listening servants heard voices of no earthly timbre, speaking in an unknown language. More they were unable to say, for Bruno as yet kept faithful guard over his wife's hours of mystic retreat.

At last, however, the time approached when the sittings of the Reichstag terminated, and when all who could forsook the dusty purlieus of the town for the mountains, the sea, or their country dwellings. People began to be too busy making their own plans to attend to those of their neighbours, and Bruno retired once more with his Baroness to Tiefträume Forest. There in their small cottage, with its low long veranda covered with creepers, they spent weeks—nay, months—of uninterrupted happiness. On one side of their home patches of wild moorland were beautifully interspersed with cultivated oases of garden. Towards the east rose the dark masses of the pine forest, giving with their sombre colouring an ever-fresh beauty to the foreground of lovely flowering shrubs. Passing through tangled masses of bramble and fern, the path led by bare gray rocks and tufts of purple heather to some ivy-covered bower; or you came upon some exquisite smooth-shaven little lawn, jewelled in bright patterns of many coloured flowers, and adding brilliance and perfume to the scene.

Here Alcyone and her husband wandered together, or, perhaps descending the steps at the end of their garden, stood on the brink of the little river Naecken, which tumbled and hurried through its narrow rocky channel, thus dividing them from the forest. Lower down the streamlet formed a small lake, on which a boat was kept, and where Bruno was wont to row his wife, and try to teach her unskilful hand to guide the oar. He laid these lines beside her one morning towards the end of their country sojourn when, fresh and fair as Aurora herself, she took her place at their morning meal:—

BARON BRUNO AND ALCYONE.

P. 22.

"One moment let me live the time again,

The sweet, sweet time when o'er the silvery loch

The frail bark sped, or hand-in-hand we climbed

Together, where the divided mountain path

Stopped like a thing perplexed, or haply stood

To watch yon dark blue vault where white clouds sailed

Onward and onward through the homeless sky;

Or when, returning from a mid-day ride,

We turned to gaze where far-off heathery vales

Gleamed between shadowy hills, and dark woods rained

Transparent sunshine through their golden leaves.

And sweet it was to rob the miser night,

Of her rich hours, as side by side we sat,

Seeking to chain the time that fled too fast,

By mazy labyrinths of sweet discourse;

These things can never die—there is no death

Of happy feelings, gentlest sympathies,

And that delicious sadness, whose deep tints

Fall like soft shadows o'er the sunny past.

Therefore in years to come a calm, clear voice,

Like a stray note of some forgotten tune,

Shall rise from out these happy autumn days,

Waking a melody of gentler thoughts

Through all the silent chambers of my heart."

The Baron was often obliged to return to town for a day on important business, or to attend his royal master at the Prince's Château; but Alcyone never wearied when alone with nature; and these little separations lent a new delight to the hour of reunion. Jaded and tired from his hot journey, Bruno would then seat himself in the veranda and recount to his fondly-listening wife all the little adventures of the day, while her cool, soft hand laid on his burning brow, or her gentle voice, carolling forth low songs in the silent twilight, soothed and refreshed his hard-worked brain. It was at times like these, when husband and wife were drawn very near, that Alcyone spoke of her faith, and allowed him to see and know the firm unfaltering trust that possessed her simple mind. She sometimes referred to the possibility of their separation—to her hope of ultimate reunion. When, however, she had but half uttered such words, Bruno, enfolding her in his arms, with a quivering voice would beseech her to be silent, and not break his heart.

Autumn disappeared, and next came winter with all its delightful accompaniments of snow and sleighing. Merrily tinkled the bells and fast flew the steeds under Bruno's skilful guidance, as their gaily-decorated sledge was whirled through the broad thoroughfares and snowy parks of Aronsberg. Christmas also passed by, and Santa Klaus sent joy to the hearts of myriads of children with his mysterious gifts. Months again rolled away, and the glad Easter Feast was in full celebration when, with the first sweet violets, came a dear little child to bless and brighten the home of Alcyone and her husband. They called her Violet because she bloomed into life at the same time as those fragrant flowers, and Stella was added in remembrance of the sacred mystery known only to her parents. In the fulness of his joy, Bruno dismissed, as he thought for ever, from his mind the cruel unworthy thoughts he had once been led to entertain of his bride. It would be difficult to describe this infant to those who never saw her; but let each one think of all the children he has been privileged to know. If among such dear ones he can recall some babe of a beauty too rare and fair to attain to maturity in this bleak world, then he may in some faint degree picture to himself the nameless charm that surrounded the little Violet as with a halo.

Various changes now for a time partially relieved the Baron from official duties; wrapped up in his domestic happiness, nearly a year passed swiftly by before he was once more drawn into the unceasing whirl of political and social court life.

It was already June, the busiest season in the Aronsberg world. Plunged in the necessary rounds of visiting and receiving, the Baroness had but little time to enjoy, as she wished, the society either of her husband or of the little Violet, now at a most engaging age. It is true that it was totally against her own wish that Alcyone took so active a part in the gay world. Bruno, whom nature had formed to shine in society, and gifted with marvellous conversational powers, chafed under her continual excuses, and, returning with eager zest to his old life, insisted upon the Baroness assuming that prominent place in society which was hers by right as the wife of the Prime Minister.

It was about this time that the artful Countess Olga began once more to drop poisoned words about the court concerning Alcyone. Ever on the alert to open the Baron's eyes to the folly of what she called his strange infatuation, she eagerly hailed the first signs of coolness between him and his wife. In an unguarded moment Bruno let fall some hasty expression regarding her absence from a court ball, and Olga, with honeyed words, sympathizing in his disappointment, hinted that rumour credited the Baroness with some private amusement at home, she so rarely vouch-safed to favour the court with her presence for more than the briefest possible attendance at the levees of the Grand Duchess.

Bruno's conscience smote him while he listened to the Countess von Dunkelherz's ill-natured remarks. He answered somewhat shortly that the little Violet being an only child and very delicate, absorbed much of her mother's attention, and therefore she had the best of excuses for remaining at home. A beginning had nevertheless been made, and Olga took good care to keep up her renewed intimacy with the Prime Minister.

It may have been the vitiated town air which now affected Violet's health; but she sensibly drooped, and caused her mother the keenest anxiety. Her father (prompted by his evil adviser,) although affectionate and kind, deemed his wife fanciful when she fretted over the child's altered appearance, and became more and more displeased if Alcyone absented herself from society.

There was to be a grand masked ball in honour of Prince Bertrand and Princess Berta's birthday. They were allowed to choose their own diversion, and they fixed that their father and the Grand Duchess should appear as Oberon and Titania, and that every guest should personate some fairy character. All was excitement, while the Grand Duke himself, assisted by the court painter, and somewhat guided by the predilections of his children, chose the dress to be worn by each visitor, and had it written on the card of invitation. Berta and her brother settled to represent Prince Hempseed and his sister Olivia. Other heroes and heroines too numerous to be recorded were selected. Snow-white and Rose-red, the Blue Bird, the Yellow Dwarf, Beauty and the Beast, Cinderella, and many others found suitable representatives, but the Prime Minister and his wife were requested to become, for the time being, Puss in Boots and the White Cat. At one o'clock all masks were to be removed, and a complete transformation-scene enacted, as regarded many of the characters, who would at that hour, like the White Cat and Cinderella, throw off their disguise, and, uncovering their faces, shine forth resplendent in garments the most exquisite that could be devised for the occasion. Then, marshalled in due rank, the King and Queen of Fairyland proposed to lead their motley subjects to supper. The fun grew fast and furious in the little court of Rumpel Stiltzein. Desperate were the efforts of the tailors, milliners, and shoemakers to meet the multifarious demands made on their time, which was very short; and on their invention, which was taxed to the utmost.

Alcyone from the first disliked the idea of the ball, and all the rampant merriment connected with it. Her ailing child required constant care, and she herself felt far from strong. She mooted the question of remaining at home, but Bruno would not hear of this, and indeed answered her so reproachfully when she proposed it, that she made up her mind to sacrifice her own desires, and please him by endeavouring to throw herself heartily into the affair. During the many necessary discussions with the other court ladies as to the all-important subject of dress, the Baroness was left alone with Olga, who of late had, to all appearance, been her most sympathizing friend. The crafty Countess soon extracted from Alcyone the little history of her own reluctance to appear, her husband's consequent displeasure, and her determination to gratify him by paying every possible attention to her dress.

The eventful evening at length arrived. Baron Bruno, after an early dinner, was compelled to attend for a short period an important sitting of the Reichstag. His house was at some distance from the public offices of state; he therefore took his fancy ball-dress with him, and settled to change his attire in his own small official room, while Alcyone should start at a later hour, and call for him on her way to the palace. Alcyone felt unusually sad as her husband waved her a hasty adieu and speeded off to the Reichstag. He strictly enjoined her to observe due punctuality in her engagements, as the Grand Duke wished to enter the ballroom in a grand procession formed of all his chief ministers and officers of state, court ladies, and hereditary noblemen.

Violet had perceptibly drooped more and more, though her fond father refused to see the change. He only, however, saw his little daughter at brief intervals of his busy life, when a flush of delight at his approach rounded her pale cheeks, and her dark-blue eyes sparkled with the keen joy of being tossed or fondled in his arms.

After Bruno's departure, Alcyone ascended the nursery stairs, and found Violet already in bed, but restless and uneasy, and tossing to and fro. The large windows stood wide open, though very little air seemed as yet to stir among the trees of the square in which they lived.

The mother sat down beside her child. The baby was at once comforted, and held out its little arms to be taken to her bosom. Alcyone lifted her from the cot, and, dismissing the maids, seated herself by the window in a low rocking-chair, and crooned soft lullabies to her infant. The babe did not yet sleep, but she lay soothed and quiet, gazing into her mother's sweet face, and smiling when she caught the bright sparkling of the radiant gem.

Suddenly the peaceful scene was changed; with a troubled cry the little Violet started up, and at the same instant Lady Olga stood in the doorway. Hardly apologising for her unexpected appearance in the Baroness's private apartments, Olga unfolded her extraordinary plan. After expressing great sympathy for the child's indisposition, and professing to understand fully Alcyone's distressing position, she asked leave to proceed at once to the Baroness's dressing-room, and there and then array herself in the garments of the "White Cat." As she and Alcyone were much the same height and size, this change of dress could be very easily accomplished, and would form an indistinguishable disguise; she then further proposed to set off in the carriage and personate the fair young Baroness at the ball. At first Alcyone would not listen to her artful suggestion, justly fearing the displeasure of her husband; but Olga assured her that long before the deception must at any rate cease (on the unmasking at one o'clock) she would, using the privilege of an old acquaintance, explain the whole affair to Baron Bruno, and represent to him aright the mother's fears for her child. Indeed those fears seemed but too well founded, for since Olga's entrance the baby had grown wild and feverish, and kept up an incessant moaning as if in actual pain. Harassed and perplexed therefore, Alcyone at length yielded a reluctant consent, and, ringing the bell, ordered lights to be placed in her dressing-room, and attendance to be given to aid the Countess von Dunkelherz in her somewhat difficult toilet. One consideration which weighed much with Alcyone in her final decision, was the unfortunate coincidence that this happened to be the very night of her monthly retirement—that mysterious proceeding of which her husband had now grown so impatient that she was fain never to mention it, but strove to accomplish her purpose as best she might without attracting his attention. She had all the time hoped to slip away unnoticed from the ball, but she well knew this would be a very difficult matter to accomplish, as besides her own timidity about leaving the palace by herself, her extreme beauty made her remarkable in whatever society she moved.

Still it was with a foreboding of evil she resolved for the first time to act without her husband's knowledge, and remain unbidden at home.

It is scarcely necessary to add that Olga, from frequent inquiries and a diligent system of espionage, was well aware of the mysterious and so-called solitary hours entered upon by the Baroness at stated intervals, and she was equally cognisant of the fact that the wonted period had arrived for the observance of this strange custom, and had laid her plans accordingly.

The evening wore on; after the noisy departure of the carriage containing its unusual occupant, all within the house became peaceful and silent. Without was heard the ceaseless hum of the busy city, but faint, far, and mellowed by distance. Overhead the stars twinkled cheerfully forth from the blue bed on which they had lain fast asleep during the hot reign of the sun.

It is twilight in the city,

And the sun has sunk afar,

Where a brightness gilds the pathway

Of the quiet evening star.

Dimly in the hazy distance

Twinkle all the myriad eyes

Glittering far into the darkness,

Where the mighty city lies.

Twittering through the leafy branches,

Birds are calling soft and low,

Scarcely heard amid the humming

Of the city's ceaseless flow.

Yet I hear their gentle voices,

And their evening hymn of love,

While the stars are clearer shining,

From the dark-blue heaven above.

Happy children! careless playing,

In and out beneath the trees,

With your childish hair all streaming,

Floating on the evening breeze.

Pure and blissful hours of childhood,

Never prized until gone by,

Stay, oh! stay a while! and o'er me,

Let your lingering radiance lie.

Leave a gleam of that bright sunshine

Which was ours in days of yore,

Ere we parted for life's battle,

Ere we left home's peaceful shore.

Voices then with ours were mingling,

That on earth are silent now,

Arms around us fondly twining,

That have long been still and low.

Yes—in gazing on the starlight,

Fancy sometimes strives to trace

Forms beloved amid the twilight,

Or a well-remembered face.

Angels now! yet be our guardians,

In this tearful vale below,

Shedding light around our pathway,

Giving comfort as we go.

So when life's frail chord is loos'ning,

And our eyes to sorrow close,

When the glorious morn is dawning

O'er the long sad night of woes,

Linger near us—that, when rising,

We may—child-like—meet again

Where the severed are united,

Where the weary have no pain.

Ever and anon the deep musical bell of the Reichstag clock boomed forth amid the darkening shadows, telling of time's rapid progress and remorseless flight, yet giving to many of the dwellers in Aronsberg a feeling of joyful security and safety. For the tall tower stood over and among them like some mighty guardian whose ceaseless care and unsleeping vigilance kept watch amid the city by day and by night and with cheerful voice proclaimed his vicinity—thus oftentime becoming a loved companion to weary mortals whom sickness, separation, anxiety, or sorrow kept awake through the livelong night.

Chime, Aronsberg bells, chime ceaselessly on,

Till partings be over and weary work done.

Boom o'er the broad waters, thou musical tone,

Remorseless thy knell, and I sorrow alone,

For perchance in my bosom shall waken no more,

The rapture that thrilled to thy chiming of yore.

The baby now sank to rest in its tiny cot, a heavenly smile irradiated its little countenance, as if in some happy dream it was more than compensated for the uneasy hours of pain and unrest so lately experienced.

The hour of Alcyone's isolation approached: wrapped in her long flowing robes, with her beautiful hair streaming over her shoulders, she bent over the sleeping Violet and dropt a kiss and murmured a blessing over her child; then slowly ascended the narrow stair which led to Bruno's solitary chamber. The small door opened, then closed again with a spring, and all was still, while the nurses below, whispering together, knew their mistress was alone with the stars.

Nearly an hour passed by, and tranquillity reigned around; most of the servants had gone to bed, those who remained up were in the lower and more distant parts of the house. Hasty sounds suddenly broke upon the still night air; the Baron's champing steeds drew up in the courtyard; Bruno himself, flushed and agitated, sprang rapidly up-stairs, followed by the ruthless Olga! He pushed past his astonished domestics, noisily calling and seeking Alcyone in every room, including the nursery, where he roused and startled his sleeping child. Finally he ascended his own narrow stair, and entered the study. He paused at the small door so often described, and tapping, called his wife's name once or twice; no response came; without a moment's compunction, in excited passion, he drew the key from an inner pocket, and, unlocking the door he had solemnly promised to regard as sacred, threw it violently open.

With a loud grating noise the ill-fated portal swung back on its hinges, and disclosed to his bewildered eyes a wondrous sight. Around his wife stood five or six maidens of surpassing beauty; like her—yet unlike—for oh! how clearly he could see the marks of human sorrow and care which cast their shadow over her countenance alone. Each bore on her forehead a brilliant jewel resembling Alcyone's; the most delicious perfume was wafted on the air, and an indescribable mellow glow of light emanated from and yet illuminated the lovely strangers. More than this he had not time to observe; a terrible explosion shook the house to its foundation, and he became enveloped in a choking impenetrable vapour. Olga also, who, unobserved, with a bevy of terrified servants, had followed in his footsteps, was half suffocated, seeing, however, nothing of those radiant forms.

As the light breeze dissipated the stifling fumes, Alcyone, with sorrow and dismay imprinted on her gentle features, stood inquiringly before her husband, as if to demand some explanation of this sudden violation of their compact. But now a youth, whom Bruno had never before seen, stepped from behind Alcyone, with cold and majestic mien. Bowing gravely to the Baron, he thus addressed him, in low thrilling tones: "Behold in me, Hyas, the brother of Alcyone, come hither to aid and defend my sister in the hour of need. I demand a full examination into her conduct. Before others you have doubted her and intruded on her privacy—before others her character must be cleared!"

Stunned and bewildered by these swiftly succeeding events, Bruno's ready tongue for once completely failed him. Now—alas!—when too late, he bitterly regretted his precipitation, and the credence he had too easily lent to wicked and baseless insinuations.

Instead of keeping her promise to Alcyone, and explaining aright to the Baron his wife's unpremeditated absence, Olga had made out that the whole affair was a preconceived plot which she had been induced to conceal till the last moment. She had furthermore hinted that the gravest suspicions were aroused by the Baroness's non-appearance, which of course became universally known and commented upon at the hour of unmasking. At last she had so worked upon Bruno's ardent temperament that, forgetting everything save the jealousy of the moment, he rushed wildly home, causing quite a sensation at court and doing irreparable mischief to his domestic happiness.

In spite of his sister's tearful remonstrances, Alcyone's brother now demanded of the Baron when a public inquiry could be instituted; and on hearing that it was possible on the morrow, he instantly cited the affrighted Gräfin von Dunkelherz to appear and proffer her charge against the fair Alcyone, who for the first time recognised in the Countess a deadly enemy.

Hyas furthermore insisted on keeping watch over his sister and her child until Alcyone was proved beyond blame in the eyes of the world. They were left alone together. The baffled Olga slunk away to her home. Bruno, distressed and repentant, unavailingly paced his lonely chamber until morning arrived.

At the earliest possible moment (after the late carousals of the night before) the Prime Minister demanded an audience of his sovereign, and the matter being then fully explained, the Grand Duke commanded that the trial of the Baroness should take place at noon, in the Hochplatz, a large open space surrounded by public buildings and gardens, and not far from the Grand Ducal Palace. Bombastes, at Hyas' request, also sent criers in every direction to summon the people to attend, and by twelve o'clock the vast square was filled to overflowing.

The Grand Duke and Duchess, with the lords and ladies in waiting and other state officials, sat upon a raised platform in the centre, surrounded by a guard of honour. Edlerkopf, at the head of a brilliant staff of officers, kept the immense assembly from encroaching on the crimson dais where accused and accuser were placed near at hand. Bruno, pale and heart-stricken, stood there. At some little distance Hyas and his sister sat together, their striking resemblance and singular beauty attracting every eye. It was observed that Hyas bore on his uncovered head a jewel almost surpassing in radiance that which sparkled on his sister's brow. Alcyone never raised her head, but bent over her child, whom she carried in her arms.

A profound silence reigned over the excited throng as Hyas bending low to the Duke, declared that his sister's honour had been tarnished by the foul aspersions cast upon it, and that he had traced many of these reports to the Countess von Dunkelherz; he therefore demanded that she should frankly say of what she accused the Baroness Bruno.

Olga, who by this time had entirely recovered from her previous confusion, now advanced. Craning her long neck, and glancing spitefully at the drooping form of the suffering Alcyone, she thus answered Hyas' summons:

"I charge the Lady Alcyone with being a witch. She cannot part, even for one moment, with the gem she bears on her forehead; she keeps mysterious assignations with beings from another world; and she has so bewitched her husband, the acute and learned Baron Bruno, that he is hardly accountable for his actions."

At these cruel words an ominous murmur ran through the crowd, and half stifled cries arose.—"Burn the witch!" "Deliver our Baron from her spells!" "Cut off root and branch—mother and child!" Such were some of the menaces hoarsely muttered by the surging and fickle multitude. It was with no small difficulty that Edlerkopf, at the head of his guards, restrained the populace from laying violent hands on the Baroness and her brother. Hyas, cool and collected, waited until the gathering tumult was in some measure quieted; his clear voice then penetrated far and wide. "Ye have heard, O people," he exclaimed, "the voice of the traducer; ye shall now give ear to unwilling testimony in favour of the accused."

So saying he divested himself of his long-flowing outer garment, and warning all around to preserve strict silence, he drew a large circle round himself and his sister, and also compelled the Countess von Dunkelherz, much against her will, to remain within the mystic boundary. Taking then a small packet from his breast, he scattered some powder on the ground and muttered strange words in an unknown tongue. Then arose amid the calm sunshine of that lovely summer day the sound of rushing whirlwinds and stormy gusts; a dark cloud intervened between the earth and the sun, enveloping all around in sulphureous darkness. When it cleared away, lo! high within the magic circle towered a gigantic pillar of smoke. From the centre of this terrible apparition gleamed forth two fiery eyes. A cold chill of horror ran through the spectators, though the air was hot and sultry.

Hyas now motioned to Bruno that his lips must ask the fateful question. The Baron, compelled to speak, reluctantly addressed himself thus to the hideous shape:—"Dread Spirit, whether of good or of evil, I adjure thee to tell me whether the Lady Alcyone has been true and faithful to me, and guiltless of the foul deeds ascribed to her."

"Blind mortal!" replied the cloudy phantom, "pure and transparent as the dewdrop hath the heart of Alcyone been unto thee; there breathes not on your dull earth a spirit more free from guile."

As these words fell from above, a low muttered growl of thunder was heard, while Hyas, turning to the silent, awe-struck beholders, cried aloud, "The innocence of my sister is proved by the reluctant words of Varishka, the dark genie, who could have claimed her for his own had her deeds been evil. But, alas! I fear the dread witness has exhausted one innocent life in the fierce struggle."

As he spoke thick darkness fell upon them, and when it cleared away the mysterious shape had disappeared. The bright sun poured its health-giving rays again over the panic-stricken multitude, and a cool wind blew away the last traces of the awful Varishka. All eyes were bent on Hyas, whose beauty seemed absolutely marvellous, as, tenderly embracing his sister, he turned swiftly aside into the crowd, and ere they were aware had totally disappeared from view. Loud acclamations in favour of Alcyone rang forth from the changeful thousands on either side, as they swayed to and fro preparatory to breaking up altogether.

Bruno alone stood irresolute; a thousand conflicting emotions paled his usually ruddy cheek; but his wife's sweet voice called to him. He approached her; her face was full of anxiety. "Let us return home at once," she whispered; "I fear for our babe."

And well she might, for the fragile Violet lay almost lifeless on her mother's knee, the laboured breath passing slowly through her cold lips. They drove rapidly home. The Baron, full of remorse, would fain have thrown himself at his wife's feet, but her thoughts were turned only to her suffering child, as she at last bore it into the nursery, where in happier days she had so often lulled it to sleep. For some time Bruno remained beside her, and aided in trying various restoratives. At length, summoned by his official duties, he was forced to depart. Several hours elapsed before he could absent himself from the Reichstag.

A strange hush pervaded his home as he once more entered its portals. He gained the nursery door, and, pausing, gently pushed it aside. In the waning light he beheld his wife half kneeling, half lying upon their little one's cot. Violet's face, illumined by the last rays of daylight, was pale and peaceful. It shone with a solemn light—unlike, oh! how unlike, his own playful pet! Her dark blue eyes were heavily closed, and her little hands meekly folded on her breast. The mother's voice stole on his ear—"Fare thee well, my darling! good-bye, my angel child! but only for a brief space I bid thee adieu. Thou art folded now in arms that can shelter thee more safely from the passing blast than those of thy poor mother. I shall go to thee, my Violet—but never, never more shalt thou return to me." These and many similar words were poured forth by the weeping mother as Bruno unobserved stood silently listening. His heart felt ready to burst; it seemed as if some chord within him gave way at that moment with a throb of pain.

For a long time unknown to himself Alcyone's soft influence had gradually undermined his harsh scepticism. At that moment a ray of heavenly light shot as it were from the upward pathway of his dead child into the dark recesses of his soul, and with tender humility he knelt by his wife's side and placed his hand on hers. Startled and amazed, she turned and met her husband's eye: it shone with a new and softened light; there was no need for him to explain to her what he felt. Over the death-bed of their fairest hope they for the first time experienced the ineffable yet chastened joy of sharing the same faith—of worshipping together the same unseen God.

At length Alcyone slowly rose from her knees, and casting a long, fond look on the lifeless form of her babe, she led her husband from the chamber. Together they ascended the narrow stair; together they opened the small, well-known door, and emerged, hand-in-hand, amid the now darkened twilight, upon the open roof.

"Bruno," murmured she, "the time for our separation has come; you have declared your belief in the immortality of the soul; your poor Alcyone, in the midst of her imperfections, has brought you one step nearer the gates of Paradise. I now return to my celestial home, but shall there await you, my beloved, in the sure and certain hope of a long eternity together unchequered by the sorrows that have assailed our path in this mortal world."

Thus saying, for the first time, the gentle Alcyone passionately strained her arms around her husband; the pressure relaxed, he tottered forward; he was—alone! A long trail of light shone for a moment athwart the evening sky; the peaceful Pleiades beamed forth in brightest beauty; he called aloud, but only silence reigned around; in uncontrollable emotion the strong man fell fainting to the ground.

How long he thus remained he never knew; but he woke at last to find the midnight moon shining upon him. He raised himself, confused and aching; he passed his hand across his brow—Was the past a reality? A tear rolled down his time-worn cheek which his keen eye had never shed, but it might be the cold dewdrop of the early morn. Beside him lay the coat and hat he had worn in returning from the Reichstag. It must be some long, strange dream that, coming on him exhausted and weary, had harassed his brain through the weird watches of the night.

As these thoughts coursed through his mind his eye fell on his left hand; upon it there sparkled a stone of extraordinary brilliancy, which recalled to him the gem on Alcyone's forehead. He strove to remove the jewel, but, though easily fitting to his finger, the magic circlet refused to be taken from its place.

The reality of the past then rushed upon the proud Baron's mind with the resistless force of inward conviction. Humbled and sorrowful, the great philosopher's wondrous attainments and mighty intellectual resources seemed for the moment to become as less than the dust beneath his feet. With the simple faith of a little child, he bent his knee alone before his Maker, and cried, in tones of repentant sadness, "Lord, I believe, help Thou mine unbelief."

ESGAIR: THE BRIDE OF LLYN IDWYL.

Among the mountains of Caernarvonshire none are more gloomy and precipitous than the dark sister Glydirs Fawr and Bach. Towering sublimely above the solitary waters of Llyn Idwyl, they rear their proud summits well nigh on a level with that of the loftier but less rugged Snowdon.

Where is the wayfarer who can forget a calm autumn sunset seen from those barren heights?

Valleys far and near shrouded in dim purpling mists; shadowy gigantic forms looming faintly in the deepening twilight; rose-tipped peaks floating amid a halo of glory in the evening sky; silver streamlets breaking here and there in white lines the dusky shades below; while afar, in the distance, the broad slumbering ocean bids a glittering farewell to the monarch of the day.

Such was the panorama spread before the young Llewelyn many years ago, when in toilsome search after strayed sheep he came suddenly upon the highest part of the mountain. To his wearied eyes, however, nature for the time had no charm. With hurried and anxious footsteps he leapt from rock to rock, dreading to find some of his wandering flock with broken limbs. For, as with many other Welsh mountains, the crest of the Glydir Fawr is entirely composed of huge boulders roughly hurled together; deep treacherous crevices being often entirely concealed from view by the luxuriant growth of ferns, heather, and bilberries, which yield most unsubstantial footing to the unwary.

Llewelyn's father, "Dafydd ap Gwynant," a well-known chieftain, had been slain in battle, and most of his possessions seized by his foes. The widowed Gwynneth, in terror for the safety of her only child, fled with him to the wild region now known as the pass of Nant Francon. There in solitude she reared her boy to habits of frugal simplicity. As years rolled on the widow prospered and her flocks increased. Yet still Llewelyn remained her only herd, and at eventide the steep sides of Llyn Ogwyn and Llyn Idwyl re-echoed with his loud carols and joyous shouts, as he summoned the cattle and sheep to their nightly fold.

In these remote times wolves and other wild beasts still lurked among the Welsh hills. Nor did they limit their ravages to the destruction of animals alone, but when rendered desperate by hunger visited human habitations in search of their prey. Witness the touching history of Gelert the faithful hound, whose tomb is still to be seen in the little valley over which a dog's fidelity has shed undying renown. Hence the necessity for carefully collecting the herds at nightfall within some place of security.

Llewelyn at length discovered his missing lambs on the steep northern sides of the Glydir, and herding them hurriedly together, crossed the shoulder of the mountain and descended towards Llyn Idwyl by the rugged pathway which leads past the narrow gorge now known as "the Devil's Kitchen." It was rapidly growing dark as he reached the plain, and he was hastening homewards, when by the waning light he perceived the surface of that gloomy lake to be strangely agitated. As he gazed, the head of a lovely maiden rose above the ripples, and seemed to his excited imagination to regard him with a tender wistful look. He rushed to the water's brink, and was about to cast off his coat and swim to the aid of the fair unknown, when, soft and clear as an evening bell, these words rang through the still air:—

"Three times lost, and three times won,

Canst thou win me, Dafydd's son?

Tender must thou be to me,

Tender should I be to thee.

To my mate in bridal hour

I can bring a princely dower;

But my wooing must be soon,

Ere has waned September's moon."

Enraptured by these silvery notes, Llewelyn strained every nerve to listen, and as the nymph falteringly uttered the last words he felt a magic thrill run through his frame. He became possessed with a sudden desire to behold the entire form of the beautiful being whose head alone smiled on him across the watery waste; but as he approached nearer the sweet face disappeared, the surface of the loch became glassy and still. The pale rays of the rising moon illumined only the wide level mirror of Llyn Idwyl, and amazed and bewildered the youth turned to his home.

After folding the sheep he entered the cottage. His mother had prepared a fragrant supper; but through Llewelyn's veins there ran a secret fire, and he turned restlessly from the food he was wont to relish in his calmer hours.

Gwynneth was a mother in ten thousand. Though she had wandered far to obtain the oakleaves over which she had slowly smoked the pink trout; though her hands had been stung when she robbed the wild bees of their honey for her boy; though when faint and tired from her long ramble she had risen with fresh energy to mix and bake for her son the scones he loved; yet when she saw his disquietude and lack of appetite, no murmur, no query crossed her lips. Patiently she herself partook of the humble fare, and strove to cheer her moody child, while her own heart ached with vague doubts and fears.

Hardly, however, had she cleared away the last traces of the half-consumed meal when Llewelyn extended himself full length on the deerskins at her feet, laid his hot head on her soothing lap, and by the flickering light of the fire (fed at intervals with cones from the pine forest) related to her his strange adventure.

As Gwynneth listened to his words the iron entered into her soul. Every mother can sympathize with the pang she then experienced. The child she had borne through labour, sorrow, and pain; the infant she alone nourished and brought to manly strength; the all upon which every hope, every thought of the future is centred—the widow's only son—the idol of her heart—his love is passing from her. She is no longer to him the first, the dearest. Dreams of a nearer and dearer one are wakening in his young bosom. The mother is now his confidant; but well does she know that ere long the newly-beloved will be his only thought; that into her ear alone will be poured all the aspirations of his life. That henceforth and for evermore the mother must resign her son's heart to the keeping of another. Gwynneth in that hour felt the cold hand of fate clutch her past happiness. Her pulse stood still. But she was a noble woman. She knew the law of life was resistless. Come from a race of kings, with proud resolve she nerved her wounded spirit, and casting all meaner thoughts of self aside, threw herself with ardour into the interests of her son.

While Llewelyn described the events of the evening, the mists cleared from the past and his mother dimly remembered an ancient tradition heard in days gone by. The half-forgotten legend ran thus:—A prince of royal Welsh blood fell in love with and wedded a water Nixie. No sooner, however, were his espousals accomplished than he, with his palace and all his treasures, became enchanted and covered by the waters of Llyn Idwyl, which then, at Venedotia's dread command, rose to its present height. The water god, through the marriage-tie of his beautiful child, had gained a subtle power over her human lover, and despite her entreaties worked this cruel spell to secure to her the unchanging faith of a mortal. While Gwynneth told this strange story, an old prophecy concerning this very prince, which she had often heard in her youth, suddenly flashed across her mind. Surprised it should so long have escaped her memory, she thus recited it to her listening son—

"When Rhuddlan's child with man shall mate

A light shall break on Rhuddlan's fate;

When thrice three wedded years pass by

Llyn Idwyl's waters shall run dry;

But if that wedded peace be riven,

By blows at random three times given,

Esgair must seek her father's cave,

Nor quit again the gloomy wave;

No slow revolving years shall wake

The spell-bound slumberers of the lake."

"My son," exclaimed Gwynneth, "all is now clear to me. The fair daughter of King Rhuddlan has seen and chosen you to be the deliverer of herself and her family, who once owned the greater part of Wales; but who fell under Venedotia's spell so long ago that their existence is forgotten by the oldest inhabitant. I am proud that my child should aid in restoring our ancient line of kings. But Llewelyn," murmured she, placing her hand fondly on his brown wavy locks, "you must pray for strength, and enter on this strange adventure with the aid of heavenly courage." Long into the night sat that gentle mother holding counsel with her son, and even when they sought their rude couches but scant sleep sealed their eyelids.

Next day Llewelyn fulfilled his various duties with feverish impatience, he yearned for the evening hour, and as the moon's rays fell over the lone heights of the Glydir he stood once more by Llyn Idwyl's brink, and in a low clear voice uttered these words:—

"By the Glydir's rugged side,

By thy father's captive pride,

By the strains of mortal love

Stealing o'er thee from above,

By thine own enchanted lake,

Esgair, fairest! hear and wake!"

Scarcely had he finished, when a long train of light shot across the loch, and, glittering with a thousand watery diamonds, Esgair half arose and stretched forth towards him her lovely arms. A smile of hope irradiated her pure countenance, and as Llewelyn knelt awestruck upon the beach, she slowly chanted these lines:—

"Through Llewelyn's devotion deliverance draws near;

'Twixt sunset and sunrise to-morrow be here,

Though strife be around thee yet suffer no fear

If Rhuddlan's poor daughter to thee seemeth dear;

Forget not that o'er her the sign must be crossed,

Or she and her kindred for ever are lost!"

With a parting wave of her hand Esgair slowly disappeared, and nought was visible save the reflection of the moon, which, dancing and sparkling across the dark agitated bosom of Llyn Idwyl, ended in a pathway of light at Llewelyn's feet. It was an omen of hope for the morrow, and with joyful steps he returned to his home. Here, however he was somewhat harassed by fears as to the poor accommodation they could offer to the bride.

"Dear mother," he urged, "she is a high-born princess; her hair, neck, and arms sparkle with priceless jewels. She may scorn our lowly hut, and reproach me for bringing her to so humble a home."

"Nay, my son," replied Gwynneth; "the heart of a true maiden seeketh ever something more precious than gold or riches; the love of a faithful partner is doubtless what Esgair yearns to find. It is, moreover, borne in upon me that the daughter of Rhuddlan will not come dowerless to the son of Dafydd. Be she poor, however, or be she rich, we will give her the best we have; and I tell you she will hold it dearer than life."

Heaven that night shed its own peace over the widow and her son, and their last evening alone together was long remembered by each as a time of holy calm. By day-break next morning they were already astir. Many preparations had still to be made. Llewelyn went across the hills to petition Saint Tudno to pronounce his bridal benediction. The holy father was now making his yearly pilgrimage through Wales, visiting and cheering his feeble scattered flock, who clung fast together and revered with a passionate tenderness their few and faithful teachers.

It was at an ancient farm upon the slopes of Carnedd Llewelyn that Llewelyn and his mother had, only a few days agone, knelt and received the good priest's blessing, and Gwynneth doubted not that he would consent to partake for one night of their rude hospitality, for the purpose of uniting her son and the rescued Esgair in the bands of holy wedlock.

Ere the sun had passed its meridian, Gwynneth's hopes were realized. The venerable father, guided by Llewelyn, safely reached her door, and after partaking with them of their frugal noontide meal retired to rest a while, and to resume the devotions broken in upon by his unforeseen expedition. It weighed much on his mind that no church was near wherein the espousals might be celebrated, but he was fully conscious of the difficulties of Llewelyn's position. He shrewdly suspected that until holy rites had been performed the wild spirits would do their utmost to reclaim and recapture the newly-rescued bride. Ere seeking his chamber therefore, the good father carefully sprinkled holy water around the dwelling, and fervently besought Heaven's blessing on the approaching union.

Some time before the hour of sunset Llewelyn and his mother started for the banks of Llyn Idwyl. They followed the rocky course of that little stream, which still breaks in foam from the eastern side of the loch, and babbling and brawling flows past the very stones where Gwynneth's little cottage once stood. The evening was wild and threatening, and the sky had strangely changed since Saint Tudno alighted at their dwelling. Thunder reverberating through the mountains awakened hoarse echoes on every side. Wild clouds in fantastic shapes scudded across the lowering heavens, and fitful gleams from the sinking sun threw dark shadows across their pathway. Ever and anon drenching showers brushed by in short sharp gusts, half blinding them, and causing inexplicable terror to the ponies; one of which Gwynneth rode and the other Llewelyn led for his bride. More than once, as they pursued their way, Gwynneth imagined that white arms and hooded figures waved defiance before her; but surprise and doubt held her mute, or perhaps ere she could speak the rain dashed on her face and she perceived that her fancy had conjured menacing forms from the eddying spindrift around. Llewelyn also was haunted by outbursts of mocking laughter, but when, amazed, he turned to his mother, the wild turbulence of the little streamlet taught him he had mistaken its noisy vehemence for sounds of demoniacal mirth.

At last they reached Llyn Idwyl's side. The sky once more grew calm and clear. The sun had long since disappeared behind the dark mountain, and the stars faintly twinkling overhead had already lit their feeble lamps. The lake itself, however, presented a wild scene. Furious gusts of wind agitated the surface. Sheets of spray bearing the semblance of hideous figures were dashed hither and thither. A rushing noise as of a thousand waterfalls drowned every other sound, and Llewelyn in vain tried to make his voice audible amid the din of the elements. Again and again he endeavoured to shout Esgair's name, but the mad roaring of the winds and waves was all that could be heard.

"To your knees, my son, and pray for help," whispered Gwynneth in his ear, and in despair Llewelyn sank on the ground and fervently invoked the aid of Heaven. As if in answer to his prayer, at this instant the moon tipped the frowning mountain; her bright rays irradiated the wild scene beneath and diminished in some measure the confusion and uproar. Then, white and dripping as a storm-tost waterlily, the lovely figure of Rhuddlan's daughter slowly emerged from the lake until her feet were visible. She advanced along the moon-lit path, which alone remained serene and calm. On either side horrid arms were stretched as if to grasp her shrinking form, and rude blasts of spray burst in torrents over her defenceless head.

Llewelyn knelt in silent prayer till she neared the water brink, when, springing to her side, he drew her tenderly on shore, signing at the same time on her brow the holy symbol of the cross; while wild shrieks and groans resounded across the lake. He lifted Esgair, trembling and exhausted, on the pony, where his strong arm was needed to support her. The moon suddenly disappeared behind a cloud; the rain burst forth with redoubled vehemence, while such peals of thunder broke around and above them that the startled ponies could hardly be restrained from dashing madly away. Llewelyn, well-nigh desperate, in vain strove to recognize the homeward path. Black darkness encompassed them and hid every well-known landmark from view.

Just as he was at his wits' end, suddenly gleamed afar a small bright cross, shedding divine lustre through the gloom. At the same instant there fell on their ears the faint chime of distant bells—a strange unaccustomed sound in those wild regions. They paused not, however, to question the cause of the welcome phenomena; but with gladness turned in the direction of the cross, which moved before them as they advanced; Llewelyn still supporting Esgair, and murmuring words of encouragement into her ear. More than once he received rough buffets from invisible foes, and wicked threats were whispered by the hoarse blasts; but he kept his eyes fixed steadfastly on the sacred symbol which guided them in the path of safety, and ere long the unnatural tempest spent itself. The fiery cross grew dim, and finally disappeared, and the rest of their homeward route was accomplished by the returning light of the moon.

Nearer and nearer rang the joyful bells, as if crashing forth a pæan of welcome to the belated wanderers; and what was their astonishment on coming within sight of the place where their humble dwelling lately stood amid unbroken solitudes, to observe innumerable twinkling lights borne to and fro, while, by the light of the moon, the tall battlements of some huge building rose over the site once covered by their happy little home.

Confused and perplexed, Gwynneth thought to chide her son for bringing them the wrong way. But now Esgair, with new life, sprang to the ground, and, turning towards Gwynneth, said with exceeding grace,

"This was my father's home. He bestows it willingly upon us—it is yours. But, oh! take me to your heart, and give me a mother's love."

Gwynneth hastened to alight, and clasping her new daughter to her bosom, hesitated no longer to enter the massive portals thrown wide open before them. As they stepped beneath the archway, solemn strains of music became audible. A long line of priests and choristers moved across the lofty hall within; bands of fair maidens robed in white approached Esgair, and tenderly saluting her placed her in their midst. Last of all the holy Father Tudno drew near and motioned Gwynneth and Llewelyn to his side.

Deeply agitated by a thousand conflicting emotions, Gwynneth, Esgair, and Llewelyn now beheld before them as they advanced a small chapel brilliantly lighted for high festival. With slow and reverend step Saint Tudno withdrew within the altar space, and united in holy wedlock the strangely-mated pair before him. Long and lowly did they bend before the sacred shrine, and when at length they retired down the aisles, the clear high voices of the singers rang out in joyful strains, while far overhead the jubilant bells told with their iron tongues the glad news that the first bar of fate had been undone—the condition fulfilled that ran thus in the old legend:

"When Rhuddlan's child with man shall mate

A light shall break on Rhuddlan's fate."

Time fails me to tell of the splendours of that night of rejoicing, or the magnificent appointments of the castle. But it is impossible to pass by in silence the exceeding beauty of the bride, or the manly serious grace of her bridegroom. Esgair's waving nut-brown tresses fell over her shoulders, bound here and there by priceless diamonds. Her violet eyes, her dazzling complexion, her long robe of silver sheen, displaying every motion of her graceful figure, her wondrous charm of manner,—all enchanted the beholder. She looked and moved the daughter of a hundred kings.

Llewelyn's countenance, even in that deep hour of joy, wore the chastened expression of one who has struggled and suffered. In the midst of his new-found wealth he was fain to remember, with a feeling akin to pain, that this proud castle and all its appurtenances was the heritage of his wife and her father. But as Esgair turned her soft eyes upon him, the toils of the past and the uncertainty of the future were alike forgotten, and love beamed effulgent on his soul.

Night and stillness fell over that great castle. Only alone in an upper chamber—the widowed wife—the lonely mother—wrestled in silent prayer for her children until the day broke over the east and opened to the world once more the golden gates of the sun.

On the morrow all was new and strange to Gwynneth and Llewelyn; but Esgair guided them from room to room of the splendid palace, and related to them endless tales told her by her father, of what had happened within its walls, ere the spell of enchantment consigned him and his to the dark waters of oblivion.