The Project Gutenberg EBook of There is no Death, by Florence Marryatt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: There is no Death Author: Florence Marryatt Release Date: March 20, 2012 [EBook #39212] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THERE IS NO DEATH *** Produced by Maria Grist, Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Works by Florence Marryat PUBLISHED IN THE INTERNATIONAL SERIES. |

||

|---|---|---|

| NO. | CTS. | |

| 85. | Blindfold, | 50 |

| 135. | Brave Heart and True, | 50 |

| 42. | Mount Eden, | 30 |

| 13. | On Circumstantial Evidence, | 30 |

| 148. | Risen Dead, The, | 50 |

| 77. | Scarlet Sin, A, | 50 |

| 159. | There Is No Death, | 50 |

BY

FLORENCE MARRYAT

AUTHOR OF

"LOVE'S CONFLICT," "VERONIQUE," ETC., ETC.

NEW YORK

NATIONAL BOOK COMPANY

3, 4, 5 AND 6 MISSION PLACE

Copyright, 1891,

by

United States Book Company

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

It has been strongly impressed upon me for some years past to write an account of the wonderful experiences I have passed through in my investigation of the science of Spiritualism. In doing so I intend to confine myself to recording facts. I will describe the scenes I have witnessed with my own eyes, and repeat the words I have heard with my own ears, leaving the deduction to be drawn from them wholly to my readers. I have no ambition to start a theory nor to promulgate a doctrine; above all things I have no desire to provoke an argument. I have had more than enough of arguments, philosophical, scientific, religious, and purely aggressive, to last a lifetime; and were I called upon for my definition of the rest promised to the weary, I should reply—a place where every man may hold his own opinion, and no one is permitted to dispute it.

But though I am about to record a great many incidents that are so marvellous as to be almost incredible, I do not expect to be disbelieved, except by such as are capable of deception themselves. They—conscious of their own infirmity—invariably believe that other people must be telling lies. Byron wrote, "He is a fool who denies that which he cannot disprove;" and though Carlyle gives us the comforting assurance that the population of Great Britain consists "chiefly of fools," I pin my faith upon receiving credence from the few who are not so.

Why should I be disbelieved? When the late Lady Brassey published the "Cruise of the Sunbeam," and Sir Samuel and Lady Baker related their experiences in Central Africa, and Livingstone wrote his account of the wonders he met with whilst engaged in the investigation of the source of the Nile, and Henry Stanley followed up the story and added thereto, did they anticipate the public turning up its nose at their narrations, and declaring it did not believe a word they had written? Yet their readers had to accept the facts they offered for credence, on their authority alone. Very few of them had even heard of the places described before; scarcely one in a thousand could, either from personal experience or acquired knowledge, attest the truth of the description. What was there—for the benefit of the general public—to prove that the Sunbeam had sailed round the world, or that Sir Samuel Baker had met with the rare beasts, birds, and flowers he wrote of, or that Livingstone and Stanley met and spoke with those curious, unknown tribes that never saw white men till they set eyes on them? Yet had any one of those writers affirmed that in his wanderings he had encountered a gold field of undoubted excellence, thousands of fortune-seekers would have left their native land on his word alone, and rushed to secure some of the glittering treasure.

Why? Because the authors of those books were persons well known in society, who had a reputation for veracity to maintain, and who would have been quickly found out had they dared to deceive. I claim the same grounds for obtaining belief. I have a well-known name and a public reputation, a tolerable brain, and two sharp eyes. What I have witnessed, others, with equal assiduity and perseverance, may witness for themselves. It would demand a voyage round the world to see all that the owners of the Sunbeam saw. It would demand time and trouble and money to see what I have seen, and to some people, perhaps, it would not be worth the outlay. But if I have journeyed into the Debateable Land (which so few really believe in, and most are terribly afraid of), and come forward now to tell what I have seen there, the world has no more right to disbelieve me than it had to disbelieve Lady Brassey. Because the general public has not penetrated Central Africa, is no reason that Livingstone did not do so; because the general public has not seen (and does not care to see) what I have seen, is no argument against the truth of what I write. To those who do believe in the possibility of communion with disembodied spirits, my story will be interesting perhaps, on account of its dealing throughout in a remarkable degree with the vexed question of identity and recognition. To the materialistic portion of creation who may credit me with not being a bigger fool than the remainder of the thirty-eight millions of Great Britain, it may prove a new source of speculation and research. And for those of my fellow-creatures who possess no curiosity, nor imagination, nor desire to prove for themselves what they cannot accept on the testimony of others, I never had, and never shall have, anything in common. They are the sort of people who ask you with a pleasing smile if Irving wrote "The Charge of the Light Brigade," and say they like Byron's "Sardanapalus" very well, but it is not so funny as "Our Boys."

Now, before going to work in right earnest, I do not think it is generally known that my father, the late Captain Marryat, was not only a believer in ghosts, but himself a ghost-seer. I am delighted to be able to record this fact as an introduction to my own experiences. Perhaps the ease with which such manifestations have come to me is a gift which I inherit from him, anyway I am glad he shared the belief and the power of spiritual sight with me. If there were no other reason to make me bold to repeat what I have witnessed, the circumstance would give me courage. My father was not like his intimate friends, Charles Dickens, Lord Lytton, and many other men of genius, highly strung, nervous, and imaginative. I do not believe my father had any "nerves," and I think he had very little imagination. Almost all his works are founded on his personal experiences. His forte lay in a humorous description of what he had seen. He possessed a marvellous power of putting his recollections into graphic and forcible language, and the very reason that his books are almost as popular to-day as when they were written, is because they are true histories of their time. There is scarcely a line of fiction in them. His body was as powerful and muscular as his brain. His courage was indomitable—his moral courage as well as his physical (as many people remember to their cost to this day), and his hardness of belief on many subjects is no secret. What I am about to relate therefore did not happen to some excitable, nervous, sickly sentimentalist, and I repeat that I am proud to have inherited his constitutional tendencies, and quite willing to stand judgment after him.

I have heard that my father had a number of stories to relate of supernatural (as they are usually termed) incidents that had occurred to him, but I will content myself with relating such as were proved to be (at the least) very remarkable coincidences. In my work, "The Life and Letters of Captain Marryat," I relate an anecdote of him that was entered in his private "log," and found amongst his papers. He had a younger brother, Samuel, to whom he was very much attached, and who died unexpectedly in England whilst my father, in command of H. M. S. Larne, was engaged in the first Burmese war. His men broke out with scurvy and he was ordered to take his vessel over to Pulu Pinang for a few weeks in order to get the sailors fresh fruit and vegetables. As my father was lying in his berth one night, anchored off the island, with the brilliant tropical moonlight making everything as bright as day, he saw the door of his cabin open, and his brother Samuel entered and walked quietly up to his side. He looked just the same as when they had parted, and uttered in a perfectly distinct voice, "Fred! I have come to tell you that I am dead!" When the figure entered the cabin my father jumped up in his berth, thinking it was some one coming to rob him, and when he saw who it was and heard it speak, he leaped out of bed with the intention of detaining it, but it was gone. So vivid was the impression made upon him by the apparition that he drew out his log at once and wrote down all particulars concerning it, with the hour and day of its appearance. On reaching England after the war was over, the first dispatches put into his hand were to announce the death of his brother, who had passed away at the very hour when he had seen him in the cabin.

But the story that interests me most is one of an incident which occurred to my father during my lifetime, and which we have always called "The Brown Lady of Rainham." I am aware that this narrative has reached the public through other sources, and I have made it the foundation of a Christmas story myself. But it is too well authenticated to be omitted here. The last fifteen years of my father's life were passed on his own estate of Langham, in Norfolk, and amongst his county friends were Sir Charles and Lady Townshend of Rainham Hall. At the time I speak of, the title and property had lately changed hands, and the new baronet had re-papered, painted, and furnished the Hall throughout, and come down with his wife and a large party of friends to take possession. But to their annoyance, soon after their arrival, rumors arose that the house was haunted, and their guests began, one and all (like those in the parable), to make excuses to go home again. Sir Charles and Lady Townshend might have sung, "Friend after friend departs," with due effect, but it would have had none on the general exodus that took place from Rainham. And it was all on account of a Brown Lady, whose portrait hung in one of the bedrooms, and in which she was represented as wearing a brown satin dress with yellow trimmings, and a ruff around her throat—a very harmless, innocent-looking young woman. But they all declared they had seen her walking about the house—some in the corridor, some in their bedrooms, others in the lower premises, and neither guests nor servants would remain in the Hall. The baronet was naturally very much annoyed about it, and confided his trouble to my father, and my father was indignant at the trick he believed had been played upon him. There was a great deal of smuggling and poaching in Norfolk at that period, as he knew well, being a magistrate of the county, and he felt sure that some of these depredators were trying to frighten the Townshends away from the Hall again. The last baronet had been a solitary sort of being, and lead a retired life, and my father imagined some of the tenantry had their own reasons for not liking the introduction of revelries and "high jinks" at Rainham. So he asked his friends to let him stay with them and sleep in the haunted chamber, and he felt sure he could rid them of the nuisance. They accepted his offer, and he took possession of the room in which the portrait of the apparition hung, and in which she had been often seen, and slept each night with a loaded revolver under his pillow. For two days, however, he saw nothing, and the third was to be the limit of his stay. On the third night, however, two young men (nephews of the baronet) knocked at his door as he was undressing to go to bed, and asked him to step over to their room (which was at the other end of the corridor), and give them his opinion on a new gun just arrived from London. My father was in his shirt and trousers, but as the hour was late, and everybody had retired to rest except themselves, he prepared to accompany them as he was. As they were leaving the room, he caught up his revolver, "in case we meet the Brown Lady," he said, laughing. When the inspection of the gun was over, the young men in the same spirit declared they would accompany my father back again, "in case you meet the Brown Lady," they repeated, laughing also. The three gentlemen therefore returned in company.

The corridor was long and dark, for the lights had been extinguished, but as they reached the middle of it, they saw the glimmer of a lamp coming towards them from the other end. "One of the ladies going to visit the nurseries," whispered the young Townshends to my father. Now the bedroom doors in that corridor faced each other, and each room had a double door with a space between, as is the case in many old-fashioned country houses. My father (as I have said) was in a shirt and trousers only, and his native modesty made him feel uncomfortable, so he slipped within one of the outer doors (his friends following his example), in order to conceal himself until the lady should have passed by. I have heard him describe how he watched her approaching nearer and nearer, through the chink of the door, until, as she was close enough for him to distinguish the colors and style of her costume, he recognized the figure as the facsimile of the portrait of "The Brown Lady." He had his finger on the trigger of his revolver, and was about to demand it to stop and give the reason for its presence there, when the figure halted of its own accord before the door behind which he stood, and holding the lighted lamp she carried to her features, grinned in a malicious and diabolical manner at him. This act so infuriated my father, who was anything but lamb-like in disposition, that he sprang into the corridor with a bound, and discharged the revolver right in her face. The figure instantly disappeared—the figure at which for the space of several minutes three men had been looking together—and the bullet passed through the outer door of the room on the opposite side of the corridor, and lodged in the panel of the inner one. My father never attempted again to interfere with "The Brown Lady of Rainham," and I have heard that she haunts the premises to this day. That she did so at that time, however, there is no shadow of doubt.

But Captain Marryat not only held these views and believed in them from personal experience—he promulgated them in his writings. There are many passages in his works which, read by the light of my assertion, prove that he had faith in the possibility of the departed returning to visit this earth, and in the theory of re-incarnation or living more than one life upon it, but nowhere does he speak more plainly than in the following extract from the "Phantom Ship":—

"Think you, Philip," (says Amine to her husband), "that this world is solely peopled by such dross as we are?—things of clay, perishable and corruptible, lords over beasts and ourselves, but little better? Have you not, from your own sacred writings, repeated acknowledgments and proofs of higher intelligences, mixing up with mankind, and acting here below? Why should what was then not be now, and what more harm is there to apply for their aid now than a few thousand years ago? Why should you suppose that they were permitted on the earth then and not permitted now? What has become of them? Have they perished? Have they been ordered back? to where?—to heaven? If to heaven, the world and mankind have been left to the mercy of the devil and his agents. Do you suppose that we poor mortals have been thus abandoned? I tell you plainly, I think not. We no longer have the communication with those intelligences that we once had, because as we become more enlightened we become more proud and seek them not, but that they still exist a host of good against a host of evil, invisibly opposing each other, is my conviction."

One testimony to such a belief, from the lips of my father, is sufficient. He would not have written it unless he had been prepared to maintain it. He was not one of those wretched literary cowards who we meet but too often now-a-days, who are too much afraid of the world to confess with their mouths the opinions they hold in their hearts. Had he lived to this time I believe he would have been one of the most energetic and outspoken believers in Spiritualism that we possess. So much, however, for his testimony to the possibility of spirits, good and evil, revisiting this earth. I think few will be found to gainsay the assertion that where he trod, his daughter need not be ashamed to follow.

Before the question of Spiritualism, however, arose in modern times, I had had my own little private experiences on the subject. From an early age I was accustomed to see, and to be very much alarmed at seeing, certain forms that appeared to me at night. One in particular, I remember, was that of a very short or deformed old woman, who was very constant to me. She used to stand on tiptoe to look at me as I lay in bed, and however dark the room might be, I could always see every article in it, as if illuminated, whilst she remained there.

I was in the habit of communicating these visions to my mother and sisters (my father had passed from us by that time), and always got well ridiculed for my pains. "Another of Flo's optical illusions," they would cry, until I really came to think that the appearances I saw were due to some defect in my eye-sight. I have heard my first husband say, that when he married me he thought he should never rest for an entire night in his bed, so often did I wake him with the description of some man or woman I had seen in the room. I recall these figures distinctly. They were always dressed in white, from which circumstance I imagined that they were natives who had stolen in to rob us, until, from repeated observation, I discovered they only formed part of another and more enlarged series of my "optical illusions." All this time I was very much afraid of seeing what I termed "ghosts." No love of occult science led me to investigate the cause of my alarm. I only wished never to see the "illusions" again, and was too frightened to remain by myself lest they should appear to me.

When I had been married for about two years, the head-quarters of my husband's regiment, the 12th Madras Native Infantry, was ordered to Rangoon, whilst the left wing, commanded by a Major Cooper, was sent to assist in the bombardment of Canton. Major Cooper had only been married a short time, and by rights his wife had no claim to sail with the head-quarters for Burmah, but as she had no friends in Madras, and was moreover expecting her confinement, our colonel permitted her to do so, and she accompanied us to Rangoon, settling herself in a house not far from our own. One morning, early in July, I was startled by receiving a hurried scrawl from her, containing only these words, "Come! come! come!" I set off at once, thinking she had been taken ill, but on my arrival I found Mrs. Cooper sitting up in bed with only her usual servants about her. "What is the matter?" I exclaimed. "Mark is dead," she answered me; "he sat in that chair" (pointing to one by the bedside) "all last night. I noticed every detail of his face and figure. He was in undress, and he never raised his eyes, but sat with the peak of his forage cap pulled down over his face. But I could see the back of his head and his hair, and I know it was he. I spoke to him but he did not answer me, and I am sure he is dead."

Naturally, I imagined this vision to have been dictated solely by fear and the state of her health. I laughed at her for a simpleton, and told her it was nothing but fancy, and reminded her that by the last accounts received from the seat of war, Major Cooper was perfectly well and anticipating a speedy reunion with her. Laugh as I would, however, I could not laugh her out of her belief, and seeing how low-spirited she was, I offered to pass the night with her. It was a very nice night indeed. As soon as ever we had retired to bed, although a lamp burned in the room, Mrs. Cooper declared that her husband was sitting in the same chair as the night before, and accused me of deception when I declared that I saw nothing at all. I sat up in bed and strained my eyes, but I could discern nothing but an empty arm-chair, and told her so. She persisted that Major Cooper sat there, and described his personal appearance and actions. I got out of bed and sat in the chair, when she cried out, "Don't, don't! You are sitting right on him!" It was evident that the apparition was as real to her as if it had been flesh and blood. I jumped up again fast enough, not feeling very comfortable myself, and lay by her side for the remainder of the night, listening to her asseverations that Major Cooper was either dying or dead. She would not part with me, and on the third night I had to endure the same ordeal as on the second. After the third night the apparition ceased to appear to her, and I was permitted to return home. But before I did so, Mrs. Cooper showed me her pocket-book, in which she had written down against the 8th, 9th, and 10th of July this sentence: "Mark sat by my bedside all night."

The time passed on, and no bad news arrived from China, but the mails had been intercepted and postal communication suspended. Occasionally, however, we received letters by a sailing vessel. At last came September, and on the third of that month Mrs. Cooper's baby was born and died. She was naturally in great distress about it, and I was doubly horrified when I was called from her bedside to receive the news of her husband's death, which had taken place from a sudden attack of fever at Macao. We did not intend to let Mrs. Cooper hear of this until she was convalescent, but as soon as I re-entered her room she broached the subject.

"Are there any letters from China?" she asked. (Now this question was remarkable in itself, because the mails having been cut off, there was no particular date when letters might be expected to arrive from the seat of war.) Fearing she would insist upon hearing the news, I temporized and answered her, "We have received none." "But there is a letter for me," she continued: "a letter with the intelligence of Mark's death. It is useless denying it. I know he is dead. He died on the 10th of July." And on reference to the official memorandum, this was found to be true. Major Cooper had been taken ill on the first day he had appeared to his wife, and died on the third. And this incident was the more remarkable, because they were neither of them young nor sentimental people, neither had they lived long enough together to form any very strong sympathy or accord between them. But as I have related it, so it occurred.

I had returned from India and spent several years in England before the subject of Modern Spiritualism was brought under my immediate notice. Cursorily I had heard it mentioned by some people as a dreadfully wicked thing, diabolical to the last degree, by others as a most amusing pastime for evening parties, or when one wanted to get some "fun out of the table." But neither description charmed me, nor tempted me to pursue the occupation. I had already lost too many friends. Spiritualism (so it seemed to me) must either be humbug or a very solemn thing, and I neither wished to trifle with it or to be trifled with by it. And after twenty years' continued experience I hold the same opinion. I have proved Spiritualism not to be humbug, therefore I regard it in a sacred light. For, from whatever cause it may proceed, it opens a vast area for thought to any speculative mind, and it is a matter of constant surprise to me to see the indifference with which the world regards it. That it exists is an undeniable fact. Men of science have acknowledged it, and the churches cannot deny it. The only question appears to be, "What is it, and whence does the power proceed?" If (as many clever people assert) from ourselves, then must these bodies and minds of ours possess faculties hitherto undreamed of, and which we have allowed to lie culpably fallow. If our bodies contain magnetic forces sufficient to raise substantial and apparently living forms from the bare earth, which our eyes are clairvoyant enough to see, and which can articulate words which our ears are clairaudient enough to hear—if, in addition to this, our minds can read each other's inmost thoughts, can see what is passing at a distance, and foretell what will happen in the future, then are our human powers greater than we have ever imagined, and we ought to do a great deal more with them than we do. And even regarding Spiritualism from that point of view, I cannot understand the lack of interest displayed in the discovery, to turn these marvellous powers of the human mind to greater account.

To discuss it, however, from the usual meaning given to the word, namely, as a means of communication with the departed, leaves me as puzzled as before. All Christians acknowledge they have spirits independent of their bodies, and that when their bodies die, their spirits will continue to live on. Wherein, then, lies the terror of the idea that these liberated spirits will have the privilege of roaming the universe as they will? And if they argue the impossibility of their return, they deny the records which form the only basis of their religion. No greater proof can be brought forward of the truth of Spiritualism than the truth of the Bible, which teems and bristles with accounts of it from beginning to end. From the period when the Lord God walked with Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, and the angels came to Abram's tent, and pulled Lot out of the doomed city; when the witch of Endor raised up Samuel, and Balaam's ass spoke, and Ezekiel wrote that the hair of his head stood up because "a spirit" passed before him, to the presence of Satan with Jesus in the desert, and the reappearance of Moses and Elias, the resurrection of Christ Himself, and His talking and eating with His disciples, and the final account of John being caught up to Heaven to receive the Revelations—all is Spiritualism, and nothing else. The Protestant Church that pins its faith upon the Bible, and nothing but the Bible, cannot deny that the spirits of mortal men have reappeared and been recognized upon this earth, as when the graves opened at the time of the Christ's crucifixion, and "many bodies of those that were dead arose and went into the city, and were seen of many." The Catholic Church does not attempt to deny it. All her legends and miracles (which are disbelieved and ridiculed by the Protestants aforesaid) are founded on the same truth—the miraculous or supernatural return (as it is styled) of those who are gone, though I hope to make my readers believe, as I do, that there is nothing miraculous in it, and far from being supernatural it is only a continuation of Nature. Putting the churches and the Bible, however, on one side, the History of Nations proves it to be possible. There is not a people on the face of the globe that has not its (so-called) superstitions, nor a family hardly, which has not experienced some proofs of spiritual communion with earth. Where learning and science have thrust all belief out of sight, it is only natural that the man who does not believe in a God nor a Hereafter should not credit the existence of spirits, nor the possibility of communicating with them. But the lower we go in the scale of society, the more simple and childlike the mind, the more readily does such a faith gain credence, and the more stories you will hear to justify belief. It is just the same with religion, which is hid from the wise and prudent, and revealed to babes.

If I am met here with the objection that the term "Spiritualism" has been at times mixed up with so much that is evil as to become an offence, I have no better answer to make than by turning to the irrefragable testimony of the Past and Present to prove that in all ages, and of all religions, there have been corrupt and demoralized exponents whose vices have threatened to pull down the fabric they lived to raise. Christianity itself would have been overthrown before now, had we been unable to separate its doctrine from its practice.

I held these views in the month of February, 1873, when I made one of a party of friends assembled at the house of Miss Elizabeth Philip, in Gloucester Crescent, and was introduced to Mr. Henry Dunphy of the Morning Post, both of them since gone to join the great majority. Mr. Dunphy soon got astride of his favorite hobby of Spiritualism, and gave me an interesting account of some of the séances he had attended. I had heard so many clever men and women discuss the subject before, that I had begun to believe on their authority that there must be "something in it," but I held the opinion that sittings in the dark must afford so much liberty for deception, that I would engage in none where I was not permitted the use of my eyesight.

I expressed myself somewhat after this fashion to Mr. Dunphy. He replied, "Then the time has arrived for you to investigate Spiritualism, for I can introduce you to a medium who will show you the faces of the dead." This proposal exactly met my wishes, and I gladly accepted it. Annie Thomas (Mrs. Pender Cudlip,) the novelist, who is an intimate friend of mine, was staying with me at the time and became as eager as I was to investigate the phenomena. We took the address Mr. Dunphy gave us of Mrs. Holmes, the American medium, then visiting London, and lodging in Old Quebec Street, Portman Square, but we refused his introduction, preferring to go incognito. Accordingly, the next evening, when she held a public séance, we presented ourselves at Mrs. Holmes' door; and having first removed our wedding-rings, and tried to look as virginal as possible, sent up our names as Miss Taylor and Miss Turner. I am perfectly aware that this medium was said afterwards to be untrustworthy. So may a servant who was perfectly honest, whilst in my service, leave me for a situation where she is detected in theft. That does not alter the fact that she stole nothing from me. I do not think I know a single medium of whom I have not (at some time or other) heard the same thing, and I do not think I know a single woman whom I have not also, at some time or other, heard scandalized by her own sex, however pure and chaste she may imagine the world holds her. The question affects me in neither case. I value my acquaintances for what they are to me, not for what they may be to others; and I have placed trust in my media from what I individually have seen and heard, and proved to be genuine in their presence, and not from what others may imagine they have found out about them. It is no detriment to my witness that the media I sat with cheated somebody else, either before or after. My business was only to take care that I was not cheated, and I have never, in Spiritualism, accepted anything at the hands of others that I could not prove for myself.

Mrs. Holmes did not receive us very graciously on the present occasion. We were strangers to her—probably sceptics, and she eyed us rather coldly. It was a bitter night, and the snow lay so thick upon the ground that we had some difficulty in procuring a hansom to take us from Bayswater to Old Quebec Street. No other visitors arrived, and after a little while Mrs. Holmes offered to return our money (ten shillings), as she said if she did sit with us, there would probably be no manifestations on account of the inclemency of the weather. (Often since then I have proved her assertion to be true, and found that any extreme of heat or cold is liable to make a séance a dead failure).

But Annie Thomas had to return to her home in Torquay on the following day, and so we begged the medium to try at least to show us something, as we were very curious on the subject. I am not quite sure what I expected or hoped for on this occasion. I was full of curiosity and anticipation, but I am sure that I never thought I should see any face which I could recognize as having been on earth. We waited till nine o'clock in hopes that a circle would be formed, but as no one else came, Mrs. Holmes consented to sit with us alone, warning us, however, several times to prepare for a disappointment. The lights were therefore extinguished, and we sat for the usual preliminary dark séance, which was good, perhaps, but has nothing to do with a narrative of facts, proved to be so. When it concluded, the gas was re-lit and we sat for "Spirit Faces."

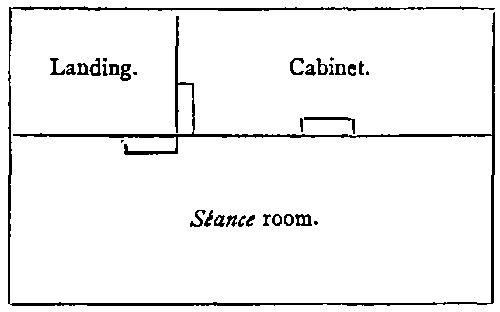

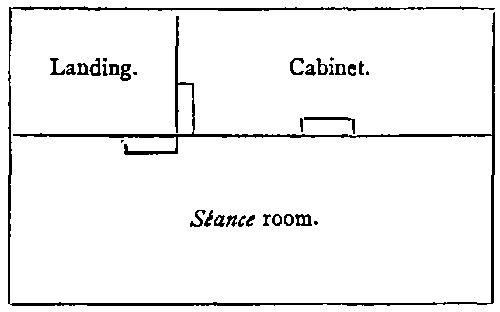

There were two small rooms connected by folding doors. Annie Thomas and I, were asked to go into the back room—to lock the door communicating with the landings, and secure it with our own seal, stamped upon a piece of tape stretched across the opening—to examine the window and bar the shutter inside—to search the room thoroughly, in fact, to see that no one was concealed in it—and we did all this as a matter of business. When we had satisfied ourselves that no one could enter from the back, Mr. and Mrs. Holmes, Annie Thomas, and I were seated on four chairs in the front room, arranged in a row before the folding doors, which were opened, and a square of black calico fastened across the aperture from one wall to the other. In this piece of calico was cut a square hole about the size of an ordinary window, at which we were told the spirit faces (if any) would appear. There was no singing, nor noise of any sort made to drown the sounds of preparation, and we could have heard even a rustle in the next room. Mr. and Mrs. Holmes talked to us of their various experiences, until, we were almost tired of waiting, when something white and indistinct like a cloud of tobacco smoke, or a bundle of gossamer, appeared and disappeared again.

"They are coming! I am glad!" said Mrs. Holmes. "I didn't think we should get anything to-night,"—and my friend and I were immediately on the tiptoe of expectation. The white mass advanced and retreated several times, and finally settled before the aperture and opened in the middle, when a female face was distinctly to be seen above the black calico. What was our amazement to recognize the features of Mrs. Thomas, Annie Thomas' mother. Here I should tell my readers that Annie's father, who was a lieutenant in the Royal Navy and captain of the coastguard at Morston in Norfolk, had been a near neighbor and great friend of my father, Captain Marryat, and their children had associated like brothers and sisters. I had therefore known Mrs. Thomas well, and recognized her at once, as, of course, did her daughter. The witness of two people is considered sufficient in law. It ought to be accepted by society. Poor Annie was very much affected, and talked to her mother in the most incoherent manner. The spirit did not appear able to answer in words, but she bowed her head or shook it, according as she wished to say "yes" or "no." I could not help feeling awed at the appearance of the dear old lady, but the only thing that puzzled me was the cap she wore, which was made of white net, quilled closely round her face, and unlike any I had ever seen her wear in life. I whispered this to Annie, and she replied at once, "It is the cap she was buried in," which settled the question. Mrs. Thomas had possessed a very pleasant but very uncommon looking face, with bright black eyes, and a complexion of pink and white like that of a child. It was some time before Annie could be persuaded to let her mother go, but the next face that presented itself astonished her quite as much, for she recognized it as that of Captain Gordon, a gentleman whom she had known intimately and for a length of time. I had never seen Captain Gordon in the flesh, but I had heard of him, and knew he had died from a sudden accident. All I saw was the head of a good-looking, fair, young man, and not feeling any personal interest in his appearance, I occupied the time during which my friend conversed with him about olden days, by minutely examining the working of the muscles of his throat, which undeniably stretched when his head moved. As I was doing so, he leaned forward, and I saw a dark stain, which looked like a clot of blood, on his fair hair, on the left side of the forehead.

"Annie! what did Captain Gordon die of?" I asked. "He fell from a railway carriage," she replied, "and struck his head upon the line." I then pointed out to her the blood upon his hair. Several other faces appeared, which we could not recognize. At last came one of a gentleman, apparently moulded like a bust in plaster of Paris. He had a kind of smoking cap upon the head, curly hair, and a beard, but from being perfectly colorless, he looked so unlike nature, that I could not trace a resemblance to any friend of mine, though he kept on bowing in my direction, to indicate that I knew, or had known him. I examined this face again and again in vain. Nothing in it struck me as familiar, until the mouth broke into a grave, amused smile at my perplexity. In a moment I recognized it as that of my dear old friend, John Powles, whose history I shall relate in extenso further on. I exclaimed "Powles," and sprang towards it, but with my hasty action the figure disappeared. I was terribly vexed at my imprudence, for this was the friend of all others I desired to see, and sat there, hoping and praying the spirit would return, but it did not. Annie Thomas' mother and friend both came back several times; indeed, Annie recalled Captain Gordon so often, that on his last appearance the power was so exhausted, his face looked like a faded sketch in water-colors, but "Powles" had vanished altogether. The last face we saw that night was that of a little girl, and only her eyes and nose were visible, the rest of her head and face being enveloped in some white flimsy material like muslin. Mrs. Holmes asked her for whom she came, and she intimated that it was for me. I said she must be mistaken, and that I had known no one in life like her. The medium questioned her very closely, and tried to put her "out of court," as it were. Still, the child persisted that she came for me. Mrs. Holmes said to me, "Cannot you remember anyone of that age connected with you in the spirit world? No cousin, nor niece, nor sister, nor the child of a friend?" I tried to remember, but I could not, and answered, "No! no child of that age." She then addressed the little spirit. "You have made a mistake. There is no one here who knows you. You had better move on." So the child did move on, but very slowly and reluctantly. I could read her disappointment in her eyes, and after she had disappeared, she peeped round the corner again and looked at me, longingly. This was "Florence," my dear lost child (as I then called her), who had left me as a little infant of ten days old, and whom I could not at first recognize as a young girl of ten years. Her identity, however, has been proved to me since, beyond all doubt, as will be seen in the chapter which relates my reunion with her, and is headed "My Spirit Child." Thus ended the first séance at which I ever assisted, and it made a powerful impression upon my mind. Mrs. Holmes, in bidding us good-night, said, "You two ladies must be very powerful mediums. I never held so successful a séance with strangers in my life before." This news elated us—we were eager to pursue our investigations, and were enchanted to think we could have séances at home, and as soon as Annie Thomas took up her residence in London, we agreed to hold regular meetings for the purpose. This was the séance that made me a student of the psychological phenomena, which the men of the nineteenth century term Spiritualism. Had it turned out a failure, I might now have been as most men are. Quien sabe? As it was, it incited me to go on and on, until I have seen and heard things which at that moment would have seemed utterly impossible to me. And I would not have missed the experience I have passed through for all the good this world could offer me.

Before I proceed to write down the results of my private and premeditated investigations, I am reminded to say a word respecting the permission I received for the pursuit of Spiritualism. As soon as I expressed my curiosity on the subject, I was met on all sides with the objection that, as I am a Catholic, I could not possibly have anything to do with the matter, and it is a fact that the Church strictly forbids all meddling with necromancy, or communion with the departed. Necromancy is a terrible word, is it not? especially to such people as do not understand its meaning, and only associate it with the dead of night and charmed circles, and seething caldrons, and the arch fiend, in propria persona, with two horns and a tail. Yet it seems strange to me that the Catholic Church, whose very doctrine is overlaid with Spiritualism, and who makes it a matter of belief that the Saints hear and help us in our prayers and the daily actions of our lives, and recommends our kissing the ground every morning at the feet of our guardian angel, should consider it unlawful for us to communicate with our departed relatives. I cannot see the difference in iniquity between speaking to John Powles, who was and is a dear and trusted friend of mine, and Saint Peter of Alcantara, who is an old man whom I never saw in this life. They were both men, both mortal, and are both spirits. Again, surely my mother who was a pious woman all her life, and is now in the other world, would be just as likely to take an interest in my welfare, and to try and promote the prospect of our future meeting, as Saint Veronica Guiliani, who is my patron. Yet were I to spend half my time in prayer before Saint Veronica's altar, asking her help and guidance, I should be doing right (according to the Church), but if I did the same thing at my mother's grave, or spoke to her at a séance, I should be doing wrong. These distinctions without a difference were hard nuts to crack, and I was bound to settle the matter with my conscience before I went on with my investigations.

It is a fact that I have met quite as many Catholics as Protestants (especially of the higher classes) amongst the investigators of Spiritualism, and I have not been surprised at it, for who could better understand and appreciate the beauty of communications from the spirit world than members of that Church which instructs us to believe in the communion of saints, as an ever-present, though invisible mystery. Whether my Catholic acquaintances had received permission to attend séances or not, was no concern of mine, but I took good care to procure it for myself, and I record it here, because rumors have constantly reached me of people having said behind my back that I can be "no Catholic" because I am a spiritualist.

My director at that time was Father Dalgairn, of the Oratory at Brompton, and it was to him I took my difficulty. I was a very constant press writer and reviewer, and to be unable to attend and report on spiritualistic meetings would have seriously militated against my professional interests. I represented this to the Father, and (although under protest) I received his permission to pursue the research in the cause of science. He did more than ease my conscience. He became interested in what I had to tell him on the subject, and we had many conversations concerning it. He also lent me from his own library the lives of such saints as had heard voices and seen visions, of those in fact who (like myself) had been the victims of "Optical Illusions." Amongst these I found the case of Saint Anne-Catherine of Emmerich, so like my own, that I began to think that I too might turn out to be a saint in disguise. It has not come to pass yet, but there is no knowing what may happen.

She used to see the spirits floating beside her as she walked to mass, and heard them asking her to pray for them as they pointed to "les taches sur leurs robes." The musical instruments used to play without hands in her presence, and voices from invisible throats sound in her ears, as they have done in mine. I have only inserted this clause, however, for the satisfaction of those Catholic acquaintances with whom I have sat at séances, and who will probably be the first to exclaim against the publication of our joint experiences. I trust they will acknowledge, after reading it, that I am not worse than themselves, though I may be a little bolder in avowing my opinions.

Before I began this chapter, I had an argument with that friend of mine called Self (who has but too often worsted me in the Battle of Life), as to whether I should say anything about table-rapping or tilting. The very fact of so common an article of furniture as a table, as an agent of communication with the unseen world, has excited so much ridicule and opens so wide a field for chicanery, that I thought it would be wiser to drop the subject, and confine myself to those phases of the science or art, or religion, or whatever the reader may like to call it, that can be explained or described on paper. The philosophers of the nineteenth century have invented so many names for the cause that makes a table turn round—tilt—or rap—that I feel quite unable (not being a philosopher) to cope with them. It is "magnetic force" or "psychic force,"—it is "unconscious cerebration" or "brain-reading"—and it is exceedingly difficult to tell the outside world of the private reasons that convince individuals that the answers they receive are not emanations from their own brains. I shall not attempt to refute their reasonings from their own standpoint. I see the difficulties in the way, so much so that I have persistently refused for many years past to sit at the table with strangers, for it is only a lengthened study of the matter that can possibly convince a person of its truth. I cannot, however, see the extreme folly myself of holding communication (under the circumstances) through the raps or tilts of a table, or any other object. These tiny indications of an influence ulterior to our own are not necessarily confined to a table. I have received them through a cardboard box, a gentleman's hat, a footstool, the strings of a guitar, and on the back of my chair, even on the pillow of my bed. And which, amongst the philosophers I have alluded to, could suggest a simpler mode of communication?

I have put the question to clever men thus: "Suppose yourself, after having been able to write and talk to me, suddenly deprived of the powers of speech and touch, and made invisible, so that we could not understand each other by signs, what better means than by taps or tilts on any article, when the right word or letter is named, could you think of by which to communicate with me?"

And my clever men have never been able to propose an easier or more sensible plan, and if anybody can suggest one, I should very much like to hear of it. The following incidents all took place through the much-ridiculed tipping of the table, but managed to knock some sense out of it nevertheless. On looking over the note book which I faithfully kept when we first held séances at home, I find many tests of identity which took place through my own mediumship, and which could not possibly have been the effects of thought-reading. I devote this chapter to their relation. I hope it will be observed with what admirable caution I have headed it. I have a few drops of Scotch blood in me by the mother's side, and I think they must have aided me here. "Curious coincidences." Why, not the most captious and unbelieving critic of them all can find fault with so modest and unpretending a title. Everyone believes in the occasional possibility of "curious coincidences."

It was not until the month of June, 1873, that we formed a home circle, and commenced regularly to sit together. We became so interested in the pursuit, that we used to sit every evening, and sometimes till three and four o'clock in the morning, greatly to our detriment, both mental and physical. We seldom sat alone, being generally joined by two or three friends from outside, and the results were sometimes very startling, as we were a strong circle. The memoranda of these sittings, sometimes with one party and sometimes with another, extend over a period of years, but I shall restrict myself to relating a few incidents that were verified by subsequent events.

The means by which we communicated with the influences around us was the usual one. We sat round the table and laid our hands upon it, and I (or anyone who might be selected for the purpose) spelled over the alphabet, and raps or tilts occurred when the desired letter was reached. This in reality is not so tedious a process as it may appear, and once used to it, one may get through a vast amount of conversation in an hour by this means. A medium is soon able to guess the word intended to be spelt, for there are not so many after all in use in general conversation.

Some one had come to our table on several occasions, giving the name of "Valerie," but refusing to say any more, so we thought she was an idle or frivolous spirit, and had been in the habit of driving her away. One evening, on the 1st of July, however, our circle was augmented by Mr. Henry Stacke, when "Valerie" was immediately spelled out, and the following conversation ensued. Mr. Stacke said to me, "Who is this?" and I replied carelessly, "O! she's a little devil! She never has anything to say." The table rocked violently at this, and the taps spelled out.

"Je ne suis pas diable."

"Hullo! Valerie, so you can talk now! For whom do you come?"

"Monsieur Stacke."

"Where did you meet him?"

"On the Continent."

"Whereabouts?"

"Between Dijon and Macon."

"How did you meet him?"

"In a railway carriage."

"What where you doing there?"

Here she relapsed into French, and said,

"Ce m'est impossible de dire."

At this juncture Mr. Stacke observed that he had never been in a train between Dijon and Macon but once in his life, and if the spirit was with him then, she must remember what was the matter with their fellow-passenger.

"Mais oui, oui—il etait fou," she replied, which proved to be perfectly correct. Mr. Stacke also remembered that two ladies in the same carriage had been terribly frightened, and he had assisted them to get into another. "Valerie" continued, "Priez pour moi."

"Pourquoi, Valerie?"

"Parce que j'ai beaucoup péché."

There was an influence who frequented our society at that time and called himself "Charlie."

He stated that his full name had been "Stephen Charles Bernard Abbot,"—that he had been a monk of great literary attainments—that he had embraced the monastic life in the reign of Queen Mary, and apostatized for political reasons in that of Elizabeth, and been "earth bound" in consequence ever since.

"Charlie" asked us to sing one night, and we struck up the very vulgar refrain of "Champagne Charlie," to which he greatly objected, asking for something more serious.

I began, "Ye banks and braes o' bonnie Doon."

"Why, that's as bad as the other," said Charlie. "It was a ribald and obscene song in the reign of Elizabeth. The drunken roysterers used to sing it in the street as they rolled home at night."

"You must be mistaken, Charlie! It's a well-known Scotch air."

"It's no more Scotch than I am," he replied. "The Scotch say they invented everything. It's a tune of the time of Elizabeth. Ask Brinley Richards."

Having the pleasure of the acquaintance of that gentleman, who was the great authority on the origin of National Ballads, I applied to him for the information, and received an answer to say that "Charlie" was right, but that Mr. Richards had not been aware of the fact himself until he had searched some old MSS. in the British Museum for the purpose of ascertaining the truth.

I was giving a sitting once to an officer from Aldershot, a cousin of my own, who was quite prepared to ridicule every thing that took place. After having teased me into giving him a séance, he began by cheating himself, and then accused me of cheating him, and altogether tired out my patience. At last I proposed a test, though with little hope of success.

"Let us ask John Powles to go down to Aldershot," I said, "and bring us word what your brother officers are doing."

"O, yes! by Jove! Capital idea! Here! you fellow Powles, cut off to the camp, will you, and go to the barracks of the 84th, and let us know what Major R—— is doing." The message came back in about three minutes. "Major R—— has just come in from duty," spelt out Powles. "He is sitting on the side of his bed, changing his uniform trousers for a pair of grey tweed."

"I'm sure that's wrong," said my cousin, "because the men are never called out at this time of the day."

It was then four o'clock, as we had been careful to ascertain. My cousin returned to camp the same evening, and the next day I received a note from him to say, "That fellow Powles is a brick. It was quite right. R—— was unexpectedly ordered to turn out his company yesterday afternoon, and he returned to barracks and changed his things for the grey tweed suit exactly at four o'clock."

But I have always found my friend Powles (when he will condescend to do anything for strangers, which is seldom) remarkably correct in detailing the thoughts and actions of absentees, sometimes on the other side of the globe.

I went one afternoon to pay an ordinary social call on a lady named Mrs. W——, and found her engaged in an earnest conversation on Spiritualism with a stout woman and a commonplace man—two as material looking individuals as ever I saw, and who appeared all the more so under a sultry August sun. As soon as Mrs. W—— saw me, she exclaimed, "O! here is Mrs. Ross-Church. She will tell you all about the spirits. Do, Mrs. Ross-Church, sit down at the table and let us have a séance."

A séance on a burning, blazing afternoon in August, with two stolid and uninteresting, and worse still, uninterested looking strangers, who appeared to think Mrs. W—— had a "bee in her bonnet." I protested—I reasoned—I pleaded—all in vain. My hostess continued to urge, and society places the guest at the mercy of her hostess. So, in an evil temper, I pulled off my gloves, and placed my hands indifferently on the table. The following words were at once rapped out—

"I am Edward G——. Did you ever pay Johnson the seventeen pounds twelve you received for my saddlery?"

The gentleman opposite to me turned all sorts of colors, and began to stammer out a reply, whilst his wife looked very confused. I asked the influence, "Who are you?" It replied, "He knows! His late colonel! Why hasn't Johnson received that money?" This is what I call an "awkward" coincidence, and I have had many such occur through me—some that have driven acquaintances away from the table, vowing vengeance against me, and racking their brains to discover who had told me of their secret peccadilloes. The gentleman in question (whose name even I do not remember) confessed that the identity and main points of the message were true, but he did not confide to us whether Johnson had ever received that seventeen pounds twelve.

I had a beautiful English greyhound, called "Clytie," a gift from Annie Thomas to me, and this dog was given to straying from my house in Colville Road, Bayswater, which runs parallel to Portobello Road, a rather objectionable quarter, composed of inferior shops, one of which, a fried fish shop, was an intolerable nuisance, and used to fill the air around with its rich perfume. On one occasion "Clytie" stayed away from home so much longer than usual, that I was afraid she was lost in good earnest, and posted bills offering a reward for her. "Charlie" came to the table that evening and said, "Don't offer a reward for the dog. Send for her."

"Where am I to send?" I asked.

"She is tied up at the fried fish shop in Portobello Road. Send the cook to see."

I told the servant in question that I had heard the greyhound was detained at the fish shop, and sent her to inquire. She returned with "Clytie." Her account was, that on making inquiries, the man in the shop had been very insolent to her, and she had raised her voice in reply; that she had then heard and recognized the sharp, peculiar bark of the greyhound from an upper storey, and, running up before the man could prevent her, she had found "Clytie" tied up to a bedstead with a piece of rope, and had called in a policeman to enable her to take the dog away. I have often heard the assertion that Spiritualism is of no practical good, and, doubtless, it was never intended to be so, but this incident was, at least, an exception to the rule.

When abroad, on one occasion, I was asked by a Catholic Abbé to sit with him. He had never seen any manifestations before, and he did not believe in them, but he was curious on the subject. I knew nothing of him further than that he was a priest, and a Jesuit, and a great friend of my sister's, at whose house I was staying. He spoke English, and the conversation was carried on in that language. He had told me beforehand that if he could receive a perfectly private test, that he should never doubt the truth of the manifestations again. I left him, therefore, to conduct the investigation entirely by himself, I acting only as the medium between him and the influence. As soon as the table moved he put his question direct, without asking who was there to answer it.

"Where is my chasuble?"

Now a priest's chasuble, I should have said, must be either hanging in the sacristy or packed away at home, or been sent away to be altered or mended. But the answer was wide of all my speculations.

"At the bottom of the Red Sea."

The priest started, but continued—

"Who put it there?"

"Elias Dodo."

"What was his object in doing so?"

"He found the parcel a burthen, and did not expect any reward for delivering it."

The Abbé really looked as if he had encountered the devil. He wiped the perspiration from his forehead, and put one more question.

"Of what was my chasuble made?"

"Your sister's wedding dress."

The priest then explained to me that his sister had made him a chasuble out of her wedding dress—one of the forms of returning thanks in the Church, but that after a while it became old fashioned, and the Bishop, going his rounds, ordered him to get another. He did not like to throw away his sister's gift, so he decided to send the old chasuble to a priest in India, where they are very poor, and not so particular as to fashion. He confided the packet to a man called Elias Dodo, a sufficiently singular name, but neither he nor the priest he sent it to had ever heard anything more of the chasuble, or the man who promised to deliver it.

A young artist of the name of Courtney was a visitor at my house. He asked me to sit with him alone, when the table began rapping out a number of consonants—a farrago of nonsense, it appeared to me, and I stopped and said so. But Mr. Courtney, who appeared much interested, begged me to proceed. When the communication was finished, he said to me, "This is the most wonderful thing I have ever heard. My father has been at the table talking to me in Welsh. He has told me our family motto, and all about my birth-place and relations in Wales." I said, "I never heard you were a Welshman." "Yes! I am," he replied, "my real name is Powell. I have only adopted the name of Courtney for professional purposes."

This was all news to me, but had it not been, I cannot speak Welsh.

I could multiply such cases by the dozen, but that I fear to tire my readers, added to which the majority of them were of so strictly private a nature that it would be impossible to put them into print. This is perhaps the greatest drawback that one encounters in trying to prove the truth of Spiritualism. The best tests we receive are when the very secrets of our hearts, which we have not confided to our nearest friends, are revealed to us. I could relate (had I the permission of the persons most interested) the particulars of a well-known law suit, in which the requisite evidence, and names and addresses of witnesses, were all given though my mediumship, and were the cause of the case being gained by the side that came to me for "information." Some of the coincidences I have related in this chapter might, however, be ascribed by the sceptical to the mysterious and unknown power of brain reading, whatever that may be, and however it may come, apart from mediumship, but how is one to account for the facts I shall tell you in my next chapter.

I was having a sitting one day in my own house with a lady friend, named Miss Clark, when a female spirit came to the table and spelt out the name "Tiny."

"Who are you?" I asked, "and for whom do you come?"

"I am a friend of Major M——" (mentioning the full name), "and I want your help."

"Are you any relation to Major M——?"

"I am the mother of his child."

"What do you wish me to do for you?"

"Tell him he must go down to Portsmouth and look after my daughter. He has not seen her for years. The old woman is dead, and the man is a drunkard. She is falling into evil courses. He must save her from them."

"What is your real name?"

"I will not give it. There is no need. He always called me 'Tiny.'"

"How old is your daughter."

"Nineteen! Her name is Emily! I want her to be married. Tell him to promise her a wedding trousseau. It may induce her to marry."

The influence divulged a great deal more on the subject which I cannot write down here. It was an account of one of those cruel acts of seduction by which a young girl had been led into trouble in order to gratify a man's selfish lust, and astonished both Miss Clark and myself, who had never heard of such a person as "Tiny" before. It was too delicate a matter for me to broach to Major M—— (who was a married man, and an intimate friend of mine), but the spirit came so many times and implored me so earnestly to save her daughter, that at last I ventured to repeat the communication to him. He was rather taken aback, but confessed it was true, and that the child, being left to his care, had been given over to the charge of some common people at Portsmouth, and he had not enquired after it for some time past. Neither had he ever heard of the death of the mother, who had subsequently married, and had a family. He instituted inquiries, however, at once, and found the statement to be quite true, and that the girl Emily, being left with no better protection than that of the drunken old man, had actually gone astray, and not long after she was had up at the police court for stabbing a soldier in a public-house—a fit ending for the unfortunate offspring of a man's selfish passions. But the strangest part of the story to the uninitiated will lie in the fact that the woman whose spirit thus manifested itself to two utter strangers, who knew neither her history nor her name, was at the time alive, and living with her husband and family, as Major M—— took pains to ascertain.

And now I have something to say on the subject of communicating with the spirits of persons still in the flesh. This will doubtless appear the most incomprehensible and fanatical assertion of all, that we wear our earthly garb so loosely, that the spirits of people still living in this world can leave the body and manifest themselves either visibly or orally to others in their normal condition. And yet it is a fact that spirits have so visited myself (as in the case I have just recorded), and given me information of which I had not the slightest previous idea. The matter has been explained to me after this fashion—that it is not really the spirit of the living person who communicates, but the spirit, or "control," that is nearest to him: in effect what the Church calls his "guardian angel," and that this guardian angel, who knows his inmost thoughts and desires better even than he knows them himself, is equally capable of speaking in his name. This idea of the matter may shift the marvel from one pair of shoulders to another, but it does not do away with it. If I can receive information of events before they occur (as I will prove that I have), I present a nut for the consideration of the public jaw, which even the scientists will find difficult to crack. It was at one time my annual custom to take my children to the sea-side, and one summer, being anxious to ascertain how far the table could be made to act without the aid of "unconscious cerebration," I arranged with my friends, Mr. Helmore and Mrs. Colnaghi, who had been in the habit of sitting with us at home, that we should continue to sit at the sea-side on Tuesday evenings as theretofore, and they should sit in London on the Thursdays, when I would try to send them messages through "Charlie," the spirit I have already mentioned as being constantly with us.

The first Tuesday my message was, "Ask them how they are getting on without us," which was faithfully delivered at their table on the following Thursday. The return message from them which "Charlie" spelled out for us on the second Tuesday, was: "Tell her London is a desert without her," to which I emphatically, if not elegantly, answered, "Fiddle-de-dee!" A few days afterwards I received a letter from Mr. Helmore, in which he said, "I am afraid 'Charlie' is already tired of playing at postman, for to all our questions about you last Thursday, he would only rap out, 'Fiddle-de-dee.'"

The circumstance to which this little episode is but an introduction happened a few days later. Mr. Colnaghi and Mr. Helmore, sitting together as usual on Thursday evening, were discussing the possibility of summoning the spirits of living persons to the table, when "Charlie" rapped three times to intimate they could.

"Will you fetch some one for us, Charlie?"

"Yes."

"Whom will you bring?"

"Mrs. Ross-Church."

"How long will it take you to do so?"

"Fifteen minutes."

It was in the middle of the night when I must have been fast asleep, and the two young men told me afterwards that they waited the results of their experiment with much trepidation, wondering (I suppose) if I should be conveyed bodily into their presence and box their ears well for their impertinence. Exactly fifteen minutes afterwards, however, the table was violently shaken and the words were spelt out. "I am Mrs. Ross-Church. How dared you send for me?" They were very penitent (or they said they were), but they described my manner as most arbitrary, and said I went on repeating, "Let me go back! Let me go back! There is a great danger hanging over my children! I must go back to my children!" (And here I would remark par parenthèse, and in contradiction of the guardian angel theory, that I have always found that whilst the spirits of the departed come and go as they feel inclined, the spirits of the living invariably beg to be sent back again or permitted to go, as if they were chained by the will of the medium.) On this occasion I was so positive that I made a great impression on my two friends, and the next day Mr. Helmore sent me a cautiously worded letter to find out if all was well with us at Charmouth, but without disclosing the reason for his curiosity.

The facts are, that on the morning of Friday, the day after the séance in London, my seven children and two nurses were all sitting in a small lodging-house room, when my brother-in-law, Dr. Henry Norris, came in from ball practice with the volunteers, and whilst exhibiting his rifle to my son, accidentally discharged it in the midst of them, the ball passing through the wall within two inches of my eldest daughter's head. When I wrote the account of this to Mr. Helmore, he told me of my visit to London and the words I had spelt out on the occasion. But how did I know of the occurrence the night before it took place? And if I—being asleep and unconscious—did not know of it, "Charlie" must have done so.

My ærial visits to my friends, however, whilst my body was in quite another place, have been made still more palpable than this. Once, when living in the Regent's Park, I passed a very terrible and painful night. Grief and fear kept me awake most of the time, and the morning found me exhausted with the emotion I had gone through. About eleven o'clock there walked in, to my surprise, Mrs. Fitzgerald (better known as a medium under her maiden name of Bessie Williams), who lived in the Goldhawk Road, Shepherd's Bush. "I couldn't help coming to you," she commenced, "for I shall not be easy until I know how you are after the terrible scene you have passed through." I stared at her. "Whom have you seen?" I asked. "Who has told you of it?" "Yourself," she replied. "I was waked up this morning between two and three o'clock by the sound of sobbing and crying in the front garden. I got out of bed and opened the window, and then I saw you standing on the grass plat in your night-dress and crying bitterly. I asked you what was the matter, and you told me so and so, and so and so." And here followed a detailed account of all that had happened in my own house on the other side of London, with the very words that had been used, and every action that had happened. I had seen no one and spoken to no one between the occurrence and the time Mrs. Fitzgerald called upon me. If her story was untrue, who had so minutely informed her of a circumstance which it was to the interest of all concerned to keep to themselves?

When I first joined Mr. d'Oyley Carte's "Patience" Company in the provinces, to play the part of "Lady Jane," I understood I was to have four days' rehearsal. However, the lady whom I succeeded, hearing I had arrived, took herself off, and the manager requested I would appear the same night of my arrival. This was rather an ordeal to an artist who had never sung on the operatic stage before, and who was not note perfect. However, as a matter of obligation, I consented to do my best, but I was very nervous. At the end of the second act, during the balloting scene, Lady Jane has to appear suddenly on the stage, with the word "Away!" I forget at this distance of time whether I made a mistake in pitching the note a third higher or lower. I know it was not out of harmony, but it was sufficiently wrong to send the chorus astray, and bring my heart up into my mouth. It never occurred after the first night, but I never stood at the wings again waiting for that particular entrance but I "girded my loins together," as it were, with a kind of dread lest I should repeat the error. After a while I perceived a good deal of whispering about me in the company, and I asked poor Federici (who played the colonel) the reason of it, particularly as he had previously asked me to stand as far from him as I could upon the stage, as I magnetized him so strongly that he couldn't sing if I was near him. "Well! do you know," he said to me in answer, "that a very strange thing occurs occasionally with reference to you, Miss Marryat. While you are standing on the stage sometimes, you appear seated in the stalls. Several people have seen it beside myself. I assure you it is true."

"But when do you see me?" I enquired with amazement.

"It's always at the same time," he answered, "just before you run on at the end of the second act. Of course it's only an appearance, but it's very queer." I told him then of the strange feelings of distrust of myself I experienced each night at that very moment, when my spirit seems to have preceded myself upon the stage.

I had a friend many years ago in India, who (like many other friends) had permitted time and separation to come between us, and alienate us from each other. I had not seen him nor heard from him for eleven years, and to all appearance our friendship was at an end. One evening the medium I have alluded to above, Mrs. Fitzgerald, who was a personal friend of mine, was at my house, and after dinner she put her feet up on the sofa—a very unusual thing for her—and closed her eyes. She and I were quite alone in the drawing-room, and after a little while I whispered softly, "Bessie, are you asleep?" The answer came from her control "Dewdrop," a wonderfully sharp Red Indian girl. "No! she's in a trance. There's somebody coming to speak to you! I don't want him to come. He'll make the medium ill. But it's no use. I see him creeping round the corner now."

"But why should it make her ill?" I argued, believing we were about to hold an ordinary séance.

"Because he's a live one, he hasn't passed over yet," replied Dewdrop, "and live ones always make my medium feel sick. But it's no use. I can't keep him out. He may as well come. But don't let him stay long."

"Who is he, Dewdrop?" I demanded curiously.

"I don't know! Guess you will! He's an old friend of yours, and his name is George." Whereupon Bessie Fitzgerald laid back on the sofa cushions, and Dewdrop ceased to speak. It was some time before there was any result. The medium tossed and turned, and wiped the perspiration from her forehead, and pushed back her hair, and beat up the cushions and threw herself back upon them with a sigh, and went through all the pantomime of a man trying to court sleep in a hot climate. Presently she opened her eyes and glanced languidly around her. Her unmistakable actions and the name "George" (which was that of my friend, then resident in India) had naturally aroused my suspicions as to the identity of the influence, and when Bessie opened her eyes, I asked softly, "George, is that you?" At the sound of my voice the medium started violently and sprung into a sitting posture, and then, looking all round the room in a scared manner, she exclaimed, "Where am I? Who brought me here?" Then catching sight of me, she continued, "Mrs. Ross-Church!—Florence! Is this your room? O! let me go! Do let me go!"

This was not complimentary, to say the least of it, from a friend whom I had not met for eleven years, but now that I had got him I had no intention of letting him go, until I was convinced of his identity. But the terror of the spirit at finding himself in a strange place seemed so real and uncontrollable that I had the greatest difficulty in persuading him to stay, even for a few minutes. He kept on reiterating, "Who brought me here? I did not wish to come. Do let me go back. I am so very cold" (shivering convulsively), "so very, very cold."

"Answer me a few questions," I said, "and then you shall go. Do you know who I am?"

"Yes, yes, you are Florence."

"And what is your name?" He gave it at full length. "And do you care for me still?"

"Very much. But let me go."

"In a minute. Why do you never write to me?"

"There are reasons. I am not a free agent. It is better as it is."

"I don't think so. I miss your letters very much. Shall I ever hear from you again?"

"Yes!"

"And see you?"

"Yes; but not yet. Let me go now. I don't wish to stay. You are making me very unhappy."

If I could describe the fearful manner in which, during this conversation, he glanced every moment at the door, like a man who is afraid of being discovered in a guilty action, it would carry with it to my readers, as it did to me, the most convincing proof that the medium's body was animated by a totally different influence from her own. I kept the spirit under control until I had fully convinced myself that he knew everything about our former friendship and his own present surroundings; and then I let him fly back to India, and wondered if he would wake up the next morning and imagine he had been laboring under nightmare.

These experiences with the spirits of the living are certainly amongst the most curious I have obtained. On more than one occasion, when I have been unable to extract the truth of a matter from my acquaintances I have sat down alone, as soon as I believed them to be asleep, and summoned their spirits to the table and compelled them to speak out. Little have they imagined sometimes how I came to know things which they had scrupulously tried to hide from me. I have heard that the power to summons the spirits of the living is not given to all media, but I have always possessed it. I can do so when they are awake as well as when they are asleep, though it is not so easy. A gentleman once dared me to do this with him, and I only conceal his name because I made him look ridiculous. I waited till I knew he was engaged at a dinner-party, and then about nine o'clock in the evening I sat down and summoned him to come to me. It was some little time before he obeyed, and when he did come, he was eminently sulky. I got a piece of paper and pencil, and from his dictation I wrote down the number and names of the guests at the dinner-table, also the dishes of which he had partaken, and then in pity for his earnest entreaties I let him go again. "You are making me ridiculous," he said, "everyone is laughing at me."

"But why? What are you doing?" I urged.

"I am standing by the mantel-piece, and I have fallen fast asleep," he answered. The next morning he came pell-mell into my presence.

"What did you do to me last night?" he demanded. "I was at the Watts Philips, and after dinner I went fast asleep with my head upon my hand, standing by the mantel-piece, and they were all trying to wake me and couldn't. Have you been playing any of your tricks upon me?"

"I only made you do what you declared I couldn't," I replied. "How did you like the white soup and the turbot, and the sweetbreads, etc., etc."

He opened his eyes at my nefariously obtained knowledge, and still more when I produced the paper written from his dictation. This is not a usual custom of mine—it would not be interesting enough to pursue as a custom—but I am a dangerous person to dare to do anything.