THE LETTER-BAG OF TOBY, M.P.

From the Lord Mayor of Dublin.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 93, December 3, 1887, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 93, December 3, 1887 Author: Various Editor: Francis Burnand Release Date: March 8, 2012 [EBook #39077] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, CHARIVARI, DEC 3, 1887 *** Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Wayne Hammond, Malcolm Farmer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Dear Toby,

The news from Ireland, not all of which finds its way into your daily papers, grows in excitement. The exploit of Mr. Douglas P-ne, M.P., of Lisfinny Castle, has taken root, and all the landed gentry among the Irish Members are fortifying themselves in their castles, and hanging themselves outside the front-door by ropes to deliver addresses to their constituents. The regular thing now is to hang out our M.P.'s on the outer wall. I do not see accounts of these proceedings in your London papers. I was, as you know, a Journalist before I was Lord Mayor; so, if you don't mind, I'll send you a few jottings. If there is anything due for lineage, please remit it anonymously to the Land League Fund "From A Sympathiser."

Foremost in this band of heroic patriots is the châtelain of Butlerstown, Joseph G-ll-s B-gg-r, M.P., Butlerstown Castle, as everyone acquainted with Ireland knows, stands on the summit of a Danish rath, and was once the seat of an O'Toole. Now it is the den of Joseph G-ll-s. For some time he has been practising a flying leap from the eastern to the western turret, a distance of fifty feet over a yawning abyss, amid the cavernous depths of which the petulant plummet has played in vain. It is thrilling, whether at early dawn, or what time the darkening wing of Night begins to flap, to hear a shrill cry of "Hear, hear!" to see a well-known figure cleaving the astonished air, and to behold Joseph G-ll-s, erewhile upright on the eastern turret, prone on that which lifts its head nearer the setting sun. To be present on one of the occasions when Joey B. reads a Blue Book for three hours to a deputation shivering in the moat, is enough to convince the dullest Saxon of the hopelessness of enthralling a nation which has given birth to such as he. As Joseph himself says, quoting, with slight variation, my own immortal verse,—

"Whether on the turret high,

Or in the moat not dry,

What matter if for Ireland dear we talk!"

But the affairs at Butlerstown should not withdraw our gaze from a not less momentous event which recently happened in the neighbourhood of Cork city. Mr. P-rn-ll, as he has recently explained to you, has not found it expedient or even necessary to take part in our recent public proceedings in Ireland. But this abstention is to a certain extent illusory. It is no secret in our inner circles that our glorious Chief was but the other day in close communication with his constituents in the city of Cork. He arrived shortly after breakfast in a balloon which was skilfully brought to pause over the rising ground by Sunday's Well. At the approach of the balloon the trained intelligence of the Police fathomed the plot. The Privy Council was immediately communicated with. Sworn information was laid, and the meeting was solemnly proclaimed by telegraph. In the meanwhile, Mr. P-rn-ll had addressed the meeting at some length and met with an enthusiastic reception. The Police massing in considerable numbers and beginning to bâton the electors, the Hon. Member poured a bag of ballast over them, and the balloon, gracefully rising, disappeared in the direction of Limerick. The proceedings then terminated.

I expect that the success of this new departure, or perhaps I should say this unexpected arrival, will encourage our great Chief to pay a series of flying visits to Ireland. His adventure was certainly happier and more successful than one which befell our esteemed friend Tim H-ly, and nearly brought to an untimely conclusion a life dear to us and of inestimable value to Ireland. Tim was announced to take the chair at a mass meeting summoned under the auspices of the local branch of the Land League of Longford. A room was taken, the word passed round, and all preparations made for a successful meeting. The Police, however, got wind of it, and of course the meeting was proclaimed. But Tim, as you may happen to know, is not the man to have his purpose lightly set aside. It was made known that Tim would make his speech and the Police might catch him if they could. You know, may be, the big factory in the thriving town of Longford—the one with a tall chimbly? Well, the word was passed along again that the bhoys were to assemble about the factory. "Would they bring a chair or a table," they said, "for Tim to stand on?" "No," said Tim, wiping his spectacles, "you leave it to me."

Meeting announced to take place at eight o'clock. On the very strike of the hour, a stentorian voice, not unfamiliar in the House of Commons, floated over the assembled multitude. "Men of Longford," it said, "we are assembled here in the exercise of our privilege as free men." First of all they could not tell where the voice came from. Looking up, behold! there was Tim planted inside the top of the tall chimbley, using it like a Bishop's pulpit. It was a capital idea, and worked admirably for half an hour, with the Police all throbbing and raging round, and Tim eyeing them quite calmly, and all the crowd roaring and cheering, and throwing up their hats, and B-lf-r getting it hot. Somehow, whether from treachery or accident no one knows, and perhaps never will know, but in the middle of one of his best sentences, Tim suddenly vanished from sight, and was a clear three minutes later picked up from among the cinders in the furnace below. The proceedings then terminated.

There is a good deal more I could tell you, Toby, my bhoy, if time permitted. I should like above all to tell you of Major O'G-rm-n's magnificent oration delivered from the main shaft of the sewer in Waterford, with his former constituents hanging on his lips and the grate of the sewer. But I am just off myself to address a meeting of my fellow citizens. This too, is of course, proclaimed, and equally of course that makes no difference. I get on the top of the Lord Mayor's coach, leaning on the Mace, and supported by the Sword-bearer. The horses move at walking pace, and I address the crowd. It's wonderful what a lot one can take out of B-lf-r that way.

"In deepest reverence and sincere love, the Reichstag is mindful of His Imperial and Royal Highness the Crown Prince. May God protect the dear life of our beloved Crown Prince, and preserve it for the welfare of the Fatherland."—Telegram from the Reichstag to the Crown Prince.

"So mote it be!" That deep and reverent prayer

In all true hearts finds echo everywhere;

Not least in those that flush with British blood.

Prince, a loved daughter from our Royal brood,

In trouble as in joy, is at your side,

Sharing your sorrow as she shared your pride.

For her dear sake, and for your own not less,

We wish you, gallant soldier-chief, success

In a dread struggle keener, sterner far

Than those you faced in the fierce lists of war.

We know—have you not proved it?—that 'twill be

Met with the same cool steadfast gallantry

As marked your bearing in more martial strife.

Punch joins in that warm prayer for "the dear life,"

And echoes, from a far yet kindred strand,

The pleading voices of the Fatherland!

As among the best books for a young man who had to be the architect of his own fortunes, some one in Mrs. Ram's hearing mentioned Thomas à Kempis. "Oh yes," exclaimed the worthy lady, "I know. He built a great part of Brighton which was named after him."

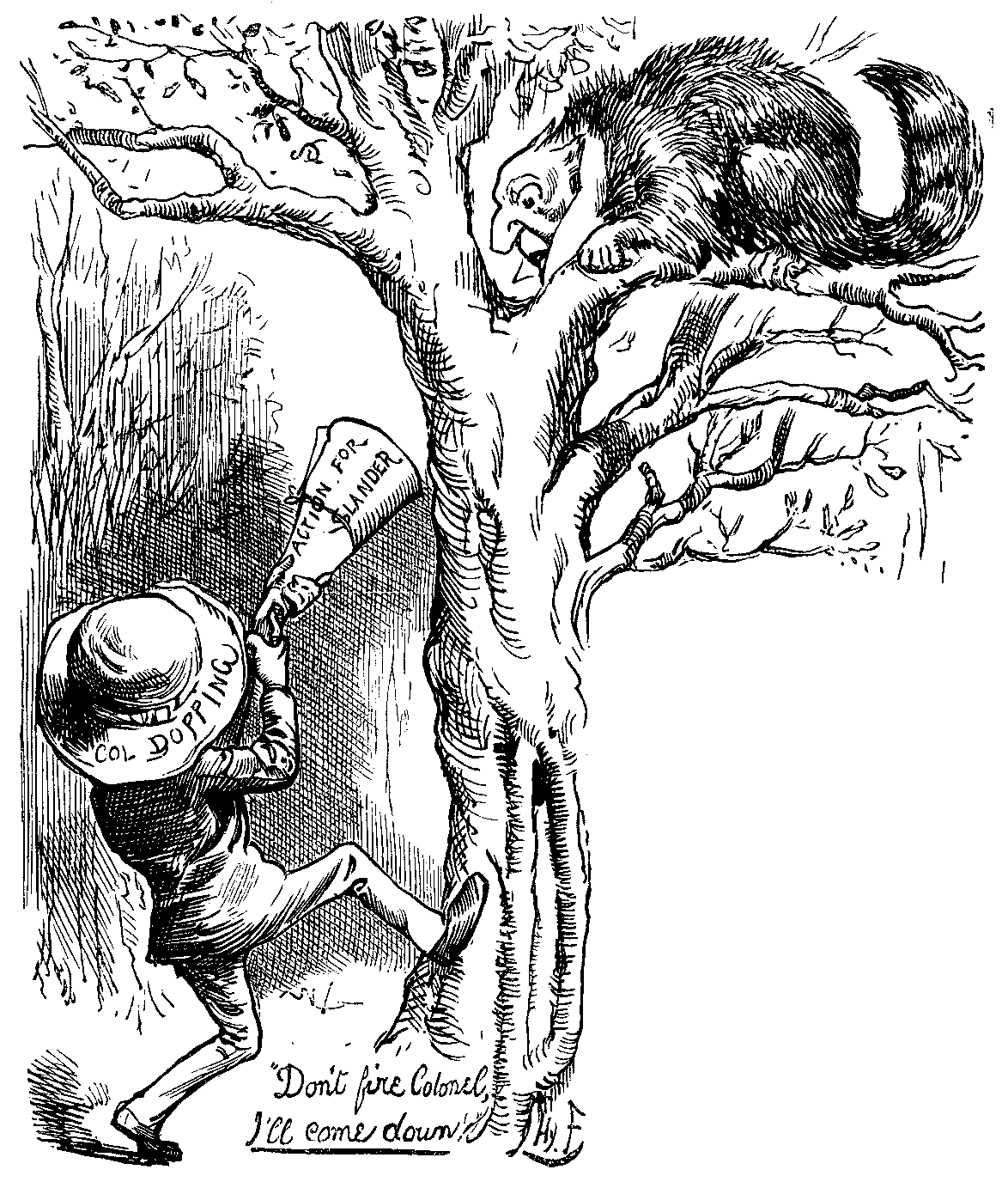

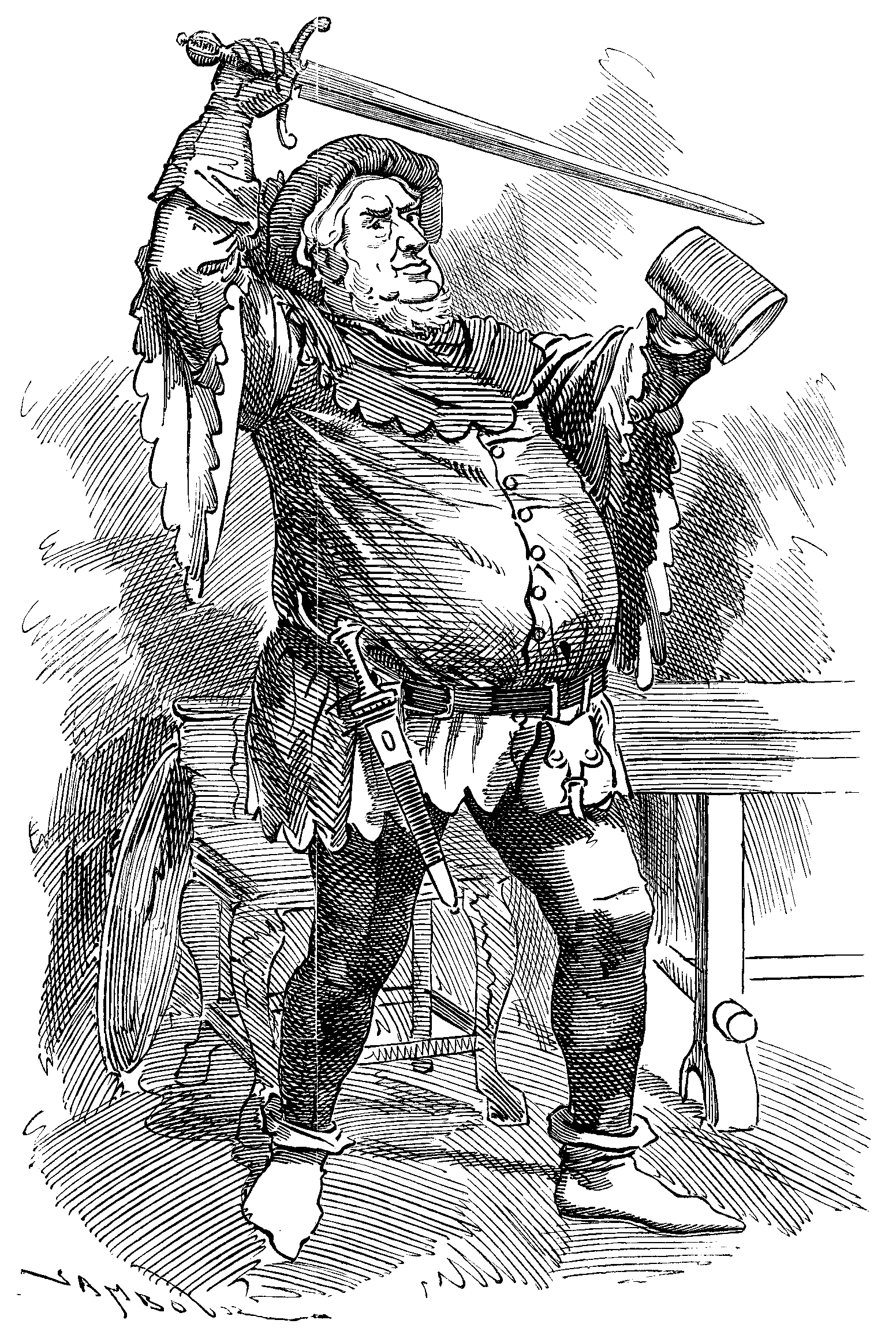

"There's no more valour in that Goschen than in a Wild Duck.".... "A plague of all Cowards still say I!"

Mrs. Ram, at this time of year, takes a great interest in the state of the weather, and studies the daily Meteorological chronicle. She says that she always reads the reports from Ben Nevis's Observatory. She hopes that, one of these fine days, this learned astronomer will be made a Knight. Sir Benjamin Nevis would be, she considers, a very nice title. "Of course," she adds, "judging by his name, he must be a Jew. They're such clever people. And, let me see, ain't there a proverb, or something of that sort, about 'the Jew of Ben Nevis'?"

My Dear Mr. Punch,

In my Autobiography, which I am glad and proud to say, has met with your cordial approbation, I have recorded how the late lamented Bishop, Dr. Sumner, said to me, "I have drunk a bottle of port wine every day since I was a boy." Well, his son, the Archdeacon, is annoyed at this statement. Now, my memory is a very good one, and if I am wrong in one point so circumstantially narrated, why not in several, why not in all? If the Bishop did not say this, to me, who did? Somebody said it, that I will swear. Who said it? If my memory fails me, is it not also likely that the Bishop's memory was not particularly good, and consequently, that he was mistaken in thinking that he had drunk a bottle a day since his boyhood? I have little doubt that the Bishop only imagined it, and perhaps he was joking. Perhaps he was playing on the words "bishop" and "port." "Bishop" was a hot drink, I fancy, made with port wine. I have no hesitation in comforting his Archidiaconal offspring by assuring him that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, his father, the Bishop, did not drink a bottle of port every day since his boyhood. He was a very fine old clergyman—I forget whether he was exactly portly or not, or whether he resided in Portman Square,—and I should say that first-rate port, such as the elixir vitæ that made a hale centenarian of Sir Moses Montefiore, taken frequently, would have tended to make him the genial prelate he was. Had he only gone into port once, that would not have sufficed to have produced such a Bishop, for "One swallow does not make a Sumner."

P.S.—The Archdeacon is satisfied, and if he will only come round to see me and bring a bottle of the port the Bishop didn't drink, why, on my word as an artist, I'll draw the cork.

"What shall he have who kills the Deer?" Why, something to eat, of course. At least this was, among others, the notion of the poor starving Cottars. And they have now given up venison-eating because the food is deer.

Two French Presidents Rolled Into One.—M. Grévy, on being told that he must resign, wept copiously. This showed a want of resignation. Curious sight, Grévy and Tears!

Sir Charles Warren has been presented with the freedom of the Leathersellers' Guild. Capital motto for Policemen in a mob, "Nothing like leather! Leather away!"

I had the cureosity one day to arsk a lerned gennelman on whom I was waiting, whether the poor fellers who lived in the world ever so many hundred years ago had got any Copperashuns. He pretended not to understand me at fust, and said, with a larf, as he dared say as they was made much as we was; that is to say, sum with large ones, and some with little ones; but when I xplained what I reely meant, he told me as they had, speshally amung the Romuns as lived in Ittaly. He was a werry amusing Gent, and when I arsked him what langwidge the Romuns torked, he tried to gammon me as they all spoke Latin, ewen the little children and all, but in coarse I wasn't quite such a hignoramus as to swaller that, as my son William, who isn't by no means a fool, learnt Latin at Skool for three year and tells me as he carn't speak it a bit. The lerned gent also told me as it was such a rum tung to speak that they hadn't not no word for "Yes!" So that if a Gent of those long days had bin a dining at the "Ship and Turtle" an bin a waited on by an Hed Waiter, like me, and had said to him "Woud you like arf-a-crown, Waiter?" the pore feller woodn't have been able to say, "Yessir!" I was jest a leetle shocked at his torking such rubbish to me, it was hardly respekful, speshally as he had ony drunk one pint of Bollinger and one of our 63 Port, but its astonishing how heasily sum peeple's heds is affected. I was in hopes as he woud have tried the experymint on me, but he didn't, but went smiling away.

I shood werry much have liked to have heard a good deal more about them werry old Copperashuns, and weather they was to be compared to that werry old 'un as I nose so well and respecs so ighly, for good deeds as well as good living. Take their werry last one as a sample. Earing of what was a going on down at Kilburn on Guy Fox day, and finding as the return train would bring me back in time for my perfeshnal dooties, I went there and found thowsands of peeple all met in a nice little new Park, that the old Lord Mare was a coming down to fust of all crissen, and then throw open to the publick. And down he came accordingly in his full state Carridge, and his full state Footmen, and his full state Sherryiffs, and their full state Carridges and Footmen, jest for all the world as if he was a going to make a call on a few Royal Princes and Dooks, insted of opening a new Park surrounded by numbers of the reel working-classes. But he always has bin a reel gennelman, and never makes no difference atween rich and poor when he can do some good. I wasn't quite near enuff to hear what he said when he made his speech, but a werry respectable reporter arterwards told me, that the Lord Mare had written a letter to Queen Wictoria to ask if he might call the Park after her. And she had wrote to him in reply, "Deer Handsum, as there's alreddy a Wictoria Park, you may call this here one the Qween's Park. Pleas to remember this 5th of Nowember, Yours trewly, W. R. I."

When the Lord Mare enounced this pleasing intelligence, thus simply exprest, lorks how we did all cheer, and a little band that had bin hid in a little tent, struck up the hole of arf a werse of God Save the Queen, at which we all took off our hats, footmen and all, and braved the bitter blarst with our bare heds. Ah, that's wot I calls trew loyalty, and long may it continue, not the cold bitter blarst, but the warm sweet loyalty, for I'm sorry to say as the unusual xposure guv me a bad cold.

I got back just in time for the Bankwet. The Lord Mare with his usual kindness had let the Chairman of the Committee, the sillibrated Mr. Woodbacon, the grate bookseller, take the Chair, and a remarkabul good un he made, setting so good a xample as regards short speeches as made ewerybody follow suit.

And now what was this hole proceeding all about? This is what I learnt from what was said:—

It wood seem then, that at Kilburn where it was wunce all green feelds, there has growed up a reglar crowd of working peeple with far more than their fair share of children and as the feelds has all come for to be bilt over, the poor little children afoursaid have been obleeged to do their playing in the streets, and the nateral or rather unnateral consequence has follered, as that numbers of the poor little deers was run over and killed. So a nice little Park has been made for 'em all to play in, where they can injoy their fresh hair and releeve their poor Mother's minds, and grow up red and strong and harty, instead of white and weak and wan. And the old Copperashun having put it all ship shape, and promist to keep it all in order for hever, arsked the Lord Mare to go down and open it, as he did, and in sitch full state that one of the natives said as it was like a lot of sunbeams suddenly cumming out on a clowdy day. So the Lord Mare finished his long list of good deeds by adding one more to 'em, and the Copperashun added one more Open Space to the many they has either secured or helped to secure. So wenever I hears a sneer at 'em I shall say, "Please to remember that 5th of November!"

Barnum's Show burnt. Of course he will rise like an American phœnix from the ashes. He will advertise it as Burnum's Show.

"By the bye, dear Professor, which would you say—Abiogén-esis, or Abiogenēs-is?"

"Neither, my dear Madam, if I could possibly help it!"

An Important Summing-up. (By Our Own Special Reporter in the recent case of Somebody or Other v. Another Person of the name of Barley).—Mr. Justice Mathew regretted being compelled to decide against Barley on the question of "quantities." Of course, there had been an error on the part of the highly respectable Corporation of Ramsgate, which might be characterised as a "sin of commission," while the neglect of their clerk to enter their arrangement with Barley on the minutes was a "sin of omission." All the witnesses in this case must be believed, as they had, à propos of Barley, taken their oats—he should say their oaths. Perhaps when the present statute came to be revised, Mr. Barley might act for the town, for which it appears he had done good service, and Barley would not have to hide under a bushel. It was clear that this sort of Barley was worth more than the present price of 28s. a quarter. Counsel on both sides had made an eloquent display of wheat—he begged pardon, he meant "wit"—and if in this judgment he had to tread on anyone's corn, he assured them that to do so went against the grain. As an official, Barley would have the sack, but sack and all could be taken up to another Court, and there, as a German speaking French would say, On beut Barley, about it still further. (The Jury thanked his Lordship, and all the parties left the Court much pleased, humming All about the Barley.

"They acted a Greek Play at Cambridge, my dear," said Mrs. Ram to a friend, "and fancy, it was written, as I am informed, by a young lady, Miss Sophie Klees. I suppose she is a student of Girton. How clever! I couldn't write it, I'm sure."

The "Quart d'heure de Rabelais," if translated into Anglo-French, may be taken to express a bad time of it with the roughs in Trafalgar Square, i.e., a mauvais quart d'heure de Rabble—eh?

The Works of Charles Dickens must have achieved great popularity in South Eastern Europe, where there is an entire country called Boz-nia.

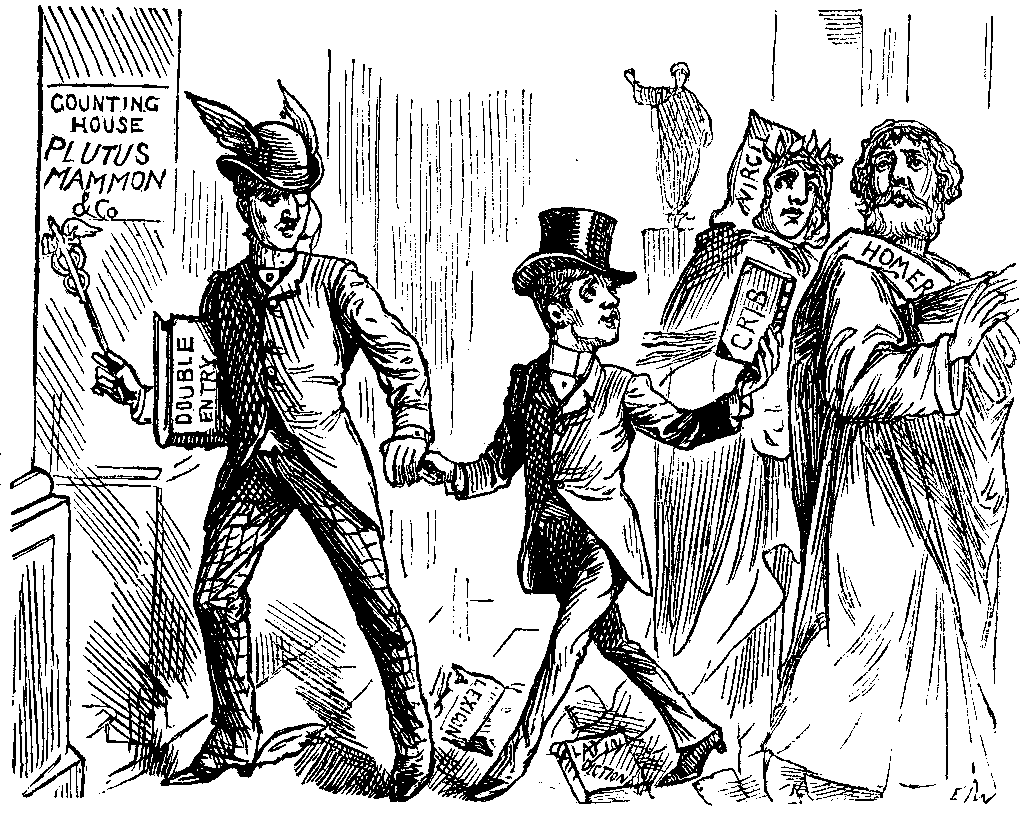

Twelve o'Clock struck, and the Fourth Form at St. Dunstan's left its class-room with a rush. The old hour of leaving off the morning's studies was still preserved. Yet, in conformity with the spirit of the times, the venerable foundation of St. Dunstan's had recently witnessed great changes. The Governing Body had taken the matter in hand, and had gone to work with a will. The teaching of Greek and Latin had been entirely suppressed, polite literature eliminated, and the whole curriculum of the school arranged solely to the provision of that glaring want of the times, a sound commercial education. To effect this, some radical changes had been necessary. The Rev. Jabez Plumkin, D.D., Oxford Prizeman, through whose unwearied exertions, for the past five-and-twenty years, St. Dunstan's had been gradually acquiring an increasing fame in the Class-lists of both Universities, had been forcibly ejected from the Head-Mastership, and his place filled by a leading member of a well-known firm of advertising stock-jobbers, and the Assistant-Masters had all been selected on similar lines.

"Company-floating," was taught by a late Promoter, who had had much experience in the creation of many bubble concerns, and "Rigging the Market" was entrusted to a Professor who was known, in his capacity as Accountant to a wholesale City Cheese Warehouse, to have contracted a thorough familiarity with this important subject of the new commercial education. Everything was done to foster a spirit of keen speculative enterprise in the boys. The whole traditions of the school were changed. The old idea of honour had died out. How to over-reach each other by sharp practice was the one idea that animated every youthful breast from the senior in the Sixth to the junior in the Under Third. The tape was always working at the Principal's desk. The study-tables were covered with Stock and Mining Journals. Even the playground was turned into a Money Market. Cricket had been banished to make way for the more exciting game of "Bulls and Bears," and the Principal passing through occasionally, would sometimes stop and say, "That's right, my boys, learn to do each other, and remember the motto of your School, 'Monies maketh man.'" Posted up upon the gates, communicated by telegraph hourly from the City, were every day to be found the latest prices. And it was to get a first look at this that the Fourth Form had just left its class-room with a rush.

A crowd of eager faces were anxiously scanning the latest quotations, and notes were being taken in a score of pocket-books, whipped out for the purpose. Tom Brown & Co.—he had earned this sobriquet from his companions for his shrewd business capacity—did not, however, join the throng, but stood a little way off, looking on, and waiting for the excitement to abate. Gradually it calmed down, and the boys broke up into little knots and groups, discussing the state of the market. Then he spoke:—

"Look here, you fellows," he said, "I've got a good thing on here, that, I fancy, will be more worth your attention than even the latest prices." He pulled a prospectus from his pocket. An interested crowd closed round him at once. "It's 'Old Mother Noggins, Limited,'" he went on, reading from the paper before him, "This Company has been started for the purpose of acquiring at wholesale prices all the tarts, bull's-eyes, apples, toffy, and ginger-beer, forming the present stock-in-trade of Old Mother Noggins's store, and for retailing the same at a figure, that will, after paying the guaranteed interest on the fourpenny debenture shares, admit of the declaration of a dividend of 14 per cent. on the ordinary paid-up share capital of the Company.

A buzz of excited admiration went up from the throng. The Fourth Form at St. Dunstan's had not for a long time had such a good thing put before it.

"I know," continued Tom, producing a bundle of forms of application from his pocket, "that you fellows, would like to hear of it. Who'll go for it?"

There was a loud responsive shout of "I!" and a dozen hands were at once stretched towards the speaker. Business commenced, and sixpences, shillings, and half-crowns were pouring into Tom's pockets faster than he could cram them there. He was making a very good morning's work of it. Presently, a dull, heavy-looking boy joined the group.

"Hullo, Flopper!" cried Tom, addressing this last arrival, "why don't you put that ten bob your Uncle sent you into this thing? I'll be bound he told you to turn it over. You won't get such a chance every day."

"What is it?" asked Flopper.

A chorus of voices instantly joined in a brief explanation of the advantages of investing in "Old Mother Noggins' Limited."

"By Jove!" said Flopper, "I don't know that I won't."

"Not if I know it," cried an authoritative voice, breaking in upon the scene. It was Snagsby, the "Sharper" who spoke. There was a general look in his direction, and a disposition to make way for him as he approached. He had been mixed up disadvantageously in a recent "corner" in marbles, and had from time to time floated several concerns that had never paid any dividends, and was generally regarded as a "queer" customer in consequence. It was for this reason that he had been nicknamed the "Sharper."

"And what do you want him to do with his money?" asked Tom, stepping forward in a defiant attitude.

"He'll put every blessed halfpenny of it into my 'General Pen-knife Supply,'" was the laconic reply. "He signed for the allotment last night."

"But I've changed my mind," pleaded Flopper, helplessly, and he handed the half-sovereign to Tom.

"You give that up!" cried the Sharper, menacingly.

"You try to take it!" replied Tom, grimly.

In another instant the Sharper had flown at Tom. There was a brief struggle. Tom hit out at him, and caught him in the face.

"Oh, that's your game, is it!" shouted the Sharper. "You'll fight me for that."

"Fight you? When and where you like," replied Tom.

There was a general cheering and throwing up of hats.

"Hooray! There's going to be a fight between the Sharper and Tom Brown & Co.," shouted the Fourth Form. They hadn't had such good news for a long time.

The whole School was there, and the third round had been fought. Betting had been fast and furious, and there had been several attempts made by the supporters of both champions to break the ring and put an end to the contest when the fortunes of the day seemed to be going against their own special favourite. But now a curious thing happened. After a little preliminary sparring in the fourth round, Tom Brown & Co., suddenly dropping on one knee, went to the ground.

In a few seconds the surprising news was known that he had given in. The sponge was thrown up, and the Sharper declared the victor. Tom was quickly surrounded by his friends, and led off the field. Flopper ran up to him. "I'm so sorry, Tom," he said, "that you should have fought in my quarrel, and have got licked."

There was a twinkle in Tom's eye. "My dear fellow," he replied. "Don't imagine I wouldn't have thrashed him; but business is business, and I got a good price for not doing so. Didn't you twig that I sold the fight?"

That night Tom Brown & Co. wrote home an enthusiastic account of his day's doings to his parents. The next morning, Tom Brown, Senior, referring to the letter with a glow of pride on his commercial face, remarked to his better-half that the boy's training seemed perfect, and that he was destined to turn out remarkably well. "I can't tell you," he added, "how I long to see that boy loose upon the Stock Exchange. He will be a credit to the family."

A book has been recently published entitled The Amateur's Guide to Architecture, by Sophie Beale. Sophie shows us how a house should be Beale't. But just imagine an Amateur Architect!!

The complaint of the Charity Organisation Society, slightly varied from Shakspeare, is that "The quality of Mercy is not trained."

What can be more dismal than the fourth day of a Fancy Bazaar for a "Sale of Work," in aid of a parochial charity? Honestly, I do not know. I fancy that even the proverbial "Mute at a funeral," must be livelier. That is my present opinion, and it was the same last Thursday, when lured by a programme quaintly printed in "old-faced" type, and having "ye" in lieu of "the," and "Maister" instead of Mister, I made my way to the Portman Rooms in Baker Street, (formerly Madame Tussaud's) and sought admission to "Old Marybone Gardens, A.D. 1670." Outside the ex depôt of Waxworks, were two persons in the costume of the last Century distributing circulars, and later on I met another couple similarly apparelled heading a procession of Sandwich-men walking down Waterloo Place. In the Hall of the Bazaar lads in the same sort of dresses, were selling programmes (marked sixpence) for twopence. I entered by a small canvass-cottage "y'clept" (as the Sale of Workers would call it) "the Rose of Normandy," and found myself in the once famous "Hall of Kings" without the figures. I discovered two or three dwarf trees, some lattice-work and a lot of canvass-covering. I must confess it did not cause me much surprise to find only a few spectators. The moment I appeared, a lady advanced and asked me in a tone of authority to take a button-hole. I refused with courtesy suggestive at once of the gallant and the miser, and the Sale of Work-woman retired rather crest-fallen. Then two girls, costumed as two females of a past but vague period, dashed at me as I turned away, and breathlessly explained that if I bought a half-crown ticket I should be entitled to a chance in a raffle for a five-guinea sofa-cushion. I slightly frowned as I expeditiously refused the invitation, and the ladies disappeared into a corner—I trust more in sorrow than in anger—to read the evening paper. In the centre of the room was a "fish pond" full of presents, where a mild-looking curate was feebly attempting to secure a prize. On the whole the entertainment was scarcely exhilarating. The programme promised "from V to VI of ye clocke" (how silly!) "a séance of Mesmerism," in two "partes," (how really stupid!) and "Maister Charles Bertram" (Why "Maister?") was to appear later on. Then at eight "of ye clocke" (dear, dear! how idiotic!) "the Welbeck Dramatic Club" (what a name!) was "to performe ye Comic Drama by L. S. Buckingham, y'clept" (of course!) "Take that Girl away." Later still "Mistresse Jarley" was to give her waxworks with the assistance of "Maister Sidney Ward," (tut, tut!) the Festival finally closing with "Music" at "X of ye clocke" (stuff and nonsense!). It will be seen that I cannot even now look at the programme (priced at sixpence and sold for twopence) without some signs of impatience. The afternoon was too young to allow of my assisting at any of these toothsome merry-makings, so after mooning about for a quarter of an hour I came away. As I left, a newly-arrived dame of mature years was putting on a nurse's cap hurriedly, evidently with the view to starting in hot pursuit of me to secure my custom for some toys. The ladies with the cushion looked at me languidly as I passed them, and then returned to a perusal of their paper. When last I had had the advantage of paying a visit to "the Portman Rooms, formerly Mme. Tussaud's," I had seen nothing but waxwork figures in eccentric attitudes. On the whole, I think the former denizens of the place looked more at home in their quaint costumes than the Sale of Workers "from Tuesday, November 22 to Saturday, November 26, inclusive!"

Finding myself in its neighbourhood, I could not help taking a turn in the present palace of the eminent "Portrait Modellist." I paid the necessary shilling and the optional sixpence, and renewed my acquaintance with "The Kings and Queens," "The Coronation Group," and "The Chamber of Horrors." A group representing a reception at the Vatican was quite new, if I except two or three funeral attendants, who, I fancy I remember, made their last (but one) appearance at the Lying in State of Pio Nono. After examining a rather cheerful presentment of the latest assassin in "The Chamber of Comparative Physiognomy" (as the Chamber of Horrors was once, for a short period, "y'clept"), I passed through a turnstile, and entered the Refreshment Department. Here I noticed that an "overflow meeting," consisting, amongst other more-or-less-interesting exhibits of Mr. Lewis Wingfield's historical costume-wearers (from the Healtheries), and that now rather-imperfectly-remembered worthy, the late Sir Bartle Frere (from the rooms above), had been humorously arranged, no doubt with a view to provoking healthy and hearty laughter. Having refreshed my mind with a hurried inspection of this delightful, albeit, somewhat miscellaneous gathering, and my body with a twopenny Bath bun, I gracefully retired, greatly pleased with the afternoon's entertainment.

What a set these Emperors, Empresses, Kings, Queens, Princes and Princesses, Dukes and Duchesses, &c., &c., and all such great people everywhere seem to have been, according to the Memoirs of Count Horace de Viel Castel (published by Messrs. Remington & Co.), who was a kind of small French Pepys, a great snob, and a Parisian Sir Benjamin Backbite. Yet there is in this Horace something of the Horatian satirist, only without the poetry.

"But Horace, Sir, was delicate, was nice," which is not exactly the characteristic of the writings of M. de Viel Castel, who tells us

"Of birth-nights, balls, and shows,

More than ten Hollinsheds, or Halls, or Stowes.

When the Queen frowned, or smiled, he knows; and what

A subtle Minister may make of that:

Who sins with whom:"——

And such like tittle-tattle ad nauseam, not sparing his own father and brother. Imagine the sort of man who, night after night, could sit down and chuckle over the composition of this precious diary! "With the exception of the President and the Princess" (Mathilde, at whose house he was perpetually dining), he says, "all the (Buonaparte) family are good for nothing."

Of the bourgeois class he writes, "They are always the same stupid, craven-hearted, vain race." He was shocked at the production of La Dame aux Camelias, and considered it as a degradation of the French stage and a disgrace to the Public that patronised the performance. To have shocked M. de Viel Castel was a feat indeed. Fould "the foxy Jew" got ten millions out of the Crédit Foncier; so the public was fool'd also. D'Orsay was "a ridiculous old doll," and the Duke of Brunswick "an old fool." He sneered at England, but considered at the moment that an alliance with us was the best policy. The Empress at one time went in for spirit-rapping, and consulted a table which told her a variety of lies about the result and duration of the Crimean War. Such a table must have been very black and supported by blacklegs, though it had sufficient french polish about it to be silent in the presence of a bishop. It is not until the last page of the Memoirs, 1864, that the name of M. de Bismarck appears. I suppose that "Society," high, low, or middle-class, has always gone on in much the same way, more or less openly, according to the spirit of the Court, since what is called "Society" came into existence; and invariably with a Viel Castel, or a Greville, or some one even less particular and more observant "among them takin' notes" for future publication. Mr. Bousfield, the translator, seems to have done his work with a judicious regard for a certain section of English readers. It strikes me that he has had the good taste to omit a few anecdotes about some of our own exalted personages which would not have been received with unmixed satisfaction in every quarter. This is only a surmise on my part, as I am unacquainted with the original work.

Let me recommend everyone who values a powerful study of character more than a merely cleverly-constructed story, to read Marzio's Crucifix, by Marion Crawford. I do not know what special opportunities the author had for the work, but the characters are individually, masterpieces. The scene between Marzio and Don Paolo, when the latter is wrapt in devout contemplation of the artist's chef d'œuvre, is most striking, and would have been more so had Marzio carried out his intention of knocking his brother down, and disposing of him out of hand.

With Mr. Saunders's The Story of some Famous Books (Elliot Stock) I was rather disappointed, in consequence of there not being enough "famous books," and not much more story than the needy knife-grinder had to tell. Still, I thank him for introducing me to a delightful name—"Theopompus of Chios"—whom, for this present, I will take as my godfather, and sign myself,

Sir Edwin. "Hullo, Angy? Stew-pan? Apron? Tripe and Onions? What on earth's up?"

The Lady Angelina. "Yes, Dearest! Since you've become a Special Constable, I'm doing my little utmost to become a Special Cook! I thought it might bind us still closer together!"

"It was all for the Union

We left fair Albion's land.

It was all for the Union

We first saw Irish land,

My Boy!

We first saw Irish land!

"All must be done that man can do.

Shall it be done in vain?

My G-sch-n, to prove that untrue

We two have crossed the main,

My Boy!

We two have crossed the main!"

He turned him round and right-about

All on the Irish shore.

Said he, "We'll give P-rn-ll a shake,

And make the Rads to roar,

My Boy!

And make the Rads to roar!"

He was a stout and trusty carle.

Said he, "A flare we'll raise,

And, spite the Leaguers' angry snarl,

We'll make the Beacon blaze,

My Boy!

We'll make the Beacon blaze!

"Who says our friends a handful are,

Our foes a serried host?

Our Beacon, blazing like a star,

Shall check the blatant boast,

My Boy!

Shall cheek the blatant boast.

"Not all are to sedition sworn,

Or shackled by the League.

Cheer up! We'll laugh, their hate to scorn,

And baffle their intrigue,

My Boy!

And baffle their intrigue.

"Puff, G-sch-n, puff! Like Boreas blow!

And I the logs will pile.

The Beacon, now a slender glow,

Shall blaze across the Isle,

My Boy!

Shall blaze across the Isle.

"Eh? What? The wood is damp, you say?

There comes more smoke than flame?

Nay; pile, and poke, and puff away!

We'll not give up the game,

My Boy!

We'll not give up the game.

"If we should let this fire die out

All on the Irish shore,

To Unionism stern and stout

Adieu for evermore,

My Boy!

Adieu for evermore!"

The Two Canons and Bean-baggers.—The Bean-baggers are likely to come badly off with two such big guns against them as Canons Liddon and McColl. Let the matter be settled amicably by agreeing that whatever it was they did see was a "What-you-McColl-it."

Fogs? Nonsense! Fogs are always mist. And the way to miss them is to go to the Institute of Painters in Oil. That will oil the wheels of life in this atrociously hibernal weather, and make existence in a fog enjoyable. There, in the well-warmed, pleasantly-lighted rooms, will you find countless pleasant pictures—delightful sea-subjects, charming landscapes, and amusing scenes, by accomplished painters, which will infuse a little Summer into the dull, depressing, brumous, filthy atmosphere of a weary London Winter. If you cannot get away to Monte Carlo, Mentone, Nice, or Rome, hasten at once and take one of Sir John Linton's excursion coupons, and personally conduct yourself—if you don't conduct yourself as you ought, you'll probably be turned out—round the well-filled galleries in Piccadilly.

Sir Drummond is ordered off to Teheran. "Well, we're successful in keeping one Wolff from our door," as Sir Gorst, Q.C., observed to Grandolph. "Poor Wolffy!" sighed Grandolph. "I shall write a fable on 'The Wolff and the Shah!'"

Sardou and Sara.—Sara B. has made a hit in what is reported to be a poor play called La Tosca, by Sardou. But in consequence of Sara's acting, it is in for a run. Che Sara sara, i.e. (free translation), "Who has seen Sara once will see Sara again."

I've no particular reason to think an account of my life will interest anybody. That being so, I don't know why I write it. But I do. I suppose it's Chance. H-xl-y (who is such fun!) calls my Memoir, because I'm a F.R.S., a case of "Fellow-De-Se."

Talking of Chance, everything that has ever happened to me has been Chance!

For instance, what could have been more a matter of luck than my choosing a house at Down? H-xl-y says something about being "Down on my luck." (What a master of style old H-xl-y is, to be sure!)

Then there was that voyage on the Sea-Mew. If it hadn't been that my Uncle kicked me six times round his garden at Shrewsbury, because I said "I'd be jiggered if I went," I don't believe I should ever have had courage to accept the appointment of Naturalist to the expedition. That voyage gave me an object in life. My nose had made me an object in life before that (vide Portrait), but Natural Selection triumphed over my nose, and so I became in due time famous, and an Ag-nose-tic!

At school I was an exceptionally naughty boy. I cannot conceive what induced me to tell another little boy that I had often produced crab-apples by taking a dead crab and burying it in an orchard, but I did. My little friend, I recollect, didn't believe me, and indeed pulled my nose (always a sore point with me, but he made its point much sorer) for telling what he called "beastly crams." We had a fight, I also remember. Perhaps I ought to call it a "struggle for existence." He was much the "fittest," and he survived. I got licked.

My extreme naughtiness continued unabated when I became a young man. Nobody expected I should ever "do" anything—except six months' hard labour! At Cambridge I was so shockingly "rowdy," that my father declared, there was no alternative but to send me into the Church. But as I was hunting with the College drag at the hour when I ought to have been in for my Ordination Examination, the Bishop failed to see matters in the same light. I then decided to be a Doctor. If I had stuck to this profession I fancy that my turn for trying experiments would have landed me in some exalted position—possibly at Newgate. As it was, after attending a lecture on Surgery, I was discovered in the local Hospital trying to cut off a patient's leg on an entirely new principle, with a pair of scissors and an old meat-saw, and I was nearly "run in" for manslaughter. I decided to give up Medicine, and a slight shindy over a supposed error of mine in calculating a score having prevented my becoming a success as a Public-house Billiard-marker, I thought I would make my mark in another way, as a breeder of race-horses. Being, however, forcibly chucked out of Newmarket Heath one day for an alleged irregularity which I never could understand, I began really to wonder what profession I was fitted to adorn.

It was at this time that the Captain of the Sea-Mew offered me that post of which I have before spoken. I accepted it, and began at once to lower the record in sea-sickness, being never once well on board ship for three whole years! It was a new experience, and altered me a good deal. From being rowdy and idle I became quiet and abnormally diligent. If you don't believe this, ask H-xl-y (who is such fun!). On returning to England I at once settled Down, and began to write books.

This work is my title to fame. It only took me thirty-three years and six months to write. I felt quite glad when it was finished. People who have read it tell me they feel the same, The row it caused was frightful! If you want to see "Soapy Sam's" slashing Quarterly Review article pulverised, read H-xl-y's reply. (But, query—isn't this scientific log-rolling?) The remark which was made, after perusing the book, by that eminent Botanist, my friend Professor Hookey, was—"Walker!" But he was soon converted.

This, also, can't interest anybody, yet I give it. I get up at 4 A.M., and take a walk. From 7 to 10 I work. After dinner—with champagne—I take another stroll. I have made most astonishing scientific discoveries at this time. I could, point out the exact spot in the road where I became convinced that the whole country had been elevated sixteen feet since the morning! H-xl-y, who was with me, quite agreed, and said that we must all have been elevated at the same time, without knowing it.

These are, of course, Lyell on Lias, and Hookey on Herbaceous Foraminifera. They are far superior to Shakspeare, who bores me. I like novels, the trashier the better. Only let 'em end well, and I don't care how they begin, or whether they begin at all. In newspapers, the best part, I think, is the Parliamentary Debates. In reading them I have often got valuable hints as to the "Origin of Speeches," and they frequently afford conclusive evidence of the "Descent of Man." I thought of bringing Parliamentary manners in as a chapter in my book on "Earth-worms," but H-xl-y advised me not to, and I didn't.

I think I've mentioned this feature before. It troubles me. It is undoubtedly of a low type, yet it has survived! Why have I not been fitted with a fitter one? It is another instance of the fact that everything—including my fame—has come to me by sheer luck. H-xl-y says "there's a Dar-winning modesty about this last remark." Also says, "I've found the 'Philosopher's Tone.'" (What screaming fun H-xl-y always is!)

Perhaps I may be allowed to say one word as to the Photographs preceding these volumes. They aren't the least little bit like me! In Volume One I appear as the unmistakable "Country Butcher." In Volume Two I am "The Gorilla Asleep," or "Beetle-brow Napping" (after a beetle-hunt, probably). Volume Three represents me as the Typical Brigand of Transpontine Melodrama.

Why, too, has the Photographer insisted on bringing out that unfortunate feature of mine so prominently?

Why? indeed! Who nose?

The roses were blowing, like whales in the sea

Where the apple-bloom icebergs plunged fearless and free,

And the larks carolled madly their high jubilee

In the ether.

The daisies ran riot in sunshine and shade,

And the call of the cuckoo was heard from the glade,

Where Summer with mellow monotony play'd

On her zither.

Ho, larks and roses!

Hey, the bonny weather!

Hey, we rose at morning prime;

Ho, we lark'd together!

'Mid roses and larks in our shallop we glide

By Inglesham poplars, on Teddington's tide,

Where the water of Thame under Sinodun slide,

And at Marlow,

By Cliveden's green caverns, and Abingdon's walls,

Where wirgles the Windrush, where Eynsham weir falls,

By Sonning, or Sandford (whose lasher recalls

Mr. Barlow).

Oh, larks, and ro(w)ses

On the shining river;

Silver water-lilies, love;

Love will last for ever!

But the blooms turn'd to apples for urchins to munch,

And the roses were sold at a penny a bunch,

And the larks were served up for an Alderman's lunch,

Dead and cold, love;

And the lustre has faded from tresses and cheek,

And the eyes do not sparkle, the eyes that I seek,

And the temper is strong and the logic is weak

Of my old love.

Oh, larks, and ro(w)ses

On the shining river;

Silver water-lilies, love;

Love will last for ever!

But the blooms turn'd to apples for urchins to munch,

And the roses were sold at a penny a bunch,

And the larks were served up for an Alderman's lunch,

Dead and cold, love;

And the lustre has faded from tresses and cheek,

And the eyes do not sparkle, the eyes that I seek,

And the temper is strong and the logic is weak

Of my old love.

No larks and roses

In a winter gloaming;

Ruby-red love's nose is;

Chilblain time a-coming'.

The Watchword of the Sugar-Bounty Conference.—"England expects that every man (and woman) will pay an import duty."

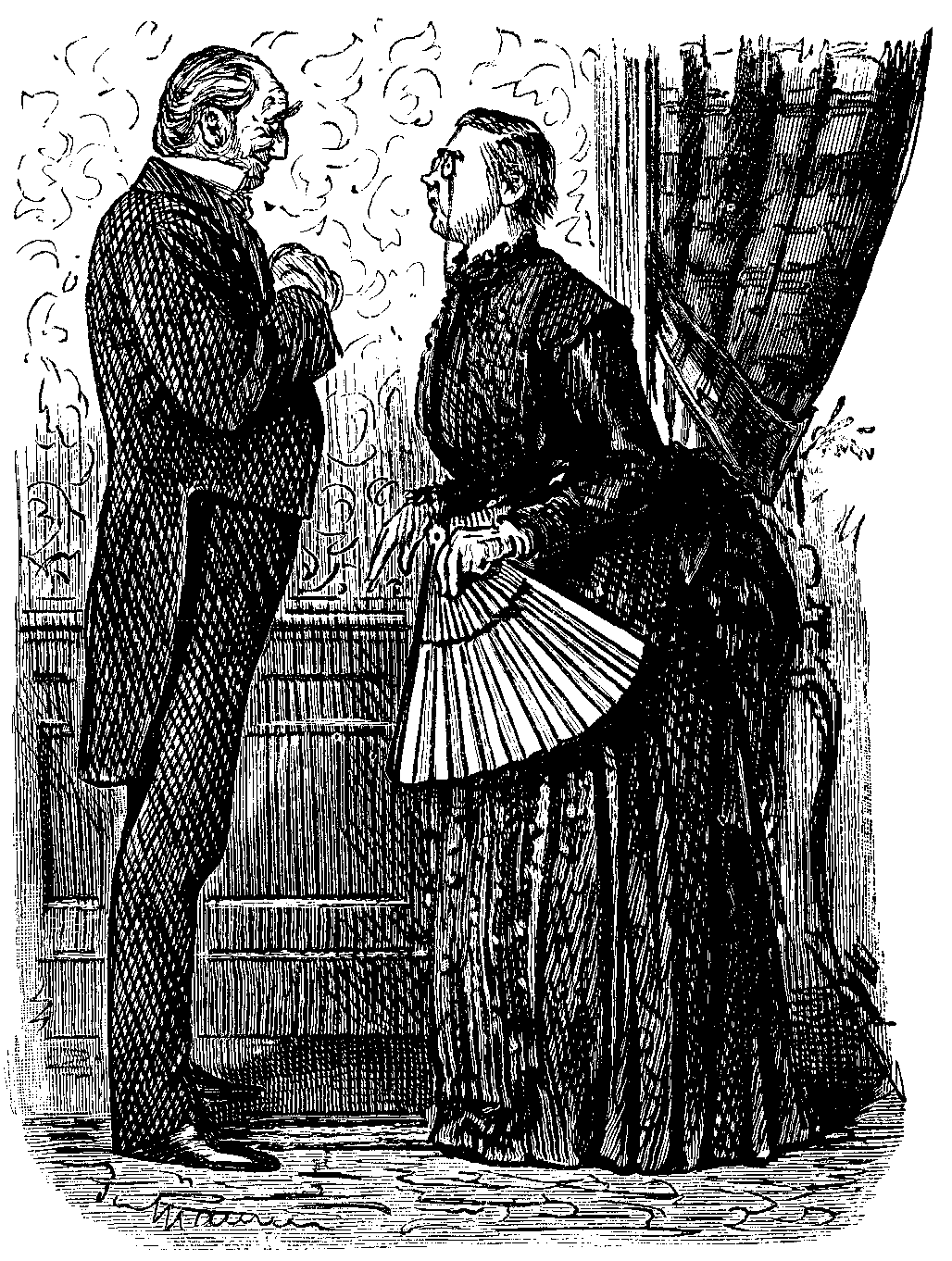

Pastor. "How I do regret, my dear Madam, to see you wearing these sad Habiliments of Woe!"

I found myself a huckster's pleasure-place,

Wherein 'twas horrible to dwell.

I said, "O Soul, the object of our race

Is ever one—to sell."

A huge-walled wilderness of ways it was,

With hoardings of exceeding height,

Which no one without pangs of fear, could pass,

And spasms of affright.

Its purpose, though, was plain; 'twas simply pelf;

Whether a woman wild of glare,

Or a colossal man shaving himself,

All, all meant money there.

"And while the world rolls round and round," I said,

"Advertisement is the one thing

Which need concern the wise and worldly head

Of huckster, histrio, king."

To which my soul made answer readily,—

"In patience I must fain abide

In these vast vistas of vulgarity.

Stretching on every side."

Full of long-reaching bulks of board it was,

Where, glaring forth from ghostly gloom,

Were gibbering monkeys grinning in a glass,

In a dame's dressing-room.

And some were hung with daubs of green and blue,

As gaudy as a cheap Cremorne,

Where actors postured in the public view,

Some frantic, some forlorn.

One seemed all glare and gore—a stabbing hand,

A woman flopping with a groan;

An ill-drawn idiot trying to look grand,

Big-nosed, and high in bone.

One showed an ochre coast and emerald waves;

You seemed to see them rise and fall,

As infant supers—wretched little slaves—

Under the canvass crawl.

And one a full-faced, flashed comedian—low—

Showing his teeth, with nervous strain,

With queer goggle-eyes striking like a blow,

And causing quite a pain.

And one a miser, hoarding fruits of toil,

In front a bony beak, behind,

Wisps of grey hairs all destitute of oil,

Blown hoary on the wind.

And one a foreground with three hideous hags,

Each twice as tall as life, or higher,

Medusa-monsters, clothed in wretched rags,

And crouching round a fire.

And one an English home—lantern-light poured

On a forced safe, skeleton keys,

Whilst gloating o'er the family plate there stored,

Glowered the murderer, Peace.

Nor these alone, but everything to scare,

Fit for each morbid mood of mind;

Murder and misery, want and woe were there

As large as life designed.

There was a fellow in a pretty fix,

"Tied to a corpse," all wild alarm,

Struggling across a sort of sooty Styx,

The "body" on his arm.

Or in a snow-choked city wretchedly,

Dead babe at breast, with bare blown hair,

A ruined woman crawled with quivering knee;

Two bobbies scowled at her.

Or, posing in a footlight paradise,

A group of Houris smirked to see

Young fools with clapping hands and ogling eyes

Which said, "We come for ye!"

Or else a lost and deeply wounded one,

In a wild swamp all bilious greens,

Came on a corpse a bare branch dangling on;

The ghastliest of scenes!

Holloaed a half-choked boy with horrid fear,

A brute the rope about to draw;

A second with a knife and axe was near

To give the first Lynch Law.

Or in a railway-tunnel, iron rail'd,

A man lay bound; his blood ran ice

Who looked thereon, an engine shrieked; he paled,

And fainted in a trice.

A monkey by her hair a woman clasp'd;

From her poor head it seemed half torn,

One ape-hand dragged it back; the other grasp'd

A steel blade's haft of horn.

A hideous babe in nauseous nudity,

Huge-headed, grinning like a clown,

Advertised Soap. A vile monstrosity,

The terror of the Town!

Nor these alone; but every horror rare,

Which the sensation-poisoned mind.

Imaged to advertise vile trash, was there—

As large as life design'd.

Deep dread and loathing of these horrors crude,

Fell on my Soul, hard to be borne,

She cried, "Why should these incubi intrude

And plague us night and morn?

"What! is not this a civilised town," she said,

"A spacious city, cultured, free?

Why give it up to dismalness and dread,

Murder and misery?"

In every corner of that city stood,

Unholy shapes, and spectral scares,

And fiends, and phantoms, brutal scenes of blood,

And horrible nightmares.

"We are shut up as in a tomb, girt round

With charnel scenes on every wall;

Wherever echoes of town-traffic sound,

Or human footsteps fall.

She cried, "By Jove, it is a pretty game

That Man, the Advertiser's thrall,

Should have these scenes of grimness, gore, and shame,

Shock him from every wall.

"The very cab-horses go wild with fears!

I rather fancy it is time

To stop these poster-terrors, placard-tears,

And advertising crimes.

"Yes, yes, pull down these pictured screens that are

All dedicate to gore and guilt.

Not solely for Soap-vendor or Stage-star

Was our big Babylon built!

Scene—A Promenade Concert. Interval between Parts I. and II. Crowd collecting before Platform.

Highly Respectable Matron (to female Friend). As to being beautiful, it's not for me to say, but they're clean-limbed, healthy children, thank Heaven! and what more do you want? (The Friend makes a complimentary protest.) Well, it may be so; but, to come back to her. I don't like her present home so well as I did her first—not so tasty, to my mind. She's got nice things about her, though, I will say—a nice sideboard, a nice ... (Inventory follows here.)

The Friend (darkly). All the same, it's a constant wonder to me how she can ever bring herself to sleep in that bed!

The H. R. M. I couldn't myself; but (charitably) we've not all the same feelings. (Crush increases; Female Promenader with very yellow hair passes, with apologies.) "Excuse me, Madame" (with attempt at mimicry); ah—and she needs it! The orchestra's coming back now. I didn't notice that young woman among them before—what's she going to play, I wonder?

The Friend. Whatever it is, she might look more pleasant over it!

The H. R. M. So she might—we can't all be good-looking, but we can all be pleasant—but they wouldn't have engaged her here, if she hadn't her gift!

The Friend. Oh, you may depend on it, she's got a gift—but I do call her plain, myself.

A Man with a very red nose (to Companion). And then, you see, I've this special advantage—my immense knowledge of the world. Think there's time for another before they begin again, eh?

[Companion is of that opinion; adjournment to bar of house.

First Promenader. Brayvo! Engcore! What, she won't sing no more—sssh! [Hisses furiously.

The H. R. M. There's the orchestra themselves clapping her—and they'd know what's good.

Her Friend. She was dressed very nice, I thought.

The H. R. M. I never care to see hair done up that style myself.

Ladies of Chorus tripping up from below Stage for the Vocal Valse.

Ladies of Chorus (all together). Am I too black under the eyes, dear? Mind where you're going, Miss, please! Treading on people's toes like that—the great clumsy thing! I'm next to you, aren't I? I do feel so funny, my dear, don't you? For goodness sake, don't go setting me on the giggle now!

[They range themselves modestly in a row at edge of platform.

Rude Person (in upper box with Punch squeak). Rooti-too-ti!

[Roars of laughter.

Ladies of C. (indignantly). Beast! I wish they'd give him something to make him rooti-toot, I do!

Conductor-Composer (from behind). Now, Ladies, ready please—keep the laugh steadier than you did last time, and wait for me at the repeat!

[He taps on desk: each Lady of Chorus stiffens herself perceptibly and makes a little grimace.

One Lady (in whisper), Oh, dear, I wish I was at home with my Ma! [Her companions giggle.

The H. R. M. It's as much as they can do to sing for laughing—they're called "Laughing Beauties," though. I like this one's face up at this end—she's so quiet and lady-like over it, and pretty too; they put all the pretty ones in front, but there's one quite an old woman behind. They're having all the fun down at the other end—how they are going on, to be sure!

[End of Vocal Valse: loud applause. Ladies of Chorus retire after encore with air of graceful dignity.

The Person with the Squeak. Goo'-bye, duckies!

[Roars of laughter again: renewed indignation among Chorus. Person with Squeak feels like Sheridan and Theodore Hook rolled into one.

A Young Gentleman (who has set himself to form his fiancée's mind, but finds it necessary to proceed very gradually). Now, Caroline, tell me—isn't this better than if we had gone to the Circus?

Caroline (from the provinces; unmusical; simple in her tastes). Yes, Joseph, only—(timidly)—there's more of what I call variety in a Circus—more going on, I mean.

The Y. G. (with a sense of discouragement). I quite see your meaning, dear, and it's an entirely true observation; still, you do appreciate this magnificent orchestra, don't you now?

Caroline. I should have liked it better with different coloured curtains—maize is so trying.

The Y. G. (mentally). I won't write home to them about it just yet.

Orchestra begins a "Musical Medley" with Overture to "Tannhäuser."

The Y. G. (who has lost his programme). Now, Caroline—this is Wagner—you'll like Wagner, darling, I'm sure.

Caroline (startled). Shall I? Where is he? Will he come in here? Must I speak to him?

The Y. G. No, no—he's dead—I mean, this is from his Opera—you must listen to this.

[He watches her face for the emotion he expects; "Tannhäuser" melts suddenly into "Tommy, Make Room for your Uncle."

Caroline (her face absolutely transfigured). Oh, Joseph, dear—Wagner's perfectly lovely!

The Y. G. (gloomily). I see, I shall have to put you through a course of Bach, Caroline!

Caroline (alarmed). But there's nothing whatever the matter with me, Joseph! I'm not flushed am I?

[Young Gentleman suppresses a groan.

A Lady (not much of an Opera-goer, who has been given a box at the last moment, and has insisted on her husband turning out to escort her). It was silly of you to drop that programme, Robert—I should like to know what this piece is, it seems quite familiar—(Orchestra playing "Soldiers' March" from Faust)—I know—it's Faust, Robert, Gounod's Faust!

[Much pleased with herself for recollecting an Opera she has only heard once.

Robert (sleepily). I know, my dear, all right.

[Faust melts into air from "Pinafore."

His Wife. Do you mean to say you don't remember that, Robert? how exquisite Patti was in the part, to be sure!

Robert. Umph!

["Pinafore" becomes "La ci darem"—which transforms itself without warning into "Two Lovely Black Eyes."

The Lady. There's nobody like Gounod! [Clasps her hands.

Robert (captiously). Gounod's all very well, I daresay, my dear; but it don't seem to me he's altogether original. I've heard something very like this tune before, and I'll swear it wasn't by him!

The Lady. That's very likely; all the best airs get stolen nowadays, and dressed up so as to be quite unrecognisable; but that's not Gounod's fault, is it?

[Fans herself triumphantly, after vindicating her favourite Composer. Robert slumbers.

Erratic Promenader. Beg your pardon, Sir—tha' shtick, not 'tended meet your eye, Sir—'nother gerrilm'n's eye, Sir.

Fair Promenader (to Lady Friend). And I'm sure I don't know how it is, but I'm always crying now for just nothing at all, whenever I'm alone.

The Lady Friend. That's because you give way to it, dear. Come and have something to cheer you up—you'll be a different person after it. [Advice taken; prediction verified.

The Err. Prom. I shay, here'sh lark! see tha' Bobby over there? he thinksh I'm tight! (Waltzes up to him solemnly). Kn'ive pleshure nexsht dansh you, Sir Charlesh?

The Policeman (severely). You keep your 'ands off of me, will you, and take yourself home—that's my advice to you!

Err. Prom. (outraged). You 'pear me to under 'preshionthish is Hy' Par' or Trafa——(with an effort)—Trafa-ralgarar Square. I'm goin' teash you, free Briton not goin' put up with P'lice brurality!

[Hits Policeman in the eye, and is removed, smiling feebly. Scene changes.

Lord Solly, at Paddies presuming to rail,

Must sneer at their "brogue," which the Markis finds stale.

Does he think a poor fellow must fain be a rogue

Because, born in Erin, he speaks with a brogue?

Celtic ears finds the drawl of the Saxon Swell flat,

And a Cockney may chaff at the patois of Pat.

But which is in fault—is it really so clear?—

The Irishman's tongue, or the Englishman's ear?

In a recent case on appeal, Hammond & Co. v. Bussey, Mr. Justice Bowen was understood (by Our Special Reporter) to say that a judgment relating to coals must be decided by the principles of Coke. The Master of the Rolls and Mr. Justice Fry concurred; the latter observing that in winter a coal merchant must always be a Bussey person, though his Lordship admitted that this had nothing to do with the case. The Master of the Rolls and Mr. Justice Bowen at once concurred.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume

93, December 3, 1887, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, CHARIVARI, DEC 3, 1887 ***

***** This file should be named 39077-h.htm or 39077-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/9/0/7/39077/

Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Wayne Hammond,

Malcolm Farmer and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.