The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Supernatural Claims Of Christianity

Tried By Two Of Its Own Rules, by Lionel Lisle

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Supernatural Claims Of Christianity Tried By Two Of Its Own Rules

The Two Tests

Author: Lionel Lisle

Release Date: December 22, 2011 [EBook #38380]

Last Updated: January 25, 2013

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUPERNATURAL CLAIMS ***

Produced by David Widger

| CHAPTER I. | THE BIRTH OF JESUS, AND THE SUPERNATURAL EVENTS CONNECTED |

| CHAPTER II. | THE SUPERNATURAL TESTIMONIES DURING THE LIFETIME OF JESUS |

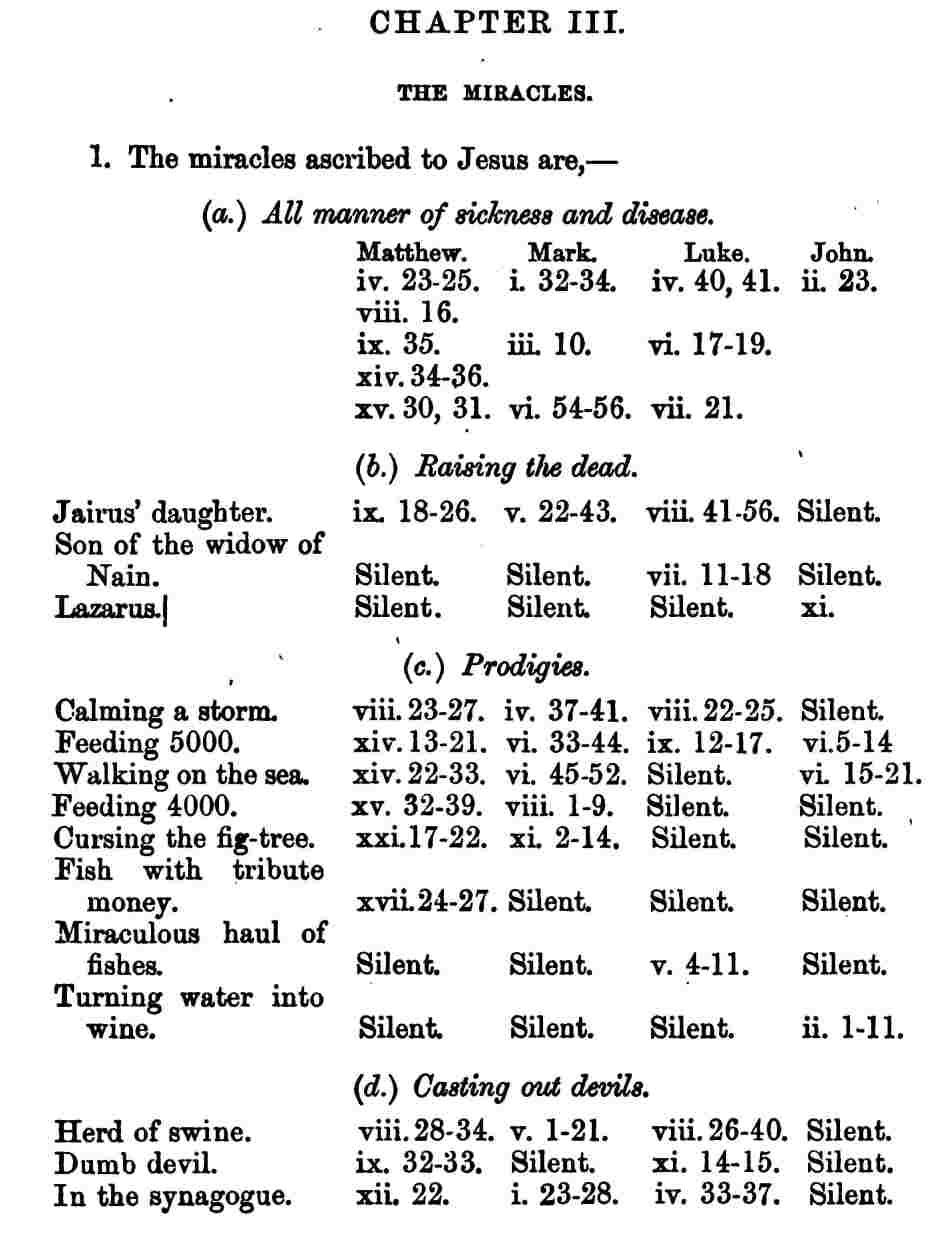

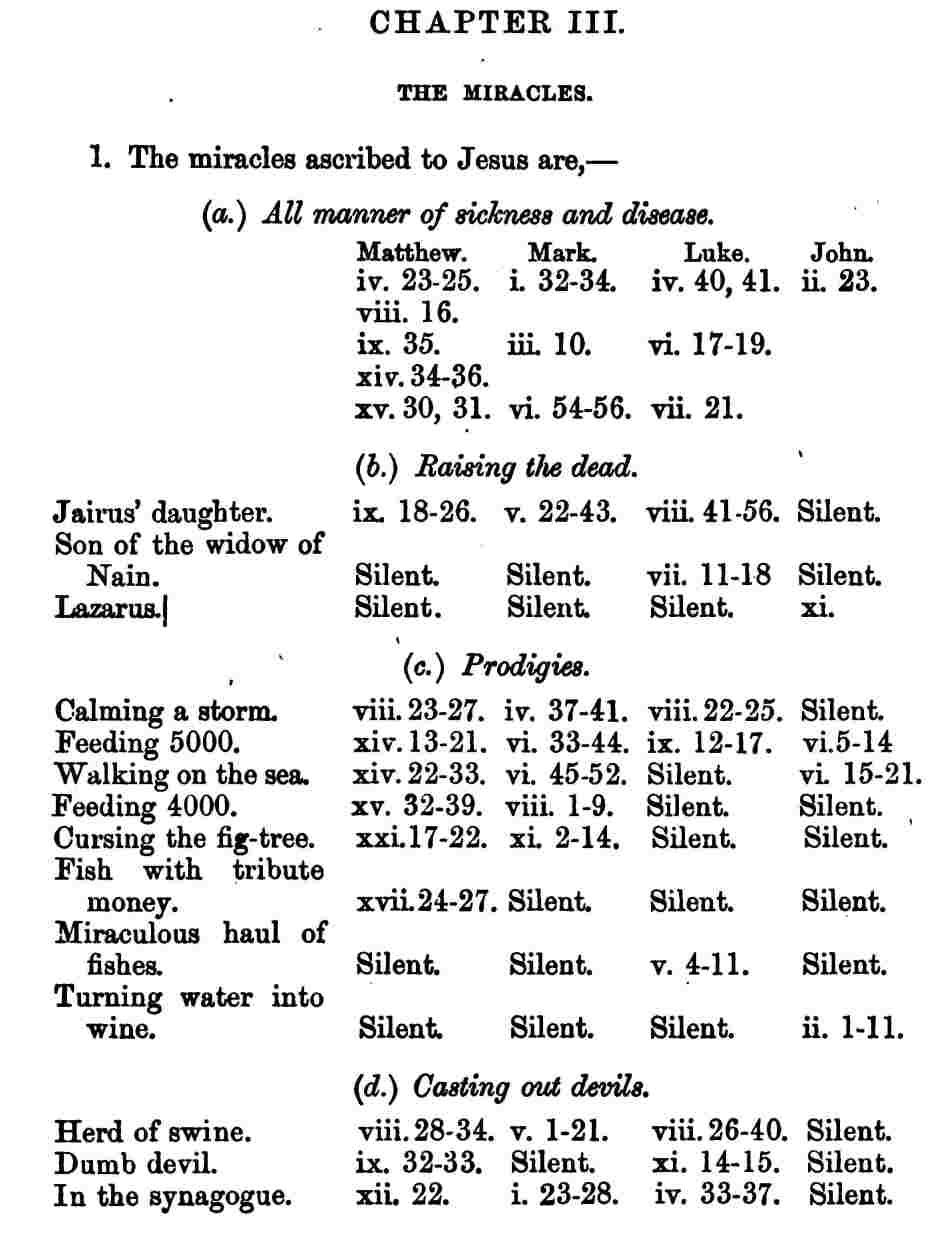

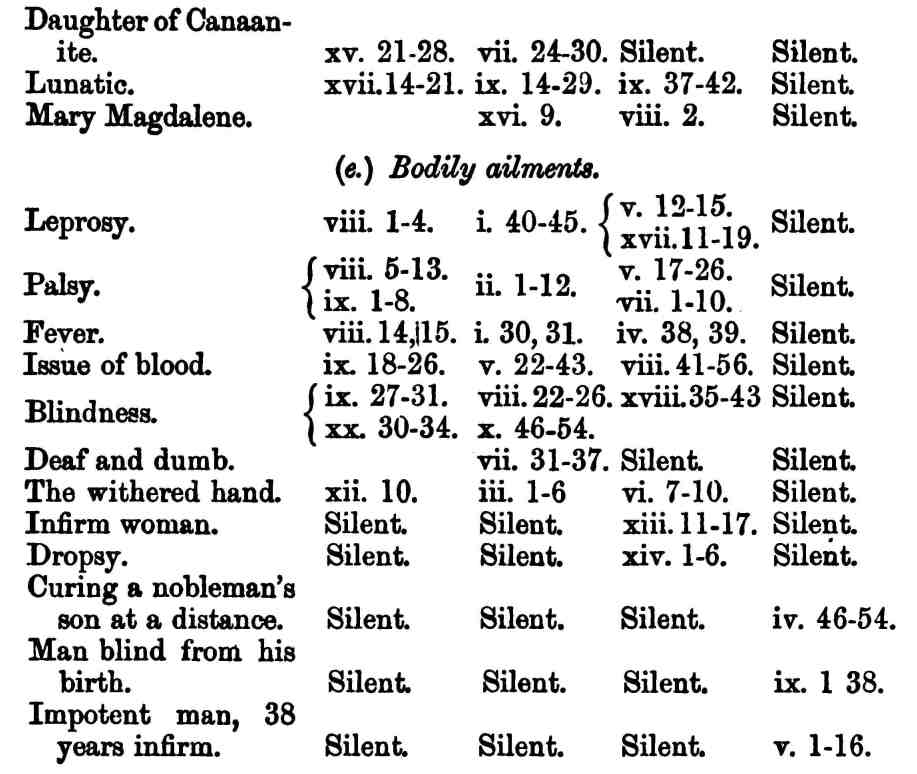

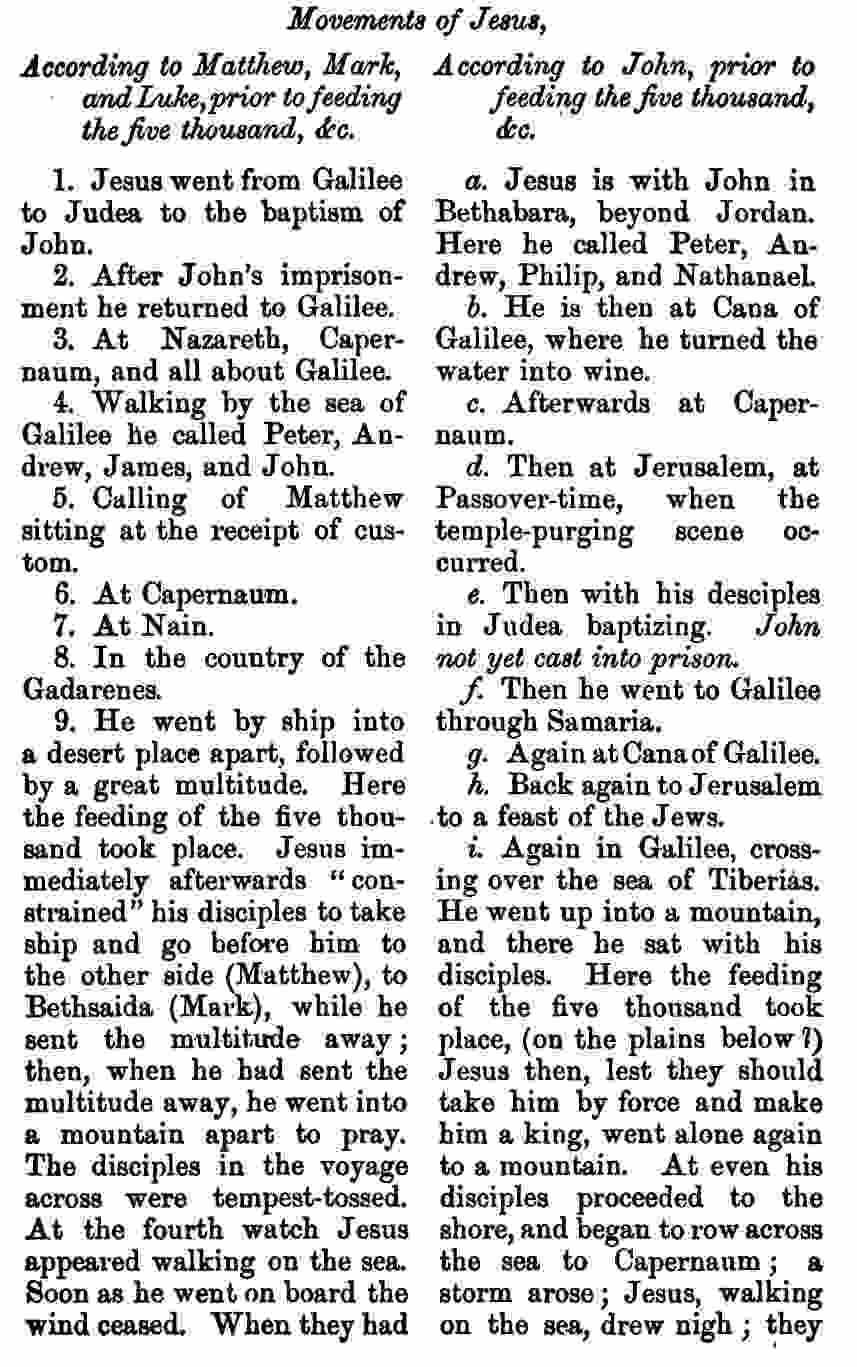

| CHAPTER III. | THE MIRACLES |

| CHAPTER IV. | THE FULFILMENT OF PROPHECY |

| CHAPTER V. | THE RESURRECTION AND ASCENSION OF JESUS |

| CHAPTER VI. | CONCLUSION |

"The following treatise was not originally written for publication; but as it faithfully represents the process by which the minds of some, brought up in reverence and affection for the Christian faith, were relieved from the vague state of doubt that resulted on their cherished beliefs being overthrown or shaken by the course of modern thought, it has been suggested that it may, perhaps, be useful to others in the same position. Although their hold on the reason and intellect may have been lost or weakened, still the supernatural authority, the hopes, and the terrors of the gospel continue to cling to the heart and conscience, until they are effectually dislodged by considerations of mightier mastery over the heart and conscience. 'The strong man armed keepeth his palace' until the stronger appears. Then the whole faculties, mental and moral, are set free, and brought into accord in the cause of Truth."—Preface to the First Issue.

Some of the principles of inquiry into the truth or falsehood of the Christian evidences laid down by the ablest divines of the last generation are wholly admirable in themselves, viewed apart from the application of them by these divines. Dr. Chalmers, for instance, whose single-mindedness in devotion to truth and right was on a level with his mighty intellect and strong and clear perceptions, held: "There is a class of men who may feel disposed to overrate its evidences, because they are anxious to give every support and stability to a system which they conceive to be most intimately connected with the dearest hopes and wishes of humanity; because their imagination is carried away by the sublimity of its doctrines, or their heart engaged by that amiable morality which is so much calculated to improve and adorn the face of society. Now, we are ready to admit, that as the object of the inquiry is not the character but the truth of Christianity, the philosopher should be careful to protect his mind from the delusion of its charms. He should separate the exercises of the understanding from the tendencies of the fancy or of the heart. He should be prepared to follow the light of evidence, though it may lead him to conclusions the most painful and melancholy. He should train his mind to all the hardihood of abstract and unfeeling intelligence. He should give up everything to the supremacy of argument, and be able to renounce, without a sigh, all the tenderest prepossessions of infancy, the moment that truth demands of him the sacrifice." Dr. Chalmers would evidently see no beauty in moral precepts apart from the truth of the testimony to the authority on which they rest.

Again he wrote: "With them" (his own class of Christians) "the argument is adduced to a narrower compass. Is the testimony of the apostles and first Christians sufficient to establish the credibility of the facts which are recorded in the New Testament? The question is made to rest exclusively on the character of this testimony, and the circumstances attending it, and no antecedent theory of their own is suffered to mingle with the investigation. If the historical evidence of Christianity is found to be conclusive they conceive the investigation to be at an end, and that nothing remains on their part but an act of unconditional submission to all its doctrines.... We profess ourselves to belong to the latter description of Christians. We hold by the insufficiency of Nature to pronounce upon the intrinsic merits of any revelation, and think that the authority of every revelation rests mainly upon its historical and experimental evidences, and upon such marks of honesty in the composition itself as would apply to any human performance." And in another portion of the same work: "We are not competent to judge of the conduct of the Almighty in given circumstances. Here we are precluded by the nature of the subject from the benefit of observation. There is no antecedent experience to guide or to enlighten us. It is not for man to assume what is right or proper or natural for the Almighty to do. It is not in the mere spirit of piety that we say so: it is in the spirit of the soundest experimental philosophy." Elsewhere he prefers the atheist, or what would now be called the agnostic, to the deist, who, rejecting revelation, professes belief in a God fashioned according to the constitution of his own mind.

The question may, with clearness perhaps, be thus stated: Religion, in its true and highest sense, is the endeavour of man to place himself in a right position to the Power and to the laws of the Universe. If that Power has spoken audibly to man, in man's language, and revealed what that right position is, we must take the message as it has been given, and implicitly submit to and be guided by it. Dr. Chalmers, on the soundest truth-seeking principles, but, as I venture to think, with imperfect knowledge, and contrary to what his conclusions would have been had he lived now, decided that there was evidence that the Power of the Universe had spoken audibly to man, by a special messenger from on high—the very Son of God. The effect, therefore, on him was, as he states, "unconditional submission." But if the Power of the Universe has not spoken audibly to man, in man's language, then, on the same principles, there is no other position towards that Power, possible to man, than simply one of Agnosticism. What that Power is no one can tell. The theological method—that of authority resting on revelation and supernatural power—is gone; but the laws of the Universe remain,—the laws of God, whatever God may be. Man's knowledge of and right position towards these laws will then depend solely on political, social, and scientific methods of research. In this case the truly religious man will be he who rejects authority and theological methods and doctrine, and follows with "unconditional submission" the teachings of the widest experience.

In marked, and in my view unfavourable, contrast with the principles of Dr. Chalmers, the recent address of Dean Stanley to the students of St. Andrews urges: "There is a well-known saying of St. Augustine, in one of his happiest moods, which expressed this sense of proportion long ago: 'We believe the miracles for the sake of the Gospels, not the Gospels for the sake of the miracles' Fill your minds with this saying, view it in all its consequences, observe how many maxims both of the Bible and of philosophy conform to it, and you will find yourselves in a position which will enable you to treat with equanimity half the perplexities of this subject." Here "equanimity," quite apart from their truth or falsehood, is commended towards marvels, vouched as eye-witnessed facts, for the sake of the Gospels. (See my remarks, pp. 86, 87, par. commencing Paul 1.)

Another instance, in a quite different profession, of a mind guided by a principle similar to that of Dr. Chalmers is presented by the illustrious philosopher, Mr. Faraday. One of a small body of Christians knit together in bands of love and peace, and himself the very embodiment of that high morality and love of kind, so much preached about however practised, no question appears to have crossed his mind as to the validity of the evidences on which the gospel claims rest; but, hating pretence and ever loyal to truth, he saw, with habitual clearness of judgment, that a revelation, dealing with what man cannot himself discover, must be taken, if true, implicitly as delivered. In his lecture on Mental Education before Prince Albert, in the year 1854, he said: "High as man is placed above the creatures around him, there is a higher and far more exalted position within his view; and the ways are infinite in which he occupies his thoughts about the fears, or hopes, or expectations of a future life. I believe that the truth of that future cannot be brought to his knowledge by any exertion of his mental powers, however exalted they may be; that it is made known to him by other teaching than his own, and is received through simple belief of the testimony given. Let no one suppose for a moment that the self-education I am about to commend in respect of the things of this life, extends to any considerations of the hope set before us, as if man by reasoning could find out God. It would be improper here to enter into this subject further than to claim an absolute distinction between religious and ordinary belief. I shall be reproached with the weakness of refusing to apply those mental operations, which I think good in respect of high things, to the very highest. I am content to bear the reproach. Yet, even in earthly matters, I believe that the invisible things of Him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal Power and Godhead; and I have never seen anything incompatible between those things of man which can be known by the spirit of man which is within him, and those higher things concerning his future which he cannot know by that spirit."

So that of himself, apart from revelation, Mr. Faraday's position was agnostic. Had he seen reason to reject revelation he would not have been a deist, any more than

Dr. Chalmers. There is an Eternal Power, but what it is man cannot divine. Of God or of a future state man himself can tell nothing. And the reproach from the votaries of most popular religions, which Mr. Faraday refers to, will apply equally to the agnostic who submits to revelation with his "simple belief," and to the agnostic who sees reason to reject it. Nothing would have been more utterly abhorrent to Mr. Faraday than to have his name paraded and referred to, as a Christian, in the sense in which it is alluded to in such books as the Unseen Universe, or, since his death, by many of the clergy in their sermons.

Any communications, from those interested in the subject of this treatise, addressed to me, care of the Publishers, will be gladly received and attended to.

L. L.

1st July, 1877.

1. The belief, concerning the position of mankind in this world and the next, held by the various Christians, who cling to the Old and New Testaments as the one inspired and infallible revelation of the mind and purpose of an Almighty, may be briefly summed up thus:—That the whole human race, because of the disobedience of Adam, is fallen from its original righteousness, and is under condemnation for transgression of the law or will of God; whether as Jews, to whom the law was given in certain forms of words or as Gentiles, who have the law, the knowledge of right and wrong, written on their consciences: that the eternal justice of God requires the eternal punishment of sin: that thus no escape being possible from the consequences of guilt, the result of Adam's disobedience and their own depravity, the whole human race must have perished, had it not been that God in love, and in order that he might place himself in a position to pardon sin in a way that would be consistent with eternal justice, sent his Son—the sole-begotten—into the world, who became incarnate in the person of Jesus of Nazareth: that Jesus fulfilled the will of God in his life: that his death by crucifixion has been accounted by God a full atonement for the sins of all who believe on him and his fulfilment of the law as if it had been their fulfilment: that by his atonement and righteousness they are thus restored to the divine favour: that Jesus rose from the dead on the third day: that he ascended into heaven: that he is now there waiting until all who are ordained unto eternal life shall, in course of time, be born, when he will return to earth in the glory and power of heaven: that then those who have believed in him will be raised from the dead, or, if not dead, will receive an incorruptible body and a purified mind: that the new heavens and the new earth, wherein dwelleth righteousness, shall then be inaugurated: that risen mankind, who have believed on Jesus, will thenceforth enjoy eternal bliss in direct communion with God: that those of mankind who have not believed in Jesus will also be raised from the dead, but, their sins being unatoned for, they will be punished with everlasting banishment from the presence of God: that the doom in each case will be irrevocable, everlasting.

2. The conception of the Almighty, in relation to fallen man, formed in the minds of many believers, is that of a king dealing with rebel subjects who are equally guilty, and whose lives are equally forfeit. He shows mercy to whom he will—those who are thus favoured having no right to this grace; and whom he will he leaves to deserved death—those thus left having no right to complain of the pardon of the others, as their own doom would have been the same whether the others were spared or not.

Other believers, again, rather conceive the Almighty to be in the position of a gracious benefactor, offering pardon through the merits of Jesus to any one who chooses to accept of it, the pardon not to take effect unless the sinner accepts it by acquiescing in the divine plan of salvation. And among the numerous sects into which believers are divided through opposing interpretations of various passages of the Bible, other conceptions of the Almighty and modifications of the foregoing statement of belief will be found. But all, or almost all, agree in dividing mankind into the believing and the unbelieving, the elect and the non-elect, the sheep and the goats, the saved and the lost.

Many Christians maintain that the atonement was universal; but it is doubtful if any maintain that the salvation will be universal, as belief is held to be a necessary condition or a sign of salvation.

Beyond such ideas as these there are two momentous considerations:—(1.) Whether an Almighty Maker of the universe could be such an one as, were he to carry out a scheme of salvation for a condemned race of his creatures, would do so in a way to have but a partial effect, or to be dependent on the belief or unbelief of those for whom it was devised. (2.) Whether vicarious sacrifice can in any way satisfy justice, divine or human. For what is vicarious sacrifice?—the substitution of the innocent for the guilty, whether an innocent lamb or an innocent child, or the innocent Son of the Eternal made flesh. However exalted the victim the principle is the same,—that of satisfying justice by committing so gross an injustice as enjoining or permitting the innocent to take the place of the guilty. Would any earthly tribunal be accounted righteous which allowed a self-sacrificing mother to substitute herself for a son, a son for a father? And does not the Christian doctrine represent its deity as the author of a proceeding so utterly unjust?

3. Christian believers, however, consider themselves as, or as having been, sinners under divine condemnation, but maintain that God can, consistently with justice, on account of the merits and death of Jesus, freely pardon their sin; and, in the hope that saving faith has been given them, they rest content in this belief, seek to live in this world in subjection to Christ's commandments, and await, after death, an entrance into bliss unspeakable, and, on Christ's Second coming, a joyful resurrection. Such, at least, is the profession; the practice does not always correspond. Christians are not unknown to history, nor possibly to the present age, whose conduct is widely at variance with their profession. But this is true of others besides believers in Christianity. They who rest content in the belief and hope just mentioned, are seldom disturbed by misgivings as to the soundness of the foundations of the Christian faith. They have no more doubt that the miraculous birth, the miracles, and the resurrection of Jesus were actual witnessed events, than they have of the assassination of Julius Caesar, or of the landing of William the Conqueror in England. And this belief seems to them to account for much. That stumbling-block to many in the way of owning that a wise and beneficent deity could be the author of such a world as this, of "a whole creation groaning and travailing in pain," disappears, in their minds, in view of the curse of God against sin, under which the earth and all it contains is, as they believe, labouring, and of the love of God in providing a way by which he could be just and yet pardon sin. It gives them, moreover, a definite, settling belief, and a hope for the future, that there is something better and different in store than life in this world. Regarding the earth and all upon it as under a curse, they profess to set their hearts on their home in heaven, on the glorious future revealed. Alas, then, if the grounds on which the prospect of this glorious future rests are worthless; if the hope is delusive; if its evil effect is, and has continually been, to divert men from applying themselves strenuously to make the best of this earth on which they live, and from heartily co-operating with their fellows to do the same; to build up brazen barriers of spiritual pride and self-complacency that sunder man from man; to foster vain-glory, strife, acrimony, and intolerance through pretence, as between opposing sects and schools, of a superior, or a more accurate, or a better defined knowledge of the mind of God.

4. The foundations of the Christian faith are the supernatural testimonies, as recorded in the New Testament, given from on high to the supernatural attributes claimed for Jesus. Many there are who profess, or by their mode of teaching imply, disbelief in these supernatural testimonies or attributes, or ignore them altogether, yet who for the sake of their position, clerical or otherwise, or to be in unison with prevailing fashion, extol Christianity as a system of high moral government and elevating tendency. All such, however, will appear to the honest and truth-loving mind but deserving of unmeasured scorn. Excepting the Jesus of the New Testament, is there any other Jesus? If the supernatural attributes there claimed for him are a pretence, he was either self-deluded or he was an impostor, or the compilers of the four gospels have borne false witness, or are recorders of inflated hearsay, or the inventors of fiction, all the while asserting that they were eye-witnesses, or narrators of the testimony of eye-witnesses. And what is to be said of a system founded either on self-delusion or imposition? Are not noble and pure doctrines put to the basest use when they are made supports of pretence and falsehood, and should they not be rescued from such contamination? Besides, Jesus scarcely claims to be the originator of new laws. His claim is far more. He is held to be the same person who gave the commandments to Moses on Sinai; and his spiritual application and extension of these laws are to be found also in the books of the Psalms and the Prophets, alleged to have been written under his own inspiration. Whether or not they are to be found elsewhere, in so-called heathen writings, is a consideration beyond the scope of this inquiry. The exhortation "to take heed and beware of covetousness, for a man's life consisteth not in the abundance of the things he possesseth," might probably be found taught and practised under other than Christian sanction,—might perhaps be discovered not to have been the guiding principle of all Christian professors. As a system, then, of moral government, or of high spiritual life, the Christianity of the New Testament professes no more than to confirm and verify, explain, fulfil, and develop the Jewish Scriptures. But its supernatural claims on behalf of Christ himself, by which it pretends to lay bare the truth as to the position of mankind in this world and the next, and to give them the hope of a new life beyond the grave, rest on the supernatural occurrences recorded. If these are true, Jesus is all he claimed to be. He is now alive, he has the destinies of the whole human race in his hands, and is to be worshipped as God. If they are not true, he was either a mere man, deluding or self-deluded, or the history of his life is a myth, however originated or developed. Truth and sincerity demand that there be no compromise between these two positions. The time has surely gone by when sound morality and brotherly kindness require the support of supernatural pretence; when religion, in the words of an ancient writer, is to be praised as an imposture devised by wise men for restraining the evil passions of the multitude. Let every true man repudiate the libel on his race implied by the most unworthy, most pernicious and despairing idea, which has for so long influenced human thought, that for the support of high morality and love of kind it is necessary to disregard or to trifle with the highest of all morality—Truth.

5. Ordinary scientific research is of little avail here. Science of itself is unable either to affirm or to deny if any power beyond and supreme over Nature exists. Whether Nature works spontaneously, and there is nothing besides matter and its inherent organising powers; or whether her various operations are carried on in fixed modes, and by determinate forces, created and sustained by an Omnipotent and Omniscient Being, the observation of cause and effect, and the induction of general laws from ascertained facts is the same. But in the latter case, the Almighty One, if he willed, might suspend or break through, or alter the regular course of Nature's working; and the question here is, whether there is any valid evidence to show that the manifestations, as recorded in the New Testament, of a nature-controlling power actually happened. If such an one, almighty, all-seeing, all-knowing, all-just, all-loving, all-merciful (such as Exodus xxxiv. 6, 7) exists, a special revelation from him to men, different from his working in the visible universe, is not a thing impossible: moreover, assuming the Christian doctrine to be true, that by sending his son Jesus into the world he meant to save only a portion of the human race, the revelation might take place in a mode suited to the knowledge and capacities of those for whom it was intended; and merely because the mode may appear absurd and unworthy of a deity (though this consideration may not be lost sight of), or because it did not take place in the way which the learned and philosophers—hitherto a small minority of mankind—might have selected, it is not to be disbelieved if the evidence is good. And it may fairly be argued that there would be no simpler way by which an Almighty could reveal his own existence, or attest the divine mission of his chosen messenger, than by instances of nature-controlling power. Again and again, then, this one consideration presses, "Is there any good evidence to show that these occurrences did really happen, that this man Jesus, claiming to be the Son of God, received certain credentials from a Power beyond and supreme over Nature?"

6. The supernatural attributes of Jesus, claimed by himself, or by his disciples for him, and held to constitute saving faith, are—

a. That he was alive from all eternity, the sole-begotten Son of God, before he appeared in this world.

b. That his birth was the result of the "overshadowing" of his virgin-mother by the "power of the Highest."

c. That while he sojourned on earth he was a union of God and man, a mortal human body with the mind and power of the Eternal.

d. That his career on earth and its results were the fulfilment of the Jewish law and prophets.

e. That he rose from the dead on the third day from his crucifixion, ascended from earth to heaven, and is now there, ever-living God and man united, with all power in heaven and in earth.

f. That he is to return in the power of the Almighty to raise the dead, and to inaugurate with his chosen an everlasting kingdom, and to banish his enemies for ever from his presence.

The supernatural events recorded in the gospels as testimonies to these supernatural attributes are—

(1.) Those connected with his birth, viz.:—The appearance of the angel Gabriel to Zacharias to announce the birth of the forerunner John, and to Mary to announce her conception of Jesus; the three appearances of the angel of the Lord to Joseph in dreams; the visit of the wise men of the East; and the appearance of the angels and of the heavenly host to the shepherds on the plains of Bethlehem. (2.) The heavenly testimonies, viz.:—The voice at the baptism. The transfiguration and the voice thereat. The voice from heaven (John xii. 28-31). To which may be added—

The testimony of the devils.

The temptation by Satan, and the subsequent ministration of angels. The earthquake and rending of the veil of the temple at the crucifixion. (3.) The miracles performed, which, if true, proved that Jesus and the first apostles had power over diseases and the course of nature.

(4.) The fulfilment of prophecy.

(5.) The resurrection from the dead, the appearances after that event, the ascension to heaven, the gifts of the apostles, and the subsequent manifestations to Paul on his way to Damascus.

7. For the purposes of this inquiry there are two simple, and what appear to be conclusive, tests ready to hand; one, a rule of evidence held sacred by Jews and Christians alike, and the other arising out of the nature of the claims made for Jesus.

(a.) Moses, or, as Christians affirm, the deity speaking by Moses, has laid down this rule of evidence in cases of guilt: "One witness shall not rise up against a man for any iniquity, or for any sin, in any sin that he sinneth: at the mouth of two witnesses or at the mouth of three witnesses shall the matter be established." This rule is commended in the New Testament in the case of offences (Matt, xviii. 16). What then can be more fair to Christianity than to examine its claims by a rule of evidence held righteous by itself? For, to put it on the very lowest grounds, the evidence necessary to establish events otherwise incredible must surely be at least equally conclusive with that necessary to convict a criminal. These are not ordinary historical statements, to be credited or not as reasonable probability, fair conjecture, or prejudice may determine, without any penal consequences-whatever, either in this world or the world to come. If a man disbelieves that King Arthur, or Romulus, or even Alexander the Great, or Julius Caesar ever existed, does it affect his welfare now or hereafter? But the gospels set forth extraordinary occurrences, disbelief of which by any one is said to render him liable to be left to perish in his sins, to endure the torments of hell evermore; and will it for a moment be asserted that a deity would expect belief involving so dire a consequence, on evidence he is said to consider insufficient for the punishment of common guilt? If, then, judged by this Mosaic rule of evidence, disbelief of the alleged supernatural testimonies to the claims of Jesus should be the righteous, and belief the unrighteous result, on whose side would a God of truth be? Would he be on the side of those who are swayed by emotion and not evidence—who imagine that their feelings are in unison with facts they have taken no pains to verify—who profess to believe because it is fashionable, or because they have been so taught from youth—who credit statements which they assert affect their relation to the Almighty and their eternal interests, on grounds on which they would not credit statements affecting their most trifling temporal interest? Would a God of truth be on their side? Surely not.

(b.) The New Testament record and doctrine are said to be a development and fulfilment of the Old. The deity of the one is the deity of the other, under a different dispensation. "The law was given by Moses, but grace and truth came by Jesus Christ." If, then, the New Testament is shown conclusively to be a development and fulfilment of the Old, this claim will be sustained. If, on the other hand, there are twisted and untenable interpretations of Old Testament texts, to make them fit in with New Testament facts; or if there are practices or doctrines or aught else upheld in the New Testament, as of God, which are hateful or foreign to the deity of the Old, such would argue deception (whether intentional or not) in the writers of the New Testament, and show that, if the deity of the Old Testament is the true God, the deity of the New is not. Christianity thus maintaining that the God of the Jewish Scriptures is the Eternal, would fall by its own supports.

8. Christian authorities, for the most part, hold that the books of the Old Testament were composed by the different writers from Moses to Malachi, during the 1100 years from B.C. 1490 to B.C. 390, and the books of the New Testament, during the first century, a.d., by the companions of Jesus, or by those who received their information from his companions. Much learning and critical research have been expended on the one hand in maintaining this position, and on the other hand in impugning it, by stigmatising the whole of some books, and portions of others, as interpolations or compositions of later times. Into so nice a question as this, it is not proposed to enter here. A conscience-satisfying belief for earnest men can in no wise rest on the doubtful and disputed conclusions and arguments of verbal critics. The object of this inquiry, then, is to consider the evidence of the alleged supernatural credentials to the claims of Jesus, so far as possible in the most favourable light in which they can be presented, and therefore it will be assumed that the books of the Old and New Testaments were written at the time generally understood, and by the persons whose names they bear; and as by most believers in Christianity these books are held to be the one infallible authority, the endeavour will be not to travel beyond them. The alleged fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy by New Testament events will be fully considered under its own head; and on the divine inspiration claimed for the writers of the New Testament narratives, one word will suffice. To relate facts seen, or facts told to the narrator by others, requires no inspiration. If any one holds that the gospels record, either in whole or in part, facts which the writers did not see, or were not told of, but which were specially revealed to their spirit by a God of truth, as having occurred, he claims more for them than they do for themselves. See Luke i. 1-4; xxiv. 48; John i. 14; xx. 30, 31; xxi. 24, 25; Acts i. 1, 3; 1 Cor. xv. 1-9; 2 Peter i. 16-18; 1 John i. 1-3. The burden of these passages is summed up in the last one—"That which we have seen and heard declare we unto you." The truth or otherwise of the supernatural events recorded professes thus to rest on the testimony of human eyes and human ears, however divinely guided and enlightened.

9. Assuming, then, that the books of the New Testament were written by those whose names they bear, what is known of the narrators? Their character for honesty and trustworthiness among their neighbours and contemporaries there is no voucher for. Yet, while no one who knew them has left aught on record to their credit, there is nothing to the contrary. True, they themselves confess that neither the miraculous pretensions of Jesus himself, nor their own testimony with reference to the supernatural events of his life, met with any credit from by far the greater part of those living at the time, who had the means of satisfying themselves of their truth or falsehood—means which no one at the present day possesses. The people of Capernaum, consigned by Jesus to hell for unbelief, or his own brothers and sisters, may, for all that any one now can tell, have been as competent and truthful, in every respect, as the publican Matthew, or the fishermen Peter and John. The Roman governors, the Jewish high-priests, Gamaliel and the other rabbis, why are they to be accounted less trustworthy, less able to discern truth from pretence, than Paul and Luke? The following particulars, with reference to its writers, are to be gleaned from the New Testament:—

(1.) Matthew, whose name the first Gospel bears, was a tax-gatherer, sitting at the receipt of custom (Matt. ix. 9), in the thirty-first year of Jesus' life, when he became a follower of Jesus. Whether they knew each other previously is not mentioned. He was alive after the crucifixion, but no separate mention is made of him subsequent to Acts i. 13.

(2.) Mark, the writer of the second Gospel, is not mentioned before Acts xii. 12 (ordinary chronology, a.d. 43 to 47), and then it is as the son of one Mary, to whose house Peter went after his miraculous liberation from prison. He accompanied Paul and Barnabas on their first mission to the Gentiles, but soon left them. A quarrel afterwards occurred between the two apostles on his account. Paul was hurt at the way in which he had turned back at the outset, and objected to take him on their second mission. Barnabas insisted that he should go. But if he is the same Mark mentioned in Colossians iv. 10, 2 Tim. iv. 11, and Philemon 24, a reconciliation with Paul had taken place, and he was alive and in Rome in a.d. 66. Again, Peter in his first epistle thus refers to him, "The church that is at Babylon, elected together with you, saluteth you, and so doth Marcus my son." It cannot be gathered from the New Testament that Mark (even if he had been the young man with the linen garment about his naked body [Mark xiv. 51, 52], as some fondly conjecture) knew anything of Jesus personally; but his own and his mother's connection with Peter is shown to have been an intimate one. From the passage in Philemon, also, it appears that he was at Rome, along with Luke, in attendance on Paul.

(3.) Of Luke, the writer of the third Gospel and of the Acts, the first mention is in Acts xvi. 10 (ordinary chronology, A.D. 53), where the "we" first appears in the narrative. Thereafter he was the almost constant companion of Paul in his journeys. He is also mentioned (2 Tim. iv. 11) as being alive in a.d. 66, in attendance on Paul in Rome. Although he claims (Luke i. 1-4) "a perfect understanding of all things from the very first," he places himself among those who received their information from the "eye-witnesses and ministers of the word;" so that he himself knew nothing of Jesus or of the events of his life. He opens his Gospel thus: "Forasmuch as many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us." In his time, then, there were many different narratives of the life of Jesus. It is not clear whether Luke considered these erroneous, and requiring correction by the "perfect understanding" possessed by himself, or whether he was merely following the example of others in setting forth in order the events as he himself understood them.

(4.) John, whose name the fourth Gospel bears, and who is held to be the author also of three epistles and the Revelation, became a follower of Jesus in the thirty-first year of Jesus' life (Matt, iv. 18, 22; Mark i. 16-20; Luke v. 1-11). He does not claim, nor is there any mention, that they were acquainted before, unless he was one of the two mentioned in John i. 37. He is said to have lived till a.d. 96. Jesus at the crucifixion (John xix. 25-27) left his mother Mary in charge of John, who had thus the very best opportunity of informing himself of all the circumstances within her knowledge.

(5.) Peter, if the first three Gospels are to be followed, became a follower of Jesus at the Sea of Galilee, at the same time as the apostle John, that is, after the imprisonment of John the Baptist (Matt. iv. 18-22; Mark i. 16-20; Luke v. 1-11). But in the fourth Gospel (John i. 40-42) both Jesus and Peter are mentioned together as following the preaching of John the Baptist. Peter is said to have died about a.d. 66.

(6.) Paul's first connection with Christianity was after his persecuting journey to Damascus (Acts ix.; ordinary chronology, a.d. 35), and it is believed that he suffered death at Rome, a.d. 68. With the exception of the miraculous appearance of Jesus while Paul was on the way to execute his persecuting mission at Damascus, and it may be the trance referred to in 2 Cor. xii. 1-4, it is not claimed for him that he possessed any knowledge of the events in the life of Jesus beyond what he learned from others.

Of the six writers in the New Testament, then, who record facts in connection with the life of Jesus, three—Matthew, John, and Peter—claim to have been his companions, and three—Mark, Luke, and Paul—with the exception just mentioned in the case of the last, received their information from others.

10. The foregoing considerations will serve to show that this inquiry into the evidence on which rest the supernatural credentials said to have been given to the claims of Jesus to the worship of mankind, will be proceeded with on the most favourable view possible for these claims—

(1.) By adopting what is held by Christians to be a divine and righteous rule of evidence,—"That at the mouth of two witnesses, or at the mouth of three witnesses, shall the matter be established."

(2.) By examining the claim of the New Testament to be a development and fulfilment of the Old.

(3.) By assuming that the books of the Old and New Testaments were written by those whose names they bear, and at the times generally believed by Christians.

(4.) By examining these books one with another, and travelling beyond them only so far as the strict requirements of the subject necessitate.

THEREWITH

Luke i., ii.; Matt i., ii.

a. The appearances of the angel Gabriel to Zacharias and Mary. b. The appearances of the angel of the Lord to Joseph in dreams.

c. The visit of the wise men of the East.

d. The appearance of the angel and the heavenly host to the shepherds on the plains of Bethlehem.

FIRST TEST.—"In the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established."

Mark and John pass by the birth and upbringing of Jesus in silence. John, who knew Mary, and to whose care Mary was consigned by the expiring Jesus, would have been the most competent of all to record her version of the wondrous experiences of her cousin, herself, and her husband, in connection with the births of John the Baptist and of Jesus, yet he has not one word concerning them. Matthew, who may have known Mary and Joseph, has only meagre statements, very unlike what would be derived directly from either of the parents. But there is nothing to show from whom Matthew obtained his information. The detailed narration of the angelic appearances is made by Luke, who, so far as is known, was never at Jerusalem at all, far less ever came into contact with Mary. What, then, have we here?

John, the companion and best loved disciple of Jesus, the custodian of Mary, the most competent of all to narrate occurrences within her knowledge,—Silent.

Mark, the son of a woman known to Peter and the other companions of Jesus, and himself a companion of Peter, who would have been aware of these occurrences, if they had been believed among the very earliest Christian circle,—Silent.

Matthew, the companion of Jesus, who may have known Mary and Joseph,—Records three angel-visits to Joseph in dreams, and the visit of the wise men of the East, but is silent as to-all the marvels of Luke.—Is silent as to Matthew's marvels, but sets forth, in detail, angel-visits to Zacharias and Mary, and the appearance to the shepherds at Bethlehem.

Luke, who narrates the testimony of others, and does not name his informants, merely stating that they were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, and who writes at least fifty years after the events referred to.

In the mouth of two, or in the mouth of three witnesses, nay, even in the mouth of one witness, is any one of these incidents established?

'But let them be examined separately in detail:—-

(a.) Luke states that while the Jewish priest Zacharias, in the order of his course, was burning incense in the temple, the angel of the Lord appeared, standing on the right side of the altar. The old priest was startled. The angel told him that his wife Elizabeth should bear a son, who should be great in the sight of the Lord, who should turn many of the children of Israel to the Lord their God, and make ready a people prepared for the Lord. Zacharias had a misgiving that the event predicted could not well happen, as he himself was an old man, and his wife "well stricken in years." Whereupon the angel announced himself to be Gabriel, who stands in the presence of God, and forthwith he inflicted dumbness on Zacharias, to last until the child was born, as a punishment for his very reasonable doubt. Hark! the clanking clog of priestcraft the harsh ring of intolerance! Punishment because of reasonable doubt of a supernatural event not verified! Are the angels, then, on the side of the persecutors? Are they so sensitive of their "ipse dixit?" Thomas the disciple, it is mentioned, dis-believed in the risen Jesus, but Jesus appeared again to satisfy his doubts. Sarah, the wife of Abraham, laughed heartily when she heard the Lord announcing to her husband that she should bear a son when her child-bearing condition was past, and was kindly rebuked. Jesus in John, and the Lord in Genesis, had a tenderness to human doubt of a reasonable character; but Luke's peremptory angel was not for one moment to be gainsaid. Is this disposition angelic or earthly? Has such a temper of mind never been known among men? But to return to the narrative. Zacharias himself was the only one who saw the angel. Aged at the date of John's birth, neither he nor his wife could have been alive when Luke wrote. Who, then, came between Zacharias and Luke? Whose report has Luke credited? This is not a question of the credibility of Zacharias or the credibility of Luke, but of some unknown go-between, one or more. And can such unknown go-between be credited in view of the silence of John and Matthew; in view of the silence of Mark, the companion of Peter, who was (John i 41) a follower of John the Baptist? Surely the hesitating Zachariases, the doubting Thomases, and the mocking Sarahs of modern times are to be dealt with tenderly.

Luke goes on to narrate that, in the sixth month afterwards, the same angel Gabriel appeared to a virgin named Mary, betrothed to Joseph, a descendant of King David. The angel hailed her as the divinely favoured among women. She was very startled, wondering what he could mean by this style of address. He proceeded to tell her that she was to be the mother of a son, to be called the Son of the Highest, who was to reign for ever. She (naturally enough, were it not that she was about to be married) asked how that could be, in view of her virgin condition. More gracious to the hesitation of the timid maiden than to that of the aged priest, he replied, "The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee; therefore, also, that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God." He then told her that her Cousin Elizabeth, hitherto barren, was in her sixth month, and asserted that with God "nothing shall be impossible." She made a sweetly-submissive speech in reply, and the angel went away. Here, again, is the same lack of connecting evidence. Mary alone saw the angel. Who were the go-betweens, the transmitters of the tale to Luke? Why the silence of Matthew, Mark, and John, especially John, Mary's custodian? Matthew mentions that Mary was found with child by the Holy Ghost; that this was revealed to Joseph in a dream; but he has not one word of the angel-visit to Mary. Moreover, in the next chapter, Luke relates a circumstance quite inconsistent with this angel-visit. The aged Simeon made some striking statements with reference to the destiny of the child, whom he met in the temple; and Luke adds, "Joseph and his mother marvelled at those things which were spoken of him." But Simeon's statements were far less strong than the angel's. Can Mary, then, have forgotten the angel's visit? Did she not tell Joseph of it? Can she have forgotten her memorable visit to Cousin Elizabeth, when they congratulated each other on their respective conditions, and when even John the Baptist, before he saw the light, leaped for joy at Mary's salutation of his mother? If not, where was there room for marvel at Simeon's vaticination?

(6.) Matthew's account commences with Joseph's discovery of the condition of his betrothed. "Before they came together she was found with child of the Holy Ghost," He does not mention how this discovery was made; if it was when Mary's condition could be no longer hid, or if Mary informed him as soon as she found herself pregnant, and then mentioned whatever grounds she had for asserting that this was the result of a supernatural "overshadowing." In any case, Matthew's account implies that at first Joseph doubted her, and thought that she had been unfaithful to him; but as he was a quiet man, averse to unnecessary scandal, he resolved to conceal her in some way. Yet, if Luke's angel-visit to Mary ever occurred, why was not Joseph informed of it at the time, for then there would have been no doubt on his mind that her conception was supernatural? Why was he not informed of the congratulatory visit to Cousin Elizabeth, of her speech and John the Baptist's joyous bound? Cousin Elizabeth, according to Luke, had no doubt that Mary was the "mother of my Lord." Joseph, her betrothed, according to Matthew, thought something quite different. While Joseph was considering the best mode of concealing Mary, the angel of the Lord appeared to him "in a dream," and directed him not to fear to take Mary to wife, for "that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost" And he obeyed; but he "knew her not till she had brought forth her first-born."

Luke's angel appeared to Zacharias and Mary in some visible shape, in broad day, or, at all events, when they were fully awake; but Matthew's angel made himself known to Joseph in dreams—why the difference!—the object being to induce Joseph to become the reputed father of a child not his own, and thus to conceal from the Jewish nation what is alleged to be the fulfilment of the prophecy that a "virgin shall be with child, and bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel," &c. Are mystery and misrepresentation, then, of divine authority? Are unbelieving Jews and Gentiles to be eternally reprobate for not allowing that a man was other than the son of his reputed parents? An Almighty maker of the universe is here represented as begetting a child by a virgin untouched by man, and so far from disposing that this should be done in a way that would be clearly verified and apparent, either to the world at large or to any select portion of it, he—eternal God—is said to have proceeded in the clandestine way of directing, by means of an angel who manifested himself in dreams, that Joseph should take this virgin to wife, and pass off the divine offspring as his own son, that thus the wondrous birth on which so much depended might be concealed.

Matthew further mentions two subsequent appearances of the angel of the Lord to Joseph in dreams, the first directing him to take the child to Egypt to be out of the way of Herod's massacre, and then, when Herod was dead, directing him to return to Judea. Luke, on the other hand, practically ignores Joseph in the whole transaction of the birth of Jesus. He makes no mention of the way in which Mary informed her lover; of the condition she was in, and merely brings him in when the birth is about to take place, as proceeding from Nazareth to Bethlehem, along with Mary, to be taxed. While Matthew avers that he was desirous of saving Mary's good name, there is nothing in Luke to show that Joseph ever knew of Mary being with child before he married her; and for all that is there stated, he may have believed that Jesus was his own son; Luke's only later reference to Joseph in connection with Jesus, is in his account of the visit to the temple, when the boy was twelve years old. Discovering that he was not among the homeward-bound company, Joseph and Mary returned to Jerusalem, and found him in the temple posing the doctors, when his mother said, "Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? Behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing." The reply was, "How is it ye sought me? Wist ye not that I must be about my Father's business?" and Luke adds, "They understood not the saying which he spake unto them." How, then, can the angel-visit to Mary be true, or the three angel-visits to the slumbering Joseph? For if these be not false, Joseph and Mary were the two human beings at the time who did understand fully who this wondrous child was.

(c and d.) The two further supernatural incidents in connection with the birth of Jesus (the wise men of the East and the appearance to the Bethlehem shepherds) remain to be considered. The details of the one are quite irreconcilable with those of the other.

(c) Matthew states that on the birth of Jesus at Bethlehem, in the reign of King Herod, certain wise men from the East came to Jerusalem. They announced that the object of their visit was to worship the new-born King of the Jews, whose natal star they had seen in the East. On hearing this Herod was much troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. Herod sent for the priests to inquire of them where Christ, the anointed one, was to be born. On the authority of the prophecy, Micah v. 2, they informed him that the Ruler of Israel was to come out of Bethlehem. Herod then had a private conference with the wise men, eagerly asked when the star appeared, charged them to proceed to Bethlehem and search for the child, and when they had found him to bring him word again that he himself might go and worship him. On leaving Herod, the very star they had seen in the East made its appearance again, and went: before them until it became stationary above the house where Jesus was. They entered the house, found Mary and her infant boy, fell down and worshipped him, and offered him gifts, gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Then being warned of God in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they went back by another route to their own country. After this, and again in a dream, Joseph was warned to take Jesus to Egypt, to avoid a massacre which Herod ordered, "when he saw that he was mocked of the wise men," of all the children in Bethlehem two years old and under, "according to the time which he had diligently inquired of the wise men." After Herod's death, Joseph was directed, in another dream, to return to Judea; but when he learned that Herod's son was reigning there he settled in Nazareth of Galilee.

Luke's account is that Joseph and Mary dwelt in Nazareth before the angel-visit to Mary; that he and Mary went up from there to Bethlehem to be taxed; that Jesus was born while they were at. Bethlehem; that he was circumcised on the eighth day; that when Mary's purification—thirty-three days—was at an end they took the babe to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord in the temple; and that when they had performed all things according to the law of the Lord, they returned to Galilee, "to their own city Nazareth."

The glaring contradiction here between Luke and Matthew need scarce be dwelt on. Luke states that Joseph and Mary came to Bethlehem from Nazareth: Matthew's account implies that they were not in Nazareth until the return from Egypt, and that going to Nazareth at all was because of a warning from God in a dream. Matthew states that they fled from Bethlehem to Egypt to avoid the wrath of Herod: Luke, that they brought the child to Jerusalem, where Herod, according to Matthew, was, and that he was openly acknowledged in the temple by Simeon and Anna. Matthew states that, at Herod's death, they went from Egypt to Nazareth, avoiding Judea; Luke, that they went straight from Jerusalem to Nazareth in a very short time after the birth of Jesus.

Matthew places the birth of Jesus in the reign of King Herod; Luke, during the taxing made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria, which, following Josephus, was not till after the death of Archelaus, Herod's successor. This discrepancy has given much anxious concern to the "reconcilers" and critics, the latest solution being a conjecture, stated to rest "on good grounds," that Cyrenius was twice governor of Syria, first towards the close of Herod's life, afterwards on the death of Archelaus. For the present purpose, it is assumed that Matthew and Luke refer to the same period.

The tale of the wise men suggests many questions. What came of them afterwards? How many were there? Where did they come from? How, when they saw the star in the East, did they know that it indicated the birth of a King of the Jews? What special Jewish appearance did it present? and what end was their heaven-directed visit to serve? Not to proclaim Jesus to the Jews as their king and ruler; not to accredit them as witnesses to proclaim his divinity far and wide; not, so far as is stated, to bring their own minds to the saving belief that he was the Saviour of the world; not even to confirm Mary and Joseph's faith—for if the angel-visits are true that would have been unnecessary; but to offer to him, the professed Lord of heaven and earth, such trumpery gifts as were laid upon the altars of the old gods, or presented to baby princes of this world.

(d.) Luke narrates that, at the birth of Jesus, a company of shepherds—how many is not mentioned—were watching their flocks at night in the fields, when "lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them, and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Fear not, for behold I bring you good tidings of great joy which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour who is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you: ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill towards men." The shepherds forthwith hastened to Bethlehem, and discovered Mary, Joseph, and the infant boy lying in a manger. Finding the vision they had seen thus exactly realised, they spread abroad, among their wondering countrymen, "the saying that was told them concerning this child." "But Mary kept all these things, and pondered them in her heart."

The question here again arises: between the shepherds, the eye-witnesses of this event, and Luke, who wrote at least fifty years after, who were the go-betweens? Or if the information came from Mary, why are Matthew, Mark, and, above all, John silent? And what became of the shepherds? When Jesus began his public ministry, where were they? Where those they informed? Joseph and Mary, by Luke's account, had come from Nazareth to Bethlehem to be taxed, and returned. Thus they would have been known in Bethlehem as belonging to Nazareth, and of the house and lineage of David. There would not then have been difficulty in keeping them in view. And would men who had seen so remarkable an appearance, to whom the angel of the Lord had spoken, who had heard the heavenly host singing, manifestations more glorious than before or since have been vouchsafed to any one, have lost sight of the wondrous child, or would those whom they informed have lost sight of him? Yet, during the three years' public appearance of Jesus, not one of them, so far as can be gathered, is to be found among his followers.

(e and d.) That the visit of the wise men of the East, and the appearance to the shepherds, can both be true, is impossible. Luke is very precise as to the length of the stay of Joseph and Mary in Bethlehem after the birth of Jesus. It extended to the eighth day for circumcision, and to the thirty-third day after this for Mary's purification. Then they left Bethlehem for Jerusalem, there "performed all things according to the law of the Lord," and returned straight to Galilee. During the forty or forty-one days of the stay at Bethlehem—five miles from Jerusalem—the shepherds were spreading abroad "the saying that was told them concerning this child." That he was a "Saviour, born in the city of David, Christ the Lord." The visit of the wise men must have occurred in the course of these forty-one days. Their inquiry put all Jerusalem in a ferment, roused Herod's jealousy, set him inquiring where Christ should be born, induced the most eager desire to find the new-born babe, that he might remove such an obstacle from his path, all the while that the shepherds in the neighboring district were publishing the glad tidings of his birth. The wise men were guided by a star to the house where Joseph and Mary stayed, saw and worshipped the wondrous child, and were warned of God in a dream to depart to their own country privately; but no such admonition to keep silence restrained the outspoken shepherds in the close vicinity of Herod. To avoid Herod's wrath, Joseph "took the young child and his mother by night and departed into Egypt," just at the time "when the days of her purification, according to the law of Moses, were accomplished, they brought him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord," Herod being at Jerusalem, and having had his jealousy roused by the tale of the wise men. Can aught more utterly irreconcilable be imagined? As, then, the falsehood of the accusers of Susanna in the Apocrypha was detected, when they were examined apart by Daniel, on the one affirming that her crime was committed "under a mastic tree" and the other "under a holm tree," so such contradiction as that between Matthew and Luke wholly destroys the credit of both narratives. What is there for a conscience-satisfying belief to rest upon?

SECOND TEST.—The claim of the New Testament to represent the Jewish Jehovah.

1.. The deity begetting a mortal child by a mortal woman, was this a Jewish or a Gentile idea? That it was not a Jewish idea will be shown when the alleged fulfilment of Isaiah vii. 14,—"Behold a virgin shall conceive" &c., is considered. That it was a common Gentile idea is most manifest. A glowing account of Jupiter's commerce with the fair ones of the earth is to be found in his amorous address to his sister-wife Juno (Iliad, Book xiv. 280-353). The other gods and goddesses in like manner bestowed their favours on mortals, and begat mortal children. Plato was said to be the child of a virgin by Apollo. Apollo appeared to her betrothed in a dream, and told him his bride was with child, on which he delayed his marriage. What is this but the tale of Mary and Joseph in another form? Which is the original? Plutarch also mentions that a similar notion was held by the Egyptians, but of male gods only. "The Egyptians, indeed, make a distinction in this case, which they think not an absurd one, that it is not impossible for a woman to be impregnated by the approach of some divine spirit, but that a man can have no corporeal intercourse with a goddess." This is an exactly similar notion to Luke's "overshadowing" of Mary. "Out of Egypt have I called my son," is perfectly true in a sense. Confucius also, in one of the sacred books of the Chinese, refers to the great Holy One, who would appear in the latter days, born of a virgin, whose name shall be the Prince of Peace.

Similar, too, are the legends of the fabled founders of some, to whom so many of the civil and religious institutions of the city were ascribed. Romulus and Remus were sons of the war-god Mars. Their mother Rhea took refuge in a cave: the meeting of the god and the mortal was attended by prodigies: the heaven was darkened, the sun eclipsed: her celestial lover announced to Rhea that she should bear twin-sons, to be renowned in arms, and then ascended in a cloud from the earth. Servius Tullius, also, had a like origin. His mother, a slave in the household of Tarquin, beheld a divine appearance on the hearth, and afterwards was "found with child" by the god. The child, when born, was named Servius, from his mother's condition. During its sleep she saw its head surrounded by flames, which were extinguished when she awakened it. The founder, likewise, of the Sabine town of Cures was a son of Mars. His mother, a virgin of noble family, seized with divine favour, while dancing in the temple, entered the shrine, and became pregnant by the god. Her son, she is told, would be of superhuman beauty, matchless in deeds of arms. So that a Roman on his conversion had merely to transfer to Jesus a like belief to those in which he had been nurtured with reference to the births of the fabled founders and ancient kings of his own city, up to whom the political and religious practices which he had been taught to regard as sacred were traced. To him there would have been nothing incredible in the story of Mary's conception. The claim of the church of Rome to be the true church of Christ may thus, in a certain sense, be cordially acquiesced in.

2. The Son of God, by a mortal woman, brought up as the child of that woman and her husband,—Is that a proceeding proper to the deity of the Old Testament? The writings and the spirit of Moses and the prophets emphatically answer, No.

But it exactly corresponds with the Grecian legends of the "father of gods and men." The suffering hero Hercules, son of Jupiter and Alcmena, brought up by her and her husband Amphitryon, is a memorable pagan tale of a kindred character.

3. The birth of an illustrious personage made manifest by a star,—Is that consistent with the attributes of the Jewish Jehovah? The stars in the Old Testament are ever referred to as witnesses to the might of the Eternal, and those who sought to divine earthly events by their courses, conjunctions, or appearances, were treated with derision. "Let now the astrologers, the stargazers, the monthly prognosticators stand up and save thee from these things that shall come upon thee." This is addressed by Isaiah, xlvii. 13, to the daughter of the Chaldeans, Babylon. Matthew's stargazing wise men would thus have been "spued out of the mouth" of the Jewish Jehovah.

(a.) The descent of the Holy Spirit, like a dove, and the voice from heaven, at his baptism. (b.) The transfiguration, and the voice then heard; also the voice from heaven, mentioned in John xii 28-31. (c.) The testimony of the devils. (d.) The forty days' fast, the temptation by Satan, and the subsequent ministration of angels. (e) The earthquake and rending of the veil of the temple at the crucifixion.

(a.) The occurrences at the baptism (Matt. iii.; Mark i. 1-11; Luke iii. 21, 22; John i. 29-34).

FIRST TEST.—"In the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established."

In the fourth gospel the account given is expressly stated to be the record of John the Baptist. It does not appear from whom the particulars in the other three gospels were derived.

With the exception of the angel-visit to Zacharias, at his birth, and the dove and voice at the baptism of Jesus, there is nothing supernatural in connection with John. He is represented as a plain-spoken, downright enthusiast, held in esteem by king and people, and as appropriating to himself the prophecy of Isaiah—"A voice of one crying in the wilderness, preparing the way of the Lord, making straight in the desert a highway for our God." He lived a rude life in the desert, practised fasting and purifying, and baptized his followers. By his outspokenness he incurred the enmity of Herodias, the wife of Herod, who obtained his head as a reward for the pleasure given to her husband by her daughter's dancing. In comparing then his record, as found in John, with the statements of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, one most marked divergence appears. The latter assert that, on Jesus coming to be baptized, the Baptist objected, saying, "I have need to be baptized of thee, comest thou to me:" thus implying a knowledge on John's part that Jesus was the Christ. Whereas the former pointedly states, on John's own authority that he did not know Jesus as the Messiah until the supernatural appearance of the dove occurred. "I knew him not, but he that sent me to baptize with water, the same said unto me," &c.. If the account in the fourth gospel then is true, Matthew's account on this point must be false, and the angel-appearance to Zacharias, and John's gladsome leap in his mother's womb on Mary's salutation of Elizabeth, are discredited. Cousin Elizabeth addressed Mary as "the mother of my Lord;" and had this been so, would not John have been brought up in the belief that Jesus was "the Lord," whose advent he was to prepare? Again, the "record" of John the Baptist in the fourth gospel does not confirm or corroborate the "voice from heaven, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased," at the baptism, mentioned in the other gospels. John would surely have heard these wondrous words, and could not well have forgotten them.

SECOND TEST.—-The claim of the New Testament to represent the Jewish Jehovah.

1. A point to be specially noticed is John's declaration, that he who sent him to baptize with water had charged him that the Messiah would be made manifest by the spirit of God descending from heaven like a dove, and alighting and remaining on him. John affirms that he bare record that Jesus was the Son of God, because in his case this condition was fulfilled. Now, who sent John to baptize with water? Is there anything in the Old Testament scriptures to give baptism with water place as an ordinance of the being therein upheld as divine, and whom both John the Baptist and Jesus claimed to represent? Not one word! Who, then, sent John to baptize with water? Did he receive his directions from angels in dreams or otherwise? Some of the lustrations in connection with the heathen temples were, however, very similar to the ordinance of baptism since practised among Christians.

2. The spirit of the Eternal in a bodily shape like a dove! is that an Old Testament prediction, an Old Testament belief? Let the following passages reply:—Isaiah xl. 25, "To whom then will ye liken me, or shall I be equal? saith the Holy One. Lift up your eyes on high, and behold who hath created these things, that bringeth out their host by number," &c. Deut. iv. 15-17,—"Take ye therefore good heed unto yourselves; for ye saw no manner of similitude on the day that the Lord spake unto you in Horeb out of the midst of the fire: lest ye corrupt yourselves, and make you a graven image, the similitude of any figure, the likeness of male or female, the likeness of any beast that is on the earth, the likeness of any winged fowl that flieth in the air," &c. Here then, at the very outset, are John the Baptist and Jesus represented as connected with a marvellous event, utterly abhorrent to the Old Testament deity, whose will and purpose they claimed to be fulfilling!

But though the conception of the deity appearing in the shape of any bird or beast was wholly foreign to the Old Testament writers, it was one quite familiar to the heathen world. In the Iliad, for instance, the god Sleep, like the shrill bird of night, alighting, perched on the loftiest fir on Mount Ida, to aid the amorous design of Juno on mightiest Jove; Apollo and Pallas were seated on a lofty beech, like two vultures, to watch the duel between Ajax and Hector. The Egyptian deities had each their appropriate symbol-beast, bird, or reptile. A dove, as an emblem of meekness and peace, was no doubt deemed by the gospel compilers the most fitting of what they wished to convey as the mission of Jesus; but the conception being heathen, and not Jewish, it discredits the claim of Christianity, that the New Testament is a continuation and fulfilment of the Old.

(h) The transfiguration, &c. (Matt. xvii. 1-13; Mark ix, 243; Luke ix. 28-36). Jesus took Peter and James and John along with him into a high mountain apart to pray. While praying he was transfigured before them; his face shone as the sun; his raiment glistened; Moses and Elias appeared in glory talking with him, and spoke of the decease which he should accomplish at Jerusalem; Peter and the others were heavy with sleep, but when awake they saw his glory and the two that were with him; Peter, in bewilderment, suggested that three tabernacles be made, one for Jesus, one for Moses, and one for Elias; a bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice out of the cloud said, "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased." On this the disciples fell on their faces in fear, and when they revived they saw no one except Jesus himself. He charged them to conceal what they had seen until after his resurrection.

John makes no mention of the transfiguration; but in chapter xii 28-30, when Jesus is at Jerusalem "exhorting the people, and praying, Father, glorify thy name; then came there a voice from heaven, saying, I have both glorified it, and will glorify it again. The people, there-tore, that stood by and heard it said that it thundered, others said, An angel spake to him. Jesus answered and said, This voice came not because of me, but for your sakes."

Peter, 2nd epistle i. 17,—"For he received from God the Father honour and glory, when there came such a voice to him from the excellent glory, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased. And this voice, which came from heaven, we heard when we were with him in the holy mount."

The idea is an old one that because light of intense brilliancy dazzles the human eye it is therefore the dwelling-place and the raiment of the inhabitants of heaven, pictured thus as a refulgent abode with refulgent beings. "Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment" (Psalm civ. 2); "At length do thou come, we pray, with a cloud thy shining shoulders veiled, O Augur Apollo!" (Horace i. 2, 31,) are instances. Glory and dazzling light meant the same thing. Now, light is known to be one of the forms in which force manifests itself, convertible into the other force-forms, and the other force-forms, convertible into it. Still, the account of the transfiguration, if the evidence on which it rests were at all trustworthy, would be a very important credential to the supernatural pretensions of Jesus, under the claim that such special manifestations of a Power beyond and supreme over Nature were made so as best to suit the comprehension of those for whom they were intended, and as showing that Jesus could so command the force-forms of Nature as to irradiate his person at will. What, then, is the evidence? The persons who witnessed the occurrence were Peter, James, and John, and while it lasted they were in a state of bewilderment, and part of the time asleep. Jesus commanded them to conceal what they had seen until after his resurrection. Matthew, therefore, could not have heard of it at the time it happened, and he does not state from whom he received the particulars he narrates. Perhaps from the forward Peter, who, in his epistle quoted above, confirms the account. For, strange to say, John, the other eye-witness, has not one word in support of the supernatural appearance on the mount of transfiguration. Of three eyewitnesses there is only the testimony of one, Peter; and although John, one of the others, has written an account of the life of Jesus, he passes by this striking event in silence. So the evidence fails. Can it, then, have been a dream of Peter, when with Jesus, James, and John in some lonely mountain in Galilee?

But though John does not mention the marvellous transfiguration, and the voice from heaven then heard, he does narrate a somewhat similar occurrence, in broad day, at Jerusalem. But Matthew, who would have been present, does not confirm John's statement. What, then, is to be said? What faith can righteously rest on such testimony?

(c.) The testimonies of the devils (Matt. viii. 29; xxxi. 32; Mark i. 24; i. 34; iii 11, 12; v. 7; Luke iv. 34; iv. 41; viii. 28).

(1.) Devils, who came out of many, cried out that Jesus was Christ, the Son of God; but he rebuked them and suffered them not to speak, because they knew him. (2.) Some expressed fear of his power thus, "Let us alone, what have we to do with thee, Jesus of Nazareth? Art thou come to destroy us? to torment us before the time? I know thee who thou art, the Holy One of God." (3.) The following remarkable event is recorded: A man with an unclean spirit, untamable, who had burst asunder his chains and fetters, and was always, night and day, in the mountains and among the tombs, crying and cutting himself with stones, saw Jesus afar off, ran and worshipped him, exclaiming, "What have I to do with thee, Jesus, the Son of the most high God? I adjure thee by God that thou torment me not." Jesus asked him, "What is thy name?" and he replied, "My name is Legion, for we are many." Jesus cast out the legion, and, at their own request, gave c them permission to enter a herd of two thousand swine feeding close by, with the result that they all ran violently down a steep place into the sea, and were choked. What became of the devils is not mentioned.

Paul (1 Cor. x. 20) states, "The things which the Gentiles sacrifice, they sacrifice to devils, and not to God," devils here being synonymous with the idols or gods of the Gentiles. In the following four passages in which devils are mentioned in the Old Testament (Lev. xvii. 7; Deut. xxxii. 17; 2 Chron. xi. 15; Psalm cvi. 37), the word is used in exactly the same sense as by Paul. "Devils," then, as indwelling unclean spirits, madly swaying their victims, or producing lunacy, blindness, dumbness, or other infirmities, are beings or influences quite unknown to the Old Testament writers. Moreover, in the Old Testament the heathen gods, though called devils, are derided as powerless. (See Elijah's mockery of Baal, and such passages as Psalm cxxxv. 15, 18.) In the fourth Gospel, too, there is scarcely any confirmation of the unclean spirits. The Jews, indeed, tell Jesus that he hath a devil, and is mad, showing a belief on their part of possession in some form; but John does not corroborate one single instance of the devil-manifestations and exorcisms so prominently set forth in the other Gospels. If, then, in Jesus' time there was a notion current among the Jews that madness and natural diseases and defects were manifestations of the so-called evil principle, or were evil spirits or influences, whence was this most erroneous doctrine derived? Certainly not from their own Old Testament writings. So far, therefore, the Old Testament discredits the accounts in Matthew, Mark, and Luke of the devils and their influences. It does not recognise beings or powers acting in the way described. And John's silence constitutes a fatal defect in the evidence in support of these manifestations.

In the Old Testament (in such passages as Lev. xix. 31; xx. 27; Deut. xviii. 9, 12; Isa. viii. 19) reference is made to wizards, witches, and familiar spirits. Although the more ignorant and idol-affecting Israelites, and the Godforsaken Saul were attracted by such pretences, it does not appear that Moses or the prophets believed that they were real powers. Isaiah viii. 19 implies the contrary. Moses calls them the "abominations of those nations" whom the Lord was to drive out of Palestine from before the children of Israel. The gift they assumed was blasphemy against Jehovah, usurpation of the prerogative of him who "alone doeth wondrous things;" and this being so, they were to be cut off from among his people. But the possession of a familiar spirit with a gift of divination, or the power of witchcraft, or the evil spirit which put dissension between Abimelech and the Shechemites, or the evil spirit from the Lord manifested in Saul's jealousy of David, and occasionally succumbing to the charm of David's harp, or the lying spirit put by the Lord in the mouths of the prophets of Ahab, differ greatly from such evil spirits,—personal, separate from their victims, entering in, and coming out of them, as the "legion" mentioned above, or the demon-torn youth (Luke ix. 37, 42), or the devil that was dumb (Luke xi. 14).*

* The Assyrians and Babylonians, however, among whom the

captive Jews were afterwards placed, believed that the world

teemed with malignant spirits, who were the authors of the

various diseases to which mankind are subject. The Jews of

the Talmud were imbued with the same idea.

In the Apocryphal book of Tobit, also, the evil spirit Asmodeus, who killed the seven husbands of Raguel's daughter as they approached her, and who was at last driven forth by the smoke of the "ashes of the perfumes and of the heart and liver of a fish," so that he "fled into the utmost parts of Egypt, and the angel bound him," differs from the New Testament evil spirits in that he is represented rather as "attendant" on the maiden, than as "indwelling," but has this similarity to them that he is mentioned as a distinct person, exercising a malignant influence.

In a stela found at Thebes it is recorded that Barneses XII., while on his way through Mesopotamia to collect tribute, was so enraptured with the charms of a chieftain's daughter that he married her. Her father afterwards came to Thebes, to beg of the king the services of a physician to effect the cure of a younger daughter possessed by an evil spirit. The physician sent, like Jesus' disciples (Luke ix. 40), could not cast him out, and eleven years later the father went again to Thebes to sue the gods of Egypt for more effectual aid. The king then gave him the use of the ark of the god Chons, which on arriving in Mesopotamia, after a journey of eighteen months, immediately drove forth the evil spirit from out his victim. On this the Mesopotamian chieftain was unwilling to part with the ark; but after retaining it three years and nine months, being warned in a dream in which he saw the deity fly back to Egypt in the shape of a golden hawk, he returned the ark to Egypt, in the thirty-third year of Rameses.