The Project Gutenberg EBook of Frédérique; vol. 1, by Charles Paul de Kock This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Frédérique; vol. 1 Author: Charles Paul de Kock Release Date: December 17, 2011 [EBook #38331] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRÉDÉRIQUE; VOL. 1 *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

Copyright 1905 by G. Barrie & Sons

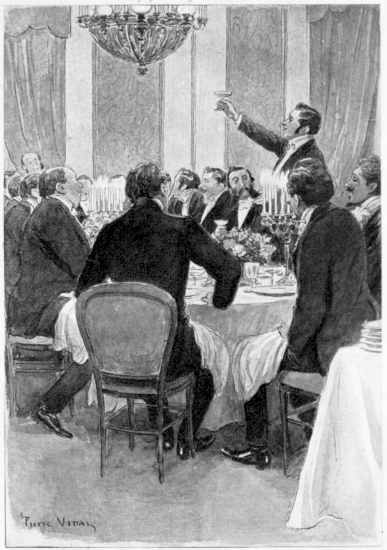

A GENTLEMEN'S DINNER AT DEFFIEUX'S

"Now, then, messieurs, as one should never be ungrateful, as one should bestow at least a single thought on those who have made one happy, I drink to my mistresses, messieurs, to whom I bid a last farewell to-day!"

THE JEFFERSON PRESS

BOSTON NEW YORK

Copyrighted, 1903-1904, by G. B. & Sons.

FRÉDÉRIQUE

| I | —A GENTLEMEN'S DINNER AT DEFFIEUX'S |

| II | —THE CHAPTER OF CONFIDENCES.—THREE SOUS |

| III | —BLIND-MAN'S-BUFF.—AT THE WINDOWS.—IN A BALLOON |

| IV | —THE LOST KEY |

| V | —FILLETTES, GRISETTES, AND LORETTES |

| VI | —MONSIEUR FOUVENARD'S BONNE FORTUNE.—THE GINGERBREAD WOMAN |

| VII | —MADEMOISELLE MIGNONNE |

| VIII | —AN EXPEDIENT |

| IX | —THE WEDDING PARTY IN THE FRONT ROOMS |

| X | —A PINCH OF SNUFF.—A FAMILY TABLEAU |

| XI | —MADAME FRÉDÉRIQUE |

| XII | —THE WEDDING PARTY IN THE REAR ROOM |

| XIII | —THE BRIDE AND GROOM AND THEIR KINSFOLK |

| XIV | —A YOUNG DANDY.—A DELIGHTFUL HUSBAND |

| XV | —A VAGABOND |

| XVI | —MADAME LANDERNOY |

| XVII | —MADAME SORDEVILLE AND HER RECEPTION |

| XVIII | —BARON VON BRUNZBRACK |

| XIX | —THE LITTLE SUPPER PARTY |

| XX | —BETWEEN THE PIPE AND THE CHAMPAGNE |

| XXI | —CONFIDENCES |

| XXII | —MONSIEUR DAUBERNY |

| XXIII | —A MOMENT OF FORGETFULNESS |

| XXIV | —COQUETRY AND BACCARAT.—A FIASCO |

| XXV | —A YOUNG MOTHER |

| XXVI | —THE SQUIRREL |

| XXVII | —A CONSULTATION |

| XXVIII | —A WORD OF ADVICE.—AN ASSIGNATION |

| XXIX | —AN ENCOUNTER ON THE CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES |

| XXX | —CONFIDENCE IS OF SLOW GROWTH |

| XXXI | —DISAPPOINTED HOPES |

| XXXII | —A REVELATION |

"A lady said to me one day:

"'Monsieur Rochebrune, would it be possible for you to love two women at once?'

"'I give you my word, madame,' I answered, frankly, 'that I could love half a dozen, and perhaps more; for it has often happened that I have loved more than two at the same time.'

"My reply called forth, on the part of the lady in question, a gesture in which there was something very like indignation, and she said, in a decidedly sarcastic tone:

"'For my part, monsieur, I assure you that I would not be content with a sixth of the heart of a man whom I had distinguished by my favor; and if I were foolish enough to feel the slightest inclination for him, I should very soon be cured of it when I saw that his love was such a commonplace sentiment.'

"Well, messieurs, you would never believe how much injury my frankness did me, not only with that lady—I had no designs upon her, although she was young and pretty; but in society, in the houses which she frequents, and at which I myself visit, she repeated what I had said to her; and many ladies, to whom I would gladly have paid court, received me so coldly at the first compliment that I saw very plainly that they had an unfavorable opinion of me—all because, instead of being a hypocrite and dissembler, I said plainly what I thought. I tell you, messieurs, it's a great mistake to say what you think, in society. I have repented more than once of having given vent to those outpourings of the heart which we should confide only to those who know us well enough to judge us fairly; but, as society is always disposed to believe in evil rather than in good, if we have a failing, it is magnified into a vice; if we confess to a foible, we are supposed to have dangerous passions. Therefore, it is much better to lie; and yet, it seems to me, that, if I were a woman, I should prefer a lover who frankly confessed his infidelities, to one who tried to deceive me."

"If I were a woman, I should prefer a man who loved nobody but me, and would be faithful to me."

"Oh! parbleu! what an idea! It isn't certain, by any means, that all women would prefer such a man. There are faithful lovers who are so tiresome!"

"And inconstant ones who are so attractive!"

"I go even further, myself, and maintain that the very fact that a man is faithful more than a little while makes him a terrible bore. He drives his mistress mad with his sighs, his protestations of love; he caresses her too much; he thinks of nothing but kissing her. There's nothing that women get so tired of as of being kissed."

"Oho! do you think so, my little Balloquet? That simply proves that you're a bad kisser, or that you're not popular. On the contrary, women adore caressing men; I know what I'm talking about."

"Oh! what a conceited creature this Fouvenard is! Think of it, messieurs! he would make us believe that the women adore him!"

"Well! why not?"

"Your nose is too much turned up; women like Roman noses. You can never look sentimental with a nose like a trumpet."

"So you think that a man must have a languorous, melancholy air, in order to make conquests, do you? Balloquet, you make me tired!"

"I'll give you points at that game whenever you choose, Fouvenard. We will take these gentlemen for judges. Tell the waiter to bring up six women,—of any condition and from any quarter, I don't care what one,—and we'll see which of us two they will prefer. What do you say?"

Young Balloquet's proposal aroused general laughter, and a gentleman who sat beside me observed to me:

"It might well be that the ladies wouldn't have anything to say to either of them. What do you think?"

"I think that any ladies who would consent to grace our dessert, at the behest of a waiter, would do it only on one condition; and men don't make a conquest of such women, as they give themselves to everybody."

"Parbleu! messieurs, it is very amiable of us to listen to this discussion between Fouvenard and Balloquet as to which of them a woman would think the uglier; for my part, I prefer to demand an explanation of what Rochebrune said just now. He talked a long while, and I've no doubt he said some very nice things; but as I didn't quite understand him, I request an explanation of the picture, or the key to the riddle, if there is one."

"Yes, yes, the key; for I didn't understand him, either."

"Well, I did; I followed his reasoning: he says that a man can love a dozen women at once."

"A dozen! why not thirty-six? What Turks you are, messieurs! Rochebrune didn't say that."

"Yes, I did. Isn't it true?"

"Messieurs, I desire the floor."

"You may talk in a minute, Montricourt—after Rochebrune."

"A toast first of all, messieurs!"

"Oh! of course! When the host proposes a toast, we should be boors if we refused to honor it.—Fill the cups, waiter!"

"This is very pretty, drinking champagne from cups; it recalls the banquets of antiquity—those famous feasts that Lucullus gave in the hall of Apollo, or of Mars."

"Yes! those old bucks knew how to dine; every one of his suppers cost Lucullus about thirty-nine thousand francs in our money."

"Bah! don't talk to me about your Romans, my dear fellow; I shall never take those people for models. They spent a lot of money for one repast, but that doesn't prove that they knew how to eat. In the first place, they lay on beds at the table! As if one could eat comfortably lying down! It's like eating on the grass, which is as unpleasant as can be; nobody likes eating on the grass but lovers, and they are thinking of something besides eating. As for your cups, they're pretty to look at, I agree, but they're less convenient for drinking than glasses, and the champagne doesn't foam so much in a cup; and then, you don't have the pleasure of making it foam all over again by striking your glass."

"Say what you will, Monsieur Rouffignard, the Romans knew how to live."

"Because they wore wreaths of roses at their meals, perhaps?"

"Well, it isn't so very unpleasant to have flowers on your head."

"Oh! don't talk to me, Monsieur Dumouton; let's all try wearing a wreath of roses, and you'll see what we look like—genuine buffoons, paraders, and nothing else!"

"Simply because our dress isn't suited to it, monsieur; our style of dress is very disobliging, it isn't suited to anything; with the tunic and cloak falling in graceful folds, the wreath on the head was not absurd. And the slaves who served the ambrosia—in tableau vivant costumes—weren't they attractive to the eye?"

"Oh, yes! slaves of both sexes! That was refined, and no mistake. I tell you that your Romans were infernal debauchees; they put up with—aye, cultivated all the vices! Why, monsieur, what do you say to the Senators who had the effrontery to propose a decree that Cæsar, then fifty-seven years of age, should possess all the women he desired?"

"'Ah! le joli droit! ah! le joli droit du seigneur!'"

"I would like right well to know if he made use of that right."

"Fichtre! he must have been a very great man!"

"Don't you know what used to be said of him: that he was the husband of all the women?"

"Yes, and we know the rest."

"I say, you, over there! Haven't you nearly finished talking about your Romans?"

"What about our host's toast?—Come, Dupréval, we're waiting; the guns are loaded, the matches lighted."

"Silence at the end of the table! Dupréval is going to speak! Great God! what chatterers those fellows are!"

"It's not we, messieurs, that you hear; it's the music. Hark, listen! they're dancing; there are wedding parties all about us—two or three at least."

"What is there surprising in that? Aren't there always wedding feasts going on at Deffieux's?"

"For my part, if I kept a restaurant, and had such a class of patrons, I would take for my sign: the Maid of Orléans."

"Oh! that would be very injudicious: many brides would refuse to have their wedding feasts at your place."

"Hush! Dupréval is getting up; he's going to speak."

"As you know, messieurs, this is my last dinner party as a bachelor, for I am to be married in a fortnight. Before settling down, before becoming transformed into a sedate and virtuous mortal, I determined to get you all together; I wanted to enjoy once more with you a few of those moments of freedom and folly which have—a little too often, perhaps—marked my bachelor days with a white stone. Now, then, messieurs, as one should never be ungrateful, as one should bestow at least a single thought on those who have made one happy, I drink to my mistresses, messieurs, to whom I bid a last farewell to-day!"

"Here's to Dupréval's mistresses!"

"And to our own, messieurs!"

"To the ladies in general, and to the one I love in particular!"

"To their shapely legs and little feet!"

"To their blue eyes and fair hair!"

"I prefer brunettes!"

"To their graceful figures!"

"To the Hottentot Venus!"

"To the destruction of corns on the feet!"

"Oh! of course, Balloquet has to make one of his foolish remarks!"

"Messieurs, pardon me for interrupting you, but, in proposing a toast to my mistresses, pray don't think that I mean to imply that I have several. I am no such rake as Rochebrune is, in that respect; one at a time is enough for me. I intended simply to address a parting thought to those I have had during the whole of my bachelor life. That point being settled, I now yield the floor to our friend, who, I believe, was about to reply to the questions that had been put to him, when I proposed my toast."

Thereupon the whole company turned their eyes toward me, for, I fancy, you understand that I am Rochebrune. Perhaps it would not be a bad idea for me to tell you at once what I was doing and in whose company I was at that moment, at Deffieux's. Indeed, there are people who would have begun with that, before introducing you to a dinner party at which the guests are still unknown to you; but I like to turn aside from the travelled roads—not from a desire to be original, but from taste.

What am I? Oh! not much of anything! For, after all, what does a man amount to who has not great renown, great talent, an illustrious reputation, or an immense fortune? A clown, a Liliputian, an atom lost in the crowd. But you will tell me that the world is made up in larger part of atoms than of giants, and that the main thing is not so much to fill a large space as to fill worthily such space as one does fill.

Unluckily, I was not wise enough for that. Having come into possession of a neat little fortune rather early in life,—about fifteen thousand francs a year,—but having neither father nor mother to guide and advise me, I was left my own master rather too soon, I fancy; for while the reason matures quickly in adversity, the contrary is ordinarily true in the bosom of opulence.

You see some mere boys, who are compelled to work in order to support their families, exhibit the intelligence and courage of a full-grown man. But place those same youths in the lap of Fortune, and they will do all the foolish things that come into their heads. Why? Because, no doubt, it is natural to love pleasure; and when we are prudent and virtuous, it is very rarely due to our own volition, but rather to circumstances, and, above all, to adversity. Which proves that adversity has its good side. But, with your permission, we will return to myself.

My name is Charles Rochebrune. I am no longer young, having passed my thirtieth birthday. How time flies! it is shocking! to be thirty years old and no further advanced than I am! Indeed, instead of advancing, I believe that I have fallen back. At twenty I had fifteen thousand francs a year, and now I have but eight. If I go on like this, in a few years more I shall have nothing at all. But have I not acquired some experience, some talent, in return for my money? No experience, I fancy, as I constantly fall into the same errors I used to be guilty of years ago. And talent?—very little, I assure you! because I attempted to acquire all the talents, and could never make up my mind to rely on a single one. I had a vocation for the arts; the result was that I tried them all, and know a little something of each one; which means that I know nothing at all of any value. Painter, sculptor, musician, poet, in turn, I have grazed the surface of them all, but gone to the root of none. Ah! lamentable fickleness of taste, of character! No sooner had I studied a certain thing a little while, than the fatal tendency to change, which is my second nature, caused me to turn my ambition toward some other object. I would say to myself: "I have made a mistake; it is not painting that electrifies me, that sets my soul on fire, but music."—And I would lay aside my brushes, to bang on a piano; and when I had made it shriek for an hour, I would imagine that I was a composer and could safely be employed to write an opera.

There is but one sentiment which has never varied, in my case, and that is my love for the ladies; and yet they say that in my relations with them I have retained my fondness for changing. But if one loves flowers, must one pluck only a single one? I love bouquets à la jardinière.

And, after all, who can say that I would not have been constant if I had found a woman who loved me dearly, and who continued to love me, no matter what happened? This last phrase means many things, which the ladies will readily understand. But I have one very great failing as to them. I will not confide it to you yet; you will discover it soon enough, as you become better acquainted with me.

I said a moment ago that my parents—that is to say, my father—left me some property. My mother had had two husbands, and I was the son of her second marriage. As she had nothing when she married my father, it is to him that I am indebted for the fortune which I have employed so ill hitherto.

But, after all, have I employed it so ill, if I have been happy? Ah! the fact is that I am not at all certain that I have been really happy in this life of dissipation, folly, incessant change, regrets, and hopes so often disappointed. I determined to settle down, to do what is called making an end of things, which means marrying; albeit marriage is not always the end of our follies, and is often the beginning of our troubles. I loved my fiancée; I was not madly in love with her, but I liked her, and I thought that she was fond of me. An unforeseen occurrence broke off my projected marriage, and since then I have entirely renounced all such ideas, because a similar occurrence might have a similar result. What was it? Ah! that is my secret; I am not as yet intimate enough with you to tell you everything.

I seem to have been talking a long while about myself; you must be sadly bored. I propose now to make you acquainted with most of the gentlemen who were my table companions at Deffieux's; I say "most of them," for there were fifteen of us, and I did not know them all.

Let us begin with the host, Dupréval, who was giving the dinner, as he told us, to commemorate his final adieu to his bachelorhood.

Dupréval is a solicitor; an excellent fellow, neither handsome nor ugly, but a financier, a man of figures and calculations; he is entering into marriage as one enters into any large commercial speculation. He will certainly keep his word and abandon the follies of a bachelor, or I shall be very much astonished; he is a man who will make his way in the world; he has a goal—wealth; and he marches constantly toward it, never turning aside from the path.

I admire such men, unbending in their determination, and incapable of being turned aside from the line of conduct they have marked out for themselves; I admire them, but I shall never imitate them. Chance is such a fascinating thing, and it is such good fun to trust to it!

Next to Dupréval sat a stout young man, of medium height, but heavily built, high-colored, with the bloom and brilliancy of the peach ever on his cheeks. Unluckily, that never-failing freshness of complexion was his only beauty, if, indeed, such pronounced coloring is a beauty. His face beamed with good humor and denoted a leader in merrymaking; his mouth was a considerable gulf, and his eyes were infinitesimal; but, by way of compensation for occupying so little space, they were constantly in motion and very bright, their expression being decidedly bold when they rested upon the fair sex. His head was covered with a forest of flaxen hair. Such was Monsieur Balloquet, medical student; indeed, I believe he was a full-fledged doctor; but he had little practice, or, rather, none at all; he thought only of enjoying himself, like many doctors of his age. However, I do not mean to speak ill of Balloquet; for he was a very good fellow, and we were good friends.

Next to him was a young man of medium height, very thin, and with a very yellow complexion. An enormous beard, moustache, and whiskers covered so much of his face that one could see little more than his nose, which was long and thin, and his eyes, which were sunken and overshadowed by eyebrows that threatened to spread like his beard. This gentleman had an air of excessive weariness; that was all that one could make out beneath the chestnut shrubbery that had overgrown his face. His name was Fouvenard. I believe that he was in trade; but his business, whatever it was, seemed to have worn him out. But that fact did not prevent him from talking all the time of his past conquests and his present love affairs.

At my left was a rotund old party, with an amiable expression, and a full-blown, rubicund face. It was Monsieur Rouffignard, auctioneer, who was no longer young, but held his own manfully with the young men. He did not lag behind at table; indeed, I have an idea that he did not lag behind anywhere.

The next beyond was a very good-looking young man named Montricourt. He had rather a self-sufficient air, and, if you did not know him well, you might have called him conceited; but on talking with him, you found him much more agreeable than his pretentious costume would lead you to suppose.

Next came a man of thirty-six to forty years of age, rather ugly than handsome, with a round face, smooth hair, a shifty eye, and an equivocal smile, who spoke very slowly, and always seemed to reflect upon what he was going to say. His tone was honeyed, and his manners excessively polite. He was a clerk at the Treasury, by name Monsieur Faisandé. When someone, at the beginning of the dinner, said a few words that were a trifle free in tone, I noticed that he frowned, as a lady might have done who had strayed among us by mistake. After drinking five or six different kinds of wine, he pursed his lips less; but at every loose word that escaped us,—and such things are inevitable at a men's dinner which has no diplomatic object,—Monsieur Faisandé exclaimed:

"Hum! hum! Oh! messieurs, that's a little too bad! you go too far!"

"I may be mistaken," I thought; "but I would stake my head that Monsieur Faisandé is a hypocrite. That offended modesty is, to say the least, out of place, and almost discourteous toward the rest of us; for it seems a criticism of our conversation. In heaven's name, did the man think that if he came to dinner with a party of men, most of them young, and all high livers, he would hear no broad talk? There can be nothing so insufferable at a party as one of those people who seem determined to benumb your gayety by their sullen looks and their stiff manners. When such a person does appear in a merry company, he should be courteously turned out of doors."

What would you say of a doctor who should keep crying out during a dinner:

"Don't eat so much; you'll make yourself ill; don't take any of this, it's indigestible; don't drink any of that wine, it's too strong!"

No, indeed; at table the doctor disappears, or allows you to eat and drink anything; nobody can be more accommodating, even with his patients. And if doctors are so indulgent to the caprices of the stomach, by what right does a pedant or a hypocrite undertake to put my mind on a strict diet, and reprove the freedom of my conversation? There is an old proverb that says: "We must laugh with the fools;" or, if you please: "We must howl with the wolves."—Whence I conclude that it is, to say the least, in bad taste to appear shocked by a loose word or a vulgar jest, in such a company; and this Monsieur Faisandé's virtue seemed to be all the more doubtful because of his behavior.

In my review of the guests I must not forget Monsieur Dumouton, although I only knew him then from having been once or twice in his company. He was an individual who did not seem to be universally popular. Not that he had an unattractive physique; on the contrary, he was a tall, slender man, rather well than ill looking; his face was amiable, his strongly marked features did not lack character; his bright, black eyes and high color seemed to indicate a native of the Midi, although there was no trace of such origin in his speech. But poor Monsieur Dumouton was always dressed in such strange fashion, that it was difficult, on glancing at his costume, to avoid forming a melancholy opinion of his resources.

Imagine a threadbare coat, once green, but beginning to turn yellow, and made after the style of a dozen years before—that is to say, very short in front; in truth, it was also short in the skirts, which were very scant, and hardly hid the seat of his trousers, which were olive green and only just reached to his ankles, and fitted as close about the thigh and knee as a rope dancer's tights. His boots were always innocent of blacking, but, by way of compensation, were often coated with mud. Add to all this a plaid waistcoat, double-breasted, and buttoned to the chin; a black cravat, twisted into a rope; no shirt, collar, or gloves; and a beard that was usually of about three days' growth: such was Monsieur Dumouton's ordinary costume.

You will assume, perhaps, that he had donned other clothes to dine with us; if so, you would make a mistake: it seemed that he was not fond of change. Perhaps he had his reasons for that. However, he had made some slight ameliorations: he had a false collar, and a white muslin cravat, the ends of which were tied in a large knot that stood out conspicuously against the soiled background formed by the coat and waistcoat.

I cannot tell why it was that I imagined I had seen that cravat playing the part of draw-curtain at a window; it was an unkind thought, I confess, and I did my utmost to discard it; but, as you must know, evil thoughts are more persistent than good ones; and whenever my eyes fell on the ends of that enormous cravat, it seemed to me that I was sitting by a window.

I must tell you now who this gentleman was who dressed so ill. You will be greatly surprised to learn that he was an author—yes, a "truly author," as the children say; a man who wrote his plays himself,—especially as he had not the wherewithal to buy any,—and plays which were often very pretty, and which had been acted, and were being acted still, with success.

But, you will tell me, we have passed the time when men of letters, dramatic authors, earned barely enough to keep them alive; to-day, the stage sometimes leads to wealth even; but it does not follow by any means that all the nurslings of the Muses are destined to acquire wealth. One may be unfortunate, dissipated, reckless; and once in the mire, it is hard to extricate one's self therefrom, unless one has a firm, immovable determination, unbounded courage, and a still greater capacity for work; and everybody has not these. I cannot say what had been the trouble with Monsieur Dumouton, what reverses he had had; I did not know just how he was placed at that time; but, judging from his costume, it was impossible to escape the supposition that he had known adversity. Moreover, a few words that Dupréval let fall concerning this man of letters recurred to my memory. He always said, when Dumouton was mentioned:

"Poor fellow! he has all he can do to keep body and soul together! He has plenty of intelligence, too; but he's such a careless devil!"

Whence I concluded that Dumouton was a penniless author; I do not say, a worthless author. However, I was delighted to be in his company; for he was jovial, clever, and entirely free from conceit; so what did I care for his threadbare coat? I saw around the table several handsomely dressed men, who amounted to nothing under their fine clothes.

I have introduced you now to all of my companions who were not strangers to me; as for the others—why, if they say anything that makes it worth our while to listen to them, we shall not fail to hear it.

I have told you that all eyes were fixed on me, and that everybody was waiting to hear what I might have to say in justification or explanation of what I had advanced on the subject of men who love several women at once. For my part, I admit that, far from thinking about what reply I should make to those gentlemen, I was busily engaged in watching Dumouton, who was stowing away the contents of all the dessert plates within his reach, although he was not eating. When he could find nothing else on the plates that were near him, he attacked one of those pasteboard structures, usually covered with candies or small cakes, which no one ever touches, because they are intended simply as decorations for the table, and one of them often does duty for several months. I saw one of the waiters glare at him furiously when he saw what he was doing, and I said to myself:

"I wonder if that poor Dumouton is in the same position as Frédérick Lemaître in Le Joueur, when he stuffs bread into his pocket, saying: 'For my family!'"

"Well, Rochebrune! are you going to speak to-day?" said Dupréval.

"What do you mean?"

"What you were going to tell us."

"Oh! I beg your pardon, messieurs! You see, the wine we have drunk has confused my memory, and I should find it hard to recall what I said to you just now. And, to tell you the truth, instead of making speeches about the best way of loving, which never prove anything, because every man loves in his own way, which is the best to his mind, it seems to me that it would be much more amusing for each of us to tell about one of his bonnes fortunes, old or new, according to his pleasure.—What do you say, messieurs?"

My suggestion was welcomed by enthusiastic plaudits; only Monsieur Faisandé made a wry face, and muttered:

"The deuce, messieurs, tell one of our bonnes fortunes! Why, that's a very delicate subject. I didn't suppose that such things were talked about, as a general rule. Discretion, messieurs, is the duty of an honorable man, and, above all, of a lady's man."

"Oh! bless my soul, Monsieur Faisandé, if you don't mention any names, there's no indiscretion; and, as we are entitled to go back to ancient history, how in the devil are you going to recognize the characters?"

"This Monsieur Faisandé is very austere and very modest," murmured my neighbor, the bulky Rouffignard. "He is very foolish to venture with ne'er-do-wells of our temper."

"Especially," said Montricourt, "as the fellow's a great nuisance."

"Well, then, messieurs, Rochebrune's suggestion being adopted, who's to begin?"

"Parbleu! yourself, Dupréval; the honor is yours."

"Very good. Then it will be my right-hand neighbor's turn, and so on around the table."

Dupréval emptied his glass, to put himself into a more suitable disposition for telling his story. Meanwhile, I watched Dumouton, who had entirely stripped one ornament and persistently kept his hands out of sight under the table. As some of the guests continued to converse, Dupréval struck his glass with his knife and cried:

"Silence, messieurs!"

Everybody ceased talking, took a drink, and prepared to listen to the host, who began thus:

"At that time, messieurs, I was a third-class clerk to a solicitor, and my pockets were seldom well lined. My father gave me six francs a week for pocket money; as you may imagine, my diversions were very few, and I often spent my whole allowance on Sunday; then I was obliged either to procure my amusement gratis during the week, or to abstain entirely; the latter alternative, I believe, is disagreeable at any age.

"One fine day—or rather, one evening—I was at the play, and found myself behind two very pretty grisettes—there were grisettes in those days; unluckily, they are now vanishing from the face of the earth, like poodles and melon raisers. For my part, I regret them exceedingly—not the melon raisers or the poodles, but the grisettes; they are replaced nowadays by lorettes, who can't hold a candle to them. Our friend Dumouton, by the way, has done a very amusing little sketch on grisettes, lorettes, and fillettes, which I will request him to repeat to you in a moment, and——"

"Question!"

"The speaker is not keeping to his subject."

"That is true, messieurs. Excuse me.—Well, I was at the play, behind two grisettes, and I had only three sous in my pocket; that was all I had left after buying my ticket, and it was Monday. Such was my plight. However, that didn't prevent me from making eyes at one of the damsels, whose saucy face attracted me. For her part, she responded promptly to my glances; the firing was well maintained on both sides, and seemed to promise a very warm engagement. I opened a conversation, and she answered. The young ladies were not prudes, by any means; they laughed heartily at every joke that I indulged in, and I indulged in a good many; I was in funds in that respect only.

"It was summer, and the theatre was very warm. Several times my grisettes had wiped their faces, crying:

"'Dieu! how hot it is!'

"'How I would like a good, cool drink!'

"'That's so; something cool and refreshing would go to the spot, pure or with water.'

"When they expressed themselves in such terms, I made a pretence of looking about the house, humming unconcernedly. With my three sous, I could have given each of them a stick of barley sugar, but that is hardly refreshing. I remember that an orange girl persisted in walking back and forth in front of us, and in holding her basket under my nose, and that I trod on her foot so hard that the poor girl turned pale and hurried away, shrieking.

"At last the play came to an end, and my grisettes went out; I went with them, still talking, but taking care to fall behind when we passed a café. They did not live together; and when I was alone with the one to whom I was particularly attentive, I obtained a rendezvous for the next day, at nightfall.

"When the next day came, I was no richer, for my office mates were, for the most part, as hard up as I. However, I was faithful to my appointment, all the same, still with my three sous in my pocket.

"My charmer was on time. I walked her about the streets at least two hours. She remarked from time to time that she was tired; but, instead of replying, I would passionately squeeze one of her hands, and the heat of my love made her forget her fatigue. Unluckily, she lived with an old relation—of which sex I don't know; I do know that that fact made it impossible for me to go to her room, and I had to leave her at her door.

"The next evening, at dusk, we met again. I had the shrewdness to take her outside the barrier; it was a superb night, and we strolled along the new boulevards. I tried to coax her out into the country; she refused, on the ground that she was tired. She expected me to suggest a cab, no doubt, but I knew better.

"The next day, another rendezvous. My grisette wanted to go to the Jardin des Plantes. When we came to Pont d'Austerlitz, I had to spend two of my three sous, and for tolls, not for refreshment; that seemed cruel, but there was no alternative. We strolled a long while around the garden, which is an admirable place for lovers, because some of the paths are always deserted; my conquest was affable and sentimental, but I replied all awry to what she said and to the questions she asked. I was haunted by a secret apprehension; I was thinking about going home, about Pont d'Austerlitz, which she would certainly insist on crossing again, as it was the shortest way to her house; and I said to myself: 'I have only five centimes left. Shall I pay for her and let her go alone? Shall I make her take another route? Or shall I run across at full speed and defy the tollman?'—Neither plan seemed to promise well, and you can imagine that my mind was in a turmoil; so that my young companion kept saying to me:

"'What on earth are you thinking about, monsieur? You don't answer my questions; you seem to be thinking about something besides me. You're not very agreeable this evening.'

"I did my utmost to be talkative, attentive, and gallant; but, in a few minutes, my preoccupation returned. At last my grisette, irritated by my behavior, declared that she wanted to go home, that she was tired of walking, that I had walked her about so much the last two or three days that her heels were swollen as badly as when she used to have chilblains. So she dragged me away toward the exit. That was the decisive moment. I began to talk about going home another way that I knew about, which was much pleasanter than the way we had come. But my grisette took her turn at not listening, and when we were out of the garden, and I tried to lead her to the left, she hung back.

"'Why, where are you going?' she cried.

"'I assure you that it's much pleasanter and shorter by the other bridge.'

"'You're joking, I suppose! the idea of going back through narrow streets instead of the boulevards! Monsieur is making fun of me!'

"I couldn't possibly prevail upon her; she dropped my arm and made straight for the bridge.

"'Well!' I said to myself, with a sigh; 'there's nothing left for me to do.'

"I followed her. When she reached the tollman, I tossed my last sou on the table and said to my charmer:

"'Go on, I will follow you.'

"She crossed the bridge, supposing that some natural cause detained me a moment. Meanwhile, I gazed at the river, considering whether I would jump in and swim to the other bank. But I'm not a fine swimmer, and I did not feel as brave as Leander, although the Seine is narrower than the Hellespont. Instead of swimming, I ran along the quays to the next bridge; when I got there, I was almost out of breath, but that did not prevent me from running across the bridge, then back along the Seine to the beginning of Boulevard Bourdon. But that is quite a long distance, and, although I ran almost all the way, it took quite a long time. I arrived at last, but I looked in vain for my inamorata; I could not find her. Tired of waiting for me, or piqued by my failure to overtake her, she had evidently gone home alone.

"The next day, I went to our usual place of meeting, but she did not come. I waited there for her several days—to no purpose; and at last I wrote to her, requesting a reply. She sent me a very laconic one: 'You made a fool of me,' she wrote; 'and after walking my legs off for four days, as if I was an omnibus horse, you left me in the middle of a bridge. I've had enough of it, monsieur; you won't take me to walk any more.'—And thus that intrigue came to an end; for I never saw my grisette again; but I haven't forgotten the adventure. Let it serve you as a lesson, messieurs, if you should ever happen to find yourselves with only three sous in your pocket."

Dupréval's tale amused the company immensely. Monsieur Dumouton, who was better able, perhaps, than any of the rest of us, to understand our friend's plight, exclaimed:

"Oh! that's true! it's very dangerous to take any chances in a lady's company, if you haven't any money in your pocket! It's a thing I always avoid."

It was young Balloquet's turn. The bulky, fair-haired man opened his mouth as if he were going to sing an operatic aria, and began:

"Dupréval has just told us of an adventure which was not a bonne fortune, messieurs, for it didn't end happily for him; I propose to tell you of one that can fairly be called a genuine A-Number-One bonne fortune. It happened at a fête champêtre given by a friend of mine at his charming country place in the outskirts of Sceaux."

"Don't name the place," Monsieur Faisandé interrupted; "there's no need of it, and it might betray the originals of your story."

"Mon Dieu! Monsieur Faisandé, you seem to be terribly afraid of disclosures. Is it because you fear your excellent wife may be involved?"

The Treasury clerk turned as red as a poppy.

"I don't know why you indulge in jests of that sort, Monsieur Balloquet," he cried; "it's very bad taste, monsieur!"

"Then let me speak, monsieur, and don't keep putting your oar into our conversation; your mock-modest air doesn't deceive anybody. People who make such a show of decorum, and who are so strict in their language, are often greater libertines and rakes than those whose language they censure."

Monsieur Faisandé's cheeks changed from the hue of a poppy to that of a turnip; but he made no reply, and looked down at his plate, which led us to think that Balloquet had hit the mark. The latter resumed his story:

"As I was saying, I was at a magnificent open-air fête. There were some charming women there, and among them one with whom I had been in love a long while, but had been able to get no further than to whisper a burning word in her ear now and then; for she had a husband, who, while he was not jealous, was always at his wife's side. The dear man was very much in love with his wife, and bored her to death with his caresses. Sometimes he forgot himself so far as to kiss her before company, which was execrable form; and by dint of sentimentality and caresses he had succeeded in making himself insufferable to her. Yes, messieurs, this goes to prove what I said just now to Fouvenard: women don't like to be loved too much. Excess in any direction is a mistake. Moreover, nothing makes a man look so foolish as a superabundance of love. Well, while we were playing games and strolling about the gardens, Monsieur Three-Stars—I'll call him Three-Stars, which will not compromise anybody, I fancy—kissed his wife again before the whole company; and she flew into a rage and made a scene with him, forbidding him to come near her again during the evening. The fond husband was in despair, and cudgelled his brains to think of some means of becoming reconciled to his wife. After long consideration, he took me by the arm and said:

"'My dear Monsieur Balloquet, I believe I have found what I was looking for.'

"'Have you lost something?' said I.

"'You don't understand. I am trying to think of some way to compel my wife to let me kiss her, and it is very difficult, because she is cross with me now. But this is what I have thought of: I am going to suggest a game of blind-man's-buff, and I will ask to be it, on condition that I may kiss the person I catch, when I guess who it is. When I catch my wife, be good enough to cough, so as to let me know; in that way I shall not make a mistake, and she'll have to let me kiss her.'

"I warmly applauded Monsieur Three-Stars's plan; his idea of blind-man's-buff seemed to me very amusing. He made his proposition, it was accepted, and he was blindfolded. Now, while he groped his way about, the rest of the party thought it would be a good joke to leave him there and go to another part of the garden. I escorted Madame Three-Stars. The garden was very extensive, with grottoes and labyrinths and some extremely dark clumps of shrubbery. I will not tell you just where I took the lady, but our walk was quite long; and when we returned to our starting point, the poor husband was still groping about with the handkerchief over his eyes. When he heard us coming, he hurried toward us; I coughed,—to give him that satisfaction was the least I could do,—he named his wife and kissed her. Then, delighted with his idea, he replaced the handkerchief over his eyes, requesting to be it again. We acceded to his wish, and he was it three times in succession. That, messieurs, is what I call a bonne fortune."

"Your story is exactly after the style of Boccaccio!" laughed Montricourt.—"If this goes on, messieurs, we shall be able to publish a sequel to the Decameron."

"It's Fouvenard's turn."

The hairy gentleman passed his hand across his forehead, saying:

"I am searching my memory, messieurs. I have had so many adventures! I am afraid of mixing them up. You see, it's like calling on a man for a ballad who has written a great many; he doesn't know any, because he knows too many. I beg you to be good enough to leave me till the last; meanwhile, I will disentangle my memories and try to select something choice, with a Regency flavor."

"All right! Fouvenard passes the bank on to Monsieur Reffort.—Go on, Reffort."

Reffort was a personage who had not said four words during the dinner, but had contented himself with laughing idiotically at what the others said. He was the possessor of a more than insignificant face, and turned as red as fire when he was addressed. He rolled his eyes over the dessert, played with his knife, and murmured at last:

"Faith! messieurs, it embarrasses me to speak, because—I must admit that—on my word of honor, it has never happened to me."

"What's that, Reffort? It has never happened to you! What in the devil do you mean by that? Explain yourself."

"Can it be that Monsieur Reffort is as a man what Jeanne d'Arc was as a woman?" cried Rouffignard. "In that case, I demand that he be cast in a mould, that a statuette be made of him and sold for the benefit of the Société de Tempérance."

Roars of laughter arose on all sides. Monsieur Reffort laughed with the rest, albeit with a somewhat annoyed air, and rejoined:

"You go too far, messieurs; I didn't mean what you think, but simply that I am not a man for love intrigues. I shouldn't know how to go about it; and, faith! when my thoughts turn to love, there are priestesses of Venus, and——"

"Very good, Monsieur Reffort; we don't ask for anything more; we'll call that bonnes fortunes for cash. Next."

"Messieurs," said the gentleman who came next, in a sentimental tone, "the best day of my life was that on which I stole a garter at a wedding party, at Prés-Saint-Gervais—I made a mistake as to the leg; but I saw such a pretty one, and took it for the bride's. In fact, I didn't want to go out from under the table. Unluckily, that charming limb belonged to a lady of fifty; but she was kind enough to make me a present of her garter."

"And you have worn it on your heart ever since?"

"No; but I have kept it under glass. That's my only bonne fortune!"

"I, messieurs," said a young man, who sat next to the last speaker, "was shut up once for twelve hours in a closet full of bottles of liqueurs; and when my mistress was able at last to release me, I was dead drunk; I had tasted everything, to pass the time away. Finding me in that condition, the lady was obliged to send for a messenger, who took me on his back like a bale, and on the way downstairs let me roll down one whole flight. Since then I have had a horror of bonnes fortunes."

"Your turn, Raymond."

"I once fell in love with a lady who roomed opposite me. As you can imagine, I was always hanging out of my window. She was very pretty, but she didn't reply to my glances; indeed, she often left her window when I appeared at mine. But I wasn't discouraged by that. I followed her everywhere: in the street, in omnibuses, to the theatre; I wrote her twenty notes, but she didn't answer them, and my persistence seemed to offend her rather than to touch her heart. As I could think of nothing else to do, I determined one day to try to make her jealous. I interviewed one of the damsels to whom Monsieur Reffort alluded, and, for a consideration, she came to my rooms one afternoon. I placed her on my balcony, so that she might be in full view; I urged her to behave decently, and retired to await the result of my experiment.

"My neighbor appeared at her window. It was impossible for her not to see my damsel. I was enchanted, and said to myself: 'She sees that I am with another, and she will surely be annoyed.' Moreover, the young woman I had hired was very pretty and might pass for a creditable conquest, having, in accordance with my orders, clothed herself in a very stylish gown. But imagine my sensations when she began to smoke an enormous cigar, a genuine panetela! I tried to remonstrate; she answered that it was good form. I had become resigned to the cigar, when she suddenly called out to a young man who passed along the street: 'Monsieur Ernest, don't expect me to pose for you as Venus to-morrow. I am posing here, where I get double pay, and don't have to be all naked as I do at your studio, where I'm always catching cold in the head and other places.'

"Judge of my despair! my neighbor must have heard, for she laughed till she cried. You can imagine that I dismissed my poseuse instantly. But see what strange creatures women are! For the next few days, I was so depressed and shamefaced that I dared not show myself at my window. Well! then it was that my neighbor deigned at last to answer one of my notes, and I became the happiest of men."

"We might call that the 'window intrigue.'—Now, Roland."

Monsieur Roland was a young blade with enormous whiskers, and all the self-possession and frou-frou of a commercial traveller. He threw out his chest when he began to speak.

"I adored a lady who resisted my advances, messieurs. One day I succeeded in inducing her to go up in a balloon with me. When we were once in the air, I said to her: 'My dear love, if you continue to be cruel, I'll cut a hole in the balloon, and it will be all over with both of us.'—My charmer ceased to resist me, and I assure you, messieurs, that it's very pleasant to make love among the clouds."

"I call for an encore for that."

"And I am wondering whether Roland always has a balloon at his disposal, already inflated, to enable him to triumph over women who try to resist him."

"What, messieurs! do you doubt the truth of my story?"

"On the contrary, it is delicious," said Montricourt; "I am simply trying to think of one that would be worthy to serve as a pendant to your balloon."

"For my part, messieurs," said a tall man with blue spectacles, "as I am very near-sighted, my bonnes fortunes have almost always ended unfortunately. When I had been attentive to a young woman, if I went to see her the next day, I was sure to throw myself at her mother's knees and say sweet things to her, thinking that I was talking to the daughter. However, one day, a lady, to whom I had been paying court with marked ardor, consented to come to breakfast with me. Imagine my delight! But she said to me: 'For heaven's sake, don't keep on your spectacles, for I think you are frightfully ugly in them; I detest spectacles.'—To satisfy her, after ordering the daintiest of breakfasts and donning the most elegant costume you can imagine, I took off my spectacles and awaited the visit that was to make me the happiest of mortals. At last there was a knock at my door. I ran to open it, holding my arms in front of me, for I could see almost nothing at all, being short-sighted to the last degree; but I was certain that it was a woman who came in, because I touched her dress. I didn't give her time to speak to me—I was so madly in love! I took her in my arms; she tried to cry out, and I stifled her shrieks with my kisses. Not until it was too late did I hear her voice saying:

"'Mon Dieu! monsieur, whatever's the matter with you this morning? You must have swallowed a fulminating powder!'

"Impressed by the accent of that voice, I ran for my spectacles and put them on. Imagine my wrath! I had insulted my concierge! The excellent woman had brought me a letter from my fair one saying that it was impossible for her to come. Since then, I beg you to believe that I have never made love without my spectacles."

This tale called forth hearty laughter. Then a stout party told us at great length that his wife had been his only bonne fortune.

We all blessed that gentleman, who well deserved the Cross and our esteem.

Monsieur Faisandé's turn having arrived, he reflected, assumed a solemn expression, and held forth thus:

"Love, messieurs, is not such an entertaining, enjoyable, happy-go-lucky affair as you all seem to think. Most of you seek to enter into an intrigue solely to amuse yourselves; but the results, messieurs, all the results that may ensue from cohabitation between a man and a woman, from the carnal sin, from——"

"I was perfectly sure that Monsieur Faisandé would be more indecent than the rest of us when he began upon this subject," said Balloquet; "he has a way of preaching morality that would make a vivandière blush."

"I should be very glad to know what you consider unseemly in my language, Monsieur Balloquet?"

"Your language is excellently well chosen; it is technical; but you produce the effect of a medical book on me; they are most estimable works in themselves, but young women mustn't be allowed to read them. Pray go on, Monsieur Faisandé; I am terribly sorry that I interrupted you, you were beginning so well!"

The Treasury clerk pursed his lips and continued, emphasizing every word:

"I have never had any bonnes fortunes, messieurs; and I don't propose to begin now that I am married."

"What a hypocrite!" muttered my stout neighbor. "I don't know the fellow's wife, but I pity her; for I am convinced that she has a mighty poor fellow for a husband."

"What, Monsieur Faisandé! not even some trivial little bit of fooling to tell us? Come, search your memory, did nothing ever happen to you in the Cité? in Rue aux Fèves or Rue Saint-Éloy? There are plenty of frail damsels on those streets, they say."

This time Monsieur Faisandé turned green; he did not know which way to look, and stammered a few inaudible words. Dupréval, observing his evident discomfort, and wishing to put an end to a scene which threatened to lose its comic aspect, hastily asked Montricourt to take the floor.

The dandy smoothed the nascent beard that adorned his chin, then said in a low voice, assuming a serious air:

"What I am about to tell you, messieurs, may seem improbable to you. Understand that I have had a pair of wings made—yes, messieurs, a pair of wings as magnificent as an eagle's. I fasten them under my arms, and then, as you can imagine, I go wherever I choose. When a woman attracts me, I fly in at her window, even if she lives on the fifth floor; I carry her off, and I win her in mid-air! It's a wonderful thing!"

"I beg your pardon," said Monsieur Roland, ironically; "while you are making love in mid-air, you can't keep your wings at work; so you must fall. Look at the birds; they always light to do their billing and cooing."

"I anticipated that difficulty, my dear fellow; so, before I launch myself in the air, I always make myself fast to your balloon, which holds me up."

This witticism ranged all the laughers on Montricourt's side, and even Monsieur Roland decided to admit defeat.

It was now the turn of Monsieur Rouffignard, the corpulent bon vivant who sat next to me.

"My story won't be long," he said; "I rush my love affairs through on time; I don't like to have things drag along. I was in love with a woman who wasn't handsome, but had a fine figure; and I'm a great fellow for shape; I tell you, I set store by shape! To speak without periphrasis, I prefer what's underneath to what's outside. Well! I was making love to a lady who had little to boast of in the way of features; but such a superb bust! such well-rounded hips! I said to myself: 'If all that's only as firm and hard as a plum pudding, it will be all right; for, after all, one can't expect to find marble unless he goes to a statue.'—I would have been glad to have a chance to appraise, by means of a slight caress, more or less innocent, the real value of what I admired, but my inamorata didn't understand that sort of play; as soon as I made a motion to touch her, she'd shriek and wriggle and scratch. 'I shall never triumph over such untamed virtue as this,' I said to myself. But one fine day—that is to say, one evening, she agreed to meet me. She gave me leave to call between ten and eleven. I took good care to be prompt. Madame lived alone. She opened the door herself, and admitted me; but I was surprised to find that she had no light. I presumed that it was simply excess of modesty, and that defeat in the dark would be less trying to her; I had the more reason to think so, because she offered only a slight resistance. I began to grow audacious, but fancy my disappointment; instead of what I had hoped to find, I found nothing but cliquettes—that is to say, bones, of different degrees of sharpness. My audacity gave place to alarm; I recalled the romance of the Monk, and the story of La Nonne Sanglante; I began to be afraid that I was alone with a skeleton. But I had in my pocket one of those devices which we smokers use to obtain a light. I lighted it, without warning my fair; she shrieked when she saw the flame, and I did the same when I found that I was tête-à-tête with a beanpole. All I had admired was false. I alleged a sudden indisposition, and fled. Since then, whenever that lady meets me, she glares at me as if she would strike me dead. I am very sorry for her, but one shouldn't pretend to be a millionaire when one doesn't own a single foot of ground."

It was my turn to relate my adventures. I have had amusing ones and sad ones; but, presuming that the sentimental sort would be misplaced on that occasion, I determined on this:

"The scene is laid in the country, messieurs, in a delightful region about five leagues from Paris. I had gone there to pass a fortnight with a friend of mine who has a house in that neighborhood; he had consumption, and was living on milk exclusively; so I leave you to guess whether the establishment was a lively one. However, one should be willing sometimes to make sacrifices to friendship. And then, too, there was a house near by, occupied by several tenants, among them a charming young widow whom I had met in society in Paris. She was a blonde, with tender blue eyes and a languishing smile, and an expert coquette, I assure you! You will say that all women are; but there are gradations. I renewed my acquaintance with her; in the country, as you have lots of time to yourself, love does its work much more quickly than in town; and then, the delicious shade, the verdure, the charming retired nooks where you can hear nothing but the twittering of birds—are not all these made to incline one's heart to sentiment, to invite to love? A welcome invitation, which it is so pleasant to hear! In a word, I made such progress with my lovely widow, that nothing remained but to obtain a tête-à-tête. That, however, was not so easy as you may think. The house where my blonde lived was occupied by a lot of inquisitive, gossiping, evil-tongued people, whose greatest delight was to busy themselves about what others were doing. That is the principal occupation of fools in the country; they get up in the morning to spy on their neighbors, and do not go to bed happy if they have not done or said some spiteful thing during the day. My attentions to the pretty widow had been remarked; so they instantly passed the word around to watch us, to dog our steps; she and I could not move, without the whole province knowing it. All those bourgeois and clowns of the pumpkin family were worthy to be police-men in Paris; and I thought seriously of recommending them to monsieur le préfet.

"The result was that we had to act with great secrecy. The house where my widow lived had a large garden. All gardens have a small gate; and each tenant was supplied with a key to the little gate of the garden in question, which opened into a lovely meadow. Several times, when talking with my inamorata in the evening, I had urged her to give me her key, so that I could get into the garden. By waiting until midnight, I was certain to avoid meeting any of her fellow boarders, for all of them went to bed at ten o'clock, as a rule. My constant refrain was: 'Let me have the key; or else let me in at midnight.'

"At last, one evening when we had met at a neighbor's, as we left the house my blonde came to me, took my hand, and whispered in my ear:

"'Come to-night.'

"Imagine my joy, my ecstasy! I walked quickly away from her, lest she should change her mind. Everybody went home, myself with the rest; I longed so for the time when they should all be asleep! My friend's old cuckoo clock struck twelve. I left my room at once, stepping lightly, stole from the house, and hastened to the meadow. I sat down on the grass, a few steps from the gate, and waited impatiently until it should open to admit me to the summit of felicity.

"Half an hour passed, and the gate did not open. I said to myself: 'Someone near her has not gone to bed yet, I suppose, and she's afraid to come down; I must be patient.'—Another half-hour passed and the gate remained closed. I stood up, thinking that she might have left it unlocked so that I could go in. I ran to the gate to find out, but it was locked on the inside. I walked back and forth, I sat down and stood up, keeping my eyes always fixed on that gate, which did not open. I thought of everything that could possibly have delayed my lovely widow, or kept her from coming. One o'clock struck, then the half, then two.—'She has made a fool of me,' I said to myself; 'she won't come at all! But what object could she possibly have in keeping me waiting all night? Does my love deserve such a cruel disappointment? In fact, did she not, of her own motion, tell me to come to-night? No, it isn't possible that she purposely makes me pass such wretched hours here.'

"I could not make up my mind to go. Still hoping, I said to myself at the faintest sound: 'She's coming; here she is!'—But the sound ceased, and she did not appear. Thereupon I would walk away a few steps, but again and again I returned.

"Day broke at last, and with it my last hope vanished! For people rise very early in the country, and, when it was light, I knew very well that the lady would not risk her reputation by coming out to me. So I returned to my friend's house, with despair in my heart, swearing that I would never again address, that I would never look at, that woman who had made such a fool of me.

"But the next day, chance, or rather our own volition, brought us together. I was on the point of heaping reproaches on her, but she gave me no time; with a wrathful glance, she said to me in a voice that shook with indignation:

"'Your conduct is shameful, monsieur: the idea of making sport of me so! of making me pass a whole night in the most intense anxiety! For I had the kindness to believe that something must have happened to you; but I was mistaken. Why, in heaven's name, did you ask for a thing which you did not want? It is perfectly shocking! I detest you, and I forbid you ever to speak to me again!'

"You can imagine my amazement at this harangue. Instead of apologizing, I overwhelmed her with complaints and reproaches for the sleepless night I had passed at the garden gate. My manner was so genuine and so sincere, that the young widow interrupted me.—'What!' she exclaimed; 'you passed the night in the fields? Pray, why didn't you come in, monsieur?'

"'Come in? by what means, madame?'

"'Why, with the key to the little gate, which I myself gave you.'

"'You gave me the key?'

"'Yes, monsieur; last night, when I spoke to you, I put it in your hand.'

"Everything was explained. I remembered perfectly that when she whispered to me she had taken my hand; and that was when she gave me the key—or, rather, when she thought that I received it; but, alas! she was mistaken; the key fell noiselessly on the grass, and neither of us noticed it. You see, messieurs, what trifles happiness depends upon. I asked pardon and claimed another assignation; but with women a lost opportunity is seldom recovered.—'Try to find the key,' she said. I hastened to the place where she had spoken to me the night before. Alas! in vain did I scratch the ground and examine every tuft of grass; I did not find the key. A few days later, the pretty blonde went away, and I never saw her again."

I had performed my task; Dumouton and Fouvenard alone remained to be heard. The latter having requested the privilege of speaking last, the man of letters in the yellowish-green coat bowed gracefully and began:

"To speak of one's bonnes fortunes, messieurs, is to speak of the ladies; with me, it is to speak of fillettes, grisettes, or lorettes; for as to bourgeois dames or great ladies, married or single, I have always deemed them too virtuous to be the objects of my attachment. That is my individual opinion; opinions are free. Allow me, therefore, to indulge in a brief digression concerning fillettes, grisettes, and lorettes. I know that my colleague, Alexandre Dumas, has discussed this subject; but there are subjects that are inexhaustible—always attractive and interesting: women and love enjoy that blessed privilege.

"It has been said that Paris is the paradise of women. Ah! messieurs, he who said that can never have visited the tiny chambers, the closets, the attics, sometimes even the garrets, where that charming sex often lacks the first essentials of life; sometimes by its own fault, sometimes by the fault of destiny, or, to speak more accurately, of those cruel monsters of men, who play so important a part in the story of these young women.

"The fillettes of Paris are the daughters of honest bourgeois or artisans, whose parents, too much engrossed by their labor or by the care of their business, put them out as apprentices, or as shopgirls, or, as happens in the majority of cases, leave them at home to look after the housework and keep house.

"Imagine a girl of fourteen to sixteen years of age, taken from her school, and, all of a sudden, because her father has become a widower, or because her mother sits at a counter all day, burdened with the whole charge of the household. She has no maid to assist her; for if she had, she would be a demoiselle, not a fillette. The demoiselles have had a good education, they have had teachers who have tried to enlighten their minds and their judgment and to train their hearts; indeed, they are supposed to know a great many things; but they are entitled to do nothing at all during the day, just because they are demoiselles.

"The fillettes, on the contrary, have to do everything, and generally are taught nothing. But you should see how they manage the household that has been thrown on their hands—mere children, who were playing with their dolls yesterday. Ordinarily, they begin by sweeping, very early; but if the lodging consists only of a single room and a cabinet, the housework is never finished till the end of the day—when it is finished at all. To be sure, the fillette doesn't work long at any one thing; she is required to change her occupation every minute; indeed, it rarely happens that she dresses herself entirely. The young woman whom you meet on the street early in the morning, carelessly dressed, in shoes down at heel, with unkempt hair, dirty hands, and a modest manner, is a fillette.

"She has just begun to sweep, and suddenly she drops the broom, which sometimes falls against a pane of glass and breaks it; but the young housekeeper doesn't mind that. She starts to remove her curl papers; she removes one, she removes two—but just as she has her hand on the third, she remembers that she hasn't skimmed the stew; so she abandons her hair, runs to get the skimmer, and brandishes that utensil, humming Guido's song:

"'Hélas! il a fui comme une ombre!'

And to give more expression to her song, more passion to her voice, she often holds the skimmer lovingly to her heart. But as she sings, her eyes happen to fall on her canary's cage; she hastens thither, for she remembers that she hasn't given the bird anything to eat for two days. But as she is on the point of opening the cage, it occurs to her that she would do well to think about her own breakfast; so she turns her back on the canary, to go and visit the pantry. What she finds there does not suit her; so she goes down to the fruit stall to buy some fresh eggs. But on the way, she changes her mind; she prefers preserves, so she goes into the grocer's, where she meets a young woman who has been her schoolmate. They chat, and sometimes the chance meeting carries them a long way.

"'Come with me a minute,' says her friend; 'I live close by, and I'll show you a dress my fiancé sent me from Lyon.'

"'Oh! so you've got a fiancé, have you? are you going to be married?'

"'Yes, in two months.'

"'That's funny.'

"'Why is it funny?'

"'Because they don't ever think about marrying me.'

"'You're too young.'

"'I'm only a year younger'n you. But my folks would rather keep me at home to do the housework.'

"'Come, and I'll give you some candy I got when I was a godmother.'

"'Have you been a godmother? Oh! what a lucky girl you are! you have everything!'

"It is very hard to resist the invitation of a friend who offers us candy. The fillette forgets her housework, her stew, her canary, and even her breakfast, as she chats with her old schoolmate, who has been a godmother and is engaged.

"When at last she goes home, just as she is entering the house, she is saluted, and sometimes accosted, by a young man of most respectable aspect, whom she invariably meets when she goes out. I leave you to judge at what hour the housework will be done and the soup skimmed.

"This young man is not a lover as yet, but he closely resembles a man in love, and if ill fortune sometimes be-falls the fillette, who is at fault? Is she the one to be blamed? should we not charge it rather to the parents, who so shamefully neglect those who have neither strength, nor sense, nor experience, to resist the seductions of the world?

"Paris is swarming with these fillettes, messieurs; some remain virtuous, although they live among dangers; as they have no fortune, they do not always find husbands, but pass from the fillette stage to that of an old maid, without becoming better housekeepers by the change.

"As for the grisettes, that's another story. The grisette loves pleasure; she wants it, she must have it. She has at least one lover; when she has only one, she is a most exemplary grisette. However, they do not pretend to be any better than they are; they make no parade of false virtue; they are neither prudish nor shy; they cultivate students, actors, artists, the theatre, balls,—out of doors or indoors,—promenades, dance halls, restaurants; and they do not recoil at the thought of a private dining-room.

"The grisette is a gourmand, and is almost always hungry; she is wild over truffles, but is perfectly content to stuff herself with potatoes; she adores meringues, but regales herself daily with biscuit and tarts; she would climb a greased pole for a glass of champagne, but does not refuse a mug of cider.

"You know as well as I, messieurs, that when you have treated a grisette to a dainty dinner, you must not conclude that her appetite is satisfied. On leaving the table, if you are in the country, the grisette will suggest shooting for macaroons, and will consume several dozen; then she will ask for a drink of milk, and a piece of rye bread to soak in it; then she will want some cherries, then beer and gingerbread. In Paris, you will have to supply her with barley sugar, syrups, punch, and Italian cheese.

"Let us do the grisette of Paris justice; she is active, frisky, alluring, provoking; she is not always pretty, but she has a certain—I don't know what to call it—a sort of chic, which always finds followers. She handles the simplest materials in such a way as to make herself a pretty little costume; she often wears an apron, and a cap almost always; she rarely puts anything else on her head, and she is very wise; for her face, which is captivating in a cap, loses much of its charm under a bonnet, unless it be a bibi, the front of which never extends beyond the end of her nose.

"The grisette is a milliner, or laundress, or dressmaker, or embroiderer, or burnisher, or stringer of pearls, or something else—but she has a trade. To be sure, she seldom works at it. Suggest a trip into the country, a donkey ride, a bachelor breakfast, a dinner at La Chaumière, a ticket to the play, and the shop or workroom or desk may go to the deuce.

"So long as we can afford her amusement, she will think of nothing else; but when her lover hasn't a sou, she will return to her work as cheerily as if she were going to dine at Passoir's, or to do a little cancan at the Château-Rouge; for, messieurs, you may be sure of one thing—the grisette is a philosopher, she takes things as they come, money for what it is worth, and men for what they do for her. She loves passionately for a fortnight; she believes then that it will last all her life, and proposes to her lover that they go to live on a desert island, like Crusoe, and eat raw vegetables and shell-fish. As she is very fond of radishes and oysters, she thinks that she will be able to accustom herself to that diet; but in a moment she forgets all about that scheme, and cries:

"'Ah! how I would like some roast veal, and some lettuce salad garnished with hard-boiled eggs! Take me to Asnières, Dodolphe, and we'll dine out of doors; and I'll pluck some daisies and pull off the petals and find out your real sentiments, for the daisies never lie. If it stops at passionately, I'll kiss you on the left eye; if it tells me that you don't love me at all, I'll stick pins into your legs. What better proofs of love do you want?'

"But Dodolphe finds himself sometimes on his uppers.

"'You say you haven't got any money?' cries the grisette; 'bah! what a nuisance it is that one always has to have money to live on and enjoy one's self! Wait a minute; I've got a merino dress and a winter shawl; it's summer now, so I don't need 'em. They'll be better off at my aunt's than they are in my room, for there are moths there; they'll be better taken care of, and with what I can get on 'em we'll go and have some sport.'

"The grisette carries out her plan: she puts her clothes in pawn, without regret or melancholy. If she had money, she would give it to her lover. As she often spends all that he has, it seems natural to her to spend with him all that she has: she is neither stingy, saving, nor selfish.

"A grisette's lodging is a curious place; but she hasn't always a lodging to herself; very often she simply perches here and there. She will stay a week with her lover, three weeks with a friend of her own sex, and the rest of the time with her fruiterer or her concierge. When, by any chance, she does possess a domicile and furniture of her own, the grisette's bosom swells with pride, even when the furniture in question consists of nothing more than a cot, a mirror, and one broken chair. She takes delight in saying: 'I shall stay at home this evening,' or: 'I don't expect to leave home to-morrow. I have an idea of doing my room over in color; it's all the style now, especially yellow; when it's well rubbed, it makes more effect than furniture.'

"It is she who writes on her door, with a piece of Spanish chalk, when she goes out: I am at my nabor's, down one flite.

"But the grisette is not obliged to know the rules of orthography; and if she spoke the purest French, her conversation would probably seem less amusing; there are so many people who attract by their bad qualities.

"Sometimes the grisette ventures to give an evening party. When she is in the mood, she will invite as many as seven people. On such occasions, the bed does duty as a divan, the blinds as benches, the cooking stove as a table, and the lamp from the staircase is placed on the mantel to take the place of a chandelier. Punch is brewed in a soup tureen, and tea in a saucepan; they drink from egg cups, there is one spoon for three persons, and the hostess's shawl serves as a table cloth and as a napkin for all the company; all of which does not prevent the guests from laughing and enjoying themselves; for the most genuine enjoyment is not that which costs the most. This is not a new maxim, but it is very consoling to those who are not favored by fortune."

As he said this, Dumouton glanced down at himself, with a profound sigh. But encouraged, I doubt not, by a glimpse of the ends of his cravat, by that profusion of linen, to which he was not accustomed, he speedily resumed his smiling expression and continued his discourse.

"I come now, messieurs, to the last division of my trilogy, the lorettes, who are grisettes of the front rank—the tip-toppers! By that I mean that they are sought by the fashionable lions, the dandies, the Jockey Club—in a word, by those gentry who have a liking for spending money freely with women, and who have the means to do it.

"The lorettes live in the Chaussée d'Antin, the Nouvelle-Athènes, the Champs-Élysées, the quarter of sport, of the turf, or, if you prefer, of the horse traders. They are found, too, in quite large numbers, in the new streets. When a fine house is completed—that is to say, when the stairs are in place, so that the different floors are accessible, the proprietor lets apartments to lorettes, to dry the walls, as they say. They hire dainty suites, freshly decorated; everyone knows that they won't pay their rent, but the rooms are let to them because they draw people to the house; they attract other tenants; not honest bourgeois—nay, nay!—but fashionable young men, rich old bachelors, and sometimes men with stylish carriages.

"By the way, the lorette is exceedingly frank in this respect. One of them was inspecting a beautiful suite on Rue Mazagran, when the concierge, who probably did not know whom he was dealing with, was simple enough to tell her the price, repeating several times that she could not have it for less than fifteen hundred francs. Irritated by his persistence, the lorette stared at him as if he were a monstrosity, exclaiming:

"'Look you, monsieur, who do you think you're talking to? What difference does it make to me what the rent is, when I never pay?'

"The lorette dresses stylishly and coquettishly; she leaves a trail of perfume behind her. She has magnificent bouquets, and her gloves are the object of much solicitude. At a distance, one might take her for a lady of rank and fashion; but to hear her speak is fatal, and the illusion vanishes at once, her language being infinitely less pure than the polish on her boots.

"The lorette seeks to eclipse the grisette, whom she pretends to look down upon, but to whom she is vastly inferior, none the less. She has no lover, she has keepers. And yet she is not a kept woman, for such a one sometimes remains a long while with the same monsieur, whereas the lorette is constantly changing.

"The grisette likes young men; the lorette prefers men of mature years.

"The Hippodrome and the Cirque des Champs-Élysées are the resorts which the lorettes particularly affect. In the afternoon, they go thither to admire the bold horse-men jumping fences, or the women driving chariots in the ring. The Hippodrome audience being, as a rule, frivolous, dandified, and fashionable,—especially on weekdays,—these ladies are almost certain to make their expenses.

"In the evening, they go to admire Baucher; they jump up and down in ecstasy on their benches when Auriol makes some new hair-raising plunge. The lorette is never tired of repeating to her spouse—for so she calls her friend of the moment—that she knows nothing more beautiful than a horse.