.. .. .. ..

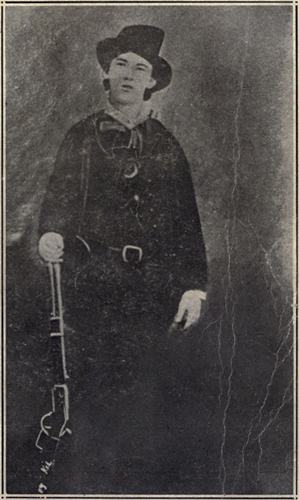

whose youthful

daring has never

been equalled in

the annals of

criminal history.

pierced his heart

he was less than

twenty-two years

of age, and had

killed twenty-one

men, Indians not

included.

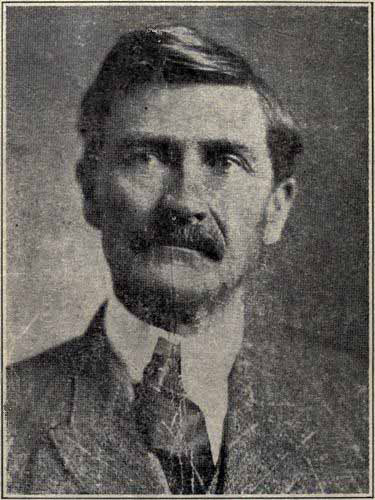

CHAS. A. SIRINGO

Project Gutenberg's History of 'Billy the Kid', by Chas. A. Siringo This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: History of 'Billy the Kid' Author: Chas. A. Siringo Release Date: November 17, 2011 [EBook #38039] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF 'BILLY THE KID' *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

| HISTORY OF .. .. .. .. |

“BILLY THE KID” |

| A cowboy outlaw whose youthful daring has never been equalled in the annals of criminal history. |

|

| When a bullet pierced his heart he was less than twenty-two years of age, and had killed twenty-one men, Indians not included. | |

| |

| BY CHAS. A. SIRINGO |

The true life of the most daring young outlaw of the age.

He was the leading spirit in the bloody Lincoln County, New Mexico, war. When a bullet from Sheriff Pat Garett’s pistol pierced his breast he was only twenty-one years of age, and had killed twenty-one men, not counting Indians. His six years of daring outlawry has never been equalled in the annals of criminal history.

By CHAS. A. SIRINGO.

Author of:

“Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony,” “A Cowboy Detective,” and “A Lone Star Cowboy.”

To my friend, George S. Tweedy—an honest, easy-going, second Abraham Lincoln; this little volume is affectionately dedicated by the author,

CHAS. A. SIRINGO.

Copyrighted 1920, by Chas. A. Siringo.

All rights reserved.

The author feels that he is capable of writing a true and unvarnished history of “Billy the Kid,” as he was personally acquainted with him, and assisted in his capture, by furnishing Sheriff Pat Garrett with three of his fighting cowboys—Jas. H. East, Lee Hall and Lon Chambers.

The facts set down in this narrative were gotten from the lips of “Billy the Kid,” himself, and from such men as Pat Garrett, John W. Poe, Kip McKinnie, Charlie Wall, the Coe brothers, Tom O’Phalliard, Henry Brown, John Middleton, Martin Chavez, and Ash Upson. All these men took an active part, for or against, the “Kid.” Ash Upson had known him from childhood, and was [Pg 4]considered one of the family, for several years, in his mother’s home.

Other facts were gained from the lips of Mrs. Charlie Bowdre, who kept “Billy the Kid,” hid out at her home in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, after he had killed his two guards and escaped.

CHAS. A. SIRINGO.

BILLY BONNEY KILLS HIS FIRST TWO MEN, AND BECOMES A DARING OUTLAW IN THE REPUBLIC OF MEXICO.

In the slum district of the great city of New York, on the 23rd day of

November, 1859, a blue-eyed baby boy was born to William H. Bonney and his

good looking, auburn haired young wife, Kathleen. Being their first child

he was naturally the joy of their hearts. Later, another baby boy

followed.

In 1862 William H. Bonney shook the dust of New York City from his shoes and emigrated to Coffeeville, Kansas, on the northern border of the Indian Territory, with his little family.

[Pg 6]Soon after settling down in Coffeeville, Mr. Bonney died. Then the young widow moved to the Territory of Colorado, where she married a Mr. Antrim.

Shortly after this marriage, the little family of four moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the end of the old Santa Fe trail.

Here they opened a restaurant, and one of their first boarders was Ash Upson, then doing work on the Daily New Mexican.

Little, blue-eyed, Billy Bonney, was then about five years of age, and became greatly attached to good natured, jovial, Ash Upson, who spent much of his leisure time playing with the bright boy.

Three years later, when the hero of our story was about eight years old, Ash Upson and the Antrim family pulled up stakes and moved to the booming silver[Pg 7] mining camp of Silver City, in the southwestern part of the Territory of New Mexico.

Here Mr. and Mrs. Antrim established a new restaurant, and had Ash Upson as the star boarder.

Naturally their boarders were made up of all classes, both women and men,—some being gamblers and toughs of the lowest order.

Amidst these surroundings, Billy Bonney grew up. He went to school and was a bright scholar. When not at school, Billy was associating with tough men and boys, and learning the art of gambling and shooting.

This didn’t suit Mr. Antrim, who became a cruel step-father, according to Billy Bonney’s way of thinking.

Jesse Evans, a little older than Billy, was a young tough who was a hero in Billy’s estimation. They became fast[Pg 8] friends, and bosom companions. In the years to come they were to fight bloody battles side by side, as friends, and again as bitter enemies.

As a boy, Mr. Upson says Billy had a sunny disposition, but when aroused had an uncontrollable temper.

At the tender age of twelve, young Bonney made a trip to Fort Union, New Mexico, and there gambled with the negro soldiers. One “black nigger” cheated Billy, who shot him dead. This story I got from the lips of “Billy the Kid” in 1878.

Making his way back to Silver City he kept the secret from his fond mother, who was the idol of his heart.

One day Billy’s mother was passing a crowd of toughs on the street. One of them made an insulting remark about her. Billy, who was in the crowd, heard it. He struck the fellow in the face with[Pg 9] his fist, then picked up a rock from the street. The “tough” made a rush at Billy, and as he passed Ed. Moulton he planted a blow back of his ear, and laid him sprawling on the ground.

This act cemented a friendship between Ed. Moulton and the future young outlaw.

About three weeks later Ed. Moulton got into a fight with two toughs in Joe Dyer’s saloon. He was getting the best of the fight. The young blacksmith who had insulted Mrs. Antrim and who had been knocked down by Ed. Moulton, saw a chance for revenge. He rushed at Moulton with an uplifted chair. Billy Bonney was standing near by, on nettles, ready to render assistance to his benefactor, at a moment’s notice. The time had now arrived. He sprang at the blacksmith and stabbed him with a knife three times. He fell over dead.

[Pg 10]Billy ran out of the saloon, his right hand dripping with human blood.

Now to his dear mother’s arms, where he showered her pale cheeks with kisses for the last time.

Realizing the result of his crime, he was soon lost in the pitchy darkness of the night, headed towards the southwest, afoot. For three days and nights Billy wandered through the cactus covered hills, without seeing a human being.

Luck finally brought him to a sheep camp, where the Mexican herder gave him food.

From the sheep camp he went to McKnight’s ranch and stole a horse, riding away without a saddle.

Three weeks later a boy and a grown man rode into Camp Bowie, a government post. Both were on a skinny, sore-back pony. This new found companion[Pg 11] had a name and history of his own, which he was nursing in secret. He gave his name to Billy as “Alias,” and that was the name he was known by around Camp Bowie.

Finally Billy, having disposed of his sore-back pony, started out for the Apache Indian Reservation, with “Alias,” afoot. They were armed with an old army rifle and a six-shooter, which they had borrowed from soldiers.

About ten miles southwest of Camp Bowie these two young desperados came onto three Indians, who had twelve ponies, a lot of pelts and several saddles, besides good fire-arms, and blankets. In telling of the affair afterwards, Billy said: “It was a ground-hog case. Here were twelve good ponies, a supply of blankets, and five heavy loads of pelts. Here were three blood-thirsty savages revelling in luxury and refusing help to[Pg 12] two free-born, white, American citizens, foot-sore and hungry. The plunder had to change hands. As one live Indian could place a hundred United States soldiers on our trail, the decision was made.

“In about three minutes there were three dead Indians stretched out on the ground, and with their ponies and plunder we skipped. There was no fight. It was the softest thing I ever struck.”

About one hundred miles from this bloody field of battle, the surplus ponies and plunder were sold and traded off to a band of Texas emigrants.

Finally the two young brigands settled down in Tucson, where Billy’s skill as a monte dealer, and card player kept them in luxuriant style, and gave them prestige among the sporting fraternity.

Becoming tired of town life, the two desperadoes hit the trail for San Simon,[Pg 13] where they beat a band of Indians out of a lot of money in a “fake” horse race.

The next we hear of Billy Bonney is in the State of Sonora, Old Mexico, where he went alone, according to his own statement.

In Sonora he joined issues with a Mexican gambler named Melquiades Segura. One night the two murdered a monte dealer, Don Jose Martinez, and secured his “bank roll.”

Now the two desperadoes shook the dust of Sonora from their feet and landed in the city of Chihuahua, the capital of the State of Chihuahua, several hundred miles to the eastward, across the Sierra Madres mountains.

A FIERCE BATTLE WITH APACHE INDIANS. SINGLE HANDED BILLY BONNEY LIBERATES SEGURA FROM JAIL.

In the city of Chihuahua, the two desperadoes led a hurrah life among the

sporting elements. Finally their money was gone and their luck at cards

went against them. Then Billy and Segura held up and robbed several monte

dealers, when on the way home after their games had closed for the night.

One of these monte dealers had offended Billy, which caused his death.

One morning before the break of day, this monte dealer was on his way home; a peon was carrying his fat “bank roll” in a buckskin bag, finely decorated with gold and silver threads.

[Pg 15]When nearing his residence in the outskirts of the city, Segura and young Bonney made a charge from behind a vacant adobe building. The one-sided battle was soon over. A popular Mexican gambler lay stretched dead on the ground. The peon willingly gave up the sack of gold and silver.

Now towards the Texas border, in a north-easterly direction, a distance of three hundred miles, as fast as their mounts could carry them.

When their horses began to grow tired, other mounts were secured. Their bills were paid enroute, with gold doubloons taken from the buckskin sack.

On reaching the Rio Grande river, which separates Texas from the Republic of Mexico, the young outlaws separated for the time being.

Billy Bonney finally met up with his Silver City chum, Jesse Evans, and they[Pg 16] became partners in crime, in the bordering state of Texas, and the Territories of New Mexico and Arizona. Many robberies and some murders were committed by these smooth-faced boys, and they had many narrow escapes from death, or capture. Fresh horses were always at their command, as they were experts with the lasso, and the scattering ranchmen all had bands of ponies on the range.

On one occasion the boys ate dinner with a party of Texas emigrants, and were well treated. Leaving the emigrant camp, a band of renegade Apache Indians were seen skulking in the hills. The boys concealed themselves to await results, as they felt sure a raid was to be made on the emigrants, who were headed for the Territory of Arizona. There were only three men in the party, and several women and children.

[Pg 17]Just at dusk, the boys, who were stealing along their trail in the low, flint covered hills, heard shooting.

Realizing that a battle was on, Billy Bonney and Jesse Evans put spurs to their mounts and reached the camp just in time.

By this time it was dark. The three men had succeeded in standing off the Indians for awhile, but finally a rush was made on the camp, by the reds, with blood curdling war whoops.

At that moment the two young heroes charged among the Indians and sprang off their horses, with Winchester rifles in hand.

For a few moments the battle raged. One bullet shattered the stock of Billy’s rifle, cripping his left hand slightly. He then dropped the rifle and used his pistol.

When the battle was over, eight dead[Pg 18] Indians lay on the ground.

The emigrants had shielded themselves by getting behind the wagons. Two of the men were slightly wounded, and the other dangerously shot through the stomach. One little girl had a fractured skull from a blow on the head with a rifle. The mother of the child fainted on seeing her daughter fall.

In telling of this battle, Billy Bonney said the war-whoops shouted by himself and Jesse, as they charged into the band of Indians, helped to win the battle. He said a bullet knocked the heel off one of his boots, and that Jesse’s hat was shot off his head. He felt sure that the man shot through the stomach died, though he never heard of the party after separating.

Soon after the Indian battle Billy Bonney and Jesse Evans landed in the Mexican village of La Mesilla, New [Pg 19]Mexico, and there met up with some of Jesse’s chums. Their names were Jim McDaniels, Bill Morton, and Frank Baker.

During their stay in Mesilla, Jim McDaniels christened Billy Bonney, “Billy the Kid,” and that name stuck to him to the time of his death.

Finally these three tough cowboys started for the Pecos river with Jesse Evans. “Billy the Kid” promised to join them later, as he had received word that his Old Mexico chum, Segura, was in jail in San Elizario, Texas, below El Paso. This word had been brought by a Mexican boy, sent by Segura.

The “Kid” told the boy to wait in Mesilla till he and Segura got there.

It was the fall of 1876. Mounted on his favorite gray horse, “Billy the Kid” started at six o’clock in the evening for the eighty-one mile ride to San Elizario.

[Pg 20]A swift ride brought him into El Paso, then called Franklin, a distance of fifty-six miles, before midnight. Here he dismounted in front of Peter Den’s saloon to let his noble “Gray” rest. While waiting, he had a few drinks of whiskey, and fed “Gray” some crackers, there being no horse feed at the saloon.

Now for the twenty-five mile dash down the Rio Grande river, over a level road to San Elizario. It was made in quick time. Daylight had not yet begun to break.

Dismounting in front of the jail, the “Kid” knocked on the front door. The Mexican jailer asked; “Quien es?” (Who’s that?)

The “Kid” replied in good Spanish: “Open up, we have two American prisoners here.”

The heavy front door was opened, and the jailer found a cocked pistol pointed[Pg 21] at him. Now the frightened guard gave up his pistol and the keys to the cell in which Segura was shackled and handcuffed.

In the rear of the jail building there was another guard asleep. He was relieved of his fire-arms and dagger.

When Segura was free of irons the two guards were gagged so they couldn’t give an alarm, and chained to a post.

The two outlaws started out in the darkest part of the night, just before day, Segura on “Gray” and the “Kid” trotting by his side, afoot.

An hour later the two desperadoes were at a confederate’s ranch across the Rio Grande river, in Old Mexico.

After filling up with a hot breakfast, the “Kid” was soon asleep, while Segura kept watch for officers. The “Kid’s” noble “Gray” was fed and[Pg 22] with a mustang, kept hidden out in the brush.

Now the ranchman rode into San Elizario to post himself on the jail break.

Hurrying back to the ranch, he advised his two guests to “hit the high places,” as there was great excitement in San Elizario.

Reaching La Mesilla, New Mexico, the two young outlaws found the boy who had carried the message to “Billy the Kid,” from Segura, and rewarded him with a handful of Mexican gold.

“BILLY THE KID” AND SEGURA MAKE SUCCESSFUL ROBBERY RAIDS INTO MEXICO. A BATTLE WITH INDIANS. THE “KID” JOINS HIS CHUM, JESSE EVANS.

After a few daring raids into Old Mexico, with Segura, the “Kid” landed in

La Mesilla, New Mexico.

Here he fell in with a wild young man by the name of Tom O’Keefe. Together, they started for the Pecos river to meet Jesse Evans and his companions.

Instead of taking the wagon road, the two venturesome boys cut across the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation, which took in most of the high Guadalupe range of mountains, which separates the Pecos and Rio Grande rivers.

[Pg 24]First they rode into El Paso, Texas, and loaded a pack mule with provisions.

A few days out of El Paso, the boys ran out of water, and were puzzled as to which way to ride.

Finally a fresh Indian trail was found, evidently leading to water. It was followed to the mouth of a deep canyon. For fear of running into a trap, the “Kid” decided to take the canteen and go afoot, leaving his mount and the pack mule with O’Keefe, who was instructed to come to his rescue should he hear yelling and shooting.

A mile of cautious traveling brought the “Kid” to a cool spring of water. The ground was tramped hard with fresh pony and Indian tracks.

After filling the canteen, and drinking all the water he could hold, the “Kid” started down the canyon to join his companion.

[Pg 25]He hadn’t gone far when Indians, afoot, began pouring out of the cliff to the right, which cut off his retreat down the canyon. There was nothing to do but return towards the spring, as fast as his legs could carry him.

The twenty half-naked braves were gaining on him, and shouting blood-curdling war-whoops.

Like a pursued mountain lion, the “Kid” sprang into the jungles of a steep cliff. Foot by foot his way was made to a place of concealment.

The Indians seeing him leave the trail, scrambled up into the bushy cliff. Now the “Kid’s” trusty pistol began to talk, and several young braves, who were leading the chase passed to the “happy hunting ground.” The “Kid” said the body of one young buck went down the cliff and caught on the over-hanging[Pg 26] limb of a dead tree, and there hung suspended in plain view.

Many shots were fired at the “Kid” when he sprang from one hiding place to another. One bullet struck a rock near his head, and the splinters gave him slight wounds on the face and neck.

Reaching the extreme top of a high peak, the young outlaw felt safe, as he could see no reds on his trail. Being exhausted he soon fell asleep. On hearing the yelling and shooting, Tom O’Keefe stampeded, leaving the “Kid’s” mount and the pack mule where they stood.

Reaching a high bluff, which was impossible for a horse to climb, O’Keefe quit his mount and took it afoot. From cliff to cliff, he made his way towards the top of a peak. Finally his keen eyesight caught the figure of a man, far away across a deep canyon, trying to reach the top of a mountain peak. He[Pg 27] surmised that the bold climber must be the “Kid.”

At last young O’Keefe’s strength gave out and he lay down to sleep. His hands and limbs were bleeding from the scratches received from sharp rocks, and he was craving water.

Being refreshed from his long night’s sleep, the “Kid” headed for the big red sun, which was just creeping up out of the great “Llano Estacado,” (Staked Plains), over a hundred miles to the eastward, across the Pecos river.

Finally water was struck and he was happy. Then he filled up on wild berries, which were plentiful along the borders of the small sparkling stream of water.

Three days later the young hero outlaw reached a cow-camp on the Rio Pecos. He made himself known to the cowboys, who gave him a good horse to[Pg 28] ride, and conducted him to the Murphy-Dolan cow-camp, where his chum, Jesse Evans, was employed. In this camp the “Kid” also met his former friends, McDaniels, Baker, and Morton.

Here the “Kid” was told of the smouldering cattle war between the Murphy-Dolan faction on one side, and the cattle king, John S. Chisum, on the other.

Many small cattle owners were arrayed with the firm of Murphy and Dolan, who owned a large store in Lincoln, and were the owners of many cattle.

On John S. Chisum’s side were Alex A. McSween, a prominent lawyer of Lincoln—the County seat of Lincoln County—and a wealthy Englishman by the name of John S. Tunstall, who had only been in America a year.

McSween and Tunstall had formed a[Pg 29] co-partnership in the cattle business, and had established a general trading store in Lincoln.

It was now the early spring of 1877. Jesse Evans tried to persuade “Billy the Kid” to join the Murphy-Dolan faction, but he argued that he first had to find Tom O’Keefe, dead or alive, as it was against his principles to desert a chum in time of danger.

For nearly a year a storm had been brewing between John Chisum and the smaller ranchmen. Chisum claimed all the range in the Pecos valley, from Fort Sumner to the Texas line, a distance of over two hundred miles.

Naturally there was much mavericking, in other words, stealing unbranded young animals from the Chisum bands of cattle, which ranged about twenty-five miles on each side of the Pecos river.

[Pg 30]Chisum owned from forty to sixty thousand cattle on this “Jingle-bob” range. His cattle were marked with a long “Jingle-bob” hanging down from the dew-lap. In branding calves the Chisum cowboys would slash the dew-lap above the breast, leaving a chunk of hide and flesh hanging downward. When the wound healed the animal was well marked with a dangling “Jingle-bob.” Thus did the Chisum outfit get the name of the “Jingle-bobs.”

Well mounted and armed, “Billy the Kid” started in search of Tom O’Keefe. He was found at Las Cruces, three miles from La Mesilla, the County seat of Dona Ana County, New Mexico. It was a happy meeting between the two smooth-faced boys. Each had to relate his experience during and after the Indian trouble.

O’Keefe had gone back to the place[Pg 31] where he had left the “Kid’s” mount and the pack mule. There he found the “Kid’s” horse shot dead, but no sign of the mule. His own pony ran away with the saddle, when he sprang from his back.

Now O’Keefe struck out afoot, towards the west, living on berries and such game as he could kill, finally landing in Las Cruces, where he swore off being the companion of a daring young outlaw.

“Billy the Kid” tried to persuade O’Keefe to accompany him back to the Pecos valley, to take part in the approaching cattle war, but Tom said he had had enough of playing “bad-man from Bitter Creek.”

Now the “Kid” went to a ranch, where he had left his noble “Gray,” and with him started back towards the Pecos river.

THE STARTING OF THE BLOODY LINCOLN COUNTY WAR. THE MURDER OF TUNSTALL. “BILLY THE KID” IS PARTIALLY REVENGED WHEN HE KILLS MORTON AND BAKER.

Arriving back at the Murphy-Dolan cow-camp on the Pecos river, “Billy the

Kid” was greeted by his friends, McDaniels, Morton and Baker, who

persuaded him to join the Murphy and Dolan outfit, and become one of their

fighting cowboys. This he agreed to do, and was put on the pay-roll at

good wages.

The summer and fall of 1877 passed along with only now and then a scrap between the factions. But the clouds of war were lowering, and the “Kid” was anxious for a battle.

[Pg 33]Still he was not satisfied to be at war with the whole-souled young Englishman, John S. Tunstall, whom he had met on several occasions.

On one of his trips to the Mexican town of Lincoln, to “blow in” his accumulated wages, the “Kid” met Tunstall, and expressed regret at fighting against him.

The matter was talked over and “Billy the Kid” agreed to switch over from the Murphy-Dolan faction. Tunstall at once put him under wages and told him to make his headquarters at their cow-camp on the Rio Feliz, which flowed into the Pecos from the west.

Now the “Kid” rode back to camp and told the dozen cowboys there of his new deal. They tried to persuade him of his mistake, but his mind was made up and couldn’t be changed.

In the argument, Baker abused the[Pg 34] “Kid” for going back on his friends. This came very near starting a little war in that camp. The “Kid” made Baker back down when he offered to shoot it out with him on the square.

Before riding away on his faithful “Gray,” the “Kid” expressed regrets at having to fight against his chum Jesse Evans, in the future.

At the Rio Feliz cow camp, the “Kid” made friends with all the cowboys there, and with Tunstall and McSween, when he rode into Lincoln to have a good time at the Mexican “fandangos” (dances.)

A few “killings” took place on the Pecos river during the fall, but “Billy the Kid” was not in these fights.

In the early part of December, 1877, the “Kid” received a letter from his Mexican chum whom he had liberated from the jail in San Elizario, Texas, Melquiades Segura, asking that he meet[Pg 35] him at their friend’s ranch across the Rio Grande river, in Old Mexico, on a matter of great importance.

Mounted on “Gray,” the “Kid” started. Meeting Segura, he found that all he wanted was to share a bag of Mexican gold with him.

While visiting Segura, a war started in San Elizario over the Guadalupe Salt Lakes, in El Paso County, Texas.

These Salt Lakes had supplied the natives along the Rio Grande river with free salt for more than a hundred years. An American by the name of Howard, had leased them from the State of Texas, and prohibited the people from taking salt from them.

A prominent man by the name of Louis Cardis, took up the fight for the people. Howard and his men were captured and allowed their liberty under[Pg 36] the promise that they would leave the Salt Lakes free for the people’s use.

Soon after, Howard killed Louis Cardis in El Paso. This worked the natives up to a high pitch.

Under the protection of a band of Texas Rangers, Howard returned to San Elizario, twenty-five miles below El Paso.

On reaching San Elizario the citizens turned out in mass and besieged the Rangers and the Howard crowd, in a house.

Many citizens of Old Mexico, across the river, joined the mob. Among them being Segura and his confederate, at whose ranch “Billy the Kid” and Segura were stopping.

As “Billy the Kid” had no interest in the fight, he took no part, but was an eye witness to it, in the village of San Elizario.

[Pg 37]Near the house in which Howard and the Rangers took refuge, lived Captain Gregario Garcia, and his three sons, Carlos, Secundio, and Nazean-ceno Garcia. On the roof of their dwelling they constructed a fort, and with rifles, assisted in protecting Howard and the Rangers from the mob.

The fight continued for several days. Finally, against the advice of Captain Gregario Garcia, the Rangers surrendered. They were escorted up the river towards El Paso, and liberated. Howard, Charlie Ellis, John Atkinson, and perhaps one or two other Americans, were taken out and shot dead by the mob. Thus ended one of the bloody battles which “Billy the Kid” enjoyed as a witness.

The following year the present Governor of New Mexico, Octaviano A. Larrazolo, settled in San Elizario, Texas,[Pg 38] and married the pretty daughter of Carlos Garcia, who, with his father and two brothers, so nobly defended Howard and the Rangers.

Now “Billy the Kid,” with his pockets bulging with Mexican gold, given him by Segura, returned to the Tunstall-McSween cow camp, on the Rio Feliz, in Lincoln County, New Mexico.

In the month of February, 1878, W. S. Morton, who held a commission as deputy sheriff, raised a posse of fighting cowboys and went to one of the Tunstall cow-camps on the upper Ruidoso river, to attach some horses, which were claimed by the Murphy-Dolan outfit.

Tunstall was at the camp with some of his employes, who “hid out” on the approach of Morton and the posse.

It was claimed by Morton that Tunstall fired the first shot, but that story[Pg 39] was not believed by the opposition.

In the fight, Tunstall and his mount were killed. While laying on his face gasping for breath, Tom Hill, who was later killed while robbing a sheep camp, placed a rifle to the back of his head and blew out his brains.

This murder took place on the 18th day of February, 1878.

Before sunset a runner carried the news to “Billy the Kid,” on the Rio Feliz. His anger was at the boiling point on hearing of the foul murder. He at once saddled his horse and started to Lincoln, to consult with Lawyer McSween.

Now the Lincoln County war was on with a vengeance and hatred, and the “Kid” was to play a leading hand in it. He swore that he would kill every man who took part in the murder of his friend Tunstall.

[Pg 40]At that time, Lincoln County, New Mexico, was the size of some states, about two hundred miles square, and only a few thousand inhabitants, mostly Mexicans, scattered over its surface.

On reaching the town of Lincoln, the “Kid” was informed by McSween that E. M. Bruer had been sworn in as a special constable, and was making up a posse to arrest the murderers of Tunstall.

“Billy the Kid” joined the Bruer posse, and they started for the Rio Pecos river.

On the 6th day of March, the Bruer posse ran onto five mounted men at the lower crossing of the Rio Penasco, six miles from the Pecos river. They fled and were pursued by Bruer and his crowd.

Two of the fleeing cowboys separated from their companions. The “Kid” [Pg 41]recognized them as Morton and Baker, his former friends. He dashed after them, and the rest of the posse followed his lead.

Shots were being fired back and forth. At last Morton’s and Baker’s mounts fell over dead. The two men then crawled into a sink-hole to shield their bodies from the bullets.

A parley was held, and the two men surrendered, after Bruer had promised them protection. The “Kid” protested against giving this pledge. He remarked: “My time will come.”

Now the posse started for the Chisum home ranch, on South Spring river, with the two handcuffed prisoners.

On the morning of the 9th day of March, the Bruer posse started with the prisoners for Lincoln, but pretended to be headed for Fort Sumner.

The posse was made up of the following[Pg 42] men: R. M. Bruer, J. G. Skurlock, Charlie Bowdre, “Billy the Kid,” Henry Brown, Frank McNab, Fred Wayt, Sam Smith, Jim French, John Middleton and McClosky.

After traveling five miles they came to the little village of Roswell. Here they stopped to allow Morton time to write a letter to his cousin, the Hon. H. H. Marshall, of Richmond, Virginia.

Ash Upson was the postmaster in Roswell, and Morton asked him to notify his cousin in Virginia, if the posse failed to keep their pledge of protection.

McClosky, who was standing near, remarked: “If harm comes to you two, they will have to kill me first.”

The party started out about 10 A. M. from Roswell. About 4 P. M., Martin Chavez of Picacho, arrived in Roswell and reported to Ash Upson that the posse and their prisoners had quit the[Pg 43] main road to Lincoln and had turned off in the direction of Agua Negra, an unfrequented watering place. This move satisfied the postmaster that the doom of Morton and Baker was sealed.

On March the eleventh, Frank McNab, one of the Bruer posse, rode up to the post-office and dismounted. Mr. Upson expressed surprise and told him that he supposed he was in Lincoln by this time. Now McNab confessed that Morton, Baker and McClosky were dead.

Later, Ash Upson got the particulars from “Billy the Kid” of the killing.

The “Kid” and Charlie Bowdre were riding in the lead as they neared Blackwater Spring. McClosky and Middleton rode by the side of the two prisoners. The balance of the posse followed behind.

Finally Brown and McNab spurred up their horses and rode up to [Pg 44]McClosky and Middleton. McNab shoved a cocked pistol at McClosky’s head saying: “You are the s— of a b— that’s got to die before harm can come to these fellows, are you?”

Now the trigger was pulled and McClosky fell from his horse, dead, shot through the head.

“Billy the Kid” heard the shot and wheeled his horse around in time to see the two prisoners dashing away on their mounts. The “Kid” fired twice and Morton and Baker fell from their horses, dead. No doubt it was a put up job to allow the “Kid” to kill the murderers of his friend Tunstall, with his own hands.

The posse rode on to Lincoln, all but McNab, who returned to Roswell. The bodies of McClosky, Morton and Baker were left where they fell. Later they were buried by some sheep herders.

[Pg 45]Thus ends the first chapter of the bloody Lincoln County war.

THE MURDER OF SHERIFF BRADY AND HIS DEPUTY, HINDMAN, BY THE “KID” AND HIS BAND. “BILLY THE KID” AND JESSE EVANS MEET AS ENEMIES AND PART AS FRIENDS.

On returning to Lincoln, “Billy the Kid” had many consultations with

Lawyer McSween about the murder of Tunstall. It was agreed to never let up

until all the murderers were in their graves.

The “Kid” heard that one of Tunstall’s murderers was seen around Dr. Blazer’s saw mill, near the Mescalero[Pg 46] Apache Indian Reservation, on South Fork, about forty miles from Lincoln. He at once notified Officer Dick Bruer, who made up a posse to search for Roberts, an ex-soldier, a fine rider, and a dead shot.

As the posse rode up to Blazer’s saw mill from the east, Roberts came galloping up from the west. The “Kid” put spurs to his horse and made a dash at him. Both had pulled their Winchester rifles from the scabbards. Both men fired at the same time, Robert’s bullet went whizzing past the “Kid’s” ear, while the one from “Billy the Kid’s” rifle, found lodgment in Robert’s body. It was a death wound, but gave Roberts time to prove his bravery, and fine marksmanship.

He fell from his mount and found concealment in an outhouse, from where he fought his last battle.

[Pg 47]The posse men dismounted and found concealment behind the many large saw logs, scattered over the ground.

For a short time the battle raged, while the lifeblood was fast flowing from Robert’s wound. One of his bullets struck Charlie Bowdre, giving him a serious wound. Another bullet cut off a finger from George Coe’s hand. Still another went crashing through Dick Bruer’s head, as he peeped over a log to get a shot at Roberts; Bruer fell over dead. This was Robert’s last shot, as he soon expired from the wound “Billy the Kid” had given him.

A grave yard was now started on a round hill near the Blazer saw mill, and in later years, Mr. and Mrs. George Nesbeth, a little girl, and a strange man, who had died with their boots on—being[Pg 48] fouly murdered—were buried in this miniature “Boot Hill” cemetery.

Two of the participants in the battle at Blazer’s saw mill, Frank and George Coe, are still alive, being highly respected ranchmen on the Ruidoso river, where both have raised large families.

After the battle at Blazer’s mill, the Coe brothers joined issues with “Billy the Kid” and fought other battles against the Murphy-Dolan faction. In one battle Frank Coe was arrested and taken to the Lincoln jail. Through the aid of friends he made his escape.

Now that their lawful leader, Dick Bruer, was in his grave, the posse returned to Lincoln. Here they formed themselves into a band, without lawful authority, to avenge the murder of Tunstall, until not one was left alive. By common consent, “Billy the Kid” was appointed their leader.

[Pg 49]In Lincoln, lived one of “Billy the Kid’s” enemies, J. B. Mathews, known as Billy Mathews. While he had taken no part in the killing of Tunstall, he had openly expressed himself in favor of Jimmie Dolan and Murphy, and against the other faction.

On the 28th day of March, Billy Mathews, unarmed, met the “Kid” on the street by accident. Mathews started into a doorway, just as the “Kid” cut down on him with a rifle. The bullet shattered the door frame above his head.

Major William Brady, a brave and honest man, was the sheriff of Lincoln County. He was partial to the Murphy-Dolan faction, and this offended the opposition. He held warrants for “Billy the Kid” and his associates, for the killing of Morton, Baker, and Roberts.

On the first day of April, 1878, Sheriff Brady left the Murphy-Dolan store,[Pg 50] accompanied by George Hindman and J. B. Mathews to go to the Court House and announce that no term of court would be held at the regular April term.

The sheriff and his two companions carried rifles in their hands, as in those days every male citizen who had grown to manhood, went well armed.

The Tunstall and McSween store stood about midway between the Murphy-Dolan store and the Court House.

In the rear of the Tunstall-McSween store, there was an adobe corral, the east side of which projected beyond the store building, and commanded a view of the street, over which the sheriff had to pass. On the top of this corral wall, “Billy the Kid” and his “warriors” had cut grooves in which to rest their rifles.

As the sheriff and party came in sight, a volley was fired at them from the[Pg 51] adobe fence. Brady and Hindman fell mortally wounded, and Mathews found shelter behind a house on the south side of the street.

Ike Stockton, who afterwards became a killer of men, and a bold desperado, in northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado, and who was killed in Durango, Colorado, at that time kept a saloon in Lincoln, and was a friend of the “Kid’s.” He ran out of his saloon to the wounded officers. Hindman called for water; Stockton ran to the Bonita river, nearby, and brought him a drink in his hat.

About this time, “Billy the Kid” leaped over the adobe wall and ran to the fallen officers. As he raised Sheriff Brady’s rifle from the ground, J. B. Mathews fired at him from his hiding place. The ball shattered the stock of the sheriff’s rifle and plowed a furrow[Pg 52] through the “Kid’s” side, but it proved not to be a dangerous wound.

Now “Billy the Kid” broke for shelter at the McSween home. Some say that he fired a parting shot into Sheriff Brady’s head. Others dispute it. At any rate both Brady and Hindman lay dead on the main street of Lincoln.

This cold-blooded murder angered many citizens of Lincoln against the “Kid” and his crowd. Now they became outlaws in every sense of the word.

From now on the “Kid” and his “warriors” made their headquarters at McSween’s residence, when not scouting over the country searching for enemies, who sanctioned the killing of Tunstall.

Often this little band of “warriors” would ride through the streets of Lincoln to defy their enemies, and be royally treated by their friends.

Finally, George W. Peppin was [Pg 53]appointed Sheriff of the County, and he appointed a dozen or more deputies to help uphold the law. Still bloodshed and anarchy continued throughout the County, as the “Kid’s” crowd were not idle.

San Patricio, a Mexican plaza on the Ruidoso river, about eight miles below Lincoln, was a favorite hangout for the “Kid” and his “warriors,” as most of the natives there were their sympathizers.

One morning, before breakfast, in San Patricio, Jose Miguel Sedillo brought the “Kid” news that Jesse Evans and a crowd of “Seven River Warriors” were prowling around in the hills, near the old Bruer ranch, where a band of the Chisum-McSween horses were being kept.

Thinking that their intentions were to steal these horses, the “Kid” and party[Pg 54] started without eating breakfast. In the party, besides the “Kid,” were Charlie Bowdre, Henry Brown, J. G. Skerlock, John Middleton, and a young Texan by the name of Tom O’Phalliard, who had lately joined the gang.

On reaching the hills, the party split, the “Kid” taking Henry Brown with him.

Soon the “Kid” heard shooting in the direction taken by the balance of his party. Putting spurs to his mount, he dashed up to Jesse Evans and four of his “warriors,” who had captured Charlie Bowdre, and was joking him about his leader, the “Kid.” He remarked: “We are hungry, and thought we would roast the ‘Kid’ for breakfast. We want to hear him bleat.”

At that moment a horseman dashed up among them from an arroyo. With a smile, Charlie Bowdre said, pointing[Pg 55] at the “Kid;” “There comes your breakfast, Jesse!”

With drawn pistol, “Old Gray” was checked up in front of his former chum in crime, Jesse Evans.

With a smile, Jesse remarked: “Well, Billy, this is a h—l of a way to introduce yourself to a private picnic party.”

The “Kid” replied: “How are you, Jesse? It’s a long time since we met.”

Jesse said: “I understand you are after the men who killed that Englishman. I, nor none of my men were there.”

“I know you wasn’t, Jesse,” replied the “Kid.” “If you had been, the ball would have been opened before now.”

Soon the “Kid” was joined by the rest of his party and both bands separated in peace.

“BILLY THE KID” AND GANG STAND OFF A POSSE AT THE CHISUM RANCH. A BLOODY BATTLE IN LINCOLN, WHICH LASTED THREE DAYS.

As time went on, Sheriff Peppin appointed new deputies on whom he could

depend. Among these being Marion Turner, of the firm of Turner & Jones,

merchants at Roswell, on the Pecos river.

For several years, Turner had been employed by cattle king John Chisum, and up to May, 1878 had helped to fight his battles, but for some reason he had seceded and became Chisum’s bitter enemy.

Marion Turner was put in charge of the Sheriff’s forces in the Pecos valley,[Pg 57] and soon had about forty daring cowboys and cattlemen under his command. Roswell was their headquarters.

Early in July, “Billy the Kid” and fourteen of his followers rode up to the Chisum headquarters ranch, five miles from Roswell, to make that their rendezvous.

Turner with his force tried to oust the “Kid” and gang from their stronghold, but found it impossible, owing to the house being built like a fort to stand off Indians, but he kept out spies to catch the “Kid” napping.

One morning, Turner received word that the “Kid” and party had left for Fort Sumner on the upper Pecos river. The trail was followed about twenty miles up the river, where it switched off towards Lincoln, a distance of about eighty or ninety miles.

The trail was followed to Lincoln,[Pg 58] where it was found that “Billy the Kid” and gang had taken possession of McSween’s fine eleven-room residence, and were prepared to stand off an army.

On arriving in Lincoln with his posse, Turner was joined by Sheriff Peppin and his deputies, and they made the “Big House,” as the Murphy-Dolan store was called, their headquarters.

For three days shots were fired back and forth from the buildings, which were far apart.

On the morning of July 19th, 1878, Marion Turner concluded to take some of his men to the McSween residence and demand the surrender of the “Kid” and his “warriors.” With Turner were his business partner, John A. Jones and eight other fearless men.

At that moment the “Kid” and party were in a rear room holding a consultation,[Pg 59] otherwise some of the advancing party might have been killed.

On reaching the thick adobe wall of the building, through which portholes had been cut, Turner and his men found protection against the wall between these openings.

When the “Kid” and party returned to the port-holes they were hailed by Turner, who demanded their surrender, as he had warrants for their arrest.

The “Kid” replied: “We, too, hold warrants for you and your gang, which we will serve on you, hot from the muzzles of our guns.”

About this time Lieut. Col. Dudley, of the Ninth Cavalry, arrived from Ft. Stanton with a company of infantry and some artillery.

Planting his cannons midway between the belligerent parties, Col. Dudley proclaimed that he would turn his guns[Pg 60] loose on the first of the two, who fired over the heads of his command.

Despite this warning, shots were fired back and forth, but no harm was done.

Now Martin Chavez, who at this writing is a prosperous merchant in Santa Fe, rode up with thirty-five Mexicans, whom he had deputized to protect McSween and the “Kid’s” party.

Col. Dudley asked him under what authority he was acting. He replied that he held a certificate as deputy sheriff under Brady. Col. Dudley told him that as Sheriff Brady was dead, and a new sheriff had been appointed, his commission was not in effect. Still he proclaimed that he would protect the “Kid” and McSween.

Now Col. Dudley ordered Chavez off the field of battle, or he would have his men fire on them. When the guns were pointed in their direction, the Chavez[Pg 61] crowd retreated to the Ellis Hotel. Here he ordered his followers to fire on the soldiers if they opened up on the “Kid” and party with their cannon.

Toward night the Turner men, who were up against the McSween residence, between the port-holes, managed to set fire to the front door and windows. A strong wind carried the blaze to the woodwork of other rooms.

Mrs. McSween and her three lady friends had left the building before the fight started. She had made one trip back to see her husband. The firing ceased while she was in the house.

In the front parlor, Mrs. McSween had a fine piano. To prevent it from burning, the “Kid” moved it from one room to another until it was finally in the kitchen.

The crowd made merry around the piano, singing and “pawing the ivory,”[Pg 62] as the “Kid” expressed it to the writer a few months later.

After dark, when the fiery flames began to lick their way into the kitchen, where the smoke begrimed band were congregated, a question of surrender was discussed, but the “Kid” put his veto on the move. He stood near the outer door of the kitchen, with his rifle, and swore he would kill the first man who cried surrender. He had planned to wait until the last minute, then all rush out of the door together, and make a run for the Bonita river, a distance of about fifty yards.

Finally the heat became so great, the kitchen door was thrown open.

At this moment one Mexican became frightened and called out at the top of his voice not to shoot, that they would surrender. The “Kid” struck the [Pg 63]fellow over the head with his rifle and knocked him senseless.

When the Mexican called out that they would surrender, Robert W. Beckwith, a cattleman of Seven Rivers, and John Jones, stepped around the corner of the building in full view of the kitchen door.

A shot was fired at Beckwith and wounded him on the hand. Then Beckwith opened fire and shot Lawyer McSween, though this was not a death shot. Another shot from Beckwith’s gun killed Vicente Romero. Now the “Kid” planted a bullet in Beckwith’s head, and he fell over dead. Leaping over Beckwith’s body, the band made a run for the river. The “Kid” was in the lead yelling: “Come on, boys!” Tom O’Phalliard was in the rear. He made his escape amidst flying bullets, without a scratch, although he had stopped to pick[Pg 64] up his friend Harvey Morris. Finding him dead he dropped the body.

McSween fell dead in the back yard with nine bullets in his body, which was badly scorched by the fire, before he left the building.

It was 10 P. M. when the fight had ended. Seven men had been killed and many wounded. Only two of Turner’s posse were killed, while the “Kid” lost five,—McSween, Morris and three Mexicans.

“BILLY THE KID” KILLS TWO MORE MEN. AT THE HEAD OF A RECKLESS BAND, HE STEALS HORSES BY THE WHOLESALE. HE BECOMES DESPERATELY IN LOVE WITH MISS DULCUIEA DEL TOBOSO.

After their escape from Lincoln, “Billy the Kid” got his little band

together, and made a business of stealing stock and gambling. Their

headquarters were made in the hills near Fort Stanton—only a few miles

above Lincoln. The soldiers at the Fort paid no attention to them.

Now Governor Lew Wallace, the famous author of “Ben Hur,” of Santa Fe, the capital of the Territory of New Mexico, issued a proclamation granting a[Pg 66] pardon to “Billy the Kid” and his followers, if they would quit their lawlessness, but the “Kid” laughed it off as a joke.

On the 5th day of August, “Billy the Kid” and gang rode up in plain view of the Mescalero Indian Agency and began rounding up a band of horses.

A Jew by the name of Bernstein, mounted a horse and said he would go out and stop them. He was warned of the danger, but persisted in his purpose of preventing the stealing of their band of gentle saddle horses.

When Mr. Bernstein rode up to the gang and told them to “vamoose,” in other words, to hit the road, the “Kid” drew his rifle and shot the poor Jew dead. This was the “Kid’s” most cowardly act. His excuse was that he “didn’t like a Jew, nohow.”

During the fall the government had[Pg 67] given a contract to a large gang of Mexicans to put up several hundred tons of hay at $25 a ton. As they drew their pay, the “Kid” and gang were on hand to deal monte and win their money.

When the contract was finished, there was no more business for the “Kid’s” monte game, so with his own hand, as told to the author by himself, he set fire to the hay stacks one windy night.

Now the Government gave another contract for several hundred tons of hay at $50 a ton—as the work had to be rushed before frost killed the grass.

When pay day came around the “Kid’s” monte game was raking in money again.

The new stacks were allowed to stand, as it was too late in the season to cut the grass for more hay.

During the fall the “Kid” and some[Pg 68] of his gang made trips to Fort Sumner. Bowdre and Skurlock always remained near their wives in Lincoln, but finally those two outlaws moved their families to “Sumner,” where a rendezvous was established. Here one of their gang, who always kept in the dark, and worked on the sly, lived with his Mexican wife, a sister to the wife of Pat Garrett. His name was Barney Mason, and he carried a curse of God on his brow for the killing of John Farris, a cowboy friend of the writer’s, in the early winter of 1878.

On one of his trips to Fort Sumner, “Billy the Kid” fell desperately in love with a pretty little seventeen-year-old half-breed Mexican girl, whom we will call Miss Dulcinea del Toboso. She was a daughter of a once famous man, and a sister to a man who owned sheep on a thousand hills. The falling in love with this pretty, young miss, was virtually[Pg 69] the cause of “Billy the Kid’s” death, as up to the last he hovered around Fort Sumner like a moth around a blazing candle. He had no thought of getting his wings singed; he couldn’t resist the temptation of visiting this pretty little miss.

During the month of September, 1878, the “Kid” and part of his gang visited the town of Lincoln, and on leaving there stole a large band of fine range horses from Charlie Fritz and others.

This band of horses was driven to Fort Sumner, thence east to Tascosa in the wild Panhandle of Texas, on the Canadian river.

While disposing of these horses to the cattlemen and cowboys, the “Kid” and his gang camped for several weeks at the “LX” cattle ranch, twenty miles below Tascosa.

It was here, during the months of [Pg 70]October and November, 1878, that the writer made the acquaintance of “Billy the Kid,” Tom O’Phalliard, Henry Brown, Fred Wyat, John Middleton, and others of the gang whose names can’t be recalled.

The author had just returned from Chicago where he had taken a shipment of fat steers, and found this gang of outlaws camped under some large cottonwood trees, within a few hundred yards of the “LX” headquarter ranch house.

For a few weeks, much of my time was spent with “Billy the Kid.” We became quite chummy. He presented me with a nicely bound book, in which he wrote his autograph. I had previously given him a fine meerschaum cigar holder.

While loafing in their camp, we passed off the time playing cards and shooting at marks. With our Colt’s 45 pistols I could hit the mark as often as[Pg 71] the “Kid,” but when it came to quick shooting, he could get in two shots to my one.

I found “Billy the Kid” to be a good natured young man. He was always cheerful and smiling. Being still in his teens, he had no sign of a beard. His eyes were a hazel blue, and his brown hair was long and curly. The skin on his face was tanned to a chestnut brown, and was as soft and tender as a baby’s. He weighed about one hundred and forty pounds, and was five feet, eight inches tall. His only defects were two upper front teeth, which projected outward from his well shaped mouth.

During his many visits to Tascosa, where whiskey was plentiful, the “Kid” never got drunk. He seemed to drink more for sociability than for the “love of liquor.”

Here Henry Brown and Fred Wyat[Pg 72] quit the “Kid’s” outlaw gang and went to the Chickasaw Nation, in the Indian Territory, where the parents of half-breed Fred Wyat lived.

It is said that Fred Wyat, in later years, served as a member of the Oklahoma Legislature.

Henry Brown became City Marshal of Caldwell, Kansas, and while wearing his star rode to the nearby town of Medicine Lodge, with three companions and in broad day light, held up the bank, killing the president, Wiley Payne, and his cashier, George Jeppert. This put an end to Henry Brown, as the enraged citizens mobbed the whole band of “bad men.”

The snow had begun to fly when the “Kid” and the remnant of his gang returned to Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

One of his followers, John Middleton, had sworn off being an outlaw and rode[Pg 73] away from Tascosa, for southern Kansas, where the author met him in later years. He had settled down to a peaceful life.

The “Kid” made his headquarters at Fort Sumner, so as to be near his sweetheart. He made several raids into Lincoln County to steal cattle and horses. On one of these trips to Lincoln County, his respect for women and children, avoided a bloody battle with United States soldiers.

In the month of February, 1879, Wm. H. McBroom, at the head of a United States surveying crew, established a camp at the Roberts ranch on the Penasco creek, in the Pecos valley.

While absent with most of his crew, Mr. McBroom left a young man, twenty-two years of age, Will M. Tipton, in charge of the camp and extra mules. A young Mexican by the name of Nicholas[Pg 74] Gutierez was detailed to help young Tipton care for the stock.

Their camp was within a few hundred feet of the Roberts home, on the bank of the creek. One morning Mr. Roberts started up the river to Roswell to buy supplies, leaving his wife, grown daughter, and five-year-old son at the ranch.

Late that evening, Captain Hooker and some negro soldiers pitched camp near the Roberts home. They had several American prisoners with them, to be taken to Fort Stanton and placed in jail.

That night after supper, Mr. Will M. Tipton, who at this writing, 1920, is a highly respected citizen of Santa Fe, New Mexico, says he and Nicolas Gutierez were sitting on the bank of the creek in their camp. He was playing a guitar while Nicolas was singing. Just then a horseman climbed up the steep embankment[Pg 75] from the bed of the creek, and dismounted.

This stranger began asking questions about the soldiers’ camp, where the camp-fires blazed brilliantly in the pitchy darkness.

Finally the stranger gave a shrill whistle, and soon a companion rode into camp, out of the bed of the creek.

This second visitor was a slender, boyish young man, who seemed anxious to learn all about the soldiers’ camp.

In a few moments three negro soldiers strolled into camp and chatted awhile. When they left to return to their quarters, the two strangers bade Tipton and his companion goodnight, and rode down the bed of the creek.

At noon next day, Mr. Roberts returned from Roswell. On meeting young Tipton, he remarked: “You boys had ‘Billy the Kid’ as a visitor last night.”[Pg 76] He then told of meeting the “Kid” and his band of “warriors” that morning, and of how the “Kid” told of his visit to the McBroom camp. He told Will Tipton that the small young man was the “Kid.”

“Billy the Kid” had told Roberts that they had planned to make a charge into the soldiers’ camp and liberate the prisoners, who were friends of theirs, but finding that Mrs. Roberts and the children were alone, and that the soldiers’ camp was so near the Roberts home, they gave up the proposed battle, knowing that the shooting would disturb Mrs. Roberts and the family.

Mr. Roberts explained to Mr. Tipton that he had always fed the “Kid” and his “warriors” when they happened by his place, hence their friendship for him.

Now the “Kid” and his party rode to Lincoln to use their influence in a peaceful[Pg 77] way to liberate their friends, whom Capt. Hooker intended to turn over to the new sheriff of Lincoln County.

In Lincoln the “Kid” met his former chum, Jesse Evans, and they started out to celebrate the meeting. With Jesse Evans was a desperado named William Campbell.

One night a lawyer named Chapman, who had been sent from Las Vegas to settle up the McSween estate, was in the saloon, when Campbell shot at his feet to make him dance. The lawyer protested indignantly and was shot dead by Campbell.

Jimmie Dolan and J. B. Mathews, being present, were later arrested, along with Campbell, for this killing.

Dolan and Mathews came clear at the preliminary trial, and Campbell was bound over to the Grand Jury. He was taken to Fort Stanton and placed in[Pg 78] jail. There he made his escape and has never been heard of in that part of the country since.

Now “Billy the Kid” and Tom O’Phalliard rode back to Fort Sumner, but soon returned to Lincoln, where they were arrested by Sheriff Kimbrall and his deputies—merely as a matter of performing their duty, but with no intention of disgracing them. They were turned over to Deputy Sheriff T. B. Longworth and guarded in the home of Don Juan Patron, where they were wined and dined.

On the 21st day of March, 1879, Deputy Sheriff Longworth received orders to place his two prisoners in the town jail—a filthy hole.

Arriving at the jail door, the “Kid” told Mr. Longworth that he had been in this jail once before, and he swore he would never go into it again, but to[Pg 79] avoid making trouble, he would go back on his pledge.

On a pine door to one of the cells, the “Kid” wrote with his pencil: “William Bonney was incarcerated first time, December 22nd, 1878—Second time, March 21st, 1879, and hope I will never be again. W. H. Bonney.”

This inscription showed on the old jail door for many years after it was written.

The first time the “Kid” was put in this jail he walked right out, and this second time, he broke down the door when he got ready to go.

After breaking out of the jail, the “Kid” and O’Phalliard spent a couple of weeks in Lincoln, carrying their rifles whenever they walked through the street, in plain view of the sheriff.

In April, they returned to Fort Sumner and were joined by Charlie Bowdre[Pg 80] and Skurlock. Jesse Evans had left for the lower Pecos, where he was later killed, according to reports.

The summer was spent by the “Kid” and his followers stealing cattle and horses.

In October they went to Roswell and stole 118 head of John Chisum’s fattest steers, and later sold them to Colorado beef buyers. The “Kid” claimed that Chisum owed him for fighting his battles during the Lincoln County war, and he was using this method to get his pay.

From now on, for the next year, the “Kid” and gang did a wholesale business in stealing cattle. Tom Cooper and his gang had joined issues with the “Kid” and party, and they established headquarters at the Portales Lake—a salty body of water at the foot of the Staked Plains, about seventy-five miles east of Fort Sumner.

[Pg 81]Here a permanent camp was pitched against a cliff of rock, at a fresh water spring, and it afterward became noted as “Billy the Kid’s” cave. A rock wall had been built against the cliff to take in the spring, and afforded protection as a fort in case of a surprise from Indians or law-officers.

They had the whole country to themselves, as there were no inhabitants—only drifting bands of buffalo hunters.

Raids were made into the Texas Panhandle, the western line being a few miles east of their camp, and fat steers stolen from the “LX” and “LIT” cattle ranges on the Canadian river.

These herds of stolen steers were driven to Tularosa, in Dona Ana County, New Mexico, and turned over to Pat Cohglin, the “King of Tularosa,” who had a contract to furnish beef to the U. S. soldiers at Ft. Stanton. Cohglin[Pg 82] had made a deal with “Billy the Kid” to buy all the steers he could steal in the Texas Panhandle, and deliver to him in Tularosa.

In January, 1880, the “Kid” added another notch on the handle of his pistol as a mankiller. He and a crowd of the Chisum cowboys were celebrating in Bob Hargroves’ saloon in Fort Sumner. A bad-man from Texas, by the name of Joe Grant, was filling his hide full of “Kill-me-quick” whiskey, in the Hargroves’ saloon.

Grant pulled a fine, ivory-handled Colt’s pistol from the scabbard of Cowboy Finan, putting his own pistol in place of it.

Here the “Kid” asked Grant to let him look at this beautiful, ivory-handled pistol. The request was granted. Then the “Kid” revolved the cylinder and saw there were two empty chambers. He[Pg 83] let the hammer down so that the first two attempts to shoot would be failures.

Now the pretty pistol was handed back to Grant and he stuck it in his scabbard.

A little later Grant stepped behind the bar, so as to face the crowd, and jerking his pistol, he began knocking glasses off the bar with it. Eyeing “Billy the Kid,” he remarked: “Pard, I’ll kill a man quicker than you will, for the whiskey.”

The “Kid” accepted the challenge. Grant fired at the “Kid,” but the hammer struck on an empty chamber. Now the “Kid” planted a ball between Grant’s eyes and he fell over dead.

At the Bosque Grande, on the Pecos river, the three Dedrick boys, Sam, Dan, and Mose, owned a ranch, which became quite a rendezvous for the “Kid’s” and Tom Cooper’s gangs. From here the herds of stolen Panhandle, Texas, cattle[Pg 84] were started across the waterless desert to the foot of the Capitan mountains, a distance of about one hundred miles.

Here Dave Rudabaugh, who had the previous fall killed the jailer in Las Vegas in trying to liberate his friend, Webb, joined “Billy the Kid’s” gang. Also Billy Wilson and Tom Pickett joined the party, and their time was spent stealing cattle and horses.

“BILLY THE KID” ADDS ONE MORE NOTCH TO HIS GUN AS A KILLER. TRAPPED AT LAST BY PAT GARRETT AND POSSE. TWO OF HIS GANG KILLED. IN JAIL AT SANTA FE.

In the year 1879, rich gold ore had been struck on Baxter mountain, three[Pg 85]

miles from White Oaks Spring, about thirty miles north of Lincoln, and the

new town of White Oaks was established, with a population of about one

thousand souls.

The “Kid” had many friends in this hurrah mining camp. He had shot up the town, and was wanted by the law officers.

On the 23rd day of November, 1880, the “Kid” celebrated his birthday in White Oaks, under cover, among friends.

On riding out of town with his gang after dark, he took one friendly shot at Deputy Sheriff Jim Woodland, who was standing in front of the Pioneer Saloon. The chances are he had no intention of shooting Woodland, as he was a warm friend to his chum, Tom O’Phalliard, who was riding by his side. O’Phalliard and Jim Woodland had come to New Mexico from Texas together, a few years[Pg 86] previous. Woodland is still a resident of Lincoln County, with a permanent home on the large Block cattle ranch.

This shot woke up Deputy Sheriffs Jim Carlyle and J. N. Bell, who fired parting shots at the gang, as they galloped out of town.

The next day a posse was made up of leading citizens of White Oaks with Deputy Sheriff Will Hudgens and Jim Carlyle in command. They followed the trail of the outlaw gang to Coyote Spring, where they came onto the gang in camp. Shots were exchanged. “Billy the Kid” had sprung onto his horse, which was shot from under him.

When the “Kid’s” gang fired on the posse, Johnny Hudgens’ mount fell over dead, shot in the head.

The weather was bitter cold and snow lay on the ground. Without overcoat or gloves, “Billy the Kid” rushed for the[Pg 87] hills, afoot, after his horse fell. The rest of the gang had become separated, and each one looked out for himself.

In the outlaws’ camp the posse found a good supply of grub and plunder.

Jim Carlyle appropriated the “Kid’s” gloves and put them on his hands. No doubt they were the real cause of his death later.

With “Billy the Kid’s” saddle, overcoat and the other plunder found in the outlaws’ camp, the posse returned to White Oaks, arriving there about dark.

It would seem from all accounts that “Billy the Kid” trailed the posse into White Oaks, where he found shelter at the Dedrick and West Livery Stable. He was seen on the street during the night.

On November 27th, a posse of White Oaks citizens under command of Jim Carlyle and Will Hudgens, rode to the Jim Greathouse road-ranch, about forty[Pg 88] miles north, arriving there before daylight. Their horses were secreted, and they made breastworks of logs and brush, so as to cover the ranch house, which was known to be a rendezvous of the “Kid’s” gang.

After daylight the cook came out of the house with a nosebag and ropes to hunt the horses which had been hobbled the evening before.

This cook, Steck, was captured by the posse behind the breastworks. He confessed that the “Kid” and his gang were in the house.

Now Steck was sent to the house with a note to the “Kid” demanding his surrender. The reply he sent back by Steck read: “You can only take me a corpse.”

The proprietor of the ranch, Jim Greathouse, accompanied Steck back to the posse behind the logs.

Jimmie Carlyle suggested that he go[Pg 89] to the house unarmed and have a talk with the “Kid.” Will Hudgens wouldn’t agree to this until after Greathouse said he would remain to guarantee Carlyle’s safe return. That if the “Kid” should kill Carlyle, they could take his life.

A time limit was set for Carlyle’s return, or Greathouse would be killed. This was written on a note and sent by Steck to the “Kid.”

When Carlyle entered the saloon, in the front part of the log building, the “Kid” greeted him in a friendly manner, but seeing his gloves sticking out of Carlyle’s coat pocket, he grabbed them, saying: “What in the h—l are you doing with my gloves?” Of course this brought back the misery he had endured without gloves after the posse raided their camp at Coyote Spring.

Here he invited Carlyle up to the bar[Pg 90] to take his last drink on earth—as he said he intended to kill him when the whiskey was down.

After Carlyle had drained his glass the “Kid” pulled his pistol and told him to say his prayers before he fired.

With a laugh the “Kid” put up his pistol, saying, “Why, Jimmie, I wouldn’t kill you. Let’s all take another friendly drink.”

Now the time was spent singing and dancing. Every time the gang took a drink, Carlyle had to join them in a social glass.

The “Kid” afterwards told friends that he had no intention of killing Carlyle, that he just wanted to detain him till after dark, so they could make a dash for liberty.

The time had just expired when the posse were to kill Jim Greathouse, if Carlyle was not back. At that moment a[Pg 91] man behind the breastworks fired a shot at the house. Carlyle supposed this shot had killed Greathouse, which would result in his own death. He leaped for the glass window, taking sash and all with him. The “Kid” fired a bullet into him. When he struck the ground he began crawling away on his hands and knees, as he was badly wounded. Now the “Kid” finished him with a well aimed shot from his pistol.

The men behind the logs were witnesses to this murder,—as they could see Carlyle crawling away from the window. Now they opened fire with a vengeance on the building. The gang had previously piled sacks of grain and flour against the doors, to keep out the bullets.

In the excitement, Jim Greathouse slipped away from the posse and ran through the woods. Finding one of his[Pg 92] own hobbled ponies, he mounted him and rode away. He was later shot by desperado Joe Fowler, with a double-barrel shot gun, as he lay in bed asleep. This murder took place on Joe Fowler’s cattle ranch west of Socorro, New Mexico.

After dark the posse concluded to return to White Oaks, as they were cold and hungry. They had brought no grub with them, and they dared not build a fire to keep warm, for fear of being shot by the gang.

A few hours later the “Kid” and gang made a break for liberty, intending to fight the posse to a finish, they not knowing that the officers had departed.

All night the gang waded through the deep snow, afoot. They arrived at Mr. Spence’s ranch at daylight, and ate a hearty breakfast. Then continued their[Pg 93] journey towards Anton Chico on the Pecos river.

About daylight that morning, Will Hudgens, Johnny Hurley, and Jim Brent made up a large posse and started to the Greathouse road-ranch. Arriving there, they found the place vacated. The buildings were set afire, then the journey continued on the gang’s trail, in the deep snow.

A highly respected citizen, by the name of Spence, had established a road-ranch on a cut-off road between White Oaks and Las Vegas. The gang’s trail led up to this ranch, and Mr. Spence acknowledged cooking breakfast for them.

Now Mr. Spence was dragged to a tree with a rope around his neck to hang him. Many of the posse protested against the hanging of Spence, and his life was spared, but revenge was taken by burning up his buildings.

[Pg 94]The “Kid’s” trail was now followed into a rough, hilly country and there abandoned. Then the posse returned to White Oaks.

In Anton Chico, the “Kid” and his party stole horses and saddles, and rode down the Pecos river.

A few days later, Pat Garrett, the sheriff of Lincoln County, arrived in Anton Chico from Fort Sumner, to make up a posse to run down the “Kid” and his gang.

At this time the writer and Bob Roberson had arrived in Anton Chico from Tascosa, Texas, with a crew of fighting cowboys, to help run down the “Kid,” and put a stop to the stealing of Panhandle, Texas, cattle.

The author had charge of five “warriors,” Jas. H. East, Cal Polk, Lee Hall, Frank Clifford (Big-Foot Wallace), and Lon Chambers. We were armed to the[Pg 95] teeth, and had four large mules to draw the mess-wagon, driven by the Mexican cook, Francisco.

Bob Roberson was in charge of five riders and a mess-wagon.

At our camp, west of Anton Chico, Pat Garrett met us, and we agreed to loan him a few of our “warriors.” The writer turned over to him three men, Jim East, Lon Chambers and Lee Hall. Bob Roberson turned over to him three cowboys, Tom Emmory, Bob Williams, and Louis Bozeman.

We then continued our journey to White Oaks in a raging snow storm.

Pat Garrett started down the Pecos river with his crew, consisting of our six cowboys, his brother-in-law, Barney Mason, and Frank Stewart, who had been acting as detective for the Panhandle cattlemen’s association.

At Fort Sumner, Pat Garrett [Pg 96]deputized Charlie Rudolph and a few Mexican friends, to join the crowd which now numbered about thirteen men.

Finding that the “Kid” and party had been in Fort Sumner, and made the old abandoned United States Hospital building, where lived Charlie Bowdre and his half-breed Mexican wife, their headquarters, Pat Garrett concluded to camp there. He figured that the outlaws would return and visit Mrs. Charlie Bowdre, whose husband was one of the outlaw band.

In order to get a true record of the capture of “Billy the Kid” and gang, the author wrote to James H. East, of Douglas, Arizona, for the facts. Jim East is the only known living participant in that tragic event. His reputation for honesty and truthfulness is above par wherever he is known. He served eight years as sheriff of Oldham[Pg 97] County, Texas, at Tascosa, and was city marshal for several years in Douglas, Arizona.

Herewith his letter to the writer is printed in full:

“Douglas, Arizona,

May 1st, 1920.

Dear Charlie:

Yours of the 29th received, and contents noted. I will try to answer your questions, but you know after a lapse of forty years, one’s memory may slip a cog. First: We were quartered in the old Government Hospital building in Ft. Sumner, the night of the first fight. Lon Chambers was on guard. Our horses were in Pete Maxwell’s stable. Sheriff Pat Garrett, Tom Emory, Bob Williams, and Barney Mason were playing poker on a blanket on the floor.

[Pg 98]I had just laid down on my blanket in the corner, when Chambers ran in and told us that the ‘Kid’ and his gang were coming. It was about eleven o’clock at night. We all grabbed our guns and stepped out in the yard.

Just then the ‘Kid’s’ men came around the corner of the old hospital building, in front of the room occupied by Charlie Bowdre’s woman and her mother. Tom O’Phalliard was riding in the lead. Garrett yelled out: ‘Throw up your hands!’ But O’Phalliard jerked his pistol. Then the shooting commenced. It being dark, the shooting was at random.

Tom O’Phalliard was shot through the body, near the heart, and lost control of his horse. ‘Kid’ and the rest of his men whirled[Pg 99] their horses and ran up the road.

O’Phalliard’s horse came up near us, and Tom said: ‘Don’t shoot any more, I am dying.’ We helped him off his horse and took him in, and laid him down on my blanket. Pat and the other boys then went back to playing poker.

I got Tom some water. He then cussed Garrett and died, in about thirty minutes after being shot.

The horse that Dave Rudabaugh was riding was shot, but not killed instantly. We found the dead horse the next day on the trail, about one mile or so east of Ft. Sumner.

After Dave’s horse fell down from loss of blood, he got up behind Billy Wilson, and they all went to Wilcox’s ranch that night.

The next morning a big snow storm set in and put out their trail,[Pg 100] so we laid over in Sumner and buried Tom O’Phalliard.

The next night, after the fight, it cleared off and about midnight, Mr. Wilcox rode in and reported to us that the “Kid,” Dave Rudabaugh, Billy Wilson, Tom Pickett, and Charlie Bowdre, had eaten supper at his ranch about dark, then pulled out for the little rock house at Stinking Spring. So we saddled up and started about one o’clock in the morning.

We got to the rock house just before daylight. Our horses were left with Frank Stewart and some of the other boys under guard, while Garrett took Lee Hall, Tom Emory and myself with him. We crawled up the arroyo to within about thirty feet of the door, where we lay down in the snow.

[Pg 101]There was no window in this house, and only one door, which we would cover with our guns.

The “Kid” had taken his race mare into the house, but the other three horses were standing near the door, hitched by ropes to the vega poles.

Just as day began to show, Charlie Bowdre came out to feed his horse, I suppose, for he had a moral in one hand. Garrett told him to throw up his hands, but he grabbed at his six-shooter. Then Garrett and Lee Hall both shot him in the breast. Emory and I didn’t shoot, for there was no use to waste ammunition then.

Charlie turned and went into the house, and we heard the ‘Kid’ say to him: ‘Charlie, you are done for. Go out and see if you can’t get one[Pg 102] of the s—of—b’s before you die.’

Charlie then walked out with his hand on his pistol, but was unable to shoot. We didn’t shoot, for we could see he was about dead. He stumbled and fell on Lee Hall. He started to speak, but the words died with him.

Now Garrett, Lee, Tom and I, fired several shots at the ropes which held the horses, and cut them loose—all but one horse which was half way in the door. Garrett shot him down, and that blocked the door, so the ‘Kid’ could not make a wolf dart on his mare.

We then held a medicine talk with the Kid, but of course couldn’t see him. Garrett asked him to give up, Billy answered: ‘Go to h—l, you long-legged s— of a b!’

Garrett then told Tom Emory[Pg 103] and I to go around to the other side of the house, as we could hear them trying to pick out a port-hole. Then we took it, time about, guarding the house all that day. When nearly sundown, we saw a white handkerchief on a stick, poked out of the chimney. Some of us crawled up the arroyo near enough to talk to ‘Billy.’ He said they had no show to get away, and wanted to surrender, if we would give our word not to fire into them, when they came out. We gave the promise, and they came out with their hands up, but that traitor, Barney Mason, raised his gun to shoot the ‘Kid,’ when Lee Hall and I covered Barney and told him to drop his gun, which he did.

Now we took the prisoners and the body of Charlie Bowdre to the[Pg 104] Wilcox ranch, where we stayed until next day. Then to Ft. Sumner, where we delivered the body of Bowdre to his wife. Garrett asked Louis Bousman and I to take Bowdre in the house to his wife. As we started in with him, she struck me over the head with a branding iron, and I had to drop Charlie at her feet. The poor woman was crazy with grief. I always regretted the death of Charlie Bowdre, for he was a brave man, and true to his friends to the last.

Before we left Ft. Sumner with the prisoners for Santa Fe, the ‘Kid’ asked Garrett to let Tom Emory and I go along as guards, which, as you know, he did.

The ‘Kid’ made me a present of his Winchester rifle, but old Beaver Smith made such a roar about an[Pg 105] account he said ‘Billy’ owed him, that at the request of ‘Billy,’ I gave old Beaver the gun. I wish now I had kept it.

On the road to Santa Fe, the ‘Kid’ told Garrett this: That those who live by the sword, die by the sword. Part of that prophecy has come true. Pat Garrett got his, but I am still alive.

I must close. You may use any quotations from my letters, for they are true. Good luck to you. Mrs. East joins me in best wishes.