Henry James.

1912.

Project Gutenberg's The Letters of Henry James, Vol. II, by Henry James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Letters of Henry James, Vol. II Author: Henry James Editor: Percy Lubbock Release Date: November 16, 2011 [EBook #38035] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF HENRY JAMES, V.2 *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SELECTED AND EDITED BY

PERCY LUBBOCK

VOLUME II

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1920

COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

| CONTENTS | ||

|---|---|---|

| VI. | Rye (continued): 1904-1909 | |

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 1 | |

| Letters: | ||

| To W. D. Howells | 8 | |

| To Edward Lee Childe | 10 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 12 | |

| To Mrs. Julian Sturgis | 14 | |

| To J. B. Pinker | 15 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 16 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 18 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 19 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 22 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 24 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 29 | |

| To Edward Warren | 31 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 32 | |

| To William James | 34 | |

| To Miss Margaret James | 36 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 37 | |

| To William James | 42 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 45 | |

| To Paul Harvey | 47 | |

| To William James | 50 | |

| To William James | 52 | |

| To Miss Margaret James | 53 | |

| To Mrs. Dew-Smith | 55 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 56 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 58 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 61 | |

| To Gaillard T. Lapsley | 62 | |

| To Bruce Porter | 65 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 67 | |

| To William James, junior | 71 | |

| To Howard Sturgis | 72 | |

| To Howard Sturgis | 74 | |

| To Madame Wagnière | 76 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 78 | |

| To Miss Gwenllian Palgrave | 81 | |

| To William James | 82 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 84 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 87 | |

| To Dr. and Mrs. J. William White | 88 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 90 | |

| To Gaillard T. Lapsley | 92 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 94 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 96 | |

| To W. D. Howells | 98 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 104 | |

| To J. B. Pinker | 105 | |

| To Miss Ellen Emmet | 107 | |

| To George Abbot James | 110 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 112 | |

| To George Abbot James | 113 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 114 | |

| To Mrs. Henry White | 117 | |

| To W. D. Howells | 118 | |

| To Edward Lee Childe | 120 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 122 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 123 | |

| To Arthur Christopher Benson | 125 | |

| To Charles Sayle | 127 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 129 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 131 | |

| To William James | 134 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 137 | |

| To Miss Henrietta Reubell | 139 | |

| To William James | 140 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 142 | |

| To Madame Wagnière | 144 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 146 | |

| To Owen Wister | 148 | |

| VII. | Rye and Chelsea: 1910-1914 | |

| Preface | 151 | |

| Letters: | ||

| To T. Bailey Saunders | 155 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 156 | |

| To Miss Jessie Allen | 158 | |

| To Mrs. Bigelow | 159 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 160 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 161 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 163 | |

| To Bruce Porter | 164 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 165 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 167 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 168 | |

| To Mrs. Charles Hunter | 170 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 171 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 173 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 175 | |

| To Miss Rhoda Broughton | 178 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 180 | |

| To C. E. Wheeler | 183 | |

| To Dr. J. William White | 184 | |

| To T. Bailey Saunders | 186 | |

| To Sir T. H. Warren | 188 | |

| To Miss Ellen Emmet (Mrs. Blanchard Rand) | 189 | |

| To Howard Sturgis | 192 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 194 | |

| To Mrs. John L. Gardner | 195 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 197 | |

| To Mrs. Wilfred Sheridan | 199 | |

| To Miss Alice Runnells | 201 | |

| To Mrs. Frederic Harrison | 202 | |

| To Miss Theodora Bosanquet | 204 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 205 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 208 | |

| To W. E. Norris | 211 | |

| To Miss M. Betham Edwards | 213 | |

| To Wilfred Sheridan | 215 | |

| To Walter V. R. Berry | 217 | |

| To W. D. Howells | 221 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 227 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 229 | |

| To Lady Bell | 231 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 234 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 236 | |

| To Miss Rhoda Broughton | 238 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 239 | |

| To R. W. Chapman | 241 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 244 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 246 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 248 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 250 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 252 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 255 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 257 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 261 | |

| To Mrs. Humphry Ward | 264 | |

| To Mrs. Humphry Ward | 265 | |

| To Gaillard T. Lapsley | 267 | |

| To John Bailey | 269 | |

| To Dr. J. William White | 272 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 274 | |

| To Mrs. Bigelow | 278 | |

| To Robert C. Witt | 280 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 281 | |

| To A. F. de Navarro | 286 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 288 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 293 | |

| To Mrs. Henry White | 296 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 299 | |

| To Bruce Porter | 302 | |

| To Lady Ritchie | 304 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 305 | |

| To Percy Lubbock | 310 | |

| To Two Hundred and Seventy Friends | 311 | |

| To Mrs. G. W. Prothero | 313 | |

| To William James, junior | 314 | |

| To Miss Rhoda Broughton | 317 | |

| To Mrs. Alfred Sutro | 319 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 322 | |

| To Mrs. Archibald Grove | 324 | |

| To William Roughead | 327 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 329 | |

| To Howard Sturgis | 330 | |

| To Mrs. G. W. Prothero | 332 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 333 | |

| To Logan Pearsall Smith | 337 | |

| To C. Hagberg Wright | 339 | |

| To Robert Bridges | 341 | |

| To André Raffalovich | 343 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 345 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 348 | |

| To Bruce L. Richmond | 350 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 352 | |

| To Compton Mackenzie | 354 | |

| To William Roughead | 356 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 357 | |

| To Dr. J. William White | 358 | |

| To Henry Adams | 360 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 361 | |

| To Arthur Christopher Benson | 364 | |

| To Mrs. Humphry Ward | 366 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 367 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 369 | |

| To William Roughead | 371 | |

| To William Roughead | 373 | |

| To Mrs. Alfred Sutro | 375 | |

| To Sir Claude Phillips | 376 | |

| VIII. | The War 1914-1916 | |

| Preface | 379 | |

| Letters: | ||

| To Howard Sturgis | 382 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 385 | |

| To Mrs. Alfred Sutro | 387 | |

| To Miss Rhoda Broughton | 389 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 391 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 392 | |

| To William James, junior | 394 | |

| To Mrs. W. K. Clifford | 397 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 399 | |

| To Mrs. R. W. Gilder | 401 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 403 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 405 | |

| To Mrs. T. S. Perry | 406 | |

| To Miss Rhoda Broughton | 408 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 409 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 412 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 414 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 416 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 419 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 423 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 425 | |

| To Mrs. T. S. Perry | 427 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 430 | |

| To Miss Grace Norton | 431 | |

| To Mrs. Dacre Vincent | 434 | |

| To the Hon. Evan Charteris | 436 | |

| To Compton Mackenzie | 437 | |

| To Miss Elizabeth Norton | 441 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 444 | |

| To Mrs. Henry Cabot Lodge | 447 | |

| To Mrs. William James | 449 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 452 | |

| To the Hon. Evan Charteris | 453 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 456 | |

| To Thomas Sergeant Perry | 459 | |

| To Edward Marsh | 462 | |

| To Edward Marsh | 464 | |

| To Mrs. Wharton | 465 | |

| To Edward Marsh | 468 | |

| To G. W. Prothero | 469 | |

| To Wilfred Sheridan | 470 | |

| To Edward Marsh | 472 | |

| To Edward Marsh | 474 | |

| To Compton Mackenzie | 475 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 477 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 480 | |

| To J. B. Pinker | 482 | |

| To Frederic Harrison | 483 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 485 | |

| To H. G. Wells | 487 | |

| To Henry James, junior | 490 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 492 | |

| To John S. Sargent | 493 | |

| To Wilfred Sheridan | 494 | |

| To Edmund Gosse | 496 | |

| To Mrs. Wilfred Sheridan | 499 | |

| To Hugh Walpole | 501 | |

| Index | 503 | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |

|---|---|

| Henry James, from a Photograph by E. O. Hoppé | Frontispiece |

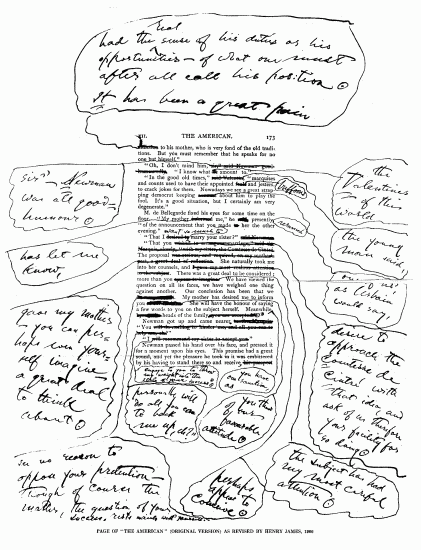

| Page of "the American" (original Version) as Revised by Henry James, 1906 | to face page 70. |

The much-debated visit to America took place at last in 1904, and in ten very full months Henry James secured that renewed saturation in American experience which he desired before it should be too late for his advantage. He saw far more of his country in these months than he had ever seen in old days. He went with the definite purpose of writing a book of impressions, and these were to be principally the impressions of a "restored absentee," reviving the sunken and overlaid memories of his youth. But his memories were practically of New York, Newport and Boston only; to the country beyond he came for the most part as a complete stranger; and his voyage of new discovery proved of an interest as great as that which he found in revisiting ancient haunts. The American Scene, rather than the letters he was able to write in the midst of such a stir of movement, gives his account of the adventure. On the spot the daily assault of sensation, besetting him wherever he turned, was too insistent for deliberate report; he quickly saw that his book would have to be postponed for calmer hours at home; and his letters are those of a man almost overwhelmed by the amount that is being thrown upon his power of absorption. But the book he eventually wrote shews how fully that power was equal to it all—losing or wasting none of it, meeting and reacting to every moment. Ten months of America poured into his imagination, as he intended they should, a vast mass of strange material—the familiar part of it now after so many years the strangest of all, perhaps; and his imagination worked upon it in one unbroken rage of interest. He was now more than sixty years old, but for such adventures of perception and discrimination his strength was greater than ever.

He sailed from England at the end of August, 1904, and spent most of the autumn with William James and his family, first at Chocorua, their country-home in the mountains of New Hampshire, and then at Cambridge. The rule he had made in advance against the paying of other visits was abandoned at once; he was in the centre of too many friendships and too many opportunities for extending and enlarging them. With Cambridge still as his headquarters he widely improved his knowledge of New England, which had never reached far into the countryside. At Christmas he was in New York—the place that was much more his home, as he still felt, than Boston had ever become, yet of all his American past the most unrecognisable relic in the portentous changes of twenty years. He struck south, through Philadelphia and Washington, in the hope of meeting the early Virginian spring; but it happened to be a year of unusually late snows, and his impressions of the southern country, most of which was quite unknown to him, were unfortunately marred. He found the right sub-tropical benignity in Florida, but a particular series of engagements brought him back after a brief stay. It had been natural that he should be invited to celebrate his return to America by lecturing in public; but that he should do so, and even with enjoyment, was more surprising, and particularly so to himself. He began by delivering a discourse on "The Lesson of Balzac"—a closely wrought critical study, very attractive in form and tone—at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, and was immediately solicited to repeat it elsewhere. He did this in the course of the winter at various other places, so providing himself at once with the means and the occasion for much more travel and observation than he had expected. By Chicago, St. Louis, and Indianapolis he reached California in April, 1905. "The Lesson of Balzac" was given several times, until for a second visit to Bryn Mawr he wrote another paper, "The Question of our Speech"—an amusing and forcible appeal for care in the treatment of spoken English. The two lectures were afterwards published in America, but have not appeared in England.

The beauty and amenity of California was an unexpected revelation to him, and it is clear that his experience of the west, though it only lasted for a few weeks, was fully as fruitful as all that had gone before. Unluckily he did not write the continuation of The American Scene, which was to have carried the record on from Florida to the Pacific coast; so that this part of his journey is only to be followed in a few hurried letters of the time. He was soon back in the east, at New York and Cambridge again, beginning by now to feel that the cup of his sensations was all but as full as it would hold. The longing to discharge it into prose before it had lost its freshness grew daily stronger; a year's absence from his work had almost tired him out. But he paid several last visits before sailing for home, and it was definitely in this American summer that he acquired a taste which was to bring him an immensity of pleasure on repeated occasions for the rest of his life. The use of the motor-car for wide and leisurely sweeps through summer scenery was from now onward an interest and a delight to which many friends were glad to help him—in New England at this time, later on at home, in France and in Italy. It renewed the romance of travel for him, revealing fresh aspects in the scenes of old wanderings, and he enjoyed the opportunity of sinking into the deep background of country life, which only came to him with emancipation from the railway.

He reached Lamb House again in August, 1905, and immediately set to work on his American book. It grew at such a rate that he presently found he had filled a large volume without nearly exhausting his material; but by that time the whole experience seemed remote and faint, and he felt it impossible to go further with it. The wreckage of San Francisco, moreover, by the great earthquake and fire of 1906, drove his own Californian recollections still further from his mind. He left The American Scene a fragment, therefore, and turned to another occupation which engaged him very closely for the next two years. This was the preparation of the revised and collected edition of his works, or at least of so much of his fiction as he could find room for in a limited number of volumes. To read his own books was an entirely new amusement to him; they had always been rigidly thrust out of sight from the moment they were finished and done with; and he came back now to his early novels with a perfectly detached critical curiosity. He took each of them in hand and plunged into the enormous toil, not indeed of modifying its substance in any way—where he was dissatisfied with the substance he rejected it altogether—but of bringing its surface, every syllable of its diction, to the level of his exigent taste. At the same time, in the prefaces to the various volumes, he wrote what became in the end a complete exposition of his theory of the art of fiction, intertwined with the memories of past labour that he found everywhere in the much-forgotten pages. It all represented a great expenditure of time and trouble, besides the postponement of new work; and there is no doubt that he was deeply disappointed by the half-hearted welcome that the edition met with after all, schooled as he was in such discouragements.

While he was on this work he scarcely stirred from Lamb House except for occasional interludes of a few weeks in London; and it was not until the spring of 1907 that he allowed himself a real holiday. He then went abroad for three months, beginning with a visit to Mr. and Mrs. Wharton in Paris and a motor-tour with them over a large part of western and southern France. With all his French experience, Paris of the Faubourg St. Germain and France of the remote country-roads were alike almost new to him, and the whole episode was matter of the finest sort for his imagination. From The American to The Ambassadors he had written scores of pages about Paris, but none more romantic than a paragraph or two of The Velvet Glove, in which he recorded an impression of this time—a sight of the quays and the Seine on a blue and silver April night. From Paris he passed on to his last visit, as it proved, to his beloved Italy. It was the tenth he had made since his settlement in England in 1876. Like every one else, perhaps, who has ever known Rome in youth, he found Rome violated and vulgarised in his age, but here too the friendly "chariot of fire" helped him to a new range of discoveries at Subiaco, Monte Cassino, and in the Capuan plain. He spent a few days at a friend's house on the mountain-slope below Vallombrosa, and a few more, the best of all, in Venice, at the ever-glorious Palazzo Barbaro. That was the end of Italy, but he was again in Paris for a short while in the following spring, 1908, motoring thither from Amiens with his hostess of the year before.

Meanwhile his return to continuous work on fiction, still ardently desired by him, had been further postponed by a recrudescence of his old theatrical ambitions, stimulated, no doubt, by the comparative failure of the laborious edition of his works. He had taken no active step himself, but certain advances had been made to him from the world of the theatre, and with a mixture of motives he responded so far as to revise and re-cast a couple of his earlier plays and to write a new one. The one-act "Covering End" (which had appeared in The Two Magics, disguised as a short story) became "The High Bid," in three acts; it was produced by Mr. and Mrs. Forbes Robertson at Edinburgh in March, 1908, and repeated by them in London in the following February, for a few afternoon performances at His Majesty's Theatre. "The Other House," a play dating from a dozen years back which also had seen the light only as a narrative, was taken in hand again with a view to its production by another company, and "The Outcry" was written for a third. The two latter schemes were not carried out in the end, chiefly on account of the troubled time of illness which fell on Henry James with the beginning of 1910 and which made it necessary for him to lay aside all work for many months. But this new intrusion of the theatre into his life was happily a much less agitating incident than his earlier experience of the same sort; his expectations were now fewer and his composure was more securely based. The misfortune was that again a considerable space of time was lost to the novel—and in particular to the novel of American life that he had designed to be one of the results of his year of repatriation. The blissful hours of dictation in the garden-house at Rye were interrupted while he was at work on the plays; he found he could compass the concision of the play-form only by writing with his own hand, foregoing the temptation to expand and develop which came while he created aloud. But his keenest wish was to get back to the novel once more, and he was clearing the way to it at the end of 1909 when all his plans were overturned by a long and distressing illness. He never reached the American novel until four years later, and he did not live to finish it.

Dictated.

Lamb House, Rye.

Jan. 8th, 1904.

My dear Howells,

I am infinitely beholden to you for two good letters, the second of which has come in to-day, following close on the heels of the first and greeting me most benevolently as I rise from the couch of solitary pain. Which means nothing worse than that I have been in bed with odious and inconvenient gout, and have but just tumbled out to deal, by this helpful machinery, with dreadful arrears of Christmas and New Year's correspondence. Not yet at my ease for writing, I thus inflict on you without apology this unwonted grace of legibility.

It warms my heart, verily, to hear from you in so encouraging and sustaining a sense—in fact makes me cast to the winds all timorous doubt of the energy of my intention. I know now more than ever how much I want to "go"—and also a good deal of why. Surely it will be a blessing to commune with you face to face, since it is such a comfort and a cheer to do so even across the wild winter sea. Will you kindly say to Harvey for me that I shall have much pleasure in talking with him here of the question of something serialistic in the North American, and will broach the matter of an "American" novel in no other way until I see him. It comes home to me much, in truth, that, after my immensely long absence, I am not quite in a position to answer in advance for the quantity and quality, the exact form and colour, of my "reaction" in presence of the native phenomena. I only feel tolerably confident that a reaction of some sort there will be. What affects me as indispensable—or rather what I am conscious of as a great personal desire—is some such energy of direct action as will enable me to cross the country and see California, and also have a look at the South. I am hungry for Material, whatever I may be moved to do with it; and, honestly, I think, there will not be an inch or an ounce of it unlikely to prove grist to my intellectual and "artistic" mill. You speak of one's possible "hates" and loves—that is aversions and tendernesses—in the dire confrontation; but I seem to feel, about myself, that I proceed but scantly, in these chill years, by those particular categories and rebounds; in short that, somehow, such fine primitive passions lose themselves for me in the act of contemplation, or at any rate in the act of reproduction. However, you are much more passionate than I, and I will wait upon your words, and try and learn from you a little to be shocked and charmed in the right places. What mainly appals me is the idea of going a good many months without a quiet corner to do my daily stint; so much so in fact that this is quite unthinkable, and that I shall only have courage to advance by nursing the dream of a sky-parlour of some sort, in some cranny or crevice of the continent, in which my mornings shall remain my own, my little trickle of prose eventuate, and my distracted reason thereby maintain its seat. If some gifted creature only wanted to exchange with me for six or eight months and "swap" its customary bower, over there, for dear little Lamb House here, a really delicious residence, the trick would be easily played. However, I see I must wait for all tricks. This is all, or almost all, to-day—all except to reassure you of the pleasure you give me by your remarks about the Ambassadors and cognate topics. The "International" is very presumably indeed, and in fact quite inevitably, what I am chronically booked for, so that truly, even, I feel it rather a pity, in view of your so benevolent colloquy with Harvey, that a longish thing I am just finishing should not be disponible for the N.A.R. niche; the niche that I like very much the best, for serialisation, of all possible niches. But "The Golden Bowl" isn't, alas, so employable.... Fortunately, however, I still cling to the belief that there are as good fish in the sea—that is, my sea!... You mention to me a domestic event—in Pilla's life—which interests me scarce the less for my having taken it for granted. But I bless you all. Yours always,

HENRY JAMES.

The name of this friend, an American long settled in France, has already occurred (vol. i. p. 50) in connection with H. J.'s early residence in Paris. Mr. Childe (who died in 1911) is known as the biographer of his uncle, General Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate forces in the American Civil War.

Lamb House, Rye.

January 19th, 1904.

My dear old Friend,

...You write in no high spirits—over our general milieu or moment; but high spirits are not the accompaniment of mature wisdom, and yours are doubtless as good as mine. Like yourself, I put in long periods in the country, which on the whole (on this mild and rather picturesque south coast) I find in my late afternoon of life, a good and salutary friend. And I haven't your solace of companionship—I dwell in singleness save for an occasional imported visitor—who is usually of a sex, however, not materially to mitigate my celibacy! I have a small—a very nice perch in London, to which I sometimes go—in a week or two, for instance, for two or three months. But I return hither, always, with zest—from the too many people and things and words and motions—into the peaceful possession of (as I grow older) my more and more precious home hours. I have a household of good books, and reading tends to take for me the place of experience—or rather to become itself (pour qui sait lire) experience concentrated. You will say this is a dull picture, but I cultivate dulness in a world grown too noisy. Besides, as an antidote to it, I have committed myself to going some time this year to America—my first expedition thither for 21 years. If I do go (and it is inevitable,) I shall stay six or eight months—and shall be probably much and variously impressed and interested. But I am already gloating over the sentiments with which I shall expatriate myself here.

You ask what is being published and "thought" here—to which I reply that England never was the land of ideas, and that it is now less so than ever. Morley's Life of Gladstone, in three big volumes, is formidable, but rich, and is very well done; a type of frank, exhaustive, intimate biography, such as has been often well produced here, but much less in France: partly, perhaps, because so much cannot be told about the lives—private lives—of the grands hommes there. Of course the book is largely a history of English politics for the last 50 years—but very human and vivid. As for talk, I hear very little—none in this rusticity; but if I pay a visit of three days, as I do occasionally, I become aware that the Free Traders and the Chamberlainites s'entredévorent. The question bristles for me, with the rebarbative; but my prejudices and dearest traditions are all on the side of the system that has "made England great"—and everything I am most in sympathy with in the country appears to be still on the side of it, notably the better—the best—sort of the younger men. Chamberlain hasn't in the least captured these.... But it's the midnight hour, and my fire, while I write, has gone out. I return again, most heartily, your salutation; I send the friendliest greeting to Mrs. Lee Childe and to the dear old Perthuis, well remembered of me, and very tenderly, and I am, my dear Childe, your very faithful old friend,

HENRY JAMES.

Lamb House, Rye.

January 27th, 1904.

My dear Norris,

I have as usual a charming letter from you too long unanswered; and my sense of this is the sharper as, in spite of your eccentric demonstration of your—that is of our disparities, or whatever (or at least of your lurid implication of them,) it all comes round, after all, to our having infinitely much in common. For I too am making arrangements to be "cremated," and my mind keeps yours company in whatever pensive hovering yours may indulge in over the graceful operations at Woking. If you will only agree to postpone these, on your own part, to the latest really convenient date, I would quite agree to testify to our union of friendship by availing myself of the same occasion (it might come cheaper for two!) and undergoing the process with you. I find I do desire, from the moment the question becomes a really practical one, to throw it as far into the future as possible. Save at the frequent moments when I desire to die very soon, almost immediately, I cling to life and propose to make it last. I blush for the frivolity, but there are still so many things I want to do! I give you more or less an illustration of this, I feel, when I tell you that I go up to town tomorrow, for eight or ten weeks, and that I believe I have made arrangements (or incurred the making of them by others) to meet Rhoda Broughton in the evening (à peine arrivé) at dinner. But I shall make in fact a shorter winter's end stay than usual, for I have really committed myself to what is for me a great adventure later in the year; I have taken my passage for the U.S. toward the end of August, and with that long absence ahead of me I shall have to sit tight in the interval. So I shall come back early in April, to begin to "pack," at least morally; and the moral preparation will (as well as the material) be the greater as it's definitely visible to me that I must, if possible, let this house for the six or nine months....

But what a sprawling scrawl I have written you! And it's long past midnight. Good morning! Everything else I meant to say (though there isn't much) is crowded out.

Yours always and ever,

HENRY JAMES.

Julian Sturgis, novelist and poet, a friend of H. J.'s by many ties, had died on the day this letter was written.

Reform Club, Pall Mall, S.W.

April 13, 1904.

Dearest Mrs. Julian,

I ask myself how I can write to you and yet how I cannot, for my heart is full of the tenderest and most compassionate thought of you, and I can't but vainly say so. And I feel myself thinking as tenderly of him, and of the laceration of his consciousness of leaving you and his boys, of giving you up and ceasing to be for you what he so devotedly was. And that makes me pity him more than words can say—with the wretchedness of one's not having been able to contribute to help or save him. But there he is in his sacrifice—a beautiful, noble, stainless memory, without the shadow upon him, or the shadow of a shadow, of a single grossness or meanness or ugliness—the world's dust on the nature of thousands of men. Everything that was high and charming in him comes out as one holds on to him, and when I think of my friendship of so many years with him I see it all as fairness and felicity. And then I think of your admirable years and I find no words for your loss. I only desire to keep near you and remain more than ever yours,

HENRY JAMES.

Mr. Pinker was now acting, as he continued to do till the end, as H. J.'s literary agent. This letter refers to The Golden Bowl.

Lamb House, Rye.

May 20th, 1904.

Dear Mr. Pinker,

I will indeed let you have the whole of my MS. on the very first possible day, now not far off; but I have still, absolutely, to finish, and to finish right.... I have been working on the book with unremitting intensity the whole of every blessed morning since I began it, some thirteen months ago, and I am at present within but some twelve or fifteen thousand words of Finis. But I can work only in my own way—a deucedly good one, by the same token!—and am producing the best book, I seem to conceive, that I have ever done. I have really done it fast, for what it is, and for the way I do it—the way I seem condemned to; which is to overtreat my subject by developments and amplifications that have, in large part, eventually to be greatly compressed, but to the prior operation of which the thing afterwards owes what is most durable in its quality. I have written, in perfection, 200,000 words of the G.B.—with the rarest perfection!—and you can imagine how much of that, which has taken time, has had to come out. It is not, assuredly, an economical way of work in the short run, but it is, for me, in the long; and at any rate one can proceed but in one's own manner. My manner however is, at present, to be making every day—it is now a question of a very moderate number of days—a straight step nearer my last page, comparatively close at hand. You shall have it, I repeat, with the very minimum further delay of which I am capable. I do not seem to know, by the way, when it is Methuen's desire that the volume shall appear—I mean after the postponements we have had. The best time for me, I think, especially in America, will be about next October, and I promise you the thing in distinct time for that. But you will say that I am "over-treating" this subject too! Believe me yours ever,

HENRY JAMES.

Lamb House, Rye.

July 26th, 1904.

Dearest H.

Your letter from Chocorua, received a day or two ago, has a rare charm and value for me, and in fact brings to my eyes tears of gratitude and appreciation! I can't tell you how I thank you for offering me your manly breast to hurl myself upon in the event of my alighting on the New York dock, four or five weeks hence, in abject and craven terror—which I foresee as a certainty; so that I accept without shame or scruple the beautiful and blessed offer of aid and comfort that you make me. I have it at heart to notify you that you will in all probability bitterly repent of your generosity, and that I shall be sure to become for you a dead-weight of the first water, the most awful burden, nuisance, parasite, pestilence and plaster that you have ever known. But this said, I prepare even now to me cramponner to you like grim death, trusting to you for everything and invoking you from moment to moment as my providence and saviour. I go on assuming that I shall get off from Southampton in the Kaiser Wilhelm II, of the North German Lloyd line, on August 24th—the said ship being, I believe, a "five-day" boat, which usually gets in sometime on the Monday. Of course it will be a nuisance to you, my arriving in New York—if I do arrive; but that got itself perversely and fatefully settled some time ago, and has now to be accepted as of the essence. Since you ask me what my desire is likely to he, I haven't a minute's hesitation in speaking of it as a probable frantic yearning to get off to Chocorua, or at least to Boston and its neighbourhood, by the very first possible train, and it may be on the said Monday. I shall not have much heart for interposing other things, nor any patience for it to speak of, so long as I hang off from your mountain home; yet, at the same time, if the boat should get in late, and it were possible to catch the Connecticut train, I believe I could bend my spirit to go for a couple of days to the Emmets', on the condition that you can go with me. So, and so only, could I think of doing it. Very kindly, therefore, let them know this, by wire or otherwise, in advance, and determine for me yourself whichever you think the best move. Grace Norton writes me from Kirkland Street that she expects me there, and Mrs. J. Gardner writes me from Brookline that she absolutely counts on me; in consequence of all of which I beseech you to hold on to me tight and put me through as much as possible like an express parcel, paying 50 cents and taking a brass check for me. I shall write you again next month, and meanwhile I'm delighted at the prospect of your being able to spend September in the mountain home. I have all along been counting on that as a matter of course, but now I see it was fatuous to do so—and yet rejoice but the more that this is in your power.... But good-night, dearest H.—with many caresses all round, ever your affectionate

HENRY JAMES.

Chocorua, N.H., U.S.A.

September 16th, 1904.

My dear, dear Lucy C.!

One's too dreadful—I receive your note and your wire of August 23rd, in far New England, under another sky and in such another world. I don't know by what deviltry I missed them at the last, save by that of the Reform being closed for cleaning and the use of the Union (other Club) fraught with other errors and delays. But the Wednesday a.m. at Waterloo was horrible for crowd and confusion (passengers for ship so in their thousands,) and I can't be sorry you weren't in the crush (mainly of rich German-American Jews!) But that is ancient history, and the worst of this, now, here, is that, spent with letter-writing (my American postbag swollen to dreadfulness, more and more, and interviewers only kept at bay till I get to Boston and New York,) I can only make you to-night this incoherent signal, waiting till some less burdened hour to be more decent and more vivid. I came straight up here (where I have been just a fortnight,) and these New Hampshire mountains, forests, lakes, are of a beauty that I hadn't (from my 18th-20th years) dared to remember as so great. And such golden September weather—though already turning to what the leaf enclosed (picked but by reaching out of window) is a very poor specimen of. It is a pure bucolic and Arcadian, wildly informal and un-"frilled" life—but sweet to me after long years—and with many such good old homely, farmy New England things to eat! Yet a she-interviewer pushed into it yesterday all the way from New York, 400 miles, and we ten miles from a station, on the mere chance of me, and I took pity and your advice, and surrendered to her more or less, on condition that I shouldn't have to read her stuff—and I shan't! So you see I am well in—and to-morrow I go to other places (one by one) and shall be in deeper. It's a vast, queer, wonderful country—too unspeakable as yet, and of which this is but a speck on the hem of the garment! Forgive this poverty of wearied pen to your good old

HENRY JAMES.

The Mount,

Lenox, Mass.

October 27th, 1904.

My dear Gosse,

The weeks have been many and crowded since I received, not very many days after my arrival, your incisive letter from the depths of the so different world (from this here;) but it's just because they have been so animated, peopled and pervaded, that they have rushed by like loud-puffing motor-cars, passing out of my sight before I could step back out of the dust and the noise long enough to dash you off such a response as I could fling after them to be carried to you. And during my first three or four here my postbag was enormously—appallingly—heavy: I almost turned tail and re-embarked at the sight of it. And then I wanted above all, before writing you, to make myself a notion of how, and where, and even what, I was. I have turned round now a good many times, though still, for two months, only in this corner of a corner of a corner, that is round New England; and the postbag has, happily, shrunken a good bit (though with liabilities, I fear, of re-expanding,) and this exquisite Indian summer day sleeps upon these really admirable little Massachusetts mountains, lakes and woods, in a way that lulls my perpetual sense of precipitation. I have moved from my own fireside for long years so little (have been abroad, till now, but once, for ten years previous) that the mere quantity of movement remains something of a terror and a paralysis to me—though I am getting to brave it, and to like it, as the sense of adventure, of holiday and romance, and above all of the great so visible and observable world that stretches before one more and more, comes through and makes the tone of one's days and the counterpoise of one's homesickness. I am, at the back of my head and at the bottom of my heart, transcendently homesick, and with a sustaining private reference, all the while (at every moment, verily,) to the fact that I have a tight anchorage, a definite little downward burrow, in the ancient world—a secret consciousness that I chink in my pocket as if it were a fortune in a handful of silver. But, with this, I have a most charming and interesting time, and [am] seeing, feeling, how agreeable it is, in the maturity of age, to revisit the long neglected and long unseen land of one's birth—especially when that land affects one as such a living and breathing and feeling and moving great monster as this one is. It is all very interesting and quite unexpectedly and almost uncannily delightful and sympathetic—partly, or largely from my intense impression (all this glorious golden autumn, with weather like tinkling crystal and colours like molten jewels) of the sweetness of the country itself, this New England rural vastness, which is all that I've seen. I've been only in the country—shamelessly visiting and almost only old friends and scattered relations—but have found it far more beautiful and amiable than I had ever dreamed, or than I ventured to remember. I had seen too little, in fact, of old, to have anything, to speak of, to remember—so that seeing so many charming things for the first time I quite thrill with the romance of elderly and belated discovery. Of Boston I haven't even had a full day—of N.Y. but three hours, and I have seen nothing whatever, thank heaven, of the "littery" world. I have spent a few days at Cambridge, Mass., with my brother, and have been greatly struck with the way that in the last 25 years Harvard has come to mass so much larger and to have gathered about her such a swarm of distinguished specialists and such a big organization of learning. This impression is increased this year by the crowd of foreign experts of sorts (mainly philosophic etc.) who have been at the St. Louis congress and who appear to be turning up overwhelmingly under my brother's roof—but who will have vanished, I hope, when I go to spend the month of November with him—when I shall see something of the goodly Boston. The blot on my vision and the shadow on my path is that I have contracted to write a book of Notes—without which contraction I simply couldn't have come; and that the conditions of life, time, space, movement etc. (really to see, to get one's material,) are such as to threaten utterly to frustrate for me any prospect of simultaneous work—which is the rock on which I may split altogether—wherefore my alarm is great and my project much disconcerted; for I have as yet scarce dipped into the great Basin at all. Only a large measure of Time can help me—to do anything as decent as I want: wherefore pray for me constantly; and all the more that if I can only arrive at a means of application (for I see, already, from here, my Tone) I shall do, verily, a lovely book. I am interested, up to my eyes—at least I think I am! But you will fear, at this rate, that I am trying the book on you already. I may have to return to England only as a saturated sponge and wring myself out there. I hope meanwhile that your own saturations, and Mrs. Nelly's, prosper, and that the Pyrenean, in particular, continued rich and ample. If you are having the easy part of your year now, I hope you are finding in it the lordliest, or rather the unlordliest leisure.... I commend you all to felicity and am, my dear Gosse, yours always,

HENRY JAMES.

Boston.

[Dec. 15, 1904.]

My dear Norris,

There is nothing to which I find my situation in this great country less favourable than to this order of communication; yet I greatly wish, 1st, to thank you for your beautiful letter of as long ago as Sept. 12th (from Malvern,) and 2nd, not to fail of having some decent word of greeting on your table for Xmas morning. The conditions of time and space, at this distance, are such as to make nice calculations difficult, and I shall probably be frustrated of the felicity of dropping on you by exactly the right post. But I send you my affectionate blessing and I aspire, at the most, to lurk modestly in the Heap. You were in exile (very elegant exile, I rather judge) when you last wrote, but you will now, I take it, be breathing again bland Torquay (bland, not blond)—a process having, to my fancy, a certain analogy and consonance with that of quaffing bland Tokay. This is neither Tokay nor Torquay—this slightly arduous process, or adventure, of mine, though very nearly as expensive, on the whole, as both of those luxuries combined. I am just now amusing myself with bringing the expense up to the point of ruin by having come back to Boston, after an escape (temporary, to New York,) to conclude a terrible episode with the Dentist—which is turning out an abyss of torture and tedium. I am promised (and shall probably enjoy) prodigious results from it—but the experience, the whole business, has been so fundamental and complicated that anguish and dismay only attend it while it goes on—embellished at the most by an opportunity to admire the miracles of American expertness. These are truly a revelation and my tormentor a great artist, but he will have made a cruelly deep dark hole in my time (very precious for me here) and in my pocket—the latter of such a nature that I fear no patching of all my pockets to come will ever stop the leak. But meanwhile it has all made me feel quite domesticated, consciously assimilated to the system; I am losing the precious sense that everything is strange (which I began by hugging close,) and it is only when I know I am quite whiningly homesick en dessous, for L.H. and Pall Mall, that I remember I am but a creature of the surface. The surface, however, has its points; New York is appalling, fantastically charmless and elaborately dire; but Boston has quality and convenience, and now that one sees American life in the longer piece one profits by many of its ingenuities. The winter, as yet, is radiant and bell-like (in its frosty clearness;) the diffusion of warmth, indoors, is a signal comfort, extraordinarily comfortable in the travelling, by day—I don't go in for nights; and a marvel the perfect organisation of the universal telephone (with interviews and contacts that begin in 2 minutes and settle all things in them;) a marvel, I call it, for a person who hates notewriting as I do—but an exquisite curse when it isn't an exquisite blessing. I expect to be free to return to N.Y., the formidable in a few days—where I shall inevitably have to stay another month; after which I hope for sweeter things—Washington, which is amusing, and the South, and eventually California—with, probably, Mexico. But many things are indefinite—only I shall probably stay till the end of June. I suppose I am much interested—for the time passes inordinately fast. Also the country is unlike any other—to one's sensation of it; those of Europe, from State to State, seem to me less different from each other than they are all different from this—or rather this from them. But forgive a fatigued and obscure scrawl. I am really done and demoralized with my interminable surgical (for it comes to that) ordeal. Yet I wish you heartily all peace and plenty and am yours, my dear Norris, very constantly,

HENRY JAMES.

The Breakers Hotel,

Palm Beach,

Florida.

February 16th, 1905.

My dear Gosse,

I seem to myself to be (under the disadvantage of this extraordinary process of "seeing" my native country) perpetually writing letters; and yet I blush with the consciousness of not having yet got round to you again—since the arrival of your so genial New Year's greeting. I have been lately in constant, or at least in very frequent, motion, on this large comprehensive scale, and the right hours of recueillement and meditation, of private communication, in short, are very hard to seize. And when one does seize them, as you know, one is almost crushed by the sense of accumulated and congested matter. So I won't attempt to remount the stream of time save the most sketchily in the world. It was from Lenox, Mass., I think, in the far-away prehistoric autumn, that I last wrote you. I reverted thence to Boston, or rather, mainly, to my brother's kindly roof at Cambridge, hard by—where, alas, my five or six weeks were harrowed and ravaged by an appalling experience of American transcendent Dentistry—a deep dark abyss, a trap of anguish and expense, into which I sank unwarily (though, I now begin to see, to my great profit in the short human hereafter,) of which I have not yet touched the fin fond. (I mention it as accounting for treasures of wrecked time—I could do nothing else whatever in the state into which I was put, while the long ordeal went on: and this has left me belated as to everything—"work," correspondence, impressions, progress through the land.) But I was (temporarily) liberated at last, and fled to New York, where I passed three or four appalled midwinter weeks (Dec. and early Jan.;) appalled, mainly, I mean, by the ferocious discomfort this season of unprecedented snow and ice puts on in that altogether unspeakable city—from which I fled in turn to Philadelphia and Washington. (I am going back to N.Y. for three or four weeks of developed spring—I haven't yet (in a manner) seen it or cowardly "done" it.) Things and places southward have been more manageable—save that I lately spent a week of all but polar rigour at the high-perched Biltmore, in North Carolina, the extraordinary colossal French château of George Vanderbilt in the said N.C. mountains—the house 2500 feet in air, and a thing of the high Rothschild manner, but of a size to contain two or three Mentmores and Waddesdons.... Philadelphia and Washington would yield me a wild range of anecdote for you were we face to face—will yield it me then; but I can only glance and pass—glance at the extraordinary and rather personally-fascinating President—who was kind to me, as was dear J. Hay even more, and wondrous, blooming, aspiring little Jusserand, all pleasant welcome and hospitality. But I liked poor dear queer flat comfortable Philadelphia almost ridiculously (for what it is—extraordinarily cossu and materially civilized,) and saw there a good deal of your friend—as I think she is—Agnes Repplier, whom I liked for her bravery and (almost) brilliancy. (You'll be glad to hear that she is extraordinarily better, up to now, these two years, of the malady by which her future appeared so compromised.) However, I am tracing my progress on a scale, and the hours melt away—and my letter mustn't grow out of my control. I have worked down here, yearningly, and for all too short a stay—but ten days in all; but Florida, at this southernmost tip, or almost, does beguile and gratify me—giving me my first and last (evidently) sense of the tropics, or à peu près, the subtropics, and revealing to me a blandness in nature of which I had no idea. This is an amazing winter-resort—the well-to-do in their tens, their hundreds, of thousands, from all over the land; the property of a single enlightened despot, the creator of two monster hotels, the extraordinary agrément of which (I mean of course the high pitch of mere monster-hotel amenity) marks for me [how] the rate at which, the way in which, things are done over here changes and changes. When I remember the hotels of twenty-five years ago even! It will give me brilliant chapters on hotel-civilization. Alas, however, with perpetual movement and perpetual people and very few concrete objects of nature or art to make use of for assimilation, my brilliant chapters don't get themselves written—so little can they be notes of the current picturesque—like one's European notes. They can only be notes on a social order, of vast extent, and I see with a kind of despair that I shall be able to do here little more than get my saturation, soak my intellectual sponge—reserving the squeezing-out for the subsequent, ah, the so yearned-for peace of Lamb House. It's all interesting, but it isn't thrilling—though I gather everything is more really curious and vivid in the West—to which and California, and to Mexico if I can, I presently proceed. Cuba lies off here at but twelve hours of steamer—and I am heartbroken at not having time for a snuff of that flamboyant flower.

Saint Augustine, Feb. 18th.

I had to break off day before yesterday, and I have completed meanwhile, by having come thus far north, my sad sacrifice of an intenser exoticism. I am stopping for two or three days at the "oldest city in America"—two or three being none too much to sit in wonderment at the success with which it has outlived its age. The paucity of the signs of the same has perhaps almost the pathos the signs themselves would have if there were any. There is rather a big and melancholy and "toned" (with a patina) old Spanish fort (of the 16th century,) but horrible little modernisms surround it. On the other hand this huge modern hotel (Ponce de Leon) is in the style of the Alhambra, and the principal church ("Presbyterian") in that of the mosque of Cordova. So there are compensations—and a tiny old Spanish cathedral front ("earliest church built in America"—late 16th century,) which appeals with a yellow ancientry. But I must pull off—simply sticking in a memento[A] (of a public development, on my desperate part) which I have no time to explain. This refers to a past exploit, but the leap is taken, is being renewed; I repeat the horrid act at Chicago, Indianapolis, St. Louis, San Francisco and later on in New York—have already done so at Philadelphia (always to "private" "literary" or Ladies' Clubs—at Philadelphia to a vast multitude, with Miss Repplier as brilliant introducer. At Bryn Mawr to 700 persons—by way of a little circle.) In fine I have waked up conférencier, and find, to my stupefaction, that I can do it. The fee is large, of course—otherwise! Indianapolis offers £100 for 50 minutes! It pays in short travelling expenses, and the incidental circumstances and phenomena are full of illustration. I can't do it often—but for £30 a time I should easily be able to. Only that would be death. If I could come back here to abide I think I should really be able to abide in (relative) affluence: one can, on the spot, make so much more money—or at least I might. But I would rather live a beggar at Lamb House—and it's to that I shall return. Let my biographer, however, recall the solid sacrifice I shall have made. I have just read over your New Year's eve letter and it makes me so homesick that the bribe itself will largely seem to have been on the side of the reversion—the bribe to one's finest sensibility. I have published a novel—"The Golden Bowl"—here (in two vols.) in advance (15 weeks ago) of the English issue—and the latter will be (I don't even know if it's out yet in London) in so comparatively mean and fine-printed a London form that I have no heart to direct a few gift copies to be addressed. I shall convey to you somehow the handsome New York page—don't read it till then. The thing has "done" much less ill here than anything I have ever produced.

But good-night, verily—with all love to all, and to Mrs. Nelly in particular.

Yours always,

HENRY JAMES.

[A] Card of admission to a lecture by H. J. (The Lesson of Balzac), Bryn Mawr College, Jan. 19, 1905.

Hotel Ponce de Leon,

St. Augustine, Florida.

February 21st, '05.

Dearest old Friend!

I am leaving this subtropical Floridian spot from one half hour to another, but the horror of not having for so long despatched a word to you, the shame and grief and contrition of it, are so strong, within me, that I simply seize the passing moment by the hair of its head and glare at it till it pauses long enough to let me—as it were—embrace you. Yet I feel, have felt, all along, that you will have understood, and that words are wasted in explaining the obvious. Letters, all these weeks and weeks, day to day and hour to hour letters, have fluttered about me in a dense crowd even as the San Marco pigeons, in Venice, round him who appears to have corn to scatter. So the whole queer time has gone in my scattering corn—scattering and chattering, and being chattered and scattered to, and moving from place to place, and surrendering to people (the only thing to do here—since things, apart from people, are nil;) in staying with them, literally, from place to place and week to week (though with old friends, as it were, alone—that is mostly, thank God—to avoid new obligations:) doing that as the only solution of the problem of "seeing" the country. I am seeing, very well—but the weariness of so much of so prolonged and sustained a process is, at times, surpassing. It would be a strain, a weariness (kept up so,) anywhere; and it is extraordinarily tiresome, on occasions, here. Vastness of space and distance, of number and quantity, is the element in which one lives: it is a great complication alone to be dealing with a country that has fifty principal cities—each a law unto itself—and unto you: England, poor old dear, having (to speak of) but one. On the other hand it is distinctly interesting—the business and the country, as a whole; there are no exquisite moments (save a few of a funniness that comes to that;) but there are none from which one doesn't get something....And meanwhile I am lecturing a little to pay the Piper, as I go—for high fees (of course) and as yet but three or four times. But they give me gladly £50 for 50 minutes (a pound a minute—like Patti!)—and always for the same lecture (as yet:) The Lesson of Balzac. I do it beautifully—feel as if I had discovered my vocation—at any rate amaze myself. It is well—for without it I don't see how I could have held out.

...This winter has been a hideous succession of huge snow-blizzards, blinding polar waves, and these southernmost places, even, are not their usual soft selves. Yet the very south tiptoe of Florida, from which I came three days ago, has an air as of molten liquid velvet, and the palm and the orange, the pine-apple, the scarlet hibiscus, the vast magnolia and the sapphire sea, make it a vision of very considerable beguilement. I wanted to put over to Cuba—but one night from this coast; but it was, for reasons, not to be done—reasons of time and money. I shall try for Mexico—and meanwhile pray for me hard. My visit is doing—has done—my little reputation here, save the mark, great good. The Golden Bowl is in its fourth edition—unprecedented! You see I "answer" your last newses and things not at all—not even the note of anxiety about T. Such are these cruelties, these ferocities of separation. But I drink in everything you tell me, and I cherish you all always and am yours and the children's twain ever so constantly,

HENRY JAMES.

University Club,

Chicago.

March 19th, 1905.

Dearest Edward,

This is but a mere breathless blessing hurled at you, as it were, between trains and in ever so grateful joy in your brave double letter (of the lame hand, hero that you are!) which has just overtaken me here. I'm not pretending to write—I can't; it's impossible amid the movement and obsession and complication of all this overwhelming muchness of space and distance and time (consumed,) and above all of people (consuming.) I start in a few hours straight for California—enter my train this, Monday, night 7.30, and reach Los Angeles and Pasadena at 2.30 Thursday afternoon. The train has, I believe, barber's shops, bathrooms, stenographers and typists; so that if I can add a postscript, without too much joggle, I will. But you will say "Here is joggle enough," for alack, I am already (after 17 days of the "great Middle West") rather spent and weary, weary of motion and chatter, and oh, of such an unimagined dreariness of ugliness (on many, on most sides!) and of the perpetual effort of trying to "do justice" to what one doesn't like. If one could only damn it and have done with it! So much of it is rank with good intentions. And then the "kindness"—the princely (as it were) hospitality of these clubs; besides the sense of power, huge and augmenting power (vast mechanical, industrial, social, financial) everywhere! This Chicago is huge, infinite (of potential size and form, and even of actual;) black, smoky, old-looking, very like some preternaturally boomed Manchester or Glasgow lying beside a colossal lake (Michigan) of hard pale green jade, and putting forth railway antennae of maddening complexity and gigantic length. Yet this club (which looks old and sober too!) is an abode of peace, a benediction to me in the looming largeness; I live here, and they put one up (always, everywhere,) with one's so excellent room with perfect bathroom and w.c. of its own, appurtenant (the universal joy of this country, in private houses or wherever; a feature that is really almost a consolation for many things.) I have been to the south, the far end of Florida &c—but prefer the far end of Sussex! In the heart of golden orange-groves I yearned for the shade of the old L.H. mulberry tree. So you see I am loyal, and I sail for Liverpool on July 4th. I go up the whole Pacific coast to Vancouver, and return to New York (am due there April 26th) by the Canadian-Pacific railway (said to be, in its first half, sublime.) But I scribble beyond my time. Your letters are really a blessed breath of brave old Britain. But oh for a talk in a Westminster panelled parlour, or a walk on far-shining Camber sands! All love to Margaret and the younglings. I have again written to Jonathan—he will have more news of me for you. Yours, dearest Edward, almost in nostalgic rage, and at any rate in constant affection,

HENRY JAMES.

Hotel del Coronado,

Coronado Beach, California.

Wednesday night,

April 5th, 1905.

Dearest Alice,

I must write you again before I leave this place (which I do tomorrow noon;) if only to still a little the unrest of my having condemned myself, all too awkwardly, to be so long without hearing from you. I haven't all this while—that is these several days—had the letters which I am believing you will have forwarded to Monterey sent down to me here. This I have abstained from mainly because, having stopped over here these eight or nine days to write, in extreme urgency, an article, and wishing to finish it at any price, I have felt that I should go to pieces as an author if a mass of arrears of postal matter should come tumbling in upon me—and particularly if any of it should be troublous. However, I devoutly hope none of it has been troublous—and I have done my best to let you know (in any need of wiring etc.) where I have been. Also the letterless state has added itself to the deliciously simplified social state to make me taste the charming sweetness and comfort of this spot. California, on these terms, when all is said (Southern C. at least—which, however, the real C., I believe, much repudiates,) has completely bowled me over—such a delicious difference from the rest of the U.S. do I find in it. (I speak of course all of nature and climate, fruits and flowers; for there is absolutely nothing else, and the sense of the shining social and human inane is utter.) The days have been mostly here of heavenly beauty, and the flowers, the wild flowers just now in particular, which fairly rage, with radiance, over the land, are worthy of some purer planet than this. I live on oranges and olives, fresh from the tree, and I lie awake nights to listen, on purpose, to the languid list of the Pacific, which my windows overhang. I wish poor heroic Harry could be here—the thought of whose privations, while I wallow unworthy, makes me (tell him with all my love) miserably sick and poisons much of my profit. I go back to Los Angeles to-morrow, to (as I wrote you last) re-utter my (now loathly) Lecture to a female culture club of 900 members (whom I make pay me through the nose,) and on Saturday p.m. 8th, I shall be at Monterey (Hotel del Monte.) But my stay there is now condemned to bitterest brevity and my margin of time for all the rest of this job is so rapidly shrinking that I see myself brûlant mes étapes, alas, without exception, and cutting down my famous visit to Seattle to a couple of days. It breaks my heart to have so stinted myself here—but it was inevitable, and no one had given me the least inkling that I should find California so sympathetic. It is strange and inconvenient, how little impression of anything any one ever takes the trouble to give one beforehand. I should like to stay here all April and May. But I am writing more than my time permits—my article is still to finish. I ask you no questions—you will have told me everything. I live in the hope that the news from Wm. will have been good. At least at Monterey, may there be some.... But good night—with great and distributed tenderness. Yours, dearest Alice, always and ever,

HENRY JAMES.

Dictated.

95 Irving Street,

Cambridge, Mass.

July 2nd, 1905.

Dearest W.,

I am ticking this out at you for reasons of convenience that will be even greater for yourself, I think, than for me.... Your good letter of farewell reached me at Lenox, from which I returned but last evening—to learn, however, from A., every circumstance of your departure and of your condition, as known up to date. The grim grey Chicago will now be your daily medium, but will put forth for you, I trust, every such flower of amenity as it is capable of growing. May you not regret, at any point, having gone so far to meet its queer appetites. Alice tells me that you are to go almost straight thence (though with a little interval here, as I sympathetically understand) to the Adirondacks: where I hope for you as big a bath of impersonal Nature as possible, with the tub as little tainted, that is, by the soapsuds of personal: in other words, all the "board" you need, but no boarders. I seem greatly to mislike, not to say deeply to mistrust, the Adirondack boarder....I greatly enjoyed the whole Lenox countryside, seeing it as I did by the aid of the Whartons' big strong commodious new motor, which has fairly converted me to the sense of all the thing may do for one and one may get from it. The potent way it deals with a country large enough for it not to rudoyer, but to rope in, in big free hauls, a huge netful of impressions at once—this came home to me beautifully, convincing me that if I were rich I shouldn't hesitate to take up with it. A great transformer of life and of the future! All that country charmed me; we spent the night at Ashfield and motored back the next day, after a morning there, by an easy circuit of 80 miles between luncheon and a late dinner; a circuit easily and comfortably prolonged for the sake of good roads....But I mustn't rattle on. I have still innumerable last things to do. But the portents are all propitious—absit any ill consequence of this fatuity! I am living, at Alice's instance, mainly on huge watermelon, dug out in spadefuls, yet light to carry. But good bye now. Your last hints for the "Speech" are much to the point, and I will try even thus late to stick them in. May every comfort attend you!

Ever yours,

HENRY JAMES.

The project of a book on London was never carried further, though certain pages of the autobiographical fragment, The Middle Years, written in 1914-15, no doubt shew the kind of line it would have taken.

Lamb House, Rye.

November 3rd, 1905.

Dearest Peg,

...In writing to your father (which, however, I shall not be able to do by this same post) I will tell him a little better what has been happening to me and why I have been so unsociable. This unsociability is in truth all that has been happening—as it has been the reverse of the medal, so to speak, of the great arrears and urgent applications (to work) that awaited me here after I parted with you. I have been working in one way and another with great assiduity, squeezing out my American Book with all desirable deliberation, and yet in a kind of panting dread of the matter of it all melting and fading from me before I have worked it off. It does melt and fade, over here, in the strangest way—and yet I did, I think, while with you, so successfully cultivate the impression and the saturation that even my bare residuum won't be quite a vain thing. I really find in fact that I have more impressions than I know what to do with; so that, evidently, at the rate I am going, I shall have pegged out two distinct volumes instead of one. I have already produced almost the substance of one—which I have been sending to "Harper" and the N.A.R., as per contract; though publication doesn't begin, apparently, in those periodicals till next month. And then (please mention to your Dad) all the time I haven't been doing the American Book, I have been revising with extreme minuteness three or four of my early works for the Edition Définitive (the settlement of some of the details of which seems to be hanging fire a little between my "agent" and my New York publishers; not, however, in a manner to indicate, I think, a real hitch.) Please, however, say nothing whatever, any of you to any one, about the existence of any such plan. These things should be spoken of only when they are in full feather. That for your Dad—I mean the information as well as the warning, in particular; on whom, you see, I am shamelessly working off, after all, a good deal of my letter. Mention to him also that still other tracts of my time, these last silent weeks, have gone, have had to go, toward preparing for a job that I think I mentioned to him while with you—my pledge, already a couple of years old to do a romantical-psychological-pictorial "social" London (of the general form, length, pitch, and "type" of Marion Crawford's Ave Roma Immortalis) for the Macmillans; and I have been feeling so nervous of late about the way America has crowded me off it, that I have had, for assuagement of my nerves, to begin, with piety and prayer, some of the very considerable reading the task will require of me. All this to show you that I haven't been wantonly uncommunicative. But good-night, dear Peg; I am going to do another for Aleck. With copious embraces,

HENRY JAMES.

Lamb House, Rye.

November 19th, 1905.

My dear Wells,

If I take up time and space with telling you why I have not sooner written to thank you for your magnificent bounty, I shall have, properly, to steal it from my letter, my letter itself; a much more important matter. And yet I must say, in three words, that my course has been inevitable and natural. I found your first munificence here on returning from upwards of 11 months in America, toward the end of July—returning to the mountain of arrears produced by almost a year's absence and (superficially, thereby) a year's idleness. I recognized, even from afar (I had already done so) that the Utopia was a book I should desire to read only in the right conditions of coming to it, coming with luxurious freedom of mind, rapt surrender of attention, adequate honours, for it of every sort. So, not bolting it like the morning paper and sundry, many, other vulgarly importunate things, and knowing, moreover, I had already shown you that though I was slow I was safe, and even certain, I "came to it" only a short time since, and surrendered myself to it absolutely. And it was while I was at the bottom of the crystal well that Kipps suddenly appeared, thrusting his honest and inimitable head over the edge and calling down to me, with his note of wondrous truth, that he had business with me above. I took my time, however, there below (though "below" be a most improper figure for your sublime and vertiginous heights,) and achieved a complete saturation; after which, reascending and making out things again, little by little, in the dingy air of the actual, I found Kipps, in his place, awaiting me—and from his so different but still so utterly coercive embrace I have just emerged. It was really very well he was there, for I found (and it's even a little strange) that I could read you only—after you—and don't at all see whom else I could have read. But now that this is so I don't see either, my dear Wells, how I can "write" you about these things—they make me want so infernally to talk with you, to see you at length. Let me tell you, however, simply, that they have left me prostrate with admiration, and that you are, for me, more than ever, the most interesting "literary man" of your generation—in fact, the only interesting one. These things do you, to my sense, the highest honour, and I am lost in amazement at the diversity of your genius. As in everything you do (and especially in these three last Social imaginations), it is the quality of your intellect that primarily (in the Utopia) obsesses me and reduces me—to that degree that even the colossal dimensions of your Cheek (pardon the term that I don't in the least invidiously apply) fails to break the spell. Indeed your Cheek is positively the very sign and stamp of your genius, valuable to-day, as you possess it, beyond any other instrument or vehicle, so that when I say it doesn't break the charm, I probably mean that it largely constitutes it, or constitutes the force: which is the force of an irony that no one else among us begins to have—so that we are starving, in our enormities and fatuities, for a sacred satirist (the satirist with irony—as poor dear old Thackeray was the satirist without it,) and you come, admirably, to save us. There are too many things to say—which is so exactly why I can't write. Cheeky, cheeky, cheeky is any young-man-at-Sandgate's offered Plan for the life of Man—but so far from thinking that a disqualification of your book, I think it is positively what makes the performance heroic. I hold, with you, that it is only by our each contributing Utopias (the cheekier the better) that anything will come, and I think there is nothing in the book truer and happier than your speaking of this struggle of the rare yearning individual toward that suggestion as one of the certain assistances of the future. Meantime you set a magnificent example—of caring, of feeling, of seeing, above all, and of suffering from, and with, the shockingly sick actuality of things. Your epilogue tag in italics strikes me as of the highest, of an irresistible and touching beauty. Bravo, bravo, my dear Wells!

And now, coming to Kipps, what am I to say about Kipps but that I am ready, that I am compelled, utterly to drivel about him? He is not so much a masterpiece as a mere born gem—you having, I know not how, taken a header straight down into mysterious depths of observation and knowledge, I know not which and where, and come up again with this rounded pearl of the diver. But of course you know yourself how immitigably the thing is done—it is of such a brilliancy of true truth. I really think that you have done, at this time of day, two particular things for the first time of their doing among us. (1) You have written the first closely and intimately, the first intelligently and consistently ironic or satiric novel. In everything else there has always been the sentimental or conventional interference, the interference of which Thackeray is full. (2) You have for the very first time treated the English "lower middle" class, etc., without the picturesque, the grotesque, the fantastic and romantic interference of which Dickens, e.g., is so misleadingly, of which even George Eliot is so deviatingly, full. You have handled its vulgarity in so scientific and historic a spirit, and seen the whole thing all in its own strong light. And then the book has throughout such extraordinary life; everyone in it, without exception, and every piece and part of it, is so vivid and sharp and raw. Kipps himself is a diamond of the first water, from start to finish, exquisite and radiant; Coote is consummate, Chitterlow magnificent (the whole first evening with Chitterlow perhaps the most brilliant thing in the book—unless that glory be reserved for the way the entire matter of the shop is done, including the admirable image of the boss.) It all in fine, from cover to cover, does you the greatest honour, and if we had any other than skin-deep criticism (very stupid, too, at that,) it would have immense recognition.

I repeat that these things have made me want greatly to see you. Is it thinkable to you that you might come over at this ungenial season, for a night—some time before Xmas? Could you, would you? I should immensely rejoice in it. I am here till Jan. 31st—when I go up to London for three months. I go away, probably, for four or five days at Xmas—and I go away for next Saturday-Tuesday. But apart from those dates I would await you with rapture.

And let me say just one word of attenuation of my (only apparent) meanness over the Golden Bowl. I was in America when that work appeared, and it was published there in 2 vols. and in very charming and readable form, each vol. but moderately thick and with a legible, handsome, large-typed page. But there came over to me a copy of the London issue, fat, vile, small-typed, horrific, prohibitive, that so broke my heart that I vowed I wouldn't, for very shame, disseminate it, and I haven't, with that feeling, had a copy in the house or sent one to a single friend. I wish I had an American one at your disposition—but I have been again and again depleted of all ownership in respect to it. You are very welcome to the British brick if you, at this late day, will have it.

I greet Mrs Wells and the Third Party very cordially and am yours, my dear Wells, more than ever,

HENRY JAMES.

Lamb House, Rye.

November 23rd, 1905.

Dearest William,