The Project Gutenberg EBook of Poems, by Arthur Macy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Poems Author: Arthur Macy Release Date: November 13, 2011 [EBook #37999] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

POEMS

BY ARTHUR MACY

With an Introduction by

WILLIAM ALFRED HOVEY

W. B. CLARKE CO.

BOSTON

1905

COPYRIGHT 1905 BY MARY T. MACY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Editors of The Youth's Companion, St. Nicholas, and The Smart Set, The H. B. Stevens Company, The Oliver Ditson Company, and Messrs. G. Schirmer & Company, have kindly permitted the republication of several poems in this collection.

INTRODUCTION

Arthur Macy was a Nantucket boy of Quaker extraction. His name alone is evidence of this, for it is safe to say that a Macy, wherever found in the United States, is descended from that sturdy old Quaker who was one of those who bought Nantucket from the Indians, paid them fairly for it, treated them with justice, and lived on friendly terms with them. In many ways Arthur Macy showed that he was a Nantucketer and, at least by descent, a Quaker. He often used phrases peculiar to our island in the sea, and was given, in conversation at least, to similes which smacked of salt water. Almost the last time I saw him he said, "I'm coming round soon for a good long gam."

He was a many-sided man. In his intercourse with a friend like myself he would show the side which he thought would interest me, and that only. He was above all things cheery, and, to his praise be it said, he hated a bore. I remember that a mutual friend was talking baseball to me by the yard. Arthur was sitting by, listening. It was a subject in which he was much interested. Nevertheless,[vi] turning to our mutual friend, he said, "Don't talk baseball to him. He don't care anything about it, he don't know anything about it, and he don't want to." On the other hand, although little given to telling of his war experiences, he was always ready to talk over the old days with me. Of what he did himself, he modestly said but little, but of the services of others, more especially of the men in the ranks, he was generous in his praise.

Early in the war Macy enlisted in Company B, 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry. He was twice wounded on the first day at Gettysburg, and managed to crawl into the town and get as far as the steps of the Court House, which was fast filling with wounded from both sides. His sense of humor was in evidence even at such a time. A Confederate officer rode up and asked, "Have those men in there got arms?" Quick as a flash Macy answered: "Some of them have and some of them haven't." He remained in this Court-House hospital, a prisoner within the Confederate lines, until the battle was over and Lee's army retreated. All wounded prisoners who could walk were forced to go with them, but Macy's wound was in the foot, and, fortunately for him, he was spared the horrors of a Southern prison.

[vii]He was on duty later at the Naval Academy Hospital in Annapolis, presided over by Dr. Vanderkieft, perhaps as efficient a general hospital administrator as the army had. I knew Dr. Vanderkieft very well, and was on duty at his hospital when the exchanged prisoners came back from Andersonville. Although Macy and I never met there, it came out in our talk that we were there at the same time. He served his full three years, and was honorably discharged about the close of the war.

It is given to but few to have the keen sense of humor which he possessed. Quick and keen at repartee, he never practised it save when worth while. He never said the clearly obvious thing. Failing something better than that, he held his peace.

Had it not been for his disinclination to publish his verses, he long ago would have had a national reputation. His reason for this disinclination, as I gathered from many talks with him, was that he did not consider his work of sufficiently high poetic standard. Every one praised his choice of words, his wonderful facility in rhyme, the perfection of his metre, and the daintiness and delicacy of his verse. "All right," he would say, "but that[viii] is not Poetry with a big P, and that is the only kind that should be published. And there is mighty little of it." It is fortunate that this severe judgment, creditable as it was to him, is not to prevail. Lovers of the beautiful are not to be robbed of "Sit Closer, Friends," nor of "A Poet's Lesson," and many who never heard of that remarkable Spanish pachyderm will take delight in the story of "The Rollicking Mastodon," whose home was "in the trunk of a Tranquil Tree." The greater part of his verses with which I am familiar I heard at Papyrus Club dinners. He was an early member, and one of the most esteemed. He was fairly sure to have something in his pocket, and the presiding officer never called upon him in vain.

It was so at the Saint Botolph Club, of which he was long a member. Whenever there was an "occasion" when the need of verse seemed indicated, Arthur Macy could be counted on. His "Saint Botolph," which has become the Club song, and will be sung as long as the Club endures, was written for a Twelfth Night revel at my request. It has a peculiarly old English flavor. He makes of the Saint, not the jolly friar nor yet the severe recluse, but just a good, kind old man who "was loved by[ix] the sinners and loved by the good," one who was certain that there must be sin so long as

| "A few get the loaves and many get the crumbs, And some are born fingers and some are born thumbs." |

And here we get a glimpse of Arthur Macy's view of life, which was certainly broad and generous, with a philosophic flavor.

Arthur Macy had a business side of which his Club intimates had but slight knowledge. He represented, in New England, one of the great commercial agencies of the country. His knowledge of business men, of their standing, commercially and financially, was extended and intimate, and was relied upon by our merchants and others as a basis for giving credit. His office work required the closest attention to details and the exercise of the most careful judgment. The whole success of such a company as that which he represented depends upon the reliability of the information which it gives. Without this it has no reason for existence. It was to Arthur Macy that the merchants of Boston largely turned for information concerning their customers scattered throughout New England, and it was because of his success in obtaining such information and his thorough knowledge of the business[x] in all its details that the superior officers of the company placed such implicit confidence in his judgment and so high a value upon his advice. And in the conduct of this business he showed his Quaker straightforwardness. His work was not at all of the "detective" sort. If information was wanted concerning a man's business by those who had dealings with him, Macy went directly to the man himself, and told him that it was for his own best interest to show just where he stood, and, above all things, to tell the exact truth. Honest men had the truth told about them, and profited by it. Dishonest men and secretive men were passed over in severe silence, and their credit suffered accordingly. Few of those who sought Arthur Macy for business information ever suspected that they were talking to a poet and man of letters.

I have not sought to tell Arthur Macy's life story. Neither have I entered upon any detailed consideration of his verse. It is for the reader to peruse the pages that follow and draw his own conclusion. I have merely tried to give a glimpse of the characteristics of one of the most charming personalities I ever knew.

William Alfred Hovey.

St. Botolph Club,

Boston, June 7, 1905.

CONTENTS

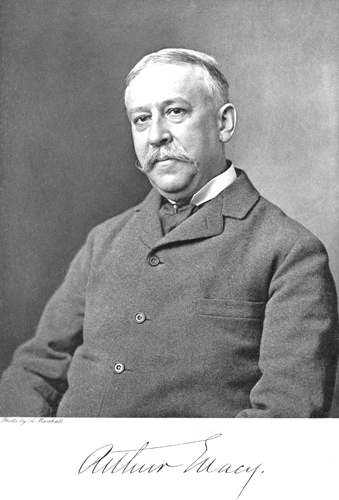

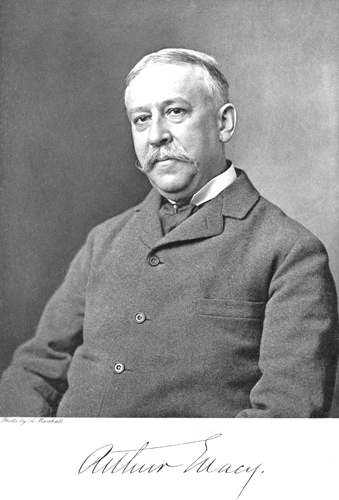

| Frontispiece | Portrait of Arthur Macy |

| Introduction | v |

| POEMS | |

| In Remembrance | 1 |

| The Old Café | 4 |

| At Marliave's | 8 |

| The Passing of the Rose | 9 |

| A Valentine | 10 |

| Disenchantment | 12 |

| Constancy | 15 |

| A Poet's Lesson | 17 |

| "Place aux Dames" | 19 |

| All on a Golden Summer Day | 20 |

| Prismatic Boston | 21 |

| The Book Hunter | 25 |

| The Three Voices | 27 |

| Easy Knowledge | 28 |

| Susan Scuppernong | 29 |

| The Hatband | 30 |

| The Oyster | 31 |

| Wind and Rain | 32 |

| The Flag | 34 |

| My Masterpiece | 36[xii] |

| A Ballade of Montaigne | 40 |

| The Criminal | 42 |

| A Bit of Color | 45 |

| Dinner Favors | 48 |

| The Moper | 51 |

| Various Valentines | 54 |

| Were all the World like You | 59 |

| Here and There | 60 |

| Uncle Jogalong | 62 |

| The Indifferent Mariner | 64 |

| On a Library Wall | 66 |

| Mrs. Mulligatawny | 67 |

| Euthanasia | 70 |

| Dainty Little Love | 71 |

| To M. | 72 |

| The Song | 73 |

| At Twilight Time | 76 |

| Céleste | 78 |

| Thistle-Down | 80 |

| The Slumber Song | 81 |

| Thou art to Me | 82 |

| Love | 83 |

| The Stranger-Man | 84 |

| The Honeysuckle Vine | 86 |

| Saint Botolph | 87 |

| The Gurgling Imps | 90 |

| The Worm will Turn | 91 |

| The Boston Cats | 94 |

| The Jonquil Maid | 96 |

| The Rollicking Mastodon | 99[xiii] |

| The Five Senses | 102 |

| Economy | 103 |

| Idylettes of the Queen | 105 |

| To M. E. | 110 |

| Bon Voyage | 111 |

| The Book of Life | 112 |

POEMS

IN REMEMBRANCE

[W. L. C.]

|

SIT closer, friends, around the board! Death grants us yet a little time. Now let the cheering cup be poured, And welcome song and jest and rhyme. Enjoy the gifts that fortune sends. Sit closer, friends! And yet, we pause. With trembling lip We strive the fitting phrase to make; Remembering our fellowship, Lamenting Destiny's mistake. We marvel much when Fate offends, And claims our friends. Companion of our nights of mirth,[2] Where all were merry who were wise; Does Death quite understand your worth, And know the value of his prize? I doubt me if he comprehends— He knows no friends. And in that realm is there no joy Of comrades and the jocund sense? Can Death so utterly destroy— For gladness grant no recompense? And can it be that laughter ends With absent friends? Oh, scholars whom we wisest call, Who solve great questions at your ease, We ask the simplest of them all, And yet you cannot answer these! And is it thus your knowledge ends, To comfort friends? Dear Omar! should You chance to meet Our Brother Somewhere in the Gloom, Pray give to Him a Message sweet,[3] From Brothers in the Tavern Room. He will not ask who 'tis that sends, For We were Friends. Again a parting sail we see; Another boat has left the shore. A kinder soul on board has she Than ever left the land before. And as her outward course she bends, Sit closer, friends! |

THE OLD CAFÉ

|

YOU know, Don't you, Joe, Those merry evenings long ago? You know the room, the narrow stair, The wreaths of smoke that circled there, The corner table where we sat For hours in after-dinner chat, And magnified Our little world inside. You know, Don't you, Joe? Ah, those nights divine! The simple, frugal wine, The airs on crude Italian strings, The joyous, harmless revelings, Just fit for us—or kings! At times a quaint and wickered flask Of rare Chianti, or from the homelier cask Of modest Pilsener a stein or so,[5] Amid the merry talk would flow; Or red Bordeaux From vines that grew where dear Montaigne Held his domain. And you remember that dark eye, None too shy; In fact, she seemed a bit too free For you and me. You know, Don't you, Joe? Then Pegasus I knew, And then I read to you My callow rhymes So many, many times; And something in the place Lent them a certain grace, Until I scarce believed them mine, Under the magic of the wine; But now I read them o'er, And see grave faults I had not seen before, And wonder how You could have listened with such placid brow,[6] And somehow apprehend You sank the critic in the friend. You know, Don't you, Joe? And when we talked of books, How learned were our looks! And few the bards we could not quote, From gay Catullus' lines to Milton's purer note. Mayhap we now are wiser men, But we knew more than all the scholars then; And our conceit Was grand, ineffable, complete! We know, Don't we, Joe? Gone are those golden nights Of innocent Bohemian delights, And we are getting on; And anon, Years sad and tremulous May be in store for us; But should we ever meet[7] Upon some quiet street, And you discover in an old man's eye Some transient sparkle of the days gone by, Then you will guess, perchance, The meaning of the glance; You'll know, Won't you, Joe? |

AT MARLIAVE'S

|

AT Marliave's when eventide Finds rare companions at my side, The laughter of each merry guest At quaint conceit, or kindly jest, Makes golden moments swiftly glide. No voice unkind our faults to chide, Our smallest virtue magnified; And friendly hand to hand is pressed At Marliave's. I lay my years and cares aside Accepting what the gods provide, I ask not for a lot more blest, Nor do I crave a sweeter rest Than that which comes with eventide At Marliave's. |

THE PASSING OF THE ROSE

|

A White Rose said, "How fair am I. Behold a flower that cannot die!" A lover brushed the dew aside, And fondly plucked it for his bride. "A fitting choice!" the White Rose cried. The maiden wore it in her hair; The Rose, contented to be there, Still proudly boasted, "None so fair!" Then close she pressed it to her lips, But, weary of companionships, The flower within her bosom slips. O'ercome by all the beauty there, It straight confessed, "Dear maid, I swear 'Tis you, and you alone, are fair!" Turning its humbled head aside, The envious Rose, lamenting, died. |

A VALENTINE

[From a Very Little Boy to a Very Little Girl]

|

THIS is a valentine for you. Mother made it. She's real smart, I told her that I loved you true And you were my sweetheart. And then she smiled, and then she winked, And then she said to father, "Beginning young!" and then he thinked, And then he said, "Well, rather." Then mother's eyes began to shine, And then she made this valentine: "If you love me as I love you, No knife shall cut our love in two," And father laughed and said, "How new!" And then he said, "It's time for bed." So, when I'd said my prayers,[11] Mother came running up the stairs And told me I might send the rhymes, And then she kissed me lots of times. Then I turned over to the wall And cried about you, and—that's all. |

DISENCHANTMENT

|

TIME and I have fallen out; We, who were such steadfast friends. So slowly has it come about That none may tell when it began; Yet sure am I a cunning plan Runs through it all; And now, beyond recall, Our friendship ends, And ending, there remains to me The memory of disloyalty. Long years ago Time tripping came With promise grand, And sweet assurances of fame; And hand in hand Through fairy-land Went he and I together In bright and golden weather. Then, then I had not learned to doubt, For friends were gods, and faith was sure, And words were truth, and deeds were pure,[13] Before we had our falling out; And life, all hope, was fair to see, When Time made promise sweet to me. When first my faithless friend grew cold I sought to knit a closer bond, But he, less fond, Sad days and years upon me rolled, Pressed me with care, With envy tinged the boyhood hair, And ploughed unwelcome furrows in Where none had been. In vain I begged with trembling lip For our old sweet companionship, And saw, 'mid prayers and tears devout, The presage of our falling out. And now I know Time has no friends, Nor pity lends, But touches all With heavy finger soon or late; And as we wait[14] The Reaper's call, The sickle's fatal sweep, We strive in vain to keep One truth inviolate, One cherished fancy free from doubt. It was not so Long years ago, Before we had our falling out. If Time would come again to me, And once more take me by the hand For golden walks through fairy-land, I could forgive the treachery That stole my youth And what of truth Was mine to know; Nor would I more his love misdoubt; And I would throw My arms around him so, That he'd forgive the falling out! |

CONSTANCY

|

I FIRST saw Phebe when the show'rs Had just made brighter all the flow'rs; Yet she was fair As any there, And so I loved her hours and hours. Then I met Helen, and her ways Set my untutored heart ablaze. I loved at sight And deemed it right To worship her for days and days. Yet when I gazed on Clara's cheeks And spoke the language Cupid speaks, O'er all the rest She seemed the best, And so I loved her weeks and weeks. But last of Love's sweet souvenirs Was Delia with her sighs and tears. Of her it seemed[16] I'd always dreamed, And so I loved her years and years. But now again with Phebe met, I love the first one of the set. "Fickle," you say? I answer, "Nay, My heart is true to one quartette." |

A POET'S LESSON

|

POET, my master, come, tell me true, And how are your verses made? Ah! that is the easiest thing to do:— You take a cloud of a silvern hue, A tender smile or a sprig of rue, With plenty of light and shade, And weave them round in syllables rare, With a grace and skill divine; With the earnest words of a pleading prayer, With a cadence caught from a dulcet air, A tale of love and a lock of hair, Or a bit of a trailing vine. Or, delving deep in a mine unwrought, You find in the teeming earth The golden vein of a noble thought; The soul of a statesman still unbought, Or a patriot's cry with anguish fraught For the land that gave him birth. A brilliant youth who has lost his way[18] On the winding road of life; A sculptor's dream of the plastic clay; A painter's soul in a sunset ray; The sweetest thing a woman can say, Or a struggling nation's strife. A boy's ambition; a maiden's star, Unrisen, but yet to be; A glimmering light that shines afar For a sinking ship on a moaning bar; An empty sleeve; a veteran's scar; Or a land where men are free. And if the poet's hand be strong To weave the web of a deathless song, And if a master guide the pen To words that reach the hearts of men, And if the ear and the touch be true, It's the easiest thing in the world to do! |

"PLACE AUX DAMES"

[To M.]

|

WITH brilliant friends surrounding me, So cosy at the Club I'm sitting; While you at home I seem to see, Attending strictly to your knitting. When women have their rights, my dear, We'll hear no more of wrongs so shocking:— You with your friends shall gather here; I'll stay at home and darn the stocking! |

ALL ON A GOLDEN SUMMER DAY

|

ALL on a golden summer day, As through the leaves a single ray Of yellow sunshine finds its way So bright, so bright; The wakened birds that blithely sing Seem welcoming another spring; While all the woods are murmuring So light, so light. All on a golden summer day, When to my heart a single ray Of tender kindness finds its way, So bright, so bright; Then comes sweet hope and bravely dares To break the chain that sorrow wears— And all my burdens, all my cares Are light, so light! |

PRISMATIC BOSTON

|

FAIR city by the famed Batrachian Pool, Wise in the teachings of the Concord School; Home of the Eurus, paradise of cranks, Stronghold of thrift, proud in your hundred banks; Land of the mind-cure and the abstruse book, The Monday lecture and the shrinking Cook; Where twin-lensed maidens, careless of their shoes, In phrase Johnsonian oft express their views; Where realistic pens invite the throng To mention "spades," lest "shovels" should be wrong; Where gaping strangers read the thrilling ode To Pilgrim Trousers on the West-End road; Where strange sartorial questions as to pants Offend our "sisters, cousins, and our aunts;" Where men expect by simple faith and prayer To lift a lid and find a dollar there; Where labyrinthine lanes that sinuous creep Make Theseus sigh and Ariadne weep; Where clubs gregarious take commercial risks 'Mid fluctuations of alluring disks;[22] Where Beacon Hill is ever proud to show Her reeking veins of liquid indigo; To thee, fair land, I dedicate my song, And tell how simple, artless minds go wrong. A Common Councilman, with lordly air, One day went strolling down through Copley Square. Within his breast there beat a spotless heart; His taste was pure, his soul was steeped in art. For he had worshiped oft at Cass's shrine, Had daily knelt at Cogswell's fount divine, And chaste surroundings of the City Hall Had taught him much, and so he knew it all. Proud, in a sack coat and a high silk hat, Content in knowing just "where he was at," He wandered on, till gazing toward the skies, A nameless horror met his modest eyes; For where the artist's chisel had engrossed An emblem fit on Boston's proudest boast, There stood aloft, with graceful equipoise, Two very small, unexpurgated boys. Filled with solicitude for city youth,[23] Whose morals suffer when they're told the truth, Whose ethic standards high and higher rise, When taught that God and nature are but lies, In haste he to the council chamber hied, His startled fellow-members called aside, His fearful secret whispering disclosed, Till all their separate joints were ankylosed. Appalling was the silence at his tale; Democrats turned red, Republicans turned pale. What mugwumps turned 'tis difficult to think, But probably they compromised on pink. When these stern moralists had their breaths regained, And told how deeply they were shocked and pained, They then resolved how wrong our children are, Said, "Boys should be contented with a scar," Rebuked Dame Nature for her deadly sins, And damned trustees who foster "Heavenly Twins." O Councilmen, if it were left for you To say what art is false and what is true, What strange anomalies would the world behold! Dolls would be angels, dross would count for gold;[24] Vice would be virtue, virtues would be taints; Gods would be devils, Councilmen be saints; And this sage law by your wise minds be built: "No boy shall live if born without a kilt." Then you'd resolve, to soothe all moral aches, "We're always right, but God has made mistakes." |

THE BOOK HUNTER

|

I'VE spent all my money in chasing For books that are costly and rare; I've made myself bankrupt in tracing Each prize to its ultimate lair. And now I'm a ruined collector, Impoverished, ragged, and thin, Reduced to a vanishing spectre, Because of my prodigal sin. How often I've called upon Foley, The man who's a friend of the cranks; Knows books that are witty or holy, And whether they're prizes or blanks. For volumes on paper or vellum He has a most accurate eye, And always is willing to sell 'em To dreamers like me who will buy. My purse requires fences and hedges, Alas! it will never stay shut; My coat-sleeves now have deckle edges,[26] My hair is unkempt and "uncut." My coat is a true first edition, And rusty from shoulder to waist; My trousers are out of condition, Their "colophon" worn and defaced. My shoes have been long out of fashion, "Crushed leather" they both seem to be; My hat is a thing for compassion, The kind that is labelled "n. d." My vest from its binding is broken, It's what the French call a relique; What I think of it cannot be spoken, Its catalogue mark is "unique." I'm a book that is thumbed and untidy, The only one left of the set; I'm sure I was issued on Friday, For fate is unkind to me yet. My text has been cruelly garbled By a destiny harder than flint; But I wait for my grave to be "marbled," And then I shall be out of print. |

THE THREE VOICES

|

THERE once was a man who asked for pie, In a piping voice up high, up high; And when he asked for a salmon roe, He spoke in a voice down low, down low; But when he said he had no choice, He always spoke in a medium voice. I cannot tell the reason why He sometimes spoke up high, up high; And why he sometimes spoke down low, I do not know, I do not know; And why he spoke in the medium way, Don't ask me, for I cannot say. |

EASY KNOWLEDGE

|

HOW nice 'twould be if knowledge grew On bushes, as the berries do! Then we could plant our spelling seed, And gather all the words we need. The sums from off our slates we'd wipe, And wait for figures to be ripe, And go into the fields, and pick Whole bushels of arithmetic; Or if we wished to learn Chinese, We'd just go out and shake the trees; And grammar then, in all the towns, Would grow with proper verbs and nouns; And in the gardens there would be Great bunches of geography; And all the passers-by would stop, And marvel at the knowledge crop; And I my pen would cease to push, And pluck my verses from a bush! |

SUSAN SCUPPERNONG

|

SILLY Susan Scuppernong Cried so hard and cried so long, People asked her what was wrong. She replied, "I do not know Any reason for my woe— I just feel like feeling so." |

THE HATBAND

|

MY hatband goes around my hat, And while there's nothing strange in that, It seems just like a lazy man Who leaves off where he first began. But then this fact is always true, The band does what it ought to do, And is more useful than the man, Because it does the best it can. |

THE OYSTER

|

TWO halves of an oyster shell, each a shallow cup; Here once lived an oyster before they ate him up. Oyster shells are smooth inside; outside very rough; Very little room to spare, but he had enough. Bedroom, parlor, kitchen, or cellar there was none; Just one room in all the house—oysters need but one. And he was never troubled by wind or rain or snow, For he had a roof above, another one below. I wonder if they fried him, or cooked him in a stew, And sold him at a fair, and passed him off for two. I wonder if the oysters all have names like us, And did he have a name like "John" or "Romulus"? I wonder if his parents wept to see him go; I wonder who can tell; perhaps the mermaids know. I wonder if our sleep the most of us would dread, If we slept like oysters, a million in a bed! |

WIND AND RAIN

|

THE rain came down on Boston Town, And the people said, "Oh, dear! It's early yet for our annual wet,— 'Twas dry this time last year." In heavy suits and rubber boots They went to the weather man, And said, "Dear friend, do you intend To change your present plan?" In tones of scorn, he said, "Begone! I've ordered a week of rain. Away! disperse! or I'll do worse, And order a hurricane!" They sneered, "Oh, oh!" and they laughed, "Ho, ho!" And they said, "You surely jest. Your threats are vain, for a hurricane Is the thing that we like best. "Our throats are tinned, and a sharp east wind[33] We really couldn't do without; But we complain of too much rain, And we think we'd like a drought." So the weather man took a palm-leaf fan And he waved it up on high, And he swept away the clouds so gray, And the sun shone out in the sky. And the sun shines down on Boston Town, And the weather still is clear; And they set their clocks by the equinox, And never the east wind fear. |

THE FLAG

|

HERE comes The Flag! Hail it! Who dares to drag Or trail it? Give it hurrahs,— Three for the stars, Three for the bars. Uncover your head to it! The soldiers who tread to it Shout at the sight of it, The justice and right of it, The unsullied white of it, The blue and red of it, And tyranny's dread of it! Here comes The Flag! Cheer it! Valley and crag Shall hear it. Fathers shall bless it,[35] Children caress it. All shall maintain it. No one shall stain it, Cheers for the sailors that fought on the wave for it, Cheers for the soldiers that always were brave for it, Tears for the men that went down to the grave for it! Here comes The Flag! |

MY MASTERPIECE

|

I WROTE the truest, tend'rest song The world had ever heard; And clear, melodious, and strong, And sweet was every word. The flowing numbers came to me Unbidden from the heart; So pure the strain, that poesy Seemed something more than art. No doubtful cadence marred a line, So tunefully it flowed, And through the measure, all divine The fire of genius glowed. So deftly were the verses wrought, So fair the legend told, That every word revealed a thought, And every thought was gold. Mine was the charm, the power, the skill, The wisdom of the years; 'Twas mine to move the world at will[37] To laughter or to tears. For subtile pleasantry was there, And brilliant flash of wit; Now, pleading eyes were raised in prayer, And now with smiles were lit. I sang of hours when youth was king, And of one happy spot Where life and love were everything, And time was half forgot. Of gracious days in woodland ways, When every flower and tree Seemed echoing the sweetest phrase From lips in Arcadie. Of sagas old and Norseman bands That sailed o'er northern seas; Enchanting tales of fairy lands And strange philosophies. I sang of Egypt's fairest queen, With passion's fatal curse; Of that pale, sad-faced Florentine,[38] As deathless as his verse. Of time of the Arcadian Pan, When dryads thronged the trees— When Atalanta swiftly ran With fleet Hippomenes. Brave stories, too, did I relate Of battle-flags unfurled; Of glorious days when Greece was great— When Rome was all the world! Of noble deeds for noble creeds, Of woman's sacrifice— The mother's stricken heart that bleeds For souls in Paradise. Anon I told a tale of shame, And while in tears I slept, Behold! a white-robed angel came And read the words and wept! And so I wrote my perfect song, In such a wondrous key, I heard the plaudits of the throng,[39] And fame awaited me. Alas! the sullen morning broke, And came the tempest's roar: 'Mid discord trembling I awoke, And lo! my dream was o'er! Yet often in the quiet night My song returns to me; I seize the pen, and fain would write My long lost melody. But dreaming o'er the words, ere long Comes vague remembering, And fades away the sweetest song That man can ever sing! |

A BALLADE OF MONTAIGNE

|

I SIT before the firelight's glow With all the world in apogee, And con good Master Florio With pipe a-light; and as I see Queen Bess herself with book a-knee, Reading it o'er and o'er again, Here, 'neath my cosy mantel-tree, I smoke my pipe and read Montaigne. Now howls the wind and drives the snow; The traveler shivers on the lea; While, with my precious folio, Behold a happy devotee To book and warmth and reverie! The blast upon the window-pane Disturbs me not, as trouble-free, I smoke my pipe and read Montaigne. I am content, and thus I know[41] A mind as calm as summer sea,— A heart that stranger is to woe. To happiness I hold the key In this rare, sweet philosophy; And while the Fates so fair ordain, Well pleased with Destiny's decree, I smoke my pipe and read Montaigne. |

| ENVOY |

|

Dear Prince! aye, more than prince to me, Thou monarch of immortal reign! Always thy subject I would be, And smoke my pipe and read Montaigne! |

THE CRIMINAL

|

CRIME flourishes throughout the land, And bids defiance to the law, And wicked deeds on every hand O'erwhelm our souls with awe! I know one hardened criminal Whose maidenhood with crime begins; Who, safe behind a prison wall, Should expiate her sins. She is a thief whene'er she smiles, For then she steals my heart from me, And keeps it with a maiden's wiles, And never sets it free. She plunders sighs from humankind, She pilfers tears I would not weep, She robs me of my peace of mind, And she purloins my sleep. Of lawless ways she stands confessed,[43] And is a burglar bold whene'er She finds a weakness in my breast, And slyly enters there. A gambler she, whose arts entrance, Whose victims yield without demur; Content to play Love's game of chance And lose their hearts to her. A graver crime is hers; for, when Her matchless beauty I admire, Of arson she is guilty then, And sets my heart on fire. A bandit, preying on mankind, Her captives by the score increase; No hand can e'er their chains unbind, No ransom bring release. She is a cruel murderess Whene'er her eyes send forth a dart, And as she holds me in duress It stabs me to the heart. Crime flourishes throughout the land,[44] And bids defiance to the law, And wicked deeds on every hand O'erwhelm our souls with awe! |

A BIT OF COLOR

[Paris, 1896]

|

OH, damsel fair at the Porte Maillot, With the soft blue eyes that haunt me so, Pray what should I do When a girl like you Bestows her smile, her glance, and her sigh On the first fond fool that is passing by, Who listens and longs as the sweet words flow From her pretty red lips at the Porte Maillot? There were lips as red ere you were born, Now wreathed in smiles, now curled in scorn, And other bright eyes With their truth and lies, That broke the heart and turned the brain Of many a tender, lovelorn swain; But never, I ween, brought half the woe That comes from the lips at the Porte Maillot. A charming picture, there you stand,[46] A perfect work from a master's hand! With your face so fair And your wondrous hair, Your glorious color, your light and shade, And your classic head that the gods have made, Your cheeks with crimson all aglow, As you wait for a lover at the Porte Maillot. There are gorgeous tints in the jeweled crown, There are brilliant shades when the sun goes down; But your lips vie With the western sky, And give to the world so rare a hue That the painter must learn his art anew, And the sunset borrow a brighter glow From the lips of the girl at the Porte Maillot. Come, tell me truly, fair-haired youth, Do her eyes flash love, her lips speak truth? Or does she beguile With her glance and smile, And burn you, spurn you all day long[47] With a Circe's art and a Siren's song? Ah! would that your foolish heart might know The lie in the heart at the Porte Maillot! |

DINNER FAVORS

TO S.

|

I FILL my goblet to the brim And clink the glasses rim to rim. Across the board I waft a kiss With thanks for such an hour as this, And clasping joy, bid sorrow flee, And welcome you my vis-à-vis. |

TO A. R. C.

|

Of all the joys on earth that be There is no sweeter one to me Than sitting with a merry lass From consommé to demi-tasse. And yet a golden hour I'd steal, Reverse the order of the meal, And countermarching, backward stray[49] From demi-tasse to consommé. |

TO S. B. F.

|

Give me but a bit to eat, And an hour or two, Just a salad and a sweet, And a chat with you. Give me table full or bare, Crust or rich ragout; But whatever be the fare, Always give me you. |

THE HOST

|

Between the two perplexed I go, A shuttlecock, tossed to and fro. I gaze on one, and know that she Is all that womankind can be; I seek the other, and she seems [50]The perfect idol of my dreams; And so between the charming pair My heart is ever in the air. And yet, although it be my fate To hover indeterminate, I rest content, nor ask for more Than this sweet game of battledore. |

THE MOPER

|

THE Moper mopeth all the day; He mopeth eke at night; And never is the Moper gay, But, grim and serious alway, He is a sorry sight. He liketh not the merry quip; He hateth other men; Escheweth he companionship, Nor doth he e'er essay to trip The light fantastic ten. He seeketh not where murm'ring brooks With rippling music flow. He seeth naught in woman's looks, And never readeth he in books Except they tell of woe. He e'en forgetteth that the sun,[52] Likewise God's balmy air, Were made to gladden every one; But he preferreth both to shun, And taketh not his share. He careth not for merry wights Who drink Château Yquem, But he would set the world to rights By peopling it with eremites— And very few of them. When children sport with merry glee, He thinketh they are wild, And with them doth so disagree It seemeth verily that he Hath never been a child. He thinketh that it is not right Rare dishes to discuss, And knoweth not the keen delight Of one that hath an appetite Yclepèd ravenous. Of goodly raiment he hath none,[53] He calleth it "display;" Wherefore the urchin poketh fun, Because he looketh like that one Unholy men call "jay." And so we see this foolish man All pleasant things doth scorn. Good folk, pray God to change his plan, And cheer the Moper if He can, Or let no more be born! |

VARIOUS VALENTINES

I

FROM A BIBLIOPHILE

|

LYKE some choise booke thou arte toe mee, Bound all so daintilie; And 'neath the covers faire Are contents true and rare. Ne wolde I looke Ne reade inne any other booke If I belyke could find therein the charte And indice to thy hearte. The Great Wise Authour made but one Of this edition, then was don; And were this onlie copie mine, Then wolde I write therein, "My Valentyne." |

II

FROM AN INCONSTANT-CONSTANT

(After Henri Murger)

|

Though I love many maidens fair As fondly as a heart may dare, Yet still are you the only one True goddess of my pantheon. And though my life is like a song, Each maid a stanza, clear and strong, Yet always I return again To you who are the sweet refrain. |

III

FROM A COMMERCIAL LOVER

|

If I were but a syndicate, And love were merchandise, I'd buy it at the market rate, And hold it for a rise. And should the price of all this love[56] Bound upward like a ball, And reach 1000 or above, Still you should have it all. |

IV

FROM AN UNCERTAIN MARKSMAN

|

I send you two kisses Wrapped up in a rhyme; From Love's warm abysses I send you two kisses; If one of them misses Please wait till next time, And I'll send you three kisses Wrapped up in a rhyme. |

V

FROM A CONCHOLOGIST

|

Were I a murm'ring ocean shell Pressed close against your ear, My constant whisperings would tell[57] A story sweet to hear. I'd make the message from the sea Love's tidings on the shore, And I would woo with words so true That you could ask no more. So if some silvern nautilus Lay close beside your cheek, And you should hear a language dear Unto the heart I seek, You'll know within the simple shell That murmurs o'er and o'er I send to you a love more true Than e'er was breathed before. |

VI

FROM A HYPERBOLIST

|

Take all the love that e'er was told Since first the world began, Increase it twenty thousand-fold[58] (If mathematics can), Add all the love the world shall see Till Gabriel's final call, And when compared with mine 'twill be Infinitesimal. |

WERE ALL THE WORLD LIKE YOU

|

WERE all the world like you, my dear, Were all the world like you, Oh, there'd be darts in all our hearts From sunset to the dew. For life would be Love's jubilee Where all were two and two, And lovers' rhyme the only crime, Were all the world like you, my dear, Were all the world like you. Were all the world like you, my dear, Were all the world like you, There'd be no pain nor clouds nor rain, No kisses overdue; But sweetest sighs and pleading eyes, Where Cupid's arrow flew, And lovers' rhyme the only crime, Were all the world like you, my dear, Were all the world like you. |

HERE AND THERE

|

SWEET Phyllis went a-rambling here and there, Here and there. Her eyes were blue and golden was her hair. She said, "Oh, life is strange; I'm sure I need a change; 'Tis sad for one to ramble here and there, Here and there." Young Strephon went a-rambling here and there, Here and there. He sighed, "It needs but two to make a pair. If I should meet a maid Not in the least afraid, How happy we'd go rambling here and there, Here and there." As youth and maid went rambling here and there, Here and there, They met, and loved at sight, for both were fair;[61] And neither youth nor maid Was in the least afraid, And hand in hand they ramble here and there, Here and there. |

UNCLE JOGALONG

|

MY dear old Uncle Jogalong Was very slow, was very slow, And said he thought that folks were wrong To hurry so, to hurry so. When he walked out upon the street To take the air, to take the air, It seemed almost as if his feet Were fastened there, were fastened there. He thought that traveling by rail Was hurrying and scurrying, But said the slow and creeping snail Was just the thing, was just the thing. He thought a hasty appetite An awful crime, an awful crime, So never finished breakfast, quite, Till dinner time, till dinner time. He said the world turned round so fast[63] He could not stay, he could not stay, And so he said "Good-by" at last, And went away, and went away. |

THE INDIFFERENT MARINER

|

I'M a tough old salt, and it's never I care A penny which way the wind is, Or whether I sight Cape Finisterre, Or make a port at the Indies. Some folks steer for a port to trade, And some steer north for the whaling; Yet never I care a damn just where I sail, so long's I'm sailing. You never can stop the wind when it blows, And you can't stop the rain from raining; Then why, oh, why, go a-piping of your eye When there's no sort o' use in complaining? My face is browned and my lungs are sound, And my hands they are big and calloused. I've a little brown jug I sometimes hug, And a little bread and meat for ballast. But I keep no log of my daily grog,[65] For what's the use o' being bothered? I drink a little more when the wind's offshore, And most when the wind's from the no'th'ard. Of course with a chill if I'm took quite ill, And my legs get weak and toddly, At the jug I pull, and turn in full, And sleep the sleep of the godly. But whether I do or whether I don't, Or whether the jug's my failing, It's never I care a damn just where I sail, so long's I'm sailing. |

ON A LIBRARY WALL

|

WHEN faltering fingers bid me cease to write, And, laying down the pen, I seek the Night, May those, to whom the Daylight still is sweet, With loving lips my name ofttimes repeat. And should Belshazzar's spirit hither stray, And linger o'er the lines I write to-day, May he, who wept for Babylonia's fall, Look kindly at this "writing on the wall"! |

MRS. MULLIGATAWNY

|

Mrs. Mulligatawny said, "I'm sure it's going to rain." Mr. Mulligatawny said, "To me it's very plain." William Mulligatawny said, "It must rain, anyhow." Mary Mulligatawny said, "I feel it raining now." And yet there were no clouds in sight, and 'twas a pleasant day, But Mrs. Mulligatawny always liked to have her way. With Mrs. Mulligatawny the family all agreed, For all the Mulligatawnys feared her very much indeed, And did, whenever they were bid, As Mrs. Mulligatawny did, And tried to think, as they were taught, As Mrs. Mulligatawny thought. Mrs. Mulligatawny said, "Now two and two are three." Mr. Mulligatawny said, "I'm sure they ought to be." William Mulligatawny said, "Arithmetic is wrong." Mary Mulligatawny said, "It's been so all along."[68] Now two and two do not make three, and three they never were; But Mrs. Mulligatawny said 'twas near enough for her. With Mrs. Mulligatawny the family all agreed, For all the Mulligatawnys feared her very much indeed, And did, whenever they were bid, As Mrs. Mulligatawny did, And tried to think, as they were taught, As Mrs. Mulligatawny thought. Mrs. Mulligatawny fell out of the world one day. Mr. Mulligatawny said, "I don't know what to say." William Mulligatawny said, "I don't know what to do." Mary Mulligatawny said, "I feel the same as you." Mrs. Mulligatawny left the family sitting there. They couldn't think, they couldn't move, because they didn't dare; For Mrs. Mulligatawny had always thought for them, And all the Mulligatawnys thought the same as Mrs. M., And did, whenever they were bid,[69] As Mrs. Mulligatawny did, And tried to think, as they were taught, As Mrs. Mulligatawny thought. |

EUTHANASIA

[To E. C.]

|

OH, drop your eyelids down, my lady; Oh, drop your eyelids down. 'Twere well to keep your bright eyes shady For pity of the town! But should there any glances be, I pray you give them all to me; For though my life be lost thereby, It were the sweetest death to die! |

DAINTY LITTLE LOVE

|

DAINTY little Love came tripping Down the hill, Smiling as he thought of sipping Sweets at will. SHE said, "No, Love must go." Dainty little Love came tripping Down the hill. Dainty little Love went sighing Up the hill, All his little hopes were dying— Love was ill. Vain he tried Tears to hide. Dainty little Love went sighing Up the hill. |

TO M.

|

SWEET visions came to me in sleep, Ah! wondrous fair to see; And in my mind I strove to keep The dream to tell to thee. But morning broke with golden gleam, And shone upon thy face, And life was lovelier than a dream, And dreams had lost their grace. |

THE SONG

|

I HEARD an old, familiar air Strummed idly by a careless hand, Yet in the melody were rare, Sweet echoings from childhood land. The well-remembered mother touch, The wise denials and consents, The trivial sorrows that were much, Small pleasures that were large events; The fancies, dreams, strange wonderings, The daily problems unexplained, Momentous as the cares of kings That on unhappy thrones have reigned, Came back with each unstudied tone; And came that song remembered best, Which, with a sweetness all its own, Once lulled the play-worn child to rest. And there, secure as Tarik's height,[74] He slumbered, shielded from alarms, Safe from the mystery of night, Close folded in the mother's arms. Then Israel's mighty songs of old, And all the modern masters' art, Were less than simple lays that told The secret of the mother's heart. The sweetest melody that flows From lips that win the world's applause Charms not like that which childhood knows, Unfettered by the curb of laws. For though we rise to nobler themes, To grander harmonies attain, Their lives not in the academes The magic of the simpler strain. And we may spurn the cruder song, Or name it anything we will, Denounce the artifice as wrong,[75] Yet to the child 'tis music still. Thus, list'ning to an idle air, Struck lightly by a careless hand, I heard, amid the cadence there, The sweetest song of childhood land. |

AT TWILIGHT TIME

|

AT twilight time when tolls the chime, And saddest notes are falling, A lonely bird with plaintive word Across the dusk is calling. Vain doth it wait for one dear mate, That ne'er shall know the morrow; Then sinks to rest with drooping crest In one long dream of sorrow. Dearest, when night is here, To thee I'm calling, Sadly as tear on tear Is slowly falling, Oh, fold me near, more near— In love enthralling! Here on thy breast, While life shall last, With thee I stay.[77] Here will I rest Till night is past, And comes the day! |

CÉLESTE

|

OF sweethearts I have had a score, And time may bring as many more; Tho' I remember all the rest, Just now I worship dear Céleste; Hers may not be the greatest love, But ah! it is the latest love. For little Cupid's never stupid, As I've found out; And love is truest when 'tis newest, Beyond a doubt, beyond a doubt. Of sweethearts I have had a score, Céleste says I deserve no more; I take revenge on dear Céleste, By telling her I love her best; Hers may not be the greatest love, But ah! it is the latest love. For little Cupid's never stupid,[79] As I've found out; And love is truest when 'tis newest, Beyond a doubt, beyond a doubt. |

THISTLE-DOWN

|

THE thistle-down floats on the air, the air, Whenever the soft wind blows, And the wind can tell just where, just where The feathery thistle-down goes. And it tells the bird in a single word, Who whispers it low to the bee; And they try to keep the mystery deep, And none of them tell it to me. But I know well, though they never will tell, Where the thistle-down goes when it says "Farewell," It floats and floats away on the air, And goes where the wind goes—everywhere! |

SLUMBER SONG

|

GENTLY fall the shadows gray, Daylight softly veiling; Now to Dreamland we'll away, Sailing, sailing, sailing. Little eyes were made for sleeping, Little heads were made for rest, Golden locks were made for keeping Close to mother's breast; Little hands were made for folding, Little lips should never sigh; What dear mother's arms are holding, Love alone can buy. Gently fall the shadows gray, Daylight softly veiling; Now to Dreamland we'll away, Sailing, sailing, sailing. |

THOU ART TO ME

|

THOU art to me As are soft breezes to a summer sea; As stars unto the night; Or when the day is born, As sunrise to the morn; As peace unto the fading of the light. Thou art to me As one sweet flower upon a barren lea; As rest to toiling hands; As one clear spring amid the desert sands; As smiles to maidens' lips; As hope to friends that wait for absent ships; As happiness to youth; As purity to truth; As sweetest dreams to sleep; As balm to wounded hearts that weep. All, all that I would have thee be Thou art to me. |

LOVE

[Trio]

|

OH, love hits all humanity, humanity, my dear; But after all it's vanity, a vanity, I fear; And sometimes 'tis insanity, insanity, so queer; Humanity, yes, a vanity, yes, insanity so queer. And love is often curious, so curious to see, And oftentimes is spurious, so spurious, ah, me! And surely 'tis injurious, injurious when free, So curious, yes, and spurious, yes, injurious when free. Oh, love brings much anxiety, anxiety and grief, But seasoned with propriety, propriety, relief, It's mixed with joy and piety, but piety is brief; Anxiety, yes, propriety, yes, but piety is brief. Oh, young love's all timidity, timidity, I'm told, Gains courage with rapidity, rapidity, so bold, With traces of acidity, acidity, when old; Timidity, yes, rapidity, yes, acidity, when old. |

THE STRANGER-MAN

|

"NOW what is that, my daughter dear, upon thy cheek so fair?" "'Tis but a kiss, my mother dear—kind fortune sent it there. It was a courteous stranger-man that gave it unto me, And it is passing red because it was the last of three." "A kiss indeed! my daughter dear; I marvel in surprise! Such conduct with a stranger-man I fear me was not wise." "Methought the same, my mother dear, and so at three forbore, Although the courteous stranger-man vowed he had many more." "Now prithee, daughter, quickly go, and bring the stranger here, And bid him hie and bid him fly to me, my daughter dear; For times be very, very hard, and blessings eke so rare,[85] I fain would meet a stranger-man that hath a kiss to spare." |

THE HONEYSUCKLE VINE

|

'TWAS a tender little honeysuckle vine That smiled and danced in the warm sunshine, And spied a maid as fair as all maids be, Who said, "Little honeysuckle, come up to me." So it climbed and climbed in the sun and the shade, And all summer long at her window stayed; For that is the way that honeysuckles go, And that is the way that true loves grow. Then the loving little honeysuckle vine Kissed the little maid in the warm sunshine; But the winter came with an angry frown, And the false little maid shut the window down; And the sorrowing vine on the wintry side Mourned and mourned for the love that died, And faded away in the wind and snow,— And that is the way that some loves go. |

SAINT BOTOLPH

|

Saint Botolph flourished in the olden time, In the days when the saints were in their prime. Oh, his feet were bare and bruised and cold, But his heart was warm and as pure as gold. And the kind old saint with his gown and his hood Was loved by the sinners and loved by the good, For he made the sinners as pure as the snow, And the good men needed him to keep them so. |

| CHORUS |

|

Then drink, brave gentlemen, drink with me To the Lincolnshire saint by the old North Sea. A glass and a toast and a song and a rhyme To the barefooted saint of the olden time. He loved a friend and a flagon of wine, When the friend was true and the bottle was fine. He would raise his glass with a knowing wink, And this was the toast he would always drink:— "Oh, here's to the good and the bad men too,[88] For without them saints would have nothing to do. Oh, I love them both and I love them well, But which I love better, I never can tell." |

| CHORUS |

|

Then drink, brave gentlemen, drink with me To the Lincolnshire saint by the old North Sea. A glass and a toast and a song and a rhyme To the barefooted saint of the olden time. As he journeyed along on the king's highway He gave all the boys and the girls "Good-day," And never a child saw the hood and gown But ran to the father of Botolph's Town. He'd a word for the wicked, and he called them kin, And he said, "I am certain that there must be sin While a few get the loaves and many get the crumbs, And some are born fingers and some born thumbs." |

| CHORUS |

|

Then drink, brave gentlemen, drink with me To the Lincolnshire saint by the old North Sea. A glass and a toast and a song and a rhyme[89] To the barefooted saint of the olden time. But the saint grew old, and sorry the day When his life went out with the tide in the bay; But he left a name and he left a creed Of the cheerful life and the kindly deed. Then remember the man of the days of old Whose heart was warm and as pure as gold, And remember the tears and the prayers he gave For any poor devil with a soul to save. |

| CHORUS |

|

Then drink, brave gentlemen, drink with me To the Lincolnshire saint by the old North Sea. A glass and a toast and a song and a rhyme To the barefooted saint of the olden time. |

THE GURGLING IMPS

|

THE Gurgling Imps of Mummery Mum Lived in the Land of the Crimson Plum, And a language very strange had they, 'Twas merely a chattering ricochet. The Gurgling Imps of Mummery Mum Caught hummingbirds for the sake of the hum, Their cheeks were flushed with a sable tinge, Their eyelids hung on a silver hinge. The Gurgling Imps of Mummery Mum Called each other "My charming chum," And floated in tears of joy to see Their relatives hung in a cranberry tree. The Gurgling Imps of Mummery Mum Stole the whole of a half of a crumb, And a wind arose and blew the Imps Way off to the Land of the Lazy Limps. |

THE WORM WILL TURN

|

I'M a gentle, meek, and patient human worm; Unattractive, Rather active, With a sense of right, original but firm. I was taught to be forgiving, For my enemies to pray; But what's the use of living If you never can repay All the little animosities that in your bosom burn— Oh, it's pleasant to remember that "the worm will turn." I'm so gentle and so patient and so meek, Unpretending, Unoffending. But if, perchance, you smite me on the cheek, I will never turn the other, As I was taught to do By a puritanic mother, Whose theology was blue. Your experience will widen when explicitly you learn[92] How a modest, mild, submissive little worm will turn. I'm so subtle and so crafty and so sly. I am humble, But I "tumble" To the slightest oscillation of the eye. When others think they're winning A fabulous amount, Then I do a little sinning On my personal account, And in my quiet, simple way a modest stipend earn As they slowly grasp the bitter fact that worms will turn. Oh, human worms are curious little things; Inoffensive, Rather pensive Till it comes to using little human stings. Oh, then avoid intrusion If you would be discreet, And cultivate seclusion In an underground retreat. And whenever you are tempted the lowly worm to spurn,[93] Just bear in mind that little line, "The worm will turn." |

THE BOSTON CATS

|

A Little Cat played on a silver flute, And a Big Cat sat and listened; The Little Cat's strains gave the Big Cat pains, And a tear on his eyelid glistened. Then the Big Cat said, "Oh, rest awhile;" But the Little Cat said, "No, no; For I get pay for the tunes I play;" And the Big Cat answered, "Oh! If you get pay for the tunes you play, I'm afraid you'll play till you drop; You'll spoil your health in the race for wealth, So I'll give you more to stop." Said the Little Cat, "Hush! you make me blush; Your offer is unusually kind; Though it's very, very hard to leave the back yard, I'll accept if you don't mind." So the Big Cat gave him a thousand pounds[95] And a silver brush and a comb, And a country seat on Beacon Street, Right under the State House dome. And the Little Cat sits with other little kits, And watches the bright sun rise; And the voice of the flute is long since mute, And the Big Cat dries his eyes. |

THE JONQUIL MAID

|

A LITTLE Maid sat in a Jonquil Tree, Singing alone, In a low love-tone, And the wind swept by with a wistful moan; For he longed to stay With the Maid all day; But he knew As he blew It was true That the dew Would never, never dry If the wind should die; So he hurried away where the rosebuds grew. And while to the Land of the Rose went he, Singing alone, In a low love-tone, A Little Maid sat in a Jonquil Tree. The Little Maid's eyes had a rainbow hue,[97] And her sunset hair Was woven with care In a knot that was fit for a Psyche to wear; And she pressed her lips With her finger tips, Threw a sly Kiss to try If he'd sigh In reply, And said with a laugh, "Oh, it's not one half As sweet as I give when there's Some One nigh." And while to the Rosebud Land went he, Singing alone, In a low love-tone, A Little Maid sat in a Jonquil Tree. The wind swept back to the Jonquil Tree At the close of day, In the twilight gray; But the sweet Little Maid had stolen away; And whither she's flown[98] Will never be known Till the Rose As it blows Shall disclose All it knows Of the Maid so fair With the sunset hair. And the sad wind comes and sighs and goes, And dreams of the day when he blew so free, When singing alone, In a low love-tone, A Little Maid sat in a Jonquil Tree. |

THE ROLLICKING MASTODON

|

A Rollicking Mastodon lived in Spain, In the trunk of a Tranquil Tree. His face was plain, but his jocular vein Was a burst of the wildest glee. His voice was strong and his laugh so long That people came many a mile, And offered to pay a guinea a day For the fractional part of a smile. The Rollicking Mastodon's laugh was wide— Indeed, 'twas a matter of family pride; And oh! so proud of his jocular vein Was the Rollicking Mastodon over in Spain. The Rollicking Mastodon said one day, "I feel that I need some air, For a little ozone's a tonic for bones, As well as a gloss for the hair." So he skipped along and warbled a song In his own triumphulant way. His smile was bright and his skip was light[100] As he chirruped his roundelay. The Rollicking Mastodon tripped along, And sang what Mastodons call a song; But every note of it seemed to pain The Rollicking Mastodon over in Spain. A Little Peetookle came over the hill, Dressed up in a bollitant coat; And he said, "You need some harroway seed, And a little advice for your throat." The Mastodon smiled and said, "My child, There's a chance for your taste to grow. If you polish your mind, you'll certainly find How little, how little you know." The Little Peetookle, his teeth he ground At the Mastodon's singular sense of sound; For he felt it a sort of musical stain On the Rollicking Mastodon over in Spain. "Alas! and alas! has it come to this pass?" Said the Little Peetookle: "Dear me! It certainly seems your horrible screams[101] Intended for music must be." The Mastodon stopped; his ditty he dropped, And murmured, "Good-morning, my dear! I never will sing to a sensitive thing That shatters a song with a sneer!" The Rollicking Mastodon bade him "adieu." Of course, 'twas a sensible thing to do; For Little Peetookle is spared the strain Of the Rollicking Mastodon over in Spain. |

THE FIVE SENSES

|

OH, why do men their glasses clink When good old honest wine they drink? Wine is so excellent a thing To lowest subject, or to highest king, That every sense alike should share The pleasure that can banish care. Thus may each merry eye behold The sparkle of the red or gold. Our lips may feel the goblet's edge And taste the loving cup we pledge. While from each foaming glass escape The precious perfumes of the grape. But ah, we hear it not, and so We give the touch that all men know. And thus do all the senses share The pleasure that can banish care. And that is why the glasses clink When good old honest wine we drink. |

ECONOMY

[A Valentine]

|

I SEND, O sweetest friend, A kiss; Such as fair ladies gave Of old, when knights were brave, And smiles were won Through foes undone. And this will be For you to give again to me; And then, its present errand o'er, I'll give it unto you once more, Ere briefest time elapse, With interest, perhaps. Its mission spent, Again to me it may be lent. And thus, day after day, As we a simple law obey, Forever, to and fro,[104] The selfsame kiss will go; A busy shuttle that shall weave A web of love, to soften and relieve Our daily care. And so, As thus we share, With lip to lip, Our frugal partnership, One kiss will always do For two. And, oh, how easy it will be To practice this economy! |

IDYLETTES OF THE QUEEN

I.—SHE

|

I FAIN would write on pleasant themes; So let me prate Awhile of Kate; And if my rhyming effort seems Uncouth or rough, At any rate, She's Kate, And that's enough. |

II.—HER EYES

|

Her eyes are bright— I cannot say "like stars at night," Nor can I say "Like the Orb of Day," Because such phrases are archaic. [106]And if I swear That they compare With diamonds rare, That's too prosaic. I've hunted my thesaurus through, "The Century" and "Webster," too, But all in vain; 'Tis therefore plain That they who made these books so wise Had never seen her eyes! |

III.—HER GOWN

|

When Kate puts on her Sunday gown And goes to church all in her best, The watchful gargoyles looking down Relax their most forbidding frown, And smile with kindly interest. Discerning gargoyles! could I be One of your number looking down, [107]With you I surely would agree And share your amiability At sight of Kate and Sunday gown. |

IV.—HER KNOWLEDGE

|

How much she knows no one can tell; But she can read and write and spell, Divide and multiply and add, And name the apples Thomas had When John enticed him five to sell. For "jelly" she does not say "jell," Nor horrify us with "umbrell," For all of which we're very glad— How much she knows! She knows the oyster by his shell, Detects the newsboy by his yell, Enumerates the bones in shad, And thinks my poetry is bad. Well! well! well! well! well! well! well! well! How much she knows! |

V.—HER SIGH

|

When she utters a sigh 'Tis a breath from the roses, And a-hovering nigh, When she utters a sigh, The bees wonder why No garden discloses. When she utters a sigh 'Tis a breath from the roses. |

VI.—HER RING

|

Her ring goes round her finger. Oh, foolish thing! Were I a ring, I'd not "go round"—I'd linger! |

VII.—HER FAULTS

|

Of faults she has but one, And that is, she has none. |

VIII.—HER VOICE

|

Sweet and soothing, rhythmic, tuneful, Dulcet, mellow, unbassoonful, Zither, 'cello, lute, guitar, And there you are! |

IX.—HER LOVE

|

Do you love me? R. S. V. P. |

TO M. E.

|

WE keep in step as years roll by; You march behind and I before:— The path is new to you; but I Have passed the ground you're walking o'er. Yet I march on with measured tread, And looking back, I smile and greet you:— I fear the order, "Halt!" Instead, Would I might countermarch and meet you. |

BON VOYAGE

[To O. R.]

|

OUT from the Land of the Future, into the Land of the Past A comrade sails to the East, the sport of the wave and the blast. Oh, billow and breeze, be kind, and temper your strength to your guest, Kind for the sake of the friend,—for the sake of the hands he pressed. Oh, tenderest billow and breeze, welcome him even as we Would welcome if you were the friend and we were the wind and the sea! Welcome, protect him, and waft him westward and homeward at last Into the Land of the Future, out from the Land of the Past! |

THE BOOK OF LIFE

|

WHOSO his book of life doth con From title-leaf to colophon May read, if he but wrongly look, Some sorry pages in his book. But if he read aright each line, Interpreting the scheme divine, 'Twill be most fair to look upon From title-leaf to colophon. |

The Riverside Press

Electrotyped and printed by H. O. Houghton & Co.

Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Poems, by Arthur Macy

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS ***

***** This file should be named 37999-h.htm or 37999-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/7/9/9/37999/

Produced by Suzanne Shell, David E. Brown and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any