This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Secret History of the Court of England, from the Accession of George the Third to the Death of George the Fourth, Volume I (of 2)

Including, Among Other Important Matters, Full Particulars of the Mysterious Death of the Princess Charlotte

Author: Lady Anne Hamilton

Release Date: September 29, 2011 [eBook #37570]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SECRET HISTORY OF THE COURT OF ENGLAND, FROM THE ACCESSION OF GEORGE THE THIRD TO THE DEATH OF GEORGE THE FOURTH, VOLUME I (OF 2)***

| Note: | Project Gutenberg also has Volume II of this work. See http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/37571 |

Transcriber's Note:

Due to an accusation of libel, some pages had to be rewritten and reprinted before the book was bound. Pages 1-24 were not printed and are missing from the original. See the Preface for more information.

The original uses two kinds of blockquotes--one type has words in a smaller font, and the other uses extra white space before and after the quotation. The transcriber has used wider margins to represent the smaller font and higher line heights to represent the quotations with extra white space.

Variations in spelling and hyphenation have been left as in the original. A few typographical errors have been corrected. A complete list as well as other notes can be found after the text.

A row of asterisks represents an ellipsis in a poetry quotation.

Click on the page number to see an image of the page.

[i]

[ii]

[iii]

The source from whence this Work proceeds will be a sufficient guarantee for the facts it contains. A high sense of duty and honor has prompted these details which have for many years been on the eve of publication. It will be worthy of the perusal of The Great because it will serve as a mirror, and they who do not see themselves, or their actions reflected, will not take offence at the unvarnished Picture—it may afford real benefit to the Statesman and Politician, by the ample testimony it gives, that when Justice is perverted, the most lamentable consequences ensue; and to that class of Society whose station is more humble, it may unfold the designing characters by whom they have so frequently been deceived. They only are competent to detail the scenes and intrigues of a Court, who have been most intimately acquainted with it, and it must at all times be acknowledged, that it is a climate not very conducive to the growth of Virtue, not very frequently the abode of Truth—yet although its atmosphere is so tainted, its giddy crowd is thought enviably happy. The fallacy of such opinions is here set forth to public view, by one who has spent much of her time in the interior of a Court, and whose immediate knowledge of the then passing events, give [iv]ability to narrate them faithfully. Many, very many, facts are here omited, which hereafter shall appear, and there is little doubt, but that some general good may result from an unprejudiced and calm perusal of the subjects subjoined.

[v]

How far the law of Libel (as it now stands) may affect is best to be ascertained by a reference to the declaration of Lord Abingdon, in 1779, and inserted, verbatim, at page 69—1st vol. of this "Secret History." The following Pages are intended as a benefit, not to do injury. If the facts could not have been maintained proper methods ought to have been adopted to have caused the most minute enquiry and investigation upon the subject. Many an Arrow has been shot, and innumerable suspicions entertained from what motive, and by whose hand the bow was drawn, yet here all mystery ceases, and an open avowal is made:—Would to Heaven for the honor of human nature that the subjoined documents were falsehoods and calumniations invented for the purpose of maligning character, or for personal resentments—but the unusual corroboration of events, places, times, and persons, will not admit the probability. In the affair of the ever lamented Death of the Princess Charlotte, the three important Letters commencing at page 369, vol. 1st, are of essential importance, and deserve the most grave and deliberate enquiry—for the first time they now appear in print. The subjects connected with the Royal Mother are also of deep interest. The conduct of the English Government towards Napoleon is [vi]introduced, to give a true and impartial view of the reasons which dictated such arbitrary and unjust measures enforced against that Great Man, and which will ever remain a blot upon the British Nation. These unhandsome derelictions from honorable conduct could alone be expressed by those who were well informed upon private subjects. Respect for the illustrious Dead has materially encouraged the inclination to give publicity to scenes, which were as revolting in themselves as they were cruel and most heart-rending to the Victims: throughout the whole, it is quite apparent that certain Persons were obnoxious to the Ruling Authorities, and the sequel will prove, that the extinction of such Persons was resolved upon, let the means and measures to obtain that object be what they might. During this period we find those who had long been opposed in Political sentiments, to all appearance perfectly reconciled, and adhering to that party from whom they might expect the greatest honors and advancement in the State. We need only refer as proofs for this, to the late "Spencer Percival," and "George Canning"—who to obtain preferment joined the confederations formed against an unprotected Princess, and yet who previously had been the most strenuous defenders of the same Lady's cause.—Well may it be observed that Vanity is too powerful,

[vii]These remarks are not intended as any disparagement to the private characters or virtues of those statesmen whose talent was great and well cultivated, but to establish the position which it is the object of this work to show that Justice has not been fairly and impartially administered when the requirement was in opposition to the Royal wish or the administration.

Within these volumes will also be found urgent remonstrances against the indignities offered to the people of Ireland, whose forebearance has been great, and whose sorrows are without a parallel, and who merit the same regard as England and Scotland.—Much is omited relative to the private conduct of persons who occupy high stations, but should it be needful, it shall be published, and all the correspondence connected therewith. It is true much honor will not be derived from such explanations, but they are forthcoming if requisite.

The generality of readers will not criticise severely upon the diction of these prefatory remarks; they will rather have their attention turned to the truths submitted to them, and the end in view,—that end is for the advancement of the best interests of Society—to unite more closely each member in the bonds of friendship and amity, and to expose the hidden causes which for so long a period have been barriers to concord, unity, and happiness

"MAY GOD DEFEND THE RIGHT."

[viii]

[25]

The secret history of the Court of England, during the last two reigns, will afford the reflecting mind abundant matter for regret and abhorrence. It has, however, been so much the fashion for historians to speak of kings and their ministers in all the fulsome terms of flattery, that the inquirer frequently finds it a matter of great difficulty to arrive at truth. But, fearless of consequences, we will speak of facts as they really occurred, and only hope our readers will accompany us in the recital with feelings, unwarped by party prejudice, and with a determination to judge the actions of kings, lords, and commons, not as beings of a superior order, but as men. Minds thus constituted will have little difficulty in tracing the origin of our present evils, or of perceiving

We commence with the year

about which period George the Third was pressed by his ministers to make choice of some royal lady, [26]and demand her in marriage. They urged this under the pretext, that such a connexion was indispensably necessary to give stability to the monarchy, to assist the progressive improvements in morality and religion, and to benefit all artificers, by making a display at court of their ingenious productions. His majesty heard the proposal with an aching heart; and, to many of his ministers, he seemed as if labouring under bodily indisposition. Those persons, however, who were in the immediate confidence of the king, felt no surprise at the distressing change so apparent in the countenance of his majesty, the cause of which may be traced in the following particulars:

The unhappy sovereign, while Prince of Wales, was in the daily habit of passing through St. James' street, and its immediate vicinity. In one of his favourite rides through that part of town, he saw a very engaging young lady, who appeared, by her dress, to be a member of the Society of Friends. The prince was much struck by the delicacy and lovely appearance of this female, and, for several succeeding days, was observed to walk out alone. At length, the passion of his royal highness arrived at such a point, that he felt his happiness depended upon receiving the lady in marriage.

Every individual in his immediate circle, or in the list of the privy council, was very narrowly questioned by the prince, though in an indirect manner, to ascertain who was most to be trusted, that he might secure, honorably, the possession of the object [27]of his ardent wishes. His royal highness, at last, confided his views to his next brother, Edward, Duke of York, and another person, who were the only witnesses to the legal marriage of the Prince of Wales to the before-mentioned lady, Hannah Lightfoot, which took place at Curzon-street Chapel, May Fair, in the year 1759.

This marriage was productive of issue, the particulars of which, however, we pass over for the present, and only look to the results of the union.

Shortly after the prince came to the throne, by the title of George the Third, ministers became suspicious of his marriage with the quakeress. At length, they were informed of the important fact, and immediately determined to annul it. After innumerable schemes how they might best attain this end, and thereby frustrate the king's wishes, they devised the "Royal Marriage Act," by which every prince or princess of the blood might not marry or intermarry with any person of less degree. This act, however, was not passed till thirteen years after George the Third's union with Miss Lightfoot, and therefore it could not render such marriage illegal.

From the moment the ministry became aware of his majesty's alliance to the lady just named, they took possession of their watch-tower, and determined that the new sovereign should henceforth do even as their will dictated; while the unsuspecting mind of George the Third was easily beguiled into their specious devices. In the absence of the king's beloved brother, Edward, Duke of York, (who was [28]then abroad for a short period) his majesty was assured by his ministers that no cognizance would be taken at any time of his late unfortunate amour and marriage; and persuaded him, that the only stability he could give to his throne was demanding the hand of the Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburgh Strelitz. Every needful letter and paper for the negotiation was speedily prepared for the king's signature, which, in due course, each received; and thus was the foundation laid for this ill-fated prince's future malady!

Who can reflect upon the blighted first love of this monarch, without experiencing feelings of pity for his early sorrows! With his domestic habits, had he only been allowed to live with the wife of his choice, his reign might have passed in harmony and peace, and the English people now been affluent, happy, and contented. Instead of which, his unfeeling ministers compelled him to marry one of the most selfish, vindictive, and tyrannical women that ever disgraced human nature! At the first sight of the German princess, the king actually shrunk from her gaze; for her countenance was of that cast that too plainly told of the nature of the spirit working within.

On the 18th of September, the king was obliged to subscribe to the formal ceremony of a marriage with the before-named lady, at the palace of St. James. His majesty's brother Edward, who was one of the witnesses to the king's first marriage with Miss Lightfoot, was now also present, and used every endeavour to support his royal brother through the "trying [29]ordeal," not only by first meeting the princess on her entrance into the garden, but also at the altar.

In the mean time, the Earl of Abercorn informed the princess of the previous marriage of the king, and of the then existence of his majesty's wife; and Lord Harcourt advised the princess to well inform herself of the policy of the kingdoms, as a measure for preventing much future disturbance in the country, as well as securing an uninterrupted possession of the throne to her issue. Presuming, therefore, that this German princess had hitherto been an open and ingenuous character, (which are certainly traits very rarely to be found in the mind of a German of her grade) such expositions, intimations, and dark mysteries, were ill calculated to nourish honorable feelings, but would rather operate as a check to their further existence.

To the public eye, the newly-married pair were contented with each other;—alas! it was because each feared an exposure to the nation. The king reproached himself that he had not fearlessly avowed the only wife of his affections; the queen, because she feared an explanation that the king was guilty of bigamy, and thereby her claim, as also that of her progeny, (if she should have any) would be known to be illegitimate. It appears as if the result of these reflections formed a basis for the misery of millions, and added to that number millions then unborn. The secret marriage of the king proved a pivot, on which the destiny of kingdoms was to turn.

[30]At this period of increased anxiety to his majesty, Miss Lightfoot was disposed of during a temporary absence of his brother Edward, and from that time no satisfactory tidings ever reached those most interested in her welfare. The only information that could be obtained was, that a young gentleman, named Axford, was offered a large amount, to be paid on the consummation of his marriage with Miss Lightfoot, which offer he willingly accepted.

The king was greatly distressed to ascertain the fate of his much-beloved and legally-married wife, the quakeress, and entrusted Lord Chatham to go in disguise, and endeavour to trace her abode; but the search proving fruitless, the king was again almost distracted.

Every one in the queen's confidence was expected to make any personal sacrifice of feeling whenever her majesty might require it; and, consequently, new emoluments, honors, and posts of dignity, were continually needful for the preservation of such unnatural friendships. From this period, new creations of peers were enrolled; and, as it became expedient to increase the number of the "privy cabal," the nation was freely called upon, by extra taxation and oppressive burdens of various kinds, to supply the necessary means to support this vile system of bribery and misrule!

We have dwelt upon this important period, because we wish our countrymen to see the origin of our overgrown national debt,—the real cause of England's present wretchedness.

[31]The coronation of their majesties passed over, a few days after their marriage, without any remarkable feature, save that of an additional expense to the nation. The queen generally appeared at ease, though she seized upon every possible occasion to slight all persons from whom she feared any state explanation, which might prove inimical to her wishes. The wily queen thought this would effectually prevent their frequent appearance at court, as well as cause their banishment from the council-chamber.

A bill was passed this year to fix the civil list at the annual sum of EIGHT HUNDRED THOUSAND POUNDS, payable out of the consolidated fund, in lieu of the hereditary revenue, settled on the late king.

Another act passed, introduced to parliament by a speech from the throne, for the declared purpose of giving additional security to the independence of the judges. Although there was a law then in force, passed in the reign of William the Third, for continuing the commissions of judges during their good behaviour, they were legally determined on the death of the reigning sovereign. By this act, however, their continuance in office was made independent of the royal demise.

Twelve millions of money were raised by loans this year, and the interest thereon agreed to be paid by an additional duty of three shillings per barrel on all strong beer or ale,—the sinking fund being a collateral security. The imposition of this tax was received by the people as it deserved to be; for every [32]labourer and mechanic severally felt himself insulted by so oppressive an act.

The year

was ushered in by the hoarse clarion of war. England declared against Spain, while France and Spain became opposed to Portugal, on account of her alliance with Great Britain. These hostilities, however, were not of long duration; for preliminaries of peace were signed, before the conclusion of the year, by the English and French plenipotentiaries at Fontainbleau.

By this treaty, the original cause of the war was removed by the cession of Canada to England. This advantage, if advantage it may be called, cost this country eighteen millions of money, besides the loss of three hundred thousand men! Every friend of humanity must shudder at so wanton a sacrifice of life, and so prodigious an expenditure of the public money! But this was only the commencement of the reign of imbecility and Germanism.

On the 12th of August, her majesty was safely delivered of a prince. Court etiquette requires numerous witnesses of the birth of an heir-apparent to the British throne. On this occasion, however, her majesty's extraordinary delicacy dispensed with a strict adherence to the forms of state; for only the Archbishop of Canterbury was allowed to be in the room. But there were more powerful reasons [33]than delicacy for this unusual privacy, which will hereafter appear.

On the 18th of September following, the ceremony of christening the royal infant was performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in the great council-chamber of his majesty's palace, and the young prince was named George, Augustus, Frederick.

In this year, the city of Havannah surrendered to the English, whose troops were commanded by Lord Albermarle and Admiral Pococke. Nine sail of the line and four frigates were taken in the harbour; three of the line had been previously sunk by the enemy, and two were destroyed on the stocks. The plunder in money and merchandize was supposed to have amounted to three millions sterling, while the sum raised by the land-tax, at four shillings in the pound, from 1756 to 1760 inclusive, also produced ten millions of money! But to what purpose this amount was devoted remained a profound secret to those from whom it was extorted.

In the November of this year, the famous Peter Annet was sentenced by the Court of King's Bench to be imprisoned one month, to stand twice in the pillory within that time, and afterwards to be kept to hard labour in Bridewell for a year. The reader may feel surprised when informed that all the enormity this man had been guilty of consisted in nothing more than writing the truth of the government, which was published in his "Free Inquirer." [34]The unmerited punishment, however, had only this effect: it made him glory in suffering for the cause of liberty and truth.

was a continuation of the misrule which characterized the preceding year.

In May, Lord Bute resigned the office of First Lord of the Treasury, and the conduct of the earl became a question of much astonishment and criticism. He was the foundation-stone of Toryism, in its most arbitrary form; and there cannot be a doubt that his lordship's influence over the state machinery was the key-stone of all the mischiefs and miseries of the nation. It was Lord Bute's opinion, that all things should be made subservient to the queen, and he framed his measures accordingly.

The earl was succeeded by Mr. George Grenville. Little alteration for the better, however, was manifested in the administration, although the characters and principles of the new ministers were supposed to be of a liberal description; but this may possibly be accounted for by the Earls of Halifax and Egremont continuing to be the secretaries of state.

In this memorable year, the celebrated John Wilkes, editor of "The North Briton," was committed to the Tower, for an excellent, though biting, criticism on his majesty's speech to the two houses of parliament. The queen vigorously promoted this unconstitutional and tyrannical act of [35]the new government, which was severely censured by many members of the House of Commons. Among the rest, Mr. Pitt considered the act as an infringement upon the rights of the people; and, although he condemned the libel, he said he would come at the author fairly,—not by an open breach of the constitution, and a contempt of all restraint. Wilkes, however, came off triumphantly, and his victory was hailed with delight by his gratified countrymen.

In the midst of this public agitation, the queen, on the 16th of August, burdened the nation with her second son, Frederick, afterwards created Duke of York, Bishop of Osnaburgh, and many other et ceteras, which produced a good round sum, and, we should think, more than sufficient to support this Right Reverend Father in God, at the age of—eleven months!

Colonel Gréme, who had been chiefly instrumental in bringing about the marriage of the Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburgh with the King of England, was this year appointed Master of St. Catherine, near the Tower, an excellent sinecure in the peculiar gift of the queen!

The most important public event on the continent was, the death of Augustus, third King of Poland, and Elector of Saxony, who had lately returned to his electoral dominions, from which he had been banished for six years, in consequence of the war. Immediately after his demise, his eldest son and successor to the electorate declared himself a candidate [36]for the crown of Poland, in which ambition he was supposed to be countenanced by the Court of Vienna; but he fell a victim to the small-pox, a few weeks after his father's death.

During the year

much public anxiety and disquietude was manifested. Mr. Wilkes again appeared before a public tribunal for publishing opinions not in accordance with the reigning powers. The House of Commons sat so early as seven o'clock in the morning to consider his case, and the speaker actually remained in the chair for twenty hours, so important was the matter considered.

About the end of this year, the king became much indisposed, and exhibited the first signs of that mental aberration, which, in after years, so heavily afflicted him. The nation, in general, supposed this to have arisen from his majesty's anxiety upon the fearful aspect of affairs, which was then of the most gloomy nature, both at home and abroad. Little, indeed, did the multitudes imagine the real cause; little did the private gentleman, the industrious tradesman, the worthy mechanic, or the labourer, think that their sovereign was living in splendid misery, bereft of the dearest object of his solicitude, and compelled to associate with the woman he all but detested!

Nature had not formed George the Third for a [37]king; she had not been profuse to him either in elegance of manners, or capacity of mind; but he seemed more fitted to shine in a domestic circle, where his affections were centred, and in that sphere only. But, with all hereditary monarchies, an incompetent person has the same claim as a man adorned with every requisite and desirable ability!

In this year, Lord Albermarle received TWENTY THOUSAND POUNDS as his share in the Havannah prize-money; while one pound, two shillings, and six-pence was thought sufficient for a corporal, and thirteen shillings and five-pence for a private! How far this disbursement was consistent with equity, we leave every honest member of society to determine.

In December, a most excellent edict was registered in the parliament of Paris, by which the King of France abolished the society of Jesuits for ever.

Early in the year

the queen was pressingly anxious that her marriage with the king should again be solemnized; and, as the queen was then pregnant, his majesty readily acquiesced in her wishes. Dr. Wilmot, by his majesty's appointment, performed the ceremony at their palace at Kew. The king's brother, Edward, was present upon this occasion also, as he had been on the two former ones.

Under the peculiar distractions of this year, it [38]was supposed, the mind of the sovereign was again disturbed. To prevent a recurrence of such interruptions to the royal authority, a law was passed, empowering his majesty to appoint the queen, or other member of the royal family, assisted by a council, to act as regent of the kingdom. Although his majesty's blank of intellect was but of short duration, it proved of essential injury to the people generally. The tyrannical queen, presuming on the authority of this bill, exercised the most unlimited sway over national affairs. She supplied her own requirements and opinions, in unison with her trusty-bought clan, who made it apparent that these suggestions were offered by the king, and were his settled opinions, upon the most deliberate investigation of all matters and things connected therewith!

During the king's indisposition, he was most passionate in his requests, that the wife of his choice should be brought to him. The queen, judging her influence might be of much consequence to quell the perturbation of her husband's mind, was, agreeably to her own request, admitted to the solitary apartment of the king. It is true he recognised her, but it was followed by extreme expressions of disappointment and disgust! The queen was well acquainted with all subjects connected with his majesty's unfortunate passion and marriage; therefore, she thought it prudent to stifle expressions of anger or sorrow, and, as soon as decency permitted, left the place, resolving thenceforth to manage the helm herself.

[39]On the 31st of October, his majesty's uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, died suddenly at his house in Upper Grosvenor-street, in the forty-fifth year of his age; and on the 28th of December, his majesty's youngest brother, Prince Frederick William, also expired, in the sixteenth year of his age.

On December 1st,

his majesty's sister, Matilda, was married to the King of Denmark, and the Duke of York was proxy on the occasion. Soon afterwards, his royal highness took leave of his brother, and set out on a projected tour through Germany, and other parts of the continent. The queen was most happy to say "Adieu," and, for the first time, felt something like ease on his account.

The supplies granted for the service of this year, although the people were in the most distressed state, amounted to eight millions, two hundred and seventy-three thousand, two hundred and eighty pounds!

In the year

the noble-minded and generous Duke of York was married to a descendant of the Stuarts, an amiable and conciliating lady, not only willing, but anxious, to live without the splendour of royal parade, and [40]desirous also of evading the flatteries and falsehoods of a court.

In August, the duke lived very retired in a chateau near Monaco, in Italy, blessed and happy in the society of his wife. She was then advancing in pregnancy, and his solicitude for her was sufficient to have deeply interested a heart less susceptible than her own. Their marriage was kept from public declaration, but we shall refer to the proofs hereafter. In the ensuing month, it was announced that (17th September) the duke "died of a malignant fever," in the twenty-ninth year of his age, and the news was immediately communicated to the King of England. The body was said to be embalmed, (?) and then put on board his majesty's ship Montreal, to be brought to England. His royal highness was interred on the evening of November 3rd, in the royal vault of King Henry the Seventh's Chapel.

The fate of the duke's unfortunate and inconsolable widow, and that of the infant, to whom she soon after gave birth, must be reserved for its appropriate place in this history.

The high price of provisions this year occasioned much distress and discontent, and excited tumults in various parts of the kingdom. Notwithstanding this, ministers attempted to retain every tax that had been imposed during the late war, and appeared perfectly callous to the sufferings of the productive classes. Even the land-tax, of four shillings in the pound, was attempted to be continued, though [41]contrary to all former custom; but the country gentlemen became impatient of this innovation, and contrived to get a bill introduced into the House of Commons, to reduce it to three shillings in the pound. This was carried by a great majority, in spite of all the efforts of the ministry to the contrary! The defeat of the ministers caused a great sensation at the time, as it was the first money-bill in which any ministry had been disappointed since the revolution of 1688! But what can any ministers do against the wishes of a determined people? If the horse knew his own strength, would he submit to the dictation of his rider?

On account of the above bill being thrown out, ministers had considerable difficulty in raising the necessary supplies for the year, which were estimated at eight millions and a half, including, we suppose, secret-service money, which was now in great demand.

The king experienced a fluctuating state of health, sometimes improving, again retrograding, up to the year

In his speech, in the November of this year, his majesty announced, that much disturbance had been exhibited in some of the colonies, and a disposition manifested to throw aside their dependence upon Great Britain. Owing to this circumstance, a new office was created, under the name of "Secretary of [42]State for the Colonies," and to which the Earl of Hillsborough was appointed.

The Earl of Chatham having resigned, parliament was dissolved. Party spirit running high, the electioneering contests were unusually violent, and serious disorders occurred. Mr. Wilkes was returned for Middlesex; but, being committed to the King's Bench for libels on the government, the mob rescued Wilkes from the soldiers, who were conducting him thither. The military were ordered to fire on the people, and one man, who was singled out and pursued by the soldiers, was shot dead. A coroner's inquest brought this in wilful murder, though the higher authorities not only acquitted the magistrates and soldiers, but actually returned public thanks to them!

At this period, the heart sickens at the relations given of the punishments inflicted on many private soldiers in the guards. They were each allowed only four-pence per day. If they deserted and were re-taken, the poor delinquents suffered the dreadful infliction of five hundred lashes. The victims thus flagellated very seldom escaped with life! In the navy, also, the slightest offence or neglect was punished with inexpressible tortures. This infamous treatment of brave men can only be accounted for by the fact, that officers in the army and navy either bought their situations, or received them as a compensation for some SECRET SERVICE performed for, or by the request of, the queen and her servile ministry. Had officers been promoted from the ranks, [43]for performing real services to their country, they would have then possessed more commiseration for their brothers in arms.

We must here do justice to the character of George the Third from all intentional tyranny. Many a time has this monarch advocated the cause of the productive classes, and as frequently have his ministers, urged on by the queen, defeated his most sanguine wishes, until he found himself a mere cipher in the affairs of state. The king's simplicity of style and unaffected respect for the people would have induced him to despise the gorgeous pageantry of state; he had been happy, indeed, to have been "the real father of his subjects." His majesty well knew that the public good ought to be the sole aim of all governments, and that for this purpose a prince is invested with the regal crown. A king is not to employ his authority, patronage, and riches, merely to gratify his own lusts and ambition; but, if need require it, he ought even to sacrifice his own ease and pleasure for the benefit of his country. We give George the Third credit for holding these sentiments, which, however, only increased his regrets, as he really had no power to act,—that power being in the possession of his queen, and other crafty and designing persons, to whose opinions and determinations he had become a perfect slave! It is to be regretted that he had not sufficient nerve to eject such characters from his councils; for assuredly the nation would have been, to a man, willing to [44]protect him from their vile machinations; but once subdued, he was subdued for ever.

From the birth, a prince is the subject of flattery, and is even caressed for his vicious propensities; nay, his minions never appear before him without a mask, while every artifice that cunning can suggest is practised to deceive him. He is not allowed to mix in general society, and therefore is ignorant of the wants and wishes of the people over whom he is destined to reign. When he becomes a king, his counsellors obtain his signature whenever they desire it; and, as his extravagance increases, so must sums of money, in some way or other, be extorted from his suffering and oppressed subjects. Should his ministers prove ambitious, war is the natural result, and the money of the poor is again in request to furnish means for their own destruction! Whereas, had the prince been associated with the intelligent and respectable classes of society, he might have warded off the evil, and, instead of desolating war, peace might have shed her gentle influence over the land. Another barbarous custom is, the injunction imposed upon royal succession, that they shall not marry only with their equals in birth. But is not this a violation of the most vital interests and solemn engagements to which humanity have subscribed? What unhappiness has not such an unnatural doctrine produced? Quality of blood ought only to be recognized by corresponding nobility of sentiments, principles, and actions. He that is debarred from [45]possessing the object of his virtuous regard is to be pitied, whether he be a king or a peasant; and we can hardly wonder at his sinking into the abyss of carelessness, imbecility, and even madness.

In February,

the first of those deficiencies in the civil list, which had occurred from time to time, was made known to parliament, by a message in the name of the unhappy king, but who only did as he was ordered by his ministerial cabal. This debt amounted to five hundred thousand pounds, and his majesty was tutored to say, that he relied on the zeal and affection of his faithful Commons to enable him to discharge it! The principal part of this money was expended upon wretches, of the most abandoned description, for services performed against the welfare of England.

The year

proved one of much political interest. The queen was under the necessity of retiring a little from the apparent part she had taken in the affairs of state; nevertheless, she was equally active; but, from policy, did not appear so. Another plan to deceive the people being deemed necessary, invitations for splendid parties were given, in order to [46]assume an appearance of confidence and quietness, which her majesty could not, and did not, possess.

In this year, Lord Chatham publicly avowed his sentiments in these words: "Infuse a portion of health into the constitution, to enable it to bear its infirmities." Previous to making this remark, his lordship, of course, was well acquainted with the causes of the then present distresses of the country, as well as the sources from whence those causes originated. But one generous patriot is not sufficient to put a host of antagonists to flight. The earl's measures were too mild to be heeded by the minions of the queen then in power; his intention being "to persuade and soften, not to irritate and offend." We may infer that, had he been merely a "party man," he would naturally concur in any enterprise likely to create a bustle without risk to himself; but, upon examination, he appears to have loved the cause of independence, and was willing to support it by every personal sacrifice.

About this time, the Duke of Grafton resigned his office of First Lord of the Treasury, in which he was succeeded by that disgrace to his country, Lord North, who then commenced his long and disastrous administration. Dr. Wilmot was a friendly preceptor to this nobleman, while at the university; but it was frequently a matter of regret to the worthy doctor, that his lordship had not imbibed those patriotic principles which he had so strongly endeavoured to inculcate; and he has been known to observe, that Lord North's administration called for [47]the most painful animadversions, inasmuch as he advocated the enaction of laws of the most arbitrary character.

Mr. Wilkes, previous to the meeting of the Commons in January, was not only acquitted, but had damages, to a large amount, awarded him; and the king expressed a desire, that such damages should be paid out of his privy purse. The Earl of Halifax, who signed the warrant for his committal to the Tower in 1763, was finally so disappointed that he offered his resignation, though he afterwards accepted the privy seal.

It was during this year, that the celebrated "Letters of Junius" first appeared. These compositions were distinguished as well by the force and elegance of their style as by the violence of their attacks on individuals. The first of these letters was printed in the "Public Advertiser," of December the 19th, and addressed to the king, animadverting on all the errors of his reign, and speaking of his ministers in terms of equal contempt and abhorrence. An attempt was made to suppress this letter by the strong arm of the law; but the effort proved abortive, as the jury acquitted the printer, who was the person prosecuted. Junius (though under a feigned name) was the most competent person to speak fully upon political subjects. He had long been the bosom friend of the king, and spent all his leisure time at court. No one, therefore, could better judge of the state of public affairs than himself, and his sense of duty to the nation animated him to plead for the [48]long-estranged rights of the people; indeed, upon many occasions, he displayed such an heroic firmness, such an invincible love of truth, and such an unconquerable sense of honor, that he permitted his talents to be exercised freely in the cause of public justice, and subscribed his addenda under an envelope, rather than injure his prince, or leave the interests of his countrymen to the risk of fortuitous circumstances. We know of whom we speak, and therefore feel authorized to assert, that in his character were concentrated the steady friend of the prince as well as of the people.

Numerous disquisitions have been written to prove the identity of Junius; but, in spite of many arguments to the contrary, we recognize him in the person of the Rev. James Wilmot, D.D., Rector of Barton-on-the-Heath, and Aulcester, Warwickshire, and one of his majesty's justices of the peace for that county.

Dr. Wilmot was born in 1720, and, during his stay at the university, became intimately acquainted with Dr. Johnson, Lord Archer, and Lord Plymouth, as well as Lord North, who was then entered at Trinity College. From these gentlemen, the doctor imbibed his political opinions, and was introduced to the first society in the kingdom. At the age of thirty, Dr. Wilmot was confidently entrusted with the most secret affairs of state, and was also the bosom friend of the Prince of Wales, afterwards George the Third, who at that time was under the entire tutorage of Lord Bute. To this nobleman, Dr. Wilmot [49]had an inveterate hatred, for he despised the selfish principles of Toryism. As soon as the Princess of Mecklenburgh (the late Queen Charlotte) arrived in this country in 1761, Dr. Wilmot was introduced, as the especial friend of the king, and this will at once account for his being chosen to perform the second marriage-ceremony of their majesties at Kew palace, as before related.

A circumstance of rather a singular nature occurred to Dr. Wilmot, in the year 1765, inasmuch as it was the immediate cause of the bold and decisive line of conduct which he afterwards adopted. It was simply this: the doctor received an anonymous letter, requesting an interview with the writer in Kensington Gardens. The letter was written in Latin, and sealed, the impression of which was a Medusa's head. The doctor at first paid no attention to it; but during the week he received four similar requests, written by the same hand; and, upon the receipt of the last, Dr. Wilmot provided himself with a brace of pocket pistols, and proceeded to the gardens at the hour appointed. The doctor felt much surprised when he was accosted by—Lord Bute! who immediately suggested that Dr. Wilmot should assist the administration, as her majesty had entire confidence in him! The doctor briefly declined, and very soon afterwards commenced his political career. Thus the German princess always endeavoured to inveigle the friends of the people.

Lord Chatham had been introduced to Dr. Wilmot [50]by the Duke of Cumberland; and it was from these associations with the court and the members of the several administrations, that the doctor became so competent to write his unparalleled "Letters of Junius."

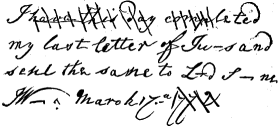

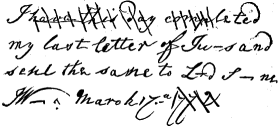

We here subjoin an incontrovertible proof of Dr. Wilmot's being the author of the work alluded to:

This is a fac-simile of the doctor's hand-writing, and must for ever set at rest the long-disputed question of "Who is the author of Junius?"

The people were really in need of the advocacy of a writer like Junius, for their burdens at this time were of the most grievous magnitude. Although the country was not in danger from foreign enemies, in order to give posts of command, honor, and emolument, to the employed sycophants at court, our navy was increased, nominal situations were provided; while all the means to pay for such services were again ordered to be drawn from the people!

was productive of little else than harassing distresses [51]to the poor labourer and mechanic. At this period, it was not unusual to tear the husband from the wife, and the parent from the child, and immure them within the damp and noisome walls of a prison, to prevent any interposition on the part of the suffering multitudes. Yes, countrymen, such tyranny was practised to ensure the secrecy of truth, and to destroy the wishes of a monarch, who was rendered incompetent to act for himself.

Various struggles were made this year to curb the power of the judges, particularly in cases relating to the liberty of the press, and also to destroy the power vested in the Attorney-General of prosecuting ex-officio, without the intervention of a grand jury, or the forms observed by courts of law in other cases. But the boroughmongers and minions of the queen were too powerful for the liberal party in the House of Commons, and the chains of slavery were, consequently, rivetted afresh.

A question of great importance also occurred this year respecting the privileges of the House of Commons. It had become the practice of newspaper writers to take the liberty, not before ventured upon, of printing the speeches of the members, under their respective names; some of which in the whole, and others in essential parts, were spurious productions, and, in any case, contrary to the standing orders of the House. A complaint on this ground having been made by a member against two of the printers, an order was issued for their attendance, with which they refused to comply; a second order was given [52]with no better success. At length, one of the printers being taken into custody under the authority of the speaker's warrant, he was carried before the celebrated Alderman John Wilkes, who, regarding the caption as illegal, not only discharged the man, but bound him over to prosecute his captor, for assault and false imprisonment. Two more printers, being apprehended and carried before Alderman Wilkes and the Lord Mayor, Crosby, were, in like manner, discharged. The indignation of the House was then directed against the city magistrates, and various measures adopted towards them. The contest finally terminated in favor of the printers, who have ever since continued to publish the proceedings of parliament, and the speeches of the members, without obstacle.

In this year, the marriage of the Duke of Cumberland with Mrs. Horton took place. The king appeared electrified when the matter was communicated to him, and declared that he never would forgive his royal brother's conduct, who, being informed of his majesty's sentiments, thus wrote to him: "Sire, my welfare will ensure your own; you cannot condemn an affair there is a precedent for, even in your own person!"—alluding to his majesty's marriage with Hannah Lightfoot. His majesty was compelled to acknowledge this marriage, from the Duke of Cumberland having made a confidant of Colonel Luttrell, brother of Mrs. Horton, with regard to several important state secrets which had occurred in the years 1759, 1760, 1761, 1762, and 1763.

[53]This Duke of Cumberland also imbibed the family complaint of BIGAMY; for he had been married, about twelve months previous, to a daughter of Dr. Wilmot, who, of course, remonstrated against such unjust treatment. The king solemnly assured Dr. Wilmot that he might rely upon his humanity and honor. The doctor paused, and had the courage to say, in reply, "I have once before relied upon the promises of your majesty! But"—"Hush! hush!" said the king, interrupting him, "I know what you are going to say; but do not disturb me with wills and retrospection of past irreparable injury."

The death of the Earl of Halifax, soon after the close of the session in this year, caused a vacancy; and the Duke of Grafton returned to office, as keeper of the privy seal. His grace was a particular favourite with the queen, but much disliked by the intelligent and reflecting part of the community.

The political atmosphere bore a gloomy aspect at the commencement of

and petitions from the people were sent to the king and the two houses of parliament, for the repeal of what they believed to be unjust and pernicious laws upon the subject of religious liberty. Several clergymen of the established church prayed to be liberated from their obligation to subscribe to the "Thirty-nine Articles." But it was urged, in opposition to the petitions, that government had an undoubted [54]right to establish and maintain such a system of instruction as the ministers thereof deemed most suitable for the public benefit. But expedience and right are as far asunder, in truth, as is the distance from pole to pole. The policy of the state required some new source from whence to draw means for the secret measures needful for prolonging the existence of its privacy; and it was therefore deemed expedient to keep politics and religion as close together as possible, by enforcing the strictest obedience of all demands made upon the clergy, in such forms and at such times as should best accord with the political system of the queen. In consequence of which, the petitions were rejected by a majority of 217 boroughmongers against 71 real representatives of the people!

An act, passed this session, for "Making more effectual provisions to guard the descendants of the late king, George the Second, from marrying without the approbation of his majesty, his heirs, and successors, first had and obtained," was strenuously opposed by the liberal party in every stage of its progress through both houses. It was generally supposed to have had its origin in the marriage contracted but a few months before by the Duke of Cumberland with Mrs. Horton, relict of Colonel Horton, and daughter of Lord Irnham; and also in a private, though long-suspected, marriage of the Duke of Gloucester to the Countess-dowager of Waldegrave, which the duke at this time openly avowed. But were there not other reasons which [55]operated on the mind of the queen (for the poor king was only a passive instrument in her power) to force this bill into a law? Had she not an eye to her husband's former alliance with the quakeress, and the Duke of York's marriage in Italy? The latter was even more dangerous to her peace than the former; for the duke had married a descendant of the Stuarts!

Lord Chatham made many representations to the king and queen of the improper and injudicious state of the penal laws. He cited an instance of unanswerable disproportion; namely, that, on the 14th of July, two persons were publicly whipped round Covent Garden market, in accordance with the sentence passed upon them; but mark the difference of the crimes for which they were so punished: one was for stealing a bunch of radishes; the other, for debauching his own niece! In vain, however, did this friend of humanity represent the unwise, unjust, and inconsistent tenour of such laws. The king was anxious to alter them immediately; but the queen was decided in her opinion, that they ought to be left entirely to the pleasure and opinion of the judges, well knowing they would not disobey her will upon any point of law, or equity, so called. Thus did the nation languish under the tyrannical usurpation of a German princess, whose disposition and talents were much better calculated to give laws to the brute creation than to interfere with English jurisprudence!

In November of this year, it was announced that [56]the king earnestly desired parliament should take into consideration the state of the East India Company. But the king was ignorant of the subject; though it was true, the queen desired it; because she received vast emoluments from the various situations purchased by individuals under the denomination of cadets, &c. Of course, her majesty's will was tantamount to law.

The Earl of Chatham resolved once more to speak to the queen upon the state of things, and had an audience for that purpose. As an honest man, he very warmly advocated the cause of the nation, and represented the people to be in a high state of excitement, adding, that "if they be repelled, they must be repelled by force!" And to whom ought an unhappy suffering people to have had recourse but to the throne, whose power sanctioned the means used to drain their purses? The queen, however, was still unbending; she not only inveighed against the candour and sentiments of the earl, but requested she might not again be troubled by him upon such subjects! Before retiring, Lord Chatham said, "Your majesty must excuse me if I say, the liberty of the subject is the surest protection to the monarch, and if the prince protects the guilty, instead of punishing them, time will convince him, that he has judged erroneously, and acted imprudently."

The earl retired; but "his labouring breast knew not peace," and he resolved, for the last time, to see the king in private. An interview was requested, and as readily granted. "Well, well," said the king, [57]"I hope no bad news?" "No bad news, your majesty; but I wish to submit to your opinion a few questions." "Quite right, quite right," said the king, "tell me all." The earl did so, and, after his faithful appeal to the king, concluded by saying, "My sovereign will excuse me, but I can no longer be a party to the deceptions pawned upon the people, as I am, and consider myself to be, amenable to God and my conscience!" Would that England had possessed a few more such patriots!

This year will ever be memorable in history as the commencement of that partition of Poland, between three contiguous powers,—Russia, Austria, and Prussia,—which has served as an example and apology for all those shameful violations of public right and justice that have stained the modern annals of Europe. The unfortunate Poles appealed in vain to Great Britain, France, and Spain, and the States-general of Holland, on the atrocious perfidy and injustice of these proceedings. After some unavailable remonstrances, the diet was compelled, at the point of the bayonet, to sign a treaty for the formal cession of the several districts which the three usurpers had fixed upon and guaranteed to each other. The partitioning legitimates also generously made a present of an aristocratic constitution to the suffering Poles.

In the year

commercial credit was greatly injured by extensive [58]failures in England and Holland. The distress and embarrassment of the mercantile classes were farther augmented by a great diminution in the gold coin, in consequence of wear and fraud,—such loss, by act of parliament, being thrown upon the holders!

At this time, the discontents which had long been manifest in the American colonies broke out into open revolt. The chief source of irritation against the mother country was the impolitic measure of retaining a trifling duty on tea, as an assertion of the right of the British parliament to tax the colonies.

The year

bore a gloomy and arbitrary character, with wars abroad and uneasiness at home. The county of Nottingham omitted to raise their militia in the former year, and in this they were fined two thousand pounds.

Louis the Fifteenth of France died this year of the small-pox, caught from a country girl, introduced to him by Madame du Barré to gratify his sensual desires. He was in the sixty-fourth year of his age, and in the fifty-ninth of his reign. The gross debaucheries into which he had sank, with the despotic measures he had adopted towards the Chamber of Deputies in his latter years, had entirely deprived him of his appellation of the [59]"Well-beloved." Few French sovereigns have left a less-respected memory.

was also a year of disquiet. The City of London addressed the throne, and petitioned against the existing grievances, expressing their strong abhorrence of the measures adopted towards the Americans, justifying their resistance, and beseeching his majesty to dismiss his ministers. The invisible power of the queen, however, prevented their receiving redress, and the ministers were retained, contrary to all petition and remonstrance. Upon these occasions, the king was obliged to submit to any form of expression, dictated by the minister, that minister being under the entire controul of the queen; and though the nation seemed to wear a florid countenance, it was sick at heart. Lord North was a very considerable favourite with her majesty; while his opponents, Messrs. Fox and Burke, were proportionately disliked. The Duke of Grafton now felt tired of his situation, and told the queen that he could no longer continue in office; in consequence of which, the Earl of Dartmouth received the privy seal.

The Americans, in the mean time, were vigorously preparing for what they conceived to be inevitable—a war. Various attempts, notwithstanding, were made by the enlightened and liberal-minded part of the community to prevent ministers from [60]continuing hostilities against them. That noble and persevering patriot, Lord Chatham, raised his warning voice against it. "I wish," said he, "not to lose a day in this urgent, pressing crisis; an hour now lost in allaying ferments in America, may produce YEARS OF CALAMITY! Never will I desert, in any stage of its progress, the conduct of this momentous business. Unless fettered to my bed by the extremity of sickness, I will give it unremitted attention; I will knock at the gates of this sleeping and confounded ministry, and will, if it be possible, rouse them to a sense of their danger. The recall of your army, I urge as necessarily preparatory to the restoration of your peace. By this it will appear that you are disposed to treat amicably and equitably, and to consider, revise, and repeal, if it should be found necessary, as I affirm it will, those violent acts and declarations which have disseminated confusion throughout the empire. Resistance to these acts was necessary, and therefore just; and your vain declaration of the omnipotence of Parliament, and your imperious doctrines of the necessity of submission, will be found equally impotent to convince or enslave America, who feels that tyranny is equally intolerable, whether it be exercised by an individual part of the legislature, or by the collective bodies which compose it!"

How prophetic did this language afterwards prove! Oh! England, how hast thou been cursed by debt and blood through the impotency and villany of thy rulers!

[61]In the year

the Earl of Harcourt was charged with a breach of privilege; but his services for the queen operated as a sufficient reason for rejecting the matter of complaint.

So expensive did the unjust and disgraceful war with America prove this year, that more than nine millions were supplied for its service! In order to raise this shameful amount, extra taxes were levied on newspapers, deeds, and other matters of public utility. Thus were the industrious and really productive classes imposed upon, and their means exhausted, to gratify the inordinate wishes of a German princess, now entitled to be the cause of their misery and ruin. The queen knew that war required soldiers and sailors, and that these soldiers and sailors must have officers over them, which would afford her an opportunity of selling commissions or of bestowing them upon some of her favourites. So that these things contributed to her majesty's individual wealth and power, what cared she for the increase of the country's burdens!

It is wonderful to reflect upon the means with which individuals in possession of power have contrived, in all ages and in all countries, to controul mankind. From thoughtlessness and the absence of knowledge, the masses of people have been made to contend, with vehemence and courageous enterprise, [62]against their own interests, and for the benefit of those mercenary wretches by whom they have been enslaved! How monstrous it is, that, to gratify the sanguinary feelings of one tyrant, thousands of human beings should go forth to the field of battle as willing sacrifices! Ignorance alone has produced such lamentable results; for a thirst after blood is never so effectually quenched as when it is repressed by the influence of knowledge, which teaches humility, moderation, benevolence, and the practice of every other virtue. In civilized society, there cannot be an equality of property; and, from the dissimilarity in human organization, there cannot be equality in the power and vigour of the mind. All men, however, are entitled to, and ought to enjoy, a perfect equality in civil and political rights. In the absence of this just condition, a nation can only be partially free. The people of such a nation exist under unequal laws, and those persons upon whom injuries are inflicted by the partial operation of those laws are, it must be conceded, the victims of an authority which they cannot controul. Such was, unhappily, the condition of the English people at this period. To prevent truth from having an impartial hearing and explanation, the plans of government were obliged to be of an insincere and unjust character. The consequences were, the debasement of morals, and the prostitution of the happiness and rights of the people. But Power was in the grasp of Tyranny, attended on each side by Pride and Cruelty; while Fear presented an excuse for Silence and Apathy, and left [63]Artifice and Avarice to extend their baneful influence over society. British courage was stifled by arbitrary persecutions, fines, and imprisonment, which threatened to overwhelm all who dared to resist the tide of German despotism. Had unity and resolution been the watch-words of the sons of Britain, what millions of debt might have been prevented! what oceans of blood might have been saved! The iniquitous ministers who dictated war with America should have suffered as traitors to their country, which would have been their fate had not blind ignorance and servility, engendered by priests and tyrants, through the impious frauds of church and state, overwhelmed the better reason of the great mass of mankind! It was, we say, priestcraft and statecraft that kindled this unjustifiable war, in order to lower human nature, and induce men to butcher each other under the most absurd, frivolous, and wicked pretences. Englishmen, at the commencement of the American war, appear to have been no better than wretched captives, without either courage, reason, or virtue, from whom the queen's banditti of gaolers shut out the glorious light of day. There were, however, some few patriots who raised their voices in opposition to the abominable system then in practice, and many generous-hearted men who boldly refused to fight against the justified resistance of the Americans; but the general mass remained inactive, cowardly inactive, against their merciless oppressors. The queen pretended to lament the sad state of affairs, while she did all in her power to continue the misrule!

[64]At the commencement of

the several states of Europe had their eyes fixed on the contest between this country and the colonies. The French government assisted the Americans with fleets and armies, though they did not enter into the contest publicly. Queen Charlotte still persevered in her designs against America, and bore entire sway over her unfortunate husband. The country, as might be expected, was in a state of great excitement, owing to the adoption of measures inimical to the wishes and well-being of the people. The greater power the throne assumed, the larger amounts were necessarily drawn from the people, to reward fawning courtiers and borough proprietors.

This year, thirteen millions of money were deemed needful for the public service, and the debts of the civil list a second time discharged! At this time, the revenue did not amount to eight millions, and to supply the consequent deficiency, new taxes were again levied upon the people; for ministers carried all their bills, however infamous they might be, by large majorities!

In May, Lord Chatham again addressed the "peers," and called their attention to the necessity of changing the proceedings of government. Although bowed down by age and infirmity, and bearing a crutch in each hand, he delivered his sentiments, with all the ardour of youth, in these words: "I wish the removal of accumulated grievances, and the [65]repeal of every oppressive act which have been passed since the year 1763! I am experienced in spring hopes and vernal promises, but at last will come your equinoctial disappointment."

On another occasion, he said, "I will not join in congratulation on misfortune and disgrace! It is necessary to instruct the throne in the language of truth! We must dispel the delusions and darkness which envelop it. I am old and weak, and at present unable to say more; but my feelings and indignation were too strong to permit me to say less." Alas! this patriot stood nearly alone. In his opinion, the good of the people was the supreme law; but this was opposed to the sentiments of the hirelings of state and their liberal mistress.

As a last effort, the earl resolved to seek an audience of the queen, and the request was readily complied with. The day previous to his last speech, delivered in the House of Lords, this interview took place. His lordship pressed the queen to relieve the people, and, by every possible means, to mitigate the public burdens. But, though her majesty was gentle in her language, she expressed herself positively and decisively as being adverse to his views; and took the opportunity of reminding him of the secrecy of state affairs. As Lord Chatham had once given his solemn promise never to permit those secrets to transpire, he resolved faithfully to keep his engagement, though their disclosure would have opened the eyes of the public to the disgraceful proceedings of herself and ministers. The noble earl retired [66]from his royal audience in much confusion and agitation of mind; and on the following day, April the 7th, went to the House, and delivered a most energetic speech, which was replied to by the Duke of Richmond. Lord Chatham afterwards made an effort to rise, as if labouring to give expression to some great idea; but, before he could utter a word, pressed his hand on his bosom, and fell down in a convulsive fit. The Duke of Cumberland and Lord Temple caught him in their arms, and removed him into the prince's chamber. Medical assistance being immediately rendered, in a short time his lordship in some measure recovered, and was removed to his favourite villa at Hayes, in Kent. Hopes of his complete restoration to health, however, proved delusive, and on the 10th of May,

this venerable and noble friend of humanity expired, in the seventieth year of his age.

The news of the earl's death was not disagreeable to the queen; and she thenceforth determined to increase, rather than decrease, her arbitrary measures. Ribbons, stars, and garters, were bestowed upon those who lent their willing aid to support her system of oppression, while thousands were perishing in want to supply the means.

Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, this year, were servile enough to raise regiments at their own expense; but the independent and brave [67]citizens of London, steady to their principles, that the war was unjust, refused to follow so mean an example!

The year

exhibits a miserable period in the history of Ireland. Her manufactures declined, and the people became, consequently, much dissatisfied; but their distresses were, at first, not even noticed by the English parliament. At length, however, an alarm of INVASION took place, and ministers allowed twenty thousand Irish volunteers to carry arms. The ministers, who before had been callous to their distresses, found men in arms were not to be trifled with, and the Irish people obtained a promise of an extension of trade, which satisfied them for the time.

Large sums were again required to meet the expenses of the American war, and, the minister being supported by the queen, every vote for supplies was carried by great majorities; for the year's service alone fifteen millions were thus agreed to. As the family of the king increased, extra sums were also deemed requisite for each of his children; and what amounts could not be raised by taxation were procured by loans,—thus insulting the country, by permitting its expenditure to exceed its means of income to an enormous extent.

Many representations were made to Lord North, that public opinion was opposed to the system pursued by ministers; but he was inflexible, and the generous interpositions of some members of the [68]Upper House proved also unavailing. The independent members of the Commons remonstrated, and Mr. Burke brought forward plans for the reduction of the national expenditure and the diminution of the influence of the crown; but they were finally rejected, though not until violent conflicts had taken place, in which Lord North found himself more than once in the minority.

About this time, Mr. Dunning, a lawyer and an eminent speaker, advocated, in a most sensible manner, the necessity of taking into consideration the affairs of Ireland; but ministers defeated the intended benefit, and substituted a plan of their own, which they had previously promised to Ireland; namely, to permit a free exportation of their woollen manufactures. The unassuming character of that oppressed people never appeared to greater advantage than at this period, as even this resolution was received by them with the warmest testimonies of joy and gratitude.

There cannot be a doubt, that if the Irish had been honestly represented, their honor and ardour would have been proverbial; but they have almost always been neglected and insulted. The queen had taken Lord North's advice, and acquainted herself with the native character of the Irish, by which she became aware that, if that people generally possessed information, they would prove a powerful balance against the unjust system then in force. At this time, there was not an Irishman acquainted with any state secrets; her majesty, therefore, did not [69]fear an explanation from that quarter, or she dare not have so oppressed them.

To provide for the exigencies of state, twelve millions of money, in addition to the former fifteen millions, were required this year; and thus were the sorrows of a suffering people increased, and they themselves forced to forge their own chains of oppression!

Numerous were the prosecutions against the press this year; among the rest, Mr. Parker, printer of "The General Advertiser," was brought before the "House of Hereditaries," for publishing a libel on one of its noble members. That there were a few intelligent and liberal-minded men in the House of Lords at this time, we do not wish to deny. The memorable speech of Lord Abingdon proved his lordship to be one of these, and, as this speech so admirably distinguishes PRIVILEGE from TYRANNY, we hope to be excused for introducing it in our pages. We give it in his lordship's own words:

"My Lords,—Although there is no noble lord more zealously attached to the privileges of this House than I am, yet when I see those privileges interfering with, and destructive of, the rights of the people, there is no one among the people more ready to oppose those privileges than myself. And, my lords, my reason is this: that the privileges of neither house of parliament were ever constitutionally given to either to combat with the rights of the people. They were given, my lords, that each branch of the legislature might defend itself against the encroachments of the other, and to preserve that balance entire, which is essential to the preservation of all.

"This was the designation, this is the use of privilege; and in this unquestionable shape let us apply it. Let us apply it against the encroachments of the crown, and not suffer any lord (if any such there be) who, having clambered up into the house upon the ladder [70]of prerogative, might wish to yield up our privileges to that prerogative. Let us make use of our privileges against the other house of parliament, whenever occasion shall make it necessary, but not against the people. This is the distinction and this the meaning of privilege. The people are under the law, and we are the legislators. If they offend, let them be punished according to law, where we have our remedy. If we are injured in our reputations, the law has provided us with a special remedy. We are entitled to the action of scandalum magnatum,—a privilege peculiar to ourselves. For these reasons, then, my lords, when the noble earl made his motion for the printer to be brought before this House, and when the end of that motion was answered by the author of the paper complained of giving up his name, I was in great hopes that the motion would have been withdrawn. I am sorry it was not; and yet, when I say this, I do not mean to wish that an inquiry into the merits of that paper should not be made. As it stands at present, the noble lord accused therein is the disgrace of this House, and the scandal of government. I therefore trust, for his own honor, for the honor of this House, that that noble lord will not object to, but will himself insist upon, the most rigid inquiry into his conduct.

"But, my lords, to call for a printer, in the case of a libel, when he gives up his author (although a modern procedure) is not founded in law; for in the statute of Westminster, the 1st, chapter 34, it is said, 'None shall report any false and slanderous news or tales of great men, whereby any discord may arise betwixt the king and his people, on pain of imprisonment, until they bring forth the author.' The statutes of the 2d of Richard the Second, chapter 5, and the 14th of the same reign, are to the same effect. It is there enacted, that 'No person shall devise, or tell any false news or lies of any lord, prelate, officer of the government, judge, &c., by which any slander shall happen to their persons, or mischief come to the kingdom, upon pain of being imprisoned; and where any one hath told false news or lies, and cannot produce the author, he shall suffer imprisonment, and be punished by the king's counsel.' Here, then, my lords, two things are clearly pointed out, to wit, the person to be punished, and what the mode of punishment is. The person to be punished is the author, when produced; the mode of punishment is by the king's counsel; so that, in the present case, the printer having given up the author, he is discharged from punishment: and if the privilege of punishment had been in this House, the right is barred by these statutes; for how is the punishment to be had? Not by this House, but by the king's counsel. And, [71]my lords, it cannot be otherwise; for, if it were, the freedom of the press were at an end; and for this purpose was this modern doctrine, to answer modern views, invented,—a doctrine which I should ever stand up in opposition to, if even the right of its exercise were in us. But the right is not in us: it is a jurisdiction too summary for the freedom of our constitution, and incompatible with liberty. It takes away the trial by jury; which king, lords, and commons, have not a right to do. It is to make us accusers, judges, jury, and executioners too, if we please. It is to give us an executive power, to which, in our legislative capacities, we are not entitled. It is to give us a power, which even the executive power itself has not, which the prerogative of the crown dare not assume, which the king himself cannot exercise. My lords, the king cannot touch the hair of any man's head in this country, though he be guilty of high treason, but by means of the law. It is the law that creates the offence; it is a jury that must determine the guilt; it is the law that affixes the punishment; and all other modes of proceeding are ILLEGAL. Why then, my lords, are we to assume to ourselves an executive power, with which even the executive power itself is not entrusted? I am aware, my lords, it will be said that this House, in its capacity of a court of justice, has a right to call for evidence at its bar, and to punish the witness who shall not attend. I admit it, my lords; and I admit it not only as a right belonging to this House, but as a right essential to every court of justice; for, without this right, justice could not be administered. But, my lords, was this House sitting as a court of justice (for we must distinguish between our judicial and our legislative capacities) when Mr. Parker was ordered to be taken into custody, and brought before this House? If so, at whose suit was Mr. Parker to be examined? Where are the records? Where are the papers of appeal? Who is the plaintiff, and who the defendant? There is nothing like it before your lordships; for if there had, and Mr. Parker, in such case, had disobeyed the order of this House, he was not only punishable for his contumacy and contempt, but every magistrate in the kingdom was bound to assist your lordships in having him forthcoming at your lordship's bar. Whereas, as it is, every magistrate in the kingdom is bound, by the law of the land, to release Mr. Parker, if he be taken into custody by the present order of this House. Nothing can be more true, than that in our judicial capacity, we have a right to call for evidence at our bar, and to punish the witness if he does not appear. The whole body of the law supports us in this right. But, under the pretext of [72]privilege, to bring a man by force to the bar, when we have our remedy at law; to accuse, condemn, and punish that man, at the mere arbitrary will and pleasure of this House, not sitting as a court of justice, is tyranny in the abstract. It is against law; it is subversive of the constitution; it is incompetent to this House; and, therefore, my lords, thinking as I do, that this House has no right forcibly to bring any man to its bar, but in the discharge of its proper functions, as a court of judicature, I shall now move your lordships, 'that the body of W. Parker, printer of the General Advertiser, be released from the custody of the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, and that the order for the said Parker, being brought to the bar of this House be now discharged.'

"Before I sit down, I will just observe to your lordships, that I know that precedents may be adduced in contradiction to the doctrine I have laid down. But, my lords, precedents cannot make that legal and constitutional which is, in itself, illegal and unconstitutional. IF THE PRECEDENTS OF THIS REIGN ARE TO BE RECEIVED AS PRECEDENTS IN THE NEXT, THE LORD HAVE MERCY ON THOSE WHO ARE TO COME AFTER US!!!

"There is one observation more I would make, and it is this: I would wish noble lords to consider, how much it lessens the dignity of this House, to agitate privileges which you have not power to enforce. It hurts the constitution of parliament, and, instead of being respected, makes us contemptible. That privilege which you cannot exercise, and of right too, disdain to keep."

If the country had been blessed with a majority of such patriots as Lord Abingdon, what misery had been prevented! what lives had been saved!

Early in the year