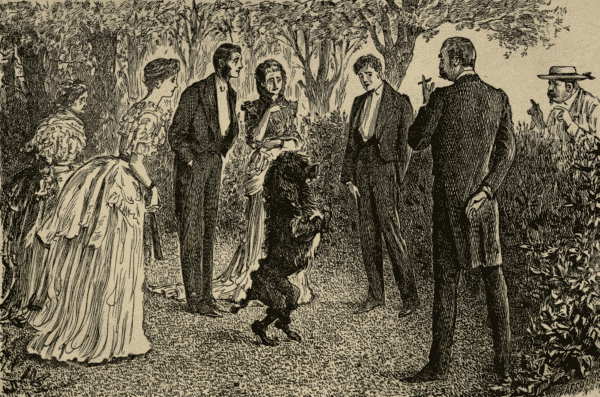

'IT'S MY BINGO, FOR ALL THAT!'

'IT'S MY BINGO, FOR ALL THAT!'

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Black Poodle, by F. Anstey

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Black Poodle

And Other Tales

Author: F. Anstey

Release Date: August 28, 2011 [EBook #37235]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BLACK POODLE ***

Produced by David Clarke, Katie Hernandez and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

&c.

'IT'S MY BINGO, FOR ALL THAT!'

'IT'S MY BINGO, FOR ALL THAT!'

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY,

72 FIFTH AVENUE.

1896.

The Author begs to state that the stories which are collected in this volume made their first appearance in 'Belgravia,' the 'Cornhill Magazine,' the 'Graphic,' 'Longman's Magazine,' 'Mirth,' and 'Temple Bar,' respectively, and he takes this opportunity of expressing his thanks to those Editors to whose courtesy he is indebted for permission to reprint them.

| PAGE | |

| The Black Poodle | 1 |

| The Story of a Sugar Prince | 46 |

| The Return of Agamemnon | 69 |

| The Wraith of Barnjum | 93 |

| A Toy Tragedy | 115 |

| An Undergraduate's Aunt | 149 |

| The Siren | 168 |

| The Curse of the Catafalques | 182 |

| A Farewell Appearance | 232 |

| Accompanied on the Flute | 256 |

have set myself the task of relating in the course of this story, without suppressing or altering a single detail, the most painful and humiliating episode in my life.

I do this, not because it will give me the least pleasure, but simply because it affords me an opportunity of extenuating myself which has hitherto been wholly denied to me.[ 2]

As a general rule I am quite aware that to publish a lengthy explanation of one's conduct in any questionable transaction is not the best means of recovering a lost reputation; but in my own case there is one to whom I shall never more be permitted to justify myself by word of mouth—even if I found myself able to attempt it. And as she could not possibly think worse of me than she does at present, I write this, knowing it can do me no harm, and faintly hoping that it may come to her notice and suggest a doubt whether I am quite so unscrupulous a villain, so consummate a hypocrite, as I have been forced to appear in her eyes.

The bare chance of such a result makes me perfectly indifferent to all else: I cheerfully expose to the derision of the whole reading world the story of my weakness and my shame, since by doing so I may possibly rehabilitate myself somewhat in the good opinion of one person.

Having said so much, I will begin my confession without further delay:—

My name is Algernon Weatherhead, and I may add that I am in one of the Government departments; that I am an only son, and live at home with my mother.

We had had a house at Hammersmith until just before the period covered by this history, when, our lease expiring, my mother decided that my health required country air at the close of the day, and so we[ 3] took a 'desirable villa residence' on one of the many new building estates which have lately sprung up in such profusion in the home counties.

We have called it 'Wistaria Villa.' It is a pretty little place, the last of a row of detached villas, each with its tiny rustic carriage gate and gravel sweep in front, and lawn enough for a tennis court behind, which lines the road leading over the hill to the railway station.

I could certainly have wished that our landlord, shortly after giving us the agreement, could have found some other place to hang himself in than one of our attics, for the consequence was that a housemaid left us in violent hysterics about every two months, having learnt the tragedy from the tradespeople, and naturally 'seen a somethink' immediately afterwards.

Still it is a pleasant house, and I can now almost forgive the landlord for what I shall always consider an act of gross selfishness on his part.

In the country, even so near town, a next-door neighbour is something more than a mere numeral; he is a possible acquaintance, who will at least consider a new-comer as worth the experiment of a call. I soon knew that 'Shuturgarden,' the next house to our own, was occupied by a Colonel Currie, a retired Indian officer; and often, as across the low boundary wall I caught a glimpse of a graceful girlish figure flitting about amongst the rose-bushes in the neighbouring garden, I would lose myself in pleasant anticipations of a time not far distant when the[ 4] wall which separated us would be (metaphorically) levelled.

I remember—ah, how vividly!—the thrill of excitement with which I heard from my mother on returning from town one evening that the Curries had called, and seemed disposed to be all that was neighbourly and kind.

I remember, too, the Sunday afternoon on which I returned their call—alone, as my mother had already done so during the week. I was standing on the steps of the Colonel's villa waiting for the door to open when I was startled by a furious snarling and yapping behind, and, looking round, discovered a large poodle in the act of making for my legs.

He was a coal-black poodle, with half of his right ear gone, and absurd little thick moustaches at the end of his nose; he was shaved in the sham-lion fashion, which is considered, for some mysterious reason, to improve a poodle, but the barber had left sundry little tufts of hair which studded his haunches capriciously.

I could not help being reminded, as I looked at him, of another black poodle which Faust entertained for a short time, with unhappy results, and I thought that a very moderate degree of incantation would be enough to bring the fiend out of this brute.

He made me intensely uncomfortable, for I am of a slightly nervous temperament, with a constitutional horror of dogs and a liability to attacks of[ 5] diffidence on performing the ordinary social rites under the most favourable conditions, and certainly the consciousness that a strange and apparently savage dog was engaged in worrying the heels of my boots was the reverse of reassuring.

The Currie family received me with all possible kindness: 'So charmed to make your acquaintance, Mr. Weatherhead,' said Mrs. Currie, as I shook hands. 'I see,' she added pleasantly, 'you've brought the doggie in with you.' As a matter of fact, I had brought the doggie in at the ends of my coat-tails, but it was evidently no unusual occurrence for visitors to appear in this undignified manner, for she detached him quite as a matter of course, and, as soon as I was sufficiently collected, we fell into conversation.

I discovered that the Colonel and his wife were childless, and the slender willowy figure I had seen across the garden wall was that of Lilian Roseblade, their niece and adopted daughter. She came into the room shortly afterwards, and I felt, as I went through the form of an introduction, that her sweet fresh face, shaded by soft masses of dusky brown hair, more than justified all the dreamy hopes and fancies with which I had looked forward to that moment.

She talked to me in a pretty, confidential, appealing way, which I have heard her dearest friends censure as childish and affected, but I thought then that her manner had an indescribable charm and[ 6] fascination about it, and the memory of it makes my heart ache now with a pang that is not all pain.

Even before the Colonel made his appearance I had begun to see that my enemy, the poodle, occupied an exceptional position in that household. It was abundantly clear by the time I took my leave.

He seemed to be the centre of their domestic system, and even lovely Lilian revolved contentedly around him as a kind of satellite; he could do no wrong in his owner's eyes, his prejudices (and he was a narrow-minded animal) were rigorously respected, and all domestic arrangements were made with a primary view to his convenience.

I may be wrong, but I cannot think that it is wise to put any poodle upon such a pedestal as that. How this one in particular, as ordinary a quadruped as ever breathed, had contrived to impose thus upon his infatuated proprietors, I never could understand, but so it was—he even engrossed the chief part of the conversation, which after any lull seemed to veer round to him by a sort of natural law.

I had to endure a long biographical sketch of him—what a Society paper would call an 'anecdotal photo'—and each fresh anecdote seemed to me to exhibit the depraved malignity of the beast in a more glaring light, and render the doting admiration of the family more astounding than ever.

'Did you tell Mr. Weatherhead, Lily, about Bingo' (Bingo was the poodle's preposterous name)[ 7] 'and Tacks? No? Oh, I must tell him that—it'll make him laugh. Tacks is our gardener down in the village (d'ye know Tacks?). Well, Tacks was up here the other day, nailing up some trellis-work at the top of a ladder, and all the time there was Master Bingo sitting quietly at the foot of it looking on, wouldn't leave it on any account. Tacks said he was quite company for him. Well, at last, when Tacks had finished and was coming down, what do you think that rascal there did? Just sneaked quietly up behind and nipped him in both calves and ran off. Been looking out for that the whole time! Ha, ha!—deep that, eh?'

I agreed with an inward shudder that it was very deep, thinking privately that, if this was a specimen of Bingo's usual treatment of the natives, it would be odd if he did not find himself deeper still before—probably just before—he died.

'Poor faithful old doggie!' murmured Mrs. Currie; 'he thought Tacks was a nasty burglar, didn't he? he wasn't going to see Master robbed, was he?'

'Capital house-dog, sir,' struck in the Colonel. 'Gad, I shall never forget how he made poor Heavisides run for it the other day! Ever met Heavisides of the Bombay Fusiliers? Well, Heavisides was staying here, and the dog met him one morning as he was coming down from the bath-room. Didn't recognise him in "pyjamas" and a dressing-gown, of[ 8] course, and made at him. He kept poor old Heavisides outside the landing window on the top of the cistern for a quarter of an hour, till I had to come and raise the siege!'

Such were the stories of that abandoned dog's blunderheaded ferocity to which I was forced to listen, while all the time the brute sat opposite me on the hearthrug, blinking at me from under his shaggy mane with his evil bleared eyes, and deliberating where he would have me when I rose to go.

This was the beginning of an intimacy which soon displaced all ceremony. It was very pleasant to go in there after dinner, even to sit with the Colonel over his claret and hear more stories about Bingo, for afterwards I could go into the pretty drawing-room and take my tea from Lilian's hands, and listen while she played Schubert to us in the summer twilight.

The poodle was always in the way, to be sure, but even his ugly black head seemed to lose some of its ugliness and ferocity when Lilian laid her pretty hand on it.

On the whole I think that the Currie family were well disposed towards me; the Colonel considering me as a harmless specimen of the average eligible young man—which I certainly was—and Mrs. Currie showing me favour for my mother's sake, for whom she had taken a strong liking.

As for Lilian, I believed I saw that she soon sus[ 9]pected the state of my feelings towards her and was not displeased by it. I looked forward with some hopefulness to a day when I could declare myself with no fear of a repulse.

But it was a serious obstacle in my path that I could not secure Bingo's good opinion on any terms. The family would often lament this pathetically themselves. 'You see,' Mrs. Currie would observe in apology, 'Bingo is a dog that does not attach himself easily to strangers'—though for that matter I thought he was unpleasantly ready to attach himself to me.

I did try hard to conciliate him. I brought him propitiatory buns—which was weak and ineffectual, as he ate them with avidity, and hated me as bitterly as ever, for he had conceived from the first a profound contempt for me and a distrust which no blandishments of mine could remove. Looking back now, I am inclined to think it was a prophetic instinct that warned him of what was to come upon him through my instrumentality.

Only his approbation was wanting to establish for me a firm footing with the Curries, and perhaps determine Lilian's wavering heart in my direction; but, though I wooed that inflexible poodle with an assiduity I blush to remember, he remained obstinately firm.

Still, day by day, Lilian's treatment of me was more encouraging; day by day I gained in the esteem of her uncle and aunt; I began to hope that[ 10] soon I should be able to disregard canine influence altogether.

Now there was one inconvenience about our villa (besides its flavour of suicide) which it is necessary to mention here. By common consent all the cats of the neighbourhood had selected our garden for their evening reunions. I fancy that a tortoiseshell kitchen cat of ours must have been a sort of leader of local feline society—I know she was 'at home,' with music and recitations, on most evenings.

My poor mother found this interfered with her after-dinner nap, and no wonder, for if a cohort of ghosts had been 'shrieking and squealing,' as Calpurnia puts it, in our back garden, or it had been fitted up as a crèche for a nursery of goblin infants in the agonies of teething, the noise could not possibly have been more unearthly.

We sought for some means of getting rid of the nuisance: there was poison of course, but we thought it would have an invidious appearance, and even lead to legal difficulties, if each dawn were to discover an assortment of cats expiring in hideous convulsions in various parts of the same garden.

Firearms, too, were open to objection, and would scarcely assist my mother's slumbers, so for some time we were at a loss for a remedy. At last, one day, walking down the Strand, I chanced to see (in an evil hour) what struck me as the very thing—it was an air-gun of superior construction displayed in a[ 11] gunsmith's window. I went in at once, purchased it, and took it home in triumph; it would be noiseless, and would reduce the local average of cats without scandal—one or two examples, and feline fashion would soon migrate to a more secluded spot.

I lost no time in putting this to the proof. That same evening I lay in wait after dusk at the study window, protecting my mother's repose. As soon as I heard the long-drawn wail, the preliminary sputter, and the wild stampede that followed, I let fly in the direction of the sound. I suppose I must have something of the national sporting instinct in me, for my blood was tingling with excitement; but the feline constitution assimilates lead without serious inconvenience, and I began to fear that no trophy would remain to bear witness to my marksmanship.

But all at once I made out a dark indistinct form slinking in from behind the bushes. I waited till it crossed a belt of light which streamed from the back kitchen below me, and then I took careful aim and pulled the trigger.

This time at least I had not failed—there was a smothered yell, a rustle—and then silence again. I ran out with the calm pride of a successful revenge to bring in the body of my victim, and I found underneath a laurel, no predatory tom-cat, but (as the discerning reader will no doubt have foreseen long since) the quivering carcase of the Colonel's black poodle![ 12]

I intend to set down here the exact unvarnished truth, and I confess that at first, when I knew what I had done, I was not sorry. I was quite innocent of any intention of doing it, but I felt no regret. I even laughed—madman that I was—at the thought that there was the end of Bingo at all events; that impediment was removed, my weary task of conciliation was over for ever!

But soon the reaction came; I realised the tremendous nature of my deed, and shuddered. I had done that which might banish me from Lilian's side for ever! All unwittingly I had slaughtered a kind of sacred beast, the animal around which the Currie household had wreathed their choicest affections! How was I to break it to them? Should I send Bingo in with a card tied to his neck and my regrets and compliments? That was too much like a present of game. Ought I not to carry him in myself? I would wreathe him in the best crape, I would put on black for him—the Curries would hardly consider a taper and a white sheet, or sackcloth and ashes, an excessive form of atonement—but I could not grovel to quite such an abject extent.

I wondered what the Colonel would say. Simple and hearty as a general rule, he had a hot temper on occasions, and it made me ill as I thought, would he and, worse still, would Lilian believe it was really an accident? They knew what an interest I had in[ 13] silencing the deceased poodle—would they believe the simple truth?

I vowed that they should believe me. My genuine remorse and the absence of all concealment on my part would speak powerfully for me. I would choose a favourable time for my confession; that very evening I would tell all.

Still I shrank from the duty before me, and as I knelt down sorrowfully by the dead form and respectfully composed his stiffening limbs, I thought that it was unjust of Fate to place a well-meaning man, whose nerves were not of iron, in such a position.

Then, to my horror, I heard a well-known ringing tramp on the road outside, and smelt the peculiar fragrance of a Burmese cheroot. It was the Colonel himself, who had been taking out the doomed Bingo for his usual evening run.

I don't know how it was exactly, but a sudden panic came over me. I held my breath, and tried to crouch down unseen behind the laurels; but he had seen me, and came over at once to speak to me across the hedge.

He stood there, not two yards from his favourite's body! Fortunately it was unusually dark that evening.

'Ha, there you are, eh?' he began heartily; 'don't rise, my boy, don't rise.' I was trying to put myself in front of the poodle, and did not rise—at least, only my hair did.[ 14]

'You're out late, ain't you?' he went on; 'laying out your garden, hey?'

I could not tell him that I was laying out his poodle! My voice shook as, with a guilty confusion that was veiled by the dusk, I said it was a fine evening—which it was not.

'Cloudy, sir,' said the Colonel, 'cloudy—rain before morning, I think. By the way, have you seen anything of my Bingo in here?'

This was the turning point. What I ought to have done was to say mournfully, 'Yes, I'm sorry to say I've had a most unfortunate accident with him—here he is—the fact is, I'm afraid I've shot him!'

But I couldn't. I could have told him at my own time, in a prepared form of words—but not then. I felt I must use all my wits to gain time and fence with the questions.

'Why,' I said with a leaden airiness, 'he hasn't given you the slip, has he?'

'Never did such a thing in his life!' said the Colonel, warmly; 'he rushed off after a rat or a frog or something a few minutes ago, and as I stopped to light another cheroot I lost sight of him. I thought I saw him slip in under your gate, but I've been calling him from the front there and he won't come out.'

No, and he never would come out any more. But the Colonel must not be told that just yet. I temporised again: 'If,' I said unsteadily, 'if he had[ 15] slipped in under the gate, I should have seen him. Perhaps he took it into his head to run home?'

'Oh, I shall find him on the doorstep, I expect, the knowing old scamp! Why, what d'ye think was the last thing he did, now?'

I could have given him the very latest intelligence; but I dared not. However, it was altogether too ghastly to kneel there and laugh at anecdotes of Bingo told across Bingo's dead body; I could not stand that! 'Listen,' I said suddenly, 'wasn't that his bark? There again; it seems to come from the front of your house, don't you think?'

'Well,' said the Colonel, 'I'll go and fasten him up before he's off again. How your teeth are chattering—you've caught a chill, man—go indoors at once and, if you feel equal to it, look in half an hour later about grog time, and I'll tell you all about it. Compliments to your mother. Don't forget—about grog time!' I had got rid of him at last, and I wiped my forehead, gasping with relief. I would go round in half an hour, and then I should be prepared to make my melancholy announcement. For, even then, I never thought of any other course, until suddenly it flashed upon me with terrible clearness that my miserable shuffling by the hedge had made it impossible to tell the truth! I had not told a direct lie, to be sure, but then I had given the Colonel the impression that I had denied having seen the dog. Many people can appease their consciences by reflect[ 16]ing that, whatever may be the effect their words produce, they did contrive to steer clear of a downright lie. I never quite knew where the distinction lay, morally, but there is that feeling—I have it myself.

Unfortunately, prevarication has this drawback, that, if ever the truth comes to light, the prevaricator is in just the same case as if he had lied to the most shameless extent, and for a man to point out that the words he used contained no absolute falsehood will seldom restore confidence.

I might of course still tell the Colonel of my misfortune, and leave him to infer that it had happened after our interview, but the poodle was fast becoming cold and stiff, and they would most probably suspect the real time of the occurrence.

And then Lilian would hear that I had told a string of falsehoods to her uncle over the dead body of their idolised Bingo—an act, no doubt, of abominable desecration, of unspeakable profanity in her eyes!

If it would have been difficult before to prevail on her to accept a bloodstained hand, it would be impossible after that. No, I had burnt my ships, I was cut off for ever from the straightforward course; that one moment of indecision had decided my conduct in spite of me—I must go on with it now and keep up the deception at all hazards.

It was bitter. I had always tried to preserve as many of the moral principles which had been instilled[ 17] into me as can be conveniently retained in this grasping world, and it had been my pride that, roughly speaking, I had never been guilty of an unmistakable falsehood.

But henceforth, if I meant to win Lilian, that boast must be relinquished for ever! I should have to lie now with all my might, without limit or scruple, to dissemble incessantly, and 'wear a mask,' as the poet Bunn beautifully expressed it long ago, 'over my hollow heart.' I felt all this keenly—I did not think it was right—but what was I to do?

After thinking all this out very carefully, I decided that my only course was to bury the poor animal where he fell and say nothing about it. With some vague idea of precaution I first took off the silver collar he wore, and then hastily interred him with a garden-trowel and succeeded in removing all traces of the disaster.

I fancy I felt a certain relief in the knowledge that there would now be no necessity to tell my pitiful story and risk the loss of my neighbours' esteem.

By-and-by, I thought, I would plant a rose-tree over his remains, and some day, as Lilian and I, in the noontide of our domestic bliss, stood before it admiring its creamy luxuriance, I might (perhaps) find courage to confess that the tree owed some of that luxuriance to the long-lost Bingo.

There was a touch of poetry in this idea that lightened my gloom for the moment.[ 18]

I need scarcely say that I did not go round to Shuturgarden that evening. I was not hardened enough for that yet—my manner might betray me, and so I very prudently stayed at home.

But that night my sleep was broken by frightful dreams. I was perpetually trying to bury a great gaunt poodle, which would persist in rising up through the damp mould as fast as I covered him up.... Lilian and I were engaged, and we were in church together on Sunday, and the poodle, resisting all attempts to eject him, forbade our banns with sepulchral barks.... It was our wedding-day, and at the critical moment the poodle leaped between us and swallowed the ring.... Or we were at the wedding-breakfast, and Bingo, a grizzly black skeleton with flaming eyes, sat on the cake and would not allow Lilian to cut it. Even the rose-tree fancy was reproduced in a distorted form—the tree grew, and every blossom contained a miniature Bingo, which barked; and as I woke I was desperately trying to persuade the Colonel that they were ordinary dog-roses.

I went up to the office next day with my gloomy secret gnawing my bosom, and, whatever I did, the spectre of the murdered poodle rose before me. For two days after that I dared not go near the Curries, until at last one evening after dinner I forced myself to call, feeling that it was really not safe to keep away any longer.[ 19]

My conscience smote me as I went in. I put on an unconscious easy manner, which was such a dismal failure that it was lucky for me that they were too much engrossed to notice it.

I never before saw a family so stricken down by a domestic misfortune as the group I found in the drawing-room, making a dejected pretence of reading or working. We talked at first—and hollow talk it was—on indifferent subjects, till I could bear it no longer, and plunged boldly into danger.

'I don't see the dog,' I began. 'I suppose you—you found him all right the other evening, Colonel?' I wondered as I spoke whether they would not notice the break in my voice, but they did not.

'Why, the fact is,' said the Colonel, heavily, gnawing his grey moustache, 'we've not heard anything of him since: he's—he's run off!'

'Gone, Mr. Weatherhead; gone without a word!' said Mrs. Currie, plaintively, as if she thought the dog might at least have left an address.

'I wouldn't have believed it of him,' said the Colonel; 'it has completely knocked me over. Haven't been so cut up for years—the ungrateful rascal!'

'Oh, Uncle!' pleaded Lilian, 'don't talk like that; perhaps Bingo couldn't help it—perhaps some one has s-s-shot him!'

'Shot!' cried the Colonel, angrily. 'By heaven! if I thought there was a villain on earth capable of shooting that poor inoffensive dog, I'd——Why[ 20] should they shoot him, Lilian? Tell me that! I—I hope you won't let me hear you talk like that again. You don't think he's shot, eh, Weatherhead?'

I said—Heaven forgive me!—that I thought it highly improbable.

'He's not dead!' cried Mrs. Currie. 'If he were dead I should know it somehow—I'm sure I should! But I'm certain he's alive. Only last night I had such a beautiful dream about him. I thought he came back to us, Mr. Weatherhead, driving up in a hansom cab, and he was just the same as ever—only he wore blue spectacles, and the shaved part of him was painted a bright red. And I woke up with the joy—so, you know, it's sure to come true!'

It will be easily understood what torture conversations like these were to me, and how I hated myself as I sympathised and spoke encouraging words concerning the dog's recovery, when I knew all the time he was lying hid under my garden mould. But I took it as a part of my punishment, and bore it all uncomplainingly; practice even made me an adept in the art of consolation—I believe I really was a great comfort to them.

I had hoped that they would soon get over the first bitterness of their loss, and that Bingo would be first replaced and then forgotten in the usual way; but there seemed no signs of this coming to pass.

The poor Colonel was too plainly fretting himself ill about it; he went pottering about forlornly[ 21]— advertising, searching, and seeing people, but all of course to no purpose, and it told upon him. He was more like a man whose only son and heir had been stolen, than an Anglo-Indian officer who had lost a poodle. I had to affect the liveliest interest in all his inquiries and expeditions, and to listen to, and echo, the most extravagant eulogies of the departed, and the wear and tear of so much duplicity made me at last almost as ill as the Colonel himself.

I could not help seeing that Lilian was not nearly so much impressed by my elaborate concern as her relatives; and sometimes I detected an incredulous look in her frank brown eyes that made me very uneasy. Little by little, a rift widened between us, until at last in despair I determined to know the worst before the time came when it would be hopeless to speak at all. I chose a Sunday evening as we were walking across the green from church in the golden dusk, and then I ventured to speak to her of my love. She heard me to the end, and was evidently very much agitated. At last she murmured that it could not be, unless—no, it never could be now.

'Unless what?' I asked. 'Lilian—Miss Roseblade, something has come between us lately: you will tell me what that something is, won't you?'

'Do you want to know really?' she said, looking up at me through her tears. 'Then I'll tell you: it—it's Bingo!'

I started back overwhelmed. Did she know all?[ 22] If not, how much did she suspect? I must find out that at once! 'What about Bingo?' I managed to pronounce, with a dry tongue.

'You never l-loved him when he was here,' she sobbed; 'you know you didn't!'

I was relieved to find it was no worse than this.

'No,' I said candidly; 'I did not love Bingo. Bingo didn't love me, Lilian; he was always looking out for a chance of nipping me somewhere. Surely you won't quarrel with me for that!'

'Not for that,' she said; 'only, why do you pretend to be so fond of him now, and so anxious to get him back again? Uncle John believes you, but I don't. I can see quite well that you wouldn't be glad to find him. You could find him easily if you wanted to!'

'What do you mean, Lilian?' I said hoarsely. 'How could I find him?' Again I feared the worst.

'You're in a Government office,' cried Lilian and if you only chose, you could easily g-get G-Government to find Bingo! What's the use of Government if it can't do that? Mr. Travers would have found him long ago if I'd asked him!'

Lilian had never been so childishly unreasonable as this before, and yet I loved her more madly than ever; but I did not like this allusion to Travers, a rising barrister, who lived with his sister in a pretty cottage near the station, and had shown symptoms of being attracted by Lilian.[ 23]

He was away on circuit just then, luckily, but at least even he would have found it a hard task to find Bingo—there was comfort in that.

'You know that isn't just, Lilian,' I observed 'But only tell me what you want me to do?'

'Bub—bub—bring back Bingo!' she said.

'Bring back Bingo!' I cried in horror. 'But suppose I can't—suppose he's out of the country, or—dead, what then, Lilian?'

'I can't help it,' she said; 'but I don't believe he is out of the country or dead. And while I see you pretending to Uncle that you cared awfully about him, and going on doing nothing at all, it makes me think you're not quite—quite sincere! And I couldn't possibly marry any one while I thought that of him. And I shall always have that feeling unless you find Bingo!'

It was of no use to argue with her; I knew Lilian by that time. With her pretty caressing manner she united a latent obstinacy which it was hopeless to attempt to shake. I feared, too, that she was not quite certain as yet whether she cared for me or not, and that this condition of hers was an expedient to gain time.

I left her with a heavy heart. Unless I proved my worth by bringing back Bingo within a very short time, Travers would probably have everything his own way. And Bingo was dead!

However, I took heart. I thought that perhaps[ 24] if I could succeed by my earnest efforts in persuading Lilian that I really was doing all in my power to recover the poodle, she might relent in time, and dispense with his actual production.

So, partly with this object, and partly to appease the remorse which now revived and stung me deeper than before, I undertook long and weary pilgrimages after office hours. I spent many pounds in advertisements; I interviewed dogs of every size, colour, and breed, and of course I took care to keep Lilian informed of each successive failure. But still her heart was not touched; she was firm. If I went on like that, she told me, I was certain to find Bingo one day—then, but not before, would her doubts be set at rest.

I was walking one day through the somewhat squalid district which lies between Bow Street and High Holborn, when I saw, in a small theatrical costumier's window, a handbill stating that a black poodle had 'followed a gentleman' on a certain date, and if not claimed and the finder remunerated before a stated time, would be sold to pay expenses.

I went in and got a copy of the bill to show Lilian, and although by that time I scarcely dared to look a poodle in the face, I thought I would go to the address given and see the animal, simply to be able to tell Lilian I had done so.

The gentleman whom the dog had very unaccountably followed was a certain Mr. William Blagg, who kept a little shop near Endell Street, and called himself a bird-fancier, though I should scarcely have[ 25] credited him with the necessary imagination. He was an evil-browed ruffian in a fur cap, with a broad broken nose and little shifty red eyes, and after I had told him what I wanted, he took me through a horrible little den, stacked with piles of wooden, wire, and wicker prisons, each quivering with restless, twittering life, and then out into a back yard, in which were two or three rotten old kennels and tubs. 'That there's him,' he said, jerking his thumb to the farthest tub; 'follered me all the way 'ome from Kinsington Gardings, he did. Kim out, will yer?'

And out of the tub there crawled slowly, with a snuffling whimper and a rattling of its chain, the identical dog I had slain a few evenings before!

At least, so I thought for a moment, and felt as if I had seen a spectre; the resemblance was so exact—in size, in every detail, even to the little clumps of hair about the hind parts, even to the lop of half an ear, this dog might have been the 'doppel-gänger' of the deceased Bingo. I suppose, after all, one black poodle is very like any other black poodle of the same size, but the likeness startled me.

I think it was then that the idea occurred to me that here was a miraculous chance of securing the sweetest girl in the whole world, and at the same time atoning for my wrong by bringing back gladness with me to Shuturgarden. It only needed a little boldness; one last deception, and I could embrace truthfulness once more.

Almost unconsciously, when my guide turned[ 26] round and asked,' Is that there dawg yourn?' I said hurriedly, 'Yes, yes—that's the dog I want, that—that's Bingo!'

'He don't seem to be a puttin' of 'isself out about seeing you again,' observed Mr. Blagg, as the poodle studied me with a calm interest.

'Oh, he's not exactly my dog, you see,' I said; 'he belongs to a friend of mine!'

He gave me a quick furtive glance. 'Then maybe you're mistook about him,' he said: 'and I can't run no risks. I was a goin' down in the country this 'ere werry evenin' to see a party as lives at Wistaria Willa,—he's been a hadwertisin' about a black poodle, he has!'

'But look here,' I said, 'that's me.'

He gave me a curious leer. 'No offence, you know, guv'nor,' he said, 'but I should wish for some evidence as to that afore I part with a vallyable dawg like this 'ere!'

'Well,' I said, 'here's one of my cards; will that do for you?'

He took it and spelt it out with a pretence of great caution, but I saw well enough that the old scoundrel suspected that if I had lost a dog at all, it was not this particular dog. 'Ah,' he said, as he put it in his pocket, 'if I part with him to you, I must be cleared of all risks. I can't afford to get into trouble about no mistakes. Unless you likes to leave him for a day or two, you must pay accordin', you see.'[ 27]

I wanted to get the hateful business over as soon as possible. I did not care what I paid—Lilian was worth all the expense! I said I had no doubt myself as to the real ownership of the animal, but I would give him any sum in reason, and would remove the dog at once.

And so we settled it. I paid him an extortionate sum, and came away with a duplicate poodle, a canine counterfeit which I hoped to pass off at Shuturgarden as the long-lost Bingo.

I know it was wrong—it even came unpleasantly near dog-stealing—but I was a desperate man. I saw Lilian gradually slipping away from me, I knew that nothing short of this could ever recall her, I was sorely tempted, I had gone far on the same road already, it was the old story of being hung for a sheep. And so I fell.

Surely some who read this will be generous enough to consider the peculiar state of the case, and mingle a little pity with their contempt.

I was dining in town that evening and took my purchase home by a late train; his demeanour was grave and intensely respectable; he was not the animal to commit himself by any flagrant indiscretion—he was gentle and tractable, too, and in all respects an agreeable contrast in character to the original. Still, it may have been the after-dinner workings of conscience, but I could not help fancying that I saw a certain look in the creature's eyes, as if he were aware[ 28] that he was required to connive at a fraud, and rather resented it.

If he would only be good enough to back me up! Fortunately, however, he was such a perfect facsimile of the outward Bingo, that the risk of detection was really inconsiderable.

When I got him home, I put Bingo's silver collar round his neck—congratulating myself on my forethought in preserving it, and took him in to see my mother. She accepted him as what he seemed, without the slightest misgiving; but this, though it encouraged me to go on, was not decisive, the spurious poodle would have to encounter the scrutiny of those who knew every tuft on the genuine animal's body!

Nothing would have induced me to undergo such an ordeal as that of personally restoring him to the Curries. We gave him supper, and tied him up on the lawn, where he howled dolefully all night, and buried bones.

The next morning I wrote a note to Mrs. Currie, expressing my pleasure at being able to restore the lost one, and another to Lilian, containing only the words, 'Will you believe now that I am sincere?' Then I tied both round the poodle's neck and dropped him over the wall into the Colonel's garden just before I started to catch my train to town.

I had an anxious walk home from the station that evening; I went round by the longer way, trembling[ 29] the whole time lest I should meet any of the Currie household, to which I felt myself entirely unequal just then. I could not rest until I knew whether my fraud had succeeded, or if the poodle to which I had entrusted my fate had basely betrayed me; but my suspense was happily ended as soon as I entered my mother's room. 'You can't think how delighted those poor Curries were to see Bingo again,'she said at once; 'and they said such charming things about you, Algy—Lilian, particularly—quite affected she seemed, poor child! And they wanted you to go round and dine there and be thanked to-night, but at last I persuaded them to come to us instead. And they're going to bring the dog to make friends. Oh, and I met Frank Travers; he's back from circuit again now, so I asked him in too, to meet them!'

I drew a deep breath of relief. I had played a desperate game—but I had won! I could have wished, to be sure, that my mother had not thought of bringing in Travers on that of all evenings—but I hoped that I could defy him after this.

The Colonel and his people were the first to arrive; he and his wife being so effusively grateful that they made me very uncomfortable indeed; Lilian met me with downcast eyes, and the faintest possible blush, but she said nothing just then. Five minutes afterwards, when she and I were alone together in the conservatory, where I had brought her on pretence of showing a new begonia, she laid[ 30] her hand on my sleeve and whispered, almost shyly, 'Mr. Weatherhead—Algernon! Can you ever forgive me for being so cruel and unjust to you?' And I replied that, upon the whole, I could.

We were not in that conservatory long, but, before we left it, beautiful Lilian Roseblade had consented to make my life happy. When we re-entered the drawing-room, we found Frank Travers, who had been told the story of the recovery, and I observed his jaw fall as he glanced at our faces, and noted the triumphant smile which I have no doubt mine wore, and the tender dreamy look in Lilian's soft eyes. Poor Travers, I was sorry for him, although I was not fond of him. Travers was a good type of the rising young Common Law barrister; tall, not bad-looking, with keen dark eyes, black whiskers, and the mobile forensic mouth, which can express every shade of feeling, from deferential assent to cynical incredulity; possessed, too, of an endless flow of conversation that was decidedly agreeable, if a trifle too laboriously so, he had been a dangerous rival. But all that was over now—he saw it himself at once, and during dinner sank into dismal silence, gazing pathetically at Lilian, and sighing almost obtrusively between the courses. His stream of small talk seemed to have been cut off at the main.

'You've done a kind thing, Weatherhead,' said the Colonel. 'I can't tell you all that dog is to me, and how I missed the poor beast. I'd quite given up[ 31] all hope of ever seeing him again, and all the time there was Weatherhead, Mr. Travers, quietly searching all London till he found him! I shan't forget it. It shows a really kind feeling.'

I saw by Travers's face that he was telling himself he would have found fifty Bingos in half the time—if he had only thought of it; he smiled a melancholy assent to all the Colonel said, and then began to study me with an obviously depreciatory air.

'You can't think,' I heard Mrs. Currie telling my mother, 'how really touching it was to see poor dear Bingo's emotion at seeing all the old familiar objects again! He went up and sniffed at them all in turn, quite plainly recognising everything. And he was quite put out to find that we had moved his favourite ottoman out of the drawing-room. But he is so penitent, too, and so ashamed of having run away; he hardly dares to come when John calls him, and he kept under a chair in the hall all the morning—he wouldn't come in here either, so we had to leave him in your garden.'

'He's been sadly out of spirits all day,' said Lilian; 'he hasn't bitten one of the tradespeople.'

'Oh, he's all right, the rascal!' said the Colonel, cheerily; 'he'll be after the cats again as well as ever in a day or two.'

'Ah, those cats!' said my poor innocent mother. 'Algy, you haven't tried the air-gun on them again lately, have you? They're worse than ever.'[ 32]

I troubled the Colonel to pass the claret; Travers laughed for the first time. 'That's a good idea,' he said, in that carrying 'bar-mess' voice of his; 'an air-gun for cats, ha, ha! Make good bags, eh, Weatherhead?' I said that I did, very good bags, and felt I was getting painfully red in the face.

'Oh, Algy is an excellent shot—quite a sportsman,' said my mother. 'I remember, oh, long ago, when we lived at Hammersmith, he had a pistol, and he used to strew crumbs in the garden for the sparrows, and shoot at them out of the pantry window; he frequently hit one.'

'Well,' said the Colonel, not much impressed by these sporting reminiscences, 'don't go rolling over our Bingo by mistake, you know, Weatherhead, my boy. Not but what you've a sort of right after this—only don't. I wouldn't go through it all twice for anything.'

'If you really won't take any more wine,' I said hurriedly, addressing the Colonel and Travers, 'suppose we all go out and have our coffee on the lawn? It—it will be cooler there.' For it was getting very hot indoors, I thought.

I left Travers to amuse the ladies—he could do no more harm now; and taking the Colonel aside, I seized the opportunity, as we strolled up and down the garden path, to ask his consent to Lilian's engagement to me. He gave it cordially. 'There's not a man in England,' he said, 'that I'd sooner see her married to[ 33] after to-day. You're a quiet steady young fellow, and you've a good kind heart. As for the money, that's neither here nor there; Lilian won't come to you without a penny, you know. But really, my boy, you can hardly believe what it is to my poor wife and me to see that dog. Why, bless my soul, look at him now! What's the matter with him, eh?'

To my unutterable horror I saw that that miserable poodle, after begging unnoticed at the tea-table for some time, had retired to an open space before it, where he was now industriously standing on his head.

We gathered round and examined the animal curiously, as he continued to balance himself gravely in his abnormal position. 'Good gracious, John,' cried Mrs. Currie, 'I never saw Bingo do such a thing before in his life!'

'Very odd,' said the Colonel, putting up his glasses; 'never learnt that from me.'

'I tell you what I fancy it is,' I suggested wildly. 'You see, he was always a sensitive, excitable animal, and perhaps the—the sudden joy of his return has gone to his head—upset him, you know.'

They seemed disposed to accept this solution, and indeed I believe they would have credited Bingo with every conceivable degree of sensibility; but I felt myself that if this unhappy animal had many more of these accomplishments I was undone, for the original Bingo had never been a dog of parts.[ 34]

'It's very odd,' said Travers, reflectively, as the dog recovered his proper level, 'but I always thought that it was half the right ear that Bingo had lost?'

'So it is, isn't it?' said the Colonel. 'Left, eh? Well, I thought myself it was the right.'

My heart almost stopped with terror—I had altogether forgotten that. I hastened to set the point at rest. 'Oh, it was the left,' I said positively; 'I know it because I remember so particularly thinking how odd it was that it should be the left ear, and not the right!' I told myself this should be positively my last lie.

'Why odd?' asked Frank Travers, with his most offensive Socratic manner.

'My dear fellow, I can't tell you,' I said impatiently; 'everything seems odd when you come to think at all about it.'

'Algernon,' said Lilian later on, 'will you tell Aunt Mary and Mr. Travers, and—and me, how it was you came to find Bingo? Mr. Travers is quite anxious to hear all about it.'

I could not very well refuse; I sat down and told the story, all my own way. I painted Blagg, perhaps, rather bigger and blacker than life, and described an exciting scene, in which I recognised Bingo by his collar in the streets, and claimed and bore him off then and there in spite of all opposition.

I had the inexpressible pleasure of seeing Travers[ 35] grinding his teeth with envy as I went on, and feeling Lilian's soft, slender hand glide silently into mine as I told my tale in the twilight.

All at once, just as I reached the climax, we heard the poodle barking furiously at the hedge which separated my garden from the road. 'There's a foreign-looking man staring over the hedge,' said Lilian; 'Bingo always did hate foreigners.'

There certainly was a swarthy man there, and, though I had no reason for it then, somehow my heart died within me at the sight of him.

'Don't be alarmed, sir,' cried the Colonel, 'the dog won't bite you—unless there's a hole in the hedge anywhere.'

The stranger took off his small straw hat with a sweep. 'Ah, I am not afraid,' he said, and his accent proclaimed him a Frenchman, 'he is not enrage at me. May I ask, is it pairmeet to speak wiz Misterre Vezzered?'

I felt I must deal with this person alone, for I feared the worst; and, asking them to excuse me, I went to the hedge and faced the Frenchman with the frightful calm of despair. He was a short, stout little man, with blue cheeks, sparkling black eyes, and a vivacious walnut-coloured countenance; he wore a short black alpaca coat, and a large white cravat with an immense oval malachite brooch in the centre of it, which I mention because I found myself staring mechanically at it during the interview.[ 36]

'My name is Weatherhead,' I began, with the bearing of a detected pickpocket. 'Can I be of any service to you?'

'Of a great service,' he said emphatically; 'you can restore to me ze poodle vich I see zere!'

Nemesis had called at last in the shape of a rival claimant. I staggered for an instant; then I said, 'Oh, I think you are under a mistake—that dog is not mine.'

'I know it,' he said; 'zere 'as been leetle mistake, so if ze dog is not to you, you give him back to me, hein?'

'I tell you,' I said, 'that poodle belongs to the gentleman over there.' And I pointed to the Colonel, seeing that it was best now to bring him into the affair without delay.

'You are wrong,' he said doggedly; 'ze poodle is my poodle! And I was direct to you—it is your name on ze carte!' And he presented me with that fatal card which I had been foolish enough to give to Blagg as a proof of my identity. I saw it all now; the old villain had betrayed me, and to earn a double reward had put the real owner on my track.

I decided to call the Colonel at once, and attempt to brazen it out with the help of his sincere belief in the dog.

'Eh, what's that; what's it all about?' said the Colonel, bustling up, followed at intervals by the others.[ 37]

The Frenchman raised his hat again. 'I do not vant to make a trouble,' he began, 'but zere is leetle mistake. My word of honour, sare, I see my own poodle in your garden. Ven I appeal to zis gentilman to restore 'im he reffer me to you.'

'You must allow me to know my own dog, sir,' said the Colonel. 'Why, I've had him from a pup. Bingo, old boy, you know your master, don't you?'

But the brute ignored him altogether, and began to leap wildly at the hedge, in frantic efforts to join the Frenchman. It needed no Solomon to decide his ownership!

'I tell you, you 'ave got ze wrong poodle—it is my own dog, my Azor! He remember me well, you see? I lose him it is three, four days.... I see a nottice zat he is found, and ven I go to ze address zey tell me, "Oh, he is reclaim, he is gone wiz a strangaire who has advertise." Zey show me ze placard, I follow 'ere, and ven I arrive, I see my poodle in ze garden before me!'

'But look here,' said the Colonel, impatiently; 'it's all very well to say that, but how can you prove it? I give you my word that the dog belongs to me! You must prove your claim, eh, Travers?'

'Yes,' said Travers, judicially, 'mere assertion is no proof: it's oath against oath, at present.'

'Attend an instant—your poodle was he 'ighly train, had he some talents—a dog viz tricks, eh?'

'No, he's not,' said the Colonel; 'I don't like to[ 38] see dogs taught to play the fool—there's none of that nonsense about him, sir!'

'Ah, remark him well, then. Azor, mon chou, danse donc un peu!'

And on the foreigner's whistling a lively air, that infernal poodle rose on his hind legs and danced solemnly about half-way round the garden! We inside followed his movements with dismay. 'Why, dash it all!' cried the disgusted Colonel, 'he's dancing along like a d——d mountebank! But it's my Bingo for all that!'

'You are not convince? You shall see more. Azor, ici! Pour Beesmarck, Azor!' (the poodle barked ferociously). 'Pour Gambetta!' (he wagged his tail and began to leap with joy). 'Meurs pour la Patrie!'—and the too-accomplished animal rolled over as if killed in battle!

'Where could Bingo have picked up so much French!' cried Lilian, incredulously.

'Or so much French history?' added that serpent Travers.

'Shall I command 'im to jomp, or reverse 'imself?' inquired the obliging Frenchman.

'We've seen that, thank you,' said the Colonel, gloomily. 'Upon my word, I don't know what to think. It can't be that that's not my Bingo after all—I'll never believe it!'

I tried a last desperate stroke. 'Will you come round to the front?' I said to the Frenchman; 'I'll[ 39] let you in, and we can discuss the matter quietly.' Then, as we walked back together, I asked him eagerly what he would take to abandon his claims and let the Colonel think the poodle was his after all.

He was furious—he considered himself insulted; with great emotion he informed me that the dog was the pride of his life (it seems to be the mission of black poodles to serve as domestic comforts of this priceless kind!), that he would not part with him for twice his weight in gold.

'Figure,' he began, as we joined the others, 'zat zis gentilman 'ere 'as offer me money for ze dog! He agrees zat it is to me, you see? Ver well zen, zere is no more to be said!'

'Why, Weatherhead, have you lost faith too, then?' said the Colonel.

I saw that it was no good—all I wanted now was to get out of it creditably and get rid of the Frenchman. 'I'm sorry to say,' I replied, 'that I'm afraid I've been deceived by the extraordinary likeness. I don't think, on reflection, that that is Bingo!'

'What do you think, Travers?' asked the Colonel.

'Well, since you ask me,' said Travers, with quite unnecessary dryness, 'I never did think so.'

'Nor I,' said the Colonel; 'I thought from the first that was never my Bingo. Why, Bingo would make two of that beast!'

And Lilian and her aunt both protested that they had had their doubts from the first.[ 40]

'Zen you pairmeet zat I remove 'im?' said the Frenchman.

'Certainly' said the Colonel; and after some apologies on our part for the mistake, he went off in triumph, with the detestable poodle frisking after him.

When he had gone the Colonel laid his hand kindly on my shoulder. 'Don't look so cut up about it, my boy,' he said; 'you did your best—there was a sort of likeness, to any one who didn't know Bingo as we did.'

Just then the Frenchman again appeared at the hedge. 'A thousand pardons,' he said, 'but I find zis upon my dog—it is not to me. Suffer me to restore it viz many compliments.'

It was Bingo's collar. Travers took it from his hand and brought it to us.

'This was on the dog when you stopped that fellow, didn't you say?' he asked me.

One more lie—and I was so-weary of falsehood! 'Y-yes,' I said reluctantly, that was so.'

'Very extraordinary,' said Travers; 'that's the wrong poodle beyond a doubt, but when he's found, he's wearing the right dog's collar! Now how do you account for that?'

'My good fellow,' I said impatiently, 'I'm not in the witness-box. I can't account for it. It—it's a mere coincidence!'

'But look here, my dear Weatherhead,' argued Travers (whether in good faith or not I never could[ 41] quite make out), 'don't you see what a tremendously important link it is? Here's a dog who (as I understand the facts) had a silver collar, with his name engraved on it, round his neck at the time he was lost. Here's that identical collar turning up soon afterwards round the neck of a totally different dog! We must follow this up; we must get at the bottom of it somehow! With a clue like this, we're sure to find out, either the dog himself, or what's become of him! Just try to recollect exactly what happened, there's a good fellow. This is just the sort of thing I like!'

It was the sort of thing I did not enjoy at all. 'You must excuse me to-night, Travers,' I said uncomfortably; 'you see, just now it's rather a sore subject for me—and I'm not feeling very well!' I was grateful just then for a reassuring glance of pity and confidence from Lilian's sweet eyes which revived my drooping spirits for the moment.

'Yes, we'll go into it to-morrow, Travers,' said the Colonel; 'and then—hullo, why, there's that confounded Frenchman again!'

It was indeed; he came prancing back delicately, with a malicious enjoyment on his wrinkled face. 'Once more I return to apologise,' he said. 'My poodle 'as permit 'imself ze grave indiscretion to make a very big 'ole at ze bottom of ze garden!'

I assured him that it was of no consequence. 'Perhaps,' he replied, looking steadily at me through his keen half-shut eyes, 'you vill not say zat ven you[ 42] regard ze 'ole. And you others, I spik to you: somtimes von loses a somzing vich is qvite near all ze time. It is ver droll, eh? my vord, ha, ha, ha!' And he ambled off, with an aggressively fiendish laugh that chilled my blood.

'What the dooce did he mean by that, eh?' said the Colonel, blankly.

'Don't know,' said Travers; 'suppose we go and inspect the hole?'

But before that I had contrived to draw near it myself, in deadly fear lest the Frenchman's last words had contained some innuendo which I had not understood.

It was light enough still for me to see something, at the unexpected horror of which I very nearly fainted.

That thrice accursed poodle which I had been insane enough to attempt to foist upon the Colonel must, it seems, have buried his supper the night before very near the spot in which I had laid Bingo, and in his attempts to exhume his bone had brought the remains of my victim to the surface!

There the corpse lay, on the very top of the excavations. Time had not, of course, improved its appearance, which was ghastly in the extreme, but still plainly recognisable by the eye of affection.

'It's a very ordinary hole,' I gasped, putting myself before it and trying to turn them back. 'Nothing in it—nothing at all!'[ 43]

'Except one Algernon Weatherhead, Esq., eh?' whispered Travers jocosely in my ear.

'No, but,' persisted the Colonel, advancing, 'look here! Has the dog damaged any of your shrubs?'

'No, no!' I cried piteously, 'quite the reverse. Let's all go indoors now; it's getting so cold!'

'See, there is a shrub or something uprooted!' said the Colonel, still coming nearer that fatal hole. 'Why, hullo, look there! What's that?'

Lilian, who was by his side, gave a slight scream. 'Uncle,' she cried, 'it looks like—like Bingo!'

The Colonel turned suddenly upon me. 'Do you hear?' he demanded, in a choked voice. 'You hear what she says? Can't you speak out? Is that our Bingo?'

I gave it up at last; I only longed to be allowed to crawl away under something! 'Yes,' I said in a dull whisper, as I sat down heavily on a garden seat, 'yes ... that's Bingo ... misfortune ... shoot him ... quite an accident!'

There was a terrible explosion after that; they saw at last how I had deceived them, and put the very worst construction upon everything. Even now I writhe impotently at times, and my cheeks smart and tingle with humiliation, as I recall that scene—the Colonel's very plain speaking, Lilian's passionate reproaches and contempt, and her aunt's speechless prostration of disappointment.

I made no attempt to defend myself; I was not[ 44] perhaps the complete villain they deemed me, but I felt dully that no doubt it all served me perfectly right.

Still I do not think I am under any obligation to put their remarks down in black and white here.

Travers had vanished at the first opportunity—whether out of delicacy, or the fear of breaking out into unseasonable mirth, I cannot say; and shortly afterwards the others came to where I sat silent with bowed head, and bade me a stern and final farewell.

And then, as the last gleam of Lilian's white dress vanished down the garden path, I laid my head down on the table amongst the coffee-cups and cried like a beaten child.

I got leave as soon as I could and went abroad. The morning after my return I noticed, while shaving, that there was a small square marble tablet placed against the wall of the Colonel's garden. I got my opera-glass and read—and pleasant reading it was—the following inscription:—

IN AFFECTIONATE MEMORY

OF

B I N G O,

SECRETLY AND CRUELLY PUT TO DEATH,

IN COLD BLOOD;

BY A

NEIGHBOUR AND FRIEND.

JUNE, 1881

If this explanation of mine ever reaches my neighbours' eyes, I humbly hope they will have the humanity either to take away or tone down that tablet. They cannot conceive what I suffer, when curious visitors insist, as they do every day, in spelling out the words from our windows, and asking me countless questions about them!

Sometimes I meet the Curries about the village, and, as they pass me with averted heads, I feel myself growing crimson. Travers is almost always with Lilian now. He has given her a dog—a fox-terrier—and they take ostentatiously elaborate precautions to keep it out of my garden.

I should like to assure them here that they need not be under any alarm. I have shot one dog.[ 46]

f course he may have been really a fairy prince, and I should be sorry to contradict any one who chose to say so. For he was only about three inches high, he had rose-pink cheeks and bright yellow curling locks, he wore a doublet and hose which fitted him perfectly, and a little cap and feather, all of delicately contrasted shades of blue—and this does seem a fair description of a fairy prince.

But then he was painted—very cleverly—but still only painted, on a slab of prepared sugar, and his back was a plain white blank; while the regular fairies all have more than one side to them, and I am obliged to say that I never before happened to come across a real fairy prince who was nothing but paint and sugar.

For all that he may, as I said before, have been a fairy prince, and whether he was or not does not matter in the least—for he at any rate quite believed he was one.[ 47]

As yet there had been very little romance or enchantment in his life, which, as far as he could remember, had all been spent in a long shop, full of sweet and subtle scents, where the walls were lined with looking-glass and fitted with shelves on which stood rows of glass jars, containing pastilles and jujubes of every colour, shape, and flavour in the world—a shop where, in summer, a strange machine for making cooling drinks gurgled and sputtered all day long, and in winter, the large plate-glass windows were filled with boxes made of painted silk from Paris, so charmingly expensive and useless that rich people bought them eagerly to give to one another.

The prince generally lay on one of the counters between two beds of sugar roses and violets in a glass case, on either side of which stood a figure of highly coloured plaster.

One was a major of some unknown regiment; he had an immense head, with goggling eyes and a very red complexion, and this head would unscrew so that he could be filled with comfits, which, though it hurt him fearfully every time this was done, he was proud of, because it always astonished people.

The other figure was an old brown gipsy woman in a red cloak and a striped petticoat, with a head which, although it wouldn't take off, was always nodding and grinning mysteriously from morning to night.

It was to her that the prince (for we shall have to call him 'the prince,' as I don't know his other name[ 48] —if he ever had one) owed all his notions of Fairyland and his high birth.

'You let the old gipsy alone for knowing a prince when she sees one,' she would say, nodding at him with encouragement. 'They've kept you out of your rights all this time; but wait a while, and see if one of these clumsy giants that are always bustling in and out doesn't help you; you'll be restored to your kingdom, never fear!'

But the major used to get angry at her prophecies: 'It's all nonsense,' he used to say, 'the boy's no more a prince than I am, and he'll never be noticed by anybody, unless he learns to unscrew his head and hold comfits—like a soldier and a gentleman!'

However, the prince believed the gipsy, and every morning, as the shutters were taken down, and grey mist, brilliant sunshine, or brown fog stole into the close shop, he wondered whether the day had come which would see his restoration to his kingdom.

And at last the day really came; some one who had been buying sugar violets and roses noticed the prince in the middle of them and bought him too, to his immense delight. 'What did the old gipsy tell you, eh?' said the old woman, wagging her head wisely; 'you see, it has all come true!'

Even the major was convinced now, for, before the prince had been packed up, he whispered to him that if at any time he wanted a commander-in-chief, why, he knew where to send for him. 'Yes, I will[ 49] remember,' said the prince; 'and you,' he added to the gipsy, 'you shall be my prime minister!'—for he was so ignorant of politics that he actually thought an old woman could be prime minister.

And then, before he could finish saying good-bye and hearing their congratulations, he was covered with several wrappers of white paper and plunged into complete darkness, which he did not mind at all, he was so happy.

After that he remembered no more until he was unwrapped and placed upright on the top of a dazzling white dome which stood in the very centre of a long plain, where a host of the strangest forms were scattered about in bewildering confusion.

On each side of him tall twisted trunks of sparkling glass and silver sprang high into the air, and from their tops the cool green branches swayed gently down, while round their bases velvet-petalled flowers bloomed in a bed of soft moss.

Farther away, an exquisite temple, made of a sort of delicate gold-coloured crystal, rose out of the crowd of gorgeous things that surrounded it, and this crowd, as the prince's eyes became accustomed to the splendour, gradually separated itself into various forms of loveliness.

He saw high curiously moulded masses of transparent amber, within which ruby and emerald gems glowed dimly; mounds of rose-flushed snow, and blocks of creamy marble; and in the space between[ 50] these were huge platforms of silver and porcelain, on which were piled heaps of treasures that he knew must be priceless, though he could not guess what they were all used for.

But amidst all these were certain grim shapes; some seemed to be the carcases of fearful beasts, whose heads had all been struck off, but who had evidently shown such courage in death that they had earned the respect of the brave hunters who had vanquished them—for rosettes had been pinned on their rough breasts, and their stiffened limbs were bound together by bright-hued ribbons.

Then there was one monstrous head of some brute larger still, which could not have been quite killed even then, for its tawny eyes were still glaring with fury—the prince could easily have stood upright between its grinning jaws if he had wanted to do so; but he had no intention of doing any such thing, for though he was quite as brave as most fairy princes he was not foolhardy.

And there were big enchanted castles with no doors nor windows in them, and inhabited by restless monsters—dragons most likely—who had thrust their scaly black claws through the roofs.

Perhaps he was a little frightened by some of the ugliest shapes at first, but he soon grew used to them, and had no room for any other feelings than pride and joy. For this was Fairyland at last, stranger and more beautiful than anything he could have dreamed of—he had come into his kingdom![ 51]

He was going to live in that lacework palace; those dragons would come fawning out of their lairs presently, and do homage to him; these formidable dead creatures had been slain to do him honour; and he was the rightful owner of all these treasures of gold, and silk, and gems.

He must not forget, he thought, that he owed it all to the good-natured giants who had brought him here: no, when they came in—as of course they would—to pay their respects, he would thank them graciously and reward them liberally out of his new wealth.

There was a silver giraffe, stiff and old-fashioned, under a palm-tree hard by, which must have guessed from the prince's proud gay smile that he was deceiving himself and had no idea of his real position.

But the giraffe did not make any attempt to warn him, either because it had seen so many things all round it consumed in its day that the selfish fear that it too would be cut up and handed round some evening kept it preoccupied and silent, or else because, being only electro-plated and hollow inside, it had no feelings of any kind.

By-and-by the doors opened, and delicious bursts of music floated into the room, mingled with scraps of conversation and ripples of fresh laughter; servants came noiselessly in and increased the glare of a kind of sun that hung above the plain, and a host of smaller lights suddenly started up and shone softly through shades of silk and paper.[ 52]

The music stopped, the laughter and voices grew louder and came nearer, there was the sound of approaching feet—and then a whole army of mortals surrounded the prince's kingdom.

They were a far smaller and finer race than the giants he had seen hitherto, with pretty fresh complexions, and wearing, some of them, soft shimmering dresses that he thought only fairies ever wore. After a little confusion, they ranged themselves in one long line completely round the plain; the taller beings glided softly about behind, and the prince prepared himself to receive their congratulations with proper dignity and modesty.

But these giants certainly had very odd ways of showing their loyalty, for they saluted him with a clinking and clattering so deafening that they would have drowned the noise of a million gnomes forging fairy armour, while every now and then came a loud report, after which a golden sparkling cascade fell creaming and bubbling from somewhere above into the crystal reservoirs prepared for it.

It was all very gratifying, no doubt—and yet, though they all pretended to be honouring him, no one seemed to pay him any more particular attention; he thought perhaps they might be feeling abashed in his presence, and that he must manage to reassure them.

But while he was thinking how he could best do this, he began to be aware that along the whole of[ 53] that glittering plain things were being done without his permission which were scandalous and insulting—he saw the grisly carcases cut swiftly into pieces with flashing blades, or torn limb from limb deliberately; all the dragons were attacked and overpowered, and hauled out unresisting from their strongholds; even the fierce head was gashed hideously behind the ears!

He tried to speak and ask them what they meant by such audacity, but he could not make them hear as he could the major and the old gipsy; so he was obliged to look on while one by one the trophies dedicated to his glory were changed to shapeless heaps of ruin.

And, unless he was mistaken, the greater part of them were actually disappearing from sight altogether! It seemed impossible, for where could they all go to? and yet nothing now remained of the huge carcases but a meagre framework of bone, hanging together by shreds of skin; the strong castles were roofless walls with gaping breaches in them; and could it be that the more attractive objects were beginning to melt away in the same mysterious manner? Was it enchantment, or how—how on earth did they manage to do it?

He was no happier when he found out—for though, of course, to us eating is quite an ordinary everyday affair, only think what a shock the first sight of it must have been to a delicate fairy prince,[ 54] whose mouth was simply a cherry-coloured curve, and not made to open on any terms!

He saw all the treasures he had looked upon as his very own being lifted to a long line of mouths of all sizes and shapes; the mouths opened to various widths, and—the treasures vanished, he could not tell how or where.

The mellow amber tottered and quivered for a while and was gone; even the solid creamy marble was hacked in pieces and absorbed; nothing, however beautiful or fantastic, escaped instant annihilation between those terrible bars of scarlet and flashing ivory.

Could this be Fairyland, this plain where all things beautiful were doomed—or had they brought him back to his kingdom only to make this cruel fun of him, and destroy his riches one by one before his eyes?

But before he could find any answers to these sad questions he chanced to look straight in front of him, and there he saw a face which made his little sugar heart almost melt within him, with a curious feeling, half pleasure, half pain, that was quite new to him.

It was a girl's face, of course, and the prince had not looked at her very long before he forgot all about his kingdom.

He was relieved to see that she at least was too generous to join in the work of destruction that was going on all around her—indeed, she seemed to dislike it as much as he did himself, for only a little of the tinted snow passed her soft lips.[ 55]

Now and then she laughed a little silvery laugh, and shook out her rippling gold-brown hair at something the being next to her said—a great boy-mortal, with a red face, bold eyes, and grasping brown hands, which were fatal to everything within their range.

How the prince did hate that boy!—he found to his joy that he could understand what they said, and began to listen jealously to their conversation.

'I say,' the boy (whose name, it seemed, was Bertie) was saying, as he received a plateful of floating fragments of the lacework palace, 'you aren't eating anything, Mabel. Don't you care about suppers? I do.'

'I'm not hungry,' she said, evidently feeling this a distinction; 'I've been out so much this fortnight.'

'How jolly!' he observed, 'I only wish I had. But I say,' he added confidentially, 'won't they make you take a grey powder soon? They would me.'

'I'm never made to take anything at all nasty,' she said—and the prince was indignant that any one should have dared to think otherwise.

'I suppose,' continued the boy, 'you didn't manage to get any of that cake the conjurer made in Uncle John's hat, did you?'

'No, indeed,' she said, and made a little face; 'I don't think I should like cake that came out of anybody's hat!'

'It was very decent cake,' he said; 'I got a lot of[ 56] it. I was afraid it might spoil my appetite for supper—but it hasn't.'

'What a very greedy boy you are, Bertie,' she remarked; 'I suppose you could eat anything?'

'At home I think I could, pretty nearly,' he said, with a proud confidence, 'but not at old Tokoe's, I can't. Tokoe's is where I go to school, you know. I can't stand the resurrection-pie on Saturdays—all the week they save up the bones and rags and things, and when it comes up——'

'I don't want to hear,' she interrupted; 'you talk about nothing but horrid things to eat, and it isn't a bit interesting.'

Bertie allowed himself a brief interval for refreshment unalloyed by conversation, after which he began again: 'Mabel, if they have dancing after supper, dance with me.'

'Are you sure you know how to dance?' she inquired rather fastidiously.

'Oh, I can get through all right,' he replied. 'I've learnt. It's not harder than drilling. I can dance the Highland Schottische and the Swedish dance, any-way.'

'Any one can dance those. I don't call that dancing,' she said.

'Well, but try me once, Mabel; say you will,' said he.

'I don't believe they will have dancing,' she said; 'there are so many very young children here and[ 57] they get in the way so. But I hope there won't be any more games—games are stupid.'

'Only to girls,' said Bertie; 'girls never care about any fun.'

'Not your kind of fun,' she said, a little vaguely. 'I don't mind hide-and-seek in a nice old house with long passages and dark corners and secret panels—and ghosts even—that's jolly; but I don't care much about running round and round a row of silly chairs, trying to sit down when the music stops and keep other people out—I call it rude.'

'You didn't seem to think it so rude just now,' he retorted; 'you were laughing quite as much as any one; and I saw you push young Bobby Meekin off the last chair of all, and sit on it yourself, anyhow.'

'Bertie, you didn't,' she cried, flushing angrily.

'I did though.'

'But I tell you I didn't!

'And I say you did!'

'If you will go on saying I did, when I'm quite sure I never did anything of the sort,' she said, 'please don't speak to me again; I shan't answer if you do. And I think you're a particularly ill-bred boy—not polite, like my brothers.'

'Your brothers are every bit as rude as I am. If they aren't, they're milksops—I should be sorry to be a milksop.'

'My brothers are not milksops—they could fight[ 58] you!' she cried, with a little defiant ring in her voice that the prince thought perfectly charming.

'As if a girl knew anything about fighting,' said Bertie; 'why, I could fight your brothers all stuck in a row!'

'That you couldn't,' from Mabel, and 'I could then, so now!' from Bertie, until at last Mabel refused to answer any more of Bertie's taunts, as they grew decidedly offensive; and, finding that she took refuge in disdainful silence, he consumed tart after tart with gloomy determination.

And then all at once, Mabel, having nothing to do, chanced to look across to the white dome on which the prince was standing, and she opened her beautiful grey eyes with a pleased surprise as she saw him.

All this time the prince had been falling deeper and deeper in love with her; at first he had felt almost certain that she was a princess and his destined bride; he was rather small for her, certainly, though he did not know how very much smaller he was; but Fairyland, he had always been told, was full of resources—he could easily be filled out to her size, or, better still, she might be brought down to his.