The Project Gutenberg EBook of What Works: Schools Without Drugs, by United States Department of Education This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: What Works: Schools Without Drugs Author: United States Department of Education Release Date: August 15, 2011 [EBook #37097] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT WORKS: SCHOOLS WITHOUT DRUGS *** Produced by Curtis Weyant and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

What Works

SCHOOLS

WITHOUT

DRUGS

United States Department of Education

William J. Bennett, Secretary

1986

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

August 4, 1986

Drug and alcohol abuse touches all Americans in one form or another, but it is our children who are most vulnerable to its influence. As parents and teachers, we need to educate ourselves about the dangers of drugs so that we can then teach our children. And we must go further still by convincing them that drugs are morally wrong.

Now, as more and more individuals and groups are speaking out, young people are finding it easier to say no to drugs. Encouraged by a growing public outcry and their own strength of conviction, students are forming peer support groups in opposition to drug use. It has been encouraging to see how willingly young people take healthy attitudes and ideas to heart when they are exposed to an environment that fosters those values.

Outside the home, the school is the most influential environment for our children. This means that schools must protect children from the presence of drugs, and nurture values that help them reject drugs.

Schools Without Drugs provides the kind of practical knowledge parents, educators, students and communities can use to keep their schools drug-free. Only if our schools are free from drugs can we protect our children and insure that they can get on with the enterprise of learning.

"It is a sad and sobering reality that trying drugs is no longer the exception among high school students. It is the norm."

—California Attorney General John Van De Kemp Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1986

When 13- to 18-year-olds were asked to name the biggest problems facing young people today, drugs led their list. The proportion of teens with this perception has risen steadily in recent years. No other issue approaches this level of concern.

Four out of five teens believe current laws against both the sale and the use of drugs (including marijuana) are not strict enough.

—The Gallup Youth Surveys, 1985 and 1986

"Policy is useless without action! Drugs do not have to be tolerated on our school campuses. Policy to that effect is almost universally on the books. Drugs remain on campus because consistent, equitable and committed enforcement is lacking."

—Bill Rudolph, Principal, Northside High School, Atlanta, Georgia

Testimony submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on Special

Investigations, July 1984

"… We have a right to be protected from drugs."

—Cicely Senior, a seventh-grader,

McFarland Junior High,

Washington, D.C.

William J. Bennett

Secretary of Education

The foremost responsibility of any society is to nurture and protect its children. In America today, the most serious threat to the health and well-being of our children is drug use.

For the past year and a half, I have had the privilege of teaching our children in the classrooms of this country. I have met some outstanding teachers and administrators and many wonderful children. I have taken time during these visits to discuss the problem of drug use with educators and with police officers working in drug enforcement across the country. Their experience confirms the information reported in major national studies: drug use by children is at alarming levels. Use of some of the most harmful drugs is increasing. Even more troubling is the fact that children are using drugs at younger ages. Students today identify drugs as a major problem among their schoolmates as early as the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades.

Drug use impairs memory, alertness, and achievement. Drugs erode the capacity of students to perform in school, to think and act responsibly. The consequences of using drugs can last a lifetime. The student who cannot read at age 8 can, with effort, be taught at 9. But when a student clouds his mind with drugs, he may become a lifelong casualty. Research tells us that students who use marijuana regularly are twice as likely as their classmates to average D's and F's, and we know that drop-outs are twice as likely to be frequent drug users as graduates.

In addition, drug use disrupts the entire school. When drug use and drug dealing are rampant—when many students often do not show up for class and teachers cannot control them when they do—education throughout the school suffers.

Drug use is found among students in the city and country, among the rich, the poor, and the middle class. Many schools have yet to implement effective drug enforcement measures. In some schools, drug deals at lunch are common. In others, intruders regularly enter the building to sell drugs to students. Even schools with strict drug policies on paper do not always enforce them effectively.

Schools Without Drugs provides a practical synthesis of the most reliable and significant findings available on drug use by school-age youth. It tells how extensive drug use is and how dangerous it is. It tells how drug use starts, how it progresses, and how it can be identified. Most important, it tells how it can be stopped. It recommends strategies—and describes particular communities—that have succeeded in beating drugs. It concludes with a list of resources and organizations that parents, students, and educators can turn to for help.

This book is designed to be used by parents, teachers, principals, religious and community leaders, and all other adults—and students—who want to know what works in drug use prevention. It emphasizes concrete and practical information. An earlier book, a summary of research findings on teaching and learning called What Works, has already proved useful to parents, teachers, and administrators. I hope this book will be as useful to the American people.

This book focuses on preventing drug use. It should be emphasized that the term drug use, as contained in the recommendations in the book, includes the use of alcohol by children. Alcohol is an illegal drug for minors and should be treated as such. This book does not discuss techniques for treating drug users. Treatment usually requires professional help; treatment services are included in the resources section at the end of the book. But the purpose of the book is to help prevent drug use in the first place.

The information in this book is based on the research of drug prevention experts, and on interviews with parent organizations and school officials working in drug prevention in all 50 States and the District of Columbia. Although this volume is a product of the U.S. Department of Education, I am grateful for the assistance the Department received from groups and individuals across the country. It was not possible to include all the information we gathered, but I wish to thank the many groups that offered their help.

No one can be a good citizen alone, as Plato tells us. No one is going to solve our drug problem alone, either. But when parents, schools, and communities pull together, drugs can be stopped. Drugs have been beaten in schools like Northside High School in Atlanta, profiled in this book. Preventing drug experimentation is the key. It requires drug education starting in the first grades of elementary school. It requires clear policies against drug use and consistent enforcement of those policies. And it requires the cooperation of school boards, principals, teachers, law enforcement personnel, parents, and students.

Schools are uniquely situated to be part of the solution to student drug use. Children spend much of their time in school. Furthermore, schools, along with families and religious institutions, are major influences in transmitting ideals and standards of right and wrong. Thus, although the problems of drug use extend far beyond the schools, it is critical that our offensive on drugs center in the schools.

My purpose in releasing this handbook, therefore, is to help all of us—parents and children, teachers and principals, legislators and taxpayers—work more effectively in combating drug use. Knowing the dangers of drugs is not enough. Each of us must also act to prevent the sale and use of drugs. We must work to see that drug use is not tolerated in our homes, in our schools, or in our communities. Because of drugs, children are failing, suffering, and dying. We have to get tough, and we have to do it now.

A Plan for Achieving Schools Without Drugs

PARENTS:

1. Teach standards of right and wrong, and demonstrate these standards through personal example.

2. Help children to resist peer pressure to use drugs by supervising their activities, knowing who their friends are, and talking with them about their interests and problems.

3. Be knowledgeable about drugs and signs of drug use. When symptoms are observed, respond promptly.

SCHOOLS:

4. Determine the extent and character of drug use and establish a means of monitoring that use regularly.

5. Establish clear and specific rules regarding drug use that include strong corrective actions.

6. Enforce established policies against drug use fairly and consistently. Implement security measures to eliminate drugs on school premises and at school functions.

7. Implement a comprehensive drug prevention curriculum for kindergarten through grade 12, teaching that drug use is wrong and harmful and supporting and strengthening resistance to drugs.

8. Reach out to the community for support and assistance in making the school's antidrug policy and program work. Develop collaborative arrangements in which school personnel, parents, school boards, law enforcement officers, treatment organizations, and private groups can work together to provide necessary resources.

STUDENTS:

9. Learn about the effects of drug use, the reasons why drugs are harmful, and ways to resist pressures to try drugs.

10. Use an understanding of the danger posed by drugs to help other students avoid them. Encourage other students to resist drugs, persuade those using drugs to seek help, and report those selling drugs to parents and the school principal.

COMMUNITIES:

11. Help schools fight drugs by providing them with the expertise and financial resources of community groups and agencies.

12. Involve local law enforcement agencies in all aspects of drug prevention: assessment, enforcement, and education. The police and courts should have well-established and mutually supportive relationships with the schools.

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| INTRODUCTION | iv | |

| WHAT CAN WE DO? | vii | |

| CHILDREN AND DRUGS | 1 | |

| Extent of Drug Use | 5 | |

| Fact Sheet: Drugs and Dependence | 6 | |

| How Drug Use Develops | 7 | |

| Fact Sheet: Cocaine: Crack | 8 | |

| Effects of Drug Use | 9 | |

| Drug Use and Learning | 10 | |

| A PLAN FOR ACTION | 11 | |

| What Parents Can Do | ||

| Instilling Responsibility | 13 | |

| Supervision | 15 | |

| Fact Sheet: Signs of Drug Use | 16 | |

| Recognizing Drug Use | 17 | |

| What Schools Can Do | ||

| Assessing the Problem | 19 | |

| Setting Policy | 21 | |

| Enforcing Policy | 23 | |

| Fact Sheet: Legal Questions on Search and Seizure | 24 | |

| Fact Sheet: Legal Questions on Suspension and Expulsion | 25 | |

| Fact Sheet: Tips for Selecting Drug Prevention Materials | 26 | |

| Teaching About Drug Prevention | 27 | |

| Enlisting the Community | 29 | |

| What Students Can Do | ||

| Learning the Facts | 31 | |

| Helping Fight Drug Use | 33 | |

| What Communities Can Do | ||

| Providing Support | 37 | |

| Tough Law Enforcement | 39 | |

| CONCLUSION | 40 | |

| SPECIAL SECTIONS | ||

| Teaching About Drug Prevention | 44 | |

| How the Law Can Help | 49 | |

| Resources | 59 | |

| Specific Drugs and Their Effects | 59 | |

| Sources of Information | 67 | |

| References | 74 | |

| Acknowledgments | 78 | |

| Ordering Information | ||

"I felt depressed and hurt all the time. I hated myself for the way I hurt my parents and treated them so cruelly, and for the way I treated others. I hated myself the most, though, for the way I treated myself. I would take drugs until I overdosed, and fell further and further in school and work and relationships with others. I just didn't care anymore whether I lived or died. I stopped going to school altogether.... I felt constantly depressed and began having thoughts of suicide, which scared me a lot! I didn't know where to turn...."

—"Stewart," a high school student

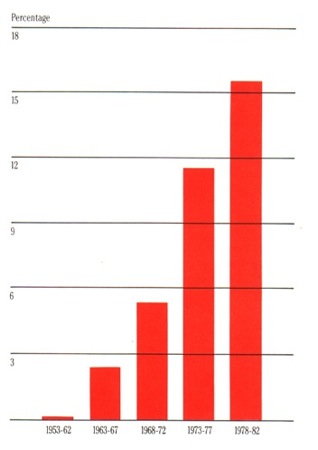

Chart 1

Percentage of 13-Year-Olds Who Have Used Marijuana, 1953-1982

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse Household Survey 1982

Children and Drugs

Americans have consistently identified drug use among the top problems confronting the Nation's schools. Yet many do not recognize the degree to which their own children, their own schools, and their own communities are at risk.

Research shows that drug use among children is 10 times more prevalent than parents suspect. In addition, many students know that their parents do not recognize the extent of drug use, and this leads them to believe that they can use drugs with impunity.

School administrators and teachers often are unaware that their students are using and selling drugs, frequently on school property. School officials who are aware of the situation in their schools admit, as has Ralph Egers, superintendent of schools in South Portland, Maine, that "We'd like to think that our kids don't have this problem, but the brightest kid from the best family in the community could have the problem."

The facts are:

Continuing misconceptions about the drug problem stand in the way of corrective action. The following section outlines the nature and extent of the problem and summarizes the latest research on the effects of drugs on students and schools.

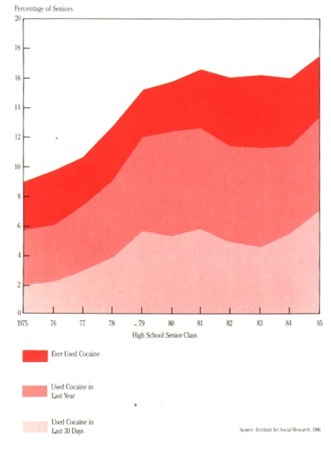

Chart 2

Percentage of High School Seniors Who Have Used Cocaine

Source: Institute for Social Research 1986

Drug use is widespread among American schoolchildren. The United States has the highest rate of teenage drug use of any industrialized nation. The drug problem in this country is 10 times greater than in Japan, for example. Sixty-one percent of high school seniors have used drugs. Marijuana use remains at an unacceptably high level; 41 percent of 1985 seniors reported using it in the last year, and 26 percent said they had used it at least once in the previous month. Thirteen percent of seniors indicated that they had used cocaine in the past year. This is the highest level ever observed, more than twice the proportion in 1975.

Many students purchase and use drugs at school. A recent study of teenagers contacting a cocaine hotline revealed that 57 percent of the respondents bought most of their drugs at school. Among 1985 high school seniors, one-third of the marijuana users reported that they had smoked marijuana at school. Of the seniors who used amphetamines during the past year, two-thirds reported having taken them at school.

The drug problem affects all types of students. All regions and all types of communities show high levels of drug use. Forty-three percent of 1985 high school seniors in nonmetropolitan areas reported illicit drug use in the previous year, while the rate for seniors in large metropolitan areas was 50 percent. Although higher proportions of males are involved in illicit drug use, especially heavy drug use, the gap between the sexes is lessening. The extent to which high school seniors reported having used marijuana is about the same for blacks and whites; for other types of drugs reported, use is slightly higher among whites.

Initial drug use occurs at an increasingly early age. The percentage of students using drugs by the sixth grade has tripled over the last decade. In the early 1960's, marijuana use was virtually nonexistent among 13-year-olds, but now about one in six 13-year-olds has used marijuana.

Drugs and Dependence

Drugs cause physical and emotional dependence. Users may develop an overwhelming craving for specific drugs, and their bodies may respond to the presence of drugs in ways that lead to increased drug use.

Social influences play a key role in making drug use attractive to children.

The first temptations to use drugs may come in social situations in the form of pressures to "act grown up" and "have a good time" by smoking cigarettes or using alcohol or marijuana.

A 1983 Weekly Reader survey found that television and movies had the greatest influence on fourth graders in making drugs and alcohol seem attractive; other children had the second greatest influence. From the fifth grade on, peers played an increasingly important role, while television and movies consistently had the second greatest influence.

The survey offers insights into why students take drugs. For all children, the most important reason for taking marijuana is to "fit in with others." "To feel older" is the second main reason for children in grades four and five, and "to have a good time" for those in grades six to twelve. This finding reinforces the need for prevention programs beginning in the early grades—programs that focus on teaching children to resist peer pressure and on making worthwhile and enjoyable drug-free activities available to them.

Students who turn to more potent drugs usually do so after first using cigarettes and alcohol, and then marijuana. Initial attempts may not produce a "high"; however, students who continue to use drugs learn that drugs can alter their thoughts and feelings. The greater a student's involvement with marijuana, the more likely it is the student will begin to use other drugs in conjunction with marijuana.

Drug use frequently progresses in stages—from occasional use, to regular use, to multiple drug use, and ultimately to total dependency. With each successive stage, drug use intensifies, becomes more varied, and results in increasingly debilitating effects.

But this progression is not inevitable. Drug use can be stopped at any stage. However, the more involved children are with drugs, the more difficult it is for them to stop. The best way to fight drug use is to begin prevention efforts before children start using drugs. Prevention efforts that focus on young children are the most effective means to fight drug use.

Cocaine: Crack

Cocaine use is the fastest growing drug problem in America. Most alarming is the recent availability of cocaine in a cheap but potent form called crack or rock. Crack is a purified form of cocaine that is smoked.

The drugs students are taking today are more potent, more dangerous, and more addictive than ever.

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the effects of drugs. Drugs threaten normal development in a number of ways:

Drug suppliers have responded to the increasing demand for drugs by developing new strains, producing reprocessed, purified drugs, and using underground laboratories to create more powerful forms of illegal drugs. Consequently, users are exposed to heightened or unknown levels of risk.

Drugs erode the self-discipline and motivation necessary for learning. Pervasive drug use among students creates a climate in the schools that is destructive to learning. Research shows that drug use can cause a decline in academic performance. This has been found to be true for students who excelled in school prior to drug use as well as for those with academic or behavioral problems prior to use. According to one study, students using marijuana were twice as likely to average D's and F's as other students. The decline in grades often reverses when drug use is stopped.

Drug use is closely tied to truancy and dropping out of school. High school seniors who are heavy drug users are more than three times as likely to skip school as nonusers. About one-fifth of heavy users skipped 3 or more schooldays a month, more than six times the truancy rate of nonusers. In a Philadelphia study, dropouts were almost twice as likely to be frequent drug users as were high school graduates; four in five dropouts used drugs regularly.

Drug use is associated with crime and misconduct that disrupt the maintenance of an orderly and safe school conducive to learning. Drugs not only transform schools into marketplaces for dope deals, they also lead to the destruction of property and to classroom disorder. Among high school seniors, heavy drug users were two-and-one-half times as likely to vandalize school property and almost three times as likely to have been involved in a fight at school as nonusers. Students on drugs create a climate of apathy, disruption, and disrespect for others. For example, among teenage callers to a national cocaine hotline, 44 percent reported that they sold drugs and 31 percent said that they stole from family, friends, or employers to buy drugs. A drug-ridden environment is a strong deterrent to learning not only for drug users, but for other students as well.

In order to combat student drug use most effectively, the entire community must be involved: parents, schools, students, law enforcement authorities, religious groups, social service agencies, and the media. They all must transmit a single consistent message that drug use is wrong, dangerous, and will not be tolerated. This message must be reinforced through strong, consistent law enforcement and disciplinary measures.

The following recommendations and examples describe actions that can be taken by parents, schools, students, and communities to stop drug use. These recommendations are derived from research and from the experiences of schools throughout the country. They show that the drug problem can be overcome.

WHAT PARENTS CAN DO

Parents

Recommendation #1:

Teach standards of right and wrong and demonstrate these standards through personal example.

Children who are brought up to value individual responsibility and self-discipline and to have a clear sense of right and wrong are less likely to try drugs than those who are not. Parents can help to instill these ideals by:

Northside High School,

Atlanta, Georgia

Northside High School enrolls 1,400 students from 52 neighborhoods. In 1977, drug use was so prevalent that the school was known as "Fantasy Island." Students smoked marijuana openly at school, and police were called to the school regularly.

The combined efforts of a highly committed group of parents and an effective new principal succeeded in solving Northside's drug problem. Determined to stop drug use both inside and outside the school, parents organized and took the following actions:

The new principal, Bill Rudolph, also committed his energy and expertise to fighting the drug problem. Rudolph established a tough policy for students who were caught possessing or dealing drugs. "Illegal drug offenses do not lead to detention hall but to court," he stated. When students were caught, he immediately called the police and then notified their parents. Families were given the names of drug education programs and were urged to participate. One option available to parents was drug education offered by other parents.

Today, Northside is a different school. In 1984-85, only three drug-related incidents were reported. Academic achievement has improved dramatically; student test scores have risen every year since the 1977-78 school year. Scores on standardized achievement tests rose to well above the national average, placing Northside among the top schools in the district for the 1984-85 school year.

Parents

Recommendation #2:

Help children to resist peer pressure to use drugs by supervising their activities, knowing who their friends are, and talking with them about their interests and problems.

When parents take an active interest in their children's behavior, they provide the guidance and support children need to resist drugs. Parents can do this by:

In addition, parents can work with the school in its efforts to fight drugs by:

Signs of Drug Use

Changing patterns of performance, appearance, and behavior may signal use of drugs. The items in the first category listed below provide direct evidence of drug use; the items in the other categories offer signs that may indicate drug use. For this reason, adults should look for extreme changes in children's behavior, changes that together form a pattern associated with drug use.

Signs of Drugs and Drug Paraphernalia

Identification with Drug Culture

Signs of Physical Deterioration

Dramatic Changes in School Performance

Changes in Behavior

Parents

Recommendation #3:

Be knowledgeable about drugs and signs of drug use. When symptoms are observed, respond promptly.

Parents are in the best position to recognize early signs of drug use in their children. In order to prepare themselves, they should:

Parents who suspect their children are using drugs often must deal with their own emotions of anger, resentment, and guilt. Frequently they deny the evidence and postpone confronting their children. Yet the earlier a drug problem is found and faced, the less difficult it is to overcome. If parents suspect their children are using drugs, they should:

WHAT SCHOOLS CAN DO

Schools

Recommendation #4:

Determine the extent and character of drug use and establish a means of monitoring that use regularly.

School personnel should be informed about the extent of drugs in their school. School boards, superintendents, and local public officials should support school administrators in their efforts to assess the extent of the drug problem and to combat it.

In order to guide and evaluate effective drug prevention efforts, schools need to:

Anne Arundel County School District,

Annapolis, Maryland

In response to evidence of a serious drug problem in 1979-80, the school district of Anne Arundel County implemented a strict new policy covering both elementary and secondary students. It features notification of police, involvement of parents, and use of alternative education programs for offenders. School officials take the following steps when students are found using or possessing drugs:

Distribution and sale of drugs are also grounds for expulsion, and a student expelled for these offenses is ineligible to participate in the Alternative Drug Program.

As a result of these steps, the number of drug offenses has declined by 58 percent, from 507 in 1979-80 to 211 in 1984-85.

Schools

Recommendation #5:

Establish clear and specific rules regarding drug use that include strong corrective actions.

School policies should clearly establish that drug use, possession, and sale on the school grounds and at school functions will not be tolerated. These policies should apply to both students and school personnel, and may include prevention, intervention, treatment, and disciplinary measures.

School policies should:

Eastside High School,

Paterson, New Jersey

Eastside High School is located in an inner-city neighborhood and enrolls 3,200 students. Before 1982, drug dealing was rampant. Intruders had easy access to the school and sold drugs on the school premises. Drugs were used in school stairwells and bathrooms. Gangs armed with razors and knives roamed the hallways.

A new principal, Joe Clark, was instrumental in ridding the school of drugs and violence. Hired in 1982, Clark established order, enlisted the help of police officers in drug prevention education, and raised academic standards. Among the actions he took were:

As a result of actions such as these, Eastside has been transformed. Today there is no evidence of drug use in the school. Intruders no longer have access to the school; hallways and stairwells are safe. Academic performance has improved substantially: in 1981-82, only 56 percent of the 9th graders passed the State's basic skills test in math; in 1984-85, 91 percent passed. In reading, the percentage of 9th graders passing the State basic skills test rose from 40 percent in 1981-82 to 67 percent in 1984-85.

Schools

Recommendation #6:

Enforce established policies against drug use fairly and consistently. Implement security measures to eliminate drugs on school premises and at school functions.

Ensure that everyone understands the policy and the procedures that will be followed in case of infractions. Make copies of the school policy available to all parents, teachers, and students, and take other steps to publicize the policy.

Impose strict security measures to bar access to intruders and prohibit student drug trafficking. Enforcement policies should correspond to the severity of the school's drug problem. For example:

Review enforcement practices regularly to ensure that penalties are uniformly and fairly applied.

Legal Questions on Search and Seizure

In 1985, the Supreme Court for the first time analyzed the application in the public school setting of the Fourth Amendment prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures. The Court sought to craft a rule that would balance the need of school authorities to maintain order and the privacy rights of students. The questions in this section summarize the decisions of the Supreme Court and of lower Federal courts. School officials should consult with legal counsel in formulating their policies.

What legal standard applies to school officials who search students and their possessions for drugs?

The Supreme Court has held that school officials may institute a search if there are "reasonable grounds" to believe that the search will reveal evidence that the student has violated or is violating either the law or the rules of the school.

Do school officials need a search warrant to conduct a search for drugs?

No, not if they are carrying out the search independent of the police and other law enforcement officials. A more stringent legal standard may apply if law enforcement officials are involved in the search.

How extensive can a search be?

The scope of the permissible search will depend on whether the measures used during the search are reasonably related to the purpose of the search and are not excessively intrusive in light of the age and sex of the student being searched. The more intrusive the search, the greater the justification that will be required by the courts.

Do school officials have to stop a search when they find the object of the search?

Not necessarily. If a search reveals items suggesting the presence of other evidence of crime or misconduct, the school official may continue the search. For example, if a teacher is justifiably searching a student's purse for cigarettes and finds rolling papers, it will be reasonable (subject to any local policy to the contrary) for the teacher to search the rest of the purse for evidence of drugs.

Can school officials search student lockers?

Reasonable grounds to believe that a particular student locker contains evidence of a violation of the law or school rules will generally justify a search of that locker. In addition, some courts have upheld written school policies that authorize school officials to inspect student lockers at any time.

Fact Sheet

Legal Questions on Suspension and Expulsion

The following questions and answers briefly describe several Federal requirements that apply to the use of suspension and expulsion as disciplinary tools in public schools. These may not reflect all laws, policies, and judicial precedents applicable to any given school district. School officials should consult with legal counsel to determine the application of these laws in their schools and to ensure that all legal requirements are met.

What Federal procedural requirements apply to suspension or expulsion?

Can students be suspended or expelled from school for use, possession, or sale of drugs?

Generally, yes. A school may suspend or expel students in accordance with the terms of its discipline policy. A school policy may provide for penalties of varying severity, including suspension or expulsion, to respond to drug-related offenses. It is helpful to be explicit about the types of offenses that will be punished and about the penalties that may be imposed for particular types of offenses (e.g., use, possession, or sale of drugs). Generally, State and local law will determine the range of sanctions permitted.

(For a more detailed discussion of legal issues, see pages 49-58.)

Tips for Selecting Drug Prevention Materials

In evaluating drug prevention materials, keep the following points in mind:

Check the date of publication.

Material published before 1980 may be outdated and even recently published materials may be inaccurate.

Look for "warning flag" phrases and concepts.

These expressions, many of which appear frequently in "pro-drug" material, falsely imply that there is a "safe" use of mind-altering drugs: experimental use, recreational use, social use, controlled use, responsible use, use/abuse.

"Mood-altering" is a deceptive euphemism for mind-altering.

The implication of the phrase "mood-altering" is that only temporary feelings are involved. The fact is that mood changes are biological changes in the brain.

"There are no 'good' or 'bad' drugs, just improper use":

This is a popular semantic camouflage in pro-drug literature. It confuses young people and minimizes the distinct chemical differences among substances.

"The child's own decision":

Parents cannot afford to leave such hazardous choices to their children. It is the parents' responsibility to do all in their power to provide the information and the protection to assure their children a drug-free childhood and adolescence.

Be alert for contradictory messages.

Often an author gives a pro-drug message and then covers his tracks by including "cautions" about how to use drugs.

Make certain the health consequences revealed in current research are adequately described.

Literature should make these facts clear: The high potency of marijuana on the market today makes it more dangerous than ever; THC, a psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, is fat soluble and its accumulation in the body has many adverse biological effects; cocaine can cause death and is one of the most addictive drugs known to man.

Demand material that sets positive standards of behavior for children.

The message conveyed must be an expectation that children can say no to drugs. The publication and its message must provide the information and must support caring family involvement to reinforce the child's courage to stay drug free.

Schools

Teaching About Drug Prevention

Recommendation #7:

Implement a comprehensive drug prevention curriculum from kindergarten through grade 12, teaching that drug use is wrong and harmful and supporting and strengthening resistance to drugs.

A model program would have these main objectives:

In developing a program, school staff should:

In implementing a program, school staff should:

(For more detailed information on topics and learning activities to incorporate in a drug prevention program, see pages 44-48.)

Samuel Gompers Vocational-Technical High School,

New York City

Samuel Gompers Vocational-Technical High School is located in the South Bronx in New York City. Enrollment is 1,500 students; 95 percent are from low-income families.

In June, 1977, an article in the New York Times likened Gompers to a "war zone." Students smoked marijuana and sold drugs both inside the school and on the school grounds; the police had to be called in daily.

In 1979, the school board hired a new principal, Victor Herbert, who turned the school around. Herbert established order, implemented a drug awareness program, involved the private sector, and instilled pride in the school among students. Among the actions he took:

The results of Herbert's actions were remarkable. In 1985, there were no known incidents of students using alcohol or drugs in school or on school grounds, and only one incident of violence was reported. The percentage of students reading at or above grade level increased from 45 percent in 1979-80 to 67 percent in 1984-85.

Recommendation #8:

Reach out to the community for support and assistance in making the school's antidrug policy and program work. Develop collaborative arrangements in which school personnel, parents, school boards, law enforcement officers, treatment organizations, and private groups can work together to provide necessary resources.

School officials should recognize that they cannot solve the drug problem alone. They need to get the community behind their efforts by taking action to:

WHAT STUDENTS CAN DO

Students

Recommendation #9.

Learn about the effects of drug use, the reasons why drugs are harmful, and ways to resist pressures to try drugs. Students can arm themselves with the knowledge to resist drug use by:

R. H. Watkins High School of Jones County, Mississippi, has developed a pledge, excerpted below, which sets forth the duties and responsibilities of student counselors in its peer counseling program.

Responsibility Pledge for a Peer Counselor, R. H. Watkins High School

As a drug education peer counselor you have the opportunity to help the youth of our community develop to their full potential without the interference of illegal drug use. It is a responsibility you must not take lightly. Therefore, please read the following responsibilities you will be expected to fulfill next school year and discuss them with your parents or guardians.

Responsibilities of a Peer Counselor

Understand and be able to clearly state your beliefs and attitudes about drug use among teens and adults.

Remain drug free.

Maintain an average of C or better in all classes.

Maintain a citizenship average of B or better.

Participate in some club or extracurricular activity that emphasizes the positive side of school life.

Successfully complete training for the program, including, for example, units on the identification and symptoms of drug abuse, history and reasons for drug abuse, and the legal/economic aspects of drug abuse.

Successfully present monthly programs on drug abuse in each of the elementary and junior high schools of the Laurel City school system, and to community groups, churches, and statewide groups as needed.

Participate in rap sessions or individual counseling sessions with Laurel City school students.

Attend at least one Jones County Drug Council meeting per year, attend the annual Drug Council Awards Banquet, work in the Drug Council Fair exhibit and in any Drug Council workshops, if needed.

Grades and credit for Drug Education will be awarded on successful completion of and participation in all the above-stated activities.

| _____________________________ | __________________________________ | |

| Student's Signature | Parent's or Guardian's Signature |

Students

Recommendation #10:

Use an understanding of the danger posed by drugs to help other students avoid them. Encourage other students to resist drugs, persuade those using drugs to seek help, and report those selling drugs to parents and the school principal.

Although students are the primary victims of drug use in the schools, drug use cannot be stopped or prevented unless students actively participate in this effort.

Students can help fight drug use by:

· Participating in open discussions about the extent of the problem at their own school.

Greenway Middle School,

Phoenix, Arizona

Greenway Middle School is in a rapidly growing area of Phoenix. The student population of 950 is highly transient.

Greenway developed a comprehensive drug prevention program in the 1979-80 school year. The program provides strict sanctions for students caught with drugs, but its main emphasis is on prevention. Features include:

Under Greenway's drug policy, first-time offenders who are caught using or possessing drugs are suspended for 6 to 10 days. First-time offenders who are caught selling drugs are subject to expulsion. The policy is enforced in close cooperation with the local police department.

As a result of the Greenway program, drug use and disciplinary referrals declined dramatically between 1979-80 and 1984-85. The number of drug-related referrals to the school's main office decreased by 78 percent; overall, discipline-related referrals decreased by 62 percent.

WHAT COMMUNITIES CAN DO

Project DARE,

Los Angeles, California

The police department and school district have teamed up to create DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education), now operating in 405 schools from kindergarten through grade 8 in Los Angeles. Fifty-two carefully selected and trained frontline officers are teaching students to say no to drugs, build their self-esteem, manage stress, resist prodrug media messages, and develop other skills to keep them drug free. In addition, officers spend time on the playground at recess so that students can get to know them. Meetings are held with teachers, principals, and parents to discuss the curriculum.

Research has shown that DARE has improved students' attitudes about themselves, increased their sense of responsibility for themselves and to police, and strengthened resistance to drugs. For example, before the DARE program began, 51 percent of fifth-grade students equated drug use with having more friends. After training, only 8 percent reported this attitude.

DARE has also changed parent attitudes through an evening program to teach parents about drugs, the symptoms of drug use, and ways to increase family communication. Before DARE, 32 percent of parents thought that it was all right for children to drink alcohol at a party as long as adults were present. After DARE, no parents reported such a view. Before DARE, 61 percent thought that there was nothing parents could do about their children's use of drugs; only 5 percent said so after the program.

As a result of the high level of acceptance by principals, teachers, the community, and students, DARE has spread from 50 elementary schools in 1983 to all 347 elementary and 58 junior high schools in Los Angeles. DARE will soon be fully implemented in Virginia.

Communities

Recommendation #11:

Help schools fight drugs by providing them with the expertise and financial resources of community groups and agencies.

Law enforcement agencies and the courts can:

Social service and health agencies can:

Businesses can:

Parent groups can:

Print and broadcast media can:

Operation SPECDA,

New York City

Operation SPECDA (School Program to Educate and Control Drug Abuse) is a cooperative program of the New York City Board of Education and the police department. It operates in 154 schools, serving students and their parents from kindergarten through grade 12. SPECDA has two aims: education and enforcement. Police help provide classes and presentations on drug abuse in the schools. At the same time, they concentrate enforcement efforts within a two-block radius of schools to create a drug-free corridor for students.

The enforcement aspect has had some impressive victories. Police have made 7,500 arrests to date, 66 percent in the vicinity of elementary schools. In addition, they have seized narcotics valued at more than $1 million, as well as $1 million in cash and 139 firearms.

SPECDA provides a simultaneous focus on education. Carefully selected police officers team with drug abuse counselors to lead discussion sessions throughout the fifth and sixth grades. The discussions emphasize the building of good character and self-respect; the dangers of drug use; civic responsibility and the consequences of actions; and constructive alternatives to drug abuse.

Similar presentations are made in school assemblies for students from kindergarten through grade 4 and in the junior and senior high schools. An evening workshop for parents helps them reinforce the SPECDA message.

An evaluation of participants in SPECDA demonstrates that a majority of the students have become more aware of the dangers of drug use, and show strong positive attitudes toward SPECDA police officers and drug counselors. When interviewed, students have indicated a strengthened resolve to resist drugs.

Communities

Recommendation #12:

Involve local law enforcement agencies in all aspects of drug prevention: assessment, enforcement, and education. The police and courts should have well-established and mutually supportive relationships with the schools.

Community groups can:

Law enforcement agencies, in cooperation with schools, can:

Drugs threaten our children's lives, disrupt our schools, and shatter families. Drug-related crimes overwhelm our courts, social service agencies, and police. This situation need not and must not continue.

Across America schools and communities have found ways to turn the tide in the battle against drugs. The methods they have used and the actions they have taken are described in this volume. We know what works. We know that drug use can be stopped.

But we also know that defeating drugs is not easy. We cannot expect the schools to do the job without the help of parents, police, the courts, and other community groups. Drugs will only be beaten when all of us work together to deliver a firm, consistent message to those who would use or sell drugs: a message that illegal drugs will not be tolerated. It is time to join in a national effort to achieve schools without drugs.

SPECIAL SECTIONS

TEACHING ABOUT DRUG PREVENTION

Teaching About Drug Prevention: Sample Topics and Learning Activities

An effective drug prevention curriculum covers a broad set of education objectives. This section presents a model program for consideration by State and local school authorities who have the responsibility to design a curriculum that meets local needs and priorities. The program consists of four objectives, plus sample topics and learning activities.

OBJECTIVE 1: To value and maintain sound personal health; to understand how drugs affect health.

An effective drug prevention education program instills respect for a healthy body and mind and imparts knowledge of how the body functions, how personal habits contribute to good health, and how drugs affect the body.

At the early elementary level, children learn how to care for their bodies. Knowledge about habits, medicine, and poisons lays the foundation for learning about drugs. Older children begin to learn about the drug problem and study those drugs to which they are most likely to be exposed. The curriculum for secondary school students is increasingly drug-specific as students learn about the effects of certain drugs on their bodies and on adolescent maturation.

Sample topics for elementary school:

Sample topics for secondary school:

Children tend to be present-oriented and are likely to feel invulnerable to long-term effects of drugs. For this reason, they should be taught about the short-term effects of drug use—such as impact on appearance, alertness, and coordination—as well as about the cumulative effects.

Sample learning activities for elementary school:

Sample learning activities for high school:

When an expert visits a class, both the class and the expert should be prepared in advance. Students should learn about the expert's profession and prepare questions to ask during the visit. The expert should know what the objectives of the session are and how the session fits into previous and subsequent learning. The expert should participate in a discussion or classroom activity, not simply appear as a speaker.

OBJECTIVE 2: To respect laws and rules prohibiting drugs.

The program teaches children to respect rules and laws as the embodiment of social values and as tools for protecting individuals and society. It provides specific instruction about laws concerning drugs.

Students in the early grades learn to identify rules and to understand their importance, while older students learn about the school drug code and laws regulating drugs.

Sample topics for elementary school:

Sample topics for secondary school:

Sample learning activities for elementary school:

Sample learning activities for secondary school:

OBJECTIVE 3: To recognize and resist pressures to use drugs.

Social influences play a key role in encouraging children to try drugs. Pressures to use drugs come from internal sources, such as a child's desire to feel included in a group or to demonstrate independence, and external influences, such as the opinions and example of friends, older children, and adults, and media messages.

Students must learn to identify these pressures. They must then learn how to counteract messages to use drugs and gain practice in saying no. The education program emphasizes influences on behavior, responsible decision-making, and techniques for resisting pressures to use drugs.

Sample topics for elementary through high school:

Sample learning activities for elementary through high school:

OBJECTIVE 4: To promote activities that reinforce the positive, drug-free elements of student life.

School activities that provide students opportunities to have fun without drugs—and to contribute to the school community—build momentum for peer pressure not to use drugs. These school activities also nurture positive examples by giving older students opportunities for leadership related to drug prevention.

Sample activities:

Federal law accords school officials broad authority to regulate student conduct and supports reasonable and fair disciplinary action. The Supreme Court recently reaffirmed that the constitutional rights of students in school are not "automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings." [1] Rather, recognizing that "in recent years … drug use and violent crime in the schools have become major social problems," the Court has emphasized the importance of effective enforcement of school rules. [2] On the whole, a school "is allowed to determine the methods of student discipline and need not exercise its discretion with undue timidity." [3]

An effective campaign against drug use requires a basic understanding of legal techniques for searching and seizing drugs and drug-related material, for suspending and expelling students involved with drugs, and for assisting law enforcement officials in the prosecution of drug offenders. Such knowledge will both help schools identify and penalize students who use or sell drugs at school and enable school officials to uncover the evidence needed to support prosecutions under Federal and State criminal laws that contain strong penalties for drug use and sale. In many cases, school officials can be instrumental in successful prosecutions.

In addition to the general Federal statutes that make it a crime to possess or distribute a controlled substance, there are special Federal laws designed to protect children and schools from drugs:

An important part of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 makes it a Federal crime to sell drugs in or near a public or private elementary or secondary school. Under this new "schoolhouse" law, sales within 1,000 feet of school grounds are punishable by up to double the sentence that would apply if the sale occurred elsewhere. Even more serious mandatory penalties are available for repeat offenders. [4]

Distribution or sale to minors of controlled substances is also a Federal crime. When anyone over age 21 sells drugs to anyone under 18, the seller runs the risk that he will receive up to double the sentence that would apply to a sale to an adult. Here too, more serious penalties can be imposed on repeat offenders. [5]

By working with Federal and State prosecutors in their area, schools can help to ensure that these laws and others are used to make children and schools off-limits to drugs.

The following pages describe in general terms the Federal laws applicable to the development of an effective school drug policy. This handbook is not a compendium of all laws that may apply to a school district, and it is not intended to provide legal advice on all issues that may arise. School officials must recognize that many legal issues in the school context are also governed, in whole or in part, by State and local laws, which, given their diversity, cannot be covered here. Advice should be sought from legal counsel in order to understand the applicable laws and to ensure that the school's policies and actions make full use of the available methods of enforcement.

Most private schools, particularly those that receive little or no financial assistance from public sources and are not associated with a public entity, enjoy a greater degree of legal flexibility with respect to combating the sale and use of illegal drugs. Depending on the terms of their contracts with enrolled students, such schools may be largely free of the restrictions that normally apply to drug searches or the suspension or expulsion of student drug users. Private school officials should consult legal counsel to determine what enforcement measures may be available to them.

School procedures should reflect the available legal means for combating drug use. These procedures should be known to and understood by school administrators and teachers as well as students, parents, and law enforcement officials. Everyone should be aware that school authorities have broad power within the law to take full, appropriate, and effective action against drug offenders. Additional sources of information on legal issues in school drug policy are listed at the end of this handbook.

SEARCHING FOR DRUGS WITHIN THE SCHOOL

In some circumstances, the most important tool for controlling drug use is an effective program of drug searches. School administrators should not condone the presence of drugs anywhere on school property. The presence of any drugs or drug-related materials in school can mean only one thing—that drugs are being used or distributed in school. Schools committed to fighting drugs should do everything they can to determine whether school grounds are being used to facilitate the possession, use, or distribution of drugs and to prevent such crimes.

In order to institute an effective drug search policy in schools with a substantial problem, school officials can take several steps. First, they can identify the specific areas in the school where drugs are likely to be found or used. Student lockers, bathrooms, and "smoking areas" are obvious candidates. Second, school administrators can clearly announce in writing at the beginning of the school year that these areas will be subject to unannounced searches and that students should consider such areas "public" rather than "private." The more clearly a school specifies that these portions of the school's property are public, the less likely it is that a court will conclude that students retain any reasonable expectation of privacy in these places and the less justification will be needed to search such locations.

School officials should, therefore, formulate and disseminate to all students and staff a written policy that will permit an effective program of drug searches. Courts have usually upheld locker searches where schools have established written policies under which the school retains joint control over student lockers, maintains duplicate or master keys for all lockers, and reserves the right to inspect lockers at any time. [6] While this has not become established law in every part of the country, it will be easier to justify locker searches in schools that have such policies. Moreover, the mere existence of such policies can have a salutary effect. If students know that their lockers may be searched, drug users will find it much more difficult to maintain quantities of drugs in school.

The effectiveness of such searches may be improved with the use of specially trained dogs. Courts have generally held that the use of dogs to detect drugs on or in objects such as lockers, ventilators, or desks as opposed to persons, is not a "search" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. [7] Accordingly, school administrators are generally justified in using dogs in this way.

It is important to remember that any illicit drugs and drug-related items discovered at school are evidence that may be used in a criminal trial. School officials should be careful, first, to protect the evidentiary integrity of such seizures by making sure that the items are obtained in permissible searches, since unlawfully acquired evidence will not be admissible in criminal proceedings. Second, school officials should work closely with local law enforcement officials to preserve, in writing, the nature and circumstances of any seizure of drug contraband. In a criminal prosecution, the State must prove that the items produced as evidence in court are the same items that were seized from the suspect. Thus, the State must establish a "chain of custody" over the seized items which accounts for the possession of the evidence from the moment of its seizure to the moment it is introduced in court. School policy regarding the disposition of drug-related items should include procedures for the custody and safekeeping of drugs and drug-related materials prior to their removal by the police and procedures for recording the circumstances regarding the seizure.

Searching Students

In some circumstances, teachers or other school personnel will wish to search a student whom they believe to be in possession of drugs. The Supreme Court has stated that searches may be carried out according to "the dictates of reason and common sense." [8] The Court has recognized that the need of school authorities to maintain order justifies searches that might otherwise be unreasonable if undertaken by police officers or in the larger community. Thus the Court held in 1985 that school officials, unlike the police, do not need "probable cause" to conduct a search. Nor do they need a search warrant. [9]

Under the Supreme Court's ruling:

Interpretation of "Reasonable Grounds"

Lower courts are beginning to interpret and apply the "reasonable grounds" standard in the school setting. From these cases it appears that courts will require more than general suspicion, curiosity, rumor, or a hunch to justify searching a student or his possessions. Factors that will help sustain a search include the observation of specific and describable behavior or activities leading one reasonably to believe that a given student is engaging in or has engaged in prohibited conduct. The more specific the evidence in support of searching a particular student, the more likely the search will be upheld. For example, courts using a "reasonable grounds" (or similar) standard have upheld the right of school officials to search:

Scope of the Permissible Search

School officials are authorized to conduct searches within reasonable limits. The Supreme Court has described two aspects of these limits. First, when officials conduct a search, they must use only measures that are reasonably related to the purpose of the search; second, the search may not be excessively intrusive in light of the age or sex of the student. For example, if a teacher believes she has seen one student passing a marijuana cigarette to another student, she might reasonably search the students and any nearby belongings in which the students might have tried to hide the drug. If it turns out that what the teacher saw was a stick of gum, she would have no justification for any further search for drugs.

The more intrusive the search, the greater the justification that will be required by the courts. A search of a student's jacket or bookbag can often be justified as reasonable. At the other end of the spectrum, strip searches are considered a highly intrusive invasion of an individual's privacy and are viewed with disfavor by the courts (although even these searches have been upheld in certain extraordinary circumstances).

School officials do not necessarily have to stop a search if they find what they are looking for. If the search of a student reveals items that create reasonable grounds for suspecting that he may also possess other evidence of crime or misconduct, the school officials may continue the search. For example, if a teacher justifiably searches a student's purse for cigarettes and finds rolling papers like those used for marijuana cigarettes, it will then be reasonable for the teacher to search the rest of the purse for other evidence of drugs.

Consent

If a student consents to a search, the search is permissible, regardless of whether there would otherwise be reasonable grounds for the search. To render such a search valid, however, the student must give consent knowingly and voluntarily.

Establishing whether the student's consent was voluntary can be difficult, and the burden is on the school officials to prove voluntary consent. If a student agrees to be searched out of fear or as a result of other coercion, that consent will probably be found invalid. Similarly, if school officials indicate that a student must agree to a search or if the student is very young or otherwise unaware that he has the right to object, his consent will also be held invalid. School officials may find it helpful to explain to students that they need not consent to a search. In some cases, standard consent forms may be useful.

If a student is asked to consent to a search and refuses, that refusal does not mean that the search may not be conducted. Rather, in the absence of consent, school officials retain the authority to conduct a search when there are reasonable grounds to justify it, as described previously.

Special Types of Student Searches

Schools with severe drug problems may occasionally wish to resort to more intrusive searches, such as the use of trained dogs or urinalysis to screen students for drug use. The Supreme Court has yet to address these issues. The following paragraphs explain the existing rulings on these subjects by other courts:

SUSPENSION AND EXPULSION

A school policy may lawfully provide for penalties of varying severity, including suspension and expulsion, to respond to drug-related offenses. The Supreme Court has recently held that because schools "need to be able to impose disciplinary sanctions for a wide range of unanticipated conduct disruptive of the educational process," a school's disciplinary rules need not be as detailed as a criminal code. [17] Nonetheless, it is helpful for school policies to be explicit about the types of offenses that will be punished and about the penalties that may be imposed for each of these (e.g., use, possession, or sale of drugs). State and local law will usually determine the range of sanctions that is permissible. In general, courts will require only that the penalty imposed for drug-related misconduct be rationally related to the severity of the offense.

School officials should not forget that they have jurisdiction to impose punishment for some drug-related offenses that occur off campus. Depending upon State and local laws, schools are often able to punish conduct at off-campus, school-sponsored events as well as off-campus conduct that has a direct and immediate effect on school activities.

Procedural Guidelines

Students facing suspension or expulsion from school are entitled under the U.S. Constitution and most State constitutions to common sense due process protections of notice and an opportunity to be heard. Because the Supreme Court has recognized that a school's ability to maintain order would be impeded if formal procedures were required every time school authorities sought to discipline a student, the Court has held that the nature and formality of the "hearing" will depend on the severity of the sanction being imposed.

A formal hearing is not required when a school seeks to suspend a student for 10 days or less. [18] The Supreme Court has held that due process in that situation requires only that:

The Supreme Court has also stated that more formal procedures may be required for suspensions longer than 10 days and for expulsions. Although the Court has not established specific procedures to be followed in those situations, other Federal courts [19] have set the following guidelines for expulsions. These guidelines would apply to suspensions longer than 10 days as well:

Many States have laws governing the procedures required for suspensions and expulsions. Because applicable statutes and judicial rulings vary across the country, local school districts may enjoy a greater or lesser degree of flexibility in establishing procedures for suspensions and expulsions.

School officials must also be aware of the special procedures that apply to suspension or expulsion of handicapped students under Federal law and regulations. [20]

Effect of Criminal Proceedings Against a Student

A school may usually pursue disciplinary action against a student regardless of the status of any outside criminal prosecution. That is, Federal law does not require the school to await the outcome of the criminal prosecution before initiating proceedings to suspend or expel a student or to impose whatever other penalty is appropriate for the violation of the school's rules. In addition, a school is generally free under Federal law to discipline a student when there is evidence that the student has violated a school rule, even if a juvenile court has acquitted (or convicted) the student or if local authorities have declined to prosecute criminal charges stemming from the same incident. Schools may wish to discuss this subject with counsel.

Effect of Expulsion

State and local law will determine the effect of expelling a student from school. Some State laws require the provision of alternative schooling for students below a certain age. In other areas, expulsion may mean the removal from public schools for the balance of the school year or even the permanent denial of access to the public school system.

CONFIDENTIALITY OF EDUCATION RECORDS

To rid their schools of drugs, school officials will periodically need to report drug-related crimes to police and to assist local law enforcement authorities in detecting and prosecuting drug offenders. In doing so, schools will need to take steps to ensure compliance with Federal and State laws governing confidentiality of student records.

The Federal law that addresses this issue is the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), [21] which applies to any school that receives Federal funding and which limits the disclosure of certain information about students that is contained in education records. [22] Under FERPA, disclosure of information in education records to individuals or entities other than parents, students, and school officials is only permissible in specified situations. [23] In many cases, unless the parents or an eligible student [24] provides written consent, FERPA will limit a school's ability to turn over education records or to disclose information from them to the police. Such disclosure is permitted, however, if (1) it is required by a court order or subpoena, or (2) it is warranted by a health or safety emergency. In the first of these two cases, reasonable efforts must be made to notify the student's parents before the disclosure is made. FERPA also permits disclosure if a State law enacted before November 19, 1974, specifically requires disclosure to State and local officials.

Schools should be aware, however, that because FERPA only governs information in education records, it does not limit disclosure of other information. Thus, school employees are free to disclose any information of which they become aware through personal observation. For example, a teacher who witnesses a drug transaction may, when the police arrive, report what he witnessed. Similarly, evidence seized from a student during a search is not an education record and may be turned over to the police without constraint.

State laws and school policies may impose additional, and sometimes more restrictive, requirements regarding the disclosure of information about students. Since this area of the law is complicated, it is especially important that an attorney be involved in formulating school policy under FERPA and applicable State laws.

OTHER LEGAL ISSUES

Lawsuits Against Schools or School Officials

Disagreements between parents or students and school officials about disciplinary measures usually can be resolved informally. Occasionally, however, a school's decisions and activities relating to disciplinary matters are the subject of lawsuits by parents or students against administrators, teachers, and school systems. For these reasons, it is advisable that school districts obtain adequate insurance coverage for themselves and for all school personnel for liability arising from disciplinary actions.

Suits may be brought in Federal or State court; typically, they are based on a claim that a student's constitutional or statutory rights have been violated. Frequently, these suits will seek to revoke the school district's imposition of some disciplinary measure, for example, by ordering the reinstatement of a student who has been expelled or suspended. Suits may also attempt to recover money damages from the school district or the employee involved, or both, however, court awards of money damages are extremely rare. Moreover, although there can be no guarantee of a given result in any particular case, courts in recent years have tended to discourage such litigation.

In general, disciplinary measures imposed reasonably and in accordance with established legal requirements will be upheld by the courts. As a rule, Federal judges will not substitute their interpretations of school rules or regulations for those of local school authorities or otherwise second-guess reasonable decisions by school officials. [25] In addition, school officials are entitled to a qualified good faith immunity from personal liability for damages for having violated a student's Federal constitutional or civil rights. [26] When this immunity applies, it shields school officials from any personal liability for money damages. Thus, as a general matter, personal liability is very rare, because officials should not be held personally liable unless their actions are clearly unlawful, unreasonable, or arbitrary.

When a court does award damages, the award may be "compensatory" or "punitive." Compensatory damages are awarded to compensate the student for injuries actually suffered as a result of the violation of his or her rights and cannot be based upon the abstract "value" or "importance" of the constitutional rights in question. [27] The burden is on the student to prove that he suffered actual injury as a result of the deprivation. Thus, a student who is suspended, but not under the required procedures, will not be entitled to compensation if he would have been suspended had a proper hearing been held. If the student cannot prove that the failure to hold a hearing itself caused him some compensable harm, then the student is entitled to no more than nominal damages, such as $1.00. [28] "Punitive damages" are awarded to punish the perpetrator of the injury. Normally, punitive damages are awarded only when the conduct in question is malicious, unusually reckless, or otherwise reprehensible.

Parents and students can also claim that actions by a school or school officials have violated State law. For example, it can be asserted that a teacher "assaulted" a student in violation of a State criminal law. The procedures and standards in actions involving such violations are determined by each State. Some States provide a qualified immunity from tort liability under standards similar to the "good faith" immunity in Federal civil rights actions. Other States provide absolute immunity under their law for actions taken in the course of a school official's duties.

Nondiscrimination in Enforcement of Discipline

Federal law applicable to programs or activities receiving Federal financial assistance prohibits school officials who are administering discipline from discriminating against students on the basis of race, color, national origin, or sex. Schools should therefore administer their discipline policies even-handedly, without regard to such considerations. Thus, as a general matter, students with similar disciplinary records who violate the same rule in the same way should be treated similarly. For example, if male and female students with no prior record of misbehavior are caught together smoking marijuana, it would not, in the absence of other relevant factors, be advisable for the school to suspend the male for 10 days while imposing only an afternoon detention on the female. Such divergent penalties for the same offense may be appropriate, however, if, for example, the student who received the harsher punishment had a history of misconduct or committed other infractions after this first confrontation with school authorities.

School officials should also be aware of and adhere to the special rules and procedures for the disciplining of handicapped students under the Education of the Handicapped Act, 20 USC § 1400-20, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 USC § 794.

(For legal citations, see reference section.)

Specific Drugs and Their Effects

CANNABIS

Effects

All forms of cannabis have negative physical and mental effects. Several regularly observed physical effects of cannabis are a substantial increase in the heart rate, bloodshot eyes, a dry mouth and throat, and increased appetite.

Use of cannabis may impair or reduce short-term memory and comprehension, alter sense of time, and reduce ability to perform tasks requiring concentration and coordination, such as driving a car. Research also shows that students do not retain knowledge when they are "high." Motivation and cognition may be altered, making the acquisition of new information difficult. Marijuana can also produce paranoia and psychosis.

Because users often inhale the unfiltered smoke deeply and then hold it in their lungs as long as possible, marijuana is damaging to the lungs and pulmonary system. Marijuana smoke contains more cancer-causing agents than tobacco.

Long-term users of cannabis may develop psychological dependence and require more of the drug to get the same effect. The drug can become the center of their lives.

| Type | What is it called? | What does it look like? |

How is it used? |

|---|---|---|---|

Marijuana |

Pot Grass Weed Reefer Dope Mary Jane Sinsemilla Acapulco Gold Thai Sticks |

Dried parsley mixed with stems that may include seeds |

Eaten Smoked |

Tetrahydro-cannabinol |

THC |

Soft gelatin capsules |

Taken orally Smoked |

Hashish |

Hash |

Brown or black cakes or balls |

Eaten Smoked |

Hashish Oil |

Hash Oil |

Concentrated syrupy liquid varying in color from clear to black |

Smoked—mixed with tobacco |

INHALANTS

Effects

Immediate negative effects of inhalants include nausea, sneezing, coughing, nose-bleeds, fatigue, lack of coordination, and loss of appetite. Solvents and aerosol sprays also decrease the heart and respiratory rates, and impair judgment. Amyl and butyl nitrite cause rapid pulse, headaches, and involuntary passing of urine and feces. Long-term use may result in hepatitis or brain hemorrhage.

Deeply inhaling the vapors, or using large amounts over a short period of time, may result in disorientation, violent behavior, unconsciousness, or death. High concentrations of inhalants can cause suffocation by displacing the oxygen in the lungs or by depressing the central nervous system to the point that breathing stops.

Long-term use can cause weight loss, fatigue, electrolyte imbalance, and muscle fatigue. Repeated sniffing of concentrated vapors over time can permanently damage the nervous system.

| Type | What is it called? | What does it look like? |

How is it used? |

|---|---|---|---|

Nitrous Oxide |

Laughing gas Whippets |

Propellant for whipped cream in aerosol spray can Small 8-gram metal cylinder sold with a balloon or pipe (buzz bomb) |

Vapors inhaled |

Amyl Nitrite |

Poppers Snappers |

Clear yellowish liquid in ampules |

Vapors inhaled |

Butyl Nitrite |

Rush Bolt Locker room Bullet Climax |

Packaged in small bottles |

Vapors inhaled |

Chlorohydrocarbons |

Aerosol sprays |

Aerosol paint cans Containers of cleaning fluid |

Vapors inhaled |

Hydrocarbons |

Solvents |

Cans of aerosol propellants, gasoline, glue, paint thinner |

Vapors inhaled |

STIMULANT: COCAINE

Effects

Cocaine stimulates the central nervous system. Its immediate effects include dilated pupils and elevated blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature. Occasional use can cause a stuffy or runny nose, while chronic use can ulcerate the mucous membrane of the nose. Injecting cocaine with unsterile equipment can cause AIDS, hepatitis, and other diseases. Preparation of freebase, which involves the use of volatile solvents, can result in death or injury from fire or explosion. Cocaine can produce psychological and physical dependency, a feeling that the user cannot function without the drug. In addition, tolerance develops rapidly.