The Project Gutenberg EBook of City Ballads, by Will Carleton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: City Ballads

Author: Will Carleton

Release Date: August 3, 2011 [EBook #36954]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CITY BALLADS ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Dianne Nolan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

"THESE ARE THE SPIRES THAT WERE GLEAMING."

CITY BALLADS

BY

WILL CARLETON

AUTHOR OF "FARM BALLADS" "FARM LEGENDS" "FARM FESTIVALS"

"YOUNG FOLKS' CENTENNIAL RHYMES" ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

TO

ADÓRA

FRIEND, COMRADE, LOVER, WIFE

[Pg 9]

PREFACE.

When city people go among forests and hills, they drink in the fresh

air and weird scenery of rural surroundings, with much more relish,

enjoyment, and appreciation, than do the life-long residents they

find there.

For the same reason, the great drama of metropolitan existence falls

most forcibly upon those just from the clear streams and green

meadows of the country. Their impressions then are deeper, and their

feelings more intense than if they were city born and bred.

With the latter fact in view, this book is an effort to reproduce

some of the effects of city scenes and character upon the intellect

and imagination of two people from the country:

First, a young student, who has travelled the well-beaten roads of a

college course, but is just entering real life, and now for the

first time walks the paved and palace-bordered streets of which he

has heard and read so much.

Second, an old farmer, with very little "book-learning," but a clear

brain, a warm heart, and independent judgment, and a habit of

philosophizing upon everything he sees, which habit he brings to the

city, and applies to the strange facts he witnesses.

These, with certain incidental thoughts and characters encountered

and discussed, constitute the present work. It will be found, as

intended, sketchy and suggestive rather than elaborate and complete.

Note-books and diaries are designed, not so much for the history of

a career or an event, as a light to the memory, a stimulus to the

imagination, and a help to the heart.[Pg 10]

It is the hope of the author that his book may perform those offices

for you, his readers, and that it will rouse your pity of pain, your

enjoyment of honest mirth, your hatred of sham and wrong, and your

love and adoration of the Resolute and the Good, and their winsome

child, the Beautiful.

In which case he shakes hands with his large and loved constituency,

and continues happy.

W. C.

[Pg 11]

CONTENTS.

| | Page |

| WEALTH | 15 |

| Including |

| The Lovely Young Man | 28 |

| If I'd a Million Millions | 35 |

| Farmer Stebbins on Rollers | 40 |

| WANT | 46 |

| Including |

| That Swamp of Death | 53 |

| A Sewing-Girl's Diary | 64 |

| FIRE | 75 |

| Including |

| When Prometheus Stole the Flame | 77 |

| Flash: The Fireman's Story | 79 |

| How we Fought the Fire | 84 |

| "You will Tell me Where is Conrad?" | 90 |

| WATER | 93 |

| Including |

| The Dead Stowaway | 97 |

| The Wedding of the Towns | 102 |

| Farmer Stebbins at Ocean Grove | 107 |

| VICE | 113 |

| Including |

| The Boy-convict's Story | 115 |

| Farmer Stebbins on the Bowery | 119 |

| Farmer Stebbins Ahead | 124 |

| The Slugging-match | 130 |

| VIRTUE | 132 |

| Including |

| More Ways than One | 136 |

| The March of the Children | 141 |

| TRAVEL | 143 |

| Including |

| Her Tour | 144 |

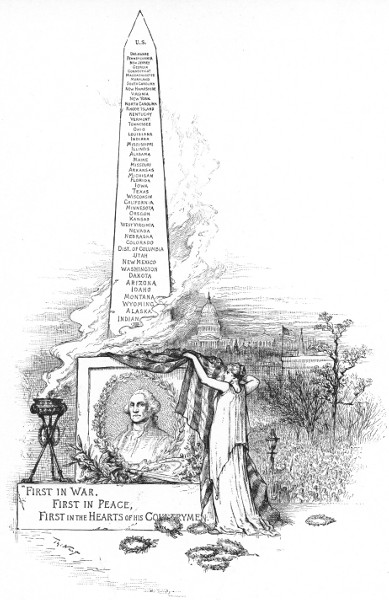

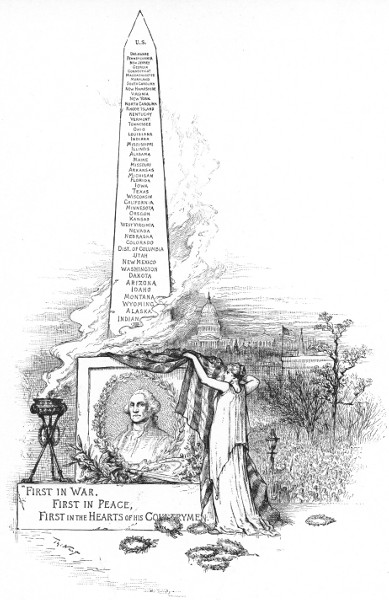

| At the Summit of the Washington Monument | 148 |

| The Silent Wheel | 155 |

| Farmer and Wheel; or, The New Lochinvar | 157 |

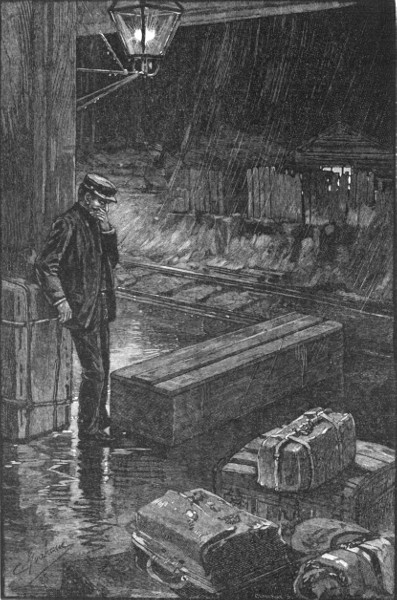

| Only a Box | 166 |

| HOME | 170 |

| Including |

| Let the Cloth be White | 172 |

[Pg 12]

[Pg 13]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| | Page |

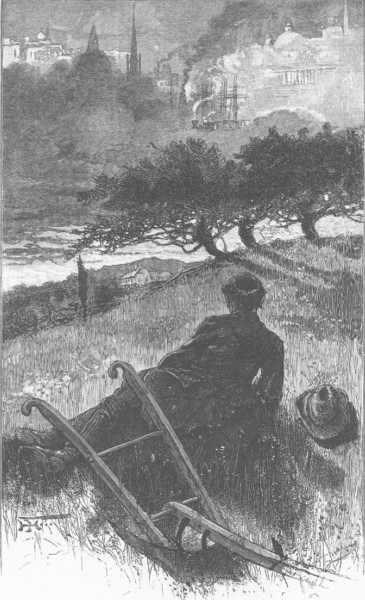

| "These are the spires that were gleaming" | Frontispiece. |

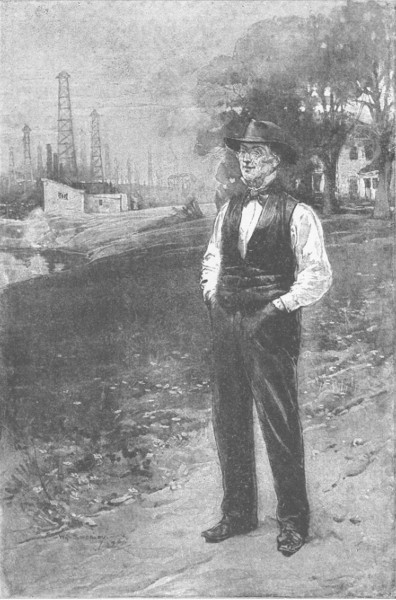

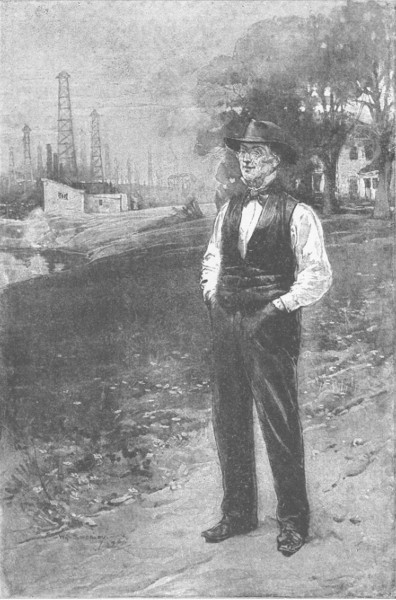

| "I saw tall derricks by the hundred rise" | 21 |

| "I reached my hand down for it and it stopped" | 29 |

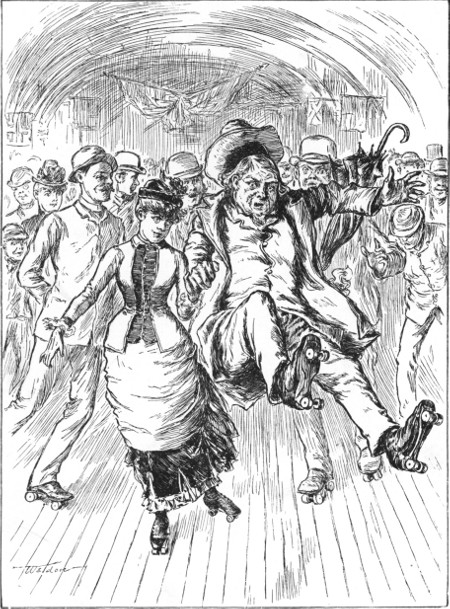

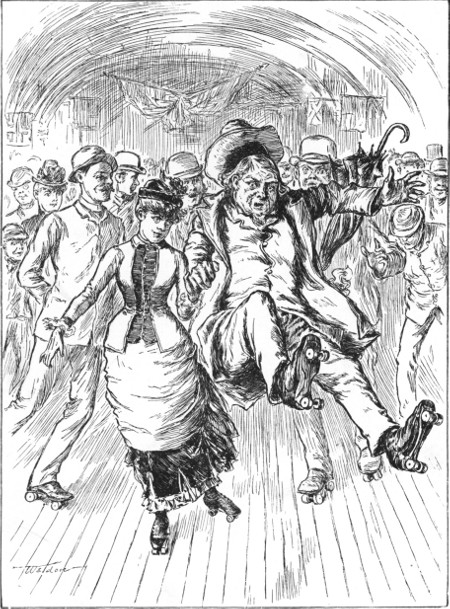

| "When all to once the wheels departed suddenly above, an' took along my heels" | 43 |

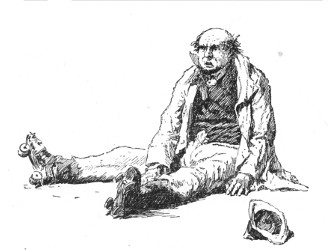

| Farmer Stebbins on Rollers | 45 |

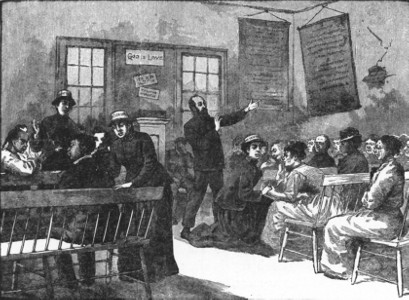

| "Yes, it's straight and true, good preacher, every word that you have said" | 51 |

| "Choked and strangled by the foul breath of the chimneys over there" | 54 |

| "Oh, the air is pure and wholesome where some babies coo and rest, and they trim |

| them out with ribbons, and they feed them with the best" | 55 |

| "Weary old man with the snow-drifted hair, not by your fault are you suffering there" | 59 |

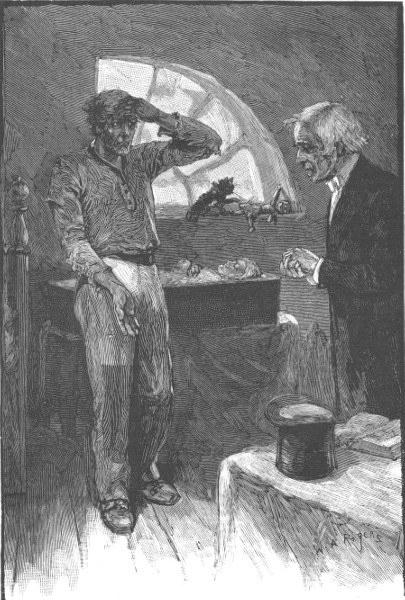

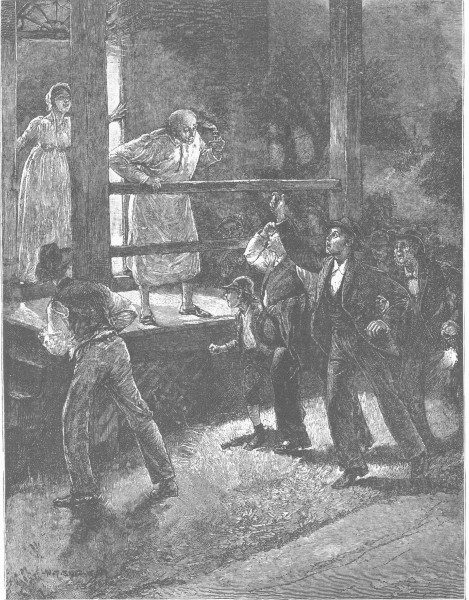

| "Is't the same girl that stood, one night, there in the wide hall's thrilling light?" | 65 |

| "And hateful hunger has come in" | 69 |

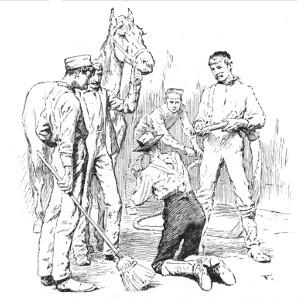

| "He begged that horse's pardon upon his bended knees" | 80 |

| "Away he rushed like a cyclone for the head o' 'Number Three'" | 82 |

| "Laid down in his harness" | 83 |

| How we Fought the Fire | 87 |

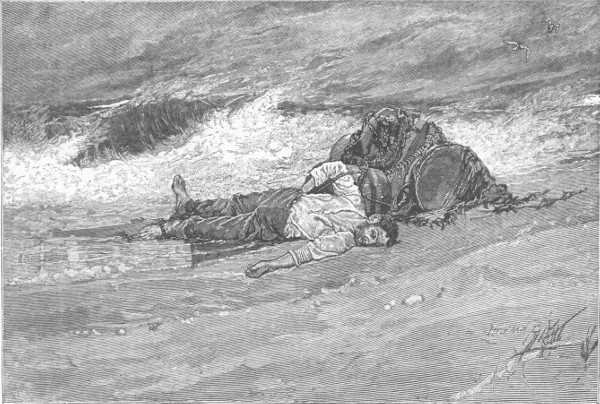

| "Battered and bruised, forever abused, he lay by the moaning sea" | 99 |

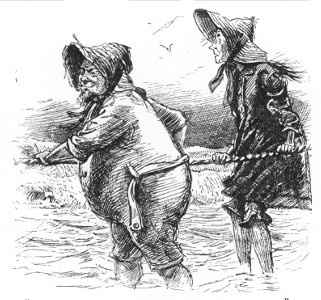

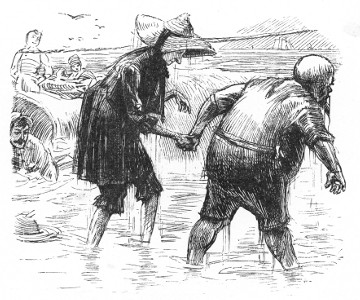

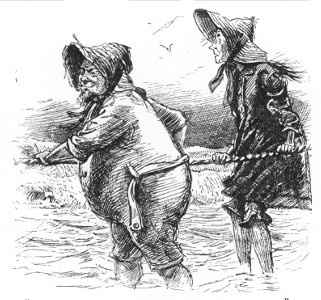

| "Miss Sunnyhopes she waded out" | 108 |

| "Two inland noodles, for our first acquaintance with the sea" | 109 |

| "A-floating on her dainty back" | 110 |

| "I tried to kick this 'lovely wave'" | 110 |

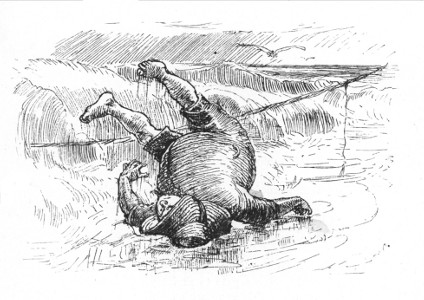

| "Heels over head—all in a bunch!" | 111 |

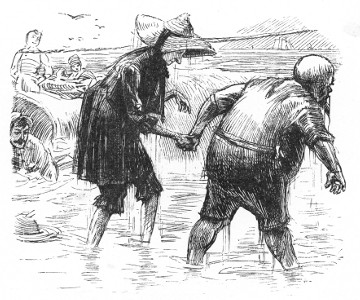

| "We voted that we'd had enough" | 111 |

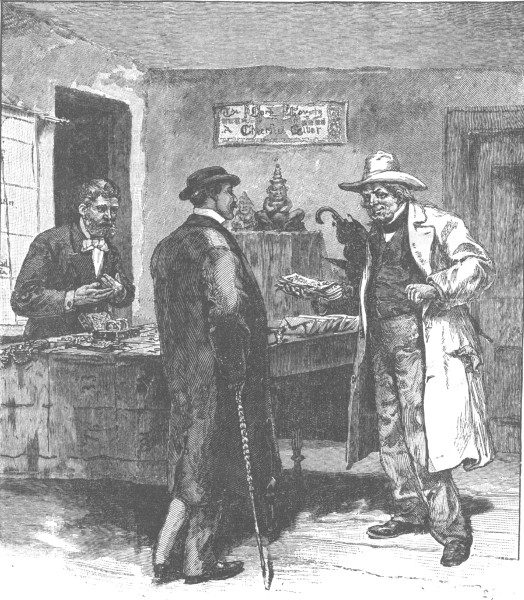

| "To make four hundred dollars clear, an' help the children too" | 121 |

| "We come 'thin part of one of it" | 123 |

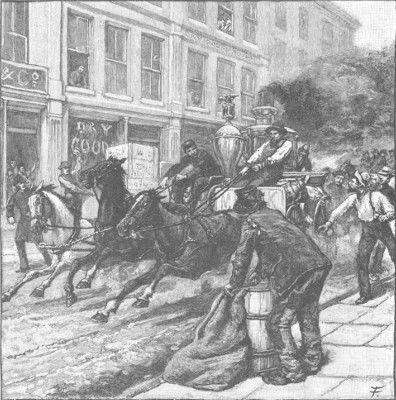

| "They 'put their heads together' in a new an' painful way" | 127 |

| "He makes himself a bigger fool than all the fools he makes" | 129 |

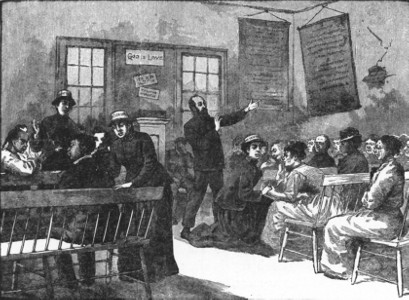

| The Salvation Army | 140 |

| The March of the Children | 141 |

| From the Monument | 149 |

| "And he stood there, like a colonel, with her trembling on his arm" | 159 |

| Chasing the Bicycle | 163 |

| "Only a box, secure and strong, rough and wooden, and six feet long" | 167 |

| "And carry back, from out our plenteous store, enough to keep himself a fortnight |

| more" | 172 |

| "The hungry city children are coming here to-night" | 173 |

| "He heard its soft tones through the cottages creep, from fond mothers singing their |

| babies to sleep" | 177 |

[Pg 14]

[Pg 15]

CITY BALLADS.

WEALTH.

[From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Here in The City I ponder,

Through its long pathways I wander.

These are the spires that were gleaming

All through my juvenile dreaming.

This is The Something I heard, far away,

When, at the close of a tired Summer day,

Resting from work on the lap of a lawn,

Gazing to whither The Sun-god had gone,

Leaving behind him his mantles of gold—

This is The Something by which I was told;

"Bend your head, dreamer, and listen—

Come to my splendors that glisten!

Either to triumph they call you,

Or to what worst could befall you!"

This is The Something that thrilled my desires,

When the weird Morning had kindled his fires,

And the gray city of clouds in the east

Lighted its streets as for pageant or feast,

Whisp'ring—my spirit elating—

"Come to me, boy, I am waiting!

Bring me your muscle and spirit and brain—

Here to my glory-strewn, ruin-strewn plain!"

[Pg 16]

Treading the trough of the furrow,

Digging where life-rootlets burrow,

Blade of the food-harvest swinging,

In the barns toiling and singing,

Breath of a hay-meadow smelling,

Forest-trees loving and felling—

Where'er my spirit was turning,

Lived that mysterious yearning!

When in the old country school-house I conned

Legends of life in the broad world beyond—

When in the trim hamlet-college I cast

Wondering glances at days that were past—

Ever I longed for the walls and the streets,

And the rich conflict that energy meets!

So I have come: but The City is great

Bearing me down like a brute with its weight.

So I have come: but The City is cold,

And I am lonelier now than of old.

Yet, 'tis the same restless story:

Even to fail here were glory!

Grand, to be part of this ocean

Of matter and mind and emotion!

Here flow the streams of endeavor,

Cityward trending forever.—

Wheat-stalks that tassel the field,

Harvests of opulent yield,

Grass-blades that fence with each other,

Flower-blossoms—sister and brother—

Roots that are sturdy and tender,

Stalks in your thrift and your splendor,

Mind that is fertile and daring,

Face that true beauty is wearing—

[Pg 17]

All that is strongest and fleetest,

All that are dainty and sweetest.

Look to the domes and the glittering spires,

Waiting for you with majestic desires!

List to The City's gaunt, thunderous roar,

Calling and calling for you evermore!

Long in the fields you may labor and wait—

You and your tribe may come early or late;

Beauty and excellence dwell and will dwell

Oft amid garden and moorland and fell;

Long generations may hold them,

Centuries oft can enfold them;

But the rich City's they some time shall be,

Sure as the spring is the food of the sea.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

September 20, 18—.

Wind in the south-west; weather wondrous fine;

Thermometer 'twixt seventy-eight and nine.

Ground rather dry; sun flails us over-warm;

It's most time for the equinoctial storm.

Family healthy as could be desired;

Except we're somewhat mind and body tired

At moving over such a lengthy road,

And settling down here in our town abode,

And wrestling with the pains that filter through one

When he gives up an old home for a new one.

Old Calendar, you've always stood me true;

Now I'll change works, and do the same by you!

You're just as good as when, with aching arm,

I cleared and worked that eighty-acre farm!

And every night, in those hard, dear old days,

'Twas one of my most unconditional ways,

When to my labors I had said Good-night,

And recompensed my home-made appetite,

[Pg 18]

And talked with Wife, and traded family views,

And gathered all the latest township news,

And dealt my sons a sly fraternal hit,

And flirted with my daughters just a bit,

And through the papers tried my way to see,

So the world shouldn't slip out from under me,

As I was saying—in those sweet old days,

'Twas one of my most unconditional ways,

To go to you, old book, before I'd sleep,

And hand you over all the day to keep.

I gave you up what weather I could find,

Likewise the different phases of my mind;

What my hard hands from morn to night had done,

And what my mind had been subsisting on;

What accidents had touched my brain with doubt,

And what successes it had whittled out;

How well I had been able to control

The weather fluctuations of my soul;

What progress or what failures I had made

In spying round and stealing Nature's trade;

The seeds of actions planted long ago,

And whether they had blossomed out or no;

And oft, from what you of the past could tell,

I've learned to steer my future pretty well.

And now I'm rich (who ever thought 'twould be!)

I'll stand by you, as you have stood by me;

And now I'm "City people"—having moved

(My circumstances suddenly improved)

Into this town, with some quick-gotten pelf,

To educate my children and myself,

And give my wife, who has a pedigree,

A chance to flutter round her family tree,

And show her natural city airs and graces

(Which didn't "take" quite so well in country places)

Now we are here, old fellow, while we stay

I'll give you all the news from day to day.[Pg 19]

I'll find the good that in this city lurks,

By regular, systematic, hard days' works;

I'll rummage fearless round amongst the harm,

As when I hoed up thistles on my farm;

Shake hands with Virtue, help Sin while I spurn it,

And if there's anything to learn, I'll learn it.

How little I suspected, by the way—

Scrambling for pennies in that patch of clay,

The bare expenses of our lives to meet—

That waves of wealth were washing at my feet!

And when my hard and rather lazy soil

Sprung a leak upward with petroleum-oil—

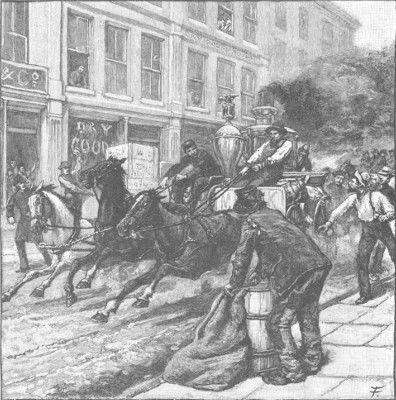

When, through the wonder in my glad old eyes,

I saw tall derricks by the hundred rise,

Flinging wealth at me with unceasing hand,

And turning to a mine my hard old land,

Until it seemed as if the spell would hold

Till every blade of grass was turned to gold—

I felt, as never yet had come to me,

How little round the curves of life we see;

Or, in our rushings on, suspect or view

What sort of stations we are coming to!

It brought a similar twinge—though not so bad—

As once, when losing every cent I had.

But still it could not shift my general views;

My mind didn't faint at one good piece of news.

I think I'd too much ballast 'neath my sail

To be capsized by one good prosperous gale

(Same as I didn't lie down and give up all

That other time, when tipped up by a squall).

I didn't go spreeing for my money's sake,

Or with my business matters lie awake;

'Twould never do, as I informed my wife,

To let a little money spoil our life!

And now I'm rich (who ever thought 'twould be!)

I'll look about, and see what I can see;

[Pg 20]Appoint myself a visiting committee,

With power to act in all parts of the city;

Growl when I must, commend whene'er I can,

And lose no chance to help my fellow-man.

For he who joy on others' paths has thrown,

Will find there's some left over for his own;

And he who leads his brother toward the sky,

Will in the journey bring himself more nigh.

And what I see and think, in my own way,

I'll tell to you, Old Calendar, each day;

And if I choose to do the same in rhyme,

What jury would convict me of a crime?

For every one, from palaces to attics,

Has caught, some time or other, The Rhythmatics.

[From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Still through The City I ponder,

Still do I wonder and wander.

City—unconscious descendant

Of olden-time cities resplendent!

Child of rich forefathers hoary,

Clad in their gloom and their glory!—

Dream I of you in the rich, mellow past,

Throbbing with life, and with Death overcast.

Thebes—not to you, crushed and ghastly and dumb,

Even the wreck-loving Ivy will come!

Where stood your hundred broad, world-famous gates,

Now a black Arab for charity waits.

Not like this City—metropolis bold—

Where the whole world brings its goods and its gold!

Babylon—here the queen's gardens climbed high,

Painting their flowers on the blue of the sky:

[Pg 21]

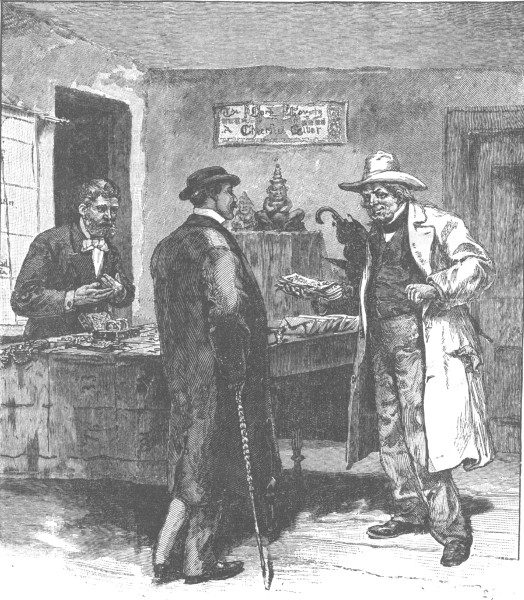

"I SAW TALL DERRICKS BY THE HUNDRED RISE."

[Pg 22]

[Pg 23]

This is where sinners, one asinine hour,

Thought they could travel to Heaven by tower.

(How like some sinners to-day, whose desires

Mount by the way of their greed-builded spires!)

Troy—of rare riches and valor possessed,

Ruined fore'er by one beautiful guest—

(Here many Helens, though less of renown,

Do for some men what she did for a town!)

Wondrous Palmyra, whose island of green,

'Mid the bleak sand, reared the beautiful queen

(Sweet-faced Zenobia, peerless

Proud in her virtue, and fearless)

In this metropolis, virtuously grand,

Many a queen is a joy to the land!

Tyre—the huge pillars that groaned under thee,

Rest in the depths of a desolate sea;

Long may it be ere the spray's salted showers

Foam o'er the walls of this city of ours!

Mound-men's vast cities, whose graves we accost,

Even your names are in ruins—and lost.

What if, some time when this nation is nought,

Vainly our names in our graves should be sought!

Cities that yet are to flourish,

That the rich Future must nourish!

Where will you take up your stations—

Where set your massive foundations?

Where are the slumbering meadows,

Dreaming of clouds through their shadows,

That by rough wheels rudely shaken,

Into new life shall awaken?

Harbors that placidly float

Nought but the fisherman's boat,[Pg 24]

Think you of fleets that shall lie

Under the blue of your sky;

When shall be built on your land

Palaces wealthily grand;

When in your face from tall spires

Gleam the electrical fires?

Cities that yet are to be,

You are not phantoms to me!

You are as certain and sure

As that Old Time shall endure.

Stars in the distant, mysterious sky,

Flashing and flaming and dancing on high,

Each is an earth to its millions,

Each has its domes and pavilions.

Cities, I see you—by reasoning led—

On the great map with blue leaves overhead.

Seaport and lakeport and rich inland town,

Capital city, and village of brown;

Thanking the prairie-food-givers,

Strung on the winding star-rivers.

Earths that can signal to earths, every one,

With the bright torches you stole from the sun,

Each on its surface has strown

Cities and towns of its own,

Fraught with their crimes and their graces,

Full of mysterious places.

They are no myths unto me—

Clearly their outlines I see;

Millions of towns I descry

Hanging o'er me from the sky.

Still through the paths of the town,

Dreaming, I walk up and down.

[Pg 25]Is it so much of a wonder—

Part of this whole, yet asunder,

I in this throng, and I only—

That I am wretched and lonely?

Loneliness—loneliness ever—

Leaving me utterly, never!

Yes, I am part of this ocean

Of matter and mind and emotion;

Yet how entirely apart,

Severed in mind and in heart!

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

September 25, 18—.

Wealth—wealth—wealth—wealth! I never had been led,

From all I'd thought and dreamed and heard and read,

To think so much wealth, in whatever while,

Could be raked up into one shining pile!

Not long ago, a hundred dollars clear,

Big as a hay-stack would to me appear.

When first a thousand dollars made me smile,

I sympathized with Crœsus quite a while;

But looking round here makes me feel the same

As if I hadn't a nickel to my name!

Wealth—wealth! why, every acre I behold

Has cost a mine of Californi' gold!

The very ground one building here might fill

Would almost buy the town of Tompkins Hill!

There isn't a house my scrutiny has crossed

But catches several figures in its cost;

And when your eyes into the parlor go

('Mongst things they leave the curtains up to show),

And see the carpets, rugs, and draperies rich,

That twine ten dollars into every stitch,[Pg 26]

And view great pictures that such prices hold

As if the painter's brush were dipped in gold;

And when along the roads great buggies glide,

With covers on, and rich-dressed folks inside,

And up on top a man to drive the team—

As fat as any cat brought up on cream

(Man and team both), the driver dressed as gay

As if he meant to marry that same day,

Or wed his boss's daughter that same night

(Which some consider as the coachman's right,

And think it's understood, when he engages,

A daughter should be thrown in with his wages),

When even the horses, as so many do,

Wear jewelry that cost a farm or two,

You wonder in what tree-top grew the cash

To buy so much reality and trash!

Wealth—wealth—wealth—wealth! the very corner stores

Are gold-mines from the ceilings to the floors!

The shop we thought would ruin Cousin Phil,

Because 'twas over-large for Tompkins Hill,

Would, in the small vest-pocket, lose its way,

Of one man's place I wandered through to-day!

And then the banks—a hundred on one street—

As full of money as an egg of meat

(Although one never knows beyond a doubt

What colored chickens they'll be hatching out);

And then the churches—elegant to view—

An independent fortune in each pew.

One window-pane in one big church that's here

Cost more than our old preacher made per year!

(A city pastor's salary, I declare,

Would keep him all his life, with cash to spare,

A-preaching in that little house of wood,

Holding his hearers' eyes in all he could,[Pg 27]

With rolling meadows and green trees in view,

And fresh-complexioned streamlets wandering through);

And then the rich school-houses in this town,

Where children can be taught up-stairs and down,

Swifter (if not so thorough), I suppose,

Than in the small log school-house, where I rose

From Numeration to the Rule of Three,

And had Irregular Verbs whipped into me;

And then the railroad stations, where, each day,

Fortunes on wheels rush in and drive away;

And then the steamboats paddling up and down—

Towns swimming on their way from town to town;

And then the ladies, in both street and store,

Done up in silks and satins, spangled o'er

As if it had rained diamonds for an hour,

And they had gone and stood out in the shower;

And then the rich and idle-houred young men—

The rising generation's "Upper 10"

(With the "1" left off), who each day, no doubt,

Spend twice as much as all my "setting out,"

When Father said, "The family craft is full;

Launch your own craft and show us how to pull."

I often think, when past a dandy glides,

Throwing his (father's) money on all sides,

And peeking under each young lady's veil,

As if he'd bought her at a mortgage sale,

How shrewd it was of him, right on the start,

To have a father who was rich and smart!

(Folks often pride themselves much, by-the-way,

Because their parents greater were than they.)

Walking to-day along Fifth Avenue,

A slip of paper on the sidewalk flew

[Pg 28]

Before my eyes—some one the same had dropped;

I reached my hand down for it and it stopped.

I picked it up—the reading on't was queer;

I think, perhaps, I'll paste it right in here.

THE LOVELY YOUNG MAN.

Oh the elements varied—the exquisite plan—

That are used in constructing the lovely young man!

His face he has easily made to possess

The expression of nothing within to express;

His hair is oiled glossily back of his ears,

Atop of his head an equator appears;

His scanty mustache has symmetrical bends,

Is groomed with precision, and waxed at both ends;

His darling complexion, bewitching to see,

Is powdered the same as a lady's might be.

And this is the dear whom the newspapers rude

Have scornfully treated, and christened the——.

The mental equipment I'll tell, if I can,

That Nature has given the lovely young man:

A set of emotions consistently weak,

To go with a creature so gentle and meek;

A will no opposing can break or surmount

(Concerning all matters of no great account);

A reasoning wheel, quite correctly revolved

(When used on small questions already resolved);

A taste for each gaudy and glistening thing

That grows on the vision and dies on the wing.

Elaborate methods and principles crude

Encompass the mental estate of the——.

The outer habiliments hastily scan,

Employed in adorning the lovely young man!

His feet two triangular cases have sought,

By which his five toes to a focus are brought;

[Pg 29]

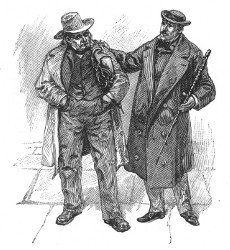

"I REACHED MY HAND DOWN FOR IT AND IT STOPPED."

[Pg 30]

[Pg 31]

The sheathes that enfold his propellers within

Are on the most intimate terms with his skin;

His starch-tortured collar on tip-toe appears,

Desirous of learning the length of his ears;

And fifteen-sixteenths of his brain, very nigh,

Has run all to blossom and stopped in his tie.

Such some of the splendors mad Fashion has strewed

All over the surface comprising the——.

Oh measure the brief philological span

Of the high-pressure words of the lovely young man!—

"B' Jauve! you daun't sayh saw! youah playing it low!

Aw, auyn't she a daisy! I knaw her, y' knaw.

She's thweet on me, somehow, though why I dawn't say,

It cawn't be my beauty, it must be my way!

Did you notith, laust night, Chawley Johnson's neck-tie?

It paralyzed me, and I thought I should d-i-e!

He's quite a sound fellaw to talk to awhile;

It's weally a pity he isn't our style!"

And thus talks forever, with slight interlude,

The creature that lately was christened a——.

Oh boys! there are several hundreds of ways

To make yourselves small to the average gaze;

Of which some will cost you considerably less,

Accomplishing nearly an equal success.

Go purchase a gilded hand-organ some day,

And stand on the corner and solemnly play;

Envelop yourselves in the skin of an ape,

Assuming his methods as well, as his shape;

Submit to refined zoological charms,

And carry a lap-dog about in your arms;

But don't let Destruction upon you intrude.

So far as to make you down into a——.

I think I saw, a minute's half or less,

The young girl who composed this spiteful mess;[Pg 32]

She watched me pick it up, made a half rush

Toward me, and then retreated with a blush.

I called, before she vanished from my vision,

"My dear, I think you've lost your composition!"

But she dodged off, as if she seemed to doubt it,

And, I suppose, went on to school without it.

Pacing the question over, far and near,

I think the little maid was too severe.

Sweet Charity can roof much sin, they tell,

Why shouldn't it shelter foolishness as well?

When we draw rein and look about a minute,

We see no field but God is somewhere in it;

He made the eagle and the lion, I've heard;

Why not the monkey and the chipping-bird?

[From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Pavement and window and wall

What is the cost of you all?

Parlor and boudoir and stair,

Crowded with furniture rare;

Gems from the mountains and seas,

Spires that out-measure the trees;

Chamber and palace and hall—

What is the price of you all?

[Voices.]

What did we cost? Bend ear;

What did we cost? Now hear.

Several millions men,

There in the field and fen.

Look! they are stripped and grim,

Sturdy of voice and limb.

[Pg 33]Painfully, now, they toil

Into the sullen soil;

Stabbing the hills and meads,

Planting the silent seeds.

Into each streaming face

Glides the hot sun apace.

You in the thoughtful guise,

You with the dreamy eyes—

"Why do you labor so?

Where do your earnings go?—

"A goodly part to the rulers that form the powers that be;

A modest part, if lucky, for my family and for me;

And all the rest for the splendors that fringe the river and sea."

[Voices.]

What did we cost? Bend ear;

What did we cost? Now hear.

Listen! the factory wall

Sends out its morning call.

Hear the machinery's din;

Look at the folks within.

Child with a poor, pale face;

Woman with hurried grace;

Man with the look half wise;

Girl with the handsome eyes.

How the long spindles whirl!

How the rich webs unfurl!

Maid with the orbs that quiver

With light from "Over the River,"[1]

Why are you toiling so?

Where do your wages go?—

"A goodly part to the owners, whoever they may be;

A little part to the living of those I love and me;

And all the rest to the cities that gem the river and sea."

[Pg 34][1] As is well known, the weird, inimitable poem, "Over the River,"

was written by a factory girl.

[Voices.]

What do we cost? Now hear;

Hearken, with eye and ear.

Several thousand men,

There in the hill and glen;

Forward, march! Take aim!

Fire! now a storm of flame!

Shriek and curse and shout;

Death-beds lying about.

Man with the kingly face,

There in that gory place

Bleeding and writhing so

(Well a moment ago),

Tell me, in mangled tones—

Tell us, amid your groans,

What do they buy with war?

What were you fighting for?—

"For country and for glory, and for the powers that be;

To deck with pride and honor the family dear to me;

And to defend our cities that gem the river and sea."

[Voices.]

What do we cost? Bend ear:

No; you will never hear.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

November 1, 18—.

Wind north-east; weather getting cross and cool;

Wife and the children gone to Sunday-school.

And I—not very well—am home again,

Holding a conversation with my pen.

And all that I can make it say to me

Is Wealth, wealth, wealth! how much I hear and see!

[Pg 35]

Strange, how, on human brains, sixteen times o'er,

Is stamped and carved the magic word of More!

Some several thousands to my credit lie

In a small bank on Wall Street, handy by;

But I can't help contriving what I'd do

If I possessed the whole Sub-Treasury too;

Or if I had (to take a modest tone)

A million million dollars, all my own!

The subject took so strong a growth in me,

I overtalked the same, last night, at tea;[2]

And so my oldest daughter (who can rhyme,

And strikes some notes that with her father's chime)

Became with that same foolishness possessed,

So much so that it would not let her rest,

But hung about her bedside all the night

And brought its capabilities in sight.

So much so that she threw it into verse

As bad as that her father writes—or worse.

And then, with some unconscious girlish grace,

And blushes chasing all about her face,

She, in a way I've learned to understand

Quite accident'ly, slipped it in my hand.

It was not made in public to appear,

But, privately, I'll paste it right in here:

[2] Our dinner is at noon; our supper, six,

We have not yet learned all the city tricks.

IF I'D A MILLION MILLIONS.

If I'd a million millions—

Just think! a million millions!—

What wouldn't I do—what couldn't I do—

If I'd a million millions?

From every forest's finest tree

My many-gabled house should be;

With silver threads from golden looms

Should be attired my palace-rooms;[Pg 36]

My blossomed table have the best

Of all the East and all the West;

My bed should be a daintier thing

Than ever sheltered queen or king;

What wouldn't I do,

What couldn't I do,

If I'd a million millions?

If I'd a million millions—

A good, square million millions—

With gratefulness my friends should bless

Me and my million millions!

None that had e'er befriended me

But he a millionaire should be;

Who kindly words of me had told,

Should find their silver turned to gold;

And he who did but just advance

The sunbeam of a friendly glance

In my affliction's cloudy day

Should have rich, unexpected pay.

What wouldn't I do,

What couldn't I do,

If I'd a million millions?

If I'd a million millions—

Just think! a million millions!—

How many coals on hostile souls

I'd heap with all my millions!

No enemy that earned my hate

Should for a fiery guerdon wait;

With roses sweet I'd twine him o'er

Until the thorns should prick him sore

(How much of credit may be claimed

For sweetly making foes ashamed

I do not know; it may depend

On how much true love we extend);

But love outpoured

I could afford,

If I'd a million millions!

[Pg 37]

An honest million millions—

Just think! a million millions!

The poor should bless the strange success

That gave me all those millions!

I'd slaughter every hungry wight

Within the circle of my sight,

And resurrect him with such food

As should go far to make him good;

No poor-house but must bow its head

And gaze at cottage walls instead;

And hungry paupers soon should see

A year of genuine jubilee.

Nought should alloy

Their perfect joy,

That could be saved by millions!

Just think! a million millions!—

The care of all those millions!

And after all, what would befall

A life with all those millions?

Would not the lucre clog my brain,

And make me hard and cold and vain?

Might not my treasure win my heart,

And make me loath with it to part?

How could I tell, by mortal sign,

Betwixt my money's friends and mine?

And then, the greed, and strife, and curse,

The world brings round a princely purse:

Perhaps my soul,

Upon the whole,

Is best, without the millions!

[From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Now comes the Christmas-tide:

Love wakes on every side;

Mirth smiles from every eye;

Wreaths greet the passer-by.

[Pg 38]

Who, full of haughty pride,

Loves not the Christmas-tide?

He who, with av'rice low,

Cares not to joy bestow.

God save the wretch denied

Love for the Christmas-tide!

God tell his hardened heart

Pure joy must joy impart!

Who, close to grief allied,

Grieves 'mid the Christmas-tide?

She who, at Sorrow's call,

Now mourns the loss of all.

God save the dear bereft—

Teach her the mercies left!

Show her that clouds may yet

Lift, ere her sun be set!

Who lonely must abide

All through the Christmas-tide?

He who has never known

Love-passion of his own.

So follows he his fate,

Friendly but desolate;

So—sad—his heart must hide

All through the Christmas-tide!

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

December 25, 18—.

Wind in the north-east; snow in wagon-loads;

Good sleighing everywhere on all the roads.

Family healthy, sensible, and pleasant,

And each one got the proper Christmas-present.[Pg 39]

(At least it seems so, for they all act suited,

And Santa Claus's taste hasn't been disputed.)

Our family room is filled with tasty mixings

Of evergreens and other woman-fixings;

The open grate makes things look rich and mellow,

With good hard coals the fire has painted yellow;[3]

Pictures peep from the walls, with thought all through them,

That set me studying every time I view them;

There's certain books upon the centre-table

That say what I'd have said if I'd been able;

And, measuring up this room with honest style,

'Tisn't a bad place to be in for a while.

And so I sit here, thinking, musing, dreaming,

About the world and all its curious scheming,

And, full of certainty-begotten doubt,

Wondering what this life is all about

(From all that I can learn I'm not to blame,

For wiser men have often done the same).

We went a mile or two, last night, to see

The decorations on a Christmas-tree;

I spied, hung on that sapling's gilded arms,

Things that would buy a couple good sized farms;

And just upon our way home, I should guess

We met some fifty people, more or less,

Who needed, to make passable their days,

A decent share of what those farms would raise.

But here's the question: should those ill-to-do

Deprive rich people of their comforts too?

Because there are some people lack for bread,

Must others' minds and fancies go unfed?

It's quite a puzzle, which I don't know whether

My clumsy mind knows how to put together;

[Pg 40]

But one thing's sure: wants satisfied wants breed—

The more folks get, the more they seem to need.

Then, one man lives on what would starve another,

And what is joy for you might kill your brother.

[3] Although to me it doesn't contain the charm

Of our old, wide log fire-place on the farm.

January 5, 18—.

Went to a skating-rink a little while,

To see them slide in the new-fangled style;

And, strange enough, this eve a letter came

From a friend—Abdiel Stebbins is his name—

A cousin of my aunt, Sophia Dean;

A wise old man, but clumsy like, and green.

He's on a visit in a neighboring city,

And he has been a-skating—more's the pity!

He tells it in a manner quite sincere;

I think perhaps I'll paste it right in here:

[FARMER STEBBINS ON ROLLERS.]

Rochester, January 4.

Dear Cousin John:

We got here safe—my worthy wife an' me—

An' put up at James Sunnyhopes'—a pleasant place to be;

An' Isabel, his oldest girl, is home from school just now,

An' pets me with her manners all her young man will allow;

An' his good wife has monstrous sweet an' culinary ways:

It is a summery place to pass a few cold winter days.

Besides, I've various cast-iron friends in different parts o' town,

That's always glad to have me call whenever I come down;

But t'other day, when 'mongst the same I undertook to roam,

I could not find a single one that seemed to be to home!

An' when I asked their whereabouts, the answer was, "I think,

If you're a-goin' down that way, you'll find 'em at the Rink."

I asked what night the Lyceum folks would hold their next debate—

(I've sometimes gone an' helped 'em wield the cares of Church an' State),[Pg 41]

An' if protracted meetin's now was holdin' anywhere

(I like to get my soul fed up with fresh celestial fare);

Or when the next church social was; they'd give a knowin' wink,

An' say, "I b'lieve there's nothin' now transpirin' but the Rink."

"What is this 'Rink?'" I innocent inquired, that night at tea.

"Oh, you must go," said Isabel, "this very night with me!

And Mrs. Stebbins she must go, an' skate there with us, too!"

My wife replied, "My dear, just please inform me when I do.

But you two go." An' so we went, an' saw a circus there,

With which few sights I've ever struck will anyways compare.

It seems a good-sized meetin'-house had given up its pews

(The church an' pastor had resigned, from spiritual blues),

An' several acres of the floor was made a skatin' ground,

Where folks of every shape an' size went skippin' round an' round;

An' in the midst a big brass band was helpin' on the fun,

An' everything was gay as sixteen weddin's joined in one.

I've seen small insects crazy-like go circlin' through the air,

An' wondered if they thought some time they'd maybe get somewhere;

I've seen a million river-bugs go scootin' round an' round,

An' wondered what 'twas all about, or what they'd lost or found;

But men an' women, boys an' girls, upon a hard-wood floor,

All whirlin' round like folks possessed, I never saw before.

An' then it straight came back to me, the things I'd read an' heard

About the rinks, an' how their ways was wicked an' absurd;

I'd learned somewhere that skatin' wasn't a healthy thing to do—

But there was Doctor Saddlebags—his fam'ly with him, too!

I'd heard that 'twasn't a proper place for Christian folks to seek—

Old Deacon Perseverance Jinks flew past me like a streak!

Then Sister Is'bel Sunnyhopes put on a pair o' skates,

An' started off as if she'd run through several different States.

My goodness! how that gal showed up! I never did opine

That she could twist herself to look so charmin' an' so fine;

And then a fellow that she knew took hold o' hands with her,

A sort o' double crossways like, an' helped her, as it were.[Pg 42]

I used to skate; an' 'twas a sport of which I once was fond.

Why, I could write my autograph on Tompkins' saw-mill pond.

Of course to slip on runners, that is one thing, one may say,

An' movin' round on casters is a somewhat different way;

But when the fun that fellow had came flashin' to my eye,

I says, "I'm young again; by George, I'll skate once more or die!"

A little boy a pair o' skates to fit my boots soon found—

He had to put 'em on for me (I weigh three hundred pound);

An' then I straightened up an' says, "Look here, you younger chaps,

You think you're runnin' some'at past us older heads, perhaps.

If this young lady here to me will trust awhile her fate,

I'll go around a dozen times an' show you how to skate."

She was a niceish, plump young gal, I'd noticed quite a while,

An' she reached out her hands with 'most too daughterly a smile;

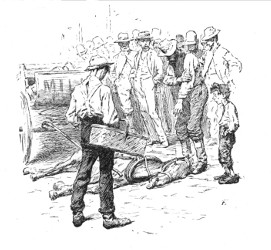

But off we pushed with might an' main; when all to once the wheels

Departed suddenly above, an' took along my heels;

My head assailed the floor as if 'twas tryin' to get through,

An' all the stars I ever saw arrived at once in view.

'Twas sing'lar (as not quite unlike a saw-log there I lay)

How many of the other folks was goin' that same way;

They stumbled over me in one large animated heap,

An' formed a pile o' legs an' arms not far from ten foot deep;

But after they had all climbed off, in rather fierce surprise,

I lay there like a saw-log still—considerin' how to rise.

Then, dignified I rose, with hands upon my ample waist,

An' then sat down again with large and very painful haste;

An' rose again, and started off to find a place to rest,

Then on my gentle stomach stood, an' tore my meetin' vest;

When Sister Sunnyhopes slid up as trim as trim could be,

An' she an' her young fellow took compassionate charge o' me.

Then after I'd got off the skates an' flung 'em out o' reach,

I rose, while all grew hushed an' still, an' made the followin' speech:

"My friends, I've struck a small idea (an' struck it pretty square),

Which physic'ly an' morally will some attention bear:

[Pg 43]

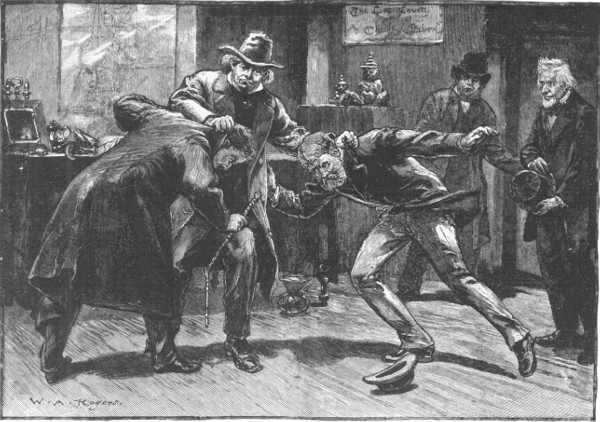

"...WHEN ALL TO ONCE THE WHEELS

DEPARTED SUDDENLY ABOVE, AN' TOOK ALONG MY HEELS."

[Pg 44]

[Pg 45]

Those who their balance can preserve are safe here any day,

An' those who can't, I rather think, had better keep away."

Then I limped out with very strong unprecedented pains,

An' hired a horse at liberal rates to draw home my remains;

An' lay abed three days, while wife laughed at an' nursed me well,

An' used up all the arnica two drug-stores had to sell;

An' when Miss Is'bel Sunnyhopes said, "Won't you skate some more?"

I answered, "Not while I remain on this terrestrial shore."

[Pg 46]

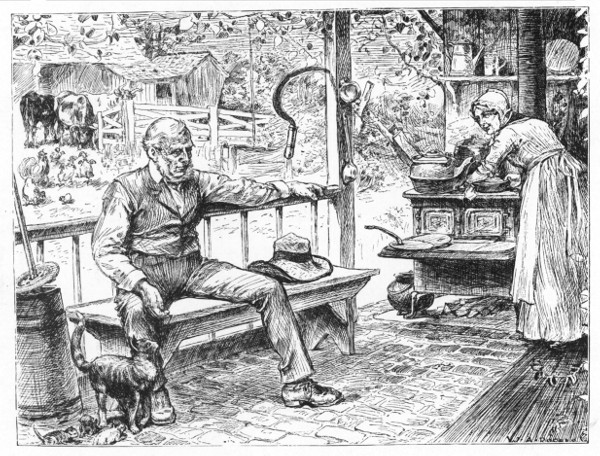

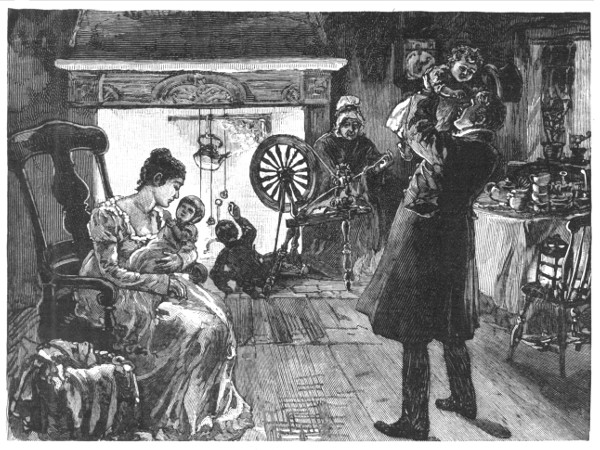

FARMER STEBBINS ON ROLLERS.

WANT.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

February 5, 18—.

Want—want—want—want! O God! forgive the crime,

If I, asleep, awake, at any time,

Upon my bended knees, my back, my feet,

In church, on bed, on treasure-lighted street,

Have ever hinted, or, much less, have pleaded

That I hadn't ten times over all I needed!

Lord save my soul! I never knew the way

That people starve along from day to day;

May gracious Heaven forgive me, o'er and o'er,

That I have never found these folks before!

Of course some news of it has come my way,

Like a faint echo on a drowsy day;

At home I "gave," whene'er by suffering grieved,

And called it "Charity," and felt relieved;

And thought that I was never undertasked,

If I bestowed when with due deference asked.

But no one finds the poorest poor, I doubt,

Unless he goes himself and hunts them out;

And when you get real suffering among,

Be thankful if your heart-strings are not wrung!

These thoughts sobbed through me this cold, snowy day,

As carefully I picked a dubious way

'Mongst nakedness and want on every side,

And a rough, masculine angel for my guide,[Pg 47]

Who goes about among affliction's heirs,

And gives his life to piece out some of theirs.

Up—up—up—up! and yet, I am afraid,

Farther from Heaven at every step we made!

Gaunt, hungry creatures stood on every side

With cheeks drawn close and sad eyes opened wide,

Filled to the brim with greedy, starving prayers,

As we went past them up the creaking stairs.

And I peeped into rooms 'twas death to see

(Or, rather, they peeped darkly out at me)—

Such as I wouldn't have had the cheek to 've shown

To any swine I've ever chanced to own.

'Twas sad to see, in this great misery-cup,

How guilt and innocence were all mixed up:

Here lay a fellow, stupid, dull, and dumb,

Whose breath was like a broken keg of rum;

And there a baby, looking scared and odd,

Who had not been a week away from God.

Here a clean woman, toiling for her bread;

And there a wretch whose dirty heart was dead.

Here a sound rascal, lazy, loud, and bold;

And there the helpless, weak and sick and old.

Want—want! O Lord! forgive me, o'er and o'er,

That I haven't found these suffering folks before!

We had a decent poor-house in our town,

And I would often drive my spare horse down,

And take a little stroll among them there,

And try to cheer their every-day despair,

And with their little wants and worries join,

And chink round 'mongst them with small bits of coin

(Done up in good advice, somewhat severe),

And send them Christmas turkeys every year;

Then, in my cosy home, think, with a grin,

What a fine, liberal angel I had been.

But here, O heavens! I find them, high and low,

Hundreds of pauper-houses in a row![Pg 48]

And suffering—suffering—in a shape, I vow,

That makes my poor old tears run even now!

For city trouble, any one will find,

Is more ingenious than the country kind,

And has a thousand cute-invented ways

To torture men and shorten off their days.

And while we wonder that God made it so,

He doesn't seem very anxious we should know;

But He is willing we should search His plan,

And pry around and find out all we can;

And I suspect, when pains and troubles fall,

That every one is useful, after all.

At any rate, the miseries that I see

Are useful in their good effects on me;

And though that isn't a great thing, on the whole

(Though Heaven does put a premium on each soul),

Yet there are several people, I suspect,

Who need a little of that same effect;

And if they do not get it, old and young,

'Twill be because I've lost my poor old tongue.

One more small portion of God's plan I see

Concerning its effect on "even me:"

And that's its leading me, by methods queer,

To be some help to these poor people here.

For now I promise, from this very night,

And hereby put it down in black and white,

That out of every day that's given me yet,

And out of every dollar I can get,

And out of every talent, small or large,

That God sees fit to put into my charge,

A part shall be devoted—square and sure—

To God's own suffering, struggling, dying poor!

[Pg 49] [From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Poverty, why wast thou born

In the world's earliest morn?

Why hast thou lived all the years,

Sowing thy pains and thy tears?

Roaming about thou art seen,

Crooked, decrepit, and lean;

Travelling all the world through—

Suffering's "wandering Jew."

Thin and unkempt is thy hair,

Fleshless as parchment thy cheek,

Sad and ungainly thine air,

Hollow the words thou dost speak,

Bony and grasping thy hand,

Dreary thy days in the land.

Poverty, why wast thou born

Under the world's quiet scorn?

Poverty, thou hast been seen

Clad in a comelier mien.

Oft, to the clear-seeing eyes,

Thou art a saint in disguise.

Discipline rich thou hast brought,

Lessons of labor and thought.

Oft, in thy dreariest night,

Virtue gleams sturdy and bright;

Oft, from thy scantiest hour,

Grow the beginnings of power;

Oft, 'mongst thy squalors and needs

Live such magnificent deeds

As the proud angels will crown

There in their gold-streeted town;

Oft, from thy high garrets, throng

Notes of magnificent song,[Pg 50]

That, from sad day unto day,

Float through the ages away.

Poverty—brave or forlorn—

God knoweth why thou wast born.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

February 12, 18—.

Wind in the South; a fresh, sweet, winter day;

'Twould have been sad to see it go away,

If 'twere not that the sunset's signal-lights

Glimmered awhile across the Jersey heights,

Then, lightly dancing o'er the river, came

And set some New York windows all aflame.

(From a clear sunset I can always borrow

God's sweet half promise of a fair to-morrow.)

But, while I gazed upon that splendid sight,

My mind would take a heavy, care-winged flight

Up to a small back garret, far away,

Where I had stood at two o'clock to-day.

Want—want—want—want! it hung 'round everywhere;

It threw its odors on the sickly air!

The room was somewhat smaller, to begin,

Than I would put a span of horses in;

The floor was rough and damp as floor could be;

No picture on the walls but Poverty;

The bed was ragged, scanty, hard, and drear;

A rough-made, empty crib was standing near;

The "window" 'd never felt the sun's warm stare,

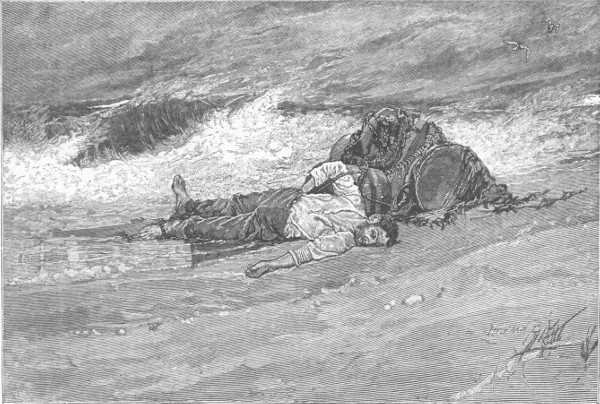

Or breathed a breath of good old-fashioned air;

[Pg 51]

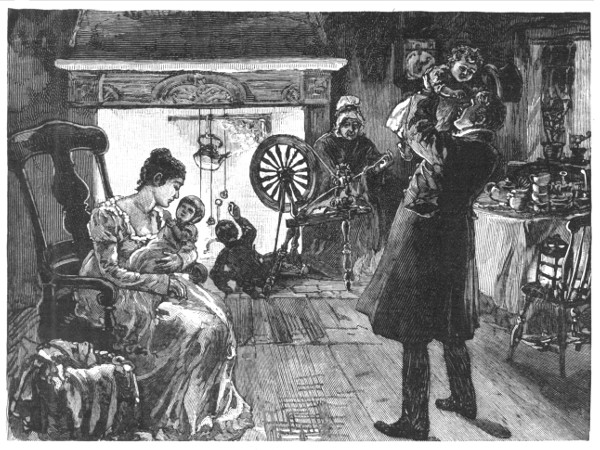

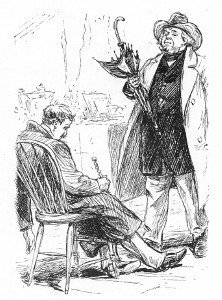

"YES, IT'S STRAIGHT AND TRUE, GOOD PREACHER, EVERY WORD THAT YOU HAVE SAID."

"YES, IT'S STRAIGHT AND TRUE, GOOD PREACHER, EVERY WORD THAT YOU HAVE SAID."

[Pg 52]

A little, worn-out doll some child had had,

Looking, like its surroundings, rough and sad,

[Pg 53]

And dressed in rags and pinched and famine-faced,

But bearing still some marks of girlish taste;

A gaunt, gray kitten, showing every sign

That it was on the last life of its nine,

Though trying hard to feel quite sleek and fat,

And not a very care-worn, desolate cat;

A man, so grieved my heart can see him now,

With frightful sorrow printed on his brow;

A rough, wood coffin stood there near the bed,

Looking uneasy even for the dead;

A little, pallid face I saw therein—

A niceish-looking child she must have been,

As sweet as ever need to feed a glance,

If she had only had one-half a chance.

But still, she woke a thought I could not smother—

"That child was murdered in some way or other."[4]

And my opinion didn't seem much amiss

When the man spoke up, something like to this:

[4] All this, above the shoulder, I could see,

Of an old preacher who had come with me—

A man who, 'mongst those garrets, earns, they say,

A house and lot in heaven every day.

[THAT SWAMP OF DEATH.]

Yes, it's straight and true, good Preacher, every word that you have said;

Do not think these tears unmanly—they're the first ones I have shed!

But they kind o' beat and pounded 'gainst my aching heart and brain,

And they would not be let go of, and they gave me extra pain.

I am just a laboring man, sir—work for food and rags and sleep,

And I hardly know the meaning of the life I slave to keep;

But I know when times are cheery, or my heart is made of lead;

I know sorrow when I see it, and—I know my girl is dead!

[Pg 54]

No, she isn't much to look at—just a plainish bit of clay,

Of the sort of perished children that die 'round here every day;

And how she could break a heart up you'd be slow to understand,

But she held mine, Mr. Preacher, in that little withered hand!

There are lots of prettier children, with a face and form more fine—

Let their parents love and pet them—but this little one was mine!

There was no one else to cling to when we two were torn apart,

And it's death—this amputation of the strong arms of the heart!

I am just an ignorant man, sir, of the kind that digs and delves,

But I've learned that human beings cannot stay in by themselves;

They will reach out after something, be it good or be it bad,

And my heart on hers had settled, and—the girl was all I had!

"CHOKED AND STRANGLED BY THE FOUL BREATH OF THE CHIMNEYS OVER THERE."

Yes, it's solid, Mr. Preacher, every word

that you have said—

God loves children while they're living,

and adopts them when they're dead;

But I cannot help contriving, do the very best I can,

That it wasn't God's mercy took her, but the selfishness of man!

[Pg 55]

Why, she lay here, faint and gasping, moaning for a bit of air,

Choked and strangled by the foul breath of the chimneys over there;

It climbed through every window, and crept under every door,

And I tried to bar against it, and she only choked the more.

"OH, THE AIR IS PURE AND WHOLESOME WHERE SOME BABIES COO AND REST,

AND THEY TRIM THEM OUT WITH RIBBONS, AND THEY FEED THEM WITH THE BEST."

She would lie there, with the old look that poor children somehow get;

She had learned to use her patience, and she did not cry or fret,

But would lift her little face up, so piteous and so fair,

And would whisper, "I am dying for a little breath of air!"

[Pg 56]

If she'd gone off through the sunlight, 'twouldn't have seemed so hard to me,

Or among the fresh cool breezes that come sweeping from the sea;

But it's nothing less than murder when my darling's every breath

Chokes and strangles with the poison from that chimney swamp of death!

Oh, it's not enough those people own the very ground we tread,

And the shelter that we crouch in, and the tools that earn our bread;

They must place their blotted mortgage on the air and on the sky,

And shut out our little heaven, till our children pine and die!

Oh, the air is pure and wholesome where some babies coo and rest,

And they trim them out with ribbons, and they feed them with the best;

But the love they bear is mockery to the gracious God on high,

If to give those children luxuries some one else's child must die!

Oh, we wear the cheapest clothing, and our meals are scant and brief,

And perhaps those fellows fancy there's a cheaper grade of grief;

But the people all around here, losing children, friends, and mates,

Can inform them that Affliction hasn't any under-rates.

I'm no grumbler at the rulers of "this free and happy land,"

And I don't go 'round explaining things I do not understand;

But I know there's something treacherous in the working of the law,

When we get a dose of poison out of every breath we draw.

I have talked too much, good Preacher, and I hope you won't be vexed,

But I'm going to make a sermon with that white face for a text;

And I'll preach it, and I'll preach it, till I set the people wild

O'er the heartless, reckless grasping of the men who killed my child!

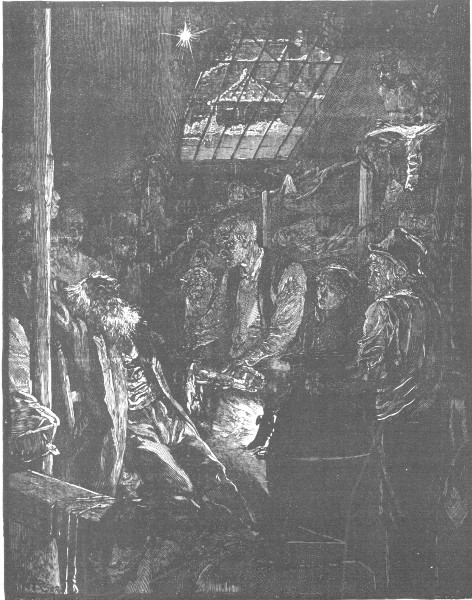

[From Arthur Selwyn's Note-book.]

Still do I write—day-time and night—

That which I see in my leisurely flight.

What is this sign that is claiming the sight?—

"Lodgings within here, at five cents per night!"

[Pg 57]

Let me examine this cheap-entered nest,

Pay my five cents, and go in with the rest;

Let me jot down with sly pen, but sincere,

What, in this garret, I see, smell, and hear.

Great, gloomy den! where, on close-clustered shelves,

Shelterless wretches can shelter themselves;

Pestilence-drugged is the murderous air,

Full of the breathings of want and despair!

Horrible place!—where The Crushed Race

Winces 'neath Poverty's dolefullest blight—

Bivouac of suffering, sin, and disgrace:

What can you look for, at five cents per night?

Hustle them in, jostle them in,

Many of nation, and divers of kin;

Sallow, and yellow, and tawny of skin—

Hustle them, bustle them, jostle them in!

Handfuls of withered but suffering clay,

Swept from the East by oppression away;

Baffled adventurers, conquered and pressed

Back from the gates of the glittering West;

Men who with indolence, folly, and guile

Carelessly slighted Prosperity's smile;

Men who have struggled 'gainst Destiny's frown,

Inch after inch, till she hunted them down.

Scores in a tier—pile them up here—

Many of peoples and divers of kin;

Drift of the nations, from far and from near,

Hustle them, bustle them, jostle them in!

Islands of green, mistily seen,

Hover in visions these sleepers between;

Beautiful memories, cozy and clean,

Restfully precious, and sweetly serene.[Pg 58]

Womanly kisses have softened the brow

Lying in drunken bewilderment now;

Infantile faces have cuddled for rest

Here on this savage and rag-covered breast.

Lucky the wretch who, in Poverty's ways,

Bears not the burden of "happier days:"

Many a midnight is gloomier yet

By the remembrance of stars that have set!

Echoes of pain, drearily plain,

Come of old melodies sweet and serene;

Images sad to the heart and the brain

Rise out of memories cozy and green.

Hustle them in, bustle them in,

Fetid with squalor, and reeking with gin,

Loaded with misery, folly, and sin—

Hustle them, bustle them, jostle them in!

Few are the sorrows so hopelessly drear

But they have sad representatives here;

Never a crime so complete and confessed

But has come hither for one night of rest.

Seeds that the thorns of diseases may bear

Float on the putrid and smoke-laden air;

Ghosts of destruction are haunting each breath—

Soft-stepping agents, commissioned by Death.

Crowd them in rows, comrades or foes,

Deadened with liquor and deafened with din,

Fugitives out of the frosts and the snows,

Hustle them, bustle them, jostle them in!

[Pg 59]

"WEARY OLD MAN WITH THE SNOW-DRIFTED HAIR,

NOT BY YOUR FAULT ARE YOU SUFFERING THERE."

"WEARY OLD MAN WITH THE SNOW-DRIFTED HAIR,

NOT BY YOUR FAULT ARE YOU SUFFERING THERE."

[Pg 60]

Guilt has not pressed unto its breast

All who are taking this dingy unrest:

Innocence often is Misery's guest;

Sorrow may strike at the brightest and best.[Pg 61]

You from whom hope, but not feeling, has fled,

This is your refuge from pauperhood's bed;

Timorous lad with a sensitive face,

You have no record of crime and disgrace;

Weary old man with the snow-drifted hair,

Not by your fault are you suffering there,

Never a child of your cherishing nigh—

'Tis not for sin you so drearily die.

Pain, in all lands, smites with two hands—

Guilty and good may encounter the test;

Misery's cord is of different strands;

Sorrow may strike at the brightest and best.

Sympathy's tear, warm and sincere,

Cannot but glisten while lingering near.

Edge not away, sir, in horror of fear,

These are your brothers—this family here!

What if Misfortune had made you forlorn

With her stiletto as well as her scorn?

What if some fiend had been making you sure

With more temptation than flesh could endure?

What if you deep in the slums had been born,

Cradled in villany, christened in scorn?

What if your toys had been tainted with crime?

What if your baby hands dabbled in slime?

Judge them with ruth. Maybe, in truth,

It is not they, but their luck, that is here.

Fancy your growth from a sin-nurtured youth;

Pity their weakness, and give them a tear.

Help them get out; help them keep out!

Labor to teach them what life is about;

Give them a hand unencumbered with doubt;

Feed them and clothe them, but pilot them out![Pg 62]

Mortals depraved, whatsoe'er they have been,

Soonest can mend from assistance within.

Warm them and feed them—they're beasts, even then;

Teach them and love them—they grow into men.

You who 'mid luxuries costly and grand

Decorate homes with munificent hand,

Use, in some measure, your exquisite arts

For the improvement of minds and of hearts.

Lilies must grow up from below,

Where the strong rootlets are twining about;

Goodness and honesty ever must flow

From the heart-centres—to blossom without.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

February 28, 18—.

Wind in the west; no symptoms of a thaw;

The coldest, bleakest day I ever saw.

And I'm housed up, with nothing much to do

Except to read the papers through and through.

"Died of starvation!"—what does this all mean?

Stores of provisions everywhere are seen.

"Died of starvation!"—here's the place and name

Right in the paper; let us blush for shame!

This city wastes what any one would call

Nine hundred times enough to feed us all;

And yet folks die in garret, hut, and street,

Simply because there isn't enough to eat!

Oh, heavens! there runs a great big Norway rat,

Sleek as a banker, and almost as fat;

He daily breakfasts, dines, and sups, and thrives

On what would save a pair of human lives;

[Pg 63]

He rears a family with his own fat features,

On food we lock up from our fellow-creatures;

And human beings fall down by the way,

And die for want of food, this very day!

"Frozen to death!"—the worse than useless moth

May feed, this year, on bales and bales of cloth;

Untouched, ten million tons of coal can lie,

While God's own human beings freeze and die!

"Died of starvation!"—waves of golden wheat

All summer dashed and glistened at our feet;

Dull, senseless grain is stored in buildings high,

And God's own human beings starve and die!

I would not rob from rich men what they earn,

But I would have them sweet compassion learn;

Oh, do not Pity's gentle voice defy,

While God's own human beings starve and die!

March 5, 18—.

Died of starvation!—yes, it has been done;

To-day I've seen a hunger-murdered one,

Who had a perfect right, it seemed to me,

The mistress of a happy home to be;

And yet we found her on a ragged bed,

One white arm underneath a shapely head;

Her long, bright hair was lying, fold on fold,

Like finest threads spun from a bar of gold;

Her face was chiselled after beauty's style,

And want had not hewn out its witching smile;

'Twas like white marble half endowed with breath—

The face of this sweet maiden—starved to death!

Not far from where she lay, so sadly lone,

Her calendar, or "diary," was thrown;

They let me have it when the law had read

This plaintive, girlish message from the dead.

[Pg 64]

It doesn't look well among these notes to stay,

Of one who feeds on blessings every day;

But I will put it in here, for my heart

To look at when I feel too proud and smart!

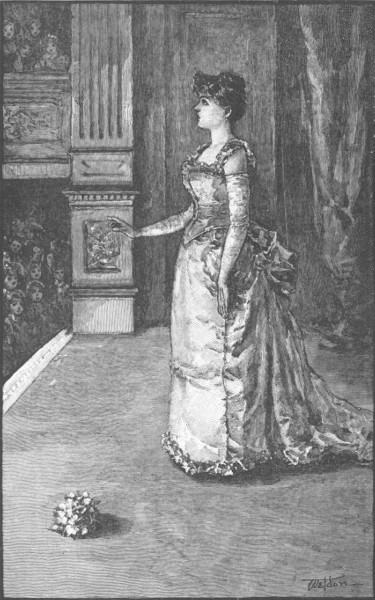

A SEWING-GIRL'S DIARY.

February 1, 18—.

Here—am I here?

Or is it fancy, born of fear?

Yes—O God, save me!—this is I,

And not some wretch of whom I've read,

In that bright girlhood, when the sky

Each night strewed star-dust o'er my head;

When each morn meant a gala-day,

And all my little world was gay.

I had not felt the touch of Care;

I'd heard of something called Despair,

But knew it only by its name.

(How far it seemed!—how soon it came!)

Yes, all the bright years hurried by;

Sorrow was near, and—this is I!

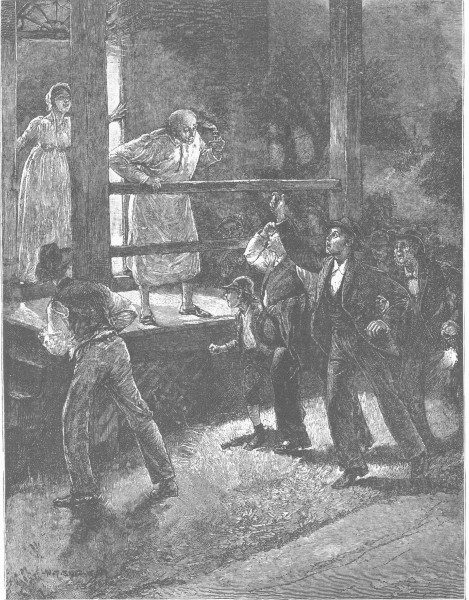

Is't the same girl that stood, one night,

There in the wide hall's thrilling light,

With all the costly robes astir

That love and pride had bought for her?

How the great crowd, 'mid their kind din,

Gazed with gaunt eyes and drank me in!

And then they hushed at each low word,

So Death himself might have been heard,

To hear me mournfully rehearse

The tender Hood's pathetic verse

About the woman who, half dead,

Stitched her frail life in every thread.

How little then I knew the need!

Yet for my own sex I did plead,

And my heart crept on each word's track

Till soft sobs from the crowd came back.

[Pg 65]

"IS'T THE SAME GIRL THAT STOOD, ONE NIGHT,

THERE IN THE WIDE HALL'S THRILLING LIGHT?"

[Pg 66]

[Pg 67]

I saw my sister, streaming-eyed,

Yet bearing still a face of pride:

Oh, sister! when you looked at me

With that quick yearning glance of love,

Did you peer on, to what might be—

What is?—and is it known above?

When that great throng a shout did raise,

And gave me words of heart-felt praise,

And loving eyes their incense burned

Till my young girlish head was turned—

Did your clear eye see farther then

A moment past all mortal ken,

And in the dreary scene I drew

Did my own form appear to you?

It might have been; grief was o'er-nigh,

And—God, have pity!—this is I,

Treading a steep and dang'rous way,

And—earning twenty cents a day!

February 5, 18—.

Father, this is the time we hailed

As your bright birthday. We ne'er failed

To throng about with love's fond arts,

And bring you presents from our hearts;

Your pleasure filled our day with bliss;

Oh what a different one from this!

My love, my father! how you stood

'Twixt me and all that was not good!

How, each o'er-hurried breath I drew,

My girl-heart turned and clung to you!

How near comes back that dismal day

You sat, sad-faced, with naught to say,

From morn till night! I did not dare

Even to ask to soothe your care;

I knew it was too sadly grand

To feel the light touch of my hand.

[Pg 68]

Ah! friends you loved had gone astray,

And swept our competence away;

And oh, I strove so hard to save

Your honored gray hairs from the grave!

Too late! your sun went down o'er-soon,

Clouded, in life's mid-afternoon.

You guarded me with patience rare

From e'en the shadow of a care;

You called me "Princess;" and my room

Was dressed as palaces might be;

And—here I am amid this gloom

That mocks, insults, and murders me,

Striving a garret's rent to pay,

And—earning twenty cents a day!

February 20, 18—.

I cannot well afford to write—

My fingers are in call elsewhere;

But I must voice my black despair,

Or I should die before 'twas night.

I have no mother now to call,

And seek her heart, and tell her all.

O, Mother! well I know you rest

In yonder heaven, serene and blest:

How sadly, strangely sweet 'twould be

To know you knew and pitied me!

And yet I would not have you dream

E'en of the dagger's faintest gleam

That's pointing at my maiden breast.

Rest on, sweet mother, sweetly rest!

And still I feel your loving art,

Sometimes upon my aching heart.

That night I stood upon the pier,

And the gray river swept so near,

And glanced up at me in a way

Some one with friendly voice might say,

"Come to my arms and rest, poor girl."

And I leaned down with head awhirl,

And heart so heavy it might sink

Me underneath the river's brink,

A hand I could not feel or see

Drew me away and fondled me;

A voice I felt, unheard, though near,

Said, "Wait! you must not enter here,

And press against me with one stain.

Poor girl, not long you need remain!"

[Pg 69]

"AND HATEFUL HUNGER HAS COME IN."

"AND HATEFUL HUNGER HAS COME IN."

[Pg 70]

But, O sweet mother! I must write[Pg 71]

The words that would be said to-night,

If you could hold my tired head here!

I cannot see one gleam of cheer;

This is a garret room, so bleak

The cold air stings my fading cheek;

Fireless my room, my garb is thin,

And hateful Hunger has come in,

And says, "Toil on, you foolish one!

You shall be mine when all is done."

Two days and nights of pain and dread

I've gnawed upon a crust of bread

(For what scant nourishment 'twould give)

So hard, I could not eat and live!

O mother! I to God shall pray

This tale in heaven may ne'er be told;

For you are where whole streets are gold,

And I—earn twenty cents a day!

February 22, 18—.

He never loved me. For no one

Could love and do as he has done.

How my heart clung and clung to him,

E'en when respect and faith grew dim;

His lightest touch could thrill me so!

Weak girl, 'twas hard to bid him go.

Though wayward was his heart I knew,

I would have sworn that he was true!

[Pg 72]

Oh, how I loved him! or maybe

Loved some one that I thought was he.

They brought me—what? his mangled corse?

Would God they had! They brought me worse.

I saw one who should bear his name,

One whose pale face was fiercely grieved,

One whom he wantonly deceived,

And sentenced to a life of shame.

That was the end. I could not wed

A man whose nobler self was dead.

O, man!—a brave and god-like race,

But you can be so vile and base!

And when there is no urgent need,

You can protect us well indeed;

But when adversity is near,

When the wave breaks upon our head,

When we are crushed with want and dread,

Then we have most from you to fear.

Why do men strangely look me o'er

When I their mercy need the more?

Do they not know a girl may taste

The dregs of want and yet be chaste?

Should woman sell her soul away

To save its manacles of clay?

February 23, 1885.

All honest means of life have failed.

The small accomplishments I've tried

That pleased friends in my days of pride,

Are naught; but vice has not prevailed,

And, thank Heaven, should not, though my heart

Were torn a thousand times apart.

But God shield helpless girls alway

Who live on twenty cents a day!

[Pg 73] February 24, 1885.

Weak, weak, still weaker do I grow:

My mournful fate I can but know;

God, keep me not long here, I pray,

To toil—on twenty cents a day!

February 26, 1885.

Oh, horrors! is it—is it true

What I have read?—if I but knew!

O, God, tell me where can I fly,

Not to be found when I shall die!

They say dead waifs are oft by night

Robbed of a decent burial's right;

That fiends the friendless bodies bear

To crowds of waiting students, where

Men tear them up for men to see.

O, God, sweet God, do pity me!

And I will humbly pray to men:

If this should come within the ken

Of one who lives a true-loved life,

Of one who sister has, or wife;

One who loves women for the best

That is in them, whose lips have pressed

Pure, genuine lips, whom women trust,

Whose heart is free from loathsome lust;

One whom I would have loved if he

Brother or husband were to me—

I ask you—nay, I do command

With that imperiousness you so

Like from a white and shapely hand—

I order you—but no, no, no;

I am past that—I humbly pray

That you will see that I unmarred

Have Christian burial. Guard, oh guard,

You men with manly hearts and souls,

My poor dead body from the ghouls!

[Pg 74]

I strove alway to keep it pure

As the soul in me; it has been

Type of the thoughts that lived within,

The white slave of what shall endure,

My spirit's loved though humble mate;

Let none its white limbs desecrate!

Weaker—yet weaker—'tis to die

This sharp pain bids me. Ah! good-bye,

World that I was too weak for—

March 10, 18—.

Back from a journey; mournful, it is true,

But mingled with a deep-down sweetness, too.

After the law with that poor girl was done,

I found permission with the proper one,

And, though such things by law could not occur,

In my heart-family I adopted her.

(Help much too late to benefit her, living—

It's that way with a good share of our giving!)

But, with a father's love, "Poor girl!" I said,

"You shall have all that I can give you, dead!"

I found, by lightning inquiries I made,

The graveyard where her own loved ones were laid;

I had her body tenderly removed,

And placed among the dear ones that she loved,

With all the honor that the poor, sweet child

Would have if Fortune still upon her smiled.

And when once more the flowers of summer blow,

My wife and daughters and myself will go

And make the sad but grateful duty ours

To see her last earth-dwelling roofed with flowers.

[Pg 75]

FIRE.

[From Farmer Harrington's Calendar.]

March 15, 18—.

Fire!—fire!—fire!—fire!—it sets me in a craze

To see a first-class building all ablaze;

A burning house resembles, when I'm nigh,

Some old acquaintance just about to die;

For structures that a person often sees

Look some like human beings—same as trees.

(There used to be some trees on my old place

That I'd know anywhere—just by their face.)

And when, last night, some bells began to cry,

And big fire-engines rushed and rattled by,

In just three minutes down the stairs I strode,

And hurried—somewhat dressed—into the road

(Partly to help a bit, if so might be,

And partly, I suppose, to hear and see).

It was a dark and thunder-stormy night;

There wasn't one inch of honest sky in sight;

Great black-finned clouds were swimming through the air,

And now and then their lightning-eyes would glare,

And, like a lot of cannon far away,

Some peals of thunder came from o'er the bay.

'Twas one of those strange nights I can't explain,

That make you think they're just a-going to rain,

But never do—save now and then a trace

Of a small drop comes dashing on your face;

One of those nights that try to keep you vexed[Pg 76]

And wondering as to what will happen next.

I like such times: they kind of draw me nearer

To things unseen, and make all mystery clearer.

I ran like sin, and reached the fire at last:

A good-sized church was going, pretty fast.

(I'd noticed it a hundred times or more,

And several times had stepped inside the door.)

The burglar flames within had prowled around

A long time previous to their being found,

Till they had gained such foothold and such might

They'd turned to robbers—stealing plain in sight.

The dome and spires had on them flags of red;

They soon came thundering down from overhead.

It looked as if infernal spirits came,

To take this church away, in smoke and flame!

I wondered, in that wild, expensive glare,

How many of the home-robbed flock were there

To see the shelter where their souls had fed

Swept from existence by that broom of red.

Here was the family pew, so long time prized;

There was the font where they had been baptized;

Here was the altar, where one day they stood,

Started for Heaven, and promised to be good;

Or where they'd wept around some cherished love

Who'd "taken a letter" to The Church above.

And still I thought, as my eyes soulward turned,

How many things there are that can't be burned;

But still we cling, and cling, and hate to part

With the place where we found them on the start.

A sneerish sort of fellow stood by me,

And said, "To such extent as I can see,