Project Gutenberg's A New Medley of Memories, by David Hunter-Blair This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A New Medley of Memories Author: David Hunter-Blair Release Date: July 11, 2011 [EBook #36700] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A NEW MEDLEY OF MEMORIES *** Produced by Al Haines

A NEW MEDLEY OF MEMORIES

BY THE

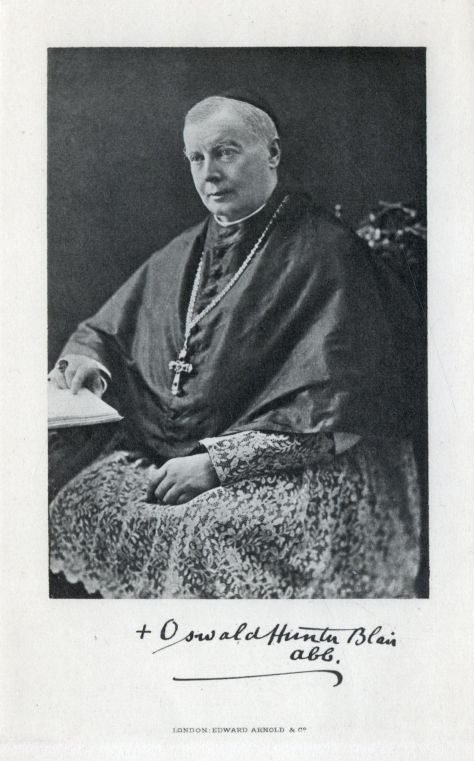

RIGHT REV. SIR DAVID HUNTER-BLAIR

BT., O.S.B., M.A.

TITULAR ABBOT OF DUNFERMLINE

WITH PORTRAIT

LONDON

EDWARD ARNOLD & CO.

1922

[All rights reserved]

TO THE

MASTER AND SCHOLARS

OF

SAINT BENET'S HALL, OXFORD,

IN MEMORY OF

TEN HAPPY YEARS.

Some kindly critics of my Medley of Memories, and not a few private correspondents (most of them unknown to me) have been good enough to express a lively hope that I would continue my reminiscences down to a later date than the year 1903, when I closed the volume with my jubilee birthday.

It is in response to this wish that I have here set down some of my recollections of the succeeding decade, concluding with the outbreak of the Great War.

One is rather "treading on eggshells" when printing impressions of events and persons so near our own time. But I trust that there is nothing unkind in these more recent memories, any more than in the former. There should not be; for I have experienced little but kindness during a now long life; and I approach the Psalmist's limit of days with only grateful sentiments towards the many friends who have helped to make that life a happy as well as a varied one.

DAVID O. HUNTER-BLAIR, O.S.B.

S. Paulo, Brazil,

March, 1922.

PAGE

CHAPTER I.—1903-1904.

The Premier Duke—Oxford Chancellorship—A Silver Jubilee—In

Canterbury Close—Hyde Park Oratory—Oxford under Water—"Twopence

each" at Christ Church—Church Music—Gregorian Centenary in

Rome—Pope Pius X.—Pilgrims and Autograph—Cradle of the

Benedictine Order . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

CHAPTER II.—1904.

"Sermons from Stones"—Alcestis at Bradfield—Whimsical

Texts—Old Masters at Ushaw—A Mozart-Wagner Festival—Bismarck

and William II.—"Longest Word" Competition—Medal-week at

St. Andrews—Oxford Rhodes Scholars—Liddell and Scott—Lord

Rosebery at the Union—Oxford Portraits—Wytham

Abbey—Christmas in Bute . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

CHAPTER III.—1905.

A "Catholic Demonstration"—Boy-prodigies—Spring Days in

Naples—"C.-B." at Oxford—Medical Sceptics—Blenheim

Hospitality—A Scoto-Irish Wedding—Dunskey

Transformed—Lunatics up-to-date—Eton War Memorial—Four

Thousand Guests at Arundel—At Exton Park—Abbotsford and

Blairquhan—Lothair's Bride . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

CHAPTER IV.—1905-1906.

Modern Gothic—Contrasts in South Wales—Chamberlain's Last

Speech—A Catholic Dining-club—Lovat Scouts' Memorial—A Tory

débâcle—Hampshire Marriages—On the Côte d'Azur—Three

Weddings—An Old Irish Peer—Guernsey in June—A Coming of Age

on the Cotswolds—The Warwick Pageant—Bank Holiday at

Scarborough . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

CHAPTER V.—1906-1907.

Melrose and Westminster—Newman Memorial Church—The Evil

Eye—Catholic Scholars at Oxford—Grace before Meat—A

Literary Dinner—A Jamaica Tragedy—An Abbatial

Blessing—Deaths of Oxford friends—Robinson Ellis—A Genteel

Watering-place—Visit to Dover—Pageants at Oxford and

Bury—Hugh Benson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

CHAPTER VI.—1907-1908.

Benedictine Honours at Oxford—Anecdotes from Sir

Hubert—Everingham and Bramham—Early Rising—Mass in a

Deer-forest—A Bishop's Visiting-cards—A Miniature College—Our

New Chancellor—Bodley's Librarian—Dean Burgon—A Welsh

Bishop—Illness and Convalescence—H.M.S. Victory . . . . . . . 94

CHAPTER VII.—1908. Miss Broughton at Oxford—Notable Trees—An Infantile Rest-cure—Equestrians from Italy—"The Colours"—A Parson's Statistics—Two Anxious Mammas—"Let us Kill Something"—Scottish Dessert—A Highland Bazaar—I Resign Mastership of Hall—Notes on Newman—Scriptural Heraldry—Myres Macership—Scots Catholic Judge—At a château in Picardy—Excursions from Oxford—St. Andrew's Day at Cardiff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113 CHAPTER VIII.—1908-1909. Christmas at Beaufort—Annus mirabilis—Kenelm Vaughan—A "Heathen Turk"—Sven Hedin—Centenary of Darwin—Oxford and Louvain—Hugh Cecil on the House of Commons—Arundel itself again—The Bridegroom's Father weeps—Cambridge Fisher Society—Bodleian Congestion—Shackleton at Albert Hall—Oakamoor, Faber, and Pugin—Welsh Pageant—Hampton Court—Father Hell and Mr. Dams!—A Bishop's Portrait—Gleann Mor Gathering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132 CHAPTER IX.—1909-1910. The White Garden at Beaufort—Andrew Lang—A Holy Well—The new Ladycross—"My terrible Great-uncle!"—Off to Brazil—-King's Birthday on Board—-The New City Beautiful—Arrival at S. Paulo—-An Abbey Rebuilding—Cosmopolitan State and City—College of S. Bento—Stray Englishmen—Progressive Paulistas—Education in Brazil . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151 CHAPTER X.—1910. Provost Hornby—Christmas in Brazil—Architecture in S. Paulo—The Snake-farm—Guests at the Abbey—End of the Isolation of Fort Augustus—A Benedictine Festival—Sinister Italians—Death of Edward VII.—Brazilian Funerals—Popular Devotion—"Fradesj estrangeiros"—Football in the Tropics—Homeward Voyage—Santos and Madeira—Sir John Benn . . 170 CHAPTER XI.—1910-1911. A Wiesbaden Eye Klinik—The Rhine in Rain—Cologne and Brussels—Wedding in the Hop-Country—The New Departure at Fort Augustus—St. Andrew's without Angus—Oxford Again—Highland Marriage at Oratory—One Eye versus Two—Cambridge versus Oxford—-A Question of Colour—Ex-King Manuel—A Great Church at Norwich—Ave Verum in the Kirk—Fort Augustus Post-bag . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189 CHAPTER XII.—1911. Monks and Salmon—FitzAlan Chapel—April on Thames-side—My sacerdotal Jubilee—Kinemacolor—Apparition at an Abbey—St. Lucius—Faithful Highlanders—Hay Centenary—Nuns for S. Paulo—A Brief Marriage Ceremony—Pagan Mass-music—Seventeen New Cardinals—Doune Castle—A Quest for our Abbey Church—Great Coal Strike—at Stonyhurst and Ware—Katherine Howard—Twentieth-Century Chinese—An Anglo-Italian Abbey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 208

CHAPTER XIII.—1912-1913.

A Concert for Cripples—Queen Amélie—May at Aix-les-Bains—A

Sample Savoyards—Hautecombe—A "Picture of the Year"—A

Benedictine O.T.C.—Pugin's "Blue Pencil"—My nomination

as Prior—Fort Augustus and the Navy—Work in the

Monastery—Ladies in the Enclosure—A Bishop's Jubilee—A

Modern Major Pendennis—My Election to Abbacy—Installation

Ceremonies—Empress Eugénie at Farnborough—A Week at Monte

Cassino—Fatiguing Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

CHAPTER XIV.—1913-1914.

St Anselm's, Rome—Election of a Primate—My Uncle's

Grave—Milan and Maredsous—Canterbury Revisited—An Oratorian

Festival—Poetical Bathos—A Benedictine Chapter—King of

Uganda at Fort Augustus—Threefold Work of our Abbey—Funeral

of Bishop Turner—Bute Chapel at Westminster—A

Patriarchal Lay-brother—Abbot Gasquet a Cardinal—Corpus

Christi at Arundel—Eucharistic Congress at Cardiff—The Great

War—Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246

APPENDIX I. Novissima Verba . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

II. Darwin's Credo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

INDEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

I take up again the thread of these random recollections in the autumn of 1903, the same autumn in which I kept my jubilee birthday at St. Andrews. I went from there successively to the Herries' at Kinharvie, the Ralph Kerrs at Woodburn, near Edinburgh, and the Butes at Mountstuart, meeting, curiously enough, at all three places Norfolk and his sister, Lady Mary Howard—though it was not so curious after all, as the Duke was accustomed to visit every autumn his Scottish relatives at these places, as well as the Loudouns in their big rather out-at-elbows castle in Ayrshire. He had no taste at all either for shooting, fishing, or riding, or for other country pursuits such as farming, forestry, or the like; but he made himself perfectly happy during these country house visits. The least exacting of guests, he never required to be amused, contenting himself with a game of croquet (the only outdoor game he favoured), an occasional long walk, and a daily romp with his young relatives, the children of the house, who were all devoted to him. He read the newspapers perfunctorily, {2} but seldom opened a book: he knew and cared little for literature, science, or art, with the single exception of architecture, in which he was keenly interested. The most devout of Catholics, he was nothing of an ecclesiologist: official and hereditary chief of the College of Arms, he was profoundly uninterested in heraldry, whether practically or historically:[1] the head of the nobility of England, he was so little of a genealogist that he was never at pains to correct the proof—annually submitted to him as to others—of the preposterous details of his pedigree as set forth in the pages of "Burke." I seem to be describing an ignoramus; but the interesting thing was that the Duke, with all his limitations, was really nothing of the kind. He could, and did, converse on a great variety of subjects in a very clear-headed and intelligent way; there was something engaging about his utter unpretentiousness and deference to the opinions of others; and he had mastered the truth that the secret of successful conversation is to talk about what interests the other man and not what interests oneself. No one could, in fact, talk to the Duke much, or long, without getting to love him; and every one who came into contact with him in their several degrees, from princes and prelates and politicians to cabmen and crossing-sweepers, did love him. "His Grace 'as a good 'eart, that's what 'e 'as," said the old lady who used to keep the crossing nearly opposite Norfolk House, and sat against the railings {3} with her cat and her clean white apron (I think she did her sweeping by deputy); "he'll never cross the square, whatever 'urry 'e's in, without saying a kind word to me." One sees him striding down Pall Mall in his shabby suit, one gloveless hand plucking at his black beard, the other wagging in constant salutation of passing friends, and his kind brown eyes peering from under the brim of a hat calculated to make the late Lord Hardwicke turn in his grave. A genuine man—earnest, simple, affable, sincere, and yet ducal too; with a certain grave native dignity which sat strangely well on him, and on which it was impossible ever to presume. Panoplied in such dignity when occasion required, as in great public ceremonies, our homely little Duke played his part with curious efficiency; and it was often remarked that in State pageants the figure of the Earl Marshal was always one of the most striking in the splendid picture.

The only country seat which the premier Duke owned besides Arundel Castle was Derwent Hall, a fine old Jacobean house in the Derwent valley, on the borders of Yorkshire and Derbyshire. The Duke had lent this place for some years past to his only brother as his country residence (he later bequeathed it to him by will); and herein this same autumn I paid a pleasant visit to Lord and Lady Edmund Talbot, on my way south to Oxford. In London I went to see the rich and sombre chapel of the Holy Souls just finished in Westminster Cathedral, at the expense of my old friend Mrs. Walmesley (née Weld Blundell). The Archbishop's white marble cathedra was in course of erection in the sanctuary, and preparations were going forward {4} for his enthronement.[2] Eight immense pillars of onyx were lying on the floor, and the great painted rood leaned against the wall. I was glad to see some signs of progress.

Our principal domestic interest, on reassembling at Oxford for Michaelmas Term, was the prospect of exchanging the remote and incommodious semi-detached villa, in which our Benedictine Hall had been hitherto housed, for the curious mansion near Folly Bridge, built on arches above the river, "standing in its own grounds," as auctioneers say (it could not well stand in any one else's!), and known to most Oxonians as Grandpont House. Besides the Thames bubbling and swirling at its foundations, it had a little lake of its own, and was (except by a very circuitous détour) accessible only by punt. Rather fascinating! we all thought; but when the pundits from Ampleforth Abbey came to inspect, the floods happened to be out everywhere, and our prospective Hall looked so like Noah's Ark floating on a waste of waters, that they did not "see their way"[3] to approve of either the site or the house.

Oxford was preoccupied at this time with the question of who was to succeed to the Chancellorship {5} vacant by the death of Lord Salisbury. I attended a meeting of the Conservative caucus summoned to discuss the matter at the President's lodgings at St. John's. These gatherings were generally amusing, as the President (most unbending of old Tories) used to make occasional remarks of a disconcerting kind. On this occasion he treated us to some reminiscences of the great Chancellors of the past, adding, "I look round the ranks of prominent men in the country, including cabinet ministers and ex-ministers, and I see few if any men of outstanding or even second-rate ability"—the point of the joke being that next to him was seated the late Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, whose presence and counsel had been specially invited. The names of Lords Goschen, Lansdowne, Rosebery, and Curzon were mentioned, the first-named being evidently the favourite. "Scholar, statesman, financier, educationalist," I wrote of him in the Westminster Gazette a day or two later, "a distinguished son of Oriel, versatile, prudent and popular.... The Fates seem to point to Lord Goschen as the one who shall sit in the vacant chair."[4]

Another less famous Oriel man, my old friend Mgr. Tylee, was in Oxford this autumn, on his annual visitation of his old college, and came to see me several times. He gravely assured me that he had "preached his last sermon in India"; but this was {6} a false alarm. The good monsignore was as great a "farewellist" as Madame Patti or the late Mr. Sims Reeves, and at least three years later I heard that he was meditating another descent on Hindostan; though why he went there, or why he stayed away, I imagine few people either knew or cared.[5]

We were all interested this term in the award of the senior Kennicott Hebrew scholarship to a Catholic, Frederic Ingle of St. John's, who had already, previous to his change of creed, gained the Pusey and Ellerton Prize, and other honours in {7} Scriptural subjects. One could not help wondering whether it came as a little surprise to the Anglican examiners to find that they had awarded the scholarship to a young man studying for the Catholic priesthood at the Collegio Beda in Rome, an institution specially founded for the ecclesiastical education of converts to the Roman Church. The "Hertford" this year, by the way, the Blue Ribbon of Latin scholarship, was also held by a Catholic, a young Jesuit of Pope's Hall—Cyril Martindale, the most brilliant scholar of his time at Oxford, who carried off practically every classical distinction the university had to offer. The "Hertford" was won next year (1904) by another Catholic, Wilfrid Greene, scholar of Christ Church.

I celebrated in 1903 not only my fiftieth birthday, but the silver jubilee of my entrance into the Benedictine Order; and I went to keep the latter interesting anniversary at Belmont Priory in Herefordshire, where twenty-five years before (December 8, 1878) I had received the novice's habit. Two or three of the older members of the community, who had been my fellow-novices in those far-off days, were still in residence there; and from them and all I received a warm welcome and many kind congratulations. These jubilees, golden and silver, are apt to make one moralize; and some words from an unknown or forgotten source were in my mind at this time:

Such dates are milestones on the grey, monotonous road of our lives: they are eddying pools in the stream of time, in which the memory rests for a moment, like the whirling leaf in the torrent, until it is caught up anew, and carried on by the resistless current towards the everlasting ocean.

Soon after the end of term I made my way northwards, to spend Christmas, as so many before, with the Lovats at Beaufort, where the topic of interest was the engagement, just announced, of Norfolk to his cousin, elder daughter of Lord Herries. We played our traditional game of croquet in the sunshine of Christmas Day, and spent a pleasant fortnight, of which, however, the end was saddened for me by the premature death of my niece's husband, Charles Orr Ewing, M.P. They had only just finished the beautiful house they had built on the site of my old home, Dunskey, and were looking forward to happy years there.

I was at Arundel for a few days after New Year, and found the Duke very busy with improvements, inspecting new gardening operations, and so on; "and after all," he said, "some one will be coming by-and-by who may not like it!" From Arundel I dawdled along the south coast to Canterbury, and paid a delightful visit to my old friends Canon and Mrs. Moore at their charming residence (incorporating the ancient monastic guest-house) in the close. I spent hours exploring the glorious cathedral—the most interesting (me judice) if not the most beautiful in England. The close, too, really is a close, with a watchman singing out in the small hours, "Past two o'clock—misty morning—a-all's we-e-ell!" and the enclosure so complete that though we could hear the Bishop of Dover's dinner-bell on the other side of the wall, my host and hostess had to drive quite a long way round, through the mediæval gate-house, to join the episcopal dinner-party. Their schoolboy son invited me that night to accompany the watchman (an old {9} greybeard sailor with a Guy Fawkes lantern, who looked himself like a relic of the Middle Ages) in his eleven o'clock peregrination round the cathedral. A weird experience! the vast edifice totally dark[6] save for the flickering gleam of the single candle, in whose wavering light pillars and arches and chantries and tombs peered momentarily out of the gloom like petrified ghosts.

I saw other interesting things at Canterbury, notably St. Martin's old church (perhaps the most venerable in the kingdom),[7] and left for London, where, walking through Hyde Park on a sunshiny Sunday morning, I lingered awhile to watch the perfervid stump-orators wasting their eloquence on the most listless of audiences. "Come along, Mary Ann, let's give one of the other blokes a turn," was the prevailing sentiment; but I did manage to catch one gem from a Free Thought spouter, whose advocacy of post mortem annihilation was being violently assailed by one of his hearers. "Do you mean to tell me," shouted the heckler, "that when I am dead I fade absolutely away and am done with for ever?"—to which query came the prompt {10} reply, "I sincerely hope so, sir!"[8] Lord Cathcart (a great frequenter of the Park), to whom I repeated the above repartee, amused me by quoting an unconsciously funny phrase he had heard from a labour orator near the Marble Arch: "What abaht the working man? The working man is the backbone of this country—and I tell you strite, that backbone 'as got to come to the front!"[9]

I left Paddington for Oxford in absolutely the blackest fog I had ever seen: it turned brown at Baling, grey at Maidenhead, and at Didcot the sun was shining quite cheerfully. I found the floods almost unprecedentedly high, and the "loved city" abundantly justifying its playful sobriquet of "Spires and Ponds." A Catholic freshman, housed in the ground floor of Christ Church Meadow-buildings, described to me his dismay at the boldness and voracity of the rats which invaded his rooms from the meadows when the floods were out. The feelings of Lady Bute when she visited Oxford about this time, and found her treasured son—who had boarded at a private tutor's at Harrow, and had never roughed it in his life—literally immured in an underground cellar beneath Peckwater Quad, may be {11} better imagined than described. It is fair to add that the youth himself had made no complaint, and shouted with laughter when I paid him a visit in his extraordinary subterranean quarters in the richest college in Oxford.

The last words remind me of a visit paid me during this term by Dom Ferotin and a colleague from Farnborough Abbey. Escorting my guests through Christ Church, I mentioned the revenue of the House as approximately £80,000 a year, a sum which sounded colossal when translated into francs. "Deux millions par an! mais c'est incroyable," was their comment, as we mounted the great Jacobean staircase. "Twopence each, please," said the nondescript individual who threw open the hall door. It was an anti-climax; but we "did" the pictures without further remark, and I remember noticing an extraordinary resemblance (which the guide also observed) to the distinguished French Benedictine in the striking portrait of Dr. Liddon hanging near the fireplace. We lunched with my friend Grissell in High Street, meeting there the Baron de Bertouche, a young man with a Danish father and a Scottish mother, born in Italy, educated in France, owning property in Belgium, and living in Wales—too much of a cosmopolitan, it seemed to me, to be likely to get the commission in the Pope's Noble Guard which appeared at that time to be his chief ambition.[10]

I remember two lectures about this time: one to the Newman Society about Dickens, by old Percy Fitzgerald, who almost wept at hearing irreverent undergraduates avow that the Master's pathos was "all piffle," and that Paul Dombey and Little Nell made them sick; the other a paper on "Armour" (his special hobby) by Lord Dillon. I asked him if he could corroborate what I had heard as a boy, that men who took down their ancestral armour from their castle walls to buckle on for the great Eglinton Tournament, seventy years ago, found that they could not get into it! I was surprised that this fact (if it be a fact) was new to so great an authority as Lord Dillon; but we had no time to discuss the matter. Mr. Justice Walton, the Catholic judge, also came down and addressed the "Newman," I forget on what subject; but I remember his being "heckled" on the question as to whether a barrister was justified in conscience in defending (say) a murderer of whose guilt he was personally convinced. The judge maintained that he was.

February 15 was Norfolk's wedding-day—a quiet and pious ceremony, after his own heart, in the private chapel at Everingham. I recollect the date, because I attended that evening a French play—Molière's Les Femmes Savantes—at an Oxford convent school. It was quite well done, entirely by girls; but the unique feature was that the "men" of the comedy were attired as to coats, waistcoats, wigs and lace jabots in perfectly correct Louis XIV. style, but below the waist—in petticoats! the result being that they ensconced themselves as far as possible, throughout the play, behind {13} tables and chairs, and showed no more of their legs than the Queen of Spain.

Going down to Arundel for Holy Week and Easter, I read in The Times Hugh Macnaghten's strangely moving lines on Hector Macdonald,[11] whose tragic death was announced this week. Easter was late this year, the weather balmy, and the spring advanced; and the park and the whole countryside starred with daffodils and anemones, primroses and hyacinths. Between the many church services we enjoyed some delightful rambles; and the Duke's marriage had made no difference to his love of croquet and of the inevitable game of "ten questions" after dinner. The great church looked beautiful on Easter morning, with its wealth of spring flowers; and the florid music was no doubt finely rendered, though I do not like Gounod in church at Easter or at any other time. I refrained, however, when my friend the organist asked me what I thought of his choir, from replying, as Cardinal Capranica did to a similar question from Pope Nicholas V.—"that it seemed to him like a sack of young swine, for he heard a great noise, but could distinguish nothing articulate!"[12]

All the clergy of St. Philip's church dined at the castle on Easter Sunday evening; and the young Duchess, wearing her necklace of big diamonds (Sheffield's wedding present), was a most kind and pleasant hostess. Two days later my friend Father MacCall and I left England en route for Rome, crossing from Newhaven to Dieppe in three-quarters of a gale. Infandum jubes.... The boat was miserable, so was the passage; but we survived it, hurried on through France and Italy (our direttissimo halting at all kinds of unnecessary places), and reached Rome at the hour of Ave Maria, almost exactly twenty-six years since my previous visit. What memories, as from our modest pension in the Via Sistina we looked once again on the familiar and matchless prospect! My companion hurried off at once to the bedside of a fever-stricken friend; and my first pilgrimage was of course to St. Peter's. I felt, as I swung aside the heavy "baby-crusher,"[13] {15} and entered, almost holding my breath, that strange sense of exhilaration which Eugénie de Ferronays described so perfectly.[14] Preparations were on foot for the coming festa,[15] and the "Sanpietrini" flying, as of old, a hundred feet from the floor, hanging crimson brocades—a fearsome spectacle. On Sunday we Benedictines kept the Gregorian festival at our own great basilica of St. Paul's; but the chief celebration was next day at St. Peter's, where Pope Pius X. himself pontificated in the presence of 40,000 people, and a choir of a thousand monks (of which I had the privilege of being one) rendered the Gregorian music with thrilling effect. All was as in the great days of old—the Papal March blown on silver trumpets; the long procession up the great nave of abbots, bishops, and cardinals, conspicuous among them Cardinals Rampolla, with his fine features and grave penetrating look, and Merry del Val (the youthful Secretary of State), tall, dark, and strikingly handsome; the Pontifical Court, chamberlains in their quaint mediæval dress; and, finally, high on his sedia gestatoria, with the white peacock-feather fans waving on right and left, the venerable figure of the Pope, mitred, and wearing his long embroidered manto: turning kind eyes from side to side on the vast concourse, and {16} blessing them with uplifted hand as he passed. His Holiness celebrated the Mass with wonderful devotion, as quiet and collected as if he had been alone in his oratory. High above our heads, at the Elevation, the silver trumpets sounded the well-known melody, and the Swiss Guards round the altar brought down their halberts with a crash on the pavement.[16] After the great function I lunched with the Giustiniani Bandinis in the Foro Trajano, where three generations of the princely family were living together, in Roman patriarchal fashion. But (quantum mutatus!) the old Prince had sold his historic palace in the Corso;[17] and his heir, Mondragone, who talked to me of sending his son to Christ Church as the Master of Kynnaird, seemed to shy at the expense.[18] They had all been at St. Peter's, in the tribune of the "Patriciato," that morning, and were unanimous (so like Romans!) in their {17} verdict that the glorious Gregorian music would have been much more appropriate to a funeral!

I was happy to enjoy a nearer view of the Holy Father before leaving Rome, in a private audience which he gave to the English Catholic Union. A slightly stooping figure, bushy grey hair, a rather care-worn kind face, a large penetrating eye—this was my first impression. His manner was wonderfully simple and courteous; and by his wish ("s'accommodarsi") we sat down in a little group around him. This absence of formality was, I thought, no excuse for the bad manners of a lady of rank, who pulled out a fountain pen, and asked his Holiness to sign the photograph of her extensive family.[19] The Pope looked at the little implement and shook his head. "Non capisco queste cose de nuova moda," he said; and we followed him into another room—I think his private library—where he seated himself before a great golden inkstand, and with a long quill pen wrote beneath the family group a verse from the hundred and twenty-seventh Psalm.[20] I had an opportunity of asking, not for an autograph, but for a blessing on our Oxford Benedictines, and on my mother-house at Fort Augustus.

Next day my friend and I left Rome for Monte Cassino—my first visit to the cradle of our venerable Order. I was deeply impressed, and felt, perhaps, on the summit of the holy mount, nearer heaven, both materially and spiritually, than I had ever {18} done before. To celebrate Mass above the shrine of Saint Benedict, at an altar designed by Raphael, was my Sunday privilege. The visitors at the abbey and a devout crowd of contadini (many of them from the foot of the mountain) were my congregation; and the monks sang the plain-chant mass grouped round a huge illuminated Graduale on an enormous lectern. Three memorable days here, and I had to hasten northward, halting very briefly to renew old enchanting memories of Florence and Milan, and reaching Oxford just in time for the opening of the summer term.

[1] Lord Bute once told me that it was from him that the Earl Marshal first learned the meaning and origin of the honourable augmentation (the demi-lion of Scotland) which he bore on his coat-armorial.

[2] One of the first acts of Pope Pius X. had been to translate Bishop Bourne of Southwark to the metropolitan see of Westminster, in succession to Cardinal Vaughan, who had died on June 19. Archbishop Bourne became a Cardinal in 1911.

[3] My father used to hate this "new-fangled phrase," as he called it. "'See my way'! What does the man mean by 'see my way'? No, I do not 'see my way,'" he used to protest when a request for a subscription or donation was prefaced by this unlucky formula, and the appeal was instantly consigned to the waste-paper basket.

[4] Lord Goschen was elected on November 2 without a contest, the only other candidate "in the running" (Lord Rosebery) having declined to stand unless unopposed. Our new Chancellor lived to hold the office for little more than three years, dying in February, 1907.

[5] Tylee's sole connection with India was that he had once been domestic chaplain to Lord Ripon, who, however (much to his chagrin), left him behind in England when he went out as Viceroy. When the monsignore preached at St. Andrews, as he occasionally did when visiting George Angus there, the latter used to advertise him in the local newspaper as "ex-chaplain to the late Viceroy of India," which pleased him not a little. He was fond of preaching, and carried about with him in a tin box (proof against white ants) a pile of sermons, mostly translated by himself from the great French orators of the eighteenth century, and laboriously committed to memory. I remember his once firing off at the astonished congregation of a small seaside chapel, à propos des bottes, Bossuet's funeral oration on Queen Henrietta Maria.

Through a friend at the Vatican, Tylee got a brief or rescript from the Pope, who was told that he went to preach in India, and commended him in the document, with some reference to the missionary labours of St. Francis Xavier in that country. The monsignore was immensely proud of this. "Haven't you seen my Papal Bull?" he would cry when India cropped up in conversation, as it generally did in his presence. The fact was that when in India the good man used to stay with a Commissioner or General commanding, and deliver one of his famous sermons in the station or garrison church, to a handful of British Catholics or Irish soldiers. He never learned a word of any native language, and did no more missionary work in India than if he had stayed at home in his Kensington villa.

[6] The Dean, my host told me, whilst prowling about the crypt in semi-darkness once noticed one of the chapels lit up by a rosy gleam. The Chapter was promptly summoned, and the canon-sacrist interrogated as to how and why a votive red lamp had been suspended before an altar without decanal authority. The crypt verger was called in to explain the phenomenon. "Bless your heart, Mr. Dean," said the good man, "that ain't no red lamp you saw—only an old oil stove which I fished up and put in that chapel to try and dry up the damp a bit."

[7] I suppose that there had been a Christian church on the site for thirteen centuries. On the day of my visit it was locked and barred—discouraging to pilgrims.

[8] The converse of this story is that of the orthodox but sadly prosy preacher who was demonstrating at great length the certainty of his own immortality. "Yes, my brethren, the mighty mountains shall one day be cast into the sea, but I shall live on. Nay, the seas themselves, the vast oceans which cover the greater part of the earth, shall dry up; but not I—not I!" And the congregation really thought that he never would!

[9] One more instance of Park repartee I must chronicle: the Radical politician shouting, "I want land reform—I want housing reform—I want education reform—I want——" and the disconcerting interruption, "Chloroform!"

[10] His mother, though a Catholic like himself, was a devotee of "Father Ignatius," and lived at Llanthony. She travelled about everywhere with the visionary "Monk of the Church of England," acting as pew-opener, money-taker, and general mistress of the ceremonies at his lectures, and had published an extraordinary biography of him.

[11] Have they ever been reprinted? I know not. Here they are:—

"Leave him alone:

The death forgotten, and the truth unknown.

Enough to know

Whate'er he feared, he never feared a foe.

Believe the best,

O English hearts! and leave him to his rest."

[12] These words were penned in 1449 by one whom a contemporary layman described on his death as "the wisest, the most perfect, the most learned, and the holiest prelate whom the Church has in our day possessed." His beautiful tomb is in the Minerva church in Rome. Exactly a century later (1549) Cirillo Franchi wrote on the same subject, and in the same vein, to Ugolino Gualteruzzi: "It is their greatest happiness to contrive that while one is saying Sanctus, the other should say Sabaoth, and a third Gloria tua, with certain howls, bellowings, and guttural sounds, so that they more resemble cats in January than flowers in May!"

Who recalls now Ruskin's famous invective against modern Italian music, in which, after lauding a part-song, "done beautifully and joyfully," which he heard in a smithy in Perugia, he goes on: "Of bestial howling, and entirely frantic vomiting up of hopelessly damned souls through their still carnal throats, I have heard more than, please God, I will endeavour to hear ever again, in one of his summers." It is fair to say that the reference here is probably not to church music.

[13] The name which we English used playfully to give to the great heavy leather curtains which hang at the entrance of the Roman churches.

[14] Speaking of the impression of triumph which one receives on entering St. Peter's, she continues: "Tandis que dans les églises gothiques, l'impression est de s'agenouiller, de joindre les mains avec un sentiment d'humble prière et de profond regret, dans St. Pierre, au contraire, le mouvement involuntaire serait d'ouvrir les bras en signe de joie, de relever la tête avec bonheur et épanouissement."—Récit d'une Soeur, ii. 298.

[15] The thirteenth centenary of St. Gregory the Great (d. March 12, 1904).

[16] It was at this supreme moment that an Englishman of the baser sort once rose to his feet, and looking round exclaimed, "Is there no one in this vast assemblage who will lift up his voice with me, and protest against this idolatry?" "If you don't get down in double quick time," retorted an American who was on his knees close by, "there's one man in this vast assemblage who will lift up his foot and kick you out of the church!"

[17] A day or two after writing these lines (1921) I heard that this famous palazzo had been acquired as an official residence by the Brazilian Ambassador to the Quirinal.

[18] The Scottish Earldom of Newburgh (1660), of which Kynnaird was the second title, had been adjudged to Prince Bandini's mother by the House of Lords in 1858. The Duca Mandragone consulted me as to the expense of three years at Oxford for his son. He thought the sum I named very reasonable; but I really believe he supposed me to be quoting the figure in lire, not in pounds sterling, which he found quite impossible.

[19] Would Lady X—— (who was familiar with Courts) have acted thus in an audience granted her by King Edward VII.? I rather think not.

[20] Verse 4. "Filii tui sicut noveliæ olivarum, in circuitu mensæ tuæ."

Abbot Gasquet, who had many friends in Oxford, was much in residence there during the summer of 1904, as he was giving the weekly conferences to our undergraduates. His host, Mgr. Kennard, usually asked me to dinner on Sundays, "to keep the Abbot going," which released me from the chilly collation (cold mutton and cold rhubarb pie), the orthodox Sabbath evening fare in so many households.[1] I recall the lovely Sundays of this summer term, and the crowds of peripatetic dons and clerics in the parks and on the river bank: many of them, I fancy, the serious-minded persons who would have thought it their duty, a year previously, to attend the afternoon university sermon, lately abolished. The afternoon discourse had come to be allotted to the second-rate preachers; and I had heard of a clergyman who, when charged with walking in the country instead of attending at St. Mary's, defended himself by saying that he preferred "sermons from stones" to sermons from "sticks!"[2]

The biggest clerical gathering I ever saw in Oxford was on a bright May afternoon in 1904, when hundreds of parsons were whipped up from the country to oppose the abolition of the statute restricting the honour-theology examinerships to clergymen. Scores of black-coats were hanging about the Clarendon Buildings, waiting to go in and vote; and they "boo'd" and cat-called in the theatre, refusing to let their opponents be heard. They carried their point by an enormous majority.[3]

Kennard took me to London, on another day in May, to see the Academy—some astonishing Sargents, Mrs. Wertheimer all in black, with diamonds which made you wink, and the Duchess of Sutherland in arsenic green, painted against a background of dewy magnolia-leaves, extraordinarily vivid and brilliant. I was at Blenheim a few days later, and admired there (besides the wonderful tapestries and a roomful of Reynolds's) two striking portraits—one by Helleu, the other by Carolus-Duran—of the young American Duchess of Marlborough.

An enjoyable event in June was the quadrennial open-air Greek play at Bradfield College—Alcestis on this occasion, not so thrilling as Agamemnon four years ago, but very well done, and the death of the heroine really very touching. A showery {21} garden party at beautiful Osterley followed close on this: the Crown Prince of Sweden, who was the guest of honour, had forgotten to announce the hour of his arrival, was not met at the station, and walked up in the rain. I sat for a time with Bishop Patterson and the old Duke of Rutland (looking very tottery), and we spoke of odd texts for sermons. The Bishop mentioned a "total abstinence" preacher who could find nothing more suitable than "The young men who carried the bier stood still"! The Duke's contribution was the verse "Let him that is on the housetop not come down," the sermon being against "chignons," and the actual text the last half of the verse—"Top-knot come down"! They were both pleased with my reminiscence of a sermon preached against Galileo, in 1615, from the text, "Viri Galilæi, quid statis aspicientes in coelum?"

As soon as I could after term I went north to Scotland, where I was engaged to superintend the Oxford Local examinations at the Benedictine convent school at Dumfries. It was a new experience for me to preside over school-girls! I found them much less fidgety than boys, but it struck me that the masses of hair tumbling into their eyes and over their desks must be a nuisance: however, I suppose they are used to it. The convent, founded by old Lady Herries, was delightfully placed atop of a high hill, overlooking the river Nith, the picturesque old Border town, and a wide expanse of my native Galloway. My work over, I went on to visit the Edmonstoune-Cranstouns at their charming home close to the tumbling Clyde. I found them entertaining a party of Canadian bowlers and their ladies; {22} and in the course of the day we were all decorated with the Order of the Maple-leaf! I went south after this to spend a few days with my good old friend Bishop Wilkinson, at Ushaw College, near Durham, of which he was president. An old Harrovian, and one of the few survivors of Newman's companions at Littlemore, he was himself a Durham man (his father had owned a large estate in the county), and had been a keen farmer, as well as an excellent parish priest, before his elevation to the bishopric of Hexham. He showed me all over the finely equipped college (which he had done much to improve), and pointing out a Dutch landscape, with cattle grazing, hanging in a corridor, remarked, "That is by a famous 'old master.' I don't know much about pictures, but I do know something about cows; and God never made a cow like that one!"[4] The good old man held an ordination during my visit, and was quite delighted (being himself a thorough John Bull) that "John Bull" happened to be the name of one of his candidates for the priesthood. "Come again soon," he said, when I kissed his ring as I took my leave; "they give us wine at table when there is a guest, and I do like a glass of sherry with my lunch." The old bishop lived for nearly four years longer, but I never saw him again.

I was delighted with a visit I paid a little later to Hawkesyard Priory, the newly acquired property {23} of the Dominicans in Staffordshire: a handsome modern house (now their school) in a finely-timbered park, and close by the new monastery, its spacious chapel, with carved oak stalls, a great sculptured reredos recalling All Souls or New College, and an organ which had been in our chapel at Eton in my school days. I made acquaintance here with the young Blackfriar who was to matriculate in the autumn at our Benedictine Hall—the first swallow, it was hoped, of the Dominican summer, the revival of the venerable Order of Preachers in gremio universitatis.[5]

A kind and musical friend[6] insisted on carrying me off this August to Munich, to attend the Mozart-Wagner festival there. We stayed at the famous old "Four Seasons," and I enjoyed renewing acquaintance, after more than thirty years, with a city which seemed to me very like what it was in 1871. The Mozart operas (at the small Residenz-theater) were rather disappointing. The title-rôle in Don Giovanni was perfectly done by Feinhals; but Anna and Elvira squalled, not even in tune. The enchanting music of Zauberflöte hardly compensated for the tedious story; and no one except the {24} Sarastro (one Hesch, a Viennese) was first-class. The Wagner plays, in the noble new Prinz Regenten theatre, pleased me much more: Knote and Van Rooy were quite excellent, and Feinhals even better as the Flying Dutchman than as Don Giovanni. I heard more Mozart on the Assumption in our Benedictine basilica of St. Boniface—the Twelfth Mass, done by a mixed choir in the gallery! I preferred the Sunday high mass at the beautiful old Frauenkirche, with its exquisite stained glass, and its towers crowned with the curious renaissance cupolas which the Müncheners first called "Italian caps," and later "masskrüge," or beer-mugs. I admired the attention and devotion of the great congregation at the cathedral: a few stood, nearly all knelt, throughout the long service, but no one seemed to think of sitting.

We made one day the pleasant steamer trip round Lake Starnberg, with its pretty wooded shores, and the dim mysterious snow-clad Alps (Wetterstein and other peaks) looming in the background. A middle-aged Graf on board (I think an ex-diplomatist) talked interestingly on many subjects, Bismarck among others. He said that the only serious attempt at reconciliation between him and the Kaiser, ten years before, had been frustrated not by the latter but by Bismarck himself, who was constantly ridiculing the young Emperor both in public and in private. It was odd, he added, how the number three had pervaded Bismarck's life and personality. His motto was "In Trinitate robur": he had served three emperors, fought in three wars, signed three treaties of peace, established the Triple Alliance, had three children and three estates; and {25} his arms were a trefoil and three oak-leaves. Talking of Austria, our friend quoted a dictum of Talleyrand (very interesting in 1921)—"Austria is the House of Lords of Europe: as long as it is not dissolved it will restrain the Commons." Dining together in our hotel at Munich, he told us that the "Four Seasons" possessed, or had possessed, the finest wine in Europe, having bought up Prince Metternich's famous cellar (including his priceless Johannisberger and Steinberger Cabinet hocks) at his death. Of Metternich he said it was a fact that in 1825 Cardinal Albani was instructed by the Pope to sound the great statesman as to whether he desired a Cardinal's hat—"in which case," added his Holiness, "I will propose him in the next Secret Consistory."

We were much amused at reading in a local newspaper the result of a "longest word" competition. The prize-winners were "Transvaaltruppentropentransport trampelthiertreibentrauungsthränentragödie," and "Mekkamuselmannenmeuchelmördermohrenmuttermarmormonumentenmacher"![7] I had hitherto considered the longest existing word to be the Cherokee "Winitawigeginaliskawlungtanawneletisesti"; it was given me by a French missionary to that North American tribe, whom I once met at the Comte de Franqueville's house in Paris, {26} and who said it meant, "They-will-now-have-finished-their-compliments-to-you-and-to-me"! I remember the same good priest telling me that when the first French missionary bishop went to New Zealand, he found the natives incapable of pronouncing the word "eveque" or "bishop," their language consisting of only thirteen letters, mostly vowels and liquids. He therefore coined the word picopo, from "episcopus," which the natives applied to all Catholics. English Catholics they called picopo poroyaxono, from Port Jackson (Sydney), which most of them had visited in trading ships; while French Catholics were known as picopo wee-wee, from the constantly-heard words, "Oui, oui."

Our pleasant sojourn at Munich over, we made a bee-line home (as we had done from England to Bavaria), without stopping anywhere en route, as I was bound to be present at certain religious celebrations at Woodchester Priory, in the Vale of Stroud. I was always much attracted by the Gloucestershire home of the Dominican Order: it was built of the warm cream-coloured stone of the district, and with its gables, low spire, and high-pitched roofs looked as if it really belonged to the pretty village, and was not, like most modern monasteries, a mere accretion of incongruous buildings round an uninteresting dwelling-house.[8] From Woodchester I went over one day to Weston Birt, a vast ornate neo-Jacobean mansion set in the loveliest gardens, and a not unworthy country pendant to the owner's {27} palace in Park Lane, to which (as I told my hostess) I once adjudged the second place among the great houses of London.[9]

I spent the rest of the Long Vacation at Fort Augustus, whither the summer-like autumn had attracted many visitors, and where a golf-course had been lately opened. Golf, too, and nothing but golf, was in the air during my annual visit to St. Andrews, which coincided with the Medal Week there. A lady told me that, looking for a book to give her golfing daughter on her birthday, she was tempted by a pretty volume called Evangeline, Tale of a Caddie, and was disappointed to find that Longfellow meant something quite different by "Acadie!" "Medal Day" was perfect, and the crowd enormous. I was passing the links as two famous competitors (Laidlaw and Mure Fergusson) came in—a cordon round the putting-green, and masses of spectators watching with bated breath. No cheers or enthusiasm as at cricket or football—a curious (and I thought depressing) spectacle. In the club I came on old Lord —— (of Session), anathematizing his luck and his partner, as his manner was. Some one told me that it was only at golf that he really let himself go. Once in Court he addressed a small boy, whose head hardly appeared above the witness-box, with dignified solicitude: "Tell me, my boy, do you understand the nature of an {28} oath?" "Aye, my lord," came the youngster's prompt response, "ain't I your caddie?"

I think that it was at the climax of the medal-week festivities that the news came of the sudden death (in his sleep) of Sir William Harcourt at Nuneham, to which he had only lately succeeded. He had survived just ten years the crowning disappointment of his life, his passing-over for the premiership on the final resignation of Gladstone. He had long outlived (no small achievement) the intense unpopularity of his early years; and it seemed almost legendary to recall how three members of parliament had once resolved to invite to dinner the individual they disliked most in the world. Covers were laid (as the reporters say) for six; but only one guest turned up—Sir William Vernon Harcourt, who had been invited by all three!

I reached Oxford in October to find our Benedictine Hall migrated from the suburbs to a much more commodious site in dull but rather dignified Beaumont Street.[10] The proximity of a hideous "Gothic" hotel, and of the ponderous pseudo-Italian Ashmolean Galleries, did not appeal to us; but the site was conveniently central, and was moreover holy ground, for we were within the actual enclosure of the old Carmelite Priory, and close to Benedictine {29} Worcester, beyond which Cistercian Rowley (on the actual site of whose high altar now stands the bookstall of the L.N.W.R. station!) and Augustinian Oseney had stretched out into the country. One of my first guests in Beaumont Street was Alfred Plowden, the witty and genial Metropolitan magistrate, then just sixty, but as good-looking as ever, and full of amusing yarns about his Westminster and Brasenose days. I think he was the best raconteur I ever met, and one of the most eloquent of speakers when once "off" on a subject in which he was really interested. On this occasion he got started on Jamaica, where he had been private secretary to the Governor after leaving Oxford; and his description of his experiences in that fascinating island was delightful to listen to.

Lord Ralph Kerr's son Philip, who got his First Class in history in June, came up this term to try for an All Souls fellowship. There is a sharp competition nowadays for these university plums; and the qualification is no longer, as the old jibe ran, "bene natus, bene vestitus, medocriter doctus." I prefer the older and sounder standard—"bene legere, bene construere, bene cantare." There seemed, by the way, a certain whimsicality in some cases in the qualifications for the Rhodes Scholarships here. I had a call about this time from the Archbishop of St. John's, Newfoundland, who wished to interest me in a scholar from that colony (called Sidney Herbert!) who was coming up after Christmas. His Grace said that the youth had been required to pass three "tests"—a religious one from his parish priest, an intellectual one, from the authorities of his college, and a social one, from {30} his classmates; and I felt some curiosity as to the nature of the last-named.[11] Amusing stories were current at this time about the Rhodes Scholars. One young don told me that an American scholar had replied, when asked what was his religion, "Well, sir, I can best describe myself as a quasi-Christian scientist."—"Do you think," the don asked me, "he meant the word 'quasi' to apply to 'Christian' or to 'scientist'?" Another young American drifted into Keble, but never attended chapel—a circumstance unheard-of in that exclusively Anglican preserve. Questioned as to whether he was not a member of the "Protestant Episcopal Church" (if not, what on earth was he doing at Keble?), he rejoined, "Certainly not; he was a 'Latter-day Saint'!" He was deported without delay to a rather insignificant college, where it was unkindly said that the Head was so delighted to get a saint of any kind that he welcomed him with open arms.[12]

A Rhodes Scholar, who had been also a fellow of his university in U.S.A., showed himself so lamentably below the expected standard, that his Oxford tutor expressed his surprise at a scholar {31} and a fellow knowing so little. "I think you somewhat misapprehend the position," was the reply. "In the University of X—— fellowships are awarded for purely political reasons." To another college tutor, who voiced his disappointment that after a complete course at his own university a Rhodes Scholar should be so deplorably deficient in Greek and Latin, came the ready explanation: "In the university where I was raised, sir, we only skim the classics!" A Balliol Rhodes Scholar, who had failed to present the essential weekly essay, replied to his tutor's expostulation, in the inimitable drawl of the Middle West: "Well, sir, I have not found myself able to com-pose an essay on the theme indicated by the college authorities; but I have brought you instead a few notes of my own on the po-sition of South Dakota in American politics."

The mention of classics reminds me that the question of the retention or abolition of compulsory Greek was a burning one at this time. Congregation had voted for its abolition in the summer of 1904; but on November 29 we reversed that decision by a majority of 36. I met Dean Liddell's widow at dinner that week, and said that I supposed that she, like myself, was old-fashioned enough to want Greek retained. "Of course I am," said the old lady: "Think of the Lexicon!" which I had in truth forgotten for the moment, as well as the comfortable addition which it no doubt made to her jointure. Rushforth of St. Mary Hall, to whom I repeated this little dialogue after dinner, told me that he possessed a letter from Scott to Liddell, calling his attention to Aristoph. Lys., v. 1263, and {32} adding, "Do you think that [Greek: chunagè parséne] in this line means 'a hunting parson'?" Talking of Greek, I interested my friends by citing two lines from the Ajax, which (I had never seen this noticed) required only a change from plural to singular to be a perfect invocation to the Blessed Virgin:

[Greek: Kalô darógon tèn te párthena,

aeí th horônta panta ten brotois pathè.][13]

A distinguished visitor to Oxford this autumn was Lord Rosebery, who came up to open—no, that is not the word: to unveil—but I do not think it was ever veiled: let us say to inaugurate, Frampton's fine bust of Lord Salisbury in the Union debating-hall. To pronounce the panegyric of a political opponent, with whose principles, practice, and ideals he had always been profoundly at variance, was just the task for Lord Rosebery to perform with perfect tact, eloquence and taste. His speech was a complete success, and so was his graceful and polished tribute to the young president of the Union, W. G. Gladstone, whose likeness, with his high collar and sleekly-brushed black hair, to the youthful portrait of his illustrious grandfather, immediately behind him, was quite noticeable.

A whimsical incident in connection with this visit of the ex-premier may be, at this distance of time, recalled without offence. I had repeated to his Oxford hostess a story told me by the Principal of a Scottish university, of how Lord Rosebery, engaged to speak at a great Liberal meeting in a {33} northern city, found himself previously dining with a fanatically teetotal Provost, who provided for his guests no other liquid refreshment than orangeade in large glass jugs. As this depressing beverage circulated, the Liberal leader's spirits fell almost to zero; and it was by the advice of my friend the principal that, between the dinner and the meeting, he drove ventre à terre to an hotel, and quaffed a pint of dry champagne before mounting the platform and making a speech of fiery eloquence, which the good provost attributed entirely to the orangeade! The lady, unknown to me, passed on this delectable story to one of the Union Committee, who took it very seriously: the result being that when Lord Rosebery reached the committee-room, just before the inauguration ceremony, a grave young man whispered to him confidentially: "There are tea and coffee here; but I have got your pint of chaœpagne behind that screen: will you come and have it now?" "Well, do you know?" said the great man with his usual tact,[14] "I think for once in a way I will have a cup of coffee!" I do not suppose he ever knew exactly why this untimely pint of champagne was proffered to him by his undergraduate hosts; and he probably thought no more about the matter.

Lunching with my friend Bishop Mitchinson, the {34} little Master of Pembroke, I was shown his new portrait in the hall—quite a good painting, but not a bit like him, though not in that respect singular among our Oxford portraits. The supposed picture of Devorguilla, foundress of Balliol, is, I have been assured, the likeness of an Oxford baker's daughter, who was tried for bigamy in the eighteenth century. An even more barefaced imposture is the "portrait" of Egglesfield (chaplain to Queen Philippa, wife of Edward III, and founder of Queen's), which hangs, or hung, in the hall of that college. It is really, and manifestly, the likeness of a seventeenth-century French prelate—probably Bossuet—in the episcopal dress of the time of Louis XIV! Most of our Magdalen portraits are, I think, authentic; but then they do not profess to represent personages of the early Middle Ages! The best and most interesting portraits at Oxford belong to the nineteenth century. I always enjoyed showing my friends those of Tait and Manning, side by side in Balliol Hall, and recalling how their college tutor once remarked, when they had left his room after a lecture: "Those two undergraduates are worthy and talented young men: I hope I shall live to see them both archbishops!" His prophetic wish was duly fulfilled, though he had probably never dreamt of Canterbury and Westminster!

I remember pleasant visits this autumn to the Abingdons at Wytham Abbey, their fine old place, set in loveliest woods, within an easy drive of Oxford. "Why Abbey?" I asked my host, who did not seem to know that the place had never been a monastery, though part of the house was of the fifteenth century. Lord Abingdon himself was a kind {35} of patriarch,[15] with a daughter married four and twenty years, and a small son not yet four. He was trying to dispose of some of his land for building, but without great success. The Berkshire side of the Thames (to my mind far the most beautiful and attractive) was not the popular quarter for extensions from Oxford, which was spreading far out towards the north in the uninteresting directions of Banbury and Woodstock.

Term over, I went north to spend Christmas with the Butes at Mountstuart, where I found my young host, as was only natural, much interested in a recent decision of the Scottish Courts, which had diverted into his pocket £40,000 which his father had bequeathed to two of the Scottish Catholic dioceses.[16] My Christmas here (the first for many years) was saddened by old memories; for I missed at every turn the pervading presence of my lost friend, to whose taste and genius the varied beauty of his island home was so largely due. However, our large party of young people gave the right note {36} of hilarity to the time; and if there was little sunshine without (I noted that we had never a gleam from Christmas to New Year), there was plenty of warmth and brightness and merriment within. The graceful crypt (all that was yet available) of the lovely chapel was fragrant and bright with tuberoses, chrysanthemums and white hyacinths; and the religious services of the season were carried out with the care and reverence which had been the rule, under Lord Bute's supervision, for more than thirty years. The day after New Year, young Bute left home for London and Central Africa (the attraction of the black man never seemed to pall on him), and I made my way to our Highland Abbey to spend the remainder of the Christmas vacation.

[1] "Do you very much mind dining in the middle of the day?" a would-be hostess at St. Andrews once asked George Angus. "Oh, not a bit," was his reply, "as long as I get another dinner in the evening!"

[2] It was, I think, a Scottish critic who suggested an emendation of the line, "Sermons from stones, books in the running brooks." Obviously, he said, the transposition was a clerical error, the true reading being, "Sermons from books, stones in the running brooks!"

[3] Another attempt, nine years later, to abolish the same statute was decisively defeated; but in 1920 the restriction of degrees in divinity to Anglican clergymen was removed by a unanimous vote, though the examinerships are still confined to clergymen.

[4] "Well, now, that is not my idea of an owl," said a casual visitor to a bird-stuffer's shop, looking at one sitting on a perch in a rather dark corner. "Isn't it?" replied the bird-stuffer dryly, peering up over his spectacles. "Well, it's God's, anyhow." The owl was a live one!

[5] The "young Blackfriar" obtained (in History) the first First Class gained in our Hall, rose to be Provincial of his Order in England, and had the happiness of seeing, on August 15, 1921, the foundation stone of a Dominican church and priory laid at Oxford.

[6] Music was his hobby: by profession he was a chemist, and the City Analyst of Oxford. I introduced him as such to dear Mgr. Kennard, who promptly asked us both to dinner, and during the meal laboriously discussed the mediæval history of Oxford, which he had carefully "mugged up" beforehand. He had understood me to say that my friend's position was that of City Annalist!

[7] The English of these uncouth concatenations, which are at least evidence of the facility with which any number of German words can be strung together into one, appears to be (as far as I can unravel them): 1. "The tearful tragedy of the marriage of a dromedary-driver on the transport of Transvaal troops to the tropics." 2. "The maker of a marble monument for the Moorish mother of a wholesale assassin among the Mussulmans at Mecca." Pro-dee-gious!

[8] Such were nearly all our Benedictine priories in England—a circumstance which added to their historic interest, if not to their architectural homogeneity.

[9] I was once invited to write an article on the "six finest houses in London." The word "finest," of course, wants defining. However, my selection, in order of merit, was:—Holland House (perhaps rather a country house in the metropolitan area than a London house), Dorchester, Stafford, Bridgewater, and Montagu Houses, and Gwydyr House, Whitehall. How many Londoners know the last-named?

[10] Built about a century previously, to provide proper access to Worcester College, then and long afterwards dubbed (from its remoteness and inaccessibility) "Botany Bay." The only approach to it had been by a narrow lane, across which linen from the wash used to hang, and once impeded the dignified progress of a Vice-Chancellor. "If there is a college there," cried the potentate in a passion, "there must be a road to it." And the result was Beaumont Street!

[11] Oxonians know the tradition that an All Souls candidate is invited to dinner at high table, and given cherry pie; and that careful note is taken as to the manner in which he deals with the stones!

[12] A subsequent legend related that the undergraduates of his new college were greatly interested in discovering (from reference to an encyclopædia) that a Latter-day Saint was equivalent to a Mormon. "Where were the freshman's wives?" was the natural inquiry. Answer came there none; but the excitement grew intense when it was rumoured that he had applied to a fellow of Magdalen for six ladies' tickets for the chapel service.

[13] "And I call to my assistance her who is ever a Virgin

And who ever looks on all the sufferings among men."

—SOPH. AJAX. v. 835.

[14] "My lord! my lord!" a Midlothian farmer (who had just been served with an iced soufflé) whispered to his host at a tenants' dinner at Dalmeny: "I'm afraid there's something wrang wi' the pudden: it's stane cauld." Lord Rosebery instantly called a footman, and spoke to him in an undertone. "No, do you know?" he said, turning to his guest with a smile, "it is quite right. I find that this kind of pudding is meant to be cold!"

[15] Less so, however, than the then Earl of Leicester (the second), between whose eldest daughter (already a grandmother) and youngest child there was an interval of some fifty years. Lord Ronald Gower once told Queen Victoria (who liked such titbits of family gossip) the astonishing, if not unique, fact that Lord Leicester married exactly a century after his father. The Queen flatly refused to believe it; and as the Court was at the moment at Aix-les-Bains, Lord Ronald was for the time unable to adduce documentary evidence that he was not "pulling her Majesty's leg." The respective dates were, as a matter of fact, 1775 and 1875.

[16] Lord Bute could never do anything quite like other people; and his legacies to Galloway and Argyll had been hampered by conditions to which no Catholic bishop, even if he accepted them for himself, could possibly bind his successor.

There had been an official visitation, by Abbot Gasquet, of our abbey at Fort Augustus in January, 1905. I had been unable to attend it, but the news reached me at Oxford that one of its results had been the resignation of his office by the abbot. This was not so important as it sounded; for the Holy See did not "see its way" (horrid phrase!) to accept the proffered resignation, and the abbot remained in office.

I attended this month a Catholic "Demonstration," as it was called (a word I always hated), in honour of the Bishop of Birmingham—or the "Catholic Bishop of Oxford," as an enthusiastic convert, who had set up a bookshop in the city, with a large portrait of Bishop Ilsley in the window, chose to designate him. The function was in the town hall, and Father Bernard Vaughan made one of his most florid orations, which got terribly on the nerves of good old Sir John Day (the Catholic judge), who sat next me on the platform. "Why on earth doesn't somebody stop him?" he whispered to me in a loud "aside," as the eloquent Jesuit "let himself go" on the subject of the Pope and the King. On the other hand, I heard the Wesleyan Mayor, who was in the chair, murmur to his {38} neighbour, "This is eloquence indeed!" "Vocal relief" (as the reporters say at classical concerts) was afforded by a capital choir, which sang with amazing energy, "Faith of our Fathers," and Faber's sentimental hymn, the opening words of which—"Full in the pant" ... are apt to call forth irreverent smiles.

I took Bernard Vaughan (who knew little of Oxford) a walk round the city on Sunday afternoon. We looked into one of the most "advanced" churches, where a young curate, his biretta well on the back of his head, was catechising a class of children. "Tell me, children," we heard him say, "who was the first Protestant?" "The Devil, Father!" came the shrill response. "Yes, quite right, the Devil!" and we left the church much edified.

There was good music to be heard in Oxford in those early days of the year; and I attended some enjoyable concerts with a music-loving member of my Hall. The boy-prodigies, of whom there were several above the horizon at this time, generally had good audiences at Oxford; and I used to find something inexplicably uncanny in the attainments and performances of these gifted youngsters—Russian, German and English. Astonishing technique—as far as was possible for half-grown fingers—one might fairly look for; but whence the sehnsucht, the passionate yearning, that one seemed to find in some, at least, of their interpretations? That they should feel it appears incredible: yet it could not have been a mere imitative monkey-trick, a mere echo of the teaching of their master. And why should there be this precocious development in music alone, of all the arts? These things want {39} explaining psychologically. I was amused at one of these recitals to hear the eminent violinist Marie Hall (who happened to be sitting next me) say that the boy (it was the Russian Mischa Elman) could not possibly play Bazzini's Ronde des Lutins (he did play it, and admirably), and also that he had suddenly "struck," to the dismay of his impresario, against appearing as a "wunderkind" in sailor kit and short socks, and had insisted on a dress suit!

The Torpids were rowed in icy weather this year; I took Lady Gainsborough and her daughter on to Queen's barge; and Queen's (in which they were interested) made, with the help of two Rhodes Scholars, two bumps, amid shouts of "Go it, Quaggas!"—a new petit nom since my time, when only the Halls had nicknames. Tuckwell, of an older generation than mine, reports in his reminiscences how St. Edmund Hall, in his time, was encouraged by cries from the bank of "On, St. Edmund, on!" and not, as in these degenerate days, "Go it, Teddy!" It was a novelty on the river to see the coaching done from bicycles instead of from horseback. But bicycles were ubiquitous at Oxford, and doubtless of the greatest service; and my young Benedictines and I went far afield awheel on architectural and other excursions. Passing the broken and battered park railings of beautiful Nuneham (not yet repaired by Squire "Lulu"[1]), my companion commented on their condition; and I told him the legend of the former owner, who was so {40} disconsolate at the death of his betrothed (a daughter of Dean Liddell) on their wedding-day, that he never painted or repaired his park railings again!

I heard at the end of February of the engagement (concluded in a beauty-spot of the Italian Riviera) of my young friend Bute—he would not be twenty-four till June—to Augusta Bellingham. A boy-and-girl attachment which had found its natural and happy conclusion—that was the whole story, though the papers, of course, were full of impossibly romantic tales about both the young people. They went off straight to Rome, in Christian fashion, to ask the Pope's blessing on their betrothal; and I just missed them there, for I had the happiness this spring of another brief visit to Italy, at the invitation of a Neapolitan friend. I spent two or three delightful weeks at the Bertolini Palace, high above dear dirty Naples, with an entrancing view over the sunlit bay, and Vesuvius (quite quiescent) in the background. I found the city not much changed in thirty years, and, as always, much more attractive than its queer and half-savage population. Watching the cab-drivers trying to urge their lumbering steeds into a canter, I thought how oddly different are the sounds employed by different nations to make their horses go. The Englishman makes the well-known untransferable click with his tongue: the Norwegian imitates the sound of a kiss: the Arab rolls an r-r-r: the Neapolitan coachman barks Wow! wow! wow! The subject is worth developing.

I met at Naples, among other people, Sir Charles Wyndham, with his unmistakable "Criterion" voice, and as cynically amusing off the stage as he generally {41} was on it. He reminded me of what I had forgotten—that I had once shown him all over our Abbey at Fort Augustus. I told him of a lecture Beerbohm Tree had recently given at Oxford, and showed him my copy of a striking passage[2] which I had transcribed from a shorthand note of the lecture. "Noble words," the veteran actor agreed, "I know them well; but they were not written for his Oxford lecture. I remember them a dozen or more years ago, in an address he gave (I think in 1891) to the Playgoers' Club; and the last clause ran—'to point in the twilight of a waning century to the greater light beyond.' Those words would not of course be applicable in 1904."

I had looked forward to a day in the museum, with its wonderful sculptures and unique relics of Pompeii; but I was lost there, for the whole collection was being rearranged, and no catalogue available. The Cathedral too was closed, being under restoration—for the sixth time in six centuries! Some of the Neapolitan churches seemed to me sadly wanting in internal order and cleanliness, an exception being a spotless and perfectly-kept convent chapel on the hill, conveniently near me for daily mass. The German Emperor made, with his customary suddenness, a descent on Naples during {42} my stay. The quays and streets were hastily decorated, and there was a ferment of excitement everywhere; but I fled from the hurly-burly by cable-railway (funicolì-funicolà!) to the heights of San Martino, to visit the desecrated and abandoned Certosa, now a "national monument": tourists trampling about the lovely church with their hats on. It made me sick, and I told the astonished guide so. The cloister garth, with its sixty white marble columns, charmed and impressed me; but all molto triste. Three old Carthusian monks, I heard, were still permitted to huddle in some corner of their monastery till they dropped and died.[3]

A day I spent at Lucerne on my way home, in fog, snow, and sleet (no sign of spring), I devoted partly to the "Kriegs-und-Frieden" Museum—chiefly kriegs! with an astonishingly complete collection of all things appertaining to war. I went to Downside on my arrival in England, had some talk with the kind abbot on Fort Augustus affairs, and admired the noble church, a wonderful landmark with its lofty tower, choir now quite complete externally, and chevet of flanking chapels. I got to Arundel in time for the functions of Holy Week, and thought I had seen nothing more beautiful in Italy than St. Philip's great church on Maundy Thursday, its "chapel of repose" bright with lilies, azaleas and tulips, tall silver candlesticks and hangings of rose-coloured velvet. I had landed in {43} England speechless with a cold caught at Lucerne, and could neither sing nor preach. Summer Term at Oxford opened with a snowstorm, and May Day was glacial. I found I had been elected to the new County Club, a good house with a really charming garden, and (to paraphrase Angelo Cyrus Bantam) "rendered bewitching by the absence of —— undergraduates, who have an amalgamation of themselves at the Union." The most noteworthy visitor to the Union this term was Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (then leader of the Opposition), who made a somewhat vitriolic speech, lasting an hour, against the Government. The 550 undergraduates present listened, cheered frequently—and voted against him by a large majority, a good deal (I heard afterwards) to the old gentleman's chagrin.

The Archbishop of Westminster (Dr. Bourne) came to Oxford in May as the guest of Mgr. Kennard, who illuminated in his honour the garden and quad of his pretty old house in St. Aldate's, and gave a dinner and big reception, at neither of which I could be present, being laid up from a bicycle-accident. It was Eights-week, and his Grace saw the races one evening, and I think was also present at a Newman Society debate, when a motion advocating the setting up of a Catholic University in Ireland by the Government was rejected by a considerable majority.[4] I was able to hobble to Balliol a few days later, when Sir Victor Horsley delivered {44} the Boyle lecture to a crowded and distinguished audience. I noted down as interesting one thing he said (I fancy it was a quotation from somebody else[5]): "Every scientific truth passes through three stages: in the first it is decried as absurd; in the second it is said to be opposed to revealed religion; in the third everybody knew it before!" Sir Victor's lecture left me, rightly or wrongly, under the impression that he was something of a sceptic; and I asked my neighbour, a clerical don of note, from Keble, why so many medical bigwigs seemed inclined to atheism. He answered (oddly enough) that it was only what David had prophesied long ago when he asked despairingly (Psalm lxxxvii. 11), Numquid medici suscitabunt et confitebuntur tibi? ("Shall the physicians rise up and praise Thee?")—a curious little bit of exegesis from an Anglican.[6]

June 16 was a busy day—a garden party at Blenheim, with special trains for the Oxford guests; the Duchess, in blue and white and a big black hat, welcoming her guests in her low, sweet, and curiously un-American voice, and the little Duke rather affable in khaki (he was encamped with the Oxfordshire Hussars in the park). We sat about under the big cedars, and there was organ-music in the cool {45} white library, where I noticed that Sargent's very odd group of the ducal family had been hung—with not altogether happy effect—as a pendant to the famous and beautiful group painted by Reynolds. I got back to Oxford just in time for the festival dinner of the Canning and Chatham Clubs, at which my old schoolfellow Alfred Lyttelton, Hugh Cecil, and other Tory notabilities, were guests. Alfred spoke admirably: Hugh, though loudly called upon, refused to speak at all. The President of Magdalen, by whom I sat, told me in pained tones how some Christ Church undergraduates, suadente diabolo, had recently scaled the wall into Magdalen deer-park, had dragged (Heaven knew how) over the wall two of our sacrosanct fallow deer, and had turned the poor brutes loose in the "High"—an outrage without precedent in the college annals. I duly sympathized.