![[The

image of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

etext transcriber's note: The printed page has been replicated. Misspellings and odd capitalizations have not been corrected.

BAB: A Sub-Deb

MARY ROBERTS RINEHART

![[The

image of the title page is unavailable.]](images/title.png)

By Mary Roberts Rinehart

Author of

“The Window at the White Cat,”

“Where There’s A Will,” “The After House,”

“Tish,” Etc.

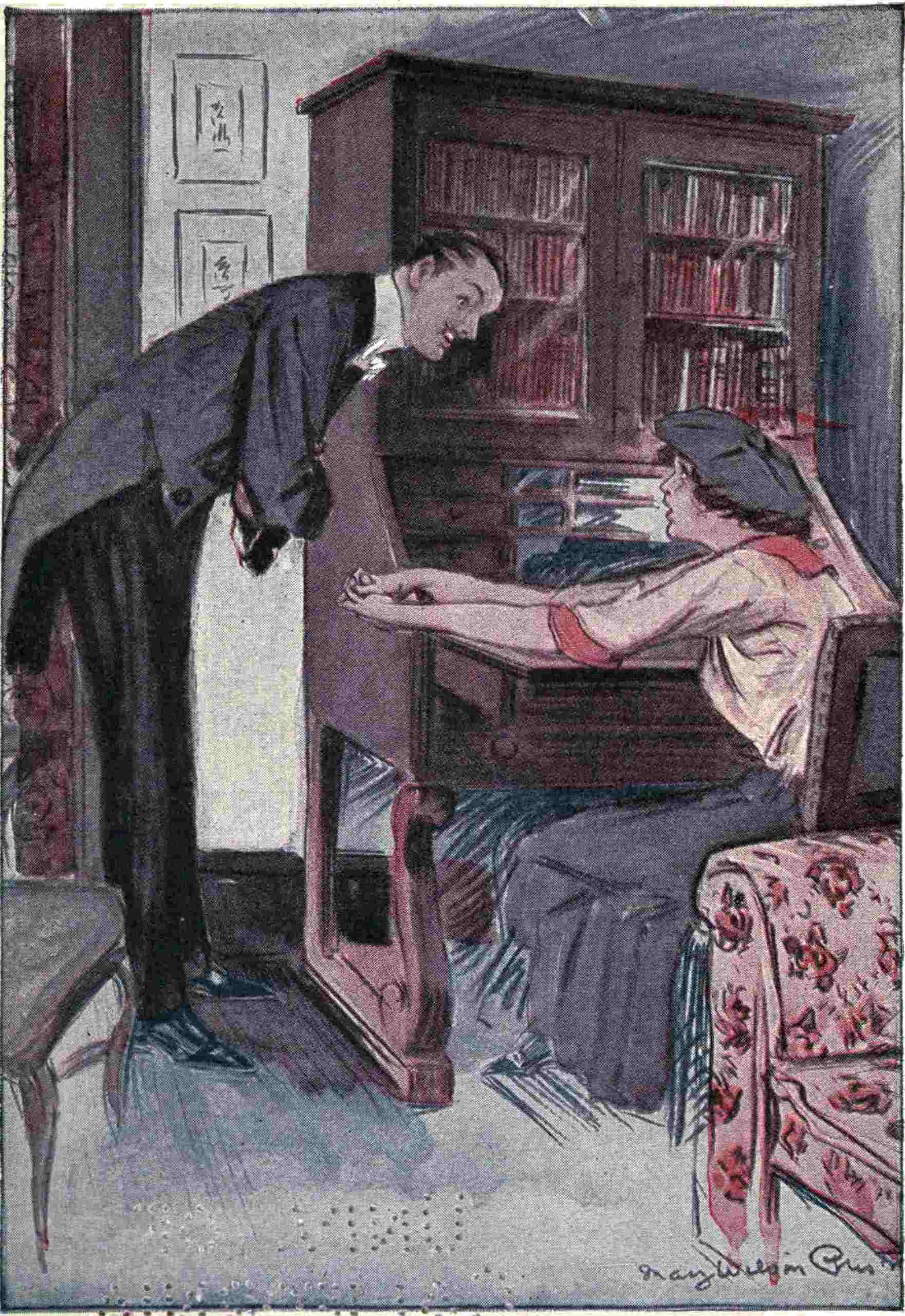

With Frontispiece

By MAY WILSON PRESTON

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by Arrangements with George H. Doran Company

COPYRIGHT, 1917

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1916 AND 1917, BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Sub-Deb | 13 |

| II | Theme: The Celebrity | 79 |

| III | Her Dairy | 147 |

| IV | Bab’s Burglar | 209 |

| V | The G. A. C. | 281 |

THE SUB-DEB: A THEME WRITTEN AND SUBMITTED IN LITERATURE CLASS BY BARBARA PUTNAM ARCHIBALD, 1917.

DEFINITION OF A THEME:

A theme is a piece of writing, either true or made up by the author, and consisting of Introduction, Body and Conclusion. It should contain Unity, Coherence, Emphasis, Perspecuity, Vivacity, and Presision. It may be ornamented with dialogue, discription and choice quotations.

SUBJECT OF THEME:

An interesting Incident of My Christmas Holadays.

INTRODUCTION:

“A tyrant’s power in rigor is exprest.”—Dryden.

I HAVE decided to relate with Presision what occurred during my recent Christmas holaday. Although I was away from this school only four days, returning unexpectedly the day after Christmas, a number of Incidents occurred which I beleive I should narate.

It is only just and fair that the Upper House, at{14} least, should know of the injustice of my exile, and that it is all the result of Circumstances over which I had no controll.

For I make this apeal, and with good reason. Is it any fault of mine that my sister Leila is 20 months older than I am? Naturaly, no.

Is it fair also, I ask, that in the best society, a girl is a Sub-Deb the year before she comes out, and although mature in mind, and even maturer in many ways than her older sister, the latter is treated as a young lady, enjoying many privileges, while the former is treated as a mere child, in spite, as I have observed, of only 20 months difference? I wish to place myself on record that it is not fair.

I shall go back, for a short time, to the way things were at home when I was small. I was very strictly raised. With the exception of Tommy Gray, who lives next door and only is about my age, I was never permitted to know any of the Other Sex.

Looking back, I am sure that the present way society is organized is really to blame for everything. I am being frank, and that is the way I feel. I was too strictly raised. I always had a Governess taging along. Until I came here to school I had never walked to the corner of the next street unattended. If it wasn’t Mademoiselle it was mother’s maid, and if it wasn’t either of them, it was mother herself, telling me to hold my toes out and my shoulder blades in. As I have said, I never knew any of the Other Sex, except the miserable little beasts at dancing school. I used to{15} make faces at them when Mademoiselle was putting on my slippers and pulling out my hair bow. They were totaly uninteresting, and I used to put pins in my sash, so that they would get scratched.

Their pumps mostly squeaked, and nobody noticed it, although I have known my parents to dismiss a Butler who creaked at the table.

When I was sent away to school, I expected to learn something of life. But I was disapointed. I do not desire to criticize this Institution of Learning. It is an excellent one, as is shown by the fact that the best Families send their daughters here. But to learn life one must know something of both sides of it, Male and Female. It was, therefore, a matter of deep regret to me to find that, with the exception of the Dancing Master, who has three children, and the Gardner, there were no members of the sterner sex to be seen.

The Athletic Coach was a girl! As she has left now to be married, I venture to say that she was not what Lord Chesterfield so uphoniously termed “Suaviter in modo, fortater in re.”

When we go out to walk we are taken to the country, and the three matinees a year we see in the city are mostly Shakspeare, aranged for the young. We are allowed only certain magazines, the Atlantic Monthly and one or two others, and Barbara Armstrong was penalized for having a framed photograph of her brother in running clothes.

At the school dances we are compeled to dance with each other, and the result is that when at home{16} at Holaday parties I always try to lead, which annoys the boys I dance with.

Notwithstanding all this it is an excellent school. We learn a great deal, and our dear Principle is a most charming and erudite person. But we see very little of Life. And if school is a preparation for Life, where are we?

Being here alone since the day after Christmas, I have had time to think everything out. I am naturally a thinking person. And now I am no longer indignant. I realize that I was wrong, and that I am only paying the penalty that I deserve although I consider it most unfair to be given French translation to do. I do not object to going to bed at nine o’clock, although ten is the hour in the Upper House, because I have time then to look back over things, and to reflect, to think.

BODY OF THEME:

I now approach the narative of what happened during the first four days of my Christmas Holiday.

For a period before the fifteenth of December, I was rather worried. All the girls in the school were getting new clothes for Christmas parties, and their Families were sending on invitations in great numbers, to various festivaties that were to occur when they went home.

Nothing, however, had come for me, and I was wor{17}ried. But on the 16th mother’s visiting Secretary sent on four that I was to accept, with tiped acceptances for me to copy and send. She also sent me the good news that I was to have two party dresses, and I was to send on my measurements for them.

One of the parties was a dinner and theater party, to be given by Carter Brooks on New Year’s Day. Carter Brooks is the well-known Yale Center, although now no longer such but selling advertizing, etcetera.

It is tradgic to think that, after having so long anticapated that party, I am now here in sackcloth and ashes, which is a figure of speech for the Peter Thompson uniform of the school, with plain white for evenings and no jewellry.

It was with anticapatory joy, therefore, that I sent the acceptances and the desired measurements, and sat down to cheerfully while away the time in studies and the various duties of school life, until the Holadays.

However, I was not long to rest in piece, for in a few days I received a letter from Carter Brooks, as follows:

Dear Barbara: It was sweet of you to write me so promptly, although I confess to being rather astonished as well as delighted at being called “Dearest.” The signature too was charming, “Ever thine.” But, dear child, won’t you write at once and tell me why the waist, bust and hip measurements? And the request to have them really low in the neck?

Ever thine,

Carter.

It will be perceived that I had sent him the letter to mother, by mistake.

I was very unhappy about it. It was not an auspisious way to begin the Holadays, especially the low neck. Also I disliked very much having told him my waist measure which is large owing to Basket Ball.

As I have stated before, I have known very few of the Other Sex, but some of the girls had had more experience, and in the days before we went home, we talked a great deal about things. Especially Love. I felt that it was rather over-done, particularly in fiction. Also I felt and observed at divers times that I would never marry. It was my intention to go upon the stage, although modafied since by what I am about to relate.

The other girls say that I look like Julia Marlowe.

Some of the girls had boys who wrote to them, and one of them—I refrain from giving her name—had a Code. You read every third word. He called her “Couzin” and he would write like this:

Dear Couzin: I am well. Am just about crazy this week to go home. See notice enclosed you football game.

And so on and on. Only what it really said was “I am crazy to see you.”

(In giving this Code I am betraying no secrets, as they have quarreled and everything is now over between them.){19}

As I had nobody, at that time, and as I had visions of a Career, I was a man-hater. I acknowledge that this was a pose. But after all, what is life but a pose?

“Stupid things!” I always said. “Nothing in their heads but football and tobacco smoke. Women,” I said, “are only their playthings. And when they do grow up and get a little intellagence they use it in making money.”

There has been a story in the school—I got it from one of the little girls—that I was disapointed in love in early youth, the object of my atachment having been the Tener in our Church choir at home. I daresay I should have denied the soft impeachment, but I did not. It was, although not appearing so at the time, my first downward step on the path that leads to destruction.

“The way of the Transgresser is hard”—Bible.

I come now to the momentous day of my return to my dear home for Christmas. Father and my sister Leila, who from now on I will term “Sis,” met me at the station. Sis was very elegantly dressed, and she said:

“Hello, Kid,” and turned her cheek for me to kiss.

She is, as I have stated, but 20 months older than I, and depends altogether on her clothes for her beauty. In the morning she is plain, although having a good skin. She was trimmed up with a bouquet of violets as large as a dishpan, and she covered them with her hands when I kissed her.{20}

She was waved and powdered, and she had on a perfectly new Outfit. And I was shabby. That is the exact word. Shabby. If you have to hang your entire Wardrobe in a closet ten inches deep, and put it over you on cold nights, with the steam heat shut off at ten o’clock, it does not make it look any better.

My father has always been my favorite member of the family, and he was very glad to see me. He has a great deal of tact, also, and later on he slipped ten dollars in my purse in the motor. I needed it very much, as after I had paid the porter and bought luncheon, I had only three dollars left and an I. O. U. from one of the girls for seventy-five cents, which this may remind her, if it is read in class, she has forgoten.

“Good heavens, Barbara,” Sis said, while I hugged father, “you certainly need to be pressed.”

“I daresay I’ll be the better for a hot iron,” I retorted, “but at least I shan’t need it on my hair.” My hair is curly while hers is straight.

“Boarding school wit!” she said, and stocked to the motor.

Mother was in the car and glad to see me, but as usual she managed to restrain her enthusiasm. She put her hands over some Orkids she was wearing when I kissed her. She and Sis were on their way to something or other.

“Trimmed up like Easter hats, you two!” I said.

“School has not changed you, I fear, Barbara,” mother observed. “I hope you are studying hard.”

“Exactly as hard as I have to. No more, no less,{21}” I regret to confess that I replied. And I saw Sis and mother exchange glances of signifacance.

We dropped them at the Reception and father went to his office and I went on home alone. And all at once I began to be embittered. Sis had everything, and what had I? And when I got home, and saw that Sis had had her room done over, and ivory toilet things on her dressing table, and two perfectly huge boxes of candy on a stand and a Ball Gown laid out on the bed, I almost wept.

My own room was just as I had left it. It had been the night nursery, and there was still the dent in the mantel where I had thrown a hair brush at Sis, and the ink spot on the carpet at the foot of the bed, and everything.

Mademoiselle had gone, and Hannah, mother’s maid, came to help me off with my things. I slammed the door in her face, and sat down on the bed and raged.

They still thought I was a little girl. They patronised me. I would hardly have been surprised if they had sent up a bread and milk supper on a tray. It was then and there that I made up my mind to show them that I was no longer a mere child. That the time was gone when they could shut me up in the nursery and forget me. I was seventeen years and eleven days old, and Juliet, in Shakspeare, was only sixteen when she had her well-known affair with Romeo.

I had no plan then. It was not until the next afternoon that the thing sprung (sprang?) full-pannoplied from the head of Jove.{22}

The evening was rather dreary. The family was going out, but not until nine thirty, and mother and Leila went over my clothes. They sat, Sis in pink chiffon and mother in black and silver, and Hannah took out my things and held them up. I was obliged to silently sit by, while my rags and misery were exposed.

“Why this open humiliation?” I demanded at last. “I am the family Cinderella, I admit it. But it isn’t necessary to lay so much emphacis on it, is it?”

“Don’t be sarcastic, Barbara,” said mother. “You are still only a Child, and a very untidy Child at that. What do you do with your elbows to rub them through so? It must have taken patience and aplication.”

“Mother,” I said, “am I to have the party dresses?”

“Two. Very simple.”

“Low in the neck?”

“Certainly not. A small v, perhaps.”

“I’ve got a good neck.”

She rose impressively.

“You amaze and shock me, Barbara,” she said coldly.

“I shouldn’t have to wear tulle around my shoulders to hide the bones!” I retorted. “Sis is rather thin.”

“You are a very sharp-tongued little girl,” mother said, looking up at me. I am two inches taller than she is.

“Unless you learn to curb yourself, there will be no parties for you, and no party dresses.{23}”

This was the speach that broke the Camel’s back. I could endure no more.

“I think,” I said, “that I shall get married and end everything.”

Need I explain that I had no serious intention of taking the fatal step? But it was not deliberate mendasity. It was Despair.

Mother actually went white. She cluched me by the arm and shook me.

“What are you saying?” she demanded.

“I think you heard me, mother,” I said, very politely. I was however thinking hard.

“Marry whom? Barbara, answer me.”

“I don’t know. Anybody.”

“She’s trying to frighten you, mother,” Sis said. “There isn’t anybody. Don’t let her fool you.”

“Oh, isn’t there?” I said in a dark and portentious manner.

Mother gave me a long look, and went out. I heard her go into father’s dressing-room. But Sis sat on my bed and watched me.

“Who is it, Bab?” she asked. “The dancing teacher? Or your riding master? Or the school plumber?”

“Guess again.”

“You’re just enough of a little Simpleton to get tied up to some wreched creature and disgrace us all.”

I wish to state here that until that moment I had no intention of going any further with the miserable business. I am naturaly truthful, and Deception is hateful to me. But when my sister uttered the above dis{24}pariging remark I saw that, to preserve my own dignaty, which I value above precious stones, I would be compelled to go on.

“I’m perfectly mad about him,” I said. “And he’s crazy about me.”

“I’d like very much to know,” Sis said, as she stood up and stared at me, “how much you are making up and how much is true.”

None the less, I saw that she was terrafied. The family Kitten, to speak in allegory, had become a Lion and showed its clause.

When she had gone out I tried to think of some one to hang a love affair to. But there seemed to be nobody. They knew perfectly well that the dancing master had one eye and three children, and that the clergyman at school was elderly, with two wives. One dead.

I searched my Past, but it was blameless. It was empty and bare, and as I looked back and saw how little there had been in it but imbibing wisdom and playing basket-ball and tennis, and typhoid fever when I was fourteen and almost having to have my head shaved, a great wave of bitterness agatated me.

“Never again,” I observed to myself with firmness. “Never again, if I have to invent a member of the Other Sex.”

At that time, however, owing to the appearance of Hannah with a mending basket, I got no further than his name.

It was Harold. I decided to have him dark, with{25} a very small black mustache, and Passionate eyes. I felt, too, that he would be jealous. The eyes would be of the smouldering type, showing the green-eyed monster beneath.

I was very much cheered up. At least they could not ignore me any more, and I felt that they would see the point. If I was old enough to have a lover—especialy a jealous one with the aformentioned eyes—I was old enough to have the necks of my frocks cut out.

While they were getting their wraps on in the lower hall, I counted my money. I had thirteen dollars. It was enough for a Plan I was beginning to have in mind.

“Go to bed early, Barbara,” mother said when they were ready to go out.

“You don’t mind if I write a letter, do you?”

“To whom?”

“Oh, just a letter,” I said, and she stared at me coldly.

“I daresay you will write it, whether I consent or not. Leave it on the hall table, and it will go out with the morning mail.”

“I may run out to the box with it.”

“I forbid your doing anything of the sort.”

“Oh, very well,” I responded meekly.

“If there is such haste about it, give it to Hannah to mail.”

“Very well,” I said.

She made an excuse to see Hannah before she left,{26} and I knew that I was being watched. I was greatly excited, and happier than I had been for weeks. But when I had settled myself in the Library, with the paper in front of me, I could not think of anything to say in a letter. So I wrote a poem instead.

The last verse did not scan, exactly, but I wished to use the word “marry” if possible. It would show, I felt, that things were really serious and impending. A love affair is only a love affair, but Marriage is Marriage, and the end of everything.

It was at that moment, 10 o’clock, that the Strange Thing occurred which did not seem strange at all at the time, but which developed into so great a mystery later on. Which was to actualy threaten my reason and which, flying on winged feet, was to send me back here to school the day after Christmas and put my seed pearl necklace in the safe deposit vault. Which was very unfair, for what had my necklace to do with it? And just now, when I need comfort, it—the necklace—would help to releive my exile.{27}

Hannah brought me in a cup of hot milk, with a Valentine’s malted milk tablet dissolved in it.

As I stirred it around, it occurred to me that Valentine would be a good name for Harold. On the spot I named him Harold Valentine, and I wrote the name on the envelope that had the poem inside, and addressed it to the town where this school gets its mail.

It looked well written out. “Valentine,” also, is a word that naturaly connects itself with affairs de cour. And I felt that I was safe, for as there was no Harold Valentine, he could not call for the letter at the post office, and would therefore not be able to cause me any trouble, under any circumstances. And, furthermore, I knew that Hannah would not mail the letter anyhow, but would give it to mother. So, even if there was a Harold Valentine, he would never get it.

Comforted by these reflections, I drank my malted milk, ignorant of the fact that Destiny, “which never swerves, nor yields to men the helm”—Emerson, was stocking at my heels.

Between sips, as the expression goes, I addressed the envelope to Harold Valentine, and gave it to Hannah. She went out the front door with it, as I had expected, but I watched from a window, and she turned right around and went in the area way. So that was all right.

It had worked like a Charm. I could tear my hair now when I think how well it worked. I ought to have been suspicious for that very reason. When{28} things go very well with me at the start, it is a sure sign that they are going to blow up eventualy.

Mother and Sis slept late the next morning, and I went out stealthily and did some shopping. First I bought myself a bunch of violets, with a white rose in the center, and I printed on the card:

“My love is like a white, white rose. H.” And sent it to myself.

It was deception, I acknowledge, but having put my hand to the Plow, I did not intend to steer a crooked course. I would go straight to the end. I am like that in everything I do. But, on delibarating things over, I felt that Violets, alone and unsuported, were not enough. I felt that if I had a photograph, it would make everything more real. After all, what is a love affair without a picture of the Beloved Object?

So I bought a photograph. It was hard to find what I wanted, but I got it at last in a stationer’s shop, a young man in a checked suit with a small mustache—the young man, of course, not the suit. Unluckaly, he was rather blonde, and had a dimple in his chin. But he looked exactly as though his name ought to be Harold.

I may say here that I chose “Harold,” not because it is a favorite name of mine, but because it is romantic in sound. Also because I had never known any one named Harold and it seemed only discrete.

I took it home in my muff and put it under my pillow where Hannah would find it and probably take it to mother. I wanted to buy a ring too, to hang on a{29} ribbon around my neck. But the violets had made a fearful hole in my thirteen dollars.

I borrowed a stub pen at the stationer’s and I wrote on the photograph, in large, sprawling letters, ‘To you from me.”

“There,” I said to myself, when I put it under the pillow. “You look like a photograph, but you are really a bomb-shell.”

As things eventuated, it was. More so, indeed.

Mother sent for me when I came in. She was sitting in front of her mirror, having the vibrater used on her hair, and her manner was changed. I guessed that there had been a family Counsel over the poem, and that they had decided to try kindness.

“Sit down, Barbara,” she said. “I hope you were not lonely last night?”

“I am never lonely, mother. I always have things to think about.”

I said this in a very pathetic tone.

“What sort of things?” mother asked, rather sharply.

“Oh—things,” I said vaguely. “Life is such a mess, isn’t it?”

“Certainly not. Unless one makes it so.”

“But it is so difficult. Things come up and—and it’s hard to know what to do. The only way, I suppose, is to be true to one’s beleif in one’s self.”

“Take that thing off my head and go out, Hannah,” mother snapped. “Now then, Barbara, what in the world has come over you?{30}”

“Over me? Nothing.”

“You are being a silly child.”

“I am no longer a child, mother. I am seventeen. And at seventeen there are problems. After all, one’s life is one’s own. One must decide——”

“Now, Barbara, I am not going to have any nonsense. You must put that man out of your head.”

“Man? What man?”

“You think you are in love with some drivelling young Fool. I’m not blind, or an idot. And I won’t have it.”

“I have not said that there is anyone, have I?” I said in a gentle voice. “But if there was, just what would you propose to do, mother?”

“If you were three years younger I’d propose to spank you.” Then I think she saw that she was taking the wrong method, for she changed her Tactics. “It’s the fault of that Silly School,” she said. (Note: These are my mother’s words, not mine.) “They are hot-beds of sickley sentamentality. They——”

And just then the violets came, addressed to me. Mother opened them herself, her mouth set.

“My love is like a white, white rose,” she said. “Barbara, do you know who sent these?”

“Yes, mother,” I said meekly. This was quite true. I did.

I am indeed sorry to record that here my mother lost her temper, and there was no end of a fuss. It ended by mother offering me a string of seed pearls for Christmas, and my party dresses cut V front and back,{31} if I would, as she phrazed it, “put him out of my silly head.”

“I shall have to write one letter, mother,” I said, “to—to break things off. I cannot tear myself out of another’s Life without a word.”

She sniffed.

“Very well,” she said. “One letter. I trust you to make it only one.”

I come now to the next day. How true it is, that “Man’s life is but a jest, a dream, a shadow, bubble, air, a vapour at the best!”

I spent the morning with mother at the dressmakers and she chose two perfectly spiffing things, one of white chiffon over silk, made modafied Empire, with little bunches of roses here and there on it, and when she and the dressmaker were hagling over the roses, I took the scizzors and cut the neck of the lining two inches lower in front. The effect was posatively impressive. The other was blue over orkid, a perfectly passionate combination.

When we got home some of the girls had dropped in, and Carter Brooks and Sis were having tea in the den. I am perfectly sure that Sis threw a cigarette in the fire when I went in. When I think of my sitting here alone, when I have done nothing, and Sis playing around and smoking cigarettes, and nothing said, all for a difference of 20 months, it makes me furious.

“Let’s go in and play with the children, Leila,” he said. “I’m feeling young today.{32}”

Which was perfectly silly. He is not Methuzala. Although thinking himself so, or almost.

Well, they went into the drawing room. Elaine Adams was there waiting for me, and Betty Anderson and Jane Raleigh. And I hadn’t been in the room five minutes before I knew that they all knew. It turned out later that Hannah was engaged to the Adams’s butler, and she had told him, and he had told Elaine’s governess, who is still there and does the ordering, and Elaine sends her stockings home for her to darn.

Sis had told Carter, too, I saw that, and among them they had rather a good time. Carter sat down at the piano and struck a few chords, chanting “My Love is like a white, white rose.”

“Only you know,” he said, turning to me, “that’s wrong. It ought to be a ‘red, red rose.’”

“Certainly not. The word is ‘white.’”

“Oh, is it?” he said, with his head on one side. “Strange that both you and Harold should have got it wrong.”

I confess to a feeling of uneasiness at that moment.

Tea came, and Carter insisted on pouring.

“I do so love to pour!” he said. “Really, after a long day’s shopping, tea is the only thing that keeps me going until dinner. Cream or lemon, Leila dear?”

“Both,” Sis said in an absent manner, with her eyes on me. “Barbara, come into the den a moment. I want to show you mother’s Xmas gift.”

She stocked in ahead of me, and lifted a book from the table. Under it was the photograph.{33}

“You wretched child!” she said. “Where did you get that?”

“That’s not your affair, is it?”

“I’m going to make it my affair. Did he give it to you?”

“Have you read what’s written on it?”

“Where did you meet him?”

I hesitated because I am by nature truthfull. But at last I said:

“At school.”

“Oh,” she said slowly. “So you met him at school! What was he doing there? Teaching elocution?”

“Elocution!”

“This is Harold, is it?”

“Certainly.” Well, he was Harold, if I chose to call him that, wasn’t he? Sis gave a little sigh.

“You’re quite hopeless, Bab. And, although I’m perfectly sure you want me to take the thing to mother, I’ll do nothing of the sort.”

She flung it into the fire. I was raging. It had cost me a dollar. It was quite brown when I got it out, and a corner was burned off. But I got it.

“I’ll thank you to burn your own things,” I said with dignaty. And I went back to the drawing room.

The girls and Carter Brooks were talking in an undertone when I got there. I knew it was about me. And Jane came over to me and put her arm around me.

“You poor thing!” she said. “Just fight it out. We’re all with you.{34}”

“I’m so helpless, Jane.” I put all the despair I could into my voice. For after all, if they were going to talk about my private Affairs behind my back, I felt that they might as well have something to talk about. As Jane’s second couzin once removed is in this school and as Jane will probably write her all about it, I hope this Theme is read aloud in class, so she will get it all straight. Jane is imaginative and may have a wrong idea of things.

“Don’t give in. Let them bully you. They can’t really do anything. And they’re scared. Leila is positively sick.”

“I’ve promised to write and break it off,” I said in a tence tone.

“If he really loves you,” said Jane, “the letter won’t matter.” There was a thrill in her voice. Had I not been uneasy at my deciet, I to would have thrilled.

Some fresh muffins came in just then and I was starveing. But I waved them away, and stood staring at the fire.

I am writing all of this as truthfully as I can. I am not defending myself. What I did I was driven to, as any one can see. It takes a real shock to make the average Familey wake up to the fact that the youngest daughter is not the Familey baby at seventeen. All I was doing was furnishing the shock. If things turned out badly, as they did, it was because I rather overdid the thing. That is all. My motives were perfectly ireproachible.

Well, they fell on the muffins like pigs, and I could{35} hardly stand it. So I wandered into the den, and it occurred to me to write the letter then. I felt that they all expected me to do something anyhow.

If I had never written the wretched letter things would be better now. As I say, I overdid. But everything had gone so smoothly all day that I was decieved. But the real reason was a new set of furs. I had secured the dresses and the promise of the necklace on a Poem and a Photograph, and I thought that a good love letter might bring a muff. It all shows that it does not do to be grasping.

Had I not written the letter, there would have been no tradgedy.

But I wrote it and if I do say it, it was a letter. I commenced it “Darling,” and I said I was mad to see him, and that I would always love him. But I told him that the Familey objected to him, and that this was to end everything between us. They had started the phonograph in the library, and were playing “The Rosary.” So I ended with a verse from that. It was really a most affecting letter. I almost wept over it myself, because, if there had been a Harold, it would have broken his Heart.

Of course I meant to give it to Hannah to mail, and she would give it to mother. Then, after the family had read it and it had got in its work, including the set of furs, they were welcome to mail it. It would go to the Dead Letter Office, since there was no Harold. It could not come back to me, for I had only signed it “Barbara.” I had it all figured out carefully.{36} It looked as if I had everything to gain, including the furs, and nothing to lose. Alas, how little I knew!

“The best laid plans of mice and men gang aft aglay.” Burns.

Carter Brooks ambled into the room just as I sealed it and stood gazing down at me.

“You’re quite a Person these days, Bab,” he said. “I suppose all the customary Xmas kisses are being saved this year for what’s his name.”

“I don’t understand you.”

“For Harold. You know, Bab, I think I could bear up better if his name wasn’t Harold.”

“I don’t see how it concerns you,” I responded.

“Don’t you? With me crazy about you for lo, these many years! First as a baby, then as a sub-sub-deb, and now as a sub-deb. Next year, when you are a real Debutante——”

“You’ve concealed your infatuation bravely.”

“It’s been eating me inside. A green and yellow melancholly—hello! A letter to him!”

“Why, so it is,” I said in a scornfull tone.

He picked it up, and looked at it. Then he started and stared at me.

“No!” he said. “It isn’t possible! It isn’t old Valentine!”

Positively, my knees got cold. I never had such a shock.

“It—it certainly is Harold Valentine,” I said feebly.

“Old Hal!” he muttered. “Well, who would have thought it! And not a word to me about it, the{37} secretive old duffer!” He held out his hand to me. “Congratulations, Barbara,” he said heartily. “Since you absolutely refuse me, you couldn’t do better. He’s the finest chap I know. If it’s Valentine the Familey is kicking up such a row about, you leave it to me. I’ll tell them a few things.”

I was stunned. Would anybody have beleived it? To pick a name out of the air, so to speak, and off a malted milk tablet, and then to find that it actualy belonged to some one—was sickning.

“It may not be the one you know,” I said desperately. “It—it’s a common name. There must be plenty of Valentines.”

“Sure there are, lace paper and Cupids—lots of that sort. But there’s only one Harold Valentine, and now you’ve got him pinned to the wall! I’ll tell you what I’ll do, Barbara. I’m a real friend of yours. Always have been. Always will be. The chances are against the Familey letting him get this letter. I’ll give it to him.”

“Give it to him?”

“Why, he’s here. You know that, don’t you? He’s in town over the holadays.”

“Oh, no!” I said in a gasping Voice.

“Sorry,” he said. “Probably meant it as a surprize to you. Yes, he’s here, with bells on.”

He then put the letter in his pocket before my very eyes, and sat down on the corner of the writing table!

“You don’t know how all this has releived my{38} mind,” he said. “The poor chap’s been looking down. Not interested in anything. Of course this explains it. He’s the sort to take Love hard. At college he took everything hard—like to have died once with German meazles.”

He picked up a book, and the charred picture was underneath. He pounced on it. “Pounced” is exactly the right word.

“Hello!” he said. “Familey again, I suppose. Yes, it’s Hal, all right. Well, who would have thought it!”

My last hope died. Then and there I had a nervous chill. I was compelled to prop my chin on my hand to keep my teeth from chattering.

“Tell you what I’ll do,” he said, in a perfectly cheerfull tone that made me cold all over. “I’ll be the Cupid for your Valentine. See? Far be it from me to see Love’s young dream wiped out by a hard-hearted Familey. I’m going to see this thing through. You count on me, Barbara. I’ll arrange that you get a chance to see each other, Familey or no Familey. Old Hal has been looking down his nose long enough. When’s your first party?”

“Tomorrow night,” I gasped out.

“Very well. Tomorrow night it is. It’s the Adams’s, isn’t it, at the Club?”

I could only nod. I was beyond speaking. I saw it all clearly. I had been wicked in decieving my dear Familey and now I was to pay the Penalty. He would know at once that I had made him up, or rather he did{39} not know me and therefore could not possibly be in Love with me. And what then?

“But look here,” he said, “if I take him there as Valentine, the Familey will be on, you know. We’d better call him something else. Got any choice as to a name?”

“Carter,” I said franticaly. “I think I’d better tell you. I——”

“How about calling him Grosvenor?” he babbled on. “Grosvenor’s a good name. Ted Grosvenor—that ought to hit them between the eyes. It’s going to be rather a lark, Miss Bab!”

And of course just then mother came in, and the Brooks idiot went in and poured her a cup of tea, with his little finger stuck out at a right angel, and every time he had a chance he winked at me.

I wanted to die.

When they had all gone home it seemed like a bad dream, the whole thing. It could not be true. I went upstairs and manacured my nails, which usually comforts me, and put my hair up like Leila’s.

But nothing could calm me. I had made my own Fate, and must lie in it. And just then Hannah slipped in with a box in her hands and her eyes frightened.

“Oh, Miss Barbara!” she said. “If your mother sees this!”

I dropped my manacure scizzors, I was so alarmed. But I opened the box, {40}and clutched the envelope inside. It said “from H——.” Then Carter was right. There was an H after all!

Hannah was rolling her hands in her apron and her eyes were poping out of her head.

“I just happened to see the boy at the door,” she said, with her silly teeth chattering. “Oh, Miss Barbara, if Patrick had answered the bell! What shall we do with them?”

“You take them right down the back stairs,” I said. “As if it was an empty box. And put it outside with the waist papers. Quick.”

She gathered the thing up, but of course mother had to come in just then and they met in the doorway. She saw it all in one glance, and she snatched the card out of my hand.

“From H——!” she read. “Take them out, Hannah, and throw them away. No, don’t do that. Put them on the Servant’s table.” Then, when the door had closed, she turned to me. “Just one more ridiculous Episode of this kind, Barbara,” she said, “and you go back to school—Xmas or no Xmas.”

I will say this. If she had shown the faintest softness, I’d have told her the whole thing. But she did not. She looked exactly as gentle as a macadam pavment. I am one who has to be handled with Gentleness. A kind word will do anything with me, but harsh treatment only makes me determined. I then become inflexable as iron.

That is what happened then. Mother took the wrong course and threatened, which as I have stated{41} is fatal, as far as I am concerned. I refused to yeild an inch, and it ended in my having my dinner in my room, and mother threatening to keep me home from the Party the next night. It was not a threat, if she had only known it.

But when the next day went by, with no more flowers, and nothing aparently wrong except that mother was very dignafied with me, I began to feel better. Sis was out all day, and in the afternoon Jane called me up.

“How are you?” she said.

“Oh, I’m all right.”

“Everything smooth?”

“Well, smooth enough.”

“Oh, Bab,” she said. “I’m just crazy about it. All the girls are.”

“I knew they were crazy about something.”

“You poor thing, no wonder you are bitter,” she said. “Somebody’s coming. I’ll have to ring off. But don’t you give in, Bab. Not an inch. Marry your Heart’s Desire, no matter who butts in.”

Well, you can see how it was. Even then I could have told father and mother, and got out of it somehow. But all the girls knew about it, and there was nothing to do but go on.

All that day every time I thought of the Party my heart missed a beat. But as I would not lie and say that I was ill—I am naturaly truthful, as far as possible—I was compelled to go, although my heart was breaking.{42}

I am not going to write much about the party, except a slight discription, which properly belongs in every Theme.

All Parties for the school set are alike. The boys range from knickerbockers to college men in their Freshmen year, and one is likely to dance half the evening with youngsters that one saw last in their perambulaters. It is rather startling to have about six feet of black trouser legs and white shirt front come and ask one to dance and then to get one’s eyes raised as far as the top of what looks like a particularly thin pair of tree trunks and see a little boy’s face.

As this Theme is to contain discription I shall discribe the ball room of the club where the eventful party occurred.

The ball room is white, with red hangings, and looks like a Charlotte Russe with maraschino cherries. Over the fireplace they had put “Merry Christmas,” in electric lights, and the chandaliers were made into Christmas trees and hung with colored balls. One of the balls fell off during the Cotillion, and went down the back of one of the girl’s dresses, and they were compelled to up-end her and shake her out in the dressing room.

The favors were insignifacant, as usual. It is not considered good taste to have elaberate things for the school crowd. But when I think of the silver things Sis always brought home, and remember that I took away about six Christmas Stockings, a toy Baloon,{43} four Whistles, a wooden Canary in a cage and a box of Talcum Powder, I feel that things are not fair in this World.

Hannah went with me, and in the motor she said:

“Oh, Miss Barbara, do be careful. The Familey is that upset.”

“Don’t be a silly,” I said. “And if the Familey is half as upset as I am, it is throwing a fit at this minute.”

We were early, of course. My mother beleives in being on time, and besides, she and Sis wanted the motor later. And while Hannah was on her knees taking off my carriage boots, I suddenly decided that I could not go down. Hannah turned quite pale when I told her.

“What’ll your mother say?” she said. “And you with your new dress and all! It’s as much as my life is worth to take you back home now, Miss Barbara.”

Well, that was true enough. There would be a Riot if I went home, and I knew it.

“I’ll see the Stuard and get you a cup of tea,” Hannah said. “Tea sets me up like anything when I’m nervous. Now please be a good girl, Miss Barbara, and don’t run off, or do anything foolish.”

She wanted me to promise, but I would not, although I could not have run anywhere. My legs were entirely numb.

In a half hour at the utmost I knew all would be known, and very likely I would be a homless wanderer on the earth. For I felt that never, never could I{44} return to my Dear Ones, when my terrable actions became known.

Jane came in while I was sipping the tea and she stood off and eyed me with sympathy.

“I don’t wonder, Bab!” she said. “The idea of your Familey acting so outragously! And look here——” She bent over me and whispered it. “Don’t trust Carter too much. He is perfectly infatuated with Leila, and he will play into the hands of the enemy. Be careful.”

“Loathesome creature!” was my response. “As for trusting him, I trust no one, these days.”

“I don’t wonder your Faith is gone,” she observed. But she was talking with one eye on a mirror.

“Pink makes me pale,” she said. “I’ll bet the maid has a drawer full of rouge. I’m going to see. How about a touch for you? You look gastly.”

“I don’t care how I look,” I said, recklessly. “I think I’ll sprain my ankle and go home. Anyhow I am not allowed to use rouge.”

“Not allowed!” she observed. “What has that got to do with it? I don’t understand you, Bab; you are totaly changed.”

“I am suffering,” I said. I was to.

Just then the maid brought me a folded note. Hannah was hanging up my wraps, and did not see it. Jane’s eyes fairly bulged.

“I hope you have saved the Cotillion for me,” it {45}said. And it was signed H——!

“Good gracious,” Jane said breathlessly. “Don’t tell me he is here, and that that’s from him!”

I had to swallow twice before I could speak. Then I said, solemnly:

“He is here, Jane. He has followed me. I am going to dance the Cotillion with him although I shall probably be disinherited and thrown out into the World, as a result.”

I have no recollection whatever of going down the staircase and into the ballroom. Although I am considered rather brave, and once saved one of the smaller girls from drowning, as I need not remind the school, when she was skating on thin ice, I was frightened. I remember that, inside the door, Jane said “Courage!” in a low tence voice, and that I stepped on somebody’s foot and said “Certainly” instead of apologizing. The shock of that brought me around somewhat, and I managed to find Mrs. Adams and Elaine, and not disgrace myself. Then somebody at my elbow said:

“All right, Barbara. Everything’s fixed.”

It was Carter.

“He’s waiting in the corner over there,” he said. “We’d better go through the formalaty of an introduction. He’s positively twittering with excitement.”

“Carter,” I said desparately. “I want to tell you somthing first. I’ve got myself in an awful mess. I——”

“Sure you have,” he said. “That’s why I’m here, to help you out. Now you be calm, and there’s no reason why you two can’t have the evening of your{46} young lives. I wish I could fall in Love. It must be bully.”

“Carter——!”

“Got his note, didn’t you?”

“Yes, I——”

“Here we are,” said Carter. “Miss Archibald, I would like to present Mr. Grosvenor.”

Somebody bowed in front of me, and then straightened up and looked down at me. It was the man of the Picture, little mustache and all. My mouth went perfectly dry.

It is all very well to talk about Romance and Love, and all that sort of thing. But I have concluded that amorus experiences are not always agreeable. And I have discovered something else. The moment anybody is crazy about me I begin to hate him. It is curious, but I am like that. I only care as long as they, or he, is far away. And the moment I touched H’s white kid glove, I knew I loathed him.

“Now go to it, you to,” Carter said in cautious tone. “Don’t be conspicuous. That’s all.”

And he left us.

“Suppose we dance this. Shall we?” said H. And the next moment we were gliding off. He danced very well. I will say that. But at the time I was too much occupied with hateing him to care about dancing, or anything. But I was compelled by my pride to see things through. We are a very proud Familey and never show our troubles, though our hearts be torn with anguish.{47}

“Think,” he said, when we had got away from the band, “think of our being together like this!”

“It’s not so surprizing, is it? We’ve got to be together if we are dancing.”

“Not that. Do you know, I never knew so long a day as this has been. The thought of meeting you—er—again, and all that.”

“You needn’t rave for my benefit,” I said freesingly. “You know perfectly well that you never saw me before.”

“Barbara! With your dear little Letter in my breast pocket at this moment!”

“I didn’t know men had breast pockets in their evening clothes.”

“Oh well, have it your own way. I’m too happy to quarrel,” he said. “How well you dance—only, let me lead, won’t you? How strange it is to think that we have never danced together before!”

“We must have a talk,” I said desparately. “Can’t we go somwhere, away from the noise?”

“That would be conspicuous, wouldn’t it, under the circumstances? If we are to overcome the Familey objection to me, we’ll have to be cautious, Barbara.”

“Don’t call me Barbara,” I snapped. “I know perfectly well what you think of me, and I——”

“I think you are wonderful,” he said. “Words fail me when I try to tell you what I am thinking. You’ve saved the Cotillion for me, haven’t you? If not, I’m going to claim it anyhow. It is my right.”

He said it in the most determined manner, as if{48} everything was settled. I felt like a rat in a trap, and Carter, watching from a corner, looked exactly like a cat. If he had taken his hand in its white glove and washed his face with it, I would hardly have been surprized.

The music stopped, and somebody claimed me for the next. Jane came up, too, and cluched my arm.

“You lucky thing!” she said. “He’s perfectly handsome. And oh, Bab, he’s wild about you. I can see it in his eyes.”

“Don’t pinch, Jane,” I said coldly. “And don’t rave. He’s an idiot.”

She looked at me with her mouth open.

“Well, if you don’t want him, pass him on to me,” she said, and walked away.

It was too silly, after everything that had happened, to dance the next dance with Willie Graham, who is still in knickerbockers, and a full head shorter than I am. But that’s the way with a Party for the school crowd, as I’ve said before. They ask all ages, from perambulaters up, and of course the little boys all want to dance with the older girls. It is deadly stupid.

But H seemed to be having a good time. He danced a lot with Jane, who is a wreched dancer, with no sense of time whatever. Jane is not pretty, but she has nice eyes, and I am not afraid, second couzin once removed or no second couzin once removed, to say she used them.

Altogether, it was a terrible evening. I danced three dances out of four with knickerbockers, and one{49} with old Mr. Adams, who is fat and rotates his partner at the corners by swinging her on his waistcoat. Carter did not dance at all, and every time I tried to speak to him he was taking a crowd of the little girls to the fruit-punch bowl.

I determined to have things out with H during the Cotillion, and tell him that I would never marry him, that I would Die first. But I was favored a great deal, and when we did have a chance the music was making such a noise that I would have had to shout. Our chairs were next to the band.

But at last we had a minute, and I went out to the verandah, which was closed in with awnings. He had to follow, of course, and I turned and faced him.

“Now,” I said, “this has got to stop.”

“I don’t understand you, Bab.”

“You do, perfectly well,” I stormed. “I can’t stand it. I am going crazy.”

“Oh,” he said slowly. “I see. I’ve been dancing too much with the little girl with the eyes! Honestly, Bab, I was only doing it to disarm suspicion. My Every Thought is of you.”

“I mean,” I said, as firmly as I could, “that this whole thing has got to stop. I can’t stand it.”

“Am I to understand,” he said solemnly, “that you intend to end everything?”

I felt perfectly wild and helpless.

“After that Letter!” he went on. “After that sweet Letter! You said, you know, that you were mad to see me, and that—it is almost too sacred to repeat,{50} even to you—that you would always love me. After that Confession I refuse to agree that all is over. It can never be over.”

“I daresay I am losing my mind,” I said. “It all sounds perfectly natural. But it doesn’t mean anything. There can’t be any Harold Valentine; because I made him up. But there is, so there must be. And I am going crazy.”

“Look here,” he stormed, suddenly quite raving, and throwing out his right hand. It would have been terrably dramatic, only he had a glass of punch in it. “I am not going to be played with. And you are not going to jilt me without a reason. Do you mean to deny everything? Are you going to say, for instance, that I never sent you any violets? Or gave you my Photograph, with an—er—touching inscription on it?” Then, appealingly, “You can’t mean to deny that Photograph, Bab!”

And then that lanky wretch of an Eddie Perkins brought me a toy Baloon, and I had to dance, with my heart crushed.

Nevertheless, I ate a fair supper. I felt that I needed Strength. It was quite a grown-up supper, with boullion and creamed chicken and baked ham and sandwitches, among other things. But of course they had to show it was a ‘kid’ party, after all. For instead of coffee we had milk.

Milk! When I was going through a tradgedy. For if it is not a tradgedy to be engaged to a man one never saw before, what is it?{51}

All through the refreshments I could feel that his eyes were on me. And I hated him. It was all well enough for Jane to say he was handsome. She wasn’t going to have to marry him. I detest dimples in chins. I always have. And anybody could see that it was his first mustache, and soft, and that he took it round like a mother pushing a new baby in a perambulater. It was sickning.

I left just after supper. He did not see me when I went upstairs, but he had missed me, for when Hannah and I came down, he was at the door, waiting. Hannah was loaded down with silly favors, and lagged behind, which gave him a chance to speak to me. I eyed him coldly and tried to pass him, but I had no chance.

“I’ll see you tomorrow, dearest,” he whispered.

“Not if I can help it,” I said, looking straight ahead. Hannah had dropped a stocking—not her own. One of the Xmas favors—and was fumbling about for it.

“You are tired and unerved to-night, Bab. When I have seen your father tomorrow, and talked to him——”

“Don’t you dare to see my father.”

“—— and when he has agreed to what I propose,” he went on, without paying any atention to what I had said, “you will be calmer. We can plan things.”

Hannah came puffing up then, and he helped us into the motor. He was very careful to see that we were covered with the robes, and he tucked Hannah’s feet{52} in. She was awfully flattered. Old Fool! And she babbled about him until I wanted to slap her.

“He’s a nice young man. Miss Bab,” she said. “That is, if he’s the One. And he has nice manners. So considerate. Many a party I’ve taken your sister to, and never before——”

“I wish you’d shut up, Hannah,” I said. “He’s a Pig, and I hate him.”

She sulked after that, and helped me out of my things at home without a word. When I was in bed, however, and she was hanging up my clothes, she said:

“I don’t know what’s got into you, Miss Barbara. You are that cross that there’s no living with you.”

“Oh, go away,” I said.

“And what’s more,” she added, “I don’t know but what your mother ought to know about these goings-on. You’re only a little girl, with all your high and mightiness, and there’s going to be no scandal in this Familey if I can help it.”

I put the bedclothes over my head, and she went out.

But of course I could not sleep. Sis was not home yet, or mother, and I went into Sis’s room and got a novel from her table. It was the story of a woman who had married a man in a hurry, and without really loving him, and when she had been married a year, and hated the very way her husband drank his coffee and cut the ends off his cigars, she found some one she really loved with her Whole Heart. And it was too late. But she wrote him one Letter, the other man,{53} you know, and it caused a lot of trouble. So she said—I remember the very words—

“Half the troubles in the world are caused by Letters. Emotions are changable things”—this was after she had found that she really loved her husband after all, but he had had to shoot himself before she found it out, although not fataly—“but the written word does not change. It remains always, embodying a dead truth and giving it apparent life. No woman should ever put her thoughts on paper.”

She got the Letter back, but she had to steal it. And it turned out that the other man had really only wanted her money all the time.

That story was a real ilumination to me. I shall have a great deal of money when I am of age, from my grandmother. I saw it all. It was a trap sure enough. And if I was to get out I would have to have the letter.

It was the Letter that put me in his power.

The next day was Xmas. I got a lot of things, including the necklace, and a mending basket from Sis, with the hope that it would make me tidey, and father had bought me a set of Silver Fox, which mother did not approve of, it being too expencive for a young girl to wear, according to her. I must say that for an hour or two I was happy enough.

But the afternoon was terrable. We keep open house on Xmas afternoon, and father makes a champagne punch, and somebody pours tea, although nobody drinks it, and there are little cakes from the Club,{54} and the house is decorated with poin—(Memo: Not in the Dictionery and I cannot spell it, although not usualy troubled as to spelling.)

At eleven o’clock the mail came in, and mother sorted it over, while father took a gold piece out to the post-man.

There were about a million cards, and mother glanced at the addresses and passed them round. But suddenly she frowned. There was a small parcel, addressed to me.

“This looks like a Gift, Barbara,” she said. And preceded to open it.

My heart skipped two beats, and then hamered. Mother’s mouth was set as she tore off the paper and opened the box. There was a card, which she glanced at, and underneath, was a book of poems.

“Love Lyrics,” said mother, in a terrable voice. “To Barbara, from H——”

“Mother——” I began, in an ernest tone.

“A child of mine recieving such a book from a man!” she went on. “Barbara, I am speachless.”

But she was not speachless. If she was speachless for the next half hour, I would hate to hear her really converse. And all that I could do was to bear it. For I had made a Frankenstein—see the book read last term by the Literary Society—not out of grave-yard fragments, but from malted milk tablets, so to speak, and now it was pursuing me to an early grave. For I felt that I simply could not continue to live.

“Now—where does he live?{55}”

“I—don’t know, mother.”

“You sent him a Letter.”

“I don’t know where he lives, anyhow.”

“Leila,” mother said, “will you ask Hannah to bring my smelling salts?”

“Aren’t you going to give me the book?” I asked. “It—it sounds interesting.”

“You are shameless,” mother said, and threw the thing into the fire. A good many of my things seemed to be going into the fire at that time. I cannot help wondering what they would have done if it had all happened in the summer, and no fires burning. They would have felt quite helpless, I imagine.

Father came back just then, but he did not see the Book, which was then blazing with a very hot red flame. I expected mother to tell him, and I daresay I should not have been surprised to see my furs follow the book. I had got into the way of expecting to see things burning that do not belong in a fireplace. But mother did not tell him.

I have thought over this a great deal, and I beleive that now I understand. Mother was unjustly putting the blame for everything on this School, and mother had chosen the School. My father had not been much impressed by the catalogue. “Too much dancing room and not enough tennis courts,” he had said. This, of course, is my father’s opinion. Not mine.

The real reason, then, for mother’s silence was that she disliked confessing that she made a mistake in her choice of a School.{56}

I ate very little Luncheon and my only comfort was my seed pearls. I was wearing them, for fear the door-bell would ring, and a Letter or flowers would arrive from H. In that case I felt quite sure that someone, in a frenzy, would burn the Pearls also.

The afternoon was terrable. It rained solid sheets, and Patrick, the butler, gave notice three hours after he had recieved his Xmas presents, on account of not being let off for early mass.

But my father’s punch is famous, and people came, and stood around and buzzed, and told me I had grown and was almost a young lady. And Tommy Gray got out of his cradle and came to call on me, and coughed all the time, with a whoop. He developed the whooping cough later. He had on his first long trousers, and a pair of lavender Socks and a Tie to match. He said they were not exactly the same shade, but he did not think it would be noticed. Hateful child!

At half past five, when the place was jamed, I happened to look up. Carter Brooks was in the hall, and behind him was H. He had seen me before I saw him, and he had a sort of sickley grin, meant to denote joy. I was talking to our Bishop at the time, and he was asking me what sort of services we had in the school chapel.

I meant to say “non-sectarian,” but in my surprize and horror I regret to say that I said, “vegetarian.” Carter Brooks came over to me like a cat to a saucer of milk, and pulled me off into a corner.{57}

“It’s all right,” he said. “I ’phoned mama, and she said to bring him. He’s known as Grosvenor here, of course. They’ll never suspect a thing. Now, do I get a small ‘thank you’?”

“I won’t see him.”

“Now look here, Bab,” he protested, “you two have got to make this thing up. You are a pair of Idiots, quarreling over nothing. Poor old Hal is all broken up. He’s sensative. You’ve got to remember how sensative he is.”

“Go away,” I cried, in broken tones. “Go away, and take him with you.”

“Not until he had spoken to your Father,” he observed, setting his jaw. “He’s here for that, and you know it. You can’t play fast and loose with a man, you know.”

“Don’t you dare to let him speak to father!”

He shrugged his shoulders.

“That’s between you to, of course,” he said. “It’s not up to me. Tell him yourself, if you’ve changed your mind. I don’t intend,” he went on, impressively, “to have any share in ruining his life.”

“Oh piffle,” I said. I am aware that this is slang, and does not belong in a Theme. But I was driven to saying it.

I got through the crowd by using my elbows. I am afraid I gave the Bishop quite a prod, and I caught Mr. Andrews on his rotateing waistcoat. But I was desparate.

Alas, I was too late.{58}

The caterer’s man, who had taken Patrick’s place in a hurry, was at the punch bowl, and father was gone. I was just in time to see him take H. into his library and close the door.

Here words fail me. I knew perfectly well that beyond that door H, whom I had invented and who therefore simply did not exist, was asking for my Hand. I made up my mind at once to run away and go on the stage, and I had even got part way up the stairs, when I remembered that, with a dollar for the picture and five dollars for the violets and three dollars for the hat pin I had given Sis, and two dollars and a quarter for mother’s handkercheif case, I had exactly a dollar and seventy-five cents in the world.

I was trapped.

I went up to my room, and sat and waited. Would father be violent, and throw H. out and then come upstairs, pale with fury and disinherit me? Or would the whole Familey conspire together, when the people had gone, and send me to a convent? I made up my mind, if it was the convent, to take the veil and be a nun. I would go to nurse lepers, or something, and then, when it was too late, they would be sorry.

The stage or the convent, nun or actress? Which?

I left the door open, but there was only the sound of revelry below. I felt then that it was to be the convent. I pinned a towel around my face, the way the nuns wear whatever they call them, and from the side it was very becoming. I really did look like Julia{59} Marlowe, especialy as my face was very sad and tradgic.

At something before seven every one had gone, and I heard Sis and mother come upstairs to dress for dinner. I sat and waited, and when I heard father I got cold all over. But he went on by, and I heard him go into mother’s room and close the door. Well, I knew I had to go through with it, although my life was blasted. So I dressed and went downstairs.

Father was the first down. He came down whistling.

It is perfectly true. I could not beleive my ears.

He approached me with a smileing face.

“Well, Bab,” he said, exactly as if nothing had happened, “have you had a nice day?”

He had the eyes of a bacilisk, that creature of Fable.

“I’ve had a lovely day, Father,” I replied. I could be bacilisk-ish also.

There is a mirror over the drawing room mantle, and he turned me around until we both faced it.

“Up to my ears,” he said, referring to my heighth. “And Lovers already! Well, I daresay we must make up our minds to lose you.”

“I won’t be lost,” I declared, almost violently. “Of course, if you intend to shove me off your hands, to the first Idiot who comes along and pretends a lot of stuff, I——”

“My dear child!” said father, looking surprised. “Such an outburst! All I was trying to say, before your mother comes down, is that I—well, that I under{60}stand and that I shall not make my little girl unhappy by—er—by breaking her Heart.”

“Just what do you mean by that, father?”

He looked rather uncomfortable, being one who hates to talk sentament.

“It’s like this, Barbara,” he said. “If you want to marry this young man—and you have made it very clear that you do—I am going to see that you do it. You are young, of course, but after all your dear mother was not much older than you are when I married her.”

“Father!” I cried, from an over-flowing heart.

“I have noticed that you are not happy, Barbara,” he said. “And I shall not thwart you, or allow you to be thwarted. In affairs of the Heart, you are to have your own way.”

“I want to tell you something!” I cried. “I will not be cast off! I——”

“Tut, tut,” said Father. “Who is casting you off? I tell you that I like the young man, and give you my blessing, or what is the present-day equivelent for it, and you look like a figure of Tradgedy!”

But I could endure no more. My own father had turned on me and was rending me, so to speak. With a breaking heart and streaming eyes I flew to my Chamber.

There, for hours I paced the floor.

Never, I determined, would I marry H. Better death, by far. He was a scheming Fortune-hunter, but to tell the family that was to confess all. And I{61} would never confess. I would run away before I gave Sis such a chance at me. I would run away, but first I would kill Carter Brooks.

Yes, I was driven to thoughts of murder. It shows how the first false step leads down and down, to crime and even to death. Oh never, never, gentle reader, take that first False Step. Who knows to what it may lead!

“One false Step is never retreived.” Gray—On a Favorite Cat.

I reflected also on how the woman in the book had ruined her life with a letter. “The written word does not change,” she had said. “It remains always, embodying a dead truth and giving it apparent life.”

“Apparent life” was exactly what my letter had given to H. Frankenstein. That was what I called him, in my agony. I felt that if only I had never written the Letter there would have been no trouble. And another awful thought came to me: Was there an H after all? Could there be an H?

Once the French teacher had taken us to the theater in New York, and a woman sitting on a chair and covered with a sheet, had brought a man out of a perfectly empty Cabinet, by simply willing to do it. The Cabinet was empty, for four respectible looking men went up and examined it, and one even measured it with a Tape-measure.

She had materialised him, out of nothing.

And while I had had no Cabinet, there are many things in this world “that we do not dream of in our{62} Philosophy.” Was H. a real person, or a creature of my disordered brain? In plain and simple language, could there be such a Person?

I feared not.

And if there was no H, really, and I married him, where would I be?

There was a ball at the Club that night, and the Familey all went. No one came to say good-night to me, and by half past ten I was alone with my misery. I knew Carter Brooks would be at the ball, and H also, very likely, dancing around as agreably as if he really existed, and I had not made him up.

I got the book from Sis’s room again, and re-read it. The woman in it had been in great trouble, too, with her husband cleaning his revolver and making his will. And at last she had gone to the apartments of the man who had her letters, in a taxicab covered with a heavy veil, and had got them back. He had shot himself when she returned—the husband—but she burned the letters and then called a Doctor, and he was saved. Not the doctor, of course. The husband.

The villain’s only hold on her had been the letters, so he went to South Africa and was gored by an elephant, thus passing out of her life.

Then and there I knew that I would have to get my letter back from H. Without it he was powerless. The trouble was that I did not know where he was staying. Even if he came out of a Cabinet, the Cabinet would have to be somewhere, would it not?

I felt that I would have to meet gile with gile.{63} And to steal one’s own letter is not really stealing. Of course if he was visiting any one and pretending to be a real person, I had no chance in the world. But if he was stopping at a hotel I thought I could manage. The man in the book had had an apartment, with a Japanese servant, who went away and drew plans of American Forts in the kitchen and left the woman alone with the desk containing the Letter. But I daresay that was unusualy lucky and not the sort of thing to look forward to.

With me, to think is to act. Hannah was out, it being Xmas and her brother-in-law having a wake, being dead, so I was free to do anything I wanted to.

First I called the Club and got Carter Brooks on the telephone.

“Carter,” I said, “I—I am writing a letter. Where is—where does H. stay?”

“Who?”

“H.—Mr. Grosvenor.”

“Why, bless your ardent little Heart! Writing, are you? It’s sublime, Bab!”

“Where does he live?”

“And is it all alone you are, on Xmas Night!” he burbled. (This is a word from Alice in Wonderland, and although not in the dictionery, is quite expressive.)

“Yes,” I replied, bitterly. “I am old enough to be married off without my consent, but I am not old enough for a real Ball. It makes me sick.{64}”

“I can smuggle him here, if you want to talk to him.”

“Smuggle!” I said, with scorn. “There is no need to smuggle him. The Familey is crazy about him. They are flinging me at him.”

“Well, that’s nice,” he said. “Who’d have thought it! Shall I bring him to the ’phone?”

“I don’t want to talk to him. I hate him.”

“Look here,” he observed, “if you keep that up, he’ll begin to beleive you. Don’t take these little quarrels too hard, Barbara. He’s so happy to-night in the thought that you——”

“Does he live in a Cabinet, or where?”

“In a what? I don’t get that word.”

“Don’t bother. Where shall I send his letter?”

Well, it seemed he had an apartment at the Arcade, and I rang off. It was after eleven by that time, and by the time I had got into my school mackintosh and found a heavy veil of mother’s and put it on, it was almost half past.

The house was quiet, and as Patrick had gone, there was no one around in the lower Hall. I slipped out and closed the door behind me, and looked for a taxicab, but the veil was so heavy that I hailed our own limousine, and Smith had drawn up at the curb before I knew him.

“Where to, lady?” he said. “This is a private car, but I’ll take you anywhere in the city for a dollar.”

A flush of just indignation rose to my cheek, at the knowledge that Smith was using our car for a taxicab!{65} And just as I was about to speak to him severely, and threaten to tell father, I remembered, and walked away.

“Make it seventy-five cents,” he called after me. But I went on. It was terrable to think that Smith could go on renting our car to all sorts of people, covered with germs and everything, and that I could never report it to the Familey.

I got a real taxi at last, and got out at the Arcade, giving the man a quarter, although ten cents would have been plenty as a tip.

I looked at him, and I felt that he could be trusted.

“This,” I said, holding up the money, “is the price of Silence.”

But if he was trustworthy he was not subtile, and he said:

“The what, miss?”

“If any one asks if you have driven me here, you have not,” I explained, in an impressive manner.

He examined the quarter, even striking a match to look at it. Then he replied: “I have not!” and drove away.

Concealing my nervousness as best I could, I entered the doomed Building. There was only a hall boy there, asleep in the elevator, and I looked at the thing with the names on it. “Mr. Grosvenor” was on the fourth floor.

I wakened the boy, and he yawned and took me to the fourth floor. My hands were stiff with nervousness by that time, but the boy was half asleep, and{66} evadently he took me for some one who belonged there, for he said “Goodnight” to me, and went on down. There was a square landing with two doors, and “Grosvenor” was on one. I tried it gently. It was unlocked.

“Facilus descensus in Avernu.”

I am not defending myself. What I did was the result of desparation. But I cannot even write of my sensations as I stepped through that fatal portal, without a sinking of the heart. I had, however, had suficient forsight to prepare an alabi. In case there was some one present in the apartment I intended to tell a falshood, I regret to confess, and to say that I had got off at the wrong floor.

There was a sort of hall, with a clock and a table, and a shaded electric lamp, and beyond that the door was open into a sitting room.

There was a small light burning there, and the remains of a wood fire in the fireplace. There was no Cabinet however.

Everything was perfectly quiet, and I went over to the fire and warmed my hands. My nails were quite blue, but I was strangly calm. I took off mother’s veil, and my mackintosh, so I would be free to work, and I then looked around the room. There were a number of photographs of rather smart looking girls, and I curled my lip scornfully. He might have fooled them but he could not decieve me. And it added to my bitterness to think that at that moment the villain was dancing—and flirting probably—while I was driven to{67} actual theft to secure the Letter that placed me in his power.

When I had stopped shivering I went to his desk. There were a lot of letters on the top, all addressed to him as Grosvenor. It struck me suddenly as strange that if he was only visiting, under an assumed name, in order to see me, that so many people should be writing to him as Mr. Grosvenor. And it did not look like the room of a man who was visiting, unless he took a freight car with him on his travels.

There was a mystery. All at once I knew it.

My letter was not on the desk, so I opened the top drawer. It seemed to be full of bills, and so was the one below it. I had just started on the third drawer, when a terrable thing happened.

“Hello!” said some one behind me.

I turned my head slowly, and my heart stopped.

The porteres into the passage had opened, and a Gentleman in his evening clothes was standing there.

“Just sit still, please,” he said, in a perfectly cold voice. And he turned and locked the door into the hall. I was absolutely unable to speak. I tried once, but my tongue hit the roof of my mouth like the clapper of a bell.

“Now,” he said, when he had turned around. “I wish you would tell me some good reason why I should not hand you over to the Police.”

“Oh, please don’t!” I said.

“That’s eloquent. But not a reason. I’ll sit down{68} and give you a little time. I take it, you did not expect to find me here.”

“I’m in the wrong apartment. That’s all,” I said. “Maybe you’ll think that’s an excuse and not a reason. I can’t help it if you do.”

“Well,” he said, “that explains some things. It’s pretty well known, I fancy, that I have little worth stealing, except my good name.”

“I was not stealing,” I replied in a sulky manner.

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “It is an ugly word. We will strike it from the record. Would you mind telling me whose apartment you intended to—er—investigate? If this is the wrong one, you know.”

“I was looking for a Letter.”

“Letters, letters!” he said. “When will you women learn not to write letters. Although”—he looked at me closely—“you look rather young for that sort of thing.” He sighed. “It’s born in you, I daresay,” he said.

Well, for all his patronizing ways, he was not very old himself.

“Of course,” he said, “if you are telling the truth—and it sounds fishy, I must say—it’s hardly a Police matter, is it? It’s rather one for diplomasy. But can you prove what you say?”

“My word should be suficient,” I replied stiffly. “How do I know that you belong here?”

“Well, you don’t, as a matter of fact. Suppose you take my word for that, and I agree to beleive what you say about the wrong apartment. Even then it’s rather{69} unusual. I find a pale and determined looking young lady going through my desk in a business-like manner. She says she has come for a Letter. Now the question is, is there a Letter? If so, what Letter?”

“It is a love letter,” I said.

“Don’t blush over such a confession,” he said. “If it is true, be proud of it. Love is a wonderful thing. Never be ashamed of being in love, my child.”

“I am not in love,” I cried with bitter furey.

“Ah! Then it is not your letter!”

“I wrote it.”

“But to simulate a passion that does not exist—that is sackrilege. It is——”

“Oh, stop talking,” I cried, in a hunted tone. “I can’t bear it. If you are going to arrest me, get it over.”

“I’d rather not arrest you, if we can find a way out. You look so young, so new to Crime! Even your excuse for being here is so naïve, that I—won’t you tell me why you wrote a love letter, if you are not in love? And whom you sent it to? That’s important, you see, as it bears on the case. I intend,” he said, “to be judgdicial, unimpassioned, and quite fair.”

“I wrote a love letter,” I explained, feeling rather cheered, “but it was not intended for any one. Do you see? It was just a love letter.”

“Oh,” he said. “Of course. It is often done. And after that?{70}”

“Well, it had to go somewhere. At least I felt that way about it. So I made up a name from some malted milk tablets——”

“Malted milk tablets!” he said, looking bewildered.

“Just as I was thinking up a name to send it to,” I explained, “Hannah—that’s mother’s maid, you know—brought in some hot milk and some malted milk tablets, and I took the name from them.”

“Look here,” he said, “I’m unpredjudiced and quite calm, but isn’t the ‘mother’s maid’ rather piling it on?”

“Hannah is mother’s maid, and she brought in the milk and the tablets. I should think,” I said, growing sarcastic, “that so far it is clear to the dullest mind.”

“Go on,” he said, leaning back and closing his eyes. “You named the letter for your mother’s maid—I mean for the malted milk. Although you have not yet stated the name you chose; I never heard of any one named Milk, and as to the other, while I have known some rather thoroughly malted people—however, let that go.”

“Valentine’s tablets,” I said. “Of course, you understand,” I said, bending forward, “there was no such Person. I made him up. The Harold was made up too—Harold Valentine.”

“I see. Not clearly, perhaps, but I have a gleam of intellagence.”