The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lost in the Jungle, by Paul Du Chaillu

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Lost in the Jungle

Narrated for Young People

Author: Paul Du Chaillu

Release Date: June 5, 2011 [EBook #36324]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LOST IN THE JUNGLE ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Katie Hernandez and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

NARRATED FOR YOUNG PEOPLE.

THE COUNTRY OF THE DWARFS. Illustrated. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

MY APINGI KINGDOM. Illustrated. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

LOST IN THE JUNGLE. Illustrated. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

WILD LIFE UNDER THE EQUATOR. Illustrated. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

STORIES OF THE GORILLA COUNTRY. Illustrated. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

EXPLORATIONS AND ADVENTURES IN EQUATORIAL AFRICA. Illustrated. New Edition. 8vo, Cloth, $5 00.

A JOURNEY TO ASHANGO LAND, and Further Penetration into Equatorial Africa. New Edition. Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $5 00.

Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.

Sent by mail, postage prepaid, to any part of the United States, on receipt of the price.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

Harper & Brothers,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of New York.

CHAPTER I. | |

| Paul's Letter to his Young Friends, in which he prepares them for being "Lost in the Jungle." | Page 11 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| A queer Canoe.—On the Rembo.—We reach the Niembouai.—A deserted Village.—Gazelle attacked by a Snake.—Etia wounded by a Gorilla. | 14 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| Harpooning a Manga.—A great Prize.—Our Canoe capsized.—Description of the Manga.—Return to Camp. | 23 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| We go into the Forest.—Hunt for Ebony-trees.—The Fish-eagles.—Capture of a young Eagle.—Impending Fight with them.—Fearful roars of Gorillas.—Gorillas breaking down Trees. | 28 |

CHAPTER V. | |

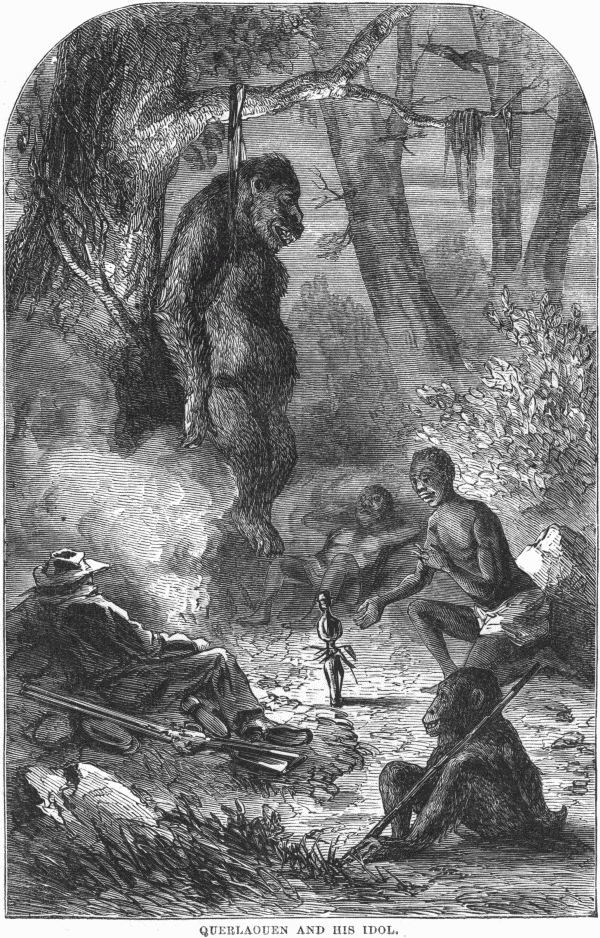

| Lost.—Querlaouen says we are Bewitched.—Monkeys and Parrots.—A deserted Village.—Strange Scene before an Idol.—Bringing in the Wounded.—An Invocation. | 37 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| A white Gorilla.—Meeting two Gorillas.—The Female runs away.—The Man Gorilla shows fight.—He is killed.—His immense Hands and Feet.—Strange Story of a Leopard and a Turtle. | 48 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| Return to the Ovenga River.—The Monkeys and their Friends the Birds.—They live together.—Watch by Moonlight for Game.—Kill an Oshengui. | 55 |

| [vi] CHAPTER VIII. | |

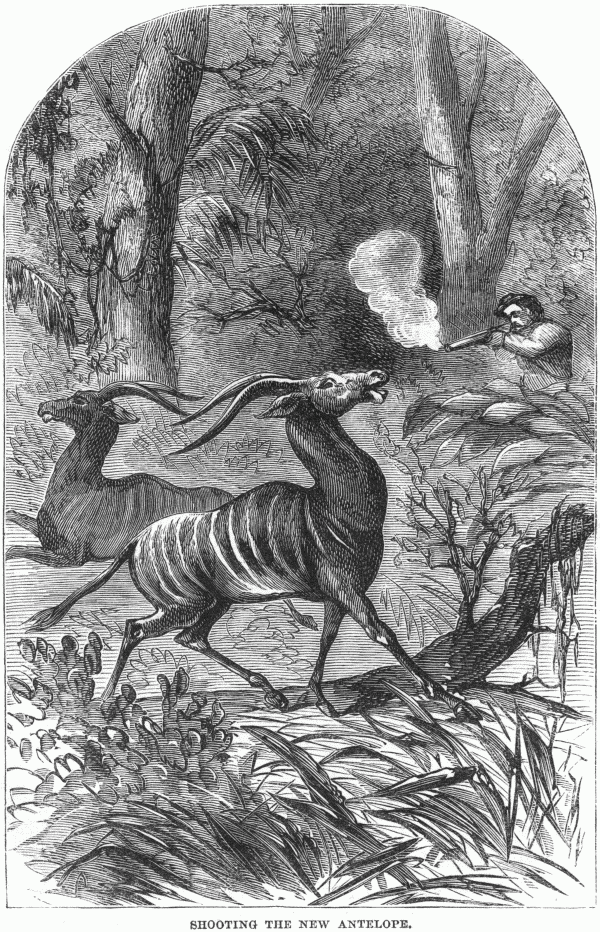

| We are in a Canoe.—Outfit for Hunting.—See a beautiful Antelope.—Kill it.—It is a new Species.—River and forest Swallows. | 62 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| We hear the Cry of a young Gorilla.—Start to capture him.—Fight with "his Father."—We kill him.—Kill the Mother.—Capture of the Baby.—Strange Camp Scene. | 70 |

CHAPTER X. | |

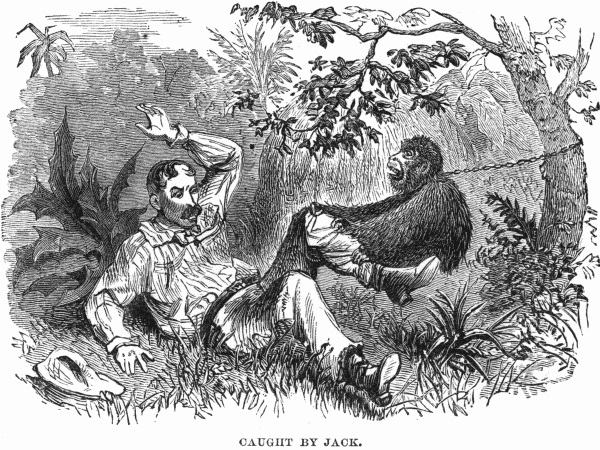

| Jack will have his own way.—He seizes my Leg.—He tears my Pantaloons.—He growls at me.—He refuses cooked Food.—Jack makes his Bed.—Jack sleeps with one Eye open.—Jack is intractable. | 81 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| Start after Land-crabs.—Village of the Crabs.—Each Crab knows his House.—Great flight of Crabs.—They bite hard.—Feast on the Slain.—A herd of Hippopotami. | 87 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| Strange Spiders.—The House-spider.—How they capture their Prey.—How they Fight.—Fight between a Wasp and a Spider.—The Spider has its Legs cut off, and is carried away.—Burrow Spider watching for its Prey. | 94 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

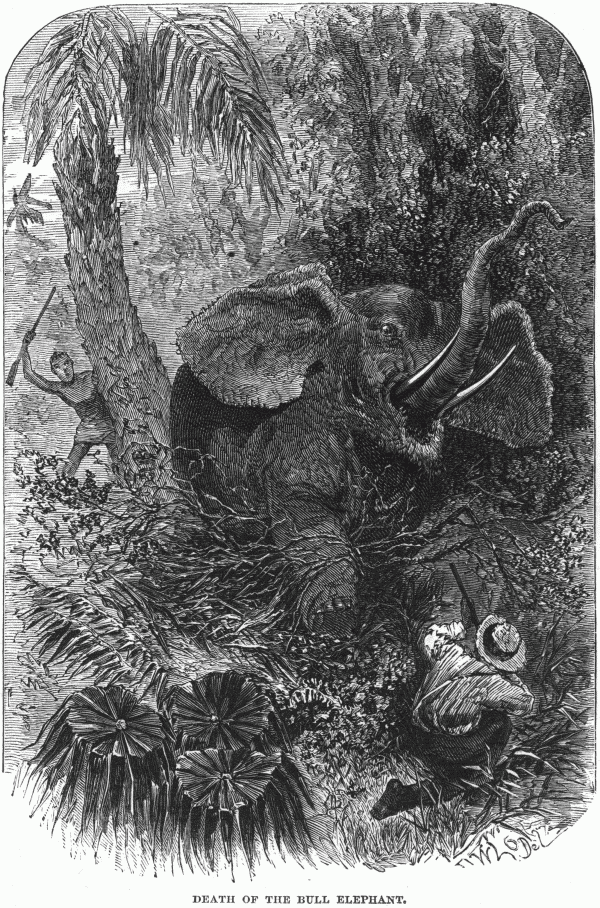

| We continue our Wanderings.—Joined by Etia.—We starve.—Gambo and Etia go in search of Berries.—A herd of Elephants.—The rogue Elephant charges me.—He is killed.—He tumbles down near me.—Story of Redjioua. | 106 |

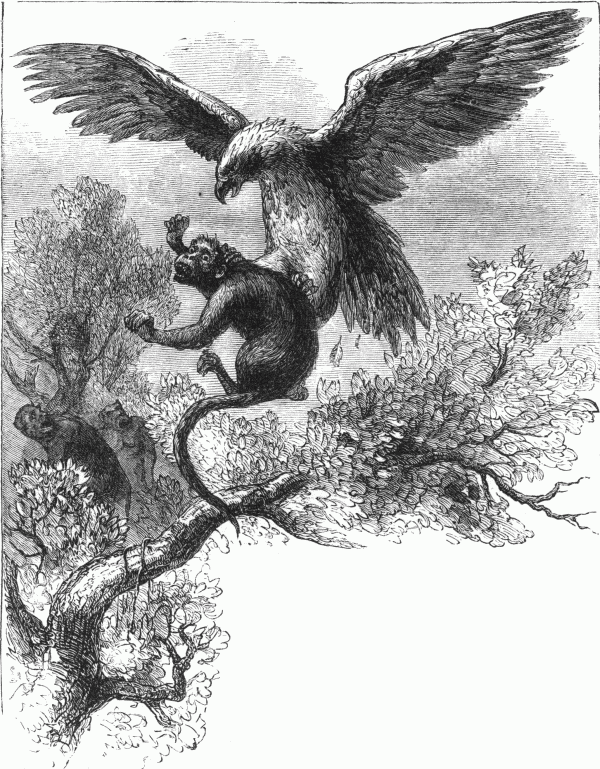

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A formidable Bird.—The People are afraid of it.—A Baby carried off by the Guanionien.—A Monkey also seized.—I discover a Guanionien Nest.—I watch for the Eagles. | 119 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

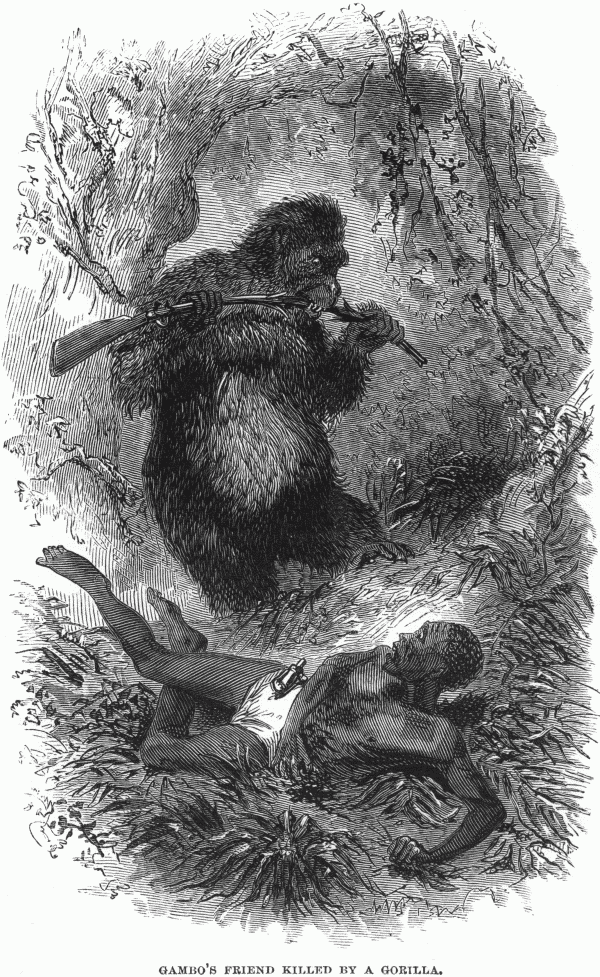

| The Cascade of Niama-Biembai.—A native Camp.—Starting for the Hunt.—A Man attacked by a Gorilla.—His Gun broken.—The Man dies.—His Burial. | 127 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Funeral of the Gorilla's Victim.—A Man's Head for the Alumbi.—The Snake and the Guinea-fowl.—Snake killed.—Visit to the House of the Alumbi.—Determine to visit the Sea-coast. | 137 |

| [vii] CHAPTER XVII. | |

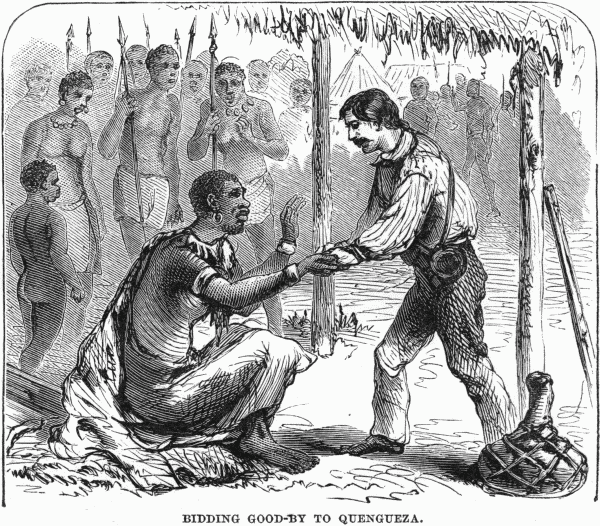

| At Washington once more.—Delights of the Sea-shore.—I have been made a Makaga.—Friends object to my Return into the Jungle.—Quengueza taken Sick.—Gives a Letter to his Nephew.—Taking leave. | 142 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

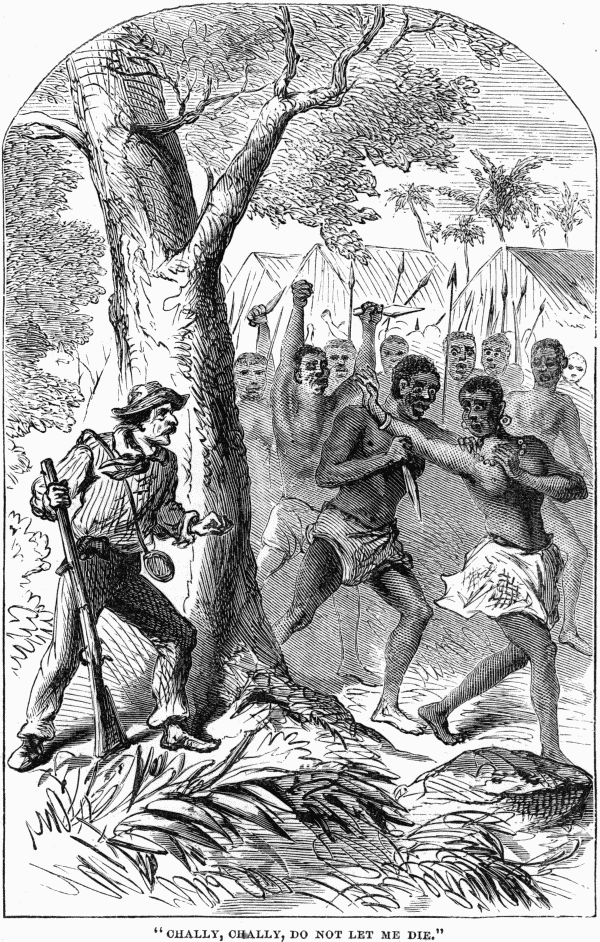

| Departure.—Arrival at Goumbi.—The People ask for the King.—A Death-panic in Goumbi.—A Doctor sent for.—Death to the Aniembas.—Three Women accused.—They are tried and killed. | 148 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

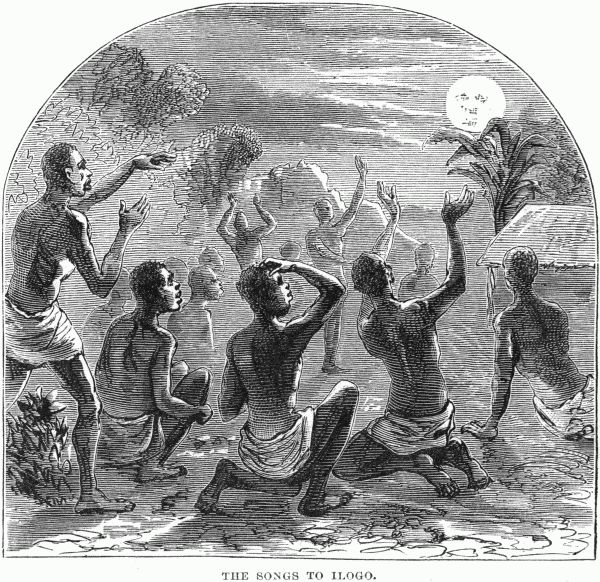

| Quengueza orders Ilogo to be consulted about his Illness.—What the People think of Ilogo.—A nocturnal Séance.—Song to Ilogo.—A female Medium.—What Ilogo said. | 162 |

CHAPTER XX. | |

| Departure from Goumbi.—Querlaouen's Village.—Find it deserted.—Querlaouen dead.—He has been killed by an Elephant.—Arrive at Obindji's Town.—Meeting with Querlaouen's Widow.—Neither Malaouen nor Gambo at home. | 167 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Leave for Ashira Land.—In a Swamp.—Cross the Mountains.—A Leopard after us.—Reach the Ashira Country. | 175 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Great Mountains.—Ashira Land is beautiful.—The People are afraid.—Reach Akoonga's Village.—King Olenda sends Messengers and Presents.—I reach Olenda's Village. | 181 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

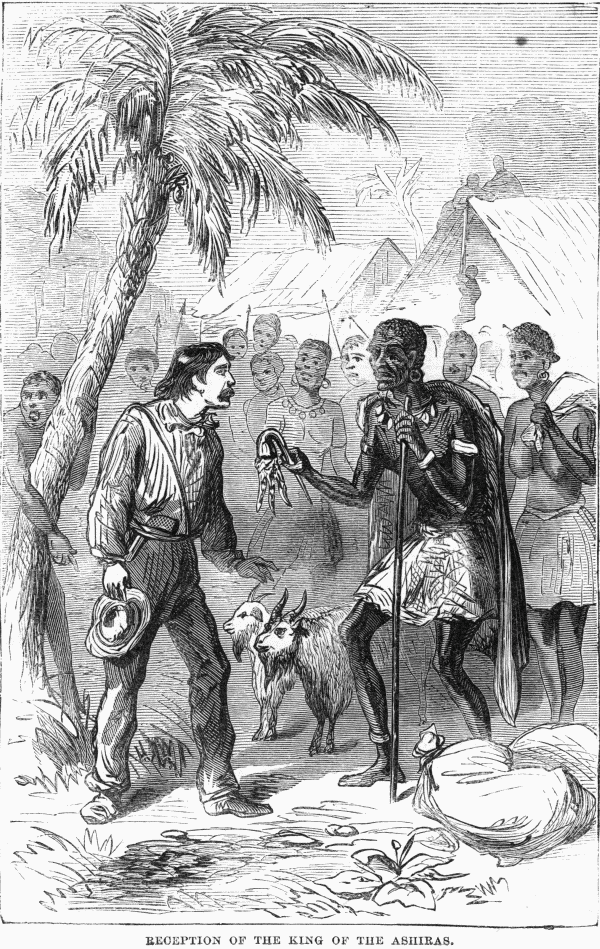

| King Olenda comes to receive me.—He is very old.—Never saw a Man so old before.—He beats his Kendo.—He salutes me with his Kombo.—Kings alone can wear the Kendo. | 185 |

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| They all come to see me.—They say I have an Evil Eye.—Ashira Villages.—Olenda gives a great Ball in my Honor.—Beer-houses.—Goats coming out of a Mountain alive. | 190 |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Ascension of the Ofoubou-Orèrè and Andelè Mountains.—The Ashiras bleed their Hands.—Story of a Fight between a Gorilla and a Leopard.—The Gorilla and the Elephant.—Wild Boars. | 197 |

| [viii] CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Propose to start for Haunted Mountains.—Olenda says it can not be done.—At last I leave Olenda Village.—A Tornado.—We are Lost.—We fight a Gorilla.—We kill a Leopard.—Return to Olenda. | 203 |

CHAPTER XXVII. | |

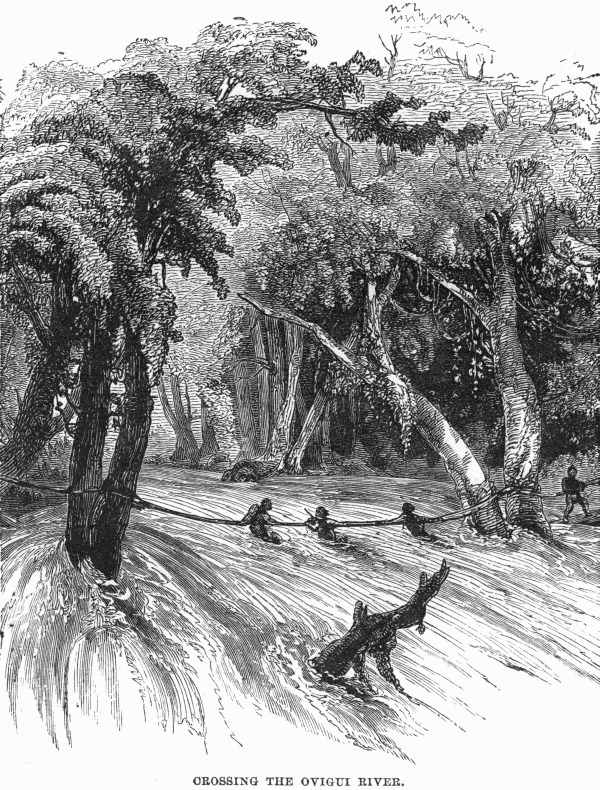

| Departure for the Apingi Country.—The Ovigui River.—Dangerous Bridge to Cross.—How the Bridge was built.—Glad to escape Drowning.—On the Way.—Reach the Oloumy. | 217 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

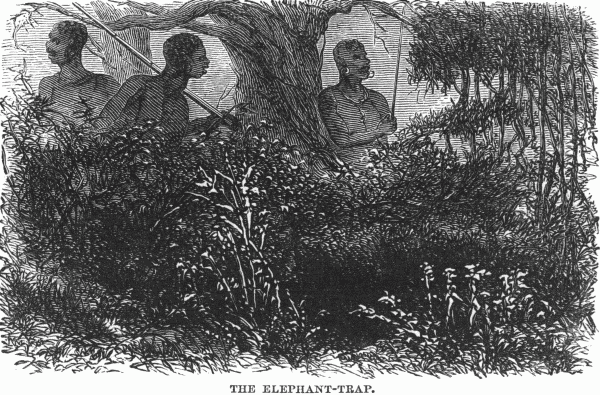

| A Gorilla.—How he attacked me.—I kill him.—Minsho tells a Story of two Gorillas fighting.—We meet King Remandji.—I fall into an Elephant-pit.—Reach Apingi Land. | 226 |

CHAPTER XXIX. | |

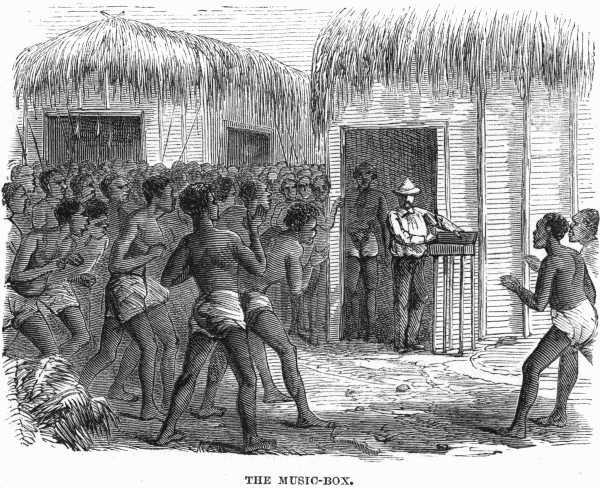

| First Day in Apingi Land.—I fire a Gun.—The Natives are Frightened.—I give the King a Waistcoat.—He wears it.—The Sapadi People.—The Music-box.—I must make a Mountain of Beads. | 238 |

CHAPTER XXX. | |

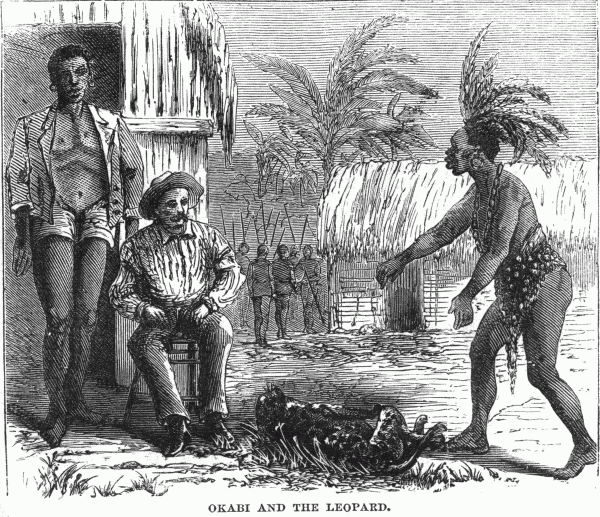

| A large Fleet of Canoes.—We ascend the River.—The King paddles my Canoe.—Agobi's Village.—We upset.—The King is furious.—Okabi, the Charmer.—I read the Bible.—The People are afraid. | 246 |

CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| A great Crowd of Strangers.—I am made a King.—I remain in my Kingdom.—Good-by to the Young Folks. | 258 |

| PAGE | |

| Shooting a Leopard | Frontispiece. |

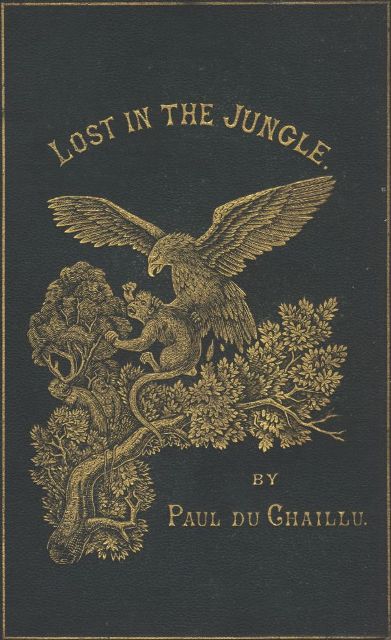

| The Royal Canoe | 15 |

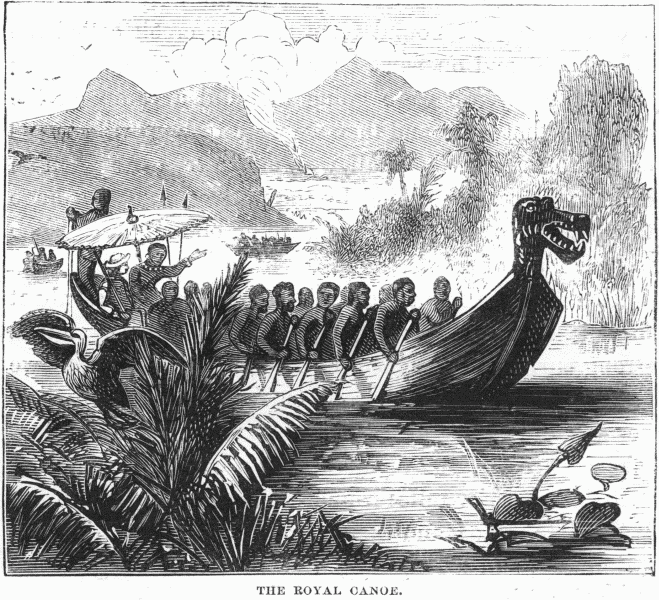

| The Manga | 25 |

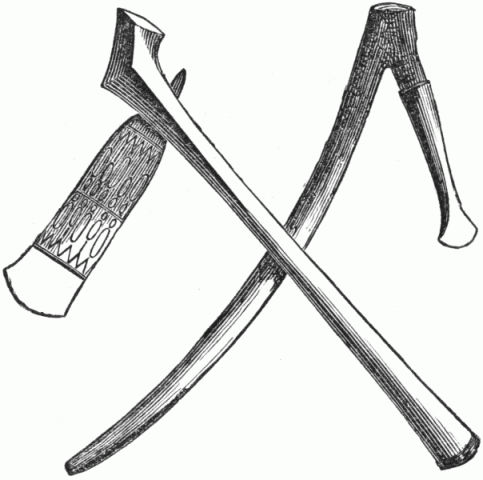

| The Mpano | 29 |

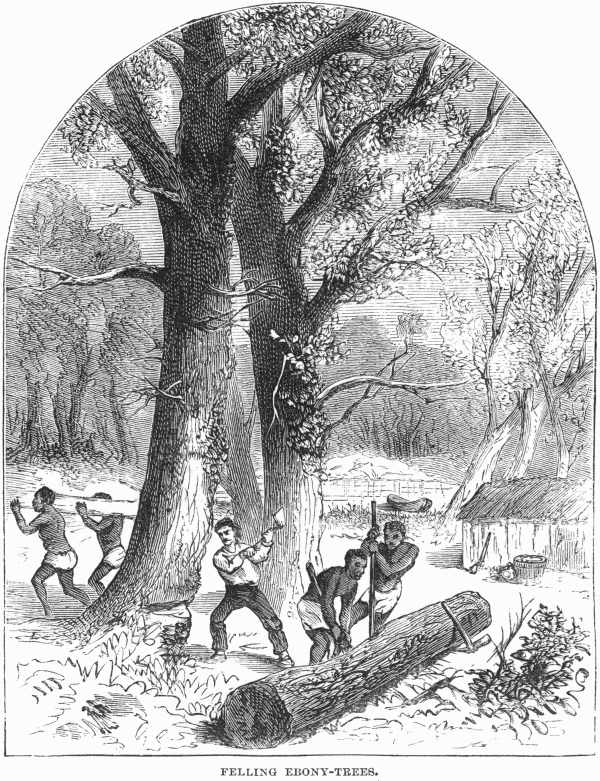

| Felling Ebony-Trees | 31 |

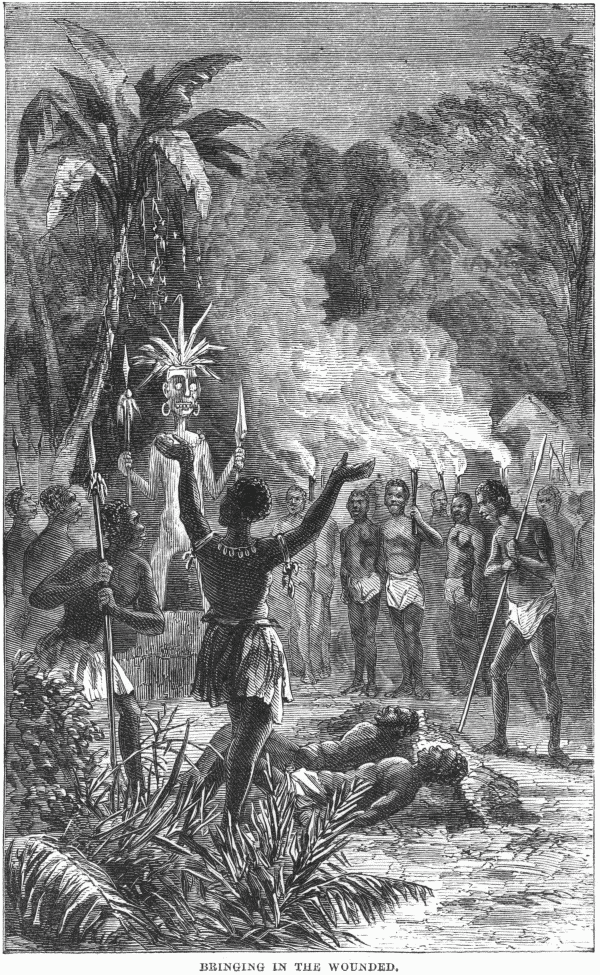

| Bringing in the Wounded | 43 |

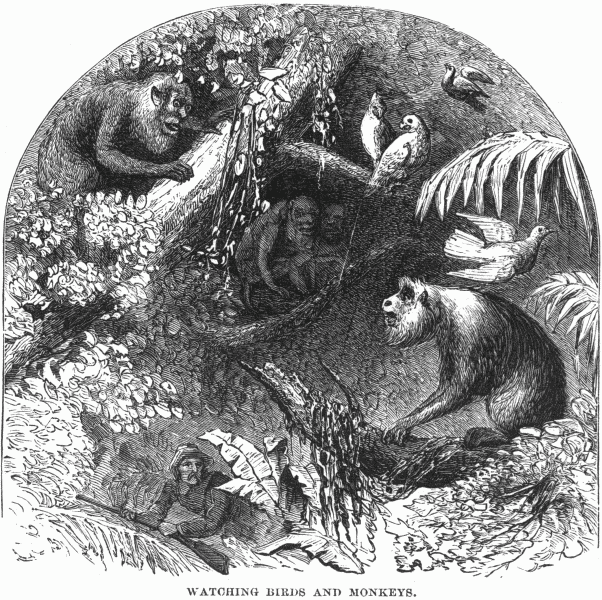

| Watching Birds and Monkeys | 57 |

| Shooting the new Antelope | 66 |

| Querlaouen and his Idol | 78 |

| Caught by Jack | 82 |

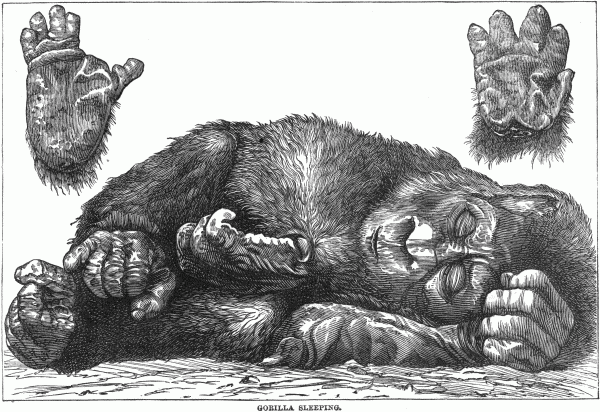

| Gorilla Sleeping | 85 |

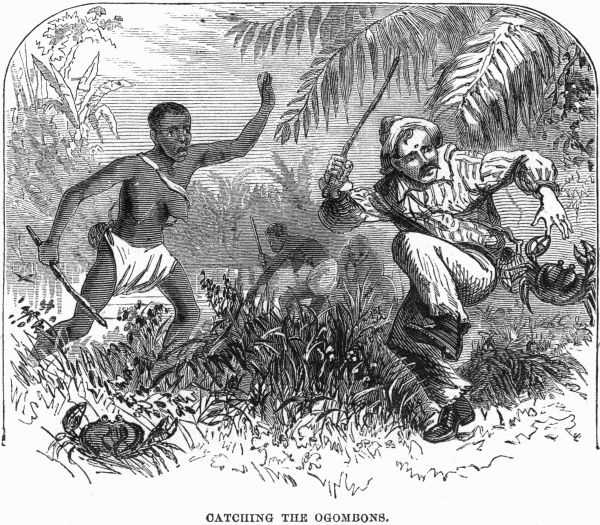

| Catching the Ogombons | 90 |

| Bit by a Spider | 99 |

| Death of the Bull Elephant | 111 |

| Guanionien carrying off a Mondi | 122 |

| Gambo's Friend killed by a Gorilla | 133 |

| Bidding Good-by to Quengueza | 147 |

| "Chally, Chally, do not let me Die" | 155 |

| The Songs to Ilogo | 163 |

| Giving Beads to Querlaouen's Wife | 173 |

| Going to Ashira Land | 177 |

| Reception of the King of the Ashiras | 186 |

| The Kendo | 189 |

| Drinking Plantain Beer | 193 |

| Attack on the Wild Boars | 201 |

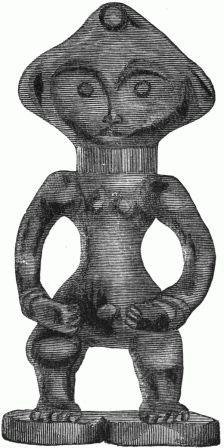

| An Ashira Idol | 202 |

| Crossing the Ovigui River | 222 |

| The Elephant-Trap | 233 |

| The Music-Box | 243 |

| Okabi and the Leopard | 252 |

| My Housekeeper | 256 |

PAUL'S LETTER TO HIS YOUNG FRIENDS, IN WHICH HE PREPARES THEM FOR BEING "LOST IN THE JUNGLE."

My dear Young Folks,—In the first book which I wrote for you, we traveled together through the Gorilla Country, and saw not only the gigantic apes, but also the cannibal tribes which eat men.

In the second book we continued our hunting, and met leopards, elephants, hippopotami, wild boars, great serpents, etc., etc. We were stung and chased by the fierce Bashikouay ants, and plagued by flies.

Last spring, your friend Paul, not satisfied with writing for young folks, took it into his head to lecture before them. When I mentioned the subject to my acquaintances, many of them laughed at the notion of my lecturing to you, and a few remarked, "This is another of your queer notions." I did not see it!!! I thought I would try.

Thousands of young folks came to your friend Paul's[12] lectures in Boston, Brooklyn, and New York; not only did my young friends come, but a great many old folks were also seen among them.

The intelligent, eager faces of his young hearers, their sparkling eyes, spoke to him more eloquently than words could do, and told him that he had done well to go into the great jungle of Equatorial Africa, and that they liked to hear what he had done and what he had seen.

When he asked the girls and boys of New York if he should write more books for them, the tremendous cheers and hurras they gave him in reply told him that he had better go to work.

When, at the end of his third lecture, he made his appearance in the old clothes he had worn in Africa, and said he would be happy to shake hands with his young hearers, the rush then made assured him that they were his friends. Oh! how your hearty hand-shaking gladdened the heart of your friend Paul; he felt so happy as your small hands passed in and out of his!

Before writing this new volume, I went to my good and esteemed friends, my publishers in Franklin Square, and asked them what they thought of a new book for Young Folks.

"Certainly," they said; "by all means, Friend Paul. Write a new book, for Stories of the Gorilla Country and Wild Life under the Equator are in great demand."

I immediately took hold of my old journals, removed the African dust from them, and went to work, and now we are going to be Lost in the Jungle.

There are countries and savages with which you have[13] been made acquainted in the two preceding volumes of which you will hear no more. Miengai, Ngolai, and Makinda are not to lead us through a country of cannibals. Aboko will slay no more elephants with me. Fasiko and Niamkala are to be left in their own country, and to many a great chief we have said good-by forever.

If we have left good friends and tribes of savage men, we will go into new countries and among other strange people. We shall have lots of adventures; we will slay more wild beasts, and will have, fierce encounters with them, and some pretty narrow escapes. We will have some very hard times when "lost in the jungle;" we will be hungry and starving for many a day; we will see how curiously certain tribes live, what they eat and drink, how they build, and what they worship; and, before the end of our wanderings, you will see your friend Paul made KING over a strange people! It makes him laugh even now when he thinks of it.

I am sure we will not always like our life in the woods, but I hope, nevertheless, that you will not be sorry to have gone with me in the strange countries where I am now to lead you.

Let us get ready to start. Let us prepare our rifles, guns, and revolvers, and take with us a large quantity of shoes, quinine, powder, bullets, shot, and lots of beads and other things to make presents to the kings and people we shall meet. Oh dear, what loads! and every thing has to be carried on the backs of men! I shudder when I think of the trouble; but never mind; we shall get through our trials, sickness, and dangers safely. En avant! that is to say, forward!

A QUEER CANOE.—ON THE REMBO.—WE REACH THE NIEMBOUAI.—A DESERTED VILLAGE.—GAZELLE ATTACKED BY A SNAKE.—ETIA WOUNDED BY A GORILLA.

The sun is hot; it is midday. The flies are plaguing us; the boco, the nchouna, the ibolai are hard at work, and the question is, which of these three flies will bite us the hardest; they feel lively, for they like this kind of weather, and they swarm round our canoes.

I wish you could have seen the magnificent canoes we had; they were made of single trunks of huge trees. We had left the village of Goumbi, where my good friend Quengueza, of whom I have spoken before, and the best friend I had in Africa, reigned.

Our canoes were paddling against the current of the narrow and deep River Rembo. You may well ask yourselves where is the place for which I am bound. If you had seen us you might have thought we were going to make war, for the canoes were full of men who were covered with all their war fetiches; their faces were painted, and they were loaded with implements of war. The drums beat furiously, and the paddlers, as we ascended, were singing war-songs, and at times they would sing praises in honor of their king, saying that Quengueza was above all kings.[15]

Quengueza and I were in the royal canoe, a superb piece of wood over sixty feet long, the prow being an imitation of an immense crocodile's head, whose jaws were wide open, showing its big, sharp, pointed teeth. This was emblematic, and meant that it would swallow all the enemies of the king. In our canoe there were more than sixty paddlers. At the stern was seated old Quengueza, the queen, who held an umbrella over the head of his majesty, and myself, and seated back of us all was Adouma, the king's nephew, who was armed with an immense paddle, by which he guided the canoe.

How warm it was! Every few minutes I dipped my old Panama hat, which was full of green leaves, into the[16] water, and also my umbrella, for, I tell you, the sun seemed almost as hot as fire. The bodies of the poor paddlers were shining with the oil that exuded from their skin.

If you had closely inspected our canoes you would have seen a great number of axes; also queer-looking harpoons, the use of which you might well be curious about. We were bound for a river or creek called the Niembouai, and on what I may call an African picnic; that is to say, we were going to build a camp on the banks of that river, and then we were to hunt wild beasts of the forest, but, above all, we were to try to harpoon an enormous creature called by the natives manga, a huge thing living in fresh water, and which one might imagine to be a kind of whale.

The distance from Goumbi to Niembouai was about fifteen miles. After three hours' paddling against a strong current we reached the Niembouai River. As we entered this stream the strong current ceased; the water became sluggish, and seemed to expand into a kind of lake, covered in many places with a queer kind of long tufted reed. For miles round the country looked entirely desolate. Now and then a flock of pelicans were seen swimming, and a long-legged crane was looking on the shore for fish.

At the mouth of the Niembouai, on a high hill, stood an abandoned Bakalai village called Akaka; the chief, whom I had known, was dead, and the people had fled for fear of the evil spirits. Nothing was left of the village but a few plantain-trees; the walls of the huts had all tumbled down.

How dreary all seemed for miles round Akaka. The[17] lands were overflowed, and, as I have said before, were covered with reeds. Far off against the sky, toward the east-northeast, towered high mountain peaks, which I hoped to explore. They rose blue against the sky, and seemed, as I looked at them through my telescope, to be covered with vegetation to their very tops. These mountains were the home of wild men and still wilder beasts. I thought at once how nice it would be for me to plant the Stars and Stripes on the highest mountains there.

As we advanced farther up the river the mountains were lost sight of, and still we paddled up the Niembouai. Canoe after canoe closed upon us, until at last the whole fleet of King Quengueza were abreast of the royal canoe, when I fired a gun, which was responded to by a terrific yell from all the men.

Then Quengueza, with a loud voice, gave the order to make for a spot to which he pointed, where we were to land and build our camp. Soon afterward we reached the place, and found the land dry, covered with huge trees to protect us from the intense heat of the sun, from the heavy dews of night, and from slight showers.

The men all scattered into the forest, some to cut long poles and short sticks for our beds; others went to collect palm-leaves to make a kind of matting to be used as roofing. The first thing to be done was for the people to make a nice olako for their king and myself.

Our shelter was hardly finished when a terrible rainstorm burst upon us, preceded by a most terrific tornado, for we were in the month of March. By sunset the storm was all over; it cooled the air deliciously, for the heat had been intense. At noon, under the shade of my[18] umbrella while in the canoe, the thermometer showed 119° Fahrenheit.

We had brought lots of food, and many women had accompanied us, who were to fish, and were also to cook for the people. The harpoons were well taken care of, for we fully expected to harpoon a few of the mangas.

The manga canoes were to arrive during the night, for the canoes we had were not fit for the capture of such large game.

In the evening old Quengueza was seated by the side of a bright fire; the good old man seemed quite happy. He had brought with him a jug of palm wine, from which he took a drink from time to time, until he began to feel the effects of the beverage, and became somewhat jolly. His subjects were clustered in groups around several huge fires, which blazed so brightly that the whole forest seemed to be lighted by them.

I put my two mats on my bed of leaves, hung my musquito nets as a protection against the swarms of musquitoes, then laid myself down under it with one of my guns at my side, placed my revolvers under my head, and bid good-night to Quengueza.

I did not intend to go right to sleep, but wished to listen to the talk of the people. The prospect of having plenty of meat to eat appeared to make them merry, and after each one had told his neighbor how much he could eat if he had it, and that he could eat more manga than any other man that he knew, the subject of food was exhausted. Then came stories of adventures with savage beasts and with ghosts.

We had in company many great men. The chief of them all was good old Quengueza, formerly a great war[19]rior. After the king came Rapero Ouendogo, Azisha Olenga, Adouma, Rakenga Rikati Kombe, and Wombi—all men of courage and daring, belonging to the Abouya, a clan of warriors and hunters.

We had slaves also; among them many belonged to the king—slaves that loved him, and whose courage was as great as that of any man belonging to the tribe. Among them was Etia, the mighty and great slayer of gorillas and elephants. Etia provided game for Quengueza's table; he was one of the beloved slaves of the king, and he was also a great friend of mine. We were, indeed, old friends, for we had hunted a good deal together.

On a sudden all merriment stopped, for Ouendogo had shouted "let Etia tell us some of his hunting adventures." This order was received with a tremendous cheer, and Etia was placed in the centre. How eager were the eyes and looks of those who knew the story-telling gift of their friend Etia, who began thus: "Years ago, I remember it as well as if it were but yesterday, I was in a great forest at the foot of a high hill, through which a little stream was murmuring; the jungle was dense, so much so that I could hardly see a few steps ahead of me; I was walking carefully along, very carefully, for I was hunting after the gorilla, and I had already met with the footprints of a huge one. I looked on the right, on the left, and ahead of me, and I wished I had had four eyes, that is, two more eyes on the back of my head, for I was afraid that a great gorilla might spring upon me from behind."

We all got so impatient to hear the story that we shouted all at once, "Go on, Etia, go on. What did you[20] see in the bush? Tell us quick." But Etia was not to be hurried faster than he chose. After a short pause, he continued: "I do not know why, but a feeling of fear crept over me. I had a presentiment that something queer was going to happen. I stood still and looked all round me.

"Suddenly I spied a huge python coiled round a tree near to a little brook. The serpent was perfectly quiet. His huge body was coiled several times round the tree close to the ground, and there he was waiting for animals to come and drink. It was the dry season, and water was very scarce, and many animals came to that spring to drink. I can see, even to this day, its glittering eyes. Its color was almost identical with that of the bark of the tree. I immediately lay down behind another tree, for I had come also in search of game, and I could do nothing better than wait for the beasts to come there and drink.

"Ere long I spied a ncheri 'gazelle' coming; she approached unsuspicious of any danger. Just as she was in the act of drinking, the snake sprang upon the little beast and coiled himself round it. For a short time there was a desperate struggle; the folds of the snake became tighter and tighter round the body of the poor animal. I could see how slowly, but how surely the snake was squeezing its prey to death. A few smothered cries, and all was over; the animal was dead. Then the snake left the tree and began to swallow the gazelle, commencing at the head. It crushed the animal more and more in its folds. I could hear the bones crack, and I could see the animal gradually disappearing down the throat of the snake."[21]

"Why did you not, Etia, kill the snake at once?" shouted one man, "and then you would have had the ncheri for your dinner?" "Wait," replied Etia.

"After I had watched the snake for a short time, I took my cutlass and cut the big creature to pieces. That night I slept near the spot. I lighted a big fire, cooked a piece of the snake for my meal, and went to sleep.

"The next morning I started early, and went off to hunt. I had not been long in the forest before I heard a noise; it was a gorilla. I immediately got my gun ready, and moved forward to meet him. I crept through the jungle flat on 'my belly,' and soon I could see the great beast tearing down the lower branches of a tree loaded with fruit. Suddenly he stopped, and I shouted to him, 'Kombo (male gorilla), come here! come here!' He turned round and gave a terrific yell or roar, his fierce, glaring eyes looked toward me, he raised his big long arms as if to lay hold of me, and then advanced. We were very near, for I had approached quite close before I shouted my defiance to him.

"When he was almost touching me, I leveled my gun—that gun which my father, King Quengueza, had given me—that gun for which I have made a fetich, and which never misses an animal—then I fired. The big beast tottered, and, as it fell, one of his big hands got hold of one of my legs; his big, thick, huge fingers, as he gave his death-gasp, contracted themselves; I gave a great cry of pain, and, seizing my battle-axe, I dealt a fearful stroke and broke its arm just above the joint. But his fingers and nails had gone deep into my flesh, which it lacerated and tore."

Etia pointed to his leg, and continued: "I have nev[22]er gotten over it to this day, though it is so long ago that very few of you that are here to-night were born then. I began to bleed and bleed, and feared that the bone of my leg was broken. I left the body of the gorilla in the woods, but took its head with me, and that head I have still in my plantation; and at times," added Etia, "its jaws open during the night, and it roars and says, 'Etia, why have you killed me?' I am sure that gorilla had been a man before. That is the reason I am lame to this day. I succeeded in reaching my pindi (plantation), and my wife took care of me; but from that day I have hated gorillas, and I have vowed that I would kill as many of them as I could."

The story of Etia had the effect of awakening every one. They all shouted that Etia is a great hunter, that Etia had been bewitched before he started that time, and that if it had not been for Etia having a powerful monda (fetich), he would have been killed by the gorilla.

Our story-telling was interrupted by the arrival of canoes, just built for the fishing of the manga. These canoes were unlike other canoes; they were flat-bottomed, as flat as a board; the sides were straight, and both ends were sharp-pointed, and, when loaded, with two men, did not draw in the water, I am sure, half an inch. They glided over the water, causing scarcely a ripple. There was no seat, and a man had to paddle standing up, the paddle being almost as long as a man. These canoes were about twenty-five feet long, and from eighteen to twenty inches broad. In them were several queer kinds of harpoons, which were to be used in capturing the mangas.

HARPOONING A MANGA.—A GREAT PRIZE.—OUR CANOE CAPSIZED.—DESCRIPTION OF THE MANGA.—RETURN TO CAMP.

The next morning, very early, if you had been on the banks of the Niembouai, you would have seen me on one of those long flat-bottomed canoes which I have described to you, and in it you would likewise have seen two long manga harpoons.

A man by the name of Ratenou, who had the reputation of being one of the best manga harpooners, and of knowing where they were to be found, was with me. He was covered with fetiches, and had in a pot a large quantity of leaves of a certain shrub, which had been mashed with water and then dried. This mixture, when scattered on the water, is said to attract the manga.

When we left the shore, being less of an expert than Ratenou, and not being able to stand up so easily as he did, I seated myself at the bottom of the canoe. Ratenou recommended me not to move at all, and while he paddled I could not even hear the dip of his paddle in the water, so gently did our boat glide along.

We crossed the Niembouai to the opposite shore, where we lay by among the reeds. By that time the twilight had just made its appearance, and you know the twilight[24] is of short duration under the equator; indeed, there is hardly any at all.

Ratenou threw on the water, not far from where we lay in watch, some of the green stuff he had in the pot, and we had not waited long before I saw, coming along the surface of the water, a huge beast, which gave two or three puffs and then disappeared. My man watched intently, and in the mean time moved the canoe toward the spot. We came from behind, so that the animal could not see us, and, just as the manga came to the surface of the water once more, and gave three gentle puffs, Ratenou sent the harpoon with tremendous force into his body. The huge creature, with a furious dash and jerk at the line, made for the bottom of the river. Ratenou let the line slip, but held back as much as he dared, in order thus to increase the pain inflicted on the beast. The suspense and excitement were great. The animal dashed down to the bottom with impetuous haste, but the harpoon was fast in him, and held him. We watched the rope going out with the utmost anxiety. The harpoon has hardly struck the manga when our canoe goes with fearful rapidity. The native's rope proved too short; there was not enough of it to let it go. Every moment I fully expected to upset, and did not relish the idea at all. Finally the rope slackened; the manga was getting exhausted. At last no strain was observable; the beast was dead. Without apparently much effort, the line was hauled in, and presently I saw the huge beast alongside the canoe.

"Let us upset the canoe," said Ratenou.

"What!" said I.

"Let us upset the canoe." The good fellow, who was[25] not overloaded with clothes, thought that to be an easy task; but I did not look at the proposal quite in the same light; so I said, "Ratenou, let us paddle the canoe to the shore, and I will get out." It was hardly said before it was done. I landed, and then the huge manga was tied to the canoe, the latter was capsized over its back, and then we turned it over again.

This was a big prize, for there is no meat so much thought of among the savages as that of the manga. We immediately made for the camp, and were received with uproarious cheers.

The canoe was upset once more, and the big freshwater monster was dragged ashore. It was hard work, for the huge beast must have weighed from fifteen to eighteen hundred pounds.

What a queer-looking thing it was! The manga is a new species of manatee. Its body is of a dark lead-color; the skin is very thick and smooth, and covered in all parts with single bristly hairs, from half an inch to an[26] inch in length; but the hairs are at a distance from each other, so that the skin appears almost smooth. The eyes are small—very small; it has a queer-looking head, the upper and lower parts of the lips having very hard and bristly hair.

The manga is unlike the whale in this, that it has two paddles, which are used as hands; and, when the flesh or skin is removed, the skeleton of the paddles looks very much like the bony frame of a hand. I have named this curious species after my most esteemed friend, Professor Owen, of London, Manatus Oweni.

The skin of the manga, when dried, is of a most beautiful amber color; the nearer the middle of the back, the more beautiful and intense the yellow. The skin is there more than one inch in thickness. When fresh it has a milky color, but when it dries, and the water goes off, it turns yellow. That part of the back is carefully cut in strips by the natives, who make whips with it, just in the same way as they do with the hippopotamus hide, and these whips are used extensively on the backs of their wives.

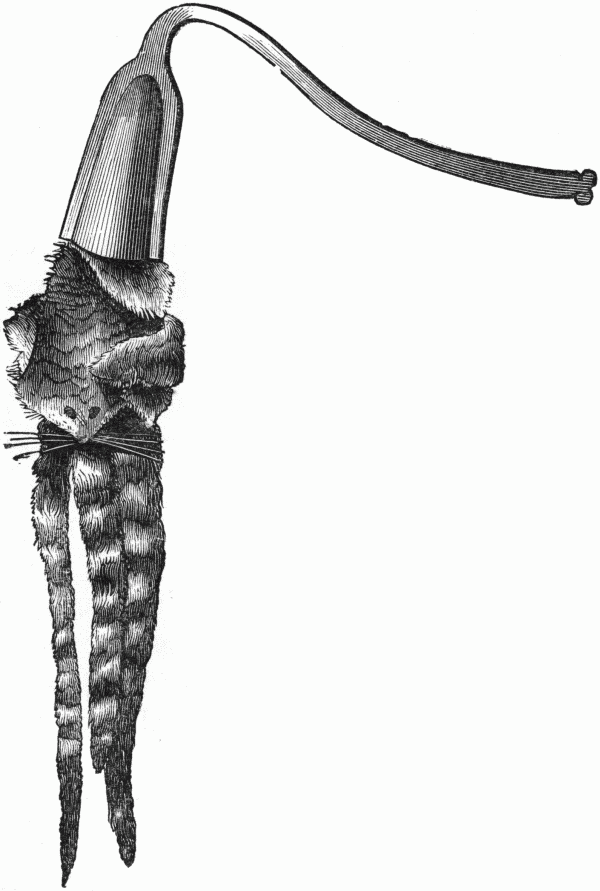

The large, broad tail, which is shown in the engraving, is used by them as a rudder, while their hands are used as paddles. These hands, unlike those of seals, have no claws or nails. This manga was eleven feet long, and the body looked quite huge.

Mangas feed entirely on grass and the leaves of trees, the branches of which fall into the water; they feed, also, on the grass found at the bottom of the rivers.

In looking at such curious shaped things, I could not help thinking what queer animals were found on our globe.[27]

The doctor was greatly rejoiced at our success. Then came the ceremony of cutting up the beast; but, before commencing, Ratenon, the manga doctor, went through some ceremony round the carcase which he did not want any one to see. After a little he began to cut up the meat.

It was very fat; on the stomach the fat must have been about two inches thick. The lean meat was white, with a reddish tinge, and looked very nice. It is delicious, something like pork, but finer grained and of sweeter flavor. It must be smoked for a few days in order to have it in perfection.

We cut the body into pieces of about half a pound each, and put them on the oralas and smoked Master Manga. The fragrance filled our camp.

The manga belongs to the small but singular group of animals classed as Sirenia.

I have often watched these manga feeding on the leaves of trees, the branches of which hung close to the water. The manga's head only shows above the water. When thus seen, the manga bears a curious resemblance to a human being. They never go ashore, and do not crawl even partly out of the water. They must sometimes weigh as much as two to three thousand pounds.

WE GO INTO THE FOREST.—HUNT FOR EBONY-TREES.—THE FISH-EAGLES.—CAPTURE OF A YOUNG EAGLE.—IMPENDING FIGHT WITH THEM.—FEARFUL ROARS OF GORILLAS.—GORILLAS BREAKING DOWN TREES.

Several weeks have passed since we left the Niembouai. I have been alone with my three great hunters, Querlaouen, Gambo, and Malaouen. We are sworn friends; we have resolved to live in the woods and to wander through them. Several times since we left our manga-fishing we have been "lost in the jungle."

We have had some very hard times, but splendid hunting; and on the evening of that day of which I speak, we were quietly seated somewhere near the left bank of the River Ovenga, by the side of a bright fire, and, at the same time my men enjoyed their smoke, we talked over the future prospects of our life in the forest.

That evening I said, "Boys, let us go into the forest and look for ebony-trees; I want to find them; I must take some of that wood with me when I go back to the land of 'the spirits.'" Malouen, Gambo, and Querlaouen shouted at once, "Let us go in search of the ebony-tree; let us choose a spot where we shall be able to find game." For I must tell you that good eating was one of the weak points of my three friends.

The ebony-tree is scattered through the forest in clus[29]ters. It is one of the finest and most-graceful among the many lovely trees that adorn the African forest. Its leaves are long, sharp-pointed, and of a dark green color. Its bark is smooth, and also a dark green. The trunk rises straight as an arrow. Queer to say, the ebony-tree, when old, becomes hollow, and even some of its branches are hollow. Next to the bark is a white "sap-wood." Generally that sap-wood is three or four inches thick; so, unless one knows the tree by the bark, the first few blows of an axe would not reveal to him the dark, black wood found inside. Young ebony-trees of two feet diameter are often perfectly white; then, as the tree grows bigger, the black part is streaked with the white, and as the tree matures, the black predominates, and eventually takes the place of the white. The wood of the ebony-tree is very hard; the grain short and very brittle.

You can see that it is no slight work to cut down such big trees with the small axes we had, such as represented in the accompanying drawing. I show you, also, the[30] drawing of a mpano, which is the instrument used in hollowing out the trunks of trees to make canoes.

After wandering for some hours we found several ebony-trees. How beautiful they were, and how graceful was the shape of their sharp-pointed leaves! These trees were not very far from the river, or I should rather say from a creek which fell into the Ovenga River, so that it would not be difficult to carry our ebony logs to the banks and there load them on canoes.

We immediately went to work and built a nice camp. We had with us two boys, Njali and Nola, who had been sent with a canoe laden with provisions from one of Querlaouen's plantations, and which his wife had forwarded to us. Some bunches of plantains were of enormous size. There were two bunches of bananas for me, and sundry baskets of cassava and peanuts. There was also a little parcel of dried fish, which Querlaouen's wife had sent specially to her friend Chally.

We set to work, and soon succeeded in felling two ebony-trees. We arranged to go hunting in the morning, and cut the wood into billets in the afternoon. As we were not in a hurry, and it was rather hard work, we determined to take our time.

By the side of our camp we had a beautiful little stream, where we obtained our drinking water, and a little below that spot there was a charming place where we could take a bath.

Not far from our camp there was a creek called Eliva Mono (the Mullet's Creek), so named on account of the great number of mullets which at a certain season of the year come there to spawn. Besides the mono, the creek contained great numbers of a fish called condo. Large and tall trees grew on the banks of the creek.[31]

This creek was at that time of the year a resort for the large fish-eagles. These birds could look down from the tops of the high trees, on which they perched, upon the water below, and watch for their finny prey.

The waters of the creek were so quiet that half the time not a ripple could be seen on them. High up on[32] some of the trees could be seen the nests belonging to these birds of prey.

There were several eagles, and they belonged to two different species. One was called by the natives coungou, and was known all over the country, for it is found as far as the sea. Its body was white, and of the size of a fowl, and it had black wings, the spread of which was very great, and the birds were armed with thick and strong talons. The females were of a gray color.

Another eagle was also found on the creek. It was a larger bird, of dark color, and called by the natives the compagnondo (Tephrodornis ocreatus). The shrill cries of this bird could be heard at a great distance, sounding strangely in the midst of the great solitude. Both these eagles feed on fish, and two of the coungous had their nest on the top of a very high tree, and in that nest there were young ones. The nest was built, like most of the fish-eagles' nests, with sticks of trees, and occupied a space of several feet in diameter. When once the nest is built it is occupied a good number of years in succession. It is generally placed between the forks of the branches, and can be seen at a great distance. Each year the nest requires repairs, which both the male and female birds attend to. These coungous seemed very much attached to each other. After one of a pair had been shot, I would hear the solitary one calling for its mate, and it would remain day after day near the spot, and at last would either take another mate or fly off to another country. When a pair of coungous, male and female, were killed, then the next year another couple would take possession of their nest.

I often watched the coungous' nest. They were al[33]ways on the look-out for fish. Now and then they would dive and seize a fine mullet, which they would carry up to their young and feed them. How quick they were in their motion! Sometimes one would catch a fish so big and heavy that it seemed hardly strong enough to rise in the air with it. The natives say that sometimes the eagles are carried under the water when they have caught a fish too big for their strength, and from whose body they can not extricate their firmly-fixed talons before the fish dives to the bottom.

When the old birds approached the nest with food the young ones became very noisy, evincing their impatience for the treat of fresh fish, with which the parents sometimes hovered over the nest as if desirous of tantalizing their appetite.

One day I took it into my head to have the tree cut down, so that I could examine the nest. The old birds were greatly excited, for they saw that something was wrong. At last the tree fell with a great crash. I immediately made for the nest, and I can not tell you what a stench arose from it; it was fearful. Remnants of decayed fish and many other kinds of offal made a smell which it was surprising the young eagles could endure. In the mean time the young ones had tumbled out of the nest, and while we were looking for them, and just after I had captured one, the parents came swooping down. Goodness! I thought I was going to be attacked by them, for they hovered round, sometimes coming quite close to me; once or twice I thought my hat at least would be carried off. Becoming worried, I raised my gun and fired, and killed the male; then the female got frightened and flew away. The young were covered[34] with gray down. They must certainly possess very limited powers of smell, for I can not see how any living thing could exist in the midst of such odors.

On one of my excursions up the creek I discovered another coungou nest, and, as it was not built in a very high tree, I determined to examine its economy. So, with pretty hard work, I climbed up another tree, from whence, with the aid of my field-telescope, I could watch all that went on in the nest, which contained two young eagles. During the first few days the old birds would feed their young by tearing the flesh of the fish with their beaks, while their talons held it fast. When the coungous are young, the male and female have the same gray plumage, which in the male turns white and black when old.

One fine afternoon I left the camp all alone, Gambo, Malaouen, and Querlaouen being fast asleep. Before I knew it, I found myself far away, for I had been thinking of home and of friends, and, walking in a good hunting path, I had gone farther than I thought, and time had fled pleasantly. I carried on my shoulder a double-barrel, smooth-bore gun, intending to take a short walk in the woods. When I looked at my watch, it was 2 o'clock! I had been gone three hours. Just as I was ready to turn back, I thought I heard distant thunder. I listened attentively, and I perceived that the noise was not thunder, but the terrific roar of a gorilla at some distance. Though it was getting late, I thought I would go in that direction; so I took out the small shot with which one of the barrels of my gun was loaded, and put in a heavy bullet instead. My revolvers were in the belt round my waist, and had been loaded that very[35] morning. As I approached the spot where the beast was, the more awful sounded the roar, till at last the whole forest re-echoed with the din, and appeared to shake with the tremendous voice of the animal. It was awful; it was appalling to hear. What lungs the monster had, to enable him to emit so deep and awe-inspiring a noise. The other inhabitants of the forest seemed to be silent; the few birds that were in it had stopped their warbling. Suddenly I heard a crash—two crashes. The animal was in the act of breaking the limbs of trees. Then the noise of the breaking of trees ceased, and the roar of the monster recommenced. This time it was answered by a weaker roar. The echoes swelled and died away from hill to hill, and the whole forest was filled with the din. The man gorilla and his wife were talking together: they no doubt understood each other, but I could not hear any articulate sound. I stopped and examined my gun. Just as I got ready to enter the jungle from the hunting-path to go after the male gorilla, the roaring ceased. I waited for its renewal, but the silence of the forest was no more to be disturbed that day.

After waiting half an hour I hurried back toward the camp. I walked as fast as I could, for I was afraid that darkness would overtake me. Six o'clock found me in the woods; the sun had just set, and the short twilight of the equator which followed the setting of the sun warned me to hurry faster than ever if I wanted to reach the camp. Hark! I hear voices. What can these voices be, those of friends or enemies? I moved from the hunting-path and ascended an adjacent tree, but soon I heard voices that I recognized as those of Malaouen and[36] Querlaouen shouting "Moguizi, where are you? Moguizi, where are you?" I responded "I am coming! I am coming!" and soon after they gave a tremendous hurrah; we had met.

We soon reached the camp, and I rested my weary limbs by the side of a blazing fire and dried my clothes, which were quite wet, for I had crossed several little streams.

LOST.—QUERLAOUEN SAYS WE ARE BEWITCHED.—MONKEYS AND PARROTS.—A DESERTED VILLAGE.—STRANGE SCENE BEFORE AN IDOL.—BRINGING IN THE WOUNDED.—AN INVOCATION.

We soon after left the left bank of the Ovenga and crossed over to the other side, but not before having carefully stored under shelter the billets of ebony-wood we had taken so much pains to cut, and which I wanted to take home with me.

The country where we now were was very wild, and seemed entirely uninhabited. At any rate, we did not know of any people or village for miles round.

After wandering for many, many days through the forest, we came suddenly on a path. Immediately Querlaouen, Gambo, Malaouen, and I held a great council, and, in order not to be heard in case some one might pass, we went back half a mile farther from the path in the forest. Then we seated ourselves, and began to speak in a low voice.

Querlaouen spoke first, and said that he did not know the country, and could not tell what we had better do, except that every one should have his gun ready, and his powder and bullets handy, his eyes wide open, and his ears ready to catch even the sound of a falling leaf or the footsteps of a gazelle.[38]

Gambo said Querlaouen was right.

Then Malouen rose and said: "For days we have been in these woods, and we have seen no living being, no path; we have fed on wild honey, on berries, nuts, and fruits, and to-day we have at last come upon a path. We know that the path has been made by some people or other. It is true we know that we are in the Ashankolo Mountains; that the tribe of Bakalai, living there, are a fighting people; but," he said, "he thought it was better to go back and follow the path until we came to the place where the people lived."

Querlaouen got up and said: "We have been lost in this forest, and, though we look all round us, there is not a tree we recognize; the little streams we pass we know not. The ant-hills we have seen are not the same as those in our own country. The large stones are not of the shape of the stones we are accustomed to look upon. We must have been bewitched before we left the village."

This suggestion of friend Querlaouen was received by a cheer from my two other fellows, I being the only one that did not believe in what he said.

"For," continued he, "this has never happened to us before. Yes, somebody wants to bewitch us."

While he thus talked, his gentle and amiable face assumed a fierce expression, and the other two said "Yes, somebody wants to bewitch us; but he had better look out, for surely he will die."

At last I said, "Let us get back to the path, and follow it; perhaps we will meet some strange adventure."

Just as we rose to move on we heard the chatter of[39] monkeys, and we made for the spot whence the sound proceeded, in the hope that we might kill one or two. Carefully we went through the jungle, the prospect of killing a monkey filling our hearts with joy; for we could already, in anticipation, see a bright fire blazing, and some part of a monkey boiling in the little iron pot we carried with us; for myself, I imagined a nice piece roasting on a bright charcoal fire.

At last we came to the foot of a very high tree, and, raising our heads, we could see several monkeys. The tree was so tremendously high that the monkeys hardly appeared larger than squirrels. How could our small shot reach the top of that tree, which was covered with red berries, upon which the monkeys were quietly feeding? Although we could not reach them, they were not to be left in undisturbed possession, for a large flock of gray parrots, with red tails, flew round and round the tree, screeching angry defiance at the monkeys, who had at first been hidden by the thick leaves. The monkeys screamed back fierce menaces, running out on the slender branches in vain endeavor to catch their feathered opponents, who would fly off, only to return with still more angry cries. Both parrots and monkeys being out of reach of our guns, we were obliged to leave them to settle the right of possession to the rich red fruit.

How weary we were when we struck the path again! and, having first passed a field of plantain-trees, we at last arrived at a village.

Not a living creature was to be seen in it. Not even a goat, a fowl, or a dog, although we found several fires smouldering, from which the smoke still ascended. We proceeded carefully, for we did not know what kind of[40] people inhabited this village. But I said, "Boys, let us go straight through the place."

So we went on until we came to an ouandja (a building), where, in a dark corner of a room, stood a huge image of an idol. Oh! how ugly it was. It represented a woman with a wide-open mouth, through which protruded a long, sharp-pointed iron tongue.

At the foot of the idol we found the skulls of all kinds of animals, elephants, leopards, hyenas, monkeys, and squirrels—even of crocodiles; and skins of snakes, intermingled with bunches of dry, queer-looking leaves, the ashes of burnt bones, and the shells of huge land turtles.

How horribly strange the big idol looked in the corner! It made me shudder.

The village was deserted, darkness was coming on, and the question now was, What were we going to do? Should we sleep in that forlorn-looking village or not? If we staid there the villagers might return when we were asleep.

For some time we regarded each other in silence; then I said, "Boys, I think we had better sleep in the forest, away from the path, but not far from the village." Gambo, Malouen, and Querlaouen shouted with one voice, "That is so. Let us sleep in the forest, for this village seems to us full of aniemba (witchcraft)."

So we returned to the jungle, and collected large leaves to be used for roofing a hut which was quickly built with limbs from dead trees that lay scattered about, yielding also a plentiful supply of wood for a rousing fire. When every thing was ready, I pulled my matchbox from my bag and lighted our fire.[41]

Night came, and all life seemed to go to rest. Now and then I could hear the cry of some wild night animal, which had left his lair in search of prey, and was calling for its mate.

Before midnight we were aroused by the muttering of distant thunder; a tornado was coming. The trees began to shake violently, the wind became terrific; soon we heard the branches of trees breaking; then the trees themselves began to fall, and with such a crash as to alarm us greatly. Suddenly, not far from our hut, one of the big giant trees of the forest came down with a fearful noise, and crushing in its mighty fall dozens of other trees, one of them adjoining our camp. We got up in the twinkle of an eye, frightened out of our wits, for we fancied the whole forest was going to tumble down. The monkeys chattered; a terrific roar from a gorilla resounded through the forest, mingling with the howls of hyenas. Snakes, no doubt, were crawling about. Immediately after the falling of the great tree near us we heard a novel and tremendous noise in the jungle, coming from a herd of elephants fleeing in dismay, and breaking down every thing in their path.

"Goodness gracious!" I shouted, in English, "what does all this mean? Are we going to be buried alive in the forest?" The words were scarcely out of my mouth when there came a blinding flash of lightning, instantaneously followed by a peal of thunder like a volley from a hundred cannon, that seemed to shake the very earth to its foundation; and then the rain fell in torrents, and soon deluged the ground. Happily, we knew what we were about when we built our fires, for we had started them on the top of large logs of wood, so[42] arranged that it would have required more than a foot of water on the ground before it could reach the fires and extinguish them. Then our leaves were so broad and nicely arranged that they entirely protected us from the storm, and our shelter was perfected by the branches of the great tree which, in falling, had apparently threatened our destruction.

The terrible hubbub lasted some hours, the continued lightning and thunder preventing sleep; but toward 4 o'clock in the morning the storm ceased, and all again became quiet; only the dripping of the water from the leaves could be heard; then we went to sleep, but not before having arranged our fires in such a manner that we could go to rest in comparative safety.

In the early morning, before dawn, and while we were only half awake, I thought I heard the sound of a human voice. Listen! We all listened attentively, and Gambo laid down with his ears to the ground, and then he declared that he distinctly heard voices in the direction of the village. There was no doubt—the people had returned.

"Let us go," said I, "and find out what kind of neighbors these are. We have our guns and plenty of ammunition, so we need not fear them; but let us act with caution."

This was agreed to. So, leaving our camp, we quietly crept near the village, until we gained a spot from whence we could see all that was going on. Men with lighted torches were entering the village, and four of them bore what, to all appearances, was a dead body, which they deposited before the huge idol, now moved out into the open street. The gleam of the torches revealed to us that this prostrate body had been pierced by many spears, part of which still remained in it.[43]

Every man was armed to the teeth, but not a woman was visible. The scene was strange and wild. Not a word was uttered after the body of the wounded man had been laid on the ground. How strange and wild the men looked by the lurid glare of their torches! Their bodies were painted and covered with fetiches. Just back of the huts stood the tall trees, whose branches moved to and fro in the wind. I could hear its whispers as it passed through the foliage of the trees. The stars were shining beautifully, and a few fleecy white clouds were floating above our heads. I wish you could have seen us as we lay flat on the ground. Our eyes must have been bright indeed as we looked on the wild scene; and this I know, that our hearts were beating strongly as we lay close together. If, perchance, one of us had been seized with a fit of sneezing, or a fit of coughing, it might have been the end of us, for the savages would have been alarmed, and, believing us to be enemies, would at once have attacked us; so we had started on a rather risky business. I had never thought of it before; it was always so with me at that time. I thought of the danger after I was in it.

Soon another batch of men made their appearance, carrying another wounded man, who appeared almost dead, and they laid him by the side of the other, and then the women came in, carrying their babies and leading their children.

There stood the huge idol looking grimly at the scene. How ugly it seemed, with its copper eyes and wide-open mouth, which showed two rows of sharp-pointed teeth![45] In one of its hands it held a sharp-pointed knife, and in the other it held a bearded spear. It had a necklace of leopards' teeth, and its hideous head was decorated with birds' feathers. One side of its face was painted yellow, the other white; the forehead was painted red, and a black stripe did duty for eyebrows. I could not make out whether it represented a male or a female.

By its side stood the people, as silent as the idol itself.

At last a man came in front of the idol, and at once, by the language he spoke in, we knew him to be a Bakalai.

"Mbuiti," he said, addressing the idol, "we have been to the war, and now we have returned. There lie before thee two of our number; look at them. You see the spear-wounds that have gone into their bodies. They can not talk. When they were strong they went to the jungle and shot game, and when they had killed it they always brought some to give thee; many times they have brought to thee antelopes, wild boars, and other wild beasts. They have brought thee sugar-cane, ground-nuts, plantains, and bananas; they have given thee palm wine to drink. Oh, Mbuiti, do thou heal them!" And all the people shouted "Do make them well." How queer their voices resounded in the forest!

Suddenly all the torches were extinguished, and the village was again in darkness. Not a voice was heard; complete silence followed. They were evidently afraid of an attack, and retired quietly to their huts.

I was very glad that we had managed to see all this without having been discovered; did not think it safe, however, to move away before giving the villagers time to fall asleep, and then we realized new causes for[46] apprehension. It was not a very pleasant or safe thing to be out in this jungle in the early morning before it was light. We might tread on a snake, or lay hold of one folded among the lower branches of the trees on which we laid our hands; or a wandering leopard might be prowling round; and, as there certainly were gorillas in the neighborhood, we might come on a tree which a female gorilla with a baby had climbed into for the night, and then we should have the old fellow upon us showing fight. I confess I did not care to fight gorillas in the dark. Again, a party of Bashikouay might be encountered, when nothing would be left for us but flight.

After our breakfast of nuts and berries, the question naturally arose, Shall we go back to the strange village? "Certainly not," at once said Querlaouen; "we do not know what kind of Bakalai they are."

When my turn to speak came, I said, "Boys, why not go and learn from these people the causes which led to their affray, and at the same time learn exactly in what part of the forest we are?"

For about a minute we were all silent. My three savages were thinking about my proposal; then Malaouen said, "Chaillie, we had better not go. Who knows? it may be that the wounded men we saw the people bringing into the village were found speared in the path, and, if so, we might be suspected of being the men who speared them. Then," said he, "what a palaver we should get in! and there would be no other way for us to get out of our troubles except by fighting. You know that the Bakalai here fight well." We all gave our assent to Malaouen's wise talk, for I must tell you, boys, my three men had good common sense, and many a time[47] have I listened to their counsels. "Besides, we have a good deal of hunting to do," said Malaouen, "and we had better attend to it."

"Yes," we all said, with one voice. "Let us attend to our hunting. Let us have a jolly good time in the woods, and kill as many gorillas, elephants, leopards, antelopes, wild boars, and other wild beasts as we can." It being settled we should not go back to the village, we all got up, looked at our guns carefully, and plunged into the woods once more.

If you could have seen us, you would have said, What wild kind of chaps these four fellows are! Indeed we did look wild. We did not mind it; our hearts were bound together, we were such great friends. I am sure many of you who read these pages would have been our friends also, if you had been there.

A WHITE GORILLA.—MEETING TWO GORILLAS.—THE FEMALE RUNS AWAY.—THE MAN GORILLA SHOWS FIGHT.—HE IS KILLED.—HIS IMMENSE HANDS AND FEET.—STRANGE STORY OF A LEOPARD AND A TURTLE.

Some time has elapsed since that strange night-scene I have described to you in the preceding chapter. We had gone, as you are aware, into the woods hunting for wild game. All I can say is, that I wish some of you had been with us. We had a glorious time! lots of fun, and cleared that part of the forest of the few wild beasts that were in it: one elephant, one gorilla, three antelopes, two wild boars were killed, besides smaller game, and some queer-looking birds. Once or twice we had pretty narrow escapes.

I wish you had been with us to enjoy the thunder and lightning. It would have given you an idea of the noise the thunder can make, and the brightness a flash of lightning can attain; how heavy the rain can fall; and a tornado would have shown you how strong the wind can blow. For the thunder we hear and the rains that fall at home can not give us any conception of what takes place in the mountainous and woody regions of Equatorial Africa. After all, there is some enjoyment in being "lost in the jungle" in the country in which I have taken you to travel with me.[49]

Once more I am in sight of the Ovenga. For some time the people inhabiting the banks of that river had whispered among themselves that a white gorilla had been seen. At first the story of a white gorilla was believed in by only a few, but at last the white gorilla's appearance was the talk of every body. Gambo, Querlaouen, and Malaouen were firm believers in it.

Both men and women would come back to their villages and assure the people that they had had a glimpse of the creature. He looked so old he could hardly walk. His hair was perfectly white, and he was terribly wrinkled. He must have lived forever in the forest, and was, no doubt, the great-grandfather of hundreds of gorillas. His wife must have died long ago. He was a monster in size. Then old men said they remembered, when they were boys, that a man disappeared from the village; perhaps he had been caught by that very gorilla.

"How is it," said I to the people, "that I have never seen a white gorilla?" They would answer, "There are white-headed men, so there are white-haired gorillas. A white gorilla is not often to be seen, for when he becomes so old that he turns white, he lives quite alone, and in a part of the forest where people can not go, for the jungle is too thick there. He seems to be too knowing, and keeps out of the way of the hunting-path." "Of course," they would add, "its skin remains black."

Day after day we went through the forest to see if we could get a glimpse of the white gorilla. We had been a whole week in quest of the white gorilla, never camping twice in the same spot; often Malaouen and Querlaouen declared that they would go and hunt alone, while Gambo and I, with a boy we had with us, should[50] choose our own course, always appointing a certain place near a hunting-path where we could all meet at sunset.

On the last day of the week, we had been on the hunt for several hours, when we came upon tolerably fresh tracks of a gorilla; judging by the immense footprints he had left on the ground, he must be a monster—a tremendous big fellow. Was he a white gorilla or not? These tracks we followed cautiously, and at last, in a densely-wooded and quite dark ravine, we came suddenly upon two gorillas, a male and a female. The old man gorilla was by the side of his wife, fondly regarding her. They had no baby. How dark and horrid their intensely black faces appeared! I watched them for a few minutes, for, thanks to the dense jungle in which we were concealed, I was not perceived at once. But, on a sudden, the female uttered a cry of alarm, and ran off before we could get a shot at her, being lost to sight in a moment. We were not in a hurry to fire at her. Of course the male must be killed first; it is ten times safer to get him out of the way.

The male had no idea of running off. As soon as the female disappeared, he gazed all round with his savage-looking eyes. He then rose slowly from his haunches, and at once faced us, uttering a roar of rage at our evidently untimely intrusion, coming as we had to disturb him and frighten his wife, when they were quietly seated side by side. Gambo and I were accompanied by the boy, who carried our provisions and an extra gun, a double-barrel smooth bore. The boy fell to the rear of us, and we stood side by side and awaited the advance of the hideous monster. In the dim half-light of the ravine, his features working with rage; his gloomy,[51] treacherous, mischievous gray eyes; his rapidly-agitated and frightful, satyr-like face, had a horrid look, enough to make one fancy him really a spirit of the damned, a very devil. How his hair moved up and down on the top of his head.

He advanced upon us by starts, as it is their fashion—as I have told you in my other books—pausing to beat his fists upon his vast breast, which gave out a dull, hollow sound, like some great base-drum with a skin of oxhide. Then, showing his enormous teeth at the same time, he made the forest ring with his short, tremendous, powerful bark, which he followed by a roar, the refrain of which is singularly like the loud muttering of thunder. The earth really shook under our feet—the noise was frightful. I have heard lions' roars, but certainly the lion's roar can not be compared with that of the gorilla.

We stood our ground for at least three long minutes—at least it seemed so to me—the guns in our hands, before the great beast was near enough for a safe shot. During this time I could not help thinking that I had heard that a man had been killed only a few days before; and, as I looked at the gorilla in front of me, I thought that if I missed the beast, I would be killed also. So I said to myself, "Be careful, friend Paul, for if you miss the fellow, he won't miss you." I realized the horror of a poor fellow when, with empty gun, he stands before his remorseless enemy, who, not with a sudden spring like the leopard, but with a slow, vindictive look, comes to put him to death.

At last he stood before us at a distance of six yards. Once more he paused, and Gambo and I raised our guns[52] as he again began to roar and beat his chest, and just as he took another step forward, we fired, and down he tumbled, almost at our feet, upon his face—dead. But he was not the white gorilla.

How glad I was. I saw at once that we had killed the very animal I wanted. His height was five feet nine inches, measured to the tip of the toes. His arms spread nine feet. His chest had a circumference of sixty-two inches. His arms were of most prodigious muscular strength. His hands, those terrible, claw-like weapons, almost like a man's, having the same shaped nails, and with one blow of which he can tear out the bowels of a man and break his ribs or arms, were of immense size. I could understand how terrible a blow could be struck with such a hand, moved by such an arm, all swollen into great bunches of muscular fibres.

When I took hold of his hands, I shall not say in mine, for his were so large that my hands looked like those of a baby by the side of his. How cold his hands were, how callous, how thick and black the nails, as black as his face and skin. What a huge foot he possessed! Where is the giant that could show such prodigious feet?

We disemboweled the monster on the spot. Malouen and Querlaouen, who had heard our guns, joined us, and we built a camp close by. My three fellows were very fond of gorilla's meat, and they had a great treat. The brain was carefully saved by them.

In the evening Gambo told us some stories, one of which, the last one, I will relate to you. It relates to the leopard, and goes to prove that this ferocious animal has no friend.[53]

THE LEGEND OF CONIAMBIÉ.

Coniambié was a king, who made an orambo (a trap) in which a ncheri (gazelle) was caught. After it had been caught, it cried and called for its companion; then a ngivo (another gazelle) was caught. The ngivo cried, and a wild boar came and was caught; then an antelope came, and was caught; afterward a bongo and a buffalo came, and all were caught, and all of them died in the trap. At that time Coniambié was in the mountains. A leopard was caught also, but did not die. Then came a turtle, who released the leopard from the trap. Then the leopard wanted to kill the turtle which had saved him. The leopard got hold of the turtle to kill it, but the turtle, seeing this, drew her head, legs, and tail inside her shell, but not before she had managed to get into the hollow of an old tree, with the leopard after her in the hollow, and he could not get away. The tree is called ogana, and bears a berry on which monkeys are fond of feeding. So there came to the tree at this time, for the purpose of feeding, a miengai, or white-mustached monkey; a ndova, the white-nosed monkey; a nkago, the red-headed monkey; an oganagana, a blackish monkey; a mondi, which has very long black hair; a nchegai and a pondi, who all came to eat the berries. When the leopard heard the noise of the monkeys, he shouted, "Monkeys, come and release me!" Then they came and helped the leopard out of the hole. But the leopard, instead of being grateful, fought with the monkeys, and ate the nkago and the ndova. Then the monkey called a mpondi said, "Mai! mai! That is so; that is so! You leopards are noted rogues. The leopard and the goat do not live together at the same place. We[54] came to help you, and, as soon as you were helped, you began to kill us. Mai! mai! you are a rogue."

Moral.

The reason why the leopard wanders solitary and alone is on account of his roguery; he is not to be trusted. There are men who can not be trusted any more than the leopard.

We shouted with one voice, "That is so; there are men who can not be any more trusted than the leopard, for they are so treacherous and deceitful."

Then we canvassed the bad qualities of the leopard, and concluded that he had not a single friend in the forest.

After this story was concluded we gave another look to our fires, and then went to sleep. This was the way, Young Folks, we spent many of our evenings when we were not too tired traveling in the great forest.

RETURN TO THE OVENGA RIVER.—THE MONKEYS AND THEIR FRIENDS THE BIRDS.—THEY LIVE TOGETHER.—WATCH BY MOONLIGHT FOR GAME.—KILL AN OSHENGUI.

After wandering through the forest for many days, we reached once more the banks of the River Rembo Ovenga, the waters of which had fallen twelve or fifteen feet, for we are in the dry season. The numerous aquatic birds and waders which come with the dry weather give the river a lively, pleasant appearance. The white sand which lines many parts of the shore is beautiful. The mornings are cool, and sometimes foggy. The dark green of the well-wooded banks had something grand about it. I, poor and lonely traveler, had a charming scene before me. The stream is still yellow, but far less so than in the rainy season. Then the rains were driving down a turbulent tide laden with mud washed down from the mountains and valleys; now the waters roll on placidly, as though all was peace and civilization on their borders.

New birds had come. The otters were plentiful, and fed on the fish that were thick in the stream.

In that great jungle beasts had been scarce for some time, and we had a hard time to get food.

But what a glorious time we had by ourselves in that forest! Oh how I enjoyed rambling in that jungle,[56] though toiling hard, and often hungry and sick! How glad I always was when I returned to the banks of the Rembo Ovenga! I loved that river, for I knew that its waters, as they glided down, would disappear in that very ocean whose waves bathed the shores of both the Old and the New World. At times, when seated on its banks, I could not help it, I would think of friends absent, but dear to me. I remembered those I loved—I remembered the boys and girls who were slowly but surely growing men and women, but who were still young folks in my memory, though years were flying fast. The lad of the jungle had become a man also; his mustache had made its appearance, and had grown a good deal; his face had become older—probably he found it so when perchance he gazed in the looking-glass he carried with him. Disease, anxiety, sleepless nights, and traveling under the burning sun had begun to do their work; but, in despite of all, my heart was still young, and I loved more than ever those friends I had left behind.

I had come back to Obindji to see if I could get some plantains or smoked cassada, and then intended to return to the woods in search of new animals and new insects. King Obindji welcomed me, and was delighted to see Malaouen, Querlaouen, and Gambo once more, and his wives got food ready for us. Then we started again for the forest. I took with me lots of small shot of different sizes for birds, and once more we would get lost in the jungle, but from time to time we would come back to the uninhabited banks of the wild Ovenga to look at our river.

One day, wandering in the forest, I spied a queer-looking bird I had not seen before, and I immediately got[57] ready to chase it. This bird was called by the natives the monkey-bird (Buceros albocrystatus).

As I was looking at that queer bird I spied a monkey, two monkeys, three monkeys, four, five, six, ten monkeys. These monkeys looked very small, and were called oshengui by the natives. Then I saw more of the queer birds, and lo! I perceived they were all playing with these little monkeys—yes, playing with these oshenguis.

Strange indeed they looked, with their long-feathered tail, queer-looking body, and strange big beak. They followed those little monkeys as they leaped from branch[58] to branch; sometimes I thought they would rest on the backs of the monkeys, but no, they would perch close to them, and then the monkey and the bird would look at each other. I never heard a note from the birds—they were as silent as the trees themselves. The oshengui would look at them and utter a kind of kee, kee, kee, and then they would move on, and the birds would follow.

Day after day I would meet those birds, and then I would look for the monkeys, and was sure to see them. No wonder they are called the monkey-bird. But then I never saw them follow any monkeys but the oshengui. I wondered why they followed them; I could not imagine the reason. I never saw them resting on the birds, but I noticed that these birds were fond of the fruits and berries the oshneguis feed upon. Then the question arose, Did the birds follow the monkeys, or the monkeys the birds? I came to the conclusion that the birds followed the monkeys, whom they could hear telling them, as it were, where they could get food without searching for it.

I tried to discover where these birds made their nests, but never found one in the country of the Rembo.

Now let us come to their companions, the monkeys. How small are these oshenguis! They are the smallest monkeys of that part of Africa. Their color was of a yellowish tinge; they had long, but not prehensile tails, for the monkeys with prehensile tails are found in America. It is a frolicsome and innocent little animal. Strange to say, the common people, who eat all kinds of monkeys, would not eat that one—why, I could not tell. His cry is very plaintive and sad, and is not heard far off, like the cry of other monkeys. As sure as you live, when you meet them hopping about the branches overhead,[59] you may say that water is not far off. They always sleep on trees whose branches overhang a water-course. They all sleep on the same tree. How queer they look, with their tails hanging down! To see the mother carrying her young, and the young clinging to the mother, is a sight worth seeing, for these baby monkeys do not look bigger than rats, and, when quite young, not much bigger than large mice. Strange to say, though very young monkeys can not walk, from the very day they are born they seem to be able to cling with their hands to the breast of their mother; for young monkeys must help themselves, or they would drop to the ground.

So we may say that the oshengui and the monkey-bird are almost inseparable friends, and we must let them wander in the great jungle in search of their food while we look for other birds and animals.

There were also in the forest several varieties of tigercat, the name of which is very similar to that of the little monkeys, the oshengui, I have just spoken to you about.

There are several species of these cats, but I am going to speak to you of the Genetta Fieldiana. You will say, "What a queer name!" Not at all. I have told you that I often remembered him in Africa, and I named this animal after my friend, Mr. Cyrus W. Field. I described this animal in the proceedings of the Boston Natural History Society.

These oshenguis are perfect little plagues. They are very sly; they never sleep at night; they are then wandering in search of prey—of something to kill. They see better at night than in broad daylight. During the day they hide in some hollow tree, or in the midst of a clus[60]ter of thick, dead branches, which are so close together that you can not see what is inside. They will crawl in there and remain till night comes. The darker the night, the bolder their deeds; for on a dark night they will come into the villages, knowing that every body is generally asleep between two or three o'clock in the morning, manage to get into some poultry-house—I do not know how—and then pounce upon the poor chickens and strangle them. They will destroy the whole lot of them, suck their blood, and if they can, they will drag one away. If you have a parrot they will try to get at it. Sometimes they will climb trees and get their prey among the birds. The green wild pigeons, the partridges, the wild ducks and cranes, sleeping on the banks of rivers, are good food for them, for they are very fond of the feathered tribe.

One morning, on the banks of a creek not far from our camp, I saw the footprints of an oshengui on the sands. It had been there, I could see, the night before.

I had two or three chickens, which I kept carefully. I wanted to see if I could not get a few eggs, for I had not for a long time tasted any, and I wondered if the oshengui would come and eat my chickens. Poor chickens! they have to look sharp in that country, for they have many enemies among the snakes and the species of wild-cats of the forest, besides the hawks.

The moon was declining, and rose about one o'clock in the morning, and shone just bright enough to enable me to see. So, towards one o'clock, I took one of my chickens and tied it to a stick on the bank of the little creek near our camp, and hid myself, not far off, on the edge of the forest. I took with me two guns, one loaded with bullets in case I should meet larger game I did not[61] bargain for, and the other loaded with shot, which I intended for the oshengui, if it came.

The light from the moon was dim, as I have said, but just enough for me to see. I hoped that the oshengui would come from the direction opposite to where I was. The poor fowl began to cackle, frightened at being in a strange place, and no doubt having an instinctive knowledge of insecurity. It cackled and cackled from time to time, and then would try to go to sleep, but could not; it seemed to comprehend impending danger.