Project Gutenberg's The Sandman: His Farm Stories, by William J. Hopkins This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Sandman: His Farm Stories Author: William J. Hopkins Illustrator: Ada Clendenin Williamson Release Date: May 22, 2011 [EBook #36185] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SANDMAN: HIS FARM STORIES *** Produced by Eric Skeet, Beginners Projects and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The Sandman: His Farm Stories

The Sandman: More Farm Stories

The Sandman: His Ship Stories

The Sandman: His Sea Stories

The Sandman: His Animal Stories

The Sandman: His Kittycat Stories

The Sandman: His Bunny Stories

The Sandman: His Puppy Stories

The Sandman: His Songs and Rhymes

The Sandman: His Indian Stories

The Sandman: His Fairy Stories

The Sandman: His Japanese Stories

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

Copyright, 1902

By The Page Company

All rights reserved

Made in U.S.A.

PRINTED BY THE COLONIAL PRESS INC.

CLINTON, MASS., U.S.A.

To

that

Little John

of to-day

who has inspired these stories

of that other

Little John

of long ago

this volume is

most affectionately

dedicated

Whatever may be thought of these stories by older people, they have served, with some others, to induce a certain little boy to go to sleep, and for nearly three years my one listener has heard them repeated many times, and his interest has never flagged. As the farm stories slowly grew in number, they entirely displaced the other stories, and that farm has become as real in the mind of my audience as it was in fact when little John was driving the cows, or planting the corn, seventy-five years ago.

The detail, which may seem excessive to an older critic, was in every case, until I had learned to put it in at the start, the result of a searching cross-examination. If the bars were not put up again, the cows might get out; and if the oxen did not pass, on their return, all the familiar objects, how did they get back to the barn? It is the young critics that I hope to please, those whose years count no more than six. If they like these farm stories half as well as my own young critic likes them, I shall be satisfied.

William J. Hopkins.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Oxen Story | 13 |

| II. | The Fine-Hominy Story | 21 |

| III. | The Apple Story | 36 |

| IV. | The Whole Wheat Story | 47 |

| V. | The Stump Story | 59 |

| VI. | The Horsie Story | 64 |

| VII. | The Log Story | 71 |

| VIII. | The Uncle Sam Story | 80 |

| IX. | The Market Story | 84 |

| X. | The Maple-Sugar Story | 96 |

| XI. | The Rail Fence Story | 110 |

| XII. | The Cow Story | 120 |

| XIII. | The Hay Story | 135 |

| XIV. | The Fireplace Story | 146 |

| XV. | The Baking Story | 156 |

| XVI. | The Swimming Story | 165 |

| XVII. | The Chicken Story | 175 |

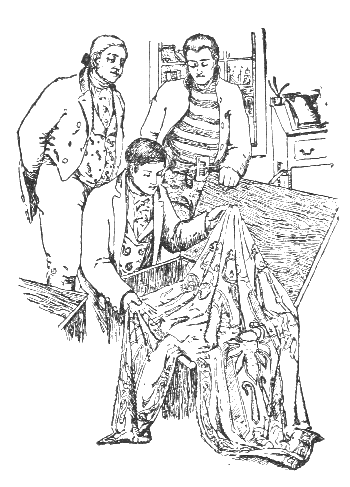

| XVIII. | The Shawl Story | 184 |

| XIX. | The Buying-Farm Story | 198 |

| XX. | The Butter Story | 203 |

| XXI. | The Bean-Pole Story | 210 |

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. And

in the fence was a wide gate to let the

wagons through to the barn. And the

wagons, going through, had made a track

that led up past the kitchen door and

past the shed and past the barn and past

the orchard to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. And

in the fence was a wide gate to let the

wagons through to the barn. And the

wagons, going through, had made a track

that led up past the kitchen door and

past the shed and past the barn and past

the orchard to the wheat-field.

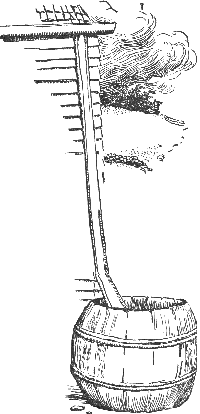

Not far from the kitchen door was a well, with a bucket tied by a rope to the end of a great long pole. And when they wanted water, they let the bucket down into the well and pulled it up full of water. They used this water to drink, and to wash their faces and hands, and to wash the dishes: but it wasn't good to wash clothes, because it wouldn't make good soap-suds. To get water to wash the clothes, they had a great enormous hogshead at the corner of the house.

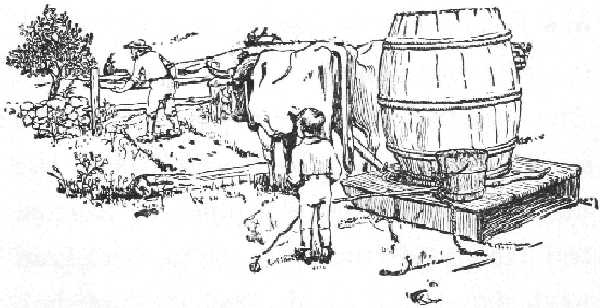

And when it rained, the rain fell on the roof, and ran down the roof to the gutter, and ran down the gutter to the spout, and ran down the spout to the hogshead. And when they wanted water to wash the clothes, they took some of the water out of the hogshead. But when it had not rained for a long time, there was no water in the hogshead. Then they got out the drag and put a barrel on it, and the old oxen came out from the barn, and put their heads down low; and Uncle John put the yoke over their necks, and put the bows under and fastened them, and hooked the chain of the drag to the yoke. There wasn't any harness, and there weren't any reins.

Then he said "Gee up there, Buck; gee up there, Star." And the old oxen started walking slowly along, dragging the drag, with the barrel on it, along the ground. And Uncle John walked along beside them, carrying a long whip or a long stick with a sharp end; and little John walked along by the drag.

And they walked slowly out of the yard into the road and along the road until they came to a big field with a stone wall around it, and a big gate in the stone wall. It wasn't a regular gate, but at each side of the open place in the wall there was a post with holes in it. And long bars went across and rested in the holes. And the old oxen stopped, and Uncle John took the bars down and laid them on the ground. Then the oxen started and walked through the gate and across the field until they came to the river. And when they came to the river, they stopped. The little river and the field are not there now, because the people put a great enormous heap of dirt across, and the river couldn't get through. The water ran in and couldn't get out, and spread out all over the field and made a big pond. And they had some great pipes under the ground, all the way to Boston. And the water runs through the pipes to Boston, and the people use it there to drink, and wash faces and hands, and wash dishes, and wash clothes.

Well, when the old oxen stopped at the river, Uncle John took his bucket and dipped it in the river, and poured the water into the barrel until the barrel was full. Then he said "Gee up there," and the old oxen started slowly walking across the field. And the drag tilted around on the rough ground, and the water splashed about in the barrel, and slopped over the top of the barrel on to the drag, and on to the ground. And the oxen walked out of the gate into the road and stopped. And Uncle John put the bars back into the holes, and the old oxen started again and walked slowly along the road, until they came to the farm-house, and in at the big gate, and up to the kitchen door, and there they stopped. And Uncle John unhooked the chain from the yoke, and took out the bows, and took off the yoke, and the old oxen walked into the barn and went to sleep. And they left the drag with the barrel of water by the kitchen door.

And the next morning, when they wanted water to wash the clothes, there was the barrel of water, all ready.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and it was painted white

and had green blinds, and it stood not far

from the road. And

in the fence was a wide gate to let the

wagons through to the barn. And the

wagons, going through, had made a track

that led up past the kitchen door and

past the shed and past the barn and past

the orchard to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and it was painted white

and had green blinds, and it stood not far

from the road. And

in the fence was a wide gate to let the

wagons through to the barn. And the

wagons, going through, had made a track

that led up past the kitchen door and

past the shed and past the barn and past

the orchard to the wheat-field.

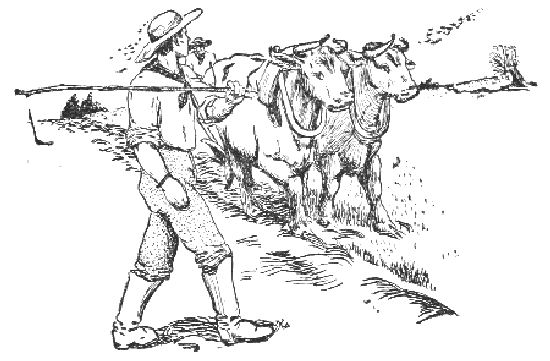

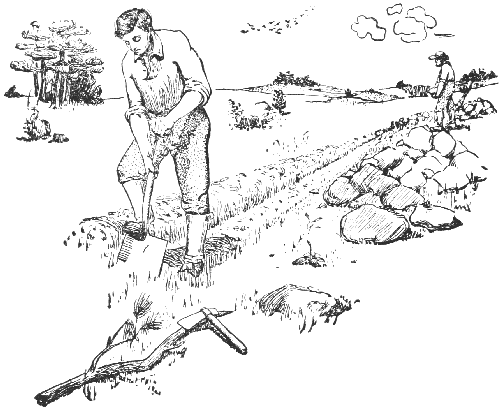

Not far from the house there was a field where corn grew; and when the winter was over and the snow was gone and it was beginning to get warm, Uncle John got the old oxen out of the barn. And the oxen put their heads down, and Uncle John put the yoke over and the bows under, and he put the plough on the drag and hooked the drag chain to the yoke. Then he said: "Gee up there, Buck; gee up there, Star."

So the old oxen started walking slowly along the wagon track and out of the gate into the road. Uncle Solomon and Uncle John walked along beside them, and little John walked behind; and they walked along until they came to the corn-field. Then the oxen stopped and Uncle John took the bars down out of the holes in the posts, and the oxen geed up again through the gate into the corn-field.

Then Uncle John unhooked the chain from the drag and hooked it to the plough and said "Gee up" again, and the oxen started walking along across the field, dragging the plough. Uncle Solomon held the handles, and the plough dug into the ground and turned up the dirt into a great heap on one side and left a deep furrow—a kind of a long hollow—all across the field where it had gone. And the old oxen walked across the field, around and around, making the furrow and turning up the dirt, until they had been all over the field.

Then Uncle John unhooked the chain from the plough and hooked it on to the harrow. The harrow is a big kind of a frame that has diggers like little ploughs sticking down all over the under side of it. And the oxen dragged the harrow over the field and the little teeth broke up the lumps of dirt and smoothed it over and made it soft, so that the seeds could grow.

Then Uncle John unhooked the chain from the harrow and hooked it to the drag and put the plough on the drag and said "Gee up," and the oxen walked along through the gateway and along the road until they came to the farm-house. And they went in at the wide gate and up the wagon track until they came to the shed, and there they stopped. Then Uncle John unhooked the chain and took off the yoke, and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep; and Uncle John put the drag in the shed.

The next day Uncle John took a great bag full of corn, and put it over his shoulder and started walking along to the corn-field; and little John walked behind. And when they got to the corn-field, Uncle John put the great bag of corn on the ground and put some in a little bag and gave it to little John. Then Uncle John began walking across the field and little John walked behind. And at every step Uncle John stopped and made five little holes in the ground; and then he took another step and made five other little holes. And little John came after and he put one grain of corn in each hole and brushed the dirt over. And they went all over the field, putting the corn in the ground, and when it was all covered over, they went away and left it.

Then the rain came and fell on the field and sank into the ground, and the sun shone and warmed it, and the corn began to grow. And soon the little green blades pushed through the ground like grass, and got bigger and bigger and taller and taller until when the summer was almost over they were great corn-stalks as high as Uncle John's head; and on each stalk were the ears of corn, wrapped up tight in green leaves, and at the top was the tassel that waved about.

Then, when the tassel got yellow and brown and the leaves began to dry up, Uncle John knew it was time to gather the corn, for it was ripe. Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John came out with great heavy, sharp knives and cut down all the corn-stalks and pulled the ears of corn off the stalks. And little John came and helped pull off the leaves from around the ears. Then the old oxen came out of the barn and Uncle John put the yoke over their necks and the bows up under and hooked the tongue of the ox-cart to the yoke. And he said "Gee up there," and the old oxen began walking slowly along, dragging the cart; and they went out the wide gate and along the road to the corn-field.

Then Uncle John and Uncle Solomon tossed the ears of corn into the cart; and when it was full, the old oxen started again, walking slowly along, back to the farm-house, in through the wide gate and up the wagon track and in at the wide door of the barn. And Uncle John put all the ears of corn into a kind of pen in the barn and the old oxen dragged the cart back to the corn-field to get it filled again; and so they did until all the ears of corn were in the pen.

And then Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the cart and put the cart in the shed, and he took off the yoke, and the oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

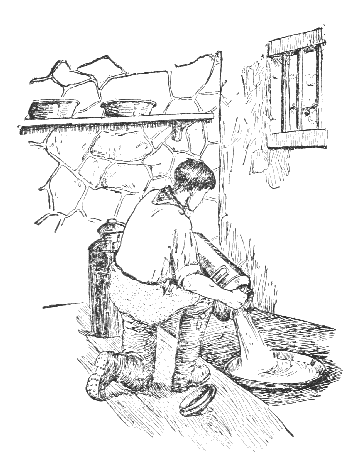

The next morning Uncle Solomon and Uncle John and little John all went out to the barn and sat on little stools—low stools with three legs, that they sit on when they milk the cows—and rubbed the kernels of corn off the cobs. Then Uncle John put all the corn into bags and put it away; and he put the cobs in the shed, to use in making fires.

Then, one morning, Uncle John got out the oxen, and they put their heads down, and he put the yoke over their necks and the bows up under, and he hooked the tongue of the ox-cart to the yoke; and he said "Gee up there," and they walked into the barn. Then Uncle John put all the bags of corn into the cart, and he put little John up on the cart, and the old oxen started again and walked slowly along, down the wagon track, out the wide gate, and into the road.

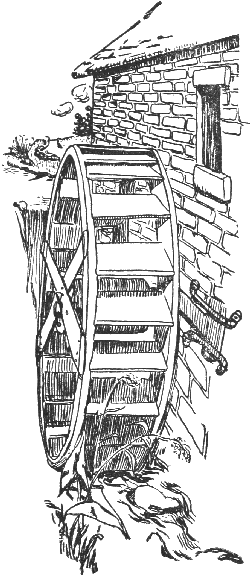

Then they turned along the road, not the way to the field where they got the water, but the other way. And they walked a long way until they came to a place where there was a building beside a little river. And on the outside of the building was a great enormous wheel, so big that it reached down and dipped into the water.

And when the water in the little river flowed along, it made the great wheel turn around; and this made a great heavy stone inside the building turn around on top of another stone. Now the building is called a Mill, and the big wheel outside is called a Mill-Wheel, and the stones are called Mill-Stones; and the man that takes care of the mill is called the Miller.

Now the miller was sitting in the doorway of the mill; and when he saw Uncle John and little John and the ox-cart filled with bags, he got up and came out, and called to Uncle John: "Good morning. What can I do for you this morning?" And Uncle John said: "I've got some corn to grind."

So the oxen stopped, and little John got down, and the miller and Uncle John took all the bags of corn into the mill, and the oxen lay down and went to sleep.

Then Uncle John and little John sat down on some logs in the mill, and the miller asked Uncle John how he wanted the corn ground. So Uncle John said he wanted some of it just cracked, and some of it ground into fine hominy, and some of it into meal.

Then the miller fixed the stones so they would just crack the corn, and he poured the corn in at a place where it would run down between the stones, and he started the stone turning. When the corn was cracked, he put it into the bags again, and tied them up.

Then he fixed the stones so they would grind the corn into fine hominy, and he poured the corn in, and it came out ground into fine hominy. Then he put the fine hominy into the bags again and tied them up.

Then he fixed the stones so they would grind the corn into meal, and he poured the corn in, and it came out ground into meal. Then he put the meal into the bags again and tied them up. And the miller kept two bags of each kind to pay for grinding the corn; but the other bags he put into the ox-cart.

Then the oxen got up and little John was lifted up and the old oxen started walking slowly along home again. And they walked a long time until they came to the wide gate, and they turned in at the gate and up the wagon track to the kitchen door, and there they stopped. And Uncle John took one of the bags of meal into the kitchen and gave it to Aunt Deborah.

And he said: "Here's your meal, Deborah."

And Aunt Deborah said: "All right. I'll make some Johnny-cake for breakfast to-morrow."

And the rest of the meal was put away in the store-room until they wanted it; for they had enough to last them all winter and some to take to market besides. Then Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the cart from the yoke and put the cart in the shed. And he took off the yoke and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field.

In the orchard grew many apple-trees. Some had yellow apples and some had green apples and some had red apples and some had brown apples. And the yellow apples got ripe before the summer was over; but the green apples and the red apples and the brown apples were not ripe until the summer was over and it was beginning to get cold.

So, one day, after the summer was over and it was beginning to get cold, Uncle John saw that the apples on one of the trees were ready to be picked. And they were red apples. So he got out the old oxen, and they put their heads down and he put the yoke over and the bows under and hooked the tongue of the ox-cart to the yoke. Then he said: "Gee up there, Buck; gee up there, Star." And the old oxen began walking slowly along, past the barn to the orchard. And they turned in through the wide gate into the orchard and went along until they came to the right tree.

Then they stopped and Uncle John took a basket and climbed up into the tree. And he picked the apples very carefully and put them into the basket. And when the basket was full, he climbed down from the tree and emptied the basket carefully into the cart. Then he climbed up again and filled the basket again; and so he did until the cart was full. Then Uncle John said: "Gee up there;" and the old oxen started and turned around and walked slowly back to the barn and in at the big door. Then Uncle John took all the apples out of the cart and put them in a kind of pen, and the old oxen started again and walked slowly back to the orchard.

So Uncle John gathered all the apples from that tree and put them in the pen in the barn. Then he unhooked the tongue of the cart and took off the yoke, and the old oxen went to their places and went to sleep.

The next morning, Uncle Solomon and Uncle John and little John all went out to the barn, and they took little three-legged stools that had one end higher than the other,—the kind they used when they milked the cows,—and they sat on these stools and looked over all the apples, one by one. The apples that were very nice indeed they put in some barrels that were there; and the apples that were good, but not quite so nice and big, they put in a pile on the floor; and the apples that had specks on them or holes in them, or that were twisted, they put in another pile. And this last pile they gave to the horses and cows and oxen and pigs, and the apples in the barrels were to go to market, or for the people to eat.

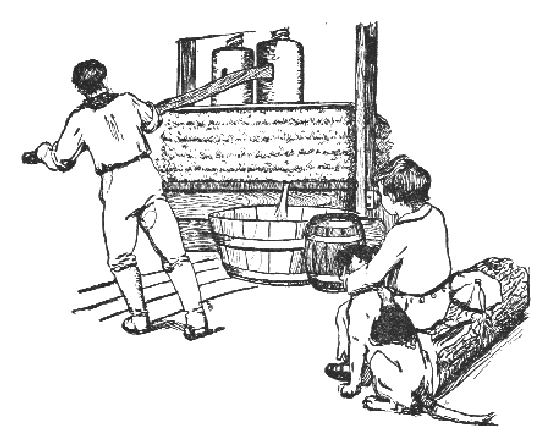

Then Uncle John got out the old oxen and they put their heads down low, and he put the yoke over and the bows under and hooked the tongue of the ox-cart to the yoke. And he put into the cart all the apples that were in the first pile, those that were good but not quite big enough to put in the barrels, and he put two empty kegs—little barrels—on the top of the load. Then the old oxen started walking slowly along, out of the barn and along the wagon track past the shed and past the kitchen door and through the gate into the road. And they turned along the road, not the way to the field where they went to get water, but the other way. And Uncle John walked beside, and little John ran ahead, and they went along until they came to a little house by the side of the road, and there they stopped. Then Uncle John opened the door of the little house and they went in. And inside there was nothing but a log against the wall, to sit on, and in the middle of the room a kind of a thing they called a cider-press. It had a place to put the apples in, and a flat cover that came down on top, and a screw and a long handle above. Besides the cider-press, there was a chopper to chop the apples into little pieces.

Then little John sat down on the log and Uncle John put the apples in the chopper and chopped them up fine. Then he put some chopped apples, with some straw over them, in the place that was meant for apples, and then he took hold of the long handle, and walked around and around. That made the screw turn and the cover squeeze down on the apples so that the juice ran out below into the keg that was put there. And when the juice was all squeezed out of those apples, he walked around the other way, holding the handle, and that made the cover lift up. Then he took out the squeezed apples and put in some other apples and squeezed them the same way. And when all the apples in the cart had been squeezed, both kegs were full of juice. And they call the juice cider.

So Uncle John put the great stoppers that they call bungs into the bung-holes in the kegs, so that the cider would not run out. Then he put the kegs in the cart, and little John came out of the little house and Uncle John shut the door, and the old oxen turned around and walked slowly along until they came to the gate, and they walked up the track to the kitchen door, and there they stopped. Then Uncle John and Uncle Solomon took the kegs down into the cellar, and they took out a little bung near the bottom of one of the kegs, and put in a wooden spigot—a kind of a faucet. Then they set that keg on a shelf, so that a pitcher or a mug could go under the spigot.

Then Uncle John took the yoke off the oxen and they went into the barn and went to sleep.

After supper that evening, Uncle Solomon and Uncle John were sitting in the sitting-room and Uncle John spoke to little John, and said: "John, I think I would like a drink of cider."

So little John took a pitcher and went down into the cellar, and his mother held a light while he put the pitcher under the spigot and turned the spigot; and the cider ran into the pitcher, and when enough had run in he turned the spigot the other way and the cider stopped running. Then he carried the cider up to his father, and his father drank it.

And when Uncle John had drunk the cider, he said to Uncle Solomon: "Father, that's pretty good cider; you'd better have some."

And Uncle Solomon said: "Don't care if I do." So little John had to go down cellar again and get another pitcher of cider.

Those two kegs of cider lasted for a while and then more apples were ripe and they made enough cider to last all winter and some to send to market besides.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. And in

the fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to a gate in a stone wall, where

the bars were across; and through that

field and another gate where the bars

were across, into the maple-sugar woods.

And in that field wheat grew.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds,

and it stood not far

from the road. And in

the fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to a gate in a stone wall, where

the bars were across; and through that

field and another gate where the bars

were across, into the maple-sugar woods.

And in that field wheat grew.

When the summer was nearly over and the corn and most of the other things had got ripe and had been gathered, Uncle John got out the old oxen and put the yoke over their necks and the bows up under; and he hooked the drag chain to the yoke and put the plough on the drag and said: "Gee up there, Buck; gee up there, Star." And the old oxen started slowly along past the barn and past the orchard to the wheat-field.

Then Uncle John took the plough off the drag and unhooked the chain from the drag and hooked it to the plough. Uncle Solomon held the handles of the plough and the old oxen started walking slowly across the field dragging the plough; and the plough dug into the ground and turned the earth up at one side and made a deep furrow where it had gone. So they went all around the field and around until it was all ploughed.

Then Uncle John unhooked the chain from the plough and hooked it to the harrow; and the old oxen started and walked slowly back and forth across the field, and the teeth of the harrow broke up the lumps of dirt and made it all soft. And when the field was all harrowed, Uncle John unhooked the chain from the harrow and hooked it to the drag and put the plough on the drag, and the old oxen walked slowly back to the barn. And Uncle John unhooked the chain and took off the yoke; and the oxen went to their places in the barn and went to sleep, and the drag was in the shed.

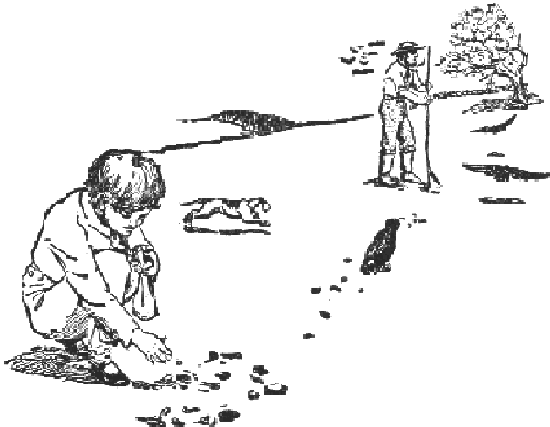

The next morning, Uncle John put some whole wheat in a big bag and put the bag over his shoulder and walked along past the orchard to the wheat-field. And when he got to the wheat-field, he put the bag down on the ground and put some of the wheat in a little bag that he had hanging from his shoulder. And then he began walking across the field, and as he walked along he took up a handful of wheat and threw it far out so that it scattered over the ground. And that way he scattered all the wheat so that it lay in the soft ground, and then he went away and left it.

And the rain fell and the sun shone on the field and the wheat began to grow. And soon the little green blades pushed up through the ground like grass; and the wheat grew higher and higher until it was as high as little John's knees. And then the summer was all over and it was beginning to get cold; so the wheat stopped growing and stayed just as high as that all winter and the snow covered it.

And when the winter was over and it began to get warm, the snow melted away and the wheat began to grow again; and it got taller and taller until it was as tall as Uncle John's waist. And then the little tassels at the top of each stem got yellow and brown and the wheat was ripe. This was in the beginning of the summer.

Then Uncle John and Uncle Solomon got their scythes and their whetstones and started very early in the morning to the wheat-field. And they sharpened their scythes with the whetstones and swung the scythes back and forth and began to cut down the wheat. Every time the scythe swung, it cut through the stalks of wheat and they fell down on the ground. And they walked along over the field, swinging the scythes and cutting down the wheat, until all the wheat was cut. Then they went home and left it lying there in the sun.

The next morning Uncle John got out the oxen and they put their heads down low, and he put the yoke over and the bows under and hooked the tongue of the cart to the yoke and said "Gee up there." And the old oxen walked slowly along, past the barn and past the orchard to the wheat-field.

And the sun had dried the stalks of wheat and the tassels. The tassels are a lot of little cases, on a fine stem; and in each little case is a grain of whole wheat. When the tassels are dry, the little cases are all ready to break open.

Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John took their long forks and put the wheat in the cart, and when the cart was full the old oxen walked slowly back to the barn and in at the great doors.

There were great enormous doors in the side of the barn, big enough for a wagon to go through when it was piled up high with a load of hay or of wheat. And in the other side of the barn were other great enormous doors, so that the wagon could go right through the barn; and between the doors was only the great open floor with nothing on it. On one side of this open place were the cows, and on the other side were the horses and the oxen, and the cart went in between, with the wheat in it.

Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John took the wheat out of the cart and put it on the floor of the barn; and the old oxen started again and walked out the other door and back to the wheat-field. Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John filled the cart again and the oxen dragged that wheat to the barn; and they did the same way until all the wheat was on the barn floor. Then Uncle John took off the yoke and the old oxen went to their places and went to sleep.

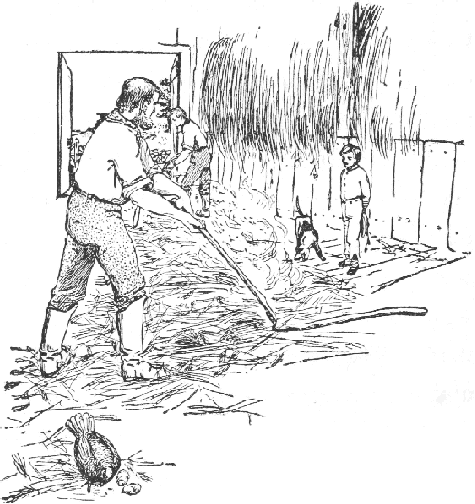

The next morning Uncle Solomon and Uncle John went to the barn, and each took down from a nail a long smooth stick that had another smooth stick fastened to its end by a piece of leather so that it flapped about. This was to beat the wheat with, and they called it a flail.

And so Uncle Solomon and Uncle John stood in amidst the wheat on the barn floor and whacked it with the flails so that they made a great noise—whack! whack!—on the floor. And the little cases broke open and the grains of whole wheat fell out and dropped between the stalks to the barn floor. And the pieces of the broken cases blew out from the great barn doors; for the doors were open at both sides and the wind blew through. These broken pieces that blow away, they call chaff.

Then when Uncle Solomon and Uncle John had whacked for a long time, and they thought that all the whole wheat had come out of the cases, they hung up the flails and took their long forks and lifted up the stalks of the wheat and shook them so that all the grains of wheat might drop through; and they put the dried stalks of the wheat in a corner of the hay-loft above where the cows slept. These dried stalks they call straw, and they put it for the horses and the cows and the oxen to sleep on.

And when the straw was all put away, there was all the wheat on the floor; and they gathered it up and put it into bags. And they had enough to make whole wheat flour to last all winter, and to feed the chickens and every kind of a thing that they wanted to use wheat for, and there was enough to take some to market besides.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds.

And when this farm-house

was just built,

before it was Uncle Solomon's, the man

that lived there wanted some fields where

he could plant his corn and his potatoes

and his wheat. But the places where the

fields would be were all covered with trees.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds.

And when this farm-house

was just built,

before it was Uncle Solomon's, the man

that lived there wanted some fields where

he could plant his corn and his potatoes

and his wheat. But the places where the

fields would be were all covered with trees.

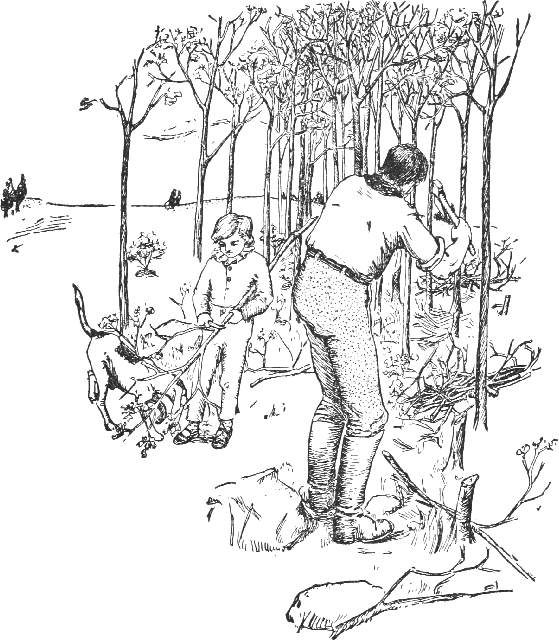

So in the winter when the snow was on the ground, he went out and cut down the trees with his axe. And the great big trees he carried to the mill, and they were sawed up into boards; that is another story. And the branches and the small trees he chopped up with his axe to burn in the fireplaces. Then the field was all covered with the stumps of the trees and with great rocks.

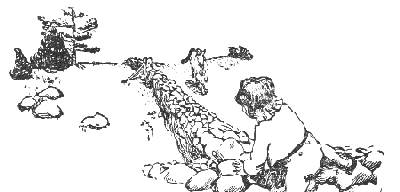

Then, when it began to get warm, after the winter was over, the man got out the old oxen. There were two pairs of oxen, and they came out of the barn and put down their heads, and the man put the yokes over their necks and the bows up under, and he hooked great chains to the yokes. And he hooked one chain to the drag, and took his whip and said: "Gee up there, Buck; gee up there, Star." And the old oxen began walking slowly along to the field.

Then the man unhooked the drag, and fastened one of the chains to a stump, and hooked the other chain to that chain, and said: "Gee up there." And all the oxen began to pull as hard as they could, and all of a sudden out came the stump with a lot of dirt. And he pulled out all the stumps the same way, and stood them up at the back of the field, where they made a kind of a fence with the roots sticking slanting up into the air.

Then there were the big rocks all over the field. And the man fastened the chains to a rock and the old oxen pulled as hard as they could, and out came the rock and they put it on the drag. And then the man saw where he wanted his fence; and they dug a trench and put flat rocks on the bottom and then the biggest rocks they had on the flat rocks. And they pulled all the rocks out of the ground with the chains, and put them on the drag, and the old oxen pulled them over to the trench, and the man piled them up and built a wall.

Building the wall took a long time—a good many days. And when the oxen had pulled all the rocks out of the ground and dragged them over to the wall, the field was all soft and ready to be ploughed. So the oxen started walking along, out of the field, along the road, dragging the drag. And they went in at the big gate and up past the kitchen door to the barn. Then the man unhooked the chains and took off the yokes and the oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field. Not very

far from that farm-house there was a

field where the horses and cows used to

go to eat the grass. That was the same

field where they went to get water from

the river; and in the wall that was

between that field and the next, there was

a wide gateway. At each side of the gateway

there was a post with holes in it, and

long bars went across and rested in the

holes. And when the bars were across,

the horses and cows couldn't go through

to the other field. But when the bars

were taken out of the holes, then the

horses and cows could go through as

much as they wanted to and eat the grass

in either field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field. Not very

far from that farm-house there was a

field where the horses and cows used to

go to eat the grass. That was the same

field where they went to get water from

the river; and in the wall that was

between that field and the next, there was

a wide gateway. At each side of the gateway

there was a post with holes in it, and

long bars went across and rested in the

holes. And when the bars were across,

the horses and cows couldn't go through

to the other field. But when the bars

were taken out of the holes, then the

horses and cows could go through as

much as they wanted to and eat the grass

in either field.

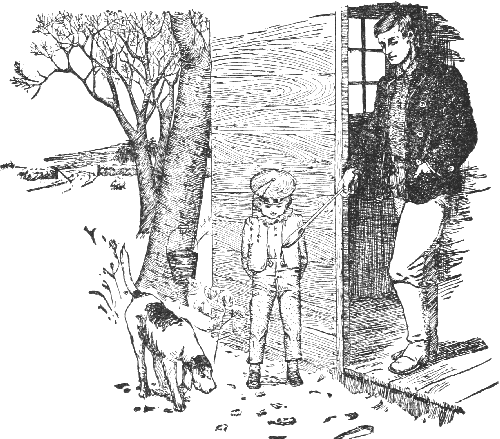

One day little John was going across the field because it was the short way; and there was a horse in the field, eating the grass, and the bars were down. It was a kind, pleasant horse, but he liked to have fun. And when he saw the little boy going across the field, he thought he would have fun, so he ran after him.

Little John saw the horse coming and he was frightened. He was near the wall that was between the two fields, and he ran as hard as he could and got to the wall before the horse caught him. Then he began to climb over the wall into the next field.

And the horse saw what he was doing and ran down the field, beside the wall, and through the gate and back on the other side; and he got there just as the little boy was getting down. And little John heard the horse's feet on the ground—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump— and he looked around and he saw the horse galloping up by the wall. Then he was frightened and he began to climb back again over the wall as fast as he could.

And the horse saw what he was doing and ran down the field, beside the wall, and through the gate and back on the other side; and he got there just as the little boy was getting down. And little John heard the horse's feet on the ground—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump— and he looked around and he saw the horse galloping up by the wall. Then he was frightened and he began to climb back again over the wall as fast as he could.

And the horse saw what he was doing and ran down the field, beside the wall, and through the gate and back on the other side; and he got there just as the little boy was getting down. And little John heard the horse's feet on the ground—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump—ca-tha-lump— and he looked around and he saw the horse galloping up by the wall. Then he was frightened and he began to climb over the wall again. But every time he had climbed over the wall between the fields, he had gone a little nearer to the road, until he was near enough to the wall between the field and the road to reach that. And this time, instead of climbing back into the other field, he climbed over into the road.

And poor little John was very much frightened and ran along the road crying, and got home, and his father saw him and asked him: "What's the matter, John?" And then little John told his father about the horse. And his father laughed and said that the horse was a kind horse but he liked to have fun; and little John better not go there any more. And so the little boy did not go through that field again, but went around by the road.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field. But when

this farm-house was just built, there

wasn't any wheat-field or any other field,

and the places where the fields would be

were all covered with trees. And that

was a long time before Uncle Solomon

had the farm.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a little track that

went up past the kitchen door and past

the shed and past the barn and past the

orchard to the wheat-field. But when

this farm-house was just built, there

wasn't any wheat-field or any other field,

and the places where the fields would be

were all covered with trees. And that

was a long time before Uncle Solomon

had the farm.

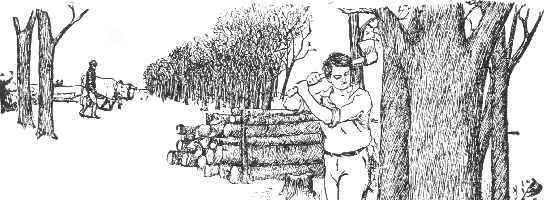

So the man that built the farm-house took his axe, one day, when the snow was on the ground, and he went to the place where he wanted the fields and he began to cut down the trees. There were big trees and little trees, and it took him a long time to cut down all the trees on the place where the field would be. He cut off all the branches, and the branches and the little trees he cut up with his axe to burn in the fireplaces; and he piled all that wood near the kitchen door. But the big logs—the trunks of the big trees after the branches were cut off—he was going to take to the mill, to have them sawed into boards.

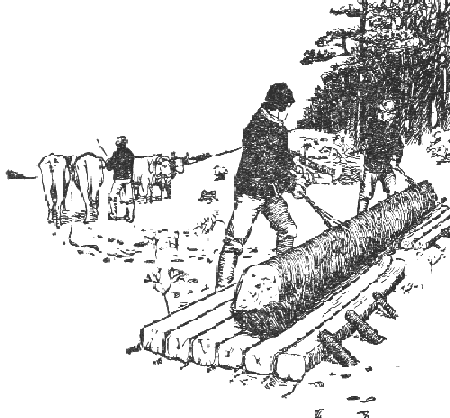

So, one morning, after that was all done, the man got out the oxen. There were two yoke of oxen—two oxen they call a "yoke" of oxen, because two are yoked together—and they came out of the barn and put their heads down and he put the yokes over and the bows under and he hooked the tongue of a great sled to each yoke. And on each sled was a great chain.

Then he said: "Gee up there," and the oxen all started walking slowly along, and they walked out of the wide gate and along the road until they came to the place where the trees were all cut down, and there they stopped. And the sleds were beside one of the big logs, one sled at each end.

Then they unhooked the tongues of the sleds from the yokes and led the oxen out of the way. And the man and two other men that were helping him put some little logs sloping from the ground up to the sleds, and with poles that had hooks on the ends they rolled the great log up the little logs on to the sleds, so that it rested on them. And there was one sled under each end, but under the middle there was nothing. Then they fastened that log to the sleds, so that it couldn't roll off, and they rolled another log up on the other side and fastened that; and they rolled another log up on top of the first two. Then they fastened the tongue of each sled to the logs, and the logs were held on with the great chains, so they couldn't roll off. Then they hooked a chain to the first sled and to one of the yokes, and another chain from that yoke to the other yoke. And the man said: "Gee up there," and all the oxen pulled as hard as they could, and the sleds started sliding along the ground on the snow and into the road. And the oxen walked slowly along the road, pulling the sleds with the logs on them, for a long way.

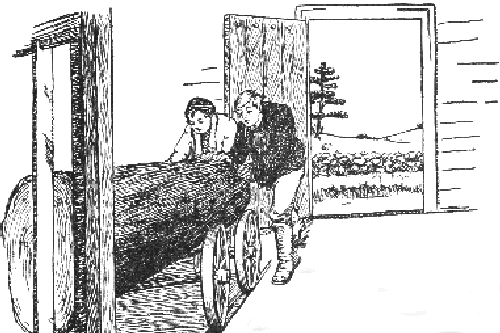

When they had gone along the road for a long way, they came to a place where there was a building beside a little river. And on the side of the building was a wheel so large that it reached down into the water. And when the water ran along, it made the wheel turn around and that made a big saw go, inside the building.

And the oxen pulled the sleds with the logs up beside the building and there was a strong carriage that ran on wheels on a track. And the men unfastened the chains and rolled a log off on to the carriage and fastened it there. Then they pushed on the carriage and it rolled along toward the saw, and the saw was going.

And the end of the log came against the saw and the saw made a great screeching noise and began to cut into the log, and it kept on cutting and the men pushed, and the saw cut all the way through the log, to the other end, and that piece fell off. That piece was round on one side and flat on the other.

Then they rolled the carriage back and fastened the log farther over and pushed it up against the saw again, and the saw cut off another piece that was flat on both sides. That piece was a board. And that way they cut the log all up into boards, and then they cut up the other logs the same way.

When the logs were all cut into boards, the men put the boards on the sleds and fastened them on just the same way the logs had been fastened, and the oxen started and turned around and walked along the road until they came to the farm-house; and they turned in at the gate and went up past the kitchen door to the place where the shed was going to be, and there they stopped. And the men took the boards off and put them on the ground in a pile, so that the man would have them there to build the shed. For the shed wasn't built then. The barn was built first and then the house.

And the other big logs they took to the saw-mill on other days and sawed them up into boards, so that the man had all the boards he needed to build the shed and the chicken house and all the other things and some to give to the men for helping him.

And when that was done, the man took off the yokes and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

In that farm-house lived Uncle Solomon and Uncle John; and little Charles and little John and their mother Aunt Deborah; and little Sam and his mother Aunt Phyllis. Uncle Solomon was Uncle John's father and Uncle John was little John's father, so that Uncle Solomon was little John's grandfather. And little Sam was Uncle Solomon's little boy, so that little Sam was little John's uncle. But little Sam was a littler boy than little John.

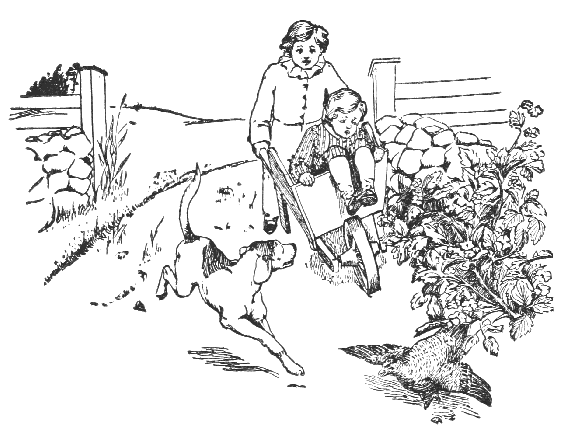

Little John and Uncle Sam used to play together; and one day when little John was wheeling Uncle Sam in the wheelbarrow, he thought it would be fun to tip him out. So he tipped Uncle Sam right out into some bushes, and Uncle Sam scratched his face and began to cry. And Uncle Solomon heard his little boy crying, and he came running out of the house. Then he saw little John and the wheelbarrow, and little Sam in the bushes, crying, and he knew that little John had tipped little Sam out of the wheelbarrow.

So Uncle Solomon was angry, and he grabbed little John by the back of his collar and the back of his trousers, and he lifted him up and gave him a great swing, and he tossed little John right over the wall. And little John came down in some bushes and got his face scratched a little, but he didn't cry. He just got up and ran around the wall and went into the house another way, and kept out of Uncle Solomon's way. But he didn't tip Uncle Sam into the bushes any more.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

One morning, after the summer was over and all the different things had got ripe and had been gathered, Uncle John woke up when the old rooster crowed, very early, long before it was light. And he got up and put on his clothes, and Aunt Deborah got up too, and they went down-stairs.

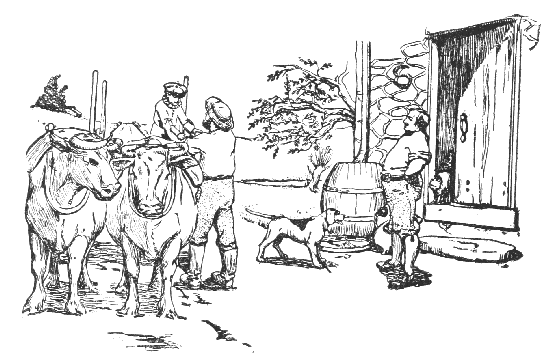

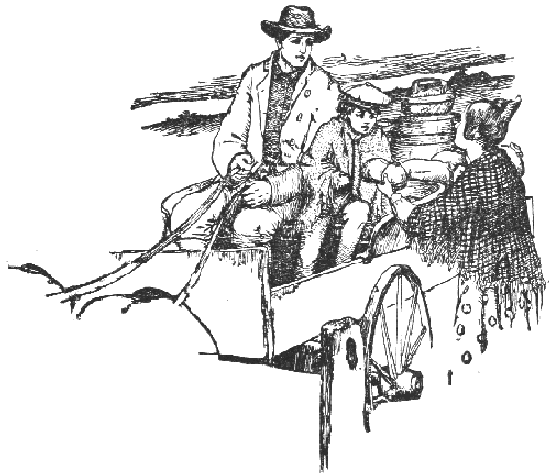

Then, while Aunt Deborah fixed the fire and got breakfast ready, Uncle John went out to the barn. He gave the horses their breakfast, and when they had eaten it he took them out of their stalls and put the harness on and led them out to the shed. Then he hitched them to the big wagon and he made them back the wagon up to the place where all the things were put that were to go to market.

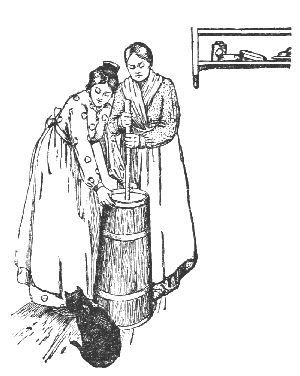

Then Uncle Solomon came out and helped, and they put into the wagon all the barrels of apples that they could get in, and they put in a lot of squashes and turnips and some kegs of cider and some bags of meal and fine hominy and some butter that Aunt Deborah and Aunt Phyllis had made and some other things. And when these things were all in the wagon, breakfast was ready, and Uncle John fastened the horses to a post and went in to breakfast. And all this they had to do by the light of a lantern, because it wasn't daylight yet.

Then, when Uncle John and little John had had their breakfast, they came out of the house, and Uncle John put little John up on the high seat and he unhitched the horses and climbed up on the high seat beside him. And then Aunt Deborah came out of the house and handed Uncle John a little bundle, and he put the bundle under the seat. In the bundle was some luncheon for Uncle John and little John; and for the horses there was some luncheon too, oats in a pail that hung under the wagon, one pail for each horse. And a lantern hung beside the seat, for it wasn't daylight yet.

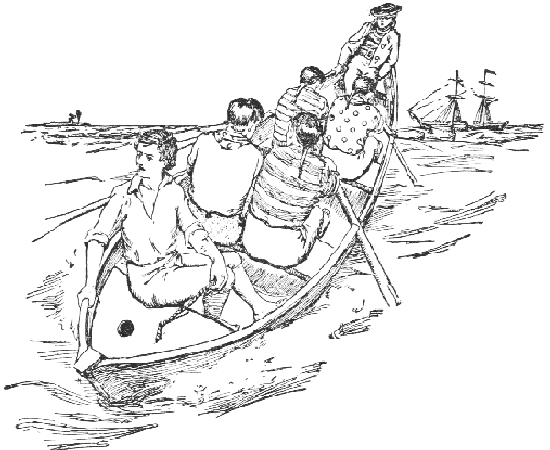

When they were all ready, Uncle John said: "Get up," and the horses started walking down the little track into the road and along the road. The horses wanted to trot, but Uncle John wouldn't let them because it isn't good for horses to trot when they have just had their breakfast; and he held on to the reins tight and they had to walk. So they walked along for awhile and it was very dark; and pretty soon Uncle John let the horses trot. And they trotted along the road for a long time and at last it began to get light, and little John was very glad, for he was cold. Then Uncle John blew out the lantern and after awhile the sun came up and shone on them and made them warm. And the horses trotted along for a long time and at last they began to come to the city, and it was very early.

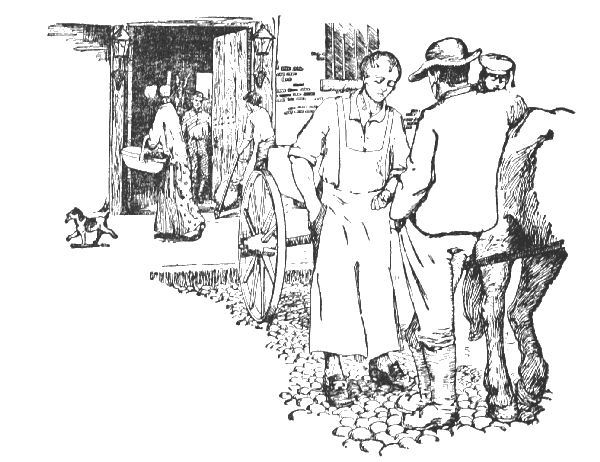

So the horses dragged the wagon through the city streets, and there were not many people in the streets, for they had not had their breakfasts. And by and by they came to the shops and little John saw the boys opening the doors of the shops and sweeping the shops and the sidewalks; and so they went along until they came to a great open place. And in the middle of the open place was a big building, and all about it were wagons, some standing in the middle of the street and some backed up to the curbstone. All these wagons had come in from the country, bringing the things to eat; and the building was a market, and the men in the market bought the things from the men that drove the wagons, and the people that lived in the houses came down afterward and bought the things from the market-men.

Then Uncle John drove the horses up to the sidewalk and he got out and hitched the horses to a post and told little John not to get off the seat; and Uncle John went into the market. When he had been gone some time, he came back and a market-man came with him. The market-man had a long white apron on and no coat; and he looked at the barrels of apples and the squashes and the turnips and the kegs of cider and the bags of meal and the butter and the other things, and he thought about it for a few minutes and then he said: "Well, I'll give you twenty dollars for the lot."

And Uncle John thought for a few minutes and then he said: "Well, I ought to get more for all that. It's all first-class. But I suppose I'd better let it go and get back."

So Uncle John unhitched the horses and backed the wagon up to the sidewalk. Then he took the bridles off the horses' heads and took the buckets of oats from under the wagon; and he put the pails on boxes at the horses' heads, one for each horse, and the horses began to eat the oats.

Then a man came out of the market, wheeling a truck—a kind of a little cart with iron wheels—and he helped the market-man take the barrels out of the wagon, and the squashes and turnips and the kegs of cider and the bags of meal and the butter and the other things. And they put them on the truck, a part at a time, and he wheeled them into the market. Then, when that was all done, the market-man took some money from his pocket and counted twenty dollars and handed it to Uncle John. And then the horses had finished eating the oats, and Uncle John took the pails and hung them under the wagon again and put the bridles on the horses' heads.

Then Uncle John climbed up on the high seat beside little John and took the reins in his hands and said "Get up"; and the horses started and went across the open place to a great stone that was hollowed out and was full of water. And the horses each took a great drink of water and then they lifted up their heads and started along the streets.

And pretty soon Uncle John stopped them at a shop, and he went in and bought some things that Aunt Deborah wanted, and he paid the shop-man some of the money the market-man had given him. Then they went to another shop and Uncle John bought some more things. And after that they didn't stop at any shops, but the horses trotted along through the streets until they were out of the city and going along the road in the country that led to the farm-house.

By and by they came to a steep hill and the horses stopped trotting and walked, for they were tired. And Uncle John fastened the reins and took the bundle from under the seat and undid it, and in it were bread and butter and hard eggs and gingerbread and a bottle of nice milk. And Uncle John and little John ate the nice things and liked them, for they were both very hungry.

Then they got to the top of the hill and Uncle John took up the reins again and said "Get up," and the horses trotted along for a long time until they came to the farm-house; and they turned in at the wide gate and went up to the kitchen door and there they stopped. And Uncle John got down and took little John down. Little John was glad to get off the high seat, for he had been there a long time and he was very tired.

So he went into the house and Uncle John unhitched the horses from the wagon and put the wagon in the shed. And he took the horses to the barn and took off their harness and put them in their stalls, and they went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field; and through the

wheat-field to the maple-sugar woods.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field; and through the

wheat-field to the maple-sugar woods.

One day, when the winter was almost over and it was beginning to get warmer, Uncle John got out the old oxen. And they came out and put their heads down and he put the yoke over and the bows under, and he hooked the tongue of the sled to the yoke; for the snow was not all melted, and enough was on the ground for the sled to go on.

Then he put on the sled his axe and Uncle Solomon's, and a lot of buckets and a lot of wooden spouts he had made, and the big saw. Then he put little John on the sled and said "Gee up there," and Uncle Solomon came too, and they walked along beside the sled. And the old oxen walked slowly along the track past the barn and past the orchard to the wide gate that led into the wheat-field, and there they stopped. And Uncle John took down the bars and the oxen went through the gate and across the wheat-field, and stopped at the wide gate on the other side of the field. Then Uncle John took down those bars and the old oxen started and walked through and along the little road in the maple-sugar woods until they came to a little house beside the road, and there they stopped.

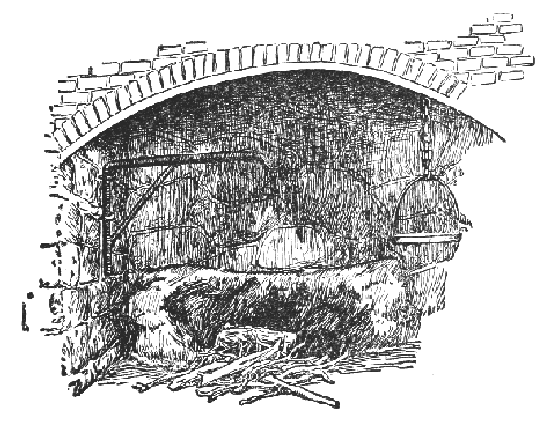

Then Uncle John opened the door of the little house; and inside, it was about as big as a little room that a little boy sleeps in. And in one corner was a chimney, and in front of the chimney was a great enormous iron kettle, set up on a little low brick wall that was just like a part of the chimney turned along the ground. In the front was a hole in the low wall, so that wood could be put in, and at the back, under the kettle, there was a hole into the chimney, so that the smoke would go up the chimney and out at the top. And in one corner of the little house were some square iron pans.

Then Uncle John put two of the buckets down in the house, and the big saw; and he shut the door and the oxen started and walked along until they came where were some maple-sugar trees, and there they stopped. Then Uncle John and Uncle Solomon took their axes and went to the trees and they made little notches in the trees, low down, so that there was room to put a bucket under. And they drove a spout in each notch and put a bucket under each spout. And then they went to other trees and made a notch in each tree and drove in a spout and put a bucket under and so they did until they had used up all their buckets.

Then the old oxen walked along until they came to a pile of wood that was cut up all ready to burn; and there they stopped and Uncle Solomon and Uncle John put the wood on the sled. Then they said: "Gee up," and the oxen walked back to the little house, and they took the wood off the sled. And the wood was in great long sticks, too long to put in the place under the kettle. So Uncle John got the big saw from the little house and he and Uncle Solomon sawed the wood into small sticks and piled it up nicely.

Then they put the saw on the sled and shut the door of the little house and the old oxen started walking back along the little road, dragging the sled, with the saw and the axes and little John. And they went through the gate into the wheat-field and Uncle John put the bars back; and they went across the wheat-field and through the gate at the other side, and Uncle John put those bars back. And they walked along past the orchard and past the barn to the shed.

And Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the sled and took off the yoke, and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

The next morning, Uncle John and little John started along the little road, past the shed and past the barn and past the orchard; and they climbed over the bars into the wheat-field, and went through the wheat-field and climbed over the bars into the maple-sugar woods. Then they walked along until they came to the little house, and Uncle John opened the door of the house and took out the two buckets he had left there.

Then they went to some of the maple-sugar trees where they had put buckets the day before, and the sap was dripping slowly into the buckets—drip—drop—drip—drop—and the buckets were nearly half full. So Uncle John poured the sap from those buckets into the empty buckets and went along to some other trees and poured the sap from those buckets in with the other, and the buckets he carried were full. So he took them back to the little house and emptied them into the big kettle.

Then he went to other trees and filled the two buckets again with the sap that had dripped, and emptied that into the kettle. And so he did until he had taken all the sap that had dripped.

Then he put wood under the big kettle and lighted it, and the fire burned and the sap got hot and after a while it began to boil. And while it was boiling, Uncle John stirred the sap once in a while with a wooden stirring thing he had made. And when it had boiled a long time, he dipped out a little with the stirrer and went to the door and dropped it in the snow, so that when it got cool he could see whether it was boiled enough. But it wasn't done enough, and he let it boil longer, and then he dropped some more in the snow; and this time he thought it was about right for maple-syrup.

So he dipped sap out of the kettle into a keg that was in the little house, until the keg was full. And then he put the bung into the bung-hole and set the keg in the corner.

Then Uncle John put more wood on the fire and the sap boiled a long time. And at last he thought it was done enough for maple-sugar; and he dipped some out with the stirrer and went to the door and dropped it in the snow. And when it got cold, he saw that it was hard, and was just right for maple-sugar. So he took the little square pans that were in the corner of the house and he dipped the boiled sap from the kettle into the pans and set them in the snow outside.

Then he let the fire go out, and when the sugar in the pans was hard, he brought it into the house, and shut the door and started along the little road, and little John after. They walked along through the maple-sugar woods and climbed the bars into the wheat-field, and walked across the wheat-field and climbed the bars at the other side, and walked along past the orchard and past the barn and past the shed to the kitchen door, and there they went in.

The next morning, Uncle John and little John went to the maple-sugar woods again, and Uncle John got some more sap and boiled it and made maple-syrup and maple-sugar. And so they did every day until they had taken all the sap that the trees ought to give.

Then Uncle John got out the old oxen and they put their heads down and he put the yoke over and the bows under, and he hooked the tongue of the sled to the yoke. Then he said "Gee up there," and the oxen started walking along past the barn and past the orchard, and Uncle John took down the bars at the wheat-field and they went through and across the field, and he took down the bars at the other side and they walked through and along the road in the maple-sugar woods until they came to the little house.

There they stopped, and Uncle John opened the door and put the kegs on the sled, and all the little squares of maple-sugar and all the buckets and all the spouts that he had pulled out of the trees. And he shut the door of the little house, and the oxen started and walked back along the road through the maple-sugar woods into the wheat-field, and Uncle John put up the bars. And they walked across the wheat-field and through the gate at the other side, and Uncle John put up those bars; and they walked along past the orchard and past the barn, and little John came after.

Then the old oxen dragged the sled to the place where they kept the things that were to go to market, and Uncle John took off the maple-syrup and the maple-sugar and put them in that place. But some of the maple-syrup and some of the maple-sugar he put in the cellar for themselves to use; for little Charles and little John and little Sam liked maple-sugar and they liked maple-syrup on bread. And there was enough maple-syrup and maple-sugar to last them a long time and a lot to go to market besides.

Then Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the sled from the yoke and put the sled in the shed; and he took off the yoke and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field; and through the

wheat-field to the maple-sugar woods.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field; and through the

wheat-field to the maple-sugar woods.

All about were other fields; and one of them was a great enormous field where Uncle John used to let the horses and cows go to eat the grass, after he had got the hay in. This field was so big that Uncle John thought it would be better if it was made into two fields. He couldn't put a stone wall across it, because all the stones in the field had been made into the wall that went around the outside. So he thought an easy way would be to put a rail fence across.

So, one day, when it was winter and snow was on the ground, Uncle John and Uncle Solomon took their axes and walked along the little track, past the barn and past the orchard, and climbed over the bars into the wheat-field. Then they walked across the wheat-field and climbed over the bars into the maple-sugar woods; and they walked along the road in the woods until they came to a place where were some trees that were just the right size to make rails and posts. They were not maple-sugar trees, but a different kind.

Then they cut down enough of these trees to make all the rails and all the posts they wanted; and they cut off all the branches and they cut some of the trees into logs that were just long enough for rails, and they cut the other trees into logs that were just long enough for posts. Then they took the rail logs and with their axes they split each one all along from one end to the other, until it was in six pieces. Each piece was a rail. But the post logs they didn't split.

Then they left the logs and the rails lying there and walked back, and climbed over into the wheat-field, and went across the wheat-field and climbed over at the other side, and walked past the orchard and past the barn and past the shed and went in at the kitchen door.

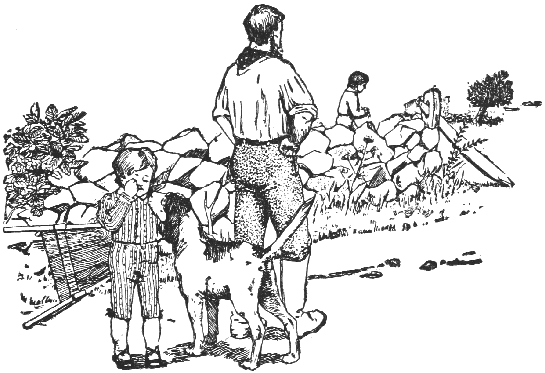

The next morning, Uncle John got out the old oxen, and they put their heads down low, and he put the yoke over and the bows under, and hooked the tongue of the sled to the yoke. Then he said: "Gee up there," and they started walking slowly along, past the barn and past the orchard to the wheat-field; and Uncle John took down the bars and they walked across the wheat-field, and he took down the bars at the other side. Then the old oxen walked through the gate and along the road to the place where the post logs and the rails were; and Uncle Solomon had come too, and little John. But they didn't let little John come when they cut the trees down, because they were afraid he might get hurt.

Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John piled the rails on the sled, and the post logs on top, and the old oxen started and walked along the road and through into the wheat-field and across the field, and Uncle John put the bars up after the oxen had gone through the gates. Then they dragged the sled along past the orchard and past the barn to the shed. There they stopped and Uncle John and Uncle Solomon took off the logs and the rails. The rails were piled up under the shed, to dry; but the logs they had to make square, and holes had to be bored in them before they would be posts. Then Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the sled from the yoke and took off the yoke, and the old oxen went into the barn.

The next day, Uncle John took an axe that was a queer shape, and he made the post logs square. Then he bored the holes in the logs for the rails to go in, and piled the posts up under the shed. They were all ready to set into the ground, but the ground was frozen hard, and they couldn't be set until the winter was over and the ground was soft.

After the winter was over and it was getting warm, the ground melted out and got soft. Then Uncle John and Uncle Solomon took a crowbar—a great, heavy iron bar with a sharp end—and a shovel, and they went to the great enormous field. Then they saw where they wanted the fence to be, and they dug a lot of holes in the ground, all in a row, to put the posts in.

Then they went back and Uncle John got out the oxen and put the yoke over and the bows under and hooked the tongue of the cart to the yoke. On the cart they piled the posts, and there were so many they had to come back for another load. Then the oxen started and walked down the little track and out through the wide gate into the road, and along the road to the great enormous field where the holes were all dug for the posts. Then Uncle Solomon and Uncle John put the posts in the holes and pounded the dirt down hard.

Then the oxen walked back along the road to the farm-house and in at the gate and up to the shed. And Uncle John put the rails on the cart and the oxen walked back to the field again and in beside the row of posts. And Uncle John took the rails off the cart and put them in the holes in the posts, so that they went across from one post to the next. And in each post were four holes, and four rails went across.

Then the oxen went a little farther and the rails were put in between the next posts, and so on until the rails reached all the way across the field, and the fence was done. And when Uncle John wanted the cows or the horses to go through, he could take down the rails at any part of the fence.

Then the old oxen started walking back out of the field into the road and along the road to the farm-house. And they went in at the wide gate and up the track past the kitchen door to the shed, and there they stopped.

And Uncle John unhooked the tongue of the cart from the yoke and put the cart in the shed. And he took off the yoke and the old oxen went into the barn and went to sleep.

And that's all.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

NCE upon a time there

was a farm-house, and

it was painted white

and had green blinds;

and it stood not far

from the road. In the

fence was a wide gate to let the wagons

through to the barn. And the wagons,

going through, had made a track that led

up past the kitchen door and past the

shed and past the barn and past the orchard

to the wheat-field.

One morning, the old rooster crowed very early, as soon as it began to be light. And that waked Uncle John and Aunt Deborah, and Uncle Solomon and Aunt Phyllis. And they all got up and put on their clothes and came down-stairs. Then Aunt Deborah and Aunt Phyllis went about their work in the kitchen, getting things for breakfast and fixing the fire; and Uncle Solomon and Uncle John went out to the barn. Uncle Solomon looked after the horses and gave them their breakfast, and Uncle John looked after the cows.

Between the two great doors of the barn there was a great open place so that the wagons could go right through; and that was where they threshed the wheat. And on one side were the stalls for the horses and the places for the oxen, and on the other side were the places for the cows. In the corner of the barn next to the horses was the harness-room, and in the corner next to the cows was the milk-room.

There were two big horses and two big oxen and six cows. The horses were in stalls, but the cows didn't have stalls. They stood in a row on a kind of a low platform, with their heads toward the open place in the middle of the barn. Each cow had her head through a kind of frame made of two boards that went up from the floor, so that when the boards were fastened at the top she couldn't get her head out, but she could move it up and down all she wanted to. And when they wanted to let the cows out, they unfastened one of the boards and let it down. But Uncle John didn't like the frames for the cows, so he never fastened the boards at all, but he put a chain around the neck of each cow and hooked the other end to a post.

In front of each cow was a little low wall, about as high as her neck, and just behind the wall was a trough that they call a manger, where they could put hay or meal or other things for the cow to eat, so that she could reach it. Just over the manger of each cow was a hole in the floor of the loft where the hay was, so that they could put hay through and it would fall right into the manger, in front of the cow. In winter the cows had hay, but in summer they didn't have hay, because they could eat the grass, and that was better.

So, when Uncle John went to look after the cows, he didn't climb up to the loft and pitch some hay down through the holes, as he would do in winter, but he took a wooden measure and went to a big box that they call a bin. It stood in the corner next to the milk-room, and it was full of meal that was ground up from corn at the mill. And he gave each cow a measureful of meal and put it in the manger so that she could eat it.

Then he went to the milk-room and got the big milk pails and his milking-stool. The milking-stool was a little stool that had three legs, and one of the legs was shorter than the other two, so that it sloped.

Then Uncle John put the milking-stool down by a cow, and the pail was between his knees, resting on the end of the stool. And he milked the cow and the milk spurted into the pail. And when she had given all the milk she had, the pail was about half full.

Then Uncle John went to the next cow and milked her, and when that pail was full, he took the other pail. And so he milked all the cows, one after the other, and when both the pails were full, he took them to the milk-room and poured the milk through a strainer into a big can. And the cows were eating their meal all the time they were being milked.

At the side of the barn, behind the cows, was a door that opened into the cow-yard. A sloping place led down from the barn to the ground, so that the cows could walk down into the yard. In the winter, the cows stayed in the cow-yard while they were out of the barn, because it was sunny and warm, and there was no grass in the field for them to eat. A high fence was all around the yard, and in one corner was a tub made of a hogshead cut in two, and a pump was beside it. And the tub was always full of water, so that the cows could drink whenever they were thirsty. So, when Uncle John had milked all the cows, he opened the door into the cow-yard, and he unhooked the chains from the necks of the cows, one after another. And the cows turned around and walked through the door and down the sloping place into the cow-yard, the leader first, and every cow took a drink from the tub in the corner of the yard. Then they stood by the gate, waiting for little John to come.

When a lot of cows are together, one of the cows is always the leader, and she always goes first, wherever they go. If any other cow tries to go first, the leader butts that one and makes her go behind. Or if the other cow doesn't want to go behind, they put their horns together and push, and the one that pushes harder is the leader.

So the cows waited at the gate, and little John had come down-stairs and Aunt Deborah had given him a piece of johnny-cake, because breakfast wasn't ready and little boys are always hungry. Then little John came to the gate to the cow-yard, and opened the gate, and the cows hurried to go through the gate, the leader first, and the others following after. And they went along the little track and through the gate into the road, and along the road to the great enormous field. And there they stopped, for the bars were up and they had to wait for little John to come along and let them down, so that they could go through.

And little John came running along, eating his piece of johnny-cake, and kicking up the dirt with his bare feet, for in the summer-time he didn't wear any shoes or stockings. And he came to the gate and he let the bars down at one end, and the cows stepped over the bars carefully, the leader first, and went into the field. And little John put the bars up again, so that the cows couldn't get out, and he turned around and ran back to the farm-house to get his breakfast.

When the cows were all in the field, they began to eat the grass; and they walked slowly about, eating the grass, until they had had all they wanted. Then they went over to the corner of the field, where there was a stream of water running along, and each cow took a drink of water. In the middle of the field was a big tree with long branches and a great many leaves, so that under the tree it was shady and cool. By the time the cows had eaten all the grass they wanted, it was hot out in the sun, and they all walked over to the big tree and got in the cool shade.