The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Romance of Toronto, by Annie Gregg Savigny

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Romance of Toronto

A Novel

Author: Annie Gregg Savigny

Release Date: April 21, 2011 [EBook #35927]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A ROMANCE OF TORONTO ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

"I would like the Government to forbid the publication of all novels that did not end well."—Darwin.

"What would the world do without story-books."—Dickens.

In the following pages are two plots, one of which was told me by an actor therein; the other I have myself watched from its first page to its last, being living facts in living lives of fair Toronto's children.

THE AUTHOR.

CHAPTER I. Toronto a Fair Matron

CHAPTER II. Who is Who in a Medley

CHAPTER III. Instantaneous Photographs

CHAPTER IV. The Foot-ball of Circumstance

CHAPTER V. A Bona Dea

CHAPTER VI. Coffee and Chit-Chat

CHAPTER VII. Across the Sea to a Witch's Caldron

CHAPTER VIII. A Troubled Spirit

CHAPTER IX. Vultures Habited as Christian Pew-holders

CHAPTER X. A Lucifer Match

CHAPTER XI. Their "Rank is but the Guinea's Stamp"

CHAPTER XII. On the Rack

CHAPTER XIII. Lucifer's Votaries Rampant

CHAPTER XIV. Fencing Off Confidence

CHAPTER XV. The Tree of Knowledge

CHAPTER XVI. The Oath in the Tower of Toronto University

CHAPTER XVII. Birds of Prey

CHAPTER XVIII. The Islet-gemmed St. Lawrence

CHAPTER XIX. Eye-openers

CHAPTER XX. "Your Een Were Like a Spell"

CHAPTER XXI. A Happy New Year

CHAPTER XXII. "Better Lo'ed Ye Canna Be"

CHAPTER XXIII. The Three Links

CHAPTER XXIV. A Hand of Ice Lay on Her Heart

CHAPTER XXV. "Here Awa', There Awa'"

CHAPTER XXVI. Electric Tips Among the Roses

CHAPTER XXVII. A Serpent in Paradise

CHAPTER XXVIII. Squaring Accounts

CHAPTER XXIX. "Mair Sweet Than I Can Tell"

Two gentlemen friends saunter arm in arm up and down the deck of the palace steamer Chicora as she enters our beautiful Lake Ontario from the picturesque Niagara River, on a perfect day in delightful September, when the blue canopy of the heavens seems so far away, one wonders that the mirrored surface of the lake can reflect its color.

"Do you know, Buckingham, you puzzle me; you were evidently happier in our little circle at the Hoffman House than in billiard, smoking, or reading-rooms, and just now in the saloon you seemed so content with Miss Crew, my wife and our boy, that I again wonder a man with these tastes, and who has made his little pile, does not marry," said Mr. Dale, in flute-like tones, distinctly English in accent. "I really think, my dear fellow, you would be happier in big New York city with some one in it to make a home for you."

"I am quite sure your words are kindly meant, Dale, but look at me," he says tranquilly, "I am not dwarfed by care, being six feet in my stockings, I have no worrying lines written on my forehead, and between you and I, I am fifty; to be sure I am bald and grey, but that is New York life, a bachelor life, then, has not served me ill; there is a woman at Toronto I should like as my wife, but until I can give her the few luxuries I now deem necessities, I shall remain as I am."

"I regret your decision, Buckingham, it is a rock many men split on, this waiting for wealth and missing wifely companionship."

"Perhaps you are right; but I should not care to risk it," he says, calmly.

"And you a speculator!" his friend said, smiling. At this they drifted into business and some joint investments in Canadian mineral locations, when Dale said:

"You must excuse me now, Buckingham, I promised my wife to go and read her a letter descriptive of Toronto, as we, you know, have not been there."

"Who is the writer, if I may know?"

"Our mutual friend at Toronto, Mrs. Gower."

"Oh, I am with you then," he said, with unusual eagerness, a fact noted by his friend.

Entering the saloon, Mrs. Dale, a pretty little woman, fashionably dressed, with Irish blue eyes and raven hair, said, lifting her head:

"Excuse my recumbent position, but I feel as if my head wasn't level, if I try to sit up; ditto, Miss Crew."

"Where is Garfield, Ella?"

"Over there with those boys; now read away, hubby, it will do my head good."

"Very well, let me see where the description commences (the personal part I may pass). Here it is:

"Toronto is a fair matron with many children, whom she has planted out on either side and north of her as far as her great arms can stretch. She lies north and south, while her lips speak loving words to her off-spring, and to her spouse, the County of York; when she rests she pillows her head on the pine-clad hills of sweet Rosedale, while her feet lave at pleasure in the blue waters of beautiful Lake Ontario.

"Her favorite children are Parkdale, Rosedale, and Scarboro'; Parkdale to her west, ambitious and clear-sighted, handsome and well-built, the sportive lake at his feet, in which his children revel at eve; her daughter, charming Rosedale, in society and quite the fashion even to the immense bouquet she carries at all seasons—now of autumn leaves, from the hand of Dame Nature; now of the floral beauties from her own gardens and conservatories, again, of beauteous ferns gathered in her own woods across her handsome bridges.

"Scarboro', fair Toronto's favorite son, of whom she is justly proud, is a handsome young warrior, fearless as his own heights, robust as his own trees, which seem as one gazes down his deep ravine, like so many giants marching upwards as though panting to reach the blue pavilioned heavens where they would fain rest their heads.

"From the time spring thaws the sceptre out of the frozen hand of winter, until again he is king, the breath of Scarboro' is redolent of the rose, honeysuckle and sweet-briar, with a rapid succession of the loveliest wild flowers in Canada beneath one's feet, a veritable carpet of sweet-scented blossoms has her son Scarboro'.

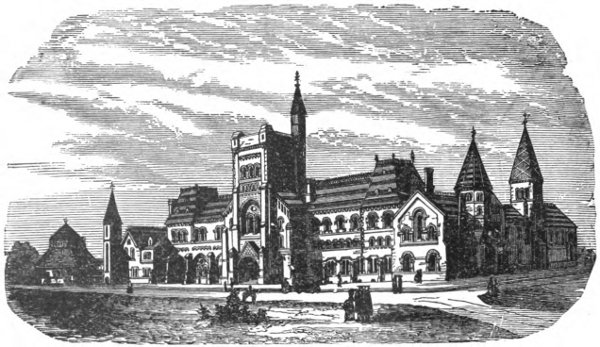

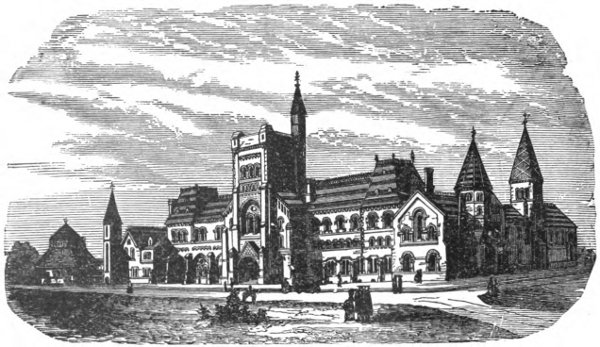

"Fair Toronto is also herself richly robed and jewelled, her necklet being of picturesque villas, in Rosedale and on Bloor Street; under her corsage, covered with beauteous blossoms from her Horticultural Gardens, her Normal School grounds, etc., her heart throbs with pride as she thinks of her gems, the spires from her one hundred and twenty churches glistening in heaven's sunbeams; of her magnificent University of Toronto, with its great Norman tower, which cost her nearly $500,000; her handsome Trinity College, in third period pointed English style; her Knox College, her hotels, her opera houses, her stately banks; with her diamonds, of which she is vastly proud, and which are her great newspaper offices—the most valuable being those of first water, viz., her Church papers as finger-posts, with her Sentinel as guard; her independent, cultured Mail; her mighty clear-Grit Globe; her brilliant, knowing Grip; her often-quoted World; her racy town-cry News; her social Saturday Night; her Life, her Week, her Truth, with her Evening Telegram, the whole set being so valued by fair Toronto, that she would as soon be minus her daily bread as her newspapers.

"It would take too long to enumerate the many attractions fair Toronto offers—some of those within her walls having throats full of song, others in the 'Harmony Club,' others elocutionists, with orators and athletes; her Cyclorama of Sedan, her Zoo—to which only a trifle pays the piper—her interesting museums, her fine art galleries.

"And again, one word of her pet river, her picturesque Humber, where lovers meet, poets dream, and fairies dwell; yes, as Imrie says:

"'Glide we up the Humber river,

Where the rushes sigh and quiver,

Plight our love to each forever,

Love that will not die.'

"Such, dear Mr. and Mrs. Dale, is my lay of Toronto, which I hope you will like well enough to come and sojourn here awhile. You say, Mrs. Dale, that you have 'willed' to go to an hotel, if so, I shall say no more of my wish, for 'a woman's will dies hard on the field, or on the sward;' but when your will is carried out, should you sigh for home-life come to me—even then Holmnest will have open doors. You may be grave or gay, you may be en déshabillé in mind and robing, or you may have your war-paint on for the watchful eye of Grundy, be it as you will it, you are ever welcome, only tell dear Diogenes not to come in his tub. I can give you both amusement enough in many subjects or objects at which to level your glass, for Toronto society is in many instances an amusing spectacle, a droll conglomeration.

"Yours as always,

"Elaine Gower."

"Well, Buckingham, what think you of fair Toronto?" asked Dale, as he finished reading.

"I think that, though unusual, a Fair Matron has had ample justice from a fair woman."

"I want to-morrow and Mrs. Gower right now," said Mrs. Dale, "as Garfield says when he is promised a treat."

"Toronto must be a fine city, and covering a large area," said Miss Crew.

"Mrs. Gower has a taste for metaphor; I never heard her in that style before, that is to any extent," said Buckingham.

"I am intensely practical," said Dale; "but confess Toronto described in metaphor sounds more musical, at all events, than in plain brick and mortar style."

"Emerson says," said Buckingham, "men are ever lapsing into a beggarly habit in which everything that is not cyphering is hustled out of sight, and I think he is right."

"We cannot help it, it is the tendency of the age; but what have we here, Buckingham? What's the excitement about?"

"Oh, we are only nearing Hanlon's Point; the ladies had better come outside; every scene will be in gala dress. Miss Crew, can I assist you?"

said Dale, coming with the crowd to view the scene.

But since Moore so sang, the hills of the noble red man have disappeared, save as a boundary to our fair city; the pale faces, in the interests of progress and civilization, would have it so; and Bloor Street, to the north, is now reached by a gradual ascent of one hundred and fifty feet above the lake level. But now the stately and comfortable palace steamer, Chicora, with a goodly number of souls on board, is rounding Hanlon's Point, and entering our beautiful Bay, when the illumined city, with the Industrial Exhibition of 1887 in full swing, burst upon the view. The bands of music in and about the city, at the Horticultural Gardens and on the fair grounds, with the hum of many voices, fill the evening air with a glad song of joy.

"What a sparkling scene," cried Mrs. Dale; "see, Garfield, my boy, all the boats lit from bow to stern."

"They look as pretty as you in your diamonds, mamma."

"It is quite a pretty sight, and the city also," said Miss Crew; "I had no idea Canada could attempt anything to equal this."

"So much for England's instructions of her 'young ideas how to shoot,' as to her colonies, Miss Crew," said Dale; "Come, confess that a few squaws, bearing torches, with their lordly half smoking the calumet, was the utmost you expected."

"Oh, Mr. Dale, please don't exaggerate our ignorance in this respect; I am not quite so bad as a lady at home, who thought Toronto a chain of mountains, and Ottawa an Indian chief."

"One of Fenimore Cooper's, I hope," laughed Buckingham, "who hunted buffalo on the boundless prairie, instead of your lean gophers who hunt rusty bacon from agents who, some say, use him to swindle the public and line their own pockets. But listen; what a medley of sounds."

"And lights," cried Mrs. Dale; "it looks as if annexation was on, and they were firing up some of our gold dollars as sky rockets."

"It's pretty good for Canada, mamma," said Garfield, patronisingly.

"You say Toronto is quite a business centre, Buckingham?"

"Oh, yes; quite so; it makes one think of commercial union. Do you advocate it, Dale?"

"Well, as you know, Buckingham, I am not even yet sufficiently Americanised to look upon it from other than a British standpoint, and so do not advocate it, as it seems a slight to the Mother Country. What is your idea of advantages derived by Canada were it a fait accompli?"

"She would gain larger markets; her natural resources would be developed, especially her mineral, in which I am," he added, jokingly, "looking out for the interest of that most important number one, while also number two would benefit in home manufactures."

"You amuse me; I honestly believe number one is a universal lever; yet still in a way we are each patriotic; but, again, you must see that commercial union would be the forerunner of annexation."

"Yes, likely, though not for some time, but evolution will bring that about in a natural sort of way, as a final settlement of all vexed questions, whether," he added laughingly, "of humanity or—fish."

"Oh, I don't know that, but you have the fish at all events and mean to keep them too; humanity may follow, but I should not like to see the colonies hoist another flag. But here we are at last, at the portals of the Queen City, and such a multitude of people makes one feel as if one might be crowded out," he said, uneasily, as the Chicora came in at Yonge Street wharf.

"Don't bother your head about your rooms, Dale, you secured them by telegram."

"I did, ten days ago, though."

"You never fear, they will be all right, the manager is a thorough business man," he said quietly, gathering up the belongings of the ladies.

"You are invaluable, Mr. Buckingham," said Mrs. Dale, "and are as gallant as if you had as many wives as Blue Beard."

"Rather a scaly compliment, Buckingham," laughed his friend.

"She means well, but the fish are not far off," he answered, picking up Garfield, and giving his arm to quiet Miss Crew.

"What a moving sea of faces!" exclaimed Miss Crew.

"Yes, quite a few, and look as if they required laundrying—bodies, bones, and all."

"Here, Garfield, though you are 'very old' as you say, you had better take my hand," said Miss Crew, nervously, as Mr. Buckingham set him down on the wharf.

"Oh, no, he must go with his father," cried Mrs. Dale.

"Oh, I reckon a New York boy can elbow his way through that mean crowd." And darting through the mass of people, causing the collapse of not a few tournures, and with the aid of one of his mother's bonnet pins giving many a woman cause to scream as she unconsciously cleared his path by getting out of his way, he is on the outskirts of the crowd.

"Say, hackman, drive me off right smart to the Queen's!"

"Is it all square, young gent?"

"Yes; dimes sure as Vanderbilt money."

"Oh, I mean you are but a kid to go it alone."

"Chestnuts!"

And taking another hack, "Pooh, Bah!" quieting his scruples by pocketing a double insult they are off.

"I feel sure Garfield is quite safe, Ella, and probably choosing a cab for us; here, take my arm dear, and don't be nervous, Buckingham is looking after Miss Crew."

But he is on ahead making inquiries.

"Yes, sir, the young gent is all right, if you take my hack we'll catch him, I lost him by being too careful like."

"Your boy is all right, Mrs. Dale, if you jump in quick we'll overtake him; allow me, Miss Crew."

"Thank heaven," said his mother fervently, "tell the man to go as quick as he can through this crowd; there he is, the young scamp, waving to us, there, on ahead, a pair of light greys."

"And here we are, and your boy of the period waiting to welcome us."

"Welcome to the Queen City," he said, pulling off his skull cap.

"You frightened your mother, my boy; see that you don't repeat this; remember she is nervous."

"Glad I ain't a woman, they are all nerves and bustles; here, give us a kiss, mamma, I only wanted to show you I aint a baby."

"There! there! that will do, my bonnet! my bangs! such a bustle as I've been in about you, I wish you were in long clothes."

"Then I'd have to wear a bustle too!"

"Ella you look tired, we had best let them show us our rooms at once; Buckingham, we shall have some dinner together, I hope."

"Yes, I shall meet you here, and go in with you."

"This is pleasant, rooms en suite, and you beside us, Miss Crew," said Mrs. Dale.

And now, while they refresh themselves by bath and toilette, a word of them: Mr. Dale, like his friend Buckingham, has reached fifty, is grey, also wearing short side whiskers and moustache. He is a man of sterling worth of character, honest as the day; a man whose word was never doubted, who, having seen much of life, was apt to be a trifle cynical; but withal, so generous that his criticisms on men and things are more on the surface than even he imagines. A good friend, a kind husband to the pretty, penniless girl, Ella Swift, whom he had married in New York eleven years ago, and though unlike in character, there is so much love between them that their wedded happiness flows on with never a rift in the rill; and though she does not look into life and its many vexed questions with his depth of thought, still, in other ways her brain is quite as active—a kindly, social astronomer, she loves to unravel mysteries in the lives about her, to set love affairs going to her liking, she not caring to soar above the drawing-room, leaving Wall Street, the Corn Exchange, and railway stocks to her astute husband, who has inherited English gold, to which he is adding or losing in speculations the American eagle. With some thought of changing their residence to fair Toronto, they had a year ago given up house, and have been residing at the Hoffman House, New York City; then engaging Miss Crew, as governess to their only child of nine years. Mr. Dale had been somewhat doubtful as to the advisability of giving the position to Miss Crew, who merely answering their advertisement in the New York Herald, stating nervously that she was without references, as the people she had been with had gone West; but she was a fair, delicate, lady-like, religious girl, interesting Mrs. Dale at once by her loneliness and reticence; above all, Garfield took to her, and she gained an influence for good over him at once; and by this time both Mr. and Mrs. Dale have come to consider her as one of themselves, though having decided to place their son at boarding-school until such time as they take up house.

Mr. Buckingham is, as we know, an eligible bachelor, fine-looking, tall, as we have heard, and a man of many dollars; a calmly quiet man (a trait from his German mother), who has lost two fortunes, but who will not play for high stakes again, as he does not care to begin over again at fifty, with nearly all he craves in his grasp; two women jilted him when fortune frowned, but taking it coolly, he merely told himself it was the dollar they had cared for, not he. Passionately fond of music, a skilled performer, the piano has been mistress and wife to him; if he marries he will be a good husband, but if he does not, he will be almost as happy in the best musical circle wherever his home may be.

Having dined, our friends gathered for a few moments' social chat before retiring, when Mrs. Dale said, "I expect, Mr. Buckingham, you feel as important as one of Barnum's show-men in your role, for you are aware you and Mrs. Gower must trot us round to see the lions."

"Any man, Mrs. Dale, would feel important as your cicerone, and in company with Mrs. Gower."

"How polite you are. Oh, Henry, I see by the News, "Fantasma" is on at the Grand Opera House; even if it is late, let us go."

"Nonsense, dear, we have seen it often enough."

"If you are tired, very well; but I wanted to make a spectacle of myself this time, and the ladies green with envy over my new heliotrope satin."

"Well, if that isn't self-abnegation," laughed Buckingham.

"Oh, you needn't sympathize, I only feel as the peacock when he spreads his tail."

"How many churches did Mrs. Gower say there are here?" asked Miss Crew.

"One hundred and twenty; so you will have a choice of roads heavenward, Miss Crew," answered Buckingham.

"Yes, there are a number of roads, and only one guide-book," she answered, thoughtfully.

"Mrs. Gower will put you on the right track," he said quietly.

Here Mr. Dale returned, saying in pleased tones, "Well, Ella, I have telephoned Mrs. Gower of our arrival, and she says she will call at 11 a.m., then do the Exhibition, where we are to remain until we see Pekin bombarded."

"That is in the evening, and the best part of it this perfect weather; may I come?" said Buckingham.

"Assuredly."

"Thanks, and au revoir."

"Good night."

"Nothing is more deeply punished than the neglect of the affinities by which alone society should be formed and the insane levity of choosing our associates by other's eyes," read a lady, musingly, as Emerson's essays fall from her knees to the soft carpet under her cushioned feet.

"Yes, nothing is more deeply punished," she half chanted in a musical voice, while a grave, troubled look came to the dark eyes, and a quiver of pain to the sensitive lips. "And well do you and I know it, Tyr, though you are only a dog," she continued, as she patted a brown retriever beside her. "Yes, you and I, Tyr, like only affinities; the others seem to us mongrels, and to us don't seem good. I wonder if they were so pronounced in the first week when the world was young; but fancy is travelling without reason; they were all thorough-breds in the good old days, and one does not read of anything like Emerson's words on affinities, or a case similar to my own; but I am half asleep, Tyr; watch by me, good old dog."

And leaning her head back against the soft green velvet cushioned back of the rattan chair, Somnus is not wooed in vain; indeed, one might imagine the god of slumber had wound a garland of poppies about her brow, so does she sleep as an infant.

As she rests, a word of her. A Canadian; a native of Toronto, with far-away English kin; above the medium height; dark, comely, and slightly embonpoint; a woman of thirty, but with that troubled look at present on her face looking older; generous, warm-hearted and conscientious; with more than the average force of character; too sensitive in days past; too impulsive, even yet, in this world of "they daily mistake my words." Even at thirty, she has had years of trouble; has been dragged in the dust under Fortune's wheel, that others might ride aloft at her expense; earning her "dinner of herbs" that "Pooh Bah" in the plural, may have the "stalled ox." But at last she rests, and summer friends would again know her, who fled at her first out-at-elbow gown; but experience is a good teacher, she will cherish only those who have cherished her in her dark days. Society also now desires her company in polite bids to its various webs, in shape of dinners and lunches, with its other numerous distractions, knowing she is in possession of a rather pretentious little home, and is in a position to repay; for society is a debit and credit system.

"Once a widow always a widow" was not the motto of Mrs. Gower, and so she would have again wed, again gone to God's altar; but the angel of death forbade, using his scythe almost as the words of the church pronounced them man and wife, and the bridal gown of the morning gave place ere the sun had set to the black robes of a second widowhood. Truly, "Sorrow there seemeth more of thee than we can bear and live;" yet still we live, was her cry. The death of her friend, just at the time manly counsel would have saved her little fortune from vultures, habited as Christian pew-holders! was very hard, not to speak of that intense loneliness, the death of husband, wife, or betrothed, brings into one's life; one is as though struck mentally and physically blind, not knowing where to turn or whose hand to take; for until such relations are severed by death, one does not realize how one has leaned on the one in the multitude.

"But," she would say, "one must harden oneself to the inevitable, to Heaven's will, if one would keep one's reason;" and in time the sudden death of the man she had so passionately loved, was as some terrible dream. Not as she dreams away the moments now in her pretty restful library, with its rattan furniture, cushioned and trimmed in olive-green velvet; one side a library of her pet authors, with Davenport near; walls painted in alternate green and cream panels; on the light ground are lilies from nature, gathered from Ashbridge's Bay, and near the Island; nestling in their bed of green leaves an English ivy trails around the pretty Queen Anne mantel, with two tall palms, which bring content to the canary as the perfume from the blossoms on the stand give pleasure to the sleeping mistress of Holmnest.

Her own individuality is stamped upon its walls also, for on each alternate dark green panel is some pretty bits of painting, bric-a-brac, or motto; one reads, "Let ilka ane gang their ain gait," showing her dislike to meddling in another's business; another reads, "The greatest of these is charity;" and over a bust of Shakspeare are his own words, "No profit goes where is no pleasure taken; in brief, sir, study what you most affect."

But she dreams, and what a troubled expression. At this moment a coupé drives up a north-west avenue of our city, stops at the gate of Holmnest, when a gentleman, hurriedly springing out, saying, "come back for me in about an hour-and-a-half, Somers," enters the picturesque grounds, has reached the veranda and hall door on south side of pretty Holmnest, rings, when a boy, in neat blue suit, answers.

"Is Mrs. Gower at home, Thomas?"

"Yes, sir; in the library."

"Very well, you need not announce me, I know the way;" and hastening his steps he passes through a square hall, done in the warm tints now in vogue, sunbeams coming softened through artistic panes of stained glass, showing vases on brackets filled with flowers, which would delight "Bel Thistlethwaite," with a few appropriate pictures, giving life to the walls; the door of the library is ajar; he enters.

"Asleep!" he exclaims, softly; "with Emerson's thoughts for dreams and Tyr as watch; but what a troubled expression," he thinks, seating himself, evidently quite at home; a man, too, one would like to be at home with, if there be any truth in physiognomy, a handsome man, five feet eleven in height, dark hair and moustache, kindly blue eyes, amiability stamped on his face; a man who, had events shaped themselves that way, would have made an heroic self-sacrificing soldier of the Cross.

He is scarcely seated when the occupant awakes with a start and a terrified exclamation of "Oh!" at which the dog places his fore-paws on her knees, with a whine of sympathy, as her friend, Mr. Cole, comes forward with outstretched hand.

"When did you arrive; is it so late; you received my message to dine with the Dales and Smyths with me this evening? but I am half dreaming yet; of course you did, for you answered 'Yes.' Getting yourself in trim for leap-year, I suppose," she said, smiling; "but how is it you are in your office coat? I want you to look your very best, as you are to take in a young lady, a Miss Crew, who comes with the Dales; she is a super-excellent sort of girl."

"Has she money?" he says, laughingly.

"Oh, you need not pretend to be a fortune-hunter to me; I know you too well for that; but remember, I prophesy you will lose your heart to her. But, oh, Charlie, I have had such a horrible dream," and she presses one hand to her forehead, at which the lace rufflings fall back from her sleeve, showing a very good arm, her gown of ecru soft summer bunting, becoming her style, "that dream will haunt me unless you let me tell it you, Charlie."

"Oh, that's the use you put me to, is it? all right, fire away, I'll interpret; it was only a mistake the baptizing me Charlie, when I have to play the part of Joseph."

"Well, in the first part, oh Joseph, I had been reading this morning what held my mind as to the ascent from Paris of the æronauts, Mallet and Jovis; their courage, and Mother Shipton's prophecy impressed me sufficiently as to dream, with the words of Emerson as to affinities also in my mind, that a party of us—you, the Dales, Mrs. St. Clair, Miss Hall, Mr. Buckingham, and myself, with a gentleman who was masked—had been taking part in an entertainment in the Pavilion, Horticultural Gardens, in aid of the Hospital for sick children; we gave readings, vocal and instrumental music, and laughed inwardly and glowed outwardly, as we everyone, regardless of merit, received repeated recalls, when afterwards the recalcitrant balloon, which refused to inflate, when we gazed in vain at the fair grounds, did ascend after our performance, which fact emptied the Pavilion ere we had concluded our last effort, everyone flying, as we do at Toronto, as though there was a drop curtain with the words in flaming colors, 'The de'il take the hind-most;' the building was empty as our last supreme effort frightened the few dead-heads who had slunk in; we then laughingly made a rush to the balloon ascension, and determined there and then to further distinguish ourselves by becoming æronauts pro tem. What made it ridiculously droll, Joseph, was the fact that the men in charge chanted continuously Emerson's words that had impressed me ere I slept—'Nothing is more deeply punished than the neglect of the affinities.' I was nearest the basket, and wild with reckless spirit. As I remember, myself stepped in; the owners seemed at variance who was to pose or rise," she said, smilingly, "as my affinity, that is of yourself, Messrs. Dale, Buckingham, or the man with the mask, when, finally, they signed to the latter to enter; I was nothing loth, for his voice, a sweet tenor, had charmed me; up we went, when to my horror your béte noir, Mr. Cobbe, sprang from among the branches of a tall tree into the basket.

"'Too much ballast,' he cried, throwing out all the owners had provided us with; we ascended rapidly—a feeling of faintness seizing me—up, up; I feel the sensation now," she said with a tremor; "up, up, nearing the feathery clouds, looking like down from the wings of angels. 'Too much ballast,' he again cried, excitedly springing on the masked man, first tearing off his mask, disclosing the essentially manly face of a gentleman whom I frequently meet, but am not acquainted with, but in whom I take an interest, because of his tender care of a little lady I used to see with him; Mr. Cobbe springing on him with the words, 'too much ballast; down with affinities!' hurled the poor fellow to earth, at which I cried out as you heard; his fall was a something too awfully real; one's nerves for the time suffer as severely as though all was reality," she added in a pre-occupied tone, as though mind was burdened with latent thought.

"But 'all's well that ends well;' Mr. Cobbe is in mid air, where I fervently hope he will remain."

"But you forget the poor man who was hurled to the earth; I know his face so well."

"And I know yours, Mrs. Gower, and you are safe and so am I; and as Joseph, I interpret that you are to give your charming self to an affinity, and don't fly too high."

"The first part of your speech is epicurean, in your second you play the mentor," she said, laughingly; "but in your face I see you have something to tell me; go now to the telephone and tell them to send you your dress coat, for you have no time to go all the way to the Walker House and be back by seven."

"No use; I cannot stay for dinner."

"Cannot stay! Why?"

"My father writes me he is going to sail for England at once, and wishes me to meet him at London."

"Well, you ought not to look so grave over such a meditated trip, Charlie, it will make a new man of you; and instead of betaking yourself to the Preston baths, a sea voyage, I should say, will set you up, making you forget the word rheumatism better than any sulphur bath in all Canada."

"But," he said, in serio-comic tones, "what do you think of my being forced into annexation?"

"Only that you use the word 'forced,' I should say I congratulate you."

"At the same time that you keep your own freedom, though," he said, despondently; seeing her look of gravity, he continued, touching her hand, "beg pardon, Elaine, I should not say that, knowing your past; but," he said brightly, "I should like to see you wed an affinity."

"I am afraid such pleasant fate is not for me," she said, gravely.

"Do you believe in predestination, Mrs. Gower?" he says, abruptly.

"What next! from annexation to dogma. Tell me all about yourself, and it is too lovely an Indian summer day to remain in the house, come to my favorite seat in the garden."

"Where I shall give you an instantaneous photograph, from my father's pen, of the girl I am predestined to change the name of."

"From your father's pen!"

As they near a knoll under a clump of trees commanding a view of the road, a gentleman sauntering up the street gazes, as many do, at Holmnest with its pretty grounds.

"Look, quick, Charlie," said Mrs. Gower, in low and rapid tones, apparently intent on spreading a rug on the rustic bench, "there he is, I mean——"

"Well, I only see a very ordinary and thoroughly independent looking man, seeming as though he feared nothing, not even you, and as if Toronto was built for him."

At this Mrs. Gower, laughing merrily, says, "And not for the Lieutenant-Governor, Mayor Howland, Archbishop Lynch, or the 'caller herrin'-man.'"

As the soft laughter fell on the air, the stranger looked towards them, and looked so intently, that involuntarily his hand is raised to his head and his hat lifted.

"You say you have not met him, Mrs. Gower; you are a very prudent woman, I must say, coming out here in your white gown, with ribbons the color of a peach, creating a sensation; you had better wed an affinity since you won't have me, and get a protector at once."

"That is the man I dreamed of whom the æronauts dubbed my affinity; it's too bad we are not acquainted, instead of only getting instantaneous photographs of each other."

"What a trial!" he said, ironically; "but still," he added, as with a sudden remembrance, "I have, strange to say, had occasion to say, hang the conventionalities, more than once, with reference to a fair-haired girl with blue eyes, that seem, when I think of her, to follow me; no later, too, than this morning at W. A. Murray's door, as you I have had only instantaneous photographs of her; once before at a window in New York city, also there in a suspension car; it is not that I have fallen in love with her—not by a long chalk, but she seems to have been in my life some time, that by a trick of memory I have lost; but I advise you, Mrs. Gower, not to allow that man to bow to you again."

"Oh, he only lifted his hat in apology; but I wish you were not going away, and that I could see this girl."

"I wish I hadn't to; but this is the way time flies whenever I come to Holmnest; I am forgetting that I came to tell you I am just now the foot-ball of circumstance, which compels me to cross seas to have a halter put around my neck in wedding a girl whom I have never seen."

"Even if you have to, Charlie, you may love her at first sight, so don't take it to heart; if it is so that she is no affinity, you will suffer only as many others," she says gravely, "in having a taste of the tantalus punishment, in losing what we would fain grasp; but tell me all about it, as my dinner guests will be soon arriving, and I did so want you for—myself, as well as for Miss Crew."

"That's the first sympathetic word you have said, 'for yourself,'" he said, touching her hand, "but I am to be always for somebody else," he said, a little sadly; "but I see you think I am never going to begin, so here goes: My father, as you have heard me say, did not marry a second time, not that he did not again fall a victim to the tender passion, but that the miscreator, circumstance, putting in an oar, sent him out of England, when his bride-elect that was to be, was coerced into marrying her guardian (one Edward Villiers, of Bayswater, London,) by his sister-in-law, a domestic tyrant, and his housekeeper; who, knowing to rid himself of her presence he would probably wed a woman of as strong a will as her own, when she, penniless, would be thrust out, told lies, not white ones, of my father, that he had married in Canada, intercepting his letters, and heaven knows what; at all events, Lucifer's agent triumphed, for on my father going across the water to claim her and scold her for her silence, he found her a wife with a baby girl, when, to reduce a three-volume story to a line, they, in despair, wept and raved, nearly heart broken, vowing that I and the little one should wed and inherit all the yellow sovereigns; and so, Elaine, it comes to pass in years of evolution this youngster has become of age, and I am presented with her as my bride. I have always known of this contract, but you know the kind of man I am, ever shoving the unpleasant into a corner; for the bare idea of marrying a woman for money has always been repugnant to me."

"I should say it has, for with you it has ever been 'more blessed to give than to receive.'"

"I don't know that, but to hasten, breathing time is at last not given me, I am summoned to England by those people and by my father's wish, who sends me a copy of the will of the late Mrs. Villiers, a clause of which I shall read to you; but what a bore I am to you."

"Nonsense; who have I poured my life puzzles into the ear of but your own kind self—turn about is fair play, and besides, yours is a sensational life story, and so more interesting than thoughts from the clever pens of Haggard or Mannville, Fenn, or our own Watson Griffin."

"Well, the will reads ... 'on my dearly loved daughter, my little (Pearl) Margaret Villiers attaining her majority and becoming the wife of the aforesaid Charles Babbington-Cole, son of my loved friend Hugh Babbington-Cole, of Civil Service, Ottawa, Canada, my said daughter shall enter into possession of all my real and personal property, she to be sole executrix, and to inherit all, (with, I hope, the advice of Dr. Annesley, of London, and Hugh Babbington-Cole aforesaid,) and subject to the following bequests: To my step-daughter, Margaret Elizabeth Villiers, I leave my forgiveness for her unvarying unkindness to myself with my copy of the Christian Martyrs. To my dear friend, Sarah Kane, five hundred pounds sterling and my wearing apparel. To my husband's sister-in-law, Elizabeth Stone, I will and bequeath my piano and music for use in her mission work, with the hope that sweet notes of music will make her less acid to the children of God's poor to whom she brings the Gospel message of peace, etc., etc.'"

"So! your late mother-in-law made a point there, the self-righteous woman weighted religion then as now. I have always predicted, because of your open palm, that you would never be a rich man, Charlie; I little thought the precious metal with a wife would pour into your lap at the same time; if you only knew her and cared for her," she said, musingly, when, noting his troubled look, she said brightly, picking a beautifully tinted maple leaf from his shoulder, "See here, old man, take this crimson-hued leaf as a good omen, and we will read from it that your home-bound path, I mean back to Holmnest and Toronto, will be a path of crimson roses; and now tell me, does the girl write you, and is it in a stand and deliver manner? If so, I fear my verdict upon her will be lacking in charity."

"No, my pater has letters from her which he does not forward; but here is the last one from my father, in which he says: ... 'I have received several letters from Broadlawns, Bayswater, England, and from Margaret also, in which they tell me time's up, your bride elect is of age, and naturally anxious to come into possession of her property. I need not go over the whole matter again with you, my boy, but I do most earnestly advise you to start at once, the daughter of my lost Margaret must be good and true, even though Villiers was her father; she should be pretty, also fair hair and sky-blue eyes (in woman's parlance). I saw her when her poor mother made her will in 1872. Pearl was then about five years old; she cannot fail to be attracted by yourself, if Dickson does not flatter you, and I don't think so; your good looks are honestly come by, so you needn't blush.

"'And now to business; enclosed you will find a cheque for five hundred dollars, for you are like me more than in appearance, you don't save. What an income you will have shortly, instead of bookkeeping on the paltry salary of $800 per annum, you and Mrs. Cole, ahem! will roll about King Street the envy of the town, with an income of £5,000 sterling per annum. While I shall have the pleasure of seeing some of your mechanical ideas patented, and their models in the buildings here, your nose and the grindstone will part company; how glad I am that you have not fallen in love and married; and now I ask you, believing it to be best, believing it to be for your happiness, to leave for the seaboard on receipt of this; my chief has given me a three weeks' leave, so shall run across, but to save time, as I have business at Quebec, shall sail from there; meet me at Morley's, London, Trafalgar Square. If my memory plays me no trick, I shall sail by the Circassian, Sept. 16th, you take the City of Chicago, one day later from New York.

"'And now, pour le present, farewell; you don't know how I have set my heart on this matter, if I were ill, the knowledge that the little daughter of my own love was your wife would cure me.

"'Social events are right down smart with us; in fact Ottawa is booming. Rumor says our next tid-bit will be an elopement in high life; even the soldiers can't keep the enemy from poaching; but we must be blind and deaf 'till Grundy says now.'

"'The American consul is a very knight of labor at present, minus their short hours, as quite a large number are leaving for, to them, the land of promise, the United States, whether they fly from the taxes or the cold, I have not interviewed them; by the way, you will be the better for a warm heart beating against your own this winter. And now one word of self, I shall be glad of the run across the water, for I feel anything but smart. I wish we could have crossed together. Farewell, my boy, till we meet at Morley's.

"How strange it all seems, Charlie," she said dreamily. "I shall miss you so much, I do hope she is amiable and lovable, you and she must come to me until you get settled; poor fellow, you look stunned."

"I am paralyzed! it at last is so sudden, but why do you smile?"

"At a remark you made at the Smyth's, or I rather think it was when escorting me home, that 'you deserved a good wife, for you had never sinned, never told a lie.' So let us hope in your case virtue will have a reward."

"See! I must go, your guests are arriving; how I wish you had no one this evening, and I might dine with you alone."

"My wish too, on this your last visit, unfettered."

"That means you cannot bolster me up in this case, as you have more than once heretofore; that I am in for it," he says, looking at her sorrowfully.

"Yes, you are regularly hemmed in, and as I have been before now, so are you at present the mere foot-ball of circumstances, but 'out of every evil comes some good,' they say, and as your father says," she added with forced gaiety, for she is sad at the thought of snapping of old ties. "You will be the better of a warm heart beside your own in our winter climate; and above all, remember the good omen of this maple leaf; here, take it with you," she says, pinning it to his coat, the suspicion of a tear in her eyes.

"Good bye, Elaine, if it must be so; pray that I may come out of it all right, for I feel horribly depressed; and only you say I must go, would, I believe, show the white feather; I wish I might kiss you good-bye; there is that fellow, Cobbe, coming in, remember, that 'nothing is more deeply punished than the neglect of the affinities.' God bless you; farewell."

And leaving by a side gate and entering a passing hack, one of the kindest-hearted sons of fair Toronto takes his first step to another land; easily led, yielding to a degree, he is now led by the wish of a dead woman, by the iron will of a living one, his father following their beckoning hand also.

In animated converse with her guests during the half-hour ere dinner is announced, the mistress of Holmnest makes a picture one's eyes dwell on—the folds of her soft summer gown hang gracefully, while fitting her figure like the glove of a Frenchwoman; fond of a new sensation—as is the way of mortals—this of playing the hostess to a few chosen friends in a home of her own once more, is pleasurable excitement; there is a softness of expression, a tenderness in the dark eyes, engendered by the fact of her sympathy having been acted upon by the leave-taking, on such an errand too, of her friend Cole, which lends to her an additional charm. The consciousness also that she is looking well, gives, as is natural to most women, a pleasurable feeling in whatever is on the tapis, with the knowledge also, that her little dinner will be perfect, her guests harmonious—save one.

"So you think Toronto is rather a fair matron after all, Mrs. Dale, and that your New York robes blend harmoniously with the other effects at the Queens?"

"I reckon I do, Mrs. Gower; you did not say a word too much in her praise; I remember saying to Henry before we started, my last season's gowns would do."

"And you like Toronto also, Mr. Dale," continued his hostess.

"Yes, better than any other Canadian town I have visited; it is very simply laid out, one couldn't lose oneself if one tried."

"It is laid out like a what do you call it, like a chess-board," said Captain Tremaine, an Irishman.

"Yes, not unlike," continued Dale, "and as to quiet, one would think the curfew rang; I noticed it particularly coming from the Reform Club the other night."

"We all notice how quiet our streets are at night, and after your London and New York City, we must seem to you as if we had taken a sedative," said Mrs. Gower, taking his arm to the dining-room; "but where is Miss Crew, Mr. Dale?"

"She was too fatigued to come, she foolishly overtaxed her strength, taking my boy to the Industrial Home, at Mimico, I think she said."

"That's correct, it's a pet scheme of Mayor Howland's, and a worthy one too."

"Yes, so she said; they also visited your Normal School, and talked of the Cyclorama of Sedan."

"Indeed! they have overtaxed the brain and memory, I fear; what does Garfield say to it all?"

"Chatters like a magpie over the superior glories of New York, but is honestly pleased after all."

"I expect your little son is English only in name."

"Yes, and in his love for a good dinner," he said, laughingly.

"Well, from all we Canadians hear, there is every reason he should, an English dinner is enough 'to tempt even ghosts to pass the Styx for more substantial feasts,'" she said, gaily.

"Mrs. Gower is always up to the latest in remembering the tastes of her guests," said Mrs. Dale to her left-hand neighbor, Mr. Buckingham, as tiny crescents of melon preceded the soup.

"That she is," he said, complacently; "no man would sigh for his club dinner, did our hostess cater for him."

"Goodness knows what Henry would do if our bank stopped payment, or our Pittsburg foundries shut down; for I know no more about cooking than Jay Gould's baby," she said, discussing a plate of delicious oyster soup.

"He, I expect, makes himself heard on the feeding bottle," said lively Mrs. Smyth.

"But you are unusually candid as to your short-comings, Mrs. Dale," continued Buckingham, amusedly.

"Because I can afford to be; were I poor, I reckon I should pawn off my mamma's tea-cakes on my young man as my own, as men in love believe anything—they are as dull as Broadway without millinery."

"By the way, Mrs. Dale, talking of millinery, where are your bonnets going to, they are three stories and a mansard at present?"

"Oh, only a cupola, Mr. Buckingham, on which birds will perch."

"How so; I was under the impression the bird hunt is a thing of the past?"

"No, indeed! not while there are men in the field."

"How so; I do not follow you?"

"Stupid, you are born huntsmen, our bonnets are a perch for a decoy, and," she added, looking at him archly, "our faces are under them."

Here there was merry laughter from Mrs. Gower and Captain Tremaine, the former saying gaily,

"You would not accomplish it, the strength of will of one of the party would keep the whole uppermost. I appeal to Mr. Smyth."

"I am with you, Mrs. Gower; Tremaine must go under, even though he is an Irishman."

"Irish questions always do get muddled, eh, Smyth?" said Dale, jokingly, seeing that Smyth, intent on dinner, had not heard the argument.

"That they do, Dale. Which is it, Mrs. Gower, the Coercion Bill or Home Rule?"

"Neither," she said, laughingly, "we were on the 'Peace Party' (you remember the meeting at the Gardens, on last Sunday); and I have been suggesting that the Body Guard bury their pretty uniforms, and Captain Tremaine raises the war-cry of, 'bury the Peace Party, chairman and all, first.'"

"Oh, that's it! Tremaine knows the indomitable will of one of them would cause more dust to be kicked up than one sees on a March day on Yonge Street."

"Out-voted, Captain Tremaine, we weep 'salt tears' over your becoming uniform; but seriously speaking, though a High Court of Arbitration would be a grand spectacle, it will be only after years of evolution, and when, as Mr. Blake, the chairman said, 'the voice of the private soldier, instead of the general officer, is heard.'"

"If I should ever have the ill-fortune to be drafted," said Smyth, laughingly, "I should fight to the death against my enrolment; an hospital nurse, like the Quaker-love, would suit me better; such rations as a man gets on the field."

"I know for a fact," said Dale; "that recruiting during the present year in England, has been far below the average of the last few years."

"Indeed! I was not aware," said Buckingham.

"By the way, Smyth," said Tremaine, "have you seen, what do you call him, 'Henry Thompson,' in his defence or answer to his critics?"

"I have, and he was able for them every time."

"Are you speaking of the journalist who went to jail in the interests of the Globe?" asked Dale.

"Yes."

"His defence was capital, I thought," said Dale, "and I especially liked the way he stands up for his craft. 'There is no class of men,' he says bravely, 'in existence, animated by more humane motives than working newspaper men.'"

"I also read his reply with pleasure," said Mrs. Gower, "and reading it, thought what a clever and original fellow he must be."

"Talmage and Silcox have been lauding the power of the press to the skies," said Smyth; "they made me wish I surveyed the earth from an editor's chair, rather than from a tree I climbed to escape York mud."

"Have you heard how the Grand is going to cater to our dramatic taste this coming season, Mr. Buckingham?" asked Mrs. Gower.

"Just a whisper, Mrs. Gower, as to Emma Juch, Langtry and Siddons."

"Yes; so far so good. Have you heard that the rail makes no special rates for travelling companies?"

"I have; so you may expect that those who will pay the high toll, will be those of the highest standard."

"Then I suppose (though it seems selfish) we should be content with the rail rates as they are."

"You will enjoy the debates, Dale," said Smyth, "in the Local House during the session; Meredith is just the man to lead our party."

"But I am not sure that it is our party, Smyth; I scarcely know how I should vote here; if Meredith is right, why doesn't he prove to Ontario that Mowat has held the reins too long?"

"So he will before next election," replied Smyth, with a satisfied air.

"Don't be too sure, Mr. Smyth, eloquent though he be," said his hostess; "while that clever Demosthenes of his party, Hon. C. F. Frazer, says him nay."

"Do you meditate a long stay, Buckingham, in this the white-washed city of the Dominion?" asked Tremaine.

"Yes, off and on all winter; you know I intend to purchase some of your mineral lands, since you allow them to lie undeveloped," he added, jestingly.

"You see, Capt. Tremaine," said Mrs. Gower, merrily, "the American Eagle done in silver is not as yet plenty with us."

"Don't despair, Tremaine, Commercial Union is looming up," said Buckingham.

"Treason! treason!" laughed Tremaine, "for we know what it would father."

"Hear, hear," cried Smyth.

"Oh, I don't know," laughed Mrs. Gower, "they say it is the Main-e idea for settling; here's a pretty mess! here's a pretty mess—of fish!"

"We can wait," said Buckingham, quietly, "evolution will bring about the Maine idea, with you also."

"Did you say you are going to Maine, Mr. Buckingham, we cannot do without you now," said pretty Mrs. St. Clair, caressingly.

"Thank you, Mrs. St. Clair, I do not go; but even if so, you would, I fear, miss me less than your latest fad in the pet quadruped."

"How severe you are, Mr. Buckingham. Are all New York men so, Mrs. Dale?" She sighed, having a penchant for him.

"It's annexation, Mrs. St. Clair," said Mrs. Dale, mischievously.

"Annexation! is Mr. Buckingham going to be married?"

"I believe so." At this juncture Master Noah St. Clair, who had come instead of his father, was interested in other than his plate, while his mother said reproachfully:

"It cannot be true, Mr. Buckingham."

"Mrs. Dale is disposed to be facetious, Mrs. St. Clair; you must not swear by everything she says."

"That is an evasive answer, and I am dying to know; tell me, dear Mrs. Dale, what it means?"

"Which, annexation, or Mr. Buckingham?" said her tormentor.

"Oh, both, of course," she said, breathlessly.

"Both; well, when I come to take a good look at him, Mrs. St. Clair, he looks important rather than severe, his reason is, he believes, the best part of Canada pines for annexation; comprenez vous?"

"Oh, is that what you meant," she replied, with a relieved air, when, catching her son's eye, she said, with assumed carelessness, "I do miss my men friends so much when they marry."

"He is as cold as ice," whispered Mr. Cobbe, who, though a man of birth and breeding, prides himself upon being a flirt; "he is an icicle, I wonder you waste your warmth upon him."

"Nice man," she thought, "and only the second time I've met him; he must be in love with me, too, poor fellow," and, in an undertone, she says, "That's the way all you men speak of each other, but he is only so before people."

"You had better throw him over, an Irish heart is warmer than an American," he said, in his deep tones, into her ear.

"But the poor fellow would break his heart," she whispered, her cheeks flushing; he, equally vain, continued:

"Not he, a successful speculation would console him; and I—and I would console you."

"Are you always so susceptible?" she asked, turning her pretty enamelled face around to be admired.

"No, indeed; but a man doesn't meet as pretty a woman as you every day, as your mirror must tell you."

"How you gentlemen flatter," well aware that he is admiring her pretty hand and delicate wrist, as she holds aloft a bunch of transparent grapes.

"Not you," and for the moment he meant it; the particular she of the hour feasting on the nectar her soul loves, never dreaming that the next passable looking female in propinquity with him will be also steeped to the lips in the same food, "not you," he said, with a fond look.

"Thank you," she said, prettily, and with the faith of her early teens, "I must tell you a pretty compliment a gentleman paid me at the 'Kirmiss' last season, he said 'I was a madrigal in Dresden china.'"

"Too cold, too cold," he said, thickly, managing to press her fingers as they rose from the table, ere she laid her hand on the arm of Mr. Smyth, to whom she had been allotted, but who never spoiled his dinner by giving beauty her natural food.

On Mr. Dale declining to linger, leading his hostess back to her pretty drawing-room, she said in his ear:

"You have dubbed me queen of Holmnest, therefore must obey when I bid you back to the dining-room for a smoke."

"What a lovely little home you have, Mrs. Gower," said her friend, Mrs. Smyth, seating herself near her hostess, the pale blue plush of the padded chair contrasting well with her fair hair, pink cheeks and pretty grey eyes.

"That chair becomes you at all events, dear," said her hostess, seeing that a maid deftly passed coffee bright as decanted wine, afterwards small bouquets of beautiful pansies and clematis among her guests, from huge glass and Japanese bowls.

"I could scarcely believe Will, when he wrote me of your good fortune, you know, the children and I were at Muskoka."

"Yes, I knew you would be glad. I bought this pretty little place the week you left, it seemed after years of waiting, my money (what is left of it) all came right in a day; you do not know how glad I am to at last see you in a home of my own—and in a chair pretty enough to become you, dear," she added more brightly.

"Oh, you always make the most of small kindnesses shown you, we were only too glad to have you."

"Be that as it may, I shall always remember the bright hours with yourselves in the dark days of my life," she said, warmly.

"When did you see Charlie?" asked Mrs. Smyth, in an undertone, for there are other ears.

"This afternoon."

"This afternoon!"

"Yes; and you will be surprised to learn he takes the rail for the seaboard to-night."

"To-night! Why, and whither, it must be a sudden move, for he was up for a smoke with Will the other night and said nothing of it; but," she added, laughingly, "he prefers a lady confidant when it's Mrs. Gower.

"Don't you think, Lilian, that the opposite sex is usually chosen to lend an ear?" she said, carelessly, to conceal a feeling of sadness at the out-going of her friend; for she is aware that the old friendly intercourse is broken, now that he has gone to his wedding.

"He has gone to be married; I suppose, he said something to us a long time ago about it, but he told it in a clouded kind of way; I wish he had confided in me, for Will would not care a fig, but every woman doesn't draw such a prize as I. Perhaps when you get number two he will not allow the opposite sex to confide; but talking of the green-eyed monster, reminds me of two scandals on our street." As she now raised her voice, the other ladies pricked up their ears. Mrs. Dale exclaiming:

"Scandals! sounds like Bertha Clay's novels. May poor Mrs. Tremaine and self come in. We have been on sermons, servants, and the latest infants; a scandal will be as refreshing as Mrs. Gower's coffee."

"I guarantee you an appreciative audience, Mrs. Smyth," laughed her hostess, "curtain rises over 'another mud-hole for us to play in.'"

"What a case you are, Mrs. Gower, but I must cut them short, for I would not for worlds Will and the other gentlemen come in while they are on."

"No fear of scandals in your home, Mrs. Smyth," said Mrs. Tremaine, "with Will always first."

"That's so; well, to begin, before I went to Muskoka, a lady and daughter came to reside near us. As they went to our church, Will said call; I did. Since my return, I heard from Mr. Cobbe," here turning suddenly to Mrs. St. Clair, to whom Mrs. Gower had overlooked introducing her, said: "I beg pardon, I should not name names." Continuing, "Mr. Cobbe told me the young lady had been married, and divorced. Some young fellow, in a good position down East, hearing she had some ready cash, wed and deserted her at close of honeymoon. Well, the other evening she was married again! at the house quite privately, and to whom do you think? to none other than, as the newspapers state, Norman Ferguson MacIntyre!"

"To Norman MacIntyre! oh, what a pity," cried Mrs. Tremaine, in dismay, "his mother and sisters are such pleasant people, and had very different hopes for him; it is simply dreadful."

"But he can throw her overboard, I am sure," cried Mrs. Dale. "If he only have his wits about him, the first marriage likely took place in Canada, the divorce across the line, don't you see; she is the precious prize of the gay deceiver, your friend is free."

"But, even if this be so, Mrs. Dale," said Mrs. Smyth, excitedly, "no girl will care to marry poor Norman afterwards."

"I am willing to stake our Pittsburg foundry on his chances," said Mrs. Dale, cooly.

"And I, Holmnest," echoed Mrs. Gower, "poor Norman has but to stand in the market-place."

"I think they have both lowered their social standing; don't you, Mrs. Tremaine?" said Mrs. Smyth.

"I do, indeed."

"It altogether depends upon their bank account," said their hostess, sententiously; "and now for your next, for your mouth is still full of news, dear."

"Oh, yes; but my next is a bona fide married couple."

"But are they according to the Church Prayer Book?" said Mrs. Dale, with her innocent air.

"Oh, yes, certainly; and some say she is like a china doll, and the husband, a great big, ugly, black-looking tyrant; but the gentlemen are coming, and I must cut it short, and only say that a man handsome as Lucifer."

"Before the fall, I suppose," said her hostess.

"Yes, yes, you naughty woman. Well, they say this handsome fellow is there whenever the husband is out, and a pock-marked red-headed boy (some say their son) is there to watch the pretty wife, and their name is St. Clair." Sensation!

At this moment a pin is ran into the arm of the breathless narrator.

"Oh, mercy!" she cried, looking around discovering the boy Noah St. Clair, whom every one had forgotten seated on a footstool behind her, who said vengefully, indicating by a gesture Mrs. St. Clair and himself, "That's our name; it's us."

"Gracious, Mrs. Gower, what have I done? Pardon me, I was under the impression that this lady's name was Cobbe. I don't know how I got things muddled; I thought she was some relative of our Mr. Cobbe."

"Never mind, dear; I should have introduced you; don't apologize; there are other St. Clairs in Toronto than my friends."

"I don't mind it in the least," purred the pretty doll; "some one is always talking about me. Women are jealous of my complexion and all my admirers; but I think my name is prettier than Cobbe."

"Yet 'tell my name again to me,' am always here at beauty's call," said Mr. Cobbe, hearing his name on entering with the other gentlemen.

"You, as a Bona Dea, have been our toast, Mrs. Gower," said Buckingham, quietly, as he sank into a chair near her own.

"And my inclinations, I hope," she said, laughingly, "with no saving clause as to their being virtuous."

"I appeal to your memory of the 'Antiquary,' Mrs. Gower; could any man living toast you as the Rev. Mr. Battergowl did Miss Grisel Monkbarns?"

"I don't know; perhaps some would desire to make a proviso."

"Then they would err; I should give a woman of your stamp any length of line."

"Thank you; your confidence would not be misplaced, when in honor bound I have ever felt as though I did not belong to myself."

"I should judge so; underlying your gaiety conscientiousness holds you to an extent few would dream of; you have frequently sacrificed yourself to a mistaken sense of duty. Am I not right?"

"Yes; I have been a slave to what I used to think the voice of conscience, but which I am now sure was extreme sensitiveness, and a sort of moral cowardice; but how strange you should read me so truly."

"Not at all, I am a phrenologist; if you will allow me the very great privilege, I shall read your character to you in some quiet hour."

"With very great pleasure. And now will you do me another favor? Make my piano sing and speak to us."

"Thank you; I should like to try your instrument. It is from Mason & Risch, I see."

Having arranged a table at whist and euchre, Mrs. Gower seated herself to enjoy the entrancing music, while looking over some photographs to amuse the boy Noah St. Clair, but it was not to be, for the voice of Mr. Cobbe said in her ear:

"This won't do; you must come to the library with me; I have not had a single word with you all evening, and am, as you are aware, an uninvited guest."

"Why invite you, Philip? Alas! there is invariably discord with your presence," she says sadly, in the lowest of tones, moving away from the curious gaze of the boy.

"Sit here, Elaine, if you positively refuse to leave the room with me," he said excitedly, indicating a tête-à-tête sofa not within ear-shot of her guests, managing to detain her until, the hours creeping on apace, freighted with the music of soft laughter, and ravishing songs without words by the skilled performer, Mr. Buckingham, when pretty Mrs. Dale's sweet voice is heard, as she rises from the table, saying triumphantly:

"Win! of course we won. Why, Mr. Dale will tell you, Mr. Smyth, that in our card circle at New York, mine is dubbed 'the winning hand.'"

"Indeed! no wonder at our good fortune. Congratulate us, Mrs. Gower; we won three straight games, all by reason of the admirable forethought of my partner," cried Smyth, exultantly.

"Forethought always comes in a head's length, Mr. Smyth. Now, if you could only gain a pocket edition of the winning hand, your surveys would yield you a gold mine," said his hostess, gaily.

"Instead of as now, a few promissory notes," laughed Smyth.

"The gentlemen have been envying you your monopoly of Mrs. Gower, Mr. Cobbe," said lively Mrs. Smyth, in an undertone; "she is an awful flirt, you had better take care of yourself," she added, mischievously.

"I mean to," he said savagely, and with latent meaning, adding, "she is as fickle as her clime; I hope," he said, endeavoring to control himself, "all you ladies are not so heartless."

"Oh, no; we are as constant as the sun, compared to her," she said, half jokingly.

"Would you be so to me," he said thickly, and coming near her.

"Go away, Mr. Cobbe; don't look at me like that, you awful man," she whispered, laughingly.

"When may I call, you are the right sort of woman," he continued, persistently.

"Will says so, any way," she said, archly.

"Say to-morrow," he persisted.

"Will!" she cried, mischievously, "Mr. Cobbe's compliments, and desires to know when he will find you in your sanctum, he wishes to smoke the pipe of peace with you."

"Hang it," thought Cobbe, "she has no ambition beyond Will; give me the Australian women after all."

"Almost any evening, Cobbe, I am always good for a smoke; but my wife says I'd better retrench, the house of Smyth is increasing so rapidly; good-night."

"May I see you home, Mrs. St. Clair?" asked Mr. Cobbe, fervidly.

"It would be too sweet—but oh!" and her arm above the elbow is rubbed, for the boy Noah has pinched her severely, saying,

"I'll tell papa."

At this juncture Thomas appeared, saying, a coupé had arrived for Mrs. St. Clair and Master Noah.

"I must see you to-morrow, Mrs. Gower, after office hours," said Cobbe, adding, on meeting the sharp eye of Mrs. Dale, "I have something very particular to tell you."

"Say the day after, Mr. Cobbe, please; I shall endeavor to restrain my curiosity so long, even though I am a woman."

"No, no, I must see you to-morrow at five p.m.," he said, impulsively.

"The yeas have it this time, Mr. Cobbe. Mrs. Gower belongs to us for to-morrow," said Mrs. Dale, drawing her wrap about her, over her cream-silk robe, slashed with blue velvet, and laced amid innumerable buttonholes, her innocent look only apparent while, in reality, she is dissecting him, "our kind hostess does some of the lions with us to-morrow afternoon; the evening, she spends with us at the Queen's."

"Yes, we have no end of a bill for to-morrow," said Mr. Dale; "the Normal School, Mount Pleasant Cemetery, office of the Mail, and the University of Toronto."

At this there was a transformation scene, the face of Mr. Cobbe changing like a flash from inane sulkiness to jubilant triumph.

"To the University! then Mrs. Gower will tell you what a paradise we enjoyed, when I alone was her companion there," he said, with excitement; and having previously made his adieu, he departed, chuckling inwardly at his parting shot, and thinking for once she is nonplussed. "She is too high-spirited to sleep comfortably to-night, if so, she'll dream of me in spite of herself."

"What a funny man!" exclaimed Mrs. Dale, "reminds me of a Jack on wires. If I were in your place, Mrs. Gower, I'd hand him over to his mother to bring up over again; till to-morrow, farewell."

"Au revoir, dear."

"Good night, Mrs. Gower," said Buckingham, with a firm hand-clasp; "your evenings leave one nothing to wish for, save for their continuance."

"If your words have life, prove them by coming again; good night."

Broadlawns, on the outskirts of Bayswater, London, England, on the evening Charles Babbington-Cole, from Toronto, Canada, is expected, is all aglow with lights; its exterior a goodly spectacle with its many windows. A long, low, rambling house, the front relieved by cornice and architrave, and an immense portico from which white stone steps, wide and worn by many feet, lead to the lawns and gardens, which are gay with bright flowers, intersected with old-fashioned serpentine walks; one would call it not inaptly a garden of roses, such were their number, such their variety and beauty. Great masses of rhododendrons, with the fragrant honeysuckle, sweet-briar, and lauristina lent perfume to the air. Some fine oaks, with beech and graceful locusts, gave beauty to the lawns; stone stables, with farm and carriage houses at the back, with paved court-yard, and kitchen-garden luxuriant in growth, a very horn of plenty.

"A lovely spot, an ideal home," said numerous passers-by to and from the modern Babylon. Alas! that the interior should be a very inferno; in the library are assembled the family, for a family talk.

Miss Villiers, to whom did we not give precedence, would trample on some one to gain first place. Timothy Stone, her maternal uncle, and Elizabeth Stone, his sister and Aunt to Miss Villiers; the latter by sheer strength of will, since her babyhood, has ruled at Broadlawns, even though, owing to disastrous speculation, the whole family were penniless, save for the large fortune of her step-mother, Miss Villiers lived for, moved and had her being for kingdom. Intensely selfish, and totally devoid of feeling, an apt pupil of her aunt and uncle, she regards all sentiment, romance or disinterested acts of kindness as mawkish, unpractical foolishness.

A word of her looks. In height, five feet two, round shoulders slightly high, thin spare figure, a brunette in coloring; stony eyes of piercing blackness, always cold and searching as though planted closely in the forehead to read one through, as to whether any of her dark secrets have been discovered; a hook nose, thin, determined lips; hair black as the wing of a raven; the back of her head covered with short, snake-like curls, the front was drawn back in straight bands, thus giving prominence to features already too unclassically so.

As far as a man can be said to resemble a woman, so did, in looks and character, Timothy Stone his niece, save that his once coal-black hair is now white; his fishy eyes sunken, though keen as a razor; in height, five feet ten; of spare, alert figure, active as a prize racer, knowing as the jockey who rides him.

Elizabeth Stone is an older counter-part of her niece, save that she wears that fashionable mantle of to-day—the cloak of religion, in which, unlike her brother, she is so comfortable as never to allow it to fall from her angular shoulders.

The library, an old-fashioned, cold looking room, furnished in black oak, everything being in spotless order, from books biblical and secular, to Aunt Elizabeth's hands, folded just so on her stiff gown of black silk, as to cause one to long for déshabillé somewhere other than in the principles of those present.

"The only one whom we have to fear is Sarah Kane, and you, Margaret, will keep her about the place in spite of all I can say," said her uncle, in crabbed tones; "mark my words, you are housing a rod for your own back by your abominable self-will."

"I am no fool; did I dismiss her I should convert her into a deadly enemy at once; but, as I have before had occasion to remark, Uncle Timothy, that, thanks to your tuition and blood, I am quite able to take care of myself, and minus your interference."

"Don't squabble with her, Timothy, when the man Providence is sending her as a husband may be in our midst at any moment; as you heard at the hotel, he is now in the city."

"Oh bosh, Elizabeth, keep that tone under your church hymnal, as I do; between ourselves it is slightly out of place," and he smiled sarcastically.

"No, Timothy, in spite of the sinful example you set me, I shall keep my lamp trimmed and burning; providence is very good to us in laying low of fever, at Montreal, Hugh Babbington-Cole, thus giving him time to repent, as also preventing his presence at the wedding of Margaret."

"At which you have been making mountains of mole hills," said her brother, grimly. "Babbington-Cole could not possibly remember what Margaret and Pearl looked like in eighteen-seventy."

"Your memory is as usual convenient, Timothy, relentless time would have shown him the difference in years, of a girl just of age, and a woman of thirty-nine."

"Enough, Aunt Elizabeth," interrupted her niece, pale with rage, "I simply won't allow you to allude to the subject of ages; if I am to play the role of twenty-one, the sooner I get into the part the better for us all; we all serve our own ends in this game, self-interest is, and ever has been, our strongest motive. For myself, I hate Pearl Villiers as I hated my step-mother before her, and I shall not willingly leave Broadlawns merely because we have no income to keep it up, when, by personating my step-sister—fortunately of my own Christian, as well as surname, thanks to the British habit of perpetuating family names—I gain the wherewithal to either remain in this peaceful English home," she said, ironically, "or roam across seas with the husband or crank I am about to wed—a crank! to revolve the wheels of fortune, while I leave you both here like a pair of cooing doves. You, Aunt Elizabeth, gain your revenge on Mr. Babbington-Cole for his preference for my step-mother to yourself; oh, you needn't wince, my ears have been put to their proper use. You, Uncle, were spurned by my angel step-mother, you, pining not for her, but her yellow sovereigns, so...."

"You are a witch, Margaret; how the d——l did you find it out?"

"Timothy, Timothy, be good enough not to swear in my presence."

"Oh, I have gleaned the truth in various devious paths from Sarah Kane in a weak mood, also letters, and I have not lost my sense of hearing; as you have told me since I could lisp that my wits are sharper than Rodgers' cutlery; yes, if Broadlawns went to its owner or the hammer, you joined the Salvation Army, and my step-sister dangled the purse, I feel it in my bones that I could now rival my tutors in living by my wits," she said, cruelly.

"You are not devoid of common sense, Margaret; and as we may not have another opportunity before your importunate suitor appears, I shall refresh your memory by reading again a clause or two of your late step-mother's will ... 'to my husband, Henry Villiers, I bequeath the life use of one thousand pounds sterling per annum; at his death I will and bequeath the whole of my real and personal property to my only daughter (Pearl) Margaret Villiers ... on my little (Pearl) Margaret Villiers attaining her majority, and becoming the wife of the aforesaid Charles Babbington-Cole, son of my friend, Hugh Babbington-Cole, of the Civil Service, Ottawa, Canada; my said daughter shall enter into possession of all my real and personal property, with the advice of Dr. Annesley, of London, England, or Hugh Babbington-Cole, Esquire, aforesaid, my said daughter to inherit all, subject to the following gifts. To Sarah Kane, five hundred pounds sterling and my wearing apparel; my piano, harp and music, I will and bequeath to the sister-in-law of my husband, Elizabeth Stone, for her mission-work, with the hope that their sweet notes will make her less acid to my poor little daughter, as also to the daughters of the poor to whom she brings the Gospel message of peace. To my step-daughter, Margaret Villiers, I leave my forgiveness for her persistent and unvarying unkindness to myself, with my copy of the Christian Martyrs.'"

"Fool!" muttered her step-daughter, vengefully.

"Poor, carnal creature, we are now ordained to be almoners of the gold she would have spent sinfully on her daughter; we are saving Pearl from the perils of the rich, for easier is it for a camel to go through the——"

"Enough of that cant, Aunt; please keep it bottled up, it don't go down with us," interrupted her niece, hastily.

"The will is plain enough, considering that it was written by herself, and witnessed by Dr. Annesley, and that sneak, Silas Jones; how much the latter knows is hard to tell, I have pumped him indirectly without avail; Annesley, being a busy London physician, will not bother himself in the matter now that Villiers is dead; he has no more love for us than we for him; our card is to expedite your union with speed and privacy; you will most likely go to Canada, as I expect Charles (as we best accustom ourselves to call him) will prefer such arrangement; I shall pay you regularly——"